User login

HSCT may age T cells as much as 30 years

Photo by Chad McNeeley

New research suggests hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT) may increase the molecular age of peripheral blood T cells.

The study showed an increase in peripheral blood T-cell senescence in patients with hematologic malignancies who were treated with autologous (auto-) or allogeneic (allo-) HSCT.

The patients had elevated levels of p16INK4a, a known marker of cellular senescence.

Auto-HSCT in particular had a strong effect on p16INK4a, increasing the expression of this marker to a degree comparable to 30 years of chronological aging.

Researchers reported these findings in EBioMedicine.

“We know that transplant is life-prolonging, and, in many cases, it’s life-saving for many patients with blood cancers and other disorders,” said study author William Wood, MD, of the University of North Carolina School of Medicine in Chapel Hill.

“At the same time, we’re increasingly recognizing that survivors of transplant are at risk for long-term health problems, and so there is interest in determining what markers may exist to help predict risk for long-term health problems or even in helping choose which patients are best candidates for transplantation.”

With this in mind, Dr Wood and his colleagues looked at levels of p16INK4a in 63 patients who underwent auto- or allo-HSCT to treat myeloma, lymphoma, or leukemia. The researchers assessed p16INK4a expression in T cells before HSCT and 6 months after.

Among auto-HSCT recipients, there were no baseline characteristics associated with pre-transplant p16INK4a expression.

However, allo-HSCT recipients had significantly higher pre-transplant p16INK4a levels the more cycles of chemotherapy they received before transplant (P=0.003), if they had previously undergone auto-HSCT (P=0.01), and if they had been exposed to alkylating agents (P=0.01).

After transplant, allo-HSCT recipients had a 1.93-fold increase in p16INK4a expression (P=0.0004), and auto-HSCT recipients had a 3.05-fold increase (P=0.002).

The researchers said the measured change in p16INK4a from pre- to post-HSCT in allogeneic recipients likely underestimates the age-promoting effects of HSCT, given that the pre-HSCT levels were elevated in the recipients from prior therapeutic exposure.

The researchers also pointed out that this study does not show a clear connection between changes in p16INK4a levels and the actual function of peripheral blood T cells, but they did say that p16INK4a is “arguably one of the best in vivo markers of cellular senescence and is directly associated with age-related deterioration.”

So the results of this research suggest the forced bone marrow repopulation associated with HSCT accelerates the molecular aging of peripheral blood T cells.

“Many oncologists would not be surprised by the finding that stem cell transplant accelerates aspects of aging,” said study author Norman Sharpless, MD, of the University of North Carolina School of Medicine.

“We know that, years after a curative transplant, stem cell transplant survivors are at increased risk for blood problems that can occur with aging, such as reduced immunity, increased risk for bone marrow failure, and increased risk of blood cancers. What is important about this work, however, is that it allows us to quantify the effect of stem cell transplant on molecular age.” ![]()

Photo by Chad McNeeley

New research suggests hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT) may increase the molecular age of peripheral blood T cells.

The study showed an increase in peripheral blood T-cell senescence in patients with hematologic malignancies who were treated with autologous (auto-) or allogeneic (allo-) HSCT.

The patients had elevated levels of p16INK4a, a known marker of cellular senescence.

Auto-HSCT in particular had a strong effect on p16INK4a, increasing the expression of this marker to a degree comparable to 30 years of chronological aging.

Researchers reported these findings in EBioMedicine.

“We know that transplant is life-prolonging, and, in many cases, it’s life-saving for many patients with blood cancers and other disorders,” said study author William Wood, MD, of the University of North Carolina School of Medicine in Chapel Hill.

“At the same time, we’re increasingly recognizing that survivors of transplant are at risk for long-term health problems, and so there is interest in determining what markers may exist to help predict risk for long-term health problems or even in helping choose which patients are best candidates for transplantation.”

With this in mind, Dr Wood and his colleagues looked at levels of p16INK4a in 63 patients who underwent auto- or allo-HSCT to treat myeloma, lymphoma, or leukemia. The researchers assessed p16INK4a expression in T cells before HSCT and 6 months after.

Among auto-HSCT recipients, there were no baseline characteristics associated with pre-transplant p16INK4a expression.

However, allo-HSCT recipients had significantly higher pre-transplant p16INK4a levels the more cycles of chemotherapy they received before transplant (P=0.003), if they had previously undergone auto-HSCT (P=0.01), and if they had been exposed to alkylating agents (P=0.01).

After transplant, allo-HSCT recipients had a 1.93-fold increase in p16INK4a expression (P=0.0004), and auto-HSCT recipients had a 3.05-fold increase (P=0.002).

The researchers said the measured change in p16INK4a from pre- to post-HSCT in allogeneic recipients likely underestimates the age-promoting effects of HSCT, given that the pre-HSCT levels were elevated in the recipients from prior therapeutic exposure.

The researchers also pointed out that this study does not show a clear connection between changes in p16INK4a levels and the actual function of peripheral blood T cells, but they did say that p16INK4a is “arguably one of the best in vivo markers of cellular senescence and is directly associated with age-related deterioration.”

So the results of this research suggest the forced bone marrow repopulation associated with HSCT accelerates the molecular aging of peripheral blood T cells.

“Many oncologists would not be surprised by the finding that stem cell transplant accelerates aspects of aging,” said study author Norman Sharpless, MD, of the University of North Carolina School of Medicine.

“We know that, years after a curative transplant, stem cell transplant survivors are at increased risk for blood problems that can occur with aging, such as reduced immunity, increased risk for bone marrow failure, and increased risk of blood cancers. What is important about this work, however, is that it allows us to quantify the effect of stem cell transplant on molecular age.” ![]()

Photo by Chad McNeeley

New research suggests hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT) may increase the molecular age of peripheral blood T cells.

The study showed an increase in peripheral blood T-cell senescence in patients with hematologic malignancies who were treated with autologous (auto-) or allogeneic (allo-) HSCT.

The patients had elevated levels of p16INK4a, a known marker of cellular senescence.

Auto-HSCT in particular had a strong effect on p16INK4a, increasing the expression of this marker to a degree comparable to 30 years of chronological aging.

Researchers reported these findings in EBioMedicine.

“We know that transplant is life-prolonging, and, in many cases, it’s life-saving for many patients with blood cancers and other disorders,” said study author William Wood, MD, of the University of North Carolina School of Medicine in Chapel Hill.

“At the same time, we’re increasingly recognizing that survivors of transplant are at risk for long-term health problems, and so there is interest in determining what markers may exist to help predict risk for long-term health problems or even in helping choose which patients are best candidates for transplantation.”

With this in mind, Dr Wood and his colleagues looked at levels of p16INK4a in 63 patients who underwent auto- or allo-HSCT to treat myeloma, lymphoma, or leukemia. The researchers assessed p16INK4a expression in T cells before HSCT and 6 months after.

Among auto-HSCT recipients, there were no baseline characteristics associated with pre-transplant p16INK4a expression.

However, allo-HSCT recipients had significantly higher pre-transplant p16INK4a levels the more cycles of chemotherapy they received before transplant (P=0.003), if they had previously undergone auto-HSCT (P=0.01), and if they had been exposed to alkylating agents (P=0.01).

After transplant, allo-HSCT recipients had a 1.93-fold increase in p16INK4a expression (P=0.0004), and auto-HSCT recipients had a 3.05-fold increase (P=0.002).

The researchers said the measured change in p16INK4a from pre- to post-HSCT in allogeneic recipients likely underestimates the age-promoting effects of HSCT, given that the pre-HSCT levels were elevated in the recipients from prior therapeutic exposure.

The researchers also pointed out that this study does not show a clear connection between changes in p16INK4a levels and the actual function of peripheral blood T cells, but they did say that p16INK4a is “arguably one of the best in vivo markers of cellular senescence and is directly associated with age-related deterioration.”

So the results of this research suggest the forced bone marrow repopulation associated with HSCT accelerates the molecular aging of peripheral blood T cells.

“Many oncologists would not be surprised by the finding that stem cell transplant accelerates aspects of aging,” said study author Norman Sharpless, MD, of the University of North Carolina School of Medicine.

“We know that, years after a curative transplant, stem cell transplant survivors are at increased risk for blood problems that can occur with aging, such as reduced immunity, increased risk for bone marrow failure, and increased risk of blood cancers. What is important about this work, however, is that it allows us to quantify the effect of stem cell transplant on molecular age.” ![]()

Why and How ACOs Must Evolve

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) triumphantly announced in January 2016 that 121 new participants had joined 1 of its 3 accountable care organization (ACO) programs, and that the various ACOs had together saved the federal government $411 million in 2014 while improving on various quality metrics.[1] Yet even as the ACO model has gathered political momentum and shown promise in reducing payer spending in the short term, it is facing growing scrutiny that it may be insufficient to support meaningful care delivery transformation.

Different ACO models differ in their financial details, but the fundamental theme is the same: healthcare organizations earn bonuses, or shared savings, if they bill payers less than their projected fee‐for‐service revenue (known as the spending benchmark) and meet quality measures. In double‐sided ACO models, if fee‐for‐service revenue exceeds the benchmark, ACOs are also fined. In contrast with traditional fee‐for‐service, in which payments are tied directly to price and volume of services, ACOs were envisioned as a business model that would enable health systems to thrive by improving the care efficiency and clinical outcomes of their patient populations.

