User login

Racial disparities in cesarean delivery rates

CASE Patient wants to reduce her risk of cesarean delivery (CD)

A 30-year-old primigravid woman expresses concern about her increased risk for CD as a Black woman. She has been reading in the news about the increased risks of CD and birth complications, and she asks what she can do to decrease her risk of having a CD.

What is the problem?

Recently, attention has been called to the stark racial disparities in severe maternal morbidity and mortality. Cesarean delivery rates illustrate an area in obstetric management in which racial disparities exist. It is well known that morbidity associated with CD is much higher than morbidity associated with vaginal delivery, which begs the question of whether disparities in mode of delivery may play a role in the disparity in maternal morbidity and mortality.

In the United States, 32% of all births between 2018 and 2020 were by CD. However, only 31% of White women delivered via CD as compared with 36% of Black women and 33% of Asian women.1 In 2021, the primary CD rates were 26% for Black women, 24% for Asian women, 21% for Hispanic women, and 22% for White women.2 This racial disparity, particularly between Black and White women, has been seen across nulliparous, term, singleton, vertex (NTSV) groups as well as multiparous women with prior vaginal delivery.3,4 The disparity persists after adjusting for risk factors.

A secondary analysis of groups deemed at low risk for CD within the ARRIVE trial study group reported the adjusted relative risk of CD birth for Black women as 1.21 (95% confidence interval [CI], 1.03–1.42) compared with White women and 1.26 (95% CI, 1.08–1.46) for Hispanic women.5 The investigators estimated that this accounted for 15% of excess maternal morbidity.5 These studies also have shown that a disparity exists in indication for CD, with Black women more likely to have a CD for the diagnosis of nonreassuring fetal tracing while White women are more likely to have a CD for failure to progress.

Patients who undergo CD are less likely to breastfeed, and they have a more difficult recovery, increased risks of infection, thromboembolic events, and increased risks for future pregnancy. Along with increased focus on racial disparities in obstetrics outcomes within the medical community, patients also have become more attuned to these racial disparities in maternal morbidity as this has increasingly become a topic of focus within the mainstream media.

What is behind differences in mode of delivery?

The drivers of racial inequities in mode of delivery remain unclear. One might question whether increased prevalence of morbidities in pregnancy, such as diabetes and hypertension, in minority women might influence the disparity in CD. However, the disparity persists in studies of low-risk women and in studies that statistically adjust for factors that include preeclampsia, obesity, diabetes, and fetal growth restriction, which argues that maternal morbidity alone is not responsible for the differences observed.

Race is a social construct, and as such there is no biologically plausible explanation for the racial disparities in CD rates. Differences in health outcomes should be considered a result of the impact of racism. Disparities can be influenced by patient level, provider level, and systemic level factors.6 Provider biases have a negative impact on care for minority groups and they influence disparities in health care.7 The subjectivity involved in diagnoses of nonreassuring fetal tracing as an indication for CD creates an opportunity for implicit biases and discrimination to enter decision-making for indications for CD. Furthermore, no differences have been seen in Apgar score or admission to the neonatal intensive care unit in studies where indication of nonreassuring fetal heart tracing drove the disparity for CD.5

A study that retrospectively compared labor management strategies intended to reduce CD rates, such as application of guidelines for failed induction of labor, arrest of dilation, arrest of descent, nonreassuring fetus status, or cervical ripening, did not observe differential use of labor management strategies intended to reduce CD rate.8 By contrast, Hamm and colleagues observed that implementation of a standardized induction protocol was associated with a decreased CD rate among Black women but not non-Black women and the standardized protocol was associated with a decrease in the racial disparity in CD.9 A theory behind their findings is that provider bias is less when there is implementation of a standardized protocol, algorithm, or guidelines, which in turn reduces disparity in mode of delivery.

Clearly, more research is needed for the mechanisms behind inequities in mode of delivery and the influence of provider factors. Future studies also are needed to evaluate how patient level factors, including belief systems and culture preferences, and how system level factors, such as access to prenatal care and the health system processes, are associated with CD rates.

Next steps

While the mechanisms that drive the disparities in CD rate and indication may remain unclear, there are potential areas of intervention to decrease CD rates among minority and Black women.

Continuous support from a doula or layperson has been shown to decrease rates of cesarean birth,10,11 and evidence indicates that minority women are interested in doula support but are less likely than White women to have access to doula care.12 Programs that provide doula support for Black women are an intervention that would increase access to support and advocacy during labor for Black women.

Group prenatal care is another strategy that is associated with improved perinatal outcomes among Black women, including decreased rates of preterm birth.13 In women randomly assigned to group prenatal care or individual prenatal visits, there was a trend toward decreased CD rate, although this was not significant. Overall, increased support and engagement during prenatal care and delivery will benefit our Black patients.

