User login

Webcast: Factors that contribute to overall contraceptive efficacy and risks

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

Access Dr. Burkman's Webcasts on contraception:

- Obesity and contraceptive efficacy and risks

- How to use the CDC's online tools to manage complex cases in contraception

Helpful resource for your practice:

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

Access Dr. Burkman's Webcasts on contraception:

- Obesity and contraceptive efficacy and risks

- How to use the CDC's online tools to manage complex cases in contraception

Helpful resource for your practice:

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

Access Dr. Burkman's Webcasts on contraception:

- Obesity and contraceptive efficacy and risks

- How to use the CDC's online tools to manage complex cases in contraception

Helpful resource for your practice:

ISC: Cryptogenic stroke linked to PSVT in absence of atrial fibrillation

LOS ANGELES – Paroxysmal supraventricular tachycardia is associated with subsequent ischemic stroke in patients without documented atrial fibrillation, according to a claims analysis of 42,152 Medicare enrollees at least 66 years old.

Atrial fibrillation accounts for perhaps 30% of cryptogenic strokes, “so clearly there’s something more to the story than just atrial fibrillation in” the other 70%, said investigator Dr. Hooman Kamel, a neurologist at Weill Cornell Medical College, New York. “Most cryptogenic strokes seem like they are embolic. The question is what are the undiscovered sources of embolism?”

Dr. Kamel and his colleagues focused on paroxysmal supraventricular tachycardia (PSVT) even though it’s generally considered benign. But “PSVT is increasingly recognized as a marker for underlying atrial dysfunction, especially in older patients. In some cases, the abnormal atrial substrate could cause thromboembolism even before atrial fibrillation [AF] appears,” he said at the International Stroke Conference.

To ensure regular heart rhythm monitoring, the study was limited to patients with implanted pacemakers or defibrillators. Patients with AF or stroke before or at the time of device implantation were excluded.

After a median of 1.8 years of follow-up, 2,245 patients (5.3%) were diagnosed with PSVT, and 1,007 (2.4%) had an ischemic stroke. The incidence of stroke without PSVT diagnosis was 0.95% per year, but 2.17% per year with a preceding PSVT diagnosis (P less than .001). Adjusting for age, gender, income, hypertension, diabetes, heart failure, and other potential confounders, the team found that a diagnosis of PSVT was associated with a doubling of ischemic stroke risk (HR, 2.0; 95% CI, 1.3-3.0), and an almost quadrupling of the risk for embolic stroke (HR, 3.6; 95% CI, 1.1-11.8).

“A lot more work needs to be done to nail this down, but potentially we are broadening the pool of atrial markers for stroke risk. These results build on recent findings that disturbances of atrial rhythm and function other than AF may” lead to stroke, Dr. Kamel said.

It’s way too soon to consider atrial ablation for PSVT to reduce stroke risk, he said, but his team is interrogating its administrative data for clues of its utility. “The idea of ablation for stroke is really interesting. I think ablation should help reduce the risk of stroke. It’s a really important question, and we don’t know the answer yet. There’s a lot more to be learned, [but] there does seem to be a definite progression from PSVT to AF,” Dr. Kamel said.

The National Institutes of Health funded the work. Dr. Kamel is a speaker for Genentech.

LOS ANGELES – Paroxysmal supraventricular tachycardia is associated with subsequent ischemic stroke in patients without documented atrial fibrillation, according to a claims analysis of 42,152 Medicare enrollees at least 66 years old.

Atrial fibrillation accounts for perhaps 30% of cryptogenic strokes, “so clearly there’s something more to the story than just atrial fibrillation in” the other 70%, said investigator Dr. Hooman Kamel, a neurologist at Weill Cornell Medical College, New York. “Most cryptogenic strokes seem like they are embolic. The question is what are the undiscovered sources of embolism?”

Dr. Kamel and his colleagues focused on paroxysmal supraventricular tachycardia (PSVT) even though it’s generally considered benign. But “PSVT is increasingly recognized as a marker for underlying atrial dysfunction, especially in older patients. In some cases, the abnormal atrial substrate could cause thromboembolism even before atrial fibrillation [AF] appears,” he said at the International Stroke Conference.

To ensure regular heart rhythm monitoring, the study was limited to patients with implanted pacemakers or defibrillators. Patients with AF or stroke before or at the time of device implantation were excluded.

After a median of 1.8 years of follow-up, 2,245 patients (5.3%) were diagnosed with PSVT, and 1,007 (2.4%) had an ischemic stroke. The incidence of stroke without PSVT diagnosis was 0.95% per year, but 2.17% per year with a preceding PSVT diagnosis (P less than .001). Adjusting for age, gender, income, hypertension, diabetes, heart failure, and other potential confounders, the team found that a diagnosis of PSVT was associated with a doubling of ischemic stroke risk (HR, 2.0; 95% CI, 1.3-3.0), and an almost quadrupling of the risk for embolic stroke (HR, 3.6; 95% CI, 1.1-11.8).

“A lot more work needs to be done to nail this down, but potentially we are broadening the pool of atrial markers for stroke risk. These results build on recent findings that disturbances of atrial rhythm and function other than AF may” lead to stroke, Dr. Kamel said.

It’s way too soon to consider atrial ablation for PSVT to reduce stroke risk, he said, but his team is interrogating its administrative data for clues of its utility. “The idea of ablation for stroke is really interesting. I think ablation should help reduce the risk of stroke. It’s a really important question, and we don’t know the answer yet. There’s a lot more to be learned, [but] there does seem to be a definite progression from PSVT to AF,” Dr. Kamel said.

The National Institutes of Health funded the work. Dr. Kamel is a speaker for Genentech.

LOS ANGELES – Paroxysmal supraventricular tachycardia is associated with subsequent ischemic stroke in patients without documented atrial fibrillation, according to a claims analysis of 42,152 Medicare enrollees at least 66 years old.

Atrial fibrillation accounts for perhaps 30% of cryptogenic strokes, “so clearly there’s something more to the story than just atrial fibrillation in” the other 70%, said investigator Dr. Hooman Kamel, a neurologist at Weill Cornell Medical College, New York. “Most cryptogenic strokes seem like they are embolic. The question is what are the undiscovered sources of embolism?”

Dr. Kamel and his colleagues focused on paroxysmal supraventricular tachycardia (PSVT) even though it’s generally considered benign. But “PSVT is increasingly recognized as a marker for underlying atrial dysfunction, especially in older patients. In some cases, the abnormal atrial substrate could cause thromboembolism even before atrial fibrillation [AF] appears,” he said at the International Stroke Conference.

To ensure regular heart rhythm monitoring, the study was limited to patients with implanted pacemakers or defibrillators. Patients with AF or stroke before or at the time of device implantation were excluded.

After a median of 1.8 years of follow-up, 2,245 patients (5.3%) were diagnosed with PSVT, and 1,007 (2.4%) had an ischemic stroke. The incidence of stroke without PSVT diagnosis was 0.95% per year, but 2.17% per year with a preceding PSVT diagnosis (P less than .001). Adjusting for age, gender, income, hypertension, diabetes, heart failure, and other potential confounders, the team found that a diagnosis of PSVT was associated with a doubling of ischemic stroke risk (HR, 2.0; 95% CI, 1.3-3.0), and an almost quadrupling of the risk for embolic stroke (HR, 3.6; 95% CI, 1.1-11.8).

“A lot more work needs to be done to nail this down, but potentially we are broadening the pool of atrial markers for stroke risk. These results build on recent findings that disturbances of atrial rhythm and function other than AF may” lead to stroke, Dr. Kamel said.

It’s way too soon to consider atrial ablation for PSVT to reduce stroke risk, he said, but his team is interrogating its administrative data for clues of its utility. “The idea of ablation for stroke is really interesting. I think ablation should help reduce the risk of stroke. It’s a really important question, and we don’t know the answer yet. There’s a lot more to be learned, [but] there does seem to be a definite progression from PSVT to AF,” Dr. Kamel said.

The National Institutes of Health funded the work. Dr. Kamel is a speaker for Genentech.

AT THE INTERNATIONAL STROKE CONFERENCE

Key clinical point: Paroxysmal supraventricular tachycardia could be an atrial marker for increased stroke risk when atrial fibrillation is not present, but additional research needs to confirm the finding.

