User login

Axillary surgery not always indicated in BC patients with 1-2 positive sentinel lymph nodes undergoing mastectomy

Key clinical point: In patients with cT1-2 N0 breast cancer (BC) who underwent mastectomy and had 1-2 positive nodes on sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB), the rate of local-regional recurrence (LRR) was extremely low regardless of completion axillary node dissection (CLND) or radiation therapy.

Major finding: The 5-year cumulative incidence rate of overall LRR was comparable between patients who underwent vs did not undergo CLND (1.8% vs 1.3%; P = .93), with the receipt of post-mastectomy radiation therapy not affecting the LRR rate in both categories of patients who underwent SLNB alone and SLNB with CLND (P = .1638 for both).

Study details: Findings are from the analysis of a prospective institutional database including 548 patients with cT1-2 N0 BC who underwent mastectomy and had 1-2 positive lymph nodes on SLNB, and 77% of these patients underwent CLND.

Disclosures: This study was supported by the PH and Fay Etta Robinson Distinguished Professorship in Cancer Research and other sources. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Zaveri S et al. Extremely low incidence of local-regional recurrences observed among T1-2 N1 (1 or 2 positive SLNs) breast cancer patients receiving upfront mastectomy without completion axillary node dissection. Ann Surg Oncol. 2023 (Jul 17). doi: 10.1245/s10434-023-13942-1

Key clinical point: In patients with cT1-2 N0 breast cancer (BC) who underwent mastectomy and had 1-2 positive nodes on sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB), the rate of local-regional recurrence (LRR) was extremely low regardless of completion axillary node dissection (CLND) or radiation therapy.

Major finding: The 5-year cumulative incidence rate of overall LRR was comparable between patients who underwent vs did not undergo CLND (1.8% vs 1.3%; P = .93), with the receipt of post-mastectomy radiation therapy not affecting the LRR rate in both categories of patients who underwent SLNB alone and SLNB with CLND (P = .1638 for both).

Study details: Findings are from the analysis of a prospective institutional database including 548 patients with cT1-2 N0 BC who underwent mastectomy and had 1-2 positive lymph nodes on SLNB, and 77% of these patients underwent CLND.

Disclosures: This study was supported by the PH and Fay Etta Robinson Distinguished Professorship in Cancer Research and other sources. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Zaveri S et al. Extremely low incidence of local-regional recurrences observed among T1-2 N1 (1 or 2 positive SLNs) breast cancer patients receiving upfront mastectomy without completion axillary node dissection. Ann Surg Oncol. 2023 (Jul 17). doi: 10.1245/s10434-023-13942-1

Key clinical point: In patients with cT1-2 N0 breast cancer (BC) who underwent mastectomy and had 1-2 positive nodes on sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB), the rate of local-regional recurrence (LRR) was extremely low regardless of completion axillary node dissection (CLND) or radiation therapy.

Major finding: The 5-year cumulative incidence rate of overall LRR was comparable between patients who underwent vs did not undergo CLND (1.8% vs 1.3%; P = .93), with the receipt of post-mastectomy radiation therapy not affecting the LRR rate in both categories of patients who underwent SLNB alone and SLNB with CLND (P = .1638 for both).

Study details: Findings are from the analysis of a prospective institutional database including 548 patients with cT1-2 N0 BC who underwent mastectomy and had 1-2 positive lymph nodes on SLNB, and 77% of these patients underwent CLND.

Disclosures: This study was supported by the PH and Fay Etta Robinson Distinguished Professorship in Cancer Research and other sources. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Zaveri S et al. Extremely low incidence of local-regional recurrences observed among T1-2 N1 (1 or 2 positive SLNs) breast cancer patients receiving upfront mastectomy without completion axillary node dissection. Ann Surg Oncol. 2023 (Jul 17). doi: 10.1245/s10434-023-13942-1

Concomitant use of proton pump inhibitors with palbociclib may affect survival outcomes in breast cancer

Key clinical point: Patients with advanced or metastatic breast cancer (BC) who received concomitant proton pump inhibitors (PPI) plus palbociclib experienced less favorable survival outcomes compared with those who received palbociclib only.

Major finding: Patients who received concomitant PPI + palbociclib vs only palbociclib had significantly shorter progression-free survival (hazard ratio [HR] 1.76; 95% CI 1.46-2.13) and overall survival (HR 2.72; 95% CI 2.07-3.53) rates.

Study details: This retrospective cohort study included 1310 patients with hormone receptor-positive and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-negative advanced or metastatic BC, of which 344 and 966 patients received concomitant PPI + palbociclib and palbociclib only, respectively.

Disclosures: This study was funded by Sungkyunkwan University (South Korea), the Korean Ministry of Education, and the National Research Foundation of Korea. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Lee J-E et al. Concomitant use of proton pump inhibitors and palbociclib among patients with breast cancer. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6(7):e2324852 (Jul 21). doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.24852

Key clinical point: Patients with advanced or metastatic breast cancer (BC) who received concomitant proton pump inhibitors (PPI) plus palbociclib experienced less favorable survival outcomes compared with those who received palbociclib only.

Major finding: Patients who received concomitant PPI + palbociclib vs only palbociclib had significantly shorter progression-free survival (hazard ratio [HR] 1.76; 95% CI 1.46-2.13) and overall survival (HR 2.72; 95% CI 2.07-3.53) rates.

Study details: This retrospective cohort study included 1310 patients with hormone receptor-positive and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-negative advanced or metastatic BC, of which 344 and 966 patients received concomitant PPI + palbociclib and palbociclib only, respectively.

Disclosures: This study was funded by Sungkyunkwan University (South Korea), the Korean Ministry of Education, and the National Research Foundation of Korea. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Lee J-E et al. Concomitant use of proton pump inhibitors and palbociclib among patients with breast cancer. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6(7):e2324852 (Jul 21). doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.24852

Key clinical point: Patients with advanced or metastatic breast cancer (BC) who received concomitant proton pump inhibitors (PPI) plus palbociclib experienced less favorable survival outcomes compared with those who received palbociclib only.

Major finding: Patients who received concomitant PPI + palbociclib vs only palbociclib had significantly shorter progression-free survival (hazard ratio [HR] 1.76; 95% CI 1.46-2.13) and overall survival (HR 2.72; 95% CI 2.07-3.53) rates.

Study details: This retrospective cohort study included 1310 patients with hormone receptor-positive and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-negative advanced or metastatic BC, of which 344 and 966 patients received concomitant PPI + palbociclib and palbociclib only, respectively.

Disclosures: This study was funded by Sungkyunkwan University (South Korea), the Korean Ministry of Education, and the National Research Foundation of Korea. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Lee J-E et al. Concomitant use of proton pump inhibitors and palbociclib among patients with breast cancer. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6(7):e2324852 (Jul 21). doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.24852

Morning vs. afternoon exercise debate: A false dichotomy

Should we be exercising in the morning or afternoon? Before a meal or after a meal?

Popular media outlets, researchers, and clinicians seem to love these debates. I hate them. For me, it’s a false dichotomy. A false dichotomy is when people argue two sides as if only one option exists. A winner must be crowned, and a loser exists. But

Some but not all research suggests that morning fasted exercise may be the best time of day and condition to work out for weight control and training adaptations. Morning exercise may be a bit better for logistical reasons if you like to get up early. Some of us are indeed early chronotypes who rise early, get as much done as we can, including all our fitness and work-related activities, and then head to bed early (for me that is about 10 PM). Getting an early morning workout seems to fit with our schedules as morning larks.

But if you are a late-day chronotype, early exercise may not be in sync with your low morning energy levels or your preference for leisure-time activities later in the day. And lots of people with diabetes prefer to eat and then exercise. Late chronotypes are less physically active in general, compared with early chronotypes, and those who train in the morning tend to have better training adherence and expend more energy overall throughout the day. According to Dr. Normand Boulé from the University of Alberta, Edmonton, who presented on the topic of exercise time of day at the recent scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association in San Diego, morning exercise in the fasted state tends to be associated with higher rates of fat oxidation, better weight control, and better skeletal muscle adaptations over time, compared with exercise performed later in the day. Dr Boulé also proposed that fasted exercise might be superior for training adaptations and long-term glycemia if you have type 2 diabetes.

But the argument for morning-only exercise falls short when we look specifically at postmeal glycemia, according to Dr. Jenna Gillen from the University of Toronto, who faced off against Dr. Boulé at a debate at the meeting and also publishes on the topic. She pointed out that mild to moderate intensity exercising done soon after meals typically results in fewer glucose spikes after meals in people with diabetes, and her argument is supported by at least one recent meta-analysis where postmeal walking was best for improving glycemia in those with prediabetes and type 2 diabetes.

The notion that postmeal or afternoon exercise is best for people with type 2 diabetes is also supported by a recent reexamination of the original Look AHEAD Trial of over 2,400 adults with type 2 diabetes, wherein the role of lifestyle intervention on cardiovascular outcomes was the original goal. In this recent secondary analysis of the Look AHEAD Trial, those most active in the afternoon (between 1:43 p.m. and 5:00 p.m.) had the greatest improvements in their overall glucose control after 1 year of the intensive lifestyle intervention, compared with exercise at other times of day. Afternoon exercisers were also more likely to have complete “remission” of their diabetes, as defined by no longer needing any glucose-lowering agents to control their glucose levels. But this was not a study that was designed for determining whether exercise time of day matters for glycemia because the participants were not randomly assigned to a set time of day for their activity, and glycemic control was not the primary endpoint (cardiovascular events were).