However, because health systems only earn shared savings bonuses if they reduce their fee‐for‐service revenue, ACOs do not have a clear business case for moving toward value‐oriented care. ThedaCare, the best performing Pioneer ACO in the first year of the program, reported that successful reduction of preventable hospital admissions led to shared savings payments. However, those payments did not cover the reduced fee‐for‐service revenue, leading to diminished overall financial performance.[2] Only 5% of the 434 Shared Savings Program ACOs have agreed to double‐sided contracts, suggesting discomfort with the structure of the model.[1] Although ACOs have continued to grow in overall number, the programs have experienced significant churn, with over two thirds of Pioneer ACOs leaving over the last 3 years. This suggests widespread commitment to the principle of population health but a struggle by health systems to make the specific models financially viable.[3]

How can payers reshape the ACO model to better support value‐oriented care delivery transformation while maintaining its key cost control elements? One strategy is for CMS to establish a pathway for adding care delivery interventions to the fee‐for‐service schedule for ACOs, a concept we call population health billing. Payers have shown some interest in supporting population health efforts via fee‐for‐service: for example, in 2015 CMS established the chronic care management fee, which pays a per patient per month fee for care coordination of Medicare beneficiaries with 2 or more chronic conditions, and the transitional care management fee, which reimburses a postdischarge office visit focused on managing a patient's transition out of the hospital.[4] UnitedHealthcare has begun reimbursing virtual physician visits for some self‐insured employers.[5]

These isolated efforts should be rolled up into a systematic pathway for population health interventions to become billable under fee‐for‐service for organizations in Medicare ACO contracts. CMS and institutional provider associations, whose technical committees generate the majority of billing codes, could together adopt a formal set of criteria to grade the evidence basis of population health interventions in terms of their impact on clinical outcomes, care quality, and care value, similar to the National Quality Forum's work with quality metrics, and establish a formal process by which interventions with demonstrated efficacy can be assigned billing values in a timely, rigorous, and transparent manner. Candidates for population health billing codes could include high‐risk case management, virtual visits, and home‐based primary care. ACOs would be free to determine which, if any, particular interventions to adopt.

ACOs must currently invest in population health programs with out‐of‐pocket funds and bet that reductions in preventable healthcare utilization result in sufficient shared savings to compensate for both program costs and lost fee‐for‐service profit. Even clinically successful programs are often unable to reach this high threshold.[6] A recent New England Journal of Medicine article lamented a common theme among studies of population health interventions: clinical success, but financial unsustainability.[7] CMS' Comprehensive Primary Care Initiative, which provides about 500 primary care practices with case management fees to redesign their care delivery, resulted in a reduced volume of primary care visits and improved patient communication but no cost savings to Medicare after accounting for program fees (14). Congressional analysis found that although case management programs with substantial physician interaction reduced Medicare expenditures by an average of 6%, only 1 out of 34 programs achieved statistically significant savings to Medicare relative to their program fees alone.[8] E‐consults, when a specialist physician provides recommendations to a primary doctor by reviewing a patient's chart electronically, are associated with decreased wait times, high primary provider satisfaction, and lower costs compared to traditional care, yet adoption among ACOs has been limited by the opportunity cost of fee‐for‐service revenue.[9] In reducing Medicare costs and hence their own fee‐for‐service revenue by $300 million in their first year, Pioneer ACOs were only collectively granted bonuses of about $77 million against the significant operating and capital costs of population health.[10] The financial challenges of ACOs are a reflection of the difficulty in consistently developing a fiscally and clinically successful set of population health interventions under current ACO financial rules.