Data from a survey of 2,000 members of the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine suggest that obstetrics clinicians do recognize that disparities in birth outcomes exist. While clinicians recognize this, these data also identified that there are deficits in clinician knowledge regarding these disparities.14 More than half of surveyed clinicians disagreed that their personal biases affect how they care for patients. Robust data demonstrate broad-reaching differences in the diagnosis and treatment of Black and White patients by physicians across specialties.7 Such surveys illustrate that there is a need for more education regarding disparities, racism in medicine, and implicit bias. As race historically has been used to estimate increased maternal morbidity or likelihood of failure for vaginal birth after CD, we must challenge the idea that race itself confers the increased risks and educate clinicians to recognize that race is a proxy for socioeconomic disadvantages and racism.15

The role of nurses in mode of delivery only recently has been evaluated. An interesting recent cohort study demonstrated a reduction in the NTSV CD rate with dissemination of nurse-specific CD rates, which again may suggest that differing nursing and obstetric clinician management in labor may decrease CD rates.16 Dashboards can serve as a tool within the electronic medical record that can identify unit- or clinician-specific trends and variations in care, and they could serve to identify and potentially reduce group disparities in CDs as well as other obstetric quality metrics.17

Lastly, it is imperative to have evidence-based guidelines and standardized protocols regarding labor management and prenatal care in order to reduce racial disparities. Additional steps to reduce Black-White differences in CD rates and indications should be addressed from multiple levels. These initiatives should include provider training and education, interventions to support minority women through labor and activate patient engagement in their prenatal care, hospital monitoring of racial disparities in CD rates, and standardizing care. Future research should focus on further understanding the mechanisms behind disparities in obstetrics as well as the efficacy of interventions in reducing this gap. ●

- March of Dimes. Peristats: Delivery method. Accessed September 10, 2022. https://www.marchofdimes.org/peristats/data?top=8&lev=1&stop=86&ftop=355®=99&obj=1&slev=1

- Osterman MJK. Changes in primary and repeat cesarean delivery: United States, 2016-2021. Vital Statistics Rapid Release; no. 21. Hyattsville, Maryland: National Center for Health Statistics. July 2022. https://dx.doi.org/10.15620/cdc:117432

- Okwandu IC, Anderson M, Postlethwaite D, et al. Racial and ethnic disparities in cesarean delivery and indications among nulliparous, term, singleton, vertex women. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2022;9:1161-1171. doi:10.1007/s40615-021-01057-w.

- Williams A, Little SE, Bryant AS, et al. Mode of delivery and unplanned cesarean: differences in rates and indication by race, ethnicity, and sociodemographic characteristics. Am J Perinat. June 12, 2022. doi:10.1055/a-1785-8843.

- Debbink MP, Ugwu LG, Grobman WA, et al; Eunice Kennedy Schriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units (MFMU) Network. Racial and ethnic inequities in cesarean birth and maternal morbidity in a low-risk, nulliparous cohort. Obstet Gynecol. 2022;139:73-82. doi:10.1097/aog.0000000000004620.

- Kilbourne AM, Switzer G, Hyman K, et al. Advancing health disparities research within the health care system: a conceptual framework. Am J Public Health. 2006;96:2113-2121. doi:10.2105/ajph.2005.077628.

- Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Understanding and Eliminating Racial and Ethnic Disparities; Smedley BD, Stith AY, Nelson AR, eds. Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care. National Academies Press; 2003. doi:10.17226/12875.

- Yee LM, Costantine MM, Rice MM, et al; Eunice Kennedy Schriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units (MFMU) Network. Racial and ethnic differences in utilization of labor management strategies intended to reduce cesarean delivery rates. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130:1285-1294. doi:10.1097/aog.0000000000002343.

- Hamm RF, Srinivas SK, Levine LD. A standardized labor induction protocol: impact on racial disparities in obstetrical outcomes. Am J Obstet Gynecol MFM. 2020;2:100148. doi:10.1016/j.ajogmf.2020.100148.

- Kennell J, Klaus M, McGrath S, et al. Continuous emotional support during labor in a US hospital: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 1991;265:2197-2201. doi:10.1001/jama.1991.03460170051032.

- Bohren MA, Hofmeyr GJ, Sakala C, et al. Continuous support for women during childbirth. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;7:CD003766. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd003766.pub6.

- Declercq ER, Sakala C, Corry MP, et al. Listening to Mothers III: Pregnancy and Birth. Childbirth Connection; May 2013. Accessed September 16, 2022. https://www.nationalpartnership.org/our-work/resources/health-care/maternity/listening-to-mothers-iii-pregnancy-and-birth-2013.pdf

- Ickovics JR, Kershaw TS, Westdahl C, et al. Group prenatal care and perinatal outcomes: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;110(2 pt 1):330-339. doi:10.1097/01.aog.0000275284.24298.23.

