User login

Gender wage gap varies by specialty

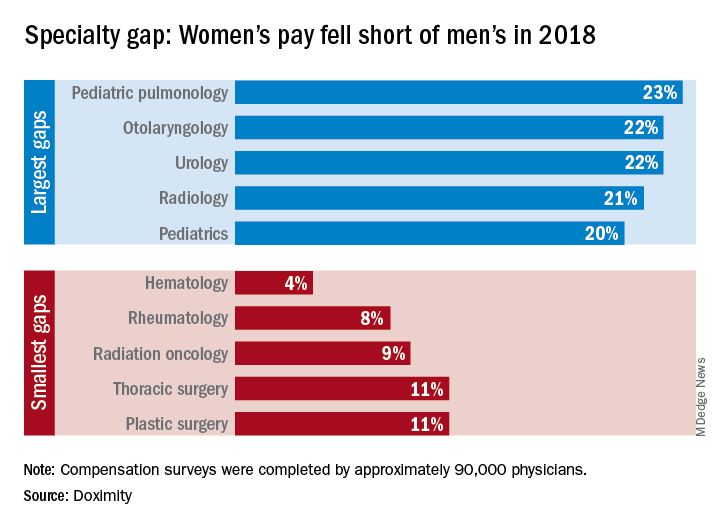

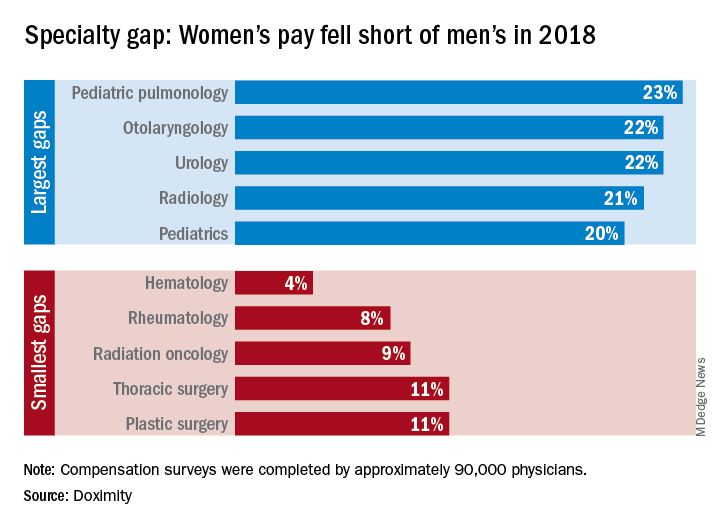

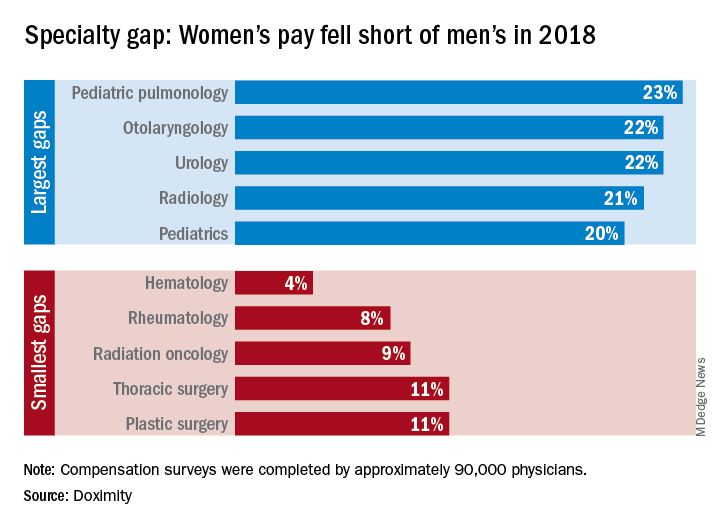

There is no specialty in which women physicians make as much as men, but hematology came the closest in 2018, according to a new survey by the medical social network Doximity.

Female hematologists averaged $309,000 in earnings in 2018, just 4% less than their male counterparts, who brought in an average of $323,000. Rheumatology had the next-smallest gap, 8%, between women and men, followed by radiation oncology at 9% and thoracic surgery and plastic surgery at 11% each, Doximity reported March 26. All of the 90,000 physicians involved in the survey worked at least 40 hours per week.

At the other end of the scale is pediatric pulmonology, home of the largest gender wage gap. Average compensation for women in the specialty was $195,000, or 23% less than the $253,000 that men received. Women in otolaryngology and urology were next, earning 22% less than men in those specialties, while women in radiology and pediatrics averaged 21% and 20% less, respectively, than men, Doximity said in its report.

The gender wage gap has been persistent, but the latest data show that it is starting to close as the earnings curve for male physicians flattened in 2018 while pay increased for female physicians.

“Compensation transparency is a powerful force. As more data becomes available to us, exposing the pay gap between men and women, we see more movements to rectify this issue,” said Christopher Whaley, PhD, of the University of California, Berkeley, School of Public Health, who was lead author of the study.

To account for differences in specialty, geography, and physician-specific factors, the Doximity researchers used “a multivariate regression with fixed effects for provider specialty and [metropolitan statistical area].” They also controlled for how long each physician has been in practice and their self-reported average hours worked.

There is no specialty in which women physicians make as much as men, but hematology came the closest in 2018, according to a new survey by the medical social network Doximity.

Female hematologists averaged $309,000 in earnings in 2018, just 4% less than their male counterparts, who brought in an average of $323,000. Rheumatology had the next-smallest gap, 8%, between women and men, followed by radiation oncology at 9% and thoracic surgery and plastic surgery at 11% each, Doximity reported March 26. All of the 90,000 physicians involved in the survey worked at least 40 hours per week.

At the other end of the scale is pediatric pulmonology, home of the largest gender wage gap. Average compensation for women in the specialty was $195,000, or 23% less than the $253,000 that men received. Women in otolaryngology and urology were next, earning 22% less than men in those specialties, while women in radiology and pediatrics averaged 21% and 20% less, respectively, than men, Doximity said in its report.

The gender wage gap has been persistent, but the latest data show that it is starting to close as the earnings curve for male physicians flattened in 2018 while pay increased for female physicians.

“Compensation transparency is a powerful force. As more data becomes available to us, exposing the pay gap between men and women, we see more movements to rectify this issue,” said Christopher Whaley, PhD, of the University of California, Berkeley, School of Public Health, who was lead author of the study.

To account for differences in specialty, geography, and physician-specific factors, the Doximity researchers used “a multivariate regression with fixed effects for provider specialty and [metropolitan statistical area].” They also controlled for how long each physician has been in practice and their self-reported average hours worked.

There is no specialty in which women physicians make as much as men, but hematology came the closest in 2018, according to a new survey by the medical social network Doximity.

Female hematologists averaged $309,000 in earnings in 2018, just 4% less than their male counterparts, who brought in an average of $323,000. Rheumatology had the next-smallest gap, 8%, between women and men, followed by radiation oncology at 9% and thoracic surgery and plastic surgery at 11% each, Doximity reported March 26. All of the 90,000 physicians involved in the survey worked at least 40 hours per week.

At the other end of the scale is pediatric pulmonology, home of the largest gender wage gap. Average compensation for women in the specialty was $195,000, or 23% less than the $253,000 that men received. Women in otolaryngology and urology were next, earning 22% less than men in those specialties, while women in radiology and pediatrics averaged 21% and 20% less, respectively, than men, Doximity said in its report.

The gender wage gap has been persistent, but the latest data show that it is starting to close as the earnings curve for male physicians flattened in 2018 while pay increased for female physicians.

“Compensation transparency is a powerful force. As more data becomes available to us, exposing the pay gap between men and women, we see more movements to rectify this issue,” said Christopher Whaley, PhD, of the University of California, Berkeley, School of Public Health, who was lead author of the study.

To account for differences in specialty, geography, and physician-specific factors, the Doximity researchers used “a multivariate regression with fixed effects for provider specialty and [metropolitan statistical area].” They also controlled for how long each physician has been in practice and their self-reported average hours worked.

Hospital medicine grows globally

Hospital medicine is growing in popularity in some foreign countries, speakers said during Monday afternoon’s session, “International Hospital Medicine in the United Arab Emirates, Brazil and Holland.” The presenters discussed some of the history of hospital medicine in each of those countries as well as some current challenges.

Hospital medicine in the Netherlands started in about 2012, said Marjolein de Boom, MD, a hospitalist at Haaglanden Medical Centre. The country has its own 3-year training program for hospitalists, who first started to work in hospitals in the country in 2015. “It’s a relatively new and young specialty,” said Dr. de Boom, with 39 hospitalists in the country working in 8 of the 80 Dutch hospitals. Another 25 or so hospitalists are in training, “so it’s a growing profession,” she said. A Dutch chapter of SHM has been in place since 2017.

Hospitals in the Netherlands permit physicians to serve as hospitalists in different specialties depending on their needs. For example, Dr. de Boom works in the oncology department, as well as the surgical and trauma surgery units. One challenge has been to get more physicians interested in the hospitalist program because it’s newer and not as well-known, she said.

Hospital medicine in the United Arab Emirates also is a newer concept. The American model of hospital medicine was first introduced to the region in 2014 by the Cleveland Clinic in Abu Dhabi, said Mahmoud Al-Hawamdeh, MD, MBA, SFHM, FACP, chair of hospital medicine at the medical center. “Before that, inpatient hospital care was done by traditional family and internal medicine physicians, general practitioners, and residents,” he said.

