User login

Gadolinium Intermediate Elimination and Persistent Symptoms After Magnetic Resonance Imaging Contrast Agent Exposure

Gadolinium Intermediate Elimination and Persistent Symptoms After Magnetic Resonance Imaging Contrast Agent Exposure

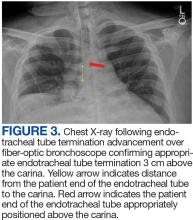

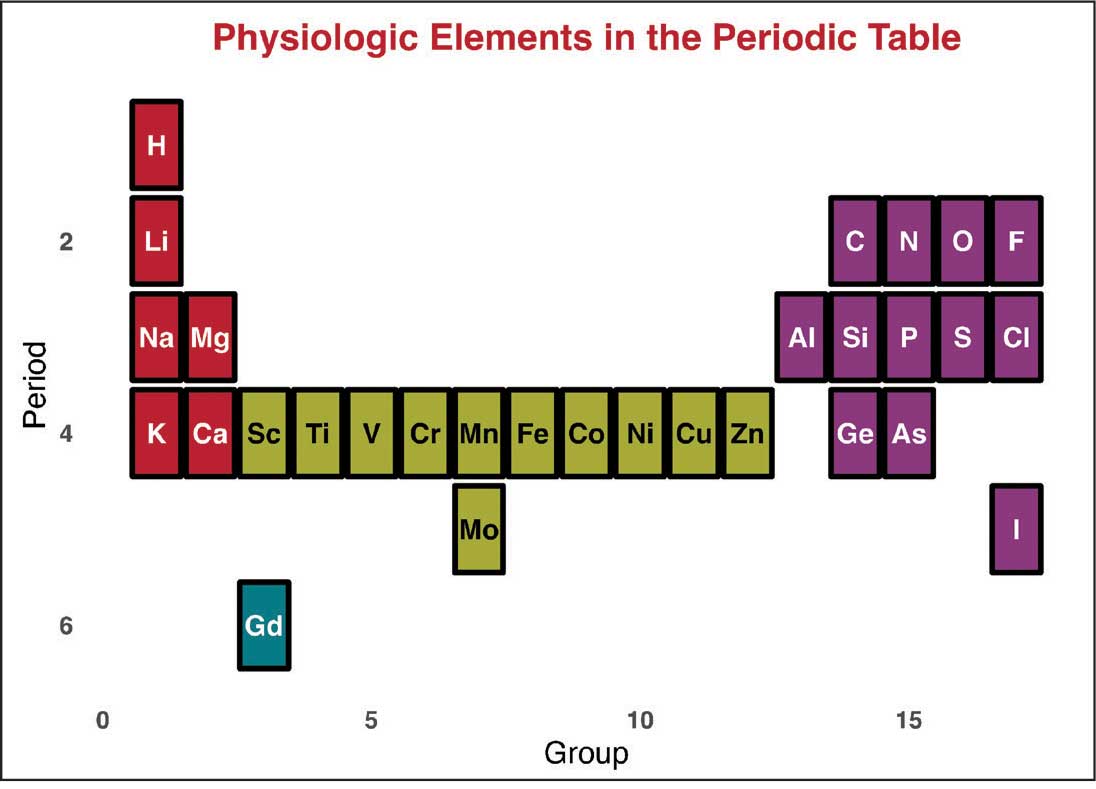

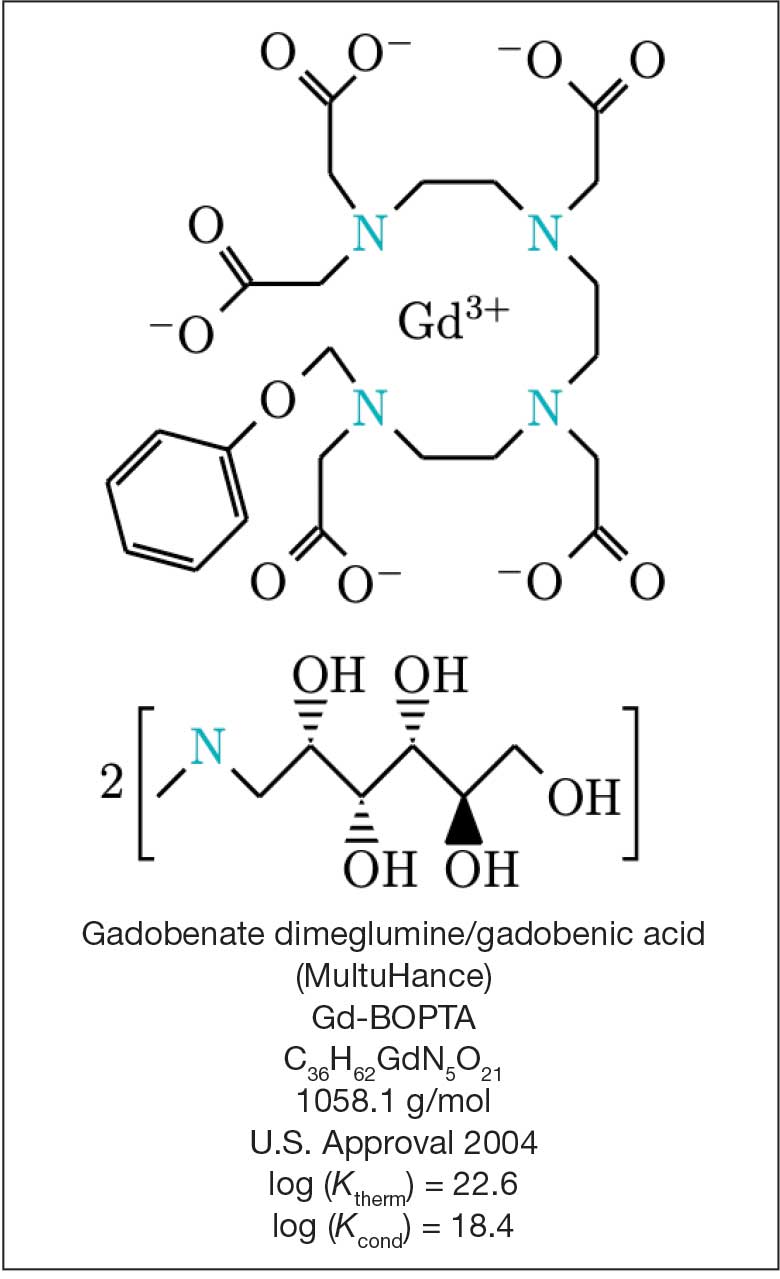

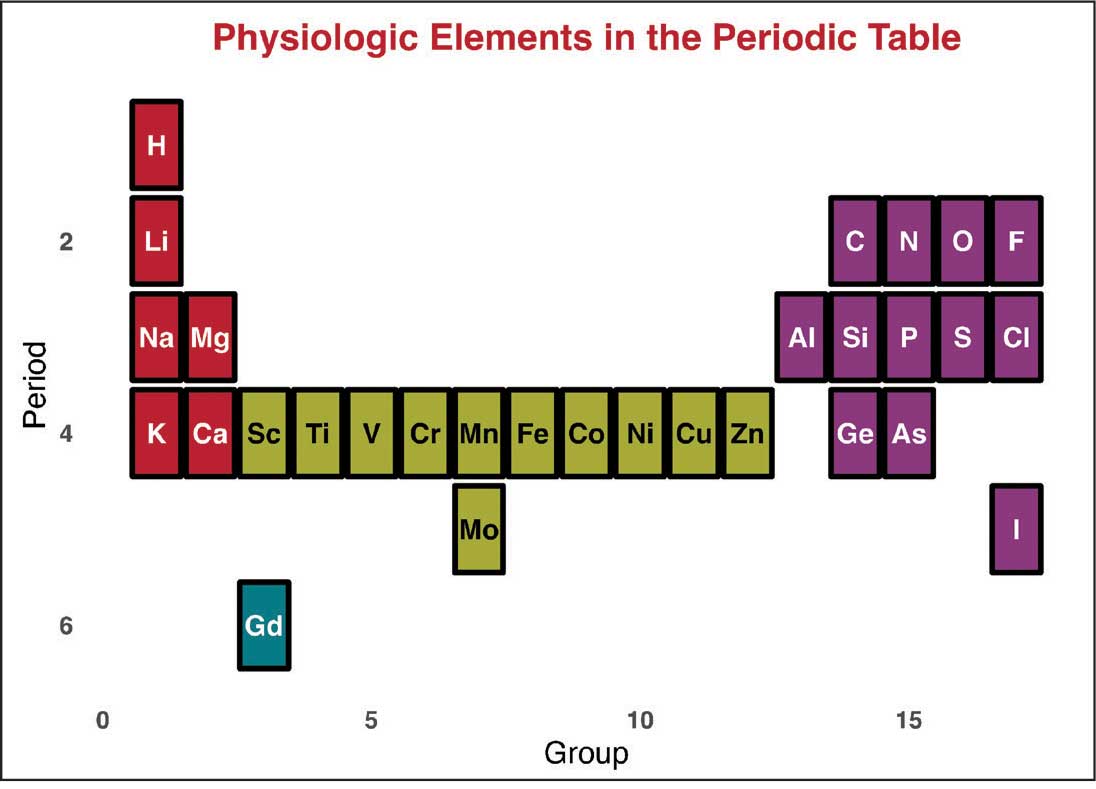

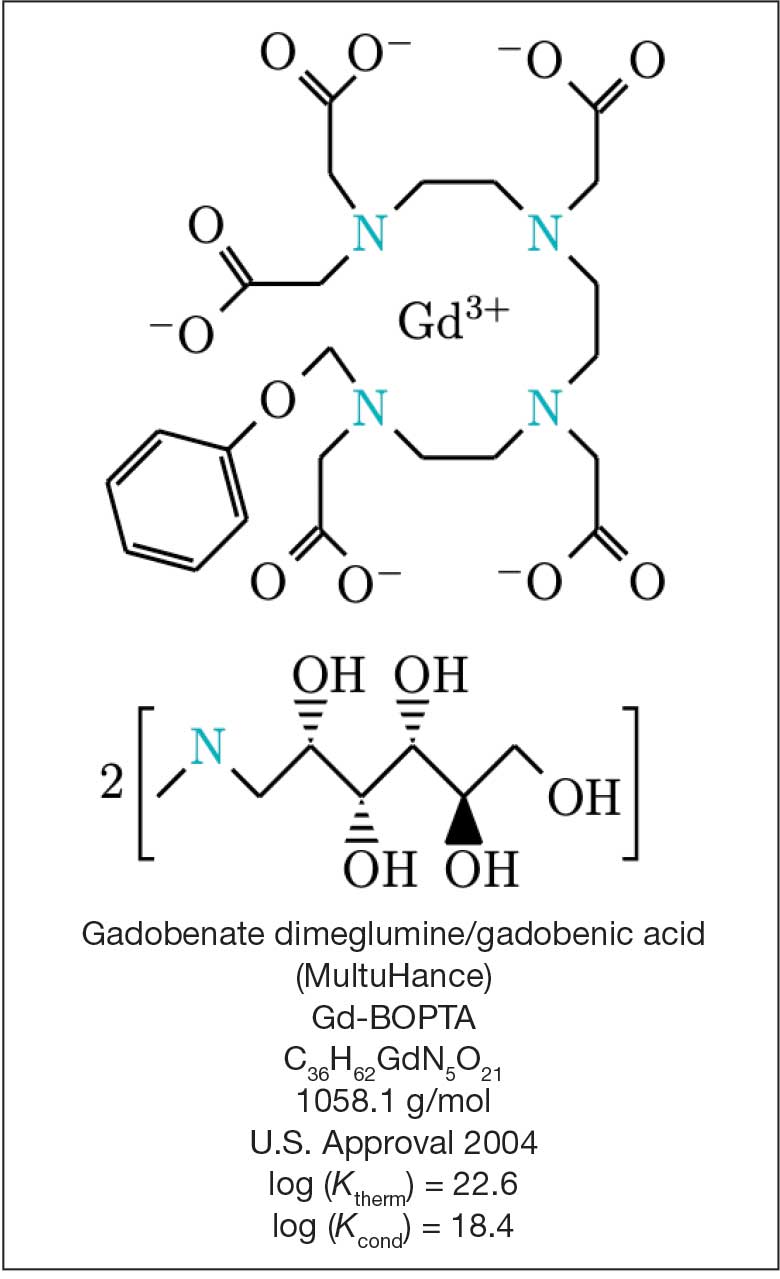

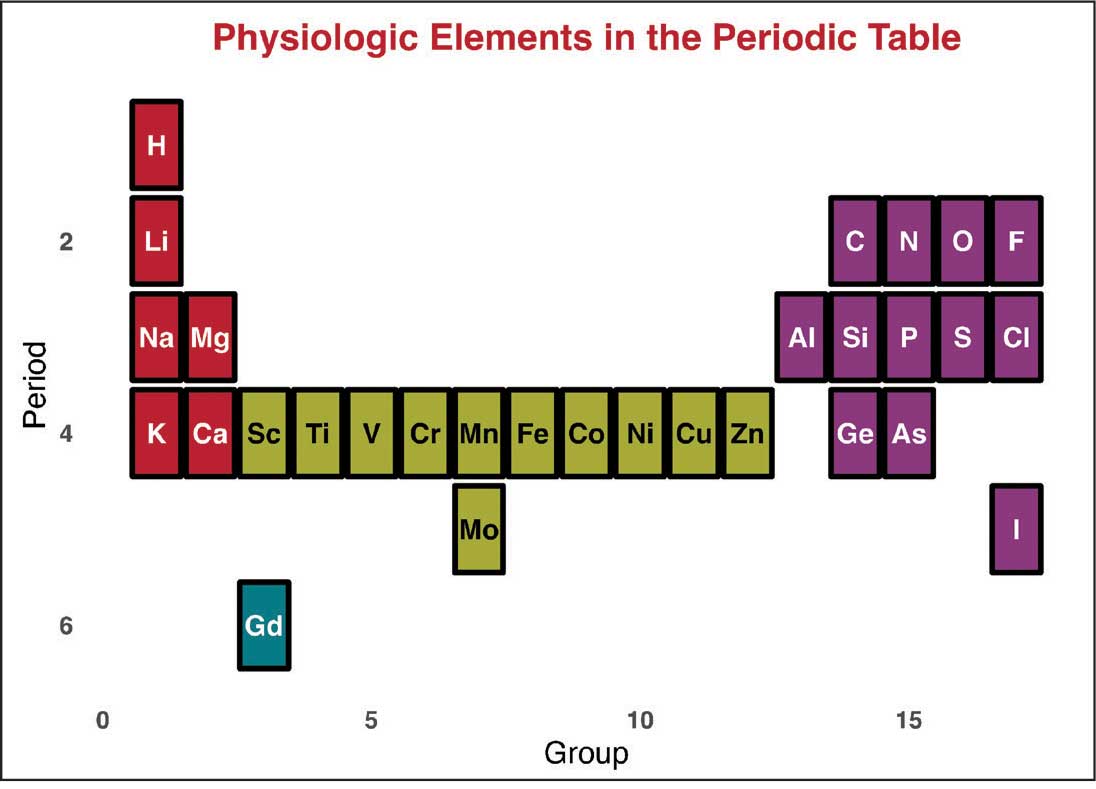

Magnetic resonance image (MRI) contrast agents can induce profound complications, including gadolinium encephalopathy, kidney injury, gadolinium-associated plaques, and progressive systemic fibrosis, which can be fatal.1-10 About 50% of MRIs use gadolinium-based contrast (Gd3+), a toxic rare earth metal ion that enhances imaging but requires binding with pharmaceutical ligands to reduce toxicity and promote renal elimination (Figure 1). Despite these measures, Gd3+ can persist in the body, including the brain.11,12 Wastewater treatment fails to remove these agents, making Gd3+ a growing pollutant in water and the food chain.13-15 Because Gd3+ is a rare earth metal ion in the milieu intérieur, there is an urgent need to study its biological and long-term effects (Appendix 1).

Case Presentation

A 65-year-old Vietnam-era veteran presented to nephrology at the Raymond G. Murphy Veterans Affairs Medical Center (RGMVAMC) in Albuquerque, New Mexico, for evaluation of gadolinium-induced symptoms. His medical history included metabolic syndrome, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, hypogonadism, cervical spondylosis, and an elevated prostate-specific antigen, previously assessed with a contrast-enhanced MRI in 2019 (Gadobenic acid, 19 mL). Surgical history included cervical fusion and ankle hardware.

The patient had a scheduled MRI 25 days earlier, following an elevated prostate specific antigen test result, prompting urologic surveillance and concern for malignancy. In preparation for the contrast-enhanced MRI, his right arm was cannulated with a line primed with gadobenic acid contrast. Though the technician stated the infusion had not started, the patient’s symptoms began shortly after entry into the scanner, before any programmed pulse sequences. The patient experienced claustrophobia, diaphoresis, palpitations, xerostomia, dysgeusia, shortness of breath, and a sensation of heat in his groin, chest, “kidneys,” and lower back. The MRI was terminated prematurely in response to the patient’s acute symptomatology. The patient continued experiencing new symptoms intermittently during the following week, including lightheadedness, headaches, right clavicular pain, raspy voice, edema, and a sense of doom.

