User login

Trustworthy Recommendations: A Closer Look Inside the AGA’s Clinical Guideline Development Process

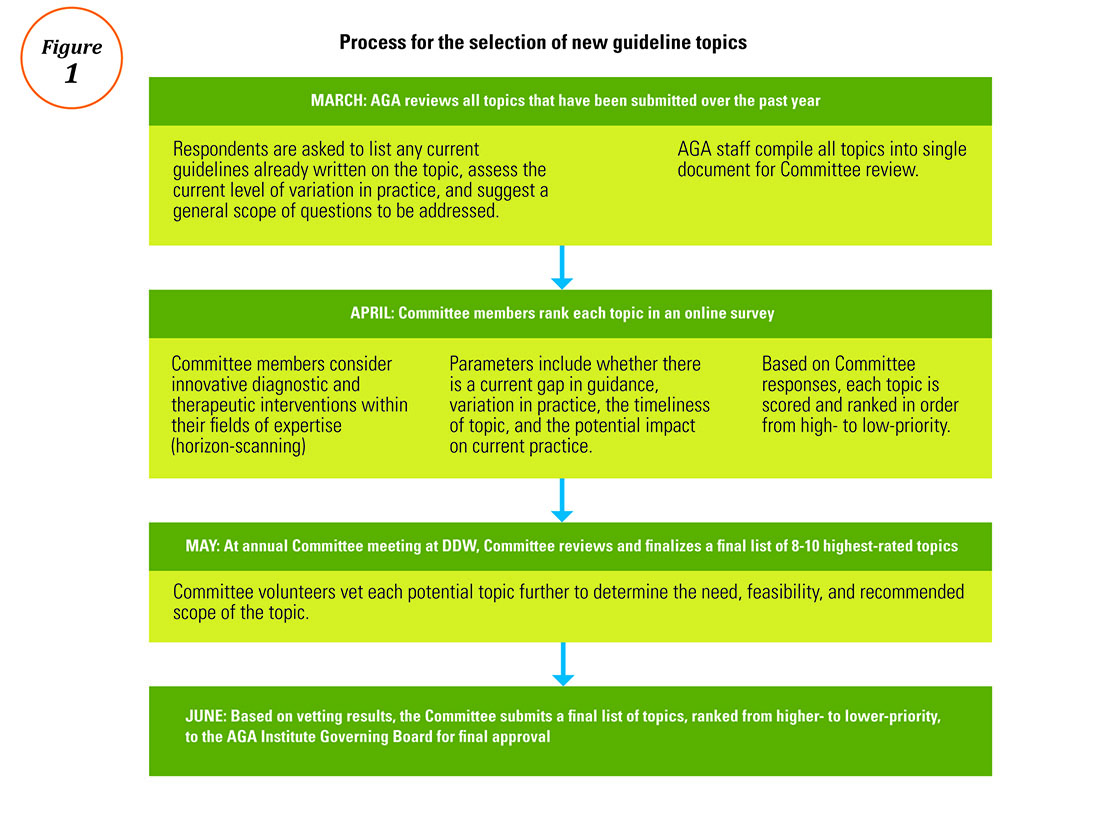

The AGA understands how important it is for busy physicians to have access to the most trustworthy, actionable, and evidence-based guidelines in order to achieve the highest possible quality of patient care. According to a 2016 survey, AGA members ranked guidelines as the most important of all AGA-specific benefits, giving guidelines an average of 4.61 out of 5 (where 5 was defined as “extremely important”). The AGA’s guidelines landing page (www.gastro.org/guidelines) has long been the most frequently accessed page on the AGA website.

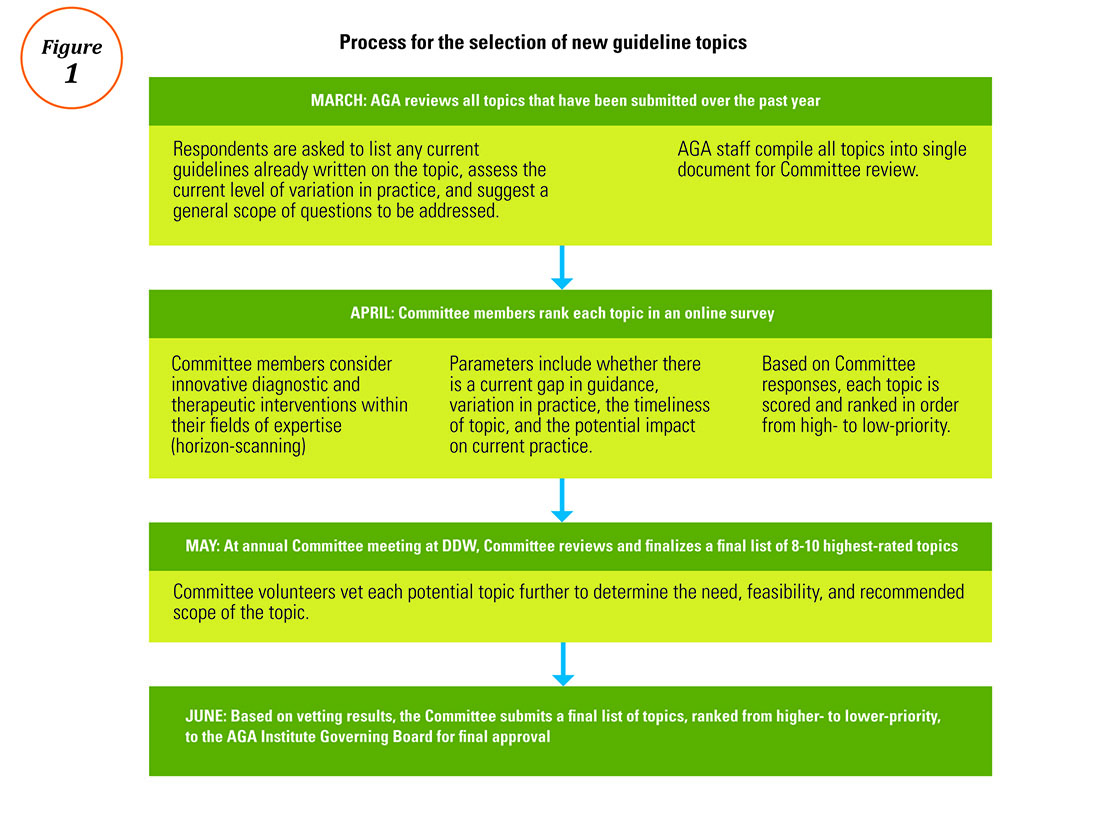

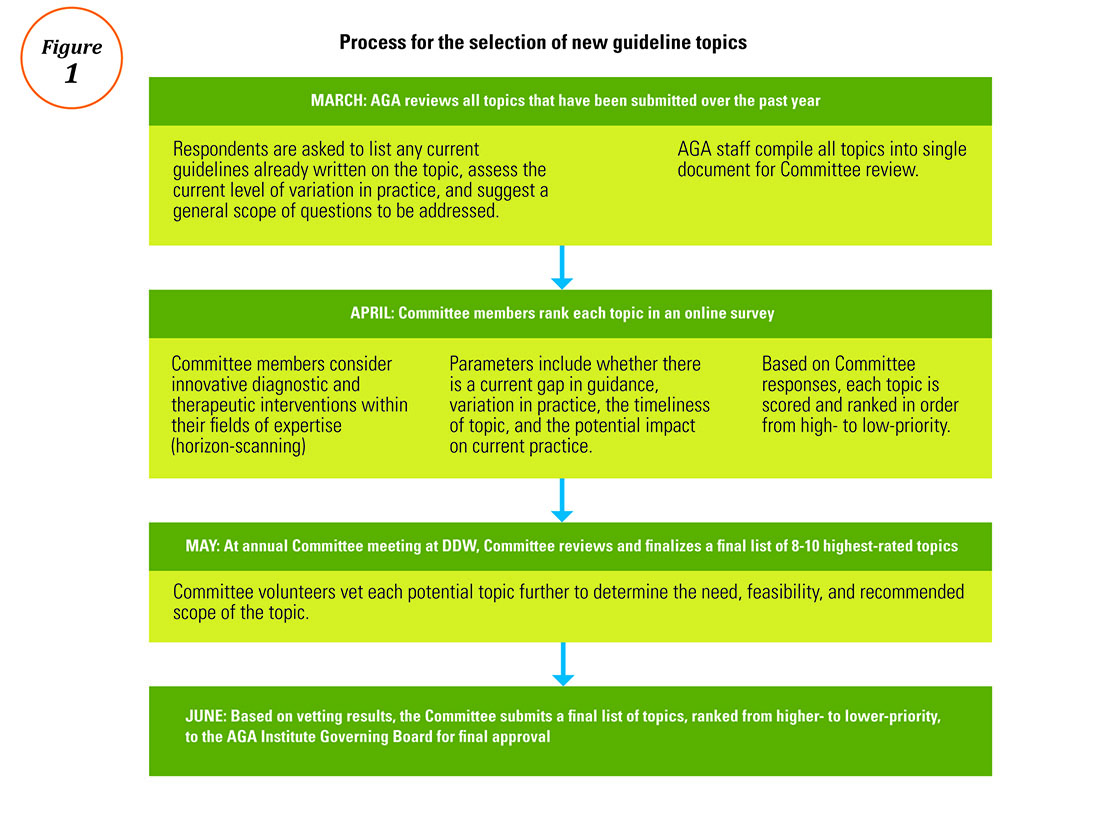

The life cycle of an AGA guideline

In 2010, the AGA Institute officially adopted the GRADE (Grades of Recommendation Assessment, Development, and Evaluation) methodology for the development of all future guidelines. Since the publication of our first GRADE-based guideline in 2013, the AGA has developed and published 12 guidelines with an additional 11 more to be published by 2019. Based on the systematic rigor of the GRADE approach, the AGA’s guideline development process was created to result in clinical recommendations that are not only evidence based but actionable and responsive to varying patient needs and preferences at the point of care.

All told, a single AGA guideline costs around $45,000 and takes approximately 24 months to complete and publish. Currently, the AGA is working to pilot new methods of shortening the time to publication through the development of rapid reviews within a focused topic (e.g., opioid-induced constipation).1 The development of each guideline requires a team of one or more specially trained GRADE methodologists, two or more content experts, a medical librarian, a panel of three or more guideline authors, two AGA staff members, and the Clinical Guidelines Committee Chair.

Determining the focused questions. First, the entire team of physician-authors determines a list of focused questions that the guideline will address. This list of focused questions is translated into a table of Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcomes (PICOs) that operationalize the general questions into search terms utilized by the medical librarian to run the systematic search as well as define the final scope of the guideline. The focused questions and related PICOs are sent to the Governing Board for review and approval.

Developing the technical review. Over the next several months, the methodologist and content experts meet on a weekly basis to review the search results question-by-question and develop the technical review of evidence that will form the basis of the clinical recommendations. For each PICO, the technical review assesses the entire body of evidence and rates the overall quality of evidence gathered for each outcome related to the PICOs (from “very low” to “low” to “moderate” to “high”).

Drafting the clinical recommendations. The technical review presents the findings of the literature along with the authors’ assessment of the evidence quality. At a face-to-face meeting, these results are presented by the technical review authors to the guideline panel, who are responsible for developing the official guideline document. The role of the guideline panel is to understand the quality of evidence and determine an ultimate list of clinical recommendations and assign a strength (strong or conditional) to each recommendation, all while considering important factors such as the balance between benefits and downsides, potential variability in patients’ values and preferences, and impact on resource utilization. Oftentimes, but not always, recommendations based on higher-quality evidence for which most patients would request the recommended course of action translate into strong recommendations. Recommendations based on lower-quality evidence and those for which there is a higher variability in patient values or issues surrounding resource utilization are more likely to be conditional.

