User login

Women and Heart Disease

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

Sex-discordant transfusions don’t increase death risk

Photo by Elise Amendola

There is no association between sex-discordant blood transfusions and the risk of death after cardiac surgery, according to research published in Circulation.

Two previous studies suggested that patients who received red blood cells (RBCs) from a donor of the opposite sex had an increased risk of death after cardiac surgery.

However, the current study showed no significant difference between same-sex and opposite-sex donor-recipient pairs.

The researchers said the reason for the difference between the new and older studies is that, in the new study, the team “carefully adjusted” for the number of transfusions performed and allowed for the effect of RBC transfusions on mortality to differ between men and women.

“The consequences of the findings from [the earlier studies], if proved true, would have been immense and necessitated radical changes to how blood transfusions are managed around the world,” said Martin Holzmann, MD, PhD, of Karolinska Institutet in Stockholm, Sweden.

“Our results clearly show that there is no real connection between sex-discordant blood transfusions and the risk of death.”

Therefore, Dr Holzmann and his colleagues believe there is no need to consider donor sex when allocating RBC units for transfusion.

To come to this conclusion, the researchers analyzed data on 45,090 patients who underwent cardiac surgery and received at least 1 RBC transfusion.

All patients were adults who had undergone isolated coronary artery bypass grafting, isolated valve repair/replacement surgery, or a combination of these procedures between 1997 and 2012.

The researchers estimated the relative hazard of death in relation to exposure to sex-discordant transfusions, adjusting their analyses for potential confounding factors, such as patient sex, age, blood group, and number of transfusions.

Results

The researchers found that women were more likely to receive sex-discordant transfusions than same-sex transfusions—45.3% and 19.8%, respectively. And patients who received sex-discordant transfusions tended to receive more transfusions—a mean of 4.2 vs 2.0 for same-sex transfusions.

However, there were no other significant differences between the sex-discordant and same-sex groups.

The researchers noted that, during the 30-day follow-up period, there were more deaths among patients who received sex-discordant transfusions than those who did not—1701 (4.9%) and 205 (1.9%), respectively.

However, when the team adjusted for potential confounding factors, the relative risk of death was similar for patients who received at least 1 unit of sex-discordant blood and those who did not. The hazard ratio was 0.97 at 30 days of follow-up, 0.97 at the 2-year mark, and 0.98 at 10 years of follow-up.

The risk of death did increase as the number of sex-discordant units transfused increased. However, the increase was not statistically significant. ![]()

Photo by Elise Amendola

There is no association between sex-discordant blood transfusions and the risk of death after cardiac surgery, according to research published in Circulation.

Two previous studies suggested that patients who received red blood cells (RBCs) from a donor of the opposite sex had an increased risk of death after cardiac surgery.

However, the current study showed no significant difference between same-sex and opposite-sex donor-recipient pairs.

The researchers said the reason for the difference between the new and older studies is that, in the new study, the team “carefully adjusted” for the number of transfusions performed and allowed for the effect of RBC transfusions on mortality to differ between men and women.

“The consequences of the findings from [the earlier studies], if proved true, would have been immense and necessitated radical changes to how blood transfusions are managed around the world,” said Martin Holzmann, MD, PhD, of Karolinska Institutet in Stockholm, Sweden.

“Our results clearly show that there is no real connection between sex-discordant blood transfusions and the risk of death.”

Therefore, Dr Holzmann and his colleagues believe there is no need to consider donor sex when allocating RBC units for transfusion.

To come to this conclusion, the researchers analyzed data on 45,090 patients who underwent cardiac surgery and received at least 1 RBC transfusion.

All patients were adults who had undergone isolated coronary artery bypass grafting, isolated valve repair/replacement surgery, or a combination of these procedures between 1997 and 2012.

The researchers estimated the relative hazard of death in relation to exposure to sex-discordant transfusions, adjusting their analyses for potential confounding factors, such as patient sex, age, blood group, and number of transfusions.

Results

The researchers found that women were more likely to receive sex-discordant transfusions than same-sex transfusions—45.3% and 19.8%, respectively. And patients who received sex-discordant transfusions tended to receive more transfusions—a mean of 4.2 vs 2.0 for same-sex transfusions.

However, there were no other significant differences between the sex-discordant and same-sex groups.

The researchers noted that, during the 30-day follow-up period, there were more deaths among patients who received sex-discordant transfusions than those who did not—1701 (4.9%) and 205 (1.9%), respectively.

However, when the team adjusted for potential confounding factors, the relative risk of death was similar for patients who received at least 1 unit of sex-discordant blood and those who did not. The hazard ratio was 0.97 at 30 days of follow-up, 0.97 at the 2-year mark, and 0.98 at 10 years of follow-up.

The risk of death did increase as the number of sex-discordant units transfused increased. However, the increase was not statistically significant. ![]()

Photo by Elise Amendola

There is no association between sex-discordant blood transfusions and the risk of death after cardiac surgery, according to research published in Circulation.

Two previous studies suggested that patients who received red blood cells (RBCs) from a donor of the opposite sex had an increased risk of death after cardiac surgery.

However, the current study showed no significant difference between same-sex and opposite-sex donor-recipient pairs.

The researchers said the reason for the difference between the new and older studies is that, in the new study, the team “carefully adjusted” for the number of transfusions performed and allowed for the effect of RBC transfusions on mortality to differ between men and women.

“The consequences of the findings from [the earlier studies], if proved true, would have been immense and necessitated radical changes to how blood transfusions are managed around the world,” said Martin Holzmann, MD, PhD, of Karolinska Institutet in Stockholm, Sweden.

“Our results clearly show that there is no real connection between sex-discordant blood transfusions and the risk of death.”

Therefore, Dr Holzmann and his colleagues believe there is no need to consider donor sex when allocating RBC units for transfusion.

To come to this conclusion, the researchers analyzed data on 45,090 patients who underwent cardiac surgery and received at least 1 RBC transfusion.

All patients were adults who had undergone isolated coronary artery bypass grafting, isolated valve repair/replacement surgery, or a combination of these procedures between 1997 and 2012.

The researchers estimated the relative hazard of death in relation to exposure to sex-discordant transfusions, adjusting their analyses for potential confounding factors, such as patient sex, age, blood group, and number of transfusions.

Results

The researchers found that women were more likely to receive sex-discordant transfusions than same-sex transfusions—45.3% and 19.8%, respectively. And patients who received sex-discordant transfusions tended to receive more transfusions—a mean of 4.2 vs 2.0 for same-sex transfusions.

However, there were no other significant differences between the sex-discordant and same-sex groups.

The researchers noted that, during the 30-day follow-up period, there were more deaths among patients who received sex-discordant transfusions than those who did not—1701 (4.9%) and 205 (1.9%), respectively.

However, when the team adjusted for potential confounding factors, the relative risk of death was similar for patients who received at least 1 unit of sex-discordant blood and those who did not. The hazard ratio was 0.97 at 30 days of follow-up, 0.97 at the 2-year mark, and 0.98 at 10 years of follow-up.

The risk of death did increase as the number of sex-discordant units transfused increased. However, the increase was not statistically significant. ![]()

EC grants drug orphan designation for PNH

The European Commission (EC) has granted orphan drug designation to RA101495 for the treatment of paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria (PNH).

RA101495 is a synthetic macrocyclic peptide inhibitor of complement component C5.

Ra Pharmaceuticals is developing RA101495 as a self-administered, subcutaneous injection for the treatment of PNH, refractory generalized myasthenia gravis, and lupus nephritis.

RA101495 binds complement C5 with subnanomolar affinity and allosterically inhibits its cleavage into C5a and C5b upon activation of the classical, alternative, or lectin pathways.

RA101495 also directly binds to C5b, disrupting the interaction between C5b and C6 and preventing assembly of the membrane attack complex.

According to Ra Pharmaceuticals, repeat dosing of RA101495 in vivo has demonstrated “sustained and predictable” inhibition of complement activity with an “excellent” safety profile.

The company also said phase 1 data have suggested that RA101495 is potent inhibitor of C5-mediated hemolysis with a favorable safety profile.

Preclinical research involving RA101495 was presented at the 2015 ASH Annual Meeting, and phase 1 data were presented at the 21st Congress of the European Hematology Association earlier this year.

RA101495’s orphan designation

The EC grants orphan designation to therapies intended to treat life-threatening or chronically debilitating conditions affecting no more than 5 in 10,000 people in the European Union, and where no satisfactory treatment is available.