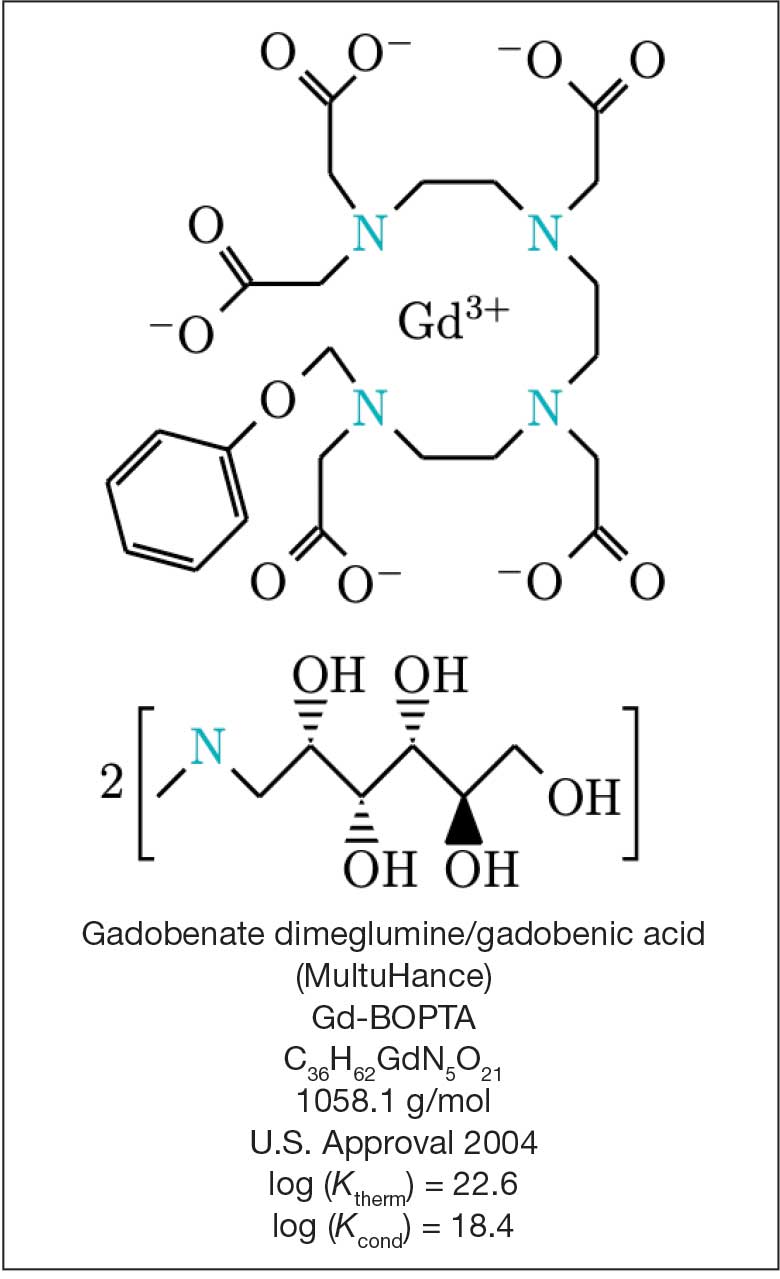

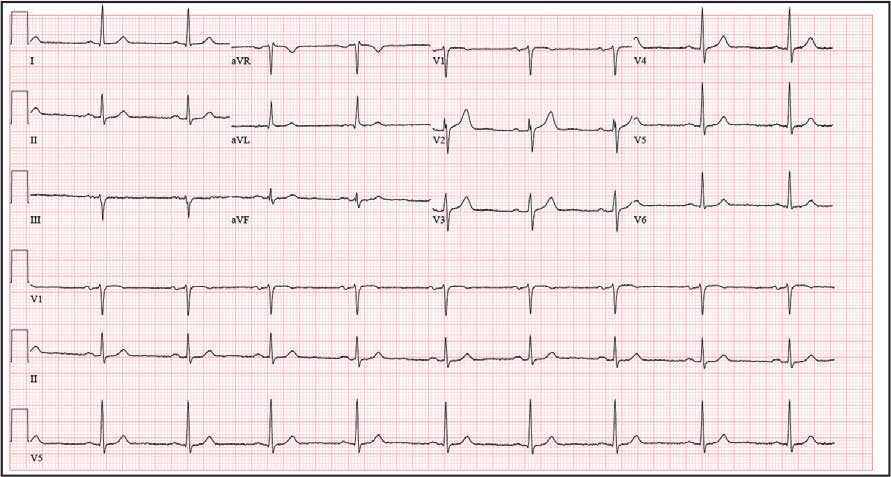

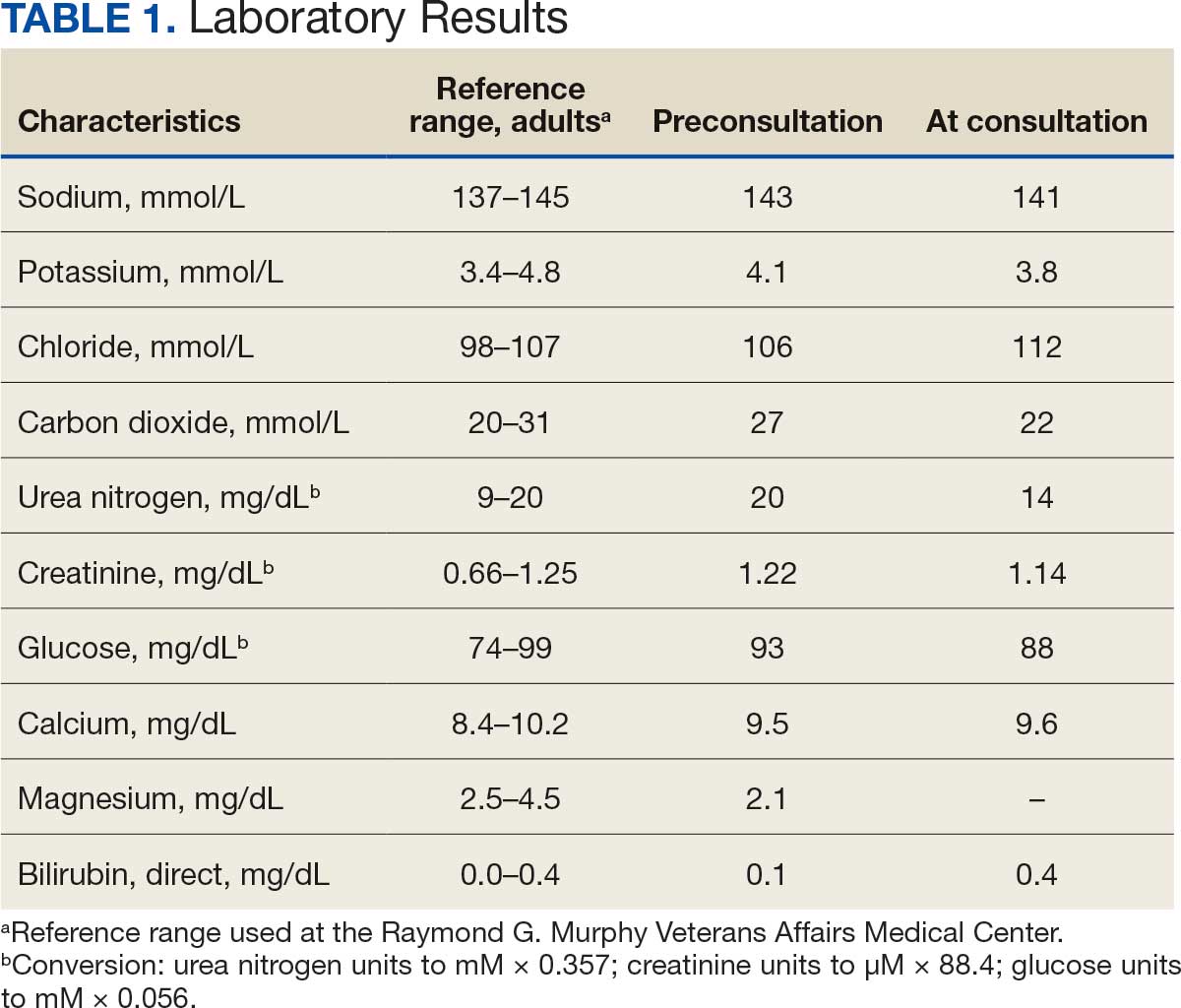

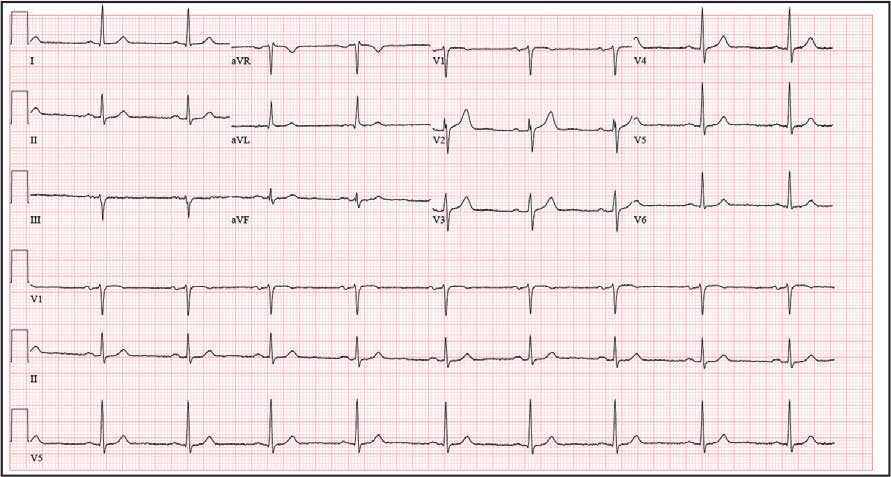

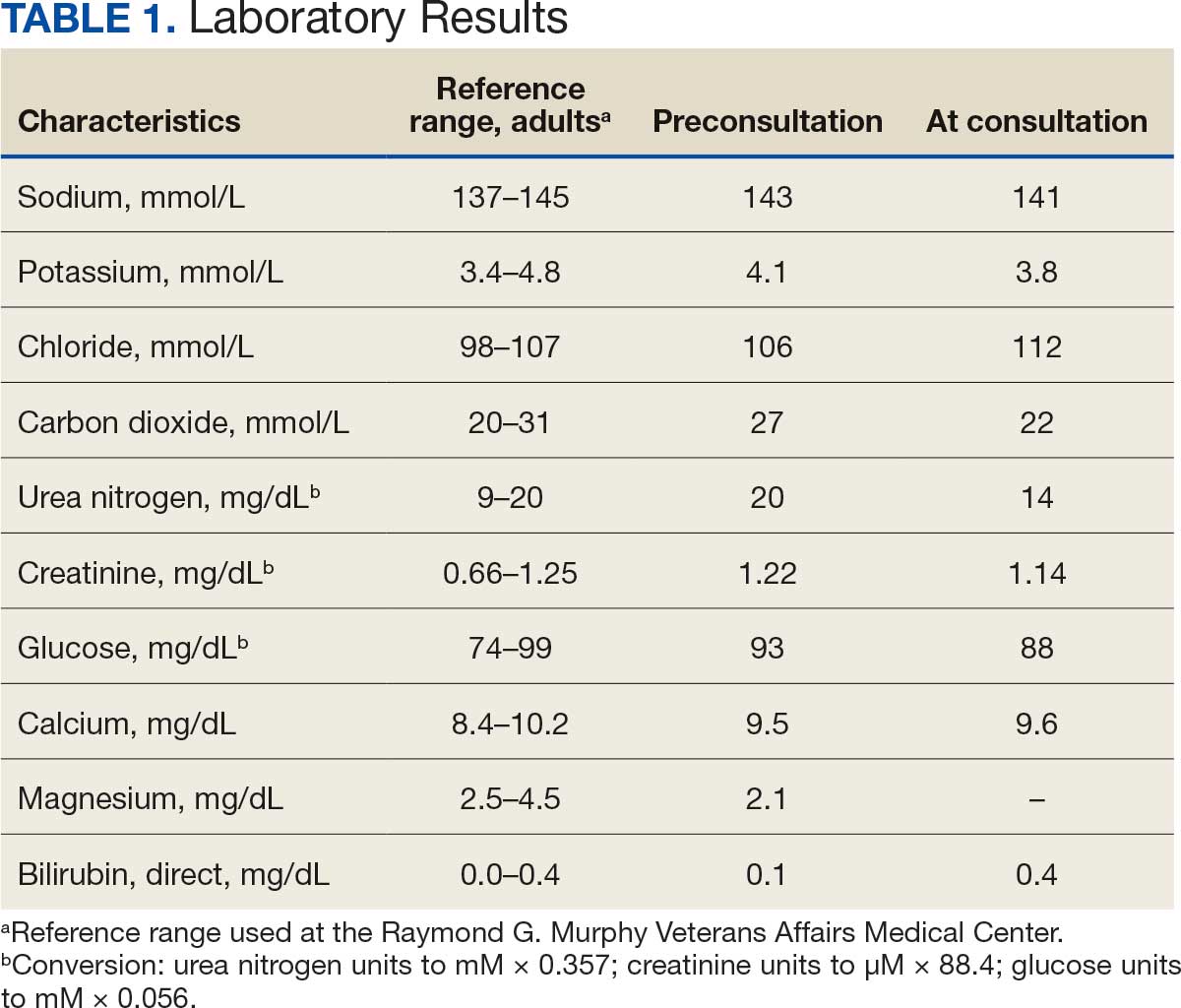

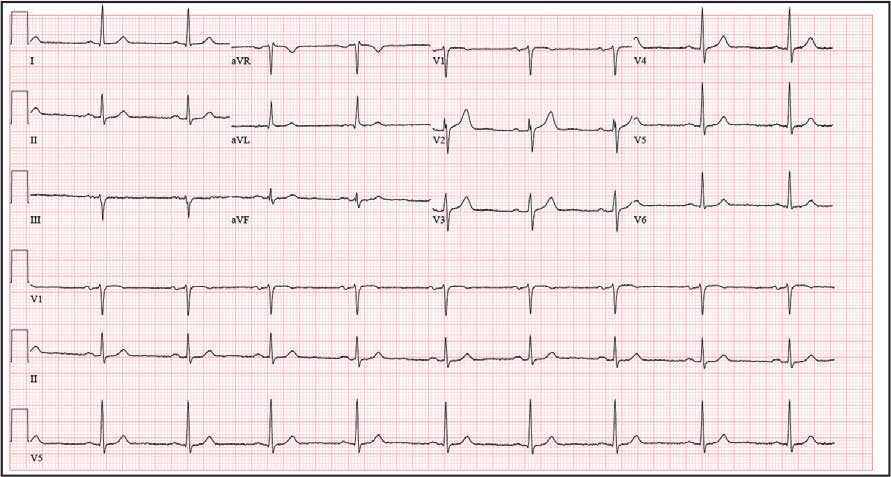

The patient presented to the RGMVAMC emergency department (ED) 8 days after the MRI with worsening symptoms and was hospitalized for 10 days. During this time, he was referred to nephrology for outpatient evaluation. While awaiting his nephrology appointment, the patient presented to the RGMVAMC ED 20 days after the initial episode with ongoing symptoms. “I thought I was dying,” he said. Laboratory results and a 12-lead electrocardiogram showed a finely static background, wide P waves (> 80 ms) with notching in lead II, sinusoidal P waves in V1, R transition in V2, RR’ in V2, ST flat in lead III, and sinus bradycardia (Table 1 and Appendix 2).

The patient’s medical and surgical histories were reviewed at the nephrology evaluation 25 days following the MRI. He reported that household water was sourced from a well and that he filtered his drinking water with a reverse osmosis system. He served in the US Army for 10 years as an engineer specializing in mechanical systems, power generation, and vehicles. Following Army retirement, the patient served in the US Air Force Reserves for 15 years, working as a crew chief in pneudraulics. The patient reported stopping tobacco use 1 year before and also reported regular use of a broad array of prescription medications and dietary supplements, including dexamethasone (4 mg twice daily), fluticasone nasal spray (50 mcg per nostril, twice daily), ibuprofen (400 mg twice daily, as needed), loratadine (10 mg daily), aspirin (81 mg daily), and metoprolol succinate (50 mg nightly). In addition, he reported consistent use of cholecalciferol (3000 IU daily), another supplemental vitamin D preparation, chelated magnesium glycinate (3 tablets daily for bone issues), turmeric (1 tablet daily), a multivitamin (Living Green Liquid Gel, daily), and a mega-B complex.

Physical examination revealed a well-nourished, tall man with hypertension (145/87 mmHg) and bilateral lower extremity edema. Oral examination showed poor dentition, including missing molars (#1-3, #14-16, #17-19, #30-31), with the anterior teeth replaced by bridges supported by dental implants. The review of systems was otherwise unremarkable, with nocturia noted before the consultation.

Serum and urine gadolinium testing, (Mayo Clinic Laboratories) revealed gadolinium levels of 0.3 mcg/24 h in the urine and 0.1 ng/mL in the serum. Nonzero values indicated detectable gadolinium, suggesting retention. The patient had a prior gadolinium exposure during a 2019 MRI (about 1340 days before) and suspected a repeat exposure on day 0, although the MRI technician stated that no contrast was administered. Given his elevated vitamin D levels, the patient was advised to minimize dietary supplements, particularly vitamin D, to avoid confounding symptoms. The plan included monitoring symptoms and a follow-up evaluation with repeat laboratory tests on day 116.