But hold on a minute. I said this was a false-dichotomy argument. It is. Just because it may or may not be “better” for your glucose to exercise in the morning vs. afternoon, if you have diabetes, it doesn’t mean you have to choose one or the other. You could choose neither (okay, that’s bad), both, or you could alternate between the two. For me this argument is like saying; “There only one time of day to save money”; “to tell a joke”; “to eat a meal” (okay, that’s another useless debate); or “do my laundry” (my mother once told me it’s technically cheaper after 6 p.m.!).

I live with diabetes, and I take insulin. I like how morning exercise in the form of a run with my dog wakes me up, sets me up for the day with positive thoughts, helps generate lots of creative ideas, and perhaps more importantly for me, it tends not to result in hypoglycemia because my insulin on board is lowest then.

Exercise later in the day is tricky when taking insulin because it tends to result in a higher insulin “potency effect” with prandial insulins. However, I still like midday activity and late-day exercise. For example, taking an activity break after lunch blunts the rise in my glucose and breaks up my prolonged sitting time in the office. After-dinner exercise allows me to spend a little more time with my wife, dog, or friends outdoors as the hot summer day begins to cool off. On Monday nights, I play basketball because that’s the only time we can book the gymnasium and that may not end until 9:45 p.m. (15 minutes before I want to go to bed; if you remember, I am a lark). That can result in two frustrating things related to my diabetes: It can cause an immediate rise in my glucose because of a competitive stress response and then a drop in my glucose overnight when I’m sleeping. But I still do it. I know that the training I’m doing at any point of the day will benefit me in lots of little ways, and I think we all need to take as many opportunities to be physically active as we possibly can. My kids and I coin this our daily “fitness opportunities,” and it does not matter to me if its morning, noon, or night!

It’s time to make the headlines and arguments stop. There is no wrong time of day to exercise. At least not in my opinion.

Dr. Riddle is a full professor in the school of kinesiology and health science at York University and senior scientist at LMC Diabetes & Endocrinology, both in Toronto. He has disclosed financial relationships with Dexcom, Eli Lilly, Indigo Diabetes, Insulet, Novo Nordisk, Sanofi, Supersapiens, and Zucara Therapeutics.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Should we be exercising in the morning or afternoon? Before a meal or after a meal?

Popular media outlets, researchers, and clinicians seem to love these debates. I hate them. For me, it’s a false dichotomy. A false dichotomy is when people argue two sides as if only one option exists. A winner must be crowned, and a loser exists. But

Some but not all research suggests that morning fasted exercise may be the best time of day and condition to work out for weight control and training adaptations. Morning exercise may be a bit better for logistical reasons if you like to get up early. Some of us are indeed early chronotypes who rise early, get as much done as we can, including all our fitness and work-related activities, and then head to bed early (for me that is about 10 PM). Getting an early morning workout seems to fit with our schedules as morning larks.

But if you are a late-day chronotype, early exercise may not be in sync with your low morning energy levels or your preference for leisure-time activities later in the day. And lots of people with diabetes prefer to eat and then exercise. Late chronotypes are less physically active in general, compared with early chronotypes, and those who train in the morning tend to have better training adherence and expend more energy overall throughout the day. According to Dr. Normand Boulé from the University of Alberta, Edmonton, who presented on the topic of exercise time of day at the recent scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association in San Diego, morning exercise in the fasted state tends to be associated with higher rates of fat oxidation, better weight control, and better skeletal muscle adaptations over time, compared with exercise performed later in the day. Dr Boulé also proposed that fasted exercise might be superior for training adaptations and long-term glycemia if you have type 2 diabetes.

But the argument for morning-only exercise falls short when we look specifically at postmeal glycemia, according to Dr. Jenna Gillen from the University of Toronto, who faced off against Dr. Boulé at a debate at the meeting and also publishes on the topic. She pointed out that mild to moderate intensity exercising done soon after meals typically results in fewer glucose spikes after meals in people with diabetes, and her argument is supported by at least one recent meta-analysis where postmeal walking was best for improving glycemia in those with prediabetes and type 2 diabetes.

The notion that postmeal or afternoon exercise is best for people with type 2 diabetes is also supported by a recent reexamination of the original Look AHEAD Trial of over 2,400 adults with type 2 diabetes, wherein the role of lifestyle intervention on cardiovascular outcomes was the original goal. In this recent secondary analysis of the Look AHEAD Trial, those most active in the afternoon (between 1:43 p.m. and 5:00 p.m.) had the greatest improvements in their overall glucose control after 1 year of the intensive lifestyle intervention, compared with exercise at other times of day. Afternoon exercisers were also more likely to have complete “remission” of their diabetes, as defined by no longer needing any glucose-lowering agents to control their glucose levels. But this was not a study that was designed for determining whether exercise time of day matters for glycemia because the participants were not randomly assigned to a set time of day for their activity, and glycemic control was not the primary endpoint (cardiovascular events were).

But hold on a minute. I said this was a false-dichotomy argument. It is. Just because it may or may not be “better” for your glucose to exercise in the morning vs. afternoon, if you have diabetes, it doesn’t mean you have to choose one or the other. You could choose neither (okay, that’s bad), both, or you could alternate between the two. For me this argument is like saying; “There only one time of day to save money”; “to tell a joke”; “to eat a meal” (okay, that’s another useless debate); or “do my laundry” (my mother once told me it’s technically cheaper after 6 p.m.!).

I live with diabetes, and I take insulin. I like how morning exercise in the form of a run with my dog wakes me up, sets me up for the day with positive thoughts, helps generate lots of creative ideas, and perhaps more importantly for me, it tends not to result in hypoglycemia because my insulin on board is lowest then.

Exercise later in the day is tricky when taking insulin because it tends to result in a higher insulin “potency effect” with prandial insulins. However, I still like midday activity and late-day exercise. For example, taking an activity break after lunch blunts the rise in my glucose and breaks up my prolonged sitting time in the office. After-dinner exercise allows me to spend a little more time with my wife, dog, or friends outdoors as the hot summer day begins to cool off. On Monday nights, I play basketball because that’s the only time we can book the gymnasium and that may not end until 9:45 p.m. (15 minutes before I want to go to bed; if you remember, I am a lark). That can result in two frustrating things related to my diabetes: It can cause an immediate rise in my glucose because of a competitive stress response and then a drop in my glucose overnight when I’m sleeping. But I still do it. I know that the training I’m doing at any point of the day will benefit me in lots of little ways, and I think we all need to take as many opportunities to be physically active as we possibly can. My kids and I coin this our daily “fitness opportunities,” and it does not matter to me if its morning, noon, or night!

It’s time to make the headlines and arguments stop. There is no wrong time of day to exercise. At least not in my opinion.

Dr. Riddle is a full professor in the school of kinesiology and health science at York University and senior scientist at LMC Diabetes & Endocrinology, both in Toronto. He has disclosed financial relationships with Dexcom, Eli Lilly, Indigo Diabetes, Insulet, Novo Nordisk, Sanofi, Supersapiens, and Zucara Therapeutics.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Should we be exercising in the morning or afternoon? Before a meal or after a meal?

Popular media outlets, researchers, and clinicians seem to love these debates. I hate them. For me, it’s a false dichotomy. A false dichotomy is when people argue two sides as if only one option exists. A winner must be crowned, and a loser exists. But

Some but not all research suggests that morning fasted exercise may be the best time of day and condition to work out for weight control and training adaptations. Morning exercise may be a bit better for logistical reasons if you like to get up early. Some of us are indeed early chronotypes who rise early, get as much done as we can, including all our fitness and work-related activities, and then head to bed early (for me that is about 10 PM). Getting an early morning workout seems to fit with our schedules as morning larks.

But if you are a late-day chronotype, early exercise may not be in sync with your low morning energy levels or your preference for leisure-time activities later in the day. And lots of people with diabetes prefer to eat and then exercise. Late chronotypes are less physically active in general, compared with early chronotypes, and those who train in the morning tend to have better training adherence and expend more energy overall throughout the day. According to Dr. Normand Boulé from the University of Alberta, Edmonton, who presented on the topic of exercise time of day at the recent scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association in San Diego, morning exercise in the fasted state tends to be associated with higher rates of fat oxidation, better weight control, and better skeletal muscle adaptations over time, compared with exercise performed later in the day. Dr Boulé also proposed that fasted exercise might be superior for training adaptations and long-term glycemia if you have type 2 diabetes.

But the argument for morning-only exercise falls short when we look specifically at postmeal glycemia, according to Dr. Jenna Gillen from the University of Toronto, who faced off against Dr. Boulé at a debate at the meeting and also publishes on the topic. She pointed out that mild to moderate intensity exercising done soon after meals typically results in fewer glucose spikes after meals in people with diabetes, and her argument is supported by at least one recent meta-analysis where postmeal walking was best for improving glycemia in those with prediabetes and type 2 diabetes.

