User login

Bundle can decrease CLABSI incidence

Staphylococcus infection

Photo by Bill Branson

A central catheter maintenance bundle can decrease the incidence of central line-associated bloodstream infections (CLABSIs), according to a study published in the American Journal of Critical Care.

A team from the healthcare company Select Medical developed and implemented the bundle at 30 long-term acute care hospitals.

The team used infection prevention guidelines from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention as the core of the bundle, with mandatory use of alcohol-based central catheter caps and chlorhexidine gluconate dressings.

Ongoing education of clinical staff about the protocol and a checklist to track compliance were also key elements of the initiative.

At each hospital, staff nurses who demonstrated competency in the care of central catheters monitored implementation of the bundle for the initial 6 months of the study.

Researchers reviewed the medical records of 6660 patients discharged during the 14 months prior to the study and 6559 patients discharged after implementation of the bundle. Patient days and central catheter days before and after the bundle was implemented were comparable.

Six months after the bundle was implemented, the CLABSI standardized infection rate had dropped 29%. The rate was 1.28 in the 6 months before the bundle was implemented and 0.96 six months after implementation.

There was a mean reduction of 4.5 CLABSIs per hospital for 14 months after the bundle was implemented.

“Our results encourage the development and implementation of similar bundles as effective infection reduction strategies in [long-term acute care hospitals],” said study author Antony Grigonis, PhD, vice-president of quality and healthcare analytics at Select Medical.

“Preventing these infections can help reduce complications and the length of stay for other patients. This infection reduction could also translate to a savings of approximately $3.7 million annually for the 30 long-term acute care hospitals studied.”

Select Medical, which is based in Mechanicsburg, Pennsylvania, owns long-term acute care and inpatient rehabilitation hospitals, as well as occupational health and physical therapy clinics. ![]()

Staphylococcus infection

Photo by Bill Branson

A central catheter maintenance bundle can decrease the incidence of central line-associated bloodstream infections (CLABSIs), according to a study published in the American Journal of Critical Care.

A team from the healthcare company Select Medical developed and implemented the bundle at 30 long-term acute care hospitals.

The team used infection prevention guidelines from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention as the core of the bundle, with mandatory use of alcohol-based central catheter caps and chlorhexidine gluconate dressings.

Ongoing education of clinical staff about the protocol and a checklist to track compliance were also key elements of the initiative.

At each hospital, staff nurses who demonstrated competency in the care of central catheters monitored implementation of the bundle for the initial 6 months of the study.

Researchers reviewed the medical records of 6660 patients discharged during the 14 months prior to the study and 6559 patients discharged after implementation of the bundle. Patient days and central catheter days before and after the bundle was implemented were comparable.

Six months after the bundle was implemented, the CLABSI standardized infection rate had dropped 29%. The rate was 1.28 in the 6 months before the bundle was implemented and 0.96 six months after implementation.

There was a mean reduction of 4.5 CLABSIs per hospital for 14 months after the bundle was implemented.

“Our results encourage the development and implementation of similar bundles as effective infection reduction strategies in [long-term acute care hospitals],” said study author Antony Grigonis, PhD, vice-president of quality and healthcare analytics at Select Medical.

“Preventing these infections can help reduce complications and the length of stay for other patients. This infection reduction could also translate to a savings of approximately $3.7 million annually for the 30 long-term acute care hospitals studied.”

Select Medical, which is based in Mechanicsburg, Pennsylvania, owns long-term acute care and inpatient rehabilitation hospitals, as well as occupational health and physical therapy clinics. ![]()

Staphylococcus infection

Photo by Bill Branson

A central catheter maintenance bundle can decrease the incidence of central line-associated bloodstream infections (CLABSIs), according to a study published in the American Journal of Critical Care.

A team from the healthcare company Select Medical developed and implemented the bundle at 30 long-term acute care hospitals.

The team used infection prevention guidelines from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention as the core of the bundle, with mandatory use of alcohol-based central catheter caps and chlorhexidine gluconate dressings.

Ongoing education of clinical staff about the protocol and a checklist to track compliance were also key elements of the initiative.

At each hospital, staff nurses who demonstrated competency in the care of central catheters monitored implementation of the bundle for the initial 6 months of the study.

Researchers reviewed the medical records of 6660 patients discharged during the 14 months prior to the study and 6559 patients discharged after implementation of the bundle. Patient days and central catheter days before and after the bundle was implemented were comparable.

Six months after the bundle was implemented, the CLABSI standardized infection rate had dropped 29%. The rate was 1.28 in the 6 months before the bundle was implemented and 0.96 six months after implementation.

There was a mean reduction of 4.5 CLABSIs per hospital for 14 months after the bundle was implemented.

“Our results encourage the development and implementation of similar bundles as effective infection reduction strategies in [long-term acute care hospitals],” said study author Antony Grigonis, PhD, vice-president of quality and healthcare analytics at Select Medical.

“Preventing these infections can help reduce complications and the length of stay for other patients. This infection reduction could also translate to a savings of approximately $3.7 million annually for the 30 long-term acute care hospitals studied.”

Select Medical, which is based in Mechanicsburg, Pennsylvania, owns long-term acute care and inpatient rehabilitation hospitals, as well as occupational health and physical therapy clinics. ![]()

A Perfect Storm: Patterns of care

Editor’s Note: This is the third installment of a five-part monthly series that will discuss the pathologic, genomic, and health system factors that contribute to the racial survival disparity in breast cancer. The series, which is adapted from an article that originally appeared in CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians1, a journal of the American Cancer Society, will also review exciting and innovative interventions to close the survival gap. This month’s column reviews patterns of care – the second element in the perfect storm.

Mammography

Despite advances in breast cancer imaging technology, the mainstay of breast cancer screening has remained mammography. Chu et al.2 found that African American women have less early-stage disease in every age group for each hormone receptor status, and this raises the concern that mammography screening might be inadequate in this population. Although historically, African American women used mammography less than did white women, this difference has fortunately disappeared with time.3 According to results from the 2010 National Health Interview Survey, among women who were 40 years or older, 50.6% of non-Hispanic African Americans and 51.5% of non-Hispanic whites reported having had a mammogram within the past year.4

Although mammography uptake may be similar between these groups, there are still differences both in quality and in follow-up of abnormal imaging results. A study of mammography capacity and quality in a large urban setting found that the facilities that served predominantly minority women were more likely to be public institutions (31% vs. 0%) and less likely to be academic (27% vs. 71%), less likely to have digital mammography (18% vs. 71%), and less likely to have dedicated breast imaging specialists reading the films (23% vs. 87%). The authors concluded that the mammography process was broken, with quality differences in the manner in which the centers provided care and reported results.5

The accompanying graphic illustrates the disparities seen in breast cancer mammography and care for women in underserved communities on Chicago’s South Side. As the figure demonstrates, there are fewer mammography centers on the city’s South Side, with the concentration of breast cancer imaging and treatment resources localized in the more affluent communities of central and northern Chicago. A total of 300,000 women who were eligible for screening went unscreened because of improper management of resources.

Highlighting the importance of location in breast cancer care, Gehlert et al.6 asserted that ensuring that inner-city health facilities have up-to-date, well-maintained equipment and that mammographers have access to continuing training and opportunities for consultation should help reduce breast cancer mortality in African Americans.

With respect to follow-up of abnormal imaging results, a large retrospective cohort study of 6,722 women with abnormal mammogram results seen at a New York academic medical center from January 2002 through December 2002 found longer times to diagnostic follow-up for African American versus white women. The median number of days to diagnostic follow-up was 20 for African American patients versus 14 for white patients. In addition, racial disparities remained significant after the researchers controlled for age, Breast Imaging Reporting and Data System (BI-RADS) category, insurance status, provider practice location, and median household income. More important, in women with a BI-RADS classification of 4 or 5 – signifying a lesion seen on mammography that is either suspicious for or highly suggestive of malignancy, respectively – the median number of days to follow-up among those without same-day additional imaging was 26 for African Americans and 14 for whites (P < .05).7

Delays in treatment

A cascade of delays also has been documented in breast cancer care for African American women. Silber et al.8 investigated factors associated with differences in breast cancer outcomes in a large population-based study using Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER)-Medicare data. The mean time from diagnosis to treatment was 29.2 days for African Americans versus 22.5 days for whites (P < .001). The authors also found that African Americans were more likely to have very-long treatment delays. At least 6% of African Americans did not initiate treatment within the first 3 months of diagnosis, whereas only 3% of whites failed to start treatment (P < .001). Gwyn et al.9 also found potentially clinically significant treatment delays more often for African American women than for white women. The time from medical consultation to the initiation of treatment was longer than 3 months for 22.4% of African American women versus 14.3% of white women. Three months was chosen as a clinically significant time period, because Richards et al.10 demonstrated that a delay ≥ to 3 months affects survival. Thus, delays in the diagnosis and treatment of African American women are factors that worsen the survival gap.

