User login

More Hospitalists Opt for Part-Time Work Schedules

An increasing number of hospitalists are pursuing part-time schedules to cater to lifestyle demands and personal desires. According to a 2010 survey conducted by the American Medical Group Management Association and Cejka Search, 21% of physicians in the U.S. are working part time, compared with only 13% in 2005.

Among those part-time physicians, the fastest-growing segments are men approaching retirement and women in the early to middle stages of their careers. Senior physicians who are tired of the commitment that comes with full-time employment increasingly are opting for part-time employment as a transition into retirement. Physicians with young children are seeking part-time employment to be more active in child-rearing.

The medical community generally has welcomed the opportunity to incorporate part-time physicians into hospital settings as a way to maintain female physicians, senior physicians, and physicians in specialties experiencing shortages. Physicians who are retained on a part-time basis should be cognizant of the following areas of the physician’s employment or independent contractor agreement:

- Independent contractor or employee status;

- Compensation;

- Benefits;

- Professional liability (malpractice) insurance; and

- Restrictive covenants.

Independent Contractor vs. Employee

Oftentimes, physicians assume that just because he or she is working part time, he or she is an independent contractor. That is an inaccurate assumption. The amount of time a physician works is not the determining factor as to whether someone is an employee or an independent contractor of the practice or hospital. Whether a physician is an employee or an independent contractor is a distinction with real consequences for tax purposes and protections under federal and state labor and employment laws.

Generally, labor and employment laws provide protections for employees, but these protections do not extend to independent contractors. With regard to taxes, if a hospitalist is an employee, the employer is required to withhold income, Social Security, and Medicare taxes, and pay unemployment tax on wages paid to the hospitalist. Conversely, if a hospitalist is an independent contractor, the practice or hospital will not withhold or pay taxes on payments to the hospitalist; rather, the individual hospitalist will be responsible for making those payments to the IRS and state tax authorities. It is imperative that the contract clearly indicates whether the hospitalist is an employee or an independent contractor, as well as the corresponding responsibilities of the parties.

Compensation and Benefits

Partial compensation for part-time work is logical, but determining a fair and competitive compensation package is not always as straightforward when it comes to part-timers. There are two general models that practices and hospitals use to determine compensation for hospitalists working part time. First, the physician may be paid a percentage of a full-time physician’s salary, based on the number of hours worked. Second, the physician may receive a per diem rate or an hourly rate. As with full-time physicians, there are various ways to formulate a part-time physician’s compensation, and the method used should be explicitly outlined in the physician’s employment or independent contractor agreement.

Benefit plans and arrangements (such as health, dental, vision, retirement plan, pension plan, disability coverage, life insurance, etc.) frequently are provided to employees and infrequently provided to independent contractors. Whether a physician who is working part time will receive benefits will vary from employer to employer. A threshold issue, however, is whether a part-time worker is even eligible to receive certain benefits. Many health, dental, and vision plans require employees to work a minimum of 30 hours a week on a regular basis, thus excluding part-time employees who work fewer hours. For retirement and pension plans, employees typically must work a minimum of 1,000 hours per year to be eligible to participate. Even if a hospitalist’s employment agreement provides that the hospitalist may receive benefits from the employer, the agreement may also provide that such a provision is subject to the terms and conditions of the particular benefit plans or arrangements.

Professional Liability (Malpractice) Insurance

While some practices or hospitals pay for a part-time physician’s malpractice insurance premiums, many shift some or all of these costs to the physician. Many insurance providers offer malpractice plans for physicians practicing part time, with reduced premiums and reduced coverage.

When negotiating a compensation package, payment for malpractice insurance should be considered. A physician also must be aware of what is excluded from coverage. For example, if a physician works part time with Hospital A and part time with Hospital B, and Hospital A provides malpractice coverage for the physician, it cannot be assumed that such coverage will cover the physician’s work with Hospital B. In this case, the physician may need a separate policy for work performed through Hospital B.

Restrictive Covenants

Although a physician might only be employed on a part-time basis, the employer might nevertheless want to protect itself by including restrictive covenants (i.e. noncompetition and nonsolicitation clauses) in the physician’s employment agreement. A part-time physician must be careful that the restrictive covenants do not jeopardize their other career objectives. For example, in the example described above with the physician working part time for both Hospital A and Hospital B, a noncompetition clause in the physician’s employment agreement with Hospital A could prohibit the physician from working at another hospital, including Hospital B.

Retaining part-time hospitalists is an increasingly attractive option for physician practices and hospitals, and part-time work is an increasingly attractive option for physicians. The items described above are just a few of the provisions that are unique to the part-time physician relationship that should be reflected in the physician’s employment or independent contractor agreement.

Steven M. Harris, Esq., is a nationally recognized healthcare attorney and a member of the law firm McDonald Hopkins LLC in Chicago. Write to him at [email protected].

An increasing number of hospitalists are pursuing part-time schedules to cater to lifestyle demands and personal desires. According to a 2010 survey conducted by the American Medical Group Management Association and Cejka Search, 21% of physicians in the U.S. are working part time, compared with only 13% in 2005.

Among those part-time physicians, the fastest-growing segments are men approaching retirement and women in the early to middle stages of their careers. Senior physicians who are tired of the commitment that comes with full-time employment increasingly are opting for part-time employment as a transition into retirement. Physicians with young children are seeking part-time employment to be more active in child-rearing.

The medical community generally has welcomed the opportunity to incorporate part-time physicians into hospital settings as a way to maintain female physicians, senior physicians, and physicians in specialties experiencing shortages. Physicians who are retained on a part-time basis should be cognizant of the following areas of the physician’s employment or independent contractor agreement:

- Independent contractor or employee status;

- Compensation;

- Benefits;

- Professional liability (malpractice) insurance; and

- Restrictive covenants.

Independent Contractor vs. Employee

Oftentimes, physicians assume that just because he or she is working part time, he or she is an independent contractor. That is an inaccurate assumption. The amount of time a physician works is not the determining factor as to whether someone is an employee or an independent contractor of the practice or hospital. Whether a physician is an employee or an independent contractor is a distinction with real consequences for tax purposes and protections under federal and state labor and employment laws.

Generally, labor and employment laws provide protections for employees, but these protections do not extend to independent contractors. With regard to taxes, if a hospitalist is an employee, the employer is required to withhold income, Social Security, and Medicare taxes, and pay unemployment tax on wages paid to the hospitalist. Conversely, if a hospitalist is an independent contractor, the practice or hospital will not withhold or pay taxes on payments to the hospitalist; rather, the individual hospitalist will be responsible for making those payments to the IRS and state tax authorities. It is imperative that the contract clearly indicates whether the hospitalist is an employee or an independent contractor, as well as the corresponding responsibilities of the parties.

Compensation and Benefits

Partial compensation for part-time work is logical, but determining a fair and competitive compensation package is not always as straightforward when it comes to part-timers. There are two general models that practices and hospitals use to determine compensation for hospitalists working part time. First, the physician may be paid a percentage of a full-time physician’s salary, based on the number of hours worked. Second, the physician may receive a per diem rate or an hourly rate. As with full-time physicians, there are various ways to formulate a part-time physician’s compensation, and the method used should be explicitly outlined in the physician’s employment or independent contractor agreement.

Benefit plans and arrangements (such as health, dental, vision, retirement plan, pension plan, disability coverage, life insurance, etc.) frequently are provided to employees and infrequently provided to independent contractors. Whether a physician who is working part time will receive benefits will vary from employer to employer. A threshold issue, however, is whether a part-time worker is even eligible to receive certain benefits. Many health, dental, and vision plans require employees to work a minimum of 30 hours a week on a regular basis, thus excluding part-time employees who work fewer hours. For retirement and pension plans, employees typically must work a minimum of 1,000 hours per year to be eligible to participate. Even if a hospitalist’s employment agreement provides that the hospitalist may receive benefits from the employer, the agreement may also provide that such a provision is subject to the terms and conditions of the particular benefit plans or arrangements.