- Jain J, Moroz L. Strategies to reduce disparities in maternal morbidity and mortality: patient and provider education. Semin Perinatol. 2017;41:323-328. doi:10.1053/j.semperi.2017.04.010.

- Vyas DA, Jones DS, Meadows AR, et al. Challenging the use of race in the vaginal birth after cesarean section calculator. Womens Health Issues. 2019;29:201-204. doi:10.1016/j.whi.2019.04.007.

- Greene NH, Schwartz N, Gregory KD. Association of primary cesarean delivery rate with dissemination of nurse-specific cesarean delivery rates. Obstet Gynecol. 2022;140:610-612. doi:10.1097/aog.0000000000004919.

- Howell EA, Brown H, Brumley J, et al. Reduction of peripartum racial and ethnic disparities. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;131:770782. doi:10.1097/aog.0000000000002475.

CASE Patient wants to reduce her risk of cesarean delivery (CD)

A 30-year-old primigravid woman expresses concern about her increased risk for CD as a Black woman. She has been reading in the news about the increased risks of CD and birth complications, and she asks what she can do to decrease her risk of having a CD.

What is the problem?

Recently, attention has been called to the stark racial disparities in severe maternal morbidity and mortality. Cesarean delivery rates illustrate an area in obstetric management in which racial disparities exist. It is well known that morbidity associated with CD is much higher than morbidity associated with vaginal delivery, which begs the question of whether disparities in mode of delivery may play a role in the disparity in maternal morbidity and mortality.

In the United States, 32% of all births between 2018 and 2020 were by CD. However, only 31% of White women delivered via CD as compared with 36% of Black women and 33% of Asian women.1 In 2021, the primary CD rates were 26% for Black women, 24% for Asian women, 21% for Hispanic women, and 22% for White women.2 This racial disparity, particularly between Black and White women, has been seen across nulliparous, term, singleton, vertex (NTSV) groups as well as multiparous women with prior vaginal delivery.3,4 The disparity persists after adjusting for risk factors.

A secondary analysis of groups deemed at low risk for CD within the ARRIVE trial study group reported the adjusted relative risk of CD birth for Black women as 1.21 (95% confidence interval [CI], 1.03–1.42) compared with White women and 1.26 (95% CI, 1.08–1.46) for Hispanic women.5 The investigators estimated that this accounted for 15% of excess maternal morbidity.5 These studies also have shown that a disparity exists in indication for CD, with Black women more likely to have a CD for the diagnosis of nonreassuring fetal tracing while White women are more likely to have a CD for failure to progress.

Patients who undergo CD are less likely to breastfeed, and they have a more difficult recovery, increased risks of infection, thromboembolic events, and increased risks for future pregnancy. Along with increased focus on racial disparities in obstetrics outcomes within the medical community, patients also have become more attuned to these racial disparities in maternal morbidity as this has increasingly become a topic of focus within the mainstream media.

What is behind differences in mode of delivery?

The drivers of racial inequities in mode of delivery remain unclear. One might question whether increased prevalence of morbidities in pregnancy, such as diabetes and hypertension, in minority women might influence the disparity in CD. However, the disparity persists in studies of low-risk women and in studies that statistically adjust for factors that include preeclampsia, obesity, diabetes, and fetal growth restriction, which argues that maternal morbidity alone is not responsible for the differences observed.

Race is a social construct, and as such there is no biologically plausible explanation for the racial disparities in CD rates. Differences in health outcomes should be considered a result of the impact of racism. Disparities can be influenced by patient level, provider level, and systemic level factors.6 Provider biases have a negative impact on care for minority groups and they influence disparities in health care.7 The subjectivity involved in diagnoses of nonreassuring fetal tracing as an indication for CD creates an opportunity for implicit biases and discrimination to enter decision-making for indications for CD. Furthermore, no differences have been seen in Apgar score or admission to the neonatal intensive care unit in studies where indication of nonreassuring fetal heart tracing drove the disparity for CD.5

A study that retrospectively compared labor management strategies intended to reduce CD rates, such as application of guidelines for failed induction of labor, arrest of dilation, arrest of descent, nonreassuring fetus status, or cervical ripening, did not observe differential use of labor management strategies intended to reduce CD rate.8 By contrast, Hamm and colleagues observed that implementation of a standardized induction protocol was associated with a decreased CD rate among Black women but not non-Black women and the standardized protocol was associated with a decrease in the racial disparity in CD.9 A theory behind their findings is that provider bias is less when there is implementation of a standardized protocol, algorithm, or guidelines, which in turn reduces disparity in mode of delivery.

