User login

Decreased ICU Duty Hours Does Not Affect Patient Mortality

Clinical question: Does the reduction in work hours for residents affect mortality in medical and surgical ICUs?

Background: A reduction in work hours for residents was enforced in July 2003. Several prior studies using administrative or claims data did not show an association of the reduced work hours for residents with mortality in teaching hospitals when compared with nonteaching hospitals.

Study design: Observational retrospective registry cohort.

Setting: Twelve academic, 12 community, and 16 nonteaching hospitals in the U.S.

Synopsis: Data from 230,151 patients were extracted as post-hoc analysis from a voluntary clinical registry that uses a well-validated severity-of-illness scoring system. The exposure was defined as date of admission to ICU within two years before and after the reform. Hospitals were categorized as academic, community with residents, or nonteaching. Sophisticated statistical analyses were performed, including interaction terms for teaching status and time. To test the effect the reduced work hours had on mortality, the mortality trends of academic hospitals and community hospitals with residents were compared with the baseline trend of nonteaching hospitals. After risk adjustments, all hospitals had improved in-hospital and ICU mortality after the reform. None of the statistical improvements were significantly different.

Study limitations include the selection bias, as only highly motivated hospitals participating in the registry were included, and misclassification bias, as not all hospitals implemented the reform at the same time. Nevertheless, this study supports the consistent literature on the topic and adds a more robust assessment of severity of illness.

Bottom line: The restriction on resident duty hours does not appear to affect patient mortality.

Citation: Prasad M, Iwashyna TJ, Christie JD, et al. Effect of work-hours regulations on intensive care unit mortality in United States teaching hospitals. Crit Care Med. 2009;37(9):2564-2569.

Clinical question: Does the reduction in work hours for residents affect mortality in medical and surgical ICUs?

Background: A reduction in work hours for residents was enforced in July 2003. Several prior studies using administrative or claims data did not show an association of the reduced work hours for residents with mortality in teaching hospitals when compared with nonteaching hospitals.

Study design: Observational retrospective registry cohort.

Setting: Twelve academic, 12 community, and 16 nonteaching hospitals in the U.S.

Synopsis: Data from 230,151 patients were extracted as post-hoc analysis from a voluntary clinical registry that uses a well-validated severity-of-illness scoring system. The exposure was defined as date of admission to ICU within two years before and after the reform. Hospitals were categorized as academic, community with residents, or nonteaching. Sophisticated statistical analyses were performed, including interaction terms for teaching status and time. To test the effect the reduced work hours had on mortality, the mortality trends of academic hospitals and community hospitals with residents were compared with the baseline trend of nonteaching hospitals. After risk adjustments, all hospitals had improved in-hospital and ICU mortality after the reform. None of the statistical improvements were significantly different.

Study limitations include the selection bias, as only highly motivated hospitals participating in the registry were included, and misclassification bias, as not all hospitals implemented the reform at the same time. Nevertheless, this study supports the consistent literature on the topic and adds a more robust assessment of severity of illness.

Bottom line: The restriction on resident duty hours does not appear to affect patient mortality.

Citation: Prasad M, Iwashyna TJ, Christie JD, et al. Effect of work-hours regulations on intensive care unit mortality in United States teaching hospitals. Crit Care Med. 2009;37(9):2564-2569.

Clinical question: Does the reduction in work hours for residents affect mortality in medical and surgical ICUs?

Background: A reduction in work hours for residents was enforced in July 2003. Several prior studies using administrative or claims data did not show an association of the reduced work hours for residents with mortality in teaching hospitals when compared with nonteaching hospitals.

Study design: Observational retrospective registry cohort.

Setting: Twelve academic, 12 community, and 16 nonteaching hospitals in the U.S.

Synopsis: Data from 230,151 patients were extracted as post-hoc analysis from a voluntary clinical registry that uses a well-validated severity-of-illness scoring system. The exposure was defined as date of admission to ICU within two years before and after the reform. Hospitals were categorized as academic, community with residents, or nonteaching. Sophisticated statistical analyses were performed, including interaction terms for teaching status and time. To test the effect the reduced work hours had on mortality, the mortality trends of academic hospitals and community hospitals with residents were compared with the baseline trend of nonteaching hospitals. After risk adjustments, all hospitals had improved in-hospital and ICU mortality after the reform. None of the statistical improvements were significantly different.

Study limitations include the selection bias, as only highly motivated hospitals participating in the registry were included, and misclassification bias, as not all hospitals implemented the reform at the same time. Nevertheless, this study supports the consistent literature on the topic and adds a more robust assessment of severity of illness.

Bottom line: The restriction on resident duty hours does not appear to affect patient mortality.

Citation: Prasad M, Iwashyna TJ, Christie JD, et al. Effect of work-hours regulations on intensive care unit mortality in United States teaching hospitals. Crit Care Med. 2009;37(9):2564-2569.

Initiatives Aim at Improving HIV and Mental Health Services

Two new HHS initiatives will expand health services for people with HIV and for people with mental health and substance use disorders.

A new 3-year multi-agency project, Partnerships for Care: Health Departments and Health Centers Collaborating to Improve HIV Health Outcomes, is putting $11 million toward integrating high-quality HIV services into primary care. Run jointly by the CDC and the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA), and funded through the Affordable Care Act and HHS Minority AIDS Initiative Fund, the program will develop innovative partnerships between health centers and state health departments in Florida, Massachusetts, Maryland, and New York. The HRSA-funded health centers will work with CDC-funded state health departments to expand the provision of HIV prevention, testing, care, and treatment services, especially among racial and ethnic minorities.

In June 2014, CDC awarded cooperative agreements to the 4 state health departments to begin putting the program into practice in communities most affected by HIV. Those health departments identified 22 health centers as their partners; the health centers are eligible to apply for funding to support workforce development, infrastructure development, HIV service delivery, partnership building, and quality improvement activities.

The HHS also announced $54.6 million in funding to support 221 health centers in 47 states and Puerto Rico to establish or expand behavioral health services for over 450,000 patients. The funds will be used for hiring new mental health professionals, adding mental health and substance use disorder health services, and employing integrated models of primary care.

In 2013, more than 1.2 million patients visited health centers for behavioral health services. The new grant funding, said HHS Secretary Sylvia M. Burwell, will “further reduce the barriers that too often prevent people from getting the help they need for mental health problems. Health centers with these awards are on the front lines of better integrating mental health into primary care and improving access to care through the Affordable Care Act.”

For more information on the projects and their funding, visit http://www.hrsa.gov/grants/apply/assistance/bphchiv and http://www.hrsa.gov/about/news/2014tables/behavioralhealth.

Two new HHS initiatives will expand health services for people with HIV and for people with mental health and substance use disorders.

A new 3-year multi-agency project, Partnerships for Care: Health Departments and Health Centers Collaborating to Improve HIV Health Outcomes, is putting $11 million toward integrating high-quality HIV services into primary care. Run jointly by the CDC and the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA), and funded through the Affordable Care Act and HHS Minority AIDS Initiative Fund, the program will develop innovative partnerships between health centers and state health departments in Florida, Massachusetts, Maryland, and New York. The HRSA-funded health centers will work with CDC-funded state health departments to expand the provision of HIV prevention, testing, care, and treatment services, especially among racial and ethnic minorities.

In June 2014, CDC awarded cooperative agreements to the 4 state health departments to begin putting the program into practice in communities most affected by HIV. Those health departments identified 22 health centers as their partners; the health centers are eligible to apply for funding to support workforce development, infrastructure development, HIV service delivery, partnership building, and quality improvement activities.

The HHS also announced $54.6 million in funding to support 221 health centers in 47 states and Puerto Rico to establish or expand behavioral health services for over 450,000 patients. The funds will be used for hiring new mental health professionals, adding mental health and substance use disorder health services, and employing integrated models of primary care.

In 2013, more than 1.2 million patients visited health centers for behavioral health services. The new grant funding, said HHS Secretary Sylvia M. Burwell, will “further reduce the barriers that too often prevent people from getting the help they need for mental health problems. Health centers with these awards are on the front lines of better integrating mental health into primary care and improving access to care through the Affordable Care Act.”