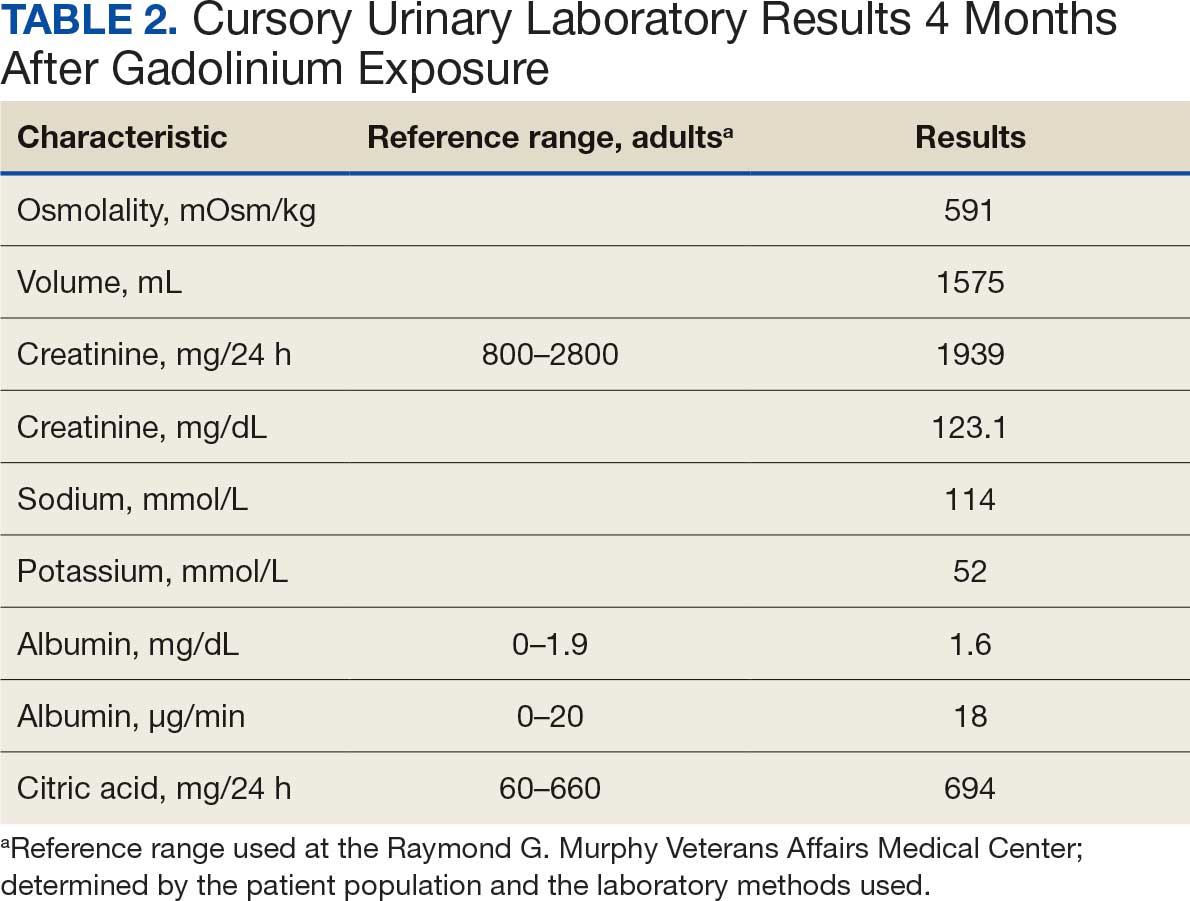

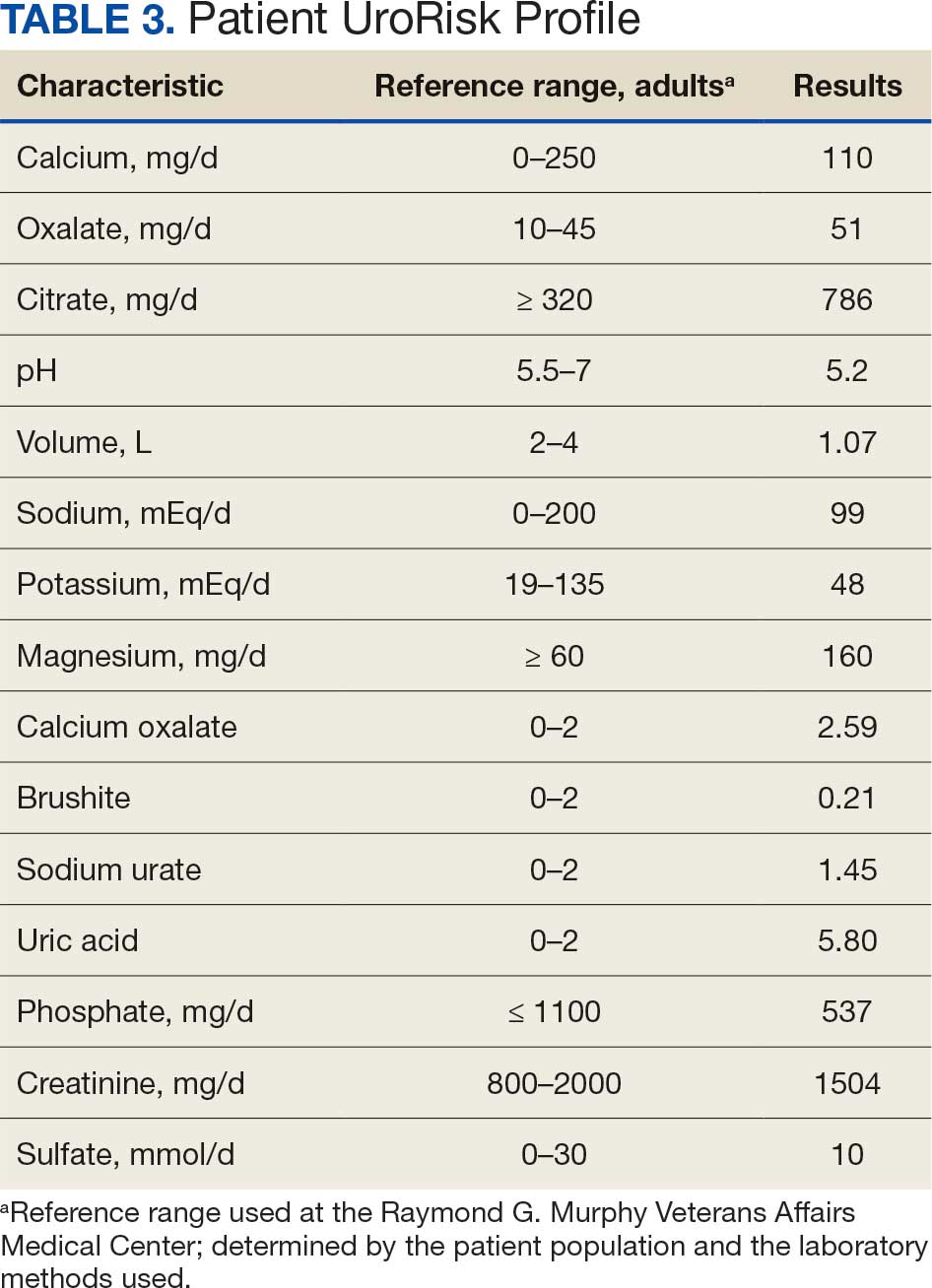

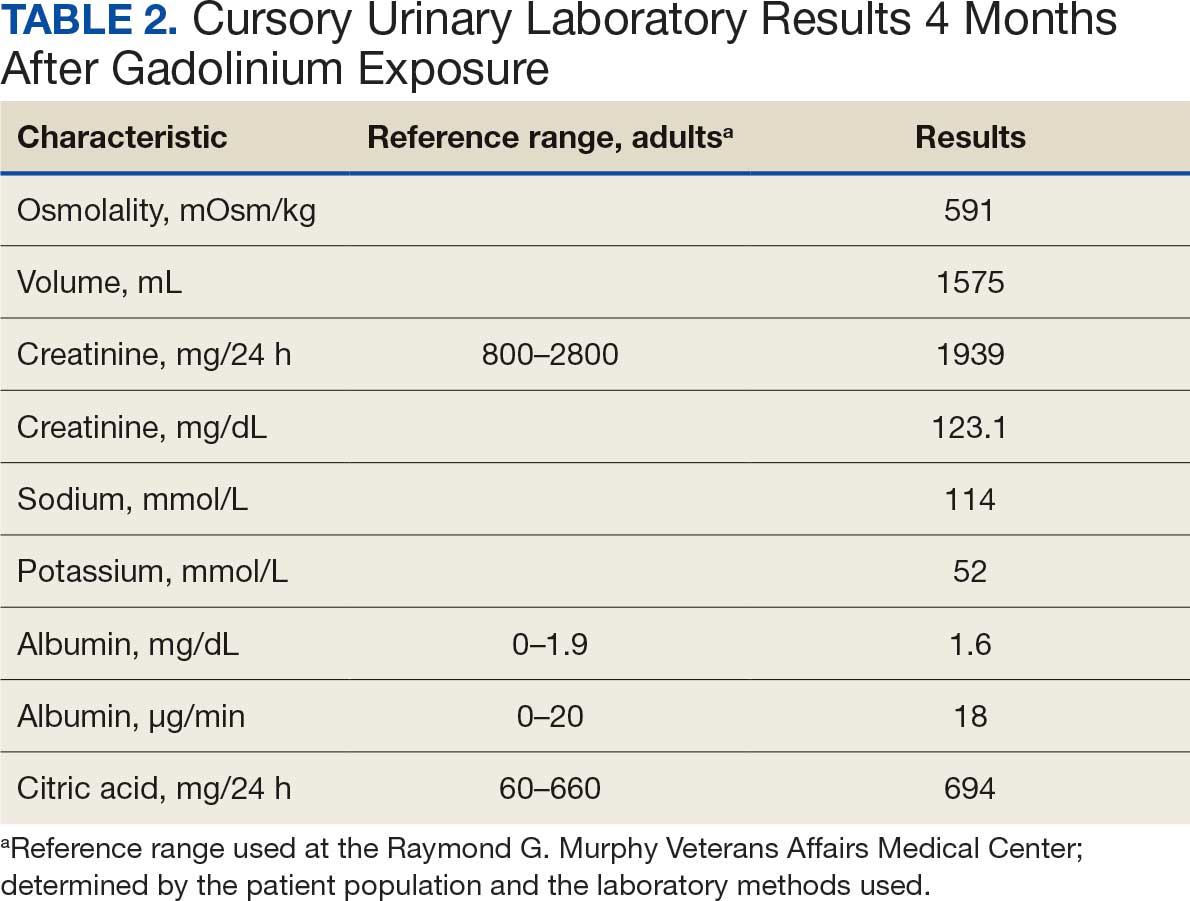

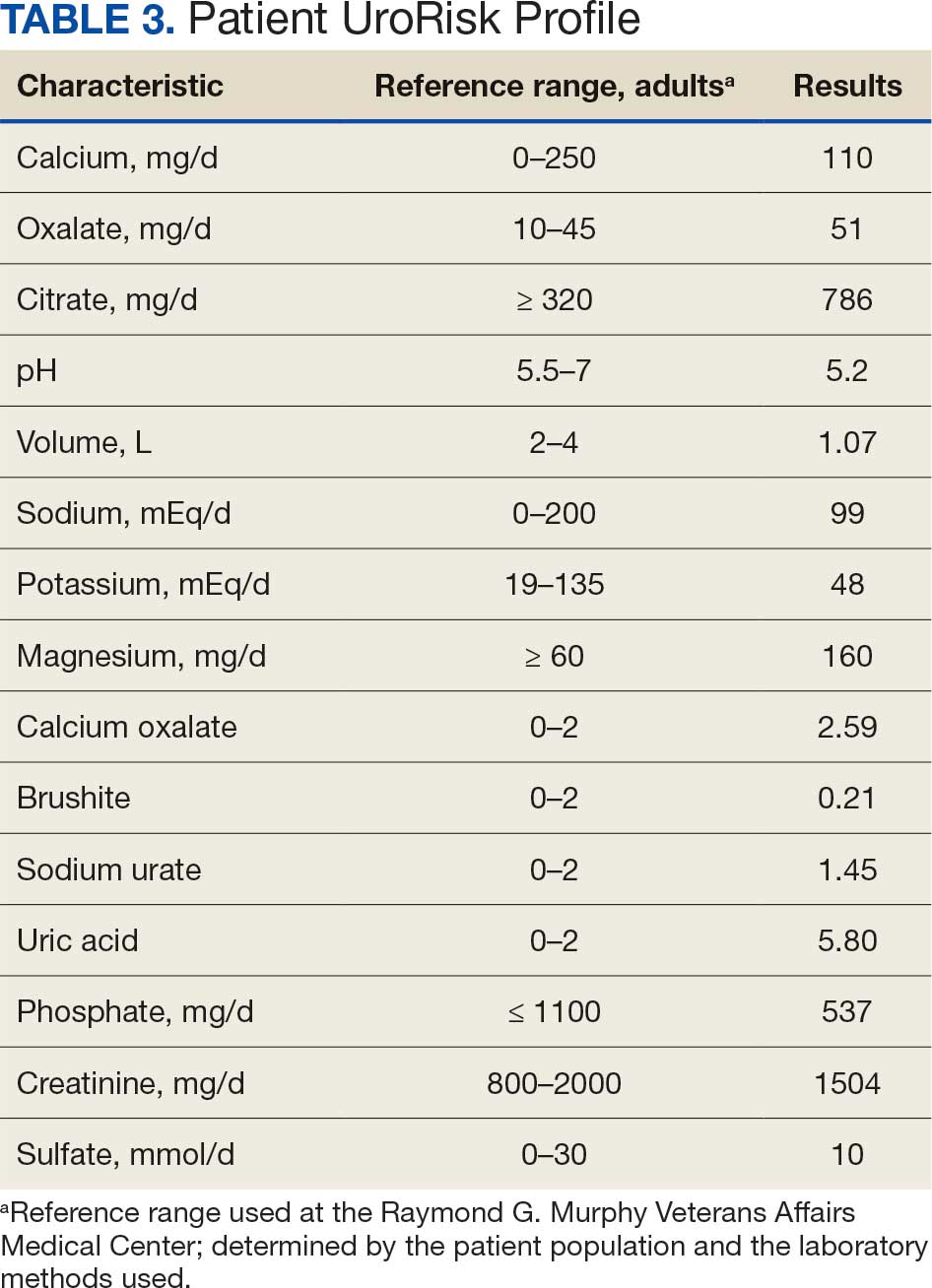

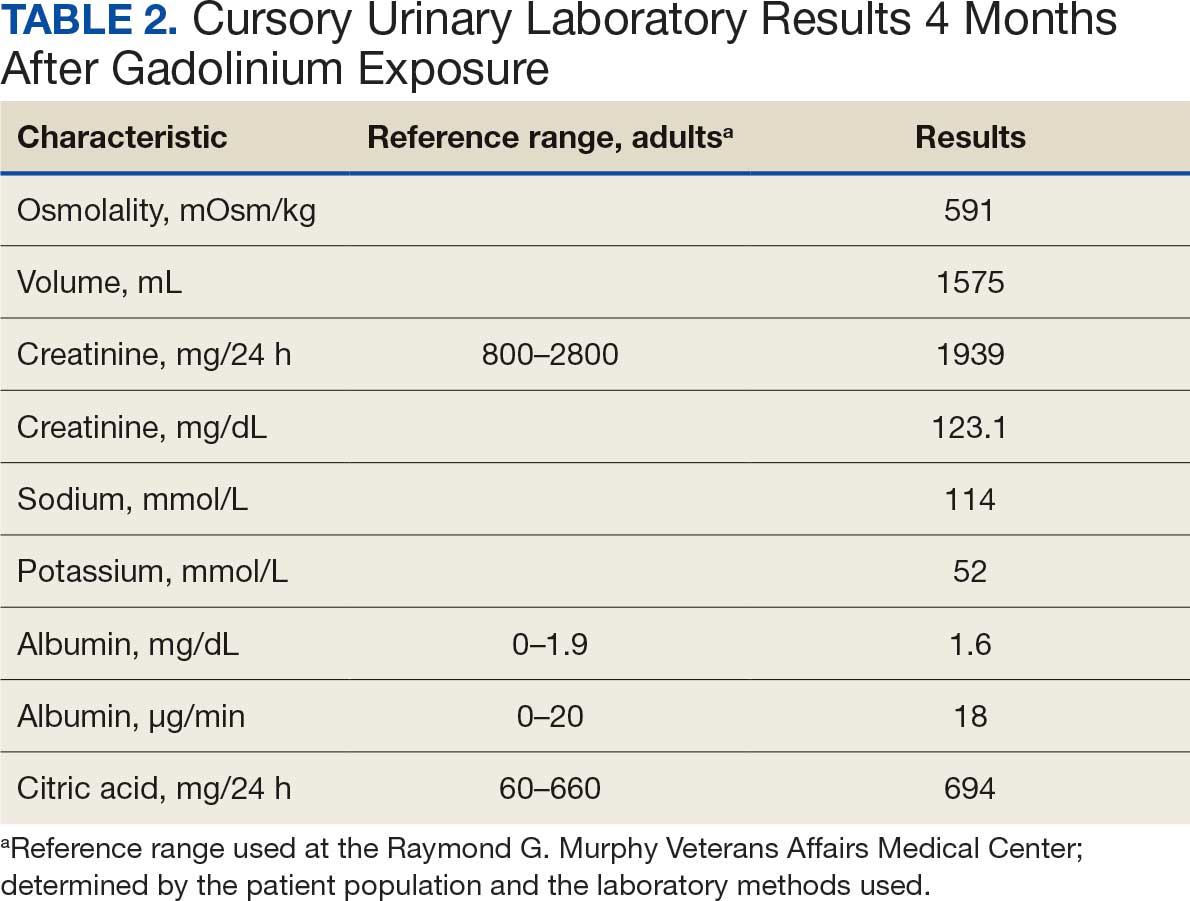

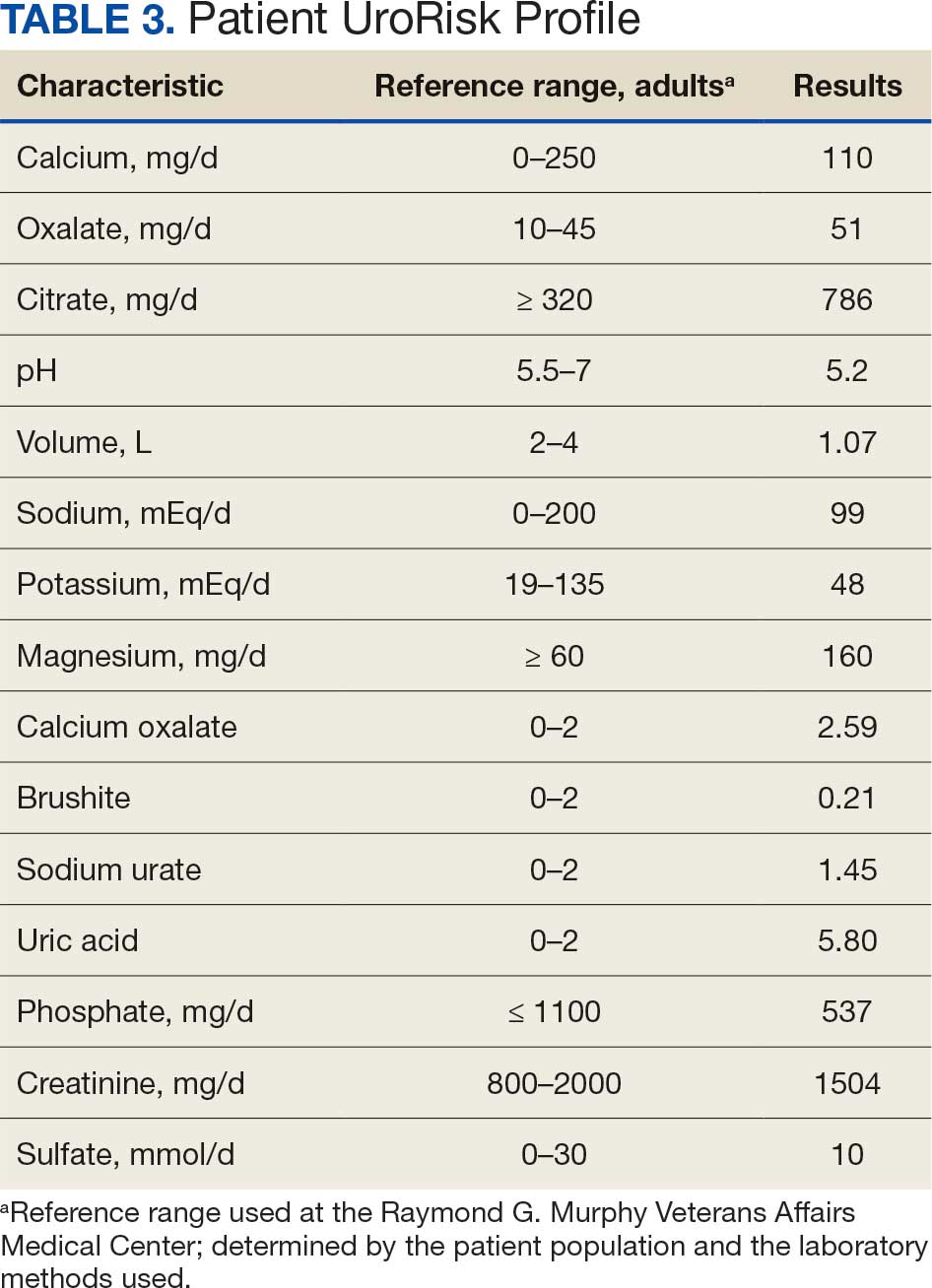

At the nephrology follow-up 4 months postexposure, the patient's symptoms had primarily abated, with a marked reduction in the previously noted metallic dysgeusia. Physical examination remained consistent with prior findings. He was afebrile (97.7 °F) with a blood pressure of 111/72 mmHg, a pulse of 63 beats per minute, and an oxygen saturation of 98% on ambient air. Laboratory analysis revealed serum and urine gadolinium levels below detectable thresholds (< 0.1 ng/mL and < 0.1 mcg/24 h). A 24-hour creatinine clearance, calculated from a urine volume of 1300 mL, measured at an optimal 106 mL/min, indicating preserved renal function (Tables 2 and 3). Of note, his 24-hour oxalate was above the reference range, with a urine pH below the reference range and a high supersaturation index for calcium oxalate.

