User login

Latest recommendations for the 2017-2018 flu season

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recently reported details of the 2016-2017 influenza season in Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report1 and at the June meeting of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. The CDC monitors influenza activity using several systems, and last flu season was shown to be moderately severe, starting in December in the Western United States, moving east, and peaking in February.

During the peak, 5.1% of outpatient visits were attributed to influenza-like illnesses, and 8.2% of reported deaths were due to pneumonia and influenza. For the whole influenza season, there were more than 18,000 confirmed influenza-related hospitalizations, with 60% of these occurring among those ≥65 years.1 Confirmed influenza-associated pediatric deaths totaled 98.1

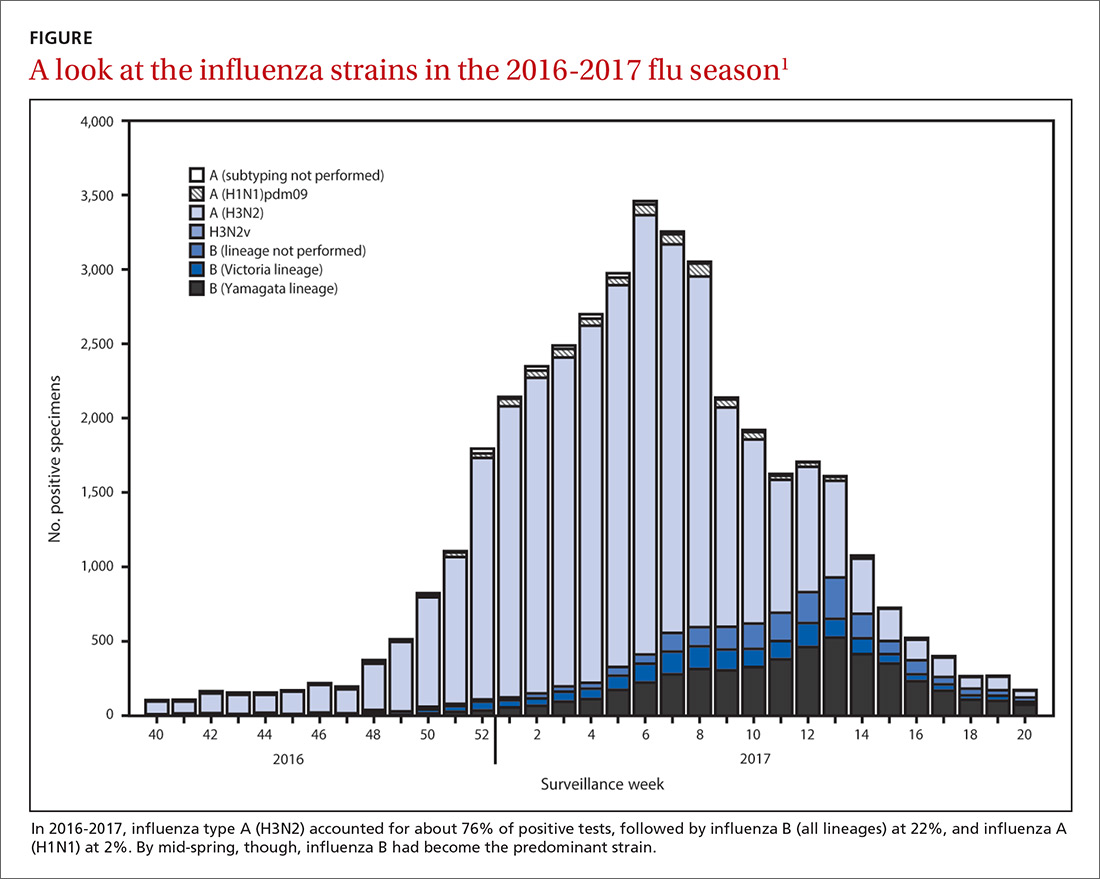

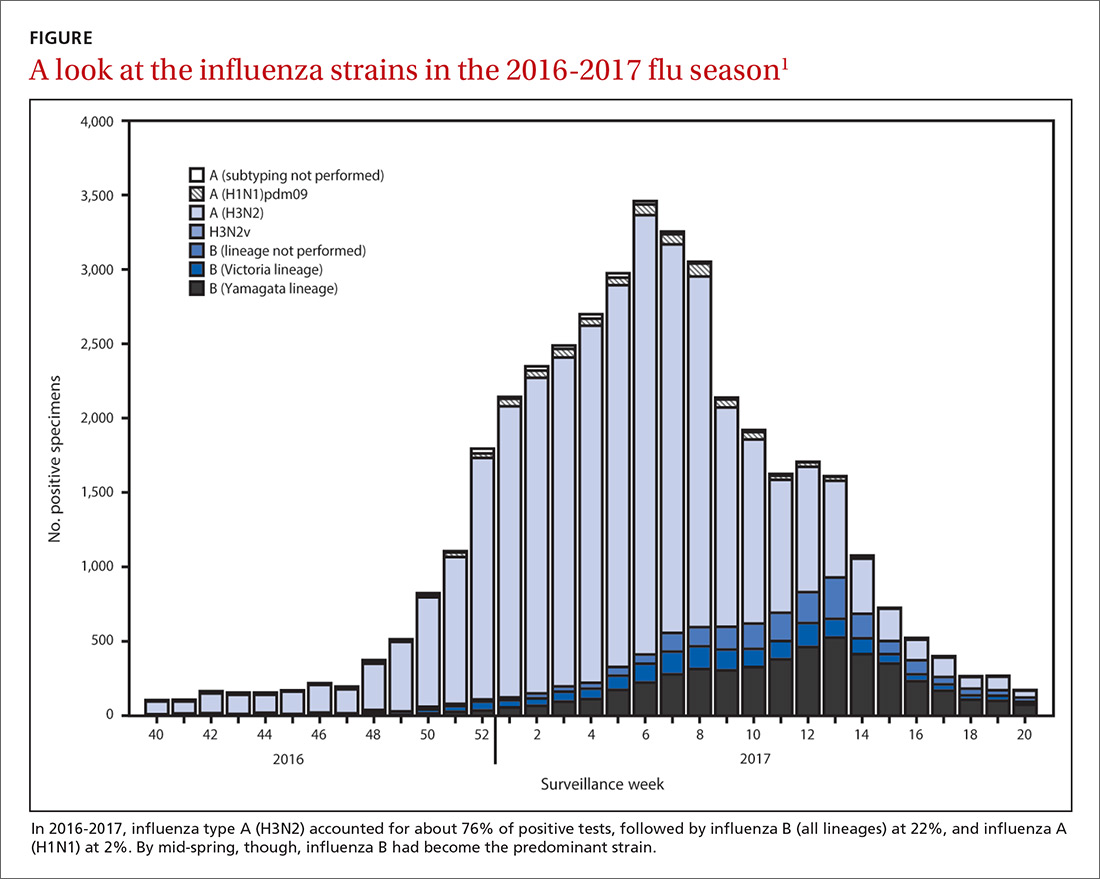

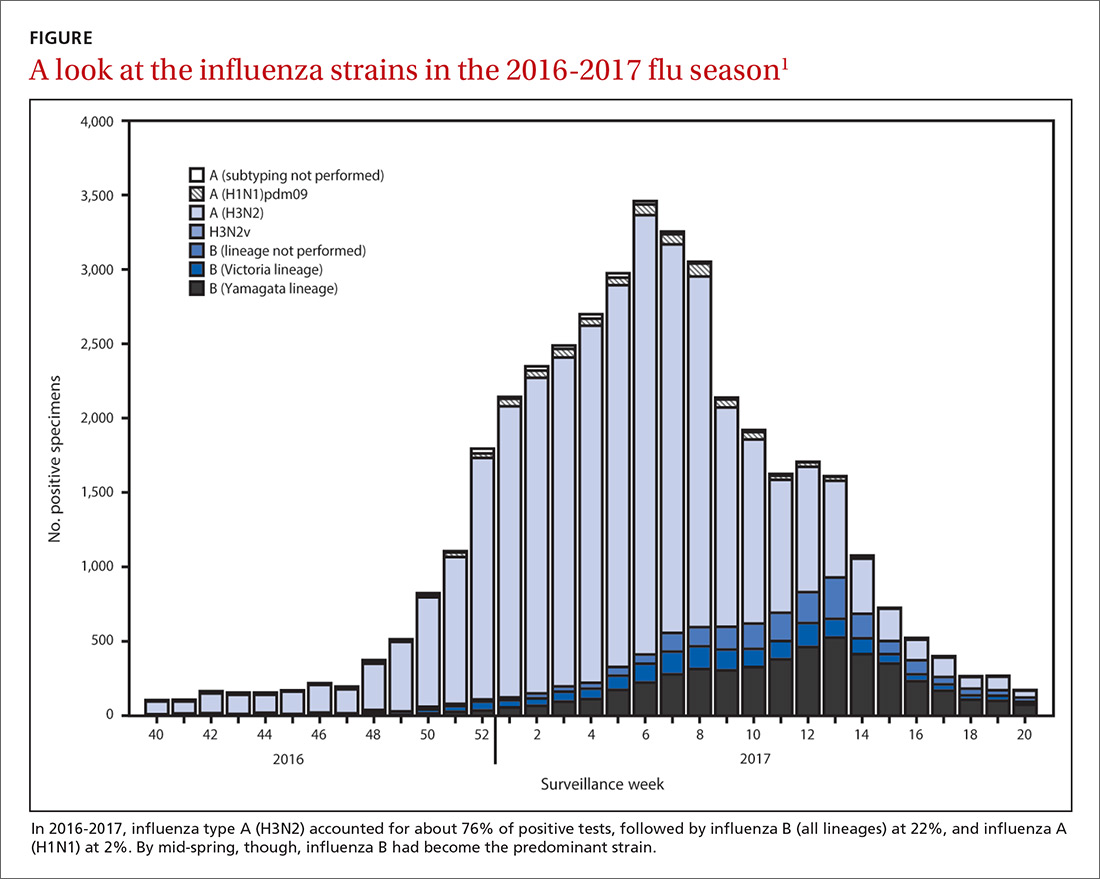

The predominant influenza strain last year was type A (H3N2), accounting for about 76% of positive tests in public health laboratories (FIGURE).1 This was followed by influenza B (all lineages) at 22%, and influenza A (H1N1), accounting for only 2%. However, in early April, the predominant strain changed from A (H3N2) to influenza B. Importantly, all viruses tested last year were sensitive to oseltamivir, zanamivir, and peramivir. No antiviral resistance was detected to these neuraminidase inhibitors.

Good news and bad news on vaccine effectiveness. The good news: Circulating viruses were a close match to those contained in the vaccine. The bad news: Vaccine effectiveness at preventing illness was estimated to be just 34% against A (H3N2) and 56% against influenza B viruses.1 There has been no analysis of the relative effectiveness of different vaccines and vaccine types.

The past 6 influenza seasons have revealed a pattern of lower vaccine effectiveness against A (H3N2) compared with effectiveness against A (H1N1) and influenza B viruses. While vaccine effectiveness is not optimal, routine universal use still prevents a great deal of mortality and morbidity. It’s estimated that in 2012-2013, vaccine effectiveness (comparable to that in 2016-2017) prevented 5.6 million illnesses, 2.7 million medical visits, 61,500 hospitalizations, and 1800 deaths.1

More good news: Vaccine safety studies are reassuring

The CDC monitors influenza vaccine safety by using several sources, including the Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System and the Vaccine Safety Datalink.2

Changes for the 2017-2018 influenza season

The composition of influenza vaccine products for the 2017-2018 season will differ slightly from last year’s formulation in the H1N1 component. Viral antigens to be included in the trivalent products are A/Michigan (H1N1), A/Hong Kong (H3N2), and B/Brisbane.3 Quadrivalent products will add B/Phuket to the other 3 antigens.3 A wide array of influenza vaccine products is available. Each one is described on the CDC Web site.4

Two minor changes in the recommendations were made at the June ACIP meeting.5 Afluria is approved by the FDA for use in children starting at age 5 years. ACIP had recommended that its use be reserved for children 9 years and older because previous influenza seasons had raised concerns about increased rates of febrile seizures in children younger than age 9. These concerns have been resolved, however, and the ACIP recommendations are now in concert with those of the FDA for this product.

