User login

Air travel and venous thromboembolism: Minimizing the risk

Editor’s Note: The views expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not reflect the official policy or position of the Department of State or the United States Government. This version of the article was peer-reviewed.

Venous thromboembolism (VTE) associated with travel has emerged as an important public health concern over the past decade. Numerous epidemiologic and case control studies have reported air travel as a risk factor for the development of VTE and have attempted to determine who is at risk and which precautions need to be taken to prevent this potentially fatal event.1–7 Often referred to as “traveler’s thrombosis” or “flight-related deep vein thrombosis,” VTE can also develop after long trips by automobile, bus, or train.8,9 Although the absolute risk is very low, this threat appears to be about three times higher in travelers and increases with longer trips.3

See related patient information material

This article focuses on defining VTE and recognizing its clinical features, as well as providing recommendations and guidelines to prevent, diagnose, and treat this complication in people who travel.

WHAT IS VENOUS THROMBOEMBOLISM?

Deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism represent different manifestations of the same clinical entity, ie, VTE. VTE is a common, lethal disease that affects hospitalized and nonhospitalized patients, frequently recurs, is often overlooked, may be asymptomatic, and may result in long-term complications that include pulmonary hypertension and the postthrombotic syndrome.

Deep vein thrombosis of the upper extremities is generally related to an indwelling venous catheter or a central line being used for long-term administration of antibiotics, chemotherapy, or nutrition. A condition known as Paget-Schroetter syndrome or “effort thrombosis” may be seen in younger or athletic people who have a history of strenuous or unusual arm exercise.

RISK FACTORS FOR VTE

Common inherited risk factors include:

- Factor V Leiden mutation

- Prothrombin gene mutation G20210A

- Hyperhomocysteinemia

- Deficiency of the natural anticoagulant proteins C, S, or antithrombin

- Elevated levels of factor VIII (may be inherited or acquired).

Acquired risk factors include:

- Older age

- Immobilization or stasis (such as sitting for long periods of time while traveling)

- Surgery (most notably orthopedic procedures including hip and knee replacement and repair of a hip fracture)

- Trauma

- Stroke

- Acute medical illness (including congestive heart failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, pneumonia)

- The antiphospholipid syndrome (consisting of a lupus anticoagulant, anticardiolipin antibodies, or both)

- Pregnancy and the postpartum state

- Use of oral contraceptives or hormone replacement therapy

- Cancer (including the myeloproliferative disorders) and certain chemotherapeutic agents

- Obesity (a body mass index > 30 kg/m2, see www.nhlbisupport.com/bmi/)

- Inflammatory bowel disease

- Previous VTE

- A central venous catheter or pacemaker

- Nephrotic syndrome.

In addition, emerging risk factors more recently recognized include male sex, persistence of elevated factor VIII levels, and the continued presence of an elevated D-dimer level or deep vein thrombosis on duplex ultrasonography once anticoagulation treatment is completed. There is also evidence of an association between VTE and risk factors for atherosclerotic arterial disease such as smoking, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and diabetes.

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS OF VTE

Patients with deep vein thrombosis may complain of pain, swelling, or both in the leg or arm. Physical examination may reveal increased warmth, tenderness, erythema, edema, or dilated (collateral) veins, most notable on the upper thigh or calf (for deep vein thrombosis in the lower extremity) or the chest wall (for upper-extremity deep vein thrombosis). The examiner may also observe a tender, palpable cord, which represents a superficial vein thrombosis involving the great and small saphenous veins (Figure 1). In extreme situations, the limb may be cyanotic or gangrenous.

DIAGNOSIS OF VTE

Clinical examination alone is generally insufficient to confirm a diagnosis of deep vein thrombosis or pulmonary embolism. Venous duplex ultrasonography is the most dependable investigation for deep vein thrombosis, but other tests include D-dimer and imaging studies such as computed tomographic venography or magnetic resonance venography of the lower extremities. A more invasive approach is venography; formerly considered the gold standard, it is now generally used only when the diagnosis is in doubt after noninvasive testing. The diagnosis of acute pulmonary embolism is best made by spiral computed tomography.

Other studies that may prove helpful include a ventilation-perfusion lung scan for patients who cannot undergo computed tomography due to a contrast allergy or renal insufficiency. Pulmonary angiography, while the gold standard, is less commonly used today, given the specificity and sensitivity of computed tomography.

Echocardiography at the bedside may be useful for patients too sick to move, although the study may not be diagnostic unless thrombi are seen in the heart or pulmonary arteries.

TREATMENT OF VTE

For acute deep venous thrombosis

Acute deep vein thrombosis is now treated on an outpatient basis under most circumstances.

Unfractionated heparin is given intravenously for patients who need to be hospitalized, or subcutaneously in full dose for inpatient or outpatient treatment.

Low-molecular-weight heparins are available in subcutaneous preparations and can be given on an outpatient basis.

Fondaparinux (Arixtra), a factor Xa inhibitor, can also be given subcutaneously on an outpatient basis. Equivalent products are available outside the United States.

Warfarin (Coumadin), an oral vitamin K inhibitor, is the agent of choice for long-term management of deep vein thrombosis.

Other oral agents are available outside the United States.

For pulmonary embolism

Outpatient treatment of pulmonary embolism is not yet advised: an initial hospitalization is necessary. The same anticoagulants used for deep vein thrombosis are also used for acute pulmonary embolism.

Empiric treatment in underdeveloped countries

VTE may be an even greater concern on an outbound trip to a remote area, where medical care capabilities may be less than ideal and diagnostic and treatment options may be limited.

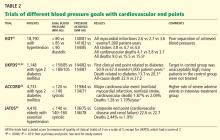

If there is a high pretest probability of acute VTE (Table 2, Table 3) and no diagnostic methods are available, empiric treatment with any of the parenteral anticoagulant agents listed in Table 4 is an option until the diagnosis can be confirmed. Caveats:

- Care must be taken to be certain there is not a strong contraindication to the use of anticoagulation, such as bleeding or a drug allergy.

- Neither unfractionated heparin nor any of the low-molecular-weight heparins should be given to a patient who has a history of heparin-induced thrombocytopenia.

- In patients who have chronic kidney disease (creatinine clearance less than 30 mL/minute), the dosage of low-molecular-weight heparins must be adjusted and factor Xa inhibitors avoided. Both of these types of anticoagulants should be avoided in patients on hemodialysis.

More aggressive therapy

Under select circumstances a more aggressive approach to the treatment of VTE may be necessary. These options are usually indicated for a patient with a massive deep vein thrombosis of a lower extremity and for certain patients with an upper extremity deep vein thrombosis. Treatments include catheter-directed thrombolytic therapy and endovenous or surgical thrombectomy.

Thrombolytic therapy is recommended for a patient with an acute pulmonary embolism who is clinically unstable (systolic blood pressure lower than 90 mm Hg), if there is no contraindication to its use (bleeding risk or recent stroke or surgery). Thrombolytic therapy is also an option for those at low risk of bleeding with an acute pulmonary embolism who have signs and symptoms of right heart failure proven by echocardiography.

Surgical pulmonary embolectomy for acute massive pulmonary embolism and mechanical thrombectomy for extensive deep vein thrombosis are generally available only at highly sophisticated tertiary care centers.

An inferior vena cava filter is advised in patients with acute deep vein thrombosis or pulmonary embolism who cannot be fully anticoagulated, to prevent the clot from migrating from the lower extremities to the lungs. These filters are available as either permanent or temporary implants. Some temporary versions can remain in place for up to 150 days after insertion.

PREVENTION OF VTE

Prevention is the standard of care for all patients admitted to the hospital and in select individuals as outpatients who are at high risk of VTE.

Mechanical compression (graduated compression stockings, intermittent pneumatic compression devices) has proven effective in reducing the incidence of deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism postoperatively in patients who cannot take anticoagulants. One study has demonstrated that compression stockings may also be effective in preventing VTE during travel.12

ABSOLUTE RISK IS LOW

Over the past decade, special attention has been paid to travel as a risk factor for developing VTE.13 Traveler’s thrombosis has become an important public health concern. Numerous publications and epidemiologic studies have targeted air travel in an attempt to determine who is at risk and what precautions are necessary to prevent this complication.1–7,9

The incidence of VTE following air travel is reported to be 3.2 per 1,000 person-years.4 While this incidence is relatively low, it is still 3.2 times higher than in the healthy population that is not flying.

