User login

COPPS-2 curtails colchicine enthusiasm in cardiac surgery

Patients undergoing cardiac surgery who took colchicine had significantly less postpericardiotomy syndrome than did those on placebo, but this protective effect did not extend to postoperative atrial fibrillation and pericardial or pleural effusions in the double-blind COPPS-2 trial.

The failure of colchicine to prevent postoperative atrial fibrillation (AF) was probably due to more frequent adverse events (36 vs. 21 with placebo), especially gastrointestinal intolerance (26 vs. 12), and drug discontinuation (39 vs. 32), since a prespecified on-treatment analysis showed a significant reduction in AF in patients tolerating the drug, Dr. Massimo Imazio reported at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

"The high rate of adverse effects is a reason for concern and suggests that colchicine should be considered only in well-selected patients," Dr. Imazio and his associates wrote in an article on COPPS-2 simultaneously published online (JAMA 2014 [doi:10.1001/jama.2014.11026]).

Colchicine has been a promising strategy for postpericardiotomy syndrome prevention, besting methylprednisolone and aspirin in a large meta-analysis (Am. J. Cardiol. 2011;108:575-9).

In the largest trial, COPPS (Colchicine for the Prevention of the Postpericardiotomy Syndrome), Dr. Imazio reported that colchicine significantly reduced the incidence of postpericardiotomy syndrome (8.9% vs. 21.1%), postoperative pericardial effusions (relative risk reduction, 43.9%), and pleural effusions (RRR, 52.3%) at 12 months, compared with placebo (Am. Heart J. 2011;162:527-32 and Eur. Heart J. 2010;31:2749-54). Colchicine was given for 1 month, beginning on the third postoperative day with a 1-mg twice-daily loading dose.

In COPPS-2, the 360 consecutive candidates for cardiac surgery also were given colchicine or placebo for 1 month, but treatment was started 48-72 hours before surgery to pretreat patients and improve colchicine’s ability to prevent postoperative systemic inflammation and its complications.

Colchicine also was administered using weight-based dosing (0.5 mg twice daily in patients weighing at least 70 kg or 0.5 mg once daily in those under 70 kg), and they avoided the loading dose in an effort to improve adherence.

"However, we observed a 2-fold increase of adverse effects and study drug discontinuations compared with those reported in the COPPS trial, likely due to significant vulnerability of patients in the perioperative phase, when the use of antibiotics and proton pump inhibitors is common and also increases the risk of gastrointestinal effects (e.g., diarrhea)," explained Dr. Imazio of Maria Vittoria Hospital and the University of Torino (Italy).

Still, colchicine provided significant protection in the COPPS-2 primary outcome of postpericardiotomy syndrome, compared with placebo (19.4% vs. 29.4%; 95% confidence interval, 1.1%-18.7%). The number needed to treat was 10.

The outcome did not differ significantly among predetermined subgroups based on age, sex, and presence or absence of pericardial effusion, although colchicine was especially efficacious in the setting of systemic inflammation with elevated C-reactive protein, the authors noted.

The intention-to-treat analysis revealed no significant differences between the colchicine and placebo groups for postoperative AF (33.9% vs. 41.7%; 95% CI, –2.2%-17.6%) or postoperative pericardial/pleural effusion (57.2% vs. 58.9%; 95% CI, –8.5%-11.7%).

The prespecified on-treatment analysis, however, showed a 14.2% absolute difference in postoperative AF, favoring colchicine over placebo (27% vs. 41.2%; 95% CI, 3.3%-24.7%).

"While the efficacy of colchicine for postpericardiotomy syndrome prevention is confirmed, the extent of efficacy for postoperative AF needs to be further investigated in future trials," Dr. Imazio stated.

Ongoing studies also will better clarify the potential of colchicine using lower doses that may be better tolerated.

The 360 patients were evenly randomized from 11 centers in Italy between March 2012 and March 2014. Their mean age was 67.5 years, 69% were men, and 36% had planned valvular surgery. Key exclusion criteria were absence of sinus rhythm at enrollment, urgent cardiac surgery, cardiac transplantation, and contraindications to colchicine.

COPPS-2 was supported by the Italian National Health Service and FARGIM. Acarpia provided the study drug. Dr. Imazio reported no conflicts of interest. A coauthor reported consultancy for Servier, serving on an advisory board for Boehringer Ingelheim, and lecturer fees from Abbott, AstraZeneca, Merck, Serono, Richter Gedeon, and Teva.

Patients undergoing cardiac surgery who took colchicine had significantly less postpericardiotomy syndrome than did those on placebo, but this protective effect did not extend to postoperative atrial fibrillation and pericardial or pleural effusions in the double-blind COPPS-2 trial.

The failure of colchicine to prevent postoperative atrial fibrillation (AF) was probably due to more frequent adverse events (36 vs. 21 with placebo), especially gastrointestinal intolerance (26 vs. 12), and drug discontinuation (39 vs. 32), since a prespecified on-treatment analysis showed a significant reduction in AF in patients tolerating the drug, Dr. Massimo Imazio reported at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

"The high rate of adverse effects is a reason for concern and suggests that colchicine should be considered only in well-selected patients," Dr. Imazio and his associates wrote in an article on COPPS-2 simultaneously published online (JAMA 2014 [doi:10.1001/jama.2014.11026]).

Colchicine has been a promising strategy for postpericardiotomy syndrome prevention, besting methylprednisolone and aspirin in a large meta-analysis (Am. J. Cardiol. 2011;108:575-9).

In the largest trial, COPPS (Colchicine for the Prevention of the Postpericardiotomy Syndrome), Dr. Imazio reported that colchicine significantly reduced the incidence of postpericardiotomy syndrome (8.9% vs. 21.1%), postoperative pericardial effusions (relative risk reduction, 43.9%), and pleural effusions (RRR, 52.3%) at 12 months, compared with placebo (Am. Heart J. 2011;162:527-32 and Eur. Heart J. 2010;31:2749-54). Colchicine was given for 1 month, beginning on the third postoperative day with a 1-mg twice-daily loading dose.

In COPPS-2, the 360 consecutive candidates for cardiac surgery also were given colchicine or placebo for 1 month, but treatment was started 48-72 hours before surgery to pretreat patients and improve colchicine’s ability to prevent postoperative systemic inflammation and its complications.

Colchicine also was administered using weight-based dosing (0.5 mg twice daily in patients weighing at least 70 kg or 0.5 mg once daily in those under 70 kg), and they avoided the loading dose in an effort to improve adherence.

"However, we observed a 2-fold increase of adverse effects and study drug discontinuations compared with those reported in the COPPS trial, likely due to significant vulnerability of patients in the perioperative phase, when the use of antibiotics and proton pump inhibitors is common and also increases the risk of gastrointestinal effects (e.g., diarrhea)," explained Dr. Imazio of Maria Vittoria Hospital and the University of Torino (Italy).

Still, colchicine provided significant protection in the COPPS-2 primary outcome of postpericardiotomy syndrome, compared with placebo (19.4% vs. 29.4%; 95% confidence interval, 1.1%-18.7%). The number needed to treat was 10.

The outcome did not differ significantly among predetermined subgroups based on age, sex, and presence or absence of pericardial effusion, although colchicine was especially efficacious in the setting of systemic inflammation with elevated C-reactive protein, the authors noted.

The intention-to-treat analysis revealed no significant differences between the colchicine and placebo groups for postoperative AF (33.9% vs. 41.7%; 95% CI, –2.2%-17.6%) or postoperative pericardial/pleural effusion (57.2% vs. 58.9%; 95% CI, –8.5%-11.7%).

The prespecified on-treatment analysis, however, showed a 14.2% absolute difference in postoperative AF, favoring colchicine over placebo (27% vs. 41.2%; 95% CI, 3.3%-24.7%).

"While the efficacy of colchicine for postpericardiotomy syndrome prevention is confirmed, the extent of efficacy for postoperative AF needs to be further investigated in future trials," Dr. Imazio stated.

Ongoing studies also will better clarify the potential of colchicine using lower doses that may be better tolerated.

The 360 patients were evenly randomized from 11 centers in Italy between March 2012 and March 2014. Their mean age was 67.5 years, 69% were men, and 36% had planned valvular surgery. Key exclusion criteria were absence of sinus rhythm at enrollment, urgent cardiac surgery, cardiac transplantation, and contraindications to colchicine.

COPPS-2 was supported by the Italian National Health Service and FARGIM. Acarpia provided the study drug. Dr. Imazio reported no conflicts of interest. A coauthor reported consultancy for Servier, serving on an advisory board for Boehringer Ingelheim, and lecturer fees from Abbott, AstraZeneca, Merck, Serono, Richter Gedeon, and Teva.

Patients undergoing cardiac surgery who took colchicine had significantly less postpericardiotomy syndrome than did those on placebo, but this protective effect did not extend to postoperative atrial fibrillation and pericardial or pleural effusions in the double-blind COPPS-2 trial.

