User login

Two-Way Street

Brad Schmidt, MD, can remember recruiting hospitalists to the HM program at Dean Clinic at St. Mary’s Hospital in Madison, Wis., seven years ago. He was a young doctor, just a couple of years removed from residency.

Back then, having Dr. Schmidt recruit hospitalists was a matter of necessity. He was the only hospitalist practicing at St. Mary’s. Today, hospitalists continue to be in charge of recruiting at Dean’s 18-physician HM department, but now it’s by design.

“It’s critical for hospitalists to get involved, because doctors being recruited want to be part of a team. They want to know how they would be contributing,” says Dr. Schmidt, who is the medical director of eight departments, including the HM department. “I also think it’s important for people to know who they are going to be working with.”

For hospitalists looking to advance their careers, being recruited by a group that heavily involves its own hospitalists in the process can provide an opportunity to get an in-depth look at the prospective job and community, observes Kenneth G. Simone, DO, FHM, founder and president of Hospitalist and Practice Solutions, a practice-management consultancy based in Veazie, Maine. At the same time, hospitalists who are active in recruitment efforts are helping their own pursuits, says Dr. Simone, a member of Team Hospitalist and author of several HM-centered books, including “Hospitalist Recruit-ment and Retention.”

It gives new meaning to the saying recruiting is a two-way street. In this case, it’s a two-way street to success if hospitalists at both ends of the recruitment process use the situation to their advantage.

Candidate Advantage

If given the chance to interact with hospitalists at a potential job, a candidate should really pay attention to what the workday is like, Dr. Simone says. How is the workload? What kind of specialist support are the hospitalists getting? Are primary-care physicians (PCPs) referring patients to the group? Is there a good rapport with nursing staff?

“As a candidate, I should be asking why they are looking for a provider,” Dr. Simone says. “Is it growth? Is it turnover due to burnout?”

Having hospitalists engaged in the recruitment effort gives a candidate a great opportunity to ask questions he or she might not be comfortable asking of a director or hospital human resources personnel, Dr. Simone says. A candidate also gets a chance to observe the level of collegiality among prospective coworkers and gauge if the hospitalists are happy in the workplace and with the community.

—Kenneth G. Simone, DO, FHM, president, Hospitalist and Practice Solutions, Veazie, Maine, Team Hospitalist member

“They want to know that they are not just a cog in the wheel, not just a person filling a shift,” Dr. Schmidt explains. “By and large, they want to be part of a team.”

According to Drs. Simone and Schmidt, hospitalist job candidates should make an effort to:

- Ask potential colleagues to show them the local neighborhoods, services, and cultural and entertainment amenities;

- Get the e-mail addresses and phone numbers of the hospitalists to contact them with any follow-up questions after the interview and site visit; and

- Meet the group’s newest hospitalists, as they are the people who are in the best position to talk about the job transition.

A candidate’s goal is to gather enough information to determine if the job opportunity is the best fit for them and their family, Dr. Schmidt says. But candidates must remember that the time they spend and the conversations they share with the group’s hospitalists are still part of the interview process, Dr. Simone emphasizes. “If the person interviewing for a job has a lot of questions about vacation time and workload, that could send a signal that he or she doesn’t have a good work ethic,” he says.

Conversely, candidates should be wary of any program that doesn’t in some degree include their hospitalists in the recruitment process. It could mean that the group is trying to hide something, or that morale is so low that the hospitalists don’t want to promote the program. “I personally would be very uncomfortable not knowing who my partners would be,” Dr. Schmidt says.

Other red flags to look out for are constant references to the job’s competitive salary, which could indicate problems in other areas that the hospitalist practice is trying to mask, and no references to challenging issues the group is facing. If the group appears too good to be true, it probably is, Dr. Simone says.

Recruitment = Leadership

Hospitalists who get involved in their group’s recruitment efforts show their employer and supervisor that they are team players and care about the group and its future. It shows they are willing to help the program beyond providing patient care, and it demonstrates to both current and future employers that they have valuable professional characteristics and skills.

“Hospitalists who are good at recruiting show that they are a leader, a good communicator, and a positive person,” Dr. Simone says. “They can put this on a resume and give examples of what they did to help bring a quality provider to the team.”

When recruiting, be honest about the program’s strengths and weaknesses. “You want to avoid telling a candidate something a program is not,” Dr. Schmidt says. “You should be open about the program’s goals, workload, and expectations.”

Hospitalists who help in recruiting can frame the challenges a program is facing in a positive light. If an HM program is having trouble with, for example, a pulmonology group that is understaffed, the hospitalist recruiting candidates could explain the program is temporarily cross-covering patients at night until a new specialist can be found, Dr. Simone explains. He also notes it’s always best to place negatives into a context that shows the hospitalist group is working on a solution.

Getting engaged in recruiting also helps a hospitalist improve their current job by strengthening their team with good doctors who care about doing quality work, Drs. Schmidt and Simone say.

And that is more important than building a resume. TH

Lisa Ryan is a freelance writer based in New Jersey.

Brad Schmidt, MD, can remember recruiting hospitalists to the HM program at Dean Clinic at St. Mary’s Hospital in Madison, Wis., seven years ago. He was a young doctor, just a couple of years removed from residency.

Back then, having Dr. Schmidt recruit hospitalists was a matter of necessity. He was the only hospitalist practicing at St. Mary’s. Today, hospitalists continue to be in charge of recruiting at Dean’s 18-physician HM department, but now it’s by design.

“It’s critical for hospitalists to get involved, because doctors being recruited want to be part of a team. They want to know how they would be contributing,” says Dr. Schmidt, who is the medical director of eight departments, including the HM department. “I also think it’s important for people to know who they are going to be working with.”

For hospitalists looking to advance their careers, being recruited by a group that heavily involves its own hospitalists in the process can provide an opportunity to get an in-depth look at the prospective job and community, observes Kenneth G. Simone, DO, FHM, founder and president of Hospitalist and Practice Solutions, a practice-management consultancy based in Veazie, Maine. At the same time, hospitalists who are active in recruitment efforts are helping their own pursuits, says Dr. Simone, a member of Team Hospitalist and author of several HM-centered books, including “Hospitalist Recruit-ment and Retention.”

It gives new meaning to the saying recruiting is a two-way street. In this case, it’s a two-way street to success if hospitalists at both ends of the recruitment process use the situation to their advantage.

Candidate Advantage

If given the chance to interact with hospitalists at a potential job, a candidate should really pay attention to what the workday is like, Dr. Simone says. How is the workload? What kind of specialist support are the hospitalists getting? Are primary-care physicians (PCPs) referring patients to the group? Is there a good rapport with nursing staff?

“As a candidate, I should be asking why they are looking for a provider,” Dr. Simone says. “Is it growth? Is it turnover due to burnout?”

Having hospitalists engaged in the recruitment effort gives a candidate a great opportunity to ask questions he or she might not be comfortable asking of a director or hospital human resources personnel, Dr. Simone says. A candidate also gets a chance to observe the level of collegiality among prospective coworkers and gauge if the hospitalists are happy in the workplace and with the community.

—Kenneth G. Simone, DO, FHM, president, Hospitalist and Practice Solutions, Veazie, Maine, Team Hospitalist member

“They want to know that they are not just a cog in the wheel, not just a person filling a shift,” Dr. Schmidt explains. “By and large, they want to be part of a team.”

According to Drs. Simone and Schmidt, hospitalist job candidates should make an effort to:

- Ask potential colleagues to show them the local neighborhoods, services, and cultural and entertainment amenities;

- Get the e-mail addresses and phone numbers of the hospitalists to contact them with any follow-up questions after the interview and site visit; and

- Meet the group’s newest hospitalists, as they are the people who are in the best position to talk about the job transition.