Major finding: The incidence of stroke without PSVT diagnosis was 0.95% per year, but 2.17% per year with a preceding PSVT diagnosis (P less than .001).

Data source: Retrospective cohort of 42,152 Medicare enrollees.

Disclosures: The National Institutes of Health funded the work. The presenter is a speaker for Genentech.

In newly diagnosed hypertension with OSA, adding CPAP augmented the benefits of losartan

In patients with new-onset hypertension and obstructive sleep apnea, continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) therapy plus antihypertensive treatment with losartan led to reductions in systolic blood pressure beyond those achieved with losartan alone, a two-phase study found.

“Adding CPAP treatment to losartan may reduce blood pressure in a clinically relevant way if the patients are compliant with the device,” said Dr. Erik Thunström of the Sahlgrenska Academy at the University of Gothenburg, Sweden, and his associates.

In their open-label study, 89 men and women with new-onset untreated hypertension – 54 of whom were found to have obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) through a home sleep study and 35 of whom were determined to not have OSA – were treated for 6 weeks with losartan, 50 mg daily. Ambulatory 24-hour blood pressure monitoring was performed before and after treatment.

The patients with OSA were then randomized to receive 6 weeks of nightly add-on CPAP therapy or to continue losartan alone. Ambulatory 24-hour blood pressure monitoring was performed again.

Losartan alone reduced blood pressure in patients with hypertension and concomitant OSA, but the effect was smaller than that seen in patients without OSA. Statistically significant differences were seen in the mean net reduction in morning systolic blood pressure and morning mean arterial pressure. Overall, losartan appeared to be less effective at night and during the early morning hours in patients with OSA, the researchers reported.

After 6 weeks of losartan alone, a blood pressure less than 130/80 mm Hg was achieved by 12.5% of the patients with OSA and by 29% of the patients without OSA.

After 6 weeks of add-on CPAP therapy, 25% of patients with OSA achieved blood pressures less than 130/80 mm Hg. The differences in blood pressures for the OSA patients receiving CPAP plus losartan and those receiving losartan alone were 4.4 mm Hg for 24-hour systolic blood pressure, 1.9 mm Hg for diastolic, and 2.5 mm Hg for mean arterial pressure.

The most “robust” blood pressure changes were seen in the patients who used CPAP therapy for more than 4 hours every night, reducing the mean 24-hour systolic blood pressure by 6.5 mm Hg, the diastolic pressure by 3.8 mm Hg, and the mean arterial blood pressure by 4.6 mm Hg, the researchers reported (Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016 Feb.;193:310-20). “Adding CPAP to treatment with losartan reduced the mean 24-hour systolic blood pressure by 6.5 mm Hg in the subgroup of patients with OSA who were adherent with CPAP,” they wrote.

Patients included in the study all had a body mass index of 35 kg/m2; those with OSA had slightly higher BMIs that did not differ significantly from those without OSA.

That CPAP seems to have additive blood pressure–lowering effect when used concomitantly with losartan “favors the idea that it contributes to a further down-regulation of RAAS [renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system] activity in new-onset hypertension and OSA,” the authors wrote.

RAAS activity is often changed in hypertension, and in animal studies it has been shown to be up-regulated by intermittent hypoxia. Angiotensin II receptor antagonists are thus viewed as a good choice in the treatment of patients with OSA and new-onset hypertension, they wrote.

Treating OSA may make hypertension easier to address pharmacologically. The effect of CPAP on blood pressure is relatively small when all patients are considered but is more substantial and clinically important for those who use CPAP for more than 4 hours per night.

Can treatment of OSA effectively reduce blood pressure in an otherwise asymptomatic hypertensive patient with OSA? I believe the study would suggest that the answer remains “maybe.”

Most of the patients in the study would require a higher dose of losartan or an additional antihypertensive drug, even while using CPAP, to get to target blood pressures. Getting patients to use CPAP is a difficult task, as is adherence with any long-term pharmacologic management.

All in all, however, CPAP could contribute to blood pressure control while also improving quality of life and possibly reducing the risk for cardiovascular disease.

Dr. David P. White is with Harvard Medical School in Boston. His comments are excerpted from an accompanying editorial (Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016 Feb;193:238-9).

Treating OSA may make hypertension easier to address pharmacologically. The effect of CPAP on blood pressure is relatively small when all patients are considered but is more substantial and clinically important for those who use CPAP for more than 4 hours per night.

Can treatment of OSA effectively reduce blood pressure in an otherwise asymptomatic hypertensive patient with OSA? I believe the study would suggest that the answer remains “maybe.”

Most of the patients in the study would require a higher dose of losartan or an additional antihypertensive drug, even while using CPAP, to get to target blood pressures. Getting patients to use CPAP is a difficult task, as is adherence with any long-term pharmacologic management.

All in all, however, CPAP could contribute to blood pressure control while also improving quality of life and possibly reducing the risk for cardiovascular disease.

Dr. David P. White is with Harvard Medical School in Boston. His comments are excerpted from an accompanying editorial (Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016 Feb;193:238-9).

Treating OSA may make hypertension easier to address pharmacologically. The effect of CPAP on blood pressure is relatively small when all patients are considered but is more substantial and clinically important for those who use CPAP for more than 4 hours per night.

Can treatment of OSA effectively reduce blood pressure in an otherwise asymptomatic hypertensive patient with OSA? I believe the study would suggest that the answer remains “maybe.”

Most of the patients in the study would require a higher dose of losartan or an additional antihypertensive drug, even while using CPAP, to get to target blood pressures. Getting patients to use CPAP is a difficult task, as is adherence with any long-term pharmacologic management.

All in all, however, CPAP could contribute to blood pressure control while also improving quality of life and possibly reducing the risk for cardiovascular disease.

Dr. David P. White is with Harvard Medical School in Boston. His comments are excerpted from an accompanying editorial (Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016 Feb;193:238-9).

In patients with new-onset hypertension and obstructive sleep apnea, continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) therapy plus antihypertensive treatment with losartan led to reductions in systolic blood pressure beyond those achieved with losartan alone, a two-phase study found.

“Adding CPAP treatment to losartan may reduce blood pressure in a clinically relevant way if the patients are compliant with the device,” said Dr. Erik Thunström of the Sahlgrenska Academy at the University of Gothenburg, Sweden, and his associates.

In their open-label study, 89 men and women with new-onset untreated hypertension – 54 of whom were found to have obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) through a home sleep study and 35 of whom were determined to not have OSA – were treated for 6 weeks with losartan, 50 mg daily. Ambulatory 24-hour blood pressure monitoring was performed before and after treatment.

The patients with OSA were then randomized to receive 6 weeks of nightly add-on CPAP therapy or to continue losartan alone. Ambulatory 24-hour blood pressure monitoring was performed again.

Losartan alone reduced blood pressure in patients with hypertension and concomitant OSA, but the effect was smaller than that seen in patients without OSA. Statistically significant differences were seen in the mean net reduction in morning systolic blood pressure and morning mean arterial pressure. Overall, losartan appeared to be less effective at night and during the early morning hours in patients with OSA, the researchers reported.

After 6 weeks of losartan alone, a blood pressure less than 130/80 mm Hg was achieved by 12.5% of the patients with OSA and by 29% of the patients without OSA.

After 6 weeks of add-on CPAP therapy, 25% of patients with OSA achieved blood pressures less than 130/80 mm Hg. The differences in blood pressures for the OSA patients receiving CPAP plus losartan and those receiving losartan alone were 4.4 mm Hg for 24-hour systolic blood pressure, 1.9 mm Hg for diastolic, and 2.5 mm Hg for mean arterial pressure.

The most “robust” blood pressure changes were seen in the patients who used CPAP therapy for more than 4 hours every night, reducing the mean 24-hour systolic blood pressure by 6.5 mm Hg, the diastolic pressure by 3.8 mm Hg, and the mean arterial blood pressure by 4.6 mm Hg, the researchers reported (Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016 Feb.;193:310-20). “Adding CPAP to treatment with losartan reduced the mean 24-hour systolic blood pressure by 6.5 mm Hg in the subgroup of patients with OSA who were adherent with CPAP,” they wrote.

Patients included in the study all had a body mass index of 35 kg/m2; those with OSA had slightly higher BMIs that did not differ significantly from those without OSA.

