User login

Is it safe to discharge patients with anemia?

Background: Anemia is common in hospitalized patients and is associated with short- and long-term morbidity and mortality. Current evidence shows that reduced red blood cell (RBC) use and more restrictive transfusion practices do not increase short-term mortality; however, few data exist on the long-term outcomes of anemia.

Study design: Retrospective cohort study.

Setting: Integrated health care system (Kaiser Permanente) with 21 hospitals located in Northern California.

Synopsis: From 2010 to 2014, there were 801,261 hospitalizations among 445,371 patients who survived to discharge. The prevalence of moderate anemia (hemoglobin between 7 and 10 g/dL) at hospital discharge increased from 20% to 25% (P less than .001) while RBC transfusions decreased by 28% (P less than .001). Resolution of moderate anemia within 6 months of hospital discharge decreased from 42% to 34% (P less than .001). RBC transfusion and rehospitalization rates at 6 months decreased as well. During the study period, adjusted 6-month mortality decreased from 16.1% to 15.6% (P = .04) in patients with moderate anemia.

Given the retrospective design of this study, data must be interpreted with caution in determining a causal relationship. The authors also acknowledge that there may be unmeasured confounding variables not accounted for in the study results.

Bottom line: Despite higher rates of moderate anemia at discharge, there was not an associated rise in subsequent RBC transfusions, readmissions, or mortality in the 6 months after hospital discharge.

Citation: Roubinian NH et al. Long-term outcomes among patients discharged from the hospital with moderate anemia: A retrospective cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2019 Jan 14. doi: 10.7326/M17-3253.

Dr. Schmit is an associate professor of medicine in the division of general and hospital medicine at UT Health San Antonio and a hospitalist at South Texas Veterans Health Care System, also in San Antonio.

Background: Anemia is common in hospitalized patients and is associated with short- and long-term morbidity and mortality. Current evidence shows that reduced red blood cell (RBC) use and more restrictive transfusion practices do not increase short-term mortality; however, few data exist on the long-term outcomes of anemia.

Study design: Retrospective cohort study.

Setting: Integrated health care system (Kaiser Permanente) with 21 hospitals located in Northern California.

Synopsis: From 2010 to 2014, there were 801,261 hospitalizations among 445,371 patients who survived to discharge. The prevalence of moderate anemia (hemoglobin between 7 and 10 g/dL) at hospital discharge increased from 20% to 25% (P less than .001) while RBC transfusions decreased by 28% (P less than .001). Resolution of moderate anemia within 6 months of hospital discharge decreased from 42% to 34% (P less than .001). RBC transfusion and rehospitalization rates at 6 months decreased as well. During the study period, adjusted 6-month mortality decreased from 16.1% to 15.6% (P = .04) in patients with moderate anemia.

Given the retrospective design of this study, data must be interpreted with caution in determining a causal relationship. The authors also acknowledge that there may be unmeasured confounding variables not accounted for in the study results.

Bottom line: Despite higher rates of moderate anemia at discharge, there was not an associated rise in subsequent RBC transfusions, readmissions, or mortality in the 6 months after hospital discharge.

Citation: Roubinian NH et al. Long-term outcomes among patients discharged from the hospital with moderate anemia: A retrospective cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2019 Jan 14. doi: 10.7326/M17-3253.

Dr. Schmit is an associate professor of medicine in the division of general and hospital medicine at UT Health San Antonio and a hospitalist at South Texas Veterans Health Care System, also in San Antonio.

Background: Anemia is common in hospitalized patients and is associated with short- and long-term morbidity and mortality. Current evidence shows that reduced red blood cell (RBC) use and more restrictive transfusion practices do not increase short-term mortality; however, few data exist on the long-term outcomes of anemia.

Study design: Retrospective cohort study.

Setting: Integrated health care system (Kaiser Permanente) with 21 hospitals located in Northern California.

Synopsis: From 2010 to 2014, there were 801,261 hospitalizations among 445,371 patients who survived to discharge. The prevalence of moderate anemia (hemoglobin between 7 and 10 g/dL) at hospital discharge increased from 20% to 25% (P less than .001) while RBC transfusions decreased by 28% (P less than .001). Resolution of moderate anemia within 6 months of hospital discharge decreased from 42% to 34% (P less than .001). RBC transfusion and rehospitalization rates at 6 months decreased as well. During the study period, adjusted 6-month mortality decreased from 16.1% to 15.6% (P = .04) in patients with moderate anemia.

Given the retrospective design of this study, data must be interpreted with caution in determining a causal relationship. The authors also acknowledge that there may be unmeasured confounding variables not accounted for in the study results.

Bottom line: Despite higher rates of moderate anemia at discharge, there was not an associated rise in subsequent RBC transfusions, readmissions, or mortality in the 6 months after hospital discharge.

Citation: Roubinian NH et al. Long-term outcomes among patients discharged from the hospital with moderate anemia: A retrospective cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2019 Jan 14. doi: 10.7326/M17-3253.

Dr. Schmit is an associate professor of medicine in the division of general and hospital medicine at UT Health San Antonio and a hospitalist at South Texas Veterans Health Care System, also in San Antonio.

Beta-blockers effective, safe for HFrEF with renal dysfunction

PARIS – Beta-blocking drugs were as effective for improving survival in patients with moderately severe renal dysfunction as they were in patients with normal renal function in a meta-analysis of more than 13,000 patients, a finding that seemed to solidify the role for this drug class for essentially all similar heart failure patients, regardless of their renal function.

This evidence could reshape usual care because “renal impairment is often considered a barrier in clinical practice” for starting a beta-blocker drug in patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF), Dipak Kotecha, MBChB, said at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

“We have shown with sufficient sample size that beta-blockers are effective in reducing mortality in patient with HFrEF and in sinus rhythm, even in those with an eGFR [estimated glomerular filtration rate] of 30-44 mL/min per 1.73 m2,” said Dr. Kotecha, a cardiologist at the University of Birmingham (England). “The results suggest that renal impairment should not obstruct the prescription and maintenance of beta-blockers in patients with HFrEF.”

“This important study was a novel attempt to look at [HFrEF] patients with renal insufficiency to see whether they received the same benefit from beta-blockers as other patients, and they did. So renal insufficiency is not a reason to withhold beta-blockers” from these patients, commented Mariell Jessup, MD, a heart failure physician and chief science and medical officer for the American Heart Association in Dallas. “The onus is on clinicians to find a reason not to give a beta-blocker to a patient with HFrEF because they are generally well tolerated and they can have enormous benefit, as we saw in this study,” she said in a video interview.

The analysis run by Dr. Kotecha and associates used data collected in 11 of the pivotal randomized, controlled trial run for beta-blockers during the 1990s and early 2000s, with each study comparing bucindolol, bisoprolol, carvedilol, metoprolol XL, or nebivolol against placebo. The studies collectively enrolled 18,637 patients, which the investigators whittled down in their analysis to 17,433 after excluding patients with a left ventricular ejection fraction below 50% or who were undocumented. The subgroup with HFrEF included 13,861 patient in sinus rhythm at entry, 2,879 with atrial fibrillation, and 693 with an unknown atrial status. The main analysis ran in the 13,861 patients with HFrEF and in sinus rhythm; 14% of this cohort had an eGFR of 30-44 mL/min per 1.73 m2 and 27% had an eGFR of 45-59 mL/min per 1.73 m2. The median age of all patients in the main analysis was 65 years, 23% were women, and their median left ventricular ejection fraction was 27%.

During follow-up of about 3 years, the impact of beta-blocker treatment on survival, compared with placebo, was “substantial” for all strata of patients by renal function, except for those with eGFRs below 30 mL/min per 1.73 m2. (Survival was similar regardless of beta-blocker treatment in the small number of patients with severe renal dysfunction.) The number needed to treat to prevent 1 death in patients with an eGFR of 30-44 mL/min per 1.73 m2 was 21, the same as among patients with an eGFR of 90 mL/min per 1.73 m2 or more, Dr. Kotecha said.

Among the subgroup of patients with atrial fibrillation, beta-blockers appeared to exert no survival benefit, compared with placebo. The investigators did not assess the survival benefits exerted by any individual beta-blocker, compared with the others, and Dr. Kotecha stressed that “my belief is that this is a class effect” and is roughly similar across all the beta-blockers used in the studies.

The analysis also showed good safety and tolerability of the beta-blockers in patients with renal dysfunction. The incidence of adverse events leading to treatment termination was very similar in the beta-blocker and placebo arms, and more than three-quarters of patients in each of the two subgroups with renal dysfunction were maintained on more than 50% of their target beta-blocker dosage.

Dr. Kotecha has been an advisor to Bayer, a speaker on behalf of Atricure, and has received research funding from GlaxoSmithKline and Menarini. Dr. Jessup had no disclosures.

This analysis of individual patient data is very important and extends our knowledge. The results confirm that beta-blocker treatment reduces mortality in patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) and in sinus rhythm who also have moderately severe renal dysfunction with an estimated glomerular filtration rate as low as 30-44 mL/min per 1.73 m2. This is good news for patients with HFrEF and kidney disease. Clinicians often use comorbidities as a reason not to prescribe or up-titrate beta-blockers. These results show that beta-blockers can be used at guideline-directed dosages, even in patients with renal dysfunction. The findings highlight the importance of not looking for excuses to not treat patients with a beta-blocker. Do not worry about renal function.

Theresa A. McDonagh, MD, professor of cardiology at King’s College, London, made these comments as designated discussant for Dr. Kotecha’s report. She had no disclosures.