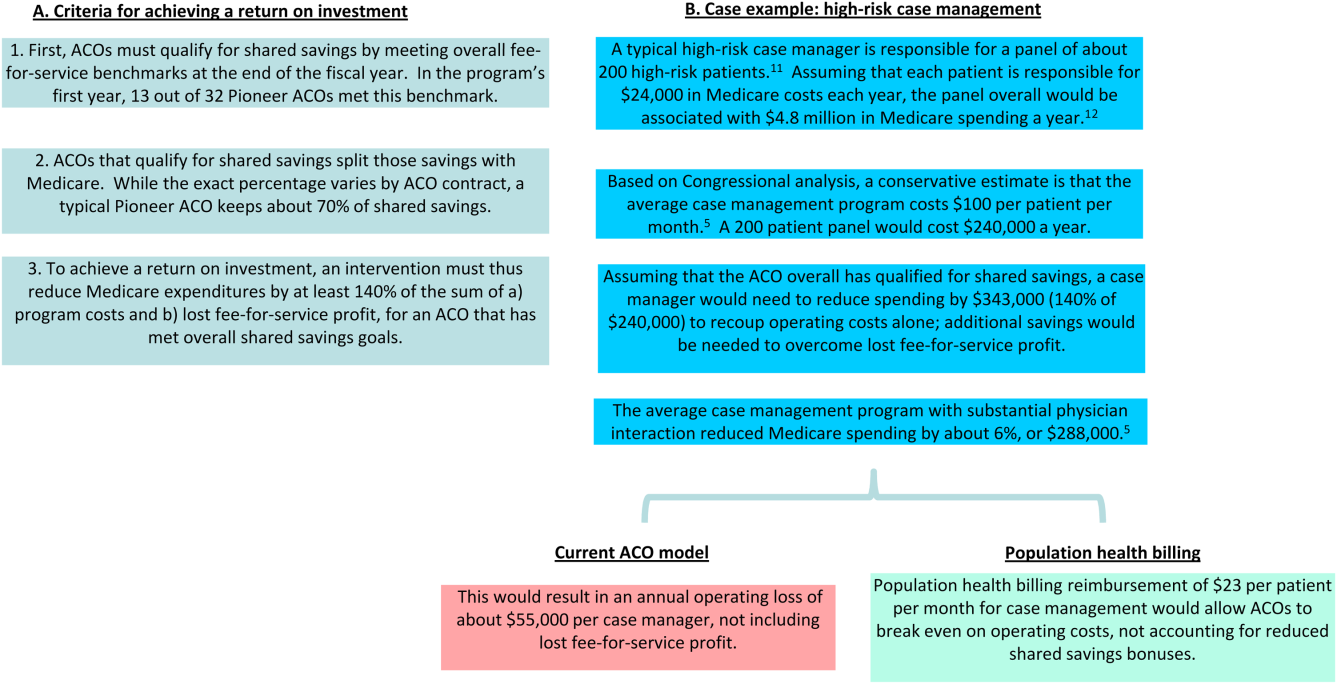

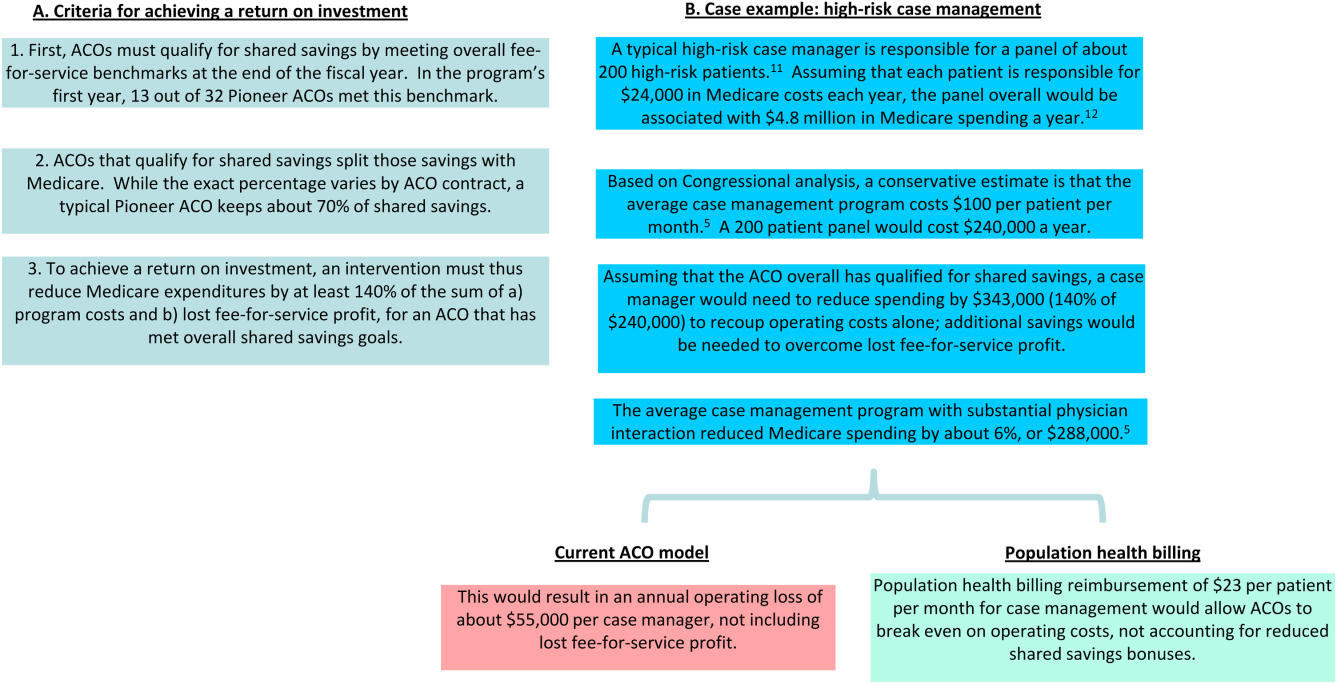

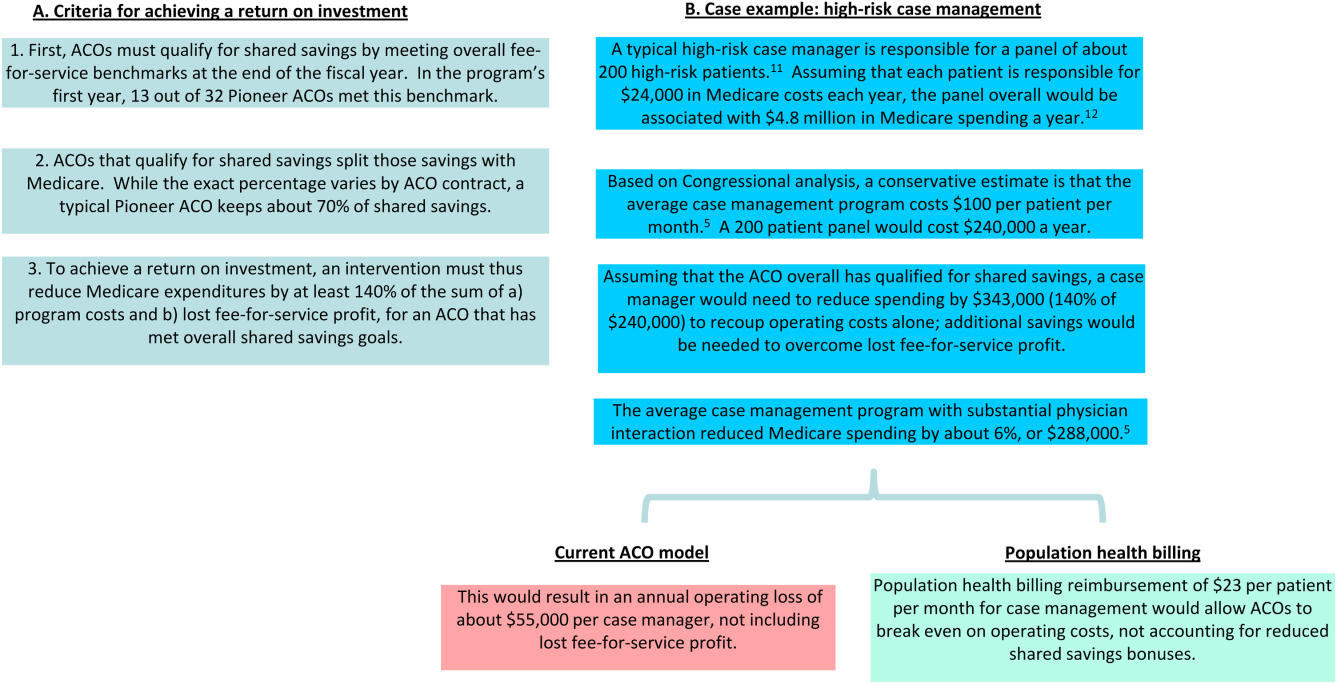

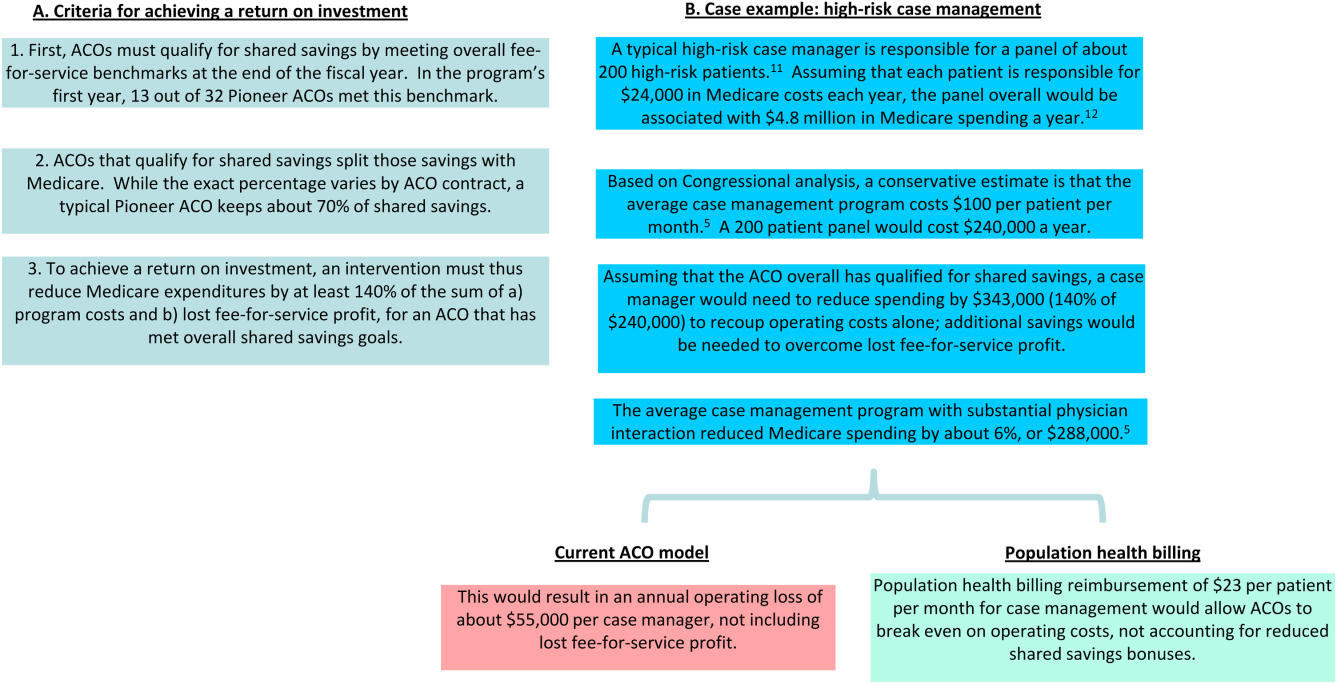

In Figure 1, we use high‐risk case management as an example to demonstrate how population billing could work. Population health billing could provide a per patient, per month fee‐for‐service payment to ACOs for high‐risk case management services. This payment would count against ACOs' spending benchmarks at the end of the year. By helping cover the operating costs of these programs, population health billing would make value‐oriented interventions significantly more sustainable compared to the current ACO models.

In providing fee‐for‐service revenue for population health interventions, population health billing would break the inherent tension between fee‐for‐service and shared savings bonuses. It would allow ACOs to transition ever‐greater portions of revenue from traditional transactional‐based sources toward shared savings, without requiring success in accountable care to mean fee‐for‐service losses. This is an important threshold for operational leaders who must integrate population health, which currently represent loss centers on balance sheets, within existing profitable fee‐for‐service business lines.

Some observers may argue that allowing billable care delivery interventions may encourage practices to roll out interventions that meet billing requirements but have little meaningful impact on population health; the efficacy of care delivery interventions is clearly dependent on the context of the health system and quality of execution. This concern is the same fundamental concern of fee‐for‐service reimbursement as a whole. However, because ACOs are paid bonuses for reducing fee‐for‐service revenue, they would have an incentive to only develop and bill for population health interventions they believe would have a meaningful return on investment in reducing healthcare costs. The fundamental incentives of ACOs would remain the same‐ to reduce healthcare spending by better managing the costs of their patient populations. Others may argue that population health billing would build upon our fee‐for‐service system that many have advocated we must move past. But ACO initiatives and bundled payments are similarly built upon a foundation of fee‐for‐service.

Whereas a greater number of billable services will likely reduce CMS' short‐term savings from ACO programs, the ACO model must offer a sustainable business case for care delivery reform to ultimately bend long‐term healthcare costs. Payers are not obligated to ensure that providers maintain historical income levels, but over the long term providers will not make the sizable infrastructure investments, such as integrated information technology platforms, data analytics, and risk management, required to deliver value‐based care without a sustainable business case. To limit the costs of population health billing, Medicare should restrict it to ACO contracts that allow for penalties. The fee‐for‐service reimbursement rates under population health billing could also be tied to performance on quality metrics, similar to how Medicare fee‐for‐service hospital reimbursement is linked to performance on value‐based metrics.[13]

In addition, this reduction in short‐term cost savings may actually improve the sustainability of the ACO model. Every year, each ACO's spending benchmark is re‐based, or recalculated based on the most recent spending data. This means that ACOs that successfully reduce their fee‐for‐service revenue below their spending benchmark will face an even lower benchmark the next year and have to reduce their costs even further, creating an unsustainable trend. Because population health billing would count against the spending benchmark, it would help slow down this race to the bottom while driving forward value‐oriented care delivery transformation.

ACOs have a number of other design problems, including high rates of patient churn, imperfect quality metrics that do not adequately capture the scope of population‐level health, and lags in data access.[14] The Next Generation ACO model addresses some of these concerns. For example, it allows ACOs to prospectively define their patient populations. Yet many challenges remain. Population health billing does not solve all of these problems, but it will improve the ability of health systems to meaningfully pivot toward a value‐oriented strategy.

As physicians and ACO operational leaders, we believe in the clinical and policy vision behind the ACO model but have also struggled with the limitations of the model to meaningfully support care delivery transformation. If CMS truly wants to meaningfully transform US healthcare from volume‐based to value‐based, it must invest in the needed care redesign even at the expense of short‐term cost savings.

