User login

The Child With Persistent Hives

Persistent hives, or chronic urticaria, can be challenging to diagnose, treat, and manage. This condition is also somewhat common—I see it often at Miami Children's Hospital.

Persistent hives are distinctive from an acute presentation because they typically last 6 weeks or longer. They are not only frustrating for physicians—the etiology is identified in only a minority of affected children, but this disease can significantly impair quality of life for patients and their families.

Infections are a common cause of persistent hives. Other conditions to consider in your differential diagnosis include drug and food allergies, physical urticaria (caused by exposure to heat or cold), autoimmune disease, erythema multiforme minor, and dermatographism. Dermatographism is a condition in which stroking or scratching the skin with a dull instrument causes a raised welt, or wheal, to appear because of increased mast cell activation. The skin generally appears pale in the center with a red flare on either side. A physical allergy causes this type of urticaria.

In conjunction with the physical examination, review all medications taken in the last 6 weeks, including but not limited to new agents. Also ask the patient and parents about the type of foods the child consumed within the last several weeks with regularity.

A long-acting antihistamine, with 24-hour coverage, can be helpful. For some children with persistent hives, you may need to think outside the box and prescribe both a short-acting and long-acting antihistamine. The short-acting agent can be used to control an acute presentation while the long-acting drug provides maintenance.

If the condition improves with antihistamines and the hives are not interfering with quality of life or sleep, then you should feel comfortable treating the child.

If antihistamine therapy is not helpful, the lesions are interfering with lifestyle or sleep, or the patient complains of swelling, it is appropriate to refer the child to a specialist for additional work-up. Swelling is often a presenting sign with chronic urticaria, and typically it is generalized or affects the hands or face. The swelling often makes the patient and family uncomfortable.

If you decide to order laboratory testing prior to a specialist referral, a complete blood count, an erythrocyte sedimentation rate assay, a liver function test, and thyroid studies can be useful. But you also can simply refer the patient to an allergist or immunologist, and we can order the testing.

In contrast, a food-specific immunoglobulin G test is not helpful for the assessment of a child with persistent hives. This laboratory assay should not be ordered because it only adds to the cost of the diagnosis without aiding in the clinical diagnosis.

If you are fortunate and can identify the cause of the chronic urticaria—which only occurs in 5%-20% of cases—it calls for strict avoidance. This is another aspect where persistent hives differ from an acute presentation, because the etiology of an acute condition is more frequently found and subsequently may be avoided by the child.

Also educate the patient that persistent hives can be daily or episodic. Again, if the patient is lucky, the lesions resolve in less than 1 year. However, inform the patient that—in some cases—the hives can persist for several years.

Persistent hives, or chronic urticaria, can be challenging to diagnose, treat, and manage. This condition is also somewhat common—I see it often at Miami Children's Hospital.

Persistent hives are distinctive from an acute presentation because they typically last 6 weeks or longer. They are not only frustrating for physicians—the etiology is identified in only a minority of affected children, but this disease can significantly impair quality of life for patients and their families.

Infections are a common cause of persistent hives. Other conditions to consider in your differential diagnosis include drug and food allergies, physical urticaria (caused by exposure to heat or cold), autoimmune disease, erythema multiforme minor, and dermatographism. Dermatographism is a condition in which stroking or scratching the skin with a dull instrument causes a raised welt, or wheal, to appear because of increased mast cell activation. The skin generally appears pale in the center with a red flare on either side. A physical allergy causes this type of urticaria.

In conjunction with the physical examination, review all medications taken in the last 6 weeks, including but not limited to new agents. Also ask the patient and parents about the type of foods the child consumed within the last several weeks with regularity.

A long-acting antihistamine, with 24-hour coverage, can be helpful. For some children with persistent hives, you may need to think outside the box and prescribe both a short-acting and long-acting antihistamine. The short-acting agent can be used to control an acute presentation while the long-acting drug provides maintenance.

If the condition improves with antihistamines and the hives are not interfering with quality of life or sleep, then you should feel comfortable treating the child.

If antihistamine therapy is not helpful, the lesions are interfering with lifestyle or sleep, or the patient complains of swelling, it is appropriate to refer the child to a specialist for additional work-up. Swelling is often a presenting sign with chronic urticaria, and typically it is generalized or affects the hands or face. The swelling often makes the patient and family uncomfortable.

If you decide to order laboratory testing prior to a specialist referral, a complete blood count, an erythrocyte sedimentation rate assay, a liver function test, and thyroid studies can be useful. But you also can simply refer the patient to an allergist or immunologist, and we can order the testing.

In contrast, a food-specific immunoglobulin G test is not helpful for the assessment of a child with persistent hives. This laboratory assay should not be ordered because it only adds to the cost of the diagnosis without aiding in the clinical diagnosis.

If you are fortunate and can identify the cause of the chronic urticaria—which only occurs in 5%-20% of cases—it calls for strict avoidance. This is another aspect where persistent hives differ from an acute presentation, because the etiology of an acute condition is more frequently found and subsequently may be avoided by the child.

Also educate the patient that persistent hives can be daily or episodic. Again, if the patient is lucky, the lesions resolve in less than 1 year. However, inform the patient that—in some cases—the hives can persist for several years.

Persistent hives, or chronic urticaria, can be challenging to diagnose, treat, and manage. This condition is also somewhat common—I see it often at Miami Children's Hospital.

Persistent hives are distinctive from an acute presentation because they typically last 6 weeks or longer. They are not only frustrating for physicians—the etiology is identified in only a minority of affected children, but this disease can significantly impair quality of life for patients and their families.

Infections are a common cause of persistent hives. Other conditions to consider in your differential diagnosis include drug and food allergies, physical urticaria (caused by exposure to heat or cold), autoimmune disease, erythema multiforme minor, and dermatographism. Dermatographism is a condition in which stroking or scratching the skin with a dull instrument causes a raised welt, or wheal, to appear because of increased mast cell activation. The skin generally appears pale in the center with a red flare on either side. A physical allergy causes this type of urticaria.

In conjunction with the physical examination, review all medications taken in the last 6 weeks, including but not limited to new agents. Also ask the patient and parents about the type of foods the child consumed within the last several weeks with regularity.

A long-acting antihistamine, with 24-hour coverage, can be helpful. For some children with persistent hives, you may need to think outside the box and prescribe both a short-acting and long-acting antihistamine. The short-acting agent can be used to control an acute presentation while the long-acting drug provides maintenance.

If the condition improves with antihistamines and the hives are not interfering with quality of life or sleep, then you should feel comfortable treating the child.

If antihistamine therapy is not helpful, the lesions are interfering with lifestyle or sleep, or the patient complains of swelling, it is appropriate to refer the child to a specialist for additional work-up. Swelling is often a presenting sign with chronic urticaria, and typically it is generalized or affects the hands or face. The swelling often makes the patient and family uncomfortable.

If you decide to order laboratory testing prior to a specialist referral, a complete blood count, an erythrocyte sedimentation rate assay, a liver function test, and thyroid studies can be useful. But you also can simply refer the patient to an allergist or immunologist, and we can order the testing.

In contrast, a food-specific immunoglobulin G test is not helpful for the assessment of a child with persistent hives. This laboratory assay should not be ordered because it only adds to the cost of the diagnosis without aiding in the clinical diagnosis.

If you are fortunate and can identify the cause of the chronic urticaria—which only occurs in 5%-20% of cases—it calls for strict avoidance. This is another aspect where persistent hives differ from an acute presentation, because the etiology of an acute condition is more frequently found and subsequently may be avoided by the child.

Also educate the patient that persistent hives can be daily or episodic. Again, if the patient is lucky, the lesions resolve in less than 1 year. However, inform the patient that—in some cases—the hives can persist for several years.

