User login

Eliminating Adverse Events and Redundant Tests Could Generate U.S. Healthcare Savings

Clinical question: Using available data, what is the estimated cost savings of eliminating adverse events and avoiding redundant tests?

Background: Reimbursement schemes are changing such that hospitals are reimbursed less for some adverse events. This financial disincentive is expected to spark interest in improved patient safety. The authors sought to model the cost savings generated by eliminating redundant testing and adverse events from literature-based estimates.

Study design: Development of conceptual model to identify common or costly adverse events, redundant tests, and simulated costs.

Setting: Literature review, expert opinion, data from safety organizations and epidemiologic studies, and patient data from the 2004 National Inpatient Data Sample.

Synopsis: The conceptual model identified 5.7 million adverse events in U.S. hospitals, of which 3 million were considered preventable. The most common events included hospital-acquired infections (82% preventable), adverse drug events (26%), falls (33%), and iatrogenic thromboembolic events (62%). The calculated cost savings totaled $16.6 billion (5.5% of total inpatient costs) for adverse events and $8.2 billion for the elimination of redundant tests. When looking at hospital subtypes, the greatest savings would come from major teaching hospitals.

This study is limited by its use of published and heterogeneous data spanning a 15-year period. The authors did not include events for which there was no epidemiologic or cost data. As hospital-care changes and technology is adopted, it is uncertain how this changes the costs, prevalence, and the preventable nature of these events. The model was not consistently able to identifying high- and low-risk patients. For instance, in some models, all patients were considered at risk for events.

Bottom line: Based on a conceptual model of 2004 hospitalized patients, eliminating preventable adverse events could have saved $16.6 billion, while eliminating redundant tests could have saved another $8 billion.

Citation: Jha AK, Chan DC, Ridgway AB, Franz C, Bates DW. Improving safety and eliminating redundant tests: cutting costs in U.S. hospitals. Health Aff (Millwood). 2009;28(5):1475-1484.

Clinical question: Using available data, what is the estimated cost savings of eliminating adverse events and avoiding redundant tests?

Background: Reimbursement schemes are changing such that hospitals are reimbursed less for some adverse events. This financial disincentive is expected to spark interest in improved patient safety. The authors sought to model the cost savings generated by eliminating redundant testing and adverse events from literature-based estimates.

Study design: Development of conceptual model to identify common or costly adverse events, redundant tests, and simulated costs.

Setting: Literature review, expert opinion, data from safety organizations and epidemiologic studies, and patient data from the 2004 National Inpatient Data Sample.

Synopsis: The conceptual model identified 5.7 million adverse events in U.S. hospitals, of which 3 million were considered preventable. The most common events included hospital-acquired infections (82% preventable), adverse drug events (26%), falls (33%), and iatrogenic thromboembolic events (62%). The calculated cost savings totaled $16.6 billion (5.5% of total inpatient costs) for adverse events and $8.2 billion for the elimination of redundant tests. When looking at hospital subtypes, the greatest savings would come from major teaching hospitals.

This study is limited by its use of published and heterogeneous data spanning a 15-year period. The authors did not include events for which there was no epidemiologic or cost data. As hospital-care changes and technology is adopted, it is uncertain how this changes the costs, prevalence, and the preventable nature of these events. The model was not consistently able to identifying high- and low-risk patients. For instance, in some models, all patients were considered at risk for events.

Bottom line: Based on a conceptual model of 2004 hospitalized patients, eliminating preventable adverse events could have saved $16.6 billion, while eliminating redundant tests could have saved another $8 billion.

Citation: Jha AK, Chan DC, Ridgway AB, Franz C, Bates DW. Improving safety and eliminating redundant tests: cutting costs in U.S. hospitals. Health Aff (Millwood). 2009;28(5):1475-1484.

Clinical question: Using available data, what is the estimated cost savings of eliminating adverse events and avoiding redundant tests?

Background: Reimbursement schemes are changing such that hospitals are reimbursed less for some adverse events. This financial disincentive is expected to spark interest in improved patient safety. The authors sought to model the cost savings generated by eliminating redundant testing and adverse events from literature-based estimates.

Study design: Development of conceptual model to identify common or costly adverse events, redundant tests, and simulated costs.

Setting: Literature review, expert opinion, data from safety organizations and epidemiologic studies, and patient data from the 2004 National Inpatient Data Sample.

Synopsis: The conceptual model identified 5.7 million adverse events in U.S. hospitals, of which 3 million were considered preventable. The most common events included hospital-acquired infections (82% preventable), adverse drug events (26%), falls (33%), and iatrogenic thromboembolic events (62%). The calculated cost savings totaled $16.6 billion (5.5% of total inpatient costs) for adverse events and $8.2 billion for the elimination of redundant tests. When looking at hospital subtypes, the greatest savings would come from major teaching hospitals.

This study is limited by its use of published and heterogeneous data spanning a 15-year period. The authors did not include events for which there was no epidemiologic or cost data. As hospital-care changes and technology is adopted, it is uncertain how this changes the costs, prevalence, and the preventable nature of these events. The model was not consistently able to identifying high- and low-risk patients. For instance, in some models, all patients were considered at risk for events.

Bottom line: Based on a conceptual model of 2004 hospitalized patients, eliminating preventable adverse events could have saved $16.6 billion, while eliminating redundant tests could have saved another $8 billion.

Citation: Jha AK, Chan DC, Ridgway AB, Franz C, Bates DW. Improving safety and eliminating redundant tests: cutting costs in U.S. hospitals. Health Aff (Millwood). 2009;28(5):1475-1484.

The Risk and Treatment for Wilms Tumors

Q) In school, they always emphasized the abdominal exam to rule out Wilms tumors. Are Wilms tumors still with us? Has treatment and evaluation changed?

Wilms tumor is a renal cancer found most commonly in children younger than 9 and represents approximately 7% of all malignancies in children.8,9 It can occur in one or both kidneys, with earlier diagnosis noted with bilateral involvement. Risk is highest among non-Hispanic white persons and African-Americans and lowest among Asians.8

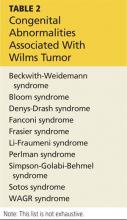

Wilms tumor develops due to a genetic mutation in the WT1 gene located on the 11p13 chromosome. Defects are also noted on the 11p15 chromosome and the p53 tumor suppressor gene.10 Urbach et al recently identified a relationship between the LIN28 gene and Wilms tumor.11 Tumors develop when embryonic renal cells that should cease growing at the time of birth continue to grow in the postnatal period. Wilms tumor can be familial or sporadic. It can also be associated with various congenital anomalies manifested within various syndromes (see Table 2), as well as isolated genitourinary abnormalities, especially in boys.10

Most children present with a palpable, smooth, firm, generally painless mass in the abdomen; those who have bilateral renal involvement usually present earlier than those with unilateral involvement. Palpation of the abdomen during examination, if vigorous, can result in rupture of the renal capsule and tumor spillage. Additional symptoms include hematuria, fever, and hypertension. Referral to pediatric oncology is imperative.12

Definitive diagnosis is made by histologic evaluation following biopsy or surgical excision.13 Other possible diagnostic tests include but are not limited to abdominal ultrasound or CT; chest CT (to rule out metastatic lung disease); urinalysis (to evaluate for hematuria and proteinuria); liver function studies (to evaluate for hepatic involvement); and laboratory studies to measure coagulation, serum calcium, blood urea nitrogen, creatinine, and complete blood count.

Histologic examination for staging (I-V) occurs following surgical excision of the tumor. There are two staging systems available: the National Wilms Tumor Study, based on postoperative tumor evaluation, and the International Society of Pediatric Oncology, based on postchemotherapy evaluation.13

Treatment options include surgical excision (including complete nephrectomy of the affected kidney), chemotherapy based on tumor staging, and internal and/or external radiation therapy.13

Susan E. Brown, MS, ARNP,

ACNP-BC, CCRN

Great River Nephrology,

West Burlington, Iowa

REFERENCES

1. United States Renal Data System. Annual data report: atlas of chronic kidney disease and end-stage renal disease in the United States (2012). www.usrds.org/2012/view/v1_01.aspx. Accessed October 19, 2014.