This analysis of individual patient data is very important and extends our knowledge. The results confirm that beta-blocker treatment reduces mortality in patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) and in sinus rhythm who also have moderately severe renal dysfunction with an estimated glomerular filtration rate as low as 30-44 mL/min per 1.73 m2. This is good news for patients with HFrEF and kidney disease. Clinicians often use comorbidities as a reason not to prescribe or up-titrate beta-blockers. These results show that beta-blockers can be used at guideline-directed dosages, even in patients with renal dysfunction. The findings highlight the importance of not looking for excuses to not treat patients with a beta-blocker. Do not worry about renal function.

Theresa A. McDonagh, MD, professor of cardiology at King’s College, London, made these comments as designated discussant for Dr. Kotecha’s report. She had no disclosures.

This analysis of individual patient data is very important and extends our knowledge. The results confirm that beta-blocker treatment reduces mortality in patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) and in sinus rhythm who also have moderately severe renal dysfunction with an estimated glomerular filtration rate as low as 30-44 mL/min per 1.73 m2. This is good news for patients with HFrEF and kidney disease. Clinicians often use comorbidities as a reason not to prescribe or up-titrate beta-blockers. These results show that beta-blockers can be used at guideline-directed dosages, even in patients with renal dysfunction. The findings highlight the importance of not looking for excuses to not treat patients with a beta-blocker. Do not worry about renal function.

Theresa A. McDonagh, MD, professor of cardiology at King’s College, London, made these comments as designated discussant for Dr. Kotecha’s report. She had no disclosures.

PARIS – Beta-blocking drugs were as effective for improving survival in patients with moderately severe renal dysfunction as they were in patients with normal renal function in a meta-analysis of more than 13,000 patients, a finding that seemed to solidify the role for this drug class for essentially all similar heart failure patients, regardless of their renal function.

This evidence could reshape usual care because “renal impairment is often considered a barrier in clinical practice” for starting a beta-blocker drug in patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF), Dipak Kotecha, MBChB, said at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

“We have shown with sufficient sample size that beta-blockers are effective in reducing mortality in patient with HFrEF and in sinus rhythm, even in those with an eGFR [estimated glomerular filtration rate] of 30-44 mL/min per 1.73 m2,” said Dr. Kotecha, a cardiologist at the University of Birmingham (England). “The results suggest that renal impairment should not obstruct the prescription and maintenance of beta-blockers in patients with HFrEF.”

“This important study was a novel attempt to look at [HFrEF] patients with renal insufficiency to see whether they received the same benefit from beta-blockers as other patients, and they did. So renal insufficiency is not a reason to withhold beta-blockers” from these patients, commented Mariell Jessup, MD, a heart failure physician and chief science and medical officer for the American Heart Association in Dallas. “The onus is on clinicians to find a reason not to give a beta-blocker to a patient with HFrEF because they are generally well tolerated and they can have enormous benefit, as we saw in this study,” she said in a video interview.

The analysis run by Dr. Kotecha and associates used data collected in 11 of the pivotal randomized, controlled trial run for beta-blockers during the 1990s and early 2000s, with each study comparing bucindolol, bisoprolol, carvedilol, metoprolol XL, or nebivolol against placebo. The studies collectively enrolled 18,637 patients, which the investigators whittled down in their analysis to 17,433 after excluding patients with a left ventricular ejection fraction below 50% or who were undocumented. The subgroup with HFrEF included 13,861 patient in sinus rhythm at entry, 2,879 with atrial fibrillation, and 693 with an unknown atrial status. The main analysis ran in the 13,861 patients with HFrEF and in sinus rhythm; 14% of this cohort had an eGFR of 30-44 mL/min per 1.73 m2 and 27% had an eGFR of 45-59 mL/min per 1.73 m2. The median age of all patients in the main analysis was 65 years, 23% were women, and their median left ventricular ejection fraction was 27%.

During follow-up of about 3 years, the impact of beta-blocker treatment on survival, compared with placebo, was “substantial” for all strata of patients by renal function, except for those with eGFRs below 30 mL/min per 1.73 m2. (Survival was similar regardless of beta-blocker treatment in the small number of patients with severe renal dysfunction.) The number needed to treat to prevent 1 death in patients with an eGFR of 30-44 mL/min per 1.73 m2 was 21, the same as among patients with an eGFR of 90 mL/min per 1.73 m2 or more, Dr. Kotecha said.

Among the subgroup of patients with atrial fibrillation, beta-blockers appeared to exert no survival benefit, compared with placebo. The investigators did not assess the survival benefits exerted by any individual beta-blocker, compared with the others, and Dr. Kotecha stressed that “my belief is that this is a class effect” and is roughly similar across all the beta-blockers used in the studies.

The analysis also showed good safety and tolerability of the beta-blockers in patients with renal dysfunction. The incidence of adverse events leading to treatment termination was very similar in the beta-blocker and placebo arms, and more than three-quarters of patients in each of the two subgroups with renal dysfunction were maintained on more than 50% of their target beta-blocker dosage.

Dr. Kotecha has been an advisor to Bayer, a speaker on behalf of Atricure, and has received research funding from GlaxoSmithKline and Menarini. Dr. Jessup had no disclosures.

PARIS – Beta-blocking drugs were as effective for improving survival in patients with moderately severe renal dysfunction as they were in patients with normal renal function in a meta-analysis of more than 13,000 patients, a finding that seemed to solidify the role for this drug class for essentially all similar heart failure patients, regardless of their renal function.

This evidence could reshape usual care because “renal impairment is often considered a barrier in clinical practice” for starting a beta-blocker drug in patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF), Dipak Kotecha, MBChB, said at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

“We have shown with sufficient sample size that beta-blockers are effective in reducing mortality in patient with HFrEF and in sinus rhythm, even in those with an eGFR [estimated glomerular filtration rate] of 30-44 mL/min per 1.73 m2,” said Dr. Kotecha, a cardiologist at the University of Birmingham (England). “The results suggest that renal impairment should not obstruct the prescription and maintenance of beta-blockers in patients with HFrEF.”

“This important study was a novel attempt to look at [HFrEF] patients with renal insufficiency to see whether they received the same benefit from beta-blockers as other patients, and they did. So renal insufficiency is not a reason to withhold beta-blockers” from these patients, commented Mariell Jessup, MD, a heart failure physician and chief science and medical officer for the American Heart Association in Dallas. “The onus is on clinicians to find a reason not to give a beta-blocker to a patient with HFrEF because they are generally well tolerated and they can have enormous benefit, as we saw in this study,” she said in a video interview.

The analysis run by Dr. Kotecha and associates used data collected in 11 of the pivotal randomized, controlled trial run for beta-blockers during the 1990s and early 2000s, with each study comparing bucindolol, bisoprolol, carvedilol, metoprolol XL, or nebivolol against placebo. The studies collectively enrolled 18,637 patients, which the investigators whittled down in their analysis to 17,433 after excluding patients with a left ventricular ejection fraction below 50% or who were undocumented. The subgroup with HFrEF included 13,861 patient in sinus rhythm at entry, 2,879 with atrial fibrillation, and 693 with an unknown atrial status. The main analysis ran in the 13,861 patients with HFrEF and in sinus rhythm; 14% of this cohort had an eGFR of 30-44 mL/min per 1.73 m2 and 27% had an eGFR of 45-59 mL/min per 1.73 m2. The median age of all patients in the main analysis was 65 years, 23% were women, and their median left ventricular ejection fraction was 27%.

During follow-up of about 3 years, the impact of beta-blocker treatment on survival, compared with placebo, was “substantial” for all strata of patients by renal function, except for those with eGFRs below 30 mL/min per 1.73 m2. (Survival was similar regardless of beta-blocker treatment in the small number of patients with severe renal dysfunction.) The number needed to treat to prevent 1 death in patients with an eGFR of 30-44 mL/min per 1.73 m2 was 21, the same as among patients with an eGFR of 90 mL/min per 1.73 m2 or more, Dr. Kotecha said.

Among the subgroup of patients with atrial fibrillation, beta-blockers appeared to exert no survival benefit, compared with placebo. The investigators did not assess the survival benefits exerted by any individual beta-blocker, compared with the others, and Dr. Kotecha stressed that “my belief is that this is a class effect” and is roughly similar across all the beta-blockers used in the studies.

The analysis also showed good safety and tolerability of the beta-blockers in patients with renal dysfunction. The incidence of adverse events leading to treatment termination was very similar in the beta-blocker and placebo arms, and more than three-quarters of patients in each of the two subgroups with renal dysfunction were maintained on more than 50% of their target beta-blocker dosage.

Dr. Kotecha has been an advisor to Bayer, a speaker on behalf of Atricure, and has received research funding from GlaxoSmithKline and Menarini. Dr. Jessup had no disclosures.

