User login

EPO may cut risk of brain abnormalities in preterm infants

Credit: Bertrand Devouard

Erythropoietin (EPO) can reduce the risk of brain injury in preterm infants, a new study suggests.

Infants who received 3 doses of EPO within 42 hours of birth were less likely than their untreated peers to have abnormal scores for white matter injury, white matter signal intensity, periventricular white matter loss, and gray matter injury.

Russia Ha-Vinh Leuchter, MD, of the University Hospital of Geneva in Switzerland, and her colleagues recounted these findings in JAMA.

The researchers evaluated 495 infants who were born in Switzerland between 2005 and 2012—at 26 weeks of gestation to 31 weeks and 6 days of gestation.

The children were randomized to receive EPO (n=256) or placebo (n=239) intravenously at 3 time points: before they reached 3 hours of age, at 12 to 18 hours after birth, and at 36 to 42 hours after birth.

Due to the limited availability of MRI, the researchers were only able to assess brain injury in a nonrandomized subset of 165 infants. Seventy-seven of these children received EPO, and 88 received placebo.

The patients underwent MRI at a median gestation age of 40 weeks and 5 days (range, 35 weeks and 5 days to 44 weeks and 6 days).

“We found that the brains of the children who had received the treatment had much less damage than those in the control group,” Dr Ha-Vinh Leuchter said. “This is the first time that the beneficial effect of the EPO hormone on the brains of premature babies has been shown.”

Specifically, the results showed that, at term-equivalent age, infants treated with EPO were less likely than controls to have abnormal scores for white matter injury (22% vs 36%), white matter signal intensity (3% vs 11%), periventricular white matter loss (18% vs 33%), and gray matter injury (7% vs 19%).

These results are only the first part of this study, according to the researchers. The second—and main—part of the work will focus on the neurocognitive development of these children, who will take part in various developmental tests at 2 and 5 years of age.

“[The tests] should confirm the effect that EPO treatment has on the neurodevelopmental disabilities that very premature babies often show during their infancy,” said Petra Hüppi, MD, also of the University Hospital of Geneva.

“If this does turn out to be the case, we will have taken an important step in preventing brain damage and its long-term consequences in premature babies.” ![]()

Credit: Bertrand Devouard

Erythropoietin (EPO) can reduce the risk of brain injury in preterm infants, a new study suggests.

Infants who received 3 doses of EPO within 42 hours of birth were less likely than their untreated peers to have abnormal scores for white matter injury, white matter signal intensity, periventricular white matter loss, and gray matter injury.

Russia Ha-Vinh Leuchter, MD, of the University Hospital of Geneva in Switzerland, and her colleagues recounted these findings in JAMA.

The researchers evaluated 495 infants who were born in Switzerland between 2005 and 2012—at 26 weeks of gestation to 31 weeks and 6 days of gestation.

The children were randomized to receive EPO (n=256) or placebo (n=239) intravenously at 3 time points: before they reached 3 hours of age, at 12 to 18 hours after birth, and at 36 to 42 hours after birth.

Due to the limited availability of MRI, the researchers were only able to assess brain injury in a nonrandomized subset of 165 infants. Seventy-seven of these children received EPO, and 88 received placebo.

The patients underwent MRI at a median gestation age of 40 weeks and 5 days (range, 35 weeks and 5 days to 44 weeks and 6 days).

“We found that the brains of the children who had received the treatment had much less damage than those in the control group,” Dr Ha-Vinh Leuchter said. “This is the first time that the beneficial effect of the EPO hormone on the brains of premature babies has been shown.”

Specifically, the results showed that, at term-equivalent age, infants treated with EPO were less likely than controls to have abnormal scores for white matter injury (22% vs 36%), white matter signal intensity (3% vs 11%), periventricular white matter loss (18% vs 33%), and gray matter injury (7% vs 19%).

These results are only the first part of this study, according to the researchers. The second—and main—part of the work will focus on the neurocognitive development of these children, who will take part in various developmental tests at 2 and 5 years of age.

“[The tests] should confirm the effect that EPO treatment has on the neurodevelopmental disabilities that very premature babies often show during their infancy,” said Petra Hüppi, MD, also of the University Hospital of Geneva.

“If this does turn out to be the case, we will have taken an important step in preventing brain damage and its long-term consequences in premature babies.” ![]()

Credit: Bertrand Devouard

Erythropoietin (EPO) can reduce the risk of brain injury in preterm infants, a new study suggests.

Infants who received 3 doses of EPO within 42 hours of birth were less likely than their untreated peers to have abnormal scores for white matter injury, white matter signal intensity, periventricular white matter loss, and gray matter injury.

Russia Ha-Vinh Leuchter, MD, of the University Hospital of Geneva in Switzerland, and her colleagues recounted these findings in JAMA.

The researchers evaluated 495 infants who were born in Switzerland between 2005 and 2012—at 26 weeks of gestation to 31 weeks and 6 days of gestation.

The children were randomized to receive EPO (n=256) or placebo (n=239) intravenously at 3 time points: before they reached 3 hours of age, at 12 to 18 hours after birth, and at 36 to 42 hours after birth.

Due to the limited availability of MRI, the researchers were only able to assess brain injury in a nonrandomized subset of 165 infants. Seventy-seven of these children received EPO, and 88 received placebo.

The patients underwent MRI at a median gestation age of 40 weeks and 5 days (range, 35 weeks and 5 days to 44 weeks and 6 days).

“We found that the brains of the children who had received the treatment had much less damage than those in the control group,” Dr Ha-Vinh Leuchter said. “This is the first time that the beneficial effect of the EPO hormone on the brains of premature babies has been shown.”

Specifically, the results showed that, at term-equivalent age, infants treated with EPO were less likely than controls to have abnormal scores for white matter injury (22% vs 36%), white matter signal intensity (3% vs 11%), periventricular white matter loss (18% vs 33%), and gray matter injury (7% vs 19%).

These results are only the first part of this study, according to the researchers. The second—and main—part of the work will focus on the neurocognitive development of these children, who will take part in various developmental tests at 2 and 5 years of age.

“[The tests] should confirm the effect that EPO treatment has on the neurodevelopmental disabilities that very premature babies often show during their infancy,” said Petra Hüppi, MD, also of the University Hospital of Geneva.

“If this does turn out to be the case, we will have taken an important step in preventing brain damage and its long-term consequences in premature babies.” ![]()

Enrollment terminated in anticoagulant trial

Credit: Andre E.X. Brown

Regado Biosciences, Inc., has permanently terminated enrollment in the phase 3 REGULATE-PCI trial due to serious allergic reactions in patients treated with the Revolixys Kit (also known as REG-1).

The kit is a 2-component system consisting of pegnivacogin, an anticoagulant aptamer specifically targeting coagulation factor IXa, and its complementary oligonucleotide active control agent, anivamersen.

The REGULATE-PCI trial is a comparison of the Revolixys Kit and bivilarudin in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention.

A data and safety monitoring board analyzed data from the roughly 3250 patients initially enrolled in the trial and discovered serious allergic reactions in patients treated with Revolixys.

“The [board] indicated that the level of serious allergic adverse events associated with Revolixys was of a frequency and severity such that they recommended that we do not enroll any further patients in the REGULATE-PCI trial,” said David J. Mazzo, PhD, CEO of Regado.

“We will now undertake a complete review of the unblinded database from REGULATE-PCI, which we expect will take several months to complete.”

Dr Mazzo did not provide details as to the type of allergic reactions patients experienced or the incidence of these events. He did say the exact cause of the reactions is unknown, but the data review and investigation should reveal that information.

The review should also provide information that will help Regado decide how to move forward with its development of Revolixys (REG-1) and a related system known as REG-2.

For more information on REG-1 and REG-2, visit Regado’s website. For more information on REGULATE-PCI, visit clinicaltrials.gov. ![]()

Credit: Andre E.X. Brown

Regado Biosciences, Inc., has permanently terminated enrollment in the phase 3 REGULATE-PCI trial due to serious allergic reactions in patients treated with the Revolixys Kit (also known as REG-1).

The kit is a 2-component system consisting of pegnivacogin, an anticoagulant aptamer specifically targeting coagulation factor IXa, and its complementary oligonucleotide active control agent, anivamersen.

The REGULATE-PCI trial is a comparison of the Revolixys Kit and bivilarudin in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention.

