User login

October 21 Is Deadline for NORD Research Grant Abstracts

The deadline has been extended to October 21 to submit letters of intent and abstracts for National Organization for Rare Disorders (NORD) research grants for studies related to the following rare diseases:

- Alveolar capillary dysplasia with misalignment of the pulmonary veins (ACD/MPV)

- Appendix cancer and pseudomyxoma peritonei (PMP)

- Autoimmune polyglandular syndrome type 1 (APS Type 1)

- Homocystinuria due to cystathionine beta-synthase deficiency

- Malonic aciduria

- Stiff person syndrome

The NORD Research Grant Program encourages meritorious scientific and clinical research toward new diagnostics, treatments, and/or cures for rare diseases. NORD’s program provides seed grants to clinicians and academic scientists for translational or clinical studies. Data generated in these studies may then be used by researchers to obtain additional funding from government or industry sponsors. Two of NORD’s previous research grants have resulted in FDA-approved orphan products to treat rare diseases. Submissions should be sent to [email protected]. Click here to view each Request for Proposal in full.

The deadline has been extended to October 21 to submit letters of intent and abstracts for National Organization for Rare Disorders (NORD) research grants for studies related to the following rare diseases:

- Alveolar capillary dysplasia with misalignment of the pulmonary veins (ACD/MPV)

- Appendix cancer and pseudomyxoma peritonei (PMP)

- Autoimmune polyglandular syndrome type 1 (APS Type 1)

- Homocystinuria due to cystathionine beta-synthase deficiency

- Malonic aciduria

- Stiff person syndrome

The NORD Research Grant Program encourages meritorious scientific and clinical research toward new diagnostics, treatments, and/or cures for rare diseases. NORD’s program provides seed grants to clinicians and academic scientists for translational or clinical studies. Data generated in these studies may then be used by researchers to obtain additional funding from government or industry sponsors. Two of NORD’s previous research grants have resulted in FDA-approved orphan products to treat rare diseases. Submissions should be sent to [email protected]. Click here to view each Request for Proposal in full.

The deadline has been extended to October 21 to submit letters of intent and abstracts for National Organization for Rare Disorders (NORD) research grants for studies related to the following rare diseases:

- Alveolar capillary dysplasia with misalignment of the pulmonary veins (ACD/MPV)

- Appendix cancer and pseudomyxoma peritonei (PMP)

- Autoimmune polyglandular syndrome type 1 (APS Type 1)

- Homocystinuria due to cystathionine beta-synthase deficiency

- Malonic aciduria

- Stiff person syndrome

The NORD Research Grant Program encourages meritorious scientific and clinical research toward new diagnostics, treatments, and/or cures for rare diseases. NORD’s program provides seed grants to clinicians and academic scientists for translational or clinical studies. Data generated in these studies may then be used by researchers to obtain additional funding from government or industry sponsors. Two of NORD’s previous research grants have resulted in FDA-approved orphan products to treat rare diseases. Submissions should be sent to [email protected]. Click here to view each Request for Proposal in full.

A tool to help limit patients’ sodium intake

The average American consumes about 3400 mg/d of sodium, which is more than double the 1500 mg recommended by the American Heart Association.1 Excess sodium added to foods during commercial processing and preparation represents the main source of sodium intake in American diets.2 Nevertheless, adding salt at the table is still very common, and people who add salt at the table have 1.5 g higher salt intakes than those who do not add salt.3 And as we know, high sodium intake has been associated with elevated blood pressure and an increased rate of cardiovascular disease.4

I have designed a self-produced “Salt Awareness—Limit Today” (SALT) label (FIGURE). This label is attached to the cap of a salt shaker in such a way that less salt flows through the openings of the cap. Moreover, the label serves as a reminder to limit salt intake in general. The feedback I have received from my patients has been extremely positive; they report increased awareness and decreased sodium intake. I mention it here so that others may benefit.

Zvi Weizman, MD

Beer-Sheva, Israel

1. Cobb LK, Anderson CA, Elliott P, et al; American Heart Association Council on Lifestyle and Metabolic Health. Methodological issues in cohort studies that relate sodium intake to cardiovascular disease outcomes: a science advisory from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2014;129:1173-1186.

2. Jackson SL, King SM, Zhao L, et al. Prevalence of excess sodium intake in the United States - NHANES, 2009-2012. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;64:1393-1397.

3. Webster J, Su’a SA, Ieremia M, et al. Salt intakes, knowledge, and behavior in Samoa: Monitoring salt-consumption patterns through the World Health Organization’s surveillance of noncommunicable disease risk factors (STEPS). J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2016.

4. Mozaffarian D, Fahimi S, Singh GM, et al; Global Burden of Diseases Nutrition and Chronic Diseases Expert Group. Global sodium consumption and death from cardiovascular causes. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:624-634.

The average American consumes about 3400 mg/d of sodium, which is more than double the 1500 mg recommended by the American Heart Association.1 Excess sodium added to foods during commercial processing and preparation represents the main source of sodium intake in American diets.2 Nevertheless, adding salt at the table is still very common, and people who add salt at the table have 1.5 g higher salt intakes than those who do not add salt.3 And as we know, high sodium intake has been associated with elevated blood pressure and an increased rate of cardiovascular disease.4

I have designed a self-produced “Salt Awareness—Limit Today” (SALT) label (FIGURE). This label is attached to the cap of a salt shaker in such a way that less salt flows through the openings of the cap. Moreover, the label serves as a reminder to limit salt intake in general. The feedback I have received from my patients has been extremely positive; they report increased awareness and decreased sodium intake. I mention it here so that others may benefit.

Zvi Weizman, MD

Beer-Sheva, Israel

The average American consumes about 3400 mg/d of sodium, which is more than double the 1500 mg recommended by the American Heart Association.1 Excess sodium added to foods during commercial processing and preparation represents the main source of sodium intake in American diets.2 Nevertheless, adding salt at the table is still very common, and people who add salt at the table have 1.5 g higher salt intakes than those who do not add salt.3 And as we know, high sodium intake has been associated with elevated blood pressure and an increased rate of cardiovascular disease.4

I have designed a self-produced “Salt Awareness—Limit Today” (SALT) label (FIGURE). This label is attached to the cap of a salt shaker in such a way that less salt flows through the openings of the cap. Moreover, the label serves as a reminder to limit salt intake in general. The feedback I have received from my patients has been extremely positive; they report increased awareness and decreased sodium intake. I mention it here so that others may benefit.

Zvi Weizman, MD

Beer-Sheva, Israel

1. Cobb LK, Anderson CA, Elliott P, et al; American Heart Association Council on Lifestyle and Metabolic Health. Methodological issues in cohort studies that relate sodium intake to cardiovascular disease outcomes: a science advisory from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2014;129:1173-1186.

2. Jackson SL, King SM, Zhao L, et al. Prevalence of excess sodium intake in the United States - NHANES, 2009-2012. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;64:1393-1397.

3. Webster J, Su’a SA, Ieremia M, et al. Salt intakes, knowledge, and behavior in Samoa: Monitoring salt-consumption patterns through the World Health Organization’s surveillance of noncommunicable disease risk factors (STEPS). J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2016.

4. Mozaffarian D, Fahimi S, Singh GM, et al; Global Burden of Diseases Nutrition and Chronic Diseases Expert Group. Global sodium consumption and death from cardiovascular causes. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:624-634.

1. Cobb LK, Anderson CA, Elliott P, et al; American Heart Association Council on Lifestyle and Metabolic Health. Methodological issues in cohort studies that relate sodium intake to cardiovascular disease outcomes: a science advisory from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2014;129:1173-1186.

2. Jackson SL, King SM, Zhao L, et al. Prevalence of excess sodium intake in the United States - NHANES, 2009-2012. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;64:1393-1397.

3. Webster J, Su’a SA, Ieremia M, et al. Salt intakes, knowledge, and behavior in Samoa: Monitoring salt-consumption patterns through the World Health Organization’s surveillance of noncommunicable disease risk factors (STEPS). J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2016.

4. Mozaffarian D, Fahimi S, Singh GM, et al; Global Burden of Diseases Nutrition and Chronic Diseases Expert Group. Global sodium consumption and death from cardiovascular causes. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:624-634.

Point-of-care ultrasound: It’s no replacement for the stethoscope

In his August editorial, Dr. Hickner noted that an article in the issue prompted him to “wonder whether ultrasound might become the stethoscope of the future” (J Fam Pract. 2016;65:516). To that I say that we need to avoid conflating the stethoscope with point-of-care ultrasound (POCUS).

It is well documented that auscultation skills rapidly deteriorate (specifically in the cardiology realm) in clinical practice.1 This may occur because many physicians already think ultrasound can replace actually listening to their patients’ hearts. The motto has become, “I’ll just order an echo.”

POCUS is an imaging modality. Period. It can be used to auscultate, but Doppler ultrasound is not as precise as the stethoscope when used by a practiced listener for identifying the source and subtle characteristics of murmurs.2 The stethoscope remains an outstanding, inexpensive, and convenient screening tool and its use needs to be emphasized.

I strongly believe in training all medical students in POCUS—but as a complementary and adjunctive tool—not as something to replace a perfectly functional piece of equipment used around the world to provide good care.

Todd Fredricks, DO

Athens, Ohio

1. Vukanovic-Criley JM, Hovanesyan A, Criley SR, et al. Confidential testing of cardiac examination competency in cardiology and noncardiology faculty and trainees: a multicenter study. Clin Cardiol. 2010;33:738-745.

2. Tavel ME. Cardiac auscultation. A glorious past—but does it have a future? Circulation. 1996;93:1250-1253.

In his August editorial, Dr. Hickner noted that an article in the issue prompted him to “wonder whether ultrasound might become the stethoscope of the future” (J Fam Pract. 2016;65:516). To that I say that we need to avoid conflating the stethoscope with point-of-care ultrasound (POCUS).

It is well documented that auscultation skills rapidly deteriorate (specifically in the cardiology realm) in clinical practice.1 This may occur because many physicians already think ultrasound can replace actually listening to their patients’ hearts. The motto has become, “I’ll just order an echo.”

POCUS is an imaging modality. Period. It can be used to auscultate, but Doppler ultrasound is not as precise as the stethoscope when used by a practiced listener for identifying the source and subtle characteristics of murmurs.2 The stethoscope remains an outstanding, inexpensive, and convenient screening tool and its use needs to be emphasized.

I strongly believe in training all medical students in POCUS—but as a complementary and adjunctive tool—not as something to replace a perfectly functional piece of equipment used around the world to provide good care.

Todd Fredricks, DO

Athens, Ohio

In his August editorial, Dr. Hickner noted that an article in the issue prompted him to “wonder whether ultrasound might become the stethoscope of the future” (J Fam Pract. 2016;65:516). To that I say that we need to avoid conflating the stethoscope with point-of-care ultrasound (POCUS).

It is well documented that auscultation skills rapidly deteriorate (specifically in the cardiology realm) in clinical practice.1 This may occur because many physicians already think ultrasound can replace actually listening to their patients’ hearts. The motto has become, “I’ll just order an echo.”

POCUS is an imaging modality. Period. It can be used to auscultate, but Doppler ultrasound is not as precise as the stethoscope when used by a practiced listener for identifying the source and subtle characteristics of murmurs.2 The stethoscope remains an outstanding, inexpensive, and convenient screening tool and its use needs to be emphasized.

I strongly believe in training all medical students in POCUS—but as a complementary and adjunctive tool—not as something to replace a perfectly functional piece of equipment used around the world to provide good care.

Todd Fredricks, DO

Athens, Ohio

1. Vukanovic-Criley JM, Hovanesyan A, Criley SR, et al. Confidential testing of cardiac examination competency in cardiology and noncardiology faculty and trainees: a multicenter study. Clin Cardiol. 2010;33:738-745.

2. Tavel ME. Cardiac auscultation. A glorious past—but does it have a future? Circulation. 1996;93:1250-1253.

1. Vukanovic-Criley JM, Hovanesyan A, Criley SR, et al. Confidential testing of cardiac examination competency in cardiology and noncardiology faculty and trainees: a multicenter study. Clin Cardiol. 2010;33:738-745.

2. Tavel ME. Cardiac auscultation. A glorious past—but does it have a future? Circulation. 1996;93:1250-1253.

Rethinking A1C targets for patients with mental illness?

The article, “Diabetes update: Your guide to the latest ADA standards,” by Shubrook, et al (J Fam Pract. 2016;65:310-318) is a precise review of current recommendations for diabetes. We would like to draw attention, however, to comorbid diabetes and mental illness.

Diabetes and serious mental illness often coincide, making the treatment of both conditions difficult and leading to higher rates of complications.1

The American Diabetes Association (ADA)’s “Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes” recognizes that hemoglobin A1C targets for patients should be individualized.2 We consider it important to discus

For example, a more lenient A1C goal may be appropriate when:

- the assessment of the patient shows that he or she is struggling with active symptoms of mental illness

- new medications with undesirable metabolic effects are prescribed or titrated

- social support is poor

- patients have limited confidence in their ability to accomplish tasks and goals

- patients have cognitive limitations

- patients abuse substances.

We suggest that when factors are favorable (eg, younger patient, well-controlled serious mental illness, adequate support, good cognitive skills, no hazardous use of substances, good level of confidence in the ability to control diabetes), the A1C target can be set lower. When the factors are less favorable (eg, older patient, poorly controlled mental illness, abusing substances, cognitive impairment), the target should be set higher and incrementally reduced as care engagement, circumstances, and symptom control improve.

There is a need for further research to investigate the factors that can impact diabetes self-management in patients with comorbid mental illness.

Corinna Falck-Ytter, MD

Stephanie W. Kanuch, MEd

Richard McCormick, PhD

Michael Purdum, PhD

Neal V. Dawson, MD

Shari D. Bolen, MD, MPH

Martha Sajatovic, MD

Cleveland, Ohio

1. Ducat L, Philipson LH, Anderson BJ. The mental health comorbidities of diabetes. JAMA. 2014;312:691-692.

2. American Diabetes Association. Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes—2016. Diabetes Care. 2016;39(Suppl 1). Available at: http://care.diabetesjournals.org/content/diacare/suppl/2015/12/21/39.Supplement_1.DC2/2016-Standards-of-Care.pdf. Accessed May 18, 2016.