Professional Liability (Malpractice) Insurance

While some practices or hospitals pay for a part-time physician’s malpractice insurance premiums, many shift some or all of these costs to the physician. Many insurance providers offer malpractice plans for physicians practicing part time, with reduced premiums and reduced coverage.

When negotiating a compensation package, payment for malpractice insurance should be considered. A physician also must be aware of what is excluded from coverage. For example, if a physician works part time with Hospital A and part time with Hospital B, and Hospital A provides malpractice coverage for the physician, it cannot be assumed that such coverage will cover the physician’s work with Hospital B. In this case, the physician may need a separate policy for work performed through Hospital B.

Restrictive Covenants

Although a physician might only be employed on a part-time basis, the employer might nevertheless want to protect itself by including restrictive covenants (i.e. noncompetition and nonsolicitation clauses) in the physician’s employment agreement. A part-time physician must be careful that the restrictive covenants do not jeopardize their other career objectives. For example, in the example described above with the physician working part time for both Hospital A and Hospital B, a noncompetition clause in the physician’s employment agreement with Hospital A could prohibit the physician from working at another hospital, including Hospital B.

Retaining part-time hospitalists is an increasingly attractive option for physician practices and hospitals, and part-time work is an increasingly attractive option for physicians. The items described above are just a few of the provisions that are unique to the part-time physician relationship that should be reflected in the physician’s employment or independent contractor agreement.

Steven M. Harris, Esq., is a nationally recognized healthcare attorney and a member of the law firm McDonald Hopkins LLC in Chicago. Write to him at [email protected].

An increasing number of hospitalists are pursuing part-time schedules to cater to lifestyle demands and personal desires. According to a 2010 survey conducted by the American Medical Group Management Association and Cejka Search, 21% of physicians in the U.S. are working part time, compared with only 13% in 2005.

Among those part-time physicians, the fastest-growing segments are men approaching retirement and women in the early to middle stages of their careers. Senior physicians who are tired of the commitment that comes with full-time employment increasingly are opting for part-time employment as a transition into retirement. Physicians with young children are seeking part-time employment to be more active in child-rearing.

The medical community generally has welcomed the opportunity to incorporate part-time physicians into hospital settings as a way to maintain female physicians, senior physicians, and physicians in specialties experiencing shortages. Physicians who are retained on a part-time basis should be cognizant of the following areas of the physician’s employment or independent contractor agreement:

- Independent contractor or employee status;

- Compensation;

- Benefits;

- Professional liability (malpractice) insurance; and

- Restrictive covenants.

Independent Contractor vs. Employee

Oftentimes, physicians assume that just because he or she is working part time, he or she is an independent contractor. That is an inaccurate assumption. The amount of time a physician works is not the determining factor as to whether someone is an employee or an independent contractor of the practice or hospital. Whether a physician is an employee or an independent contractor is a distinction with real consequences for tax purposes and protections under federal and state labor and employment laws.

Generally, labor and employment laws provide protections for employees, but these protections do not extend to independent contractors. With regard to taxes, if a hospitalist is an employee, the employer is required to withhold income, Social Security, and Medicare taxes, and pay unemployment tax on wages paid to the hospitalist. Conversely, if a hospitalist is an independent contractor, the practice or hospital will not withhold or pay taxes on payments to the hospitalist; rather, the individual hospitalist will be responsible for making those payments to the IRS and state tax authorities. It is imperative that the contract clearly indicates whether the hospitalist is an employee or an independent contractor, as well as the corresponding responsibilities of the parties.

Compensation and Benefits

Partial compensation for part-time work is logical, but determining a fair and competitive compensation package is not always as straightforward when it comes to part-timers. There are two general models that practices and hospitals use to determine compensation for hospitalists working part time. First, the physician may be paid a percentage of a full-time physician’s salary, based on the number of hours worked. Second, the physician may receive a per diem rate or an hourly rate. As with full-time physicians, there are various ways to formulate a part-time physician’s compensation, and the method used should be explicitly outlined in the physician’s employment or independent contractor agreement.

Benefit plans and arrangements (such as health, dental, vision, retirement plan, pension plan, disability coverage, life insurance, etc.) frequently are provided to employees and infrequently provided to independent contractors. Whether a physician who is working part time will receive benefits will vary from employer to employer. A threshold issue, however, is whether a part-time worker is even eligible to receive certain benefits. Many health, dental, and vision plans require employees to work a minimum of 30 hours a week on a regular basis, thus excluding part-time employees who work fewer hours. For retirement and pension plans, employees typically must work a minimum of 1,000 hours per year to be eligible to participate. Even if a hospitalist’s employment agreement provides that the hospitalist may receive benefits from the employer, the agreement may also provide that such a provision is subject to the terms and conditions of the particular benefit plans or arrangements.

Professional Liability (Malpractice) Insurance

While some practices or hospitals pay for a part-time physician’s malpractice insurance premiums, many shift some or all of these costs to the physician. Many insurance providers offer malpractice plans for physicians practicing part time, with reduced premiums and reduced coverage.

When negotiating a compensation package, payment for malpractice insurance should be considered. A physician also must be aware of what is excluded from coverage. For example, if a physician works part time with Hospital A and part time with Hospital B, and Hospital A provides malpractice coverage for the physician, it cannot be assumed that such coverage will cover the physician’s work with Hospital B. In this case, the physician may need a separate policy for work performed through Hospital B.

Restrictive Covenants

Although a physician might only be employed on a part-time basis, the employer might nevertheless want to protect itself by including restrictive covenants (i.e. noncompetition and nonsolicitation clauses) in the physician’s employment agreement. A part-time physician must be careful that the restrictive covenants do not jeopardize their other career objectives. For example, in the example described above with the physician working part time for both Hospital A and Hospital B, a noncompetition clause in the physician’s employment agreement with Hospital A could prohibit the physician from working at another hospital, including Hospital B.

Retaining part-time hospitalists is an increasingly attractive option for physician practices and hospitals, and part-time work is an increasingly attractive option for physicians. The items described above are just a few of the provisions that are unique to the part-time physician relationship that should be reflected in the physician’s employment or independent contractor agreement.

Steven M. Harris, Esq., is a nationally recognized healthcare attorney and a member of the law firm McDonald Hopkins LLC in Chicago. Write to him at [email protected].

Hospitalist Edward Ma, MD, Embraces the Entrepreneurial Spirit

Edward Ma, MD, wasn’t sure what he wanted to be when he grew up. As a biology student at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia, he says friends “peer-pressured” him to choose a career in medicine. Once the decision was made and he began his training, he found out he was pretty good at the doctor thing.

“I realized that I like this,” he says. “I told myself, ‘I’m going to go for it.’”

Dr. Ma also realized he had a liking for business, and where better to study business than at Penn’s Wharton School of Business? He hasn’t completed an MBA, but he’s taken post-grad courses focused on healthcare management. And now he’s combining that knowledge with his experiences as a hospitalist and medical director to develop a consulting business.

“That sort of evolved because I sort of have a big mouth. When I see something wrong, or something that could be done better, I tend to vocalize it,” says Dr. Ma, medical director of hospitalist services at 168-bed Brandywine Hospital in Coatesville, Pa. “The biggest opportunity is to really help a hospitalist group realize its potential and its value.”