2. Kopp JB, Nelson GW, Sampath K, et al. APOL1 genetic variants in focal segmental glomerulosclerosis and HIV-associated nephropathy.

J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;22(11):2129-2137.

3. Parsa A, Kao L, Xie D, et al; AASK and CRIC Study Investigators. APOL1 risk variants, race and progression of chronic kidney disease.

N Engl J Med. 2013;369:2183-2196.

4. Foster MC, Coresh J, Fornage M, et al. APOL1 variants associate with increased risk of CKD among African Americans. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2013;24(9):1484-1491.

5. Lipkowitz MS, Freedman BI, Langefeld CD, et al; AASK Investigators. Apolipoprotein L1 gene variants associate with hypertension-attributed nephropathy and the rate of kidney function decline in African Americans. Kidney Int. 2013;83(1):114–120.

6. Reeves-Daniel AM, DePalma JA, Bleyer AJ, et al. The APOL1 gene and allograft survival after kidney transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2011;11(5):1025-1030.

7. Partners Healthcare Personalized Medicine. Order APOL1 genotyping test for non-diabetic nephropathy kidney disease. http://personal izedmedicine.partners.org/Laboratory-For-Molecular-Medicine/Ordering/Kidney-Dis ease/APOL1-Gene-Sequencing.aspx. Accessed October 19, 2014.

8. Grovas A, Fremgen A, Rauck A, et al. The National Cancer Data Base report on patterns of childhood cancers in the United States. Cancer. 1997;80(12):2321-2332.

9. Johns Hopkins Medicine. Wilm’s tumor. www.hopkinsmedicine.org/kimmel_cancer_center/centers/pediatric_oncology/cancer_types/wilms_tumor.html. Accessed October 19, 2014.

10. Dome JS, Huff V. Wilms tumor overview. In: Pagon RA, Adam MP, Ardinger HH, et al (eds). GeneReviews® [Internet]. Seattle, WA: University of Washington, Seattle; 1993-2014. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK1294/. Accessed October 19, 2014.

11. Urbach A, Yermalovich A, Zhang J, et al. Lin28 sustains early renal progenitors and induces Wilms tumor. Genes & Dev. 2014;28:971-982.

12. Fernandez C, Geller JI, Ehrlich PF, et al. Renal tumors. In: Pizzo P, Poplack D (eds). Principles and Practice of Pediatric Oncology. 6th ed, St Louis, MO: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. 2011; 861.

13. Metzger ML, Dome JS. Current therapy for Wilms’ tumor. Oncologist. 2005;10(10):815-826.

Q) In school, they always emphasized the abdominal exam to rule out Wilms tumors. Are Wilms tumors still with us? Has treatment and evaluation changed?

Wilms tumor is a renal cancer found most commonly in children younger than 9 and represents approximately 7% of all malignancies in children.8,9 It can occur in one or both kidneys, with earlier diagnosis noted with bilateral involvement. Risk is highest among non-Hispanic white persons and African-Americans and lowest among Asians.8

Wilms tumor develops due to a genetic mutation in the WT1 gene located on the 11p13 chromosome. Defects are also noted on the 11p15 chromosome and the p53 tumor suppressor gene.10 Urbach et al recently identified a relationship between the LIN28 gene and Wilms tumor.11 Tumors develop when embryonic renal cells that should cease growing at the time of birth continue to grow in the postnatal period. Wilms tumor can be familial or sporadic. It can also be associated with various congenital anomalies manifested within various syndromes (see Table 2), as well as isolated genitourinary abnormalities, especially in boys.10

Most children present with a palpable, smooth, firm, generally painless mass in the abdomen; those who have bilateral renal involvement usually present earlier than those with unilateral involvement. Palpation of the abdomen during examination, if vigorous, can result in rupture of the renal capsule and tumor spillage. Additional symptoms include hematuria, fever, and hypertension. Referral to pediatric oncology is imperative.12

Definitive diagnosis is made by histologic evaluation following biopsy or surgical excision.13 Other possible diagnostic tests include but are not limited to abdominal ultrasound or CT; chest CT (to rule out metastatic lung disease); urinalysis (to evaluate for hematuria and proteinuria); liver function studies (to evaluate for hepatic involvement); and laboratory studies to measure coagulation, serum calcium, blood urea nitrogen, creatinine, and complete blood count.

Histologic examination for staging (I-V) occurs following surgical excision of the tumor. There are two staging systems available: the National Wilms Tumor Study, based on postoperative tumor evaluation, and the International Society of Pediatric Oncology, based on postchemotherapy evaluation.13

Treatment options include surgical excision (including complete nephrectomy of the affected kidney), chemotherapy based on tumor staging, and internal and/or external radiation therapy.13

Susan E. Brown, MS, ARNP,

ACNP-BC, CCRN

Great River Nephrology,

West Burlington, Iowa

REFERENCES

1. United States Renal Data System. Annual data report: atlas of chronic kidney disease and end-stage renal disease in the United States (2012). www.usrds.org/2012/view/v1_01.aspx. Accessed October 19, 2014.

2. Kopp JB, Nelson GW, Sampath K, et al. APOL1 genetic variants in focal segmental glomerulosclerosis and HIV-associated nephropathy.

J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;22(11):2129-2137.

3. Parsa A, Kao L, Xie D, et al; AASK and CRIC Study Investigators. APOL1 risk variants, race and progression of chronic kidney disease.

N Engl J Med. 2013;369:2183-2196.

4. Foster MC, Coresh J, Fornage M, et al. APOL1 variants associate with increased risk of CKD among African Americans. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2013;24(9):1484-1491.

5. Lipkowitz MS, Freedman BI, Langefeld CD, et al; AASK Investigators. Apolipoprotein L1 gene variants associate with hypertension-attributed nephropathy and the rate of kidney function decline in African Americans. Kidney Int. 2013;83(1):114–120.

6. Reeves-Daniel AM, DePalma JA, Bleyer AJ, et al. The APOL1 gene and allograft survival after kidney transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2011;11(5):1025-1030.

7. Partners Healthcare Personalized Medicine. Order APOL1 genotyping test for non-diabetic nephropathy kidney disease. http://personal izedmedicine.partners.org/Laboratory-For-Molecular-Medicine/Ordering/Kidney-Dis ease/APOL1-Gene-Sequencing.aspx. Accessed October 19, 2014.

8. Grovas A, Fremgen A, Rauck A, et al. The National Cancer Data Base report on patterns of childhood cancers in the United States. Cancer. 1997;80(12):2321-2332.

9. Johns Hopkins Medicine. Wilm’s tumor. www.hopkinsmedicine.org/kimmel_cancer_center/centers/pediatric_oncology/cancer_types/wilms_tumor.html. Accessed October 19, 2014.

10. Dome JS, Huff V. Wilms tumor overview. In: Pagon RA, Adam MP, Ardinger HH, et al (eds). GeneReviews® [Internet]. Seattle, WA: University of Washington, Seattle; 1993-2014. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK1294/. Accessed October 19, 2014.

11. Urbach A, Yermalovich A, Zhang J, et al. Lin28 sustains early renal progenitors and induces Wilms tumor. Genes & Dev. 2014;28:971-982.

12. Fernandez C, Geller JI, Ehrlich PF, et al. Renal tumors. In: Pizzo P, Poplack D (eds). Principles and Practice of Pediatric Oncology. 6th ed, St Louis, MO: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. 2011; 861.

13. Metzger ML, Dome JS. Current therapy for Wilms’ tumor. Oncologist. 2005;10(10):815-826.

Q) In school, they always emphasized the abdominal exam to rule out Wilms tumors. Are Wilms tumors still with us? Has treatment and evaluation changed?