Misuse of treatment

Once treatment is initiated, African Americans often receive inappropriate therapy, studies have demonstrated. In a prospective analysis of 957 patients in 101 oncology practices, Griggs et al.11 found more frequent use of non–guideline concordant adjuvant chemotherapy regimens in African American women. In a univariate analysis, African American patients were more likely than were whites to receive a nonstandard regimen (19% vs. 11%; P = .047). Although we will discuss further in this column whether guidelines based on clinical trials are appropriate for African American patients, the study demonstrates that these women are not uniformly receiving standard-of-care treatment.

Underuse of treatment

In addition to misuse of treatment, studies also have examined undertreatment of African American patients with breast cancer. One study investigated chemotherapy administration among African American patients with stage I-III breast cancer at 10 different treatment sites. Compared with white patients, African Americans received a lower dose proportion (actual vs. expected dose) and lower relative dose intensity.

The authors found that between-group differences in biological and medical characteristics, such as tolerance of therapy, comorbidities, and leukocyte counts, did not explain these variations in treatment. In fact, despite the association between lower leukocyte counts and African American ethnicity, there was no evidence that white blood cell levels accounted for the difference in dose proportion or relative dose intensity. Significantly, the authors discovered that more African Americans had chemotherapy dose reductions in the first cycle of treatment, perhaps indicating physician assumptions regarding African American patients’ ability to tolerate chemotherapy.12

Silber et al.8 also examined differences in the administration of chemotherapy between white and African American breast cancer patients. The authors found that 3.7% of African Americans received both an anthracycline and a taxane; that figure rose to 5.0% among whites who were matched to African Americans at presentation.

Bickell et al.13 explored further racial disparity in the underuse of adjuvant breast cancer treatment. The researchers examined the medical records of 677 women treated surgically for stage I or II breast cancer. The study defined underuse as omissions of radiotherapy after breast-conserving surgery, adjuvant chemotherapy after resection of hormone receptor–negative tumors ≥ 1 cm, or hormonal therapy for receptor-positive tumors ≥ 1 cm. Underuse of appropriate adjuvant treatment was found in 34% of African American patients versus 16% of white patients (P less than .001). There were racial disparities present in all three adjuvant therapies assessed.

Hormonal therapy has been shown effective in clinical trials for preventing breast cancer recurrence and death in women with early-stage breast cancer.14 The study by Bickell et al.13 documented underuse of this treatment in African American patients. Partridge et al.15 conducted the largest study of oral antineoplastic use outside of a clinical trial setting. Their study consisted of 2,378 primary breast cancer patients enrolled in New Jersey’s Medicaid or pharmaceutical assistance program; the main outcome was the number of days covered by filled tamoxifen prescriptions in the first year of therapy. The study found that nonwhite patients had significantly lower adherence rates than did whites. Although further investigation is needed to determine the drivers of this nonadherence in African American patients, medication cost has been proposed as a significant factor leading to underuse of these agents. Streeter et al.16 analyzed a nationally representative pharmacy claims database for oral antineoplastics and calculated abandonment rates for the initial claim. Not surprisingly, high cost sharing and low incomes were associated with a higher abandonment rate (P < .05). Despite being an important component of health equity research, treatment adherence has been identified by the Association of American Medical Colleges as a critically underrepresented area of disparities-focused health services research.17 More attention to this area is needed to understand the underuse of hormonal therapies in African American breast cancer patients.

The treatment strategies that have been shown to be delayed, underused, or misused in African American patients in the aforementioned studies have improved disease-free and overall survival in large randomized trials. Furthermore, diminished total dose and dose intensity of adjuvant chemotherapy both have been associated with lower breast cancer survival rates.18,19 These quality-of-care failures in breast cancer treatment for minority patients are thought to partially explain the survival disparity between African Americans and whites. It has been proposed that patients in both groups derive a similar benefit from systemic therapy when it is administered in accordance with their clinical and pathologic presentation,20 but that assumption becomes more nuanced when the clinical trial experience is reviewed.

Clinical trial experience

Dignam20 examined survival by race in several National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project trials. He found that the benefit from systemic adjuvant therapy for reductions in disease recurrence and mortality was comparable between African American and white patients. His survey of trials consistently indicated equivalent disease-free survival, but a mortality deficit for African Americans also was found consistently. Among African Americans, the excess risk of mortality was 21% for those who were lymph node–negative and 17% for those who were lymph node–positive. The excess mortality risk was thought to be attributable to greater mortality from noncancer causes among African American patients rather than a failure of African Americans to respond to breast cancer treatment.

In contrast to Dignam’s findings20, Hershman et al.21 assessed the association between race and treatment discontinuation/delay, white blood cell counts, and survival in women enrolled in the Southwest Oncology Group adjuvant breast cancer trials. The study found that African American women were significantly more likely to experience treatment discontinuation/delay than were white women (87% vs. 81%, respectively; P = .04). These delays were not accounted for by toxicities, which were experienced in similar proportions by race. African American women also were more likely to miss appointments (19% vs. 9%; P = .0002); perhaps, as Hassett and Griggs22 speculated, this finding speaks to economic barriers, including the inability to arrange alternate child care, miss work, or afford transportation to the clinic. Despite these barriers to care for African American patients, they still received the same mean relative dose intensity (87% vs. 86%).

In their survival analysis, Hershman et al.21 controlled for treatment-related factors such as dose reductions and delays, body surface area, baseline white blood cell counts, and other predictors of survival and still found that African Americans had worse disease-free and overall survival than did white women. The authors concluded that the study was “unable to demonstrate that any factor related to treatment quality or delivery contributed to racial differences in survival between the groups.”21 The study thus established two important findings related to the disparity gap. First, even in the controlled setting of a clinical trial, African American patients faced barriers to optimal treatment,22 and second, despite attempts to control for treatment quality and delivery, African American women still had worse outcomes. These findings suggest that tumor biology and genomics remain important.

In next month’s installment, we will discuss interventions aimed at closing the racial survival disparity in breast cancer. Eliminating racial disparities in cancer mortality through effective interventions has become an increasingly important imperative in federal, state, and community health care programs.

Other installments of this column can be found in the Related Content box.

1. Daly B, Olopade OI. A perfect storm: How tumor biology, genomics, and health care delivery patterns collide to create a racial survival disparity in breast cancer and proposed interventions for change. CA Cancer J Clin. 2015 May-Jun;65(3):221-38.

2. Chu KC, Lamar CA, Freeman HP. Racial disparities in breast carcinoma survival rates: Separating factors that affect diagnosis from factors that affect treatment. Cancer. 2003 Jun;97(11):2853-60.

3. DeLancey JO, Thun MJ, Jemal A, Ward EM. Recent trends in black-white disparities in cancer mortality. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2008 Nov;17(11):2908-12.

4. DeSantis C, Naishadham D, Jemal A. Cancer statistics for African Americans, 2013. CA Cancer J Clin. 2013 Nov;63(3):151-66.

5. Ansell D, Grabler P, Whitman S, et al. A community effort to reduce the black/white breast cancer mortality disparity in Chicago. Cancer Causes Control. 2009 Nov;20(9):1681-8.

6. Gehlert S, Sohmer D, Sacks T, Mininger C, McClintock M, Olopade O. Targeting health disparities: a model linking upstream determinants to downstream interventions. Health Aff (Millwood). 2008 Mar-Apr;27(2):339-49.

7. Press R, Carrasquillo O, Sciacca RR, Giardina EG. Racial/ethnic disparities in time to follow-up after an abnormal mammogram. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2008 Jul;17(6):923-30.

8. Silber JH, Rosenbaum PR, Clark AS, et al. Characteristics associated with differences in survival among black and white women with breast cancer. JAMA. 2013 Jul;310(4):389-397.

9. Gwyn K, Bondy ML, Cohen DS, et al. Racial differences in diagnosis, treatment, and clinical delays in a population-based study of patients with newly diagnosed breast carcinoma. Cancer. 2004 Apr;100(8):1595-604.

10. Richards MA, Westcombe AM, Love SB, Littlejohns P, Ramirez AJ. Influence of delay on survival in patients with breast cancer: a systematic review. Lancet. 1999 Apr 3;353(9159):1119-26.

11. Griggs JJ, Culakova E, Sorbero ME, et al. Social and racial differences in selection of breast cancer adjuvant chemotherapy regimens. J Clin Oncol. 2007 Jun 20;25(18):2522-7.