Pediatric VTE Surge Draws Skeptical Response

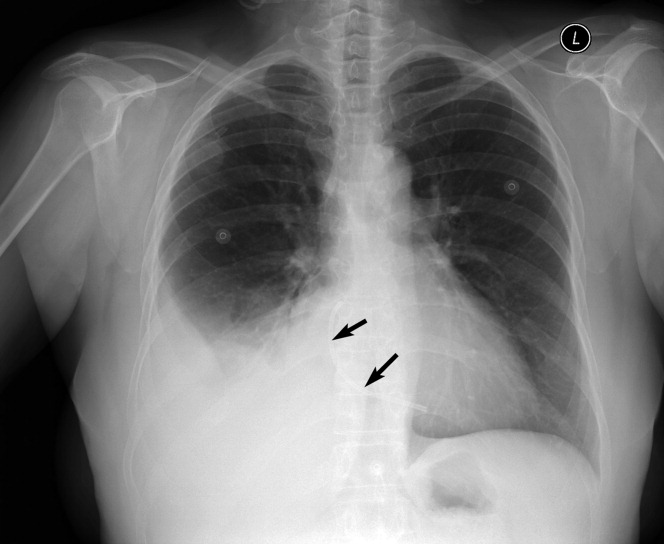

In the wake of a study that showed a 70% spike in the rate of VTE in pediatric hospitals, pediatric hospitalists and others are calling for a deeper analysis of the data.

The seven-year, multicenter study measured 11,337 hospitalized patients under the age of 18. Researchers found the annual rate of VTE increased by 70%, to 58 cases from 34 cases per 10,000 (P<0.001) (Pediatrics 2009;124(4):1001-1008). Several pediatricians note that the increase looks outsized because there has been little research on the topic over the past decade. Those interviewed say they expect more research in the future to define the breadth of the problem and potential solutions.

“I don’t think we think there’s been a seven-fold increase,” says Janna Journeycake, MD, MSCS, director of the Hemophilia and Thrombosis Program at Children's Medical Center, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center at Dallas. “It was there all along. We just didn’t know how to recognize it.”

Mark Shen, MD, medical director of hospital medicine at Dell Children’s Medical Center in Austin, Texas, and The Hospitalist's pediatric editor, attributes a large part of the study’s findings to more awareness of VTE in the pediatric community and increases in serious bone and joint infections that lead to more central lines, a risk factor for VTE. Dr. Shen also points out that as physicians learn more about pediatric VTE, it is expected that the rate of its incidence will increase. “Before, we wouldn’t look for signs of a clot unless there were physical signs of swelling, discomfort, or shortness of breath,” he adds. “Now we are much quicker to go and do an ultrasound or look for some kind of thromboembolism.”

Dr. Journeycake sees pediatric hospitalists as the vanguard in moving forward, as long as they stay vigilant to recognize the warning signs. “The job of the hospitalist is to recognize the certain medical conditions in which VTE are most likely,” she says. “They are going to be the most critically ill kids, the ones with deep-seated infection, such as osteomyelitis, mastoiditis. … Those are going to be children with central venous catheters. Hospitalists need to realize this complication exists.”

In the wake of a study that showed a 70% spike in the rate of VTE in pediatric hospitals, pediatric hospitalists and others are calling for a deeper analysis of the data.

The seven-year, multicenter study measured 11,337 hospitalized patients under the age of 18. Researchers found the annual rate of VTE increased by 70%, to 58 cases from 34 cases per 10,000 (P<0.001) (Pediatrics 2009;124(4):1001-1008). Several pediatricians note that the increase looks outsized because there has been little research on the topic over the past decade. Those interviewed say they expect more research in the future to define the breadth of the problem and potential solutions.

“I don’t think we think there’s been a seven-fold increase,” says Janna Journeycake, MD, MSCS, director of the Hemophilia and Thrombosis Program at Children's Medical Center, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center at Dallas. “It was there all along. We just didn’t know how to recognize it.”

Mark Shen, MD, medical director of hospital medicine at Dell Children’s Medical Center in Austin, Texas, and The Hospitalist's pediatric editor, attributes a large part of the study’s findings to more awareness of VTE in the pediatric community and increases in serious bone and joint infections that lead to more central lines, a risk factor for VTE. Dr. Shen also points out that as physicians learn more about pediatric VTE, it is expected that the rate of its incidence will increase. “Before, we wouldn’t look for signs of a clot unless there were physical signs of swelling, discomfort, or shortness of breath,” he adds. “Now we are much quicker to go and do an ultrasound or look for some kind of thromboembolism.”

Dr. Journeycake sees pediatric hospitalists as the vanguard in moving forward, as long as they stay vigilant to recognize the warning signs. “The job of the hospitalist is to recognize the certain medical conditions in which VTE are most likely,” she says. “They are going to be the most critically ill kids, the ones with deep-seated infection, such as osteomyelitis, mastoiditis. … Those are going to be children with central venous catheters. Hospitalists need to realize this complication exists.”

In the wake of a study that showed a 70% spike in the rate of VTE in pediatric hospitals, pediatric hospitalists and others are calling for a deeper analysis of the data.

The seven-year, multicenter study measured 11,337 hospitalized patients under the age of 18. Researchers found the annual rate of VTE increased by 70%, to 58 cases from 34 cases per 10,000 (P<0.001) (Pediatrics 2009;124(4):1001-1008). Several pediatricians note that the increase looks outsized because there has been little research on the topic over the past decade. Those interviewed say they expect more research in the future to define the breadth of the problem and potential solutions.

“I don’t think we think there’s been a seven-fold increase,” says Janna Journeycake, MD, MSCS, director of the Hemophilia and Thrombosis Program at Children's Medical Center, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center at Dallas. “It was there all along. We just didn’t know how to recognize it.”

Mark Shen, MD, medical director of hospital medicine at Dell Children’s Medical Center in Austin, Texas, and The Hospitalist's pediatric editor, attributes a large part of the study’s findings to more awareness of VTE in the pediatric community and increases in serious bone and joint infections that lead to more central lines, a risk factor for VTE. Dr. Shen also points out that as physicians learn more about pediatric VTE, it is expected that the rate of its incidence will increase. “Before, we wouldn’t look for signs of a clot unless there were physical signs of swelling, discomfort, or shortness of breath,” he adds. “Now we are much quicker to go and do an ultrasound or look for some kind of thromboembolism.”

Dr. Journeycake sees pediatric hospitalists as the vanguard in moving forward, as long as they stay vigilant to recognize the warning signs. “The job of the hospitalist is to recognize the certain medical conditions in which VTE are most likely,” she says. “They are going to be the most critically ill kids, the ones with deep-seated infection, such as osteomyelitis, mastoiditis. … Those are going to be children with central venous catheters. Hospitalists need to realize this complication exists.”

Prevention Prowess

Three medical centers have been nationally recognized for innovative approaches to preventing DVT and its potentially fatal complications. Central to each of the prevention strategies is a risk assessment tool that is easy to use, built directly into routine care, and linked directly to guideline-recommended choices for prophylaxis.

The North American Thrombosis Forum (NATF), in coordination with the pharmaceutical company Eisai Inc., recognized the following centers with the first DVTeamCare Hospital Award:

- The University of California at San Diego Medical Center was awarded as a representative of medical centers with more than 200 beds. The hospital embedded its VTE prevention protocol into admission, transfer, and perioperative order sets across all medical and surgical services, says Gregory A. Maynard, MD, chief of the division of hospital medicine. The protocol flags three levels of DVT risk, notes possible contraindications for a particular kind of patient, and presents a set of options for guideline-recommended prophylaxis. The protocol can be paper- or computer-based.

- The Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore, also awarded as a representative for medical centers with more than 200 beds, developed a mandatory computer-based decision support system to facilitate specialty-specific risk factor assessment and the application of risk-appropriate VTE prophylaxis.

- The Washington, D.C., Veterans Affairs Medical Center won in the category representing medical centers with fewer than 200 beds. The hospital designed a seven-step process that walks providers through an evidence-based risk-factor assessment to determine appropriate thromboprophylactic therapy.

The DVTeamCare Hospital Award reflects NATF's goal of enhancing thrombosis education, prevention, diagnosis, and treatment to improve patient outcomes, says NATF Executive Director Ilene Sussman, PhD.

Dr. Maynard and his UCSD colleagues have made their DVT prophylaxis toolkit available to other hospitalists wanting to lead similar efforts in their own hospital. The toolkit is posted both on the AHRQ and SHM Web sites.

"SHM and AHRQ should feel proud about this because we were one of the first places to do this successfully at such a high level," Dr. Maynard says. "We partnered with others and with SHM to build similar toolkits. SHM built VTE prevention collaboratives that enroll hospitalist leaders and mentor them through the process of VTE prevention performance improvement, tracking results longitudinally. Divya Shroff and her group in Washington, D.C., were enrolled in that VTE prevention collaborative. Their team won an award in VTE prevention by following the road map and by coming up with a good order set for DVT prevention that could be used in their VA hospital and in many other VAs across the country. I think that speaks to the strength of the concepts that we're using."

