User login

A 46-year-old man with fever, ST-segment elevation

An otherwise healthy 46-year-old man presents with fever, chills, and rigors that began 1 day ago. He reports shortness of breath, nausea, neck pain, sore throat, and right-sided jaw pain, but no chest pain, headache, or photophobia.

His vital signs are within normal limits, except for a temperature of 38.5°C (101.3°F). His jugular venous pressure and heart sounds are normal, and no focal deficit or nuchal rigidity is elicited. Laboratory tests (hemography, biochemistry panel, and cardiac biomarkers) are normal. An enzyme immunoassay for influenza A and B is negative, as is a rapid antigen detection test for streptococcal infection.

Q: What is the most likely diagnosis?

- Acute myocardial infarction

- Coronary vasospasm

- Brugada syndrome

- Acute pericarditis

- Acute meningitis

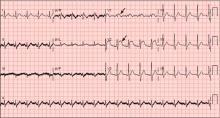

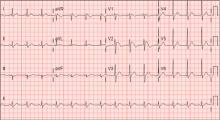

A: ST elevation commonly represents acute myocardial infarction, but it is associated with other conditions, including Prinzmetal angina, hyperkalemia, hypercalcemia, early repolarization, Brugada syndrome, and acute pericarditis.1 These conditions should be considered before an invasive intervention. The ECG findings (ST elevation in the right precordial leads) in this patient were consistent with those of Brugada syndrome.

WHAT IS BRUGADA SYNDROME?

Brugada syndrome is an arrhythmogenic disease characterized by ST-segment elevation in the right precordial leads, right bundle branch block, and a high incidence of sudden cardiac death in younger people.2 It accounts for 4% of all sudden deaths.3

Three different types of changes on ECG have been associated with Brugada syndrome. Type 1 is a coved ST-segment elevation of at least 2 mm, followed by a negative T wave, with little or no isoelectric separation, and present in more than one right precordial lead (from V1 to V3). Type 2 and type 3 patterns on ECG show the same 2-mm or greater J-point elevation, but a positive T wave gives the “saddleback” appearance to the ST-T portion.

Brugada syndrome is confirmed when a type 1 pattern is observed in conjunction with one of the following:

- Documented ventricular fibrillation

- Polymorphic ventricular tachycardia

- A family history of sudden cardiac death at 45 years of age or younger

- Type 1 pattern on ECG in family members

- Ventricular tachycardia that can be induced with programmed electrical stimulation

- Syncope

- Nocturnal agonal respiration.3

This patient had type 1 changes on ECG but none of the above findings.

Brugada syndrome is inherited as an autosomal dominant trait, and mutations in gene SCN5A account for 18% to 30% of cases.3 These mutations impair the function of the sodium channel current, leading to an unopposed outward shift of net transmembrane current at the end of phase 1 of the right ventricular epicardial action potential. Interestingly, changes on ECG that are associated with Brugada syndrome are often dynamic or concealed and are unmasked by sodium channel blockers, fever, vagotonic agents, adrenergic agonists or antagonists, and various electrolyte abnormalities.3

At temperatures above the physiologic range, the inward sodium current is reduced, either because of failure of expression of sodium channels or because of premature closing of the sodium channels in genetically susceptible individuals.4 Therefore, fever can unmask Brugada syndrome, as it did in our patient.

For patients with symptomatic Brugada syndrome, the only current treatment is implantation of a cardioverter-defibrillator.5 Patients without symptoms may benefit from an electrophysiologic study for risk stratification, and an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator is recommended for those in whom ventricular fibrillation can be induced.3,5

CASE CONTINUED

The patient remained febrile after catheterization and received vancomycin (Vancocin) and ceftriaxone (Rocephin) empirically for presumed meningitis. Multiple peripheral blood cultures grew gram-positive cocci in pairs and chains, which were identified as Streptococcus pneumoniae. His fever abated soon after the antibiotic therapy was started.

Lumbar puncture was not done. Transesophageal echocardiography revealed no vegetations, with preserved ejection fraction. The patient has no family history of sudden death and no personal history of syncope or presyncope.

On hospital day 3, although his fever was gone, ECG still showed a Brugada pattern. He was discharged home on a 3-week regimen of intravenous penicillin, with plans for appropriate follow-up, and he was counseled that his family should be screened. An electrophysiologic study was not done, and he had no symptoms 1 year later.

As seen in this patient, Brugada syndrome is important to consider in the differential diagnosis in young patients who present with fever and ST elevations.

- Wang K, Asinger RW, Marriott HJ. ST-segment elevation in conditions other than acute myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med 2003; 349:2128–2135.

- Brugada P, Brugada J. Right bundle branch block, persistent ST segment elevation and sudden cardiac death: a distinct clinical and electrocardiographic syndrome. A multicenter report. J Am Coll Cardiol 1992; 20:1391–1396.

- Antzelevitch C, Brugada P, Borggrefe M, et al. Brugada syndrome: report of the second consensus conference: endorsed by the Heart Rhythm Society and the European Heart Rhythm Association. Circulation 2005; 111:659–670.

- Dumaine R, Towbin JA, Brugada P, et al. Ionic mechanisms responsible for the electrocardiographic phenotype of the Brugada syndrome are temperature dependent. Circ Res 1999; 85:803–809.

- Antzelevitch C, Nof E. Brugada syndrome: recent advances and controversies. Curr Cardiol Rep 2008; 10:376–383.

An otherwise healthy 46-year-old man presents with fever, chills, and rigors that began 1 day ago. He reports shortness of breath, nausea, neck pain, sore throat, and right-sided jaw pain, but no chest pain, headache, or photophobia.

His vital signs are within normal limits, except for a temperature of 38.5°C (101.3°F). His jugular venous pressure and heart sounds are normal, and no focal deficit or nuchal rigidity is elicited. Laboratory tests (hemography, biochemistry panel, and cardiac biomarkers) are normal. An enzyme immunoassay for influenza A and B is negative, as is a rapid antigen detection test for streptococcal infection.

Q: What is the most likely diagnosis?

- Acute myocardial infarction

- Coronary vasospasm

- Brugada syndrome

- Acute pericarditis

- Acute meningitis

A: ST elevation commonly represents acute myocardial infarction, but it is associated with other conditions, including Prinzmetal angina, hyperkalemia, hypercalcemia, early repolarization, Brugada syndrome, and acute pericarditis.1 These conditions should be considered before an invasive intervention. The ECG findings (ST elevation in the right precordial leads) in this patient were consistent with those of Brugada syndrome.

WHAT IS BRUGADA SYNDROME?

Brugada syndrome is an arrhythmogenic disease characterized by ST-segment elevation in the right precordial leads, right bundle branch block, and a high incidence of sudden cardiac death in younger people.2 It accounts for 4% of all sudden deaths.3

Three different types of changes on ECG have been associated with Brugada syndrome. Type 1 is a coved ST-segment elevation of at least 2 mm, followed by a negative T wave, with little or no isoelectric separation, and present in more than one right precordial lead (from V1 to V3). Type 2 and type 3 patterns on ECG show the same 2-mm or greater J-point elevation, but a positive T wave gives the “saddleback” appearance to the ST-T portion.

Brugada syndrome is confirmed when a type 1 pattern is observed in conjunction with one of the following:

- Documented ventricular fibrillation

- Polymorphic ventricular tachycardia

- A family history of sudden cardiac death at 45 years of age or younger

- Type 1 pattern on ECG in family members

- Ventricular tachycardia that can be induced with programmed electrical stimulation

- Syncope

- Nocturnal agonal respiration.3

This patient had type 1 changes on ECG but none of the above findings.

Brugada syndrome is inherited as an autosomal dominant trait, and mutations in gene SCN5A account for 18% to 30% of cases.3 These mutations impair the function of the sodium channel current, leading to an unopposed outward shift of net transmembrane current at the end of phase 1 of the right ventricular epicardial action potential. Interestingly, changes on ECG that are associated with Brugada syndrome are often dynamic or concealed and are unmasked by sodium channel blockers, fever, vagotonic agents, adrenergic agonists or antagonists, and various electrolyte abnormalities.3

At temperatures above the physiologic range, the inward sodium current is reduced, either because of failure of expression of sodium channels or because of premature closing of the sodium channels in genetically susceptible individuals.4 Therefore, fever can unmask Brugada syndrome, as it did in our patient.

For patients with symptomatic Brugada syndrome, the only current treatment is implantation of a cardioverter-defibrillator.5 Patients without symptoms may benefit from an electrophysiologic study for risk stratification, and an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator is recommended for those in whom ventricular fibrillation can be induced.3,5

CASE CONTINUED

The patient remained febrile after catheterization and received vancomycin (Vancocin) and ceftriaxone (Rocephin) empirically for presumed meningitis. Multiple peripheral blood cultures grew gram-positive cocci in pairs and chains, which were identified as Streptococcus pneumoniae. His fever abated soon after the antibiotic therapy was started.

Lumbar puncture was not done. Transesophageal echocardiography revealed no vegetations, with preserved ejection fraction. The patient has no family history of sudden death and no personal history of syncope or presyncope.

