User login

Food for thought: Dangerous weight loss in an older adult

CASE Fixated on health and nutrition

At the insistence of her daughter, Ms. L, age 75, presents to the emergency department (ED) for self-neglect and severe weight loss, with a body mass index (BMI) of 13.5 kg/m2 (normal: 18.5 to 24.9 kg/m2). When asked why she is in the ED, Ms. L says she doesn’t know. She attributes her significant weight loss (approximately 20 pounds in the last few months) to gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD). She constantly worries about her esophagus. She had been diagnosed with esophageal dysphagia 7 years ago after undergoing radiofrequency ablation for esophageal cancer. Ms. L fixates on the negative effects certain foods and ingredients might have on her stomach and esophagus.

Following transfer from the ED, Ms. L is involuntarily admitted to our inpatient unit. Although she acknowledges weight loss, she minimizes the severity of her illness and indicates she would like to gain weight, but only by eating healthy foods she is comfortable with, including kale, quinoa, and vegetables. Ms. L says that she has always been interested in “healthful foods” and that she “loves sugar,” but “it’s bad for you,” mentioning that “sugar fuels cancer.” She has daily thoughts about sugar causing cancer. Ms. L also mentions that she stopped eating flour, sugar, fried food, and oils because those foods affect her “stomach acid” and cause “pimples on my face and weight loss.” While in the inpatient unit, Ms. L requests a special diet and demands to know the origin and ingredients of the foods she is offered. She emphasizes that her esophageal cancer diagnosis and dysphagia exacerbate worries that certain foods cause cancer, and wants to continue her diet restrictions. Nonetheless, she says she wants to get healthy, and denies an intense fear of gaining weight or feeling fat.

HISTORY Multiple psychiatric diagnoses

Ms. L lives alone and enjoys spending time with her grandchildren, visiting museums, and listening to classical music. However, her family, social workers, and records from a previous psychiatric hospitalization reveal that Ms. L has a history of psychiatric illness and fears regarding certain types of foods for much of her adult life. Ms. L’s family also described a range of compulsive behaviors, including shoplifting, hoarding art, multiple plastic surgeries, and phases where Ms. L ate only frozen yogurt without sugar.

Ms. L’s daughter reported that Ms. L had seen a psychologist in the late 1990s for depression and had been diagnosed with obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) and attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder in the early 2000s. In 2006, during a depressive episode after her divorce, Ms. L had a suicide attempt with pills and alcohol, and was hospitalized. Records from that stay described a history of mood dysregulation with fears regarding food and nutrition. Ms. L was treated with aripiprazole 5 mg/d. A trial of trazodone 25 mg/d did not have any effect. When discharged, she was receiving lamotrigine 100 mg/d. However, her daughter believes she stopped taking all psychiatric medications shortly after discharge.

Her daughter says that in the past 2 years, Ms. L has seen multiple doctors for treatment of somatic gastrointestinal (GI) complaints. A 2018 note from a social worker indicated that Ms. L endorsed taking >80 supplements per day and constantly researched nutrition online. In the months leading to her current hospitalization, Ms. L suffered from severe self-neglect and fear regarding foods she felt were not healthy for her. She had stopped leaving her apartment.

Continue to: EVALUATION Poor insight, normal lab results...

EVALUATION Poor insight, normal lab results

During her evaluation, Ms. L appears cachectic and frail. She has a heavily constricted affect and is guarded, dismissive, and vague. Although her thought processes are linear and goal-directed, her insight into her condition is extremely poor and she appears surprised when clinicians inform her that her self-neglect would lead to death. Instead, Ms. L insists she is eating healthily and demonstrates severe anxiety in relation to her GI symptoms.

Ms. L is oriented to person, place, and time. She scores 27/30 on the Montreal Cognitive Assessment, indicating normal cognition. She denies any depressive symptoms or suicidal intent. She does not appear to be internally preoccupied and denies having auditory or visual hallucinations or manic symptoms.

A neurologic examination reveals that her cranial nerves are normal, and cerebellar function, strength, and sensory testing are intact. Her gait is steady and she walks without a walker. Despite her severely low BMI and recent history of self-neglect, Ms. L’s laboratory results are remarkably normal and show no liver, metabolic, or electrolyte abnormalities, no signs of infection, and normal vitamin B12 levels. She has slightly elevated creatinine and blood urea nitrogen levels, but a normal glomerular filtration rate.

Her medical history is significant for squamous cell esophageal cancer, treated with radiofrequency ablation. Although Ms. L is constantly worried about the recurrence of cancer, pathology reports demonstrate no esophageal dysplasia. However, she does show evidence of an approximately 1 cm × 1 cm mild, noncircumferential esophageal stenosis, likely resulting from radiofrequency ablation.

[polldaddy:11079394]