Each of the award-winning protocols will be presented at an NATF-sponsored program April 9 at Harvard Medical School in Boston. After the presentation, the winning protocols and implementation plans will be available at www.DVTeamCareAward.com to help other hospitals enhance their efforts to prevent DVT.

Three medical centers have been nationally recognized for innovative approaches to preventing DVT and its potentially fatal complications. Central to each of the prevention strategies is a risk assessment tool that is easy to use, built directly into routine care, and linked directly to guideline-recommended choices for prophylaxis.

The North American Thrombosis Forum (NATF), in coordination with the pharmaceutical company Eisai Inc., recognized the following centers with the first DVTeamCare Hospital Award:

- The University of California at San Diego Medical Center was awarded as a representative of medical centers with more than 200 beds. The hospital embedded its VTE prevention protocol into admission, transfer, and perioperative order sets across all medical and surgical services, says Gregory A. Maynard, MD, chief of the division of hospital medicine. The protocol flags three levels of DVT risk, notes possible contraindications for a particular kind of patient, and presents a set of options for guideline-recommended prophylaxis. The protocol can be paper- or computer-based.

- The Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore, also awarded as a representative for medical centers with more than 200 beds, developed a mandatory computer-based decision support system to facilitate specialty-specific risk factor assessment and the application of risk-appropriate VTE prophylaxis.

- The Washington, D.C., Veterans Affairs Medical Center won in the category representing medical centers with fewer than 200 beds. The hospital designed a seven-step process that walks providers through an evidence-based risk-factor assessment to determine appropriate thromboprophylactic therapy.

The DVTeamCare Hospital Award reflects NATF's goal of enhancing thrombosis education, prevention, diagnosis, and treatment to improve patient outcomes, says NATF Executive Director Ilene Sussman, PhD.

Dr. Maynard and his UCSD colleagues have made their DVT prophylaxis toolkit available to other hospitalists wanting to lead similar efforts in their own hospital. The toolkit is posted both on the AHRQ and SHM Web sites.

"SHM and AHRQ should feel proud about this because we were one of the first places to do this successfully at such a high level," Dr. Maynard says. "We partnered with others and with SHM to build similar toolkits. SHM built VTE prevention collaboratives that enroll hospitalist leaders and mentor them through the process of VTE prevention performance improvement, tracking results longitudinally. Divya Shroff and her group in Washington, D.C., were enrolled in that VTE prevention collaborative. Their team won an award in VTE prevention by following the road map and by coming up with a good order set for DVT prevention that could be used in their VA hospital and in many other VAs across the country. I think that speaks to the strength of the concepts that we're using."

Each of the award-winning protocols will be presented at an NATF-sponsored program April 9 at Harvard Medical School in Boston. After the presentation, the winning protocols and implementation plans will be available at www.DVTeamCareAward.com to help other hospitals enhance their efforts to prevent DVT.

Three medical centers have been nationally recognized for innovative approaches to preventing DVT and its potentially fatal complications. Central to each of the prevention strategies is a risk assessment tool that is easy to use, built directly into routine care, and linked directly to guideline-recommended choices for prophylaxis.

The North American Thrombosis Forum (NATF), in coordination with the pharmaceutical company Eisai Inc., recognized the following centers with the first DVTeamCare Hospital Award:

- The University of California at San Diego Medical Center was awarded as a representative of medical centers with more than 200 beds. The hospital embedded its VTE prevention protocol into admission, transfer, and perioperative order sets across all medical and surgical services, says Gregory A. Maynard, MD, chief of the division of hospital medicine. The protocol flags three levels of DVT risk, notes possible contraindications for a particular kind of patient, and presents a set of options for guideline-recommended prophylaxis. The protocol can be paper- or computer-based.

- The Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore, also awarded as a representative for medical centers with more than 200 beds, developed a mandatory computer-based decision support system to facilitate specialty-specific risk factor assessment and the application of risk-appropriate VTE prophylaxis.

- The Washington, D.C., Veterans Affairs Medical Center won in the category representing medical centers with fewer than 200 beds. The hospital designed a seven-step process that walks providers through an evidence-based risk-factor assessment to determine appropriate thromboprophylactic therapy.

The DVTeamCare Hospital Award reflects NATF's goal of enhancing thrombosis education, prevention, diagnosis, and treatment to improve patient outcomes, says NATF Executive Director Ilene Sussman, PhD.

Dr. Maynard and his UCSD colleagues have made their DVT prophylaxis toolkit available to other hospitalists wanting to lead similar efforts in their own hospital. The toolkit is posted both on the AHRQ and SHM Web sites.

"SHM and AHRQ should feel proud about this because we were one of the first places to do this successfully at such a high level," Dr. Maynard says. "We partnered with others and with SHM to build similar toolkits. SHM built VTE prevention collaboratives that enroll hospitalist leaders and mentor them through the process of VTE prevention performance improvement, tracking results longitudinally. Divya Shroff and her group in Washington, D.C., were enrolled in that VTE prevention collaborative. Their team won an award in VTE prevention by following the road map and by coming up with a good order set for DVT prevention that could be used in their VA hospital and in many other VAs across the country. I think that speaks to the strength of the concepts that we're using."

Each of the award-winning protocols will be presented at an NATF-sponsored program April 9 at Harvard Medical School in Boston. After the presentation, the winning protocols and implementation plans will be available at www.DVTeamCareAward.com to help other hospitals enhance their efforts to prevent DVT.

Injury Predictors After Inpatient Falls

An estimated 2% to 15% of all hospitalized patients experience at least one fall.1 Approximately 30% of such falls result in injury and up to 6% may be serious in nature.1, 2 These injuries can result in pain, functional impairment, disability, or even death, and can contribute to longer lengths of stay, increased health care costs, and nursing home placement.25 As a result, inpatient falls have become a major priority for hospital quality assurance programs, and hospital risk management departments have begun to target inpatient falls as a source of legal liability.13, 6, 7 Recently, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services announced that it will no longer pay for preventable complications of hospitalizations, including falls and fall‐related injury.8

Much of the literature on falls comes from community and long‐term care settings, and only a few studies have investigated falls during acute care hospitalization.3, 9, 10 From these studies, risk factors for inpatient falls have been identified and various models have been developed to predict an individual patient's risk of falling. However, unlike in the community setting, interventions to prevent falls in the acute care setting have not proven to be beneficial.11, 12 Commonly used approaches including restraints, alarms, bracelets, or having a volunteer sit with high‐risk patients have not been found to be effective.13, 14 Only 1 study found a multicomponent care plan that targeted specific risk factors in older inpatients to be associated with a reduced relative risk of recorded falls.15 Given this dearth of consistent evidence for the prevention of falls in hospitalized inpatients, the American Geriatrics Society has identified this as a gap area for future research.16

There are also limited data regarding predictors of injury after inpatient falls. A few small studies have identified potential risk factors for sustaining an injury after a fall in acute care, such as age >75 years, altered mental status, increased comorbidities, visual impairment, falls in the bathroom, and admission to a geriatric psychiatry floor.2, 5, 17 However, to our knowledge, there are no studies that have identified potential characteristics of inpatients found immediately after a fall that predict an injury. Providers who assess inpatients who have fallen need guidance on how to identify those in need of further evaluation and testing. This study sought to quantify the types and severity of injuries resulting from inpatient falls and to identify predictors of injury after a fall among a cohort of patients who fell at an urban academic medical center.

Patients and Methods

Patient Population

The study population included all inpatients on 13 medical and surgical units who experienced a fall between January 1, 2006 and December 31, 2006, while hospitalized at an 1171‐bed urban academic medical center. Telemetry, intensive care, pediatric, psychiatric, rehabilitation, and obstetrics or gynecology units were excluded from this analysis; the patients on these units are special populations that are qualitatively different than other acute care patients and have a different set of risk factor for falls and predictors of fall‐related injury. The study was approved by the institutional review board of the Mount Sinai School of Medicine.

Data Collection

Inpatient falls were identified retrospectively by review of hospital incident reports, which are most often completed by the unit nurses. In our institution, all falls generate an incident report. Using a standardized abstraction form, patient characteristics, circumstances surrounding falls, and fall‐related injuries were collected from the reports.