Clearly, more research is needed for the mechanisms behind inequities in mode of delivery and the influence of provider factors. Future studies also are needed to evaluate how patient level factors, including belief systems and culture preferences, and how system level factors, such as access to prenatal care and the health system processes, are associated with CD rates.

Next steps

While the mechanisms that drive the disparities in CD rate and indication may remain unclear, there are potential areas of intervention to decrease CD rates among minority and Black women.

Continuous support from a doula or layperson has been shown to decrease rates of cesarean birth,10,11 and evidence indicates that minority women are interested in doula support but are less likely than White women to have access to doula care.12 Programs that provide doula support for Black women are an intervention that would increase access to support and advocacy during labor for Black women.

Group prenatal care is another strategy that is associated with improved perinatal outcomes among Black women, including decreased rates of preterm birth.13 In women randomly assigned to group prenatal care or individual prenatal visits, there was a trend toward decreased CD rate, although this was not significant. Overall, increased support and engagement during prenatal care and delivery will benefit our Black patients.

Data from a survey of 2,000 members of the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine suggest that obstetrics clinicians do recognize that disparities in birth outcomes exist. While clinicians recognize this, these data also identified that there are deficits in clinician knowledge regarding these disparities.14 More than half of surveyed clinicians disagreed that their personal biases affect how they care for patients. Robust data demonstrate broad-reaching differences in the diagnosis and treatment of Black and White patients by physicians across specialties.7 Such surveys illustrate that there is a need for more education regarding disparities, racism in medicine, and implicit bias. As race historically has been used to estimate increased maternal morbidity or likelihood of failure for vaginal birth after CD, we must challenge the idea that race itself confers the increased risks and educate clinicians to recognize that race is a proxy for socioeconomic disadvantages and racism.15

The role of nurses in mode of delivery only recently has been evaluated. An interesting recent cohort study demonstrated a reduction in the NTSV CD rate with dissemination of nurse-specific CD rates, which again may suggest that differing nursing and obstetric clinician management in labor may decrease CD rates.16 Dashboards can serve as a tool within the electronic medical record that can identify unit- or clinician-specific trends and variations in care, and they could serve to identify and potentially reduce group disparities in CDs as well as other obstetric quality metrics.17

Lastly, it is imperative to have evidence-based guidelines and standardized protocols regarding labor management and prenatal care in order to reduce racial disparities. Additional steps to reduce Black-White differences in CD rates and indications should be addressed from multiple levels. These initiatives should include provider training and education, interventions to support minority women through labor and activate patient engagement in their prenatal care, hospital monitoring of racial disparities in CD rates, and standardizing care. Future research should focus on further understanding the mechanisms behind disparities in obstetrics as well as the efficacy of interventions in reducing this gap. ●

CASE Patient wants to reduce her risk of cesarean delivery (CD)

A 30-year-old primigravid woman expresses concern about her increased risk for CD as a Black woman. She has been reading in the news about the increased risks of CD and birth complications, and she asks what she can do to decrease her risk of having a CD.

What is the problem?

Recently, attention has been called to the stark racial disparities in severe maternal morbidity and mortality. Cesarean delivery rates illustrate an area in obstetric management in which racial disparities exist. It is well known that morbidity associated with CD is much higher than morbidity associated with vaginal delivery, which begs the question of whether disparities in mode of delivery may play a role in the disparity in maternal morbidity and mortality.

In the United States, 32% of all births between 2018 and 2020 were by CD. However, only 31% of White women delivered via CD as compared with 36% of Black women and 33% of Asian women.1 In 2021, the primary CD rates were 26% for Black women, 24% for Asian women, 21% for Hispanic women, and 22% for White women.2 This racial disparity, particularly between Black and White women, has been seen across nulliparous, term, singleton, vertex (NTSV) groups as well as multiparous women with prior vaginal delivery.3,4 The disparity persists after adjusting for risk factors.

A secondary analysis of groups deemed at low risk for CD within the ARRIVE trial study group reported the adjusted relative risk of CD birth for Black women as 1.21 (95% confidence interval [CI], 1.03–1.42) compared with White women and 1.26 (95% CI, 1.08–1.46) for Hispanic women.5 The investigators estimated that this accounted for 15% of excess maternal morbidity.5 These studies also have shown that a disparity exists in indication for CD, with Black women more likely to have a CD for the diagnosis of nonreassuring fetal tracing while White women are more likely to have a CD for failure to progress.