On hospital day 3, although his fever was gone, ECG still showed a Brugada pattern. He was discharged home on a 3-week regimen of intravenous penicillin, with plans for appropriate follow-up, and he was counseled that his family should be screened. An electrophysiologic study was not done, and he had no symptoms 1 year later.

As seen in this patient, Brugada syndrome is important to consider in the differential diagnosis in young patients who present with fever and ST elevations.

An otherwise healthy 46-year-old man presents with fever, chills, and rigors that began 1 day ago. He reports shortness of breath, nausea, neck pain, sore throat, and right-sided jaw pain, but no chest pain, headache, or photophobia.

His vital signs are within normal limits, except for a temperature of 38.5°C (101.3°F). His jugular venous pressure and heart sounds are normal, and no focal deficit or nuchal rigidity is elicited. Laboratory tests (hemography, biochemistry panel, and cardiac biomarkers) are normal. An enzyme immunoassay for influenza A and B is negative, as is a rapid antigen detection test for streptococcal infection.

Q: What is the most likely diagnosis?

- Acute myocardial infarction

- Coronary vasospasm

- Brugada syndrome

- Acute pericarditis

- Acute meningitis

A: ST elevation commonly represents acute myocardial infarction, but it is associated with other conditions, including Prinzmetal angina, hyperkalemia, hypercalcemia, early repolarization, Brugada syndrome, and acute pericarditis.1 These conditions should be considered before an invasive intervention. The ECG findings (ST elevation in the right precordial leads) in this patient were consistent with those of Brugada syndrome.

WHAT IS BRUGADA SYNDROME?

Brugada syndrome is an arrhythmogenic disease characterized by ST-segment elevation in the right precordial leads, right bundle branch block, and a high incidence of sudden cardiac death in younger people.2 It accounts for 4% of all sudden deaths.3

Three different types of changes on ECG have been associated with Brugada syndrome. Type 1 is a coved ST-segment elevation of at least 2 mm, followed by a negative T wave, with little or no isoelectric separation, and present in more than one right precordial lead (from V1 to V3). Type 2 and type 3 patterns on ECG show the same 2-mm or greater J-point elevation, but a positive T wave gives the “saddleback” appearance to the ST-T portion.

Brugada syndrome is confirmed when a type 1 pattern is observed in conjunction with one of the following:

- Documented ventricular fibrillation

- Polymorphic ventricular tachycardia

- A family history of sudden cardiac death at 45 years of age or younger

- Type 1 pattern on ECG in family members

- Ventricular tachycardia that can be induced with programmed electrical stimulation

- Syncope

- Nocturnal agonal respiration.3

This patient had type 1 changes on ECG but none of the above findings.

Brugada syndrome is inherited as an autosomal dominant trait, and mutations in gene SCN5A account for 18% to 30% of cases.3 These mutations impair the function of the sodium channel current, leading to an unopposed outward shift of net transmembrane current at the end of phase 1 of the right ventricular epicardial action potential. Interestingly, changes on ECG that are associated with Brugada syndrome are often dynamic or concealed and are unmasked by sodium channel blockers, fever, vagotonic agents, adrenergic agonists or antagonists, and various electrolyte abnormalities.3

At temperatures above the physiologic range, the inward sodium current is reduced, either because of failure of expression of sodium channels or because of premature closing of the sodium channels in genetically susceptible individuals.4 Therefore, fever can unmask Brugada syndrome, as it did in our patient.

For patients with symptomatic Brugada syndrome, the only current treatment is implantation of a cardioverter-defibrillator.5 Patients without symptoms may benefit from an electrophysiologic study for risk stratification, and an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator is recommended for those in whom ventricular fibrillation can be induced.3,5

CASE CONTINUED

The patient remained febrile after catheterization and received vancomycin (Vancocin) and ceftriaxone (Rocephin) empirically for presumed meningitis. Multiple peripheral blood cultures grew gram-positive cocci in pairs and chains, which were identified as Streptococcus pneumoniae. His fever abated soon after the antibiotic therapy was started.

Lumbar puncture was not done. Transesophageal echocardiography revealed no vegetations, with preserved ejection fraction. The patient has no family history of sudden death and no personal history of syncope or presyncope.

On hospital day 3, although his fever was gone, ECG still showed a Brugada pattern. He was discharged home on a 3-week regimen of intravenous penicillin, with plans for appropriate follow-up, and he was counseled that his family should be screened. An electrophysiologic study was not done, and he had no symptoms 1 year later.

As seen in this patient, Brugada syndrome is important to consider in the differential diagnosis in young patients who present with fever and ST elevations.

- Wang K, Asinger RW, Marriott HJ. ST-segment elevation in conditions other than acute myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med 2003; 349:2128–2135.

- Brugada P, Brugada J. Right bundle branch block, persistent ST segment elevation and sudden cardiac death: a distinct clinical and electrocardiographic syndrome. A multicenter report. J Am Coll Cardiol 1992; 20:1391–1396.

- Antzelevitch C, Brugada P, Borggrefe M, et al. Brugada syndrome: report of the second consensus conference: endorsed by the Heart Rhythm Society and the European Heart Rhythm Association. Circulation 2005; 111:659–670.

- Dumaine R, Towbin JA, Brugada P, et al. Ionic mechanisms responsible for the electrocardiographic phenotype of the Brugada syndrome are temperature dependent. Circ Res 1999; 85:803–809.

- Antzelevitch C, Nof E. Brugada syndrome: recent advances and controversies. Curr Cardiol Rep 2008; 10:376–383.

- Wang K, Asinger RW, Marriott HJ. ST-segment elevation in conditions other than acute myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med 2003; 349:2128–2135.

- Brugada P, Brugada J. Right bundle branch block, persistent ST segment elevation and sudden cardiac death: a distinct clinical and electrocardiographic syndrome. A multicenter report. J Am Coll Cardiol 1992; 20:1391–1396.

- Antzelevitch C, Brugada P, Borggrefe M, et al. Brugada syndrome: report of the second consensus conference: endorsed by the Heart Rhythm Society and the European Heart Rhythm Association. Circulation 2005; 111:659–670.

- Dumaine R, Towbin JA, Brugada P, et al. Ionic mechanisms responsible for the electrocardiographic phenotype of the Brugada syndrome are temperature dependent. Circ Res 1999; 85:803–809.

- Antzelevitch C, Nof E. Brugada syndrome: recent advances and controversies. Curr Cardiol Rep 2008; 10:376–383.

Leukemia cutis

Q: What is the most likely diagnosis?

- Leukemia cutis

- Drug reaction

- Sweet syndrome

- Erythema multiforme

- Urticaria

A: The correct answer is leukemia cutis, defined as a cutaneous infiltration by neoplastic leukocytes.1 When the leukocytes are primarily granulocytic precursors, the terms myeloid sarcoma, granulocytic sarcoma, chloroma, and primary extramedullary leukemia have been used.2 The term monoblastic sarcoma has been used when the cutaneous infiltrate is composed of neoplastic monocytic precursors.2

Leukemia cutis most commonly manifests as erythematous papules and nodules, single or multiple, of varying sizes, and afflicting one or more body sites; it typically is asymptomatic.3 It occurs in 10% to 15% of patients with acute myeloid leukemia4 and is itself a poor prognostic sign.5 The cutaneous changes may pre-date the hematologic manifestations and may even herald a relapse.6

In patients presenting with extramedullary leukemia and no bone marrow or blood involvement, the importance of preemptive chemotherapy for acute myelogenous leukemia has recently been emphasized.7

CASE CONTINUED

The patient undergoes further testing with bone marrow aspiration and trephination, which are diagnostic of acute myeloid leukemia with myelodysplastic changes: the studies reveal a clear excess of myeloblasts (accounting for 40% to 50% of nucleated cells) and clearly dysplastic erythropoiesis and myelopoiesis. Bone marrow cytogenetic analysis reveals a complex abnormal female karyotype with multiple numerical and structural abnormalities, in particular deletion of the long arm of chromosome 5, suggestive of a poor prognosis.

Skin biopsy reveals a normal epidermis but dermal perivascular involvement with a reactive T-lymphocyte infiltrate associated with immature myeloid elements, characterized by positive staining to myeloperoxidase, in keeping with leukemia cutis. It should be noted that histopathologic confirmation of leukemia cutis can be challenging, as the condition can adopt a variety of patterns, and clinicopathologic correlation is often warranted.

The patient is treated with a cycle of cytarabine-based chemotherapy, and her skin eruption transiently improves. However, her clinical condition subsequently deteriorates; she has a relapse of leukemia, with the rash returning more florid and angry-looking than previously. She is subsequently managed palliatively and passes away 3 weeks later.

THE OTHER DIAGNOSTIC CHOICES

Sweet syndrome or acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis is often seen in association with hematologic malignancies, but the lesions are typically tender, and histopathology reveals an intense dermal neutrophilic infiltrate.6

Erythema multiforme is associated with malignancy, but its characteristic concentric “target” lesions are typically acral and symmetrical in their distribution; their histopathology is inflammatory.8

The patient had not been on any regular medications and her rash could not have been medication-induced.

Urticaria presents with pruritic evanescent wheals, which rarely last more than 12 hours.9 Our patient had a fixed and entirely asymptomatic rash, which in addition did not have the histopathologic features of urticaria—namely, dermal edema involved with an infiltrate made of lymphocytes and eosinophils.9

- Strutton G. Cutaneous infiltrates: lymphomatous and leukemic. In:Weedon D, editor. Skin Pathology, 2nd ed. New York, NY: Churchill Livingstone, 2002:1118–1120.

