User login

Long-term management of patients with unstable angina and NSTEMI

- Immediately upon presentation of non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI), aspirin therapy (81–325 mg) should be initiated (A). If aspirin is contraindicated, clopidogrel (300-mg loading dose followed by 75 mg/d) should be administered (A).

- In patients for whom an early noninterventional approach is planned, or for patients not at high risk of bleeding for whom percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) is planned, clopidogrel 75 mg (once daily) should be added to aspirin therapy as quickly as possible and continued for up to 9 months (B).

- Aggressive low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol-lowering therapy and general cardiovascular risk reduction are important in long-term management of these patients. Thus, a fibrate or niacin should be administered if the high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol is <40 mg/dL (B).

- In patients with LDL cholesterol >100 mg/dL, HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors (statins) and diet should be started during admission and continued after discharge (B).

In the long-term care of patients with acute coronary syndrome, recently published w that prognostic benefits improve with more aggressive antiplatelet therapy for those at high risk for recurrent events. Moreover, long-term care should include aggressive LDL cholesterol-lowering therapy and use of beta-blockers and angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors, in addition to diet modification and exercise.

STEMI and NSTEMI: The new nomenclature

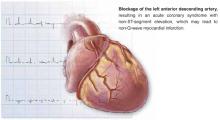

Coronary artery disease, the leading cause of death in the United States,1 can manifest in many ways involving a constellation of symptoms, electrocardiogram changes, and serum markers. These acute coronary syndromes result from decreased coronary blood flow and cause chest discomfort, usually at rest, with or without characteristic radiation, or such comparable anginal equivalents as weakness, dyspnea, and diaphoresis.

STEMI. An elevated ST-segment with elevated levels of such cardiac markers as creatine kinase myocardial band or troponin I or troponin T are consistent with a diagnosis of ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI). The old term, acute myocardial infarction, was defined by the presence of pathological Q waves (Q wave MI).

NSTEMI. Patients with elevated serum levels of creatine kinase myocardial band or troponin I or troponin T, but no ST-segment elevation, are said to have non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI).

Unstable angina. Normal levels of serum cardiac markers and an absence of ST-elevation are consistent with a diagnosis of unstable angina (Figure). Of patients with STEMI, most will ultimately experience a Q-wave MI; a minority will have a non–Q-wave MI. Of patients with NSTEMI, most will sustain a non–Q-wave MI, while a minority will sustain a Q-wave MI.

Unstable angina and NSTEMI are urgent and life-threatening problems. Chest pain and related symptoms account for 5.3 million visits to US emergency departments per year2 and account for 1.4 million hospitalizations annually.3 Approximately 15% of those presenting with unstable angina and NSTEMI go on to (re)infarct or die within 30 days.4

FIGURE

Unstable angina and NSTEMI

FIGURE

Nomenclature of acute coronary syndrome

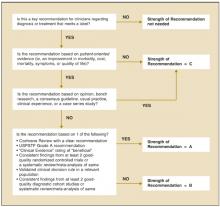

ACC/AHA Guidelines

In 2000 the American College of Cardiology and the American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) Task Force on Practice Guidelines published their evidence-based recommendations for treatment of unstable angina/NSTEMI following an exhaustive review of the literature.

New trials in acute coronary syndromes

Since 2000, knowledge of acute coronary syndromes advanced considerably with results of large pivotal randomized controlled studies, which necessitated updating the ACC/AHA guidelines just 21 months after their completion. The most notable of these studies were the Clopidogrel in Unstable Angina to Prevent Recurrent Ischemic Events (CURE) trial,6 the Percutaneous Coronary Intervention (PCI)-CURE7 subset analysis, and the Myocardial Ischemia Reduction with Aggressive Cholesterol Lowering (MIRACL) trial.8

Although incorporation of antiplatelet therapy is the focus of this article, the ultimate objective of the new revised guidelines is improved clinical outcomes for patients with acute coronary syndromes by improving early risk assessment, using revascularization procedures aggressively when risk for future cardiac events is high, using short- and long-term antiplatelet and antithrombotic agents, and modifying long-term risk.

2002 revised guidelines

The studies reviewed in the 2002 revised guidelines assessed multiple therapies in the reduction of recurrent MI, stroke, and other cardiovascular events following patients’ presentation with unstable angina and NSTEMI. The studies also evaluated traditional therapies for acute coronary syndromes, such as unfractionated heparin, beta-blockers, and aspirin, as well as more recent therapies, including low-molecular-weight heparin, antiplatelet therapy (parenteral glycoprotein IIb/IIIa [GP IIb/IIIa] antagonists and ADP-receptor antagonists [thienopyridines]), lipid-lowering therapy (HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors, or statins), and antihypertensive agents.2

The results of these trials have lead to changes in the initial management of patients following an new ischemic event, as well as the choice of medical therapy begun in the hospital and continued following discharge. Patients are given an individualized medical regimen based on specific needs that include in-hospital findings relating to the type of recent procedure, risk factors for subsequent ischemic events and drug tolerability. Such a regimen, although beyond the scope of this discussion, can be recalled as “ABCDE,” for Anti-platelet agents/ACE inhibitors, Beta-blockers, Blood pressure control, Cholesterol (lipid)-lowering agents, Cigarette cessation, Diet modification, Diabetes control, Exercise, and Education.

Important changes in long-term management

For most primary care physicians—with the possible exception of those in rural areas, who are faced with the burden of emergent care—the most important aspect of the revised guidelines is the changes in recommendations for long-term management of patients with unstable angina and NSTEMI. The goal of these new recommendations is to reduce the risk of subsequent cardiovascular events, such as death, recurrent MI, congestive heart failure, and stroke. Based on the results of the groundbreaking studies reviewed by the ACC/AHA panel, major changes to the original guidelines were necessary for the areas of long-term antiplatelet therapy and risk reduction.

TABLE

ACC/AHA task force classifications on patient evaluation and therapy

| Levels of evidence | ||

|---|---|---|

| A (highest) | B (intermediate) | C (lowest) |

| Data derived from multiple randomized clinical trials involving large numbers of patients. | Data derived from limited number of randomized clinical trials involving small numbers of patients or from analyses of nonrandomized trials or observation registries. | Basis of recommendation from expert opinion. large numbers of patients. |

| Recommendations made were based on expert analyses of published data. | ||

Antiplatelet therapy

Antiplatelet therapy—aspirin, GP IIb/IIIa antagonists, or an ADP-receptor antagonist (eg, clopidogrel)—is critical in the treatment and management of patients with unstable angina/NSTEMI.2 Based on the ACC/AHA Task Force classification (Table), aspirin (81–325 mg) should be initiated as quickly as possible after the condition is recognized, and continued indefinitely (SOR: A).

Clopidogrel (300-mg loading dose followed by 75 mg/d) should be administered to patients unable to take aspirin (SOR: A). In addition, clopidogrel 75 mg (once daily) should be added to aspirin therapy as quickly as possible and continued for up to 9 months in patients for whom an early noninterventional approach is planned (SOR: A), or for patients with a planned PCI who are not at high risk of bleeding (SOR: B).2

The CURE trial: clopidogrel and aspirin

The principal studies underlying the new recommendations for long-term antiplatelet therapy are the CURE trial6 and the PCI-CURE7 subset analysis. In the CURE trial, 12,562 patients who presented with unstable angina/NSTEMI within 24 hours following the onset of symptoms were randomized to receive clopidogrel (loading dose of 300 mg followed by 75 mg/d) with aspirin or placebo with aspirin for 3 to 12 months (mean follow-up, 9 months).

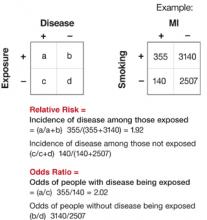

The relative risk (RR) of the primary composite outcome including incidence of cardiovascular death, nonfatal MI, or stroke was lower by 20% (RR=0.80; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.72–0.90; P<.001) in the clopidogrel arm. Similarly, a composite outcome also including revascularization was lower by 14% (RR=0.86; P<.001) for those who received clopidogrel. Benefits were seen in all risk groups. A significant increase in bleeding events was observed in the group that received clopidogrel plus aspirin compared with aspirin alone (major bleeding, P=.001; minor bleeding, P<.001).6

CURE patients were followed for up to 1 year, with a mean follow-up period of 9 months. In addition to the early benefits seen, from day 31 up to 1 year there was a highly significant incremental reduction of 18% in the primary outcome (P<.001) with clopidogrel.7

The PCI-CURE subset: Percutaneous coronary interventions

In the PCI-CURE trial, a subset of patients recruited for CURE who underwent PCI was pretreated with aspirin 325 mg and clopidogrel 75 mg for a median of 10 days. These patients received either clopidogrel or ticlopidine for 4 weeks, and then were restarted on either clopidogrel 75 mg (80%) or placebo in addition to aspirin for an additional mean of 8 months with up to 1 year of follow-up.

