User login

The eyes: A window into the past

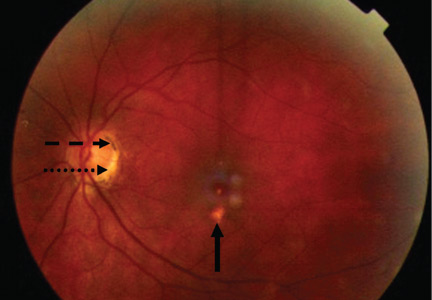

A 34-year-old woman living in southern California presents for a routine physical examination. During the eye examination, the physician notices “spots” on the retina and refers the patient to a retinal specialist.

The patient has no complaints about her vision. She has myopia (−4.5 diopters), corrected with glasses. She has no family history of ocular disease. Her medical history is unremarkable, and she is taking no medications.

THE MOST LIKELY DIAGNOSIS

The lesions raise the suspicion of histoplasmosis, but since the patient has no other evidence of histoplasmosis, the likely diagnosis is presumed ocular histoplasmosis syndrome (POHS).

Further questioning reveals that the woman grew up on a farm in the Ohio River valley, one of two areas in the United States where Histoplasma capsulatum is highly endemic.1 (The other area is the Mississippi River valley.)

As this case shows, POHS is important to consider, especially in areas where H capsulatum is not endemic, to avert a lengthy workup for other causes of retinal lesions. It also shows the importance of a thorough history, including previous residences and travel.2

Pathogenesis is uncertain

In histoplasmosis, the infection is acquired by inhalation of microconidia of H capsulatum, usually via disruption of the soil (as in farming) and especially in areas where there are bird roosts. Infection is often asymptomatic, and fewer than 1% of people exposed develop a clinical illness 7 to 21 days after exposure.3

In disseminated histoplasmosis, eye involvement manifests as panophthalmitis or uveitis, caused by yeast implantation. The finding of eye lesions typical of histoplasmosis but in the absence of signs of disseminated histoplasmosis— as in POHS—is much more common, seen in perhaps 1% to 5% of residents in highly endemic areas.4

The pathogenesis of POHS and its association with histoplasmosis are still unclear.4–7 Some have proposed a cellular immune response to deposited fungal antigens. Others contend that patients with specific human leukocyte antigen types (eg, B7, DR2) may be susceptible.4H capsulatum DNA has been isolated in one case of POHS,6 and the classic ocular lesions are prevalent in people who live in the Ohio River valley.7 Therefore, even though a definitive causative relationship between H capsulatum exposure and POHS has not been proven, the ocular lesions are presumed to be the result of previous exposure to H capsulatum, as in this case.

Establishing the diagnosis of POHS

Most cases of POHS are detected on routine eye examination. The diagnosis is confirmed by a dilated eye examination showing peripheral, punched-out, atrophic scars (“histospots”), which represent focal defects in the Bruch membrane, along with a history of living in an area endemic for H capsulatum. Histo-spots range from 0.2 to 0.7 disk diameters and can occur as single or multiple lesions.8 Most often, both eyes are involved, albeit asymmetrically.9 Some areas may contain pigment deposits, as in this case.8 Peripapillary atrophy, a thinning of the retina immediately surrounding the head of the optic nerve, is also characteristic of POHS. Active inflammation in the anterior chamber and vitreous are absent.

Although most patients with POHS do not have a documented diagnosis of previous clinical Histoplasma infection, they may have a positive histoplasmin skin test, as well as lung, liver, or spleen calcifications. However, skin testing is not recommended as it may exacerbate POHS,9 and serologic testing is usually negative.10

POHS has most commonly been diagnosed in whites ages 20 to 50 (mean age 35). Men and women appear to be equally affected.

The potential for vision loss

Very few patients with ophthalmoscopic evidence of POHS develop visual symptoms.7 Still, there is a risk of choroidal neovascularization at the site of the choroidal scars. These new vessels can hemorrhage, causing impaired central vision (distorted vision, blind spots).

The trigger for choroidal neovascularization is unknown; exposure to fungal antigens and eye surgery such as LASIK have been proposed. 11 Choroidal neovascularization usually occurs 10 to 20 years after scar formation and occurs in fewer than 5% of POHS patients.10,12

HOW THE PATIENT WAS MANAGED

Given that the patient had POHS with no evidence of neovascularization, she was followed with serial visual assessments using an Amsler grid.11 For POHS with choroidal neovascularization, treatment focuses on reducing the risk of vascular complications and includes oral corticosteroids, intravitreal corticosteroid injections, laser photocoagulation, and photodynamic therapy with verteporfin (Visudyne). 4,10,13–15 Antifungal treatment is not useful, as the lesions are not proven to be caused by active infection.10

Future treatments may include antiangiogenic drugs and gene therapy.9

Since her diagnosis, the patient’s visual tests have been stable, with no neovascularization.

- Edwards LB, Acquaviva FA, Livesay VT, Cross FW, Palmer CE. An atlas of sensitivity to tuberculin, PPD-B, and histoplasmin in the United States. Am Rev Respir Dis 1969; 99: suppl:1–132.

- Wheat LJ. Histoplasmosis: a review for clinicians from non-endemic areas. Mycoses 2006; 49:274–282.

- Kauffman CA. Histoplasmosis: a clinical and laboratory update. Clin Microbiol Rev 2007; 20:115–132.

- Prasad AG, Van Gelder RN. Presumed ocular histoplasmosis syndrome. Curr Opin Ophthalmol 2005; 16:364–368.

- Ongkosuwito JV, Kortbeek LM, Van der Lelij A, et al. Aetiological study of the presumed ocular histoplasmosis syndrome in the Netherlands. Br J Ophthalmol 1999; 83:535–539.

- Spencer WH, Chan CC, Shen DF, Rao NA. Detection of Histoplasma capsulatum DNA in lesions of chronic ocular histoplasmosis syndrome. Arch Ophthalmol 2003; 121:1551–1555.

- Find SL. Ocular histoplasmosis syndrome. Int Ophthalmol Clin 1977; 17:75–87.

- McMillan TA, Lashkari K. Ocular histoplasmosis. Int Ophthalmol Clin 1996; 36:179–186.

- Ciulla TA, Piper HC, Xiao M, Wheat LJ. Presumed ocular histoplasmosis syndrome: update on epidemiology, pathogenesis, and photodynamic, antiangiogenic, and surgical therapies. Curr Opin Ophthalmol 2001; 12:442–449.

- Oliver A, Ciulla TA, Comer GM. New and classic insights into presumed ocular histoplasmosis syndrome and its treatment. Curr Opin Ophthalmol 2005; 16:160–165.

- Trevino R, Salvat R. Preventing reactivation of ocular histoplasmosis: guidance for patients at risk. Optometry 2006; 77:10–16.

- Macular Photocoagulation Study Group. Five-year followup of fellow eyes of individuals with ocular histoplasmosis and unilateral extrafoveal or juxtafoveal choroidal neovascularization. Arch Ophthalmol 1996; 114:677–688.

- Rosenfeld PJ, Saperstein DA, Bressler NM, et al; Verteporfin in Ocular Histoplasmosis Study Group. Photodynamic therapy with verteporfin in ocular histoplasmosis: uncontrolled, open-label 2-year study. Ophthalmology 2004; 111:1725–1733.

- Shah GK, Blinder KJ, Hariprasad SM, et al. Photodynamic therapy for juxtafoveal choroidal neovascularization due to ocular histoplasmosis syndrome. Retina 2005; 25:26–32.

- Rechtman E, Allen VD, Danis RP, Pratt LM, Harris A, Speicher MA. Intravitreal triamcinolone for choroidal neovascularization in ocular histoplasmosis syndrome. Am J Ophthalmol 2003; 136:739–741.

A 34-year-old woman living in southern California presents for a routine physical examination. During the eye examination, the physician notices “spots” on the retina and refers the patient to a retinal specialist.

The patient has no complaints about her vision. She has myopia (−4.5 diopters), corrected with glasses. She has no family history of ocular disease. Her medical history is unremarkable, and she is taking no medications.

THE MOST LIKELY DIAGNOSIS

The lesions raise the suspicion of histoplasmosis, but since the patient has no other evidence of histoplasmosis, the likely diagnosis is presumed ocular histoplasmosis syndrome (POHS).

Further questioning reveals that the woman grew up on a farm in the Ohio River valley, one of two areas in the United States where Histoplasma capsulatum is highly endemic.1 (The other area is the Mississippi River valley.)

As this case shows, POHS is important to consider, especially in areas where H capsulatum is not endemic, to avert a lengthy workup for other causes of retinal lesions. It also shows the importance of a thorough history, including previous residences and travel.2

Pathogenesis is uncertain

In histoplasmosis, the infection is acquired by inhalation of microconidia of H capsulatum, usually via disruption of the soil (as in farming) and especially in areas where there are bird roosts. Infection is often asymptomatic, and fewer than 1% of people exposed develop a clinical illness 7 to 21 days after exposure.3

In disseminated histoplasmosis, eye involvement manifests as panophthalmitis or uveitis, caused by yeast implantation. The finding of eye lesions typical of histoplasmosis but in the absence of signs of disseminated histoplasmosis— as in POHS—is much more common, seen in perhaps 1% to 5% of residents in highly endemic areas.4

The pathogenesis of POHS and its association with histoplasmosis are still unclear.4–7 Some have proposed a cellular immune response to deposited fungal antigens. Others contend that patients with specific human leukocyte antigen types (eg, B7, DR2) may be susceptible.4H capsulatum DNA has been isolated in one case of POHS,6 and the classic ocular lesions are prevalent in people who live in the Ohio River valley.7 Therefore, even though a definitive causative relationship between H capsulatum exposure and POHS has not been proven, the ocular lesions are presumed to be the result of previous exposure to H capsulatum, as in this case.

