User login

Obesity Therapies: What Will the Future Bring?

“Obesity only recently caught the public’s attention as a disease,” Matthias Blüher, MD, professor of medicine at the Leipzig University and director of the Helmholtz Institute for Metabolism, Obesity and Vascular Research, Leipzig, Germany, told attendees in a thought-provoking presentation at the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD) 2024 Annual Meeting.

Even though the attitudes around how obesity is perceived may be relatively new, Blüher believes they are nonetheless significant. As a sign of how the cultural headwinds have shifted, he noted the 2022 film The Whale, which focuses on a character struggling with obesity. As Blüher pointed out, not only did the film’s star, Brendan Fraser, receive an Academy Award for his portrayal but he also theorized that the majority of celebrities in the audience were likely taking new weight loss medications.

“I strongly believe that in the future, obesity treatment will carry less stigma. It will be considered not as a cosmetic problem, but as a progressive disease.”

He sees several changes in the management of obesity likely to occur on the near horizon, beginning with when interventions directed at treating it will begin.

Obesity treatment should start at a young age, he said, because if you have overweight at ages 3-6 years, the likelihood of becoming an adult with obesity is approximately 90%. “Looking ahead, shouldn’t we put more emphasis on this age group?”

Furthermore, he hopes that clinical trials will move beyond body weight and body mass index (BMI) as their main outcome parameters. Instead, “we should talk about fat distribution, fat or adipose tissue function, muscle loss, body composition, and severity of disease.”

Blüher pointed to the recently published framework for the diagnosis, staging, and management of obesity in adults put forward by the European Association for the Study of Obesity. It states that obesity should be staged not based on BMI or body weight alone but also on an individual›s medical, functional, and psychological (eg, mental health and eating behavior) status.

“The causes of obesity are too complex to be individually targeted,” he continued, unlike examples such as hypercholesterolemia or smoking cessation, where clinicians may have one target to address.

“But overeating, slow metabolism, and low physical activity involve socio-cultural factors, global food marketing, and many other factors. Therefore, clinicians should be setting health targets, such as improving sleep apnea and improving physical functioning, rather than a kilogram number.”

Three Pillars of Treatment

Right now, clinicians have three pillars of treatments available, Blüher said. The first is behavioral intervention, including strategies such as counseling, diet, exercise, self-monitoring, stress management, and sleep management.

“We know that these behavioral aspects typically lack adherence and effect size, but they’re important, and for a certain group of people, they may be the best and safest treatment.”

The second pillar is pharmacotherapy, and the third is surgery.

Each pillar poses questions for future research, he explained.

“First, do we really need more evidence that behavioral interventions typically fail in the long run and are prone to rebound of body weight and health issues? No. Or which diet is best? We have hundreds of diet interventions, all of which basically show very similar outcomes. They lead to an average weight loss of 3% to 5% and do improve health conditions associated with obesity.”

When it comes to pharmacotherapies, Blüher does believe clinicians need more options.

Depending on affordability and access, glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) semaglutide will likely become the first-line therapy for most people living with obesity who want to take medications, he suggested. The dual glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP)/GLP-1 tirzepatide will be reserved for those with more severe conditions.

“But this is not the end of the story,” he said. “The pipelines for obesity pharmacotherapies are full, and they have different categories. We are optimistic that we will have more therapies not only for type 2 diabetes (T2D) but also for obesity. Combinations such as CagriSema (cagrilintide + semaglutide, currently indicated for T2D) may outperform the monotherapies. We have to see if they’re as safe, and we have to wait for phase 3 trials and long-term outcomes.”

“The field is open for many combinations, ideas and interactions among the incretin-based signaling systems, but personally, I think that the triple agonists have a very bright future,” Blüher said.

For example, retatrutide, an agonist of the GIP, GLP-1, and glucagon receptors, showed promise in a phase 2 trial. Although that was not a comparative study, “the average changes in body weight suggest that in a dose-dependent manner, you can expect even more weight loss than with tirzepatide.”

Treating the Causes

The future of obesity therapy might also be directed at the originating factors that cause it, Blüher suggested, adding that “treating the causes is a dream of mine.”

One example of treating the cause is leptin therapy, as shown in a 1999 study of recombinant leptin in a child with congenital leptin deficiency. A more recent example is setmelanotide treatment for proopiomelanocortin deficiency.

“We are at the beginning for these causative treatments of obesity, and I hope that the future will hold much more of these insights and targets, as in cancer therapy.”

“Finally,” he said, “We eat with our brain. And so in the future, we also will be better able to use our knowledge about the complex neural circuits that are obesogenic, and how to target them. In doing so, we can learn from surgeons because obesity surgery is very effective in changing the anatomy, and we also observe hormonal changes. We see that ghrelin, GLP-1, peptide YY, and many others are affected when the anatomy changes. Why can’t we use that knowledge to design drugs that resemble or mimic the effect size of bariatric surgery?”

And that goes to the third pillar of treatment and the question of whether the new weight loss drugs may replace surgery, which also was the topic of another EASD session.

Blüher doesn’t see that happening for at least a decade, given that there is still an effect-size gap between tirzepatide and surgery, especially for individuals with T2D. In addition, he noted, there will still be nonresponders to drugs, and clinicians are not treating to target yet. Looking ahead, he foresees a combination of surgery and multi-receptor agonists.

“I believe that obesity won’t be cured in the future, but we will have increasingly better lifelong management with a multidisciplinary approach, although behavioral interventions still will not be as successful as pharmacotherapy and bariatric surgery,” he concluded.

Q&A

During the question-and-answer session following his lecture, several attendees asked Blüher for his thoughts around other emerging areas in this field. One wanted to know whether microbiome changes might be a future target for obesity treatment.

“So far, we don’t really understand which bacteria, which composition, at which age, and at which part of the intestine need to be targeted,” Blüher responded. “Before we know that mechanistically, I think it would be difficult, but it could be an avenue to go for, though I’m a little less optimistic about it compared to other approaches.”

Given that obesity is not one disease, are there cluster subtypes, as for T2D — eg, the hungry brain, the hungry gut, low metabolism — that might benefit from individualized treatment, another attendee asked.

“We do try to subcluster people living with obesity,” Blüher said. “We did that based on adipose tissue expression signatures, and indeed there is large heterogeneity. But we are far from addressing the root causes and all subtypes of the disease, and that would be a requirement before we could personalize treatment in that way.”

Next, an attendee asked what is responsible for the differential weight loss in people with diabetes and people without? Blüher responded that although he doesn’t have the answer, he does have hypotheses.

“One could be that the disease process — eg, deterioration of beta cell function, of the balance of hormones such as insulin and leptin, of inflammatory parameters, of insulin resistance — is much more advanced in diseases such as T2D and sleep apnea. Maybe it then takes more to address comorbid conditions such as inflammation and insulin resistance. Therefore, combining current therapies with insulin sensitizers, for example, could produce better results.”

What about using continuous glucose monitoring to help people stick to their diet?

“That’s an important question that speaks to personalized treatment,” he said. “It applies not only to continuous glucose monitoring but also to nutrition and other modes of self-monitoring, which seem to be among the most successful tools for long-term weight maintenance.”

Blüher finished by saying, “As we look into the future, I hope that there will be better approaches for all aspects of personalized medicine, whether it is nutrition, exercise, pharmacotherapy, or even surgical procedures.”

Blüher received honoraria for lectures and/or served as a consultant to Amgen, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Daiichi Sankyo, Eli Lilly, Novo Nordisk, Novartis, Pfizer, and Sanofi.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

“Obesity only recently caught the public’s attention as a disease,” Matthias Blüher, MD, professor of medicine at the Leipzig University and director of the Helmholtz Institute for Metabolism, Obesity and Vascular Research, Leipzig, Germany, told attendees in a thought-provoking presentation at the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD) 2024 Annual Meeting.

Even though the attitudes around how obesity is perceived may be relatively new, Blüher believes they are nonetheless significant. As a sign of how the cultural headwinds have shifted, he noted the 2022 film The Whale, which focuses on a character struggling with obesity. As Blüher pointed out, not only did the film’s star, Brendan Fraser, receive an Academy Award for his portrayal but he also theorized that the majority of celebrities in the audience were likely taking new weight loss medications.

