User login

Facecards Improve Familiarity with Physician Names but Not Satisfaction

Clinical question: Do facecards improve patients’ familiarity with physicians and increase satisfaction, trust, and agreement with physicians?

Background: Facecards can improve patients’ knowledge of names and roles of physicians, but their impact on other outcomes is unclear. This pilot trial was designed to assess facecards’ impact on patient satisfaction, trust, or agreement with physicians.

Study design: Cluster, randomized controlled trial (RCT).

Setting: A large teaching hospital in the United States.

Synopsis: Patients (n=138) were randomized to receive either facecards with the name and picture of their hospitalists, as well as a brief description of the hospitalist’s role (n=66), or to receive traditional communication (n=72). There were no significant differences in patient age, sex, or race.

Patients who received a facecard were more likely to correctly identify their hospital physician (89.1% vs. 51.1%; P< 0.01) and were more likely to correctly identify the role of their hospital physician than those in the control group (67.4% vs. 16.3%; P<0.01).

Patients who received a facecard rated satisfaction, trust, and agreement slightly higher compared with those who had not received a card, but the results were not statistically significant (P values 0.27, 0.32, 0.37, respectively.) The authors note that larger studies may be needed to see a difference in these areas.

Bottom line: Facecards improve patients’ knowledge of the names and roles of hospital physicians but have no clear impact on satisfaction with, trust of, or agreement with physicians.

Citation: Simons Y, Caprio T, Furiasse N, Kriss, M, Williams MV, O’Leary KJ. The impact of facecards on patients’ knowledge, satisfaction, trust, and agreement with hospitalist physicians: a pilot study. J Hosp Med. 2014;9(3):137-141.

Clinical question: Do facecards improve patients’ familiarity with physicians and increase satisfaction, trust, and agreement with physicians?

Background: Facecards can improve patients’ knowledge of names and roles of physicians, but their impact on other outcomes is unclear. This pilot trial was designed to assess facecards’ impact on patient satisfaction, trust, or agreement with physicians.

Study design: Cluster, randomized controlled trial (RCT).

Setting: A large teaching hospital in the United States.

Synopsis: Patients (n=138) were randomized to receive either facecards with the name and picture of their hospitalists, as well as a brief description of the hospitalist’s role (n=66), or to receive traditional communication (n=72). There were no significant differences in patient age, sex, or race.

Patients who received a facecard were more likely to correctly identify their hospital physician (89.1% vs. 51.1%; P< 0.01) and were more likely to correctly identify the role of their hospital physician than those in the control group (67.4% vs. 16.3%; P<0.01).

Patients who received a facecard rated satisfaction, trust, and agreement slightly higher compared with those who had not received a card, but the results were not statistically significant (P values 0.27, 0.32, 0.37, respectively.) The authors note that larger studies may be needed to see a difference in these areas.

Bottom line: Facecards improve patients’ knowledge of the names and roles of hospital physicians but have no clear impact on satisfaction with, trust of, or agreement with physicians.

Citation: Simons Y, Caprio T, Furiasse N, Kriss, M, Williams MV, O’Leary KJ. The impact of facecards on patients’ knowledge, satisfaction, trust, and agreement with hospitalist physicians: a pilot study. J Hosp Med. 2014;9(3):137-141.

Clinical question: Do facecards improve patients’ familiarity with physicians and increase satisfaction, trust, and agreement with physicians?

Background: Facecards can improve patients’ knowledge of names and roles of physicians, but their impact on other outcomes is unclear. This pilot trial was designed to assess facecards’ impact on patient satisfaction, trust, or agreement with physicians.

Study design: Cluster, randomized controlled trial (RCT).

Setting: A large teaching hospital in the United States.

Synopsis: Patients (n=138) were randomized to receive either facecards with the name and picture of their hospitalists, as well as a brief description of the hospitalist’s role (n=66), or to receive traditional communication (n=72). There were no significant differences in patient age, sex, or race.

Patients who received a facecard were more likely to correctly identify their hospital physician (89.1% vs. 51.1%; P< 0.01) and were more likely to correctly identify the role of their hospital physician than those in the control group (67.4% vs. 16.3%; P<0.01).

Patients who received a facecard rated satisfaction, trust, and agreement slightly higher compared with those who had not received a card, but the results were not statistically significant (P values 0.27, 0.32, 0.37, respectively.) The authors note that larger studies may be needed to see a difference in these areas.

Bottom line: Facecards improve patients’ knowledge of the names and roles of hospital physicians but have no clear impact on satisfaction with, trust of, or agreement with physicians.

Citation: Simons Y, Caprio T, Furiasse N, Kriss, M, Williams MV, O’Leary KJ. The impact of facecards on patients’ knowledge, satisfaction, trust, and agreement with hospitalist physicians: a pilot study. J Hosp Med. 2014;9(3):137-141.

New Oral Anticoagulants Safe and Effective for Atrial Fibrillation Treatment

Clinical question: Is there a difference in efficacy and safety among new oral anticoagulants compared to warfarin in subgroups of patients with atrial fibrillation (Afib)?

Background: Studies of new oral anticoagulants have demonstrated that these agents are at least as safe and effective as warfarin for prevention of stroke and systemic embolism in Afib. This study was designed to look at available phase 3 randomized trials, with the goal of subgroup analysis for both efficacy and bleeding risks.

Study design: Meta-analysis.

Setting: Phase 3 randomized controlled trials of patients with Afib.

Synopsis: The analysis included four trials of Afib patients randomized to receive warfarin or a novel oral anticoagulant (NOAC), including dabigatran, rivaroxaban, apixaban, and edoxaban. In total, 42,411 patients received an NOAC and 29,272 patients received warfarin. Separate analyses were performed for high-dose and low-dose NOACs.

The high-dose NOAC demonstrated a 19% reduction in stroke and systemic embolic events as compared to warfarin, largely due to the reduction of hemorrhagic strokes by the NOAC. The low-dose NOAC showed similar efficacy to warfarin for reduction of stroke and systemic embolic events, with an increase noted in the subset of ischemic stroke in low-dose NOAC. Both doses of NOAC demonstrated a significant reduction in all-cause mortality. NOAC showed a non-significant reduction in bleeding compared to warfarin; however, subset analysis demonstrated an increase in gastrointestinal bleeding with high-dose NOAC and a significant reduction in intracranial hemorrhage with low-dose NOAC.

A notable limitation of the study is that it only included clinical trials in the analysis.

Bottom line: In relation to stroke, systemic embolic events, and all-cause mortality, new oral anticoagulants showed a favorable efficacy and safety profile as compared to warfarin in Afib patients.

Citation: Ruff CT, Giugliano RP, Braunwald E, et al. Comparison of the efficacy and safety of new oral anticoagulants with warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation: a meta-analysis of randomised trials. Lancet. 2014;383(9921):955-962.

Clinical question: Is there a difference in efficacy and safety among new oral anticoagulants compared to warfarin in subgroups of patients with atrial fibrillation (Afib)?

Background: Studies of new oral anticoagulants have demonstrated that these agents are at least as safe and effective as warfarin for prevention of stroke and systemic embolism in Afib. This study was designed to look at available phase 3 randomized trials, with the goal of subgroup analysis for both efficacy and bleeding risks.

Study design: Meta-analysis.

Setting: Phase 3 randomized controlled trials of patients with Afib.

Synopsis: The analysis included four trials of Afib patients randomized to receive warfarin or a novel oral anticoagulant (NOAC), including dabigatran, rivaroxaban, apixaban, and edoxaban. In total, 42,411 patients received an NOAC and 29,272 patients received warfarin. Separate analyses were performed for high-dose and low-dose NOACs.

The high-dose NOAC demonstrated a 19% reduction in stroke and systemic embolic events as compared to warfarin, largely due to the reduction of hemorrhagic strokes by the NOAC. The low-dose NOAC showed similar efficacy to warfarin for reduction of stroke and systemic embolic events, with an increase noted in the subset of ischemic stroke in low-dose NOAC. Both doses of NOAC demonstrated a significant reduction in all-cause mortality. NOAC showed a non-significant reduction in bleeding compared to warfarin; however, subset analysis demonstrated an increase in gastrointestinal bleeding with high-dose NOAC and a significant reduction in intracranial hemorrhage with low-dose NOAC.

A notable limitation of the study is that it only included clinical trials in the analysis.

Bottom line: In relation to stroke, systemic embolic events, and all-cause mortality, new oral anticoagulants showed a favorable efficacy and safety profile as compared to warfarin in Afib patients.

Citation: Ruff CT, Giugliano RP, Braunwald E, et al. Comparison of the efficacy and safety of new oral anticoagulants with warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation: a meta-analysis of randomised trials. Lancet. 2014;383(9921):955-962.

