User login

A third of serious malpractice claims due to diagnostic error

A third of medical malpractice cases associated with patient death or permanent disability result from diagnostic errors by health providers, an analysis finds.

Lead investigator David E. Newman-Toker, MD, PhD, of Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, and colleagues reviewed malpractice claims during 2006-2015 from medical liability insurer CRICO’s Comparative Benchmarking System database, which represents 30% of all malpractice claims in the United States.

Investigators sought to identify diseases accounting for the majority of serious diagnosis-related harms associated with the claims. Of 55,377 closed claims, researchers identified 11,592 diagnostic error cases, of which 7,379 resulted in high-severity harm.

Of the high-severity claims, 34% stemmed from inaccurate or delayed diagnosis (Diagnosis 2019 Jul 11. doi. org/10.1515/dx-2019-0019).

The majority of diagnostic mistakes (74%) causing the most severe harm were attributable to cancer (38%), vascular events (23%), and infection (14%). These cases resulted in nearly $2 billion in malpractice payouts over a 10-year period, investigators found.

Clinical judgment factors were the primary reason behind the alleged errors, specifically: failure or delay in ordering a diagnostic test, narrow diagnostic focus with failure to establish a differential diagnosis, failure to appreciate and reconcile relevant symptoms or test results, and failure or delay in obtaining consultation or referral and misinterpretation of diagnostic studies.

“Diagnostic errors are the most common, the most catastrophic, and the most costly of medical errors,” Dr. Newman-Toker said at a press conference July 11. “We know that this is a major problem, at an individual, personal level, but also at a societal level and something we really have to take action toward fixing.”

This study breaks new ground by drilling into the major diseases most commonly associated with diagnostic errors, Dr. Newman-Toker said. In the cancer category, the most common cancers linked to severe harm were lung, breast, colorectal, prostate, and melanoma. In the vascular category, the most common conditions were stroke; myocardial infarction; venous thromboembolism; aortic aneurysm and dissection; and arterial thromboembolism. In the area of infection, sepsis; meningitis and encephalitis; spinal abscess; pneumonia; and endocarditis were the most common infections identified.

The findings provide a starting point to make improvements in the area of medical errors, said Dr. Newman-Toker, president of the Society to Improve Diagnosis in Medicine, an organization that aims to improve diagnosis and eliminate harm from diagnostic error.

“Although diagnostic errors happen everywhere, across all of medicine in every discipline with every disease, we might be able to take a big chunk out of this problem if we save a lot of lives and prevent a lot disability and if we focus some energy on tackling these problems,” he said. “It at least gives us a starting place and a roadmap for how to move the ball forward in this regard.”

The Society to Improve Diagnosis in Medicine has called on Congress to invest more funding into research to address diagnostic errors. Society CEO and cofounder Paul L. Epner noted that the 2019 House appropriations bill proposes not less than $4 million for diagnostic safety and quality research, which is up from $2 million last year.

“It’s a small step, but in the right direction,” Mr. Epner said. “[However,] the federal investment in research remains trivially small in relation to the public burden. That’s why we urge Congress to commit to research funding levels proportionate to the societal cost, in both human lives and in dollars.”

[email protected]

A third of medical malpractice cases associated with patient death or permanent disability result from diagnostic errors by health providers, an analysis finds.

Lead investigator David E. Newman-Toker, MD, PhD, of Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, and colleagues reviewed malpractice claims during 2006-2015 from medical liability insurer CRICO’s Comparative Benchmarking System database, which represents 30% of all malpractice claims in the United States.

Investigators sought to identify diseases accounting for the majority of serious diagnosis-related harms associated with the claims. Of 55,377 closed claims, researchers identified 11,592 diagnostic error cases, of which 7,379 resulted in high-severity harm.

Of the high-severity claims, 34% stemmed from inaccurate or delayed diagnosis (Diagnosis 2019 Jul 11. doi. org/10.1515/dx-2019-0019).

The majority of diagnostic mistakes (74%) causing the most severe harm were attributable to cancer (38%), vascular events (23%), and infection (14%). These cases resulted in nearly $2 billion in malpractice payouts over a 10-year period, investigators found.

Clinical judgment factors were the primary reason behind the alleged errors, specifically: failure or delay in ordering a diagnostic test, narrow diagnostic focus with failure to establish a differential diagnosis, failure to appreciate and reconcile relevant symptoms or test results, and failure or delay in obtaining consultation or referral and misinterpretation of diagnostic studies.

“Diagnostic errors are the most common, the most catastrophic, and the most costly of medical errors,” Dr. Newman-Toker said at a press conference July 11. “We know that this is a major problem, at an individual, personal level, but also at a societal level and something we really have to take action toward fixing.”

This study breaks new ground by drilling into the major diseases most commonly associated with diagnostic errors, Dr. Newman-Toker said. In the cancer category, the most common cancers linked to severe harm were lung, breast, colorectal, prostate, and melanoma. In the vascular category, the most common conditions were stroke; myocardial infarction; venous thromboembolism; aortic aneurysm and dissection; and arterial thromboembolism. In the area of infection, sepsis; meningitis and encephalitis; spinal abscess; pneumonia; and endocarditis were the most common infections identified.

The findings provide a starting point to make improvements in the area of medical errors, said Dr. Newman-Toker, president of the Society to Improve Diagnosis in Medicine, an organization that aims to improve diagnosis and eliminate harm from diagnostic error.

“Although diagnostic errors happen everywhere, across all of medicine in every discipline with every disease, we might be able to take a big chunk out of this problem if we save a lot of lives and prevent a lot disability and if we focus some energy on tackling these problems,” he said. “It at least gives us a starting place and a roadmap for how to move the ball forward in this regard.”

The Society to Improve Diagnosis in Medicine has called on Congress to invest more funding into research to address diagnostic errors. Society CEO and cofounder Paul L. Epner noted that the 2019 House appropriations bill proposes not less than $4 million for diagnostic safety and quality research, which is up from $2 million last year.

“It’s a small step, but in the right direction,” Mr. Epner said. “[However,] the federal investment in research remains trivially small in relation to the public burden. That’s why we urge Congress to commit to research funding levels proportionate to the societal cost, in both human lives and in dollars.”

[email protected]

A third of medical malpractice cases associated with patient death or permanent disability result from diagnostic errors by health providers, an analysis finds.

Lead investigator David E. Newman-Toker, MD, PhD, of Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, and colleagues reviewed malpractice claims during 2006-2015 from medical liability insurer CRICO’s Comparative Benchmarking System database, which represents 30% of all malpractice claims in the United States.

Investigators sought to identify diseases accounting for the majority of serious diagnosis-related harms associated with the claims. Of 55,377 closed claims, researchers identified 11,592 diagnostic error cases, of which 7,379 resulted in high-severity harm.

Of the high-severity claims, 34% stemmed from inaccurate or delayed diagnosis (Diagnosis 2019 Jul 11. doi. org/10.1515/dx-2019-0019).

The majority of diagnostic mistakes (74%) causing the most severe harm were attributable to cancer (38%), vascular events (23%), and infection (14%). These cases resulted in nearly $2 billion in malpractice payouts over a 10-year period, investigators found.

Clinical judgment factors were the primary reason behind the alleged errors, specifically: failure or delay in ordering a diagnostic test, narrow diagnostic focus with failure to establish a differential diagnosis, failure to appreciate and reconcile relevant symptoms or test results, and failure or delay in obtaining consultation or referral and misinterpretation of diagnostic studies.

“Diagnostic errors are the most common, the most catastrophic, and the most costly of medical errors,” Dr. Newman-Toker said at a press conference July 11. “We know that this is a major problem, at an individual, personal level, but also at a societal level and something we really have to take action toward fixing.”

This study breaks new ground by drilling into the major diseases most commonly associated with diagnostic errors, Dr. Newman-Toker said. In the cancer category, the most common cancers linked to severe harm were lung, breast, colorectal, prostate, and melanoma. In the vascular category, the most common conditions were stroke; myocardial infarction; venous thromboembolism; aortic aneurysm and dissection; and arterial thromboembolism. In the area of infection, sepsis; meningitis and encephalitis; spinal abscess; pneumonia; and endocarditis were the most common infections identified.

The findings provide a starting point to make improvements in the area of medical errors, said Dr. Newman-Toker, president of the Society to Improve Diagnosis in Medicine, an organization that aims to improve diagnosis and eliminate harm from diagnostic error.

“Although diagnostic errors happen everywhere, across all of medicine in every discipline with every disease, we might be able to take a big chunk out of this problem if we save a lot of lives and prevent a lot disability and if we focus some energy on tackling these problems,” he said. “It at least gives us a starting place and a roadmap for how to move the ball forward in this regard.”

The Society to Improve Diagnosis in Medicine has called on Congress to invest more funding into research to address diagnostic errors. Society CEO and cofounder Paul L. Epner noted that the 2019 House appropriations bill proposes not less than $4 million for diagnostic safety and quality research, which is up from $2 million last year.