Establishing the diagnosis of POHS

Most cases of POHS are detected on routine eye examination. The diagnosis is confirmed by a dilated eye examination showing peripheral, punched-out, atrophic scars (“histospots”), which represent focal defects in the Bruch membrane, along with a history of living in an area endemic for H capsulatum. Histo-spots range from 0.2 to 0.7 disk diameters and can occur as single or multiple lesions.8 Most often, both eyes are involved, albeit asymmetrically.9 Some areas may contain pigment deposits, as in this case.8 Peripapillary atrophy, a thinning of the retina immediately surrounding the head of the optic nerve, is also characteristic of POHS. Active inflammation in the anterior chamber and vitreous are absent.

Although most patients with POHS do not have a documented diagnosis of previous clinical Histoplasma infection, they may have a positive histoplasmin skin test, as well as lung, liver, or spleen calcifications. However, skin testing is not recommended as it may exacerbate POHS,9 and serologic testing is usually negative.10

POHS has most commonly been diagnosed in whites ages 20 to 50 (mean age 35). Men and women appear to be equally affected.

The potential for vision loss

Very few patients with ophthalmoscopic evidence of POHS develop visual symptoms.7 Still, there is a risk of choroidal neovascularization at the site of the choroidal scars. These new vessels can hemorrhage, causing impaired central vision (distorted vision, blind spots).

The trigger for choroidal neovascularization is unknown; exposure to fungal antigens and eye surgery such as LASIK have been proposed. 11 Choroidal neovascularization usually occurs 10 to 20 years after scar formation and occurs in fewer than 5% of POHS patients.10,12

HOW THE PATIENT WAS MANAGED

Given that the patient had POHS with no evidence of neovascularization, she was followed with serial visual assessments using an Amsler grid.11 For POHS with choroidal neovascularization, treatment focuses on reducing the risk of vascular complications and includes oral corticosteroids, intravitreal corticosteroid injections, laser photocoagulation, and photodynamic therapy with verteporfin (Visudyne). 4,10,13–15 Antifungal treatment is not useful, as the lesions are not proven to be caused by active infection.10

Future treatments may include antiangiogenic drugs and gene therapy.9

Since her diagnosis, the patient’s visual tests have been stable, with no neovascularization.

A 34-year-old woman living in southern California presents for a routine physical examination. During the eye examination, the physician notices “spots” on the retina and refers the patient to a retinal specialist.

The patient has no complaints about her vision. She has myopia (−4.5 diopters), corrected with glasses. She has no family history of ocular disease. Her medical history is unremarkable, and she is taking no medications.

THE MOST LIKELY DIAGNOSIS

The lesions raise the suspicion of histoplasmosis, but since the patient has no other evidence of histoplasmosis, the likely diagnosis is presumed ocular histoplasmosis syndrome (POHS).

Further questioning reveals that the woman grew up on a farm in the Ohio River valley, one of two areas in the United States where Histoplasma capsulatum is highly endemic.1 (The other area is the Mississippi River valley.)

As this case shows, POHS is important to consider, especially in areas where H capsulatum is not endemic, to avert a lengthy workup for other causes of retinal lesions. It also shows the importance of a thorough history, including previous residences and travel.2

Pathogenesis is uncertain

In histoplasmosis, the infection is acquired by inhalation of microconidia of H capsulatum, usually via disruption of the soil (as in farming) and especially in areas where there are bird roosts. Infection is often asymptomatic, and fewer than 1% of people exposed develop a clinical illness 7 to 21 days after exposure.3

In disseminated histoplasmosis, eye involvement manifests as panophthalmitis or uveitis, caused by yeast implantation. The finding of eye lesions typical of histoplasmosis but in the absence of signs of disseminated histoplasmosis— as in POHS—is much more common, seen in perhaps 1% to 5% of residents in highly endemic areas.4

The pathogenesis of POHS and its association with histoplasmosis are still unclear.4–7 Some have proposed a cellular immune response to deposited fungal antigens. Others contend that patients with specific human leukocyte antigen types (eg, B7, DR2) may be susceptible.4H capsulatum DNA has been isolated in one case of POHS,6 and the classic ocular lesions are prevalent in people who live in the Ohio River valley.7 Therefore, even though a definitive causative relationship between H capsulatum exposure and POHS has not been proven, the ocular lesions are presumed to be the result of previous exposure to H capsulatum, as in this case.

Establishing the diagnosis of POHS

Most cases of POHS are detected on routine eye examination. The diagnosis is confirmed by a dilated eye examination showing peripheral, punched-out, atrophic scars (“histospots”), which represent focal defects in the Bruch membrane, along with a history of living in an area endemic for H capsulatum. Histo-spots range from 0.2 to 0.7 disk diameters and can occur as single or multiple lesions.8 Most often, both eyes are involved, albeit asymmetrically.9 Some areas may contain pigment deposits, as in this case.8 Peripapillary atrophy, a thinning of the retina immediately surrounding the head of the optic nerve, is also characteristic of POHS. Active inflammation in the anterior chamber and vitreous are absent.

Although most patients with POHS do not have a documented diagnosis of previous clinical Histoplasma infection, they may have a positive histoplasmin skin test, as well as lung, liver, or spleen calcifications. However, skin testing is not recommended as it may exacerbate POHS,9 and serologic testing is usually negative.10

POHS has most commonly been diagnosed in whites ages 20 to 50 (mean age 35). Men and women appear to be equally affected.

The potential for vision loss

Very few patients with ophthalmoscopic evidence of POHS develop visual symptoms.7 Still, there is a risk of choroidal neovascularization at the site of the choroidal scars. These new vessels can hemorrhage, causing impaired central vision (distorted vision, blind spots).

The trigger for choroidal neovascularization is unknown; exposure to fungal antigens and eye surgery such as LASIK have been proposed. 11 Choroidal neovascularization usually occurs 10 to 20 years after scar formation and occurs in fewer than 5% of POHS patients.10,12

HOW THE PATIENT WAS MANAGED

Given that the patient had POHS with no evidence of neovascularization, she was followed with serial visual assessments using an Amsler grid.11 For POHS with choroidal neovascularization, treatment focuses on reducing the risk of vascular complications and includes oral corticosteroids, intravitreal corticosteroid injections, laser photocoagulation, and photodynamic therapy with verteporfin (Visudyne). 4,10,13–15 Antifungal treatment is not useful, as the lesions are not proven to be caused by active infection.10

Future treatments may include antiangiogenic drugs and gene therapy.9

Since her diagnosis, the patient’s visual tests have been stable, with no neovascularization.

- Edwards LB, Acquaviva FA, Livesay VT, Cross FW, Palmer CE. An atlas of sensitivity to tuberculin, PPD-B, and histoplasmin in the United States. Am Rev Respir Dis 1969; 99: suppl:1–132.

- Wheat LJ. Histoplasmosis: a review for clinicians from non-endemic areas. Mycoses 2006; 49:274–282.

- Kauffman CA. Histoplasmosis: a clinical and laboratory update. Clin Microbiol Rev 2007; 20:115–132.

- Prasad AG, Van Gelder RN. Presumed ocular histoplasmosis syndrome. Curr Opin Ophthalmol 2005; 16:364–368.

- Ongkosuwito JV, Kortbeek LM, Van der Lelij A, et al. Aetiological study of the presumed ocular histoplasmosis syndrome in the Netherlands. Br J Ophthalmol 1999; 83:535–539.

- Spencer WH, Chan CC, Shen DF, Rao NA. Detection of Histoplasma capsulatum DNA in lesions of chronic ocular histoplasmosis syndrome. Arch Ophthalmol 2003; 121:1551–1555.

- Find SL. Ocular histoplasmosis syndrome. Int Ophthalmol Clin 1977; 17:75–87.

- McMillan TA, Lashkari K. Ocular histoplasmosis. Int Ophthalmol Clin 1996; 36:179–186.

- Ciulla TA, Piper HC, Xiao M, Wheat LJ. Presumed ocular histoplasmosis syndrome: update on epidemiology, pathogenesis, and photodynamic, antiangiogenic, and surgical therapies. Curr Opin Ophthalmol 2001; 12:442–449.

- Oliver A, Ciulla TA, Comer GM. New and classic insights into presumed ocular histoplasmosis syndrome and its treatment. Curr Opin Ophthalmol 2005; 16:160–165.

- Trevino R, Salvat R. Preventing reactivation of ocular histoplasmosis: guidance for patients at risk. Optometry 2006; 77:10–16.

- Macular Photocoagulation Study Group. Five-year followup of fellow eyes of individuals with ocular histoplasmosis and unilateral extrafoveal or juxtafoveal choroidal neovascularization. Arch Ophthalmol 1996; 114:677–688.

- Rosenfeld PJ, Saperstein DA, Bressler NM, et al; Verteporfin in Ocular Histoplasmosis Study Group. Photodynamic therapy with verteporfin in ocular histoplasmosis: uncontrolled, open-label 2-year study. Ophthalmology 2004; 111:1725–1733.

- Shah GK, Blinder KJ, Hariprasad SM, et al. Photodynamic therapy for juxtafoveal choroidal neovascularization due to ocular histoplasmosis syndrome. Retina 2005; 25:26–32.

- Rechtman E, Allen VD, Danis RP, Pratt LM, Harris A, Speicher MA. Intravitreal triamcinolone for choroidal neovascularization in ocular histoplasmosis syndrome. Am J Ophthalmol 2003; 136:739–741.