12. Griggs JJ, Sorbero ME, Stark AT, Heininger SE, Dick AW. Racial disparity in the dose and dose intensity of breast cancer adjuvant chemotherapy. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2003 Sep;81(1):21-31.

13. Bickell NA, Wang JJ, Oluwole S, et al. Missed opportunities: racial disparities in adjuvant breast cancer treatment. J Clin Oncol. 2006 Mar 20;24(9):1357-62. 14. Fisher B, Costantino J, Redmond C, et al. A randomized clinical trial evaluating tamoxifen in the treatment of patients with node-negative breast cancer who have estrogen-receptor-positive tumors. N Engl J Med. 1989 Feb 23;320(8):479-84.

15. Partridge AH, Wang PS, Winer EP, Avorn J. Nonadherence to adjuvant tamoxifen therapy in women with primary breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2003 Feb 15;21(4):602-6.

16. Streeter SB, Schwartzberg L, Husain N, Johnsrud M. Patient and plan characteristics affecting abandonment of oral oncolytic prescriptions. J Oncol Pract. 2011 Jul;7(3 Suppl):46s-51s.

17. Alberti PM KN, Sutton K, Johnson BH, Holve E. The state of health equity research: closing knowledge gaps to address inequities. ©2014 Association of American Medical Colleges. May not be reproduced or distributed without prior permission.

18. Wood WC, Budman DR, Korzun AH, et al. Dose and dose intensity of adjuvant chemotherapy for stage II, node-positive breast carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 1994 May 5;330(18):1253-9.

19. Budman DR, Berry DA, Cirrincione CT, et al. Dose and dose intensity as determinants of outcome in the adjuvant treatment of breast cancer. The Cancer and Leukemia Group B. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1998 Aug 19;90(16):1205-11.

20. Dignam JJ. Efficacy of systemic adjuvant therapy for breast cancer in African-American and Caucasian women. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2001(30):36-43.

21. Hershman DL, Unger JM, Barlow WE, et al. Treatment quality and outcomes of African American versus white breast cancer patients: retrospective analysis of Southwest Oncology studies S8814/S8897. J Clin Oncol. 2009 May;27(13):2157-62.

22. Hassett MJ, Griggs JJ. Disparities in breast cancer adjuvant chemotherapy: moving beyond yes or no. J Clin Oncol. 2009 May 1;27(13):2120-1.

Bobby Daly, MD, MBA, is the chief fellow in the section of hematology/oncology at the University of Chicago Medicine. His clinical focus is breast and thoracic oncology, and his research focus is health services. Specifically, Dr. Daly researches disparities in oncology care delivery, oncology health care utilization, aggressive end-of-life oncology care, and oncology payment models. He received his MD and MBA from Harvard Medical School and Harvard Business School, both in Boston, and a BA in Economics and History from Stanford (Calif.) University. He was the recipient of the Dean’s Award at Harvard Medical and Business Schools.

Olufunmilayo Olopade, MD, FACP, OON, is the Walter L. Palmer Distinguished Service Professor of Medicine and Human Genetics, and director, Center for Global Health at the University of Chicago. She is adopting emerging high throughput genomic and informatics strategies to identify genetic and nongenetic risk factors for breast cancer in order to implement precision health care in diverse populations. This innovative approach has the potential to improve the quality of care and reduce costs while saving more lives.

Disclosures: Dr. Olopade serves on the Medical Advisory Board for CancerIQ. Dr. Daly serves as a director of Quadrant Holdings Corporation and receives compensation from this entity. Frontline Medical Communications is a subsidiary of Quadrant Holdings Corporation.

Published in conjunction with Susan G. Komen®.

Editor’s Note: This is the third installment of a five-part monthly series that will discuss the pathologic, genomic, and health system factors that contribute to the racial survival disparity in breast cancer. The series, which is adapted from an article that originally appeared in CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians1, a journal of the American Cancer Society, will also review exciting and innovative interventions to close the survival gap. This month’s column reviews patterns of care – the second element in the perfect storm.

Mammography

Despite advances in breast cancer imaging technology, the mainstay of breast cancer screening has remained mammography. Chu et al.2 found that African American women have less early-stage disease in every age group for each hormone receptor status, and this raises the concern that mammography screening might be inadequate in this population. Although historically, African American women used mammography less than did white women, this difference has fortunately disappeared with time.3 According to results from the 2010 National Health Interview Survey, among women who were 40 years or older, 50.6% of non-Hispanic African Americans and 51.5% of non-Hispanic whites reported having had a mammogram within the past year.4

Although mammography uptake may be similar between these groups, there are still differences both in quality and in follow-up of abnormal imaging results. A study of mammography capacity and quality in a large urban setting found that the facilities that served predominantly minority women were more likely to be public institutions (31% vs. 0%) and less likely to be academic (27% vs. 71%), less likely to have digital mammography (18% vs. 71%), and less likely to have dedicated breast imaging specialists reading the films (23% vs. 87%). The authors concluded that the mammography process was broken, with quality differences in the manner in which the centers provided care and reported results.5

The accompanying graphic illustrates the disparities seen in breast cancer mammography and care for women in underserved communities on Chicago’s South Side. As the figure demonstrates, there are fewer mammography centers on the city’s South Side, with the concentration of breast cancer imaging and treatment resources localized in the more affluent communities of central and northern Chicago. A total of 300,000 women who were eligible for screening went unscreened because of improper management of resources.

Highlighting the importance of location in breast cancer care, Gehlert et al.6 asserted that ensuring that inner-city health facilities have up-to-date, well-maintained equipment and that mammographers have access to continuing training and opportunities for consultation should help reduce breast cancer mortality in African Americans.

With respect to follow-up of abnormal imaging results, a large retrospective cohort study of 6,722 women with abnormal mammogram results seen at a New York academic medical center from January 2002 through December 2002 found longer times to diagnostic follow-up for African American versus white women. The median number of days to diagnostic follow-up was 20 for African American patients versus 14 for white patients. In addition, racial disparities remained significant after the researchers controlled for age, Breast Imaging Reporting and Data System (BI-RADS) category, insurance status, provider practice location, and median household income. More important, in women with a BI-RADS classification of 4 or 5 – signifying a lesion seen on mammography that is either suspicious for or highly suggestive of malignancy, respectively – the median number of days to follow-up among those without same-day additional imaging was 26 for African Americans and 14 for whites (P < .05).7

Delays in treatment

A cascade of delays also has been documented in breast cancer care for African American women. Silber et al.8 investigated factors associated with differences in breast cancer outcomes in a large population-based study using Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER)-Medicare data. The mean time from diagnosis to treatment was 29.2 days for African Americans versus 22.5 days for whites (P < .001). The authors also found that African Americans were more likely to have very-long treatment delays. At least 6% of African Americans did not initiate treatment within the first 3 months of diagnosis, whereas only 3% of whites failed to start treatment (P < .001). Gwyn et al.9 also found potentially clinically significant treatment delays more often for African American women than for white women. The time from medical consultation to the initiation of treatment was longer than 3 months for 22.4% of African American women versus 14.3% of white women. Three months was chosen as a clinically significant time period, because Richards et al.10 demonstrated that a delay ≥ to 3 months affects survival. Thus, delays in the diagnosis and treatment of African American women are factors that worsen the survival gap.

Misuse of treatment

Once treatment is initiated, African Americans often receive inappropriate therapy, studies have demonstrated. In a prospective analysis of 957 patients in 101 oncology practices, Griggs et al.11 found more frequent use of non–guideline concordant adjuvant chemotherapy regimens in African American women. In a univariate analysis, African American patients were more likely than were whites to receive a nonstandard regimen (19% vs. 11%; P = .047). Although we will discuss further in this column whether guidelines based on clinical trials are appropriate for African American patients, the study demonstrates that these women are not uniformly receiving standard-of-care treatment.

Underuse of treatment

In addition to misuse of treatment, studies also have examined undertreatment of African American patients with breast cancer. One study investigated chemotherapy administration among African American patients with stage I-III breast cancer at 10 different treatment sites. Compared with white patients, African Americans received a lower dose proportion (actual vs. expected dose) and lower relative dose intensity.

The authors found that between-group differences in biological and medical characteristics, such as tolerance of therapy, comorbidities, and leukocyte counts, did not explain these variations in treatment. In fact, despite the association between lower leukocyte counts and African American ethnicity, there was no evidence that white blood cell levels accounted for the difference in dose proportion or relative dose intensity. Significantly, the authors discovered that more African Americans had chemotherapy dose reductions in the first cycle of treatment, perhaps indicating physician assumptions regarding African American patients’ ability to tolerate chemotherapy.12

Silber et al.8 also examined differences in the administration of chemotherapy between white and African American breast cancer patients. The authors found that 3.7% of African Americans received both an anthracycline and a taxane; that figure rose to 5.0% among whites who were matched to African Americans at presentation.