In situations where there is already an approved standard of care—such as with PNH, where the monoclonal antibody eculizumab (Soliris) is currently available—the EC requires companies developing a potential orphan drug to provide evidence that the drug is expected to provide significant benefits over the standard of care.

In the case of RA101495, the decision to grant orphan designation was based on the potential for improved patient convenience with subcutaneous self-administration, as well as the potential to treat patients who do not respond to eculizumab.

Orphan designation provides the company developing a drug with regulatory and financial incentives, including protocol assistance, 10 years of market exclusivity once the drug is approved, and, in some cases, reductions in fees. ![]()

The European Commission (EC) has granted orphan drug designation to RA101495 for the treatment of paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria (PNH).

RA101495 is a synthetic macrocyclic peptide inhibitor of complement component C5.

Ra Pharmaceuticals is developing RA101495 as a self-administered, subcutaneous injection for the treatment of PNH, refractory generalized myasthenia gravis, and lupus nephritis.

RA101495 binds complement C5 with subnanomolar affinity and allosterically inhibits its cleavage into C5a and C5b upon activation of the classical, alternative, or lectin pathways.

RA101495 also directly binds to C5b, disrupting the interaction between C5b and C6 and preventing assembly of the membrane attack complex.

According to Ra Pharmaceuticals, repeat dosing of RA101495 in vivo has demonstrated “sustained and predictable” inhibition of complement activity with an “excellent” safety profile.

The company also said phase 1 data have suggested that RA101495 is potent inhibitor of C5-mediated hemolysis with a favorable safety profile.

Preclinical research involving RA101495 was presented at the 2015 ASH Annual Meeting, and phase 1 data were presented at the 21st Congress of the European Hematology Association earlier this year.

RA101495’s orphan designation

The EC grants orphan designation to therapies intended to treat life-threatening or chronically debilitating conditions affecting no more than 5 in 10,000 people in the European Union, and where no satisfactory treatment is available.

In situations where there is already an approved standard of care—such as with PNH, where the monoclonal antibody eculizumab (Soliris) is currently available—the EC requires companies developing a potential orphan drug to provide evidence that the drug is expected to provide significant benefits over the standard of care.

In the case of RA101495, the decision to grant orphan designation was based on the potential for improved patient convenience with subcutaneous self-administration, as well as the potential to treat patients who do not respond to eculizumab.

Orphan designation provides the company developing a drug with regulatory and financial incentives, including protocol assistance, 10 years of market exclusivity once the drug is approved, and, in some cases, reductions in fees. ![]()

The European Commission (EC) has granted orphan drug designation to RA101495 for the treatment of paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria (PNH).

RA101495 is a synthetic macrocyclic peptide inhibitor of complement component C5.

Ra Pharmaceuticals is developing RA101495 as a self-administered, subcutaneous injection for the treatment of PNH, refractory generalized myasthenia gravis, and lupus nephritis.

RA101495 binds complement C5 with subnanomolar affinity and allosterically inhibits its cleavage into C5a and C5b upon activation of the classical, alternative, or lectin pathways.

RA101495 also directly binds to C5b, disrupting the interaction between C5b and C6 and preventing assembly of the membrane attack complex.

According to Ra Pharmaceuticals, repeat dosing of RA101495 in vivo has demonstrated “sustained and predictable” inhibition of complement activity with an “excellent” safety profile.

The company also said phase 1 data have suggested that RA101495 is potent inhibitor of C5-mediated hemolysis with a favorable safety profile.

Preclinical research involving RA101495 was presented at the 2015 ASH Annual Meeting, and phase 1 data were presented at the 21st Congress of the European Hematology Association earlier this year.

RA101495’s orphan designation

The EC grants orphan designation to therapies intended to treat life-threatening or chronically debilitating conditions affecting no more than 5 in 10,000 people in the European Union, and where no satisfactory treatment is available.

In situations where there is already an approved standard of care—such as with PNH, where the monoclonal antibody eculizumab (Soliris) is currently available—the EC requires companies developing a potential orphan drug to provide evidence that the drug is expected to provide significant benefits over the standard of care.

In the case of RA101495, the decision to grant orphan designation was based on the potential for improved patient convenience with subcutaneous self-administration, as well as the potential to treat patients who do not respond to eculizumab.

Orphan designation provides the company developing a drug with regulatory and financial incentives, including protocol assistance, 10 years of market exclusivity once the drug is approved, and, in some cases, reductions in fees. ![]()

Robotic Technology Produces More Conservative Tibial Resection Than Conventional Techniques in UKA

Unicompartmental knee arthroplasty (UKA) is considered a less invasive approach for the treatment of unicompartmental knee arthritis when compared with total knee arthroplasty (TKA), with optimal preservation of kinematics.1 Despite excellent functional outcomes, conversion to TKA may be necessary if the UKA fails, or in patients with progressive knee arthritis. Some studies have found UKA conversion to TKA to be comparable with primary TKA,2,3 whereas others have found that conversion often requires bone graft, augments, and stemmed components and has increased complications and inferior results compared to primary TKA.4-7 While some studies report that <10% of UKA conversions to TKA require augments,2 others have found that as many as 76% require augments.4-8

Schwarzkopf and colleagues9 recently demonstrated that UKA conversion to TKA is comparable with primary TKA when a conservative tibial resection is performed during the index procedure. However, they reported increased complexity when greater tibial resection was performed and thicker polyethylene inserts were used at the time of the index UKA. The odds ratio of needing an augment or stem during the conversion to TKA was 26.8 (95% confidence interval, 3.71-194) when an aggressive tibial resection was performed during the UKA.9 Tibial resection thickness may thus be predictive of anticipated complexity of UKA revision to TKA and may aid in preoperative planning.

Robotic assistance has been shown to enhance the accuracy of bone preparation, implant component alignment, and soft tissue balance in UKA.10-15 It has yet to be determined whether this improved accuracy translates to improved clinical performance or longevity of the UKA implant. However, the enhanced accuracy of robotic technology may result in more conservative tibial resection when compared to conventional UKA and may be advantageous if conversion to TKA becomes necessary.

The purpose of this study was to compare the distribution of polyethylene insert sizes implanted during conventional and robotic-assisted UKA. We hypothesized that robotic assistance would demonstrate more conservative tibial resection compared to conventional methods of bone preparation.

Methods

We retrospectively compared the distribution of polyethylene insert sizes implanted during consecutive conventional and robotic-assisted UKA procedures. Several manufacturers were queried to provide a listing of the polyethylene insert sizes utilized, ranging from 8 mm to 14 mm. The analysis included 8421 robotic-assisted UKA cases and 27,989 conventional UKA cases. Data were provided by Zimmer Biomet and Smith & Nephew regarding conventional cases, as well as Blue Belt Technologies (now part of Smith & Nephew) and MAKO Surgical (now part of Stryker) regarding robotic-assisted cases. (Dr. Lonner has an ongoing relationship as a consultant with Blue Belt Technologies, whose data was utilized in this study.) Using tibial insert thickness as a surrogate measure of the extent of tibial resection, an insert size of ≥10 mm was defined as aggressive while <10 mm was considered conservative. This cutoff was established based on its corresponding resection level with primary TKA and the anticipated need for augments. Statistical analysis was performed using a Mann-Whitney-Wilcoxon test. Significance was set at P < .05.

Results

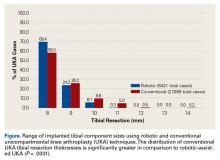

Tibial resection thickness was found to be most commonly conservative in nature, with sizes 8-mm and 9-mm polyethylene inserts utilized in the majority of both robotic-assisted and conventional UKA cases. However, statistically more 8-mm and 9-mm polyethylene inserts were used in the robotic group (93.6%) than in the conventional group (84.5%) (P < .0001; Figure). Aggressive tibial resection, requiring tibial inserts ≥10 mm, was performed in 6.4% of robotic-assisted cases and 15.5% of conventional cases.

Discussion

Robotic assistance enhances the accuracy of bone preparation, implant component alignment, and soft tissue balance in UKA.10-15 It has yet to be determined whether this improved accuracy translates to improved clinical performance or longevity of the UKA implant. However, we demonstrate that the enhanced accuracy of robotic technology results in more conservative tibial resection when compared to conventional techniques with a potential benefit suggested in the literature upon conversion to TKA.