- Edwards LB, Acquaviva FA, Livesay VT, Cross FW, Palmer CE. An atlas of sensitivity to tuberculin, PPD-B, and histoplasmin in the United States. Am Rev Respir Dis 1969; 99: suppl:1–132.

- Wheat LJ. Histoplasmosis: a review for clinicians from non-endemic areas. Mycoses 2006; 49:274–282.

- Kauffman CA. Histoplasmosis: a clinical and laboratory update. Clin Microbiol Rev 2007; 20:115–132.

- Prasad AG, Van Gelder RN. Presumed ocular histoplasmosis syndrome. Curr Opin Ophthalmol 2005; 16:364–368.

- Ongkosuwito JV, Kortbeek LM, Van der Lelij A, et al. Aetiological study of the presumed ocular histoplasmosis syndrome in the Netherlands. Br J Ophthalmol 1999; 83:535–539.

- Spencer WH, Chan CC, Shen DF, Rao NA. Detection of Histoplasma capsulatum DNA in lesions of chronic ocular histoplasmosis syndrome. Arch Ophthalmol 2003; 121:1551–1555.

- Find SL. Ocular histoplasmosis syndrome. Int Ophthalmol Clin 1977; 17:75–87.

- McMillan TA, Lashkari K. Ocular histoplasmosis. Int Ophthalmol Clin 1996; 36:179–186.

- Ciulla TA, Piper HC, Xiao M, Wheat LJ. Presumed ocular histoplasmosis syndrome: update on epidemiology, pathogenesis, and photodynamic, antiangiogenic, and surgical therapies. Curr Opin Ophthalmol 2001; 12:442–449.

- Oliver A, Ciulla TA, Comer GM. New and classic insights into presumed ocular histoplasmosis syndrome and its treatment. Curr Opin Ophthalmol 2005; 16:160–165.

- Trevino R, Salvat R. Preventing reactivation of ocular histoplasmosis: guidance for patients at risk. Optometry 2006; 77:10–16.

- Macular Photocoagulation Study Group. Five-year followup of fellow eyes of individuals with ocular histoplasmosis and unilateral extrafoveal or juxtafoveal choroidal neovascularization. Arch Ophthalmol 1996; 114:677–688.

- Rosenfeld PJ, Saperstein DA, Bressler NM, et al; Verteporfin in Ocular Histoplasmosis Study Group. Photodynamic therapy with verteporfin in ocular histoplasmosis: uncontrolled, open-label 2-year study. Ophthalmology 2004; 111:1725–1733.

- Shah GK, Blinder KJ, Hariprasad SM, et al. Photodynamic therapy for juxtafoveal choroidal neovascularization due to ocular histoplasmosis syndrome. Retina 2005; 25:26–32.

- Rechtman E, Allen VD, Danis RP, Pratt LM, Harris A, Speicher MA. Intravitreal triamcinolone for choroidal neovascularization in ocular histoplasmosis syndrome. Am J Ophthalmol 2003; 136:739–741.

An erythematous plaque on the arm

A healthy 68-year-old farmer presents with an asymptomatic skin lesion on his right arm that appeared spontaneously without trauma or bite 5 months ago and has grown progressively since then.

Q: Which is the most likely diagnosis?

- Squamous cell carcinoma

- Cutaneous lymphoma

- Cutaneous mycobacteriosis

- Sarcoidosis

- Lichen planus

As for the other possibilities:

Cutaneous lymphoma, characterized by atypical proliferation of T or B lymphocytes in the skin, usually presents as a slow-growing indurated nodule or plaque.

Cutaneous mycobacteriosis is caused by infection with Mycobacterium tuberculosis, M leprae, or M marinum. Caseous granulomas are often found on histopathologic study, but special culture and polymerase chain reaction tests are necessary for the diagnosis. Clinically, the lesion is an indurated nodule or plaque that grows slowly, with decreased sensitivity in the case of leprosy, and with a sporotrichoid pattern in the case of M marinum infection.

Our patient underwent a tuberculin skin test, which was negative, as were polymerase chain reaction testing and culture of the biopsy material for mycobacteria.

Sarcoidosis is a systemic disease of unknown cause characterized by noncaseous granulomas in the lungs, mediastinum, lymph nodes, or other sites.1 Cutaneous involvement includes nonspecific clinical forms (eg, nodosum erythema) and other more specific forms (eg, maculopapular, subcutaneous, cicatricial, or lupus pernio variants). This patient has no granulomas on skin biopsy.

Lichen planus is a chronic inflammatory disease of unknown cause that affects the skin, genitalia, mucous membranes, or appendages. It appears as pruritic purple polygonal papules with Wickham striae, usually affecting the wrists and ankles.

A COMMON FORM OF SKIN CANCER

Squamous cell carcinoma and basal cell carcinoma account for 95% of cases of nonmelanomatous skin cancer, and the incidence of squamous cell carcinoma has been increasing.

Long-term exposure to ultraviolet radiation (ie, sunlight), often related to occupation, is the most common cause of squamous cell carcinoma. Other risk factors include thermal injury or burns, ionizing radiation, human papilloma virus infection, immunosuppressive therapy (eg, after organ transplantation2), exposure to chemical carcinogens, and diseases such as xeroderma pigmentosum or oculocutaneous albinism. Unlike basal cell carcinoma, which usually arises de novo, squamous cell carcinoma often arises from precursor lesions, such as actinic keratosis and Bowen disease.

Squamous cell carcinoma commonly manifests as shallow ulcers, often with a keratinous crust and an elevated, indurated border, but also as plaques or nodules, as in this patient. Incipient lesions present as erythematous, firm, keratotic papules, but the lesions on sun-exposed areas such as the head or neck can be pigmented.

The surrounding skin usually shows changes of actinic damage, usually with ulceration, scaling, crusting, or verrucous appearance. When the lesion presents as an erythematous plaque, as in this patient, mycobacterial infection and cutaneous lymphoma should be ruled out. Histologic studies and culture for mycobacteria are necessary for an acute diagnosis. Other conditions in the differential diagnosis are keratoacanthoma, cutaneous metastasis, and sarcoidosis.

The only way to confirm the diagnosis of squamous cell carcinoma is to obtain a specimen by biopsy or surgical excision. Histologic features include atypical keratinocytes extending from the epidermis to the dermis, with dyskeratosis, intercellular bridges, variable central keratinization, and “horn pearls,” depending on how well or how poorly differentiated the tumor.3 Most squamous cell carcinomas arise in solar keratoses, usually at the periphery of the tumor.

Most squamous cell carcinomas are only locally aggressive. Tumors greater than 5 mm in thickness have a 20% risk of metastasis.

TREATMENT OPTIONS

Surgical excision is the most common treatment. Other options are cryotherapy, topical chemotherapy, curettage and electrodesiccation, radiotherapy, and Mohs micrographic surgery. Photodynamic therapy or imiquimod (Aldara) are used only for noninvasive forms.

The possibility of metastasis should be investigated in cases of extensive squamous cell carcinoma, when mucous membranes are affected, and when squamous cell lesions are poorly differentiated.

Our patient’s tumor was removed, with adequate safety margins in surface and depth, and with dermo-epidermal graft closure. The lesion has not recurred at 9 months of follow-up.

- Hunninghake GW, Costabel U, Ando M, et al. ATS/ERS/WASOG statement on sarcoidosis. American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society/World Association of Sarcoidosis and other Granulomatous Disorders. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis 1999; 16:149–173.

- Rubel JR, Milford EL, Abdi R. Cutaneous neoplasms in renal transplant recipients. Eur J Dermatol 2002; 12:532–535.

- Cassarino DS, Derienzo DP, Barr RJ. Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma: a comprehensive clinicopathologic classification—part two. J Cutan Pathol 2006; 33:261–279.

A healthy 68-year-old farmer presents with an asymptomatic skin lesion on his right arm that appeared spontaneously without trauma or bite 5 months ago and has grown progressively since then.

Q: Which is the most likely diagnosis?

- Squamous cell carcinoma

- Cutaneous lymphoma

- Cutaneous mycobacteriosis

- Sarcoidosis

- Lichen planus

As for the other possibilities:

Cutaneous lymphoma, characterized by atypical proliferation of T or B lymphocytes in the skin, usually presents as a slow-growing indurated nodule or plaque.

Cutaneous mycobacteriosis is caused by infection with Mycobacterium tuberculosis, M leprae, or M marinum. Caseous granulomas are often found on histopathologic study, but special culture and polymerase chain reaction tests are necessary for the diagnosis. Clinically, the lesion is an indurated nodule or plaque that grows slowly, with decreased sensitivity in the case of leprosy, and with a sporotrichoid pattern in the case of M marinum infection.

Our patient underwent a tuberculin skin test, which was negative, as were polymerase chain reaction testing and culture of the biopsy material for mycobacteria.

Sarcoidosis is a systemic disease of unknown cause characterized by noncaseous granulomas in the lungs, mediastinum, lymph nodes, or other sites.1 Cutaneous involvement includes nonspecific clinical forms (eg, nodosum erythema) and other more specific forms (eg, maculopapular, subcutaneous, cicatricial, or lupus pernio variants). This patient has no granulomas on skin biopsy.

Lichen planus is a chronic inflammatory disease of unknown cause that affects the skin, genitalia, mucous membranes, or appendages. It appears as pruritic purple polygonal papules with Wickham striae, usually affecting the wrists and ankles.

