User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack nav-ce-stack__large-screen')]

header[@id='header']

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

footer[@id='footer']

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

div[contains(@class, 'view-medstat-quiz-listing-panes')]

Hearing loss tied to decline in physical functioning

published online in JAMA Network Open.

Hearing loss is associated with slower gait and, in particular, worse balance, the data suggest.

“Because hearing impairment is amenable to prevention and management, it potentially serves as a target for interventions to slow physical decline with aging,” the researchers said.

To examine how hearing impairment relates to physical function in older adults, Pablo Martinez-Amezcua, MD, PhD, MHS, a researcher in the department of epidemiology at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, and colleagues analyzed data from the ongoing Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study.

ARIC initially enrolled more than 15,000 adults in Maryland, Minnesota, Mississippi, and North Carolina between 1987 and 1989. In the present study, the researchers focused on data from 2,956 participants who attended a study visit between 2016 and 2017, during which researchers assessed their hearing using pure tone audiometry.

Hearing-study participants had an average age of 79 years, about 58% were women, and 80% were White. Approximately 33% of the participants had normal hearing, 40% had mild hearing impairment, 23% had moderate hearing impairment, and 4% had severe hearing impairment.

Participants had also undergone assessment of physical functioning at study visits between 2011 and 2019, including a fast-paced 2-minute walk test to measure their walking endurance. Another assessment, the Short Physical Performance Battery (SPPB), tests balance, gait speed, and chair stands (seated participants stand up and sit back down five times as quickly as possible while their arms are crossed).

Dr. Martinez-Amezcua and colleagues found that severe hearing impairment was associated with a lower average SPPB score compared with normal hearing in a regression analysis. Specifically, compared with those with normal hearing, participants with severe hearing impairment were more likely to have low scores on the SPPB (odds ratio, 2.72), balance (OR, 2.72), and gait speed (OR, 2.16).

However, hearing impairment was not significantly associated with the chair stand test results. The researchers note that chair stands may rely more on strength, whereas balance and gait speed may rely more on coordination and movement.

The team also found that people with worse hearing tended to walk a shorter distance during the 2-minute walk test. Compared with participants with normal hearing, participants with moderate hearing impairment walked 2.81 meters less and those with severe hearing impairment walked 5.31 meters less on average, after adjustment for variables including age, sex, and health conditions.

Participants with hearing impairment also tended to have faster declines in physical function over time.

Various mechanisms could explain associations between hearing and physical function, the authors said. For example, an underlying condition such as cardiovascular disease might affect both hearing and physical function. Damage to the inner ear could affect vestibular and auditory systems at the same time. In addition, hearing impairment may relate to cognition, depression, or social isolation, which could influence physical activity.

“Age-related hearing loss is traditionally seen as a barrier for communication,” Dr. Martinez-Amezcua told this news organization. “In the past decade, research on the consequences of hearing loss has identified it as a risk factor for cognitive decline and dementia. Our findings contribute to our understanding of other negative outcomes associated with hearing loss.”

Randomized clinical trials are the best way to assess whether addressing hearing loss might improve physical function, Dr. Martinez-Amezcua said. “Currently there is one clinical trial (ACHIEVE) that will, among other outcomes, study the impact of hearing aids on cognitive and physical function,” he said.

Although interventions may not reverse hearing loss, hearing rehabilitation strategies, including hearing aids and cochlear implants, may help, he added. Educating caregivers and changing a person’s environment can also reduce the effects hearing loss has on daily life, Dr. Martinez-Amezcua said.

“We rely so much in our sense of vision for activities of daily living that we tend to underestimate how important hearing is, and the consequences of hearing loss go beyond having trouble communicating with someone,” he said.

This study and prior research “raise the intriguing idea that hearing may provide essential information to the neural circuits underpinning movement in our environment and that correction for hearing loss may help promote physical well-being,” Willa D. Brenowitz, PhD, MPH, and Margaret I. Wallhagen, PhD, GNP-BC, both at the University of California, San Francisco, wrote in an accompanying commentary. “While this hypothesis is appealing and warrants further investigation, there are multiple other potential explanations of such an association, including potential sources of bias that may affect observational studies such as this one.”

Beyond treating hearing loss, interventions such as physical therapy or tai chi may benefit patients, they suggested.

Because many changes occur during older age, it can be difficult to understand which factor is influencing another, Dr. Brenowitz said in an interview. There are potentially relevant mechanisms through which hearing could affect cognition and physical functioning. Still another explanation could be that some people are “aging in a faster way” than others, Dr. Brenowitz said.

Dr. Martinez-Amezcua and a coauthor disclosed receiving sponsorship from the Cochlear Center for Hearing and Public Health. Another author, Frank R. Lin, MD, PhD, directs the research center, which is partly funded by a philanthropic gift from Cochlear to the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. Dr. Lin also disclosed personal fees from Frequency Therapeutics and Caption Call. One author serves on a scientific advisory board for Shoebox and Good Machine Studio.

Dr. Wallhagen has served on the board of trustees of the Hearing Loss Association of America and is a member of the board of the Hearing Loss Association of America–California. Dr. Wallhagen also received funding for a pilot project on the impact of hearing loss on communication in the context of chronic serious illness from the National Palliative Care Research Center outside the submitted work.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

published online in JAMA Network Open.

Hearing loss is associated with slower gait and, in particular, worse balance, the data suggest.

“Because hearing impairment is amenable to prevention and management, it potentially serves as a target for interventions to slow physical decline with aging,” the researchers said.

To examine how hearing impairment relates to physical function in older adults, Pablo Martinez-Amezcua, MD, PhD, MHS, a researcher in the department of epidemiology at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, and colleagues analyzed data from the ongoing Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study.

ARIC initially enrolled more than 15,000 adults in Maryland, Minnesota, Mississippi, and North Carolina between 1987 and 1989. In the present study, the researchers focused on data from 2,956 participants who attended a study visit between 2016 and 2017, during which researchers assessed their hearing using pure tone audiometry.

Hearing-study participants had an average age of 79 years, about 58% were women, and 80% were White. Approximately 33% of the participants had normal hearing, 40% had mild hearing impairment, 23% had moderate hearing impairment, and 4% had severe hearing impairment.

Participants had also undergone assessment of physical functioning at study visits between 2011 and 2019, including a fast-paced 2-minute walk test to measure their walking endurance. Another assessment, the Short Physical Performance Battery (SPPB), tests balance, gait speed, and chair stands (seated participants stand up and sit back down five times as quickly as possible while their arms are crossed).

Dr. Martinez-Amezcua and colleagues found that severe hearing impairment was associated with a lower average SPPB score compared with normal hearing in a regression analysis. Specifically, compared with those with normal hearing, participants with severe hearing impairment were more likely to have low scores on the SPPB (odds ratio, 2.72), balance (OR, 2.72), and gait speed (OR, 2.16).

However, hearing impairment was not significantly associated with the chair stand test results. The researchers note that chair stands may rely more on strength, whereas balance and gait speed may rely more on coordination and movement.

The team also found that people with worse hearing tended to walk a shorter distance during the 2-minute walk test. Compared with participants with normal hearing, participants with moderate hearing impairment walked 2.81 meters less and those with severe hearing impairment walked 5.31 meters less on average, after adjustment for variables including age, sex, and health conditions.

Participants with hearing impairment also tended to have faster declines in physical function over time.

Various mechanisms could explain associations between hearing and physical function, the authors said. For example, an underlying condition such as cardiovascular disease might affect both hearing and physical function. Damage to the inner ear could affect vestibular and auditory systems at the same time. In addition, hearing impairment may relate to cognition, depression, or social isolation, which could influence physical activity.

“Age-related hearing loss is traditionally seen as a barrier for communication,” Dr. Martinez-Amezcua told this news organization. “In the past decade, research on the consequences of hearing loss has identified it as a risk factor for cognitive decline and dementia. Our findings contribute to our understanding of other negative outcomes associated with hearing loss.”

Randomized clinical trials are the best way to assess whether addressing hearing loss might improve physical function, Dr. Martinez-Amezcua said. “Currently there is one clinical trial (ACHIEVE) that will, among other outcomes, study the impact of hearing aids on cognitive and physical function,” he said.

Although interventions may not reverse hearing loss, hearing rehabilitation strategies, including hearing aids and cochlear implants, may help, he added. Educating caregivers and changing a person’s environment can also reduce the effects hearing loss has on daily life, Dr. Martinez-Amezcua said.

“We rely so much in our sense of vision for activities of daily living that we tend to underestimate how important hearing is, and the consequences of hearing loss go beyond having trouble communicating with someone,” he said.

This study and prior research “raise the intriguing idea that hearing may provide essential information to the neural circuits underpinning movement in our environment and that correction for hearing loss may help promote physical well-being,” Willa D. Brenowitz, PhD, MPH, and Margaret I. Wallhagen, PhD, GNP-BC, both at the University of California, San Francisco, wrote in an accompanying commentary. “While this hypothesis is appealing and warrants further investigation, there are multiple other potential explanations of such an association, including potential sources of bias that may affect observational studies such as this one.”