The findings of this study have important implications for patients undergoing conversion of UKA to TKA, potentially optimizing the ease of revision and clinical outcomes. The outcomes of UKA conversion to TKA are often considered inferior to those of primary TKA, compromised by bone loss, need for augmentation, and challenges of restoring the joint line and rotation.9,16-22 Barrett and Scott18 reported only 66% of patients had good or excellent results at an average of 4.6 years of follow-up after UKA conversion to TKA. Over 50% required stemmed implants and bone graft or bone cement augmentation to address osseous insufficiency. The authors suggested that the primary determinant of the complexity of the conversion to TKA was the surgical technique used in the index procedure. They concluded that UKA conversion to TKA can be as successful as a primary TKA and primary TKA implants can be used without bone augmentation or stems during the revision procedure if minimal tibial bone is resected at the time of the index UKA.18 Schwarzkopf and colleagues9 supported this conclusion when they found that aggressive tibial resection during UKA resulted in the need for bone graft, stem, wedge, or augment in 70% of cases when converted to TKA. Similarly, Khan and colleagues23 found that 26% of patients required bone grafting and 26% required some form of augmentation, and Springer and colleagues3 reported that 68% required a graft, augment, or stem.3,22 Using data from the New Zealand Joint Registry, Pearse and colleagues5 reported that revision TKA components were necessary in 28% of patients and concluded that converting a UKA to TKA gives a less reliable result than primary TKA, and with functional results that are not significantly better than a revision from a TKA.

Conservative tibial resection during UKA minimizes the complexity and concerns of bone loss upon conversion to TKA. Schwarzkopf and colleagues9 found 96.6% of patients with conservative tibial resection received a primary TKA implant, without augments or stems. Furthermore, patients with a primary TKA implant showed improved tibial survivorship, with revision as an end point, compared with patients who received a TKA implant that required stems and augments or bone graft for support.9 Also emphasizing the importance of minimal tibial resection, O’Donnell and colleagues8 compared a cohort of patients undergoing conversion of a minimal resection resurfacing onlay-type UKA to TKA with a cohort of patients undergoing primary TKA. They found that 40% of patients required bone grafting for contained defects, 3.6% required metal augments, and 1.8% required stems.8 There was no significant difference between the groups in terms of range of motion, functional outcome, or radiologic outcomes. The authors concluded that revision of minimal resection resurfacing implants to TKA is associated with similar results to primary TKA and is superior to revision of UKA with greater bone loss. Prior studies have shown that one of the advantages of robotic-assisted UKA is the accuracy and precision of bone resection. The present study supports this premise by showing that tibial resection is significantly more conservative using robotic-assisted techniques when using tibial component thickness as a surrogate for extent of bone resection. While our study did not address implant durability or the impact of conservative resection on conversion to TKA, studies referenced above suggest that the conservative nature of bone preparation would have a relevant impact on the revision of the implant to TKA.

Our study is a retrospective case series that reports tibial component thickness as a surrogate for volume of tibial resection during UKA. While the implication is that more conservative tibial resection may optimize durability and ease of conversion to TKA, future study will be needed to compare robotic-assisted and conventional cases of UKA upon conversion to TKA in order to ascertain whether the more conventional resections of robotic-assisted UKA in fact lead to revision that is comparable with primary TKA in terms of bone loss at the time of revision, components utilized, the need for bone graft, augments, or stems, and clinical outcomes. Given the method of data collection in this study, we could not control for clinical deformity, selection bias, surgeon experience, or medial vs lateral knee compartments. These potential confounders represent weaknesses of this study.

In conclusion, conversion of UKA to TKA may be associated with significant osseous insufficiency, which may compromise patient outcomes in comparison to primary TKA. Studies have shown that UKA conversion to TKA is comparable to primary TKA when minimal tibial resection is performed during the UKA, and the need for augmentation, grafting or stems is increased with more aggressive tibial resection. This study has shown that when robotic assistance is utilized, tibial resection is more precise, less variable, and more conservative compared to conventional techniques.

Am J Orthop. 2016;45(7):E465-E468. Copyright Frontline Medical Communications Inc. 2016. All rights reserved.

1. Patil S, Colwell CW Jr, Ezzet KA, D’Lima DD. Can normal knee kinematics be restored with unicompartmental knee replacement? J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;87(2):332-338.

2. Johnson S, Jones P, Newman JH. The survivorship and results of total knee replacements converted from unicompartmental knee replacements. Knee. 2007;14(2):154-157.

3. Springer BD, Scott RD, Thornhill TS. Conversion of failed unicompartmental knee arthroplasty to TKA. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2006;446:214-220.

4. Järvenpää J, Kettunen J, Miettinen H, Kröger H. The clinical outcome of revision knee replacement after unicompartmental knee arthroplasty versus primary total knee arthroplasty: 8-17 years follow-up study of 49 patients. Int Orthop. 2010;34(5):649-653.

5. Pearse AJ, Hooper GJ, Rothwell AG, Frampton C. Osteotomy and unicompartmental knee arthroplasty converted to total knee arthroplasty: data from the New Zealand Joint Registry. J Arthroplasty. 2012;27(10):1827-1831.

6. Rancourt MF, Kemp KA, Plamondon SM, Kim PR, Dervin GF. Unicompartmental knee arthroplasties revised to total knee arthroplasties compared with primary total knee arthroplasties. J Arthroplasty. 2012;27(8 Suppl):106-110.

7. Sierra RJ, Kassel CA, Wetters NG, Berend KR, Della Valle CJ, Lombardi AV. Revision of unicompartmental arthroplasty to total knee arthroplasty: not always a slam dunk! J Arthroplasty. 2013;28(8 Suppl):128-132.

8. O’Donnell TM, Abouazza O, Neil MJ. Revision of minimal resection resurfacing unicondylar knee arthroplasty to total knee arthroplasty: results compared with primary total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2013;28(1):33-39.

9. Schwarzkopf R, Mikhael B, Li L, Josephs L, Scott RD. Effect of initial tibial resection thickness on outcomes of revision UKA. Orthopedics. 2013;36(4):e409-e414.

10. Conditt MA, Roche MW. Minimally invasive robotic-arm-guided unicompartmental knee arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2009;91 Suppl 1:63-68.

11. Dunbar NJ, Roche MW, Park BH, Branch SH, Conditt MA, Banks SA. Accuracy of dynamic tactile-guided unicompartmental knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2012;27(5):803-808.e1.

12. Karia M, Masjedi M, Andrews B, Jaffry Z, Cobb J. Robotic assistance enables inexperienced surgeons to perform unicompartmental knee arthroplasties on dry bone models with accuracy superior to conventional methods. Adv Orthop. 2013;2013:481039.

13. Lonner JH, John TK, Conditt MA. Robotic arm-assisted UKA improves tibial component alignment: a pilot study. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2010;468(1):141-146.

14. Lonner JH, Smith JR, Picard F, Hamlin B, Rowe PJ, Riches PE. High degree of accuracy of a novel image-free handheld robot for unicondylar knee arthroplasty in a cadaveric study. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2015;473(1):206-212.

15. Smith JR, Picard F, Rowe PJ, Deakin A, Riches PE. The accuracy of a robotically-controlled freehand sculpting tool for unicondylar knee arthroplasty. Bone Joint J. 2013;95-B(suppl 28):68.

16. Chakrabarty G, Newman JH, Ackroyd CE. Revision of unicompartmental arthroplasty of the knee. Clinical and technical considerations. J Arthroplasty. 1998;13(2):191-196.

17. Levine WN, Ozuna RM, Scott RD, Thornhill TS. Conversion of failed modern unicompartmental arthroplasty to total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 1996;11(7):797-801.

18. Barrett WP, Scott RD. Revision of failed unicondylar unicompartmental knee arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1987;69(9):1328-1335.

19. Padgett DE, Stern SH, Insall JN. Revision total knee arthroplasty for failed unicompartmental replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1991;73(2):186-190.

20. Aleto TJ, Berend ME, Ritter MA, Faris PM, Meneghini RM. Early failure of unicompartmental knee arthroplasty leading to revision. J Arthroplasty. 2008;23(2):159-163.

21. McAuley JP, Engh GA, Ammeen DJ. Revision of failed unicompartmental knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2001;(392):279-282.22. Böhm I, Landsiedl F. Revision surgery after failed unicompartmental knee arthroplasty: a study of 35 cases. J Arthroplasty. 2000;15(8):982-989.

23. Khan Z, Nawaz SZ, Kahane S, Ester C, Chatterji U. Conversion of unicompartmental knee arthroplasty to total knee arthroplasty: the challenges and need for augments. Acta Orthop Belg. 2013;79(6):699-705.