A COMMON FORM OF SKIN CANCER

Squamous cell carcinoma and basal cell carcinoma account for 95% of cases of nonmelanomatous skin cancer, and the incidence of squamous cell carcinoma has been increasing.

Long-term exposure to ultraviolet radiation (ie, sunlight), often related to occupation, is the most common cause of squamous cell carcinoma. Other risk factors include thermal injury or burns, ionizing radiation, human papilloma virus infection, immunosuppressive therapy (eg, after organ transplantation2), exposure to chemical carcinogens, and diseases such as xeroderma pigmentosum or oculocutaneous albinism. Unlike basal cell carcinoma, which usually arises de novo, squamous cell carcinoma often arises from precursor lesions, such as actinic keratosis and Bowen disease.

Squamous cell carcinoma commonly manifests as shallow ulcers, often with a keratinous crust and an elevated, indurated border, but also as plaques or nodules, as in this patient. Incipient lesions present as erythematous, firm, keratotic papules, but the lesions on sun-exposed areas such as the head or neck can be pigmented.

The surrounding skin usually shows changes of actinic damage, usually with ulceration, scaling, crusting, or verrucous appearance. When the lesion presents as an erythematous plaque, as in this patient, mycobacterial infection and cutaneous lymphoma should be ruled out. Histologic studies and culture for mycobacteria are necessary for an acute diagnosis. Other conditions in the differential diagnosis are keratoacanthoma, cutaneous metastasis, and sarcoidosis.

The only way to confirm the diagnosis of squamous cell carcinoma is to obtain a specimen by biopsy or surgical excision. Histologic features include atypical keratinocytes extending from the epidermis to the dermis, with dyskeratosis, intercellular bridges, variable central keratinization, and “horn pearls,” depending on how well or how poorly differentiated the tumor.3 Most squamous cell carcinomas arise in solar keratoses, usually at the periphery of the tumor.

Most squamous cell carcinomas are only locally aggressive. Tumors greater than 5 mm in thickness have a 20% risk of metastasis.

TREATMENT OPTIONS

Surgical excision is the most common treatment. Other options are cryotherapy, topical chemotherapy, curettage and electrodesiccation, radiotherapy, and Mohs micrographic surgery. Photodynamic therapy or imiquimod (Aldara) are used only for noninvasive forms.

The possibility of metastasis should be investigated in cases of extensive squamous cell carcinoma, when mucous membranes are affected, and when squamous cell lesions are poorly differentiated.

Our patient’s tumor was removed, with adequate safety margins in surface and depth, and with dermo-epidermal graft closure. The lesion has not recurred at 9 months of follow-up.

A healthy 68-year-old farmer presents with an asymptomatic skin lesion on his right arm that appeared spontaneously without trauma or bite 5 months ago and has grown progressively since then.

Q: Which is the most likely diagnosis?

- Squamous cell carcinoma

- Cutaneous lymphoma

- Cutaneous mycobacteriosis

- Sarcoidosis

- Lichen planus

As for the other possibilities:

Cutaneous lymphoma, characterized by atypical proliferation of T or B lymphocytes in the skin, usually presents as a slow-growing indurated nodule or plaque.

Cutaneous mycobacteriosis is caused by infection with Mycobacterium tuberculosis, M leprae, or M marinum. Caseous granulomas are often found on histopathologic study, but special culture and polymerase chain reaction tests are necessary for the diagnosis. Clinically, the lesion is an indurated nodule or plaque that grows slowly, with decreased sensitivity in the case of leprosy, and with a sporotrichoid pattern in the case of M marinum infection.

Our patient underwent a tuberculin skin test, which was negative, as were polymerase chain reaction testing and culture of the biopsy material for mycobacteria.

Sarcoidosis is a systemic disease of unknown cause characterized by noncaseous granulomas in the lungs, mediastinum, lymph nodes, or other sites.1 Cutaneous involvement includes nonspecific clinical forms (eg, nodosum erythema) and other more specific forms (eg, maculopapular, subcutaneous, cicatricial, or lupus pernio variants). This patient has no granulomas on skin biopsy.

Lichen planus is a chronic inflammatory disease of unknown cause that affects the skin, genitalia, mucous membranes, or appendages. It appears as pruritic purple polygonal papules with Wickham striae, usually affecting the wrists and ankles.

A COMMON FORM OF SKIN CANCER

Squamous cell carcinoma and basal cell carcinoma account for 95% of cases of nonmelanomatous skin cancer, and the incidence of squamous cell carcinoma has been increasing.

Long-term exposure to ultraviolet radiation (ie, sunlight), often related to occupation, is the most common cause of squamous cell carcinoma. Other risk factors include thermal injury or burns, ionizing radiation, human papilloma virus infection, immunosuppressive therapy (eg, after organ transplantation2), exposure to chemical carcinogens, and diseases such as xeroderma pigmentosum or oculocutaneous albinism. Unlike basal cell carcinoma, which usually arises de novo, squamous cell carcinoma often arises from precursor lesions, such as actinic keratosis and Bowen disease.

Squamous cell carcinoma commonly manifests as shallow ulcers, often with a keratinous crust and an elevated, indurated border, but also as plaques or nodules, as in this patient. Incipient lesions present as erythematous, firm, keratotic papules, but the lesions on sun-exposed areas such as the head or neck can be pigmented.

The surrounding skin usually shows changes of actinic damage, usually with ulceration, scaling, crusting, or verrucous appearance. When the lesion presents as an erythematous plaque, as in this patient, mycobacterial infection and cutaneous lymphoma should be ruled out. Histologic studies and culture for mycobacteria are necessary for an acute diagnosis. Other conditions in the differential diagnosis are keratoacanthoma, cutaneous metastasis, and sarcoidosis.

The only way to confirm the diagnosis of squamous cell carcinoma is to obtain a specimen by biopsy or surgical excision. Histologic features include atypical keratinocytes extending from the epidermis to the dermis, with dyskeratosis, intercellular bridges, variable central keratinization, and “horn pearls,” depending on how well or how poorly differentiated the tumor.3 Most squamous cell carcinomas arise in solar keratoses, usually at the periphery of the tumor.

Most squamous cell carcinomas are only locally aggressive. Tumors greater than 5 mm in thickness have a 20% risk of metastasis.

TREATMENT OPTIONS

Surgical excision is the most common treatment. Other options are cryotherapy, topical chemotherapy, curettage and electrodesiccation, radiotherapy, and Mohs micrographic surgery. Photodynamic therapy or imiquimod (Aldara) are used only for noninvasive forms.

The possibility of metastasis should be investigated in cases of extensive squamous cell carcinoma, when mucous membranes are affected, and when squamous cell lesions are poorly differentiated.

Our patient’s tumor was removed, with adequate safety margins in surface and depth, and with dermo-epidermal graft closure. The lesion has not recurred at 9 months of follow-up.

- Hunninghake GW, Costabel U, Ando M, et al. ATS/ERS/WASOG statement on sarcoidosis. American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society/World Association of Sarcoidosis and other Granulomatous Disorders. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis 1999; 16:149–173.

- Rubel JR, Milford EL, Abdi R. Cutaneous neoplasms in renal transplant recipients. Eur J Dermatol 2002; 12:532–535.

- Cassarino DS, Derienzo DP, Barr RJ. Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma: a comprehensive clinicopathologic classification—part two. J Cutan Pathol 2006; 33:261–279.

- Hunninghake GW, Costabel U, Ando M, et al. ATS/ERS/WASOG statement on sarcoidosis. American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society/World Association of Sarcoidosis and other Granulomatous Disorders. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis 1999; 16:149–173.

- Rubel JR, Milford EL, Abdi R. Cutaneous neoplasms in renal transplant recipients. Eur J Dermatol 2002; 12:532–535.

- Cassarino DS, Derienzo DP, Barr RJ. Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma: a comprehensive clinicopathologic classification—part two. J Cutan Pathol 2006; 33:261–279.

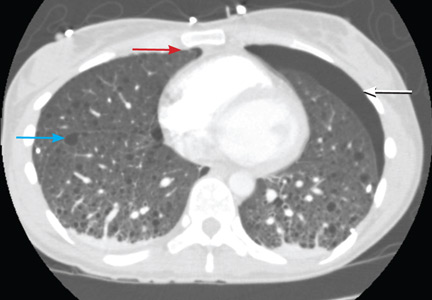

Recurrent spontaneous pneumothorax

Q: Which is the most likely diagnosis?

- Pulmonary Langerhans cell histiocytosis

- Cystic fibrosis

- Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia

- Alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency

- Tuberous sclerosis complex with lymphangioleiomyomatosis

A: The correct diagnosis is tuberous sclerosis complex with lymphangioleiomyomatosis. The lymphangioleiomyomatosis was suggested by the CT findings, by the recurrence of pneumothorax, and, later, by biopsy results. Lymphangioleiomyomatosis occurs in about 30% of women with the tuberous sclerosis complex.1 However, 10% to 15% of women with lymphangioleiomyomatosis do not have tuberous sclerosis complex, 2 in which case the condition is called sporadic lymphangioleiomyomatosis.