Beyond treating hearing loss, interventions such as physical therapy or tai chi may benefit patients, they suggested.

Because many changes occur during older age, it can be difficult to understand which factor is influencing another, Dr. Brenowitz said in an interview. There are potentially relevant mechanisms through which hearing could affect cognition and physical functioning. Still another explanation could be that some people are “aging in a faster way” than others, Dr. Brenowitz said.

Dr. Martinez-Amezcua and a coauthor disclosed receiving sponsorship from the Cochlear Center for Hearing and Public Health. Another author, Frank R. Lin, MD, PhD, directs the research center, which is partly funded by a philanthropic gift from Cochlear to the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. Dr. Lin also disclosed personal fees from Frequency Therapeutics and Caption Call. One author serves on a scientific advisory board for Shoebox and Good Machine Studio.

Dr. Wallhagen has served on the board of trustees of the Hearing Loss Association of America and is a member of the board of the Hearing Loss Association of America–California. Dr. Wallhagen also received funding for a pilot project on the impact of hearing loss on communication in the context of chronic serious illness from the National Palliative Care Research Center outside the submitted work.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

published online in JAMA Network Open.

Hearing loss is associated with slower gait and, in particular, worse balance, the data suggest.

“Because hearing impairment is amenable to prevention and management, it potentially serves as a target for interventions to slow physical decline with aging,” the researchers said.

To examine how hearing impairment relates to physical function in older adults, Pablo Martinez-Amezcua, MD, PhD, MHS, a researcher in the department of epidemiology at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, and colleagues analyzed data from the ongoing Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study.

ARIC initially enrolled more than 15,000 adults in Maryland, Minnesota, Mississippi, and North Carolina between 1987 and 1989. In the present study, the researchers focused on data from 2,956 participants who attended a study visit between 2016 and 2017, during which researchers assessed their hearing using pure tone audiometry.

Hearing-study participants had an average age of 79 years, about 58% were women, and 80% were White. Approximately 33% of the participants had normal hearing, 40% had mild hearing impairment, 23% had moderate hearing impairment, and 4% had severe hearing impairment.

Participants had also undergone assessment of physical functioning at study visits between 2011 and 2019, including a fast-paced 2-minute walk test to measure their walking endurance. Another assessment, the Short Physical Performance Battery (SPPB), tests balance, gait speed, and chair stands (seated participants stand up and sit back down five times as quickly as possible while their arms are crossed).

Dr. Martinez-Amezcua and colleagues found that severe hearing impairment was associated with a lower average SPPB score compared with normal hearing in a regression analysis. Specifically, compared with those with normal hearing, participants with severe hearing impairment were more likely to have low scores on the SPPB (odds ratio, 2.72), balance (OR, 2.72), and gait speed (OR, 2.16).

However, hearing impairment was not significantly associated with the chair stand test results. The researchers note that chair stands may rely more on strength, whereas balance and gait speed may rely more on coordination and movement.

The team also found that people with worse hearing tended to walk a shorter distance during the 2-minute walk test. Compared with participants with normal hearing, participants with moderate hearing impairment walked 2.81 meters less and those with severe hearing impairment walked 5.31 meters less on average, after adjustment for variables including age, sex, and health conditions.

Participants with hearing impairment also tended to have faster declines in physical function over time.

Various mechanisms could explain associations between hearing and physical function, the authors said. For example, an underlying condition such as cardiovascular disease might affect both hearing and physical function. Damage to the inner ear could affect vestibular and auditory systems at the same time. In addition, hearing impairment may relate to cognition, depression, or social isolation, which could influence physical activity.

“Age-related hearing loss is traditionally seen as a barrier for communication,” Dr. Martinez-Amezcua told this news organization. “In the past decade, research on the consequences of hearing loss has identified it as a risk factor for cognitive decline and dementia. Our findings contribute to our understanding of other negative outcomes associated with hearing loss.”

Randomized clinical trials are the best way to assess whether addressing hearing loss might improve physical function, Dr. Martinez-Amezcua said. “Currently there is one clinical trial (ACHIEVE) that will, among other outcomes, study the impact of hearing aids on cognitive and physical function,” he said.

Although interventions may not reverse hearing loss, hearing rehabilitation strategies, including hearing aids and cochlear implants, may help, he added. Educating caregivers and changing a person’s environment can also reduce the effects hearing loss has on daily life, Dr. Martinez-Amezcua said.

“We rely so much in our sense of vision for activities of daily living that we tend to underestimate how important hearing is, and the consequences of hearing loss go beyond having trouble communicating with someone,” he said.

This study and prior research “raise the intriguing idea that hearing may provide essential information to the neural circuits underpinning movement in our environment and that correction for hearing loss may help promote physical well-being,” Willa D. Brenowitz, PhD, MPH, and Margaret I. Wallhagen, PhD, GNP-BC, both at the University of California, San Francisco, wrote in an accompanying commentary. “While this hypothesis is appealing and warrants further investigation, there are multiple other potential explanations of such an association, including potential sources of bias that may affect observational studies such as this one.”

Beyond treating hearing loss, interventions such as physical therapy or tai chi may benefit patients, they suggested.

Because many changes occur during older age, it can be difficult to understand which factor is influencing another, Dr. Brenowitz said in an interview. There are potentially relevant mechanisms through which hearing could affect cognition and physical functioning. Still another explanation could be that some people are “aging in a faster way” than others, Dr. Brenowitz said.

Dr. Martinez-Amezcua and a coauthor disclosed receiving sponsorship from the Cochlear Center for Hearing and Public Health. Another author, Frank R. Lin, MD, PhD, directs the research center, which is partly funded by a philanthropic gift from Cochlear to the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. Dr. Lin also disclosed personal fees from Frequency Therapeutics and Caption Call. One author serves on a scientific advisory board for Shoebox and Good Machine Studio.

Dr. Wallhagen has served on the board of trustees of the Hearing Loss Association of America and is a member of the board of the Hearing Loss Association of America–California. Dr. Wallhagen also received funding for a pilot project on the impact of hearing loss on communication in the context of chronic serious illness from the National Palliative Care Research Center outside the submitted work.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

COVID-19: Guiding vaccinated patients through to the ‘new normal’

As COVID-related restrictions are lifting and the streets, restaurants, and events are filling back up, we must encourage our patients to take inventory. It is time to help them create posttraumatic growth.

As we help them navigate this part of the pandemic, encourage them to ask what they learned over the last year and how they plan to integrate what they’ve been through to successfully create the “new normal.”

The Biden administration had set a goal of getting at least one shot to 70% of American adults by July 4, and that goal will not be reached. That shortfall, combined with the increase of the highly transmissible Delta variant of SARS-CoV-2 means that we and our patients must not let our guards completely down. At the same time, we can encourage our vaccinated patients to get back to their prepandemic lives – to the extent that they feel comfortable doing so.

Ultimately, this is about respecting physical and emotional boundaries. How do we greet vaccinated people now? Is it okay to shake hands, hug, or kiss to greet a friend or family member – or should we continue to elbow bump – or perhaps wave? Should we confront family members who have opted not to get vaccinated for reasons not related to health? Is it safe to visit with older relatives who are vaccinated? What about children under 12 who are not?

Those who were on the front lines of the pandemic faced unfathomable pain and suffering – and mental and physical exhaustion. And we know that the nightmare is not over. Several areas of the country with large numbers of unvaccinated people could face “very dense outbreaks,” in large part because of the Delta variant.

As we sort through the remaining challenges, I urge us all to reflect. We have been in this together and will emerge together. We know that the closer we were to the trauma, the longer recovery will take.

Ask patients to consider what is most important to resume and what can still wait. Some are eager to jump back into the deep end of the pool; others prefer to continue to wait cautiously. Families need to be on the same page as they assess risks and opportunities going forward, because household spread continues to be at the highest risk. Remind patients that the health of one of us affects the health of all of us.

Urge patients to take time to explore the following questions as they process the pandemic. We can also ask ourselves these same questions and share them with colleagues who are also rebuilding.

- Did you prioritize your family more? How can you continue to spend quality time them as other opportunities emerge?

- Did you have to withdraw from friends/coworkers and family members because of the pandemic? If so, how can you reincorporate them in our lives?

- Did you send more time caring for yourself with exercise and meditation? Can those new habits remain in place as life presents more options? How can you continue to make time for self-care while adding back other responsibilities?

- Did you eat better or worse in quarantine? Can you maintain the positive habits you developed as you venture back to restaurants, parties, and gatherings?

- What habits did you break that you are now better off without?

- What new habits or hobbies did you create that you want to continue?

- What hobbies should you resume that you missed during the last year?

- What new coping skills have you gained?

- Has your alcohol consumption declined or increased during the pandemic?