Long-term administration of clopidogrel 75 mg following PCI resulted in a 30% reduction (RR=0.70; 95% CI, 0.50–0.70; P=.03) in cardiovascular death, MI, and any revascularization, with a 31% reduction in cardiovascular death or MI (P=.002) compared with placebo. Major bleeding rates were similar between groups (P=.64).9

The CREDO study

The new guidelines for long-term antiplatelet therapy are further supported by the subsequently published Clopidogrel for the Reduction of Events During Observation (CREDO) study.10 CREDO demonstrated a 26.9% relative risk reduction in the combined risk of death, MI, or stroke (95% CI, 3.9%–44.4%; P=.02) in patients with long-term (12 months) aspirin plus clopidogrel 75 mg therapy compared with aspirin plus placebo in 2116 patients undergoing elective PCI or deemed at high likelihood of undergoing PCI. There was no significant increase in the risk of major bleeding (P=.07) between the placebo and clopidogrel arms.

Risk reduction

The revised guidelines also included updated recommendations for risk reduction. It is now recommended that a fibrate or niacin be administered if the HDL cholesterol level is <40 mg/dL (SOR: B).2 Further, statins and a heart-healthy diet should be started during admission and continued after discharge for patients with LDL cholesterol >100 mg/dL (SOR: B).2

This recommendation is based in part on the MIRACL trial, in which 3086 acute coronary syndrome patients treated with atorvastatin, 24 to 96 hours after hospital admission, demonstrated a significant reduction in the composite rate of death, nonfatal MI, resuscitated cardiac arrest, or recurrent ischemia compared with those who received placebo (14.8% vs 17.4%) (RR=0.84; 95% CI, 0.70–1.00; P=.048). Patients were followed for up to 16 weeks after starting therapy. Abnormal liver transaminases (>3 times upper limit of normal) occurred more often in the atorvastatin group than the placebo group (2.5% vs 0.6%; P<.001).8

- Atorvastatin • Lipitor

- Clopidogrel • Plavix

- Ticlopidine • Ticlid

Correspondence

John S. Banas, MD, FACC, Morristown Memorial Hospital, 100 Madison Ave, Morristown, NJ 07960. E-mail: [email protected].

1. American Heart Association. Heart and Stroke Statistical Update. Available at: www.americanheart.org. Accessed on March 31, 2004.

2. Braunwald E, Antman EM, Beasley JW, et al. ACC/AHA guideline update for the management of patients with unstable angina and non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction—2002: summary article: report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation 2002;106:1893-1900.

3. Graves EJ, Kozak LJ. Detailed diagnoses and procedures, National Hospital Discharge Survey, 1996. National Center for Health Statistics. Vital Health Stat 1998;13:i-iii,1-151.

4. The Pursuit Trial Investigators. Inhibition of platelet glycoprotein IIb/IIIa with eptifibatide in patients with acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med 1998;339:436-443.

5. Braunwald E, Antman EM, Beasley JW, et al. ACC/AHA guidelines for the management of patients with unstable angina and non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Committee on the Management of Patients With Unstable Angina). J Am Coll Cardiol 2000;36:970-1062.

6. Yusuf S, Zhao F, Mehta SR, Chrolavicius S, Tognoni G, Fox KK. Effects of clopidogrel in addition to aspirin in patients with acute coronary syndromes without ST-segment elevation. N Eng J Med 2001;345:494-502.

7. Mehta SR, Yusuf S. Short- and long-term oral antiplatelet therapy in acute coronary syndromes and percutaneous coronary interventions. J Am Coll Cardiol 2003;41:79S-88S.

8. Schwartz GG, Olsson AG, Ezekowitz MD, et al. Effects of atorvastatin on early recurrent ischemic events in acute coronary syndromes: the MIRACL study, a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2001;285:1711-1718.

9. Mehta SR, Yusuf S, Peters RJ, et al. Effects of pretreatment with clopidogrel and aspirin followed by long-term therapy in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention: the PCI-CURE study. Lancet 2001;358:527-533.

10. Steinhubl SR, Berger PB. Mann JT for the CREDO Investigators. Early and sustained dual oral antiplatelet therapy following percutaneous coronary intervention. A randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2002;288:2411-2420.

11. Antman EM, Braunwald E. Acute myocardial infarction. In: Braunwald E, ed. Heart Disease: A Textbook of Cardiovascular Medicine. Philadelphia, Pa: WB Saunders, 1997.

- Immediately upon presentation of non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI), aspirin therapy (81–325 mg) should be initiated (A). If aspirin is contraindicated, clopidogrel (300-mg loading dose followed by 75 mg/d) should be administered (A).

- In patients for whom an early noninterventional approach is planned, or for patients not at high risk of bleeding for whom percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) is planned, clopidogrel 75 mg (once daily) should be added to aspirin therapy as quickly as possible and continued for up to 9 months (B).

- Aggressive low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol-lowering therapy and general cardiovascular risk reduction are important in long-term management of these patients. Thus, a fibrate or niacin should be administered if the high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol is <40 mg/dL (B).

- In patients with LDL cholesterol >100 mg/dL, HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors (statins) and diet should be started during admission and continued after discharge (B).

In the long-term care of patients with acute coronary syndrome, recently published w that prognostic benefits improve with more aggressive antiplatelet therapy for those at high risk for recurrent events. Moreover, long-term care should include aggressive LDL cholesterol-lowering therapy and use of beta-blockers and angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors, in addition to diet modification and exercise.

STEMI and NSTEMI: The new nomenclature

Coronary artery disease, the leading cause of death in the United States,1 can manifest in many ways involving a constellation of symptoms, electrocardiogram changes, and serum markers. These acute coronary syndromes result from decreased coronary blood flow and cause chest discomfort, usually at rest, with or without characteristic radiation, or such comparable anginal equivalents as weakness, dyspnea, and diaphoresis.

STEMI. An elevated ST-segment with elevated levels of such cardiac markers as creatine kinase myocardial band or troponin I or troponin T are consistent with a diagnosis of ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI). The old term, acute myocardial infarction, was defined by the presence of pathological Q waves (Q wave MI).

NSTEMI. Patients with elevated serum levels of creatine kinase myocardial band or troponin I or troponin T, but no ST-segment elevation, are said to have non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI).

Unstable angina. Normal levels of serum cardiac markers and an absence of ST-elevation are consistent with a diagnosis of unstable angina (Figure). Of patients with STEMI, most will ultimately experience a Q-wave MI; a minority will have a non–Q-wave MI. Of patients with NSTEMI, most will sustain a non–Q-wave MI, while a minority will sustain a Q-wave MI.

Unstable angina and NSTEMI are urgent and life-threatening problems. Chest pain and related symptoms account for 5.3 million visits to US emergency departments per year2 and account for 1.4 million hospitalizations annually.3 Approximately 15% of those presenting with unstable angina and NSTEMI go on to (re)infarct or die within 30 days.4

FIGURE

Unstable angina and NSTEMI

FIGURE

Nomenclature of acute coronary syndrome

ACC/AHA Guidelines

In 2000 the American College of Cardiology and the American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) Task Force on Practice Guidelines published their evidence-based recommendations for treatment of unstable angina/NSTEMI following an exhaustive review of the literature.

New trials in acute coronary syndromes

Since 2000, knowledge of acute coronary syndromes advanced considerably with results of large pivotal randomized controlled studies, which necessitated updating the ACC/AHA guidelines just 21 months after their completion. The most notable of these studies were the Clopidogrel in Unstable Angina to Prevent Recurrent Ischemic Events (CURE) trial,6 the Percutaneous Coronary Intervention (PCI)-CURE7 subset analysis, and the Myocardial Ischemia Reduction with Aggressive Cholesterol Lowering (MIRACL) trial.8

Although incorporation of antiplatelet therapy is the focus of this article, the ultimate objective of the new revised guidelines is improved clinical outcomes for patients with acute coronary syndromes by improving early risk assessment, using revascularization procedures aggressively when risk for future cardiac events is high, using short- and long-term antiplatelet and antithrombotic agents, and modifying long-term risk.

2002 revised guidelines

The studies reviewed in the 2002 revised guidelines assessed multiple therapies in the reduction of recurrent MI, stroke, and other cardiovascular events following patients’ presentation with unstable angina and NSTEMI. The studies also evaluated traditional therapies for acute coronary syndromes, such as unfractionated heparin, beta-blockers, and aspirin, as well as more recent therapies, including low-molecular-weight heparin, antiplatelet therapy (parenteral glycoprotein IIb/IIIa [GP IIb/IIIa] antagonists and ADP-receptor antagonists [thienopyridines]), lipid-lowering therapy (HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors, or statins), and antihypertensive agents.2

The results of these trials have lead to changes in the initial management of patients following an new ischemic event, as well as the choice of medical therapy begun in the hospital and continued following discharge. Patients are given an individualized medical regimen based on specific needs that include in-hospital findings relating to the type of recent procedure, risk factors for subsequent ischemic events and drug tolerability. Such a regimen, although beyond the scope of this discussion, can be recalled as “ABCDE,” for Anti-platelet agents/ACE inhibitors, Beta-blockers, Blood pressure control, Cholesterol (lipid)-lowering agents, Cigarette cessation, Diet modification, Diabetes control, Exercise, and Education.