Laboratory data for anemia (hemoglobin < 12.0 g/dL), low albumin (<3.5 g/dL), elevated creatinine (>1.5 mg/dL), prolonged partial thromboplastin time (>35 seconds), and elevated international normalized ratio (INR > 1.3), were extracted from the patient's computerized medical record, if available. Number of days from admission to the fall, length of stay to the nearest hundredth of a day, and discharge disposition were also recorded for each patient.

Results of all radiographic studies, including x‐ray, ultrasound, computed tomography (CT), and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), performed within 2 weeks after the fall were obtained. The indication for the imaging study was assessed from the order given to the radiology department and from the patient's medical record. A positive finding on an imaging study was defined as evidence of intracranial hemorrhage, fracture, joint effusion, soft‐tissue swelling, or any other injury potentially caused by trauma. Fall‐related injury was defined as positive findings on any of these imaging studies that were performed as a result of the fall. Evaluation of fall‐related injuries was conducted by a reviewer blinded to the baseline patient characteristics and laboratory data.

Statistical Analyses

Baseline characteristics and risk factors of patients with and without fall‐related injuries were compared using the chi square test or Student t test as appropriate. Univariate and multivariate logistic regression were used to calculate adjusted odds ratios (ORs) for injury after an inpatient fall. The multivariate model was developed using a manual forward method. Prior research shows that patients with recurrent falls do so in the same manner and for the same reasons.2, 3, 17 Thus, analyses were performed including only the first fall episode as the outcome of interest. Analyses were performed with SPSS statistical software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL) using 2‐sided P values.

Results

During the study period, 513 inpatients sustained 636 falls at the Mount Sinai Medical Center. There were 54,257 admissions to the hospital with 322,670 total patient days during this time. Therefore the fall incidence rate was 1.97 falls per 1,000 patient days. Characteristics of inpatients who fell are shown in Table 1. Most patients had 1 fall episode; however, 95 patients (19%) fell multiple times (range, 2‐6 events). There were no significant differences between recurrent fallers and those who fell once with respect to baseline characteristics, injuries sustained, or discharge disposition.

| Characteristic | Number of Patients (n = 513) [number (%)] |

|---|---|

| |

| Age (years) | 70 (21‐104) |

| Age >75 years | 202 (39) |

| Male gender | 255 (50) |

| Assessed at risk of falling | |

| Yes | 378 (74) |

| No | 2 (5) |

| Unknown | 110 (21) |

| Number of falls | |

| 1 | 418 (82) |

| 2 | 78 (15) |

| 3 | 10 (2) |

| 4 | 4 (1) |

| 5 | 2 (0.4) |

| 6 | 1 (0.2) |

| Multiple falls | 95 (19) |

Fall Circumstances

The majority of patients who fell (74%) had been assessed by the nursing staff as being at risk for falling prior to the event. Overall, most falls (73%) occurred on medical rather than surgical units. The units with the most falls were geriatrics, neurology, and general medicine. Details about circumstances surrounding the falls are shown in Table 2. In most instances (71%) patients were found on the floor after the fall while less than 8% of falls were witnessed. Approximately 12% of patients received sedatives within 4 hours of falling (40% opioids, 30% benzodiazepines, 16% zolpidem, and 14% other). Laboratory values at the time of fall revealed that 70% of patients who fell were anemic, 62% had low albumin, and 19% had an elevated creatinine. Almost 20% of the patients had a prolonged partial thromboplastin time (PTT) and 18% had an elevated INR.

| Characteristic | Number of Falls (n = 513) [number (%)]* |

|---|---|

| |

| Location | |

| Medical unit | 374 (73) |

| Surgical unit | 139 (27) |

| Time | |

| Day shift (7:00 AM to 6:59 PM) | 225 (44) |

| Night shift (7:00 PM to 6:59 AM) | 282 (56) |

| Character of fall | |

| Assisted to floor | 15 (3) |

| Fall alleged | 92 (18) |

| Fall witnessed | 39 (8) |

| Found on Floor | 363 (71) |

| Unknown | 4 (<1) |

| Fall‐related activity | |

| Ambulation | 164 (32) |

| Bathroom | 122 (24) |

| Bed | 21 (4) |

| Chair | 19 (4) |

| Other/unknown | 187 (36) |

| Mental status | |

| Oriented | 274 (53) |

| Confused | 151 (29) |

| Unknown | 88 (17) |

| Activity level ordered | |

| Ambulatory | 246 (48) |

| Nonambulatory | 135 (26) |

| Unknown | 132 (26) |

| Siderails | |

| Complete | 15 (3) |

| Partial | 352 (69) |

| None | 15 (3) |

| Unknown | 126 (25) |

| Environmental obstacle | |

| None | 355 (69) |

| Wet | 20 (4) |

| Debris | 2 (<1) |

| Unknown | 136 (27) |

| Restraints | |

| Yes | 3 (<1) |

| No | 374 (73) |

| Unknown | 136 (27) |

| Sedative use | |

| Total | 64 (12) |

| Opioids | 28 (6) |

| Benzos | 21 (4) |

| Antipsychotics | 7 (1) |

| Other | 8 (2) |

| Evidence of trauma | |

| Yes | 25 (5) |

| No | 285 (56) |

| Unknown | 203 (40) |

The median number of days from patient admission until they fell was 4 days (range, 0‐134), with 70% of patients falling within the first week of admission. In general, there was no difference in fall rate by time of day, though slightly more falls (56%) occurred during the night shift (7 PM to 7 AM).

Fall‐related Outcomes

Twenty‐five patients (5%) had evidence of trauma on physical exam after the fall, including lacerations, swelling, and ecchymoses, as documented by the evaluating nurse. A total of 120 imaging procedures were ordered following the first fall; when all inpatient falls were included, 145 imaging procedures were ordered. Most imaging studies (87%) did not show significant findings. Among studies with positive findings, the most common abnormality was fracture, including 3 hip, 1 humeral, 1 vertebral, 1 nasal, and 1 rib fracture. Other injuries found on imaging studies included 1 subdural hematoma, 1 acute cerebral infarct, 2 soft‐tissue hematomas, and 2 knee effusions. The acute cerebral infarct was not considered to be a result of the fall. Additionally, 3 patients had soft‐tissue swelling noted on head CT and 1 had Foley catheter‐related trauma.

The average length of stay for the 513 inpatients who fell was 20 days (range, 7‐444) compared to 6 days for all patients admitted to the hospital during the same period. Among inpatients who fell, there was no statistical difference in length of stay between those who did and those who did not have a fall‐related injury found on imaging. More than one‐half (53%) of the patients who fell were discharged to home, 21% to rehabilitation facilities, 12% to nursing homes, and 9% died during the hospitalization.

Results of Univariate Analysis

Univariate predictors of injury after a fall are shown in Table 3. Patients having evidence of trauma indicated by the evaluating nurse after a fall had an increased risk for having an abnormal imaging study (OR = 14.7, P < 0.001). Having an activity level of ambulatory ordered by the provider (OR = 2.5, P = 0.09), falling during the night shift (OR = 2.5, P = 0.11), having ambulation as the fall‐related activity (OR = 2.2, P = 0.12), and older age (P = 0.19) all showed a trend toward higher rates of injury being found after a fall. There was no significant association between fall‐related injury and being an elderly patient (age > 75 years), sedative use, falling in the bathroom, or having an elevated PTT or INR.

| Variable | Patients without injury (n = 497) [number (%)] | Patients with injury (n = 16) [number (%)] | OR | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Elderly | 195 (39) | 7 (44) | 1.2 | 0.72 |

| Gender male | 245 (49) | 10 (63) | 1.7 | 0.30 |

| Location surgical unit | 142 (29) | 6 (38) | 1.5 | 0.44 |

| At risk of falling prior to event | 365 (73) | 13 (8) | 1.6 | 0.49 |

| Protocol in place | 338 (68) | 11 (69) | 1.0 | 0.95 |

| Activity level ambulatory | 235 (47) | 11 (69) | 2.5 | 0.09 |

| Occurrence on night shift | 270 (54) | 12 (75) | 2.5 | 0.11 |

| Restraint use | 3 (1) | 0 (0) | ||

| Sedative within 4 hours | 61 (12) | 3 (19) | 1.6 | 0.44 |

| Fall related to ambulation | 156 (31) | 8 (50) | 2.2 | 0.12 |

| Evidence of trauma | 19 (4) | 6 (38) | 14.7 | <0.001 |

| Prolonged PTT | 93 (19) | 5 (31) | 1.9 | 0.29 |

| Elevated INR | 90 (18) | 3 (19) | 1.0 | 0.96 |

| Anemia | 351 (71) | 9 (56) | 0.6 | 0.32 |

| Elevated creatinine | 97 (20) | 2 (13) | 0.7 | 0.60 |

| Low albumin | 309 (62) | 8 (50) | 1.6 | 0.58 |

Multivariate Predictors of Injury

In multivariate analysis, after adjusting for age and sex, evidence of trauma after a fall (OR = 24.6, P < 0.001) and having an activity level of ambulatory ordered by the provider (OR = 7.3, P = 0.01) were independent predictors of injury being found on imaging studies (Table 4). Analyses limited to the 120 patients who had imaging found that the association between evidence of trauma (OR = 6.22, P = 0.02) and having an activity level of ambulatory ordered (OR = 5.53, P = 0.04) remained statistically significant.