A candidate’s goal is to gather enough information to determine if the job opportunity is the best fit for them and their family, Dr. Schmidt says. But candidates must remember that the time they spend and the conversations they share with the group’s hospitalists are still part of the interview process, Dr. Simone emphasizes. “If the person interviewing for a job has a lot of questions about vacation time and workload, that could send a signal that he or she doesn’t have a good work ethic,” he says.

Conversely, candidates should be wary of any program that doesn’t in some degree include their hospitalists in the recruitment process. It could mean that the group is trying to hide something, or that morale is so low that the hospitalists don’t want to promote the program. “I personally would be very uncomfortable not knowing who my partners would be,” Dr. Schmidt says.

Other red flags to look out for are constant references to the job’s competitive salary, which could indicate problems in other areas that the hospitalist practice is trying to mask, and no references to challenging issues the group is facing. If the group appears too good to be true, it probably is, Dr. Simone says.

Recruitment = Leadership

Hospitalists who get involved in their group’s recruitment efforts show their employer and supervisor that they are team players and care about the group and its future. It shows they are willing to help the program beyond providing patient care, and it demonstrates to both current and future employers that they have valuable professional characteristics and skills.

“Hospitalists who are good at recruiting show that they are a leader, a good communicator, and a positive person,” Dr. Simone says. “They can put this on a resume and give examples of what they did to help bring a quality provider to the team.”

When recruiting, be honest about the program’s strengths and weaknesses. “You want to avoid telling a candidate something a program is not,” Dr. Schmidt says. “You should be open about the program’s goals, workload, and expectations.”

Hospitalists who help in recruiting can frame the challenges a program is facing in a positive light. If an HM program is having trouble with, for example, a pulmonology group that is understaffed, the hospitalist recruiting candidates could explain the program is temporarily cross-covering patients at night until a new specialist can be found, Dr. Simone explains. He also notes it’s always best to place negatives into a context that shows the hospitalist group is working on a solution.

Getting engaged in recruiting also helps a hospitalist improve their current job by strengthening their team with good doctors who care about doing quality work, Drs. Schmidt and Simone say.

And that is more important than building a resume. TH

Lisa Ryan is a freelance writer based in New Jersey.

Brad Schmidt, MD, can remember recruiting hospitalists to the HM program at Dean Clinic at St. Mary’s Hospital in Madison, Wis., seven years ago. He was a young doctor, just a couple of years removed from residency.

Back then, having Dr. Schmidt recruit hospitalists was a matter of necessity. He was the only hospitalist practicing at St. Mary’s. Today, hospitalists continue to be in charge of recruiting at Dean’s 18-physician HM department, but now it’s by design.

“It’s critical for hospitalists to get involved, because doctors being recruited want to be part of a team. They want to know how they would be contributing,” says Dr. Schmidt, who is the medical director of eight departments, including the HM department. “I also think it’s important for people to know who they are going to be working with.”

For hospitalists looking to advance their careers, being recruited by a group that heavily involves its own hospitalists in the process can provide an opportunity to get an in-depth look at the prospective job and community, observes Kenneth G. Simone, DO, FHM, founder and president of Hospitalist and Practice Solutions, a practice-management consultancy based in Veazie, Maine. At the same time, hospitalists who are active in recruitment efforts are helping their own pursuits, says Dr. Simone, a member of Team Hospitalist and author of several HM-centered books, including “Hospitalist Recruit-ment and Retention.”

It gives new meaning to the saying recruiting is a two-way street. In this case, it’s a two-way street to success if hospitalists at both ends of the recruitment process use the situation to their advantage.

Candidate Advantage

If given the chance to interact with hospitalists at a potential job, a candidate should really pay attention to what the workday is like, Dr. Simone says. How is the workload? What kind of specialist support are the hospitalists getting? Are primary-care physicians (PCPs) referring patients to the group? Is there a good rapport with nursing staff?

“As a candidate, I should be asking why they are looking for a provider,” Dr. Simone says. “Is it growth? Is it turnover due to burnout?”

Having hospitalists engaged in the recruitment effort gives a candidate a great opportunity to ask questions he or she might not be comfortable asking of a director or hospital human resources personnel, Dr. Simone says. A candidate also gets a chance to observe the level of collegiality among prospective coworkers and gauge if the hospitalists are happy in the workplace and with the community.

—Kenneth G. Simone, DO, FHM, president, Hospitalist and Practice Solutions, Veazie, Maine, Team Hospitalist member

“They want to know that they are not just a cog in the wheel, not just a person filling a shift,” Dr. Schmidt explains. “By and large, they want to be part of a team.”

According to Drs. Simone and Schmidt, hospitalist job candidates should make an effort to:

- Ask potential colleagues to show them the local neighborhoods, services, and cultural and entertainment amenities;

- Get the e-mail addresses and phone numbers of the hospitalists to contact them with any follow-up questions after the interview and site visit; and

- Meet the group’s newest hospitalists, as they are the people who are in the best position to talk about the job transition.

A candidate’s goal is to gather enough information to determine if the job opportunity is the best fit for them and their family, Dr. Schmidt says. But candidates must remember that the time they spend and the conversations they share with the group’s hospitalists are still part of the interview process, Dr. Simone emphasizes. “If the person interviewing for a job has a lot of questions about vacation time and workload, that could send a signal that he or she doesn’t have a good work ethic,” he says.

Conversely, candidates should be wary of any program that doesn’t in some degree include their hospitalists in the recruitment process. It could mean that the group is trying to hide something, or that morale is so low that the hospitalists don’t want to promote the program. “I personally would be very uncomfortable not knowing who my partners would be,” Dr. Schmidt says.

Other red flags to look out for are constant references to the job’s competitive salary, which could indicate problems in other areas that the hospitalist practice is trying to mask, and no references to challenging issues the group is facing. If the group appears too good to be true, it probably is, Dr. Simone says.

Recruitment = Leadership

Hospitalists who get involved in their group’s recruitment efforts show their employer and supervisor that they are team players and care about the group and its future. It shows they are willing to help the program beyond providing patient care, and it demonstrates to both current and future employers that they have valuable professional characteristics and skills.

“Hospitalists who are good at recruiting show that they are a leader, a good communicator, and a positive person,” Dr. Simone says. “They can put this on a resume and give examples of what they did to help bring a quality provider to the team.”

When recruiting, be honest about the program’s strengths and weaknesses. “You want to avoid telling a candidate something a program is not,” Dr. Schmidt says. “You should be open about the program’s goals, workload, and expectations.”

Hospitalists who help in recruiting can frame the challenges a program is facing in a positive light. If an HM program is having trouble with, for example, a pulmonology group that is understaffed, the hospitalist recruiting candidates could explain the program is temporarily cross-covering patients at night until a new specialist can be found, Dr. Simone explains. He also notes it’s always best to place negatives into a context that shows the hospitalist group is working on a solution.

Getting engaged in recruiting also helps a hospitalist improve their current job by strengthening their team with good doctors who care about doing quality work, Drs. Schmidt and Simone say.

And that is more important than building a resume. TH

Lisa Ryan is a freelance writer based in New Jersey.

Change You Should Believe In

Christina Payne, MD, is a third-year resident at Emory University Hospital in Atlanta who will begin her first hospitalist job, with Emory in September. In spite of her dearth of practical experience, she already has experience researching one of the most vexing problems confronting HM: how to improve transitions of care.

Dr. Payne has been studying the benefits of a structured electronic tool that generates a standardized sign-out list of a hospital team’s full census at the time of shift change, compared with the usual, highly variable sign-out practices of medical residents. At a poster presentation at Internal Medicine 2010 in April in Toronto, Dr. Payne and colleagues reported that residents using the tool were twice as confident at performing handoffs, had lower rates of perceived near-miss events, and were happier.1

“Hospitalists everywhere are starting to realize the importance of trying to reduce opportunities for human error that occur during care transitions,” Dr. Payne says. “The biggest thing I learned from this research is the importance of standardizing the handoff process [with information communicated consistently].