“I strongly believe that in the future, obesity treatment will carry less stigma. It will be considered not as a cosmetic problem, but as a progressive disease.”

He sees several changes in the management of obesity likely to occur on the near horizon, beginning with when interventions directed at treating it will begin.

Obesity treatment should start at a young age, he said, because if you have overweight at ages 3-6 years, the likelihood of becoming an adult with obesity is approximately 90%. “Looking ahead, shouldn’t we put more emphasis on this age group?”

Furthermore, he hopes that clinical trials will move beyond body weight and body mass index (BMI) as their main outcome parameters. Instead, “we should talk about fat distribution, fat or adipose tissue function, muscle loss, body composition, and severity of disease.”

Blüher pointed to the recently published framework for the diagnosis, staging, and management of obesity in adults put forward by the European Association for the Study of Obesity. It states that obesity should be staged not based on BMI or body weight alone but also on an individual›s medical, functional, and psychological (eg, mental health and eating behavior) status.

“The causes of obesity are too complex to be individually targeted,” he continued, unlike examples such as hypercholesterolemia or smoking cessation, where clinicians may have one target to address.

“But overeating, slow metabolism, and low physical activity involve socio-cultural factors, global food marketing, and many other factors. Therefore, clinicians should be setting health targets, such as improving sleep apnea and improving physical functioning, rather than a kilogram number.”

Three Pillars of Treatment

Right now, clinicians have three pillars of treatments available, Blüher said. The first is behavioral intervention, including strategies such as counseling, diet, exercise, self-monitoring, stress management, and sleep management.

“We know that these behavioral aspects typically lack adherence and effect size, but they’re important, and for a certain group of people, they may be the best and safest treatment.”

The second pillar is pharmacotherapy, and the third is surgery.

Each pillar poses questions for future research, he explained.

“First, do we really need more evidence that behavioral interventions typically fail in the long run and are prone to rebound of body weight and health issues? No. Or which diet is best? We have hundreds of diet interventions, all of which basically show very similar outcomes. They lead to an average weight loss of 3% to 5% and do improve health conditions associated with obesity.”

When it comes to pharmacotherapies, Blüher does believe clinicians need more options.

Depending on affordability and access, glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) semaglutide will likely become the first-line therapy for most people living with obesity who want to take medications, he suggested. The dual glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP)/GLP-1 tirzepatide will be reserved for those with more severe conditions.

“But this is not the end of the story,” he said. “The pipelines for obesity pharmacotherapies are full, and they have different categories. We are optimistic that we will have more therapies not only for type 2 diabetes (T2D) but also for obesity. Combinations such as CagriSema (cagrilintide + semaglutide, currently indicated for T2D) may outperform the monotherapies. We have to see if they’re as safe, and we have to wait for phase 3 trials and long-term outcomes.”

“The field is open for many combinations, ideas and interactions among the incretin-based signaling systems, but personally, I think that the triple agonists have a very bright future,” Blüher said.

For example, retatrutide, an agonist of the GIP, GLP-1, and glucagon receptors, showed promise in a phase 2 trial. Although that was not a comparative study, “the average changes in body weight suggest that in a dose-dependent manner, you can expect even more weight loss than with tirzepatide.”

Treating the Causes

The future of obesity therapy might also be directed at the originating factors that cause it, Blüher suggested, adding that “treating the causes is a dream of mine.”

One example of treating the cause is leptin therapy, as shown in a 1999 study of recombinant leptin in a child with congenital leptin deficiency. A more recent example is setmelanotide treatment for proopiomelanocortin deficiency.

“We are at the beginning for these causative treatments of obesity, and I hope that the future will hold much more of these insights and targets, as in cancer therapy.”

“Finally,” he said, “We eat with our brain. And so in the future, we also will be better able to use our knowledge about the complex neural circuits that are obesogenic, and how to target them. In doing so, we can learn from surgeons because obesity surgery is very effective in changing the anatomy, and we also observe hormonal changes. We see that ghrelin, GLP-1, peptide YY, and many others are affected when the anatomy changes. Why can’t we use that knowledge to design drugs that resemble or mimic the effect size of bariatric surgery?”

And that goes to the third pillar of treatment and the question of whether the new weight loss drugs may replace surgery, which also was the topic of another EASD session.

Blüher doesn’t see that happening for at least a decade, given that there is still an effect-size gap between tirzepatide and surgery, especially for individuals with T2D. In addition, he noted, there will still be nonresponders to drugs, and clinicians are not treating to target yet. Looking ahead, he foresees a combination of surgery and multi-receptor agonists.

“I believe that obesity won’t be cured in the future, but we will have increasingly better lifelong management with a multidisciplinary approach, although behavioral interventions still will not be as successful as pharmacotherapy and bariatric surgery,” he concluded.

Q&A

During the question-and-answer session following his lecture, several attendees asked Blüher for his thoughts around other emerging areas in this field. One wanted to know whether microbiome changes might be a future target for obesity treatment.

“So far, we don’t really understand which bacteria, which composition, at which age, and at which part of the intestine need to be targeted,” Blüher responded. “Before we know that mechanistically, I think it would be difficult, but it could be an avenue to go for, though I’m a little less optimistic about it compared to other approaches.”

Given that obesity is not one disease, are there cluster subtypes, as for T2D — eg, the hungry brain, the hungry gut, low metabolism — that might benefit from individualized treatment, another attendee asked.

“We do try to subcluster people living with obesity,” Blüher said. “We did that based on adipose tissue expression signatures, and indeed there is large heterogeneity. But we are far from addressing the root causes and all subtypes of the disease, and that would be a requirement before we could personalize treatment in that way.”

Next, an attendee asked what is responsible for the differential weight loss in people with diabetes and people without? Blüher responded that although he doesn’t have the answer, he does have hypotheses.

“One could be that the disease process — eg, deterioration of beta cell function, of the balance of hormones such as insulin and leptin, of inflammatory parameters, of insulin resistance — is much more advanced in diseases such as T2D and sleep apnea. Maybe it then takes more to address comorbid conditions such as inflammation and insulin resistance. Therefore, combining current therapies with insulin sensitizers, for example, could produce better results.”

What about using continuous glucose monitoring to help people stick to their diet?

“That’s an important question that speaks to personalized treatment,” he said. “It applies not only to continuous glucose monitoring but also to nutrition and other modes of self-monitoring, which seem to be among the most successful tools for long-term weight maintenance.”

Blüher finished by saying, “As we look into the future, I hope that there will be better approaches for all aspects of personalized medicine, whether it is nutrition, exercise, pharmacotherapy, or even surgical procedures.”

Blüher received honoraria for lectures and/or served as a consultant to Amgen, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Daiichi Sankyo, Eli Lilly, Novo Nordisk, Novartis, Pfizer, and Sanofi.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

“Obesity only recently caught the public’s attention as a disease,” Matthias Blüher, MD, professor of medicine at the Leipzig University and director of the Helmholtz Institute for Metabolism, Obesity and Vascular Research, Leipzig, Germany, told attendees in a thought-provoking presentation at the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD) 2024 Annual Meeting.

Even though the attitudes around how obesity is perceived may be relatively new, Blüher believes they are nonetheless significant. As a sign of how the cultural headwinds have shifted, he noted the 2022 film The Whale, which focuses on a character struggling with obesity. As Blüher pointed out, not only did the film’s star, Brendan Fraser, receive an Academy Award for his portrayal but he also theorized that the majority of celebrities in the audience were likely taking new weight loss medications.

“I strongly believe that in the future, obesity treatment will carry less stigma. It will be considered not as a cosmetic problem, but as a progressive disease.”

He sees several changes in the management of obesity likely to occur on the near horizon, beginning with when interventions directed at treating it will begin.

Obesity treatment should start at a young age, he said, because if you have overweight at ages 3-6 years, the likelihood of becoming an adult with obesity is approximately 90%. “Looking ahead, shouldn’t we put more emphasis on this age group?”

Furthermore, he hopes that clinical trials will move beyond body weight and body mass index (BMI) as their main outcome parameters. Instead, “we should talk about fat distribution, fat or adipose tissue function, muscle loss, body composition, and severity of disease.”