Unicompartmental knee arthroplasty (UKA) is considered a less invasive approach for the treatment of unicompartmental knee arthritis when compared with total knee arthroplasty (TKA), with optimal preservation of kinematics.1 Despite excellent functional outcomes, conversion to TKA may be necessary if the UKA fails, or in patients with progressive knee arthritis. Some studies have found UKA conversion to TKA to be comparable with primary TKA,2,3 whereas others have found that conversion often requires bone graft, augments, and stemmed components and has increased complications and inferior results compared to primary TKA.4-7 While some studies report that <10% of UKA conversions to TKA require augments,2 others have found that as many as 76% require augments.4-8

Schwarzkopf and colleagues9 recently demonstrated that UKA conversion to TKA is comparable with primary TKA when a conservative tibial resection is performed during the index procedure. However, they reported increased complexity when greater tibial resection was performed and thicker polyethylene inserts were used at the time of the index UKA. The odds ratio of needing an augment or stem during the conversion to TKA was 26.8 (95% confidence interval, 3.71-194) when an aggressive tibial resection was performed during the UKA.9 Tibial resection thickness may thus be predictive of anticipated complexity of UKA revision to TKA and may aid in preoperative planning.

Robotic assistance has been shown to enhance the accuracy of bone preparation, implant component alignment, and soft tissue balance in UKA.10-15 It has yet to be determined whether this improved accuracy translates to improved clinical performance or longevity of the UKA implant. However, the enhanced accuracy of robotic technology may result in more conservative tibial resection when compared to conventional UKA and may be advantageous if conversion to TKA becomes necessary.

The purpose of this study was to compare the distribution of polyethylene insert sizes implanted during conventional and robotic-assisted UKA. We hypothesized that robotic assistance would demonstrate more conservative tibial resection compared to conventional methods of bone preparation.

Methods

We retrospectively compared the distribution of polyethylene insert sizes implanted during consecutive conventional and robotic-assisted UKA procedures. Several manufacturers were queried to provide a listing of the polyethylene insert sizes utilized, ranging from 8 mm to 14 mm. The analysis included 8421 robotic-assisted UKA cases and 27,989 conventional UKA cases. Data were provided by Zimmer Biomet and Smith & Nephew regarding conventional cases, as well as Blue Belt Technologies (now part of Smith & Nephew) and MAKO Surgical (now part of Stryker) regarding robotic-assisted cases. (Dr. Lonner has an ongoing relationship as a consultant with Blue Belt Technologies, whose data was utilized in this study.) Using tibial insert thickness as a surrogate measure of the extent of tibial resection, an insert size of ≥10 mm was defined as aggressive while <10 mm was considered conservative. This cutoff was established based on its corresponding resection level with primary TKA and the anticipated need for augments. Statistical analysis was performed using a Mann-Whitney-Wilcoxon test. Significance was set at P < .05.

Results

Tibial resection thickness was found to be most commonly conservative in nature, with sizes 8-mm and 9-mm polyethylene inserts utilized in the majority of both robotic-assisted and conventional UKA cases. However, statistically more 8-mm and 9-mm polyethylene inserts were used in the robotic group (93.6%) than in the conventional group (84.5%) (P < .0001; Figure). Aggressive tibial resection, requiring tibial inserts ≥10 mm, was performed in 6.4% of robotic-assisted cases and 15.5% of conventional cases.

Discussion

Robotic assistance enhances the accuracy of bone preparation, implant component alignment, and soft tissue balance in UKA.10-15 It has yet to be determined whether this improved accuracy translates to improved clinical performance or longevity of the UKA implant. However, we demonstrate that the enhanced accuracy of robotic technology results in more conservative tibial resection when compared to conventional techniques with a potential benefit suggested in the literature upon conversion to TKA.

The findings of this study have important implications for patients undergoing conversion of UKA to TKA, potentially optimizing the ease of revision and clinical outcomes. The outcomes of UKA conversion to TKA are often considered inferior to those of primary TKA, compromised by bone loss, need for augmentation, and challenges of restoring the joint line and rotation.9,16-22 Barrett and Scott18 reported only 66% of patients had good or excellent results at an average of 4.6 years of follow-up after UKA conversion to TKA. Over 50% required stemmed implants and bone graft or bone cement augmentation to address osseous insufficiency. The authors suggested that the primary determinant of the complexity of the conversion to TKA was the surgical technique used in the index procedure. They concluded that UKA conversion to TKA can be as successful as a primary TKA and primary TKA implants can be used without bone augmentation or stems during the revision procedure if minimal tibial bone is resected at the time of the index UKA.18 Schwarzkopf and colleagues9 supported this conclusion when they found that aggressive tibial resection during UKA resulted in the need for bone graft, stem, wedge, or augment in 70% of cases when converted to TKA. Similarly, Khan and colleagues23 found that 26% of patients required bone grafting and 26% required some form of augmentation, and Springer and colleagues3 reported that 68% required a graft, augment, or stem.3,22 Using data from the New Zealand Joint Registry, Pearse and colleagues5 reported that revision TKA components were necessary in 28% of patients and concluded that converting a UKA to TKA gives a less reliable result than primary TKA, and with functional results that are not significantly better than a revision from a TKA.

Conservative tibial resection during UKA minimizes the complexity and concerns of bone loss upon conversion to TKA. Schwarzkopf and colleagues9 found 96.6% of patients with conservative tibial resection received a primary TKA implant, without augments or stems. Furthermore, patients with a primary TKA implant showed improved tibial survivorship, with revision as an end point, compared with patients who received a TKA implant that required stems and augments or bone graft for support.9 Also emphasizing the importance of minimal tibial resection, O’Donnell and colleagues8 compared a cohort of patients undergoing conversion of a minimal resection resurfacing onlay-type UKA to TKA with a cohort of patients undergoing primary TKA. They found that 40% of patients required bone grafting for contained defects, 3.6% required metal augments, and 1.8% required stems.8 There was no significant difference between the groups in terms of range of motion, functional outcome, or radiologic outcomes. The authors concluded that revision of minimal resection resurfacing implants to TKA is associated with similar results to primary TKA and is superior to revision of UKA with greater bone loss. Prior studies have shown that one of the advantages of robotic-assisted UKA is the accuracy and precision of bone resection. The present study supports this premise by showing that tibial resection is significantly more conservative using robotic-assisted techniques when using tibial component thickness as a surrogate for extent of bone resection. While our study did not address implant durability or the impact of conservative resection on conversion to TKA, studies referenced above suggest that the conservative nature of bone preparation would have a relevant impact on the revision of the implant to TKA.

Our study is a retrospective case series that reports tibial component thickness as a surrogate for volume of tibial resection during UKA. While the implication is that more conservative tibial resection may optimize durability and ease of conversion to TKA, future study will be needed to compare robotic-assisted and conventional cases of UKA upon conversion to TKA in order to ascertain whether the more conventional resections of robotic-assisted UKA in fact lead to revision that is comparable with primary TKA in terms of bone loss at the time of revision, components utilized, the need for bone graft, augments, or stems, and clinical outcomes. Given the method of data collection in this study, we could not control for clinical deformity, selection bias, surgeon experience, or medial vs lateral knee compartments. These potential confounders represent weaknesses of this study.

In conclusion, conversion of UKA to TKA may be associated with significant osseous insufficiency, which may compromise patient outcomes in comparison to primary TKA. Studies have shown that UKA conversion to TKA is comparable to primary TKA when minimal tibial resection is performed during the UKA, and the need for augmentation, grafting or stems is increased with more aggressive tibial resection. This study has shown that when robotic assistance is utilized, tibial resection is more precise, less variable, and more conservative compared to conventional techniques.

Am J Orthop. 2016;45(7):E465-E468. Copyright Frontline Medical Communications Inc. 2016. All rights reserved.

Unicompartmental knee arthroplasty (UKA) is considered a less invasive approach for the treatment of unicompartmental knee arthritis when compared with total knee arthroplasty (TKA), with optimal preservation of kinematics.1 Despite excellent functional outcomes, conversion to TKA may be necessary if the UKA fails, or in patients with progressive knee arthritis. Some studies have found UKA conversion to TKA to be comparable with primary TKA,2,3 whereas others have found that conversion often requires bone graft, augments, and stemmed components and has increased complications and inferior results compared to primary TKA.4-7 While some studies report that <10% of UKA conversions to TKA require augments,2 others have found that as many as 76% require augments.4-8

Schwarzkopf and colleagues9 recently demonstrated that UKA conversion to TKA is comparable with primary TKA when a conservative tibial resection is performed during the index procedure. However, they reported increased complexity when greater tibial resection was performed and thicker polyethylene inserts were used at the time of the index UKA. The odds ratio of needing an augment or stem during the conversion to TKA was 26.8 (95% confidence interval, 3.71-194) when an aggressive tibial resection was performed during the UKA.9 Tibial resection thickness may thus be predictive of anticipated complexity of UKA revision to TKA and may aid in preoperative planning.