“It’s a small step, but in the right direction,” Mr. Epner said. “[However,] the federal investment in research remains trivially small in relation to the public burden. That’s why we urge Congress to commit to research funding levels proportionate to the societal cost, in both human lives and in dollars.”

[email protected]

Patients with COPD at heightened risk for community-acquired pneumonia requiring hospitalization

Patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease are at a significantly increased risk for hospitalization for community-acquired pneumonia (CAP), compared with patients without COPD, a large prospective study has found.

Jose Bordon, MD, and colleagues aimed to define incidence and outcomes of COPD patients hospitalized with pneumonia in the city of Louisville, Ky., and to extrapolate the burden of disease in the U.S. population. They conducted a secondary analysis of data from the University of Louisville Pneumonia Study, a prospective population-based cohort study of all hospitalized adults with CAP who were residents in the city of Louisville, Ky., from June 1, 2014, to May 31, 2016.

COPD prevalence in the city of Louisville was derived via data from the 2014 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) as well as from the 2014 National Health Interview Survey (NHIS). In addition, the researchers analyzed clinical outcomes including time to clinical stability (TCS), length of hospital stay (LOS), and mortality, according to Dr. Bordon, an infectious disease specialist at Providence Health Center, Washington, and colleagues on behalf of the University of Louisville Pneumonia Study Group.

The researchers found an 18-fold greater incidence of community-acquired pneumonia in patients with COPD, compared with non-COPD patients.

A total of 18,246 individuals aged 40 and older with COPD were estimated to live in Louisville, Ky. The researchers found that 3,419 COPD patients were hospitalized due to CAP in Louisville during the 2-year study period. COPD patients, compared with non-COPD patients, were more likely to have a history of heart failure, more ICU admissions, and use of mechanical ventilation, compared with patients without COPD. The two groups had similar pneumonia severity index scores, and 17% received oral steroids prior to admission. COPD patients had more pneumococcal pneumonia, despite receiving pneumococcal vaccine significantly more often than non-COPD patients.

The annual incidence of hospitalized CAP was 9,369 cases per 100,000 COPD patients in the city of Louisville. In the same period, the incidence of CAP in patients without COPD was 509 per 100,000, a more than 18-fold difference.

Although the incidence of CAP in COPD patients was much higher than in those without, the difference didn’t appear to have an impact on clinical outcomes. There were no clinical differences among patients with vs. without COPD in regard to time to reach clinical improvement and time of hospital discharge, and in-hospital mortality was not statistically significantly different between the groups, the authors reported. The mortality of COPD patients during hospitalization, at 30 days, at 6 months, and at 1 year was 5.6% of patients, 11.9%, 24.3%, and 33.0%, respectively vs. 6.6%, 14.2%, 24.2%, and 30.1% in non-COPD patients. However, 1-year all-cause mortality was a significant 25% greater among COPD patients, as might be expected by the progression and effects of the underlying disease.

“[Our] observations mean that nearly 1 in 10 persons with COPD will be hospitalized annually due to CAP. This translates into approximately 500,000 COPD patients hospitalized with CAP every year in the U.S., resulting in a substantial burden of approximately 5 billion U.S. dollars in hospitalization costs,” the researchers stated.

“Modifiable factors associated with CAP such as tobacco smoking and immunizations should be health interventions to prevent the burden of CAP in COPD patients,” even though “pneumococcal vaccination was used more often in the COPD population than in other CAP patients, but pneumococcal pneumonia still occurred at a numerically higher rate,” they noted.

The study was supported by the University of Louisville, Ky., with partial support from Pfizer. The authors reported having no conflicts.

SOURCE: Bordon JM et al. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2019 Jun 26; doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2019.06.025.

Patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease are at a significantly increased risk for hospitalization for community-acquired pneumonia (CAP), compared with patients without COPD, a large prospective study has found.

Jose Bordon, MD, and colleagues aimed to define incidence and outcomes of COPD patients hospitalized with pneumonia in the city of Louisville, Ky., and to extrapolate the burden of disease in the U.S. population. They conducted a secondary analysis of data from the University of Louisville Pneumonia Study, a prospective population-based cohort study of all hospitalized adults with CAP who were residents in the city of Louisville, Ky., from June 1, 2014, to May 31, 2016.

COPD prevalence in the city of Louisville was derived via data from the 2014 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) as well as from the 2014 National Health Interview Survey (NHIS). In addition, the researchers analyzed clinical outcomes including time to clinical stability (TCS), length of hospital stay (LOS), and mortality, according to Dr. Bordon, an infectious disease specialist at Providence Health Center, Washington, and colleagues on behalf of the University of Louisville Pneumonia Study Group.

The researchers found an 18-fold greater incidence of community-acquired pneumonia in patients with COPD, compared with non-COPD patients.

A total of 18,246 individuals aged 40 and older with COPD were estimated to live in Louisville, Ky. The researchers found that 3,419 COPD patients were hospitalized due to CAP in Louisville during the 2-year study period. COPD patients, compared with non-COPD patients, were more likely to have a history of heart failure, more ICU admissions, and use of mechanical ventilation, compared with patients without COPD. The two groups had similar pneumonia severity index scores, and 17% received oral steroids prior to admission. COPD patients had more pneumococcal pneumonia, despite receiving pneumococcal vaccine significantly more often than non-COPD patients.

The annual incidence of hospitalized CAP was 9,369 cases per 100,000 COPD patients in the city of Louisville. In the same period, the incidence of CAP in patients without COPD was 509 per 100,000, a more than 18-fold difference.

Although the incidence of CAP in COPD patients was much higher than in those without, the difference didn’t appear to have an impact on clinical outcomes. There were no clinical differences among patients with vs. without COPD in regard to time to reach clinical improvement and time of hospital discharge, and in-hospital mortality was not statistically significantly different between the groups, the authors reported. The mortality of COPD patients during hospitalization, at 30 days, at 6 months, and at 1 year was 5.6% of patients, 11.9%, 24.3%, and 33.0%, respectively vs. 6.6%, 14.2%, 24.2%, and 30.1% in non-COPD patients. However, 1-year all-cause mortality was a significant 25% greater among COPD patients, as might be expected by the progression and effects of the underlying disease.

“[Our] observations mean that nearly 1 in 10 persons with COPD will be hospitalized annually due to CAP. This translates into approximately 500,000 COPD patients hospitalized with CAP every year in the U.S., resulting in a substantial burden of approximately 5 billion U.S. dollars in hospitalization costs,” the researchers stated.

“Modifiable factors associated with CAP such as tobacco smoking and immunizations should be health interventions to prevent the burden of CAP in COPD patients,” even though “pneumococcal vaccination was used more often in the COPD population than in other CAP patients, but pneumococcal pneumonia still occurred at a numerically higher rate,” they noted.

The study was supported by the University of Louisville, Ky., with partial support from Pfizer. The authors reported having no conflicts.

SOURCE: Bordon JM et al. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2019 Jun 26; doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2019.06.025.

Patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease are at a significantly increased risk for hospitalization for community-acquired pneumonia (CAP), compared with patients without COPD, a large prospective study has found.

Jose Bordon, MD, and colleagues aimed to define incidence and outcomes of COPD patients hospitalized with pneumonia in the city of Louisville, Ky., and to extrapolate the burden of disease in the U.S. population. They conducted a secondary analysis of data from the University of Louisville Pneumonia Study, a prospective population-based cohort study of all hospitalized adults with CAP who were residents in the city of Louisville, Ky., from June 1, 2014, to May 31, 2016.

COPD prevalence in the city of Louisville was derived via data from the 2014 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) as well as from the 2014 National Health Interview Survey (NHIS). In addition, the researchers analyzed clinical outcomes including time to clinical stability (TCS), length of hospital stay (LOS), and mortality, according to Dr. Bordon, an infectious disease specialist at Providence Health Center, Washington, and colleagues on behalf of the University of Louisville Pneumonia Study Group.

The researchers found an 18-fold greater incidence of community-acquired pneumonia in patients with COPD, compared with non-COPD patients.

A total of 18,246 individuals aged 40 and older with COPD were estimated to live in Louisville, Ky. The researchers found that 3,419 COPD patients were hospitalized due to CAP in Louisville during the 2-year study period. COPD patients, compared with non-COPD patients, were more likely to have a history of heart failure, more ICU admissions, and use of mechanical ventilation, compared with patients without COPD. The two groups had similar pneumonia severity index scores, and 17% received oral steroids prior to admission. COPD patients had more pneumococcal pneumonia, despite receiving pneumococcal vaccine significantly more often than non-COPD patients.

The annual incidence of hospitalized CAP was 9,369 cases per 100,000 COPD patients in the city of Louisville. In the same period, the incidence of CAP in patients without COPD was 509 per 100,000, a more than 18-fold difference.