Blüher pointed to the recently published framework for the diagnosis, staging, and management of obesity in adults put forward by the European Association for the Study of Obesity. It states that obesity should be staged not based on BMI or body weight alone but also on an individual›s medical, functional, and psychological (eg, mental health and eating behavior) status.

“The causes of obesity are too complex to be individually targeted,” he continued, unlike examples such as hypercholesterolemia or smoking cessation, where clinicians may have one target to address.

“But overeating, slow metabolism, and low physical activity involve socio-cultural factors, global food marketing, and many other factors. Therefore, clinicians should be setting health targets, such as improving sleep apnea and improving physical functioning, rather than a kilogram number.”

Three Pillars of Treatment

Right now, clinicians have three pillars of treatments available, Blüher said. The first is behavioral intervention, including strategies such as counseling, diet, exercise, self-monitoring, stress management, and sleep management.

“We know that these behavioral aspects typically lack adherence and effect size, but they’re important, and for a certain group of people, they may be the best and safest treatment.”

The second pillar is pharmacotherapy, and the third is surgery.

Each pillar poses questions for future research, he explained.

“First, do we really need more evidence that behavioral interventions typically fail in the long run and are prone to rebound of body weight and health issues? No. Or which diet is best? We have hundreds of diet interventions, all of which basically show very similar outcomes. They lead to an average weight loss of 3% to 5% and do improve health conditions associated with obesity.”

When it comes to pharmacotherapies, Blüher does believe clinicians need more options.

Depending on affordability and access, glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) semaglutide will likely become the first-line therapy for most people living with obesity who want to take medications, he suggested. The dual glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP)/GLP-1 tirzepatide will be reserved for those with more severe conditions.

“But this is not the end of the story,” he said. “The pipelines for obesity pharmacotherapies are full, and they have different categories. We are optimistic that we will have more therapies not only for type 2 diabetes (T2D) but also for obesity. Combinations such as CagriSema (cagrilintide + semaglutide, currently indicated for T2D) may outperform the monotherapies. We have to see if they’re as safe, and we have to wait for phase 3 trials and long-term outcomes.”

“The field is open for many combinations, ideas and interactions among the incretin-based signaling systems, but personally, I think that the triple agonists have a very bright future,” Blüher said.

For example, retatrutide, an agonist of the GIP, GLP-1, and glucagon receptors, showed promise in a phase 2 trial. Although that was not a comparative study, “the average changes in body weight suggest that in a dose-dependent manner, you can expect even more weight loss than with tirzepatide.”

Treating the Causes

The future of obesity therapy might also be directed at the originating factors that cause it, Blüher suggested, adding that “treating the causes is a dream of mine.”

One example of treating the cause is leptin therapy, as shown in a 1999 study of recombinant leptin in a child with congenital leptin deficiency. A more recent example is setmelanotide treatment for proopiomelanocortin deficiency.

“We are at the beginning for these causative treatments of obesity, and I hope that the future will hold much more of these insights and targets, as in cancer therapy.”

“Finally,” he said, “We eat with our brain. And so in the future, we also will be better able to use our knowledge about the complex neural circuits that are obesogenic, and how to target them. In doing so, we can learn from surgeons because obesity surgery is very effective in changing the anatomy, and we also observe hormonal changes. We see that ghrelin, GLP-1, peptide YY, and many others are affected when the anatomy changes. Why can’t we use that knowledge to design drugs that resemble or mimic the effect size of bariatric surgery?”

And that goes to the third pillar of treatment and the question of whether the new weight loss drugs may replace surgery, which also was the topic of another EASD session.

Blüher doesn’t see that happening for at least a decade, given that there is still an effect-size gap between tirzepatide and surgery, especially for individuals with T2D. In addition, he noted, there will still be nonresponders to drugs, and clinicians are not treating to target yet. Looking ahead, he foresees a combination of surgery and multi-receptor agonists.

“I believe that obesity won’t be cured in the future, but we will have increasingly better lifelong management with a multidisciplinary approach, although behavioral interventions still will not be as successful as pharmacotherapy and bariatric surgery,” he concluded.

Q&A

During the question-and-answer session following his lecture, several attendees asked Blüher for his thoughts around other emerging areas in this field. One wanted to know whether microbiome changes might be a future target for obesity treatment.

“So far, we don’t really understand which bacteria, which composition, at which age, and at which part of the intestine need to be targeted,” Blüher responded. “Before we know that mechanistically, I think it would be difficult, but it could be an avenue to go for, though I’m a little less optimistic about it compared to other approaches.”

Given that obesity is not one disease, are there cluster subtypes, as for T2D — eg, the hungry brain, the hungry gut, low metabolism — that might benefit from individualized treatment, another attendee asked.

“We do try to subcluster people living with obesity,” Blüher said. “We did that based on adipose tissue expression signatures, and indeed there is large heterogeneity. But we are far from addressing the root causes and all subtypes of the disease, and that would be a requirement before we could personalize treatment in that way.”

Next, an attendee asked what is responsible for the differential weight loss in people with diabetes and people without? Blüher responded that although he doesn’t have the answer, he does have hypotheses.

“One could be that the disease process — eg, deterioration of beta cell function, of the balance of hormones such as insulin and leptin, of inflammatory parameters, of insulin resistance — is much more advanced in diseases such as T2D and sleep apnea. Maybe it then takes more to address comorbid conditions such as inflammation and insulin resistance. Therefore, combining current therapies with insulin sensitizers, for example, could produce better results.”

What about using continuous glucose monitoring to help people stick to their diet?

“That’s an important question that speaks to personalized treatment,” he said. “It applies not only to continuous glucose monitoring but also to nutrition and other modes of self-monitoring, which seem to be among the most successful tools for long-term weight maintenance.”

Blüher finished by saying, “As we look into the future, I hope that there will be better approaches for all aspects of personalized medicine, whether it is nutrition, exercise, pharmacotherapy, or even surgical procedures.”

Blüher received honoraria for lectures and/or served as a consultant to Amgen, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Daiichi Sankyo, Eli Lilly, Novo Nordisk, Novartis, Pfizer, and Sanofi.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM EASD 2024

White Matter Shows Decline After Bipolar Diagnosis

based on data from 88 individuals.

Patients with bipolar disorder demonstrate cognitive impairment and brain structure abnormalities, including global white matter loss, that have been associated with poor outcomes, but data on the stability or progression of neuroanatomical changes are limited, wrote Julian Macoveanu, PhD, of Copenhagen University Hospital, Denmark, and colleagues.

In a study published in The Journal of Affective Disorders, the researchers identified 97 adults aged 18 to 60 years with recently diagnosed bipolar disorder and matched them with 66 healthy controls. Participants were enrolled in the larger Bipolar Illness Onset (BIO) study. All participants underwent structural MRI and neuropsychological testing at baseline and were in full or partial remission based on total scores of 14 or less on the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale and the Young Mania Rating Scale. Approximately half of the participants (50 bipolar patients and 38 controls) participated in follow-up scans and testing after 6-27 months (mean 16 months), because of limited resources, according to the researchers.

The researchers compared changes in cortical gray matter volume and thickness, total cerebral white matter, hippocampal and amygdala volumes, estimated brain age, and cognitive functioning over time. In addition, they examined within-patient associations between baseline brain structure abnormalities and later mood episodes.

Overall, bipolar patients (BD) showed a significant decrease in total cerebral white matter from baseline, compared with healthy controls (HC) in mixed models (P = .006). “This effect was driven by BD patients showing a decrease in WM volume over time compared to HC who remained stable,” the researchers wrote, and the effect persisted in a post hoc analysis adjusting for subsyndromal symptoms and body mass index.

BD patients also had a larger amygdala volume at baseline and follow-up than HC, but no changes were noted between the groups. Changes in hippocampal volume also remained similar between the groups.

Analysis of cognitive data showed no significant differences in trajectories between BD patients and controls across cognitive domains or globally; although BD patients performed worse than controls at both time points.

BD patients in general experienced lower functioning and worse quality of life, compared with controls, but the trajectories of each group were similar for both functional and quality of life.