Patients who undergo CD are less likely to breastfeed, and they have a more difficult recovery, increased risks of infection, thromboembolic events, and increased risks for future pregnancy. Along with increased focus on racial disparities in obstetrics outcomes within the medical community, patients also have become more attuned to these racial disparities in maternal morbidity as this has increasingly become a topic of focus within the mainstream media.

What is behind differences in mode of delivery?

The drivers of racial inequities in mode of delivery remain unclear. One might question whether increased prevalence of morbidities in pregnancy, such as diabetes and hypertension, in minority women might influence the disparity in CD. However, the disparity persists in studies of low-risk women and in studies that statistically adjust for factors that include preeclampsia, obesity, diabetes, and fetal growth restriction, which argues that maternal morbidity alone is not responsible for the differences observed.

Race is a social construct, and as such there is no biologically plausible explanation for the racial disparities in CD rates. Differences in health outcomes should be considered a result of the impact of racism. Disparities can be influenced by patient level, provider level, and systemic level factors.6 Provider biases have a negative impact on care for minority groups and they influence disparities in health care.7 The subjectivity involved in diagnoses of nonreassuring fetal tracing as an indication for CD creates an opportunity for implicit biases and discrimination to enter decision-making for indications for CD. Furthermore, no differences have been seen in Apgar score or admission to the neonatal intensive care unit in studies where indication of nonreassuring fetal heart tracing drove the disparity for CD.5

A study that retrospectively compared labor management strategies intended to reduce CD rates, such as application of guidelines for failed induction of labor, arrest of dilation, arrest of descent, nonreassuring fetus status, or cervical ripening, did not observe differential use of labor management strategies intended to reduce CD rate.8 By contrast, Hamm and colleagues observed that implementation of a standardized induction protocol was associated with a decreased CD rate among Black women but not non-Black women and the standardized protocol was associated with a decrease in the racial disparity in CD.9 A theory behind their findings is that provider bias is less when there is implementation of a standardized protocol, algorithm, or guidelines, which in turn reduces disparity in mode of delivery.

Clearly, more research is needed for the mechanisms behind inequities in mode of delivery and the influence of provider factors. Future studies also are needed to evaluate how patient level factors, including belief systems and culture preferences, and how system level factors, such as access to prenatal care and the health system processes, are associated with CD rates.

Next steps

While the mechanisms that drive the disparities in CD rate and indication may remain unclear, there are potential areas of intervention to decrease CD rates among minority and Black women.

Continuous support from a doula or layperson has been shown to decrease rates of cesarean birth,10,11 and evidence indicates that minority women are interested in doula support but are less likely than White women to have access to doula care.12 Programs that provide doula support for Black women are an intervention that would increase access to support and advocacy during labor for Black women.

Group prenatal care is another strategy that is associated with improved perinatal outcomes among Black women, including decreased rates of preterm birth.13 In women randomly assigned to group prenatal care or individual prenatal visits, there was a trend toward decreased CD rate, although this was not significant. Overall, increased support and engagement during prenatal care and delivery will benefit our Black patients.

Data from a survey of 2,000 members of the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine suggest that obstetrics clinicians do recognize that disparities in birth outcomes exist. While clinicians recognize this, these data also identified that there are deficits in clinician knowledge regarding these disparities.14 More than half of surveyed clinicians disagreed that their personal biases affect how they care for patients. Robust data demonstrate broad-reaching differences in the diagnosis and treatment of Black and White patients by physicians across specialties.7 Such surveys illustrate that there is a need for more education regarding disparities, racism in medicine, and implicit bias. As race historically has been used to estimate increased maternal morbidity or likelihood of failure for vaginal birth after CD, we must challenge the idea that race itself confers the increased risks and educate clinicians to recognize that race is a proxy for socioeconomic disadvantages and racism.15

The role of nurses in mode of delivery only recently has been evaluated. An interesting recent cohort study demonstrated a reduction in the NTSV CD rate with dissemination of nurse-specific CD rates, which again may suggest that differing nursing and obstetric clinician management in labor may decrease CD rates.16 Dashboards can serve as a tool within the electronic medical record that can identify unit- or clinician-specific trends and variations in care, and they could serve to identify and potentially reduce group disparities in CDs as well as other obstetric quality metrics.17

Lastly, it is imperative to have evidence-based guidelines and standardized protocols regarding labor management and prenatal care in order to reduce racial disparities. Additional steps to reduce Black-White differences in CD rates and indications should be addressed from multiple levels. These initiatives should include provider training and education, interventions to support minority women through labor and activate patient engagement in their prenatal care, hospital monitoring of racial disparities in CD rates, and standardizing care. Future research should focus on further understanding the mechanisms behind disparities in obstetrics as well as the efficacy of interventions in reducing this gap. ●

- March of Dimes. Peristats: Delivery method. Accessed September 10, 2022. https://www.marchofdimes.org/peristats/data?top=8&lev=1&stop=86&ftop=355®=99&obj=1&slev=1

- Osterman MJK. Changes in primary and repeat cesarean delivery: United States, 2016-2021. Vital Statistics Rapid Release; no. 21. Hyattsville, Maryland: National Center for Health Statistics. July 2022. https://dx.doi.org/10.15620/cdc:117432

- Okwandu IC, Anderson M, Postlethwaite D, et al. Racial and ethnic disparities in cesarean delivery and indications among nulliparous, term, singleton, vertex women. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2022;9:1161-1171. doi:10.1007/s40615-021-01057-w.