Although the incidence of CAP in COPD patients was much higher than in those without, the difference didn’t appear to have an impact on clinical outcomes. There were no clinical differences among patients with vs. without COPD in regard to time to reach clinical improvement and time of hospital discharge, and in-hospital mortality was not statistically significantly different between the groups, the authors reported. The mortality of COPD patients during hospitalization, at 30 days, at 6 months, and at 1 year was 5.6% of patients, 11.9%, 24.3%, and 33.0%, respectively vs. 6.6%, 14.2%, 24.2%, and 30.1% in non-COPD patients. However, 1-year all-cause mortality was a significant 25% greater among COPD patients, as might be expected by the progression and effects of the underlying disease.

“[Our] observations mean that nearly 1 in 10 persons with COPD will be hospitalized annually due to CAP. This translates into approximately 500,000 COPD patients hospitalized with CAP every year in the U.S., resulting in a substantial burden of approximately 5 billion U.S. dollars in hospitalization costs,” the researchers stated.

“Modifiable factors associated with CAP such as tobacco smoking and immunizations should be health interventions to prevent the burden of CAP in COPD patients,” even though “pneumococcal vaccination was used more often in the COPD population than in other CAP patients, but pneumococcal pneumonia still occurred at a numerically higher rate,” they noted.

The study was supported by the University of Louisville, Ky., with partial support from Pfizer. The authors reported having no conflicts.

SOURCE: Bordon JM et al. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2019 Jun 26; doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2019.06.025.

FROM CLINICAL MICROBIOLOGY AND INFECTION

C-reactive protein testing reduced antibiotic prescribing in patients with COPD exacerbation

, according to a recent randomized, controlled trial.

Point-of-care C-reactive protein (CRP) testing led to fewer antibiotic prescriptions at the initial consultation, according to investigators participating in the PACE study, a multicenter, open-label trial of more than 600 patients with COPD enrolled at one of 86 general practices in the United Kingdom.

Patient-reported antibiotic use over the next 4 weeks was more than 20 percentage points lower for the group managed with the point-of-care strategy, compared with those who received usual care, according to the investigators, led by Christopher C. Butler, FMedSci, of the Nuffield Department of Primary Care Health Sciences at the University of Oxford (England).

Less antibiotic use and fewer prescriptions did not compromise patient-reported, disease-specific quality of life, added Dr. Butler and colleagues. Their report appears in the New England Journal of Medicine.

In the United States and in Europe, more than 80% of COPD patients with acute exacerbations will receive an antibiotic prescription, according to Dr. Butler and coauthors.

“Although many patients who have acute exacerbations of COPD are helped by these treatments, others are not,” wrote the investigators, noting that in one hospital-based study, about one in five such exacerbations were thought to be due to noninfectious causes.

The present study included patients at least 40 years of age who presented to a primary care practice with an acute exacerbation and at least one of the three Anthonisen criteria (increased dyspnea, sputum production, and sputum purulence) intended to guide antibiotic therapy in COPD. A total of 325 were randomly assigned to the CRP testing group, and 324 to a group that received just usual care.

Antibiotic use was reported by fewer patients in the CRP testing group, compared with the usual-care group (57.0% vs. 77.4%; adjusted odds ratio, 0.31, 95% confidence interval, 0.20-0.47), the investigators reported.

Only 47.7% of patients in the CRP-guided group received antibiotic prescriptions at the initial consultation, vs. 69.7% of patients in the usual care group.

Hospitalizations over 6 months of follow-up were reported for 8.6% and 9.3% of patients in the CRP-guided and usual-care groups, respectively, while diagnoses of pneumonia were recorded for 3.0% and 4.0%. There was no clinically important difference between groups in the rate of antibiotic-related adverse effects.

“The evidence from our trial suggests that CRP-guided antibiotic prescribing for COPD exacerbations in primary care clinics may reduce patient-reported use of antibiotics and the prescribing of antibiotics by clinicians,” Dr. Butler and colleagues said in a discussion of these results.

Findings from the study by Dr. Butler and colleagues are “compelling enough” to support C-reactive protein (CRP) testing to guide antibiotic use in patient who have acute exacerbations of COPD, wrote the authors of an accompanying editorial.

“The trial achieved its objective, which was to show that CRP testing safely reduces antibiotic use,” stated Allan S. Brett, MD, and Majdi N. Al-Hasan, MB,BS, of the department of medicine at the University of South Carolina, Columbia.

Point-of-care testing of CRP could be applied even more broadly in clinical practice, Dr. Brett and Dr. Al-Hasan wrote, since testing has been shown to reduce prescribing of antibiotics for suspected lower respiratory tract infections and other common presentations in patients with no COPD.

“Whether primary care practices in the United States would embrace point-of-care CRP testing is another matter, given the regulatory requirements for in-office laboratory testing and uncertainty about reimbursement,” they noted.

Reduced antibiotic prescribing in patients with COPD likely has certain benefits, including reducing risk of Clostridioides difficile colitis, according to the authors.

By contrast, the current study did not determine which COPD patients might benefit from antibiotics, if any, nor which antibiotic might be warranted for those patients.

The study was supported by the Health Technology Assessment Program of the UK National Institute for Health Research. Dr. Butler reported disclosures related to Roche Molecular Systems and Roche Molecular Diagnostics, among others.

SOURCE: Butler CC et al. N Engl J Med. 2019 Jul 10;381:111-20. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1803185.

, according to a recent randomized, controlled trial.

Point-of-care C-reactive protein (CRP) testing led to fewer antibiotic prescriptions at the initial consultation, according to investigators participating in the PACE study, a multicenter, open-label trial of more than 600 patients with COPD enrolled at one of 86 general practices in the United Kingdom.

Patient-reported antibiotic use over the next 4 weeks was more than 20 percentage points lower for the group managed with the point-of-care strategy, compared with those who received usual care, according to the investigators, led by Christopher C. Butler, FMedSci, of the Nuffield Department of Primary Care Health Sciences at the University of Oxford (England).

Less antibiotic use and fewer prescriptions did not compromise patient-reported, disease-specific quality of life, added Dr. Butler and colleagues. Their report appears in the New England Journal of Medicine.

In the United States and in Europe, more than 80% of COPD patients with acute exacerbations will receive an antibiotic prescription, according to Dr. Butler and coauthors.

“Although many patients who have acute exacerbations of COPD are helped by these treatments, others are not,” wrote the investigators, noting that in one hospital-based study, about one in five such exacerbations were thought to be due to noninfectious causes.

The present study included patients at least 40 years of age who presented to a primary care practice with an acute exacerbation and at least one of the three Anthonisen criteria (increased dyspnea, sputum production, and sputum purulence) intended to guide antibiotic therapy in COPD. A total of 325 were randomly assigned to the CRP testing group, and 324 to a group that received just usual care.

Antibiotic use was reported by fewer patients in the CRP testing group, compared with the usual-care group (57.0% vs. 77.4%; adjusted odds ratio, 0.31, 95% confidence interval, 0.20-0.47), the investigators reported.

Only 47.7% of patients in the CRP-guided group received antibiotic prescriptions at the initial consultation, vs. 69.7% of patients in the usual care group.

Hospitalizations over 6 months of follow-up were reported for 8.6% and 9.3% of patients in the CRP-guided and usual-care groups, respectively, while diagnoses of pneumonia were recorded for 3.0% and 4.0%. There was no clinically important difference between groups in the rate of antibiotic-related adverse effects.

“The evidence from our trial suggests that CRP-guided antibiotic prescribing for COPD exacerbations in primary care clinics may reduce patient-reported use of antibiotics and the prescribing of antibiotics by clinicians,” Dr. Butler and colleagues said in a discussion of these results.

Findings from the study by Dr. Butler and colleagues are “compelling enough” to support C-reactive protein (CRP) testing to guide antibiotic use in patient who have acute exacerbations of COPD, wrote the authors of an accompanying editorial.

“The trial achieved its objective, which was to show that CRP testing safely reduces antibiotic use,” stated Allan S. Brett, MD, and Majdi N. Al-Hasan, MB,BS, of the department of medicine at the University of South Carolina, Columbia.

Point-of-care testing of CRP could be applied even more broadly in clinical practice, Dr. Brett and Dr. Al-Hasan wrote, since testing has been shown to reduce prescribing of antibiotics for suspected lower respiratory tract infections and other common presentations in patients with no COPD.

“Whether primary care practices in the United States would embrace point-of-care CRP testing is another matter, given the regulatory requirements for in-office laboratory testing and uncertainty about reimbursement,” they noted.

Reduced antibiotic prescribing in patients with COPD likely has certain benefits, including reducing risk of Clostridioides difficile colitis, according to the authors.

By contrast, the current study did not determine which COPD patients might benefit from antibiotics, if any, nor which antibiotic might be warranted for those patients.

The study was supported by the Health Technology Assessment Program of the UK National Institute for Health Research. Dr. Butler reported disclosures related to Roche Molecular Systems and Roche Molecular Diagnostics, among others.