Dr. Ma joined Team Hospitalist in April 2012. Although his side business is evolving via “word of mouth,” he still spends the majority of his time in the hospital directing a six-member HM group and caring for hospitalized patients.

Question: What do you like most about caring for patients?

Answer: I like the acuity of the care. The acuity of the illness is pretty high for our patients, and you can see very quickly the impact hospitalists can have. A lot of outpatient medicine is preventive care, so usually you don’t have an immediate problem that needs to be fixed, whereas in HM, the patients are acutely ill and there’s an ability to get these patients better—and see a change in their medical condition in a day or two. There’s more immediate gratification in terms of the effort that we put in caring for a patient.

Q: What do you like least?

A: The paperwork. At my hospital, a lot of it is computerized. But there are tons of checklists, tons of quality measures that need to be addressed, which is good. Still, it ends up bogging down our ability to take care of the patient. For example, a patient comes in for pneumonia and you have to make sure that some of their chronic issues (e.g. diabetes) are addressed. Have they had their hemoglobin A1C checked in the last 60 days? Does it really matter right now when we’re taking care of the patient’s pneumonia that we have to address this? Smoking cessation, yes, it’s very important, and we need to address this, but is it really necessary that we do this at this point when a patient is really ill? I think there’s a lot of these government regulations that they want us to take care of sometimes in the acute setting, which sometimes feels awkward or not necessarily time-appropriate.

Q: You say your training as an internist prepared you for a seamless transition to a hospitalist job, but you also think IM training is “doing a disservice to medicine.” How so?

A: Don’t get me wrong, I love hospital medicine. But I think what we really need is more primary-care doctors. This is not just my commentary on hospital medicine, but all subspecialties. I know specifically speaking that we need more outpatient internists, outpatient family physicians. If there are many internists, they’re not going to have as much need for cardiology or GI, or a lot of other subspecialties. There’s enough of a population of internists that would satisfy the need for internists and obviously the need for subspecialties.

Q: What’s the biggest change in HM you’ve witnessed since you started 10 years ago?

A: Our acceptance as a field by the medical community. Other physicians have now come to be very accepting of our role as the primary caretakers of their hospitalized patients.

Q: Do you consider yourself to have an entrepreneurial spirit or are you more of a solutions-oriented physician?

A: I have more of the entrepreneurial spirit. I’ve been talking to a lot of hospitalists, and what I encourage them to do is completely counter to the current healthcare environment. I’ve been encouraging them to say, “Let’s get a bunch of us together and set up our own hospitalist practice and do it in a way that we can have a certain level of autonomy, but also do it in a way that we can collaborate with the hospital, work intimately with them, and get certain guarantees from them. And do it privately, so that we can maintain our autonomy.” I think that’s important because I see the difference between the private practices and the practices that are owned by a health system. People just care so much more when it’s their own practice.

Q: What are the biggest challenges you face as medical director?

A: Getting everyone to work as a team. Everyone has a different schedule, differing values, and priorities. It’s very important that we work as a team because when one person does something, it impacts what somebody else does.

Q: What’s the most important thing to know when starting an HM group or fixing a broken group?

A: For fixing a group, you have to look at the values of the group of doctors. What are the values? What are the objectives? What are the professional goals? What I’ve encountered in HM is a lot of people are just coming in to get a paycheck. They come in, they do their job, and they like to take care of patients. Don’t get me wrong about that, but they like the freedom and the high competition that’s provided by hospital medicine. Oftentimes they come in, they do their jobs very well, they take care of their patients, and then they’re out the door. They don’t really have an interest in building up that practice or building up something for the hospital. We as doctors are all part of a medical community, we’re part of a medical staff, and it’s very important for us to get involved.

Q: Last year, you became president of SHM’s Philadelphia Tri-State Region chapter. What are your goals?

A: I’ve always been involved with the chapter, but I saw it as a good opportunity to network and talk with more hospitalists. I wanted to get their viewpoints on things and bounce ideas. I’m a very vocal person, so when I hear a good idea, I like to spread it amongst other people. And if I see something that someone said was bad and I hear it from enough people, I like to bring it up and discuss with everybody.

Q: What’s the best part of being an SHM member?

A: Getting to interact with a lot of my colleagues. To see what struggles they’re going through, to see that their struggles are very similar to the struggles that my group is going through, that we’re all in the same boat, and that we need to collaborate a little more to make things work. Instead of each practice trying to reinvent the wheel, we can try to work together and build off each other.

Richard Quinn is a freelance writer in New Jersey.

Edward Ma, MD, wasn’t sure what he wanted to be when he grew up. As a biology student at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia, he says friends “peer-pressured” him to choose a career in medicine. Once the decision was made and he began his training, he found out he was pretty good at the doctor thing.

“I realized that I like this,” he says. “I told myself, ‘I’m going to go for it.’”

Dr. Ma also realized he had a liking for business, and where better to study business than at Penn’s Wharton School of Business? He hasn’t completed an MBA, but he’s taken post-grad courses focused on healthcare management. And now he’s combining that knowledge with his experiences as a hospitalist and medical director to develop a consulting business.

“That sort of evolved because I sort of have a big mouth. When I see something wrong, or something that could be done better, I tend to vocalize it,” says Dr. Ma, medical director of hospitalist services at 168-bed Brandywine Hospital in Coatesville, Pa. “The biggest opportunity is to really help a hospitalist group realize its potential and its value.”

Dr. Ma joined Team Hospitalist in April 2012. Although his side business is evolving via “word of mouth,” he still spends the majority of his time in the hospital directing a six-member HM group and caring for hospitalized patients.

Question: What do you like most about caring for patients?

Answer: I like the acuity of the care. The acuity of the illness is pretty high for our patients, and you can see very quickly the impact hospitalists can have. A lot of outpatient medicine is preventive care, so usually you don’t have an immediate problem that needs to be fixed, whereas in HM, the patients are acutely ill and there’s an ability to get these patients better—and see a change in their medical condition in a day or two. There’s more immediate gratification in terms of the effort that we put in caring for a patient.

Q: What do you like least?

A: The paperwork. At my hospital, a lot of it is computerized. But there are tons of checklists, tons of quality measures that need to be addressed, which is good. Still, it ends up bogging down our ability to take care of the patient. For example, a patient comes in for pneumonia and you have to make sure that some of their chronic issues (e.g. diabetes) are addressed. Have they had their hemoglobin A1C checked in the last 60 days? Does it really matter right now when we’re taking care of the patient’s pneumonia that we have to address this? Smoking cessation, yes, it’s very important, and we need to address this, but is it really necessary that we do this at this point when a patient is really ill? I think there’s a lot of these government regulations that they want us to take care of sometimes in the acute setting, which sometimes feels awkward or not necessarily time-appropriate.

Q: You say your training as an internist prepared you for a seamless transition to a hospitalist job, but you also think IM training is “doing a disservice to medicine.” How so?

A: Don’t get me wrong, I love hospital medicine. But I think what we really need is more primary-care doctors. This is not just my commentary on hospital medicine, but all subspecialties. I know specifically speaking that we need more outpatient internists, outpatient family physicians. If there are many internists, they’re not going to have as much need for cardiology or GI, or a lot of other subspecialties. There’s enough of a population of internists that would satisfy the need for internists and obviously the need for subspecialties.

Q: What’s the biggest change in HM you’ve witnessed since you started 10 years ago?

A: Our acceptance as a field by the medical community. Other physicians have now come to be very accepting of our role as the primary caretakers of their hospitalized patients.

Q: Do you consider yourself to have an entrepreneurial spirit or are you more of a solutions-oriented physician?

