User login

A Deadly Month

The results of a new Journal of General Internal Medicine study that associates a 10% increase in medication-error-related deaths in teaching hospitals in July should not be ignored by hospitalists, says an associate residency program director.

Majid E. Cina, MD, FACP, a hospitalist and associate director at the University of Maryland School of Medicine in Baltimore, says the implication is that errors made by new medical interns are responsible for the spike, but HM leaders in academic settings shouldn’t draw too solid a conclusion. The spike could be tied to interns across a variety of departments, or the result of a series of other factors outside the scope of researchers.

“Correlations made by such studies are inherently flawed, with no certain cause-effect relationship established despite all attempts to control variables,” Dr. Cina says. “Still, these data cannot be ignored. ... Program directors should take heed.”

Researchers reported that inside medical institutions, in counties containing teaching hospitals, fatal medication errors spiked 10% in July and in no other month (JR=1.10; [1.06-1.14]) (J Gen Intern Med. 2010 Aug;25(8):774-779). Counties without teaching hospitals in the region had no spikes, and the greater the concentration of teaching hospitals in a region, the greater the July spike (R=0.80; P=0.005).

“After assessing competing explanations, we concluded that the July mortality spike results at least partly from changes associated with the arrival of new medical residents,” the study authors wrote.

Dr. Cina says his institution prioritizes the care of patients in July. Additional staff is put in place at the beginning of internships, which start a week early to allow for a smooth transition period. Senior staff also work longer hours in July, in close contact with residents on “a steep learning curve,” he says. “I recognized my work days will be much longer in July,” Dr. Cina adds.

As an academic hospitalist, Dr. Cina noted that new rules proposed by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) to reduce resident work hours might help mitigate medication-error-related deaths. Those regulations could go into effect in July 2011.

The results of a new Journal of General Internal Medicine study that associates a 10% increase in medication-error-related deaths in teaching hospitals in July should not be ignored by hospitalists, says an associate residency program director.

Majid E. Cina, MD, FACP, a hospitalist and associate director at the University of Maryland School of Medicine in Baltimore, says the implication is that errors made by new medical interns are responsible for the spike, but HM leaders in academic settings shouldn’t draw too solid a conclusion. The spike could be tied to interns across a variety of departments, or the result of a series of other factors outside the scope of researchers.

“Correlations made by such studies are inherently flawed, with no certain cause-effect relationship established despite all attempts to control variables,” Dr. Cina says. “Still, these data cannot be ignored. ... Program directors should take heed.”

Researchers reported that inside medical institutions, in counties containing teaching hospitals, fatal medication errors spiked 10% in July and in no other month (JR=1.10; [1.06-1.14]) (J Gen Intern Med. 2010 Aug;25(8):774-779). Counties without teaching hospitals in the region had no spikes, and the greater the concentration of teaching hospitals in a region, the greater the July spike (R=0.80; P=0.005).

“After assessing competing explanations, we concluded that the July mortality spike results at least partly from changes associated with the arrival of new medical residents,” the study authors wrote.

Dr. Cina says his institution prioritizes the care of patients in July. Additional staff is put in place at the beginning of internships, which start a week early to allow for a smooth transition period. Senior staff also work longer hours in July, in close contact with residents on “a steep learning curve,” he says. “I recognized my work days will be much longer in July,” Dr. Cina adds.

As an academic hospitalist, Dr. Cina noted that new rules proposed by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) to reduce resident work hours might help mitigate medication-error-related deaths. Those regulations could go into effect in July 2011.

The results of a new Journal of General Internal Medicine study that associates a 10% increase in medication-error-related deaths in teaching hospitals in July should not be ignored by hospitalists, says an associate residency program director.

Majid E. Cina, MD, FACP, a hospitalist and associate director at the University of Maryland School of Medicine in Baltimore, says the implication is that errors made by new medical interns are responsible for the spike, but HM leaders in academic settings shouldn’t draw too solid a conclusion. The spike could be tied to interns across a variety of departments, or the result of a series of other factors outside the scope of researchers.

“Correlations made by such studies are inherently flawed, with no certain cause-effect relationship established despite all attempts to control variables,” Dr. Cina says. “Still, these data cannot be ignored. ... Program directors should take heed.”

Researchers reported that inside medical institutions, in counties containing teaching hospitals, fatal medication errors spiked 10% in July and in no other month (JR=1.10; [1.06-1.14]) (J Gen Intern Med. 2010 Aug;25(8):774-779). Counties without teaching hospitals in the region had no spikes, and the greater the concentration of teaching hospitals in a region, the greater the July spike (R=0.80; P=0.005).

“After assessing competing explanations, we concluded that the July mortality spike results at least partly from changes associated with the arrival of new medical residents,” the study authors wrote.

Dr. Cina says his institution prioritizes the care of patients in July. Additional staff is put in place at the beginning of internships, which start a week early to allow for a smooth transition period. Senior staff also work longer hours in July, in close contact with residents on “a steep learning curve,” he says. “I recognized my work days will be much longer in July,” Dr. Cina adds.

As an academic hospitalist, Dr. Cina noted that new rules proposed by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) to reduce resident work hours might help mitigate medication-error-related deaths. Those regulations could go into effect in July 2011.

In the Literature: Research You Need to Know

Clinical question: Does the presence of deep vein thrombosis (DVT) in patients with pulmonary embolism (PE) have any prognostic value?

Background: There are variable mortality rates among patients with PE because of heterogeneous presentations. Concomitant DVT in patients with PE has an uncertain prognostic significance.

Study design: Prospective cohort study.

Setting: Hospital ED in Madrid, Spain.

Synopsis: Adult outpatients from the ED who underwent evaluation for possible acute PE from January 2003 through October 2007 were screened for DVT. Patients with a history of previous venous thromboembolism (VTE) were excluded.

The primary outcome of the study was all-cause mortality. Secondary outcomes included PE-specific mortality and recurrent symptomatic VTE.

Patients with concomitant DVT had an increased risk for recurrent VTE, along with increased risk of all-cause mortality and PE-specific mortality compared with those without concomitant DVT.

Bottom line: Assessment of the presence of absence of DVT can assist in risk stratification of patients with acute PE.

Citation: Jimenez D, Aujesky D, Diaz G, et al. Prognostic significance of deep vein thrombosis in patients presenting with acute symptomatic pulmonary embolism. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;181(9):983-991.

Reviewed for TH eWireby Alexander R. Carbo, MD, SFHM; Lauren Doctoroff, MD; John Fani Srour, MD; Matthew Hill, MD; Nancy Torres-Finnerty, MD, FHM; Anita Vanka, MD; Hospital Medicine Program, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston.

For more physician reviews of HM-related research, visit our website.

Clinical question: Does the presence of deep vein thrombosis (DVT) in patients with pulmonary embolism (PE) have any prognostic value?

Background: There are variable mortality rates among patients with PE because of heterogeneous presentations. Concomitant DVT in patients with PE has an uncertain prognostic significance.

Study design: Prospective cohort study.

Setting: Hospital ED in Madrid, Spain.

Synopsis: Adult outpatients from the ED who underwent evaluation for possible acute PE from January 2003 through October 2007 were screened for DVT. Patients with a history of previous venous thromboembolism (VTE) were excluded.

The primary outcome of the study was all-cause mortality. Secondary outcomes included PE-specific mortality and recurrent symptomatic VTE.

Patients with concomitant DVT had an increased risk for recurrent VTE, along with increased risk of all-cause mortality and PE-specific mortality compared with those without concomitant DVT.

Bottom line: Assessment of the presence of absence of DVT can assist in risk stratification of patients with acute PE.

Citation: Jimenez D, Aujesky D, Diaz G, et al. Prognostic significance of deep vein thrombosis in patients presenting with acute symptomatic pulmonary embolism. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;181(9):983-991.

Reviewed for TH eWireby Alexander R. Carbo, MD, SFHM; Lauren Doctoroff, MD; John Fani Srour, MD; Matthew Hill, MD; Nancy Torres-Finnerty, MD, FHM; Anita Vanka, MD; Hospital Medicine Program, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston.

For more physician reviews of HM-related research, visit our website.

Clinical question: Does the presence of deep vein thrombosis (DVT) in patients with pulmonary embolism (PE) have any prognostic value?

Background: There are variable mortality rates among patients with PE because of heterogeneous presentations. Concomitant DVT in patients with PE has an uncertain prognostic significance.

Study design: Prospective cohort study.

Setting: Hospital ED in Madrid, Spain.

Synopsis: Adult outpatients from the ED who underwent evaluation for possible acute PE from January 2003 through October 2007 were screened for DVT. Patients with a history of previous venous thromboembolism (VTE) were excluded.

The primary outcome of the study was all-cause mortality. Secondary outcomes included PE-specific mortality and recurrent symptomatic VTE.

Patients with concomitant DVT had an increased risk for recurrent VTE, along with increased risk of all-cause mortality and PE-specific mortality compared with those without concomitant DVT.

Bottom line: Assessment of the presence of absence of DVT can assist in risk stratification of patients with acute PE.

Citation: Jimenez D, Aujesky D, Diaz G, et al. Prognostic significance of deep vein thrombosis in patients presenting with acute symptomatic pulmonary embolism. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;181(9):983-991.

Reviewed for TH eWireby Alexander R. Carbo, MD, SFHM; Lauren Doctoroff, MD; John Fani Srour, MD; Matthew Hill, MD; Nancy Torres-Finnerty, MD, FHM; Anita Vanka, MD; Hospital Medicine Program, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston.

For more physician reviews of HM-related research, visit our website.

IHE Presenting as Chest Pain

Intramural hematoma of the esophagus (IHE) is a rare clinical entity. The majority of cases occur following esophageal instrumentation; however, other causes have been described.14 Rarely, IHE may develop spontaneously. We report a case of apparent spontaneous IHE (SIHE) in a patient presenting with acute‐onset chest pain and dysphagia who was taking low‐dose aspirin, bisphosphonate, and iron supplementation therapy. We highlight the evaluation of chest pain in these patients and the importance of considering the association between esophageal pathology and less commonly implicated medications which may increase the risk of esophageal injury.