That CPAP seems to have additive blood pressure–lowering effect when used concomitantly with losartan “favors the idea that it contributes to a further down-regulation of RAAS [renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system] activity in new-onset hypertension and OSA,” the authors wrote.

RAAS activity is often changed in hypertension, and in animal studies it has been shown to be up-regulated by intermittent hypoxia. Angiotensin II receptor antagonists are thus viewed as a good choice in the treatment of patients with OSA and new-onset hypertension, they wrote.

In patients with new-onset hypertension and obstructive sleep apnea, continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) therapy plus antihypertensive treatment with losartan led to reductions in systolic blood pressure beyond those achieved with losartan alone, a two-phase study found.

“Adding CPAP treatment to losartan may reduce blood pressure in a clinically relevant way if the patients are compliant with the device,” said Dr. Erik Thunström of the Sahlgrenska Academy at the University of Gothenburg, Sweden, and his associates.

In their open-label study, 89 men and women with new-onset untreated hypertension – 54 of whom were found to have obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) through a home sleep study and 35 of whom were determined to not have OSA – were treated for 6 weeks with losartan, 50 mg daily. Ambulatory 24-hour blood pressure monitoring was performed before and after treatment.

The patients with OSA were then randomized to receive 6 weeks of nightly add-on CPAP therapy or to continue losartan alone. Ambulatory 24-hour blood pressure monitoring was performed again.

Losartan alone reduced blood pressure in patients with hypertension and concomitant OSA, but the effect was smaller than that seen in patients without OSA. Statistically significant differences were seen in the mean net reduction in morning systolic blood pressure and morning mean arterial pressure. Overall, losartan appeared to be less effective at night and during the early morning hours in patients with OSA, the researchers reported.

After 6 weeks of losartan alone, a blood pressure less than 130/80 mm Hg was achieved by 12.5% of the patients with OSA and by 29% of the patients without OSA.

After 6 weeks of add-on CPAP therapy, 25% of patients with OSA achieved blood pressures less than 130/80 mm Hg. The differences in blood pressures for the OSA patients receiving CPAP plus losartan and those receiving losartan alone were 4.4 mm Hg for 24-hour systolic blood pressure, 1.9 mm Hg for diastolic, and 2.5 mm Hg for mean arterial pressure.

The most “robust” blood pressure changes were seen in the patients who used CPAP therapy for more than 4 hours every night, reducing the mean 24-hour systolic blood pressure by 6.5 mm Hg, the diastolic pressure by 3.8 mm Hg, and the mean arterial blood pressure by 4.6 mm Hg, the researchers reported (Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016 Feb.;193:310-20). “Adding CPAP to treatment with losartan reduced the mean 24-hour systolic blood pressure by 6.5 mm Hg in the subgroup of patients with OSA who were adherent with CPAP,” they wrote.

Patients included in the study all had a body mass index of 35 kg/m2; those with OSA had slightly higher BMIs that did not differ significantly from those without OSA.

That CPAP seems to have additive blood pressure–lowering effect when used concomitantly with losartan “favors the idea that it contributes to a further down-regulation of RAAS [renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system] activity in new-onset hypertension and OSA,” the authors wrote.

RAAS activity is often changed in hypertension, and in animal studies it has been shown to be up-regulated by intermittent hypoxia. Angiotensin II receptor antagonists are thus viewed as a good choice in the treatment of patients with OSA and new-onset hypertension, they wrote.

FROM AMERICAN JOURNAL OF RESPIRATORY AND CRITICAL CARE MEDICINE

Key clinical point: In patients with new-onset hypertension and obstructive sleep apnea, adding continuous positive airway pressure may reduce blood pressure levels further than achieved with losartan alone.

Major finding: In adherent patients, CPAP reduced the mean 24-hour systolic blood pressure by an additional 6.5 mm Hg as compared to the levels seen in patients on losartan alone.

Data source: A study of 89 men and women with new-onset untreated hypertension who were treated with losartan for 6 weeks and tested for OSA. In a second 6-week study, patients found to have OSA were randomized to receive CPAP or no CPAP.

Disclosures: The researchers had no relevant financial disclosures.

Sleep apnea found in 57% of veterans with PTSD

Obstructive sleep apnea syndrome (OSAS) was diagnosed in more than half of 200 active duty service members with combat-related post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) who were studied at Walter Reed Army Medical Center in Washington.

Compared with age-matched peers with just one of these disorders, the service members with PTSD and OSAS had poorer somnolence and sleep-related quality of life and were less adherent and responsive to positive airway pressure therapy.

The findings “highlight the need for a high index of suspicion and a comprehensive approach to identifying and treating sleep-disordered breathing in these patients,” Dr. Christopher J. Lettieri of the Uniformed Services University in Bethesda, Md., and his associates wrote (Chest. 2016 Feb;149[2]:483-90). “Given the prevalence of OSAS in patients with PTSD and its adverse impact on symptoms and adherence, early identification may improve outcomes.”

In the observational cohort study, 200 consecutive active duty service members who were diagnosed with PTSD as part of post-deployment screening underwent sleep evaluations regardless of whether there was clinical suspicion of sleep-disordered breathing. More than half – about 57% – were diagnosed with OSAS. Almost 60% of the study group had mild traumatic brain injury, which has been connected in prior research to obstructive sleep apnea, and many had comorbid insomnia. Those who were diagnosed with OSAS were older and had higher BMIs than those not found to have OSAS.

All 200 patients were compared with 50 consecutive age-matched control patients who had OSAS but had not been deployed and did not have PTSD, as well as with 50 age-matched service members without prior deployment or either of the two disorders. All of the patients diagnosed with OSAS were prescribed positive airway pressure (PAP) therapy and evaluated after a month.

Sleep quality was poor in the majority of patients with PTSD, and OSAS and PTSD were both independently associated with increased daytime sleepiness and lower quality-of-life index scores. However, patients with both conditions fared significantly worse, particularly with respect to quality of life as measured by the Functional Outcomes of Sleep Questionnaire (FOSQ).

FOSQ scores were abnormal at baseline in 60% of those with PTSD and OSAS, 43% with PTSD alone, 24% with OSAS alone, and 7% of those with neither condition.

Service members with both conditions also were less likely to adhere to therapy; 30% regularly used continuous PAP therapy, compared with 55% of those who had OSAS alone.

And while continuous PAP therapy improved daytime sleepiness and quality of life in patients with both PTSD and OSAS, the degree of improvement was less than that experienced by those with OSAS alone. PTSD “represents an independent barrier to the effective treatment of OSAS and should prompt multipronged and individualized care,” they wrote.

The researchers reported having no financial disclosures.

Obstructive sleep apnea syndrome (OSAS) was diagnosed in more than half of 200 active duty service members with combat-related post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) who were studied at Walter Reed Army Medical Center in Washington.

Compared with age-matched peers with just one of these disorders, the service members with PTSD and OSAS had poorer somnolence and sleep-related quality of life and were less adherent and responsive to positive airway pressure therapy.

The findings “highlight the need for a high index of suspicion and a comprehensive approach to identifying and treating sleep-disordered breathing in these patients,” Dr. Christopher J. Lettieri of the Uniformed Services University in Bethesda, Md., and his associates wrote (Chest. 2016 Feb;149[2]:483-90). “Given the prevalence of OSAS in patients with PTSD and its adverse impact on symptoms and adherence, early identification may improve outcomes.”

In the observational cohort study, 200 consecutive active duty service members who were diagnosed with PTSD as part of post-deployment screening underwent sleep evaluations regardless of whether there was clinical suspicion of sleep-disordered breathing. More than half – about 57% – were diagnosed with OSAS. Almost 60% of the study group had mild traumatic brain injury, which has been connected in prior research to obstructive sleep apnea, and many had comorbid insomnia. Those who were diagnosed with OSAS were older and had higher BMIs than those not found to have OSAS.

All 200 patients were compared with 50 consecutive age-matched control patients who had OSAS but had not been deployed and did not have PTSD, as well as with 50 age-matched service members without prior deployment or either of the two disorders. All of the patients diagnosed with OSAS were prescribed positive airway pressure (PAP) therapy and evaluated after a month.