- Williams A, Little SE, Bryant AS, et al. Mode of delivery and unplanned cesarean: differences in rates and indication by race, ethnicity, and sociodemographic characteristics. Am J Perinat. June 12, 2022. doi:10.1055/a-1785-8843.

- Debbink MP, Ugwu LG, Grobman WA, et al; Eunice Kennedy Schriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units (MFMU) Network. Racial and ethnic inequities in cesarean birth and maternal morbidity in a low-risk, nulliparous cohort. Obstet Gynecol. 2022;139:73-82. doi:10.1097/aog.0000000000004620.

- Kilbourne AM, Switzer G, Hyman K, et al. Advancing health disparities research within the health care system: a conceptual framework. Am J Public Health. 2006;96:2113-2121. doi:10.2105/ajph.2005.077628.

- Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Understanding and Eliminating Racial and Ethnic Disparities; Smedley BD, Stith AY, Nelson AR, eds. Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care. National Academies Press; 2003. doi:10.17226/12875.

- Yee LM, Costantine MM, Rice MM, et al; Eunice Kennedy Schriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units (MFMU) Network. Racial and ethnic differences in utilization of labor management strategies intended to reduce cesarean delivery rates. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130:1285-1294. doi:10.1097/aog.0000000000002343.

- Hamm RF, Srinivas SK, Levine LD. A standardized labor induction protocol: impact on racial disparities in obstetrical outcomes. Am J Obstet Gynecol MFM. 2020;2:100148. doi:10.1016/j.ajogmf.2020.100148.

- Kennell J, Klaus M, McGrath S, et al. Continuous emotional support during labor in a US hospital: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 1991;265:2197-2201. doi:10.1001/jama.1991.03460170051032.

- Bohren MA, Hofmeyr GJ, Sakala C, et al. Continuous support for women during childbirth. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;7:CD003766. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd003766.pub6.

- Declercq ER, Sakala C, Corry MP, et al. Listening to Mothers III: Pregnancy and Birth. Childbirth Connection; May 2013. Accessed September 16, 2022. https://www.nationalpartnership.org/our-work/resources/health-care/maternity/listening-to-mothers-iii-pregnancy-and-birth-2013.pdf

- Ickovics JR, Kershaw TS, Westdahl C, et al. Group prenatal care and perinatal outcomes: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;110(2 pt 1):330-339. doi:10.1097/01.aog.0000275284.24298.23.

- Jain J, Moroz L. Strategies to reduce disparities in maternal morbidity and mortality: patient and provider education. Semin Perinatol. 2017;41:323-328. doi:10.1053/j.semperi.2017.04.010.

- Vyas DA, Jones DS, Meadows AR, et al. Challenging the use of race in the vaginal birth after cesarean section calculator. Womens Health Issues. 2019;29:201-204. doi:10.1016/j.whi.2019.04.007.

- Greene NH, Schwartz N, Gregory KD. Association of primary cesarean delivery rate with dissemination of nurse-specific cesarean delivery rates. Obstet Gynecol. 2022;140:610-612. doi:10.1097/aog.0000000000004919.

- Howell EA, Brown H, Brumley J, et al. Reduction of peripartum racial and ethnic disparities. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;131:770782. doi:10.1097/aog.0000000000002475.

- March of Dimes. Peristats: Delivery method. Accessed September 10, 2022. https://www.marchofdimes.org/peristats/data?top=8&lev=1&stop=86&ftop=355®=99&obj=1&slev=1

- Osterman MJK. Changes in primary and repeat cesarean delivery: United States, 2016-2021. Vital Statistics Rapid Release; no. 21. Hyattsville, Maryland: National Center for Health Statistics. July 2022. https://dx.doi.org/10.15620/cdc:117432

- Okwandu IC, Anderson M, Postlethwaite D, et al. Racial and ethnic disparities in cesarean delivery and indications among nulliparous, term, singleton, vertex women. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2022;9:1161-1171. doi:10.1007/s40615-021-01057-w.