Clinical question: Is there a difference in efficacy and safety among new oral anticoagulants compared to warfarin in subgroups of patients with atrial fibrillation (Afib)?

Background: Studies of new oral anticoagulants have demonstrated that these agents are at least as safe and effective as warfarin for prevention of stroke and systemic embolism in Afib. This study was designed to look at available phase 3 randomized trials, with the goal of subgroup analysis for both efficacy and bleeding risks.

Study design: Meta-analysis.

Setting: Phase 3 randomized controlled trials of patients with Afib.

Synopsis: The analysis included four trials of Afib patients randomized to receive warfarin or a novel oral anticoagulant (NOAC), including dabigatran, rivaroxaban, apixaban, and edoxaban. In total, 42,411 patients received an NOAC and 29,272 patients received warfarin. Separate analyses were performed for high-dose and low-dose NOACs.

The high-dose NOAC demonstrated a 19% reduction in stroke and systemic embolic events as compared to warfarin, largely due to the reduction of hemorrhagic strokes by the NOAC. The low-dose NOAC showed similar efficacy to warfarin for reduction of stroke and systemic embolic events, with an increase noted in the subset of ischemic stroke in low-dose NOAC. Both doses of NOAC demonstrated a significant reduction in all-cause mortality. NOAC showed a non-significant reduction in bleeding compared to warfarin; however, subset analysis demonstrated an increase in gastrointestinal bleeding with high-dose NOAC and a significant reduction in intracranial hemorrhage with low-dose NOAC.

A notable limitation of the study is that it only included clinical trials in the analysis.

Bottom line: In relation to stroke, systemic embolic events, and all-cause mortality, new oral anticoagulants showed a favorable efficacy and safety profile as compared to warfarin in Afib patients.

Citation: Ruff CT, Giugliano RP, Braunwald E, et al. Comparison of the efficacy and safety of new oral anticoagulants with warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation: a meta-analysis of randomised trials. Lancet. 2014;383(9921):955-962.

Sepsis Diagnoses Are Common in ED, but Many Septic Patients in the ED Do Not Receive Antibiotics

Clinical question: Has the frequency of sepsis rates, along with administration of antibiotics in U.S. emergency departments (EDs), changed over time?

Background: Prior studies reviewing discharge data from hospitals suggest an increase of sepsis over time; however, little epidemiological research has evaluated the diagnosis of sepsis and antibiotic use in ED settings.

Study design: Retrospective, four-stage probability sample.

Setting: National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (NHAMCS).

Synopsis: The NHAMCS includes a sample of all U.S. ED visits, except federal, military, and VA hospitals. According to NHAMCS data, an estimated 1.3 billion visits by adults to U.S. EDs occurred from 1994-2009, or approximately 81 million visits per year. Explicit sepsis was defined by the presence of the following, with ICD-9 codes: septicemia (038), sepsis (995.91), severe sepsis (995.92), or septic shock (785.52). Implicit sepsis was defined as a code indicating infection plus a code indicting organ dysfunction.

In U.S. EDs, explicit sepsis did not become more prevalent from 1994-2009; however, implicitly diagnosed sepsis increased by 7% every two years. There were 260,000 explicit sepsis-related ED visits per year, or 1.23 visits per 1,000 U.S. population. In-hospital mortality was 17% and 9% for the explicit and implicit diagnosis groups, respectively. On review of the explicit sepsis group, only 61% of the patients were found to have received antibiotics in the ED. The rate did increase over the time studied, from 52% in 1994-1997 to 69% in 2006-2009.

The study was limited by the retrospective analysis of data not designed to track sepsis or antibiotic use.

Bottom Line: Explicitly recognized sepsis remained stable in the ED setting from 1994-2009, and early antibiotic use has improved during this time, but there is still much opportunity for improvement.

Citation: Filbin MR, Arias SA, Camargo CA Jr, Barche A, Pallin DJ. Sepsis visits and antibiotic utilization in the U.S. emergency departments. Crit Care Med. 2014;42(3):528-535.

Clinical question: Has the frequency of sepsis rates, along with administration of antibiotics in U.S. emergency departments (EDs), changed over time?

Background: Prior studies reviewing discharge data from hospitals suggest an increase of sepsis over time; however, little epidemiological research has evaluated the diagnosis of sepsis and antibiotic use in ED settings.

Study design: Retrospective, four-stage probability sample.

Setting: National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (NHAMCS).

Synopsis: The NHAMCS includes a sample of all U.S. ED visits, except federal, military, and VA hospitals. According to NHAMCS data, an estimated 1.3 billion visits by adults to U.S. EDs occurred from 1994-2009, or approximately 81 million visits per year. Explicit sepsis was defined by the presence of the following, with ICD-9 codes: septicemia (038), sepsis (995.91), severe sepsis (995.92), or septic shock (785.52). Implicit sepsis was defined as a code indicating infection plus a code indicting organ dysfunction.

In U.S. EDs, explicit sepsis did not become more prevalent from 1994-2009; however, implicitly diagnosed sepsis increased by 7% every two years. There were 260,000 explicit sepsis-related ED visits per year, or 1.23 visits per 1,000 U.S. population. In-hospital mortality was 17% and 9% for the explicit and implicit diagnosis groups, respectively. On review of the explicit sepsis group, only 61% of the patients were found to have received antibiotics in the ED. The rate did increase over the time studied, from 52% in 1994-1997 to 69% in 2006-2009.

The study was limited by the retrospective analysis of data not designed to track sepsis or antibiotic use.

Bottom Line: Explicitly recognized sepsis remained stable in the ED setting from 1994-2009, and early antibiotic use has improved during this time, but there is still much opportunity for improvement.

Citation: Filbin MR, Arias SA, Camargo CA Jr, Barche A, Pallin DJ. Sepsis visits and antibiotic utilization in the U.S. emergency departments. Crit Care Med. 2014;42(3):528-535.

Clinical question: Has the frequency of sepsis rates, along with administration of antibiotics in U.S. emergency departments (EDs), changed over time?

Background: Prior studies reviewing discharge data from hospitals suggest an increase of sepsis over time; however, little epidemiological research has evaluated the diagnosis of sepsis and antibiotic use in ED settings.

Study design: Retrospective, four-stage probability sample.

Setting: National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (NHAMCS).

Synopsis: The NHAMCS includes a sample of all U.S. ED visits, except federal, military, and VA hospitals. According to NHAMCS data, an estimated 1.3 billion visits by adults to U.S. EDs occurred from 1994-2009, or approximately 81 million visits per year. Explicit sepsis was defined by the presence of the following, with ICD-9 codes: septicemia (038), sepsis (995.91), severe sepsis (995.92), or septic shock (785.52). Implicit sepsis was defined as a code indicating infection plus a code indicting organ dysfunction.

In U.S. EDs, explicit sepsis did not become more prevalent from 1994-2009; however, implicitly diagnosed sepsis increased by 7% every two years. There were 260,000 explicit sepsis-related ED visits per year, or 1.23 visits per 1,000 U.S. population. In-hospital mortality was 17% and 9% for the explicit and implicit diagnosis groups, respectively. On review of the explicit sepsis group, only 61% of the patients were found to have received antibiotics in the ED. The rate did increase over the time studied, from 52% in 1994-1997 to 69% in 2006-2009.

The study was limited by the retrospective analysis of data not designed to track sepsis or antibiotic use.

Bottom Line: Explicitly recognized sepsis remained stable in the ED setting from 1994-2009, and early antibiotic use has improved during this time, but there is still much opportunity for improvement.

Citation: Filbin MR, Arias SA, Camargo CA Jr, Barche A, Pallin DJ. Sepsis visits and antibiotic utilization in the U.S. emergency departments. Crit Care Med. 2014;42(3):528-535.

Multifaceted Discharge Interventions Reduce Rates of Pediatric Readmission and Post-Hospital ED Utilization

Clinical question: Do interventions at discharge reduce the rate of readmissions and post-hospitalization ED visits among pediatric patients?

Background: Readmissions are a high-priority quality measure in both the adult and pediatric settings. Although a broadening body of literature is evaluating the impact of interventions on readmissions in adult populations, the literature does not contain a similar breadth of assessments of interventions in the pediatric setting.

Study design: Systematic review.

Setting: English-language articles studying pediatric inpatient discharge interventions.

Synopsis: A total of 1,296 unique articles were identified from PubMed and the Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature. Additional articles were identified on review of references, yielding 14 articles that met inclusion criteria. Included studies evaluated the effect of pediatric discharge interventions on the primary outcomes of hospital readmission or post-hospitalization ED visits. Interventions focused on three main patient populations: asthma, cancer, and prematurity.

Six studies demonstrated statistically significant reductions in readmissions and/or ED visits, while two studies actually demonstrated an increase in post-discharge utilization. All successful interventions began in the inpatient setting and were multifaceted, with four of six studies including an educational component and a post-discharge follow-up component.