Sleep quality was poor in the majority of patients with PTSD, and OSAS and PTSD were both independently associated with increased daytime sleepiness and lower quality-of-life index scores. However, patients with both conditions fared significantly worse, particularly with respect to quality of life as measured by the Functional Outcomes of Sleep Questionnaire (FOSQ).

FOSQ scores were abnormal at baseline in 60% of those with PTSD and OSAS, 43% with PTSD alone, 24% with OSAS alone, and 7% of those with neither condition.

Service members with both conditions also were less likely to adhere to therapy; 30% regularly used continuous PAP therapy, compared with 55% of those who had OSAS alone.

And while continuous PAP therapy improved daytime sleepiness and quality of life in patients with both PTSD and OSAS, the degree of improvement was less than that experienced by those with OSAS alone. PTSD “represents an independent barrier to the effective treatment of OSAS and should prompt multipronged and individualized care,” they wrote.

The researchers reported having no financial disclosures.

Obstructive sleep apnea syndrome (OSAS) was diagnosed in more than half of 200 active duty service members with combat-related post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) who were studied at Walter Reed Army Medical Center in Washington.

Compared with age-matched peers with just one of these disorders, the service members with PTSD and OSAS had poorer somnolence and sleep-related quality of life and were less adherent and responsive to positive airway pressure therapy.

The findings “highlight the need for a high index of suspicion and a comprehensive approach to identifying and treating sleep-disordered breathing in these patients,” Dr. Christopher J. Lettieri of the Uniformed Services University in Bethesda, Md., and his associates wrote (Chest. 2016 Feb;149[2]:483-90). “Given the prevalence of OSAS in patients with PTSD and its adverse impact on symptoms and adherence, early identification may improve outcomes.”

In the observational cohort study, 200 consecutive active duty service members who were diagnosed with PTSD as part of post-deployment screening underwent sleep evaluations regardless of whether there was clinical suspicion of sleep-disordered breathing. More than half – about 57% – were diagnosed with OSAS. Almost 60% of the study group had mild traumatic brain injury, which has been connected in prior research to obstructive sleep apnea, and many had comorbid insomnia. Those who were diagnosed with OSAS were older and had higher BMIs than those not found to have OSAS.

All 200 patients were compared with 50 consecutive age-matched control patients who had OSAS but had not been deployed and did not have PTSD, as well as with 50 age-matched service members without prior deployment or either of the two disorders. All of the patients diagnosed with OSAS were prescribed positive airway pressure (PAP) therapy and evaluated after a month.

Sleep quality was poor in the majority of patients with PTSD, and OSAS and PTSD were both independently associated with increased daytime sleepiness and lower quality-of-life index scores. However, patients with both conditions fared significantly worse, particularly with respect to quality of life as measured by the Functional Outcomes of Sleep Questionnaire (FOSQ).

FOSQ scores were abnormal at baseline in 60% of those with PTSD and OSAS, 43% with PTSD alone, 24% with OSAS alone, and 7% of those with neither condition.

Service members with both conditions also were less likely to adhere to therapy; 30% regularly used continuous PAP therapy, compared with 55% of those who had OSAS alone.

And while continuous PAP therapy improved daytime sleepiness and quality of life in patients with both PTSD and OSAS, the degree of improvement was less than that experienced by those with OSAS alone. PTSD “represents an independent barrier to the effective treatment of OSAS and should prompt multipronged and individualized care,” they wrote.

The researchers reported having no financial disclosures.

FROM CHEST

Key clinical point: Obstructive sleep apnea is prevalent in service members with PTSD.

Major finding: More than 57% of active duty service members with combat-related PTSD were diagnosed with OSAS.

Data source: A case-controlled observational cohort study conducted at an academic military medical center and involving 200 consecutive patients with PTSD.

Disclosures: Dr. Lettieri and his colleagues did not report any conflicts of interest.

Expert advises how to use shingles vaccine in rheumatology patients

MAUI, HAWAII – The herpes zoster vaccine is particularly important in patients with rheumatic diseases because their risks of shingles and postherpetic neuralgia are substantially higher than in the general population, Dr. John J. Cush observed at the 2016 Rheumatology Winter Clinical Symposium.

This is a live attenuated virus vaccine, and the rules regarding its use in patients with rheumatic diseases are fairly complicated. Here’s what physicians need to know: the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices say the shingles vaccine can safely be given to patients on prednisone at less than 20 mg/day, azathioprine at up to 3 mg/kg/day, or methotrexate at up to 0.4 mg/kg/week, which works out to about 25 mg/week in anyone weighing more than 136 pounds.

However, the shingles vaccine is contraindicated in patients on recombinant biologic agents, including tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitors, abatacept (Orencia), rituximab (Rituxan), or Janus kinase inhibitors, explained Dr. Cush, professor of medicine and rheumatology at Baylor University, Dallas, and director of clinical rheumatology at the Baylor Research Institute.

The lifetime risk of shingles in the general population is roughly one in three. The risk in patients with rheumatoid arthritis is roughly twice that of the age-matched general population, and the risks are substantially greater than that in individuals with other rheumatic diseases, including lupus and granulomatosis with polyangiitis.

Payers cover the vaccine in patients age 60 or older. The vaccine is approved for and has been shown to be effective in 50- to 59-year-olds as well, but that typically entails an out-of-pocket expense of around $200.

Given that close to 60% of all rheumatoid arthritis patients will eventually be placed on biologic therapy, Dr. Cush believes in seizing any opportunity to give the shingles vaccine in age-appropriate patients beforehand. However, he advises against temporarily stopping a biologic for the express purpose of administering the live virus vaccine.

“Find the opportunity: between changes in medication, after they have surgery, during a lapse in therapy,” he suggested.

It’s recommended that Zostavax be deferred until after a patient has been off biologic therapy or high-dose steroids for at least 4 weeks, and that a biologic agent shouldn’t be started for 2-4 weeks after vaccination.

The shingles vaccine can safely be given with multiple inactivated virus vaccines such as an influenza vaccine or pneumococcal vaccine on a single day.

Controversy surrounds the issue of whether TNF inhibitors increase the risk of shingles. Several retrospective studies have reported they do. But the largest retrospective study, involving more than 33,000 new users of anti-TNF agents, found that patients with rheumatoid arthritis, psoriasis, psoriatic arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, and other inflammatory diseases who initiated anti-TNF therapy weren’t at any higher risk of herpes zoster than those who started on methotrexate or other nonbiologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (JAMA. 2013 Mar 6;309[9]:887-95). The lead investigator in this study, Dr. Kevin L. Winthrop of Oregon Health and Science University, Portland, is currently conducting a prospective study in an effort to confirm these findings.

The recommendation against giving the zoster vaccine to patients while on biologics is based upon the theoretical risk that exposure to the live attenuated virus will trigger an acute shingles attack. However, when Dr. Cush conducted a survey of his fellow rheumatologists, they reported that among more than a collective 200 patients inadvertently given the vaccine while on biologic therapy, not one case of shingles subsequently occurred over the short term.

More persuasively, Dr. Jeffrey R. Curtis of the University of Alabama at Birmingham and coinvestigators conducted a formal retrospective study of close to a half-million Medicare patients and found there were no cases of herpes zoster or varicella within 42 days following inadvertent vaccination of 633 patients while on biologics. During a median 2-year follow-up of Medicare patients with rheumatoid arthritis and other immune-mediated diseases, herpes zoster vaccination was associated with a 39% reduction in the risk of shingles (JAMA. 2012 Jul 4;308[1]:43-9).

“You shouldn’t be vaccinating for herpes zoster while patients are on a biologic, but you know what? If it happens, don’t wig out. Move on and try to avoid it,” Dr. Cush advised.

In any event, this is an issue that is eventually likely to go away. An inactivated virus vaccine for the prevention of shingles is now in clinical trials. It appears to be more effective than the current vaccine, according to the rheumatologist.

He reported having no financial interests relevant to his presentation.

MAUI, HAWAII – The herpes zoster vaccine is particularly important in patients with rheumatic diseases because their risks of shingles and postherpetic neuralgia are substantially higher than in the general population, Dr. John J. Cush observed at the 2016 Rheumatology Winter Clinical Symposium.