Bickell et al.13 explored further racial disparity in the underuse of adjuvant breast cancer treatment. The researchers examined the medical records of 677 women treated surgically for stage I or II breast cancer. The study defined underuse as omissions of radiotherapy after breast-conserving surgery, adjuvant chemotherapy after resection of hormone receptor–negative tumors ≥ 1 cm, or hormonal therapy for receptor-positive tumors ≥ 1 cm. Underuse of appropriate adjuvant treatment was found in 34% of African American patients versus 16% of white patients (P less than .001). There were racial disparities present in all three adjuvant therapies assessed.

Hormonal therapy has been shown effective in clinical trials for preventing breast cancer recurrence and death in women with early-stage breast cancer.14 The study by Bickell et al.13 documented underuse of this treatment in African American patients. Partridge et al.15 conducted the largest study of oral antineoplastic use outside of a clinical trial setting. Their study consisted of 2,378 primary breast cancer patients enrolled in New Jersey’s Medicaid or pharmaceutical assistance program; the main outcome was the number of days covered by filled tamoxifen prescriptions in the first year of therapy. The study found that nonwhite patients had significantly lower adherence rates than did whites. Although further investigation is needed to determine the drivers of this nonadherence in African American patients, medication cost has been proposed as a significant factor leading to underuse of these agents. Streeter et al.16 analyzed a nationally representative pharmacy claims database for oral antineoplastics and calculated abandonment rates for the initial claim. Not surprisingly, high cost sharing and low incomes were associated with a higher abandonment rate (P < .05). Despite being an important component of health equity research, treatment adherence has been identified by the Association of American Medical Colleges as a critically underrepresented area of disparities-focused health services research.17 More attention to this area is needed to understand the underuse of hormonal therapies in African American breast cancer patients.

The treatment strategies that have been shown to be delayed, underused, or misused in African American patients in the aforementioned studies have improved disease-free and overall survival in large randomized trials. Furthermore, diminished total dose and dose intensity of adjuvant chemotherapy both have been associated with lower breast cancer survival rates.18,19 These quality-of-care failures in breast cancer treatment for minority patients are thought to partially explain the survival disparity between African Americans and whites. It has been proposed that patients in both groups derive a similar benefit from systemic therapy when it is administered in accordance with their clinical and pathologic presentation,20 but that assumption becomes more nuanced when the clinical trial experience is reviewed.

Clinical trial experience

Dignam20 examined survival by race in several National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project trials. He found that the benefit from systemic adjuvant therapy for reductions in disease recurrence and mortality was comparable between African American and white patients. His survey of trials consistently indicated equivalent disease-free survival, but a mortality deficit for African Americans also was found consistently. Among African Americans, the excess risk of mortality was 21% for those who were lymph node–negative and 17% for those who were lymph node–positive. The excess mortality risk was thought to be attributable to greater mortality from noncancer causes among African American patients rather than a failure of African Americans to respond to breast cancer treatment.

In contrast to Dignam’s findings20, Hershman et al.21 assessed the association between race and treatment discontinuation/delay, white blood cell counts, and survival in women enrolled in the Southwest Oncology Group adjuvant breast cancer trials. The study found that African American women were significantly more likely to experience treatment discontinuation/delay than were white women (87% vs. 81%, respectively; P = .04). These delays were not accounted for by toxicities, which were experienced in similar proportions by race. African American women also were more likely to miss appointments (19% vs. 9%; P = .0002); perhaps, as Hassett and Griggs22 speculated, this finding speaks to economic barriers, including the inability to arrange alternate child care, miss work, or afford transportation to the clinic. Despite these barriers to care for African American patients, they still received the same mean relative dose intensity (87% vs. 86%).

In their survival analysis, Hershman et al.21 controlled for treatment-related factors such as dose reductions and delays, body surface area, baseline white blood cell counts, and other predictors of survival and still found that African Americans had worse disease-free and overall survival than did white women. The authors concluded that the study was “unable to demonstrate that any factor related to treatment quality or delivery contributed to racial differences in survival between the groups.”21 The study thus established two important findings related to the disparity gap. First, even in the controlled setting of a clinical trial, African American patients faced barriers to optimal treatment,22 and second, despite attempts to control for treatment quality and delivery, African American women still had worse outcomes. These findings suggest that tumor biology and genomics remain important.

In next month’s installment, we will discuss interventions aimed at closing the racial survival disparity in breast cancer. Eliminating racial disparities in cancer mortality through effective interventions has become an increasingly important imperative in federal, state, and community health care programs.

Other installments of this column can be found in the Related Content box.

1. Daly B, Olopade OI. A perfect storm: How tumor biology, genomics, and health care delivery patterns collide to create a racial survival disparity in breast cancer and proposed interventions for change. CA Cancer J Clin. 2015 May-Jun;65(3):221-38.

2. Chu KC, Lamar CA, Freeman HP. Racial disparities in breast carcinoma survival rates: Separating factors that affect diagnosis from factors that affect treatment. Cancer. 2003 Jun;97(11):2853-60.

3. DeLancey JO, Thun MJ, Jemal A, Ward EM. Recent trends in black-white disparities in cancer mortality. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2008 Nov;17(11):2908-12.

4. DeSantis C, Naishadham D, Jemal A. Cancer statistics for African Americans, 2013. CA Cancer J Clin. 2013 Nov;63(3):151-66.

5. Ansell D, Grabler P, Whitman S, et al. A community effort to reduce the black/white breast cancer mortality disparity in Chicago. Cancer Causes Control. 2009 Nov;20(9):1681-8.

6. Gehlert S, Sohmer D, Sacks T, Mininger C, McClintock M, Olopade O. Targeting health disparities: a model linking upstream determinants to downstream interventions. Health Aff (Millwood). 2008 Mar-Apr;27(2):339-49.

7. Press R, Carrasquillo O, Sciacca RR, Giardina EG. Racial/ethnic disparities in time to follow-up after an abnormal mammogram. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2008 Jul;17(6):923-30.

8. Silber JH, Rosenbaum PR, Clark AS, et al. Characteristics associated with differences in survival among black and white women with breast cancer. JAMA. 2013 Jul;310(4):389-397.

9. Gwyn K, Bondy ML, Cohen DS, et al. Racial differences in diagnosis, treatment, and clinical delays in a population-based study of patients with newly diagnosed breast carcinoma. Cancer. 2004 Apr;100(8):1595-604.

10. Richards MA, Westcombe AM, Love SB, Littlejohns P, Ramirez AJ. Influence of delay on survival in patients with breast cancer: a systematic review. Lancet. 1999 Apr 3;353(9159):1119-26.

11. Griggs JJ, Culakova E, Sorbero ME, et al. Social and racial differences in selection of breast cancer adjuvant chemotherapy regimens. J Clin Oncol. 2007 Jun 20;25(18):2522-7.

12. Griggs JJ, Sorbero ME, Stark AT, Heininger SE, Dick AW. Racial disparity in the dose and dose intensity of breast cancer adjuvant chemotherapy. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2003 Sep;81(1):21-31.

13. Bickell NA, Wang JJ, Oluwole S, et al. Missed opportunities: racial disparities in adjuvant breast cancer treatment. J Clin Oncol. 2006 Mar 20;24(9):1357-62. 14. Fisher B, Costantino J, Redmond C, et al. A randomized clinical trial evaluating tamoxifen in the treatment of patients with node-negative breast cancer who have estrogen-receptor-positive tumors. N Engl J Med. 1989 Feb 23;320(8):479-84.

15. Partridge AH, Wang PS, Winer EP, Avorn J. Nonadherence to adjuvant tamoxifen therapy in women with primary breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2003 Feb 15;21(4):602-6.

16. Streeter SB, Schwartzberg L, Husain N, Johnsrud M. Patient and plan characteristics affecting abandonment of oral oncolytic prescriptions. J Oncol Pract. 2011 Jul;7(3 Suppl):46s-51s.

17. Alberti PM KN, Sutton K, Johnson BH, Holve E. The state of health equity research: closing knowledge gaps to address inequities. ©2014 Association of American Medical Colleges. May not be reproduced or distributed without prior permission.

18. Wood WC, Budman DR, Korzun AH, et al. Dose and dose intensity of adjuvant chemotherapy for stage II, node-positive breast carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 1994 May 5;330(18):1253-9.