Influenza immunization with an inactivated influenza vaccine product has been recommended for all pregnant women. Safety data are increasingly available for other product options as well, and ACIP now recommends vaccination in pregnancy with any age-appropriate product except for live attenuated influenza vaccine. 5

Antivirals: Give as needed, even before lab confirmation

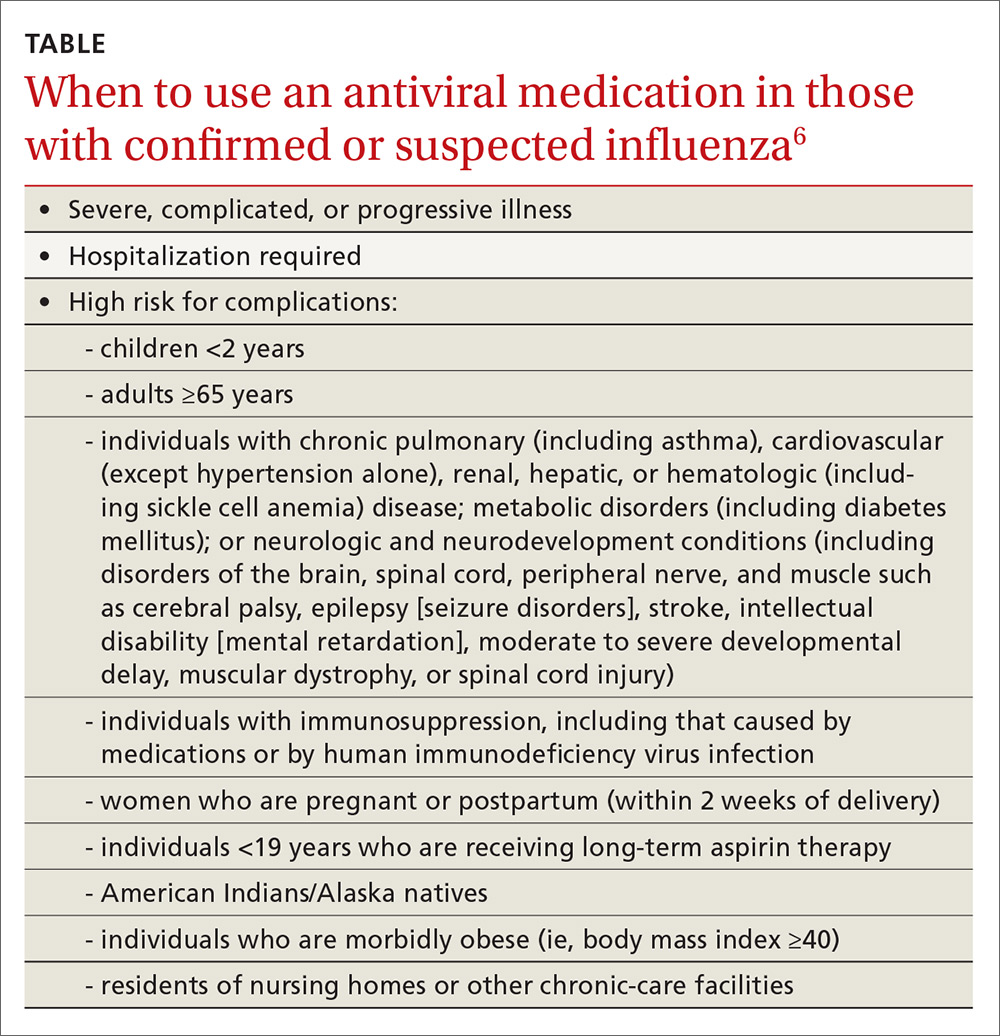

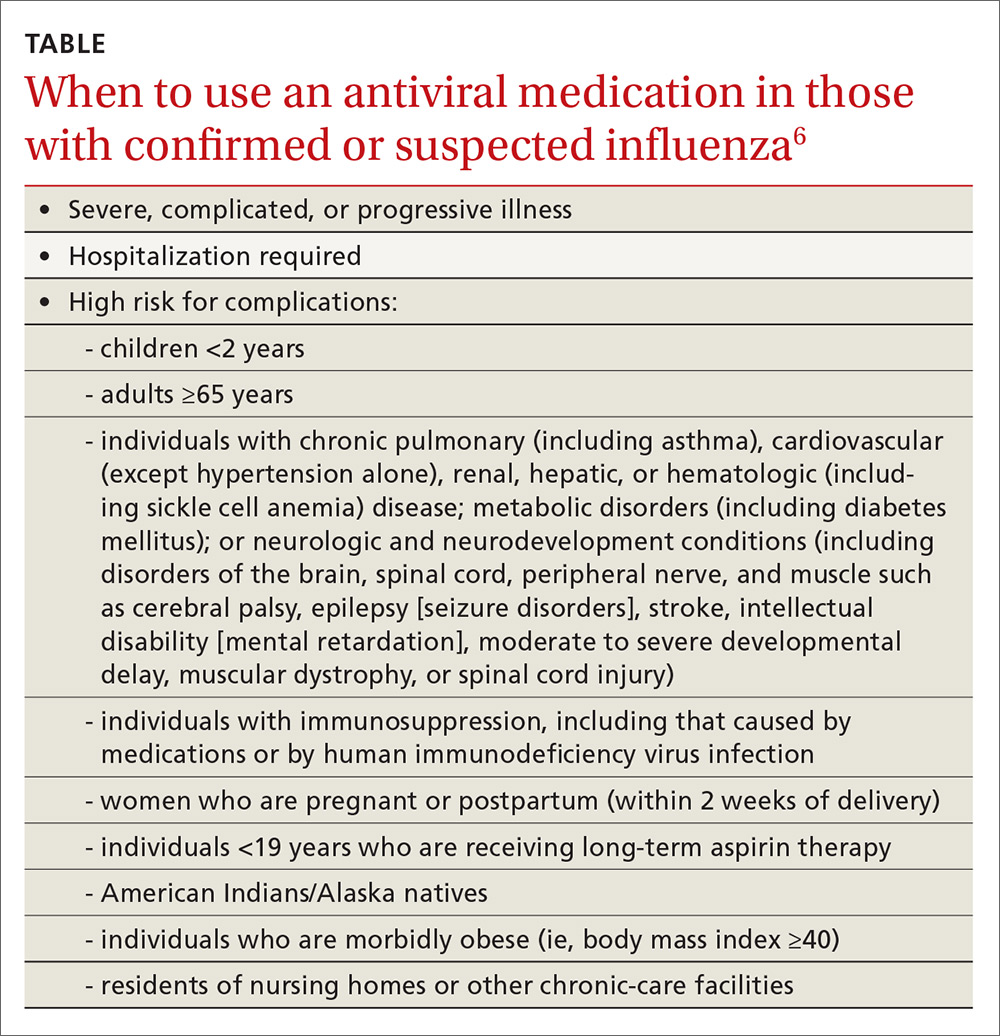

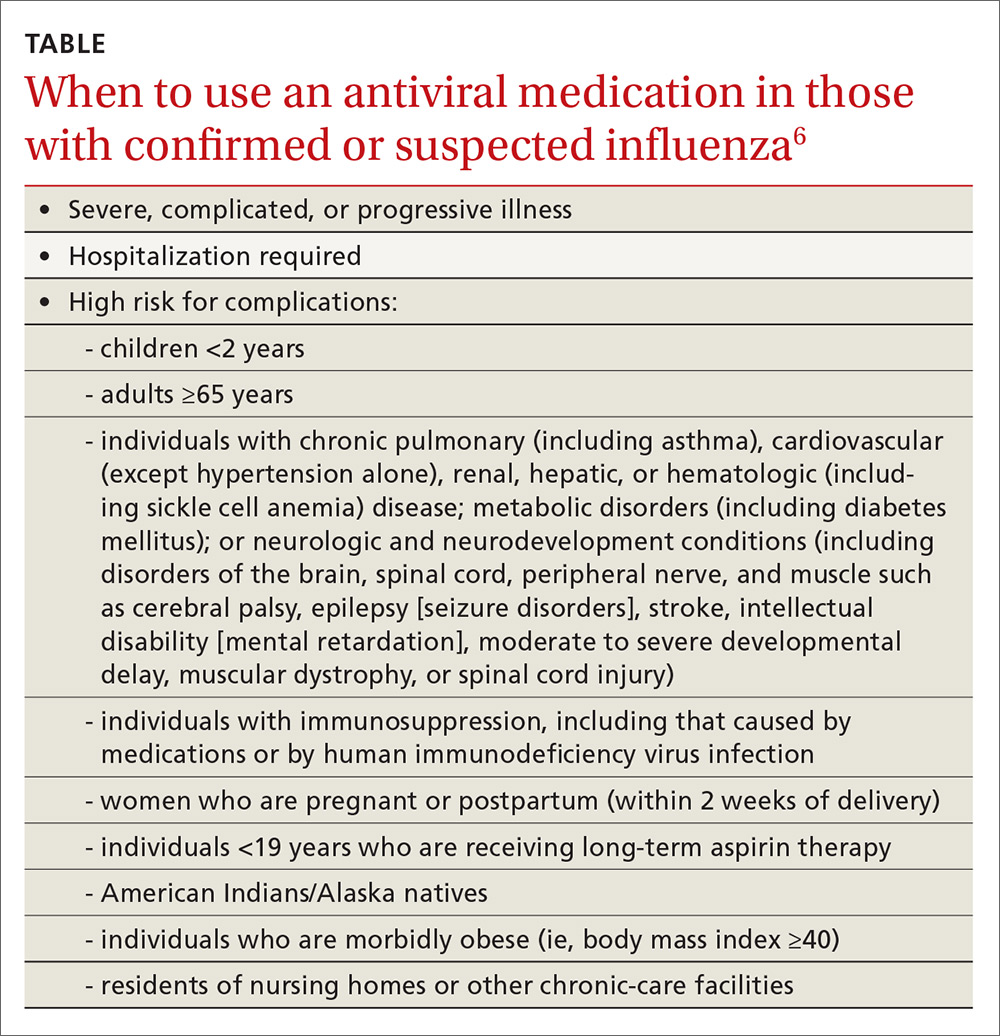

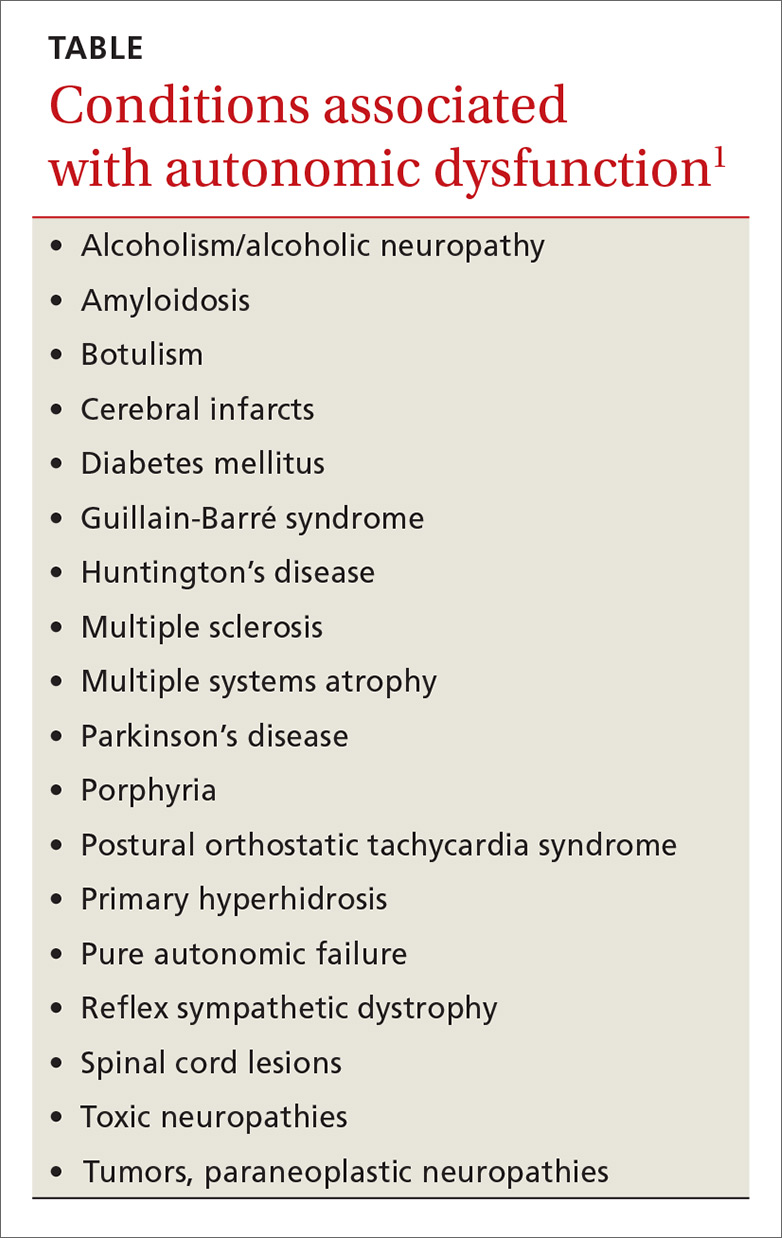

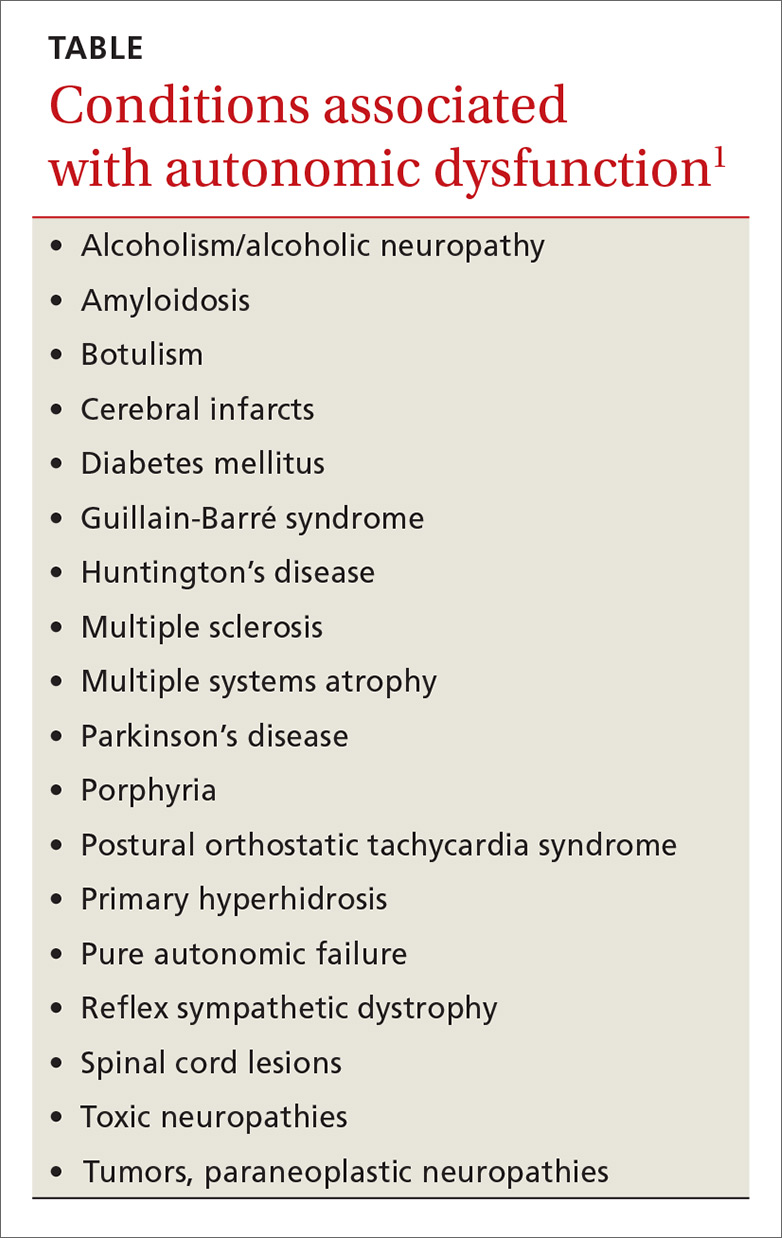

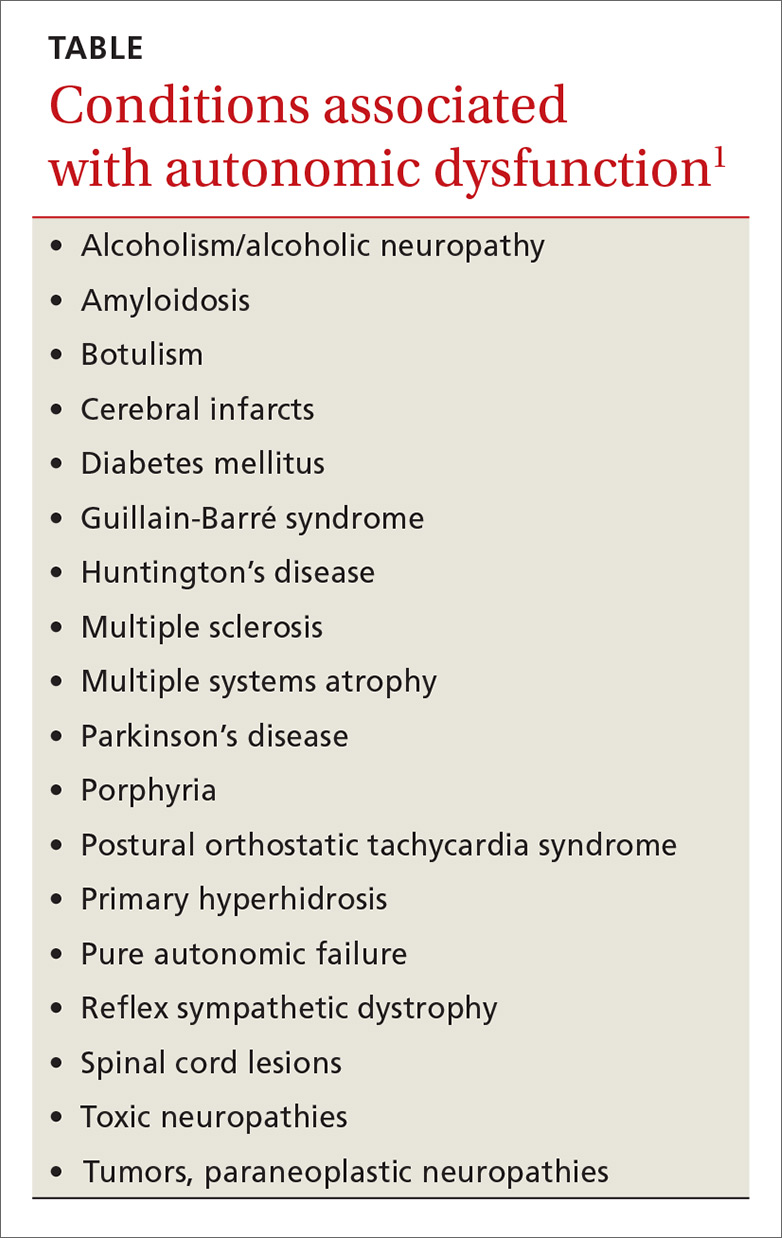

The CDC recommends antiviral medication for individuals with confirmed or suspected influenza who have severe, complicated, or progressive illness, who require hospitalization, or who are at high risk of complications from influenza (TABLE6). Start treatment without waiting for laboratory confirmation for those with suspected influenza who are seriously ill. Outcomes are best when antivirals are started within 48 hours of illness onset, but they can be started even after this “window” has passed.

Once antiviral treatment has begun, make sure the full 5-day course is completed regardless of culture or rapid-test results.6 Use only neuraminidase inhibitors, as there is widespread resistance to adamantanes among influenza A viruses.

Influenza can occur year round

Rates of influenza infection are low in the summer, but cases do occur. Be especially alert if patients with influenza-like illness have been exposed to swine or poultry; they may have contracted a novel influenza A virus. Report such cases to the state or local health department so that staff can facilitate laboratory testing of viral subtypes. Follow the same protocol for patients with influenza symptoms who have traveled to areas where avian influenza viruses have been detected. The CDC is interested in detecting novel influenza viruses, which can start a pandemic.

Prepare for the 2017-2018 influenza season

Family physicians can help prevent influenza and its associated morbidity and mortality in several ways. Offer immunization to all patients, and immunize all health care personnel in your offices and clinics. Treat with antivirals those for whom they are recommended. Prepare office triage policies that prevent patients with flu symptoms from mixing with other patients, ensure that clinic infection control practices are enforced, and advise ill patients to avoid exposing others.7 Finally, stay current on influenza epidemiology and changes in recommendations for treatment and vaccination.

1. Blanton L, Alabi N, Mustaquim D, et al. Update: Influenza activity in the United States during the 2016-2017 season and composition of the 2017-2018 influenza vaccine. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;66:668-676.

2. Shimabukuro T. End-of-season update: 2016-2017 influenza vaccine safety monitoring. Presented at: meeting of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices; June 21, 2017; Atlanta, Ga. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/meetings/downloads/slides-2017-06/flu-04-shimabukuro.pdf. Accessed August 1, 2017.

3. CDC. Frequently asked flu questions 2017-2018 influenza season. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/flu/about/season/flu-season-2017-2018.htm. Accessed July 17, 2017.

4. CDC. Influenza vaccines — United States, 2016-17 influenza season. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/flu/protect/vaccine/vaccines.htm. Accessed July 17, 2017.

5. Grohskopf L. Influenza WG considerations and proposed recommendations. Presented at: meeting of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices; June 21, 2017; Atlanta, Ga. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/meetings/downloads/slides-2017-06/flu-06-grohskopf.pdf. Accessed August 1, 2017.

6. CDC. Use of antivirals. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/flu/professionals/antivirals/antiviral-use-influenza.htm#Box. Accessed July 17, 2017.

7. CDC. Prevention strategies for seasonal influenza in healthcare settings. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/flu/professionals/infectioncontrol/healthcaresettings.htm. Accessed July 17, 2017.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recently reported details of the 2016-2017 influenza season in Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report1 and at the June meeting of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. The CDC monitors influenza activity using several systems, and last flu season was shown to be moderately severe, starting in December in the Western United States, moving east, and peaking in February.

During the peak, 5.1% of outpatient visits were attributed to influenza-like illnesses, and 8.2% of reported deaths were due to pneumonia and influenza. For the whole influenza season, there were more than 18,000 confirmed influenza-related hospitalizations, with 60% of these occurring among those ≥65 years.1 Confirmed influenza-associated pediatric deaths totaled 98.1