In addition to the guideline document, the guideline panel also drafts a Clinical Decision Support Tool, which illustrates the clinical recommendations within a visual algorithm. At the same time, AGA staff draft a patient summary that explains the recommendations in plain language. This summary can be used by physicians to improve clinical communication and shared decision making with their patients.2

Revising the guideline. Each AGA technical review goes through two layers of review: once by an anonymous peer-review panel of three content experts, and again during a 30-day public comment period in which both the technical review and guideline are posted for public input. The authors take all input into consideration while finalizing the documents, which are sent to the Governing Board for final approval. Once approved by the Board, the technical review, guideline, and all related materials are submitted for publication in Gastroenterology. In addition to print publication, each guideline is disseminated on the AGA website and through the official Clinical Guidelines mobile app (available via the App Store and Google Play), which includes interactive versions of the Clinical Decision Support Tools and plain-language summaries that can be sent via e-mail to patients at the point of care. The AGA is currently pursuing future directions for the dissemination and implementation of our guidelines, such as the seamless integration of clinical recommendations into electronic health records to further improve decision making and facilitate quality measurement and improvement.

Conclusion

Not all clinical guidelines are created with equal rigor. Clinicians should examine guidelines closely and consider whether or not they follow the Institute of Medicine’s standards for trustworthy clinical guidelines: Is the focus on transparency? Is a rigorous conflict of interest system in place that eliminates major sources of financial and intellectual conflict? Was an unconflicted GRADE-trained methodologist involved in ensuring that a systematic review process is followed and the method of rating the quality of evidence and strength of recommendation follows published principles? Are the recommendations clear and actionable?3 AGA Institute guidelines are developed with the goal of striking a balance between presenting the highest ideals of evidence-based medicine while remaining responsive to the needs of everyday practitioners dealing with real patients in real clinical settings.

Ms. Siedler is the director of clinical practice at the AGA Institute national office in Bethesda, Md.; Dr. Falck-Ytter is a professor of medicine at Case-Western Reserve University, Cleveland, chair of the AGA Institute Clinical Guidelines Committee, and chief of the division of gastroenterology at the Louis Stokes VA Medical Center in Cleveland. The authors disclose no conflicts of interest.

References

1. Hanson B., Siedler M., Falck-Ytter Y., Sultan S. Introducing the rapid review: How the AGA is working to get trustworthy clinical guidelines to practitioners in less time. AGA Perspectives. 2017; in press.

2. Siedler M., Allen J., Falck-Ytter Y., Weinberg D. AGA clinical practice guidelines: Robust, evidence-based tools for guiding clinical care decisions. Gastroenterology. 2015;149:493-5.

3. Institute of Medicine: Standards for developing trustworthy clinical practice guidelines. Available at http://www.nationalacademies.org/hmd/Reports/2011/Clinical-Practice-Guidelines-We-Can-Trust/Standards.aspx. Last accessed May 2017.Process for the selection of new guideline topics

The AGA understands how important it is for busy physicians to have access to the most trustworthy, actionable, and evidence-based guidelines in order to achieve the highest possible quality of patient care. According to a 2016 survey, AGA members ranked guidelines as the most important of all AGA-specific benefits, giving guidelines an average of 4.61 out of 5 (where 5 was defined as “extremely important”). The AGA’s guidelines landing page (www.gastro.org/guidelines) has long been the most frequently accessed page on the AGA website.

The life cycle of an AGA guideline

In 2010, the AGA Institute officially adopted the GRADE (Grades of Recommendation Assessment, Development, and Evaluation) methodology for the development of all future guidelines. Since the publication of our first GRADE-based guideline in 2013, the AGA has developed and published 12 guidelines with an additional 11 more to be published by 2019. Based on the systematic rigor of the GRADE approach, the AGA’s guideline development process was created to result in clinical recommendations that are not only evidence based but actionable and responsive to varying patient needs and preferences at the point of care.

All told, a single AGA guideline costs around $45,000 and takes approximately 24 months to complete and publish. Currently, the AGA is working to pilot new methods of shortening the time to publication through the development of rapid reviews within a focused topic (e.g., opioid-induced constipation).1 The development of each guideline requires a team of one or more specially trained GRADE methodologists, two or more content experts, a medical librarian, a panel of three or more guideline authors, two AGA staff members, and the Clinical Guidelines Committee Chair.

Determining the focused questions. First, the entire team of physician-authors determines a list of focused questions that the guideline will address. This list of focused questions is translated into a table of Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcomes (PICOs) that operationalize the general questions into search terms utilized by the medical librarian to run the systematic search as well as define the final scope of the guideline. The focused questions and related PICOs are sent to the Governing Board for review and approval.

Developing the technical review. Over the next several months, the methodologist and content experts meet on a weekly basis to review the search results question-by-question and develop the technical review of evidence that will form the basis of the clinical recommendations. For each PICO, the technical review assesses the entire body of evidence and rates the overall quality of evidence gathered for each outcome related to the PICOs (from “very low” to “low” to “moderate” to “high”).

Drafting the clinical recommendations. The technical review presents the findings of the literature along with the authors’ assessment of the evidence quality. At a face-to-face meeting, these results are presented by the technical review authors to the guideline panel, who are responsible for developing the official guideline document. The role of the guideline panel is to understand the quality of evidence and determine an ultimate list of clinical recommendations and assign a strength (strong or conditional) to each recommendation, all while considering important factors such as the balance between benefits and downsides, potential variability in patients’ values and preferences, and impact on resource utilization. Oftentimes, but not always, recommendations based on higher-quality evidence for which most patients would request the recommended course of action translate into strong recommendations. Recommendations based on lower-quality evidence and those for which there is a higher variability in patient values or issues surrounding resource utilization are more likely to be conditional.

In addition to the guideline document, the guideline panel also drafts a Clinical Decision Support Tool, which illustrates the clinical recommendations within a visual algorithm. At the same time, AGA staff draft a patient summary that explains the recommendations in plain language. This summary can be used by physicians to improve clinical communication and shared decision making with their patients.2

Revising the guideline. Each AGA technical review goes through two layers of review: once by an anonymous peer-review panel of three content experts, and again during a 30-day public comment period in which both the technical review and guideline are posted for public input. The authors take all input into consideration while finalizing the documents, which are sent to the Governing Board for final approval. Once approved by the Board, the technical review, guideline, and all related materials are submitted for publication in Gastroenterology. In addition to print publication, each guideline is disseminated on the AGA website and through the official Clinical Guidelines mobile app (available via the App Store and Google Play), which includes interactive versions of the Clinical Decision Support Tools and plain-language summaries that can be sent via e-mail to patients at the point of care. The AGA is currently pursuing future directions for the dissemination and implementation of our guidelines, such as the seamless integration of clinical recommendations into electronic health records to further improve decision making and facilitate quality measurement and improvement.

Conclusion

Not all clinical guidelines are created with equal rigor. Clinicians should examine guidelines closely and consider whether or not they follow the Institute of Medicine’s standards for trustworthy clinical guidelines: Is the focus on transparency? Is a rigorous conflict of interest system in place that eliminates major sources of financial and intellectual conflict? Was an unconflicted GRADE-trained methodologist involved in ensuring that a systematic review process is followed and the method of rating the quality of evidence and strength of recommendation follows published principles? Are the recommendations clear and actionable?3 AGA Institute guidelines are developed with the goal of striking a balance between presenting the highest ideals of evidence-based medicine while remaining responsive to the needs of everyday practitioners dealing with real patients in real clinical settings.

Ms. Siedler is the director of clinical practice at the AGA Institute national office in Bethesda, Md.; Dr. Falck-Ytter is a professor of medicine at Case-Western Reserve University, Cleveland, chair of the AGA Institute Clinical Guidelines Committee, and chief of the division of gastroenterology at the Louis Stokes VA Medical Center in Cleveland. The authors disclose no conflicts of interest.

References

1. Hanson B., Siedler M., Falck-Ytter Y., Sultan S. Introducing the rapid review: How the AGA is working to get trustworthy clinical guidelines to practitioners in less time. AGA Perspectives. 2017; in press.

2. Siedler M., Allen J., Falck-Ytter Y., Weinberg D. AGA clinical practice guidelines: Robust, evidence-based tools for guiding clinical care decisions. Gastroenterology. 2015;149:493-5.

3. Institute of Medicine: Standards for developing trustworthy clinical practice guidelines. Available at http://www.nationalacademies.org/hmd/Reports/2011/Clinical-Practice-Guidelines-We-Can-Trust/Standards.aspx. Last accessed May 2017.Process for the selection of new guideline topics

The AGA understands how important it is for busy physicians to have access to the most trustworthy, actionable, and evidence-based guidelines in order to achieve the highest possible quality of patient care. According to a 2016 survey, AGA members ranked guidelines as the most important of all AGA-specific benefits, giving guidelines an average of 4.61 out of 5 (where 5 was defined as “extremely important”). The AGA’s guidelines landing page (www.gastro.org/guidelines) has long been the most frequently accessed page on the AGA website.

The life cycle of an AGA guideline

In 2010, the AGA Institute officially adopted the GRADE (Grades of Recommendation Assessment, Development, and Evaluation) methodology for the development of all future guidelines. Since the publication of our first GRADE-based guideline in 2013, the AGA has developed and published 12 guidelines with an additional 11 more to be published by 2019. Based on the systematic rigor of the GRADE approach, the AGA’s guideline development process was created to result in clinical recommendations that are not only evidence based but actionable and responsive to varying patient needs and preferences at the point of care.

All told, a single AGA guideline costs around $45,000 and takes approximately 24 months to complete and publish. Currently, the AGA is working to pilot new methods of shortening the time to publication through the development of rapid reviews within a focused topic (e.g., opioid-induced constipation).1 The development of each guideline requires a team of one or more specially trained GRADE methodologists, two or more content experts, a medical librarian, a panel of three or more guideline authors, two AGA staff members, and the Clinical Guidelines Committee Chair.

Determining the focused questions. First, the entire team of physician-authors determines a list of focused questions that the guideline will address. This list of focused questions is translated into a table of Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcomes (PICOs) that operationalize the general questions into search terms utilized by the medical librarian to run the systematic search as well as define the final scope of the guideline. The focused questions and related PICOs are sent to the Governing Board for review and approval.

Developing the technical review. Over the next several months, the methodologist and content experts meet on a weekly basis to review the search results question-by-question and develop the technical review of evidence that will form the basis of the clinical recommendations. For each PICO, the technical review assesses the entire body of evidence and rates the overall quality of evidence gathered for each outcome related to the PICOs (from “very low” to “low” to “moderate” to “high”).

Drafting the clinical recommendations. The technical review presents the findings of the literature along with the authors’ assessment of the evidence quality. At a face-to-face meeting, these results are presented by the technical review authors to the guideline panel, who are responsible for developing the official guideline document. The role of the guideline panel is to understand the quality of evidence and determine an ultimate list of clinical recommendations and assign a strength (strong or conditional) to each recommendation, all while considering important factors such as the balance between benefits and downsides, potential variability in patients’ values and preferences, and impact on resource utilization. Oftentimes, but not always, recommendations based on higher-quality evidence for which most patients would request the recommended course of action translate into strong recommendations. Recommendations based on lower-quality evidence and those for which there is a higher variability in patient values or issues surrounding resource utilization are more likely to be conditional.

In addition to the guideline document, the guideline panel also drafts a Clinical Decision Support Tool, which illustrates the clinical recommendations within a visual algorithm. At the same time, AGA staff draft a patient summary that explains the recommendations in plain language. This summary can be used by physicians to improve clinical communication and shared decision making with their patients.2

Revising the guideline. Each AGA technical review goes through two layers of review: once by an anonymous peer-review panel of three content experts, and again during a 30-day public comment period in which both the technical review and guideline are posted for public input. The authors take all input into consideration while finalizing the documents, which are sent to the Governing Board for final approval. Once approved by the Board, the technical review, guideline, and all related materials are submitted for publication in Gastroenterology. In addition to print publication, each guideline is disseminated on the AGA website and through the official Clinical Guidelines mobile app (available via the App Store and Google Play), which includes interactive versions of the Clinical Decision Support Tools and plain-language summaries that can be sent via e-mail to patients at the point of care. The AGA is currently pursuing future directions for the dissemination and implementation of our guidelines, such as the seamless integration of clinical recommendations into electronic health records to further improve decision making and facilitate quality measurement and improvement.