There are 43 hospitalists at Cleveland Clinic, Abu Dhabi, said Dr. Al-Hawamdeh. They cover about 50%-60% of inpatient services, as well as handle admissions for vascular surgery, ophthalmology, and some general services; they also comanage postcardiac surgery care, he said. “It has been a tremendous success to implement hospital medicine in the care for the inpatient with improved quality metrics, reduced length of stay, and improved patient satisfaction.”

However, there are some challenges, such as educating patients and families about the role of hospitalists, cultural barriers, and the lack of a postdischarge follow-up network and institutions such as skilled nursing facilities. Dr. Al-Hawamdeh worked with physicians from Johns Hopkins Aramco Healthcare and Hamad Medical Corporation to establish an SHM Middle East chapter in 2016.

In Brazil, hospital medicine started to take hold in 2004, said Guilherme Barcellos, MD, SFHM. At that time, just a few doctors were true hospitalists. Dr. Barcellos helped create two hospitalist societies in the country. Hospitalists balancing multiple jobs is still very common, but decreasing, he said, while hospital employment and medical group participation is increasing.

“It was a high-pressure environment, crying out for efficiency, that drove forward Brazilian hospital medicine,” Dr. Barcellos said, “together with new reimbursement models, surgical redesigns, primary care recognition and structure.”

Some challenges remain in Brazil as well, he said. Fancy private hospitals announce they have hospitalists when they may not. In addition, the role of generalists and subspecialists, and the role of certifications, is not always clear. But hospitalists are gaining a foothold, participating in a Choosing Wisely initiative in the country and organizing several conferences.

Hospital medicine is growing in popularity in some foreign countries, speakers said during Monday afternoon’s session, “International Hospital Medicine in the United Arab Emirates, Brazil and Holland.” The presenters discussed some of the history of hospital medicine in each of those countries as well as some current challenges.

Hospital medicine in the Netherlands started in about 2012, said Marjolein de Boom, MD, a hospitalist at Haaglanden Medical Centre. The country has its own 3-year training program for hospitalists, who first started to work in hospitals in the country in 2015. “It’s a relatively new and young specialty,” said Dr. de Boom, with 39 hospitalists in the country working in 8 of the 80 Dutch hospitals. Another 25 or so hospitalists are in training, “so it’s a growing profession,” she said. A Dutch chapter of SHM has been in place since 2017.

Hospitals in the Netherlands permit physicians to serve as hospitalists in different specialties depending on their needs. For example, Dr. de Boom works in the oncology department, as well as the surgical and trauma surgery units. One challenge has been to get more physicians interested in the hospitalist program because it’s newer and not as well-known, she said.

Hospital medicine in the United Arab Emirates also is a newer concept. The American model of hospital medicine was first introduced to the region in 2014 by the Cleveland Clinic in Abu Dhabi, said Mahmoud Al-Hawamdeh, MD, MBA, SFHM, FACP, chair of hospital medicine at the medical center. “Before that, inpatient hospital care was done by traditional family and internal medicine physicians, general practitioners, and residents,” he said.

There are 43 hospitalists at Cleveland Clinic, Abu Dhabi, said Dr. Al-Hawamdeh. They cover about 50%-60% of inpatient services, as well as handle admissions for vascular surgery, ophthalmology, and some general services; they also comanage postcardiac surgery care, he said. “It has been a tremendous success to implement hospital medicine in the care for the inpatient with improved quality metrics, reduced length of stay, and improved patient satisfaction.”

However, there are some challenges, such as educating patients and families about the role of hospitalists, cultural barriers, and the lack of a postdischarge follow-up network and institutions such as skilled nursing facilities. Dr. Al-Hawamdeh worked with physicians from Johns Hopkins Aramco Healthcare and Hamad Medical Corporation to establish an SHM Middle East chapter in 2016.

In Brazil, hospital medicine started to take hold in 2004, said Guilherme Barcellos, MD, SFHM. At that time, just a few doctors were true hospitalists. Dr. Barcellos helped create two hospitalist societies in the country. Hospitalists balancing multiple jobs is still very common, but decreasing, he said, while hospital employment and medical group participation is increasing.

“It was a high-pressure environment, crying out for efficiency, that drove forward Brazilian hospital medicine,” Dr. Barcellos said, “together with new reimbursement models, surgical redesigns, primary care recognition and structure.”

Some challenges remain in Brazil as well, he said. Fancy private hospitals announce they have hospitalists when they may not. In addition, the role of generalists and subspecialists, and the role of certifications, is not always clear. But hospitalists are gaining a foothold, participating in a Choosing Wisely initiative in the country and organizing several conferences.

Hospital medicine is growing in popularity in some foreign countries, speakers said during Monday afternoon’s session, “International Hospital Medicine in the United Arab Emirates, Brazil and Holland.” The presenters discussed some of the history of hospital medicine in each of those countries as well as some current challenges.

Hospital medicine in the Netherlands started in about 2012, said Marjolein de Boom, MD, a hospitalist at Haaglanden Medical Centre. The country has its own 3-year training program for hospitalists, who first started to work in hospitals in the country in 2015. “It’s a relatively new and young specialty,” said Dr. de Boom, with 39 hospitalists in the country working in 8 of the 80 Dutch hospitals. Another 25 or so hospitalists are in training, “so it’s a growing profession,” she said. A Dutch chapter of SHM has been in place since 2017.

Hospitals in the Netherlands permit physicians to serve as hospitalists in different specialties depending on their needs. For example, Dr. de Boom works in the oncology department, as well as the surgical and trauma surgery units. One challenge has been to get more physicians interested in the hospitalist program because it’s newer and not as well-known, she said.

Hospital medicine in the United Arab Emirates also is a newer concept. The American model of hospital medicine was first introduced to the region in 2014 by the Cleveland Clinic in Abu Dhabi, said Mahmoud Al-Hawamdeh, MD, MBA, SFHM, FACP, chair of hospital medicine at the medical center. “Before that, inpatient hospital care was done by traditional family and internal medicine physicians, general practitioners, and residents,” he said.

There are 43 hospitalists at Cleveland Clinic, Abu Dhabi, said Dr. Al-Hawamdeh. They cover about 50%-60% of inpatient services, as well as handle admissions for vascular surgery, ophthalmology, and some general services; they also comanage postcardiac surgery care, he said. “It has been a tremendous success to implement hospital medicine in the care for the inpatient with improved quality metrics, reduced length of stay, and improved patient satisfaction.”

However, there are some challenges, such as educating patients and families about the role of hospitalists, cultural barriers, and the lack of a postdischarge follow-up network and institutions such as skilled nursing facilities. Dr. Al-Hawamdeh worked with physicians from Johns Hopkins Aramco Healthcare and Hamad Medical Corporation to establish an SHM Middle East chapter in 2016.

In Brazil, hospital medicine started to take hold in 2004, said Guilherme Barcellos, MD, SFHM. At that time, just a few doctors were true hospitalists. Dr. Barcellos helped create two hospitalist societies in the country. Hospitalists balancing multiple jobs is still very common, but decreasing, he said, while hospital employment and medical group participation is increasing.

“It was a high-pressure environment, crying out for efficiency, that drove forward Brazilian hospital medicine,” Dr. Barcellos said, “together with new reimbursement models, surgical redesigns, primary care recognition and structure.”

Some challenges remain in Brazil as well, he said. Fancy private hospitals announce they have hospitalists when they may not. In addition, the role of generalists and subspecialists, and the role of certifications, is not always clear. But hospitalists are gaining a foothold, participating in a Choosing Wisely initiative in the country and organizing several conferences.

In transgender care, questions are the answer

New York OBGYN Zoe I. Rodriguez, MD, a pioneer in the care of transgender people, has witnessed a remarkable evolution in medicine.

Years ago, providers knew little to nothing about the unique needs of transgender patients. Now, Dr. Rodriguez said, “there’s tremendous interest in being able to competently treat and address transgender individuals.”

But increased awareness has come with a dose of worry. Providers are often afraid they’ll say or do the wrong thing.

Dr. Rodriguez, who is an assistant professor at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, will help hospitalists gain confidence in treating transgender patients at an HM19 session on Tuesday. “I hope to eliminate this element of fear,” she said. “It’s just really about treating people with respect and dignity and having the knowledge to care for them appropriately.”

The United States is home to an estimated 1.4 million transgender people, and every one has a preferred name and preferred pronouns. It’s crucial for physicians to understand name and pronoun preferences and use them, Dr. Rodriguez said.

At her practice, an intake form asks patients how they wish to be addressed. “I know this information by the time I walk into the exam room,” she said.

For hospitalists, she said, getting this information beforehand may not be possible. In that case, she said, ask questions of the patient and don’t be afraid to get it wrong.

“Mistakes happen all the time,” Dr. Rodriguez said. “People will correct you if you misgender them or call them other than their preferred name. As long as the mistakes are not willful, apologize and move on.”

It’s also important to understand the special needs that transgender patients may – or may not – have. For example, not every transgender patient takes hormones. Even if a patient does, the hormones may not affect as many body processes as you might assume, Dr. Rodriguez said.

Also, not every transgender person has had surgery. However, it can be helpful to understand what surgery entails. “If they get their surgery done in Thailand, a popular destination, and they need treatment in Topeka for an issue related to their surgery, it would be good for the hospitalist to understand what’s done during the surgery.”

In her session, Dr. Rodriguez will also talk about creating an LGBT-friendly environment. “These patients are already feeling very vulnerable and marginalized within these vast health systems,” she said. “It makes a big difference to know that someone is there and gets it.”