The failure of colchicine to prevent postoperative atrial fibrillation (AF) was probably due to more frequent adverse events (36 vs. 21 with placebo), especially gastrointestinal intolerance (26 vs. 12), and drug discontinuation (39 vs. 32), since a prespecified on-treatment analysis showed a significant reduction in AF in patients tolerating the drug, Dr. Massimo Imazio reported at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

"The high rate of adverse effects is a reason for concern and suggests that colchicine should be considered only in well-selected patients," Dr. Imazio and his associates wrote in an article on COPPS-2 simultaneously published online (JAMA 2014 [doi:10.1001/jama.2014.11026]).

Colchicine has been a promising strategy for postpericardiotomy syndrome prevention, besting methylprednisolone and aspirin in a large meta-analysis (Am. J. Cardiol. 2011;108:575-9).

In the largest trial, COPPS (Colchicine for the Prevention of the Postpericardiotomy Syndrome), Dr. Imazio reported that colchicine significantly reduced the incidence of postpericardiotomy syndrome (8.9% vs. 21.1%), postoperative pericardial effusions (relative risk reduction, 43.9%), and pleural effusions (RRR, 52.3%) at 12 months, compared with placebo (Am. Heart J. 2011;162:527-32 and Eur. Heart J. 2010;31:2749-54). Colchicine was given for 1 month, beginning on the third postoperative day with a 1-mg twice-daily loading dose.

In COPPS-2, the 360 consecutive candidates for cardiac surgery also were given colchicine or placebo for 1 month, but treatment was started 48-72 hours before surgery to pretreat patients and improve colchicine’s ability to prevent postoperative systemic inflammation and its complications.

Colchicine also was administered using weight-based dosing (0.5 mg twice daily in patients weighing at least 70 kg or 0.5 mg once daily in those under 70 kg), and they avoided the loading dose in an effort to improve adherence.

"However, we observed a 2-fold increase of adverse effects and study drug discontinuations compared with those reported in the COPPS trial, likely due to significant vulnerability of patients in the perioperative phase, when the use of antibiotics and proton pump inhibitors is common and also increases the risk of gastrointestinal effects (e.g., diarrhea)," explained Dr. Imazio of Maria Vittoria Hospital and the University of Torino (Italy).

Still, colchicine provided significant protection in the COPPS-2 primary outcome of postpericardiotomy syndrome, compared with placebo (19.4% vs. 29.4%; 95% confidence interval, 1.1%-18.7%). The number needed to treat was 10.

The outcome did not differ significantly among predetermined subgroups based on age, sex, and presence or absence of pericardial effusion, although colchicine was especially efficacious in the setting of systemic inflammation with elevated C-reactive protein, the authors noted.

The intention-to-treat analysis revealed no significant differences between the colchicine and placebo groups for postoperative AF (33.9% vs. 41.7%; 95% CI, –2.2%-17.6%) or postoperative pericardial/pleural effusion (57.2% vs. 58.9%; 95% CI, –8.5%-11.7%).

The prespecified on-treatment analysis, however, showed a 14.2% absolute difference in postoperative AF, favoring colchicine over placebo (27% vs. 41.2%; 95% CI, 3.3%-24.7%).

"While the efficacy of colchicine for postpericardiotomy syndrome prevention is confirmed, the extent of efficacy for postoperative AF needs to be further investigated in future trials," Dr. Imazio stated.

Ongoing studies also will better clarify the potential of colchicine using lower doses that may be better tolerated.

The 360 patients were evenly randomized from 11 centers in Italy between March 2012 and March 2014. Their mean age was 67.5 years, 69% were men, and 36% had planned valvular surgery. Key exclusion criteria were absence of sinus rhythm at enrollment, urgent cardiac surgery, cardiac transplantation, and contraindications to colchicine.

COPPS-2 was supported by the Italian National Health Service and FARGIM. Acarpia provided the study drug. Dr. Imazio reported no conflicts of interest. A coauthor reported consultancy for Servier, serving on an advisory board for Boehringer Ingelheim, and lecturer fees from Abbott, AstraZeneca, Merck, Serono, Richter Gedeon, and Teva.

FROM THE ESC CONGRESS 2014

Key clinical point: Perioperative use of colchicine should be considered only in well-selected patients.

Major finding: Perioperative colchicine use cut the incidence of postpericardiotomy syndrome, but not postoperative atrial fibrillation or pericardial/pleural effusion.

Data source: Double-blind, randomized clinical trial in 360 consecutive candidates for heart surgery.

Disclosures: COPPS-2 was supported by the Italian National Health Service and FARGIM. Acarpia provided the study drug. Dr. Imazio reported no conflicts of interest. A coauthor reported consultancy for Servier, serving on an advisory board for Boehringer Ingelheim, and lecturer fees from Abbott, AstraZeneca, Merck, Serono, Richter Gedeon, and Teva.

FDA approves generic decitabine for MDS

Credit: Bill Branson

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved decitabine for injection, a generic version of Dacogen, to treat patients with myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS).

Decitabine is indicated for previously treated and untreated patients with de novo and secondary MDS of all French-American-British subtypes—refractory anemia, refractory anemia with ringed sideroblasts, refractory anemia with excess blasts, refractory anemia with excess blasts in transformation, and chronic myelomonocytic leukemia—as well as intermediate-1, intermediate-2, and high-risk International Prognostic Scoring System groups.

Decitabine will be marketed in 20 mL single-dose glass vials containing 50 mg decitabine—the same size and strength as the brand name drug. The dosing regimen is identical as well.

InnoPharma developed the generic formulation of decitabine and entered into an agreement with Sandoz Inc. Sandoz will sell, market, and distribute decitabine in the US. InnoPharma is set to be acquired by Pfizer Inc., but the transaction is subject to US regulatory approval.

The FDA approved another generic form of decitabine for the treatment of MDS in July 2013. That drug is a product of Dr Reddy’s Laboratories Limited.

Dacogen has been FDA-approved to treat MDS since May 2006. Dacogen is a registered trademark used by Eisai Inc. under license from Astex Pharmaceuticals Inc. ![]()

Credit: Bill Branson

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved decitabine for injection, a generic version of Dacogen, to treat patients with myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS).

Decitabine is indicated for previously treated and untreated patients with de novo and secondary MDS of all French-American-British subtypes—refractory anemia, refractory anemia with ringed sideroblasts, refractory anemia with excess blasts, refractory anemia with excess blasts in transformation, and chronic myelomonocytic leukemia—as well as intermediate-1, intermediate-2, and high-risk International Prognostic Scoring System groups.

Decitabine will be marketed in 20 mL single-dose glass vials containing 50 mg decitabine—the same size and strength as the brand name drug. The dosing regimen is identical as well.

InnoPharma developed the generic formulation of decitabine and entered into an agreement with Sandoz Inc. Sandoz will sell, market, and distribute decitabine in the US. InnoPharma is set to be acquired by Pfizer Inc., but the transaction is subject to US regulatory approval.

The FDA approved another generic form of decitabine for the treatment of MDS in July 2013. That drug is a product of Dr Reddy’s Laboratories Limited.

Dacogen has been FDA-approved to treat MDS since May 2006. Dacogen is a registered trademark used by Eisai Inc. under license from Astex Pharmaceuticals Inc. ![]()

Credit: Bill Branson

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved decitabine for injection, a generic version of Dacogen, to treat patients with myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS).

Decitabine is indicated for previously treated and untreated patients with de novo and secondary MDS of all French-American-British subtypes—refractory anemia, refractory anemia with ringed sideroblasts, refractory anemia with excess blasts, refractory anemia with excess blasts in transformation, and chronic myelomonocytic leukemia—as well as intermediate-1, intermediate-2, and high-risk International Prognostic Scoring System groups.

Decitabine will be marketed in 20 mL single-dose glass vials containing 50 mg decitabine—the same size and strength as the brand name drug. The dosing regimen is identical as well.

InnoPharma developed the generic formulation of decitabine and entered into an agreement with Sandoz Inc. Sandoz will sell, market, and distribute decitabine in the US. InnoPharma is set to be acquired by Pfizer Inc., but the transaction is subject to US regulatory approval.

The FDA approved another generic form of decitabine for the treatment of MDS in July 2013. That drug is a product of Dr Reddy’s Laboratories Limited.

Dacogen has been FDA-approved to treat MDS since May 2006. Dacogen is a registered trademark used by Eisai Inc. under license from Astex Pharmaceuticals Inc. ![]()

Problems Identified by Advice Line Calls

The period immediately following hospital discharge is particularly hazardous for patients.[1, 2, 3, 4, 5] Problems occurring after discharge may result in high rates of rehospitalization and unscheduled visits to healthcare providers.[6, 7, 8, 9, 10] Numerous investigators have tried to identify patients who are at increased risk for rehospitalizations within 30 days of discharge, and many studies have examined whether various interventions could decrease these adverse events (summarized in Hansen et al.[11]). An increasing fraction of patients discharged by medicine and surgery services have some or all of their care supervised by hospitalists. Thus, hospitals increasingly look to hospitalists for ways to reduce rehospitalizations.