While all of the studies evaluated sought to enhance the transitional care from the inpatient to outpatient setting, only the interventions that included one responsible party (individual or team) with expertise in the medical condition providing oversight and support were successful in reducing the specified outcomes. A significant limitation was that many of the studies identified were not sufficiently powered to detect either outcome of interest.

Bottom line: A multifaceted intervention involving educational and post-discharge follow-up components with an experienced individual or team supporting the transition is associated with a reduction in hospital readmissions and post-discharge ED utilization.

Citation: Auger KA, Kenyon CC, Feudtner C, Davis MM. Pediatric hospital discharge interventions to reduce subsequent utilization: a systematic review [published online ahead of print December 20, 2013]. J Hosp Med.

Clinical question: Do interventions at discharge reduce the rate of readmissions and post-hospitalization ED visits among pediatric patients?

Background: Readmissions are a high-priority quality measure in both the adult and pediatric settings. Although a broadening body of literature is evaluating the impact of interventions on readmissions in adult populations, the literature does not contain a similar breadth of assessments of interventions in the pediatric setting.

Study design: Systematic review.

Setting: English-language articles studying pediatric inpatient discharge interventions.

Synopsis: A total of 1,296 unique articles were identified from PubMed and the Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature. Additional articles were identified on review of references, yielding 14 articles that met inclusion criteria. Included studies evaluated the effect of pediatric discharge interventions on the primary outcomes of hospital readmission or post-hospitalization ED visits. Interventions focused on three main patient populations: asthma, cancer, and prematurity.

Six studies demonstrated statistically significant reductions in readmissions and/or ED visits, while two studies actually demonstrated an increase in post-discharge utilization. All successful interventions began in the inpatient setting and were multifaceted, with four of six studies including an educational component and a post-discharge follow-up component.

While all of the studies evaluated sought to enhance the transitional care from the inpatient to outpatient setting, only the interventions that included one responsible party (individual or team) with expertise in the medical condition providing oversight and support were successful in reducing the specified outcomes. A significant limitation was that many of the studies identified were not sufficiently powered to detect either outcome of interest.

Bottom line: A multifaceted intervention involving educational and post-discharge follow-up components with an experienced individual or team supporting the transition is associated with a reduction in hospital readmissions and post-discharge ED utilization.

Citation: Auger KA, Kenyon CC, Feudtner C, Davis MM. Pediatric hospital discharge interventions to reduce subsequent utilization: a systematic review [published online ahead of print December 20, 2013]. J Hosp Med.

Clinical question: Do interventions at discharge reduce the rate of readmissions and post-hospitalization ED visits among pediatric patients?

Background: Readmissions are a high-priority quality measure in both the adult and pediatric settings. Although a broadening body of literature is evaluating the impact of interventions on readmissions in adult populations, the literature does not contain a similar breadth of assessments of interventions in the pediatric setting.

Study design: Systematic review.

Setting: English-language articles studying pediatric inpatient discharge interventions.

Synopsis: A total of 1,296 unique articles were identified from PubMed and the Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature. Additional articles were identified on review of references, yielding 14 articles that met inclusion criteria. Included studies evaluated the effect of pediatric discharge interventions on the primary outcomes of hospital readmission or post-hospitalization ED visits. Interventions focused on three main patient populations: asthma, cancer, and prematurity.

Six studies demonstrated statistically significant reductions in readmissions and/or ED visits, while two studies actually demonstrated an increase in post-discharge utilization. All successful interventions began in the inpatient setting and were multifaceted, with four of six studies including an educational component and a post-discharge follow-up component.

While all of the studies evaluated sought to enhance the transitional care from the inpatient to outpatient setting, only the interventions that included one responsible party (individual or team) with expertise in the medical condition providing oversight and support were successful in reducing the specified outcomes. A significant limitation was that many of the studies identified were not sufficiently powered to detect either outcome of interest.

Bottom line: A multifaceted intervention involving educational and post-discharge follow-up components with an experienced individual or team supporting the transition is associated with a reduction in hospital readmissions and post-discharge ED utilization.

Citation: Auger KA, Kenyon CC, Feudtner C, Davis MM. Pediatric hospital discharge interventions to reduce subsequent utilization: a systematic review [published online ahead of print December 20, 2013]. J Hosp Med.

Woman, 66, With Persistent Abdominal and Back Pain

A 66-year-old Latin American woman presented to the emergency department (ED) with persistent abdominal and back pain of about one month’s duration. She had visited another ED eight days earlier for similar symptoms and was discharged home with a mild opioid pain medication and a proton pump inhibitor. However, she said that she had received neither a diagnosis nor an explanation for her symptoms.

Medical history, obtained with the assistance of an interpreter because the patient was not fluent in English, included hypertension, coronary artery disease, and hyperlipidemia; these had gone untreated for at least two years. She denied any personal or family history of cancer or endocrine disorders. Surgical history included a cholecystectomy and a percutaneous coronary intervention for an unknown coronary artery lesion.

She had a 14-pack-year history of cigarette smoking. Her medications included only ibuprofen and hydrocodone, and she had no known drug allergies. The patient denied use of herbal preparations or vitamin supplements and unusual dietary practices.

Review of systems revealed occasional dizziness, constipation, decreased appetite, and some mild confusion noted by family members, but no fever, chills, palpitations, chest pain, shortness of breath, muscle spasm, or weakness. Vital signs were normal. Physical examination was remarkable for tenderness of the upper quadrants of the abdomen with deep palpation, without guarding or rebound. Bony tenderness at the right anterior costal margin of the rib cage was also noted.

Laboratory work-up revealed marked hypercalcemia (15.4 mg/dL), electrolyte abnormalities, anemia, impaired renal function, and elevated alkaline phosphatase and globulin levels (see Table 1). In addition, a plain abdominal x-ray series was negative for acute findings, but x-rays of the right ribs revealed a fracture of the sixth rib and osteopenia.

Continued >>

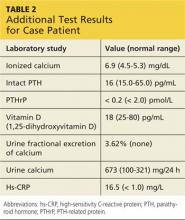

The patient was admitted to the hospital for treatment of hypercalcemia and hypokalemia and for work-up of elevated alkaline phosphatase and abdominal pain. Upon admission, serum ionized calcium measurement confirmed true hypercalcemia. Additional diagnostic tests were then ordered to help differentiate between parathyroid hormone (PTH)–mediated and non-PTH–mediated causes for the hypercalcemia (see Table 2).

The patient’s PTH level was normal and the urine fractional excretion of calcium level was high, ruling out familial hypocalciuric hypercalcemia (FHH), in which urine calcium level is low. A measurement of PTH-related protein (PTHrP), secreted by some cancers, was normal, suggesting exclusion of solid tumor malignancy. Vitamin D toxicity was ruled out because the patient’s 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D level was low.

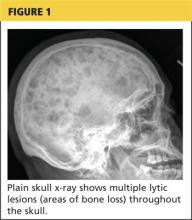

The patient continued to experience vague abdominal, back, and rib pain that seemed to migrate daily and worsened with movement. A skeletal x-ray was performed and revealed numerous lytic lesions of the skull (Figure 1), midright humerus (Figure 2), and distal left radius.

Continue for discussion >>

DISCUSSION

Hypercalcemia is a relatively common presentation in primary care. The most frequent causes are primary hyperparathyroidism and malignancy.1 One in 500 patients will be diagnosed incidentally with asymptomatic hypercalcemia caused by underlying hyperparathyroidism.1

Clinical manifestations of hypercalcemia can range from no symptoms to multisystem disease. Fatigue, nausea, vomiting, constipation, bone pain, osteoporosis, nephrolithiasis, mental status changes, hypertension, anemia, elevated creatinine, and cardiac arrhythmias are among the more common clinical conditions associated with hypercalcemia (hence the mnemonic “stones, bones, abdominal moans, and psychic groans” for its signs and symptoms).1

Diagnostic overview

Causes of hypercalcemia are numerous and can be broken down into two categories: PTH-mediated and non-PTH–mediated. PTH-mediated causes include primary and secondary hyperparathyroidism and FHH. Non-PTH–mediated causes include vitamin D toxicity, solid tumor malignancy with or without metastasis, multiple myeloma (MM) and other plasma cell dyscrasias, granulomatous disease such as sarcoid, and some medications.1

The differential diagnosis for hypercalcemia begins with measurement of the patient’s intact PTH level. An elevated or high-normal result indicates a PTH-mediated cause, so 24-hour measurement of excretion of urinary calcium is the next step. A low or low-normal PTH level (< 20 pg/mL), however, suggests the cause is non-PTH-mediated.2 The diagnostic approach in this situation is more challenging because testing to exclude or confirm various potential causes can be expensive and time-consuming. The degree of hypercalcemia, however, can aid in the diagnosis: Primary hyperparathyroidism is often associated with borderline or mild hypercalcemia, while calcium values > 13 mg/dL are more common in patients with malignancies.2

PTH elevates calcium levels in the blood when ionized (free) calcium levels are low by increasing gastrointestinal absorption, decreasing urinary excretion, and increasing bone resorption.3 With malignant tumors such as lung, breast, and renal cell, osteolytic metastases can destroy the bone, resulting in release of calcium. In other cases, solid-tumor cancers produce PTHrP, which increases serum calcium. This latter situation is referred to as humoral hypercalcemia of malignancy.3 Lymphoma and granulomatous disease, such as sarcoid, can be associated with excess production of 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D.2 If vitamin D is elevated but PTH and PTHrP are normal, a chest x-ray should be obtained to evaluate the patient for sarcoid or lymphoma.