The authors’ observations

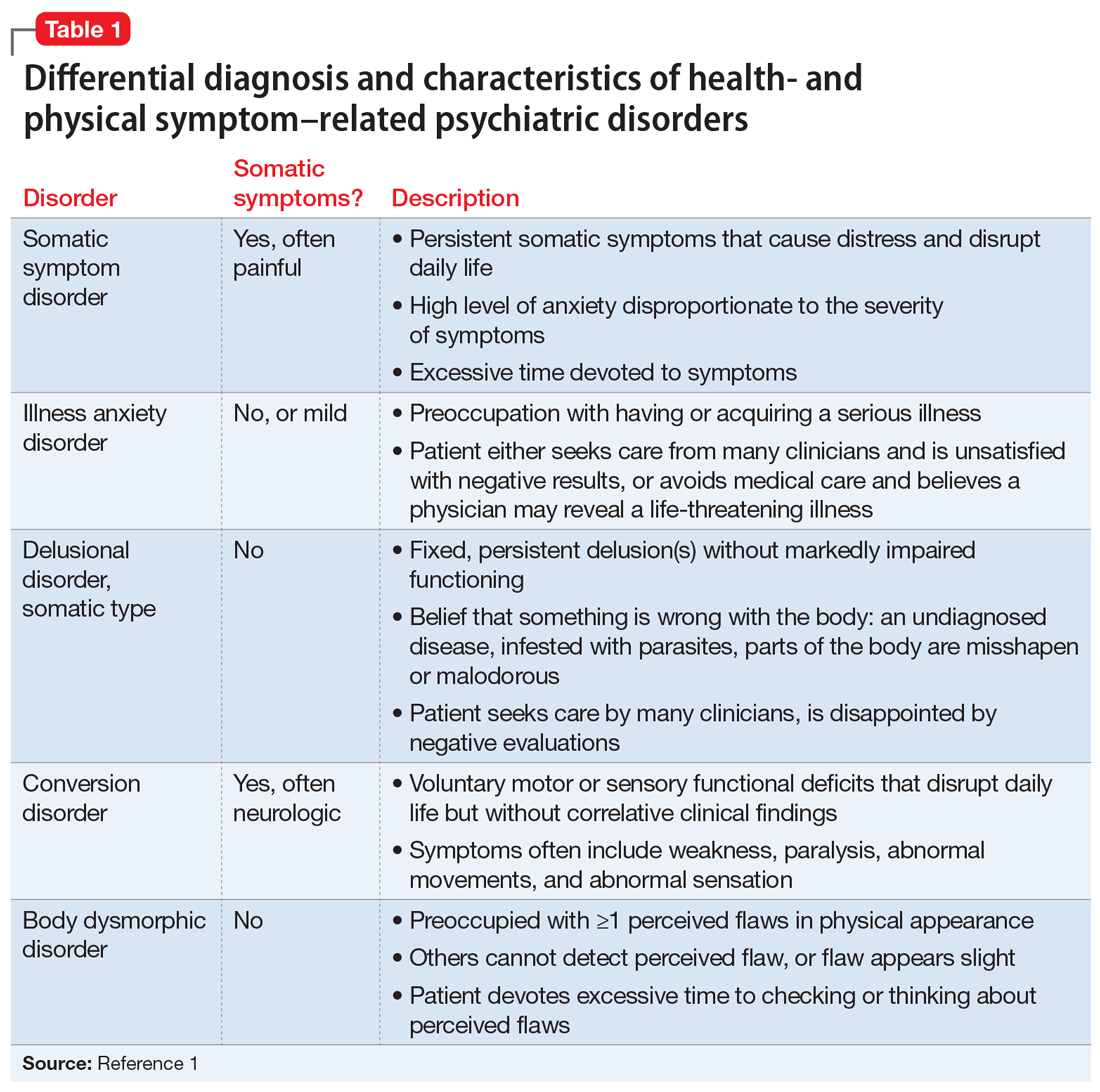

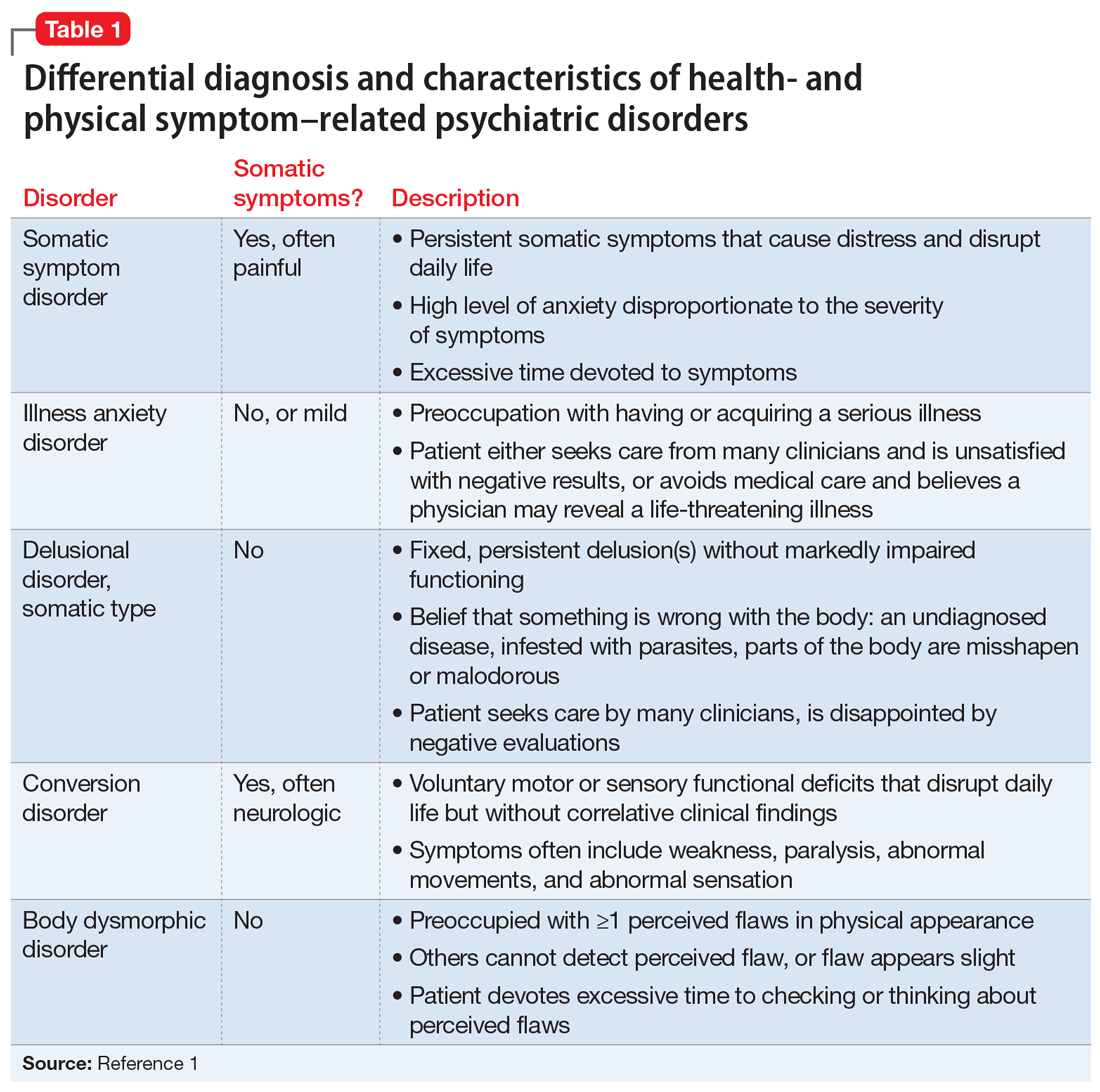

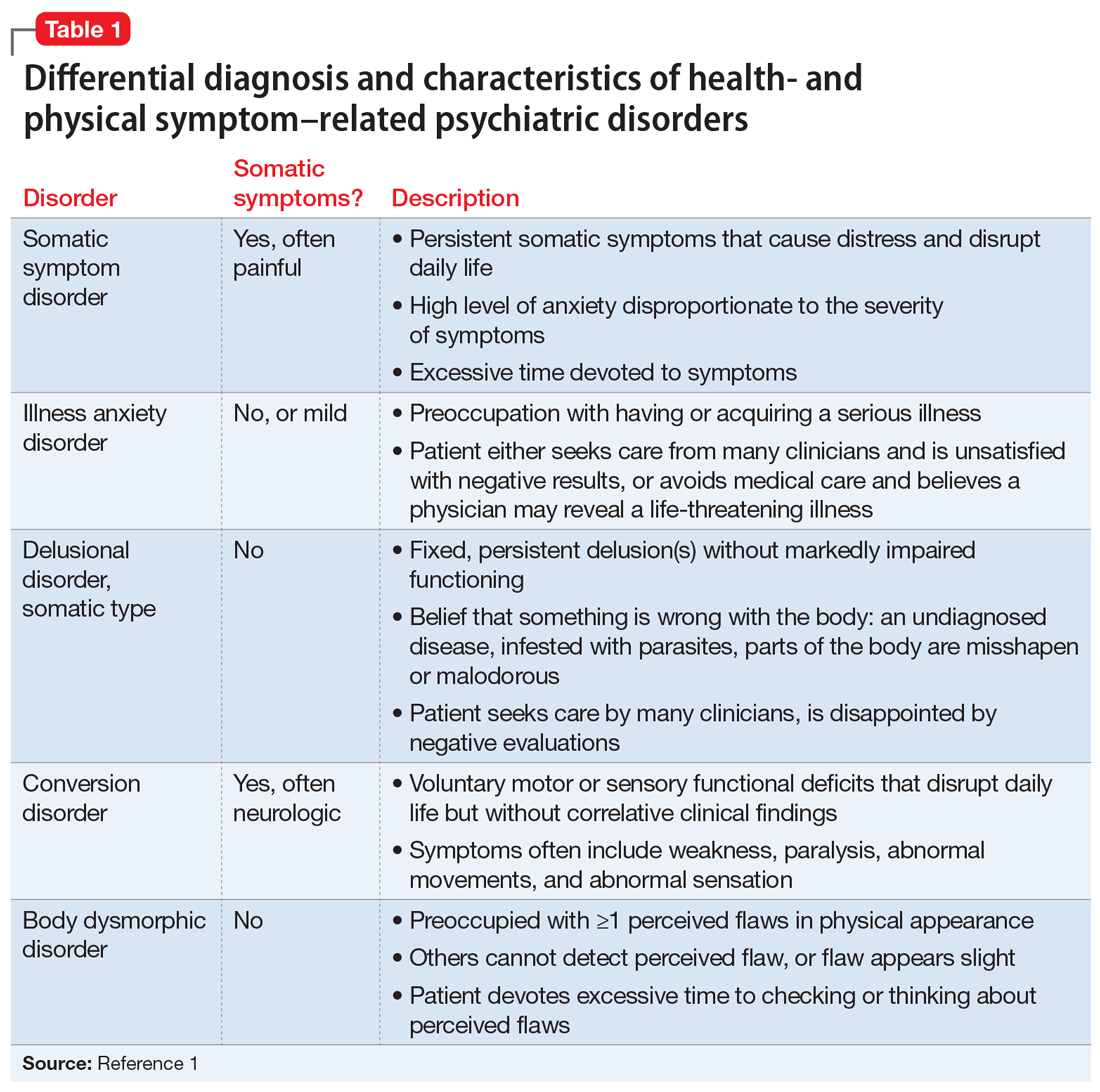

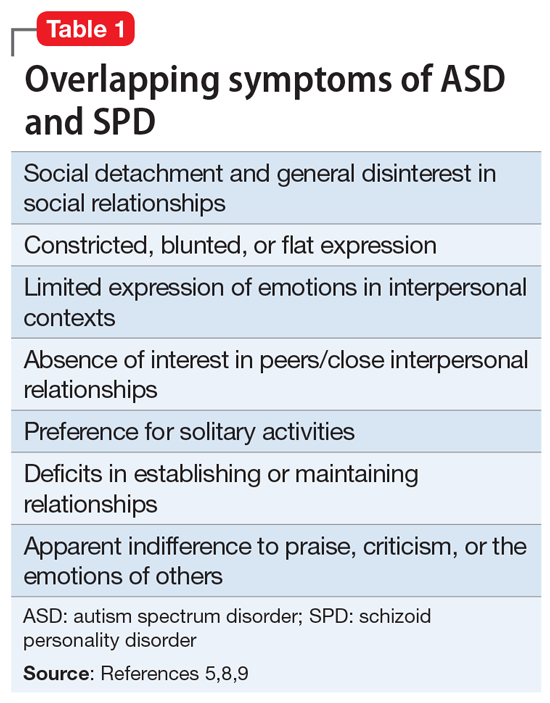

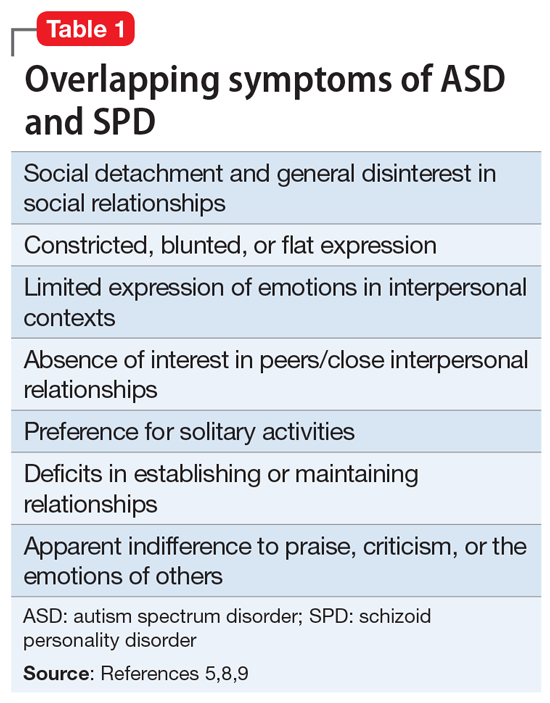

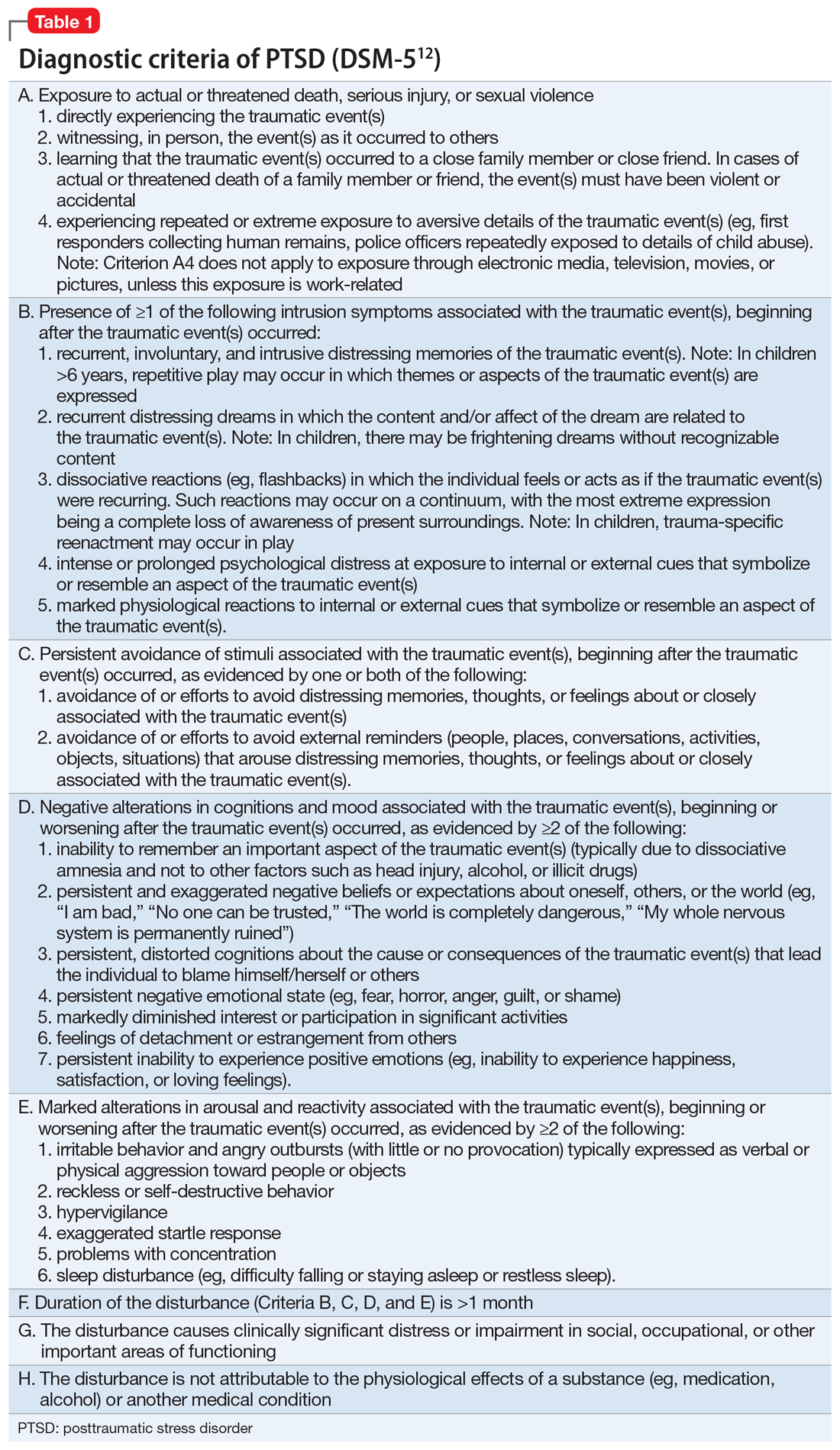

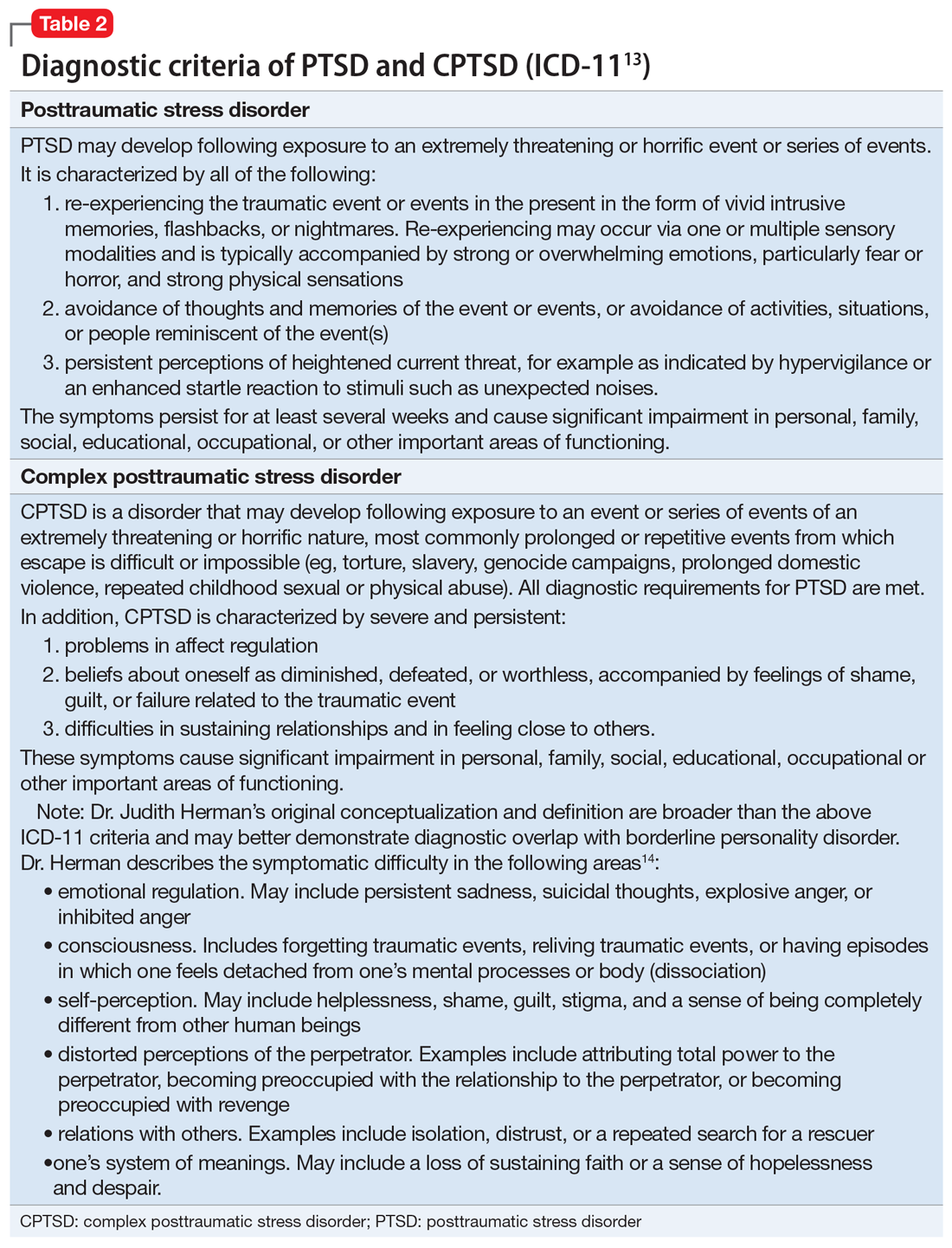

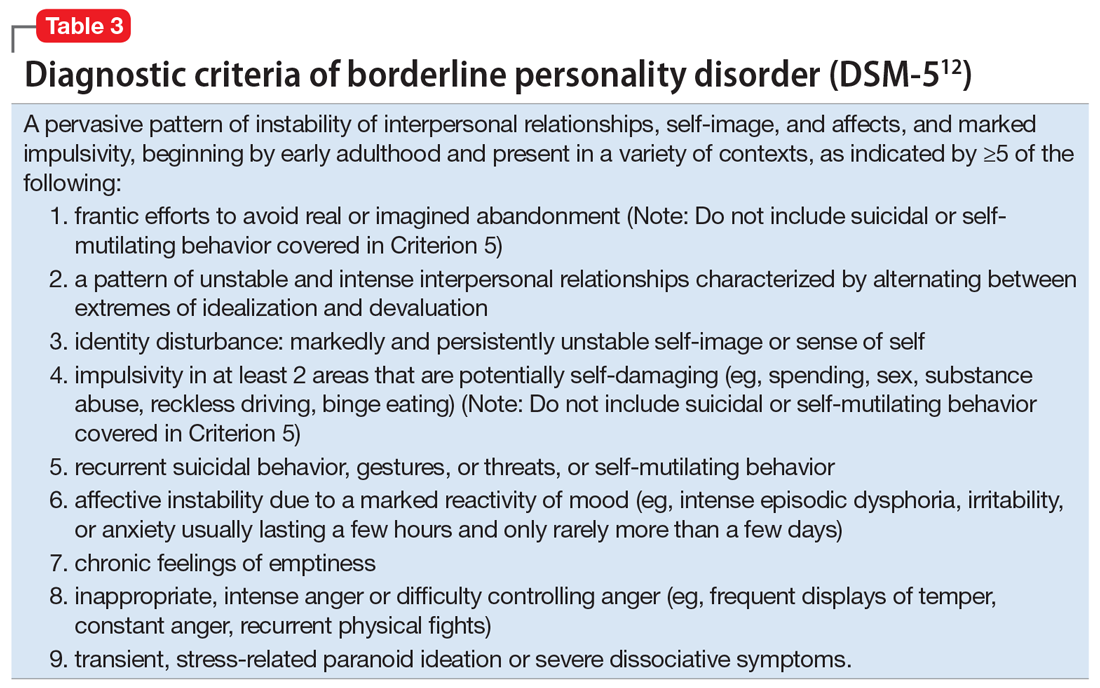

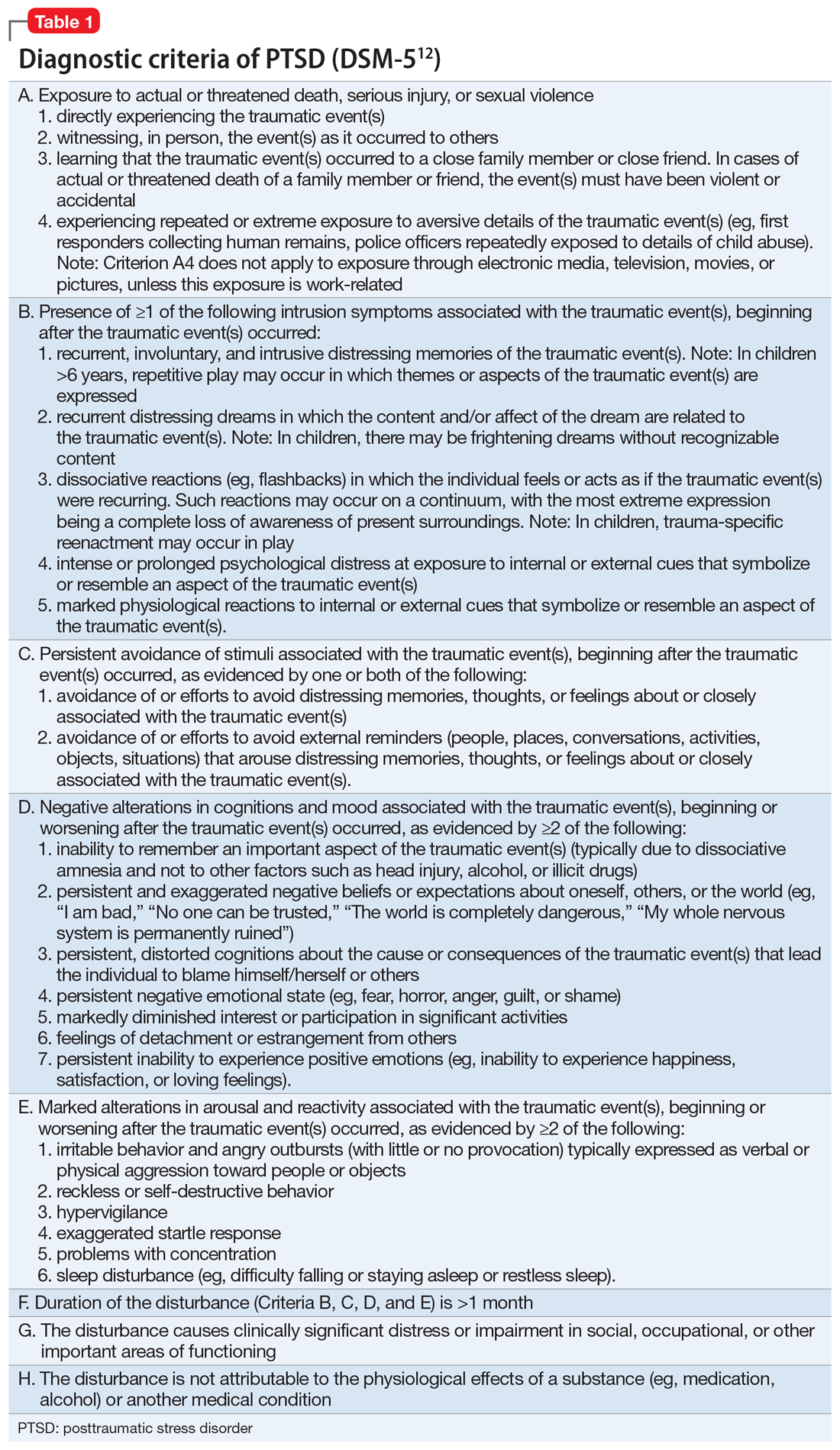

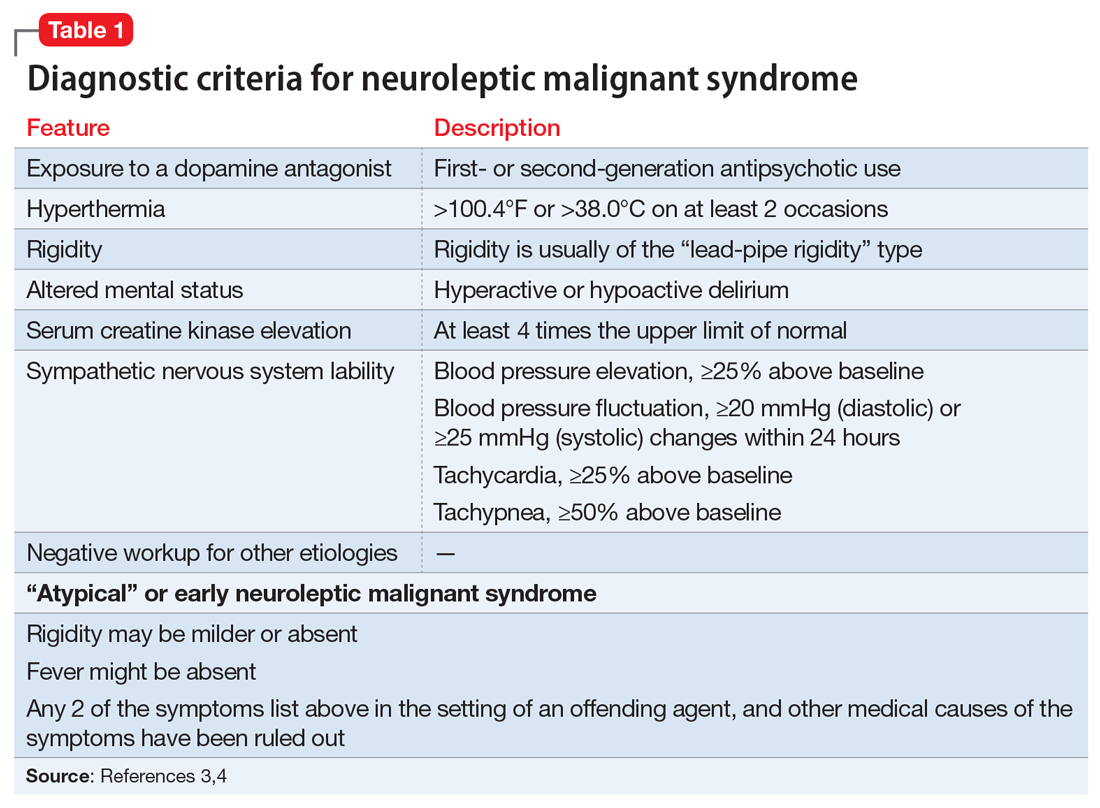

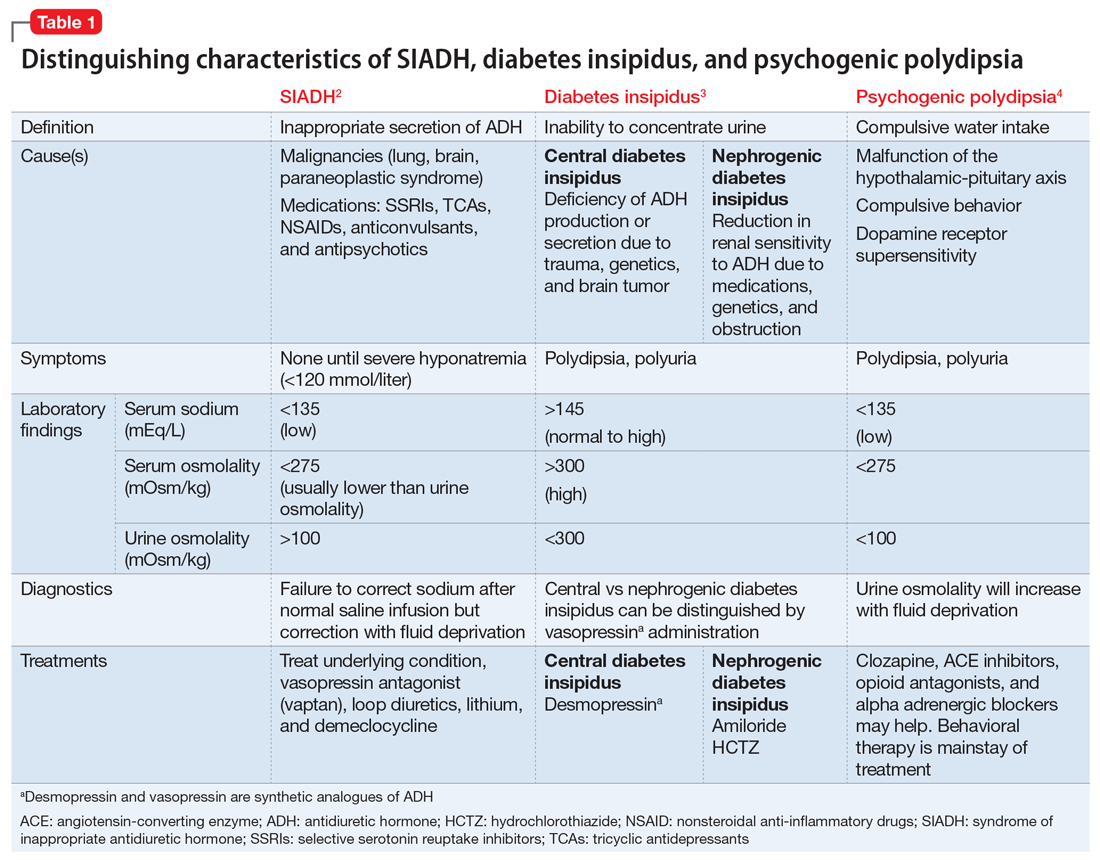

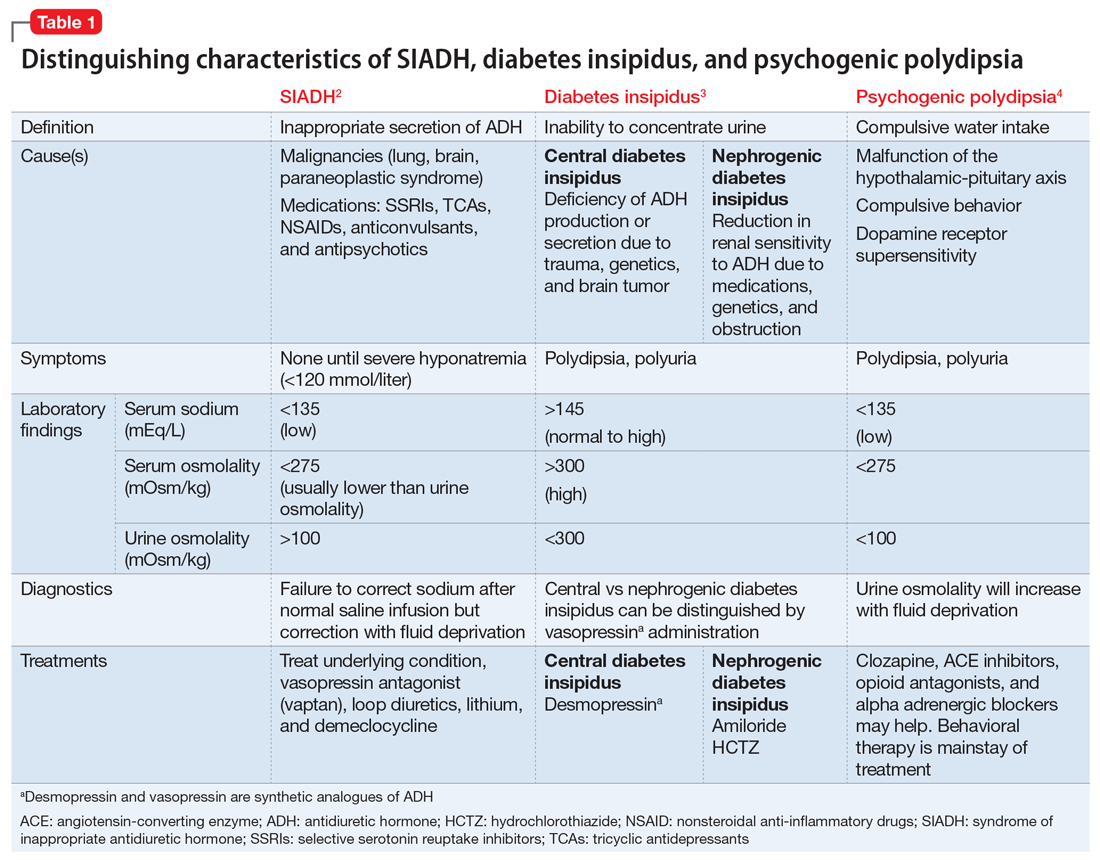

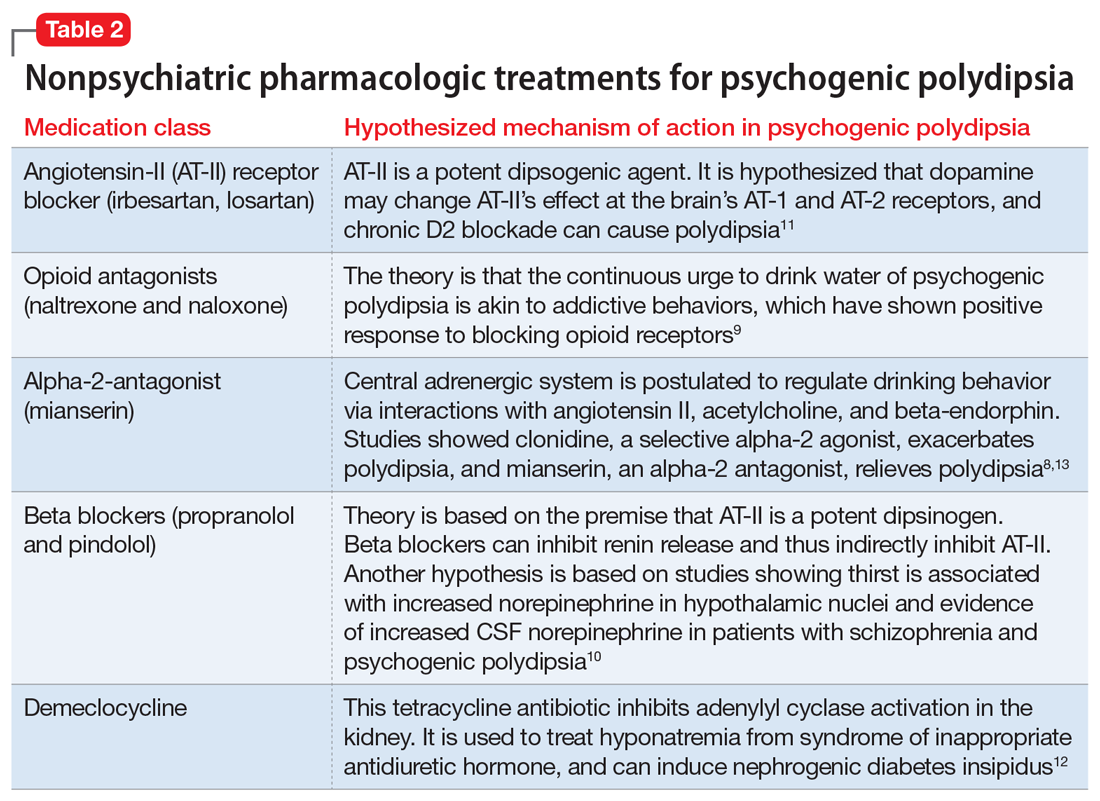

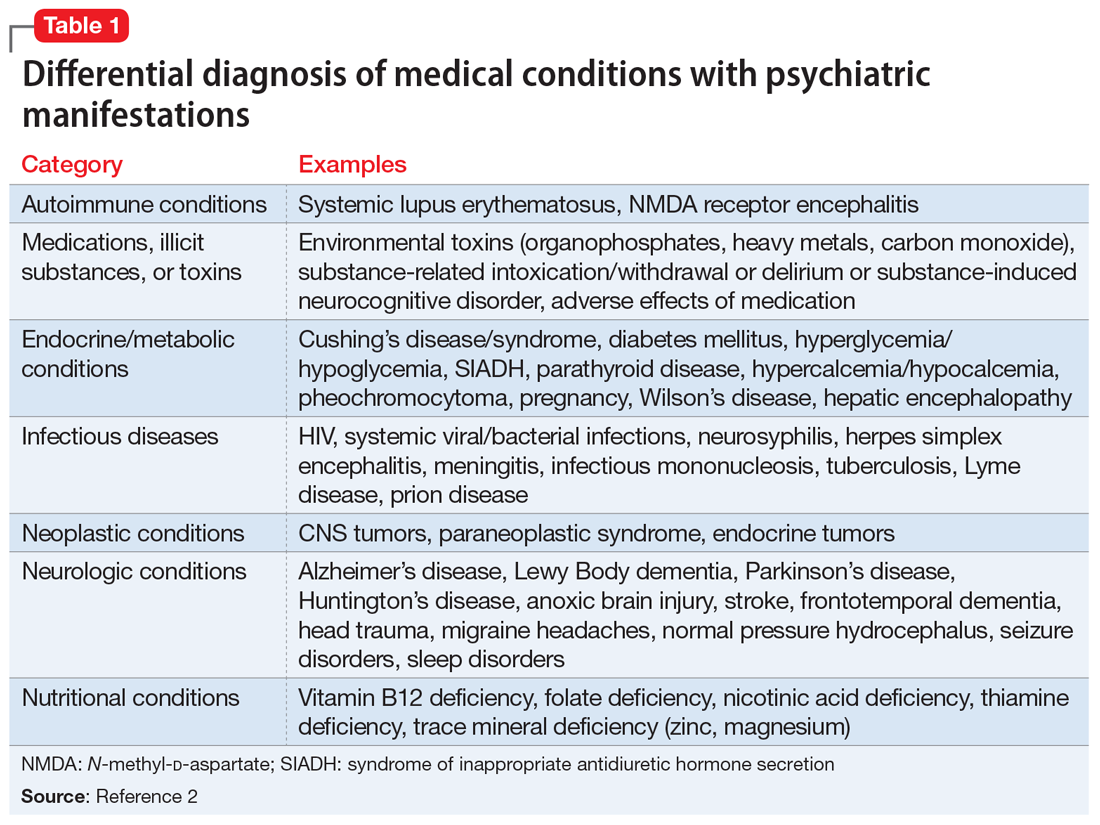

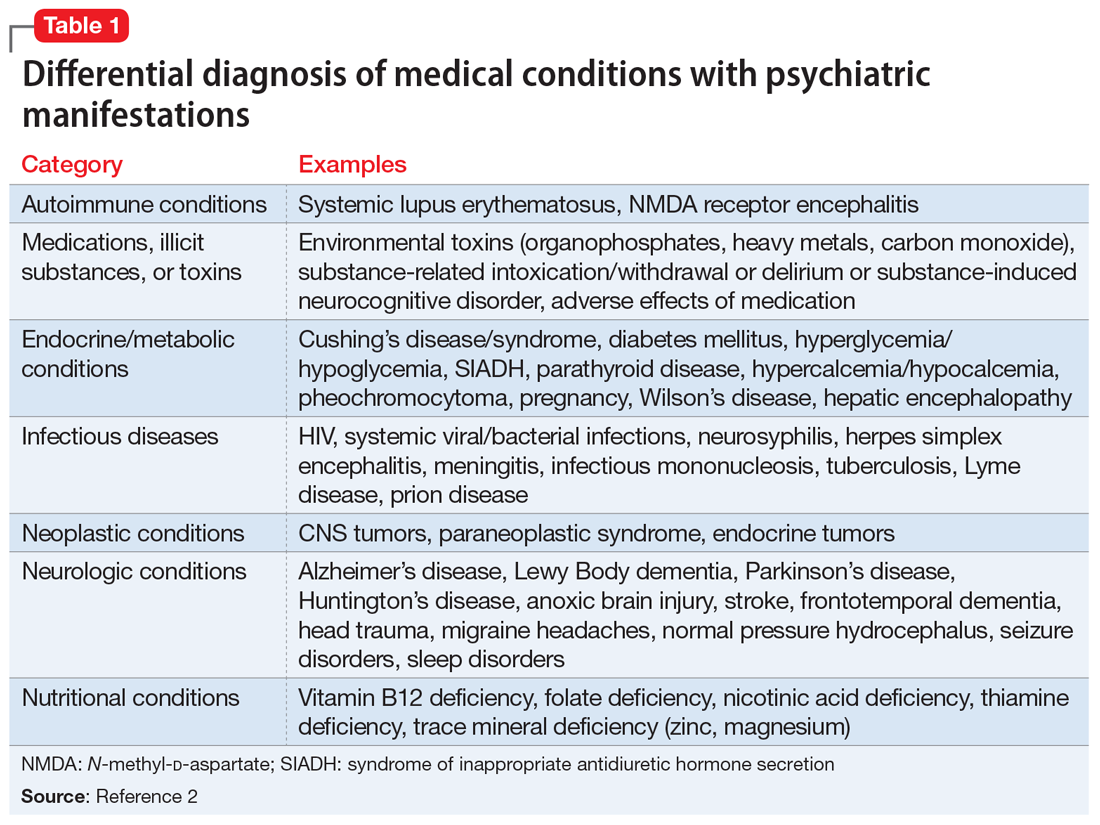

Several health- and physical symptom-related psychiatric disorders have overlapping features, which can complicate the differential diagnosis (Table 11). Ms. L presented to the ED with a severely low BMI of 13.5 kg/m2, obsessions regarding specific types of food, and preoccupations regarding her esophagus. Despite her extensive psychiatric history (including intense fears regarding food), we ruled out a primary psychotic disorder because she did not describe auditory or visual hallucinations and never appeared internally preoccupied. While her BMI and persistent minimization of the extent of her disease meet criteria for anorexia nervosa, she denied body dysmorphia and did not have any fear of gaining weight.