The predominant influenza strain last year was type A (H3N2), accounting for about 76% of positive tests in public health laboratories (FIGURE).1 This was followed by influenza B (all lineages) at 22%, and influenza A (H1N1), accounting for only 2%. However, in early April, the predominant strain changed from A (H3N2) to influenza B. Importantly, all viruses tested last year were sensitive to oseltamivir, zanamivir, and peramivir. No antiviral resistance was detected to these neuraminidase inhibitors.

Good news and bad news on vaccine effectiveness. The good news: Circulating viruses were a close match to those contained in the vaccine. The bad news: Vaccine effectiveness at preventing illness was estimated to be just 34% against A (H3N2) and 56% against influenza B viruses.1 There has been no analysis of the relative effectiveness of different vaccines and vaccine types.

The past 6 influenza seasons have revealed a pattern of lower vaccine effectiveness against A (H3N2) compared with effectiveness against A (H1N1) and influenza B viruses. While vaccine effectiveness is not optimal, routine universal use still prevents a great deal of mortality and morbidity. It’s estimated that in 2012-2013, vaccine effectiveness (comparable to that in 2016-2017) prevented 5.6 million illnesses, 2.7 million medical visits, 61,500 hospitalizations, and 1800 deaths.1

More good news: Vaccine safety studies are reassuring

The CDC monitors influenza vaccine safety by using several sources, including the Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System and the Vaccine Safety Datalink.2

Changes for the 2017-2018 influenza season

The composition of influenza vaccine products for the 2017-2018 season will differ slightly from last year’s formulation in the H1N1 component. Viral antigens to be included in the trivalent products are A/Michigan (H1N1), A/Hong Kong (H3N2), and B/Brisbane.3 Quadrivalent products will add B/Phuket to the other 3 antigens.3 A wide array of influenza vaccine products is available. Each one is described on the CDC Web site.4

Two minor changes in the recommendations were made at the June ACIP meeting.5 Afluria is approved by the FDA for use in children starting at age 5 years. ACIP had recommended that its use be reserved for children 9 years and older because previous influenza seasons had raised concerns about increased rates of febrile seizures in children younger than age 9. These concerns have been resolved, however, and the ACIP recommendations are now in concert with those of the FDA for this product.

Influenza immunization with an inactivated influenza vaccine product has been recommended for all pregnant women. Safety data are increasingly available for other product options as well, and ACIP now recommends vaccination in pregnancy with any age-appropriate product except for live attenuated influenza vaccine. 5

Antivirals: Give as needed, even before lab confirmation

The CDC recommends antiviral medication for individuals with confirmed or suspected influenza who have severe, complicated, or progressive illness, who require hospitalization, or who are at high risk of complications from influenza (TABLE6). Start treatment without waiting for laboratory confirmation for those with suspected influenza who are seriously ill. Outcomes are best when antivirals are started within 48 hours of illness onset, but they can be started even after this “window” has passed.

Once antiviral treatment has begun, make sure the full 5-day course is completed regardless of culture or rapid-test results.6 Use only neuraminidase inhibitors, as there is widespread resistance to adamantanes among influenza A viruses.

Influenza can occur year round

Rates of influenza infection are low in the summer, but cases do occur. Be especially alert if patients with influenza-like illness have been exposed to swine or poultry; they may have contracted a novel influenza A virus. Report such cases to the state or local health department so that staff can facilitate laboratory testing of viral subtypes. Follow the same protocol for patients with influenza symptoms who have traveled to areas where avian influenza viruses have been detected. The CDC is interested in detecting novel influenza viruses, which can start a pandemic.

Prepare for the 2017-2018 influenza season

Family physicians can help prevent influenza and its associated morbidity and mortality in several ways. Offer immunization to all patients, and immunize all health care personnel in your offices and clinics. Treat with antivirals those for whom they are recommended. Prepare office triage policies that prevent patients with flu symptoms from mixing with other patients, ensure that clinic infection control practices are enforced, and advise ill patients to avoid exposing others.7 Finally, stay current on influenza epidemiology and changes in recommendations for treatment and vaccination.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recently reported details of the 2016-2017 influenza season in Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report1 and at the June meeting of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. The CDC monitors influenza activity using several systems, and last flu season was shown to be moderately severe, starting in December in the Western United States, moving east, and peaking in February.