A data and safety monitoring board analyzed data from the roughly 3250 patients initially enrolled in the trial and discovered serious allergic reactions in patients treated with Revolixys.

“The [board] indicated that the level of serious allergic adverse events associated with Revolixys was of a frequency and severity such that they recommended that we do not enroll any further patients in the REGULATE-PCI trial,” said David J. Mazzo, PhD, CEO of Regado.

“We will now undertake a complete review of the unblinded database from REGULATE-PCI, which we expect will take several months to complete.”

Dr Mazzo did not provide details as to the type of allergic reactions patients experienced or the incidence of these events. He did say the exact cause of the reactions is unknown, but the data review and investigation should reveal that information.

The review should also provide information that will help Regado decide how to move forward with its development of Revolixys (REG-1) and a related system known as REG-2.

For more information on REG-1 and REG-2, visit Regado’s website. For more information on REGULATE-PCI, visit clinicaltrials.gov. ![]()

Credit: Andre E.X. Brown

Regado Biosciences, Inc., has permanently terminated enrollment in the phase 3 REGULATE-PCI trial due to serious allergic reactions in patients treated with the Revolixys Kit (also known as REG-1).

The kit is a 2-component system consisting of pegnivacogin, an anticoagulant aptamer specifically targeting coagulation factor IXa, and its complementary oligonucleotide active control agent, anivamersen.

The REGULATE-PCI trial is a comparison of the Revolixys Kit and bivilarudin in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention.

A data and safety monitoring board analyzed data from the roughly 3250 patients initially enrolled in the trial and discovered serious allergic reactions in patients treated with Revolixys.

“The [board] indicated that the level of serious allergic adverse events associated with Revolixys was of a frequency and severity such that they recommended that we do not enroll any further patients in the REGULATE-PCI trial,” said David J. Mazzo, PhD, CEO of Regado.

“We will now undertake a complete review of the unblinded database from REGULATE-PCI, which we expect will take several months to complete.”

Dr Mazzo did not provide details as to the type of allergic reactions patients experienced or the incidence of these events. He did say the exact cause of the reactions is unknown, but the data review and investigation should reveal that information.

The review should also provide information that will help Regado decide how to move forward with its development of Revolixys (REG-1) and a related system known as REG-2.

For more information on REG-1 and REG-2, visit Regado’s website. For more information on REGULATE-PCI, visit clinicaltrials.gov. ![]()

Study outlines risk factors for solid organ cancers after liver transplantation

SAN FRANCISCO – The indication for liver transplant, the selection of immunosuppression therapy, and smoking status influence the long-term risk of new solid organ malignancies after liver transplantation, Dr. Sebastian Rademacher reported at the 2014 World Transplant Congress.

Multivariate analysis showed that recipients’ risk of a new solid organ cancer was elevated for those who had a history of smoking (1.89). Risk was reduced for recipients who received tacrolimus, compared with cyclosporine A (0.56), and for patients who had primary biliary cirrhosis/primary sclerosing cholangitis (0.47) or hepatitis C infection (0.21) as the indication for transplantation.

"I think we have to reoptimize and reevaluate the currently used immunosuppressive regimens," Dr. Rademacher said. "We have to adapt cancer surveillance programs for high-risk patients. Further studies into surveillance protocols and surrogate markers and long-term outcomes are recommended."

Researchers led by Dr. Rademacher, a surgeon at the Campus Virchow Clinic, Charité, Berlin, retrospectively studied 1,179 consecutive adults who underwent liver transplantation between 1988 and 2002 and had follow-up evaluations until 2013. Patients were 47 years old, on average, at the time of transplantation, and the median follow-up was 13.3 years.

Their 20-year cumulative incidence of solid organ cancers was 14%, he reported at the congress, which was sponsored by the American Society of Transplant Surgeons. The mean age at cancer diagnosis was 56 years.

The researchers used age- and sex-matched individuals from the German general population for comparison. The standardized incidence ratio in transplant recipients was 1.2 for breast cancer, 9.4 for cancer of the oropharynx and larynx, 1.7 for cancers of the colon and rectum, 3.0 for lung cancer, 3.9 for esophageal and stomach cancers, 4.5 for kidney and bladder cancers, and 4.6 for cancers of the female genitourinary system.

"We tried to evaluate the different immunosuppressive regimens and, over time, we had, I think, 27 different primary regimens," Dr. Rademacher said. Steroid-free regimens and low-dose steroid were part of that consideration, "but we segregated them out. For the five most frequent regimens, there was no significance. We assessed immunosuppressive regimens given over at least 2 years, but there was no difference between the regimens. Also, the trough levels of tacrolimus did not have any significant influence," he said.

The investigators did not have data on cumulative immunosuppression or mTOR [mammalian target of rapamycin] inhibitors, which were introduced late in the study period, according to Dr. Rademacher, who disclosed no relevant conflicts of interest. A surrogate marker of immunosuppression, rejection frequency, did not significantly predict the development of solid organ malignancies.

The devil is in the details of this study. The incidence of solid organ tumors being high in the immunosuppressed population is well known, well documented. The difficulty is getting at what is driving that risk.

Lots of things have changed in immunosuppressive therapy over the last 20-25-years. The authors give us a snapshot, but they weren’t able to tell us whether the changes in immunosuppression had any impact on cancer risk, especially in regard to specific types of cancers.

Dr. Darius Mirza of the University of Birmingham, England, was the session cochair at the meeting. He made his remarks in an interview after the session and declared having no relevant conflicts of interest.

The devil is in the details of this study. The incidence of solid organ tumors being high in the immunosuppressed population is well known, well documented. The difficulty is getting at what is driving that risk.

Lots of things have changed in immunosuppressive therapy over the last 20-25-years. The authors give us a snapshot, but they weren’t able to tell us whether the changes in immunosuppression had any impact on cancer risk, especially in regard to specific types of cancers.

Dr. Darius Mirza of the University of Birmingham, England, was the session cochair at the meeting. He made his remarks in an interview after the session and declared having no relevant conflicts of interest.

The devil is in the details of this study. The incidence of solid organ tumors being high in the immunosuppressed population is well known, well documented. The difficulty is getting at what is driving that risk.

Lots of things have changed in immunosuppressive therapy over the last 20-25-years. The authors give us a snapshot, but they weren’t able to tell us whether the changes in immunosuppression had any impact on cancer risk, especially in regard to specific types of cancers.

Dr. Darius Mirza of the University of Birmingham, England, was the session cochair at the meeting. He made his remarks in an interview after the session and declared having no relevant conflicts of interest.

SAN FRANCISCO – The indication for liver transplant, the selection of immunosuppression therapy, and smoking status influence the long-term risk of new solid organ malignancies after liver transplantation, Dr. Sebastian Rademacher reported at the 2014 World Transplant Congress.

Multivariate analysis showed that recipients’ risk of a new solid organ cancer was elevated for those who had a history of smoking (1.89). Risk was reduced for recipients who received tacrolimus, compared with cyclosporine A (0.56), and for patients who had primary biliary cirrhosis/primary sclerosing cholangitis (0.47) or hepatitis C infection (0.21) as the indication for transplantation.

"I think we have to reoptimize and reevaluate the currently used immunosuppressive regimens," Dr. Rademacher said. "We have to adapt cancer surveillance programs for high-risk patients. Further studies into surveillance protocols and surrogate markers and long-term outcomes are recommended."

Researchers led by Dr. Rademacher, a surgeon at the Campus Virchow Clinic, Charité, Berlin, retrospectively studied 1,179 consecutive adults who underwent liver transplantation between 1988 and 2002 and had follow-up evaluations until 2013. Patients were 47 years old, on average, at the time of transplantation, and the median follow-up was 13.3 years.

Their 20-year cumulative incidence of solid organ cancers was 14%, he reported at the congress, which was sponsored by the American Society of Transplant Surgeons. The mean age at cancer diagnosis was 56 years.

The researchers used age- and sex-matched individuals from the German general population for comparison. The standardized incidence ratio in transplant recipients was 1.2 for breast cancer, 9.4 for cancer of the oropharynx and larynx, 1.7 for cancers of the colon and rectum, 3.0 for lung cancer, 3.9 for esophageal and stomach cancers, 4.5 for kidney and bladder cancers, and 4.6 for cancers of the female genitourinary system.