The article, “Diabetes update: Your guide to the latest ADA standards,” by Shubrook, et al (J Fam Pract. 2016;65:310-318) is a precise review of current recommendations for diabetes. We would like to draw attention, however, to comorbid diabetes and mental illness.

Diabetes and serious mental illness often coincide, making the treatment of both conditions difficult and leading to higher rates of complications.1

The American Diabetes Association (ADA)’s “Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes” recognizes that hemoglobin A1C targets for patients should be individualized.2 We consider it important to discus

For example, a more lenient A1C goal may be appropriate when:

- the assessment of the patient shows that he or she is struggling with active symptoms of mental illness

- new medications with undesirable metabolic effects are prescribed or titrated

- social support is poor

- patients have limited confidence in their ability to accomplish tasks and goals

- patients have cognitive limitations

- patients abuse substances.

We suggest that when factors are favorable (eg, younger patient, well-controlled serious mental illness, adequate support, good cognitive skills, no hazardous use of substances, good level of confidence in the ability to control diabetes), the A1C target can be set lower. When the factors are less favorable (eg, older patient, poorly controlled mental illness, abusing substances, cognitive impairment), the target should be set higher and incrementally reduced as care engagement, circumstances, and symptom control improve.

There is a need for further research to investigate the factors that can impact diabetes self-management in patients with comorbid mental illness.

Corinna Falck-Ytter, MD

Stephanie W. Kanuch, MEd

Richard McCormick, PhD

Michael Purdum, PhD

Neal V. Dawson, MD

Shari D. Bolen, MD, MPH

Martha Sajatovic, MD

Cleveland, Ohio

The article, “Diabetes update: Your guide to the latest ADA standards,” by Shubrook, et al (J Fam Pract. 2016;65:310-318) is a precise review of current recommendations for diabetes. We would like to draw attention, however, to comorbid diabetes and mental illness.

Diabetes and serious mental illness often coincide, making the treatment of both conditions difficult and leading to higher rates of complications.1

The American Diabetes Association (ADA)’s “Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes” recognizes that hemoglobin A1C targets for patients should be individualized.2 We consider it important to discus

For example, a more lenient A1C goal may be appropriate when:

- the assessment of the patient shows that he or she is struggling with active symptoms of mental illness

- new medications with undesirable metabolic effects are prescribed or titrated

- social support is poor

- patients have limited confidence in their ability to accomplish tasks and goals

- patients have cognitive limitations

- patients abuse substances.

We suggest that when factors are favorable (eg, younger patient, well-controlled serious mental illness, adequate support, good cognitive skills, no hazardous use of substances, good level of confidence in the ability to control diabetes), the A1C target can be set lower. When the factors are less favorable (eg, older patient, poorly controlled mental illness, abusing substances, cognitive impairment), the target should be set higher and incrementally reduced as care engagement, circumstances, and symptom control improve.

There is a need for further research to investigate the factors that can impact diabetes self-management in patients with comorbid mental illness.

Corinna Falck-Ytter, MD

Stephanie W. Kanuch, MEd

Richard McCormick, PhD

Michael Purdum, PhD

Neal V. Dawson, MD

Shari D. Bolen, MD, MPH

Martha Sajatovic, MD

Cleveland, Ohio

1. Ducat L, Philipson LH, Anderson BJ. The mental health comorbidities of diabetes. JAMA. 2014;312:691-692.

2. American Diabetes Association. Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes—2016. Diabetes Care. 2016;39(Suppl 1). Available at: http://care.diabetesjournals.org/content/diacare/suppl/2015/12/21/39.Supplement_1.DC2/2016-Standards-of-Care.pdf. Accessed May 18, 2016.

1. Ducat L, Philipson LH, Anderson BJ. The mental health comorbidities of diabetes. JAMA. 2014;312:691-692.

2. American Diabetes Association. Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes—2016. Diabetes Care. 2016;39(Suppl 1). Available at: http://care.diabetesjournals.org/content/diacare/suppl/2015/12/21/39.Supplement_1.DC2/2016-Standards-of-Care.pdf. Accessed May 18, 2016.

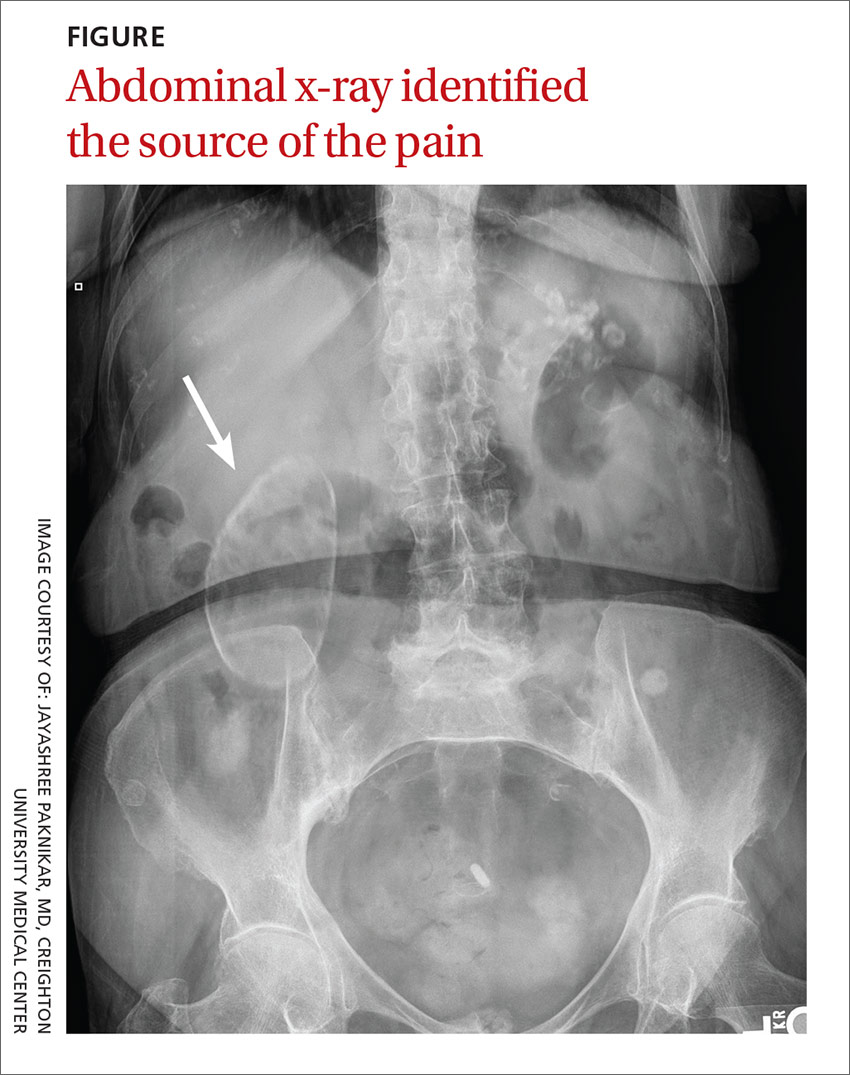

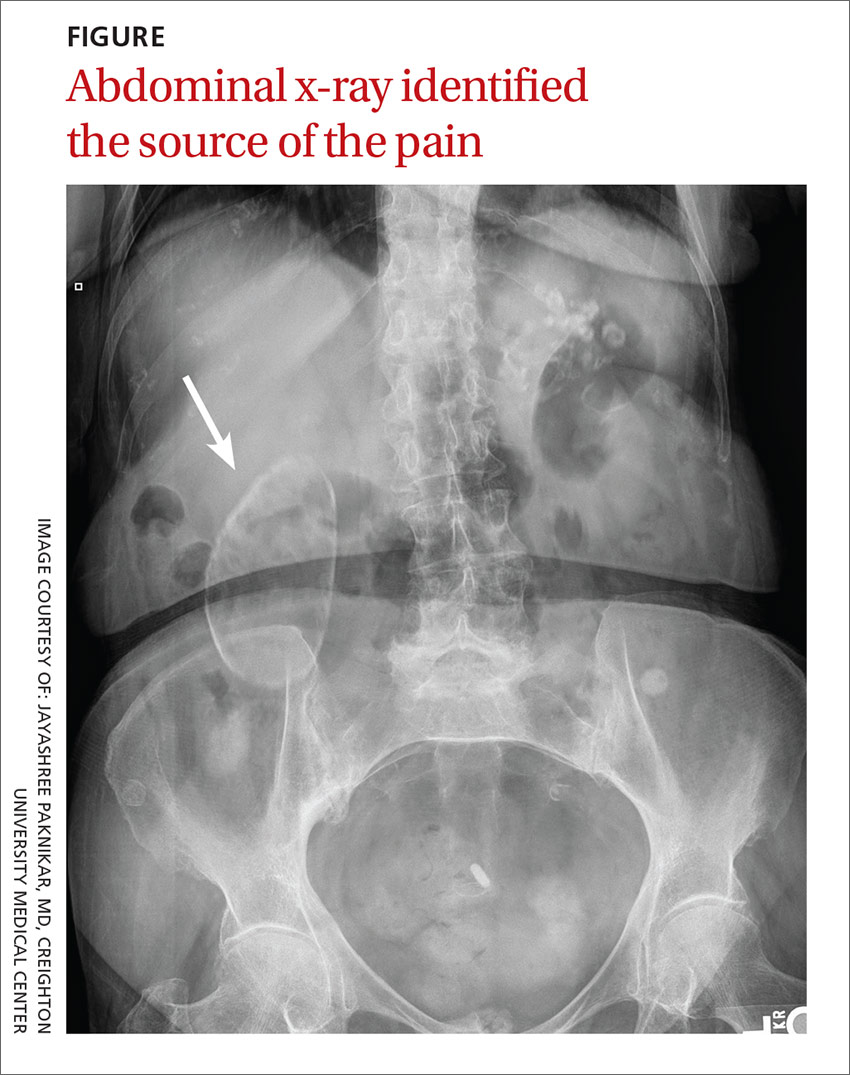

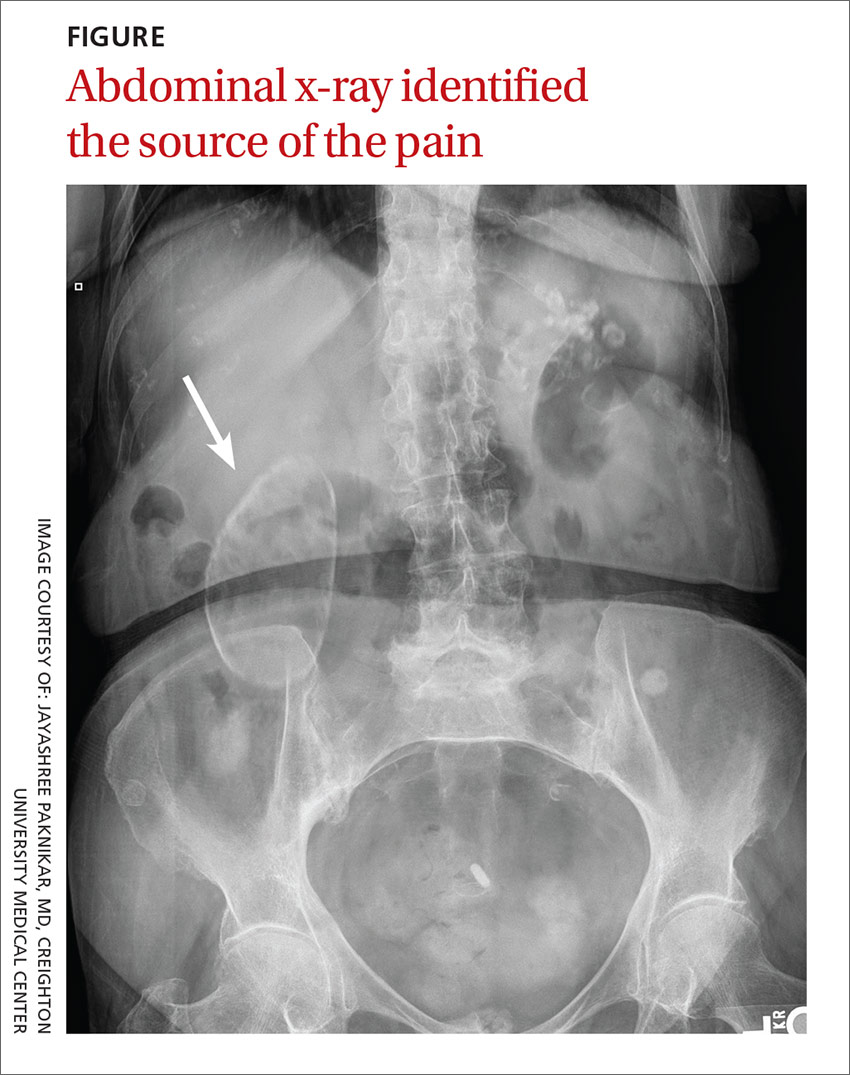

Recurrent right upper quadrant abdominal pain

An 88-year-old woman presented to our primary care clinic with recurrent right upper quadrant abdominal pain. Her history was negative for nausea, fever, vomiting, chest pain, heartburn, back pain, or changes in bowel movement patterns. There was no association between the pain and her eating patterns. She described the pain as dull, and rated it as a 4 to 5 out of 10. A physical examination was unremarkable except for a minimally tender mass in the right upper quadrant that was detected during palpation of the abdomen. A Murphy’s test was negative. A comprehensive metabolic panel, complete blood count, lipase test, amylase test, abdominal ultrasound, and abdominal x-ray (FIGURE) were ordered.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Porcelain gallbladder

We diagnosed this patient with porcelain gallbladder based on her history, physical exam, and x-ray, which revealed a well-defined air gas bubble encased in a calcified pouch. (The patient’s lab work was unremarkable and the ultrasound revealed the same findings as seen on the x-ray.)