“It is essential to keep communication lines open,” Dr. Payne adds. “No tool can replace the importance of communication between doctors and the need to sit down and talk. The ideal signout happens in a quiet room where the two of you can talk about active patients and achieve rapport. But, realistically, how often does that happen?”

Standardization is one of a handful of strategies hospitalists, researchers, and policymakers are using to tackle transitions—both in-hospital handoffs and post-discharge transitions—with outpatient care. Some hospitalists are using practice simulations and training strategies; others have implemented medication reconciliation checks at every discharge, checklists and other communication strategies, team-based quality-improvement (QI) initiatives, and new technologies to enhance and streamline communication. Some interventions follow the patient from the hospital to the community physician with a phone call, follow-up clinic, or other contact; others aim to empower the patient to be a better self-advocate. But for hospitalists, the challenge is to communicate the right amount of transfer information to the right receiver at the right time.

No matter the technique, the goal is the same: Improve the handoff and discharge process in a way that promotes efficiency and patient safety. And hospitalists are at the forefront of the changing landscape of care transitions.

Under the Microscope

Care transitions of all kinds are under the magnifying glass of national healthcare reform, with growing recognition of the need to make care safer and reduce the preventable, costly hospital readmissions caused by incomplete handoffs. Care transitions for hospitalists include internal handoffs, both at daily shift changes and at service changes when an outgoing provider is leaving after a period of consecutive daily shifts. These typically involve a sign-out process and face-to-face encounter, with some kind of written backup. One teaching institution reported that such handoffs take place 4,000 times per day in the hospital, or 1.6 million times per year.2

—Arpana Vidyarthi, MD, University of California at San Francisco

Geographical transitions can be from one floor or department to another, or out the hospital door to another facility or home. Transitions typically involve a discharge process and a written discharge summary. Care transitions also include hospital admissions, which put the hospitalist in the role of handoff receiver rather than initiator, plus a variety of other transitions involving nurses, physician extenders, and other practitioners.

Each transition is a major decision point in the course of a patient’s hospitalization; each transition also presents a time of heightened vulnerability (e.g., potential communication breakdowns, medication errors, patient anxiety or confusion, etc.). In fact, according to a Transitions of Care Consensus Policy Statement published in 2009 by SHM and five other medical societies, handoffs are ubiquitous in HM, with significant patient safety and quality deficiencies in handoffs existing in the current system.3

Poor communication at the time of handoff has been implicated in near-misses and adverse events in a variety of healthcare contexts, including 70% of hospital sentinel events studied by The Joint Commission, which named standardized handoffs (with an opportunity for interactive communication) as a National Patient Safety Goal in 2006.4 The federal government is studying care transitions, supporting demonstration projects for Medicare enrollees, and including readmission rates in national hospital report card data.

“Transitions of care and handoffs are a huge focus right now because of the increased fragmentation of care in the United States. Hospitalists are in charge of a greater percentage of hospitalized patients, which means more coordination of care is needed,” says Vineet Arora, MD, MA, FHM, assistant professor of medicine and associate director of the internal-medicine residency at the University of Chicago, and chair of the SHM task force on handoffs.

Inadequate communication and poor care transitions can undermine hospitalists’ best care-planning efforts, erode patients’ and families’ confidence and satisfaction with hospital care, and leave primary-care physicians (PCPs) feeling unsatisfied with the relationship. As many as 1 in 5 Medicare beneficiary hospitalizations result in a readmission within 30 days, and while not all of these are preventable, far too many are.5 Another prospective cohort study found that 1 in 5 patients discharged from the hospital to the home experienced an adverse event within three weeks of discharge.6 Complex comorbidities, advanced age, unknown PCP, and limited healthcare literacy present hospitalists with extremely difficult transitions.

Patient safety and cost control are the linchpins to national efforts to improve transitions of care. Dr. Arora recently coauthored an original research paper, which will be published in the Journal of Hospital Medicine in September, showing older hospitalized patients are twice as likely to report problems after discharge if their PCPs were not aware they were hospitalized.

“With escalating healthcare costs, people are looking at ways to save money and reduce redundant care,” Dr. Arora explains, pointing out, as an example, repeated tests resulting from inadequate communication between healthcare providers.

The System Must Change

“All of the effort we put into saving someone’s life—the years of experience, training, medical school, and residency—all of it comes to bear on that hospitalized patient. And it can all be unraveled at the time of discharge if it’s not handled properly,” says Arpana Vidyarthi, MD, a hospitalist and director of quality at the University of California at San Francisco.

Dr. Vidyarthi views in-hospital and discharge transitions as integrally related. “The analysis is similar, even if different techniques may be needed,” she says, adding that, fundamentally, it involves having a system that allows people—or forces them—to do the “right thing.”

That’s why achieving effective care transitions will require more than just a standardized tool or process, Dr. Vidyarthi says. “This is about understanding the ways people communicate and finding ways to train them to communicate better,” she says. “The problem we have is not a lack of information, but how to communicate what, to whom, and when.”

What’s really needed, Dr. Vidyarthi says, is a hospital’s commitment to more effective transitions and its hospitalists’ leadership in driving a comprehensive, multidisciplinary, team- and evidence-based QI process. The new process should be a QI-based solution to a hospital’s care-transitions issues. “Before you can standardize your process, you need to understand it,” she says. “This is a complex problem, and it needs a multifaceted solution. But this lies squarely within the hospitalist arena. We’re part of everything that happens in the hospital.

—Anuj Dalal, MD, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston

Hospital administrators are looking to HM to solve transition and readmission problems now, says Tina Budnitz, MPH, BOOST Project Director (Better Outcomes for Older Adults through Safe Transitions). She expects the scrutiny from the C-suite, legislators, and watchdog groups to increase as the spotlight continues to shine on the healthcare system.

“Any hospitalist can act as a leader in their institution,” Budnitz says. “Be a change agent, pull a group together, and start asking questions: Do we have safe care-transitions practices and processes in place? Just by asking the right question, you can be a catalyst for the system.”

Budnitz also emphasizes the importance of teamwork in the hospital setting. “How can I help my teammates? What am I communicating to the nurses on rounds?” she says. “Can you initiate dialogue with your outpatient medical groups: ‘These faxes we’re sending you—is that information getting to you in ways and times that are helpful? And, by the way, when your patient is admitted, this information would really help me.’ ”

Innovative Strategies

One of the most important initiatives responding to concerns about care transitions is Project BOOST (www.hos pitalmedicine.org/BOOST), a comprehensive toolkit for improving a hospital’s transitions of care. The project aims to build a national consensus for best practices in transitions; collaborate with representatives from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), and the Joint Commission; and develop a national resource library, Budnitz says.

“Project BOOST not only puts forth best practices for admitting patients, planning for discharge, and then doing the discharge, it also helps show facilities how to change their systems, with resources and tools for analyzing and re-engineering the system,” she says. “Sites get one-to-one assistance from a mentor.”

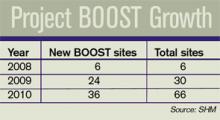

Six hospitals signed on to the pilot program in 2008; 24 more joined last year. In January, SHM announced a collaborative with the University of Michigan and Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan for 15 Michigan hospitals to receive training and mentorship starting in May. And last month, SHM and the California HealthCare Foundation announced a Project BOOST initiative for 20 of the health system’s hospitals (see “California Dreamin’”, p. 6). Other free resources offered on the BOOST Web portal include clinical, data collection, and project management tools. SHM also has a DVD that explains how to use the “teachback” method to improve communication with patients.

Jennifer Myers, MD, FHM, assistant professor of clinical medicine and patient-safety officer at the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia, is a Project BOOST participant who spearheaded a process change to improve the quality of her facility’s discharge summary, along with accompanying resident education.7 The discharge summary recently was integrated with the hospital’s electronic health record (EHR) system.

