User login

Observations on the CATIE Schizophrenia StudyHow Should the Data Be Translated Into Clinical Practice?

How Should the Data Be Translated Into Clinical Practice?

A supplement to Clinical Psychiatry News and supported by Pfizer, Inc.

A panel of experts met in November 2005 in Washington, DC, to discuss the first published results of the Clinical Antipsychotic Trials of Intervention Effectiveness (CATIE) schizophrenia study. Participants included several principal study investigators as well as experts in the treatment and management of schizophrenia and bipolar illness. The content of this supplement is based in part on that discussion.

Click Here to view the supplement.

Faculty

Peter F. Buckley, MD

Medical College of Georgia

School of Medicine

Grant/Research Support: Astra/Zeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb Company, Eli Lilly and Company, Janssen Pharmaceutica, LP, Pfizer Inc., and Solvay Pharmaceuticals, Inc. Consultant/Received Honoraria: Abbott Laboratories, Alamo Pharmaceuticals, LLC, AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly, Janssen, and Pfizer.

Joseph P. McEvoy, MD

Duke University

Medical Center

Clinical Grant Support: AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly, Janssen, and Pfizer Inc. Consultant: GlaxoSmithKline, Eli Lilly, and Pfizer.

Topics

• Design

• Overview of Results

• Dosing

• Metabolics

• Clinical Implications of CATIE Phase I

• Beyond Phase I

• Implications of CATIE Beyond Schizophrenia

• Conclusion

A supplement to Clinical Psychiatry News and supported by Pfizer, Inc.

A panel of experts met in November 2005 in Washington, DC, to discuss the first published results of the Clinical Antipsychotic Trials of Intervention Effectiveness (CATIE) schizophrenia study. Participants included several principal study investigators as well as experts in the treatment and management of schizophrenia and bipolar illness. The content of this supplement is based in part on that discussion.

Click Here to view the supplement.

Faculty

Peter F. Buckley, MD

Medical College of Georgia

School of Medicine

Grant/Research Support: Astra/Zeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb Company, Eli Lilly and Company, Janssen Pharmaceutica, LP, Pfizer Inc., and Solvay Pharmaceuticals, Inc. Consultant/Received Honoraria: Abbott Laboratories, Alamo Pharmaceuticals, LLC, AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly, Janssen, and Pfizer.

Joseph P. McEvoy, MD

Duke University

Medical Center

Clinical Grant Support: AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly, Janssen, and Pfizer Inc. Consultant: GlaxoSmithKline, Eli Lilly, and Pfizer.

Topics

• Design

• Overview of Results

• Dosing

• Metabolics

• Clinical Implications of CATIE Phase I

• Beyond Phase I

• Implications of CATIE Beyond Schizophrenia

• Conclusion

A supplement to Clinical Psychiatry News and supported by Pfizer, Inc.

A panel of experts met in November 2005 in Washington, DC, to discuss the first published results of the Clinical Antipsychotic Trials of Intervention Effectiveness (CATIE) schizophrenia study. Participants included several principal study investigators as well as experts in the treatment and management of schizophrenia and bipolar illness. The content of this supplement is based in part on that discussion.

Click Here to view the supplement.

Faculty

Peter F. Buckley, MD

Medical College of Georgia

School of Medicine

Grant/Research Support: Astra/Zeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb Company, Eli Lilly and Company, Janssen Pharmaceutica, LP, Pfizer Inc., and Solvay Pharmaceuticals, Inc. Consultant/Received Honoraria: Abbott Laboratories, Alamo Pharmaceuticals, LLC, AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly, Janssen, and Pfizer.

Joseph P. McEvoy, MD

Duke University

Medical Center

Clinical Grant Support: AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly, Janssen, and Pfizer Inc. Consultant: GlaxoSmithKline, Eli Lilly, and Pfizer.

Topics

• Design

• Overview of Results

• Dosing

• Metabolics

• Clinical Implications of CATIE Phase I

• Beyond Phase I

• Implications of CATIE Beyond Schizophrenia

• Conclusion

How Should the Data Be Translated Into Clinical Practice?

How Should the Data Be Translated Into Clinical Practice?

Bacterial Contamination of Work Wear

In September 2007, the British Department of Health developed guidelines for health care workers regarding uniforms and work wear that banned the traditional white coat and other long‐sleeved garments in an attempt to decrease nosocomial bacterial transmission.1 Similar policies have recently been adopted in Scotland.2 Interestingly, the National Health Service report acknowledged that evidence was lacking that would support that white coats and long‐sleeved garments caused nosocomial infection.1, 3 Although many studies have documented that health care work clothes are contaminated with bacteria, including methicillin‐resistant Staphylococcal aureus (MRSA) and other pathogenic species,413 none have determined whether avoiding white coats and switching to short‐sleeved garments decreases bacterial contamination.

We performed a prospective, randomized, controlled trial designed to compare the extent of bacterial contamination of physicians' white coats with that of newly laundered, standardized short‐sleeved uniforms. Our hypotheses were that infrequently cleaned white coats would have greater bacterial contamination than uniforms, that the extent of contamination would be inversely related to the frequency with which the coats were washed, and that the increased contamination of the cuffs of the white coats would result in increased contamination of the skin of the wrists. Our results led us also to assess the rate at which bacterial contamination of short‐sleeved uniforms occurs during the workday.

Methods

The study was conducted at Denver Health, a university‐affiliated public safety‐net hospital and was approved by the Colorado Multiple Institutional Review Board.

Trial Design

The study was a prospective, randomized, controlled trial. No protocol changes occurred during the study.

Participants

Participants included residents and hospitalists directly caring for patients on internal medicine units between August 1, 2008 and November 15, 2009.

Intervention

Subjects wore either a standard, newly laundered, short‐sleeved uniform or continued to wear their own white coats.

Outcomes

The primary end point was the percentage of subjects contaminated with MRSA. Cultures were collected using a standardized RODAC imprint method14 with BBL RODAC plates containing trypticase soy agar with lecithin and polysorbate 80 (Becton Dickinson, Sparks, MD) 8 hours after the physicians started their work day. All physicians had cultures obtained from the breast pocket and sleeve cuff (long‐sleeved for the white coats, short‐sleeved for the uniforms) and from the skin of the volar surface of the wrist of their dominant hand. Those wearing white coats also had cultures obtained from the mid‐biceps level of the sleeve of the dominant hand, as this location closely approximated the location of the cuffs of the short‐sleeved uniforms.

Cultures were incubated in ambient air at 35C‐37C for 1822 hours. After incubation, visible colonies were counted using a dissecting microscope to a maximum of 200 colonies at the recommendation of the manufacturer. Colonies that were morphologically consistent with Staphylococcus species by colony growth and Gram stain were further tested for coagulase using a BactiStaph rapid latex agglutination test (Remel, Lenexa, KS). If positive, these colonies were subcultured to sheep blood agar (Remel, Lenexa, KS) and BBL MRSA Chromagar (Becton Dickinson, Sparks, MD) and incubated for an additional 1824 hours. Characteristic growth on blood agar that also produced mauve‐colored colonies on chromagar was taken to indicate MRSA.

A separate set of 10 physicians donned newly laundered, short‐sleeved uniforms at 6:30 AM for culturing from the breast pocket and sleeve cuff of the dominant hand prior to and 2.5, 5, and 8 hours after they were donned by the participants (with culturing of each site done on separate days to avoid the effects of obtaining multiple cultures at the same site on the same day). These cultures were not assessed for MRSA.

At the time that consent was obtained, all participants completed an anonymous survey that assessed the frequency with which they normally washed or changed their white coats.

Sample Size

Based on the finding that 20% of our first 20 participants were colonized with MRSA, we determined that to find a 25% difference in the percentage of subjects colonized with MRSA in the 2 groups, with a power of 0.8 and P < 0.05 being significant (2‐sided Fisher's exact test), 50 subjects would be needed in each group.

Randomization

Randomization of potential participants occurred 1 day prior to the study using a computer‐generated table of random numbers. The principal investigator and a coinvestigator enrolled participants. Consent was obtained from those randomized to wear a newly laundered standard short‐sleeved uniform at the time of randomization so that they could don the uniforms when arriving at the hospital the following morning (at approximately 6:30 AM). Physicians in this group were also instructed not to wear their white coats at any time during the day they were wearing the uniforms. Physicians randomized to wear their own white coats were not notified or consented until the day of the study, a few hours prior to the time the cultures were obtained. This approach prevented them from either changing their white coats or washing them prior to the time the cultures were taken.

Because our study included both employees of the hospital and trainees, a number of protection measures were required. No information of any sort was collected about those who agreed or refused to participate in the study. In addition, the request to participate in the study did not come from the person's direct supervisor.

Statistical Methods

All data were collected and entered using Excel for Mac 2004 version 11.5.4. All analyses were performed using SAS Enterprise Guide 4.1 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC).

The Wilcoxon rank‐sum test and chi square analysis were used to seek differences in colony count and percentage of cultures with MRSA, respectively, in cultures obtained: (1) from the sleeve cuffs and pockets of the white coats compared with those from the sleeve cuffs and pockets of the uniforms, (2) from the sleeve cuffs of the white coats compared with those from the sleeve cuffs of the short‐sleeved uniforms, (3) from the mid‐biceps area of the sleeve sof the white coats compared with those from the sleeve cuffs of the uniforms, and (4) from the skin of the wrists of those wearing white coats compared with those wearing the uniforms. Bonferroni's correction for multiple comparisons was applied, with a P < 0.125 indicating significance.

Friedman's test and repeated‐measures logistic regression were used to seek differences in colony count or of the percentage of cultures with MRSA, respectively, on white coats or uniforms by site of culture on both garments. A P < 0.05 indicated significance for these analyses.

The Kruskal‐Wallis and chi‐square tests were utilized to test the effect of white coat wash frequency on colony count and MRSA contamination, respectively.

All data are presented as medians with 95% confidence intervals or proportions.