Tuberous sclerosis complex can involve the nerves (seizures, brain tumors), the lungs (lymphangioleiomyomatosis, causing pneumothorax or chylothorax), and the skin; skin lesions include facial angiofibromas (Figure 1), ash-leaf spot (Figure 2), and shagreen patch (Figure 3). It is also associated with abdominal involvement (lymphangiomyomas, renal angiomyolipomas).3

Lymphangioleiomyomatosis usually presents as spontaneous pneumothorax in women of childbearing age. After initial stabilization of pneumothorax with simple aspiration or thoracostomy, the patient should undergo ipsilateral chemical or surgical pleurodesis, as the risk of recurrent pneumothorax is greater than 70%.4 Single or bilateral lung transplantation has been accepted as therapy for end-stage pulmonary lymphangioleiomyomatosis, characterized by recurrent pneumothoraces and chylous pleural fluid collections causing respiratory failure (marked dyspnea, hypoxemia, and reductions in forced expiratory volume in the first second of expiration and in diffusing capacity for carbon monoxide. Recurrence of lymphangioleiomyomatosis in the allograft lung is rare.5 Hormone therapies such as intramuscular progesterone, oral progestins, or gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists have been used for lymphangioleiomyomatosis (not pneumothorax), but they are no longer recommended.

Pulmonary Langerhans cell histiocytosis, cystic fibrosis, Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia, and alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency have all been associated with spontaneous pneumothorax.

Pulmonary Langerhans cell histiocytosis can affect multiple systems, including lung, skin, bone, and the pituitary gland. More than 90% of patients have a history of smoking.6 Chest radiography reveals a reticulonodular pattern with involvement of the middle and upper lobes. Later, the nodules tend to cavitate and form contiguous cysts that may mimic lymphangioleiomyomatosis on a high-resolution chest CT.

Cystic fibrosis is most often diagnosed before the age of 3.7 In adults, it can present as sinus and pulmonary disease (chronic cough with sputum production, chronic sinusitis with nasal polyposis, radiographic evidence of bronchiectasis and, less commonly, pneumothorax); as a gastrointestinal tract and nutritional abnormality (pancreatic insufficiency, distal intestinal obstruction, focal biliary cirrhosis); and as male infertility.

Pneumocystis jiroveciipneumonia occurs mainly in patients on chronic immunosuppressive drugs or with immune deficiency due to HIV infection. Typical radiographic features are bilateral perihilar interstitial infiltrates that become increasingly homogeneous and diffuse as the disease progresses. Less common findings include solitary or multiple nodules, upper-lobe infiltrates in patients receiving aerosolized pentamidine (NebuPent), pneumatoceles, and pneumothorax.8

Alpha-1 antitrypsin is an inhibitor of neutrophil elastase. Deficiency is associated with severe, early-onset panacinar emphysema with a basilar predominance, with chronic liver disease including cirrhosis, and less commonly with panniculitis and vasculitis associated with antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody.9 Coalescence of panacinar emphysema leads to the formation of bullae and is important in the development of spontaneous pneumothorax.10

The patient underwent bilateral talc pleurodesis. Lung biopsy at the same time confirmed lymphangioleiomyomatosis. One month later, the right pneumothorax recurred, and she underwent pleurodesis in the right hemithorax with tetracycline. Six months after the second pleurodesis, she was asymptomatic.

- Costello LC, Hartman TE, Ryu JH. High frequency of pulmonary lymphangioleiomyomatosis in women with tuberous sclerosis complex. Mayo Clin Proc 2000; 75:591–594.

- Strizheva GD, Carsillo T, Kruger WD, Sullivan EJ, Ryu JH, Henske EP. The spectrum of mutations in TSC1 and TSC2 in women with tuberous sclerosis and lymphangiomyomatosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2001; 163:253–258.

- McCormack FX. Lymphangioleiomyomatosis: a clinical update. Chest 2008; 133:507–516.

- Almoosa KF, Ryu JH, Mendez J, et al. Management of pneumothorax in lymphangioleiomyomatosis: effects on recurrence and lung transplantation complications. Chest 2006; 129:1274–1281.

- Benden C, Rea F, Behr J, et al. Lung transplantation for lymphangioleiomyomatosis: the European Experience. J Heart Lung Transplant 2009; 28:1–7.

- Vassallo R, Ryu JH, Colby TV, Hartman T, Limper AH. Pulmonary Langerhans’-cell histiocytosis. N Engl J Med 2000; 342:1969–1978.

- Boyle MP. Adult cystic fibrosis. JAMA 2007; 298:1787–1793.

- Thomas CF, Limper AH. Pneumocystis pneumonia. N Engl J Med 2004; 350:2487–2498.

- Silverman EK, Sandhaus RA. Clinical practice. Alpha1-antitrypsin deficiency. N Engl J Med 2009; 360:2749–2757.

- Anderson AE, Furlaneto JA, Foraker AG. Bronchopulmonary derangements in nonsmokers. Am Rev Respir Dis 1970; 101:518–527.

Q: Which is the most likely diagnosis?

- Pulmonary Langerhans cell histiocytosis

- Cystic fibrosis

- Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia

- Alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency

- Tuberous sclerosis complex with lymphangioleiomyomatosis

A: The correct diagnosis is tuberous sclerosis complex with lymphangioleiomyomatosis. The lymphangioleiomyomatosis was suggested by the CT findings, by the recurrence of pneumothorax, and, later, by biopsy results. Lymphangioleiomyomatosis occurs in about 30% of women with the tuberous sclerosis complex.1 However, 10% to 15% of women with lymphangioleiomyomatosis do not have tuberous sclerosis complex, 2 in which case the condition is called sporadic lymphangioleiomyomatosis.

Tuberous sclerosis complex can involve the nerves (seizures, brain tumors), the lungs (lymphangioleiomyomatosis, causing pneumothorax or chylothorax), and the skin; skin lesions include facial angiofibromas (Figure 1), ash-leaf spot (Figure 2), and shagreen patch (Figure 3). It is also associated with abdominal involvement (lymphangiomyomas, renal angiomyolipomas).3

Lymphangioleiomyomatosis usually presents as spontaneous pneumothorax in women of childbearing age. After initial stabilization of pneumothorax with simple aspiration or thoracostomy, the patient should undergo ipsilateral chemical or surgical pleurodesis, as the risk of recurrent pneumothorax is greater than 70%.4 Single or bilateral lung transplantation has been accepted as therapy for end-stage pulmonary lymphangioleiomyomatosis, characterized by recurrent pneumothoraces and chylous pleural fluid collections causing respiratory failure (marked dyspnea, hypoxemia, and reductions in forced expiratory volume in the first second of expiration and in diffusing capacity for carbon monoxide. Recurrence of lymphangioleiomyomatosis in the allograft lung is rare.5 Hormone therapies such as intramuscular progesterone, oral progestins, or gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists have been used for lymphangioleiomyomatosis (not pneumothorax), but they are no longer recommended.

Pulmonary Langerhans cell histiocytosis, cystic fibrosis, Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia, and alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency have all been associated with spontaneous pneumothorax.

Pulmonary Langerhans cell histiocytosis can affect multiple systems, including lung, skin, bone, and the pituitary gland. More than 90% of patients have a history of smoking.6 Chest radiography reveals a reticulonodular pattern with involvement of the middle and upper lobes. Later, the nodules tend to cavitate and form contiguous cysts that may mimic lymphangioleiomyomatosis on a high-resolution chest CT.

Cystic fibrosis is most often diagnosed before the age of 3.7 In adults, it can present as sinus and pulmonary disease (chronic cough with sputum production, chronic sinusitis with nasal polyposis, radiographic evidence of bronchiectasis and, less commonly, pneumothorax); as a gastrointestinal tract and nutritional abnormality (pancreatic insufficiency, distal intestinal obstruction, focal biliary cirrhosis); and as male infertility.

Pneumocystis jiroveciipneumonia occurs mainly in patients on chronic immunosuppressive drugs or with immune deficiency due to HIV infection. Typical radiographic features are bilateral perihilar interstitial infiltrates that become increasingly homogeneous and diffuse as the disease progresses. Less common findings include solitary or multiple nodules, upper-lobe infiltrates in patients receiving aerosolized pentamidine (NebuPent), pneumatoceles, and pneumothorax.8

Alpha-1 antitrypsin is an inhibitor of neutrophil elastase. Deficiency is associated with severe, early-onset panacinar emphysema with a basilar predominance, with chronic liver disease including cirrhosis, and less commonly with panniculitis and vasculitis associated with antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody.9 Coalescence of panacinar emphysema leads to the formation of bullae and is important in the development of spontaneous pneumothorax.10

The patient underwent bilateral talc pleurodesis. Lung biopsy at the same time confirmed lymphangioleiomyomatosis. One month later, the right pneumothorax recurred, and she underwent pleurodesis in the right hemithorax with tetracycline. Six months after the second pleurodesis, she was asymptomatic.

Q: Which is the most likely diagnosis?

- Pulmonary Langerhans cell histiocytosis

- Cystic fibrosis

- Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia

- Alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency

- Tuberous sclerosis complex with lymphangioleiomyomatosis

A: The correct diagnosis is tuberous sclerosis complex with lymphangioleiomyomatosis. The lymphangioleiomyomatosis was suggested by the CT findings, by the recurrence of pneumothorax, and, later, by biopsy results. Lymphangioleiomyomatosis occurs in about 30% of women with the tuberous sclerosis complex.1 However, 10% to 15% of women with lymphangioleiomyomatosis do not have tuberous sclerosis complex, 2 in which case the condition is called sporadic lymphangioleiomyomatosis.