Important changes in long-term management

For most primary care physicians—with the possible exception of those in rural areas, who are faced with the burden of emergent care—the most important aspect of the revised guidelines is the changes in recommendations for long-term management of patients with unstable angina and NSTEMI. The goal of these new recommendations is to reduce the risk of subsequent cardiovascular events, such as death, recurrent MI, congestive heart failure, and stroke. Based on the results of the groundbreaking studies reviewed by the ACC/AHA panel, major changes to the original guidelines were necessary for the areas of long-term antiplatelet therapy and risk reduction.

TABLE

ACC/AHA task force classifications on patient evaluation and therapy

| Levels of evidence | ||

|---|---|---|

| A (highest) | B (intermediate) | C (lowest) |

| Data derived from multiple randomized clinical trials involving large numbers of patients. | Data derived from limited number of randomized clinical trials involving small numbers of patients or from analyses of nonrandomized trials or observation registries. | Basis of recommendation from expert opinion. large numbers of patients. |

| Recommendations made were based on expert analyses of published data. | ||

Antiplatelet therapy

Antiplatelet therapy—aspirin, GP IIb/IIIa antagonists, or an ADP-receptor antagonist (eg, clopidogrel)—is critical in the treatment and management of patients with unstable angina/NSTEMI.2 Based on the ACC/AHA Task Force classification (Table), aspirin (81–325 mg) should be initiated as quickly as possible after the condition is recognized, and continued indefinitely (SOR: A).

Clopidogrel (300-mg loading dose followed by 75 mg/d) should be administered to patients unable to take aspirin (SOR: A). In addition, clopidogrel 75 mg (once daily) should be added to aspirin therapy as quickly as possible and continued for up to 9 months in patients for whom an early noninterventional approach is planned (SOR: A), or for patients with a planned PCI who are not at high risk of bleeding (SOR: B).2

The CURE trial: clopidogrel and aspirin

The principal studies underlying the new recommendations for long-term antiplatelet therapy are the CURE trial6 and the PCI-CURE7 subset analysis. In the CURE trial, 12,562 patients who presented with unstable angina/NSTEMI within 24 hours following the onset of symptoms were randomized to receive clopidogrel (loading dose of 300 mg followed by 75 mg/d) with aspirin or placebo with aspirin for 3 to 12 months (mean follow-up, 9 months).

The relative risk (RR) of the primary composite outcome including incidence of cardiovascular death, nonfatal MI, or stroke was lower by 20% (RR=0.80; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.72–0.90; P<.001) in the clopidogrel arm. Similarly, a composite outcome also including revascularization was lower by 14% (RR=0.86; P<.001) for those who received clopidogrel. Benefits were seen in all risk groups. A significant increase in bleeding events was observed in the group that received clopidogrel plus aspirin compared with aspirin alone (major bleeding, P=.001; minor bleeding, P<.001).6

CURE patients were followed for up to 1 year, with a mean follow-up period of 9 months. In addition to the early benefits seen, from day 31 up to 1 year there was a highly significant incremental reduction of 18% in the primary outcome (P<.001) with clopidogrel.7

The PCI-CURE subset: Percutaneous coronary interventions

In the PCI-CURE trial, a subset of patients recruited for CURE who underwent PCI was pretreated with aspirin 325 mg and clopidogrel 75 mg for a median of 10 days. These patients received either clopidogrel or ticlopidine for 4 weeks, and then were restarted on either clopidogrel 75 mg (80%) or placebo in addition to aspirin for an additional mean of 8 months with up to 1 year of follow-up.

Long-term administration of clopidogrel 75 mg following PCI resulted in a 30% reduction (RR=0.70; 95% CI, 0.50–0.70; P=.03) in cardiovascular death, MI, and any revascularization, with a 31% reduction in cardiovascular death or MI (P=.002) compared with placebo. Major bleeding rates were similar between groups (P=.64).9

The CREDO study

The new guidelines for long-term antiplatelet therapy are further supported by the subsequently published Clopidogrel for the Reduction of Events During Observation (CREDO) study.10 CREDO demonstrated a 26.9% relative risk reduction in the combined risk of death, MI, or stroke (95% CI, 3.9%–44.4%; P=.02) in patients with long-term (12 months) aspirin plus clopidogrel 75 mg therapy compared with aspirin plus placebo in 2116 patients undergoing elective PCI or deemed at high likelihood of undergoing PCI. There was no significant increase in the risk of major bleeding (P=.07) between the placebo and clopidogrel arms.

Risk reduction

The revised guidelines also included updated recommendations for risk reduction. It is now recommended that a fibrate or niacin be administered if the HDL cholesterol level is <40 mg/dL (SOR: B).2 Further, statins and a heart-healthy diet should be started during admission and continued after discharge for patients with LDL cholesterol >100 mg/dL (SOR: B).2

This recommendation is based in part on the MIRACL trial, in which 3086 acute coronary syndrome patients treated with atorvastatin, 24 to 96 hours after hospital admission, demonstrated a significant reduction in the composite rate of death, nonfatal MI, resuscitated cardiac arrest, or recurrent ischemia compared with those who received placebo (14.8% vs 17.4%) (RR=0.84; 95% CI, 0.70–1.00; P=.048). Patients were followed for up to 16 weeks after starting therapy. Abnormal liver transaminases (>3 times upper limit of normal) occurred more often in the atorvastatin group than the placebo group (2.5% vs 0.6%; P<.001).8

- Atorvastatin • Lipitor

- Clopidogrel • Plavix

- Ticlopidine • Ticlid

Correspondence

John S. Banas, MD, FACC, Morristown Memorial Hospital, 100 Madison Ave, Morristown, NJ 07960. E-mail: [email protected].

- Immediately upon presentation of non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI), aspirin therapy (81–325 mg) should be initiated (A). If aspirin is contraindicated, clopidogrel (300-mg loading dose followed by 75 mg/d) should be administered (A).

- In patients for whom an early noninterventional approach is planned, or for patients not at high risk of bleeding for whom percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) is planned, clopidogrel 75 mg (once daily) should be added to aspirin therapy as quickly as possible and continued for up to 9 months (B).

- Aggressive low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol-lowering therapy and general cardiovascular risk reduction are important in long-term management of these patients. Thus, a fibrate or niacin should be administered if the high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol is <40 mg/dL (B).

- In patients with LDL cholesterol >100 mg/dL, HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors (statins) and diet should be started during admission and continued after discharge (B).

In the long-term care of patients with acute coronary syndrome, recently published w that prognostic benefits improve with more aggressive antiplatelet therapy for those at high risk for recurrent events. Moreover, long-term care should include aggressive LDL cholesterol-lowering therapy and use of beta-blockers and angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors, in addition to diet modification and exercise.

STEMI and NSTEMI: The new nomenclature

Coronary artery disease, the leading cause of death in the United States,1 can manifest in many ways involving a constellation of symptoms, electrocardiogram changes, and serum markers. These acute coronary syndromes result from decreased coronary blood flow and cause chest discomfort, usually at rest, with or without characteristic radiation, or such comparable anginal equivalents as weakness, dyspnea, and diaphoresis.

STEMI. An elevated ST-segment with elevated levels of such cardiac markers as creatine kinase myocardial band or troponin I or troponin T are consistent with a diagnosis of ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI). The old term, acute myocardial infarction, was defined by the presence of pathological Q waves (Q wave MI).

NSTEMI. Patients with elevated serum levels of creatine kinase myocardial band or troponin I or troponin T, but no ST-segment elevation, are said to have non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI).

Unstable angina. Normal levels of serum cardiac markers and an absence of ST-elevation are consistent with a diagnosis of unstable angina (Figure). Of patients with STEMI, most will ultimately experience a Q-wave MI; a minority will have a non–Q-wave MI. Of patients with NSTEMI, most will sustain a non–Q-wave MI, while a minority will sustain a Q-wave MI.

Unstable angina and NSTEMI are urgent and life-threatening problems. Chest pain and related symptoms account for 5.3 million visits to US emergency departments per year2 and account for 1.4 million hospitalizations annually.3 Approximately 15% of those presenting with unstable angina and NSTEMI go on to (re)infarct or die within 30 days.4

FIGURE

Unstable angina and NSTEMI

FIGURE

Nomenclature of acute coronary syndrome

ACC/AHA Guidelines

In 2000 the American College of Cardiology and the American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) Task Force on Practice Guidelines published their evidence-based recommendations for treatment of unstable angina/NSTEMI following an exhaustive review of the literature.