Wilms tumor is a renal cancer found most commonly in children younger than 9 and represents approximately 7% of all malignancies in children.8,9 It can occur in one or both kidneys, with earlier diagnosis noted with bilateral involvement. Risk is highest among non-Hispanic white persons and African-Americans and lowest among Asians.8

Wilms tumor develops due to a genetic mutation in the WT1 gene located on the 11p13 chromosome. Defects are also noted on the 11p15 chromosome and the p53 tumor suppressor gene.10 Urbach et al recently identified a relationship between the LIN28 gene and Wilms tumor.11 Tumors develop when embryonic renal cells that should cease growing at the time of birth continue to grow in the postnatal period. Wilms tumor can be familial or sporadic. It can also be associated with various congenital anomalies manifested within various syndromes (see Table 2), as well as isolated genitourinary abnormalities, especially in boys.10

Most children present with a palpable, smooth, firm, generally painless mass in the abdomen; those who have bilateral renal involvement usually present earlier than those with unilateral involvement. Palpation of the abdomen during examination, if vigorous, can result in rupture of the renal capsule and tumor spillage. Additional symptoms include hematuria, fever, and hypertension. Referral to pediatric oncology is imperative.12

Definitive diagnosis is made by histologic evaluation following biopsy or surgical excision.13 Other possible diagnostic tests include but are not limited to abdominal ultrasound or CT; chest CT (to rule out metastatic lung disease); urinalysis (to evaluate for hematuria and proteinuria); liver function studies (to evaluate for hepatic involvement); and laboratory studies to measure coagulation, serum calcium, blood urea nitrogen, creatinine, and complete blood count.

Histologic examination for staging (I-V) occurs following surgical excision of the tumor. There are two staging systems available: the National Wilms Tumor Study, based on postoperative tumor evaluation, and the International Society of Pediatric Oncology, based on postchemotherapy evaluation.13

Treatment options include surgical excision (including complete nephrectomy of the affected kidney), chemotherapy based on tumor staging, and internal and/or external radiation therapy.13

Susan E. Brown, MS, ARNP,

ACNP-BC, CCRN

Great River Nephrology,

West Burlington, Iowa

REFERENCES

1. United States Renal Data System. Annual data report: atlas of chronic kidney disease and end-stage renal disease in the United States (2012). www.usrds.org/2012/view/v1_01.aspx. Accessed October 19, 2014.

2. Kopp JB, Nelson GW, Sampath K, et al. APOL1 genetic variants in focal segmental glomerulosclerosis and HIV-associated nephropathy.

J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;22(11):2129-2137.

3. Parsa A, Kao L, Xie D, et al; AASK and CRIC Study Investigators. APOL1 risk variants, race and progression of chronic kidney disease.

N Engl J Med. 2013;369:2183-2196.

4. Foster MC, Coresh J, Fornage M, et al. APOL1 variants associate with increased risk of CKD among African Americans. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2013;24(9):1484-1491.

5. Lipkowitz MS, Freedman BI, Langefeld CD, et al; AASK Investigators. Apolipoprotein L1 gene variants associate with hypertension-attributed nephropathy and the rate of kidney function decline in African Americans. Kidney Int. 2013;83(1):114–120.

6. Reeves-Daniel AM, DePalma JA, Bleyer AJ, et al. The APOL1 gene and allograft survival after kidney transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2011;11(5):1025-1030.

7. Partners Healthcare Personalized Medicine. Order APOL1 genotyping test for non-diabetic nephropathy kidney disease. http://personal izedmedicine.partners.org/Laboratory-For-Molecular-Medicine/Ordering/Kidney-Dis ease/APOL1-Gene-Sequencing.aspx. Accessed October 19, 2014.

8. Grovas A, Fremgen A, Rauck A, et al. The National Cancer Data Base report on patterns of childhood cancers in the United States. Cancer. 1997;80(12):2321-2332.

9. Johns Hopkins Medicine. Wilm’s tumor. www.hopkinsmedicine.org/kimmel_cancer_center/centers/pediatric_oncology/cancer_types/wilms_tumor.html. Accessed October 19, 2014.

10. Dome JS, Huff V. Wilms tumor overview. In: Pagon RA, Adam MP, Ardinger HH, et al (eds). GeneReviews® [Internet]. Seattle, WA: University of Washington, Seattle; 1993-2014. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK1294/. Accessed October 19, 2014.

11. Urbach A, Yermalovich A, Zhang J, et al. Lin28 sustains early renal progenitors and induces Wilms tumor. Genes & Dev. 2014;28:971-982.

12. Fernandez C, Geller JI, Ehrlich PF, et al. Renal tumors. In: Pizzo P, Poplack D (eds). Principles and Practice of Pediatric Oncology. 6th ed, St Louis, MO: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. 2011; 861.

13. Metzger ML, Dome JS. Current therapy for Wilms’ tumor. Oncologist. 2005;10(10):815-826.

High Perioperative Oxygen Fraction Does Not Improve Surgical-Site Infection Frequency after Abdominal Surgery

Clinical question: Does the use of 80% oxygen perioperatively in abdominal surgery decrease the frequency of surgical-site infection within 14 days without increasing the rate of pulmonary complications?

Background: Low oxygen tension in wounds can negatively impact immune response and healing. Increasing inspiratory oxygen fraction during the perioperative period translates into higher wound oxygen tension. However, the benefit of increased oxygen fraction therapy in abdominal surgery healing and complications is not clear, nor is the frequency of pulmonary complications.

Study design: Patient- and observer-blinded clinical trial.

Setting: Fourteen Danish hospitals from October 2006 to October 2008.

Synopsis: Patients were randomized to receive a fraction of inspired oxygen (FIO2) of 0.80 or 0.30. The primary outcome—surgical-site infection in the superficial or deep wound or intra-abdominal cavity within 14 days of surgery—was defined using Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) criteria. Secondary outcomes included pulmonary complications within 14 days (pneumonia, atelectasis, or respiratory failure), 30-day mortality, duration of post-op course, ICU stay within 14 days post-op, and any abdominal operation within 14 days. The 1,386 patients were enrolled in the intention-to-treat analysis.

Infection occurred in 19.1% of patients given 0.80 FIO2 and in 20.1% of patients given 0.30 FIO2; odds ratio of 0.94 (95% CI 0.72 to 1.22; P=0.64). Numbers of pulmonary complications were not significantly different between the groups.

This trial included acute and nonacute laparotomies with followup for adverse outcomes. Study limitations included the inability to ensure that both groups received timely antibiotics and prevention for hypothermia. Of patients in the 30% FIO2 group, 7.3% required higher oxygen administration. Additionally, infection might have been underestimated in 11.3% of patients who were not followed up on between days 13 and 30.

Bottom line: High oxygen concentration administered during and after laparotomy did not lead to fewer surgical site infections, nor did it significantly increase the frequency of pulmonary complications or death.

Citation: Meyhoff CS, Wetterslev J, Jorgensen LN, et al. Effect of high perioperative oxygen fraction on surgical site infection and pulmonary complications after abdominal surgery: the PROXI randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2009;302(14):1543-1550.

Clinical question: Does the use of 80% oxygen perioperatively in abdominal surgery decrease the frequency of surgical-site infection within 14 days without increasing the rate of pulmonary complications?

Background: Low oxygen tension in wounds can negatively impact immune response and healing. Increasing inspiratory oxygen fraction during the perioperative period translates into higher wound oxygen tension. However, the benefit of increased oxygen fraction therapy in abdominal surgery healing and complications is not clear, nor is the frequency of pulmonary complications.

Study design: Patient- and observer-blinded clinical trial.

Setting: Fourteen Danish hospitals from October 2006 to October 2008.

Synopsis: Patients were randomized to receive a fraction of inspired oxygen (FIO2) of 0.80 or 0.30. The primary outcome—surgical-site infection in the superficial or deep wound or intra-abdominal cavity within 14 days of surgery—was defined using Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) criteria. Secondary outcomes included pulmonary complications within 14 days (pneumonia, atelectasis, or respiratory failure), 30-day mortality, duration of post-op course, ICU stay within 14 days post-op, and any abdominal operation within 14 days. The 1,386 patients were enrolled in the intention-to-treat analysis.