The notion that postmeal or afternoon exercise is best for people with type 2 diabetes is also supported by a recent reexamination of the original Look AHEAD Trial of over 2,400 adults with type 2 diabetes, wherein the role of lifestyle intervention on cardiovascular outcomes was the original goal. In this recent secondary analysis of the Look AHEAD Trial, those most active in the afternoon (between 1:43 p.m. and 5:00 p.m.) had the greatest improvements in their overall glucose control after 1 year of the intensive lifestyle intervention, compared with exercise at other times of day. Afternoon exercisers were also more likely to have complete “remission” of their diabetes, as defined by no longer needing any glucose-lowering agents to control their glucose levels. But this was not a study that was designed for determining whether exercise time of day matters for glycemia because the participants were not randomly assigned to a set time of day for their activity, and glycemic control was not the primary endpoint (cardiovascular events were).

But hold on a minute. I said this was a false-dichotomy argument. It is. Just because it may or may not be “better” for your glucose to exercise in the morning vs. afternoon, if you have diabetes, it doesn’t mean you have to choose one or the other. You could choose neither (okay, that’s bad), both, or you could alternate between the two. For me this argument is like saying; “There only one time of day to save money”; “to tell a joke”; “to eat a meal” (okay, that’s another useless debate); or “do my laundry” (my mother once told me it’s technically cheaper after 6 p.m.!).

I live with diabetes, and I take insulin. I like how morning exercise in the form of a run with my dog wakes me up, sets me up for the day with positive thoughts, helps generate lots of creative ideas, and perhaps more importantly for me, it tends not to result in hypoglycemia because my insulin on board is lowest then.

Exercise later in the day is tricky when taking insulin because it tends to result in a higher insulin “potency effect” with prandial insulins. However, I still like midday activity and late-day exercise. For example, taking an activity break after lunch blunts the rise in my glucose and breaks up my prolonged sitting time in the office. After-dinner exercise allows me to spend a little more time with my wife, dog, or friends outdoors as the hot summer day begins to cool off. On Monday nights, I play basketball because that’s the only time we can book the gymnasium and that may not end until 9:45 p.m. (15 minutes before I want to go to bed; if you remember, I am a lark). That can result in two frustrating things related to my diabetes: It can cause an immediate rise in my glucose because of a competitive stress response and then a drop in my glucose overnight when I’m sleeping. But I still do it. I know that the training I’m doing at any point of the day will benefit me in lots of little ways, and I think we all need to take as many opportunities to be physically active as we possibly can. My kids and I coin this our daily “fitness opportunities,” and it does not matter to me if its morning, noon, or night!

It’s time to make the headlines and arguments stop. There is no wrong time of day to exercise. At least not in my opinion.

Dr. Riddle is a full professor in the school of kinesiology and health science at York University and senior scientist at LMC Diabetes & Endocrinology, both in Toronto. He has disclosed financial relationships with Dexcom, Eli Lilly, Indigo Diabetes, Insulet, Novo Nordisk, Sanofi, Supersapiens, and Zucara Therapeutics.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

ER+ BC patients discontinuing hormone therapy tend to discontinue cardiovascular therapy

Key clinical point: Discontinuing adjuvant hormone therapy (HT) was associated with a higher likelihood of discontinuing cardiovascular therapy and an increased risk for mortality due to cardiovascular diseases in patients with estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer (ER+ BC).

Major finding: Compared with patients who continued adjuvant HT, the rate of discontinuing cardiovascular therapy was higher among patients who discontinued HT within a period of 3 months before (incidence rate ratio [IRR] 1.83; 95% CI 1.41-2.37) and after (IRR 2.31; 95% CI 1.74-3.05) adjuvant HT discontinuation. Discontinuation of adjuvant HT was also associated with a higher risk for death due to cardiovascular diseases (hazard ratio 1.79; 95% CI 1.15-2.81).

Study details: Findings are from a population-based cohort study including 5493 patients with nonmetastatic ER+ BC who initiated adjuvant HT and concomitantly used cardiovascular therapy.

Disclosures: This study was supported by grants from the Swedish Research Council and other sources. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: He W et al. Concomitant discontinuation of cardiovascular therapy and adjuvant hormone therapy among patients with breast cancer. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6(7):e2323752 (Jul 17). doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.23752

Key clinical point: Discontinuing adjuvant hormone therapy (HT) was associated with a higher likelihood of discontinuing cardiovascular therapy and an increased risk for mortality due to cardiovascular diseases in patients with estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer (ER+ BC).

Major finding: Compared with patients who continued adjuvant HT, the rate of discontinuing cardiovascular therapy was higher among patients who discontinued HT within a period of 3 months before (incidence rate ratio [IRR] 1.83; 95% CI 1.41-2.37) and after (IRR 2.31; 95% CI 1.74-3.05) adjuvant HT discontinuation. Discontinuation of adjuvant HT was also associated with a higher risk for death due to cardiovascular diseases (hazard ratio 1.79; 95% CI 1.15-2.81).

Study details: Findings are from a population-based cohort study including 5493 patients with nonmetastatic ER+ BC who initiated adjuvant HT and concomitantly used cardiovascular therapy.

Disclosures: This study was supported by grants from the Swedish Research Council and other sources. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: He W et al. Concomitant discontinuation of cardiovascular therapy and adjuvant hormone therapy among patients with breast cancer. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6(7):e2323752 (Jul 17). doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.23752

Key clinical point: Discontinuing adjuvant hormone therapy (HT) was associated with a higher likelihood of discontinuing cardiovascular therapy and an increased risk for mortality due to cardiovascular diseases in patients with estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer (ER+ BC).

Major finding: Compared with patients who continued adjuvant HT, the rate of discontinuing cardiovascular therapy was higher among patients who discontinued HT within a period of 3 months before (incidence rate ratio [IRR] 1.83; 95% CI 1.41-2.37) and after (IRR 2.31; 95% CI 1.74-3.05) adjuvant HT discontinuation. Discontinuation of adjuvant HT was also associated with a higher risk for death due to cardiovascular diseases (hazard ratio 1.79; 95% CI 1.15-2.81).

Study details: Findings are from a population-based cohort study including 5493 patients with nonmetastatic ER+ BC who initiated adjuvant HT and concomitantly used cardiovascular therapy.

Disclosures: This study was supported by grants from the Swedish Research Council and other sources. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: He W et al. Concomitant discontinuation of cardiovascular therapy and adjuvant hormone therapy among patients with breast cancer. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6(7):e2323752 (Jul 17). doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.23752

Breast cancer diagnosis within 5 years of childbirth associated with poor prognosis

Key clinical point: A diagnosis of breast cancer (BC) within the first 5 years of childbirth was associated with aggressive clinicopathological characteristics and unfavorable survival outcomes.

Major finding: Women diagnosed with post-partum BC (PPBC) within 5 years of childbirth showed more aggressive disease characteristics than nulliparous women with BC and women diagnosed with PPBC ≥ 5 years after childbirth (clinical stage T3: 5.9% vs 3.3% and 3.9%, respectively, or higher lymph node metastases: 40.6% vs 27.8% and 34.7%, respectively) and had the worst survival rates (hazard ratio 1.55; P = .004).

Study details: This study retrospectively reviewed 32,628 premenopausal women aged 20-50 years who underwent BC surgery, of which 508 women were nulliparous and 2406 women were diagnosed with BC within 5 years of childbirth.

Disclosures: This study was supported by the Korean Breast Cancer Society. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Paik PS et al for the Korean Breast Cancer Society. Clinical characteristics and prognosis of postpartum breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2023 (Aug 5). doi: 10.1007/s10549-023-07069-w

Key clinical point: A diagnosis of breast cancer (BC) within the first 5 years of childbirth was associated with aggressive clinicopathological characteristics and unfavorable survival outcomes.

Major finding: Women diagnosed with post-partum BC (PPBC) within 5 years of childbirth showed more aggressive disease characteristics than nulliparous women with BC and women diagnosed with PPBC ≥ 5 years after childbirth (clinical stage T3: 5.9% vs 3.3% and 3.9%, respectively, or higher lymph node metastases: 40.6% vs 27.8% and 34.7%, respectively) and had the worst survival rates (hazard ratio 1.55; P = .004).

Study details: This study retrospectively reviewed 32,628 premenopausal women aged 20-50 years who underwent BC surgery, of which 508 women were nulliparous and 2406 women were diagnosed with BC within 5 years of childbirth.

Disclosures: This study was supported by the Korean Breast Cancer Society. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Paik PS et al for the Korean Breast Cancer Society. Clinical characteristics and prognosis of postpartum breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2023 (Aug 5). doi: 10.1007/s10549-023-07069-w

Key clinical point: A diagnosis of breast cancer (BC) within the first 5 years of childbirth was associated with aggressive clinicopathological characteristics and unfavorable survival outcomes.

Major finding: Women diagnosed with post-partum BC (PPBC) within 5 years of childbirth showed more aggressive disease characteristics than nulliparous women with BC and women diagnosed with PPBC ≥ 5 years after childbirth (clinical stage T3: 5.9% vs 3.3% and 3.9%, respectively, or higher lymph node metastases: 40.6% vs 27.8% and 34.7%, respectively) and had the worst survival rates (hazard ratio 1.55; P = .004).

Study details: This study retrospectively reviewed 32,628 premenopausal women aged 20-50 years who underwent BC surgery, of which 508 women were nulliparous and 2406 women were diagnosed with BC within 5 years of childbirth.

Disclosures: This study was supported by the Korean Breast Cancer Society. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Paik PS et al for the Korean Breast Cancer Society. Clinical characteristics and prognosis of postpartum breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2023 (Aug 5). doi: 10.1007/s10549-023-07069-w

Presence of lobular carcinoma in situ associated with improved prognosis in invasive lobular carcinoma of the breast

Key clinical point: Patients with invasive lobular carcinoma (ILC) of the breast showed worse prognostic outcomes than patients with ILC who also had lobular carcinoma in situ (LCIS).