The researchers found no significant differences over time in total white matter, hippocampus, or amygdala volumes between BD patients who experienced at least one mood episode during the study period and those who remained in remission.

The findings were limited by several factors including the small sample size and limited generalizability of the findings because of the restriction to patients in full or partial remission, the researchers noted. Other limitations included the variation in follow-up time and the potential impact of psychotropic medication use.

However, the results were strengthened by the use of neuropsychiatric testing in addition to MRI to compare brain structure and cognitive function, the researchers said. The data suggest that both amygdala volume and cognitive impairment may be stable markers of BD soon after diagnosis, but that decreases in white matter may stem from disease progression.

The BIO study is funded by the Mental Health Services, Capital Region of Denmark, the Danish Council for Independent Research, Medical Sciences, Weimans Fund, Markedsmodningsfonden, Gangstedfonden, Læge Sofus Carl Emil og hustru Olga Boris Friis’ legat, Helsefonden, Innovation Fund Denmark, Copenhagen Center for Health Technology (CACHET), EU H2020 ITN, Augustinusfonden, and The Capital Region of Denmark. Macoveanu had no financial conflicts to disclose.

based on data from 88 individuals.

Patients with bipolar disorder demonstrate cognitive impairment and brain structure abnormalities, including global white matter loss, that have been associated with poor outcomes, but data on the stability or progression of neuroanatomical changes are limited, wrote Julian Macoveanu, PhD, of Copenhagen University Hospital, Denmark, and colleagues.

In a study published in The Journal of Affective Disorders, the researchers identified 97 adults aged 18 to 60 years with recently diagnosed bipolar disorder and matched them with 66 healthy controls. Participants were enrolled in the larger Bipolar Illness Onset (BIO) study. All participants underwent structural MRI and neuropsychological testing at baseline and were in full or partial remission based on total scores of 14 or less on the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale and the Young Mania Rating Scale. Approximately half of the participants (50 bipolar patients and 38 controls) participated in follow-up scans and testing after 6-27 months (mean 16 months), because of limited resources, according to the researchers.

The researchers compared changes in cortical gray matter volume and thickness, total cerebral white matter, hippocampal and amygdala volumes, estimated brain age, and cognitive functioning over time. In addition, they examined within-patient associations between baseline brain structure abnormalities and later mood episodes.

Overall, bipolar patients (BD) showed a significant decrease in total cerebral white matter from baseline, compared with healthy controls (HC) in mixed models (P = .006). “This effect was driven by BD patients showing a decrease in WM volume over time compared to HC who remained stable,” the researchers wrote, and the effect persisted in a post hoc analysis adjusting for subsyndromal symptoms and body mass index.

BD patients also had a larger amygdala volume at baseline and follow-up than HC, but no changes were noted between the groups. Changes in hippocampal volume also remained similar between the groups.

Analysis of cognitive data showed no significant differences in trajectories between BD patients and controls across cognitive domains or globally; although BD patients performed worse than controls at both time points.

BD patients in general experienced lower functioning and worse quality of life, compared with controls, but the trajectories of each group were similar for both functional and quality of life.

The researchers found no significant differences over time in total white matter, hippocampus, or amygdala volumes between BD patients who experienced at least one mood episode during the study period and those who remained in remission.

The findings were limited by several factors including the small sample size and limited generalizability of the findings because of the restriction to patients in full or partial remission, the researchers noted. Other limitations included the variation in follow-up time and the potential impact of psychotropic medication use.

However, the results were strengthened by the use of neuropsychiatric testing in addition to MRI to compare brain structure and cognitive function, the researchers said. The data suggest that both amygdala volume and cognitive impairment may be stable markers of BD soon after diagnosis, but that decreases in white matter may stem from disease progression.

The BIO study is funded by the Mental Health Services, Capital Region of Denmark, the Danish Council for Independent Research, Medical Sciences, Weimans Fund, Markedsmodningsfonden, Gangstedfonden, Læge Sofus Carl Emil og hustru Olga Boris Friis’ legat, Helsefonden, Innovation Fund Denmark, Copenhagen Center for Health Technology (CACHET), EU H2020 ITN, Augustinusfonden, and The Capital Region of Denmark. Macoveanu had no financial conflicts to disclose.

based on data from 88 individuals.

Patients with bipolar disorder demonstrate cognitive impairment and brain structure abnormalities, including global white matter loss, that have been associated with poor outcomes, but data on the stability or progression of neuroanatomical changes are limited, wrote Julian Macoveanu, PhD, of Copenhagen University Hospital, Denmark, and colleagues.

In a study published in The Journal of Affective Disorders, the researchers identified 97 adults aged 18 to 60 years with recently diagnosed bipolar disorder and matched them with 66 healthy controls. Participants were enrolled in the larger Bipolar Illness Onset (BIO) study. All participants underwent structural MRI and neuropsychological testing at baseline and were in full or partial remission based on total scores of 14 or less on the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale and the Young Mania Rating Scale. Approximately half of the participants (50 bipolar patients and 38 controls) participated in follow-up scans and testing after 6-27 months (mean 16 months), because of limited resources, according to the researchers.

The researchers compared changes in cortical gray matter volume and thickness, total cerebral white matter, hippocampal and amygdala volumes, estimated brain age, and cognitive functioning over time. In addition, they examined within-patient associations between baseline brain structure abnormalities and later mood episodes.

Overall, bipolar patients (BD) showed a significant decrease in total cerebral white matter from baseline, compared with healthy controls (HC) in mixed models (P = .006). “This effect was driven by BD patients showing a decrease in WM volume over time compared to HC who remained stable,” the researchers wrote, and the effect persisted in a post hoc analysis adjusting for subsyndromal symptoms and body mass index.

BD patients also had a larger amygdala volume at baseline and follow-up than HC, but no changes were noted between the groups. Changes in hippocampal volume also remained similar between the groups.

Analysis of cognitive data showed no significant differences in trajectories between BD patients and controls across cognitive domains or globally; although BD patients performed worse than controls at both time points.

BD patients in general experienced lower functioning and worse quality of life, compared with controls, but the trajectories of each group were similar for both functional and quality of life.

The researchers found no significant differences over time in total white matter, hippocampus, or amygdala volumes between BD patients who experienced at least one mood episode during the study period and those who remained in remission.

The findings were limited by several factors including the small sample size and limited generalizability of the findings because of the restriction to patients in full or partial remission, the researchers noted. Other limitations included the variation in follow-up time and the potential impact of psychotropic medication use.

However, the results were strengthened by the use of neuropsychiatric testing in addition to MRI to compare brain structure and cognitive function, the researchers said. The data suggest that both amygdala volume and cognitive impairment may be stable markers of BD soon after diagnosis, but that decreases in white matter may stem from disease progression.

The BIO study is funded by the Mental Health Services, Capital Region of Denmark, the Danish Council for Independent Research, Medical Sciences, Weimans Fund, Markedsmodningsfonden, Gangstedfonden, Læge Sofus Carl Emil og hustru Olga Boris Friis’ legat, Helsefonden, Innovation Fund Denmark, Copenhagen Center for Health Technology (CACHET), EU H2020 ITN, Augustinusfonden, and The Capital Region of Denmark. Macoveanu had no financial conflicts to disclose.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF AFFECTIVE DISORDERS

Heard of ApoB Testing? New Guidelines

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

I've been hearing a lot about apolipoprotein B (apoB) lately. It keeps popping up, but I've not been sure where it fits in or what I should do about it. The new Expert Clinical Consensus from the National Lipid Association now finally gives us clear guidance.

ApoB is the main protein that is found on all atherogenic lipoproteins. It is found on low-density lipoprotein (LDL) but also on other atherogenic lipoprotein particles. Because it is a part of all atherogenic particles, it predicts cardiovascular (CV) risk more accurately than does LDL cholesterol (LDL-C).

ApoB and LDL-C tend to run together, but not always. While they are correlated fairly well on a population level, for a given individual they can diverge; and when they do, apoB is the better predictor of future CV outcomes. This divergence occurs frequently, and it can occur even more frequently after treatment with statins. When LDL decreases to reach the LDL threshold for treatment, but apoB remains elevated, there is the potential for misclassification of CV risk and essentially the risk for undertreatment of someone whose CV risk is actually higher than it appears to be if we only look at their LDL-C. The consensus statement says, "Where there is discordance between apoB and LDL-C, risk follows apoB."