Dr. Rodriguez also plans to emphasize the importance of staying aware and up to date about transgender issues. “It’s a continuum,” she said. “There will be more evolution as people come up with new terminologies and words to describe their gender expression and identity. It will be crucially important for physicians to be aware and respectful.”

What Hospitalists Need to Know About Caring for Transgender Patients

Tuesday, 3:50 - 4:30 p.m.

Maryland A/1-3

New York OBGYN Zoe I. Rodriguez, MD, a pioneer in the care of transgender people, has witnessed a remarkable evolution in medicine.

Years ago, providers knew little to nothing about the unique needs of transgender patients. Now, Dr. Rodriguez said, “there’s tremendous interest in being able to competently treat and address transgender individuals.”

But increased awareness has come with a dose of worry. Providers are often afraid they’ll say or do the wrong thing.

Dr. Rodriguez, who is an assistant professor at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, will help hospitalists gain confidence in treating transgender patients at an HM19 session on Tuesday. “I hope to eliminate this element of fear,” she said. “It’s just really about treating people with respect and dignity and having the knowledge to care for them appropriately.”

The United States is home to an estimated 1.4 million transgender people, and every one has a preferred name and preferred pronouns. It’s crucial for physicians to understand name and pronoun preferences and use them, Dr. Rodriguez said.

At her practice, an intake form asks patients how they wish to be addressed. “I know this information by the time I walk into the exam room,” she said.

For hospitalists, she said, getting this information beforehand may not be possible. In that case, she said, ask questions of the patient and don’t be afraid to get it wrong.

“Mistakes happen all the time,” Dr. Rodriguez said. “People will correct you if you misgender them or call them other than their preferred name. As long as the mistakes are not willful, apologize and move on.”

It’s also important to understand the special needs that transgender patients may – or may not – have. For example, not every transgender patient takes hormones. Even if a patient does, the hormones may not affect as many body processes as you might assume, Dr. Rodriguez said.

Also, not every transgender person has had surgery. However, it can be helpful to understand what surgery entails. “If they get their surgery done in Thailand, a popular destination, and they need treatment in Topeka for an issue related to their surgery, it would be good for the hospitalist to understand what’s done during the surgery.”

In her session, Dr. Rodriguez will also talk about creating an LGBT-friendly environment. “These patients are already feeling very vulnerable and marginalized within these vast health systems,” she said. “It makes a big difference to know that someone is there and gets it.”

Dr. Rodriguez also plans to emphasize the importance of staying aware and up to date about transgender issues. “It’s a continuum,” she said. “There will be more evolution as people come up with new terminologies and words to describe their gender expression and identity. It will be crucially important for physicians to be aware and respectful.”

What Hospitalists Need to Know About Caring for Transgender Patients

Tuesday, 3:50 - 4:30 p.m.

Maryland A/1-3

New York OBGYN Zoe I. Rodriguez, MD, a pioneer in the care of transgender people, has witnessed a remarkable evolution in medicine.

Years ago, providers knew little to nothing about the unique needs of transgender patients. Now, Dr. Rodriguez said, “there’s tremendous interest in being able to competently treat and address transgender individuals.”

But increased awareness has come with a dose of worry. Providers are often afraid they’ll say or do the wrong thing.

Dr. Rodriguez, who is an assistant professor at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, will help hospitalists gain confidence in treating transgender patients at an HM19 session on Tuesday. “I hope to eliminate this element of fear,” she said. “It’s just really about treating people with respect and dignity and having the knowledge to care for them appropriately.”

The United States is home to an estimated 1.4 million transgender people, and every one has a preferred name and preferred pronouns. It’s crucial for physicians to understand name and pronoun preferences and use them, Dr. Rodriguez said.

At her practice, an intake form asks patients how they wish to be addressed. “I know this information by the time I walk into the exam room,” she said.

For hospitalists, she said, getting this information beforehand may not be possible. In that case, she said, ask questions of the patient and don’t be afraid to get it wrong.

“Mistakes happen all the time,” Dr. Rodriguez said. “People will correct you if you misgender them or call them other than their preferred name. As long as the mistakes are not willful, apologize and move on.”

It’s also important to understand the special needs that transgender patients may – or may not – have. For example, not every transgender patient takes hormones. Even if a patient does, the hormones may not affect as many body processes as you might assume, Dr. Rodriguez said.

Also, not every transgender person has had surgery. However, it can be helpful to understand what surgery entails. “If they get their surgery done in Thailand, a popular destination, and they need treatment in Topeka for an issue related to their surgery, it would be good for the hospitalist to understand what’s done during the surgery.”

In her session, Dr. Rodriguez will also talk about creating an LGBT-friendly environment. “These patients are already feeling very vulnerable and marginalized within these vast health systems,” she said. “It makes a big difference to know that someone is there and gets it.”

Dr. Rodriguez also plans to emphasize the importance of staying aware and up to date about transgender issues. “It’s a continuum,” she said. “There will be more evolution as people come up with new terminologies and words to describe their gender expression and identity. It will be crucially important for physicians to be aware and respectful.”

What Hospitalists Need to Know About Caring for Transgender Patients

Tuesday, 3:50 - 4:30 p.m.

Maryland A/1-3

ABIM contests class-action lawsuit, asks judge to dismiss

Attorneys for the American Board of Internal Medicine have asked Judge Robert Kelly of the United States District Court for the Eastern District of Pennsylvania to dismiss a class-action lawsuit against the board’s maintenance of certification (MOC) program.

The legal challenge, filed Dec. 6, 2018, claims that ABIM charges inflated monopoly prices for maintaining certification, that the organization is forcing physicians to purchase MOC, and that ABIM is inducing employers and others to require ABIM certification as a condition of employment.

The four plaintiff-physicians are asking a judge to find ABIM in violation of federal antitrust law and to bar the board from continuing its MOC process. The suit is filed as a class action on behalf of all internists and subspecialists required by ABIM to purchase MOC to maintain their certification. On Jan. 23 of this year, the suit was amended to include racketeering and unjust enrichment claims.

In a motion filed March 18, attorneys for ABIM asserted that the plaintiffs fail to prove that board certification – initial certification and continuing certification – are two separate products that ABIM is unlawfully tying, and for that reason, their antitrust claims are invalid, according to the motion.

“Plaintiffs may disagree with ABIM and members of the medical community on whether ABIM certification provides them value, but their claims have no basis in the law,” Richard J. Baron, MD, ABIM president and CEO said in a statement. “With advances in medical science and technology occurring constantly, periodic assessments are critical to ensure internists are staying current and continuing to meet high performance standards in their field.”

Two other lawsuits challenging MOC, one against the American Board of Psychiatry and Neurology and another against the American Board of Radiology, are ongoing.

More than $200,000 has been raised by doctors and their supporters nationwide through a GoFundMe campaign launched by Practicing Physicians of America to pay for the plaintiffs’ legal costs.

Attorneys for the American Board of Internal Medicine have asked Judge Robert Kelly of the United States District Court for the Eastern District of Pennsylvania to dismiss a class-action lawsuit against the board’s maintenance of certification (MOC) program.

The legal challenge, filed Dec. 6, 2018, claims that ABIM charges inflated monopoly prices for maintaining certification, that the organization is forcing physicians to purchase MOC, and that ABIM is inducing employers and others to require ABIM certification as a condition of employment.

The four plaintiff-physicians are asking a judge to find ABIM in violation of federal antitrust law and to bar the board from continuing its MOC process. The suit is filed as a class action on behalf of all internists and subspecialists required by ABIM to purchase MOC to maintain their certification. On Jan. 23 of this year, the suit was amended to include racketeering and unjust enrichment claims.

In a motion filed March 18, attorneys for ABIM asserted that the plaintiffs fail to prove that board certification – initial certification and continuing certification – are two separate products that ABIM is unlawfully tying, and for that reason, their antitrust claims are invalid, according to the motion.

“Plaintiffs may disagree with ABIM and members of the medical community on whether ABIM certification provides them value, but their claims have no basis in the law,” Richard J. Baron, MD, ABIM president and CEO said in a statement. “With advances in medical science and technology occurring constantly, periodic assessments are critical to ensure internists are staying current and continuing to meet high performance standards in their field.”

Two other lawsuits challenging MOC, one against the American Board of Psychiatry and Neurology and another against the American Board of Radiology, are ongoing.

More than $200,000 has been raised by doctors and their supporters nationwide through a GoFundMe campaign launched by Practicing Physicians of America to pay for the plaintiffs’ legal costs.

Attorneys for the American Board of Internal Medicine have asked Judge Robert Kelly of the United States District Court for the Eastern District of Pennsylvania to dismiss a class-action lawsuit against the board’s maintenance of certification (MOC) program.

The legal challenge, filed Dec. 6, 2018, claims that ABIM charges inflated monopoly prices for maintaining certification, that the organization is forcing physicians to purchase MOC, and that ABIM is inducing employers and others to require ABIM certification as a condition of employment.

The four plaintiff-physicians are asking a judge to find ABIM in violation of federal antitrust law and to bar the board from continuing its MOC process. The suit is filed as a class action on behalf of all internists and subspecialists required by ABIM to purchase MOC to maintain their certification. On Jan. 23 of this year, the suit was amended to include racketeering and unjust enrichment claims.

In a motion filed March 18, attorneys for ABIM asserted that the plaintiffs fail to prove that board certification – initial certification and continuing certification – are two separate products that ABIM is unlawfully tying, and for that reason, their antitrust claims are invalid, according to the motion.