Major finding: Patients with ILC + LCIS vs ILC only had better median distant recurrence-free survival (DRFS; 16.8 vs 10.1 years; hazard ratio [HR] 0.55; P < .0001) and overall survival (OS; 18.9 vs 13.7 years; HR 0.62; P < .0001) rates, with the absence of LCIS being associated with poor prognosis in terms of both DRFS (adjusted HR 1.78; P < .0001) and OS (adjusted HR 1.60; P < .0001) outcomes.

Study details: This observational, population-based investigation included the data of 4217 patients with stages I-III ILC (of whom 45% had co-existing LCIS) from the MD Anderson breast cancer prospectively collected electronic database.

Disclosures: This study was partly supported by the US National Institutes of Health/National Cancer Institute Cancer Center Support Grant. Five authors declared receiving consulting fees or research support from various sources. The other authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Mouabbi JA et al. Absence of lobular carcinoma in situ is a poor prognostic marker in invasive lobular carcinoma. Eur J Cancer. 2023;191:113250 (Jul 21). doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2023.113250

Key clinical point: Patients with invasive lobular carcinoma (ILC) of the breast showed worse prognostic outcomes than patients with ILC who also had lobular carcinoma in situ (LCIS).

Major finding: Patients with ILC + LCIS vs ILC only had better median distant recurrence-free survival (DRFS; 16.8 vs 10.1 years; hazard ratio [HR] 0.55; P < .0001) and overall survival (OS; 18.9 vs 13.7 years; HR 0.62; P < .0001) rates, with the absence of LCIS being associated with poor prognosis in terms of both DRFS (adjusted HR 1.78; P < .0001) and OS (adjusted HR 1.60; P < .0001) outcomes.

Study details: This observational, population-based investigation included the data of 4217 patients with stages I-III ILC (of whom 45% had co-existing LCIS) from the MD Anderson breast cancer prospectively collected electronic database.

Disclosures: This study was partly supported by the US National Institutes of Health/National Cancer Institute Cancer Center Support Grant. Five authors declared receiving consulting fees or research support from various sources. The other authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Mouabbi JA et al. Absence of lobular carcinoma in situ is a poor prognostic marker in invasive lobular carcinoma. Eur J Cancer. 2023;191:113250 (Jul 21). doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2023.113250

Key clinical point: Patients with invasive lobular carcinoma (ILC) of the breast showed worse prognostic outcomes than patients with ILC who also had lobular carcinoma in situ (LCIS).

Major finding: Patients with ILC + LCIS vs ILC only had better median distant recurrence-free survival (DRFS; 16.8 vs 10.1 years; hazard ratio [HR] 0.55; P < .0001) and overall survival (OS; 18.9 vs 13.7 years; HR 0.62; P < .0001) rates, with the absence of LCIS being associated with poor prognosis in terms of both DRFS (adjusted HR 1.78; P < .0001) and OS (adjusted HR 1.60; P < .0001) outcomes.

Study details: This observational, population-based investigation included the data of 4217 patients with stages I-III ILC (of whom 45% had co-existing LCIS) from the MD Anderson breast cancer prospectively collected electronic database.

Disclosures: This study was partly supported by the US National Institutes of Health/National Cancer Institute Cancer Center Support Grant. Five authors declared receiving consulting fees or research support from various sources. The other authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Mouabbi JA et al. Absence of lobular carcinoma in situ is a poor prognostic marker in invasive lobular carcinoma. Eur J Cancer. 2023;191:113250 (Jul 21). doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2023.113250

Alcohol consumption may not worsen prognosis in BC

Key clinical point: Consumption of alcohol during and 6 months after breast cancer (BC) diagnosis did not negatively impact mortality rates in women who survived BC.

Major finding: The occasional consumption of alcohol (0.36 to < 0.6 g/day) during BC diagnosis (hazard ratio [HR] 0.71; 95% CI 0.54-0.94) and 6 months after BC diagnosis (HR 0.67; 95% CI 0.47-0.94) was associated with a lower risk for all-cause mortality in women with body mass index ≥ 30 kg/m2.

Study details: This study analyzed 3659 BC survivors from The Pathways Study (a prospective cohort study) who were diagnosed with stages I-IV invasive BC.

Disclosures: This study was supported by the US National Cancer Institute. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Kwan ML et al. Alcohol consumption and prognosis and survival in breast cancer survivors: The Pathways Study. Cancer. 2023 (Aug 9). doi: 10.1002/cncr.34972

Key clinical point: Consumption of alcohol during and 6 months after breast cancer (BC) diagnosis did not negatively impact mortality rates in women who survived BC.

Major finding: The occasional consumption of alcohol (0.36 to < 0.6 g/day) during BC diagnosis (hazard ratio [HR] 0.71; 95% CI 0.54-0.94) and 6 months after BC diagnosis (HR 0.67; 95% CI 0.47-0.94) was associated with a lower risk for all-cause mortality in women with body mass index ≥ 30 kg/m2.

Study details: This study analyzed 3659 BC survivors from The Pathways Study (a prospective cohort study) who were diagnosed with stages I-IV invasive BC.

Disclosures: This study was supported by the US National Cancer Institute. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Kwan ML et al. Alcohol consumption and prognosis and survival in breast cancer survivors: The Pathways Study. Cancer. 2023 (Aug 9). doi: 10.1002/cncr.34972

Key clinical point: Consumption of alcohol during and 6 months after breast cancer (BC) diagnosis did not negatively impact mortality rates in women who survived BC.

Major finding: The occasional consumption of alcohol (0.36 to < 0.6 g/day) during BC diagnosis (hazard ratio [HR] 0.71; 95% CI 0.54-0.94) and 6 months after BC diagnosis (HR 0.67; 95% CI 0.47-0.94) was associated with a lower risk for all-cause mortality in women with body mass index ≥ 30 kg/m2.

Study details: This study analyzed 3659 BC survivors from The Pathways Study (a prospective cohort study) who were diagnosed with stages I-IV invasive BC.

Disclosures: This study was supported by the US National Cancer Institute. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Kwan ML et al. Alcohol consumption and prognosis and survival in breast cancer survivors: The Pathways Study. Cancer. 2023 (Aug 9). doi: 10.1002/cncr.34972

Primary care vision testing rates in children low

In data from the 2018-2020 National Survey of Children’s Health, an annual, nationally representative cross-sectional study, fewer than half of children aged 3-5 with private insurance received vision testing, with rates even lower in those lacking private insurance. The findings point to unmet eye care needs, especially in young children for whom early testing to ward off vision loss is highly recommended.

The report was published online in JAMA Ophthalmology by Olivia J. Killeen MD, MS, an ophthalmologist during the study in the department of ophthalmology and visual sciences at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, and colleagues.

Future work should focus on improving primary care provider vision screening rates, especially for the 3- to 5-year age group, the authors wrote.

“Because children often are not aware they have an eye problem, routine vision testing in the primary care setting can help identify those with potential eye disease,” Dr. Killeen said. “We have an opportunity to improve the early detection and treatment of eye disease by improving primary care vision testing.”

Childhood vision testing, which falls into the vital signs section of the wellness check, is critical because undiagnosed problems can cause amblyopia or “lazy eye.” The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends vision testing at well-child visits starting at age 3. Regional studies,however, have suggested low rates of PCP vision testing.

Study findings

In a sample of 89,936 participants, with a mean age of 10 years (51.1% male), an estimated 30.7% overall received vision testing in primary care. Adjusted odds of vision testing in primary care decreased by 41% (odds ratio, 0.59; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.49-0.72) for uninsured and by 24% (OR, 0.76; 95% CI, 0.70-0.82) for publicly insured participants vs. those with private insurance.

Adjusted estimated probability of vision testing was 22% (95% CI, 18.8%-25.2%) for uninsured participants, 26.6% (95% CI, 25.3%-27.9%) for those publicly insured, and 32.3% (95% CI, 31.4%-33.%) for those privately insured.

In children aged 3-5, estimated probability was 29.7% (95% CI, 25.6%-33.7%) for those uninsured, 35.2% (95% CI, 33.1%-37.3%) for those publicly insured, and 41.6% (95% CI, 39.8%-43.5%) for those privately insured – all well under 50%. The children least likely to be tested, regardless of insurance status, were adolescents aged 12-17.

Commenting on the study but not involved in it, Natalie J. Choi, MD, assistant professor of family medicine at Northwestern Medicine in Chicago, noted that the authors did not address other screening venues such as schools. She also pointed out that it is challenging for primary care physicians to address all the recommended prevention measures in addition to acute issues during an office visit.

“Oftentimes parents are the first to notice a concern about vision, and parental concerns are routinely addressed in primary care,” she said.

According to Dr. Killeen, vision testing should always be worked into the exam flow as a routine part of well-child visits. “There are devices called photoscreeners which provide automated vision tests for young children and can save a lot of time and make vision testing less burdensome for physicians and their staff,” she said. Not all primary care offices, however, offer these testing modalities.

Dr. Choi said low vision screening rates are part of the larger problem of preventive care. “In the study, the percentage of children attending a preventive health visit within the last 12 months varied by insurance coverage and was definitely not 100%,” she said. “Investing in preventive medicine helps us identify things before they become a problem, so I would love to see the number of well-child checks increase.” Identifying this gap in vision care is one of many steps, she said.