Infection occurred in 19.1% of patients given 0.80 FIO2 and in 20.1% of patients given 0.30 FIO2; odds ratio of 0.94 (95% CI 0.72 to 1.22; P=0.64). Numbers of pulmonary complications were not significantly different between the groups.

This trial included acute and nonacute laparotomies with followup for adverse outcomes. Study limitations included the inability to ensure that both groups received timely antibiotics and prevention for hypothermia. Of patients in the 30% FIO2 group, 7.3% required higher oxygen administration. Additionally, infection might have been underestimated in 11.3% of patients who were not followed up on between days 13 and 30.

Bottom line: High oxygen concentration administered during and after laparotomy did not lead to fewer surgical site infections, nor did it significantly increase the frequency of pulmonary complications or death.

Citation: Meyhoff CS, Wetterslev J, Jorgensen LN, et al. Effect of high perioperative oxygen fraction on surgical site infection and pulmonary complications after abdominal surgery: the PROXI randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2009;302(14):1543-1550.

Clinical question: Does the use of 80% oxygen perioperatively in abdominal surgery decrease the frequency of surgical-site infection within 14 days without increasing the rate of pulmonary complications?

Background: Low oxygen tension in wounds can negatively impact immune response and healing. Increasing inspiratory oxygen fraction during the perioperative period translates into higher wound oxygen tension. However, the benefit of increased oxygen fraction therapy in abdominal surgery healing and complications is not clear, nor is the frequency of pulmonary complications.

Study design: Patient- and observer-blinded clinical trial.

Setting: Fourteen Danish hospitals from October 2006 to October 2008.

Synopsis: Patients were randomized to receive a fraction of inspired oxygen (FIO2) of 0.80 or 0.30. The primary outcome—surgical-site infection in the superficial or deep wound or intra-abdominal cavity within 14 days of surgery—was defined using Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) criteria. Secondary outcomes included pulmonary complications within 14 days (pneumonia, atelectasis, or respiratory failure), 30-day mortality, duration of post-op course, ICU stay within 14 days post-op, and any abdominal operation within 14 days. The 1,386 patients were enrolled in the intention-to-treat analysis.

Infection occurred in 19.1% of patients given 0.80 FIO2 and in 20.1% of patients given 0.30 FIO2; odds ratio of 0.94 (95% CI 0.72 to 1.22; P=0.64). Numbers of pulmonary complications were not significantly different between the groups.

This trial included acute and nonacute laparotomies with followup for adverse outcomes. Study limitations included the inability to ensure that both groups received timely antibiotics and prevention for hypothermia. Of patients in the 30% FIO2 group, 7.3% required higher oxygen administration. Additionally, infection might have been underestimated in 11.3% of patients who were not followed up on between days 13 and 30.

Bottom line: High oxygen concentration administered during and after laparotomy did not lead to fewer surgical site infections, nor did it significantly increase the frequency of pulmonary complications or death.

Citation: Meyhoff CS, Wetterslev J, Jorgensen LN, et al. Effect of high perioperative oxygen fraction on surgical site infection and pulmonary complications after abdominal surgery: the PROXI randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2009;302(14):1543-1550.

Short Course of Oral Antibiotics Effective for Acute Osteomyelitis and Septic Arthritis in Children

By Mark Shen, MD

Clinical question: Is a short course (less than four weeks) of antibiotics effective for the treatment of acute osteomyelitis and septic arthritis?

Background: The optimal duration of treatment for acute bone and joint infections in children has not been assessed adequately in prospectively designed trials. Historically, intravenous (IV) antibiotics in four- to six-week durations have been recommended, although the evidence for this practice is limited. There is widespread variation in both the route of administration (oral vs. IV) and duration of this treatment.

Study design: Prospective cohort study.

Setting: Two children’s hospitals in Australia.

Synopsis: Seventy children ages 17 and under who presented to two tertiary-care children’s hospitals with osteomyelitis or septic arthritis were enrolled. Primary surgical drainage was performed for patients with septic arthritis. Intravenous antibiotics were administered for at least three days, and until clinical symptoms improved and the C-reactive protein levels had stabilized. Patients then were transitioned to oral antibiotics and discharged to complete a minimum of three weeks of therapy.

Fifty-nine percent of patients were converted to oral antibiotics by day three, 86% by day five of therapy. Based on clinical and hematologic assessment, 83% of patients had oral antibiotics stopped at the three-week followup and remained well through the 12-month follow-up period.

This study essentially involved prospective data collection for a cohort of children receiving standardized care. Although the results suggest that a majority of children can be treated with a three-week course of oral antibiotics, the results would have been further strengthened by an explicit protocol with well-defined criteria for the oral to IV transition and cessation of antibiotic therapy. Additional limitations include pathogens and antibiotic choices that might not be applicable to North American populations.

Bottom line: After initial intravenous therapy, a three-week course of oral antibiotics can be effective for acute osteomyelitis and septic arthritis in children.

Citation: Jagodzinski NA, Kanwar R, Graham K, Bache CE. Prospective evaluation of a shortened regimen of treatment for acute osteomyelitis and septic arthritis in children. J Pediatr Orthop. 2009;29(5):518-525.

By Mark Shen, MD

Clinical question: Is a short course (less than four weeks) of antibiotics effective for the treatment of acute osteomyelitis and septic arthritis?

Background: The optimal duration of treatment for acute bone and joint infections in children has not been assessed adequately in prospectively designed trials. Historically, intravenous (IV) antibiotics in four- to six-week durations have been recommended, although the evidence for this practice is limited. There is widespread variation in both the route of administration (oral vs. IV) and duration of this treatment.

Study design: Prospective cohort study.

Setting: Two children’s hospitals in Australia.

Synopsis: Seventy children ages 17 and under who presented to two tertiary-care children’s hospitals with osteomyelitis or septic arthritis were enrolled. Primary surgical drainage was performed for patients with septic arthritis. Intravenous antibiotics were administered for at least three days, and until clinical symptoms improved and the C-reactive protein levels had stabilized. Patients then were transitioned to oral antibiotics and discharged to complete a minimum of three weeks of therapy.

Fifty-nine percent of patients were converted to oral antibiotics by day three, 86% by day five of therapy. Based on clinical and hematologic assessment, 83% of patients had oral antibiotics stopped at the three-week followup and remained well through the 12-month follow-up period.

This study essentially involved prospective data collection for a cohort of children receiving standardized care. Although the results suggest that a majority of children can be treated with a three-week course of oral antibiotics, the results would have been further strengthened by an explicit protocol with well-defined criteria for the oral to IV transition and cessation of antibiotic therapy. Additional limitations include pathogens and antibiotic choices that might not be applicable to North American populations.

Bottom line: After initial intravenous therapy, a three-week course of oral antibiotics can be effective for acute osteomyelitis and septic arthritis in children.

Citation: Jagodzinski NA, Kanwar R, Graham K, Bache CE. Prospective evaluation of a shortened regimen of treatment for acute osteomyelitis and septic arthritis in children. J Pediatr Orthop. 2009;29(5):518-525.

By Mark Shen, MD

Clinical question: Is a short course (less than four weeks) of antibiotics effective for the treatment of acute osteomyelitis and septic arthritis?

Background: The optimal duration of treatment for acute bone and joint infections in children has not been assessed adequately in prospectively designed trials. Historically, intravenous (IV) antibiotics in four- to six-week durations have been recommended, although the evidence for this practice is limited. There is widespread variation in both the route of administration (oral vs. IV) and duration of this treatment.

Study design: Prospective cohort study.

Setting: Two children’s hospitals in Australia.

Synopsis: Seventy children ages 17 and under who presented to two tertiary-care children’s hospitals with osteomyelitis or septic arthritis were enrolled. Primary surgical drainage was performed for patients with septic arthritis. Intravenous antibiotics were administered for at least three days, and until clinical symptoms improved and the C-reactive protein levels had stabilized. Patients then were transitioned to oral antibiotics and discharged to complete a minimum of three weeks of therapy.