Hypercalcemia work-up

The work-up for suspected hypercalcemia begins with measurement of the patient’s calcium level. Because calcium is bound to albumin in the blood, the standard serum calcium test may not reflect the true calcium level. (If albumin is high, the calcium level will be high, and vice versa.)1 The true (serum ionized) calcium level (also known as corrected calcium level) should always be calculated to confirm true hypercalcemia. A formula commonly used to calculate the corrected calcium level is

Corrected calcium (mg/dL) = (measured calcium [mg/dL]) + 0.8 (4.0 – serum albumin [mg/dL])

Direct measurement of the serum ionized calcium level is not affected by the albumin level and can also confirm true hypercalcemia.4

Once hypercalcemia is confirmed, the next step is to measure the patient’s intact PTH level.

If intact PTH is elevated or high normal, consider primary hyperparathyroidism or FHH and confirm by obtaining the urine calcium level.

• If urine calcium level is high (> 200 mg/24 h), the diagnosis is primary hyperparathyroidism.

• If urine calcium level is low (< 100 mg/24 h), the diagnosis is FHH.

If intact PTH is low, consider non–PTH-mediated causes and confirm by obtaining PTHrP and vitamin D levels.

• If PTHrP level is elevated, scan for malignancy.

• If 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D level is elevated, order a chest x-ray to rule out sarcoid or lymphoma.

• If both PTHrP and vitamin D levels are normal, order both serum protein electrophoresis (SPEP) and urine protein electrophoresis (UPEP) with immunofixation to rule out MM.

• If vitamin D level is elevated, check vitamin and herbal supplement use for excessive vitamin D intake.

Treatment of symptomatic hypercalcemia

The goals of treatment of symptomatic hypercalcemia are to reduce the serum calcium level to the normal range and to treat the underlying cause.1 Mild hypercalcemia (calcium level, 10-12 mg/dL) is typically asymptomatic and does not need to be treated. Moderate hypercalcemia (calcium level, 12-14 mg/dL) may not require treatment unless the patient is symptomatic and/or has had an acute rise in calcium level.1 In mild to moderate hypercalcemia, the serum calcium level should be monitored to establish a trend.

Treatment for symptomatic moderate and severe hypercalcemia (calcium level, > 14 mg/dL) typically involves a similar regimen:

• Volume expansion with isotonic saline at an initial rate of 2 to 4 L/d, which is then adjusted to achieve 200 mL/h of continuous urine output. IV furosemide can be used with caution (10-20 mg IV as needed) to promote diuresis if volume overload is a concern (furosemide promotes renal excretion of calcium).

• Administration of subcutaneous calcitonin (4-8 IU/kg, repeated every 6 h for 24 h). Calcitonin works rapidly to lower calcium levels in 4 to 6 h.

• Concurrent administration of IV bisphosphonate (zoledronic acid [4 mg over 15 min] or pamidronate [60-90 mg over 4 h]). Pamidronate is superior for reversal of malignancy-related hypercalcemia.1

Hypercalcemia and multiple myeloma

MM is a malignant neoplasm of plasma cells that accounts for approximately 1% of all cancers and about 10% of hematologic malignancies in the United States, with a median patient age of 70 at diagnosis.5-7 In MM, myeloma cells induce the secretion of cytokines and growth factors that alter plasma cells, activate osteoclasts, suppress osteoblasts, cause abnormal interactions between plasma cells and bone marrow, and stimulate aberrant angiogenesis.8 Osteoclastic bone resorption produces hypercalcemia as well as the lytic lesions seen on x-ray.7

Approximately 74% of patients present with typical MM symptoms of calcium elevation in the blood, renal insufficiency, anemia, and bone lesions, known as CRAB symptoms, but other myeloma-related manifestations may be present.9

Diagnostic criteria for MM include the following (all three must be present):10

• Monoclonal bone marrow plasma cells ≥ 10% and/or a biopsy-proven plasmacytoma

• Monoclonal protein in the serum and/or urine (if none is detected, disease is nonsecretory and diagnosis requires ≥ 30% bone marrow plasma cells and/or biopsy-proven plasmacytoma)

• Myeloma-related organ dysfunction, indicated by at least one of the CRAB symptoms.

In the absence of CRAB symptoms, an asymptomatic patient may have an MM precursor syndrome: monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance or smoldering (or indolent) MM.10

Treatment of multiple myeloma

In recent years, the use of induction therapy followed by autologous stem cell transplantation and the development of novel therapeutic agents have extended overall survival for patients with MM. These agents include proteasome inhibitors (bortezomib and the second-generation carfilzomib)11 and immunomodulators (thalidomide and the second-generation lenalidomide). Early diagnosis and treatment can improve progression-free survival as well as overall survival, including recovery of renal function for patients with renal failure.12 With survival ranging from one year or less—with aggressive disease—to 10 years or more for patients with responsive disease,7 there remains no cure for MM.

Outcome for the case patient >>

OUTCOME FOR THE CASE PATIENT

Further work-up included SPEP and UPEP with immunofixation, which revealed marked IgG free λ light chains with an M (monoclonal) component, making MM a very likely diagnosis. Confirmation by means of bone marrow biopsy was indicated, but the patient refused the procedure.

The patient’s hypercalcemia was treated by IV administration of calcitonin with isotonic saline. This reduced the serum calcium level from 15.4 mg/dL to 10.6 mg/dL within 48 hours. One dose of ergocalciferol (vitamin D2) was then administered to promote intestinal absorption of calcium and support bone mineralization, further lowering the patient’s serum calcium level to a normal 8.9 mg/dL. Hypokalemia was treated with oral potassium supplementation.

The patient, now stable, was referred to the hematology/oncology and bone mineral metabolism clinics and was discharged from the hospital. She did not keep those appointments and was lost to follow-up.

CONCLUSION

The most common causes of hypercalcemia are hyperparathyroidism and malignancy. Most cases do not require treatment unless the calcium level is >14 mg/dL and/or the patient is symptomatic. Red flag symptoms include weakness, abdominal pain, mental status changes, and coma.4 Primary care clinicians should suspect MM in older patients with laboratory findings of hypercalcemia, anemia, and renal dysfunction, with lytic lesions on x-ray.

REFERENCES

1. Carroll MF, Schade DS. A practical approach to hypercalcemia. Am Fam Physician. 2003;67(9):1959-1966.

2. Endres DB. Investigation of hypercalcemia. Clin Biochem. 2012;45(12):

954-963.

3. Moe SM. Disorders involving calcium, phosphorus, and magnesium. Prim Care. 2008;35(2):215-237.

4. Sharma B, Misicko NE. How should you evaluate elevated calcium in an asymptomatic patient? J Fam Pract. 2008;57(4):267-269.

5. Siegel R, Naishadham D, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2013. CA Cancer J Clin. 2013;63(1):11-30.

6. Kyle RA, Gertz MA, Witzig TE, et al. Review of 1027 patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma. Mayo Clin Proc. 2003;78(1):21-33.

7. Shaheen SP, Talwalkar SS, Medeiros LJ. Multiple myeloma and immunosecretory disorders: an update. Adv Anat Pathol. 2008;15(4):196-210.

8. Palumbo A, Anderson K. Multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(11): 1046-1060.

9. Talamo G, Farooq U, Zangari M, et al. Beyond the CRAB symptoms: a study of presenting clinical manifestations of multiple myeloma. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2010;10(6):464-468.

10. Palumbo A, Sezer O, Kyle R, et al. International Myeloma Working Group guidelines for the management of multiple myeloma patients ineligible for standard high-dose chemotherapy with autologous stem cell transportation. Leukemia. 2009;23(10):1716-1730.

11. Kyprolis [package insert]. South San Francisco, CA: Onyx Pharmaceuticals, Inc; 2012.

12. Suyani E, Sucak GT, Erten Y, et al. Evaluation of multiple myeloma patients presenting with renal failure in a university hospital in the year 2010. Ren Fail. 2012;34(2):257-262.