This work was supported by the University of Michigan National Clinician Scholars Program and by an unrestricted grant to the University of Michigan Department of Ophthalmology and Visual Sciences from Research to Prevent Blindness. Study coauthor Brian C. Stagg, MD, reported a grant from the National Eye Institute during the conduct of the study. Dr. Choi disclosed no conflicts of interest relevant to her comments.

In data from the 2018-2020 National Survey of Children’s Health, an annual, nationally representative cross-sectional study, fewer than half of children aged 3-5 with private insurance received vision testing, with rates even lower in those lacking private insurance. The findings point to unmet eye care needs, especially in young children for whom early testing to ward off vision loss is highly recommended.

The report was published online in JAMA Ophthalmology by Olivia J. Killeen MD, MS, an ophthalmologist during the study in the department of ophthalmology and visual sciences at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, and colleagues.

Future work should focus on improving primary care provider vision screening rates, especially for the 3- to 5-year age group, the authors wrote.

“Because children often are not aware they have an eye problem, routine vision testing in the primary care setting can help identify those with potential eye disease,” Dr. Killeen said. “We have an opportunity to improve the early detection and treatment of eye disease by improving primary care vision testing.”

Childhood vision testing, which falls into the vital signs section of the wellness check, is critical because undiagnosed problems can cause amblyopia or “lazy eye.” The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends vision testing at well-child visits starting at age 3. Regional studies,however, have suggested low rates of PCP vision testing.

Study findings

In a sample of 89,936 participants, with a mean age of 10 years (51.1% male), an estimated 30.7% overall received vision testing in primary care. Adjusted odds of vision testing in primary care decreased by 41% (odds ratio, 0.59; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.49-0.72) for uninsured and by 24% (OR, 0.76; 95% CI, 0.70-0.82) for publicly insured participants vs. those with private insurance.

Adjusted estimated probability of vision testing was 22% (95% CI, 18.8%-25.2%) for uninsured participants, 26.6% (95% CI, 25.3%-27.9%) for those publicly insured, and 32.3% (95% CI, 31.4%-33.%) for those privately insured.

In children aged 3-5, estimated probability was 29.7% (95% CI, 25.6%-33.7%) for those uninsured, 35.2% (95% CI, 33.1%-37.3%) for those publicly insured, and 41.6% (95% CI, 39.8%-43.5%) for those privately insured – all well under 50%. The children least likely to be tested, regardless of insurance status, were adolescents aged 12-17.

Commenting on the study but not involved in it, Natalie J. Choi, MD, assistant professor of family medicine at Northwestern Medicine in Chicago, noted that the authors did not address other screening venues such as schools. She also pointed out that it is challenging for primary care physicians to address all the recommended prevention measures in addition to acute issues during an office visit.

“Oftentimes parents are the first to notice a concern about vision, and parental concerns are routinely addressed in primary care,” she said.

According to Dr. Killeen, vision testing should always be worked into the exam flow as a routine part of well-child visits. “There are devices called photoscreeners which provide automated vision tests for young children and can save a lot of time and make vision testing less burdensome for physicians and their staff,” she said. Not all primary care offices, however, offer these testing modalities.

Dr. Choi said low vision screening rates are part of the larger problem of preventive care. “In the study, the percentage of children attending a preventive health visit within the last 12 months varied by insurance coverage and was definitely not 100%,” she said. “Investing in preventive medicine helps us identify things before they become a problem, so I would love to see the number of well-child checks increase.” Identifying this gap in vision care is one of many steps, she said.

This work was supported by the University of Michigan National Clinician Scholars Program and by an unrestricted grant to the University of Michigan Department of Ophthalmology and Visual Sciences from Research to Prevent Blindness. Study coauthor Brian C. Stagg, MD, reported a grant from the National Eye Institute during the conduct of the study. Dr. Choi disclosed no conflicts of interest relevant to her comments.

In data from the 2018-2020 National Survey of Children’s Health, an annual, nationally representative cross-sectional study, fewer than half of children aged 3-5 with private insurance received vision testing, with rates even lower in those lacking private insurance. The findings point to unmet eye care needs, especially in young children for whom early testing to ward off vision loss is highly recommended.

The report was published online in JAMA Ophthalmology by Olivia J. Killeen MD, MS, an ophthalmologist during the study in the department of ophthalmology and visual sciences at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, and colleagues.

Future work should focus on improving primary care provider vision screening rates, especially for the 3- to 5-year age group, the authors wrote.

“Because children often are not aware they have an eye problem, routine vision testing in the primary care setting can help identify those with potential eye disease,” Dr. Killeen said. “We have an opportunity to improve the early detection and treatment of eye disease by improving primary care vision testing.”

Childhood vision testing, which falls into the vital signs section of the wellness check, is critical because undiagnosed problems can cause amblyopia or “lazy eye.” The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends vision testing at well-child visits starting at age 3. Regional studies,however, have suggested low rates of PCP vision testing.

Study findings

In a sample of 89,936 participants, with a mean age of 10 years (51.1% male), an estimated 30.7% overall received vision testing in primary care. Adjusted odds of vision testing in primary care decreased by 41% (odds ratio, 0.59; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.49-0.72) for uninsured and by 24% (OR, 0.76; 95% CI, 0.70-0.82) for publicly insured participants vs. those with private insurance.

Adjusted estimated probability of vision testing was 22% (95% CI, 18.8%-25.2%) for uninsured participants, 26.6% (95% CI, 25.3%-27.9%) for those publicly insured, and 32.3% (95% CI, 31.4%-33.%) for those privately insured.

In children aged 3-5, estimated probability was 29.7% (95% CI, 25.6%-33.7%) for those uninsured, 35.2% (95% CI, 33.1%-37.3%) for those publicly insured, and 41.6% (95% CI, 39.8%-43.5%) for those privately insured – all well under 50%. The children least likely to be tested, regardless of insurance status, were adolescents aged 12-17.

Commenting on the study but not involved in it, Natalie J. Choi, MD, assistant professor of family medicine at Northwestern Medicine in Chicago, noted that the authors did not address other screening venues such as schools. She also pointed out that it is challenging for primary care physicians to address all the recommended prevention measures in addition to acute issues during an office visit.

“Oftentimes parents are the first to notice a concern about vision, and parental concerns are routinely addressed in primary care,” she said.

According to Dr. Killeen, vision testing should always be worked into the exam flow as a routine part of well-child visits. “There are devices called photoscreeners which provide automated vision tests for young children and can save a lot of time and make vision testing less burdensome for physicians and their staff,” she said. Not all primary care offices, however, offer these testing modalities.

Dr. Choi said low vision screening rates are part of the larger problem of preventive care. “In the study, the percentage of children attending a preventive health visit within the last 12 months varied by insurance coverage and was definitely not 100%,” she said. “Investing in preventive medicine helps us identify things before they become a problem, so I would love to see the number of well-child checks increase.” Identifying this gap in vision care is one of many steps, she said.

This work was supported by the University of Michigan National Clinician Scholars Program and by an unrestricted grant to the University of Michigan Department of Ophthalmology and Visual Sciences from Research to Prevent Blindness. Study coauthor Brian C. Stagg, MD, reported a grant from the National Eye Institute during the conduct of the study. Dr. Choi disclosed no conflicts of interest relevant to her comments.

FROM JAMA OPHTHALMOLOGY

Telehealth visit helps reconnect adolescents lost to follow-up

A telehealth primary care visit more than doubled the well-visit show rate for a cohort of hard-to-reach adolescents, results of a small pilot study show.

Brian P. Jenssen, MD, MSHP, department of pediatrics, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, led the pilot study and the project team, which included physicians, researchers, and experts in innovation, quality improvement, and data analytics.

Findings were published online in Annals of Family Medicine.

Keeping adolescents in consistent primary care can be challenging for many reasons. The study authors note, “Only 50% of adolescents have had a health supervision visit in the past year, missing a critical opportunity for clinicians to influence health, development, screening, and counseling.”

Interest high in hard-to-reach group

This study included a particularly hard-to-reach group of 18-year-old patients at an urban primary care clinic who were lost to follow-up and had Medicaid insurance. They had not completed a well visit in more than 2 years and had a history of no-show visits.

Interest in the pilot program was high. The authors write: “We contacted patients (or their caregivers) to gauge interest in a virtual well visit with a goal to fill five telehealth slots in one evening block with one clinician. Due to high patient interest and demand, we expanded to 15 slots over three evenings, filling the slots after contacting just 24 patients.”

Professional organizations have recommended a telehealth/in-person hybrid care model to meet hard-to-reach adolescents “wherever they are,” the authors note, but the concept has not been well studied.

Under the hybrid model, the first visit is through telehealth and in-person follow-up is scheduled as needed.

Navigators contacted patients to remind them of the appointment, and helped activate the patient portal and complete previsit screening questions for depression and other health risks.

Telehealth visits were billed as preventive visits and in-person follow-up visits as no-charge nurse visits, and these payments were supported by Medicaid.

Sharp increase in show rate

In the pilot study, of the 15 patients scheduled for the telehealth visit, 11 connected virtually (73% show rate). Of those, nine needed in-person follow-up, and five completed the follow-up.

Before the intervention, the average well-visit show rate for this patient group was 33%.

Clinicians counseled all the patients about substance use and safe sex. One patient screened positive for depression and was then connected to services. Two patients were started on birth control.