Discussion

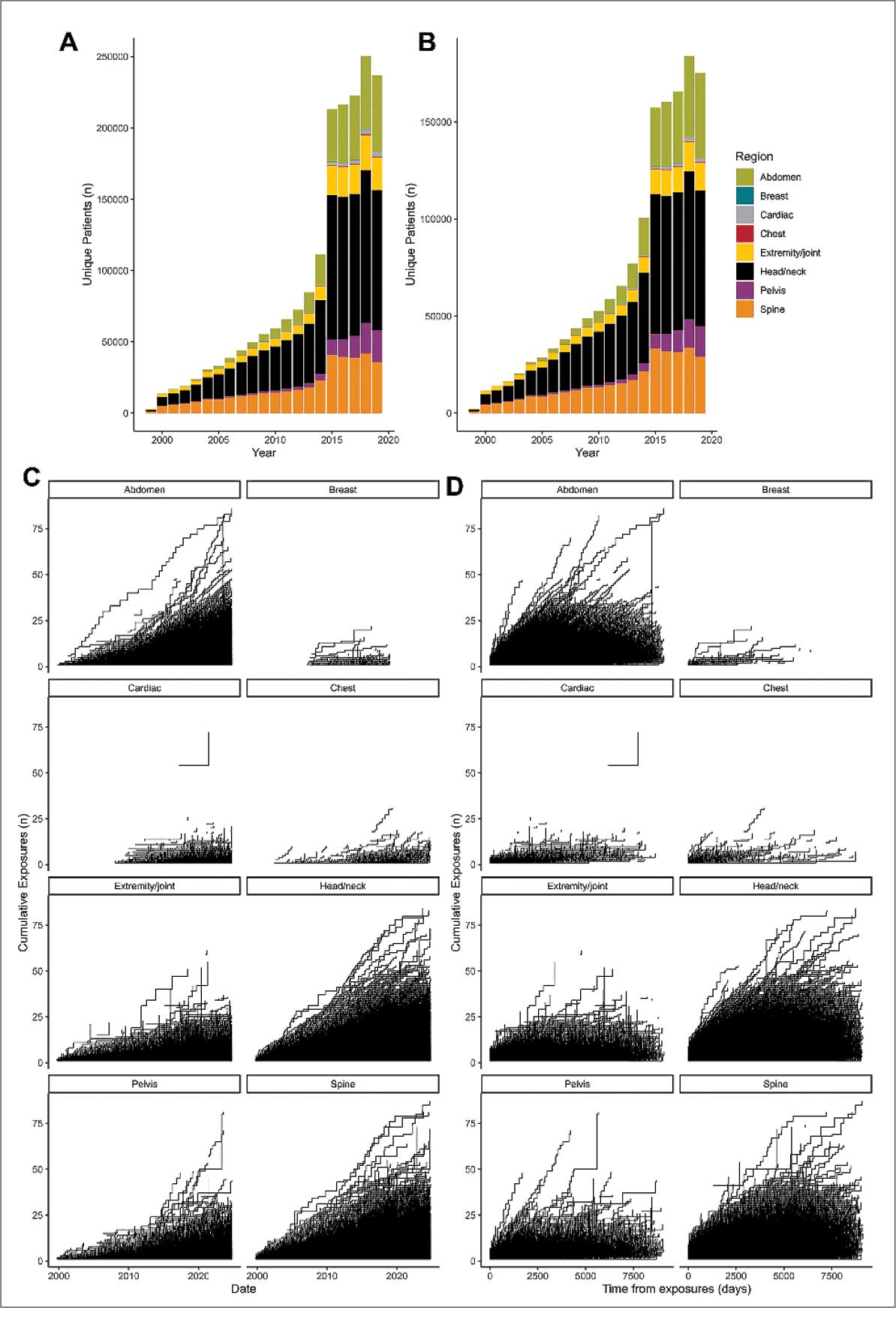

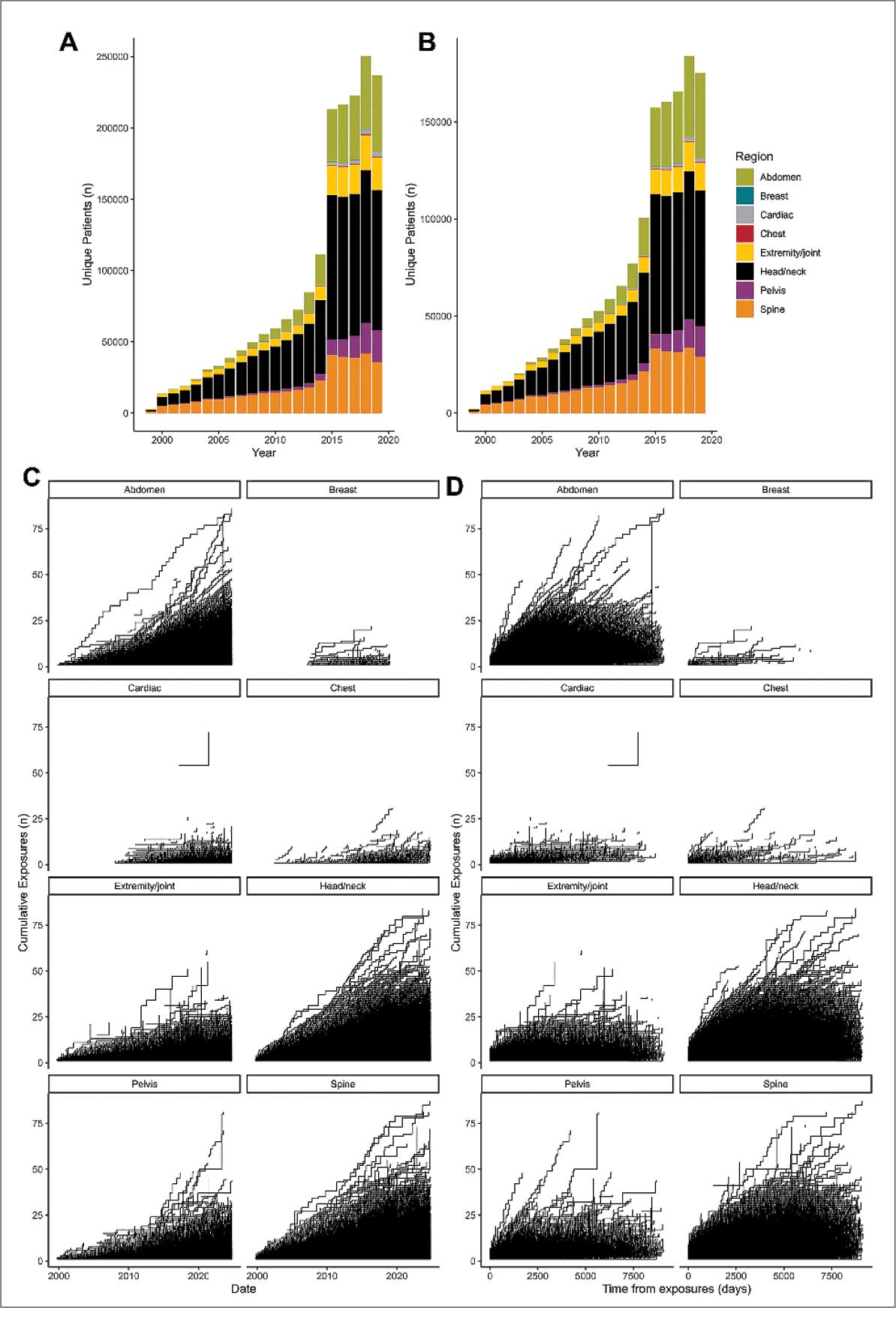

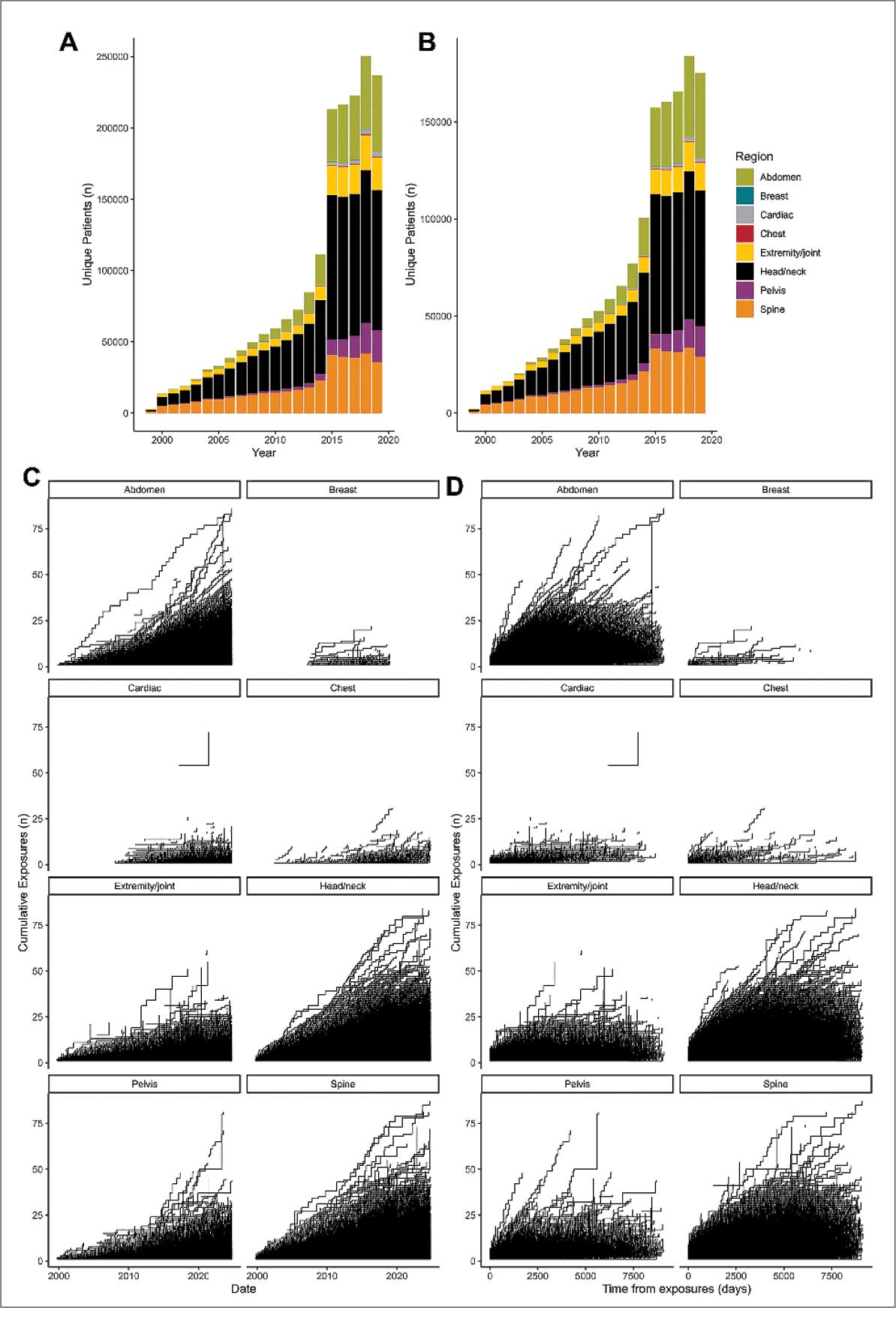

Use of enhanced MRI has increased in the Veterans Health Administration (Figure 2). A growing range of indications for enhanced procedures (eg, cardiac MRI) has contributed to this rise. The market has grown with new gadolinium-based contrast agents, such as gadopiclenol. However, reliance on untested assumptions about the safety of newer agents and need for robust clinical trials pose potential risks to patient safety.

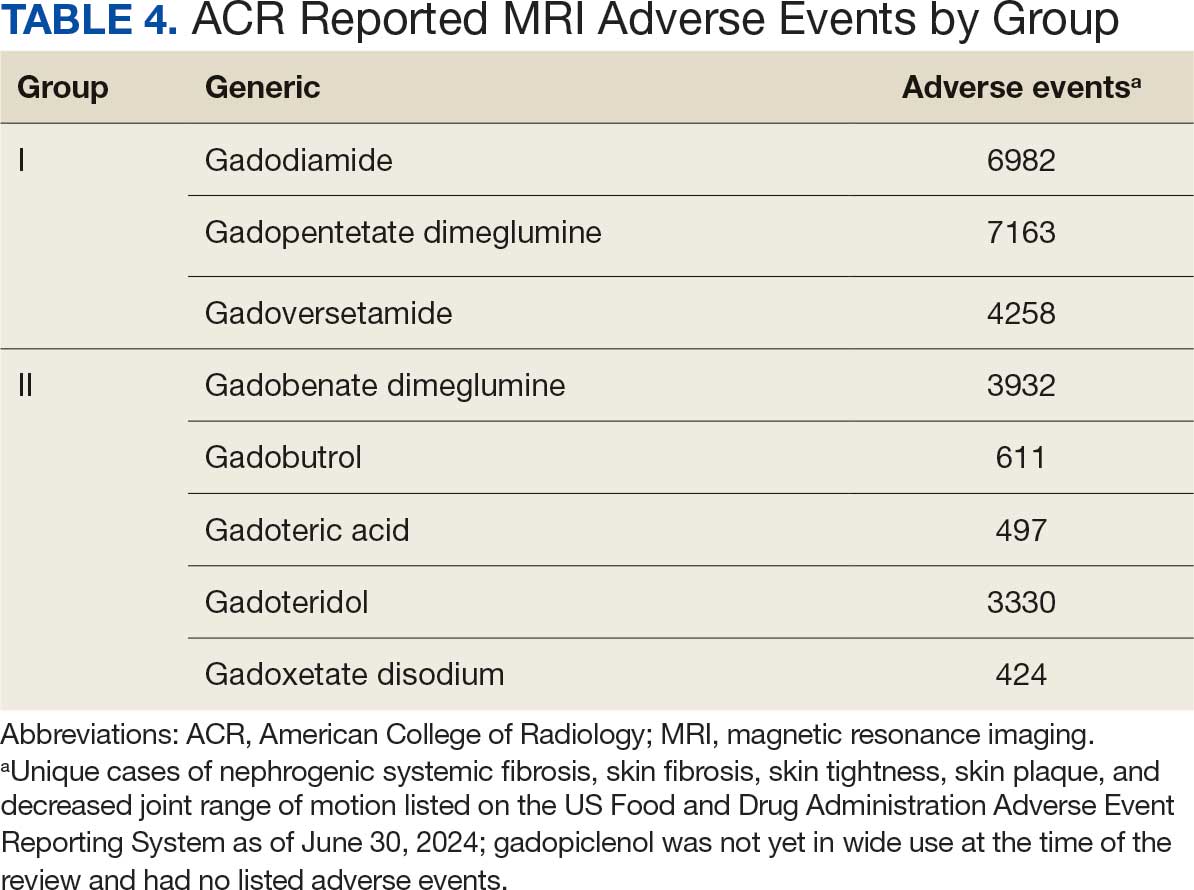

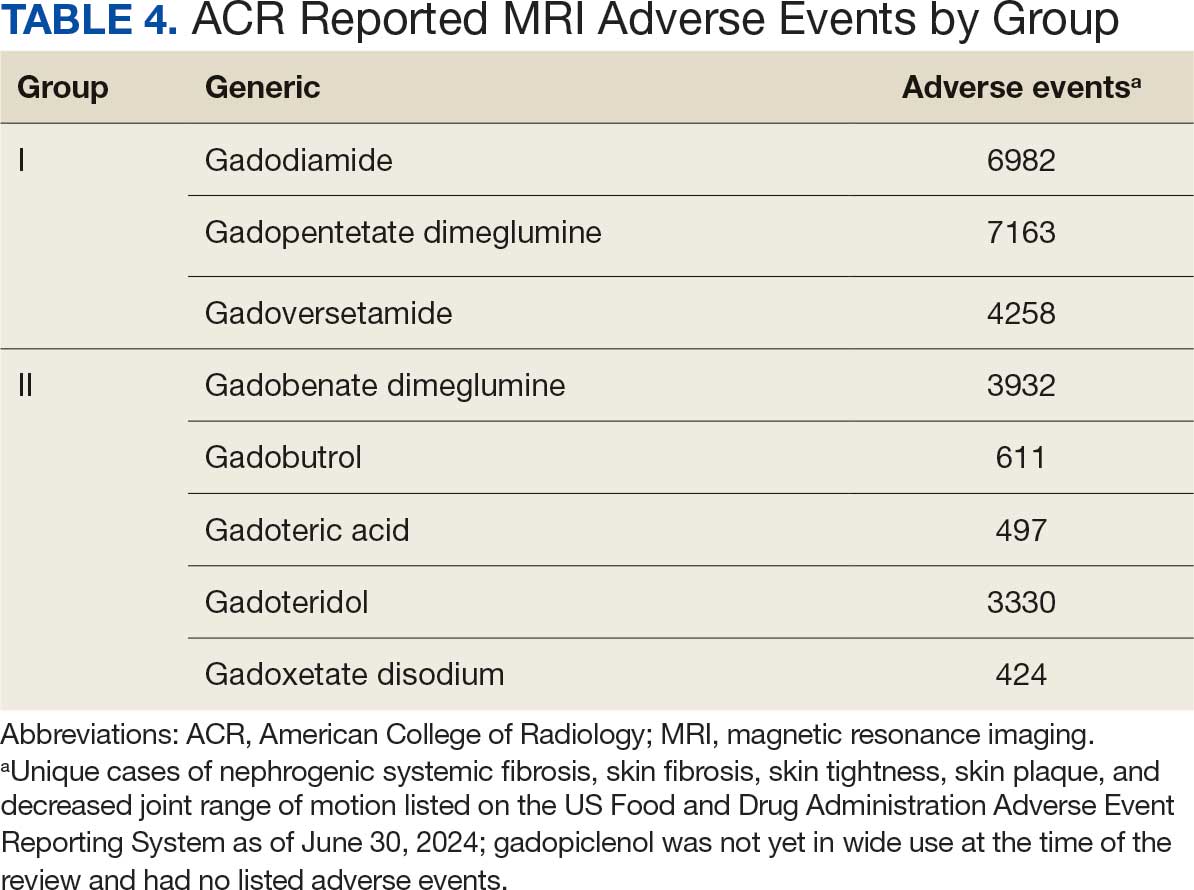

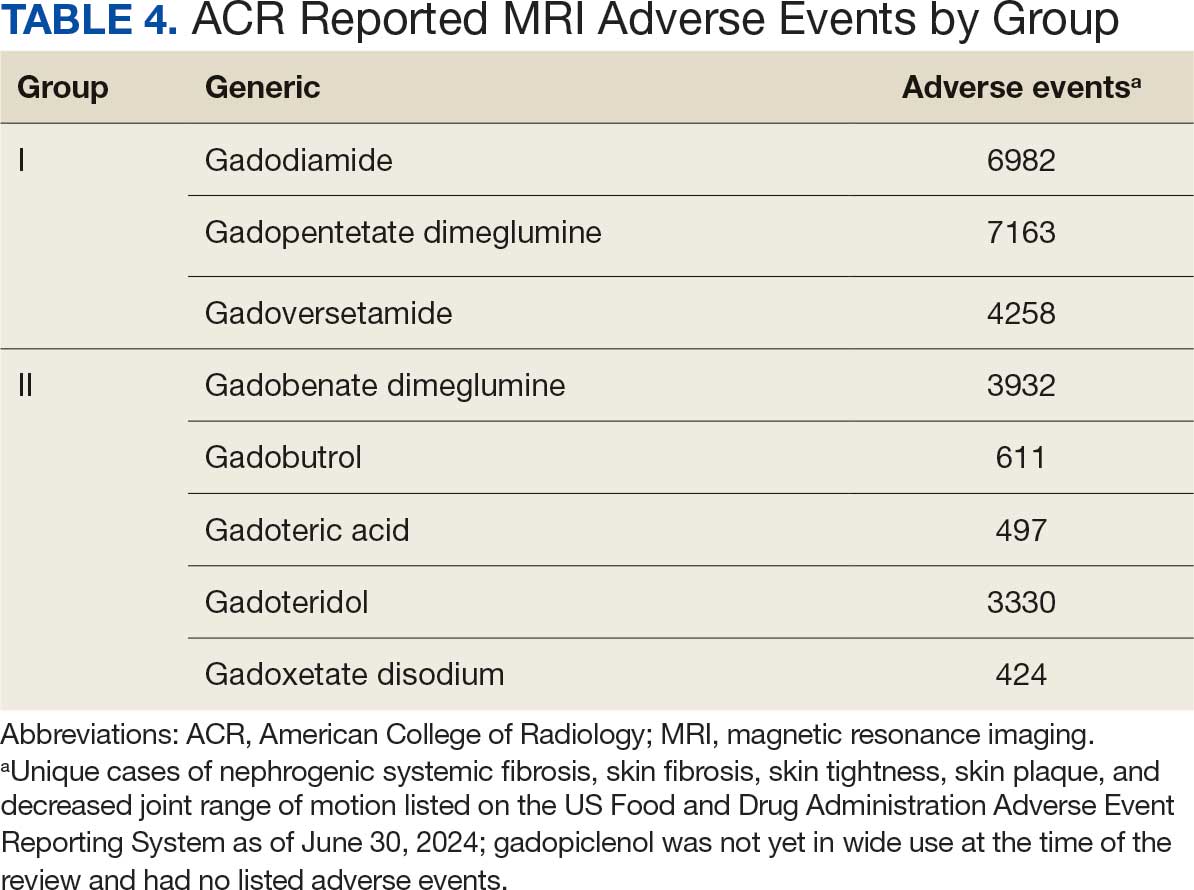

Without prospective evidence, the American College of Radiology (ACR) classifies gadolinium-based contrast agents into 3 groups: Group 1, associated with the highest number of nephrogenic systemic fibrosis cases; Group 2, linked to few, if any, unconfounded cases; and Group 3, where data on nephrogenic systemic fibrosis risk have been limited. As of April 2024, the ACR reclassified Group 3 agents (Ablavar/Vasovist/Angiomark and Primovist/Eovist) into Group 2. Curiously, Vueway and Elucirem were approved in late 2022 and should clearly be categorized as Group 3 (Table 4).There were 19 cases of nephrogenic systemic fibrosis or similar manifestations, 8 of which were unconfounded by other factors. These patients had been exposed to gadobutrol, often combined with other agents. Gadobutrol—like other Group 2 agents—has been associated with nephrogenic systemic fibrosis.16,17 Despite US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) documentation of rising reports, many clinicians remain unaware that nephrogenic systemic fibrosis is increasingly linked to Group 2 agents classified by the ACR.18 While declines in reported cases of nephrogenic systemic fibrosis may suggest reduced incidence, this trend may reflect diminished clinical vigilance and underreporting, particularly given emerging evidence implicating even Group 2 gadolinium-based contrast agents in delayed and underrecognized presentations. This information has yet to permeate the medical community, particularly among nephrologists. Considering these cases, revisiting the ACR guidelines may be prudent.