“Plaintiffs may disagree with ABIM and members of the medical community on whether ABIM certification provides them value, but their claims have no basis in the law,” Richard J. Baron, MD, ABIM president and CEO said in a statement. “With advances in medical science and technology occurring constantly, periodic assessments are critical to ensure internists are staying current and continuing to meet high performance standards in their field.”

Two other lawsuits challenging MOC, one against the American Board of Psychiatry and Neurology and another against the American Board of Radiology, are ongoing.

More than $200,000 has been raised by doctors and their supporters nationwide through a GoFundMe campaign launched by Practicing Physicians of America to pay for the plaintiffs’ legal costs.

Surge of gabapentinoids for pain lacks supporting evidence

Many clinicians are prescribing the gabapentinoid drugs pregabalin (Lyrica) and gabapentin (Neurontin) for off-label treatment of pain, despite a lack of supporting data or approval from the Food and Drug Administration, according to investigators.

Over the past 15 years, use of gabapentinoids has tripled, a level of growth that cannot be explained by prescriptions for approved indications, reported coauthors Christopher W. Goodman, MD, and Allan S. Brett, MD, of the University of South Carolina, Columbia. Instead, clinicians are turning to gabapentinoids, partly as an option to substitute for opioids, which now have greater prescribing restrictions as a result of the current opioid crisis.

Although clinicians may cite guidelines that support off-label use of gabapentinoids for pain, the investigators warned that many of these recommendations stand on shaky ground.

“Clinicians who prescribe gabapentinoids off-label for pain should be aware of the limited evidence and should acknowledge to patients that potential benefits are uncertain for most off-label uses,” the investigators wrote in a clinical review published online March 25 in JAMA Internal Medicine.

The investigators narrowed down 677 publications to 84 papers describing the use of gabapentinoids for outpatient noncancer pain syndromes for which they are not FDA approved; 54 for gabapentin and 30 for pregabalin. In the domain of analgesia, both agents are currently FDA-approved for postherpetic neuralgia, while pregabalin is additionally approved for pain associated with fibromyalgia and neuropathic pain from diabetic neuropathy and spinal cord injury. Indications in reviewed studies ranged broadly, from conditions somewhat related to those currently approved, such as unspecified neuropathy, to dissimilar conditions, such as chronic pancreatitis and burn injury.

The investigators summarized findings from randomized clinical trials while using case studies to illustrate potential problems with off-label use. In addition, they reviewed the history of gabapentinoids and sources of recommendations for off-label use, such as guidelines and previous review articles.

Six major findings were reported: (1) evidence supporting gabapentin for diabetic neuropathy pain is “mixed at best”; (2) evidence supporting gabapentin for nondiabetic neuropathies is very limited; (3) evidence does not support gabapentinoids for radiculopathy or low back pain; (4) gabapentin has minimal benefit for fibromyalgia pain, based on minimal evidence; (5) evidence does not support gabapentinoids for acute herpes zoster pain; and (6) in almost all studies for other painful indications, gabapentinoids were ineffective or “associated with small analgesic effects that were statistically significant but of questionable clinical importance.”

Case studies complemented this overview, highlighting related clinical dilemmas that the investigators encounter “repeatedly” during inpatient and outpatient care. Along with off-label use, such as gabapentinoid prescriptions for acute sciatica, the investigators reported cases in which neuropathy was diagnosed in place of nonspecific lower body pain to facilitate gabapentin prescription. They also described apparent disregard for risks of polypharmacy in prescriptions for elderly patients and rote use of gabapentinoids in patients with diabetic neuropathy who did not have sufficient discomfort to warrant prescription.

The investigators also cited a number of problems with the language of reviews and guidelines involving gabapentinoids.

“The wording in many guidelines and review articles reinforces an inflated view of gabapentinoid effectiveness or fails to distinguish carefully between evidence-based and non–evidence-based recommendations,” they wrote, adding that clinicians may have misconceptions about neuropathic pain. “One unintended effect of the broad definition [of neuropathic pain] might be to create a mistaken perception that an effective drug for one type of neuropathic pain is effective for all neuropathic pain, regardless of underlying etiology or mechanism,” the investigators suggested.

Another facet of prescribing behavior could be explained in economic terms. Pregabalin, sold under the brand name Lyrica, is considerably more expensive than gabapentin; however, the investigators warned that the similarity of these agents does not equate with interchangeability, noting differences in bioavailability and rate of absorption.

“Unfortunately, published direct comparisons between the 2 drugs in double-blind studies of patients with chronic noncancer pain are virtually nonexistent,” the investigators wrote.

In addition to questionable effectiveness of gabapentinoids for off-label chronic noncancer pain syndromes, Dr. Goodman and Dr. Brett noted that the drugs produce a “substantial incidence of dizziness, somnolence, and gait disturbance.”

They also described a new trend of gabapentinoid abuse and diversion, which may not be surprising, considering that gabapentinoids are reported to augment opioid-induced euphoria.

“Evidence of misuse of gabapentinoids is accumulating and likely related to the opioid epidemic. A recent review article reported an overall population prevalence of gabapentinoid ‘misuse and abuse’ as high as 1%, with substantially higher prevalence noted among patients with opioid use disorders,” the investigators wrote. “This trend is troubling, particularly because concomitant use of opioids and gabapentinoids is associated with increased odds of opioid-related death. Whether these concerns apply to patients receiving long-term prescribed opioid therapy is unclear.”

In the era of the opioid crisis, the investigators acknowledged that many clinicians have serious concerns about adequately treating chronic noncancer pain.

“Comprehensive management of pain in primary care settings is difficult. It requires time and resources that are frequently unavailable,” the investigators wrote. “Many patients with chronic pain have limited or no access to high-quality pain practices or to nonpharmacologic interventions, such as cognitive behavior therapy.”

The investigators reported no external funding or conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Goodman CW et al. JAMA Intern Med. 2019 Mar 25. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.0086

Many clinicians are prescribing the gabapentinoid drugs pregabalin (Lyrica) and gabapentin (Neurontin) for off-label treatment of pain, despite a lack of supporting data or approval from the Food and Drug Administration, according to investigators.

Over the past 15 years, use of gabapentinoids has tripled, a level of growth that cannot be explained by prescriptions for approved indications, reported coauthors Christopher W. Goodman, MD, and Allan S. Brett, MD, of the University of South Carolina, Columbia. Instead, clinicians are turning to gabapentinoids, partly as an option to substitute for opioids, which now have greater prescribing restrictions as a result of the current opioid crisis.

Although clinicians may cite guidelines that support off-label use of gabapentinoids for pain, the investigators warned that many of these recommendations stand on shaky ground.

“Clinicians who prescribe gabapentinoids off-label for pain should be aware of the limited evidence and should acknowledge to patients that potential benefits are uncertain for most off-label uses,” the investigators wrote in a clinical review published online March 25 in JAMA Internal Medicine.

The investigators narrowed down 677 publications to 84 papers describing the use of gabapentinoids for outpatient noncancer pain syndromes for which they are not FDA approved; 54 for gabapentin and 30 for pregabalin. In the domain of analgesia, both agents are currently FDA-approved for postherpetic neuralgia, while pregabalin is additionally approved for pain associated with fibromyalgia and neuropathic pain from diabetic neuropathy and spinal cord injury. Indications in reviewed studies ranged broadly, from conditions somewhat related to those currently approved, such as unspecified neuropathy, to dissimilar conditions, such as chronic pancreatitis and burn injury.

The investigators summarized findings from randomized clinical trials while using case studies to illustrate potential problems with off-label use. In addition, they reviewed the history of gabapentinoids and sources of recommendations for off-label use, such as guidelines and previous review articles.

Six major findings were reported: (1) evidence supporting gabapentin for diabetic neuropathy pain is “mixed at best”; (2) evidence supporting gabapentin for nondiabetic neuropathies is very limited; (3) evidence does not support gabapentinoids for radiculopathy or low back pain; (4) gabapentin has minimal benefit for fibromyalgia pain, based on minimal evidence; (5) evidence does not support gabapentinoids for acute herpes zoster pain; and (6) in almost all studies for other painful indications, gabapentinoids were ineffective or “associated with small analgesic effects that were statistically significant but of questionable clinical importance.”

Case studies complemented this overview, highlighting related clinical dilemmas that the investigators encounter “repeatedly” during inpatient and outpatient care. Along with off-label use, such as gabapentinoid prescriptions for acute sciatica, the investigators reported cases in which neuropathy was diagnosed in place of nonspecific lower body pain to facilitate gabapentin prescription. They also described apparent disregard for risks of polypharmacy in prescriptions for elderly patients and rote use of gabapentinoids in patients with diabetic neuropathy who did not have sufficient discomfort to warrant prescription.

The investigators also cited a number of problems with the language of reviews and guidelines involving gabapentinoids.

“The wording in many guidelines and review articles reinforces an inflated view of gabapentinoid effectiveness or fails to distinguish carefully between evidence-based and non–evidence-based recommendations,” they wrote, adding that clinicians may have misconceptions about neuropathic pain. “One unintended effect of the broad definition [of neuropathic pain] might be to create a mistaken perception that an effective drug for one type of neuropathic pain is effective for all neuropathic pain, regardless of underlying etiology or mechanism,” the investigators suggested.

Another facet of prescribing behavior could be explained in economic terms. Pregabalin, sold under the brand name Lyrica, is considerably more expensive than gabapentin; however, the investigators warned that the similarity of these agents does not equate with interchangeability, noting differences in bioavailability and rate of absorption.

“Unfortunately, published direct comparisons between the 2 drugs in double-blind studies of patients with chronic noncancer pain are virtually nonexistent,” the investigators wrote.