Disclosures: Dr. Chen was formerly a consultant for Partners HealthCare, a Pioneer ACO, and a physician fellow on the Pioneer ACO Team at the Center for Medicare & Medicaid Innovation. He currently serves on the advisory board of Radial Analytics and is a resident physician at Massachusetts General Hospital. Dr. Ackerly was formerly the associate medical director for Population Health and Continuing Care at Partners HealthCare and an Innovation Advisor to the Center for Medicare & Medicaid Innovation. He currently serves as the Chief Clinical Officer of naviHealth. Dr. Gottlieb was formerly the President and Chief Executive Officer of Partners HealthCare and currently serves as the Chief Executive Officer of Partners In Health. The views represented here are those of the authors' and do not represent the views of Partners HealthCare, Massachusetts General Hospital, naviHealth, or Partners In Health.

- U.S. Department of Health 310:1341–1342.

- , , , . Performance differences in year 1 of the Pioneer accountable care organizations. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:1927–1936.

- , , , , . Medicare chronic care management payments and financial returns to primary care practice: a modeling study. Ann Intern Med. 2015;163:580–588.

- UnitedHealthcare. UnitedHealthcare covers virtual care physician visits, expanding consumers' access to affordable health care options. Available at: http://www.uhc.com/news‐room/2015‐news‐release‐archive/unitedhealthcare‐covers‐virtual‐care‐physician‐visits. Published April 30, 2015. Accessed February 6, 2016.

- , , . Toward increased adoption of complex care management. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:491–493.

- , , . Asymmetric thinking about return on investment. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(7):606–608.

- . Lessons from Medicare's demonstration projects on disease management and care coordination. Washington, D.C.: Congressional Budget Office, Health and Human Resources Division, working paper 2012‐01, 2012. Available at: http://www.cbo.gov/sites/default/files/cbofiles/attachments/WP2012‐01_Nelson_Medicare_DMCC_Demonstrations.pdf. Published January 2012. Accessed June 15, 2015.

- , , , . A safety‐net system gains efficiencies through ‘eReferrals’ to specialists. Health Aff (Millwood). 2010;29:969–971.

- Centers for Medicare MGH Medicare Demonstration Project for High-Cost Beneficiaries. Available at: http://www.massgeneral.org/News/assets/pdf/CMS_project_phase1FactSheet.pdf. Accessed April 2, 2016.

- , , , et al. Two-Year Costs and Quality in the Comprehensive Primary Care Initiative. N Engl J Med. 2016; DOI: 10.1056/NEJMsa1414953.

- , . Beyond ACOs and bundled payments: Medicare's shift toward accountability in fee‐for‐service. JAMA. 2014;311:673–674.

- , , , , . ACO model should encourage efficient care delivery. Healthc (Amst). 2015;3(3):150–152.

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) triumphantly announced in January 2016 that 121 new participants had joined 1 of its 3 accountable care organization (ACO) programs, and that the various ACOs had together saved the federal government $411 million in 2014 while improving on various quality metrics.[1] Yet even as the ACO model has gathered political momentum and shown promise in reducing payer spending in the short term, it is facing growing scrutiny that it may be insufficient to support meaningful care delivery transformation.

Different ACO models differ in their financial details, but the fundamental theme is the same: healthcare organizations earn bonuses, or shared savings, if they bill payers less than their projected fee‐for‐service revenue (known as the spending benchmark) and meet quality measures. In double‐sided ACO models, if fee‐for‐service revenue exceeds the benchmark, ACOs are also fined. In contrast with traditional fee‐for‐service, in which payments are tied directly to price and volume of services, ACOs were envisioned as a business model that would enable health systems to thrive by improving the care efficiency and clinical outcomes of their patient populations.

However, because health systems only earn shared savings bonuses if they reduce their fee‐for‐service revenue, ACOs do not have a clear business case for moving toward value‐oriented care. ThedaCare, the best performing Pioneer ACO in the first year of the program, reported that successful reduction of preventable hospital admissions led to shared savings payments. However, those payments did not cover the reduced fee‐for‐service revenue, leading to diminished overall financial performance.[2] Only 5% of the 434 Shared Savings Program ACOs have agreed to double‐sided contracts, suggesting discomfort with the structure of the model.[1] Although ACOs have continued to grow in overall number, the programs have experienced significant churn, with over two thirds of Pioneer ACOs leaving over the last 3 years. This suggests widespread commitment to the principle of population health but a struggle by health systems to make the specific models financially viable.[3]

How can payers reshape the ACO model to better support value‐oriented care delivery transformation while maintaining its key cost control elements? One strategy is for CMS to establish a pathway for adding care delivery interventions to the fee‐for‐service schedule for ACOs, a concept we call population health billing. Payers have shown some interest in supporting population health efforts via fee‐for‐service: for example, in 2015 CMS established the chronic care management fee, which pays a per patient per month fee for care coordination of Medicare beneficiaries with 2 or more chronic conditions, and the transitional care management fee, which reimburses a postdischarge office visit focused on managing a patient's transition out of the hospital.[4] UnitedHealthcare has begun reimbursing virtual physician visits for some self‐insured employers.[5]

These isolated efforts should be rolled up into a systematic pathway for population health interventions to become billable under fee‐for‐service for organizations in Medicare ACO contracts. CMS and institutional provider associations, whose technical committees generate the majority of billing codes, could together adopt a formal set of criteria to grade the evidence basis of population health interventions in terms of their impact on clinical outcomes, care quality, and care value, similar to the National Quality Forum's work with quality metrics, and establish a formal process by which interventions with demonstrated efficacy can be assigned billing values in a timely, rigorous, and transparent manner. Candidates for population health billing codes could include high‐risk case management, virtual visits, and home‐based primary care. ACOs would be free to determine which, if any, particular interventions to adopt.

ACOs must currently invest in population health programs with out‐of‐pocket funds and bet that reductions in preventable healthcare utilization result in sufficient shared savings to compensate for both program costs and lost fee‐for‐service profit. Even clinically successful programs are often unable to reach this high threshold.[6] A recent New England Journal of Medicine article lamented a common theme among studies of population health interventions: clinical success, but financial unsustainability.[7] CMS' Comprehensive Primary Care Initiative, which provides about 500 primary care practices with case management fees to redesign their care delivery, resulted in a reduced volume of primary care visits and improved patient communication but no cost savings to Medicare after accounting for program fees (14). Congressional analysis found that although case management programs with substantial physician interaction reduced Medicare expenditures by an average of 6%, only 1 out of 34 programs achieved statistically significant savings to Medicare relative to their program fees alone.[8] E‐consults, when a specialist physician provides recommendations to a primary doctor by reviewing a patient's chart electronically, are associated with decreased wait times, high primary provider satisfaction, and lower costs compared to traditional care, yet adoption among ACOs has been limited by the opportunity cost of fee‐for‐service revenue.[9] In reducing Medicare costs and hence their own fee‐for‐service revenue by $300 million in their first year, Pioneer ACOs were only collectively granted bonuses of about $77 million against the significant operating and capital costs of population health.[10] The financial challenges of ACOs are a reflection of the difficulty in consistently developing a fiscally and clinically successful set of population health interventions under current ACO financial rules.

In Figure 1, we use high‐risk case management as an example to demonstrate how population billing could work. Population health billing could provide a per patient, per month fee‐for‐service payment to ACOs for high‐risk case management services. This payment would count against ACOs' spending benchmarks at the end of the year. By helping cover the operating costs of these programs, population health billing would make value‐oriented interventions significantly more sustainable compared to the current ACO models.

In providing fee‐for‐service revenue for population health interventions, population health billing would break the inherent tension between fee‐for‐service and shared savings bonuses. It would allow ACOs to transition ever‐greater portions of revenue from traditional transactional‐based sources toward shared savings, without requiring success in accountable care to mean fee‐for‐service losses. This is an important threshold for operational leaders who must integrate population health, which currently represent loss centers on balance sheets, within existing profitable fee‐for‐service business lines.

Some observers may argue that allowing billable care delivery interventions may encourage practices to roll out interventions that meet billing requirements but have little meaningful impact on population health; the efficacy of care delivery interventions is clearly dependent on the context of the health system and quality of execution. This concern is the same fundamental concern of fee‐for‐service reimbursement as a whole. However, because ACOs are paid bonuses for reducing fee‐for‐service revenue, they would have an incentive to only develop and bill for population health interventions they believe would have a meaningful return on investment in reducing healthcare costs. The fundamental incentives of ACOs would remain the same‐ to reduce healthcare spending by better managing the costs of their patient populations. Others may argue that population health billing would build upon our fee‐for‐service system that many have advocated we must move past. But ACO initiatives and bundled payments are similarly built upon a foundation of fee‐for‐service.