Conclusion

Not all clinical guidelines are created with equal rigor. Clinicians should examine guidelines closely and consider whether or not they follow the Institute of Medicine’s standards for trustworthy clinical guidelines: Is the focus on transparency? Is a rigorous conflict of interest system in place that eliminates major sources of financial and intellectual conflict? Was an unconflicted GRADE-trained methodologist involved in ensuring that a systematic review process is followed and the method of rating the quality of evidence and strength of recommendation follows published principles? Are the recommendations clear and actionable?3 AGA Institute guidelines are developed with the goal of striking a balance between presenting the highest ideals of evidence-based medicine while remaining responsive to the needs of everyday practitioners dealing with real patients in real clinical settings.

Ms. Siedler is the director of clinical practice at the AGA Institute national office in Bethesda, Md.; Dr. Falck-Ytter is a professor of medicine at Case-Western Reserve University, Cleveland, chair of the AGA Institute Clinical Guidelines Committee, and chief of the division of gastroenterology at the Louis Stokes VA Medical Center in Cleveland. The authors disclose no conflicts of interest.

References

1. Hanson B., Siedler M., Falck-Ytter Y., Sultan S. Introducing the rapid review: How the AGA is working to get trustworthy clinical guidelines to practitioners in less time. AGA Perspectives. 2017; in press.

2. Siedler M., Allen J., Falck-Ytter Y., Weinberg D. AGA clinical practice guidelines: Robust, evidence-based tools for guiding clinical care decisions. Gastroenterology. 2015;149:493-5.

3. Institute of Medicine: Standards for developing trustworthy clinical practice guidelines. Available at http://www.nationalacademies.org/hmd/Reports/2011/Clinical-Practice-Guidelines-We-Can-Trust/Standards.aspx. Last accessed May 2017.Process for the selection of new guideline topics

Advice on Choosing Your GI Career Path

Mariam Naveed, MD, opened a discussion in the Early Career Group forum in AGA Community that invited GIs to share how or when they knew which career path was the best fit. Among those sharing their stories were Peter Liang, MD, MPH; Avinash Ketwaroo, MD; Maisa Abdalla, MD, MPH; Tara Altepeter, MD; Elliot Tapper, MD; and Brijen Shah, MD. Their expertise spans across the GI spectrum, including academia, research, drug development, and regulatory science.

For Dr. Liang, the key to succeeding on the research path is to be passionate about your topic(s), enjoy reading and writing, and be able to accept constructive criticism and rejection. Dr. Altepeter encourages all GIs early in their career to be open to exploring a variety of career options, as regulatory science was not a career path she was aware of at the beginning of training.

The conversation continued when trainee and early career members brought their career-specific questions, including the possibility of achieving tenure without publishing.

View a summary of advice shared at http://community.gastro.org/calling. The discussions around finding your GI calling are in the AGA Community Early Career Group, at http://community.gastro.org/EarlyCareerGroup.

Mariam Naveed, MD, opened a discussion in the Early Career Group forum in AGA Community that invited GIs to share how or when they knew which career path was the best fit. Among those sharing their stories were Peter Liang, MD, MPH; Avinash Ketwaroo, MD; Maisa Abdalla, MD, MPH; Tara Altepeter, MD; Elliot Tapper, MD; and Brijen Shah, MD. Their expertise spans across the GI spectrum, including academia, research, drug development, and regulatory science.

For Dr. Liang, the key to succeeding on the research path is to be passionate about your topic(s), enjoy reading and writing, and be able to accept constructive criticism and rejection. Dr. Altepeter encourages all GIs early in their career to be open to exploring a variety of career options, as regulatory science was not a career path she was aware of at the beginning of training.

The conversation continued when trainee and early career members brought their career-specific questions, including the possibility of achieving tenure without publishing.

View a summary of advice shared at http://community.gastro.org/calling. The discussions around finding your GI calling are in the AGA Community Early Career Group, at http://community.gastro.org/EarlyCareerGroup.

Mariam Naveed, MD, opened a discussion in the Early Career Group forum in AGA Community that invited GIs to share how or when they knew which career path was the best fit. Among those sharing their stories were Peter Liang, MD, MPH; Avinash Ketwaroo, MD; Maisa Abdalla, MD, MPH; Tara Altepeter, MD; Elliot Tapper, MD; and Brijen Shah, MD. Their expertise spans across the GI spectrum, including academia, research, drug development, and regulatory science.

For Dr. Liang, the key to succeeding on the research path is to be passionate about your topic(s), enjoy reading and writing, and be able to accept constructive criticism and rejection. Dr. Altepeter encourages all GIs early in their career to be open to exploring a variety of career options, as regulatory science was not a career path she was aware of at the beginning of training.

The conversation continued when trainee and early career members brought their career-specific questions, including the possibility of achieving tenure without publishing.

View a summary of advice shared at http://community.gastro.org/calling. The discussions around finding your GI calling are in the AGA Community Early Career Group, at http://community.gastro.org/EarlyCareerGroup.

Be Kind to Yourself: Preventing Burnout in New GIs Through Self-Compassion

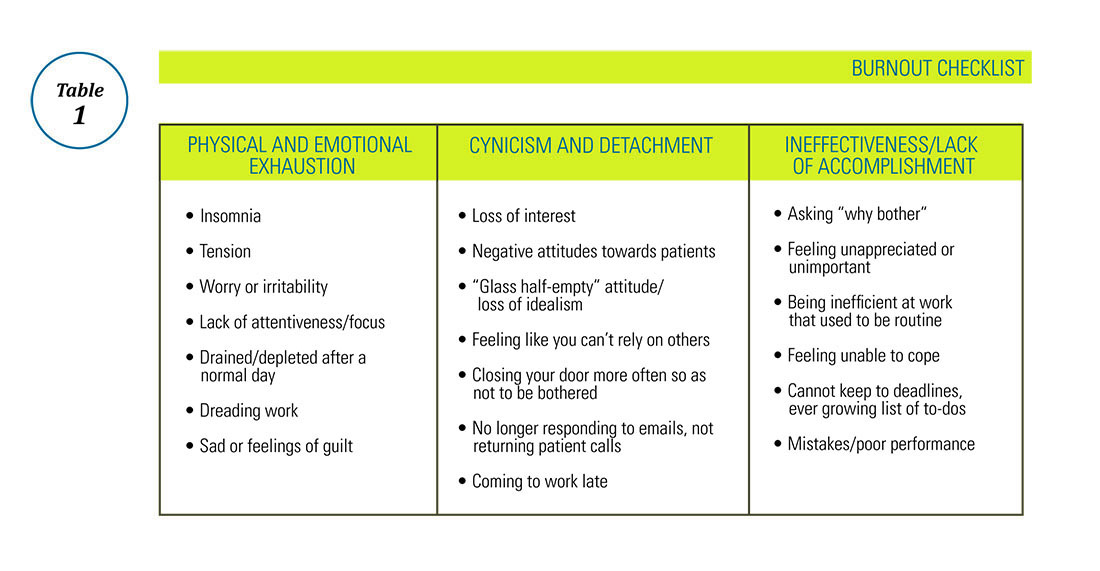

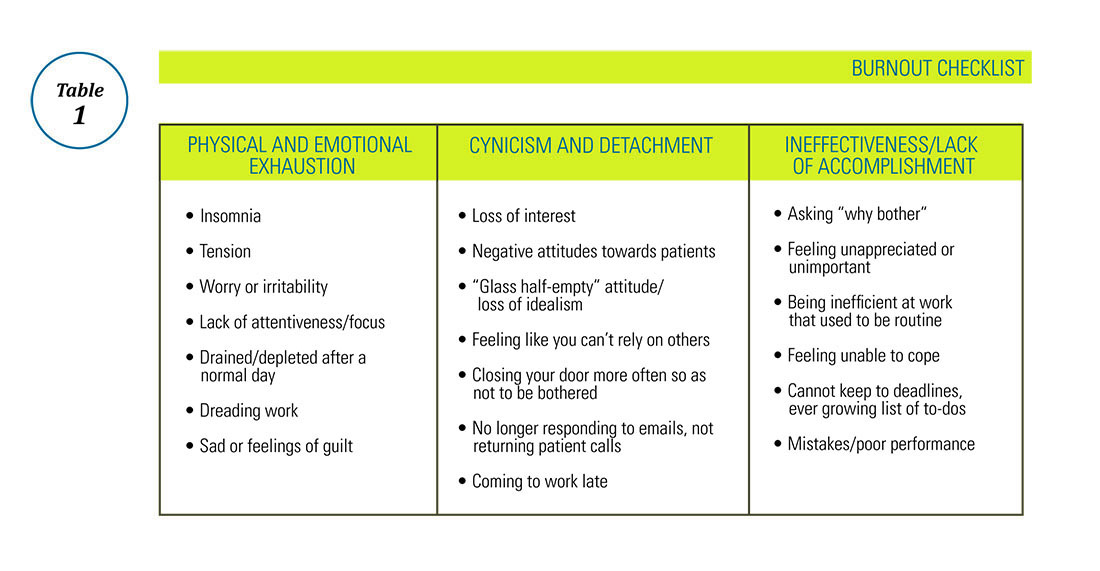

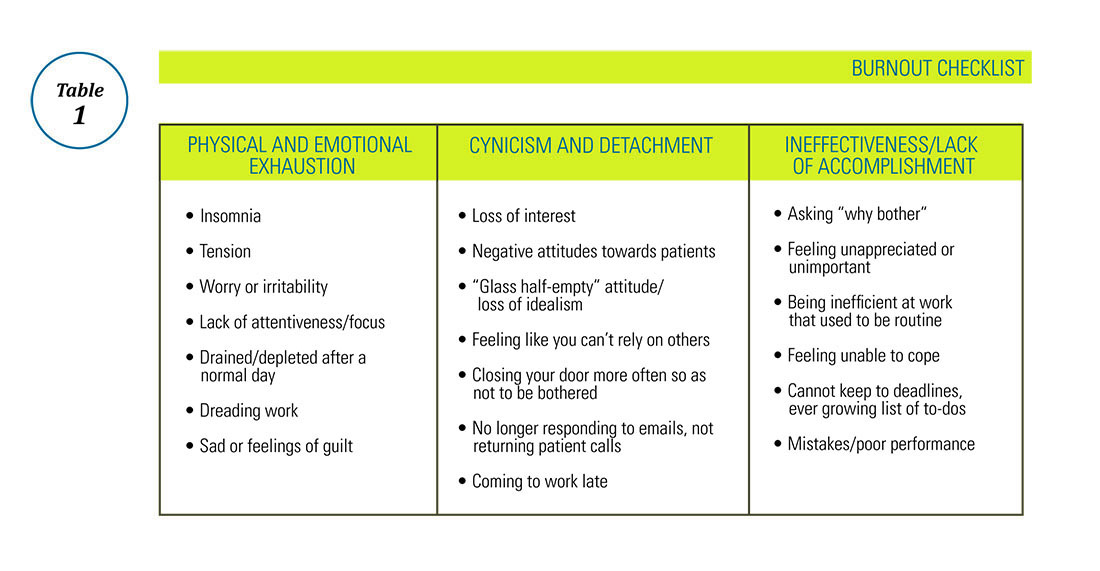

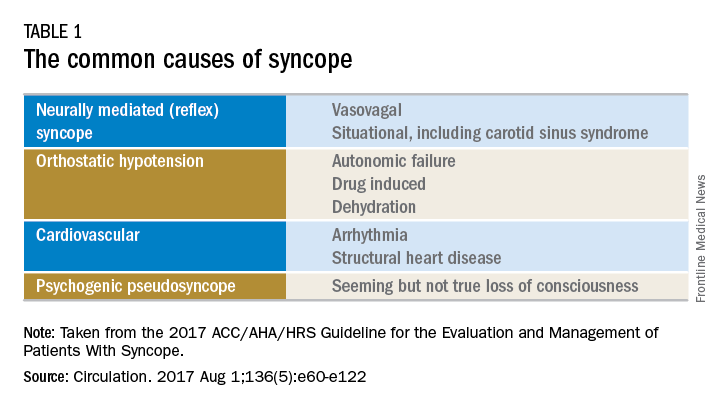

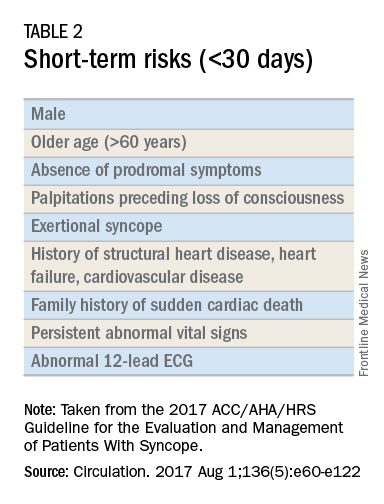

Physician burnout is a growing epidemic, particularly in the early careers of gastroenterologists. Up to 50% of new physicians and trainees experience burnout with the first 3 years of independent practice.1 The negative consequences of burnout are well known – medical errors, depression, substance abuse, and even suicide.2,3 To meet criteria for burnout syndrome (Table 1), one must have two of three core symptoms, often experienced as phases: 1) physical and emotional exhaustion; 2) cynicism and detachment; and 3) feelings of ineffectiveness and lack of accomplishment.4