For more information on the projects and their funding, visit http://www.hrsa.gov/grants/apply/assistance/bphchiv and http://www.hrsa.gov/about/news/2014tables/behavioralhealth.

Two new HHS initiatives will expand health services for people with HIV and for people with mental health and substance use disorders.

A new 3-year multi-agency project, Partnerships for Care: Health Departments and Health Centers Collaborating to Improve HIV Health Outcomes, is putting $11 million toward integrating high-quality HIV services into primary care. Run jointly by the CDC and the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA), and funded through the Affordable Care Act and HHS Minority AIDS Initiative Fund, the program will develop innovative partnerships between health centers and state health departments in Florida, Massachusetts, Maryland, and New York. The HRSA-funded health centers will work with CDC-funded state health departments to expand the provision of HIV prevention, testing, care, and treatment services, especially among racial and ethnic minorities.

In June 2014, CDC awarded cooperative agreements to the 4 state health departments to begin putting the program into practice in communities most affected by HIV. Those health departments identified 22 health centers as their partners; the health centers are eligible to apply for funding to support workforce development, infrastructure development, HIV service delivery, partnership building, and quality improvement activities.

The HHS also announced $54.6 million in funding to support 221 health centers in 47 states and Puerto Rico to establish or expand behavioral health services for over 450,000 patients. The funds will be used for hiring new mental health professionals, adding mental health and substance use disorder health services, and employing integrated models of primary care.

In 2013, more than 1.2 million patients visited health centers for behavioral health services. The new grant funding, said HHS Secretary Sylvia M. Burwell, will “further reduce the barriers that too often prevent people from getting the help they need for mental health problems. Health centers with these awards are on the front lines of better integrating mental health into primary care and improving access to care through the Affordable Care Act.”

For more information on the projects and their funding, visit http://www.hrsa.gov/grants/apply/assistance/bphchiv and http://www.hrsa.gov/about/news/2014tables/behavioralhealth.

Bortezomib can treat chronic GVHD, study shows

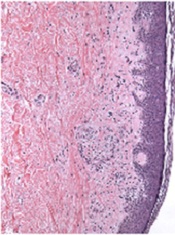

Credit: PLOS ONE

The proteasome inhibitor bortezomib can treat chronic graft-vs-host disease (GVHD), according to research published in Blood.

The study showed that bortezomib provides better outcomes than existing treatments and does not impair the graft-vs-tumor effect.

“Bortezomib helped a group of patients who desperately needed a treatment, having failed multiple different therapies,” said study author Mehrdad Abedi, MD, of the University of California, Davis.

“The drug fights chronic graft-vs-host disease, and, unlike other GVHD therapies such as steroid, cyclosporine, or mycophenolate, it treats chronic GVHD without dampening the graft-vs-tumor effect, which can be critically important to help patients avoid relapse. In fact, because bortezomib is an anticancer drug, it potentially attacks cancer cells in its own right.”

The researchers first studied bortezomib in mice and found the drug suppresses the donor immune cells that cause GVHD.

“We then tested this concept in patients with chronic GVHD . . . ,” Dr Abedi said. “Almost all the patients who tolerated and remained on the treatment responded. In some cases, individual responses were quite dramatic. We were able to stop their other immunosuppressive medications and keep the patients under control with just weekly injections of bortezomib.”

Dr Abedi added that one patient had severe hemolytic anemia that did not respond to several lines of therapy.

“After receiving bortezomib, the patient’s symptoms improved, and we were able to take her completely off steroid and other immunosuppressive medications,” he said. “Another person had multiple ulcers, which completely healed. These were patients who had been on all different kinds of medications and had no response.”

This research is ongoing. Dr Abedi and his colleagues are now looking at a potential oral version of the drug and a similar agent that would alleviate the need for weekly injections and could have fewer side effects.

This research was funded by the National Cancer Institute, the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, and Millennium Pharmaceuticals, makers of bortezomib. ![]()

Credit: PLOS ONE

The proteasome inhibitor bortezomib can treat chronic graft-vs-host disease (GVHD), according to research published in Blood.

The study showed that bortezomib provides better outcomes than existing treatments and does not impair the graft-vs-tumor effect.

“Bortezomib helped a group of patients who desperately needed a treatment, having failed multiple different therapies,” said study author Mehrdad Abedi, MD, of the University of California, Davis.

“The drug fights chronic graft-vs-host disease, and, unlike other GVHD therapies such as steroid, cyclosporine, or mycophenolate, it treats chronic GVHD without dampening the graft-vs-tumor effect, which can be critically important to help patients avoid relapse. In fact, because bortezomib is an anticancer drug, it potentially attacks cancer cells in its own right.”

The researchers first studied bortezomib in mice and found the drug suppresses the donor immune cells that cause GVHD.

“We then tested this concept in patients with chronic GVHD . . . ,” Dr Abedi said. “Almost all the patients who tolerated and remained on the treatment responded. In some cases, individual responses were quite dramatic. We were able to stop their other immunosuppressive medications and keep the patients under control with just weekly injections of bortezomib.”

Dr Abedi added that one patient had severe hemolytic anemia that did not respond to several lines of therapy.

“After receiving bortezomib, the patient’s symptoms improved, and we were able to take her completely off steroid and other immunosuppressive medications,” he said. “Another person had multiple ulcers, which completely healed. These were patients who had been on all different kinds of medications and had no response.”

This research is ongoing. Dr Abedi and his colleagues are now looking at a potential oral version of the drug and a similar agent that would alleviate the need for weekly injections and could have fewer side effects.

This research was funded by the National Cancer Institute, the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, and Millennium Pharmaceuticals, makers of bortezomib. ![]()

Credit: PLOS ONE

The proteasome inhibitor bortezomib can treat chronic graft-vs-host disease (GVHD), according to research published in Blood.

The study showed that bortezomib provides better outcomes than existing treatments and does not impair the graft-vs-tumor effect.

“Bortezomib helped a group of patients who desperately needed a treatment, having failed multiple different therapies,” said study author Mehrdad Abedi, MD, of the University of California, Davis.

“The drug fights chronic graft-vs-host disease, and, unlike other GVHD therapies such as steroid, cyclosporine, or mycophenolate, it treats chronic GVHD without dampening the graft-vs-tumor effect, which can be critically important to help patients avoid relapse. In fact, because bortezomib is an anticancer drug, it potentially attacks cancer cells in its own right.”

The researchers first studied bortezomib in mice and found the drug suppresses the donor immune cells that cause GVHD.

“We then tested this concept in patients with chronic GVHD . . . ,” Dr Abedi said. “Almost all the patients who tolerated and remained on the treatment responded. In some cases, individual responses were quite dramatic. We were able to stop their other immunosuppressive medications and keep the patients under control with just weekly injections of bortezomib.”

Dr Abedi added that one patient had severe hemolytic anemia that did not respond to several lines of therapy.

“After receiving bortezomib, the patient’s symptoms improved, and we were able to take her completely off steroid and other immunosuppressive medications,” he said. “Another person had multiple ulcers, which completely healed. These were patients who had been on all different kinds of medications and had no response.”

This research is ongoing. Dr Abedi and his colleagues are now looking at a potential oral version of the drug and a similar agent that would alleviate the need for weekly injections and could have fewer side effects.

This research was funded by the National Cancer Institute, the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, and Millennium Pharmaceuticals, makers of bortezomib. ![]()

Team creates functional vascular grafts in a week

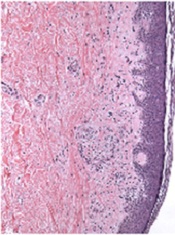

Credit: Robert Emilsson

Researchers have found they can engineer vascular grafts using autologous peripheral blood and successfully transplant them into patients with portal vein thrombosis.

The team said this research provides early evidence for generating personalized blood vessels using stem cells from a blood sample rather than the bone marrow.