SOURCE: Butler CC et al. N Engl J Med. 2019 Jul 10;381:111-20. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1803185.

, according to a recent randomized, controlled trial.

Point-of-care C-reactive protein (CRP) testing led to fewer antibiotic prescriptions at the initial consultation, according to investigators participating in the PACE study, a multicenter, open-label trial of more than 600 patients with COPD enrolled at one of 86 general practices in the United Kingdom.

Patient-reported antibiotic use over the next 4 weeks was more than 20 percentage points lower for the group managed with the point-of-care strategy, compared with those who received usual care, according to the investigators, led by Christopher C. Butler, FMedSci, of the Nuffield Department of Primary Care Health Sciences at the University of Oxford (England).

Less antibiotic use and fewer prescriptions did not compromise patient-reported, disease-specific quality of life, added Dr. Butler and colleagues. Their report appears in the New England Journal of Medicine.

In the United States and in Europe, more than 80% of COPD patients with acute exacerbations will receive an antibiotic prescription, according to Dr. Butler and coauthors.

“Although many patients who have acute exacerbations of COPD are helped by these treatments, others are not,” wrote the investigators, noting that in one hospital-based study, about one in five such exacerbations were thought to be due to noninfectious causes.

The present study included patients at least 40 years of age who presented to a primary care practice with an acute exacerbation and at least one of the three Anthonisen criteria (increased dyspnea, sputum production, and sputum purulence) intended to guide antibiotic therapy in COPD. A total of 325 were randomly assigned to the CRP testing group, and 324 to a group that received just usual care.

Antibiotic use was reported by fewer patients in the CRP testing group, compared with the usual-care group (57.0% vs. 77.4%; adjusted odds ratio, 0.31, 95% confidence interval, 0.20-0.47), the investigators reported.

Only 47.7% of patients in the CRP-guided group received antibiotic prescriptions at the initial consultation, vs. 69.7% of patients in the usual care group.

Hospitalizations over 6 months of follow-up were reported for 8.6% and 9.3% of patients in the CRP-guided and usual-care groups, respectively, while diagnoses of pneumonia were recorded for 3.0% and 4.0%. There was no clinically important difference between groups in the rate of antibiotic-related adverse effects.

“The evidence from our trial suggests that CRP-guided antibiotic prescribing for COPD exacerbations in primary care clinics may reduce patient-reported use of antibiotics and the prescribing of antibiotics by clinicians,” Dr. Butler and colleagues said in a discussion of these results.

Findings from the study by Dr. Butler and colleagues are “compelling enough” to support C-reactive protein (CRP) testing to guide antibiotic use in patient who have acute exacerbations of COPD, wrote the authors of an accompanying editorial.

“The trial achieved its objective, which was to show that CRP testing safely reduces antibiotic use,” stated Allan S. Brett, MD, and Majdi N. Al-Hasan, MB,BS, of the department of medicine at the University of South Carolina, Columbia.

Point-of-care testing of CRP could be applied even more broadly in clinical practice, Dr. Brett and Dr. Al-Hasan wrote, since testing has been shown to reduce prescribing of antibiotics for suspected lower respiratory tract infections and other common presentations in patients with no COPD.

“Whether primary care practices in the United States would embrace point-of-care CRP testing is another matter, given the regulatory requirements for in-office laboratory testing and uncertainty about reimbursement,” they noted.

Reduced antibiotic prescribing in patients with COPD likely has certain benefits, including reducing risk of Clostridioides difficile colitis, according to the authors.

By contrast, the current study did not determine which COPD patients might benefit from antibiotics, if any, nor which antibiotic might be warranted for those patients.

The study was supported by the Health Technology Assessment Program of the UK National Institute for Health Research. Dr. Butler reported disclosures related to Roche Molecular Systems and Roche Molecular Diagnostics, among others.

SOURCE: Butler CC et al. N Engl J Med. 2019 Jul 10;381:111-20. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1803185.

FROM THE NEW ENGLAND JOURNAL OF MEDICINE

Higher omega-3 fatty acid levels cut heart failure risk

Higher levels of eicosapentaenoic acid, a type of omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid, were associated with a significantly reduced risk of heart failure in a large, multi-ethnic cohort of adults in the United States.

Despite the potential benefits of omega-3s eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) for heart health, their use has been controversial, although data in a mouse model showed that dietary EPA was protective against heart failure, wrote Robert C. Block, MD, of the University of Rochester (N.Y.), and colleagues. Their report is in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

To examine the impact of EPA on heart failure in humans, the researchers used data from the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA), a longitudinal cohort study of U.S. adults, including those who are African American, Hispanic, Asian, and white.

The researchers included 6,562 MESA participants aged 45-84 years from six communities. Participants underwent a baseline exam between July 2000 and July 2002 that included phospholipid measurements used to identify plasma EPA percentage, and they completed study visits approximately every other year for a median follow-up of 13 years.

A total of 292 heart failure events occurred during the follow-up period: 128 with reduced ejection fraction (EF less than 45%), 110 with preserved ejection fraction (EF at least 45%), and 54 with unknown EF status.

The percent EPA for individuals without heart failure was significantly higher compared with those with heart failure (0.76% vs. 0.69%, P =.005). The association remained significant after the researchers controlled for age, sex, race, body mass index, smoking, diabetes, blood pressure, lipids and lipid-lowering drugs, albuminuria, and the lead fatty acid (defined as the fatty acid with the largest in-cluster correlation).

An EPA level greater than 2.5% was considered sufficient to prevent heart failure based on prior definitions. A total of 73% of the participants had insufficient EPA (less than 1.0%), 2.4% had marginal levels (1.0%-2.5%), and 4.5% had sufficient levels. However, given that EPA levels can be easily and safely increased with the consumption of seafood or fish oil capsules, increasing EPA is a feasible heart failure prevention strategy, the researchers said.

The study included 2,532 white, 1,794 black, 1,442 Hispanic, and 794 Chinese participants. Overall, the fewest Hispanic participants met the criteria for sufficient EPA (1.4%), followed by black (4.4%), white (4.9%), and Chinese participants (9.8%).

The study findings were limited by several factors, including relatively few participants with preserved ejection fractions and sufficient EPA levels, as well as the inability to account for changes in omega-3 levels and other risk factors over time, the researchers noted.

“We consider this study to strongly determine a benefit of EPA exists, but insufficient to determine whether a threshold for %EPA exists near 3%,” they said. They proposed a follow-up study including individuals with higher levels of EPA to better detect a protective effect.

Lead author Dr. Block had no financial conflicts to disclose. Several coauthors received honoraria from Amarin Pharmaceuticals. The study was funded in part by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute.

The study findings suggest that revisiting omega-3 fatty acids to improve outcomes in patients with or at risk of cardiovascular disease may be worthwhile. Not only did the study predict heart failure in a range of ethnicities, but the same authors showed previously in animal models that these dietary supplements can preserve left ventricular function and reduce interstitial fibrosis.

The question is: Is it sufficient to give dietary recommendations of an increased fish consumption, or do we need to take purified pharmaceutical supplements such as those tested in trials? In other words, shall we have to go to the fish market or to the pharmacy to elevate our circulating levels of omega-3 fatty acids and, in this way, to try to prevent (or treat) HF?

The answer, at least in part, lies in additional large, randomized clinical trials that test high doses of omega-3 fatty acids along and combined with pharmacological and nonpharmacological treatments. Considering the very favorable tolerability and safety profile of this therapeutic approach, any positive results of these trials could provide us with an additional strategy to improve the outcomes of patients with HF or at high risk to develop it.

Aldo P. Maggioni, MD, of the ANMCO Research Center Heart Care Foundation, in Florence, Italy, made these remarks in an editorial. He disclosed honoraria for participation in committees of studies sponsored by Bayer, Novartis, and Fresenius.

The study findings suggest that revisiting omega-3 fatty acids to improve outcomes in patients with or at risk of cardiovascular disease may be worthwhile. Not only did the study predict heart failure in a range of ethnicities, but the same authors showed previously in animal models that these dietary supplements can preserve left ventricular function and reduce interstitial fibrosis.

The question is: Is it sufficient to give dietary recommendations of an increased fish consumption, or do we need to take purified pharmaceutical supplements such as those tested in trials? In other words, shall we have to go to the fish market or to the pharmacy to elevate our circulating levels of omega-3 fatty acids and, in this way, to try to prevent (or treat) HF?

The answer, at least in part, lies in additional large, randomized clinical trials that test high doses of omega-3 fatty acids along and combined with pharmacological and nonpharmacological treatments. Considering the very favorable tolerability and safety profile of this therapeutic approach, any positive results of these trials could provide us with an additional strategy to improve the outcomes of patients with HF or at high risk to develop it.