“We’ve gone from dictating the discharge summary to an electronic version completed by the hospitalist, with prompts for key components of the summary, which allows us to create summaries more efficiently—ideally on the day of discharge, but usually within 48 hours,” Dr. Myers says. “We previously researched whether teaching made a difference in the quality of discharges; we found that it did. So we look forward to standardizing our teaching approach around this important topic for all residents.”

Another care-transitions innovation receiving a lot of attention from the government and the private sector is Project RED (Re-Engineered Discharge), led by Brian Jack, MD, vice chair of the department of family medicine at Boston Medical Center. The Project RED research group develops and tests strategies to improve the hospital discharge process to promote patient safety and reduce rehospitalization rates.

“We used re-engineering tools borrowed from other fields, brought together experts from all over the hospital, divided up the whole discharge process, and identified key principles,” Dr. Jack explains. The resulting discharge strategy is reflected in an 11-item checklist of discrete, mutually reinforcing components, which have been shown to reduce rehospitalization rates by 32% while raising patient satisfaction.8 It includes comprehensive discharge and after-hospital plans, a nurse discharge advocate, and a medication reconciliation phone call to the patient. A virtual “patient advocate,” a computerized avatar named Louise, is now being tested. If successful, it will allow patients to interact with a touch-screen teacher of the after-care plan who has time to work at the patient’s pace.

Technology and Transitions

Informatics can be a key player in facilitating care transitions, says Anuj Dalal, MD, a hospitalist and instructor in medicine at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston. He is using one of his hospital’s technological strengths—a well-established, firewall-protected e-mail system—to help improve the discharge process.

“We decided to try to improve awareness of test results pending at the time of discharge,” Dr. Dalal explains. “We created an intervention that automatically triggers an e-mail with the finalized test results to the responsible providers. The intervention creates a loop of communication between the inpatient attending and the PCP. What we hope to show in our research over the next year or two is whether the intervention actually increases awareness of test results by providers.”

One thing to remember is that “all kinds of things can go wrong with care transitions,” no matter the size of the institution, the experience of the staff, or technological limitations, says Vineet Chopra, MD, FACP, a hospitalist at the University of Michigan Health System in Ann Arbor. “The problems of transitions vary from place to place, day to day, time of day, shift changes; and let’s not forget physician extenders and the other members of the healthcare team,” he says. “The more complicated the team, the more complicated the information needing to be handed off becomes.”

Before he joined the group at the university, Dr. Chopra worked at a community hospital, St. Joseph’s Mercy Hospital in Hot Springs, Ark. “It’s hard to come up with a one-size-fits-all solution when there are so many variables,” he says. At the community hospital, “we mandated that the hospitalist call the PCP at the time of discharge. At the academic medical center, we share an EHR with the PCPs and can reach them electronically. We are required to have the discharge summary in the computer before the patient leaves the hospital, and we mandate that hospitalists are reachable by e-mail or phone when they are off.

“I’m not a believer in throwing more technology at problems and just adding more layers of information tools,” Dr. Chopra adds. “Hospitalists who used to carry stethoscopes now also have a clipboard, phone, pager, PDA, and nine different signouts in their pockets. What we want to do is make their life easier. Here, we are looking at technology as a means to do that.”

Dr. Chopra and hospitalist colleague Prasanth Gosineni, MD, have been working with an Ann Arbor tech company called Synaptin to develop a lightweight, mobile client application designed to work on smartphones. Still in pilot testing, it would allow for task-oriented and priority-based messaging in real time and the systematic transfer of important information for the next hospitalist shift.

“You need to be able to share information in a systematic way, but that’s only half of the answer. The other half is the ability to ask specific questions,” Dr. Chopra says. “Technology doesn’t take away from the face-to-face encounter that needs to happen. Nothing will replace face time, but part of the solution is to provide data efficiently and in a way that is easily accessible.”

Dr. Chopra admits that EHR presents both positives and negatives to improved transitions and patient care, “depending on how well it works and what smart features it offers,” he says, “but also recognizing that EHR and other technologies have also taken us farther away from face-to-face exchanges. Some would say that’s part of the problem.”

Handoffs, discharges, and other transitions are ubiquitous in HM—and fraught with the potential for costly and harmful errors. The ideal of an interactive, face-to-face handoff simply is not available for many care transitions. However, hospitalists are challenged to find solutions that will work in their hospitals, with their teams, and their types of patients. Patients and policymakers expect nothing less. TH

Larry Beresford is a freelance writer based in Oakland, Calif.

References

- Payne C, Stein J, Dressler D. Implementation of a structured electronic tool to improve patient handoffs and resident satisfaction. Poster abstract: Internal Medicine 2010, April 21-24, 2010, Toronto.

- Vidyarthi AR. Triple Handoff. AHRQ WebM&M website. Available at: webmm.ahrq.gov/case.aspx? caseID=134. Published May 2006. Accessed May 29, 2010.

- Snow V, Beck D, Budnitz T, et al. Transitions of Care Consensus Policy Statement: American College of Physicians, Society of General Internal Medicine, Society of Hospital Medicine, American Geriatrics Society, American College of Emergency Physicians, and Society for Academic Emergency Medicine. J Hosp Med. 2009;4(6):364-370.

- 2006 National Patient Safety Goals. The Joint Commission website. Available at: www.jointcommission.org/PatientSafety/NationalPatientSafetyGoals/06_npsgs.htm. Accessed June 8, 2010.

- Jencks SF, Williams MV, Coleman EA. Rehospitalizations among patients in the Medicare fee-for-service program. N Engl J Med. 2009; 2:360:1418-1428.

- Forster AJ, Murff HJ, Peterson JF, Gandhi TK, Bates DW. The incidence and severity of adverse events affecting patients after discharge from the hospital. Ann Intern Med. 2003;138(3):161-167.

- Myers JS, Jaipaul CK, Kogan JR, Krekun S, Bellini LM, Shea JA. Are discharge summaries teachable? The effects of a discharge summary curriculum on the quality of discharge summaries in an internal medicine residency program. Acad Med. 2006; 81(10):S5-S8.

- Jack BW, Chetty VK, Anthony D, et al. A reengineered hospital discharge program to decrease rehospitalization: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150(3):178-187.

- Arora VM, Manjarrez E, Dressler DD, Basaviah P, Halasyamani L, Kripalani S. Hospitalist handoffs: a systematic review and task force recommendations. J Hosp Med. 2009;4(7): 433-440.

- Halasyamani L, Kripalani S, Coleman E, et al. Transition of care for hospitalized elderly patients—development of a discharge checklist for hospitalists. J Hosp Med. 2006;1(6):354-360.

- Schnipper JL, Kirwin JL, Cotugno MC, et al. Role of pharmacist counseling in preventing adverse drug events after hospitalization. Arch Int Med. 2006;166(5):565-571.

- Dudas V, Bookwalter T, Kerr KM, Pantilat SZ. The impact of follow-up telephone calls to patients after hospitalization. Am J Med. 2001;111(9B): 26S-30S.

Christina Payne, MD, is a third-year resident at Emory University Hospital in Atlanta who will begin her first hospitalist job, with Emory in September. In spite of her dearth of practical experience, she already has experience researching one of the most vexing problems confronting HM: how to improve transitions of care.

Dr. Payne has been studying the benefits of a structured electronic tool that generates a standardized sign-out list of a hospital team’s full census at the time of shift change, compared with the usual, highly variable sign-out practices of medical residents. At a poster presentation at Internal Medicine 2010 in April in Toronto, Dr. Payne and colleagues reported that residents using the tool were twice as confident at performing handoffs, had lower rates of perceived near-miss events, and were happier.1

“Hospitalists everywhere are starting to realize the importance of trying to reduce opportunities for human error that occur during care transitions,” Dr. Payne says. “The biggest thing I learned from this research is the importance of standardizing the handoff process [with information communicated consistently].