Patients discharged from our hospital are instructed to call an advice line (AL) if and when questions or concerns arise. Accordingly, we examined when these calls were made and what issues were raised, with the idea that the information collected might identify aspects of our discharge processes that needed improvement.

METHODS

Study Design

We conducted a prospective study of a cohort consisting of all unduplicated patients with a matching medical record number in our data warehouse who called our AL between September 1, 2011 and September 1, 2012, and reported being hospitalized or having surgery (inpatient or outpatient) within 30 days preceding their call. We excluded patients who were incarcerated, those who were transferred from other hospitals, those admitted for routine chemotherapy or emergent dialysis, and those discharged to a skilled nursing facility or hospice. The study involved no intervention. It was approved by the Colorado Multiple Institutional Review Board.

Setting

The study was conducted at Denver Health Medical Center, a 525‐bed, university‐affiliated, public safety‐net hospital. At the time of discharge, all patients were given paperwork that listed the telephone number of the AL and written instructions in English or Spanish telling them to call the AL or their primary care physician if they had any of a list of symptoms that was selected by their discharging physician as being relevant to that specific patient's condition(s).

The AL was established in 1997 to provide medical triage to patients of Denver Health. It operates 24 hours a day, 7 days per week, and receives approximately 100,000 calls per year. A language line service is used with nonEnglish‐speaking callers. Calls are handled by a nurse who, with the assistance of a commercial software program (E‐Centaurus; LVM Systems, Phoenix, AZ) containing clinical algorithms (Schmitt‐Thompson Clinical Content, Windsor, CO), makes a triage recommendation. Nurses rarely contact hospital or clinic physicians to assist with triage decisions.

Variables Assessed

We categorized the nature of the callers' reported problem(s) to the AL using the taxonomy summarized in the online appendix (see Supporting Appendix in the online version of this article). We then queried our data warehouse for each patient's demographic information, patient‐level comorbidities, discharging service, discharge date and diagnoses, hospital length of stay, discharge disposition, and whether they had been hospitalized or sought care in our urgent care center or emergency department within 30 days of discharge. The same variables were collected for all unduplicated patients who met the same inclusion and exclusion criteria and were discharged from Denver Health during the same time period but did not call the AL.

Statistics

Data were analyzed using SAS Enterprise Guide 4.1 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC). Because we made multiple statistical comparisons, we applied the Bonferroni correction when comparing patients calling the AL with those who did not, such that P<0.004 indicated statistical significance. A Student t test or a Wilcoxon rank sum test was used to compare continuous variables depending on results of normality tests. 2 tests were used to compare categorical variables. The intervals between hospital discharge and the call to the AL for patients discharged from medicine versus surgery services were compared using a log‐rank test, with P<0.05 indicating statistical significance.

RESULTS

During the 1‐year study period, 19,303 unique patients were discharged home with instructions regarding the use of the AL. A total of 310 patients called the AL and reported being hospitalized or having surgery within the preceding 30 days. Of these, 2 were excluded (1 who was incarcerated and 1 who was discharged to a skilled nursing facility), leaving 308 patients in the cohort. This represented 1.5% of the total number of unduplicated patients discharged during this same time period (minus the exclusions described above). The large majority of the calls (277/308, 90%) came directly from patients. The remaining 10% came from a proxy, usually a patient's family member. Compared with patients who were discharged during the same time period who did not call the AL, those who called were more likely to speak English, less likely to speak Spanish, more likely to be medically indigent, had slightly longer lengths of stays for their index hospitalization, and were more likely to be discharged from surgery than medicine services (particularly following inpatient surgery) (Table 1).

| Patient Characteristics | Patients Calling Advice Line After Discharge, N=308 | Patients Not Calling Advice Line After Discharge, N=18,995 | P Valuea |

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Age, y (meanSD) | 4217 | 3921 | 0.0210 |

| Gender, female, n (%) | 162 (53) | 10,655 (56) | |

| Race/ethnicity, n (%) | 0.1208 | ||

| Hispanic/Latino/Spanish | 129 (42) | 8,896 (47) | |

| African American | 44 (14) | 2,674 (14) | |

| White | 125 (41) | 6,569 (35) | |

| Language, n (%) | <0.0001 | ||

| English | 273 (89) | 14,236 (79) | |

| Spanish | 32 (10) | 3,744 (21) | |

| Payer, n (%) | |||

| Medicare | 45 (15) | 3,013 (16) | |

| Medicaid | 105 (34) | 7,777 (41) | 0.0152 |

| Commercial | 49 (16) | 2,863 (15) | |

| Medically indigentb | 93 (30) | 3,442 (18) | <0.0001 |

| Self‐pay | 5 (1) | 1,070 (5) | |

| Primary care provider, n (%)c | 168 (55) | 10,136 (53) | 0.6794 |

| Psychiatric comorbidity, n (%) | 81 (26) | 4,528 (24) | 0.3149 |

| Alcohol or substance abuse comorbidity, n (%) | 65 (21) | 3,178 (17) | 0.0417 |

| Discharging service, n (%) | <0.0001 | ||

| Surgery | 193 (63) | 7,247 (38) | |

| Inpatient | 123 (40) | 3,425 (18) | |

| Ambulatory | 70 (23) | 3,822 (20) | |

| Medicine | 93 (30) | 6,038 (32) | |

| Pediatric | 4 (1) | 1,315 (7) | |

| Obstetric | 11 (4) | 3,333 (18) | |

| Length of stay, median (IQR) | 2 (04.5) | 1 (03) | 0.0003 |

| Inpatient medicine | 4 (26) | 3 (15) | 0.0020 |

| Inpatient surgery | 3 (16) | 2 (14) | 0.0019 |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index, median (IQR) | |||