REPORTING FROM THE ESC CONGRESS 2019

Women’s residency and subspecialty choices diverging

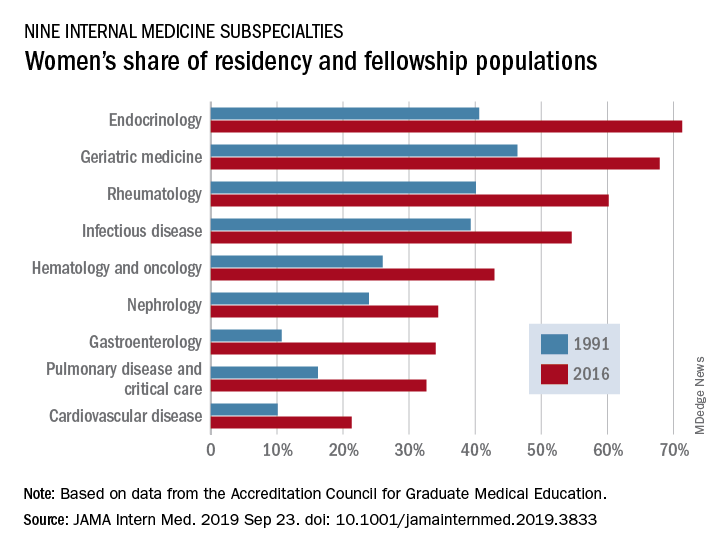

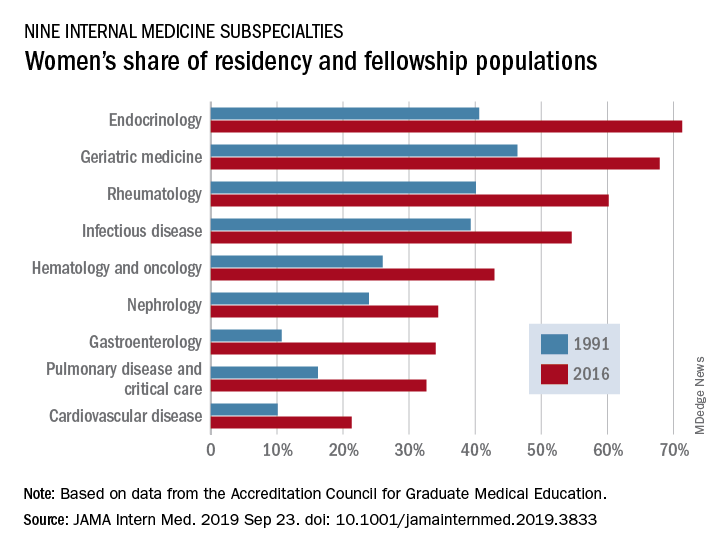

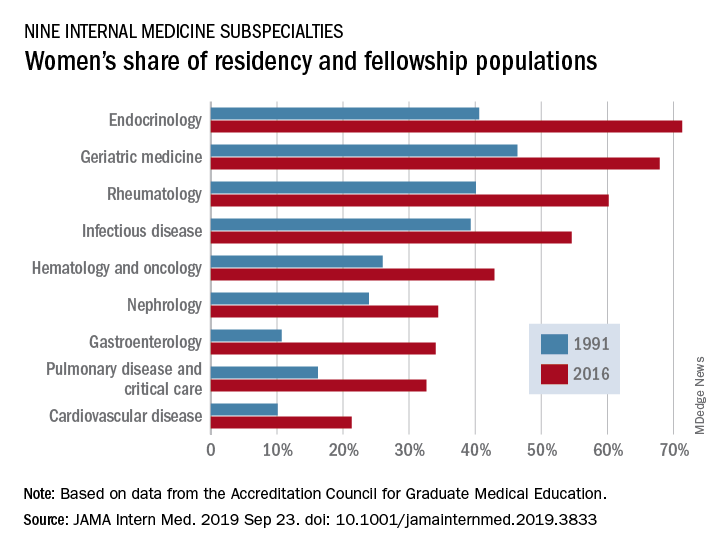

Women made up 43.2% of the internal medicine resident population in 2016, compared with 30.2% in 1991. Over that same time, however, the percentage of women in subspecialty fellowships dropped from 33.3% to 23.6%, Anna T. Stone, MD, and associates wrote in a research letter published in JAMA Internal Medicine.

“Many factors are associated with the decisions of medical students in choosing an internal medicine residency, including their sex, educational experience, views of patient care, and lifestyle perceptions. Similar considerations apply to subspecialty training,” wrote Dr. Stone of the department of cardiology at St. Vincent Hospital and Heart Center, Indianapolis, and associates.

When the investigators focused on a subset of nine internal medicine subspecialties, they saw growth: “The percentage of women entering each of the fields [residents plus fellows] increased over time, with variations between specialty and some year-to-year variations within a specialty.”

Although none of the nine subspecialties had been majority women in 1991, by 2016 women made up more than half of the residents and fellows in four: endocrinology (71.3%), geriatric medicine (67.9%), rheumatology (60.2%), and infectious disease (54.6%), according to data from the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education.

And then there’s cardiology. Its low rate of participation among women – the only one of the nine subspecialties under 35% – “is an important issue that the cardiology profession should continue to address,” they wrote.

In a survey of internal medicine residents conducted by other researchers, women were more likely than men to report that they had never considered cardiology as a career choice, Dr. Stone and associates noted, and women in the survey “had different perceptions of cardiology than men.”

SOURCE: Stone AT et al. JAMA Intern Med. 2019 Sep 23. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.3833.

Women made up 43.2% of the internal medicine resident population in 2016, compared with 30.2% in 1991. Over that same time, however, the percentage of women in subspecialty fellowships dropped from 33.3% to 23.6%, Anna T. Stone, MD, and associates wrote in a research letter published in JAMA Internal Medicine.

“Many factors are associated with the decisions of medical students in choosing an internal medicine residency, including their sex, educational experience, views of patient care, and lifestyle perceptions. Similar considerations apply to subspecialty training,” wrote Dr. Stone of the department of cardiology at St. Vincent Hospital and Heart Center, Indianapolis, and associates.

When the investigators focused on a subset of nine internal medicine subspecialties, they saw growth: “The percentage of women entering each of the fields [residents plus fellows] increased over time, with variations between specialty and some year-to-year variations within a specialty.”

Although none of the nine subspecialties had been majority women in 1991, by 2016 women made up more than half of the residents and fellows in four: endocrinology (71.3%), geriatric medicine (67.9%), rheumatology (60.2%), and infectious disease (54.6%), according to data from the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education.

And then there’s cardiology. Its low rate of participation among women – the only one of the nine subspecialties under 35% – “is an important issue that the cardiology profession should continue to address,” they wrote.

In a survey of internal medicine residents conducted by other researchers, women were more likely than men to report that they had never considered cardiology as a career choice, Dr. Stone and associates noted, and women in the survey “had different perceptions of cardiology than men.”

SOURCE: Stone AT et al. JAMA Intern Med. 2019 Sep 23. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.3833.

Women made up 43.2% of the internal medicine resident population in 2016, compared with 30.2% in 1991. Over that same time, however, the percentage of women in subspecialty fellowships dropped from 33.3% to 23.6%, Anna T. Stone, MD, and associates wrote in a research letter published in JAMA Internal Medicine.

“Many factors are associated with the decisions of medical students in choosing an internal medicine residency, including their sex, educational experience, views of patient care, and lifestyle perceptions. Similar considerations apply to subspecialty training,” wrote Dr. Stone of the department of cardiology at St. Vincent Hospital and Heart Center, Indianapolis, and associates.

When the investigators focused on a subset of nine internal medicine subspecialties, they saw growth: “The percentage of women entering each of the fields [residents plus fellows] increased over time, with variations between specialty and some year-to-year variations within a specialty.”

Although none of the nine subspecialties had been majority women in 1991, by 2016 women made up more than half of the residents and fellows in four: endocrinology (71.3%), geriatric medicine (67.9%), rheumatology (60.2%), and infectious disease (54.6%), according to data from the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education.

And then there’s cardiology. Its low rate of participation among women – the only one of the nine subspecialties under 35% – “is an important issue that the cardiology profession should continue to address,” they wrote.

In a survey of internal medicine residents conducted by other researchers, women were more likely than men to report that they had never considered cardiology as a career choice, Dr. Stone and associates noted, and women in the survey “had different perceptions of cardiology than men.”

SOURCE: Stone AT et al. JAMA Intern Med. 2019 Sep 23. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.3833.

FROM JAMA INTERNAL MEDICINE

Machine learning–derived risk score predicts heart failure risk in diabetes patients

PHILADELPHIA – For patients with high-risk diabetes, a novel, machine learning–derived risk score based on 10 common clinical variables can identify those facing a heart failure risk of up to nearly 20% over the ensuing 5 years, an investigator said at the annual meeting of the Heart Failure Society of America.

The risk score, dubbed WATCH-DM, has greater accuracy in predicting incident heart failure than traditional risk-based models, and requires no specific cardiovascular biomarkers or imaging, according to Muthiah Vaduganathan, MD, MPH, a cardiologist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and faculty at Harvard Medical School in Boston.

The tool may help inform risk-based monitoring and introduction of sodium-glucose transporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors, which have been shown in multiple clinical trials to prevent heart failure in at-risk patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), Dr. Vaduganathan said.

“Patients identified at high risk based on WATCH-DM should be strongly considered for initiation of SGLT2 inhibitors in clinical practice,” Dr. Vaduganathan said in an interview.

WATCH-DM is available online at cvriskscores.com. Work is underway to integrate the tool into electronic health record systems at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center in Dallas. “I expect that to be launched in the next year,” he said.

The WATCH-DM score was developed based on data from the ACCORD (Action to Control Cardiovascular Risk in Diabetes) trial, including 8,756 T2DM patients with inadequate glycemic control at high cardiovascular risk and no heart failure at baseline.

Starting with 147 variables, the investigators used a decision-tree machine learning approach to identify predictors of heart failure.

“What machine learning does is automate the variable selection process, as a form of artificial intelligence,” Dr. Vaduganathan said.

The WATCH-DM risk score was based on the 10 best-performing predictors as selected by machine learning, including body mass index, age, systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure, fasting plasma glucose, serum creatinine, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, QRS duration, prior myocardial infarction, and prior coronary artery bypass grafting.

The 5-year risk of heart failure was just 1.1% for patients with WATCH-DM scores in the lowest quintile, increasing in a graded fashion to nearly 20% (17.4%) in the highest quintile, study results show.

Findings of the study were simultaneously published in the journal Diabetes Care.

Dr. Vaduganathan said he is supported by an award from Harvard Catalyst. He provided disclosures related to Amgen, AstraZeneca, Baxter Healthcare, Bayer AG, Boehringer Ingelheim (advisory boards), and with Novartis and the National Institutes of Health (participation on clinical endpoint committees).