Porcelain gallbladder is a rare condition.1 It is characterized by intramural calcifications of the gallbladder wall, which is rarely seen with chronic cholecystitis.2

There are a few theories behind the etiology of porcelain gallbladder. One theory is that gallstones can irritate the gallbladder wall, leading to inflammation and then calcification. Others believe that porcelain gallbladder is due to the obstruction of cystic ducts, which leads to bile stasis in the gallbladder, followed by the accumulation of calcium carbonate salts.3

Patients may present with biliary pain or a firm palpable mass in the right upper quadrant. However, patients are often asymptomatic.4

Cancer risk. There is about a 2% to 3% risk of gallbladder cancer in patients with porcelain gallbladder.5 The nature of the calcification has been linked to the probability that a patient will develop gallbladder cancer. Specifically, there is a higher probability of gallbladder cancer if discontinuous calcification is noted, or if only some portion of the gallbladder wall has calcified.6 About 80% of all gallbladder cancers are adenocarcinomas.6

Differential diagnosis includes GERD, cholecystitis

Right upper quadrant pain is associated with acute hepatitis, acute cholecystitis, acute pancreatitis, gastroesophageal reflex disease (GERD), ulcers, and umbilical hernias. In this patient’s case, her history and physical examination made a number of diagnoses less likely, including acute cholecystitis, GERD, ulcers, and an umbilical hernia. In addition, normal values on the patient’s lipase and amylase tests ruled out pancreatitis.

Imaging brought things into focus. The most significant finding in this case was the abdominal x-ray, which showed a well-defined air gas bubble encased in a calcified pouch.

In addition to an x-ray or an ultrasound, a computed tomography scan can confirm the diagnosis of porcelain gallbladder.

For most patients, cholecystectomy is recommended

Treatment and management is based on the pattern of calcification and the patient’s current health status. If there is incomplete calcification, cholecystectomy is warranted. Cholecystectomy may also be warranted when a patient is symptomatic and has complete calcification of the gallbladder. Regardless of the pattern of calcification, imaging surveillance of the patient is necessary. Moreover, cholecystectomy is preferred regardless of the status of the calcification if the patient is a good surgical candidate.7

It is important to send the gallbladder for histopathological examination after it is removed to determine the likelihood of malignancy.7 If cancer is ruled out, then no further work-up is necessary. If cancer is detected, then further evaluation, including additional surgery, may be necessary.

Our patient was a good surgical candidate, so we recommended cholecystectomy. The patient underwent surgery and the pathology report was negative for cancer.

CORRESPONDENCE

Pradeepa Vimalachandran, MD, MPH, 601 North 30th Street, Suite 6720, Omaha, NE 68131; [email protected].

1. Kane RA, Jacobs R, Katz J, et al. Porcelain gallbladder: ultrasound and CT appearance. Radiology. 1984;152:137-141.

2. Ochsner SF, Carrera GM. Calcification of the gallbladder (“porcelain gallbladder”). Am J Roentgenol Radium Ther Nucl Med. 1963;89:847-853.

3. Stephen AE, Berger DL. Carcinoma in the porcelain gallbladder: a relationship revisited. Surgery. 2001;129:699-703.

4. Geller SA, de Campos FP. Porcelain gallbladder. Autops Case Rep. 2015;5:5-7.

5. Towfigh S, McFadden DW, Cortina GR, et al. Porcelain gallbladder is not associated with gallbladder carcinoma. Am Surg. 2001;67:7-10.

6. Brown KM, Geller DA. Porcelain gallbladder and risk of gallbladder cancer. Arch Surg. 2011;146:1148.

7. Khan ZS, Livingston EH, Huerta S. Reassessing the need for prophylactic surgery in patients with porcelain gallbladder: case series and systematic review of the literature. Arch Surg. 2011;146:1143-1147.

An 88-year-old woman presented to our primary care clinic with recurrent right upper quadrant abdominal pain. Her history was negative for nausea, fever, vomiting, chest pain, heartburn, back pain, or changes in bowel movement patterns. There was no association between the pain and her eating patterns. She described the pain as dull, and rated it as a 4 to 5 out of 10. A physical examination was unremarkable except for a minimally tender mass in the right upper quadrant that was detected during palpation of the abdomen. A Murphy’s test was negative. A comprehensive metabolic panel, complete blood count, lipase test, amylase test, abdominal ultrasound, and abdominal x-ray (FIGURE) were ordered.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Porcelain gallbladder

We diagnosed this patient with porcelain gallbladder based on her history, physical exam, and x-ray, which revealed a well-defined air gas bubble encased in a calcified pouch. (The patient’s lab work was unremarkable and the ultrasound revealed the same findings as seen on the x-ray.)

Porcelain gallbladder is a rare condition.1 It is characterized by intramural calcifications of the gallbladder wall, which is rarely seen with chronic cholecystitis.2

There are a few theories behind the etiology of porcelain gallbladder. One theory is that gallstones can irritate the gallbladder wall, leading to inflammation and then calcification. Others believe that porcelain gallbladder is due to the obstruction of cystic ducts, which leads to bile stasis in the gallbladder, followed by the accumulation of calcium carbonate salts.3

Patients may present with biliary pain or a firm palpable mass in the right upper quadrant. However, patients are often asymptomatic.4

Cancer risk. There is about a 2% to 3% risk of gallbladder cancer in patients with porcelain gallbladder.5 The nature of the calcification has been linked to the probability that a patient will develop gallbladder cancer. Specifically, there is a higher probability of gallbladder cancer if discontinuous calcification is noted, or if only some portion of the gallbladder wall has calcified.6 About 80% of all gallbladder cancers are adenocarcinomas.6

Differential diagnosis includes GERD, cholecystitis

Right upper quadrant pain is associated with acute hepatitis, acute cholecystitis, acute pancreatitis, gastroesophageal reflex disease (GERD), ulcers, and umbilical hernias. In this patient’s case, her history and physical examination made a number of diagnoses less likely, including acute cholecystitis, GERD, ulcers, and an umbilical hernia. In addition, normal values on the patient’s lipase and amylase tests ruled out pancreatitis.

Imaging brought things into focus. The most significant finding in this case was the abdominal x-ray, which showed a well-defined air gas bubble encased in a calcified pouch.

In addition to an x-ray or an ultrasound, a computed tomography scan can confirm the diagnosis of porcelain gallbladder.

For most patients, cholecystectomy is recommended

Treatment and management is based on the pattern of calcification and the patient’s current health status. If there is incomplete calcification, cholecystectomy is warranted. Cholecystectomy may also be warranted when a patient is symptomatic and has complete calcification of the gallbladder. Regardless of the pattern of calcification, imaging surveillance of the patient is necessary. Moreover, cholecystectomy is preferred regardless of the status of the calcification if the patient is a good surgical candidate.7

It is important to send the gallbladder for histopathological examination after it is removed to determine the likelihood of malignancy.7 If cancer is ruled out, then no further work-up is necessary. If cancer is detected, then further evaluation, including additional surgery, may be necessary.

Our patient was a good surgical candidate, so we recommended cholecystectomy. The patient underwent surgery and the pathology report was negative for cancer.

CORRESPONDENCE

Pradeepa Vimalachandran, MD, MPH, 601 North 30th Street, Suite 6720, Omaha, NE 68131; [email protected].

An 88-year-old woman presented to our primary care clinic with recurrent right upper quadrant abdominal pain. Her history was negative for nausea, fever, vomiting, chest pain, heartburn, back pain, or changes in bowel movement patterns. There was no association between the pain and her eating patterns. She described the pain as dull, and rated it as a 4 to 5 out of 10. A physical examination was unremarkable except for a minimally tender mass in the right upper quadrant that was detected during palpation of the abdomen. A Murphy’s test was negative. A comprehensive metabolic panel, complete blood count, lipase test, amylase test, abdominal ultrasound, and abdominal x-ray (FIGURE) were ordered.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Porcelain gallbladder

We diagnosed this patient with porcelain gallbladder based on her history, physical exam, and x-ray, which revealed a well-defined air gas bubble encased in a calcified pouch. (The patient’s lab work was unremarkable and the ultrasound revealed the same findings as seen on the x-ray.)

Porcelain gallbladder is a rare condition.1 It is characterized by intramural calcifications of the gallbladder wall, which is rarely seen with chronic cholecystitis.2

There are a few theories behind the etiology of porcelain gallbladder. One theory is that gallstones can irritate the gallbladder wall, leading to inflammation and then calcification. Others believe that porcelain gallbladder is due to the obstruction of cystic ducts, which leads to bile stasis in the gallbladder, followed by the accumulation of calcium carbonate salts.3

Patients may present with biliary pain or a firm palpable mass in the right upper quadrant. However, patients are often asymptomatic.4

Cancer risk. There is about a 2% to 3% risk of gallbladder cancer in patients with porcelain gallbladder.5 The nature of the calcification has been linked to the probability that a patient will develop gallbladder cancer. Specifically, there is a higher probability of gallbladder cancer if discontinuous calcification is noted, or if only some portion of the gallbladder wall has calcified.6 About 80% of all gallbladder cancers are adenocarcinomas.6

Differential diagnosis includes GERD, cholecystitis

Right upper quadrant pain is associated with acute hepatitis, acute cholecystitis, acute pancreatitis, gastroesophageal reflex disease (GERD), ulcers, and umbilical hernias. In this patient’s case, her history and physical examination made a number of diagnoses less likely, including acute cholecystitis, GERD, ulcers, and an umbilical hernia. In addition, normal values on the patient’s lipase and amylase tests ruled out pancreatitis.

Imaging brought things into focus. The most significant finding in this case was the abdominal x-ray, which showed a well-defined air gas bubble encased in a calcified pouch.

In addition to an x-ray or an ultrasound, a computed tomography scan can confirm the diagnosis of porcelain gallbladder.

For most patients, cholecystectomy is recommended

Treatment and management is based on the pattern of calcification and the patient’s current health status. If there is incomplete calcification, cholecystectomy is warranted. Cholecystectomy may also be warranted when a patient is symptomatic and has complete calcification of the gallbladder. Regardless of the pattern of calcification, imaging surveillance of the patient is necessary. Moreover, cholecystectomy is preferred regardless of the status of the calcification if the patient is a good surgical candidate.7

It is important to send the gallbladder for histopathological examination after it is removed to determine the likelihood of malignancy.7 If cancer is ruled out, then no further work-up is necessary. If cancer is detected, then further evaluation, including additional surgery, may be necessary.

Our patient was a good surgical candidate, so we recommended cholecystectomy. The patient underwent surgery and the pathology report was negative for cancer.

CORRESPONDENCE

Pradeepa Vimalachandran, MD, MPH, 601 North 30th Street, Suite 6720, Omaha, NE 68131; [email protected].

1. Kane RA, Jacobs R, Katz J, et al. Porcelain gallbladder: ultrasound and CT appearance. Radiology. 1984;152:137-141.

2. Ochsner SF, Carrera GM. Calcification of the gallbladder (“porcelain gallbladder”). Am J Roentgenol Radium Ther Nucl Med. 1963;89:847-853.

3. Stephen AE, Berger DL. Carcinoma in the porcelain gallbladder: a relationship revisited. Surgery. 2001;129:699-703.

4. Geller SA, de Campos FP. Porcelain gallbladder. Autops Case Rep. 2015;5:5-7.

5. Towfigh S, McFadden DW, Cortina GR, et al. Porcelain gallbladder is not associated with gallbladder carcinoma. Am Surg. 2001;67:7-10.

6. Brown KM, Geller DA. Porcelain gallbladder and risk of gallbladder cancer. Arch Surg. 2011;146:1148.

7. Khan ZS, Livingston EH, Huerta S. Reassessing the need for prophylactic surgery in patients with porcelain gallbladder: case series and systematic review of the literature. Arch Surg. 2011;146:1143-1147.

1. Kane RA, Jacobs R, Katz J, et al. Porcelain gallbladder: ultrasound and CT appearance. Radiology. 1984;152:137-141.

2. Ochsner SF, Carrera GM. Calcification of the gallbladder (“porcelain gallbladder”). Am J Roentgenol Radium Ther Nucl Med. 1963;89:847-853.

3. Stephen AE, Berger DL. Carcinoma in the porcelain gallbladder: a relationship revisited. Surgery. 2001;129:699-703.

4. Geller SA, de Campos FP. Porcelain gallbladder. Autops Case Rep. 2015;5:5-7.

5. Towfigh S, McFadden DW, Cortina GR, et al. Porcelain gallbladder is not associated with gallbladder carcinoma. Am Surg. 2001;67:7-10.

6. Brown KM, Geller DA. Porcelain gallbladder and risk of gallbladder cancer. Arch Surg. 2011;146:1148.

7. Khan ZS, Livingston EH, Huerta S. Reassessing the need for prophylactic surgery in patients with porcelain gallbladder: case series and systematic review of the literature. Arch Surg. 2011;146:1143-1147.

Does knuckle popping lead to arthritis?

EVIDENCE-BASED ANSWER:

No, habitual knuckle popping, or cracking (over the course of several decades) isn’t associated with clinical or radiographic evidence of osteoarthritis (strength of recommendation [SOR]: B, retrospective cohort and case control studies). However, attempting to pop the knuckles can produce acute soft tissue injury (SOR: C, case reports).

Evidence summary

A cross-sectional study found no correlation between knuckle popping and osteoarthritis (OA) of the hand.1 Investigators recruited 300 consecutive patients (ages 45 years and older, mean age 63 years) and evaluated them for a history of habitual knuckle popping (74 of 300 patients, mean duration 35 years) and hand arthritis or dysfunction. Investigators excluded patients with neuromuscular, inflammatory, or malignant diseases.

Investigators found OA equally in both patients who did and didn’t pop their knuckles (12 of 74 vs 36 of 226, respectively; P nonsignificant); joint swelling was more common in participants with a history of knuckle popping (84% vs 6%; P<.01). Investigators didn’t describe how OA was diagnosed or specify which joints were affected.

Another cross-sectional study also found no correlation between habitual knuckle popping of the metacarpal phalangeal joint and the prevalence of OA in that joint.2 Investigators recruited 28 patients (mean age 78.5 years; 23 women and 5 men) from a Jewish home for the aged and asked them whether they had habitually cracked their knuckles during their lifetime. They then performed clinical and radiographic hand examinations (excluding patients with a history of traumatic injury, rheumatoid arthritis, gout, chondrocalcinosis, and hemochromatosis).

Knuckle popping didn’t correlate with OA of the metacarpal phalanges (1 of 15 knuckle popping patients vs 5 of 13 patients who didn’t pop their knuckles; P=.06). All 6 patients with radiographic evidence of OA showed involvement at the metacarpal phalangeal and distal interphalangeal joints, whether or not they popped their knuckles.