A: I have more of the entrepreneurial spirit. I’ve been talking to a lot of hospitalists, and what I encourage them to do is completely counter to the current healthcare environment. I’ve been encouraging them to say, “Let’s get a bunch of us together and set up our own hospitalist practice and do it in a way that we can have a certain level of autonomy, but also do it in a way that we can collaborate with the hospital, work intimately with them, and get certain guarantees from them. And do it privately, so that we can maintain our autonomy.” I think that’s important because I see the difference between the private practices and the practices that are owned by a health system. People just care so much more when it’s their own practice.

Q: What are the biggest challenges you face as medical director?

A: Getting everyone to work as a team. Everyone has a different schedule, differing values, and priorities. It’s very important that we work as a team because when one person does something, it impacts what somebody else does.

Q: What’s the most important thing to know when starting an HM group or fixing a broken group?

A: For fixing a group, you have to look at the values of the group of doctors. What are the values? What are the objectives? What are the professional goals? What I’ve encountered in HM is a lot of people are just coming in to get a paycheck. They come in, they do their job, and they like to take care of patients. Don’t get me wrong about that, but they like the freedom and the high competition that’s provided by hospital medicine. Oftentimes they come in, they do their jobs very well, they take care of their patients, and then they’re out the door. They don’t really have an interest in building up that practice or building up something for the hospital. We as doctors are all part of a medical community, we’re part of a medical staff, and it’s very important for us to get involved.

Q: Last year, you became president of SHM’s Philadelphia Tri-State Region chapter. What are your goals?

A: I’ve always been involved with the chapter, but I saw it as a good opportunity to network and talk with more hospitalists. I wanted to get their viewpoints on things and bounce ideas. I’m a very vocal person, so when I hear a good idea, I like to spread it amongst other people. And if I see something that someone said was bad and I hear it from enough people, I like to bring it up and discuss with everybody.

Q: What’s the best part of being an SHM member?

A: Getting to interact with a lot of my colleagues. To see what struggles they’re going through, to see that their struggles are very similar to the struggles that my group is going through, that we’re all in the same boat, and that we need to collaborate a little more to make things work. Instead of each practice trying to reinvent the wheel, we can try to work together and build off each other.

Richard Quinn is a freelance writer in New Jersey.

Edward Ma, MD, wasn’t sure what he wanted to be when he grew up. As a biology student at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia, he says friends “peer-pressured” him to choose a career in medicine. Once the decision was made and he began his training, he found out he was pretty good at the doctor thing.

“I realized that I like this,” he says. “I told myself, ‘I’m going to go for it.’”

Dr. Ma also realized he had a liking for business, and where better to study business than at Penn’s Wharton School of Business? He hasn’t completed an MBA, but he’s taken post-grad courses focused on healthcare management. And now he’s combining that knowledge with his experiences as a hospitalist and medical director to develop a consulting business.

“That sort of evolved because I sort of have a big mouth. When I see something wrong, or something that could be done better, I tend to vocalize it,” says Dr. Ma, medical director of hospitalist services at 168-bed Brandywine Hospital in Coatesville, Pa. “The biggest opportunity is to really help a hospitalist group realize its potential and its value.”

Dr. Ma joined Team Hospitalist in April 2012. Although his side business is evolving via “word of mouth,” he still spends the majority of his time in the hospital directing a six-member HM group and caring for hospitalized patients.

Question: What do you like most about caring for patients?

Answer: I like the acuity of the care. The acuity of the illness is pretty high for our patients, and you can see very quickly the impact hospitalists can have. A lot of outpatient medicine is preventive care, so usually you don’t have an immediate problem that needs to be fixed, whereas in HM, the patients are acutely ill and there’s an ability to get these patients better—and see a change in their medical condition in a day or two. There’s more immediate gratification in terms of the effort that we put in caring for a patient.

Q: What do you like least?

A: The paperwork. At my hospital, a lot of it is computerized. But there are tons of checklists, tons of quality measures that need to be addressed, which is good. Still, it ends up bogging down our ability to take care of the patient. For example, a patient comes in for pneumonia and you have to make sure that some of their chronic issues (e.g. diabetes) are addressed. Have they had their hemoglobin A1C checked in the last 60 days? Does it really matter right now when we’re taking care of the patient’s pneumonia that we have to address this? Smoking cessation, yes, it’s very important, and we need to address this, but is it really necessary that we do this at this point when a patient is really ill? I think there’s a lot of these government regulations that they want us to take care of sometimes in the acute setting, which sometimes feels awkward or not necessarily time-appropriate.

Q: You say your training as an internist prepared you for a seamless transition to a hospitalist job, but you also think IM training is “doing a disservice to medicine.” How so?

A: Don’t get me wrong, I love hospital medicine. But I think what we really need is more primary-care doctors. This is not just my commentary on hospital medicine, but all subspecialties. I know specifically speaking that we need more outpatient internists, outpatient family physicians. If there are many internists, they’re not going to have as much need for cardiology or GI, or a lot of other subspecialties. There’s enough of a population of internists that would satisfy the need for internists and obviously the need for subspecialties.

Q: What’s the biggest change in HM you’ve witnessed since you started 10 years ago?

A: Our acceptance as a field by the medical community. Other physicians have now come to be very accepting of our role as the primary caretakers of their hospitalized patients.

Q: Do you consider yourself to have an entrepreneurial spirit or are you more of a solutions-oriented physician?

A: I have more of the entrepreneurial spirit. I’ve been talking to a lot of hospitalists, and what I encourage them to do is completely counter to the current healthcare environment. I’ve been encouraging them to say, “Let’s get a bunch of us together and set up our own hospitalist practice and do it in a way that we can have a certain level of autonomy, but also do it in a way that we can collaborate with the hospital, work intimately with them, and get certain guarantees from them. And do it privately, so that we can maintain our autonomy.” I think that’s important because I see the difference between the private practices and the practices that are owned by a health system. People just care so much more when it’s their own practice.

Q: What are the biggest challenges you face as medical director?

A: Getting everyone to work as a team. Everyone has a different schedule, differing values, and priorities. It’s very important that we work as a team because when one person does something, it impacts what somebody else does.

Q: What’s the most important thing to know when starting an HM group or fixing a broken group?

A: For fixing a group, you have to look at the values of the group of doctors. What are the values? What are the objectives? What are the professional goals? What I’ve encountered in HM is a lot of people are just coming in to get a paycheck. They come in, they do their job, and they like to take care of patients. Don’t get me wrong about that, but they like the freedom and the high competition that’s provided by hospital medicine. Oftentimes they come in, they do their jobs very well, they take care of their patients, and then they’re out the door. They don’t really have an interest in building up that practice or building up something for the hospital. We as doctors are all part of a medical community, we’re part of a medical staff, and it’s very important for us to get involved.

Q: Last year, you became president of SHM’s Philadelphia Tri-State Region chapter. What are your goals?

A: I’ve always been involved with the chapter, but I saw it as a good opportunity to network and talk with more hospitalists. I wanted to get their viewpoints on things and bounce ideas. I’m a very vocal person, so when I hear a good idea, I like to spread it amongst other people. And if I see something that someone said was bad and I hear it from enough people, I like to bring it up and discuss with everybody.

Q: What’s the best part of being an SHM member?

A: Getting to interact with a lot of my colleagues. To see what struggles they’re going through, to see that their struggles are very similar to the struggles that my group is going through, that we’re all in the same boat, and that we need to collaborate a little more to make things work. Instead of each practice trying to reinvent the wheel, we can try to work together and build off each other.

Richard Quinn is a freelance writer in New Jersey.