During the peak, 5.1% of outpatient visits were attributed to influenza-like illnesses, and 8.2% of reported deaths were due to pneumonia and influenza. For the whole influenza season, there were more than 18,000 confirmed influenza-related hospitalizations, with 60% of these occurring among those ≥65 years.1 Confirmed influenza-associated pediatric deaths totaled 98.1

The predominant influenza strain last year was type A (H3N2), accounting for about 76% of positive tests in public health laboratories (FIGURE).1 This was followed by influenza B (all lineages) at 22%, and influenza A (H1N1), accounting for only 2%. However, in early April, the predominant strain changed from A (H3N2) to influenza B. Importantly, all viruses tested last year were sensitive to oseltamivir, zanamivir, and peramivir. No antiviral resistance was detected to these neuraminidase inhibitors.

Good news and bad news on vaccine effectiveness. The good news: Circulating viruses were a close match to those contained in the vaccine. The bad news: Vaccine effectiveness at preventing illness was estimated to be just 34% against A (H3N2) and 56% against influenza B viruses.1 There has been no analysis of the relative effectiveness of different vaccines and vaccine types.

The past 6 influenza seasons have revealed a pattern of lower vaccine effectiveness against A (H3N2) compared with effectiveness against A (H1N1) and influenza B viruses. While vaccine effectiveness is not optimal, routine universal use still prevents a great deal of mortality and morbidity. It’s estimated that in 2012-2013, vaccine effectiveness (comparable to that in 2016-2017) prevented 5.6 million illnesses, 2.7 million medical visits, 61,500 hospitalizations, and 1800 deaths.1

More good news: Vaccine safety studies are reassuring

The CDC monitors influenza vaccine safety by using several sources, including the Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System and the Vaccine Safety Datalink.2

Changes for the 2017-2018 influenza season

The composition of influenza vaccine products for the 2017-2018 season will differ slightly from last year’s formulation in the H1N1 component. Viral antigens to be included in the trivalent products are A/Michigan (H1N1), A/Hong Kong (H3N2), and B/Brisbane.3 Quadrivalent products will add B/Phuket to the other 3 antigens.3 A wide array of influenza vaccine products is available. Each one is described on the CDC Web site.4

Two minor changes in the recommendations were made at the June ACIP meeting.5 Afluria is approved by the FDA for use in children starting at age 5 years. ACIP had recommended that its use be reserved for children 9 years and older because previous influenza seasons had raised concerns about increased rates of febrile seizures in children younger than age 9. These concerns have been resolved, however, and the ACIP recommendations are now in concert with those of the FDA for this product.

Influenza immunization with an inactivated influenza vaccine product has been recommended for all pregnant women. Safety data are increasingly available for other product options as well, and ACIP now recommends vaccination in pregnancy with any age-appropriate product except for live attenuated influenza vaccine. 5

Antivirals: Give as needed, even before lab confirmation

The CDC recommends antiviral medication for individuals with confirmed or suspected influenza who have severe, complicated, or progressive illness, who require hospitalization, or who are at high risk of complications from influenza (TABLE6). Start treatment without waiting for laboratory confirmation for those with suspected influenza who are seriously ill. Outcomes are best when antivirals are started within 48 hours of illness onset, but they can be started even after this “window” has passed.

Once antiviral treatment has begun, make sure the full 5-day course is completed regardless of culture or rapid-test results.6 Use only neuraminidase inhibitors, as there is widespread resistance to adamantanes among influenza A viruses.

Influenza can occur year round

Rates of influenza infection are low in the summer, but cases do occur. Be especially alert if patients with influenza-like illness have been exposed to swine or poultry; they may have contracted a novel influenza A virus. Report such cases to the state or local health department so that staff can facilitate laboratory testing of viral subtypes. Follow the same protocol for patients with influenza symptoms who have traveled to areas where avian influenza viruses have been detected. The CDC is interested in detecting novel influenza viruses, which can start a pandemic.

Prepare for the 2017-2018 influenza season

Family physicians can help prevent influenza and its associated morbidity and mortality in several ways. Offer immunization to all patients, and immunize all health care personnel in your offices and clinics. Treat with antivirals those for whom they are recommended. Prepare office triage policies that prevent patients with flu symptoms from mixing with other patients, ensure that clinic infection control practices are enforced, and advise ill patients to avoid exposing others.7 Finally, stay current on influenza epidemiology and changes in recommendations for treatment and vaccination.

1. Blanton L, Alabi N, Mustaquim D, et al. Update: Influenza activity in the United States during the 2016-2017 season and composition of the 2017-2018 influenza vaccine. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;66:668-676.

2. Shimabukuro T. End-of-season update: 2016-2017 influenza vaccine safety monitoring. Presented at: meeting of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices; June 21, 2017; Atlanta, Ga. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/meetings/downloads/slides-2017-06/flu-04-shimabukuro.pdf. Accessed August 1, 2017.

3. CDC. Frequently asked flu questions 2017-2018 influenza season. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/flu/about/season/flu-season-2017-2018.htm. Accessed July 17, 2017.

4. CDC. Influenza vaccines — United States, 2016-17 influenza season. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/flu/protect/vaccine/vaccines.htm. Accessed July 17, 2017.

5. Grohskopf L. Influenza WG considerations and proposed recommendations. Presented at: meeting of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices; June 21, 2017; Atlanta, Ga. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/meetings/downloads/slides-2017-06/flu-06-grohskopf.pdf. Accessed August 1, 2017.

6. CDC. Use of antivirals. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/flu/professionals/antivirals/antiviral-use-influenza.htm#Box. Accessed July 17, 2017.

7. CDC. Prevention strategies for seasonal influenza in healthcare settings. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/flu/professionals/infectioncontrol/healthcaresettings.htm. Accessed July 17, 2017.

1. Blanton L, Alabi N, Mustaquim D, et al. Update: Influenza activity in the United States during the 2016-2017 season and composition of the 2017-2018 influenza vaccine. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;66:668-676.

2. Shimabukuro T. End-of-season update: 2016-2017 influenza vaccine safety monitoring. Presented at: meeting of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices; June 21, 2017; Atlanta, Ga. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/meetings/downloads/slides-2017-06/flu-04-shimabukuro.pdf. Accessed August 1, 2017.

3. CDC. Frequently asked flu questions 2017-2018 influenza season. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/flu/about/season/flu-season-2017-2018.htm. Accessed July 17, 2017.

4. CDC. Influenza vaccines — United States, 2016-17 influenza season. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/flu/protect/vaccine/vaccines.htm. Accessed July 17, 2017.

5. Grohskopf L. Influenza WG considerations and proposed recommendations. Presented at: meeting of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices; June 21, 2017; Atlanta, Ga. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/meetings/downloads/slides-2017-06/flu-06-grohskopf.pdf. Accessed August 1, 2017.

6. CDC. Use of antivirals. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/flu/professionals/antivirals/antiviral-use-influenza.htm#Box. Accessed July 17, 2017.

7. CDC. Prevention strategies for seasonal influenza in healthcare settings. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/flu/professionals/infectioncontrol/healthcaresettings.htm. Accessed July 17, 2017.

Individualizing immunization for international travelers

International travel, whether for business, pleasure, child adoption, medical tourism, or adventure, continues to grow. In 2015, more than 70 million US citizens traveled internationally.1 Many individuals contact family physicians first about their plans for travel and questions about travel-related health advice. This article provides an overview of the vaccines recommended for travelers headed to international destinations. Because country-specific vaccination recommendations and requirements for entry and departure change over time, check the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Web site for up-to-date requirements and recommendations (www.cdc.gov/travel).

Vaccine schedules vary according to destination and individual risks

There is no single vaccination schedule that applies to all travelers. Each schedule should be individualized based on the traveler’s destination, risk assessment, previous immunizations, health status, and time available before departure.2,3 Pregnant or immunocompromised travelers should seek advice from an experienced travel medicine consultant on the immunization recommendations specifically meant for them.4,5