Emotional exhaustion, one of the earliest symptoms of burnout syndrome was reported to be as high as 63% among gastroenterologists in a survey study I conducted with colleagues a few years ago.5 Similar findings are noted amongst colorectal surgeons.6 We also noted in our study that burnout levels were highest in junior versus senior attendings, with junior attendings reporting more stress related to performing endoscopies and making split-second decisions. Interventional endoscopists may have been disproportionately affected by the latter, reporting that they were more likely to think about possible mistakes they made after work, have difficulty sleeping due to thinking about their day, and have difficulty separating work and personal life.5 Male and female physicians may progress through the phases of burnout differently, with men being more likely to experience cynicism and depersonalization first, followed by fatigue. Men may also not necessarily experience the third phase of feeling ineffective, which can be particularly dangerous because they will continue to push until there is a serious consequence. Women tend to go through all three phases of burnout beginning with emotional exhaustion, with a more rapid progression through the cynicism phase, and may end up spending the majority of their time feeling ineffective and limited in their accomplishments, a recipe for leaving medicine entirely.7

Prevention of burnout through self-compassion

Even though it may sometimes be easy to forget, most of us chose medicine as our profession because of our inherent compassion towards others and desire to care for those in need. But have we properly learned how to apply that same compassion to ourselves?

Self-compassion is one of the primary qualities of a happy, flourishing, resilient individual.8 Self-compassion is a psychological skill that can be applied to feelings of inadequacy, failure, or lack of control and includes: 1) self-kindness, 2) belief in a common humanity, and 3) mindfulness.8

Are you self-compassionate? Take a quiz!

Self-kindness requires us to treat ourselves as kindly as we would a friend or patient in the same situation. We must consciously choose not to use harsh, self-critical language when we make mistakes. We are taught not to berate our trainees for mistakes in the clinical setting – we can be taught not to berate ourselves for shortcomings as well. Self-kindness also requires that we provide ourselves with sympathy when we experience disappointments through no fault of our own (e.g. despite all my best efforts, this clinical initiative failed) and give ourselves the opportunity to nurture and soothe ourselves when we experience pain.6 Belief in a common humanity fosters engagement with others, recognizing that nobody is perfect and that others suffer as well. Isolating ourselves because we feel ashamed, embarrassed, or “crazy” in our experience of a situation only increases our suffering. As we engage with others, we are able to view things from a different perspective and also recognize that others around us have problems too. Indeed, social support may be one of the best buffers against burnout, particularly cynicism.12 A recent meta-analysis concluded that a combination of institutional engagement techniques including reduced hours and support groups as well as access to individual behavioral techniques such as mindfulness could reduce or prevent burnout.13

I have previously commented on the practice of mindfulness in the AGA Community forums and, as a potentially stand-alone component of self-compassion training,14 recommend it here as well. In addition to traditional mindfulness-based stress-reduction courses and mindfulness meditation practice found in many hospitals and community centers, individual meditation focused on loving kindness or gratitude as well as mindful exercises such as writing a self-compassionate letter or statements to yourself can be used to offset burnout in daily life.15 From the perspective of reducing burnout, mindfulness allows us to look at our feelings of cynicism, exhaustion, and inadequacy without judgment, to view them as symptoms rather than ugly truths about ourselves and that rather than avoid or suppress these feelings, to be mindful and compassionate toward them.

Finally, in the spirit of self-compassion, we must not judge ourselves for needing the help of others to navigate adversity – whether that support comes from our personal or professional life, or is provided by a mental health professional, we deserve to be taken care of as much as our patients do.

For more information, please visit the following, helpful resources: www.CenterForMSC.org, www.Self-Compassion.org, and www.MindfulSelfCompassion.org.

Dr. Keefer is director, psychobehavioral research, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, division of gastroenterology, New York, N.Y.

References

1. West C.P., Shanafelt T.D., Kolars J.C. JAMA. 2011;306[9]:952-60.

2. Maslach C., Leiter M.P. World Psychiatry. 2016;15[2]:103-11.

3. Ahola K., Honkonen T., Kivimaki M., et al. J Occup Environ Med. 2006;48[10]:1023-30.

4. Ahola K., Honkonen T., Isometsa E., et al. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2006;41[1]:11-7.

5. Farber B.A. J Clin Psychol. 2000;56[5]:589-94.

6. Keswani R.N., Taft T.H., Cote G.A., Keefer L. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106[10]:1734-40.

7. Sharma A., Sharp D.M., Walker L.G., Monson J.R. Psychooncology. 2008;17[6]:570-6.

8. Houkes I., Winants Y., Twellaar M., Verdonk P. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:240.

9. Neff K.D. Hum Dev. 2009;52[4]:211-4.

10. de Vente W., van Amsterdam J.G., Olff M., Kamphuis J.H., Emmelkamp P.M. Biomed Res Int. 2015;2015:431725.

11. Rockliff H., Karl A., McEwan K., Gilbert J., Matos M., Gilbert P. Effects of intranasal oxytocin on ‘compassion focused imagery’. Emotion. 2011;11[6]:1388-96.

12. Porges S.W. Biol Psychol. 2007;74[2]:301-7.

13. Breines J.G., Chen S. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 2012;38[9]:1133-43.

14. Heffernan M., Quinn G.M.T., Sister R.M., Fitzpatrick JJ. Int J Nurs Pract. 2010;16[4]:366-73.

15. Crocker J., Canevello A. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2008;95[3]:555-75.

16. Thompson G., McBride R.B., Hosford C.C., Halaas G. Teach Learn Med. 2016;28[2]:174-82.

17. Nie Z., Jin Y., He L., et al. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2015;8[10]:19144-9.

18. West C.P., Dyrbye L.N., Erwin P.J., Shanafelt T.D. Lancet. 2016. Nov 5;388(10057)2272-81.

19. Luchterhand C., Rakel D., Haq C., et al. WMJ. 2015;114[3]:105-9.

20. Montero-Marin J., Tops M., Manzanera R, Piva Demarzo MM, Alvarez de Mon M, Garcia-Campayo J. Front Psychol. 2015;6:1895.

Physician burnout is a growing epidemic, particularly in the early careers of gastroenterologists. Up to 50% of new physicians and trainees experience burnout with the first 3 years of independent practice.1 The negative consequences of burnout are well known – medical errors, depression, substance abuse, and even suicide.2,3 To meet criteria for burnout syndrome (Table 1), one must have two of three core symptoms, often experienced as phases: 1) physical and emotional exhaustion; 2) cynicism and detachment; and 3) feelings of ineffectiveness and lack of accomplishment.4

Emotional exhaustion, one of the earliest symptoms of burnout syndrome was reported to be as high as 63% among gastroenterologists in a survey study I conducted with colleagues a few years ago.5 Similar findings are noted amongst colorectal surgeons.6 We also noted in our study that burnout levels were highest in junior versus senior attendings, with junior attendings reporting more stress related to performing endoscopies and making split-second decisions. Interventional endoscopists may have been disproportionately affected by the latter, reporting that they were more likely to think about possible mistakes they made after work, have difficulty sleeping due to thinking about their day, and have difficulty separating work and personal life.5 Male and female physicians may progress through the phases of burnout differently, with men being more likely to experience cynicism and depersonalization first, followed by fatigue. Men may also not necessarily experience the third phase of feeling ineffective, which can be particularly dangerous because they will continue to push until there is a serious consequence. Women tend to go through all three phases of burnout beginning with emotional exhaustion, with a more rapid progression through the cynicism phase, and may end up spending the majority of their time feeling ineffective and limited in their accomplishments, a recipe for leaving medicine entirely.7

Prevention of burnout through self-compassion

Even though it may sometimes be easy to forget, most of us chose medicine as our profession because of our inherent compassion towards others and desire to care for those in need. But have we properly learned how to apply that same compassion to ourselves?

Self-compassion is one of the primary qualities of a happy, flourishing, resilient individual.8 Self-compassion is a psychological skill that can be applied to feelings of inadequacy, failure, or lack of control and includes: 1) self-kindness, 2) belief in a common humanity, and 3) mindfulness.8

Are you self-compassionate? Take a quiz!

Self-kindness requires us to treat ourselves as kindly as we would a friend or patient in the same situation. We must consciously choose not to use harsh, self-critical language when we make mistakes. We are taught not to berate our trainees for mistakes in the clinical setting – we can be taught not to berate ourselves for shortcomings as well. Self-kindness also requires that we provide ourselves with sympathy when we experience disappointments through no fault of our own (e.g. despite all my best efforts, this clinical initiative failed) and give ourselves the opportunity to nurture and soothe ourselves when we experience pain.6 Belief in a common humanity fosters engagement with others, recognizing that nobody is perfect and that others suffer as well. Isolating ourselves because we feel ashamed, embarrassed, or “crazy” in our experience of a situation only increases our suffering. As we engage with others, we are able to view things from a different perspective and also recognize that others around us have problems too. Indeed, social support may be one of the best buffers against burnout, particularly cynicism.12 A recent meta-analysis concluded that a combination of institutional engagement techniques including reduced hours and support groups as well as access to individual behavioral techniques such as mindfulness could reduce or prevent burnout.13

I have previously commented on the practice of mindfulness in the AGA Community forums and, as a potentially stand-alone component of self-compassion training,14 recommend it here as well. In addition to traditional mindfulness-based stress-reduction courses and mindfulness meditation practice found in many hospitals and community centers, individual meditation focused on loving kindness or gratitude as well as mindful exercises such as writing a self-compassionate letter or statements to yourself can be used to offset burnout in daily life.15 From the perspective of reducing burnout, mindfulness allows us to look at our feelings of cynicism, exhaustion, and inadequacy without judgment, to view them as symptoms rather than ugly truths about ourselves and that rather than avoid or suppress these feelings, to be mindful and compassionate toward them.

Finally, in the spirit of self-compassion, we must not judge ourselves for needing the help of others to navigate adversity – whether that support comes from our personal or professional life, or is provided by a mental health professional, we deserve to be taken care of as much as our patients do.

For more information, please visit the following, helpful resources: www.CenterForMSC.org, www.Self-Compassion.org, and www.MindfulSelfCompassion.org.

Dr. Keefer is director, psychobehavioral research, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, division of gastroenterology, New York, N.Y.

References

1. West C.P., Shanafelt T.D., Kolars J.C. JAMA. 2011;306[9]:952-60.

2. Maslach C., Leiter M.P. World Psychiatry. 2016;15[2]:103-11.

3. Ahola K., Honkonen T., Kivimaki M., et al. J Occup Environ Med. 2006;48[10]:1023-30.

4. Ahola K., Honkonen T., Isometsa E., et al. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2006;41[1]:11-7.

5. Farber B.A. J Clin Psychol. 2000;56[5]:589-94.

6. Keswani R.N., Taft T.H., Cote G.A., Keefer L. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106[10]:1734-40.

7. Sharma A., Sharp D.M., Walker L.G., Monson J.R. Psychooncology. 2008;17[6]:570-6.

8. Houkes I., Winants Y., Twellaar M., Verdonk P. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:240.

9. Neff K.D. Hum Dev. 2009;52[4]:211-4.

10. de Vente W., van Amsterdam J.G., Olff M., Kamphuis J.H., Emmelkamp P.M. Biomed Res Int. 2015;2015:431725.

11. Rockliff H., Karl A., McEwan K., Gilbert J., Matos M., Gilbert P. Effects of intranasal oxytocin on ‘compassion focused imagery’. Emotion. 2011;11[6]:1388-96.