Years spent cracking knuckles doesn’t predict OA

A case control study found no correlation between OA in the hands and habitual knuckle popping.3 Investigators recruited 215 patients 50 to 89 years old who had received a radiograph of their right hand during the previous 5 years and divided them into cases with OA (135 patients), and controls without OA (80 patients). Patients completed questionnaires assessing the prevalence (20%), frequency (1 to 20 times per day), and duration (26 to 36 years) of knuckle popping.

Patients most commonly popped proximal interphalangeal joints (15.9%) followed by metacarpal phalangeal joints (13.5%), distal interphalangeal joints (6.1%), and first carpal metacarpal joints (2.3%). OA most often affected the distal interphalangeal joint (68.4%), followed by the first carpal metacarpal (57.1%), proximal interphalangeal (54.1%), and metacarpal phalangeal joints (28.6%). Investigators found no difference in the prevalence of knuckle popping between cases and controls (18% in cases vs 23.2% in controls; P=.361).

When investigators evaluated total knuckle popping exposure in “crack years” (number of times per day multiplied by years) in the distal interphalangeal or metacarpal phalangeal joints, they found no significant association between crack years and OA (distal interphalangeal joint, mean 108 crack years; metacarpal phalangeal joint, mean 75 crack years).

50 years of knuckle popping without ill effects

An n-of-1 case control study found similar results.4 The researcher, a physician, popped only the knuckles of his left hand, twice a day, for 50 years. He compared his hands at the end of the trial and found no arthritis in either hand and no visible differences.

But knuckle popping does have a downside

A paper described 2 case reports of acute injuries sustained during attempted knuckle popping—a partial tear of the ulnar collateral ligament of the thumb and subluxation of the extensor tendon of the fifth digit.5 Both injuries were associated with forceful manipulation of the digits, and both resolved with conservative management within 4 weeks.

1. Castellanos J, Axelrod D. Effect of habitual knuckle cracking on hand function. Ann Rheum Dis. 1990;49:308-309.

2. Swezey RL, Swezey SE. The consequences of habitual knuckle cracking. West J Med. 1975;122:377-379.

3. Deweber K, Olszewski M, Ortolano R. Knuckle cracking and hand osteoarthritis. J Am Board Fam Med. 2011;24:169-174.

4. Unger DL. Does knuckle cracking lead to arthritis of the fingers? Arthritis Rheum. 1998;41:949-950.

5. Chan PS, Steinberg DR, Bozentka DJ. Consequences of knuckle cracking: a report of two acute injuries. Am J Orthop (Belle Mead NJ). 1999;28:113-114.

EVIDENCE-BASED ANSWER:

No, habitual knuckle popping, or cracking (over the course of several decades) isn’t associated with clinical or radiographic evidence of osteoarthritis (strength of recommendation [SOR]: B, retrospective cohort and case control studies). However, attempting to pop the knuckles can produce acute soft tissue injury (SOR: C, case reports).

Evidence summary

A cross-sectional study found no correlation between knuckle popping and osteoarthritis (OA) of the hand.1 Investigators recruited 300 consecutive patients (ages 45 years and older, mean age 63 years) and evaluated them for a history of habitual knuckle popping (74 of 300 patients, mean duration 35 years) and hand arthritis or dysfunction. Investigators excluded patients with neuromuscular, inflammatory, or malignant diseases.

Investigators found OA equally in both patients who did and didn’t pop their knuckles (12 of 74 vs 36 of 226, respectively; P nonsignificant); joint swelling was more common in participants with a history of knuckle popping (84% vs 6%; P<.01). Investigators didn’t describe how OA was diagnosed or specify which joints were affected.

Another cross-sectional study also found no correlation between habitual knuckle popping of the metacarpal phalangeal joint and the prevalence of OA in that joint.2 Investigators recruited 28 patients (mean age 78.5 years; 23 women and 5 men) from a Jewish home for the aged and asked them whether they had habitually cracked their knuckles during their lifetime. They then performed clinical and radiographic hand examinations (excluding patients with a history of traumatic injury, rheumatoid arthritis, gout, chondrocalcinosis, and hemochromatosis).

Knuckle popping didn’t correlate with OA of the metacarpal phalanges (1 of 15 knuckle popping patients vs 5 of 13 patients who didn’t pop their knuckles; P=.06). All 6 patients with radiographic evidence of OA showed involvement at the metacarpal phalangeal and distal interphalangeal joints, whether or not they popped their knuckles.

Years spent cracking knuckles doesn’t predict OA

A case control study found no correlation between OA in the hands and habitual knuckle popping.3 Investigators recruited 215 patients 50 to 89 years old who had received a radiograph of their right hand during the previous 5 years and divided them into cases with OA (135 patients), and controls without OA (80 patients). Patients completed questionnaires assessing the prevalence (20%), frequency (1 to 20 times per day), and duration (26 to 36 years) of knuckle popping.

Patients most commonly popped proximal interphalangeal joints (15.9%) followed by metacarpal phalangeal joints (13.5%), distal interphalangeal joints (6.1%), and first carpal metacarpal joints (2.3%). OA most often affected the distal interphalangeal joint (68.4%), followed by the first carpal metacarpal (57.1%), proximal interphalangeal (54.1%), and metacarpal phalangeal joints (28.6%). Investigators found no difference in the prevalence of knuckle popping between cases and controls (18% in cases vs 23.2% in controls; P=.361).

When investigators evaluated total knuckle popping exposure in “crack years” (number of times per day multiplied by years) in the distal interphalangeal or metacarpal phalangeal joints, they found no significant association between crack years and OA (distal interphalangeal joint, mean 108 crack years; metacarpal phalangeal joint, mean 75 crack years).

50 years of knuckle popping without ill effects

An n-of-1 case control study found similar results.4 The researcher, a physician, popped only the knuckles of his left hand, twice a day, for 50 years. He compared his hands at the end of the trial and found no arthritis in either hand and no visible differences.

But knuckle popping does have a downside

A paper described 2 case reports of acute injuries sustained during attempted knuckle popping—a partial tear of the ulnar collateral ligament of the thumb and subluxation of the extensor tendon of the fifth digit.5 Both injuries were associated with forceful manipulation of the digits, and both resolved with conservative management within 4 weeks.

EVIDENCE-BASED ANSWER:

No, habitual knuckle popping, or cracking (over the course of several decades) isn’t associated with clinical or radiographic evidence of osteoarthritis (strength of recommendation [SOR]: B, retrospective cohort and case control studies). However, attempting to pop the knuckles can produce acute soft tissue injury (SOR: C, case reports).

Evidence summary

A cross-sectional study found no correlation between knuckle popping and osteoarthritis (OA) of the hand.1 Investigators recruited 300 consecutive patients (ages 45 years and older, mean age 63 years) and evaluated them for a history of habitual knuckle popping (74 of 300 patients, mean duration 35 years) and hand arthritis or dysfunction. Investigators excluded patients with neuromuscular, inflammatory, or malignant diseases.

Investigators found OA equally in both patients who did and didn’t pop their knuckles (12 of 74 vs 36 of 226, respectively; P nonsignificant); joint swelling was more common in participants with a history of knuckle popping (84% vs 6%; P<.01). Investigators didn’t describe how OA was diagnosed or specify which joints were affected.

Another cross-sectional study also found no correlation between habitual knuckle popping of the metacarpal phalangeal joint and the prevalence of OA in that joint.2 Investigators recruited 28 patients (mean age 78.5 years; 23 women and 5 men) from a Jewish home for the aged and asked them whether they had habitually cracked their knuckles during their lifetime. They then performed clinical and radiographic hand examinations (excluding patients with a history of traumatic injury, rheumatoid arthritis, gout, chondrocalcinosis, and hemochromatosis).

Knuckle popping didn’t correlate with OA of the metacarpal phalanges (1 of 15 knuckle popping patients vs 5 of 13 patients who didn’t pop their knuckles; P=.06). All 6 patients with radiographic evidence of OA showed involvement at the metacarpal phalangeal and distal interphalangeal joints, whether or not they popped their knuckles.

Years spent cracking knuckles doesn’t predict OA

A case control study found no correlation between OA in the hands and habitual knuckle popping.3 Investigators recruited 215 patients 50 to 89 years old who had received a radiograph of their right hand during the previous 5 years and divided them into cases with OA (135 patients), and controls without OA (80 patients). Patients completed questionnaires assessing the prevalence (20%), frequency (1 to 20 times per day), and duration (26 to 36 years) of knuckle popping.

Patients most commonly popped proximal interphalangeal joints (15.9%) followed by metacarpal phalangeal joints (13.5%), distal interphalangeal joints (6.1%), and first carpal metacarpal joints (2.3%). OA most often affected the distal interphalangeal joint (68.4%), followed by the first carpal metacarpal (57.1%), proximal interphalangeal (54.1%), and metacarpal phalangeal joints (28.6%). Investigators found no difference in the prevalence of knuckle popping between cases and controls (18% in cases vs 23.2% in controls; P=.361).

When investigators evaluated total knuckle popping exposure in “crack years” (number of times per day multiplied by years) in the distal interphalangeal or metacarpal phalangeal joints, they found no significant association between crack years and OA (distal interphalangeal joint, mean 108 crack years; metacarpal phalangeal joint, mean 75 crack years).

50 years of knuckle popping without ill effects

An n-of-1 case control study found similar results.4 The researcher, a physician, popped only the knuckles of his left hand, twice a day, for 50 years. He compared his hands at the end of the trial and found no arthritis in either hand and no visible differences.

But knuckle popping does have a downside

A paper described 2 case reports of acute injuries sustained during attempted knuckle popping—a partial tear of the ulnar collateral ligament of the thumb and subluxation of the extensor tendon of the fifth digit.5 Both injuries were associated with forceful manipulation of the digits, and both resolved with conservative management within 4 weeks.

1. Castellanos J, Axelrod D. Effect of habitual knuckle cracking on hand function. Ann Rheum Dis. 1990;49:308-309.

2. Swezey RL, Swezey SE. The consequences of habitual knuckle cracking. West J Med. 1975;122:377-379.

3. Deweber K, Olszewski M, Ortolano R. Knuckle cracking and hand osteoarthritis. J Am Board Fam Med. 2011;24:169-174.

4. Unger DL. Does knuckle cracking lead to arthritis of the fingers? Arthritis Rheum. 1998;41:949-950.

5. Chan PS, Steinberg DR, Bozentka DJ. Consequences of knuckle cracking: a report of two acute injuries. Am J Orthop (Belle Mead NJ). 1999;28:113-114.

1. Castellanos J, Axelrod D. Effect of habitual knuckle cracking on hand function. Ann Rheum Dis. 1990;49:308-309.

2. Swezey RL, Swezey SE. The consequences of habitual knuckle cracking. West J Med. 1975;122:377-379.

3. Deweber K, Olszewski M, Ortolano R. Knuckle cracking and hand osteoarthritis. J Am Board Fam Med. 2011;24:169-174.

4. Unger DL. Does knuckle cracking lead to arthritis of the fingers? Arthritis Rheum. 1998;41:949-950.

5. Chan PS, Steinberg DR, Bozentka DJ. Consequences of knuckle cracking: a report of two acute injuries. Am J Orthop (Belle Mead NJ). 1999;28:113-114.

Evidence-based answers from the Family Physicians Inquiries Network

Epistaxis, mass in right nostril • Dx?

THE CASE

A 49-year-old woman visited our family medicine clinic because she’d had 3 episodes of epistaxis during the previous month. She’d already visited the emergency department, and the doctor there had treated her symptomatically and referred her to our clinic.

On physical examination, we noted a whitish mass in the patient’s right nostril that was attached to the nasal septum. The patient’s vital signs were within normal limits. She had a history of hypertension, depression, anxiety, gastroesophageal reflux disease, and post-traumatic stress disorder. Her medications included amlodipine-benazepril, atenolol-chlorthalidone, citalopram, clonazepam, prazosin, and omeprazole. The patient lived alone and denied using tobacco or illicit drugs, but she drank one to 2 glasses of brandy every day. She denied any past medical or family history of similar complaints, autoimmune disorders, or skin rashes.

A complete blood count, international normalized ratio, sedimentation rate, anti-nuclear antibody test, and an anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody panel were normal.

THE DIAGNOSIS

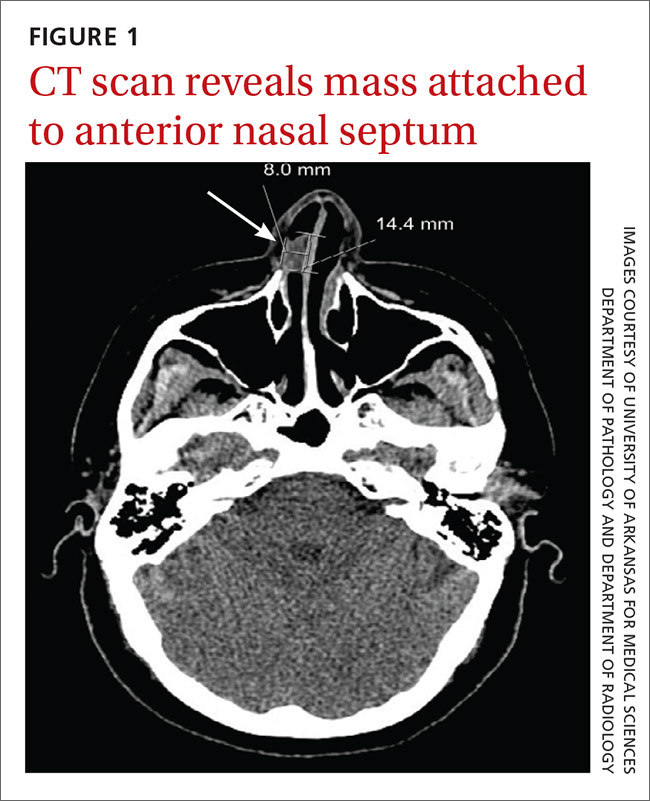

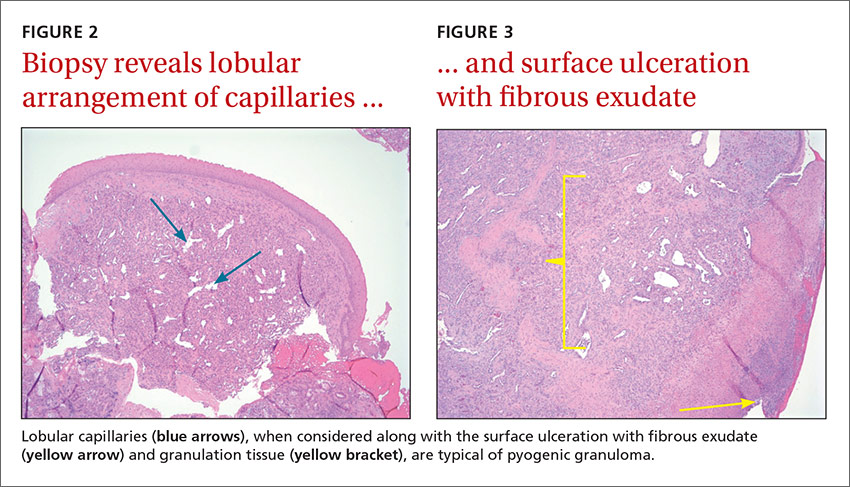

We referred the patient to an ear, nose, and throat doctor for a nasal endoscopy and a biopsy, which showed granulation tissue. A maxillofacial computed tomography (CT) scan revealed a 1.44 cm x 0.8 cm polypoid soft tissue mass in the right nasal cavity adherent to the nasal septum with no posterior extension (FIGURE 1).

