User login

Severely painful vesicular rash

The family physician (FP) recognized the multiple vesicles on the patient’s hands as pompholyx, also known as dyshidrotic eczema. The term “pompholyx” means bubble, while the term “dyshidrotic” means "difficult sweating," as problems with sweating were once believed to be the cause of this condition. Some dermatologists prefer the name “vesicular hand dermatitis.” Regardless of the terminology, this can be a mild condition that is a minor nuisance or a severe chronic condition that impairs the patient's quality of life.

The FP prescribed 0.1% triamcinolone cream to be applied twice daily and gave the patient a referral to a dermatologist. While waiting for the dermatology appointment, the patient was not improving, so she went to an emergency room, where she received a prescription for oral prednisone.

When she arrived at the dermatology office, she stated that neither the topical cream nor the oral prednisone helped to improve the rash on her hands. The dermatologist performed patch testing and discovered that she had a contact allergy to topical steroids. He withdrew the steroids and started her on oral cyclosporine, which cleared the rash.

One major lesson from this case is that patients can actually be allergic to topical steroids. Referral to Dermatology was appropriate as the complexity of this case was beyond the scope of family medicine.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R. Hand eczema. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:597-602.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The family physician (FP) recognized the multiple vesicles on the patient’s hands as pompholyx, also known as dyshidrotic eczema. The term “pompholyx” means bubble, while the term “dyshidrotic” means "difficult sweating," as problems with sweating were once believed to be the cause of this condition. Some dermatologists prefer the name “vesicular hand dermatitis.” Regardless of the terminology, this can be a mild condition that is a minor nuisance or a severe chronic condition that impairs the patient's quality of life.

The FP prescribed 0.1% triamcinolone cream to be applied twice daily and gave the patient a referral to a dermatologist. While waiting for the dermatology appointment, the patient was not improving, so she went to an emergency room, where she received a prescription for oral prednisone.

When she arrived at the dermatology office, she stated that neither the topical cream nor the oral prednisone helped to improve the rash on her hands. The dermatologist performed patch testing and discovered that she had a contact allergy to topical steroids. He withdrew the steroids and started her on oral cyclosporine, which cleared the rash.

One major lesson from this case is that patients can actually be allergic to topical steroids. Referral to Dermatology was appropriate as the complexity of this case was beyond the scope of family medicine.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R. Hand eczema. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:597-602.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The family physician (FP) recognized the multiple vesicles on the patient’s hands as pompholyx, also known as dyshidrotic eczema. The term “pompholyx” means bubble, while the term “dyshidrotic” means "difficult sweating," as problems with sweating were once believed to be the cause of this condition. Some dermatologists prefer the name “vesicular hand dermatitis.” Regardless of the terminology, this can be a mild condition that is a minor nuisance or a severe chronic condition that impairs the patient's quality of life.

The FP prescribed 0.1% triamcinolone cream to be applied twice daily and gave the patient a referral to a dermatologist. While waiting for the dermatology appointment, the patient was not improving, so she went to an emergency room, where she received a prescription for oral prednisone.

When she arrived at the dermatology office, she stated that neither the topical cream nor the oral prednisone helped to improve the rash on her hands. The dermatologist performed patch testing and discovered that she had a contact allergy to topical steroids. He withdrew the steroids and started her on oral cyclosporine, which cleared the rash.

One major lesson from this case is that patients can actually be allergic to topical steroids. Referral to Dermatology was appropriate as the complexity of this case was beyond the scope of family medicine.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R. Hand eczema. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:597-602.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

Trial supports naproxen over low-dose colchicine for acute gout

BIRMINGHAM, ENGLAND – Naproxen may be considered the first-choice treatment for patients with acute gout in primary care, based on the results of the CONTACT (Colchicine or Naproxen Treatment for Acute Gout) trial.

“Our findings suggest that both naproxen and low-dose colchicine are effective treatments for acute gout,” Edward Roddy, MD, said at the British Society for Rheumatology annual conference.

The trial results showed, however, that there might be “a small, early treatment difference” favoring naproxen, and that the nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug “appeared to be associated with fewer side effects and less use of rescue analgesia for gout than low-dose colchicine,” said Dr. Roddy, a rheumatologist at Keele University, Staffordshire, England.

CONTACT was a multicenter, randomized, open-label trial involving 399 patients recruited at 100 primary care practices. Participants were mostly men (87%) and had a mean age of 59 years.

“The eligibility criteria were designed to reflect the pragmatic nature of the trial, but also to enable us to recruit the sorts of patients in whom either treatment option would be appropriate in routine practice,” Dr. Roddy explained.

Patients were eligible for inclusion if they had consulted a general practitioner for gout in the preceding 2 years and had a recent attack of acute gout that had been clinically assessed. Patients with medical or other contraindications to using either drug were excluded.

After giving their informed consent and completing a baseline questionnaire, patients were randomized to receive either naproxen as a single 750-mg dose, then as 250 mg three times a day for a maximum of 7 days, which is the licensed dose for gout in the United Kingdom, or 500 mcg of colchicine three times a day for 4 days. Patients completed a daily diary for 1 week, noting any pain, side effects, and analgesic drug use and then completed a follow-up questionnaire 4 weeks later.

The primary outcome was the worst pain intensity experienced in the preceding 24 hours, assessed on days 1-7 with a 10-point numeric rating scale (where 10 was the worst pain experienced).

The results showed that pain was reduced to a similar extent in both groups, with a mean difference in pain score between the treatments of 0.20 (95% confidence interval, –0.60 to 0.20) at 7 days and 0.08 (95% CI, –0.54 to 0.39) at 4 weeks’ follow-up, after adjustment for patients’ age, sex, and individual pain scores at baseline.

Greater mean improvement in pain intensity was seen with naproxen than colchicine on the second day of treatment, with a mean difference in pain scores between the groups of 0.48 (95% CI, –0.86 to –0.09) but not on any other day.

During the first 7 days of the study, diarrhea was the most commonly reported side effect occurring in the low-dose colchicine arm, reported by 43.2% of patients vs. 18.0% of those treated with naproxen (adjusted odds ratio, 3.04; 95% CI, 1.75-5.27). Conversely, constipation was a less frequently reported side effect occurring in 4.8% and 18.7% of patients, respectively (OR, 0.20; 95% CI, 0.08-0.49).

Patients treated with low-dose colchicine were also more likely than those treated with naproxen to report headache during the first 7 days (20.5% vs. 10.7%; OR, 1.90; 95% CI, 1.01-3.58).

There were no deaths in the study, and the three serious adverse events that occurred were thought to be unrelated to the study treatment. One NSAID-treated patient developed hospital-acquired pneumonia after elective heart valve surgery, and another NSAID-treated patient had noncardiac chest pain needing hospital treatment. One patient in the colchicine arm developed osteomyelitis that required hospitalization, but it was later thought that the patient might not have had gout to start with.

Between days 1 and 7 of the study, patients treated with low-dose colchicine were more likely to use other analgesic medications than were those treated with naproxen. This included the use of acetaminophen (23.6% vs. 13.4%; adjusted OR, 2.04; 95% CI, 1.10-3.78) and codeine (14.6% vs. 4.7%; aOR, 3.38; 95% CI, 1.45-7.91).

Patients in the low-dose colchicine group were also more likely to use an NSAID other than naproxen at week 4 than were those in the naproxen arm (24.0% vs. 13.4%; aOR, 1.93; 95% CI, 1.05-3.55).

Other secondary endpoints assessed showed no significant difference between the treatments, including changes in global assessment of response, acute gout recurrence, number of health care consultations, and ability to work.

The study was funded by the National Institute for Health Research School for Primary Care Research. Dr. Roddy had no conflicts of interest.

It’s not surprising that a relatively high dose of an NSAID like naproxen worked well for acute gout in the CONTACT study. That has been shown for multiple NSAIDs, although the quality of that evidence has been questioned (Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014 Sep 16;[9]:CD010120). What’s surprising is that colchicine did so well. It would have been informative to include the percentage of patients that responded to each treatment based on a predefined criterion, such as a 50% or greater reduction in pain scores at a given time point. The total colchicine dose used is on the high end of the “low dose” protocols, at 6.0 mg over 4 days, identical to the maximum low-dose over 4 days using current U.S. guidelines (Arthritis Care Res. 2012;64:1447-61). The higher dose may account for its efficacy, but also undoubtedly contributed to the high diarrhea rate of 43% (Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62:1060-8).