During the in-person follow-up, all patients received vaccinations (influenza, meningococcal, and/or COVID-19) and were screened for sexually transmitted infection. Eight patients completed the satisfaction survey and all said they liked the convenience of the telehealth visit.

Telehealth may reduce barriers for teens

Anthony Cheng, MD, a family medicine physician at Oregon Health & Science University in Portland, who was not part of the study, said he found the hybrid model promising.

One reason is that telehealth eliminates the need for transportation to medical appointments, which can be a barrier for adolescents.

Among the top causes of death for young people are mental health issues and addressing those, Dr. Cheng noted, is well-suited to a telehealth visit.

“There’s so much we can do if we can establish a relationship and maintain a relationship with our patients as young adults,” he said. “People do better when they have a regular source of care.”

He added that adolescents also have grown up communicating via screens so it’s often more comfortable for them to communicate with health care providers this way.

Dr. Cheng said adopting such a model may be difficult for providers reluctant to switch from the practice model with which they are most comfortable.

“We prefer to do things we have the most confidence in,” he said. “It does take an investment to train staff and build your own clinical comfort. If that experience wasn’t good over the past 3 years, you may be anxious to get back to your normal way of doing business.”

The authors and Dr. Cheng have no relevant financial relationships to disclose.

A telehealth primary care visit more than doubled the well-visit show rate for a cohort of hard-to-reach adolescents, results of a small pilot study show.

Brian P. Jenssen, MD, MSHP, department of pediatrics, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, led the pilot study and the project team, which included physicians, researchers, and experts in innovation, quality improvement, and data analytics.

Findings were published online in Annals of Family Medicine.

Keeping adolescents in consistent primary care can be challenging for many reasons. The study authors note, “Only 50% of adolescents have had a health supervision visit in the past year, missing a critical opportunity for clinicians to influence health, development, screening, and counseling.”

Interest high in hard-to-reach group

This study included a particularly hard-to-reach group of 18-year-old patients at an urban primary care clinic who were lost to follow-up and had Medicaid insurance. They had not completed a well visit in more than 2 years and had a history of no-show visits.

Interest in the pilot program was high. The authors write: “We contacted patients (or their caregivers) to gauge interest in a virtual well visit with a goal to fill five telehealth slots in one evening block with one clinician. Due to high patient interest and demand, we expanded to 15 slots over three evenings, filling the slots after contacting just 24 patients.”

Professional organizations have recommended a telehealth/in-person hybrid care model to meet hard-to-reach adolescents “wherever they are,” the authors note, but the concept has not been well studied.

Under the hybrid model, the first visit is through telehealth and in-person follow-up is scheduled as needed.

Navigators contacted patients to remind them of the appointment, and helped activate the patient portal and complete previsit screening questions for depression and other health risks.

Telehealth visits were billed as preventive visits and in-person follow-up visits as no-charge nurse visits, and these payments were supported by Medicaid.

Sharp increase in show rate

In the pilot study, of the 15 patients scheduled for the telehealth visit, 11 connected virtually (73% show rate). Of those, nine needed in-person follow-up, and five completed the follow-up.

Before the intervention, the average well-visit show rate for this patient group was 33%.

Clinicians counseled all the patients about substance use and safe sex. One patient screened positive for depression and was then connected to services. Two patients were started on birth control.

During the in-person follow-up, all patients received vaccinations (influenza, meningococcal, and/or COVID-19) and were screened for sexually transmitted infection. Eight patients completed the satisfaction survey and all said they liked the convenience of the telehealth visit.

Telehealth may reduce barriers for teens

Anthony Cheng, MD, a family medicine physician at Oregon Health & Science University in Portland, who was not part of the study, said he found the hybrid model promising.

One reason is that telehealth eliminates the need for transportation to medical appointments, which can be a barrier for adolescents.

Among the top causes of death for young people are mental health issues and addressing those, Dr. Cheng noted, is well-suited to a telehealth visit.

“There’s so much we can do if we can establish a relationship and maintain a relationship with our patients as young adults,” he said. “People do better when they have a regular source of care.”

He added that adolescents also have grown up communicating via screens so it’s often more comfortable for them to communicate with health care providers this way.

Dr. Cheng said adopting such a model may be difficult for providers reluctant to switch from the practice model with which they are most comfortable.

“We prefer to do things we have the most confidence in,” he said. “It does take an investment to train staff and build your own clinical comfort. If that experience wasn’t good over the past 3 years, you may be anxious to get back to your normal way of doing business.”

The authors and Dr. Cheng have no relevant financial relationships to disclose.

A telehealth primary care visit more than doubled the well-visit show rate for a cohort of hard-to-reach adolescents, results of a small pilot study show.

Brian P. Jenssen, MD, MSHP, department of pediatrics, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, led the pilot study and the project team, which included physicians, researchers, and experts in innovation, quality improvement, and data analytics.

Findings were published online in Annals of Family Medicine.

Keeping adolescents in consistent primary care can be challenging for many reasons. The study authors note, “Only 50% of adolescents have had a health supervision visit in the past year, missing a critical opportunity for clinicians to influence health, development, screening, and counseling.”

Interest high in hard-to-reach group

This study included a particularly hard-to-reach group of 18-year-old patients at an urban primary care clinic who were lost to follow-up and had Medicaid insurance. They had not completed a well visit in more than 2 years and had a history of no-show visits.

Interest in the pilot program was high. The authors write: “We contacted patients (or their caregivers) to gauge interest in a virtual well visit with a goal to fill five telehealth slots in one evening block with one clinician. Due to high patient interest and demand, we expanded to 15 slots over three evenings, filling the slots after contacting just 24 patients.”

Professional organizations have recommended a telehealth/in-person hybrid care model to meet hard-to-reach adolescents “wherever they are,” the authors note, but the concept has not been well studied.

Under the hybrid model, the first visit is through telehealth and in-person follow-up is scheduled as needed.

Navigators contacted patients to remind them of the appointment, and helped activate the patient portal and complete previsit screening questions for depression and other health risks.

Telehealth visits were billed as preventive visits and in-person follow-up visits as no-charge nurse visits, and these payments were supported by Medicaid.

Sharp increase in show rate

In the pilot study, of the 15 patients scheduled for the telehealth visit, 11 connected virtually (73% show rate). Of those, nine needed in-person follow-up, and five completed the follow-up.

Before the intervention, the average well-visit show rate for this patient group was 33%.

Clinicians counseled all the patients about substance use and safe sex. One patient screened positive for depression and was then connected to services. Two patients were started on birth control.

During the in-person follow-up, all patients received vaccinations (influenza, meningococcal, and/or COVID-19) and were screened for sexually transmitted infection. Eight patients completed the satisfaction survey and all said they liked the convenience of the telehealth visit.

Telehealth may reduce barriers for teens

Anthony Cheng, MD, a family medicine physician at Oregon Health & Science University in Portland, who was not part of the study, said he found the hybrid model promising.

One reason is that telehealth eliminates the need for transportation to medical appointments, which can be a barrier for adolescents.

Among the top causes of death for young people are mental health issues and addressing those, Dr. Cheng noted, is well-suited to a telehealth visit.

“There’s so much we can do if we can establish a relationship and maintain a relationship with our patients as young adults,” he said. “People do better when they have a regular source of care.”

He added that adolescents also have grown up communicating via screens so it’s often more comfortable for them to communicate with health care providers this way.

Dr. Cheng said adopting such a model may be difficult for providers reluctant to switch from the practice model with which they are most comfortable.

“We prefer to do things we have the most confidence in,” he said. “It does take an investment to train staff and build your own clinical comfort. If that experience wasn’t good over the past 3 years, you may be anxious to get back to your normal way of doing business.”

The authors and Dr. Cheng have no relevant financial relationships to disclose.

FROM ANNALS OF INTERNAL MEDICINE

Adenomyosis: Why we need to reassess our understanding of this condition

CASE Painful, heavy menstruation and recurrent pregnancy loss

A 37-year-old woman (G3P0030) with a history of recurrent pregnancy loss presents for evaluation. She had 3 losses—most recently a miscarriage at 22 weeks with a cerclage in place. She did not undergo any surgical procedures for these losses. Hormonal and thrombophilia workup is negative and semen analysis is normal. She reports a history of painful, heavy periods for many years, as well as dyspareunia and occasional post-coital bleeding. Past medical history was otherwise unremarkable. Pelvic magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed focal thickening of the junctional zone up to 15 mm with 2 foci of T2 hyperintensities suggesting adenomyosis (FIGURE 1).

How do you counsel this patient regarding the MRI findings and their impact on her fertility?