New trials in acute coronary syndromes

Since 2000, knowledge of acute coronary syndromes advanced considerably with results of large pivotal randomized controlled studies, which necessitated updating the ACC/AHA guidelines just 21 months after their completion. The most notable of these studies were the Clopidogrel in Unstable Angina to Prevent Recurrent Ischemic Events (CURE) trial,6 the Percutaneous Coronary Intervention (PCI)-CURE7 subset analysis, and the Myocardial Ischemia Reduction with Aggressive Cholesterol Lowering (MIRACL) trial.8

Although incorporation of antiplatelet therapy is the focus of this article, the ultimate objective of the new revised guidelines is improved clinical outcomes for patients with acute coronary syndromes by improving early risk assessment, using revascularization procedures aggressively when risk for future cardiac events is high, using short- and long-term antiplatelet and antithrombotic agents, and modifying long-term risk.

2002 revised guidelines

The studies reviewed in the 2002 revised guidelines assessed multiple therapies in the reduction of recurrent MI, stroke, and other cardiovascular events following patients’ presentation with unstable angina and NSTEMI. The studies also evaluated traditional therapies for acute coronary syndromes, such as unfractionated heparin, beta-blockers, and aspirin, as well as more recent therapies, including low-molecular-weight heparin, antiplatelet therapy (parenteral glycoprotein IIb/IIIa [GP IIb/IIIa] antagonists and ADP-receptor antagonists [thienopyridines]), lipid-lowering therapy (HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors, or statins), and antihypertensive agents.2

The results of these trials have lead to changes in the initial management of patients following an new ischemic event, as well as the choice of medical therapy begun in the hospital and continued following discharge. Patients are given an individualized medical regimen based on specific needs that include in-hospital findings relating to the type of recent procedure, risk factors for subsequent ischemic events and drug tolerability. Such a regimen, although beyond the scope of this discussion, can be recalled as “ABCDE,” for Anti-platelet agents/ACE inhibitors, Beta-blockers, Blood pressure control, Cholesterol (lipid)-lowering agents, Cigarette cessation, Diet modification, Diabetes control, Exercise, and Education.

Important changes in long-term management

For most primary care physicians—with the possible exception of those in rural areas, who are faced with the burden of emergent care—the most important aspect of the revised guidelines is the changes in recommendations for long-term management of patients with unstable angina and NSTEMI. The goal of these new recommendations is to reduce the risk of subsequent cardiovascular events, such as death, recurrent MI, congestive heart failure, and stroke. Based on the results of the groundbreaking studies reviewed by the ACC/AHA panel, major changes to the original guidelines were necessary for the areas of long-term antiplatelet therapy and risk reduction.

TABLE

ACC/AHA task force classifications on patient evaluation and therapy

| Levels of evidence | ||

|---|---|---|

| A (highest) | B (intermediate) | C (lowest) |

| Data derived from multiple randomized clinical trials involving large numbers of patients. | Data derived from limited number of randomized clinical trials involving small numbers of patients or from analyses of nonrandomized trials or observation registries. | Basis of recommendation from expert opinion. large numbers of patients. |

| Recommendations made were based on expert analyses of published data. | ||

Antiplatelet therapy

Antiplatelet therapy—aspirin, GP IIb/IIIa antagonists, or an ADP-receptor antagonist (eg, clopidogrel)—is critical in the treatment and management of patients with unstable angina/NSTEMI.2 Based on the ACC/AHA Task Force classification (Table), aspirin (81–325 mg) should be initiated as quickly as possible after the condition is recognized, and continued indefinitely (SOR: A).

Clopidogrel (300-mg loading dose followed by 75 mg/d) should be administered to patients unable to take aspirin (SOR: A). In addition, clopidogrel 75 mg (once daily) should be added to aspirin therapy as quickly as possible and continued for up to 9 months in patients for whom an early noninterventional approach is planned (SOR: A), or for patients with a planned PCI who are not at high risk of bleeding (SOR: B).2

The CURE trial: clopidogrel and aspirin

The principal studies underlying the new recommendations for long-term antiplatelet therapy are the CURE trial6 and the PCI-CURE7 subset analysis. In the CURE trial, 12,562 patients who presented with unstable angina/NSTEMI within 24 hours following the onset of symptoms were randomized to receive clopidogrel (loading dose of 300 mg followed by 75 mg/d) with aspirin or placebo with aspirin for 3 to 12 months (mean follow-up, 9 months).

The relative risk (RR) of the primary composite outcome including incidence of cardiovascular death, nonfatal MI, or stroke was lower by 20% (RR=0.80; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.72–0.90; P<.001) in the clopidogrel arm. Similarly, a composite outcome also including revascularization was lower by 14% (RR=0.86; P<.001) for those who received clopidogrel. Benefits were seen in all risk groups. A significant increase in bleeding events was observed in the group that received clopidogrel plus aspirin compared with aspirin alone (major bleeding, P=.001; minor bleeding, P<.001).6

CURE patients were followed for up to 1 year, with a mean follow-up period of 9 months. In addition to the early benefits seen, from day 31 up to 1 year there was a highly significant incremental reduction of 18% in the primary outcome (P<.001) with clopidogrel.7

The PCI-CURE subset: Percutaneous coronary interventions

In the PCI-CURE trial, a subset of patients recruited for CURE who underwent PCI was pretreated with aspirin 325 mg and clopidogrel 75 mg for a median of 10 days. These patients received either clopidogrel or ticlopidine for 4 weeks, and then were restarted on either clopidogrel 75 mg (80%) or placebo in addition to aspirin for an additional mean of 8 months with up to 1 year of follow-up.

Long-term administration of clopidogrel 75 mg following PCI resulted in a 30% reduction (RR=0.70; 95% CI, 0.50–0.70; P=.03) in cardiovascular death, MI, and any revascularization, with a 31% reduction in cardiovascular death or MI (P=.002) compared with placebo. Major bleeding rates were similar between groups (P=.64).9

The CREDO study

The new guidelines for long-term antiplatelet therapy are further supported by the subsequently published Clopidogrel for the Reduction of Events During Observation (CREDO) study.10 CREDO demonstrated a 26.9% relative risk reduction in the combined risk of death, MI, or stroke (95% CI, 3.9%–44.4%; P=.02) in patients with long-term (12 months) aspirin plus clopidogrel 75 mg therapy compared with aspirin plus placebo in 2116 patients undergoing elective PCI or deemed at high likelihood of undergoing PCI. There was no significant increase in the risk of major bleeding (P=.07) between the placebo and clopidogrel arms.

Risk reduction

The revised guidelines also included updated recommendations for risk reduction. It is now recommended that a fibrate or niacin be administered if the HDL cholesterol level is <40 mg/dL (SOR: B).2 Further, statins and a heart-healthy diet should be started during admission and continued after discharge for patients with LDL cholesterol >100 mg/dL (SOR: B).2

This recommendation is based in part on the MIRACL trial, in which 3086 acute coronary syndrome patients treated with atorvastatin, 24 to 96 hours after hospital admission, demonstrated a significant reduction in the composite rate of death, nonfatal MI, resuscitated cardiac arrest, or recurrent ischemia compared with those who received placebo (14.8% vs 17.4%) (RR=0.84; 95% CI, 0.70–1.00; P=.048). Patients were followed for up to 16 weeks after starting therapy. Abnormal liver transaminases (>3 times upper limit of normal) occurred more often in the atorvastatin group than the placebo group (2.5% vs 0.6%; P<.001).8

- Atorvastatin • Lipitor

- Clopidogrel • Plavix

- Ticlopidine • Ticlid

Correspondence

John S. Banas, MD, FACC, Morristown Memorial Hospital, 100 Madison Ave, Morristown, NJ 07960. E-mail: [email protected].

1. American Heart Association. Heart and Stroke Statistical Update. Available at: www.americanheart.org. Accessed on March 31, 2004.

2. Braunwald E, Antman EM, Beasley JW, et al. ACC/AHA guideline update for the management of patients with unstable angina and non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction—2002: summary article: report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation 2002;106:1893-1900.

3. Graves EJ, Kozak LJ. Detailed diagnoses and procedures, National Hospital Discharge Survey, 1996. National Center for Health Statistics. Vital Health Stat 1998;13:i-iii,1-151.

4. The Pursuit Trial Investigators. Inhibition of platelet glycoprotein IIb/IIIa with eptifibatide in patients with acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med 1998;339:436-443.

5. Braunwald E, Antman EM, Beasley JW, et al. ACC/AHA guidelines for the management of patients with unstable angina and non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Committee on the Management of Patients With Unstable Angina). J Am Coll Cardiol 2000;36:970-1062.

6. Yusuf S, Zhao F, Mehta SR, Chrolavicius S, Tognoni G, Fox KK. Effects of clopidogrel in addition to aspirin in patients with acute coronary syndromes without ST-segment elevation. N Eng J Med 2001;345:494-502.

7. Mehta SR, Yusuf S. Short- and long-term oral antiplatelet therapy in acute coronary syndromes and percutaneous coronary interventions. J Am Coll Cardiol 2003;41:79S-88S.

8. Schwartz GG, Olsson AG, Ezekowitz MD, et al. Effects of atorvastatin on early recurrent ischemic events in acute coronary syndromes: the MIRACL study, a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2001;285:1711-1718.