Variation by age in neutropenic complications among patients with cancer receiving chemotherapy

Background Age is among the most important risk factors for neutropenia-related hospitalization, but evidence is limited regarding the relative contributions of age and other risk factors.

Objective To explore the associations among patient age, other risk factors, and neutropenic complications in patients with cancer receiving myelosuppressive chemotherapy.

Methods This retrospective cohort study, which used a US commercial insurance claims database, included patients aged 40 years or older with non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL), breast cancer, or lung cancer who initiated chemotherapy between January 1, 2006 and March 31, 2010. The primary endpoint was the risk of neutropenia-related hospitalization during the first chemotherapy course. We used cubic spline modeling to estimate the association between neutropenia-related hospitalization and age, adjusting for patient and treatment characteristics. Logistic regression analyses examined the effects of other risk factors.

Results A total of 15,638 patients were included (NHL, n = 2,506; breast cancer, n = 9,110; lung cancer, n = 4,022), mean age 56-66 years. Neutropenia-related hospitalization occurred in 8.7% of NHL patients, 4.2% of breast cancer patients, and 3.9% of lung cancer patients. The association between age and the risk of neutropenia-related hospitalization was stronger in NHL than in lung or breast cancer. Patient comorbidities and chemotherapy characteristics had considerable effects on risk of neutropenia-related hospitalization.

Limitations Disease stage and other clinical factors could not be identified from the claims data.

Conclusion In addition to age, oncologists should evaluate individual patient risk factors including patient comorbidities and type of chemotherapy regimen.

*To read the full article, click on the PDF icon at the top of this introduction.

Background Age is among the most important risk factors for neutropenia-related hospitalization, but evidence is limited regarding the relative contributions of age and other risk factors.

Objective To explore the associations among patient age, other risk factors, and neutropenic complications in patients with cancer receiving myelosuppressive chemotherapy.

Methods This retrospective cohort study, which used a US commercial insurance claims database, included patients aged 40 years or older with non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL), breast cancer, or lung cancer who initiated chemotherapy between January 1, 2006 and March 31, 2010. The primary endpoint was the risk of neutropenia-related hospitalization during the first chemotherapy course. We used cubic spline modeling to estimate the association between neutropenia-related hospitalization and age, adjusting for patient and treatment characteristics. Logistic regression analyses examined the effects of other risk factors.

Results A total of 15,638 patients were included (NHL, n = 2,506; breast cancer, n = 9,110; lung cancer, n = 4,022), mean age 56-66 years. Neutropenia-related hospitalization occurred in 8.7% of NHL patients, 4.2% of breast cancer patients, and 3.9% of lung cancer patients. The association between age and the risk of neutropenia-related hospitalization was stronger in NHL than in lung or breast cancer. Patient comorbidities and chemotherapy characteristics had considerable effects on risk of neutropenia-related hospitalization.

Limitations Disease stage and other clinical factors could not be identified from the claims data.

Conclusion In addition to age, oncologists should evaluate individual patient risk factors including patient comorbidities and type of chemotherapy regimen.

*To read the full article, click on the PDF icon at the top of this introduction.

Background Age is among the most important risk factors for neutropenia-related hospitalization, but evidence is limited regarding the relative contributions of age and other risk factors.

Objective To explore the associations among patient age, other risk factors, and neutropenic complications in patients with cancer receiving myelosuppressive chemotherapy.

Methods This retrospective cohort study, which used a US commercial insurance claims database, included patients aged 40 years or older with non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL), breast cancer, or lung cancer who initiated chemotherapy between January 1, 2006 and March 31, 2010. The primary endpoint was the risk of neutropenia-related hospitalization during the first chemotherapy course. We used cubic spline modeling to estimate the association between neutropenia-related hospitalization and age, adjusting for patient and treatment characteristics. Logistic regression analyses examined the effects of other risk factors.

Results A total of 15,638 patients were included (NHL, n = 2,506; breast cancer, n = 9,110; lung cancer, n = 4,022), mean age 56-66 years. Neutropenia-related hospitalization occurred in 8.7% of NHL patients, 4.2% of breast cancer patients, and 3.9% of lung cancer patients. The association between age and the risk of neutropenia-related hospitalization was stronger in NHL than in lung or breast cancer. Patient comorbidities and chemotherapy characteristics had considerable effects on risk of neutropenia-related hospitalization.

Limitations Disease stage and other clinical factors could not be identified from the claims data.

Conclusion In addition to age, oncologists should evaluate individual patient risk factors including patient comorbidities and type of chemotherapy regimen.

*To read the full article, click on the PDF icon at the top of this introduction.

Working with other disciplines

Optimizing Home Health Care: Enhanced Value and Improved Outcomes

Supplement Editor:

William Zafirau, MD

Supplement Co-Editors:

Steven H. Landers, MD, MPH, and Cindy Vunovich, RN, BSN, MSM

Contents

Introduction—Medicine’s future: Helping patients stay healthy at home

Steven H. Landers, MD, MPH

Care transitions and advanced home care models

Improving patient outcomes with better care transitions: The role for home health

Michael O. Fleming, MD, and Tara Trahan Haney

Improving outcomes and lowering costs by applying advanced models of in-home care

Peter A. Boling, MD; Rashmi V. Chandekar, MD; Beth Hungate, MS, ANP-BC; Martha Purvis, MSN; Rachel Selby-Penczak, MD; and Linda J. Abbey, MD

Home care for knee replacement and heart failure

In-home care following total knee replacement

Mark I. Froimson, MD, MBA

Home-based care for heart failure: Cleveland Clinic's "Heart Care at Home" transitional care program

Eiran Z. Gorodeski, MD, MPH; Sandra Chlad, NP; and Seth Vilensky, MBA

Technology innovations and palliative care

The case for "connected health" at home

Steven H. Landers, MD, MPH

Innovative models of home-based palliative care

Margherita C. Labson, RN, MSHSA, CPHQ, CCM; Michele M. Sacco, MS; David E. Weissman, MD; Betsy Gornet, FACHE; and Brad Stuart, MD

Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine interview

Accountable care and patient-centered medical homes: Implications for office-based practice

An interview with David L. Longworth, MD

Supplement Editor:

William Zafirau, MD

Supplement Co-Editors:

Steven H. Landers, MD, MPH, and Cindy Vunovich, RN, BSN, MSM

Contents

Introduction—Medicine’s future: Helping patients stay healthy at home

Steven H. Landers, MD, MPH

Care transitions and advanced home care models

Improving patient outcomes with better care transitions: The role for home health

Michael O. Fleming, MD, and Tara Trahan Haney

Improving outcomes and lowering costs by applying advanced models of in-home care

Peter A. Boling, MD; Rashmi V. Chandekar, MD; Beth Hungate, MS, ANP-BC; Martha Purvis, MSN; Rachel Selby-Penczak, MD; and Linda J. Abbey, MD

Home care for knee replacement and heart failure

In-home care following total knee replacement

Mark I. Froimson, MD, MBA

Home-based care for heart failure: Cleveland Clinic's "Heart Care at Home" transitional care program

Eiran Z. Gorodeski, MD, MPH; Sandra Chlad, NP; and Seth Vilensky, MBA

Technology innovations and palliative care

The case for "connected health" at home

Steven H. Landers, MD, MPH

Innovative models of home-based palliative care

Margherita C. Labson, RN, MSHSA, CPHQ, CCM; Michele M. Sacco, MS; David E. Weissman, MD; Betsy Gornet, FACHE; and Brad Stuart, MD

Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine interview

Accountable care and patient-centered medical homes: Implications for office-based practice

An interview with David L. Longworth, MD

Supplement Editor:

William Zafirau, MD

Supplement Co-Editors:

Steven H. Landers, MD, MPH, and Cindy Vunovich, RN, BSN, MSM

Contents

Introduction—Medicine’s future: Helping patients stay healthy at home

Steven H. Landers, MD, MPH

Care transitions and advanced home care models

Improving patient outcomes with better care transitions: The role for home health

Michael O. Fleming, MD, and Tara Trahan Haney

Improving outcomes and lowering costs by applying advanced models of in-home care

Peter A. Boling, MD; Rashmi V. Chandekar, MD; Beth Hungate, MS, ANP-BC; Martha Purvis, MSN; Rachel Selby-Penczak, MD; and Linda J. Abbey, MD

Home care for knee replacement and heart failure

In-home care following total knee replacement

Mark I. Froimson, MD, MBA

Home-based care for heart failure: Cleveland Clinic's "Heart Care at Home" transitional care program

Eiran Z. Gorodeski, MD, MPH; Sandra Chlad, NP; and Seth Vilensky, MBA

Technology innovations and palliative care

The case for "connected health" at home

Steven H. Landers, MD, MPH

Innovative models of home-based palliative care

Margherita C. Labson, RN, MSHSA, CPHQ, CCM; Michele M. Sacco, MS; David E. Weissman, MD; Betsy Gornet, FACHE; and Brad Stuart, MD

Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine interview

Accountable care and patient-centered medical homes: Implications for office-based practice

An interview with David L. Longworth, MD

Introduction—Medicine’s future: Helping patients stay healthy at home

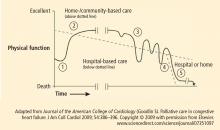

Home-based care will undoubtedly play an increasingly important role in the health care system as the United States seeks ways to provide cost-effective and compassionate care to a growing population of older adults with chronic illness. “Home health care,” a term that refers more specifically to visiting nurses, therapists, and related services, is currently the prominent home care model in this country.

Home health services were developed around the start of the 20th century to address the unmet health and social needs of vulnerable populations living in the shadows. Today, there are more than 10,000 home health agencies and visiting nurse organizations across the country that care for millions of homebound patients each year. With the onset of health reform and the increasing focus on value and “accountability,” there are many opportunities and challenges for home health providers and the physicians, hospitals, and facilities they work with to try to find the best ways to keep patients healthy at home and drive value for society.

There is a paucity of medical and health services literature to guide providers and policymakers’ decisions about the right types and approaches to care at home. Maybe this is because academic centers and American medicine became so focused on acute institutional care in the past half century that the home has been overlooked. However, that pendulum is likely swinging back as almost every sober analysis of our current health care environment suggests a need for better care for the chronically ill at home and in the community. It is important that research and academic enterprises emphasize scholarly efforts to understand and improve home and community care so that the anticipated shift in care to home is informed by the best possible evidence, ultimately ensuring that patients get the best possible care.

The articles in this online, CME-certified Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine supplement address contemporary topics in home health and other home-based care concepts. The authors have diverse backgrounds and discuss issues related to technology, palliative care, care transitions, heart failure, knee replacement, primary care, and health reform. Several articles share concepts and outcomes from innovative approaches being developed throughout the country to help patients succeed at home, especially when returning home from a hospitalization.

The articles should improve readers’ understanding of a wide range of initiatives and ideas for how home health and home care might look in the future delivery system. The authors also raise numerous yet-unanswered questions and opportunities for future study. The needs for further home care research from clinical, public health, and policy perspectives are evident. Health care is going home, and this transformation will be enhanced and possibly accelerated by thoughtful research and synthesis.

I am incredibly thankful to my fellow authors, and hope that we have produced a useful supplement that will help readers in their efforts to assist the most vulnerable patients and families in their efforts to remain independent at home.

Home-based care will undoubtedly play an increasingly important role in the health care system as the United States seeks ways to provide cost-effective and compassionate care to a growing population of older adults with chronic illness. “Home health care,” a term that refers more specifically to visiting nurses, therapists, and related services, is currently the prominent home care model in this country.

Home health services were developed around the start of the 20th century to address the unmet health and social needs of vulnerable populations living in the shadows. Today, there are more than 10,000 home health agencies and visiting nurse organizations across the country that care for millions of homebound patients each year. With the onset of health reform and the increasing focus on value and “accountability,” there are many opportunities and challenges for home health providers and the physicians, hospitals, and facilities they work with to try to find the best ways to keep patients healthy at home and drive value for society.

There is a paucity of medical and health services literature to guide providers and policymakers’ decisions about the right types and approaches to care at home. Maybe this is because academic centers and American medicine became so focused on acute institutional care in the past half century that the home has been overlooked. However, that pendulum is likely swinging back as almost every sober analysis of our current health care environment suggests a need for better care for the chronically ill at home and in the community. It is important that research and academic enterprises emphasize scholarly efforts to understand and improve home and community care so that the anticipated shift in care to home is informed by the best possible evidence, ultimately ensuring that patients get the best possible care.

The articles in this online, CME-certified Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine supplement address contemporary topics in home health and other home-based care concepts. The authors have diverse backgrounds and discuss issues related to technology, palliative care, care transitions, heart failure, knee replacement, primary care, and health reform. Several articles share concepts and outcomes from innovative approaches being developed throughout the country to help patients succeed at home, especially when returning home from a hospitalization.

The articles should improve readers’ understanding of a wide range of initiatives and ideas for how home health and home care might look in the future delivery system. The authors also raise numerous yet-unanswered questions and opportunities for future study. The needs for further home care research from clinical, public health, and policy perspectives are evident. Health care is going home, and this transformation will be enhanced and possibly accelerated by thoughtful research and synthesis.

I am incredibly thankful to my fellow authors, and hope that we have produced a useful supplement that will help readers in their efforts to assist the most vulnerable patients and families in their efforts to remain independent at home.

Home-based care will undoubtedly play an increasingly important role in the health care system as the United States seeks ways to provide cost-effective and compassionate care to a growing population of older adults with chronic illness. “Home health care,” a term that refers more specifically to visiting nurses, therapists, and related services, is currently the prominent home care model in this country.

Home health services were developed around the start of the 20th century to address the unmet health and social needs of vulnerable populations living in the shadows. Today, there are more than 10,000 home health agencies and visiting nurse organizations across the country that care for millions of homebound patients each year. With the onset of health reform and the increasing focus on value and “accountability,” there are many opportunities and challenges for home health providers and the physicians, hospitals, and facilities they work with to try to find the best ways to keep patients healthy at home and drive value for society.

There is a paucity of medical and health services literature to guide providers and policymakers’ decisions about the right types and approaches to care at home. Maybe this is because academic centers and American medicine became so focused on acute institutional care in the past half century that the home has been overlooked. However, that pendulum is likely swinging back as almost every sober analysis of our current health care environment suggests a need for better care for the chronically ill at home and in the community. It is important that research and academic enterprises emphasize scholarly efforts to understand and improve home and community care so that the anticipated shift in care to home is informed by the best possible evidence, ultimately ensuring that patients get the best possible care.

The articles in this online, CME-certified Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine supplement address contemporary topics in home health and other home-based care concepts. The authors have diverse backgrounds and discuss issues related to technology, palliative care, care transitions, heart failure, knee replacement, primary care, and health reform. Several articles share concepts and outcomes from innovative approaches being developed throughout the country to help patients succeed at home, especially when returning home from a hospitalization.

The articles should improve readers’ understanding of a wide range of initiatives and ideas for how home health and home care might look in the future delivery system. The authors also raise numerous yet-unanswered questions and opportunities for future study. The needs for further home care research from clinical, public health, and policy perspectives are evident. Health care is going home, and this transformation will be enhanced and possibly accelerated by thoughtful research and synthesis.