"We tried to evaluate the different immunosuppressive regimens and, over time, we had, I think, 27 different primary regimens," Dr. Rademacher said. Steroid-free regimens and low-dose steroid were part of that consideration, "but we segregated them out. For the five most frequent regimens, there was no significance. We assessed immunosuppressive regimens given over at least 2 years, but there was no difference between the regimens. Also, the trough levels of tacrolimus did not have any significant influence," he said.

The investigators did not have data on cumulative immunosuppression or mTOR [mammalian target of rapamycin] inhibitors, which were introduced late in the study period, according to Dr. Rademacher, who disclosed no relevant conflicts of interest. A surrogate marker of immunosuppression, rejection frequency, did not significantly predict the development of solid organ malignancies.

SAN FRANCISCO – The indication for liver transplant, the selection of immunosuppression therapy, and smoking status influence the long-term risk of new solid organ malignancies after liver transplantation, Dr. Sebastian Rademacher reported at the 2014 World Transplant Congress.

Multivariate analysis showed that recipients’ risk of a new solid organ cancer was elevated for those who had a history of smoking (1.89). Risk was reduced for recipients who received tacrolimus, compared with cyclosporine A (0.56), and for patients who had primary biliary cirrhosis/primary sclerosing cholangitis (0.47) or hepatitis C infection (0.21) as the indication for transplantation.

"I think we have to reoptimize and reevaluate the currently used immunosuppressive regimens," Dr. Rademacher said. "We have to adapt cancer surveillance programs for high-risk patients. Further studies into surveillance protocols and surrogate markers and long-term outcomes are recommended."

Researchers led by Dr. Rademacher, a surgeon at the Campus Virchow Clinic, Charité, Berlin, retrospectively studied 1,179 consecutive adults who underwent liver transplantation between 1988 and 2002 and had follow-up evaluations until 2013. Patients were 47 years old, on average, at the time of transplantation, and the median follow-up was 13.3 years.

Their 20-year cumulative incidence of solid organ cancers was 14%, he reported at the congress, which was sponsored by the American Society of Transplant Surgeons. The mean age at cancer diagnosis was 56 years.

The researchers used age- and sex-matched individuals from the German general population for comparison. The standardized incidence ratio in transplant recipients was 1.2 for breast cancer, 9.4 for cancer of the oropharynx and larynx, 1.7 for cancers of the colon and rectum, 3.0 for lung cancer, 3.9 for esophageal and stomach cancers, 4.5 for kidney and bladder cancers, and 4.6 for cancers of the female genitourinary system.

"We tried to evaluate the different immunosuppressive regimens and, over time, we had, I think, 27 different primary regimens," Dr. Rademacher said. Steroid-free regimens and low-dose steroid were part of that consideration, "but we segregated them out. For the five most frequent regimens, there was no significance. We assessed immunosuppressive regimens given over at least 2 years, but there was no difference between the regimens. Also, the trough levels of tacrolimus did not have any significant influence," he said.

The investigators did not have data on cumulative immunosuppression or mTOR [mammalian target of rapamycin] inhibitors, which were introduced late in the study period, according to Dr. Rademacher, who disclosed no relevant conflicts of interest. A surrogate marker of immunosuppression, rejection frequency, did not significantly predict the development of solid organ malignancies.

AT THE 2014 WORLD TRANSPLANT CONGRESS

Key clinical point: Immunosuppression regimen selection influences risk for solid cancers after liver transplantation.

Major Finding: Risk of a new solid organ cancer was reduced for liver transplant recipients who got tacrolimus, compared with cyclosporine A (0.56), for their immunosuppression regimen.

Data Source: A retrospective cohort study of 1,179 adults who underwent liver transplantation between 1988 and 2002

Disclosures: Dr. Rademacher disclosed no relevant conflicts of interest.

Early elimination of cyclosporine after heart transplant has renal benefit

SAN FRANCISCO – Use of an everolimus-containing regimen with early stopping of cyclosporine after de novo heart transplantation improves renal function and reduces cardiac allograft vasculopathy, without compromising graft outcomes, new data suggest.

These was among key findings of the randomized, open-label SCHEDULE (Scandinavian Heart Transplant Everolimus De Novo Study with Early Calcineurin Inhibitor Avoidance) reported at the 2014 World Transplant Congress.

"Renal dysfunction and cardiac allograft vasculopathy are markers for increased morbidity and mortality after heart transplantation," lead author Dr. Vilborg Sigurdardottir commented when introducing the study.

Patients in the trial were randomized evenly to a three-drug regimen containing the calcineurin inhibitor cyclosporine (Sandimmune) or to a four-drug regimen also containing the mTOR inhibitor everolimus (Zortress) with discontinuation of cyclosporine at week 7-11. Everolimus is currently approved by the Food and Drug Administration to prevent graft rejection in kidney and liver transplant recipients and, under another brand name, to treat some cancers.

Measured glomerular filtration rate (GFR) at 12 months, the trial’s primary outcome, was 30% better in the everolimus group than in the cyclosporine group (79.8 vs. 61.5 mL/min per 1.73 m2; P less than .001), according to results presented at the congress and recently published (Am. J. Transplant. 2014;14:1828-38).

The urinary albumin-creatinine ratio was higher in the everolimus group, but none of the patients had nephrotic levels of proteinuria.

Rates of adverse events were similar, with the exception that the everolimus group had a lower rate of cytomegalovirus infection (5% vs. 30%) and a higher rate of pneumonia (12% vs. 3%), Dr. Sigurdardottir reported at the congress, which was sponsored by the American Society of Transplant Surgeons.

The incidence of biopsy-proven acute rejection of at least grade 2R was greater with everolimus (40% vs. 18%, P = .01). However, at 12 months, the groups did not differ with respect to left ventricular function as assessed by echocardiography and biomarkers, and, in a cardiac reserve substudy, with respect to cardiac output and pulmonary capillary wedge pressure.

The incidence of cardiac allograft vasculopathy, defined as a mean media-intima thickness of at least 0.5 mm on intravascular ultrasound (IVUS), was lower in the everolimus group (51% vs. 65%, P less than .01), and progression assessed as the change in percent atheroma volume was slower in that group.

"Everolimus initiation and early cyclosporine elimination in de novo heart transplant recipients showed a highly significant improvement of renal function in terms of measured GFR, a reduced incidence of cytomegalovirus [a confirmatory result of previous large-scale studies], similar numbers of adverse and serious adverse events, and an increased incidence of treated acute rejection, however, without hemodynamic compromise and with preserved cardiac function and preserved cardiac reserve," concluded Dr. Sigurdardottir, who is medical director of heart transplantation at the Transplant Institute, Sahlgrenska University Hospital, Gothenburg, Sweden. "We saw also favorable coronary remodeling and less graft vasculopathy, as previously shown."

Among patients whose donor hearts had such disease, the increase in media-intima thickness and percent atheroma volume was less with everolimus than with cyclosporine, Dr. Sigurdardottir said. "Interestingly, we saw here that the total atheroma volume decreased between baseline and 12 months in the everolimus group in the patients who had preexisting donor disease."

An attendee from Norway said, "I am a nephrologist, and if I were to get a new heart, I’d rather have a GFR of 61 and no rejection than a GFR of 73 with rejection. Have you looked at the development of donor-specific antibodies in the ones who had rejection, because I’d like to live for more than a year – I’d like to live 3 years or 5 years or 10 years."

"You are absolutely right. At the time of transplantation, we would be looking at the acute problems, and we often see the kidney dysfunction, so we want to do something about that. But of course these studies need to tell us how patients fare longer term," Dr. Sigurdardottir agreed. None of the patients were found to have donor-specific antibodies, but the trial protocol did not mandate routine measurement, she said.

An attendee from Los Angeles commented, "We tried to do CNI [calcineurin inhibitor] weaning in 2006 and had hemodynamically compromised rejection. Now, I congratulate you on being innovative and having quadruple therapy from the get-go and then taking off the CNI. But the issue of increased rejection is important because ISHLT [International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation] data show that that does lead to poorer outcome. It is countered by your improvement in renal function, but also your IVUS result, I think, is very important as well."