Fifty-nine percent of patients were converted to oral antibiotics by day three, 86% by day five of therapy. Based on clinical and hematologic assessment, 83% of patients had oral antibiotics stopped at the three-week followup and remained well through the 12-month follow-up period.

This study essentially involved prospective data collection for a cohort of children receiving standardized care. Although the results suggest that a majority of children can be treated with a three-week course of oral antibiotics, the results would have been further strengthened by an explicit protocol with well-defined criteria for the oral to IV transition and cessation of antibiotic therapy. Additional limitations include pathogens and antibiotic choices that might not be applicable to North American populations.

Bottom line: After initial intravenous therapy, a three-week course of oral antibiotics can be effective for acute osteomyelitis and septic arthritis in children.

Citation: Jagodzinski NA, Kanwar R, Graham K, Bache CE. Prospective evaluation of a shortened regimen of treatment for acute osteomyelitis and septic arthritis in children. J Pediatr Orthop. 2009;29(5):518-525.

Computer-Based Reminders Have Small to Modest Effect on Care Processes

Clinical question: Do on-screen, computer-based clinical reminders improve adherence to target processes of care or clinical outcomes?

Background: Gaps between practice guidelines and routine care are caused, in part, by the inability of clinicians to access or recall information at the point of care. Although automated reminder systems offer the promise of “just in time” recommendations, studies of electronic reminders have demonstrated mixed results.

Study design: Literature review and meta-analysis.

Setting: Multiple databases and information repositories, including MEDLINE, EMBASE, and CINAHL.

Synopsis: The authors conducted a literature search to identify randomized and quasi-randomized controlled trials measuring the effect of computer-based reminders on process measures or clinical outcomes. To avoid statistical challenges inherent in unit-of-analysis errors, the authors reported median improvement in process adherence or median change in clinical endpoints.

Out of a pool of 2,036 citations, 28 studies detailing 32 comparative analyses were included. Across the 28 studies, reminders resulted in a median improvement in target process adherence of 4.2% (3.3% for prescribing behavior, 2.8% for test ordering). Eight comparisons reported dichotomous clinical endpoints and collectively showed a median absolute improvement of 2.5%.

The greatest contribution to measured treatment effects came from large academic centers with well-established electronic health records and robust informatics departments. No characteristics of the reminder system or the clinical context were associated with the magnitude of impact. A potential limitation in reporting median effects across studies is that all studies were given equal weight.

Bottom line: Electronic reminders appear to have a small, positive effect on clinician adherence to recommended processes, although it is uncertain what contextual or design features are responsible for the greatest treatment effect.

Citation: Shojania K, Jennings A, Mayhew A, Ramsay CR, Eccles MP, Grimshaw J. The effects of on-screen, point of care computer reminders on processes and outcomes of care. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009(3):CD001096. TH

Clinical question: Do on-screen, computer-based clinical reminders improve adherence to target processes of care or clinical outcomes?

Background: Gaps between practice guidelines and routine care are caused, in part, by the inability of clinicians to access or recall information at the point of care. Although automated reminder systems offer the promise of “just in time” recommendations, studies of electronic reminders have demonstrated mixed results.

Study design: Literature review and meta-analysis.

Setting: Multiple databases and information repositories, including MEDLINE, EMBASE, and CINAHL.

Synopsis: The authors conducted a literature search to identify randomized and quasi-randomized controlled trials measuring the effect of computer-based reminders on process measures or clinical outcomes. To avoid statistical challenges inherent in unit-of-analysis errors, the authors reported median improvement in process adherence or median change in clinical endpoints.

Out of a pool of 2,036 citations, 28 studies detailing 32 comparative analyses were included. Across the 28 studies, reminders resulted in a median improvement in target process adherence of 4.2% (3.3% for prescribing behavior, 2.8% for test ordering). Eight comparisons reported dichotomous clinical endpoints and collectively showed a median absolute improvement of 2.5%.

The greatest contribution to measured treatment effects came from large academic centers with well-established electronic health records and robust informatics departments. No characteristics of the reminder system or the clinical context were associated with the magnitude of impact. A potential limitation in reporting median effects across studies is that all studies were given equal weight.

Bottom line: Electronic reminders appear to have a small, positive effect on clinician adherence to recommended processes, although it is uncertain what contextual or design features are responsible for the greatest treatment effect.

Citation: Shojania K, Jennings A, Mayhew A, Ramsay CR, Eccles MP, Grimshaw J. The effects of on-screen, point of care computer reminders on processes and outcomes of care. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009(3):CD001096. TH

Clinical question: Do on-screen, computer-based clinical reminders improve adherence to target processes of care or clinical outcomes?

Background: Gaps between practice guidelines and routine care are caused, in part, by the inability of clinicians to access or recall information at the point of care. Although automated reminder systems offer the promise of “just in time” recommendations, studies of electronic reminders have demonstrated mixed results.

Study design: Literature review and meta-analysis.

Setting: Multiple databases and information repositories, including MEDLINE, EMBASE, and CINAHL.

Synopsis: The authors conducted a literature search to identify randomized and quasi-randomized controlled trials measuring the effect of computer-based reminders on process measures or clinical outcomes. To avoid statistical challenges inherent in unit-of-analysis errors, the authors reported median improvement in process adherence or median change in clinical endpoints.

Out of a pool of 2,036 citations, 28 studies detailing 32 comparative analyses were included. Across the 28 studies, reminders resulted in a median improvement in target process adherence of 4.2% (3.3% for prescribing behavior, 2.8% for test ordering). Eight comparisons reported dichotomous clinical endpoints and collectively showed a median absolute improvement of 2.5%.

The greatest contribution to measured treatment effects came from large academic centers with well-established electronic health records and robust informatics departments. No characteristics of the reminder system or the clinical context were associated with the magnitude of impact. A potential limitation in reporting median effects across studies is that all studies were given equal weight.

Bottom line: Electronic reminders appear to have a small, positive effect on clinician adherence to recommended processes, although it is uncertain what contextual or design features are responsible for the greatest treatment effect.

Citation: Shojania K, Jennings A, Mayhew A, Ramsay CR, Eccles MP, Grimshaw J. The effects of on-screen, point of care computer reminders on processes and outcomes of care. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009(3):CD001096. TH

Patient Participation in Medication Reconciliation at Discharge Helps Detect Prescribing Discrepancies

Clinical question: Does the inclusion of a medication adherence counseling session during a hospital discharge reconciliation process reduce discrepancies in the final medication regimen?

Background: Inadvertent medication prescribing errors are an important cause of preventable adverse drug events and commonly occur at transitions of care. Although medication reconciliation processes can identify errors, the best strategies for implementation remain unclear.

Study design: Prospective, observational cohort.

Setting: A 550-bed teaching hospital in the Netherlands.

Synopsis: Of 437 patients admitted to a pulmonary ward and screened for eligibility, 267 were included in the analysis. A pharmacy specialist reviewed all available community prescription records, inpatient documentation, and discharge medication lists in an effort to identify discrepancies. Potential errors were discussed with the prescriber. Then, the pharmacy specialist interviewed the patient and provided additional counseling. Any new discrepancies were discussed with the prescriber. All questions raised by the pharmacist were recorded, as were all subsequent prescriber interventions.

The primary outcome measure was the number of interventions made as a result of pharmacy review. A total of 940 questions were asked. At least one intervention was recorded for 87% of patients before counseling (mean 2.7 interventions/patient) and for 97% of patients after (mean 5.3 interventions/patient). Discrepancies were addressed for 63.7% of patients before counseling and 72.5% after. Pharmacotherapy was optimized for 67.2% of patients before counseling and 76.3% after.

Bottom line: Patient engagement in the medication reconciliation process incrementally improves the quality of the history and helps identify clinically meaningful discrepancies at the time of hospital discharge.

Citation: Karapinar-Carkit F, Borgsteede S, Zoer J, Smit HJ, Egberts AC, van den Bemt P. Effect of medication reconciliation with and without patient counseling on the number of pharmaceutical interventions among patients discharged from the hospital. Ann Pharmacother. 2009;43(6):1001-1010.