Suchitra Sumitran-Holgersson, PhD, of Sahlgrenska University Hospital in Sweden, and her colleagues described the work in EBioMedicine.

The researchers tested their new method on two young children with portal vein thrombosis.

The team used the patients’ own stem cells to grow new blood vessels, a procedure that had been performed at Sahlgrenska University Hospital once before. The novel finding was that they could do this without extracting the cells from the bone marrow.

The researchers took decellularized allogeneic vascular scaffolds and repopulated them with peripheral whole blood in a bioreactor.

The team found they could use 25 mL of blood, the minimum quantity needed to obtain enough stem cells. And the extraction procedure worked the first time.

“Not only that, but the blood itself accelerated growth of the new vein,” Dr Sumitran-Holgersson said. “The entire process took only a week, as opposed to a month in the first case. The blood contains substances that naturally promote growth.”

Dr Sumitran-Holgersson and her colleagues have treated three patients thus far. Two of those patients are still doing well and have veins that are functioning as they should. In the third case, the child is under medical surveillance, and the outcome is more uncertain.

“We believe that this technological progress can lead to dissemination of the method for the benefit of additional groups of patients, such as those with varicose veins or myocardial infarction, who need new blood vessels,” Dr Sumitran-Holgersson said. “Our dream is to be able to grow complete organs as a way of overcoming the current shortage from donors.” ![]()

Credit: Robert Emilsson

Researchers have found they can engineer vascular grafts using autologous peripheral blood and successfully transplant them into patients with portal vein thrombosis.

The team said this research provides early evidence for generating personalized blood vessels using stem cells from a blood sample rather than the bone marrow.

Suchitra Sumitran-Holgersson, PhD, of Sahlgrenska University Hospital in Sweden, and her colleagues described the work in EBioMedicine.

The researchers tested their new method on two young children with portal vein thrombosis.

The team used the patients’ own stem cells to grow new blood vessels, a procedure that had been performed at Sahlgrenska University Hospital once before. The novel finding was that they could do this without extracting the cells from the bone marrow.

The researchers took decellularized allogeneic vascular scaffolds and repopulated them with peripheral whole blood in a bioreactor.

The team found they could use 25 mL of blood, the minimum quantity needed to obtain enough stem cells. And the extraction procedure worked the first time.

“Not only that, but the blood itself accelerated growth of the new vein,” Dr Sumitran-Holgersson said. “The entire process took only a week, as opposed to a month in the first case. The blood contains substances that naturally promote growth.”

Dr Sumitran-Holgersson and her colleagues have treated three patients thus far. Two of those patients are still doing well and have veins that are functioning as they should. In the third case, the child is under medical surveillance, and the outcome is more uncertain.

“We believe that this technological progress can lead to dissemination of the method for the benefit of additional groups of patients, such as those with varicose veins or myocardial infarction, who need new blood vessels,” Dr Sumitran-Holgersson said. “Our dream is to be able to grow complete organs as a way of overcoming the current shortage from donors.” ![]()

Credit: Robert Emilsson

Researchers have found they can engineer vascular grafts using autologous peripheral blood and successfully transplant them into patients with portal vein thrombosis.

The team said this research provides early evidence for generating personalized blood vessels using stem cells from a blood sample rather than the bone marrow.

Suchitra Sumitran-Holgersson, PhD, of Sahlgrenska University Hospital in Sweden, and her colleagues described the work in EBioMedicine.

The researchers tested their new method on two young children with portal vein thrombosis.

The team used the patients’ own stem cells to grow new blood vessels, a procedure that had been performed at Sahlgrenska University Hospital once before. The novel finding was that they could do this without extracting the cells from the bone marrow.

The researchers took decellularized allogeneic vascular scaffolds and repopulated them with peripheral whole blood in a bioreactor.

The team found they could use 25 mL of blood, the minimum quantity needed to obtain enough stem cells. And the extraction procedure worked the first time.

“Not only that, but the blood itself accelerated growth of the new vein,” Dr Sumitran-Holgersson said. “The entire process took only a week, as opposed to a month in the first case. The blood contains substances that naturally promote growth.”

Dr Sumitran-Holgersson and her colleagues have treated three patients thus far. Two of those patients are still doing well and have veins that are functioning as they should. In the third case, the child is under medical surveillance, and the outcome is more uncertain.

“We believe that this technological progress can lead to dissemination of the method for the benefit of additional groups of patients, such as those with varicose veins or myocardial infarction, who need new blood vessels,” Dr Sumitran-Holgersson said. “Our dream is to be able to grow complete organs as a way of overcoming the current shortage from donors.” ![]()

Guidelines for children’s bronchiolitis treatment issued by AAP

The main treatment for bronchiolitis in young children should be support and observation, according to new clinical practice guidelines for diagnosing, managing, and preventing bronchiolitis.

The guidelines apply to children aged 1-23 months and emphasize clinical diagnosis and no medications except nebulized hypertonic saline for infants hospitalized with bronchiolitis, wrote Dr. Shawn L. Ralston, Dr. Allan S. Lieberthal, and their associates (Pediatrics 2014 October 27 [doi:10.1542/peds.2014-2742]). These guidelines update and replace the ones issued by the American Academy of Pediatrics in 2006 (Pediatrics 2006 118:1774-93). The findings are based on a review of the evidence in the Cochrane Library, Medline, and the Cumulative Index of Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL) from 2004 through May 2014.

The most notable change to these updated guidelines, according to Dr. Lieberthal, is the preventive recommendation for palivizumab, which is now not indicated for children born at 29 weeks’ gestation or older unless they have hemodynamically significant heart disease or chronic lung disease of prematurity (those born at less than 32 weeks’ gestation who needed at least 21% oxygen for their first month). Infants who qualify for prophylactic palivizumab should receive five monthly doses during respiratory syncytial virus season.

Dr. Lieberthal noted in an interview that several other recommendations state that certain treatments should not be used at all rather than simply not being routinely used. These include albuterol, epinephrine, corticosteroids, chest physiotherapy, and antibiotics.

“Bronchiolitis is a self-limited viral illness,” he said. Because it is diagnosed by signs and symptoms, no lab tests, oximetry, imaging, or other tests are needed, and treatment involves only support and observation. “None of the treatments that have been tested have been shown to affect the outcome of the illness,” said Dr. Lieberthal, who practices general pediatrics and clinical pediatric pulmonology at Kaiser-Permanente in Panorama City, Calif.

Dr. Ralston noted in an interview that a new recommendation exists for using hypertonic saline to children who are hospitalized for bronchiolitis (although not in the emergency department), but the evidence for it is weak and its therapeutic value limited.

“This medication appears to have a slow onset and to provide a favorable response only in settings where patients are hospitalized for longer than is typical in most U.S. hospitals, as most of the studies were performed outside the U.S.,” said Dr. Ralston, a pediatrician at Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center, Lebanon, N.H.

The guidelines also note that clinicians “may choose not to administer supplemental oxygen if the oxyhemoglobin saturation exceeds 90%” in children, although the evidence for this recommendation is also weak. Children should receive nasogastric or intravenous fluids if they cannot maintain oral hydration.

Parents should be advised that children who avoid secondhand tobacco smoke and are exclusively breastfed for at least 6 months have a reduced risk of bronchiolitis. Further, anyone caring for a child with bronchiolitis should disinfect their hands using an alcohol-based rub or soap and water after direct contact with the child and the child’s immediate environment.

Dr. Ralston said that important points stressed in both this recommendation and in the previous one include clinical diagnosis and avoiding exposure to tobacco smoke to reduce children’s risk of bronchiolitis.

“This guideline is mostly about what you shouldn’t do for the disease since because of the high volume of disease bronchiolitis represents a major area of unnecessary medical intervention in children,” she said. “We know that the vast majority of children will suffer only side effects from the medications or testing typically used in bronchiolitis care.”

Funding was provided by the American Academy of Pediatrics with travel support from the American Academy of Family Physicians, the American College of Chest Physicians, the American Thoracic Society, and the American College of Emergency Physicians for their representatives.