A 66-year-old Latin American woman presented to the emergency department (ED) with persistent abdominal and back pain of about one month’s duration. She had visited another ED eight days earlier for similar symptoms and was discharged home with a mild opioid pain medication and a proton pump inhibitor. However, she said that she had received neither a diagnosis nor an explanation for her symptoms.

Medical history, obtained with the assistance of an interpreter because the patient was not fluent in English, included hypertension, coronary artery disease, and hyperlipidemia; these had gone untreated for at least two years. She denied any personal or family history of cancer or endocrine disorders. Surgical history included a cholecystectomy and a percutaneous coronary intervention for an unknown coronary artery lesion.

She had a 14-pack-year history of cigarette smoking. Her medications included only ibuprofen and hydrocodone, and she had no known drug allergies. The patient denied use of herbal preparations or vitamin supplements and unusual dietary practices.

Review of systems revealed occasional dizziness, constipation, decreased appetite, and some mild confusion noted by family members, but no fever, chills, palpitations, chest pain, shortness of breath, muscle spasm, or weakness. Vital signs were normal. Physical examination was remarkable for tenderness of the upper quadrants of the abdomen with deep palpation, without guarding or rebound. Bony tenderness at the right anterior costal margin of the rib cage was also noted.

Laboratory work-up revealed marked hypercalcemia (15.4 mg/dL), electrolyte abnormalities, anemia, impaired renal function, and elevated alkaline phosphatase and globulin levels (see Table 1). In addition, a plain abdominal x-ray series was negative for acute findings, but x-rays of the right ribs revealed a fracture of the sixth rib and osteopenia.

Continued >>

The patient was admitted to the hospital for treatment of hypercalcemia and hypokalemia and for work-up of elevated alkaline phosphatase and abdominal pain. Upon admission, serum ionized calcium measurement confirmed true hypercalcemia. Additional diagnostic tests were then ordered to help differentiate between parathyroid hormone (PTH)–mediated and non-PTH–mediated causes for the hypercalcemia (see Table 2).

The patient’s PTH level was normal and the urine fractional excretion of calcium level was high, ruling out familial hypocalciuric hypercalcemia (FHH), in which urine calcium level is low. A measurement of PTH-related protein (PTHrP), secreted by some cancers, was normal, suggesting exclusion of solid tumor malignancy. Vitamin D toxicity was ruled out because the patient’s 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D level was low.

The patient continued to experience vague abdominal, back, and rib pain that seemed to migrate daily and worsened with movement. A skeletal x-ray was performed and revealed numerous lytic lesions of the skull (Figure 1), midright humerus (Figure 2), and distal left radius.

Continue for discussion >>

DISCUSSION

Hypercalcemia is a relatively common presentation in primary care. The most frequent causes are primary hyperparathyroidism and malignancy.1 One in 500 patients will be diagnosed incidentally with asymptomatic hypercalcemia caused by underlying hyperparathyroidism.1

Clinical manifestations of hypercalcemia can range from no symptoms to multisystem disease. Fatigue, nausea, vomiting, constipation, bone pain, osteoporosis, nephrolithiasis, mental status changes, hypertension, anemia, elevated creatinine, and cardiac arrhythmias are among the more common clinical conditions associated with hypercalcemia (hence the mnemonic “stones, bones, abdominal moans, and psychic groans” for its signs and symptoms).1

Diagnostic overview

Causes of hypercalcemia are numerous and can be broken down into two categories: PTH-mediated and non-PTH–mediated. PTH-mediated causes include primary and secondary hyperparathyroidism and FHH. Non-PTH–mediated causes include vitamin D toxicity, solid tumor malignancy with or without metastasis, multiple myeloma (MM) and other plasma cell dyscrasias, granulomatous disease such as sarcoid, and some medications.1

The differential diagnosis for hypercalcemia begins with measurement of the patient’s intact PTH level. An elevated or high-normal result indicates a PTH-mediated cause, so 24-hour measurement of excretion of urinary calcium is the next step. A low or low-normal PTH level (< 20 pg/mL), however, suggests the cause is non-PTH-mediated.2 The diagnostic approach in this situation is more challenging because testing to exclude or confirm various potential causes can be expensive and time-consuming. The degree of hypercalcemia, however, can aid in the diagnosis: Primary hyperparathyroidism is often associated with borderline or mild hypercalcemia, while calcium values > 13 mg/dL are more common in patients with malignancies.2

PTH elevates calcium levels in the blood when ionized (free) calcium levels are low by increasing gastrointestinal absorption, decreasing urinary excretion, and increasing bone resorption.3 With malignant tumors such as lung, breast, and renal cell, osteolytic metastases can destroy the bone, resulting in release of calcium. In other cases, solid-tumor cancers produce PTHrP, which increases serum calcium. This latter situation is referred to as humoral hypercalcemia of malignancy.3 Lymphoma and granulomatous disease, such as sarcoid, can be associated with excess production of 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D.2 If vitamin D is elevated but PTH and PTHrP are normal, a chest x-ray should be obtained to evaluate the patient for sarcoid or lymphoma.

Hypercalcemia work-up

The work-up for suspected hypercalcemia begins with measurement of the patient’s calcium level. Because calcium is bound to albumin in the blood, the standard serum calcium test may not reflect the true calcium level. (If albumin is high, the calcium level will be high, and vice versa.)1 The true (serum ionized) calcium level (also known as corrected calcium level) should always be calculated to confirm true hypercalcemia. A formula commonly used to calculate the corrected calcium level is

Corrected calcium (mg/dL) = (measured calcium [mg/dL]) + 0.8 (4.0 – serum albumin [mg/dL])

Direct measurement of the serum ionized calcium level is not affected by the albumin level and can also confirm true hypercalcemia.4

Once hypercalcemia is confirmed, the next step is to measure the patient’s intact PTH level.

If intact PTH is elevated or high normal, consider primary hyperparathyroidism or FHH and confirm by obtaining the urine calcium level.

• If urine calcium level is high (> 200 mg/24 h), the diagnosis is primary hyperparathyroidism.

• If urine calcium level is low (< 100 mg/24 h), the diagnosis is FHH.

If intact PTH is low, consider non–PTH-mediated causes and confirm by obtaining PTHrP and vitamin D levels.

• If PTHrP level is elevated, scan for malignancy.

• If 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D level is elevated, order a chest x-ray to rule out sarcoid or lymphoma.

• If both PTHrP and vitamin D levels are normal, order both serum protein electrophoresis (SPEP) and urine protein electrophoresis (UPEP) with immunofixation to rule out MM.

• If vitamin D level is elevated, check vitamin and herbal supplement use for excessive vitamin D intake.

Treatment of symptomatic hypercalcemia

The goals of treatment of symptomatic hypercalcemia are to reduce the serum calcium level to the normal range and to treat the underlying cause.1 Mild hypercalcemia (calcium level, 10-12 mg/dL) is typically asymptomatic and does not need to be treated. Moderate hypercalcemia (calcium level, 12-14 mg/dL) may not require treatment unless the patient is symptomatic and/or has had an acute rise in calcium level.1 In mild to moderate hypercalcemia, the serum calcium level should be monitored to establish a trend.

Treatment for symptomatic moderate and severe hypercalcemia (calcium level, > 14 mg/dL) typically involves a similar regimen:

• Volume expansion with isotonic saline at an initial rate of 2 to 4 L/d, which is then adjusted to achieve 200 mL/h of continuous urine output. IV furosemide can be used with caution (10-20 mg IV as needed) to promote diuresis if volume overload is a concern (furosemide promotes renal excretion of calcium).

• Administration of subcutaneous calcitonin (4-8 IU/kg, repeated every 6 h for 24 h). Calcitonin works rapidly to lower calcium levels in 4 to 6 h.

• Concurrent administration of IV bisphosphonate (zoledronic acid [4 mg over 15 min] or pamidronate [60-90 mg over 4 h]). Pamidronate is superior for reversal of malignancy-related hypercalcemia.1

Hypercalcemia and multiple myeloma

MM is a malignant neoplasm of plasma cells that accounts for approximately 1% of all cancers and about 10% of hematologic malignancies in the United States, with a median patient age of 70 at diagnosis.5-7 In MM, myeloma cells induce the secretion of cytokines and growth factors that alter plasma cells, activate osteoclasts, suppress osteoblasts, cause abnormal interactions between plasma cells and bone marrow, and stimulate aberrant angiogenesis.8 Osteoclastic bone resorption produces hypercalcemia as well as the lytic lesions seen on x-ray.7

Approximately 74% of patients present with typical MM symptoms of calcium elevation in the blood, renal insufficiency, anemia, and bone lesions, known as CRAB symptoms, but other myeloma-related manifestations may be present.9

Diagnostic criteria for MM include the following (all three must be present):10

• Monoclonal bone marrow plasma cells ≥ 10% and/or a biopsy-proven plasmacytoma

• Monoclonal protein in the serum and/or urine (if none is detected, disease is nonsecretory and diagnosis requires ≥ 30% bone marrow plasma cells and/or biopsy-proven plasmacytoma)

• Myeloma-related organ dysfunction, indicated by at least one of the CRAB symptoms.