- Brunning RD, Matutes E, Flandria F, et al. In: Jaffe ES, Harris NL, Stein H, Vardiman JW, editors. World Health Organization Classification of Tumours: Pathology and Genetics of Tumours of Haematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues. Lyon, France: IARC Press, 2001:104–105.

- Watson KM, Mufti G, Salisbury JR, du Vivier AW, Creamer D. Spectrum of clinical presentation, treatment and prognosis in a series of eight patients with leukaemia cutis. Clin Exp Dermatol 2006; 31:218–221.

- Agis H, Weltermann A, Fonatsch C, et al. A comparative study on demographic, hematological, and cytogenetic findings and prognosis in acute myeloid leukemia with and without leukemia cutis. Ann Hematol 2002; 81:90–95.

- Kaddu S, Zenahlik P, Beham-Schmid C, Kerl H, Cerroni L. Specific cutaneous infiltrates in patients with myelogenous leukemia: a clinicopathologic study of 26 patients with assessment of diagnostic criteria. J Am Acad Dermatol 1999; 40:966–978.

- Cutaneous aspects of leukemia. In: Braun-Falco O, Plewig G, Wolff HH, Burgdorf WHC, editors. Dermatology, 2nd ed. Berlin: Springer, 2000:1640–1648.

- Tsimberidou AM, Kantarjian HM, Wen S, et al. Myeloid sarcoma is associated with superior event-free survival and overall survival compared with acute myeloid leukemia. Cancer 2008; 113:1370–1378.

- Erythemato-papulo-squamous diseases. In: Braun-Falco O, Plewig G, Wolff HH, Burgdorf WHC. Dermatology, 2nd ed. Berlin: Springer, 2000.

- Urticaria, angioedema and anaphylaxis. In: Braun-Falco O, Plewig G, Wolff HH, Burgdorf WHC. Dermatology, 2nd ed. Berlin: Springer, 2000.

Q: What is the most likely diagnosis?

- Leukemia cutis

- Drug reaction

- Sweet syndrome

- Erythema multiforme

- Urticaria

A: The correct answer is leukemia cutis, defined as a cutaneous infiltration by neoplastic leukocytes.1 When the leukocytes are primarily granulocytic precursors, the terms myeloid sarcoma, granulocytic sarcoma, chloroma, and primary extramedullary leukemia have been used.2 The term monoblastic sarcoma has been used when the cutaneous infiltrate is composed of neoplastic monocytic precursors.2

Leukemia cutis most commonly manifests as erythematous papules and nodules, single or multiple, of varying sizes, and afflicting one or more body sites; it typically is asymptomatic.3 It occurs in 10% to 15% of patients with acute myeloid leukemia4 and is itself a poor prognostic sign.5 The cutaneous changes may pre-date the hematologic manifestations and may even herald a relapse.6

In patients presenting with extramedullary leukemia and no bone marrow or blood involvement, the importance of preemptive chemotherapy for acute myelogenous leukemia has recently been emphasized.7

CASE CONTINUED

The patient undergoes further testing with bone marrow aspiration and trephination, which are diagnostic of acute myeloid leukemia with myelodysplastic changes: the studies reveal a clear excess of myeloblasts (accounting for 40% to 50% of nucleated cells) and clearly dysplastic erythropoiesis and myelopoiesis. Bone marrow cytogenetic analysis reveals a complex abnormal female karyotype with multiple numerical and structural abnormalities, in particular deletion of the long arm of chromosome 5, suggestive of a poor prognosis.

Skin biopsy reveals a normal epidermis but dermal perivascular involvement with a reactive T-lymphocyte infiltrate associated with immature myeloid elements, characterized by positive staining to myeloperoxidase, in keeping with leukemia cutis. It should be noted that histopathologic confirmation of leukemia cutis can be challenging, as the condition can adopt a variety of patterns, and clinicopathologic correlation is often warranted.

The patient is treated with a cycle of cytarabine-based chemotherapy, and her skin eruption transiently improves. However, her clinical condition subsequently deteriorates; she has a relapse of leukemia, with the rash returning more florid and angry-looking than previously. She is subsequently managed palliatively and passes away 3 weeks later.

THE OTHER DIAGNOSTIC CHOICES

Sweet syndrome or acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis is often seen in association with hematologic malignancies, but the lesions are typically tender, and histopathology reveals an intense dermal neutrophilic infiltrate.6

Erythema multiforme is associated with malignancy, but its characteristic concentric “target” lesions are typically acral and symmetrical in their distribution; their histopathology is inflammatory.8

The patient had not been on any regular medications and her rash could not have been medication-induced.

Urticaria presents with pruritic evanescent wheals, which rarely last more than 12 hours.9 Our patient had a fixed and entirely asymptomatic rash, which in addition did not have the histopathologic features of urticaria—namely, dermal edema involved with an infiltrate made of lymphocytes and eosinophils.9

Q: What is the most likely diagnosis?

- Leukemia cutis

- Drug reaction

- Sweet syndrome

- Erythema multiforme

- Urticaria

A: The correct answer is leukemia cutis, defined as a cutaneous infiltration by neoplastic leukocytes.1 When the leukocytes are primarily granulocytic precursors, the terms myeloid sarcoma, granulocytic sarcoma, chloroma, and primary extramedullary leukemia have been used.2 The term monoblastic sarcoma has been used when the cutaneous infiltrate is composed of neoplastic monocytic precursors.2

Leukemia cutis most commonly manifests as erythematous papules and nodules, single or multiple, of varying sizes, and afflicting one or more body sites; it typically is asymptomatic.3 It occurs in 10% to 15% of patients with acute myeloid leukemia4 and is itself a poor prognostic sign.5 The cutaneous changes may pre-date the hematologic manifestations and may even herald a relapse.6

In patients presenting with extramedullary leukemia and no bone marrow or blood involvement, the importance of preemptive chemotherapy for acute myelogenous leukemia has recently been emphasized.7

CASE CONTINUED

The patient undergoes further testing with bone marrow aspiration and trephination, which are diagnostic of acute myeloid leukemia with myelodysplastic changes: the studies reveal a clear excess of myeloblasts (accounting for 40% to 50% of nucleated cells) and clearly dysplastic erythropoiesis and myelopoiesis. Bone marrow cytogenetic analysis reveals a complex abnormal female karyotype with multiple numerical and structural abnormalities, in particular deletion of the long arm of chromosome 5, suggestive of a poor prognosis.

Skin biopsy reveals a normal epidermis but dermal perivascular involvement with a reactive T-lymphocyte infiltrate associated with immature myeloid elements, characterized by positive staining to myeloperoxidase, in keeping with leukemia cutis. It should be noted that histopathologic confirmation of leukemia cutis can be challenging, as the condition can adopt a variety of patterns, and clinicopathologic correlation is often warranted.

The patient is treated with a cycle of cytarabine-based chemotherapy, and her skin eruption transiently improves. However, her clinical condition subsequently deteriorates; she has a relapse of leukemia, with the rash returning more florid and angry-looking than previously. She is subsequently managed palliatively and passes away 3 weeks later.

THE OTHER DIAGNOSTIC CHOICES

Sweet syndrome or acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis is often seen in association with hematologic malignancies, but the lesions are typically tender, and histopathology reveals an intense dermal neutrophilic infiltrate.6

Erythema multiforme is associated with malignancy, but its characteristic concentric “target” lesions are typically acral and symmetrical in their distribution; their histopathology is inflammatory.8

The patient had not been on any regular medications and her rash could not have been medication-induced.

Urticaria presents with pruritic evanescent wheals, which rarely last more than 12 hours.9 Our patient had a fixed and entirely asymptomatic rash, which in addition did not have the histopathologic features of urticaria—namely, dermal edema involved with an infiltrate made of lymphocytes and eosinophils.9

- Strutton G. Cutaneous infiltrates: lymphomatous and leukemic. In:Weedon D, editor. Skin Pathology, 2nd ed. New York, NY: Churchill Livingstone, 2002:1118–1120.

- Brunning RD, Matutes E, Flandria F, et al. In: Jaffe ES, Harris NL, Stein H, Vardiman JW, editors. World Health Organization Classification of Tumours: Pathology and Genetics of Tumours of Haematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues. Lyon, France: IARC Press, 2001:104–105.

- Watson KM, Mufti G, Salisbury JR, du Vivier AW, Creamer D. Spectrum of clinical presentation, treatment and prognosis in a series of eight patients with leukaemia cutis. Clin Exp Dermatol 2006; 31:218–221.

- Agis H, Weltermann A, Fonatsch C, et al. A comparative study on demographic, hematological, and cytogenetic findings and prognosis in acute myeloid leukemia with and without leukemia cutis. Ann Hematol 2002; 81:90–95.

- Kaddu S, Zenahlik P, Beham-Schmid C, Kerl H, Cerroni L. Specific cutaneous infiltrates in patients with myelogenous leukemia: a clinicopathologic study of 26 patients with assessment of diagnostic criteria. J Am Acad Dermatol 1999; 40:966–978.