| Variable | All Patients (n = 513) | Patients with Imaging (n = 120)* | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | P Value | OR | P Value | |

| ||||

| Age | 1.03 | 0.17 | 1.016 | 0.52 |

| Gender | 3.19 | 0.11 | 2.843 | 0.17 |

| Evidence of trauma | 24.63 | <0.001 | 6.22 | 0.02 |

| Activity level ambulatory | 7.33 | 0.01 | 5.53 | 0.04 |

Discussion

Inpatient falls are common and result in significant patient morbidity and increased healthcare costs. Falls in the acute care setting have also proven to be difficult to prevent and as a result have become a priority for patient safety and hospital quality.

Our study confirms that a high percentage of patients with an initial fall will have recurrent falls.1 Additionally, the majority of patients in this cohort fell despite having been assessed as at risk for falling prior to the event. The types of injuries sustained after inpatient falls (eg, subdural hematoma, multiple fractures, joint effusions, other hematomas, and soft‐tissue swelling) are similar to those found by other authors.2, 3, 17, 18

In this study, inpatient falls were associated with an almost 2‐week increase in length of stay. Though we cannot say that this was directly due to falls, and an increased length of stay may just be a marker of severity of illness, this association warrants further study, perhaps with a matched control group of patients who did not fall, and has implications for healthcare cost containment.

We found that having evidence of trauma after a fall and having an activity level of ambulatory ordered by the provider were independent predictors of injury being found after an inpatient fall. It seems intuitive that patients who have physical evidence of trauma, such as lacerations or bruising, would be more likely to have an underlying injury. Clinically, this confirms that providers should have a high index of suspicion for injury being found on imaging studies in such patients. Similar findings have been noted in the emergency medicine literature that further support the validity of our findings.19

Less clear are the reasons for the observed association between having an activity level of ambulatory ordered and higher risk of injury after an inpatient fall. Prior studies have found that ambulatory inpatients are less likely to use assistive devices that they use at home while hospitalized and are less likely to call for help; these factors may contribute to falls.2, 3 However, the interpretation of this finding is limited by the fact that 26% of the patients who fell had an unknown activity level ordered.

Altered mental status, comorbidity, age > 75 years, visual impairment, falling in the bathroom, and being on a geriatric psychiatry floor have previously been found to be risk factors for sustaining an injury after an inpatient fall.2, 5, 17 Conversely, this study did not find altered mental status to be a significant predictor of injury. One reason may be that this was subjectively determined by the evaluating nurse and not by a standardized measure of cognitive impairment. Patients who are oriented may also be more likely to report unwitnessed falls and injuries than patients with altered mental status.3

There was also no association between age and fall‐related injury in our cohort. On univariate analysis, patients who were older in age were more likely to have an injury found after an inpatient fall but this was not statistically significant. Previous authors have suggested that today's inpatients are increasingly ill and may have risk factors for falls and injuries that are independent of age, such as multiple comorbid conditions or deconditioning.3

We hypothesized that patients who are anticoagulated and had an elevated INR or PTT would be more likely to sustain an injury. Anemic inpatients have also been found to be at increased risk of falls.20 We found no significant association between fall‐related injury being found on imaging studies and anemia, low albumin, elevated creatinine, prolonged PTT, or elevated INR. Not every patient who fell had these laboratory values available. However, even when only inpatients who fell and had laboratory tests were included in the analysis, there was still no association with fall‐related injury.

This study has several limitations. First, a low number of serious injuries was found on imaging studies after inpatient falls in this cohort; this limited the power of the study to identify predictors of fall‐related injury.

Second, fall‐related injury was defined as a positive finding on imaging studies within 2 weeks of an inpatient fall. Thus, some fall‐related injuries may have been missed in patients who did not have imaging. However, any patient who had a serious injury after a fall and remained hospitalized would likely have had symptoms such as pain or altered mental status that would have led to an imaging study. Moreover, the analysis was repeated including only inpatients who fell and had imaging, and the association between having evidence of trauma and having an activity level of ambulatory ordered and sustaining a fall‐related injury remained significant.

Third, we relied on hospital incident reports to identify inpatient falls. These reports yield a limited amount of information and may be inaccurate or incomplete. A recent study also raised concern that incident reports significantly underreport actual fall incidence.21 However, previous studies have found no indication that falls are underreported and suggest that incident reports are an established custom in hospital culture.1, 22 Medical staff are aware that administrators want to keep track of hospital fall rates for both quality improvement and documentation for risk management.1, 22 It is unlikely that severe falls or falls leading to serious injury are not reported. A different source of underreporting may actually be failure of patients to tell the medical team about an unwitnessed fall. Older patients may be concerned they will be placed in nursing homes and those with memory loss may forget to report a minor fall. Education of patients and family members could improve reporting of inpatient falls and further our understanding of contributing factors.

Finally, although the evaluation of fall‐related injuries was conducted by a blinded reviewer, the potential for bias does exist among even the best‐intentioned reviewers. Additionally, there may be some degree of variability within the reviewer's data abstraction.

This study adds valuable information about the epidemiology of inpatient falls at large, urban, tertiary‐care academic medical centers, including characteristics of patients who fell, circumstances surrounding falls, injuries sustained, and predictors of fall‐related injury found on imaging. Although additional research is essential to identify methods to effectively prevent inpatient falls, this study contributes to the limited data in this area, can guide providers who are evaluating inpatients who have fallen, and may be used to design future investigations. It is imperative that measures are identified to avoid the frequent adverse outcomes that result from inpatient falls. Insurance companies, hospital administrators, patients, and providers will be demanding that a safe environment be a key component of quality of care measures.

This study draws attention to the scope of the problem at our institution that is common to hospitals across the country. In our study, our academic medical center had a fall rate consistent with published reports, but new efforts have been focused on quality improvement in this area. An interdisciplinary fall prevention committee has been formed that includes physicians, nurses, patient care assistants, physical therapists, pharmacists, and representatives from information technology (IT). Currently, a program of a fall risk‐factor assessment with targeted interventions to reduce those risk factors is being developed for all high‐risk patients and will be piloted on inpatient units.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Susan Emro, BS, Department of Health Policy, Susan Davis, MS, MPH, RN, CNAA, Department of Nursing, and Albert Siu, MD, MSPH, Brookdale Department of Geriatrics and Adult Development, for their review of this article. Author contributions were as followsconception and design: S.M.B, R.K., and T.M.; collection and assembly of data: S.M.B.; analysis and interpretation of the data: S.M.B, R.K., and J.W.; drafting of the article: S.M.B.; critical revision of the article for important intellectual content: R.K. and J.W.; final approval of the article: S.M.B, R.K., and J.W.; statistical expertise: J.W.; obtaining of funding: S.M.B.

- ,,,.Risk of falls for hospitalized patients: a predictive model based on routinely available data.J Clin Epidemiol.2001;54(12):1258–1266.

- ,,, et al.A case‐control study of patient, medication, and care‐related risk factors for inpatient falls.J Gen Intern Med.2005;20(2):116–122.

- ,,, et al.Characteristics and circumstances of falls in a hospital setting: a prospective analysis.J Gen Intern Med.2004;19(7):732–739.

- ,,,.Falls and consequent injuries in hospitalized patients: effects of an interdisciplinary falls prevention program.BMC Health Serv Res.2006;6:69.

- ,,,.Serious falls in hospitalized patients: correlates and resource utilization.Am J Med.1995;99(2):137–143.