Case Report

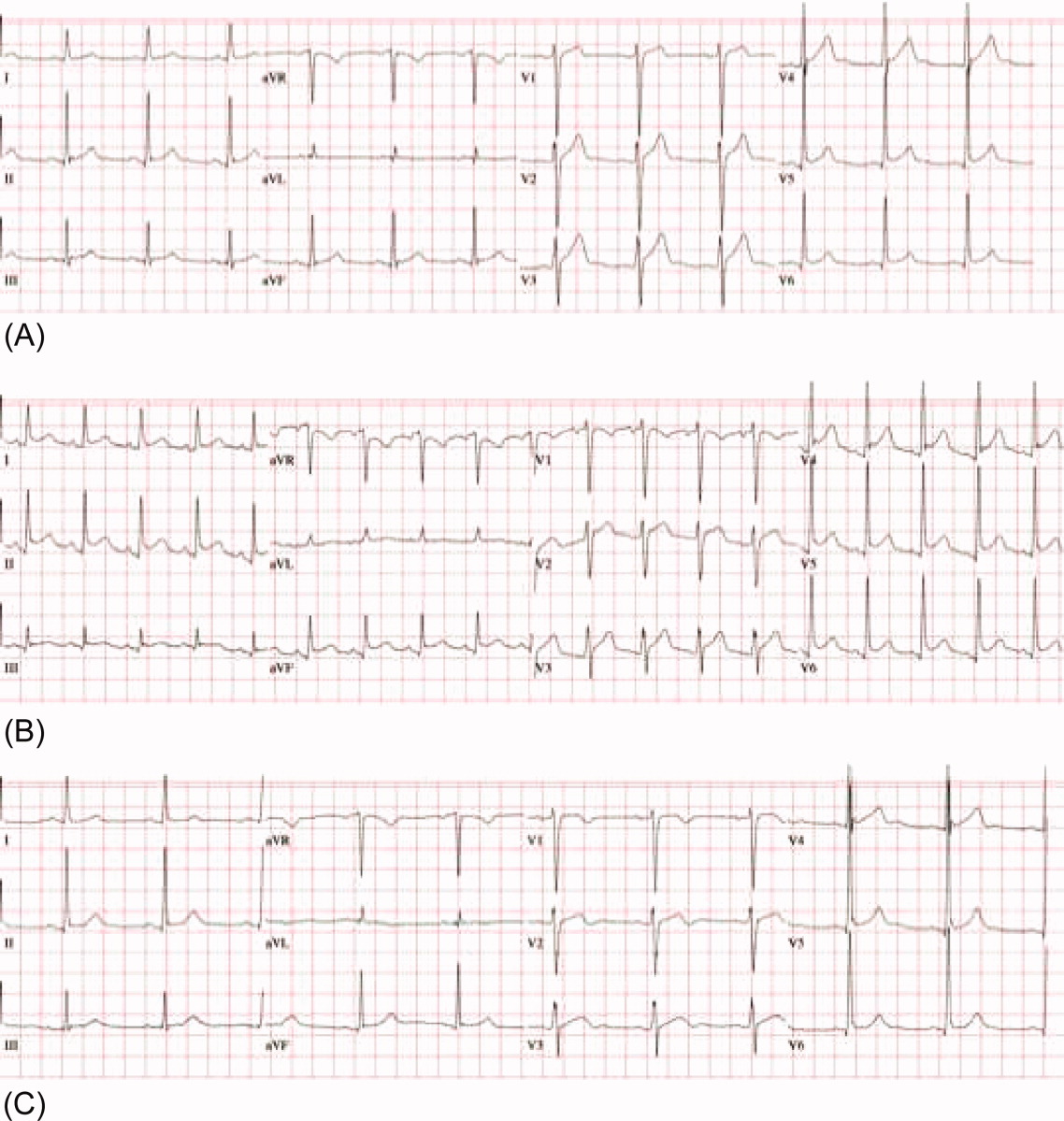

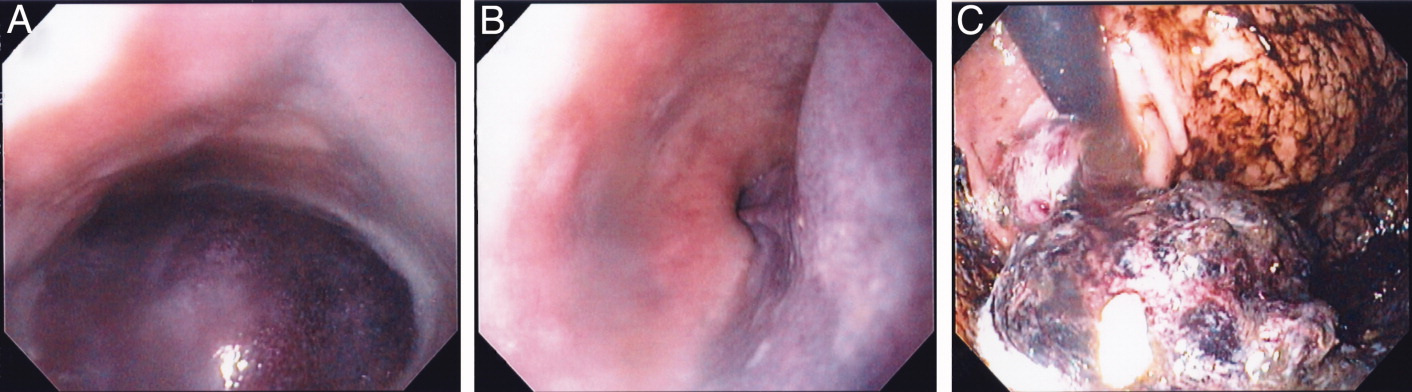

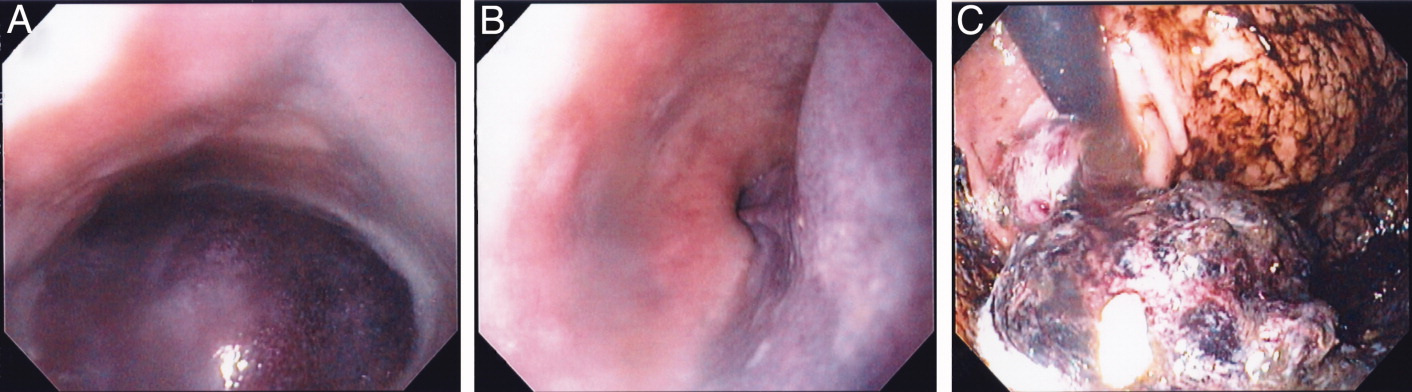

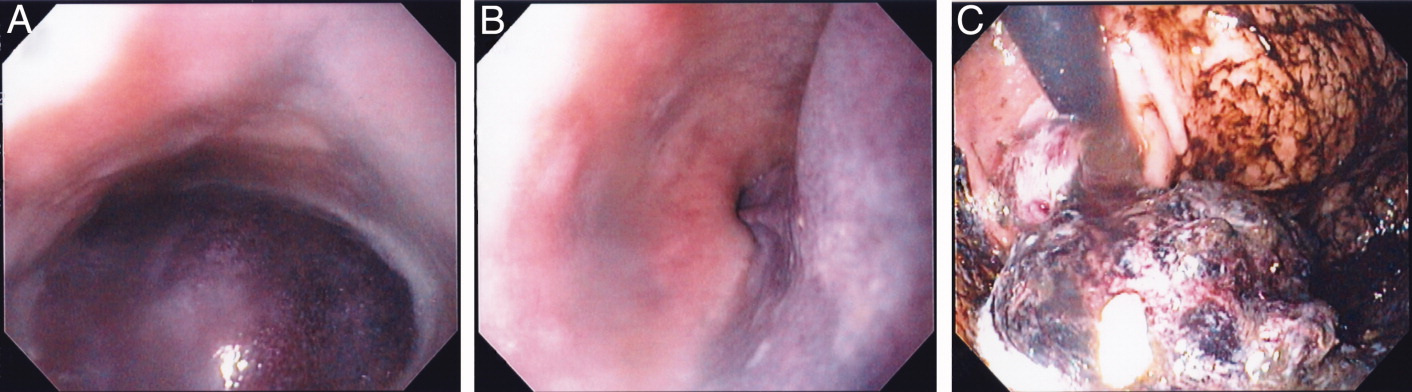

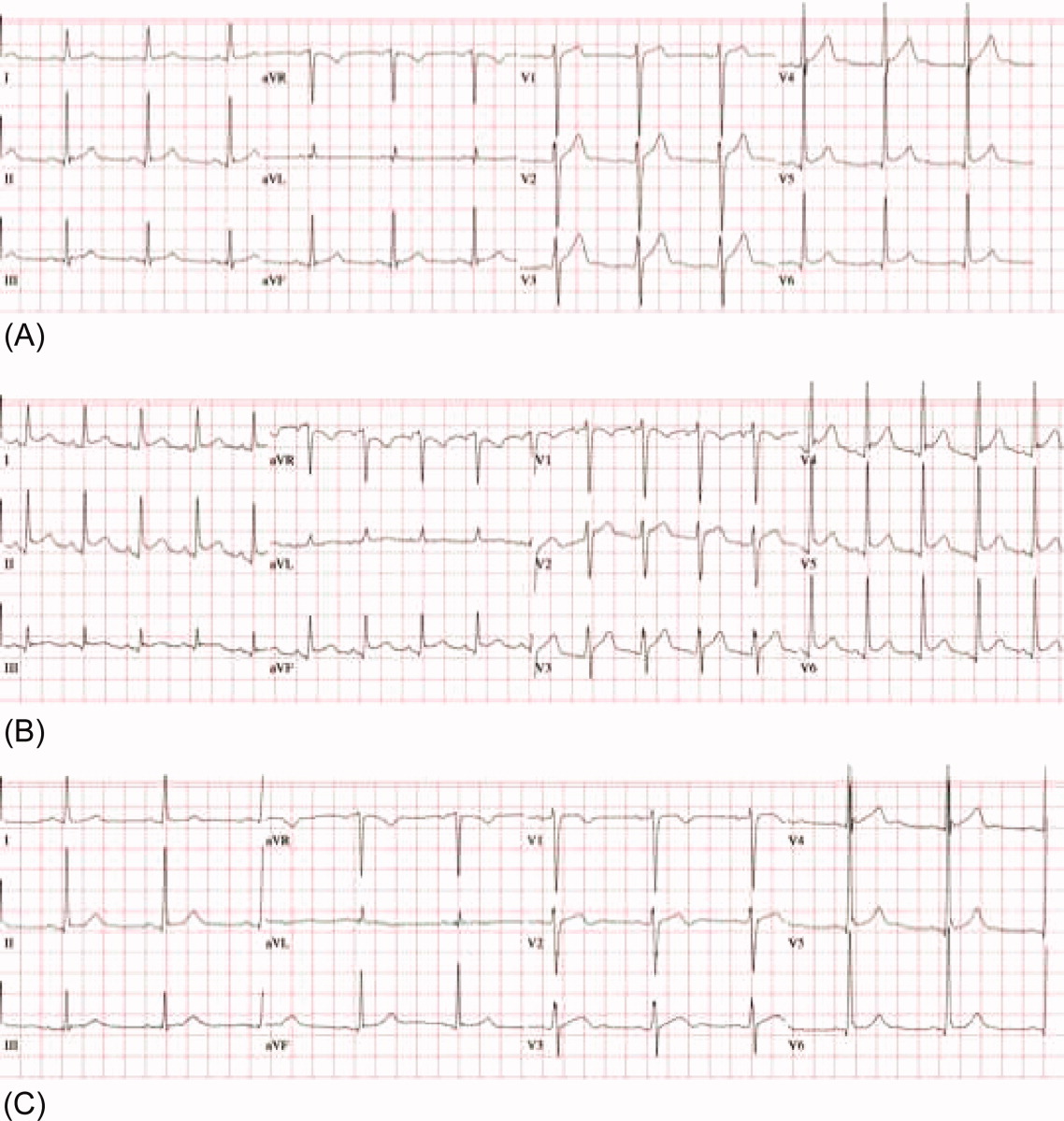

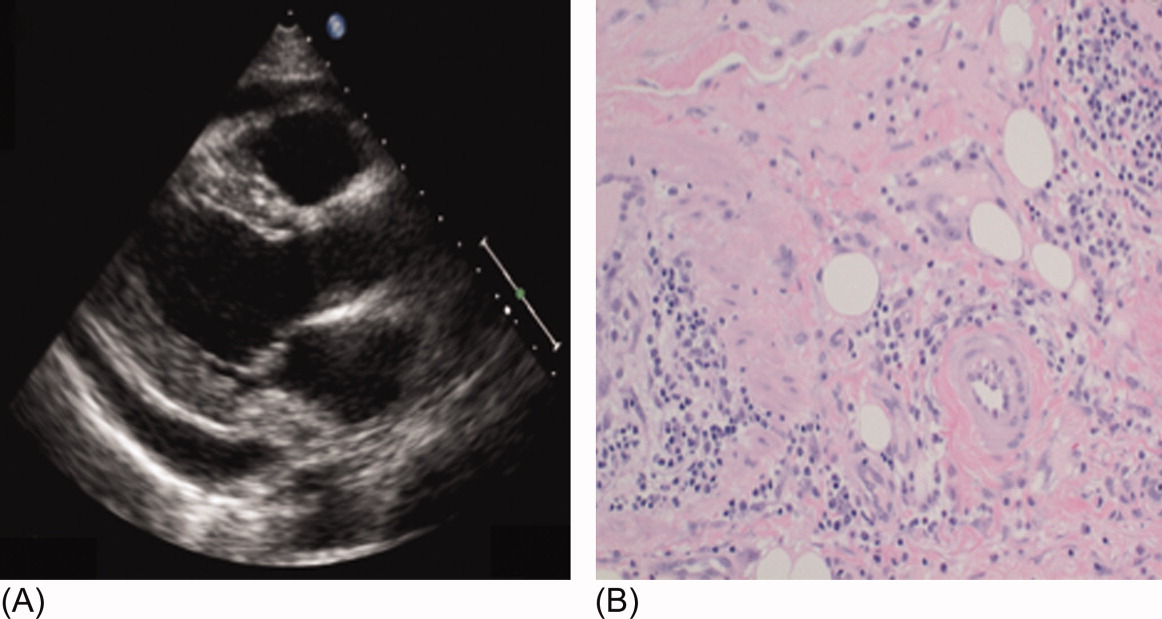

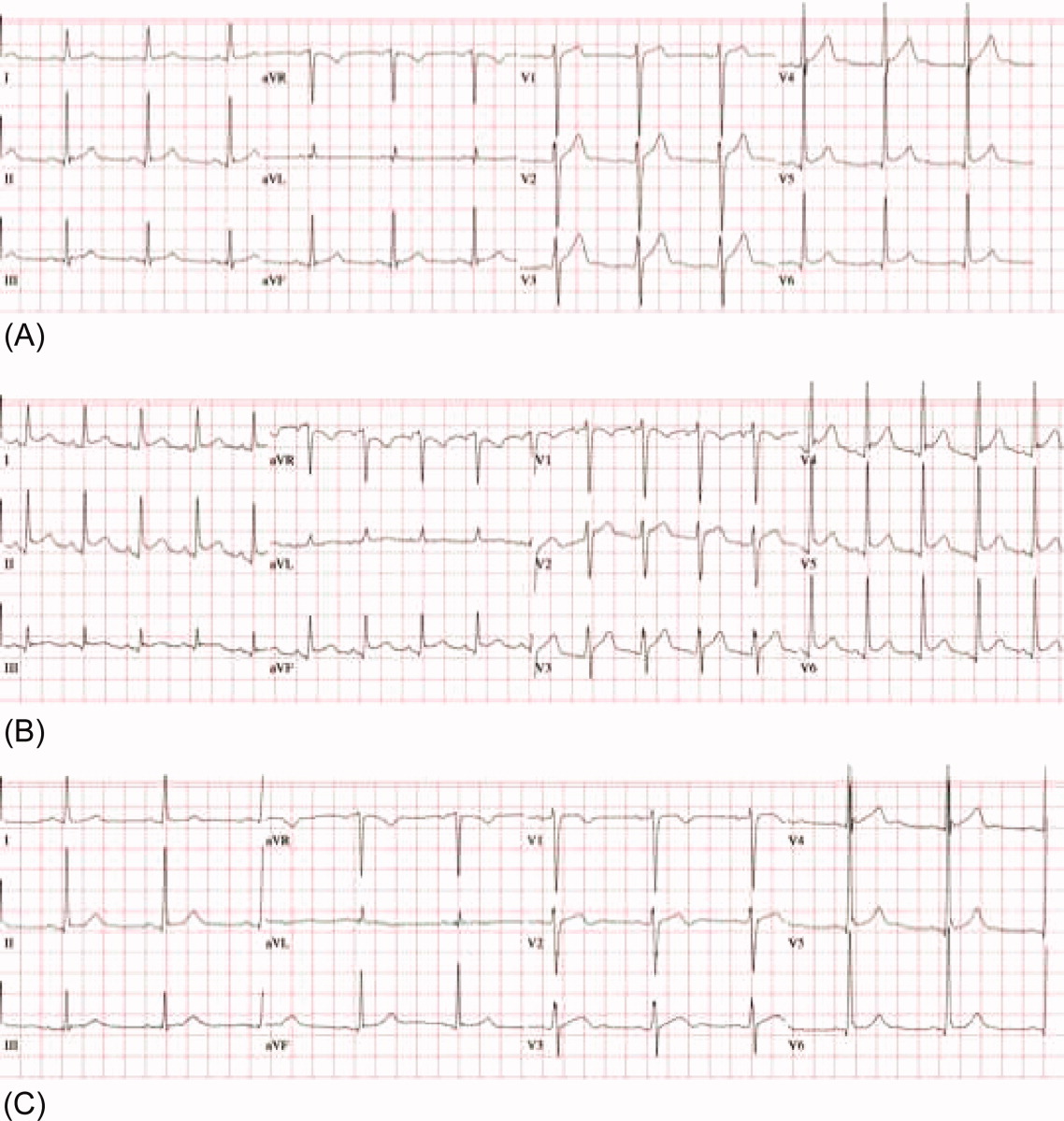

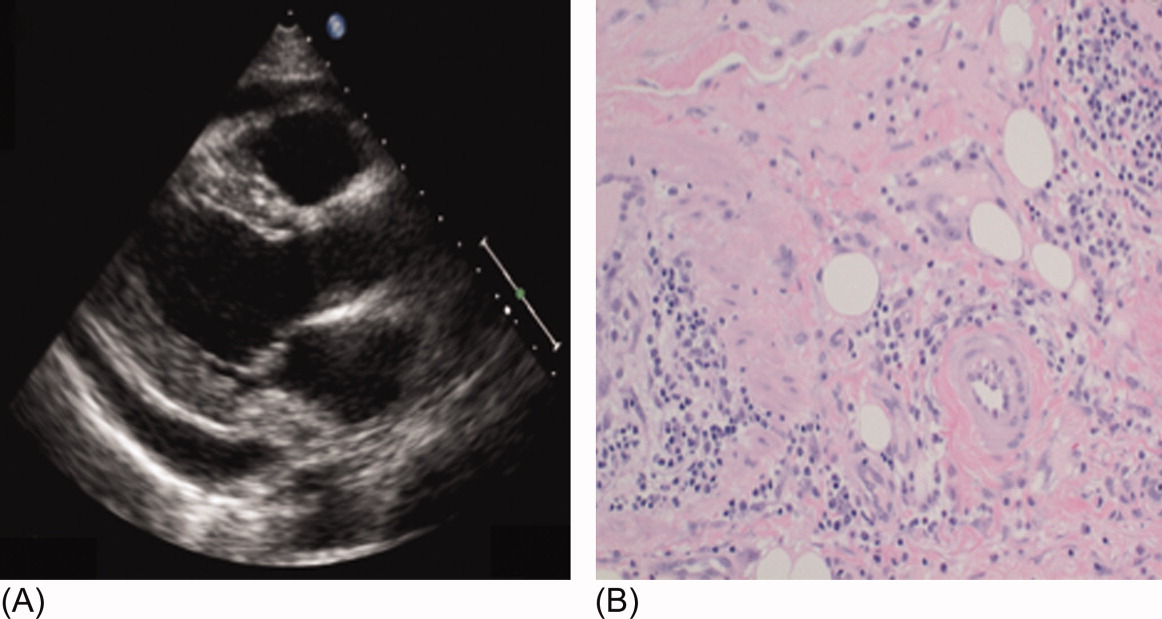

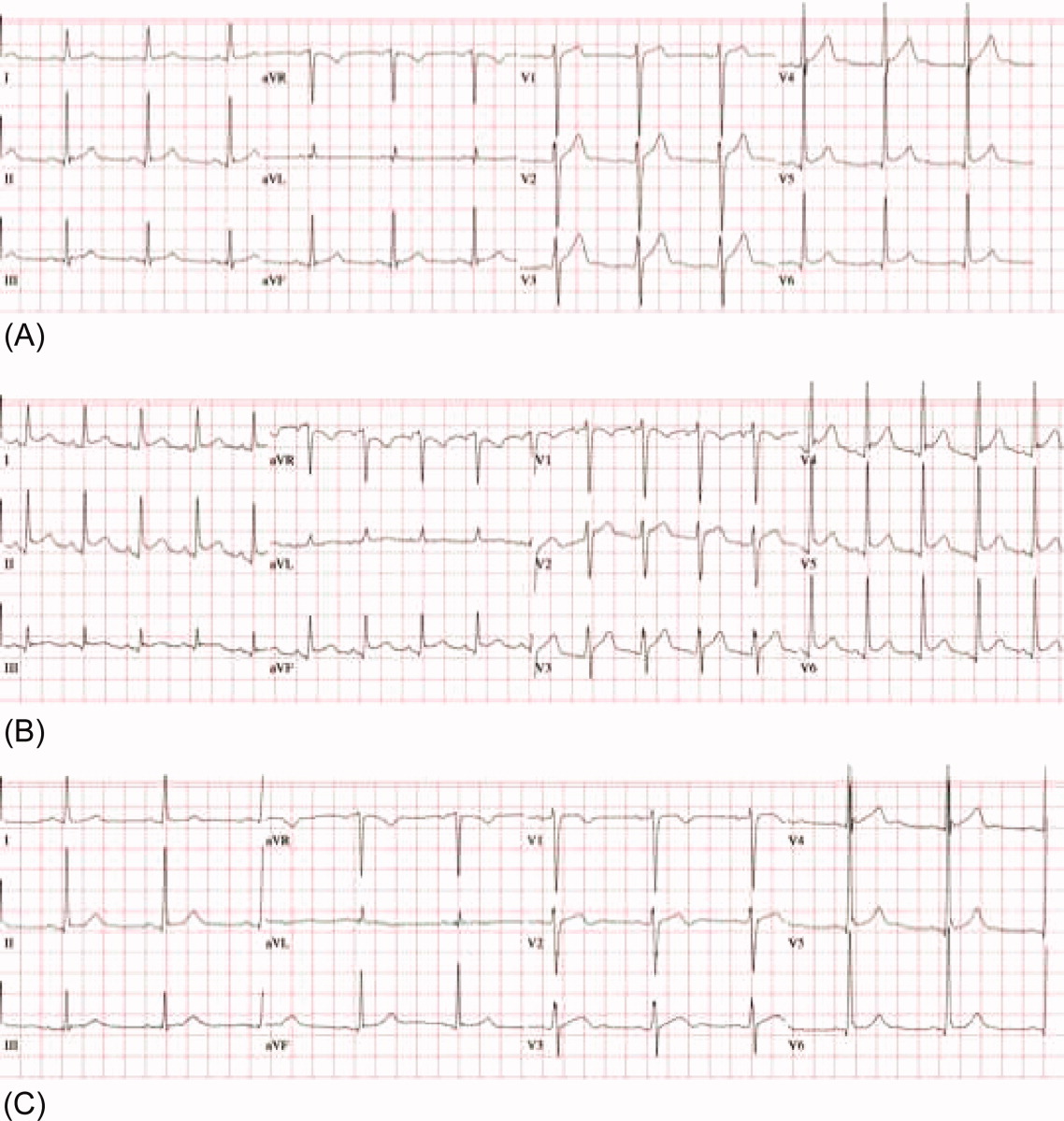

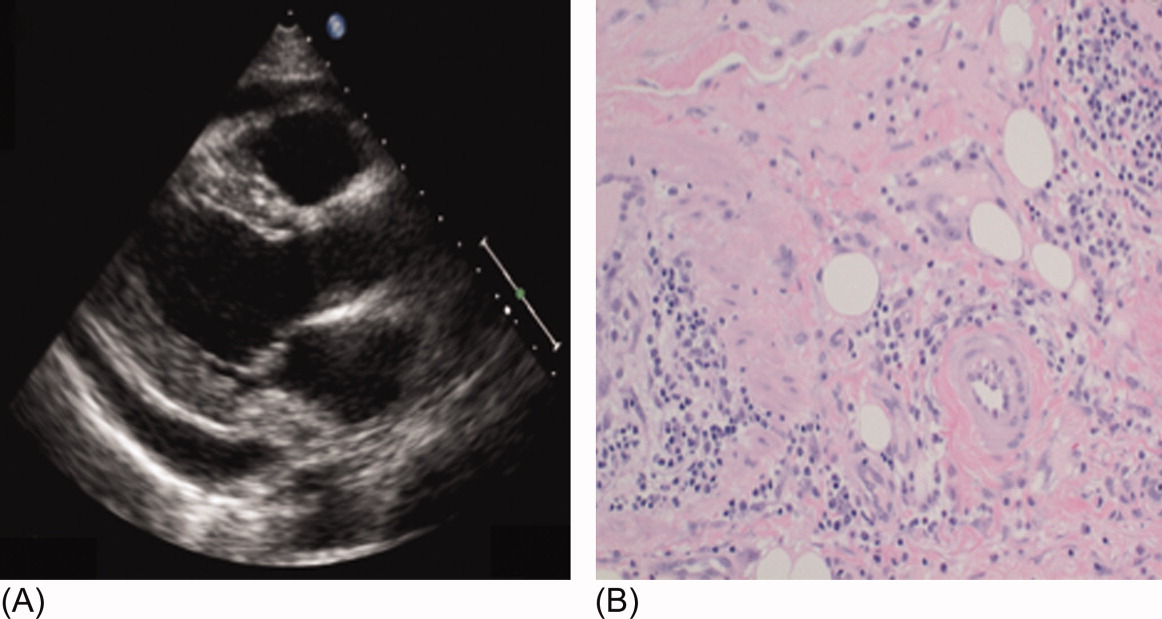

An 80‐year‐old Hispanic female with a history of osteoporosis, hypertension, and anemia presumed secondary to long‐standing noninsulin‐dependent diabetes mellitus presented with severe, abrupt‐onset, epigastric and retrosternal chest pain following ingestion of a banana. Home medications included aspirin (81 mg daily), alendronate (70 mg weekly), and ferrous sulfate (300 mg 3 times daily). She experienced nausea and minimal vomiting without hematemesis following the onset of pain. She admitted to several weeks of progressive dysphagia leading up to this event, but denied persistent vomiting, straining, foreign body ingestion, or trauma. At admission, the patient was afebrile with heart rate (HR) = 88, blood pressure (BP) = 172/88, pulse oximetry = 99% on room air, hemoglobin = 9.0 g/dL, hematocrit = 26.5%, platelets = 191,000, and international normalized ratio (INR) = 1.04. Electrocardiogram and cardiac enzymes were negative for myocardial infarction. Chest radiograph did not show a widened mediastinum. A computed tomography (CT) scan of the chest demonstrated diffuse thickening of the esophageal wall. Upper endoscopy demonstrated a large, purple, nonpulsatile submucosal mass protruding into and nearly occluding the esophageal lumen (Figure 1A). This mass extended 22 cm along the esophagus and terminated at the esophagogastric junction. There was suggestion of a potential distal mucosal tear and visible clot (Figure 1B, C). An endoscopy performed 6 years prior was unremarkable for esophagitis, stricture, mass, or hemorrhage.

The patient remained nil‐per‐os and was managed conservatively with intravenous fluids, antiemetics, and acid‐suppression therapy. Due to persistent odynophagia, the patient did not tolerate per‐os nutrition, and a percutaneous gastrostomy tube was placed nonendoscopically for temporary nutritional support. The patient's hospital stay was complicated by deep vein thrombosis of the right peroneal vein, for which she underwent inferior vena cava filter placement. She was discharged 18 days following admission. Alendronate and aspirin were discontinued and not reinitiated, and a follow‐up CT scan 6 weeks posthospitalization demonstrated complete resolution of the hematoma.