SOURCE: HFSA 2019; Segar MW, Vaduganathan M et al. Diabetes Care. doi: 10.2337/dc19-0587.

PHILADELPHIA – For patients with high-risk diabetes, a novel, machine learning–derived risk score based on 10 common clinical variables can identify those facing a heart failure risk of up to nearly 20% over the ensuing 5 years, an investigator said at the annual meeting of the Heart Failure Society of America.

The risk score, dubbed WATCH-DM, has greater accuracy in predicting incident heart failure than traditional risk-based models, and requires no specific cardiovascular biomarkers or imaging, according to Muthiah Vaduganathan, MD, MPH, a cardiologist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and faculty at Harvard Medical School in Boston.

The tool may help inform risk-based monitoring and introduction of sodium-glucose transporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors, which have been shown in multiple clinical trials to prevent heart failure in at-risk patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), Dr. Vaduganathan said.

“Patients identified at high risk based on WATCH-DM should be strongly considered for initiation of SGLT2 inhibitors in clinical practice,” Dr. Vaduganathan said in an interview.

WATCH-DM is available online at cvriskscores.com. Work is underway to integrate the tool into electronic health record systems at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center in Dallas. “I expect that to be launched in the next year,” he said.

The WATCH-DM score was developed based on data from the ACCORD (Action to Control Cardiovascular Risk in Diabetes) trial, including 8,756 T2DM patients with inadequate glycemic control at high cardiovascular risk and no heart failure at baseline.

Starting with 147 variables, the investigators used a decision-tree machine learning approach to identify predictors of heart failure.

“What machine learning does is automate the variable selection process, as a form of artificial intelligence,” Dr. Vaduganathan said.

The WATCH-DM risk score was based on the 10 best-performing predictors as selected by machine learning, including body mass index, age, systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure, fasting plasma glucose, serum creatinine, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, QRS duration, prior myocardial infarction, and prior coronary artery bypass grafting.

The 5-year risk of heart failure was just 1.1% for patients with WATCH-DM scores in the lowest quintile, increasing in a graded fashion to nearly 20% (17.4%) in the highest quintile, study results show.

Findings of the study were simultaneously published in the journal Diabetes Care.

Dr. Vaduganathan said he is supported by an award from Harvard Catalyst. He provided disclosures related to Amgen, AstraZeneca, Baxter Healthcare, Bayer AG, Boehringer Ingelheim (advisory boards), and with Novartis and the National Institutes of Health (participation on clinical endpoint committees).

SOURCE: HFSA 2019; Segar MW, Vaduganathan M et al. Diabetes Care. doi: 10.2337/dc19-0587.

PHILADELPHIA – For patients with high-risk diabetes, a novel, machine learning–derived risk score based on 10 common clinical variables can identify those facing a heart failure risk of up to nearly 20% over the ensuing 5 years, an investigator said at the annual meeting of the Heart Failure Society of America.

The risk score, dubbed WATCH-DM, has greater accuracy in predicting incident heart failure than traditional risk-based models, and requires no specific cardiovascular biomarkers or imaging, according to Muthiah Vaduganathan, MD, MPH, a cardiologist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and faculty at Harvard Medical School in Boston.

The tool may help inform risk-based monitoring and introduction of sodium-glucose transporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors, which have been shown in multiple clinical trials to prevent heart failure in at-risk patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), Dr. Vaduganathan said.

“Patients identified at high risk based on WATCH-DM should be strongly considered for initiation of SGLT2 inhibitors in clinical practice,” Dr. Vaduganathan said in an interview.

WATCH-DM is available online at cvriskscores.com. Work is underway to integrate the tool into electronic health record systems at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center in Dallas. “I expect that to be launched in the next year,” he said.

The WATCH-DM score was developed based on data from the ACCORD (Action to Control Cardiovascular Risk in Diabetes) trial, including 8,756 T2DM patients with inadequate glycemic control at high cardiovascular risk and no heart failure at baseline.

Starting with 147 variables, the investigators used a decision-tree machine learning approach to identify predictors of heart failure.

“What machine learning does is automate the variable selection process, as a form of artificial intelligence,” Dr. Vaduganathan said.

The WATCH-DM risk score was based on the 10 best-performing predictors as selected by machine learning, including body mass index, age, systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure, fasting plasma glucose, serum creatinine, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, QRS duration, prior myocardial infarction, and prior coronary artery bypass grafting.

The 5-year risk of heart failure was just 1.1% for patients with WATCH-DM scores in the lowest quintile, increasing in a graded fashion to nearly 20% (17.4%) in the highest quintile, study results show.

Findings of the study were simultaneously published in the journal Diabetes Care.

Dr. Vaduganathan said he is supported by an award from Harvard Catalyst. He provided disclosures related to Amgen, AstraZeneca, Baxter Healthcare, Bayer AG, Boehringer Ingelheim (advisory boards), and with Novartis and the National Institutes of Health (participation on clinical endpoint committees).

SOURCE: HFSA 2019; Segar MW, Vaduganathan M et al. Diabetes Care. doi: 10.2337/dc19-0587.

REPORTING FROM HFSA 2019

Reversal agents for direct-acting oral anticoagulants

Summary of guidelines published in the Journal of Hospital Medicine

When on call for admissions, a hospitalist receives a request from a colleague to admit an octogenarian man with an acute uncomplicated deep vein thrombosis to start heparin, bridging to warfarin. The patient has no evidence of postphlebitic syndrome, pulmonary embolism, or right-sided heart strain. The hospitalist asks her colleague if he had considered treating the patient in the ambulatory setting using a direct-acting oral anticoagulant (DOAC). After all, this would save the patient an unnecessary hospitalization, weekly international normalized ratio checks, and other important lifestyle changes. In response, the colleague voices concern that the “new drugs don’t have antidotes.”