Aldo P. Maggioni, MD, of the ANMCO Research Center Heart Care Foundation, in Florence, Italy, made these remarks in an editorial. He disclosed honoraria for participation in committees of studies sponsored by Bayer, Novartis, and Fresenius.

The study findings suggest that revisiting omega-3 fatty acids to improve outcomes in patients with or at risk of cardiovascular disease may be worthwhile. Not only did the study predict heart failure in a range of ethnicities, but the same authors showed previously in animal models that these dietary supplements can preserve left ventricular function and reduce interstitial fibrosis.

The question is: Is it sufficient to give dietary recommendations of an increased fish consumption, or do we need to take purified pharmaceutical supplements such as those tested in trials? In other words, shall we have to go to the fish market or to the pharmacy to elevate our circulating levels of omega-3 fatty acids and, in this way, to try to prevent (or treat) HF?

The answer, at least in part, lies in additional large, randomized clinical trials that test high doses of omega-3 fatty acids along and combined with pharmacological and nonpharmacological treatments. Considering the very favorable tolerability and safety profile of this therapeutic approach, any positive results of these trials could provide us with an additional strategy to improve the outcomes of patients with HF or at high risk to develop it.

Aldo P. Maggioni, MD, of the ANMCO Research Center Heart Care Foundation, in Florence, Italy, made these remarks in an editorial. He disclosed honoraria for participation in committees of studies sponsored by Bayer, Novartis, and Fresenius.

Higher levels of eicosapentaenoic acid, a type of omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid, were associated with a significantly reduced risk of heart failure in a large, multi-ethnic cohort of adults in the United States.

Despite the potential benefits of omega-3s eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) for heart health, their use has been controversial, although data in a mouse model showed that dietary EPA was protective against heart failure, wrote Robert C. Block, MD, of the University of Rochester (N.Y.), and colleagues. Their report is in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

To examine the impact of EPA on heart failure in humans, the researchers used data from the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA), a longitudinal cohort study of U.S. adults, including those who are African American, Hispanic, Asian, and white.

The researchers included 6,562 MESA participants aged 45-84 years from six communities. Participants underwent a baseline exam between July 2000 and July 2002 that included phospholipid measurements used to identify plasma EPA percentage, and they completed study visits approximately every other year for a median follow-up of 13 years.

A total of 292 heart failure events occurred during the follow-up period: 128 with reduced ejection fraction (EF less than 45%), 110 with preserved ejection fraction (EF at least 45%), and 54 with unknown EF status.

The percent EPA for individuals without heart failure was significantly higher compared with those with heart failure (0.76% vs. 0.69%, P =.005). The association remained significant after the researchers controlled for age, sex, race, body mass index, smoking, diabetes, blood pressure, lipids and lipid-lowering drugs, albuminuria, and the lead fatty acid (defined as the fatty acid with the largest in-cluster correlation).

An EPA level greater than 2.5% was considered sufficient to prevent heart failure based on prior definitions. A total of 73% of the participants had insufficient EPA (less than 1.0%), 2.4% had marginal levels (1.0%-2.5%), and 4.5% had sufficient levels. However, given that EPA levels can be easily and safely increased with the consumption of seafood or fish oil capsules, increasing EPA is a feasible heart failure prevention strategy, the researchers said.

The study included 2,532 white, 1,794 black, 1,442 Hispanic, and 794 Chinese participants. Overall, the fewest Hispanic participants met the criteria for sufficient EPA (1.4%), followed by black (4.4%), white (4.9%), and Chinese participants (9.8%).

The study findings were limited by several factors, including relatively few participants with preserved ejection fractions and sufficient EPA levels, as well as the inability to account for changes in omega-3 levels and other risk factors over time, the researchers noted.

“We consider this study to strongly determine a benefit of EPA exists, but insufficient to determine whether a threshold for %EPA exists near 3%,” they said. They proposed a follow-up study including individuals with higher levels of EPA to better detect a protective effect.

Lead author Dr. Block had no financial conflicts to disclose. Several coauthors received honoraria from Amarin Pharmaceuticals. The study was funded in part by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute.

Higher levels of eicosapentaenoic acid, a type of omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid, were associated with a significantly reduced risk of heart failure in a large, multi-ethnic cohort of adults in the United States.

Despite the potential benefits of omega-3s eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) for heart health, their use has been controversial, although data in a mouse model showed that dietary EPA was protective against heart failure, wrote Robert C. Block, MD, of the University of Rochester (N.Y.), and colleagues. Their report is in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

To examine the impact of EPA on heart failure in humans, the researchers used data from the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA), a longitudinal cohort study of U.S. adults, including those who are African American, Hispanic, Asian, and white.

The researchers included 6,562 MESA participants aged 45-84 years from six communities. Participants underwent a baseline exam between July 2000 and July 2002 that included phospholipid measurements used to identify plasma EPA percentage, and they completed study visits approximately every other year for a median follow-up of 13 years.

A total of 292 heart failure events occurred during the follow-up period: 128 with reduced ejection fraction (EF less than 45%), 110 with preserved ejection fraction (EF at least 45%), and 54 with unknown EF status.

The percent EPA for individuals without heart failure was significantly higher compared with those with heart failure (0.76% vs. 0.69%, P =.005). The association remained significant after the researchers controlled for age, sex, race, body mass index, smoking, diabetes, blood pressure, lipids and lipid-lowering drugs, albuminuria, and the lead fatty acid (defined as the fatty acid with the largest in-cluster correlation).

An EPA level greater than 2.5% was considered sufficient to prevent heart failure based on prior definitions. A total of 73% of the participants had insufficient EPA (less than 1.0%), 2.4% had marginal levels (1.0%-2.5%), and 4.5% had sufficient levels. However, given that EPA levels can be easily and safely increased with the consumption of seafood or fish oil capsules, increasing EPA is a feasible heart failure prevention strategy, the researchers said.

The study included 2,532 white, 1,794 black, 1,442 Hispanic, and 794 Chinese participants. Overall, the fewest Hispanic participants met the criteria for sufficient EPA (1.4%), followed by black (4.4%), white (4.9%), and Chinese participants (9.8%).

The study findings were limited by several factors, including relatively few participants with preserved ejection fractions and sufficient EPA levels, as well as the inability to account for changes in omega-3 levels and other risk factors over time, the researchers noted.

“We consider this study to strongly determine a benefit of EPA exists, but insufficient to determine whether a threshold for %EPA exists near 3%,” they said. They proposed a follow-up study including individuals with higher levels of EPA to better detect a protective effect.

Lead author Dr. Block had no financial conflicts to disclose. Several coauthors received honoraria from Amarin Pharmaceuticals. The study was funded in part by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute.

FROM JACC

Key clinical point: Adults with high levels of eicosapentaenoic acid had significantly lower risk of heart failure than did those with lower levels of EPA.

Major finding: The percent EPA was 0.76% for individuals without heart failure vs. 0.69% for those who suffered heart failure (P = .005).

Study details: An analysis of 6,562 adults aged 45-84 years in the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis.

Disclosures: Lead author Dr. Block had no financial conflicts to disclose. Several coauthors received honoraria from Amarin Pharmaceuticals. The study was funded in part by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute.

Dealing with staffing shortfalls

Five options for covering unfilled positions

Being in stressful situations is part of being a hospitalist. During a hospitalist’s work shift, one of the key determinants of stress is adequate staffing. With use of survey data from 569 hospital medicine groups (HMGs) across the nation, one of the topics examined in the 2018 State of Hospital Medicine Report is how HMGs cope with unfilled hospitalist physician positions.

The survey presented five options for covering unfilled hospitalist physician positions: use of locum tenens, use of moonlighters, use of voluntary extra shifts by the HMG’s existing hospitalists, use of required extra shifts, and leaving some shifts uncovered. Recipients were instructed to select all options that applied, so totals exceeded 100%. The data is organized according to HMGs that serve adults only, children only, and both adults and children.

For all three types of HMGs, the most common tactic to fill coverage gaps is through voluntary extra shifts by existing clinicians, reportedly used by 70.3% of HMGs that cover adults only, 66.7% by those that cover children only, and 76.9% by those that cover both adults and children. Data for adults-only HMGs was further broken down by geographic region, academic status, teaching status, group size, and employment model. Among adults-only HMGs, there is a direct correlation between group size and having members voluntarily work extra shifts, with 91.1% of groups with 30 or more full-time equivalent positions employing this tactic.

For HMGs that cover adults only and those that cover children only, the second most common tactic is to use moonlighters (57.4% and 53.3% respectively), while use of moonlighters is the third most commonly employed surveyed tactic for HMGs that cover both adults and children (53.8%).

HMGs that serve both adults and children were much more likely to utilize locum tenens to cover unfilled positions (69.2%) than were groups that serve adults only (44.0%) or children only (26.7%). The variability in the use of locum tenens is likely because of the willingness and/or ability of the respective groups to afford this option because it is generally the most expensive option of those surveyed.