| Inpatient medicine | 1 (04) | 1 (02) | 0.0435 |

| Inpatient surgery | 0 (01) | 0 (01) | 0.0240 |

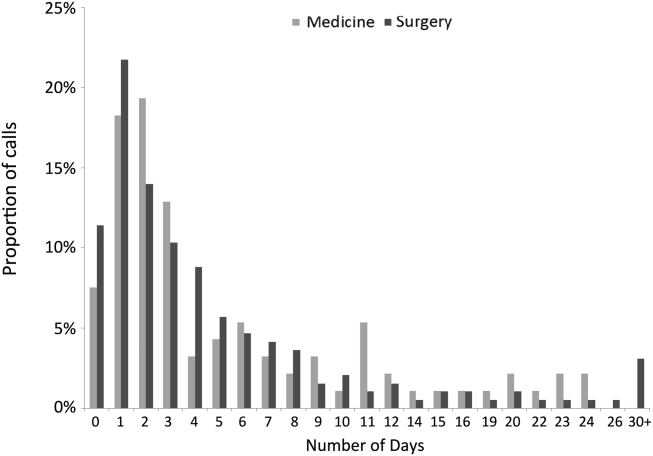

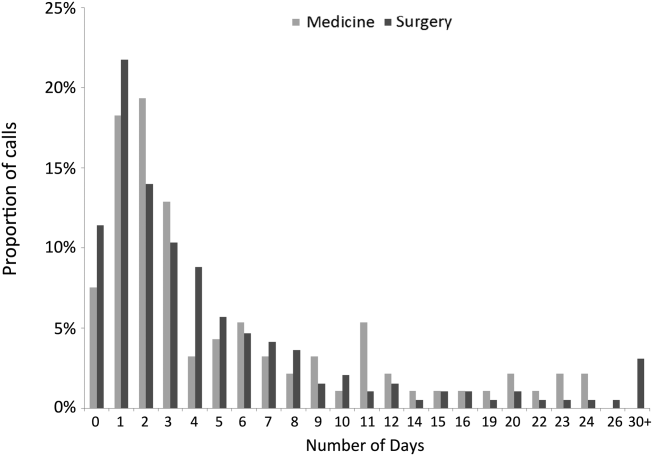

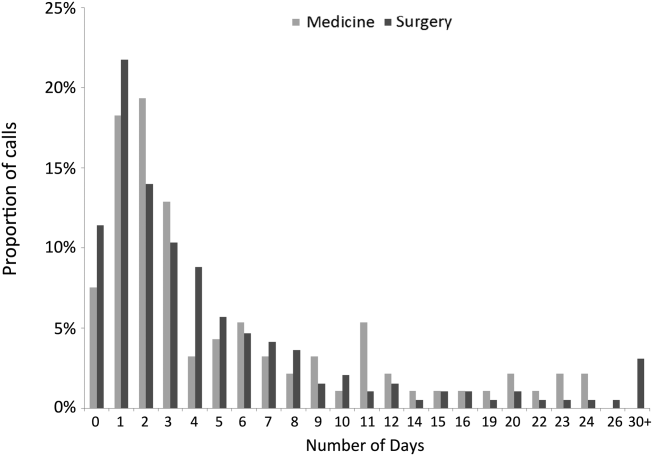

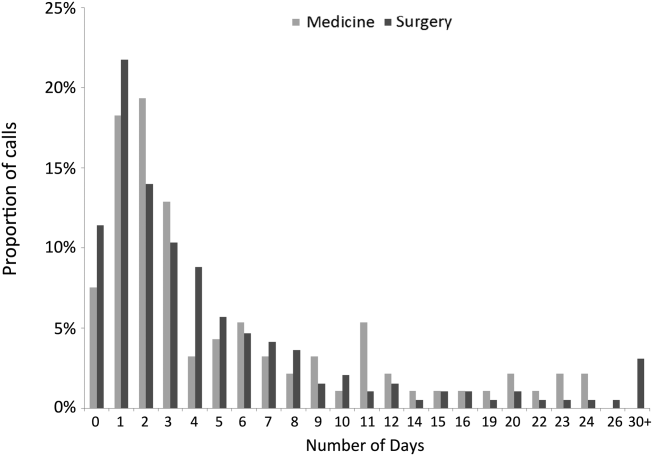

The median time from hospital discharge to the call was 3 days (interquartile range [IQR], 16), but 31% and 47% of calls occurred within 24 or 48 hours of discharge, respectively. Ten percent of patients called the AL the same day of discharge (Figure 1). We found no difference in timing of the calls as a function of discharging service.

The 308 patients reported a total of 612 problems or concerns (meanstandard deviation number of complaints per caller=21), the large majority of which (71%) were symptom‐related (Table 2). The most common symptom was uncontrolled pain, reported by 33% and 40% of patients discharged from medicine and surgery services, respectively. The next most common symptoms related to the gastrointestinal system and to surgical site issues in medicine and surgery patients, respectively (data not shown).

| Total Cohort, n (%) | Patients Discharged From Medicine, n (%) | Patients Discharged From Surgery, n (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients | Complaints | Patients | Complaints | Patients | Complaints | |

| Symptom related | 280 (91) | 433 (71) | 89 (96) | 166 (77) | 171 (89) | 234 (66) |

| Discharge instructions | 65 (21) | 81 (13) | 18 (19) | 21 (10) | 43 (22) | 56 (16) |

| Medication related | 65 (21) | 87 (14) | 19 (20) | 25 (11) | 39 (20) | 54 (15) |

| Other | 10 (3) | 11 (2) | 4 (4) | 4 (2) | 6 (3) | 7 (2) |

| Total | 612 (100) | 216 (100) | 351 (100) | |||

Sixty‐five patients, representing 21% of the cohort, reported 81 problems understanding or executing discharge instructions. No difference was observed between the fraction of these problems reported by patients from medicine versus surgery (19% and 22%, respectively, P=0.54).

Sixty‐five patients, again representing 21% of the cohort, reported 87 medication‐related problems, 20% from both the medicine and surgery services (P=0.99). Medicine patients more frequently reported difficulties understanding their medication instructions, whereas surgery patients more frequently reported lack of efficacy of medications, particularly with respect to pain control (data not shown).

Thirty percent of patients who called the AL were advised by the nurse to go to the emergency department immediately. Medicine patients were more likely to be triaged to the emergency department compared with surgery patients (45% vs 22%, P<0.0001).

The 30‐day readmission rates and the rates of unscheduled urgent or emergent care visits were higher for patients calling the AL compared with those who did not call (46/308, 15% vs 706/18,995, 4%, and 92/308, 30% vs 1303/18,995, 7%, respectively, both P<0.0001). Similar differences were found for patients discharged from medicine or surgery services who called the AL compared with those who did not (data not shown, both P<0.0001). The median number of days between AL call and rehospitalization was 0 (IQR, 02) and 1 (IQR, 08) for medicine and surgery patients, respectively. Ninety‐three percent of rehospitalizations were related to the index hospitalization, and 78% of patients who were readmitted had no outpatient encounter in the interim between discharge and rehospitalization.

DISCUSSION

We investigated the source and nature of patient telephone calls to an AL following a hospitalization or surgery, and our data revealed the following important findings: (1) nearly one‐half of the calls to the AL occurred within the first 48 hours following discharge; (2) the majority of the calls came from surgery patients, and a greater fraction of patients discharged from surgery services called the AL than patients discharged from medicine services; (3) the most common issues were uncontrolled pain, questions about medications, and problems understanding or executing aftercare instructions (particularly pertaining to the care of surgical wounds); and (4) patients calling the AL had higher rates of 30‐day rehospitalization and of unscheduled urgent or emergent care visits.

The utilization of our patient‐initiated call line was only 1.5%, which was on the low end of the 1% to 10% reported in the literature.[7, 12] This can be attributed to a number of issues that are specific to our system. First, the discharge instructions provided to our patients stated that they should call their primary care provider or the AL if they had questions. Accordingly, because approximately 50% of our patients had a primary care provider in our system, some may have preferentially contacted their primary care provider rather than the AL. Second, the instructions stated that the patients should call if they were experiencing the symptoms listed on the instruction sheet, so those with other problems/complaints may not have called. Third, AL personnel identified patients as being in our cohort by asking if they had been discharged or underwent a surgical procedure within 30‐days of their call. This may have resulted in the under‐reporting of patients who were hospitalized or had outpatient surgical procedures. Fourth, there may have been a number of characteristics specific to patients in our system that reduced the frequency with which they utilized the AL (eg, access to telephones or other community providers).

Most previous studies of patient‐initiated call lines have included them as part of multi‐intervention pre‐ and/or postdischarge strategies.[7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13] One prior small study compared the information reported by 37 patients who called an AL with that elicited by nurse‐initiated patient contact.[12] The most frequently reported problems in this study were medication‐related issues (43%). However, this study only included medicine patients and did not document the proportion of calls occurring at various time intervals.

The problems we identified (in both medicine and surgery patients) have previously been described,[2, 3, 4, 13, 14, 15, 16] but all of the studies reporting these problems utilized calls that were initiated by health care providers to patients at various fixed intervals following discharge (ie, 730 days). Most of these used a scripted approach seeking responses to specific questions or outcomes, and the specific timing at which the problems arose was not addressed. In contrast, we examined unsolicited concerns expressed by patients calling an AL following discharge whenever they felt sufficient urgency to address whatever problems or questions arose. We found that a large fraction of calls occurred on the day of or within the first 48 hours following discharge, much earlier than when provider‐initiated calls in the studies cited above occurred. Accordingly, our results cannot be used to compare the utility of patient‐ versus provider‐initiated calls, or to suggest that other hospitals should create an AL system. Rather, we suggest that our findings might be complementary to those reported in studies of provider‐initiated calls and only propose that by examining calls placed by patients to ALs, problems with hospital discharge processes (some of which may result in increased rates of readmission) may be discovered.

The observation that such a large fraction of calls to our AL occurred within the first 48 hours following discharge, together with the fact that many of the questions asked or concerns raised pertained to issues that should have been discussed during the discharge process (eg, pain control, care of surgical wounds), suggests that suboptimal patient education was occurring prior to discharge as was suggested by Henderson and Zernike.[17] This finding has led us to expand our patient education processes prior to discharge on both medicine and surgery services. Because our hospitalists care for approximately 90% of the patients admitted to medicine services and are increasingly involved in the care of patients on surgery services, they are integrally involved with such quality improvement initiatives.

To our knowledge this is the first study in the literature that describes both medicine and surgery patients who call an AL because of problems or questions following hospital discharge, categorizes these problems, determines when the patients called following their discharge, and identifies those who called as being at increased risk for early rehospitalizations and unscheduled urgent or emergent care visits. Given the financial penalties issued to hospitals with high 30‐day readmission rates, these patients may warrant more attention than is customarily available from telephone call lines or during routine outpatient follow‐up. The majority of patients who called our AL had Medicare, Medicaid, or a commercial insurance, and, accordingly, may have been eligible for additional services such as home visits and/or expedited follow‐up appointments.