DISCUSSION

Pyogenic granuloma (PG) is a benign vascular tumor of the skin and mucous membranes that is not associated with an infection. Rather, it is a hyperplastic, neovascular, inflammatory response to an angiogenic stimulus. Several enhancers and inhibitors of angiogenesis have been shown to play a role in PG, including hormones, medications, and local injury. In fact, a local injury or hormonal factor is identified as a stimulus in more than half of PG patients.1

The hormone connection. Estrogen promotes production of nerve growth factor, granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor, basic fibroblast growth factor, vascular endothelial growth factor, and transforming growth factor beta 1. Progesterone enhances inflammatory mediators as well. Although there are no direct receptors for estrogen and progesterone in the oral and nasal mucosa, some of these pro-inflammatory effects create an environment conducive to the development of PG. This is supported by several studies documenting an increased incidence of PGs with oral contraceptive use and regression of PGs after childbirth.2-4

Medication may play a role. Drug-induced PG has also been described in several studies.5,6 Offending medications include systemic and topical retinoids, capecitabine, etoposide, 5-fluorouracil, cyclosporine, docetaxel, and human immunodeficiency virus protease inhibitors.

Local injury may also be a culprit. Nasal PGs are commonly attached to the anterior septum and typically result from nasal packing, habitual picking, or nose boring.7 In this particular case, however, we were unable to identify the irritant.

The classic presentation

PG classically presents as a painless mass that spontaneously develops over days to weeks. The mass can be sessile or pedunculated, and is frequently hemorrhagic. Intranasal PG usually presents with epiphora.7 While the prevalence of intraoral PG was found to be one in 25,000 individuals3, data for nasal lesions is scarce. Most cases of PG are seen in the second and third decades of life.1,3 In children, PG is slightly more predominant in males.1,3 Mucosal lesions, however, have a higher incidence in females.1,3 Granuloma gravidarum, the term used to describe mucosal PG in pregnant females, was found in 0.2% to 5% of pregnancies.2,3,8

Differential Dx includes warts, squamous cell carcinoma

The differential diagnosis of PG includes Spitz nevus, glomus tumors, common warts, amelanotic melanoma, squamous cell carcinoma, basal cell carcinoma, Kaposi’s sarcoma, bacillary angiomatosis, infantile hemangioma, and angiolymphoid hyperplasia, among others.3,5 Foreign bodies, nasal polyps, angiofibroma, meningocele, Wegener’s granulomatosis, and sarcoidosis should also be considered.

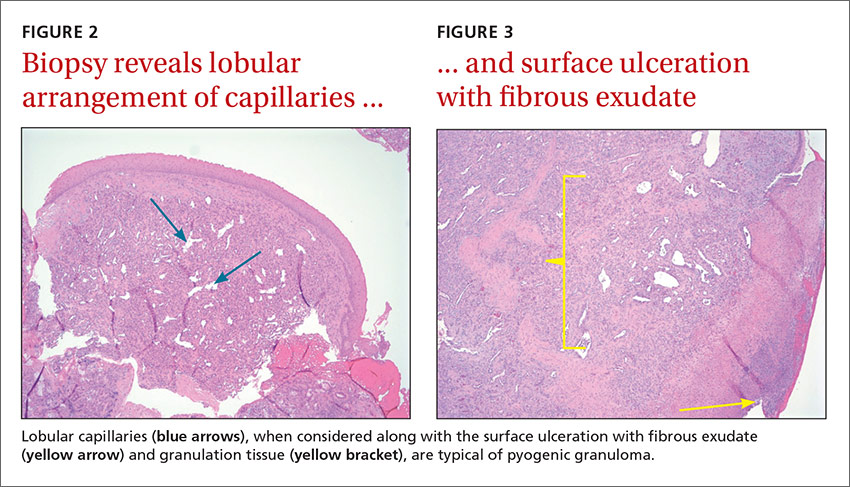

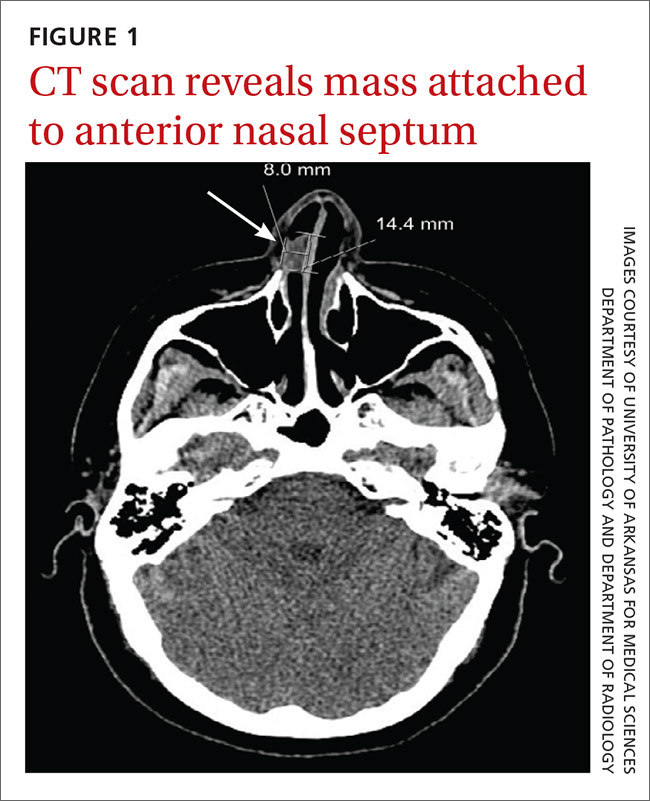

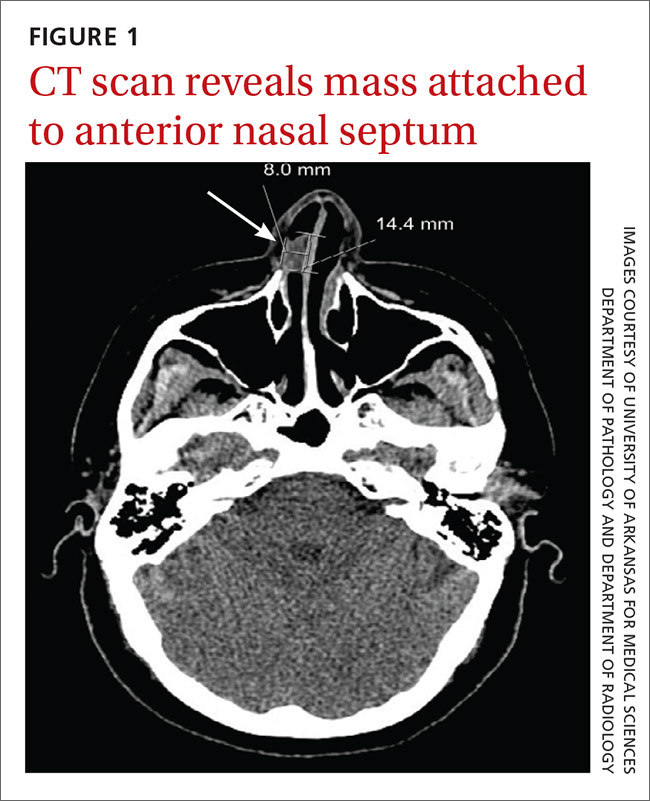

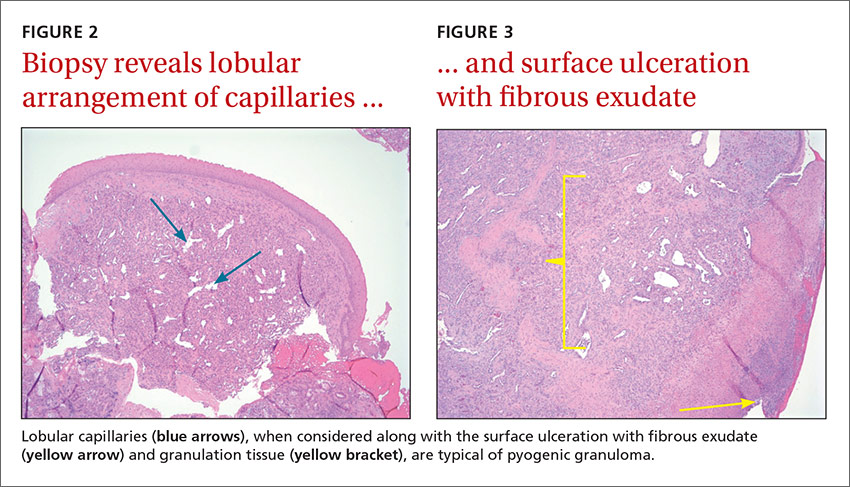

Radiologic evaluation may be beneficial—especially with nasal lesions—when looking for findings suggestive of malignancy. Both CT and magnetic resonance imaging with contrast identify PG as a soft tissue mass with lobulated contours,9,10 but histopathologic analysis is required to confirm the diagnosis. The histopathologic appearance of PG is characterized by a polypoid lesion with circumscribed anastomosing networks of capillaries arranged in one or more lobules at the base in an edematous and fibroblastic stroma.

Treatment is determined by the location and size of the lesion

The most suitable treatment is determined by considering the location of the lesion, the characteristics of the lesion (morphology/size), its amenability to surgery, risk of scar formation, and the presence or absence of a causative irritant. Excision is often preferred because it yields a specimen for pathologic analysis. Alternative treatments include electrocautery, cryotherapy, laser therapy, and intralesional and topical agents,3,6,7 but the recurrence rate is higher (up to 15%) with some of these modalities, when compared with excision (3.6%).3

Our patient underwent excision of the mass and was seen for an annual follow-up appointment. All of her symptoms resolved and no recurrence was noted.

THE TAKEAWAY

Although PG is a common and benign condition, it is rarely seen in the nasal cavity without an obvious history of a possible irritant. PG should be considered as a diagnosis for rapidly growing cutaneous or mucosal hemorrhagic lesions. Appropriate tissue pathology is essential to rule out malignancy and other serious conditions, such as bacillary angiomatosis and Wegener’s granulomatosis.

Treatment is usually required to avoid the frequent complications of ulceration and bleeding. Surgical treatments are preferred. The location of the lesion largely determines whether referral to a specialist is necessary.

1. Harris MN, Desai R, Chuang TY, et al. Lobular capillary hemangiomas: An epidemiologic report, with emphasis on cutaneous lesions. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;42:1012-1016.

2. Yuan K, Jin YT, Lin MT. The detection and comparison of angiogenesis-associated factors in pyogenic granuloma by immunohistochemistry. J Periodontol. 2000;71:701-709.

3. Giblin AV, Clover AJ, Athanassopoulos A, et al. Pyogenic granuloma–the quest for optimum treatment: audit of treatment of 408 cases. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2007;60:1030-1035.

4. Steelman R, Holmes D. Pregnancy tumor in a 16-year-old: case report and treatment considerations. J Clin Pediatr Dent. 1992;16:217-218.

5. Jafarzadeh H, Sanatkhani M, Mohtasham N. Oral pyogenic granuloma: a review. J Oral Sci. 2006;48:167-175.

6. Piraccini BM, Bellavista S, Misciali C, et al. Periungual and subungual pyogenic granuloma. Br J Dermatol. 2010;163:941-953.

7. Ozcan C, Apa DD, Görür K. Pediatric lobular capillary hemangioma of the nasal cavity. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2004;261:449-451.

8. Henry F, Quatresooz P, Valverde-Lopez JC, et al. Blood vessel changes during pregnancy: a review. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2006;7:65-69.

9. Puxeddu R, Berlucchi M, Ledda GP, et al. Lobular capillary hemangioma of the nasal cavity: A retrospective study on 40 patients. Am J Rhinol. 2006;20:480-484.

10. Maroldi R, Berlucchi M, Farina D, et al. Benign neoplasms and tumor-like lesions. In: Maroldi R, Nicolai P, eds. Imaging in Treatment Planning for Sinonasal Diseases. Berlin, Heidelberg, New York: Springer-Verlag; 2005:107-158.

THE CASE

A 49-year-old woman visited our family medicine clinic because she’d had 3 episodes of epistaxis during the previous month. She’d already visited the emergency department, and the doctor there had treated her symptomatically and referred her to our clinic.

On physical examination, we noted a whitish mass in the patient’s right nostril that was attached to the nasal septum. The patient’s vital signs were within normal limits. She had a history of hypertension, depression, anxiety, gastroesophageal reflux disease, and post-traumatic stress disorder. Her medications included amlodipine-benazepril, atenolol-chlorthalidone, citalopram, clonazepam, prazosin, and omeprazole. The patient lived alone and denied using tobacco or illicit drugs, but she drank one to 2 glasses of brandy every day. She denied any past medical or family history of similar complaints, autoimmune disorders, or skin rashes.

A complete blood count, international normalized ratio, sedimentation rate, anti-nuclear antibody test, and an anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody panel were normal.

THE DIAGNOSIS

We referred the patient to an ear, nose, and throat doctor for a nasal endoscopy and a biopsy, which showed granulation tissue. A maxillofacial computed tomography (CT) scan revealed a 1.44 cm x 0.8 cm polypoid soft tissue mass in the right nasal cavity adherent to the nasal septum with no posterior extension (FIGURE 1).