The more serious complication of VTE, ie, acute pulmonary embolism, occurs less often. In three studies, the reported incidence ranged from 1.65 per million patients in flights longer than 8 hours to a high of 4.8 per million patients in flights longer than 12 hours or distances exceeding 10,000 km (6,200 miles).5,14,15 For the 400 passengers on the average long-haul flight of 12 hours, there is at most a 0.2% chance that somebody on the plane will have a symptomatic VTE).

RISK FACTORS IN LONG-DISTANCE TRAVELERS

The risk of traveler’s thrombosis has recently attracted the attention of passengers and the airline industry. Airlines are now openly discussing the risk and providing reminders such as exercises that should be undertaken in-flight (see the patient information page that accompanies this article). Some airlines are recommending that all patients consult their doctor to assess their personal risk of deep vein thrombosis before flying.

The most common risk factors for VTE in travelers are well established and are additive (Table 1). The extent of the additive risk, however, is not entirely clear.

What is clear is that when VTE occurs it is a life-altering and life-threatening event. If it occurs on an outbound trip, the local resources and capabilities available at the destination may not be adequate for optimal treatment. If a traveler experiences a VTE event on an outbound trip, an emergency return trip to the continental United States or a regional center of expertise may be required. There is an additive risk with this subsequent travel event if the patient is not given immediate treatment first (Table 4). Hence, treatment prior to evacuation should be strongly considered.

The traveler must also be aware that VTE can be recognized up to 2 months after a long-haul flight, though it is especially a concern within the first 2 weeks after travel.2,4,16,17

RECOMMENDATIONS FOR LONG-DISTANCE AIR TRAVELERS

Each person should be evaluated on a case-by-case basis for his or her need for VTE prophylaxis. Medical guidelines for airline passengers have been published by the Aerospace Medical Association and the American College of Chest Physicians (ACCP).18,19 In general, travelers should:

- Exercise the legs by flexing and extending the ankles at regular intervals while seated (see the patient information material that accompanies this article) and frequently contracting the calf muscles.

- Walk about the cabin periodically, 5 minutes for every hour on longer-duration flights (over 4 hours) and when flight conditions permit.

- Drink adequate amounts of water and fruit juices to maintain good hydration.17

- Avoid alcohol and caffeinated beverages, which are dehydrating.

- Be careful about eating too much during the flight.

- Request an aisle seat if you are at risk

- Do not place baggage underneath the seat in front of you, because that reduces the ability to move the legs.

- Do not sleep in a cramped position, and avoid the use of any type of sleep aid.

- Avoid wearing constrictive clothing around the lower extremities or waist.

We recommend that all airplane passengers take the steps listed above to reduce venous stasis and avoid dehydration, even though these measures have not been proven effective in clinical trials.19

The ACCP further advises that decisions about pharmacologic prophylaxis of VTE for airplane passengers at high risk should be made on an individual basis, considering that there are potential adverse effects of prophylaxis and that these may outweigh the benefits. For long-distance travelers with additional risk factors for VTE, we suggest the following:

- Use of properly fitted, below-the-knee graduated compression stockings providing 15 to 30 mm Hg of pressure at the ankle (particularly when large varicosities or leg edema is present)

- For people at very high risk, a single prophylactic dose of a low-molecular-weight heparin or a factor Xa inhibitor injected just before departure (Table 5)

- Aspirin is not recommended as it is not effective for the prevention of VTE.20

SUMMARY FOR THE AIR TRAVELER

All travelers on long flights should perform standard VTE prophylaxis exercises (see the patient information pages accompanying this article). Although VTE is uncommon, people with additional risk factors who travel frequently either on multiple flights in a short period of time or on very long flights should be evaluated on a case-by-case basis for a more aggressive approach to prevention (compression support hose or prophylactic administration of a low-molecular-weight heparin or a factor Xa inhibitor).

Should a VTE event occur during travel, the patient should seek medical care immediately. The standard evaluation of a patient with a suspected VTE should include an estimation of the pretest probability of disease (Table 2, Table 3), followed by duplex ultrasonography of the upper or lower extremity to detect a deep vein thrombosis. If symptoms dictate, then spiral computed tomography, ventilation-perfusion lung scan, or pulmonary angiography (where available) should be ordered to diagnose acute pulmonary embolism. A positive D-dimer blood test alone is not diagnostic and may not be available in more remote locations. A negative D-dimer test result is most helpful to exclude VTE.

Standard therapy for VTE is immediate treatment with one of the anticoagulants listed in Table 4, unless the patient has a contraindication to treatment, such as bleeding or allergy. Immediate evacuation is recommended if the patient has a life-threatening pulmonary embolism, defined as hemodynamic instability (hypotension with a blood pressure under 90 mm Hg systolic or signs of right heart failure) that cannot be treated at a local facility. An air ambulance should be used to transport these patients. If the patient has an iliofemoral deep vein thrombosis, it is also advisable that he or she be considered for evacuation if severe symptoms are present, such as pain, swelling, or cyanosis. Unless contraindicated, all patients should be given either full-dose intravenous or full-dose subcutaneous heparin or subcutaneous injection of a readily available low-molecular-weight heparin preparations or factor Xa inhibitor at once.21

- Brenner B. Interventions to prevent venous thrombosis after air travel, are they necessary? Yes. J Thromb Haemost 2006; 4:2302–2305.

- Cannegieter SC, Doggen CJM, van Houwellingen HC, et al. Travel-related venous thrombosis: results from a large population-based case control study (MEGA Study). PLoS Med 2006; 3:1258–1265.

- Chandra D, Parisini E, Mozaffarian D. Meta-analysis: travel and risk for venous thromboembolism. Ann Intern Med 2009; 151:180–190.

- Kuipers S, Cannegieter SC, Middeldorp S, et al. The absolute risk of venous thrombosis after air travel: a cohort study of 8,755 employees of international organizations. PLoS Med 2007; 4:1508–1514.

- Kuipers S, Schreijer AJM, Cannegieter SC, et al. Travel and venous thrombosis: a systematic review. J Intern Med 2007; 262:615–634.

- Lehmann R, Suess C, Leus M, et al. Incidence, clinical characteristics, and long-term prognosis of travel-associated pulmonary embolism. Eur Heart J 2009; 30:233–241.

- Philbrick JT, Shumate R, Siadaty MS, et al. Air travel and venous thromboembolism: a systematic review. J Gen Intern Med 2007; 22:107–114.

- Cruickshank JM, Gorlin R, Jennett B. Air travel and thrombotic episodes: the economy class syndrome. Lancet 1988; 2:497–498.

- Bagshaw M. Traveler’s thrombosis: a review of deep vein thrombosis associated with travel. Air Transport Medicine Committee, Aerospace Medical Association. Aviat Space Environ Med 2001; 72:848–851.

- Wells PS, Owens C, Doucette S, et al. Does this patient have deep vein thrombosis? JAMA 2006; 295:199–207.

- Arnason T, Wells PS, Forester AJ. Appropriateness of diagnostic strategies for evaluating suspected venous thromboembolism. Thromb Haemost 2007; 97:195–201.

- Clarke M, Hopewell S, Juszcak E, Eisinga A, Kjeldstrøm M. Compression stockings in preventing deep vein thrombosis in airline passengers. Cochrane Database of Syst Rev 2006; Apr 19( 2):CD004002. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.

- Kuipers S, Cannegieter SC, Middeldorp S, et al. Use of preventive measures for travel-related venous thrombosis in professionals who attend medical conferences. J Thromb Haemost 2006; 4:2373–2376.

- Perez-Rodriguez E, Jimenez D, Diaz G, et al. Incidence of air travel-related pulmonary embolism in the Madrid-Barajas Airport. Arch Intern Med 2003; 163:2766–2770.

- Lapostolle F, Surget V, Borron SW, et al. Severe pulmonary embolism associated with air travel. N Engl J Med 2001; 345:779–783.

- Kelman CW, Kortt MA, Becker NG, et al. Deep vein thrombosis and air travel: record linkage study. BMJ 2003; 327:1072–1076.

- Eklof B, Kistner RL, Masuda EM, et al. Venous thromboembolism in association with prolonged air travel. Dermatol Surg 1996; 22:637–641.

- Moyle J. Medical guidelines for airline travel. Aviat Space Environ Med 2003: 74:1009.

- Geerts WH, Bergqvist B, Pineo GF, et al. Prevention of venous thromboembolism: American College of Chest Physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest 2008; 133:381S–453S.

- Rosendaal FR. Interventions to prevent venous thrombosis after air travel: are they necessary? No. J Thromb Haemost 2006; 4:2306–2307.