Our study has a number of limitations. First, it is a single‐center study, so the results might not generalize to other institutions. Second, because the study was performed in a university‐affiliated, public safety‐net hospital, patient characteristics and the rates and types of postdischarge concerns that we observed might differ from those encountered in different types of hospitals and/or from those in nonteaching institutions. We would suggest, however, that the idea of using concerns raised by patients discharged from any type of hospital in calls to ALs may similarly identify problems with that specific hospital's discharge processes. Third, the information collected from the AL came from summaries provided by nurses answering the calls rather than from actual transcripts. This could have resulted in insufficient or incorrect information pertaining to some of the variables assessed in Table 2. The information presented in Table 1, however, was obtained from our data warehouse after matching medical record numbers. Fourth, we could have underestimated the number of patients who had 30‐day rehospitalizations and/or unplanned for urgent or emergent care visits if patients sought care at other hospitals. Fifth, the number of patients calling the AL was too small to allow us to do any type of robust matching or multivariable analysis. Accordingly, the differences that appeared between patients who called and those who did not (ie, English speakers, being medically indigent, the length of stay for the index hospitalization and the discharging service) could be the result of inadequate matching or interactions among the variables. Although matching or multivariate analysis might have yielded different associations between patients who called the AL versus those who did not, those who called the AL still had an increased risk of readmission and urgent or emergent visits and may still benefit from targeted interventions. Finally, the fact that only 1.5% of unique patients who were discharged called the AL could have biased our results. Because only 55% and 53% of the patients who did or did not call the AL, respectively, saw primary care physicians within our system within the 3 years prior to their index hospitalization (P=0.679), the frequency of calls to the AL that we observed could have underestimated the frequency with which patients had contact with other care providers in the community.

In summary, information collected from patient‐initiated calls to our AL identified several aspects of our discharge processes that needed improvement. We concluded that our predischarge educational processes for both medicine and surgery services needed modification, especially with respect to pain management, which problems to expect after hospitalization or surgery, and how to deal with them. The high rates of 30‐day rehospitalization and of unscheduled urgent or emergent care visits among patients calling the AL identifies them as being at increased risk for these outcomes, although the likelihood of these events may be related to factors other than just calling the AL.

- , , , , . Implementation of the care transitions intervention: sustainability and lessons learned. Prof Case Manag. 2009;14(6):282–293.

- , , , et al. Problems after discharge and understanding of communication with their primary care physicians among hospitalized seniors: a mixed methods study. J Hosp Med. 2010;5(7):385–391.

- , , , et al. Adverse events among medical patients after discharge from hospital. CMAJ. 2004;170(3):345–349.

- , , , , . The incidence and severity of adverse events affecting patients after discharge from the hospital. Ann Intern Med. 2003;138(3):161–167.

- , , . Post‐hospitalization transitions: examining the effects of timing of primary care provider follow‐up. J Hosp Med. 2010;5(7):392–397.

- , , , . Telephone follow‐up after discharge from the hospital: does it make a difference? Appl Nurs Res. 1996;9(2) 47–52.

- , , , et al. The effect of real‐time teleconsultations between hospital‐based nurses and patients with severe COPD discharged after an exacerbation. J Telemed Telecare. 2013;19(8):466–474.

- , , , , , . A randomized, controlled trial of an intensive community nurse‐supported discharge program in preventing hospital readmissions of older patients with chronic lung disease. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52(8):1240–1246.

- , , , et al. Effects of education and support on self‐care and resource utilization in patients with heart failure. Eur Heart J. 1999;20(9):673–682.

- , , , et al. Comprehensive discharge planning and home follow‐up of hospitalized elders: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 1999;281(7):613–620.

- , , , , . Interventions to reduce 30‐day rehospitalization: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155(8):520–528.

- , , , . Complementary telephone strategies to improve postdischarge communication. Am J Med. 2012;125(1):28–30.

- , , , , , . Integrated postdischarge transitional care in a hospitalist system to improve discharge outcome: an experimental study. BMC Med. 2011;9:96.

- , , , , , . Patient experiences after hospitalizations for elective surgery. Am J Surg. 2014;207(6):855–862.

- , , . Complications after discharge for surgical patients. ANZ J Surg. 2004;74(3):92–97.

- , , , . Surgeons are overlooking post‐discharge complications: a prospective cohort study. World J Surg. 2014;38(5):1019–1025.

- , . A study of the impact of discharge information for surgical patients. J Adv Nurs. 2001;35(3):435–441.

The period immediately following hospital discharge is particularly hazardous for patients.[1, 2, 3, 4, 5] Problems occurring after discharge may result in high rates of rehospitalization and unscheduled visits to healthcare providers.[6, 7, 8, 9, 10] Numerous investigators have tried to identify patients who are at increased risk for rehospitalizations within 30 days of discharge, and many studies have examined whether various interventions could decrease these adverse events (summarized in Hansen et al.[11]). An increasing fraction of patients discharged by medicine and surgery services have some or all of their care supervised by hospitalists. Thus, hospitals increasingly look to hospitalists for ways to reduce rehospitalizations.

Patients discharged from our hospital are instructed to call an advice line (AL) if and when questions or concerns arise. Accordingly, we examined when these calls were made and what issues were raised, with the idea that the information collected might identify aspects of our discharge processes that needed improvement.

METHODS

Study Design

We conducted a prospective study of a cohort consisting of all unduplicated patients with a matching medical record number in our data warehouse who called our AL between September 1, 2011 and September 1, 2012, and reported being hospitalized or having surgery (inpatient or outpatient) within 30 days preceding their call. We excluded patients who were incarcerated, those who were transferred from other hospitals, those admitted for routine chemotherapy or emergent dialysis, and those discharged to a skilled nursing facility or hospice. The study involved no intervention. It was approved by the Colorado Multiple Institutional Review Board.

Setting

The study was conducted at Denver Health Medical Center, a 525‐bed, university‐affiliated, public safety‐net hospital. At the time of discharge, all patients were given paperwork that listed the telephone number of the AL and written instructions in English or Spanish telling them to call the AL or their primary care physician if they had any of a list of symptoms that was selected by their discharging physician as being relevant to that specific patient's condition(s).

The AL was established in 1997 to provide medical triage to patients of Denver Health. It operates 24 hours a day, 7 days per week, and receives approximately 100,000 calls per year. A language line service is used with nonEnglish‐speaking callers. Calls are handled by a nurse who, with the assistance of a commercial software program (E‐Centaurus; LVM Systems, Phoenix, AZ) containing clinical algorithms (Schmitt‐Thompson Clinical Content, Windsor, CO), makes a triage recommendation. Nurses rarely contact hospital or clinic physicians to assist with triage decisions.

Variables Assessed

We categorized the nature of the callers' reported problem(s) to the AL using the taxonomy summarized in the online appendix (see Supporting Appendix in the online version of this article). We then queried our data warehouse for each patient's demographic information, patient‐level comorbidities, discharging service, discharge date and diagnoses, hospital length of stay, discharge disposition, and whether they had been hospitalized or sought care in our urgent care center or emergency department within 30 days of discharge. The same variables were collected for all unduplicated patients who met the same inclusion and exclusion criteria and were discharged from Denver Health during the same time period but did not call the AL.

Statistics

Data were analyzed using SAS Enterprise Guide 4.1 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC). Because we made multiple statistical comparisons, we applied the Bonferroni correction when comparing patients calling the AL with those who did not, such that P<0.004 indicated statistical significance. A Student t test or a Wilcoxon rank sum test was used to compare continuous variables depending on results of normality tests. 2 tests were used to compare categorical variables. The intervals between hospital discharge and the call to the AL for patients discharged from medicine versus surgery services were compared using a log‐rank test, with P<0.05 indicating statistical significance.

RESULTS

During the 1‐year study period, 19,303 unique patients were discharged home with instructions regarding the use of the AL. A total of 310 patients called the AL and reported being hospitalized or having surgery within the preceding 30 days. Of these, 2 were excluded (1 who was incarcerated and 1 who was discharged to a skilled nursing facility), leaving 308 patients in the cohort. This represented 1.5% of the total number of unduplicated patients discharged during this same time period (minus the exclusions described above). The large majority of the calls (277/308, 90%) came directly from patients. The remaining 10% came from a proxy, usually a patient's family member. Compared with patients who were discharged during the same time period who did not call the AL, those who called were more likely to speak English, less likely to speak Spanish, more likely to be medically indigent, had slightly longer lengths of stays for their index hospitalization, and were more likely to be discharged from surgery than medicine services (particularly following inpatient surgery) (Table 1).

| Patient Characteristics | Patients Calling Advice Line After Discharge, N=308 | Patients Not Calling Advice Line After Discharge, N=18,995 | P Valuea |