I am incredibly thankful to my fellow authors, and hope that we have produced a useful supplement that will help readers in their efforts to assist the most vulnerable patients and families in their efforts to remain independent at home.

Improving patient outcomes with better care transitions: The role for home health

The US health care system faces many challenges. Quality, cost, access, fragmentation, and misalignment of incentives are only a few. The most pressing dilemma is how this challenged system will handle the demographic wave of aging Americans. Our 21st-century population is living longer with a greater chronic disease burden than its predecessors, and has reasonable expectations of quality care. No setting portrays this challenge more clearly than that of transition: the transfer of a patient and his or her care from the hospital or facility setting to the home. Addressing this challenge requires that we adopt a set of proven effective interventions that can improve quality of care, meet the needs of the patients and families we serve, and lower the staggering economic and social burden of preventable hospital readmissions.

The Medicare system, designed in 1965, has not kept pace with the needs and challenges of the rapidly aging US population. Further, the system is not aligned with today’s—and tomorrow’s—needs. In 1965, average life expectancy for Americans was 70 years; by 2020, that average is predicted to be nearly 80 years.1 In 2000, one in eight Americans, or 12% of the US population, was aged 65 years or older.2 It is expected that by 2030, this group will represent 19% of the population. This means that in 2030, some 72 million Americans will be aged 65 or older—more than twice the number in this age group in 2000.2

The 1965 health care system focused on treating acute disease, but the health care system of the 21st century must effectively manage chronic disease. The burden of chronic disease is especially significant for aging patients, who are likely to be under the care of multiple providers and require multiple medications and ever-higher levels of professional care. The management and sequelae of chronic diseases frequently lead to impaired quality of life as well as significant expense for Medicare.

The discrepancy between our health care system and unmet needs is acutely obvious at the time of hospital discharge. In fact, the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (MedPAC) has stated that this burden of unmet needs at hospital discharge is primarily driven by hospital admissions and readmissions.3 Thirty-day readmission rates among older Medicare beneficiaries range from 15% to 25%.4–6 Disagreement persists regarding what percentage of hospital readmissions within 30 days might be preventable. A systematic review of 34 studies has reported that, on average, 27% of readmissions were preventable.7

To address the challenge of avoidable readmissions, our home health and hospice care organization, Amedisys, Inc., developed a care transitions initiative designed to improve quality of life, improve patient outcomes, and prevent unnecessary hospital readmissions. This article, which includes an illustrative case study, describes the initiative and the outcomes observed during its first 12 months of testing.

CASE STUDY

Mrs. Smith is 84 years old and lives alone in her home. She suffers from mild to moderate dementia and heart failure (HF). Mrs. Smith’s daughter is her main caregiver, talking to Mrs. Smith multiple times a day and stopping by Mrs. Smith’s house at least two to three times a week.

Mrs. Smith was admitted to the hospital after her daughter brought her to the emergency department over the weekend because of shortness of breath. This was her third visit to the emergency department within the past year, with each visit resulting in a hospitalization. Because of questions regarding her homebound status, home health was not considered part of the care plan during either of Mrs. Smith’s previous discharges.

Hospitalists made rounds over the weekend and notified Mrs. Smith that she would be released on Tuesday morning; because of her weakness and disorientation, the hospitalist issued an order for home health and a prescription for a new HF medication. Upon hearing the news on Monday of the planned discharge, Mrs. Smith and her daughter selected the home health provider they wished to use and, within the next few hours, a care transitions coordinator (CTC) visited them in the hospital.

The CTC, a registered nurse, talked with Mrs. Smith about her illness, educating her on the impact of diet on her condition and the medications she takes, including the new medication prescribed by the hospitalist. Most importantly, the CTC talked to Mrs. Smith about her personal goals during her recovery. For example, Mrs. Smith loves to visit her granddaughter, where she spends hours at a time watching her great-grandchildren play. Mrs. Smith wants to control her HF so that she can continue these visits that bring her such joy.

Mrs. Smith’s daughter asked the CTC if she would make Mrs. Smith’s primary care physician aware of the change in medication and schedule an appointment within the next week. The CTC did so before Mrs. Smith left the hospital. She also completed a primary care discharge notification, which documented Mrs. Smith’s discharge diagnoses, discharge medications, important test results, and the date of the appointment, and e-faxed it to Mrs. Smith’s primary care physician. The CTC also communicated with the home health nurse who would care for Mrs. Smith following discharge, reviewing her clinical needs as well as her personal goals.

Mrs. Smith’s daughter was present when the home health nurse conducted the admission and in-home assessment. The home health nurse educated both Mrs. Smith and her daughter about foods that might exacerbate HF, reinforcing the education started in the hospital by the CTC. In the course of this conversation, Mrs. Smith’s daughter realized that her mother had been eating popcorn late at night when she could not sleep. The CTC helped both mother and daughter to understand that the salt in her popcorn could have an impact on Mrs. Smith’s illness that would likely result in rehospitalization and an increase in medication dosage; this educational process enhanced the patient’s understanding of her disease and likely reduced the chances of her emergency department–rehospitalization cycle continuing.

INTERVENTION

The design of the Amedisys care transitions initiative is based on work by Naylor et al8 and Coleman et al,6 who are recognized in the home health industry for their models of intervention at the time of hospital discharge. The Amedisys initiative’s objective is to prevent avoidable readmissions through patient and caregiver health coaching and care coordination, starting in the hospital and continuing through completion of the patient’s home health plan of care. Table 1 compares the essential interventions of the Naylor and Coleman models with those of the Amedisys initiative.

The Amedisys initiative includes these specific interventions:

- use of a CTC;

- early engagement of the patient, caregiver, and family with condition-specific coaching;

- careful medication management; and

- physician engagement with scheduling and reminders of physician visits early in the transition process.

Using a care transitions coordinator

Amedisys has placed CTCs in the acute care facilities that it serves. The CTC’s responsibility is to ensure that patients transition safely home from the acute care setting. With fragmentation of care, patients are most vulnerable during the initial few days postdischarge; this is particularly true for the frail elderly. Consequently, the CTC meets with the patient and caregiver as soon as possible upon his or her referral to Amedisys to plan the transition home from the facility and determine the resources needed once home. The CTC becomes the patient’s “touchpoint” for any questions or problems that arise between the time of discharge and the time when an Amedisys nurse visits the patient’s home.

Early engagement and coaching

The CTC uses a proprietary tool, Bridge to Healt0hy Living, to begin the process of early engagement, education, and coaching. This bound notebook is personalized for each patient with the CTC’s name and 24-hour phone contact information. The CTC records the patient’s diagnoses as well as social and economic barriers that may affect the patient’s outcomes. The diagnoses are written in the notebook along with a list of the patient’s medications that describes what each drug is for, its exact dosage, and instructions for taking it.

Coaching focuses on the patient’s diagnoses and capabilities, with discussion of diet and lifestyle needs and identification of “red flags” about each condition. The CTC asks the patient to describe his or her treatment goals and care plan. Ideally, the patient or a family member puts the goals and care plan in writing in the notebook in the patient’s own words; this strategy makes the goals and plan more meaningful and relevant to the patient. The CTC revisits this information at each encounter with the patient and caregiver.

Patient/family and caregiver engagement are crucial to the success of the initiative with frail, older patients.8,9 One 1998 study indicated that patient and caregiver satisfaction with home health services correlated with receiving information from the home health staff regarding medications, equipment and supplies, and self-care; further, the degree of caregiver burden was inversely related to receipt of information from the home health staff.10 The engagement required for the patient and caregiver to record the necessary information in the care transitions tool improves the likelihood of their understanding and adhering to lifestyle, behavioral, and medication recommendations.