- Kearon C, Ginsberg JS, Julian JA, et al; Fixed-Dose Heparin (FIDO) Investigators. Comparison of fixed-dose weight-adjusted unfractionated heparin and low-molecular-weight heparin for acute treatment of venous thromboembolism. JAMA 2006; 296:935–942.

Editor’s Note: The views expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not reflect the official policy or position of the Department of State or the United States Government. This version of the article was peer-reviewed.

Venous thromboembolism (VTE) associated with travel has emerged as an important public health concern over the past decade. Numerous epidemiologic and case control studies have reported air travel as a risk factor for the development of VTE and have attempted to determine who is at risk and which precautions need to be taken to prevent this potentially fatal event.1–7 Often referred to as “traveler’s thrombosis” or “flight-related deep vein thrombosis,” VTE can also develop after long trips by automobile, bus, or train.8,9 Although the absolute risk is very low, this threat appears to be about three times higher in travelers and increases with longer trips.3

See related patient information material

This article focuses on defining VTE and recognizing its clinical features, as well as providing recommendations and guidelines to prevent, diagnose, and treat this complication in people who travel.

WHAT IS VENOUS THROMBOEMBOLISM?

Deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism represent different manifestations of the same clinical entity, ie, VTE. VTE is a common, lethal disease that affects hospitalized and nonhospitalized patients, frequently recurs, is often overlooked, may be asymptomatic, and may result in long-term complications that include pulmonary hypertension and the postthrombotic syndrome.

Deep vein thrombosis of the upper extremities is generally related to an indwelling venous catheter or a central line being used for long-term administration of antibiotics, chemotherapy, or nutrition. A condition known as Paget-Schroetter syndrome or “effort thrombosis” may be seen in younger or athletic people who have a history of strenuous or unusual arm exercise.

RISK FACTORS FOR VTE

Common inherited risk factors include:

- Factor V Leiden mutation

- Prothrombin gene mutation G20210A

- Hyperhomocysteinemia

- Deficiency of the natural anticoagulant proteins C, S, or antithrombin

- Elevated levels of factor VIII (may be inherited or acquired).

Acquired risk factors include:

- Older age

- Immobilization or stasis (such as sitting for long periods of time while traveling)

- Surgery (most notably orthopedic procedures including hip and knee replacement and repair of a hip fracture)

- Trauma

- Stroke

- Acute medical illness (including congestive heart failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, pneumonia)

- The antiphospholipid syndrome (consisting of a lupus anticoagulant, anticardiolipin antibodies, or both)

- Pregnancy and the postpartum state

- Use of oral contraceptives or hormone replacement therapy

- Cancer (including the myeloproliferative disorders) and certain chemotherapeutic agents

- Obesity (a body mass index > 30 kg/m2, see www.nhlbisupport.com/bmi/)

- Inflammatory bowel disease

- Previous VTE

- A central venous catheter or pacemaker

- Nephrotic syndrome.

In addition, emerging risk factors more recently recognized include male sex, persistence of elevated factor VIII levels, and the continued presence of an elevated D-dimer level or deep vein thrombosis on duplex ultrasonography once anticoagulation treatment is completed. There is also evidence of an association between VTE and risk factors for atherosclerotic arterial disease such as smoking, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and diabetes.

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS OF VTE

Patients with deep vein thrombosis may complain of pain, swelling, or both in the leg or arm. Physical examination may reveal increased warmth, tenderness, erythema, edema, or dilated (collateral) veins, most notable on the upper thigh or calf (for deep vein thrombosis in the lower extremity) or the chest wall (for upper-extremity deep vein thrombosis). The examiner may also observe a tender, palpable cord, which represents a superficial vein thrombosis involving the great and small saphenous veins (Figure 1). In extreme situations, the limb may be cyanotic or gangrenous.

DIAGNOSIS OF VTE

Clinical examination alone is generally insufficient to confirm a diagnosis of deep vein thrombosis or pulmonary embolism. Venous duplex ultrasonography is the most dependable investigation for deep vein thrombosis, but other tests include D-dimer and imaging studies such as computed tomographic venography or magnetic resonance venography of the lower extremities. A more invasive approach is venography; formerly considered the gold standard, it is now generally used only when the diagnosis is in doubt after noninvasive testing. The diagnosis of acute pulmonary embolism is best made by spiral computed tomography.

Other studies that may prove helpful include a ventilation-perfusion lung scan for patients who cannot undergo computed tomography due to a contrast allergy or renal insufficiency. Pulmonary angiography, while the gold standard, is less commonly used today, given the specificity and sensitivity of computed tomography.

Echocardiography at the bedside may be useful for patients too sick to move, although the study may not be diagnostic unless thrombi are seen in the heart or pulmonary arteries.

TREATMENT OF VTE

For acute deep venous thrombosis

Acute deep vein thrombosis is now treated on an outpatient basis under most circumstances.

Unfractionated heparin is given intravenously for patients who need to be hospitalized, or subcutaneously in full dose for inpatient or outpatient treatment.

Low-molecular-weight heparins are available in subcutaneous preparations and can be given on an outpatient basis.

Fondaparinux (Arixtra), a factor Xa inhibitor, can also be given subcutaneously on an outpatient basis. Equivalent products are available outside the United States.

Warfarin (Coumadin), an oral vitamin K inhibitor, is the agent of choice for long-term management of deep vein thrombosis.

Other oral agents are available outside the United States.

For pulmonary embolism

Outpatient treatment of pulmonary embolism is not yet advised: an initial hospitalization is necessary. The same anticoagulants used for deep vein thrombosis are also used for acute pulmonary embolism.

Empiric treatment in underdeveloped countries

VTE may be an even greater concern on an outbound trip to a remote area, where medical care capabilities may be less than ideal and diagnostic and treatment options may be limited.

If there is a high pretest probability of acute VTE (Table 2, Table 3) and no diagnostic methods are available, empiric treatment with any of the parenteral anticoagulant agents listed in Table 4 is an option until the diagnosis can be confirmed. Caveats:

- Care must be taken to be certain there is not a strong contraindication to the use of anticoagulation, such as bleeding or a drug allergy.

- Neither unfractionated heparin nor any of the low-molecular-weight heparins should be given to a patient who has a history of heparin-induced thrombocytopenia.

- In patients who have chronic kidney disease (creatinine clearance less than 30 mL/minute), the dosage of low-molecular-weight heparins must be adjusted and factor Xa inhibitors avoided. Both of these types of anticoagulants should be avoided in patients on hemodialysis.

More aggressive therapy

Under select circumstances a more aggressive approach to the treatment of VTE may be necessary. These options are usually indicated for a patient with a massive deep vein thrombosis of a lower extremity and for certain patients with an upper extremity deep vein thrombosis. Treatments include catheter-directed thrombolytic therapy and endovenous or surgical thrombectomy.

Thrombolytic therapy is recommended for a patient with an acute pulmonary embolism who is clinically unstable (systolic blood pressure lower than 90 mm Hg), if there is no contraindication to its use (bleeding risk or recent stroke or surgery). Thrombolytic therapy is also an option for those at low risk of bleeding with an acute pulmonary embolism who have signs and symptoms of right heart failure proven by echocardiography.

Surgical pulmonary embolectomy for acute massive pulmonary embolism and mechanical thrombectomy for extensive deep vein thrombosis are generally available only at highly sophisticated tertiary care centers.

An inferior vena cava filter is advised in patients with acute deep vein thrombosis or pulmonary embolism who cannot be fully anticoagulated, to prevent the clot from migrating from the lower extremities to the lungs. These filters are available as either permanent or temporary implants. Some temporary versions can remain in place for up to 150 days after insertion.

PREVENTION OF VTE

Prevention is the standard of care for all patients admitted to the hospital and in select individuals as outpatients who are at high risk of VTE.

Mechanical compression (graduated compression stockings, intermittent pneumatic compression devices) has proven effective in reducing the incidence of deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism postoperatively in patients who cannot take anticoagulants. One study has demonstrated that compression stockings may also be effective in preventing VTE during travel.12

ABSOLUTE RISK IS LOW

Over the past decade, special attention has been paid to travel as a risk factor for developing VTE.13 Traveler’s thrombosis has become an important public health concern. Numerous publications and epidemiologic studies have targeted air travel in an attempt to determine who is at risk and what precautions are necessary to prevent this complication.1–7,9

The incidence of VTE following air travel is reported to be 3.2 per 1,000 person-years.4 While this incidence is relatively low, it is still 3.2 times higher than in the healthy population that is not flying.