- Cutaneous aspects of leukemia. In: Braun-Falco O, Plewig G, Wolff HH, Burgdorf WHC, editors. Dermatology, 2nd ed. Berlin: Springer, 2000:1640–1648.

- Tsimberidou AM, Kantarjian HM, Wen S, et al. Myeloid sarcoma is associated with superior event-free survival and overall survival compared with acute myeloid leukemia. Cancer 2008; 113:1370–1378.

- Erythemato-papulo-squamous diseases. In: Braun-Falco O, Plewig G, Wolff HH, Burgdorf WHC. Dermatology, 2nd ed. Berlin: Springer, 2000.

- Urticaria, angioedema and anaphylaxis. In: Braun-Falco O, Plewig G, Wolff HH, Burgdorf WHC. Dermatology, 2nd ed. Berlin: Springer, 2000.

- Strutton G. Cutaneous infiltrates: lymphomatous and leukemic. In:Weedon D, editor. Skin Pathology, 2nd ed. New York, NY: Churchill Livingstone, 2002:1118–1120.

- Brunning RD, Matutes E, Flandria F, et al. In: Jaffe ES, Harris NL, Stein H, Vardiman JW, editors. World Health Organization Classification of Tumours: Pathology and Genetics of Tumours of Haematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues. Lyon, France: IARC Press, 2001:104–105.

- Watson KM, Mufti G, Salisbury JR, du Vivier AW, Creamer D. Spectrum of clinical presentation, treatment and prognosis in a series of eight patients with leukaemia cutis. Clin Exp Dermatol 2006; 31:218–221.

- Agis H, Weltermann A, Fonatsch C, et al. A comparative study on demographic, hematological, and cytogenetic findings and prognosis in acute myeloid leukemia with and without leukemia cutis. Ann Hematol 2002; 81:90–95.

- Kaddu S, Zenahlik P, Beham-Schmid C, Kerl H, Cerroni L. Specific cutaneous infiltrates in patients with myelogenous leukemia: a clinicopathologic study of 26 patients with assessment of diagnostic criteria. J Am Acad Dermatol 1999; 40:966–978.

- Cutaneous aspects of leukemia. In: Braun-Falco O, Plewig G, Wolff HH, Burgdorf WHC, editors. Dermatology, 2nd ed. Berlin: Springer, 2000:1640–1648.

- Tsimberidou AM, Kantarjian HM, Wen S, et al. Myeloid sarcoma is associated with superior event-free survival and overall survival compared with acute myeloid leukemia. Cancer 2008; 113:1370–1378.

- Erythemato-papulo-squamous diseases. In: Braun-Falco O, Plewig G, Wolff HH, Burgdorf WHC. Dermatology, 2nd ed. Berlin: Springer, 2000.

- Urticaria, angioedema and anaphylaxis. In: Braun-Falco O, Plewig G, Wolff HH, Burgdorf WHC. Dermatology, 2nd ed. Berlin: Springer, 2000.

A 40-year-old woman with excoriated skin lesions

She denies any history of itching, insect bites, exposure to new medications or jewelry, allergies, recent change in medications, travel, or intravenous drug abuse.

Q: Which is the most likely diagnosis?

- Allergic contact dermatitis

- Xerosis

- Dermatotillomania

- Folliculitis

- Infestation (scabies)

A: Dermatotillomania, ie, pathologic skin picking, is the correct diagnosis. On further questioning, the patient reveals that the wounds have been self-inflicted over many years, starting in her adolescence. The wounds are located only in areas she can reach. She admits that social and emotional stressors had made the condition significantly worse and that lately she had lost control of her skin-picking. She denies nail-biting, trichotillomania, or obsessive-compulsive behavior.

As for the other possible diagnoses:

Allergic contact dermatitis occurs when contact with a particular substance elicits a hypersensitivity reaction. This reaction is of the delayed type (type IV). The affected individual can develop skin erythema and swelling with vesicles that are intensely pruritic at the contact site. The erythema may become evident hours after exposure, or not until weeks later, which can make the diagnosis difficult at times.

Our patient’s lesions were not pruritic, and she denied recent exposure to allergens.

Xerosis. Xerotic (dry) skin is usually rough, with fine scales and fissures. Xerosis can affect people of all ages and is often more intense during the winter. It affects mainly the arms, legs, and hands. Patients note pruritus, which can be treated with liberal use of emollients and tepid water baths.

Our patient’s lesions were scarred, hyperpigmented, and nonpruritic.

Folliculitis is a superficial infection of the hair follicle that presents as an erythematous pustule on the extremities, buttocks, or scalp. The pustule can be tender to palpation and can progress to an abscess that requires incision and drainage and intravenous antibiotics. A moist environment and poor hygiene are predisposing factors. Staphylococcus aureus is the culprit in most cases.

Our patient’s lesions were on the chest and upper back, where hair follicles were sparse or absent, and there was no erythema or tenderness.

Scabies is a skin infestation with Sarcoptes scabiei mites, which burrow in the skin and cause intense pruritus, especially at night. Scabies usually affects the sides and webs of the fingers and skin folds. Sexual contact is a common way of transmission; however, transmission can also occur by sharing beds and towels.

Patients with dermatotillomania lack intense pruritus, and skin-picking occurs during the day, while the patient is awake.

SELF-INFLICTED WOUNDS

Pathologic skin-picking, neurotic excoriation, excoriated acne, or dermatotillomania results from scratching, picking, gouging, or squeezing of one’s skin via teeth, fingernails, tweezers, or other objects.1–3 Lesions are usually found on skin that the patient can easily reach, such as the face, chest, upper and lower extremities, and upper back.4

The prevalence of pathologic skin-picking is estimated at 2% in dermatology patients.5 The overall prevalence of psychiatric disorders in all dermatology outpatients is estimated at 30% to 40%. Women outnumber men with this disorder.6

Dermatotillomania is thought to be on the spectrum of obsessive-compulsive disorder, in which patients exhibit impulses and compulsions.5 It starts in childhood or early adulthood, with an average lifetime duration of 21 years.7 It is usually associated with anxiety, depression, obsessive-compulsive traits, eating disorders, body dysmorphic disorders, or hypochondriasis. Psychosocial stress is the main trigger. Patients report feelings of tension and stress before picking and relief while picking; there is no suicidal ideation.8

Treatments are both pharmacologic and behavioral.9 Cognitive behavioral therapy and habit reversal therapy have each been successful when used alone.8 In addition, several case reports10 and double-blind studies11,12 have shown that treatment with a selective serotonin-reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) can reduce pathologic skin-picking.13,14 However, SSRIs have also been reported to induce or aggravate this behavior in patients with underlying mild skin-picking and a family history of skin-picking.15 Thus, it is pertinent to extract a detailed history from the patient before prescribing an SSRI.

We referred our patient for behavioral therapy and prescribed fluoxetine (Prozac) 20 mg daily. She showed improvement in symptoms in 4 weeks and has since stopped skin-picking completely.

- Arnold LM. Phenomenology and therapeutic options for dermatotillomania. Expert Rev Neurother 2002; 2:725–730.

- Bohne A, Keuthen N, Wilhelm S. Pathologic hairpulling, skin picking, and nail biting. Ann Clin Psychiatry 2005; 17:227–232.

- Gattu S, Rashid RM, Khachemoune A. Self-induced skin lesions: a review of dermatitis artefacta. Cutis 2009; 84:247–251.

- Keuthen NJ, Deckersbach T, Wilhelm S, et al. Repetitive skin-picking in a student population and comparison with a sample of self-injurious skin-pickers. Psychosomatics 2000; 41:210–215.

- Arnold LM, Auchenbach MB, McElroy SL. Psychogenic excoriation. Clinical features, proposed diagnostic criteria, epidemiology and approaches to treatment. CNS Drugs 2001; 15:351–359.

- Wilhelm S, Keuthen NJ, Deckersbach T, et al. Self-injurious skin picking: clinical characteristics and comorbidity. J Clin Psychiatry 1999; 60:454–459.

- Gupta MA, Gupta AK, Haberman HF. Neurotic excoriations: a review and some new perspectives. Compr Psychiatry 1986; 27:381–386.

- Rosenbaum MS, Ayllon T. The behavioral treatment of neurodermatitis through habit-reversal. Behav Res Ther 1981; 19:313–318.

- Deckersbach T, Wilhelm S, Keuthen N. Self-injurious skin picking: clinical characteristics, assessment methods, and treatment modalities. Brief Treatment and Crisis Intervention 2003; 3:249–260.

- Sharma H. Psychogenic excoriation responding to fluoxetine: a case report. J Indian Med Assoc 2008; 106:245,262.

- Bloch MR, Elliott M, Thompson H, Koran LM. Fluoxetine in pathologic skin-picking: open-label and double-blind results. Psychosomatics 2001; 42:314–319.

- Simeon D, Stein DJ, Gross S, Islam N, Schmeidler J, Hollander E. A double-blind trial of fluoxetine in pathologic skin picking. J Clin Psychiatry 1997; 58:341–347.

- Gupta MA, Gupta AK. The use of antidepressant drugs in dermatology. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2001; 15:512–518.