At the time of hospital discharge, the CTC arranges the patient’s appointment with the primary care physician and records this in the patient’s notebook. The date and time for the patient’s first home nursing visit is also arranged and recorded so that the patient and caregiver know exactly when to expect that visit.

Medication management

The first home nursing visit typically occurs within 24 hours of hospital discharge. During this visit, the home health nurse reviews the Bridge to Healthy Living tool and uses it to guide care in partnership with the patient, enhancing adherence to the care plan. The nurse reviews the patient’s medications, checks them against the hospital discharge list, and then asks about other medications that might be in a cabinet or the refrigerator that the patient might be taking. At each subsequent visit, the nurse reviews the medication list and adjusts it as indicated if the patient’s physicians have changed any medication. If there has been a medication change, this is communicated by the home health nurse to all physicians caring for the patient.

The initial home nursing visit includes an environmental assessment with observation for hazards that could increase the risk for falls or other injury. The nurse also reinforces coaching on medications, red flags, and dietary or lifestyle issues that was begun by the CTC in the hospital.

Physician engagement

Physician engagement in the transition process is critical to reducing avoidable rehospitalizations. Coleman’s work has emphasized the need for the patient to follow up with his or her primary care physician within 1 week of discharge; but too frequently, the primary care physician is unaware that the patient was admitted to the hospital, and discharge summaries may take weeks to arrive. The care transitions initiative is a relationship-based, physician-led care delivery model in which the CTC serves as the funnel for information-sharing among all providers engaged with the patient. Although the CTC functions as the information manager, a successful transition requires an unprecedented level of cooperation among physicians and other health care providers. Health care is changing; outcomes must improve and costs must decrease. Therefore, this level of cooperation is no longer optional, but has become mandatory.

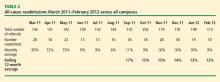

OUTCOMES

The primary outcome measure in the care transitions initiative was the rate of nonelective rehospitalization related to any cause, recurrence, or exacerbation of the index hospitalization diagnosis-related group, comorbid conditions, or new health problems. The Amedisys care transitions initiative was tested in three large, academic institutions in the northeast and southeast United States for 12 months. The 12-month average readmission rate (as calculated month by month) in the last 6 months of the study decreased from 17% to 12% (Table 2). During this period both patient and physician satisfaction were enhanced, according to internal survey data.

CALL TO ACTION

Americans want to live in their own homes as long as possible. In fact, when elderly Americans are admitted to a hospital, what is actually occurring is that they are being “discharged from their communities.”11 A health care delivery system that provides a true patient-centered approach to care recognizes that this situation often compounds issues of health care costs and quality. Adequate transitional care can provide simpler and more cost-effective options. If a CTC and follow-up care at home had been provided to Mrs. Smith and her daughter upon the first emergency room visit earlier in the year (see “Case study,” page e-S2), Mrs. Smith might have avoided multiple costly readmissions. Each member of the home health industry and its partners should be required to provide a basic set of evidence-based care transition elements to the patients they serve. By coordinating care at the time of discharge, some of the fragmentation that has become embedded in our system might be overcome.

- Life expectancy—United States. Data360 Web site. http://www.data360.org/dsg.aspx?Data_Set_Group_Id=195. Accessed August 15, 2012.

- Aging statistics. Administration on Aging Web site. http://www.aoa.gov/aoaroot/aging_statistics/index.aspx. Updated September 1, 2011. Accessed August 15, 2012.

- Report to the Congress. Medicare Payment Policy. Medicare Payment Advisory Commission Web site. http://medpac.gov/documents/Mar08_EntireReport.pdf. Published March 2008. Accessed August 15, 2012.

- Coleman EA, Min S, Chomiak A, Kramer AM. Post-hospital care transitions: patterns, complications, and risk identification. Health Serv Res 2004; 39:1449–1465.

- Quality initiatives—general information. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Web site. http://www.cms.hhs.gov/QualityInitiativesGenInfo/15_MQMS.asp. Updated April 4, 2012. Accessed August 15, 2012.

- Coleman EA, Parry C, Chalmers S, Min SJ. The care transitions intervention: results of a randomized controlled trial. Arch Intern Med 2006; 166:1822–1828.

- van Walraven C, Bennett C, Jennings A, Austin PC, Forster AJ. Proportion of hospital readmissions deemed avoidable: a systematic review [published online ahead of print]. CMAJ 2011; 183:E391–E402. 10.1503/cmaj.101860

- Naylor MD, Brooten D, Campbell R, et al. Comprehensive discharge planning and home follow-up of hospitalized elders: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 1999; 281:613–620.

- Coleman EA, Smith JD, Frank JC, Min S, Parry C, Kramer AM. Preparing patients and caregivers to participate in care delivered across settings: the Care Transitions Intervention. J Am Geriatr Soc 2004; 52:1817–1825.

- Weaver FM, Perloff L, Waters T. Patients’ and caregivers’ transition from hospital to home: needs and recommendations. Home Health Care Serv Q 1998; 17:27–48.

- Fleming MO. The value of healthcare at home. Presented at: American Osteopathic Visiting Professorship, Louisiana State University Health System; April 12, 2012; New Orleans, LA.

The US health care system faces many challenges. Quality, cost, access, fragmentation, and misalignment of incentives are only a few. The most pressing dilemma is how this challenged system will handle the demographic wave of aging Americans. Our 21st-century population is living longer with a greater chronic disease burden than its predecessors, and has reasonable expectations of quality care. No setting portrays this challenge more clearly than that of transition: the transfer of a patient and his or her care from the hospital or facility setting to the home. Addressing this challenge requires that we adopt a set of proven effective interventions that can improve quality of care, meet the needs of the patients and families we serve, and lower the staggering economic and social burden of preventable hospital readmissions.

The Medicare system, designed in 1965, has not kept pace with the needs and challenges of the rapidly aging US population. Further, the system is not aligned with today’s—and tomorrow’s—needs. In 1965, average life expectancy for Americans was 70 years; by 2020, that average is predicted to be nearly 80 years.1 In 2000, one in eight Americans, or 12% of the US population, was aged 65 years or older.2 It is expected that by 2030, this group will represent 19% of the population. This means that in 2030, some 72 million Americans will be aged 65 or older—more than twice the number in this age group in 2000.2

The 1965 health care system focused on treating acute disease, but the health care system of the 21st century must effectively manage chronic disease. The burden of chronic disease is especially significant for aging patients, who are likely to be under the care of multiple providers and require multiple medications and ever-higher levels of professional care. The management and sequelae of chronic diseases frequently lead to impaired quality of life as well as significant expense for Medicare.

The discrepancy between our health care system and unmet needs is acutely obvious at the time of hospital discharge. In fact, the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (MedPAC) has stated that this burden of unmet needs at hospital discharge is primarily driven by hospital admissions and readmissions.3 Thirty-day readmission rates among older Medicare beneficiaries range from 15% to 25%.4–6 Disagreement persists regarding what percentage of hospital readmissions within 30 days might be preventable. A systematic review of 34 studies has reported that, on average, 27% of readmissions were preventable.7

To address the challenge of avoidable readmissions, our home health and hospice care organization, Amedisys, Inc., developed a care transitions initiative designed to improve quality of life, improve patient outcomes, and prevent unnecessary hospital readmissions. This article, which includes an illustrative case study, describes the initiative and the outcomes observed during its first 12 months of testing.

CASE STUDY