9. Mehta SR, Yusuf S, Peters RJ, et al. Effects of pretreatment with clopidogrel and aspirin followed by long-term therapy in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention: the PCI-CURE study. Lancet 2001;358:527-533.

10. Steinhubl SR, Berger PB. Mann JT for the CREDO Investigators. Early and sustained dual oral antiplatelet therapy following percutaneous coronary intervention. A randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2002;288:2411-2420.

11. Antman EM, Braunwald E. Acute myocardial infarction. In: Braunwald E, ed. Heart Disease: A Textbook of Cardiovascular Medicine. Philadelphia, Pa: WB Saunders, 1997.

1. American Heart Association. Heart and Stroke Statistical Update. Available at: www.americanheart.org. Accessed on March 31, 2004.

2. Braunwald E, Antman EM, Beasley JW, et al. ACC/AHA guideline update for the management of patients with unstable angina and non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction—2002: summary article: report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation 2002;106:1893-1900.

3. Graves EJ, Kozak LJ. Detailed diagnoses and procedures, National Hospital Discharge Survey, 1996. National Center for Health Statistics. Vital Health Stat 1998;13:i-iii,1-151.

4. The Pursuit Trial Investigators. Inhibition of platelet glycoprotein IIb/IIIa with eptifibatide in patients with acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med 1998;339:436-443.

5. Braunwald E, Antman EM, Beasley JW, et al. ACC/AHA guidelines for the management of patients with unstable angina and non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Committee on the Management of Patients With Unstable Angina). J Am Coll Cardiol 2000;36:970-1062.

6. Yusuf S, Zhao F, Mehta SR, Chrolavicius S, Tognoni G, Fox KK. Effects of clopidogrel in addition to aspirin in patients with acute coronary syndromes without ST-segment elevation. N Eng J Med 2001;345:494-502.

7. Mehta SR, Yusuf S. Short- and long-term oral antiplatelet therapy in acute coronary syndromes and percutaneous coronary interventions. J Am Coll Cardiol 2003;41:79S-88S.

8. Schwartz GG, Olsson AG, Ezekowitz MD, et al. Effects of atorvastatin on early recurrent ischemic events in acute coronary syndromes: the MIRACL study, a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2001;285:1711-1718.

9. Mehta SR, Yusuf S, Peters RJ, et al. Effects of pretreatment with clopidogrel and aspirin followed by long-term therapy in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention: the PCI-CURE study. Lancet 2001;358:527-533.

10. Steinhubl SR, Berger PB. Mann JT for the CREDO Investigators. Early and sustained dual oral antiplatelet therapy following percutaneous coronary intervention. A randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2002;288:2411-2420.

11. Antman EM, Braunwald E. Acute myocardial infarction. In: Braunwald E, ed. Heart Disease: A Textbook of Cardiovascular Medicine. Philadelphia, Pa: WB Saunders, 1997.

Treating type 2 diabetes: Targeting the causative factors

- Self-monitoring of blood glucose is an integral component of diabetes therapy and should always be included in the management plan (SOR:C).

- Medical nutrition therapy should be individualized, preferably by a registered dietitian familiar with diabetes (SOR:B).

- A regular physical activity program is recommended for all patients with diabetes who are capable of participating (SOR:B).

- When a monotherapy fails, combine drugs with different mechanisms of action to achieve an additive effect (SOR:A).

- The combination of sulfonylurea and metformin has proven effective in many studies. One showed that initial treatment with glyburide/metformin improved glycemic control better than either glyburide or metformin monotherapy (SOR: A).

Glycemic control in diabetes begins with a patient’s adherence to several nonpharmacologic measures. Without such a commitment, success in controlling the disease will be difficult to achieve, and otherwise appropriate drug therapy will be hindered.

Most antidiabetic agents comparably reduce glycosylated hemoglobin (A1c) levels. However, a particular agent may be preferred depending on a patient’s characteristics. And some circumstances call for combination therapy. This article reviews the advantages and disadvantages of the many pharmacologic treatments for glucose control and hyperglycemia in type 2 diabetes.

Benefits Of Diabetes Control

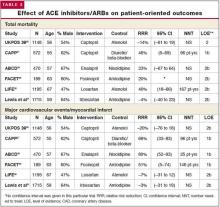

The benefits of diabetes control are detailed in this issue of THE JOURNAL OF FAMILY PRACTICE (“Strategies to reduce complications in type 2 diabetes,” pages 366–374). For every percentage-point reduction in hemoglobin A1c, it is possible to achieve a 22% to 35% reduction in microvascular complications.1,2 Cardiovascular disease can be reduced in patients with diabetes by treating hypertension3,4 and hyperlipidemia, prescribing aspirin therapy, using angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors, and with smoking cessation.5,6

Targets For Glycemic Control

The American Diabetes Association’s (ADA) recommended targets for glycemic control are a preprandial blood glucose level of 80–120 mg/dL, a bedtime blood glucose level of 100–140 mg/dL, and a hemoglobin A1c level of <7% (with a level of >8% requiring additional measures). Hemoglobin A1c is the best determinant of glycemic exposure, and its mean value is a nationally recognized indicator of how well diabetes is being managed.7 The American College of Endocrinology has adopted a more aggressive approach by designating an A1c level of 6.5% as both a target and action level.8

Self-monitoring of blood glucose

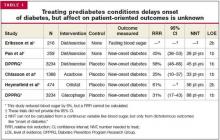

Self-monitoring of blood glucose (SMBG) is an integral component of diabetes therapy (strength of recommendation [SOR]: C) and should always be included in the management plan (SOR: C). The optimal frequency and timing of SMBG for type 2 diabetes is not known, but they should be sufficient to facilitate reaching glucose goals. The A1c test should be performed at least semi-annually for patients with stable glycemic control, and quarterly for patients not meeting glycemic goals or those who are changing therapy. A1c levels and mean plasma glucose levels can be approximately correlated (Table 1).7

TABLE 1

Correlation between hemoglobin A1clevels and mean plasma glucose levels

| Hemoglobin A1c(%) | Mean plasma glucose (mg/dL) |

|---|---|

| 6 | 135 |

| 7 | 170 |

| 8 | 205 |

| 9 | 240 |

| 10 | 275 |

| 11 | 310 |

| 12 | 345 |

Nonpharmacologic Therapy

Nonpharmacologic measures remain the cornerstone of managing type 2 diabetes. Hyperglycemia adversely and reversibly affects both insulin resistance and insulin secretion. Improvement in glycemic control can occur through dietary modification and regular exercise.

A recent meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials of diabetes patient education observed a net decrease in HbA1c of 0.32% in intervention groups vs control.9 Interventions that included a face-to-face delivery, cognitive reframing teaching method, and exercise content were more likely to improve glycemic control.

Education

Lifestyle changes involving diet, exercise, and usually weight loss are key to effective management of diabetes. If patients are to change their behavior, they must be given detailed training.6 Self-management also necessitates that patients engage in problem solving. This requires that each aspect of the management plan is understood and agreed upon by the patient and providers, and that the goals and treatment plan are individualized and reasonable.

Diet: recommend soluble fiber, reduce calories

Medical nutrition therapy should be individualized and preferably provided by a registered dietitian familiar with diabetes (SOR: B). The goals of nutrition therapy, according to the ADA, are to attain recommended body weight and prevent or reverse obesity. The means of achieving these goals are nutrition assessment and modification of nutrient intake and lifestyle through healthy food choices and physical activity.7

A high intake of dietary fiber (particularly the soluble type) above the level recommended by the ADA improves glycemic control, decreases hyperinsulinemia, and lowers plasma lipid concentrations.10

Hypocaloric diets cause glucose plasma levels to fall, in some cases to a normal level with a weight loss of even 5 to 10 pounds.7,11 Hypoglycemic medications are of course most effective in nonobese persons. But effectiveness is also improved if weight that is gained can be limited. Despite the clear benefit of weight loss, only a few patients are able to attain and maintain substantial weight loss. Maintenance of a reduced or elevated body weight is associated with compensatory changes in energy expenditure, which oppose the maintenance of body weight that is different from the usual weight.13 Part of the individualization of therapy is respect of personal and cultural preferences, lifestyles, and financial considerations.

Physical activity: a little goes a long way

A regular physical activity program is recommended for all patients with diabetes who are capable of participating (SOR: B).7 It improves blood glucose control, reduces cardiovascular risk factors, aids weight loss, and enhances well being.7 A recently published prospective cohort study showed that walking at least 2 hours a week was associated with a 39% lower all-cause mortality (hazard rate ratio [HRR], 0.61; 95% CI, 0.48–0.78) and a 34% lower cardiovascular mortality (HRR, 0.66; 95% CI, 0.45–0.96) across a diverse spectrum of adults with diabetes. The NNT (to prevent 1 death per year) is 61 for patients who walk at least 2 hours/week.14

In prescribing a physical activity plan for a patient, consider cardiovascular disease risk factors or complications to minimize the risk of untoward events. Micro- and macrovascular disease are of course prevalent among persons with diabetes, often resulting in functional limitations that make exercise more difficult.