These guidelines, written with clarity, give incredibly direct and helpful direction on the diagnosis and treatment of bronchiolitis. It is great that they are coming out now, prior to RSV season. Bronchiolitis is a clinical diagnosis and these guidelines reaffirm that there is not usually any need for x-ray or laboratory confirmation of the diagnosis. The guidelines are primarily important for clarifying, based on the evidence, that many commonly used treatments, including albuterol, epinephrine, and steroids are not recommended for treatment of bronchiolitis as they are simply not helpful.

The guidance on administration of palivizumab is also important. It should not be administered in infants with a gestational age of > 29 weeks, and it should be reserved for infants in the first year of life who had a gestational age < 32 weeks and who had hemodynamically significant heart disease or chronic lung disease of prematurity.

Neil Skolnik, M.D., is the associate director of the family medicine program at Abington (Pa.) Memorial Hospital and professor of family and community medicine at Temple University in Philadelphia.

These guidelines, written with clarity, give incredibly direct and helpful direction on the diagnosis and treatment of bronchiolitis. It is great that they are coming out now, prior to RSV season. Bronchiolitis is a clinical diagnosis and these guidelines reaffirm that there is not usually any need for x-ray or laboratory confirmation of the diagnosis. The guidelines are primarily important for clarifying, based on the evidence, that many commonly used treatments, including albuterol, epinephrine, and steroids are not recommended for treatment of bronchiolitis as they are simply not helpful.

The guidance on administration of palivizumab is also important. It should not be administered in infants with a gestational age of > 29 weeks, and it should be reserved for infants in the first year of life who had a gestational age < 32 weeks and who had hemodynamically significant heart disease or chronic lung disease of prematurity.

Neil Skolnik, M.D., is the associate director of the family medicine program at Abington (Pa.) Memorial Hospital and professor of family and community medicine at Temple University in Philadelphia.

These guidelines, written with clarity, give incredibly direct and helpful direction on the diagnosis and treatment of bronchiolitis. It is great that they are coming out now, prior to RSV season. Bronchiolitis is a clinical diagnosis and these guidelines reaffirm that there is not usually any need for x-ray or laboratory confirmation of the diagnosis. The guidelines are primarily important for clarifying, based on the evidence, that many commonly used treatments, including albuterol, epinephrine, and steroids are not recommended for treatment of bronchiolitis as they are simply not helpful.

The guidance on administration of palivizumab is also important. It should not be administered in infants with a gestational age of > 29 weeks, and it should be reserved for infants in the first year of life who had a gestational age < 32 weeks and who had hemodynamically significant heart disease or chronic lung disease of prematurity.

Neil Skolnik, M.D., is the associate director of the family medicine program at Abington (Pa.) Memorial Hospital and professor of family and community medicine at Temple University in Philadelphia.

The main treatment for bronchiolitis in young children should be support and observation, according to new clinical practice guidelines for diagnosing, managing, and preventing bronchiolitis.

The guidelines apply to children aged 1-23 months and emphasize clinical diagnosis and no medications except nebulized hypertonic saline for infants hospitalized with bronchiolitis, wrote Dr. Shawn L. Ralston, Dr. Allan S. Lieberthal, and their associates (Pediatrics 2014 October 27 [doi:10.1542/peds.2014-2742]). These guidelines update and replace the ones issued by the American Academy of Pediatrics in 2006 (Pediatrics 2006 118:1774-93). The findings are based on a review of the evidence in the Cochrane Library, Medline, and the Cumulative Index of Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL) from 2004 through May 2014.

The most notable change to these updated guidelines, according to Dr. Lieberthal, is the preventive recommendation for palivizumab, which is now not indicated for children born at 29 weeks’ gestation or older unless they have hemodynamically significant heart disease or chronic lung disease of prematurity (those born at less than 32 weeks’ gestation who needed at least 21% oxygen for their first month). Infants who qualify for prophylactic palivizumab should receive five monthly doses during respiratory syncytial virus season.

Dr. Lieberthal noted in an interview that several other recommendations state that certain treatments should not be used at all rather than simply not being routinely used. These include albuterol, epinephrine, corticosteroids, chest physiotherapy, and antibiotics.

“Bronchiolitis is a self-limited viral illness,” he said. Because it is diagnosed by signs and symptoms, no lab tests, oximetry, imaging, or other tests are needed, and treatment involves only support and observation. “None of the treatments that have been tested have been shown to affect the outcome of the illness,” said Dr. Lieberthal, who practices general pediatrics and clinical pediatric pulmonology at Kaiser-Permanente in Panorama City, Calif.

Dr. Ralston noted in an interview that a new recommendation exists for using hypertonic saline to children who are hospitalized for bronchiolitis (although not in the emergency department), but the evidence for it is weak and its therapeutic value limited.

“This medication appears to have a slow onset and to provide a favorable response only in settings where patients are hospitalized for longer than is typical in most U.S. hospitals, as most of the studies were performed outside the U.S.,” said Dr. Ralston, a pediatrician at Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center, Lebanon, N.H.

The guidelines also note that clinicians “may choose not to administer supplemental oxygen if the oxyhemoglobin saturation exceeds 90%” in children, although the evidence for this recommendation is also weak. Children should receive nasogastric or intravenous fluids if they cannot maintain oral hydration.

Parents should be advised that children who avoid secondhand tobacco smoke and are exclusively breastfed for at least 6 months have a reduced risk of bronchiolitis. Further, anyone caring for a child with bronchiolitis should disinfect their hands using an alcohol-based rub or soap and water after direct contact with the child and the child’s immediate environment.

Dr. Ralston said that important points stressed in both this recommendation and in the previous one include clinical diagnosis and avoiding exposure to tobacco smoke to reduce children’s risk of bronchiolitis.

“This guideline is mostly about what you shouldn’t do for the disease since because of the high volume of disease bronchiolitis represents a major area of unnecessary medical intervention in children,” she said. “We know that the vast majority of children will suffer only side effects from the medications or testing typically used in bronchiolitis care.”

Funding was provided by the American Academy of Pediatrics with travel support from the American Academy of Family Physicians, the American College of Chest Physicians, the American Thoracic Society, and the American College of Emergency Physicians for their representatives.

The main treatment for bronchiolitis in young children should be support and observation, according to new clinical practice guidelines for diagnosing, managing, and preventing bronchiolitis.

The guidelines apply to children aged 1-23 months and emphasize clinical diagnosis and no medications except nebulized hypertonic saline for infants hospitalized with bronchiolitis, wrote Dr. Shawn L. Ralston, Dr. Allan S. Lieberthal, and their associates (Pediatrics 2014 October 27 [doi:10.1542/peds.2014-2742]). These guidelines update and replace the ones issued by the American Academy of Pediatrics in 2006 (Pediatrics 2006 118:1774-93). The findings are based on a review of the evidence in the Cochrane Library, Medline, and the Cumulative Index of Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL) from 2004 through May 2014.

The most notable change to these updated guidelines, according to Dr. Lieberthal, is the preventive recommendation for palivizumab, which is now not indicated for children born at 29 weeks’ gestation or older unless they have hemodynamically significant heart disease or chronic lung disease of prematurity (those born at less than 32 weeks’ gestation who needed at least 21% oxygen for their first month). Infants who qualify for prophylactic palivizumab should receive five monthly doses during respiratory syncytial virus season.

Dr. Lieberthal noted in an interview that several other recommendations state that certain treatments should not be used at all rather than simply not being routinely used. These include albuterol, epinephrine, corticosteroids, chest physiotherapy, and antibiotics.

“Bronchiolitis is a self-limited viral illness,” he said. Because it is diagnosed by signs and symptoms, no lab tests, oximetry, imaging, or other tests are needed, and treatment involves only support and observation. “None of the treatments that have been tested have been shown to affect the outcome of the illness,” said Dr. Lieberthal, who practices general pediatrics and clinical pediatric pulmonology at Kaiser-Permanente in Panorama City, Calif.

Dr. Ralston noted in an interview that a new recommendation exists for using hypertonic saline to children who are hospitalized for bronchiolitis (although not in the emergency department), but the evidence for it is weak and its therapeutic value limited.