This understanding leads to the places where measurement of apoB may be helpful:

In patients with borderline atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease risk in whom a shared decision about statin therapy is being determined and the patient prefers not to start a statin, apoB can be useful for further risk stratification. If apoB suggests low risk, then statin therapy could be withheld, and if apoB is high, that would favor starting statin therapy. Certain common conditions, such as obesity and insulin resistance, can lead to smaller cholesterol-depleted LDL particles that result in lower LDL-C, but elevated apoB levels in this circumstance may drive the decision to treat with a statin.

In patients already treated with statins, but a decision must be made about whether treatment intensification is warranted. If the LDL-C is to goal and apoB is above threshold, treatment intensification may be considered. In patients who are not yet to goal, based on an elevated apoB, the first step is intensification of statin therapy. After that, intensification would be the same as has already been addressed in my review of the 2022 ACC Expert Consensus Decision Pathway on the Role of Nonstatin Therapies for LDL-Cholesterol Lowering.

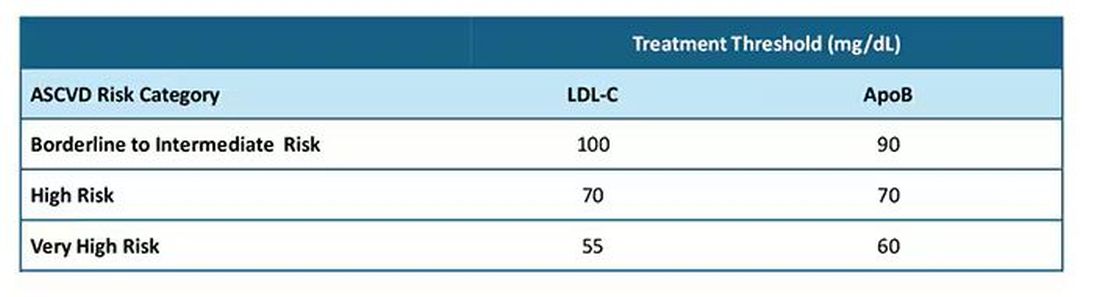

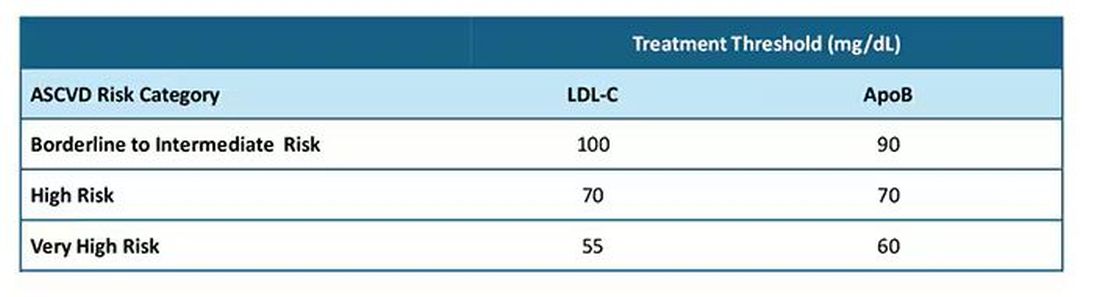

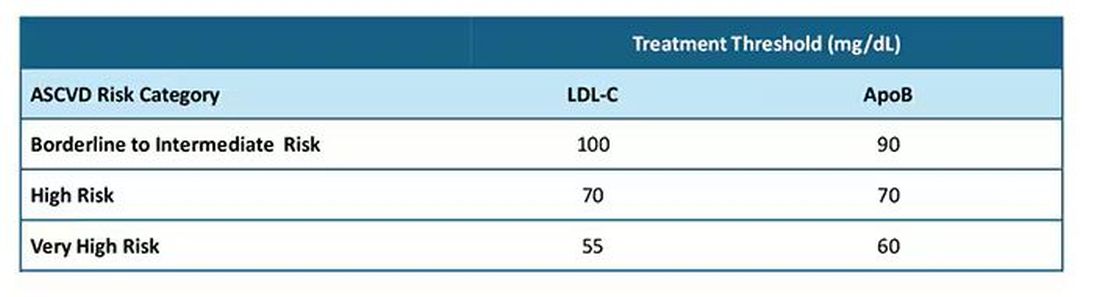

After clarifying the importance of apoB in providing additional discrimination of CV risk, the consensus statement clarifies the treatment thresholds, or goals for treatment, for apoB that correlate with established LDL-C thresholds, as shown in this table:

Let me be really clear: The consensus statement does not say that we need to measure apoB in all patients or that such measurement is the standard of care. It is not. It says, and I'll quote, "At present, the use of apoB to assess the effectiveness of lipid-lowering therapies remains a matter of clinical judgment." This guideline is helpful in pointing out the patients most likely to benefit from this additional measurement, including those with hypertriglyceridemia, diabetes, visceral adiposity, insulin resistance/metabolic syndrome, low HDL-C, or very low LDL-C levels.

In summary, measurement of apoB can be helpful for further risk stratification in patients with borderline or intermediate LDL-C levels, and for deciding whether further intensification of lipid-lowering therapy may be warranted when the LDL threshold has been reached.

Lipid management is something that we do every day in the office. This is new information, or at least clarifying information, for most of us. Hopefully it is helpful. I'm interested in your thoughts on this topic, including whether and how you plan to use apoB measurements.

Dr. Skolnik, Professor, Department of Family Medicine, Sidney Kimmel Medical College, Thomas Jefferson University, Philadelphia; Associate Director, Department of Family Medicine, Abington Jefferson Health, Abington, Pennsylvania, disclosed ties with AstraZeneca, Teva, Eli Lilly, Boehringer Ingelheim, Sanofi, Sanofi Pasteur, GlaxoSmithKline, Merck, and Bayer.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

I've been hearing a lot about apolipoprotein B (apoB) lately. It keeps popping up, but I've not been sure where it fits in or what I should do about it. The new Expert Clinical Consensus from the National Lipid Association now finally gives us clear guidance.

ApoB is the main protein that is found on all atherogenic lipoproteins. It is found on low-density lipoprotein (LDL) but also on other atherogenic lipoprotein particles. Because it is a part of all atherogenic particles, it predicts cardiovascular (CV) risk more accurately than does LDL cholesterol (LDL-C).

ApoB and LDL-C tend to run together, but not always. While they are correlated fairly well on a population level, for a given individual they can diverge; and when they do, apoB is the better predictor of future CV outcomes. This divergence occurs frequently, and it can occur even more frequently after treatment with statins. When LDL decreases to reach the LDL threshold for treatment, but apoB remains elevated, there is the potential for misclassification of CV risk and essentially the risk for undertreatment of someone whose CV risk is actually higher than it appears to be if we only look at their LDL-C. The consensus statement says, "Where there is discordance between apoB and LDL-C, risk follows apoB."

This understanding leads to the places where measurement of apoB may be helpful:

In patients with borderline atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease risk in whom a shared decision about statin therapy is being determined and the patient prefers not to start a statin, apoB can be useful for further risk stratification. If apoB suggests low risk, then statin therapy could be withheld, and if apoB is high, that would favor starting statin therapy. Certain common conditions, such as obesity and insulin resistance, can lead to smaller cholesterol-depleted LDL particles that result in lower LDL-C, but elevated apoB levels in this circumstance may drive the decision to treat with a statin.

In patients already treated with statins, but a decision must be made about whether treatment intensification is warranted. If the LDL-C is to goal and apoB is above threshold, treatment intensification may be considered. In patients who are not yet to goal, based on an elevated apoB, the first step is intensification of statin therapy. After that, intensification would be the same as has already been addressed in my review of the 2022 ACC Expert Consensus Decision Pathway on the Role of Nonstatin Therapies for LDL-Cholesterol Lowering.