Results

Participant Flow

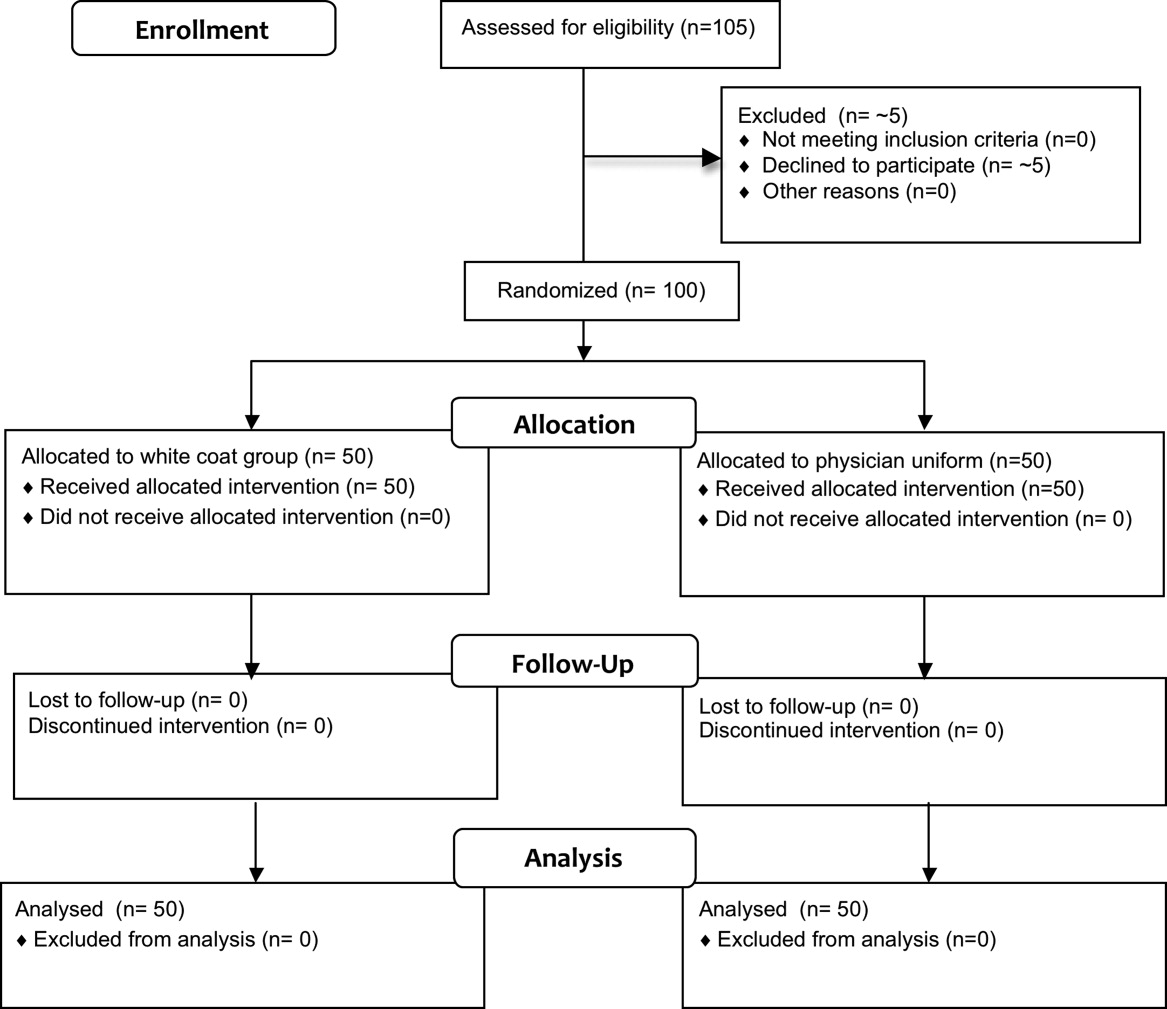

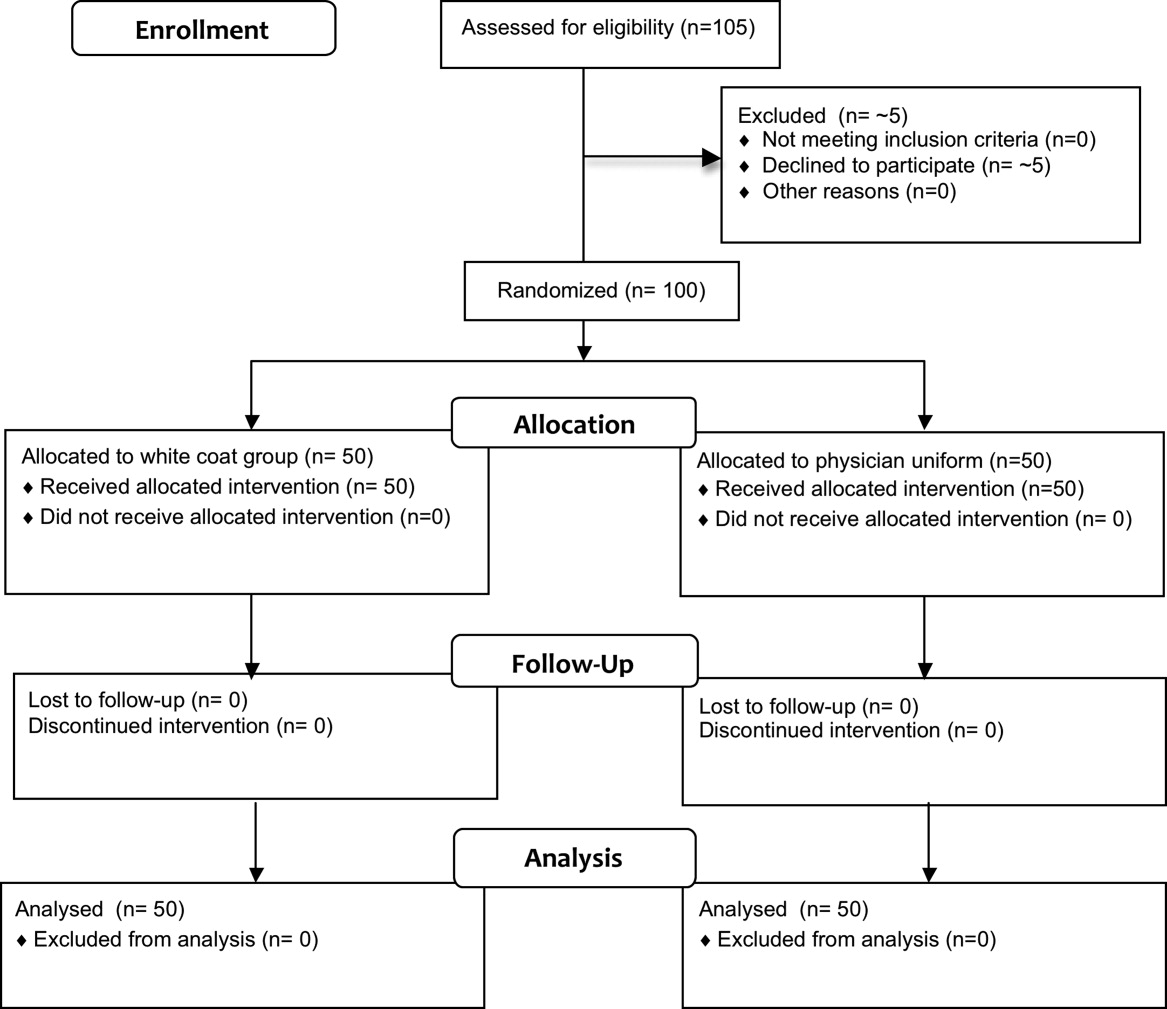

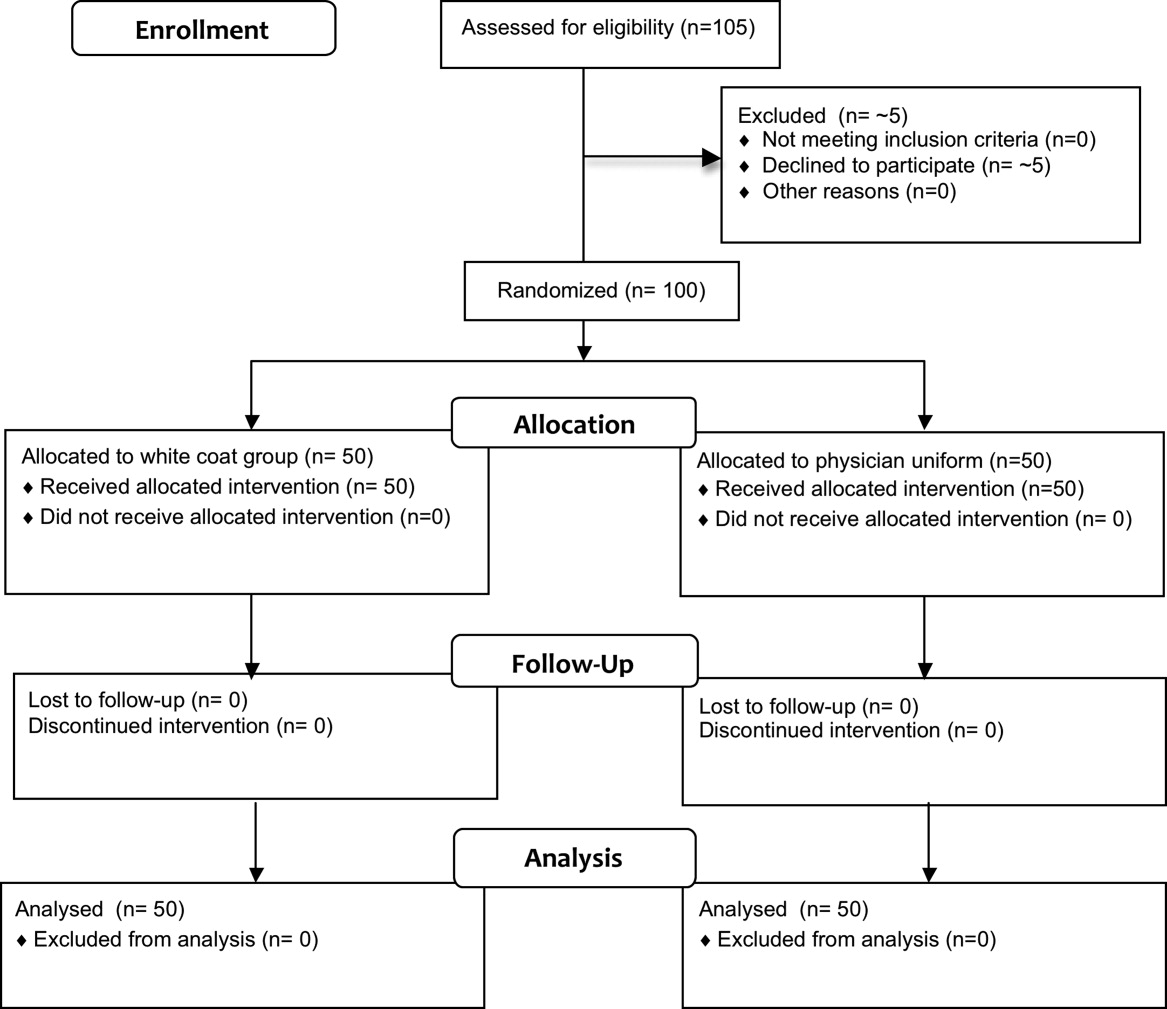

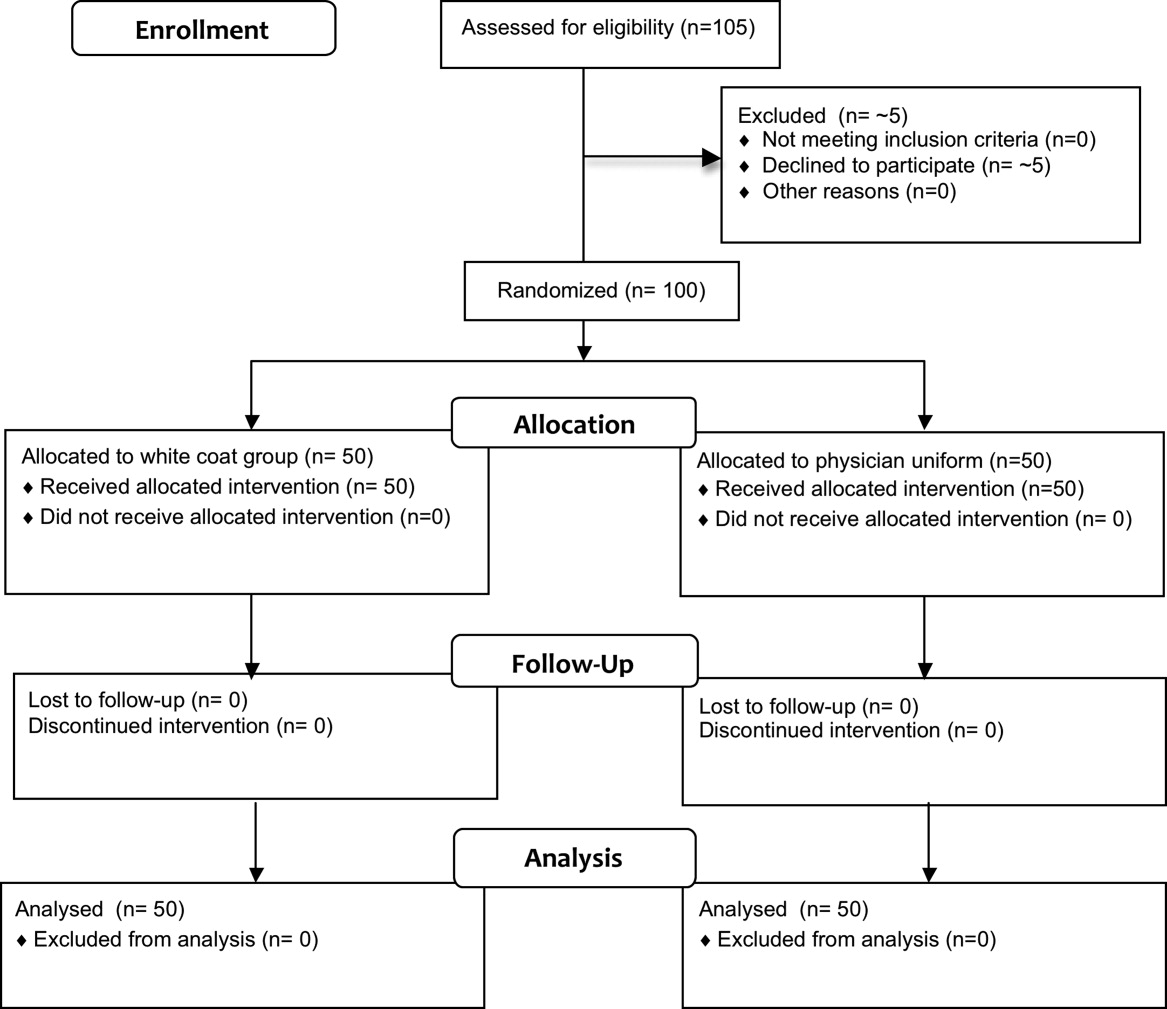

Fifty physicians were studied in each group, all of whom completed the survey. In general, more than 95% of potential participants approached agreed to participate in the study (Figure 1).

Recruitment

The first and last physicians were studied in August 2008 and November 2009, respectively. The trial ended when the specified number of participants (50 in each group) had been enrolled.

Data on Entry

No data were recorded from the participants at the time of randomization in compliance with institutional review board regulations pertaining to employment issues that could arise when studying members of the workforce.

Outcomes

No significant differences were found between the colony counts cultured from white coats (104 [80127]) versus newly laundered uniforms (142 [83213]), P = 0.61. No significant differences were found between the colony counts cultured from the sleeve cuffs of the white coats (58.5 [4866]) versus the uniforms (37 [2768]), P = 0.07, or between the colony counts cultured from the pockets of the white coats (45.5 [3254]) versus the uniforms (74.5 [4897], P = 0.040. Bonferroni corrections were used for multiple comparisons such that a P < 0.0125 was considered significant. Cultures from at least 1 site of 8 of 50 physicians (16%) wearing white coats and 10 of 50 physicians (20%) wearing short‐sleeved uniforms were positive for MRSA (P = .60).

Colony counts were greater in cultures obtained from the sleeve cuffs of the white coats compared with the pockets or mid‐biceps area (Table 1). For the uniforms, no difference in colony count in cultures from the pockets versus sleeve cuffs was observed. No difference was found when comparing the number of subjects with MRSA contamination of the 3 sites of the white coats or the 2 sites of the uniforms (Table 1).

| White Coat (n = 50) | P | Uniforms (n = 50) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Colony count, median (95% CI) | ||||

| Sleeve cuff | 58.5 (4866) | < 0.0001 | 37.0 (2768) | 0.25 |

| 45.5 (3254) | 74.5 (4897) | |||

| Mid‐biceps area of sleeve | 25.5 (2029) | |||

| MRSA contamination, n (%) | ||||

| Sleeve cuff | 4 (8%) | 0.71 | 6 (12%) | 0.18 |

| 5 (10%) | 9 (18%) | |||

| Mid‐biceps area of sleeve | 3 (6%) |

No difference was observed with respect to colony count or the percentage of subjects positive for MRSA in cultures obtained from the mid‐biceps area of the white coats versus those from the cuffs of the short‐sleeved uniforms (Table 2).

| White Coat Mid‐Biceps (n = 50) | Uniform Sleeve Cuff (n = 50) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Colony count, median (95% CI) | 25.5 (2029) | 37.0 (2768) | 0.07 |

| MRSA contamination, n (%) | 3 (6%) | 6 (12%) | 0.49 |

No difference was observed with respect to colony count or the percentage of subjects positive for MRSA in cultures obtained from the volar surface of the wrists of subjects wearing either of the 2 garments (Table 3).

| White Coat (n = 50) | Uniform (n = 50) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Colony count, median (95% CI) | 23.5 (1740) | 40.5 (2859) | 0.09 |

| MRSA Contamination, n (% of subjects) | 3 (6%) | 5 (10%) | 0.72 |