Christopher M. Burns, MD, is a rheumatologist at Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center, Lebanon, N.H. He has no relevant disclosures.

It’s not surprising that a relatively high dose of an NSAID like naproxen worked well for acute gout in the CONTACT study. That has been shown for multiple NSAIDs, although the quality of that evidence has been questioned (Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014 Sep 16;[9]:CD010120). What’s surprising is that colchicine did so well. It would have been informative to include the percentage of patients that responded to each treatment based on a predefined criterion, such as a 50% or greater reduction in pain scores at a given time point. The total colchicine dose used is on the high end of the “low dose” protocols, at 6.0 mg over 4 days, identical to the maximum low-dose over 4 days using current U.S. guidelines (Arthritis Care Res. 2012;64:1447-61). The higher dose may account for its efficacy, but also undoubtedly contributed to the high diarrhea rate of 43% (Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62:1060-8).

Christopher M. Burns, MD, is a rheumatologist at Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center, Lebanon, N.H. He has no relevant disclosures.

It’s not surprising that a relatively high dose of an NSAID like naproxen worked well for acute gout in the CONTACT study. That has been shown for multiple NSAIDs, although the quality of that evidence has been questioned (Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014 Sep 16;[9]:CD010120). What’s surprising is that colchicine did so well. It would have been informative to include the percentage of patients that responded to each treatment based on a predefined criterion, such as a 50% or greater reduction in pain scores at a given time point. The total colchicine dose used is on the high end of the “low dose” protocols, at 6.0 mg over 4 days, identical to the maximum low-dose over 4 days using current U.S. guidelines (Arthritis Care Res. 2012;64:1447-61). The higher dose may account for its efficacy, but also undoubtedly contributed to the high diarrhea rate of 43% (Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62:1060-8).

Christopher M. Burns, MD, is a rheumatologist at Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center, Lebanon, N.H. He has no relevant disclosures.

BIRMINGHAM, ENGLAND – Naproxen may be considered the first-choice treatment for patients with acute gout in primary care, based on the results of the CONTACT (Colchicine or Naproxen Treatment for Acute Gout) trial.

“Our findings suggest that both naproxen and low-dose colchicine are effective treatments for acute gout,” Edward Roddy, MD, said at the British Society for Rheumatology annual conference.

The trial results showed, however, that there might be “a small, early treatment difference” favoring naproxen, and that the nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug “appeared to be associated with fewer side effects and less use of rescue analgesia for gout than low-dose colchicine,” said Dr. Roddy, a rheumatologist at Keele University, Staffordshire, England.

CONTACT was a multicenter, randomized, open-label trial involving 399 patients recruited at 100 primary care practices. Participants were mostly men (87%) and had a mean age of 59 years.

“The eligibility criteria were designed to reflect the pragmatic nature of the trial, but also to enable us to recruit the sorts of patients in whom either treatment option would be appropriate in routine practice,” Dr. Roddy explained.

Patients were eligible for inclusion if they had consulted a general practitioner for gout in the preceding 2 years and had a recent attack of acute gout that had been clinically assessed. Patients with medical or other contraindications to using either drug were excluded.

After giving their informed consent and completing a baseline questionnaire, patients were randomized to receive either naproxen as a single 750-mg dose, then as 250 mg three times a day for a maximum of 7 days, which is the licensed dose for gout in the United Kingdom, or 500 mcg of colchicine three times a day for 4 days. Patients completed a daily diary for 1 week, noting any pain, side effects, and analgesic drug use and then completed a follow-up questionnaire 4 weeks later.

The primary outcome was the worst pain intensity experienced in the preceding 24 hours, assessed on days 1-7 with a 10-point numeric rating scale (where 10 was the worst pain experienced).

The results showed that pain was reduced to a similar extent in both groups, with a mean difference in pain score between the treatments of 0.20 (95% confidence interval, –0.60 to 0.20) at 7 days and 0.08 (95% CI, –0.54 to 0.39) at 4 weeks’ follow-up, after adjustment for patients’ age, sex, and individual pain scores at baseline.

Greater mean improvement in pain intensity was seen with naproxen than colchicine on the second day of treatment, with a mean difference in pain scores between the groups of 0.48 (95% CI, –0.86 to –0.09) but not on any other day.

During the first 7 days of the study, diarrhea was the most commonly reported side effect occurring in the low-dose colchicine arm, reported by 43.2% of patients vs. 18.0% of those treated with naproxen (adjusted odds ratio, 3.04; 95% CI, 1.75-5.27). Conversely, constipation was a less frequently reported side effect occurring in 4.8% and 18.7% of patients, respectively (OR, 0.20; 95% CI, 0.08-0.49).

Patients treated with low-dose colchicine were also more likely than those treated with naproxen to report headache during the first 7 days (20.5% vs. 10.7%; OR, 1.90; 95% CI, 1.01-3.58).

There were no deaths in the study, and the three serious adverse events that occurred were thought to be unrelated to the study treatment. One NSAID-treated patient developed hospital-acquired pneumonia after elective heart valve surgery, and another NSAID-treated patient had noncardiac chest pain needing hospital treatment. One patient in the colchicine arm developed osteomyelitis that required hospitalization, but it was later thought that the patient might not have had gout to start with.

Between days 1 and 7 of the study, patients treated with low-dose colchicine were more likely to use other analgesic medications than were those treated with naproxen. This included the use of acetaminophen (23.6% vs. 13.4%; adjusted OR, 2.04; 95% CI, 1.10-3.78) and codeine (14.6% vs. 4.7%; aOR, 3.38; 95% CI, 1.45-7.91).

Patients in the low-dose colchicine group were also more likely to use an NSAID other than naproxen at week 4 than were those in the naproxen arm (24.0% vs. 13.4%; aOR, 1.93; 95% CI, 1.05-3.55).

Other secondary endpoints assessed showed no significant difference between the treatments, including changes in global assessment of response, acute gout recurrence, number of health care consultations, and ability to work.

The study was funded by the National Institute for Health Research School for Primary Care Research. Dr. Roddy had no conflicts of interest.

BIRMINGHAM, ENGLAND – Naproxen may be considered the first-choice treatment for patients with acute gout in primary care, based on the results of the CONTACT (Colchicine or Naproxen Treatment for Acute Gout) trial.

“Our findings suggest that both naproxen and low-dose colchicine are effective treatments for acute gout,” Edward Roddy, MD, said at the British Society for Rheumatology annual conference.

The trial results showed, however, that there might be “a small, early treatment difference” favoring naproxen, and that the nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug “appeared to be associated with fewer side effects and less use of rescue analgesia for gout than low-dose colchicine,” said Dr. Roddy, a rheumatologist at Keele University, Staffordshire, England.

CONTACT was a multicenter, randomized, open-label trial involving 399 patients recruited at 100 primary care practices. Participants were mostly men (87%) and had a mean age of 59 years.

“The eligibility criteria were designed to reflect the pragmatic nature of the trial, but also to enable us to recruit the sorts of patients in whom either treatment option would be appropriate in routine practice,” Dr. Roddy explained.

Patients were eligible for inclusion if they had consulted a general practitioner for gout in the preceding 2 years and had a recent attack of acute gout that had been clinically assessed. Patients with medical or other contraindications to using either drug were excluded.

After giving their informed consent and completing a baseline questionnaire, patients were randomized to receive either naproxen as a single 750-mg dose, then as 250 mg three times a day for a maximum of 7 days, which is the licensed dose for gout in the United Kingdom, or 500 mcg of colchicine three times a day for 4 days. Patients completed a daily diary for 1 week, noting any pain, side effects, and analgesic drug use and then completed a follow-up questionnaire 4 weeks later.

The primary outcome was the worst pain intensity experienced in the preceding 24 hours, assessed on days 1-7 with a 10-point numeric rating scale (where 10 was the worst pain experienced).

The results showed that pain was reduced to a similar extent in both groups, with a mean difference in pain score between the treatments of 0.20 (95% confidence interval, –0.60 to 0.20) at 7 days and 0.08 (95% CI, –0.54 to 0.39) at 4 weeks’ follow-up, after adjustment for patients’ age, sex, and individual pain scores at baseline.