“It is essential to keep communication lines open,” Dr. Payne adds. “No tool can replace the importance of communication between doctors and the need to sit down and talk. The ideal signout happens in a quiet room where the two of you can talk about active patients and achieve rapport. But, realistically, how often does that happen?”

Standardization is one of a handful of strategies hospitalists, researchers, and policymakers are using to tackle transitions—both in-hospital handoffs and post-discharge transitions—with outpatient care. Some hospitalists are using practice simulations and training strategies; others have implemented medication reconciliation checks at every discharge, checklists and other communication strategies, team-based quality-improvement (QI) initiatives, and new technologies to enhance and streamline communication. Some interventions follow the patient from the hospital to the community physician with a phone call, follow-up clinic, or other contact; others aim to empower the patient to be a better self-advocate. But for hospitalists, the challenge is to communicate the right amount of transfer information to the right receiver at the right time.

No matter the technique, the goal is the same: Improve the handoff and discharge process in a way that promotes efficiency and patient safety. And hospitalists are at the forefront of the changing landscape of care transitions.

Under the Microscope

Care transitions of all kinds are under the magnifying glass of national healthcare reform, with growing recognition of the need to make care safer and reduce the preventable, costly hospital readmissions caused by incomplete handoffs. Care transitions for hospitalists include internal handoffs, both at daily shift changes and at service changes when an outgoing provider is leaving after a period of consecutive daily shifts. These typically involve a sign-out process and face-to-face encounter, with some kind of written backup. One teaching institution reported that such handoffs take place 4,000 times per day in the hospital, or 1.6 million times per year.2

—Arpana Vidyarthi, MD, University of California at San Francisco

Geographical transitions can be from one floor or department to another, or out the hospital door to another facility or home. Transitions typically involve a discharge process and a written discharge summary. Care transitions also include hospital admissions, which put the hospitalist in the role of handoff receiver rather than initiator, plus a variety of other transitions involving nurses, physician extenders, and other practitioners.

Each transition is a major decision point in the course of a patient’s hospitalization; each transition also presents a time of heightened vulnerability (e.g., potential communication breakdowns, medication errors, patient anxiety or confusion, etc.). In fact, according to a Transitions of Care Consensus Policy Statement published in 2009 by SHM and five other medical societies, handoffs are ubiquitous in HM, with significant patient safety and quality deficiencies in handoffs existing in the current system.3

Poor communication at the time of handoff has been implicated in near-misses and adverse events in a variety of healthcare contexts, including 70% of hospital sentinel events studied by The Joint Commission, which named standardized handoffs (with an opportunity for interactive communication) as a National Patient Safety Goal in 2006.4 The federal government is studying care transitions, supporting demonstration projects for Medicare enrollees, and including readmission rates in national hospital report card data.

“Transitions of care and handoffs are a huge focus right now because of the increased fragmentation of care in the United States. Hospitalists are in charge of a greater percentage of hospitalized patients, which means more coordination of care is needed,” says Vineet Arora, MD, MA, FHM, assistant professor of medicine and associate director of the internal-medicine residency at the University of Chicago, and chair of the SHM task force on handoffs.

Inadequate communication and poor care transitions can undermine hospitalists’ best care-planning efforts, erode patients’ and families’ confidence and satisfaction with hospital care, and leave primary-care physicians (PCPs) feeling unsatisfied with the relationship. As many as 1 in 5 Medicare beneficiary hospitalizations result in a readmission within 30 days, and while not all of these are preventable, far too many are.5 Another prospective cohort study found that 1 in 5 patients discharged from the hospital to the home experienced an adverse event within three weeks of discharge.6 Complex comorbidities, advanced age, unknown PCP, and limited healthcare literacy present hospitalists with extremely difficult transitions.

Patient safety and cost control are the linchpins to national efforts to improve transitions of care. Dr. Arora recently coauthored an original research paper, which will be published in the Journal of Hospital Medicine in September, showing older hospitalized patients are twice as likely to report problems after discharge if their PCPs were not aware they were hospitalized.

“With escalating healthcare costs, people are looking at ways to save money and reduce redundant care,” Dr. Arora explains, pointing out, as an example, repeated tests resulting from inadequate communication between healthcare providers.

The System Must Change

“All of the effort we put into saving someone’s life—the years of experience, training, medical school, and residency—all of it comes to bear on that hospitalized patient. And it can all be unraveled at the time of discharge if it’s not handled properly,” says Arpana Vidyarthi, MD, a hospitalist and director of quality at the University of California at San Francisco.

Dr. Vidyarthi views in-hospital and discharge transitions as integrally related. “The analysis is similar, even if different techniques may be needed,” she says, adding that, fundamentally, it involves having a system that allows people—or forces them—to do the “right thing.”

That’s why achieving effective care transitions will require more than just a standardized tool or process, Dr. Vidyarthi says. “This is about understanding the ways people communicate and finding ways to train them to communicate better,” she says. “The problem we have is not a lack of information, but how to communicate what, to whom, and when.”

What’s really needed, Dr. Vidyarthi says, is a hospital’s commitment to more effective transitions and its hospitalists’ leadership in driving a comprehensive, multidisciplinary, team- and evidence-based QI process. The new process should be a QI-based solution to a hospital’s care-transitions issues. “Before you can standardize your process, you need to understand it,” she says. “This is a complex problem, and it needs a multifaceted solution. But this lies squarely within the hospitalist arena. We’re part of everything that happens in the hospital.

—Anuj Dalal, MD, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston

Hospital administrators are looking to HM to solve transition and readmission problems now, says Tina Budnitz, MPH, BOOST Project Director (Better Outcomes for Older Adults through Safe Transitions). She expects the scrutiny from the C-suite, legislators, and watchdog groups to increase as the spotlight continues to shine on the healthcare system.

“Any hospitalist can act as a leader in their institution,” Budnitz says. “Be a change agent, pull a group together, and start asking questions: Do we have safe care-transitions practices and processes in place? Just by asking the right question, you can be a catalyst for the system.”

Budnitz also emphasizes the importance of teamwork in the hospital setting. “How can I help my teammates? What am I communicating to the nurses on rounds?” she says. “Can you initiate dialogue with your outpatient medical groups: ‘These faxes we’re sending you—is that information getting to you in ways and times that are helpful? And, by the way, when your patient is admitted, this information would really help me.’ ”

Innovative Strategies

One of the most important initiatives responding to concerns about care transitions is Project BOOST (www.hos pitalmedicine.org/BOOST), a comprehensive toolkit for improving a hospital’s transitions of care. The project aims to build a national consensus for best practices in transitions; collaborate with representatives from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), and the Joint Commission; and develop a national resource library, Budnitz says.

“Project BOOST not only puts forth best practices for admitting patients, planning for discharge, and then doing the discharge, it also helps show facilities how to change their systems, with resources and tools for analyzing and re-engineering the system,” she says. “Sites get one-to-one assistance from a mentor.”

Six hospitals signed on to the pilot program in 2008; 24 more joined last year. In January, SHM announced a collaborative with the University of Michigan and Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan for 15 Michigan hospitals to receive training and mentorship starting in May. And last month, SHM and the California HealthCare Foundation announced a Project BOOST initiative for 20 of the health system’s hospitals (see “California Dreamin’”, p. 6). Other free resources offered on the BOOST Web portal include clinical, data collection, and project management tools. SHM also has a DVD that explains how to use the “teachback” method to improve communication with patients.

Jennifer Myers, MD, FHM, assistant professor of clinical medicine and patient-safety officer at the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia, is a Project BOOST participant who spearheaded a process change to improve the quality of her facility’s discharge summary, along with accompanying resident education.7 The discharge summary recently was integrated with the hospital’s electronic health record (EHR) system.

“We’ve gone from dictating the discharge summary to an electronic version completed by the hospitalist, with prompts for key components of the summary, which allows us to create summaries more efficiently—ideally on the day of discharge, but usually within 48 hours,” Dr. Myers says. “We previously researched whether teaching made a difference in the quality of discharges; we found that it did. So we look forward to standardizing our teaching approach around this important topic for all residents.”