Discussion

Esophageal injuries include lacerations (Mallory‐Weiss syndrome), perforations (Boerhaave's syndrome), and hematomas (ie, IHE). IHE is by far the least common of these 3 pathologies and, despite increasing reports, it remains a rare clinical entity. Criblez et al.,4 in a review of 91 cases, found that only 35% of patients present with the classic triad of retrosternal chest pain, dysphagia/odynophagia, and hematemesis, while 99% present with at least 1 of these.5 Presentations mimic other cardiothoracic emergencies including myocardial infarction,6 pulmonary embolism,2 aortic dissection,6 and aortoesophageal fistula. Misdiagnosis of IHE and treatment with anticoagulant or thrombolytic therapy can have disastrous consequences, including death.5 Electrocardiograms, chest radiographs, and cardiac enzymes are often normal, as in this case. Endoscopy, performed cautiously, typically reveals a nonpulsatile, purple, submucosal mass. CT, which is rapid, noninvasive, and capable of differentiating between esophageal and life‐threatening thoracomediastinal pathology, frequently demonstrates thickening of the posterior wall of the esophagus with a long, smooth filling‐defect and luminal narrowing.7 Conservative management is the mainstay of treatment with most patients receiving acid suppression and antiemetic therapy. Surgical treatment and antibiotics (in cases of suspected infection) are required infrequently and should be used conservatively when necessary. The vast majority of patients recover spontaneously. Long‐term complications are rare.

IHE most frequently results from esophageal instrumentation, but other antecedent causes have been described. In contrast, SIHE occurs without warning, frequently developing in the absence of vomiting or hematemesis. Since SIHE was first reported in 1970,8 many authors have postulated potential mechanisms of hematoma formation. Controversy remains as to the precise etiology, but recent reports emphasize the association between SIHE and antiplatelet therapy, including low‐dose aspirin,9, 10 aspirin plus dipyridamole,11 and clopidogrel.12 Few studies have identified mechanisms for why the hemorrhage remains in the esophagus and why other parts of the gastrointestinal tract or other organ systems are not involved.