DISCUSSION

Pyogenic granuloma (PG) is a benign vascular tumor of the skin and mucous membranes that is not associated with an infection. Rather, it is a hyperplastic, neovascular, inflammatory response to an angiogenic stimulus. Several enhancers and inhibitors of angiogenesis have been shown to play a role in PG, including hormones, medications, and local injury. In fact, a local injury or hormonal factor is identified as a stimulus in more than half of PG patients.1

The hormone connection. Estrogen promotes production of nerve growth factor, granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor, basic fibroblast growth factor, vascular endothelial growth factor, and transforming growth factor beta 1. Progesterone enhances inflammatory mediators as well. Although there are no direct receptors for estrogen and progesterone in the oral and nasal mucosa, some of these pro-inflammatory effects create an environment conducive to the development of PG. This is supported by several studies documenting an increased incidence of PGs with oral contraceptive use and regression of PGs after childbirth.2-4

Medication may play a role. Drug-induced PG has also been described in several studies.5,6 Offending medications include systemic and topical retinoids, capecitabine, etoposide, 5-fluorouracil, cyclosporine, docetaxel, and human immunodeficiency virus protease inhibitors.

Local injury may also be a culprit. Nasal PGs are commonly attached to the anterior septum and typically result from nasal packing, habitual picking, or nose boring.7 In this particular case, however, we were unable to identify the irritant.

The classic presentation

PG classically presents as a painless mass that spontaneously develops over days to weeks. The mass can be sessile or pedunculated, and is frequently hemorrhagic. Intranasal PG usually presents with epiphora.7 While the prevalence of intraoral PG was found to be one in 25,000 individuals3, data for nasal lesions is scarce. Most cases of PG are seen in the second and third decades of life.1,3 In children, PG is slightly more predominant in males.1,3 Mucosal lesions, however, have a higher incidence in females.1,3 Granuloma gravidarum, the term used to describe mucosal PG in pregnant females, was found in 0.2% to 5% of pregnancies.2,3,8

Differential Dx includes warts, squamous cell carcinoma

The differential diagnosis of PG includes Spitz nevus, glomus tumors, common warts, amelanotic melanoma, squamous cell carcinoma, basal cell carcinoma, Kaposi’s sarcoma, bacillary angiomatosis, infantile hemangioma, and angiolymphoid hyperplasia, among others.3,5 Foreign bodies, nasal polyps, angiofibroma, meningocele, Wegener’s granulomatosis, and sarcoidosis should also be considered.

Radiologic evaluation may be beneficial—especially with nasal lesions—when looking for findings suggestive of malignancy. Both CT and magnetic resonance imaging with contrast identify PG as a soft tissue mass with lobulated contours,9,10 but histopathologic analysis is required to confirm the diagnosis. The histopathologic appearance of PG is characterized by a polypoid lesion with circumscribed anastomosing networks of capillaries arranged in one or more lobules at the base in an edematous and fibroblastic stroma.

Treatment is determined by the location and size of the lesion

The most suitable treatment is determined by considering the location of the lesion, the characteristics of the lesion (morphology/size), its amenability to surgery, risk of scar formation, and the presence or absence of a causative irritant. Excision is often preferred because it yields a specimen for pathologic analysis. Alternative treatments include electrocautery, cryotherapy, laser therapy, and intralesional and topical agents,3,6,7 but the recurrence rate is higher (up to 15%) with some of these modalities, when compared with excision (3.6%).3

Our patient underwent excision of the mass and was seen for an annual follow-up appointment. All of her symptoms resolved and no recurrence was noted.

THE TAKEAWAY

Although PG is a common and benign condition, it is rarely seen in the nasal cavity without an obvious history of a possible irritant. PG should be considered as a diagnosis for rapidly growing cutaneous or mucosal hemorrhagic lesions. Appropriate tissue pathology is essential to rule out malignancy and other serious conditions, such as bacillary angiomatosis and Wegener’s granulomatosis.

Treatment is usually required to avoid the frequent complications of ulceration and bleeding. Surgical treatments are preferred. The location of the lesion largely determines whether referral to a specialist is necessary.

THE CASE

A 49-year-old woman visited our family medicine clinic because she’d had 3 episodes of epistaxis during the previous month. She’d already visited the emergency department, and the doctor there had treated her symptomatically and referred her to our clinic.

On physical examination, we noted a whitish mass in the patient’s right nostril that was attached to the nasal septum. The patient’s vital signs were within normal limits. She had a history of hypertension, depression, anxiety, gastroesophageal reflux disease, and post-traumatic stress disorder. Her medications included amlodipine-benazepril, atenolol-chlorthalidone, citalopram, clonazepam, prazosin, and omeprazole. The patient lived alone and denied using tobacco or illicit drugs, but she drank one to 2 glasses of brandy every day. She denied any past medical or family history of similar complaints, autoimmune disorders, or skin rashes.

A complete blood count, international normalized ratio, sedimentation rate, anti-nuclear antibody test, and an anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody panel were normal.

THE DIAGNOSIS

We referred the patient to an ear, nose, and throat doctor for a nasal endoscopy and a biopsy, which showed granulation tissue. A maxillofacial computed tomography (CT) scan revealed a 1.44 cm x 0.8 cm polypoid soft tissue mass in the right nasal cavity adherent to the nasal septum with no posterior extension (FIGURE 1).

DISCUSSION

Pyogenic granuloma (PG) is a benign vascular tumor of the skin and mucous membranes that is not associated with an infection. Rather, it is a hyperplastic, neovascular, inflammatory response to an angiogenic stimulus. Several enhancers and inhibitors of angiogenesis have been shown to play a role in PG, including hormones, medications, and local injury. In fact, a local injury or hormonal factor is identified as a stimulus in more than half of PG patients.1

The hormone connection. Estrogen promotes production of nerve growth factor, granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor, basic fibroblast growth factor, vascular endothelial growth factor, and transforming growth factor beta 1. Progesterone enhances inflammatory mediators as well. Although there are no direct receptors for estrogen and progesterone in the oral and nasal mucosa, some of these pro-inflammatory effects create an environment conducive to the development of PG. This is supported by several studies documenting an increased incidence of PGs with oral contraceptive use and regression of PGs after childbirth.2-4

Medication may play a role. Drug-induced PG has also been described in several studies.5,6 Offending medications include systemic and topical retinoids, capecitabine, etoposide, 5-fluorouracil, cyclosporine, docetaxel, and human immunodeficiency virus protease inhibitors.

Local injury may also be a culprit. Nasal PGs are commonly attached to the anterior septum and typically result from nasal packing, habitual picking, or nose boring.7 In this particular case, however, we were unable to identify the irritant.

The classic presentation

PG classically presents as a painless mass that spontaneously develops over days to weeks. The mass can be sessile or pedunculated, and is frequently hemorrhagic. Intranasal PG usually presents with epiphora.7 While the prevalence of intraoral PG was found to be one in 25,000 individuals3, data for nasal lesions is scarce. Most cases of PG are seen in the second and third decades of life.1,3 In children, PG is slightly more predominant in males.1,3 Mucosal lesions, however, have a higher incidence in females.1,3 Granuloma gravidarum, the term used to describe mucosal PG in pregnant females, was found in 0.2% to 5% of pregnancies.2,3,8

Differential Dx includes warts, squamous cell carcinoma

The differential diagnosis of PG includes Spitz nevus, glomus tumors, common warts, amelanotic melanoma, squamous cell carcinoma, basal cell carcinoma, Kaposi’s sarcoma, bacillary angiomatosis, infantile hemangioma, and angiolymphoid hyperplasia, among others.3,5 Foreign bodies, nasal polyps, angiofibroma, meningocele, Wegener’s granulomatosis, and sarcoidosis should also be considered.

Radiologic evaluation may be beneficial—especially with nasal lesions—when looking for findings suggestive of malignancy. Both CT and magnetic resonance imaging with contrast identify PG as a soft tissue mass with lobulated contours,9,10 but histopathologic analysis is required to confirm the diagnosis. The histopathologic appearance of PG is characterized by a polypoid lesion with circumscribed anastomosing networks of capillaries arranged in one or more lobules at the base in an edematous and fibroblastic stroma.

Treatment is determined by the location and size of the lesion

The most suitable treatment is determined by considering the location of the lesion, the characteristics of the lesion (morphology/size), its amenability to surgery, risk of scar formation, and the presence or absence of a causative irritant. Excision is often preferred because it yields a specimen for pathologic analysis. Alternative treatments include electrocautery, cryotherapy, laser therapy, and intralesional and topical agents,3,6,7 but the recurrence rate is higher (up to 15%) with some of these modalities, when compared with excision (3.6%).3

Our patient underwent excision of the mass and was seen for an annual follow-up appointment. All of her symptoms resolved and no recurrence was noted.

THE TAKEAWAY

Although PG is a common and benign condition, it is rarely seen in the nasal cavity without an obvious history of a possible irritant. PG should be considered as a diagnosis for rapidly growing cutaneous or mucosal hemorrhagic lesions. Appropriate tissue pathology is essential to rule out malignancy and other serious conditions, such as bacillary angiomatosis and Wegener’s granulomatosis.

Treatment is usually required to avoid the frequent complications of ulceration and bleeding. Surgical treatments are preferred. The location of the lesion largely determines whether referral to a specialist is necessary.

1. Harris MN, Desai R, Chuang TY, et al. Lobular capillary hemangiomas: An epidemiologic report, with emphasis on cutaneous lesions. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;42:1012-1016.

2. Yuan K, Jin YT, Lin MT. The detection and comparison of angiogenesis-associated factors in pyogenic granuloma by immunohistochemistry. J Periodontol. 2000;71:701-709.

3. Giblin AV, Clover AJ, Athanassopoulos A, et al. Pyogenic granuloma–the quest for optimum treatment: audit of treatment of 408 cases. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2007;60:1030-1035.

4. Steelman R, Holmes D. Pregnancy tumor in a 16-year-old: case report and treatment considerations. J Clin Pediatr Dent. 1992;16:217-218.

5. Jafarzadeh H, Sanatkhani M, Mohtasham N. Oral pyogenic granuloma: a review. J Oral Sci. 2006;48:167-175.

6. Piraccini BM, Bellavista S, Misciali C, et al. Periungual and subungual pyogenic granuloma. Br J Dermatol. 2010;163:941-953.

7. Ozcan C, Apa DD, Görür K. Pediatric lobular capillary hemangioma of the nasal cavity. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2004;261:449-451.

8. Henry F, Quatresooz P, Valverde-Lopez JC, et al. Blood vessel changes during pregnancy: a review. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2006;7:65-69.

9. Puxeddu R, Berlucchi M, Ledda GP, et al. Lobular capillary hemangioma of the nasal cavity: A retrospective study on 40 patients. Am J Rhinol. 2006;20:480-484.

10. Maroldi R, Berlucchi M, Farina D, et al. Benign neoplasms and tumor-like lesions. In: Maroldi R, Nicolai P, eds. Imaging in Treatment Planning for Sinonasal Diseases. Berlin, Heidelberg, New York: Springer-Verlag; 2005:107-158.

1. Harris MN, Desai R, Chuang TY, et al. Lobular capillary hemangiomas: An epidemiologic report, with emphasis on cutaneous lesions. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;42:1012-1016.

2. Yuan K, Jin YT, Lin MT. The detection and comparison of angiogenesis-associated factors in pyogenic granuloma by immunohistochemistry. J Periodontol. 2000;71:701-709.

3. Giblin AV, Clover AJ, Athanassopoulos A, et al. Pyogenic granuloma–the quest for optimum treatment: audit of treatment of 408 cases. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2007;60:1030-1035.

4. Steelman R, Holmes D. Pregnancy tumor in a 16-year-old: case report and treatment considerations. J Clin Pediatr Dent. 1992;16:217-218.

5. Jafarzadeh H, Sanatkhani M, Mohtasham N. Oral pyogenic granuloma: a review. J Oral Sci. 2006;48:167-175.

6. Piraccini BM, Bellavista S, Misciali C, et al. Periungual and subungual pyogenic granuloma. Br J Dermatol. 2010;163:941-953.

7. Ozcan C, Apa DD, Görür K. Pediatric lobular capillary hemangioma of the nasal cavity. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2004;261:449-451.

8. Henry F, Quatresooz P, Valverde-Lopez JC, et al. Blood vessel changes during pregnancy: a review. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2006;7:65-69.

9. Puxeddu R, Berlucchi M, Ledda GP, et al. Lobular capillary hemangioma of the nasal cavity: A retrospective study on 40 patients. Am J Rhinol. 2006;20:480-484.

10. Maroldi R, Berlucchi M, Farina D, et al. Benign neoplasms and tumor-like lesions. In: Maroldi R, Nicolai P, eds. Imaging in Treatment Planning for Sinonasal Diseases. Berlin, Heidelberg, New York: Springer-Verlag; 2005:107-158.

One lab finding, 2 vastly different causes

CASE 1

A 13-month-old boy who was recently adopted from Ethiopia presented to a primary care physician with a 3-week history of bloody diarrhea accompanied by flatulence and bloating. Stool cultures were positive for Campylobacter and Shigella. He was prescribed azithromycin but saw only moderate improvement. He was then referred to the Infectious Diseases Department. Neonatal, pregnancy, and immunization histories were unknown and a review of systems was unremarkable. On exam, the child looked well; he weighed 9.6 kg (15th percentile), was 69.5 cm long (<3rd percentile), and his head circumference was 45 cm (10th percentile). Head and neck, cardiorespiratory, and abdominal examinations were unremarkable.

A complete blood count (CBC) showed an elevated white blood cell (WBC) count of 26 x 109/L (normal: 4-10 x 109/L) with predominant eosinophilia (10.4 x 109/L or 40.1% of WBCs; normal: <0.45 x 109/L or 0%-8%). Hemoglobin and platelets were within normal limits. Stool testing for ova and parasites showed Strongyloides stercoralis larvae. Strongyloides serology was negative and Filaria serology was equivocal.

CASE 2

A 15-year-old boy was assessed for a 3-week history of fever and eosinophilia. He had enlarged cervical lymph nodes, a new rash, and had lost 4 pounds. He denied gastrointestinal symptoms, dyspnea, headaches, or chest pain. His past medical and family histories were unremarkable and he reported no drug use or allergies. He had traveled to Cuba with his family for 15 days 3 months prior to presentation. He recalled diarrhea while traveling, which resolved spontaneously. He and his family had traveled “off the beaten track,” eating foods prepared at local establishments and swimming in local rivers. He received pre-travel immunizations.