12. Porges S.W. Biol Psychol. 2007;74[2]:301-7.

13. Breines J.G., Chen S. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 2012;38[9]:1133-43.

14. Heffernan M., Quinn G.M.T., Sister R.M., Fitzpatrick JJ. Int J Nurs Pract. 2010;16[4]:366-73.

15. Crocker J., Canevello A. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2008;95[3]:555-75.

16. Thompson G., McBride R.B., Hosford C.C., Halaas G. Teach Learn Med. 2016;28[2]:174-82.

17. Nie Z., Jin Y., He L., et al. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2015;8[10]:19144-9.

18. West C.P., Dyrbye L.N., Erwin P.J., Shanafelt T.D. Lancet. 2016. Nov 5;388(10057)2272-81.

19. Luchterhand C., Rakel D., Haq C., et al. WMJ. 2015;114[3]:105-9.

20. Montero-Marin J., Tops M., Manzanera R, Piva Demarzo MM, Alvarez de Mon M, Garcia-Campayo J. Front Psychol. 2015;6:1895.

Physician burnout is a growing epidemic, particularly in the early careers of gastroenterologists. Up to 50% of new physicians and trainees experience burnout with the first 3 years of independent practice.1 The negative consequences of burnout are well known – medical errors, depression, substance abuse, and even suicide.2,3 To meet criteria for burnout syndrome (Table 1), one must have two of three core symptoms, often experienced as phases: 1) physical and emotional exhaustion; 2) cynicism and detachment; and 3) feelings of ineffectiveness and lack of accomplishment.4

Emotional exhaustion, one of the earliest symptoms of burnout syndrome was reported to be as high as 63% among gastroenterologists in a survey study I conducted with colleagues a few years ago.5 Similar findings are noted amongst colorectal surgeons.6 We also noted in our study that burnout levels were highest in junior versus senior attendings, with junior attendings reporting more stress related to performing endoscopies and making split-second decisions. Interventional endoscopists may have been disproportionately affected by the latter, reporting that they were more likely to think about possible mistakes they made after work, have difficulty sleeping due to thinking about their day, and have difficulty separating work and personal life.5 Male and female physicians may progress through the phases of burnout differently, with men being more likely to experience cynicism and depersonalization first, followed by fatigue. Men may also not necessarily experience the third phase of feeling ineffective, which can be particularly dangerous because they will continue to push until there is a serious consequence. Women tend to go through all three phases of burnout beginning with emotional exhaustion, with a more rapid progression through the cynicism phase, and may end up spending the majority of their time feeling ineffective and limited in their accomplishments, a recipe for leaving medicine entirely.7

Prevention of burnout through self-compassion

Even though it may sometimes be easy to forget, most of us chose medicine as our profession because of our inherent compassion towards others and desire to care for those in need. But have we properly learned how to apply that same compassion to ourselves?

Self-compassion is one of the primary qualities of a happy, flourishing, resilient individual.8 Self-compassion is a psychological skill that can be applied to feelings of inadequacy, failure, or lack of control and includes: 1) self-kindness, 2) belief in a common humanity, and 3) mindfulness.8

Are you self-compassionate? Take a quiz!

Self-kindness requires us to treat ourselves as kindly as we would a friend or patient in the same situation. We must consciously choose not to use harsh, self-critical language when we make mistakes. We are taught not to berate our trainees for mistakes in the clinical setting – we can be taught not to berate ourselves for shortcomings as well. Self-kindness also requires that we provide ourselves with sympathy when we experience disappointments through no fault of our own (e.g. despite all my best efforts, this clinical initiative failed) and give ourselves the opportunity to nurture and soothe ourselves when we experience pain.6 Belief in a common humanity fosters engagement with others, recognizing that nobody is perfect and that others suffer as well. Isolating ourselves because we feel ashamed, embarrassed, or “crazy” in our experience of a situation only increases our suffering. As we engage with others, we are able to view things from a different perspective and also recognize that others around us have problems too. Indeed, social support may be one of the best buffers against burnout, particularly cynicism.12 A recent meta-analysis concluded that a combination of institutional engagement techniques including reduced hours and support groups as well as access to individual behavioral techniques such as mindfulness could reduce or prevent burnout.13

I have previously commented on the practice of mindfulness in the AGA Community forums and, as a potentially stand-alone component of self-compassion training,14 recommend it here as well. In addition to traditional mindfulness-based stress-reduction courses and mindfulness meditation practice found in many hospitals and community centers, individual meditation focused on loving kindness or gratitude as well as mindful exercises such as writing a self-compassionate letter or statements to yourself can be used to offset burnout in daily life.15 From the perspective of reducing burnout, mindfulness allows us to look at our feelings of cynicism, exhaustion, and inadequacy without judgment, to view them as symptoms rather than ugly truths about ourselves and that rather than avoid or suppress these feelings, to be mindful and compassionate toward them.

Finally, in the spirit of self-compassion, we must not judge ourselves for needing the help of others to navigate adversity – whether that support comes from our personal or professional life, or is provided by a mental health professional, we deserve to be taken care of as much as our patients do.

For more information, please visit the following, helpful resources: www.CenterForMSC.org, www.Self-Compassion.org, and www.MindfulSelfCompassion.org.

Dr. Keefer is director, psychobehavioral research, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, division of gastroenterology, New York, N.Y.

References

1. West C.P., Shanafelt T.D., Kolars J.C. JAMA. 2011;306[9]:952-60.

2. Maslach C., Leiter M.P. World Psychiatry. 2016;15[2]:103-11.

3. Ahola K., Honkonen T., Kivimaki M., et al. J Occup Environ Med. 2006;48[10]:1023-30.

4. Ahola K., Honkonen T., Isometsa E., et al. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2006;41[1]:11-7.

5. Farber B.A. J Clin Psychol. 2000;56[5]:589-94.

6. Keswani R.N., Taft T.H., Cote G.A., Keefer L. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106[10]:1734-40.

7. Sharma A., Sharp D.M., Walker L.G., Monson J.R. Psychooncology. 2008;17[6]:570-6.

8. Houkes I., Winants Y., Twellaar M., Verdonk P. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:240.

9. Neff K.D. Hum Dev. 2009;52[4]:211-4.

10. de Vente W., van Amsterdam J.G., Olff M., Kamphuis J.H., Emmelkamp P.M. Biomed Res Int. 2015;2015:431725.

11. Rockliff H., Karl A., McEwan K., Gilbert J., Matos M., Gilbert P. Effects of intranasal oxytocin on ‘compassion focused imagery’. Emotion. 2011;11[6]:1388-96.

12. Porges S.W. Biol Psychol. 2007;74[2]:301-7.

13. Breines J.G., Chen S. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 2012;38[9]:1133-43.

14. Heffernan M., Quinn G.M.T., Sister R.M., Fitzpatrick JJ. Int J Nurs Pract. 2010;16[4]:366-73.

15. Crocker J., Canevello A. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2008;95[3]:555-75.

16. Thompson G., McBride R.B., Hosford C.C., Halaas G. Teach Learn Med. 2016;28[2]:174-82.

17. Nie Z., Jin Y., He L., et al. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2015;8[10]:19144-9.

18. West C.P., Dyrbye L.N., Erwin P.J., Shanafelt T.D. Lancet. 2016. Nov 5;388(10057)2272-81.

19. Luchterhand C., Rakel D., Haq C., et al. WMJ. 2015;114[3]:105-9.

20. Montero-Marin J., Tops M., Manzanera R, Piva Demarzo MM, Alvarez de Mon M, Garcia-Campayo J. Front Psychol. 2015;6:1895.