Greater mean improvement in pain intensity was seen with naproxen than colchicine on the second day of treatment, with a mean difference in pain scores between the groups of 0.48 (95% CI, –0.86 to –0.09) but not on any other day.

During the first 7 days of the study, diarrhea was the most commonly reported side effect occurring in the low-dose colchicine arm, reported by 43.2% of patients vs. 18.0% of those treated with naproxen (adjusted odds ratio, 3.04; 95% CI, 1.75-5.27). Conversely, constipation was a less frequently reported side effect occurring in 4.8% and 18.7% of patients, respectively (OR, 0.20; 95% CI, 0.08-0.49).

Patients treated with low-dose colchicine were also more likely than those treated with naproxen to report headache during the first 7 days (20.5% vs. 10.7%; OR, 1.90; 95% CI, 1.01-3.58).

There were no deaths in the study, and the three serious adverse events that occurred were thought to be unrelated to the study treatment. One NSAID-treated patient developed hospital-acquired pneumonia after elective heart valve surgery, and another NSAID-treated patient had noncardiac chest pain needing hospital treatment. One patient in the colchicine arm developed osteomyelitis that required hospitalization, but it was later thought that the patient might not have had gout to start with.

Between days 1 and 7 of the study, patients treated with low-dose colchicine were more likely to use other analgesic medications than were those treated with naproxen. This included the use of acetaminophen (23.6% vs. 13.4%; adjusted OR, 2.04; 95% CI, 1.10-3.78) and codeine (14.6% vs. 4.7%; aOR, 3.38; 95% CI, 1.45-7.91).

Patients in the low-dose colchicine group were also more likely to use an NSAID other than naproxen at week 4 than were those in the naproxen arm (24.0% vs. 13.4%; aOR, 1.93; 95% CI, 1.05-3.55).

Other secondary endpoints assessed showed no significant difference between the treatments, including changes in global assessment of response, acute gout recurrence, number of health care consultations, and ability to work.

The study was funded by the National Institute for Health Research School for Primary Care Research. Dr. Roddy had no conflicts of interest.

Key clinical point:

Major finding: The mean difference in pain score between the treatments was 0.20 (95% CI, –0.60 to 0.20) at 7 days, but there was greater mean improvement in pain intensity on day 2 with naproxen.

Data source: The Colchicine or Naproxen Treatment for Acute Gout trial, a randomized, multicenter, open-label trial involving 399 patients with acute gout.

Disclosures: The study was funded by the National Institute for Health Research School for Primary Care Research. Dr. Roddy had no conflicts of interest.

ASCO updates NSCLC guidelines for adjuvant therapy

Adjuvant cisplatin-based chemotherapy is recommended for routine use in non–small cell lung cancer patients with stage IIA, IIB, or IIIA disease who have undergone complete surgical resections, according to updated guidelines from the American Society of Clinical Oncology.

In patients with stage IA disease, the guidelines recommend against cisplatin-based chemotherapy. The new guidelines are based on a systematic review current to January 2016 and an American Society for Radiation Oncology guideline and systematic review, which ASCO had already endorsed, which formed the basis for recommendations on adjuvant radiation therapy, Mark G. Kris, MD, and panel authors said (J Clin Oncol. 2017 April 26. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.72.4401).

The guidelines, available online, also recommend against routine cisplatin-based chemotherapy in patients with stage IB disease, but they suggest an evaluation of these patients to explore the pros and cons of adjuvant chemotherapy.

With respect to radiation, the authors recommend against it for patients with resected stage I or stage II disease, and they recommend against it for routine use in patients with stage IIIA. However, in patients with IIIA N2 disease, patients should be evaluated postoperatively, in consultation with a medical oncologist, for the potential risks and benefits of adjuvant radiation.

The authors also provide some recommendations for communicating with patients regarding treatment decisions. There are few studies examining this question, so the recommendations are based on low-quality evidence.

Non–small cell lung cancer patients may have complex social, psychological, and medical issues, and discussions should be carried out with this in mind. Pain, impaired breathing, and fatigue are common after surgery, and smoking cessation can lead to short-term stress as a result of nicotine withdrawal. Older patients may have a range of comorbidities.

Studies show that patients are most satisfied if they feel that physicians allow them to share in the decision making, and if they are given sufficient time to choose. To that end, the authors recommend a session dedicated to discussion of adjuvant therapy.

Communicating risk of death is challenging for many reasons. Patients should be asked how they would like to hear about their risks: some prefer general terms, while others may opt for numbers, charts, or graphs. The guidelines include a risk chart that can help patients understand the potential benefits and risks of chemotherapy.

The study authors report financial relationships with numerous pharmaceutical companies.

Adjuvant cisplatin-based chemotherapy is recommended for routine use in non–small cell lung cancer patients with stage IIA, IIB, or IIIA disease who have undergone complete surgical resections, according to updated guidelines from the American Society of Clinical Oncology.

In patients with stage IA disease, the guidelines recommend against cisplatin-based chemotherapy. The new guidelines are based on a systematic review current to January 2016 and an American Society for Radiation Oncology guideline and systematic review, which ASCO had already endorsed, which formed the basis for recommendations on adjuvant radiation therapy, Mark G. Kris, MD, and panel authors said (J Clin Oncol. 2017 April 26. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.72.4401).

The guidelines, available online, also recommend against routine cisplatin-based chemotherapy in patients with stage IB disease, but they suggest an evaluation of these patients to explore the pros and cons of adjuvant chemotherapy.

With respect to radiation, the authors recommend against it for patients with resected stage I or stage II disease, and they recommend against it for routine use in patients with stage IIIA. However, in patients with IIIA N2 disease, patients should be evaluated postoperatively, in consultation with a medical oncologist, for the potential risks and benefits of adjuvant radiation.

The authors also provide some recommendations for communicating with patients regarding treatment decisions. There are few studies examining this question, so the recommendations are based on low-quality evidence.

Non–small cell lung cancer patients may have complex social, psychological, and medical issues, and discussions should be carried out with this in mind. Pain, impaired breathing, and fatigue are common after surgery, and smoking cessation can lead to short-term stress as a result of nicotine withdrawal. Older patients may have a range of comorbidities.

Studies show that patients are most satisfied if they feel that physicians allow them to share in the decision making, and if they are given sufficient time to choose. To that end, the authors recommend a session dedicated to discussion of adjuvant therapy.

Communicating risk of death is challenging for many reasons. Patients should be asked how they would like to hear about their risks: some prefer general terms, while others may opt for numbers, charts, or graphs. The guidelines include a risk chart that can help patients understand the potential benefits and risks of chemotherapy.

The study authors report financial relationships with numerous pharmaceutical companies.

Adjuvant cisplatin-based chemotherapy is recommended for routine use in non–small cell lung cancer patients with stage IIA, IIB, or IIIA disease who have undergone complete surgical resections, according to updated guidelines from the American Society of Clinical Oncology.

In patients with stage IA disease, the guidelines recommend against cisplatin-based chemotherapy. The new guidelines are based on a systematic review current to January 2016 and an American Society for Radiation Oncology guideline and systematic review, which ASCO had already endorsed, which formed the basis for recommendations on adjuvant radiation therapy, Mark G. Kris, MD, and panel authors said (J Clin Oncol. 2017 April 26. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.72.4401).

The guidelines, available online, also recommend against routine cisplatin-based chemotherapy in patients with stage IB disease, but they suggest an evaluation of these patients to explore the pros and cons of adjuvant chemotherapy.

With respect to radiation, the authors recommend against it for patients with resected stage I or stage II disease, and they recommend against it for routine use in patients with stage IIIA. However, in patients with IIIA N2 disease, patients should be evaluated postoperatively, in consultation with a medical oncologist, for the potential risks and benefits of adjuvant radiation.

The authors also provide some recommendations for communicating with patients regarding treatment decisions. There are few studies examining this question, so the recommendations are based on low-quality evidence.

Non–small cell lung cancer patients may have complex social, psychological, and medical issues, and discussions should be carried out with this in mind. Pain, impaired breathing, and fatigue are common after surgery, and smoking cessation can lead to short-term stress as a result of nicotine withdrawal. Older patients may have a range of comorbidities.