Robotic assistance has been shown to enhance the accuracy of bone preparation, implant component alignment, and soft tissue balance in UKA.10-15 It has yet to be determined whether this improved accuracy translates to improved clinical performance or longevity of the UKA implant. However, the enhanced accuracy of robotic technology may result in more conservative tibial resection when compared to conventional UKA and may be advantageous if conversion to TKA becomes necessary.

The purpose of this study was to compare the distribution of polyethylene insert sizes implanted during conventional and robotic-assisted UKA. We hypothesized that robotic assistance would demonstrate more conservative tibial resection compared to conventional methods of bone preparation.

Methods

We retrospectively compared the distribution of polyethylene insert sizes implanted during consecutive conventional and robotic-assisted UKA procedures. Several manufacturers were queried to provide a listing of the polyethylene insert sizes utilized, ranging from 8 mm to 14 mm. The analysis included 8421 robotic-assisted UKA cases and 27,989 conventional UKA cases. Data were provided by Zimmer Biomet and Smith & Nephew regarding conventional cases, as well as Blue Belt Technologies (now part of Smith & Nephew) and MAKO Surgical (now part of Stryker) regarding robotic-assisted cases. (Dr. Lonner has an ongoing relationship as a consultant with Blue Belt Technologies, whose data was utilized in this study.) Using tibial insert thickness as a surrogate measure of the extent of tibial resection, an insert size of ≥10 mm was defined as aggressive while <10 mm was considered conservative. This cutoff was established based on its corresponding resection level with primary TKA and the anticipated need for augments. Statistical analysis was performed using a Mann-Whitney-Wilcoxon test. Significance was set at P < .05.

Results

Tibial resection thickness was found to be most commonly conservative in nature, with sizes 8-mm and 9-mm polyethylene inserts utilized in the majority of both robotic-assisted and conventional UKA cases. However, statistically more 8-mm and 9-mm polyethylene inserts were used in the robotic group (93.6%) than in the conventional group (84.5%) (P < .0001; Figure). Aggressive tibial resection, requiring tibial inserts ≥10 mm, was performed in 6.4% of robotic-assisted cases and 15.5% of conventional cases.

Discussion

Robotic assistance enhances the accuracy of bone preparation, implant component alignment, and soft tissue balance in UKA.10-15 It has yet to be determined whether this improved accuracy translates to improved clinical performance or longevity of the UKA implant. However, we demonstrate that the enhanced accuracy of robotic technology results in more conservative tibial resection when compared to conventional techniques with a potential benefit suggested in the literature upon conversion to TKA.

The findings of this study have important implications for patients undergoing conversion of UKA to TKA, potentially optimizing the ease of revision and clinical outcomes. The outcomes of UKA conversion to TKA are often considered inferior to those of primary TKA, compromised by bone loss, need for augmentation, and challenges of restoring the joint line and rotation.9,16-22 Barrett and Scott18 reported only 66% of patients had good or excellent results at an average of 4.6 years of follow-up after UKA conversion to TKA. Over 50% required stemmed implants and bone graft or bone cement augmentation to address osseous insufficiency. The authors suggested that the primary determinant of the complexity of the conversion to TKA was the surgical technique used in the index procedure. They concluded that UKA conversion to TKA can be as successful as a primary TKA and primary TKA implants can be used without bone augmentation or stems during the revision procedure if minimal tibial bone is resected at the time of the index UKA.18 Schwarzkopf and colleagues9 supported this conclusion when they found that aggressive tibial resection during UKA resulted in the need for bone graft, stem, wedge, or augment in 70% of cases when converted to TKA. Similarly, Khan and colleagues23 found that 26% of patients required bone grafting and 26% required some form of augmentation, and Springer and colleagues3 reported that 68% required a graft, augment, or stem.3,22 Using data from the New Zealand Joint Registry, Pearse and colleagues5 reported that revision TKA components were necessary in 28% of patients and concluded that converting a UKA to TKA gives a less reliable result than primary TKA, and with functional results that are not significantly better than a revision from a TKA.

Conservative tibial resection during UKA minimizes the complexity and concerns of bone loss upon conversion to TKA. Schwarzkopf and colleagues9 found 96.6% of patients with conservative tibial resection received a primary TKA implant, without augments or stems. Furthermore, patients with a primary TKA implant showed improved tibial survivorship, with revision as an end point, compared with patients who received a TKA implant that required stems and augments or bone graft for support.9 Also emphasizing the importance of minimal tibial resection, O’Donnell and colleagues8 compared a cohort of patients undergoing conversion of a minimal resection resurfacing onlay-type UKA to TKA with a cohort of patients undergoing primary TKA. They found that 40% of patients required bone grafting for contained defects, 3.6% required metal augments, and 1.8% required stems.8 There was no significant difference between the groups in terms of range of motion, functional outcome, or radiologic outcomes. The authors concluded that revision of minimal resection resurfacing implants to TKA is associated with similar results to primary TKA and is superior to revision of UKA with greater bone loss. Prior studies have shown that one of the advantages of robotic-assisted UKA is the accuracy and precision of bone resection. The present study supports this premise by showing that tibial resection is significantly more conservative using robotic-assisted techniques when using tibial component thickness as a surrogate for extent of bone resection. While our study did not address implant durability or the impact of conservative resection on conversion to TKA, studies referenced above suggest that the conservative nature of bone preparation would have a relevant impact on the revision of the implant to TKA.

Our study is a retrospective case series that reports tibial component thickness as a surrogate for volume of tibial resection during UKA. While the implication is that more conservative tibial resection may optimize durability and ease of conversion to TKA, future study will be needed to compare robotic-assisted and conventional cases of UKA upon conversion to TKA in order to ascertain whether the more conventional resections of robotic-assisted UKA in fact lead to revision that is comparable with primary TKA in terms of bone loss at the time of revision, components utilized, the need for bone graft, augments, or stems, and clinical outcomes. Given the method of data collection in this study, we could not control for clinical deformity, selection bias, surgeon experience, or medial vs lateral knee compartments. These potential confounders represent weaknesses of this study.

In conclusion, conversion of UKA to TKA may be associated with significant osseous insufficiency, which may compromise patient outcomes in comparison to primary TKA. Studies have shown that UKA conversion to TKA is comparable to primary TKA when minimal tibial resection is performed during the UKA, and the need for augmentation, grafting or stems is increased with more aggressive tibial resection. This study has shown that when robotic assistance is utilized, tibial resection is more precise, less variable, and more conservative compared to conventional techniques.

Am J Orthop. 2016;45(7):E465-E468. Copyright Frontline Medical Communications Inc. 2016. All rights reserved.

1. Patil S, Colwell CW Jr, Ezzet KA, D’Lima DD. Can normal knee kinematics be restored with unicompartmental knee replacement? J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;87(2):332-338.

2. Johnson S, Jones P, Newman JH. The survivorship and results of total knee replacements converted from unicompartmental knee replacements. Knee. 2007;14(2):154-157.

3. Springer BD, Scott RD, Thornhill TS. Conversion of failed unicompartmental knee arthroplasty to TKA. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2006;446:214-220.

4. Järvenpää J, Kettunen J, Miettinen H, Kröger H. The clinical outcome of revision knee replacement after unicompartmental knee arthroplasty versus primary total knee arthroplasty: 8-17 years follow-up study of 49 patients. Int Orthop. 2010;34(5):649-653.

5. Pearse AJ, Hooper GJ, Rothwell AG, Frampton C. Osteotomy and unicompartmental knee arthroplasty converted to total knee arthroplasty: data from the New Zealand Joint Registry. J Arthroplasty. 2012;27(10):1827-1831.

6. Rancourt MF, Kemp KA, Plamondon SM, Kim PR, Dervin GF. Unicompartmental knee arthroplasties revised to total knee arthroplasties compared with primary total knee arthroplasties. J Arthroplasty. 2012;27(8 Suppl):106-110.