The more serious complication of VTE, ie, acute pulmonary embolism, occurs less often. In three studies, the reported incidence ranged from 1.65 per million patients in flights longer than 8 hours to a high of 4.8 per million patients in flights longer than 12 hours or distances exceeding 10,000 km (6,200 miles).5,14,15 For the 400 passengers on the average long-haul flight of 12 hours, there is at most a 0.2% chance that somebody on the plane will have a symptomatic VTE).

RISK FACTORS IN LONG-DISTANCE TRAVELERS

The risk of traveler’s thrombosis has recently attracted the attention of passengers and the airline industry. Airlines are now openly discussing the risk and providing reminders such as exercises that should be undertaken in-flight (see the patient information page that accompanies this article). Some airlines are recommending that all patients consult their doctor to assess their personal risk of deep vein thrombosis before flying.

The most common risk factors for VTE in travelers are well established and are additive (Table 1). The extent of the additive risk, however, is not entirely clear.

What is clear is that when VTE occurs it is a life-altering and life-threatening event. If it occurs on an outbound trip, the local resources and capabilities available at the destination may not be adequate for optimal treatment. If a traveler experiences a VTE event on an outbound trip, an emergency return trip to the continental United States or a regional center of expertise may be required. There is an additive risk with this subsequent travel event if the patient is not given immediate treatment first (Table 4). Hence, treatment prior to evacuation should be strongly considered.

The traveler must also be aware that VTE can be recognized up to 2 months after a long-haul flight, though it is especially a concern within the first 2 weeks after travel.2,4,16,17

RECOMMENDATIONS FOR LONG-DISTANCE AIR TRAVELERS

Each person should be evaluated on a case-by-case basis for his or her need for VTE prophylaxis. Medical guidelines for airline passengers have been published by the Aerospace Medical Association and the American College of Chest Physicians (ACCP).18,19 In general, travelers should:

- Exercise the legs by flexing and extending the ankles at regular intervals while seated (see the patient information material that accompanies this article) and frequently contracting the calf muscles.

- Walk about the cabin periodically, 5 minutes for every hour on longer-duration flights (over 4 hours) and when flight conditions permit.

- Drink adequate amounts of water and fruit juices to maintain good hydration.17

- Avoid alcohol and caffeinated beverages, which are dehydrating.

- Be careful about eating too much during the flight.

- Request an aisle seat if you are at risk

- Do not place baggage underneath the seat in front of you, because that reduces the ability to move the legs.

- Do not sleep in a cramped position, and avoid the use of any type of sleep aid.

- Avoid wearing constrictive clothing around the lower extremities or waist.

We recommend that all airplane passengers take the steps listed above to reduce venous stasis and avoid dehydration, even though these measures have not been proven effective in clinical trials.19

The ACCP further advises that decisions about pharmacologic prophylaxis of VTE for airplane passengers at high risk should be made on an individual basis, considering that there are potential adverse effects of prophylaxis and that these may outweigh the benefits. For long-distance travelers with additional risk factors for VTE, we suggest the following:

- Use of properly fitted, below-the-knee graduated compression stockings providing 15 to 30 mm Hg of pressure at the ankle (particularly when large varicosities or leg edema is present)

- For people at very high risk, a single prophylactic dose of a low-molecular-weight heparin or a factor Xa inhibitor injected just before departure (Table 5)

- Aspirin is not recommended as it is not effective for the prevention of VTE.20

SUMMARY FOR THE AIR TRAVELER

All travelers on long flights should perform standard VTE prophylaxis exercises (see the patient information pages accompanying this article). Although VTE is uncommon, people with additional risk factors who travel frequently either on multiple flights in a short period of time or on very long flights should be evaluated on a case-by-case basis for a more aggressive approach to prevention (compression support hose or prophylactic administration of a low-molecular-weight heparin or a factor Xa inhibitor).

Should a VTE event occur during travel, the patient should seek medical care immediately. The standard evaluation of a patient with a suspected VTE should include an estimation of the pretest probability of disease (Table 2, Table 3), followed by duplex ultrasonography of the upper or lower extremity to detect a deep vein thrombosis. If symptoms dictate, then spiral computed tomography, ventilation-perfusion lung scan, or pulmonary angiography (where available) should be ordered to diagnose acute pulmonary embolism. A positive D-dimer blood test alone is not diagnostic and may not be available in more remote locations. A negative D-dimer test result is most helpful to exclude VTE.

Standard therapy for VTE is immediate treatment with one of the anticoagulants listed in Table 4, unless the patient has a contraindication to treatment, such as bleeding or allergy. Immediate evacuation is recommended if the patient has a life-threatening pulmonary embolism, defined as hemodynamic instability (hypotension with a blood pressure under 90 mm Hg systolic or signs of right heart failure) that cannot be treated at a local facility. An air ambulance should be used to transport these patients. If the patient has an iliofemoral deep vein thrombosis, it is also advisable that he or she be considered for evacuation if severe symptoms are present, such as pain, swelling, or cyanosis. Unless contraindicated, all patients should be given either full-dose intravenous or full-dose subcutaneous heparin or subcutaneous injection of a readily available low-molecular-weight heparin preparations or factor Xa inhibitor at once.21

Editor’s Note: The views expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not reflect the official policy or position of the Department of State or the United States Government. This version of the article was peer-reviewed.

Venous thromboembolism (VTE) associated with travel has emerged as an important public health concern over the past decade. Numerous epidemiologic and case control studies have reported air travel as a risk factor for the development of VTE and have attempted to determine who is at risk and which precautions need to be taken to prevent this potentially fatal event.1–7 Often referred to as “traveler’s thrombosis” or “flight-related deep vein thrombosis,” VTE can also develop after long trips by automobile, bus, or train.8,9 Although the absolute risk is very low, this threat appears to be about three times higher in travelers and increases with longer trips.3

See related patient information material

This article focuses on defining VTE and recognizing its clinical features, as well as providing recommendations and guidelines to prevent, diagnose, and treat this complication in people who travel.

WHAT IS VENOUS THROMBOEMBOLISM?

Deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism represent different manifestations of the same clinical entity, ie, VTE. VTE is a common, lethal disease that affects hospitalized and nonhospitalized patients, frequently recurs, is often overlooked, may be asymptomatic, and may result in long-term complications that include pulmonary hypertension and the postthrombotic syndrome.

Deep vein thrombosis of the upper extremities is generally related to an indwelling venous catheter or a central line being used for long-term administration of antibiotics, chemotherapy, or nutrition. A condition known as Paget-Schroetter syndrome or “effort thrombosis” may be seen in younger or athletic people who have a history of strenuous or unusual arm exercise.

RISK FACTORS FOR VTE

Common inherited risk factors include:

- Factor V Leiden mutation

- Prothrombin gene mutation G20210A

- Hyperhomocysteinemia

- Deficiency of the natural anticoagulant proteins C, S, or antithrombin

- Elevated levels of factor VIII (may be inherited or acquired).

Acquired risk factors include:

- Older age

- Immobilization or stasis (such as sitting for long periods of time while traveling)

- Surgery (most notably orthopedic procedures including hip and knee replacement and repair of a hip fracture)

- Trauma

- Stroke

- Acute medical illness (including congestive heart failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, pneumonia)

- The antiphospholipid syndrome (consisting of a lupus anticoagulant, anticardiolipin antibodies, or both)

- Pregnancy and the postpartum state

- Use of oral contraceptives or hormone replacement therapy

- Cancer (including the myeloproliferative disorders) and certain chemotherapeutic agents

- Obesity (a body mass index > 30 kg/m2, see www.nhlbisupport.com/bmi/)

- Inflammatory bowel disease

- Previous VTE

- A central venous catheter or pacemaker

- Nephrotic syndrome.

In addition, emerging risk factors more recently recognized include male sex, persistence of elevated factor VIII levels, and the continued presence of an elevated D-dimer level or deep vein thrombosis on duplex ultrasonography once anticoagulation treatment is completed. There is also evidence of an association between VTE and risk factors for atherosclerotic arterial disease such as smoking, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and diabetes.

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS OF VTE

Patients with deep vein thrombosis may complain of pain, swelling, or both in the leg or arm. Physical examination may reveal increased warmth, tenderness, erythema, edema, or dilated (collateral) veins, most notable on the upper thigh or calf (for deep vein thrombosis in the lower extremity) or the chest wall (for upper-extremity deep vein thrombosis). The examiner may also observe a tender, palpable cord, which represents a superficial vein thrombosis involving the great and small saphenous veins (Figure 1). In extreme situations, the limb may be cyanotic or gangrenous.