19. Budman DR, Berry DA, Cirrincione CT, et al. Dose and dose intensity as determinants of outcome in the adjuvant treatment of breast cancer. The Cancer and Leukemia Group B. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1998 Aug 19;90(16):1205-11.

20. Dignam JJ. Efficacy of systemic adjuvant therapy for breast cancer in African-American and Caucasian women. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2001(30):36-43.

21. Hershman DL, Unger JM, Barlow WE, et al. Treatment quality and outcomes of African American versus white breast cancer patients: retrospective analysis of Southwest Oncology studies S8814/S8897. J Clin Oncol. 2009 May;27(13):2157-62.

22. Hassett MJ, Griggs JJ. Disparities in breast cancer adjuvant chemotherapy: moving beyond yes or no. J Clin Oncol. 2009 May 1;27(13):2120-1.

Bobby Daly, MD, MBA, is the chief fellow in the section of hematology/oncology at the University of Chicago Medicine. His clinical focus is breast and thoracic oncology, and his research focus is health services. Specifically, Dr. Daly researches disparities in oncology care delivery, oncology health care utilization, aggressive end-of-life oncology care, and oncology payment models. He received his MD and MBA from Harvard Medical School and Harvard Business School, both in Boston, and a BA in Economics and History from Stanford (Calif.) University. He was the recipient of the Dean’s Award at Harvard Medical and Business Schools.

Olufunmilayo Olopade, MD, FACP, OON, is the Walter L. Palmer Distinguished Service Professor of Medicine and Human Genetics, and director, Center for Global Health at the University of Chicago. She is adopting emerging high throughput genomic and informatics strategies to identify genetic and nongenetic risk factors for breast cancer in order to implement precision health care in diverse populations. This innovative approach has the potential to improve the quality of care and reduce costs while saving more lives.

Disclosures: Dr. Olopade serves on the Medical Advisory Board for CancerIQ. Dr. Daly serves as a director of Quadrant Holdings Corporation and receives compensation from this entity. Frontline Medical Communications is a subsidiary of Quadrant Holdings Corporation.

Published in conjunction with Susan G. Komen®.

Editor’s Note: This is the third installment of a five-part monthly series that will discuss the pathologic, genomic, and health system factors that contribute to the racial survival disparity in breast cancer. The series, which is adapted from an article that originally appeared in CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians1, a journal of the American Cancer Society, will also review exciting and innovative interventions to close the survival gap. This month’s column reviews patterns of care – the second element in the perfect storm.

Mammography

Despite advances in breast cancer imaging technology, the mainstay of breast cancer screening has remained mammography. Chu et al.2 found that African American women have less early-stage disease in every age group for each hormone receptor status, and this raises the concern that mammography screening might be inadequate in this population. Although historically, African American women used mammography less than did white women, this difference has fortunately disappeared with time.3 According to results from the 2010 National Health Interview Survey, among women who were 40 years or older, 50.6% of non-Hispanic African Americans and 51.5% of non-Hispanic whites reported having had a mammogram within the past year.4

Although mammography uptake may be similar between these groups, there are still differences both in quality and in follow-up of abnormal imaging results. A study of mammography capacity and quality in a large urban setting found that the facilities that served predominantly minority women were more likely to be public institutions (31% vs. 0%) and less likely to be academic (27% vs. 71%), less likely to have digital mammography (18% vs. 71%), and less likely to have dedicated breast imaging specialists reading the films (23% vs. 87%). The authors concluded that the mammography process was broken, with quality differences in the manner in which the centers provided care and reported results.5

The accompanying graphic illustrates the disparities seen in breast cancer mammography and care for women in underserved communities on Chicago’s South Side. As the figure demonstrates, there are fewer mammography centers on the city’s South Side, with the concentration of breast cancer imaging and treatment resources localized in the more affluent communities of central and northern Chicago. A total of 300,000 women who were eligible for screening went unscreened because of improper management of resources.

Highlighting the importance of location in breast cancer care, Gehlert et al.6 asserted that ensuring that inner-city health facilities have up-to-date, well-maintained equipment and that mammographers have access to continuing training and opportunities for consultation should help reduce breast cancer mortality in African Americans.

With respect to follow-up of abnormal imaging results, a large retrospective cohort study of 6,722 women with abnormal mammogram results seen at a New York academic medical center from January 2002 through December 2002 found longer times to diagnostic follow-up for African American versus white women. The median number of days to diagnostic follow-up was 20 for African American patients versus 14 for white patients. In addition, racial disparities remained significant after the researchers controlled for age, Breast Imaging Reporting and Data System (BI-RADS) category, insurance status, provider practice location, and median household income. More important, in women with a BI-RADS classification of 4 or 5 – signifying a lesion seen on mammography that is either suspicious for or highly suggestive of malignancy, respectively – the median number of days to follow-up among those without same-day additional imaging was 26 for African Americans and 14 for whites (P < .05).7

Delays in treatment

A cascade of delays also has been documented in breast cancer care for African American women. Silber et al.8 investigated factors associated with differences in breast cancer outcomes in a large population-based study using Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER)-Medicare data. The mean time from diagnosis to treatment was 29.2 days for African Americans versus 22.5 days for whites (P < .001). The authors also found that African Americans were more likely to have very-long treatment delays. At least 6% of African Americans did not initiate treatment within the first 3 months of diagnosis, whereas only 3% of whites failed to start treatment (P < .001). Gwyn et al.9 also found potentially clinically significant treatment delays more often for African American women than for white women. The time from medical consultation to the initiation of treatment was longer than 3 months for 22.4% of African American women versus 14.3% of white women. Three months was chosen as a clinically significant time period, because Richards et al.10 demonstrated that a delay ≥ to 3 months affects survival. Thus, delays in the diagnosis and treatment of African American women are factors that worsen the survival gap.

Misuse of treatment

Once treatment is initiated, African Americans often receive inappropriate therapy, studies have demonstrated. In a prospective analysis of 957 patients in 101 oncology practices, Griggs et al.11 found more frequent use of non–guideline concordant adjuvant chemotherapy regimens in African American women. In a univariate analysis, African American patients were more likely than were whites to receive a nonstandard regimen (19% vs. 11%; P = .047). Although we will discuss further in this column whether guidelines based on clinical trials are appropriate for African American patients, the study demonstrates that these women are not uniformly receiving standard-of-care treatment.

Underuse of treatment

In addition to misuse of treatment, studies also have examined undertreatment of African American patients with breast cancer. One study investigated chemotherapy administration among African American patients with stage I-III breast cancer at 10 different treatment sites. Compared with white patients, African Americans received a lower dose proportion (actual vs. expected dose) and lower relative dose intensity.

The authors found that between-group differences in biological and medical characteristics, such as tolerance of therapy, comorbidities, and leukocyte counts, did not explain these variations in treatment. In fact, despite the association between lower leukocyte counts and African American ethnicity, there was no evidence that white blood cell levels accounted for the difference in dose proportion or relative dose intensity. Significantly, the authors discovered that more African Americans had chemotherapy dose reductions in the first cycle of treatment, perhaps indicating physician assumptions regarding African American patients’ ability to tolerate chemotherapy.12

Silber et al.8 also examined differences in the administration of chemotherapy between white and African American breast cancer patients. The authors found that 3.7% of African Americans received both an anthracycline and a taxane; that figure rose to 5.0% among whites who were matched to African Americans at presentation.

Bickell et al.13 explored further racial disparity in the underuse of adjuvant breast cancer treatment. The researchers examined the medical records of 677 women treated surgically for stage I or II breast cancer. The study defined underuse as omissions of radiotherapy after breast-conserving surgery, adjuvant chemotherapy after resection of hormone receptor–negative tumors ≥ 1 cm, or hormonal therapy for receptor-positive tumors ≥ 1 cm. Underuse of appropriate adjuvant treatment was found in 34% of African American patients versus 16% of white patients (P less than .001). There were racial disparities present in all three adjuvant therapies assessed.

Hormonal therapy has been shown effective in clinical trials for preventing breast cancer recurrence and death in women with early-stage breast cancer.14 The study by Bickell et al.13 documented underuse of this treatment in African American patients. Partridge et al.15 conducted the largest study of oral antineoplastic use outside of a clinical trial setting. Their study consisted of 2,378 primary breast cancer patients enrolled in New Jersey’s Medicaid or pharmaceutical assistance program; the main outcome was the number of days covered by filled tamoxifen prescriptions in the first year of therapy. The study found that nonwhite patients had significantly lower adherence rates than did whites. Although further investigation is needed to determine the drivers of this nonadherence in African American patients, medication cost has been proposed as a significant factor leading to underuse of these agents. Streeter et al.16 analyzed a nationally representative pharmacy claims database for oral antineoplastics and calculated abandonment rates for the initial claim. Not surprisingly, high cost sharing and low incomes were associated with a higher abandonment rate (P < .05). Despite being an important component of health equity research, treatment adherence has been identified by the Association of American Medical Colleges as a critically underrepresented area of disparities-focused health services research.17 More attention to this area is needed to understand the underuse of hormonal therapies in African American breast cancer patients.