Tuberous sclerosis complex can involve the nerves (seizures, brain tumors), the lungs (lymphangioleiomyomatosis, causing pneumothorax or chylothorax), and the skin; skin lesions include facial angiofibromas (Figure 1), ash-leaf spot (Figure 2), and shagreen patch (Figure 3). It is also associated with abdominal involvement (lymphangiomyomas, renal angiomyolipomas).3

Lymphangioleiomyomatosis usually presents as spontaneous pneumothorax in women of childbearing age. After initial stabilization of pneumothorax with simple aspiration or thoracostomy, the patient should undergo ipsilateral chemical or surgical pleurodesis, as the risk of recurrent pneumothorax is greater than 70%.4 Single or bilateral lung transplantation has been accepted as therapy for end-stage pulmonary lymphangioleiomyomatosis, characterized by recurrent pneumothoraces and chylous pleural fluid collections causing respiratory failure (marked dyspnea, hypoxemia, and reductions in forced expiratory volume in the first second of expiration and in diffusing capacity for carbon monoxide. Recurrence of lymphangioleiomyomatosis in the allograft lung is rare.5 Hormone therapies such as intramuscular progesterone, oral progestins, or gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists have been used for lymphangioleiomyomatosis (not pneumothorax), but they are no longer recommended.

Pulmonary Langerhans cell histiocytosis, cystic fibrosis, Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia, and alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency have all been associated with spontaneous pneumothorax.

Pulmonary Langerhans cell histiocytosis can affect multiple systems, including lung, skin, bone, and the pituitary gland. More than 90% of patients have a history of smoking.6 Chest radiography reveals a reticulonodular pattern with involvement of the middle and upper lobes. Later, the nodules tend to cavitate and form contiguous cysts that may mimic lymphangioleiomyomatosis on a high-resolution chest CT.

Cystic fibrosis is most often diagnosed before the age of 3.7 In adults, it can present as sinus and pulmonary disease (chronic cough with sputum production, chronic sinusitis with nasal polyposis, radiographic evidence of bronchiectasis and, less commonly, pneumothorax); as a gastrointestinal tract and nutritional abnormality (pancreatic insufficiency, distal intestinal obstruction, focal biliary cirrhosis); and as male infertility.

Pneumocystis jiroveciipneumonia occurs mainly in patients on chronic immunosuppressive drugs or with immune deficiency due to HIV infection. Typical radiographic features are bilateral perihilar interstitial infiltrates that become increasingly homogeneous and diffuse as the disease progresses. Less common findings include solitary or multiple nodules, upper-lobe infiltrates in patients receiving aerosolized pentamidine (NebuPent), pneumatoceles, and pneumothorax.8

Alpha-1 antitrypsin is an inhibitor of neutrophil elastase. Deficiency is associated with severe, early-onset panacinar emphysema with a basilar predominance, with chronic liver disease including cirrhosis, and less commonly with panniculitis and vasculitis associated with antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody.9 Coalescence of panacinar emphysema leads to the formation of bullae and is important in the development of spontaneous pneumothorax.10

The patient underwent bilateral talc pleurodesis. Lung biopsy at the same time confirmed lymphangioleiomyomatosis. One month later, the right pneumothorax recurred, and she underwent pleurodesis in the right hemithorax with tetracycline. Six months after the second pleurodesis, she was asymptomatic.

- Costello LC, Hartman TE, Ryu JH. High frequency of pulmonary lymphangioleiomyomatosis in women with tuberous sclerosis complex. Mayo Clin Proc 2000; 75:591–594.

- Strizheva GD, Carsillo T, Kruger WD, Sullivan EJ, Ryu JH, Henske EP. The spectrum of mutations in TSC1 and TSC2 in women with tuberous sclerosis and lymphangiomyomatosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2001; 163:253–258.

- McCormack FX. Lymphangioleiomyomatosis: a clinical update. Chest 2008; 133:507–516.

- Almoosa KF, Ryu JH, Mendez J, et al. Management of pneumothorax in lymphangioleiomyomatosis: effects on recurrence and lung transplantation complications. Chest 2006; 129:1274–1281.

- Benden C, Rea F, Behr J, et al. Lung transplantation for lymphangioleiomyomatosis: the European Experience. J Heart Lung Transplant 2009; 28:1–7.

- Vassallo R, Ryu JH, Colby TV, Hartman T, Limper AH. Pulmonary Langerhans’-cell histiocytosis. N Engl J Med 2000; 342:1969–1978.

- Boyle MP. Adult cystic fibrosis. JAMA 2007; 298:1787–1793.

- Thomas CF, Limper AH. Pneumocystis pneumonia. N Engl J Med 2004; 350:2487–2498.

- Silverman EK, Sandhaus RA. Clinical practice. Alpha1-antitrypsin deficiency. N Engl J Med 2009; 360:2749–2757.

- Anderson AE, Furlaneto JA, Foraker AG. Bronchopulmonary derangements in nonsmokers. Am Rev Respir Dis 1970; 101:518–527.

- Costello LC, Hartman TE, Ryu JH. High frequency of pulmonary lymphangioleiomyomatosis in women with tuberous sclerosis complex. Mayo Clin Proc 2000; 75:591–594.

- Strizheva GD, Carsillo T, Kruger WD, Sullivan EJ, Ryu JH, Henske EP. The spectrum of mutations in TSC1 and TSC2 in women with tuberous sclerosis and lymphangiomyomatosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2001; 163:253–258.

- McCormack FX. Lymphangioleiomyomatosis: a clinical update. Chest 2008; 133:507–516.

- Almoosa KF, Ryu JH, Mendez J, et al. Management of pneumothorax in lymphangioleiomyomatosis: effects on recurrence and lung transplantation complications. Chest 2006; 129:1274–1281.

- Benden C, Rea F, Behr J, et al. Lung transplantation for lymphangioleiomyomatosis: the European Experience. J Heart Lung Transplant 2009; 28:1–7.

- Vassallo R, Ryu JH, Colby TV, Hartman T, Limper AH. Pulmonary Langerhans’-cell histiocytosis. N Engl J Med 2000; 342:1969–1978.

- Boyle MP. Adult cystic fibrosis. JAMA 2007; 298:1787–1793.

- Thomas CF, Limper AH. Pneumocystis pneumonia. N Engl J Med 2004; 350:2487–2498.

- Silverman EK, Sandhaus RA. Clinical practice. Alpha1-antitrypsin deficiency. N Engl J Med 2009; 360:2749–2757.

- Anderson AE, Furlaneto JA, Foraker AG. Bronchopulmonary derangements in nonsmokers. Am Rev Respir Dis 1970; 101:518–527.

A rare complication of infective endocarditis

An 85-year-old woman presented to the emergency department with a 2-hour history of dyspnea, dizziness, generalized weakness, nausea, and diaphoresis. Her medical history included hypertension, end-stage renal disease with hemodialysis, and atrial fibrillation.

She had an arteriovenous fistula for dialysis access in her right upper arm, with erythema around the site.

Her creatine kinase level was 1,434 U/L (normal range 30–220), creatine kinase MB 143.4 ng/mL (0.0–8.8 ng/mL), and troponin T 0.1 ng/mL (0.0–0.1 ng/mL). She had ST elevation in leads I and aVL. She was taken for emergency cardiac catheterization.

Three blood cultures were drawn on the day of cardiac catheterization. Two grew gram-positive organisms: one grew coagulase-negative Staphylococcus, and the other grew gram-positive bacilli (anaerobic, non-sporeforming). On the basis of these findings, intravenous vancomycin (Vancocin) was started. Seventy-two hours later, one of two blood cultures again grew coagulase-negative Staphylococcus. Five days after the start of antibiotic treatment, blood cultures were negative, and the patient received intravenous vancomycin for 4 weeks (from the time the blood cultures became negative) for native mitral valve endocarditis.

EMBOLISM AND ENDOCARDITIS: KEY FEATURES

An embolic event occurs in 22% to 50% of cases of infective endocarditis and can involve the lungs, bowel, other organs, or extremities.1 The incidence of embolization of the coronary arteries in patients with infective endocarditis is unknown, but in one case series2 it occurred in 8 (7.5%) of 107 cases. The most common site of coronary embolism is the LAD.3

Myocardial infarction is a rare complication of coronary artery embolization.2 It was reported in 17 (2.9%) of 586 consecutive patients with infective endocarditis.4 In patients with infectious endocarditis complicated by myocardial infarction, the death rate was nearly double that seen in patients with infective endocarditis without myocardial infarction (64% vs 33%).4

TREATMENT

The best treatment for this complication of infective endocarditis is not known, as it has not been well studied. The high death rate in these patients makes restoration of coronary perfusion essential.

Thrombolytics are usually avoided in patients with septic embolization because of concerns about concurrent intracerebral mycotic aneurysms and the risk of hemorrhage.

Percutaneous transluminal angioplasty carries a risk of distal mobilization of emboli, development of mycotic aneurysm at the balloon dilation site, or reocclusion due to a mobile embolus.5 Stent placement may improve vessel patency but carries a theoretic risk of infection in bacteremic patients. Percutaneous embolectomy has also been used either prior to or instead of stent placement.6 Surgical options include embolectomy in patients who may require surgery, and coronary artery bypass grafting for patients with chronic embolization.7

- Baddour LM, Wilson WR, Bayer AS, et al; Committee on Rheumatic Fever, Endocarditis, and Kawasaki Disease; Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young; Councils on Clinical Cardiology, Stroke, and Cardiovascular Surgery and Anesthesia; American Heart Association; Infectious Diseases Society of America. Infective endocarditis: diagnosis, antimicrobial therapy, and management of complications: a statement for healthcare professionals from the Committee on Rheumatic Fever, Endocarditis, and Kawasaki Disease, Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young, and the Councils on Clinical Cardiology, Stroke, and Cardiovascular Surgery and Anesthesia, American Heart Association: endorsed by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Circulation 2005; 111:e394–e434.

- Garvey GJ, Neu HC. Infective endocarditis—an evolving disease. A review of endocarditis at Columbia-Presbyterian Medical Center, 1968–1973. Medicine (Baltimore) 1978; 57:105–127.