- ,.Using tools to assess and prevent inpatient falls.Jt Comm J Qual Saf.2003;29(7):363–368.

- ,,.Incidence and risk factors for inpatient falls in an academic acute‐care hospital.J Nippon Med Sch.2006;73(5):265–270.

- .Nonpayment for performance? Medicare's new reimbursement rule.N Engl J Med.2007;357(16):1573–1575.

- .Clinical practice. preventing falls in elderly persons.N Engl J Med.2003;348(1):42–49.

- .Building the science of falls‐prevention research.J Am Geriatr Soc.2004;52(3):461–462.

- ,,,,,.Interventions for preventing falls in acute‐ and chronic‐care hospitals: a systematic review and meta‐analysis.J Am Geriatr Soc.2008;56(1):29–36.

- ,,, et al.Interventions for the prevention of falls in older adults: systematic review and meta‐analysis of randomised clinical trials.BMJ.2004;328(7441):680.

- ,,, et al.Acceptability of fall prevention measures for hospital inpatients.Age Ageing.2004;33(4):400–401.

- ,,, et al.Can volunteer companions prevent falls among inpatients? A feasibility study using a pre‐post comparative design.BMC Geriatr.2006;6:11.

- ,,,,.Using targeted risk factor reduction to prevent falls in older in‐patients: a randomised controlled trial.Age Ageing.2004;33(4):390–395.

- .Prevention of falls in hospital inpatients: agendas for research and practice.Age Ageing.2004;33(4):328–330.

- ,,, et al.Patterns and predictors of inpatient falls and fall‐related injuries in a large academic hospital.Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol.2005;26(10):822–827.

- ,,,,.The relationship of falls to injury among hospital in‐patients.Int J Clin Pract.2005;59(1):17–20.

- ,,,,,.Indications for computed tomography in patients with minor head injury.N Engl J Med.2000;343(2):100–105.

- ,,.Anemia increases risk for falls in hospitalized older adults: an evaluation of falls in 362 hospitalized, ambulatory, long‐term care, and community patients.J Am Med Dir Assoc.2006;7(5):287–293.

- ,,,,,.Improving the capture of fall events in hospitals: combining a service for evaluating inpatient falls with an incident report system.J Am Geriatr Soc.2008;56(4):701–704.

- ,,, et al.Attitudes and barriers to incident reporting: a collaborative hospital study.Qual Saf Health Care.2006;15(1):39–43.

An estimated 2% to 15% of all hospitalized patients experience at least one fall.1 Approximately 30% of such falls result in injury and up to 6% may be serious in nature.1, 2 These injuries can result in pain, functional impairment, disability, or even death, and can contribute to longer lengths of stay, increased health care costs, and nursing home placement.25 As a result, inpatient falls have become a major priority for hospital quality assurance programs, and hospital risk management departments have begun to target inpatient falls as a source of legal liability.13, 6, 7 Recently, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services announced that it will no longer pay for preventable complications of hospitalizations, including falls and fall‐related injury.8

Much of the literature on falls comes from community and long‐term care settings, and only a few studies have investigated falls during acute care hospitalization.3, 9, 10 From these studies, risk factors for inpatient falls have been identified and various models have been developed to predict an individual patient's risk of falling. However, unlike in the community setting, interventions to prevent falls in the acute care setting have not proven to be beneficial.11, 12 Commonly used approaches including restraints, alarms, bracelets, or having a volunteer sit with high‐risk patients have not been found to be effective.13, 14 Only 1 study found a multicomponent care plan that targeted specific risk factors in older inpatients to be associated with a reduced relative risk of recorded falls.15 Given this dearth of consistent evidence for the prevention of falls in hospitalized inpatients, the American Geriatrics Society has identified this as a gap area for future research.16

There are also limited data regarding predictors of injury after inpatient falls. A few small studies have identified potential risk factors for sustaining an injury after a fall in acute care, such as age >75 years, altered mental status, increased comorbidities, visual impairment, falls in the bathroom, and admission to a geriatric psychiatry floor.2, 5, 17 However, to our knowledge, there are no studies that have identified potential characteristics of inpatients found immediately after a fall that predict an injury. Providers who assess inpatients who have fallen need guidance on how to identify those in need of further evaluation and testing. This study sought to quantify the types and severity of injuries resulting from inpatient falls and to identify predictors of injury after a fall among a cohort of patients who fell at an urban academic medical center.

Patients and Methods

Patient Population

The study population included all inpatients on 13 medical and surgical units who experienced a fall between January 1, 2006 and December 31, 2006, while hospitalized at an 1171‐bed urban academic medical center. Telemetry, intensive care, pediatric, psychiatric, rehabilitation, and obstetrics or gynecology units were excluded from this analysis; the patients on these units are special populations that are qualitatively different than other acute care patients and have a different set of risk factor for falls and predictors of fall‐related injury. The study was approved by the institutional review board of the Mount Sinai School of Medicine.

Data Collection

Inpatient falls were identified retrospectively by review of hospital incident reports, which are most often completed by the unit nurses. In our institution, all falls generate an incident report. Using a standardized abstraction form, patient characteristics, circumstances surrounding falls, and fall‐related injuries were collected from the reports.

Laboratory data for anemia (hemoglobin < 12.0 g/dL), low albumin (<3.5 g/dL), elevated creatinine (>1.5 mg/dL), prolonged partial thromboplastin time (>35 seconds), and elevated international normalized ratio (INR > 1.3), were extracted from the patient's computerized medical record, if available. Number of days from admission to the fall, length of stay to the nearest hundredth of a day, and discharge disposition were also recorded for each patient.

Results of all radiographic studies, including x‐ray, ultrasound, computed tomography (CT), and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), performed within 2 weeks after the fall were obtained. The indication for the imaging study was assessed from the order given to the radiology department and from the patient's medical record. A positive finding on an imaging study was defined as evidence of intracranial hemorrhage, fracture, joint effusion, soft‐tissue swelling, or any other injury potentially caused by trauma. Fall‐related injury was defined as positive findings on any of these imaging studies that were performed as a result of the fall. Evaluation of fall‐related injuries was conducted by a reviewer blinded to the baseline patient characteristics and laboratory data.

Statistical Analyses

Baseline characteristics and risk factors of patients with and without fall‐related injuries were compared using the chi square test or Student t test as appropriate. Univariate and multivariate logistic regression were used to calculate adjusted odds ratios (ORs) for injury after an inpatient fall. The multivariate model was developed using a manual forward method. Prior research shows that patients with recurrent falls do so in the same manner and for the same reasons.2, 3, 17 Thus, analyses were performed including only the first fall episode as the outcome of interest. Analyses were performed with SPSS statistical software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL) using 2‐sided P values.

Results

During the study period, 513 inpatients sustained 636 falls at the Mount Sinai Medical Center. There were 54,257 admissions to the hospital with 322,670 total patient days during this time. Therefore the fall incidence rate was 1.97 falls per 1,000 patient days. Characteristics of inpatients who fell are shown in Table 1. Most patients had 1 fall episode; however, 95 patients (19%) fell multiple times (range, 2‐6 events). There were no significant differences between recurrent fallers and those who fell once with respect to baseline characteristics, injuries sustained, or discharge disposition.

| Characteristic | Number of Patients (n = 513) [number (%)] |

|---|---|

| |

| Age (years) | 70 (21‐104) |

| Age >75 years | 202 (39) |

| Male gender | 255 (50) |

| Assessed at risk of falling | |

| Yes | 378 (74) |

| No | 2 (5) |

| Unknown | 110 (21) |

| Number of falls | |

| 1 | 418 (82) |

| 2 | 78 (15) |

| 3 | 10 (2) |

| 4 | 4 (1) |

| 5 | 2 (0.4) |

| 6 | 1 (0.2) |

| Multiple falls | 95 (19) |

Fall Circumstances

The majority of patients who fell (74%) had been assessed by the nursing staff as being at risk for falling prior to the event. Overall, most falls (73%) occurred on medical rather than surgical units. The units with the most falls were geriatrics, neurology, and general medicine. Details about circumstances surrounding the falls are shown in Table 2. In most instances (71%) patients were found on the floor after the fall while less than 8% of falls were witnessed. Approximately 12% of patients received sedatives within 4 hours of falling (40% opioids, 30% benzodiazepines, 16% zolpidem, and 14% other). Laboratory values at the time of fall revealed that 70% of patients who fell were anemic, 62% had low albumin, and 19% had an elevated creatinine. Almost 20% of the patients had a prolonged partial thromboplastin time (PTT) and 18% had an elevated INR.