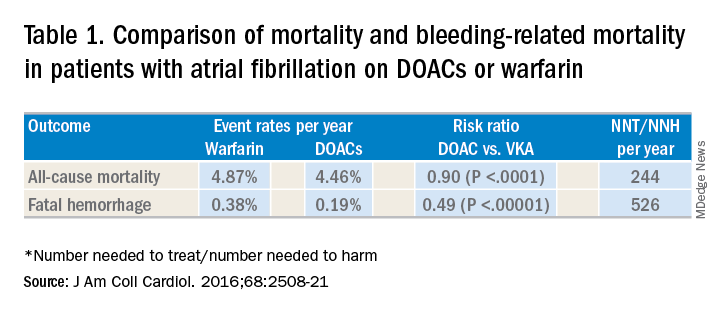

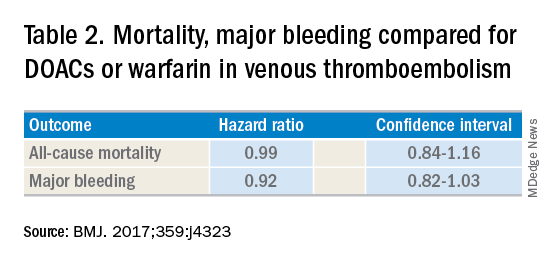

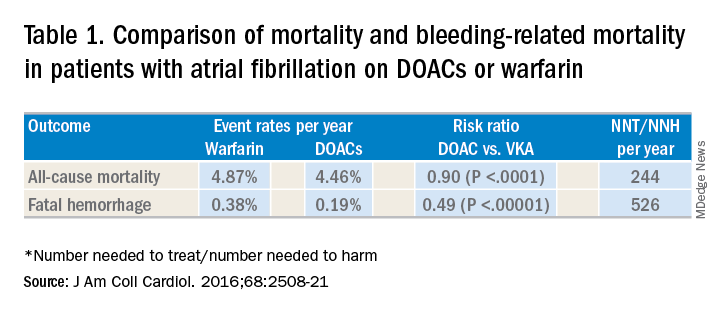

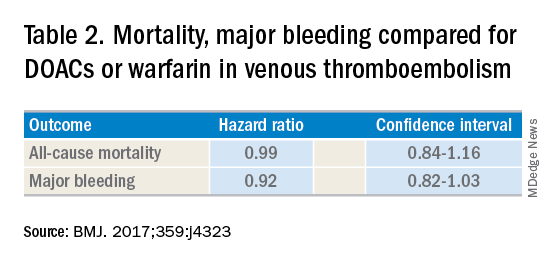

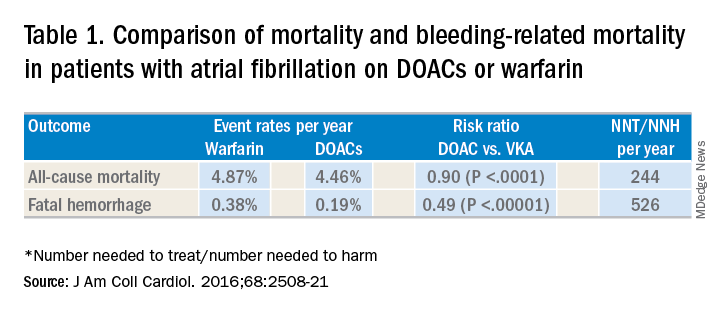

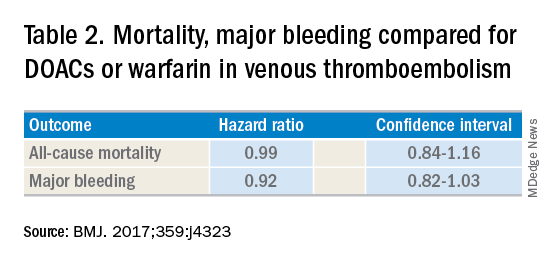

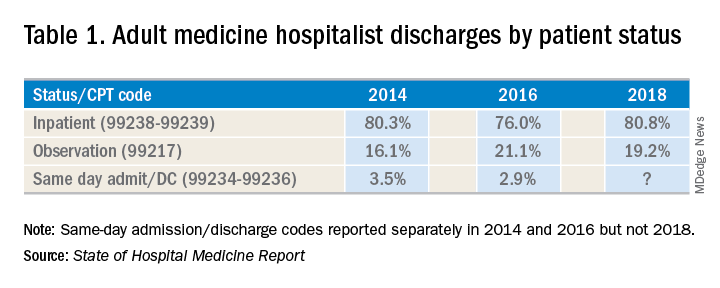

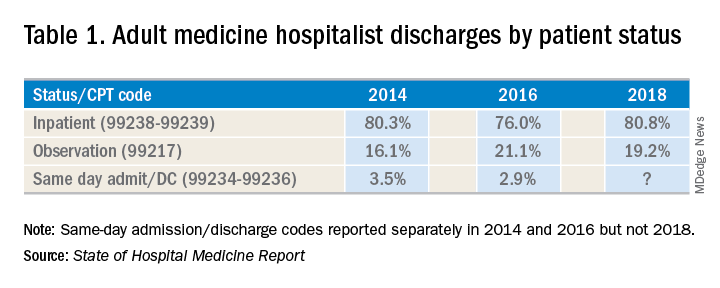

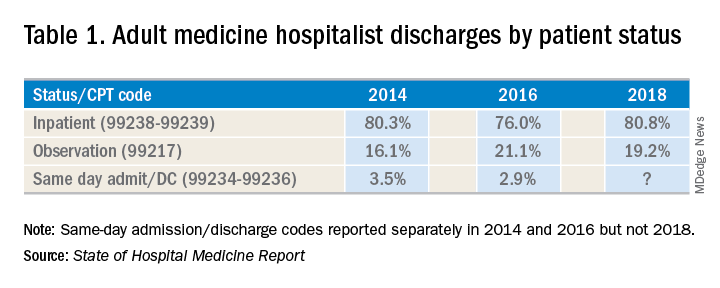

DOACs have several benefits over vitamin K antagonists (VKAs) and heparins. DOACs have quicker onset of action, can be taken by mouth, in general do not require dosage adjustment, and have fewer dietary and lifestyle modifications, compared with VKAs and heparins. In atrial fibrillation, DOACs have been shown to have lower all-cause and bleeding-related mortality than warfarin (see Table 1).1 Observational studies also suggest less risk of major bleeding with DOACs over warfarin but no difference in overall mortality when used to treat venous thromboembolism (see Table 2).2 Because of these combined advantages, DOACs are increasingly prescribed, accounting for approximately half of all oral anticoagulant prescriptions in 2014.3

Although DOACs have been shown to be as good if not superior to VKAs and heparins in these circumstances, there are situations where a DOAC should not be used. There is limited data on the safety of DOACs in patients with mechanical heart valves, liver failure, and chronic kidney disease with a creatinine clearance less than 30 mL/min.4 Therefore, warfarin is still the preferred agent in these settings. There is some data that apixaban may be safe in patients with a creatinine clearance of greater than 10 mL/min, but long-term safety studies have not been performed in patients with end-stage renal disease on hemodialysis.5 Finally, in patients requiring concomitant inducers or inhibitors of the P-glycoprotein or cytochrome P450 enzymes like antiepileptics and protease inhibitors, VKAs and heparins are favored.4

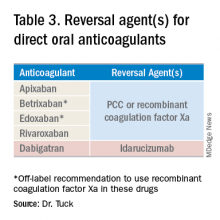

Notwithstanding their advantages, when DOACs first hit the market there were concerns that reversal agents were not available. In the August issue of the Journal of Hospital Medicine’s Clinical Guideline Highlights for the Hospitalist, Emily Gottenborg, MD, and Gregory Misky, MD, summarized guideline recommendations for reversal of the newer agents.6 This includes use of idarucizumab for patients on dabigatran and use of prothrombin complex concentrate (PCC) or recombinant coagulation factor Xa (andexanet alfa) for patients on apixaban or rivaroxaban for the treatment of life-threatening bleeding.

Idarucizumab is a monoclonal antibody developed to reverse the effects of dabigatran, the only DOAC that directly inhibits thrombin. In 2017, researchers reported on a cohort of subjects receiving idarucizumab for uncontrolled bleeding or who were on dabigatran and about to undergo an urgent procedure.7 Of those with uncontrolled bleeding, two-thirds had confirmed bleeding cessation within 24 hours. Periprocedural hemostasis was achieved in 93.4% of patients undergoing urgent procedures. However, it should be noted that use of idarucizumab conferred an increase risk (6.3%) of thrombosis within 90 days. Based on these findings, guidelines recommend use of idarucizumab in patients experiencing life-threatening bleeding, balanced against the risk of thrombosis.8

In 2018, the Food and Drug Administration approved recombinant coagulation factor Xa for treatment of life-threatening or uncontrolled bleeding in patients on apixaban or rivaroxaban.9 The approval came after a study by the ANNEXA-4 investigators showed that recombinant coagulation factor Xa quickly and effectively achieved hemostasis.10 Full study results were published in April 2019, demonstrating 82% of patients receiving the drug attained clinical hemostasis.11 However, as with idarucizumab, up to 10% of patients had a thrombotic event in the follow-up period. Use of recombinant coagulation factor Xa for treatment of life-threatening bleeding related to betrixaban and edoxaban is considered off label but is recommended by guidelines.8 Studies on investigational reversal agents for betrixaban and edoxaban are ongoing.

Both unactivated and activated PCC contain clotting factor X. Their use to control bleeding related to DOAC use is based on observational studies. In a systematic review of the nonrandomized studies, the efficacy of PCC to stem major bleeding was 69% and the risk for thromboembolism was 4%.12 There are no head-to-head studies comparing use of recombinant coagulation factor Xa and PCC. Therefore, guidelines are to use either recombinant factor Xa or PCC for the treatment of life-threatening bleeding related to DOAC use.7

As thrombosis risk heightens after use of any reversal agent, the recommendations are to resume anticoagulation within 90 days if the patient is at moderate or high risk for recurrent thromboembolism.8

After discussion with the hospitalist about the new agents available to reverse anticoagulation, the colleague decided to place the patient on a DOAC and keep the patient in his nursing home. Thankfully, the patient did not thereafter experience sustained bleeding necessitating use of these reversal agents. More importantly for the patient, he was able to stay in the comfort of his home.

Dr. Tuck is associate section chief for hospital medicine at the Veterans Affairs Medical Center in Washington, D.C.

References

1. Gómez-Outes A et al. Causes of death in anticoagulated patients with atrial fibrillation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;68:2508-21.

2. Jun M et al. Comparative safety of direct oral anticoagulants and warfarin in venous thromboembolism: multicentre, population-based, observational study. BMJ. 2017;359:j4323.

3. Barnes GD et al. National trends in ambulatory oral anticoagulant use. Am J Med. 2015;128:(1300-5).e2.

4. Reddy P et al. Practical approach to VTE management in hospitalized patients. Am J Ther. 2017;24(4):e442-67.

5. Kimachi M et al. Direct oral anticoagulants versus warfarin for preventing stroke and systemic embolic events among atrial fibrillation patients with chronic kidney disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017 Nov 6;11:CD011373.

6. Gottenborg E et al. Clinical guideline highlights for the hospitalist: The management of anticoagulation in the hospitalized adult. J Hosp Med. 2019; 14(8):499-500.

7. Pollack CV Jr et al. Idarucizumab for dabigatran reversal – full cohort analysis. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(5):431-41.

8. Witt DM et al. American Society of Hematology 2018 guidelines for management of venous thromboembolism: Optimal management of anticoagulation therapy. Blood Adv. 2018;2(22):3257-91.

9. Malarky M et al. FDA accelerated approval letter. Retrieved July 15, 2019. https://www.fda.gov/media/113285/download

10. Connolly SJ et al. Andexanet alfa for acute major bleeding associated with factor Xa inhibitors. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(12):1131-41.

11. Connolly SJ et al. Full study report of andexanet alfa for bleeding associated with factor xa inhibitors. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(14):1326-35.

12. Piran S et al. Management of direct factor Xa inhibitor–related major bleeding with prothrombin complex concentrate: A meta-analysis. Blood Adv. 2019;3(2):158-67.

Summary of guidelines published in the Journal of Hospital Medicine

Summary of guidelines published in the Journal of Hospital Medicine

When on call for admissions, a hospitalist receives a request from a colleague to admit an octogenarian man with an acute uncomplicated deep vein thrombosis to start heparin, bridging to warfarin. The patient has no evidence of postphlebitic syndrome, pulmonary embolism, or right-sided heart strain. The hospitalist asks her colleague if he had considered treating the patient in the ambulatory setting using a direct-acting oral anticoagulant (DOAC). After all, this would save the patient an unnecessary hospitalization, weekly international normalized ratio checks, and other important lifestyle changes. In response, the colleague voices concern that the “new drugs don’t have antidotes.”