“This medication appears to have a slow onset and to provide a favorable response only in settings where patients are hospitalized for longer than is typical in most U.S. hospitals, as most of the studies were performed outside the U.S.,” said Dr. Ralston, a pediatrician at Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center, Lebanon, N.H.

The guidelines also note that clinicians “may choose not to administer supplemental oxygen if the oxyhemoglobin saturation exceeds 90%” in children, although the evidence for this recommendation is also weak. Children should receive nasogastric or intravenous fluids if they cannot maintain oral hydration.

Parents should be advised that children who avoid secondhand tobacco smoke and are exclusively breastfed for at least 6 months have a reduced risk of bronchiolitis. Further, anyone caring for a child with bronchiolitis should disinfect their hands using an alcohol-based rub or soap and water after direct contact with the child and the child’s immediate environment.

Dr. Ralston said that important points stressed in both this recommendation and in the previous one include clinical diagnosis and avoiding exposure to tobacco smoke to reduce children’s risk of bronchiolitis.

“This guideline is mostly about what you shouldn’t do for the disease since because of the high volume of disease bronchiolitis represents a major area of unnecessary medical intervention in children,” she said. “We know that the vast majority of children will suffer only side effects from the medications or testing typically used in bronchiolitis care.”

Funding was provided by the American Academy of Pediatrics with travel support from the American Academy of Family Physicians, the American College of Chest Physicians, the American Thoracic Society, and the American College of Emergency Physicians for their representatives.

FROM PEDIATRICS

Key clinical point: Bronchiolitis should be diagnosed clinically and treated with support.

Major finding: Most treatments should not be administered because outcomes are not improved.

Data source: The findings are based on a review of the evidence in the Cochrane Library, Medline, and CINAHL from 2004 through May 2014.

Disclosures: Funding was provided by the American Academy of Pediatrics with travel support from the American Academy of Family Physicians, the American College of Chest Physicians, the American Thoracic Society, and the American College of Emergency Physicians for their representatives.

CHMP says ponatinib’s benefits outweigh risks

Credit: CDC

The European Medicines Agency’s (EMA) Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP) has adopted its final opinion on ponatinib (Iclusig), saying the drug’s benefits outweigh its risks.

The CHMP recommends that ponatinib continue to be used in accordance with its approved indications.

However, the drug’s product information should be updated with strengthened warnings, particularly about the risk of arterial and venous thrombotic events.

Ponatinib is approved in the European Union (EU) to treat adults with chronic phase, accelerated phase, or blast phase chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) who are resistant to dasatinib or nilotinib, who are intolerant to dasatinib or nilotinib and for whom subsequent treatment with imatinib is not clinically appropriate, or who have the T315I mutation.

The drug is also approved to treat adults with Philadelphia-chromosome positive acute lymphoblastic leukemia who are resistant to dasatinib, who cannot tolerate dasatinib and subsequent treatment with imatinib is not clinically appropriate, or who have the T315I mutation.

Roughly a year ago, follow-up data revealed that ponatinib-treated patients had a higher incidence of arterial and venous thrombotic events than was observed when the drug first gained approval. So one ponatinib trial was discontinued, and the rest were placed on partial clinical hold.

Then, ponatinib was pulled from the US market. The drug ultimately returned to the marketplace with new recommendations designed to decrease the risk of thrombotic events. The EMA also revised its recommendations for ponatinib but kept the drug on the market.

PRAC review and recommendations

Because of these risks, the EMA’s Pharmacovigilance Risk Assessment Committee (PRAC) conducted an 11-month review of the available data on ponatinib and consulted with a scientific advisory group.

The PRAC assessed the available data on the nature, frequency, and severity of arterial and venous thrombotic events. And the committee concluded that the benefits of ponatinib outweigh its risks.

The PRAC said the risk of thrombotic events is likely dose-related, but there are insufficient data to formally recommend using lower doses of ponatinib. And there is a risk that lower doses might not be as effective in all patients and in long-term treatment.

The PRAC therefore concluded that the recommended starting dose of ponatinib should remain 45 mg once a day.

However, the committee also recommended updates to the product information to provide healthcare professionals with the latest evidence, in case they want to consider reducing the dose in patients with chronic phase CML who are responding well to treatment and who might be at particular risk of thrombotic events.

In addition, PRAC recommended that healthcare professionals stop ponatinib if there has been no response after 3 months of treatment and monitor patients for high blood pressure or signs of heart problems.

The CHMP concurred with these recommendations and is forwarding them to the European Commission. The commission is expected to issue a final, legally binding decision on ponatinib in December 2014, which will be valid throughout the EU.

A new study on the safety and benefits of ponatinib is in the works to help clarify if lower doses of the drug carry a lower risk of thrombotic events while still having a beneficial effect in patients with chronic phase CML. ![]()

Credit: CDC

The European Medicines Agency’s (EMA) Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP) has adopted its final opinion on ponatinib (Iclusig), saying the drug’s benefits outweigh its risks.

The CHMP recommends that ponatinib continue to be used in accordance with its approved indications.

However, the drug’s product information should be updated with strengthened warnings, particularly about the risk of arterial and venous thrombotic events.

Ponatinib is approved in the European Union (EU) to treat adults with chronic phase, accelerated phase, or blast phase chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) who are resistant to dasatinib or nilotinib, who are intolerant to dasatinib or nilotinib and for whom subsequent treatment with imatinib is not clinically appropriate, or who have the T315I mutation.

The drug is also approved to treat adults with Philadelphia-chromosome positive acute lymphoblastic leukemia who are resistant to dasatinib, who cannot tolerate dasatinib and subsequent treatment with imatinib is not clinically appropriate, or who have the T315I mutation.

Roughly a year ago, follow-up data revealed that ponatinib-treated patients had a higher incidence of arterial and venous thrombotic events than was observed when the drug first gained approval. So one ponatinib trial was discontinued, and the rest were placed on partial clinical hold.

Then, ponatinib was pulled from the US market. The drug ultimately returned to the marketplace with new recommendations designed to decrease the risk of thrombotic events. The EMA also revised its recommendations for ponatinib but kept the drug on the market.

PRAC review and recommendations

Because of these risks, the EMA’s Pharmacovigilance Risk Assessment Committee (PRAC) conducted an 11-month review of the available data on ponatinib and consulted with a scientific advisory group.

The PRAC assessed the available data on the nature, frequency, and severity of arterial and venous thrombotic events. And the committee concluded that the benefits of ponatinib outweigh its risks.

The PRAC said the risk of thrombotic events is likely dose-related, but there are insufficient data to formally recommend using lower doses of ponatinib. And there is a risk that lower doses might not be as effective in all patients and in long-term treatment.

The PRAC therefore concluded that the recommended starting dose of ponatinib should remain 45 mg once a day.

However, the committee also recommended updates to the product information to provide healthcare professionals with the latest evidence, in case they want to consider reducing the dose in patients with chronic phase CML who are responding well to treatment and who might be at particular risk of thrombotic events.

In addition, PRAC recommended that healthcare professionals stop ponatinib if there has been no response after 3 months of treatment and monitor patients for high blood pressure or signs of heart problems.

The CHMP concurred with these recommendations and is forwarding them to the European Commission. The commission is expected to issue a final, legally binding decision on ponatinib in December 2014, which will be valid throughout the EU.

A new study on the safety and benefits of ponatinib is in the works to help clarify if lower doses of the drug carry a lower risk of thrombotic events while still having a beneficial effect in patients with chronic phase CML. ![]()

Credit: CDC

The European Medicines Agency’s (EMA) Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP) has adopted its final opinion on ponatinib (Iclusig), saying the drug’s benefits outweigh its risks.

The CHMP recommends that ponatinib continue to be used in accordance with its approved indications.

However, the drug’s product information should be updated with strengthened warnings, particularly about the risk of arterial and venous thrombotic events.