In addition to questionable effectiveness of gabapentinoids for off-label chronic noncancer pain syndromes, Dr. Goodman and Dr. Brett noted that the drugs produce a “substantial incidence of dizziness, somnolence, and gait disturbance.”

They also described a new trend of gabapentinoid abuse and diversion, which may not be surprising, considering that gabapentinoids are reported to augment opioid-induced euphoria.

“Evidence of misuse of gabapentinoids is accumulating and likely related to the opioid epidemic. A recent review article reported an overall population prevalence of gabapentinoid ‘misuse and abuse’ as high as 1%, with substantially higher prevalence noted among patients with opioid use disorders,” the investigators wrote. “This trend is troubling, particularly because concomitant use of opioids and gabapentinoids is associated with increased odds of opioid-related death. Whether these concerns apply to patients receiving long-term prescribed opioid therapy is unclear.”

In the era of the opioid crisis, the investigators acknowledged that many clinicians have serious concerns about adequately treating chronic noncancer pain.

“Comprehensive management of pain in primary care settings is difficult. It requires time and resources that are frequently unavailable,” the investigators wrote. “Many patients with chronic pain have limited or no access to high-quality pain practices or to nonpharmacologic interventions, such as cognitive behavior therapy.”

The investigators reported no external funding or conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Goodman CW et al. JAMA Intern Med. 2019 Mar 25. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.0086

Many clinicians are prescribing the gabapentinoid drugs pregabalin (Lyrica) and gabapentin (Neurontin) for off-label treatment of pain, despite a lack of supporting data or approval from the Food and Drug Administration, according to investigators.

Over the past 15 years, use of gabapentinoids has tripled, a level of growth that cannot be explained by prescriptions for approved indications, reported coauthors Christopher W. Goodman, MD, and Allan S. Brett, MD, of the University of South Carolina, Columbia. Instead, clinicians are turning to gabapentinoids, partly as an option to substitute for opioids, which now have greater prescribing restrictions as a result of the current opioid crisis.

Although clinicians may cite guidelines that support off-label use of gabapentinoids for pain, the investigators warned that many of these recommendations stand on shaky ground.

“Clinicians who prescribe gabapentinoids off-label for pain should be aware of the limited evidence and should acknowledge to patients that potential benefits are uncertain for most off-label uses,” the investigators wrote in a clinical review published online March 25 in JAMA Internal Medicine.

The investigators narrowed down 677 publications to 84 papers describing the use of gabapentinoids for outpatient noncancer pain syndromes for which they are not FDA approved; 54 for gabapentin and 30 for pregabalin. In the domain of analgesia, both agents are currently FDA-approved for postherpetic neuralgia, while pregabalin is additionally approved for pain associated with fibromyalgia and neuropathic pain from diabetic neuropathy and spinal cord injury. Indications in reviewed studies ranged broadly, from conditions somewhat related to those currently approved, such as unspecified neuropathy, to dissimilar conditions, such as chronic pancreatitis and burn injury.

The investigators summarized findings from randomized clinical trials while using case studies to illustrate potential problems with off-label use. In addition, they reviewed the history of gabapentinoids and sources of recommendations for off-label use, such as guidelines and previous review articles.

Six major findings were reported: (1) evidence supporting gabapentin for diabetic neuropathy pain is “mixed at best”; (2) evidence supporting gabapentin for nondiabetic neuropathies is very limited; (3) evidence does not support gabapentinoids for radiculopathy or low back pain; (4) gabapentin has minimal benefit for fibromyalgia pain, based on minimal evidence; (5) evidence does not support gabapentinoids for acute herpes zoster pain; and (6) in almost all studies for other painful indications, gabapentinoids were ineffective or “associated with small analgesic effects that were statistically significant but of questionable clinical importance.”

Case studies complemented this overview, highlighting related clinical dilemmas that the investigators encounter “repeatedly” during inpatient and outpatient care. Along with off-label use, such as gabapentinoid prescriptions for acute sciatica, the investigators reported cases in which neuropathy was diagnosed in place of nonspecific lower body pain to facilitate gabapentin prescription. They also described apparent disregard for risks of polypharmacy in prescriptions for elderly patients and rote use of gabapentinoids in patients with diabetic neuropathy who did not have sufficient discomfort to warrant prescription.

The investigators also cited a number of problems with the language of reviews and guidelines involving gabapentinoids.

“The wording in many guidelines and review articles reinforces an inflated view of gabapentinoid effectiveness or fails to distinguish carefully between evidence-based and non–evidence-based recommendations,” they wrote, adding that clinicians may have misconceptions about neuropathic pain. “One unintended effect of the broad definition [of neuropathic pain] might be to create a mistaken perception that an effective drug for one type of neuropathic pain is effective for all neuropathic pain, regardless of underlying etiology or mechanism,” the investigators suggested.

Another facet of prescribing behavior could be explained in economic terms. Pregabalin, sold under the brand name Lyrica, is considerably more expensive than gabapentin; however, the investigators warned that the similarity of these agents does not equate with interchangeability, noting differences in bioavailability and rate of absorption.

“Unfortunately, published direct comparisons between the 2 drugs in double-blind studies of patients with chronic noncancer pain are virtually nonexistent,” the investigators wrote.

In addition to questionable effectiveness of gabapentinoids for off-label chronic noncancer pain syndromes, Dr. Goodman and Dr. Brett noted that the drugs produce a “substantial incidence of dizziness, somnolence, and gait disturbance.”

They also described a new trend of gabapentinoid abuse and diversion, which may not be surprising, considering that gabapentinoids are reported to augment opioid-induced euphoria.

“Evidence of misuse of gabapentinoids is accumulating and likely related to the opioid epidemic. A recent review article reported an overall population prevalence of gabapentinoid ‘misuse and abuse’ as high as 1%, with substantially higher prevalence noted among patients with opioid use disorders,” the investigators wrote. “This trend is troubling, particularly because concomitant use of opioids and gabapentinoids is associated with increased odds of opioid-related death. Whether these concerns apply to patients receiving long-term prescribed opioid therapy is unclear.”

In the era of the opioid crisis, the investigators acknowledged that many clinicians have serious concerns about adequately treating chronic noncancer pain.

“Comprehensive management of pain in primary care settings is difficult. It requires time and resources that are frequently unavailable,” the investigators wrote. “Many patients with chronic pain have limited or no access to high-quality pain practices or to nonpharmacologic interventions, such as cognitive behavior therapy.”

The investigators reported no external funding or conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Goodman CW et al. JAMA Intern Med. 2019 Mar 25. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.0086

FROM JAMA INTERNAL MEDICINE

How has hospital medicine changed since you started?

HM19 attendees relay their perspectives on how the practice of hospital medicine has evolved over the course of their careers.

HM19 attendees relay their perspectives on how the practice of hospital medicine has evolved over the course of their careers.

HM19 attendees relay their perspectives on how the practice of hospital medicine has evolved over the course of their careers.