We report a case of apparent SIHE in a patient taking low‐dose aspirin, alendronate, and ferrous sulfate. While a subclinical traumatic event cannot be completely excluded, this patient lacked any apparent antecedent symptoms or other etiologic explanation. Alendronate and ferrous sulfate have been implicated in upper gastrointestinal irritation, but have not previously been associated with SIHE. Park et al.13 estimated a 3.0% incidence of esophageal or gastric events in alendronate users. Recently, esophagitis dissecans superficialis,3 esophageal dissection,14 and even fatal esophageal perforation16 have been reported in patients taking alendronate. Iron supplementation is also a recognized cause of esophageal injury. High local iron saturation may lead to concentration‐dependent absorption and thereby the formation of reactive oxygen metabolites and mucosal injury.16

We hypothesize that alendronate in combination with ferrous sulfate therapy resulted in subclinical esophageal injury predisposing our patient to SIHE. The patient reported 2 weeks of dysphagia prior to admission, suggesting a period of esophageal irritation. On endoscopy, a potential distal esophageal mucosal tear and clot were observed, which may represent a focus of injury. The interaction between this alendronate‐induced injury and chronic antiplatelet therapy may have resulted in hematoma expansion 22 cm along the esophagus. We are aware of one other report of IHE in a patient taking aspirin and alendronate published as an abstract in the Iranian Govaresh Journal.17

A spectrum of less‐commonly‐implicated medications may exert local toxicity on the esophagus and lead to de novo esophageal damage, predisposing patients to a broad spectrum of esophageal pathology, ranging from focal esophageal damage to large hematoma or perforation. Numerous medications are known to be associated with esophageal pathology through a variety of mechanisms (Table 1). Anatomic and motility disorders, as well as pill‐specific factors including contact time, coating materials, and sustained release formulations, may influence toxicity and predispose to injury.18 Elderly patients may be especially susceptible to the combined interactions between antiplatelet therapy and these commonly prescribed or over‐the‐counter medications.

| |

| Nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs | Aspirin, naproxen, ibuprofen |

| Bisphosphonates | Alendronate, etidronate, pamidronate |

| Antibiotics | Tetracycline, doxycycline, clindamycin, penicillin |

| Antiviral agents | Zalcitibine, zidovudine, nelfanavir |

| Chemotherapeutic agents | Dactinomycin, bleomycin, cytarabine, daunorubicin, 5‐fluorouracil, methotrexate, vincristine |

| Others | Ferrous sulfate, potassium chloride, ascorbic acid, multivitamins, quinidine, theophylline |

Conclusions

We report a case of apparent SIHE in an elderly woman taking low‐dose aspirin, iron, and alendronate therapy who presented with acute‐onset retrosternal chest pain and dysphagia. We emphasize the importance of including esophageal pathology in the evaluation of chest pain in these patients, particularly elderly women. We encourage a thorough examination of symptoms, including dysphagia/odynophagia, and an exhaustive medication history to identify medications less‐commonly implicated with esophageal pathology. In patients with chest pain taking these medications, clinicians must remain vigilant in their diagnostic approach to prevent misdiagnosis and inappropriate treatment.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge and thank Dr. Sonal Singh for his assistance in helping to analyze the potential drug interactions involved in this case presentation.

- ,,.Post‐sclerotherapy intramural esophageal hematoma: endoscopic and radiologic findings.Gastrointest Endosc.1992;38:102–103.

- ,,.Esophageal hematoma. Four new cases, a review, and proposed etiology.Dig Dis Sci.1981;26:1019–1024.

- ,,.Spontaneous dissecting intramural hematoma of the oesophagus: a rare cause of haematemesis and dysphagia.Endoscopy.1981;13:128–130.

- ,,,,.Intramural rupture and intramural hematoma of the esophagus: 3 case reports and literature review.Schweiz Med Wochenschr.1992;122:416–423.

- ,.Dissecting intramural hematoma of the esophagus.Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol.2000;12:1151–1161.

- ,,.Spontaneous intramural hematoma of the oesophagus: a report of three cases and review of the literature.Aust N Z J Surg.1994;64:190–193.

- ,,,,.Intramural hematoma of the esophagus: a pictorial essay.Emerg Radiol.2008;15(1):13–22.

- ,.Spontaneous cervico‐mediastinal haematoma.J Ir Med Assoc.1970;63:298.

- ,,,,,.Giant esophageal hematoma: possible association with low‐dose aspirin.Gastroenterol Hepatol.2004;27(8):460–463.

- ,,,.Intramural esophageal hematoma. Clinical and endoscopic evolution.Med Clin.2004;123(1):39.

- ,.Spontaneous intramural esophageal hematoma. Diagnosis by CT scanning.J Clin Gastroenterol.1987;9(5):546–548.

- ,,,.Intramural hematoma of the esophagus: a rare cause of chest pain.Am J Emerg Med.2008;26(7):843.e1–e2.

- ,,,.Incidence of adverse oesophageal and gastric events in alendronate users.Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf.2000;9(5):371–376.

- ,,.An elderly man with excruciating retrosternal pain and dysphagia.CMAJ.2005;172:1556.

- ,.Fatal esophageal perforation with alendronate.Am J Gastroenterol.2001;96:3212–3213.

- ,,.Erosive injury to the upper gastrointestinal tract in patients receiving iron medication: an underrecognized entitiy.Am J Surg Pathol.1999;23:1241–1247.

- ,.[A case report of esophageal intramural hematoma.] [English abstract on p.4 of the pdf].Govaresh J.2006;11(1):39–41. [Farsi] Available at: http://www.iagh.org/Portals/44fa7561‐56f7‐47e4‐a228‐477ca071e439/Volume%2011,%20Number%201,%20Spring%202006/(1)Dr_bagheri‐11‐1‐7.pdf. Accessed October 2009.

- .Esophageal disorders caused by medications, trauma, and infection. In:Feldman M, Friedman L, Brandt L, eds.Sleisenger and Fordtran's Gastrointestinal and Liver Disease.8th ed.Philadelphia:Saunders;2006:937–948.

Intramural hematoma of the esophagus (IHE) is a rare clinical entity. The majority of cases occur following esophageal instrumentation; however, other causes have been described.14 Rarely, IHE may develop spontaneously. We report a case of apparent spontaneous IHE (SIHE) in a patient presenting with acute‐onset chest pain and dysphagia who was taking low‐dose aspirin, bisphosphonate, and iron supplementation therapy. We highlight the evaluation of chest pain in these patients and the importance of considering the association between esophageal pathology and less commonly implicated medications which may increase the risk of esophageal injury.

Case Report

An 80‐year‐old Hispanic female with a history of osteoporosis, hypertension, and anemia presumed secondary to long‐standing noninsulin‐dependent diabetes mellitus presented with severe, abrupt‐onset, epigastric and retrosternal chest pain following ingestion of a banana. Home medications included aspirin (81 mg daily), alendronate (70 mg weekly), and ferrous sulfate (300 mg 3 times daily). She experienced nausea and minimal vomiting without hematemesis following the onset of pain. She admitted to several weeks of progressive dysphagia leading up to this event, but denied persistent vomiting, straining, foreign body ingestion, or trauma. At admission, the patient was afebrile with heart rate (HR) = 88, blood pressure (BP) = 172/88, pulse oximetry = 99% on room air, hemoglobin = 9.0 g/dL, hematocrit = 26.5%, platelets = 191,000, and international normalized ratio (INR) = 1.04. Electrocardiogram and cardiac enzymes were negative for myocardial infarction. Chest radiograph did not show a widened mediastinum. A computed tomography (CT) scan of the chest demonstrated diffuse thickening of the esophageal wall. Upper endoscopy demonstrated a large, purple, nonpulsatile submucosal mass protruding into and nearly occluding the esophageal lumen (Figure 1A). This mass extended 22 cm along the esophagus and terminated at the esophagogastric junction. There was suggestion of a potential distal mucosal tear and visible clot (Figure 1B, C). An endoscopy performed 6 years prior was unremarkable for esophagitis, stricture, mass, or hemorrhage.

The patient remained nil‐per‐os and was managed conservatively with intravenous fluids, antiemetics, and acid‐suppression therapy. Due to persistent odynophagia, the patient did not tolerate per‐os nutrition, and a percutaneous gastrostomy tube was placed nonendoscopically for temporary nutritional support. The patient's hospital stay was complicated by deep vein thrombosis of the right peroneal vein, for which she underwent inferior vena cava filter placement. She was discharged 18 days following admission. Alendronate and aspirin were discontinued and not reinitiated, and a follow‐up CT scan 6 weeks posthospitalization demonstrated complete resolution of the hematoma.

Discussion

Esophageal injuries include lacerations (Mallory‐Weiss syndrome), perforations (Boerhaave's syndrome), and hematomas (ie, IHE). IHE is by far the least common of these 3 pathologies and, despite increasing reports, it remains a rare clinical entity. Criblez et al.,4 in a review of 91 cases, found that only 35% of patients present with the classic triad of retrosternal chest pain, dysphagia/odynophagia, and hematemesis, while 99% present with at least 1 of these.5 Presentations mimic other cardiothoracic emergencies including myocardial infarction,6 pulmonary embolism,2 aortic dissection,6 and aortoesophageal fistula. Misdiagnosis of IHE and treatment with anticoagulant or thrombolytic therapy can have disastrous consequences, including death.5 Electrocardiograms, chest radiographs, and cardiac enzymes are often normal, as in this case. Endoscopy, performed cautiously, typically reveals a nonpulsatile, purple, submucosal mass. CT, which is rapid, noninvasive, and capable of differentiating between esophageal and life‐threatening thoracomediastinal pathology, frequently demonstrates thickening of the posterior wall of the esophagus with a long, smooth filling‐defect and luminal narrowing.7 Conservative management is the mainstay of treatment with most patients receiving acid suppression and antiemetic therapy. Surgical treatment and antibiotics (in cases of suspected infection) are required infrequently and should be used conservatively when necessary. The vast majority of patients recover spontaneously. Long‐term complications are rare.

IHE most frequently results from esophageal instrumentation, but other antecedent causes have been described. In contrast, SIHE occurs without warning, frequently developing in the absence of vomiting or hematemesis. Since SIHE was first reported in 1970,8 many authors have postulated potential mechanisms of hematoma formation. Controversy remains as to the precise etiology, but recent reports emphasize the association between SIHE and antiplatelet therapy, including low‐dose aspirin,9, 10 aspirin plus dipyridamole,11 and clopidogrel.12 Few studies have identified mechanisms for why the hemorrhage remains in the esophagus and why other parts of the gastrointestinal tract or other organ systems are not involved.

We report a case of apparent SIHE in a patient taking low‐dose aspirin, alendronate, and ferrous sulfate. While a subclinical traumatic event cannot be completely excluded, this patient lacked any apparent antecedent symptoms or other etiologic explanation. Alendronate and ferrous sulfate have been implicated in upper gastrointestinal irritation, but have not previously been associated with SIHE. Park et al.13 estimated a 3.0% incidence of esophageal or gastric events in alendronate users. Recently, esophagitis dissecans superficialis,3 esophageal dissection,14 and even fatal esophageal perforation16 have been reported in patients taking alendronate. Iron supplementation is also a recognized cause of esophageal injury. High local iron saturation may lead to concentration‐dependent absorption and thereby the formation of reactive oxygen metabolites and mucosal injury.16

We hypothesize that alendronate in combination with ferrous sulfate therapy resulted in subclinical esophageal injury predisposing our patient to SIHE. The patient reported 2 weeks of dysphagia prior to admission, suggesting a period of esophageal irritation. On endoscopy, a potential distal esophageal mucosal tear and clot were observed, which may represent a focus of injury. The interaction between this alendronate‐induced injury and chronic antiplatelet therapy may have resulted in hematoma expansion 22 cm along the esophagus. We are aware of one other report of IHE in a patient taking aspirin and alendronate published as an abstract in the Iranian Govaresh Journal.17

A spectrum of less‐commonly‐implicated medications may exert local toxicity on the esophagus and lead to de novo esophageal damage, predisposing patients to a broad spectrum of esophageal pathology, ranging from focal esophageal damage to large hematoma or perforation. Numerous medications are known to be associated with esophageal pathology through a variety of mechanisms (Table 1). Anatomic and motility disorders, as well as pill‐specific factors including contact time, coating materials, and sustained release formulations, may influence toxicity and predispose to injury.18 Elderly patients may be especially susceptible to the combined interactions between antiplatelet therapy and these commonly prescribed or over‐the‐counter medications.

| |

| Nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs | Aspirin, naproxen, ibuprofen |

| Bisphosphonates | Alendronate, etidronate, pamidronate |

| Antibiotics | Tetracycline, doxycycline, clindamycin, penicillin |

| Antiviral agents | Zalcitibine, zidovudine, nelfanavir |

| Chemotherapeutic agents | Dactinomycin, bleomycin, cytarabine, daunorubicin, 5‐fluorouracil, methotrexate, vincristine |

| Others | Ferrous sulfate, potassium chloride, ascorbic acid, multivitamins, quinidine, theophylline |

Conclusions

We report a case of apparent SIHE in an elderly woman taking low‐dose aspirin, iron, and alendronate therapy who presented with acute‐onset retrosternal chest pain and dysphagia. We emphasize the importance of including esophageal pathology in the evaluation of chest pain in these patients, particularly elderly women. We encourage a thorough examination of symptoms, including dysphagia/odynophagia, and an exhaustive medication history to identify medications less‐commonly implicated with esophageal pathology. In patients with chest pain taking these medications, clinicians must remain vigilant in their diagnostic approach to prevent misdiagnosis and inappropriate treatment.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge and thank Dr. Sonal Singh for his assistance in helping to analyze the potential drug interactions involved in this case presentation.

Intramural hematoma of the esophagus (IHE) is a rare clinical entity. The majority of cases occur following esophageal instrumentation; however, other causes have been described.14 Rarely, IHE may develop spontaneously. We report a case of apparent spontaneous IHE (SIHE) in a patient presenting with acute‐onset chest pain and dysphagia who was taking low‐dose aspirin, bisphosphonate, and iron supplementation therapy. We highlight the evaluation of chest pain in these patients and the importance of considering the association between esophageal pathology and less commonly implicated medications which may increase the risk of esophageal injury.