Ponatinib is approved in the European Union (EU) to treat adults with chronic phase, accelerated phase, or blast phase chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) who are resistant to dasatinib or nilotinib, who are intolerant to dasatinib or nilotinib and for whom subsequent treatment with imatinib is not clinically appropriate, or who have the T315I mutation.

The drug is also approved to treat adults with Philadelphia-chromosome positive acute lymphoblastic leukemia who are resistant to dasatinib, who cannot tolerate dasatinib and subsequent treatment with imatinib is not clinically appropriate, or who have the T315I mutation.

Roughly a year ago, follow-up data revealed that ponatinib-treated patients had a higher incidence of arterial and venous thrombotic events than was observed when the drug first gained approval. So one ponatinib trial was discontinued, and the rest were placed on partial clinical hold.

Then, ponatinib was pulled from the US market. The drug ultimately returned to the marketplace with new recommendations designed to decrease the risk of thrombotic events. The EMA also revised its recommendations for ponatinib but kept the drug on the market.

PRAC review and recommendations

Because of these risks, the EMA’s Pharmacovigilance Risk Assessment Committee (PRAC) conducted an 11-month review of the available data on ponatinib and consulted with a scientific advisory group.

The PRAC assessed the available data on the nature, frequency, and severity of arterial and venous thrombotic events. And the committee concluded that the benefits of ponatinib outweigh its risks.

The PRAC said the risk of thrombotic events is likely dose-related, but there are insufficient data to formally recommend using lower doses of ponatinib. And there is a risk that lower doses might not be as effective in all patients and in long-term treatment.

The PRAC therefore concluded that the recommended starting dose of ponatinib should remain 45 mg once a day.

However, the committee also recommended updates to the product information to provide healthcare professionals with the latest evidence, in case they want to consider reducing the dose in patients with chronic phase CML who are responding well to treatment and who might be at particular risk of thrombotic events.

In addition, PRAC recommended that healthcare professionals stop ponatinib if there has been no response after 3 months of treatment and monitor patients for high blood pressure or signs of heart problems.

The CHMP concurred with these recommendations and is forwarding them to the European Commission. The commission is expected to issue a final, legally binding decision on ponatinib in December 2014, which will be valid throughout the EU.

A new study on the safety and benefits of ponatinib is in the works to help clarify if lower doses of the drug carry a lower risk of thrombotic events while still having a beneficial effect in patients with chronic phase CML. ![]()

FDA approves treatment for acquired hemophilia A

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved a recombinant porcine factor VIII (FVIII) product known as Obizur to treat bleeding episodes in adults with acquired hemophilia A.

Obizur replaces the inhibited human FVIII with a recombinant porcine sequence FVIII based on the rationale that porcine FVIII is less susceptible to inactivation by circulating human FVIII antibodies.

Physicians can manage Obizur’s efficacy and safety by measuring FVIII activity levels.

The ability to measure FVIII levels gives physicians an objective marker of hemostasis that can guide dosing and prevent overdosing, said Rebecca Kruse-Jarres, MD, Director of the Hemophilia Care Program at Puget Sound Blood Center in Seattle and principal investigator of a phase 2/3 trial of Obizur.

Trial results

The FDA approved Obizur based on results of a prospective, multicenter, phase 2/3 trial in which adults with acquired hemophilia A received the product to treat serious bleeding episodes.

Twenty-nine patients were enrolled and evaluated for safety. Researchers determined that one of the patients did not actually have acquired hemophilia A, so this patient could not be evaluated for efficacy.

At 24 hours after the initial infusion, all 28 patients in the efficacy analysis had a positive response to Obizur. This meant that bleeding stopped or decreased, the patients experienced clinical stabilization or improvement, and FVIII levels were 20% or greater.

Eighty-six percent of patients (24/28) had successful treatment of their initial bleeding episode. The overall treatment success was determined by the investigator based on the ability to discontinue or reduce the dose and/or dosing frequency of Obizur.

The adverse reaction most frequently reported in the 29 patients in the safety analysis was the development of inhibitors to porcine FVIII.

Nineteen patients were negative for anti-porcine FVIII antibodies at baseline, and 5 of these patients (26%) developed anti-porcine FVIII antibodies following exposure to Obizur. Of the 10 patients with detectable anti-porcine FVIII antibodies at baseline, 2 (20%) experienced an increase in titer, and 8 (80%) decreased to a non-detectable titer.

About acquired hemophilia A and Obizur

Acquired hemophilia A is a rare but potentially life-threatening bleeding disorder caused by the development of antibodies directed against the body’s own FVIII.

Acquired hemophilia A development has been related to other medical conditions or health states, such as pregnancy, cancer, or the use of certain medications. However, in about half of acquired hemophilia A cases, no underlying cause can be found.

Diagnosis of this condition can be difficult, and the severity of bleeding can make treatment challenging.

“The approval of [Obizur] provides an important therapeutic option for use in the care of patients with this rare disease,” said Karen Midthun, MD, director of the FDA’s Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research.

The FDA previously granted Obizur orphan drug designation because it is intended for use in the treatment of a rare disease or condition. The product is manufactured by Baxter Healthcare Corporation.

Baxter said Obizur will be commercially available in the US in the coming months and is currently under regulatory review in Europe and Canada.

For more details on Obizur, see the full prescribing information. ![]()

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved a recombinant porcine factor VIII (FVIII) product known as Obizur to treat bleeding episodes in adults with acquired hemophilia A.

Obizur replaces the inhibited human FVIII with a recombinant porcine sequence FVIII based on the rationale that porcine FVIII is less susceptible to inactivation by circulating human FVIII antibodies.

Physicians can manage Obizur’s efficacy and safety by measuring FVIII activity levels.

The ability to measure FVIII levels gives physicians an objective marker of hemostasis that can guide dosing and prevent overdosing, said Rebecca Kruse-Jarres, MD, Director of the Hemophilia Care Program at Puget Sound Blood Center in Seattle and principal investigator of a phase 2/3 trial of Obizur.

Trial results

The FDA approved Obizur based on results of a prospective, multicenter, phase 2/3 trial in which adults with acquired hemophilia A received the product to treat serious bleeding episodes.

Twenty-nine patients were enrolled and evaluated for safety. Researchers determined that one of the patients did not actually have acquired hemophilia A, so this patient could not be evaluated for efficacy.

At 24 hours after the initial infusion, all 28 patients in the efficacy analysis had a positive response to Obizur. This meant that bleeding stopped or decreased, the patients experienced clinical stabilization or improvement, and FVIII levels were 20% or greater.

Eighty-six percent of patients (24/28) had successful treatment of their initial bleeding episode. The overall treatment success was determined by the investigator based on the ability to discontinue or reduce the dose and/or dosing frequency of Obizur.

The adverse reaction most frequently reported in the 29 patients in the safety analysis was the development of inhibitors to porcine FVIII.

Nineteen patients were negative for anti-porcine FVIII antibodies at baseline, and 5 of these patients (26%) developed anti-porcine FVIII antibodies following exposure to Obizur. Of the 10 patients with detectable anti-porcine FVIII antibodies at baseline, 2 (20%) experienced an increase in titer, and 8 (80%) decreased to a non-detectable titer.

About acquired hemophilia A and Obizur

Acquired hemophilia A is a rare but potentially life-threatening bleeding disorder caused by the development of antibodies directed against the body’s own FVIII.

Acquired hemophilia A development has been related to other medical conditions or health states, such as pregnancy, cancer, or the use of certain medications. However, in about half of acquired hemophilia A cases, no underlying cause can be found.

Diagnosis of this condition can be difficult, and the severity of bleeding can make treatment challenging.

“The approval of [Obizur] provides an important therapeutic option for use in the care of patients with this rare disease,” said Karen Midthun, MD, director of the FDA’s Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research.

The FDA previously granted Obizur orphan drug designation because it is intended for use in the treatment of a rare disease or condition. The product is manufactured by Baxter Healthcare Corporation.

Baxter said Obizur will be commercially available in the US in the coming months and is currently under regulatory review in Europe and Canada.