- Glazier JJ. Interventional treatment of septic coronary embolism: sailing into uncharted and dangerous waters. J Interv Cardiol 2002; 15:305–307.

- Manzano MC, Vilacosta I, San Roman JA, et al. Acute cornary syndrome in infective endocarditis. Rev Esp Cardiol 2007; 60:24–31.

- Khan F, Khakoo R, Failinger C. Managing embolic myocardial infarction in infective endocarditis: current options. J Infect 2005; 51:e101–105.

- Glazier JJ, McGinnity JG, Spears JR. Coronary embolism complicating aortic valve endocarditis: treatment with placement of an intracoronary stent. Clin Cardiol 1997; 20:885–888.

- Baek MJ, Kim HK, Yu CW, Na CY. Surgery with surgical embolectomy for mitral valve endocarditis complicated by septic coronary embolism. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2008; 33:116–118.

An 85-year-old woman presented to the emergency department with a 2-hour history of dyspnea, dizziness, generalized weakness, nausea, and diaphoresis. Her medical history included hypertension, end-stage renal disease with hemodialysis, and atrial fibrillation.

She had an arteriovenous fistula for dialysis access in her right upper arm, with erythema around the site.

Her creatine kinase level was 1,434 U/L (normal range 30–220), creatine kinase MB 143.4 ng/mL (0.0–8.8 ng/mL), and troponin T 0.1 ng/mL (0.0–0.1 ng/mL). She had ST elevation in leads I and aVL. She was taken for emergency cardiac catheterization.

Three blood cultures were drawn on the day of cardiac catheterization. Two grew gram-positive organisms: one grew coagulase-negative Staphylococcus, and the other grew gram-positive bacilli (anaerobic, non-sporeforming). On the basis of these findings, intravenous vancomycin (Vancocin) was started. Seventy-two hours later, one of two blood cultures again grew coagulase-negative Staphylococcus. Five days after the start of antibiotic treatment, blood cultures were negative, and the patient received intravenous vancomycin for 4 weeks (from the time the blood cultures became negative) for native mitral valve endocarditis.

EMBOLISM AND ENDOCARDITIS: KEY FEATURES

An embolic event occurs in 22% to 50% of cases of infective endocarditis and can involve the lungs, bowel, other organs, or extremities.1 The incidence of embolization of the coronary arteries in patients with infective endocarditis is unknown, but in one case series2 it occurred in 8 (7.5%) of 107 cases. The most common site of coronary embolism is the LAD.3

Myocardial infarction is a rare complication of coronary artery embolization.2 It was reported in 17 (2.9%) of 586 consecutive patients with infective endocarditis.4 In patients with infectious endocarditis complicated by myocardial infarction, the death rate was nearly double that seen in patients with infective endocarditis without myocardial infarction (64% vs 33%).4

TREATMENT

The best treatment for this complication of infective endocarditis is not known, as it has not been well studied. The high death rate in these patients makes restoration of coronary perfusion essential.

Thrombolytics are usually avoided in patients with septic embolization because of concerns about concurrent intracerebral mycotic aneurysms and the risk of hemorrhage.

Percutaneous transluminal angioplasty carries a risk of distal mobilization of emboli, development of mycotic aneurysm at the balloon dilation site, or reocclusion due to a mobile embolus.5 Stent placement may improve vessel patency but carries a theoretic risk of infection in bacteremic patients. Percutaneous embolectomy has also been used either prior to or instead of stent placement.6 Surgical options include embolectomy in patients who may require surgery, and coronary artery bypass grafting for patients with chronic embolization.7

An 85-year-old woman presented to the emergency department with a 2-hour history of dyspnea, dizziness, generalized weakness, nausea, and diaphoresis. Her medical history included hypertension, end-stage renal disease with hemodialysis, and atrial fibrillation.

She had an arteriovenous fistula for dialysis access in her right upper arm, with erythema around the site.

Her creatine kinase level was 1,434 U/L (normal range 30–220), creatine kinase MB 143.4 ng/mL (0.0–8.8 ng/mL), and troponin T 0.1 ng/mL (0.0–0.1 ng/mL). She had ST elevation in leads I and aVL. She was taken for emergency cardiac catheterization.

Three blood cultures were drawn on the day of cardiac catheterization. Two grew gram-positive organisms: one grew coagulase-negative Staphylococcus, and the other grew gram-positive bacilli (anaerobic, non-sporeforming). On the basis of these findings, intravenous vancomycin (Vancocin) was started. Seventy-two hours later, one of two blood cultures again grew coagulase-negative Staphylococcus. Five days after the start of antibiotic treatment, blood cultures were negative, and the patient received intravenous vancomycin for 4 weeks (from the time the blood cultures became negative) for native mitral valve endocarditis.

EMBOLISM AND ENDOCARDITIS: KEY FEATURES

An embolic event occurs in 22% to 50% of cases of infective endocarditis and can involve the lungs, bowel, other organs, or extremities.1 The incidence of embolization of the coronary arteries in patients with infective endocarditis is unknown, but in one case series2 it occurred in 8 (7.5%) of 107 cases. The most common site of coronary embolism is the LAD.3

Myocardial infarction is a rare complication of coronary artery embolization.2 It was reported in 17 (2.9%) of 586 consecutive patients with infective endocarditis.4 In patients with infectious endocarditis complicated by myocardial infarction, the death rate was nearly double that seen in patients with infective endocarditis without myocardial infarction (64% vs 33%).4

TREATMENT

The best treatment for this complication of infective endocarditis is not known, as it has not been well studied. The high death rate in these patients makes restoration of coronary perfusion essential.

Thrombolytics are usually avoided in patients with septic embolization because of concerns about concurrent intracerebral mycotic aneurysms and the risk of hemorrhage.

Percutaneous transluminal angioplasty carries a risk of distal mobilization of emboli, development of mycotic aneurysm at the balloon dilation site, or reocclusion due to a mobile embolus.5 Stent placement may improve vessel patency but carries a theoretic risk of infection in bacteremic patients. Percutaneous embolectomy has also been used either prior to or instead of stent placement.6 Surgical options include embolectomy in patients who may require surgery, and coronary artery bypass grafting for patients with chronic embolization.7

- Baddour LM, Wilson WR, Bayer AS, et al; Committee on Rheumatic Fever, Endocarditis, and Kawasaki Disease; Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young; Councils on Clinical Cardiology, Stroke, and Cardiovascular Surgery and Anesthesia; American Heart Association; Infectious Diseases Society of America. Infective endocarditis: diagnosis, antimicrobial therapy, and management of complications: a statement for healthcare professionals from the Committee on Rheumatic Fever, Endocarditis, and Kawasaki Disease, Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young, and the Councils on Clinical Cardiology, Stroke, and Cardiovascular Surgery and Anesthesia, American Heart Association: endorsed by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Circulation 2005; 111:e394–e434.

- Garvey GJ, Neu HC. Infective endocarditis—an evolving disease. A review of endocarditis at Columbia-Presbyterian Medical Center, 1968–1973. Medicine (Baltimore) 1978; 57:105–127.

- Glazier JJ. Interventional treatment of septic coronary embolism: sailing into uncharted and dangerous waters. J Interv Cardiol 2002; 15:305–307.

- Manzano MC, Vilacosta I, San Roman JA, et al. Acute cornary syndrome in infective endocarditis. Rev Esp Cardiol 2007; 60:24–31.

- Khan F, Khakoo R, Failinger C. Managing embolic myocardial infarction in infective endocarditis: current options. J Infect 2005; 51:e101–105.

- Glazier JJ, McGinnity JG, Spears JR. Coronary embolism complicating aortic valve endocarditis: treatment with placement of an intracoronary stent. Clin Cardiol 1997; 20:885–888.

- Baek MJ, Kim HK, Yu CW, Na CY. Surgery with surgical embolectomy for mitral valve endocarditis complicated by septic coronary embolism. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2008; 33:116–118.

- Baddour LM, Wilson WR, Bayer AS, et al; Committee on Rheumatic Fever, Endocarditis, and Kawasaki Disease; Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young; Councils on Clinical Cardiology, Stroke, and Cardiovascular Surgery and Anesthesia; American Heart Association; Infectious Diseases Society of America. Infective endocarditis: diagnosis, antimicrobial therapy, and management of complications: a statement for healthcare professionals from the Committee on Rheumatic Fever, Endocarditis, and Kawasaki Disease, Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young, and the Councils on Clinical Cardiology, Stroke, and Cardiovascular Surgery and Anesthesia, American Heart Association: endorsed by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Circulation 2005; 111:e394–e434.

- Garvey GJ, Neu HC. Infective endocarditis—an evolving disease. A review of endocarditis at Columbia-Presbyterian Medical Center, 1968–1973. Medicine (Baltimore) 1978; 57:105–127.

- Glazier JJ. Interventional treatment of septic coronary embolism: sailing into uncharted and dangerous waters. J Interv Cardiol 2002; 15:305–307.

- Manzano MC, Vilacosta I, San Roman JA, et al. Acute cornary syndrome in infective endocarditis. Rev Esp Cardiol 2007; 60:24–31.

- Khan F, Khakoo R, Failinger C. Managing embolic myocardial infarction in infective endocarditis: current options. J Infect 2005; 51:e101–105.

- Glazier JJ, McGinnity JG, Spears JR. Coronary embolism complicating aortic valve endocarditis: treatment with placement of an intracoronary stent. Clin Cardiol 1997; 20:885–888.