Whereas a greater number of billable services will likely reduce CMS' short‐term savings from ACO programs, the ACO model must offer a sustainable business case for care delivery reform to ultimately bend long‐term healthcare costs. Payers are not obligated to ensure that providers maintain historical income levels, but over the long term providers will not make the sizable infrastructure investments, such as integrated information technology platforms, data analytics, and risk management, required to deliver value‐based care without a sustainable business case. To limit the costs of population health billing, Medicare should restrict it to ACO contracts that allow for penalties. The fee‐for‐service reimbursement rates under population health billing could also be tied to performance on quality metrics, similar to how Medicare fee‐for‐service hospital reimbursement is linked to performance on value‐based metrics.[13]

In addition, this reduction in short‐term cost savings may actually improve the sustainability of the ACO model. Every year, each ACO's spending benchmark is re‐based, or recalculated based on the most recent spending data. This means that ACOs that successfully reduce their fee‐for‐service revenue below their spending benchmark will face an even lower benchmark the next year and have to reduce their costs even further, creating an unsustainable trend. Because population health billing would count against the spending benchmark, it would help slow down this race to the bottom while driving forward value‐oriented care delivery transformation.

ACOs have a number of other design problems, including high rates of patient churn, imperfect quality metrics that do not adequately capture the scope of population‐level health, and lags in data access.[14] The Next Generation ACO model addresses some of these concerns. For example, it allows ACOs to prospectively define their patient populations. Yet many challenges remain. Population health billing does not solve all of these problems, but it will improve the ability of health systems to meaningfully pivot toward a value‐oriented strategy.

As physicians and ACO operational leaders, we believe in the clinical and policy vision behind the ACO model but have also struggled with the limitations of the model to meaningfully support care delivery transformation. If CMS truly wants to meaningfully transform US healthcare from volume‐based to value‐based, it must invest in the needed care redesign even at the expense of short‐term cost savings.

Disclosures: Dr. Chen was formerly a consultant for Partners HealthCare, a Pioneer ACO, and a physician fellow on the Pioneer ACO Team at the Center for Medicare & Medicaid Innovation. He currently serves on the advisory board of Radial Analytics and is a resident physician at Massachusetts General Hospital. Dr. Ackerly was formerly the associate medical director for Population Health and Continuing Care at Partners HealthCare and an Innovation Advisor to the Center for Medicare & Medicaid Innovation. He currently serves as the Chief Clinical Officer of naviHealth. Dr. Gottlieb was formerly the President and Chief Executive Officer of Partners HealthCare and currently serves as the Chief Executive Officer of Partners In Health. The views represented here are those of the authors' and do not represent the views of Partners HealthCare, Massachusetts General Hospital, naviHealth, or Partners In Health.

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) triumphantly announced in January 2016 that 121 new participants had joined 1 of its 3 accountable care organization (ACO) programs, and that the various ACOs had together saved the federal government $411 million in 2014 while improving on various quality metrics.[1] Yet even as the ACO model has gathered political momentum and shown promise in reducing payer spending in the short term, it is facing growing scrutiny that it may be insufficient to support meaningful care delivery transformation.

Different ACO models differ in their financial details, but the fundamental theme is the same: healthcare organizations earn bonuses, or shared savings, if they bill payers less than their projected fee‐for‐service revenue (known as the spending benchmark) and meet quality measures. In double‐sided ACO models, if fee‐for‐service revenue exceeds the benchmark, ACOs are also fined. In contrast with traditional fee‐for‐service, in which payments are tied directly to price and volume of services, ACOs were envisioned as a business model that would enable health systems to thrive by improving the care efficiency and clinical outcomes of their patient populations.

However, because health systems only earn shared savings bonuses if they reduce their fee‐for‐service revenue, ACOs do not have a clear business case for moving toward value‐oriented care. ThedaCare, the best performing Pioneer ACO in the first year of the program, reported that successful reduction of preventable hospital admissions led to shared savings payments. However, those payments did not cover the reduced fee‐for‐service revenue, leading to diminished overall financial performance.[2] Only 5% of the 434 Shared Savings Program ACOs have agreed to double‐sided contracts, suggesting discomfort with the structure of the model.[1] Although ACOs have continued to grow in overall number, the programs have experienced significant churn, with over two thirds of Pioneer ACOs leaving over the last 3 years. This suggests widespread commitment to the principle of population health but a struggle by health systems to make the specific models financially viable.[3]

How can payers reshape the ACO model to better support value‐oriented care delivery transformation while maintaining its key cost control elements? One strategy is for CMS to establish a pathway for adding care delivery interventions to the fee‐for‐service schedule for ACOs, a concept we call population health billing. Payers have shown some interest in supporting population health efforts via fee‐for‐service: for example, in 2015 CMS established the chronic care management fee, which pays a per patient per month fee for care coordination of Medicare beneficiaries with 2 or more chronic conditions, and the transitional care management fee, which reimburses a postdischarge office visit focused on managing a patient's transition out of the hospital.[4] UnitedHealthcare has begun reimbursing virtual physician visits for some self‐insured employers.[5]

These isolated efforts should be rolled up into a systematic pathway for population health interventions to become billable under fee‐for‐service for organizations in Medicare ACO contracts. CMS and institutional provider associations, whose technical committees generate the majority of billing codes, could together adopt a formal set of criteria to grade the evidence basis of population health interventions in terms of their impact on clinical outcomes, care quality, and care value, similar to the National Quality Forum's work with quality metrics, and establish a formal process by which interventions with demonstrated efficacy can be assigned billing values in a timely, rigorous, and transparent manner. Candidates for population health billing codes could include high‐risk case management, virtual visits, and home‐based primary care. ACOs would be free to determine which, if any, particular interventions to adopt.

ACOs must currently invest in population health programs with out‐of‐pocket funds and bet that reductions in preventable healthcare utilization result in sufficient shared savings to compensate for both program costs and lost fee‐for‐service profit. Even clinically successful programs are often unable to reach this high threshold.[6] A recent New England Journal of Medicine article lamented a common theme among studies of population health interventions: clinical success, but financial unsustainability.[7] CMS' Comprehensive Primary Care Initiative, which provides about 500 primary care practices with case management fees to redesign their care delivery, resulted in a reduced volume of primary care visits and improved patient communication but no cost savings to Medicare after accounting for program fees (14). Congressional analysis found that although case management programs with substantial physician interaction reduced Medicare expenditures by an average of 6%, only 1 out of 34 programs achieved statistically significant savings to Medicare relative to their program fees alone.[8] E‐consults, when a specialist physician provides recommendations to a primary doctor by reviewing a patient's chart electronically, are associated with decreased wait times, high primary provider satisfaction, and lower costs compared to traditional care, yet adoption among ACOs has been limited by the opportunity cost of fee‐for‐service revenue.[9] In reducing Medicare costs and hence their own fee‐for‐service revenue by $300 million in their first year, Pioneer ACOs were only collectively granted bonuses of about $77 million against the significant operating and capital costs of population health.[10] The financial challenges of ACOs are a reflection of the difficulty in consistently developing a fiscally and clinically successful set of population health interventions under current ACO financial rules.

In Figure 1, we use high‐risk case management as an example to demonstrate how population billing could work. Population health billing could provide a per patient, per month fee‐for‐service payment to ACOs for high‐risk case management services. This payment would count against ACOs' spending benchmarks at the end of the year. By helping cover the operating costs of these programs, population health billing would make value‐oriented interventions significantly more sustainable compared to the current ACO models.

In providing fee‐for‐service revenue for population health interventions, population health billing would break the inherent tension between fee‐for‐service and shared savings bonuses. It would allow ACOs to transition ever‐greater portions of revenue from traditional transactional‐based sources toward shared savings, without requiring success in accountable care to mean fee‐for‐service losses. This is an important threshold for operational leaders who must integrate population health, which currently represent loss centers on balance sheets, within existing profitable fee‐for‐service business lines.

Some observers may argue that allowing billable care delivery interventions may encourage practices to roll out interventions that meet billing requirements but have little meaningful impact on population health; the efficacy of care delivery interventions is clearly dependent on the context of the health system and quality of execution. This concern is the same fundamental concern of fee‐for‐service reimbursement as a whole. However, because ACOs are paid bonuses for reducing fee‐for‐service revenue, they would have an incentive to only develop and bill for population health interventions they believe would have a meaningful return on investment in reducing healthcare costs. The fundamental incentives of ACOs would remain the same‐ to reduce healthcare spending by better managing the costs of their patient populations. Others may argue that population health billing would build upon our fee‐for‐service system that many have advocated we must move past. But ACO initiatives and bundled payments are similarly built upon a foundation of fee‐for‐service.

Whereas a greater number of billable services will likely reduce CMS' short‐term savings from ACO programs, the ACO model must offer a sustainable business case for care delivery reform to ultimately bend long‐term healthcare costs. Payers are not obligated to ensure that providers maintain historical income levels, but over the long term providers will not make the sizable infrastructure investments, such as integrated information technology platforms, data analytics, and risk management, required to deliver value‐based care without a sustainable business case. To limit the costs of population health billing, Medicare should restrict it to ACO contracts that allow for penalties. The fee‐for‐service reimbursement rates under population health billing could also be tied to performance on quality metrics, similar to how Medicare fee‐for‐service hospital reimbursement is linked to performance on value‐based metrics.[13]

In addition, this reduction in short‐term cost savings may actually improve the sustainability of the ACO model. Every year, each ACO's spending benchmark is re‐based, or recalculated based on the most recent spending data. This means that ACOs that successfully reduce their fee‐for‐service revenue below their spending benchmark will face an even lower benchmark the next year and have to reduce their costs even further, creating an unsustainable trend. Because population health billing would count against the spending benchmark, it would help slow down this race to the bottom while driving forward value‐oriented care delivery transformation.