Clinical question: Does the inclusion of a medication adherence counseling session during a hospital discharge reconciliation process reduce discrepancies in the final medication regimen?

Background: Inadvertent medication prescribing errors are an important cause of preventable adverse drug events and commonly occur at transitions of care. Although medication reconciliation processes can identify errors, the best strategies for implementation remain unclear.

Study design: Prospective, observational cohort.

Setting: A 550-bed teaching hospital in the Netherlands.

Synopsis: Of 437 patients admitted to a pulmonary ward and screened for eligibility, 267 were included in the analysis. A pharmacy specialist reviewed all available community prescription records, inpatient documentation, and discharge medication lists in an effort to identify discrepancies. Potential errors were discussed with the prescriber. Then, the pharmacy specialist interviewed the patient and provided additional counseling. Any new discrepancies were discussed with the prescriber. All questions raised by the pharmacist were recorded, as were all subsequent prescriber interventions.

The primary outcome measure was the number of interventions made as a result of pharmacy review. A total of 940 questions were asked. At least one intervention was recorded for 87% of patients before counseling (mean 2.7 interventions/patient) and for 97% of patients after (mean 5.3 interventions/patient). Discrepancies were addressed for 63.7% of patients before counseling and 72.5% after. Pharmacotherapy was optimized for 67.2% of patients before counseling and 76.3% after.

Bottom line: Patient engagement in the medication reconciliation process incrementally improves the quality of the history and helps identify clinically meaningful discrepancies at the time of hospital discharge.

Citation: Karapinar-Carkit F, Borgsteede S, Zoer J, Smit HJ, Egberts AC, van den Bemt P. Effect of medication reconciliation with and without patient counseling on the number of pharmaceutical interventions among patients discharged from the hospital. Ann Pharmacother. 2009;43(6):1001-1010.

Clinical question: Does the inclusion of a medication adherence counseling session during a hospital discharge reconciliation process reduce discrepancies in the final medication regimen?

Background: Inadvertent medication prescribing errors are an important cause of preventable adverse drug events and commonly occur at transitions of care. Although medication reconciliation processes can identify errors, the best strategies for implementation remain unclear.

Study design: Prospective, observational cohort.

Setting: A 550-bed teaching hospital in the Netherlands.

Synopsis: Of 437 patients admitted to a pulmonary ward and screened for eligibility, 267 were included in the analysis. A pharmacy specialist reviewed all available community prescription records, inpatient documentation, and discharge medication lists in an effort to identify discrepancies. Potential errors were discussed with the prescriber. Then, the pharmacy specialist interviewed the patient and provided additional counseling. Any new discrepancies were discussed with the prescriber. All questions raised by the pharmacist were recorded, as were all subsequent prescriber interventions.

The primary outcome measure was the number of interventions made as a result of pharmacy review. A total of 940 questions were asked. At least one intervention was recorded for 87% of patients before counseling (mean 2.7 interventions/patient) and for 97% of patients after (mean 5.3 interventions/patient). Discrepancies were addressed for 63.7% of patients before counseling and 72.5% after. Pharmacotherapy was optimized for 67.2% of patients before counseling and 76.3% after.

Bottom line: Patient engagement in the medication reconciliation process incrementally improves the quality of the history and helps identify clinically meaningful discrepancies at the time of hospital discharge.

Citation: Karapinar-Carkit F, Borgsteede S, Zoer J, Smit HJ, Egberts AC, van den Bemt P. Effect of medication reconciliation with and without patient counseling on the number of pharmaceutical interventions among patients discharged from the hospital. Ann Pharmacother. 2009;43(6):1001-1010.

Negative D-Dimer Test Can Safely Exclude Pulmonary Embolism in Patients at Low To Intermediate Clinical Risk

Clinical question: In patients with symptoms consistent with pulmonary embolism (PE), can evaluation with a clinical risk assessment tool and D-dimer assay identify patients who do not require CT angiography to exclude PE?

Background: D-dimer is a highly sensitive but nonspecific marker of VTE, and studies suggest that VTE can be ruled out without further imaging in patients with low clinical probability of disease and a negative D-dimer test. Nevertheless, this practice has not been adopted uniformly, and CT angiography (CTA) overuse continues.

Study design: Prospective registry cohort.

Setting: A 550-bed community teaching hospital in Chicago.

Synopsis: Consecutive patients presenting to the ED with symptoms suggestive of PE were evaluated with 1) revised Geneva score; 2) D-dimer assay; and 3) CTA. Among the 627 patients who underwent all three components of the evaluation, 44.8% were identified as low probability for PE by revised Geneva score, 52.6% as intermediate probability, and 2.6% as high probability. The overall prevalence of PE (using CTA as the gold standard) was very low (4.5%); just 2.1% of low-risk, 5.2% of intermediate-risk, and 31.2% of high-risk patients were ultimately found to have PE on CTA.

Using a cutoff of 1.2 mg/L, the D-dimer assay accurately detected all low- to intermediate-probability patients with PE (sensitivity and negative predictive value of 100%). One patient in the high probability group did have a PE, even though the patient had a D-dimer value <1.2 mg/L (sensitivity and NPV both 80%). Had diagnostic testing stopped after a negative D-dimer result in the low- to intermediate-probability patients, 172 CTAs (27%) would have been avoided.

Bottom line: In a low-prevalence cohort, no pulmonary emboli were identified by CTA in any patient with a low to intermediate clinical risk assessment and a negative quantitative D-dimer assay result.

Citation: Gupta RT, Kakarla RK, Kirshenbaum KJ, Tapson VF. D-dimers and efficacy of clinical risk estimation algorithms: sensitivity in evaluation of acute pulmonary embolism. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2009;193(2):425-430.

Clinical question: In patients with symptoms consistent with pulmonary embolism (PE), can evaluation with a clinical risk assessment tool and D-dimer assay identify patients who do not require CT angiography to exclude PE?

Background: D-dimer is a highly sensitive but nonspecific marker of VTE, and studies suggest that VTE can be ruled out without further imaging in patients with low clinical probability of disease and a negative D-dimer test. Nevertheless, this practice has not been adopted uniformly, and CT angiography (CTA) overuse continues.

Study design: Prospective registry cohort.

Setting: A 550-bed community teaching hospital in Chicago.

Synopsis: Consecutive patients presenting to the ED with symptoms suggestive of PE were evaluated with 1) revised Geneva score; 2) D-dimer assay; and 3) CTA. Among the 627 patients who underwent all three components of the evaluation, 44.8% were identified as low probability for PE by revised Geneva score, 52.6% as intermediate probability, and 2.6% as high probability. The overall prevalence of PE (using CTA as the gold standard) was very low (4.5%); just 2.1% of low-risk, 5.2% of intermediate-risk, and 31.2% of high-risk patients were ultimately found to have PE on CTA.

Using a cutoff of 1.2 mg/L, the D-dimer assay accurately detected all low- to intermediate-probability patients with PE (sensitivity and negative predictive value of 100%). One patient in the high probability group did have a PE, even though the patient had a D-dimer value <1.2 mg/L (sensitivity and NPV both 80%). Had diagnostic testing stopped after a negative D-dimer result in the low- to intermediate-probability patients, 172 CTAs (27%) would have been avoided.

Bottom line: In a low-prevalence cohort, no pulmonary emboli were identified by CTA in any patient with a low to intermediate clinical risk assessment and a negative quantitative D-dimer assay result.

Citation: Gupta RT, Kakarla RK, Kirshenbaum KJ, Tapson VF. D-dimers and efficacy of clinical risk estimation algorithms: sensitivity in evaluation of acute pulmonary embolism. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2009;193(2):425-430.

Clinical question: In patients with symptoms consistent with pulmonary embolism (PE), can evaluation with a clinical risk assessment tool and D-dimer assay identify patients who do not require CT angiography to exclude PE?

Background: D-dimer is a highly sensitive but nonspecific marker of VTE, and studies suggest that VTE can be ruled out without further imaging in patients with low clinical probability of disease and a negative D-dimer test. Nevertheless, this practice has not been adopted uniformly, and CT angiography (CTA) overuse continues.