The frequency with which physicians randomized to wearing their white coats admitted to washing or changing their coats varied markedly (Table 4). No significant differences were found with respect to total colony count (P = 0.81), colony count by site (data not shown), or percentage of physicians contaminated with MRSA (P = 0.22) as a function of washing or changing frequency (Table 4).

| White Coat Washing Frequency | Number of Subjects (%) | Total Colony Count (All Sites), Median (95% CI) | Number with MRSA Contamination, n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Weekly | 15 (30%) | 124 (107229) | 1 (7%) |

| Every 2 weeks | 21 (42%) | 156 (90237) | 6 (29%) |

| Every 4 weeks | 8 (16%) | 89 (41206) | 0 (0%) |

| Every 8 weeks | 5 (10%) | 140 (58291) | 2 (40%) |

| Rarely | 1 (2%) | 150 | 0 (0%) |

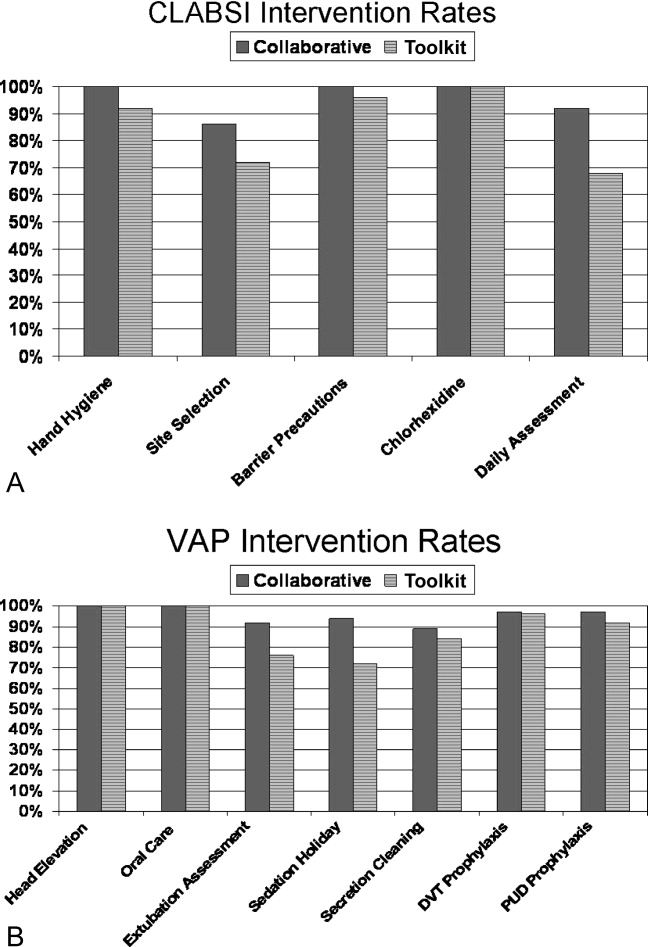

Sequential culturing showed that the newly laundered uniforms were nearly sterile prior to putting them on. By 3 hours of wear, however, nearly 50% of the colonies counted at 8 hours were already present (Figure 2).

Harms

No adverse events occurred during the course of the study in either group.

Discussion

The important findings of this study are that, contrary to our hypotheses, at the end of an 8‐hour workday, no significant differences were found between the extent of bacterial or MRSA contamination of infrequently washed white coats compared with those of newly laundered uniforms, no difference was observed with respect to the extent of bacterial or MRSA contamination of the wrists of physicians wearing either of the 2 garments, and no association was apparent between the extent of bacterial or MRSA contamination and the frequency with which white coats were washed or changed. In addition, we also found that bacterial contamination of newly laundered uniforms occurred within hours of putting them on.

Interpretation

Numerous studies have demonstrated that white coats and uniforms worn by health care providers are frequently contaminated with bacteria, including both methicillin‐sensitive and ‐resistant Staphylococcus aureus and other pathogens.413 This contamination may come from nasal or perineal carriage of the health care provider, from the environment, and/or from patients who are colonized or infected.11, 15 Although many have suggested that patients can become contaminated from contact with health care providers' clothing and studies employing pulsed‐field gel electrophoresis and other techniques have suggested that cross‐infection can occur,10, 1618 others have not confirmed this contention,19, 20 and Lessing and colleagues16 concluded that transmission from staff to patients was a rare phenomenon. The systematic review reported to the Department of Health in England,3 the British Medical Association guidelines regarding dress codes for doctors,21 and the department's report on which the new clothing guidelines were based1 concluded there was no conclusive evidence indicating that work clothes posed a risk of spreading infection to patients. Despite this, the Working Group and the British Medical Association recommended that white coats should not be worn when providing patient care and that shirts and blouses should be short‐sleeved.1 Recent evidence‐based reviews concluded that there was insufficient evidence to justify this policy,3, 22 and our data indicate that the policy will not decrease bacterial or MRSA contamination of physicians' work clothes or skin.