Requiring that members of the group work extra shifts is the least popular staffing method among adults-only HMGs (10.0%) and HMGs serving both children and adults (7.7%). This strategy is unpopular, especially when there is little advance warning. Surprisingly, 40.0% of HMGs that see children only require members to work extra shifts to cover unfilled slots. This could be because pediatric HMGs are often smaller, and it would be more difficult to absorb the work if the shift is left uncovered. In fact, many pediatric HMGs staff with only one clinician at a time, so there may be no option besides requiring someone else in the group to come in and work.Of the options surveyed, perhaps the most uncomfortable for those hospitalist physicians on duty is to leave some shifts uncovered. The rapid growth and development of the specialty of hospital medicine has made it difficult for HMGs to continuously hire qualified hospitalists fast enough to meet demand. The survey found 46.2% of HMGs that serve both adults and children and 31.4% of groups that serve adults only have employed the staffing model of going short-staffed for at least some shifts. HMGs serving children-only are much less likely to go short-staffed (20.0%).

I work with a large HMG that has more than 70 members, and when it has been short-staffed, it tries to ensure a full complement of evening and night staff as the top priority because these shifts are typically more stressful. Since we have more hospitalist capacity during the day to absorb the loss of a physician, we pull staff from their daytime rounding schedules to execute this strategy. While going short-staffed is not ideal, this option has worked for many groups out of sheer necessity.

Dr. Stephan is a hospitalist at Allina Health’s Abbott Northwestern Hospital in Minneapolis and is a member of the SHM Practice Analysis Committee.

Five options for covering unfilled positions

Five options for covering unfilled positions

Being in stressful situations is part of being a hospitalist. During a hospitalist’s work shift, one of the key determinants of stress is adequate staffing. With use of survey data from 569 hospital medicine groups (HMGs) across the nation, one of the topics examined in the 2018 State of Hospital Medicine Report is how HMGs cope with unfilled hospitalist physician positions.

The survey presented five options for covering unfilled hospitalist physician positions: use of locum tenens, use of moonlighters, use of voluntary extra shifts by the HMG’s existing hospitalists, use of required extra shifts, and leaving some shifts uncovered. Recipients were instructed to select all options that applied, so totals exceeded 100%. The data is organized according to HMGs that serve adults only, children only, and both adults and children.

For all three types of HMGs, the most common tactic to fill coverage gaps is through voluntary extra shifts by existing clinicians, reportedly used by 70.3% of HMGs that cover adults only, 66.7% by those that cover children only, and 76.9% by those that cover both adults and children. Data for adults-only HMGs was further broken down by geographic region, academic status, teaching status, group size, and employment model. Among adults-only HMGs, there is a direct correlation between group size and having members voluntarily work extra shifts, with 91.1% of groups with 30 or more full-time equivalent positions employing this tactic.

For HMGs that cover adults only and those that cover children only, the second most common tactic is to use moonlighters (57.4% and 53.3% respectively), while use of moonlighters is the third most commonly employed surveyed tactic for HMGs that cover both adults and children (53.8%).

HMGs that serve both adults and children were much more likely to utilize locum tenens to cover unfilled positions (69.2%) than were groups that serve adults only (44.0%) or children only (26.7%). The variability in the use of locum tenens is likely because of the willingness and/or ability of the respective groups to afford this option because it is generally the most expensive option of those surveyed.

Requiring that members of the group work extra shifts is the least popular staffing method among adults-only HMGs (10.0%) and HMGs serving both children and adults (7.7%). This strategy is unpopular, especially when there is little advance warning. Surprisingly, 40.0% of HMGs that see children only require members to work extra shifts to cover unfilled slots. This could be because pediatric HMGs are often smaller, and it would be more difficult to absorb the work if the shift is left uncovered. In fact, many pediatric HMGs staff with only one clinician at a time, so there may be no option besides requiring someone else in the group to come in and work.Of the options surveyed, perhaps the most uncomfortable for those hospitalist physicians on duty is to leave some shifts uncovered. The rapid growth and development of the specialty of hospital medicine has made it difficult for HMGs to continuously hire qualified hospitalists fast enough to meet demand. The survey found 46.2% of HMGs that serve both adults and children and 31.4% of groups that serve adults only have employed the staffing model of going short-staffed for at least some shifts. HMGs serving children-only are much less likely to go short-staffed (20.0%).

I work with a large HMG that has more than 70 members, and when it has been short-staffed, it tries to ensure a full complement of evening and night staff as the top priority because these shifts are typically more stressful. Since we have more hospitalist capacity during the day to absorb the loss of a physician, we pull staff from their daytime rounding schedules to execute this strategy. While going short-staffed is not ideal, this option has worked for many groups out of sheer necessity.

Dr. Stephan is a hospitalist at Allina Health’s Abbott Northwestern Hospital in Minneapolis and is a member of the SHM Practice Analysis Committee.

Being in stressful situations is part of being a hospitalist. During a hospitalist’s work shift, one of the key determinants of stress is adequate staffing. With use of survey data from 569 hospital medicine groups (HMGs) across the nation, one of the topics examined in the 2018 State of Hospital Medicine Report is how HMGs cope with unfilled hospitalist physician positions.

The survey presented five options for covering unfilled hospitalist physician positions: use of locum tenens, use of moonlighters, use of voluntary extra shifts by the HMG’s existing hospitalists, use of required extra shifts, and leaving some shifts uncovered. Recipients were instructed to select all options that applied, so totals exceeded 100%. The data is organized according to HMGs that serve adults only, children only, and both adults and children.

For all three types of HMGs, the most common tactic to fill coverage gaps is through voluntary extra shifts by existing clinicians, reportedly used by 70.3% of HMGs that cover adults only, 66.7% by those that cover children only, and 76.9% by those that cover both adults and children. Data for adults-only HMGs was further broken down by geographic region, academic status, teaching status, group size, and employment model. Among adults-only HMGs, there is a direct correlation between group size and having members voluntarily work extra shifts, with 91.1% of groups with 30 or more full-time equivalent positions employing this tactic.

For HMGs that cover adults only and those that cover children only, the second most common tactic is to use moonlighters (57.4% and 53.3% respectively), while use of moonlighters is the third most commonly employed surveyed tactic for HMGs that cover both adults and children (53.8%).

HMGs that serve both adults and children were much more likely to utilize locum tenens to cover unfilled positions (69.2%) than were groups that serve adults only (44.0%) or children only (26.7%). The variability in the use of locum tenens is likely because of the willingness and/or ability of the respective groups to afford this option because it is generally the most expensive option of those surveyed.

Requiring that members of the group work extra shifts is the least popular staffing method among adults-only HMGs (10.0%) and HMGs serving both children and adults (7.7%). This strategy is unpopular, especially when there is little advance warning. Surprisingly, 40.0% of HMGs that see children only require members to work extra shifts to cover unfilled slots. This could be because pediatric HMGs are often smaller, and it would be more difficult to absorb the work if the shift is left uncovered. In fact, many pediatric HMGs staff with only one clinician at a time, so there may be no option besides requiring someone else in the group to come in and work.Of the options surveyed, perhaps the most uncomfortable for those hospitalist physicians on duty is to leave some shifts uncovered. The rapid growth and development of the specialty of hospital medicine has made it difficult for HMGs to continuously hire qualified hospitalists fast enough to meet demand. The survey found 46.2% of HMGs that serve both adults and children and 31.4% of groups that serve adults only have employed the staffing model of going short-staffed for at least some shifts. HMGs serving children-only are much less likely to go short-staffed (20.0%).

I work with a large HMG that has more than 70 members, and when it has been short-staffed, it tries to ensure a full complement of evening and night staff as the top priority because these shifts are typically more stressful. Since we have more hospitalist capacity during the day to absorb the loss of a physician, we pull staff from their daytime rounding schedules to execute this strategy. While going short-staffed is not ideal, this option has worked for many groups out of sheer necessity.

Dr. Stephan is a hospitalist at Allina Health’s Abbott Northwestern Hospital in Minneapolis and is a member of the SHM Practice Analysis Committee.

No reduction in PE risk with vena cava filters after severe injury

MELBOURNE – Use of a prophylactic vena cava filter to trap blood clots in severely injured patients does not appear to reduce the risk of pulmonary embolism or death, according to data presented at the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis congress.

The researchers reported the outcomes of a multicenter, controlled trial in which 240 severely injured patients with a contraindication to anticoagulants were randomized to receive a vena cava filter within 72 hours of admission, or no filter. The findings were published simultaneously in the New England Journal of Medicine.

The study showed no significant differences between the filter and no-filter groups in the primary outcome of a composite of symptomatic pulmonary embolism or death from any cause at 90 days after enrollment (13.9% vs. 14.4% respectively, P = .98).

In a prespecified subgroup analysis, researchers examined patients who survived 7 days after injury and did not receive prophylactic anticoagulation in those 7 days. Among this group of patients, none of those who received the vena cava filter experienced a symptomatic pulmonary embolism between day 8 and day 90, but five patients (14.7%) in the no-filter group did.