Another care-transitions innovation receiving a lot of attention from the government and the private sector is Project RED (Re-Engineered Discharge), led by Brian Jack, MD, vice chair of the department of family medicine at Boston Medical Center. The Project RED research group develops and tests strategies to improve the hospital discharge process to promote patient safety and reduce rehospitalization rates.

“We used re-engineering tools borrowed from other fields, brought together experts from all over the hospital, divided up the whole discharge process, and identified key principles,” Dr. Jack explains. The resulting discharge strategy is reflected in an 11-item checklist of discrete, mutually reinforcing components, which have been shown to reduce rehospitalization rates by 32% while raising patient satisfaction.8 It includes comprehensive discharge and after-hospital plans, a nurse discharge advocate, and a medication reconciliation phone call to the patient. A virtual “patient advocate,” a computerized avatar named Louise, is now being tested. If successful, it will allow patients to interact with a touch-screen teacher of the after-care plan who has time to work at the patient’s pace.

Technology and Transitions

Informatics can be a key player in facilitating care transitions, says Anuj Dalal, MD, a hospitalist and instructor in medicine at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston. He is using one of his hospital’s technological strengths—a well-established, firewall-protected e-mail system—to help improve the discharge process.

“We decided to try to improve awareness of test results pending at the time of discharge,” Dr. Dalal explains. “We created an intervention that automatically triggers an e-mail with the finalized test results to the responsible providers. The intervention creates a loop of communication between the inpatient attending and the PCP. What we hope to show in our research over the next year or two is whether the intervention actually increases awareness of test results by providers.”

One thing to remember is that “all kinds of things can go wrong with care transitions,” no matter the size of the institution, the experience of the staff, or technological limitations, says Vineet Chopra, MD, FACP, a hospitalist at the University of Michigan Health System in Ann Arbor. “The problems of transitions vary from place to place, day to day, time of day, shift changes; and let’s not forget physician extenders and the other members of the healthcare team,” he says. “The more complicated the team, the more complicated the information needing to be handed off becomes.”

Before he joined the group at the university, Dr. Chopra worked at a community hospital, St. Joseph’s Mercy Hospital in Hot Springs, Ark. “It’s hard to come up with a one-size-fits-all solution when there are so many variables,” he says. At the community hospital, “we mandated that the hospitalist call the PCP at the time of discharge. At the academic medical center, we share an EHR with the PCPs and can reach them electronically. We are required to have the discharge summary in the computer before the patient leaves the hospital, and we mandate that hospitalists are reachable by e-mail or phone when they are off.

“I’m not a believer in throwing more technology at problems and just adding more layers of information tools,” Dr. Chopra adds. “Hospitalists who used to carry stethoscopes now also have a clipboard, phone, pager, PDA, and nine different signouts in their pockets. What we want to do is make their life easier. Here, we are looking at technology as a means to do that.”

Dr. Chopra and hospitalist colleague Prasanth Gosineni, MD, have been working with an Ann Arbor tech company called Synaptin to develop a lightweight, mobile client application designed to work on smartphones. Still in pilot testing, it would allow for task-oriented and priority-based messaging in real time and the systematic transfer of important information for the next hospitalist shift.

“You need to be able to share information in a systematic way, but that’s only half of the answer. The other half is the ability to ask specific questions,” Dr. Chopra says. “Technology doesn’t take away from the face-to-face encounter that needs to happen. Nothing will replace face time, but part of the solution is to provide data efficiently and in a way that is easily accessible.”

Dr. Chopra admits that EHR presents both positives and negatives to improved transitions and patient care, “depending on how well it works and what smart features it offers,” he says, “but also recognizing that EHR and other technologies have also taken us farther away from face-to-face exchanges. Some would say that’s part of the problem.”

Handoffs, discharges, and other transitions are ubiquitous in HM—and fraught with the potential for costly and harmful errors. The ideal of an interactive, face-to-face handoff simply is not available for many care transitions. However, hospitalists are challenged to find solutions that will work in their hospitals, with their teams, and their types of patients. Patients and policymakers expect nothing less. TH

Larry Beresford is a freelance writer based in Oakland, Calif.

References

- Payne C, Stein J, Dressler D. Implementation of a structured electronic tool to improve patient handoffs and resident satisfaction. Poster abstract: Internal Medicine 2010, April 21-24, 2010, Toronto.

- Vidyarthi AR. Triple Handoff. AHRQ WebM&M website. Available at: webmm.ahrq.gov/case.aspx? caseID=134. Published May 2006. Accessed May 29, 2010.

- Snow V, Beck D, Budnitz T, et al. Transitions of Care Consensus Policy Statement: American College of Physicians, Society of General Internal Medicine, Society of Hospital Medicine, American Geriatrics Society, American College of Emergency Physicians, and Society for Academic Emergency Medicine. J Hosp Med. 2009;4(6):364-370.

- 2006 National Patient Safety Goals. The Joint Commission website. Available at: www.jointcommission.org/PatientSafety/NationalPatientSafetyGoals/06_npsgs.htm. Accessed June 8, 2010.

- Jencks SF, Williams MV, Coleman EA. Rehospitalizations among patients in the Medicare fee-for-service program. N Engl J Med. 2009; 2:360:1418-1428.

- Forster AJ, Murff HJ, Peterson JF, Gandhi TK, Bates DW. The incidence and severity of adverse events affecting patients after discharge from the hospital. Ann Intern Med. 2003;138(3):161-167.

- Myers JS, Jaipaul CK, Kogan JR, Krekun S, Bellini LM, Shea JA. Are discharge summaries teachable? The effects of a discharge summary curriculum on the quality of discharge summaries in an internal medicine residency program. Acad Med. 2006; 81(10):S5-S8.

- Jack BW, Chetty VK, Anthony D, et al. A reengineered hospital discharge program to decrease rehospitalization: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150(3):178-187.

- Arora VM, Manjarrez E, Dressler DD, Basaviah P, Halasyamani L, Kripalani S. Hospitalist handoffs: a systematic review and task force recommendations. J Hosp Med. 2009;4(7): 433-440.

- Halasyamani L, Kripalani S, Coleman E, et al. Transition of care for hospitalized elderly patients—development of a discharge checklist for hospitalists. J Hosp Med. 2006;1(6):354-360.

- Schnipper JL, Kirwin JL, Cotugno MC, et al. Role of pharmacist counseling in preventing adverse drug events after hospitalization. Arch Int Med. 2006;166(5):565-571.

- Dudas V, Bookwalter T, Kerr KM, Pantilat SZ. The impact of follow-up telephone calls to patients after hospitalization. Am J Med. 2001;111(9B): 26S-30S.

Christina Payne, MD, is a third-year resident at Emory University Hospital in Atlanta who will begin her first hospitalist job, with Emory in September. In spite of her dearth of practical experience, she already has experience researching one of the most vexing problems confronting HM: how to improve transitions of care.

Dr. Payne has been studying the benefits of a structured electronic tool that generates a standardized sign-out list of a hospital team’s full census at the time of shift change, compared with the usual, highly variable sign-out practices of medical residents. At a poster presentation at Internal Medicine 2010 in April in Toronto, Dr. Payne and colleagues reported that residents using the tool were twice as confident at performing handoffs, had lower rates of perceived near-miss events, and were happier.1

“Hospitalists everywhere are starting to realize the importance of trying to reduce opportunities for human error that occur during care transitions,” Dr. Payne says. “The biggest thing I learned from this research is the importance of standardizing the handoff process [with information communicated consistently].

“It is essential to keep communication lines open,” Dr. Payne adds. “No tool can replace the importance of communication between doctors and the need to sit down and talk. The ideal signout happens in a quiet room where the two of you can talk about active patients and achieve rapport. But, realistically, how often does that happen?”