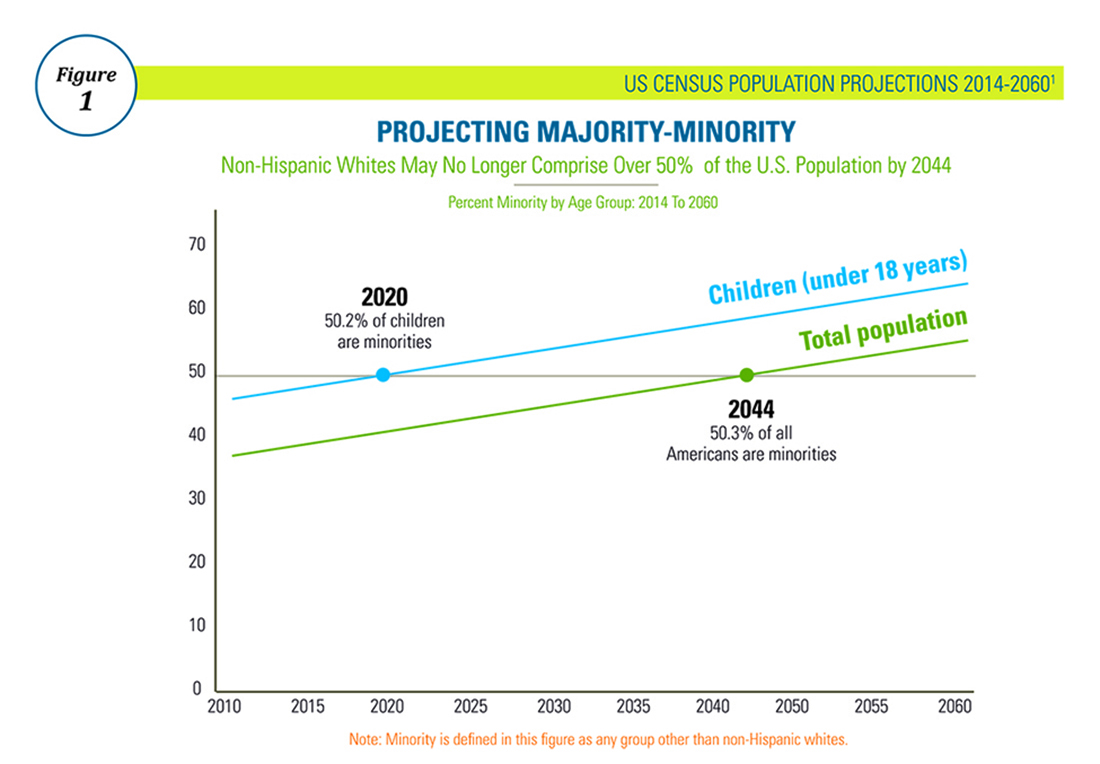

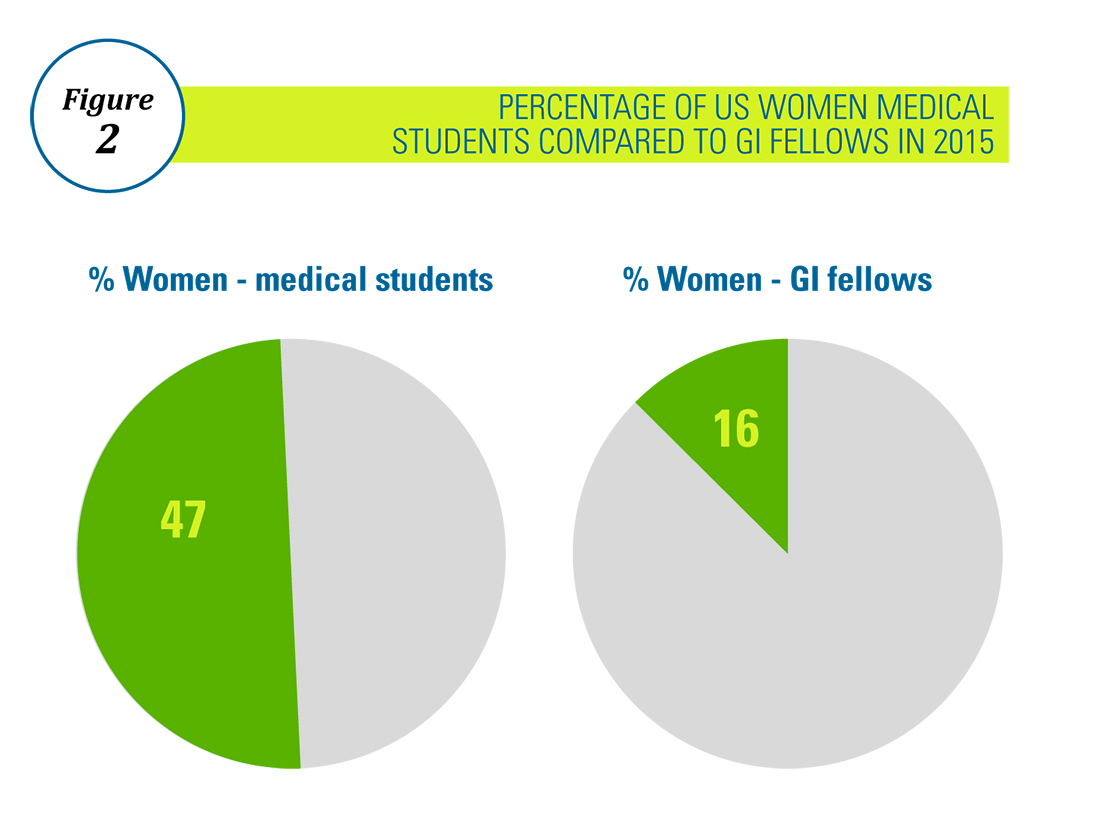

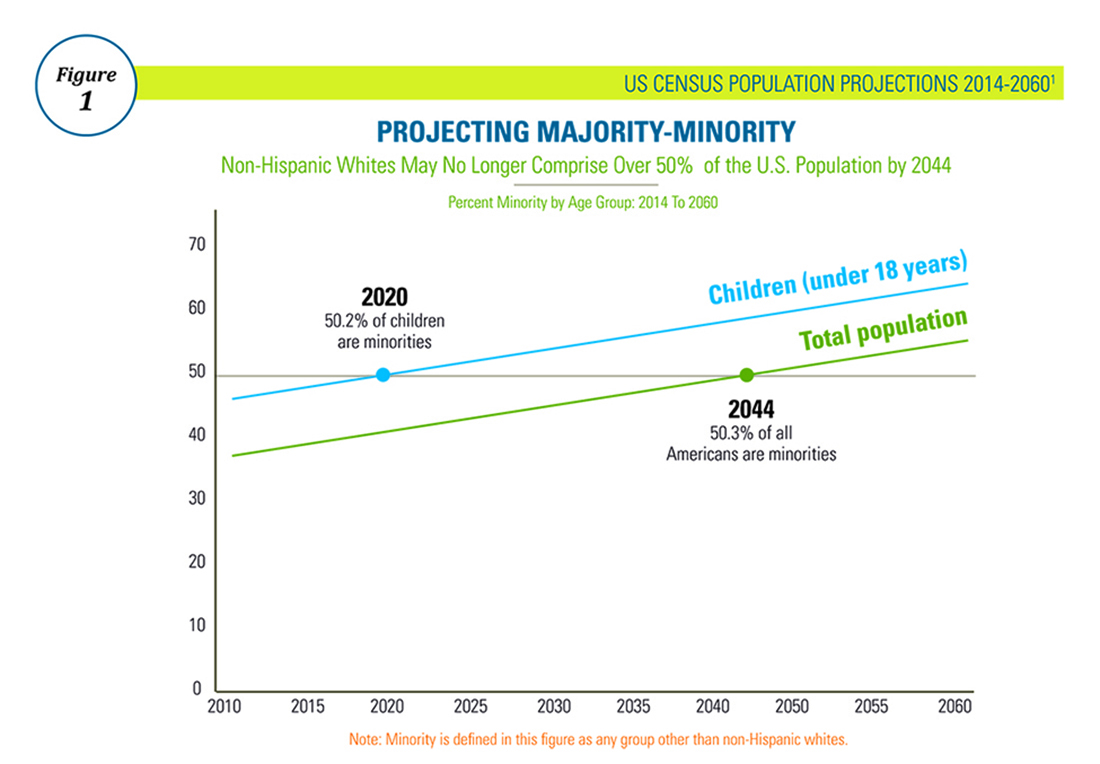

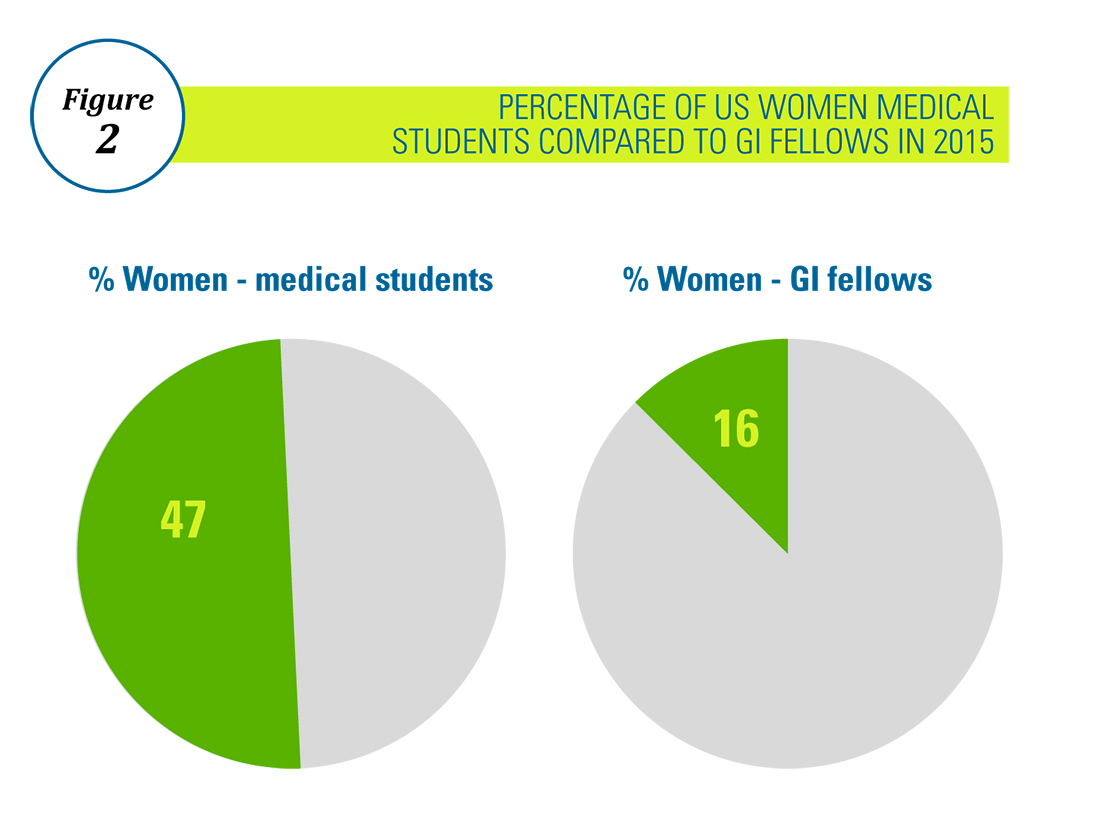

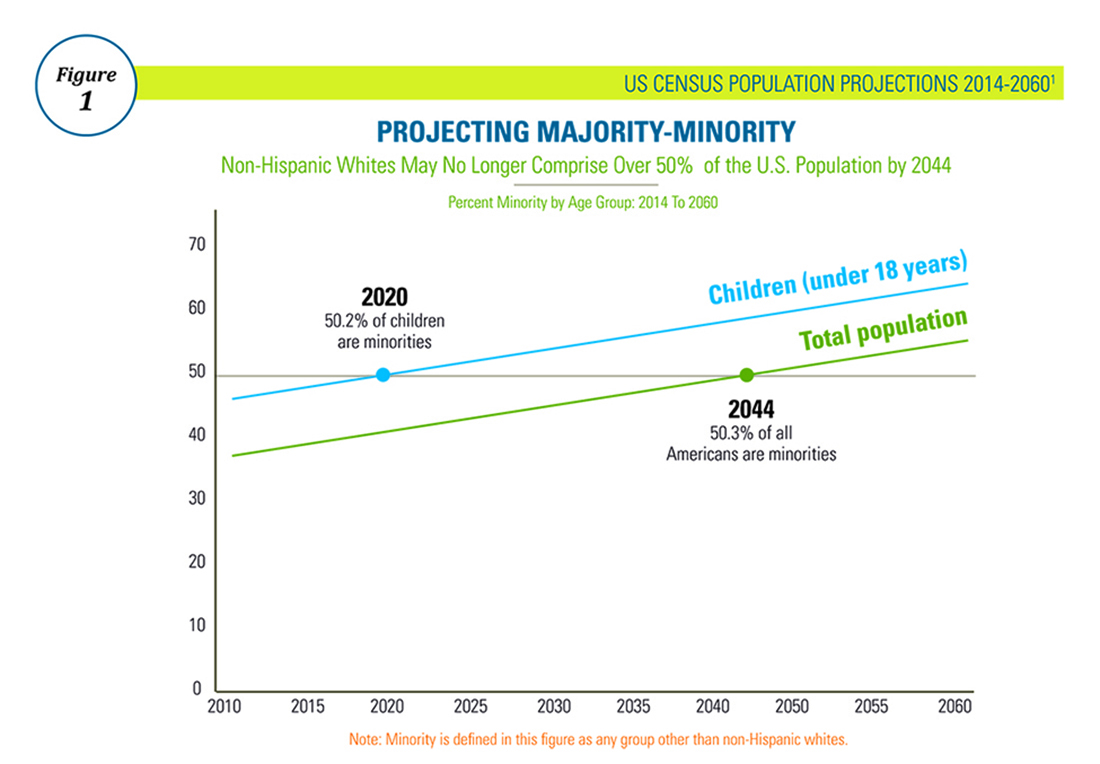

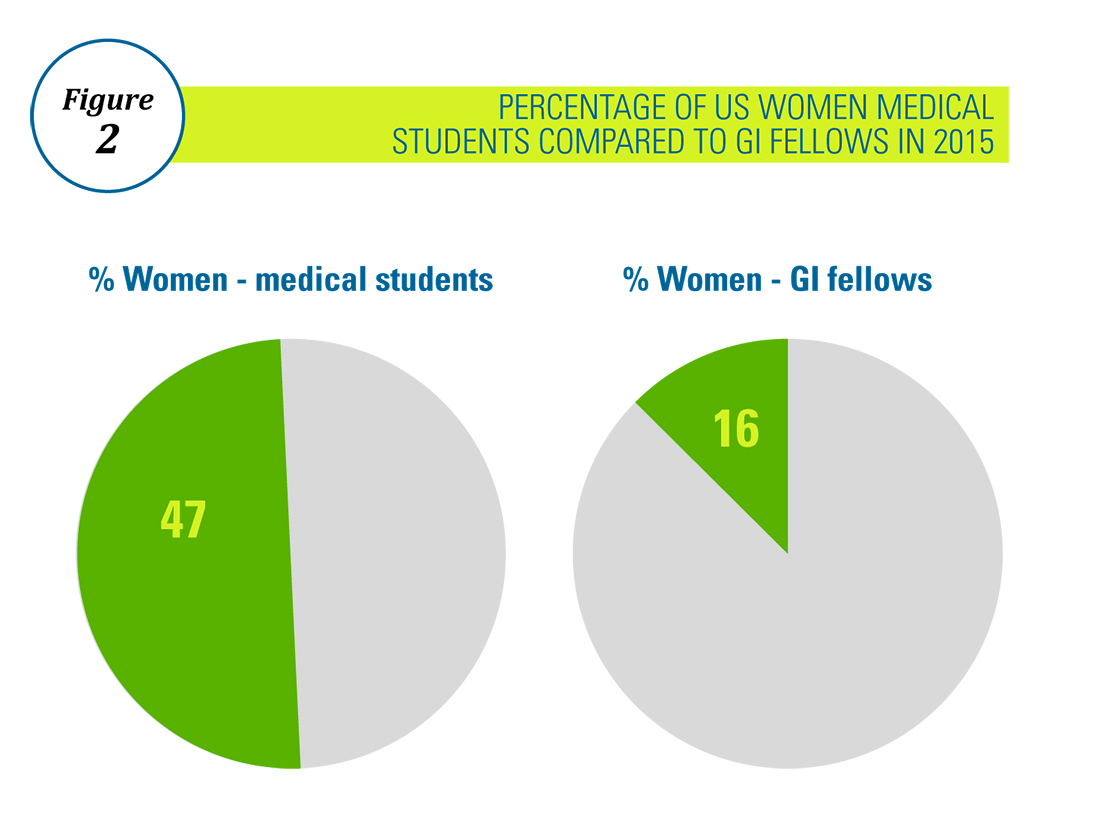

Diversity in GI Training: A Timely Goal

There is no denying that practicing medicine calls us to serve a population that is diverse in many aspects. We live and work in a world that is evolving so quickly that medical workforce demographics fail to keep pace. In the U.S. in particular, racial and ethnic diversity has already exceeded many previous forecasts and will likely continue to do so.