- Keuthen NJ, Jameson M, Loh R, Deckersbach T, Wilhelm S, Dougherty DD. Open-label escitalopram treatment for pathological skin picking. Int Clin Psychopharmacol 2007; 22:268–274.

- Denys D, van Megen HJ, Westenberg HG. Emerging skin-picking behaviour after serotonin reuptake inhibitor-treatment in patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder: possible mechanisms and implications for clinical care. J Psychopharmacol 2003; 17:127–129.

She denies any history of itching, insect bites, exposure to new medications or jewelry, allergies, recent change in medications, travel, or intravenous drug abuse.

Q: Which is the most likely diagnosis?

- Allergic contact dermatitis

- Xerosis

- Dermatotillomania

- Folliculitis

- Infestation (scabies)

A: Dermatotillomania, ie, pathologic skin picking, is the correct diagnosis. On further questioning, the patient reveals that the wounds have been self-inflicted over many years, starting in her adolescence. The wounds are located only in areas she can reach. She admits that social and emotional stressors had made the condition significantly worse and that lately she had lost control of her skin-picking. She denies nail-biting, trichotillomania, or obsessive-compulsive behavior.

As for the other possible diagnoses:

Allergic contact dermatitis occurs when contact with a particular substance elicits a hypersensitivity reaction. This reaction is of the delayed type (type IV). The affected individual can develop skin erythema and swelling with vesicles that are intensely pruritic at the contact site. The erythema may become evident hours after exposure, or not until weeks later, which can make the diagnosis difficult at times.

Our patient’s lesions were not pruritic, and she denied recent exposure to allergens.

Xerosis. Xerotic (dry) skin is usually rough, with fine scales and fissures. Xerosis can affect people of all ages and is often more intense during the winter. It affects mainly the arms, legs, and hands. Patients note pruritus, which can be treated with liberal use of emollients and tepid water baths.

Our patient’s lesions were scarred, hyperpigmented, and nonpruritic.

Folliculitis is a superficial infection of the hair follicle that presents as an erythematous pustule on the extremities, buttocks, or scalp. The pustule can be tender to palpation and can progress to an abscess that requires incision and drainage and intravenous antibiotics. A moist environment and poor hygiene are predisposing factors. Staphylococcus aureus is the culprit in most cases.

Our patient’s lesions were on the chest and upper back, where hair follicles were sparse or absent, and there was no erythema or tenderness.

Scabies is a skin infestation with Sarcoptes scabiei mites, which burrow in the skin and cause intense pruritus, especially at night. Scabies usually affects the sides and webs of the fingers and skin folds. Sexual contact is a common way of transmission; however, transmission can also occur by sharing beds and towels.

Patients with dermatotillomania lack intense pruritus, and skin-picking occurs during the day, while the patient is awake.

SELF-INFLICTED WOUNDS

Pathologic skin-picking, neurotic excoriation, excoriated acne, or dermatotillomania results from scratching, picking, gouging, or squeezing of one’s skin via teeth, fingernails, tweezers, or other objects.1–3 Lesions are usually found on skin that the patient can easily reach, such as the face, chest, upper and lower extremities, and upper back.4

The prevalence of pathologic skin-picking is estimated at 2% in dermatology patients.5 The overall prevalence of psychiatric disorders in all dermatology outpatients is estimated at 30% to 40%. Women outnumber men with this disorder.6

Dermatotillomania is thought to be on the spectrum of obsessive-compulsive disorder, in which patients exhibit impulses and compulsions.5 It starts in childhood or early adulthood, with an average lifetime duration of 21 years.7 It is usually associated with anxiety, depression, obsessive-compulsive traits, eating disorders, body dysmorphic disorders, or hypochondriasis. Psychosocial stress is the main trigger. Patients report feelings of tension and stress before picking and relief while picking; there is no suicidal ideation.8

Treatments are both pharmacologic and behavioral.9 Cognitive behavioral therapy and habit reversal therapy have each been successful when used alone.8 In addition, several case reports10 and double-blind studies11,12 have shown that treatment with a selective serotonin-reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) can reduce pathologic skin-picking.13,14 However, SSRIs have also been reported to induce or aggravate this behavior in patients with underlying mild skin-picking and a family history of skin-picking.15 Thus, it is pertinent to extract a detailed history from the patient before prescribing an SSRI.

We referred our patient for behavioral therapy and prescribed fluoxetine (Prozac) 20 mg daily. She showed improvement in symptoms in 4 weeks and has since stopped skin-picking completely.

She denies any history of itching, insect bites, exposure to new medications or jewelry, allergies, recent change in medications, travel, or intravenous drug abuse.

Q: Which is the most likely diagnosis?

- Allergic contact dermatitis

- Xerosis

- Dermatotillomania

- Folliculitis

- Infestation (scabies)

A: Dermatotillomania, ie, pathologic skin picking, is the correct diagnosis. On further questioning, the patient reveals that the wounds have been self-inflicted over many years, starting in her adolescence. The wounds are located only in areas she can reach. She admits that social and emotional stressors had made the condition significantly worse and that lately she had lost control of her skin-picking. She denies nail-biting, trichotillomania, or obsessive-compulsive behavior.

As for the other possible diagnoses:

Allergic contact dermatitis occurs when contact with a particular substance elicits a hypersensitivity reaction. This reaction is of the delayed type (type IV). The affected individual can develop skin erythema and swelling with vesicles that are intensely pruritic at the contact site. The erythema may become evident hours after exposure, or not until weeks later, which can make the diagnosis difficult at times.

Our patient’s lesions were not pruritic, and she denied recent exposure to allergens.

Xerosis. Xerotic (dry) skin is usually rough, with fine scales and fissures. Xerosis can affect people of all ages and is often more intense during the winter. It affects mainly the arms, legs, and hands. Patients note pruritus, which can be treated with liberal use of emollients and tepid water baths.

Our patient’s lesions were scarred, hyperpigmented, and nonpruritic.

Folliculitis is a superficial infection of the hair follicle that presents as an erythematous pustule on the extremities, buttocks, or scalp. The pustule can be tender to palpation and can progress to an abscess that requires incision and drainage and intravenous antibiotics. A moist environment and poor hygiene are predisposing factors. Staphylococcus aureus is the culprit in most cases.

Our patient’s lesions were on the chest and upper back, where hair follicles were sparse or absent, and there was no erythema or tenderness.

Scabies is a skin infestation with Sarcoptes scabiei mites, which burrow in the skin and cause intense pruritus, especially at night. Scabies usually affects the sides and webs of the fingers and skin folds. Sexual contact is a common way of transmission; however, transmission can also occur by sharing beds and towels.

Patients with dermatotillomania lack intense pruritus, and skin-picking occurs during the day, while the patient is awake.

SELF-INFLICTED WOUNDS

Pathologic skin-picking, neurotic excoriation, excoriated acne, or dermatotillomania results from scratching, picking, gouging, or squeezing of one’s skin via teeth, fingernails, tweezers, or other objects.1–3 Lesions are usually found on skin that the patient can easily reach, such as the face, chest, upper and lower extremities, and upper back.4

The prevalence of pathologic skin-picking is estimated at 2% in dermatology patients.5 The overall prevalence of psychiatric disorders in all dermatology outpatients is estimated at 30% to 40%. Women outnumber men with this disorder.6

Dermatotillomania is thought to be on the spectrum of obsessive-compulsive disorder, in which patients exhibit impulses and compulsions.5 It starts in childhood or early adulthood, with an average lifetime duration of 21 years.7 It is usually associated with anxiety, depression, obsessive-compulsive traits, eating disorders, body dysmorphic disorders, or hypochondriasis. Psychosocial stress is the main trigger. Patients report feelings of tension and stress before picking and relief while picking; there is no suicidal ideation.8

Treatments are both pharmacologic and behavioral.9 Cognitive behavioral therapy and habit reversal therapy have each been successful when used alone.8 In addition, several case reports10 and double-blind studies11,12 have shown that treatment with a selective serotonin-reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) can reduce pathologic skin-picking.13,14 However, SSRIs have also been reported to induce or aggravate this behavior in patients with underlying mild skin-picking and a family history of skin-picking.15 Thus, it is pertinent to extract a detailed history from the patient before prescribing an SSRI.

We referred our patient for behavioral therapy and prescribed fluoxetine (Prozac) 20 mg daily. She showed improvement in symptoms in 4 weeks and has since stopped skin-picking completely.

- Arnold LM. Phenomenology and therapeutic options for dermatotillomania. Expert Rev Neurother 2002; 2:725–730.

- Bohne A, Keuthen N, Wilhelm S. Pathologic hairpulling, skin picking, and nail biting. Ann Clin Psychiatry 2005; 17:227–232.

- Gattu S, Rashid RM, Khachemoune A. Self-induced skin lesions: a review of dermatitis artefacta. Cutis 2009; 84:247–251.

- Keuthen NJ, Deckersbach T, Wilhelm S, et al. Repetitive skin-picking in a student population and comparison with a sample of self-injurious skin-pickers. Psychosomatics 2000; 41:210–215.

- Arnold LM, Auchenbach MB, McElroy SL. Psychogenic excoriation. Clinical features, proposed diagnostic criteria, epidemiology and approaches to treatment. CNS Drugs 2001; 15:351–359.