The recommendation that long‐sleeved clothing should be avoided comes from studies indicating that cuffs of these garments are more heavily contaminated than other areas5, 8 and are more likely to come in contact with patients.1 Wong and colleagues5 reported that cuffs and lower front pockets had greater contamination than did the backs of white coats, but no difference was seen in colony count from cuffs compared with pockets. Loh and colleagues8 found greater bacterial contamination on the cuffs than on the backs of white coats, but their conclusion came from comparing the percentage of subjects with selected colony counts (ie, between 100 and 199 only), and the analysis did not adjust for repeated sampling of each participant. Apparently, colony counts from the cuffs were not different than those from the pockets. Callaghan7 found that contamination of nursing uniforms was equal at all sites. We found that sleeve cuffs of white coats had slightly but significantly more contamination with bacteria than either the pocket or the midsleeve areas, but interestingly, we found no difference in colony count from cultures taken from the skin at the wrists of the subjects wearing either garment. We found no difference in the extent of bacterial contamination by site in the subjects wearing short‐sleeved uniforms or in the percentage of subjects contaminated with MRSA by site of culture of either garment.

Contrary to our hypothesis, we found no association between the frequency with which white coats were changed or washed and the extent of bacterial contamination, despite the physicians having admitted to washing or changing their white coats infrequently (Table 4). Similar findings were reported by Loh and colleagues8 and by Treakle and colleagues.12

Our finding that contamination of clean uniforms happens rapidly is consistent with published data. Speers and colleagues4 found increasing contamination of nurses' aprons and dresses comparing samples obtained early in the day with those taken several hours later. Boyce and colleagues6 found that 65% of nursing uniforms were contaminated with MRSA after performing morning patient‐care activities on patients with MRSA wound or urine infections. Perry and colleagues9 found that 39% of uniforms that were laundered at home were contaminated with MRSA, vancomycin‐resistant enterococci, or Clostridium difficile at the beginning of the work shift, increasing to 54% by the end of a 24‐hour shift, and Babb and colleagues20 found that nearly 100% of nurses' gowns were contaminated within the first day of use (33% with Staphylococcus aureus). Dancer22 recently suggested that if staff were afforded clean coats every day, it is possible that concerns over potential contamination would be less of an issue. Our data suggest, however, that work clothes would have to be changed every few hours if the intent were to reduce bacterial contamination.

Limitations

Our study has a number of potential limitations. The RODAC imprint method only sampled a small area of both the white coats and the uniforms, and accordingly, the culture data might not accurately reflect the total degree of contamination. However, we cultured 3 areas on the white coats and 2 on the uniforms, including areas thought to be more heavily contaminated (sleeve cuffs of white coats). Although this area had greater colony counts, the variation in bacterial and MRSA contamination from all areas was small.

We did not culture the anterior nares to determine if the participants were colonized with MRSA. Normal health care workers have varying degrees of nasal colonization with MRSA, and this could account for some of the 16%‐20% MRSA contamination rate we observed. However, previous studies have shown that nasal colonization of healthcare workers only minimally contributes to uniform contamination.4

Although achieving good hand hygiene compliance has been a major focus at our hospital, we did not track the hand hygiene compliance of the physicians in either group. Accordingly, not finding reduced bacterial contamination in those wearing short‐sleeved uniforms could be explained if physicians in this group had systematically worse hand‐washing compliance than those randomized to wearing their own white coats. Our use of concurrent controls limits this possibility, as does that during the time of this study, hand hygiene compliance (assessed by monthly surreptitious observation) was approximately 90% throughout the hospital.

Despite the infrequent wash frequencies reported, the physicians' responses to the survey could have overestimated the true wash frequency as a result of the Hawthorne effect. The colony count and MRSA contamination rates observed, however, suggest that even if this occurred, it would not have altered our conclusion that bacterial contamination was not associated with wash frequency.

Generalizability

Because data were collected from a single, university‐affiliated public teaching hospital from hospitalists and residents working on the internal medicine service, the results might not be generalizable to other types of institutions, other personnel, or other services.

In conclusion, bacterial contamination of work clothes occurs within the first few hours after donning them. By the end of an 8‐hour work day, we found no data supporting the contention that long‐sleeved white coats were more heavily contaminated than were short‐sleeved uniforms. Our data do not support discarding white coats for uniforms that are changed on a daily basis or for requiring health care workers to avoid long‐sleeved garments.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Henry Fonseca and his team for providing our physician uniforms. They also thank the Denver Health Department of Medicine Small Grants program for supporting this study.

- Department of Health. Uniforms and workwear: an evidence base for developing local policy. National Health Service, September 17, 2007. Available at: http://www.dh.gov.uk/en/Publicationsandstatistics/Publications/Publicationspolicyandguidance/DH_078433. Accessed January 29,2010.

- Scottish Government Health Directorates. NHS Scotland Dress Code. Available at: http://www.sehd.scot.nhs.uk/mels/CEL2008_53.pdf. Accessed February 10,2010.

- ,,,.Uniform: an evidence review of the microbiological significance of uniforms and uniform policy in the prevention and control of healthcare‐associated infections. Report to the Department of Health (England).J Hosp Infect.2007;66:301–307.

- ,,,.Contamination of nurses' uniforms with Staphylococcus aureus.Lancet.1969;2:233–235.

- ,,.Microbial flora on doctors' white coats.Brit Med J.1991;303:1602–1604.

- ,,,.Environmental contamination due to methicillin‐resistant Staphylococcus aureus: possible infection control implications.Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol.1997;18:622–627.

- ,Bacterial contamination of nurses' uniforms: a study.Nursing Stand.1998;13:37–42.

- ,,.Bacterial flora on the white coats of medical students.J Hosp Infection.2000;45:65–68.

- ,,.Bacterial contamination of uniforms.J Hosp Infect.2001;48:238–241.

- ,,, et al.Significance of methicillin‐resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) survey in a university teaching hospital.J Infec Chemother.2003;9:172–177.

- ,,, et al.Detection of methicillin‐resistant Staphylococcus aureus and vancomycin‐resistant enterococci on the gowns and gloves of healthcare workers.Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol2008;29 (7):583–9.

- ,,,,,.Bacterial contamination of health care workers' white coats.Am J Infect Control.2009;37:101–105.

- ,,,,,.Meticillin‐resistant Staphylococcus aureus contamination of healthcare workers' uniforms in long‐term care facilities.J Hosp Infect.2009;71:170–175.

- ,,,,.Comparison of the Rodac imprint method to selective enrichment broth for recovery of vancomycin‐resistant enterococci and drug‐resistant Enterobacteriaceae from environmental surfaces.J Clin Microbiol.2000;38:4646–4648.

- ,,.Effect of clothing on dispersal of Staphylococcus aureus by males and females.Lancet.1974;2:1131–1133.

- ,,.When should healthcare workers be screened for methicillin‐resistant Staphylococcus aureus?J Hosp Infect.1996;34:205–210.

- ,,.Methicillin‐resistant Staphylococcus aureus transmission: the possible importance of unrecognized health care worker carriage.Am J Infect Control.2008;36:93–97.

- ,,, et al.Methicillin‐resistant Staphylococcus aureus carriage, infection and transmission in dialysis patients, healthcare workers and their family members.Nephrol Dial Transplant.2008;23:1659–1665.

- ,,.Are active microbiological surveillance and subsequent isolation needed to prevent the spread of methicillin‐resistant Staphylococcus aureus.Clin Infect Dis.2005;40:405–409.

- ,,.Contamination of protective clothing and nurses' uniforms in an isolation ward.J Hosp Infect.1983;4:149–157.

- British Medical Association. Uniform and dress code for doctors. December 6, 2007. Available at: http://www.bma.org.uk/employmentandcontracts/working_arrangements/CCSCdresscode051207.jsp. Accessed February 9,2010.

- .Pants, policies and paranoia.J Hosp Infect.2010;74:10–15.

In September 2007, the British Department of Health developed guidelines for health care workers regarding uniforms and work wear that banned the traditional white coat and other long‐sleeved garments in an attempt to decrease nosocomial bacterial transmission.1 Similar policies have recently been adopted in Scotland.2 Interestingly, the National Health Service report acknowledged that evidence was lacking that would support that white coats and long‐sleeved garments caused nosocomial infection.1, 3 Although many studies have documented that health care work clothes are contaminated with bacteria, including methicillin‐resistant Staphylococcal aureus (MRSA) and other pathogenic species,413 none have determined whether avoiding white coats and switching to short‐sleeved garments decreases bacterial contamination.

We performed a prospective, randomized, controlled trial designed to compare the extent of bacterial contamination of physicians' white coats with that of newly laundered, standardized short‐sleeved uniforms. Our hypotheses were that infrequently cleaned white coats would have greater bacterial contamination than uniforms, that the extent of contamination would be inversely related to the frequency with which the coats were washed, and that the increased contamination of the cuffs of the white coats would result in increased contamination of the skin of the wrists. Our results led us also to assess the rate at which bacterial contamination of short‐sleeved uniforms occurs during the workday.

Methods

The study was conducted at Denver Health, a university‐affiliated public safety‐net hospital and was approved by the Colorado Multiple Institutional Review Board.

Trial Design

The study was a prospective, randomized, controlled trial. No protocol changes occurred during the study.

Participants

Participants included residents and hospitalists directly caring for patients on internal medicine units between August 1, 2008 and November 15, 2009.

Intervention

Subjects wore either a standard, newly laundered, short‐sleeved uniform or continued to wear their own white coats.

Outcomes

The primary end point was the percentage of subjects contaminated with MRSA. Cultures were collected using a standardized RODAC imprint method14 with BBL RODAC plates containing trypticase soy agar with lecithin and polysorbate 80 (Becton Dickinson, Sparks, MD) 8 hours after the physicians started their work day. All physicians had cultures obtained from the breast pocket and sleeve cuff (long‐sleeved for the white coats, short‐sleeved for the uniforms) and from the skin of the volar surface of the wrist of their dominant hand. Those wearing white coats also had cultures obtained from the mid‐biceps level of the sleeve of the dominant hand, as this location closely approximated the location of the cuffs of the short‐sleeved uniforms.

Cultures were incubated in ambient air at 35C‐37C for 1822 hours. After incubation, visible colonies were counted using a dissecting microscope to a maximum of 200 colonies at the recommendation of the manufacturer. Colonies that were morphologically consistent with Staphylococcus species by colony growth and Gram stain were further tested for coagulase using a BactiStaph rapid latex agglutination test (Remel, Lenexa, KS). If positive, these colonies were subcultured to sheep blood agar (Remel, Lenexa, KS) and BBL MRSA Chromagar (Becton Dickinson, Sparks, MD) and incubated for an additional 1824 hours. Characteristic growth on blood agar that also produced mauve‐colored colonies on chromagar was taken to indicate MRSA.

A separate set of 10 physicians donned newly laundered, short‐sleeved uniforms at 6:30 AM for culturing from the breast pocket and sleeve cuff of the dominant hand prior to and 2.5, 5, and 8 hours after they were donned by the participants (with culturing of each site done on separate days to avoid the effects of obtaining multiple cultures at the same site on the same day). These cultures were not assessed for MRSA.

At the time that consent was obtained, all participants completed an anonymous survey that assessed the frequency with which they normally washed or changed their white coats.

Sample Size

Based on the finding that 20% of our first 20 participants were colonized with MRSA, we determined that to find a 25% difference in the percentage of subjects colonized with MRSA in the 2 groups, with a power of 0.8 and P < 0.05 being significant (2‐sided Fisher's exact test), 50 subjects would be needed in each group.