ACOs have a number of other design problems, including high rates of patient churn, imperfect quality metrics that do not adequately capture the scope of population‐level health, and lags in data access.[14] The Next Generation ACO model addresses some of these concerns. For example, it allows ACOs to prospectively define their patient populations. Yet many challenges remain. Population health billing does not solve all of these problems, but it will improve the ability of health systems to meaningfully pivot toward a value‐oriented strategy.

As physicians and ACO operational leaders, we believe in the clinical and policy vision behind the ACO model but have also struggled with the limitations of the model to meaningfully support care delivery transformation. If CMS truly wants to meaningfully transform US healthcare from volume‐based to value‐based, it must invest in the needed care redesign even at the expense of short‐term cost savings.

Disclosures: Dr. Chen was formerly a consultant for Partners HealthCare, a Pioneer ACO, and a physician fellow on the Pioneer ACO Team at the Center for Medicare & Medicaid Innovation. He currently serves on the advisory board of Radial Analytics and is a resident physician at Massachusetts General Hospital. Dr. Ackerly was formerly the associate medical director for Population Health and Continuing Care at Partners HealthCare and an Innovation Advisor to the Center for Medicare & Medicaid Innovation. He currently serves as the Chief Clinical Officer of naviHealth. Dr. Gottlieb was formerly the President and Chief Executive Officer of Partners HealthCare and currently serves as the Chief Executive Officer of Partners In Health. The views represented here are those of the authors' and do not represent the views of Partners HealthCare, Massachusetts General Hospital, naviHealth, or Partners In Health.

- U.S. Department of Health 310:1341–1342.

- , , , . Performance differences in year 1 of the Pioneer accountable care organizations. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:1927–1936.

- , , , , . Medicare chronic care management payments and financial returns to primary care practice: a modeling study. Ann Intern Med. 2015;163:580–588.

- UnitedHealthcare. UnitedHealthcare covers virtual care physician visits, expanding consumers' access to affordable health care options. Available at: http://www.uhc.com/news‐room/2015‐news‐release‐archive/unitedhealthcare‐covers‐virtual‐care‐physician‐visits. Published April 30, 2015. Accessed February 6, 2016.

- , , . Toward increased adoption of complex care management. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:491–493.

- , , . Asymmetric thinking about return on investment. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(7):606–608.

- . Lessons from Medicare's demonstration projects on disease management and care coordination. Washington, D.C.: Congressional Budget Office, Health and Human Resources Division, working paper 2012‐01, 2012. Available at: http://www.cbo.gov/sites/default/files/cbofiles/attachments/WP2012‐01_Nelson_Medicare_DMCC_Demonstrations.pdf. Published January 2012. Accessed June 15, 2015.

- , , , . A safety‐net system gains efficiencies through ‘eReferrals’ to specialists. Health Aff (Millwood). 2010;29:969–971.

- Centers for Medicare MGH Medicare Demonstration Project for High-Cost Beneficiaries. Available at: http://www.massgeneral.org/News/assets/pdf/CMS_project_phase1FactSheet.pdf. Accessed April 2, 2016.

- , , , et al. Two-Year Costs and Quality in the Comprehensive Primary Care Initiative. N Engl J Med. 2016; DOI: 10.1056/NEJMsa1414953.

- , . Beyond ACOs and bundled payments: Medicare's shift toward accountability in fee‐for‐service. JAMA. 2014;311:673–674.

- , , , , . ACO model should encourage efficient care delivery. Healthc (Amst). 2015;3(3):150–152.

- U.S. Department of Health 310:1341–1342.

- , , , . Performance differences in year 1 of the Pioneer accountable care organizations. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:1927–1936.

- , , , , . Medicare chronic care management payments and financial returns to primary care practice: a modeling study. Ann Intern Med. 2015;163:580–588.

- UnitedHealthcare. UnitedHealthcare covers virtual care physician visits, expanding consumers' access to affordable health care options. Available at: http://www.uhc.com/news‐room/2015‐news‐release‐archive/unitedhealthcare‐covers‐virtual‐care‐physician‐visits. Published April 30, 2015. Accessed February 6, 2016.

- , , . Toward increased adoption of complex care management. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:491–493.

- , , . Asymmetric thinking about return on investment. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(7):606–608.

- . Lessons from Medicare's demonstration projects on disease management and care coordination. Washington, D.C.: Congressional Budget Office, Health and Human Resources Division, working paper 2012‐01, 2012. Available at: http://www.cbo.gov/sites/default/files/cbofiles/attachments/WP2012‐01_Nelson_Medicare_DMCC_Demonstrations.pdf. Published January 2012. Accessed June 15, 2015.

- , , , . A safety‐net system gains efficiencies through ‘eReferrals’ to specialists. Health Aff (Millwood). 2010;29:969–971.

- Centers for Medicare MGH Medicare Demonstration Project for High-Cost Beneficiaries. Available at: http://www.massgeneral.org/News/assets/pdf/CMS_project_phase1FactSheet.pdf. Accessed April 2, 2016.

- , , , et al. Two-Year Costs and Quality in the Comprehensive Primary Care Initiative. N Engl J Med. 2016; DOI: 10.1056/NEJMsa1414953.

- , . Beyond ACOs and bundled payments: Medicare's shift toward accountability in fee‐for‐service. JAMA. 2014;311:673–674.

- , , , , . ACO model should encourage efficient care delivery. Healthc (Amst). 2015;3(3):150–152.

Post-Discharge Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus Infections: Epidemiology and Potential Approaches to Control

From the Division of Adult Infectious Diseases, University of Colorado Denver, Aurora, CO, and the Department of Veterans Affairs, Eastern Colorado Healthcare System, Denver, CO.

Abstract

- Objective: To review the published literature on methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) infections among patients recently discharged from hospital, with a focus on possible prevention measures.

- Methods: Literature review.

- Results: MRSA is a major cause of post-discharge infections. Risk factors for post-discharge MRSA include colonization, dependent ambulatory status, duration of hospitalization > 5 days, discharge to a long-term care facility, presence of a central venous catheter (CVC), presence of a non-CVC invasive device, a chronic wound in the post-discharge period, hemodialysis, systemic corticosteroids, and receiving anti-MRSA antimicrobial agents. Potential approaches to control include prevention of incident colonization during hospital stay, removal of nonessential CVCs and other devices, good wound debridement and care, and antimicrobial stewardship. Hand hygiene and environmental cleaning are horizontal measures that are also recommended. Decolonization may be useful in selected cases.

- Conclusion: Post-discharge MRSA infections are an important and underestimated source of morbidity and mortality. The future research agenda should include identification of post-discharge patients who are most likely to benefit from decolonization strategies, and testing those strategies.

Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) is a leading cause of morbidity and mortality due to infections of the bloodstream, lung, surgical sites, bone, and skin and soft tissues. The mortality associated with S. aureus bloodstream infections is 14% to 45% [1–4]. A bloodstream infection caused by MRSA is associated with a twofold increased mortality as compared to one caused by methicillin-sensitive S. aureus [5]. MRSA pneumonia carries a mortality of 8%, which increases to 39% when bacteremia is also present [6]. S. aureus bloodstream infection also carries a high risk of functional disability, with 65% of patients in a recent series requiring nursing home care in the recovery period [7]. In 2011 there were more than 11,000 deaths due to invasive MRSA infection in the United States [8]. Clearly S. aureus, and particularly MRSA, is a pathogen of major clinical significance.

Methicillin resistance was described in 1961, soon after methicillin became available in the 1950s. Prevalence of MRSA remained low until the 1980s, when it rapidly increased in health care settings. The predominant health care–associated strain in the United States is USA100, a member of clonal complex 5. Community-acquired MRSA infection has garnered much attention since it was recognized in 1996 [9]. The predominant community-associated strain has been USA300, a member of clonal complex 8 [10]. Following its emergence in the community, USA300 became a significant health care–associated pathogen as well [11]. The larger share of MRSA disease remains health care–associated [8]. The most recent data from the Center for Disease Control and Prevention Active Bacterial Core Surveillance system indicate that 77.6% of invasive MRSA infection is health care–associated, resulting in 9127 deaths in 2011 [8].

This article reviews the published literature on MRSA infections among patients recently discharged from hospital, with a focus on possible prevention measures.

MRSA Epidemiologic Categories

Epidemiologic investigations of MRSA categorize infections according to the presumed acquisition site, ie, in the community or in a health care setting. Older literature refers to nosocomial MRSA infection, which is now commonly referred to as hospital-onset health care–associated (HO-HCA) MRSA. A common definition of HO-HCA MRSA infection is an infection with the first positive culture on hospital day 4 or later [12]. Community-onset health care–associated MRSA (CO-HCA MRSA) is defined as infection that is diagnosed in the outpatient setting, or prior to day 4 of hospitalization, in a patient with recent health care exposure, eg, hospitalization within the past year, hemodialysis, surgery, or presence of a central venous catheter at time of presentation to the hospital [12]. Community-associated MRSA (CA-MSRSA) is infection in patients who do not meet criteria for either type of health care associated MRSA. Post-discharge MRSA infections would be included in the CO-HCA MRSA group.

Infection Control Programs

Classic infection control programs, developed in the 1960s, focused on infections that presented more than 48 to 72 hours after admission and prior to discharge from hospital. In that era, the average length of hospital stay was 1 week or more, and there was sufficient time for health care–associated infections to become clinically apparent. In recent years, length of stay has progressively shortened [13]. As hospital stays shortened, the risk that an infection caused by a health care–acquired pathogen would be identified after discharge grew. More recent studies have documented that the majority of HO-HCA infections become apparent after the index hospitalization [8,14].