- Did you neglect/decide to forgo your medical and dental care? How quickly can you safely resume that care?

- How did your value system shift this year?

- Did the people you feel closest to change?

- How can you use this trauma to appreciate life more?

Life might get very busy this summer, so encourage patients to find time to answer these questions. Journaling can be a great way to think through all that we have experienced. Our brains will need to change again to adapt. Many of us have felt sad or anxious for a quite a while, and we want to move toward more positive feelings of safety, happiness, optimism, and joy. This will take effort. After all, we have lost more than 600,000 people to COVID, and much of the world is still in the middle of the pandemic. But this will get much easier as the threat of COVID-19 continues to recede. We must now work toward creating better times ahead.

Dr. Ritvo has almost 30 years’ experience in psychiatry and is currently practicing telemedicine. She is the author of “Bekindr – The Transformative Power of Kindness” (Hellertown, Pa.: Momosa Publishing, 2018). She has no conflicts of interest.

As COVID-related restrictions are lifting and the streets, restaurants, and events are filling back up, we must encourage our patients to take inventory. It is time to help them create posttraumatic growth.

As we help them navigate this part of the pandemic, encourage them to ask what they learned over the last year and how they plan to integrate what they’ve been through to successfully create the “new normal.”

The Biden administration had set a goal of getting at least one shot to 70% of American adults by July 4, and that goal will not be reached. That shortfall, combined with the increase of the highly transmissible Delta variant of SARS-CoV-2 means that we and our patients must not let our guards completely down. At the same time, we can encourage our vaccinated patients to get back to their prepandemic lives – to the extent that they feel comfortable doing so.

Ultimately, this is about respecting physical and emotional boundaries. How do we greet vaccinated people now? Is it okay to shake hands, hug, or kiss to greet a friend or family member – or should we continue to elbow bump – or perhaps wave? Should we confront family members who have opted not to get vaccinated for reasons not related to health? Is it safe to visit with older relatives who are vaccinated? What about children under 12 who are not?

Those who were on the front lines of the pandemic faced unfathomable pain and suffering – and mental and physical exhaustion. And we know that the nightmare is not over. Several areas of the country with large numbers of unvaccinated people could face “very dense outbreaks,” in large part because of the Delta variant.

As we sort through the remaining challenges, I urge us all to reflect. We have been in this together and will emerge together. We know that the closer we were to the trauma, the longer recovery will take.

Ask patients to consider what is most important to resume and what can still wait. Some are eager to jump back into the deep end of the pool; others prefer to continue to wait cautiously. Families need to be on the same page as they assess risks and opportunities going forward, because household spread continues to be at the highest risk. Remind patients that the health of one of us affects the health of all of us.

Urge patients to take time to explore the following questions as they process the pandemic. We can also ask ourselves these same questions and share them with colleagues who are also rebuilding.

- Did you prioritize your family more? How can you continue to spend quality time them as other opportunities emerge?

- Did you have to withdraw from friends/coworkers and family members because of the pandemic? If so, how can you reincorporate them in our lives?

- Did you send more time caring for yourself with exercise and meditation? Can those new habits remain in place as life presents more options? How can you continue to make time for self-care while adding back other responsibilities?

- Did you eat better or worse in quarantine? Can you maintain the positive habits you developed as you venture back to restaurants, parties, and gatherings?

- What habits did you break that you are now better off without?

- What new habits or hobbies did you create that you want to continue?

- What hobbies should you resume that you missed during the last year?

- What new coping skills have you gained?

- Has your alcohol consumption declined or increased during the pandemic?

- Did you neglect/decide to forgo your medical and dental care? How quickly can you safely resume that care?

- How did your value system shift this year?

- Did the people you feel closest to change?

- How can you use this trauma to appreciate life more?

Life might get very busy this summer, so encourage patients to find time to answer these questions. Journaling can be a great way to think through all that we have experienced. Our brains will need to change again to adapt. Many of us have felt sad or anxious for a quite a while, and we want to move toward more positive feelings of safety, happiness, optimism, and joy. This will take effort. After all, we have lost more than 600,000 people to COVID, and much of the world is still in the middle of the pandemic. But this will get much easier as the threat of COVID-19 continues to recede. We must now work toward creating better times ahead.

Dr. Ritvo has almost 30 years’ experience in psychiatry and is currently practicing telemedicine. She is the author of “Bekindr – The Transformative Power of Kindness” (Hellertown, Pa.: Momosa Publishing, 2018). She has no conflicts of interest.

As COVID-related restrictions are lifting and the streets, restaurants, and events are filling back up, we must encourage our patients to take inventory. It is time to help them create posttraumatic growth.

As we help them navigate this part of the pandemic, encourage them to ask what they learned over the last year and how they plan to integrate what they’ve been through to successfully create the “new normal.”

The Biden administration had set a goal of getting at least one shot to 70% of American adults by July 4, and that goal will not be reached. That shortfall, combined with the increase of the highly transmissible Delta variant of SARS-CoV-2 means that we and our patients must not let our guards completely down. At the same time, we can encourage our vaccinated patients to get back to their prepandemic lives – to the extent that they feel comfortable doing so.

Ultimately, this is about respecting physical and emotional boundaries. How do we greet vaccinated people now? Is it okay to shake hands, hug, or kiss to greet a friend or family member – or should we continue to elbow bump – or perhaps wave? Should we confront family members who have opted not to get vaccinated for reasons not related to health? Is it safe to visit with older relatives who are vaccinated? What about children under 12 who are not?

Those who were on the front lines of the pandemic faced unfathomable pain and suffering – and mental and physical exhaustion. And we know that the nightmare is not over. Several areas of the country with large numbers of unvaccinated people could face “very dense outbreaks,” in large part because of the Delta variant.

As we sort through the remaining challenges, I urge us all to reflect. We have been in this together and will emerge together. We know that the closer we were to the trauma, the longer recovery will take.

Ask patients to consider what is most important to resume and what can still wait. Some are eager to jump back into the deep end of the pool; others prefer to continue to wait cautiously. Families need to be on the same page as they assess risks and opportunities going forward, because household spread continues to be at the highest risk. Remind patients that the health of one of us affects the health of all of us.

Urge patients to take time to explore the following questions as they process the pandemic. We can also ask ourselves these same questions and share them with colleagues who are also rebuilding.

- Did you prioritize your family more? How can you continue to spend quality time them as other opportunities emerge?

- Did you have to withdraw from friends/coworkers and family members because of the pandemic? If so, how can you reincorporate them in our lives?

- Did you send more time caring for yourself with exercise and meditation? Can those new habits remain in place as life presents more options? How can you continue to make time for self-care while adding back other responsibilities?

- Did you eat better or worse in quarantine? Can you maintain the positive habits you developed as you venture back to restaurants, parties, and gatherings?

- What habits did you break that you are now better off without?

- What new habits or hobbies did you create that you want to continue?

- What hobbies should you resume that you missed during the last year?

- What new coping skills have you gained?

- Has your alcohol consumption declined or increased during the pandemic?

- Did you neglect/decide to forgo your medical and dental care? How quickly can you safely resume that care?

- How did your value system shift this year?

- Did the people you feel closest to change?

- How can you use this trauma to appreciate life more?

Life might get very busy this summer, so encourage patients to find time to answer these questions. Journaling can be a great way to think through all that we have experienced. Our brains will need to change again to adapt. Many of us have felt sad or anxious for a quite a while, and we want to move toward more positive feelings of safety, happiness, optimism, and joy. This will take effort. After all, we have lost more than 600,000 people to COVID, and much of the world is still in the middle of the pandemic. But this will get much easier as the threat of COVID-19 continues to recede. We must now work toward creating better times ahead.

Dr. Ritvo has almost 30 years’ experience in psychiatry and is currently practicing telemedicine. She is the author of “Bekindr – The Transformative Power of Kindness” (Hellertown, Pa.: Momosa Publishing, 2018). She has no conflicts of interest.

Stimulant reduces ‘sluggish cognitive tempo’ in adults with ADHD

A stimulant used in patients with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder might prove useful for other comorbid symptoms, results of a randomized, crossover trial suggest.

In the trial, the investigators reported that lisdexamfetamine (Vyvanse) reduced self-reported symptoms of sluggish cognitive tempo (SCT) by 30%, in addition to lowering ADHD symptoms by more than 40%.

The drug also corrected deficits in executive brain function. Patients had fewer episodes of procrastination, were better able to prioritize, and showed improvements in keeping things in mind.

“These findings highlight the importance of assessing symptoms of sluggish cognitive tempo and executive brain function in patients when they are initially diagnosed with ADHD,” Lenard A. Adler, MD, the lead author, said in a press release. The results were published June 29, 2021, in the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry.