To address this growing concern, clinicians must adopt stricter vigilance and actively pursue updated information to mitigate patient risks tied to these contrast agents.

There exists an illusion of knowledge in disregarding the confounded exposures of MRI contrast agents. Ten distinct brands of contrast agents have been approved for clinical use. With repeated imaging, patients are often exposed to varying formulations of gadolinium-based agents. Yet investigators commonly discard these data points when assessing risk. By doing so, they assume—without evidence—that some formulations are inherently less likely to provoke adverse effects (AEs) than others. This untested presumption becomes perilous, especially given the limited understanding of the mechanisms underlying gadolinium-induced pathologies. As Aldous Huxley warned, “Facts do not cease to exist because they are ignored.”19

Gadolinium Persistence

Contrary to expectations, gadolinium persists in the body far longer than initially presumed. Symptoms associated with gadolinium exposure (SAGE) encapsulate the chronic, often enigmatic maladies tied to MRI contrast agents.20 The prolonged retention of this rare earth metal offers a compelling hypothesis for the etiology of SAGE. It has been hypothesized that Lewis base-rich metabolites increase susceptibility to gadolinium-based contrast agent complications.21

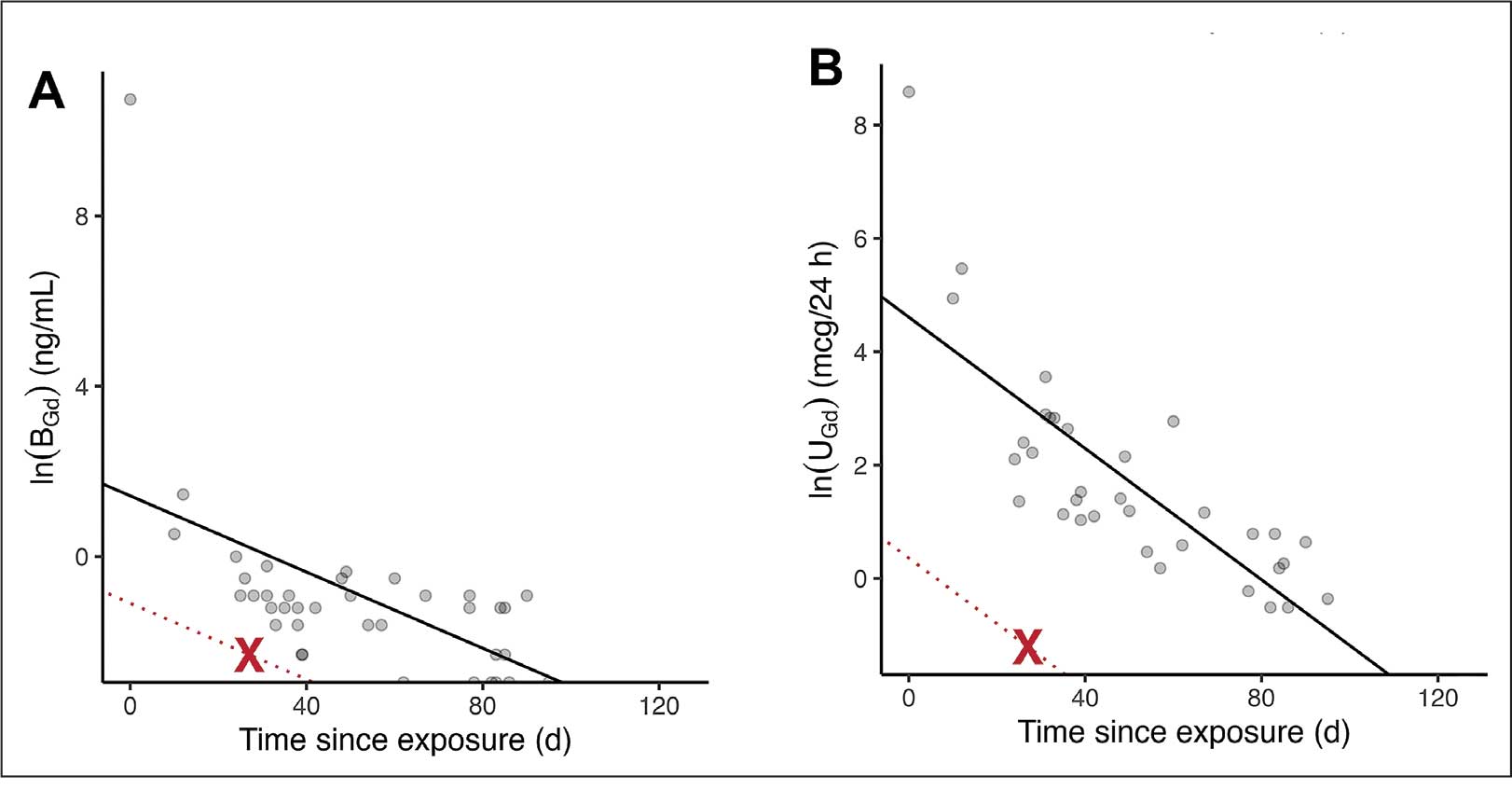

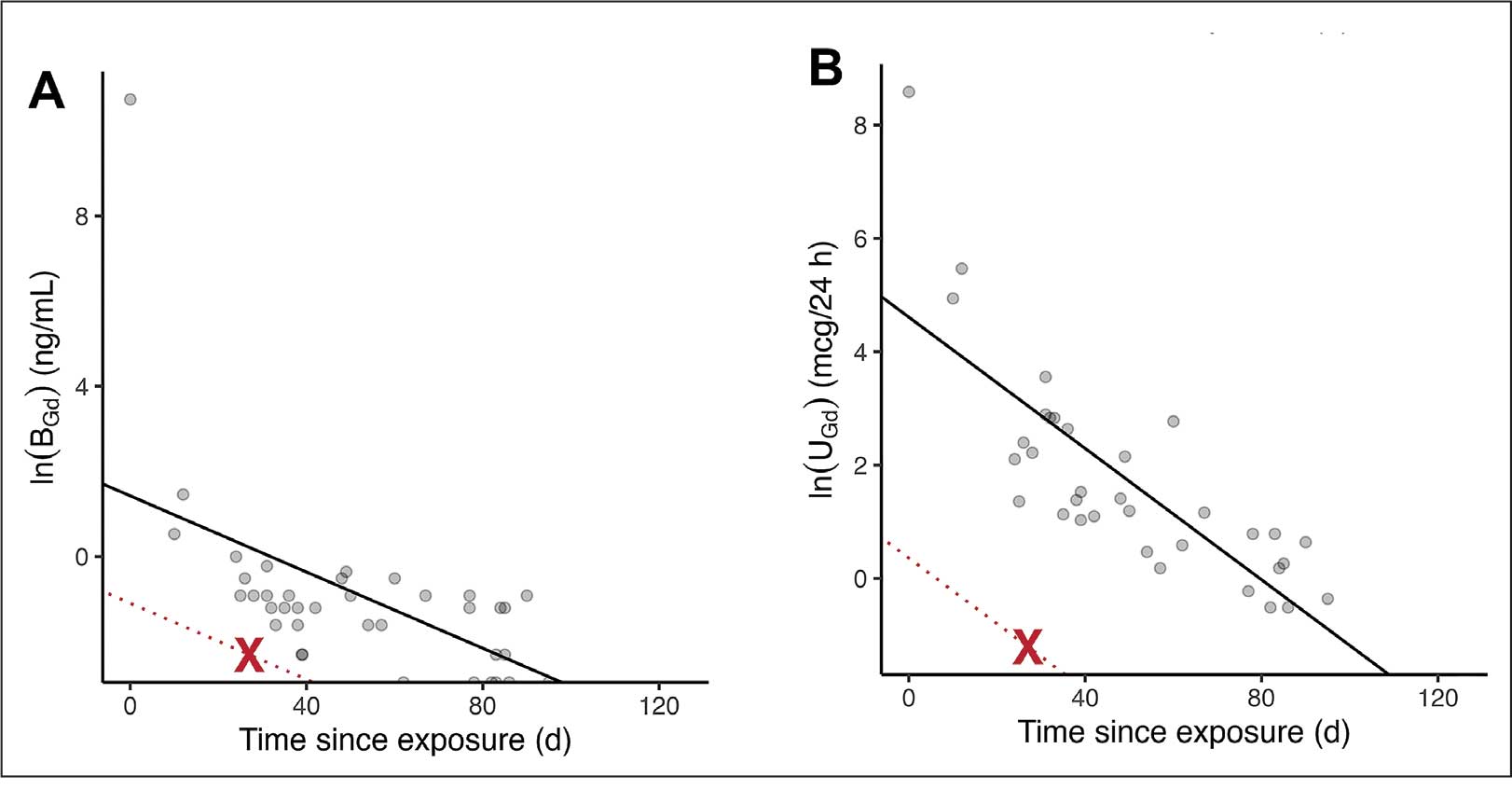

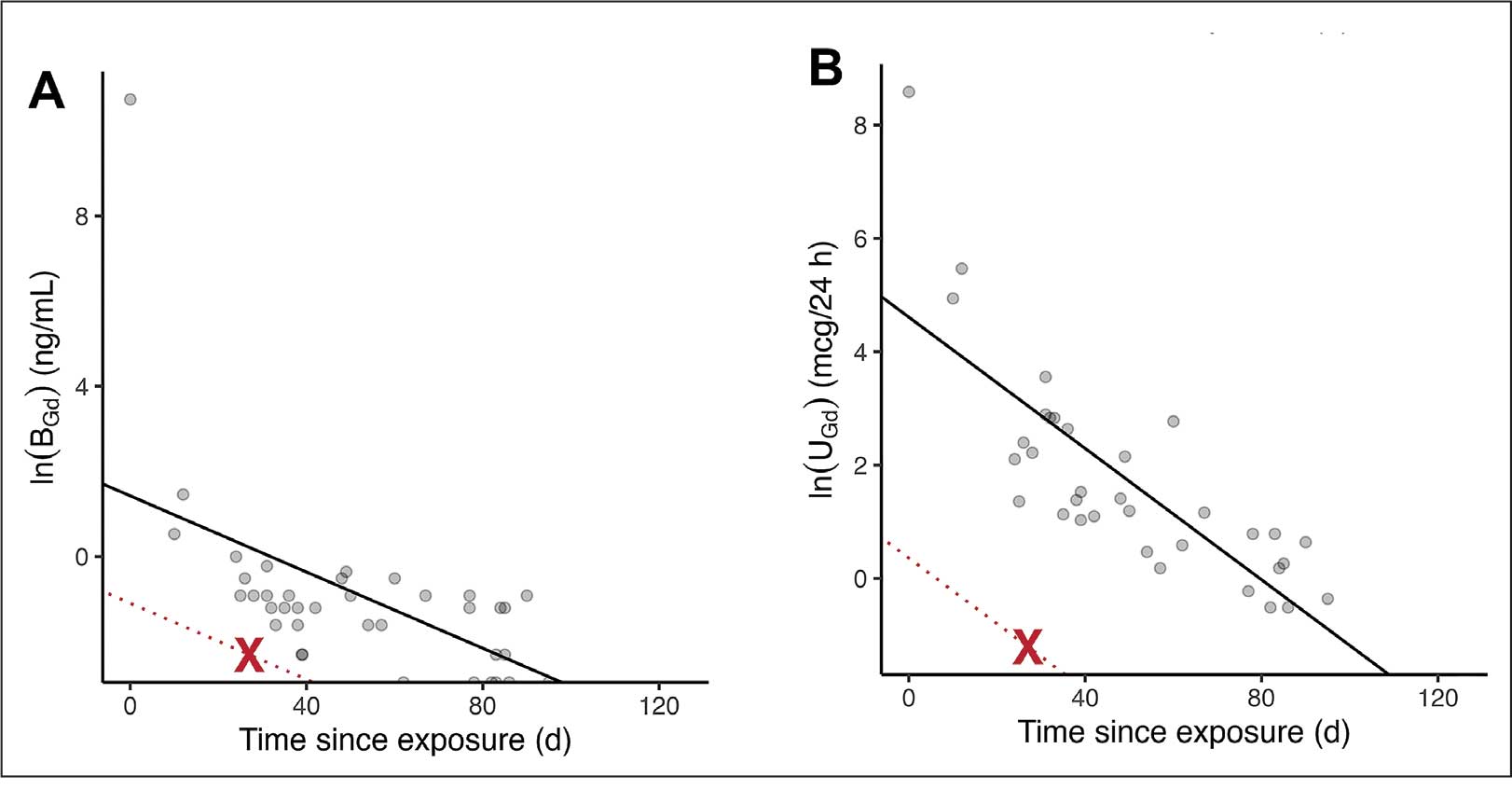

The blood and urine concentration elimination curves of gadolinium are exponential and categorized as fast, intermediate, and long-term.1 For urinary elimination, the function of the curves is exponential. The quantity of gadolinium in the urine at a time (t) after exposure (D[Gd](t)) is equal to the product of the amount of gadolinium in the sample (urine or blood) at the end of the fast elimination period (D[Gd](t0)) and the exponential decay with k being a rate constant.

To the authors’ knowledge, we are the only research team currently investigating the rate constant for the intermediate- and long-term phase gadolinium elimination. The Retention and Toxicity of Gadolinium-based Contrast Agents study was approved by the University of New Mexico Health Sciences Center Institutional Review Board on May 27, 2020 (IRB ID 19-660). The data for the patient in this case were compared with preliminary results for patients with exposure-to-measurement intervals < 100 days.

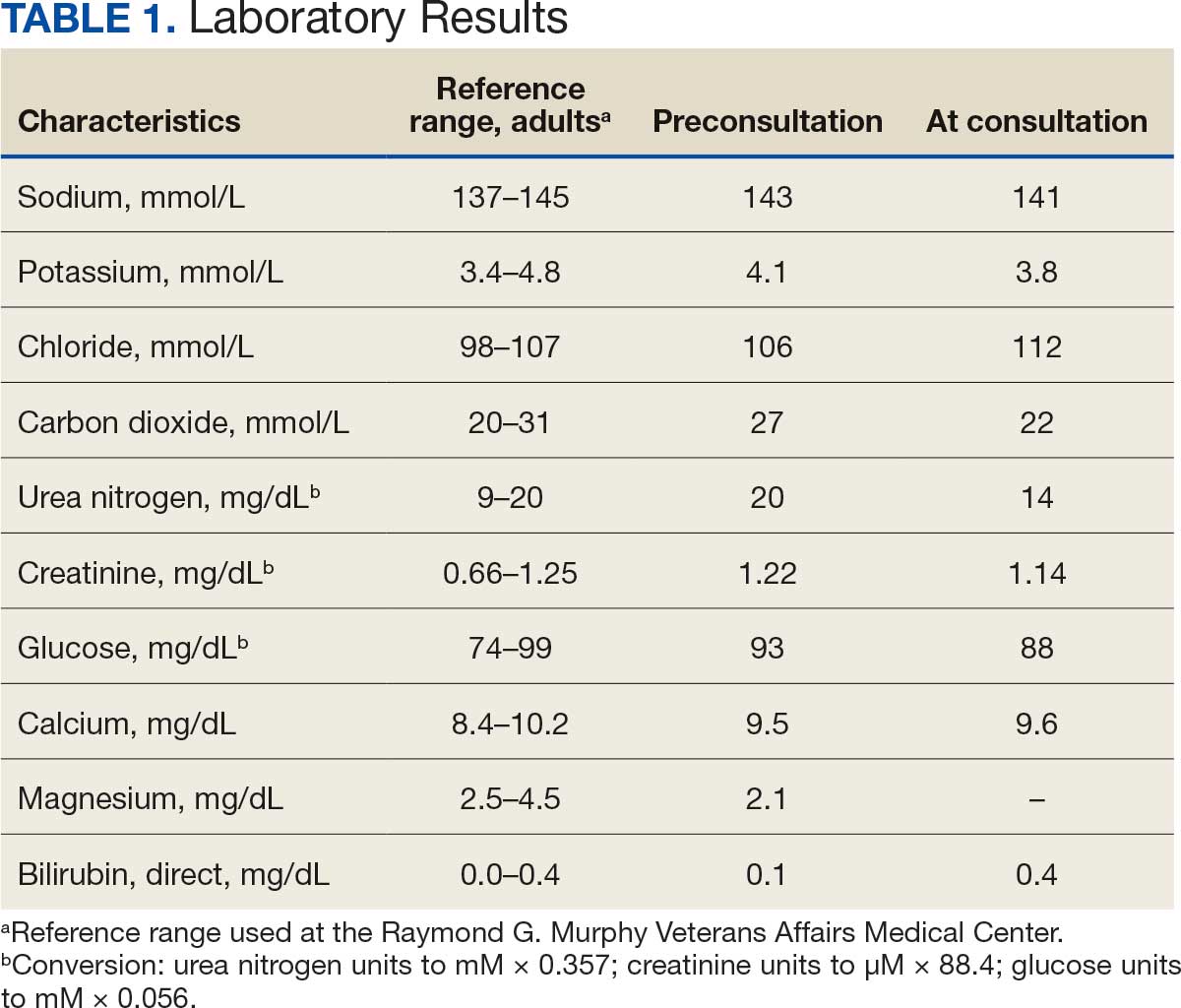

The patient in this case presented with detectable gadolinium levels in urine and serum shortly after an attempted contrast-enhanced MRI procedure (Figure 3). The presence of detectable gadolinium levels in the patient’s urine and serum suggests a likely exposure to a contrast agent about 27 days before his consultation. While the technician reported that no contrast was administered during the attempted MRI, it remains possible that a small amount was introduced during cannulation, potentially triggering the patient’s symptoms. Linear modeling of semilogarithmic plots for participants exposed to contrast agents within 100 days (urine: P = 1.8 × 10ˉ8, adjusted r² = 0.62; blood: P = .005, adjusted r² = 0.21) provided clearance rates (k values) for urine and blood. Extrapolating from these models to the presumed exposure date, the intercepts estimate that the patient received between 0.5% and 8% of a standard contrast dose.