- Wilhelm S, Keuthen NJ, Deckersbach T, et al. Self-injurious skin picking: clinical characteristics and comorbidity. J Clin Psychiatry 1999; 60:454–459.

- Gupta MA, Gupta AK, Haberman HF. Neurotic excoriations: a review and some new perspectives. Compr Psychiatry 1986; 27:381–386.

- Rosenbaum MS, Ayllon T. The behavioral treatment of neurodermatitis through habit-reversal. Behav Res Ther 1981; 19:313–318.

- Deckersbach T, Wilhelm S, Keuthen N. Self-injurious skin picking: clinical characteristics, assessment methods, and treatment modalities. Brief Treatment and Crisis Intervention 2003; 3:249–260.

- Sharma H. Psychogenic excoriation responding to fluoxetine: a case report. J Indian Med Assoc 2008; 106:245,262.

- Bloch MR, Elliott M, Thompson H, Koran LM. Fluoxetine in pathologic skin-picking: open-label and double-blind results. Psychosomatics 2001; 42:314–319.

- Simeon D, Stein DJ, Gross S, Islam N, Schmeidler J, Hollander E. A double-blind trial of fluoxetine in pathologic skin picking. J Clin Psychiatry 1997; 58:341–347.

- Gupta MA, Gupta AK. The use of antidepressant drugs in dermatology. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2001; 15:512–518.

- Keuthen NJ, Jameson M, Loh R, Deckersbach T, Wilhelm S, Dougherty DD. Open-label escitalopram treatment for pathological skin picking. Int Clin Psychopharmacol 2007; 22:268–274.

- Denys D, van Megen HJ, Westenberg HG. Emerging skin-picking behaviour after serotonin reuptake inhibitor-treatment in patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder: possible mechanisms and implications for clinical care. J Psychopharmacol 2003; 17:127–129.

- Arnold LM. Phenomenology and therapeutic options for dermatotillomania. Expert Rev Neurother 2002; 2:725–730.

- Bohne A, Keuthen N, Wilhelm S. Pathologic hairpulling, skin picking, and nail biting. Ann Clin Psychiatry 2005; 17:227–232.

- Gattu S, Rashid RM, Khachemoune A. Self-induced skin lesions: a review of dermatitis artefacta. Cutis 2009; 84:247–251.

- Keuthen NJ, Deckersbach T, Wilhelm S, et al. Repetitive skin-picking in a student population and comparison with a sample of self-injurious skin-pickers. Psychosomatics 2000; 41:210–215.

- Arnold LM, Auchenbach MB, McElroy SL. Psychogenic excoriation. Clinical features, proposed diagnostic criteria, epidemiology and approaches to treatment. CNS Drugs 2001; 15:351–359.

- Wilhelm S, Keuthen NJ, Deckersbach T, et al. Self-injurious skin picking: clinical characteristics and comorbidity. J Clin Psychiatry 1999; 60:454–459.

- Gupta MA, Gupta AK, Haberman HF. Neurotic excoriations: a review and some new perspectives. Compr Psychiatry 1986; 27:381–386.

- Rosenbaum MS, Ayllon T. The behavioral treatment of neurodermatitis through habit-reversal. Behav Res Ther 1981; 19:313–318.

- Deckersbach T, Wilhelm S, Keuthen N. Self-injurious skin picking: clinical characteristics, assessment methods, and treatment modalities. Brief Treatment and Crisis Intervention 2003; 3:249–260.

- Sharma H. Psychogenic excoriation responding to fluoxetine: a case report. J Indian Med Assoc 2008; 106:245,262.

- Bloch MR, Elliott M, Thompson H, Koran LM. Fluoxetine in pathologic skin-picking: open-label and double-blind results. Psychosomatics 2001; 42:314–319.

- Simeon D, Stein DJ, Gross S, Islam N, Schmeidler J, Hollander E. A double-blind trial of fluoxetine in pathologic skin picking. J Clin Psychiatry 1997; 58:341–347.

- Gupta MA, Gupta AK. The use of antidepressant drugs in dermatology. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2001; 15:512–518.

- Keuthen NJ, Jameson M, Loh R, Deckersbach T, Wilhelm S, Dougherty DD. Open-label escitalopram treatment for pathological skin picking. Int Clin Psychopharmacol 2007; 22:268–274.

- Denys D, van Megen HJ, Westenberg HG. Emerging skin-picking behaviour after serotonin reuptake inhibitor-treatment in patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder: possible mechanisms and implications for clinical care. J Psychopharmacol 2003; 17:127–129.

Genital lesions and acute urinary retention

He is sexually active. Nothing in his medical and surgical history would appear to contribute to his symptoms. He is not taking any medications.

His temperature is 38.5°C (101.3°F). His bladder is distended on palpation and percussion, and he has patches of vesicular and ulcerative lesions on an erythematous base over the scrotum and penis and the proximal inner thighs, lacking a dermatomal pattern. He also has decreased sensation to touch and pain perianally. Anal sphincter tone, deep tendon reflexes, and motor examination of the lower extremities are normal. The patient also lacks any positive meningeal findings. Bladder catheterization yields 1,250 mL of urine.

Q: What is the next step?

- Urine culture

- Immunofluorescence for chlamydial infection

- Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis

- Spinal myelography

- Urine toxicologic screen

A: CSF analysis is a vital diagnostic step in the evaluation of patients who present with skin rash around the genital area and acute urinary retention, to rule out acute sacral myeloradiculitis. In this disease, CSF analysis typically shows an increase in lymphocytes and a mild increase in protein. Urinary tract infection, gonorrhea, central spinal cord compression, and drug intoxication are unlikely to have this presentation. Hence, CSF analysis is the correct answer.

The patient undergoes a spinal tap. CSF analysis reveals an elevated white cell count of 85 cells/μL (reference range 0–5), with 79% lymphocytes (reference range 60%–70%), a mildly elevated protein concentration at 80 mg/dL (reference range 15–50), and a normal glucose level. Polymerase chain reaction testing of the CSF is negative for herpes simplex virus (HSV).

Magnetic resonance images of the brain and spinal cord are normal.

Polymerase chain reaction testing of specimens collected from the genital lesions detects HSV type 2 (HSV-2). Serum Venereal Disease Research Laboratory and serum human immunodeficiency virus tests are negative.

Diagnosis: HSV-2 sacral radiculitis (Elsberg syndrome).

THE PATIENT’S COURSE AND TREATMENT

The patient was initially treated symptomatically by draining the urinary bladder via a Foley catheter, followed by intermittent self-catheterization and topical application of lidocaine cream. He was also given intravenous acyclovir (Zovirax) 10 mg/kg every 8 hours for 2 days, followed by 400 mg orally every 8 hours for 10 days.

By 2 weeks, the skin lesions had resolved, and the patient reported regaining sensation in his anal and sacral areas. He also said he was able to void urine without any difficulty.

ELSBERG SYNDROME

Elsberg syndrome describes multiple disorders characterized by sacral myeloradiculitis, which can be secondary to viral infection, most commonly HSV type 2.1,2 CSF analysis and cultures should be performed. However, cultures and HSV studies of the CSF are often negative, as in this patient.3 CSF lymphocytosis along with a slightly elevated protein level is typical of this disease. It is the latent HSV reactivation in the sacral sensory ganglia that results in sensory neuronal dysfunction and subsequent loss of bladder sensation along with areflexia.

Elsberg syndrome is self-limiting and has a generally good prognosis, but complications such as necrotizing myelitis have been described.4 The combination of acute urinary retention associated with vesicular skin lesions and sensory nerve dysfunction in the sacral nerve root distribution in a young, sexually active patient is a strong clue to the diagnosis of Elsberg syndrome, a serious but treatable disease.

- Caplan LR, Kleeman FJ, Berg S. Urinary retention probably secondary to herpes genitalis. N Engl J Med 1977; 297:920–921.

- Eberhardt O, Küker W, Dichgans J, Weller M. HSV-2 sacral radiculitis (Elsberg syndrome). Neurology 2004; 63:758–759.

- Sakakibara R, Uchiyama T, Liu Z, et al. Meningitis-retention syndrome. An unrecognized clinical condition. J Neurol 2005; 252:1495–1499.

- Koskiniemi ML, Vaheri A, Manninen V, Nikki P. Ascending myelitis with high antibody titer to herpes simplex virus in the cerebrospinal fluid. J Neurol 1982; 227:187–191.

He is sexually active. Nothing in his medical and surgical history would appear to contribute to his symptoms. He is not taking any medications.

His temperature is 38.5°C (101.3°F). His bladder is distended on palpation and percussion, and he has patches of vesicular and ulcerative lesions on an erythematous base over the scrotum and penis and the proximal inner thighs, lacking a dermatomal pattern. He also has decreased sensation to touch and pain perianally. Anal sphincter tone, deep tendon reflexes, and motor examination of the lower extremities are normal. The patient also lacks any positive meningeal findings. Bladder catheterization yields 1,250 mL of urine.

Q: What is the next step?

- Urine culture

- Immunofluorescence for chlamydial infection

- Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis

- Spinal myelography

- Urine toxicologic screen

A: CSF analysis is a vital diagnostic step in the evaluation of patients who present with skin rash around the genital area and acute urinary retention, to rule out acute sacral myeloradiculitis. In this disease, CSF analysis typically shows an increase in lymphocytes and a mild increase in protein. Urinary tract infection, gonorrhea, central spinal cord compression, and drug intoxication are unlikely to have this presentation. Hence, CSF analysis is the correct answer.