The treatment strategies that have been shown to be delayed, underused, or misused in African American patients in the aforementioned studies have improved disease-free and overall survival in large randomized trials. Furthermore, diminished total dose and dose intensity of adjuvant chemotherapy both have been associated with lower breast cancer survival rates.18,19 These quality-of-care failures in breast cancer treatment for minority patients are thought to partially explain the survival disparity between African Americans and whites. It has been proposed that patients in both groups derive a similar benefit from systemic therapy when it is administered in accordance with their clinical and pathologic presentation,20 but that assumption becomes more nuanced when the clinical trial experience is reviewed.

Clinical trial experience

Dignam20 examined survival by race in several National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project trials. He found that the benefit from systemic adjuvant therapy for reductions in disease recurrence and mortality was comparable between African American and white patients. His survey of trials consistently indicated equivalent disease-free survival, but a mortality deficit for African Americans also was found consistently. Among African Americans, the excess risk of mortality was 21% for those who were lymph node–negative and 17% for those who were lymph node–positive. The excess mortality risk was thought to be attributable to greater mortality from noncancer causes among African American patients rather than a failure of African Americans to respond to breast cancer treatment.

In contrast to Dignam’s findings20, Hershman et al.21 assessed the association between race and treatment discontinuation/delay, white blood cell counts, and survival in women enrolled in the Southwest Oncology Group adjuvant breast cancer trials. The study found that African American women were significantly more likely to experience treatment discontinuation/delay than were white women (87% vs. 81%, respectively; P = .04). These delays were not accounted for by toxicities, which were experienced in similar proportions by race. African American women also were more likely to miss appointments (19% vs. 9%; P = .0002); perhaps, as Hassett and Griggs22 speculated, this finding speaks to economic barriers, including the inability to arrange alternate child care, miss work, or afford transportation to the clinic. Despite these barriers to care for African American patients, they still received the same mean relative dose intensity (87% vs. 86%).

In their survival analysis, Hershman et al.21 controlled for treatment-related factors such as dose reductions and delays, body surface area, baseline white blood cell counts, and other predictors of survival and still found that African Americans had worse disease-free and overall survival than did white women. The authors concluded that the study was “unable to demonstrate that any factor related to treatment quality or delivery contributed to racial differences in survival between the groups.”21 The study thus established two important findings related to the disparity gap. First, even in the controlled setting of a clinical trial, African American patients faced barriers to optimal treatment,22 and second, despite attempts to control for treatment quality and delivery, African American women still had worse outcomes. These findings suggest that tumor biology and genomics remain important.

In next month’s installment, we will discuss interventions aimed at closing the racial survival disparity in breast cancer. Eliminating racial disparities in cancer mortality through effective interventions has become an increasingly important imperative in federal, state, and community health care programs.

Other installments of this column can be found in the Related Content box.

1. Daly B, Olopade OI. A perfect storm: How tumor biology, genomics, and health care delivery patterns collide to create a racial survival disparity in breast cancer and proposed interventions for change. CA Cancer J Clin. 2015 May-Jun;65(3):221-38.

2. Chu KC, Lamar CA, Freeman HP. Racial disparities in breast carcinoma survival rates: Separating factors that affect diagnosis from factors that affect treatment. Cancer. 2003 Jun;97(11):2853-60.

3. DeLancey JO, Thun MJ, Jemal A, Ward EM. Recent trends in black-white disparities in cancer mortality. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2008 Nov;17(11):2908-12.

4. DeSantis C, Naishadham D, Jemal A. Cancer statistics for African Americans, 2013. CA Cancer J Clin. 2013 Nov;63(3):151-66.

5. Ansell D, Grabler P, Whitman S, et al. A community effort to reduce the black/white breast cancer mortality disparity in Chicago. Cancer Causes Control. 2009 Nov;20(9):1681-8.

6. Gehlert S, Sohmer D, Sacks T, Mininger C, McClintock M, Olopade O. Targeting health disparities: a model linking upstream determinants to downstream interventions. Health Aff (Millwood). 2008 Mar-Apr;27(2):339-49.

7. Press R, Carrasquillo O, Sciacca RR, Giardina EG. Racial/ethnic disparities in time to follow-up after an abnormal mammogram. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2008 Jul;17(6):923-30.

8. Silber JH, Rosenbaum PR, Clark AS, et al. Characteristics associated with differences in survival among black and white women with breast cancer. JAMA. 2013 Jul;310(4):389-397.

9. Gwyn K, Bondy ML, Cohen DS, et al. Racial differences in diagnosis, treatment, and clinical delays in a population-based study of patients with newly diagnosed breast carcinoma. Cancer. 2004 Apr;100(8):1595-604.

10. Richards MA, Westcombe AM, Love SB, Littlejohns P, Ramirez AJ. Influence of delay on survival in patients with breast cancer: a systematic review. Lancet. 1999 Apr 3;353(9159):1119-26.

11. Griggs JJ, Culakova E, Sorbero ME, et al. Social and racial differences in selection of breast cancer adjuvant chemotherapy regimens. J Clin Oncol. 2007 Jun 20;25(18):2522-7.

12. Griggs JJ, Sorbero ME, Stark AT, Heininger SE, Dick AW. Racial disparity in the dose and dose intensity of breast cancer adjuvant chemotherapy. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2003 Sep;81(1):21-31.

13. Bickell NA, Wang JJ, Oluwole S, et al. Missed opportunities: racial disparities in adjuvant breast cancer treatment. J Clin Oncol. 2006 Mar 20;24(9):1357-62. 14. Fisher B, Costantino J, Redmond C, et al. A randomized clinical trial evaluating tamoxifen in the treatment of patients with node-negative breast cancer who have estrogen-receptor-positive tumors. N Engl J Med. 1989 Feb 23;320(8):479-84.

15. Partridge AH, Wang PS, Winer EP, Avorn J. Nonadherence to adjuvant tamoxifen therapy in women with primary breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2003 Feb 15;21(4):602-6.

16. Streeter SB, Schwartzberg L, Husain N, Johnsrud M. Patient and plan characteristics affecting abandonment of oral oncolytic prescriptions. J Oncol Pract. 2011 Jul;7(3 Suppl):46s-51s.

17. Alberti PM KN, Sutton K, Johnson BH, Holve E. The state of health equity research: closing knowledge gaps to address inequities. ©2014 Association of American Medical Colleges. May not be reproduced or distributed without prior permission.

18. Wood WC, Budman DR, Korzun AH, et al. Dose and dose intensity of adjuvant chemotherapy for stage II, node-positive breast carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 1994 May 5;330(18):1253-9.

19. Budman DR, Berry DA, Cirrincione CT, et al. Dose and dose intensity as determinants of outcome in the adjuvant treatment of breast cancer. The Cancer and Leukemia Group B. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1998 Aug 19;90(16):1205-11.

20. Dignam JJ. Efficacy of systemic adjuvant therapy for breast cancer in African-American and Caucasian women. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2001(30):36-43.

21. Hershman DL, Unger JM, Barlow WE, et al. Treatment quality and outcomes of African American versus white breast cancer patients: retrospective analysis of Southwest Oncology studies S8814/S8897. J Clin Oncol. 2009 May;27(13):2157-62.

22. Hassett MJ, Griggs JJ. Disparities in breast cancer adjuvant chemotherapy: moving beyond yes or no. J Clin Oncol. 2009 May 1;27(13):2120-1.

Bobby Daly, MD, MBA, is the chief fellow in the section of hematology/oncology at the University of Chicago Medicine. His clinical focus is breast and thoracic oncology, and his research focus is health services. Specifically, Dr. Daly researches disparities in oncology care delivery, oncology health care utilization, aggressive end-of-life oncology care, and oncology payment models. He received his MD and MBA from Harvard Medical School and Harvard Business School, both in Boston, and a BA in Economics and History from Stanford (Calif.) University. He was the recipient of the Dean’s Award at Harvard Medical and Business Schools.

Olufunmilayo Olopade, MD, FACP, OON, is the Walter L. Palmer Distinguished Service Professor of Medicine and Human Genetics, and director, Center for Global Health at the University of Chicago. She is adopting emerging high throughput genomic and informatics strategies to identify genetic and nongenetic risk factors for breast cancer in order to implement precision health care in diverse populations. This innovative approach has the potential to improve the quality of care and reduce costs while saving more lives.

