User login

Preoperative evaluation: A time-saving algorithm

PRACTICE RECOMMENDATIONS

› Recommend that patients quit smoking 8 weeks before surgery; keep in mind, though, that quitting closer to the date of surgery does not increase the risk of complications. A

› Use the online American College of Surgeons/National Surgical Quality Improvement Program surgical risk calculator to estimate a patient’s surgical risk. C

› Send a patient directly to surgery if he or she has an estimated cardiac risk <1% or <2 risk factors of the Revised Cardiac Risk Index. B

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

About 27 million Americans undergo surgery every year1 and before doing so, they turn to you—their primary care physician—or their cardiologist for a preoperative evaluation. Of course, the goal of this evaluation is to determine an individual patient’s risk and compare it to procedural averages in an effort to identify opportunities for risk mitigation. But the preoperative evaluation is also an opportunity to make recommendations regarding perioperative management of medications. And certainly we want to conduct these evaluations in a way that is both expeditious and in keeping with the latest guidelines.

Current guidelines for preoperative evaluations are less complicated than they used to be and focus on cardiac and pulmonary risk stratification. While a risk calculator remains your primary tool, elements such as smoking cessation and identifying sleep apnea are important parts of the preop equation. In the review that follows, we present a simple algorithm (FIGURE 12-6) that we developed that can be completed in a single visit.

Cardiac assessment: A risk calculator is the primary tool

Cardiac risk estimation is perhaps the most important element in determining a patient’s overall surgical risk. But before you begin, you'll need to determine whether the preoperative evaluation of the patient is best handled by you or a specialist. Current guidelines recommend preoperative evaluation by a specialist when a patient has certain conditions, such as moderate or greater valvular stenosis/regurgitation, a cardiac implantable electronic device, pulmonary hypertension, congenital heart disease, or severe systemic disease.2

If these conditions are not present (and an immediate referral is not required), you can turn your attention to the cardiac assessment. The first step is to determine which cardiac risk calculator you’d like to use. In its comprehensive guideline on perioperative cardiovascular evaluation, the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) recommends the use of one of the 2 calculators described below.2

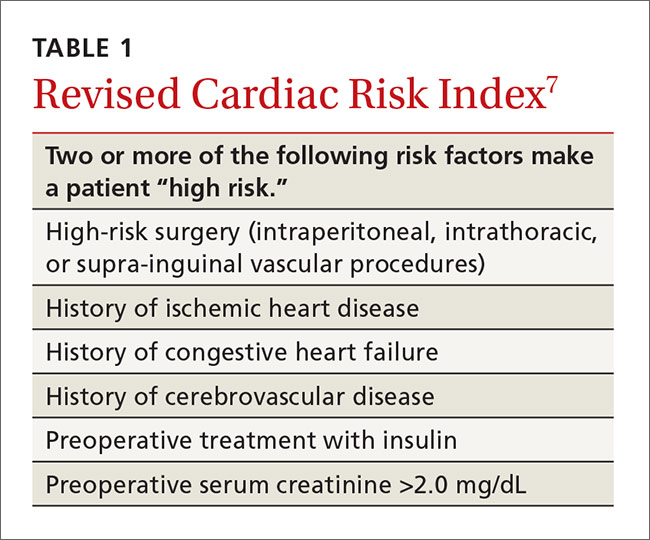

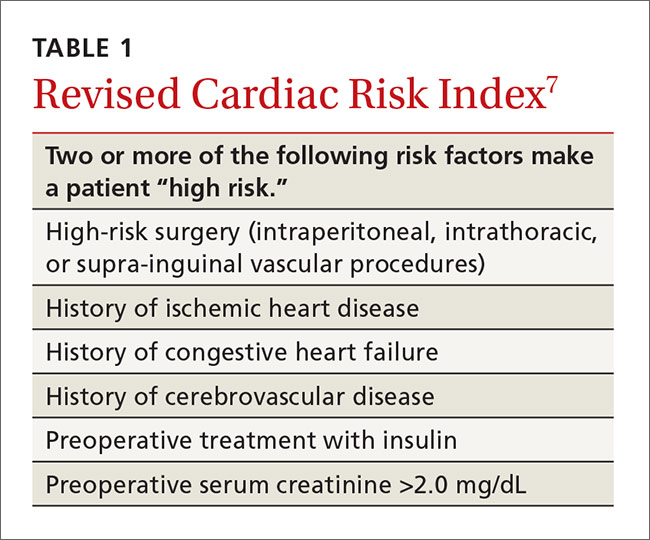

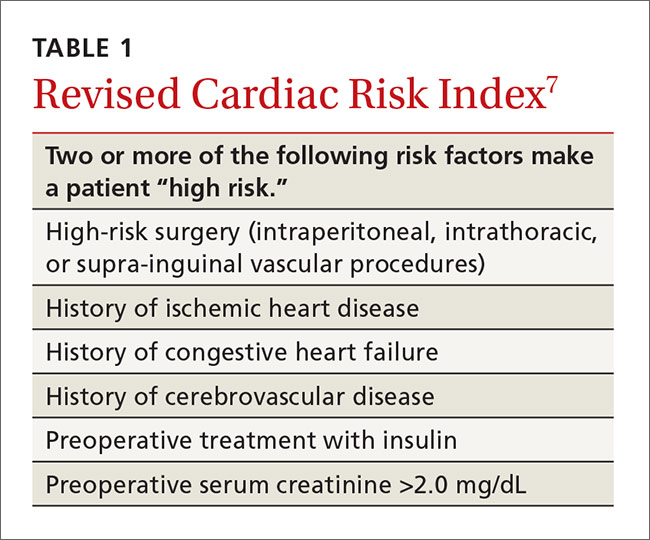

Revised Cardiac Risk Index. The most well-known cardiac risk calculator is the 6-element Revised Cardiac Risk Index (RCRI) (TABLE 1).7 Published in 1999, the RCRI was derived from a cohort of 2800 patients, verified in 1400 patients, and has been validated in numerous studies.2 Each element increases the odds of a cardiac complication by a factor of 2 to 3, and more than one positive response indicates the patient is at high risk for complications.7

The ACS NSQIP risk calculator has been criticized because it has not been validated in a group separate from the initial patient population used in its development.2 Another criticism is the inclusion of the American Society of Anesthesiologists' (ASA) classification of the overall health of the patient, a simple yet subjective and unreliable method of patient characterization.2

Choosing a calculator. The ACS NSQIP calculator may be more useful for primary care physicians because it provides individualized risks for numerous complications and is easy to use. The output page can be printed as documentation of the preoperative evaluation, and is useful for counseling patients about reconsideration of surgery or risk-reduction strategies. The RCRI is also simple to use, but considers only cardiac risk. Although the RCRI has been validated in numerous studies, the ACS NSQIP was derived from a more substantial 1.4 million patients.

Mapping out next steps based on risk score

The next step in the preoperative evaluation process is to calculate your patient’s risk score and determine whether it is low or high. If the risk is determined to be low—either an RCRI score <2 or an ACS NSQIP cardiac complication risk <1%—the patient can be referred to surgery without further evaluation.2

If the calculator suggests higher risk, the patient’s functional status should be assessed. If the patient has a functional status of >4 metabolic equivalents (METs), then the patient can be recommended for surgery without further evaluation.2 Examples of activities that are greater than 4 METs are yard work such as raking leaves, weeding, or pushing a power mower; sexual relations; climbing a flight of stairs; walking up a hill; and participating in moderate recreational activities like golf, bowling, dancing, doubles tennis, or throwing a baseball or football.9

Patient can’t perform >4 METs? If the patient does not have a functional capacity of >4 METs, further risk stratification should be considered if the results would change management.2 Prior guidelines recommended either perioperative beta-blockers to mitigate risk or coronary interventions, but both are controversial due to lack of proven benefit.

Perioperative beta-blocker use. A recommendation to consider starting beta-blockers at least one day prior to surgery remains in the 2014 ACC/AHA guidelines for patients with 3 or more RCRI risk factors.2 But a group of studies supporting beta-blocker use has been discredited due to serious flaws and fabricated data. At the same time, a large study arguing against perioperative beta-blockers has been criticized for starting high doses of beta-blockers on the day of surgery.2,10,11 In the end, mortality benefit from perioperative beta-blockers is uncertain, and the suggested reduction in cardiac events is partially offset by an increased risk of stroke.2

Stress testing is of questionable value. A patient with high cardiac risk (as evaluated with a calculator) may need to forego the surgical procedure or undergo a modified procedure. Alternatively, he or she may need to be referred to a cardiologist for consultation and possible pharmacologic nuclear stress testing. Although a normal stress test has a high negative predictive value, an abnormal test often leads to percutaneous coronary intervention or bypass surgery, and neither has been shown to reduce cardiac surgical risk.2 Percutaneous coronary interventions require a period of dual antiplatelet therapy, delaying surgery for unproven benefit.2

EKGs and echocardiograms are of limited use. An anesthesia group or surgical center will often require an electrocardiogram (EKG) as part of a preoperative evaluation, but preoperative evaluation by EKG or echocardiogram is controversial due to unproven benefits and potential risks. The 2014 ACC/AHA guidelines recommend against a 12-lead EKG for patients with low cardiac risk using the RCRI or ACS NSQIP or those who are having a low-risk procedure, such as endoscopy or cataract surgery.2 The United States Preventive Health Services Task Force also recommends against screening low-risk patients and says that screening EKGs and stress testing in asymptomatic medium- to high-risk patients is of undetermined value.12 They noted no evidence of benefit from resting or exercise EKG, with harm from a 1.7% complication rate of angiography, which is performed after up to 2.9% of exercise EKG testing.12

There are no recommendations for preoperative echocardiogram in the asymptomatic patient. Only unexplained dyspnea or other clinical signs of heart failure require an echocardiogram. For patients with known heart failure that is clinically stable, the ACC/AHA guidelines suggest that an echocardiogram should be performed within the year prior to surgery, although this is based on expert opinion.2

Because of the controversy over both coronary interventions and perioperative beta-blocker therapy, consider cardiology referral for a patient with poor functional activity level who does not meet low-risk criteria. While stress testing is acceptable, it may not lead to improved patient outcomes.