7. Sierra RJ, Kassel CA, Wetters NG, Berend KR, Della Valle CJ, Lombardi AV. Revision of unicompartmental arthroplasty to total knee arthroplasty: not always a slam dunk! J Arthroplasty. 2013;28(8 Suppl):128-132.

8. O’Donnell TM, Abouazza O, Neil MJ. Revision of minimal resection resurfacing unicondylar knee arthroplasty to total knee arthroplasty: results compared with primary total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2013;28(1):33-39.

9. Schwarzkopf R, Mikhael B, Li L, Josephs L, Scott RD. Effect of initial tibial resection thickness on outcomes of revision UKA. Orthopedics. 2013;36(4):e409-e414.

10. Conditt MA, Roche MW. Minimally invasive robotic-arm-guided unicompartmental knee arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2009;91 Suppl 1:63-68.

11. Dunbar NJ, Roche MW, Park BH, Branch SH, Conditt MA, Banks SA. Accuracy of dynamic tactile-guided unicompartmental knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2012;27(5):803-808.e1.

12. Karia M, Masjedi M, Andrews B, Jaffry Z, Cobb J. Robotic assistance enables inexperienced surgeons to perform unicompartmental knee arthroplasties on dry bone models with accuracy superior to conventional methods. Adv Orthop. 2013;2013:481039.

13. Lonner JH, John TK, Conditt MA. Robotic arm-assisted UKA improves tibial component alignment: a pilot study. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2010;468(1):141-146.

14. Lonner JH, Smith JR, Picard F, Hamlin B, Rowe PJ, Riches PE. High degree of accuracy of a novel image-free handheld robot for unicondylar knee arthroplasty in a cadaveric study. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2015;473(1):206-212.

15. Smith JR, Picard F, Rowe PJ, Deakin A, Riches PE. The accuracy of a robotically-controlled freehand sculpting tool for unicondylar knee arthroplasty. Bone Joint J. 2013;95-B(suppl 28):68.

16. Chakrabarty G, Newman JH, Ackroyd CE. Revision of unicompartmental arthroplasty of the knee. Clinical and technical considerations. J Arthroplasty. 1998;13(2):191-196.

17. Levine WN, Ozuna RM, Scott RD, Thornhill TS. Conversion of failed modern unicompartmental arthroplasty to total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 1996;11(7):797-801.

18. Barrett WP, Scott RD. Revision of failed unicondylar unicompartmental knee arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1987;69(9):1328-1335.

19. Padgett DE, Stern SH, Insall JN. Revision total knee arthroplasty for failed unicompartmental replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1991;73(2):186-190.

20. Aleto TJ, Berend ME, Ritter MA, Faris PM, Meneghini RM. Early failure of unicompartmental knee arthroplasty leading to revision. J Arthroplasty. 2008;23(2):159-163.

21. McAuley JP, Engh GA, Ammeen DJ. Revision of failed unicompartmental knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2001;(392):279-282.22. Böhm I, Landsiedl F. Revision surgery after failed unicompartmental knee arthroplasty: a study of 35 cases. J Arthroplasty. 2000;15(8):982-989.

23. Khan Z, Nawaz SZ, Kahane S, Ester C, Chatterji U. Conversion of unicompartmental knee arthroplasty to total knee arthroplasty: the challenges and need for augments. Acta Orthop Belg. 2013;79(6):699-705.

1. Patil S, Colwell CW Jr, Ezzet KA, D’Lima DD. Can normal knee kinematics be restored with unicompartmental knee replacement? J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;87(2):332-338.

2. Johnson S, Jones P, Newman JH. The survivorship and results of total knee replacements converted from unicompartmental knee replacements. Knee. 2007;14(2):154-157.

3. Springer BD, Scott RD, Thornhill TS. Conversion of failed unicompartmental knee arthroplasty to TKA. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2006;446:214-220.

4. Järvenpää J, Kettunen J, Miettinen H, Kröger H. The clinical outcome of revision knee replacement after unicompartmental knee arthroplasty versus primary total knee arthroplasty: 8-17 years follow-up study of 49 patients. Int Orthop. 2010;34(5):649-653.

5. Pearse AJ, Hooper GJ, Rothwell AG, Frampton C. Osteotomy and unicompartmental knee arthroplasty converted to total knee arthroplasty: data from the New Zealand Joint Registry. J Arthroplasty. 2012;27(10):1827-1831.

6. Rancourt MF, Kemp KA, Plamondon SM, Kim PR, Dervin GF. Unicompartmental knee arthroplasties revised to total knee arthroplasties compared with primary total knee arthroplasties. J Arthroplasty. 2012;27(8 Suppl):106-110.

7. Sierra RJ, Kassel CA, Wetters NG, Berend KR, Della Valle CJ, Lombardi AV. Revision of unicompartmental arthroplasty to total knee arthroplasty: not always a slam dunk! J Arthroplasty. 2013;28(8 Suppl):128-132.

8. O’Donnell TM, Abouazza O, Neil MJ. Revision of minimal resection resurfacing unicondylar knee arthroplasty to total knee arthroplasty: results compared with primary total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2013;28(1):33-39.

9. Schwarzkopf R, Mikhael B, Li L, Josephs L, Scott RD. Effect of initial tibial resection thickness on outcomes of revision UKA. Orthopedics. 2013;36(4):e409-e414.

10. Conditt MA, Roche MW. Minimally invasive robotic-arm-guided unicompartmental knee arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2009;91 Suppl 1:63-68.

11. Dunbar NJ, Roche MW, Park BH, Branch SH, Conditt MA, Banks SA. Accuracy of dynamic tactile-guided unicompartmental knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2012;27(5):803-808.e1.

12. Karia M, Masjedi M, Andrews B, Jaffry Z, Cobb J. Robotic assistance enables inexperienced surgeons to perform unicompartmental knee arthroplasties on dry bone models with accuracy superior to conventional methods. Adv Orthop. 2013;2013:481039.

13. Lonner JH, John TK, Conditt MA. Robotic arm-assisted UKA improves tibial component alignment: a pilot study. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2010;468(1):141-146.

14. Lonner JH, Smith JR, Picard F, Hamlin B, Rowe PJ, Riches PE. High degree of accuracy of a novel image-free handheld robot for unicondylar knee arthroplasty in a cadaveric study. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2015;473(1):206-212.

15. Smith JR, Picard F, Rowe PJ, Deakin A, Riches PE. The accuracy of a robotically-controlled freehand sculpting tool for unicondylar knee arthroplasty. Bone Joint J. 2013;95-B(suppl 28):68.

16. Chakrabarty G, Newman JH, Ackroyd CE. Revision of unicompartmental arthroplasty of the knee. Clinical and technical considerations. J Arthroplasty. 1998;13(2):191-196.

17. Levine WN, Ozuna RM, Scott RD, Thornhill TS. Conversion of failed modern unicompartmental arthroplasty to total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 1996;11(7):797-801.

18. Barrett WP, Scott RD. Revision of failed unicondylar unicompartmental knee arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1987;69(9):1328-1335.

19. Padgett DE, Stern SH, Insall JN. Revision total knee arthroplasty for failed unicompartmental replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1991;73(2):186-190.

20. Aleto TJ, Berend ME, Ritter MA, Faris PM, Meneghini RM. Early failure of unicompartmental knee arthroplasty leading to revision. J Arthroplasty. 2008;23(2):159-163.

21. McAuley JP, Engh GA, Ammeen DJ. Revision of failed unicompartmental knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2001;(392):279-282.22. Böhm I, Landsiedl F. Revision surgery after failed unicompartmental knee arthroplasty: a study of 35 cases. J Arthroplasty. 2000;15(8):982-989.

23. Khan Z, Nawaz SZ, Kahane S, Ester C, Chatterji U. Conversion of unicompartmental knee arthroplasty to total knee arthroplasty: the challenges and need for augments. Acta Orthop Belg. 2013;79(6):699-705.

Hospitalist Tracy Gulling-Leftwich, DO, Spends Her Free Time Caring for Rescue Animals

Tracy Gulling-Leftwich, DO, remembers Chewy very well. He was a 70-pound English bulldog she was caring for last year on behalf of the Rescue Ohio English Bulldogs, an English bulldog rescue group.

She soon learned that Chewy was anemic and suffered from bone cancer of the jaw. Ironically, considering his name, he could barely chew, so Dr. Gulling-Leftwich and her husband, Samuel Leftwich, pureed his food, spoon-fed the animal, and administered around-the-clock pain medications for roughly two weeks. But his pain grew too intense, and Chewy had to be euthanized.