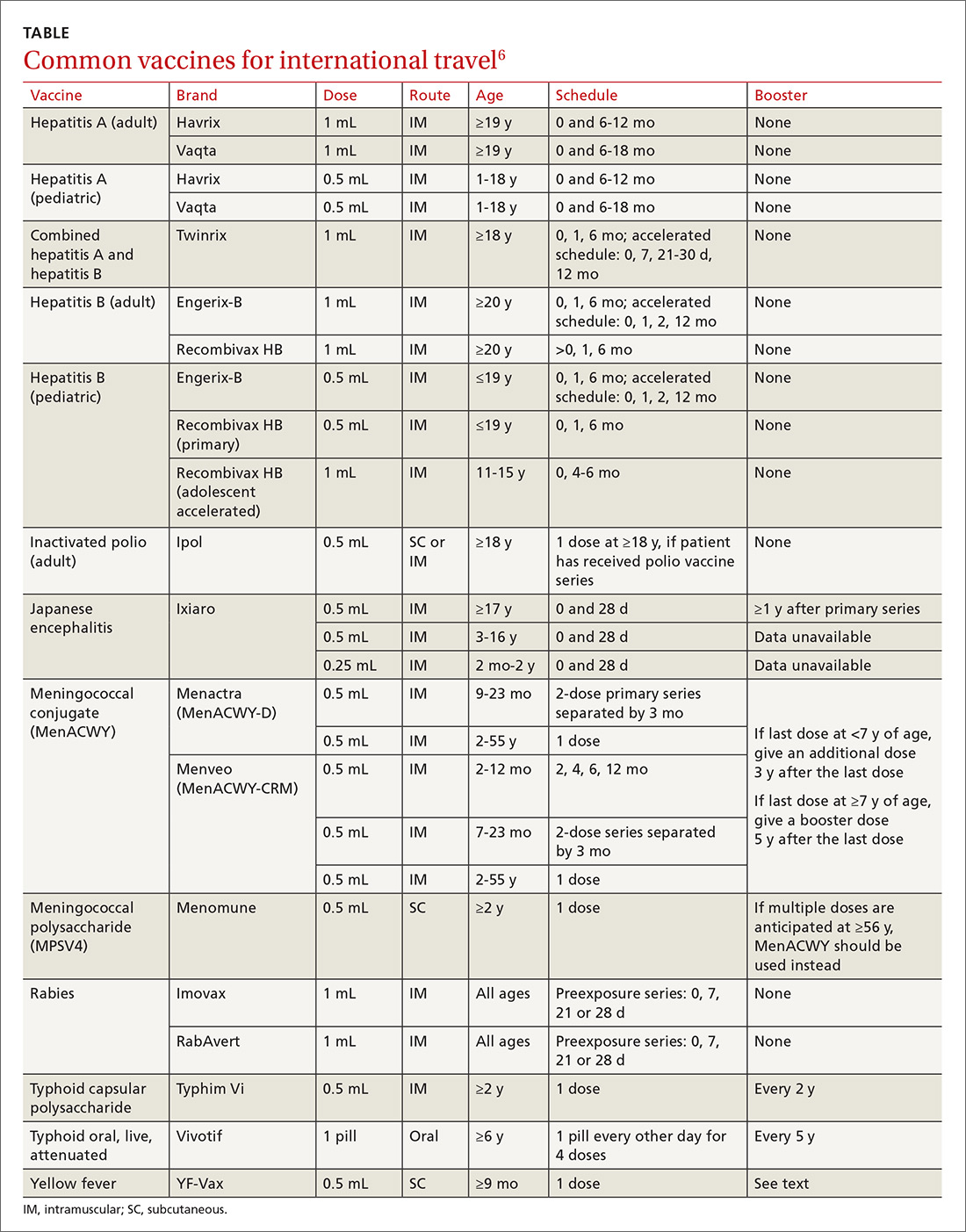

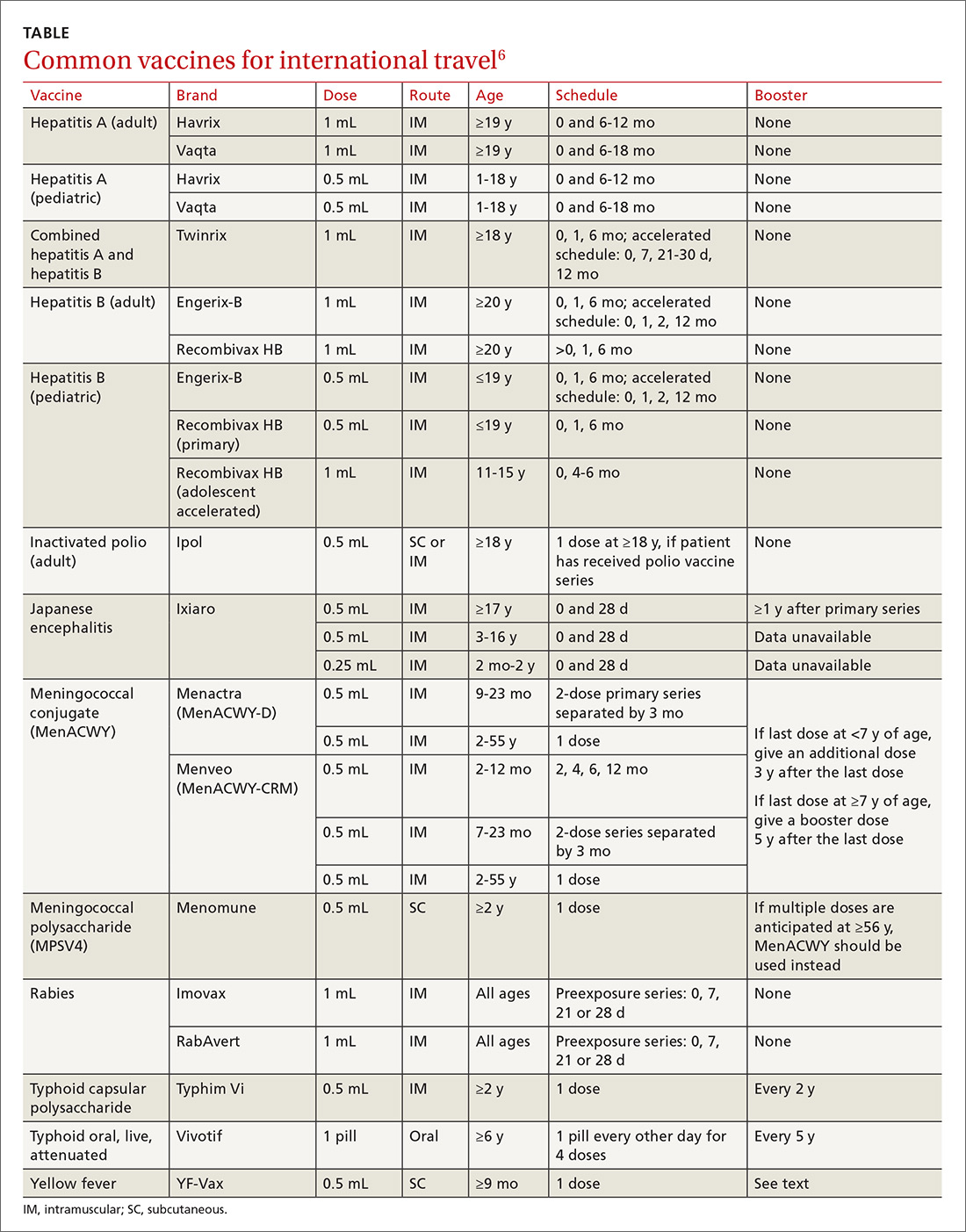

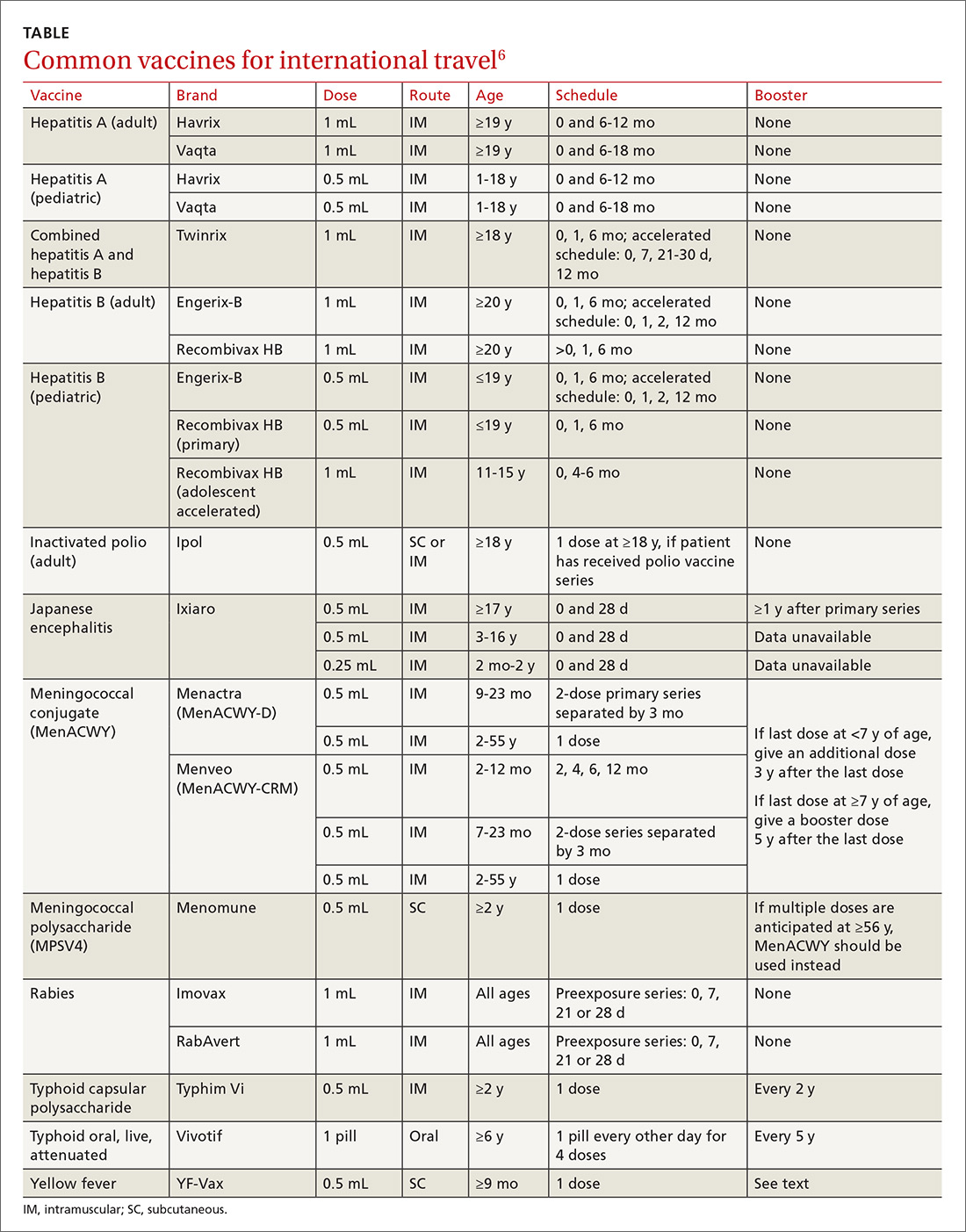

Travel vaccines (TABLE6) are generally categorized as routine, required, or recommended.

- Routine vaccines are the standard child and adult immunizations recommended by the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). These include such vaccines as diphtheria-tetanus toxoids-acellular pertussis (DTaP), inactivated polio vaccine (IPV), Haemophilus influenzae type b (Hib), hepatitis B, rotavirus and pneumococcal vaccines, and human papillomavirus (HPV).

- Required vaccines—eg, yellow fever and meningococcal vaccines—must be documented on the International Certificate of Vaccination before entry into certain countries.

- Recommended vaccines are advised based on the travel destination and anticipated activities. These would include vaccines for typhoid, rabies, Japanese encephalitis, and polio (adult booster).

Routine vaccinations may need to be accelerated

Pre-travel patient encounters are an opportunity to update routine vaccinations.7,8 Immunization against childhood diseases remains suboptimal in developing countries, where vaccine-preventable illnesses occur more frequently.9

Routine vaccines may be administered on an accelerated basis depending on geographic destination, seasonal disease variations, anticipated exposures, and known outbreaks at the time of travel.

MMR vaccine. Measles is still common in many parts of the world, and unvaccinated or incompletely vaccinated travelers are at risk of acquiring the disease and importing it to the United States (see “Measles: Why it’s still a threat,” 2017;66:446-449.) In 2015, a large, widespread measles outbreak occurred in the United States, linked to an amusement park in California, likely originating with an infected traveler who visited the park.10

All children older than 12 months should receive 2 doses of measles-mumps-rubella (MMR) vaccine separated by at least 28 days before departure (regardless of their destination). Infants between 6 and 11 months are at risk for high morbidity and may therefore receive a single dose of MMR earlier than the routinely recommended age of 12 to 15 months. Adolescents and adults without evidence of immunity against measles should get 2 doses of MMR separated by at least 28 days.11 Acceptable presumptive evidence of immunity against measles includes written documentation of adequate vaccination, laboratory evidence of immunity, laboratory confirmation of measles, or birth before 1957.

Varicella vaccine. Children, adolescents, and young adults who have received only one dose of varicella should get a second dose prior to departure. For children 7 to 12 years, the recommended minimum interval between doses is 3 months. For individuals 13 years or older, the minimum interval is 4 weeks.7,8

Influenza vaccine is routinely recommended for all travelers 6 months of age or older, as flu season varies geographically. Flu season in the Northern Hemisphere may begin as early as October and can extend until May. In the Southern Hemisphere, it may begin in April and last through September. Travelers should be vaccinated at least 2 weeks before travel in order to develop adequate immunity.12,13

Required vaccinations: Proof is needed before traveling

Yellow fever (YF) is a mosquito-borne viral illness characterized by fever, chills, headache, myalgia, and vomiting. The disease can progress to coagulopathy, shock, and multisystem organ failure.14 YF vaccine is recommended for individuals 9 months or older who are traveling to or living in areas of South America or Africa where YF virus transmission is common (map: http://www.cdc.gov/yellowfever/maps/).

YF vaccine is a live-attenuated virus formulation and, therefore, should not be given to individuals with primary immunodeficiencies, transplant recipients or patients on immunosuppressive and immunomodulatory therapies, or patients with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) whose CD4 count is below 200/mL. Other contraindications to YF vaccine are age younger than 6 months, allergy to a vaccine component, and thymic disorders. Serious adverse reactions to the vaccine are rare, but include 2 syndromes: YF-associated neurotropic disease and YF vaccine-associated viscerotropic disease.15

In many YF-endemic countries, vaccination is legally required for entry, and proof of vaccination must be documented on an International Certificate of Vaccination or Prophylaxis (ICVP). Additionally, some countries may require proof of vaccination before allowing travel through an endemic region, to prevent introduction of the disease elsewhere. Travelers with a specific contraindication to YF vaccine should obtain a waiver from a physician before traveling to a country requiring vaccination.16

The vaccination certificate is valid beginning 10 days after administration of YF vaccine. Immunity after a single dose is long lasting and may provide lifetime protection. Previously, re-vaccination was required every 10 years; however, in February 2015, ACIP approved a new recommendation stating a single dose of YF vaccine is adequate for most travelers.1

Although ACIP no longer recommends booster doses of YF vaccine for most travelers, clinicians and travelers should review the entry requirements for destination countries because changes to the International Health Regulations have not yet been fully implemented. Once this change is instituted, a completed ICVP will be valid for the lifetime of the vaccine.18,19 Country-specific requirements for YF can be found at http://www.cdc.gov/yellowfever/maps/. (Click on the link below the appropriate map.) In the United States, the YF vaccine is distributed only through approved vaccination centers. These designated clinics are listed in a registry on the CDC travel Web site at https://wwwnc.cdc.gov/travel/yellow-fever-vaccination-clinics/search.

Meningococcal disease. ACIP recommends routine vaccination against meningococcal disease for people 11 to 18 years of age and for individuals with persistent complement component deficiency, functional or anatomic asplenia, and HIV. Vaccination is recommended for travelers who visit or reside in areas where meningococcal disease is hyperendemic or epidemic, such as the meningitis belt of sub-Saharan Africa during the dry season of December to June (map: http://wwwnc.cdc.gov/travel/yellowbook/2016/infectious-diseases-related-to-travel/meningococcal-disease). Travelers to Saudi Arabia during the annual Hajj and Umrah pilgrimages are required to have a certificate of vaccination with quadrivalent (serogroups A, C, Y, W-135) meningococcal vaccine issued within 3 years (and not less than 10 days) before entry.

Several meningococcal vaccines are available in the United States. The quadrivalent vaccines are Menactra (MenACWY-D, Sanofi Pasteur) and Menveo (MenACWY-CRM, GSK). A bivalent (serogroups C and Y) conjugate vaccine MenHibrix (Hib-MenCY-TT, GSK) is also licensed for use in the United States, but infants traveling to areas with high endemic rates of meningococcal disease who received this vaccine are not protected against serogroups A and W and should receive quadrivalent meningococcal conjugate vaccine. Serogroup B vaccination is not routinely recommended for travelers. Approximately 7 to 10 days are required after vaccination for the development of protective antibody levels.7,8,20,21

Polio. Although polio has been nearly eradicated, as of the time this article was written, the disease has not been eliminated in Afghanistan, Guinea, Laos, Nigeria, or Pakistan. Other countries, such as Cameroon, Chad, and Ukraine remain vulnerable to international transmission.22 The CDC recommends that adults who are traveling to areas where wild polio virus (WPV) has circulated in the last 12 months and who are unvaccinated, incompletely vaccinated, or whose vaccination status is unknown should receive a series of 3 doses of IPV to prevent ongoing spread.23 Adults who completed the polio vaccine series as children and are traveling to areas where WPV has circulated in the last 12 months should receive a one-time booster dose of IPV.23

Infants and children in the United States should be vaccinated against polio as part of a routine age-appropriate series. If a child cannot complete the routine series before departure and is traveling to an area where WPV has circulated in the last 12 months, an accelerated schedule is recommended. Vaccination should be documented on the ICVP, as countries with active spread of poliovirus may require proof of polio vaccination upon exit. A list of the countries where the polio virus is currently circulating is available at http://polioeradication.org/polio-today/polio-now/wild-poliovirus-list/.