DIAGNOSIS OF VTE

Clinical examination alone is generally insufficient to confirm a diagnosis of deep vein thrombosis or pulmonary embolism. Venous duplex ultrasonography is the most dependable investigation for deep vein thrombosis, but other tests include D-dimer and imaging studies such as computed tomographic venography or magnetic resonance venography of the lower extremities. A more invasive approach is venography; formerly considered the gold standard, it is now generally used only when the diagnosis is in doubt after noninvasive testing. The diagnosis of acute pulmonary embolism is best made by spiral computed tomography.

Other studies that may prove helpful include a ventilation-perfusion lung scan for patients who cannot undergo computed tomography due to a contrast allergy or renal insufficiency. Pulmonary angiography, while the gold standard, is less commonly used today, given the specificity and sensitivity of computed tomography.

Echocardiography at the bedside may be useful for patients too sick to move, although the study may not be diagnostic unless thrombi are seen in the heart or pulmonary arteries.

TREATMENT OF VTE

For acute deep venous thrombosis

Acute deep vein thrombosis is now treated on an outpatient basis under most circumstances.

Unfractionated heparin is given intravenously for patients who need to be hospitalized, or subcutaneously in full dose for inpatient or outpatient treatment.

Low-molecular-weight heparins are available in subcutaneous preparations and can be given on an outpatient basis.

Fondaparinux (Arixtra), a factor Xa inhibitor, can also be given subcutaneously on an outpatient basis. Equivalent products are available outside the United States.

Warfarin (Coumadin), an oral vitamin K inhibitor, is the agent of choice for long-term management of deep vein thrombosis.

Other oral agents are available outside the United States.

For pulmonary embolism

Outpatient treatment of pulmonary embolism is not yet advised: an initial hospitalization is necessary. The same anticoagulants used for deep vein thrombosis are also used for acute pulmonary embolism.

Empiric treatment in underdeveloped countries

VTE may be an even greater concern on an outbound trip to a remote area, where medical care capabilities may be less than ideal and diagnostic and treatment options may be limited.

If there is a high pretest probability of acute VTE (Table 2, Table 3) and no diagnostic methods are available, empiric treatment with any of the parenteral anticoagulant agents listed in Table 4 is an option until the diagnosis can be confirmed. Caveats:

- Care must be taken to be certain there is not a strong contraindication to the use of anticoagulation, such as bleeding or a drug allergy.

- Neither unfractionated heparin nor any of the low-molecular-weight heparins should be given to a patient who has a history of heparin-induced thrombocytopenia.

- In patients who have chronic kidney disease (creatinine clearance less than 30 mL/minute), the dosage of low-molecular-weight heparins must be adjusted and factor Xa inhibitors avoided. Both of these types of anticoagulants should be avoided in patients on hemodialysis.

More aggressive therapy

Under select circumstances a more aggressive approach to the treatment of VTE may be necessary. These options are usually indicated for a patient with a massive deep vein thrombosis of a lower extremity and for certain patients with an upper extremity deep vein thrombosis. Treatments include catheter-directed thrombolytic therapy and endovenous or surgical thrombectomy.

Thrombolytic therapy is recommended for a patient with an acute pulmonary embolism who is clinically unstable (systolic blood pressure lower than 90 mm Hg), if there is no contraindication to its use (bleeding risk or recent stroke or surgery). Thrombolytic therapy is also an option for those at low risk of bleeding with an acute pulmonary embolism who have signs and symptoms of right heart failure proven by echocardiography.

Surgical pulmonary embolectomy for acute massive pulmonary embolism and mechanical thrombectomy for extensive deep vein thrombosis are generally available only at highly sophisticated tertiary care centers.

An inferior vena cava filter is advised in patients with acute deep vein thrombosis or pulmonary embolism who cannot be fully anticoagulated, to prevent the clot from migrating from the lower extremities to the lungs. These filters are available as either permanent or temporary implants. Some temporary versions can remain in place for up to 150 days after insertion.

PREVENTION OF VTE

Prevention is the standard of care for all patients admitted to the hospital and in select individuals as outpatients who are at high risk of VTE.

Mechanical compression (graduated compression stockings, intermittent pneumatic compression devices) has proven effective in reducing the incidence of deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism postoperatively in patients who cannot take anticoagulants. One study has demonstrated that compression stockings may also be effective in preventing VTE during travel.12

ABSOLUTE RISK IS LOW

Over the past decade, special attention has been paid to travel as a risk factor for developing VTE.13 Traveler’s thrombosis has become an important public health concern. Numerous publications and epidemiologic studies have targeted air travel in an attempt to determine who is at risk and what precautions are necessary to prevent this complication.1–7,9

The incidence of VTE following air travel is reported to be 3.2 per 1,000 person-years.4 While this incidence is relatively low, it is still 3.2 times higher than in the healthy population that is not flying.

The more serious complication of VTE, ie, acute pulmonary embolism, occurs less often. In three studies, the reported incidence ranged from 1.65 per million patients in flights longer than 8 hours to a high of 4.8 per million patients in flights longer than 12 hours or distances exceeding 10,000 km (6,200 miles).5,14,15 For the 400 passengers on the average long-haul flight of 12 hours, there is at most a 0.2% chance that somebody on the plane will have a symptomatic VTE).

RISK FACTORS IN LONG-DISTANCE TRAVELERS

The risk of traveler’s thrombosis has recently attracted the attention of passengers and the airline industry. Airlines are now openly discussing the risk and providing reminders such as exercises that should be undertaken in-flight (see the patient information page that accompanies this article). Some airlines are recommending that all patients consult their doctor to assess their personal risk of deep vein thrombosis before flying.

The most common risk factors for VTE in travelers are well established and are additive (Table 1). The extent of the additive risk, however, is not entirely clear.

What is clear is that when VTE occurs it is a life-altering and life-threatening event. If it occurs on an outbound trip, the local resources and capabilities available at the destination may not be adequate for optimal treatment. If a traveler experiences a VTE event on an outbound trip, an emergency return trip to the continental United States or a regional center of expertise may be required. There is an additive risk with this subsequent travel event if the patient is not given immediate treatment first (Table 4). Hence, treatment prior to evacuation should be strongly considered.

The traveler must also be aware that VTE can be recognized up to 2 months after a long-haul flight, though it is especially a concern within the first 2 weeks after travel.2,4,16,17

RECOMMENDATIONS FOR LONG-DISTANCE AIR TRAVELERS

Each person should be evaluated on a case-by-case basis for his or her need for VTE prophylaxis. Medical guidelines for airline passengers have been published by the Aerospace Medical Association and the American College of Chest Physicians (ACCP).18,19 In general, travelers should:

- Exercise the legs by flexing and extending the ankles at regular intervals while seated (see the patient information material that accompanies this article) and frequently contracting the calf muscles.

- Walk about the cabin periodically, 5 minutes for every hour on longer-duration flights (over 4 hours) and when flight conditions permit.

- Drink adequate amounts of water and fruit juices to maintain good hydration.17

- Avoid alcohol and caffeinated beverages, which are dehydrating.

- Be careful about eating too much during the flight.

- Request an aisle seat if you are at risk

- Do not place baggage underneath the seat in front of you, because that reduces the ability to move the legs.

- Do not sleep in a cramped position, and avoid the use of any type of sleep aid.

- Avoid wearing constrictive clothing around the lower extremities or waist.

We recommend that all airplane passengers take the steps listed above to reduce venous stasis and avoid dehydration, even though these measures have not been proven effective in clinical trials.19

The ACCP further advises that decisions about pharmacologic prophylaxis of VTE for airplane passengers at high risk should be made on an individual basis, considering that there are potential adverse effects of prophylaxis and that these may outweigh the benefits. For long-distance travelers with additional risk factors for VTE, we suggest the following:

- Use of properly fitted, below-the-knee graduated compression stockings providing 15 to 30 mm Hg of pressure at the ankle (particularly when large varicosities or leg edema is present)

- For people at very high risk, a single prophylactic dose of a low-molecular-weight heparin or a factor Xa inhibitor injected just before departure (Table 5)

- Aspirin is not recommended as it is not effective for the prevention of VTE.20

SUMMARY FOR THE AIR TRAVELER

All travelers on long flights should perform standard VTE prophylaxis exercises (see the patient information pages accompanying this article). Although VTE is uncommon, people with additional risk factors who travel frequently either on multiple flights in a short period of time or on very long flights should be evaluated on a case-by-case basis for a more aggressive approach to prevention (compression support hose or prophylactic administration of a low-molecular-weight heparin or a factor Xa inhibitor).