MRI contrast agents can cause skin disease. Systemic fibrosis is considered one of the most severe AEs. Skin pathophysiology involving myeloid cells is driven by elevated levels of monocyte chemoattractant protein-1, which recruits circulating fibroblasts via the C-C chemokine receptor 2.22,23 This occurs alongside activation of NADPH oxidase Nox4.4,24,25 Intracellular gadolinium-rich nanoparticles likely serve as catalysts for this reactive cascade.2,18,22,26,27 These particles assemble around intracellular lipid droplets and ferrule them in spiculated rare earth-rich shells that compromise cellular architecture.2,18,21,22,26,27 Frequently sequestered within endosomal compartments, they disrupt vesicular integrity and threaten cellular homeostasis. Interference with degradative systems such as the endolysosomal axis perturbs energy-recycling pathways—an insidious disturbance, particularly in cells with high metabolic demand. Skin-related symptoms are among the most frequently reported AEs, according to the FDA AE reporting system.18

Studies indicate repeated exposure to MRI contrast agents can lead to permanent gadolinium retention in the brain and other vital organs. Intravenous (IV) contrast agents cross the blood-brain barrier rapidly, while intrathecal administration has been linked to significant and lasting neurologic effects.18

Gadolinium is chemically bound to pharmaceutical ligands to enhance renal clearance and reduce toxicity. However, available data from human samples suggest potential ligand exchanges with undefined physiologic substances. This exchange may facilitate gadolinium precipitation and accumulation within cells into spiculated nanoparticles. Transmission electron microscopy reveals the formation of unilamellar bodies associated with mitochondriopathy and cellular damage, particularly in renal proximal tubules.2,18,22,26,27 It is proposed that intracellular nanoparticle formation represents a key mechanism driving the systemic symptoms observed in patients.1,2,18, 22,26,27

Any hypothesis based on free soluble gadolinium—or concept derived from it—should be discarded. The high affinity of pharmaceutical ligands for gadolinium suggests that the cationic rare earth metal remains predominantly in a ligand-bound, soluble form. It is hypothesized that gadolinium undergoes ligand exchange with physiologic substances, directly leading to nanoparticle formation. Current data demonstrate gadolinium precipitation according to the Le Chatelier’s principle. Since precipitated gadolinium does not readily re-equilibrate with pharmaceutical ligands, repeated administration of different contrast agent brands may contribute to nanoparticle growth.26

Meanwhile, a growing number of patients are turning to chelation therapy, a largely untested treatment. The premise of chelation therapy is rooted in several unproven assumptions.18,21 First, it assumes that clinically significant amounts of gadolinium persist in compartments such as the extracellular space, where they can be effectively chelated and cleared. Second, it presumes that free gadolinium is the primary driver of chronic symptoms, an assertion that remains scientifically unsubstantiated. Finally, chelation proponents overlook the potential harm caused by depleting essential physiological metals during the process, assuming without evidence that the scant removal of gadolinium outweighs the risk of physiological mineral depletion.

These assumptions underpin an unproven remedy that demands critical scrutiny. Recent findings reveal that gadolinium deposits in the skin and kidney often take the form of intracellular nanoparticles, directly challenging the foundation of chelation therapy. Chelation advocates must demonstrate that these intracellular gadolinium deposits neither trigger cellular toxicity nor initiate a cytokine cascade. Chelation supporters must prove that the systemic response to these foreign particles is unrelated to the symptoms reported by patients. Until then, the validity of chelation therapy remains highly questionable.

The causality of the symptoms, mainly whether IV gadolinium was administered, was examined. The null hypothesis stated that the patient was not exposed to gadolinium. However, this hypothesis was contradicted by the detection of gadolinium in the serum and urine 27 days after the potential exposure.

Two plausible explanations exist for the nonzero gadolinium levels detected in the serum and urine. The first possibility is that minute quantities of gadolinium were introduced during cannulation, with the amount being sufficient to persist in measurable concentrations 27 days postexposure. The second possibility is that the gadolinium originated from an MRI contrast agent administered 4 years earlier. In this scenario, gadolinium stored in organ reservoirs such as bone, liver, or kidneys may have been mobilized into the extracellular fluid compartment due to the administration of high-dose steroids 20 days after the recent contrast-enhanced MRI procedure attempt. Coyte et al reported elevated gadolinium levels in the serum, cord blood, breast milk, and placenta of pregnant women with prior exposure to MRI contrast agents.28 These findings suggest that gadolinium, stored in organs such as bone may be remobilized by variables affecting bone remodeling (eg, high-dose steroids).

Significantly, the patient exhibited elevated urinary oxalate levels. Previous research has found that oxalic acid reacts rapidly with MRI contrast agents, forming digadolinium trioxalate. While the gadolinium-rich nanoparticles identified in tissues such as the skin and kidney (including the human kidney) are amorphous, these in vitro findings establish a proof-of-concept: the intracellular environment facilitates gadolinium dissociation from pharmaceutical chelates.

Furthermore, in vitro experiments show that proteins and lysosomal pH promote this dissociation, underscoring how human metabolic conditions—particularly oxalic acid concentration—may drive intracellular gadolinium deposition.

Patient Perspective

“They put something into my body that they cannot get out.” This stark realization underpins the patient’s profound concern about gadolinium-based contrast agents and their potential long-term effects. Reflecting on his experience, the patient expressed deep fears about the unknown future impacts: “I’m concerned about my kidneys, I’m concerned about my heart, and I’m concerned about my brain. I don’t know how this stuff is going to affect me in the future.”

He drew an unsettling parallel between gadolinium and heavy metals: “Heavy metal is poison. The body does not produce this kind of stuff on its own.” His reaction to the procedure left a lasting impression, prompting him to question the logic of using a substance that cannot be purged: “Why would you put something into someone’s body that you cannot extract? Nobody—nobody—should experience what I went through.”

The patient emphasized the lack of clear research on long-term outcomes, which compounds his anxiety: “If there was research that said, ‘Well, this is only going to affect these organs for this long,’ OK, I might be able to accept that. But there is no research like that. Nobody can tell me what’s going to happen in 5 years.”

Strengths and Limitations

A significant strength of this approach is the ability to track gadolinium elimination and symptom resolution over time, supported by unique access to intermediate and long-term clearance data from our ongoing research protocol. The investigators were equipped to back-extrapolate the exposure, which provided a rare opportunity to correlate gadolinium levels with clinical outcomes. The primary limitation is the lack of a defined clinical case definition for gadolinium toxicity and limited mechanistic understanding of SAGE, which hinders diagnosis and management.

Metabolites, proteins, and lipids rich in Lewis bases could initiate this process as substrates for intracellular gadolinium sedimentation. Future studies should investigate whether metabolic conditions such as oxalate burden or altered parathyroid hormone levels modulate gadolinium compartmentalization and tissue retention. If gadolinium-rich nanoparticle formation and accumulation disrupt cellular equilibrium, it underscores an urgent need to understand the implications of long-term gadolinium retention. The research team continues to gather evidence that the gadolinium cation remains chelated from the moment MRI contrast agents are administered through to the formation of intracellular nanoparticles. Retained gadolinium nanoparticles may act as a nidus, triggering cellular signaling cascades that lead to multisymptomatic illnesses. Intracellular and insoluble retained gadolinium challenges proponents of untested chelation therapies.

Conclusions

This case highlights emerging clinical and ethical concerns surrounding gadolinium-based contrast agent use. Clinicians may benefit from considering gadolinium retention as a contributor to persistent, unexplained symptoms—particularly in patients with recent imaging exposure. As contrast use continues to rise within federal health systems, regulatory and administrative stakeholders would do well to re-examine current safety frameworks. Informed consent should reflect what is known: gadolinium can remain in the body long after administration, potentially indefinitely. The long-term consequences of cumulative exposure remain poorly defined, but the presence of a lanthanide element in human tissue warrants greater attention from researchers and regulators alike. Interest in alternative imaging modalities and long-term safety monitoring would mark progress toward more transparent, accountable care.

Jackson DB, MacIntyre T, Duarte-Miramontes V, et al. Gadolinium deposition disease: a case report and the prevalence of enhanced MRI procedures within the Veterans Health Administration. Fed Pract. 2022;39:218-225. doi:10.12788/fp.0258

Do C, DeAguero J, Brearley A, et al. Gadolinium-based contrast agent use, their safety, and practice evolution. Kidney360. 2020;1:561-568.doi:10.34067/kid.0000272019

Leyba K, Wagner B. Gadolinium-based contrast agents: why nephrologists need to be concerned. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2019;28:154-162. doi:10.1097/MNH.0000000000000475

Wagner B, Drel V, Gorin Y. Pathophysiology of gadolinium-associated systemic fibrosis. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2016;311:F1-F11. doi:10.1152/ajprenal.00166.2016

Maramattom BV, Manno EM, Wijdicks EF, et al. Gadolinium encephalopathy in a patient with renal failure. Neurology. 2005;64:1276-1278.doi:10.1212/01.WNL.0000156805.45547.6E

Sam AD II, Morasch MD, Collins J, et al. Safety of gadolinium contrast angiography in patients with chronic renal insufficiency. J Vasc Surg. 2003;38:313-318. doi:10.1016/s0741-5214(03)00315-x

Schenker MP, Solomon JA, Roberts DA. Gadolinium arteriography complicated by acute pancreatitis and acute renal failure. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2001;12:393. doi:10.1016/s1051-0443(07)61925-3

Gemery J, Idelson B, Reid S, et al. Acute renal failure after arteriography with a gadolinium-based contrast agent. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1998;171:1277-1278. doi:10.2214/ajr.171.5.9798860

Akgun H, Gonlusen G, Cartwright J Jr, et al. Are gadolinium-based contrast media nephrotoxic? A renal biopsy study. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2006;130:1354-1357. doi:10.5858/2006-130-1354-AGCMNA

Gathings RM, Reddy R, Santa Cruz D, et al. Gadolinium-associated plaques: a new, distinctive clinical entity. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:316-319. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2014.2660

McDonald RJ, McDonald JS, Kallmes DF, et al. Gadolinium deposition in human brain tissues after contrast-enhanced MR imaging in adult patients without intracranial abnormalities. Radiology. 2017;285(2):546-554. doi:10.1148/radiol.2017161595

Kanda T, Ishii K, Kawaguchi H, et al. High signal intensity in the dentate nucleus and globus pallidus on unenhanced T1-weighted MR images: relationship with increasing cumulative dose of a gadolinium-based contrast material. Radiology. 2014;270(3):834-841. doi:10.1148/radiol.13131669

Schmidt K, Bau M, Merschel G, et al. Anthropogenic gadolinium in tap water and in tap water-based beverages from fast-food franchises in six major cities in Germany. Sci Total Environ. 2019;687:1401-1408. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.07.075

Kulaksız S, Bau M. Anthropogenic gadolinium as a microcontaminant in tap water used as drinking water in urban areas and megacities. Appl Geochem. 2011;26:1877-1885.

Brunjes R, Hofmann T. Anthropogenic gadolinium in freshwater and drinking water systems. Water Res. 2020;182:115966. doi:10.1016/j.watres.2020.115966

Endrikat J, Gutberlet M, Hoffmann KT, et al. Clinical safety of gadobutrol: review of over 25 years of use exceeding 100 million administrations. Invest Radiol. 2024;59(9):605-613. doi:10.1097/RLI.0000000000001072

Elmholdt TR, Jørgensen B, Ramsing M, et al. Two cases of nephrogenic systemic fibrosis after exposure to the macrocyclic compound gadobutrol. NDT Plus. 2010;3(3):285-287. doi:10.1093/ndtplus/sfq028

Cunningham A, Kirk M, Hong E, et al. The safety of magnetic resonance imaging contrast agents. Front Toxicol. 2024;6:1376587. doi:10.3389/ftox.2024.1376587

Huxley A. Complete Essays. Volume II, 1926-1929. Chicago; 2000:227.

McDonald RJ, Weinreb JC, Davenport MS. Symptoms associated with gadolinium exposure (SAGE): a suggested term. Radiology. 2022;302(2):270-273. doi:10.1148/radiol.2021211349

Henderson IM, Benevidez AD, Mowry CD, et al. Precipitation of gadolinium from magnetic resonance imaging contrast agents may be the Brass tacks of toxicity. Magn Reson Imaging. 2025;119:110383. doi:10.1016/j.mri.2025.110383

Do C, Drel V, Tan C, et al. Nephrogenic systemic fibrosis is mediated by myeloid C-C chemokine receptor 2. J Invest Dermatol. 2019;139(10):2134-2143. doi:10.1016/j.jid.2019.03.1145

Drel VR, Tan C, Barnes JL, et al. Centrality of bone marrow in the severity of gadolinium-based contrast-induced systemic fibrosis. FASEB J. 2016;30(9):3026-3038. doi:10.1096/fj.201500188R

Bruno F, DeAguero J, Do C, et al. Overlapping roles of NADPH oxidase 4 for diabetic and gadolinium-based contrast agent-induced systemic fibrosis. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2021;320(4):F617-F627. doi:10.1152/ajprenal.00456.2020

Wagner B, Tan C, Barnes JL, et al. Nephrogenic systemic fibrosis: evidence for oxidative stress and bone marrow-derived fibrocytes in skin, liver, and heart lesions using a 5/6 nephrectomy rodent model. Am J Pathol. 2012;181(6):1941-1952. doi:10.1016/j.ajpath.2012.08.026

DeAguero J, Howard T, Kusewitt D, et al. The onset of rare earth metallosis begins with renal gadolinium-rich nanoparticles from magnetic resonance imaging contrast agent exposure. Sci Rep. 2023;13(1):2025. doi:10.1038/s41598-023-28666-1

Do C, Ford B, Lee DY, et al. Gadolinium-based contrast agents: Stimulators of myeloid-induced renal fibrosis and major metabolic disruptors. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2019;375:32-45. doi:10.1016/j.taap.2019.05.009

Coyte RM, Darrah T, Olesik J, et al. Gadolinium during human pregnancy following administration of gadolinium chelate before pregnancy. Birth Defects Res. 2023;115(14):1264-1273. doi:10.1002/bdr2.2209

Magnetic resonance image (MRI) contrast agents can induce profound complications, including gadolinium encephalopathy, kidney injury, gadolinium-associated plaques, and progressive systemic fibrosis, which can be fatal.1-10 About 50% of MRIs use gadolinium-based contrast (Gd3+), a toxic rare earth metal ion that enhances imaging but requires binding with pharmaceutical ligands to reduce toxicity and promote renal elimination (Figure 1). Despite these measures, Gd3+ can persist in the body, including the brain.11,12 Wastewater treatment fails to remove these agents, making Gd3+ a growing pollutant in water and the food chain.13-15 Because Gd3+ is a rare earth metal ion in the milieu intérieur, there is an urgent need to study its biological and long-term effects (Appendix 1).

Case Presentation

A 65-year-old Vietnam-era veteran presented to nephrology at the Raymond G. Murphy Veterans Affairs Medical Center (RGMVAMC) in Albuquerque, New Mexico, for evaluation of gadolinium-induced symptoms. His medical history included metabolic syndrome, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, hypogonadism, cervical spondylosis, and an elevated prostate-specific antigen, previously assessed with a contrast-enhanced MRI in 2019 (Gadobenic acid, 19 mL). Surgical history included cervical fusion and ankle hardware.

The patient had a scheduled MRI 25 days earlier, following an elevated prostate specific antigen test result, prompting urologic surveillance and concern for malignancy. In preparation for the contrast-enhanced MRI, his right arm was cannulated with a line primed with gadobenic acid contrast. Though the technician stated the infusion had not started, the patient’s symptoms began shortly after entry into the scanner, before any programmed pulse sequences. The patient experienced claustrophobia, diaphoresis, palpitations, xerostomia, dysgeusia, shortness of breath, and a sensation of heat in his groin, chest, “kidneys,” and lower back. The MRI was terminated prematurely in response to the patient’s acute symptomatology. The patient continued experiencing new symptoms intermittently during the following week, including lightheadedness, headaches, right clavicular pain, raspy voice, edema, and a sense of doom.

The patient presented to the RGMVAMC emergency department (ED) 8 days after the MRI with worsening symptoms and was hospitalized for 10 days. During this time, he was referred to nephrology for outpatient evaluation. While awaiting his nephrology appointment, the patient presented to the RGMVAMC ED 20 days after the initial episode with ongoing symptoms. “I thought I was dying,” he said. Laboratory results and a 12-lead electrocardiogram showed a finely static background, wide P waves (> 80 ms) with notching in lead II, sinusoidal P waves in V1, R transition in V2, RR’ in V2, ST flat in lead III, and sinus bradycardia (Table 1 and Appendix 2).

The patient’s medical and surgical histories were reviewed at the nephrology evaluation 25 days following the MRI. He reported that household water was sourced from a well and that he filtered his drinking water with a reverse osmosis system. He served in the US Army for 10 years as an engineer specializing in mechanical systems, power generation, and vehicles. Following Army retirement, the patient served in the US Air Force Reserves for 15 years, working as a crew chief in pneudraulics. The patient reported stopping tobacco use 1 year before and also reported regular use of a broad array of prescription medications and dietary supplements, including dexamethasone (4 mg twice daily), fluticasone nasal spray (50 mcg per nostril, twice daily), ibuprofen (400 mg twice daily, as needed), loratadine (10 mg daily), aspirin (81 mg daily), and metoprolol succinate (50 mg nightly). In addition, he reported consistent use of cholecalciferol (3000 IU daily), another supplemental vitamin D preparation, chelated magnesium glycinate (3 tablets daily for bone issues), turmeric (1 tablet daily), a multivitamin (Living Green Liquid Gel, daily), and a mega-B complex.

Physical examination revealed a well-nourished, tall man with hypertension (145/87 mmHg) and bilateral lower extremity edema. Oral examination showed poor dentition, including missing molars (#1-3, #14-16, #17-19, #30-31), with the anterior teeth replaced by bridges supported by dental implants. The review of systems was otherwise unremarkable, with nocturia noted before the consultation.

Serum and urine gadolinium testing, (Mayo Clinic Laboratories) revealed gadolinium levels of 0.3 mcg/24 h in the urine and 0.1 ng/mL in the serum. Nonzero values indicated detectable gadolinium, suggesting retention. The patient had a prior gadolinium exposure during a 2019 MRI (about 1340 days before) and suspected a repeat exposure on day 0, although the MRI technician stated that no contrast was administered. Given his elevated vitamin D levels, the patient was advised to minimize dietary supplements, particularly vitamin D, to avoid confounding symptoms. The plan included monitoring symptoms and a follow-up evaluation with repeat laboratory tests on day 116.

At the nephrology follow-up 4 months postexposure, the patient's symptoms had primarily abated, with a marked reduction in the previously noted metallic dysgeusia. Physical examination remained consistent with prior findings. He was afebrile (97.7 °F) with a blood pressure of 111/72 mmHg, a pulse of 63 beats per minute, and an oxygen saturation of 98% on ambient air. Laboratory analysis revealed serum and urine gadolinium levels below detectable thresholds (< 0.1 ng/mL and < 0.1 mcg/24 h). A 24-hour creatinine clearance, calculated from a urine volume of 1300 mL, measured at an optimal 106 mL/min, indicating preserved renal function (Tables 2 and 3). Of note, his 24-hour oxalate was above the reference range, with a urine pH below the reference range and a high supersaturation index for calcium oxalate.

Discussion

Use of enhanced MRI has increased in the Veterans Health Administration (Figure 2). A growing range of indications for enhanced procedures (eg, cardiac MRI) has contributed to this rise. The market has grown with new gadolinium-based contrast agents, such as gadopiclenol. However, reliance on untested assumptions about the safety of newer agents and need for robust clinical trials pose potential risks to patient safety.

Without prospective evidence, the American College of Radiology (ACR) classifies gadolinium-based contrast agents into 3 groups: Group 1, associated with the highest number of nephrogenic systemic fibrosis cases; Group 2, linked to few, if any, unconfounded cases; and Group 3, where data on nephrogenic systemic fibrosis risk have been limited. As of April 2024, the ACR reclassified Group 3 agents (Ablavar/Vasovist/Angiomark and Primovist/Eovist) into Group 2. Curiously, Vueway and Elucirem were approved in late 2022 and should clearly be categorized as Group 3 (Table 4).There were 19 cases of nephrogenic systemic fibrosis or similar manifestations, 8 of which were unconfounded by other factors. These patients had been exposed to gadobutrol, often combined with other agents. Gadobutrol—like other Group 2 agents—has been associated with nephrogenic systemic fibrosis.16,17 Despite US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) documentation of rising reports, many clinicians remain unaware that nephrogenic systemic fibrosis is increasingly linked to Group 2 agents classified by the ACR.18 While declines in reported cases of nephrogenic systemic fibrosis may suggest reduced incidence, this trend may reflect diminished clinical vigilance and underreporting, particularly given emerging evidence implicating even Group 2 gadolinium-based contrast agents in delayed and underrecognized presentations. This information has yet to permeate the medical community, particularly among nephrologists. Considering these cases, revisiting the ACR guidelines may be prudent.