The trial is groundbreaking because it is the first treatment study for ADHD with SCT in adults, Dr. Adler, director of the adult ADHD program at New York University Langone Health, said in an interview. He said that Russell A. Barkley, PhD, a clinical professor of psychiatry at Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, defines SCT as having nine cardinal symptoms: prone to daydreaming, easy boredom, trouble staying awake, feeling foggy, spaciness, lethargy, underachieving, less energy, and not processing information quickly or accurately.

Dr. Barkley, who studied more than 1,200 individuals with SCT, discovered that nearly half also had ADHD, Dr. Adler said. Those with the comorbid symptoms also had more impairment.

Whether or not the symptom set of SCT is a distinct disorder or a cotraveling symptom set that goes along with ADHD has been an area of investigation, said Dr. Adler, also a professor in the departments of psychiatry and child and adolescent psychiatry at New York University. Other known comorbid symptoms include executive function deficits and trouble with emotional control.

Stimulants to date have only shown success in children, as far as improving SCT. The goal of this study was to determine the efficacy of lisdexamfetamine on the nature and severity of ADHD symptoms and SCT behavioral indicators in adults with ADHD and SCT.

Two cohorts, alternating regimens

The investigators enrolled 38 adults with DSM-5 ADHD and SCT. Patients were recruited from two academic centers, New York University and the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai. The randomized 10-week crossover trial included two double-blind treatment periods, each 4 weeks long, with an intervening 2-week, single-blind placebo washout period.

“In crossover design, patients act as their own control, because they receive both treatments,” Dr. Adler said. Recruiting a smaller number of subjects helps to achieve significance in results.

For the first 4 weeks, participants received daily doses of either lisdexamfetamine (30-70 mg/day; mean, 59.1 mg/day) or a placebo sugar pill (mean, 66.6 mg/day). Researchers used standardized tests for SCT signs and symptoms, ADHD, and other measures of brain function to track psychiatric health on a weekly basis. After a month, the two cohorts switched regimens – those taking the placebo started the daily doses of lisdexamfetamine, and the other half stopped the drug and started taking the placebo.

Primary outcomes included the ADHD Rating Scale and Barkley Adult ADHD Rating Scale-IV SCT subscale.

Compared with placebo, adults with ADHD and comorbid SCT showed significant improvement after taking lisdexamfetamine in ratings of SCT and total ADHD symptoms. This was also true of other comorbid symptoms, such as executive function deficits.

In the crossover design, patients who received the drug first hadn’t gone fully back to baseline by the time the investigators crossed them over into the placebo group. “So, we couldn’t combine the two treatment epochs,” Dr. Adler said. However, the effect of the drug versus placebo was comparable in both study arms.

SCT alone was not studied

The trial had some limitations, mainly that it was an initial study with a modest sample size, Dr. Adler said. It also did not examine SCT alone, “so we can’t really say whether the stimulant medicine would improve SCT in patients who don’t have ADHD. What’s notable is when you look at how much of the improvement in SCT was due to improvement in ADHD, it was just 25%.” This means the effects occurring on SCT symptoms were not solely caused by effects on ADHD.

he said.

Dr. Adler would like to see treatment studies of adults with ADHD and SCT in a larger sample, potentially with other stimulants. In addition, future trials could examine the effects of stimulants on adults with SCT that do not have ADHD.

The results of this trial underscore the importance of evaluating adults with ADHD for comorbid symptoms, such as executive function and emotional control, he continued. “Impairing SCT symptoms may very well fall under that umbrella,” Dr. Adler said. “If you don’t identify them, you can’t track them in terms of treatment.”

SCT as a ‘flavor’ of ADHD

The outcome of this study demonstrates that lisdexamfetamine significantly improves both ADHD symptoms and SCT symptoms, said David W. Goodman MD, LFAPA, an assistant professor in the department of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore.

Dr. Goodman, who was not involved in the study, agreed that clinicians should be aware of SCT when assessing adults with ADHD and conceptualize SCT as a “flavor” of ADHD. “SCT is not widely recognized by clinicians outside of the research arena but will likely become an important characteristic of ADHD presentation,” he said in an interview.

“Future studies in adult ADHD should further clarify the prevalence of SCT in the ADHD population and address more specific effective treatment options,” he said.

James M. Swanson, PhD, who also was not involved with the study, agreed in an interview that it documents the clear short-term benefit of stimulants on symptoms of SCT. The study “may be very timely, since adults who were affected by COVID-19 often have residual sequelae manifested as ‘brain fog,’ which resemble SCT,” said Dr. Swanson, professor of pediatrics at the University of California, Irvine.

The study was funded by Takeda Pharmaceutical, manufacturer of lisdexamfetamine. Dr. Adler has received grant/research support and has served as a consultant from Shire/Takeda and other companies. Dr. Goodman is a scientific consultant to Takeda and other pharmaceutical companies in the ADHD arena. Dr. Swanson had no disclosures.

A stimulant used in patients with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder might prove useful for other comorbid symptoms, results of a randomized, crossover trial suggest.

In the trial, the investigators reported that lisdexamfetamine (Vyvanse) reduced self-reported symptoms of sluggish cognitive tempo (SCT) by 30%, in addition to lowering ADHD symptoms by more than 40%.

The drug also corrected deficits in executive brain function. Patients had fewer episodes of procrastination, were better able to prioritize, and showed improvements in keeping things in mind.

“These findings highlight the importance of assessing symptoms of sluggish cognitive tempo and executive brain function in patients when they are initially diagnosed with ADHD,” Lenard A. Adler, MD, the lead author, said in a press release. The results were published June 29, 2021, in the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry.

The trial is groundbreaking because it is the first treatment study for ADHD with SCT in adults, Dr. Adler, director of the adult ADHD program at New York University Langone Health, said in an interview. He said that Russell A. Barkley, PhD, a clinical professor of psychiatry at Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, defines SCT as having nine cardinal symptoms: prone to daydreaming, easy boredom, trouble staying awake, feeling foggy, spaciness, lethargy, underachieving, less energy, and not processing information quickly or accurately.

Dr. Barkley, who studied more than 1,200 individuals with SCT, discovered that nearly half also had ADHD, Dr. Adler said. Those with the comorbid symptoms also had more impairment.

Whether or not the symptom set of SCT is a distinct disorder or a cotraveling symptom set that goes along with ADHD has been an area of investigation, said Dr. Adler, also a professor in the departments of psychiatry and child and adolescent psychiatry at New York University. Other known comorbid symptoms include executive function deficits and trouble with emotional control.

Stimulants to date have only shown success in children, as far as improving SCT. The goal of this study was to determine the efficacy of lisdexamfetamine on the nature and severity of ADHD symptoms and SCT behavioral indicators in adults with ADHD and SCT.

Two cohorts, alternating regimens

The investigators enrolled 38 adults with DSM-5 ADHD and SCT. Patients were recruited from two academic centers, New York University and the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai. The randomized 10-week crossover trial included two double-blind treatment periods, each 4 weeks long, with an intervening 2-week, single-blind placebo washout period.

“In crossover design, patients act as their own control, because they receive both treatments,” Dr. Adler said. Recruiting a smaller number of subjects helps to achieve significance in results.

For the first 4 weeks, participants received daily doses of either lisdexamfetamine (30-70 mg/day; mean, 59.1 mg/day) or a placebo sugar pill (mean, 66.6 mg/day). Researchers used standardized tests for SCT signs and symptoms, ADHD, and other measures of brain function to track psychiatric health on a weekly basis. After a month, the two cohorts switched regimens – those taking the placebo started the daily doses of lisdexamfetamine, and the other half stopped the drug and started taking the placebo.

Primary outcomes included the ADHD Rating Scale and Barkley Adult ADHD Rating Scale-IV SCT subscale.

Compared with placebo, adults with ADHD and comorbid SCT showed significant improvement after taking lisdexamfetamine in ratings of SCT and total ADHD symptoms. This was also true of other comorbid symptoms, such as executive function deficits.

In the crossover design, patients who received the drug first hadn’t gone fully back to baseline by the time the investigators crossed them over into the placebo group. “So, we couldn’t combine the two treatment epochs,” Dr. Adler said. However, the effect of the drug versus placebo was comparable in both study arms.

SCT alone was not studied

The trial had some limitations, mainly that it was an initial study with a modest sample size, Dr. Adler said. It also did not examine SCT alone, “so we can’t really say whether the stimulant medicine would improve SCT in patients who don’t have ADHD. What’s notable is when you look at how much of the improvement in SCT was due to improvement in ADHD, it was just 25%.” This means the effects occurring on SCT symptoms were not solely caused by effects on ADHD.

he said.

Dr. Adler would like to see treatment studies of adults with ADHD and SCT in a larger sample, potentially with other stimulants. In addition, future trials could examine the effects of stimulants on adults with SCT that do not have ADHD.

The results of this trial underscore the importance of evaluating adults with ADHD for comorbid symptoms, such as executive function and emotional control, he continued. “Impairing SCT symptoms may very well fall under that umbrella,” Dr. Adler said. “If you don’t identify them, you can’t track them in terms of treatment.”