Filters were left in place for a median duration of 27 days (11-90 days). Among the 122 patients who received a filter – which included two patients in the control group – researchers found trapped thrombi in the filter in six patients.

Transfusion requirements, and the incidence of major and nonmajor bleeding and leg deep vein thrombosis, were similar between the filter and no-filter groups. Seven patients in the filter group (5.7%) required more than one attempt to remove the filter, and in one patient the filter had to be removed surgically.

Kwok M. Ho, PhD, of the department of intensive care medicine at Royal Perth Hospital, Australia, and coauthors wrote that while vena cava filters are widely used in trauma centers to prevent pulmonary embolism in patients at high risk of bleeding, there are conflicting recommendations regarding their use, and most studies so far have been observational.

“Given the cost and risks associated with a vena cava filter, our data suggest that there is no urgency to insert the filter in patients who can be treated with prophylactic anticoagulation within 7 days after injury,” they wrote. “Unnecessary insertion of a vena cava filter has the potential to cause harm.”

However, they noted that patients with multiple, large intracranial hematomas were particularly at risk from bleeding with anticoagulant therapy, and therefore may benefit from the use of a vena cava filter.

The Medical Research Foundation of Royal Perth Hospital and the Western Australian Department of Health funded the study. Dr. Ho reported funding from the Western Australian Department of Health and the Raine Medical Research Foundation to conduct the study, as well as serving as an adviser to Medtronic and Cardinal Health.

SOURCE: Ho KM et al. N Engl J Med. 2019 Jul 7. doi: 10.156/NEJMoa1806515.

MELBOURNE – Use of a prophylactic vena cava filter to trap blood clots in severely injured patients does not appear to reduce the risk of pulmonary embolism or death, according to data presented at the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis congress.

The researchers reported the outcomes of a multicenter, controlled trial in which 240 severely injured patients with a contraindication to anticoagulants were randomized to receive a vena cava filter within 72 hours of admission, or no filter. The findings were published simultaneously in the New England Journal of Medicine.

The study showed no significant differences between the filter and no-filter groups in the primary outcome of a composite of symptomatic pulmonary embolism or death from any cause at 90 days after enrollment (13.9% vs. 14.4% respectively, P = .98).

In a prespecified subgroup analysis, researchers examined patients who survived 7 days after injury and did not receive prophylactic anticoagulation in those 7 days. Among this group of patients, none of those who received the vena cava filter experienced a symptomatic pulmonary embolism between day 8 and day 90, but five patients (14.7%) in the no-filter group did.

Filters were left in place for a median duration of 27 days (11-90 days). Among the 122 patients who received a filter – which included two patients in the control group – researchers found trapped thrombi in the filter in six patients.

Transfusion requirements, and the incidence of major and nonmajor bleeding and leg deep vein thrombosis, were similar between the filter and no-filter groups. Seven patients in the filter group (5.7%) required more than one attempt to remove the filter, and in one patient the filter had to be removed surgically.

Kwok M. Ho, PhD, of the department of intensive care medicine at Royal Perth Hospital, Australia, and coauthors wrote that while vena cava filters are widely used in trauma centers to prevent pulmonary embolism in patients at high risk of bleeding, there are conflicting recommendations regarding their use, and most studies so far have been observational.

“Given the cost and risks associated with a vena cava filter, our data suggest that there is no urgency to insert the filter in patients who can be treated with prophylactic anticoagulation within 7 days after injury,” they wrote. “Unnecessary insertion of a vena cava filter has the potential to cause harm.”

However, they noted that patients with multiple, large intracranial hematomas were particularly at risk from bleeding with anticoagulant therapy, and therefore may benefit from the use of a vena cava filter.

The Medical Research Foundation of Royal Perth Hospital and the Western Australian Department of Health funded the study. Dr. Ho reported funding from the Western Australian Department of Health and the Raine Medical Research Foundation to conduct the study, as well as serving as an adviser to Medtronic and Cardinal Health.

SOURCE: Ho KM et al. N Engl J Med. 2019 Jul 7. doi: 10.156/NEJMoa1806515.

MELBOURNE – Use of a prophylactic vena cava filter to trap blood clots in severely injured patients does not appear to reduce the risk of pulmonary embolism or death, according to data presented at the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis congress.

The researchers reported the outcomes of a multicenter, controlled trial in which 240 severely injured patients with a contraindication to anticoagulants were randomized to receive a vena cava filter within 72 hours of admission, or no filter. The findings were published simultaneously in the New England Journal of Medicine.

The study showed no significant differences between the filter and no-filter groups in the primary outcome of a composite of symptomatic pulmonary embolism or death from any cause at 90 days after enrollment (13.9% vs. 14.4% respectively, P = .98).

In a prespecified subgroup analysis, researchers examined patients who survived 7 days after injury and did not receive prophylactic anticoagulation in those 7 days. Among this group of patients, none of those who received the vena cava filter experienced a symptomatic pulmonary embolism between day 8 and day 90, but five patients (14.7%) in the no-filter group did.

Filters were left in place for a median duration of 27 days (11-90 days). Among the 122 patients who received a filter – which included two patients in the control group – researchers found trapped thrombi in the filter in six patients.

Transfusion requirements, and the incidence of major and nonmajor bleeding and leg deep vein thrombosis, were similar between the filter and no-filter groups. Seven patients in the filter group (5.7%) required more than one attempt to remove the filter, and in one patient the filter had to be removed surgically.

Kwok M. Ho, PhD, of the department of intensive care medicine at Royal Perth Hospital, Australia, and coauthors wrote that while vena cava filters are widely used in trauma centers to prevent pulmonary embolism in patients at high risk of bleeding, there are conflicting recommendations regarding their use, and most studies so far have been observational.

“Given the cost and risks associated with a vena cava filter, our data suggest that there is no urgency to insert the filter in patients who can be treated with prophylactic anticoagulation within 7 days after injury,” they wrote. “Unnecessary insertion of a vena cava filter has the potential to cause harm.”

However, they noted that patients with multiple, large intracranial hematomas were particularly at risk from bleeding with anticoagulant therapy, and therefore may benefit from the use of a vena cava filter.

The Medical Research Foundation of Royal Perth Hospital and the Western Australian Department of Health funded the study. Dr. Ho reported funding from the Western Australian Department of Health and the Raine Medical Research Foundation to conduct the study, as well as serving as an adviser to Medtronic and Cardinal Health.

SOURCE: Ho KM et al. N Engl J Med. 2019 Jul 7. doi: 10.156/NEJMoa1806515.