Disclosures: Dr. Olopade serves on the Medical Advisory Board for CancerIQ. Dr. Daly serves as a director of Quadrant Holdings Corporation and receives compensation from this entity. Frontline Medical Communications is a subsidiary of Quadrant Holdings Corporation.

Published in conjunction with Susan G. Komen®.

An Eruption While on Total Parenteral Nutrition

The Diagnosis: Acquired Acrodermatitis Enteropathica

Acquired acrodermatitis enteropathica (AAE) is a rare disorder caused by severe zinc deficiency. Although acrodermatitis enteropathica is an autosomal-recessive disorder that typically manifests in infancy, AAE also can result from poor zinc intake, impaired absorption, or accelerated losses. There are reports of AAE in patients with zinc-deficient diets,1 eating disorders,2 bariatric and other gastrointestinal surgeries,3 malabsorptive diseases,4 and nephrotic syndrome.5

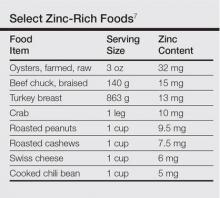

Zinc plays an important role in DNA and RNA synthesis, reactive oxygen species attenuation, and energy metabolism, allowing for proper wound healing, skin differentiation, and proliferation.6 Zinc is found in most foods, but animal protein contains higher concentrations (Table).7 Approximately 85% of zinc is stored in muscles and bones, with only a small amount of accessible zinc available in the liver. Liver stores can be depleted as quickly as 1 week.8 Total parenteral nutrition without trace element supplementation can quickly predispose patients to AAE.

|

|

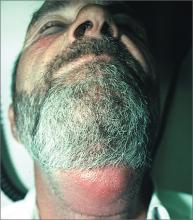

Diagnosis of this condition requires triangulation of clinical presentation, histopathology examination, and laboratory findings. Acrodermatitis enteropathica typically is characterized by dermatitis, diarrhea, and epidermal appendage findings. In its early stages, the dermatitis often manifests with angular cheilitis and paronychia.9 Patients then develop erythema, erosions, and occasionally vesicles or psoriasiform plaques in periorificial, perineal, and acral sites (Figure 1). Epidermal appendage effects include generalized alopecia and thinning nails with white transverse ridges. Although dermatologic and gastrointestinal manifestations are the most obvious, severe AAE may cause other symptoms, including mental slowing, hypogonadism, and impaired immune function.9

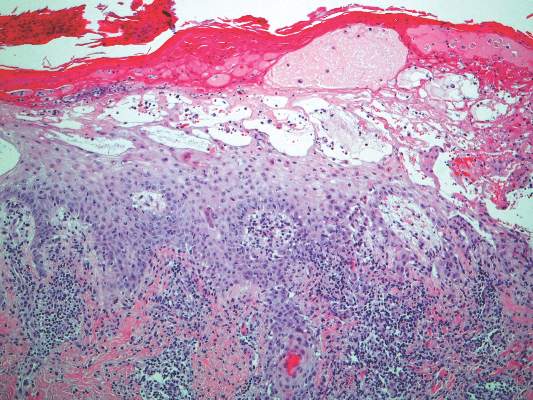

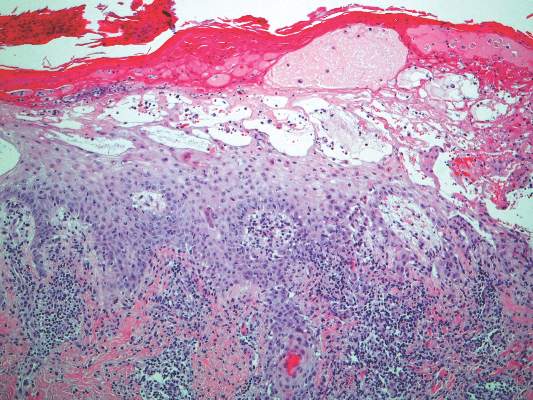

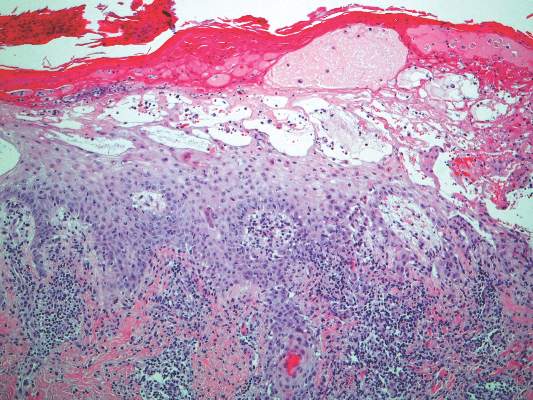

Histopathology of AAE skin lesions is similar to other nutritional deficiencies. Early changes are more specific to deficiency dermatitis and include cytoplasmic pallor and ballooning degeneration of keratinocytes in the stratum spinosum and granulosum.9 Necrolysis results in confluent keratinocyte necrosis developing into subcorneal bulla. Later in the disease course, the presentation becomes psoriasiform with keratinocyte dyskeratosis and confluent parakeratosis10 (Figure 2). Dermal edema with dilated tortuous vessels and a neutrophilic infiltrate may be present throughout disease progression.

Common laboratory abnormalities used to confirm zinc deficiency are decreased plasma zinc and alkaline phosphatase levels. Plasma zinc levels should be drawn after fasting because zinc levels decrease after food intake.9 Concurrent albumin levels should be drawn to correct for low levels caused by hypoalbuminemia. Acquired acrodermatitis enteropathica has been seen in patients with only mildly decreased plasma zinc levels or even zinc levels within reference range.11 Alkaline phosphatase metalloenzyme synthesis requires zinc and a decreased level suggests zinc deficiency even with a plasma zinc level within reference range. Alkaline phosphatase levels usually can be ascertained in a matter of hours, while the zinc levels take much longer to result.

Acquired acrodermatitis enteropathica is treated with oral elemental zinc supplementation at 1 to 2 mg/kg daily.12 Diarrhea typically resolves within 24 hours, but skin lesions heal in 1 to 2 weeks or longer. Although there is no consensus on when to discontinue zinc replacement therapy, therapy generally is not lifelong. Once the patient is zinc replete and the inciting factor has resolved, patients can discontinue supplementation without risk for recurrence.

Trace elements had not been added to our patient’s total parenteral nutrition prior to admission. Basic nutrition laboratory results and zinc levels returned markedly low: 14 μg/dL (reference range, 60–120 μg/dL). Alkaline phosphatase, a zinc-dependent protein, also was low at 12 U/L (reference range, 40–150 U/L). We added trace elements and vitamins and began empiric zinc replacement with 440 mg oral zinc sulfate daily (100 mg elemental zinc). Cephalexin was prescribed for impetiginized skin lesions. The patient noted skin improvement after 3 days on zinc replacement therapy.

- Saritha M, Gupta D, Chandrashekar L, et al. Acquired zinc deficiency in an adult female. Indian J Dermatol. 2012;57:492-494.

- Kim ST, Kang JS, Baek JW, et al. Acrodermatitis enteropathica with anorexia nervosa. J Dermatol. 2010;37:726-729.

- Bae-Harboe YS, Solky A, Masterpol KS. A case of acquired zinc deficiency. Dermatol Online J. 2012;18:1.

- Krasovec M, Frenk E. Acrodermatitis enteropathica secondary to Crohn’s disease. Dermatol Basel Switz. 1996;193:361-363.

- Reichel M, Mauro TM, Ziboh VA, et al. Acrodermatitis enteropathica in a patient with the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Arch Dermatol. 1992;128:415-417.

- Perafan-Riveros C, Franca LFS, Alves ACF, et al. Acrodermatitis enteropathica: case report and review of the literature. Pediatr Dermatol. 2002;19:426-431.

- National Nutrient Database for Standard Reference, Release 28. United States Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service website. http://ndb.nal.usda.gov/ndb/nutrients/report/nutrientsfrm?max=25&offset=0&totCount=0&nutrient1=309&nutrient2=&nutrient3=&subset=0&fg=&sort=f&measureby=m. Accessed December 14, 2015.

- McPherson RA, Pincus MR. Henry’s Clinical Diagnosis and Management by Laboratory Methods. 22nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders Elsevier; 2011.

- Maverakis E, Fung MA, Lynch PJ, et al. Acrodermatitis enteropathica and an overview of zinc metabolism. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:116-124.