SCT as a ‘flavor’ of ADHD

The outcome of this study demonstrates that lisdexamfetamine significantly improves both ADHD symptoms and SCT symptoms, said David W. Goodman MD, LFAPA, an assistant professor in the department of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore.

Dr. Goodman, who was not involved in the study, agreed that clinicians should be aware of SCT when assessing adults with ADHD and conceptualize SCT as a “flavor” of ADHD. “SCT is not widely recognized by clinicians outside of the research arena but will likely become an important characteristic of ADHD presentation,” he said in an interview.

“Future studies in adult ADHD should further clarify the prevalence of SCT in the ADHD population and address more specific effective treatment options,” he said.

James M. Swanson, PhD, who also was not involved with the study, agreed in an interview that it documents the clear short-term benefit of stimulants on symptoms of SCT. The study “may be very timely, since adults who were affected by COVID-19 often have residual sequelae manifested as ‘brain fog,’ which resemble SCT,” said Dr. Swanson, professor of pediatrics at the University of California, Irvine.

The study was funded by Takeda Pharmaceutical, manufacturer of lisdexamfetamine. Dr. Adler has received grant/research support and has served as a consultant from Shire/Takeda and other companies. Dr. Goodman is a scientific consultant to Takeda and other pharmaceutical companies in the ADHD arena. Dr. Swanson had no disclosures.

A stimulant used in patients with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder might prove useful for other comorbid symptoms, results of a randomized, crossover trial suggest.

In the trial, the investigators reported that lisdexamfetamine (Vyvanse) reduced self-reported symptoms of sluggish cognitive tempo (SCT) by 30%, in addition to lowering ADHD symptoms by more than 40%.

The drug also corrected deficits in executive brain function. Patients had fewer episodes of procrastination, were better able to prioritize, and showed improvements in keeping things in mind.

“These findings highlight the importance of assessing symptoms of sluggish cognitive tempo and executive brain function in patients when they are initially diagnosed with ADHD,” Lenard A. Adler, MD, the lead author, said in a press release. The results were published June 29, 2021, in the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry.

The trial is groundbreaking because it is the first treatment study for ADHD with SCT in adults, Dr. Adler, director of the adult ADHD program at New York University Langone Health, said in an interview. He said that Russell A. Barkley, PhD, a clinical professor of psychiatry at Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, defines SCT as having nine cardinal symptoms: prone to daydreaming, easy boredom, trouble staying awake, feeling foggy, spaciness, lethargy, underachieving, less energy, and not processing information quickly or accurately.

Dr. Barkley, who studied more than 1,200 individuals with SCT, discovered that nearly half also had ADHD, Dr. Adler said. Those with the comorbid symptoms also had more impairment.

Whether or not the symptom set of SCT is a distinct disorder or a cotraveling symptom set that goes along with ADHD has been an area of investigation, said Dr. Adler, also a professor in the departments of psychiatry and child and adolescent psychiatry at New York University. Other known comorbid symptoms include executive function deficits and trouble with emotional control.

Stimulants to date have only shown success in children, as far as improving SCT. The goal of this study was to determine the efficacy of lisdexamfetamine on the nature and severity of ADHD symptoms and SCT behavioral indicators in adults with ADHD and SCT.

Two cohorts, alternating regimens

The investigators enrolled 38 adults with DSM-5 ADHD and SCT. Patients were recruited from two academic centers, New York University and the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai. The randomized 10-week crossover trial included two double-blind treatment periods, each 4 weeks long, with an intervening 2-week, single-blind placebo washout period.

“In crossover design, patients act as their own control, because they receive both treatments,” Dr. Adler said. Recruiting a smaller number of subjects helps to achieve significance in results.

For the first 4 weeks, participants received daily doses of either lisdexamfetamine (30-70 mg/day; mean, 59.1 mg/day) or a placebo sugar pill (mean, 66.6 mg/day). Researchers used standardized tests for SCT signs and symptoms, ADHD, and other measures of brain function to track psychiatric health on a weekly basis. After a month, the two cohorts switched regimens – those taking the placebo started the daily doses of lisdexamfetamine, and the other half stopped the drug and started taking the placebo.

Primary outcomes included the ADHD Rating Scale and Barkley Adult ADHD Rating Scale-IV SCT subscale.

Compared with placebo, adults with ADHD and comorbid SCT showed significant improvement after taking lisdexamfetamine in ratings of SCT and total ADHD symptoms. This was also true of other comorbid symptoms, such as executive function deficits.

In the crossover design, patients who received the drug first hadn’t gone fully back to baseline by the time the investigators crossed them over into the placebo group. “So, we couldn’t combine the two treatment epochs,” Dr. Adler said. However, the effect of the drug versus placebo was comparable in both study arms.

SCT alone was not studied

The trial had some limitations, mainly that it was an initial study with a modest sample size, Dr. Adler said. It also did not examine SCT alone, “so we can’t really say whether the stimulant medicine would improve SCT in patients who don’t have ADHD. What’s notable is when you look at how much of the improvement in SCT was due to improvement in ADHD, it was just 25%.” This means the effects occurring on SCT symptoms were not solely caused by effects on ADHD.

he said.

Dr. Adler would like to see treatment studies of adults with ADHD and SCT in a larger sample, potentially with other stimulants. In addition, future trials could examine the effects of stimulants on adults with SCT that do not have ADHD.

The results of this trial underscore the importance of evaluating adults with ADHD for comorbid symptoms, such as executive function and emotional control, he continued. “Impairing SCT symptoms may very well fall under that umbrella,” Dr. Adler said. “If you don’t identify them, you can’t track them in terms of treatment.”

SCT as a ‘flavor’ of ADHD

The outcome of this study demonstrates that lisdexamfetamine significantly improves both ADHD symptoms and SCT symptoms, said David W. Goodman MD, LFAPA, an assistant professor in the department of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore.

Dr. Goodman, who was not involved in the study, agreed that clinicians should be aware of SCT when assessing adults with ADHD and conceptualize SCT as a “flavor” of ADHD. “SCT is not widely recognized by clinicians outside of the research arena but will likely become an important characteristic of ADHD presentation,” he said in an interview.

“Future studies in adult ADHD should further clarify the prevalence of SCT in the ADHD population and address more specific effective treatment options,” he said.

James M. Swanson, PhD, who also was not involved with the study, agreed in an interview that it documents the clear short-term benefit of stimulants on symptoms of SCT. The study “may be very timely, since adults who were affected by COVID-19 often have residual sequelae manifested as ‘brain fog,’ which resemble SCT,” said Dr. Swanson, professor of pediatrics at the University of California, Irvine.

The study was funded by Takeda Pharmaceutical, manufacturer of lisdexamfetamine. Dr. Adler has received grant/research support and has served as a consultant from Shire/Takeda and other companies. Dr. Goodman is a scientific consultant to Takeda and other pharmaceutical companies in the ADHD arena. Dr. Swanson had no disclosures.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF CLINICAL PSYCHIATRY

Managing ‘difficult’ patient encounters

“I did not like those patients… They made me angry and I found myself irritated to experience them as they seemed so distant from myself and from all that is human. This is an astonishing intolerance which brands me a poor psychiatrist.”

Sigmund Freud, Letter to István Hollós (1928)

While Freud was referring to psychotic patients,1 his evident frustration shows that difficult and challenging patients have vexed even the best of us. All physicians and other clinicians will experience patient encounters that lead to anger or frustration, or even challenge their sense of equanimity and professional identity. In short, difficult and challenging patient interactions are unavoidable, regardless of the physician’s discipline.2-5 At times, physicians might struggle with demanding, unpleasant, ungrateful, and possibly dangerous patients, while sometimes the struggle is with the patient’s family members. No physician is immune to the problem, which makes it crucial to learn to anticipate and manage difficult patient interactions, skills which are generally not taught in medical schools or residency programs.

One prospective study of clinic patients found that up to 15% of patient encounters are deemed “difficult.”6 Common scenarios include patients (or their relatives) who seek certain tests after researching symptoms online, threats of legal or social media action in response to feeling that the physician is not listening to them, demands for a second opinion after disagreeing with the physician’s diagnosis, and mistrust of doctors after presenting with symptoms and not receiving a diagnosis. It is also common to care for patients who focus on negative outcomes or fail to adhere to treatment recommendations. These encounters can make physicians feel stressed out, disrespected, abused, or even fearful if threatened. Some physicians may come to feel they are trapped in a hostile work environment with little support from their supervisors or administrators. Patients often have a complaint office or department to turn to, but there is no equivalent for physicians, who are expected to soldier on regardless.

This article highlights a model that describes poor physician-patient encounters, factors contributing to these issues, how to manage these difficult interactions, and what to do if the relationship cannot be remediated.