"Rejection is an important issue, but it is a common issue after transplantation. It was usually manageable. Since we didn’t see any hemodynamic compromise, it was up to each investigator to evaluate what to do. There were nine patients who converted to combination therapy," Dr. Sigurdardottir reported. "The future needs to tell us what the relevance of this rejection is, and we will do a follow-up at 3 and 5 years."

Dr. Sigurdardottir disclosed no relevant conflicts of interest. The trial was sponsored by Novartis, manufacturer of everolimus.

SAN FRANCISCO – Use of an everolimus-containing regimen with early stopping of cyclosporine after de novo heart transplantation improves renal function and reduces cardiac allograft vasculopathy, without compromising graft outcomes, new data suggest.

These was among key findings of the randomized, open-label SCHEDULE (Scandinavian Heart Transplant Everolimus De Novo Study with Early Calcineurin Inhibitor Avoidance) reported at the 2014 World Transplant Congress.

"Renal dysfunction and cardiac allograft vasculopathy are markers for increased morbidity and mortality after heart transplantation," lead author Dr. Vilborg Sigurdardottir commented when introducing the study.

Patients in the trial were randomized evenly to a three-drug regimen containing the calcineurin inhibitor cyclosporine (Sandimmune) or to a four-drug regimen also containing the mTOR inhibitor everolimus (Zortress) with discontinuation of cyclosporine at week 7-11. Everolimus is currently approved by the Food and Drug Administration to prevent graft rejection in kidney and liver transplant recipients and, under another brand name, to treat some cancers.

Measured glomerular filtration rate (GFR) at 12 months, the trial’s primary outcome, was 30% better in the everolimus group than in the cyclosporine group (79.8 vs. 61.5 mL/min per 1.73 m2; P less than .001), according to results presented at the congress and recently published (Am. J. Transplant. 2014;14:1828-38).

The urinary albumin-creatinine ratio was higher in the everolimus group, but none of the patients had nephrotic levels of proteinuria.

Rates of adverse events were similar, with the exception that the everolimus group had a lower rate of cytomegalovirus infection (5% vs. 30%) and a higher rate of pneumonia (12% vs. 3%), Dr. Sigurdardottir reported at the congress, which was sponsored by the American Society of Transplant Surgeons.

The incidence of biopsy-proven acute rejection of at least grade 2R was greater with everolimus (40% vs. 18%, P = .01). However, at 12 months, the groups did not differ with respect to left ventricular function as assessed by echocardiography and biomarkers, and, in a cardiac reserve substudy, with respect to cardiac output and pulmonary capillary wedge pressure.

The incidence of cardiac allograft vasculopathy, defined as a mean media-intima thickness of at least 0.5 mm on intravascular ultrasound (IVUS), was lower in the everolimus group (51% vs. 65%, P less than .01), and progression assessed as the change in percent atheroma volume was slower in that group.

"Everolimus initiation and early cyclosporine elimination in de novo heart transplant recipients showed a highly significant improvement of renal function in terms of measured GFR, a reduced incidence of cytomegalovirus [a confirmatory result of previous large-scale studies], similar numbers of adverse and serious adverse events, and an increased incidence of treated acute rejection, however, without hemodynamic compromise and with preserved cardiac function and preserved cardiac reserve," concluded Dr. Sigurdardottir, who is medical director of heart transplantation at the Transplant Institute, Sahlgrenska University Hospital, Gothenburg, Sweden. "We saw also favorable coronary remodeling and less graft vasculopathy, as previously shown."

Among patients whose donor hearts had such disease, the increase in media-intima thickness and percent atheroma volume was less with everolimus than with cyclosporine, Dr. Sigurdardottir said. "Interestingly, we saw here that the total atheroma volume decreased between baseline and 12 months in the everolimus group in the patients who had preexisting donor disease."

An attendee from Norway said, "I am a nephrologist, and if I were to get a new heart, I’d rather have a GFR of 61 and no rejection than a GFR of 73 with rejection. Have you looked at the development of donor-specific antibodies in the ones who had rejection, because I’d like to live for more than a year – I’d like to live 3 years or 5 years or 10 years."

"You are absolutely right. At the time of transplantation, we would be looking at the acute problems, and we often see the kidney dysfunction, so we want to do something about that. But of course these studies need to tell us how patients fare longer term," Dr. Sigurdardottir agreed. None of the patients were found to have donor-specific antibodies, but the trial protocol did not mandate routine measurement, she said.

An attendee from Los Angeles commented, "We tried to do CNI [calcineurin inhibitor] weaning in 2006 and had hemodynamically compromised rejection. Now, I congratulate you on being innovative and having quadruple therapy from the get-go and then taking off the CNI. But the issue of increased rejection is important because ISHLT [International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation] data show that that does lead to poorer outcome. It is countered by your improvement in renal function, but also your IVUS result, I think, is very important as well."

"Rejection is an important issue, but it is a common issue after transplantation. It was usually manageable. Since we didn’t see any hemodynamic compromise, it was up to each investigator to evaluate what to do. There were nine patients who converted to combination therapy," Dr. Sigurdardottir reported. "The future needs to tell us what the relevance of this rejection is, and we will do a follow-up at 3 and 5 years."

Dr. Sigurdardottir disclosed no relevant conflicts of interest. The trial was sponsored by Novartis, manufacturer of everolimus.

SAN FRANCISCO – Use of an everolimus-containing regimen with early stopping of cyclosporine after de novo heart transplantation improves renal function and reduces cardiac allograft vasculopathy, without compromising graft outcomes, new data suggest.

These was among key findings of the randomized, open-label SCHEDULE (Scandinavian Heart Transplant Everolimus De Novo Study with Early Calcineurin Inhibitor Avoidance) reported at the 2014 World Transplant Congress.

"Renal dysfunction and cardiac allograft vasculopathy are markers for increased morbidity and mortality after heart transplantation," lead author Dr. Vilborg Sigurdardottir commented when introducing the study.

Patients in the trial were randomized evenly to a three-drug regimen containing the calcineurin inhibitor cyclosporine (Sandimmune) or to a four-drug regimen also containing the mTOR inhibitor everolimus (Zortress) with discontinuation of cyclosporine at week 7-11. Everolimus is currently approved by the Food and Drug Administration to prevent graft rejection in kidney and liver transplant recipients and, under another brand name, to treat some cancers.

Measured glomerular filtration rate (GFR) at 12 months, the trial’s primary outcome, was 30% better in the everolimus group than in the cyclosporine group (79.8 vs. 61.5 mL/min per 1.73 m2; P less than .001), according to results presented at the congress and recently published (Am. J. Transplant. 2014;14:1828-38).

The urinary albumin-creatinine ratio was higher in the everolimus group, but none of the patients had nephrotic levels of proteinuria.

Rates of adverse events were similar, with the exception that the everolimus group had a lower rate of cytomegalovirus infection (5% vs. 30%) and a higher rate of pneumonia (12% vs. 3%), Dr. Sigurdardottir reported at the congress, which was sponsored by the American Society of Transplant Surgeons.

The incidence of biopsy-proven acute rejection of at least grade 2R was greater with everolimus (40% vs. 18%, P = .01). However, at 12 months, the groups did not differ with respect to left ventricular function as assessed by echocardiography and biomarkers, and, in a cardiac reserve substudy, with respect to cardiac output and pulmonary capillary wedge pressure.

The incidence of cardiac allograft vasculopathy, defined as a mean media-intima thickness of at least 0.5 mm on intravascular ultrasound (IVUS), was lower in the everolimus group (51% vs. 65%, P less than .01), and progression assessed as the change in percent atheroma volume was slower in that group.

"Everolimus initiation and early cyclosporine elimination in de novo heart transplant recipients showed a highly significant improvement of renal function in terms of measured GFR, a reduced incidence of cytomegalovirus [a confirmatory result of previous large-scale studies], similar numbers of adverse and serious adverse events, and an increased incidence of treated acute rejection, however, without hemodynamic compromise and with preserved cardiac function and preserved cardiac reserve," concluded Dr. Sigurdardottir, who is medical director of heart transplantation at the Transplant Institute, Sahlgrenska University Hospital, Gothenburg, Sweden. "We saw also favorable coronary remodeling and less graft vasculopathy, as previously shown."

Among patients whose donor hearts had such disease, the increase in media-intima thickness and percent atheroma volume was less with everolimus than with cyclosporine, Dr. Sigurdardottir said. "Interestingly, we saw here that the total atheroma volume decreased between baseline and 12 months in the everolimus group in the patients who had preexisting donor disease."