Optimize preventive care

Begin by ensuring that blood pressure (BP) and cholesterol are managed according to ACC/AHA guidelines. Then consider whether to start preoperative medications. You'll also want to screen for sleep apnea and discuss smoking status and cessation, if appropriate.

Initiate medications preoperatively?

In addition to having value as long-term primary prevention, there is some evidence that statins help prevent cardiac events during surgery. A randomized trial of over 200 vascular surgery patients showed that starting statins an average of 30 days prior to surgery significantly reduced cardiac complications.13 Another systematic review demonstrated that preoperative statins significantly reduce acute kidney injury from surgery.14

Unlike statins, aspirin started prior to surgery does not confer benefit. Aspirin was shown to significantly increase bleeding risk without improving cardiac outcomes in a large trial.15

Screen for sleep apnea

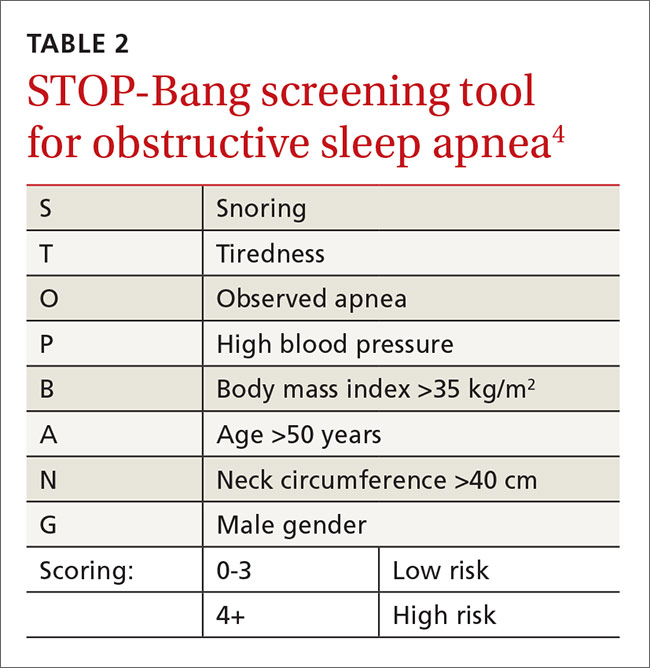

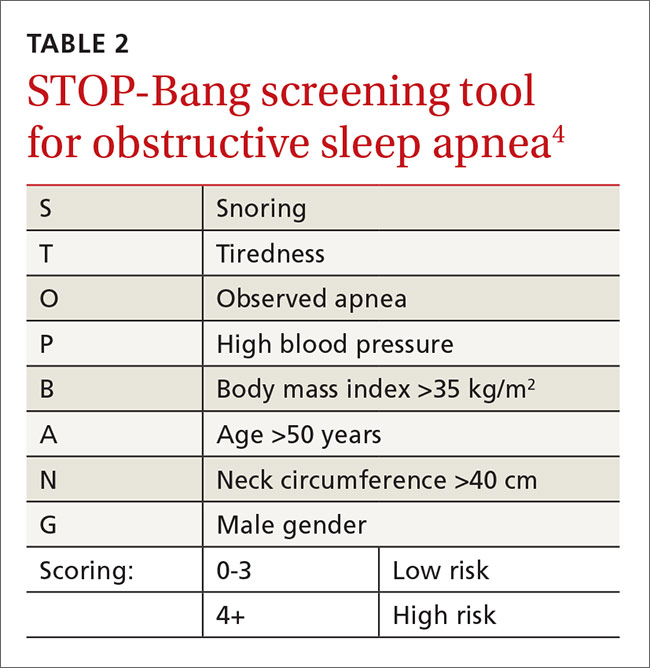

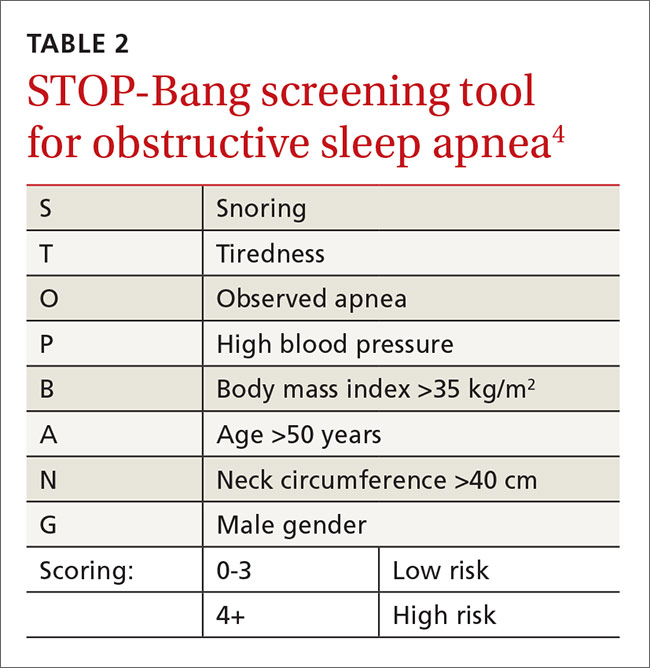

Sleep apnea increases the rate of respiratory failure between 2 and 3 times and the rate of cardiac complications about 1.5 times.16 This is a potentially correctable risk factor. The European Society of Anaesthesiology recommends clinical screening for obstructive sleep apnea using the STOP-Bang screening tool5 (TABLE 24). For its part, the ASA combines screening questions from the STOP-Bang screening questionnaire with a review of the medical record and physical exam, because the STOP-Bang questionnaire alone has an insufficient negative predictive value, ranging from 30% and 82%.6 Obstructive sleep apnea is not addressed on published pulmonary and cardiac risk tools.2,3,7,8

Is the patient a smoker?

Smoking is a reversible risk factor for pulmonary, cardiac, and infectious complications, as well as overall mortality. Perioperative smoking cessation counseling has been complicated by concerns that stopping smoking within 8 weeks of surgery might worsen postoperative outcomes. A study that looked at intraoperative sputum retrieved via tracheal suction showed that patients who had stopped smoking for 2 months or more prior to surgery had the same amount of sputum as non-smokers, while those that quit smoking <2 months before surgery were more likely to have increased intraoperative sputum volume.18 This study did not demonstrate a difference in postoperative pulmonary complications, likely because it included patients receiving minor surgeries only. But based on this study, a cessation period of 2 months was often recommended.

A recent systematic review showed that smoking cessation shortly before surgery does not increase risk.19 In fact, although the review did not show a statistically significant reduction in postoperative complications among recent quitters as compared with continued smokers, there was a trend toward a reduction in overall complications with only a slight increase in pulmonary complications.19

Address potential pulmonary complications

In addition to screening for issues that could lead to cardiac complications, it’s important to address the potential for pulmonary complications. Postoperative pulmonary complications are at least as common as cardiac complications, and include all possible respiratory related outcomes of surgery, from pneumonia to respiratory failure.

The seminal study on postoperative pulmonary complications is a systematic review published in 2006, which showed that the most important risk factors were surgery type, advanced age, ASA classification of overall health ≥II, and congestive heart failure.3 Chronic lung diseases and cigarette use were less predictive of pulmonary issues. All of these factors are included in the ACS NSQIP risk calculator.

Perioperative medication management

One aspect of the preoperative evaluation that should not be overlooked is a thorough medication reconciliation. Primary care providers can support the operative team by recommending medication adjustments prior to surgery. Several classes of medications have specific perioperative recommendations, which are summarized here.

Hypertension medications

- Beta-blockers. A patient who regularly takes a beta-blocker should continue the medication on the day of surgery and restart after surgery.2,20

- Calcium channel blockers. Calcium channel blockers can be continued through the day of surgery.2,20

- Renin-angiotensin system antagonists. Given the increased risk of hypotension following anesthesia induction, have patients refrain from taking angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blocker medications for at least 10 hours prior to surgery.20

- Diuretics. Diuretics can be given on the day of surgery, although they increase the risk of hypovolemia and electrolyte disturbances.20

Diabetes medications

- Insulin. For patients with type I diabetes, recommend basal insulin of 0.2 to 0.3 units/kg/day of long-acting insulin.21 If the patient is using an insulin pump, basal rate should be continued. For patients with type 2 diabetes, the simplest method is to use one-half the normal long-acting insulin dose on the morning of surgery.22

- Metformin. Discontinue metformin 24 hours prior to surgery because of the risk for lactic acidosis.21,22 While the risk of lactic acidosis from metformin is low, mortality rates as high as 50% have been documented after lactic acidosis occurred with similar medications.22

- Sulfonylureas. Sulfonylureas should be held on the day of surgery due to the risk of hypoglycemia and a possible increased risk of ischemia.21,22

- Thiazolidinediones, dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors, and glucagon-like peptide-1 agonists. All should be held on the day of surgery.21

Anticoagulant medications

- Vitamin K antagonists (warfarin). Discontinue warfarin 5 days prior to the procedure. The half-life is approximately 40 hours, requiring at least 5 days for the anticoagulant effect to be eliminated from the body.23 Use of bridging therapy with regular- or low-molecular weight heparin remains controversial due to increased surgical bleeding risk without evidence of a decrease in cardiovascular events.24 The patient’s risks of stroke and venous thromboembolism should be taken into account when deciding whether to use bridging therapy or not.