Case Report

An 80‐year‐old Hispanic female with a history of osteoporosis, hypertension, and anemia presumed secondary to long‐standing noninsulin‐dependent diabetes mellitus presented with severe, abrupt‐onset, epigastric and retrosternal chest pain following ingestion of a banana. Home medications included aspirin (81 mg daily), alendronate (70 mg weekly), and ferrous sulfate (300 mg 3 times daily). She experienced nausea and minimal vomiting without hematemesis following the onset of pain. She admitted to several weeks of progressive dysphagia leading up to this event, but denied persistent vomiting, straining, foreign body ingestion, or trauma. At admission, the patient was afebrile with heart rate (HR) = 88, blood pressure (BP) = 172/88, pulse oximetry = 99% on room air, hemoglobin = 9.0 g/dL, hematocrit = 26.5%, platelets = 191,000, and international normalized ratio (INR) = 1.04. Electrocardiogram and cardiac enzymes were negative for myocardial infarction. Chest radiograph did not show a widened mediastinum. A computed tomography (CT) scan of the chest demonstrated diffuse thickening of the esophageal wall. Upper endoscopy demonstrated a large, purple, nonpulsatile submucosal mass protruding into and nearly occluding the esophageal lumen (Figure 1A). This mass extended 22 cm along the esophagus and terminated at the esophagogastric junction. There was suggestion of a potential distal mucosal tear and visible clot (Figure 1B, C). An endoscopy performed 6 years prior was unremarkable for esophagitis, stricture, mass, or hemorrhage.

The patient remained nil‐per‐os and was managed conservatively with intravenous fluids, antiemetics, and acid‐suppression therapy. Due to persistent odynophagia, the patient did not tolerate per‐os nutrition, and a percutaneous gastrostomy tube was placed nonendoscopically for temporary nutritional support. The patient's hospital stay was complicated by deep vein thrombosis of the right peroneal vein, for which she underwent inferior vena cava filter placement. She was discharged 18 days following admission. Alendronate and aspirin were discontinued and not reinitiated, and a follow‐up CT scan 6 weeks posthospitalization demonstrated complete resolution of the hematoma.

Discussion

Esophageal injuries include lacerations (Mallory‐Weiss syndrome), perforations (Boerhaave's syndrome), and hematomas (ie, IHE). IHE is by far the least common of these 3 pathologies and, despite increasing reports, it remains a rare clinical entity. Criblez et al.,4 in a review of 91 cases, found that only 35% of patients present with the classic triad of retrosternal chest pain, dysphagia/odynophagia, and hematemesis, while 99% present with at least 1 of these.5 Presentations mimic other cardiothoracic emergencies including myocardial infarction,6 pulmonary embolism,2 aortic dissection,6 and aortoesophageal fistula. Misdiagnosis of IHE and treatment with anticoagulant or thrombolytic therapy can have disastrous consequences, including death.5 Electrocardiograms, chest radiographs, and cardiac enzymes are often normal, as in this case. Endoscopy, performed cautiously, typically reveals a nonpulsatile, purple, submucosal mass. CT, which is rapid, noninvasive, and capable of differentiating between esophageal and life‐threatening thoracomediastinal pathology, frequently demonstrates thickening of the posterior wall of the esophagus with a long, smooth filling‐defect and luminal narrowing.7 Conservative management is the mainstay of treatment with most patients receiving acid suppression and antiemetic therapy. Surgical treatment and antibiotics (in cases of suspected infection) are required infrequently and should be used conservatively when necessary. The vast majority of patients recover spontaneously. Long‐term complications are rare.

IHE most frequently results from esophageal instrumentation, but other antecedent causes have been described. In contrast, SIHE occurs without warning, frequently developing in the absence of vomiting or hematemesis. Since SIHE was first reported in 1970,8 many authors have postulated potential mechanisms of hematoma formation. Controversy remains as to the precise etiology, but recent reports emphasize the association between SIHE and antiplatelet therapy, including low‐dose aspirin,9, 10 aspirin plus dipyridamole,11 and clopidogrel.12 Few studies have identified mechanisms for why the hemorrhage remains in the esophagus and why other parts of the gastrointestinal tract or other organ systems are not involved.

We report a case of apparent SIHE in a patient taking low‐dose aspirin, alendronate, and ferrous sulfate. While a subclinical traumatic event cannot be completely excluded, this patient lacked any apparent antecedent symptoms or other etiologic explanation. Alendronate and ferrous sulfate have been implicated in upper gastrointestinal irritation, but have not previously been associated with SIHE. Park et al.13 estimated a 3.0% incidence of esophageal or gastric events in alendronate users. Recently, esophagitis dissecans superficialis,3 esophageal dissection,14 and even fatal esophageal perforation16 have been reported in patients taking alendronate. Iron supplementation is also a recognized cause of esophageal injury. High local iron saturation may lead to concentration‐dependent absorption and thereby the formation of reactive oxygen metabolites and mucosal injury.16

We hypothesize that alendronate in combination with ferrous sulfate therapy resulted in subclinical esophageal injury predisposing our patient to SIHE. The patient reported 2 weeks of dysphagia prior to admission, suggesting a period of esophageal irritation. On endoscopy, a potential distal esophageal mucosal tear and clot were observed, which may represent a focus of injury. The interaction between this alendronate‐induced injury and chronic antiplatelet therapy may have resulted in hematoma expansion 22 cm along the esophagus. We are aware of one other report of IHE in a patient taking aspirin and alendronate published as an abstract in the Iranian Govaresh Journal.17

A spectrum of less‐commonly‐implicated medications may exert local toxicity on the esophagus and lead to de novo esophageal damage, predisposing patients to a broad spectrum of esophageal pathology, ranging from focal esophageal damage to large hematoma or perforation. Numerous medications are known to be associated with esophageal pathology through a variety of mechanisms (Table 1). Anatomic and motility disorders, as well as pill‐specific factors including contact time, coating materials, and sustained release formulations, may influence toxicity and predispose to injury.18 Elderly patients may be especially susceptible to the combined interactions between antiplatelet therapy and these commonly prescribed or over‐the‐counter medications.

| |

| Nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs | Aspirin, naproxen, ibuprofen |

| Bisphosphonates | Alendronate, etidronate, pamidronate |

| Antibiotics | Tetracycline, doxycycline, clindamycin, penicillin |

| Antiviral agents | Zalcitibine, zidovudine, nelfanavir |

| Chemotherapeutic agents | Dactinomycin, bleomycin, cytarabine, daunorubicin, 5‐fluorouracil, methotrexate, vincristine |

| Others | Ferrous sulfate, potassium chloride, ascorbic acid, multivitamins, quinidine, theophylline |

Conclusions

We report a case of apparent SIHE in an elderly woman taking low‐dose aspirin, iron, and alendronate therapy who presented with acute‐onset retrosternal chest pain and dysphagia. We emphasize the importance of including esophageal pathology in the evaluation of chest pain in these patients, particularly elderly women. We encourage a thorough examination of symptoms, including dysphagia/odynophagia, and an exhaustive medication history to identify medications less‐commonly implicated with esophageal pathology. In patients with chest pain taking these medications, clinicians must remain vigilant in their diagnostic approach to prevent misdiagnosis and inappropriate treatment.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge and thank Dr. Sonal Singh for his assistance in helping to analyze the potential drug interactions involved in this case presentation.

- ,,.Post‐sclerotherapy intramural esophageal hematoma: endoscopic and radiologic findings.Gastrointest Endosc.1992;38:102–103.

- ,,.Esophageal hematoma. Four new cases, a review, and proposed etiology.Dig Dis Sci.1981;26:1019–1024.

- ,,.Spontaneous dissecting intramural hematoma of the oesophagus: a rare cause of haematemesis and dysphagia.Endoscopy.1981;13:128–130.

- ,,,,.Intramural rupture and intramural hematoma of the esophagus: 3 case reports and literature review.Schweiz Med Wochenschr.1992;122:416–423.

- ,.Dissecting intramural hematoma of the esophagus.Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol.2000;12:1151–1161.

- ,,.Spontaneous intramural hematoma of the oesophagus: a report of three cases and review of the literature.Aust N Z J Surg.1994;64:190–193.

- ,,,,.Intramural hematoma of the esophagus: a pictorial essay.Emerg Radiol.2008;15(1):13–22.

- ,.Spontaneous cervico‐mediastinal haematoma.J Ir Med Assoc.1970;63:298.

- ,,,,,.Giant esophageal hematoma: possible association with low‐dose aspirin.Gastroenterol Hepatol.2004;27(8):460–463.

- ,,,.Intramural esophageal hematoma. Clinical and endoscopic evolution.Med Clin.2004;123(1):39.

- ,.Spontaneous intramural esophageal hematoma. Diagnosis by CT scanning.J Clin Gastroenterol.1987;9(5):546–548.

- ,,,.Intramural hematoma of the esophagus: a rare cause of chest pain.Am J Emerg Med.2008;26(7):843.e1–e2.

- ,,,.Incidence of adverse oesophageal and gastric events in alendronate users.Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf.2000;9(5):371–376.

- ,,.An elderly man with excruciating retrosternal pain and dysphagia.CMAJ.2005;172:1556.

- ,.Fatal esophageal perforation with alendronate.Am J Gastroenterol.2001;96:3212–3213.

- ,,.Erosive injury to the upper gastrointestinal tract in patients receiving iron medication: an underrecognized entitiy.Am J Surg Pathol.1999;23:1241–1247.

- ,.[A case report of esophageal intramural hematoma.] [English abstract on p.4 of the pdf].Govaresh J.2006;11(1):39–41. [Farsi] Available at: http://www.iagh.org/Portals/44fa7561‐56f7‐47e4‐a228‐477ca071e439/Volume%2011,%20Number%201,%20Spring%202006/(1)Dr_bagheri‐11‐1‐7.pdf. Accessed October 2009.

- .Esophageal disorders caused by medications, trauma, and infection. In:Feldman M, Friedman L, Brandt L, eds.Sleisenger and Fordtran's Gastrointestinal and Liver Disease.8th ed.Philadelphia:Saunders;2006:937–948.

- ,,.Post‐sclerotherapy intramural esophageal hematoma: endoscopic and radiologic findings.Gastrointest Endosc.1992;38:102–103.

- ,,.Esophageal hematoma. Four new cases, a review, and proposed etiology.Dig Dis Sci.1981;26:1019–1024.

- ,,.Spontaneous dissecting intramural hematoma of the oesophagus: a rare cause of haematemesis and dysphagia.Endoscopy.1981;13:128–130.

- ,,,,.Intramural rupture and intramural hematoma of the esophagus: 3 case reports and literature review.Schweiz Med Wochenschr.1992;122:416–423.

- ,.Dissecting intramural hematoma of the esophagus.Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol.2000;12:1151–1161.

- ,,.Spontaneous intramural hematoma of the oesophagus: a report of three cases and review of the literature.Aust N Z J Surg.1994;64:190–193.

- ,,,,.Intramural hematoma of the esophagus: a pictorial essay.Emerg Radiol.2008;15(1):13–22.

- ,.Spontaneous cervico‐mediastinal haematoma.J Ir Med Assoc.1970;63:298.

- ,,,,,.Giant esophageal hematoma: possible association with low‐dose aspirin.Gastroenterol Hepatol.2004;27(8):460–463.

- ,,,.Intramural esophageal hematoma. Clinical and endoscopic evolution.Med Clin.2004;123(1):39.

- ,.Spontaneous intramural esophageal hematoma. Diagnosis by CT scanning.J Clin Gastroenterol.1987;9(5):546–548.

- ,,,.Intramural hematoma of the esophagus: a rare cause of chest pain.Am J Emerg Med.2008;26(7):843.e1–e2.

- ,,,.Incidence of adverse oesophageal and gastric events in alendronate users.Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf.2000;9(5):371–376.

- ,,.An elderly man with excruciating retrosternal pain and dysphagia.CMAJ.2005;172:1556.

- ,.Fatal esophageal perforation with alendronate.Am J Gastroenterol.2001;96:3212–3213.

- ,,.Erosive injury to the upper gastrointestinal tract in patients receiving iron medication: an underrecognized entitiy.Am J Surg Pathol.1999;23:1241–1247.

- ,.[A case report of esophageal intramural hematoma.] [English abstract on p.4 of the pdf].Govaresh J.2006;11(1):39–41. [Farsi] Available at: http://www.iagh.org/Portals/44fa7561‐56f7‐47e4‐a228‐477ca071e439/Volume%2011,%20Number%201,%20Spring%202006/(1)Dr_bagheri‐11‐1‐7.pdf. Accessed October 2009.

- .Esophageal disorders caused by medications, trauma, and infection. In:Feldman M, Friedman L, Brandt L, eds.Sleisenger and Fordtran's Gastrointestinal and Liver Disease.8th ed.Philadelphia:Saunders;2006:937–948.

Inpatient Hypertension Review

Hypertension (HTN) is highly prevalent in the general adult population with recent estimates from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) of 29% in the United States.1, 2 The relationship between increasing levels of blood pressure (BP) and increasing risk for cardiovascular disease events and stroke is well established.3 However, while 64% of treated HTN patients have a BP 140/90 mmHg, overall control rates for HTN in the adult population remain at approximately 44%.2 The 20% discrepancy in control rates between treated patients and the overall adult population reflects the fact that approximately 30% of patients are unaware of their HTN and that a substantial proportion of aware patients remain untreated. Historically, efforts to improve the recognition, treatment, and control of HTN have appropriately focused on the outpatient setting. However, programs to extend screening for HTN outside the clinic into the community, schools, and even dentists' offices have been around for some time.49

The potential also exists to improve the recognition, treatment, and control of HTN by focusing on hospitalized patients. Hospitalization is common in the U.S. with almost 35 million acute hospitalizations and more than 45,000 inpatient surgical procedures in 2006.10 Inpatient populations have increased in age and comorbidity over the past 3 decades whereas lengths of stay and continuity of care between the inpatient and outpatient arenas have diminished.10, 11 Multiple prior studies examining BP in different settings have noted that average BP among hospitalized patients is not systematically higher than that of outpatients.1214 Thus, patients with persistently elevated BP in the inpatient setting without mitigating factors may have HTN that will persist after hospital discharge. However, little information is available regarding the actual prevalence of HTN in the inpatient population and care patterns for inpatient HTN. Therefore, we performed a systematic review of the English‐language medical literature in order to describe the epidemiology of HTN observed in the inpatient setting.