This is a live attenuated virus vaccine, and the rules regarding its use in patients with rheumatic diseases are fairly complicated. Here’s what physicians need to know: the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices say the shingles vaccine can safely be given to patients on prednisone at less than 20 mg/day, azathioprine at up to 3 mg/kg/day, or methotrexate at up to 0.4 mg/kg/week, which works out to about 25 mg/week in anyone weighing more than 136 pounds.

However, the shingles vaccine is contraindicated in patients on recombinant biologic agents, including tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitors, abatacept (Orencia), rituximab (Rituxan), or Janus kinase inhibitors, explained Dr. Cush, professor of medicine and rheumatology at Baylor University, Dallas, and director of clinical rheumatology at the Baylor Research Institute.

The lifetime risk of shingles in the general population is roughly one in three. The risk in patients with rheumatoid arthritis is roughly twice that of the age-matched general population, and the risks are substantially greater than that in individuals with other rheumatic diseases, including lupus and granulomatosis with polyangiitis.

Payers cover the vaccine in patients age 60 or older. The vaccine is approved for and has been shown to be effective in 50- to 59-year-olds as well, but that typically entails an out-of-pocket expense of around $200.

Given that close to 60% of all rheumatoid arthritis patients will eventually be placed on biologic therapy, Dr. Cush believes in seizing any opportunity to give the shingles vaccine in age-appropriate patients beforehand. However, he advises against temporarily stopping a biologic for the express purpose of administering the live virus vaccine.

“Find the opportunity: between changes in medication, after they have surgery, during a lapse in therapy,” he suggested.

It’s recommended that Zostavax be deferred until after a patient has been off biologic therapy or high-dose steroids for at least 4 weeks, and that a biologic agent shouldn’t be started for 2-4 weeks after vaccination.

The shingles vaccine can safely be given with multiple inactivated virus vaccines such as an influenza vaccine or pneumococcal vaccine on a single day.

Controversy surrounds the issue of whether TNF inhibitors increase the risk of shingles. Several retrospective studies have reported they do. But the largest retrospective study, involving more than 33,000 new users of anti-TNF agents, found that patients with rheumatoid arthritis, psoriasis, psoriatic arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, and other inflammatory diseases who initiated anti-TNF therapy weren’t at any higher risk of herpes zoster than those who started on methotrexate or other nonbiologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (JAMA. 2013 Mar 6;309[9]:887-95). The lead investigator in this study, Dr. Kevin L. Winthrop of Oregon Health and Science University, Portland, is currently conducting a prospective study in an effort to confirm these findings.

The recommendation against giving the zoster vaccine to patients while on biologics is based upon the theoretical risk that exposure to the live attenuated virus will trigger an acute shingles attack. However, when Dr. Cush conducted a survey of his fellow rheumatologists, they reported that among more than a collective 200 patients inadvertently given the vaccine while on biologic therapy, not one case of shingles subsequently occurred over the short term.

More persuasively, Dr. Jeffrey R. Curtis of the University of Alabama at Birmingham and coinvestigators conducted a formal retrospective study of close to a half-million Medicare patients and found there were no cases of herpes zoster or varicella within 42 days following inadvertent vaccination of 633 patients while on biologics. During a median 2-year follow-up of Medicare patients with rheumatoid arthritis and other immune-mediated diseases, herpes zoster vaccination was associated with a 39% reduction in the risk of shingles (JAMA. 2012 Jul 4;308[1]:43-9).

“You shouldn’t be vaccinating for herpes zoster while patients are on a biologic, but you know what? If it happens, don’t wig out. Move on and try to avoid it,” Dr. Cush advised.

In any event, this is an issue that is eventually likely to go away. An inactivated virus vaccine for the prevention of shingles is now in clinical trials. It appears to be more effective than the current vaccine, according to the rheumatologist.

He reported having no financial interests relevant to his presentation.

MAUI, HAWAII – The herpes zoster vaccine is particularly important in patients with rheumatic diseases because their risks of shingles and postherpetic neuralgia are substantially higher than in the general population, Dr. John J. Cush observed at the 2016 Rheumatology Winter Clinical Symposium.

This is a live attenuated virus vaccine, and the rules regarding its use in patients with rheumatic diseases are fairly complicated. Here’s what physicians need to know: the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices say the shingles vaccine can safely be given to patients on prednisone at less than 20 mg/day, azathioprine at up to 3 mg/kg/day, or methotrexate at up to 0.4 mg/kg/week, which works out to about 25 mg/week in anyone weighing more than 136 pounds.

However, the shingles vaccine is contraindicated in patients on recombinant biologic agents, including tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitors, abatacept (Orencia), rituximab (Rituxan), or Janus kinase inhibitors, explained Dr. Cush, professor of medicine and rheumatology at Baylor University, Dallas, and director of clinical rheumatology at the Baylor Research Institute.

The lifetime risk of shingles in the general population is roughly one in three. The risk in patients with rheumatoid arthritis is roughly twice that of the age-matched general population, and the risks are substantially greater than that in individuals with other rheumatic diseases, including lupus and granulomatosis with polyangiitis.

Payers cover the vaccine in patients age 60 or older. The vaccine is approved for and has been shown to be effective in 50- to 59-year-olds as well, but that typically entails an out-of-pocket expense of around $200.

Given that close to 60% of all rheumatoid arthritis patients will eventually be placed on biologic therapy, Dr. Cush believes in seizing any opportunity to give the shingles vaccine in age-appropriate patients beforehand. However, he advises against temporarily stopping a biologic for the express purpose of administering the live virus vaccine.

“Find the opportunity: between changes in medication, after they have surgery, during a lapse in therapy,” he suggested.

It’s recommended that Zostavax be deferred until after a patient has been off biologic therapy or high-dose steroids for at least 4 weeks, and that a biologic agent shouldn’t be started for 2-4 weeks after vaccination.

The shingles vaccine can safely be given with multiple inactivated virus vaccines such as an influenza vaccine or pneumococcal vaccine on a single day.

Controversy surrounds the issue of whether TNF inhibitors increase the risk of shingles. Several retrospective studies have reported they do. But the largest retrospective study, involving more than 33,000 new users of anti-TNF agents, found that patients with rheumatoid arthritis, psoriasis, psoriatic arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, and other inflammatory diseases who initiated anti-TNF therapy weren’t at any higher risk of herpes zoster than those who started on methotrexate or other nonbiologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (JAMA. 2013 Mar 6;309[9]:887-95). The lead investigator in this study, Dr. Kevin L. Winthrop of Oregon Health and Science University, Portland, is currently conducting a prospective study in an effort to confirm these findings.

The recommendation against giving the zoster vaccine to patients while on biologics is based upon the theoretical risk that exposure to the live attenuated virus will trigger an acute shingles attack. However, when Dr. Cush conducted a survey of his fellow rheumatologists, they reported that among more than a collective 200 patients inadvertently given the vaccine while on biologic therapy, not one case of shingles subsequently occurred over the short term.

More persuasively, Dr. Jeffrey R. Curtis of the University of Alabama at Birmingham and coinvestigators conducted a formal retrospective study of close to a half-million Medicare patients and found there were no cases of herpes zoster or varicella within 42 days following inadvertent vaccination of 633 patients while on biologics. During a median 2-year follow-up of Medicare patients with rheumatoid arthritis and other immune-mediated diseases, herpes zoster vaccination was associated with a 39% reduction in the risk of shingles (JAMA. 2012 Jul 4;308[1]:43-9).

“You shouldn’t be vaccinating for herpes zoster while patients are on a biologic, but you know what? If it happens, don’t wig out. Move on and try to avoid it,” Dr. Cush advised.

In any event, this is an issue that is eventually likely to go away. An inactivated virus vaccine for the prevention of shingles is now in clinical trials. It appears to be more effective than the current vaccine, according to the rheumatologist.

He reported having no financial interests relevant to his presentation.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM RWCS 2016

TXA may increase risk of DVT but not PE

Photo courtesy of NIH

ORLANDO, FL—Results of a large, retrospective study suggest tranexamic acid (TXA) can reduce the need for transfusion in patients undergoing hip and knee replacement surgery without increasing the overall risk of venous thromboembolism (VTE).

However, patients treated with TXA were significantly more likely to develop deep vein thrombosis (DVT) than patients who did not receive the drug.