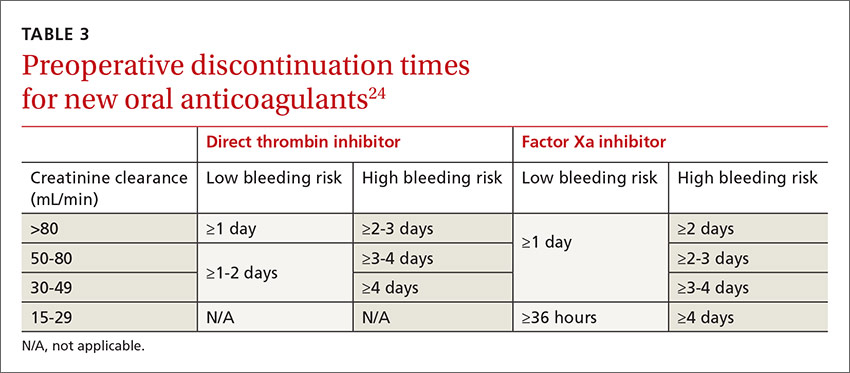

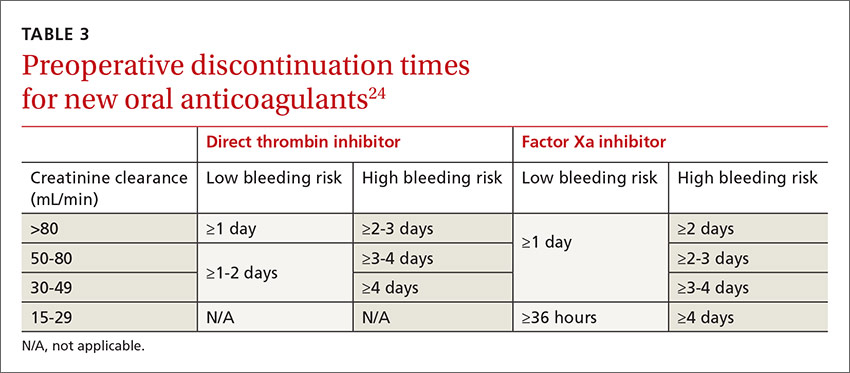

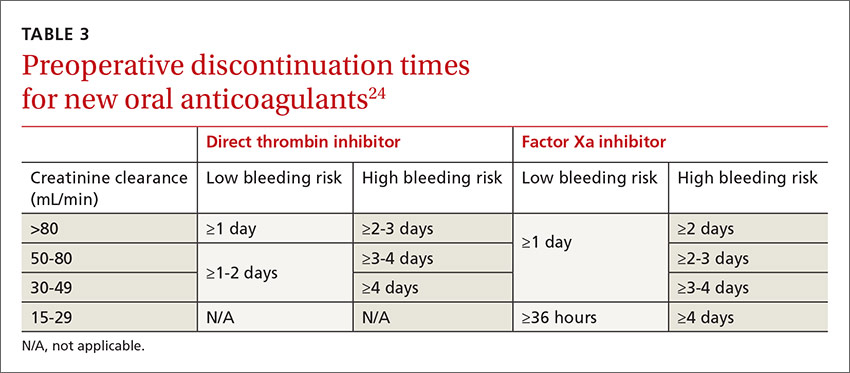

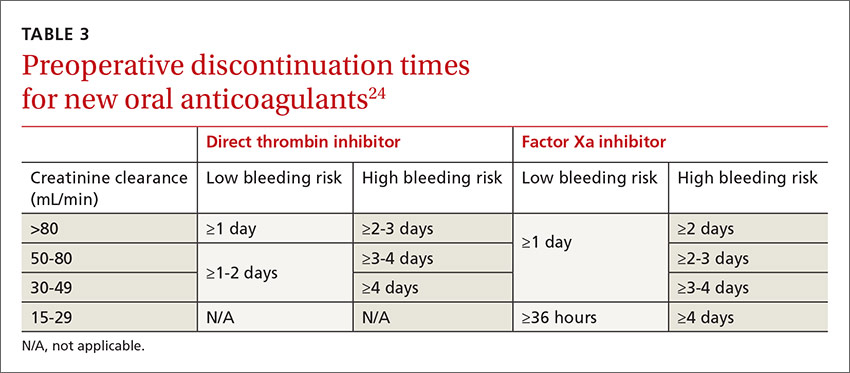

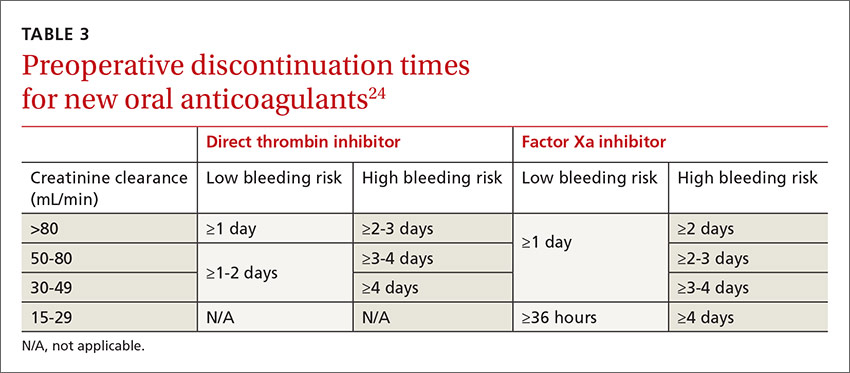

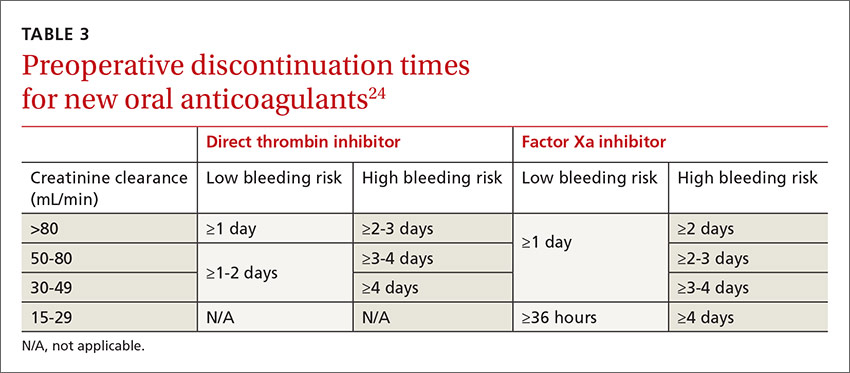

- Factor Xa inhibitor. Management of factor Xa inhibitors (rivaroxaban, apixaban) depends on the bleeding risk of the surgery and the patient’s renal function.24,25 For instance, a patient undergoing cataract surgery (low risk) needs a shorter cessation time than a patient undergoing hip arthroplasty (high risk). Discontinuation times are listed in TABLE 3.24

- Direct thrombin inhibitor. Management of direct thrombin inhibitors (dabigatran) is also dependent on surgical bleeding risk and renal function (TABLE 3).23,24

- Aspirin, clopidogrel, ticlopidine, prasugrel. All should be stopped 7 to 10 days prior to surgery to allow new platelet growth. Low-dose aspirin for secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease or primary prevention in a high-risk patient can be continued through surgery.23

Other

- Corticosteroids. Recent evidence suggests that stress-dose steroids are not needed to prevent adrenal insufficiency in patients taking corticosteroids chronically.26 These patients should continue maintenance therapy at regular dosing.26,27 Stress dosing of corticosteroids is only required when a patient has signs of adrenal insufficiency.26

- Statins. Statin medications should be continued on the day of surgery.2

- Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. NSAIDs should be stopped 5 days prior to surgery to reverse antiplatelet effects.23

CORRESPONDENCE

CDR Michael J. Arnold, Naval Hospital, 2080 Child Street, Jacksonville, FL 32214; [email protected].

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The authors thank CDR Kristian Sanchack and LCDR Dustin Smith for their assistance with this manuscript.

1. Wier LM, Steiner CA, Owens PL. Surgeries in hospital-owned outpatient facilities, 2012. HCUP Statistical Brief #188. February 2015. Available at: https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/statbriefs/sb188-Surgeries-Hospital-Outpatient-Facilities-2012.jsp. Accessed September 15, 2016.

2. Fleisher LA, Fleischmann KE, Auerbach AD, et al. 2014 ACC/AHA guideline on perioperative cardiovascular evaluation and management of patients undergoing noncardiac surgery. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;64:e77-e137.

3. Smetana GW, Lawrence VA, Cornell JE. Preoperative pulmonary risk stratification for noncardiothoracic surgery: systematic review for the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2006;144:581-595.

4. Chung F, Abdullah HR, Liao P. STOP-Bang questionnaire: a prac tical approach to screen for obstructive sleep apnea. Chest. 2016;149:631-638.

5. De Hert S, Imberger G, Carlisle J, et al. Preoperative evaluation of the adult patient undergoing non-cardiac surgery: guidelines from the European Society of Anaesthesiology. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2011;28:684-722.

6. American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Perioperative Management of Patients with Obstructive Sleep Apnea. Practice guidelines for the perioperative management of patients with obstructive sleep apnea; an updated report by the American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Perioperative Management of Patients with Obstructive Sleep Apnea. Anesthesiology. 2014;120:268-286.

7. Lee TH, Marcantonio ER, Mangione CM, et al. Derivation and prospective validation of a simple index for prediction of cardiac risk of major noncardiac surgery. Circulation. 1999;100:1043-1049.

8. Bilimoria KY, Liu Y, Paruch JL, et al. Development and evaluation of the universal ACS NSQIP surgical risk calculator: a decision aide and informed consent tool for patients and surgeons. J Am Coll Surg. 2013;217:833-842.

9. Hlatky MA, Boineau RE, Higginbotham MB, et al. A brief self-administered questionnaire to determine functional capacity (the Duke Activity Status Index). Am J Cardiol. 1989;64:651-654.

10. Bouri S, Shun-Shin MJ, Cole GD, et al. Meta-analysis of secure randomized controlled trials of B-blockade to prevent perioperative death in non-cardiac surgery. Heart. 2014;100:456-464.

11. Mounsey A, Roque JM, Egan M. Why you shouldn’t start beta-blockers before surgery. J Fam Pract. 2014;63:E15-E16.

12. Chou R, Arora B, Dana T, et al. Screening asymptomatic adults with resting or exercise electrocardiography: a review of the evidence for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155:375-385.

13. Durazzo AES, Machado FS, Ikeoka DT, et al. Reduction in cardiovascular events after vascular surgery with atorvastatin: a randomized trial. J Vasc Surg. 2004;39:967-975.

14. Pan SY, Wu VC, Huang TM, et al. Effect of preoperative statin therapy on postoperative acute kidney injury in patients undergoing major surgery: systemic review and meta-analysis. Nephrology. 2014;19:750-763.