Studies show that patients are most satisfied if they feel that physicians allow them to share in the decision making, and if they are given sufficient time to choose. To that end, the authors recommend a session dedicated to discussion of adjuvant therapy.

Communicating risk of death is challenging for many reasons. Patients should be asked how they would like to hear about their risks: some prefer general terms, while others may opt for numbers, charts, or graphs. The guidelines include a risk chart that can help patients understand the potential benefits and risks of chemotherapy.

The study authors report financial relationships with numerous pharmaceutical companies.

TNFSF13B variant linked to MS and SLE

A variant in the TNFSF13B gene has been linked to susceptibility to both multiple sclerosis and systemic lupus erythematosus, according to a report published online April 26 in the New England Journal of Medicine.

This gene encodes the cytokine B-cell activating factor (BAFF), which is essential for B-cell activation, differentiation, and survival. BAFF is targeted by agents such as belimumab that are used in the treatment of autoimmune disorders, and is primarily produced by monocytes and neutrophils, said Maristella Steri, PhD, of Istituto di Ricerca Genetica e Biomedica, Consiglio Nazionale delle Ricerche Monserrato (Italy), and her associates.

The researchers have named this TNFSF13B variation “BAFF-var.”

Previous genome-wide association studies have identified more than 110 independent signals for MS and 43 for SLE but have not yet delineated the effector mechanisms for most of these associations. To explore these mechanisms in greater detail, Dr. Steri and her associates studied the population in Sardinia, Italy, which has the highest prevalences of MS and SLE in the world.

They performed genome-wide association studies and other genetic investigations in case-control sets of 2,934 patients with MS, 411 with SLE, and 3,392 control subjects, analyzing roughly 12.2 million single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs). They ruled out rs1287404 as a likely variant driving the association and identified BAFF-var as the variant most strongly associated with MS (odds ratio, 1.27).

The investigators then replicated their findings in a series of genetic studies in case-control sets from mainland Italy (2,292 patients with MS, 503 with SLE, and 2,563 controls), Sweden (4,548 patients with MS and 3,481 controls), the United Kingdom (3,176 patients with MS and 2,958 controls), and the Iberian peninsula (1,120 patients with SLE and 1,300 controls). BAFF-var was most common across Sardinia, with a frequency of 26.5%, and became progressively less common moving northward (5.7% in Italy, 4.9% in Spain, 1.8% in the United Kingdom and Sweden).

Taken together, “these findings pinpoint BAFF-var as the variant in TNFSF13B that is most strongly associated with MS,” wrote Dr. Steri and her associates (N Engl J Med. 2017 Apr 27. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1610528).

BAFF-var also proved to be associated with SLE in case-control sets from Sardinia (OR, 1.38), mainland Italy (OR, 1.49), and the Iberian peninsula (OR, 1.55). This indicates that “the effect of BAFF-var is not restricted to MS alone,” they noted.

Further analyses showed that BAFF-var “dramatically” increased levels of soluble BAFF and circulating B cells, especially CD24+CD27+ cells, as well as total IgG, IgA, IgM, and monocytes. In one notable analysis, preclinical blood samples taken from Sardinians participating in a longitudinal study showed elevated levels of soluble BAFF in people who did not go on to develop MS until years later.

“We infer [from this] that BAFF-var is the causal variant driving an increase in soluble BAFF and a cascade of immune effects leading to increased autoimmunity risk,” Dr. Steri and her associates said.

Further study suggested that positive selection specifically favoring BAFF-var, not random genetic drift, accounted for the high frequency of this mutation in Sardinia and its progressively lower frequency moving northward. The most likely possibility is that BAFF-var was positively selected because it provided resistance to malaria, which was “strikingly prevalent” in Sardinia until it was eradicated in the 1950s. In mouse models, BAFF overexpression confers protection against lethal malaria.

“In addition, as shown here, BAFF-var increases antibody production, and classic findings showed that antibody transfer from adults with immunity to malaria to acutely infected children reduced blood-stage parasitemia and disease severity,” the investigators said.

“The evolutionary scenario we propose is that BAFF-var was selected as an adaptive response to malaria infection, resulting in an increased present-day risk of autoimmunity,” they said.

The Italian Foundation for Multiple Sclerosis, the National Institute on Aging, the Italian Ministry of Economy and Finance, the European Union, the National Human Genome Research Institute, and other organizations supported the study. Dr. Steri reported having no relevant disclosures; some of her associates reported ties to numerous industry sources.

Perhaps the next challenge is the clinical application of the findings from Steri et al. is to determine whether BAFF-var status can be used to stratify patients for a specific therapy.

These data clearly point in that direction, but the discriminatory power of this single variant may not be sufficient for clinical decision making.

In contrast, it does seem reasonable to examine whether stratifying patients according to their BAFF-var status would be useful in clinical trials assessing B-cell–directed therapies.

Thomas Korn, MD, of the Technical University of Munich and the Munich Cluster for Systems Neurology, reported ties to Biogen, Novartis, Merck Serono, and Bayer. Mohamed Oukka, PhD, of the University of Washington, Seattle, and the Center for Immunity and Immunotherapies at Seattle Children’s Research Institute, reported having no relevant disclosures. They made these remarks in an editorial accompanying Dr. Steri’s report (N Engl J Med. 2017 Apr 27. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1700720).

Perhaps the next challenge is the clinical application of the findings from Steri et al. is to determine whether BAFF-var status can be used to stratify patients for a specific therapy.

These data clearly point in that direction, but the discriminatory power of this single variant may not be sufficient for clinical decision making.

In contrast, it does seem reasonable to examine whether stratifying patients according to their BAFF-var status would be useful in clinical trials assessing B-cell–directed therapies.

Thomas Korn, MD, of the Technical University of Munich and the Munich Cluster for Systems Neurology, reported ties to Biogen, Novartis, Merck Serono, and Bayer. Mohamed Oukka, PhD, of the University of Washington, Seattle, and the Center for Immunity and Immunotherapies at Seattle Children’s Research Institute, reported having no relevant disclosures. They made these remarks in an editorial accompanying Dr. Steri’s report (N Engl J Med. 2017 Apr 27. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1700720).

Perhaps the next challenge is the clinical application of the findings from Steri et al. is to determine whether BAFF-var status can be used to stratify patients for a specific therapy.

These data clearly point in that direction, but the discriminatory power of this single variant may not be sufficient for clinical decision making.

In contrast, it does seem reasonable to examine whether stratifying patients according to their BAFF-var status would be useful in clinical trials assessing B-cell–directed therapies.

Thomas Korn, MD, of the Technical University of Munich and the Munich Cluster for Systems Neurology, reported ties to Biogen, Novartis, Merck Serono, and Bayer. Mohamed Oukka, PhD, of the University of Washington, Seattle, and the Center for Immunity and Immunotherapies at Seattle Children’s Research Institute, reported having no relevant disclosures. They made these remarks in an editorial accompanying Dr. Steri’s report (N Engl J Med. 2017 Apr 27. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1700720).

A variant in the TNFSF13B gene has been linked to susceptibility to both multiple sclerosis and systemic lupus erythematosus, according to a report published online April 26 in the New England Journal of Medicine.

This gene encodes the cytokine B-cell activating factor (BAFF), which is essential for B-cell activation, differentiation, and survival. BAFF is targeted by agents such as belimumab that are used in the treatment of autoimmune disorders, and is primarily produced by monocytes and neutrophils, said Maristella Steri, PhD, of Istituto di Ricerca Genetica e Biomedica, Consiglio Nazionale delle Ricerche Monserrato (Italy), and her associates.

The researchers have named this TNFSF13B variation “BAFF-var.”

Previous genome-wide association studies have identified more than 110 independent signals for MS and 43 for SLE but have not yet delineated the effector mechanisms for most of these associations. To explore these mechanisms in greater detail, Dr. Steri and her associates studied the population in Sardinia, Italy, which has the highest prevalences of MS and SLE in the world.

They performed genome-wide association studies and other genetic investigations in case-control sets of 2,934 patients with MS, 411 with SLE, and 3,392 control subjects, analyzing roughly 12.2 million single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs). They ruled out rs1287404 as a likely variant driving the association and identified BAFF-var as the variant most strongly associated with MS (odds ratio, 1.27).