On examination, he appeared unwell, though his vital signs were normal. He had diffuse lymphadenopathy and a petechial rash on his chest, back, upper buttocks, legs, and feet. Cardiorespiratory and abdominal examinations were unremarkable. A CBC revealed an elevated WBC count of 76.9 x 109/L with predominant eosinophilia (71.5 x 109/L or 92% of WBCs). Hemoglobin, platelets, electrolytes, and liver function tests were normal. The patient was referred to a tertiary care center and was admitted to the hospital. Stool testing for ova and parasites, as well as serology for parasitic infections, was negative. A bone marrow aspiration and biopsy were performed and revealed the diagnosis of acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL).

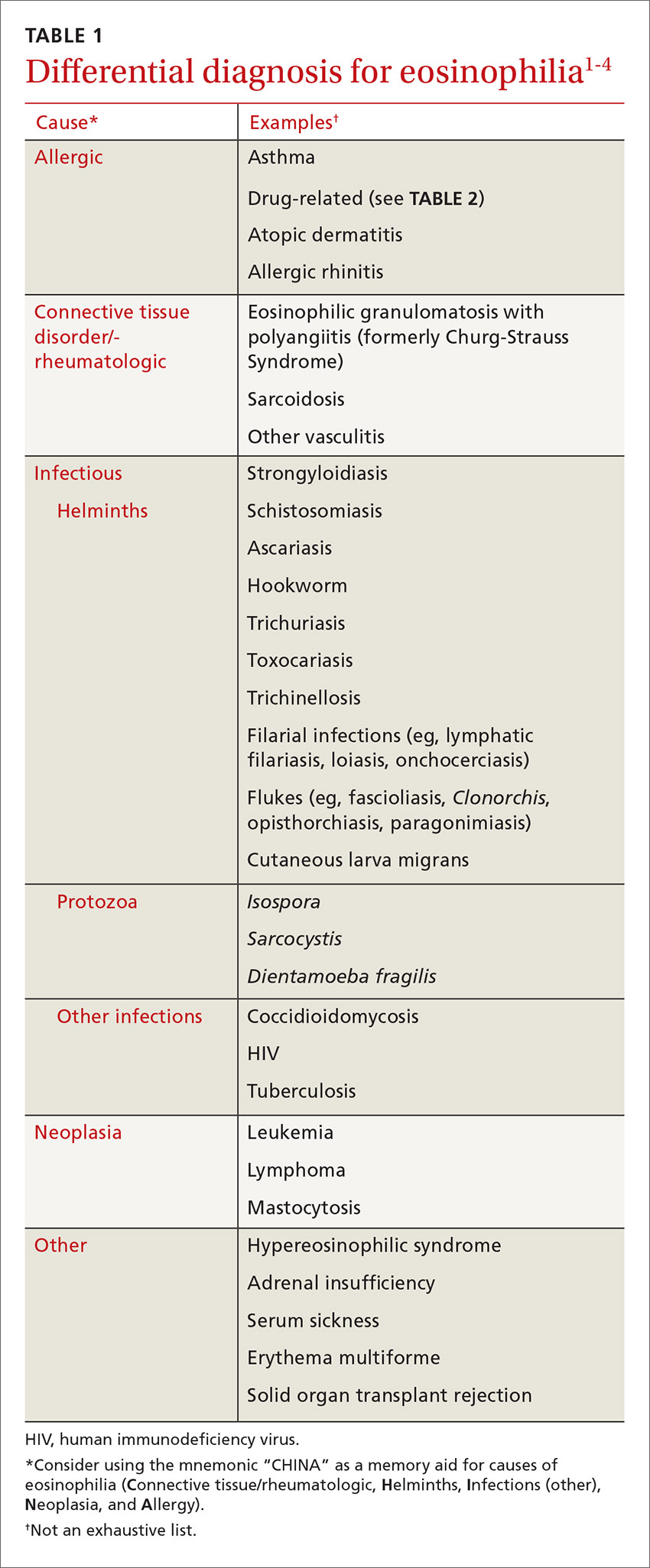

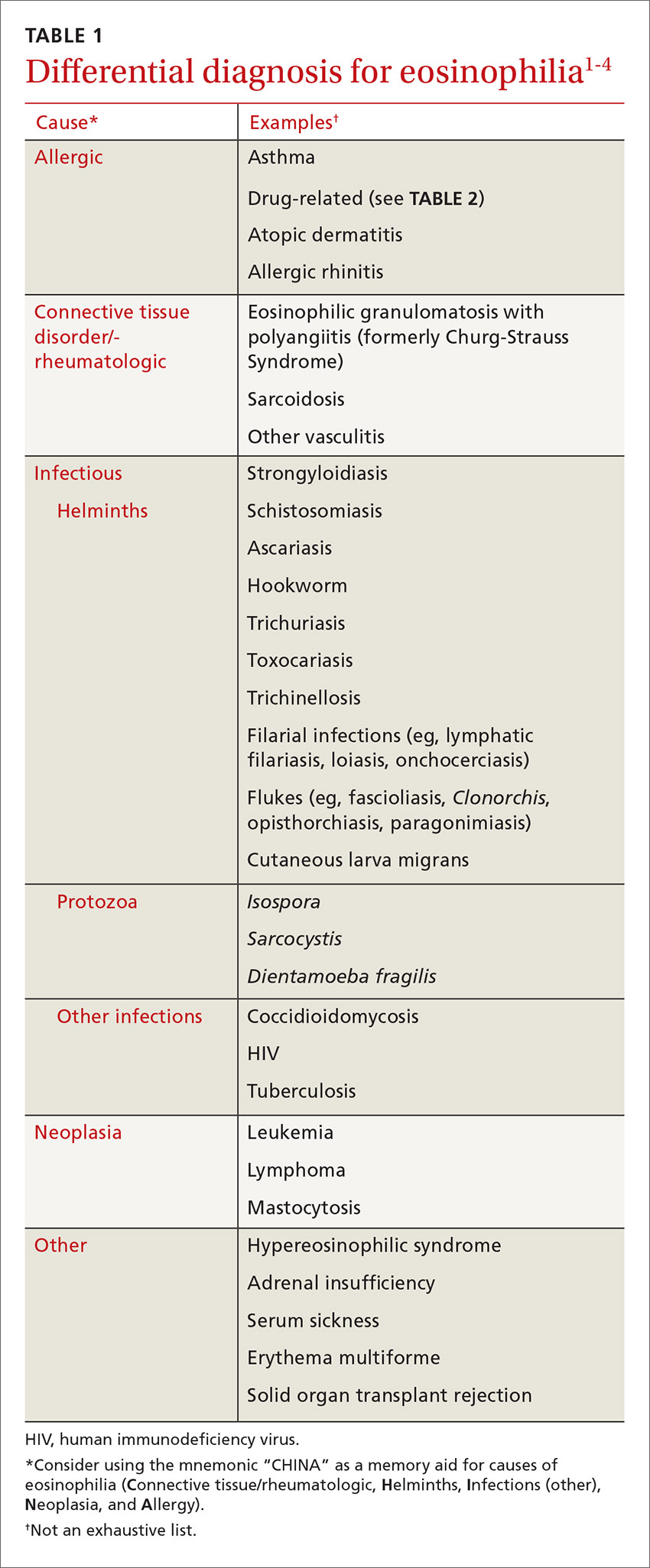

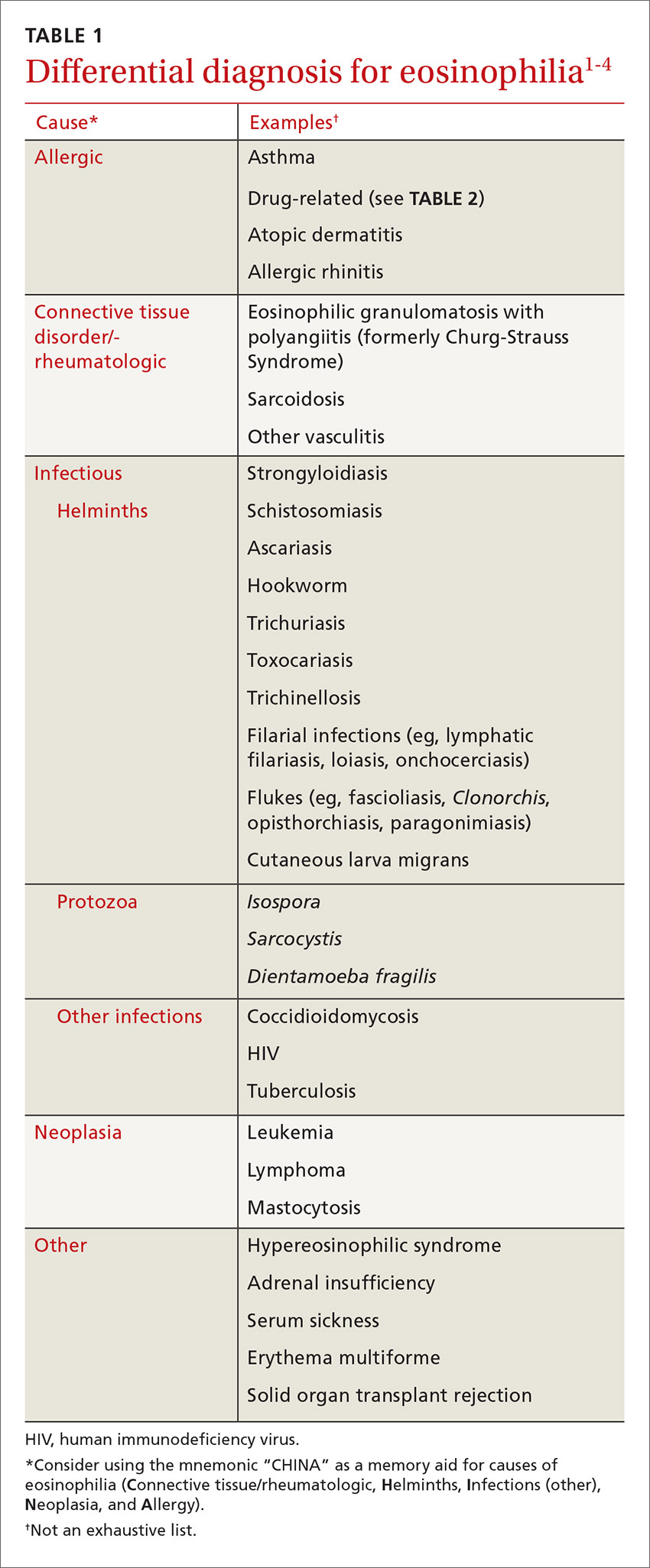

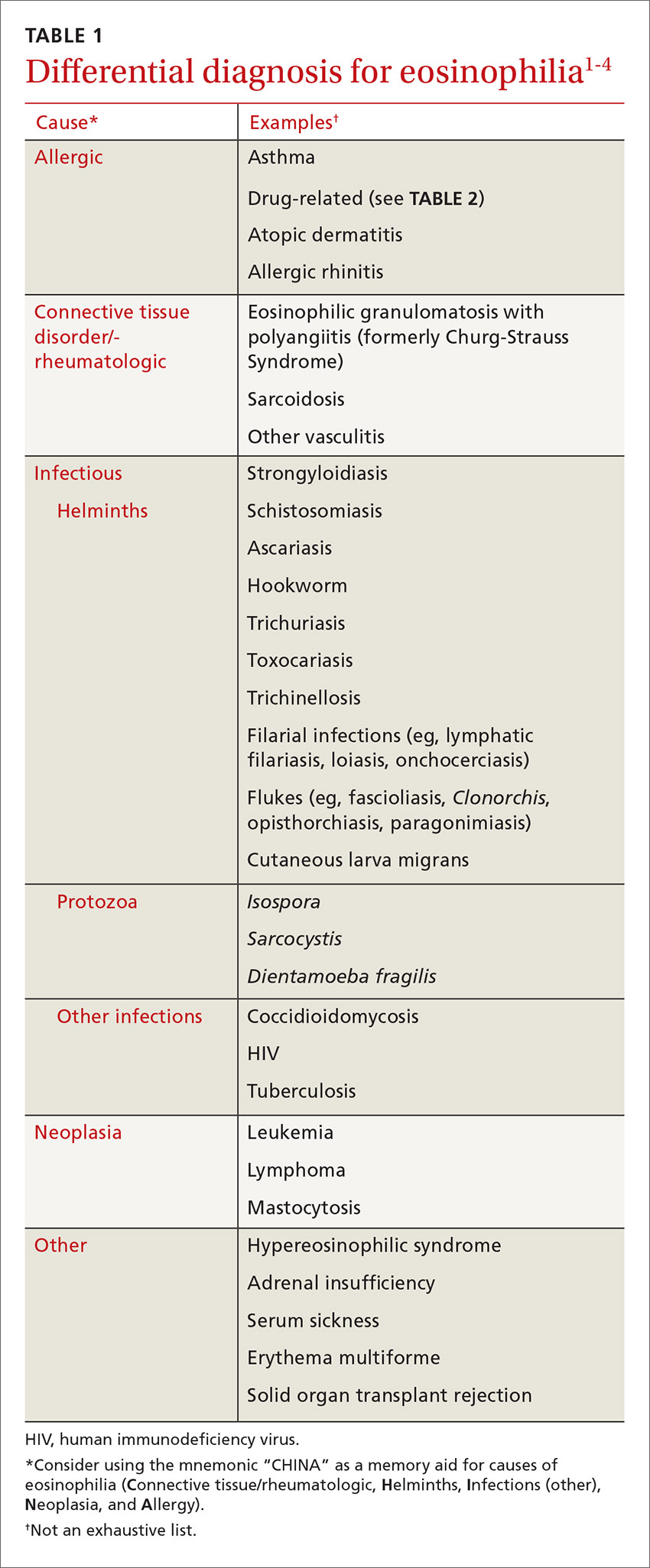

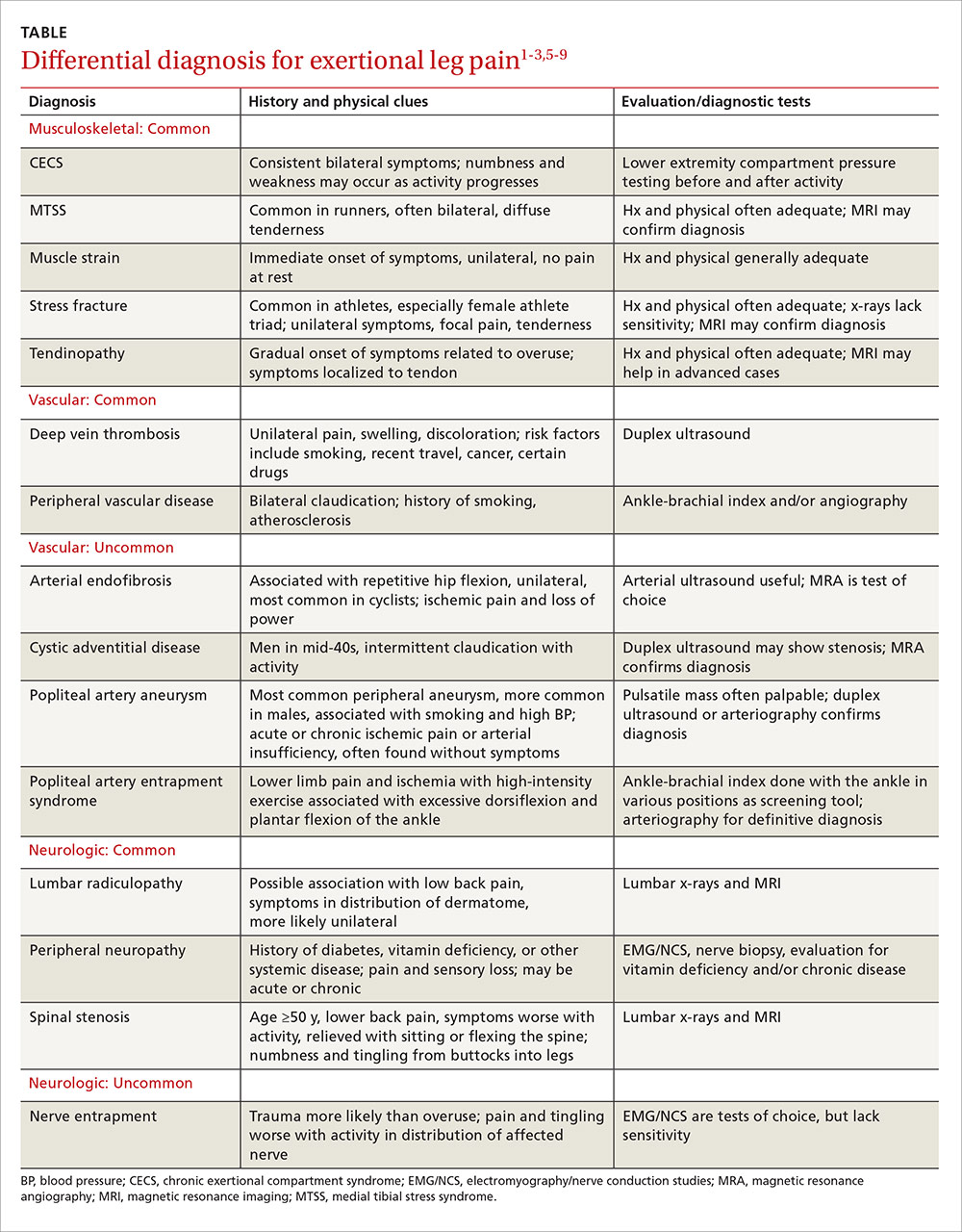

DISCUSSION

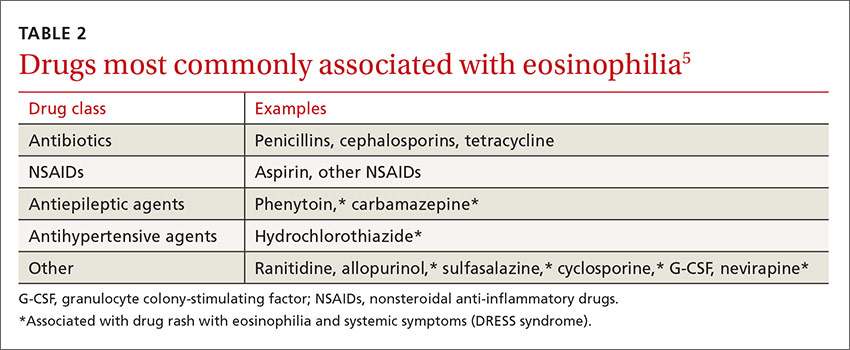

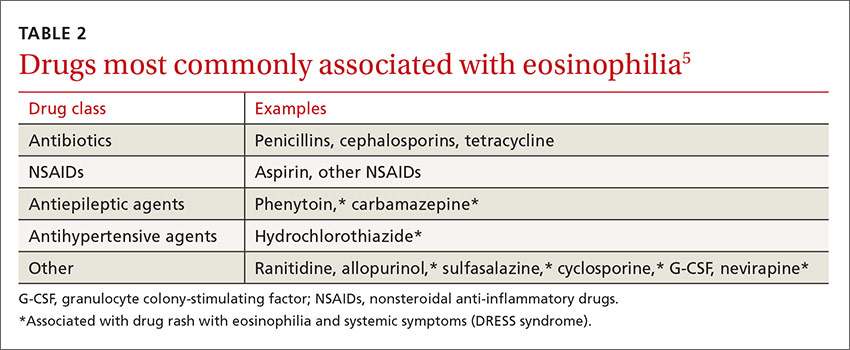

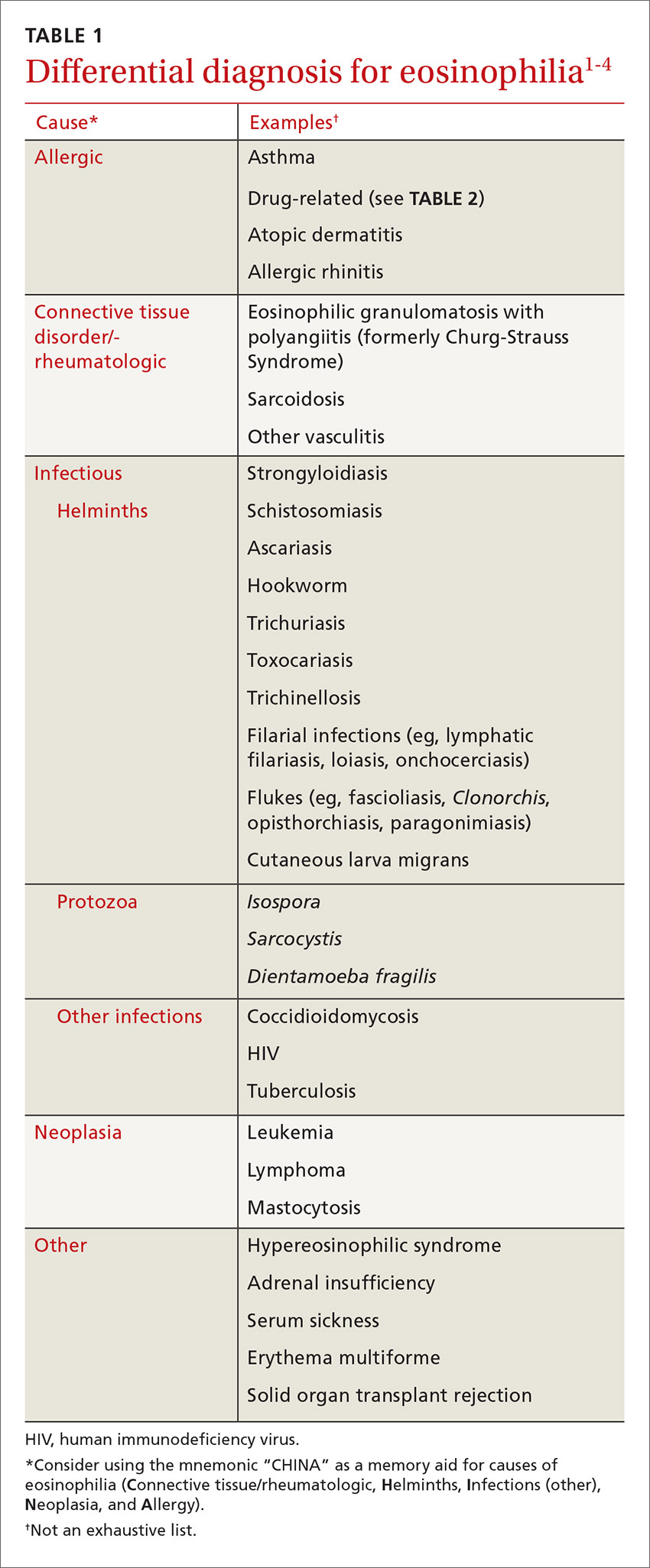

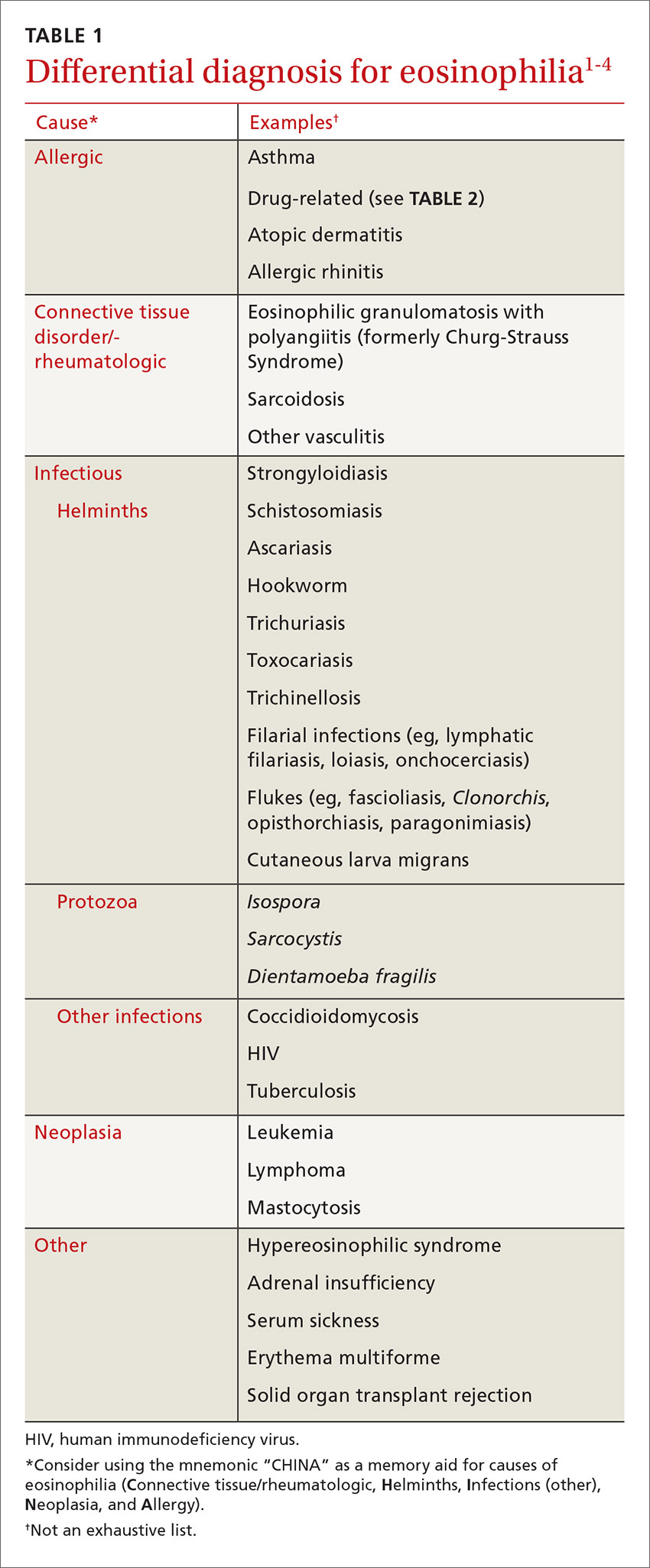

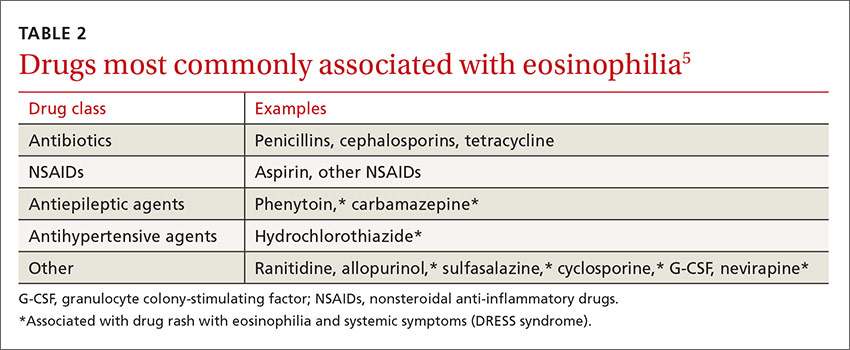