15. Devereux PJ, Mrkobrada M, Sessler DI, et al. Aspirin in patients undergoing noncardiac surgery. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:1494-1503.

16. Adesanya AO, Lee W, Greilich NB, et al. Perioperative management of obstructive sleep apnea. Chest. 2010;138:1489-1498.

17. Chung F, Nagappa M, Singh M, et al. CPAP in the perioperative setting: evidence of support. Chest. 2016;149:586-597.

18. Yamashita S, Yamaguchi H, Sakaguchi M, et al. Effect of smoking on intraoperative sputum and postoperative pulmonary complication in minor surgical patients. Respir Med. 2004;98:760-766.

19. Myers K, Hajek P, Hinds

20. Lonjaret L, Lairez O, Minville V, et al. Optimal perioperative management of arterial blood pressure. Integr Blood Press Control. 2014;7:49-59.

21. Sudhakaran S, Surani SR. Guidelines for perioperative management of the diabetic patient. Surg Res Pract. 2015;2015:284063.

22. Duncan AE. Hyperglycemia and perioperative glucose management. Curr Pharm Des. 2012;18:6195-6203.

23. Douketis JD, Spyropoulos AC, Spencer FA, et al. Perioperative management of antithrombotic therapy: antithrombotic therapy and prevention of thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines. Chest. 2012;141:e326S-e350S.

24. Faraoni D, Levy JH, Albaladejo P, et al. Updates in the perioperative and emergency management of non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants. Crit Care. 2015;19:203.

25. Shamoun F, Obeid H, Ramakrishna H. Novel anticoagulants in atrial fibrillation: monitoring, reversal and perioperative management. Biomed Res Int. 2015;2015:424031.

26. Kelly KN, Domajnko B. Perioperative stress-dose steroids. Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2013;26:163-167.

27. Scanzello CR, Nestor BJ. Perioperative management of medications used in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. HSSJ. 2006;2:141-147.

PRACTICE RECOMMENDATIONS

› Recommend that patients quit smoking 8 weeks before surgery; keep in mind, though, that quitting closer to the date of surgery does not increase the risk of complications. A

› Use the online American College of Surgeons/National Surgical Quality Improvement Program surgical risk calculator to estimate a patient’s surgical risk. C

› Send a patient directly to surgery if he or she has an estimated cardiac risk <1% or <2 risk factors of the Revised Cardiac Risk Index. B

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

About 27 million Americans undergo surgery every year1 and before doing so, they turn to you—their primary care physician—or their cardiologist for a preoperative evaluation. Of course, the goal of this evaluation is to determine an individual patient’s risk and compare it to procedural averages in an effort to identify opportunities for risk mitigation. But the preoperative evaluation is also an opportunity to make recommendations regarding perioperative management of medications. And certainly we want to conduct these evaluations in a way that is both expeditious and in keeping with the latest guidelines.

Current guidelines for preoperative evaluations are less complicated than they used to be and focus on cardiac and pulmonary risk stratification. While a risk calculator remains your primary tool, elements such as smoking cessation and identifying sleep apnea are important parts of the preop equation. In the review that follows, we present a simple algorithm (FIGURE 12-6) that we developed that can be completed in a single visit.

Cardiac assessment: A risk calculator is the primary tool

Cardiac risk estimation is perhaps the most important element in determining a patient’s overall surgical risk. But before you begin, you'll need to determine whether the preoperative evaluation of the patient is best handled by you or a specialist. Current guidelines recommend preoperative evaluation by a specialist when a patient has certain conditions, such as moderate or greater valvular stenosis/regurgitation, a cardiac implantable electronic device, pulmonary hypertension, congenital heart disease, or severe systemic disease.2

If these conditions are not present (and an immediate referral is not required), you can turn your attention to the cardiac assessment. The first step is to determine which cardiac risk calculator you’d like to use. In its comprehensive guideline on perioperative cardiovascular evaluation, the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) recommends the use of one of the 2 calculators described below.2

Revised Cardiac Risk Index. The most well-known cardiac risk calculator is the 6-element Revised Cardiac Risk Index (RCRI) (TABLE 1).7 Published in 1999, the RCRI was derived from a cohort of 2800 patients, verified in 1400 patients, and has been validated in numerous studies.2 Each element increases the odds of a cardiac complication by a factor of 2 to 3, and more than one positive response indicates the patient is at high risk for complications.7

The ACS NSQIP risk calculator has been criticized because it has not been validated in a group separate from the initial patient population used in its development.2 Another criticism is the inclusion of the American Society of Anesthesiologists' (ASA) classification of the overall health of the patient, a simple yet subjective and unreliable method of patient characterization.2

Choosing a calculator. The ACS NSQIP calculator may be more useful for primary care physicians because it provides individualized risks for numerous complications and is easy to use. The output page can be printed as documentation of the preoperative evaluation, and is useful for counseling patients about reconsideration of surgery or risk-reduction strategies. The RCRI is also simple to use, but considers only cardiac risk. Although the RCRI has been validated in numerous studies, the ACS NSQIP was derived from a more substantial 1.4 million patients.

Mapping out next steps based on risk score

The next step in the preoperative evaluation process is to calculate your patient’s risk score and determine whether it is low or high. If the risk is determined to be low—either an RCRI score <2 or an ACS NSQIP cardiac complication risk <1%—the patient can be referred to surgery without further evaluation.2

If the calculator suggests higher risk, the patient’s functional status should be assessed. If the patient has a functional status of >4 metabolic equivalents (METs), then the patient can be recommended for surgery without further evaluation.2 Examples of activities that are greater than 4 METs are yard work such as raking leaves, weeding, or pushing a power mower; sexual relations; climbing a flight of stairs; walking up a hill; and participating in moderate recreational activities like golf, bowling, dancing, doubles tennis, or throwing a baseball or football.9

Patient can’t perform >4 METs? If the patient does not have a functional capacity of >4 METs, further risk stratification should be considered if the results would change management.2 Prior guidelines recommended either perioperative beta-blockers to mitigate risk or coronary interventions, but both are controversial due to lack of proven benefit.

Perioperative beta-blocker use. A recommendation to consider starting beta-blockers at least one day prior to surgery remains in the 2014 ACC/AHA guidelines for patients with 3 or more RCRI risk factors.2 But a group of studies supporting beta-blocker use has been discredited due to serious flaws and fabricated data. At the same time, a large study arguing against perioperative beta-blockers has been criticized for starting high doses of beta-blockers on the day of surgery.2,10,11 In the end, mortality benefit from perioperative beta-blockers is uncertain, and the suggested reduction in cardiac events is partially offset by an increased risk of stroke.2

Stress testing is of questionable value. A patient with high cardiac risk (as evaluated with a calculator) may need to forego the surgical procedure or undergo a modified procedure. Alternatively, he or she may need to be referred to a cardiologist for consultation and possible pharmacologic nuclear stress testing. Although a normal stress test has a high negative predictive value, an abnormal test often leads to percutaneous coronary intervention or bypass surgery, and neither has been shown to reduce cardiac surgical risk.2 Percutaneous coronary interventions require a period of dual antiplatelet therapy, delaying surgery for unproven benefit.2

EKGs and echocardiograms are of limited use. An anesthesia group or surgical center will often require an electrocardiogram (EKG) as part of a preoperative evaluation, but preoperative evaluation by EKG or echocardiogram is controversial due to unproven benefits and potential risks. The 2014 ACC/AHA guidelines recommend against a 12-lead EKG for patients with low cardiac risk using the RCRI or ACS NSQIP or those who are having a low-risk procedure, such as endoscopy or cataract surgery.2 The United States Preventive Health Services Task Force also recommends against screening low-risk patients and says that screening EKGs and stress testing in asymptomatic medium- to high-risk patients is of undetermined value.12 They noted no evidence of benefit from resting or exercise EKG, with harm from a 1.7% complication rate of angiography, which is performed after up to 2.9% of exercise EKG testing.12

There are no recommendations for preoperative echocardiogram in the asymptomatic patient. Only unexplained dyspnea or other clinical signs of heart failure require an echocardiogram. For patients with known heart failure that is clinically stable, the ACC/AHA guidelines suggest that an echocardiogram should be performed within the year prior to surgery, although this is based on expert opinion.2

Because of the controversy over both coronary interventions and perioperative beta-blocker therapy, consider cardiology referral for a patient with poor functional activity level who does not meet low-risk criteria. While stress testing is acceptable, it may not lead to improved patient outcomes.

Optimize preventive care

Begin by ensuring that blood pressure (BP) and cholesterol are managed according to ACC/AHA guidelines. Then consider whether to start preoperative medications. You'll also want to screen for sleep apnea and discuss smoking status and cessation, if appropriate.

Initiate medications preoperatively?

In addition to having value as long-term primary prevention, there is some evidence that statins help prevent cardiac events during surgery. A randomized trial of over 200 vascular surgery patients showed that starting statins an average of 30 days prior to surgery significantly reduced cardiac complications.13 Another systematic review demonstrated that preoperative statins significantly reduce acute kidney injury from surgery.14

Unlike statins, aspirin started prior to surgery does not confer benefit. Aspirin was shown to significantly increase bleeding risk without improving cardiac outcomes in a large trial.15

Screen for sleep apnea

Sleep apnea increases the rate of respiratory failure between 2 and 3 times and the rate of cardiac complications about 1.5 times.16 This is a potentially correctable risk factor. The European Society of Anaesthesiology recommends clinical screening for obstructive sleep apnea using the STOP-Bang screening tool5 (TABLE 24). For its part, the ASA combines screening questions from the STOP-Bang screening questionnaire with a review of the medical record and physical exam, because the STOP-Bang questionnaire alone has an insufficient negative predictive value, ranging from 30% and 82%.6 Obstructive sleep apnea is not addressed on published pulmonary and cardiac risk tools.2,3,7,8

Is the patient a smoker?