Describing the ‘difficult’ patient

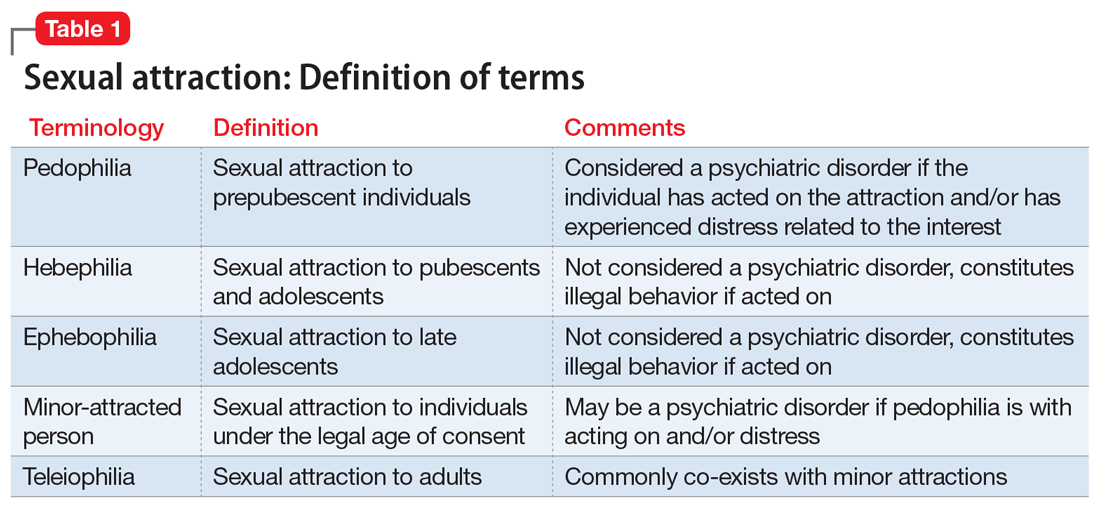

In a landmark 1978 paper, Groves7 provided one of the first descriptions of “difficult” patients. His colorful observations continue to provide useful insights. Groves emphasized that most medical texts ignore the issue of difficult patients and provide little or no guidance—which is still true 43 years later. He observed that physicians cannot avoid occasional negative feelings toward some patients. Further, Groves suggested that countertransference is often at the root of hateful reactions, a process he defines as “conscious or unconscious unbidden and unwanted hostile or sexual feelings toward the patient.”7Table 17 outlines how Groves divided “hateful” patients into several categories, and how physicians might respond to such patients.

A model for understanding difficult patient encounters

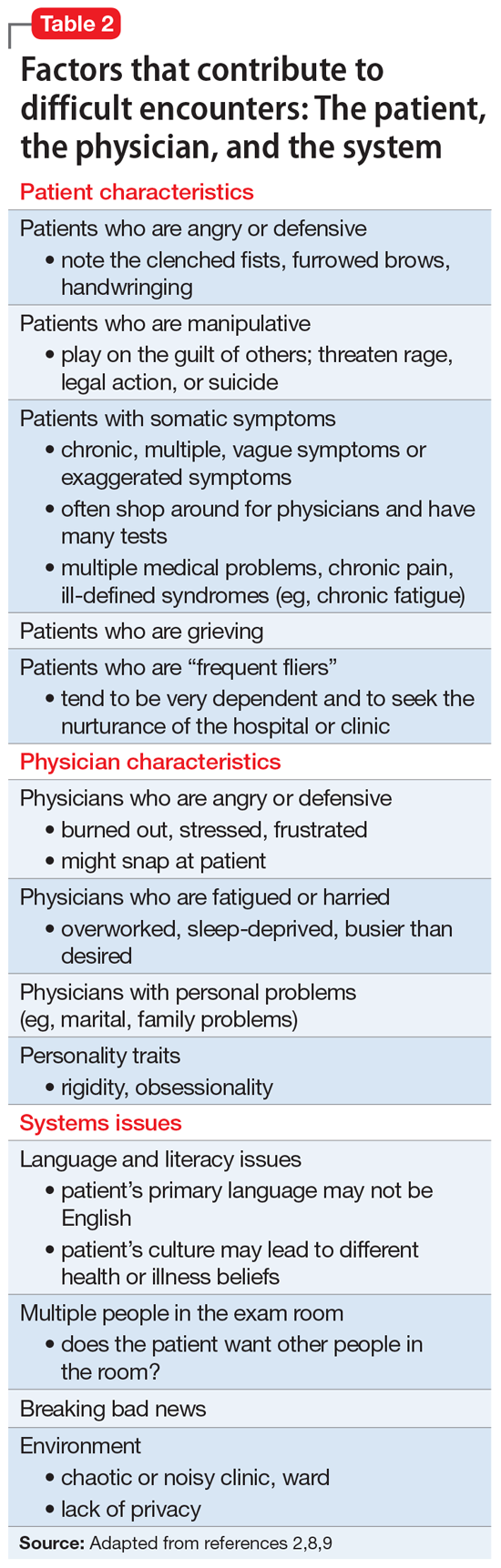

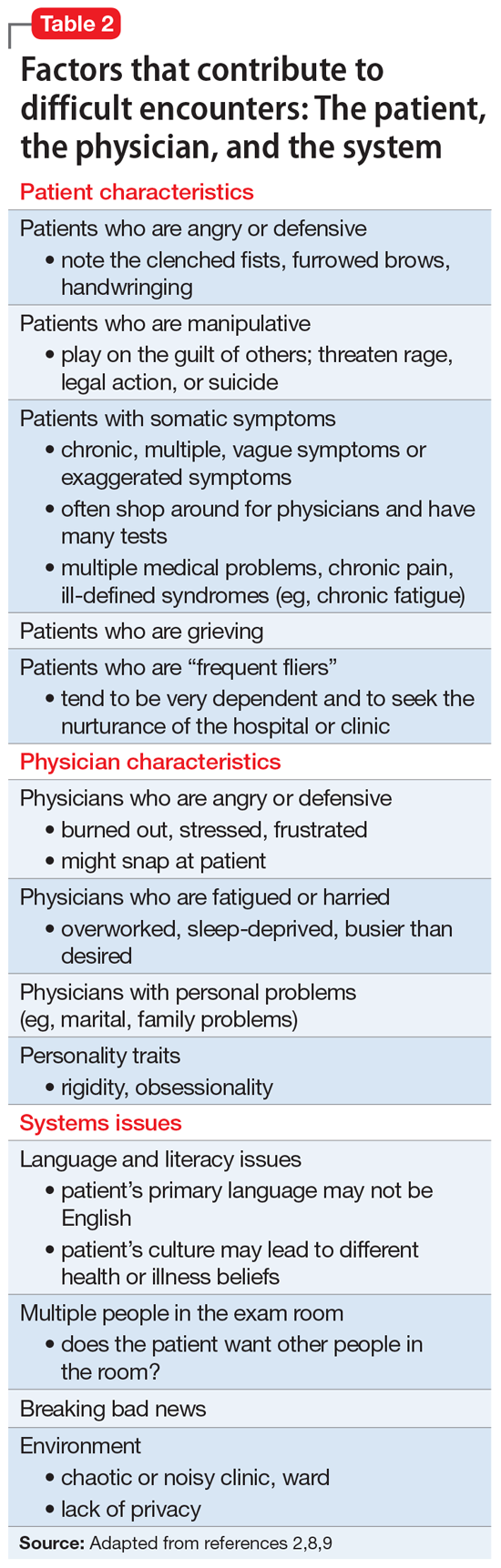

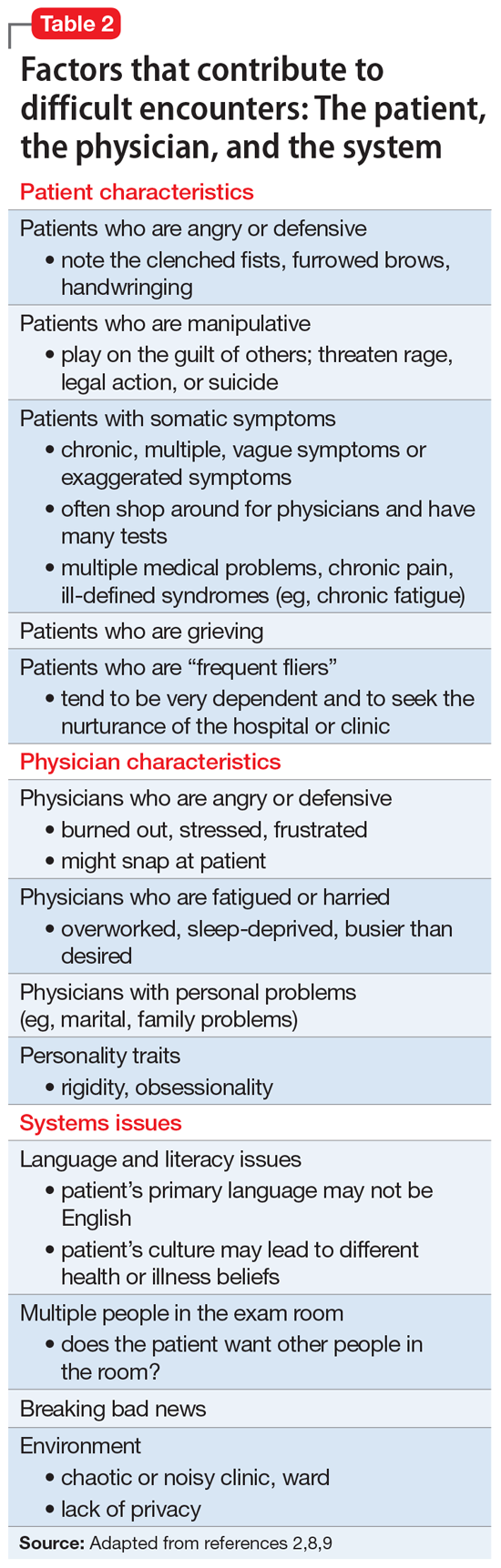

Adams and Murray2 created a model to help explain interactions with difficult or challenging patients that consists of 3 elements: the patient, the physician, and the system (ie, situation or environment). Hull and Broquet8 and Hardavella et al9 later adapted the model and described its components (Table 22,8,9).