Both routine and accelerated vaccination schedules for children and adults are published annually by the CDC and are available at http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/schedules/hcp/index.html.

Recommended vaccines

Japanese encephalitis (JE) is endemic throughout most of Asia and parts of the Western Pacific region (map: http://www.cdc.gov/japaneseencephalitis/maps/). JE vaccine is recommended for travelers who plan to spend more than a month in endemic areas during the JE virus transmission season. (In temperate areas of Asia, JE virus transmission is seasonal and usually peaks in the summer and fall. In the subtropics and tropics, transmission can occur year-round, often with a peak during the rainy season.)

This recommendation includes recurrent travelers or expatriates who are likely to visit endemic rural or agricultural areas during a high-risk period of JE virus transmission. Risk is low for travelers who spend less than a month in endemic areas and for those who confine their travel to urban centers. Nevertheless, vaccination should be considered if travel is planned for outside an urban area and includes such activities as camping, hiking, trekking, biking, fishing, hunting, or farming. Inactivated Vero cell culture-derived vaccine (Ixiaro) is the only JE vaccine licensed and available in the United States. Ixiaro is given as a 2-dose series, with the doses spaced 28 days apart. The last dose should be given at least one week before travel.24

Typhoid fever. Vaccination against typhoid fever is recommended for travelers to highly endemic areas such as the Indian subcontinent, Africa, and Central and South America. Two typhoid vaccines are available: Vi capsular polysaccharide vaccine (ViCPS) administered intramuscularly (IM), and oral live attenuated vaccine (Ty21a). Ty21a is a live vaccine and should not be given to immunocompromised people or those taking antibiotics, as it may reduce immunogenicity. Ty21a must be kept refrigerated at 35.6° F to 46.4° F (2° C - 8° C) and administered with cool liquid no warmer than 98.6° F (37° C). Both vaccines are only 50% to 80% efficacious, making access to clean food and water essential.3,5,25

Hepatitis A vaccine should be given to all children older than one year traveling to areas where there is an intermediate or high risk of the disease. Children younger than one year who are traveling to high-risk areas can receive a single dose of immunoglobulin (IG) 0.02 mL/kg IM, which provides protection for up to 3 months. One 0.06 mL/kg-dose IM provides protection for 3 to 5 months.

If travel continues, children should receive a second dose after 5 months. IG does not interfere with the response to YF vaccine, but can interfere with the response to other live injected vaccines (such as MMR and varicella).26

Hepatitis B vaccination should be administered to all unvaccinated travelers who plan to visit an area with intermediate to high prevalence of chronic hepatitis B (HBV surface antigen prevalence ≥2%). Unvaccinated travelers who may engage in high-risk sexual activity or injection drug use should receive hepatitis B vaccine regardless of destination. Additionally, travelers who access medical care for injury or illness while abroad may also be at risk of acquiring hepatitis B via contaminated blood products or medical equipment.27

Serologic testing and booster vaccination are not recommended before travel for immunocompetent adults who have been previously vaccinated. The combined hepatitis A and B vaccine provides effective and convenient dual protection for travelers and can be administered with an accelerated 0-, 7-, and 21-day schedule for last-minute travelers.7,8

Rabies remains endemic in developing countries of Africa and Asia, where appropriate post-exposure prophylaxis is limited or non-existent.28 Consider pre-exposure rabies prophylaxis for traveling patients based on the availability of rabies vaccine and immunoglobulin in their destination area, planned duration of stay, and the likelihood of animal exposure (eg, veterinarians, animal handlers, cavers, missionaries). Advise travelers who decline vaccination to avoid or minimize animal contact during travel. In the event the traveler sustains an animal bite or scratch, immediate cleansing of the wound substantially reduces the risk of infection, especially when followed by timely administration of post-exposure prophylaxis.

Post-exposure prophylaxis for unvaccinated individuals consists of local infiltration of rabies immunoglobulin at the site of the bite and a series of 4 injections of rabies vaccine over 14 days, or 5 doses over one month for immunosuppressed patients. The first dose of the 4-dose course should be administered as soon as possible after exposure. Two vaccines are licensed for use in the United States: human diploid cell vaccine (HDCV, Imovax Rabies, Sanofi Pasteur) and purified chick embryo cell vaccine (PCECV, RabAvert, Novartis Vaccines and Diagnostics). The vaccine should never be administered in the gluteal area, as this may result in lower antibody titers.29

Additionally, promising new vaccines against malaria and dengue fever are under clinical development and may be available in the near future.

CORRESPONDENCE

Vini Vijayan, MD, Division of Infectious Diseases, Arkansas Children's Hospital, 1 Children's Way, Slot 512-11, Little Rock, AR 72202; [email protected].

1. U.S. Department of Commerce, International Trade Administration, National Travel and Tourism Office (NTTO). 2015. Available at: http://travel.trade.gov/view/m-2015-O-001/index.html. Accessed July 12, 2017.

2. Hill DR, Ericsson CD, Pearson RD, et al. The practice of travel medicine: guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;43:1499-1539.

3. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The pre-travel consultation. Available at: https://wwwnc.cdc.gov/travel/yellowbook/2018/the-pre-travel-consultation/the-pre-travel-consultation. Accessed June 20, 2017.

4. Hochberg NS, Barnett ED, Chen LH, et al. International travel by persons with medical comorbidities: understanding risks and providing advice. Mayo Clin Proc. 2013;88:1231-1240.

5. Rubin LG, Levin MJ, Ljungman P, et al. 2013 IDSA clinical practice guideline for vaccination of the immunocompromised host. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;58:e44-e100.

6. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Yellow Book table of contents: Chapter 3. Available at: https://wwwnc.cdc.gov/travel/yellowbook/2018/table-of-contents. Accessed July 21, 2017.

7. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) recommended immunization schedules for persons aged 0 through 18 years—United States, 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65;86-87.

8. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices recommended immunization schedule for adults aged 19 years or older - United States, 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65:88-90.

9. Boggild AK, Castelli F, Gautret P, et al. Vaccine preventable diseases in returned international travelers: results from the GeoSentinel Surveillance Network. Vaccine. 2010;28:7389-7395.

10. Sotir MJ, Esposito DH, Barnett ED, et al. Measles in the 21st century, a continuing preventable risk to travelers: data from the GeoSentinel Global Network. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;62:210-212.

11. Measles. In: Kimberlin DW, Brady MT, Jackson MA, Long SS, eds. Red Book: 2015 Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases. 30th ed. Elk Grove Village, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics; 2015:535-546.

12. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Prevention and control of influenza with vaccines. Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices—United States, 2015-16 Influenza Season. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;64:818-825.

13. Marti F, Steffen R, Mutsch M. Influenza vaccine: a travelers’ vaccine? Expert Rev Vaccines. 2008;7:679-687.

14. Monath T, Gershman MD, Staples JE, et al. Yellow fever vaccine. In: Plotkin SA, Orenstein WA, Offit PA, eds. Vaccines. 6th ed. London, England: W.B. Saunders; 2013:870-968.

15. Staples JE, Gershman M, Fischer M. Yellow fever vaccine: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR Recomm Rep. 2010;59:1-27.

16. World Health Organization. International Health Regulations. 2nd ed. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2005. Available at: http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2008/9789241580410_eng.pdf. Accessed June 20, 2017.

17. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices: summary report. February 26, 2015. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/meetings/downloads/min-archive/min-2015-02.pdf. Accessed July 20, 2017.

18. Staples JE, Bocchini JA Jr, Rubin L, et al. Yellow fever vaccine booster doses: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, 2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;64:647-650.

19. World Health Organization. International travel and health: World–yellow fever vaccination booster. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2014. Available at: http://www.who.int/ith/updates/20140605/en. Accessed June 20, 2017.

20. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Prevention and control of meningococcal disease: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR Recomm Rep. 2013;62:1-28.

21. Memish ZA, Stephens GM, Steffen R, et al. Emergence of medicine for mass gatherings: lessons from the Hajj. Lancet Infect Dis. 2012;12:56-65.

22. World Health Organization. Twelfth meeting of the Emergency Committee under the International Health Regulations (2015) regarding the international spread of poliovirus. Available at: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/news/statements/2017/poliovirus-twelfth-ec/en/. Accessed June 21, 2017.

23. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Interim CDC Guidance for Travel to and from Countries Affected by the New Polio Vaccine Requirements. Available at http://wwwnc.cdc.gov/travel/news-announcements/polio-guidance-new-requirements. Accessed August 1, 2017.

24. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Use of Japanese encephalitis vaccine in children: recommendations of the advisory committee on immunization practices, 2013. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2013;62:898-900.

25. Mahon BE, Newton AE, Mintz ED. Effectiveness of typhoid vaccination in US travelers. Vaccine. 2014;32:3577-3579.

26. Fiore AE, Wasley A, Bell BP. Prevention of hepatitis A through active or passive immunization: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2006;55:1-23.

27. Vivancos R, Abubakar I, Hunter PR. Foreign travel, casual sex, and sexually transmitted infections: systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Infect Dis. 2010;14:e842-e851.

28. Gautret P, Harvey K, Pandey P, et al for the GeoSentinel Surveillance Network. Animal-associated exposure to rabies virus among travelers, 1997-2012. Emerg Infect Dis. 2015;21:569-577.

29. Rupprecht CE, Briggs D, Brown CM, et al; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Use of a reduced (4-dose) vaccine schedule for postexposure prophylaxis to prevent human rabies: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2010;59:1-9.

International travel, whether for business, pleasure, child adoption, medical tourism, or adventure, continues to grow. In 2015, more than 70 million US citizens traveled internationally.1 Many individuals contact family physicians first about their plans for travel and questions about travel-related health advice. This article provides an overview of the vaccines recommended for travelers headed to international destinations. Because country-specific vaccination recommendations and requirements for entry and departure change over time, check the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Web site for up-to-date requirements and recommendations (www.cdc.gov/travel).

Vaccine schedules vary according to destination and individual risks

There is no single vaccination schedule that applies to all travelers. Each schedule should be individualized based on the traveler’s destination, risk assessment, previous immunizations, health status, and time available before departure.2,3 Pregnant or immunocompromised travelers should seek advice from an experienced travel medicine consultant on the immunization recommendations specifically meant for them.4,5

Travel vaccines (TABLE6) are generally categorized as routine, required, or recommended.

- Routine vaccines are the standard child and adult immunizations recommended by the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). These include such vaccines as diphtheria-tetanus toxoids-acellular pertussis (DTaP), inactivated polio vaccine (IPV), Haemophilus influenzae type b (Hib), hepatitis B, rotavirus and pneumococcal vaccines, and human papillomavirus (HPV).

- Required vaccines—eg, yellow fever and meningococcal vaccines—must be documented on the International Certificate of Vaccination before entry into certain countries.

- Recommended vaccines are advised based on the travel destination and anticipated activities. These would include vaccines for typhoid, rabies, Japanese encephalitis, and polio (adult booster).

Routine vaccinations may need to be accelerated

Pre-travel patient encounters are an opportunity to update routine vaccinations.7,8 Immunization against childhood diseases remains suboptimal in developing countries, where vaccine-preventable illnesses occur more frequently.9

Routine vaccines may be administered on an accelerated basis depending on geographic destination, seasonal disease variations, anticipated exposures, and known outbreaks at the time of travel.

MMR vaccine. Measles is still common in many parts of the world, and unvaccinated or incompletely vaccinated travelers are at risk of acquiring the disease and importing it to the United States (see “Measles: Why it’s still a threat,” 2017;66:446-449.) In 2015, a large, widespread measles outbreak occurred in the United States, linked to an amusement park in California, likely originating with an infected traveler who visited the park.10

All children older than 12 months should receive 2 doses of measles-mumps-rubella (MMR) vaccine separated by at least 28 days before departure (regardless of their destination). Infants between 6 and 11 months are at risk for high morbidity and may therefore receive a single dose of MMR earlier than the routinely recommended age of 12 to 15 months. Adolescents and adults without evidence of immunity against measles should get 2 doses of MMR separated by at least 28 days.11 Acceptable presumptive evidence of immunity against measles includes written documentation of adequate vaccination, laboratory evidence of immunity, laboratory confirmation of measles, or birth before 1957.

Varicella vaccine. Children, adolescents, and young adults who have received only one dose of varicella should get a second dose prior to departure. For children 7 to 12 years, the recommended minimum interval between doses is 3 months. For individuals 13 years or older, the minimum interval is 4 weeks.7,8

Influenza vaccine is routinely recommended for all travelers 6 months of age or older, as flu season varies geographically. Flu season in the Northern Hemisphere may begin as early as October and can extend until May. In the Southern Hemisphere, it may begin in April and last through September. Travelers should be vaccinated at least 2 weeks before travel in order to develop adequate immunity.12,13

Required vaccinations: Proof is needed before traveling

Yellow fever (YF) is a mosquito-borne viral illness characterized by fever, chills, headache, myalgia, and vomiting. The disease can progress to coagulopathy, shock, and multisystem organ failure.14 YF vaccine is recommended for individuals 9 months or older who are traveling to or living in areas of South America or Africa where YF virus transmission is common (map: http://www.cdc.gov/yellowfever/maps/).