| Characteristic | Number of Falls (n = 513) [number (%)]* |

|---|---|

| |

| Location | |

| Medical unit | 374 (73) |

| Surgical unit | 139 (27) |

| Time | |

| Day shift (7:00 AM to 6:59 PM) | 225 (44) |

| Night shift (7:00 PM to 6:59 AM) | 282 (56) |

| Character of fall | |

| Assisted to floor | 15 (3) |

| Fall alleged | 92 (18) |

| Fall witnessed | 39 (8) |

| Found on Floor | 363 (71) |

| Unknown | 4 (<1) |

| Fall‐related activity | |

| Ambulation | 164 (32) |

| Bathroom | 122 (24) |

| Bed | 21 (4) |

| Chair | 19 (4) |

| Other/unknown | 187 (36) |

| Mental status | |

| Oriented | 274 (53) |

| Confused | 151 (29) |

| Unknown | 88 (17) |

| Activity level ordered | |

| Ambulatory | 246 (48) |

| Nonambulatory | 135 (26) |

| Unknown | 132 (26) |

| Siderails | |

| Complete | 15 (3) |

| Partial | 352 (69) |

| None | 15 (3) |

| Unknown | 126 (25) |

| Environmental obstacle | |

| None | 355 (69) |

| Wet | 20 (4) |

| Debris | 2 (<1) |

| Unknown | 136 (27) |

| Restraints | |

| Yes | 3 (<1) |

| No | 374 (73) |

| Unknown | 136 (27) |

| Sedative use | |

| Total | 64 (12) |

| Opioids | 28 (6) |

| Benzos | 21 (4) |

| Antipsychotics | 7 (1) |

| Other | 8 (2) |

| Evidence of trauma | |

| Yes | 25 (5) |

| No | 285 (56) |

| Unknown | 203 (40) |

The median number of days from patient admission until they fell was 4 days (range, 0‐134), with 70% of patients falling within the first week of admission. In general, there was no difference in fall rate by time of day, though slightly more falls (56%) occurred during the night shift (7 PM to 7 AM).

Fall‐related Outcomes

Twenty‐five patients (5%) had evidence of trauma on physical exam after the fall, including lacerations, swelling, and ecchymoses, as documented by the evaluating nurse. A total of 120 imaging procedures were ordered following the first fall; when all inpatient falls were included, 145 imaging procedures were ordered. Most imaging studies (87%) did not show significant findings. Among studies with positive findings, the most common abnormality was fracture, including 3 hip, 1 humeral, 1 vertebral, 1 nasal, and 1 rib fracture. Other injuries found on imaging studies included 1 subdural hematoma, 1 acute cerebral infarct, 2 soft‐tissue hematomas, and 2 knee effusions. The acute cerebral infarct was not considered to be a result of the fall. Additionally, 3 patients had soft‐tissue swelling noted on head CT and 1 had Foley catheter‐related trauma.

The average length of stay for the 513 inpatients who fell was 20 days (range, 7‐444) compared to 6 days for all patients admitted to the hospital during the same period. Among inpatients who fell, there was no statistical difference in length of stay between those who did and those who did not have a fall‐related injury found on imaging. More than one‐half (53%) of the patients who fell were discharged to home, 21% to rehabilitation facilities, 12% to nursing homes, and 9% died during the hospitalization.

Results of Univariate Analysis

Univariate predictors of injury after a fall are shown in Table 3. Patients having evidence of trauma indicated by the evaluating nurse after a fall had an increased risk for having an abnormal imaging study (OR = 14.7, P < 0.001). Having an activity level of ambulatory ordered by the provider (OR = 2.5, P = 0.09), falling during the night shift (OR = 2.5, P = 0.11), having ambulation as the fall‐related activity (OR = 2.2, P = 0.12), and older age (P = 0.19) all showed a trend toward higher rates of injury being found after a fall. There was no significant association between fall‐related injury and being an elderly patient (age > 75 years), sedative use, falling in the bathroom, or having an elevated PTT or INR.

| Variable | Patients without injury (n = 497) [number (%)] | Patients with injury (n = 16) [number (%)] | OR | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Elderly | 195 (39) | 7 (44) | 1.2 | 0.72 |

| Gender male | 245 (49) | 10 (63) | 1.7 | 0.30 |

| Location surgical unit | 142 (29) | 6 (38) | 1.5 | 0.44 |

| At risk of falling prior to event | 365 (73) | 13 (8) | 1.6 | 0.49 |

| Protocol in place | 338 (68) | 11 (69) | 1.0 | 0.95 |

| Activity level ambulatory | 235 (47) | 11 (69) | 2.5 | 0.09 |

| Occurrence on night shift | 270 (54) | 12 (75) | 2.5 | 0.11 |

| Restraint use | 3 (1) | 0 (0) | ||

| Sedative within 4 hours | 61 (12) | 3 (19) | 1.6 | 0.44 |

| Fall related to ambulation | 156 (31) | 8 (50) | 2.2 | 0.12 |

| Evidence of trauma | 19 (4) | 6 (38) | 14.7 | <0.001 |

| Prolonged PTT | 93 (19) | 5 (31) | 1.9 | 0.29 |

| Elevated INR | 90 (18) | 3 (19) | 1.0 | 0.96 |

| Anemia | 351 (71) | 9 (56) | 0.6 | 0.32 |

| Elevated creatinine | 97 (20) | 2 (13) | 0.7 | 0.60 |

| Low albumin | 309 (62) | 8 (50) | 1.6 | 0.58 |

Multivariate Predictors of Injury

In multivariate analysis, after adjusting for age and sex, evidence of trauma after a fall (OR = 24.6, P < 0.001) and having an activity level of ambulatory ordered by the provider (OR = 7.3, P = 0.01) were independent predictors of injury being found on imaging studies (Table 4). Analyses limited to the 120 patients who had imaging found that the association between evidence of trauma (OR = 6.22, P = 0.02) and having an activity level of ambulatory ordered (OR = 5.53, P = 0.04) remained statistically significant.

| Variable | All Patients (n = 513) | Patients with Imaging (n = 120)* | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | P Value | OR | P Value | |

| ||||

| Age | 1.03 | 0.17 | 1.016 | 0.52 |

| Gender | 3.19 | 0.11 | 2.843 | 0.17 |

| Evidence of trauma | 24.63 | <0.001 | 6.22 | 0.02 |

| Activity level ambulatory | 7.33 | 0.01 | 5.53 | 0.04 |

Discussion

Inpatient falls are common and result in significant patient morbidity and increased healthcare costs. Falls in the acute care setting have also proven to be difficult to prevent and as a result have become a priority for patient safety and hospital quality.

Our study confirms that a high percentage of patients with an initial fall will have recurrent falls.1 Additionally, the majority of patients in this cohort fell despite having been assessed as at risk for falling prior to the event. The types of injuries sustained after inpatient falls (eg, subdural hematoma, multiple fractures, joint effusions, other hematomas, and soft‐tissue swelling) are similar to those found by other authors.2, 3, 17, 18

In this study, inpatient falls were associated with an almost 2‐week increase in length of stay. Though we cannot say that this was directly due to falls, and an increased length of stay may just be a marker of severity of illness, this association warrants further study, perhaps with a matched control group of patients who did not fall, and has implications for healthcare cost containment.

We found that having evidence of trauma after a fall and having an activity level of ambulatory ordered by the provider were independent predictors of injury being found after an inpatient fall. It seems intuitive that patients who have physical evidence of trauma, such as lacerations or bruising, would be more likely to have an underlying injury. Clinically, this confirms that providers should have a high index of suspicion for injury being found on imaging studies in such patients. Similar findings have been noted in the emergency medicine literature that further support the validity of our findings.19

Less clear are the reasons for the observed association between having an activity level of ambulatory ordered and higher risk of injury after an inpatient fall. Prior studies have found that ambulatory inpatients are less likely to use assistive devices that they use at home while hospitalized and are less likely to call for help; these factors may contribute to falls.2, 3 However, the interpretation of this finding is limited by the fact that 26% of the patients who fell had an unknown activity level ordered.