To address this growing concern, clinicians must adopt stricter vigilance and actively pursue updated information to mitigate patient risks tied to these contrast agents.

There exists an illusion of knowledge in disregarding the confounded exposures of MRI contrast agents. Ten distinct brands of contrast agents have been approved for clinical use. With repeated imaging, patients are often exposed to varying formulations of gadolinium-based agents. Yet investigators commonly discard these data points when assessing risk. By doing so, they assume—without evidence—that some formulations are inherently less likely to provoke adverse effects (AEs) than others. This untested presumption becomes perilous, especially given the limited understanding of the mechanisms underlying gadolinium-induced pathologies. As Aldous Huxley warned, “Facts do not cease to exist because they are ignored.”19

Gadolinium Persistence

Contrary to expectations, gadolinium persists in the body far longer than initially presumed. Symptoms associated with gadolinium exposure (SAGE) encapsulate the chronic, often enigmatic maladies tied to MRI contrast agents.20 The prolonged retention of this rare earth metal offers a compelling hypothesis for the etiology of SAGE. It has been hypothesized that Lewis base-rich metabolites increase susceptibility to gadolinium-based contrast agent complications.21

The blood and urine concentration elimination curves of gadolinium are exponential and categorized as fast, intermediate, and long-term.1 For urinary elimination, the function of the curves is exponential. The quantity of gadolinium in the urine at a time (t) after exposure (D[Gd](t)) is equal to the product of the amount of gadolinium in the sample (urine or blood) at the end of the fast elimination period (D[Gd](t0)) and the exponential decay with k being a rate constant.

To the authors’ knowledge, we are the only research team currently investigating the rate constant for the intermediate- and long-term phase gadolinium elimination. The Retention and Toxicity of Gadolinium-based Contrast Agents study was approved by the University of New Mexico Health Sciences Center Institutional Review Board on May 27, 2020 (IRB ID 19-660). The data for the patient in this case were compared with preliminary results for patients with exposure-to-measurement intervals < 100 days.

The patient in this case presented with detectable gadolinium levels in urine and serum shortly after an attempted contrast-enhanced MRI procedure (Figure 3). The presence of detectable gadolinium levels in the patient’s urine and serum suggests a likely exposure to a contrast agent about 27 days before his consultation. While the technician reported that no contrast was administered during the attempted MRI, it remains possible that a small amount was introduced during cannulation, potentially triggering the patient’s symptoms. Linear modeling of semilogarithmic plots for participants exposed to contrast agents within 100 days (urine: P = 1.8 × 10ˉ8, adjusted r² = 0.62; blood: P = .005, adjusted r² = 0.21) provided clearance rates (k values) for urine and blood. Extrapolating from these models to the presumed exposure date, the intercepts estimate that the patient received between 0.5% and 8% of a standard contrast dose.

MRI contrast agents can cause skin disease. Systemic fibrosis is considered one of the most severe AEs. Skin pathophysiology involving myeloid cells is driven by elevated levels of monocyte chemoattractant protein-1, which recruits circulating fibroblasts via the C-C chemokine receptor 2.22,23 This occurs alongside activation of NADPH oxidase Nox4.4,24,25 Intracellular gadolinium-rich nanoparticles likely serve as catalysts for this reactive cascade.2,18,22,26,27 These particles assemble around intracellular lipid droplets and ferrule them in spiculated rare earth-rich shells that compromise cellular architecture.2,18,21,22,26,27 Frequently sequestered within endosomal compartments, they disrupt vesicular integrity and threaten cellular homeostasis. Interference with degradative systems such as the endolysosomal axis perturbs energy-recycling pathways—an insidious disturbance, particularly in cells with high metabolic demand. Skin-related symptoms are among the most frequently reported AEs, according to the FDA AE reporting system.18

Studies indicate repeated exposure to MRI contrast agents can lead to permanent gadolinium retention in the brain and other vital organs. Intravenous (IV) contrast agents cross the blood-brain barrier rapidly, while intrathecal administration has been linked to significant and lasting neurologic effects.18

Gadolinium is chemically bound to pharmaceutical ligands to enhance renal clearance and reduce toxicity. However, available data from human samples suggest potential ligand exchanges with undefined physiologic substances. This exchange may facilitate gadolinium precipitation and accumulation within cells into spiculated nanoparticles. Transmission electron microscopy reveals the formation of unilamellar bodies associated with mitochondriopathy and cellular damage, particularly in renal proximal tubules.2,18,22,26,27 It is proposed that intracellular nanoparticle formation represents a key mechanism driving the systemic symptoms observed in patients.1,2,18, 22,26,27

Any hypothesis based on free soluble gadolinium—or concept derived from it—should be discarded. The high affinity of pharmaceutical ligands for gadolinium suggests that the cationic rare earth metal remains predominantly in a ligand-bound, soluble form. It is hypothesized that gadolinium undergoes ligand exchange with physiologic substances, directly leading to nanoparticle formation. Current data demonstrate gadolinium precipitation according to the Le Chatelier’s principle. Since precipitated gadolinium does not readily re-equilibrate with pharmaceutical ligands, repeated administration of different contrast agent brands may contribute to nanoparticle growth.26

Meanwhile, a growing number of patients are turning to chelation therapy, a largely untested treatment. The premise of chelation therapy is rooted in several unproven assumptions.18,21 First, it assumes that clinically significant amounts of gadolinium persist in compartments such as the extracellular space, where they can be effectively chelated and cleared. Second, it presumes that free gadolinium is the primary driver of chronic symptoms, an assertion that remains scientifically unsubstantiated. Finally, chelation proponents overlook the potential harm caused by depleting essential physiological metals during the process, assuming without evidence that the scant removal of gadolinium outweighs the risk of physiological mineral depletion.

These assumptions underpin an unproven remedy that demands critical scrutiny. Recent findings reveal that gadolinium deposits in the skin and kidney often take the form of intracellular nanoparticles, directly challenging the foundation of chelation therapy. Chelation advocates must demonstrate that these intracellular gadolinium deposits neither trigger cellular toxicity nor initiate a cytokine cascade. Chelation supporters must prove that the systemic response to these foreign particles is unrelated to the symptoms reported by patients. Until then, the validity of chelation therapy remains highly questionable.

The causality of the symptoms, mainly whether IV gadolinium was administered, was examined. The null hypothesis stated that the patient was not exposed to gadolinium. However, this hypothesis was contradicted by the detection of gadolinium in the serum and urine 27 days after the potential exposure.

Two plausible explanations exist for the nonzero gadolinium levels detected in the serum and urine. The first possibility is that minute quantities of gadolinium were introduced during cannulation, with the amount being sufficient to persist in measurable concentrations 27 days postexposure. The second possibility is that the gadolinium originated from an MRI contrast agent administered 4 years earlier. In this scenario, gadolinium stored in organ reservoirs such as bone, liver, or kidneys may have been mobilized into the extracellular fluid compartment due to the administration of high-dose steroids 20 days after the recent contrast-enhanced MRI procedure attempt. Coyte et al reported elevated gadolinium levels in the serum, cord blood, breast milk, and placenta of pregnant women with prior exposure to MRI contrast agents.28 These findings suggest that gadolinium, stored in organs such as bone may be remobilized by variables affecting bone remodeling (eg, high-dose steroids).

Significantly, the patient exhibited elevated urinary oxalate levels. Previous research has found that oxalic acid reacts rapidly with MRI contrast agents, forming digadolinium trioxalate. While the gadolinium-rich nanoparticles identified in tissues such as the skin and kidney (including the human kidney) are amorphous, these in vitro findings establish a proof-of-concept: the intracellular environment facilitates gadolinium dissociation from pharmaceutical chelates.

Furthermore, in vitro experiments show that proteins and lysosomal pH promote this dissociation, underscoring how human metabolic conditions—particularly oxalic acid concentration—may drive intracellular gadolinium deposition.

Patient Perspective

“They put something into my body that they cannot get out.” This stark realization underpins the patient’s profound concern about gadolinium-based contrast agents and their potential long-term effects. Reflecting on his experience, the patient expressed deep fears about the unknown future impacts: “I’m concerned about my kidneys, I’m concerned about my heart, and I’m concerned about my brain. I don’t know how this stuff is going to affect me in the future.”

He drew an unsettling parallel between gadolinium and heavy metals: “Heavy metal is poison. The body does not produce this kind of stuff on its own.” His reaction to the procedure left a lasting impression, prompting him to question the logic of using a substance that cannot be purged: “Why would you put something into someone’s body that you cannot extract? Nobody—nobody—should experience what I went through.”

The patient emphasized the lack of clear research on long-term outcomes, which compounds his anxiety: “If there was research that said, ‘Well, this is only going to affect these organs for this long,’ OK, I might be able to accept that. But there is no research like that. Nobody can tell me what’s going to happen in 5 years.”

Strengths and Limitations

A significant strength of this approach is the ability to track gadolinium elimination and symptom resolution over time, supported by unique access to intermediate and long-term clearance data from our ongoing research protocol. The investigators were equipped to back-extrapolate the exposure, which provided a rare opportunity to correlate gadolinium levels with clinical outcomes. The primary limitation is the lack of a defined clinical case definition for gadolinium toxicity and limited mechanistic understanding of SAGE, which hinders diagnosis and management.

Metabolites, proteins, and lipids rich in Lewis bases could initiate this process as substrates for intracellular gadolinium sedimentation. Future studies should investigate whether metabolic conditions such as oxalate burden or altered parathyroid hormone levels modulate gadolinium compartmentalization and tissue retention. If gadolinium-rich nanoparticle formation and accumulation disrupt cellular equilibrium, it underscores an urgent need to understand the implications of long-term gadolinium retention. The research team continues to gather evidence that the gadolinium cation remains chelated from the moment MRI contrast agents are administered through to the formation of intracellular nanoparticles. Retained gadolinium nanoparticles may act as a nidus, triggering cellular signaling cascades that lead to multisymptomatic illnesses. Intracellular and insoluble retained gadolinium challenges proponents of untested chelation therapies.

Conclusions

This case highlights emerging clinical and ethical concerns surrounding gadolinium-based contrast agent use. Clinicians may benefit from considering gadolinium retention as a contributor to persistent, unexplained symptoms—particularly in patients with recent imaging exposure. As contrast use continues to rise within federal health systems, regulatory and administrative stakeholders would do well to re-examine current safety frameworks. Informed consent should reflect what is known: gadolinium can remain in the body long after administration, potentially indefinitely. The long-term consequences of cumulative exposure remain poorly defined, but the presence of a lanthanide element in human tissue warrants greater attention from researchers and regulators alike. Interest in alternative imaging modalities and long-term safety monitoring would mark progress toward more transparent, accountable care.

Magnetic resonance image (MRI) contrast agents can induce profound complications, including gadolinium encephalopathy, kidney injury, gadolinium-associated plaques, and progressive systemic fibrosis, which can be fatal.1-10 About 50% of MRIs use gadolinium-based contrast (Gd3+), a toxic rare earth metal ion that enhances imaging but requires binding with pharmaceutical ligands to reduce toxicity and promote renal elimination (Figure 1). Despite these measures, Gd3+ can persist in the body, including the brain.11,12 Wastewater treatment fails to remove these agents, making Gd3+ a growing pollutant in water and the food chain.13-15 Because Gd3+ is a rare earth metal ion in the milieu intérieur, there is an urgent need to study its biological and long-term effects (Appendix 1).

Case Presentation

A 65-year-old Vietnam-era veteran presented to nephrology at the Raymond G. Murphy Veterans Affairs Medical Center (RGMVAMC) in Albuquerque, New Mexico, for evaluation of gadolinium-induced symptoms. His medical history included metabolic syndrome, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, hypogonadism, cervical spondylosis, and an elevated prostate-specific antigen, previously assessed with a contrast-enhanced MRI in 2019 (Gadobenic acid, 19 mL). Surgical history included cervical fusion and ankle hardware.

The patient had a scheduled MRI 25 days earlier, following an elevated prostate specific antigen test result, prompting urologic surveillance and concern for malignancy. In preparation for the contrast-enhanced MRI, his right arm was cannulated with a line primed with gadobenic acid contrast. Though the technician stated the infusion had not started, the patient’s symptoms began shortly after entry into the scanner, before any programmed pulse sequences. The patient experienced claustrophobia, diaphoresis, palpitations, xerostomia, dysgeusia, shortness of breath, and a sensation of heat in his groin, chest, “kidneys,” and lower back. The MRI was terminated prematurely in response to the patient’s acute symptomatology. The patient continued experiencing new symptoms intermittently during the following week, including lightheadedness, headaches, right clavicular pain, raspy voice, edema, and a sense of doom.

The patient presented to the RGMVAMC emergency department (ED) 8 days after the MRI with worsening symptoms and was hospitalized for 10 days. During this time, he was referred to nephrology for outpatient evaluation. While awaiting his nephrology appointment, the patient presented to the RGMVAMC ED 20 days after the initial episode with ongoing symptoms. “I thought I was dying,” he said. Laboratory results and a 12-lead electrocardiogram showed a finely static background, wide P waves (> 80 ms) with notching in lead II, sinusoidal P waves in V1, R transition in V2, RR’ in V2, ST flat in lead III, and sinus bradycardia (Table 1 and Appendix 2).

The patient’s medical and surgical histories were reviewed at the nephrology evaluation 25 days following the MRI. He reported that household water was sourced from a well and that he filtered his drinking water with a reverse osmosis system. He served in the US Army for 10 years as an engineer specializing in mechanical systems, power generation, and vehicles. Following Army retirement, the patient served in the US Air Force Reserves for 15 years, working as a crew chief in pneudraulics. The patient reported stopping tobacco use 1 year before and also reported regular use of a broad array of prescription medications and dietary supplements, including dexamethasone (4 mg twice daily), fluticasone nasal spray (50 mcg per nostril, twice daily), ibuprofen (400 mg twice daily, as needed), loratadine (10 mg daily), aspirin (81 mg daily), and metoprolol succinate (50 mg nightly). In addition, he reported consistent use of cholecalciferol (3000 IU daily), another supplemental vitamin D preparation, chelated magnesium glycinate (3 tablets daily for bone issues), turmeric (1 tablet daily), a multivitamin (Living Green Liquid Gel, daily), and a mega-B complex.

Physical examination revealed a well-nourished, tall man with hypertension (145/87 mmHg) and bilateral lower extremity edema. Oral examination showed poor dentition, including missing molars (#1-3, #14-16, #17-19, #30-31), with the anterior teeth replaced by bridges supported by dental implants. The review of systems was otherwise unremarkable, with nocturia noted before the consultation.

Serum and urine gadolinium testing, (Mayo Clinic Laboratories) revealed gadolinium levels of 0.3 mcg/24 h in the urine and 0.1 ng/mL in the serum. Nonzero values indicated detectable gadolinium, suggesting retention. The patient had a prior gadolinium exposure during a 2019 MRI (about 1340 days before) and suspected a repeat exposure on day 0, although the MRI technician stated that no contrast was administered. Given his elevated vitamin D levels, the patient was advised to minimize dietary supplements, particularly vitamin D, to avoid confounding symptoms. The plan included monitoring symptoms and a follow-up evaluation with repeat laboratory tests on day 116.

At the nephrology follow-up 4 months postexposure, the patient's symptoms had primarily abated, with a marked reduction in the previously noted metallic dysgeusia. Physical examination remained consistent with prior findings. He was afebrile (97.7 °F) with a blood pressure of 111/72 mmHg, a pulse of 63 beats per minute, and an oxygen saturation of 98% on ambient air. Laboratory analysis revealed serum and urine gadolinium levels below detectable thresholds (< 0.1 ng/mL and < 0.1 mcg/24 h). A 24-hour creatinine clearance, calculated from a urine volume of 1300 mL, measured at an optimal 106 mL/min, indicating preserved renal function (Tables 2 and 3). Of note, his 24-hour oxalate was above the reference range, with a urine pH below the reference range and a high supersaturation index for calcium oxalate.

Discussion

Use of enhanced MRI has increased in the Veterans Health Administration (Figure 2). A growing range of indications for enhanced procedures (eg, cardiac MRI) has contributed to this rise. The market has grown with new gadolinium-based contrast agents, such as gadopiclenol. However, reliance on untested assumptions about the safety of newer agents and need for robust clinical trials pose potential risks to patient safety.

Without prospective evidence, the American College of Radiology (ACR) classifies gadolinium-based contrast agents into 3 groups: Group 1, associated with the highest number of nephrogenic systemic fibrosis cases; Group 2, linked to few, if any, unconfounded cases; and Group 3, where data on nephrogenic systemic fibrosis risk have been limited. As of April 2024, the ACR reclassified Group 3 agents (Ablavar/Vasovist/Angiomark and Primovist/Eovist) into Group 2. Curiously, Vueway and Elucirem were approved in late 2022 and should clearly be categorized as Group 3 (Table 4).There were 19 cases of nephrogenic systemic fibrosis or similar manifestations, 8 of which were unconfounded by other factors. These patients had been exposed to gadobutrol, often combined with other agents. Gadobutrol—like other Group 2 agents—has been associated with nephrogenic systemic fibrosis.16,17 Despite US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) documentation of rising reports, many clinicians remain unaware that nephrogenic systemic fibrosis is increasingly linked to Group 2 agents classified by the ACR.18 While declines in reported cases of nephrogenic systemic fibrosis may suggest reduced incidence, this trend may reflect diminished clinical vigilance and underreporting, particularly given emerging evidence implicating even Group 2 gadolinium-based contrast agents in delayed and underrecognized presentations. This information has yet to permeate the medical community, particularly among nephrologists. Considering these cases, revisiting the ACR guidelines may be prudent.

To address this growing concern, clinicians must adopt stricter vigilance and actively pursue updated information to mitigate patient risks tied to these contrast agents.

There exists an illusion of knowledge in disregarding the confounded exposures of MRI contrast agents. Ten distinct brands of contrast agents have been approved for clinical use. With repeated imaging, patients are often exposed to varying formulations of gadolinium-based agents. Yet investigators commonly discard these data points when assessing risk. By doing so, they assume—without evidence—that some formulations are inherently less likely to provoke adverse effects (AEs) than others. This untested presumption becomes perilous, especially given the limited understanding of the mechanisms underlying gadolinium-induced pathologies. As Aldous Huxley warned, “Facts do not cease to exist because they are ignored.”19

Gadolinium Persistence

Contrary to expectations, gadolinium persists in the body far longer than initially presumed. Symptoms associated with gadolinium exposure (SAGE) encapsulate the chronic, often enigmatic maladies tied to MRI contrast agents.20 The prolonged retention of this rare earth metal offers a compelling hypothesis for the etiology of SAGE. It has been hypothesized that Lewis base-rich metabolites increase susceptibility to gadolinium-based contrast agent complications.21

The blood and urine concentration elimination curves of gadolinium are exponential and categorized as fast, intermediate, and long-term.1 For urinary elimination, the function of the curves is exponential. The quantity of gadolinium in the urine at a time (t) after exposure (D[Gd](t)) is equal to the product of the amount of gadolinium in the sample (urine or blood) at the end of the fast elimination period (D[Gd](t0)) and the exponential decay with k being a rate constant.

To the authors’ knowledge, we are the only research team currently investigating the rate constant for the intermediate- and long-term phase gadolinium elimination. The Retention and Toxicity of Gadolinium-based Contrast Agents study was approved by the University of New Mexico Health Sciences Center Institutional Review Board on May 27, 2020 (IRB ID 19-660). The data for the patient in this case were compared with preliminary results for patients with exposure-to-measurement intervals < 100 days.