Hands-on critical care lessons provided at HM19

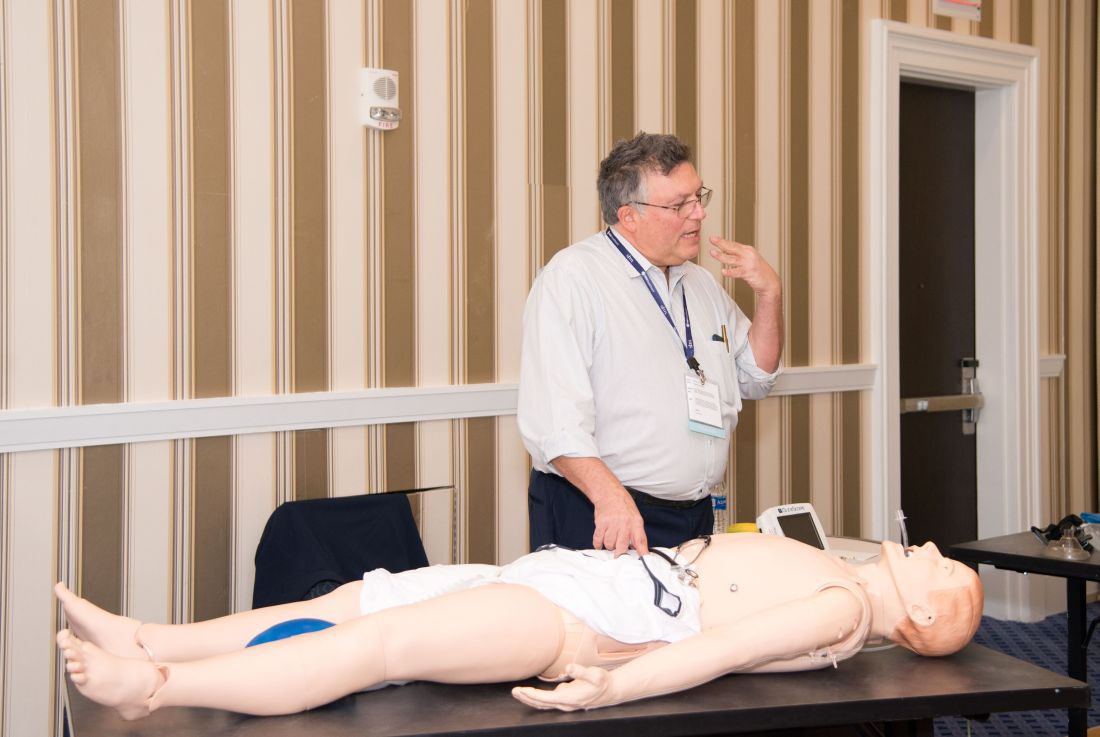

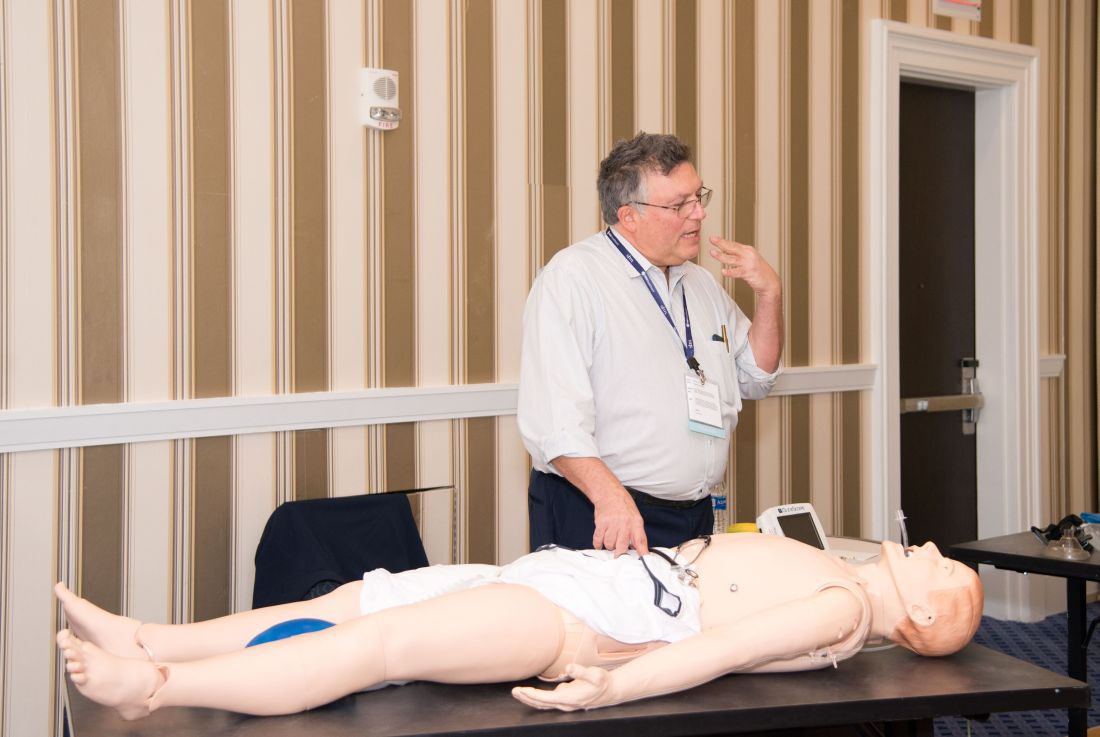

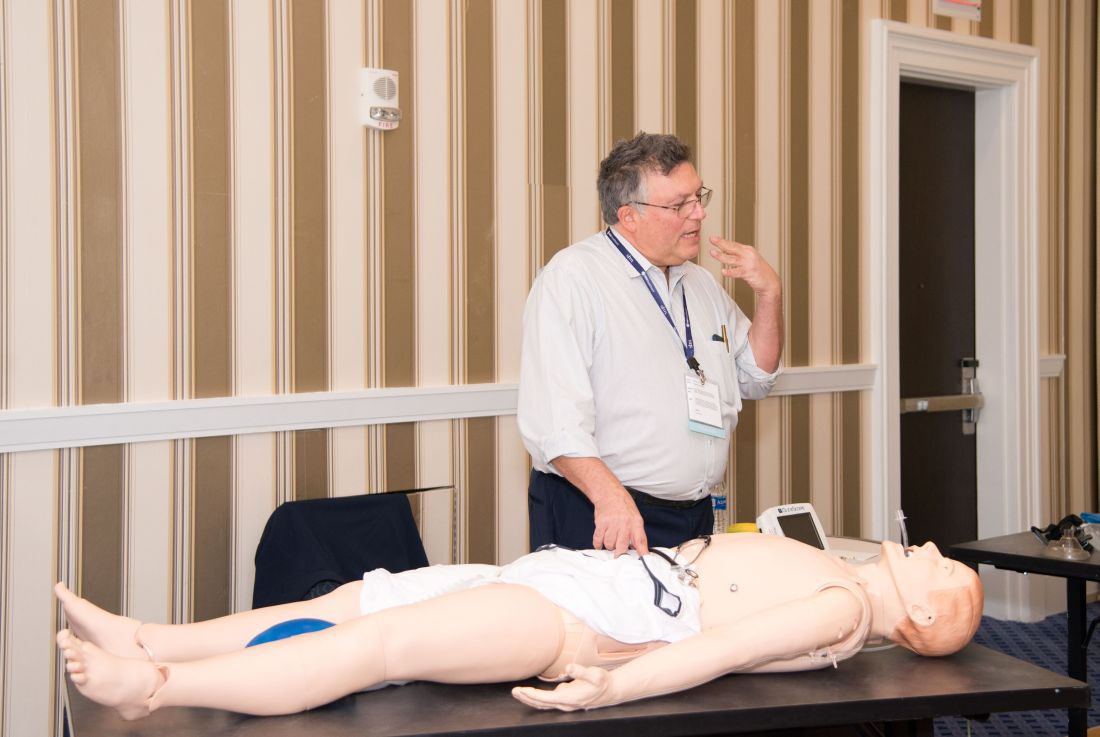

As the hospitalist tried to position the portable video laryngoscope properly in the airway of the critically ill “patient,” HM19 faculty moderator Brian Kaufman, MD, professor of medicine, anesthesiology, and neurology at New York University (NYU) School of Medicine, issued a word of caution: Rotating it into position should be done gently or there’s a risk of tearing tissue.

One step at a time, hospitalists attending the session grew more confident and knowledgeable in handling urgent matters involving patients who are critically ill, including cases of shock, mechanical ventilation, overdoses, and ultrasound.

Kevin Felner, MD, associate professor of medicine at NYU School of Medicine, said there’s a growing need for more exposure to caring for the critically ill, including intubation.

“There are a lot of hospitalists who are intubating, and they’re not formally trained in it because medicine residencies don’t typically train people to manage airways,” he said. “We’ve met hospitalists who’ve said, ‘I was hired and was told I had to manage an airway.’”

“It might massage some of the things you’re doing, make you afraid of things you should be afraid of, make you think about something that’s easy to do that you’re not doing, and make things safer,” Dr. Felner said.

In a simulation room, James Horowitz, MD, clinical assistant professor and cardiologist at NYU School of Medicine, demonstrated how to use a laryngeal mask airway (LMA), a simpler alternative to intubating the trachea for keeping an airway open. Dr. Kaufman, standing next to him, clarified how important a skill this is, especially when someone needs air in the next minute or is at risk of death.

“Knowing how to put an LMA in can be life-saving,” Dr. Kaufman said.

In a lecture on shock in the critically ill, Dr. Felner said it’s important to be nimble in handling this common problem –quickly identifying the cause, whether it’s a cardiogenic issue, a low-volume circulation problem, a question of vasodilation, or an obstructive problem. He said guidelines – such as aiming for a mean arterial pressure of 65 mm Hg –are helpful generally, but individuals routinely call for making exceptions to guidelines.

Anthony Andriotis, MD, a pulmonologist at NYU who specializes in critical care, offered an array of key points when managing patients with a ventilator. For instance, when you need to prolong a patient’s expiratory time so they can exhale air more effectively to get rid of entrapped air in their lungs, lowering their respiratory rate is far more effective than decreasing the time it takes them to breathe in or increasing the flow rate of the air they’re breathing.

Some basic points – such as remembering that it’s important to be aware of the pressure when volume control has been imposed and to be aware of volume control when the pressure has been set – are crucial, he said.

The idea behind the pre-course, Dr. Felner said, was to give hospitalists a chance to enter tricky situations with everything to gain, but nothing to lose. He described it as giving students “learning scars” – those times you made a serious error that left you with a lesson you’ll never forget.

“We’re trying to create learning scars, but in a safe scenario.”

As the hospitalist tried to position the portable video laryngoscope properly in the airway of the critically ill “patient,” HM19 faculty moderator Brian Kaufman, MD, professor of medicine, anesthesiology, and neurology at New York University (NYU) School of Medicine, issued a word of caution: Rotating it into position should be done gently or there’s a risk of tearing tissue.

One step at a time, hospitalists attending the session grew more confident and knowledgeable in handling urgent matters involving patients who are critically ill, including cases of shock, mechanical ventilation, overdoses, and ultrasound.

Kevin Felner, MD, associate professor of medicine at NYU School of Medicine, said there’s a growing need for more exposure to caring for the critically ill, including intubation.

“There are a lot of hospitalists who are intubating, and they’re not formally trained in it because medicine residencies don’t typically train people to manage airways,” he said. “We’ve met hospitalists who’ve said, ‘I was hired and was told I had to manage an airway.’”

“It might massage some of the things you’re doing, make you afraid of things you should be afraid of, make you think about something that’s easy to do that you’re not doing, and make things safer,” Dr. Felner said.

In a simulation room, James Horowitz, MD, clinical assistant professor and cardiologist at NYU School of Medicine, demonstrated how to use a laryngeal mask airway (LMA), a simpler alternative to intubating the trachea for keeping an airway open. Dr. Kaufman, standing next to him, clarified how important a skill this is, especially when someone needs air in the next minute or is at risk of death.

“Knowing how to put an LMA in can be life-saving,” Dr. Kaufman said.