Smoking is a reversible risk factor for pulmonary, cardiac, and infectious complications, as well as overall mortality. Perioperative smoking cessation counseling has been complicated by concerns that stopping smoking within 8 weeks of surgery might worsen postoperative outcomes. A study that looked at intraoperative sputum retrieved via tracheal suction showed that patients who had stopped smoking for 2 months or more prior to surgery had the same amount of sputum as non-smokers, while those that quit smoking <2 months before surgery were more likely to have increased intraoperative sputum volume.18 This study did not demonstrate a difference in postoperative pulmonary complications, likely because it included patients receiving minor surgeries only. But based on this study, a cessation period of 2 months was often recommended.

A recent systematic review showed that smoking cessation shortly before surgery does not increase risk.19 In fact, although the review did not show a statistically significant reduction in postoperative complications among recent quitters as compared with continued smokers, there was a trend toward a reduction in overall complications with only a slight increase in pulmonary complications.19

Address potential pulmonary complications

In addition to screening for issues that could lead to cardiac complications, it’s important to address the potential for pulmonary complications. Postoperative pulmonary complications are at least as common as cardiac complications, and include all possible respiratory related outcomes of surgery, from pneumonia to respiratory failure.

The seminal study on postoperative pulmonary complications is a systematic review published in 2006, which showed that the most important risk factors were surgery type, advanced age, ASA classification of overall health ≥II, and congestive heart failure.3 Chronic lung diseases and cigarette use were less predictive of pulmonary issues. All of these factors are included in the ACS NSQIP risk calculator.

Perioperative medication management

One aspect of the preoperative evaluation that should not be overlooked is a thorough medication reconciliation. Primary care providers can support the operative team by recommending medication adjustments prior to surgery. Several classes of medications have specific perioperative recommendations, which are summarized here.

Hypertension medications

- Beta-blockers. A patient who regularly takes a beta-blocker should continue the medication on the day of surgery and restart after surgery.2,20

- Calcium channel blockers. Calcium channel blockers can be continued through the day of surgery.2,20

- Renin-angiotensin system antagonists. Given the increased risk of hypotension following anesthesia induction, have patients refrain from taking angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blocker medications for at least 10 hours prior to surgery.20

- Diuretics. Diuretics can be given on the day of surgery, although they increase the risk of hypovolemia and electrolyte disturbances.20

Diabetes medications

- Insulin. For patients with type I diabetes, recommend basal insulin of 0.2 to 0.3 units/kg/day of long-acting insulin.21 If the patient is using an insulin pump, basal rate should be continued. For patients with type 2 diabetes, the simplest method is to use one-half the normal long-acting insulin dose on the morning of surgery.22

- Metformin. Discontinue metformin 24 hours prior to surgery because of the risk for lactic acidosis.21,22 While the risk of lactic acidosis from metformin is low, mortality rates as high as 50% have been documented after lactic acidosis occurred with similar medications.22

- Sulfonylureas. Sulfonylureas should be held on the day of surgery due to the risk of hypoglycemia and a possible increased risk of ischemia.21,22

- Thiazolidinediones, dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors, and glucagon-like peptide-1 agonists. All should be held on the day of surgery.21

Anticoagulant medications

- Vitamin K antagonists (warfarin). Discontinue warfarin 5 days prior to the procedure. The half-life is approximately 40 hours, requiring at least 5 days for the anticoagulant effect to be eliminated from the body.23 Use of bridging therapy with regular- or low-molecular weight heparin remains controversial due to increased surgical bleeding risk without evidence of a decrease in cardiovascular events.24 The patient’s risks of stroke and venous thromboembolism should be taken into account when deciding whether to use bridging therapy or not.

- Factor Xa inhibitor. Management of factor Xa inhibitors (rivaroxaban, apixaban) depends on the bleeding risk of the surgery and the patient’s renal function.24,25 For instance, a patient undergoing cataract surgery (low risk) needs a shorter cessation time than a patient undergoing hip arthroplasty (high risk). Discontinuation times are listed in TABLE 3.24

- Direct thrombin inhibitor. Management of direct thrombin inhibitors (dabigatran) is also dependent on surgical bleeding risk and renal function (TABLE 3).23,24

- Aspirin, clopidogrel, ticlopidine, prasugrel. All should be stopped 7 to 10 days prior to surgery to allow new platelet growth. Low-dose aspirin for secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease or primary prevention in a high-risk patient can be continued through surgery.23

Other

- Corticosteroids. Recent evidence suggests that stress-dose steroids are not needed to prevent adrenal insufficiency in patients taking corticosteroids chronically.26 These patients should continue maintenance therapy at regular dosing.26,27 Stress dosing of corticosteroids is only required when a patient has signs of adrenal insufficiency.26

- Statins. Statin medications should be continued on the day of surgery.2

- Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. NSAIDs should be stopped 5 days prior to surgery to reverse antiplatelet effects.23

CORRESPONDENCE

CDR Michael J. Arnold, Naval Hospital, 2080 Child Street, Jacksonville, FL 32214; [email protected].

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The authors thank CDR Kristian Sanchack and LCDR Dustin Smith for their assistance with this manuscript.

PRACTICE RECOMMENDATIONS

› Recommend that patients quit smoking 8 weeks before surgery; keep in mind, though, that quitting closer to the date of surgery does not increase the risk of complications. A

› Use the online American College of Surgeons/National Surgical Quality Improvement Program surgical risk calculator to estimate a patient’s surgical risk. C

› Send a patient directly to surgery if he or she has an estimated cardiac risk <1% or <2 risk factors of the Revised Cardiac Risk Index. B

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

About 27 million Americans undergo surgery every year1 and before doing so, they turn to you—their primary care physician—or their cardiologist for a preoperative evaluation. Of course, the goal of this evaluation is to determine an individual patient’s risk and compare it to procedural averages in an effort to identify opportunities for risk mitigation. But the preoperative evaluation is also an opportunity to make recommendations regarding perioperative management of medications. And certainly we want to conduct these evaluations in a way that is both expeditious and in keeping with the latest guidelines.

Current guidelines for preoperative evaluations are less complicated than they used to be and focus on cardiac and pulmonary risk stratification. While a risk calculator remains your primary tool, elements such as smoking cessation and identifying sleep apnea are important parts of the preop equation. In the review that follows, we present a simple algorithm (FIGURE 12-6) that we developed that can be completed in a single visit.

Cardiac assessment: A risk calculator is the primary tool

Cardiac risk estimation is perhaps the most important element in determining a patient’s overall surgical risk. But before you begin, you'll need to determine whether the preoperative evaluation of the patient is best handled by you or a specialist. Current guidelines recommend preoperative evaluation by a specialist when a patient has certain conditions, such as moderate or greater valvular stenosis/regurgitation, a cardiac implantable electronic device, pulmonary hypertension, congenital heart disease, or severe systemic disease.2

If these conditions are not present (and an immediate referral is not required), you can turn your attention to the cardiac assessment. The first step is to determine which cardiac risk calculator you’d like to use. In its comprehensive guideline on perioperative cardiovascular evaluation, the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) recommends the use of one of the 2 calculators described below.2

Revised Cardiac Risk Index. The most well-known cardiac risk calculator is the 6-element Revised Cardiac Risk Index (RCRI) (TABLE 1).7 Published in 1999, the RCRI was derived from a cohort of 2800 patients, verified in 1400 patients, and has been validated in numerous studies.2 Each element increases the odds of a cardiac complication by a factor of 2 to 3, and more than one positive response indicates the patient is at high risk for complications.7

The ACS NSQIP risk calculator has been criticized because it has not been validated in a group separate from the initial patient population used in its development.2 Another criticism is the inclusion of the American Society of Anesthesiologists' (ASA) classification of the overall health of the patient, a simple yet subjective and unreliable method of patient characterization.2

Choosing a calculator. The ACS NSQIP calculator may be more useful for primary care physicians because it provides individualized risks for numerous complications and is easy to use. The output page can be printed as documentation of the preoperative evaluation, and is useful for counseling patients about reconsideration of surgery or risk-reduction strategies. The RCRI is also simple to use, but considers only cardiac risk. Although the RCRI has been validated in numerous studies, the ACS NSQIP was derived from a more substantial 1.4 million patients.

Mapping out next steps based on risk score

The next step in the preoperative evaluation process is to calculate your patient’s risk score and determine whether it is low or high. If the risk is determined to be low—either an RCRI score <2 or an ACS NSQIP cardiac complication risk <1%—the patient can be referred to surgery without further evaluation.2

If the calculator suggests higher risk, the patient’s functional status should be assessed. If the patient has a functional status of >4 metabolic equivalents (METs), then the patient can be recommended for surgery without further evaluation.2 Examples of activities that are greater than 4 METs are yard work such as raking leaves, weeding, or pushing a power mower; sexual relations; climbing a flight of stairs; walking up a hill; and participating in moderate recreational activities like golf, bowling, dancing, doubles tennis, or throwing a baseball or football.9

Patient can’t perform >4 METs? If the patient does not have a functional capacity of >4 METs, further risk stratification should be considered if the results would change management.2 Prior guidelines recommended either perioperative beta-blockers to mitigate risk or coronary interventions, but both are controversial due to lack of proven benefit.

Perioperative beta-blocker use. A recommendation to consider starting beta-blockers at least one day prior to surgery remains in the 2014 ACC/AHA guidelines for patients with 3 or more RCRI risk factors.2 But a group of studies supporting beta-blocker use has been discredited due to serious flaws and fabricated data. At the same time, a large study arguing against perioperative beta-blockers has been criticized for starting high doses of beta-blockers on the day of surgery.2,10,11 In the end, mortality benefit from perioperative beta-blockers is uncertain, and the suggested reduction in cardiac events is partially offset by an increased risk of stroke.2

Stress testing is of questionable value. A patient with high cardiac risk (as evaluated with a calculator) may need to forego the surgical procedure or undergo a modified procedure. Alternatively, he or she may need to be referred to a cardiologist for consultation and possible pharmacologic nuclear stress testing. Although a normal stress test has a high negative predictive value, an abnormal test often leads to percutaneous coronary intervention or bypass surgery, and neither has been shown to reduce cardiac surgical risk.2 Percutaneous coronary interventions require a period of dual antiplatelet therapy, delaying surgery for unproven benefit.2

EKGs and echocardiograms are of limited use. An anesthesia group or surgical center will often require an electrocardiogram (EKG) as part of a preoperative evaluation, but preoperative evaluation by EKG or echocardiogram is controversial due to unproven benefits and potential risks. The 2014 ACC/AHA guidelines recommend against a 12-lead EKG for patients with low cardiac risk using the RCRI or ACS NSQIP or those who are having a low-risk procedure, such as endoscopy or cataract surgery.2 The United States Preventive Health Services Task Force also recommends against screening low-risk patients and says that screening EKGs and stress testing in asymptomatic medium- to high-risk patients is of undetermined value.12 They noted no evidence of benefit from resting or exercise EKG, with harm from a 1.7% complication rate of angiography, which is performed after up to 2.9% of exercise EKG testing.12

There are no recommendations for preoperative echocardiogram in the asymptomatic patient. Only unexplained dyspnea or other clinical signs of heart failure require an echocardiogram. For patients with known heart failure that is clinically stable, the ACC/AHA guidelines suggest that an echocardiogram should be performed within the year prior to surgery, although this is based on expert opinion.2

Because of the controversy over both coronary interventions and perioperative beta-blocker therapy, consider cardiology referral for a patient with poor functional activity level who does not meet low-risk criteria. While stress testing is acceptable, it may not lead to improved patient outcomes.