REPORTING FROM 2019 ISTH CONGRESS

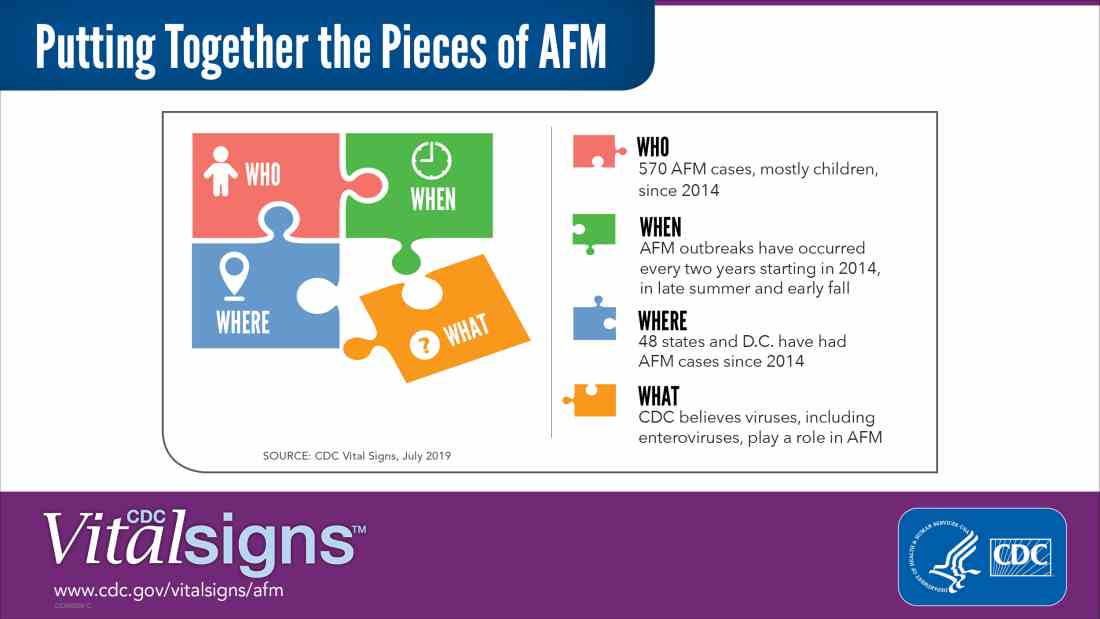

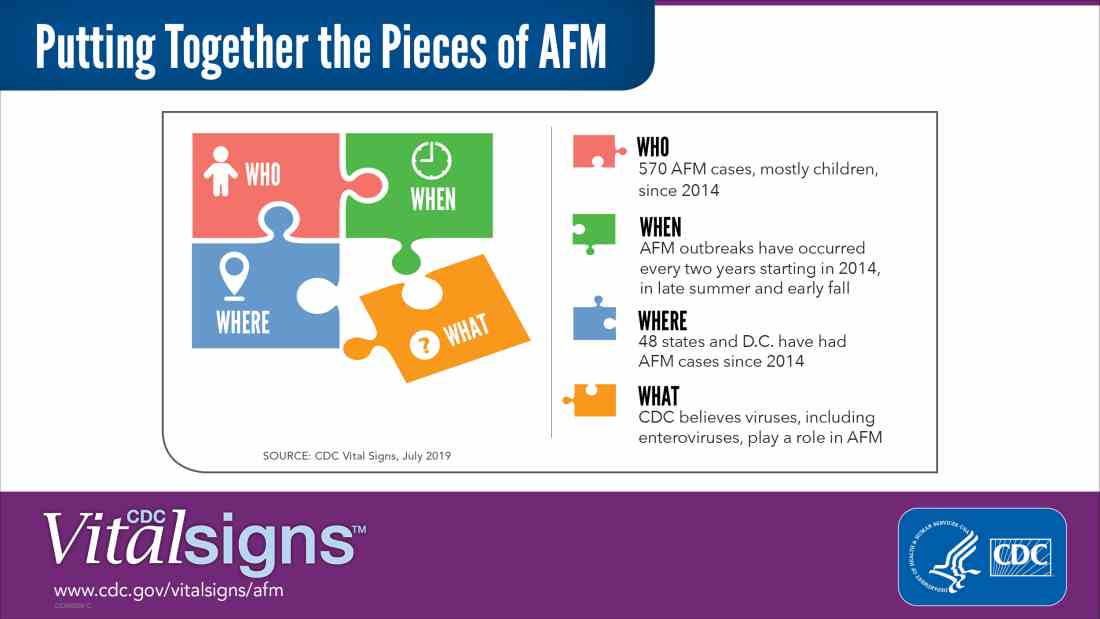

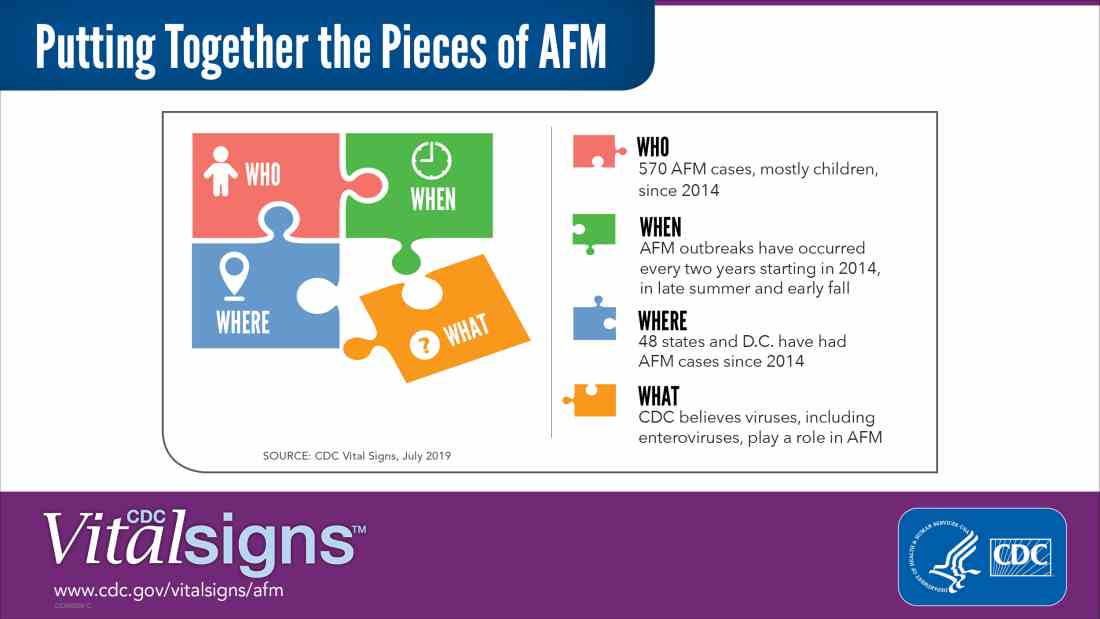

CDC: Look for early symptoms of acute flaccid myelitis, report suspected cases

the CDC said in a telebriefing.

Acute flaccid myelitis (AFM) is defined as acute, flaccid muscle weakness that occurs less than 1 week after a fever or respiratory illness. Viruses, including enterovirus, are believed to play a role in AFM, but the cause still is unknown. The disease appears mostly in children, and the average age of a patient diagnosed with AFM is 5 years.

“Doctors and other clinicians in the United States play a critical role,” Anne Schuchat, MD, principal deputy director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, said in the telebriefing. “We ask for your help with early recognition of patients with AFM symptoms, prompt specimen collection for testing, and immediate reporting of suspected AFM cases to health departments.”

While there is no proven treatment for AFM, early diagnosis is critical to getting patients the best care possible, according to a Vital Signs report released today. This means that clinicians should not wait for the CDC’s case definition before diagnosis, the CDC said.

“When specimens are collected as soon as possible after symptom onset, we have a better chance of understanding the causes of AFM, these recurrent outbreaks, and developing a diagnostic test,” Dr. Schuchat said. “Rapid reporting also helps us to identify and respond to outbreaks early and alert other clinicians and the public.”

AFM appears to follow a seasonal and biennial pattern, with the number of cases increasing mainly in the late summer and early fall. As the season approaches where AFM cases increase, CDC is asking clinicians to look out for patients with suspected AFM so cases can be reported as early as possible.

Since the CDC began tracking AFM, the number of cases has risen every 2 years. In 2018, there were 233 cases in 41 states, the highest number of reported cases since the CDC began tracking AFM following an outbreak in 2014, according to a Vital Signs report. Overall, there have been 570 cases of AFM reported in 48 states and the District of Columbia since 2014.

There is yet to be a confirmatory test for AFM, but clinicians should obtain cerebrospinal fluid, serum, stool and nasopharyngeal swab from patients with suspected AFM as soon as possible, followed by an MRI. AFM has unique MRI features , such as gray matter involvement, that can help distinguish it from other diseases characterized by acute weakness.

In the Vital Signs report, which examined AFM in 2018, 92% of confirmed cases had respiratory symptoms or fever, and 42% of confirmed cases had upper limb involvement. The median time from limb weakness to hospitalization was 1 day, and time from weakness to MRI was 2 days. Cases were reported to the CDC a median of 18 days from onset of limb weakness, but time to reporting ranged between 18 days and 36 days, said Tom Clark, MD, MPH, deputy director of the division of viral diseases at CDC.

“This delay hampers our ability to understand the causes AFM,” he said. “We believe that recognizing AFM early is critical and can lead to better patient management.”

In lieu of a diagnostic test for AFM, clinicians should make management decisions through review of patient symptoms, exam findings, MRI, other test results, and in consulting with neurology experts. The Transverse Myelitis Association also has created a support portal for 24/7 physician consultation in AFM cases.

SOURCE: Lopez A et al. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019;68:1-7 .

the CDC said in a telebriefing.

Acute flaccid myelitis (AFM) is defined as acute, flaccid muscle weakness that occurs less than 1 week after a fever or respiratory illness. Viruses, including enterovirus, are believed to play a role in AFM, but the cause still is unknown. The disease appears mostly in children, and the average age of a patient diagnosed with AFM is 5 years.

“Doctors and other clinicians in the United States play a critical role,” Anne Schuchat, MD, principal deputy director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, said in the telebriefing. “We ask for your help with early recognition of patients with AFM symptoms, prompt specimen collection for testing, and immediate reporting of suspected AFM cases to health departments.”

While there is no proven treatment for AFM, early diagnosis is critical to getting patients the best care possible, according to a Vital Signs report released today. This means that clinicians should not wait for the CDC’s case definition before diagnosis, the CDC said.

“When specimens are collected as soon as possible after symptom onset, we have a better chance of understanding the causes of AFM, these recurrent outbreaks, and developing a diagnostic test,” Dr. Schuchat said. “Rapid reporting also helps us to identify and respond to outbreaks early and alert other clinicians and the public.”

AFM appears to follow a seasonal and biennial pattern, with the number of cases increasing mainly in the late summer and early fall. As the season approaches where AFM cases increase, CDC is asking clinicians to look out for patients with suspected AFM so cases can be reported as early as possible.