An attendee from Norway said, "I am a nephrologist, and if I were to get a new heart, I’d rather have a GFR of 61 and no rejection than a GFR of 73 with rejection. Have you looked at the development of donor-specific antibodies in the ones who had rejection, because I’d like to live for more than a year – I’d like to live 3 years or 5 years or 10 years."

"You are absolutely right. At the time of transplantation, we would be looking at the acute problems, and we often see the kidney dysfunction, so we want to do something about that. But of course these studies need to tell us how patients fare longer term," Dr. Sigurdardottir agreed. None of the patients were found to have donor-specific antibodies, but the trial protocol did not mandate routine measurement, she said.

An attendee from Los Angeles commented, "We tried to do CNI [calcineurin inhibitor] weaning in 2006 and had hemodynamically compromised rejection. Now, I congratulate you on being innovative and having quadruple therapy from the get-go and then taking off the CNI. But the issue of increased rejection is important because ISHLT [International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation] data show that that does lead to poorer outcome. It is countered by your improvement in renal function, but also your IVUS result, I think, is very important as well."

"Rejection is an important issue, but it is a common issue after transplantation. It was usually manageable. Since we didn’t see any hemodynamic compromise, it was up to each investigator to evaluate what to do. There were nine patients who converted to combination therapy," Dr. Sigurdardottir reported. "The future needs to tell us what the relevance of this rejection is, and we will do a follow-up at 3 and 5 years."

Dr. Sigurdardottir disclosed no relevant conflicts of interest. The trial was sponsored by Novartis, manufacturer of everolimus.

FROM THE 2014 WORLD TRANSPLANT CONGRESS

Key clinical point: For post–heart transplant patients, early cessation of cyclosporine when using an everolimus-containing regimen appears to be safe and did not compromise graft outcomes.

Major finding: Compared with patients continued on cyclosporine, patients taken off this agent at 7-11 weeks had a 30% better measured glomerular filtration rate at 12 months.

Data source: A randomized, open-label trial of 115 patients undergoing de novo heart transplantation

Disclosures: Dr. Sigurdardottir disclosed no relevant conflicts of interest. The trial was sponsored by Novartis, manufacturer of everolimus.

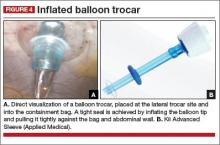

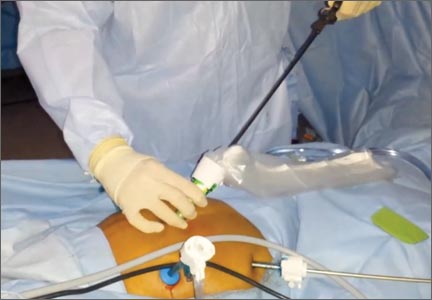

Multicenter study cites safety of power morcellation within an insufflated isolation bag

A 16-month multicenter study in which 73 patients underwent morcellation of the uterus or myomas within an insufflated isolation bag during minimally invasive (MI) hysterectomy or myomectomy recently has been published in Obstetrics & Gynecology. The researchers conclude that contained power morcellation using this technique is feasible.1

Sarah L. Cohen, MD, MPH, and colleagues at Fairview Ridges Hospital, Burnsville, Minnesota; Johns Hopkins Hospital, Baltimore, Maryland; Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston; and Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts are all high-volume surgeons experienced in advanced MI gynecologic surgical techniques.1

Patients in whom morcellation was planned at the time of MI hysterectomy or myomectomy during the study period (January 2013 through April 2014) were offered in-bag morcellation and included in the study. Exclusion criteria were known or suspected malignancy. Preoperative testing was performed to evaluate risk of genital tract cancer. Perioperative information included mode of access, type of procedure(s) performed, operative time, estimated blood loss, specimen weight, intact status of isolation bag postmorcellation, length of hospital stay, intraoperative complications, postoperative complications, readmission, and reoperation.1

The technique for morcellation within an insufflated isolation bag was developed by one of the authors, Tony Shibley, MD, for use during laparoendoscopic single-site hysterectomy (WATCH Dr. Shibley’s technique video here and listen to an interview with Dr. Shibley here.) The technique adapts to multiport laparoscopic and robot-assisted laparoscopic hysterectomy and myomectomy.1

Based on the results of their study, the authors conclude: “Morcellation within an insufflated isolation bag is a feasible technique. Methods for morcellating uterine tissue in a contained manner may provide an option to minimize the risks of open power morcellation while preserving the benefits of minimally invasive surgery.”1

In response to this study, Charles R. Rardin, MD, Associate Professor of Obstetrics and Gynecology at Brown Medical School and Women and Infants’ Hospital in Providence, Rhode Island, wrote an online editorial in Obstetrics & Gynecology.2 Dr. Rardin pointed out that “Until there are more effective screening tools to detect these unusual cancers [leiomyosarcoma], surgeons and hospitals are required to develop responses to these issues.”

He suggests that one extreme reaction to the morcellation crisis is to ban any method of morcellation entirely, leaving laparotomy as the only option for tissue extraction. Finding that logic faulty—relative value to the few at greater cost to the many—he suggests that one might also question the safety of other strategies to treat leiomyomas, including ablation and embolization.

Institutions have responded in several different ways, he says:

- Some hospitals have completely banned power morcellation (See “FDA, hospitals caution against laparoscopic power morcellation during hysterectomy and myomectomy.”

- Some allow power morcellation with additional layers of informed consent or case approval.

- One university allows power morcellation only when a uterus is less than 18 weeks’ gestation in size. Morcellation is only permitted when using an endoscopic collection bag.

He finds that Cohen and colleagues’ techniques lack formal investigation of bag integrity or tissue spread (as successful control of tissue spread was judged by a visual assessment by the surgeon). He also indicates that the technique described is better suited to single-port laparoscopy than multi-port, that single-site laparoscopy required additional training and skill, and that the incisions in single-site laparoscopy are fewer in number but larger in diameter, eliciting concern for increased hernia formation. The authors recognize that using the technique in multi-port surgery, because penetration of the bag by one or more trocars may cause a disruption in bag integrity, is in violation of the manufacturer’s recommendations.1,2 Dr. Rardin additionally expresses concern about “the passage of trocars through the peritoneal cavity, out of direct visualization until the trocar pierces the bag”2 where the camera resides. He is concerned about reducing one set of risks while increasing other risks, and suggests that vaginal hysterectomy would reduce the risk of dissemination while preserving the patient’s benefits from minimally invasive surgery.2

1. Cohen SL, Einarsson JI, Wang KC, et al. Contained power morcellation within an insufflated isolation bag [published online ahead of print August 5, 2014]. Obstet Gyncol. doi:10.1097/AOG.0000000000000421. http://journals.lww.com/greenjournal/Abstract/publishahead/Contained_Power_Morcellation_Within_an_Insufflated.99365.aspx. Accessed August 15, 2014.

2. Rardin CR. Mitigating risks of specimen extraction: Is in-bag power morcellation an answer? [published online ahead of print August 5, 2014]. Obstet Gynecol. doi:10.1097/AOG.0000000000000434. http://journals.lww.com/greenjournal/Citation/publishahead/Mitigating_Risks_of_Specimen_Extraction__Is_In_Bag.99352.aspx. Accessed August 15, 2014.