- Williams A, Little SE, Bryant AS, et al. Mode of delivery and unplanned cesarean: differences in rates and indication by race, ethnicity, and sociodemographic characteristics. Am J Perinat. June 12, 2022. doi:10.1055/a-1785-8843.

- Debbink MP, Ugwu LG, Grobman WA, et al; Eunice Kennedy Schriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units (MFMU) Network. Racial and ethnic inequities in cesarean birth and maternal morbidity in a low-risk, nulliparous cohort. Obstet Gynecol. 2022;139:73-82. doi:10.1097/aog.0000000000004620.

- Kilbourne AM, Switzer G, Hyman K, et al. Advancing health disparities research within the health care system: a conceptual framework. Am J Public Health. 2006;96:2113-2121. doi:10.2105/ajph.2005.077628.

- Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Understanding and Eliminating Racial and Ethnic Disparities; Smedley BD, Stith AY, Nelson AR, eds. Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care. National Academies Press; 2003. doi:10.17226/12875.

- Yee LM, Costantine MM, Rice MM, et al; Eunice Kennedy Schriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units (MFMU) Network. Racial and ethnic differences in utilization of labor management strategies intended to reduce cesarean delivery rates. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130:1285-1294. doi:10.1097/aog.0000000000002343.

- Hamm RF, Srinivas SK, Levine LD. A standardized labor induction protocol: impact on racial disparities in obstetrical outcomes. Am J Obstet Gynecol MFM. 2020;2:100148. doi:10.1016/j.ajogmf.2020.100148.

- Kennell J, Klaus M, McGrath S, et al. Continuous emotional support during labor in a US hospital: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 1991;265:2197-2201. doi:10.1001/jama.1991.03460170051032.

- Bohren MA, Hofmeyr GJ, Sakala C, et al. Continuous support for women during childbirth. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;7:CD003766. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd003766.pub6.

- Declercq ER, Sakala C, Corry MP, et al. Listening to Mothers III: Pregnancy and Birth. Childbirth Connection; May 2013. Accessed September 16, 2022. https://www.nationalpartnership.org/our-work/resources/health-care/maternity/listening-to-mothers-iii-pregnancy-and-birth-2013.pdf

- Ickovics JR, Kershaw TS, Westdahl C, et al. Group prenatal care and perinatal outcomes: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;110(2 pt 1):330-339. doi:10.1097/01.aog.0000275284.24298.23.

- Jain J, Moroz L. Strategies to reduce disparities in maternal morbidity and mortality: patient and provider education. Semin Perinatol. 2017;41:323-328. doi:10.1053/j.semperi.2017.04.010.

- Vyas DA, Jones DS, Meadows AR, et al. Challenging the use of race in the vaginal birth after cesarean section calculator. Womens Health Issues. 2019;29:201-204. doi:10.1016/j.whi.2019.04.007.

- Greene NH, Schwartz N, Gregory KD. Association of primary cesarean delivery rate with dissemination of nurse-specific cesarean delivery rates. Obstet Gynecol. 2022;140:610-612. doi:10.1097/aog.0000000000004919.

- Howell EA, Brown H, Brumley J, et al. Reduction of peripartum racial and ethnic disparities. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;131:770782. doi:10.1097/aog.0000000000002475.

Cutaneous Manifestations in Hereditary Alpha Tryptasemia

Hereditary alpha tryptasemia (HaT), an autosomal-dominant disorder of tryptase overproduction, was first described in 2014 by Lyons et al.1 It has been associated with multiple dermatologic, allergic, gastrointestinal (GI) tract, neuropsychiatric, respiratory, autonomic, and connective tissue abnormalities. These multisystem concerns may include cutaneous flushing, chronic pruritus, urticaria, GI tract symptoms, arthralgia, and autonomic dysfunction.2 The diverse symptoms and the recent discovery of HaT make recognition of this disorder challenging. Currently, it also is believed that HaT is associated with an elevated risk for anaphylaxis and is a biomarker for severe symptoms in disorders with increased mast cell burden such as mastocytosis.3-5

Given the potential cutaneous manifestations and the fact that dermatologic symptoms may be the initial presentation of HaT, awareness and recognition of this condition by dermatologists are essential for diagnosis and treatment. This review summarizes the cutaneous presentations consistent with HaT and discusses various conditions that share overlapping dermatologic symptoms with HaT.