Data from the Active Bacterial Core Surveillance System quantify the burden of CO-HCA MRSA disease at a national level [8,14]. However, it is not readily detected by many hospital infection surveillance programs. Avery et al studied a database constructed with California state mandated reports of MRSA infection and identified cases with MRSA present on admission. They then searched for a previous admission, within 30 days. If a prior admission was identified, the MRSA case was assigned to the hospital that had recently discharged the patient. Using this approach, they found that the incidence of health care–associated MRSA infection increased from 12.2 cases/10,000 admissions when traditional surveillance methods were used to 35.7/10,000 admissions using the revised method of assignment of health care exposure [15]. These data suggest that post-discharge MRSA disease is underappreciated by hospital infection control programs.

Lessons from Hospital-Onset MRSA

The morbidity and mortality associated with MRSA have led to the development of vigorous infection control programs to reduce the risk of health care–associated MRSA infection [16–18]. Vertical infection control strategies, ie, those focused on MRSA specifically, have included active screening for colonization, and nursing colonized patients in contact precautions. Since colonization is the antecedent to infection in most cases, prevention of transmission of MRSA from patient to patient should prevent most infections. There is ample evidence that colonized patients contaminate their immediate environment with MRSA, creating a reservoir of resistant pathogens that can be transmitted to other patients on the hands and clothing of health care workers [19,20]. Quasi-experimental studies of active screening and isolation strategies have shown decreases in MRSA transmission and infection following implementation [18]. The only randomized comparative trial of active screening and isolation versus usual care did not demonstrate benefit, possibly due to delays in lab confirmation of colonization status [21]. Horizontal infection control strategies are applied to all patients, regardless of colonization with resistant pathogens, in an attempt to decrease health care–associated infections with all pathogens. Examples of horizontal strategies are hand hygiene, environmental cleaning, and the prevention bundles for central line–associated bloodstream infection.

The Burden of Community-Onset MRSA

CO-HCA MRSA represents 60% of the burden of invasive MRSA infection [8]. While this category includes cases that have not been hospitalized, eg, patients on hemodialysis, post-discharge MRSA infection accounts for the majority of cases [15]. Recent data indicate that the incidence of HO-HCA MRSA decreased 54.2% between 2005 and 2011 [8]. This decrease in HO-HCA MRSA infection occurred concurrently with widespread implementation of vigorous horizontal infection control measures, such as bundled prevention strategies for central line–associated bloodstream infection and ventilator-associated pneumonia. The decline in CO-HCA MRSA infection has been much less steep, at 27.7%. The majority of the CO-HCA infections are in post-discharge patients. Furthermore, the incidence of CO-HCA MRSA infection may be underestimated [15].

Post-Discharge MRSA Colonization and Infection

Hospital-associated MRSA infection is reportable in many jurisdictions, but post-discharge MRSA infection is not a specific reportable condition, limiting the available surveillance data. Avery et al [15] studied ICD-9 code data for all hospitals in Orange County, California, and found that 23.5/10,000 hospital admissions were associated with a post-discharge MRSA infection. This nearly tripled the incidence of health care–associated MRSA infection, compared to surveillance that included only hospital-onset cases. Future research should refine these observations, as ICD-9 code data correlate imperfectly with chart reviews and have not yet been well validated for MRSA research.

The CDC estimated that in 2011 there were 48,353 CO-HCA MRSA infections resulting in 10,934 deaths. This estimate is derived from study of the Active Bacterial Core surveillance sample [8]. In that sample, 79% of CO-HCA MRSA infections occurred in patients hospitalized within the last year. Thus, we can estimate that there were 34,249 post-discharge MRSA infections resulting in 8638 deaths in the United States in 2011.

MRSA colonization is the antecedent to infection in the majority of cases [22]. Thus we can assess the health care burden of post-discharge MRSA by analyzing colonization as well as infection. Furthermore, the risk of MRSA colonization of household members can be addressed. Lucet et al evaluated hospital inpatients preparing for discharge to a home health care setting, and found that 12.7% of them were colonized with MRSA at the time of discharge, and 45% of them remained colonized for more than a year [23]. Patients who regained independence in activities of daily living were more likely to become free of MRSA colonization. The study provided no data on the risk of MRSA infection in the colonized patients. 19.1% of household contacts became colonized with MRSA, demonstrating that the burden of MRSA extends beyond the index patient. None of the colonized household contacts developed MRSA infection during the study period.

Risk Factors for Post-Discharge MRSA

Case control studies of patients with post-discharge invasive MRSA have shed light on risk factors for infection. While many risk factors are not modifiable, these studies may provide a road map to development of prevention strategies for the post-discharge setting. A study of hospitals in New York that participated in the Active Bacterial Core surveillance system identified a statistically significant increased risk of MRSA invasive infection among patients with several factors associated with physical disability, including a physical therapy evaluation, dependent ambulatory status, duration of hospitalization > 5 days, and discharge to a long-term care facility. Additional risk factors identified in the bivariate analysis were presence of a central venous catheter, hemodialysis, systemic corticosteroids, and receiving anti-MRSA antimicrobial agents. When subjected to multivariate analysis, however, the most significant and potent risk factor was a previous positive MRSA clinical culture (matched odds ratio 23, P < 0.001). Other significant risk factors in the multivariate analysis were hemodialysis, presence of a central venous catheter in the outpatient setting, and a visit to the emergency department [24]. A second, larger, multistate study also based on data from the Active Bacterial Core surveillance system showed that 5 risk factors were significantly associated with post-discharge invasive MRSA infection: (1) MRSA colonization, (2) a central venous catheter (CVC) present at discharge, (3) presence of a non-CVC invasive device, (4) a chronic wound in the post-discharge period, and (5) discharge to a nursing home. MRSA colonization was associated with a 7.7-fold increased odds of invasive MRSA infection, a much greater increase than any of the other risk factors [25]. Based on these results, strategies to consider include enhanced infection measures for prevention of incident MRSA colonization in the inpatient setting, decolonization therapy for those who become colonized, removal of non-essential medical devices, including central venous catheters, excellent nursing care for essential devices and wounds, hand hygiene, environmental cleaning, and antimicrobial stewardship.

Development of Strategies to Decrease Post-Discharge MRSA

While the epidemiology of post-discharge health care–associated MRSA infections has become a topic of interest to researchers, approaches to control are in their infancy. Few of the approaches have been subjected to rigorous study in the post-discharge environment. Nevertheless, some low risk, common sense strategies may be considered. Furthermore, an outline of research objectives may be constructed.

Prevention of Colonization in the Inpatient Setting

Robust infection control measures must be implemented in inpatient settings to prevent incident MRSA colonization [16,17]. Key recommendations include surveillance and monitoring of MRSA infections, adherence to standard hand hygiene guidance, environmental cleanliness, and use of dedicated equipment for patients who are colonized or infected with MRSA. Active screening for asymptomatic MRSA carriage and isolation of carriers may be implemented if routine measures are not successful.

Decolonization

Despite the best infection control programs, some patients will be colonized with MRSA at the time of hospital discharge. As detailed above, MRSA colonization is a potent risk factor for infection in the post-discharge setting, as well as in hospital inpatients [22]. A logical approach to this would be to attempt to eradicate colonization. There are several strategies for decolonization therapy, which may be used alone or in combination, including nasal mupirocin, nasal povidone-iodine, systemic antistaphylococcal drugs alone or in combination with oral rifampin, chlorhexidine bathing, or bleach baths [26–29].

A preliminary step in approaching the idea of post-discharge decolonization therapy is to show that patients can be successfully decolonized. With those data in hand, randomized trials seeking to demonstrate a decrease in invasive MRSA infections can be planned. Decolonization using nasal mupirocin has an initial success rate of 60% to 100% in a variety of patient populations [30–35]. Poor adherence to the decolonization protocol may limit success in the outpatient setting. Patients are more likely to resolve their MRSA colonization spontaneously when they regain their general health and independence in activities of daily living [23]. Colonization of other household members may provide a reservoir of MRSA leading to recolonization of the index case. Treatment of the household members may be offered, to provide more durable maintenance of the decolonized state [35]. When chronically ill patients who have been decolonized are followed longitudinally, up to 39% become colonized again, most often with the same strain [30,31]. Attempts to maintain a MRSA-free state in nursing home residents using prolonged mupirocin therapy resulted in emergence of mupirocin resistance [31]. Thus decolonization can be achieved, but is difficult to maintain, especially in debilitated, chronically ill patients. Mupirocin resistance can occur, limiting success of decolonization therapies.

Successful decolonization has been proven to reduce the risk of MRSA infection in the perioperative, dialysis, and intensive care unit settings [33,36–38]. In dialysis patients the risk of S. aureus bloodstream infection, including MRSA, can be reduced 59% with the use of mupirocin decolonization of the nares, with or without treatment of dialysis access exit sites [37]. A placebo-controlled trial demonstrated that decolonization of the nares with mupirocin reduced surgical site infections with S. aureus. All S. aureus isolates in the study were methicillin-susceptible. A second randomized controlled trial of nasal mupirocin did not achieve a statistically significant decrease in S. aureus surgical site infections, but it showed that mupirocin decolonization therapy decreased nosocomial S. aureus infections among nasal carriers [33]. 99.2% of isolates in that study et al were methicillin-susceptible. Quasi-experimental studies have shown similar benefits for surgical patients who are colonized with MRSA [39–41]. A more recent randomized trial, in ICU patients, demonstrated decreased incidence of invasive infection in patients treated with nasal mupirocin and chlorhexidine baths [38]. The common themeof these studies is that they enrolled patients who had a short-term condition, eg, surgery or critical illness, placing them at high risk for invasive MRSA infection. This maximizes the potential benefit of decolonization and minimizes the risk of emergence of resistance. Furthermore, adherence to decolonization protocols is likely to be high in the perioperative and ICU settings. To extrapolate the ICU and perioperative data to the post-discharge setting would be imprudent.