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Age, y (meanSD) | 4217 | 3921 | 0.0210 |

| Gender, female, n (%) | 162 (53) | 10,655 (56) | |

| Race/ethnicity, n (%) | 0.1208 | ||

| Hispanic/Latino/Spanish | 129 (42) | 8,896 (47) | |

| African American | 44 (14) | 2,674 (14) | |

| White | 125 (41) | 6,569 (35) | |

| Language, n (%) | <0.0001 | ||

| English | 273 (89) | 14,236 (79) | |

| Spanish | 32 (10) | 3,744 (21) | |

| Payer, n (%) | |||

| Medicare | 45 (15) | 3,013 (16) | |

| Medicaid | 105 (34) | 7,777 (41) | 0.0152 |

| Commercial | 49 (16) | 2,863 (15) | |

| Medically indigentb | 93 (30) | 3,442 (18) | <0.0001 |

| Self‐pay | 5 (1) | 1,070 (5) | |

| Primary care provider, n (%)c | 168 (55) | 10,136 (53) | 0.6794 |

| Psychiatric comorbidity, n (%) | 81 (26) | 4,528 (24) | 0.3149 |

| Alcohol or substance abuse comorbidity, n (%) | 65 (21) | 3,178 (17) | 0.0417 |

| Discharging service, n (%) | <0.0001 | ||

| Surgery | 193 (63) | 7,247 (38) | |

| Inpatient | 123 (40) | 3,425 (18) | |

| Ambulatory | 70 (23) | 3,822 (20) | |

| Medicine | 93 (30) | 6,038 (32) | |

| Pediatric | 4 (1) | 1,315 (7) | |

| Obstetric | 11 (4) | 3,333 (18) | |

| Length of stay, median (IQR) | 2 (04.5) | 1 (03) | 0.0003 |

| Inpatient medicine | 4 (26) | 3 (15) | 0.0020 |

| Inpatient surgery | 3 (16) | 2 (14) | 0.0019 |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index, median (IQR) | |||

| Inpatient medicine | 1 (04) | 1 (02) | 0.0435 |

| Inpatient surgery | 0 (01) | 0 (01) | 0.0240 |

The median time from hospital discharge to the call was 3 days (interquartile range [IQR], 16), but 31% and 47% of calls occurred within 24 or 48 hours of discharge, respectively. Ten percent of patients called the AL the same day of discharge (Figure 1). We found no difference in timing of the calls as a function of discharging service.

The 308 patients reported a total of 612 problems or concerns (meanstandard deviation number of complaints per caller=21), the large majority of which (71%) were symptom‐related (Table 2). The most common symptom was uncontrolled pain, reported by 33% and 40% of patients discharged from medicine and surgery services, respectively. The next most common symptoms related to the gastrointestinal system and to surgical site issues in medicine and surgery patients, respectively (data not shown).

| Total Cohort, n (%) | Patients Discharged From Medicine, n (%) | Patients Discharged From Surgery, n (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients | Complaints | Patients | Complaints | Patients | Complaints | |

| Symptom related | 280 (91) | 433 (71) | 89 (96) | 166 (77) | 171 (89) | 234 (66) |

| Discharge instructions | 65 (21) | 81 (13) | 18 (19) | 21 (10) | 43 (22) | 56 (16) |

| Medication related | 65 (21) | 87 (14) | 19 (20) | 25 (11) | 39 (20) | 54 (15) |

| Other | 10 (3) | 11 (2) | 4 (4) | 4 (2) | 6 (3) | 7 (2) |

| Total | 612 (100) | 216 (100) | 351 (100) | |||

Sixty‐five patients, representing 21% of the cohort, reported 81 problems understanding or executing discharge instructions. No difference was observed between the fraction of these problems reported by patients from medicine versus surgery (19% and 22%, respectively, P=0.54).

Sixty‐five patients, again representing 21% of the cohort, reported 87 medication‐related problems, 20% from both the medicine and surgery services (P=0.99). Medicine patients more frequently reported difficulties understanding their medication instructions, whereas surgery patients more frequently reported lack of efficacy of medications, particularly with respect to pain control (data not shown).

Thirty percent of patients who called the AL were advised by the nurse to go to the emergency department immediately. Medicine patients were more likely to be triaged to the emergency department compared with surgery patients (45% vs 22%, P<0.0001).

The 30‐day readmission rates and the rates of unscheduled urgent or emergent care visits were higher for patients calling the AL compared with those who did not call (46/308, 15% vs 706/18,995, 4%, and 92/308, 30% vs 1303/18,995, 7%, respectively, both P<0.0001). Similar differences were found for patients discharged from medicine or surgery services who called the AL compared with those who did not (data not shown, both P<0.0001). The median number of days between AL call and rehospitalization was 0 (IQR, 02) and 1 (IQR, 08) for medicine and surgery patients, respectively. Ninety‐three percent of rehospitalizations were related to the index hospitalization, and 78% of patients who were readmitted had no outpatient encounter in the interim between discharge and rehospitalization.

DISCUSSION

We investigated the source and nature of patient telephone calls to an AL following a hospitalization or surgery, and our data revealed the following important findings: (1) nearly one‐half of the calls to the AL occurred within the first 48 hours following discharge; (2) the majority of the calls came from surgery patients, and a greater fraction of patients discharged from surgery services called the AL than patients discharged from medicine services; (3) the most common issues were uncontrolled pain, questions about medications, and problems understanding or executing aftercare instructions (particularly pertaining to the care of surgical wounds); and (4) patients calling the AL had higher rates of 30‐day rehospitalization and of unscheduled urgent or emergent care visits.

The utilization of our patient‐initiated call line was only 1.5%, which was on the low end of the 1% to 10% reported in the literature.[7, 12] This can be attributed to a number of issues that are specific to our system. First, the discharge instructions provided to our patients stated that they should call their primary care provider or the AL if they had questions. Accordingly, because approximately 50% of our patients had a primary care provider in our system, some may have preferentially contacted their primary care provider rather than the AL. Second, the instructions stated that the patients should call if they were experiencing the symptoms listed on the instruction sheet, so those with other problems/complaints may not have called. Third, AL personnel identified patients as being in our cohort by asking if they had been discharged or underwent a surgical procedure within 30‐days of their call. This may have resulted in the under‐reporting of patients who were hospitalized or had outpatient surgical procedures. Fourth, there may have been a number of characteristics specific to patients in our system that reduced the frequency with which they utilized the AL (eg, access to telephones or other community providers).

Most previous studies of patient‐initiated call lines have included them as part of multi‐intervention pre‐ and/or postdischarge strategies.[7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13] One prior small study compared the information reported by 37 patients who called an AL with that elicited by nurse‐initiated patient contact.[12] The most frequently reported problems in this study were medication‐related issues (43%). However, this study only included medicine patients and did not document the proportion of calls occurring at various time intervals.

The problems we identified (in both medicine and surgery patients) have previously been described,[2, 3, 4, 13, 14, 15, 16] but all of the studies reporting these problems utilized calls that were initiated by health care providers to patients at various fixed intervals following discharge (ie, 730 days). Most of these used a scripted approach seeking responses to specific questions or outcomes, and the specific timing at which the problems arose was not addressed. In contrast, we examined unsolicited concerns expressed by patients calling an AL following discharge whenever they felt sufficient urgency to address whatever problems or questions arose. We found that a large fraction of calls occurred on the day of or within the first 48 hours following discharge, much earlier than when provider‐initiated calls in the studies cited above occurred. Accordingly, our results cannot be used to compare the utility of patient‐ versus provider‐initiated calls, or to suggest that other hospitals should create an AL system. Rather, we suggest that our findings might be complementary to those reported in studies of provider‐initiated calls and only propose that by examining calls placed by patients to ALs, problems with hospital discharge processes (some of which may result in increased rates of readmission) may be discovered.

The observation that such a large fraction of calls to our AL occurred within the first 48 hours following discharge, together with the fact that many of the questions asked or concerns raised pertained to issues that should have been discussed during the discharge process (eg, pain control, care of surgical wounds), suggests that suboptimal patient education was occurring prior to discharge as was suggested by Henderson and Zernike.[17] This finding has led us to expand our patient education processes prior to discharge on both medicine and surgery services. Because our hospitalists care for approximately 90% of the patients admitted to medicine services and are increasingly involved in the care of patients on surgery services, they are integrally involved with such quality improvement initiatives.

To our knowledge this is the first study in the literature that describes both medicine and surgery patients who call an AL because of problems or questions following hospital discharge, categorizes these problems, determines when the patients called following their discharge, and identifies those who called as being at increased risk for early rehospitalizations and unscheduled urgent or emergent care visits. Given the financial penalties issued to hospitals with high 30‐day readmission rates, these patients may warrant more attention than is customarily available from telephone call lines or during routine outpatient follow‐up. The majority of patients who called our AL had Medicare, Medicaid, or a commercial insurance, and, accordingly, may have been eligible for additional services such as home visits and/or expedited follow‐up appointments.