A central element of Ms. L’s presentation was her anxiety regarding how certain types of foods impact her health as well as her anxieties regarding her esophagus. While Ms. L was in remission from esophageal cancer and had a diagnosis of esophageal dysphagia, these preoccupations and obsessions regarding how certain types of foods affect her esophagus drove her to self-neglect and thus represent pathologic thought processes out of proportion to her symptoms. Illness anxiety disorder was considered because Ms. L met many of its criteria: preoccupation with having a serious illness, disproportionate preoccupation with somatic symptoms if they are present, extreme anxiety over health, and performance of health-related behaviors.1 However, illness anxiety disorder is a diagnosis of exclusion, and 1 criterion is that these symptoms cannot be explained by another mental disorder. We felt other diagnoses better fit Ms. L’s condition and ruled out illness anxiety disorder.

Ms. L’s long history of food and non-food–related obsessions and compulsions that interrupted her ability to perform daily activities were strongly suggestive for OCD. Additionally, her intense preoccupation, high level of anxiety, amount of time and energy spent seeking care for her esophagus and GERD symptoms, and the resulting significant disruption of daily life, met criteria for somatic symptom disorder (SSD). However, we did not believe that a diagnosis of OCD and SSD alone explained the entirety of Ms. L’s clinical picture. Despite ruling out anorexia nervosa, Ms. L nonetheless demonstrated disordered eating.