The patient in this case presented with detectable gadolinium levels in urine and serum shortly after an attempted contrast-enhanced MRI procedure (Figure 3). The presence of detectable gadolinium levels in the patient’s urine and serum suggests a likely exposure to a contrast agent about 27 days before his consultation. While the technician reported that no contrast was administered during the attempted MRI, it remains possible that a small amount was introduced during cannulation, potentially triggering the patient’s symptoms. Linear modeling of semilogarithmic plots for participants exposed to contrast agents within 100 days (urine: P = 1.8 × 10ˉ8, adjusted r² = 0.62; blood: P = .005, adjusted r² = 0.21) provided clearance rates (k values) for urine and blood. Extrapolating from these models to the presumed exposure date, the intercepts estimate that the patient received between 0.5% and 8% of a standard contrast dose.

MRI contrast agents can cause skin disease. Systemic fibrosis is considered one of the most severe AEs. Skin pathophysiology involving myeloid cells is driven by elevated levels of monocyte chemoattractant protein-1, which recruits circulating fibroblasts via the C-C chemokine receptor 2.22,23 This occurs alongside activation of NADPH oxidase Nox4.4,24,25 Intracellular gadolinium-rich nanoparticles likely serve as catalysts for this reactive cascade.2,18,22,26,27 These particles assemble around intracellular lipid droplets and ferrule them in spiculated rare earth-rich shells that compromise cellular architecture.2,18,21,22,26,27 Frequently sequestered within endosomal compartments, they disrupt vesicular integrity and threaten cellular homeostasis. Interference with degradative systems such as the endolysosomal axis perturbs energy-recycling pathways—an insidious disturbance, particularly in cells with high metabolic demand. Skin-related symptoms are among the most frequently reported AEs, according to the FDA AE reporting system.18

Studies indicate repeated exposure to MRI contrast agents can lead to permanent gadolinium retention in the brain and other vital organs. Intravenous (IV) contrast agents cross the blood-brain barrier rapidly, while intrathecal administration has been linked to significant and lasting neurologic effects.18

Gadolinium is chemically bound to pharmaceutical ligands to enhance renal clearance and reduce toxicity. However, available data from human samples suggest potential ligand exchanges with undefined physiologic substances. This exchange may facilitate gadolinium precipitation and accumulation within cells into spiculated nanoparticles. Transmission electron microscopy reveals the formation of unilamellar bodies associated with mitochondriopathy and cellular damage, particularly in renal proximal tubules.2,18,22,26,27 It is proposed that intracellular nanoparticle formation represents a key mechanism driving the systemic symptoms observed in patients.1,2,18, 22,26,27

Any hypothesis based on free soluble gadolinium—or concept derived from it—should be discarded. The high affinity of pharmaceutical ligands for gadolinium suggests that the cationic rare earth metal remains predominantly in a ligand-bound, soluble form. It is hypothesized that gadolinium undergoes ligand exchange with physiologic substances, directly leading to nanoparticle formation. Current data demonstrate gadolinium precipitation according to the Le Chatelier’s principle. Since precipitated gadolinium does not readily re-equilibrate with pharmaceutical ligands, repeated administration of different contrast agent brands may contribute to nanoparticle growth.26

Meanwhile, a growing number of patients are turning to chelation therapy, a largely untested treatment. The premise of chelation therapy is rooted in several unproven assumptions.18,21 First, it assumes that clinically significant amounts of gadolinium persist in compartments such as the extracellular space, where they can be effectively chelated and cleared. Second, it presumes that free gadolinium is the primary driver of chronic symptoms, an assertion that remains scientifically unsubstantiated. Finally, chelation proponents overlook the potential harm caused by depleting essential physiological metals during the process, assuming without evidence that the scant removal of gadolinium outweighs the risk of physiological mineral depletion.

These assumptions underpin an unproven remedy that demands critical scrutiny. Recent findings reveal that gadolinium deposits in the skin and kidney often take the form of intracellular nanoparticles, directly challenging the foundation of chelation therapy. Chelation advocates must demonstrate that these intracellular gadolinium deposits neither trigger cellular toxicity nor initiate a cytokine cascade. Chelation supporters must prove that the systemic response to these foreign particles is unrelated to the symptoms reported by patients. Until then, the validity of chelation therapy remains highly questionable.

The causality of the symptoms, mainly whether IV gadolinium was administered, was examined. The null hypothesis stated that the patient was not exposed to gadolinium. However, this hypothesis was contradicted by the detection of gadolinium in the serum and urine 27 days after the potential exposure.

Two plausible explanations exist for the nonzero gadolinium levels detected in the serum and urine. The first possibility is that minute quantities of gadolinium were introduced during cannulation, with the amount being sufficient to persist in measurable concentrations 27 days postexposure. The second possibility is that the gadolinium originated from an MRI contrast agent administered 4 years earlier. In this scenario, gadolinium stored in organ reservoirs such as bone, liver, or kidneys may have been mobilized into the extracellular fluid compartment due to the administration of high-dose steroids 20 days after the recent contrast-enhanced MRI procedure attempt. Coyte et al reported elevated gadolinium levels in the serum, cord blood, breast milk, and placenta of pregnant women with prior exposure to MRI contrast agents.28 These findings suggest that gadolinium, stored in organs such as bone may be remobilized by variables affecting bone remodeling (eg, high-dose steroids).

Significantly, the patient exhibited elevated urinary oxalate levels. Previous research has found that oxalic acid reacts rapidly with MRI contrast agents, forming digadolinium trioxalate. While the gadolinium-rich nanoparticles identified in tissues such as the skin and kidney (including the human kidney) are amorphous, these in vitro findings establish a proof-of-concept: the intracellular environment facilitates gadolinium dissociation from pharmaceutical chelates.

Furthermore, in vitro experiments show that proteins and lysosomal pH promote this dissociation, underscoring how human metabolic conditions—particularly oxalic acid concentration—may drive intracellular gadolinium deposition.

Patient Perspective

“They put something into my body that they cannot get out.” This stark realization underpins the patient’s profound concern about gadolinium-based contrast agents and their potential long-term effects. Reflecting on his experience, the patient expressed deep fears about the unknown future impacts: “I’m concerned about my kidneys, I’m concerned about my heart, and I’m concerned about my brain. I don’t know how this stuff is going to affect me in the future.”

He drew an unsettling parallel between gadolinium and heavy metals: “Heavy metal is poison. The body does not produce this kind of stuff on its own.” His reaction to the procedure left a lasting impression, prompting him to question the logic of using a substance that cannot be purged: “Why would you put something into someone’s body that you cannot extract? Nobody—nobody—should experience what I went through.”

The patient emphasized the lack of clear research on long-term outcomes, which compounds his anxiety: “If there was research that said, ‘Well, this is only going to affect these organs for this long,’ OK, I might be able to accept that. But there is no research like that. Nobody can tell me what’s going to happen in 5 years.”

Strengths and Limitations

A significant strength of this approach is the ability to track gadolinium elimination and symptom resolution over time, supported by unique access to intermediate and long-term clearance data from our ongoing research protocol. The investigators were equipped to back-extrapolate the exposure, which provided a rare opportunity to correlate gadolinium levels with clinical outcomes. The primary limitation is the lack of a defined clinical case definition for gadolinium toxicity and limited mechanistic understanding of SAGE, which hinders diagnosis and management.

Metabolites, proteins, and lipids rich in Lewis bases could initiate this process as substrates for intracellular gadolinium sedimentation. Future studies should investigate whether metabolic conditions such as oxalate burden or altered parathyroid hormone levels modulate gadolinium compartmentalization and tissue retention. If gadolinium-rich nanoparticle formation and accumulation disrupt cellular equilibrium, it underscores an urgent need to understand the implications of long-term gadolinium retention. The research team continues to gather evidence that the gadolinium cation remains chelated from the moment MRI contrast agents are administered through to the formation of intracellular nanoparticles. Retained gadolinium nanoparticles may act as a nidus, triggering cellular signaling cascades that lead to multisymptomatic illnesses. Intracellular and insoluble retained gadolinium challenges proponents of untested chelation therapies.

Conclusions

This case highlights emerging clinical and ethical concerns surrounding gadolinium-based contrast agent use. Clinicians may benefit from considering gadolinium retention as a contributor to persistent, unexplained symptoms—particularly in patients with recent imaging exposure. As contrast use continues to rise within federal health systems, regulatory and administrative stakeholders would do well to re-examine current safety frameworks. Informed consent should reflect what is known: gadolinium can remain in the body long after administration, potentially indefinitely. The long-term consequences of cumulative exposure remain poorly defined, but the presence of a lanthanide element in human tissue warrants greater attention from researchers and regulators alike. Interest in alternative imaging modalities and long-term safety monitoring would mark progress toward more transparent, accountable care.

Jackson DB, MacIntyre T, Duarte-Miramontes V, et al. Gadolinium deposition disease: a case report and the prevalence of enhanced MRI procedures within the Veterans Health Administration. Fed Pract. 2022;39:218-225. doi:10.12788/fp.0258

Do C, DeAguero J, Brearley A, et al. Gadolinium-based contrast agent use, their safety, and practice evolution. Kidney360. 2020;1:561-568.doi:10.34067/kid.0000272019

Leyba K, Wagner B. Gadolinium-based contrast agents: why nephrologists need to be concerned. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2019;28:154-162. doi:10.1097/MNH.0000000000000475

Wagner B, Drel V, Gorin Y. Pathophysiology of gadolinium-associated systemic fibrosis. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2016;311:F1-F11. doi:10.1152/ajprenal.00166.2016

Maramattom BV, Manno EM, Wijdicks EF, et al. Gadolinium encephalopathy in a patient with renal failure. Neurology. 2005;64:1276-1278.doi:10.1212/01.WNL.0000156805.45547.6E

Sam AD II, Morasch MD, Collins J, et al. Safety of gadolinium contrast angiography in patients with chronic renal insufficiency. J Vasc Surg. 2003;38:313-318. doi:10.1016/s0741-5214(03)00315-x

Schenker MP, Solomon JA, Roberts DA. Gadolinium arteriography complicated by acute pancreatitis and acute renal failure. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2001;12:393. doi:10.1016/s1051-0443(07)61925-3

Gemery J, Idelson B, Reid S, et al. Acute renal failure after arteriography with a gadolinium-based contrast agent. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1998;171:1277-1278. doi:10.2214/ajr.171.5.9798860

Akgun H, Gonlusen G, Cartwright J Jr, et al. Are gadolinium-based contrast media nephrotoxic? A renal biopsy study. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2006;130:1354-1357. doi:10.5858/2006-130-1354-AGCMNA

Gathings RM, Reddy R, Santa Cruz D, et al. Gadolinium-associated plaques: a new, distinctive clinical entity. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:316-319. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2014.2660

McDonald RJ, McDonald JS, Kallmes DF, et al. Gadolinium deposition in human brain tissues after contrast-enhanced MR imaging in adult patients without intracranial abnormalities. Radiology. 2017;285(2):546-554. doi:10.1148/radiol.2017161595

Kanda T, Ishii K, Kawaguchi H, et al. High signal intensity in the dentate nucleus and globus pallidus on unenhanced T1-weighted MR images: relationship with increasing cumulative dose of a gadolinium-based contrast material. Radiology. 2014;270(3):834-841. doi:10.1148/radiol.13131669

Schmidt K, Bau M, Merschel G, et al. Anthropogenic gadolinium in tap water and in tap water-based beverages from fast-food franchises in six major cities in Germany. Sci Total Environ. 2019;687:1401-1408. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.07.075

Kulaksız S, Bau M. Anthropogenic gadolinium as a microcontaminant in tap water used as drinking water in urban areas and megacities. Appl Geochem. 2011;26:1877-1885.

Brunjes R, Hofmann T. Anthropogenic gadolinium in freshwater and drinking water systems. Water Res. 2020;182:115966. doi:10.1016/j.watres.2020.115966

Endrikat J, Gutberlet M, Hoffmann KT, et al. Clinical safety of gadobutrol: review of over 25 years of use exceeding 100 million administrations. Invest Radiol. 2024;59(9):605-613. doi:10.1097/RLI.0000000000001072

Elmholdt TR, Jørgensen B, Ramsing M, et al. Two cases of nephrogenic systemic fibrosis after exposure to the macrocyclic compound gadobutrol. NDT Plus. 2010;3(3):285-287. doi:10.1093/ndtplus/sfq028

Cunningham A, Kirk M, Hong E, et al. The safety of magnetic resonance imaging contrast agents. Front Toxicol. 2024;6:1376587. doi:10.3389/ftox.2024.1376587

Huxley A. Complete Essays. Volume II, 1926-1929. Chicago; 2000:227.

McDonald RJ, Weinreb JC, Davenport MS. Symptoms associated with gadolinium exposure (SAGE): a suggested term. Radiology. 2022;302(2):270-273. doi:10.1148/radiol.2021211349

Henderson IM, Benevidez AD, Mowry CD, et al. Precipitation of gadolinium from magnetic resonance imaging contrast agents may be the Brass tacks of toxicity. Magn Reson Imaging. 2025;119:110383. doi:10.1016/j.mri.2025.110383

Do C, Drel V, Tan C, et al. Nephrogenic systemic fibrosis is mediated by myeloid C-C chemokine receptor 2. J Invest Dermatol. 2019;139(10):2134-2143. doi:10.1016/j.jid.2019.03.1145

Drel VR, Tan C, Barnes JL, et al. Centrality of bone marrow in the severity of gadolinium-based contrast-induced systemic fibrosis. FASEB J. 2016;30(9):3026-3038. doi:10.1096/fj.201500188R

Bruno F, DeAguero J, Do C, et al. Overlapping roles of NADPH oxidase 4 for diabetic and gadolinium-based contrast agent-induced systemic fibrosis. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2021;320(4):F617-F627. doi:10.1152/ajprenal.00456.2020

Wagner B, Tan C, Barnes JL, et al. Nephrogenic systemic fibrosis: evidence for oxidative stress and bone marrow-derived fibrocytes in skin, liver, and heart lesions using a 5/6 nephrectomy rodent model. Am J Pathol. 2012;181(6):1941-1952. doi:10.1016/j.ajpath.2012.08.026

DeAguero J, Howard T, Kusewitt D, et al. The onset of rare earth metallosis begins with renal gadolinium-rich nanoparticles from magnetic resonance imaging contrast agent exposure. Sci Rep. 2023;13(1):2025. doi:10.1038/s41598-023-28666-1

Do C, Ford B, Lee DY, et al. Gadolinium-based contrast agents: Stimulators of myeloid-induced renal fibrosis and major metabolic disruptors. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2019;375:32-45. doi:10.1016/j.taap.2019.05.009

Coyte RM, Darrah T, Olesik J, et al. Gadolinium during human pregnancy following administration of gadolinium chelate before pregnancy. Birth Defects Res. 2023;115(14):1264-1273. doi:10.1002/bdr2.2209

Jackson DB, MacIntyre T, Duarte-Miramontes V, et al. Gadolinium deposition disease: a case report and the prevalence of enhanced MRI procedures within the Veterans Health Administration. Fed Pract. 2022;39:218-225. doi:10.12788/fp.0258

Do C, DeAguero J, Brearley A, et al. Gadolinium-based contrast agent use, their safety, and practice evolution. Kidney360. 2020;1:561-568.doi:10.34067/kid.0000272019

Leyba K, Wagner B. Gadolinium-based contrast agents: why nephrologists need to be concerned. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2019;28:154-162. doi:10.1097/MNH.0000000000000475

Wagner B, Drel V, Gorin Y. Pathophysiology of gadolinium-associated systemic fibrosis. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2016;311:F1-F11. doi:10.1152/ajprenal.00166.2016

Maramattom BV, Manno EM, Wijdicks EF, et al. Gadolinium encephalopathy in a patient with renal failure. Neurology. 2005;64:1276-1278.doi:10.1212/01.WNL.0000156805.45547.6E

Sam AD II, Morasch MD, Collins J, et al. Safety of gadolinium contrast angiography in patients with chronic renal insufficiency. J Vasc Surg. 2003;38:313-318. doi:10.1016/s0741-5214(03)00315-x

Schenker MP, Solomon JA, Roberts DA. Gadolinium arteriography complicated by acute pancreatitis and acute renal failure. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2001;12:393. doi:10.1016/s1051-0443(07)61925-3

Gemery J, Idelson B, Reid S, et al. Acute renal failure after arteriography with a gadolinium-based contrast agent. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1998;171:1277-1278. doi:10.2214/ajr.171.5.9798860

Akgun H, Gonlusen G, Cartwright J Jr, et al. Are gadolinium-based contrast media nephrotoxic? A renal biopsy study. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2006;130:1354-1357. doi:10.5858/2006-130-1354-AGCMNA

Gathings RM, Reddy R, Santa Cruz D, et al. Gadolinium-associated plaques: a new, distinctive clinical entity. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:316-319. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2014.2660

McDonald RJ, McDonald JS, Kallmes DF, et al. Gadolinium deposition in human brain tissues after contrast-enhanced MR imaging in adult patients without intracranial abnormalities. Radiology. 2017;285(2):546-554. doi:10.1148/radiol.2017161595

Kanda T, Ishii K, Kawaguchi H, et al. High signal intensity in the dentate nucleus and globus pallidus on unenhanced T1-weighted MR images: relationship with increasing cumulative dose of a gadolinium-based contrast material. Radiology. 2014;270(3):834-841. doi:10.1148/radiol.13131669

Schmidt K, Bau M, Merschel G, et al. Anthropogenic gadolinium in tap water and in tap water-based beverages from fast-food franchises in six major cities in Germany. Sci Total Environ. 2019;687:1401-1408. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.07.075

Kulaksız S, Bau M. Anthropogenic gadolinium as a microcontaminant in tap water used as drinking water in urban areas and megacities. Appl Geochem. 2011;26:1877-1885.

Brunjes R, Hofmann T. Anthropogenic gadolinium in freshwater and drinking water systems. Water Res. 2020;182:115966. doi:10.1016/j.watres.2020.115966

Endrikat J, Gutberlet M, Hoffmann KT, et al. Clinical safety of gadobutrol: review of over 25 years of use exceeding 100 million administrations. Invest Radiol. 2024;59(9):605-613. doi:10.1097/RLI.0000000000001072

Elmholdt TR, Jørgensen B, Ramsing M, et al. Two cases of nephrogenic systemic fibrosis after exposure to the macrocyclic compound gadobutrol. NDT Plus. 2010;3(3):285-287. doi:10.1093/ndtplus/sfq028

Cunningham A, Kirk M, Hong E, et al. The safety of magnetic resonance imaging contrast agents. Front Toxicol. 2024;6:1376587. doi:10.3389/ftox.2024.1376587

Huxley A. Complete Essays. Volume II, 1926-1929. Chicago; 2000:227.

McDonald RJ, Weinreb JC, Davenport MS. Symptoms associated with gadolinium exposure (SAGE): a suggested term. Radiology. 2022;302(2):270-273. doi:10.1148/radiol.2021211349

Henderson IM, Benevidez AD, Mowry CD, et al. Precipitation of gadolinium from magnetic resonance imaging contrast agents may be the Brass tacks of toxicity. Magn Reson Imaging. 2025;119:110383. doi:10.1016/j.mri.2025.110383

Do C, Drel V, Tan C, et al. Nephrogenic systemic fibrosis is mediated by myeloid C-C chemokine receptor 2. J Invest Dermatol. 2019;139(10):2134-2143. doi:10.1016/j.jid.2019.03.1145

Drel VR, Tan C, Barnes JL, et al. Centrality of bone marrow in the severity of gadolinium-based contrast-induced systemic fibrosis. FASEB J. 2016;30(9):3026-3038. doi:10.1096/fj.201500188R

Bruno F, DeAguero J, Do C, et al. Overlapping roles of NADPH oxidase 4 for diabetic and gadolinium-based contrast agent-induced systemic fibrosis. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2021;320(4):F617-F627. doi:10.1152/ajprenal.00456.2020