Methods

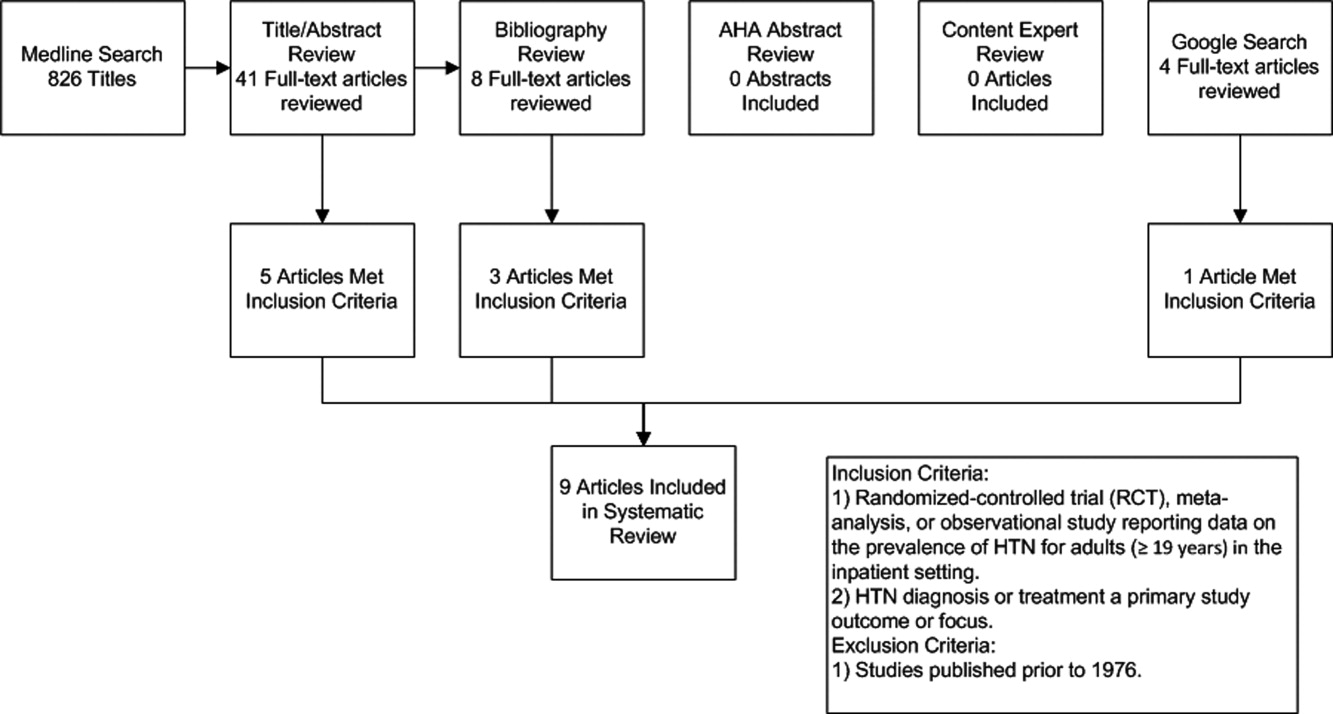

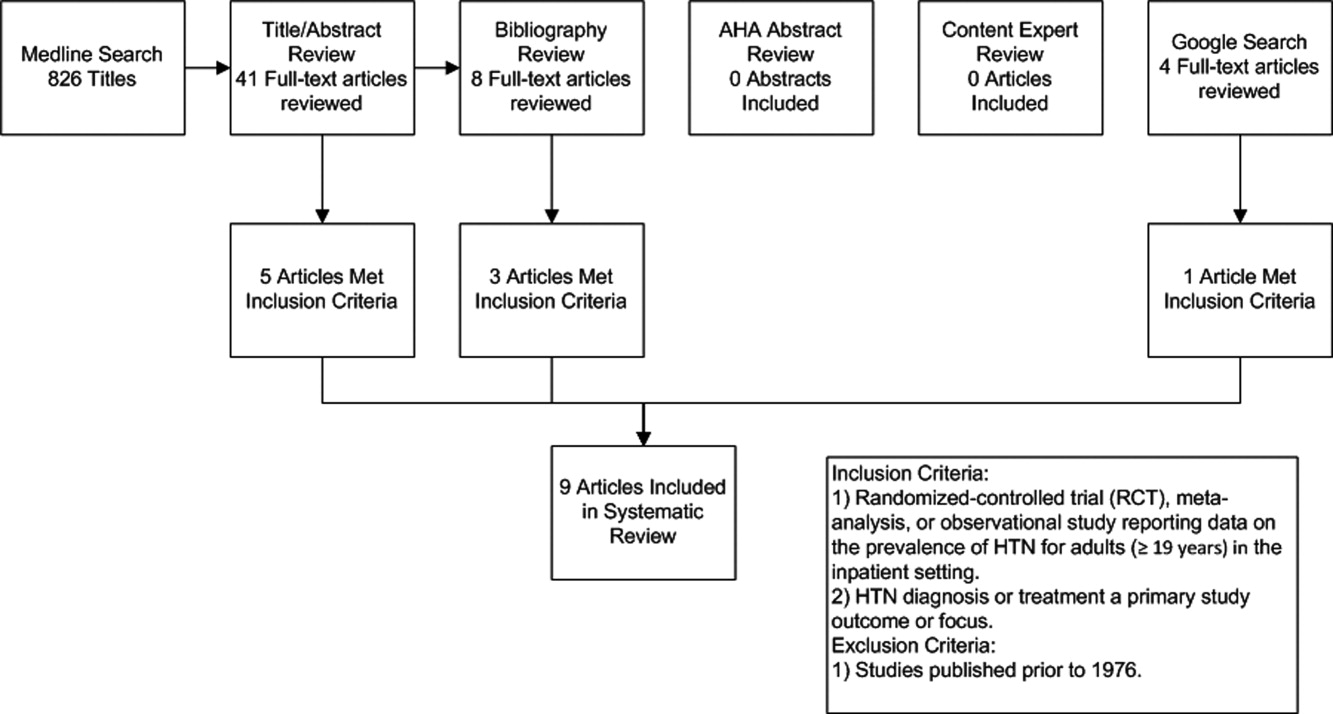

Our search strategy was designed to identify randomized‐controlled trials, meta‐analyses, and observational studies that: (1) reported estimates of the prevalence of HTN in the inpatient setting, and (2) used HTN diagnosis or treatment as a primary focus. We performed an extensive review of the peer‐reviewed, English language medical literature in MEDLINE using a predetermined search algorithm. Search terms included HTN[Mesh] or BP[Mesh]. These results were cross‐referenced with the following search terms: Inpatients[Mesh] or Hospitalization[title/abstract] or Hospitalized[title/abstract]. Articles were further narrowed using the following terms: Prevalence[Mesh] or Epidemiology[Mesh] or Treatment[title/abstract] or Management [title/abstract]. Limits employed included limiting to humans and to adults 19 years‐of‐age and older. Studies published prior to 1976 were excluded because 1976 was the first year that the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High BP published consensus guidelines for the diagnosis and management of HTN. We also excluded randomized, controlled trials that recorded measures of inpatient BP but whose focus was not HTN, because such trials would not answer the primary epidemiologic question of this review. We did include trials focused on subspecialty populations for which the diagnosis and inpatient management of HTN were key outcomes.

Next, the bibliographies of reviewed studies were investigated for additional relevant reports. Abstracts from the American Heart Association (AHA) were reviewed for the past 15 years for reports that were presented but not subsequently published and available in MEDLINE. We also searched for articles using the online Google search engine. One author (RNA) performed the preliminary MEDLINE search and abstract review with the assistance of a reference librarian (LC), and a second author (BME) also reviewed full‐text articles for potential inclusion. Ultimate decision for study inclusion was reached through discussion among authors. Finally, a list of potential articles was submitted to 2 experts in this field of study to determine whether other reports met our inclusion criteria for this systematic review but were overlooked.