These 2 cases highlight how the presentation of eosinophilia can vary and how important it is to maintain a broad differential diagnosis (TABLE 11-4). Causes of eosinophilia are numerous and can be divided into 3 categories: primary, secondary, and idiopathic.1,5 Hematologic malignancy, where eosinophilia is clonal, is an example of a primary etiology. Causes of secondary eosinophilia include infectious diseases, drugs (TABLE 25), autoimmune disorders, and allergic conditions. Prolonged eosinophilia that is >3 x 109/L is associated with end-organ damage. Dermatologic, pulmonary, gastrointestinal, and cardiac involvement is most common.2

Eosinophilia associated with parasitic infection

In returning travelers and international adoptees, multicellular helminthic parasites are the most common causes of eosinophilia, with eosinophilia occurring during tissue migration or penetration.1,3

Schistosomiasis is a chronic parasitic infection of the human vascular system. It is transmitted by contact with contaminated fresh water, where cercariae penetrate the skin. High prevalence areas include Africa and Southeast Asia. Acute infection can result in Katayama fever—a febrile illness with prominent eosinophilia that occurs 4 to 7 weeks after exposure.4 Diagnosis is primarily clinical with appropriate epidemiology, as serology may be negative early in infection. Praziquantel is the treatment of choice, though dosing varies by species, so expert consultation should be considered.