Continue to: When considering...

When considering difficult interactions, it is important to be aware that all 3 components could interact, or merely 1 or 2 could come into play, but all should be explored as possible contributing factors.

Patient factors

The patient’s role in initiating or maintaining a problematic interaction should be explored. While some physicians are tempted to conclude that a personality disorder underlies difficult interactions, research shows a more complex picture. First, not all difficult patients have a psychiatric disorder, let alone a personality disorder. Jackson and Kroenke6 reported that among 74 difficult patients in an ambulatory clinic, 29% had a depressive disorder or anxiety disorder, with 11% experiencing 2 or more disorders. Major depressive disorder was present in 8.4% patients, other depressive disorders in 17.4%, panic disorder in 1.4%, and other anxiety disorders in 14.2%.6 These researchers found that difficult patient interactions were associated with the presence of a psychiatric disorder, especially depressive or anxiety disorders, and multiple physical symptoms.

Importantly, difficult patients are not unique to psychiatry, and are found in all medical disciplines and every type of practice situation. Some problematic patients have a substance use disorder, and their difficulty might stem from intoxication, withdrawal, or drug-seeking behaviors. Psychotic disorders can be the source of difficult interactions, typically resulting from the patient’s symptoms (ie, hallucinations, delusions, or bizarre behavior). Physicians tend to be forgiving toward these patients because they understand the extent of the individual’s illness. The same is true for a patient with dementia, who might be disruptive and loud, yet clearly is not in control of their behavior.

Koekkoek et al5 reviewed 94 articles that focused on difficult patients seen in mental health settings. Most patients were male (60% to 68%), and most were age 26 to 32 years. Diagnoses of psychotic disorders and personality disorders were the most frequent, while mood and other disorders were less common. In 1 of the studies reviewed, 6% of psychiatric inpatients were considered difficult. Koekkoek et al5 proposed that there are 3 groups of difficult patients:

- care avoiders: patients with psychosis who lack insight

- care seekers: patients who are chronically ill who have trouble maintaining a steady relationship with their caregivers

- care claimers: patients who do not require long-term care, but need housing, medication, or a “declaration of incompetence.”

Physician factors

Physicians are frequent contributors to bad interactions with their patients.2,7,8 They can become angry or defensive because of burnout, stress, or frustration, which might lead them to snap or otherwise respond inappropriately to their patients. Many physicians are overworked, sleep-deprived, or busier than they would prefer. Personal problems can be preoccupying and contribute to a physician being ill-tempered or distracted (eg, marital or family problems). Some physicians are simply poor communicators and might not understand the need to adapt their communication style to their patient, instead using medical jargon the patient does not understand. Ideally, physicians should modify their language to suit the patient’s level of education, degree of medical sophistication, and cultural background.

Continue to: A physician's personality traits...

A physician’s personality traits could clash with those of the patient, particularly if the physician is especially rigid or obsessional. Rather than “going with the flow,” the overly rigid physician might become impatient with patients who fail to understand diagnostic assessments or treatment recommendations. Inefficient physicians might not be able to keep up with the daily schedule, which could fuel impatience and perhaps even lead them to think that the patient is taking too much of their valuable time. Some might not know how to convey empathy, for example when giving bad news (“The tests show you have cancer…”). Others fail to make consistent eye contact with patients without understanding its importance to communication, a problem made worse by the use of electronic medical record systems (EMRs).

Systems issues

Systems issues also contribute to suboptimal physician-patient interactions, and some issues can be attributed to administrative problems. Examples of systems issues include:

- when a patient has difficulty making an appointment and is forced to listen to a confusing menu of choices

- a busy clinic that can only offer a patient an appointment 6 months away

- crowded or noisy waiting rooms

- language barriers for patients whose primary langage is not English. Not having access to an interpreter can exacerbate their frustration

- the use of EMRs is a growing threat to positive physician-patient interactions, yet their influence is often ignored. Widely disliked by physicians,10 EMRs are required in all but the smallest independent practice settings. Many busy physicians focus their attention on the computer, giving the patient the impression that the physician is not listening to them. Many patients conclude that they are less important than the process.

The consequences of difficult interactions

Following a bad interaction, dissatisfied patients are more likely to leave the clinic or hospital and ignore medical advice. These patients might then show up in crowded emergency departments, which may lead to poor use of health care resources. For physicians, challenging situations sap their emotional energy, cause demoralization, and interfere with their sense of job fulfillment. In extreme cases, such feelings might lead the physician to dislike and even avoid the patient.

How to manage challenging situations

Taking the following steps can help physicians work through challenging situations with their patients.

Diagnose the problem. First, recognize the difficult situation, analyze it, and identify how the patient, the physician, and the system are contributing to a bad physician-patient interaction. Diagnosing the interactional difficulty should precede the diagnosis and management of the patient’s disease. Physicians should acknowledge their own contribution through their attitude or actions. Finally, determine if there are system issues that are contributing to the problem, or if it is the clinic or inpatient setting itself (eg, noisy inpatient unit).

Continue to: Maintain your cool

Maintain your cool. With any difficult interaction, a physician’s first obligation is to remain calm and professional, while modeling appropriate behavior. If the patient is angry or emotionally intense, talking over them or interrupting them only makes the situation worse. Try to see the interaction from the patient’s perspective. Both parties should work together to find a common ground.

Collaborate, respect boundaries, and empathize. One study of a group of 100 family physicians found that having the following 3 skills were essential to successfully managing situations with difficult patients11,12:

- the ability to collaborate (vs opposition)

- the appropriate use of power (vs misuse of power, or violation of boundaries by either party)

- the ability to empathize, which for most physicians involves understanding and validating the patient’s subjective experiences.

Although a description of the many facets of empathy (cognitive, affective, motivational) is beyond the scope of this article, it is worth pointing out that a patient’s positive perception of their physician’s empathy improves not only patient satisfaction but health outcomes.13 The Box describes a difficult patient whose actions changed through the collaboration and empathy of his treatment team.

Box 1

Mr. L, a 60-year-old veteran, is admitted to an inpatient unit following a suicide attempt that was prompted by eviction from his apartment. Mr. L is physically disabled and has difficulty walking without assistance. His main concern is his homelessness, and he insists that the inpatient team find a suitable “Americans with Disabilities (ADA)-compliant apartment” that he can afford on his $800 monthly income. He implies that he will kill himself if the team fails in that task. He makes it clear that his problems are the team’s problems. He is prescribed an antidepressant, and both his mood and reported suicidal ideations gradually resolve.

The team’s social worker finds an opening at a well-run veterans home, but Mr. L rejects it because he doesn’t want to “give up his independence.” The social worker finds a small apartment in a nearby community that is ADA-compliant, but Mr. L complains that it is small. He asks the resident psychiatrist, “Where will I put all my things?” The next day, after insulting the attending psychiatrist for failing to find an adequate apartment, Mr. L says from under the bedsheet: “How come none of you ever help me?”

Mr. L presents a challenge to the entire team. At times, he is rude, demanding, and entitled. The team recognizes that although he had served in the military with distinction, he is now alone after having divorced many years earlier, and nearly friendless because of his increasing disability. The team surmises that Mr. L lashes out due to frustration and feelings of powerlessness.

Resolving this conflict involves treating Mr. L with respect and listening without judgment. No one ever confronts him or argues with him. The team psychologist meets with him to help him work through his many losses. Closer to discharge, he is enrolled in several post-hospitalization programs to keep him connected with other veterans. At discharge, the hospital arranges for his belongings that had been in storage to be delivered to his new home. He is pleasant and social with his peers, and although he is still concerned about the size of the apartment, he thanks the team members for their care.