In a lecture on shock in the critically ill, Dr. Felner said it’s important to be nimble in handling this common problem –quickly identifying the cause, whether it’s a cardiogenic issue, a low-volume circulation problem, a question of vasodilation, or an obstructive problem. He said guidelines – such as aiming for a mean arterial pressure of 65 mm Hg –are helpful generally, but individuals routinely call for making exceptions to guidelines.

Anthony Andriotis, MD, a pulmonologist at NYU who specializes in critical care, offered an array of key points when managing patients with a ventilator. For instance, when you need to prolong a patient’s expiratory time so they can exhale air more effectively to get rid of entrapped air in their lungs, lowering their respiratory rate is far more effective than decreasing the time it takes them to breathe in or increasing the flow rate of the air they’re breathing.

Some basic points – such as remembering that it’s important to be aware of the pressure when volume control has been imposed and to be aware of volume control when the pressure has been set – are crucial, he said.

The idea behind the pre-course, Dr. Felner said, was to give hospitalists a chance to enter tricky situations with everything to gain, but nothing to lose. He described it as giving students “learning scars” – those times you made a serious error that left you with a lesson you’ll never forget.

“We’re trying to create learning scars, but in a safe scenario.”

As the hospitalist tried to position the portable video laryngoscope properly in the airway of the critically ill “patient,” HM19 faculty moderator Brian Kaufman, MD, professor of medicine, anesthesiology, and neurology at New York University (NYU) School of Medicine, issued a word of caution: Rotating it into position should be done gently or there’s a risk of tearing tissue.

One step at a time, hospitalists attending the session grew more confident and knowledgeable in handling urgent matters involving patients who are critically ill, including cases of shock, mechanical ventilation, overdoses, and ultrasound.

Kevin Felner, MD, associate professor of medicine at NYU School of Medicine, said there’s a growing need for more exposure to caring for the critically ill, including intubation.

“There are a lot of hospitalists who are intubating, and they’re not formally trained in it because medicine residencies don’t typically train people to manage airways,” he said. “We’ve met hospitalists who’ve said, ‘I was hired and was told I had to manage an airway.’”

“It might massage some of the things you’re doing, make you afraid of things you should be afraid of, make you think about something that’s easy to do that you’re not doing, and make things safer,” Dr. Felner said.

In a simulation room, James Horowitz, MD, clinical assistant professor and cardiologist at NYU School of Medicine, demonstrated how to use a laryngeal mask airway (LMA), a simpler alternative to intubating the trachea for keeping an airway open. Dr. Kaufman, standing next to him, clarified how important a skill this is, especially when someone needs air in the next minute or is at risk of death.

“Knowing how to put an LMA in can be life-saving,” Dr. Kaufman said.

In a lecture on shock in the critically ill, Dr. Felner said it’s important to be nimble in handling this common problem –quickly identifying the cause, whether it’s a cardiogenic issue, a low-volume circulation problem, a question of vasodilation, or an obstructive problem. He said guidelines – such as aiming for a mean arterial pressure of 65 mm Hg –are helpful generally, but individuals routinely call for making exceptions to guidelines.

Anthony Andriotis, MD, a pulmonologist at NYU who specializes in critical care, offered an array of key points when managing patients with a ventilator. For instance, when you need to prolong a patient’s expiratory time so they can exhale air more effectively to get rid of entrapped air in their lungs, lowering their respiratory rate is far more effective than decreasing the time it takes them to breathe in or increasing the flow rate of the air they’re breathing.

Some basic points – such as remembering that it’s important to be aware of the pressure when volume control has been imposed and to be aware of volume control when the pressure has been set – are crucial, he said.

The idea behind the pre-course, Dr. Felner said, was to give hospitalists a chance to enter tricky situations with everything to gain, but nothing to lose. He described it as giving students “learning scars” – those times you made a serious error that left you with a lesson you’ll never forget.

“We’re trying to create learning scars, but in a safe scenario.”

Occurrence of pulmonary embolisms in hospitalized patients nearly doubled during 2004-2015

NEW ORLEANS –

During 2004-2015 the incidence of all diagnosed pulmonary embolism (PE), based on discharge diagnoses, rose from 5.4 cases/1,000 hospitalized patients in 2004 to 9.7 cases/1,000 hospitalized patients in 2015, an 80% increase, Joshua B. Goldberg, MD said at the annual meeting of the American College of Cardiology. The incidence of major PE – defined as a patient who needed vasopressor treatment, mechanical ventilation, or had nonseptic shock – rose from 7.9% of all hospitalized PE diagnoses in 2004 to 9.7% in 2015, a 23% relative increase.

The data also documented a shifting pattern of treatment for all hospitalized patients with PE, and especially among patients with major PE. During the study period, treatment with systemic thrombolysis for all PE rose nearly threefold, and catheter-directed therapy began to show a steady rise in use from 0.2% of all patients in 2011 (and before) to 1% of all patients by 2015. Surgical intervention remained lightly used throughout, with about 0.2% of all PE patients undergoing surgery annually.

Most of these intervention options focused on patients with major PE. Among patients in this subgroup with more severe disease, use of one of these three types of interventions rose from 6% in 2004 to 12% in 2015, mostly driven by a rise in systemic thrombolysis, which jumped from 3% of major PE in 2004 to 9% in 2015. However, the efficacy of systemic thrombolysis in patients with major PE remains suspect. In 2004, 39% of patients with major PE treated with systemic thrombolysis died in hospital; in 2015 the number was 47%. “The data don’t support using systemic thrombolysis to treat major PE; the mortality is high,” noted Dr. Goldberg, a cardiothoracic surgeon at Westchester Medical Center in Valhalla, N.Y.

Although catheter-directed therapy began to be much more widely used in U.S. practice starting in about 2015, during the period studied its use for major PE held fairly steady at roughly 2%-3%, but this approach also showed substantial shortcomings for the major PE population. These sicker patients treated with catheter-directed therapy had 37% mortality in 2004 and a 31% mortality in 2015, a difference that was not statistically significant. In general, PE patients enrolled in the catheter-directed therapy trials were not as sick as the major PE patients who get treated with surgery in routine practice, Dr. Goldberg said in an interview.

The data showed much better performance using surgery, although only 1,237 patients of the entire group of 713,083 PE patients studied in the database underwent surgical embolectomy. Overall, in-hospital mortality in these patients was 22%, but in a time trend analysis, mortality among all PE patients treated with surgery fell from 32% in 2004 to 14% in 2015; among patients with major PE treated with surgery, mortality fell from 52% in 2004 to 21% in 2015.

Dr. Goldberg attributed the success of surgery in severe PE patients to the definitive nature of embolectomy and the concurrent use of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation that helps stabilize acutely ill PE patients. He also cited refinements that surgery underwent during the 2004-2015 period based on the experience managing chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension, including routine use of cardiopulmonary bypass during surgery. “Very high risk [PE] patients should go straight to surgery, unless the patient is at high risk for surgery because of conditions like prior sternotomy or very advanced age, in which case catheter-directed therapy may be a safer option, he said. He cited a recent 5% death rate after surgery at his center among patients with major PE who did not require cardiopulmonary resuscitation.

The database Dr. Goldberg and his collaborator reviewed included 12,735 patients treated by systemic thrombolysis, and 2,595 treated by catheter-directed therapy. Patients averaged 63 years old. The most common indicator of major PE was mechanical ventilation, used on 8% of all PE patients in the study. Non-septic shock occurred in 2%, and just under 1% needed vasopressor treatment.

Published guidelines on PE management from several medical groups are “vague and have numerous caveats,” Dr. Goldberg said. He is participating in an update to the 2011 PE management statement from the American College of Cardiology and American Heart Association (Circulation. 2011 April 26;123[16]:1788-1830).

The study received no commercial funding. Dr. Goldberg had no disclosures.

SOURCE: Haider A et al. J Amer Coll Cardiol. 2019 March;73:9[suppl 1]: doi: 10.1016/S0735-1097(19)32507-0

At my center, Allegheny General Hospital, we often rely on catheter-directed therapy to treat major pulmonary embolism. We now perform more catheter-directed interventions than surgical embolectomies. Generally, when treating patients with major pulmonary embolism it comes down to a choice between those two options. We rarely use systemic thrombolysis for major pulmonary embolism any more.

Raymond L. Benza, MD , is professor of medicine at Temple University College of Medicine and program director for advanced heart failure at the Allegheny Health Network in Pittsburgh. He has been a consultant to Actelion, Gilead, and United Therapeutics, and he has received research funding from Bayer. He made these comments in an interview.

At my center, Allegheny General Hospital, we often rely on catheter-directed therapy to treat major pulmonary embolism. We now perform more catheter-directed interventions than surgical embolectomies. Generally, when treating patients with major pulmonary embolism it comes down to a choice between those two options. We rarely use systemic thrombolysis for major pulmonary embolism any more.

Raymond L. Benza, MD , is professor of medicine at Temple University College of Medicine and program director for advanced heart failure at the Allegheny Health Network in Pittsburgh. He has been a consultant to Actelion, Gilead, and United Therapeutics, and he has received research funding from Bayer. He made these comments in an interview.

At my center, Allegheny General Hospital, we often rely on catheter-directed therapy to treat major pulmonary embolism. We now perform more catheter-directed interventions than surgical embolectomies. Generally, when treating patients with major pulmonary embolism it comes down to a choice between those two options. We rarely use systemic thrombolysis for major pulmonary embolism any more.

Raymond L. Benza, MD , is professor of medicine at Temple University College of Medicine and program director for advanced heart failure at the Allegheny Health Network in Pittsburgh. He has been a consultant to Actelion, Gilead, and United Therapeutics, and he has received research funding from Bayer. He made these comments in an interview.