For many people, that would end their experience with an animal organization. People typically compare the heartbreaking experience to losing a beloved family member or friend. But as an animal lover and hospitalist at the Cleveland Clinic, Dr. Gulling-Leftwich has no intentions of looking the other way whenever an animal—or human—is in need. Ever since she was in college, she has been rescuing lab rats and dogs, trying to keep them happy, healthy, and loved throughout their relatively short lives.

Underground Railroad

Dr. Gulling-Leftwich graduated from the Lake Erie College of Osteopathic Medicine in Erie, Penn., in 2007. The following year, she pursued an osteopathic rotating internship at the University of Connecticut. While attending the same university from 2008 to 2010, she completed a traditional, categorical, allopathic medicine residency.

After completing her medical education, she held several positions. She worked as a teaching hospitalist at the Hartford Hospital for one year, served as a primary-care physician for the next three years at The Hospital of Central Connecticut, and then joined the Cleveland Clinic as a hospitalist in 2014.

Her involvement in animal rescue began many years earlier while attending undergraduate school at Westminster College in New Wilmington, Penn. She tells the story how one student at the college kidnapped a rat from the school’s neuroscience lab just before Christmas break.

Since the student’s mother would not allow her to bring a rat home over the six-week holiday, Dr. Gulling-Leftwich babysat him until she returned. However, the student intended on releasing him into the wild. Fearing the worst, that the rat could not fend for itself since it had been caged and fed for many months, Dr. Gulling-Leftwich convinced the student to relinquish custody of the rat to her.

That’s how it all began. Dr. Gulling-Leftwich named the rat Templeton. She suspects he died of a pituitary tumor four years later; still, that’s a long life for a rat. Most live just two years. Just shows what a little love can do.

Since then, she has rescued approximately 21 rats from Kentucky and Connecticut. Years ago, she says, there were multiple Yahoo chat groups of people involved in an underground railroad of sorts for rescued lab rats. People would often drive the rats to different cities, even across state borders, so these rats could enjoy a permanent home.

While she has never broken into a research lab, her opinion is torn on animal research. She believes it is not necessary for consumer products, such as makeup, but can see its value in other fields of science like the development of new medications.

“What I can hope for is that we work toward finding a way of not requiring animals for research in the future,” she says.

Full House

After getting married in 2013, Dr. Gulling-Leftwich told her husband she wanted a dog. But because of their hectic schedules, no one would be home to care for the animal, so the couple waited another two years to adopt a rescue animal.

In 2015, they had purchased a house in Cleveland when they adopted Boomer, a pug and beagle designer breed, as their family pet.

“I had really wanted an English bulldog. They’re just cute, their face is squishy,” she says, adding she had been monitoring English bulldog rescue websites. “I won’t buy a puppy. I will only get a dog that needs a home.”

In September that year, the rescue organization emailed a desperate plea to its followers. Can anyone rescue an English bulldog named Chewy? Dr. Gulling-Leftwich immediately filled out the paperwork and adopted him. But Chewy only stayed with them for two weeks before he was euthanized. She brought him to the vet after he attacked Boomer.

“Chewy wasn’t being a jerk,” she says. “His attacking behavior had to do with his pain and discomfort. He had blood everywhere around his mouth. We had a hard time letting him go.”

One month later, another English bulldog named Olive joined their family. She’s roughly two years old and weighs only 30 pounds mainly because of her disease: congenital cardiomyopathy. They plan to care for Olive until she dies.

She says Olive takes six pills a day for her condition and occasionally receives nitroglycerin when she overexerts herself and passes out.

Meanwhile, Dr. Gulling-Leftwich and her husband care for one rat named Harvey and a cat called Lily in addition to the two dogs. Boomer doesn’t like Olive. Olive doesn’t like the cat. And both dogs and the cat pay no attention to the rat.

“My husband says rescuing animals and taking care of people is one of my more endearing qualities,” she says. “Then he follows it up with, ‘No, you can’t have that bunny that needs a home.’”

She believes caring for these animals balances her work in hospital medicine. While hospital patients often are in pain, act grouchy, and appear unappreciative, she says her four-legged family members are always excited to see her and routinely demonstrate unconditional love.

“You definitely have to be open-minded because you never know what you’ll be walking into when you rescue an animal,” she says, adding that rescue groups tend to pay for vet bills and medicine. “You have to be prepared for what potentially could be the worst.”

Carol Patton is a freelance writer in Las Vegas.

Tracy Gulling-Leftwich, DO, remembers Chewy very well. He was a 70-pound English bulldog she was caring for last year on behalf of the Rescue Ohio English Bulldogs, an English bulldog rescue group.

She soon learned that Chewy was anemic and suffered from bone cancer of the jaw. Ironically, considering his name, he could barely chew, so Dr. Gulling-Leftwich and her husband, Samuel Leftwich, pureed his food, spoon-fed the animal, and administered around-the-clock pain medications for roughly two weeks. But his pain grew too intense, and Chewy had to be euthanized.

For many people, that would end their experience with an animal organization. People typically compare the heartbreaking experience to losing a beloved family member or friend. But as an animal lover and hospitalist at the Cleveland Clinic, Dr. Gulling-Leftwich has no intentions of looking the other way whenever an animal—or human—is in need. Ever since she was in college, she has been rescuing lab rats and dogs, trying to keep them happy, healthy, and loved throughout their relatively short lives.

Underground Railroad

Dr. Gulling-Leftwich graduated from the Lake Erie College of Osteopathic Medicine in Erie, Penn., in 2007. The following year, she pursued an osteopathic rotating internship at the University of Connecticut. While attending the same university from 2008 to 2010, she completed a traditional, categorical, allopathic medicine residency.

After completing her medical education, she held several positions. She worked as a teaching hospitalist at the Hartford Hospital for one year, served as a primary-care physician for the next three years at The Hospital of Central Connecticut, and then joined the Cleveland Clinic as a hospitalist in 2014.

Her involvement in animal rescue began many years earlier while attending undergraduate school at Westminster College in New Wilmington, Penn. She tells the story how one student at the college kidnapped a rat from the school’s neuroscience lab just before Christmas break.

Since the student’s mother would not allow her to bring a rat home over the six-week holiday, Dr. Gulling-Leftwich babysat him until she returned. However, the student intended on releasing him into the wild. Fearing the worst, that the rat could not fend for itself since it had been caged and fed for many months, Dr. Gulling-Leftwich convinced the student to relinquish custody of the rat to her.

That’s how it all began. Dr. Gulling-Leftwich named the rat Templeton. She suspects he died of a pituitary tumor four years later; still, that’s a long life for a rat. Most live just two years. Just shows what a little love can do.

Since then, she has rescued approximately 21 rats from Kentucky and Connecticut. Years ago, she says, there were multiple Yahoo chat groups of people involved in an underground railroad of sorts for rescued lab rats. People would often drive the rats to different cities, even across state borders, so these rats could enjoy a permanent home.

While she has never broken into a research lab, her opinion is torn on animal research. She believes it is not necessary for consumer products, such as makeup, but can see its value in other fields of science like the development of new medications.

“What I can hope for is that we work toward finding a way of not requiring animals for research in the future,” she says.

Full House

After getting married in 2013, Dr. Gulling-Leftwich told her husband she wanted a dog. But because of their hectic schedules, no one would be home to care for the animal, so the couple waited another two years to adopt a rescue animal.

In 2015, they had purchased a house in Cleveland when they adopted Boomer, a pug and beagle designer breed, as their family pet.

“I had really wanted an English bulldog. They’re just cute, their face is squishy,” she says, adding she had been monitoring English bulldog rescue websites. “I won’t buy a puppy. I will only get a dog that needs a home.”

In September that year, the rescue organization emailed a desperate plea to its followers. Can anyone rescue an English bulldog named Chewy? Dr. Gulling-Leftwich immediately filled out the paperwork and adopted him. But Chewy only stayed with them for two weeks before he was euthanized. She brought him to the vet after he attacked Boomer.

“Chewy wasn’t being a jerk,” she says. “His attacking behavior had to do with his pain and discomfort. He had blood everywhere around his mouth. We had a hard time letting him go.”

One month later, another English bulldog named Olive joined their family. She’s roughly two years old and weighs only 30 pounds mainly because of her disease: congenital cardiomyopathy. They plan to care for Olive until she dies.