A 16-month multicenter study in which 73 patients underwent morcellation of the uterus or myomas within an insufflated isolation bag during minimally invasive (MI) hysterectomy or myomectomy recently has been published in Obstetrics & Gynecology. The researchers conclude that contained power morcellation using this technique is feasible.1

Sarah L. Cohen, MD, MPH, and colleagues at Fairview Ridges Hospital, Burnsville, Minnesota; Johns Hopkins Hospital, Baltimore, Maryland; Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston; and Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts are all high-volume surgeons experienced in advanced MI gynecologic surgical techniques.1

Patients in whom morcellation was planned at the time of MI hysterectomy or myomectomy during the study period (January 2013 through April 2014) were offered in-bag morcellation and included in the study. Exclusion criteria were known or suspected malignancy. Preoperative testing was performed to evaluate risk of genital tract cancer. Perioperative information included mode of access, type of procedure(s) performed, operative time, estimated blood loss, specimen weight, intact status of isolation bag postmorcellation, length of hospital stay, intraoperative complications, postoperative complications, readmission, and reoperation.1

The technique for morcellation within an insufflated isolation bag was developed by one of the authors, Tony Shibley, MD, for use during laparoendoscopic single-site hysterectomy (WATCH Dr. Shibley’s technique video here and listen to an interview with Dr. Shibley here.) The technique adapts to multiport laparoscopic and robot-assisted laparoscopic hysterectomy and myomectomy.1

Based on the results of their study, the authors conclude: “Morcellation within an insufflated isolation bag is a feasible technique. Methods for morcellating uterine tissue in a contained manner may provide an option to minimize the risks of open power morcellation while preserving the benefits of minimally invasive surgery.”1

In response to this study, Charles R. Rardin, MD, Associate Professor of Obstetrics and Gynecology at Brown Medical School and Women and Infants’ Hospital in Providence, Rhode Island, wrote an online editorial in Obstetrics & Gynecology.2 Dr. Rardin pointed out that “Until there are more effective screening tools to detect these unusual cancers [leiomyosarcoma], surgeons and hospitals are required to develop responses to these issues.”

He suggests that one extreme reaction to the morcellation crisis is to ban any method of morcellation entirely, leaving laparotomy as the only option for tissue extraction. Finding that logic faulty—relative value to the few at greater cost to the many—he suggests that one might also question the safety of other strategies to treat leiomyomas, including ablation and embolization.

Institutions have responded in several different ways, he says:

- Some hospitals have completely banned power morcellation (See “FDA, hospitals caution against laparoscopic power morcellation during hysterectomy and myomectomy.”

- Some allow power morcellation with additional layers of informed consent or case approval.

- One university allows power morcellation only when a uterus is less than 18 weeks’ gestation in size. Morcellation is only permitted when using an endoscopic collection bag.

He finds that Cohen and colleagues’ techniques lack formal investigation of bag integrity or tissue spread (as successful control of tissue spread was judged by a visual assessment by the surgeon). He also indicates that the technique described is better suited to single-port laparoscopy than multi-port, that single-site laparoscopy required additional training and skill, and that the incisions in single-site laparoscopy are fewer in number but larger in diameter, eliciting concern for increased hernia formation. The authors recognize that using the technique in multi-port surgery, because penetration of the bag by one or more trocars may cause a disruption in bag integrity, is in violation of the manufacturer’s recommendations.1,2 Dr. Rardin additionally expresses concern about “the passage of trocars through the peritoneal cavity, out of direct visualization until the trocar pierces the bag”2 where the camera resides. He is concerned about reducing one set of risks while increasing other risks, and suggests that vaginal hysterectomy would reduce the risk of dissemination while preserving the patient’s benefits from minimally invasive surgery.2

A 16-month multicenter study in which 73 patients underwent morcellation of the uterus or myomas within an insufflated isolation bag during minimally invasive (MI) hysterectomy or myomectomy recently has been published in Obstetrics & Gynecology. The researchers conclude that contained power morcellation using this technique is feasible.1

Sarah L. Cohen, MD, MPH, and colleagues at Fairview Ridges Hospital, Burnsville, Minnesota; Johns Hopkins Hospital, Baltimore, Maryland; Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston; and Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts are all high-volume surgeons experienced in advanced MI gynecologic surgical techniques.1

Patients in whom morcellation was planned at the time of MI hysterectomy or myomectomy during the study period (January 2013 through April 2014) were offered in-bag morcellation and included in the study. Exclusion criteria were known or suspected malignancy. Preoperative testing was performed to evaluate risk of genital tract cancer. Perioperative information included mode of access, type of procedure(s) performed, operative time, estimated blood loss, specimen weight, intact status of isolation bag postmorcellation, length of hospital stay, intraoperative complications, postoperative complications, readmission, and reoperation.1

The technique for morcellation within an insufflated isolation bag was developed by one of the authors, Tony Shibley, MD, for use during laparoendoscopic single-site hysterectomy (WATCH Dr. Shibley’s technique video here and listen to an interview with Dr. Shibley here.) The technique adapts to multiport laparoscopic and robot-assisted laparoscopic hysterectomy and myomectomy.1

Based on the results of their study, the authors conclude: “Morcellation within an insufflated isolation bag is a feasible technique. Methods for morcellating uterine tissue in a contained manner may provide an option to minimize the risks of open power morcellation while preserving the benefits of minimally invasive surgery.”1

In response to this study, Charles R. Rardin, MD, Associate Professor of Obstetrics and Gynecology at Brown Medical School and Women and Infants’ Hospital in Providence, Rhode Island, wrote an online editorial in Obstetrics & Gynecology.2 Dr. Rardin pointed out that “Until there are more effective screening tools to detect these unusual cancers [leiomyosarcoma], surgeons and hospitals are required to develop responses to these issues.”

He suggests that one extreme reaction to the morcellation crisis is to ban any method of morcellation entirely, leaving laparotomy as the only option for tissue extraction. Finding that logic faulty—relative value to the few at greater cost to the many—he suggests that one might also question the safety of other strategies to treat leiomyomas, including ablation and embolization.

Institutions have responded in several different ways, he says:

- Some hospitals have completely banned power morcellation (See “FDA, hospitals caution against laparoscopic power morcellation during hysterectomy and myomectomy.”

- Some allow power morcellation with additional layers of informed consent or case approval.

- One university allows power morcellation only when a uterus is less than 18 weeks’ gestation in size. Morcellation is only permitted when using an endoscopic collection bag.

He finds that Cohen and colleagues’ techniques lack formal investigation of bag integrity or tissue spread (as successful control of tissue spread was judged by a visual assessment by the surgeon). He also indicates that the technique described is better suited to single-port laparoscopy than multi-port, that single-site laparoscopy required additional training and skill, and that the incisions in single-site laparoscopy are fewer in number but larger in diameter, eliciting concern for increased hernia formation. The authors recognize that using the technique in multi-port surgery, because penetration of the bag by one or more trocars may cause a disruption in bag integrity, is in violation of the manufacturer’s recommendations.1,2 Dr. Rardin additionally expresses concern about “the passage of trocars through the peritoneal cavity, out of direct visualization until the trocar pierces the bag”2 where the camera resides. He is concerned about reducing one set of risks while increasing other risks, and suggests that vaginal hysterectomy would reduce the risk of dissemination while preserving the patient’s benefits from minimally invasive surgery.2

1. Cohen SL, Einarsson JI, Wang KC, et al. Contained power morcellation within an insufflated isolation bag [published online ahead of print August 5, 2014]. Obstet Gyncol. doi:10.1097/AOG.0000000000000421. http://journals.lww.com/greenjournal/Abstract/publishahead/Contained_Power_Morcellation_Within_an_Insufflated.99365.aspx. Accessed August 15, 2014.

2. Rardin CR. Mitigating risks of specimen extraction: Is in-bag power morcellation an answer? [published online ahead of print August 5, 2014]. Obstet Gynecol. doi:10.1097/AOG.0000000000000434. http://journals.lww.com/greenjournal/Citation/publishahead/Mitigating_Risks_of_Specimen_Extraction__Is_In_Bag.99352.aspx. Accessed August 15, 2014.

1. Cohen SL, Einarsson JI, Wang KC, et al. Contained power morcellation within an insufflated isolation bag [published online ahead of print August 5, 2014]. Obstet Gyncol. doi:10.1097/AOG.0000000000000421. http://journals.lww.com/greenjournal/Abstract/publishahead/Contained_Power_Morcellation_Within_an_Insufflated.99365.aspx. Accessed August 15, 2014.

2. Rardin CR. Mitigating risks of specimen extraction: Is in-bag power morcellation an answer? [published online ahead of print August 5, 2014]. Obstet Gynecol. doi:10.1097/AOG.0000000000000434. http://journals.lww.com/greenjournal/Citation/publishahead/Mitigating_Risks_of_Specimen_Extraction__Is_In_Bag.99352.aspx. Accessed August 15, 2014.

Point/Counterpoint: Is screening for asymptomatic carotid artery stenosis justified?