The investigators then replicated their findings in a series of genetic studies in case-control sets from mainland Italy (2,292 patients with MS, 503 with SLE, and 2,563 controls), Sweden (4,548 patients with MS and 3,481 controls), the United Kingdom (3,176 patients with MS and 2,958 controls), and the Iberian peninsula (1,120 patients with SLE and 1,300 controls). BAFF-var was most common across Sardinia, with a frequency of 26.5%, and became progressively less common moving northward (5.7% in Italy, 4.9% in Spain, 1.8% in the United Kingdom and Sweden).

Taken together, “these findings pinpoint BAFF-var as the variant in TNFSF13B that is most strongly associated with MS,” wrote Dr. Steri and her associates (N Engl J Med. 2017 Apr 27. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1610528).

BAFF-var also proved to be associated with SLE in case-control sets from Sardinia (OR, 1.38), mainland Italy (OR, 1.49), and the Iberian peninsula (OR, 1.55). This indicates that “the effect of BAFF-var is not restricted to MS alone,” they noted.

Further analyses showed that BAFF-var “dramatically” increased levels of soluble BAFF and circulating B cells, especially CD24+CD27+ cells, as well as total IgG, IgA, IgM, and monocytes. In one notable analysis, preclinical blood samples taken from Sardinians participating in a longitudinal study showed elevated levels of soluble BAFF in people who did not go on to develop MS until years later.

“We infer [from this] that BAFF-var is the causal variant driving an increase in soluble BAFF and a cascade of immune effects leading to increased autoimmunity risk,” Dr. Steri and her associates said.

Further study suggested that positive selection specifically favoring BAFF-var, not random genetic drift, accounted for the high frequency of this mutation in Sardinia and its progressively lower frequency moving northward. The most likely possibility is that BAFF-var was positively selected because it provided resistance to malaria, which was “strikingly prevalent” in Sardinia until it was eradicated in the 1950s. In mouse models, BAFF overexpression confers protection against lethal malaria.

“In addition, as shown here, BAFF-var increases antibody production, and classic findings showed that antibody transfer from adults with immunity to malaria to acutely infected children reduced blood-stage parasitemia and disease severity,” the investigators said.

“The evolutionary scenario we propose is that BAFF-var was selected as an adaptive response to malaria infection, resulting in an increased present-day risk of autoimmunity,” they said.

The Italian Foundation for Multiple Sclerosis, the National Institute on Aging, the Italian Ministry of Economy and Finance, the European Union, the National Human Genome Research Institute, and other organizations supported the study. Dr. Steri reported having no relevant disclosures; some of her associates reported ties to numerous industry sources.

A variant in the TNFSF13B gene has been linked to susceptibility to both multiple sclerosis and systemic lupus erythematosus, according to a report published online April 26 in the New England Journal of Medicine.

This gene encodes the cytokine B-cell activating factor (BAFF), which is essential for B-cell activation, differentiation, and survival. BAFF is targeted by agents such as belimumab that are used in the treatment of autoimmune disorders, and is primarily produced by monocytes and neutrophils, said Maristella Steri, PhD, of Istituto di Ricerca Genetica e Biomedica, Consiglio Nazionale delle Ricerche Monserrato (Italy), and her associates.

The researchers have named this TNFSF13B variation “BAFF-var.”

Previous genome-wide association studies have identified more than 110 independent signals for MS and 43 for SLE but have not yet delineated the effector mechanisms for most of these associations. To explore these mechanisms in greater detail, Dr. Steri and her associates studied the population in Sardinia, Italy, which has the highest prevalences of MS and SLE in the world.

They performed genome-wide association studies and other genetic investigations in case-control sets of 2,934 patients with MS, 411 with SLE, and 3,392 control subjects, analyzing roughly 12.2 million single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs). They ruled out rs1287404 as a likely variant driving the association and identified BAFF-var as the variant most strongly associated with MS (odds ratio, 1.27).

The investigators then replicated their findings in a series of genetic studies in case-control sets from mainland Italy (2,292 patients with MS, 503 with SLE, and 2,563 controls), Sweden (4,548 patients with MS and 3,481 controls), the United Kingdom (3,176 patients with MS and 2,958 controls), and the Iberian peninsula (1,120 patients with SLE and 1,300 controls). BAFF-var was most common across Sardinia, with a frequency of 26.5%, and became progressively less common moving northward (5.7% in Italy, 4.9% in Spain, 1.8% in the United Kingdom and Sweden).

Taken together, “these findings pinpoint BAFF-var as the variant in TNFSF13B that is most strongly associated with MS,” wrote Dr. Steri and her associates (N Engl J Med. 2017 Apr 27. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1610528).

BAFF-var also proved to be associated with SLE in case-control sets from Sardinia (OR, 1.38), mainland Italy (OR, 1.49), and the Iberian peninsula (OR, 1.55). This indicates that “the effect of BAFF-var is not restricted to MS alone,” they noted.

Further analyses showed that BAFF-var “dramatically” increased levels of soluble BAFF and circulating B cells, especially CD24+CD27+ cells, as well as total IgG, IgA, IgM, and monocytes. In one notable analysis, preclinical blood samples taken from Sardinians participating in a longitudinal study showed elevated levels of soluble BAFF in people who did not go on to develop MS until years later.

“We infer [from this] that BAFF-var is the causal variant driving an increase in soluble BAFF and a cascade of immune effects leading to increased autoimmunity risk,” Dr. Steri and her associates said.

Further study suggested that positive selection specifically favoring BAFF-var, not random genetic drift, accounted for the high frequency of this mutation in Sardinia and its progressively lower frequency moving northward. The most likely possibility is that BAFF-var was positively selected because it provided resistance to malaria, which was “strikingly prevalent” in Sardinia until it was eradicated in the 1950s. In mouse models, BAFF overexpression confers protection against lethal malaria.

“In addition, as shown here, BAFF-var increases antibody production, and classic findings showed that antibody transfer from adults with immunity to malaria to acutely infected children reduced blood-stage parasitemia and disease severity,” the investigators said.

“The evolutionary scenario we propose is that BAFF-var was selected as an adaptive response to malaria infection, resulting in an increased present-day risk of autoimmunity,” they said.

The Italian Foundation for Multiple Sclerosis, the National Institute on Aging, the Italian Ministry of Economy and Finance, the European Union, the National Human Genome Research Institute, and other organizations supported the study. Dr. Steri reported having no relevant disclosures; some of her associates reported ties to numerous industry sources.

Key clinical point: A variant in the TNFSF13B gene has been linked to susceptibility to both multiple sclerosis and systemic lupus erythematosus.

Major finding: BAFF-var was the TNFSF13B variant most strongly associated with MS in Sardinia (OR, 1.27), and was also associated with SLE in Sardinia (OR, 1.38), mainland Italy (OR, 1.49), and the Iberian peninsula (OR, 1.55).

Data source: A series of genome-wide association studies and other genetic studies involving thousands of patients with MS or SLE in Sardinia and confirmed in thousands of patients across Italy, Spain, Sweden, and the United Kingdom.

Disclosures: The Italian Foundation for Multiple Sclerosis, the National Institute on Aging, the Italian Ministry of Economy and Finance, the European Union, the National Human Genome Research Institute, and other organizations supported the study. Dr. Steri reported having no relevant disclosures; some of her associates reported ties to numerous industry sources.

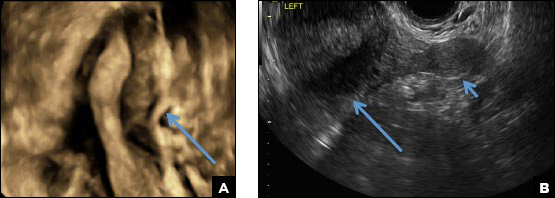

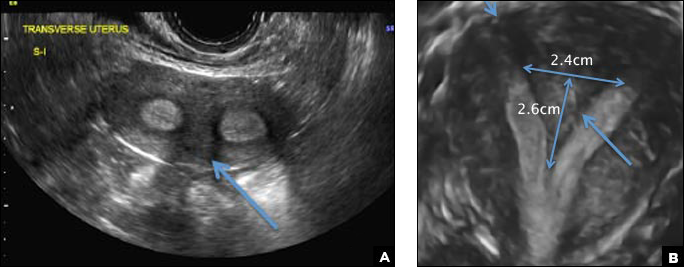

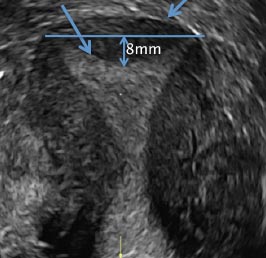

For girls with Turner syndrome, experimental fertility preservation may offer the hope of a baby of their own

ORLANDO – Fertility preservation techniques pioneered in young cancer patients may someday allow some women with Turner syndrome to give birth to their own children, without relying on donated eggs.