Other priorities

Other recommended components of care include daily aspirin use, foot care exams, tobacco cessation, pneumococcal and influenza vaccinations, and an annual dilated retinal exam.

Pharmacologic Therapy

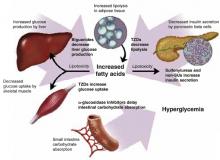

The coexisting defects in type 2 diabetes mellitus are as follows:

- resistance to insulin action in muscle

- defective pancreatic insulin secretion

- unrestrained hepatic glucose production, aggravated by increased lipolysis in adipose tissue.

Drug therapy is aimed at each of these defects, and also at reducing carbohydrate absorption in the small intestine (Figure 1). As far as antihyperglycemic effect is concerned, no one category of antidiabetic agent is favored over another.15 Except for nateglinide and α-glucosidase inhibitors (AGIs), each of the drug categories leads to a similar reduction in A1c.16 However, patient characteristics may lead to selection of a particular agent. Table 2 summarizes oral treatment options, their relative advantages and costs.

FIGURE 1

Drug therapies for coexisting defects in type 2 diabetes

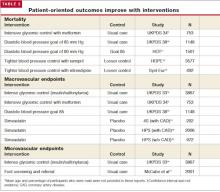

TABLE 2

Pharmacologic treatments for type 2 diabetes: monotherapies

| Target population | Advantages | Disadvantages | Dosing | Cost* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sulfonylureas | ||||

| Recent type 2 DM diagnosis | Rapid FPG reduction | Weight gain | Glyburide: 1.25–20 mg once or twice daily (micronized, 0.75–12 mg once or twice daily) | $22.80 (5 mg, #120) |

| Type 2 DM <5 years duration | Low cost | Increased risk of hypoglycemia | Glipizide: 2.5–40 mg once or twice daily (extended-release, 2.5–20 mg once daily) | $14.66 (10 mg, #120) |

| Glimepiride: 1–8 mg once daily | $51.98 (10 mg, #60) | |||

| $57.98 (4 mg, #60) | ||||

| Non-sulfonylurea secretagogues (meglitinides) | ||||

| Recent type 2 DM diagnosis | Reduced risk of hypoclycemia | Higher cost | Nateglinide: 60–120 mg 3 times daily | $85.99 (120mg, #90) |

| Elevated PPG | Short-acting | Frequent dosing | Repaglinide: 0.5–4 mg 3 or 4 times daily | $218.06 (2 mg, #240) |

| Meal-adjusted dosing | ||||

| Biguanides | ||||

| Overweight/obese | No weight gain | GI side effects | Metformin: 500–1000 mg 2 or 3 times daily | $77.99 (850 mg, #90) |

| Insulin resistant | Reduced risk of hypoglycemia | High cost | Metformin XR: 1000–2000 mg once or twice daily | $89.98 (500 mg, #120) |

| Rare lactic acidosis | ||||

| TZDs | ||||

| Insulin resistant | Reduced amount of insulin | High cost | Rosiglitazone: 4–8 mg once or twice daily | $135.99 (8 mg, #30) |

| Overweight/obese | Reduced risk of hypoglycemia | Weight gain | Pioglitazone: 15–45 mg once daily | $153.99 (45 mg, #30) |

| Slow onset of action | ||||

| Liver toxicity | ||||

| AGIs | ||||

| Elevated PPG | Reduced risk of hypoglycemia | High cost | Acarbose: 50–100 mg 3 times daily | $67.99 (100 mg, #90) |

| Contraindications to other agents | Non-systemic action | GI side effects | Miglitol: 50–100 mg 3 times daily | $66.99 (100 mg, #90) |

| *Drug costs for 30 days’ supply of maximum daily dosage. From www.drugstore.com, December 2003. | ||||

| DM, diabetes mellitus; TZD, thiazolidinediones; AGT, a-glucosidase inhibitors; FPG, fasting plasma glucose; PPG, postprandial glucose; GI, gastrointestinal | ||||

Sulfonylureas

Sulfonylureas directly increase insulin secretion by binding to the sulfonylurea receptor on pancreatic beta cells; they provide a relatively quick onset of action. First-generation sulfonylureas (eg, tolbutamide, chlorpropamide) and second-generation sulfonylureas (eg, glyburide, glipizide, glimepiride) are equivalent in their maximum hypoglycemic effect.17

Second-generation agents are used more commonly than first-generation. They all contain the sulfonylurea moiety, but different chemical substitutions in the basic molecule change pharmacokinetics, resulting in different durations of action.17 Second-generation agents are probably safer than first-generation drugs, being less likely to cause hyponatremia, disulfiram-like reactions, or prolonged hypoglycemia.18

At maximal doses, sulfonylureas lower A1c levels by 1–2 percentage points and fasting plasma glucose concentrations by 60–70 mg/dL;15 however, the glucose lowering effect typically plateaus after half the maximal recommended dose is reached. Sulfonylureas have no consistent effect on dyslipidemia. In UK Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS) 33, though improved glycemic control with sulfonylureas (or insulin) led to a 25% reduction in microvascular endpoints (mostly less retinal photocoagulation) (P<.01), sulfonylureas (or insulin) did not significantly reduce death or all-cause mortality compared with diet treatment.2

Adverse effects. The primary adverse effects of sulfonylureas are weight gain and hypoglycemia. In UKPDS 33, weight gain at 10 years was 2.6 kg (99% confidence interval [CI], 1.6–3.6) with chlorpropamide and 1.7 kg (99% CI, 0.7–2.7) with glyburide, compared with patients receiving diet therapy (each P<.001).2 In the same study, the rate of major hypoglycemic episodes (third-party help or medical intervention necessary) while on therapy was 0.4%/year for chlorpropamide and 0.6%/year for glyburide, compared with 0.1%/year for diet.

Glyburide and chlorpropamide have active metabolites with renal elimination, and they should therefore be used with caution in patients with renal insufficiency. In 1971, the University Group Diabetes Project (UGDP) observed a twofold increase in the rate of cardiovascular death among patients receiving tolbutamide compared with those receiving insulin or placebo.18 This led to a decades long debate on the validity of this conclusion.19 More recently, UKPDS 33 did not demonstrate any increased cardiovascular mortality among patients receiving glyburide or chlorpropamide, and has largely negated this earlier concern.2

Cost. Sulfonylureas are the least expensive oral agents used to treat type 2 diabetes.

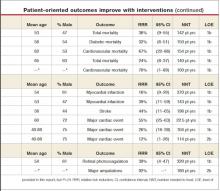

TABLE 3

Pharmacological treatments for type 2 diabetes: combination therapies

| Sulfonylureas | Meglitinides | Biguanides | TZDs | AGIs | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Double combination therapy option* | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Double combination therapy option† | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Double combination therapy option | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Double combination therapy option | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Double combination therapy option | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Double combination therapy option | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Triple combination therapy option | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Triple combination therapy option | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| If therapeutic goals are not met using the above combinations; switch to insulin with or without oral agent. | |||||

| *Available as Glucovance (metformin/glyburide) or as Metaglip (metformin/glipizide) | |||||

| † Available as Avandamet (rosiglitazone/metformin) | |||||

Non-sulfonylurea secretagogues

Like sulfonylureas, the non-sulfonylurea secretagogues (non-SU), repaglinide and nateglinide, stimulate beta cells to increase insulin secretion. However, the non-SU agents mediate their action through a different, adjacent site on the “sulfonylurea receptor.” Comparatively, the non-SU agents have a faster onset of action (20 minutes), shorter half-life (about 1.0–1.5 hours), and greater effects on postprandial glucose excursions than do sulfonylureas.20 In contrast to the sulfonylureas, the extent of insulin release with non-SU agents is glucose dependent, and therefore they may have less risk of hypoglycemia several hours after meals.15

A group of metabolic abnormalities that increase cardiovascular risk has been recognized since 1988 and has been given many names—Syndrome X, insulin resistance syndrome, dysmetabolic syndrome, The Deadly Quartet.73 The National Cholesterol Education Program Adult Treatment Panel III recently recodified this syndrome as shown below. The principles for diet and exercise discussed in this article also apply to the goals of reducing obesity and physical inactivity in the metabolic syndrome, and preliminary data suggest a reduction in the risk for type 2 diabetes (NNT per year=27; P=.000174) and for cardiovascular disease.75

| Risk factor | Defining level |

|---|---|

| Abdominal obesity | Waist circumference |

| Men | >102 cm (>40 in) |

| Women | >88 cm (>35 in) |

| Triglycerides | ≥150 mg/dL |

| HDL cholesterol | |

| Men | <40 mg/dL |

| Women | <50 mg/dL |

| Blood pressure | ≥130/85 mm Hg |

| Fasting glucose | ≥110 mg/dL |

Repaglinide lowers the A1c level by 1.7–1.9 percentage points, similar in efficacy to sulfonylureas. Nateglinide appears somewhat less efficacious and lowers A1c by 0.6–1.0 percentage points.15 Nateglinide was significantly less effective than glyburide at lowering A1c levels and the fasting plasma glucose in one 24-week study. Non-SUs added to sulfonylureas produce no additional benefit in glycemic control. The effect of non-SUs on microvascular or macrovascular endpoints is unknown.