Optimize preventive care

Begin by ensuring that blood pressure (BP) and cholesterol are managed according to ACC/AHA guidelines. Then consider whether to start preoperative medications. You'll also want to screen for sleep apnea and discuss smoking status and cessation, if appropriate.

Initiate medications preoperatively?

In addition to having value as long-term primary prevention, there is some evidence that statins help prevent cardiac events during surgery. A randomized trial of over 200 vascular surgery patients showed that starting statins an average of 30 days prior to surgery significantly reduced cardiac complications.13 Another systematic review demonstrated that preoperative statins significantly reduce acute kidney injury from surgery.14

Unlike statins, aspirin started prior to surgery does not confer benefit. Aspirin was shown to significantly increase bleeding risk without improving cardiac outcomes in a large trial.15

Screen for sleep apnea

Sleep apnea increases the rate of respiratory failure between 2 and 3 times and the rate of cardiac complications about 1.5 times.16 This is a potentially correctable risk factor. The European Society of Anaesthesiology recommends clinical screening for obstructive sleep apnea using the STOP-Bang screening tool5 (TABLE 24). For its part, the ASA combines screening questions from the STOP-Bang screening questionnaire with a review of the medical record and physical exam, because the STOP-Bang questionnaire alone has an insufficient negative predictive value, ranging from 30% and 82%.6 Obstructive sleep apnea is not addressed on published pulmonary and cardiac risk tools.2,3,7,8

Is the patient a smoker?

Smoking is a reversible risk factor for pulmonary, cardiac, and infectious complications, as well as overall mortality. Perioperative smoking cessation counseling has been complicated by concerns that stopping smoking within 8 weeks of surgery might worsen postoperative outcomes. A study that looked at intraoperative sputum retrieved via tracheal suction showed that patients who had stopped smoking for 2 months or more prior to surgery had the same amount of sputum as non-smokers, while those that quit smoking <2 months before surgery were more likely to have increased intraoperative sputum volume.18 This study did not demonstrate a difference in postoperative pulmonary complications, likely because it included patients receiving minor surgeries only. But based on this study, a cessation period of 2 months was often recommended.

A recent systematic review showed that smoking cessation shortly before surgery does not increase risk.19 In fact, although the review did not show a statistically significant reduction in postoperative complications among recent quitters as compared with continued smokers, there was a trend toward a reduction in overall complications with only a slight increase in pulmonary complications.19

Address potential pulmonary complications

In addition to screening for issues that could lead to cardiac complications, it’s important to address the potential for pulmonary complications. Postoperative pulmonary complications are at least as common as cardiac complications, and include all possible respiratory related outcomes of surgery, from pneumonia to respiratory failure.

The seminal study on postoperative pulmonary complications is a systematic review published in 2006, which showed that the most important risk factors were surgery type, advanced age, ASA classification of overall health ≥II, and congestive heart failure.3 Chronic lung diseases and cigarette use were less predictive of pulmonary issues. All of these factors are included in the ACS NSQIP risk calculator.

Perioperative medication management

One aspect of the preoperative evaluation that should not be overlooked is a thorough medication reconciliation. Primary care providers can support the operative team by recommending medication adjustments prior to surgery. Several classes of medications have specific perioperative recommendations, which are summarized here.

Hypertension medications

- Beta-blockers. A patient who regularly takes a beta-blocker should continue the medication on the day of surgery and restart after surgery.2,20

- Calcium channel blockers. Calcium channel blockers can be continued through the day of surgery.2,20

- Renin-angiotensin system antagonists. Given the increased risk of hypotension following anesthesia induction, have patients refrain from taking angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blocker medications for at least 10 hours prior to surgery.20

- Diuretics. Diuretics can be given on the day of surgery, although they increase the risk of hypovolemia and electrolyte disturbances.20

Diabetes medications

- Insulin. For patients with type I diabetes, recommend basal insulin of 0.2 to 0.3 units/kg/day of long-acting insulin.21 If the patient is using an insulin pump, basal rate should be continued. For patients with type 2 diabetes, the simplest method is to use one-half the normal long-acting insulin dose on the morning of surgery.22

- Metformin. Discontinue metformin 24 hours prior to surgery because of the risk for lactic acidosis.21,22 While the risk of lactic acidosis from metformin is low, mortality rates as high as 50% have been documented after lactic acidosis occurred with similar medications.22

- Sulfonylureas. Sulfonylureas should be held on the day of surgery due to the risk of hypoglycemia and a possible increased risk of ischemia.21,22

- Thiazolidinediones, dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors, and glucagon-like peptide-1 agonists. All should be held on the day of surgery.21

Anticoagulant medications

- Vitamin K antagonists (warfarin). Discontinue warfarin 5 days prior to the procedure. The half-life is approximately 40 hours, requiring at least 5 days for the anticoagulant effect to be eliminated from the body.23 Use of bridging therapy with regular- or low-molecular weight heparin remains controversial due to increased surgical bleeding risk without evidence of a decrease in cardiovascular events.24 The patient’s risks of stroke and venous thromboembolism should be taken into account when deciding whether to use bridging therapy or not.

- Factor Xa inhibitor. Management of factor Xa inhibitors (rivaroxaban, apixaban) depends on the bleeding risk of the surgery and the patient’s renal function.24,25 For instance, a patient undergoing cataract surgery (low risk) needs a shorter cessation time than a patient undergoing hip arthroplasty (high risk). Discontinuation times are listed in TABLE 3.24

- Direct thrombin inhibitor. Management of direct thrombin inhibitors (dabigatran) is also dependent on surgical bleeding risk and renal function (TABLE 3).23,24

- Aspirin, clopidogrel, ticlopidine, prasugrel. All should be stopped 7 to 10 days prior to surgery to allow new platelet growth. Low-dose aspirin for secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease or primary prevention in a high-risk patient can be continued through surgery.23

Other

- Corticosteroids. Recent evidence suggests that stress-dose steroids are not needed to prevent adrenal insufficiency in patients taking corticosteroids chronically.26 These patients should continue maintenance therapy at regular dosing.26,27 Stress dosing of corticosteroids is only required when a patient has signs of adrenal insufficiency.26

- Statins. Statin medications should be continued on the day of surgery.2

- Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. NSAIDs should be stopped 5 days prior to surgery to reverse antiplatelet effects.23

CORRESPONDENCE

CDR Michael J. Arnold, Naval Hospital, 2080 Child Street, Jacksonville, FL 32214; [email protected].

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The authors thank CDR Kristian Sanchack and LCDR Dustin Smith for their assistance with this manuscript.

1. Wier LM, Steiner CA, Owens PL. Surgeries in hospital-owned outpatient facilities, 2012. HCUP Statistical Brief #188. February 2015. Available at: https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/statbriefs/sb188-Surgeries-Hospital-Outpatient-Facilities-2012.jsp. Accessed September 15, 2016.

2. Fleisher LA, Fleischmann KE, Auerbach AD, et al. 2014 ACC/AHA guideline on perioperative cardiovascular evaluation and management of patients undergoing noncardiac surgery. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;64:e77-e137.

3. Smetana GW, Lawrence VA, Cornell JE. Preoperative pulmonary risk stratification for noncardiothoracic surgery: systematic review for the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2006;144:581-595.

4. Chung F, Abdullah HR, Liao P. STOP-Bang questionnaire: a prac tical approach to screen for obstructive sleep apnea. Chest. 2016;149:631-638.

5. De Hert S, Imberger G, Carlisle J, et al. Preoperative evaluation of the adult patient undergoing non-cardiac surgery: guidelines from the European Society of Anaesthesiology. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2011;28:684-722.

6. American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Perioperative Management of Patients with Obstructive Sleep Apnea. Practice guidelines for the perioperative management of patients with obstructive sleep apnea; an updated report by the American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Perioperative Management of Patients with Obstructive Sleep Apnea. Anesthesiology. 2014;120:268-286.

7. Lee TH, Marcantonio ER, Mangione CM, et al. Derivation and prospective validation of a simple index for prediction of cardiac risk of major noncardiac surgery. Circulation. 1999;100:1043-1049.

8. Bilimoria KY, Liu Y, Paruch JL, et al. Development and evaluation of the universal ACS NSQIP surgical risk calculator: a decision aide and informed consent tool for patients and surgeons. J Am Coll Surg. 2013;217:833-842.

9. Hlatky MA, Boineau RE, Higginbotham MB, et al. A brief self-administered questionnaire to determine functional capacity (the Duke Activity Status Index). Am J Cardiol. 1989;64:651-654.

10. Bouri S, Shun-Shin MJ, Cole GD, et al. Meta-analysis of secure randomized controlled trials of B-blockade to prevent perioperative death in non-cardiac surgery. Heart. 2014;100:456-464.

11. Mounsey A, Roque JM, Egan M. Why you shouldn’t start beta-blockers before surgery. J Fam Pract. 2014;63:E15-E16.

12. Chou R, Arora B, Dana T, et al. Screening asymptomatic adults with resting or exercise electrocardiography: a review of the evidence for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155:375-385.