Spontaneous conception and live birth are exceedingly rare among women with the genetic disorder. Until very recently, adoption was the only practical way for most to grow a family. In the last decade, however, fertility specialists in Europe and the United States have had good success with in vitro fertilization using donated eggs. Now, those clinicians are aiming for a higher goal: babies born from a patient’s own eggs, cryopreserved either individually or within whole ovarian tissue.

These are not pipe dreams, according to experts interviewed for this story. Autologous oocyte freezing is well established in healthy women and is now coming of age in cancer patients, with recent reports of live births. Ovarian tissue freezing and reimplantation is a much newer technique, also pioneered in cancer patients. To date, more than 70 live births have occurred from ovarian cortical tissue conservation and later transplantation in adults. Last December brought the first report of a live birth to a childhood cancer survivor who had prepubertal ovarian tissue frozen before chemotherapy. And a 2015 report detailed the case of a girl with primary ovarian failure secondary to sickle cell anemia treatment. At 25, she gave birth to a healthy child conceived from ovarian tissue removed when she was 14 years old.

Not all clinicians so enthusiastically embrace this future, however. A new set of consensus guidelines for the management of girls and women with Turner syndrome is in the works and will recommend a more conservative clinical approach, according to Nelly Mauras, MD, chief of endocrinology, diabetes, and metabolism at the Nemours Children’s Health System in Jacksonville, Fla.

A group of academic and patient advocacy stakeholders is cooperatively honing the document based on a meeting last summer in Cincinnati. These groups include the European Society of Endocrinology, the Endocrine Society, the U.S. Pediatric Endocrine Society, the European Society for Pediatric Endocrinology, Cardiology, and Reproductive Endocrinology, as well as Turner syndrome patient advocacy groups.

Dr. Mauras said the guideline will be “less discouraging” than the existing one issued in 2012 by the American Society of Reproductive Medicine. In its 2012 guidelines, the society identified Turner syndrome as a relative contraindication to pregnancy and an absolute contraindication in those with documented cardiac anomalies. However, greater experience has since been accrued in reproductive techniques of oocyte donation in Turner, with better outcomes.

The upcoming guidelines, however, will still recommend strongly against ovarian stimulation for fertility preservation for girls younger than 12, Dr. Mauras said, and will not recommend ovarian tissue conservation. “We just do not have the safety data and pregnancy outcomes that we need to give strong recommendations for these treatments,” she said. “These are still considered experimental treatments for girls with Turner syndrome.”

Turner syndrome, caused by a deletion of one X chromosome, throws a unique curve into the game – very early ovarian failure. Those with a complete deletion (45,X) begin losing their primordial ovarian follicles even before birth. Most will never experience spontaneous puberty; even if they do, their egg reserve is virtually gone soon after. Ovarian reserve may not be completely lost in girls with mosaicism, however, who have the X deletion in only a portion of their cells (46,XX/45,X). Some will enter puberty, and about 5% may even conceive spontaneously in younger years. But of the majority of Turner girls eventually experience complete ovarian failure.

This means that fertility preservation can’t be a wait-and-see issue, according to Kutluk Oktay, MD, PhD, a fertility specialist on the leading edge of this issue in the United States.

“We have to be proactive,” said Dr. Oktay, professor of obstetrics and gynecology at New York Medical College, Valhalla. “If we wait until girls are 12 or 13 to address this, a majority will have totally depleted their ovarian reserve by then. They will have no option other than an egg donor or adoption. We are suggesting that they should be screened as soon as they are diagnosed, and if they and their parents wish it, something should be done before it’s too late.”

Dr. Oktay is also the founder of fertilitypreservation.org, which specializes in advanced fertility treatments for cancer patients. He is one of a handful of physicians in the United States who advocate early oocyte harvesting in peripubertal girls and ovarian tissue harvesting in prepubertal girls with Turner syndrome. Last year, in conjunction with the Turner Syndrome Foundation, he and his colleagues published a set of guidelines for preserving fertility in these patients.

The paper recommends fertility assessment pathways for pre- and postpubertal girls. For both groups, Dr. Oktay employs serial assessments of ovarian reserve by monitoring several hormones, including follicle-stimulating hormone, luteinizing hormone, and antimüllerian hormone (AMH). Produced by primordial follicles, AMH declines as egg reserve declines over a lifetime, and is considered an accurate marker of ovarian reserve. When a girl experiences two consecutive AMH declines, egg depletion is probably accelerating. “This is the time to consider fertility preservation,” he said.

If a girl is peri- or postpubertal, the choice would probably be ovarian stimulation with the goal of retrieving mature oocytes. For prepubertal girls, the best choice is probably ovarian tissue cryopreservation. But because the egg reserve may already be spotty inside the ovary, he recommended freezing it en bloc, rather than preserving just cortical sections.

Because these techniques are only beginning to be used in young Turner patients, neither has been tested yet to see if it would result in a pregnancy. However, Dr. Oktay said, more than 80 babies have been born to women with other disorders who had ovaries frozen as adults. And European women with Turner syndrome have been successfully bearing children with donated oocytes for years.

“I don’t differentiate Europe from the U.S.,” he said. “We have no reason to believe Turner syndrome girls would be any different here than they are there.”

Pregnancy rates by egg donation in Turner syndrome patients are about half that typically seen in an otherwise healthy infertile woman, according to numerous sources; with a take-home baby rate of about 18%. There are numerous reasons for this. The miscarriage rate in Turner patients is about 44%. Women with Turner tend to have smaller uteri, with thinner endometrium, mostly because of the lack of estrogen.

But with careful management, those who do conceive can safely deliver a healthy baby, said Outi Hovatta, MD, a Finnish fertility specialist who has done extensive work in the area. “In Europe, we have been doing this quite liberally for years, and haven’t had a bad experience,” she said in an interview.

A 2013 review summarized both the success and the risks of these pregnancies. It examined obstetric and neonatal outcomes among 106 women with Turner syndrome who gave birth via egg donation from 1992 to 2011 in Sweden, Finland, and Denmark.

Most (70%) had a single embryo transferred, as virtually all guidelines recommend. Women with Turner are prone to cardiac and aortic defects that can worsen under the strain of pregnancy, or even present for the first time during gestation. Aortic dissection is a real threat; up to a third of patients with Turner experience it during adulthood, and it’s a major cause of death among them. In the Nordic series, 10 women (9%) had a known cardiac anomaly.

The multiple birth rate was 7%. More than a third (35%) developed a hypertensive disorder, including preeclampsia (20%). Four women had potentially life-threatening complications, including one with aortic dissection, one who developed mild regurgitation of the tricuspid and mitral valve, one with a mechanical heart valve who developed HELLP syndrome (hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, low platelets), and one who underwent a postpartum hysterectomy because of severe hemorrhaging.

The infants, nevertheless, did well. The preterm birth rate was 8%, with 9% of the singleton infants having a low birth weight. About 4% had a major birth defect. Of the 131 born, three died (2.3%), including a set of extremely preterm twins.

Close follow-up and cross-specialty cooperation are what make these positive outcomes possible, said Dr. Hovatta, who is now a professor emeritus at the Karolinska Institute, Sweden.

“We do everything we can to exclude things that could cause bad outcomes.” That includes extremely rigorous cardiac testing before pregnancy and continuous monitoring during it. “If a woman has any sign of cardiac anomaly, she is advised not to become pregnant. If she shows any signs of aortic dilation, we follow her extremely carefully with experienced cardiologists.”

Like Dr. Oktay, Dr. Hovatta and her European colleagues make fertility preservation an early topic of conversation. Unlike in the United States, where many girls aren’t diagnosed with the disorder until they fail to enter puberty, almost all Turner girls in Europe are identified very early in childhood. They receive early growth hormone treatment, and there is frequent consultation with interdisciplinary specialists. Fertility is spoken of early and often.