Should a VTE event occur during travel, the patient should seek medical care immediately. The standard evaluation of a patient with a suspected VTE should include an estimation of the pretest probability of disease (Table 2, Table 3), followed by duplex ultrasonography of the upper or lower extremity to detect a deep vein thrombosis. If symptoms dictate, then spiral computed tomography, ventilation-perfusion lung scan, or pulmonary angiography (where available) should be ordered to diagnose acute pulmonary embolism. A positive D-dimer blood test alone is not diagnostic and may not be available in more remote locations. A negative D-dimer test result is most helpful to exclude VTE.

Standard therapy for VTE is immediate treatment with one of the anticoagulants listed in Table 4, unless the patient has a contraindication to treatment, such as bleeding or allergy. Immediate evacuation is recommended if the patient has a life-threatening pulmonary embolism, defined as hemodynamic instability (hypotension with a blood pressure under 90 mm Hg systolic or signs of right heart failure) that cannot be treated at a local facility. An air ambulance should be used to transport these patients. If the patient has an iliofemoral deep vein thrombosis, it is also advisable that he or she be considered for evacuation if severe symptoms are present, such as pain, swelling, or cyanosis. Unless contraindicated, all patients should be given either full-dose intravenous or full-dose subcutaneous heparin or subcutaneous injection of a readily available low-molecular-weight heparin preparations or factor Xa inhibitor at once.21

- Brenner B. Interventions to prevent venous thrombosis after air travel, are they necessary? Yes. J Thromb Haemost 2006; 4:2302–2305.

- Cannegieter SC, Doggen CJM, van Houwellingen HC, et al. Travel-related venous thrombosis: results from a large population-based case control study (MEGA Study). PLoS Med 2006; 3:1258–1265.

- Chandra D, Parisini E, Mozaffarian D. Meta-analysis: travel and risk for venous thromboembolism. Ann Intern Med 2009; 151:180–190.

- Kuipers S, Cannegieter SC, Middeldorp S, et al. The absolute risk of venous thrombosis after air travel: a cohort study of 8,755 employees of international organizations. PLoS Med 2007; 4:1508–1514.

- Kuipers S, Schreijer AJM, Cannegieter SC, et al. Travel and venous thrombosis: a systematic review. J Intern Med 2007; 262:615–634.

- Lehmann R, Suess C, Leus M, et al. Incidence, clinical characteristics, and long-term prognosis of travel-associated pulmonary embolism. Eur Heart J 2009; 30:233–241.

- Philbrick JT, Shumate R, Siadaty MS, et al. Air travel and venous thromboembolism: a systematic review. J Gen Intern Med 2007; 22:107–114.

- Cruickshank JM, Gorlin R, Jennett B. Air travel and thrombotic episodes: the economy class syndrome. Lancet 1988; 2:497–498.

- Bagshaw M. Traveler’s thrombosis: a review of deep vein thrombosis associated with travel. Air Transport Medicine Committee, Aerospace Medical Association. Aviat Space Environ Med 2001; 72:848–851.

- Wells PS, Owens C, Doucette S, et al. Does this patient have deep vein thrombosis? JAMA 2006; 295:199–207.

- Arnason T, Wells PS, Forester AJ. Appropriateness of diagnostic strategies for evaluating suspected venous thromboembolism. Thromb Haemost 2007; 97:195–201.

- Clarke M, Hopewell S, Juszcak E, Eisinga A, Kjeldstrøm M. Compression stockings in preventing deep vein thrombosis in airline passengers. Cochrane Database of Syst Rev 2006; Apr 19( 2):CD004002. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.

- Kuipers S, Cannegieter SC, Middeldorp S, et al. Use of preventive measures for travel-related venous thrombosis in professionals who attend medical conferences. J Thromb Haemost 2006; 4:2373–2376.

- Perez-Rodriguez E, Jimenez D, Diaz G, et al. Incidence of air travel-related pulmonary embolism in the Madrid-Barajas Airport. Arch Intern Med 2003; 163:2766–2770.

- Lapostolle F, Surget V, Borron SW, et al. Severe pulmonary embolism associated with air travel. N Engl J Med 2001; 345:779–783.

- Kelman CW, Kortt MA, Becker NG, et al. Deep vein thrombosis and air travel: record linkage study. BMJ 2003; 327:1072–1076.

- Eklof B, Kistner RL, Masuda EM, et al. Venous thromboembolism in association with prolonged air travel. Dermatol Surg 1996; 22:637–641.

- Moyle J. Medical guidelines for airline travel. Aviat Space Environ Med 2003: 74:1009.

- Geerts WH, Bergqvist B, Pineo GF, et al. Prevention of venous thromboembolism: American College of Chest Physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest 2008; 133:381S–453S.

- Rosendaal FR. Interventions to prevent venous thrombosis after air travel: are they necessary? No. J Thromb Haemost 2006; 4:2306–2307.

- Kearon C, Ginsberg JS, Julian JA, et al; Fixed-Dose Heparin (FIDO) Investigators. Comparison of fixed-dose weight-adjusted unfractionated heparin and low-molecular-weight heparin for acute treatment of venous thromboembolism. JAMA 2006; 296:935–942.

- Brenner B. Interventions to prevent venous thrombosis after air travel, are they necessary? Yes. J Thromb Haemost 2006; 4:2302–2305.

- Cannegieter SC, Doggen CJM, van Houwellingen HC, et al. Travel-related venous thrombosis: results from a large population-based case control study (MEGA Study). PLoS Med 2006; 3:1258–1265.

- Chandra D, Parisini E, Mozaffarian D. Meta-analysis: travel and risk for venous thromboembolism. Ann Intern Med 2009; 151:180–190.

- Kuipers S, Cannegieter SC, Middeldorp S, et al. The absolute risk of venous thrombosis after air travel: a cohort study of 8,755 employees of international organizations. PLoS Med 2007; 4:1508–1514.

- Kuipers S, Schreijer AJM, Cannegieter SC, et al. Travel and venous thrombosis: a systematic review. J Intern Med 2007; 262:615–634.

- Lehmann R, Suess C, Leus M, et al. Incidence, clinical characteristics, and long-term prognosis of travel-associated pulmonary embolism. Eur Heart J 2009; 30:233–241.

- Philbrick JT, Shumate R, Siadaty MS, et al. Air travel and venous thromboembolism: a systematic review. J Gen Intern Med 2007; 22:107–114.

- Cruickshank JM, Gorlin R, Jennett B. Air travel and thrombotic episodes: the economy class syndrome. Lancet 1988; 2:497–498.

- Bagshaw M. Traveler’s thrombosis: a review of deep vein thrombosis associated with travel. Air Transport Medicine Committee, Aerospace Medical Association. Aviat Space Environ Med 2001; 72:848–851.

- Wells PS, Owens C, Doucette S, et al. Does this patient have deep vein thrombosis? JAMA 2006; 295:199–207.

- Arnason T, Wells PS, Forester AJ. Appropriateness of diagnostic strategies for evaluating suspected venous thromboembolism. Thromb Haemost 2007; 97:195–201.

- Clarke M, Hopewell S, Juszcak E, Eisinga A, Kjeldstrøm M. Compression stockings in preventing deep vein thrombosis in airline passengers. Cochrane Database of Syst Rev 2006; Apr 19( 2):CD004002. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.

- Kuipers S, Cannegieter SC, Middeldorp S, et al. Use of preventive measures for travel-related venous thrombosis in professionals who attend medical conferences. J Thromb Haemost 2006; 4:2373–2376.

- Perez-Rodriguez E, Jimenez D, Diaz G, et al. Incidence of air travel-related pulmonary embolism in the Madrid-Barajas Airport. Arch Intern Med 2003; 163:2766–2770.

- Lapostolle F, Surget V, Borron SW, et al. Severe pulmonary embolism associated with air travel. N Engl J Med 2001; 345:779–783.

- Kelman CW, Kortt MA, Becker NG, et al. Deep vein thrombosis and air travel: record linkage study. BMJ 2003; 327:1072–1076.

- Eklof B, Kistner RL, Masuda EM, et al. Venous thromboembolism in association with prolonged air travel. Dermatol Surg 1996; 22:637–641.

- Moyle J. Medical guidelines for airline travel. Aviat Space Environ Med 2003: 74:1009.

- Geerts WH, Bergqvist B, Pineo GF, et al. Prevention of venous thromboembolism: American College of Chest Physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest 2008; 133:381S–453S.