Randomization

Randomization of potential participants occurred 1 day prior to the study using a computer‐generated table of random numbers. The principal investigator and a coinvestigator enrolled participants. Consent was obtained from those randomized to wear a newly laundered standard short‐sleeved uniform at the time of randomization so that they could don the uniforms when arriving at the hospital the following morning (at approximately 6:30 AM). Physicians in this group were also instructed not to wear their white coats at any time during the day they were wearing the uniforms. Physicians randomized to wear their own white coats were not notified or consented until the day of the study, a few hours prior to the time the cultures were obtained. This approach prevented them from either changing their white coats or washing them prior to the time the cultures were taken.

Because our study included both employees of the hospital and trainees, a number of protection measures were required. No information of any sort was collected about those who agreed or refused to participate in the study. In addition, the request to participate in the study did not come from the person's direct supervisor.

Statistical Methods

All data were collected and entered using Excel for Mac 2004 version 11.5.4. All analyses were performed using SAS Enterprise Guide 4.1 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC).

The Wilcoxon rank‐sum test and chi square analysis were used to seek differences in colony count and percentage of cultures with MRSA, respectively, in cultures obtained: (1) from the sleeve cuffs and pockets of the white coats compared with those from the sleeve cuffs and pockets of the uniforms, (2) from the sleeve cuffs of the white coats compared with those from the sleeve cuffs of the short‐sleeved uniforms, (3) from the mid‐biceps area of the sleeve sof the white coats compared with those from the sleeve cuffs of the uniforms, and (4) from the skin of the wrists of those wearing white coats compared with those wearing the uniforms. Bonferroni's correction for multiple comparisons was applied, with a P < 0.125 indicating significance.

Friedman's test and repeated‐measures logistic regression were used to seek differences in colony count or of the percentage of cultures with MRSA, respectively, on white coats or uniforms by site of culture on both garments. A P < 0.05 indicated significance for these analyses.

The Kruskal‐Wallis and chi‐square tests were utilized to test the effect of white coat wash frequency on colony count and MRSA contamination, respectively.

All data are presented as medians with 95% confidence intervals or proportions.

Results

Participant Flow

Fifty physicians were studied in each group, all of whom completed the survey. In general, more than 95% of potential participants approached agreed to participate in the study (Figure 1).

Recruitment

The first and last physicians were studied in August 2008 and November 2009, respectively. The trial ended when the specified number of participants (50 in each group) had been enrolled.

Data on Entry

No data were recorded from the participants at the time of randomization in compliance with institutional review board regulations pertaining to employment issues that could arise when studying members of the workforce.

Outcomes

No significant differences were found between the colony counts cultured from white coats (104 [80127]) versus newly laundered uniforms (142 [83213]), P = 0.61. No significant differences were found between the colony counts cultured from the sleeve cuffs of the white coats (58.5 [4866]) versus the uniforms (37 [2768]), P = 0.07, or between the colony counts cultured from the pockets of the white coats (45.5 [3254]) versus the uniforms (74.5 [4897], P = 0.040. Bonferroni corrections were used for multiple comparisons such that a P < 0.0125 was considered significant. Cultures from at least 1 site of 8 of 50 physicians (16%) wearing white coats and 10 of 50 physicians (20%) wearing short‐sleeved uniforms were positive for MRSA (P = .60).

Colony counts were greater in cultures obtained from the sleeve cuffs of the white coats compared with the pockets or mid‐biceps area (Table 1). For the uniforms, no difference in colony count in cultures from the pockets versus sleeve cuffs was observed. No difference was found when comparing the number of subjects with MRSA contamination of the 3 sites of the white coats or the 2 sites of the uniforms (Table 1).

| White Coat (n = 50) | P | Uniforms (n = 50) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Colony count, median (95% CI) | ||||

| Sleeve cuff | 58.5 (4866) | < 0.0001 | 37.0 (2768) | 0.25 |

| 45.5 (3254) | 74.5 (4897) | |||

| Mid‐biceps area of sleeve | 25.5 (2029) | |||

| MRSA contamination, n (%) | ||||

| Sleeve cuff | 4 (8%) | 0.71 | 6 (12%) | 0.18 |

| 5 (10%) | 9 (18%) | |||

| Mid‐biceps area of sleeve | 3 (6%) |

No difference was observed with respect to colony count or the percentage of subjects positive for MRSA in cultures obtained from the mid‐biceps area of the white coats versus those from the cuffs of the short‐sleeved uniforms (Table 2).

| White Coat Mid‐Biceps (n = 50) | Uniform Sleeve Cuff (n = 50) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Colony count, median (95% CI) | 25.5 (2029) | 37.0 (2768) | 0.07 |

| MRSA contamination, n (%) | 3 (6%) | 6 (12%) | 0.49 |

No difference was observed with respect to colony count or the percentage of subjects positive for MRSA in cultures obtained from the volar surface of the wrists of subjects wearing either of the 2 garments (Table 3).

| White Coat (n = 50) | Uniform (n = 50) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Colony count, median (95% CI) | 23.5 (1740) | 40.5 (2859) | 0.09 |

| MRSA Contamination, n (% of subjects) | 3 (6%) | 5 (10%) | 0.72 |

The frequency with which physicians randomized to wearing their white coats admitted to washing or changing their coats varied markedly (Table 4). No significant differences were found with respect to total colony count (P = 0.81), colony count by site (data not shown), or percentage of physicians contaminated with MRSA (P = 0.22) as a function of washing or changing frequency (Table 4).

| White Coat Washing Frequency | Number of Subjects (%) | Total Colony Count (All Sites), Median (95% CI) | Number with MRSA Contamination, n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Weekly | 15 (30%) | 124 (107229) | 1 (7%) |

| Every 2 weeks | 21 (42%) | 156 (90237) | 6 (29%) |

| Every 4 weeks | 8 (16%) | 89 (41206) | 0 (0%) |

| Every 8 weeks | 5 (10%) | 140 (58291) | 2 (40%) |

| Rarely | 1 (2%) | 150 | 0 (0%) |

Sequential culturing showed that the newly laundered uniforms were nearly sterile prior to putting them on. By 3 hours of wear, however, nearly 50% of the colonies counted at 8 hours were already present (Figure 2).

Harms

No adverse events occurred during the course of the study in either group.

Discussion

The important findings of this study are that, contrary to our hypotheses, at the end of an 8‐hour workday, no significant differences were found between the extent of bacterial or MRSA contamination of infrequently washed white coats compared with those of newly laundered uniforms, no difference was observed with respect to the extent of bacterial or MRSA contamination of the wrists of physicians wearing either of the 2 garments, and no association was apparent between the extent of bacterial or MRSA contamination and the frequency with which white coats were washed or changed. In addition, we also found that bacterial contamination of newly laundered uniforms occurred within hours of putting them on.

Interpretation

Numerous studies have demonstrated that white coats and uniforms worn by health care providers are frequently contaminated with bacteria, including both methicillin‐sensitive and ‐resistant Staphylococcus aureus and other pathogens.413 This contamination may come from nasal or perineal carriage of the health care provider, from the environment, and/or from patients who are colonized or infected.11, 15 Although many have suggested that patients can become contaminated from contact with health care providers' clothing and studies employing pulsed‐field gel electrophoresis and other techniques have suggested that cross‐infection can occur,10, 1618 others have not confirmed this contention,19, 20 and Lessing and colleagues16 concluded that transmission from staff to patients was a rare phenomenon. The systematic review reported to the Department of Health in England,3 the British Medical Association guidelines regarding dress codes for doctors,21 and the department's report on which the new clothing guidelines were based1 concluded there was no conclusive evidence indicating that work clothes posed a risk of spreading infection to patients. Despite this, the Working Group and the British Medical Association recommended that white coats should not be worn when providing patient care and that shirts and blouses should be short‐sleeved.1 Recent evidence‐based reviews concluded that there was insufficient evidence to justify this policy,3, 22 and our data indicate that the policy will not decrease bacterial or MRSA contamination of physicians' work clothes or skin.

The recommendation that long‐sleeved clothing should be avoided comes from studies indicating that cuffs of these garments are more heavily contaminated than other areas5, 8 and are more likely to come in contact with patients.1 Wong and colleagues5 reported that cuffs and lower front pockets had greater contamination than did the backs of white coats, but no difference was seen in colony count from cuffs compared with pockets. Loh and colleagues8 found greater bacterial contamination on the cuffs than on the backs of white coats, but their conclusion came from comparing the percentage of subjects with selected colony counts (ie, between 100 and 199 only), and the analysis did not adjust for repeated sampling of each participant. Apparently, colony counts from the cuffs were not different than those from the pockets. Callaghan7 found that contamination of nursing uniforms was equal at all sites. We found that sleeve cuffs of white coats had slightly but significantly more contamination with bacteria than either the pocket or the midsleeve areas, but interestingly, we found no difference in colony count from cultures taken from the skin at the wrists of the subjects wearing either garment. We found no difference in the extent of bacterial contamination by site in the subjects wearing short‐sleeved uniforms or in the percentage of subjects contaminated with MRSA by site of culture of either garment.

Contrary to our hypothesis, we found no association between the frequency with which white coats were changed or washed and the extent of bacterial contamination, despite the physicians having admitted to washing or changing their white coats infrequently (Table 4). Similar findings were reported by Loh and colleagues8 and by Treakle and colleagues.12

Our finding that contamination of clean uniforms happens rapidly is consistent with published data. Speers and colleagues4 found increasing contamination of nurses' aprons and dresses comparing samples obtained early in the day with those taken several hours later. Boyce and colleagues6 found that 65% of nursing uniforms were contaminated with MRSA after performing morning patient‐care activities on patients with MRSA wound or urine infections. Perry and colleagues9 found that 39% of uniforms that were laundered at home were contaminated with MRSA, vancomycin‐resistant enterococci, or Clostridium difficile at the beginning of the work shift, increasing to 54% by the end of a 24‐hour shift, and Babb and colleagues20 found that nearly 100% of nurses' gowns were contaminated within the first day of use (33% with Staphylococcus aureus). Dancer22 recently suggested that if staff were afforded clean coats every day, it is possible that concerns over potential contamination would be less of an issue. Our data suggest, however, that work clothes would have to be changed every few hours if the intent were to reduce bacterial contamination.

Limitations

Our study has a number of potential limitations. The RODAC imprint method only sampled a small area of both the white coats and the uniforms, and accordingly, the culture data might not accurately reflect the total degree of contamination. However, we cultured 3 areas on the white coats and 2 on the uniforms, including areas thought to be more heavily contaminated (sleeve cuffs of white coats). Although this area had greater colony counts, the variation in bacterial and MRSA contamination from all areas was small.

We did not culture the anterior nares to determine if the participants were colonized with MRSA. Normal health care workers have varying degrees of nasal colonization with MRSA, and this could account for some of the 16%‐20% MRSA contamination rate we observed. However, previous studies have shown that nasal colonization of healthcare workers only minimally contributes to uniform contamination.4

Although achieving good hand hygiene compliance has been a major focus at our hospital, we did not track the hand hygiene compliance of the physicians in either group. Accordingly, not finding reduced bacterial contamination in those wearing short‐sleeved uniforms could be explained if physicians in this group had systematically worse hand‐washing compliance than those randomized to wearing their own white coats. Our use of concurrent controls limits this possibility, as does that during the time of this study, hand hygiene compliance (assessed by monthly surreptitious observation) was approximately 90% throughout the hospital.