Study design: Prospective registry cohort.

Setting: A 550-bed community teaching hospital in Chicago.

Synopsis: Consecutive patients presenting to the ED with symptoms suggestive of PE were evaluated with 1) revised Geneva score; 2) D-dimer assay; and 3) CTA. Among the 627 patients who underwent all three components of the evaluation, 44.8% were identified as low probability for PE by revised Geneva score, 52.6% as intermediate probability, and 2.6% as high probability. The overall prevalence of PE (using CTA as the gold standard) was very low (4.5%); just 2.1% of low-risk, 5.2% of intermediate-risk, and 31.2% of high-risk patients were ultimately found to have PE on CTA.

Using a cutoff of 1.2 mg/L, the D-dimer assay accurately detected all low- to intermediate-probability patients with PE (sensitivity and negative predictive value of 100%). One patient in the high probability group did have a PE, even though the patient had a D-dimer value <1.2 mg/L (sensitivity and NPV both 80%). Had diagnostic testing stopped after a negative D-dimer result in the low- to intermediate-probability patients, 172 CTAs (27%) would have been avoided.

Bottom line: In a low-prevalence cohort, no pulmonary emboli were identified by CTA in any patient with a low to intermediate clinical risk assessment and a negative quantitative D-dimer assay result.

Citation: Gupta RT, Kakarla RK, Kirshenbaum KJ, Tapson VF. D-dimers and efficacy of clinical risk estimation algorithms: sensitivity in evaluation of acute pulmonary embolism. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2009;193(2):425-430.

Patient Signout Is Not Uniformly Comprehensive and Often Lacks Critical Information

Clinical question: Do signouts vary in the quality and quantity of information, and what are the various factors affecting signout quality?

Background: Miscommunication during transfers of responsibility for hospitalized patients is common and can result in harm. Recommendations for safe and effective handoffs emphasize key content, clear communication, senior staff supervision, and adequate time for questions. Still, little is known about adherence to these recommendations in clinical practice.

Study design: Prospective, observational cohort.

Setting: Medical unit of an acute-care teaching hospital.

Synopsis: Oral signouts were audiotaped among IM house staff teams and the accompanying written signouts were collected for review of content. Signout sessions (n=88) included eight IM teams at one hospital and contained 503 patient signouts.

The median signout duration was 35 seconds (IQR 19-62) per patient. Key clinical information was present in just 62% of combined written or oral signouts. Most signouts included no questions from the recipient. Factors associated with higher rate of content inclusion included: familiarity with the patient, sense of responsibility (primary team vs. covering team), only one signout per day (as compared to sequential signout), presence of a senior resident, and comprehensive, written signouts.

Study limitations include the Hawthorne effect, as several participants mentioned that the presence of audiotape led to more comprehensive signouts than are typical. Also, the signout quality assessment in this study has not been validated with patient-safety outcomes.

Bottom line: Signouts among internal-medicine residents at this one hospital showed variability in terms of quantitative and qualitative information and often missed crucial information about patient care.

Citation: Horwitz LI, Moin T, Krumholz HM, Wang L, Bradley EH. What are covering doctors told about their patients? Analysis of sign-out among internal medicine house staff. Qual Saf Health Care. 2009;18(4):248-255.

Clinical question: Do signouts vary in the quality and quantity of information, and what are the various factors affecting signout quality?

Background: Miscommunication during transfers of responsibility for hospitalized patients is common and can result in harm. Recommendations for safe and effective handoffs emphasize key content, clear communication, senior staff supervision, and adequate time for questions. Still, little is known about adherence to these recommendations in clinical practice.

Study design: Prospective, observational cohort.

Setting: Medical unit of an acute-care teaching hospital.

Synopsis: Oral signouts were audiotaped among IM house staff teams and the accompanying written signouts were collected for review of content. Signout sessions (n=88) included eight IM teams at one hospital and contained 503 patient signouts.

The median signout duration was 35 seconds (IQR 19-62) per patient. Key clinical information was present in just 62% of combined written or oral signouts. Most signouts included no questions from the recipient. Factors associated with higher rate of content inclusion included: familiarity with the patient, sense of responsibility (primary team vs. covering team), only one signout per day (as compared to sequential signout), presence of a senior resident, and comprehensive, written signouts.

Study limitations include the Hawthorne effect, as several participants mentioned that the presence of audiotape led to more comprehensive signouts than are typical. Also, the signout quality assessment in this study has not been validated with patient-safety outcomes.

Bottom line: Signouts among internal-medicine residents at this one hospital showed variability in terms of quantitative and qualitative information and often missed crucial information about patient care.

Citation: Horwitz LI, Moin T, Krumholz HM, Wang L, Bradley EH. What are covering doctors told about their patients? Analysis of sign-out among internal medicine house staff. Qual Saf Health Care. 2009;18(4):248-255.

Clinical question: Do signouts vary in the quality and quantity of information, and what are the various factors affecting signout quality?

Background: Miscommunication during transfers of responsibility for hospitalized patients is common and can result in harm. Recommendations for safe and effective handoffs emphasize key content, clear communication, senior staff supervision, and adequate time for questions. Still, little is known about adherence to these recommendations in clinical practice.

Study design: Prospective, observational cohort.

Setting: Medical unit of an acute-care teaching hospital.

Synopsis: Oral signouts were audiotaped among IM house staff teams and the accompanying written signouts were collected for review of content. Signout sessions (n=88) included eight IM teams at one hospital and contained 503 patient signouts.

The median signout duration was 35 seconds (IQR 19-62) per patient. Key clinical information was present in just 62% of combined written or oral signouts. Most signouts included no questions from the recipient. Factors associated with higher rate of content inclusion included: familiarity with the patient, sense of responsibility (primary team vs. covering team), only one signout per day (as compared to sequential signout), presence of a senior resident, and comprehensive, written signouts.

Study limitations include the Hawthorne effect, as several participants mentioned that the presence of audiotape led to more comprehensive signouts than are typical. Also, the signout quality assessment in this study has not been validated with patient-safety outcomes.

Bottom line: Signouts among internal-medicine residents at this one hospital showed variability in terms of quantitative and qualitative information and often missed crucial information about patient care.

Citation: Horwitz LI, Moin T, Krumholz HM, Wang L, Bradley EH. What are covering doctors told about their patients? Analysis of sign-out among internal medicine house staff. Qual Saf Health Care. 2009;18(4):248-255.

Emergency Department Signout via Voicemail Yields Mixed Reviews

Clinical question: How does traditional, oral signout from emergency providers to inpatient medicine physicians compare to dictated, voicemail signout?

Background: Communication failures contribute to errors in care transition from ED to inpatient medicine units. Signout between ED providers and internal medicine (IM) physicians is typically oral (“synchronous communication”). It is not known how dictated signout to a voicemail system (“asynchronous communication”) affects the quality and safety of handoff communications.

Study design: Prospective, pre-post analysis.

Setting: A 944-bed urban academic medical center in Connecticut.

Synopsis: Surveys were administered to all IM and ED providers before and after the implementation of a voicemail signout system. In the new system, ED providers dictated signout for stable patients, rather than giving traditional synchronous telephone signout. It was the responsibility of the admitting IM physician to listen to the voicemail after receiving a text notification that a patient was being admitted.

ED providers recorded signouts in 89.5% of medicine admissions. However, voicemails were accessed only 58.5% of the time by receiving physicians. All ED providers and 56% of IM physicians believed signout was easier following the voicemail intervention. Overall, ED providers gave the quality, content, and accuracy of their signout communication higher ratings than IM physicians did; 69% of all providers felt the interaction among participants was worse following the intervention. There was no change in the rate of perceived adverse events or ICU transfers within 24 hours after admission.

This intervention was a QI initiative at a single center. Mixed results and small sample size limit generalizability of the study.

Bottom line: Asynchronous signout by voicemail increased efficiency, particularly among ED providers but decreased perceived quality of interaction between medical providers without obviously affecting patient safety.