In summary, decolonization may be a useful strategy to reduce invasive MRSA infection in post-discharge patients, but more data are needed for most patient populations. The evidence for decolonization therapy is strongest for dialysis patients, in whom implementation of routine decolonization of MRSA colonized nares is a useful intervention [37]. There are not yet clinical trials of decolonization therapy in patients at time of hospital discharge showing a reduction in invasive MRSA infection. Decolonization strategies have important drawbacks, including emergence of resistance to mupirocin, chlorhexidine, and systemic agents. Furthermore, there is a risk of hypersensitivity reactions, Clostridium difficile infection, and potential for negative impacts onthe normal microbiome. The potential for lesser efficacy in a chronically ill outpatient population must also be considered in the post-discharge setting. Randomized controlled trials with invasive infection outcomes should be performed prior to implementing routine decolonization therapy of hospital discharge patients.

Care of Invasive Devices

Discharge with a central venous catheter was associated with a 2.16-fold increased risk of invasive MRSA infection; other invasive devices were associated with a 3.03-fold increased risk [25]. Clinicians must carefully assess patients nearing discharge for any opportunity to remove invasive devices. Idle devices have been reported in inpatient settings [42] and could occur in other settings. Antimicrobial therapy is a common indication for an outpatient central venous catheter and can also be associated with increased risk of invasive MRSA infection [25,43]. Duration and route of administration of antimicrobial agents should be carefully considered, with an eye to switching to oral therapy whenever possible. When a central venous catheter must be utilized, it should be maintained as carefully as in the inpatient setting. Tools for reducing risk of catheter-associated bloodstream infection include keeping the site dry, scrubbing the hub whenever accessing the catheter, aseptic techniques for dressing changes, and chlorhexidine sponges at the insertion site [44,45]. Reporting of central line–associated bloodstream infection rates by home care agencies is an important quality measure.

Wound Care

The presence of a chronic wound in the post-discharge period is associated with a 4.41-fold increased risk of invasive MRSA infection [25]. Although randomized controlled trials are lacking, it is prudent to ensure that wounds are fully debrided to remove devitalized tissue that can be fertile ground for a MRSA infection. The burden of organisms on a chronic wound is often very large, creating high risk of resistance when exposed to antimicrobial agents. Decolonization therapy is not likely to meet with durable success in such cases and should probably be avoided, except in special circumstances, eg, in preparation for cardiothoracic surgery.

Infection Control in Nursing Home Settings

In the Active Bacterial Core cohort, discharge to a nursing home was associated with a 2.1- to 2.65-fold increased risk of invasive MRSA infection [24,25]. It is notable that the authors controlled for the Charlson comorbidity index, suggesting that nursing home care is more than a marker for comorbidity [25]. The tension between the demands of careful infection control and the home-like setting that is desirable for long-term care creates challenges in the prevention of invasive MRSA infection. Nevertheless, careful management of invasive devices and wounds and antimicrobial stewardship are strategies that may reduce the risk of invasive MRSA infection in long-term care settings. Contact precautions for colonized nursing home residents are recommended only during an outbreak [46]. Staff should be trained in proper application of standard precautions, including use of gowns and gloves when handling body fluids. A study of an aggressive program of screening, decolonization with nasal mupirocin and chlorhexidine bathing, enhanced hand hygiene and environmental cleaning demonstrated a significant reduction in MRSA colonization [47]. An increase in mupirocin resistance during the study led to a switch to retapamulin for nasal application. The Association of Practitioners of Infection Control has issued guidance for MRSA prevention in long-term care facilities [48]. The guidance focuses on surveillance for MRSA infection, performing a MRSA risk assessment, hand hygiene, and environmental cleaning.

Antimicrobial Stewardship

Antimicrobial therapy, especially with fluoroquinolones and third- or fourth-generation cephalosporins, is associated with increased risk of MRSA colonization and infection [43,49,50]. Implementation of an antimicrobial stewardship program, coupled with infection control measures, in a region of Scotland resulted in decreased incidence of MRSA infections among hospital inpatients and in the surrounding community [51]. Thus a robust antimicrobial stewardship program is likely to reduce post-discharge MRSA infections.

Role of Hand Hygiene

The importance of hand hygiene in the prevention of infection has been observed for nearly 2 centuries [52]. Multiple quasi-experimental studies have demonstrated a decreased infection rate when hand hygiene practices for health care workers were introduced or strengthened. A randomized trial in a newborn nursery documented a decrease in transmission of S. aureus when nurses washed their hands after handling a colonized infant [53]. In addition to health care providers, patient hand hygiene can reduce health care–associated infections [54]. Traditional handwashing with soap and water will be familiar to most patients and families. Waterless hand hygiene, typically using alcohol-based hand rubs, is more efficacious and convenient for cleaning hands that are not visibly soiled [52]. If products containing emollients are used, it can also reduce skin drying and cracking. Patients and families should be taught to wash their hands before and after manipulating any medical devices and caring for wounds. Education of patients and family members on the techniques and importance of hand hygiene during hospitalization and at the time of discharge is a simple, low-cost strategy to reduce post-discharge MRSA infections. Teaching can be incorporated into the daily care of patients by nursing and medical staff, both verbally and by example. As a horizontal infection control measure, hand hygiene education has the additional benefit of reducing infections due to all pathogens.

Role of Environmental Cleaning in the Home Setting

Multiple studies have found that the immediate environment of patients who are colonized or infected with MRSA is contaminated with the organism, with greater organism burdens associated with infected patients compared to those who are only colonized [55–59]. Greater environmental contamination is observed when MRSA is present in the urine or wounds of patients [59]. This can lead to transmission of MRSA to family members [23,60,61]. Risk factors for transmission include participation in the care of the patient, older age, and being the partner of the case patient. For the patient, there can be transmission to uninfected body sites and a cycle of recolonization and re-infection. Successful decolonization strategies have included frequent laundering of bedclothes and towels, as well as screening and decolonization of family members. While these strategies may succeed in decolonization, there is no consensus on efficacy in preventing infection in patients or family members. More research in this area is needed, particularly for decolonization strategies, which carry risk of resistance. Attention to cleanliness in the home is a basic hygiene measure that can be recommended.

Conclusion

Post-discharge MRSA infections are an important and underestimated source of morbidity and mortality. Strategies for prevention include infection control measures to prevent incident colonization during hospitalization, removal of any nonessential invasive devices, nursing care for essential devices, wound care, avoiding nonessential antimicrobial therapy, hand hygiene for patients and caregivers, and cleaning of the home environment. Decolonization therapies currently play a limited role, particularly in outbreak situations. The future research agenda should include identification of post-discharge patients who are most likely to benefit from decolonization strategies, and testing those strategies.

Corresponding author: Mary Bessesen, MD, InfectiousDiseases (111L), 1055 Clermont St., Denver, CO 80220, [email protected].

1. Chen SY, Wang JT, Chen TH et al. Impact of traditional hospital strain of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) and community strain of MRSA on mortality in patients with community-onset S aureus bacteremia. Medicine 2010;89:285–94.

2. Lahey T, Shah R, Gittzus J,et al. Infectious diseases consultation lowers mortality from Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia. Medicine 2009;88:263–7.

3. Chang FY, MacDonald BB, Peacock JE Jr, et al. A prospective multicenter study of Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia: incidence of endocarditis, risk factors for mortality, and clinical impact of methicillin resistance. Medicine 2003;82:322–32.

4. Blot SI, Vandewoude KH, Hoste EA, Colardyn FA. Outcome and attributable mortality in critically Ill patients with bacteremia involving methicillin-susceptible and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Arch Intern Med 2002;162:2229–35.

5. Cosgrove SE, Sakoulas G, Perencevich EN, et al. Comparison of mortality associated with methicillin-resistant and methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia: a meta-analysis. Clin Infect Dis 2003;36:53–9.

6. Schreiber MP, Chan CM, Shorr AF. Bacteremia in Staphylococcus aureus pneumonia: outcomes and epidemiology. J Crit Care 2011;26:395–401.

7. Malani PN, Rana MM, Banerjee M, Bradley SF. Staphylococcus aureus bloodstream infections: the association between age and mortality and functional status. J Am Geriatr Soc 2008;56:1485–9.

8. Dantes RM, Mu YP, Belflower RR, et al. National burden of invasive methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections, United States, 2011. JAMA Intern Med 2013;173:1970–8.

9. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Four pediatric deaths from community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus - Minnesota and North Dakota, 1997-1999. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 1999;48:707–10.

10. Diep BA, Carleton HA, Chang RF, et al. Roles of 34 virulence genes in the evolution of hospital- and community-associated strains of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. J Infect Dis 2006;193:1495–503.