There was no significant difference between the treatment groups with regard to pulmonary embolism (PE).

These results were presented at the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons (AAOS) 2016 Annual Meeting (abstract P101).

“[C]onflicting results have been published regarding the use of TXA in patients undergoing hip and knee replacement,” said study investigator Geoffrey Westrich, MD, of the Hospital for Special Surgery in New York, New York.

To assess the safety and efficacy of TXA in this patient population, Dr Westrich and his colleagues retrospectively reviewed the records of 4449 patients who had hip or knee replacement over a 6-month period.

There were 720 patients who received TXA topically, 636 who received TXA intravenously, and 3093 patients who did not receive the drug.

The investigators found that 9.7% of patients treated with either type of TXA received a blood transfusion, as did 22.1% of patients who were not treated with TXA.

TXA-treated patients received an average of 0.13 units of blood, compared to 0.37 units for patients in the non-TXA group.

The investigators said there was no significant difference in efficacy between topical and intravenous TXA.

“At our institution, TXA in either intravenous or topical form was effective in decreasing the amount of blood transfusions, as well as the number of units of blood transfused in primary and revision hip and knee replacement,” Dr Westrich said.

“Furthermore, when safety was evaluated, there was no statistically significant difference in blood clots in patients who received IV or topical TXA, reconfirming its safety.”

The odds of developing a hospital-acquired VTE was 1.63 among patients treated with TXA, which was not significantly higher than the odds for patients who did not receive the drug (P=0.24).

When the investigators evaluated DVT and PE separately, they found the TXA group had a significant increase in DVT (P=0.03) but not PE (P=0.94). ![]()

Photo courtesy of NIH

ORLANDO, FL—Results of a large, retrospective study suggest tranexamic acid (TXA) can reduce the need for transfusion in patients undergoing hip and knee replacement surgery without increasing the overall risk of venous thromboembolism (VTE).

However, patients treated with TXA were significantly more likely to develop deep vein thrombosis (DVT) than patients who did not receive the drug.

There was no significant difference between the treatment groups with regard to pulmonary embolism (PE).

These results were presented at the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons (AAOS) 2016 Annual Meeting (abstract P101).

“[C]onflicting results have been published regarding the use of TXA in patients undergoing hip and knee replacement,” said study investigator Geoffrey Westrich, MD, of the Hospital for Special Surgery in New York, New York.

To assess the safety and efficacy of TXA in this patient population, Dr Westrich and his colleagues retrospectively reviewed the records of 4449 patients who had hip or knee replacement over a 6-month period.

There were 720 patients who received TXA topically, 636 who received TXA intravenously, and 3093 patients who did not receive the drug.

The investigators found that 9.7% of patients treated with either type of TXA received a blood transfusion, as did 22.1% of patients who were not treated with TXA.

TXA-treated patients received an average of 0.13 units of blood, compared to 0.37 units for patients in the non-TXA group.

The investigators said there was no significant difference in efficacy between topical and intravenous TXA.

“At our institution, TXA in either intravenous or topical form was effective in decreasing the amount of blood transfusions, as well as the number of units of blood transfused in primary and revision hip and knee replacement,” Dr Westrich said.

“Furthermore, when safety was evaluated, there was no statistically significant difference in blood clots in patients who received IV or topical TXA, reconfirming its safety.”

The odds of developing a hospital-acquired VTE was 1.63 among patients treated with TXA, which was not significantly higher than the odds for patients who did not receive the drug (P=0.24).

When the investigators evaluated DVT and PE separately, they found the TXA group had a significant increase in DVT (P=0.03) but not PE (P=0.94). ![]()

Photo courtesy of NIH

ORLANDO, FL—Results of a large, retrospective study suggest tranexamic acid (TXA) can reduce the need for transfusion in patients undergoing hip and knee replacement surgery without increasing the overall risk of venous thromboembolism (VTE).

However, patients treated with TXA were significantly more likely to develop deep vein thrombosis (DVT) than patients who did not receive the drug.

There was no significant difference between the treatment groups with regard to pulmonary embolism (PE).

These results were presented at the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons (AAOS) 2016 Annual Meeting (abstract P101).

“[C]onflicting results have been published regarding the use of TXA in patients undergoing hip and knee replacement,” said study investigator Geoffrey Westrich, MD, of the Hospital for Special Surgery in New York, New York.

To assess the safety and efficacy of TXA in this patient population, Dr Westrich and his colleagues retrospectively reviewed the records of 4449 patients who had hip or knee replacement over a 6-month period.

There were 720 patients who received TXA topically, 636 who received TXA intravenously, and 3093 patients who did not receive the drug.

The investigators found that 9.7% of patients treated with either type of TXA received a blood transfusion, as did 22.1% of patients who were not treated with TXA.

TXA-treated patients received an average of 0.13 units of blood, compared to 0.37 units for patients in the non-TXA group.

The investigators said there was no significant difference in efficacy between topical and intravenous TXA.

“At our institution, TXA in either intravenous or topical form was effective in decreasing the amount of blood transfusions, as well as the number of units of blood transfused in primary and revision hip and knee replacement,” Dr Westrich said.

“Furthermore, when safety was evaluated, there was no statistically significant difference in blood clots in patients who received IV or topical TXA, reconfirming its safety.”

The odds of developing a hospital-acquired VTE was 1.63 among patients treated with TXA, which was not significantly higher than the odds for patients who did not receive the drug (P=0.24).

When the investigators evaluated DVT and PE separately, they found the TXA group had a significant increase in DVT (P=0.03) but not PE (P=0.94). ![]()

Changes in chromosome structure contribute to T-ALL, other cancers

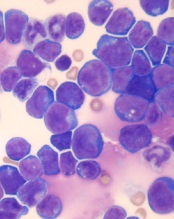

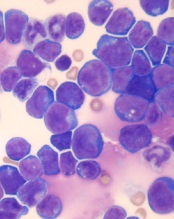

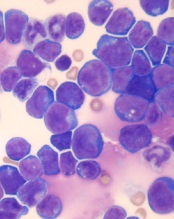

acute lymphoblastic leukemia

Image by Hind Medyouf

Breaches in looping chromosomal structures known as insulated neighborhoods can activate oncogenes capable of fueling aggressive tumor growth, according to research published in Science.

These neighborhood breaches were particularly frequent in T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (T-ALL) and esophageal and liver carcinoma.

In some cases, the breaches allowed enhancer elements to activate previously silent oncogenes.

“This new understanding of the role of chromosome structure in cancer gene misregulation reveals the powerful influence of the genome’s structure in human health and disease,” said study author Richard Young, PhD, of the Whitehead Institute for Biomedical Research in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

These findings build on previous work in which Dr Young and his colleagues charted human genome structure and described its influence on gene control in healthy cells.

By mapping the genome’s 3-dimensional conformation, the researchers found that key genes controlling cell identity are found in insulated neighborhoods, whose loops are maintained through anchor sites bound by the protein CTCF.

All essential gene regulation, including the control of proper activation and repression, takes place within these enclosed neighborhoods.

The researchers also found these CTCF loop anchor sites are maintained across various cell types in the human body and are highly conserved in primate genomes. Such widespread structural conservation led the team to hypothesize that disruptions in genome conformation might be associated with disease, including cancers.

Sure enough, subsequent systematic genomic analysis of more than 50 cancer cell types revealed mutations affecting CTCF anchor sites, which led to the loss of insulated neighborhood boundaries.

By mapping insulated neighborhoods in T-ALL, the researchers found that tumor cell genomes contain recurrent microdeletions that eliminate the boundary sites of insulated neighborhoods containing prominent T-ALL proto-oncogenes.

The team also found the genomes of esophageal and liver carcinoma samples were enriched for boundary CTCF site mutations. The genes located in the most frequently mutated neighborhoods included known proto-oncogenes and genes not previously associated with these malignancies.

“We hadn’t known if these types of mutations contributed to cancer,” Dr Young said. “Now, we have multiple examples where these disruptions activate oncogenes that play major roles in tumorigenesis.”

The researchers noted that this oncogenic mechanism may be valuable for identifying genes that drive poorly understood cancers.

“In some cancers, such as esophageal carcinoma, the most frequent genetic mutation occurs at the CTCF sites, which is quite striking,” said Denes Hnisz, PhD, a researcher in the Young lab.