Despite the infrequent wash frequencies reported, the physicians' responses to the survey could have overestimated the true wash frequency as a result of the Hawthorne effect. The colony count and MRSA contamination rates observed, however, suggest that even if this occurred, it would not have altered our conclusion that bacterial contamination was not associated with wash frequency.

Generalizability

Because data were collected from a single, university‐affiliated public teaching hospital from hospitalists and residents working on the internal medicine service, the results might not be generalizable to other types of institutions, other personnel, or other services.

In conclusion, bacterial contamination of work clothes occurs within the first few hours after donning them. By the end of an 8‐hour work day, we found no data supporting the contention that long‐sleeved white coats were more heavily contaminated than were short‐sleeved uniforms. Our data do not support discarding white coats for uniforms that are changed on a daily basis or for requiring health care workers to avoid long‐sleeved garments.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Henry Fonseca and his team for providing our physician uniforms. They also thank the Denver Health Department of Medicine Small Grants program for supporting this study.

In September 2007, the British Department of Health developed guidelines for health care workers regarding uniforms and work wear that banned the traditional white coat and other long‐sleeved garments in an attempt to decrease nosocomial bacterial transmission.1 Similar policies have recently been adopted in Scotland.2 Interestingly, the National Health Service report acknowledged that evidence was lacking that would support that white coats and long‐sleeved garments caused nosocomial infection.1, 3 Although many studies have documented that health care work clothes are contaminated with bacteria, including methicillin‐resistant Staphylococcal aureus (MRSA) and other pathogenic species,413 none have determined whether avoiding white coats and switching to short‐sleeved garments decreases bacterial contamination.

We performed a prospective, randomized, controlled trial designed to compare the extent of bacterial contamination of physicians' white coats with that of newly laundered, standardized short‐sleeved uniforms. Our hypotheses were that infrequently cleaned white coats would have greater bacterial contamination than uniforms, that the extent of contamination would be inversely related to the frequency with which the coats were washed, and that the increased contamination of the cuffs of the white coats would result in increased contamination of the skin of the wrists. Our results led us also to assess the rate at which bacterial contamination of short‐sleeved uniforms occurs during the workday.

Methods

The study was conducted at Denver Health, a university‐affiliated public safety‐net hospital and was approved by the Colorado Multiple Institutional Review Board.

Trial Design

The study was a prospective, randomized, controlled trial. No protocol changes occurred during the study.

Participants

Participants included residents and hospitalists directly caring for patients on internal medicine units between August 1, 2008 and November 15, 2009.

Intervention

Subjects wore either a standard, newly laundered, short‐sleeved uniform or continued to wear their own white coats.

Outcomes

The primary end point was the percentage of subjects contaminated with MRSA. Cultures were collected using a standardized RODAC imprint method14 with BBL RODAC plates containing trypticase soy agar with lecithin and polysorbate 80 (Becton Dickinson, Sparks, MD) 8 hours after the physicians started their work day. All physicians had cultures obtained from the breast pocket and sleeve cuff (long‐sleeved for the white coats, short‐sleeved for the uniforms) and from the skin of the volar surface of the wrist of their dominant hand. Those wearing white coats also had cultures obtained from the mid‐biceps level of the sleeve of the dominant hand, as this location closely approximated the location of the cuffs of the short‐sleeved uniforms.

Cultures were incubated in ambient air at 35C‐37C for 1822 hours. After incubation, visible colonies were counted using a dissecting microscope to a maximum of 200 colonies at the recommendation of the manufacturer. Colonies that were morphologically consistent with Staphylococcus species by colony growth and Gram stain were further tested for coagulase using a BactiStaph rapid latex agglutination test (Remel, Lenexa, KS). If positive, these colonies were subcultured to sheep blood agar (Remel, Lenexa, KS) and BBL MRSA Chromagar (Becton Dickinson, Sparks, MD) and incubated for an additional 1824 hours. Characteristic growth on blood agar that also produced mauve‐colored colonies on chromagar was taken to indicate MRSA.

A separate set of 10 physicians donned newly laundered, short‐sleeved uniforms at 6:30 AM for culturing from the breast pocket and sleeve cuff of the dominant hand prior to and 2.5, 5, and 8 hours after they were donned by the participants (with culturing of each site done on separate days to avoid the effects of obtaining multiple cultures at the same site on the same day). These cultures were not assessed for MRSA.

At the time that consent was obtained, all participants completed an anonymous survey that assessed the frequency with which they normally washed or changed their white coats.

Sample Size

Based on the finding that 20% of our first 20 participants were colonized with MRSA, we determined that to find a 25% difference in the percentage of subjects colonized with MRSA in the 2 groups, with a power of 0.8 and P < 0.05 being significant (2‐sided Fisher's exact test), 50 subjects would be needed in each group.

Randomization

Randomization of potential participants occurred 1 day prior to the study using a computer‐generated table of random numbers. The principal investigator and a coinvestigator enrolled participants. Consent was obtained from those randomized to wear a newly laundered standard short‐sleeved uniform at the time of randomization so that they could don the uniforms when arriving at the hospital the following morning (at approximately 6:30 AM). Physicians in this group were also instructed not to wear their white coats at any time during the day they were wearing the uniforms. Physicians randomized to wear their own white coats were not notified or consented until the day of the study, a few hours prior to the time the cultures were obtained. This approach prevented them from either changing their white coats or washing them prior to the time the cultures were taken.

Because our study included both employees of the hospital and trainees, a number of protection measures were required. No information of any sort was collected about those who agreed or refused to participate in the study. In addition, the request to participate in the study did not come from the person's direct supervisor.

Statistical Methods

All data were collected and entered using Excel for Mac 2004 version 11.5.4. All analyses were performed using SAS Enterprise Guide 4.1 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC).

The Wilcoxon rank‐sum test and chi square analysis were used to seek differences in colony count and percentage of cultures with MRSA, respectively, in cultures obtained: (1) from the sleeve cuffs and pockets of the white coats compared with those from the sleeve cuffs and pockets of the uniforms, (2) from the sleeve cuffs of the white coats compared with those from the sleeve cuffs of the short‐sleeved uniforms, (3) from the mid‐biceps area of the sleeve sof the white coats compared with those from the sleeve cuffs of the uniforms, and (4) from the skin of the wrists of those wearing white coats compared with those wearing the uniforms. Bonferroni's correction for multiple comparisons was applied, with a P < 0.125 indicating significance.

Friedman's test and repeated‐measures logistic regression were used to seek differences in colony count or of the percentage of cultures with MRSA, respectively, on white coats or uniforms by site of culture on both garments. A P < 0.05 indicated significance for these analyses.

The Kruskal‐Wallis and chi‐square tests were utilized to test the effect of white coat wash frequency on colony count and MRSA contamination, respectively.

All data are presented as medians with 95% confidence intervals or proportions.

Results

Participant Flow

Fifty physicians were studied in each group, all of whom completed the survey. In general, more than 95% of potential participants approached agreed to participate in the study (Figure 1).

Recruitment

The first and last physicians were studied in August 2008 and November 2009, respectively. The trial ended when the specified number of participants (50 in each group) had been enrolled.

Data on Entry

No data were recorded from the participants at the time of randomization in compliance with institutional review board regulations pertaining to employment issues that could arise when studying members of the workforce.

Outcomes

No significant differences were found between the colony counts cultured from white coats (104 [80127]) versus newly laundered uniforms (142 [83213]), P = 0.61. No significant differences were found between the colony counts cultured from the sleeve cuffs of the white coats (58.5 [4866]) versus the uniforms (37 [2768]), P = 0.07, or between the colony counts cultured from the pockets of the white coats (45.5 [3254]) versus the uniforms (74.5 [4897], P = 0.040. Bonferroni corrections were used for multiple comparisons such that a P < 0.0125 was considered significant. Cultures from at least 1 site of 8 of 50 physicians (16%) wearing white coats and 10 of 50 physicians (20%) wearing short‐sleeved uniforms were positive for MRSA (P = .60).

Colony counts were greater in cultures obtained from the sleeve cuffs of the white coats compared with the pockets or mid‐biceps area (Table 1). For the uniforms, no difference in colony count in cultures from the pockets versus sleeve cuffs was observed. No difference was found when comparing the number of subjects with MRSA contamination of the 3 sites of the white coats or the 2 sites of the uniforms (Table 1).

| White Coat (n = 50) | P | Uniforms (n = 50) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Colony count, median (95% CI) | ||||

| Sleeve cuff | 58.5 (4866) | < 0.0001 | 37.0 (2768) | 0.25 |

| 45.5 (3254) | 74.5 (4897) | |||

| Mid‐biceps area of sleeve | 25.5 (2029) | |||

| MRSA contamination, n (%) | ||||

| Sleeve cuff | 4 (8%) | 0.71 | 6 (12%) | 0.18 |

| 5 (10%) | 9 (18%) | |||

| Mid‐biceps area of sleeve | 3 (6%) |

No difference was observed with respect to colony count or the percentage of subjects positive for MRSA in cultures obtained from the mid‐biceps area of the white coats versus those from the cuffs of the short‐sleeved uniforms (Table 2).

| White Coat Mid‐Biceps (n = 50) | Uniform Sleeve Cuff (n = 50) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Colony count, median (95% CI) | 25.5 (2029) | 37.0 (2768) | 0.07 |

| MRSA contamination, n (%) | 3 (6%) | 6 (12%) | 0.49 |

No difference was observed with respect to colony count or the percentage of subjects positive for MRSA in cultures obtained from the volar surface of the wrists of subjects wearing either of the 2 garments (Table 3).

| White Coat (n = 50) | Uniform (n = 50) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Colony count, median (95% CI) | 23.5 (1740) | 40.5 (2859) | 0.09 |

| MRSA Contamination, n (% of subjects) | 3 (6%) | 5 (10%) | 0.72 |

The frequency with which physicians randomized to wearing their white coats admitted to washing or changing their coats varied markedly (Table 4). No significant differences were found with respect to total colony count (P = 0.81), colony count by site (data not shown), or percentage of physicians contaminated with MRSA (P = 0.22) as a function of washing or changing frequency (Table 4).

| White Coat Washing Frequency | Number of Subjects (%) | Total Colony Count (All Sites), Median (95% CI) | Number with MRSA Contamination, n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Weekly | 15 (30%) | 124 (107229) | 1 (7%) |

| Every 2 weeks | 21 (42%) | 156 (90237) | 6 (29%) |

| Every 4 weeks | 8 (16%) | 89 (41206) | 0 (0%) |

| Every 8 weeks | 5 (10%) | 140 (58291) | 2 (40%) |

| Rarely | 1 (2%) | 150 | 0 (0%) |

Sequential culturing showed that the newly laundered uniforms were nearly sterile prior to putting them on. By 3 hours of wear, however, nearly 50% of the colonies counted at 8 hours were already present (Figure 2).

Harms

No adverse events occurred during the course of the study in either group.

Discussion

The important findings of this study are that, contrary to our hypotheses, at the end of an 8‐hour workday, no significant differences were found between the extent of bacterial or MRSA contamination of infrequently washed white coats compared with those of newly laundered uniforms, no difference was observed with respect to the extent of bacterial or MRSA contamination of the wrists of physicians wearing either of the 2 garments, and no association was apparent between the extent of bacterial or MRSA contamination and the frequency with which white coats were washed or changed. In addition, we also found that bacterial contamination of newly laundered uniforms occurred within hours of putting them on.