The patient undergoes a spinal tap. CSF analysis reveals an elevated white cell count of 85 cells/μL (reference range 0–5), with 79% lymphocytes (reference range 60%–70%), a mildly elevated protein concentration at 80 mg/dL (reference range 15–50), and a normal glucose level. Polymerase chain reaction testing of the CSF is negative for herpes simplex virus (HSV).

Magnetic resonance images of the brain and spinal cord are normal.

Polymerase chain reaction testing of specimens collected from the genital lesions detects HSV type 2 (HSV-2). Serum Venereal Disease Research Laboratory and serum human immunodeficiency virus tests are negative.

Diagnosis: HSV-2 sacral radiculitis (Elsberg syndrome).

THE PATIENT’S COURSE AND TREATMENT

The patient was initially treated symptomatically by draining the urinary bladder via a Foley catheter, followed by intermittent self-catheterization and topical application of lidocaine cream. He was also given intravenous acyclovir (Zovirax) 10 mg/kg every 8 hours for 2 days, followed by 400 mg orally every 8 hours for 10 days.

By 2 weeks, the skin lesions had resolved, and the patient reported regaining sensation in his anal and sacral areas. He also said he was able to void urine without any difficulty.

ELSBERG SYNDROME

Elsberg syndrome describes multiple disorders characterized by sacral myeloradiculitis, which can be secondary to viral infection, most commonly HSV type 2.1,2 CSF analysis and cultures should be performed. However, cultures and HSV studies of the CSF are often negative, as in this patient.3 CSF lymphocytosis along with a slightly elevated protein level is typical of this disease. It is the latent HSV reactivation in the sacral sensory ganglia that results in sensory neuronal dysfunction and subsequent loss of bladder sensation along with areflexia.

Elsberg syndrome is self-limiting and has a generally good prognosis, but complications such as necrotizing myelitis have been described.4 The combination of acute urinary retention associated with vesicular skin lesions and sensory nerve dysfunction in the sacral nerve root distribution in a young, sexually active patient is a strong clue to the diagnosis of Elsberg syndrome, a serious but treatable disease.

He is sexually active. Nothing in his medical and surgical history would appear to contribute to his symptoms. He is not taking any medications.

His temperature is 38.5°C (101.3°F). His bladder is distended on palpation and percussion, and he has patches of vesicular and ulcerative lesions on an erythematous base over the scrotum and penis and the proximal inner thighs, lacking a dermatomal pattern. He also has decreased sensation to touch and pain perianally. Anal sphincter tone, deep tendon reflexes, and motor examination of the lower extremities are normal. The patient also lacks any positive meningeal findings. Bladder catheterization yields 1,250 mL of urine.

Q: What is the next step?

- Urine culture

- Immunofluorescence for chlamydial infection

- Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis

- Spinal myelography

- Urine toxicologic screen

A: CSF analysis is a vital diagnostic step in the evaluation of patients who present with skin rash around the genital area and acute urinary retention, to rule out acute sacral myeloradiculitis. In this disease, CSF analysis typically shows an increase in lymphocytes and a mild increase in protein. Urinary tract infection, gonorrhea, central spinal cord compression, and drug intoxication are unlikely to have this presentation. Hence, CSF analysis is the correct answer.

The patient undergoes a spinal tap. CSF analysis reveals an elevated white cell count of 85 cells/μL (reference range 0–5), with 79% lymphocytes (reference range 60%–70%), a mildly elevated protein concentration at 80 mg/dL (reference range 15–50), and a normal glucose level. Polymerase chain reaction testing of the CSF is negative for herpes simplex virus (HSV).

Magnetic resonance images of the brain and spinal cord are normal.

Polymerase chain reaction testing of specimens collected from the genital lesions detects HSV type 2 (HSV-2). Serum Venereal Disease Research Laboratory and serum human immunodeficiency virus tests are negative.

Diagnosis: HSV-2 sacral radiculitis (Elsberg syndrome).

THE PATIENT’S COURSE AND TREATMENT

The patient was initially treated symptomatically by draining the urinary bladder via a Foley catheter, followed by intermittent self-catheterization and topical application of lidocaine cream. He was also given intravenous acyclovir (Zovirax) 10 mg/kg every 8 hours for 2 days, followed by 400 mg orally every 8 hours for 10 days.

By 2 weeks, the skin lesions had resolved, and the patient reported regaining sensation in his anal and sacral areas. He also said he was able to void urine without any difficulty.

ELSBERG SYNDROME

Elsberg syndrome describes multiple disorders characterized by sacral myeloradiculitis, which can be secondary to viral infection, most commonly HSV type 2.1,2 CSF analysis and cultures should be performed. However, cultures and HSV studies of the CSF are often negative, as in this patient.3 CSF lymphocytosis along with a slightly elevated protein level is typical of this disease. It is the latent HSV reactivation in the sacral sensory ganglia that results in sensory neuronal dysfunction and subsequent loss of bladder sensation along with areflexia.

Elsberg syndrome is self-limiting and has a generally good prognosis, but complications such as necrotizing myelitis have been described.4 The combination of acute urinary retention associated with vesicular skin lesions and sensory nerve dysfunction in the sacral nerve root distribution in a young, sexually active patient is a strong clue to the diagnosis of Elsberg syndrome, a serious but treatable disease.

- Caplan LR, Kleeman FJ, Berg S. Urinary retention probably secondary to herpes genitalis. N Engl J Med 1977; 297:920–921.

- Eberhardt O, Küker W, Dichgans J, Weller M. HSV-2 sacral radiculitis (Elsberg syndrome). Neurology 2004; 63:758–759.

- Sakakibara R, Uchiyama T, Liu Z, et al. Meningitis-retention syndrome. An unrecognized clinical condition. J Neurol 2005; 252:1495–1499.

- Koskiniemi ML, Vaheri A, Manninen V, Nikki P. Ascending myelitis with high antibody titer to herpes simplex virus in the cerebrospinal fluid. J Neurol 1982; 227:187–191.

- Caplan LR, Kleeman FJ, Berg S. Urinary retention probably secondary to herpes genitalis. N Engl J Med 1977; 297:920–921.

- Eberhardt O, Küker W, Dichgans J, Weller M. HSV-2 sacral radiculitis (Elsberg syndrome). Neurology 2004; 63:758–759.

- Sakakibara R, Uchiyama T, Liu Z, et al. Meningitis-retention syndrome. An unrecognized clinical condition. J Neurol 2005; 252:1495–1499.

- Koskiniemi ML, Vaheri A, Manninen V, Nikki P. Ascending myelitis with high antibody titer to herpes simplex virus in the cerebrospinal fluid. J Neurol 1982; 227:187–191.

Cornflake-like scales on the ankles and feet

Q: On the basis of the skin findings, which test should be ordered to establish a diagnosis?

- Biopsy of the lesions

- Hemoglobin A1C

- Fungal culture

- Brush with soap and water or alcohol

- Bacterial culture

A: Patchy brown, waxy scales in a patient who neglects normal cleansing should raise the possibility of dermatosis neglecta. Hence, brushing with soap and water or alcohol is the correct answer.

In this patient, the plaques were easily removed using an alcohol-soaked swab, revealing underlying normal skin with bleeding spots. The patient’s family was instructed to lightly scrub the area daily with a washcloth, soap, and water. The lesions resolved completely over the next 3 weeks.

DERMATOSIS NEGLECTA

Dermatosis neglecta is a condition that results from the accumulation in the epidermal stratum corium of sebum, sweat, corneocytes, and bacterias in areas of unwashed skin. It affects all age groups, and it has a similar prevalence in both sexes. Sometimes, an underlying physical disability or emotional problem is the cause, other times it is due to prior trauma or hyperesthesia of the affected area. Dermatosis neglecta presents with asymptomatic areas of dark brown patches or plaque with cornflake-like scales and a verrucous surface.1–4 The diagnosis is usually easy and is based on the characteristic findings and the simple test described above. For treatment, in some cases a keratolytic lotion containing lactic acid, glycolic acid, urea, or salicylic acid is helpful.4

MISDIAGNOSIS IS EASY

Dermatosis neglecta could easily be misdiagnosed as verrucous epidermal nevus, terra firma-forme dermatosis, acanthosis nigricans, or another less common dermatosis of “dirty skin” lesions, such as confluent and reticulate papillomatosis (Gougerot-Carteaud syndrome).2–4

Verrucous epidermal nevus appears at birth or early childhood. Patients have verrucous papules and plaques that commonly follow a narrow linear distribution.

Acanthosis nigricans is characterized by broad, velvety, hyperpigmented smooth plaques on the neck, axillae, and flexures. It is related to insulin resistance, obesity, and underlying malignancy.

Confluent and reticulate papillomatosis is a rare dermatosis of unknown cause, with a pigmented reticular pattern distributed on the central trunk. Patients tend to practice normal hygiene.

Terra firma-forme dermatosis is characterized by dirt-like patches that are resistant to usual hygiene measures but that can be eliminated by rubbing with isopropyl alcohol. The cause is unknown, and it is not related to a lack of cleansing. It is considered a variant of dermatosis neglecta.