For more details on Obizur, see the full prescribing information. ![]()

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved a recombinant porcine factor VIII (FVIII) product known as Obizur to treat bleeding episodes in adults with acquired hemophilia A.

Obizur replaces the inhibited human FVIII with a recombinant porcine sequence FVIII based on the rationale that porcine FVIII is less susceptible to inactivation by circulating human FVIII antibodies.

Physicians can manage Obizur’s efficacy and safety by measuring FVIII activity levels.

The ability to measure FVIII levels gives physicians an objective marker of hemostasis that can guide dosing and prevent overdosing, said Rebecca Kruse-Jarres, MD, Director of the Hemophilia Care Program at Puget Sound Blood Center in Seattle and principal investigator of a phase 2/3 trial of Obizur.

Trial results

The FDA approved Obizur based on results of a prospective, multicenter, phase 2/3 trial in which adults with acquired hemophilia A received the product to treat serious bleeding episodes.

Twenty-nine patients were enrolled and evaluated for safety. Researchers determined that one of the patients did not actually have acquired hemophilia A, so this patient could not be evaluated for efficacy.

At 24 hours after the initial infusion, all 28 patients in the efficacy analysis had a positive response to Obizur. This meant that bleeding stopped or decreased, the patients experienced clinical stabilization or improvement, and FVIII levels were 20% or greater.

Eighty-six percent of patients (24/28) had successful treatment of their initial bleeding episode. The overall treatment success was determined by the investigator based on the ability to discontinue or reduce the dose and/or dosing frequency of Obizur.

The adverse reaction most frequently reported in the 29 patients in the safety analysis was the development of inhibitors to porcine FVIII.

Nineteen patients were negative for anti-porcine FVIII antibodies at baseline, and 5 of these patients (26%) developed anti-porcine FVIII antibodies following exposure to Obizur. Of the 10 patients with detectable anti-porcine FVIII antibodies at baseline, 2 (20%) experienced an increase in titer, and 8 (80%) decreased to a non-detectable titer.

About acquired hemophilia A and Obizur

Acquired hemophilia A is a rare but potentially life-threatening bleeding disorder caused by the development of antibodies directed against the body’s own FVIII.

Acquired hemophilia A development has been related to other medical conditions or health states, such as pregnancy, cancer, or the use of certain medications. However, in about half of acquired hemophilia A cases, no underlying cause can be found.

Diagnosis of this condition can be difficult, and the severity of bleeding can make treatment challenging.

“The approval of [Obizur] provides an important therapeutic option for use in the care of patients with this rare disease,” said Karen Midthun, MD, director of the FDA’s Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research.

The FDA previously granted Obizur orphan drug designation because it is intended for use in the treatment of a rare disease or condition. The product is manufactured by Baxter Healthcare Corporation.

Baxter said Obizur will be commercially available in the US in the coming months and is currently under regulatory review in Europe and Canada.

For more details on Obizur, see the full prescribing information. ![]()

An Antiemetic for Irritable Bowel Syndrome?

PRACTICE CHANGER

Consider prescribing ondansetron (up to 24 mg/d) for patients who have irritable bowel syndrome with diarrhea (IBS-D).1

STRENGTH OF RECOMMENDATION

B: Based on a well-done double-blind, placebo-controlled randomized controlled trial (RCT).1

ILLUSTRATIVE CASE

A 23-year-old woman who was diagnosed with irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) comes to your clinic with complaints of increased frequency of defecation with watery stools and generalized, cramping abdominal pain. She also notes increased passage of mucus and a sensation of incomplete evacuation.

She says the only thing that relieves her pain is defecation. She has tried loperamide, acetaminophen, and ibuprofen without relief. She does not have Crohn disease or ulcerative colitis. What else can you offer her that is safe and effective?

IBS is a chronic, episodic functional gastrointestinal disorder characterized by abdominal pain or discomfort and altered bowel habits: constipation (IBS-C), diarrhea (IBS-D), or alternating periods of both—mixed (IBS-M).2 The diagnosis is based on Rome III criteria, which include recurrent abdominal pain or discomfort on at least three days per month in the past three months associated with two or more of the following: improvement with defecation, onset associated with a change in frequency of stool, and onset associated with a change in form (appearance) of stool.3 IBS often is unrecognized or untreated, and as few as 25% of patients with IBS seek care.4

IBS-D affects approximately 5% of the general population in North America.5,6 IBS-D is associated with a considerably decreased quality of life and is a common cause of work absenteeism.7,8 Because many conditions can cause diarrhea, patients typically undergo numerous tests before receiving an accurate diagnosis, which creates a financial burden.9

For many patients, current IBS treatments—including fiber supplements, laxatives, antidiarrheal medications, antispasmodics, and antidepressants such as tricyclics and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors—are unsatisfactory.10 Alosetron, a 5-hydroxytryptamine 3 (5-HT3) receptor antagonist, has been used to treat IBS-D,11 but this medication was voluntarily withdrawn from the US market in 2000 due to concerns about ischemic colitis and severe constipation.12 It was reintroduced in 2002 but can be prescribed only by clinicians who enroll in a prescribing program provided by the manufacturer, and there are restrictions on its use.

Ondansetron—another 5-HT3 receptor antagonist used to treat nausea and vomiting caused by chemotherapy—may be another option for treating IBS-D. Garsed et al1 recently conducted an RCT to evaluate the efficacy of ondansetron for patients with IBS-D.

Study summary >>

STUDY SUMMARY

Ondansetron improves stool consistency, severity of IBS symptoms

In a five-week, double-blind crossover RCT, Garsed et al1 compared ondansetron with placebo for symptom relief in 120 patients who met Rome III criteria for IBS-D. All patients were ages 18 to 75 and had no evidence of inflammatory bowel disease. Exclusion criteria included pregnancy or breastfeeding, unwillingness to stop antidiarrheal medication, prior abdominal surgery other than appendectomy or cholecystectomy, or enrollment in another trial.

Patients were started on ondansetron 4 mg/d with dose titration up to 24 mg/d based on response; no dose adjustments were allowed during the last two weeks of the study. There was a two- to three-week washout between treatment periods.

The primary endpoint was average stool consistency in the last two weeks of treatment, as measured by the Bristol Stool Form (BSF) scale.13 The BSF is a visual scale that depicts stool as hard (type 1) to watery (type 7); types 3 and 4 describe normal stools. The study also looked at urgency and frequency of defecation, bowel transit time, and pain scores.

Treatment with ondansetron resulted in a small but statistically significant improvement in stool consistency. The mean difference in BSF score between ondansetron and placebo was –0.9, indicating slightly more formed stool with use of ondansetron. Scores for IBS severity—mild (a score of 75 to 175 out of 500), moderate (175 to 300), or severe (> 300)—were reduced by more points with ondansetron than with placebo (83 ± 9.8 vs 37 ± 9.7, respectively). Although this mean difference of 46 points fell just short of the 50-point threshold that is considered clinically significant, many patients exceeded this threshold.

Compared to those who received placebo, patients who took ondansetron also had less frequent defecation and lower urgency scores. Gut transit time was lengthened in the ondansetron group by 10 hours more than in the placebo group.

Pain scores did not change significantly for patients taking ondansetron, although they experienced significantly fewer days of urgency and bloating. Symptoms typically improved in as little as seven days but returned after ondansetron use stopped (typically within two weeks). Sixty-five percent of patients reported adequate relief with ondansetron, compared to 14% with placebo.

Patients whose diarrhea was more severe at baseline didn’t respond as well to ondansetron as did those whose diarrhea was less severe. The only frequent adverse effect was constipation, which occurred in 9% of patients receiving ondansetron and 2% of those on placebo.

WHAT’S NEW

Another option for IBS-D

A prior, smaller study of ondansetron that used a lower dosage (12 mg/d) suggested benefit in IBS-D.14 In that study, ondansetron decreased diarrhea and functional dyspepsia. The study by Garsed et al1 is the first large RCT to show significantly improved stool consistency, less frequent defecation, and less urgency and bloating from using ondansetron to treat IBS-D.