DOACs have several benefits over vitamin K antagonists (VKAs) and heparins. DOACs have quicker onset of action, can be taken by mouth, in general do not require dosage adjustment, and have fewer dietary and lifestyle modifications, compared with VKAs and heparins. In atrial fibrillation, DOACs have been shown to have lower all-cause and bleeding-related mortality than warfarin (see Table 1).1 Observational studies also suggest less risk of major bleeding with DOACs over warfarin but no difference in overall mortality when used to treat venous thromboembolism (see Table 2).2 Because of these combined advantages, DOACs are increasingly prescribed, accounting for approximately half of all oral anticoagulant prescriptions in 2014.3

Although DOACs have been shown to be as good if not superior to VKAs and heparins in these circumstances, there are situations where a DOAC should not be used. There is limited data on the safety of DOACs in patients with mechanical heart valves, liver failure, and chronic kidney disease with a creatinine clearance less than 30 mL/min.4 Therefore, warfarin is still the preferred agent in these settings. There is some data that apixaban may be safe in patients with a creatinine clearance of greater than 10 mL/min, but long-term safety studies have not been performed in patients with end-stage renal disease on hemodialysis.5 Finally, in patients requiring concomitant inducers or inhibitors of the P-glycoprotein or cytochrome P450 enzymes like antiepileptics and protease inhibitors, VKAs and heparins are favored.4

Notwithstanding their advantages, when DOACs first hit the market there were concerns that reversal agents were not available. In the August issue of the Journal of Hospital Medicine’s Clinical Guideline Highlights for the Hospitalist, Emily Gottenborg, MD, and Gregory Misky, MD, summarized guideline recommendations for reversal of the newer agents.6 This includes use of idarucizumab for patients on dabigatran and use of prothrombin complex concentrate (PCC) or recombinant coagulation factor Xa (andexanet alfa) for patients on apixaban or rivaroxaban for the treatment of life-threatening bleeding.

Idarucizumab is a monoclonal antibody developed to reverse the effects of dabigatran, the only DOAC that directly inhibits thrombin. In 2017, researchers reported on a cohort of subjects receiving idarucizumab for uncontrolled bleeding or who were on dabigatran and about to undergo an urgent procedure.7 Of those with uncontrolled bleeding, two-thirds had confirmed bleeding cessation within 24 hours. Periprocedural hemostasis was achieved in 93.4% of patients undergoing urgent procedures. However, it should be noted that use of idarucizumab conferred an increase risk (6.3%) of thrombosis within 90 days. Based on these findings, guidelines recommend use of idarucizumab in patients experiencing life-threatening bleeding, balanced against the risk of thrombosis.8

In 2018, the Food and Drug Administration approved recombinant coagulation factor Xa for treatment of life-threatening or uncontrolled bleeding in patients on apixaban or rivaroxaban.9 The approval came after a study by the ANNEXA-4 investigators showed that recombinant coagulation factor Xa quickly and effectively achieved hemostasis.10 Full study results were published in April 2019, demonstrating 82% of patients receiving the drug attained clinical hemostasis.11 However, as with idarucizumab, up to 10% of patients had a thrombotic event in the follow-up period. Use of recombinant coagulation factor Xa for treatment of life-threatening bleeding related to betrixaban and edoxaban is considered off label but is recommended by guidelines.8 Studies on investigational reversal agents for betrixaban and edoxaban are ongoing.

Both unactivated and activated PCC contain clotting factor X. Their use to control bleeding related to DOAC use is based on observational studies. In a systematic review of the nonrandomized studies, the efficacy of PCC to stem major bleeding was 69% and the risk for thromboembolism was 4%.12 There are no head-to-head studies comparing use of recombinant coagulation factor Xa and PCC. Therefore, guidelines are to use either recombinant factor Xa or PCC for the treatment of life-threatening bleeding related to DOAC use.7

As thrombosis risk heightens after use of any reversal agent, the recommendations are to resume anticoagulation within 90 days if the patient is at moderate or high risk for recurrent thromboembolism.8

After discussion with the hospitalist about the new agents available to reverse anticoagulation, the colleague decided to place the patient on a DOAC and keep the patient in his nursing home. Thankfully, the patient did not thereafter experience sustained bleeding necessitating use of these reversal agents. More importantly for the patient, he was able to stay in the comfort of his home.

Dr. Tuck is associate section chief for hospital medicine at the Veterans Affairs Medical Center in Washington, D.C.

References

1. Gómez-Outes A et al. Causes of death in anticoagulated patients with atrial fibrillation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;68:2508-21.

2. Jun M et al. Comparative safety of direct oral anticoagulants and warfarin in venous thromboembolism: multicentre, population-based, observational study. BMJ. 2017;359:j4323.

3. Barnes GD et al. National trends in ambulatory oral anticoagulant use. Am J Med. 2015;128:(1300-5).e2.

4. Reddy P et al. Practical approach to VTE management in hospitalized patients. Am J Ther. 2017;24(4):e442-67.

5. Kimachi M et al. Direct oral anticoagulants versus warfarin for preventing stroke and systemic embolic events among atrial fibrillation patients with chronic kidney disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017 Nov 6;11:CD011373.

6. Gottenborg E et al. Clinical guideline highlights for the hospitalist: The management of anticoagulation in the hospitalized adult. J Hosp Med. 2019; 14(8):499-500.

7. Pollack CV Jr et al. Idarucizumab for dabigatran reversal – full cohort analysis. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(5):431-41.

8. Witt DM et al. American Society of Hematology 2018 guidelines for management of venous thromboembolism: Optimal management of anticoagulation therapy. Blood Adv. 2018;2(22):3257-91.

9. Malarky M et al. FDA accelerated approval letter. Retrieved July 15, 2019. https://www.fda.gov/media/113285/download

10. Connolly SJ et al. Andexanet alfa for acute major bleeding associated with factor Xa inhibitors. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(12):1131-41.

11. Connolly SJ et al. Full study report of andexanet alfa for bleeding associated with factor xa inhibitors. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(14):1326-35.

12. Piran S et al. Management of direct factor Xa inhibitor–related major bleeding with prothrombin complex concentrate: A meta-analysis. Blood Adv. 2019;3(2):158-67.

When on call for admissions, a hospitalist receives a request from a colleague to admit an octogenarian man with an acute uncomplicated deep vein thrombosis to start heparin, bridging to warfarin. The patient has no evidence of postphlebitic syndrome, pulmonary embolism, or right-sided heart strain. The hospitalist asks her colleague if he had considered treating the patient in the ambulatory setting using a direct-acting oral anticoagulant (DOAC). After all, this would save the patient an unnecessary hospitalization, weekly international normalized ratio checks, and other important lifestyle changes. In response, the colleague voices concern that the “new drugs don’t have antidotes.”

DOACs have several benefits over vitamin K antagonists (VKAs) and heparins. DOACs have quicker onset of action, can be taken by mouth, in general do not require dosage adjustment, and have fewer dietary and lifestyle modifications, compared with VKAs and heparins. In atrial fibrillation, DOACs have been shown to have lower all-cause and bleeding-related mortality than warfarin (see Table 1).1 Observational studies also suggest less risk of major bleeding with DOACs over warfarin but no difference in overall mortality when used to treat venous thromboembolism (see Table 2).2 Because of these combined advantages, DOACs are increasingly prescribed, accounting for approximately half of all oral anticoagulant prescriptions in 2014.3

Although DOACs have been shown to be as good if not superior to VKAs and heparins in these circumstances, there are situations where a DOAC should not be used. There is limited data on the safety of DOACs in patients with mechanical heart valves, liver failure, and chronic kidney disease with a creatinine clearance less than 30 mL/min.4 Therefore, warfarin is still the preferred agent in these settings. There is some data that apixaban may be safe in patients with a creatinine clearance of greater than 10 mL/min, but long-term safety studies have not been performed in patients with end-stage renal disease on hemodialysis.5 Finally, in patients requiring concomitant inducers or inhibitors of the P-glycoprotein or cytochrome P450 enzymes like antiepileptics and protease inhibitors, VKAs and heparins are favored.4

Notwithstanding their advantages, when DOACs first hit the market there were concerns that reversal agents were not available. In the August issue of the Journal of Hospital Medicine’s Clinical Guideline Highlights for the Hospitalist, Emily Gottenborg, MD, and Gregory Misky, MD, summarized guideline recommendations for reversal of the newer agents.6 This includes use of idarucizumab for patients on dabigatran and use of prothrombin complex concentrate (PCC) or recombinant coagulation factor Xa (andexanet alfa) for patients on apixaban or rivaroxaban for the treatment of life-threatening bleeding.

Idarucizumab is a monoclonal antibody developed to reverse the effects of dabigatran, the only DOAC that directly inhibits thrombin. In 2017, researchers reported on a cohort of subjects receiving idarucizumab for uncontrolled bleeding or who were on dabigatran and about to undergo an urgent procedure.7 Of those with uncontrolled bleeding, two-thirds had confirmed bleeding cessation within 24 hours. Periprocedural hemostasis was achieved in 93.4% of patients undergoing urgent procedures. However, it should be noted that use of idarucizumab conferred an increase risk (6.3%) of thrombosis within 90 days. Based on these findings, guidelines recommend use of idarucizumab in patients experiencing life-threatening bleeding, balanced against the risk of thrombosis.8

In 2018, the Food and Drug Administration approved recombinant coagulation factor Xa for treatment of life-threatening or uncontrolled bleeding in patients on apixaban or rivaroxaban.9 The approval came after a study by the ANNEXA-4 investigators showed that recombinant coagulation factor Xa quickly and effectively achieved hemostasis.10 Full study results were published in April 2019, demonstrating 82% of patients receiving the drug attained clinical hemostasis.11 However, as with idarucizumab, up to 10% of patients had a thrombotic event in the follow-up period. Use of recombinant coagulation factor Xa for treatment of life-threatening bleeding related to betrixaban and edoxaban is considered off label but is recommended by guidelines.8 Studies on investigational reversal agents for betrixaban and edoxaban are ongoing.