Introduction

The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force has just published its latest guidance on carotid screening for asymptomatic disease, basically stating that it should not be done (see story page 1). In this Point-Counterpoint Dr. Zierler and Dr. Berland provide their views on this controversial issue. From my perspective the debate must revolve around the following questions: The gist of the USPSTF statement seems to be that screening is being performed only to detect patients with critical carotid stenosis so that an intervention (CEA or CAS) can be performed. However, shouldn’t screening also be used to identify atherosclerotic burden in order to prevent cardiovascular morbidity? Whatever the reasons for screening, should national health systems pay for screening? If not, what about individual physicians charging for screenings on selected/nonselected patients? What about free screenings? And as Dr. Zierler and Dr. Berland suggest, is screening getting a bad rap just because screening and subsequent CEA or CAS are being poorly performed? Finally, I wouldn\'t be surprised if some of the task force members have had their own carotids screened despite their negative recommendation. We would be interested in your viewpoint, so please take our online, interactive poll on our home page (bottom right) to weigh in on this important issue.

Dr. Russell Samson is the Medical Editor of Vascular Specialist.

YES: Screen, but screen well.

By Todd Berland, M.D.

Every patient with symptomatic carotid artery stenosis was asymptomatic the day before. The impact of stroke can be devastating, with a 20% mortality from the acute event and 40%-50% survival over the next 5 years. Of those surviving the initial event, a significant percentage of patients are unable to return to work, and up to 25% over the age of 65 require long-term institutional care.1 There is no doubt that the emotional, financial, and societal burden of caring for stroke patients is significant. The Asymptomatic Carotid Atherosclerosis Study and the Asymptomatic Carotid Surgery Trial demonstrated a significant reduction in stroke in asymptomatic, high-grade carotid artery stenosis patients treated with carotid endarterectomy compared to medical management alone.2,3 So wouldn’t it seem as if carotid artery screening would be beneficial?

The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommended against routine carotid screening because of its "high risk" and low reward. I believe that when a certified lab screens the appropriate population such as individuals over 55 with cardiovascular risk factors that include hypertension, diabetes, smoking, and hypercholesterolemia, and combines this with an intervention that has a low stroke and morbidity rate, then the balance is tipped and carotid screening becomes both low risk and high reward.

One of the problems with carotid ultrasound is that too many entrepreneurs have made a business of it. Suboptimal equipment is being used by uncertified technicians in medical offices and church parking lots all across this country. It’s no surprise that the false positives are going to be high in these situations. Also, when one combines all of the above with the screening of those who aren’t at risk, where the general prevalence of disease is low, it can be a recipe for disaster. This is going to lead to additional studies such as CT angiograms or possibly even cerebral angiograms, both of which have inherent risks.

Even though it’s possible to understand why the USPSTF may have concluded against routine screening, I believe that at-risk patients should be screened by a certified lab, and that physicians performing the interventions should be able to do so with low morbidity and mortality. Vascular surgeons have been marginalized over recent years as many others have become interested in finding and treating carotid disease. Most of us are either registered vascular technologists or registered physicians in vascular interpretation, and our labs are certified by the Intersocietal Accreditation Commission. We go through hours of continuing medical education in regard to vascular ultrasound, and our labs’ results are tested and certified for accuracy.

We need to convince insurance companies and the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services that these studies should be permitted only in certified labs and the results interpreted by certified physicians such as vascular surgeons.

Moreover, when indicated, the interventions should be carried out by vascular surgeons who are trained to perform both carotid endarter- ectomy and carotid artery stenting to be able to offer the patient the best individualized treatment.

Dr. Berland is director of outpatient vascular interventions at NYU Langone Medical Center.

References

1. Circulation 2012;125:188.

2. JAMA 1995:273:1421-8.

3. Lancet 2004;363:1491-502.

NO: General screening is not appropriate.

By R. Eugene Zierler, M.D.

To most vascular specialists, the concept of detecting asymptomatic carotid stenosis and intervening to prevent stroke makes intuitive sense, but is it consistent with the evidence? In 2007, the USPSTF concluded that the general asymptomatic adult population should not be screened for carotid stenosis, and this recommendation has been reiterated in a 2014 draft recommendation statement.1,2 Other groups, including our own Society for Vascular Surgery, have published similar recommendations.3,4

Arguments in favor of screening for asymptomatic carotid stenosis are often based on the results of randomized controlled trials such as the Asymptomatic Carotid Atherosclerosis Study, which was reported in 1995.5 However, while these trials are historically important, they are no longer clinically relevant. Surgical and catheter-based interventions for carotid atherosclerosis have evolved significantly in the last 2 decades, but the outcomes associated with modern intensive medical therapy have also improved dramatically.6,7 It is not clear that carotid endarterectomy or stenting is superior to current medical management for asymptomatic carotid stenosis, and new trials such as the recently announced CREST-2 are designed to answer these important questions.

The relatively poor reliability and accuracy of duplex ultrasound as a screening test for carotid stenosis is a major theme in the USPSTF draft recommendations, but in spite of this criticism, carotid duplex scanning has served as a clinically valuable method for classifying the severity of carotid stenosis for more than 30 years.8 As pointed out by others, the best way to ensure quality in the vascular laboratory is to recognize the importance of certified vascular sonographers, accredited vascular laboratories, and qualified medical staff. But despite high-quality ultrasound testing, relying on carotid stenosis as a marker of stroke risk has significant limitations. While there is an association between the degree of carotid stenosis and risk of stroke, many patients with severe carotid stenosis do not have strokes and some with moderate stenosis do have strokes. For example, it was reported that 61% of the symptomatic patients in the North American Symptomatic Carotid Endarterectomy Trial had less than 50% carotid stenosis.9 This suggests that stenosis severity alone does not identify those patients who are at the highest risk for stroke. Fortunately, the concept of the "vulnerable plaque" is promising as a means for more accurate risk stratification, and features such as intraplaque hemorrhage and thin or ruptured fibrous caps do correlate with a high risk for stroke.10 Experience has shown that these features can be characterized by ultrasound.11

So although screening of the general population for asymptomatic carotid stenosis is not justified, there still may be subgroups of patients with specific risk factors and plaque features that could benefit from early intervention, and future clinical trials will establish whether or not this hypothesis has merit. Until more data are available the issue of screening for asymptomatic carotid stenosis will continue to provoke debate on multiple levels. Carotid disease screening is not covered by insurance, so cost and ability to pay are key factors to consider. In these discussions, the health of the patient and the population must always be the first priority, and clinical decision-making should be evidence based.

Dr. Zierler is professor of surgery at the University of Washington and medical director of the D.E. Strandness Jr. Vascular Laboratory at the university’s medical center and Harborview Medical Center, Seattle. He is also an associate medical editor of Vascular Specialist.

References

1. Ann. Intern. Med. 2007;147:860-70.

2. uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/.htm.

3. JACC 2011;57:e16-94.

4. J. Vasc. Surg. 2011;54:e1-31.

5. JAMA 1995:273:1421-8.

6. Circulation 2013;127:739-42.

7. Stroke 2009;40:e573-83.

8. Vasc. Endovascular Surg. 2012;46:466-74.

9. N. Engl. J. Med. 1998;339:1415-25.

10. Imaging Med. 2010;2:63-75.

11. J. Vasc. Surg. 2010;52:1486-96.

Introduction

The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force has just published its latest guidance on carotid screening for asymptomatic disease, basically stating that it should not be done (see story page 1). In this Point-Counterpoint Dr. Zierler and Dr. Berland provide their views on this controversial issue. From my perspective the debate must revolve around the following questions: The gist of the USPSTF statement seems to be that screening is being performed only to detect patients with critical carotid stenosis so that an intervention (CEA or CAS) can be performed. However, shouldn’t screening also be used to identify atherosclerotic burden in order to prevent cardiovascular morbidity? Whatever the reasons for screening, should national health systems pay for screening? If not, what about individual physicians charging for screenings on selected/nonselected patients? What about free screenings? And as Dr. Zierler and Dr. Berland suggest, is screening getting a bad rap just because screening and subsequent CEA or CAS are being poorly performed? Finally, I wouldn\'t be surprised if some of the task force members have had their own carotids screened despite their negative recommendation. We would be interested in your viewpoint, so please take our online, interactive poll on our home page (bottom right) to weigh in on this important issue.

Dr. Russell Samson is the Medical Editor of Vascular Specialist.

YES: Screen, but screen well.

By Todd Berland, M.D.