After clarifying the importance of apoB in providing additional discrimination of CV risk, the consensus statement clarifies the treatment thresholds, or goals for treatment, for apoB that correlate with established LDL-C thresholds, as shown in this table:

Let me be really clear: The consensus statement does not say that we need to measure apoB in all patients or that such measurement is the standard of care. It is not. It says, and I'll quote, "At present, the use of apoB to assess the effectiveness of lipid-lowering therapies remains a matter of clinical judgment." This guideline is helpful in pointing out the patients most likely to benefit from this additional measurement, including those with hypertriglyceridemia, diabetes, visceral adiposity, insulin resistance/metabolic syndrome, low HDL-C, or very low LDL-C levels.

In summary, measurement of apoB can be helpful for further risk stratification in patients with borderline or intermediate LDL-C levels, and for deciding whether further intensification of lipid-lowering therapy may be warranted when the LDL threshold has been reached.

Lipid management is something that we do every day in the office. This is new information, or at least clarifying information, for most of us. Hopefully it is helpful. I'm interested in your thoughts on this topic, including whether and how you plan to use apoB measurements.

Dr. Skolnik, Professor, Department of Family Medicine, Sidney Kimmel Medical College, Thomas Jefferson University, Philadelphia; Associate Director, Department of Family Medicine, Abington Jefferson Health, Abington, Pennsylvania, disclosed ties with AstraZeneca, Teva, Eli Lilly, Boehringer Ingelheim, Sanofi, Sanofi Pasteur, GlaxoSmithKline, Merck, and Bayer.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

I've been hearing a lot about apolipoprotein B (apoB) lately. It keeps popping up, but I've not been sure where it fits in or what I should do about it. The new Expert Clinical Consensus from the National Lipid Association now finally gives us clear guidance.

ApoB is the main protein that is found on all atherogenic lipoproteins. It is found on low-density lipoprotein (LDL) but also on other atherogenic lipoprotein particles. Because it is a part of all atherogenic particles, it predicts cardiovascular (CV) risk more accurately than does LDL cholesterol (LDL-C).

ApoB and LDL-C tend to run together, but not always. While they are correlated fairly well on a population level, for a given individual they can diverge; and when they do, apoB is the better predictor of future CV outcomes. This divergence occurs frequently, and it can occur even more frequently after treatment with statins. When LDL decreases to reach the LDL threshold for treatment, but apoB remains elevated, there is the potential for misclassification of CV risk and essentially the risk for undertreatment of someone whose CV risk is actually higher than it appears to be if we only look at their LDL-C. The consensus statement says, "Where there is discordance between apoB and LDL-C, risk follows apoB."

This understanding leads to the places where measurement of apoB may be helpful:

In patients with borderline atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease risk in whom a shared decision about statin therapy is being determined and the patient prefers not to start a statin, apoB can be useful for further risk stratification. If apoB suggests low risk, then statin therapy could be withheld, and if apoB is high, that would favor starting statin therapy. Certain common conditions, such as obesity and insulin resistance, can lead to smaller cholesterol-depleted LDL particles that result in lower LDL-C, but elevated apoB levels in this circumstance may drive the decision to treat with a statin.

In patients already treated with statins, but a decision must be made about whether treatment intensification is warranted. If the LDL-C is to goal and apoB is above threshold, treatment intensification may be considered. In patients who are not yet to goal, based on an elevated apoB, the first step is intensification of statin therapy. After that, intensification would be the same as has already been addressed in my review of the 2022 ACC Expert Consensus Decision Pathway on the Role of Nonstatin Therapies for LDL-Cholesterol Lowering.

After clarifying the importance of apoB in providing additional discrimination of CV risk, the consensus statement clarifies the treatment thresholds, or goals for treatment, for apoB that correlate with established LDL-C thresholds, as shown in this table:

Let me be really clear: The consensus statement does not say that we need to measure apoB in all patients or that such measurement is the standard of care. It is not. It says, and I'll quote, "At present, the use of apoB to assess the effectiveness of lipid-lowering therapies remains a matter of clinical judgment." This guideline is helpful in pointing out the patients most likely to benefit from this additional measurement, including those with hypertriglyceridemia, diabetes, visceral adiposity, insulin resistance/metabolic syndrome, low HDL-C, or very low LDL-C levels.

In summary, measurement of apoB can be helpful for further risk stratification in patients with borderline or intermediate LDL-C levels, and for deciding whether further intensification of lipid-lowering therapy may be warranted when the LDL threshold has been reached.

Lipid management is something that we do every day in the office. This is new information, or at least clarifying information, for most of us. Hopefully it is helpful. I'm interested in your thoughts on this topic, including whether and how you plan to use apoB measurements.

Dr. Skolnik, Professor, Department of Family Medicine, Sidney Kimmel Medical College, Thomas Jefferson University, Philadelphia; Associate Director, Department of Family Medicine, Abington Jefferson Health, Abington, Pennsylvania, disclosed ties with AstraZeneca, Teva, Eli Lilly, Boehringer Ingelheim, Sanofi, Sanofi Pasteur, GlaxoSmithKline, Merck, and Bayer.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Obesity Etiology

Editor's Note: This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication.

Editor's Note: This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication.

Editor's Note: This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication.

Fewer Recurrent Cardiovascular Events Seen With TNF Inhibitor Use in Axial Spondyloarthritis

TOPLINE:

Tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitors are associated with a reduced risk for recurrent cardiovascular events in patients with radiographic axial spondyloarthritis (axSpA) and a history of cardiovascular events.

METHODOLOGY:

- The researchers conducted a nationwide cohort study using data from the Korean National Claims Database, including 413 patients diagnosed with cardiovascular events following a radiographic axSpA diagnosis.

- Of all patients, 75 received TNF inhibitors (mean age, 51.9 years; 92% men) and 338 did not receive TNF inhibitors (mean age, 60.7 years; 74.9% men).

- Patients were followed from the date of the first cardiovascular event to the date of recurrence, the last date with claims data, or up to December 2021.

- The study outcome was recurrent cardiovascular events that occurred within 28 days of the first incidence and included myocardial infarction and stroke.

- The effect of TNF inhibitor exposure on the risk for recurrent cardiovascular events was assessed using an inverse probability weighted Cox regression analysis.

TAKEAWAY:

- The incidence of recurrent cardiovascular events in patients with radiographic axSpA was 32 per 1000 person-years.

- The incidence was 19 per 1000 person-years in the patients exposed to TNF inhibitors, whereas it was 36 per 1000 person-years in those not exposed to TNF inhibitors.

- Exposure to TNF inhibitors was associated with a 67% lower risk for recurrent cardiovascular events than non-exposure (P = .038).

IN PRACTICE:

“Our data add to previous knowledge by providing more direct evidence that TNFi [tumor necrosis factor inhibitors] could reduce the risk of recurrent cardiovascular events,” the authors wrote.

SOURCE:

The study was led by Oh Chan Kwon, MD, PhD, and Hye Sun Lee, PhD, Yonsei University College of Medicine, Seoul, South Korea. It was published online on October 4, 2024, in Arthritis Research & Therapy.

LIMITATIONS:

The lack of data on certain cardiovascular risk factors such as obesity, smoking, and lifestyle may have led to residual confounding. The patient count in the TNF inhibitor exposure group was not adequate to analyze each TNF inhibitor medication separately. The study included only Korean patients, limiting the generalizability to other ethnic populations. The number of recurrent stroke events was relatively small, making it infeasible to analyze myocardial infarction and stroke separately.

DISCLOSURES:

The study was funded by Yuhan Corporation as part of its “2023 Investigator Initiated Translation Research Program.” The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

Tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitors are associated with a reduced risk for recurrent cardiovascular events in patients with radiographic axial spondyloarthritis (axSpA) and a history of cardiovascular events.

METHODOLOGY:

- The researchers conducted a nationwide cohort study using data from the Korean National Claims Database, including 413 patients diagnosed with cardiovascular events following a radiographic axSpA diagnosis.

- Of all patients, 75 received TNF inhibitors (mean age, 51.9 years; 92% men) and 338 did not receive TNF inhibitors (mean age, 60.7 years; 74.9% men).

- Patients were followed from the date of the first cardiovascular event to the date of recurrence, the last date with claims data, or up to December 2021.

- The study outcome was recurrent cardiovascular events that occurred within 28 days of the first incidence and included myocardial infarction and stroke.