“In addition, there are still many cancers whose driver mutations and oncogenes are not known, and mapping altered structures may reveal the key oncogenes in these cancers.”

In an attempt to confirm the relationship between structural disruption and oncogenesis, the researchers used genome editing techniques to introduce CTCF anchor site deletions in non-malignant cells. They found these mutations were sufficient to activate oncogenes that are silent in normal cells.

The researchers said these findings suggest future mapping of genome structure in individual cancer patients might improve diagnosis and help guide treatment protocols.

“Now that we understand how perturbations in the genome’s structure can contribute to oncogenesis, we’re developing strategies to efficiently diagnose and potentially fix these faulty neighborhoods,” said Abe Weintraub, a graduate student in the Young lab. ![]()

acute lymphoblastic leukemia

Image by Hind Medyouf

Breaches in looping chromosomal structures known as insulated neighborhoods can activate oncogenes capable of fueling aggressive tumor growth, according to research published in Science.

These neighborhood breaches were particularly frequent in T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (T-ALL) and esophageal and liver carcinoma.

In some cases, the breaches allowed enhancer elements to activate previously silent oncogenes.

“This new understanding of the role of chromosome structure in cancer gene misregulation reveals the powerful influence of the genome’s structure in human health and disease,” said study author Richard Young, PhD, of the Whitehead Institute for Biomedical Research in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

These findings build on previous work in which Dr Young and his colleagues charted human genome structure and described its influence on gene control in healthy cells.

By mapping the genome’s 3-dimensional conformation, the researchers found that key genes controlling cell identity are found in insulated neighborhoods, whose loops are maintained through anchor sites bound by the protein CTCF.

All essential gene regulation, including the control of proper activation and repression, takes place within these enclosed neighborhoods.

The researchers also found these CTCF loop anchor sites are maintained across various cell types in the human body and are highly conserved in primate genomes. Such widespread structural conservation led the team to hypothesize that disruptions in genome conformation might be associated with disease, including cancers.

Sure enough, subsequent systematic genomic analysis of more than 50 cancer cell types revealed mutations affecting CTCF anchor sites, which led to the loss of insulated neighborhood boundaries.

By mapping insulated neighborhoods in T-ALL, the researchers found that tumor cell genomes contain recurrent microdeletions that eliminate the boundary sites of insulated neighborhoods containing prominent T-ALL proto-oncogenes.

The team also found the genomes of esophageal and liver carcinoma samples were enriched for boundary CTCF site mutations. The genes located in the most frequently mutated neighborhoods included known proto-oncogenes and genes not previously associated with these malignancies.

“We hadn’t known if these types of mutations contributed to cancer,” Dr Young said. “Now, we have multiple examples where these disruptions activate oncogenes that play major roles in tumorigenesis.”

The researchers noted that this oncogenic mechanism may be valuable for identifying genes that drive poorly understood cancers.

“In some cancers, such as esophageal carcinoma, the most frequent genetic mutation occurs at the CTCF sites, which is quite striking,” said Denes Hnisz, PhD, a researcher in the Young lab.

“In addition, there are still many cancers whose driver mutations and oncogenes are not known, and mapping altered structures may reveal the key oncogenes in these cancers.”

In an attempt to confirm the relationship between structural disruption and oncogenesis, the researchers used genome editing techniques to introduce CTCF anchor site deletions in non-malignant cells. They found these mutations were sufficient to activate oncogenes that are silent in normal cells.

The researchers said these findings suggest future mapping of genome structure in individual cancer patients might improve diagnosis and help guide treatment protocols.

“Now that we understand how perturbations in the genome’s structure can contribute to oncogenesis, we’re developing strategies to efficiently diagnose and potentially fix these faulty neighborhoods,” said Abe Weintraub, a graduate student in the Young lab. ![]()

acute lymphoblastic leukemia

Image by Hind Medyouf

Breaches in looping chromosomal structures known as insulated neighborhoods can activate oncogenes capable of fueling aggressive tumor growth, according to research published in Science.

These neighborhood breaches were particularly frequent in T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (T-ALL) and esophageal and liver carcinoma.

In some cases, the breaches allowed enhancer elements to activate previously silent oncogenes.

“This new understanding of the role of chromosome structure in cancer gene misregulation reveals the powerful influence of the genome’s structure in human health and disease,” said study author Richard Young, PhD, of the Whitehead Institute for Biomedical Research in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

These findings build on previous work in which Dr Young and his colleagues charted human genome structure and described its influence on gene control in healthy cells.

By mapping the genome’s 3-dimensional conformation, the researchers found that key genes controlling cell identity are found in insulated neighborhoods, whose loops are maintained through anchor sites bound by the protein CTCF.

All essential gene regulation, including the control of proper activation and repression, takes place within these enclosed neighborhoods.

The researchers also found these CTCF loop anchor sites are maintained across various cell types in the human body and are highly conserved in primate genomes. Such widespread structural conservation led the team to hypothesize that disruptions in genome conformation might be associated with disease, including cancers.

Sure enough, subsequent systematic genomic analysis of more than 50 cancer cell types revealed mutations affecting CTCF anchor sites, which led to the loss of insulated neighborhood boundaries.

By mapping insulated neighborhoods in T-ALL, the researchers found that tumor cell genomes contain recurrent microdeletions that eliminate the boundary sites of insulated neighborhoods containing prominent T-ALL proto-oncogenes.

The team also found the genomes of esophageal and liver carcinoma samples were enriched for boundary CTCF site mutations. The genes located in the most frequently mutated neighborhoods included known proto-oncogenes and genes not previously associated with these malignancies.

“We hadn’t known if these types of mutations contributed to cancer,” Dr Young said. “Now, we have multiple examples where these disruptions activate oncogenes that play major roles in tumorigenesis.”

The researchers noted that this oncogenic mechanism may be valuable for identifying genes that drive poorly understood cancers.

“In some cancers, such as esophageal carcinoma, the most frequent genetic mutation occurs at the CTCF sites, which is quite striking,” said Denes Hnisz, PhD, a researcher in the Young lab.

“In addition, there are still many cancers whose driver mutations and oncogenes are not known, and mapping altered structures may reveal the key oncogenes in these cancers.”

In an attempt to confirm the relationship between structural disruption and oncogenesis, the researchers used genome editing techniques to introduce CTCF anchor site deletions in non-malignant cells. They found these mutations were sufficient to activate oncogenes that are silent in normal cells.

The researchers said these findings suggest future mapping of genome structure in individual cancer patients might improve diagnosis and help guide treatment protocols.

“Now that we understand how perturbations in the genome’s structure can contribute to oncogenesis, we’re developing strategies to efficiently diagnose and potentially fix these faulty neighborhoods,” said Abe Weintraub, a graduate student in the Young lab. ![]()

Can Psychology Offer a New Approach to QI?

Sound clinical reasoning is the foundation of patient safety, yet discussions of a physician’s raw thinking ability have become a “third rail” in hospitals, according to “Incorporating Metacognition into Morbidity and Mortality Rounds: The Next Frontier in Quality Improvement,” published in the Journal of Hospital Medicine. Authors David Katz, MD, MSc, and Allan S. Detsky, MD, PhD, suggest introducing concepts from cognitive psychology could help address this issue.

The underlying problem is that the search for causes of medical error focuses on systems-based issues—medication administration and dosing, communication, physician handover, etc. There’s a reluctance to talk about human decision making. In fact, in the authors’ own hospitals, improving diagnostic accuracy is almost never discussed; they suspect the same is true at other institutions.

But cognitive errors occur predictably and often, especially at times of high cognitive load (i.e., when many complex decisions are being made in a short period of time), according to research from cognitive psychology. The authors therefore suggest that introducing metacognition (or “thinking about thinking”) discussions during morbidity and mortality rounds (MMRs) might help expand the discussions so that human error can be recognized and addressed.

They suggest that cognitive heuristics be introduced to MMRs by experienced and respected clinicians who can tell stories of their own errors and the shortcuts in thinking that may have caused them.

“Thereafter, the traditional MMR format can be used: presenting a case, describing how an experienced clinician might manage the case, and then asking the audience members for comment,” they write. “Incorporating discussions of cognitive missteps, in medical and nonmedical contexts, would help normalize the understanding that even the most experienced and smartest people fall prey to them. The tone must be positive.”