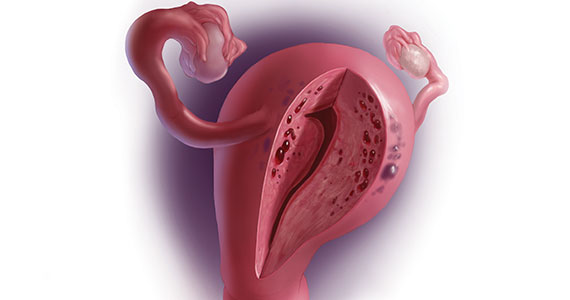

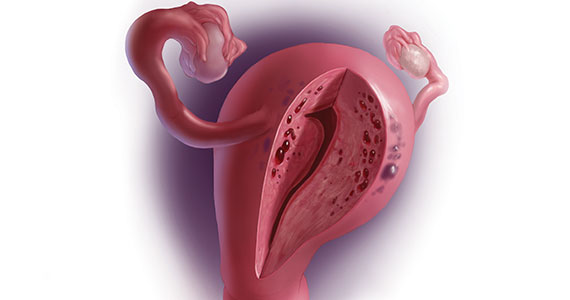

Adenomyosis is a condition in which endometrial glands and stroma are abnormally present in the uterine myometrium, resulting in smooth muscle hypertrophy and abnormal uterine contractility. Traditional teaching describes a woman in her 40s with heavy and painful menses, a “boggy uterus” on examination, who has completed childbearing and desires definitive treatment. Histologic diagnosis of adenomyosis is made from the uterine specimen at the time of hysterectomy, invariably confounding our understanding of the epidemiology of adenomyosis.

More recently, however, we are beginning to learn that this narrative is misguided. Imaging changes of adenomyosis can be seen in women who desire future fertility and in adolescents with severe dysmenorrhea, suggesting an earlier age of incidence.1 In a recent systematic review, prevalence estimates ranged from 15% to 67%, owing to varying diagnostic methods and patient inclusion criteria.2 It is increasingly being recognized as a primary contributor to infertility, with one study estimating a 30% prevalence of infertility in women with adenomyosis.3 Moreover, treatment with gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists and/or surgical excision may improve fertility outcomes.4

As we learn more about this prevalent and life-altering condition, we owe it to our patients to consider this diagnosis when counseling on dysmenorrhea, heavy menstrual bleeding, or infertility.

Anatomy of the myometrium

The myometrium is composed of the inner and outer myometrium: the inner myometrium (IM) and endometrium are of Müllerian origin, and the outer myometrium (OM) is of mesenchymal origin. The IM thickens in response to steroid hormones during the menstrual cycle with metaplasia of endometrial stromal cells into myocytes and back again, whereas the OM is not responsive to hormones.5 Emerging literature suggests the OM is further divided into a middle and outer section based on different histologic morphologies, though the clinical implications of this are not understood.6 The term “junctional zone” (JZ) refers to the imaging appearance of what is thought to be the IM. Interestingly it cannot be identified on traditional hematoxylin and eosin staining. When the JZ is thickened or demonstrates irregular borders, it is used as a diagnostic marker for adenomyosis and is postulated to play an important role in adenomyosis pathophysiology, particularly heavy menstrual bleeding and infertility.7

Continue to: Subtypes of adenomyosis...

Subtypes of adenomyosis

While various disease classifications have been suggested for adenomyosis, to date there is no international consensus. Adenomyosis is typically described in 3 forms: diffuse, focal, or adenomyoma.8 As implied, the term focal adenomyosis refers to discrete lesions surrounded by normal myometrium, whereas abnormal glandular changes are pervasive throughout the myometrium in diffuse disease. Adenomyomas are a subgroup of focal adenomyosis that are thought to be surrounded by leiomyomatous smooth muscle and may be well demarcated on imaging.9

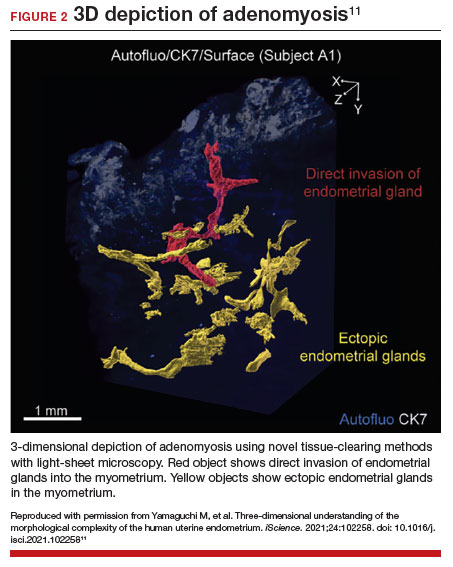

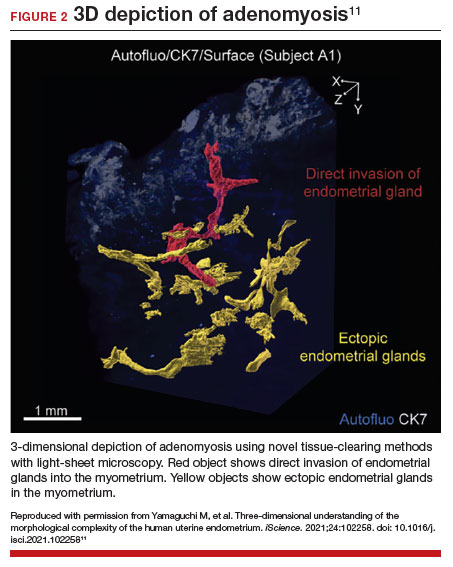

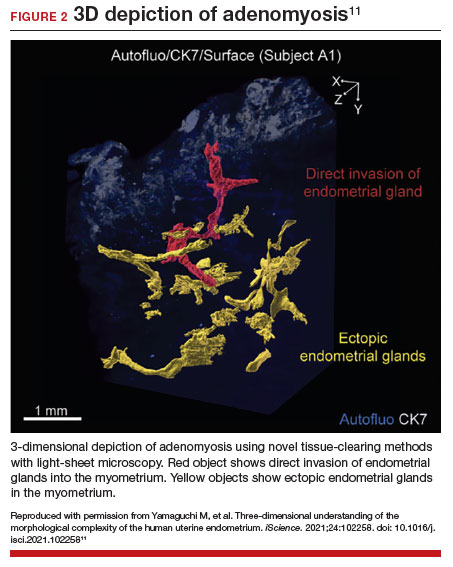

Recent research uses novel histologic imaging techniques to explore adenomyotic growth patterns in 3-dimensional (3D) reconstructions. Combining tissue-clearing methods with light-sheet fluorescence microscopy enables highly detailed 3D representations of the protein and nucleic acid structure of organs.10 For example, Yamaguchi and colleagues used this technology to explore the 3D morphological features of adenomyotic tissue and observed direct invasion of the endometrial glands into the myometrium and an “ant colony ̶ like network” of ectopic endometrial glands in the myometrium (FIGURE 2).11 These abnormal glandular networks have been visualized beyond the IM, which may not be captured on ultrasonography or MRI. While this work is still in its infancy, it has the potential to provide important insight into disease pathogenesis and to inform future therapy.

Pathogenesis

Proposed mechanisms for the development of adenomyosis include endometrial invasion, tissue injury and repair (TIAR) mechanisms, and the stem cell theory.12 According to the endometrial invasion theory, glandular epithelial cells from the basalis layer invaginate through an altered IM, slipping through weak muscle fibers and attracted by certain growth factors. In the TIAR mechanism theory, micro- or macro-trauma to the IM (whether from pregnancy, surgery, or infection) results in chronic proliferation and inflammation leading to the development of adenomyosis. Finally, the stem cell theory proposes that adenomyosis might develop from de novo ectopic endometrial tissue.

While the exact pathogenesis of adenomyosis is largely unknown, it has been associated with predictable molecular changes in the endometrium and surrounding myometrium.12 Myometrial hypercontractility is seen in patients with adenomyosis and dysmenorrhea, whereas neovascularization, high microvessel density, and abnormal uterine contractility are seen in those with abnormal uterine bleeding.13 In patients with infertility, increased inflammation, abnormal endometrial receptivity, and alterations in the myometrial architecture have been suggested to impair contractility and sperm transport.12,14

Differential growth factor expression and abnormal estrogen and progesterone signaling pathways have been observed in the IM in patients with adenomyosis, along with dysregulation of immune factors and increased inflammatory oxidative stress.12 This in turn results in myometrial hypertrophy and fibrosis, impairing normal uterine contractility patterns. This abnormal contractility may alter sperm transport and embryo implantation, and animal models that target pathways leading to fibrosis may improve endometrial receptivity.14,15 Further research is needed to elucidate specific molecular pathways and their complex interplay in this disease.

Continue to: Diagnosis...

Diagnosis

The gold standard for diagnosis of adenomyosis is histopathology from hysterectomy specimens, but specific definitions vary. Published criteria include endometrial glands within the myometrial layer greater than 0.5 to 1 low power field from the basal layer of the endometrium, endometrial glands extending deeper than 25% of the myometrial thickness, or endometrial glands a certain distance (ranging from 1-3 mm) from the basalis layer of the endometrium.16 Various methods of non-hysterectomy tissue sampling have been proposed for diagnosis, including needle, hysteroscopic, or laparoscopic sampling, but the sensitivity of these methods is poor.17 Limiting the diagnosis of adenomyosis to specimen pathology relies on invasive methods and clearly we cannot confirm the diagnosis by hysterectomy in patients with a desire for future fertility. It is for this reason that the prevalence of the disease is widely unknown.