13. Durazzo AES, Machado FS, Ikeoka DT, et al. Reduction in cardiovascular events after vascular surgery with atorvastatin: a randomized trial. J Vasc Surg. 2004;39:967-975.

14. Pan SY, Wu VC, Huang TM, et al. Effect of preoperative statin therapy on postoperative acute kidney injury in patients undergoing major surgery: systemic review and meta-analysis. Nephrology. 2014;19:750-763.

15. Devereux PJ, Mrkobrada M, Sessler DI, et al. Aspirin in patients undergoing noncardiac surgery. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:1494-1503.

16. Adesanya AO, Lee W, Greilich NB, et al. Perioperative management of obstructive sleep apnea. Chest. 2010;138:1489-1498.

17. Chung F, Nagappa M, Singh M, et al. CPAP in the perioperative setting: evidence of support. Chest. 2016;149:586-597.

18. Yamashita S, Yamaguchi H, Sakaguchi M, et al. Effect of smoking on intraoperative sputum and postoperative pulmonary complication in minor surgical patients. Respir Med. 2004;98:760-766.

19. Myers K, Hajek P, Hinds

20. Lonjaret L, Lairez O, Minville V, et al. Optimal perioperative management of arterial blood pressure. Integr Blood Press Control. 2014;7:49-59.

21. Sudhakaran S, Surani SR. Guidelines for perioperative management of the diabetic patient. Surg Res Pract. 2015;2015:284063.

22. Duncan AE. Hyperglycemia and perioperative glucose management. Curr Pharm Des. 2012;18:6195-6203.

23. Douketis JD, Spyropoulos AC, Spencer FA, et al. Perioperative management of antithrombotic therapy: antithrombotic therapy and prevention of thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines. Chest. 2012;141:e326S-e350S.

24. Faraoni D, Levy JH, Albaladejo P, et al. Updates in the perioperative and emergency management of non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants. Crit Care. 2015;19:203.

25. Shamoun F, Obeid H, Ramakrishna H. Novel anticoagulants in atrial fibrillation: monitoring, reversal and perioperative management. Biomed Res Int. 2015;2015:424031.

26. Kelly KN, Domajnko B. Perioperative stress-dose steroids. Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2013;26:163-167.

27. Scanzello CR, Nestor BJ. Perioperative management of medications used in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. HSSJ. 2006;2:141-147.

1. Wier LM, Steiner CA, Owens PL. Surgeries in hospital-owned outpatient facilities, 2012. HCUP Statistical Brief #188. February 2015. Available at: https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/statbriefs/sb188-Surgeries-Hospital-Outpatient-Facilities-2012.jsp. Accessed September 15, 2016.

2. Fleisher LA, Fleischmann KE, Auerbach AD, et al. 2014 ACC/AHA guideline on perioperative cardiovascular evaluation and management of patients undergoing noncardiac surgery. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;64:e77-e137.

3. Smetana GW, Lawrence VA, Cornell JE. Preoperative pulmonary risk stratification for noncardiothoracic surgery: systematic review for the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2006;144:581-595.

4. Chung F, Abdullah HR, Liao P. STOP-Bang questionnaire: a prac tical approach to screen for obstructive sleep apnea. Chest. 2016;149:631-638.

5. De Hert S, Imberger G, Carlisle J, et al. Preoperative evaluation of the adult patient undergoing non-cardiac surgery: guidelines from the European Society of Anaesthesiology. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2011;28:684-722.

6. American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Perioperative Management of Patients with Obstructive Sleep Apnea. Practice guidelines for the perioperative management of patients with obstructive sleep apnea; an updated report by the American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Perioperative Management of Patients with Obstructive Sleep Apnea. Anesthesiology. 2014;120:268-286.

7. Lee TH, Marcantonio ER, Mangione CM, et al. Derivation and prospective validation of a simple index for prediction of cardiac risk of major noncardiac surgery. Circulation. 1999;100:1043-1049.

8. Bilimoria KY, Liu Y, Paruch JL, et al. Development and evaluation of the universal ACS NSQIP surgical risk calculator: a decision aide and informed consent tool for patients and surgeons. J Am Coll Surg. 2013;217:833-842.

9. Hlatky MA, Boineau RE, Higginbotham MB, et al. A brief self-administered questionnaire to determine functional capacity (the Duke Activity Status Index). Am J Cardiol. 1989;64:651-654.

10. Bouri S, Shun-Shin MJ, Cole GD, et al. Meta-analysis of secure randomized controlled trials of B-blockade to prevent perioperative death in non-cardiac surgery. Heart. 2014;100:456-464.

11. Mounsey A, Roque JM, Egan M. Why you shouldn’t start beta-blockers before surgery. J Fam Pract. 2014;63:E15-E16.

12. Chou R, Arora B, Dana T, et al. Screening asymptomatic adults with resting or exercise electrocardiography: a review of the evidence for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155:375-385.

13. Durazzo AES, Machado FS, Ikeoka DT, et al. Reduction in cardiovascular events after vascular surgery with atorvastatin: a randomized trial. J Vasc Surg. 2004;39:967-975.

14. Pan SY, Wu VC, Huang TM, et al. Effect of preoperative statin therapy on postoperative acute kidney injury in patients undergoing major surgery: systemic review and meta-analysis. Nephrology. 2014;19:750-763.

15. Devereux PJ, Mrkobrada M, Sessler DI, et al. Aspirin in patients undergoing noncardiac surgery. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:1494-1503.

16. Adesanya AO, Lee W, Greilich NB, et al. Perioperative management of obstructive sleep apnea. Chest. 2010;138:1489-1498.

17. Chung F, Nagappa M, Singh M, et al. CPAP in the perioperative setting: evidence of support. Chest. 2016;149:586-597.

18. Yamashita S, Yamaguchi H, Sakaguchi M, et al. Effect of smoking on intraoperative sputum and postoperative pulmonary complication in minor surgical patients. Respir Med. 2004;98:760-766.

19. Myers K, Hajek P, Hinds

20. Lonjaret L, Lairez O, Minville V, et al. Optimal perioperative management of arterial blood pressure. Integr Blood Press Control. 2014;7:49-59.

21. Sudhakaran S, Surani SR. Guidelines for perioperative management of the diabetic patient. Surg Res Pract. 2015;2015:284063.

22. Duncan AE. Hyperglycemia and perioperative glucose management. Curr Pharm Des. 2012;18:6195-6203.

23. Douketis JD, Spyropoulos AC, Spencer FA, et al. Perioperative management of antithrombotic therapy: antithrombotic therapy and prevention of thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines. Chest. 2012;141:e326S-e350S.

24. Faraoni D, Levy JH, Albaladejo P, et al. Updates in the perioperative and emergency management of non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants. Crit Care. 2015;19:203.

25. Shamoun F, Obeid H, Ramakrishna H. Novel anticoagulants in atrial fibrillation: monitoring, reversal and perioperative management. Biomed Res Int. 2015;2015:424031.

26. Kelly KN, Domajnko B. Perioperative stress-dose steroids. Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2013;26:163-167.

27. Scanzello CR, Nestor BJ. Perioperative management of medications used in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. HSSJ. 2006;2:141-147.

It’s Not Too Late to Register for the NORD Summit

Food and Drug Administration (FDA) Commissioner Robert Califf, MD, will deliver a keynote address on the opening morning of the NORD Rare Diseases and Orphan Products Breakthrough Summit to take place Oct. 17 and 18 in Arlington Virginia. Approximately one-third of the novel new drugs approved by FDA in recent years have been “orphan” drugs for rare diseases.

Dr. Califf will be joined on the program agenda by more than 25 additional FDA speakers, including Janet Woodcock, MD, Director of FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, and Peter Marks, MD, PhD, Director of FDA’s Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research.

On Day Two of the conference, Kate Rawson, Senior Editor at Prevision Policy, will provide the morning keynote with a look ahead at possible implications of the national election for the rare disease community. The NORD Summit attracts medical professionals, patient advocates, and others to examine issues related to rare disease research, diagnosis, treatment, and patient access to care. The conference is open to all. Click here to view the agenda.

Food and Drug Administration (FDA) Commissioner Robert Califf, MD, will deliver a keynote address on the opening morning of the NORD Rare Diseases and Orphan Products Breakthrough Summit to take place Oct. 17 and 18 in Arlington Virginia. Approximately one-third of the novel new drugs approved by FDA in recent years have been “orphan” drugs for rare diseases.

Dr. Califf will be joined on the program agenda by more than 25 additional FDA speakers, including Janet Woodcock, MD, Director of FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, and Peter Marks, MD, PhD, Director of FDA’s Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research.

On Day Two of the conference, Kate Rawson, Senior Editor at Prevision Policy, will provide the morning keynote with a look ahead at possible implications of the national election for the rare disease community. The NORD Summit attracts medical professionals, patient advocates, and others to examine issues related to rare disease research, diagnosis, treatment, and patient access to care. The conference is open to all. Click here to view the agenda.

Food and Drug Administration (FDA) Commissioner Robert Califf, MD, will deliver a keynote address on the opening morning of the NORD Rare Diseases and Orphan Products Breakthrough Summit to take place Oct. 17 and 18 in Arlington Virginia. Approximately one-third of the novel new drugs approved by FDA in recent years have been “orphan” drugs for rare diseases.

Dr. Califf will be joined on the program agenda by more than 25 additional FDA speakers, including Janet Woodcock, MD, Director of FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, and Peter Marks, MD, PhD, Director of FDA’s Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research.

On Day Two of the conference, Kate Rawson, Senior Editor at Prevision Policy, will provide the morning keynote with a look ahead at possible implications of the national election for the rare disease community. The NORD Summit attracts medical professionals, patient advocates, and others to examine issues related to rare disease research, diagnosis, treatment, and patient access to care. The conference is open to all. Click here to view the agenda.

Skin findings associated with nutritional deficiencies

Although vitamin and mineral deficiencies are relatively uncommon in the United States and other developed countries, physicians must be alert to them, particularly in specific populations such as infants, pregnant women, alcoholics, vegetarians, people of lower socioeconomic status, and patients on dialysis, on certain medications, or with a history of malabsorption or gastrointestinal surgery. The skin is commonly affected by nutritional deficiencies and can provide important diagnostic clues.