Altered mental status, comorbidity, age > 75 years, visual impairment, falling in the bathroom, and being on a geriatric psychiatry floor have previously been found to be risk factors for sustaining an injury after an inpatient fall.2, 5, 17 Conversely, this study did not find altered mental status to be a significant predictor of injury. One reason may be that this was subjectively determined by the evaluating nurse and not by a standardized measure of cognitive impairment. Patients who are oriented may also be more likely to report unwitnessed falls and injuries than patients with altered mental status.3

There was also no association between age and fall‐related injury in our cohort. On univariate analysis, patients who were older in age were more likely to have an injury found after an inpatient fall but this was not statistically significant. Previous authors have suggested that today's inpatients are increasingly ill and may have risk factors for falls and injuries that are independent of age, such as multiple comorbid conditions or deconditioning.3

We hypothesized that patients who are anticoagulated and had an elevated INR or PTT would be more likely to sustain an injury. Anemic inpatients have also been found to be at increased risk of falls.20 We found no significant association between fall‐related injury being found on imaging studies and anemia, low albumin, elevated creatinine, prolonged PTT, or elevated INR. Not every patient who fell had these laboratory values available. However, even when only inpatients who fell and had laboratory tests were included in the analysis, there was still no association with fall‐related injury.

This study has several limitations. First, a low number of serious injuries was found on imaging studies after inpatient falls in this cohort; this limited the power of the study to identify predictors of fall‐related injury.

Second, fall‐related injury was defined as a positive finding on imaging studies within 2 weeks of an inpatient fall. Thus, some fall‐related injuries may have been missed in patients who did not have imaging. However, any patient who had a serious injury after a fall and remained hospitalized would likely have had symptoms such as pain or altered mental status that would have led to an imaging study. Moreover, the analysis was repeated including only inpatients who fell and had imaging, and the association between having evidence of trauma and having an activity level of ambulatory ordered and sustaining a fall‐related injury remained significant.

Third, we relied on hospital incident reports to identify inpatient falls. These reports yield a limited amount of information and may be inaccurate or incomplete. A recent study also raised concern that incident reports significantly underreport actual fall incidence.21 However, previous studies have found no indication that falls are underreported and suggest that incident reports are an established custom in hospital culture.1, 22 Medical staff are aware that administrators want to keep track of hospital fall rates for both quality improvement and documentation for risk management.1, 22 It is unlikely that severe falls or falls leading to serious injury are not reported. A different source of underreporting may actually be failure of patients to tell the medical team about an unwitnessed fall. Older patients may be concerned they will be placed in nursing homes and those with memory loss may forget to report a minor fall. Education of patients and family members could improve reporting of inpatient falls and further our understanding of contributing factors.

Finally, although the evaluation of fall‐related injuries was conducted by a blinded reviewer, the potential for bias does exist among even the best‐intentioned reviewers. Additionally, there may be some degree of variability within the reviewer's data abstraction.

This study adds valuable information about the epidemiology of inpatient falls at large, urban, tertiary‐care academic medical centers, including characteristics of patients who fell, circumstances surrounding falls, injuries sustained, and predictors of fall‐related injury found on imaging. Although additional research is essential to identify methods to effectively prevent inpatient falls, this study contributes to the limited data in this area, can guide providers who are evaluating inpatients who have fallen, and may be used to design future investigations. It is imperative that measures are identified to avoid the frequent adverse outcomes that result from inpatient falls. Insurance companies, hospital administrators, patients, and providers will be demanding that a safe environment be a key component of quality of care measures.

This study draws attention to the scope of the problem at our institution that is common to hospitals across the country. In our study, our academic medical center had a fall rate consistent with published reports, but new efforts have been focused on quality improvement in this area. An interdisciplinary fall prevention committee has been formed that includes physicians, nurses, patient care assistants, physical therapists, pharmacists, and representatives from information technology (IT). Currently, a program of a fall risk‐factor assessment with targeted interventions to reduce those risk factors is being developed for all high‐risk patients and will be piloted on inpatient units.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Susan Emro, BS, Department of Health Policy, Susan Davis, MS, MPH, RN, CNAA, Department of Nursing, and Albert Siu, MD, MSPH, Brookdale Department of Geriatrics and Adult Development, for their review of this article. Author contributions were as followsconception and design: S.M.B, R.K., and T.M.; collection and assembly of data: S.M.B.; analysis and interpretation of the data: S.M.B, R.K., and J.W.; drafting of the article: S.M.B.; critical revision of the article for important intellectual content: R.K. and J.W.; final approval of the article: S.M.B, R.K., and J.W.; statistical expertise: J.W.; obtaining of funding: S.M.B.

An estimated 2% to 15% of all hospitalized patients experience at least one fall.1 Approximately 30% of such falls result in injury and up to 6% may be serious in nature.1, 2 These injuries can result in pain, functional impairment, disability, or even death, and can contribute to longer lengths of stay, increased health care costs, and nursing home placement.25 As a result, inpatient falls have become a major priority for hospital quality assurance programs, and hospital risk management departments have begun to target inpatient falls as a source of legal liability.13, 6, 7 Recently, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services announced that it will no longer pay for preventable complications of hospitalizations, including falls and fall‐related injury.8

Much of the literature on falls comes from community and long‐term care settings, and only a few studies have investigated falls during acute care hospitalization.3, 9, 10 From these studies, risk factors for inpatient falls have been identified and various models have been developed to predict an individual patient's risk of falling. However, unlike in the community setting, interventions to prevent falls in the acute care setting have not proven to be beneficial.11, 12 Commonly used approaches including restraints, alarms, bracelets, or having a volunteer sit with high‐risk patients have not been found to be effective.13, 14 Only 1 study found a multicomponent care plan that targeted specific risk factors in older inpatients to be associated with a reduced relative risk of recorded falls.15 Given this dearth of consistent evidence for the prevention of falls in hospitalized inpatients, the American Geriatrics Society has identified this as a gap area for future research.16

There are also limited data regarding predictors of injury after inpatient falls. A few small studies have identified potential risk factors for sustaining an injury after a fall in acute care, such as age >75 years, altered mental status, increased comorbidities, visual impairment, falls in the bathroom, and admission to a geriatric psychiatry floor.2, 5, 17 However, to our knowledge, there are no studies that have identified potential characteristics of inpatients found immediately after a fall that predict an injury. Providers who assess inpatients who have fallen need guidance on how to identify those in need of further evaluation and testing. This study sought to quantify the types and severity of injuries resulting from inpatient falls and to identify predictors of injury after a fall among a cohort of patients who fell at an urban academic medical center.

Patients and Methods

Patient Population

The study population included all inpatients on 13 medical and surgical units who experienced a fall between January 1, 2006 and December 31, 2006, while hospitalized at an 1171‐bed urban academic medical center. Telemetry, intensive care, pediatric, psychiatric, rehabilitation, and obstetrics or gynecology units were excluded from this analysis; the patients on these units are special populations that are qualitatively different than other acute care patients and have a different set of risk factor for falls and predictors of fall‐related injury. The study was approved by the institutional review board of the Mount Sinai School of Medicine.

Data Collection

Inpatient falls were identified retrospectively by review of hospital incident reports, which are most often completed by the unit nurses. In our institution, all falls generate an incident report. Using a standardized abstraction form, patient characteristics, circumstances surrounding falls, and fall‐related injuries were collected from the reports.

Laboratory data for anemia (hemoglobin < 12.0 g/dL), low albumin (<3.5 g/dL), elevated creatinine (>1.5 mg/dL), prolonged partial thromboplastin time (>35 seconds), and elevated international normalized ratio (INR > 1.3), were extracted from the patient's computerized medical record, if available. Number of days from admission to the fall, length of stay to the nearest hundredth of a day, and discharge disposition were also recorded for each patient.

Results of all radiographic studies, including x‐ray, ultrasound, computed tomography (CT), and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), performed within 2 weeks after the fall were obtained. The indication for the imaging study was assessed from the order given to the radiology department and from the patient's medical record. A positive finding on an imaging study was defined as evidence of intracranial hemorrhage, fracture, joint effusion, soft‐tissue swelling, or any other injury potentially caused by trauma. Fall‐related injury was defined as positive findings on any of these imaging studies that were performed as a result of the fall. Evaluation of fall‐related injuries was conducted by a reviewer blinded to the baseline patient characteristics and laboratory data.

Statistical Analyses