CAVEATS

Ondansetron doesn’t appear to reduce pain

In Garsed et al,1 patients who received ondansetron did not experience relief from pain, which is one of the main complaints of IBS. However, this study did find slight improvement in formed stools, symptom relief that approached—but did not quite reach—clinical significance, fewer days with urgency and bloating, and less frequent defecation.

This study did not evaluate the long-term effects of ondansetron use. However, ondansetron has been used for other indications for more than 25 years and has been reported to have a low risk for adverse effects.15

CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION

Remember ondansetron is not for IBS patients with constipation

Proper use of this drug among patients with IBS is key. The primary benefits of ondansetron are limited to IBS patients who have diarrhea, and not constipation. Ondansetron should not be prescribed to IBS patients who experience constipation or those with mixed symptoms.

REFERENCES

1. Garsed K, Chernova J, Hastings M, et al. A randomised trial of ondansetron for the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome with diarrhoea. Gut. 2014;63:1617-1625.

2. Hahn BA, Yan S, Strassels S. Impact of irritable bowel syndrome on quality of life and resource use in the United States and United Kingdom. Digestion. 1999;60:77-81.

3. Drossman DA, Dumitrascu DL. Rome III: new standard for functional gastrointestinal disorders. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis. 2006;15:237-241.

4. Luscombe FA. Health-related quality of life and associated psychosocial factors in irritable bowel syndrome: a review. Qual Life Res. 2000;9:161-176.

5. Saito YA, Locke GR, Talley NJ, et al. A comparison of the Rome and Manning criteria for case identification in epidemiological investigations of irritable bowel syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:2816-2824.

6. Thompson WG, Heaton KW, Smyth GT, et al. Irritable bowel syndrome in general practice: prevalence, characteristics, and referral. Gut. 2000;46:78-82.

7. Tillisch K, Labus JS, Naliboff BD, et al. Characterization of the alternating bowel habit subtype in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:896-904.

8. Schuster MM. Diagnostic evaluation of the irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 1991;20:269-278.

9. Sandler RS, Everhart JE, Donowitz M, et al. The burden of selected digestive diseases in the United States. Gastroenterology. 2002;122:1500-1511.

10. Talley NJ. Pharmacologic therapy for the irritable bowel syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:750-758.

11. Andresen V, Montori VM, Keller J, et al. Effects of 5-hydroxytryptamine (serotonin) type 3 antagonists on symptom relief and constipation in nonconstipated irritable bowel syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6:545-555.

12. Chang L, Chey WD, Harris L, et al. Incidence of ischemic colitis and serious complications of constipation among patients using alosetron: systematic review of clinical trials and post-marketing surveillance data. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:1069-1079.

13. Heaton KW, O’Donnell LJ. An office guide to whole-gut transit time. Patients’ recollection of their stool form. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1994;19:28-30.

14. Maxton DG, Morris J, Whorwell PJ. Selective 5‐hydroxytryptamine antagonism: a role in irritable bowel syndrome and functional dyspepsia? Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1996;10:595-599.

15. Gill SK, Einarson A. The safety of drugs for the treatment of nausea and vomiting of pregnancy. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2007;6:685-694.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The PURLs Surveillance System was supported in part by Grant Number UL1RR024999 from the National Center For Research Resources, a Clinical Translational Science Award to the University of Chicago. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center For Research Resources or the National Institutes of Health.

Copyright © 2014. The Family Physicians Inquiries Network. All rights reserved.

Reprinted with permission from the Family Physicians Inquiries Network and The Journal of Family Practice. 2014;63(10):600-602.

PRACTICE CHANGER

Consider prescribing ondansetron (up to 24 mg/d) for patients who have irritable bowel syndrome with diarrhea (IBS-D).1

STRENGTH OF RECOMMENDATION

B: Based on a well-done double-blind, placebo-controlled randomized controlled trial (RCT).1

ILLUSTRATIVE CASE

A 23-year-old woman who was diagnosed with irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) comes to your clinic with complaints of increased frequency of defecation with watery stools and generalized, cramping abdominal pain. She also notes increased passage of mucus and a sensation of incomplete evacuation.

She says the only thing that relieves her pain is defecation. She has tried loperamide, acetaminophen, and ibuprofen without relief. She does not have Crohn disease or ulcerative colitis. What else can you offer her that is safe and effective?

IBS is a chronic, episodic functional gastrointestinal disorder characterized by abdominal pain or discomfort and altered bowel habits: constipation (IBS-C), diarrhea (IBS-D), or alternating periods of both—mixed (IBS-M).2 The diagnosis is based on Rome III criteria, which include recurrent abdominal pain or discomfort on at least three days per month in the past three months associated with two or more of the following: improvement with defecation, onset associated with a change in frequency of stool, and onset associated with a change in form (appearance) of stool.3 IBS often is unrecognized or untreated, and as few as 25% of patients with IBS seek care.4

IBS-D affects approximately 5% of the general population in North America.5,6 IBS-D is associated with a considerably decreased quality of life and is a common cause of work absenteeism.7,8 Because many conditions can cause diarrhea, patients typically undergo numerous tests before receiving an accurate diagnosis, which creates a financial burden.9

For many patients, current IBS treatments—including fiber supplements, laxatives, antidiarrheal medications, antispasmodics, and antidepressants such as tricyclics and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors—are unsatisfactory.10 Alosetron, a 5-hydroxytryptamine 3 (5-HT3) receptor antagonist, has been used to treat IBS-D,11 but this medication was voluntarily withdrawn from the US market in 2000 due to concerns about ischemic colitis and severe constipation.12 It was reintroduced in 2002 but can be prescribed only by clinicians who enroll in a prescribing program provided by the manufacturer, and there are restrictions on its use.

Ondansetron—another 5-HT3 receptor antagonist used to treat nausea and vomiting caused by chemotherapy—may be another option for treating IBS-D. Garsed et al1 recently conducted an RCT to evaluate the efficacy of ondansetron for patients with IBS-D.

Study summary >>

STUDY SUMMARY

Ondansetron improves stool consistency, severity of IBS symptoms

In a five-week, double-blind crossover RCT, Garsed et al1 compared ondansetron with placebo for symptom relief in 120 patients who met Rome III criteria for IBS-D. All patients were ages 18 to 75 and had no evidence of inflammatory bowel disease. Exclusion criteria included pregnancy or breastfeeding, unwillingness to stop antidiarrheal medication, prior abdominal surgery other than appendectomy or cholecystectomy, or enrollment in another trial.

Patients were started on ondansetron 4 mg/d with dose titration up to 24 mg/d based on response; no dose adjustments were allowed during the last two weeks of the study. There was a two- to three-week washout between treatment periods.

The primary endpoint was average stool consistency in the last two weeks of treatment, as measured by the Bristol Stool Form (BSF) scale.13 The BSF is a visual scale that depicts stool as hard (type 1) to watery (type 7); types 3 and 4 describe normal stools. The study also looked at urgency and frequency of defecation, bowel transit time, and pain scores.

Treatment with ondansetron resulted in a small but statistically significant improvement in stool consistency. The mean difference in BSF score between ondansetron and placebo was –0.9, indicating slightly more formed stool with use of ondansetron. Scores for IBS severity—mild (a score of 75 to 175 out of 500), moderate (175 to 300), or severe (> 300)—were reduced by more points with ondansetron than with placebo (83 ± 9.8 vs 37 ± 9.7, respectively). Although this mean difference of 46 points fell just short of the 50-point threshold that is considered clinically significant, many patients exceeded this threshold.

Compared to those who received placebo, patients who took ondansetron also had less frequent defecation and lower urgency scores. Gut transit time was lengthened in the ondansetron group by 10 hours more than in the placebo group.

Pain scores did not change significantly for patients taking ondansetron, although they experienced significantly fewer days of urgency and bloating. Symptoms typically improved in as little as seven days but returned after ondansetron use stopped (typically within two weeks). Sixty-five percent of patients reported adequate relief with ondansetron, compared to 14% with placebo.