NEW ORLEANS –

During 2004-2015 the incidence of all diagnosed pulmonary embolism (PE), based on discharge diagnoses, rose from 5.4 cases/1,000 hospitalized patients in 2004 to 9.7 cases/1,000 hospitalized patients in 2015, an 80% increase, Joshua B. Goldberg, MD said at the annual meeting of the American College of Cardiology. The incidence of major PE – defined as a patient who needed vasopressor treatment, mechanical ventilation, or had nonseptic shock – rose from 7.9% of all hospitalized PE diagnoses in 2004 to 9.7% in 2015, a 23% relative increase.

The data also documented a shifting pattern of treatment for all hospitalized patients with PE, and especially among patients with major PE. During the study period, treatment with systemic thrombolysis for all PE rose nearly threefold, and catheter-directed therapy began to show a steady rise in use from 0.2% of all patients in 2011 (and before) to 1% of all patients by 2015. Surgical intervention remained lightly used throughout, with about 0.2% of all PE patients undergoing surgery annually.

Most of these intervention options focused on patients with major PE. Among patients in this subgroup with more severe disease, use of one of these three types of interventions rose from 6% in 2004 to 12% in 2015, mostly driven by a rise in systemic thrombolysis, which jumped from 3% of major PE in 2004 to 9% in 2015. However, the efficacy of systemic thrombolysis in patients with major PE remains suspect. In 2004, 39% of patients with major PE treated with systemic thrombolysis died in hospital; in 2015 the number was 47%. “The data don’t support using systemic thrombolysis to treat major PE; the mortality is high,” noted Dr. Goldberg, a cardiothoracic surgeon at Westchester Medical Center in Valhalla, N.Y.

Although catheter-directed therapy began to be much more widely used in U.S. practice starting in about 2015, during the period studied its use for major PE held fairly steady at roughly 2%-3%, but this approach also showed substantial shortcomings for the major PE population. These sicker patients treated with catheter-directed therapy had 37% mortality in 2004 and a 31% mortality in 2015, a difference that was not statistically significant. In general, PE patients enrolled in the catheter-directed therapy trials were not as sick as the major PE patients who get treated with surgery in routine practice, Dr. Goldberg said in an interview.

The data showed much better performance using surgery, although only 1,237 patients of the entire group of 713,083 PE patients studied in the database underwent surgical embolectomy. Overall, in-hospital mortality in these patients was 22%, but in a time trend analysis, mortality among all PE patients treated with surgery fell from 32% in 2004 to 14% in 2015; among patients with major PE treated with surgery, mortality fell from 52% in 2004 to 21% in 2015.

Dr. Goldberg attributed the success of surgery in severe PE patients to the definitive nature of embolectomy and the concurrent use of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation that helps stabilize acutely ill PE patients. He also cited refinements that surgery underwent during the 2004-2015 period based on the experience managing chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension, including routine use of cardiopulmonary bypass during surgery. “Very high risk [PE] patients should go straight to surgery, unless the patient is at high risk for surgery because of conditions like prior sternotomy or very advanced age, in which case catheter-directed therapy may be a safer option, he said. He cited a recent 5% death rate after surgery at his center among patients with major PE who did not require cardiopulmonary resuscitation.

The database Dr. Goldberg and his collaborator reviewed included 12,735 patients treated by systemic thrombolysis, and 2,595 treated by catheter-directed therapy. Patients averaged 63 years old. The most common indicator of major PE was mechanical ventilation, used on 8% of all PE patients in the study. Non-septic shock occurred in 2%, and just under 1% needed vasopressor treatment.

Published guidelines on PE management from several medical groups are “vague and have numerous caveats,” Dr. Goldberg said. He is participating in an update to the 2011 PE management statement from the American College of Cardiology and American Heart Association (Circulation. 2011 April 26;123[16]:1788-1830).

The study received no commercial funding. Dr. Goldberg had no disclosures.

SOURCE: Haider A et al. J Amer Coll Cardiol. 2019 March;73:9[suppl 1]: doi: 10.1016/S0735-1097(19)32507-0

NEW ORLEANS –

During 2004-2015 the incidence of all diagnosed pulmonary embolism (PE), based on discharge diagnoses, rose from 5.4 cases/1,000 hospitalized patients in 2004 to 9.7 cases/1,000 hospitalized patients in 2015, an 80% increase, Joshua B. Goldberg, MD said at the annual meeting of the American College of Cardiology. The incidence of major PE – defined as a patient who needed vasopressor treatment, mechanical ventilation, or had nonseptic shock – rose from 7.9% of all hospitalized PE diagnoses in 2004 to 9.7% in 2015, a 23% relative increase.

The data also documented a shifting pattern of treatment for all hospitalized patients with PE, and especially among patients with major PE. During the study period, treatment with systemic thrombolysis for all PE rose nearly threefold, and catheter-directed therapy began to show a steady rise in use from 0.2% of all patients in 2011 (and before) to 1% of all patients by 2015. Surgical intervention remained lightly used throughout, with about 0.2% of all PE patients undergoing surgery annually.

Most of these intervention options focused on patients with major PE. Among patients in this subgroup with more severe disease, use of one of these three types of interventions rose from 6% in 2004 to 12% in 2015, mostly driven by a rise in systemic thrombolysis, which jumped from 3% of major PE in 2004 to 9% in 2015. However, the efficacy of systemic thrombolysis in patients with major PE remains suspect. In 2004, 39% of patients with major PE treated with systemic thrombolysis died in hospital; in 2015 the number was 47%. “The data don’t support using systemic thrombolysis to treat major PE; the mortality is high,” noted Dr. Goldberg, a cardiothoracic surgeon at Westchester Medical Center in Valhalla, N.Y.

Although catheter-directed therapy began to be much more widely used in U.S. practice starting in about 2015, during the period studied its use for major PE held fairly steady at roughly 2%-3%, but this approach also showed substantial shortcomings for the major PE population. These sicker patients treated with catheter-directed therapy had 37% mortality in 2004 and a 31% mortality in 2015, a difference that was not statistically significant. In general, PE patients enrolled in the catheter-directed therapy trials were not as sick as the major PE patients who get treated with surgery in routine practice, Dr. Goldberg said in an interview.

The data showed much better performance using surgery, although only 1,237 patients of the entire group of 713,083 PE patients studied in the database underwent surgical embolectomy. Overall, in-hospital mortality in these patients was 22%, but in a time trend analysis, mortality among all PE patients treated with surgery fell from 32% in 2004 to 14% in 2015; among patients with major PE treated with surgery, mortality fell from 52% in 2004 to 21% in 2015.

Dr. Goldberg attributed the success of surgery in severe PE patients to the definitive nature of embolectomy and the concurrent use of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation that helps stabilize acutely ill PE patients. He also cited refinements that surgery underwent during the 2004-2015 period based on the experience managing chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension, including routine use of cardiopulmonary bypass during surgery. “Very high risk [PE] patients should go straight to surgery, unless the patient is at high risk for surgery because of conditions like prior sternotomy or very advanced age, in which case catheter-directed therapy may be a safer option, he said. He cited a recent 5% death rate after surgery at his center among patients with major PE who did not require cardiopulmonary resuscitation.

The database Dr. Goldberg and his collaborator reviewed included 12,735 patients treated by systemic thrombolysis, and 2,595 treated by catheter-directed therapy. Patients averaged 63 years old. The most common indicator of major PE was mechanical ventilation, used on 8% of all PE patients in the study. Non-septic shock occurred in 2%, and just under 1% needed vasopressor treatment.

Published guidelines on PE management from several medical groups are “vague and have numerous caveats,” Dr. Goldberg said. He is participating in an update to the 2011 PE management statement from the American College of Cardiology and American Heart Association (Circulation. 2011 April 26;123[16]:1788-1830).

The study received no commercial funding. Dr. Goldberg had no disclosures.

SOURCE: Haider A et al. J Amer Coll Cardiol. 2019 March;73:9[suppl 1]: doi: 10.1016/S0735-1097(19)32507-0

REPORTING FROM ACC 2019

Planning for change in hospitalist practice management

At Sunday’s HM19 pre-course “Oh, the Places We’ll Go! Practice Management Tools for Navigating the Changing Role of Your Hospital Medicine Group,” the theme was how to anticipate and embrace changing roles as hospital medicine groups are being asked to take on more responsibility.

“The scope of hospitalist practice is evolving rapidly, both clinically and in terms of all of the other things that hospitalists are being asked to do,” said Leslie Flores, MHA, SFHM, a partner at Nelson Flores Hospital Medicine Consultants, La Quinta, Calif., and course co-director, in an interview before the pre-course. “Our goals with this program are to help leaders position their hospitalist groups for success with this changing environment that they’re living in and the changing roles of hospitalists.”

In an audience poll at the beginning of the pre-course, attendees – a majority of whom were practicing hospitalists and managers of hospitalist groups – said their biggest challenge areas were related to compensation or workflows that have not evolved to match their changing role, and disagreements over who should admit patients.

One of the goals of the session was to give hospitalist leaders ideas to address these issues, which included information on how to implement better team-based care and interdisciplinary care models within their groups, as well as how to adjust their compensation, scheduling, and staffing models to prepare for this “new world of hospitalist medicine,” said Ms. Flores.

“One of the biggest sources of contention and stress that we see in hospitalist groups is that there’s just so much change, and it’s happening so rapidly, and people are having a hard time really figuring out how to deal with all of that,” she said.