Our study has a number of limitations. First, it is a single‐center study, so the results might not generalize to other institutions. Second, because the study was performed in a university‐affiliated, public safety‐net hospital, patient characteristics and the rates and types of postdischarge concerns that we observed might differ from those encountered in different types of hospitals and/or from those in nonteaching institutions. We would suggest, however, that the idea of using concerns raised by patients discharged from any type of hospital in calls to ALs may similarly identify problems with that specific hospital's discharge processes. Third, the information collected from the AL came from summaries provided by nurses answering the calls rather than from actual transcripts. This could have resulted in insufficient or incorrect information pertaining to some of the variables assessed in Table 2. The information presented in Table 1, however, was obtained from our data warehouse after matching medical record numbers. Fourth, we could have underestimated the number of patients who had 30‐day rehospitalizations and/or unplanned for urgent or emergent care visits if patients sought care at other hospitals. Fifth, the number of patients calling the AL was too small to allow us to do any type of robust matching or multivariable analysis. Accordingly, the differences that appeared between patients who called and those who did not (ie, English speakers, being medically indigent, the length of stay for the index hospitalization and the discharging service) could be the result of inadequate matching or interactions among the variables. Although matching or multivariate analysis might have yielded different associations between patients who called the AL versus those who did not, those who called the AL still had an increased risk of readmission and urgent or emergent visits and may still benefit from targeted interventions. Finally, the fact that only 1.5% of unique patients who were discharged called the AL could have biased our results. Because only 55% and 53% of the patients who did or did not call the AL, respectively, saw primary care physicians within our system within the 3 years prior to their index hospitalization (P=0.679), the frequency of calls to the AL that we observed could have underestimated the frequency with which patients had contact with other care providers in the community.

In summary, information collected from patient‐initiated calls to our AL identified several aspects of our discharge processes that needed improvement. We concluded that our predischarge educational processes for both medicine and surgery services needed modification, especially with respect to pain management, which problems to expect after hospitalization or surgery, and how to deal with them. The high rates of 30‐day rehospitalization and of unscheduled urgent or emergent care visits among patients calling the AL identifies them as being at increased risk for these outcomes, although the likelihood of these events may be related to factors other than just calling the AL.

The period immediately following hospital discharge is particularly hazardous for patients.[1, 2, 3, 4, 5] Problems occurring after discharge may result in high rates of rehospitalization and unscheduled visits to healthcare providers.[6, 7, 8, 9, 10] Numerous investigators have tried to identify patients who are at increased risk for rehospitalizations within 30 days of discharge, and many studies have examined whether various interventions could decrease these adverse events (summarized in Hansen et al.[11]). An increasing fraction of patients discharged by medicine and surgery services have some or all of their care supervised by hospitalists. Thus, hospitals increasingly look to hospitalists for ways to reduce rehospitalizations.

Patients discharged from our hospital are instructed to call an advice line (AL) if and when questions or concerns arise. Accordingly, we examined when these calls were made and what issues were raised, with the idea that the information collected might identify aspects of our discharge processes that needed improvement.

METHODS

Study Design

We conducted a prospective study of a cohort consisting of all unduplicated patients with a matching medical record number in our data warehouse who called our AL between September 1, 2011 and September 1, 2012, and reported being hospitalized or having surgery (inpatient or outpatient) within 30 days preceding their call. We excluded patients who were incarcerated, those who were transferred from other hospitals, those admitted for routine chemotherapy or emergent dialysis, and those discharged to a skilled nursing facility or hospice. The study involved no intervention. It was approved by the Colorado Multiple Institutional Review Board.

Setting

The study was conducted at Denver Health Medical Center, a 525‐bed, university‐affiliated, public safety‐net hospital. At the time of discharge, all patients were given paperwork that listed the telephone number of the AL and written instructions in English or Spanish telling them to call the AL or their primary care physician if they had any of a list of symptoms that was selected by their discharging physician as being relevant to that specific patient's condition(s).

The AL was established in 1997 to provide medical triage to patients of Denver Health. It operates 24 hours a day, 7 days per week, and receives approximately 100,000 calls per year. A language line service is used with nonEnglish‐speaking callers. Calls are handled by a nurse who, with the assistance of a commercial software program (E‐Centaurus; LVM Systems, Phoenix, AZ) containing clinical algorithms (Schmitt‐Thompson Clinical Content, Windsor, CO), makes a triage recommendation. Nurses rarely contact hospital or clinic physicians to assist with triage decisions.

Variables Assessed

We categorized the nature of the callers' reported problem(s) to the AL using the taxonomy summarized in the online appendix (see Supporting Appendix in the online version of this article). We then queried our data warehouse for each patient's demographic information, patient‐level comorbidities, discharging service, discharge date and diagnoses, hospital length of stay, discharge disposition, and whether they had been hospitalized or sought care in our urgent care center or emergency department within 30 days of discharge. The same variables were collected for all unduplicated patients who met the same inclusion and exclusion criteria and were discharged from Denver Health during the same time period but did not call the AL.

Statistics

Data were analyzed using SAS Enterprise Guide 4.1 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC). Because we made multiple statistical comparisons, we applied the Bonferroni correction when comparing patients calling the AL with those who did not, such that P<0.004 indicated statistical significance. A Student t test or a Wilcoxon rank sum test was used to compare continuous variables depending on results of normality tests. 2 tests were used to compare categorical variables. The intervals between hospital discharge and the call to the AL for patients discharged from medicine versus surgery services were compared using a log‐rank test, with P<0.05 indicating statistical significance.

RESULTS

During the 1‐year study period, 19,303 unique patients were discharged home with instructions regarding the use of the AL. A total of 310 patients called the AL and reported being hospitalized or having surgery within the preceding 30 days. Of these, 2 were excluded (1 who was incarcerated and 1 who was discharged to a skilled nursing facility), leaving 308 patients in the cohort. This represented 1.5% of the total number of unduplicated patients discharged during this same time period (minus the exclusions described above). The large majority of the calls (277/308, 90%) came directly from patients. The remaining 10% came from a proxy, usually a patient's family member. Compared with patients who were discharged during the same time period who did not call the AL, those who called were more likely to speak English, less likely to speak Spanish, more likely to be medically indigent, had slightly longer lengths of stays for their index hospitalization, and were more likely to be discharged from surgery than medicine services (particularly following inpatient surgery) (Table 1).

| Patient Characteristics | Patients Calling Advice Line After Discharge, N=308 | Patients Not Calling Advice Line After Discharge, N=18,995 | P Valuea |

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Age, y (meanSD) | 4217 | 3921 | 0.0210 |

| Gender, female, n (%) | 162 (53) | 10,655 (56) | |

| Race/ethnicity, n (%) | 0.1208 | ||

| Hispanic/Latino/Spanish | 129 (42) | 8,896 (47) | |

| African American | 44 (14) | 2,674 (14) | |

| White | 125 (41) | 6,569 (35) | |

| Language, n (%) | <0.0001 | ||

| English | 273 (89) | 14,236 (79) | |

| Spanish | 32 (10) | 3,744 (21) | |

| Payer, n (%) | |||

| Medicare | 45 (15) | 3,013 (16) | |

| Medicaid | 105 (34) | 7,777 (41) | 0.0152 |

| Commercial | 49 (16) | 2,863 (15) | |

| Medically indigentb | 93 (30) | 3,442 (18) | <0.0001 |

| Self‐pay | 5 (1) | 1,070 (5) | |

| Primary care provider, n (%)c | 168 (55) | 10,136 (53) | 0.6794 |

| Psychiatric comorbidity, n (%) | 81 (26) | 4,528 (24) | 0.3149 |

| Alcohol or substance abuse comorbidity, n (%) | 65 (21) | 3,178 (17) | 0.0417 |

| Discharging service, n (%) | <0.0001 | ||

| Surgery | 193 (63) | 7,247 (38) | |

| Inpatient | 123 (40) | 3,425 (18) | |

| Ambulatory | 70 (23) | 3,822 (20) | |

| Medicine | 93 (30) | 6,038 (32) | |

| Pediatric | 4 (1) | 1,315 (7) | |

| Obstetric | 11 (4) | 3,333 (18) | |

| Length of stay, median (IQR) | 2 (04.5) | 1 (03) | 0.0003 |

| Inpatient medicine | 4 (26) | 3 (15) | 0.0020 |

| Inpatient surgery | 3 (16) | 2 (14) | 0.0019 |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index, median (IQR) | |||

| Inpatient medicine | 1 (04) | 1 (02) | 0.0435 |

| Inpatient surgery | 0 (01) | 0 (01) | 0.0240 |

The median time from hospital discharge to the call was 3 days (interquartile range [IQR], 16), but 31% and 47% of calls occurred within 24 or 48 hours of discharge, respectively. Ten percent of patients called the AL the same day of discharge (Figure 1). We found no difference in timing of the calls as a function of discharging service.