Interpretation

Numerous studies have demonstrated that white coats and uniforms worn by health care providers are frequently contaminated with bacteria, including both methicillin‐sensitive and ‐resistant Staphylococcus aureus and other pathogens.413 This contamination may come from nasal or perineal carriage of the health care provider, from the environment, and/or from patients who are colonized or infected.11, 15 Although many have suggested that patients can become contaminated from contact with health care providers' clothing and studies employing pulsed‐field gel electrophoresis and other techniques have suggested that cross‐infection can occur,10, 1618 others have not confirmed this contention,19, 20 and Lessing and colleagues16 concluded that transmission from staff to patients was a rare phenomenon. The systematic review reported to the Department of Health in England,3 the British Medical Association guidelines regarding dress codes for doctors,21 and the department's report on which the new clothing guidelines were based1 concluded there was no conclusive evidence indicating that work clothes posed a risk of spreading infection to patients. Despite this, the Working Group and the British Medical Association recommended that white coats should not be worn when providing patient care and that shirts and blouses should be short‐sleeved.1 Recent evidence‐based reviews concluded that there was insufficient evidence to justify this policy,3, 22 and our data indicate that the policy will not decrease bacterial or MRSA contamination of physicians' work clothes or skin.

The recommendation that long‐sleeved clothing should be avoided comes from studies indicating that cuffs of these garments are more heavily contaminated than other areas5, 8 and are more likely to come in contact with patients.1 Wong and colleagues5 reported that cuffs and lower front pockets had greater contamination than did the backs of white coats, but no difference was seen in colony count from cuffs compared with pockets. Loh and colleagues8 found greater bacterial contamination on the cuffs than on the backs of white coats, but their conclusion came from comparing the percentage of subjects with selected colony counts (ie, between 100 and 199 only), and the analysis did not adjust for repeated sampling of each participant. Apparently, colony counts from the cuffs were not different than those from the pockets. Callaghan7 found that contamination of nursing uniforms was equal at all sites. We found that sleeve cuffs of white coats had slightly but significantly more contamination with bacteria than either the pocket or the midsleeve areas, but interestingly, we found no difference in colony count from cultures taken from the skin at the wrists of the subjects wearing either garment. We found no difference in the extent of bacterial contamination by site in the subjects wearing short‐sleeved uniforms or in the percentage of subjects contaminated with MRSA by site of culture of either garment.

Contrary to our hypothesis, we found no association between the frequency with which white coats were changed or washed and the extent of bacterial contamination, despite the physicians having admitted to washing or changing their white coats infrequently (Table 4). Similar findings were reported by Loh and colleagues8 and by Treakle and colleagues.12

Our finding that contamination of clean uniforms happens rapidly is consistent with published data. Speers and colleagues4 found increasing contamination of nurses' aprons and dresses comparing samples obtained early in the day with those taken several hours later. Boyce and colleagues6 found that 65% of nursing uniforms were contaminated with MRSA after performing morning patient‐care activities on patients with MRSA wound or urine infections. Perry and colleagues9 found that 39% of uniforms that were laundered at home were contaminated with MRSA, vancomycin‐resistant enterococci, or Clostridium difficile at the beginning of the work shift, increasing to 54% by the end of a 24‐hour shift, and Babb and colleagues20 found that nearly 100% of nurses' gowns were contaminated within the first day of use (33% with Staphylococcus aureus). Dancer22 recently suggested that if staff were afforded clean coats every day, it is possible that concerns over potential contamination would be less of an issue. Our data suggest, however, that work clothes would have to be changed every few hours if the intent were to reduce bacterial contamination.

Limitations

Our study has a number of potential limitations. The RODAC imprint method only sampled a small area of both the white coats and the uniforms, and accordingly, the culture data might not accurately reflect the total degree of contamination. However, we cultured 3 areas on the white coats and 2 on the uniforms, including areas thought to be more heavily contaminated (sleeve cuffs of white coats). Although this area had greater colony counts, the variation in bacterial and MRSA contamination from all areas was small.

We did not culture the anterior nares to determine if the participants were colonized with MRSA. Normal health care workers have varying degrees of nasal colonization with MRSA, and this could account for some of the 16%‐20% MRSA contamination rate we observed. However, previous studies have shown that nasal colonization of healthcare workers only minimally contributes to uniform contamination.4

Although achieving good hand hygiene compliance has been a major focus at our hospital, we did not track the hand hygiene compliance of the physicians in either group. Accordingly, not finding reduced bacterial contamination in those wearing short‐sleeved uniforms could be explained if physicians in this group had systematically worse hand‐washing compliance than those randomized to wearing their own white coats. Our use of concurrent controls limits this possibility, as does that during the time of this study, hand hygiene compliance (assessed by monthly surreptitious observation) was approximately 90% throughout the hospital.

Despite the infrequent wash frequencies reported, the physicians' responses to the survey could have overestimated the true wash frequency as a result of the Hawthorne effect. The colony count and MRSA contamination rates observed, however, suggest that even if this occurred, it would not have altered our conclusion that bacterial contamination was not associated with wash frequency.

Generalizability

Because data were collected from a single, university‐affiliated public teaching hospital from hospitalists and residents working on the internal medicine service, the results might not be generalizable to other types of institutions, other personnel, or other services.

In conclusion, bacterial contamination of work clothes occurs within the first few hours after donning them. By the end of an 8‐hour work day, we found no data supporting the contention that long‐sleeved white coats were more heavily contaminated than were short‐sleeved uniforms. Our data do not support discarding white coats for uniforms that are changed on a daily basis or for requiring health care workers to avoid long‐sleeved garments.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Henry Fonseca and his team for providing our physician uniforms. They also thank the Denver Health Department of Medicine Small Grants program for supporting this study.

- Department of Health. Uniforms and workwear: an evidence base for developing local policy. National Health Service, September 17, 2007. Available at: http://www.dh.gov.uk/en/Publicationsandstatistics/Publications/Publicationspolicyandguidance/DH_078433. Accessed January 29,2010.

- Scottish Government Health Directorates. NHS Scotland Dress Code. Available at: http://www.sehd.scot.nhs.uk/mels/CEL2008_53.pdf. Accessed February 10,2010.

- ,,,.Uniform: an evidence review of the microbiological significance of uniforms and uniform policy in the prevention and control of healthcare‐associated infections. Report to the Department of Health (England).J Hosp Infect.2007;66:301–307.

- ,,,.Contamination of nurses' uniforms with Staphylococcus aureus.Lancet.1969;2:233–235.

- ,,.Microbial flora on doctors' white coats.Brit Med J.1991;303:1602–1604.

- ,,,.Environmental contamination due to methicillin‐resistant Staphylococcus aureus: possible infection control implications.Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol.1997;18:622–627.

- ,Bacterial contamination of nurses' uniforms: a study.Nursing Stand.1998;13:37–42.

- ,,.Bacterial flora on the white coats of medical students.J Hosp Infection.2000;45:65–68.

- ,,.Bacterial contamination of uniforms.J Hosp Infect.2001;48:238–241.

- ,,, et al.Significance of methicillin‐resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) survey in a university teaching hospital.J Infec Chemother.2003;9:172–177.

- ,,, et al.Detection of methicillin‐resistant Staphylococcus aureus and vancomycin‐resistant enterococci on the gowns and gloves of healthcare workers.Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol2008;29 (7):583–9.

- ,,,,,.Bacterial contamination of health care workers' white coats.Am J Infect Control.2009;37:101–105.

- ,,,,,.Meticillin‐resistant Staphylococcus aureus contamination of healthcare workers' uniforms in long‐term care facilities.J Hosp Infect.2009;71:170–175.

- ,,,,.Comparison of the Rodac imprint method to selective enrichment broth for recovery of vancomycin‐resistant enterococci and drug‐resistant Enterobacteriaceae from environmental surfaces.J Clin Microbiol.2000;38:4646–4648.

- ,,.Effect of clothing on dispersal of Staphylococcus aureus by males and females.Lancet.1974;2:1131–1133.

- ,,.When should healthcare workers be screened for methicillin‐resistant Staphylococcus aureus?J Hosp Infect.1996;34:205–210.

- ,,.Methicillin‐resistant Staphylococcus aureus transmission: the possible importance of unrecognized health care worker carriage.Am J Infect Control.2008;36:93–97.

- ,,, et al.Methicillin‐resistant Staphylococcus aureus carriage, infection and transmission in dialysis patients, healthcare workers and their family members.Nephrol Dial Transplant.2008;23:1659–1665.

- ,,.Are active microbiological surveillance and subsequent isolation needed to prevent the spread of methicillin‐resistant Staphylococcus aureus.Clin Infect Dis.2005;40:405–409.

- ,,.Contamination of protective clothing and nurses' uniforms in an isolation ward.J Hosp Infect.1983;4:149–157.

- British Medical Association. Uniform and dress code for doctors. December 6, 2007. Available at: http://www.bma.org.uk/employmentandcontracts/working_arrangements/CCSCdresscode051207.jsp. Accessed February 9,2010.

- .Pants, policies and paranoia.J Hosp Infect.2010;74:10–15.

- Department of Health. Uniforms and workwear: an evidence base for developing local policy. National Health Service, September 17, 2007. Available at: http://www.dh.gov.uk/en/Publicationsandstatistics/Publications/Publicationspolicyandguidance/DH_078433. Accessed January 29,2010.

- Scottish Government Health Directorates. NHS Scotland Dress Code. Available at: http://www.sehd.scot.nhs.uk/mels/CEL2008_53.pdf. Accessed February 10,2010.

- ,,,.Uniform: an evidence review of the microbiological significance of uniforms and uniform policy in the prevention and control of healthcare‐associated infections. Report to the Department of Health (England).J Hosp Infect.2007;66:301–307.

- ,,,.Contamination of nurses' uniforms with Staphylococcus aureus.Lancet.1969;2:233–235.

- ,,.Microbial flora on doctors' white coats.Brit Med J.1991;303:1602–1604.

- ,,,.Environmental contamination due to methicillin‐resistant Staphylococcus aureus: possible infection control implications.Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol.1997;18:622–627.

- ,Bacterial contamination of nurses' uniforms: a study.Nursing Stand.1998;13:37–42.

- ,,.Bacterial flora on the white coats of medical students.J Hosp Infection.2000;45:65–68.

- ,,.Bacterial contamination of uniforms.J Hosp Infect.2001;48:238–241.

- ,,, et al.Significance of methicillin‐resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) survey in a university teaching hospital.J Infec Chemother.2003;9:172–177.

- ,,, et al.Detection of methicillin‐resistant Staphylococcus aureus and vancomycin‐resistant enterococci on the gowns and gloves of healthcare workers.Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol2008;29 (7):583–9.

- ,,,,,.Bacterial contamination of health care workers' white coats.Am J Infect Control.2009;37:101–105.

- ,,,,,.Meticillin‐resistant Staphylococcus aureus contamination of healthcare workers' uniforms in long‐term care facilities.J Hosp Infect.2009;71:170–175.