In the absence of CRAB symptoms, an asymptomatic patient may have an MM precursor syndrome: monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance or smoldering (or indolent) MM.10

Treatment of multiple myeloma

In recent years, the use of induction therapy followed by autologous stem cell transplantation and the development of novel therapeutic agents have extended overall survival for patients with MM. These agents include proteasome inhibitors (bortezomib and the second-generation carfilzomib)11 and immunomodulators (thalidomide and the second-generation lenalidomide). Early diagnosis and treatment can improve progression-free survival as well as overall survival, including recovery of renal function for patients with renal failure.12 With survival ranging from one year or less—with aggressive disease—to 10 years or more for patients with responsive disease,7 there remains no cure for MM.

Outcome for the case patient >>

OUTCOME FOR THE CASE PATIENT

Further work-up included SPEP and UPEP with immunofixation, which revealed marked IgG free λ light chains with an M (monoclonal) component, making MM a very likely diagnosis. Confirmation by means of bone marrow biopsy was indicated, but the patient refused the procedure.

The patient’s hypercalcemia was treated by IV administration of calcitonin with isotonic saline. This reduced the serum calcium level from 15.4 mg/dL to 10.6 mg/dL within 48 hours. One dose of ergocalciferol (vitamin D2) was then administered to promote intestinal absorption of calcium and support bone mineralization, further lowering the patient’s serum calcium level to a normal 8.9 mg/dL. Hypokalemia was treated with oral potassium supplementation.

The patient, now stable, was referred to the hematology/oncology and bone mineral metabolism clinics and was discharged from the hospital. She did not keep those appointments and was lost to follow-up.

CONCLUSION

The most common causes of hypercalcemia are hyperparathyroidism and malignancy. Most cases do not require treatment unless the calcium level is >14 mg/dL and/or the patient is symptomatic. Red flag symptoms include weakness, abdominal pain, mental status changes, and coma.4 Primary care clinicians should suspect MM in older patients with laboratory findings of hypercalcemia, anemia, and renal dysfunction, with lytic lesions on x-ray.

REFERENCES

1. Carroll MF, Schade DS. A practical approach to hypercalcemia. Am Fam Physician. 2003;67(9):1959-1966.

2. Endres DB. Investigation of hypercalcemia. Clin Biochem. 2012;45(12):

954-963.

3. Moe SM. Disorders involving calcium, phosphorus, and magnesium. Prim Care. 2008;35(2):215-237.

4. Sharma B, Misicko NE. How should you evaluate elevated calcium in an asymptomatic patient? J Fam Pract. 2008;57(4):267-269.

5. Siegel R, Naishadham D, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2013. CA Cancer J Clin. 2013;63(1):11-30.

6. Kyle RA, Gertz MA, Witzig TE, et al. Review of 1027 patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma. Mayo Clin Proc. 2003;78(1):21-33.

7. Shaheen SP, Talwalkar SS, Medeiros LJ. Multiple myeloma and immunosecretory disorders: an update. Adv Anat Pathol. 2008;15(4):196-210.

8. Palumbo A, Anderson K. Multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(11): 1046-1060.

9. Talamo G, Farooq U, Zangari M, et al. Beyond the CRAB symptoms: a study of presenting clinical manifestations of multiple myeloma. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2010;10(6):464-468.

10. Palumbo A, Sezer O, Kyle R, et al. International Myeloma Working Group guidelines for the management of multiple myeloma patients ineligible for standard high-dose chemotherapy with autologous stem cell transportation. Leukemia. 2009;23(10):1716-1730.

11. Kyprolis [package insert]. South San Francisco, CA: Onyx Pharmaceuticals, Inc; 2012.

12. Suyani E, Sucak GT, Erten Y, et al. Evaluation of multiple myeloma patients presenting with renal failure in a university hospital in the year 2010. Ren Fail. 2012;34(2):257-262.

A 66-year-old Latin American woman presented to the emergency department (ED) with persistent abdominal and back pain of about one month’s duration. She had visited another ED eight days earlier for similar symptoms and was discharged home with a mild opioid pain medication and a proton pump inhibitor. However, she said that she had received neither a diagnosis nor an explanation for her symptoms.

Medical history, obtained with the assistance of an interpreter because the patient was not fluent in English, included hypertension, coronary artery disease, and hyperlipidemia; these had gone untreated for at least two years. She denied any personal or family history of cancer or endocrine disorders. Surgical history included a cholecystectomy and a percutaneous coronary intervention for an unknown coronary artery lesion.

She had a 14-pack-year history of cigarette smoking. Her medications included only ibuprofen and hydrocodone, and she had no known drug allergies. The patient denied use of herbal preparations or vitamin supplements and unusual dietary practices.

Review of systems revealed occasional dizziness, constipation, decreased appetite, and some mild confusion noted by family members, but no fever, chills, palpitations, chest pain, shortness of breath, muscle spasm, or weakness. Vital signs were normal. Physical examination was remarkable for tenderness of the upper quadrants of the abdomen with deep palpation, without guarding or rebound. Bony tenderness at the right anterior costal margin of the rib cage was also noted.

Laboratory work-up revealed marked hypercalcemia (15.4 mg/dL), electrolyte abnormalities, anemia, impaired renal function, and elevated alkaline phosphatase and globulin levels (see Table 1). In addition, a plain abdominal x-ray series was negative for acute findings, but x-rays of the right ribs revealed a fracture of the sixth rib and osteopenia.

Continued >>

The patient was admitted to the hospital for treatment of hypercalcemia and hypokalemia and for work-up of elevated alkaline phosphatase and abdominal pain. Upon admission, serum ionized calcium measurement confirmed true hypercalcemia. Additional diagnostic tests were then ordered to help differentiate between parathyroid hormone (PTH)–mediated and non-PTH–mediated causes for the hypercalcemia (see Table 2).

The patient’s PTH level was normal and the urine fractional excretion of calcium level was high, ruling out familial hypocalciuric hypercalcemia (FHH), in which urine calcium level is low. A measurement of PTH-related protein (PTHrP), secreted by some cancers, was normal, suggesting exclusion of solid tumor malignancy. Vitamin D toxicity was ruled out because the patient’s 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D level was low.

The patient continued to experience vague abdominal, back, and rib pain that seemed to migrate daily and worsened with movement. A skeletal x-ray was performed and revealed numerous lytic lesions of the skull (Figure 1), midright humerus (Figure 2), and distal left radius.

Continue for discussion >>

DISCUSSION

Hypercalcemia is a relatively common presentation in primary care. The most frequent causes are primary hyperparathyroidism and malignancy.1 One in 500 patients will be diagnosed incidentally with asymptomatic hypercalcemia caused by underlying hyperparathyroidism.1

Clinical manifestations of hypercalcemia can range from no symptoms to multisystem disease. Fatigue, nausea, vomiting, constipation, bone pain, osteoporosis, nephrolithiasis, mental status changes, hypertension, anemia, elevated creatinine, and cardiac arrhythmias are among the more common clinical conditions associated with hypercalcemia (hence the mnemonic “stones, bones, abdominal moans, and psychic groans” for its signs and symptoms).1

Diagnostic overview

Causes of hypercalcemia are numerous and can be broken down into two categories: PTH-mediated and non-PTH–mediated. PTH-mediated causes include primary and secondary hyperparathyroidism and FHH. Non-PTH–mediated causes include vitamin D toxicity, solid tumor malignancy with or without metastasis, multiple myeloma (MM) and other plasma cell dyscrasias, granulomatous disease such as sarcoid, and some medications.1

The differential diagnosis for hypercalcemia begins with measurement of the patient’s intact PTH level. An elevated or high-normal result indicates a PTH-mediated cause, so 24-hour measurement of excretion of urinary calcium is the next step. A low or low-normal PTH level (< 20 pg/mL), however, suggests the cause is non-PTH-mediated.2 The diagnostic approach in this situation is more challenging because testing to exclude or confirm various potential causes can be expensive and time-consuming. The degree of hypercalcemia, however, can aid in the diagnosis: Primary hyperparathyroidism is often associated with borderline or mild hypercalcemia, while calcium values > 13 mg/dL are more common in patients with malignancies.2

PTH elevates calcium levels in the blood when ionized (free) calcium levels are low by increasing gastrointestinal absorption, decreasing urinary excretion, and increasing bone resorption.3 With malignant tumors such as lung, breast, and renal cell, osteolytic metastases can destroy the bone, resulting in release of calcium. In other cases, solid-tumor cancers produce PTHrP, which increases serum calcium. This latter situation is referred to as humoral hypercalcemia of malignancy.3 Lymphoma and granulomatous disease, such as sarcoid, can be associated with excess production of 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D.2 If vitamin D is elevated but PTH and PTHrP are normal, a chest x-ray should be obtained to evaluate the patient for sarcoid or lymphoma.