She says Olive takes six pills a day for her condition and occasionally receives nitroglycerin when she overexerts herself and passes out.

Meanwhile, Dr. Gulling-Leftwich and her husband care for one rat named Harvey and a cat called Lily in addition to the two dogs. Boomer doesn’t like Olive. Olive doesn’t like the cat. And both dogs and the cat pay no attention to the rat.

“My husband says rescuing animals and taking care of people is one of my more endearing qualities,” she says. “Then he follows it up with, ‘No, you can’t have that bunny that needs a home.’”

She believes caring for these animals balances her work in hospital medicine. While hospital patients often are in pain, act grouchy, and appear unappreciative, she says her four-legged family members are always excited to see her and routinely demonstrate unconditional love.

“You definitely have to be open-minded because you never know what you’ll be walking into when you rescue an animal,” she says, adding that rescue groups tend to pay for vet bills and medicine. “You have to be prepared for what potentially could be the worst.”

Carol Patton is a freelance writer in Las Vegas.

Tracy Gulling-Leftwich, DO, remembers Chewy very well. He was a 70-pound English bulldog she was caring for last year on behalf of the Rescue Ohio English Bulldogs, an English bulldog rescue group.

She soon learned that Chewy was anemic and suffered from bone cancer of the jaw. Ironically, considering his name, he could barely chew, so Dr. Gulling-Leftwich and her husband, Samuel Leftwich, pureed his food, spoon-fed the animal, and administered around-the-clock pain medications for roughly two weeks. But his pain grew too intense, and Chewy had to be euthanized.

For many people, that would end their experience with an animal organization. People typically compare the heartbreaking experience to losing a beloved family member or friend. But as an animal lover and hospitalist at the Cleveland Clinic, Dr. Gulling-Leftwich has no intentions of looking the other way whenever an animal—or human—is in need. Ever since she was in college, she has been rescuing lab rats and dogs, trying to keep them happy, healthy, and loved throughout their relatively short lives.

Underground Railroad

Dr. Gulling-Leftwich graduated from the Lake Erie College of Osteopathic Medicine in Erie, Penn., in 2007. The following year, she pursued an osteopathic rotating internship at the University of Connecticut. While attending the same university from 2008 to 2010, she completed a traditional, categorical, allopathic medicine residency.

After completing her medical education, she held several positions. She worked as a teaching hospitalist at the Hartford Hospital for one year, served as a primary-care physician for the next three years at The Hospital of Central Connecticut, and then joined the Cleveland Clinic as a hospitalist in 2014.

Her involvement in animal rescue began many years earlier while attending undergraduate school at Westminster College in New Wilmington, Penn. She tells the story how one student at the college kidnapped a rat from the school’s neuroscience lab just before Christmas break.

Since the student’s mother would not allow her to bring a rat home over the six-week holiday, Dr. Gulling-Leftwich babysat him until she returned. However, the student intended on releasing him into the wild. Fearing the worst, that the rat could not fend for itself since it had been caged and fed for many months, Dr. Gulling-Leftwich convinced the student to relinquish custody of the rat to her.

That’s how it all began. Dr. Gulling-Leftwich named the rat Templeton. She suspects he died of a pituitary tumor four years later; still, that’s a long life for a rat. Most live just two years. Just shows what a little love can do.

Since then, she has rescued approximately 21 rats from Kentucky and Connecticut. Years ago, she says, there were multiple Yahoo chat groups of people involved in an underground railroad of sorts for rescued lab rats. People would often drive the rats to different cities, even across state borders, so these rats could enjoy a permanent home.

While she has never broken into a research lab, her opinion is torn on animal research. She believes it is not necessary for consumer products, such as makeup, but can see its value in other fields of science like the development of new medications.

“What I can hope for is that we work toward finding a way of not requiring animals for research in the future,” she says.

Full House

After getting married in 2013, Dr. Gulling-Leftwich told her husband she wanted a dog. But because of their hectic schedules, no one would be home to care for the animal, so the couple waited another two years to adopt a rescue animal.

In 2015, they had purchased a house in Cleveland when they adopted Boomer, a pug and beagle designer breed, as their family pet.

“I had really wanted an English bulldog. They’re just cute, their face is squishy,” she says, adding she had been monitoring English bulldog rescue websites. “I won’t buy a puppy. I will only get a dog that needs a home.”

In September that year, the rescue organization emailed a desperate plea to its followers. Can anyone rescue an English bulldog named Chewy? Dr. Gulling-Leftwich immediately filled out the paperwork and adopted him. But Chewy only stayed with them for two weeks before he was euthanized. She brought him to the vet after he attacked Boomer.

“Chewy wasn’t being a jerk,” she says. “His attacking behavior had to do with his pain and discomfort. He had blood everywhere around his mouth. We had a hard time letting him go.”

One month later, another English bulldog named Olive joined their family. She’s roughly two years old and weighs only 30 pounds mainly because of her disease: congenital cardiomyopathy. They plan to care for Olive until she dies.

She says Olive takes six pills a day for her condition and occasionally receives nitroglycerin when she overexerts herself and passes out.

Meanwhile, Dr. Gulling-Leftwich and her husband care for one rat named Harvey and a cat called Lily in addition to the two dogs. Boomer doesn’t like Olive. Olive doesn’t like the cat. And both dogs and the cat pay no attention to the rat.

“My husband says rescuing animals and taking care of people is one of my more endearing qualities,” she says. “Then he follows it up with, ‘No, you can’t have that bunny that needs a home.’”

She believes caring for these animals balances her work in hospital medicine. While hospital patients often are in pain, act grouchy, and appear unappreciative, she says her four-legged family members are always excited to see her and routinely demonstrate unconditional love.

“You definitely have to be open-minded because you never know what you’ll be walking into when you rescue an animal,” she says, adding that rescue groups tend to pay for vet bills and medicine. “You have to be prepared for what potentially could be the worst.”

Carol Patton is a freelance writer in Las Vegas.

CAR T-cell trial placed on hold again

Once again, the phase 2 ROCKET trial has been placed on clinical hold due to patient deaths.

In this trial, researchers are testing the chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy JCAR015 in adults with relapsed or refractory B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia.

Juno Therapeutics, Inc. voluntarily put the trial on hold after 2 more patients suffered cerebral edema and died.

A total of 5 patients have died of cerebral edema in this trial.

Juno has notified the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) of the latest clinical hold on the ROCKET trial and is working with the agency and the company’s data and safety monitoring board to determine next steps.

The ROCKET trial was previously placed on clinical hold in July, after 3 patients died of cerebral edema. The FDA lifted the hold less than a week later, allowing the trial to continue with a revised protocol.

Juno had theorized the deaths were likely a result of adding fludarabine to the conditioning regimen.

Patients enrolled in ROCKET initially received conditioning with cyclophosphamide alone, but researchers later decided to add fludarabine in the hopes of increasing efficacy. Previous trials of 2 other CAR T-cell therapies, JCAR014 and JCAR017, had suggested that adding fludarabine to conditioning could increase efficacy.

However, in the ROCKET trial, the addition of fludarabine was associated with an increase in the incidence of severe neurotoxicity and the 3 deaths from cerebral edema.

Juno said that, although other factors may have contributed to the deaths, fludarabine was the most likely culprit. So the company revised the trial protocol, and the FDA allowed ROCKET to continue with a conditioning regimen consisting of cyclophosphamide alone.

Since that time, 12 patients have been treated on the ROCKET trial. Two patients who were treated the week of November 14 developed cerebral edema and died on November 22 and 23, respectively.

In a conference call, Juno’s Chief Medical Officer Mark Gilbert, MD, said the etiology of cerebral edema is multi-factorial, and Juno will need more time to draw even preliminary conclusions about what factors contributed to the cases of cerebral edema in ROCKET.

Right now, the company is assessing data from the cases and the trial and is evaluating its options regarding the JCAR015 program.

Juno’s President and CEO Hans Bishop said the options for JCAR015 going forward include continuing the ROCKET trial with a modified protocol, beginning a new study of JCAR015, and terminating the JCAR015 development program.

Bishop said the company expects to provide an update on the status of ROCKET and JCAR015 in the next few weeks.

Juno’s other trials and plans for its other CD19-directed CAR T-cell product candidates are not affected by the issues with ROCKET and JCAR015.

ROCKET is not the first trial of JCAR015 to be placed on hold. The phase 1 trial of the therapy was placed on clinical hold in 2014, after 2 patients died of cytokine release syndrome.