The American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) recognizes that broader representation in the GI workforce requires increasing diversity at the trainee level and values this change for reasons beyond diversity for diversity’s sake. Based on education research, improving diversity at the trainee level helps learners thrive through the sharing of varied perspectives and enhancement of complex, critical thinking5. Moreover, diverse learning environments promote a culture of tolerance and understanding, tools needed to prepare trainees for future patient interactions. Diversity also translates into better patient satisfaction, as several studies have shown that physician-patient concordance on race, ethnicity, and gender result in higher patient satisfaction scores6. Additionally, minority physicians are more likely to practice in underserved areas and to conduct research addressing health care disparities, an area that will require an even greater investment as the U.S. population demographic continues to evolve3,7.

The AGA is committed to diversity, which is an inclusive concept that encompasses race, ethnicity, national origin, religion, gender, age, sexual orientation, and disability. We strive to cultivate diversity within the organization at all levels, including governance, committee structure, staffing, and program and policy development. We are committed to the following goals intended to reflect the interests of the diverse patient population we serve:

1) Promotion of diversity within the practice of gastroenterology and in the individual care of patients of all backgrounds.

2) Recruitment and retention of GI providers and researchers from diverse backgrounds and the support of the advancement of their careers.

3) Elimination of disparities in GI diseases through community engagement, research, and advocacy.

Gastroenterology has been the most competitive fellowship specialty for the past 4 consecutive years, above pediatric surgery and cardiology8. We are privileged to practice an exciting, fascinating specialty that demands diversity of skill, acuity of care, and knowledge of pathophysiology. Increased diversity among those who research, teach, and practice in this wonderful field will only enhance it, and being mindful of this goal in our recruitment and retention efforts will help us achieve it.

For more information on the AGA Institute Diversity Committee and its ongoing initiatives, please visit http://www.gastro.org/about/people/committees/diversity-committee. Additionally, any specific enquiries should be addressed to Taylor Monson ([email protected]).

Dr. Quezeda is assistant dean for admissions, assistant professor of medicine, division of gastroenterology and hepatology, University of Maryland School of Medicine, Baltimore, and a member of the AGA Institute Diversity Committee.

On behalf of the AGA Institute Diversity Committee: Rotonya M. Carr, MD (Chair, AGA Diversity Committee; assistant professor of medicine, division of gastroenterology, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia), Karen A. Chachu, MD, PhD (assistant professor of medicine, Duke University, Durham, N.C.), Elizabeth Coss, MD (clinical assistant professor, University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio), Maria Cruz-Correa, MD PhD (associate professor of medicine, biochemistry and surgery, University of Puerto Rico Comprehensive Cancer Center), Lukejohn Day, MD (associate clinical professor, University of California, San Francisco), Darrell M. Gray II, MD, MPH (assistant professor of medicine, The Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center), Esi Lamouse-Smith, MD, PhD (assistant professor of pediatrics, Columbia University, New York), Antonio Mendoza Ladd, MD (assistant professor, Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center, El Paso), and Celena NuQuay (AGA staff liaison).

References

1. Projections of the Size and Composition of the U.S. Population: 2014 to 2060 Population Estimates and Projections Current Population Reports. Colby S, Ortman JM. Issued March 2015.

2. Association of American Medical Colleges 2016 Physician Specialty Databook, https://www.aamc.org/data/workforce/reports/457712/2016-specialty-databook.html.

3. Association of American Medical Colleges Diversity in the Physician Workforce: Facts and Figures 2010.

4. Deville C, Hwang WT, Burgos R. Diversity in Graduate Medical Education in the United States by Race, Ethnicity, and Sex, 2012. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(10):1706-8.

5. Wells AS, Fox L, Cordova-Cobo D. How Racially Diverse Schools and Classrooms Can Benefit All Students. The Century Foundation, Feb 2016. https://tcf.org/content/report/how-racially-diverse-schools-and-classrooms-can-benefit-all-students/.

6. Johnson RL, Saha S, Arbelaez JJ et al. Racial and ethnic differences in patient perceptions of bias and cultural competence in health care. J Gen Intern Med. 2004 Feb;19(2):101-10.

7. Saha S, Guiton G, Wimmers PF et al. Student body racial and ethnic composition and diversity-related outcomes in US medical schools. JAMA. 2008 Sep 10;300(10):1135-45.

8. Association of American Medical Colleges, ERAS Data. https://www.aamc.org/services/eras/stats/359278/stats.html.

There is no denying that practicing medicine calls us to serve a population that is diverse in many aspects. We live and work in a world that is evolving so quickly that medical workforce demographics fail to keep pace. In the U.S. in particular, racial and ethnic diversity has already exceeded many previous forecasts and will likely continue to do so.

The American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) recognizes that broader representation in the GI workforce requires increasing diversity at the trainee level and values this change for reasons beyond diversity for diversity’s sake. Based on education research, improving diversity at the trainee level helps learners thrive through the sharing of varied perspectives and enhancement of complex, critical thinking5. Moreover, diverse learning environments promote a culture of tolerance and understanding, tools needed to prepare trainees for future patient interactions. Diversity also translates into better patient satisfaction, as several studies have shown that physician-patient concordance on race, ethnicity, and gender result in higher patient satisfaction scores6. Additionally, minority physicians are more likely to practice in underserved areas and to conduct research addressing health care disparities, an area that will require an even greater investment as the U.S. population demographic continues to evolve3,7.

The AGA is committed to diversity, which is an inclusive concept that encompasses race, ethnicity, national origin, religion, gender, age, sexual orientation, and disability. We strive to cultivate diversity within the organization at all levels, including governance, committee structure, staffing, and program and policy development. We are committed to the following goals intended to reflect the interests of the diverse patient population we serve:

1) Promotion of diversity within the practice of gastroenterology and in the individual care of patients of all backgrounds.

2) Recruitment and retention of GI providers and researchers from diverse backgrounds and the support of the advancement of their careers.

3) Elimination of disparities in GI diseases through community engagement, research, and advocacy.

Gastroenterology has been the most competitive fellowship specialty for the past 4 consecutive years, above pediatric surgery and cardiology8. We are privileged to practice an exciting, fascinating specialty that demands diversity of skill, acuity of care, and knowledge of pathophysiology. Increased diversity among those who research, teach, and practice in this wonderful field will only enhance it, and being mindful of this goal in our recruitment and retention efforts will help us achieve it.

For more information on the AGA Institute Diversity Committee and its ongoing initiatives, please visit http://www.gastro.org/about/people/committees/diversity-committee. Additionally, any specific enquiries should be addressed to Taylor Monson ([email protected]).

Dr. Quezeda is assistant dean for admissions, assistant professor of medicine, division of gastroenterology and hepatology, University of Maryland School of Medicine, Baltimore, and a member of the AGA Institute Diversity Committee.

On behalf of the AGA Institute Diversity Committee: Rotonya M. Carr, MD (Chair, AGA Diversity Committee; assistant professor of medicine, division of gastroenterology, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia), Karen A. Chachu, MD, PhD (assistant professor of medicine, Duke University, Durham, N.C.), Elizabeth Coss, MD (clinical assistant professor, University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio), Maria Cruz-Correa, MD PhD (associate professor of medicine, biochemistry and surgery, University of Puerto Rico Comprehensive Cancer Center), Lukejohn Day, MD (associate clinical professor, University of California, San Francisco), Darrell M. Gray II, MD, MPH (assistant professor of medicine, The Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center), Esi Lamouse-Smith, MD, PhD (assistant professor of pediatrics, Columbia University, New York), Antonio Mendoza Ladd, MD (assistant professor, Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center, El Paso), and Celena NuQuay (AGA staff liaison).

References

1. Projections of the Size and Composition of the U.S. Population: 2014 to 2060 Population Estimates and Projections Current Population Reports. Colby S, Ortman JM. Issued March 2015.

2. Association of American Medical Colleges 2016 Physician Specialty Databook, https://www.aamc.org/data/workforce/reports/457712/2016-specialty-databook.html.

3. Association of American Medical Colleges Diversity in the Physician Workforce: Facts and Figures 2010.

4. Deville C, Hwang WT, Burgos R. Diversity in Graduate Medical Education in the United States by Race, Ethnicity, and Sex, 2012. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(10):1706-8.

5. Wells AS, Fox L, Cordova-Cobo D. How Racially Diverse Schools and Classrooms Can Benefit All Students. The Century Foundation, Feb 2016. https://tcf.org/content/report/how-racially-diverse-schools-and-classrooms-can-benefit-all-students/.

6. Johnson RL, Saha S, Arbelaez JJ et al. Racial and ethnic differences in patient perceptions of bias and cultural competence in health care. J Gen Intern Med. 2004 Feb;19(2):101-10.

7. Saha S, Guiton G, Wimmers PF et al. Student body racial and ethnic composition and diversity-related outcomes in US medical schools. JAMA. 2008 Sep 10;300(10):1135-45.

8. Association of American Medical Colleges, ERAS Data. https://www.aamc.org/services/eras/stats/359278/stats.html.

There is no denying that practicing medicine calls us to serve a population that is diverse in many aspects. We live and work in a world that is evolving so quickly that medical workforce demographics fail to keep pace. In the U.S. in particular, racial and ethnic diversity has already exceeded many previous forecasts and will likely continue to do so.

The American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) recognizes that broader representation in the GI workforce requires increasing diversity at the trainee level and values this change for reasons beyond diversity for diversity’s sake. Based on education research, improving diversity at the trainee level helps learners thrive through the sharing of varied perspectives and enhancement of complex, critical thinking5. Moreover, diverse learning environments promote a culture of tolerance and understanding, tools needed to prepare trainees for future patient interactions. Diversity also translates into better patient satisfaction, as several studies have shown that physician-patient concordance on race, ethnicity, and gender result in higher patient satisfaction scores6. Additionally, minority physicians are more likely to practice in underserved areas and to conduct research addressing health care disparities, an area that will require an even greater investment as the U.S. population demographic continues to evolve3,7.

The AGA is committed to diversity, which is an inclusive concept that encompasses race, ethnicity, national origin, religion, gender, age, sexual orientation, and disability. We strive to cultivate diversity within the organization at all levels, including governance, committee structure, staffing, and program and policy development. We are committed to the following goals intended to reflect the interests of the diverse patient population we serve:

1) Promotion of diversity within the practice of gastroenterology and in the individual care of patients of all backgrounds.

2) Recruitment and retention of GI providers and researchers from diverse backgrounds and the support of the advancement of their careers.

3) Elimination of disparities in GI diseases through community engagement, research, and advocacy.

Gastroenterology has been the most competitive fellowship specialty for the past 4 consecutive years, above pediatric surgery and cardiology8. We are privileged to practice an exciting, fascinating specialty that demands diversity of skill, acuity of care, and knowledge of pathophysiology. Increased diversity among those who research, teach, and practice in this wonderful field will only enhance it, and being mindful of this goal in our recruitment and retention efforts will help us achieve it.

For more information on the AGA Institute Diversity Committee and its ongoing initiatives, please visit http://www.gastro.org/about/people/committees/diversity-committee. Additionally, any specific enquiries should be addressed to Taylor Monson ([email protected]).

Dr. Quezeda is assistant dean for admissions, assistant professor of medicine, division of gastroenterology and hepatology, University of Maryland School of Medicine, Baltimore, and a member of the AGA Institute Diversity Committee.