Every patient with symptomatic carotid artery stenosis was asymptomatic the day before. The impact of stroke can be devastating, with a 20% mortality from the acute event and 40%-50% survival over the next 5 years. Of those surviving the initial event, a significant percentage of patients are unable to return to work, and up to 25% over the age of 65 require long-term institutional care.1 There is no doubt that the emotional, financial, and societal burden of caring for stroke patients is significant. The Asymptomatic Carotid Atherosclerosis Study and the Asymptomatic Carotid Surgery Trial demonstrated a significant reduction in stroke in asymptomatic, high-grade carotid artery stenosis patients treated with carotid endarterectomy compared to medical management alone.2,3 So wouldn’t it seem as if carotid artery screening would be beneficial?

The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommended against routine carotid screening because of its "high risk" and low reward. I believe that when a certified lab screens the appropriate population such as individuals over 55 with cardiovascular risk factors that include hypertension, diabetes, smoking, and hypercholesterolemia, and combines this with an intervention that has a low stroke and morbidity rate, then the balance is tipped and carotid screening becomes both low risk and high reward.

One of the problems with carotid ultrasound is that too many entrepreneurs have made a business of it. Suboptimal equipment is being used by uncertified technicians in medical offices and church parking lots all across this country. It’s no surprise that the false positives are going to be high in these situations. Also, when one combines all of the above with the screening of those who aren’t at risk, where the general prevalence of disease is low, it can be a recipe for disaster. This is going to lead to additional studies such as CT angiograms or possibly even cerebral angiograms, both of which have inherent risks.

Even though it’s possible to understand why the USPSTF may have concluded against routine screening, I believe that at-risk patients should be screened by a certified lab, and that physicians performing the interventions should be able to do so with low morbidity and mortality. Vascular surgeons have been marginalized over recent years as many others have become interested in finding and treating carotid disease. Most of us are either registered vascular technologists or registered physicians in vascular interpretation, and our labs are certified by the Intersocietal Accreditation Commission. We go through hours of continuing medical education in regard to vascular ultrasound, and our labs’ results are tested and certified for accuracy.

We need to convince insurance companies and the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services that these studies should be permitted only in certified labs and the results interpreted by certified physicians such as vascular surgeons.

Moreover, when indicated, the interventions should be carried out by vascular surgeons who are trained to perform both carotid endarter- ectomy and carotid artery stenting to be able to offer the patient the best individualized treatment.

Dr. Berland is director of outpatient vascular interventions at NYU Langone Medical Center.

References

1. Circulation 2012;125:188.

2. JAMA 1995:273:1421-8.

3. Lancet 2004;363:1491-502.

NO: General screening is not appropriate.

By R. Eugene Zierler, M.D.

To most vascular specialists, the concept of detecting asymptomatic carotid stenosis and intervening to prevent stroke makes intuitive sense, but is it consistent with the evidence? In 2007, the USPSTF concluded that the general asymptomatic adult population should not be screened for carotid stenosis, and this recommendation has been reiterated in a 2014 draft recommendation statement.1,2 Other groups, including our own Society for Vascular Surgery, have published similar recommendations.3,4

Arguments in favor of screening for asymptomatic carotid stenosis are often based on the results of randomized controlled trials such as the Asymptomatic Carotid Atherosclerosis Study, which was reported in 1995.5 However, while these trials are historically important, they are no longer clinically relevant. Surgical and catheter-based interventions for carotid atherosclerosis have evolved significantly in the last 2 decades, but the outcomes associated with modern intensive medical therapy have also improved dramatically.6,7 It is not clear that carotid endarterectomy or stenting is superior to current medical management for asymptomatic carotid stenosis, and new trials such as the recently announced CREST-2 are designed to answer these important questions.

The relatively poor reliability and accuracy of duplex ultrasound as a screening test for carotid stenosis is a major theme in the USPSTF draft recommendations, but in spite of this criticism, carotid duplex scanning has served as a clinically valuable method for classifying the severity of carotid stenosis for more than 30 years.8 As pointed out by others, the best way to ensure quality in the vascular laboratory is to recognize the importance of certified vascular sonographers, accredited vascular laboratories, and qualified medical staff. But despite high-quality ultrasound testing, relying on carotid stenosis as a marker of stroke risk has significant limitations. While there is an association between the degree of carotid stenosis and risk of stroke, many patients with severe carotid stenosis do not have strokes and some with moderate stenosis do have strokes. For example, it was reported that 61% of the symptomatic patients in the North American Symptomatic Carotid Endarterectomy Trial had less than 50% carotid stenosis.9 This suggests that stenosis severity alone does not identify those patients who are at the highest risk for stroke. Fortunately, the concept of the "vulnerable plaque" is promising as a means for more accurate risk stratification, and features such as intraplaque hemorrhage and thin or ruptured fibrous caps do correlate with a high risk for stroke.10 Experience has shown that these features can be characterized by ultrasound.11

So although screening of the general population for asymptomatic carotid stenosis is not justified, there still may be subgroups of patients with specific risk factors and plaque features that could benefit from early intervention, and future clinical trials will establish whether or not this hypothesis has merit. Until more data are available the issue of screening for asymptomatic carotid stenosis will continue to provoke debate on multiple levels. Carotid disease screening is not covered by insurance, so cost and ability to pay are key factors to consider. In these discussions, the health of the patient and the population must always be the first priority, and clinical decision-making should be evidence based.

Dr. Zierler is professor of surgery at the University of Washington and medical director of the D.E. Strandness Jr. Vascular Laboratory at the university’s medical center and Harborview Medical Center, Seattle. He is also an associate medical editor of Vascular Specialist.

References

1. Ann. Intern. Med. 2007;147:860-70.

2. uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/.htm.

3. JACC 2011;57:e16-94.

4. J. Vasc. Surg. 2011;54:e1-31.

5. JAMA 1995:273:1421-8.

6. Circulation 2013;127:739-42.

7. Stroke 2009;40:e573-83.

8. Vasc. Endovascular Surg. 2012;46:466-74.

9. N. Engl. J. Med. 1998;339:1415-25.

10. Imaging Med. 2010;2:63-75.

11. J. Vasc. Surg. 2010;52:1486-96.

Introduction

The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force has just published its latest guidance on carotid screening for asymptomatic disease, basically stating that it should not be done (see story page 1). In this Point-Counterpoint Dr. Zierler and Dr. Berland provide their views on this controversial issue. From my perspective the debate must revolve around the following questions: The gist of the USPSTF statement seems to be that screening is being performed only to detect patients with critical carotid stenosis so that an intervention (CEA or CAS) can be performed. However, shouldn’t screening also be used to identify atherosclerotic burden in order to prevent cardiovascular morbidity? Whatever the reasons for screening, should national health systems pay for screening? If not, what about individual physicians charging for screenings on selected/nonselected patients? What about free screenings? And as Dr. Zierler and Dr. Berland suggest, is screening getting a bad rap just because screening and subsequent CEA or CAS are being poorly performed? Finally, I wouldn\'t be surprised if some of the task force members have had their own carotids screened despite their negative recommendation. We would be interested in your viewpoint, so please take our online, interactive poll on our home page (bottom right) to weigh in on this important issue.

Dr. Russell Samson is the Medical Editor of Vascular Specialist.

YES: Screen, but screen well.

By Todd Berland, M.D.

Every patient with symptomatic carotid artery stenosis was asymptomatic the day before. The impact of stroke can be devastating, with a 20% mortality from the acute event and 40%-50% survival over the next 5 years. Of those surviving the initial event, a significant percentage of patients are unable to return to work, and up to 25% over the age of 65 require long-term institutional care.1 There is no doubt that the emotional, financial, and societal burden of caring for stroke patients is significant. The Asymptomatic Carotid Atherosclerosis Study and the Asymptomatic Carotid Surgery Trial demonstrated a significant reduction in stroke in asymptomatic, high-grade carotid artery stenosis patients treated with carotid endarterectomy compared to medical management alone.2,3 So wouldn’t it seem as if carotid artery screening would be beneficial?

The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommended against routine carotid screening because of its "high risk" and low reward. I believe that when a certified lab screens the appropriate population such as individuals over 55 with cardiovascular risk factors that include hypertension, diabetes, smoking, and hypercholesterolemia, and combines this with an intervention that has a low stroke and morbidity rate, then the balance is tipped and carotid screening becomes both low risk and high reward.