Verbalize the difficulty. It is important to openly discuss the problem. For example, “We both have very different views about how your symptoms should be investigated, and that’s causing some difficulty between us. Do you agree?” This approach names the “elephant in the room” and avoids casting blame. It also creates a sense of shared ownership by externalizing the problem from both the patient and physician. Verbalizing the difficulty can help build trust and pave the way to working together toward a common solution.

Consider other explanations for the patient’s behavior. For example, anger directed at a physician could be due to anxiety about an unrelated matter, such as the patient’s recent job loss or impending divorce. Psychiatrists might understand this behavior better as displacement, which is considered a maladaptive defense mechanism. It is important to listen to the patient and offer empathy, which will help the patient feel supported and build a rapport that can help to resolve the encounter.

Continue to: When helping patients...

When helping patients with multiple issues, which is a common scenario, the physician might start by asking, “What would you like to address today?”14 Keep a list of the issues so you do not forget the patient’s concerns, and then ask: “What do you think is going on?” Give patients time to verbalize their concerns. Physicians should:

- validate concerns: “I understand where you’re coming from.”

- offer empathy: “I can see how difficult this has been for you.”

- reframe: “Let me make sure I hear you correctly.”

- refocus: “Let’s agree on what we need to do at this visit.”

Find common ground. When the patient and physician have different ideas on diagnosis or treatment, finding common ground is another way to resolve a difficult encounter. Difficulties arise when there appears to be little common ground, which often results from unrealistic expectations. Patients might be seen as “demanding” or “manipulative”’ if they push for a diagnosis or treatment the doctor is not comfortable with. As soon as there is some overlap and common ground, the difficulty rapidly subsides.

Set clear boundaries and limits. Physicians should set limits on what patient behavior might “cross the line.” A “behavioral contract” (or “treatment contract”) can help by setting explicit expectations. For example, showing up late for appointments or inappropriately seeking drugs of abuse (eg, opioids, benzodiazepines) might be identified as violations of the contract. Once the contract is set, the patient should be asked to restate key components. Clarify any confusion or barriers to compliance and define clear expectations. The patient should be informed of potential consequences of contract violations, including termination.

Staff members involved in the patient’s care should agree with the terms of any behavioral contract, and should receive a copy of it. Patients should have “buy in,” meaning that they have had an opportunity to provide input to the contract and have agreed to its elements. Both the physician and patient should sign the document.

When all else fails

When there is a breakdown in rapport that makes it difficult or impossible to continue offering treatment, consider termination. This could be due to threatening or abusive patient behavior, sexual advances, repeated no-shows, treatment noncompliance that jeopardizes patient safety, refusal to follow the treatment plan, or violating the terms of a behavioral contract. In some settings, it might be the failure to pay bills.

Continue to: If a patient is unable to...

If a patient is unable to follow the contract, the physician should explore possible extenuating circumstances. The physician should seek to remedy the problem and involve other team members if possible (eg, case manager, nurse), advising a patient about behaviors that could lead to termination.

If the problem is irremediable, notify the patient in writing, give them time to find another physician, and facilitate the transfer of care.15 Take steps to prevent the patient from running out of any medications associated with withdrawal or discontinuation syndromes (eg, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, benzodiazepines) during the care transition. While there is no requirement regarding the amount of time allowed, at least 30 days is typical.

Bottom Line

Difficult patient interactions are common and unavoidable. Physicians should acknowledge and recognize contributing factors in such encounters—including their own role. When handling such situations, physicians should remain calm and model appropriate behavior. Improving communication, offering empathy, and validating the patient’s concerns can help resolve factors that contribute to poor patient interactions. If efforts to remediate the physician-patient relationship fail, termination may be necessary.

Related Resources

- Koekkoek B, Berno van Meijel CNS, Hutschemaekers G. “Difficult patients” in mental health care: a review. Psychiatr Serv. 2006;57(6):795-802.

- Pereira MR, Figueiredo AF. Challenging patient-doctor interactions in psychiatry – difficult patient syndrome. European Psychiatry. 2017;41(supplement):S719. doi. org/10.1016/j.eurpsy.2017.01.1297

1. Dupont J. Ferenczi’s madness. Contemp Psychoanal. 1988;24(2):250-261.

2. Adams J, Murray R. The difficult diagnosis: the general approach to the difficult patient. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 1998;16(4):689-700.

3. Davies M. Managing challenging interactions with patients. BMJ. 2013;347:f4673. doi: https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.f4673

4. Chou C. Dealing with the “difficult” patient. Wisc Med J. 2004;103:35-38.

5. Koekkoek B, Berno van Meijel CNS, Hutschemaekers G. “Difficult patients” in mental health care: a review. Psychiatr Serv. 2006;57(6):795-802.

6. Jackson JL, Kroenke K. Difficult patient encounter in the ambulatory clinic: clinical predictors and outcomes. Arch Intern Med 1999;159(10):1069-1075.

7. Groves JE. Taking care of the hateful patient. N Eng J Med. 1978;298:883-887.

8. Hull S, Broquet K. How to manage difficult encounters. Fam Prac Manag. 2007;14(6):30-34.

9. Hardavella G, Aamli-Gaagnat A, Frille A, et al. Top tips to deal with challenging situations: doctor patient interactions. Breathe. 2017;13(2):129-135.

10. Black DW, Balon R. Editorial: electronic medical records (EMRs) and the psychiatrist shortage. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 2018;30(4):257-259.

11. Elder N, Ricer R, Tobias B. How respected family physicians manage difficult patient encounters. J Am Board Fam Med. 2006;19(6):533-541.

12. Campbell RJ. Campbell’s Psychiatric Dictionary. 8th Edition. Oxford University Press; 2004:219-220.

13. Decety J, Fotopoulou A. Why empathy has a beneficial impact on others in medicine: unifying theories. Front Behav Neurosci. 2014;8:457. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnbeh.2014.00457

14. Klugman B. The difficult patient. Accessed May 24, 2021. https://www.umassmed.edu/globalassets/office-of-continuing-medical-education/pdfs/cme-primary-care-days/e2-the-difficult-patient.pdf

15. Mossman D, Farrell HM, Gilday E. ‘Firing’ a patient: may psychiatrists unilaterally terminate care? Current Psychiatry. 2010;9(12):18-29.

“I did not like those patients… They made me angry and I found myself irritated to experience them as they seemed so distant from myself and from all that is human. This is an astonishing intolerance which brands me a poor psychiatrist.”

Sigmund Freud, Letter to István Hollós (1928)

While Freud was referring to psychotic patients,1 his evident frustration shows that difficult and challenging patients have vexed even the best of us. All physicians and other clinicians will experience patient encounters that lead to anger or frustration, or even challenge their sense of equanimity and professional identity. In short, difficult and challenging patient interactions are unavoidable, regardless of the physician’s discipline.2-5 At times, physicians might struggle with demanding, unpleasant, ungrateful, and possibly dangerous patients, while sometimes the struggle is with the patient’s family members. No physician is immune to the problem, which makes it crucial to learn to anticipate and manage difficult patient interactions, skills which are generally not taught in medical schools or residency programs.

One prospective study of clinic patients found that up to 15% of patient encounters are deemed “difficult.”6 Common scenarios include patients (or their relatives) who seek certain tests after researching symptoms online, threats of legal or social media action in response to feeling that the physician is not listening to them, demands for a second opinion after disagreeing with the physician’s diagnosis, and mistrust of doctors after presenting with symptoms and not receiving a diagnosis. It is also common to care for patients who focus on negative outcomes or fail to adhere to treatment recommendations. These encounters can make physicians feel stressed out, disrespected, abused, or even fearful if threatened. Some physicians may come to feel they are trapped in a hostile work environment with little support from their supervisors or administrators. Patients often have a complaint office or department to turn to, but there is no equivalent for physicians, who are expected to soldier on regardless.

This article highlights a model that describes poor physician-patient encounters, factors contributing to these issues, how to manage these difficult interactions, and what to do if the relationship cannot be remediated.

Describing the ‘difficult’ patient

In a landmark 1978 paper, Groves7 provided one of the first descriptions of “difficult” patients. His colorful observations continue to provide useful insights. Groves emphasized that most medical texts ignore the issue of difficult patients and provide little or no guidance—which is still true 43 years later. He observed that physicians cannot avoid occasional negative feelings toward some patients. Further, Groves suggested that countertransference is often at the root of hateful reactions, a process he defines as “conscious or unconscious unbidden and unwanted hostile or sexual feelings toward the patient.”7Table 17 outlines how Groves divided “hateful” patients into several categories, and how physicians might respond to such patients.

A model for understanding difficult patient encounters

Adams and Murray2 created a model to help explain interactions with difficult or challenging patients that consists of 3 elements: the patient, the physician, and the system (ie, situation or environment). Hull and Broquet8 and Hardavella et al9 later adapted the model and described its components (Table 22,8,9).

Continue to: When considering...