The medical literature contains few reports of dermatosis neglecta, but the true incidence is probably underestimated. Early recognition by a physician avoids the need for aggressive diagnostic and therapeutic procedures.

- Ruiz-Maldonado R, Durán-McKinster C, Tamayo-Sánchez L, Orozco-Covarrubias ML. Dermatosis neglecta: dirt crusts simulating verrucous nevi. Arch Dermatol 1999; 135:728–729.

- Akkash L, Badran D, Al-Omari AQ. Terra firma forme dermatosis. Case series and review of the literature. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges 2009; 7:102–107.

- Qadir SN, Ejaz A, Raza N. Dermatosis neglecta in a case of multiple fractures, shoulder dislocation and radial nerve palsy in a 35-year-old man: a case report. J Med Case Reports 2008; 2:347.

- Lucas JL, Brodell RT, Feldman SR. Dermatosis neglecta: a series of case reports and review of other dirty-appearing dermatoses. Dermatol Online J 2006; 12:5.

Q: On the basis of the skin findings, which test should be ordered to establish a diagnosis?

- Biopsy of the lesions

- Hemoglobin A1C

- Fungal culture

- Brush with soap and water or alcohol

- Bacterial culture

A: Patchy brown, waxy scales in a patient who neglects normal cleansing should raise the possibility of dermatosis neglecta. Hence, brushing with soap and water or alcohol is the correct answer.

In this patient, the plaques were easily removed using an alcohol-soaked swab, revealing underlying normal skin with bleeding spots. The patient’s family was instructed to lightly scrub the area daily with a washcloth, soap, and water. The lesions resolved completely over the next 3 weeks.

DERMATOSIS NEGLECTA

Dermatosis neglecta is a condition that results from the accumulation in the epidermal stratum corium of sebum, sweat, corneocytes, and bacterias in areas of unwashed skin. It affects all age groups, and it has a similar prevalence in both sexes. Sometimes, an underlying physical disability or emotional problem is the cause, other times it is due to prior trauma or hyperesthesia of the affected area. Dermatosis neglecta presents with asymptomatic areas of dark brown patches or plaque with cornflake-like scales and a verrucous surface.1–4 The diagnosis is usually easy and is based on the characteristic findings and the simple test described above. For treatment, in some cases a keratolytic lotion containing lactic acid, glycolic acid, urea, or salicylic acid is helpful.4

MISDIAGNOSIS IS EASY

Dermatosis neglecta could easily be misdiagnosed as verrucous epidermal nevus, terra firma-forme dermatosis, acanthosis nigricans, or another less common dermatosis of “dirty skin” lesions, such as confluent and reticulate papillomatosis (Gougerot-Carteaud syndrome).2–4

Verrucous epidermal nevus appears at birth or early childhood. Patients have verrucous papules and plaques that commonly follow a narrow linear distribution.

Acanthosis nigricans is characterized by broad, velvety, hyperpigmented smooth plaques on the neck, axillae, and flexures. It is related to insulin resistance, obesity, and underlying malignancy.

Confluent and reticulate papillomatosis is a rare dermatosis of unknown cause, with a pigmented reticular pattern distributed on the central trunk. Patients tend to practice normal hygiene.

Terra firma-forme dermatosis is characterized by dirt-like patches that are resistant to usual hygiene measures but that can be eliminated by rubbing with isopropyl alcohol. The cause is unknown, and it is not related to a lack of cleansing. It is considered a variant of dermatosis neglecta.

The medical literature contains few reports of dermatosis neglecta, but the true incidence is probably underestimated. Early recognition by a physician avoids the need for aggressive diagnostic and therapeutic procedures.

Q: On the basis of the skin findings, which test should be ordered to establish a diagnosis?

- Biopsy of the lesions

- Hemoglobin A1C

- Fungal culture

- Brush with soap and water or alcohol

- Bacterial culture

A: Patchy brown, waxy scales in a patient who neglects normal cleansing should raise the possibility of dermatosis neglecta. Hence, brushing with soap and water or alcohol is the correct answer.

In this patient, the plaques were easily removed using an alcohol-soaked swab, revealing underlying normal skin with bleeding spots. The patient’s family was instructed to lightly scrub the area daily with a washcloth, soap, and water. The lesions resolved completely over the next 3 weeks.

DERMATOSIS NEGLECTA

Dermatosis neglecta is a condition that results from the accumulation in the epidermal stratum corium of sebum, sweat, corneocytes, and bacterias in areas of unwashed skin. It affects all age groups, and it has a similar prevalence in both sexes. Sometimes, an underlying physical disability or emotional problem is the cause, other times it is due to prior trauma or hyperesthesia of the affected area. Dermatosis neglecta presents with asymptomatic areas of dark brown patches or plaque with cornflake-like scales and a verrucous surface.1–4 The diagnosis is usually easy and is based on the characteristic findings and the simple test described above. For treatment, in some cases a keratolytic lotion containing lactic acid, glycolic acid, urea, or salicylic acid is helpful.4

MISDIAGNOSIS IS EASY

Dermatosis neglecta could easily be misdiagnosed as verrucous epidermal nevus, terra firma-forme dermatosis, acanthosis nigricans, or another less common dermatosis of “dirty skin” lesions, such as confluent and reticulate papillomatosis (Gougerot-Carteaud syndrome).2–4

Verrucous epidermal nevus appears at birth or early childhood. Patients have verrucous papules and plaques that commonly follow a narrow linear distribution.

Acanthosis nigricans is characterized by broad, velvety, hyperpigmented smooth plaques on the neck, axillae, and flexures. It is related to insulin resistance, obesity, and underlying malignancy.

Confluent and reticulate papillomatosis is a rare dermatosis of unknown cause, with a pigmented reticular pattern distributed on the central trunk. Patients tend to practice normal hygiene.

Terra firma-forme dermatosis is characterized by dirt-like patches that are resistant to usual hygiene measures but that can be eliminated by rubbing with isopropyl alcohol. The cause is unknown, and it is not related to a lack of cleansing. It is considered a variant of dermatosis neglecta.

The medical literature contains few reports of dermatosis neglecta, but the true incidence is probably underestimated. Early recognition by a physician avoids the need for aggressive diagnostic and therapeutic procedures.

- Ruiz-Maldonado R, Durán-McKinster C, Tamayo-Sánchez L, Orozco-Covarrubias ML. Dermatosis neglecta: dirt crusts simulating verrucous nevi. Arch Dermatol 1999; 135:728–729.

- Akkash L, Badran D, Al-Omari AQ. Terra firma forme dermatosis. Case series and review of the literature. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges 2009; 7:102–107.

- Qadir SN, Ejaz A, Raza N. Dermatosis neglecta in a case of multiple fractures, shoulder dislocation and radial nerve palsy in a 35-year-old man: a case report. J Med Case Reports 2008; 2:347.

- Lucas JL, Brodell RT, Feldman SR. Dermatosis neglecta: a series of case reports and review of other dirty-appearing dermatoses. Dermatol Online J 2006; 12:5.

- Ruiz-Maldonado R, Durán-McKinster C, Tamayo-Sánchez L, Orozco-Covarrubias ML. Dermatosis neglecta: dirt crusts simulating verrucous nevi. Arch Dermatol 1999; 135:728–729.

- Akkash L, Badran D, Al-Omari AQ. Terra firma forme dermatosis. Case series and review of the literature. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges 2009; 7:102–107.

- Qadir SN, Ejaz A, Raza N. Dermatosis neglecta in a case of multiple fractures, shoulder dislocation and radial nerve palsy in a 35-year-old man: a case report. J Med Case Reports 2008; 2:347.

- Lucas JL, Brodell RT, Feldman SR. Dermatosis neglecta: a series of case reports and review of other dirty-appearing dermatoses. Dermatol Online J 2006; 12:5.

Palmoplantar eruption

A 38-year-old woman presents with recurrent asymptomatic lesions on the palms and soles and on the sides of both feet. The lesions have been developing for 2 months, unaccompanied by fever or other systemic symptoms.

Laboratory tests of C-reactive protein, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, viral serologies, and antinuclear antibodies are normal. A pustule culture is negative, and a cutaneous biopsy shows parakeratosis and elongation of rete ridges, neutrophils migrating from papillary capillaries to the epidermis, and spongiform Kogoj pustule.

Q: Which is the most likely diagnosis?

- Pustular psoriasis

- Impetigo contagiosa

- Syndrome of synovitis, acne, pustulosis, hyperostosis, osteitis (SAPHO)

- Dyshidrotic eczema

- Acute exanthematous pustulosis (drug eruption)

A: SAPHO syndrome is the most likely diagnosis. The presence of pustules and aseptic osteitis of the anterior chest wall is compatible with SAPHO syndrome. Treatment with topical clobetasol propionate (Temovate) for pustules and NSAIDs for osteitis brought a good response.

Pustular psoriasis is an uncommon type of psoriasis characterized by erythema and pustules involving the flexural and anogenital areas. Cutaneous lesions of psoriasis vulgaris may be present before an acute pustular episode. Withdrawal of systemic corticosteroids in a patient with psoriasis has been reported as a precipitating factor.