- ,,,,.Comparison of the Rodac imprint method to selective enrichment broth for recovery of vancomycin‐resistant enterococci and drug‐resistant Enterobacteriaceae from environmental surfaces.J Clin Microbiol.2000;38:4646–4648.

- ,,.Effect of clothing on dispersal of Staphylococcus aureus by males and females.Lancet.1974;2:1131–1133.

- ,,.When should healthcare workers be screened for methicillin‐resistant Staphylococcus aureus?J Hosp Infect.1996;34:205–210.

- ,,.Methicillin‐resistant Staphylococcus aureus transmission: the possible importance of unrecognized health care worker carriage.Am J Infect Control.2008;36:93–97.

- ,,, et al.Methicillin‐resistant Staphylococcus aureus carriage, infection and transmission in dialysis patients, healthcare workers and their family members.Nephrol Dial Transplant.2008;23:1659–1665.

- ,,.Are active microbiological surveillance and subsequent isolation needed to prevent the spread of methicillin‐resistant Staphylococcus aureus.Clin Infect Dis.2005;40:405–409.

- ,,.Contamination of protective clothing and nurses' uniforms in an isolation ward.J Hosp Infect.1983;4:149–157.

- British Medical Association. Uniform and dress code for doctors. December 6, 2007. Available at: http://www.bma.org.uk/employmentandcontracts/working_arrangements/CCSCdresscode051207.jsp. Accessed February 9,2010.

- .Pants, policies and paranoia.J Hosp Infect.2010;74:10–15.

Copyright © 2011 Society of Hospital Medicine

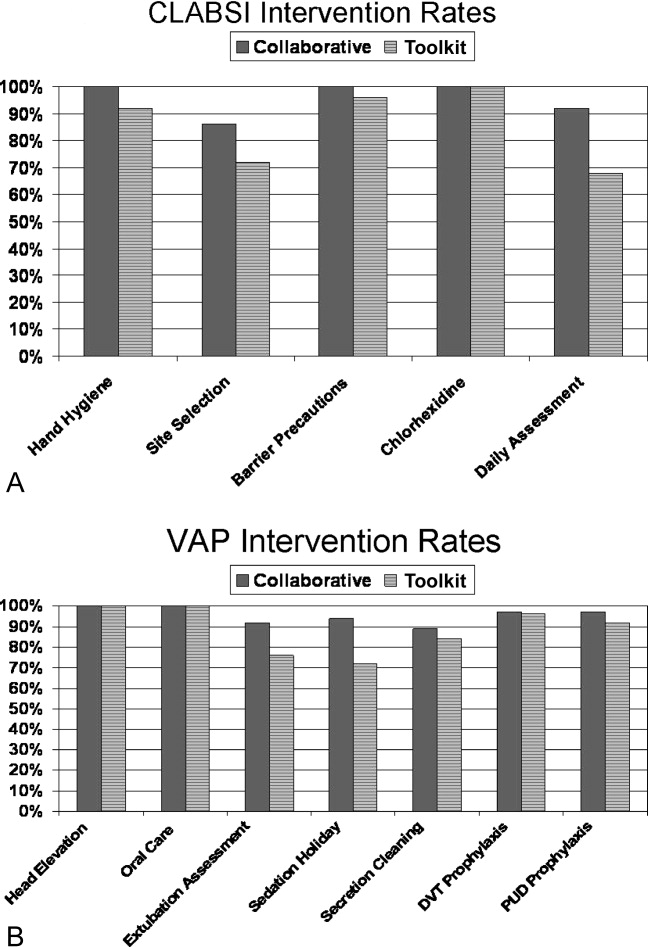

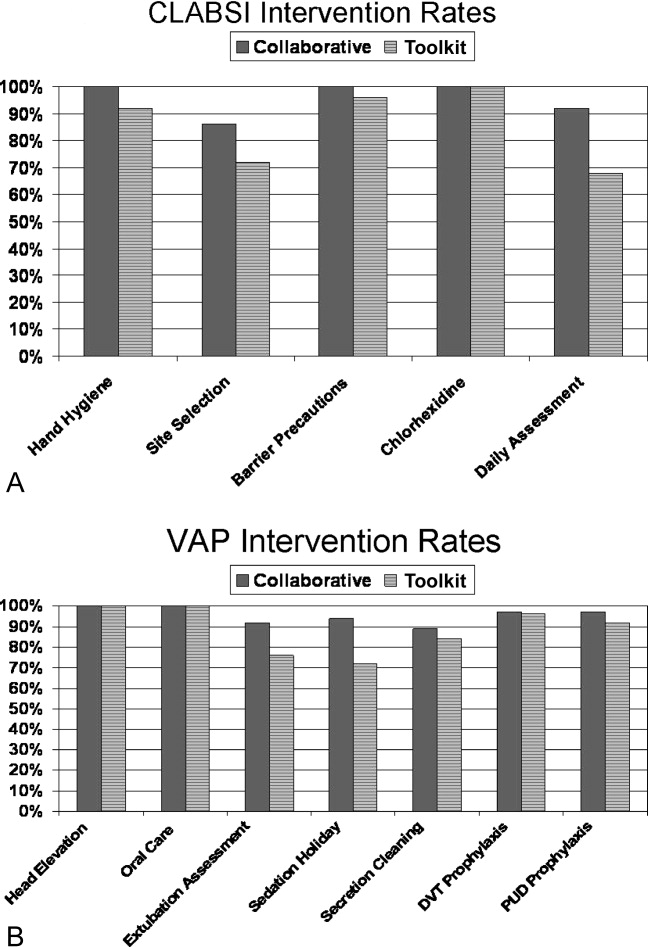

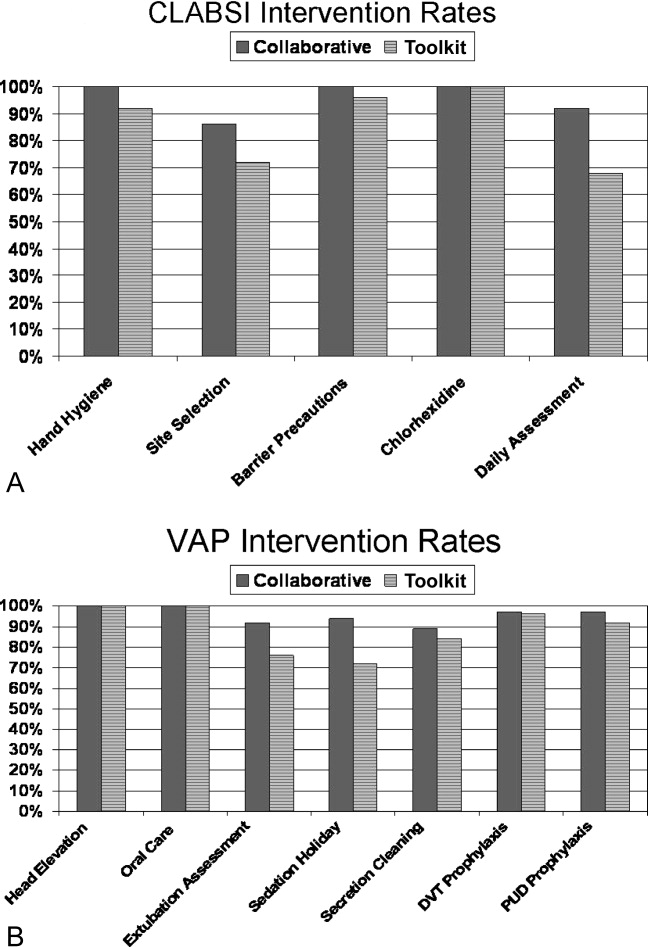

Comparing Collaborative and Toolkit QI

Continuous quality improvement (CQI) methodologies provide a framework for initiating and sustaining improvements in complex systems.1 By definition, CQI engages frontline staff in iterative problem solving using plandostudyact cycles of learning, with decision‐making based on real‐time process measurements.2 The Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI) has sponsored Breakthrough Series Collaboratives since 1996 to accelerate the uptake and impact of quality improvement (QI).3, 4 These collaboratives are typically guided by evidence‐based clinical practice guidelines, incorporate change methodologies, and rely on clinical and process improvement subject matter experts. Through the collaborative network, teams share knowledge and ideas about effective and ineffective interventions as well as strategies for overcoming barriers. The collaborative curriculum includes CQI methodology, multidisciplinary teamwork, leadership support, and tools for measurement. Participants are typically required to invest resources and send teams to face‐to‐face goal‐oriented meetings. It is costly for a large healthcare organization to incorporate travel to a learning session conference into its collaborative model. Thus, we attempted virtual learning sessions that make use of webcasts, a Web site, and teleconference calls for tools and networking.5

A recent derivative of collaboratives has been deployment of toolkits for QI. Intuition suggests that such toolkits may help to enable change, and thus some agencies advocate the simpler approach of disseminating toolkits as a change strategy.6 Toolkit dissemination is a passive approach in contrast to collaborative participation, and its effectiveness has not been critically examined in evidence‐based literature.

We sought to compare the virtual collaborative model with the toolkit model for improving care. Recommendations and guidelines for central lineassociated bloodstream infection (CLABSI) and ventilator‐associated pneumonia (VAP) prevention have not been implemented reliably, resulting in unnecessary intensive care unit (ICU) morbidity and mortality and fostering a national call for improvement.7 Our aim was to compare the effectiveness of the virtual collaborative and toolkit approaches on preventing CLABSI and VAP in the ICU.

Methods

This cluster randomized trial included medical centers within the Hospital Corporation of America (HCA), a network of hospitals located primarily in the southern United States. To minimize contamination bias between study groups within the same facility, the unit of randomization was the hospital and implementation was at the level of the ICU. The project received approval from the Vanderbilt University Institutional Review Board.

Leaders of all medical centers with at least 1 adult or pediatric ICU received an invitation from HCA leadership to participate in a QI initiative. Facility clinicians and managers completed baseline surveys (shown in the Supporting Information) on hospital characteristics, types of ICUs, patient safety climate, and QI resources between July and November 2005. Hospital‐level data were extracted from the enterprise‐wide data warehouse. Hospitals willing to participate were matched on geographic location and ICU volume and then randomized into either the Virtual Collaborative (n = 31) or Toolkit (n = 30) groups in December 20058; 1 of the hospitals was sold, yielding 29 hospitals in the Toolkit (n = 29) group. The study lasted 18 months from January 2006 through September 2007, with health careassociated infection data collected through December 2007, and follow‐up data collection through April 2008.

The QI initiative included educational opportunities, evidence‐based clinical prevention interventions, and processes and tools to implement and measure the impact of these interventions. Participants in both groups were offered interactive Web seminars during the study period; 5 of these seminars were on clinical subject matter, and 5 seminars were on patient safety, charting use of statistical process control and QI methods. The interventions were evidence‐based care bundles.9 The key interventions for preventing CLABSI were routine hand hygiene, use of chlorhexidine skin antisepsis, maximal barrier precautions during catheter insertion, catheter site and care, and avoidance of routine replacement of catheters. The key interventions to prevent VAP were routine elevation of head of the bed, regular oral care, daily sedation vacations, daily assessment of readiness to extubate, secretion cleaning, peptic ulcer disease prophylaxis, and deep vein thrombosis prophylaxis.

Toolkit Group