Adverse effects. Hypoglycemia is the primary adverse effect of non-SUs. Confirmed hypoglycemia (plasma glucose <60 mg/dL) was observed in 2.4% of patients taking nateglinide compared with 0.4% of those receiving placebo. Mild or moderate hypoglycemia occurred in 16% of repaglinide patients, 20% of glyburide patients, and 19% of glipizide patients in one-year comparative studies. Further comparative studies are needed to determine if non-SUs produce significantly less hypoglycemia and weight gain than sulfonylureas.

Cost. Non-SUs must be dosed 3 times daily at the start of meals. One relative disadvantage is their increased cost compared with sulfonylureas.

Biguanides

The only biguanide marketed in the US is metformin. Its primary action is to inhibit hepatic glucose production and, to a much lesser extent, enhance insulin sensitivity in peripheral tissues.21 Metformin does not stimulate insulin secretion and does not cause hypoglycemia when used as monotherapy, but it can potentiate hypoglycemia in combination with insulin or insulin secretagogues.

Metformin is similar in efficacy to the sulfonylureas. It lowers A1c by 1.5–2.0 percentage points and fasting plasma glucose by 60–80 mg/dL. Its antihyperglycemic efficacy is independent of patient age, duration of diabetes, or BMI.22

In the UKPDS 34 study, a subgroup of obese patients was randomized to receive intensive control (group 1, metformin; group 2, a sulfonylurea or insulin) or conventional diet therapy (group 3). Despite a similar reduction in the A1c level between the 2 intensive-treatment groups, patients treated with metformin had a 32% reduction for any diabetes-related endpoint (95% CI, 13–47; P=.002), 43% fewer diabetes-related deaths (95% CI, 9–63; P=.017), and a 36% reduction in all cause mortality, compared with the diet therapy group (95% CI, 9–55; P=.011).23

Metformin also showed significant benefit when compared with patients receiving sulfonylurea or insulin (group 2). The absolute risk of any diabetes endpoint was 29.8 vs. 40.1 (events per 1000 patient-years; P=.0034), all-cause mortality (13.5 vs 18.9; P=.021), and stroke (3.3 vs 6.2; P=.032), respectively, for metformin vs sulfonylurea or insulin (group 2). Thus, metformin is the only oral hypoglycemic agent proven to reduce macrovascular risk in overweight patients with type 2 diabetes. For perspective, in overweight patients, metformin significantly reduced all-cause mortality (NNT per year=141; 95% CI, 115–183; P=.011), and any diabetes-related outcome (NNT per year=74; 95% CI, 63–90; P=.0023), compared with diet alone.23,24

Metformin induces weight loss (2–3 kg), preferentially involving adipose tissue in obese patients with type 2 diabetes over 4 to 6 months.22,25 In UKPDS 34, weight gain was similar among those treated with metformin and diet (approximately 2 kg); weight gain over 10 years was less with metformin, however, than with sulfonylurea (approximately 4 kg) or insulin (approximately 6 kg).23 Metformin also significantly improved levels of total cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol, and triglycerides when compared with glyburide or placebo.22

Risk of lactic acidosis. Lactic acidosis associated with metformin is a rare but serious adverse event, with an estimated prevalence of 3 cases per 100,000.26 The product labeling notes most of these cases have occurred among patients with significant renal insufficiency, including both intrinsic renal disease and renal hypoperfusion. Absolute contraindications include renal disease (serum creatinine ≥1.5 mg/dL [males] and ≥1.4 mg/dL [females]), congestive heart failure requiring pharmacological treatment, and acute or chronic metabolic acidosis. It should also be discontinued at the time of radiologic studies using intravascular iodinated contrast materials.

Additional “precautionary conditions” include age ≥80 years (unless measurement of creatinine clearance demonstrates that renal function is not reduced), hepatic disease, cationic drug use, conditions associated with hypoxia (eg, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease [COPD], acute myocardial infarction, dehydration, sepsis), excessive alcohol intake, and surgery, until patient’s oral intake is resumed.

Is the risk overstated? Despite these extensive precautions, published studies show that metformin is commonly prescribed to patients with absolute contraindications.27,28 One recent study observed that 11.2% of Medicare beneficiaries hospitalized with congestive heart failure and concomitant diabetes were treated with metformin.28 In the absence of advanced renal dysfunction, metformin rarely accumulates in the body,29 and accumulation of metformin is rarely reported as a cause of lactic acidosis.30,31 Rather, tissue hypoxia acts as a trigger in most cases. Metformin should therefore be discontinued whenever tissue hypoxia is suspected.31

A recent systematic review and meta analysis found no evidence that metformin was associated with an increased risk of lactic acidosis if the drug was prescribed under study conditions, taking into account contraindications.32 Refinement and clarification of the risk for lactic acidosis in these various populations is needed, to ensure optimal patient safety and to further assess this highly effective medication.

Common adverse effects associated with metformin are diarrhea and nausea, which can be minimized by administering the drug with meals and slowly titrating the dose, or perhaps by using the extended-release formulation.

Thiazolidinediones

Thiazolidinediones (TZDs) include rosiglitazone and pioglitazone. These agents, like metformin, do not increase insulin secretion but depend on the presence of insulin for their activity. TZDs are agonists at peroxisome-proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPAR-γ) receptors in peripheral tissues such as skeletal muscle, where they increase glucose uptake.15 Thus, their predominant effect is to decrease insulin resistance.

TZDs have similar antihyperglycemic efficacy as sulfonylureas or metformin. They decrease A1c levels by 0.6–1.9 percentage points and lower fasting plasma glucose levels by 50–80 mg/dL.15 They have a slower onset of action compared with other hypoglycemic drugs, and intervals of 3 to 4 weeks should be allowed between doses before increasing the dosage. TZDs also have favorable effects on lipid levels: HDL concentrations increase and triglyceride concentrations decrease with their use.33 It is not known whether they decrease macrovascular or microvascular complications, although such studies are underway.

Adverse effects. TZDs are typically well tolerated, though weight gain of 1–3 kg, edema (4%–5%) and anemia (1%–2%) can occur. Weight gain and edema are more pronounced when TZDs are used in combination with insulin. Anemia is likely due to increased plasma volume rather than any significant hematological effect.

Due to adverse events related to volume expansion, TZDs are not recommended for patients with New York Heart Association class III or IV heart failure. A recent consensus statement from the American Heart Association and the ADA stresses that before administering TZD treatment, the physician should explore the possible presence of cardiac disease, use of other drugs that cause fluid retention, and the pathogenesis of any existing edema or dyspnea.34

Although troglitazone was removed from the market due to its association with hepatocellular injury, pioglitazone and rosiglitazone are not as convincingly associated with liver injury.15 In preapproval clinical studies, less than 0.5% of patients treated with rosiglitzone and pioglitazone had elevations in alanine transaminase (ALT) >3 times the upper limit of normal.

The incidence of hepatitis or acute liver failure from troglitazone was compared with rosiglitazone, pioglitazone, metformin, and glyburide, by analysis of spontaneously reported adverse events to the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) MEDWATCH database during the first 15 months of marketing of each drug.35,36 The incidence of hepatitis per million prescriptions was 21.5, 14.7, 9.4, 2.9, and 4.1, respectively, while the incidence of acute liver failure per 100,000 prescriptions was 4.6, 0.9, 0.8, 0.2, and 0. It appears that postmarketing data support preclinical studies, in that the incidence of acute liver failure is an order of magnitude higher for troglitazone vs. other TZDs.35 However, the FDA recommends avoiding their use in patients with baseline ALT levels >2.5 times the upper limit of normal. The FDA recently reduced the recommended frequency for ALT monitoring for pioglitazone (and is currently considering the same for rosiglitazone). Serum ALT is recommended prior to initiation and then periodically thereafter.

Cost. TZDs are expensive relative to other hypoglycemic agents.

α-glucosidase inhibitors

The α-glucosidase inhibitors (AGIs), acarbose and miglitol, act through competitive, reversible inhibition of membrane-bound intestinal α-glucosidase, which hydrolyzes complex carbohydrates to glucose and other monosaccharides. This inhibition delays glucose absorption and decreases postprandial hyperglycemia.37 Thus, they have a nonsystemic mechanism of action.

These agents cause a modest reduction in the A1c level (0.5–1.0 percentage points) and are thus less effective than sulfonylureas, metformin, or TZDs. They do not reduce fasting plasma glucose levels, but reduce postprandial hyperglycemia by 50 mg/dL.38 No long-term studies have evaluated whether AGIs reduce diabetes-related macrovascular or microvascular outcomes.