YF vaccine is a live-attenuated virus formulation and, therefore, should not be given to individuals with primary immunodeficiencies, transplant recipients or patients on immunosuppressive and immunomodulatory therapies, or patients with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) whose CD4 count is below 200/mL. Other contraindications to YF vaccine are age younger than 6 months, allergy to a vaccine component, and thymic disorders. Serious adverse reactions to the vaccine are rare, but include 2 syndromes: YF-associated neurotropic disease and YF vaccine-associated viscerotropic disease.15

In many YF-endemic countries, vaccination is legally required for entry, and proof of vaccination must be documented on an International Certificate of Vaccination or Prophylaxis (ICVP). Additionally, some countries may require proof of vaccination before allowing travel through an endemic region, to prevent introduction of the disease elsewhere. Travelers with a specific contraindication to YF vaccine should obtain a waiver from a physician before traveling to a country requiring vaccination.16

The vaccination certificate is valid beginning 10 days after administration of YF vaccine. Immunity after a single dose is long lasting and may provide lifetime protection. Previously, re-vaccination was required every 10 years; however, in February 2015, ACIP approved a new recommendation stating a single dose of YF vaccine is adequate for most travelers.1

Although ACIP no longer recommends booster doses of YF vaccine for most travelers, clinicians and travelers should review the entry requirements for destination countries because changes to the International Health Regulations have not yet been fully implemented. Once this change is instituted, a completed ICVP will be valid for the lifetime of the vaccine.18,19 Country-specific requirements for YF can be found at http://www.cdc.gov/yellowfever/maps/. (Click on the link below the appropriate map.) In the United States, the YF vaccine is distributed only through approved vaccination centers. These designated clinics are listed in a registry on the CDC travel Web site at https://wwwnc.cdc.gov/travel/yellow-fever-vaccination-clinics/search.

Meningococcal disease. ACIP recommends routine vaccination against meningococcal disease for people 11 to 18 years of age and for individuals with persistent complement component deficiency, functional or anatomic asplenia, and HIV. Vaccination is recommended for travelers who visit or reside in areas where meningococcal disease is hyperendemic or epidemic, such as the meningitis belt of sub-Saharan Africa during the dry season of December to June (map: http://wwwnc.cdc.gov/travel/yellowbook/2016/infectious-diseases-related-to-travel/meningococcal-disease). Travelers to Saudi Arabia during the annual Hajj and Umrah pilgrimages are required to have a certificate of vaccination with quadrivalent (serogroups A, C, Y, W-135) meningococcal vaccine issued within 3 years (and not less than 10 days) before entry.

Several meningococcal vaccines are available in the United States. The quadrivalent vaccines are Menactra (MenACWY-D, Sanofi Pasteur) and Menveo (MenACWY-CRM, GSK). A bivalent (serogroups C and Y) conjugate vaccine MenHibrix (Hib-MenCY-TT, GSK) is also licensed for use in the United States, but infants traveling to areas with high endemic rates of meningococcal disease who received this vaccine are not protected against serogroups A and W and should receive quadrivalent meningococcal conjugate vaccine. Serogroup B vaccination is not routinely recommended for travelers. Approximately 7 to 10 days are required after vaccination for the development of protective antibody levels.7,8,20,21

Polio. Although polio has been nearly eradicated, as of the time this article was written, the disease has not been eliminated in Afghanistan, Guinea, Laos, Nigeria, or Pakistan. Other countries, such as Cameroon, Chad, and Ukraine remain vulnerable to international transmission.22 The CDC recommends that adults who are traveling to areas where wild polio virus (WPV) has circulated in the last 12 months and who are unvaccinated, incompletely vaccinated, or whose vaccination status is unknown should receive a series of 3 doses of IPV to prevent ongoing spread.23 Adults who completed the polio vaccine series as children and are traveling to areas where WPV has circulated in the last 12 months should receive a one-time booster dose of IPV.23

Infants and children in the United States should be vaccinated against polio as part of a routine age-appropriate series. If a child cannot complete the routine series before departure and is traveling to an area where WPV has circulated in the last 12 months, an accelerated schedule is recommended. Vaccination should be documented on the ICVP, as countries with active spread of poliovirus may require proof of polio vaccination upon exit. A list of the countries where the polio virus is currently circulating is available at http://polioeradication.org/polio-today/polio-now/wild-poliovirus-list/.

Both routine and accelerated vaccination schedules for children and adults are published annually by the CDC and are available at http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/schedules/hcp/index.html.

Recommended vaccines

Japanese encephalitis (JE) is endemic throughout most of Asia and parts of the Western Pacific region (map: http://www.cdc.gov/japaneseencephalitis/maps/). JE vaccine is recommended for travelers who plan to spend more than a month in endemic areas during the JE virus transmission season. (In temperate areas of Asia, JE virus transmission is seasonal and usually peaks in the summer and fall. In the subtropics and tropics, transmission can occur year-round, often with a peak during the rainy season.)

This recommendation includes recurrent travelers or expatriates who are likely to visit endemic rural or agricultural areas during a high-risk period of JE virus transmission. Risk is low for travelers who spend less than a month in endemic areas and for those who confine their travel to urban centers. Nevertheless, vaccination should be considered if travel is planned for outside an urban area and includes such activities as camping, hiking, trekking, biking, fishing, hunting, or farming. Inactivated Vero cell culture-derived vaccine (Ixiaro) is the only JE vaccine licensed and available in the United States. Ixiaro is given as a 2-dose series, with the doses spaced 28 days apart. The last dose should be given at least one week before travel.24

Typhoid fever. Vaccination against typhoid fever is recommended for travelers to highly endemic areas such as the Indian subcontinent, Africa, and Central and South America. Two typhoid vaccines are available: Vi capsular polysaccharide vaccine (ViCPS) administered intramuscularly (IM), and oral live attenuated vaccine (Ty21a). Ty21a is a live vaccine and should not be given to immunocompromised people or those taking antibiotics, as it may reduce immunogenicity. Ty21a must be kept refrigerated at 35.6° F to 46.4° F (2° C - 8° C) and administered with cool liquid no warmer than 98.6° F (37° C). Both vaccines are only 50% to 80% efficacious, making access to clean food and water essential.3,5,25

Hepatitis A vaccine should be given to all children older than one year traveling to areas where there is an intermediate or high risk of the disease. Children younger than one year who are traveling to high-risk areas can receive a single dose of immunoglobulin (IG) 0.02 mL/kg IM, which provides protection for up to 3 months. One 0.06 mL/kg-dose IM provides protection for 3 to 5 months.

If travel continues, children should receive a second dose after 5 months. IG does not interfere with the response to YF vaccine, but can interfere with the response to other live injected vaccines (such as MMR and varicella).26

Hepatitis B vaccination should be administered to all unvaccinated travelers who plan to visit an area with intermediate to high prevalence of chronic hepatitis B (HBV surface antigen prevalence ≥2%). Unvaccinated travelers who may engage in high-risk sexual activity or injection drug use should receive hepatitis B vaccine regardless of destination. Additionally, travelers who access medical care for injury or illness while abroad may also be at risk of acquiring hepatitis B via contaminated blood products or medical equipment.27

Serologic testing and booster vaccination are not recommended before travel for immunocompetent adults who have been previously vaccinated. The combined hepatitis A and B vaccine provides effective and convenient dual protection for travelers and can be administered with an accelerated 0-, 7-, and 21-day schedule for last-minute travelers.7,8

Rabies remains endemic in developing countries of Africa and Asia, where appropriate post-exposure prophylaxis is limited or non-existent.28 Consider pre-exposure rabies prophylaxis for traveling patients based on the availability of rabies vaccine and immunoglobulin in their destination area, planned duration of stay, and the likelihood of animal exposure (eg, veterinarians, animal handlers, cavers, missionaries). Advise travelers who decline vaccination to avoid or minimize animal contact during travel. In the event the traveler sustains an animal bite or scratch, immediate cleansing of the wound substantially reduces the risk of infection, especially when followed by timely administration of post-exposure prophylaxis.

Post-exposure prophylaxis for unvaccinated individuals consists of local infiltration of rabies immunoglobulin at the site of the bite and a series of 4 injections of rabies vaccine over 14 days, or 5 doses over one month for immunosuppressed patients. The first dose of the 4-dose course should be administered as soon as possible after exposure. Two vaccines are licensed for use in the United States: human diploid cell vaccine (HDCV, Imovax Rabies, Sanofi Pasteur) and purified chick embryo cell vaccine (PCECV, RabAvert, Novartis Vaccines and Diagnostics). The vaccine should never be administered in the gluteal area, as this may result in lower antibody titers.29

Additionally, promising new vaccines against malaria and dengue fever are under clinical development and may be available in the near future.

CORRESPONDENCE

Vini Vijayan, MD, Division of Infectious Diseases, Arkansas Children's Hospital, 1 Children's Way, Slot 512-11, Little Rock, AR 72202; [email protected].

International travel, whether for business, pleasure, child adoption, medical tourism, or adventure, continues to grow. In 2015, more than 70 million US citizens traveled internationally.1 Many individuals contact family physicians first about their plans for travel and questions about travel-related health advice. This article provides an overview of the vaccines recommended for travelers headed to international destinations. Because country-specific vaccination recommendations and requirements for entry and departure change over time, check the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Web site for up-to-date requirements and recommendations (www.cdc.gov/travel).

Vaccine schedules vary according to destination and individual risks

There is no single vaccination schedule that applies to all travelers. Each schedule should be individualized based on the traveler’s destination, risk assessment, previous immunizations, health status, and time available before departure.2,3 Pregnant or immunocompromised travelers should seek advice from an experienced travel medicine consultant on the immunization recommendations specifically meant for them.4,5

Travel vaccines (TABLE6) are generally categorized as routine, required, or recommended.

- Routine vaccines are the standard child and adult immunizations recommended by the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). These include such vaccines as diphtheria-tetanus toxoids-acellular pertussis (DTaP), inactivated polio vaccine (IPV), Haemophilus influenzae type b (Hib), hepatitis B, rotavirus and pneumococcal vaccines, and human papillomavirus (HPV).

- Required vaccines—eg, yellow fever and meningococcal vaccines—must be documented on the International Certificate of Vaccination before entry into certain countries.

- Recommended vaccines are advised based on the travel destination and anticipated activities. These would include vaccines for typhoid, rabies, Japanese encephalitis, and polio (adult booster).

Routine vaccinations may need to be accelerated

Pre-travel patient encounters are an opportunity to update routine vaccinations.7,8 Immunization against childhood diseases remains suboptimal in developing countries, where vaccine-preventable illnesses occur more frequently.9

Routine vaccines may be administered on an accelerated basis depending on geographic destination, seasonal disease variations, anticipated exposures, and known outbreaks at the time of travel.

MMR vaccine. Measles is still common in many parts of the world, and unvaccinated or incompletely vaccinated travelers are at risk of acquiring the disease and importing it to the United States (see “Measles: Why it’s still a threat,” 2017;66:446-449.) In 2015, a large, widespread measles outbreak occurred in the United States, linked to an amusement park in California, likely originating with an infected traveler who visited the park.10

All children older than 12 months should receive 2 doses of measles-mumps-rubella (MMR) vaccine separated by at least 28 days before departure (regardless of their destination). Infants between 6 and 11 months are at risk for high morbidity and may therefore receive a single dose of MMR earlier than the routinely recommended age of 12 to 15 months. Adolescents and adults without evidence of immunity against measles should get 2 doses of MMR separated by at least 28 days.11 Acceptable presumptive evidence of immunity against measles includes written documentation of adequate vaccination, laboratory evidence of immunity, laboratory confirmation of measles, or birth before 1957.

Varicella vaccine. Children, adolescents, and young adults who have received only one dose of varicella should get a second dose prior to departure. For children 7 to 12 years, the recommended minimum interval between doses is 3 months. For individuals 13 years or older, the minimum interval is 4 weeks.7,8

Influenza vaccine is routinely recommended for all travelers 6 months of age or older, as flu season varies geographically. Flu season in the Northern Hemisphere may begin as early as October and can extend until May. In the Southern Hemisphere, it may begin in April and last through September. Travelers should be vaccinated at least 2 weeks before travel in order to develop adequate immunity.12,13

Required vaccinations: Proof is needed before traveling

Yellow fever (YF) is a mosquito-borne viral illness characterized by fever, chills, headache, myalgia, and vomiting. The disease can progress to coagulopathy, shock, and multisystem organ failure.14 YF vaccine is recommended for individuals 9 months or older who are traveling to or living in areas of South America or Africa where YF virus transmission is common (map: http://www.cdc.gov/yellowfever/maps/).