The 308 patients reported a total of 612 problems or concerns (meanstandard deviation number of complaints per caller=21), the large majority of which (71%) were symptom‐related (Table 2). The most common symptom was uncontrolled pain, reported by 33% and 40% of patients discharged from medicine and surgery services, respectively. The next most common symptoms related to the gastrointestinal system and to surgical site issues in medicine and surgery patients, respectively (data not shown).

| Total Cohort, n (%) | Patients Discharged From Medicine, n (%) | Patients Discharged From Surgery, n (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients | Complaints | Patients | Complaints | Patients | Complaints | |

| Symptom related | 280 (91) | 433 (71) | 89 (96) | 166 (77) | 171 (89) | 234 (66) |

| Discharge instructions | 65 (21) | 81 (13) | 18 (19) | 21 (10) | 43 (22) | 56 (16) |

| Medication related | 65 (21) | 87 (14) | 19 (20) | 25 (11) | 39 (20) | 54 (15) |

| Other | 10 (3) | 11 (2) | 4 (4) | 4 (2) | 6 (3) | 7 (2) |

| Total | 612 (100) | 216 (100) | 351 (100) | |||

Sixty‐five patients, representing 21% of the cohort, reported 81 problems understanding or executing discharge instructions. No difference was observed between the fraction of these problems reported by patients from medicine versus surgery (19% and 22%, respectively, P=0.54).

Sixty‐five patients, again representing 21% of the cohort, reported 87 medication‐related problems, 20% from both the medicine and surgery services (P=0.99). Medicine patients more frequently reported difficulties understanding their medication instructions, whereas surgery patients more frequently reported lack of efficacy of medications, particularly with respect to pain control (data not shown).

Thirty percent of patients who called the AL were advised by the nurse to go to the emergency department immediately. Medicine patients were more likely to be triaged to the emergency department compared with surgery patients (45% vs 22%, P<0.0001).

The 30‐day readmission rates and the rates of unscheduled urgent or emergent care visits were higher for patients calling the AL compared with those who did not call (46/308, 15% vs 706/18,995, 4%, and 92/308, 30% vs 1303/18,995, 7%, respectively, both P<0.0001). Similar differences were found for patients discharged from medicine or surgery services who called the AL compared with those who did not (data not shown, both P<0.0001). The median number of days between AL call and rehospitalization was 0 (IQR, 02) and 1 (IQR, 08) for medicine and surgery patients, respectively. Ninety‐three percent of rehospitalizations were related to the index hospitalization, and 78% of patients who were readmitted had no outpatient encounter in the interim between discharge and rehospitalization.

DISCUSSION

We investigated the source and nature of patient telephone calls to an AL following a hospitalization or surgery, and our data revealed the following important findings: (1) nearly one‐half of the calls to the AL occurred within the first 48 hours following discharge; (2) the majority of the calls came from surgery patients, and a greater fraction of patients discharged from surgery services called the AL than patients discharged from medicine services; (3) the most common issues were uncontrolled pain, questions about medications, and problems understanding or executing aftercare instructions (particularly pertaining to the care of surgical wounds); and (4) patients calling the AL had higher rates of 30‐day rehospitalization and of unscheduled urgent or emergent care visits.

The utilization of our patient‐initiated call line was only 1.5%, which was on the low end of the 1% to 10% reported in the literature.[7, 12] This can be attributed to a number of issues that are specific to our system. First, the discharge instructions provided to our patients stated that they should call their primary care provider or the AL if they had questions. Accordingly, because approximately 50% of our patients had a primary care provider in our system, some may have preferentially contacted their primary care provider rather than the AL. Second, the instructions stated that the patients should call if they were experiencing the symptoms listed on the instruction sheet, so those with other problems/complaints may not have called. Third, AL personnel identified patients as being in our cohort by asking if they had been discharged or underwent a surgical procedure within 30‐days of their call. This may have resulted in the under‐reporting of patients who were hospitalized or had outpatient surgical procedures. Fourth, there may have been a number of characteristics specific to patients in our system that reduced the frequency with which they utilized the AL (eg, access to telephones or other community providers).

Most previous studies of patient‐initiated call lines have included them as part of multi‐intervention pre‐ and/or postdischarge strategies.[7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13] One prior small study compared the information reported by 37 patients who called an AL with that elicited by nurse‐initiated patient contact.[12] The most frequently reported problems in this study were medication‐related issues (43%). However, this study only included medicine patients and did not document the proportion of calls occurring at various time intervals.

The problems we identified (in both medicine and surgery patients) have previously been described,[2, 3, 4, 13, 14, 15, 16] but all of the studies reporting these problems utilized calls that were initiated by health care providers to patients at various fixed intervals following discharge (ie, 730 days). Most of these used a scripted approach seeking responses to specific questions or outcomes, and the specific timing at which the problems arose was not addressed. In contrast, we examined unsolicited concerns expressed by patients calling an AL following discharge whenever they felt sufficient urgency to address whatever problems or questions arose. We found that a large fraction of calls occurred on the day of or within the first 48 hours following discharge, much earlier than when provider‐initiated calls in the studies cited above occurred. Accordingly, our results cannot be used to compare the utility of patient‐ versus provider‐initiated calls, or to suggest that other hospitals should create an AL system. Rather, we suggest that our findings might be complementary to those reported in studies of provider‐initiated calls and only propose that by examining calls placed by patients to ALs, problems with hospital discharge processes (some of which may result in increased rates of readmission) may be discovered.

The observation that such a large fraction of calls to our AL occurred within the first 48 hours following discharge, together with the fact that many of the questions asked or concerns raised pertained to issues that should have been discussed during the discharge process (eg, pain control, care of surgical wounds), suggests that suboptimal patient education was occurring prior to discharge as was suggested by Henderson and Zernike.[17] This finding has led us to expand our patient education processes prior to discharge on both medicine and surgery services. Because our hospitalists care for approximately 90% of the patients admitted to medicine services and are increasingly involved in the care of patients on surgery services, they are integrally involved with such quality improvement initiatives.

To our knowledge this is the first study in the literature that describes both medicine and surgery patients who call an AL because of problems or questions following hospital discharge, categorizes these problems, determines when the patients called following their discharge, and identifies those who called as being at increased risk for early rehospitalizations and unscheduled urgent or emergent care visits. Given the financial penalties issued to hospitals with high 30‐day readmission rates, these patients may warrant more attention than is customarily available from telephone call lines or during routine outpatient follow‐up. The majority of patients who called our AL had Medicare, Medicaid, or a commercial insurance, and, accordingly, may have been eligible for additional services such as home visits and/or expedited follow‐up appointments.

Our study has a number of limitations. First, it is a single‐center study, so the results might not generalize to other institutions. Second, because the study was performed in a university‐affiliated, public safety‐net hospital, patient characteristics and the rates and types of postdischarge concerns that we observed might differ from those encountered in different types of hospitals and/or from those in nonteaching institutions. We would suggest, however, that the idea of using concerns raised by patients discharged from any type of hospital in calls to ALs may similarly identify problems with that specific hospital's discharge processes. Third, the information collected from the AL came from summaries provided by nurses answering the calls rather than from actual transcripts. This could have resulted in insufficient or incorrect information pertaining to some of the variables assessed in Table 2. The information presented in Table 1, however, was obtained from our data warehouse after matching medical record numbers. Fourth, we could have underestimated the number of patients who had 30‐day rehospitalizations and/or unplanned for urgent or emergent care visits if patients sought care at other hospitals. Fifth, the number of patients calling the AL was too small to allow us to do any type of robust matching or multivariable analysis. Accordingly, the differences that appeared between patients who called and those who did not (ie, English speakers, being medically indigent, the length of stay for the index hospitalization and the discharging service) could be the result of inadequate matching or interactions among the variables. Although matching or multivariate analysis might have yielded different associations between patients who called the AL versus those who did not, those who called the AL still had an increased risk of readmission and urgent or emergent visits and may still benefit from targeted interventions. Finally, the fact that only 1.5% of unique patients who were discharged called the AL could have biased our results. Because only 55% and 53% of the patients who did or did not call the AL, respectively, saw primary care physicians within our system within the 3 years prior to their index hospitalization (P=0.679), the frequency of calls to the AL that we observed could have underestimated the frequency with which patients had contact with other care providers in the community.

In summary, information collected from patient‐initiated calls to our AL identified several aspects of our discharge processes that needed improvement. We concluded that our predischarge educational processes for both medicine and surgery services needed modification, especially with respect to pain management, which problems to expect after hospitalization or surgery, and how to deal with them. The high rates of 30‐day rehospitalization and of unscheduled urgent or emergent care visits among patients calling the AL identifies them as being at increased risk for these outcomes, although the likelihood of these events may be related to factors other than just calling the AL.

- , , , , . Implementation of the care transitions intervention: sustainability and lessons learned. Prof Case Manag. 2009;14(6):282–293.

- , , , et al. Problems after discharge and understanding of communication with their primary care physicians among hospitalized seniors: a mixed methods study. J Hosp Med. 2010;5(7):385–391.

- , , , et al. Adverse events among medical patients after discharge from hospital. CMAJ. 2004;170(3):345–349.