Results

Search Results

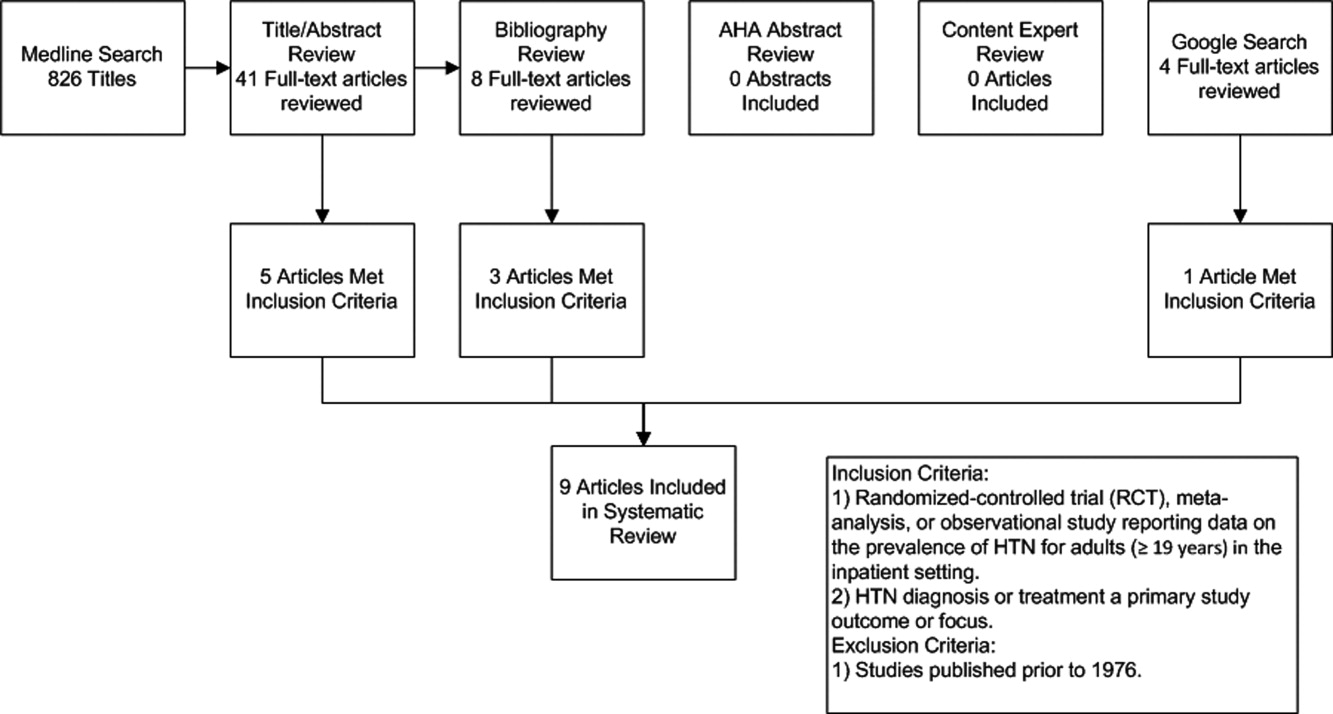

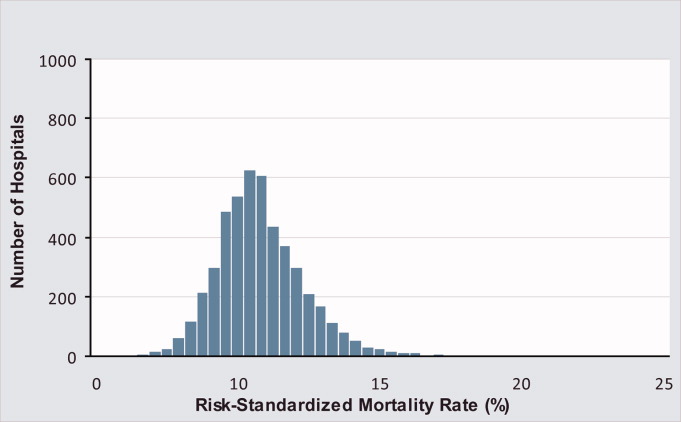

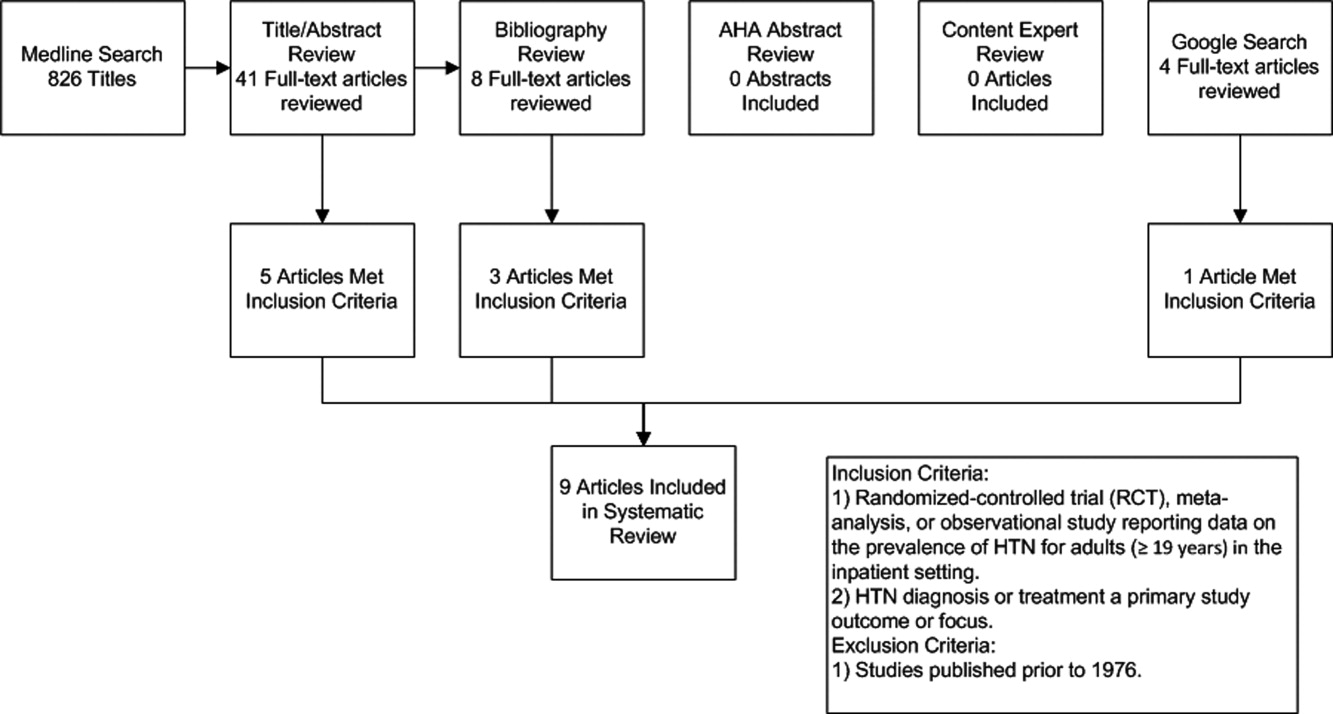

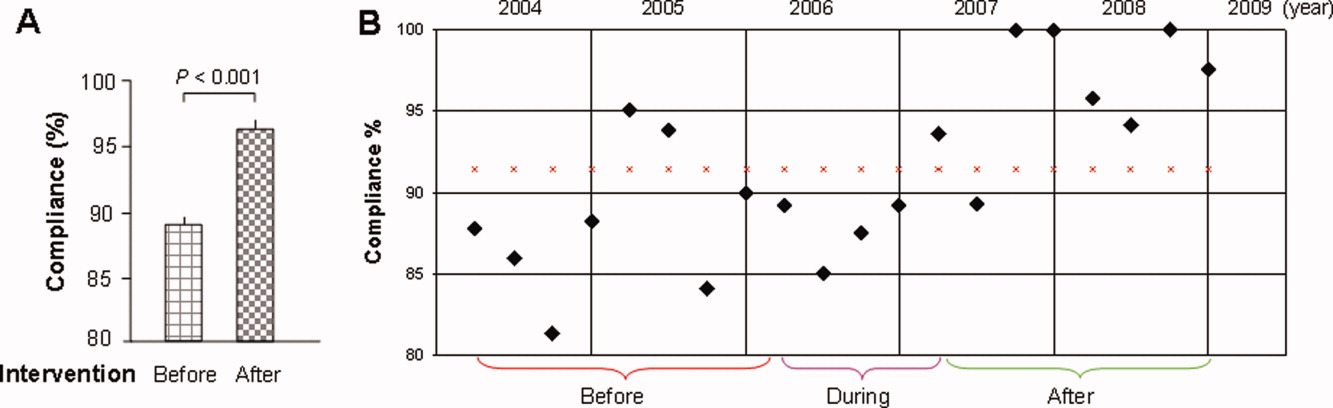

The initial MEDLINE search algorithm yielded a total of 826 articles. After title and abstract review, 41 full‐text articles were obtained for detailed review, and 5 met criteria for inclusion. Three additional articles were discovered through searching the bibliographies of the included studies. No AHA abstracts addressed this subject area. Experts were not aware of any additional studies. One article was located using a Google search. In all, 9 articles were deemed suitable for inclusion in this review. Search results at each stage are depicted in Figure 1.

Description of Included Studies

Characteristics of included studies are depicted in Table 1. Two older retrospective cohort studies reported HTN prevalence using earlier, less stringent diagnostic criteria. Shankar et al.15 abstracted data from more than 19,000 adults discharged alive from Maryland hospitals during 1978. Greenland et al.16 performed chart review for 536 medical and surgical inpatients in 1987 reporting information on the proportion of patients appropriately diagnosed as having HTN and the proportion with controlled BP on admission and at discharge based on then‐current JNC‐III criteria (HTN if BP > 160/90).

| Study | Design | Setting | Hypertension Prevalence | Diagnostic Criteria for HTN |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Shankar et al.15 (1982) | Retrospective cohort | All hospital discharges in Maryland in 1978 | 23.8% (4571/19,259) | HTN diagnosis in record or diastolic BP 100 mm Hg |

| Greenland et al.16 (1987) | Retrospective cohort | Single University Center, U.S., medical/surgical patients | 28% (143/536 ) | HTN diagnosis in record or mean of first 4 hospital BP measures 160/90 mm Hg |

| Euroaspire I17 | Retrospective cohort with prospective follow up | 9 European countries, coronary heart disease admissions | 57.8% (2553/4415) | Admission BP 140/90 mm Hg or on antihypertensive medications |

| Euroaspire II18 | Retrospective cohort with prospective follow up | 15 European countries, coronary heart disease admissions | 50.5% (2806/5556) | Mean clinic BP at 618 months follow up of 140/90 mm Hg |

| Amar et al.20 (2002) | Retrospective cohort | 77 Cardiology centers, France, ischemic heart disease admissions | 58.5% (729/1247) | HTN diagnosis in record or admission BP 140/90 mm Hg |

| Onder et al.23 (2003) | Cross‐sectional | 81 Hospitals, Italy, elderly patients with known HTN | *86.9% (3304/3807) | HTN diagnosis in record AND admission BP 140/90 mm Hg |

| Jankowski et al.19 (2005) | Retrospective cohort with prospective follow up | 3 University cardiology centers, Poland | 70.2% (593/845) | Mean clinic BP at 618 months follow up of 140/90 mm Hg |

| Conen et al.21 (2006) | Cross‐sectional | Single University Center, U.S., medical/surgical patients | 72.6% (228/314) | HTN diagnosis in record OR mean 24‐hour BP 125/80 mm Hg |

| Giantin et al.22 (2009) | Cross‐sectional | Single University Center, Italy, medical/surgical patients | 56.4% (141/250) | Mean 24‐hour BP 125/80 mm Hg |

| Clinical Question | Findings |

|---|---|

| |

| Accuracy of routine inpatient BP measurements | 56.4% to 72.6% of inpatients receiving 24 hour BP monitoring had HTN.21, 22 |

| 28% to 38% of HTN patients had masked HTN (identified by 24‐hour monitoring but not revealed by routine inpatient BP measures). | |

| Proportion of HTN patients uncontrolled on admission | 86.9% of patients with previously documented HTN were uncontrolled on admission.23 |

| Proportion of HTN patients uncontrolled at discharge | 37% to 77% of inpatients with HTN still had BP > 140/90 mm Hg at time of discharge.16, 20, 23 |

| Proportion of HTN patients without a recorded diagnosis at discharge | 8% to 44% of patients with elevated BP > 140/90 mmHg were discharged without a documented diagnosis of HTN.15, 16, 18, 19 |

| Proportion of uncontrolled HTN patients receiving intensification of therapy during index admission | 53.1% of patients with uncontrolled BP received additional antihypertensive medication upon discharge.23 |

| Proportion of HTN controlled at follow up | 50% of patients with HTN were controlled to 140/90 mm Hg at follow up.17 |

Four studies focused primarily on cardiac patients. The European Society of Cardiology survey of secondary prevention of coronary heart disease (EUROASPIRE I) and subsequent EUROASPIRE II studies used retrospective chart review and prospective follow up clinic visits with a focus on baseline patient characteristics and risk factor modification at post‐discharge follow up.17, 18 Jankowski et al.19 studied 845 similar cardiac patients discharged from 6 Polish centers. Amar et al.20 performed a retrospective cohort study using records from 77 French cardiology centers to assess the impact of BP control prior to discharge in patients with acute coronary syndromes on the prevention of subsequent nonfatal myocardial infarction (MI) and cardiac death.

Two studies utilized 24‐hour BP monitoring to diagnose HTN among inpatients, and compared this to routine inpatient measurement techniques. Conen et al.21 performed 24‐hour BP monitoring on 314 consecutive stable medical and surgical inpatients admitted to a Swiss University hospital. Giantin et al.22 also performed 24‐hour monitoring on a cohort of elderly Italian outpatients and inpatients to determine the prevalence of masked and white coat HTN in different care settings. Finally, Onder et al.23 reported on rates of uncontrolled BP and HTN management among known hypertensives as part of a series of cross‐sectional surveys performed on elderly Italian inpatients.23

Inpatient HTN Prevalence

Overall, study authors reported an HTN prevalence among inpatients that ranged from 50.5% to 72%. Estimates varied somewhat based on HTN definitions, diagnostic standards utilized, measurement techniques, and patient populations. In earlier studies HTN prevalence was reported at 23.8% to 28%, but these likely represented significant underestimates by current diagnostic standards.15, 16 High estimates by Onder et al.23 (86.9%) stem from selection criteria that included a prior billing diagnosis of HTN coupled with elevated admission blood pressures. Estimates in the 50% to 70% prevalence range were seen in studies that focused on cardiac and general medical inpatients.1722 Additional findings of included studies are listed in Table 2.

Accuracy of Inpatient BP Measures

In two studies, 24‐hour BP monitors produced prevalence estimates ranging from 56.4% to 72.6%.21, 22 In both studies, a significant proportion of patients had masked HTN, or HTN detected by 24‐hour BP monitoring alone. Also, 28% to 38% of patients without a prior HTN diagnosis, who were not detected by routine measures, were found to be hypertensive by 24‐hour monitoring. Finally, Conen et al.21 retested a subset of hypertensives with 24‐hour monitoring one month after hospitalization, and 87.5% remained categorized as hypertensive on follow‐up. Of note, it is unclear how this subset of patients was selected.

Proportion of Controlled HTN on Admission and Discharge

Because most included studies established prevalence of HTN based in part upon uncontrolled BP at hospital admission, estimates for the proportion of hypertensive patients controlled on admission were not given. However, Onder et al.23 did examine patients with a prior International Classification of Diseases, 9th edition (ICD‐9) diagnosis of HTN and uncontrolled HTN (BP 140/90) on admission. At discharge, only 23.2% of this cohort was controlled with a BP 140/90 mmHg. However, other estimates suggested that 37% to 44% of patients remained uncontrolled at discharge.16, 20

Proportion of Undiagnosed HTN

In 4 studies, the proportion of patients with elevated BP and/or a history of HTN who did not receive a diagnosis of HTN upon discharge ranged from 8.8% to 44% between cohorts.15, 16, 18, 19 Interpretation of these estimates, however, is difficult due to significant differences between the studies. For example, both earlier studies were performed during an era of higher thresholds for HTN diagnosis and lower overall HTN awareness.15, 16 Both studies of cardiac patients suggested lower rates of nondiagnosis than might have been found in general medical or surgical inpatients.18, 19 One of the 4 studies also suggested that surgical patients who were hypertensive during hospitalization were more likely than medical patients to be discharged without a HTN diagnosis (17% vs. 4%, P 0.05); although, the overall number of patients was small (18/146 remained undiagnosed).16

Proportion Receiving Intensification of Therapy

In 3 studies, prescribing practices for hypertensive inpatients were discussed. Shankar et al.15 found that only 62% of patients with a recorded HTN diagnosis received antihypertensive medications during hospitalization. Unfortunately, no information was given on the proportion of patients prescribed antihypertensive medications at the time of discharge. However, Greenland et al.16 found no net increase in BP medication use at discharge compared to admission despite 44% of patients remaining uncontrolled to 160/90 mmHg at the time of discharge. Onder et al.23 determined that BP medication was intensified in only 53.1% of hypertensive patients during hospitalization. Younger age, fewer drugs on admission, lower comorbidity index, diagnosis of congestive heart failure, lengthy hospital stay, and increasing levels of BP (systolic and diastolic) were all associated with more aggressive prescribing practices. Interestingly, Jankowski et al.19 found that treatment with a BP lowering agent at discharge was associated with the lowest odds of nontreatment at follow up (odds ratio [OR] 0.08, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.030.19).

Proportion of HTN Controlled at Follow Up

In the EuroASPIRE 1 study, 50% of HTN patients had a systolic BP of 140 mm Hg at follow up 6 months after hospitalization for MI.17 Jankowski et al.19 found that patients with documented inpatient HTN but without a recorded HTN diagnosis during index admission were 4 times more likely (19.2% vs. 4.5%, P 0.0001) to be untreated for their HTN at 6 to 18 months postdischarge, and they were less likely to be controlled at 140/90 mmHg. In a separate cohort of cardiac patients, multivariable modeling identified uncontrolled isolated systolic HTN at hospital discharge as an independent predictor of subsequent cardiac death or nonfatal MI at 6 months follow up (OR, 1.96; 95% CI, 1.153.36).20

Discussion

The present systematic review highlights the high prevalence of HTN with contemporary estimates ranging between 50% and 72% in general medical/surgical and cardiology populations. Furthermore, routine inpatient BP measurements may underestimate the prevalence of HTN among inpatients when compared to 24 hour BP monitoring; although there is no current diagnostic standard for HTN among inpatients. Among patients with uncontrolled BP on admission, BP typically remains above recommended levels at the time of discharge. Further, studies commenting on the prescribing practices at the time of discharge did not detect a strong tendency to intensify antihypertensive regimens in patients with uncontrolled inpatient HTN.16, 23 Most importantly, our data suggest that the medical literature is lacking: only 9 reports met our inclusion criteria for this review.

The validity of inpatient BP measures for making an HTN diagnosis remains a concern when asserting that the inpatient setting is appropriate for HTN screening and efforts to improve BP control. For example, BP measures might be inaccurate because of the inherent heterogeneity of patients with acute illness often with associated pain and nausea that might raise or lower BP. Inpatients often need to have their BP medications held for appropriate reasons, or they may have additional medications while hospitalized that also affect BP. Finally, BP measures in the inpatient setting are less commonly performed using standardized techniques or with accurate BP devices. However, both studies included in this review featuring follow up outpatient BP measures found high degrees of correlation between inpatient and outpatient measures.19, 21 Also, Giantin and colleagues reported that 28.6% of elderly patients who were normotensive based on routine BP measures, were actually hypertensive based on 24‐hour ambulatory BP monitoring.22

Some clinicians may have concerns about starting or titrating BP medications in dynamic hospitalized patients. Certainly, this should be done with caution and in appropriately selected patients. We would argue that achieving complete BP control during an index hospitalization as emphasized by Greenland and Amar is not always the most appropriate goal. However, appropriate recognition of persistently elevated BP does offer the opportunity to make an HTN diagnosis and to refer for future outpatient treatment or to communicate with existing primary care providers. The latter is especially important in this era of discontinuity between inpatient and outpatient care. Beginning or titrating BP medications in the hospital also has advantages for 2 reasons. First, medications started in the hospital tend to be the medications on which patients are sent home. Second, in the study by Jankowski et al.,19 the failure to prescribe an antihypertensive medication at the time of discharge was the single strongest predictor of nontreatment at 6 to 18 months follow‐up despite other follow up outpatient visits where BP medications might have been titrated.