- The effect of TNF inhibitor exposure on the risk for recurrent cardiovascular events was assessed using an inverse probability weighted Cox regression analysis.

TAKEAWAY:

- The incidence of recurrent cardiovascular events in patients with radiographic axSpA was 32 per 1000 person-years.

- The incidence was 19 per 1000 person-years in the patients exposed to TNF inhibitors, whereas it was 36 per 1000 person-years in those not exposed to TNF inhibitors.

- Exposure to TNF inhibitors was associated with a 67% lower risk for recurrent cardiovascular events than non-exposure (P = .038).

IN PRACTICE:

“Our data add to previous knowledge by providing more direct evidence that TNFi [tumor necrosis factor inhibitors] could reduce the risk of recurrent cardiovascular events,” the authors wrote.

SOURCE:

The study was led by Oh Chan Kwon, MD, PhD, and Hye Sun Lee, PhD, Yonsei University College of Medicine, Seoul, South Korea. It was published online on October 4, 2024, in Arthritis Research & Therapy.

LIMITATIONS:

The lack of data on certain cardiovascular risk factors such as obesity, smoking, and lifestyle may have led to residual confounding. The patient count in the TNF inhibitor exposure group was not adequate to analyze each TNF inhibitor medication separately. The study included only Korean patients, limiting the generalizability to other ethnic populations. The number of recurrent stroke events was relatively small, making it infeasible to analyze myocardial infarction and stroke separately.

DISCLOSURES:

The study was funded by Yuhan Corporation as part of its “2023 Investigator Initiated Translation Research Program.” The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

Tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitors are associated with a reduced risk for recurrent cardiovascular events in patients with radiographic axial spondyloarthritis (axSpA) and a history of cardiovascular events.

METHODOLOGY:

- The researchers conducted a nationwide cohort study using data from the Korean National Claims Database, including 413 patients diagnosed with cardiovascular events following a radiographic axSpA diagnosis.

- Of all patients, 75 received TNF inhibitors (mean age, 51.9 years; 92% men) and 338 did not receive TNF inhibitors (mean age, 60.7 years; 74.9% men).

- Patients were followed from the date of the first cardiovascular event to the date of recurrence, the last date with claims data, or up to December 2021.

- The study outcome was recurrent cardiovascular events that occurred within 28 days of the first incidence and included myocardial infarction and stroke.

- The effect of TNF inhibitor exposure on the risk for recurrent cardiovascular events was assessed using an inverse probability weighted Cox regression analysis.

TAKEAWAY:

- The incidence of recurrent cardiovascular events in patients with radiographic axSpA was 32 per 1000 person-years.

- The incidence was 19 per 1000 person-years in the patients exposed to TNF inhibitors, whereas it was 36 per 1000 person-years in those not exposed to TNF inhibitors.

- Exposure to TNF inhibitors was associated with a 67% lower risk for recurrent cardiovascular events than non-exposure (P = .038).

IN PRACTICE:

“Our data add to previous knowledge by providing more direct evidence that TNFi [tumor necrosis factor inhibitors] could reduce the risk of recurrent cardiovascular events,” the authors wrote.

SOURCE:

The study was led by Oh Chan Kwon, MD, PhD, and Hye Sun Lee, PhD, Yonsei University College of Medicine, Seoul, South Korea. It was published online on October 4, 2024, in Arthritis Research & Therapy.

LIMITATIONS:

The lack of data on certain cardiovascular risk factors such as obesity, smoking, and lifestyle may have led to residual confounding. The patient count in the TNF inhibitor exposure group was not adequate to analyze each TNF inhibitor medication separately. The study included only Korean patients, limiting the generalizability to other ethnic populations. The number of recurrent stroke events was relatively small, making it infeasible to analyze myocardial infarction and stroke separately.

DISCLOSURES:

The study was funded by Yuhan Corporation as part of its “2023 Investigator Initiated Translation Research Program.” The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Mechanism of Action

MOA — Mechanism of action — gets bandied about a lot.

Drug reps love it. Saying your product is a “first-in-class MOA” sounds great as they hand you a glossy brochure. It also features prominently in print ads, usually with pics of smiling people.

It’s a good thing to know, too, both medically and in a cool-science-geeky way. We want to understand what we’re prescribing will do to patients. We want to explain it to them, too.

It certainly helps to know that what we’re doing when treating a disorder using rational polypharmacy.

But at the same time we face the realization that it may not mean as much as we think it should. I don’t have to go back very far in my career to find Food and Drug Administration–approved medications that worked, but we didn’t have a clear reason why. I mean, we had a vague idea on a scientific basis, but we’re still guessing.

This didn’t stop us from using them, which is nothing new. The ancients had learned certain plants reduced pain and fever long before they understood what aspirin (and its MOA) was.

At the same time we’re now using drugs, such as the anti-amyloid treatments for Alzheimer’s disease, that should be more effective than one would think. Pulling the damaged molecules out of the brain should, on paper, make a dramatic difference ... but it doesn’t. I’m not saying they don’t have some benefit, but certainly not as much as you’d think. Of course, that’s based on our understanding of the disease mechanism being correct. We find there’s a lot more going on than we know.

Like so much in science (and this aspect of medicine is a science) the answers often lead to more questions.

Observation takes the lead over understanding in most things. Our ancestors knew what fire was, and how to use it, without any idea of what rapid exothermic oxidation was. (Admittedly, I have a degree in chemistry and can’t explain it myself anymore.)

The glossy ads and scientific data about MOA doesn’t mean much in my world if they don’t work. My patients would say the same.

Clinical medicine, after all, is both an art and a science.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Arizona.

MOA — Mechanism of action — gets bandied about a lot.

Drug reps love it. Saying your product is a “first-in-class MOA” sounds great as they hand you a glossy brochure. It also features prominently in print ads, usually with pics of smiling people.

It’s a good thing to know, too, both medically and in a cool-science-geeky way. We want to understand what we’re prescribing will do to patients. We want to explain it to them, too.

It certainly helps to know that what we’re doing when treating a disorder using rational polypharmacy.

But at the same time we face the realization that it may not mean as much as we think it should. I don’t have to go back very far in my career to find Food and Drug Administration–approved medications that worked, but we didn’t have a clear reason why. I mean, we had a vague idea on a scientific basis, but we’re still guessing.

This didn’t stop us from using them, which is nothing new. The ancients had learned certain plants reduced pain and fever long before they understood what aspirin (and its MOA) was.

At the same time we’re now using drugs, such as the anti-amyloid treatments for Alzheimer’s disease, that should be more effective than one would think. Pulling the damaged molecules out of the brain should, on paper, make a dramatic difference ... but it doesn’t. I’m not saying they don’t have some benefit, but certainly not as much as you’d think. Of course, that’s based on our understanding of the disease mechanism being correct. We find there’s a lot more going on than we know.

Like so much in science (and this aspect of medicine is a science) the answers often lead to more questions.

Observation takes the lead over understanding in most things. Our ancestors knew what fire was, and how to use it, without any idea of what rapid exothermic oxidation was. (Admittedly, I have a degree in chemistry and can’t explain it myself anymore.)

The glossy ads and scientific data about MOA doesn’t mean much in my world if they don’t work. My patients would say the same.

Clinical medicine, after all, is both an art and a science.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Arizona.

MOA — Mechanism of action — gets bandied about a lot.

Drug reps love it. Saying your product is a “first-in-class MOA” sounds great as they hand you a glossy brochure. It also features prominently in print ads, usually with pics of smiling people.

It’s a good thing to know, too, both medically and in a cool-science-geeky way. We want to understand what we’re prescribing will do to patients. We want to explain it to them, too.

It certainly helps to know that what we’re doing when treating a disorder using rational polypharmacy.

But at the same time we face the realization that it may not mean as much as we think it should. I don’t have to go back very far in my career to find Food and Drug Administration–approved medications that worked, but we didn’t have a clear reason why. I mean, we had a vague idea on a scientific basis, but we’re still guessing.

This didn’t stop us from using them, which is nothing new. The ancients had learned certain plants reduced pain and fever long before they understood what aspirin (and its MOA) was.