Hypercalcemia work-up

The work-up for suspected hypercalcemia begins with measurement of the patient’s calcium level. Because calcium is bound to albumin in the blood, the standard serum calcium test may not reflect the true calcium level. (If albumin is high, the calcium level will be high, and vice versa.)1 The true (serum ionized) calcium level (also known as corrected calcium level) should always be calculated to confirm true hypercalcemia. A formula commonly used to calculate the corrected calcium level is

Corrected calcium (mg/dL) = (measured calcium [mg/dL]) + 0.8 (4.0 – serum albumin [mg/dL])

Direct measurement of the serum ionized calcium level is not affected by the albumin level and can also confirm true hypercalcemia.4

Once hypercalcemia is confirmed, the next step is to measure the patient’s intact PTH level.

If intact PTH is elevated or high normal, consider primary hyperparathyroidism or FHH and confirm by obtaining the urine calcium level.

• If urine calcium level is high (> 200 mg/24 h), the diagnosis is primary hyperparathyroidism.

• If urine calcium level is low (< 100 mg/24 h), the diagnosis is FHH.

If intact PTH is low, consider non–PTH-mediated causes and confirm by obtaining PTHrP and vitamin D levels.

• If PTHrP level is elevated, scan for malignancy.

• If 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D level is elevated, order a chest x-ray to rule out sarcoid or lymphoma.

• If both PTHrP and vitamin D levels are normal, order both serum protein electrophoresis (SPEP) and urine protein electrophoresis (UPEP) with immunofixation to rule out MM.

• If vitamin D level is elevated, check vitamin and herbal supplement use for excessive vitamin D intake.

Treatment of symptomatic hypercalcemia

The goals of treatment of symptomatic hypercalcemia are to reduce the serum calcium level to the normal range and to treat the underlying cause.1 Mild hypercalcemia (calcium level, 10-12 mg/dL) is typically asymptomatic and does not need to be treated. Moderate hypercalcemia (calcium level, 12-14 mg/dL) may not require treatment unless the patient is symptomatic and/or has had an acute rise in calcium level.1 In mild to moderate hypercalcemia, the serum calcium level should be monitored to establish a trend.

Treatment for symptomatic moderate and severe hypercalcemia (calcium level, > 14 mg/dL) typically involves a similar regimen:

• Volume expansion with isotonic saline at an initial rate of 2 to 4 L/d, which is then adjusted to achieve 200 mL/h of continuous urine output. IV furosemide can be used with caution (10-20 mg IV as needed) to promote diuresis if volume overload is a concern (furosemide promotes renal excretion of calcium).

• Administration of subcutaneous calcitonin (4-8 IU/kg, repeated every 6 h for 24 h). Calcitonin works rapidly to lower calcium levels in 4 to 6 h.

• Concurrent administration of IV bisphosphonate (zoledronic acid [4 mg over 15 min] or pamidronate [60-90 mg over 4 h]). Pamidronate is superior for reversal of malignancy-related hypercalcemia.1

Hypercalcemia and multiple myeloma

MM is a malignant neoplasm of plasma cells that accounts for approximately 1% of all cancers and about 10% of hematologic malignancies in the United States, with a median patient age of 70 at diagnosis.5-7 In MM, myeloma cells induce the secretion of cytokines and growth factors that alter plasma cells, activate osteoclasts, suppress osteoblasts, cause abnormal interactions between plasma cells and bone marrow, and stimulate aberrant angiogenesis.8 Osteoclastic bone resorption produces hypercalcemia as well as the lytic lesions seen on x-ray.7

Approximately 74% of patients present with typical MM symptoms of calcium elevation in the blood, renal insufficiency, anemia, and bone lesions, known as CRAB symptoms, but other myeloma-related manifestations may be present.9

Diagnostic criteria for MM include the following (all three must be present):10

• Monoclonal bone marrow plasma cells ≥ 10% and/or a biopsy-proven plasmacytoma

• Monoclonal protein in the serum and/or urine (if none is detected, disease is nonsecretory and diagnosis requires ≥ 30% bone marrow plasma cells and/or biopsy-proven plasmacytoma)

• Myeloma-related organ dysfunction, indicated by at least one of the CRAB symptoms.

In the absence of CRAB symptoms, an asymptomatic patient may have an MM precursor syndrome: monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance or smoldering (or indolent) MM.10

Treatment of multiple myeloma

In recent years, the use of induction therapy followed by autologous stem cell transplantation and the development of novel therapeutic agents have extended overall survival for patients with MM. These agents include proteasome inhibitors (bortezomib and the second-generation carfilzomib)11 and immunomodulators (thalidomide and the second-generation lenalidomide). Early diagnosis and treatment can improve progression-free survival as well as overall survival, including recovery of renal function for patients with renal failure.12 With survival ranging from one year or less—with aggressive disease—to 10 years or more for patients with responsive disease,7 there remains no cure for MM.

Outcome for the case patient >>

OUTCOME FOR THE CASE PATIENT

Further work-up included SPEP and UPEP with immunofixation, which revealed marked IgG free λ light chains with an M (monoclonal) component, making MM a very likely diagnosis. Confirmation by means of bone marrow biopsy was indicated, but the patient refused the procedure.

The patient’s hypercalcemia was treated by IV administration of calcitonin with isotonic saline. This reduced the serum calcium level from 15.4 mg/dL to 10.6 mg/dL within 48 hours. One dose of ergocalciferol (vitamin D2) was then administered to promote intestinal absorption of calcium and support bone mineralization, further lowering the patient’s serum calcium level to a normal 8.9 mg/dL. Hypokalemia was treated with oral potassium supplementation.

The patient, now stable, was referred to the hematology/oncology and bone mineral metabolism clinics and was discharged from the hospital. She did not keep those appointments and was lost to follow-up.

CONCLUSION

The most common causes of hypercalcemia are hyperparathyroidism and malignancy. Most cases do not require treatment unless the calcium level is >14 mg/dL and/or the patient is symptomatic. Red flag symptoms include weakness, abdominal pain, mental status changes, and coma.4 Primary care clinicians should suspect MM in older patients with laboratory findings of hypercalcemia, anemia, and renal dysfunction, with lytic lesions on x-ray.

REFERENCES

1. Carroll MF, Schade DS. A practical approach to hypercalcemia. Am Fam Physician. 2003;67(9):1959-1966.

2. Endres DB. Investigation of hypercalcemia. Clin Biochem. 2012;45(12):

954-963.

3. Moe SM. Disorders involving calcium, phosphorus, and magnesium. Prim Care. 2008;35(2):215-237.

4. Sharma B, Misicko NE. How should you evaluate elevated calcium in an asymptomatic patient? J Fam Pract. 2008;57(4):267-269.

5. Siegel R, Naishadham D, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2013. CA Cancer J Clin. 2013;63(1):11-30.

6. Kyle RA, Gertz MA, Witzig TE, et al. Review of 1027 patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma. Mayo Clin Proc. 2003;78(1):21-33.

7. Shaheen SP, Talwalkar SS, Medeiros LJ. Multiple myeloma and immunosecretory disorders: an update. Adv Anat Pathol. 2008;15(4):196-210.

8. Palumbo A, Anderson K. Multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(11): 1046-1060.

9. Talamo G, Farooq U, Zangari M, et al. Beyond the CRAB symptoms: a study of presenting clinical manifestations of multiple myeloma. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2010;10(6):464-468.

10. Palumbo A, Sezer O, Kyle R, et al. International Myeloma Working Group guidelines for the management of multiple myeloma patients ineligible for standard high-dose chemotherapy with autologous stem cell transportation. Leukemia. 2009;23(10):1716-1730.

11. Kyprolis [package insert]. South San Francisco, CA: Onyx Pharmaceuticals, Inc; 2012.

12. Suyani E, Sucak GT, Erten Y, et al. Evaluation of multiple myeloma patients presenting with renal failure in a university hospital in the year 2010. Ren Fail. 2012;34(2):257-262.

Warfarin Initiation in Atrial Fibrillation Associated with Increased Short-Term Risk of Stroke

Clinical question: Is the initiation of warfarin associated with an increased risk of ischemic stroke in patients with atrial fibrillation (Afib)?