Reference

1. Katz D, Detsky AS. Incorporating metacognition into morbidity and mortality rounds: the next frontier in quality improvement. J Hosp Med. 2016;11(2):120-122. doi:10.1002/jhm.2505.

Sound clinical reasoning is the foundation of patient safety, yet discussions of a physician’s raw thinking ability have become a “third rail” in hospitals, according to “Incorporating Metacognition into Morbidity and Mortality Rounds: The Next Frontier in Quality Improvement,” published in the Journal of Hospital Medicine. Authors David Katz, MD, MSc, and Allan S. Detsky, MD, PhD, suggest introducing concepts from cognitive psychology could help address this issue.

The underlying problem is that the search for causes of medical error focuses on systems-based issues—medication administration and dosing, communication, physician handover, etc. There’s a reluctance to talk about human decision making. In fact, in the authors’ own hospitals, improving diagnostic accuracy is almost never discussed; they suspect the same is true at other institutions.

But cognitive errors occur predictably and often, especially at times of high cognitive load (i.e., when many complex decisions are being made in a short period of time), according to research from cognitive psychology. The authors therefore suggest that introducing metacognition (or “thinking about thinking”) discussions during morbidity and mortality rounds (MMRs) might help expand the discussions so that human error can be recognized and addressed.

They suggest that cognitive heuristics be introduced to MMRs by experienced and respected clinicians who can tell stories of their own errors and the shortcuts in thinking that may have caused them.

“Thereafter, the traditional MMR format can be used: presenting a case, describing how an experienced clinician might manage the case, and then asking the audience members for comment,” they write. “Incorporating discussions of cognitive missteps, in medical and nonmedical contexts, would help normalize the understanding that even the most experienced and smartest people fall prey to them. The tone must be positive.”

Reference

1. Katz D, Detsky AS. Incorporating metacognition into morbidity and mortality rounds: the next frontier in quality improvement. J Hosp Med. 2016;11(2):120-122. doi:10.1002/jhm.2505.

Sound clinical reasoning is the foundation of patient safety, yet discussions of a physician’s raw thinking ability have become a “third rail” in hospitals, according to “Incorporating Metacognition into Morbidity and Mortality Rounds: The Next Frontier in Quality Improvement,” published in the Journal of Hospital Medicine. Authors David Katz, MD, MSc, and Allan S. Detsky, MD, PhD, suggest introducing concepts from cognitive psychology could help address this issue.

The underlying problem is that the search for causes of medical error focuses on systems-based issues—medication administration and dosing, communication, physician handover, etc. There’s a reluctance to talk about human decision making. In fact, in the authors’ own hospitals, improving diagnostic accuracy is almost never discussed; they suspect the same is true at other institutions.

But cognitive errors occur predictably and often, especially at times of high cognitive load (i.e., when many complex decisions are being made in a short period of time), according to research from cognitive psychology. The authors therefore suggest that introducing metacognition (or “thinking about thinking”) discussions during morbidity and mortality rounds (MMRs) might help expand the discussions so that human error can be recognized and addressed.

They suggest that cognitive heuristics be introduced to MMRs by experienced and respected clinicians who can tell stories of their own errors and the shortcuts in thinking that may have caused them.

“Thereafter, the traditional MMR format can be used: presenting a case, describing how an experienced clinician might manage the case, and then asking the audience members for comment,” they write. “Incorporating discussions of cognitive missteps, in medical and nonmedical contexts, would help normalize the understanding that even the most experienced and smartest people fall prey to them. The tone must be positive.”

Reference

1. Katz D, Detsky AS. Incorporating metacognition into morbidity and mortality rounds: the next frontier in quality improvement. J Hosp Med. 2016;11(2):120-122. doi:10.1002/jhm.2505.

CRT in Patients with Heart Failure Without LBBB May Harm

NEW YORK (Reuters Health) - Cardiac resynchronization therapy (CRT) in patients with heart failure (HF) without left bundle branch block (LBBB) may not help and might even harm, according to an international group of investigators.

As Dr. Yitschak Biton told Reuters Health by email, "Our findings suggest that patients without LBBB electrocardiogram (ECG) morphology are not likely to benefit from CRT implantation and a subgroup of patients with short QRS duration might even be at higher risk for mortality."

In a January 28 online paper in Circulation: Heart Failure, Dr. Biton, of the University of Rochester Medical Center, New York, and colleagues note that the efficacy of CRT is well established in patients with both mild and moderate to severe HF symptoms. However, data on non-LBBB patients "are more limited and conflicting."

To investigate, the team examined data on 537 such patients with mild HF taking part in a larger study. At seven years, the cumulative probability of HF hospitalization or death was 45% in those randomized to an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD) and 56% in those given CRT with a defibrillator (CRT-D).

Multivariable-adjusted subgroup analysis by QRS duration showed that patients from the lower quartile (134 ms or less) had a 2.4-fold greater risk of HF hospitalization or death with CRT-D versus those with ICD-only therapy.

However, the effect of CRT-D in patients from the upper quartiles group (QRS greater than 134 ms) was neutral (hazard ratio 0.97).

In a further analysis based on PR interval, patients with prolonged QRS (more than 134 ms) and prolonged PR (at least 230 ms) were protected with CRT-D (HR 0.31). The association was neutral with prolonged QRS and shorter PR.

"Overall," the researchers conclude, "patients with mild HF but without left bundle branch block morphology did not derive clinical benefit with CRT-D during long-term follow-up. Relatively shorter QRS was associated with a significantly increased risk with CRT-D relative to implantable cardioverter-defibrillator only."

"This information should be taken into account when CRT therapy is considered in this subgroup of patients," Dr. Biton told Reuters Health.

Boston Scientific Corporation funded the clinical trial this research is based on. Five coauthors reported disclosures.

NEW YORK (Reuters Health) - Cardiac resynchronization therapy (CRT) in patients with heart failure (HF) without left bundle branch block (LBBB) may not help and might even harm, according to an international group of investigators.

As Dr. Yitschak Biton told Reuters Health by email, "Our findings suggest that patients without LBBB electrocardiogram (ECG) morphology are not likely to benefit from CRT implantation and a subgroup of patients with short QRS duration might even be at higher risk for mortality."

In a January 28 online paper in Circulation: Heart Failure, Dr. Biton, of the University of Rochester Medical Center, New York, and colleagues note that the efficacy of CRT is well established in patients with both mild and moderate to severe HF symptoms. However, data on non-LBBB patients "are more limited and conflicting."

To investigate, the team examined data on 537 such patients with mild HF taking part in a larger study. At seven years, the cumulative probability of HF hospitalization or death was 45% in those randomized to an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD) and 56% in those given CRT with a defibrillator (CRT-D).

Multivariable-adjusted subgroup analysis by QRS duration showed that patients from the lower quartile (134 ms or less) had a 2.4-fold greater risk of HF hospitalization or death with CRT-D versus those with ICD-only therapy.

However, the effect of CRT-D in patients from the upper quartiles group (QRS greater than 134 ms) was neutral (hazard ratio 0.97).

In a further analysis based on PR interval, patients with prolonged QRS (more than 134 ms) and prolonged PR (at least 230 ms) were protected with CRT-D (HR 0.31). The association was neutral with prolonged QRS and shorter PR.

"Overall," the researchers conclude, "patients with mild HF but without left bundle branch block morphology did not derive clinical benefit with CRT-D during long-term follow-up. Relatively shorter QRS was associated with a significantly increased risk with CRT-D relative to implantable cardioverter-defibrillator only."

"This information should be taken into account when CRT therapy is considered in this subgroup of patients," Dr. Biton told Reuters Health.

Boston Scientific Corporation funded the clinical trial this research is based on. Five coauthors reported disclosures.

NEW YORK (Reuters Health) - Cardiac resynchronization therapy (CRT) in patients with heart failure (HF) without left bundle branch block (LBBB) may not help and might even harm, according to an international group of investigators.

As Dr. Yitschak Biton told Reuters Health by email, "Our findings suggest that patients without LBBB electrocardiogram (ECG) morphology are not likely to benefit from CRT implantation and a subgroup of patients with short QRS duration might even be at higher risk for mortality."