Citation: Horwitz LI, Parwani V, Shah NR, et al. Evaluation of an asynchronous physician voicemail sign-out for emergency department admissions. Ann Emerg Med. 2009;54:368-378.

Clinical question: How does traditional, oral signout from emergency providers to inpatient medicine physicians compare to dictated, voicemail signout?

Background: Communication failures contribute to errors in care transition from ED to inpatient medicine units. Signout between ED providers and internal medicine (IM) physicians is typically oral (“synchronous communication”). It is not known how dictated signout to a voicemail system (“asynchronous communication”) affects the quality and safety of handoff communications.

Study design: Prospective, pre-post analysis.

Setting: A 944-bed urban academic medical center in Connecticut.

Synopsis: Surveys were administered to all IM and ED providers before and after the implementation of a voicemail signout system. In the new system, ED providers dictated signout for stable patients, rather than giving traditional synchronous telephone signout. It was the responsibility of the admitting IM physician to listen to the voicemail after receiving a text notification that a patient was being admitted.

ED providers recorded signouts in 89.5% of medicine admissions. However, voicemails were accessed only 58.5% of the time by receiving physicians. All ED providers and 56% of IM physicians believed signout was easier following the voicemail intervention. Overall, ED providers gave the quality, content, and accuracy of their signout communication higher ratings than IM physicians did; 69% of all providers felt the interaction among participants was worse following the intervention. There was no change in the rate of perceived adverse events or ICU transfers within 24 hours after admission.

This intervention was a QI initiative at a single center. Mixed results and small sample size limit generalizability of the study.

Bottom line: Asynchronous signout by voicemail increased efficiency, particularly among ED providers but decreased perceived quality of interaction between medical providers without obviously affecting patient safety.

Citation: Horwitz LI, Parwani V, Shah NR, et al. Evaluation of an asynchronous physician voicemail sign-out for emergency department admissions. Ann Emerg Med. 2009;54:368-378.

Clinical question: How does traditional, oral signout from emergency providers to inpatient medicine physicians compare to dictated, voicemail signout?

Background: Communication failures contribute to errors in care transition from ED to inpatient medicine units. Signout between ED providers and internal medicine (IM) physicians is typically oral (“synchronous communication”). It is not known how dictated signout to a voicemail system (“asynchronous communication”) affects the quality and safety of handoff communications.

Study design: Prospective, pre-post analysis.

Setting: A 944-bed urban academic medical center in Connecticut.

Synopsis: Surveys were administered to all IM and ED providers before and after the implementation of a voicemail signout system. In the new system, ED providers dictated signout for stable patients, rather than giving traditional synchronous telephone signout. It was the responsibility of the admitting IM physician to listen to the voicemail after receiving a text notification that a patient was being admitted.

ED providers recorded signouts in 89.5% of medicine admissions. However, voicemails were accessed only 58.5% of the time by receiving physicians. All ED providers and 56% of IM physicians believed signout was easier following the voicemail intervention. Overall, ED providers gave the quality, content, and accuracy of their signout communication higher ratings than IM physicians did; 69% of all providers felt the interaction among participants was worse following the intervention. There was no change in the rate of perceived adverse events or ICU transfers within 24 hours after admission.

This intervention was a QI initiative at a single center. Mixed results and small sample size limit generalizability of the study.

Bottom line: Asynchronous signout by voicemail increased efficiency, particularly among ED providers but decreased perceived quality of interaction between medical providers without obviously affecting patient safety.

Citation: Horwitz LI, Parwani V, Shah NR, et al. Evaluation of an asynchronous physician voicemail sign-out for emergency department admissions. Ann Emerg Med. 2009;54:368-378.

Emergency Department “Boarding” Results in Undesirable Events

Clinical question: What is the frequency and nature of undesirable events experienced by patients who “board” in the ED?

Background: Hospital crowding results in patients spending extended amounts of time—also known as “boarding”—in the ED as they wait for an inpatient bed. Prior studies have shown that longer ED boarding times are associated with adverse outcomes. Few studies have examined the nature and frequency of undesirable events that patients experience while boarding.

Study design: Retrospective chart review.

Setting: Urban academic medical center.

Synopsis: In this pilot study, authors reviewed the charts of patients who were treated in the ED and subsequently admitted to the hospital on three different days during the study period (n=151). More than a quarter (27.8%) of patients experienced an undesirable event, such as missing a scheduled medication, while they were boarding. Older patients, those with comorbid illnesses, and those who endured prolonged boarding times (greater than six hours) were more likely to experience an undesirable event. In addition, 3.3% of patients experienced such adverse events as suboptimal blood pressure control, hypotension, hypoxia, or arrhythmia.

This study was performed at a single center and lacks a comparison group (i.e., nonboarded patients). It is intended to serve as an exploratory study for future analysis of adverse events in boarded patients.

Bottom line: Undesirable events are common among boarded patients, although it is unknown whether they are more common than in nonboarded patients.

Citation: Liu SW, Thomas SH, Gordon JA, Hamedani AG, Weissman JS. A pilot study examining undesirable events among emergency-department boarded patients awaiting inpatient beds. Ann Emerg Med. 2009;54(3):381-385.

Clinical question: What is the frequency and nature of undesirable events experienced by patients who “board” in the ED?

Background: Hospital crowding results in patients spending extended amounts of time—also known as “boarding”—in the ED as they wait for an inpatient bed. Prior studies have shown that longer ED boarding times are associated with adverse outcomes. Few studies have examined the nature and frequency of undesirable events that patients experience while boarding.

Study design: Retrospective chart review.

Setting: Urban academic medical center.

Synopsis: In this pilot study, authors reviewed the charts of patients who were treated in the ED and subsequently admitted to the hospital on three different days during the study period (n=151). More than a quarter (27.8%) of patients experienced an undesirable event, such as missing a scheduled medication, while they were boarding. Older patients, those with comorbid illnesses, and those who endured prolonged boarding times (greater than six hours) were more likely to experience an undesirable event. In addition, 3.3% of patients experienced such adverse events as suboptimal blood pressure control, hypotension, hypoxia, or arrhythmia.

This study was performed at a single center and lacks a comparison group (i.e., nonboarded patients). It is intended to serve as an exploratory study for future analysis of adverse events in boarded patients.

Bottom line: Undesirable events are common among boarded patients, although it is unknown whether they are more common than in nonboarded patients.

Citation: Liu SW, Thomas SH, Gordon JA, Hamedani AG, Weissman JS. A pilot study examining undesirable events among emergency-department boarded patients awaiting inpatient beds. Ann Emerg Med. 2009;54(3):381-385.

Clinical question: What is the frequency and nature of undesirable events experienced by patients who “board” in the ED?

Background: Hospital crowding results in patients spending extended amounts of time—also known as “boarding”—in the ED as they wait for an inpatient bed. Prior studies have shown that longer ED boarding times are associated with adverse outcomes. Few studies have examined the nature and frequency of undesirable events that patients experience while boarding.

Study design: Retrospective chart review.

Setting: Urban academic medical center.

Synopsis: In this pilot study, authors reviewed the charts of patients who were treated in the ED and subsequently admitted to the hospital on three different days during the study period (n=151). More than a quarter (27.8%) of patients experienced an undesirable event, such as missing a scheduled medication, while they were boarding. Older patients, those with comorbid illnesses, and those who endured prolonged boarding times (greater than six hours) were more likely to experience an undesirable event. In addition, 3.3% of patients experienced such adverse events as suboptimal blood pressure control, hypotension, hypoxia, or arrhythmia.

This study was performed at a single center and lacks a comparison group (i.e., nonboarded patients). It is intended to serve as an exploratory study for future analysis of adverse events in boarded patients.

Bottom line: Undesirable events are common among boarded patients, although it is unknown whether they are more common than in nonboarded patients.

Citation: Liu SW, Thomas SH, Gordon JA, Hamedani AG, Weissman JS. A pilot study examining undesirable events among emergency-department boarded patients awaiting inpatient beds. Ann Emerg Med. 2009;54(3):381-385.