- Gonzalez JR, Botet MV, Sanchez JL. The histopathology of acrodermatitis enteropathica. Am J Dermatopathol. 1982;4:303-311.

- Macdonald JB, Connolly SM, DiCaudo DJ. Think zinc deficiency: acquired acrodermatitis enteropathica due to poor diet and common medications. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148:961-963.

- Kumar P, Lal NR, Mondal A, et al. Zinc and skin: a brief summary. Dermatol Online J. 2012;18:1.

The Diagnosis: Acquired Acrodermatitis Enteropathica

Acquired acrodermatitis enteropathica (AAE) is a rare disorder caused by severe zinc deficiency. Although acrodermatitis enteropathica is an autosomal-recessive disorder that typically manifests in infancy, AAE also can result from poor zinc intake, impaired absorption, or accelerated losses. There are reports of AAE in patients with zinc-deficient diets,1 eating disorders,2 bariatric and other gastrointestinal surgeries,3 malabsorptive diseases,4 and nephrotic syndrome.5

Zinc plays an important role in DNA and RNA synthesis, reactive oxygen species attenuation, and energy metabolism, allowing for proper wound healing, skin differentiation, and proliferation.6 Zinc is found in most foods, but animal protein contains higher concentrations (Table).7 Approximately 85% of zinc is stored in muscles and bones, with only a small amount of accessible zinc available in the liver. Liver stores can be depleted as quickly as 1 week.8 Total parenteral nutrition without trace element supplementation can quickly predispose patients to AAE.

|

|

Diagnosis of this condition requires triangulation of clinical presentation, histopathology examination, and laboratory findings. Acrodermatitis enteropathica typically is characterized by dermatitis, diarrhea, and epidermal appendage findings. In its early stages, the dermatitis often manifests with angular cheilitis and paronychia.9 Patients then develop erythema, erosions, and occasionally vesicles or psoriasiform plaques in periorificial, perineal, and acral sites (Figure 1). Epidermal appendage effects include generalized alopecia and thinning nails with white transverse ridges. Although dermatologic and gastrointestinal manifestations are the most obvious, severe AAE may cause other symptoms, including mental slowing, hypogonadism, and impaired immune function.9

Histopathology of AAE skin lesions is similar to other nutritional deficiencies. Early changes are more specific to deficiency dermatitis and include cytoplasmic pallor and ballooning degeneration of keratinocytes in the stratum spinosum and granulosum.9 Necrolysis results in confluent keratinocyte necrosis developing into subcorneal bulla. Later in the disease course, the presentation becomes psoriasiform with keratinocyte dyskeratosis and confluent parakeratosis10 (Figure 2). Dermal edema with dilated tortuous vessels and a neutrophilic infiltrate may be present throughout disease progression.

Common laboratory abnormalities used to confirm zinc deficiency are decreased plasma zinc and alkaline phosphatase levels. Plasma zinc levels should be drawn after fasting because zinc levels decrease after food intake.9 Concurrent albumin levels should be drawn to correct for low levels caused by hypoalbuminemia. Acquired acrodermatitis enteropathica has been seen in patients with only mildly decreased plasma zinc levels or even zinc levels within reference range.11 Alkaline phosphatase metalloenzyme synthesis requires zinc and a decreased level suggests zinc deficiency even with a plasma zinc level within reference range. Alkaline phosphatase levels usually can be ascertained in a matter of hours, while the zinc levels take much longer to result.

Acquired acrodermatitis enteropathica is treated with oral elemental zinc supplementation at 1 to 2 mg/kg daily.12 Diarrhea typically resolves within 24 hours, but skin lesions heal in 1 to 2 weeks or longer. Although there is no consensus on when to discontinue zinc replacement therapy, therapy generally is not lifelong. Once the patient is zinc replete and the inciting factor has resolved, patients can discontinue supplementation without risk for recurrence.

Trace elements had not been added to our patient’s total parenteral nutrition prior to admission. Basic nutrition laboratory results and zinc levels returned markedly low: 14 μg/dL (reference range, 60–120 μg/dL). Alkaline phosphatase, a zinc-dependent protein, also was low at 12 U/L (reference range, 40–150 U/L). We added trace elements and vitamins and began empiric zinc replacement with 440 mg oral zinc sulfate daily (100 mg elemental zinc). Cephalexin was prescribed for impetiginized skin lesions. The patient noted skin improvement after 3 days on zinc replacement therapy.

The Diagnosis: Acquired Acrodermatitis Enteropathica

Acquired acrodermatitis enteropathica (AAE) is a rare disorder caused by severe zinc deficiency. Although acrodermatitis enteropathica is an autosomal-recessive disorder that typically manifests in infancy, AAE also can result from poor zinc intake, impaired absorption, or accelerated losses. There are reports of AAE in patients with zinc-deficient diets,1 eating disorders,2 bariatric and other gastrointestinal surgeries,3 malabsorptive diseases,4 and nephrotic syndrome.5

Zinc plays an important role in DNA and RNA synthesis, reactive oxygen species attenuation, and energy metabolism, allowing for proper wound healing, skin differentiation, and proliferation.6 Zinc is found in most foods, but animal protein contains higher concentrations (Table).7 Approximately 85% of zinc is stored in muscles and bones, with only a small amount of accessible zinc available in the liver. Liver stores can be depleted as quickly as 1 week.8 Total parenteral nutrition without trace element supplementation can quickly predispose patients to AAE.

|

|

Diagnosis of this condition requires triangulation of clinical presentation, histopathology examination, and laboratory findings. Acrodermatitis enteropathica typically is characterized by dermatitis, diarrhea, and epidermal appendage findings. In its early stages, the dermatitis often manifests with angular cheilitis and paronychia.9 Patients then develop erythema, erosions, and occasionally vesicles or psoriasiform plaques in periorificial, perineal, and acral sites (Figure 1). Epidermal appendage effects include generalized alopecia and thinning nails with white transverse ridges. Although dermatologic and gastrointestinal manifestations are the most obvious, severe AAE may cause other symptoms, including mental slowing, hypogonadism, and impaired immune function.9

Histopathology of AAE skin lesions is similar to other nutritional deficiencies. Early changes are more specific to deficiency dermatitis and include cytoplasmic pallor and ballooning degeneration of keratinocytes in the stratum spinosum and granulosum.9 Necrolysis results in confluent keratinocyte necrosis developing into subcorneal bulla. Later in the disease course, the presentation becomes psoriasiform with keratinocyte dyskeratosis and confluent parakeratosis10 (Figure 2). Dermal edema with dilated tortuous vessels and a neutrophilic infiltrate may be present throughout disease progression.

Common laboratory abnormalities used to confirm zinc deficiency are decreased plasma zinc and alkaline phosphatase levels. Plasma zinc levels should be drawn after fasting because zinc levels decrease after food intake.9 Concurrent albumin levels should be drawn to correct for low levels caused by hypoalbuminemia. Acquired acrodermatitis enteropathica has been seen in patients with only mildly decreased plasma zinc levels or even zinc levels within reference range.11 Alkaline phosphatase metalloenzyme synthesis requires zinc and a decreased level suggests zinc deficiency even with a plasma zinc level within reference range. Alkaline phosphatase levels usually can be ascertained in a matter of hours, while the zinc levels take much longer to result.

Acquired acrodermatitis enteropathica is treated with oral elemental zinc supplementation at 1 to 2 mg/kg daily.12 Diarrhea typically resolves within 24 hours, but skin lesions heal in 1 to 2 weeks or longer. Although there is no consensus on when to discontinue zinc replacement therapy, therapy generally is not lifelong. Once the patient is zinc replete and the inciting factor has resolved, patients can discontinue supplementation without risk for recurrence.

Trace elements had not been added to our patient’s total parenteral nutrition prior to admission. Basic nutrition laboratory results and zinc levels returned markedly low: 14 μg/dL (reference range, 60–120 μg/dL). Alkaline phosphatase, a zinc-dependent protein, also was low at 12 U/L (reference range, 40–150 U/L). We added trace elements and vitamins and began empiric zinc replacement with 440 mg oral zinc sulfate daily (100 mg elemental zinc). Cephalexin was prescribed for impetiginized skin lesions. The patient noted skin improvement after 3 days on zinc replacement therapy.

- Saritha M, Gupta D, Chandrashekar L, et al. Acquired zinc deficiency in an adult female. Indian J Dermatol. 2012;57:492-494.

- Kim ST, Kang JS, Baek JW, et al. Acrodermatitis enteropathica with anorexia nervosa. J Dermatol. 2010;37:726-729.

- Bae-Harboe YS, Solky A, Masterpol KS. A case of acquired zinc deficiency. Dermatol Online J. 2012;18:1.