Adverse effects. While AGIs are virtually free of serious toxicities, patient tolerability can be a problem due to adverse gastrointestinal effects. In indirect comparisons from placebo-controlled trials, patients treated with miglitol and acarbose commonly reported abdominal pain (11.7%, 19%), diarrhea (28.7%, 31%), and flatulence (41.5%, 74%), respectively. Systemic accumulation of AGIs has been shown to increase in proportion to the degree of renal insufficiency, and their use is not recommended for patients with serum creatinine >2.0 mg/dL. However, whether such patients are at greater risk of any toxicity is unknown. Acarbose at doses above 100 mg 3 times daily has been associated with elevated serum transaminase levels; however, this risk appears negligible at standard doses.

Insulin

Insulin is the oldest therapy for diabetes, and it has no upper dose limit.39 It increases insulin levels and can reduce A1c levels by 1.5 to 2.5 percentage points. Though half of diabetes patients need insulin eventually for optimal control, historically it has been introduced late in the disease process unless patients have severe hyperglycemia (fasting blood sugar >350 mg/dL) or ketonuria.38 However, it is effective in gaining initial control, decreasing gluconeogenesis and increasing glucose uptake. Disadvantages are weight gain, hypoglycemia, and patient reluctance to give injections.

When insulin is indicated. Patients who exhibit persistent hyperglycemia despite oral hypoglycemic therapy may stop the oral drug(s) and begin insulin. By combining insulin with oral therapy, lower insulin doses may be used to achieve desired control vs using insulin alone.40 For some patients a basal supplement of insulin may be sufficient and can be given as a single dose at bedtime, without an oral hypoglycemic drug.41

Insulin regimens. Various insulin regimens are available: very rapid acting (lispro and aspart), rapid acting (regular), intermediate acting (isophane insulin [NPH] and lente) and very long acting (ultralente and glargine). Glargine insulin (Lantus) has more predictable absorption than NPH, lente, and ultralente. Lantus, compared with NPH, has been associated with less nocturnal and postprandial hypoglycemia.38,42,43 This is consistent with the peakless and longer duration of glargine compared with NPH.44 A recent randomized controlled trial demonstrated that morning insulin glargine lowered A1c levels more than a bedtime dose of NPH (–1.24 vs –0.84; 95% CI, 0.23%–0.58%) or a bedtime dose of glargine (–1.24 vs –0.96%; 95% CI, 0.11%–0.46%).45 Glargine’s only relative disadvantage is increased cost.

Combination products. Combination insulin options are 70 NPH/30 regular, 50 NPH/50 regular, and 75 lispro protamine/25 lispro. Many combinations of insulin regimens have been used successfully. The typical range of insulin needed for monotherapy is 0.4–1 U/kg/d. Once-daily injection of intermediate acting or long acting insulins at bedtime or before breakfast, once-daily or twice-daily combinations of intermediate and rapid acting insulins, and more complex regimens have been used to good effect.

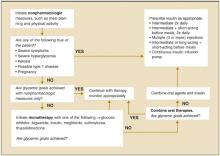

Using prandial insulin at each meal with separate basal insulin adds flexibility to meal times and doses administered.43 With multiple-dose intensive insulin therapy, a basal dose suppresses hepatic glucose output and the bolus doses enhance postprandial glucose uptake. This intensive insulin treatment reduces mortality among critically ill patients in surgical intensive care units and for those with acute myocardial infarction.46,47 An algorithm for using progressive therapy in diabetes mellitus is shown in Figure 2.48

FIGURE 2

ADA recommendations for the treatment of type 2 diabetes

Combination Therapy

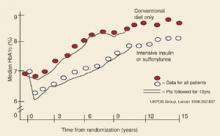

Over time glycemic control becomes more difficult, even with maximum monotherapy for patients with healthy lifestyles. It was shown in UKPDS 49 that monotherapy with sulfonylurea, metformin, or insulin eventually fails in most cases—by 3 years after diagnosis, about 50% of patients need more than monotherapy; 75% by 9 years.49 In UKPDS 33, the median A1c level increased steadily over 10 years with both conventional therapy and intensive therapy (Figure 3).2

Several options are available when monotherapy fails. Based on expert opinion, the principle is to combine drugs with different mechanisms of action to achieve an additive effect for glycemic control. Combination products may simplify the treatment regimen and improve adherence. In many instances, they may also cost less.50

Successful combinations. The combination of sulfonylurea and metformin has proven effective in many studies.22,51,52 One study showed that initial treatment with glyburide/metformin improved glycemic control better than either glyburide or metformin monotherapy (SOR: A).53,54 The addition of the non-SU secretagogues repaglinide and nateglinide to metformin significantly improved glycemic control, with repaglinide showing superiority over nateglinide.55 A TZD added to a sulfonylurea has also significantly improved A1c and fasting blood sugar results.56 Patients whose diabetes was inadequately controlled with diet alone or diet plus a sulfonylurea showed improvement with the addition of the AGI miglitol, compared with addition of placebo.57 The AGI acarbose has shown to be an effective addition to diet, metformin, sulfonylurea, and insulin.58 A TZD added to metformin has also been shown to improve glycemic control.59 A non-SU added to patients inadequately controlled with a TZD has also been effective.60

The early addition of insulin when maximal sulfonylurea therapy is inadequate has been effective.61-63 When introducing insulin, a nighttime regimen of NPH or glargine, 10 units at bedtime, is an appropriate dose (SOR: C). This is easier and less costly than often assumed, and helps improve glycemic control.64 Most patients require combination therapy as their disease progresses.39

FIGURE 3

Glycemic control in type 2 DM

Improving Outcomes

Cumulative survey data reveal a wide gap between guideline recommendations and the care patients receive.65 One study showed that physicians initiated treatment changes only after the A1c level had reached 9.0% or higher instead of the 8.0% level recommended by ADA.66 How can the quality of management be improved?

In private practices and institutions, many interventions have been shown to improve outcomes in diabetes mellitus. Education measures work, and they include chart audits, reminder cards, pharmacist collaboration, flow sheets, and nursing initiatives.67,68 Effective disease-management programs have also used clinical guidelines, outcomes reporting, coverage of glucose meters and strips, and the support of clinical leadership.69

Computerized systems that track patients and recommended laboratory tests have improved screening rates and glycemic and blood pressure control.70 Monitoring patients’ readiness to change has allowed targeted education to improve A1c levels.71 Continuity of care has also improved the quality of disease control by increasing adherence to recommended tests and exams.72

Acknowlegments

The authors thank Marie Hamer, RN, for her continuous diabetes quality improvement efforts and Jean Camarata for her editorial and reference acquisition assistance.

Corresponding author

John E. Sutherland, MD, Northeast Iowa Family Practice Residency Program, University of Iowa College of Medicine, 2055 Kimball Avenue, Waterloo, Iowa 50702. E-mail: [email protected].

1. Vinik AI, Vinik E. Prevention of the complications of diabetes. Am J Manag Care. 2003;9 suppl:S63-S80.

2. UK Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS) Group. Intensive blood-glucose control with sulphonylureas or insulin compared with conventional treatment and risk of complications in patients with type 2 diabetes (UKPDS 33). Lancet. 1998;352:837-853.

3. Arauz-Pacheco C, Parrott MA, Raskin P. American Diabetes Association Treatment of hypertension in adults with diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2004;27 (suppl):S65-67.

4. UK Prospective Diabetes Study Group. Tight blood pressure control and risk of macrovascular and microvascular complications in type 2 diabetes: UKPDS 38. BMJ. 1998;317:703-713.

5. Beckman JA, Creager MA, Libby P. Diabetes and atherosclerosis: epidemiology, pathophysiology, and management. JAMA. 2002;287:2570-2581.

6. Kendall DM, Bergenstal RM. Comprehensive management of patients with type 2 diabetes: establishing priorities of care. Am J Manag Care. 2001;7 (suppl):S327-S343.

7. American Diabetes Association. Standards of medical care in Diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2004;27(suppl):15-35.

8. Peterson KA. Diabetes management in the primary care setting: summary. Am J Med. 2002;113(suppl 6A):36S-40S.

9. Ellis SE, Speroff T, Dittus RS, Brown A, Pichert JW, Elasy TA. Diabetes patient education: A meta-analysis and meta-regression. Patient Educ Couns. 2004;52:97-105.

10. Chandalia M, Garg A, Lutjohann D, et al. Beneficial effects of high dietary fiber intake in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:1392-1398.

11. Hadden DR, Montgomery DAD, Skelly RJ, et al. Maturity onset diabetes mellitus: response to intensive dietary management. Br Med J. 1975;3:276-278.

12. Niskenen LK, Uusitupa MI, Surlund H, et al. Five-year follow-up study on plasma insulin levels in newly diagnosed NIDDM patients and nondiabetic subjects. Diabetes Care. 1009;13:41-48.

13. Leibel R, Rosenbaum M, Hirsch J. Changes in energy expenditure resulting from altered body weight. N Engl J Med. 1995;332:621-628.