Standardization is one of a handful of strategies hospitalists, researchers, and policymakers are using to tackle transitions—both in-hospital handoffs and post-discharge transitions—with outpatient care. Some hospitalists are using practice simulations and training strategies; others have implemented medication reconciliation checks at every discharge, checklists and other communication strategies, team-based quality-improvement (QI) initiatives, and new technologies to enhance and streamline communication. Some interventions follow the patient from the hospital to the community physician with a phone call, follow-up clinic, or other contact; others aim to empower the patient to be a better self-advocate. But for hospitalists, the challenge is to communicate the right amount of transfer information to the right receiver at the right time.

No matter the technique, the goal is the same: Improve the handoff and discharge process in a way that promotes efficiency and patient safety. And hospitalists are at the forefront of the changing landscape of care transitions.

Under the Microscope

Care transitions of all kinds are under the magnifying glass of national healthcare reform, with growing recognition of the need to make care safer and reduce the preventable, costly hospital readmissions caused by incomplete handoffs. Care transitions for hospitalists include internal handoffs, both at daily shift changes and at service changes when an outgoing provider is leaving after a period of consecutive daily shifts. These typically involve a sign-out process and face-to-face encounter, with some kind of written backup. One teaching institution reported that such handoffs take place 4,000 times per day in the hospital, or 1.6 million times per year.2

—Arpana Vidyarthi, MD, University of California at San Francisco

Geographical transitions can be from one floor or department to another, or out the hospital door to another facility or home. Transitions typically involve a discharge process and a written discharge summary. Care transitions also include hospital admissions, which put the hospitalist in the role of handoff receiver rather than initiator, plus a variety of other transitions involving nurses, physician extenders, and other practitioners.

Each transition is a major decision point in the course of a patient’s hospitalization; each transition also presents a time of heightened vulnerability (e.g., potential communication breakdowns, medication errors, patient anxiety or confusion, etc.). In fact, according to a Transitions of Care Consensus Policy Statement published in 2009 by SHM and five other medical societies, handoffs are ubiquitous in HM, with significant patient safety and quality deficiencies in handoffs existing in the current system.3

Poor communication at the time of handoff has been implicated in near-misses and adverse events in a variety of healthcare contexts, including 70% of hospital sentinel events studied by The Joint Commission, which named standardized handoffs (with an opportunity for interactive communication) as a National Patient Safety Goal in 2006.4 The federal government is studying care transitions, supporting demonstration projects for Medicare enrollees, and including readmission rates in national hospital report card data.

“Transitions of care and handoffs are a huge focus right now because of the increased fragmentation of care in the United States. Hospitalists are in charge of a greater percentage of hospitalized patients, which means more coordination of care is needed,” says Vineet Arora, MD, MA, FHM, assistant professor of medicine and associate director of the internal-medicine residency at the University of Chicago, and chair of the SHM task force on handoffs.

Inadequate communication and poor care transitions can undermine hospitalists’ best care-planning efforts, erode patients’ and families’ confidence and satisfaction with hospital care, and leave primary-care physicians (PCPs) feeling unsatisfied with the relationship. As many as 1 in 5 Medicare beneficiary hospitalizations result in a readmission within 30 days, and while not all of these are preventable, far too many are.5 Another prospective cohort study found that 1 in 5 patients discharged from the hospital to the home experienced an adverse event within three weeks of discharge.6 Complex comorbidities, advanced age, unknown PCP, and limited healthcare literacy present hospitalists with extremely difficult transitions.

Patient safety and cost control are the linchpins to national efforts to improve transitions of care. Dr. Arora recently coauthored an original research paper, which will be published in the Journal of Hospital Medicine in September, showing older hospitalized patients are twice as likely to report problems after discharge if their PCPs were not aware they were hospitalized.

“With escalating healthcare costs, people are looking at ways to save money and reduce redundant care,” Dr. Arora explains, pointing out, as an example, repeated tests resulting from inadequate communication between healthcare providers.

The System Must Change

“All of the effort we put into saving someone’s life—the years of experience, training, medical school, and residency—all of it comes to bear on that hospitalized patient. And it can all be unraveled at the time of discharge if it’s not handled properly,” says Arpana Vidyarthi, MD, a hospitalist and director of quality at the University of California at San Francisco.

Dr. Vidyarthi views in-hospital and discharge transitions as integrally related. “The analysis is similar, even if different techniques may be needed,” she says, adding that, fundamentally, it involves having a system that allows people—or forces them—to do the “right thing.”

That’s why achieving effective care transitions will require more than just a standardized tool or process, Dr. Vidyarthi says. “This is about understanding the ways people communicate and finding ways to train them to communicate better,” she says. “The problem we have is not a lack of information, but how to communicate what, to whom, and when.”

What’s really needed, Dr. Vidyarthi says, is a hospital’s commitment to more effective transitions and its hospitalists’ leadership in driving a comprehensive, multidisciplinary, team- and evidence-based QI process. The new process should be a QI-based solution to a hospital’s care-transitions issues. “Before you can standardize your process, you need to understand it,” she says. “This is a complex problem, and it needs a multifaceted solution. But this lies squarely within the hospitalist arena. We’re part of everything that happens in the hospital.

—Anuj Dalal, MD, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston

Hospital administrators are looking to HM to solve transition and readmission problems now, says Tina Budnitz, MPH, BOOST Project Director (Better Outcomes for Older Adults through Safe Transitions). She expects the scrutiny from the C-suite, legislators, and watchdog groups to increase as the spotlight continues to shine on the healthcare system.

“Any hospitalist can act as a leader in their institution,” Budnitz says. “Be a change agent, pull a group together, and start asking questions: Do we have safe care-transitions practices and processes in place? Just by asking the right question, you can be a catalyst for the system.”

Budnitz also emphasizes the importance of teamwork in the hospital setting. “How can I help my teammates? What am I communicating to the nurses on rounds?” she says. “Can you initiate dialogue with your outpatient medical groups: ‘These faxes we’re sending you—is that information getting to you in ways and times that are helpful? And, by the way, when your patient is admitted, this information would really help me.’ ”

Innovative Strategies

One of the most important initiatives responding to concerns about care transitions is Project BOOST (www.hos pitalmedicine.org/BOOST), a comprehensive toolkit for improving a hospital’s transitions of care. The project aims to build a national consensus for best practices in transitions; collaborate with representatives from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), and the Joint Commission; and develop a national resource library, Budnitz says.

“Project BOOST not only puts forth best practices for admitting patients, planning for discharge, and then doing the discharge, it also helps show facilities how to change their systems, with resources and tools for analyzing and re-engineering the system,” she says. “Sites get one-to-one assistance from a mentor.”

Six hospitals signed on to the pilot program in 2008; 24 more joined last year. In January, SHM announced a collaborative with the University of Michigan and Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan for 15 Michigan hospitals to receive training and mentorship starting in May. And last month, SHM and the California HealthCare Foundation announced a Project BOOST initiative for 20 of the health system’s hospitals (see “California Dreamin’”, p. 6). Other free resources offered on the BOOST Web portal include clinical, data collection, and project management tools. SHM also has a DVD that explains how to use the “teachback” method to improve communication with patients.

Jennifer Myers, MD, FHM, assistant professor of clinical medicine and patient-safety officer at the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia, is a Project BOOST participant who spearheaded a process change to improve the quality of her facility’s discharge summary, along with accompanying resident education.7 The discharge summary recently was integrated with the hospital’s electronic health record (EHR) system.

“We’ve gone from dictating the discharge summary to an electronic version completed by the hospitalist, with prompts for key components of the summary, which allows us to create summaries more efficiently—ideally on the day of discharge, but usually within 48 hours,” Dr. Myers says. “We previously researched whether teaching made a difference in the quality of discharges; we found that it did. So we look forward to standardizing our teaching approach around this important topic for all residents.”