Both unactivated and activated PCC contain clotting factor X. Their use to control bleeding related to DOAC use is based on observational studies. In a systematic review of the nonrandomized studies, the efficacy of PCC to stem major bleeding was 69% and the risk for thromboembolism was 4%.12 There are no head-to-head studies comparing use of recombinant coagulation factor Xa and PCC. Therefore, guidelines are to use either recombinant factor Xa or PCC for the treatment of life-threatening bleeding related to DOAC use.7

As thrombosis risk heightens after use of any reversal agent, the recommendations are to resume anticoagulation within 90 days if the patient is at moderate or high risk for recurrent thromboembolism.8

After discussion with the hospitalist about the new agents available to reverse anticoagulation, the colleague decided to place the patient on a DOAC and keep the patient in his nursing home. Thankfully, the patient did not thereafter experience sustained bleeding necessitating use of these reversal agents. More importantly for the patient, he was able to stay in the comfort of his home.

Dr. Tuck is associate section chief for hospital medicine at the Veterans Affairs Medical Center in Washington, D.C.

References

1. Gómez-Outes A et al. Causes of death in anticoagulated patients with atrial fibrillation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;68:2508-21.

2. Jun M et al. Comparative safety of direct oral anticoagulants and warfarin in venous thromboembolism: multicentre, population-based, observational study. BMJ. 2017;359:j4323.

3. Barnes GD et al. National trends in ambulatory oral anticoagulant use. Am J Med. 2015;128:(1300-5).e2.

4. Reddy P et al. Practical approach to VTE management in hospitalized patients. Am J Ther. 2017;24(4):e442-67.

5. Kimachi M et al. Direct oral anticoagulants versus warfarin for preventing stroke and systemic embolic events among atrial fibrillation patients with chronic kidney disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017 Nov 6;11:CD011373.

6. Gottenborg E et al. Clinical guideline highlights for the hospitalist: The management of anticoagulation in the hospitalized adult. J Hosp Med. 2019; 14(8):499-500.

7. Pollack CV Jr et al. Idarucizumab for dabigatran reversal – full cohort analysis. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(5):431-41.

8. Witt DM et al. American Society of Hematology 2018 guidelines for management of venous thromboembolism: Optimal management of anticoagulation therapy. Blood Adv. 2018;2(22):3257-91.

9. Malarky M et al. FDA accelerated approval letter. Retrieved July 15, 2019. https://www.fda.gov/media/113285/download

10. Connolly SJ et al. Andexanet alfa for acute major bleeding associated with factor Xa inhibitors. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(12):1131-41.

11. Connolly SJ et al. Full study report of andexanet alfa for bleeding associated with factor xa inhibitors. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(14):1326-35.

12. Piran S et al. Management of direct factor Xa inhibitor–related major bleeding with prothrombin complex concentrate: A meta-analysis. Blood Adv. 2019;3(2):158-67.

Hospitalist movers and shakers – September 2019

Mark Williams, MD, MHM, FACP, recently was appointed chief quality and transformation officer for the University of Kentucky’s UK HealthCare (Lexington). Dr. Williams, a tenured professor in the division of hospital medicine at the UK College of Medicine, will serve as chair of UK HealthCare’s Executive Quality Committee. Dr. Williams will lead integration of quality improvement, safety, and quality reporting with data analytics.

Dr. Williams established the first hospitalist program at a public hospital (Grady Memorial Hospital) and academic hospitalist programs at Emory University, Northwestern University, and UK HealthCare. An inaugural member of SHM, he is a past president, was the founding editor-in-chief of the Journal of Hospital Medicine and led SHM’s Project BOOST.

Also at UK HealthCare, Romil Chadha, MD, MPH, SFHM, FACP, has been named interim chief of the division of hospital medicine and medical director of Physician Information Technology Services. Previously, he was associate chief of the division of hospital medicine, and he also serves as medical director of telemetry.

Dr. Chadha is the founder of the Kentucky chapter of SHM, where he is the immediate past president. He is also the codirector of the Heartland Hospital Medicine Conference.

Amit Vashist, MD, MBA, CPE, FHM, FACP, FAPA, has been named chief clinical officer at Ballad Health, a 21-hospital health system in Northeast Tennessee, Southwest Virginia, Northwest North Carolina, and Southeast Kentucky.

In his new role, he will focus on clinical quality, value-based initiatives to improve quality while reducing cost of care, performance improvement, oversight of the clinical delivery of care and will be the liaison to the Ballad Health Clinical Council. Dr. Vashist is a member of The Hospitalist’s editorial advisory board.

Nagendra Gupta, MD, FACP, CPE, has been appointed to the American Board of Internal Medicine’s Internal Medicine Specialty Board. ABIM Specialty Boards are responsible for the broad definition of the discipline across Certification and Maintenance of Certification (MOC). Specialty Board members work with physicians and medical societies to develop Certification and MOC credentials to recognize physicians for their specialized knowledge and commitment to staying current in their field.

Dr. Gupta is a full-time practicing hospitalist with Apogee Physicians and currently serves as the director of the hospitalist program at Texas Health Arlington (Tex.) Memorial Hospital. He also serves as vice president for SHM’s North Central Texas Chapter.

T. Steen Trawick Jr., MD, was named the CEO of Christus Shreveport-Bossier Health System in Shreveport, La., in August 2019.

Dr. Trawick has worked for Christus as a pediatric hospitalist since 2005 and most recently has served concurrently as associate chief medical officer for Sound Physicians. Through Sound Physicians, Dr. Trawick oversees the hospitalist and emergency medical programs for Christus and other hospitals – 14 in total – in Texas and Louisiana. He has worked in that role for the past 6 years.

Scott Shepherd, DO, FACP, has been selected chief medical officer of the health data enrichment and integration technology company Verinovum in Tulsa, Okla. Dr. Shepherd is the medical director for hospitalist medicine and a practicing hospitalist with St. John Health System in Tulsa, and also medical director of the Center for Health Systems Innovation at his alma mater, Oklahoma State University in Stillwater.

Amanda Logue, MD, has been elevated to chief medical officer at Lafayette (La.) General Hospital. Dr. Logue assumed her role in May 2019, which includes the title of senior vice president.

Dr. Logue has worked at Lafayette General since 2009. A hospitalist/internist, her duties at the facility have included department chair of medicine, physician champion for electronic medical record implementation, medical director of the hospitalist program, and most recently chief medical information officer.

Rina Bansal, MD, MBA, recently was appointed full-time president of Inova Alexandria (Va.) Hospital, taking the reins officially after serving as acting president since November 2018. Dr. Bansal has been at Inova since 2008, when she started as a hospitalist at Inova Fairfax (Va.).

Dr. Bansal created and led Inova’s Clinical Nurse Services Hospitalist program through its department of neurosciences and has done stints as Inova Fairfax’s associate chief medical officer, medical director of Inova Telemedicine, and chief medical officer at Inova Alexandria.

James Napoli, MD, has been named chief medical officer for Blue Cross and Blue Shield of Arizona (BCBSAZ). He has manned the CMO position in an interim role since March, taking those duties on top of his role as BCBSAZ’s enterprise medical director for health care ventures and innovation.

Dr. Napoli came to BCBSAZ in 2013 after more than a decade at Abrazo Arrowhead Campus (Glendale, Ariz.) At Abrazo, he was director of hospitalist services and vice-chief of staff, on top of his efforts as a practicing hospital medicine clinician.

Dr. Napoli was previously medical director at OptumHealth, working specifically in the medical management and quality improvement areas for the health management solutions organization’s Medicare Advantage clients.

Mercy Hospital Fort Smith (Ark.) has partnered with the Ob Hospitalist Group (Greenville, S.C.) to launch an obstetric hospitalist program. OB hospitalists deliver babies when a patient’s physician cannot be present, provide emergency care, and provide support to high-risk pregnancy patients, among other duties within the hospital.

The partnership has allowed Mercy Fort Smith to create a dedicated, four-room obstetric emergency department in its Mercy Childbirth Center. Eight OB hospitalists have been hired and will provide care 24 hours a day, 7 days a week.

Mark Williams, MD, MHM, FACP, recently was appointed chief quality and transformation officer for the University of Kentucky’s UK HealthCare (Lexington). Dr. Williams, a tenured professor in the division of hospital medicine at the UK College of Medicine, will serve as chair of UK HealthCare’s Executive Quality Committee. Dr. Williams will lead integration of quality improvement, safety, and quality reporting with data analytics.

Dr. Williams established the first hospitalist program at a public hospital (Grady Memorial Hospital) and academic hospitalist programs at Emory University, Northwestern University, and UK HealthCare. An inaugural member of SHM, he is a past president, was the founding editor-in-chief of the Journal of Hospital Medicine and led SHM’s Project BOOST.

Also at UK HealthCare, Romil Chadha, MD, MPH, SFHM, FACP, has been named interim chief of the division of hospital medicine and medical director of Physician Information Technology Services. Previously, he was associate chief of the division of hospital medicine, and he also serves as medical director of telemetry.

Dr. Chadha is the founder of the Kentucky chapter of SHM, where he is the immediate past president. He is also the codirector of the Heartland Hospital Medicine Conference.

Amit Vashist, MD, MBA, CPE, FHM, FACP, FAPA, has been named chief clinical officer at Ballad Health, a 21-hospital health system in Northeast Tennessee, Southwest Virginia, Northwest North Carolina, and Southeast Kentucky.

In his new role, he will focus on clinical quality, value-based initiatives to improve quality while reducing cost of care, performance improvement, oversight of the clinical delivery of care and will be the liaison to the Ballad Health Clinical Council. Dr. Vashist is a member of The Hospitalist’s editorial advisory board.