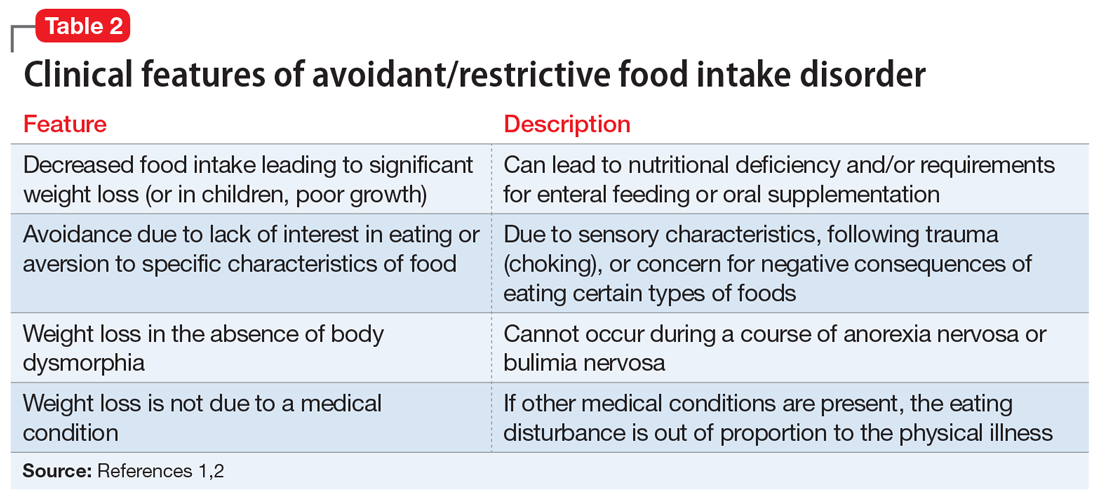

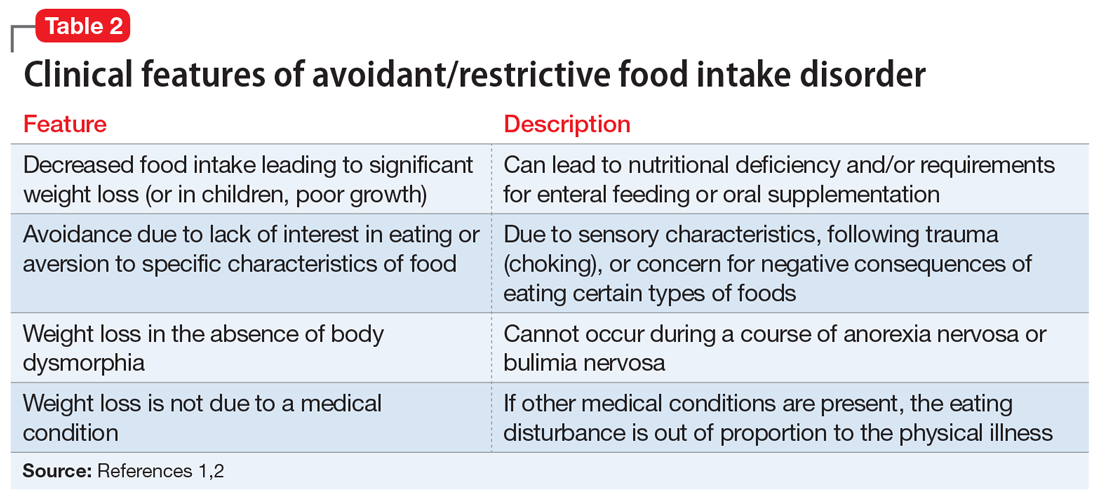

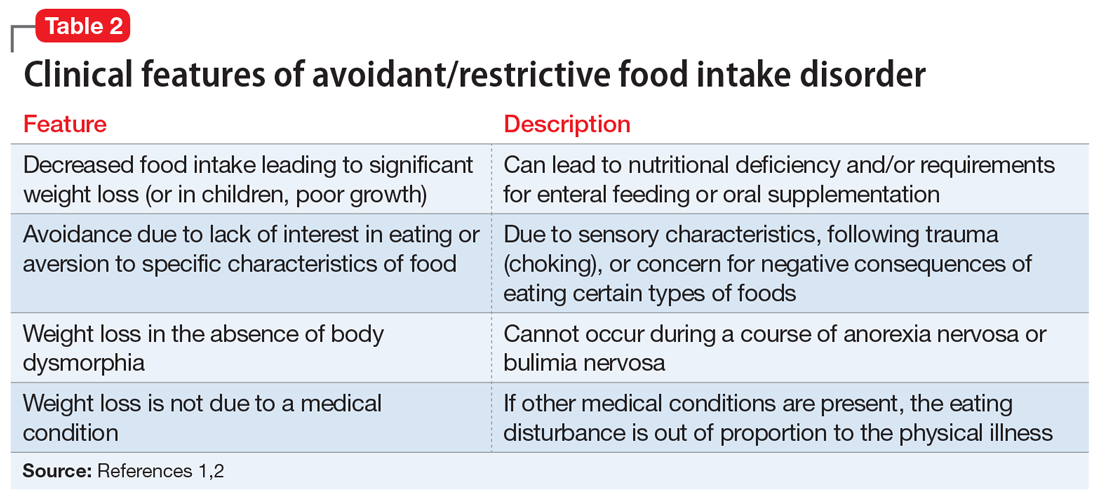

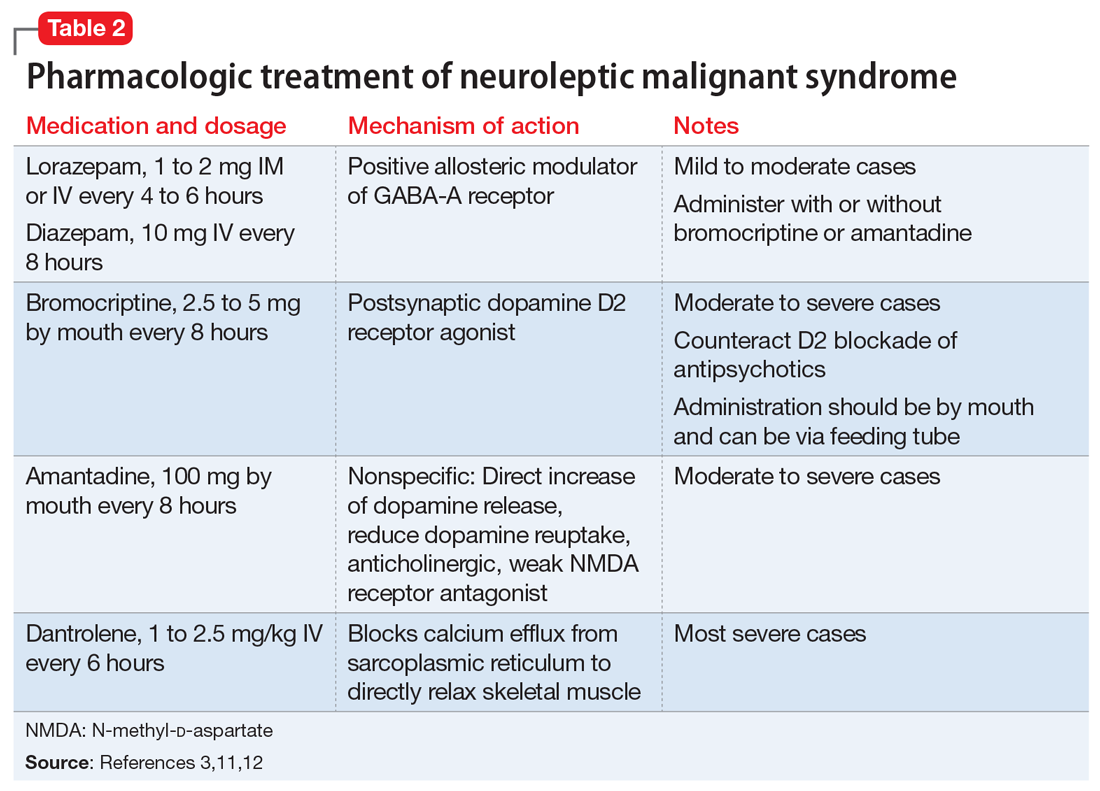

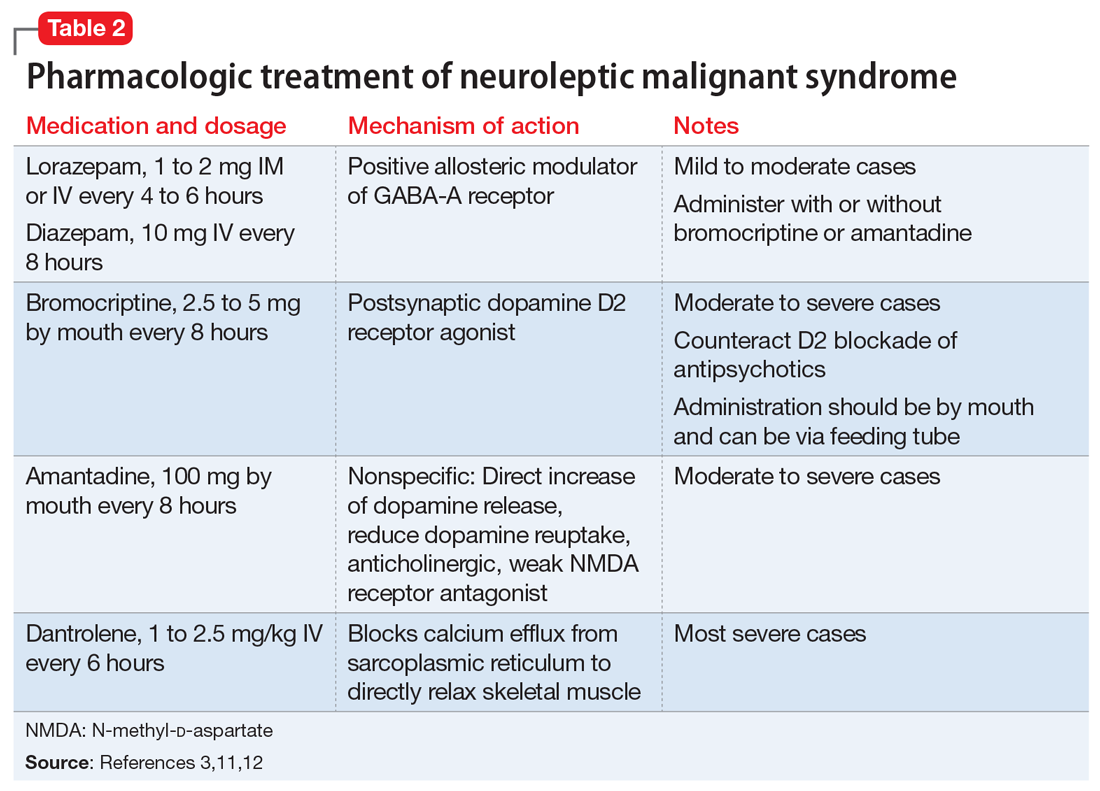

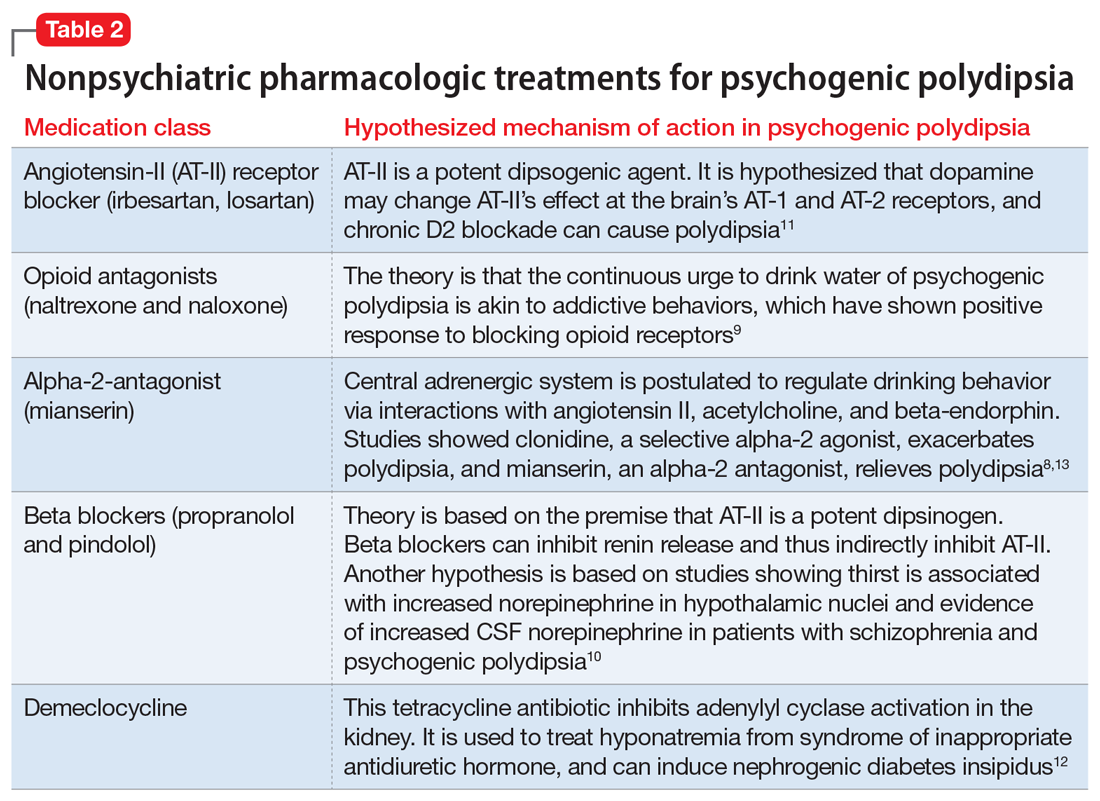

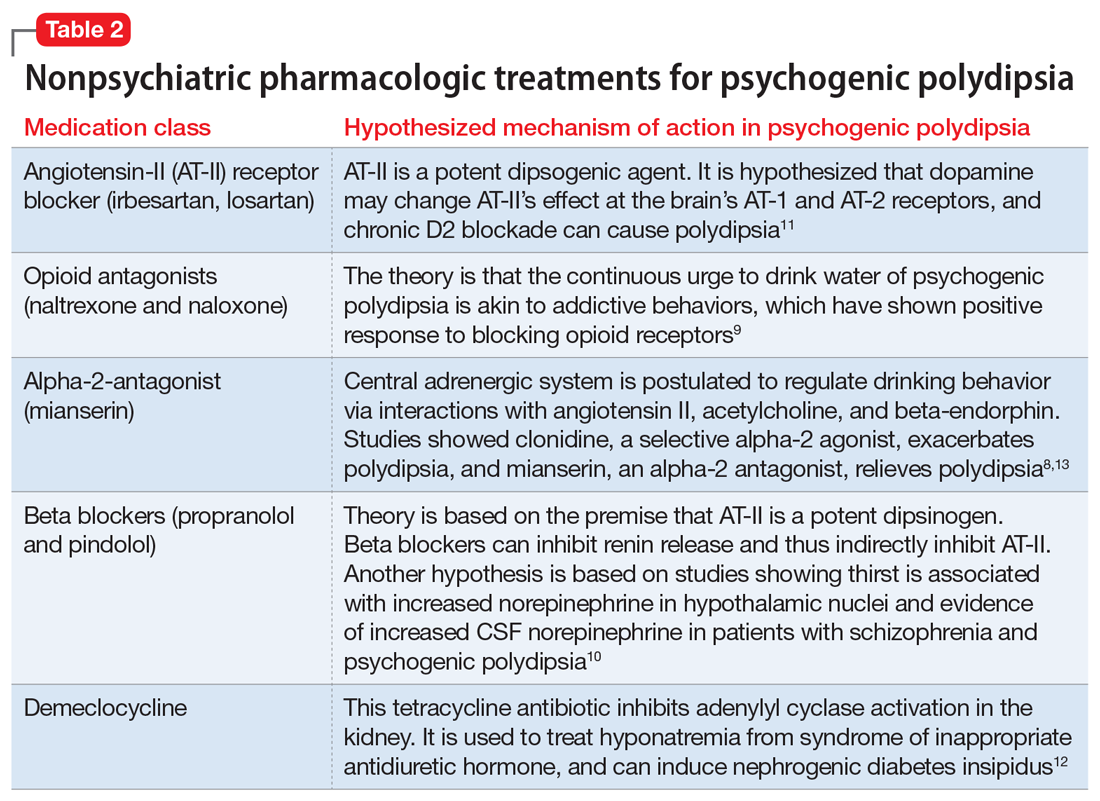

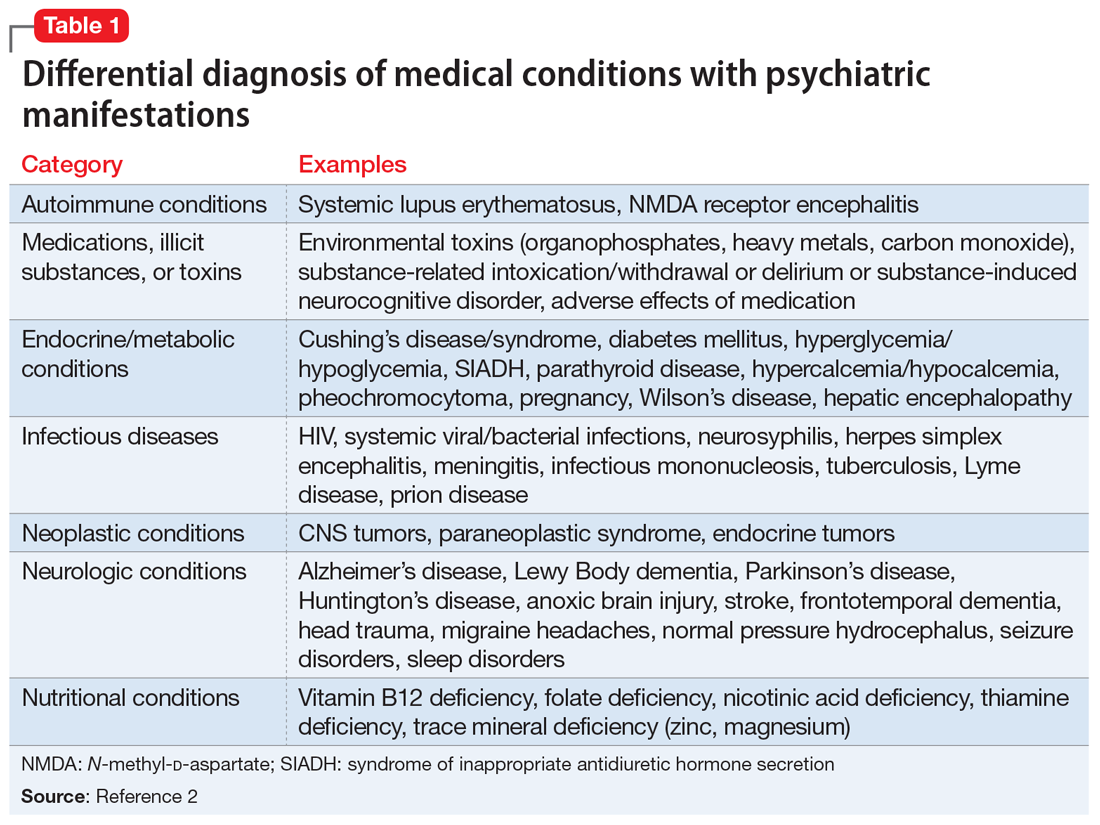

Avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder (ARFID) is an eating disorder in which patients restrict their diet and do not meet nutritional needs for any number of reasons, do not experience body dysmorphia, and do not fear weight gain.1 A common feature of ARFID is a fear of negative consequences from eating specific types of food.2 Table 21,2 summarizes additional clinical features of ARFID. Although ARFID is typically diagnosed in children and adolescents, particularly in individuals with autism with heightened sensory sensitivities, ARFID is also common among adult patients with GI disorders.3 In a retrospective chart review of 410 adults ages 18 to 90 (73% women) referred to a neurogastroenterology care center, 6.3% met the full criteria for ARFID and 17.3% had clinically significant avoidant or restrictive eating behaviors. Among patients with ARFID symptoms, 93% stated that a fear of GI symptoms was the driver of their avoidant or restrictive eating behaviors.2 Patients with GI diseases often develop dietary control and avoidance coping mechanisms to alleviate their symptoms.4 These strategies can exacerbate health anxieties and have a detrimental effect on mental health.5 Patients with GI disorders have a high degree of comorbidity with affective disorders, including anxiety disorders.6 These trends may arise from hypervigilance and the need to gain control over physical symptoms.7 Feeling a need for control, actions driven by anxiety and fear, and the need for compensatory behaviors are cardinal features of OCD and eating disorders.8 Multiple studies have demonstrated comorbidities between irritable bowel syndrome and eating disorders,9 SSD,10 and OCD.11 Taken together with observations that ARFID is also found in patients with GI disorders,2 these findings demonstrate that patients with a history of GI disease are at high risk of developing extreme health anxieties and behavioral coping strategies that can lead to disordered eating.