This article reviews the consequences of deficiencies of zinc and vitamins A, B2, B3, B6, and C, emphasizing dermatologic findings.

ZINC DEFICIENCY

Case: A colon cancer patient on total parenteral nutrition

A 65-year-old woman who had been on total parenteral nutrition for 4 months after undergoing surgical debulking for metastatic colon cancer was admitted for evaluation of a rash on her face and extremities and failure to thrive. The rash had started 10 days earlier as small red papules and vesicles on the forehead and progressed to cover the forehead and lips. She had been prescribed prednisone 20 mg daily, but the condition had not improved.

Physical examination revealed numerous violaceous papules, plaques, and vesicles on her face, legs, and feet (Figure 1). The vesicles were tender to touch and some were crusted. Biopsy of a lesion on her leg revealed psoriasiform dermatitis with prominent epidermal pallor and necrosis (Figure 2), suggestive of a nutritional deficiency.

Blood testing revealed low levels of alkaline phosphatase and zinc. She was started on zinc supplementation (3 mg/kg/day), and her cutaneous lesions improved within a month, confirming the diagnosis of zinc deficiency.

Zinc is an essential trace element

Zinc is an essential trace element required for function of many metalloproteases and transcription factors involved in reproduction, immunology, and wound repair. Additionally, its antioxidant properties help prevent ultraviolet radiation damage.1

The recommended dietary allowance (RDA) for zinc is 11 mg/day for men and 8 mg/day for women, with higher amounts for pregnant and lactating women.1 The human body does not store zinc, and meat and eggs are the most important dietary sources.1

The normal plasma zinc level is 70 to 250 µL/dL, and hypozincemia can be diagnosed with a blood test. For the test to be accurate, zinc-free tubes should be used, anticoagulants should be avoided, the blood should not come into contact with rubber stoppers, and blood should be drawn in the morning due to diurnal variation in zinc levels. Additionally, zinc levels may be transiently low secondary to infection. Thus, the clinical picture, along with zinc levels, histopathology, and clinical response to zinc supplementation are necessary for the diagnosis of zinc deficiency.2

Since zinc is required for the activity of alkaline phosphatase (a metalloenzyme), serum levels of alkaline phosphatase correlate with zinc levels and can be used as a serologic marker for zinc levels.3

Zinc deficiency is a worldwide problem, with a higher prevalence in developing countries. It can result from either inadequate diet or impaired absorption, which can be acquired or inherited.

Clinical forms of zinc deficiency

Acrodermatitis enteropathica, an inherited form of zinc deficiency, is due to a mutation in the SLC39A4 gene encoding a zinc uptake protein.4 Patients typically present during infancy a few weeks after being weaned from breast milk. Clinical presentations include diarrhea, periorificial (eg, around the mouth) and acral dermatitis, and alopecia, although only 20% of patients have all these findings at presentation.5 Occasionally, diaper rash, photosensitivity, nail dystrophy, angular stomatitis, conjunctivitis, blepharitis, and growth retardation are observed. Serum levels of zinc and alkaline phosphatase are low.5 Clinical and serologic markers improve within 2 to 3 weeks with oral zinc supplementation (2–3 mg/kg/day).

Acquired forms of zinc deficiency are linked to poor socioeconomic status, diet, infections, renal failure, pancreatic insufficiency, cystic fibrosis, and malabsorption syndromes.1,6,7 Cutaneous findings in acquired cases of zinc deficiency are similar to those seen in acrodermatitis enteropathica. Periorificial lesions are a hallmark of this condition, and angular cheilitis is an early manifestation. Eczematous annular plaques typically develop in areas subjected to repeated friction and pressure and may evolve into vesicles, pustules, and bullae.2 On biopsy study, lesions are characterized by cytoplasmic pallor, vacuolization, and necrosis of keratinocytes, which are common findings in nutritional deficiencies.8 Dystrophic nails, structural hair changes, and diminished growth of both hair and nails have been reported.2

Cutaneous lesions due to hypozincemia respond quickly to zinc supplementation (1–3 mg/kg/day), usually without permanent damage.2 However, areas of hypo- and hyperpigmentation may persist.

VITAMIN C DEFICIENCY

Case: A lung transplant recipient on peritoneal dialysis

A 59-year-old bilateral lung transplant patient with a history of chronic kidney disease on peritoneal dialysis for the past 2 years was admitted for peritonitis. He had developed tender violaceous papules and nodules coalescing into large plaques on his arms and perifollicular purpuric macules on both legs 3 days before admission (Figure 3). The lesions were painful to the touch, and some bled at times. Tender gums, bilateral edema, and corkscrew hair were also noted (corkscrew hair is shown in another patient in Figure 4).

Biopsy of a lesion on the forearm was consistent with lymphangiectasia secondary to edema. Staining for bacteria and fungi was negative.

Serologic investigation revealed low vitamin C serum levels (7 µmol/L, reference range 23–114 µmol/L). Supplementation with 1 g/day of vitamin C was started and resulted in gradual improvement of the purpura. The patient died 4 months later of complications of comorbidities.

An important antioxidant

Vitamin C, or ascorbic acid, is an important antioxidant involved in the synthesis of tyrosine, tryptophan, and folic acid and in the hydroxylation of glycine and proline, a required step in the formation of collagen.9 Humans cannot synthesize vitamin C and must acquire it in the diet.9 Plants are the most important dietary sources.9 Although vitamin C is generally not toxic and its metabolites are renally cleared, diarrhea and other gastrointestinal disturbances can occur if large amounts are ingested.10

Vitamin C deficiency is rare in developed countries and is linked to malnutrition. Risk factors include alcoholism, severe psychiatric illness, anorexia, and low socioeconomic status. Moreover, multiple conditions including stress, viral illness, smoking, fever, and use of antibiotics lead to diminished vitamin C bioavailability.9 Patients on dialysis are at increased risk of vitamin C deficiency since it is lost during the process.11

The RDA for vitamin C is 90 mg for men and 75 mg for women, with higher requirements during pregnancy and lactation.12 This is much higher than the amount needed to prevent scurvy, 10 mg/day.13

Scurvy is the classic manifestation

The classic manifestations of vitamin C deficiency are scurvy and Barlow disease, also known as infantile scurvy.

Early manifestations of vitamin C deficiency such as fatigue, mood changes, and depression appear after 1 to 3 months of inadequate intake.13 Other manifestations are anemia, bone pain, hemorrhage into joints, abnormal vision, and possibly osteoporosis.

Cutaneous findings are a hallmark of scurvy. Follicular hyperkeratosis with fragmented corkscrew hair and perifollicular hemorrhages on posterior thighs, forearms, and abdomen are pathognomonic findings that occur early in the disease.13 The cutaneous hemorrhages can become palpable, particularly in the lower limbs. Diffuse petechiae are a later finding along with ecchymosis, particularly in pressure sites such as the buttocks.13 “Woody edema” of the legs with ecchymosis, pain, and limited motion can also arise.14 Nail findings including koilonychia and splinter hemorrhages are common.13,14

Vitamin C deficiency results in poor wound healing with consequent ulcer formation due to impaired collagen synthesis. Hair abnormalities including corkscrew and swan-neck hairs are common in scurvy due to vitamin C’s role in disulfide bond formation, which is necessary for hair synthesis.13

Scurvy also affects the oral cavity: gums typically appear red, swollen, and shiny earlier in the disease and can become black and necrotic later.13 Loosening and loss of teeth is also common.13

Scurvy responds quickly to vitamin C supplementation. Patients with scurvy should receive 1 to 2 g of vitamin C daily for 2 to 3 days, 500 mg daily for the next week, and 100 mg daily for the next 1 to 3 months.15 Fatigue, pain, and confusion usually improve in the first 24 hours of treatment, cutaneous manifestations respond in 2 weeks, and hair within 1 month. Complete recovery is expected within 3 months on vitamin C supplementation.15

VITAMIN A DEFICIENCY

Case: A girl with short-bowel syndrome on total parenteral nutrition

A 14-year-old girl who had been on total parenteral nutrition for the past 3 years due to short-bowel syndrome was admitted for evaluation for a second small-bowel transplant. She complained of dry skin and dry eyes. She was found to have rough, toad-like skin with prominent brown perifollicular hyperkeratotic papules on buttocks and extremities (Figure 5). Additionally, corkscrew hairs were noted. Physical examination was consistent with phrynoderma.

Blood work revealed low levels of vitamin A (8 µg/dL, reference range 20–120 µg/dL) and vitamin C (20 µmol/L, reference range 23–114 µmol/L). After bowel transplant, her vitamin A levels normalized within 2 weeks and her skin improved without vitamin A supplementation.

Essential for protein synthesis

Vitamin A is a group of fat-soluble isoprenoids that includes retinol, retinoic acid, and beta-carotene. It is stored in hepatic stellate cells, which can release it in circulation for distribution to peripheral organs when needed.16

Vitamin A is essential for protein synthesis in the eye and is a crucial component of phototransduction.17 It is also an important modulator of the immune system, as it enhances cytotoxicity and proliferation of T cells while suppressing B-cell proliferation.18 Additionally, vitamin A plays an important role in the skin, where it promotes cell mitosis and increases epithelial thickness, the number of Langerhans cells, and glycosaminoglycan synthesis.19–21

Deficiency associated with malabsorption, liver disease, small-bowel surgery

Vitamin A deficiency is rare in developed countries overall, but it is associated with malabsorption, liver disease, and small-bowel surgery.22 Indeed, 4 years after undergoing bariatric surgery, 69% of patients in one series had deficiencies in vitamin A and other fat-soluble vitamins.23 The typical manifestations are nyctalopia (night blindness) and xerophthalmia (inability to produce tears).

Phrynoderma, or “toad skin,” is a cutaneous manifestation of vitamin A deficiency. The association between phrynoderma and vitamin A deficiency was established in 1933 when prisoners in Africa with nyctalopia, xerophthalmia, and phrynoderma showed improvement in all three conditions when treated with cod oil, which is rich in vitamin A.24