YF vaccine is a live-attenuated virus formulation and, therefore, should not be given to individuals with primary immunodeficiencies, transplant recipients or patients on immunosuppressive and immunomodulatory therapies, or patients with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) whose CD4 count is below 200/mL. Other contraindications to YF vaccine are age younger than 6 months, allergy to a vaccine component, and thymic disorders. Serious adverse reactions to the vaccine are rare, but include 2 syndromes: YF-associated neurotropic disease and YF vaccine-associated viscerotropic disease.15

In many YF-endemic countries, vaccination is legally required for entry, and proof of vaccination must be documented on an International Certificate of Vaccination or Prophylaxis (ICVP). Additionally, some countries may require proof of vaccination before allowing travel through an endemic region, to prevent introduction of the disease elsewhere. Travelers with a specific contraindication to YF vaccine should obtain a waiver from a physician before traveling to a country requiring vaccination.16

The vaccination certificate is valid beginning 10 days after administration of YF vaccine. Immunity after a single dose is long lasting and may provide lifetime protection. Previously, re-vaccination was required every 10 years; however, in February 2015, ACIP approved a new recommendation stating a single dose of YF vaccine is adequate for most travelers.1

Although ACIP no longer recommends booster doses of YF vaccine for most travelers, clinicians and travelers should review the entry requirements for destination countries because changes to the International Health Regulations have not yet been fully implemented. Once this change is instituted, a completed ICVP will be valid for the lifetime of the vaccine.18,19 Country-specific requirements for YF can be found at http://www.cdc.gov/yellowfever/maps/. (Click on the link below the appropriate map.) In the United States, the YF vaccine is distributed only through approved vaccination centers. These designated clinics are listed in a registry on the CDC travel Web site at https://wwwnc.cdc.gov/travel/yellow-fever-vaccination-clinics/search.

Meningococcal disease. ACIP recommends routine vaccination against meningococcal disease for people 11 to 18 years of age and for individuals with persistent complement component deficiency, functional or anatomic asplenia, and HIV. Vaccination is recommended for travelers who visit or reside in areas where meningococcal disease is hyperendemic or epidemic, such as the meningitis belt of sub-Saharan Africa during the dry season of December to June (map: http://wwwnc.cdc.gov/travel/yellowbook/2016/infectious-diseases-related-to-travel/meningococcal-disease). Travelers to Saudi Arabia during the annual Hajj and Umrah pilgrimages are required to have a certificate of vaccination with quadrivalent (serogroups A, C, Y, W-135) meningococcal vaccine issued within 3 years (and not less than 10 days) before entry.

Several meningococcal vaccines are available in the United States. The quadrivalent vaccines are Menactra (MenACWY-D, Sanofi Pasteur) and Menveo (MenACWY-CRM, GSK). A bivalent (serogroups C and Y) conjugate vaccine MenHibrix (Hib-MenCY-TT, GSK) is also licensed for use in the United States, but infants traveling to areas with high endemic rates of meningococcal disease who received this vaccine are not protected against serogroups A and W and should receive quadrivalent meningococcal conjugate vaccine. Serogroup B vaccination is not routinely recommended for travelers. Approximately 7 to 10 days are required after vaccination for the development of protective antibody levels.7,8,20,21

Polio. Although polio has been nearly eradicated, as of the time this article was written, the disease has not been eliminated in Afghanistan, Guinea, Laos, Nigeria, or Pakistan. Other countries, such as Cameroon, Chad, and Ukraine remain vulnerable to international transmission.22 The CDC recommends that adults who are traveling to areas where wild polio virus (WPV) has circulated in the last 12 months and who are unvaccinated, incompletely vaccinated, or whose vaccination status is unknown should receive a series of 3 doses of IPV to prevent ongoing spread.23 Adults who completed the polio vaccine series as children and are traveling to areas where WPV has circulated in the last 12 months should receive a one-time booster dose of IPV.23

Infants and children in the United States should be vaccinated against polio as part of a routine age-appropriate series. If a child cannot complete the routine series before departure and is traveling to an area where WPV has circulated in the last 12 months, an accelerated schedule is recommended. Vaccination should be documented on the ICVP, as countries with active spread of poliovirus may require proof of polio vaccination upon exit. A list of the countries where the polio virus is currently circulating is available at http://polioeradication.org/polio-today/polio-now/wild-poliovirus-list/.

Both routine and accelerated vaccination schedules for children and adults are published annually by the CDC and are available at http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/schedules/hcp/index.html.

Recommended vaccines

Japanese encephalitis (JE) is endemic throughout most of Asia and parts of the Western Pacific region (map: http://www.cdc.gov/japaneseencephalitis/maps/). JE vaccine is recommended for travelers who plan to spend more than a month in endemic areas during the JE virus transmission season. (In temperate areas of Asia, JE virus transmission is seasonal and usually peaks in the summer and fall. In the subtropics and tropics, transmission can occur year-round, often with a peak during the rainy season.)

This recommendation includes recurrent travelers or expatriates who are likely to visit endemic rural or agricultural areas during a high-risk period of JE virus transmission. Risk is low for travelers who spend less than a month in endemic areas and for those who confine their travel to urban centers. Nevertheless, vaccination should be considered if travel is planned for outside an urban area and includes such activities as camping, hiking, trekking, biking, fishing, hunting, or farming. Inactivated Vero cell culture-derived vaccine (Ixiaro) is the only JE vaccine licensed and available in the United States. Ixiaro is given as a 2-dose series, with the doses spaced 28 days apart. The last dose should be given at least one week before travel.24

Typhoid fever. Vaccination against typhoid fever is recommended for travelers to highly endemic areas such as the Indian subcontinent, Africa, and Central and South America. Two typhoid vaccines are available: Vi capsular polysaccharide vaccine (ViCPS) administered intramuscularly (IM), and oral live attenuated vaccine (Ty21a). Ty21a is a live vaccine and should not be given to immunocompromised people or those taking antibiotics, as it may reduce immunogenicity. Ty21a must be kept refrigerated at 35.6° F to 46.4° F (2° C - 8° C) and administered with cool liquid no warmer than 98.6° F (37° C). Both vaccines are only 50% to 80% efficacious, making access to clean food and water essential.3,5,25

Hepatitis A vaccine should be given to all children older than one year traveling to areas where there is an intermediate or high risk of the disease. Children younger than one year who are traveling to high-risk areas can receive a single dose of immunoglobulin (IG) 0.02 mL/kg IM, which provides protection for up to 3 months. One 0.06 mL/kg-dose IM provides protection for 3 to 5 months.

If travel continues, children should receive a second dose after 5 months. IG does not interfere with the response to YF vaccine, but can interfere with the response to other live injected vaccines (such as MMR and varicella).26

Hepatitis B vaccination should be administered to all unvaccinated travelers who plan to visit an area with intermediate to high prevalence of chronic hepatitis B (HBV surface antigen prevalence ≥2%). Unvaccinated travelers who may engage in high-risk sexual activity or injection drug use should receive hepatitis B vaccine regardless of destination. Additionally, travelers who access medical care for injury or illness while abroad may also be at risk of acquiring hepatitis B via contaminated blood products or medical equipment.27

Serologic testing and booster vaccination are not recommended before travel for immunocompetent adults who have been previously vaccinated. The combined hepatitis A and B vaccine provides effective and convenient dual protection for travelers and can be administered with an accelerated 0-, 7-, and 21-day schedule for last-minute travelers.7,8

Rabies remains endemic in developing countries of Africa and Asia, where appropriate post-exposure prophylaxis is limited or non-existent.28 Consider pre-exposure rabies prophylaxis for traveling patients based on the availability of rabies vaccine and immunoglobulin in their destination area, planned duration of stay, and the likelihood of animal exposure (eg, veterinarians, animal handlers, cavers, missionaries). Advise travelers who decline vaccination to avoid or minimize animal contact during travel. In the event the traveler sustains an animal bite or scratch, immediate cleansing of the wound substantially reduces the risk of infection, especially when followed by timely administration of post-exposure prophylaxis.

Post-exposure prophylaxis for unvaccinated individuals consists of local infiltration of rabies immunoglobulin at the site of the bite and a series of 4 injections of rabies vaccine over 14 days, or 5 doses over one month for immunosuppressed patients. The first dose of the 4-dose course should be administered as soon as possible after exposure. Two vaccines are licensed for use in the United States: human diploid cell vaccine (HDCV, Imovax Rabies, Sanofi Pasteur) and purified chick embryo cell vaccine (PCECV, RabAvert, Novartis Vaccines and Diagnostics). The vaccine should never be administered in the gluteal area, as this may result in lower antibody titers.29

Additionally, promising new vaccines against malaria and dengue fever are under clinical development and may be available in the near future.

CORRESPONDENCE

Vini Vijayan, MD, Division of Infectious Diseases, Arkansas Children's Hospital, 1 Children's Way, Slot 512-11, Little Rock, AR 72202; [email protected].

1. U.S. Department of Commerce, International Trade Administration, National Travel and Tourism Office (NTTO). 2015. Available at: http://travel.trade.gov/view/m-2015-O-001/index.html. Accessed July 12, 2017.

2. Hill DR, Ericsson CD, Pearson RD, et al. The practice of travel medicine: guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;43:1499-1539.

3. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The pre-travel consultation. Available at: https://wwwnc.cdc.gov/travel/yellowbook/2018/the-pre-travel-consultation/the-pre-travel-consultation. Accessed June 20, 2017.

4. Hochberg NS, Barnett ED, Chen LH, et al. International travel by persons with medical comorbidities: understanding risks and providing advice. Mayo Clin Proc. 2013;88:1231-1240.

5. Rubin LG, Levin MJ, Ljungman P, et al. 2013 IDSA clinical practice guideline for vaccination of the immunocompromised host. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;58:e44-e100.

6. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Yellow Book table of contents: Chapter 3. Available at: https://wwwnc.cdc.gov/travel/yellowbook/2018/table-of-contents. Accessed July 21, 2017.

7. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) recommended immunization schedules for persons aged 0 through 18 years—United States, 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65;86-87.

8. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices recommended immunization schedule for adults aged 19 years or older - United States, 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65:88-90.

9. Boggild AK, Castelli F, Gautret P, et al. Vaccine preventable diseases in returned international travelers: results from the GeoSentinel Surveillance Network. Vaccine. 2010;28:7389-7395.

10. Sotir MJ, Esposito DH, Barnett ED, et al. Measles in the 21st century, a continuing preventable risk to travelers: data from the GeoSentinel Global Network. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;62:210-212.

11. Measles. In: Kimberlin DW, Brady MT, Jackson MA, Long SS, eds. Red Book: 2015 Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases. 30th ed. Elk Grove Village, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics; 2015:535-546.

12. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Prevention and control of influenza with vaccines. Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices—United States, 2015-16 Influenza Season. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;64:818-825.

13. Marti F, Steffen R, Mutsch M. Influenza vaccine: a travelers’ vaccine? Expert Rev Vaccines. 2008;7:679-687.

14. Monath T, Gershman MD, Staples JE, et al. Yellow fever vaccine. In: Plotkin SA, Orenstein WA, Offit PA, eds. Vaccines. 6th ed. London, England: W.B. Saunders; 2013:870-968.

15. Staples JE, Gershman M, Fischer M. Yellow fever vaccine: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR Recomm Rep. 2010;59:1-27.

16. World Health Organization. International Health Regulations. 2nd ed. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2005. Available at: http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2008/9789241580410_eng.pdf. Accessed June 20, 2017.

17. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices: summary report. February 26, 2015. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/meetings/downloads/min-archive/min-2015-02.pdf. Accessed July 20, 2017.

18. Staples JE, Bocchini JA Jr, Rubin L, et al. Yellow fever vaccine booster doses: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, 2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;64:647-650.

19. World Health Organization. International travel and health: World–yellow fever vaccination booster. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2014. Available at: http://www.who.int/ith/updates/20140605/en. Accessed June 20, 2017.

20. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Prevention and control of meningococcal disease: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR Recomm Rep. 2013;62:1-28.

21. Memish ZA, Stephens GM, Steffen R, et al. Emergence of medicine for mass gatherings: lessons from the Hajj. Lancet Infect Dis. 2012;12:56-65.

22. World Health Organization. Twelfth meeting of the Emergency Committee under the International Health Regulations (2015) regarding the international spread of poliovirus. Available at: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/news/statements/2017/poliovirus-twelfth-ec/en/. Accessed June 21, 2017.

23. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Interim CDC Guidance for Travel to and from Countries Affected by the New Polio Vaccine Requirements. Available at http://wwwnc.cdc.gov/travel/news-announcements/polio-guidance-new-requirements. Accessed August 1, 2017.

24. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Use of Japanese encephalitis vaccine in children: recommendations of the advisory committee on immunization practices, 2013. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2013;62:898-900.

25. Mahon BE, Newton AE, Mintz ED. Effectiveness of typhoid vaccination in US travelers. Vaccine. 2014;32:3577-3579.

26. Fiore AE, Wasley A, Bell BP. Prevention of hepatitis A through active or passive immunization: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2006;55:1-23.