At the same time we’re now using drugs, such as the anti-amyloid treatments for Alzheimer’s disease, that should be more effective than one would think. Pulling the damaged molecules out of the brain should, on paper, make a dramatic difference ... but it doesn’t. I’m not saying they don’t have some benefit, but certainly not as much as you’d think. Of course, that’s based on our understanding of the disease mechanism being correct. We find there’s a lot more going on than we know.

Like so much in science (and this aspect of medicine is a science) the answers often lead to more questions.

Observation takes the lead over understanding in most things. Our ancestors knew what fire was, and how to use it, without any idea of what rapid exothermic oxidation was. (Admittedly, I have a degree in chemistry and can’t explain it myself anymore.)

The glossy ads and scientific data about MOA doesn’t mean much in my world if they don’t work. My patients would say the same.

Clinical medicine, after all, is both an art and a science.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Arizona.

One-Dose HPV Vaccine Program Would Be Efficient in Canada

In Canada, switching to a one-dose, gender-neutral vaccination program for human papillomavirus (HPV) could use vaccine doses more efficiently and prevent a similar number of cervical cancer cases, compared with a two-dose program, according to a new modeling analysis.

If vaccine protection remains high during the ages of peak sexual activity, all one-dose vaccination options are projected to be “substantially more efficient” than two-dose programs, even in the most pessimistic scenarios, the study authors wrote.

In addition, the scenarios projected the elimination of cervical cancer in Canada between 2032 and 2040. HPV can also lead to oral, throat, and penile cancers, and most are preventable through vaccination.

“The COVID-19 pandemic has impacted HPV vaccination in Canada, particularly among vulnerable population subgroups,” said study author Chantal Sauvageau, MD, a consultant in infectious diseases at the National Institute of Public Health of Quebec and associate professor of social and preventive medicine at the University of Laval, Quebec City, Canada.

Switching to one-dose vaccination would offer potential economic savings and programmatic flexibility, she added. The change also could enable investments aimed at increasing vaccination rates in regions where coverage is suboptimal, as well as in subgroups with a high HPV burden. Such initiatives could mitigate the pandemic’s impact on health programs and reduce inequalities.

The study was published online in CMAJ.

Vaccination Program Changes

Globally, countries have been investigating whether to shift from a two-dose to a one-dose HPV vaccine strategy since the World Health Organization’s Strategic Advisory Group of Experts on Immunization issued a single-dose recommendation in 2022.

In July, Canada’s National Advisory Committee on Immunization (NACI) updated its guidelines to recommend the single-dose approach for ages 9-20 years. The change aligns Canada with 35 other countries, including Australia and the United Kingdom. Canada›s vaccine advisory group still recommends two doses for ages 21-26 years and three doses for patients who are immunocompromised or have HIV.

To help inform new NACI policies, Sauvageau and colleagues modeled several one-dose and two-dose strategies using HPV-ADVISE, an individual-based transmission-dynamic model of HPV infections and diseases. They looked at vaccination programs in Quebec, which has a high HPV vaccine coverage rate of around 85%, and Ontario, which has lower coverage of around 65%.

For one-dose programs, the researchers analyzed noninferior (98% efficacy) and pessimistic (90% efficacy) scenarios and different average vaccine duration periods, including lifelong, 30-year, and 25-year coverage. They compared the scenarios with a two-dose program with 98% efficacy and lifelong duration, estimating the relative reduction in HPV-16 infection and cervical cancer incidence and the number of doses needed to prevent one cervical cancer case.

Overall, the model projected that gender-neutral HPV vaccine programs with either two doses or a noninferior one dose would nearly eliminate HPV-16 infection by 2040-2045 in Quebec and reduce infection by more than 90% in Ontario. Under a one-dose strategy with 90% vaccine efficacy, rebounds in HPV-16 infection would start more than 25-30 years after a switch to a lower-dose strategy, thus providing time for officials to detect any signs of waning efficacy and change policies, if needed, the authors wrote.

In addition, the model projected that a noninferior one-dose, gender-neutral HPV vaccination program would avert a similar number of cervical cancer cases, compared with a two-dose program. The reduction would be about 60% in Quebec and 55% in Ontario, compared with no vaccination. Under the most pessimistic scenario with 25-year vaccine duration, a one-dose program would be slightly less effective in averting cancer: about 3% lower than a two-dose program over 100 years.

All one-dose scenarios were projected to lead to the elimination of cervical cancer in 8-16 years — at fewer than four cervical cancer cases per 100,000 female-years.

One-dose programs would also lead to more efficient use of vaccine doses, with about 800-1000 doses needed to prevent one cervical cancer case in a one-dose program and more than 10,000 incremental doses needed to prevent one additional cervical cancer case in a two-dose program.

What Next?

In Canada, the HPV vaccine is authorized for patients aged 9-45 years. Current immunization coverage among adolescents and young adults varies across provinces and falls below the national target of 90%. In its July 2024 update, NACI estimated that 76% of 14-year-olds of both genders received at least one vaccine dose and that 67% received two doses in 2023. Vaccine uptake was slightly higher among girls than boys.

To boost the coverage rate, shifting to a one-dose schedule could appeal to young people, as well as maintain vaccination efficacy.

“When you look at the studies that have been published worldwide, the effectiveness of one dose of the HPV vaccine is actually quite high,” said Caroline Quach-Thanh, MD, professor of microbiology, infectious diseases, immunology, and pediatrics at the University of Montreal, Quebec, Canada.

Quach-Thanh, who wasn’t involved with this study, previously served as NACI chair and now serves as chair of the Quebec Immunization Committee.

“In terms of prevention of HPV infections that may lead to cancer, whether you give one dose or two doses basically gives you the same amount of protection,” she said.

However, not all physicians agree about the switch in vaccination approaches. In early October, the Federation of Medical Women of Canada released a report with 12 recommendations to increase HPV vaccination rates, including a call for healthcare providers to continue with multidose immunization schedules for now.

“Vaccination is the most powerful action we can take in preventing HPV-related cancers. Canada is falling behind, but we can get back on track if we act quickly,” said Vivien Brown, MD, chair of the group’s HPV Immunization Task Force, chair and cofounder of HPV Prevention Week in Canada, and a past president of the federation.

After the NACI update in July, the task force evaluated the risks and benefits of a single-dose vaccine regimen, she said. They concluded that a multidose schedule should continue at this time because of its proven effectiveness.

“Until more research on the efficacy of a single-dose schedule becomes available, healthcare providers and public health agencies should continue to offer patients a multidose schedule,” said Brown. “This is the only way to ensure individuals are protected against HPV infection and cancer over the long term.”

The study was supported by the Public Health Agency of Canada, the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, and Canadian Immunization Research Network. Sauvageau, Quach-Thanh, and Brown declared no relevant financial disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

In Canada, switching to a one-dose, gender-neutral vaccination program for human papillomavirus (HPV) could use vaccine doses more efficiently and prevent a similar number of cervical cancer cases, compared with a two-dose program, according to a new modeling analysis.

If vaccine protection remains high during the ages of peak sexual activity, all one-dose vaccination options are projected to be “substantially more efficient” than two-dose programs, even in the most pessimistic scenarios, the study authors wrote.

In addition, the scenarios projected the elimination of cervical cancer in Canada between 2032 and 2040. HPV can also lead to oral, throat, and penile cancers, and most are preventable through vaccination.

“The COVID-19 pandemic has impacted HPV vaccination in Canada, particularly among vulnerable population subgroups,” said study author Chantal Sauvageau, MD, a consultant in infectious diseases at the National Institute of Public Health of Quebec and associate professor of social and preventive medicine at the University of Laval, Quebec City, Canada.

Switching to one-dose vaccination would offer potential economic savings and programmatic flexibility, she added. The change also could enable investments aimed at increasing vaccination rates in regions where coverage is suboptimal, as well as in subgroups with a high HPV burden. Such initiatives could mitigate the pandemic’s impact on health programs and reduce inequalities.

The study was published online in CMAJ.

Vaccination Program Changes

Globally, countries have been investigating whether to shift from a two-dose to a one-dose HPV vaccine strategy since the World Health Organization’s Strategic Advisory Group of Experts on Immunization issued a single-dose recommendation in 2022.