The rise in “healthy” eating materials online—particularly on social media—has created an atmosphere in which misinformation regarding diet and health is common and widespread. For patients with OCD and a predisposition to health anxiety, such as Ms. L, searching online for nutrition information and healthy living habits can exacerbate food-related anxieties and can lead to a pathological drive for purity and health.12Although not included in DSM-5, orthorexia nervosa was identified in 1997 as a proposed eating disorder best characterized as an obsession with healthy eating with associated restrictive behaviors.13 Patients with this disorder are rarely focused on losing weight, and orthorexic eating behaviors have been associated with both SSD and OCD.12,14 As in Ms. L’s case, patients with orthorexia nervosa demonstrate intrusive obsessions with nutrition, spend excessive amount of time researching nutrition, and fixate on food quality.12 Throughout Ms. L’s hospitalization, even as her food-related magical thinking symptoms improved, she constantly informed her care team that she had been “eating healthily” even though she was severely cachectic. Patients with SSD and OCD prone to health anxieties are at risk of developing pathologic food beliefs and dangerous eating behaviors. These patients may benefit from psychoeducation regarding nutrition and media literacy, which are components of effective eating disorder programs.15

[polldaddy:11079399]

Continue to: The authors' observations...

The authors’ observations

How do we approach the pharmacologic treatment of patients with co-occurring eating, somatic symptom, and anxiety disorders? Olanzapine facilitates recovery in children and adolescents with ARFID by promoting eating and weight gain, and decreasing symptoms of depression and anxiety.16 Patients with orthorexia nervosa also may benefit from treatment with olanzapine, which has decreased food-related fixations, magical thinking, and delusions regarding food.17 Further, orthorexic patients with ARFID have also been shown to respond to SSRIs due to those agents’ efficacy for treating intrusive thoughts, obsessions, and preoccupations from OCD and SSD.18,19 Thus, treating Ms. L’s symptoms with olanzapine and fluoxetine targeted the intersection of several diagnoses on our differential. Olanzapine’s propensity to cause weight gain is favorable in this population, particularly patients such as Ms. L, who do not exhibit body dysmorphia or fear of gaining weight.

OUTCOME Weight gain and fewer fears

Ms. L is prescribed olanzapine 5 mg/d and fluoxetine 20 mg/d. She gains 20.6 pounds in 4 weeks. Importantly, she endorses fewer fears related to foods and expands her palate to include foods she previously considered to be unhealthy, including white bread and farm-raised salmon. Further, she spends less time thinking about food and says she has less anxiety regarding the recurrence of GI symptoms.

1. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-5. 5th ed. American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

2. Murray HB, Bailey AP, Keshishian AC. Prevalence and characteristics of avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder in adult neurogastroenterology patients. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;18(9):1995-2002.e1.

3. Görmez A, Kılıç A, Kırpınar İ. Avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder: an adult case responding to cognitive behavioral therapy. Clinical Case Studies. 2018;17(6):443-452.

4. Reed-Knight B, Squires M, Chitkara DK, et al. Adolescents with irritable bowel syndrome report increased eating-associated symptoms, changes in dietary composition, and altered eating behaviors: a pilot comparison study to healthy adolescents. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2016;28(12):1915-1920.

5. Melchior C, Desprez C, Riachi G, et al. Anxiety and depression profile is associated with eating disorders in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Front Psychiatry. 2020;10:928.

6. Mayer EA, Craske M, Naliboff BD. Depression, anxiety, and the gastrointestinal system. J Clin Psychiatry. 2001;62 Suppl 8:28-37.

7. Abraham S, Kellow J. Exploring eating disorder quality of life and functional gastrointestinal disorders among eating disorder patients. J Psychosom Res. 2011;70(4):372-377.

8. Swinbourne JM, Touyz SW. The co-morbidity of eating disorders and anxiety disorders: a review. Eur Eat Disord Rev. 2007;15(4):253-274.

9. Perkins SJ, Keville S, Schmidt U, et al. Eating disorders and irritable bowel syndrome: is there a link? J Psychosom Res. 2005;59(2):57-64.

10. Hausteiner-Wiehle C, Henningsen P. Irritable bowel syndrome: relations with functional, mental, and somatoform disorders. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20(2):6024-6030.

11. Masand PS, Keuthen NJ, Gupta S, et al. Prevalence of irritable bowel syndrome in obsessive-compulsive disorder. CNS Spectr. 2006;11(1):21-25.

12. Koven NS, Abry AW. The clinical basis of orthorexia nervosa: emerging perspectives. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2015;11:385-394.

13. Bratman S. Health food junkie. Yoga Journal. 1997;136:42-50.

14. Barthels F, Müller R, Schüth T, et al. Orthorexic eating behavior in patients with somatoform disorders. Eat Weight Disord. 2021;26(1):135-143.

15. Ciao AC, Loth K, Neumark-Sztainer D. Preventing eating disorder pathology: common and unique features of successful eating disorders prevention programs. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2014;16(7):453.

16. Brewerton TD, D’Agostino M. Adjunctive use of olanzapine in the treatment of avoidant restrictive food intake disorder in children and adolescents in an eating disorders program. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2017;27(10):920-922.

17. Moroze RM, Dunn TM, Craig Holland J, et al. Microthinking about micronutrients: a case of transition from obsessions about healthy eating to near-fatal “orthorexia nervosa” and proposed diagnostic criteria. Psychosomatics. 2015;56(4):397-403.

18. Spettigue W, Norris ML, Santos A, et al. Treatment of children and adolescents with avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder: a case series examining the feasibility of family therapy and adjunctive treatments. J Eat Disord. 2018;6:20.

19. Niedzielski A, Kaźmierczak-Wojtaś N. Prevalence of Orthorexia Nervosa and Its Diagnostic Tools-A Literature Review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(10):5488. Published 2021 May 20. doi:10.3390/ijerph18105488 Prevalence of orthorexia nervosa and its diagnostic tools-a literature review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(10):5488.

CASE Fixated on health and nutrition

At the insistence of her daughter, Ms. L, age 75, presents to the emergency department (ED) for self-neglect and severe weight loss, with a body mass index (BMI) of 13.5 kg/m2 (normal: 18.5 to 24.9 kg/m2). When asked why she is in the ED, Ms. L says she doesn’t know. She attributes her significant weight loss (approximately 20 pounds in the last few months) to gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD). She constantly worries about her esophagus. She had been diagnosed with esophageal dysphagia 7 years ago after undergoing radiofrequency ablation for esophageal cancer. Ms. L fixates on the negative effects certain foods and ingredients might have on her stomach and esophagus.

Following transfer from the ED, Ms. L is involuntarily admitted to our inpatient unit. Although she acknowledges weight loss, she minimizes the severity of her illness and indicates she would like to gain weight, but only by eating healthy foods she is comfortable with, including kale, quinoa, and vegetables. Ms. L says that she has always been interested in “healthful foods” and that she “loves sugar,” but “it’s bad for you,” mentioning that “sugar fuels cancer.” She has daily thoughts about sugar causing cancer. Ms. L also mentions that she stopped eating flour, sugar, fried food, and oils because those foods affect her “stomach acid” and cause “pimples on my face and weight loss.” While in the inpatient unit, Ms. L requests a special diet and demands to know the origin and ingredients of the foods she is offered. She emphasizes that her esophageal cancer diagnosis and dysphagia exacerbate worries that certain foods cause cancer, and wants to continue her diet restrictions. Nonetheless, she says she wants to get healthy, and denies an intense fear of gaining weight or feeling fat.

HISTORY Multiple psychiatric diagnoses

Ms. L lives alone and enjoys spending time with her grandchildren, visiting museums, and listening to classical music. However, her family, social workers, and records from a previous psychiatric hospitalization reveal that Ms. L has a history of psychiatric illness and fears regarding certain types of foods for much of her adult life. Ms. L’s family also described a range of compulsive behaviors, including shoplifting, hoarding art, multiple plastic surgeries, and phases where Ms. L ate only frozen yogurt without sugar.

Ms. L’s daughter reported that Ms. L had seen a psychologist in the late 1990s for depression and had been diagnosed with obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) and attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder in the early 2000s. In 2006, during a depressive episode after her divorce, Ms. L had a suicide attempt with pills and alcohol, and was hospitalized. Records from that stay described a history of mood dysregulation with fears regarding food and nutrition. Ms. L was treated with aripiprazole 5 mg/d. A trial of trazodone 25 mg/d did not have any effect. When discharged, she was receiving lamotrigine 100 mg/d. However, her daughter believes she stopped taking all psychiatric medications shortly after discharge.

Her daughter says that in the past 2 years, Ms. L has seen multiple doctors for treatment of somatic gastrointestinal (GI) complaints. A 2018 note from a social worker indicated that Ms. L endorsed taking >80 supplements per day and constantly researched nutrition online. In the months leading to her current hospitalization, Ms. L suffered from severe self-neglect and fear regarding foods she felt were not healthy for her. She had stopped leaving her apartment.

Continue to: EVALUATION Poor insight, normal lab results...

EVALUATION Poor insight, normal lab results

During her evaluation, Ms. L appears cachectic and frail. She has a heavily constricted affect and is guarded, dismissive, and vague. Although her thought processes are linear and goal-directed, her insight into her condition is extremely poor and she appears surprised when clinicians inform her that her self-neglect would lead to death. Instead, Ms. L insists she is eating healthily and demonstrates severe anxiety in relation to her GI symptoms.

Ms. L is oriented to person, place, and time. She scores 27/30 on the Montreal Cognitive Assessment, indicating normal cognition. She denies any depressive symptoms or suicidal intent. She does not appear to be internally preoccupied and denies having auditory or visual hallucinations or manic symptoms.

A neurologic examination reveals that her cranial nerves are normal, and cerebellar function, strength, and sensory testing are intact. Her gait is steady and she walks without a walker. Despite her severely low BMI and recent history of self-neglect, Ms. L’s laboratory results are remarkably normal and show no liver, metabolic, or electrolyte abnormalities, no signs of infection, and normal vitamin B12 levels. She has slightly elevated creatinine and blood urea nitrogen levels, but a normal glomerular filtration rate.

Her medical history is significant for squamous cell esophageal cancer, treated with radiofrequency ablation. Although Ms. L is constantly worried about the recurrence of cancer, pathology reports demonstrate no esophageal dysplasia. However, she does show evidence of an approximately 1 cm × 1 cm mild, noncircumferential esophageal stenosis, likely resulting from radiofrequency ablation.

[polldaddy:11079394]

The authors’ observations

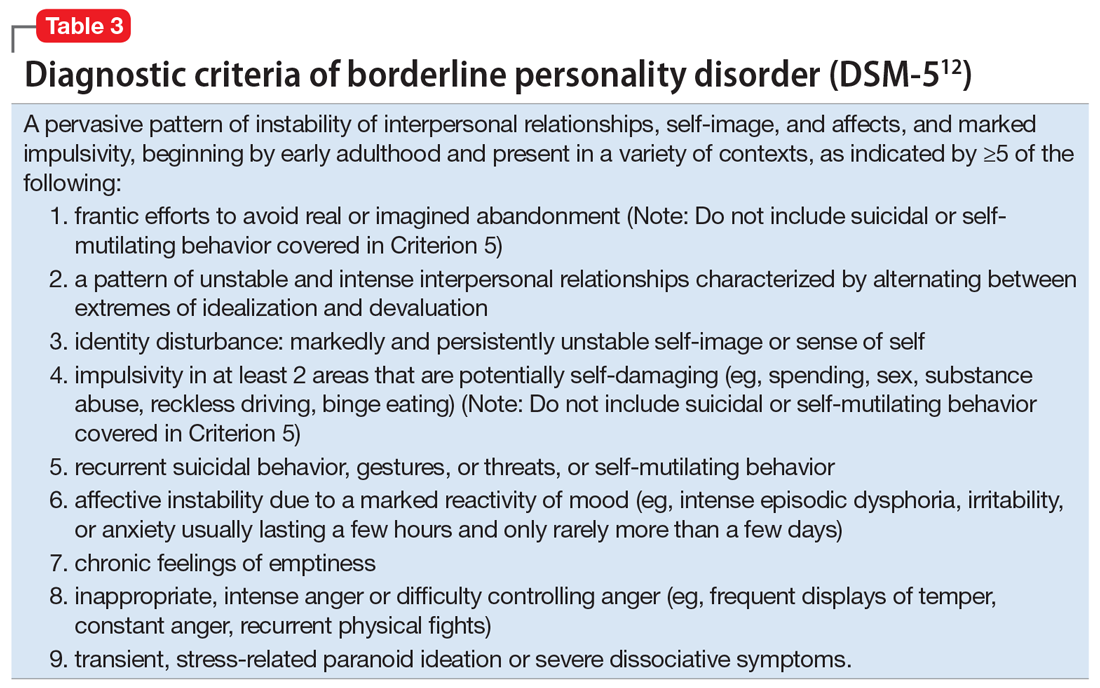

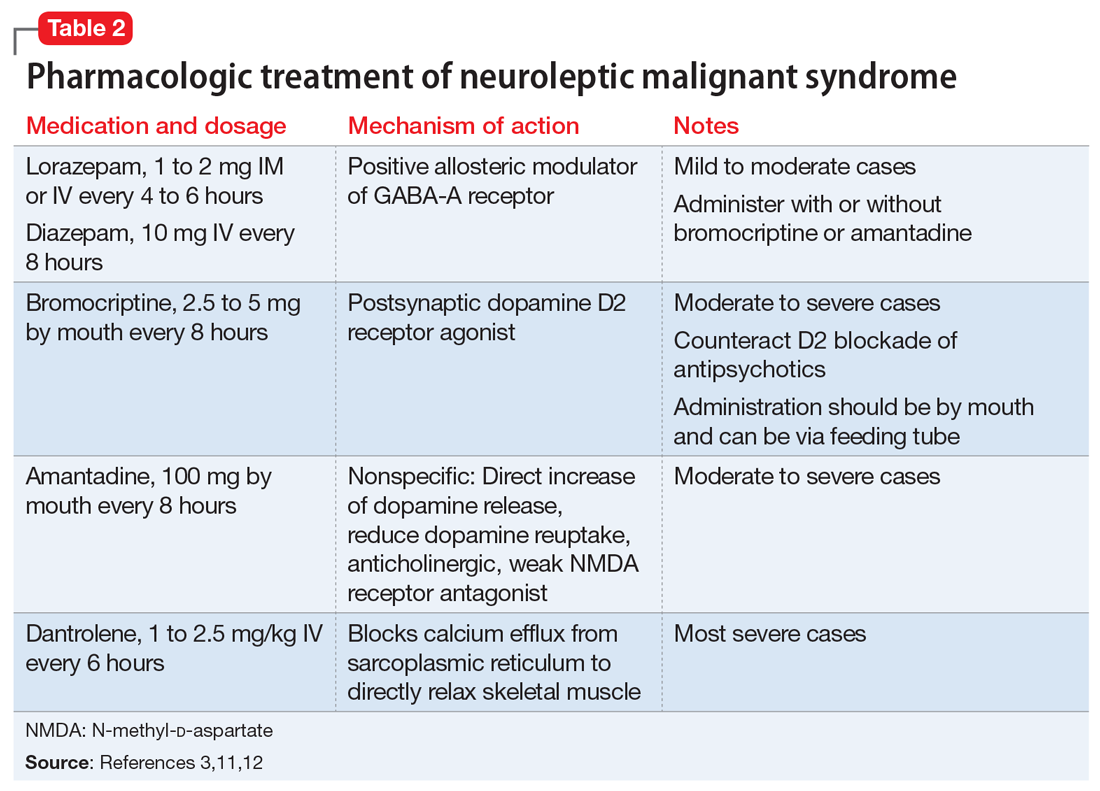

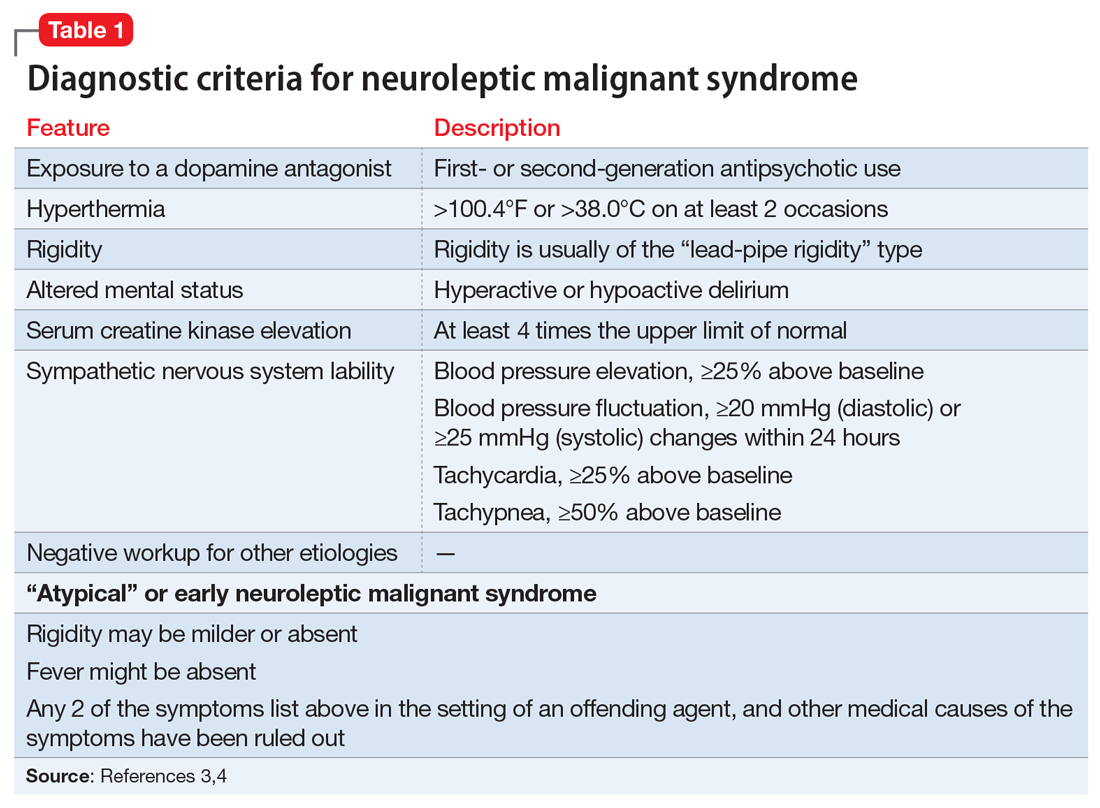

Several health- and physical symptom-related psychiatric disorders have overlapping features, which can complicate the differential diagnosis (Table 11). Ms. L presented to the ED with a severely low BMI of 13.5 kg/m2, obsessions regarding specific types of food, and preoccupations regarding her esophagus. Despite her extensive psychiatric history (including intense fears regarding food), we ruled out a primary psychotic disorder because she did not describe auditory or visual hallucinations and never appeared internally preoccupied. While her BMI and persistent minimization of the extent of her disease meet criteria for anorexia nervosa, she denied body dysmorphia and did not have any fear of gaining weight.