- Baek MJ, Kim HK, Yu CW, Na CY. Surgery with surgical embolectomy for mitral valve endocarditis complicated by septic coronary embolism. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2008; 33:116–118.

A rash on the legs and palms

Q: Which is the most likely diagnosis?

- Psoriasis

- Pityriasis rubra pilaris

- Dyshidrotic eczema

- Keratoderma

- Contact dermatitis

A: The diagnosis is pityriasis rubra pilaris, a rare condition with a prevalence of 1 in 5,000 to 50,000 new dermatology patient visits.1 It is a papulosquamous disorder that presents with areas of hyperkeratosis on an erythematous base. Large red plaques often coalesce, leaving areas of uninvolved skin (“islands of sparing”). The palms and soles often reveal a distinctive orange-red waxy keratoderma.1

Clinically, pityriasis rubra pilaris can be difficult to differentiate from psoriasis, and it can progress to disabling palmoplantar keratoderma and erythroderma.

BASIS OF THE DIAGNOSIS

The diagnosis is based on characteristic findings supported by classic features on skin biopsy. Microscopic study shows a psoriasiform dermatitis with alternating vertical and horizontal orthokeratosis and parakeratosis (the “checkerboard pattern”).

Although an underlying dysfunction in vitamin A metabolism has been suggested, the exact cause and pathogenesis of pityriasis rubra pilaris are not known.

TREATMENT

Treatment of pityriasis rubra pilaris can be difficult, as no one single treatment works for all patients. Systemic retinoids, methotrexate, phototherapy, and cyclosporine are commonly used. Recent reports have shown the effectiveness of infliximab (Remicade), a chimeric monoclonal antibody that binds to soluble and membrane-bound forms of tumor necrosis factor alpha.2,3

In our patient, after a 2-month course of acitretin (Soriatane) failed, three treatments with infliximab—5 mg/kg at baseline, at 2 weeks, and at 6 weeks—led to complete resolution of the condition.

- Selvaag E, Haedersdal M, Thomsen K. Pityriasis rubra pilaris: a retrospective study of 12 patients. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2000; 14:514–515.

- Liao WC, Mutasim DF. Infliximab for the treatment of adult-onset pityriasis rubra pilaris. Arch Dermatol 2005; 141:423–425.

- Müller H, Gattringer C, Zelger B, Höpfl R, Eisendle K. Infliximab monotherapy as first-line treatment for adultonset pityriasis rubra pilaris: case report and review of the literature on biologic therapy. J Am Acad Dermatol 2008; 59( suppl 5):S65–S70.

Q: Which is the most likely diagnosis?

- Psoriasis

- Pityriasis rubra pilaris

- Dyshidrotic eczema

- Keratoderma

- Contact dermatitis

A: The diagnosis is pityriasis rubra pilaris, a rare condition with a prevalence of 1 in 5,000 to 50,000 new dermatology patient visits.1 It is a papulosquamous disorder that presents with areas of hyperkeratosis on an erythematous base. Large red plaques often coalesce, leaving areas of uninvolved skin (“islands of sparing”). The palms and soles often reveal a distinctive orange-red waxy keratoderma.1

Clinically, pityriasis rubra pilaris can be difficult to differentiate from psoriasis, and it can progress to disabling palmoplantar keratoderma and erythroderma.

BASIS OF THE DIAGNOSIS

The diagnosis is based on characteristic findings supported by classic features on skin biopsy. Microscopic study shows a psoriasiform dermatitis with alternating vertical and horizontal orthokeratosis and parakeratosis (the “checkerboard pattern”).

Although an underlying dysfunction in vitamin A metabolism has been suggested, the exact cause and pathogenesis of pityriasis rubra pilaris are not known.

TREATMENT

Treatment of pityriasis rubra pilaris can be difficult, as no one single treatment works for all patients. Systemic retinoids, methotrexate, phototherapy, and cyclosporine are commonly used. Recent reports have shown the effectiveness of infliximab (Remicade), a chimeric monoclonal antibody that binds to soluble and membrane-bound forms of tumor necrosis factor alpha.2,3

In our patient, after a 2-month course of acitretin (Soriatane) failed, three treatments with infliximab—5 mg/kg at baseline, at 2 weeks, and at 6 weeks—led to complete resolution of the condition.

Q: Which is the most likely diagnosis?

- Psoriasis

- Pityriasis rubra pilaris

- Dyshidrotic eczema

- Keratoderma

- Contact dermatitis

A: The diagnosis is pityriasis rubra pilaris, a rare condition with a prevalence of 1 in 5,000 to 50,000 new dermatology patient visits.1 It is a papulosquamous disorder that presents with areas of hyperkeratosis on an erythematous base. Large red plaques often coalesce, leaving areas of uninvolved skin (“islands of sparing”). The palms and soles often reveal a distinctive orange-red waxy keratoderma.1

Clinically, pityriasis rubra pilaris can be difficult to differentiate from psoriasis, and it can progress to disabling palmoplantar keratoderma and erythroderma.

BASIS OF THE DIAGNOSIS

The diagnosis is based on characteristic findings supported by classic features on skin biopsy. Microscopic study shows a psoriasiform dermatitis with alternating vertical and horizontal orthokeratosis and parakeratosis (the “checkerboard pattern”).

Although an underlying dysfunction in vitamin A metabolism has been suggested, the exact cause and pathogenesis of pityriasis rubra pilaris are not known.

TREATMENT

Treatment of pityriasis rubra pilaris can be difficult, as no one single treatment works for all patients. Systemic retinoids, methotrexate, phototherapy, and cyclosporine are commonly used. Recent reports have shown the effectiveness of infliximab (Remicade), a chimeric monoclonal antibody that binds to soluble and membrane-bound forms of tumor necrosis factor alpha.2,3

In our patient, after a 2-month course of acitretin (Soriatane) failed, three treatments with infliximab—5 mg/kg at baseline, at 2 weeks, and at 6 weeks—led to complete resolution of the condition.

- Selvaag E, Haedersdal M, Thomsen K. Pityriasis rubra pilaris: a retrospective study of 12 patients. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2000; 14:514–515.

- Liao WC, Mutasim DF. Infliximab for the treatment of adult-onset pityriasis rubra pilaris. Arch Dermatol 2005; 141:423–425.

- Müller H, Gattringer C, Zelger B, Höpfl R, Eisendle K. Infliximab monotherapy as first-line treatment for adultonset pityriasis rubra pilaris: case report and review of the literature on biologic therapy. J Am Acad Dermatol 2008; 59( suppl 5):S65–S70.

- Selvaag E, Haedersdal M, Thomsen K. Pityriasis rubra pilaris: a retrospective study of 12 patients. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2000; 14:514–515.

- Liao WC, Mutasim DF. Infliximab for the treatment of adult-onset pityriasis rubra pilaris. Arch Dermatol 2005; 141:423–425.

- Müller H, Gattringer C, Zelger B, Höpfl R, Eisendle K. Infliximab monotherapy as first-line treatment for adultonset pityriasis rubra pilaris: case report and review of the literature on biologic therapy. J Am Acad Dermatol 2008; 59( suppl 5):S65–S70.

The Courvoisier sign

A 60-year-old woman has had jaundice, dark-colored urine, and light-colored stools for the past several days. She has no history of jaundice or gallstone disease.

Over a century ago, Courvoisier observed that a palpable gallbladder in a patient with obstructive jaundice is often caused by a non-calculus abnormality of the biliary system, such as pancreatic cancer or cholangiocarcinoma, distal to the insertion of the cystic duct.1–4 He attributed his findings to a higher likelihood of fibrosis of the gallbladder, with stone disease rendering it less distensible.4

Although often associated with malignancy, the Courvoisier sign can also be seen in benign processes causing obstruction of the common bile duct.5

For decades after its initial description, the Courvoisier sign was used as an important sign for the differential diagnosis of jaundice, but advances in diagnostic imaging have led to a more accurate and earlier diagnosis with less reliance on this sign. In this patient, tissue diagnosis confirmed a clinical suspicion of pancreatic adenocarcinoma.

- Anonymous. Ludwig Courvoisier (1843–1918): Courvoisier’s sign. JAMA 1968; 204:627.

- Chung RS. Pathogenesis of the “Courvoisier gallbladder.” Dig Dis Sci 1983; 28:33–38.

- Watts GT. Courvoisier’s law. Lancet 1985; 2:1293–1294.

- Fitzgerald JE, White MJ, Lobo DN. Courvoisier’s gallbladder: law or sign? World J Surg 2009; 33:886–891.

- Parmar MS. Courvoisier’s law. CMAJ 2003; 168:876–877.

A 60-year-old woman has had jaundice, dark-colored urine, and light-colored stools for the past several days. She has no history of jaundice or gallstone disease.

Over a century ago, Courvoisier observed that a palpable gallbladder in a patient with obstructive jaundice is often caused by a non-calculus abnormality of the biliary system, such as pancreatic cancer or cholangiocarcinoma, distal to the insertion of the cystic duct.1–4 He attributed his findings to a higher likelihood of fibrosis of the gallbladder, with stone disease rendering it less distensible.4

Although often associated with malignancy, the Courvoisier sign can also be seen in benign processes causing obstruction of the common bile duct.5

For decades after its initial description, the Courvoisier sign was used as an important sign for the differential diagnosis of jaundice, but advances in diagnostic imaging have led to a more accurate and earlier diagnosis with less reliance on this sign. In this patient, tissue diagnosis confirmed a clinical suspicion of pancreatic adenocarcinoma.

A 60-year-old woman has had jaundice, dark-colored urine, and light-colored stools for the past several days. She has no history of jaundice or gallstone disease.