- Rosendaal FR. Interventions to prevent venous thrombosis after air travel: are they necessary? No. J Thromb Haemost 2006; 4:2306–2307.

- Kearon C, Ginsberg JS, Julian JA, et al; Fixed-Dose Heparin (FIDO) Investigators. Comparison of fixed-dose weight-adjusted unfractionated heparin and low-molecular-weight heparin for acute treatment of venous thromboembolism. JAMA 2006; 296:935–942.

KEY POINTS

- The risk of VTE is about three times higher in passengers on long-distance flights than in the general population, although the absolute risk is still low.

- All long-distance air passengers should perform stretching exercises once an hour while in flight to prevent VTE. They should also stay hydrated.

- For patients at higher risk due to hypercoagulable conditions, physicians can consider prescribing compression stockings or an anticoagulant drug (a low-molecular-weight heparin or a factor Xa inhibitor) to be taken before the flight, or both.

- The evaluation of a patient with suspected VTE should include an estimation of the pretest probability of disease. If symptoms dictate, duplex ultrasonography of the upper or lower extremity to detect deep vein thrombosis or spiral computed tomography, ventilation-perfusion lung scan, or pulmonary angiography (where available) to diagnose an acute pulmonary embolism should be ordered.

Goal-directed antihypertensive therapy: Lower may not always be better

A 50-year-old African American woman with type 2 diabetes mellitus, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and chronic kidney disease presents for a follow-up visit. The patient had been treated with hydrochlorothiazide 25 mg/day and enalapril (Vasotec) 20 mg twice daily until 6 weeks ago. At that time her blood pressure was 160/85 mm Hg, and amlodipine (Norvasc) 10 mg/day was added to her regimen. Her other medications include glipizide (Glucotrol), metformin (Glucophage), lovastatin (Mevacor), fish oils, aspirin, calcium, and vitamin D. Her current blood pressure is 145/80 mm Hg; her serum creatinine level is 1.5 mg/dL, and her urine albumin-to-creatinine ratio is 180 mg/g.

In hypertensive patients who have diabetes or chronic kidney disease, guidelines1 call for intensification of antihypertensive therapy to reach a goal blood pressure of less than 130/80 mm Hg. What data exist to support these guidelines? And what should the clinician do?

IS MORE-INTENSE THERAPY IN THE PATIENT’S BEST INTEREST?

Often, clinicians are faced with hypertensive patients whose blood pressure, despite treatment, is higher than the accepted goal. Often, these patients are elderly and are already taking multiple medications that are costly and have significant potential adverse effects. The dilemma is whether to try to reach a target blood pressure listed in a guideline (by increasing the dosage of the current drugs or by adding a drug of a different class) or to “do no harm,” accept the patient’s blood pressure, and keep the regimen the same.1,2

The current goal blood pressure is less than 140/90 mm Hg for all but the very elderly, with more intense control recommended for patients at high risk, ie, those with diabetes mellitus, chronic kidney disease, or atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease.1

While it appears to be in the patient’s best interests to follow such guidelines, review of available data indicates that this it not necessarily so, and may even be harmful.

OBSERVATIONAL DATA AND EARLY RANDOMIZED TRIALS

Many observational studies have found that the higher one’s blood pressure, the greater one’s risk of cardiovascular events and death. Indeed, meta-analyses of these trials, which involved more than 1.5 million people, demonstrate a strong, positive, log-linear relationship between blood pressure and the incidence of cardiovascular disease and death.3–5

Further, there is no evidence of a threshold pressure below which the risk is not lower (ie, a “J-point”), starting with 115/75 mm Hg. A J-point may exist for diastolic blood pressure in elderly patients with isolated systolic hypertension6 and in patients with coronary artery disease.7 Otherwise, the observation is clear: the lower the blood pressure the better. For every 20 mm Hg lower systolic blood pressure or 10 mm Hg lower diastolic blood pressure, the risk of a cardiovascular event is about 50% less.4,5

Observational analyses also show a strong, graded relationship between blood pressure and future end-stage renal disease.8,9 Post hoc analyses indicate that chronic kidney disease progresses more slowly with lower achieved blood pressures, especially in those with higher degrees of proteinuria.10–12

However, observational data do not prove cause and effect, nor do they guarantee similar results with treatment. This requires randomized controlled trials.

RANDOMIZED TRIALS OF HYPERTENSION TREATMENT

Initial trials were aimed at determining whether hypertension should even be treated. A 1997 meta-analysis of 18 such trials comparing either low-dose diuretic therapy, high-dose diuretic therapy, or beta-blocker therapy with placebo involved 48,000 patients who were followed for an average of 5 years.13 The rates of stroke and congestive heart failure were consistently reduced, although only low-dose diuretic therapy reduced the risk of coronary heart disease and death from any cause.

More recent trials enrolled people not considered hypertensive who were randomized to receive either active drugs or placebo, or no treatment. Other trials attempted to assess non-pressure-related effects of specific agents, using other antihypertensive agents in the control group. Still other randomized controlled trials compared one agent or agents with other agents while attempting to attain equivalent blood pressure between groups. Frequently, however, there was some blood pressure difference.

Meta-analyses of most of these trials conclude that the major benefit of antihypertensive therapy—reducing rates of cardiovascular morbidity and mortality—comes from a lower attained blood pressure, irrespective of which agent is used.14–18 Exceptions exist, however. For example, specific drug classes are indicated after myocardial infarction, and in congestive heart failure and proteinuric chronic kidney disease.10,19–21

16 TRIALS OF DIFFERENT BLOOD PRESSURE TARGETS

The overriding theme of these observational data is that a lower blood pressure, whether attained naturally or with treatment, is better than a higher one from both the cardiovascular and the renal perspective.

What remains unclear is what blood pressure should be aimed for in a particular patient or group of patients. Is it a specific pressure (eg, 140/90 mm Hg), or does the change from baseline count more? Should other factors such as age or comorbidity alter this number?

Several randomized controlled trials have addressed these questions by targeting different levels of blood pressure. We are aware of at least 16 such trials in adults, including 13 with renal or cardiovascular primary end points and three with surrogate primary end points.

An unavoidable design flaw of all of these trials is their unblinded nature. Consequently, nearly all of them carry a Jadad score (a measure of quality, based on randomization and blinding)22 of 3 on a scale of 5.

NINE TRIALS WITH RENAL PRIMARY END POINTS

African American Study of Kidney Disease and Hypertension (AASK)23

Patients: 1,094 African Americans with presumed hypertensive renal disease and a measured glomerular filtration rate between 20 and 65 mL/min/1.73 m2.

Randomized blood pressure goals. Mean arterial pressure 92 mm Hg or less vs 102 to 107 mm Hg.

Results. At 4 years, the two groups had average blood pressures of 128/78 and 141/85 mm Hg, respectively. The groups did not differ in the rates of the primary end points—ie, the rate of change in the measured glomerular filtration rate over time or the composite of a 50% reduction in glomerular filtration rate, the onset of end-stage renal disease, or death.

Comments. Several issues have been raised about the internal validity of this trial.

So-called hypertensive kidney disease in African Americans (as opposed to European Americans) may be a genetic disorder related to polymorphisms of one or more genes on chromosome 22q. Initial data implicated the MYH9 gene, which encodes non-muscle myosin heavy chain II.24,25 More recent data implicate the nearby APOL1 gene encoding apolipoprotein L126 as more relevant. These polymorphisms have a much greater prevalence in African Americans and appear responsible for the higher risk of idiopathic focal segmental glomerulosclerosis and HIV-associated nephropathy in this population.24–26 Therefore, in African Americans, hypertension may in fact be the result of the kidney disease and not its primary cause, which may explain why in this and other African American populations stricter control of blood pressure did not produce a renal benefit.27,28

Also, there is the possibility of misclassification bias. A secondary analysis of data obtained by ambulatory monitoring showed that of the 377 participants whose blood pressure appeared to be under control when measured in the clinic, 70% actually had masked hypertension, ie, uncontrolled hypertension outside the clinic.29 The real difference in blood pressure between groups may well have been different than that determined in the clinic.

In addition, a prespecified secondary analysis showed no difference in the rates of cardiovascular events and death between the groups.30 However, the study was not designed to have the statistical power to detect a difference in cardiovascular events. Moreover fewer cardiovascular events occurred than expected, further reducing the study’s power to detect a difference.

Toto et al31

Toto et al reported similar results in an earlier trial in 87 hypertensive patients (77 randomized), predominantly African American, and similar concerns apply.

Lewis et al32

Patients: 129 patients with type 1 diabetes.