A central element of Ms. L’s presentation was her anxiety regarding how certain types of foods impact her health as well as her anxieties regarding her esophagus. While Ms. L was in remission from esophageal cancer and had a diagnosis of esophageal dysphagia, these preoccupations and obsessions regarding how certain types of foods affect her esophagus drove her to self-neglect and thus represent pathologic thought processes out of proportion to her symptoms. Illness anxiety disorder was considered because Ms. L met many of its criteria: preoccupation with having a serious illness, disproportionate preoccupation with somatic symptoms if they are present, extreme anxiety over health, and performance of health-related behaviors.1 However, illness anxiety disorder is a diagnosis of exclusion, and 1 criterion is that these symptoms cannot be explained by another mental disorder. We felt other diagnoses better fit Ms. L’s condition and ruled out illness anxiety disorder.

Ms. L’s long history of food and non-food–related obsessions and compulsions that interrupted her ability to perform daily activities were strongly suggestive for OCD. Additionally, her intense preoccupation, high level of anxiety, amount of time and energy spent seeking care for her esophagus and GERD symptoms, and the resulting significant disruption of daily life, met criteria for somatic symptom disorder (SSD). However, we did not believe that a diagnosis of OCD and SSD alone explained the entirety of Ms. L’s clinical picture. Despite ruling out anorexia nervosa, Ms. L nonetheless demonstrated disordered eating.

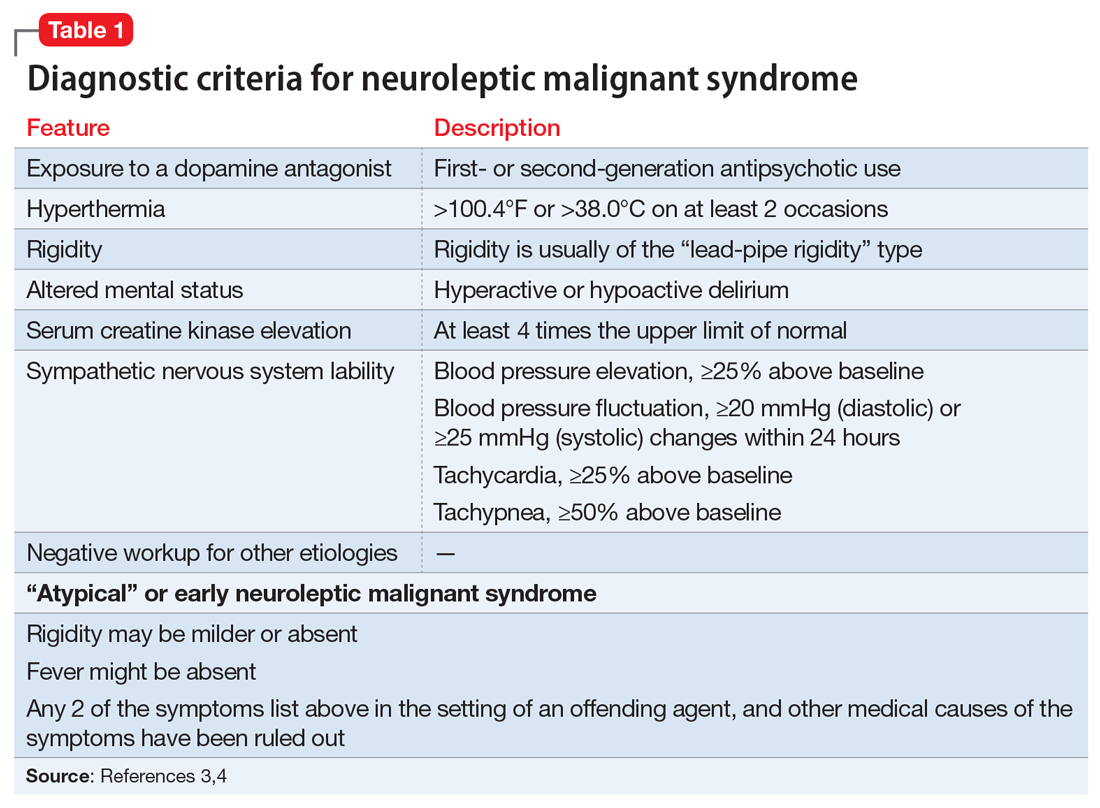

Avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder (ARFID) is an eating disorder in which patients restrict their diet and do not meet nutritional needs for any number of reasons, do not experience body dysmorphia, and do not fear weight gain.1 A common feature of ARFID is a fear of negative consequences from eating specific types of food.2 Table 21,2 summarizes additional clinical features of ARFID. Although ARFID is typically diagnosed in children and adolescents, particularly in individuals with autism with heightened sensory sensitivities, ARFID is also common among adult patients with GI disorders.3 In a retrospective chart review of 410 adults ages 18 to 90 (73% women) referred to a neurogastroenterology care center, 6.3% met the full criteria for ARFID and 17.3% had clinically significant avoidant or restrictive eating behaviors. Among patients with ARFID symptoms, 93% stated that a fear of GI symptoms was the driver of their avoidant or restrictive eating behaviors.2 Patients with GI diseases often develop dietary control and avoidance coping mechanisms to alleviate their symptoms.4 These strategies can exacerbate health anxieties and have a detrimental effect on mental health.5 Patients with GI disorders have a high degree of comorbidity with affective disorders, including anxiety disorders.6 These trends may arise from hypervigilance and the need to gain control over physical symptoms.7 Feeling a need for control, actions driven by anxiety and fear, and the need for compensatory behaviors are cardinal features of OCD and eating disorders.8 Multiple studies have demonstrated comorbidities between irritable bowel syndrome and eating disorders,9 SSD,10 and OCD.11 Taken together with observations that ARFID is also found in patients with GI disorders,2 these findings demonstrate that patients with a history of GI disease are at high risk of developing extreme health anxieties and behavioral coping strategies that can lead to disordered eating.

The rise in “healthy” eating materials online—particularly on social media—has created an atmosphere in which misinformation regarding diet and health is common and widespread. For patients with OCD and a predisposition to health anxiety, such as Ms. L, searching online for nutrition information and healthy living habits can exacerbate food-related anxieties and can lead to a pathological drive for purity and health.12Although not included in DSM-5, orthorexia nervosa was identified in 1997 as a proposed eating disorder best characterized as an obsession with healthy eating with associated restrictive behaviors.13 Patients with this disorder are rarely focused on losing weight, and orthorexic eating behaviors have been associated with both SSD and OCD.12,14 As in Ms. L’s case, patients with orthorexia nervosa demonstrate intrusive obsessions with nutrition, spend excessive amount of time researching nutrition, and fixate on food quality.12 Throughout Ms. L’s hospitalization, even as her food-related magical thinking symptoms improved, she constantly informed her care team that she had been “eating healthily” even though she was severely cachectic. Patients with SSD and OCD prone to health anxieties are at risk of developing pathologic food beliefs and dangerous eating behaviors. These patients may benefit from psychoeducation regarding nutrition and media literacy, which are components of effective eating disorder programs.15

[polldaddy:11079399]

Continue to: The authors' observations...

The authors’ observations

How do we approach the pharmacologic treatment of patients with co-occurring eating, somatic symptom, and anxiety disorders? Olanzapine facilitates recovery in children and adolescents with ARFID by promoting eating and weight gain, and decreasing symptoms of depression and anxiety.16 Patients with orthorexia nervosa also may benefit from treatment with olanzapine, which has decreased food-related fixations, magical thinking, and delusions regarding food.17 Further, orthorexic patients with ARFID have also been shown to respond to SSRIs due to those agents’ efficacy for treating intrusive thoughts, obsessions, and preoccupations from OCD and SSD.18,19 Thus, treating Ms. L’s symptoms with olanzapine and fluoxetine targeted the intersection of several diagnoses on our differential. Olanzapine’s propensity to cause weight gain is favorable in this population, particularly patients such as Ms. L, who do not exhibit body dysmorphia or fear of gaining weight.

OUTCOME Weight gain and fewer fears

Ms. L is prescribed olanzapine 5 mg/d and fluoxetine 20 mg/d. She gains 20.6 pounds in 4 weeks. Importantly, she endorses fewer fears related to foods and expands her palate to include foods she previously considered to be unhealthy, including white bread and farm-raised salmon. Further, she spends less time thinking about food and says she has less anxiety regarding the recurrence of GI symptoms.

CASE Fixated on health and nutrition

At the insistence of her daughter, Ms. L, age 75, presents to the emergency department (ED) for self-neglect and severe weight loss, with a body mass index (BMI) of 13.5 kg/m2 (normal: 18.5 to 24.9 kg/m2). When asked why she is in the ED, Ms. L says she doesn’t know. She attributes her significant weight loss (approximately 20 pounds in the last few months) to gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD). She constantly worries about her esophagus. She had been diagnosed with esophageal dysphagia 7 years ago after undergoing radiofrequency ablation for esophageal cancer. Ms. L fixates on the negative effects certain foods and ingredients might have on her stomach and esophagus.

Following transfer from the ED, Ms. L is involuntarily admitted to our inpatient unit. Although she acknowledges weight loss, she minimizes the severity of her illness and indicates she would like to gain weight, but only by eating healthy foods she is comfortable with, including kale, quinoa, and vegetables. Ms. L says that she has always been interested in “healthful foods” and that she “loves sugar,” but “it’s bad for you,” mentioning that “sugar fuels cancer.” She has daily thoughts about sugar causing cancer. Ms. L also mentions that she stopped eating flour, sugar, fried food, and oils because those foods affect her “stomach acid” and cause “pimples on my face and weight loss.” While in the inpatient unit, Ms. L requests a special diet and demands to know the origin and ingredients of the foods she is offered. She emphasizes that her esophageal cancer diagnosis and dysphagia exacerbate worries that certain foods cause cancer, and wants to continue her diet restrictions. Nonetheless, she says she wants to get healthy, and denies an intense fear of gaining weight or feeling fat.

HISTORY Multiple psychiatric diagnoses

Ms. L lives alone and enjoys spending time with her grandchildren, visiting museums, and listening to classical music. However, her family, social workers, and records from a previous psychiatric hospitalization reveal that Ms. L has a history of psychiatric illness and fears regarding certain types of foods for much of her adult life. Ms. L’s family also described a range of compulsive behaviors, including shoplifting, hoarding art, multiple plastic surgeries, and phases where Ms. L ate only frozen yogurt without sugar.

Ms. L’s daughter reported that Ms. L had seen a psychologist in the late 1990s for depression and had been diagnosed with obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) and attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder in the early 2000s. In 2006, during a depressive episode after her divorce, Ms. L had a suicide attempt with pills and alcohol, and was hospitalized. Records from that stay described a history of mood dysregulation with fears regarding food and nutrition. Ms. L was treated with aripiprazole 5 mg/d. A trial of trazodone 25 mg/d did not have any effect. When discharged, she was receiving lamotrigine 100 mg/d. However, her daughter believes she stopped taking all psychiatric medications shortly after discharge.

Her daughter says that in the past 2 years, Ms. L has seen multiple doctors for treatment of somatic gastrointestinal (GI) complaints. A 2018 note from a social worker indicated that Ms. L endorsed taking >80 supplements per day and constantly researched nutrition online. In the months leading to her current hospitalization, Ms. L suffered from severe self-neglect and fear regarding foods she felt were not healthy for her. She had stopped leaving her apartment.

Continue to: EVALUATION Poor insight, normal lab results...

EVALUATION Poor insight, normal lab results

During her evaluation, Ms. L appears cachectic and frail. She has a heavily constricted affect and is guarded, dismissive, and vague. Although her thought processes are linear and goal-directed, her insight into her condition is extremely poor and she appears surprised when clinicians inform her that her self-neglect would lead to death. Instead, Ms. L insists she is eating healthily and demonstrates severe anxiety in relation to her GI symptoms.

Ms. L is oriented to person, place, and time. She scores 27/30 on the Montreal Cognitive Assessment, indicating normal cognition. She denies any depressive symptoms or suicidal intent. She does not appear to be internally preoccupied and denies having auditory or visual hallucinations or manic symptoms.

A neurologic examination reveals that her cranial nerves are normal, and cerebellar function, strength, and sensory testing are intact. Her gait is steady and she walks without a walker. Despite her severely low BMI and recent history of self-neglect, Ms. L’s laboratory results are remarkably normal and show no liver, metabolic, or electrolyte abnormalities, no signs of infection, and normal vitamin B12 levels. She has slightly elevated creatinine and blood urea nitrogen levels, but a normal glomerular filtration rate.

Her medical history is significant for squamous cell esophageal cancer, treated with radiofrequency ablation. Although Ms. L is constantly worried about the recurrence of cancer, pathology reports demonstrate no esophageal dysplasia. However, she does show evidence of an approximately 1 cm × 1 cm mild, noncircumferential esophageal stenosis, likely resulting from radiofrequency ablation.

[polldaddy:11079394]

The authors’ observations

Several health- and physical symptom-related psychiatric disorders have overlapping features, which can complicate the differential diagnosis (Table 11). Ms. L presented to the ED with a severely low BMI of 13.5 kg/m2, obsessions regarding specific types of food, and preoccupations regarding her esophagus. Despite her extensive psychiatric history (including intense fears regarding food), we ruled out a primary psychotic disorder because she did not describe auditory or visual hallucinations and never appeared internally preoccupied. While her BMI and persistent minimization of the extent of her disease meet criteria for anorexia nervosa, she denied body dysmorphia and did not have any fear of gaining weight.

A central element of Ms. L’s presentation was her anxiety regarding how certain types of foods impact her health as well as her anxieties regarding her esophagus. While Ms. L was in remission from esophageal cancer and had a diagnosis of esophageal dysphagia, these preoccupations and obsessions regarding how certain types of foods affect her esophagus drove her to self-neglect and thus represent pathologic thought processes out of proportion to her symptoms. Illness anxiety disorder was considered because Ms. L met many of its criteria: preoccupation with having a serious illness, disproportionate preoccupation with somatic symptoms if they are present, extreme anxiety over health, and performance of health-related behaviors.1 However, illness anxiety disorder is a diagnosis of exclusion, and 1 criterion is that these symptoms cannot be explained by another mental disorder. We felt other diagnoses better fit Ms. L’s condition and ruled out illness anxiety disorder.

Ms. L’s long history of food and non-food–related obsessions and compulsions that interrupted her ability to perform daily activities were strongly suggestive for OCD. Additionally, her intense preoccupation, high level of anxiety, amount of time and energy spent seeking care for her esophagus and GERD symptoms, and the resulting significant disruption of daily life, met criteria for somatic symptom disorder (SSD). However, we did not believe that a diagnosis of OCD and SSD alone explained the entirety of Ms. L’s clinical picture. Despite ruling out anorexia nervosa, Ms. L nonetheless demonstrated disordered eating.

Avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder (ARFID) is an eating disorder in which patients restrict their diet and do not meet nutritional needs for any number of reasons, do not experience body dysmorphia, and do not fear weight gain.1 A common feature of ARFID is a fear of negative consequences from eating specific types of food.2 Table 21,2 summarizes additional clinical features of ARFID. Although ARFID is typically diagnosed in children and adolescents, particularly in individuals with autism with heightened sensory sensitivities, ARFID is also common among adult patients with GI disorders.3 In a retrospective chart review of 410 adults ages 18 to 90 (73% women) referred to a neurogastroenterology care center, 6.3% met the full criteria for ARFID and 17.3% had clinically significant avoidant or restrictive eating behaviors. Among patients with ARFID symptoms, 93% stated that a fear of GI symptoms was the driver of their avoidant or restrictive eating behaviors.2 Patients with GI diseases often develop dietary control and avoidance coping mechanisms to alleviate their symptoms.4 These strategies can exacerbate health anxieties and have a detrimental effect on mental health.5 Patients with GI disorders have a high degree of comorbidity with affective disorders, including anxiety disorders.6 These trends may arise from hypervigilance and the need to gain control over physical symptoms.7 Feeling a need for control, actions driven by anxiety and fear, and the need for compensatory behaviors are cardinal features of OCD and eating disorders.8 Multiple studies have demonstrated comorbidities between irritable bowel syndrome and eating disorders,9 SSD,10 and OCD.11 Taken together with observations that ARFID is also found in patients with GI disorders,2 these findings demonstrate that patients with a history of GI disease are at high risk of developing extreme health anxieties and behavioral coping strategies that can lead to disordered eating.

The rise in “healthy” eating materials online—particularly on social media—has created an atmosphere in which misinformation regarding diet and health is common and widespread. For patients with OCD and a predisposition to health anxiety, such as Ms. L, searching online for nutrition information and healthy living habits can exacerbate food-related anxieties and can lead to a pathological drive for purity and health.12Although not included in DSM-5, orthorexia nervosa was identified in 1997 as a proposed eating disorder best characterized as an obsession with healthy eating with associated restrictive behaviors.13 Patients with this disorder are rarely focused on losing weight, and orthorexic eating behaviors have been associated with both SSD and OCD.12,14 As in Ms. L’s case, patients with orthorexia nervosa demonstrate intrusive obsessions with nutrition, spend excessive amount of time researching nutrition, and fixate on food quality.12 Throughout Ms. L’s hospitalization, even as her food-related magical thinking symptoms improved, she constantly informed her care team that she had been “eating healthily” even though she was severely cachectic. Patients with SSD and OCD prone to health anxieties are at risk of developing pathologic food beliefs and dangerous eating behaviors. These patients may benefit from psychoeducation regarding nutrition and media literacy, which are components of effective eating disorder programs.15

[polldaddy:11079399]

Continue to: The authors' observations...