Early oocyte retrieval is common, Dr. Hovatta said. “Yes, it’s possible to wait until puberty, but for so many girls, most of the eggs have disappeared by then, so we typically don’t wait. We start looking at that option around 11 years, which is the same time we think about cryopreserving ovarian tissue.”

However, she added, as in the United States, the outcomes of these procedures are still unknown. But the existing data in other populations, the ability to carefully shepherd women through a successful pregnancy, and the willingness of families to provide the option all support further exploring them. Dr. Hovatta was at the Cincinnati gathering last summer and said she did not agree with the conservative tone she heard. Dr. Oktay also does not agree.

“This evidence we have so far is good evidence,” he said. “Look, where we are right now with Turner girls is where we were 15 years ago with cancer patients. People thought, ‘They have cancer. They should just be worrying about surviving cancer, not about their fertility.’ Now fertility counseling is a very important part of cancer care. We have all these tools available to us for cancer patients who don’t want to lose their fertility. This accumulated experience that has already been applied in other medical conditions … why not use that for Turner syndrome? This is my point: With all the data out there about the potential benefits and the ways to manage the risks, we shouldn’t have to tell girls, ‘Well, you have to become menopausal, and maybe you can adopt someday.’ That doesn’t sit well with parents any more. We want these girls to thrive. Not just to survive, but to have as close to a normal quality of life as possible.”

ORLANDO – Fertility preservation techniques pioneered in young cancer patients may someday allow some women with Turner syndrome to give birth to their own children, without relying on donated eggs.

Spontaneous conception and live birth are exceedingly rare among women with the genetic disorder. Until very recently, adoption was the only practical way for most to grow a family. In the last decade, however, fertility specialists in Europe and the United States have had good success with in vitro fertilization using donated eggs. Now, those clinicians are aiming for a higher goal: babies born from a patient’s own eggs, cryopreserved either individually or within whole ovarian tissue.

These are not pipe dreams, according to experts interviewed for this story. Autologous oocyte freezing is well established in healthy women and is now coming of age in cancer patients, with recent reports of live births. Ovarian tissue freezing and reimplantation is a much newer technique, also pioneered in cancer patients. To date, more than 70 live births have occurred from ovarian cortical tissue conservation and later transplantation in adults. Last December brought the first report of a live birth to a childhood cancer survivor who had prepubertal ovarian tissue frozen before chemotherapy. And a 2015 report detailed the case of a girl with primary ovarian failure secondary to sickle cell anemia treatment. At 25, she gave birth to a healthy child conceived from ovarian tissue removed when she was 14 years old.

Not all clinicians so enthusiastically embrace this future, however. A new set of consensus guidelines for the management of girls and women with Turner syndrome is in the works and will recommend a more conservative clinical approach, according to Nelly Mauras, MD, chief of endocrinology, diabetes, and metabolism at the Nemours Children’s Health System in Jacksonville, Fla.

A group of academic and patient advocacy stakeholders is cooperatively honing the document based on a meeting last summer in Cincinnati. These groups include the European Society of Endocrinology, the Endocrine Society, the U.S. Pediatric Endocrine Society, the European Society for Pediatric Endocrinology, Cardiology, and Reproductive Endocrinology, as well as Turner syndrome patient advocacy groups.

Dr. Mauras said the guideline will be “less discouraging” than the existing one issued in 2012 by the American Society of Reproductive Medicine. In its 2012 guidelines, the society identified Turner syndrome as a relative contraindication to pregnancy and an absolute contraindication in those with documented cardiac anomalies. However, greater experience has since been accrued in reproductive techniques of oocyte donation in Turner, with better outcomes.

The upcoming guidelines, however, will still recommend strongly against ovarian stimulation for fertility preservation for girls younger than 12, Dr. Mauras said, and will not recommend ovarian tissue conservation. “We just do not have the safety data and pregnancy outcomes that we need to give strong recommendations for these treatments,” she said. “These are still considered experimental treatments for girls with Turner syndrome.”

Turner syndrome, caused by a deletion of one X chromosome, throws a unique curve into the game – very early ovarian failure. Those with a complete deletion (45,X) begin losing their primordial ovarian follicles even before birth. Most will never experience spontaneous puberty; even if they do, their egg reserve is virtually gone soon after. Ovarian reserve may not be completely lost in girls with mosaicism, however, who have the X deletion in only a portion of their cells (46,XX/45,X). Some will enter puberty, and about 5% may even conceive spontaneously in younger years. But of the majority of Turner girls eventually experience complete ovarian failure.

This means that fertility preservation can’t be a wait-and-see issue, according to Kutluk Oktay, MD, PhD, a fertility specialist on the leading edge of this issue in the United States.

“We have to be proactive,” said Dr. Oktay, professor of obstetrics and gynecology at New York Medical College, Valhalla. “If we wait until girls are 12 or 13 to address this, a majority will have totally depleted their ovarian reserve by then. They will have no option other than an egg donor or adoption. We are suggesting that they should be screened as soon as they are diagnosed, and if they and their parents wish it, something should be done before it’s too late.”

Dr. Oktay is also the founder of fertilitypreservation.org, which specializes in advanced fertility treatments for cancer patients. He is one of a handful of physicians in the United States who advocate early oocyte harvesting in peripubertal girls and ovarian tissue harvesting in prepubertal girls with Turner syndrome. Last year, in conjunction with the Turner Syndrome Foundation, he and his colleagues published a set of guidelines for preserving fertility in these patients.

The paper recommends fertility assessment pathways for pre- and postpubertal girls. For both groups, Dr. Oktay employs serial assessments of ovarian reserve by monitoring several hormones, including follicle-stimulating hormone, luteinizing hormone, and antimüllerian hormone (AMH). Produced by primordial follicles, AMH declines as egg reserve declines over a lifetime, and is considered an accurate marker of ovarian reserve. When a girl experiences two consecutive AMH declines, egg depletion is probably accelerating. “This is the time to consider fertility preservation,” he said.

If a girl is peri- or postpubertal, the choice would probably be ovarian stimulation with the goal of retrieving mature oocytes. For prepubertal girls, the best choice is probably ovarian tissue cryopreservation. But because the egg reserve may already be spotty inside the ovary, he recommended freezing it en bloc, rather than preserving just cortical sections.

Because these techniques are only beginning to be used in young Turner patients, neither has been tested yet to see if it would result in a pregnancy. However, Dr. Oktay said, more than 80 babies have been born to women with other disorders who had ovaries frozen as adults. And European women with Turner syndrome have been successfully bearing children with donated oocytes for years.

“I don’t differentiate Europe from the U.S.,” he said. “We have no reason to believe Turner syndrome girls would be any different here than they are there.”

Pregnancy rates by egg donation in Turner syndrome patients are about half that typically seen in an otherwise healthy infertile woman, according to numerous sources; with a take-home baby rate of about 18%. There are numerous reasons for this. The miscarriage rate in Turner patients is about 44%. Women with Turner tend to have smaller uteri, with thinner endometrium, mostly because of the lack of estrogen.

But with careful management, those who do conceive can safely deliver a healthy baby, said Outi Hovatta, MD, a Finnish fertility specialist who has done extensive work in the area. “In Europe, we have been doing this quite liberally for years, and haven’t had a bad experience,” she said in an interview.

A 2013 review summarized both the success and the risks of these pregnancies. It examined obstetric and neonatal outcomes among 106 women with Turner syndrome who gave birth via egg donation from 1992 to 2011 in Sweden, Finland, and Denmark.

Most (70%) had a single embryo transferred, as virtually all guidelines recommend. Women with Turner are prone to cardiac and aortic defects that can worsen under the strain of pregnancy, or even present for the first time during gestation. Aortic dissection is a real threat; up to a third of patients with Turner experience it during adulthood, and it’s a major cause of death among them. In the Nordic series, 10 women (9%) had a known cardiac anomaly.

The multiple birth rate was 7%. More than a third (35%) developed a hypertensive disorder, including preeclampsia (20%). Four women had potentially life-threatening complications, including one with aortic dissection, one who developed mild regurgitation of the tricuspid and mitral valve, one with a mechanical heart valve who developed HELLP syndrome (hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, low platelets), and one who underwent a postpartum hysterectomy because of severe hemorrhaging.