Randomized blood pressure goals. A mean arterial pressure of either no higher than 92 mm Hg or 100 to 107 mm Hg.

Results. At 2 years, despite a difference of 6 mm Hg in mean arterial pressure, the glomerular filtration rate (measured) had declined by the same amount in the two groups. The study was underpowered for this end point. Patients in the group with the lower goal pressure were excreting significantly less protein than those in the other group, but they were received higher doses of an angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor—in this case, ramipril (Altace).

The Appropriate Blood Pressure Control in Diabetes (ABCD) trials33–35

Patients: 950 patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus and either normal or high blood pressure.

Randomized blood pressure goals. Either intensive or moderate therapy (see Table 1).

Results. At 5 years, creatinine clearance (estimated) had declined by the same amount in the two groups. However, fewer of the hypertensive patients had died in the intensive-therapy group.34 Similarly, normotensive patients had less progression of albuminuria if treated intensively.33

In the ABCD Part 2 with Valsartan (ABCD-2V) trial in normotensive patients,35 therapy with valsartan (Diovan) did not affect creatinine clearance but did reduce albuminuria. However, 75% of the patients in the moderate-treatment group were untreated.

Schrier et al36

Patients. 75 hypertensive patients with autosomal-dominant polycystic kidney disease and left ventricular hypertrophy.

Randomized blood pressure targets. Less than 120/80 mm Hg vs 135/85 to 140/90 mm Hg.

Results. After 7 years, despite a difference in average mean arterial pressure of 11 mm Hg between the groups (90 vs 101 mm Hg), there was no difference in the rate of decline of creatinine clearance. The left ventricular mass index decreased by 21% in the lower-target group and by 35% in the higher-target group (P < .01).

Modification of Diet in Renal Disease (MDRD) trial37,38

Patients: 840 patients whose measured glomerular filtration rate was between 13 and 55 mL/min/1.73 m2.

Randomized blood pressure targets. A target mean arterial pressure of less than 92 mm Hg vs less than 107 mm Hg.11,37

Results. After 2.2 years, the mean difference in mean arterial pressure was 4.7 mm Hg. There was, however, no difference in the rate of decline in the glomerular filtration rate.

In a 6-year follow-up, significantly fewer patients in the lower-blood-pressure group reached the end point of end-stage renal disease or the combined end point of end-stage renal disease or death.38 The rate of death, however, was nearly twice as high in the lower-blood-pressure group (10% vs 6%). The blood pressure and treatment during follow-up were not reported.

Comments. Internal validity is an issue, since the blood pressure and therapy during follow-up were unknown, and more patients received ACE inhibitors in the lower-blood-pressure group during the trial. Further, the higher death rate in the lower-blood-pressure group is worrisome.

The Ramipril Efficacy in Nephropathy (REIN)-2 trial39

Patients: 338 nondiabetic patients who had proteinuria and reduced creatinine clearance.

Treatment and blood pressure goals. All were treated with ramipril and randomized to intensive (< 130/80 mm Hg) vs standard control (diastolic blood pressure < 90 mm Hg) with therapy based on felodipine (Plendil).

Results. The study was terminated early because of futility. Despite a mean difference of 4.1 mm Hg systolic and 2.8 mm Hg diastolic, the groups did not differ in the rate of progression to end-stage renal disease (23% with intensive therapy vs 20% with standard therapy) or in the rate of decline of the measured glomerular filtration rate (0.22 vs 0.24 mL/min/1.73 m2/month).

Comment. The internal validity of this study can be questioned because of the low separation of achieved blood pressure and because of its early termination.

No benefit from a lower blood pressure goal in preserving kidney function

To summarize, these trials all showed no significant benefit from either targeting or achieving lower blood pressure in terms of slowing the decline of kidney function. Overall, they do not define a target and offer little support that a lower goal blood pressure is indicated with respect to the rate of loss of glomerular filtration rate in chronic kidney disease.

However, post hoc analysis of the MDRD trial indicates a statistical interaction between targeted blood pressure and degree of baseline proteinuria. At higher levels of proteinuria (≥ 1 g/day), the group with the lower blood pressure target had better outcomes.

In addition, long-term follow-up (mean of 12.2 years) of the AASK trial, including a 7-year cohort phase with nearly similar blood pressures in both groups, also indicated an interaction with targeted blood pressure and baseline proteinuria.40 Although the overall analysis was negative, there was a significant reduction in the primary end point in the group originally assigned the low target when analysis was restricted to those in the highest tertile of proteinuria. These and other data10 suggest that patients with chronic kidney disease and proteinuria may represent a distinct subset of chronic kidney disease patients who benefit from more intensive blood-pressure-lowering. However, patients in the REIN-2 trial34 and the macroalbuminuric patients in the ABCD hypertensive trial35 did not benefit from a lower targeted blood pressure despite significant proteinuria.

FOUR TRIALS WITH CARDIOVASCULAR END POINTS

The Hypertension Optimal Treatment (HOT) trial41

Patients: 18,790 patients with diastolic blood pressure between 100 and 115 mm Hg.

Randomized blood pressure goals. Diastolic pressure of equal to or less than 80, 85, or 90 mm Hg.

Results. At an average of 3.8 years, the average blood pressures in the three groups were approximately 140/81, 141/83, and 144/85 mm Hg, respectively. There was no difference between the groups in the rate of the composite primary end point of all myocardial infarctions, all strokes, and cardiovascular death. Any conclusions from this trial were compromised by the small difference in achieved blood pressures between groups.

In the 1,501 patients with diabetes, the incidence of the primary end point was 50% lower with a goal of 80 mm Hg or less than with a goal of 90 mm Hg or less.

The UK Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS)42,43

Patients: 1,148 hypertensive patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus.

Randomized blood pressure goals. Either “tight control” (aiming for < 150/85 mm Hg) or “less tight control” (aiming for < 180/105 mm Hg).

Results. At a median follow-up of 8.4 years, the attained blood pressures were 144/82 vs 154/87 mm Hg. The difference produced significant benefits, including a 24% lower rate of any diabetes-related end point, a 32% lower rate of death due to diabetes, and a nonsignificant 18% lower rate of total mortality—all co-primary end points.

The less-tight-control group had many patients with initial blood pressures below 180/105 mm Hg; hence, over 50% of patients received no antihypertensive therapy at the start of the trial. By the end of the trial 9 years later, 20% had still not been treated. This compares with only 5% of patients in the tight-control group who were not treated with antihypertensives throughout the trial. Therefore, this trial serves as better evidence for treating vs not treating, rather than defining a specific goal.

During a 10-year follow-up, blood pressure differences disappeared within 2 years.43 There was no legacy effect, as the significant differences noted during the trial were no longer present 10 years later.

Action to Control Cardiovascular Risk in Diabetes (ACCORD)44

Patients: 4,733 patients with type 2 diabetes.

Randomized blood pressure goals. Systolic blood pressure lower than either 120 or 140 mm Hg.

Results. At 4.7 years, despite a significant difference in mean systolic blood pressure of 14.2 mm Hg after the first year (119.3 vs 133.5 mm Hg), there was no difference in the primary end point of nonfatal myocardial infarction, nonfatal stroke, or cardiovascular death. There were fewer strokes in the lower-pressure group but no difference in myocardial infarctions, which were five times more common than strokes. Serious adverse events attributed to antihypertensive treatment occurred more frequently in the intensive-therapy group (3.3% vs 1.3%, P < .001).

Comment. There were fewer events than expected, possibly limiting the trial’s ability to detect a statistical difference. Compared with both the UKPDS and the diabetic population of HOT, ACCORD is much larger and more internally valid (unlike in UKPDS, nearly all patients in both groups were treated, and compared with HOT there was much greater separation of achieved pressure). It is more recent and better reflects current overall practice. It indicates that when specifically aiming for a target blood pressure, lower is not always better and comes at a price (more severe adverse events).

Japanese Trial to Assess Optimal Systolic Blood Pressure in Elderly Hypertensive Patients (JATOS)45

Patients: 4,418 patients, age 65 to 85 years, with a pretreatment systolic blood pressure above 160 mm Hg.

Randomized blood pressure goals. Systolic pressure either lower than 140 mm Hg or 140 to 160 mm Hg.

Results. At 2 years, despite a difference of 9.7/3.3 mm Hg, there was no difference in the primary end point (the combined incidence of cerebrovascular disease, cardiac and vascular disease, and renal failure). Fifty-four patients had died in the strict-treatment group and 42 in the mild-treatment group; the difference was not statistically significant.

Three other trials