The authors’ observations

How do we approach the pharmacologic treatment of patients with co-occurring eating, somatic symptom, and anxiety disorders? Olanzapine facilitates recovery in children and adolescents with ARFID by promoting eating and weight gain, and decreasing symptoms of depression and anxiety.16 Patients with orthorexia nervosa also may benefit from treatment with olanzapine, which has decreased food-related fixations, magical thinking, and delusions regarding food.17 Further, orthorexic patients with ARFID have also been shown to respond to SSRIs due to those agents’ efficacy for treating intrusive thoughts, obsessions, and preoccupations from OCD and SSD.18,19 Thus, treating Ms. L’s symptoms with olanzapine and fluoxetine targeted the intersection of several diagnoses on our differential. Olanzapine’s propensity to cause weight gain is favorable in this population, particularly patients such as Ms. L, who do not exhibit body dysmorphia or fear of gaining weight.

OUTCOME Weight gain and fewer fears

Ms. L is prescribed olanzapine 5 mg/d and fluoxetine 20 mg/d. She gains 20.6 pounds in 4 weeks. Importantly, she endorses fewer fears related to foods and expands her palate to include foods she previously considered to be unhealthy, including white bread and farm-raised salmon. Further, she spends less time thinking about food and says she has less anxiety regarding the recurrence of GI symptoms.

1. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-5. 5th ed. American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

2. Murray HB, Bailey AP, Keshishian AC. Prevalence and characteristics of avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder in adult neurogastroenterology patients. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;18(9):1995-2002.e1.

3. Görmez A, Kılıç A, Kırpınar İ. Avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder: an adult case responding to cognitive behavioral therapy. Clinical Case Studies. 2018;17(6):443-452.

4. Reed-Knight B, Squires M, Chitkara DK, et al. Adolescents with irritable bowel syndrome report increased eating-associated symptoms, changes in dietary composition, and altered eating behaviors: a pilot comparison study to healthy adolescents. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2016;28(12):1915-1920.

5. Melchior C, Desprez C, Riachi G, et al. Anxiety and depression profile is associated with eating disorders in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Front Psychiatry. 2020;10:928.

6. Mayer EA, Craske M, Naliboff BD. Depression, anxiety, and the gastrointestinal system. J Clin Psychiatry. 2001;62 Suppl 8:28-37.

7. Abraham S, Kellow J. Exploring eating disorder quality of life and functional gastrointestinal disorders among eating disorder patients. J Psychosom Res. 2011;70(4):372-377.

8. Swinbourne JM, Touyz SW. The co-morbidity of eating disorders and anxiety disorders: a review. Eur Eat Disord Rev. 2007;15(4):253-274.

9. Perkins SJ, Keville S, Schmidt U, et al. Eating disorders and irritable bowel syndrome: is there a link? J Psychosom Res. 2005;59(2):57-64.

10. Hausteiner-Wiehle C, Henningsen P. Irritable bowel syndrome: relations with functional, mental, and somatoform disorders. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20(2):6024-6030.

11. Masand PS, Keuthen NJ, Gupta S, et al. Prevalence of irritable bowel syndrome in obsessive-compulsive disorder. CNS Spectr. 2006;11(1):21-25.

12. Koven NS, Abry AW. The clinical basis of orthorexia nervosa: emerging perspectives. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2015;11:385-394.

13. Bratman S. Health food junkie. Yoga Journal. 1997;136:42-50.

14. Barthels F, Müller R, Schüth T, et al. Orthorexic eating behavior in patients with somatoform disorders. Eat Weight Disord. 2021;26(1):135-143.

15. Ciao AC, Loth K, Neumark-Sztainer D. Preventing eating disorder pathology: common and unique features of successful eating disorders prevention programs. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2014;16(7):453.

16. Brewerton TD, D’Agostino M. Adjunctive use of olanzapine in the treatment of avoidant restrictive food intake disorder in children and adolescents in an eating disorders program. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2017;27(10):920-922.

17. Moroze RM, Dunn TM, Craig Holland J, et al. Microthinking about micronutrients: a case of transition from obsessions about healthy eating to near-fatal “orthorexia nervosa” and proposed diagnostic criteria. Psychosomatics. 2015;56(4):397-403.

18. Spettigue W, Norris ML, Santos A, et al. Treatment of children and adolescents with avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder: a case series examining the feasibility of family therapy and adjunctive treatments. J Eat Disord. 2018;6:20.

19. Niedzielski A, Kaźmierczak-Wojtaś N. Prevalence of Orthorexia Nervosa and Its Diagnostic Tools-A Literature Review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(10):5488. Published 2021 May 20. doi:10.3390/ijerph18105488 Prevalence of orthorexia nervosa and its diagnostic tools-a literature review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(10):5488.

1. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-5. 5th ed. American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

2. Murray HB, Bailey AP, Keshishian AC. Prevalence and characteristics of avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder in adult neurogastroenterology patients. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;18(9):1995-2002.e1.

3. Görmez A, Kılıç A, Kırpınar İ. Avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder: an adult case responding to cognitive behavioral therapy. Clinical Case Studies. 2018;17(6):443-452.

4. Reed-Knight B, Squires M, Chitkara DK, et al. Adolescents with irritable bowel syndrome report increased eating-associated symptoms, changes in dietary composition, and altered eating behaviors: a pilot comparison study to healthy adolescents. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2016;28(12):1915-1920.

5. Melchior C, Desprez C, Riachi G, et al. Anxiety and depression profile is associated with eating disorders in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Front Psychiatry. 2020;10:928.

6. Mayer EA, Craske M, Naliboff BD. Depression, anxiety, and the gastrointestinal system. J Clin Psychiatry. 2001;62 Suppl 8:28-37.

7. Abraham S, Kellow J. Exploring eating disorder quality of life and functional gastrointestinal disorders among eating disorder patients. J Psychosom Res. 2011;70(4):372-377.

8. Swinbourne JM, Touyz SW. The co-morbidity of eating disorders and anxiety disorders: a review. Eur Eat Disord Rev. 2007;15(4):253-274.

9. Perkins SJ, Keville S, Schmidt U, et al. Eating disorders and irritable bowel syndrome: is there a link? J Psychosom Res. 2005;59(2):57-64.

10. Hausteiner-Wiehle C, Henningsen P. Irritable bowel syndrome: relations with functional, mental, and somatoform disorders. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20(2):6024-6030.

11. Masand PS, Keuthen NJ, Gupta S, et al. Prevalence of irritable bowel syndrome in obsessive-compulsive disorder. CNS Spectr. 2006;11(1):21-25.

12. Koven NS, Abry AW. The clinical basis of orthorexia nervosa: emerging perspectives. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2015;11:385-394.

13. Bratman S. Health food junkie. Yoga Journal. 1997;136:42-50.

14. Barthels F, Müller R, Schüth T, et al. Orthorexic eating behavior in patients with somatoform disorders. Eat Weight Disord. 2021;26(1):135-143.

15. Ciao AC, Loth K, Neumark-Sztainer D. Preventing eating disorder pathology: common and unique features of successful eating disorders prevention programs. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2014;16(7):453.

16. Brewerton TD, D’Agostino M. Adjunctive use of olanzapine in the treatment of avoidant restrictive food intake disorder in children and adolescents in an eating disorders program. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2017;27(10):920-922.

17. Moroze RM, Dunn TM, Craig Holland J, et al. Microthinking about micronutrients: a case of transition from obsessions about healthy eating to near-fatal “orthorexia nervosa” and proposed diagnostic criteria. Psychosomatics. 2015;56(4):397-403.

18. Spettigue W, Norris ML, Santos A, et al. Treatment of children and adolescents with avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder: a case series examining the feasibility of family therapy and adjunctive treatments. J Eat Disord. 2018;6:20.

19. Niedzielski A, Kaźmierczak-Wojtaś N. Prevalence of Orthorexia Nervosa and Its Diagnostic Tools-A Literature Review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(10):5488. Published 2021 May 20. doi:10.3390/ijerph18105488 Prevalence of orthorexia nervosa and its diagnostic tools-a literature review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(10):5488.

Depressed and awkward: Is it more than that?

CASE Treatment-resistant MDD

Ms. P, age 21, presents to the outpatient clinic. She has diagnoses of treatment-resistant major depressive disorder (MDD) and schizoid personality disorder (SPD). Ms. P was diagnosed with MDD 3 years ago after reporting symptoms of prevailing sadness for approximately 8 years, described as feelings of worthlessness, anhedonia, social withdrawal, and decreased hygiene and self-care behaviors, as well as suicidal ideation and self-harm. SPD was diagnosed 1 year earlier based on her “odd” behaviors and disheveled appearance following observation and in collateral with her family. Her odd behaviors are described as spending most of her time alone, preferring solitary activities, and having little contact with people other than her parents.

Ms. P reports that she was previously treated with citalopram, 20 mg/d, bupropion, 150 mg/d, aripiprazole, 3.75 mg/d, topiramate, 100 mg twice daily, and melatonin, 9 mg/d at bedtime, but discontinued follow-up appointments and medications after no significant improvement in symptoms.

[polldaddy:11027942]

The authors’ observations

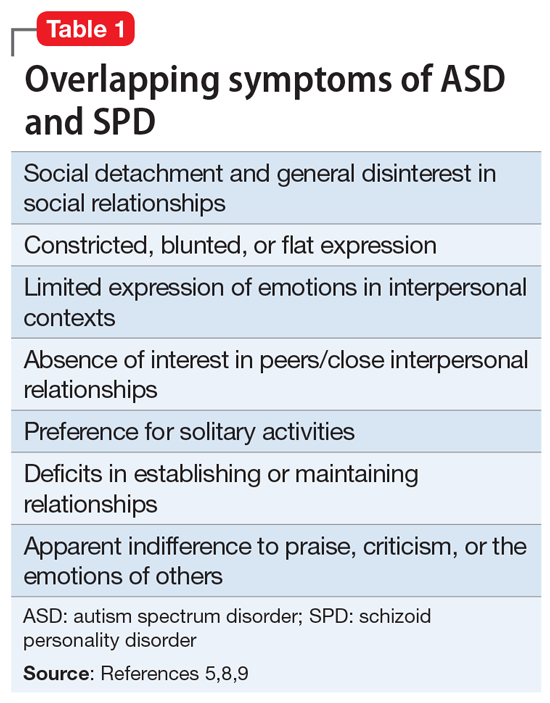

The term “schizoid” first made its debut in the medical community to describe the prodromal social withdrawal and isolation observed in schizophrenia.1 The use of schizoid to describe a personality type first occurred in DSM-III in 1980.2 SPD is a Cluster A personality disorder that groups personalities characterized by common traits that are “odd” or “eccentric” and may resemble the positive and/or negative symptoms of schizophrenia.3,4 Relatively uncommon in clinical settings, SPD includes individuals who do not desire or enjoy close relationships. Those afflicted with SPD will be described as isolated, aloof, and detached from social relationships with others, even immediate family members. Individuals with SPD may appear indifferent to criticism and praise, and may take pleasure in only a few activities. They may exhibit a general absence of affective range, which contributes to their characterization as flat, blunted, or emotionally vacant. SPD is more commonly diagnosed in males and may be present in childhood and adolescence. These children are typified by solitariness, poor peer relationships, and underachievement in school. SPD impacts 3.1% to 4.9% of the United States population and approximately 1% of community populations.5,6

EVALUATION Persistent depressive symptoms

Ms. P is accompanied by her parents for the examination. She reports a chronic, persistent sad mood, hopelessness, anergia, insomnia, anhedonia, and decreased concentration and appetite. She says she experiences episodes of intense worry, along with tension, restlessness, feelings of being on the edge, irritability, and difficulty relaxing. Socially, she is withdrawn, preferring to stay alone in her room most of the day watching YouTube or trying to write stories. She has 2 friends with whom she does not interact with in person, but rather through digital means. Ms. P has never enjoyed attending school and feels “nervous” when she is around people. She has difficulty expressing her thoughts and often looks to her parents for help. Her parents add that getting Ms. P to attend school was a struggle, which resulted in periods of home schooling throughout high school.

The treating team prescribes citalopram, 10 mg/d, and aripiprazole, 2 mg/d. On subsequent follow-up visits, Ms. P’s depression improves with an increase in citalopram to 40 mg/d. Psychotherapy is added to her treatment plan to help address the persistent social deficits, odd behavior, and anxieties.

Continue to: Evaluation Psychological assessment...

EVALUATION Psychological assessment

At her psychotherapy intake appointment with the clinical neuropsychologist, Ms. P is dressed in purple from head to toe and sits clutching her purse and looking at the ground. She is overweight with clean, fitting clothing. Ms. P takes a secondary role during most of the interview, allowing her parents to answer most questions. When asked why she is starting therapy, Ms. P replies, “Well, I’ve been using the bathroom a lot.” She describes a feeling of comfort and calmness while in the restroom. Suddenly, she asks her parents to exit the exam room for a moment. Once they leave, she leans in and whispers, “Have you ever heard of self-sabotage? I think that’s what I’m doing.”

Her mood is euthymic, with a blunted affect. She scores 2 on the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) and 10 on the Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-item scale (GAD-7), which indicates the positive impact of medication on her depressive symptoms but continuing moderate anxious distress. She endorses fear of the night, insomnia, and suicidal ideation. She reports an unusual “constant itching sensation,” resulting in hours of repetitive excoriation. Physical examination reveals several significant scars and scabs covering her bilateral upper and lower extremities. Her vocational history is brief; she had held 2 entry-level customer service positions that lasted <1 year. She was fired due to excessive bathroom use.

As the interview progresses, the intake clinician’s background in neuropsychological assessment facilitates screening for possible developmental disorders. Given the nature of the referral and psychotherapy intake, a full neuropsychological assessment is not conducted. The clinician emphasizes verbal abstraction and theory of mind. Ms. P’s IQ was estimated to be average by Wide Range Achievement Test 4 word reading and interview questions about her academic history. Questions are abstracted from the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule, Module 4, to assess for conversation ability, emotional insight, awareness and expression, relationships, and areas of functioning in daily living. Developmental history questions, such as those found on the Adaptive Behavior Assessment System, 3rd edition, help guide developmental information provided by parents in the areas of communication, emotion and eye-gaze, gestures, sensory function, language, social functioning, hygiene behavior, and specific interests.

Ms. P’s mother describes a normal pregnancy and delivery; however, she states that Ms. P was “born with problems,” including difficulty with rooting and sucking, and required gastrointestinal intubation until age 3. Cyclical vomiting followed normal food consumption. Ambulation, language acquisition, toilet training, and hygiene behavior were delayed. Ms. P experienced improvements with early intervention in intensive physical and occupational therapy.

Ms. P’s hygiene is well below average, and she requires cueing from her parents. She attended general education until she reached high school, when she began special education. She was sensitive to sensory stimulation from infancy, with sensory sensitivity to textures. Ms. P continues to report sensory sensitivity and lapses in hygiene.

She has difficulty establishing and maintaining relationships with her peers, and prefers solitary activities. Ms. P has no history of romantic relationships, although she does desire one. When asked about her understanding of various relationships, Ms. P’s responses are stereotyped, such as “I know someone is my friend because they are nice to me” and “People get married because they love each other.” She struggles to offer greater insight into the nuances that form lasting relationships and bonds. Ms. P struggles to imitate and describe the physical and internal cues of several basic emotions (eg, fear, joy, anger).

Her conversational and social skills are assessed by asking her to engage in a conversation with the examiner as if meeting for the first time. Her speech is reciprocal, aprosodic, and delayed. The conversation is one-sided, and the examiner fills in several awkward pauses. Ms. P’s gaze at times is intense and prolonged, especially when responding to questions. She tends to use descriptive statements (eg, “I like your purple pen, I like your shirt”) to engage in conversation, rather than gathering more information through reflective statements, questions, or expressing a shared interest.

Ms. P’s verbal abstraction is screened using questions from the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale, 4th edition Similarities subtest, to which she provides several responses within normal limits. Her understanding of colloquial speech is assessed by asking her the meaning of common phrases (eg, “Get knocked down 9 times, get up 10,” “Jack and Jill are 2 peas in a pod”). On many occasions, she is able to limit her response to 1 word, (eg, “resiliency”), demonstrating intact ability to decipher idioms.

[polldaddy:11027971]

The authors’ observations

Upon reflection of Ms. P’s clinical presentation and history of developmental delays, social deficits, sensory sensitivity since infancy, and repetitive behaviors (all which continue to impact her), the clinical team concluded that the diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder (ASD) helps explain the patient’s “odd” behaviors, more so than SPD.

ASD is a heterogenous, complex neuropsychiatric disorder characterized by a persistent deficit in social reciprocity, verbal, and nonverbal communication, and includes a pattern of restricted, repetitive and/or stereotyped behaviors and/or interests.5 The term “autismus” is Greek meaning “self,” and was first used to classify the qualities of “morbid self-admiration” observed in prodromal schizophrenia.7

To properly distinguish these disorders, keep in mind that patients with ASD have repetitive and restricted patterns of behaviors or interests that are not found in SPD, and experience deficits in forming, maintaining, and understanding relationships since they lack those skills, while patients with SPD are more prone to desire solitary activities and limited relationships.5,9

There has been an increased interest in determining why for some patients the diagnosis of ASD is delayed until they reach adulthood. Limited or no access to the patient’s childhood caregiver to obtain a developmental history, as well as generational differences on what constitutes typical childhood behavior, could contribute to a delayed diagnosis of ASD until adulthood. Some patients develop camouflaging strategies that allow them to navigate social expectations to a limited degree, such as learning stock phrases, imitating gestures, and telling anecdotes. Another factor to consider is that co-occurring psychiatric disorders may take center stage when patients present for mental health services.10 Fusar-Poli et al11 investigated the characteristics of patients who received a diagnosis of ASD in adulthood. They found that the median time from the initial clinical evaluation to diagnosis of ASD in adulthood was 11 years. In adults identified with ASD, their cognitive abilities ranged from average to above average, and they required less support. Additionally, they also had higher rates of being previously diagnosed with psychotic disorders and personality disorders.11

It is important to keep in mind that the wide spectrum of autism as currently defined by DSM-5 and its overlap of symptoms with other psychiatric disorders can make the diagnosis challenging for both child and adolescent psychiatrists and adult psychiatrists and might help explain why severe cases of ASD are more readily identified earlier than milder cases of ASD.10

Ms. P’s case is also an example of how women are more likely than men to be overlooked when evaluated for ASD. According to DSM-5, the estimated gender ratio for ASD is believed to be 4:1 (male:female).5 However, upon systematic review and meta-analysis, Loomes et al12 found that the gender ratio may be closer to 3:1 (male:female). These authors suggested that diagnostic bias and a failure of passive case ascertainment to estimate gender ratios as stated by DSM-5 in identifying ASD might explain the lower gender ratio.12 A growing body of evidence suggests that ASD is different in males and females. A 2019 qualitative study by Milner et al13 found that female participants reported using masking and camouflaging strategies to appear neurotypical. Compensatory behaviors were found to be linked to a delay in diagnosis and support for ASD.13

Cognitive ability as measured by IQ has also been found to be a factor in receiving a diagnosis of ASD. In a 2010 secondary analysis of a population-based study of the prevalence of ASD, Giarelli et al14found that girls with cognitive impairments as measured by IQ were less likely to be diagnosed with ASD than boys with cognitive impairment, despite meeting the criteria for ASD. Females tend to exhibit fewer repetitive behaviors than males, and tend to be more likely to show accompanying intellectual disability, which suggests that females with ASD may go unrecognized when they exhibit average intelligence with less impairment of behavior and subtler manifestation of social and communication deficits.15 Consequently, females tend to receive this diagnosis later than males.