Nagendra Gupta, MD, FACP, CPE, has been appointed to the American Board of Internal Medicine’s Internal Medicine Specialty Board. ABIM Specialty Boards are responsible for the broad definition of the discipline across Certification and Maintenance of Certification (MOC). Specialty Board members work with physicians and medical societies to develop Certification and MOC credentials to recognize physicians for their specialized knowledge and commitment to staying current in their field.

Dr. Gupta is a full-time practicing hospitalist with Apogee Physicians and currently serves as the director of the hospitalist program at Texas Health Arlington (Tex.) Memorial Hospital. He also serves as vice president for SHM’s North Central Texas Chapter.

T. Steen Trawick Jr., MD, was named the CEO of Christus Shreveport-Bossier Health System in Shreveport, La., in August 2019.

Dr. Trawick has worked for Christus as a pediatric hospitalist since 2005 and most recently has served concurrently as associate chief medical officer for Sound Physicians. Through Sound Physicians, Dr. Trawick oversees the hospitalist and emergency medical programs for Christus and other hospitals – 14 in total – in Texas and Louisiana. He has worked in that role for the past 6 years.

Scott Shepherd, DO, FACP, has been selected chief medical officer of the health data enrichment and integration technology company Verinovum in Tulsa, Okla. Dr. Shepherd is the medical director for hospitalist medicine and a practicing hospitalist with St. John Health System in Tulsa, and also medical director of the Center for Health Systems Innovation at his alma mater, Oklahoma State University in Stillwater.

Amanda Logue, MD, has been elevated to chief medical officer at Lafayette (La.) General Hospital. Dr. Logue assumed her role in May 2019, which includes the title of senior vice president.

Dr. Logue has worked at Lafayette General since 2009. A hospitalist/internist, her duties at the facility have included department chair of medicine, physician champion for electronic medical record implementation, medical director of the hospitalist program, and most recently chief medical information officer.

Rina Bansal, MD, MBA, recently was appointed full-time president of Inova Alexandria (Va.) Hospital, taking the reins officially after serving as acting president since November 2018. Dr. Bansal has been at Inova since 2008, when she started as a hospitalist at Inova Fairfax (Va.).

Dr. Bansal created and led Inova’s Clinical Nurse Services Hospitalist program through its department of neurosciences and has done stints as Inova Fairfax’s associate chief medical officer, medical director of Inova Telemedicine, and chief medical officer at Inova Alexandria.

James Napoli, MD, has been named chief medical officer for Blue Cross and Blue Shield of Arizona (BCBSAZ). He has manned the CMO position in an interim role since March, taking those duties on top of his role as BCBSAZ’s enterprise medical director for health care ventures and innovation.

Dr. Napoli came to BCBSAZ in 2013 after more than a decade at Abrazo Arrowhead Campus (Glendale, Ariz.) At Abrazo, he was director of hospitalist services and vice-chief of staff, on top of his efforts as a practicing hospital medicine clinician.

Dr. Napoli was previously medical director at OptumHealth, working specifically in the medical management and quality improvement areas for the health management solutions organization’s Medicare Advantage clients.

Mercy Hospital Fort Smith (Ark.) has partnered with the Ob Hospitalist Group (Greenville, S.C.) to launch an obstetric hospitalist program. OB hospitalists deliver babies when a patient’s physician cannot be present, provide emergency care, and provide support to high-risk pregnancy patients, among other duties within the hospital.

The partnership has allowed Mercy Fort Smith to create a dedicated, four-room obstetric emergency department in its Mercy Childbirth Center. Eight OB hospitalists have been hired and will provide care 24 hours a day, 7 days a week.

Mark Williams, MD, MHM, FACP, recently was appointed chief quality and transformation officer for the University of Kentucky’s UK HealthCare (Lexington). Dr. Williams, a tenured professor in the division of hospital medicine at the UK College of Medicine, will serve as chair of UK HealthCare’s Executive Quality Committee. Dr. Williams will lead integration of quality improvement, safety, and quality reporting with data analytics.

Dr. Williams established the first hospitalist program at a public hospital (Grady Memorial Hospital) and academic hospitalist programs at Emory University, Northwestern University, and UK HealthCare. An inaugural member of SHM, he is a past president, was the founding editor-in-chief of the Journal of Hospital Medicine and led SHM’s Project BOOST.

Also at UK HealthCare, Romil Chadha, MD, MPH, SFHM, FACP, has been named interim chief of the division of hospital medicine and medical director of Physician Information Technology Services. Previously, he was associate chief of the division of hospital medicine, and he also serves as medical director of telemetry.

Dr. Chadha is the founder of the Kentucky chapter of SHM, where he is the immediate past president. He is also the codirector of the Heartland Hospital Medicine Conference.

Amit Vashist, MD, MBA, CPE, FHM, FACP, FAPA, has been named chief clinical officer at Ballad Health, a 21-hospital health system in Northeast Tennessee, Southwest Virginia, Northwest North Carolina, and Southeast Kentucky.

In his new role, he will focus on clinical quality, value-based initiatives to improve quality while reducing cost of care, performance improvement, oversight of the clinical delivery of care and will be the liaison to the Ballad Health Clinical Council. Dr. Vashist is a member of The Hospitalist’s editorial advisory board.

Nagendra Gupta, MD, FACP, CPE, has been appointed to the American Board of Internal Medicine’s Internal Medicine Specialty Board. ABIM Specialty Boards are responsible for the broad definition of the discipline across Certification and Maintenance of Certification (MOC). Specialty Board members work with physicians and medical societies to develop Certification and MOC credentials to recognize physicians for their specialized knowledge and commitment to staying current in their field.

Dr. Gupta is a full-time practicing hospitalist with Apogee Physicians and currently serves as the director of the hospitalist program at Texas Health Arlington (Tex.) Memorial Hospital. He also serves as vice president for SHM’s North Central Texas Chapter.

T. Steen Trawick Jr., MD, was named the CEO of Christus Shreveport-Bossier Health System in Shreveport, La., in August 2019.

Dr. Trawick has worked for Christus as a pediatric hospitalist since 2005 and most recently has served concurrently as associate chief medical officer for Sound Physicians. Through Sound Physicians, Dr. Trawick oversees the hospitalist and emergency medical programs for Christus and other hospitals – 14 in total – in Texas and Louisiana. He has worked in that role for the past 6 years.

Scott Shepherd, DO, FACP, has been selected chief medical officer of the health data enrichment and integration technology company Verinovum in Tulsa, Okla. Dr. Shepherd is the medical director for hospitalist medicine and a practicing hospitalist with St. John Health System in Tulsa, and also medical director of the Center for Health Systems Innovation at his alma mater, Oklahoma State University in Stillwater.

Amanda Logue, MD, has been elevated to chief medical officer at Lafayette (La.) General Hospital. Dr. Logue assumed her role in May 2019, which includes the title of senior vice president.

Dr. Logue has worked at Lafayette General since 2009. A hospitalist/internist, her duties at the facility have included department chair of medicine, physician champion for electronic medical record implementation, medical director of the hospitalist program, and most recently chief medical information officer.

Rina Bansal, MD, MBA, recently was appointed full-time president of Inova Alexandria (Va.) Hospital, taking the reins officially after serving as acting president since November 2018. Dr. Bansal has been at Inova since 2008, when she started as a hospitalist at Inova Fairfax (Va.).

Dr. Bansal created and led Inova’s Clinical Nurse Services Hospitalist program through its department of neurosciences and has done stints as Inova Fairfax’s associate chief medical officer, medical director of Inova Telemedicine, and chief medical officer at Inova Alexandria.

James Napoli, MD, has been named chief medical officer for Blue Cross and Blue Shield of Arizona (BCBSAZ). He has manned the CMO position in an interim role since March, taking those duties on top of his role as BCBSAZ’s enterprise medical director for health care ventures and innovation.

Dr. Napoli came to BCBSAZ in 2013 after more than a decade at Abrazo Arrowhead Campus (Glendale, Ariz.) At Abrazo, he was director of hospitalist services and vice-chief of staff, on top of his efforts as a practicing hospital medicine clinician.

Dr. Napoli was previously medical director at OptumHealth, working specifically in the medical management and quality improvement areas for the health management solutions organization’s Medicare Advantage clients.

Mercy Hospital Fort Smith (Ark.) has partnered with the Ob Hospitalist Group (Greenville, S.C.) to launch an obstetric hospitalist program. OB hospitalists deliver babies when a patient’s physician cannot be present, provide emergency care, and provide support to high-risk pregnancy patients, among other duties within the hospital.

The partnership has allowed Mercy Fort Smith to create a dedicated, four-room obstetric emergency department in its Mercy Childbirth Center. Eight OB hospitalists have been hired and will provide care 24 hours a day, 7 days a week.

Drug abuse–linked infective endocarditis spiking in U.S.

Hospitalizations for infective endocarditis associated with drug abuse doubled in the United States from 2002 to 2016, in a trend investigators call “alarming,” and link to a concurrent rise in opioid abuse.

Patients tend to be younger, poorer white males, according to findings published online in the Journal of the American Heart Association.

For their research, Amer N. Kadri, MD, of the Cleveland Clinic and colleagues looked at records for nearly a million hospitalizations for infective endocarditis (IE) in the National Inpatient Sample registry. All U.S. regions saw increases in drug abuse–linked cases of IE as a share of IE hospitalizations. Incidence of drug abuse–associated IC rose from 48 cases/100,000 population in 2002 to 79/100,000 in 2016. The Midwest saw the highest rate of change, with an annual percent increase of 4.9%.

While most IE hospitalizations in the study cohort were of white men (including 68% for drug-linked cases), the drug abuse–related cases were younger (median age, 38 vs. 70 years for nondrug-related IE), and more likely male (55.5% vs. 50%). About 45% of the drug-related cases were in people receiving Medicaid, and 42% were in the lowest quartile of median household income.