On behalf of the AGA Institute Diversity Committee: Rotonya M. Carr, MD (Chair, AGA Diversity Committee; assistant professor of medicine, division of gastroenterology, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia), Karen A. Chachu, MD, PhD (assistant professor of medicine, Duke University, Durham, N.C.), Elizabeth Coss, MD (clinical assistant professor, University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio), Maria Cruz-Correa, MD PhD (associate professor of medicine, biochemistry and surgery, University of Puerto Rico Comprehensive Cancer Center), Lukejohn Day, MD (associate clinical professor, University of California, San Francisco), Darrell M. Gray II, MD, MPH (assistant professor of medicine, The Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center), Esi Lamouse-Smith, MD, PhD (assistant professor of pediatrics, Columbia University, New York), Antonio Mendoza Ladd, MD (assistant professor, Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center, El Paso), and Celena NuQuay (AGA staff liaison).

References

1. Projections of the Size and Composition of the U.S. Population: 2014 to 2060 Population Estimates and Projections Current Population Reports. Colby S, Ortman JM. Issued March 2015.

2. Association of American Medical Colleges 2016 Physician Specialty Databook, https://www.aamc.org/data/workforce/reports/457712/2016-specialty-databook.html.

3. Association of American Medical Colleges Diversity in the Physician Workforce: Facts and Figures 2010.

4. Deville C, Hwang WT, Burgos R. Diversity in Graduate Medical Education in the United States by Race, Ethnicity, and Sex, 2012. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(10):1706-8.

5. Wells AS, Fox L, Cordova-Cobo D. How Racially Diverse Schools and Classrooms Can Benefit All Students. The Century Foundation, Feb 2016. https://tcf.org/content/report/how-racially-diverse-schools-and-classrooms-can-benefit-all-students/.

6. Johnson RL, Saha S, Arbelaez JJ et al. Racial and ethnic differences in patient perceptions of bias and cultural competence in health care. J Gen Intern Med. 2004 Feb;19(2):101-10.

7. Saha S, Guiton G, Wimmers PF et al. Student body racial and ethnic composition and diversity-related outcomes in US medical schools. JAMA. 2008 Sep 10;300(10):1135-45.

8. Association of American Medical Colleges, ERAS Data. https://www.aamc.org/services/eras/stats/359278/stats.html.

Ten Financial Tips for a Worry-Free Retirement

As a contract and tax attorney for physicians for over 30 years, I have reviewed many asset summaries of late-career physicians. Although most have historically strong annual incomes of $200,000 to $400,000, accumulated wealth varies tremendously. Some physicians in their 60s have a home, a small retirement plan, and little else. Others have cash equivalents of $5,000,000 or more, no debt, real estate, and other assets. In my experience, this variance usually does not relate primarily to income differences but rather spending control and financial knowledge. If you are interested in having the opportunity to retire and not worry about finding an “early bird” special at your favorite restaurant, this article provides ten tips to help you achieve that dream.

2. Contribute to an employer retirement plan. Contribute to your employer’s Roth 401-K or regular 401-K. Add money starting the first day you are eligible at the rate of at least 5% of your compensation. By age 35, contribute no less than 10% of your compensation up to the legal maximum. In a Roth 401-K, you will have decades of tax-free accumulation. You may also enjoy the employer matching contribution, which varies from job to job. Do not take loans on 401-K plans. If you borrow and then terminate employment before completing repayment, the borrowed funds are treated as a plan distribution, subjecting them to taxation and possibly a penalty if you are under age 59.5. If switching jobs, move your 401-K retirement plan account into an IRA; do not cash it out. If necessary, you usually can withdraw funds to make a down payment on a home or for an emergency, but plan contributions should be viewed as “tomorrow” money. You can borrow to purchase a home and to finance your children’s educations but you cannot borrow to retire.

3. Be debt-free. It is easier to accumulate wealth if you are debt-free. Mortgages, student loans, and car payments should be minimized and eliminated as quickly as possible so that available net income is used to invest both through retirement plans and on an after-tax basis. Cars should be purchased, not leased as the “tax benefit” of leasing is a myth. Leasing a car is an expensive way of borrowing money, as you are effectively purchasing only the most expensive depreciating years of the car’s useful life (the initial few years). You should also not have credit card debt at any time as credit card debt means you are spending money before you earn it. Borrowing for clothing or a vacation reflects the inability to control one’s spending.

4. Use tax-advantaged investment vehicles. Interest income on your investments is taxed at ordinary income rates, perhaps 30% or more, but dividends issued from stock or stock mutual funds are taxed at lower long-term capital gains rates. Similarly, when you sell a stock or a stock mutual fund, the appreciation is taxed at long-term capital gains rates under most circumstances. As you are able to set funds aside, make sure that you are using tax-advantaged investment vehicles.

5. Consider no-load mutual funds. When investing in the stock market or otherwise, consider no-load mutual funds such as those offered by Vanguard that do not require an “investment advisor.” Such funds do not have sales charges and save you money. The greatest chance you have of underperforming the market relates to the expenses associated with investment, more so than the particular investments selected. Since almost all advisors underperform the market, you should consider investing on your own, minimizing costs, and watching your funds grow. As a younger physician with many high-income years in front of you, a good portion of your investments should be in equities to enjoy their appreciation over decades. With bank interest rates being minuscule, there is no reasonable alternative.

6. Develop a budget. If you or your spouse has an issue with shopping or overspending, it is imperative that you develop a budget: first allocating funds to long-term savings such as a retirement plan, next to short-term savings, then to unavoidable recurring costs such as rent or mortgage, student loans, food, and discretionary expenditures. The perfect time to put this in place is when you go from the salary of a resident or fellow into a full-time job and your pay increases by multifold. Read the book The Millionaire Next Door: The Surprising Secrets of America’s Wealthy by Thomas J. Stanley and gain control, as it is easy to do otherwise with an unprecedented and significant salary jump. If you start to live on your new salary, you will never be in a position to amass wealth and retire comfortably.

7. Send your kids to public, not private school. For each of your children, would you rather pay astronomic tuition bills for 4-8 years of college or 16-20 years counting grades 1-12 in private school? When you have children approaching school age, choose an A+ school district and send your kids to public school, not private school – they will still get into competitive colleges. This can save hundreds of thousands of dollars per child.

8. Fund a 529 plan. Whether or not you currently have children, you can fund a 529 plan to enjoy tax-free growth and plan for education expenses of children or future children. If you do not have children yet, you can name yourself or a different party as the beneficiary and then change it after children are born. If you do not have children, you can either use the 529 for someone else or cash the investment and recover the money including growth/loss thereon. Trying to fund college educations out of current income is difficult and it is better to prefund than to pay back student loans over many years.

9. Draft a will. If you are married or have children or both, it is imperative that you have wills drafted so that your wishes are implemented upon your passing. Many tax advantages are available without using complicated trusts and it is important that you maintain up-to-date wills should the unforeseen occur.

10. Purchase disability and life insurance. Your most valuable financial asset is your income stream over the coming years. Protect it with adequate private disability and life insurance policies. Policies provided by your employer typically end upon termination of employment and having a portable policy is important.

These tips will help you maximize your financial position over your work life and through retirement. The best time to get on the right track is yesterday; the second best time is today. Staying in shape financially is easier than messing up and then attempting to fix it.

Mr. Schiller is a physician contract and tax attorney and has practiced in Norristown, Penn. for the past 30 years. He can be contacted at 610-277-5900 or www.schillerlawassociates.com or [email protected].

As a contract and tax attorney for physicians for over 30 years, I have reviewed many asset summaries of late-career physicians. Although most have historically strong annual incomes of $200,000 to $400,000, accumulated wealth varies tremendously. Some physicians in their 60s have a home, a small retirement plan, and little else. Others have cash equivalents of $5,000,000 or more, no debt, real estate, and other assets. In my experience, this variance usually does not relate primarily to income differences but rather spending control and financial knowledge. If you are interested in having the opportunity to retire and not worry about finding an “early bird” special at your favorite restaurant, this article provides ten tips to help you achieve that dream.

2. Contribute to an employer retirement plan. Contribute to your employer’s Roth 401-K or regular 401-K. Add money starting the first day you are eligible at the rate of at least 5% of your compensation. By age 35, contribute no less than 10% of your compensation up to the legal maximum. In a Roth 401-K, you will have decades of tax-free accumulation. You may also enjoy the employer matching contribution, which varies from job to job. Do not take loans on 401-K plans. If you borrow and then terminate employment before completing repayment, the borrowed funds are treated as a plan distribution, subjecting them to taxation and possibly a penalty if you are under age 59.5. If switching jobs, move your 401-K retirement plan account into an IRA; do not cash it out. If necessary, you usually can withdraw funds to make a down payment on a home or for an emergency, but plan contributions should be viewed as “tomorrow” money. You can borrow to purchase a home and to finance your children’s educations but you cannot borrow to retire.

3. Be debt-free. It is easier to accumulate wealth if you are debt-free. Mortgages, student loans, and car payments should be minimized and eliminated as quickly as possible so that available net income is used to invest both through retirement plans and on an after-tax basis. Cars should be purchased, not leased as the “tax benefit” of leasing is a myth. Leasing a car is an expensive way of borrowing money, as you are effectively purchasing only the most expensive depreciating years of the car’s useful life (the initial few years). You should also not have credit card debt at any time as credit card debt means you are spending money before you earn it. Borrowing for clothing or a vacation reflects the inability to control one’s spending.

4. Use tax-advantaged investment vehicles. Interest income on your investments is taxed at ordinary income rates, perhaps 30% or more, but dividends issued from stock or stock mutual funds are taxed at lower long-term capital gains rates. Similarly, when you sell a stock or a stock mutual fund, the appreciation is taxed at long-term capital gains rates under most circumstances. As you are able to set funds aside, make sure that you are using tax-advantaged investment vehicles.

5. Consider no-load mutual funds. When investing in the stock market or otherwise, consider no-load mutual funds such as those offered by Vanguard that do not require an “investment advisor.” Such funds do not have sales charges and save you money. The greatest chance you have of underperforming the market relates to the expenses associated with investment, more so than the particular investments selected. Since almost all advisors underperform the market, you should consider investing on your own, minimizing costs, and watching your funds grow. As a younger physician with many high-income years in front of you, a good portion of your investments should be in equities to enjoy their appreciation over decades. With bank interest rates being minuscule, there is no reasonable alternative.

6. Develop a budget. If you or your spouse has an issue with shopping or overspending, it is imperative that you develop a budget: first allocating funds to long-term savings such as a retirement plan, next to short-term savings, then to unavoidable recurring costs such as rent or mortgage, student loans, food, and discretionary expenditures. The perfect time to put this in place is when you go from the salary of a resident or fellow into a full-time job and your pay increases by multifold. Read the book The Millionaire Next Door: The Surprising Secrets of America’s Wealthy by Thomas J. Stanley and gain control, as it is easy to do otherwise with an unprecedented and significant salary jump. If you start to live on your new salary, you will never be in a position to amass wealth and retire comfortably.

7. Send your kids to public, not private school. For each of your children, would you rather pay astronomic tuition bills for 4-8 years of college or 16-20 years counting grades 1-12 in private school? When you have children approaching school age, choose an A+ school district and send your kids to public school, not private school – they will still get into competitive colleges. This can save hundreds of thousands of dollars per child.

8. Fund a 529 plan. Whether or not you currently have children, you can fund a 529 plan to enjoy tax-free growth and plan for education expenses of children or future children. If you do not have children yet, you can name yourself or a different party as the beneficiary and then change it after children are born. If you do not have children, you can either use the 529 for someone else or cash the investment and recover the money including growth/loss thereon. Trying to fund college educations out of current income is difficult and it is better to prefund than to pay back student loans over many years.

9. Draft a will. If you are married or have children or both, it is imperative that you have wills drafted so that your wishes are implemented upon your passing. Many tax advantages are available without using complicated trusts and it is important that you maintain up-to-date wills should the unforeseen occur.

10. Purchase disability and life insurance. Your most valuable financial asset is your income stream over the coming years. Protect it with adequate private disability and life insurance policies. Policies provided by your employer typically end upon termination of employment and having a portable policy is important.

These tips will help you maximize your financial position over your work life and through retirement. The best time to get on the right track is yesterday; the second best time is today. Staying in shape financially is easier than messing up and then attempting to fix it.

Mr. Schiller is a physician contract and tax attorney and has practiced in Norristown, Penn. for the past 30 years. He can be contacted at 610-277-5900 or www.schillerlawassociates.com or [email protected].