Another care-transitions innovation receiving a lot of attention from the government and the private sector is Project RED (Re-Engineered Discharge), led by Brian Jack, MD, vice chair of the department of family medicine at Boston Medical Center. The Project RED research group develops and tests strategies to improve the hospital discharge process to promote patient safety and reduce rehospitalization rates.

“We used re-engineering tools borrowed from other fields, brought together experts from all over the hospital, divided up the whole discharge process, and identified key principles,” Dr. Jack explains. The resulting discharge strategy is reflected in an 11-item checklist of discrete, mutually reinforcing components, which have been shown to reduce rehospitalization rates by 32% while raising patient satisfaction.8 It includes comprehensive discharge and after-hospital plans, a nurse discharge advocate, and a medication reconciliation phone call to the patient. A virtual “patient advocate,” a computerized avatar named Louise, is now being tested. If successful, it will allow patients to interact with a touch-screen teacher of the after-care plan who has time to work at the patient’s pace.

Technology and Transitions

Informatics can be a key player in facilitating care transitions, says Anuj Dalal, MD, a hospitalist and instructor in medicine at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston. He is using one of his hospital’s technological strengths—a well-established, firewall-protected e-mail system—to help improve the discharge process.

“We decided to try to improve awareness of test results pending at the time of discharge,” Dr. Dalal explains. “We created an intervention that automatically triggers an e-mail with the finalized test results to the responsible providers. The intervention creates a loop of communication between the inpatient attending and the PCP. What we hope to show in our research over the next year or two is whether the intervention actually increases awareness of test results by providers.”

One thing to remember is that “all kinds of things can go wrong with care transitions,” no matter the size of the institution, the experience of the staff, or technological limitations, says Vineet Chopra, MD, FACP, a hospitalist at the University of Michigan Health System in Ann Arbor. “The problems of transitions vary from place to place, day to day, time of day, shift changes; and let’s not forget physician extenders and the other members of the healthcare team,” he says. “The more complicated the team, the more complicated the information needing to be handed off becomes.”

Before he joined the group at the university, Dr. Chopra worked at a community hospital, St. Joseph’s Mercy Hospital in Hot Springs, Ark. “It’s hard to come up with a one-size-fits-all solution when there are so many variables,” he says. At the community hospital, “we mandated that the hospitalist call the PCP at the time of discharge. At the academic medical center, we share an EHR with the PCPs and can reach them electronically. We are required to have the discharge summary in the computer before the patient leaves the hospital, and we mandate that hospitalists are reachable by e-mail or phone when they are off.

“I’m not a believer in throwing more technology at problems and just adding more layers of information tools,” Dr. Chopra adds. “Hospitalists who used to carry stethoscopes now also have a clipboard, phone, pager, PDA, and nine different signouts in their pockets. What we want to do is make their life easier. Here, we are looking at technology as a means to do that.”

Dr. Chopra and hospitalist colleague Prasanth Gosineni, MD, have been working with an Ann Arbor tech company called Synaptin to develop a lightweight, mobile client application designed to work on smartphones. Still in pilot testing, it would allow for task-oriented and priority-based messaging in real time and the systematic transfer of important information for the next hospitalist shift.

“You need to be able to share information in a systematic way, but that’s only half of the answer. The other half is the ability to ask specific questions,” Dr. Chopra says. “Technology doesn’t take away from the face-to-face encounter that needs to happen. Nothing will replace face time, but part of the solution is to provide data efficiently and in a way that is easily accessible.”

Dr. Chopra admits that EHR presents both positives and negatives to improved transitions and patient care, “depending on how well it works and what smart features it offers,” he says, “but also recognizing that EHR and other technologies have also taken us farther away from face-to-face exchanges. Some would say that’s part of the problem.”

Handoffs, discharges, and other transitions are ubiquitous in HM—and fraught with the potential for costly and harmful errors. The ideal of an interactive, face-to-face handoff simply is not available for many care transitions. However, hospitalists are challenged to find solutions that will work in their hospitals, with their teams, and their types of patients. Patients and policymakers expect nothing less. TH

Larry Beresford is a freelance writer based in Oakland, Calif.

References

- Payne C, Stein J, Dressler D. Implementation of a structured electronic tool to improve patient handoffs and resident satisfaction. Poster abstract: Internal Medicine 2010, April 21-24, 2010, Toronto.

- Vidyarthi AR. Triple Handoff. AHRQ WebM&M website. Available at: webmm.ahrq.gov/case.aspx? caseID=134. Published May 2006. Accessed May 29, 2010.

- Snow V, Beck D, Budnitz T, et al. Transitions of Care Consensus Policy Statement: American College of Physicians, Society of General Internal Medicine, Society of Hospital Medicine, American Geriatrics Society, American College of Emergency Physicians, and Society for Academic Emergency Medicine. J Hosp Med. 2009;4(6):364-370.

- 2006 National Patient Safety Goals. The Joint Commission website. Available at: www.jointcommission.org/PatientSafety/NationalPatientSafetyGoals/06_npsgs.htm. Accessed June 8, 2010.

- Jencks SF, Williams MV, Coleman EA. Rehospitalizations among patients in the Medicare fee-for-service program. N Engl J Med. 2009; 2:360:1418-1428.

- Forster AJ, Murff HJ, Peterson JF, Gandhi TK, Bates DW. The incidence and severity of adverse events affecting patients after discharge from the hospital. Ann Intern Med. 2003;138(3):161-167.

- Myers JS, Jaipaul CK, Kogan JR, Krekun S, Bellini LM, Shea JA. Are discharge summaries teachable? The effects of a discharge summary curriculum on the quality of discharge summaries in an internal medicine residency program. Acad Med. 2006; 81(10):S5-S8.

- Jack BW, Chetty VK, Anthony D, et al. A reengineered hospital discharge program to decrease rehospitalization: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150(3):178-187.

- Arora VM, Manjarrez E, Dressler DD, Basaviah P, Halasyamani L, Kripalani S. Hospitalist handoffs: a systematic review and task force recommendations. J Hosp Med. 2009;4(7): 433-440.

- Halasyamani L, Kripalani S, Coleman E, et al. Transition of care for hospitalized elderly patients—development of a discharge checklist for hospitalists. J Hosp Med. 2006;1(6):354-360.

- Schnipper JL, Kirwin JL, Cotugno MC, et al. Role of pharmacist counseling in preventing adverse drug events after hospitalization. Arch Int Med. 2006;166(5):565-571.

- Dudas V, Bookwalter T, Kerr KM, Pantilat SZ. The impact of follow-up telephone calls to patients after hospitalization. Am J Med. 2001;111(9B): 26S-30S.

California Dreamin’

Project BOOST, SHM’s popular mentorship program designed to help hospitals reduce readmissions, is headed to the most populous state in the country. In a joint venture with the California HealthCare Foundation, Project BOOST (Better Outcomes for Older Adults through Safe Transitions) will launch a groundbreaking, two-year program in 20 hospitals in the Golden State.

The California HealthCare Founda-tion will cover almost half of the $28,000 in tuition costs for each hospital accepted into the collaborative program. Individual sites will be responsible for the other $14,500.

In year one, hospitals will begin improving their discharge procedures using Project BOOST’s toolkit and one-on-one mentorships with leaders in the field. The second year of the project will focus on training additional mentors in California. The foundation has committed not only to improving outcomes in the first 20 sites, but also building a sustainable infrastructure that will allow gains to quickly spread throughout the state.

Recruiting for the California sites has just begun. Potential applicants can visit www.hospitalmedicine.org/boost for more information.

“California is a microcosm for the challenges and opportunities for hospitalized care in our healthcare system,” says Janet Nagamine, RN, MD, SFHM, program leader for the California BOOST program and an SHM board member. “We are very excited to work with the California HealthCare Foundation, one of the state’s leaders in healthcare quality improvement. … Their support will help California’s hospitals and primary-care physicians [PCPs] safely transition patients from hospital to home during that vulnerable period.”

Project BOOST’s Continued Expansion