Continue to: Treatment...

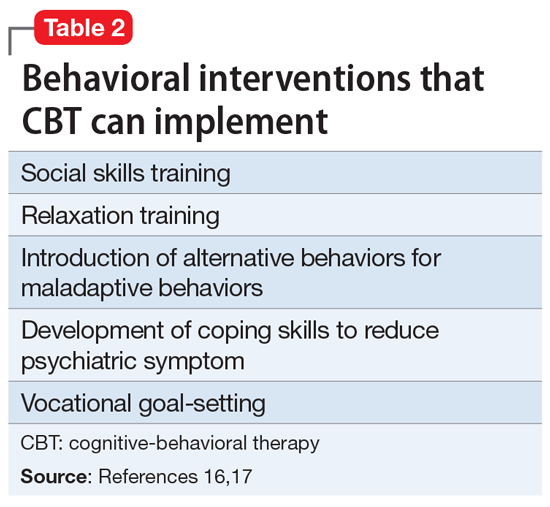

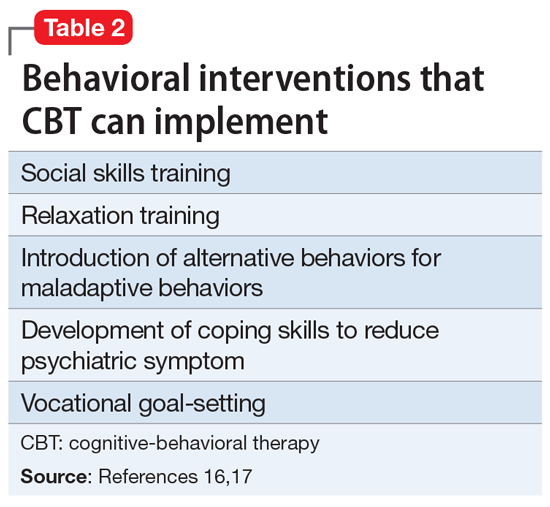

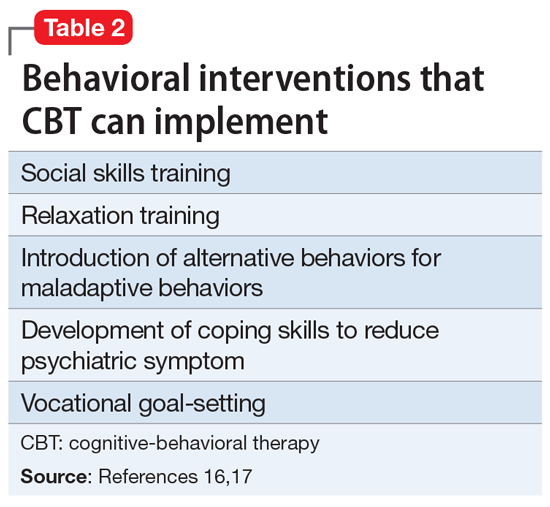

TREATMENT Adding CBT

At an interdisciplinary session several weeks later that includes Ms. P and her parents, the treatment team discusses the revised diagnoses of ASD and MDD, a treatment recommendation for cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), and continued use of medication. At this session, Ms. P discloses that she has not been consistent with her medication regimen since her last appointment, which helps explain the increase in her PHQ-9 score from 2 to 14 and GAD-7 score

[polldaddy:11027990]

The authors’ observations

CBT can be helpful in improving medication adherence, developing coping skills, and modifying maladaptive behaviors.

OUTCOME Improvement with psychotherapy

Ms. P and family agree with the team’s recommendations. The aims of Ms. P’s psychotherapy are to maintain medication compliance; implement behavioral modification, vocational rehabilitation, and community engagement; develop social skills; increase functional independence; and develop coping skills for depression and anxiety.

Bottom Line

The prevalence of schizoid personality disorder (SPD) is low, and its symptoms overlap with those of autism spectrum disorder. Therefore, before diagnosing SPD in an adult patient, it is important to obtain a detailed developmental history and include an interdisciplinary team to assess for autism spectrum disorder.

1. Fariba K, Gupta V. Schizoid personality disorder. StatPearls Publishing. Updated June 9, 2021. Accessed January 6, 2021. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK559234/

2. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-III. 3rd ed rev. American Psychiatric Association; 1987.

3. Esterberg ML, Goulding SM, Walker EF. Cluster A personality disorders: schizotypal, schizoid and paranoid personality disorders in childhood and adolescence. J Psychopathol Behav Assess. 2010;32(4):515-528. doi:10.1007/s10862-010-9183-8

4. Kalus O, Bernstein DP, Siever LJ. Schizoid personality disorder: a review of current status and implications for DSM-IV. Journal of Personality Disorders. 1993;7(1), 43-52.

5. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-5. 5th ed. American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

6. Eaton NR, Greene AL. Personality disorders: community prevalence and socio-demographic correlates. Curr Opin Psychol. 2018;21:28-32. doi:10.1016/j.copsyc.2017.09.001

7. Vatano

8. Ritsner MS. Handbook of Schizophrenia Spectrum Disorders, Volume I: Conceptual Issues and Neurobiological Advances. Springer; 2011.

9. Cook ML, Zhang Y, Constantino JN. On the continuity between autistic and schizoid personality disorder trait burden: a prospective study in adolescence. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2020;208(2):94-100. doi:10.1097/NMD.0000000000001105

10. Lai MC, Baron-Cohen S. Identifying the lost generation of adults with autism spectrum conditions. Lancet Psychiatry. 2015;2(11):1013-1027. doi:10.1016/S2215-0366(15)00277-1

11. Fusar-Poli L, Brondino N, Politi P, et al. Missed diagnoses and misdiagnoses of adults with autism spectrum disorder. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2020;10.1007/s00406-020-01189-2. doi:10.1007/s00406-020-01189-w

12. Loomes R, Hull L, Mandy WPL. What is the male-to-female ratio in autism spectrum disorder? A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2017;56(6):466-474. doi:10.1016/j.jaac.2017.03.013

13. Milner V, McIntosh H, Colvert E, et al. A qualitative exploration of the female experience of autism spectrum disorder (ASD). J Autism Dev Disord. 2019;49(6):2389-2402. doi:10.1007/s10803-019-03906-4

14. Giarelli E, Wiggins LD, Rice CE, et al. Sex differences in the evaluation and diagnosis of autism spectrum disorders among children. Disabil Health J. 2010;3(2):107-116. doi:10.1016/j.dhjo.2009.07.001

15. Frazier TW, Georgiades S, Bishop SL, et al. Behavioral and cognitive characteristics of females and males with autism in the Simons Simplex Collection. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2014;53(3):329-40.e403. doi:10.1016/j.jaac.2013.12.004

16. Julius RJ, Novitsky MA Jr, et al. Medication adherence: a review of the literature and implications for clinical practice. J Psychiatr Pract. 2009;15(1):34-44. doi:10.1097/01.pra.0000344917.43780.77

17. Spain D, Sin J, Chalder T, et al. Cognitive behaviour therapy for adults with autism spectrum disorders and psychiatric co-morbidity: a review. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders. 2015;9, 151-162. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rasd.2014.10.019

18. Bishop-Fitzpatrick L, Minshew NJ, Eack SM. A systematic review of psychosocial interventions for adults with autism spectrum disorders. J Autism Dev Disord. 2013;43(3):687-694. doi:10.1007/s10803-012-1615-8

CASE Treatment-resistant MDD

Ms. P, age 21, presents to the outpatient clinic. She has diagnoses of treatment-resistant major depressive disorder (MDD) and schizoid personality disorder (SPD). Ms. P was diagnosed with MDD 3 years ago after reporting symptoms of prevailing sadness for approximately 8 years, described as feelings of worthlessness, anhedonia, social withdrawal, and decreased hygiene and self-care behaviors, as well as suicidal ideation and self-harm. SPD was diagnosed 1 year earlier based on her “odd” behaviors and disheveled appearance following observation and in collateral with her family. Her odd behaviors are described as spending most of her time alone, preferring solitary activities, and having little contact with people other than her parents.

Ms. P reports that she was previously treated with citalopram, 20 mg/d, bupropion, 150 mg/d, aripiprazole, 3.75 mg/d, topiramate, 100 mg twice daily, and melatonin, 9 mg/d at bedtime, but discontinued follow-up appointments and medications after no significant improvement in symptoms.

[polldaddy:11027942]

The authors’ observations

The term “schizoid” first made its debut in the medical community to describe the prodromal social withdrawal and isolation observed in schizophrenia.1 The use of schizoid to describe a personality type first occurred in DSM-III in 1980.2 SPD is a Cluster A personality disorder that groups personalities characterized by common traits that are “odd” or “eccentric” and may resemble the positive and/or negative symptoms of schizophrenia.3,4 Relatively uncommon in clinical settings, SPD includes individuals who do not desire or enjoy close relationships. Those afflicted with SPD will be described as isolated, aloof, and detached from social relationships with others, even immediate family members. Individuals with SPD may appear indifferent to criticism and praise, and may take pleasure in only a few activities. They may exhibit a general absence of affective range, which contributes to their characterization as flat, blunted, or emotionally vacant. SPD is more commonly diagnosed in males and may be present in childhood and adolescence. These children are typified by solitariness, poor peer relationships, and underachievement in school. SPD impacts 3.1% to 4.9% of the United States population and approximately 1% of community populations.5,6

EVALUATION Persistent depressive symptoms

Ms. P is accompanied by her parents for the examination. She reports a chronic, persistent sad mood, hopelessness, anergia, insomnia, anhedonia, and decreased concentration and appetite. She says she experiences episodes of intense worry, along with tension, restlessness, feelings of being on the edge, irritability, and difficulty relaxing. Socially, she is withdrawn, preferring to stay alone in her room most of the day watching YouTube or trying to write stories. She has 2 friends with whom she does not interact with in person, but rather through digital means. Ms. P has never enjoyed attending school and feels “nervous” when she is around people. She has difficulty expressing her thoughts and often looks to her parents for help. Her parents add that getting Ms. P to attend school was a struggle, which resulted in periods of home schooling throughout high school.

The treating team prescribes citalopram, 10 mg/d, and aripiprazole, 2 mg/d. On subsequent follow-up visits, Ms. P’s depression improves with an increase in citalopram to 40 mg/d. Psychotherapy is added to her treatment plan to help address the persistent social deficits, odd behavior, and anxieties.

Continue to: Evaluation Psychological assessment...

EVALUATION Psychological assessment

At her psychotherapy intake appointment with the clinical neuropsychologist, Ms. P is dressed in purple from head to toe and sits clutching her purse and looking at the ground. She is overweight with clean, fitting clothing. Ms. P takes a secondary role during most of the interview, allowing her parents to answer most questions. When asked why she is starting therapy, Ms. P replies, “Well, I’ve been using the bathroom a lot.” She describes a feeling of comfort and calmness while in the restroom. Suddenly, she asks her parents to exit the exam room for a moment. Once they leave, she leans in and whispers, “Have you ever heard of self-sabotage? I think that’s what I’m doing.”

Her mood is euthymic, with a blunted affect. She scores 2 on the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) and 10 on the Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-item scale (GAD-7), which indicates the positive impact of medication on her depressive symptoms but continuing moderate anxious distress. She endorses fear of the night, insomnia, and suicidal ideation. She reports an unusual “constant itching sensation,” resulting in hours of repetitive excoriation. Physical examination reveals several significant scars and scabs covering her bilateral upper and lower extremities. Her vocational history is brief; she had held 2 entry-level customer service positions that lasted <1 year. She was fired due to excessive bathroom use.

As the interview progresses, the intake clinician’s background in neuropsychological assessment facilitates screening for possible developmental disorders. Given the nature of the referral and psychotherapy intake, a full neuropsychological assessment is not conducted. The clinician emphasizes verbal abstraction and theory of mind. Ms. P’s IQ was estimated to be average by Wide Range Achievement Test 4 word reading and interview questions about her academic history. Questions are abstracted from the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule, Module 4, to assess for conversation ability, emotional insight, awareness and expression, relationships, and areas of functioning in daily living. Developmental history questions, such as those found on the Adaptive Behavior Assessment System, 3rd edition, help guide developmental information provided by parents in the areas of communication, emotion and eye-gaze, gestures, sensory function, language, social functioning, hygiene behavior, and specific interests.

Ms. P’s mother describes a normal pregnancy and delivery; however, she states that Ms. P was “born with problems,” including difficulty with rooting and sucking, and required gastrointestinal intubation until age 3. Cyclical vomiting followed normal food consumption. Ambulation, language acquisition, toilet training, and hygiene behavior were delayed. Ms. P experienced improvements with early intervention in intensive physical and occupational therapy.

Ms. P’s hygiene is well below average, and she requires cueing from her parents. She attended general education until she reached high school, when she began special education. She was sensitive to sensory stimulation from infancy, with sensory sensitivity to textures. Ms. P continues to report sensory sensitivity and lapses in hygiene.

She has difficulty establishing and maintaining relationships with her peers, and prefers solitary activities. Ms. P has no history of romantic relationships, although she does desire one. When asked about her understanding of various relationships, Ms. P’s responses are stereotyped, such as “I know someone is my friend because they are nice to me” and “People get married because they love each other.” She struggles to offer greater insight into the nuances that form lasting relationships and bonds. Ms. P struggles to imitate and describe the physical and internal cues of several basic emotions (eg, fear, joy, anger).

Her conversational and social skills are assessed by asking her to engage in a conversation with the examiner as if meeting for the first time. Her speech is reciprocal, aprosodic, and delayed. The conversation is one-sided, and the examiner fills in several awkward pauses. Ms. P’s gaze at times is intense and prolonged, especially when responding to questions. She tends to use descriptive statements (eg, “I like your purple pen, I like your shirt”) to engage in conversation, rather than gathering more information through reflective statements, questions, or expressing a shared interest.

Ms. P’s verbal abstraction is screened using questions from the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale, 4th edition Similarities subtest, to which she provides several responses within normal limits. Her understanding of colloquial speech is assessed by asking her the meaning of common phrases (eg, “Get knocked down 9 times, get up 10,” “Jack and Jill are 2 peas in a pod”). On many occasions, she is able to limit her response to 1 word, (eg, “resiliency”), demonstrating intact ability to decipher idioms.

[polldaddy:11027971]

The authors’ observations

Upon reflection of Ms. P’s clinical presentation and history of developmental delays, social deficits, sensory sensitivity since infancy, and repetitive behaviors (all which continue to impact her), the clinical team concluded that the diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder (ASD) helps explain the patient’s “odd” behaviors, more so than SPD.

ASD is a heterogenous, complex neuropsychiatric disorder characterized by a persistent deficit in social reciprocity, verbal, and nonverbal communication, and includes a pattern of restricted, repetitive and/or stereotyped behaviors and/or interests.5 The term “autismus” is Greek meaning “self,” and was first used to classify the qualities of “morbid self-admiration” observed in prodromal schizophrenia.7

To properly distinguish these disorders, keep in mind that patients with ASD have repetitive and restricted patterns of behaviors or interests that are not found in SPD, and experience deficits in forming, maintaining, and understanding relationships since they lack those skills, while patients with SPD are more prone to desire solitary activities and limited relationships.5,9

There has been an increased interest in determining why for some patients the diagnosis of ASD is delayed until they reach adulthood. Limited or no access to the patient’s childhood caregiver to obtain a developmental history, as well as generational differences on what constitutes typical childhood behavior, could contribute to a delayed diagnosis of ASD until adulthood. Some patients develop camouflaging strategies that allow them to navigate social expectations to a limited degree, such as learning stock phrases, imitating gestures, and telling anecdotes. Another factor to consider is that co-occurring psychiatric disorders may take center stage when patients present for mental health services.10 Fusar-Poli et al11 investigated the characteristics of patients who received a diagnosis of ASD in adulthood. They found that the median time from the initial clinical evaluation to diagnosis of ASD in adulthood was 11 years. In adults identified with ASD, their cognitive abilities ranged from average to above average, and they required less support. Additionally, they also had higher rates of being previously diagnosed with psychotic disorders and personality disorders.11

It is important to keep in mind that the wide spectrum of autism as currently defined by DSM-5 and its overlap of symptoms with other psychiatric disorders can make the diagnosis challenging for both child and adolescent psychiatrists and adult psychiatrists and might help explain why severe cases of ASD are more readily identified earlier than milder cases of ASD.10

Ms. P’s case is also an example of how women are more likely than men to be overlooked when evaluated for ASD. According to DSM-5, the estimated gender ratio for ASD is believed to be 4:1 (male:female).5 However, upon systematic review and meta-analysis, Loomes et al12 found that the gender ratio may be closer to 3:1 (male:female). These authors suggested that diagnostic bias and a failure of passive case ascertainment to estimate gender ratios as stated by DSM-5 in identifying ASD might explain the lower gender ratio.12 A growing body of evidence suggests that ASD is different in males and females. A 2019 qualitative study by Milner et al13 found that female participants reported using masking and camouflaging strategies to appear neurotypical. Compensatory behaviors were found to be linked to a delay in diagnosis and support for ASD.13