The alternative to pathologic diagnosis is to identify radiologic changes that are associated with adenomyosis via either transvaginal ultrasound (TVUS) or MRI. Features suggestive of adenomyosis on MRI overlap with TVUS features, including uterine enlargement, anteroposterior myometrial asymmetry, T1- or T2-intense myometrial cysts or foci, and a thickened JZ.18 A JZ thicker than 12 mm has been thought to be predictive of adenomyosis, whereas a thickness of less than 8 mm is predictive of its absence, although the JZ may vary in thickness with the menstrual cycle.19,20 A 2021 systematic review and meta-analysis comparing MRI diagnosis with histopathologic findings reported a pooled sensitivity and specificity of 60% and 96%, respectively.21 The reported range for sensitivity and specificity is wide: 70% to 93% for sensitivity and 67% to 93% for specificity.22-24

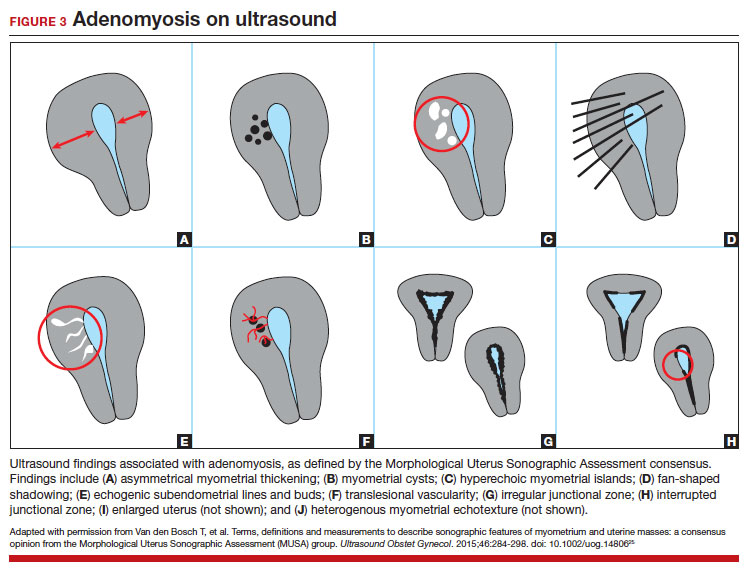

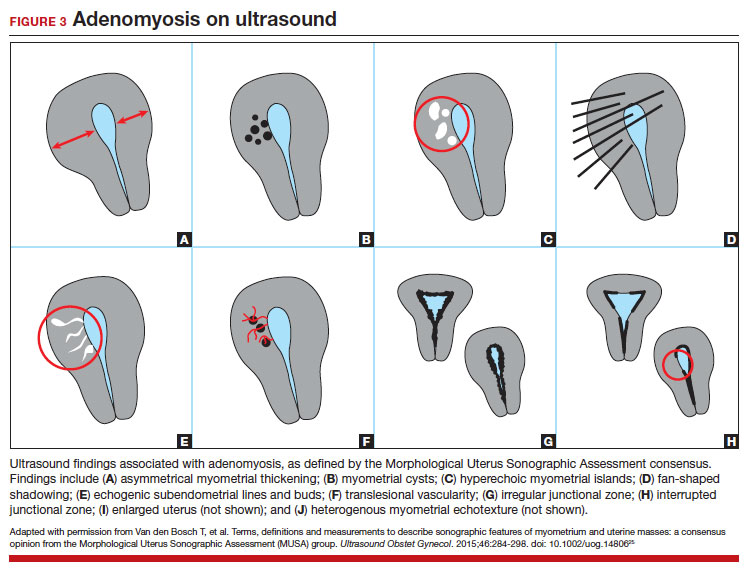

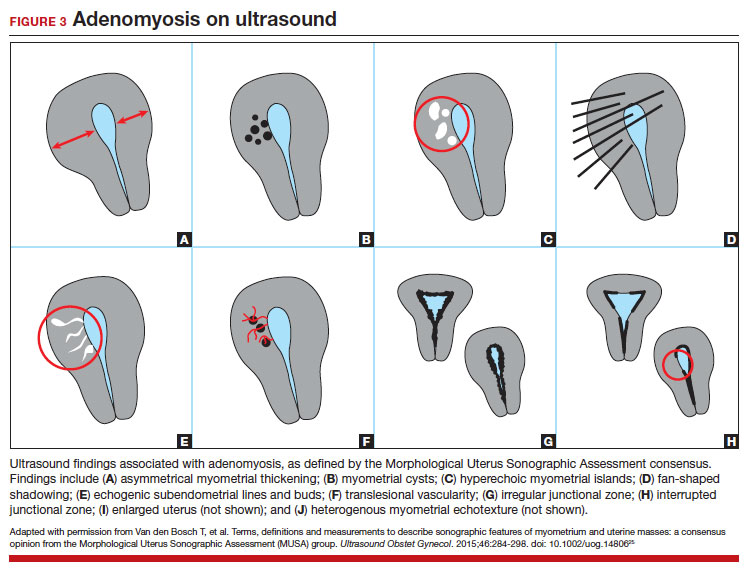

Key TVUS features associated with adenomyosis were defined in 2015 in a consensus statement released by the Morphological Uterus Sonographic Assessment (MUSA) group.25 These include a globally enlarged uterus, anteroposterior myometrial asymmetry, myometrial cysts, fan-shaped shadowing, mixed myometrial echogenicity, translesional vascularity, echogenic subendometrial lines and buds, and a thickened, irregular or discontinuous JZ (FIGURES 3 and 4).25 The accuracy of ultrasonographic diagnosis of adenomyosis using these features has been investigated in multiple systematic reviews and meta-analyses, most recently by Liu and colleagues who found a pooled sensitivity of TVUS of 81% and pooled specificity of 87%.23 The range for ultrasonographic sensitivity and specificity is wide, however, ranging from 33% to 84% for sensitivity and 64% to 100% for specificity.22 Consensus is lacking as to which TVUS features are most predictive of adenomyosis, but in general, the combination of multiple MUSA criteria (particularly myometrial cysts and irregular JZ on 3D imaging) appears to be more accurate than any one feature alone.23 The presence of fibroids may decrease the sensitivity of TVUS, and one study suggested elastography may increase the accuracy of TVUS.24,26 Moreover, given that most radiologists receive limited training on the MUSA criteria, it behooves gynecologists to become familiar with these sonographic features to be able to identify adenomyosis in our patients.

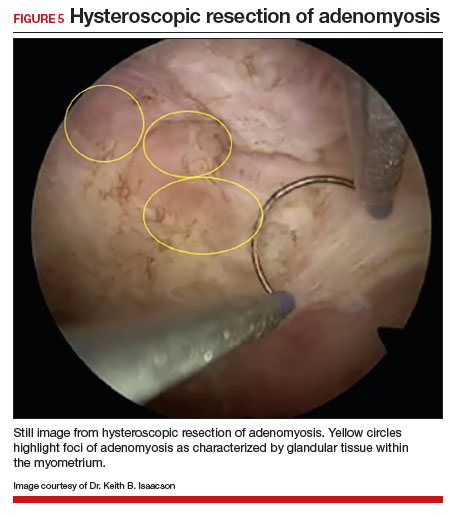

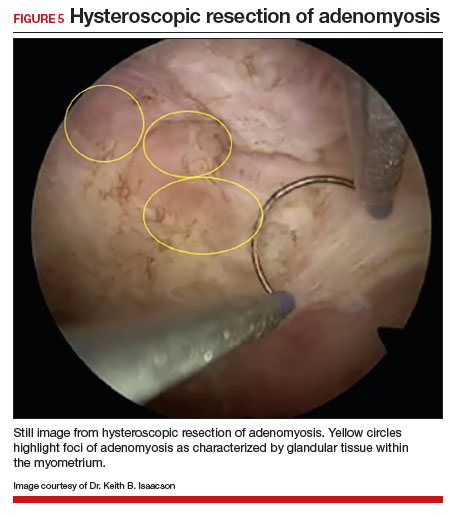

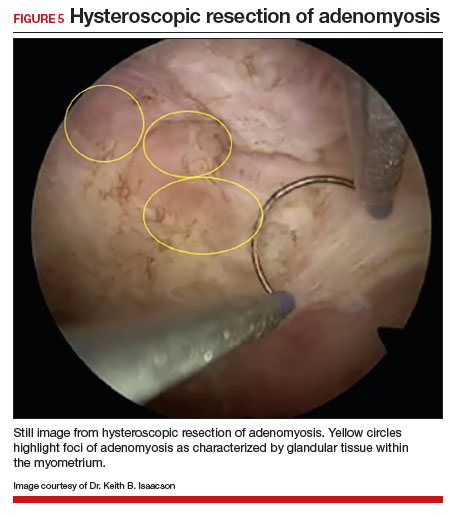

Adenomyosis also may be suspected based on hysteroscopic findings, although a normal hysteroscopy cannot rule out the disease and data are lacking to support these markers as diagnostic. Visual findings can include a “strawberry” pattern, mucosal elevation, cystic hemorrhagic lesions, localized vascularity, or endometrial defects.27 Hysteroscopy may be effective in the treatment of localized lesions, although that discussion is beyond the scope of this review.

Clinical presentation

While many women who are later diagnosed with adenomyosis are asymptomatic, the disease can present with heavy menstrual bleeding and dysmenorrhea, which occur in 50% and 30% of patients, respectively.28 Other symptoms include dyspareunia and infertility. Symptoms were previously reported to develop between the ages of 40 and 50 years; however, this is biased by diagnosis at the time of hysterectomy and the fact that younger patients are less likely to undergo definitive surgery. When using imaging criteria for diagnosis, adenomyosis might be more responsible for dysmenorrhea and chronic pelvic pain in younger patients than previously appreciated.1,29 In a recent study reviewing TVUS in 270 adolescents for any reason, adenomyosis was present in 5% of cases and this increased up to 44% in the presence of endometriosis.30