Multiple lines of evidence suggest that failure to appropriately manage HTN observed in the inpatient setting can impact subsequent medication use and disease outcomes for high‐risk patients. Amar et al.20 found that better controlled systolic BP on hospital discharge is associated with better outcomes in patients with ischemic heart disease. Only 35% of patients in one cohort admitted to the hospital with hypertensive urgency or emergency completed an outpatient follow up visit for HTN within 90 days. However, 37% were readmitted and 11% died during 3 month follow up.24 Predischarge initiation of a beta blocker in congestive heart failure patients has been associated with a nearly 18% absolute increase in rates of beta blocker use at 2 months follow‐up.25 Finally, prescription of antihypertensive medications is suboptimal for secondary stroke prevention despite a number needed to treat of 51 patients to prevent one stroke annually.26, 27

The primary limitation of this review is the paucity of published reports documenting the prevalence of inpatient HTN. It is possible that important articles were missed, but we did follow a prespecified systematic search strategy with the assistance of a trained reference librarian. Also, the definition of HTN varied significantly between studies. However, current consensus guidelines do not specifically address the diagnosis or management of HTN in the inpatient setting.28

In summary, available medical evidence suggests that HTN is a common problem observed in the hospital. Opportunities for the appropriate diagnosis of HTN and for the initiation or modification of HTN treatment are often missed. Future studies in this area are warranted to better understand the prevalence of HTN in the inpatient setting and the need to improve HTN detection, treatment, and control. Clearer diagnostic and therapeutic guidelines for the detection and treatment of inpatient HTN could contribute to further improvements in control rates of all hypertensive patients, especially if coupled with improved care transitions between the inpatient and outpatient setting.

- ,,,,.Prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control of hypertension among United States adults 1999–2004.Hypertension.2007;49:69–75.

- ,,,.Hypertension awareness, treatment, and control‐continued disparities in adults: United States, 2005–2006.NCHS Data Brief.2008;3:1–8.

- ,,,,,Prospective Studies C.Age‐specific relevance of usual blood pressure to vascular mortality: a meta‐analysis of individual data for one million adults in 61 prospective studies.Lancet.2002;360:1903–1913.

- ,,,,,.Blood pressure screening of school children in a multiracial school district: the Healthy Kids Project.Am J Hypertens.2009;22:351–356.

- ,,,,.Kidney Early Evaluation Program (KEEP). Findings from a community screening program.Diabetes Educ.2004;30(2):196–198,200–202,220.

- .Screening for traditional risk factors for cardiovascular disease: a review for oral health care providers.J Am Dent Assoc.2002;133:291–300.

- .Health screening in schools. Part II.J Pediatr.1985;107:653–661.

- ,,,.Experience with a community screening program for hypertension: results on 24,462 individuals.Eur J Cardiol.1978;7:487–497.

- .Screening for hypertension in the dental office.J Am Dent Assoc.1974;88:563–567.

- ,,,.2006 National Hospital Discharge Survey:National Center for Health Statistics;2008.

- ,,,,,.Continuity of outpatient and inpatient care by primary care physicians for hospitalized older adults.J Am Med Assoc.2009;301:1671–1680.

- ,,.Influence of hospitalization and placebo therapy on blood pressure and sympathetic function in essential hypertension.Hypertension.1981;3:113–118.

- ,,.Effect of hospitalization on conventional and 24‐hour blood pressure.Age Ageing.1995;24:25–29.

- ,,, et al.Spontaneous fall in blood pressure and reactivity of sympathetic nervous system in hospitalized patients with essential hypertension.Jpn J Med.1990;29:13–21.

- ,,,.Patterns of care for hypertension among hospitalized patients.Public Health Rep.1982;97:521–527.

- ,,.Hospitalization as an opportunity to improve hypertension recognition and control.Med Care.1987;25:717–723.

- EUROASPIRE.A European Society of Cardiology survey of secondary prevention of coronary heart disease: principal results. EUROASPIRE Study Group. European Action on Secondary Prevention through Intervention to Reduce Events.Eur Heart J.1997;18:1569–1582.

- Lifestyle and risk factor management and use of drug therapies in coronary patients from 15 countries; principal results from EUROASPIRE II Euro Heart Survey Programme.Eur Heart J.2001;22:554–572.

- ,,,.Determinants of poor hypertension management in patients with ischaemic heart disease.Blood Press.2005;14:284–292.

- ,,, et al.Hypertension control at hospital discharge after acute coronary event: influence on cardiovascular prognosis‐‐the PREVENIR study.Heart.2002;88:587–591.

- ,,,.High prevalence of newly detected hypertension in hospitalized patients: the value of in‐hospital 24‐h blood pressure measurement.J Hypertens2006;24:301–306.

- ,,, et al.Masked and white‐coat hypertension in two cohorts of elderly subjects, ambulatory and hospitalized patients.Arch Gerontol Geriatr.2009;49Suppl 1:125–128.

- ,,, et al.Impact of hospitalization on blood pressure control in Italy: results from the Italian Group of Pharmacoepidemiology in the Elderly (GIFA).Pharmacotherapy.2003;23:240–247.

- ,,, et al.Practice patterns, outcomes, and end‐organ dysfunction for patients with acute severe hypertension: The Studying the Treatment of Acute hyperTension (STAT) Registry.Am Heart J.2009;158:599–606.

- ,,,,.Predischarge initiation of carvedilol in patients hospitalized for decompensated heart failure: results of the Initiation Management Predischarge: Process for Assessment of Carvedilol Therapy in Heart Failure (IMPACT‐HF) trial.J Am Coll Cardiol.2004;43:1534–1541.

- ,,,.Antihypertensive medications prescribed at discharge after an acute ischemic cerebrovascular event.Stroke.2005;36:1944–1947.

- ,,.New Evidence for Stroke Prevention: Scientific Review.JAMA.2002;288:1388–1395.

- ,,,,.Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation and Treatment of High Blood Pressure. National High Blood Pressure Education Program Coordinating Committee.Hypertension.2003;42:1206–1252.

Hypertension (HTN) is highly prevalent in the general adult population with recent estimates from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) of 29% in the United States.1, 2 The relationship between increasing levels of blood pressure (BP) and increasing risk for cardiovascular disease events and stroke is well established.3 However, while 64% of treated HTN patients have a BP 140/90 mmHg, overall control rates for HTN in the adult population remain at approximately 44%.2 The 20% discrepancy in control rates between treated patients and the overall adult population reflects the fact that approximately 30% of patients are unaware of their HTN and that a substantial proportion of aware patients remain untreated. Historically, efforts to improve the recognition, treatment, and control of HTN have appropriately focused on the outpatient setting. However, programs to extend screening for HTN outside the clinic into the community, schools, and even dentists' offices have been around for some time.49

The potential also exists to improve the recognition, treatment, and control of HTN by focusing on hospitalized patients. Hospitalization is common in the U.S. with almost 35 million acute hospitalizations and more than 45,000 inpatient surgical procedures in 2006.10 Inpatient populations have increased in age and comorbidity over the past 3 decades whereas lengths of stay and continuity of care between the inpatient and outpatient arenas have diminished.10, 11 Multiple prior studies examining BP in different settings have noted that average BP among hospitalized patients is not systematically higher than that of outpatients.1214 Thus, patients with persistently elevated BP in the inpatient setting without mitigating factors may have HTN that will persist after hospital discharge. However, little information is available regarding the actual prevalence of HTN in the inpatient population and care patterns for inpatient HTN. Therefore, we performed a systematic review of the English‐language medical literature in order to describe the epidemiology of HTN observed in the inpatient setting.

Methods

Our search strategy was designed to identify randomized‐controlled trials, meta‐analyses, and observational studies that: (1) reported estimates of the prevalence of HTN in the inpatient setting, and (2) used HTN diagnosis or treatment as a primary focus. We performed an extensive review of the peer‐reviewed, English language medical literature in MEDLINE using a predetermined search algorithm. Search terms included HTN[Mesh] or BP[Mesh]. These results were cross‐referenced with the following search terms: Inpatients[Mesh] or Hospitalization[title/abstract] or Hospitalized[title/abstract]. Articles were further narrowed using the following terms: Prevalence[Mesh] or Epidemiology[Mesh] or Treatment[title/abstract] or Management [title/abstract]. Limits employed included limiting to humans and to adults 19 years‐of‐age and older. Studies published prior to 1976 were excluded because 1976 was the first year that the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High BP published consensus guidelines for the diagnosis and management of HTN. We also excluded randomized, controlled trials that recorded measures of inpatient BP but whose focus was not HTN, because such trials would not answer the primary epidemiologic question of this review. We did include trials focused on subspecialty populations for which the diagnosis and inpatient management of HTN were key outcomes.

Next, the bibliographies of reviewed studies were investigated for additional relevant reports. Abstracts from the American Heart Association (AHA) were reviewed for the past 15 years for reports that were presented but not subsequently published and available in MEDLINE. We also searched for articles using the online Google search engine. One author (RNA) performed the preliminary MEDLINE search and abstract review with the assistance of a reference librarian (LC), and a second author (BME) also reviewed full‐text articles for potential inclusion. Ultimate decision for study inclusion was reached through discussion among authors. Finally, a list of potential articles was submitted to 2 experts in this field of study to determine whether other reports met our inclusion criteria for this systematic review but were overlooked.

Results

Search Results

The initial MEDLINE search algorithm yielded a total of 826 articles. After title and abstract review, 41 full‐text articles were obtained for detailed review, and 5 met criteria for inclusion. Three additional articles were discovered through searching the bibliographies of the included studies. No AHA abstracts addressed this subject area. Experts were not aware of any additional studies. One article was located using a Google search. In all, 9 articles were deemed suitable for inclusion in this review. Search results at each stage are depicted in Figure 1.

Description of Included Studies

Characteristics of included studies are depicted in Table 1. Two older retrospective cohort studies reported HTN prevalence using earlier, less stringent diagnostic criteria. Shankar et al.15 abstracted data from more than 19,000 adults discharged alive from Maryland hospitals during 1978. Greenland et al.16 performed chart review for 536 medical and surgical inpatients in 1987 reporting information on the proportion of patients appropriately diagnosed as having HTN and the proportion with controlled BP on admission and at discharge based on then‐current JNC‐III criteria (HTN if BP > 160/90).

| Study | Design | Setting | Hypertension Prevalence | Diagnostic Criteria for HTN |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Shankar et al.15 (1982) | Retrospective cohort | All hospital discharges in Maryland in 1978 | 23.8% (4571/19,259) | HTN diagnosis in record or diastolic BP 100 mm Hg |

| Greenland et al.16 (1987) | Retrospective cohort | Single University Center, U.S., medical/surgical patients | 28% (143/536 ) | HTN diagnosis in record or mean of first 4 hospital BP measures 160/90 mm Hg |

| Euroaspire I17 | Retrospective cohort with prospective follow up | 9 European countries, coronary heart disease admissions | 57.8% (2553/4415) | Admission BP 140/90 mm Hg or on antihypertensive medications |

| Euroaspire II18 | Retrospective cohort with prospective follow up | 15 European countries, coronary heart disease admissions | 50.5% (2806/5556) | Mean clinic BP at 618 months follow up of 140/90 mm Hg |

| Amar et al.20 (2002) | Retrospective cohort | 77 Cardiology centers, France, ischemic heart disease admissions | 58.5% (729/1247) | HTN diagnosis in record or admission BP 140/90 mm Hg |

| Onder et al.23 (2003) | Cross‐sectional | 81 Hospitals, Italy, elderly patients with known HTN | *86.9% (3304/3807) | HTN diagnosis in record AND admission BP 140/90 mm Hg |

| Jankowski et al.19 (2005) | Retrospective cohort with prospective follow up | 3 University cardiology centers, Poland | 70.2% (593/845) | Mean clinic BP at 618 months follow up of 140/90 mm Hg |

| Conen et al.21 (2006) | Cross‐sectional | Single University Center, U.S., medical/surgical patients | 72.6% (228/314) | HTN diagnosis in record OR mean 24‐hour BP 125/80 mm Hg |

| Giantin et al.22 (2009) | Cross‐sectional | Single University Center, Italy, medical/surgical patients | 56.4% (141/250) | Mean 24‐hour BP 125/80 mm Hg |

| Clinical Question | Findings |

|---|---|

| |

| Accuracy of routine inpatient BP measurements | 56.4% to 72.6% of inpatients receiving 24 hour BP monitoring had HTN.21, 22 |

| 28% to 38% of HTN patients had masked HTN (identified by 24‐hour monitoring but not revealed by routine inpatient BP measures). | |

| Proportion of HTN patients uncontrolled on admission | 86.9% of patients with previously documented HTN were uncontrolled on admission.23 |

| Proportion of HTN patients uncontrolled at discharge | 37% to 77% of inpatients with HTN still had BP > 140/90 mm Hg at time of discharge.16, 20, 23 |

| Proportion of HTN patients without a recorded diagnosis at discharge | 8% to 44% of patients with elevated BP > 140/90 mmHg were discharged without a documented diagnosis of HTN.15, 16, 18, 19 |

| Proportion of uncontrolled HTN patients receiving intensification of therapy during index admission | 53.1% of patients with uncontrolled BP received additional antihypertensive medication upon discharge.23 |

| Proportion of HTN controlled at follow up | 50% of patients with HTN were controlled to 140/90 mm Hg at follow up.17 |