The infants, nevertheless, did well. The preterm birth rate was 8%, with 9% of the singleton infants having a low birth weight. About 4% had a major birth defect. Of the 131 born, three died (2.3%), including a set of extremely preterm twins.

Close follow-up and cross-specialty cooperation are what make these positive outcomes possible, said Dr. Hovatta, who is now a professor emeritus at the Karolinska Institute, Sweden.

“We do everything we can to exclude things that could cause bad outcomes.” That includes extremely rigorous cardiac testing before pregnancy and continuous monitoring during it. “If a woman has any sign of cardiac anomaly, she is advised not to become pregnant. If she shows any signs of aortic dilation, we follow her extremely carefully with experienced cardiologists.”

Like Dr. Oktay, Dr. Hovatta and her European colleagues make fertility preservation an early topic of conversation. Unlike in the United States, where many girls aren’t diagnosed with the disorder until they fail to enter puberty, almost all Turner girls in Europe are identified very early in childhood. They receive early growth hormone treatment, and there is frequent consultation with interdisciplinary specialists. Fertility is spoken of early and often.

Early oocyte retrieval is common, Dr. Hovatta said. “Yes, it’s possible to wait until puberty, but for so many girls, most of the eggs have disappeared by then, so we typically don’t wait. We start looking at that option around 11 years, which is the same time we think about cryopreserving ovarian tissue.”

However, she added, as in the United States, the outcomes of these procedures are still unknown. But the existing data in other populations, the ability to carefully shepherd women through a successful pregnancy, and the willingness of families to provide the option all support further exploring them. Dr. Hovatta was at the Cincinnati gathering last summer and said she did not agree with the conservative tone she heard. Dr. Oktay also does not agree.

“This evidence we have so far is good evidence,” he said. “Look, where we are right now with Turner girls is where we were 15 years ago with cancer patients. People thought, ‘They have cancer. They should just be worrying about surviving cancer, not about their fertility.’ Now fertility counseling is a very important part of cancer care. We have all these tools available to us for cancer patients who don’t want to lose their fertility. This accumulated experience that has already been applied in other medical conditions … why not use that for Turner syndrome? This is my point: With all the data out there about the potential benefits and the ways to manage the risks, we shouldn’t have to tell girls, ‘Well, you have to become menopausal, and maybe you can adopt someday.’ That doesn’t sit well with parents any more. We want these girls to thrive. Not just to survive, but to have as close to a normal quality of life as possible.”

ORLANDO – Fertility preservation techniques pioneered in young cancer patients may someday allow some women with Turner syndrome to give birth to their own children, without relying on donated eggs.

Spontaneous conception and live birth are exceedingly rare among women with the genetic disorder. Until very recently, adoption was the only practical way for most to grow a family. In the last decade, however, fertility specialists in Europe and the United States have had good success with in vitro fertilization using donated eggs. Now, those clinicians are aiming for a higher goal: babies born from a patient’s own eggs, cryopreserved either individually or within whole ovarian tissue.

These are not pipe dreams, according to experts interviewed for this story. Autologous oocyte freezing is well established in healthy women and is now coming of age in cancer patients, with recent reports of live births. Ovarian tissue freezing and reimplantation is a much newer technique, also pioneered in cancer patients. To date, more than 70 live births have occurred from ovarian cortical tissue conservation and later transplantation in adults. Last December brought the first report of a live birth to a childhood cancer survivor who had prepubertal ovarian tissue frozen before chemotherapy. And a 2015 report detailed the case of a girl with primary ovarian failure secondary to sickle cell anemia treatment. At 25, she gave birth to a healthy child conceived from ovarian tissue removed when she was 14 years old.

Not all clinicians so enthusiastically embrace this future, however. A new set of consensus guidelines for the management of girls and women with Turner syndrome is in the works and will recommend a more conservative clinical approach, according to Nelly Mauras, MD, chief of endocrinology, diabetes, and metabolism at the Nemours Children’s Health System in Jacksonville, Fla.

A group of academic and patient advocacy stakeholders is cooperatively honing the document based on a meeting last summer in Cincinnati. These groups include the European Society of Endocrinology, the Endocrine Society, the U.S. Pediatric Endocrine Society, the European Society for Pediatric Endocrinology, Cardiology, and Reproductive Endocrinology, as well as Turner syndrome patient advocacy groups.

Dr. Mauras said the guideline will be “less discouraging” than the existing one issued in 2012 by the American Society of Reproductive Medicine. In its 2012 guidelines, the society identified Turner syndrome as a relative contraindication to pregnancy and an absolute contraindication in those with documented cardiac anomalies. However, greater experience has since been accrued in reproductive techniques of oocyte donation in Turner, with better outcomes.

The upcoming guidelines, however, will still recommend strongly against ovarian stimulation for fertility preservation for girls younger than 12, Dr. Mauras said, and will not recommend ovarian tissue conservation. “We just do not have the safety data and pregnancy outcomes that we need to give strong recommendations for these treatments,” she said. “These are still considered experimental treatments for girls with Turner syndrome.”

Turner syndrome, caused by a deletion of one X chromosome, throws a unique curve into the game – very early ovarian failure. Those with a complete deletion (45,X) begin losing their primordial ovarian follicles even before birth. Most will never experience spontaneous puberty; even if they do, their egg reserve is virtually gone soon after. Ovarian reserve may not be completely lost in girls with mosaicism, however, who have the X deletion in only a portion of their cells (46,XX/45,X). Some will enter puberty, and about 5% may even conceive spontaneously in younger years. But of the majority of Turner girls eventually experience complete ovarian failure.

This means that fertility preservation can’t be a wait-and-see issue, according to Kutluk Oktay, MD, PhD, a fertility specialist on the leading edge of this issue in the United States.

“We have to be proactive,” said Dr. Oktay, professor of obstetrics and gynecology at New York Medical College, Valhalla. “If we wait until girls are 12 or 13 to address this, a majority will have totally depleted their ovarian reserve by then. They will have no option other than an egg donor or adoption. We are suggesting that they should be screened as soon as they are diagnosed, and if they and their parents wish it, something should be done before it’s too late.”

Dr. Oktay is also the founder of fertilitypreservation.org, which specializes in advanced fertility treatments for cancer patients. He is one of a handful of physicians in the United States who advocate early oocyte harvesting in peripubertal girls and ovarian tissue harvesting in prepubertal girls with Turner syndrome. Last year, in conjunction with the Turner Syndrome Foundation, he and his colleagues published a set of guidelines for preserving fertility in these patients.

The paper recommends fertility assessment pathways for pre- and postpubertal girls. For both groups, Dr. Oktay employs serial assessments of ovarian reserve by monitoring several hormones, including follicle-stimulating hormone, luteinizing hormone, and antimüllerian hormone (AMH). Produced by primordial follicles, AMH declines as egg reserve declines over a lifetime, and is considered an accurate marker of ovarian reserve. When a girl experiences two consecutive AMH declines, egg depletion is probably accelerating. “This is the time to consider fertility preservation,” he said.

If a girl is peri- or postpubertal, the choice would probably be ovarian stimulation with the goal of retrieving mature oocytes. For prepubertal girls, the best choice is probably ovarian tissue cryopreservation. But because the egg reserve may already be spotty inside the ovary, he recommended freezing it en bloc, rather than preserving just cortical sections.

Because these techniques are only beginning to be used in young Turner patients, neither has been tested yet to see if it would result in a pregnancy. However, Dr. Oktay said, more than 80 babies have been born to women with other disorders who had ovaries frozen as adults. And European women with Turner syndrome have been successfully bearing children with donated oocytes for years.

“I don’t differentiate Europe from the U.S.,” he said. “We have no reason to believe Turner syndrome girls would be any different here than they are there.”

Pregnancy rates by egg donation in Turner syndrome patients are about half that typically seen in an otherwise healthy infertile woman, according to numerous sources; with a take-home baby rate of about 18%. There are numerous reasons for this. The miscarriage rate in Turner patients is about 44%. Women with Turner tend to have smaller uteri, with thinner endometrium, mostly because of the lack of estrogen.

But with careful management, those who do conceive can safely deliver a healthy baby, said Outi Hovatta, MD, a Finnish fertility specialist who has done extensive work in the area. “In Europe, we have been doing this quite liberally for years, and haven’t had a bad experience,” she said in an interview.