Background: Two Afib trials of oral factor Xa inhibitors showed an increased risk of stroke when patients were transitioned to open label warfarin at the end of the study. Warfarin can, theoretically, lead to a transient hypercoagulable state upon treatment initiation, so further study is indicated to determine if the initiation of warfarin is associated with increased stroke risk among Afib patients.

Study design: Population-based, nested case-control.

Setting: UK Clinical Practice Research Datalink.

Synopsis: A cohort of 70,766 patients with newly diagnosed Afib was identified from a large primary care database. Conditional logistic regression was used to estimate adjusted rate ratios (RR) of stroke associated with warfarin monotherapy, classified according to time since initiation of treatment when compared to patients not on antithrombotic therapy.

Warfarin was associated with a 71% increased risk of stroke in the first 30 days of use (RR 1.71, 95% CI 1.39-2.12). Risk was highest in the first week of warfarin treatment, which is consistent with the known transient pro-coagulant effect of warfarin. Decreased risks were observed with warfarin initiation >30 days before the ischemic event (31-90 days: RR 0.50, 95% CI 0.34-0.75; >90 days: RR 0.55, 95% CI 0.50-0.61).

Limitations included the extraction of data from a database, which could lead to misclassification of diagnosis or therapy, and the observational nature of the study.

Bottom line: There may be an increased risk of ischemic stroke during the first 30 days of treatment with warfarin in patients with Afib.

Citation: Azoulay L, Dell-Aniello S, Simon T, Renoux C, Suissa S. Initiation of warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation: early effects on ischaemic strokes [published online ahead of print December 18, 2013]. Eur Heart J.

Clinical question: Is the initiation of warfarin associated with an increased risk of ischemic stroke in patients with atrial fibrillation (Afib)?

Background: Two Afib trials of oral factor Xa inhibitors showed an increased risk of stroke when patients were transitioned to open label warfarin at the end of the study. Warfarin can, theoretically, lead to a transient hypercoagulable state upon treatment initiation, so further study is indicated to determine if the initiation of warfarin is associated with increased stroke risk among Afib patients.

Study design: Population-based, nested case-control.

Setting: UK Clinical Practice Research Datalink.

Synopsis: A cohort of 70,766 patients with newly diagnosed Afib was identified from a large primary care database. Conditional logistic regression was used to estimate adjusted rate ratios (RR) of stroke associated with warfarin monotherapy, classified according to time since initiation of treatment when compared to patients not on antithrombotic therapy.

Warfarin was associated with a 71% increased risk of stroke in the first 30 days of use (RR 1.71, 95% CI 1.39-2.12). Risk was highest in the first week of warfarin treatment, which is consistent with the known transient pro-coagulant effect of warfarin. Decreased risks were observed with warfarin initiation >30 days before the ischemic event (31-90 days: RR 0.50, 95% CI 0.34-0.75; >90 days: RR 0.55, 95% CI 0.50-0.61).

Limitations included the extraction of data from a database, which could lead to misclassification of diagnosis or therapy, and the observational nature of the study.

Bottom line: There may be an increased risk of ischemic stroke during the first 30 days of treatment with warfarin in patients with Afib.

Citation: Azoulay L, Dell-Aniello S, Simon T, Renoux C, Suissa S. Initiation of warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation: early effects on ischaemic strokes [published online ahead of print December 18, 2013]. Eur Heart J.

Clinical question: Is the initiation of warfarin associated with an increased risk of ischemic stroke in patients with atrial fibrillation (Afib)?

Background: Two Afib trials of oral factor Xa inhibitors showed an increased risk of stroke when patients were transitioned to open label warfarin at the end of the study. Warfarin can, theoretically, lead to a transient hypercoagulable state upon treatment initiation, so further study is indicated to determine if the initiation of warfarin is associated with increased stroke risk among Afib patients.

Study design: Population-based, nested case-control.

Setting: UK Clinical Practice Research Datalink.

Synopsis: A cohort of 70,766 patients with newly diagnosed Afib was identified from a large primary care database. Conditional logistic regression was used to estimate adjusted rate ratios (RR) of stroke associated with warfarin monotherapy, classified according to time since initiation of treatment when compared to patients not on antithrombotic therapy.

Warfarin was associated with a 71% increased risk of stroke in the first 30 days of use (RR 1.71, 95% CI 1.39-2.12). Risk was highest in the first week of warfarin treatment, which is consistent with the known transient pro-coagulant effect of warfarin. Decreased risks were observed with warfarin initiation >30 days before the ischemic event (31-90 days: RR 0.50, 95% CI 0.34-0.75; >90 days: RR 0.55, 95% CI 0.50-0.61).

Limitations included the extraction of data from a database, which could lead to misclassification of diagnosis or therapy, and the observational nature of the study.

Bottom line: There may be an increased risk of ischemic stroke during the first 30 days of treatment with warfarin in patients with Afib.

Citation: Azoulay L, Dell-Aniello S, Simon T, Renoux C, Suissa S. Initiation of warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation: early effects on ischaemic strokes [published online ahead of print December 18, 2013]. Eur Heart J.

Variation in the Treatment of Henoch-Schönlein Purpura

Clinical question: What is the degree of variation in the inpatient management of Henoch-Schönlein purpura (HSP)?

Background: HSP is the most common pediatric vasculitis, but there are no consensus recommendations or guidelines for treatment. The amount of variation in the pharmacologic management of this disease is unknown.

Study design: Retrospective database analysis.

Setting: Thirty-six children’s hospitals affiliated with the Child Health Corporation of America.

Synopsis: The Pediatric Health Information (PHIS) database was sampled for children younger than 18 years of age with an ICD-9-CM code of HSP and discharge from a hospital that submitted appropriate data from 2000 to 2007. Only index admissions were included, and children with coexisting rheumatic conditions were excluded, for a total of 1,988 subjects.

Logistic regression analysis was used to examine the effects of patient-level standardization on hospital-level rates of therapy and the degree to which variation across hospitals occurred beyond what would be expected after standardization.

Hospital-level variation in medication use was significant (P<0.001) for corticosteroids, opiates, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), even after adjustment for severity and age at presentation.

Although variation in management is not surprising, the significant degree to which this occurred at the hospital level suggests that local institutional culture plays a dominant role in decision-making. The use of the PHIS database allows for analysis of a large population that would be otherwise difficult to study. However, significant numbers of HSP patients do not require hospitalization, and the study results might substantially over- or underestimate practice patterns. Collaborative efforts to better define optimal management of HSP are needed.

Bottom line: A significant degree of hospital-level variation exists in the inpatient management of HSP.

Citation: Weiss PF, Klink AJ, Hexem K, et al. Variation in inpatient therapy and diagnostic evaluation of children with henoch schönlein purpura. J Pediatr. 2009;155(6):812-818.e1.

Clinical question: What is the degree of variation in the inpatient management of Henoch-Schönlein purpura (HSP)?

Background: HSP is the most common pediatric vasculitis, but there are no consensus recommendations or guidelines for treatment. The amount of variation in the pharmacologic management of this disease is unknown.

Study design: Retrospective database analysis.

Setting: Thirty-six children’s hospitals affiliated with the Child Health Corporation of America.

Synopsis: The Pediatric Health Information (PHIS) database was sampled for children younger than 18 years of age with an ICD-9-CM code of HSP and discharge from a hospital that submitted appropriate data from 2000 to 2007. Only index admissions were included, and children with coexisting rheumatic conditions were excluded, for a total of 1,988 subjects.

Logistic regression analysis was used to examine the effects of patient-level standardization on hospital-level rates of therapy and the degree to which variation across hospitals occurred beyond what would be expected after standardization.

Hospital-level variation in medication use was significant (P<0.001) for corticosteroids, opiates, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), even after adjustment for severity and age at presentation.

Although variation in management is not surprising, the significant degree to which this occurred at the hospital level suggests that local institutional culture plays a dominant role in decision-making. The use of the PHIS database allows for analysis of a large population that would be otherwise difficult to study. However, significant numbers of HSP patients do not require hospitalization, and the study results might substantially over- or underestimate practice patterns. Collaborative efforts to better define optimal management of HSP are needed.

Bottom line: A significant degree of hospital-level variation exists in the inpatient management of HSP.

Citation: Weiss PF, Klink AJ, Hexem K, et al. Variation in inpatient therapy and diagnostic evaluation of children with henoch schönlein purpura. J Pediatr. 2009;155(6):812-818.e1.

Clinical question: What is the degree of variation in the inpatient management of Henoch-Schönlein purpura (HSP)?

Background: HSP is the most common pediatric vasculitis, but there are no consensus recommendations or guidelines for treatment. The amount of variation in the pharmacologic management of this disease is unknown.