Background on HaT

Mast cells are known to secrete several vasoactive mediators including tryptase and histamine when activated by foreign substances, similar to IgE-mediated hypersensitivity reactions. In their baseline state, mast cells continuously secrete immature forms of tryptases called protryptases.6 These protryptases come in 2 forms: α and β. Although mature tryptase is acutely elevatedin anaphylaxis, persistently elevated total serum tryptase levels frequently are regarded as indicative of a systemic mast cell disorder such as systemic mastocytosis (SM).3 Despite the wide-ranging phenotype of HaT, all individuals with the disorder have an elevated basal serum tryptase level (>8 ng/mL). Hereditary alpha tryptasemia has been identified as another possible cause of persistently elevated levels.2,6

Genetics and Epidemiology of HaT—The humantryptase locus at chromosome 16p13.3 is composed of 4 paralog genes: TPSG1, TPSB2, TPSAB1, and TPSD1.4 Only TPSAB1 encodes for α-tryptase, while both TPSB2 and TPSAB1 encode for β-tryptase.4 Hereditary alpha tryptasemia is an autosomal-dominant disorder resulting from a copy number increase in the α-tryptase encoding sequence within the TPSAB1 gene. Despite the wide-ranging phenotype of HaT, all individuals identified with the disorder have a basal serum tryptase level greater than 8 ng/mL, with mean (SD) levels of 15 (5) ng/mL and 24 (6) ng/mL with gene duplication and triplication, respectively (reference range, 0–11.4 ng/mL).2,6 Hereditary alpha tryptasemia likely is common and largely undiagnosed, with a recently estimated prevalence of 5% in the United Kingdom7 and 5.6% in a cohort of 125 individuals from Italy, Slovenia, and the United States.5

Implications of Increased α-tryptase Levels—After an inciting stimulus, the active portions of α-protryptase and β-protryptase are secreted as tetramers by activated mast cells via degranulation. In vitro, β-tryptase homotetramers have been found to play a role in anaphylaxis, while α-homotetramers are nearly inactive.8,9 Recently, however, it has been discovered that α2β2 tetramers also can form and do so in a higher ratio in individuals with increased α-tryptase–encoding gene copies, such as those with HaT.8 These heterotetramers exhibit unique properties compared with the homotetramers and may stimulate epidermal growth factor–like module-containing mucinlike hormone receptor 2 and protease-activated receptor 2 (PAR2). Epidermal growth factor–like module-containing mucinlike hormone receptor 2 activation likely contributes to vibratory urticaria in patients, while activation of PAR2 may have a range of clinical effects, including worsening asthma, inflammatory bowel disease, pruritus, and the exacerbation of dermal inflammation and hyperalgesia.8,10 Thus, α- and β-tryptase tetramers can be considered mediators that may influence the severity of disorders in which mast cells are naturally prevalent and likely contribute to the phenotype of those with HaT.7 Furthermore, these characteristics have been shown to potentially increase in severity with increasing tryptase levels and with increased TPSAB1 duplications.1,2 In contrast, more than 25% of the population is deficient in α-tryptase without known deleterious effects.5

Cutaneous Manifestations of HaT

A case series reported by Lyons et al1 in 2014 detailed persistent elevated basal serum tryptase levels in 9 families with an autosomal-dominant pattern of inheritance. In this cohort, 31 of 33 (94%) affected individuals had a history of atopic dermatitis (AD), and 26 of 33 (79%) affected individuals reported symptoms consistent with mast cell degranulation, including urticaria; flushing; and/or crampy abdominal pain unprovoked or triggered by heat, exercise, vibration, stress, certain foods, or minor physical stimulation.1 A later report by Lyons et al2 in 2016 identified the TPSAB1 α-tryptase–encoding sequence copy number increase as the causative entity for HaT by examining a group of 96 patients from 35 families with frequent recurrent cutaneous flushing and pruritus, sometimes associated with urticaria and sleep disruption. Flushing and pruritus were found in 45% (33/73) of those with a TPSAB1 duplication and 80% (12/15) of those with a triplication (P=.022), suggesting a gene dose effect regarding α-tryptase encoding sequence copy number and these symptoms.2

A 2019 study further explored the clinical finding of urticaria in patients with HaT by specifically examining if vibration-induced urticaria was affected by TPSAB1 gene dosage.8 A cohort of 56 volunteers—35 healthy and 21 with HaT—underwent tryptase genotyping and cutaneous vibratory challenge. The presence of TPSAB1 was significantly correlated with induction of vibration-induced urticaria (P<.01), as the severity and prevalence of the urticarial response increased along with α- and β-tryptase gene ratios.8

Urticaria and angioedema also were seen in 51% (36/70) of patients in a cohort of HaT patients in the United Kingdom, in which 41% (29/70) also had skin flushing. In contrast to prior studies, these manifestations were not more common in patients with gene triplications or quintuplications than those with duplications.7 In another recent retrospective evaluation conducted at Brigham and Women’s Hospital (Boston, Massachusetts)(N=101), 80% of patients aged 4 to 85 years with confirmed diagnoses of HaT had skin manifestations such as urticaria, flushing, and pruritus.4

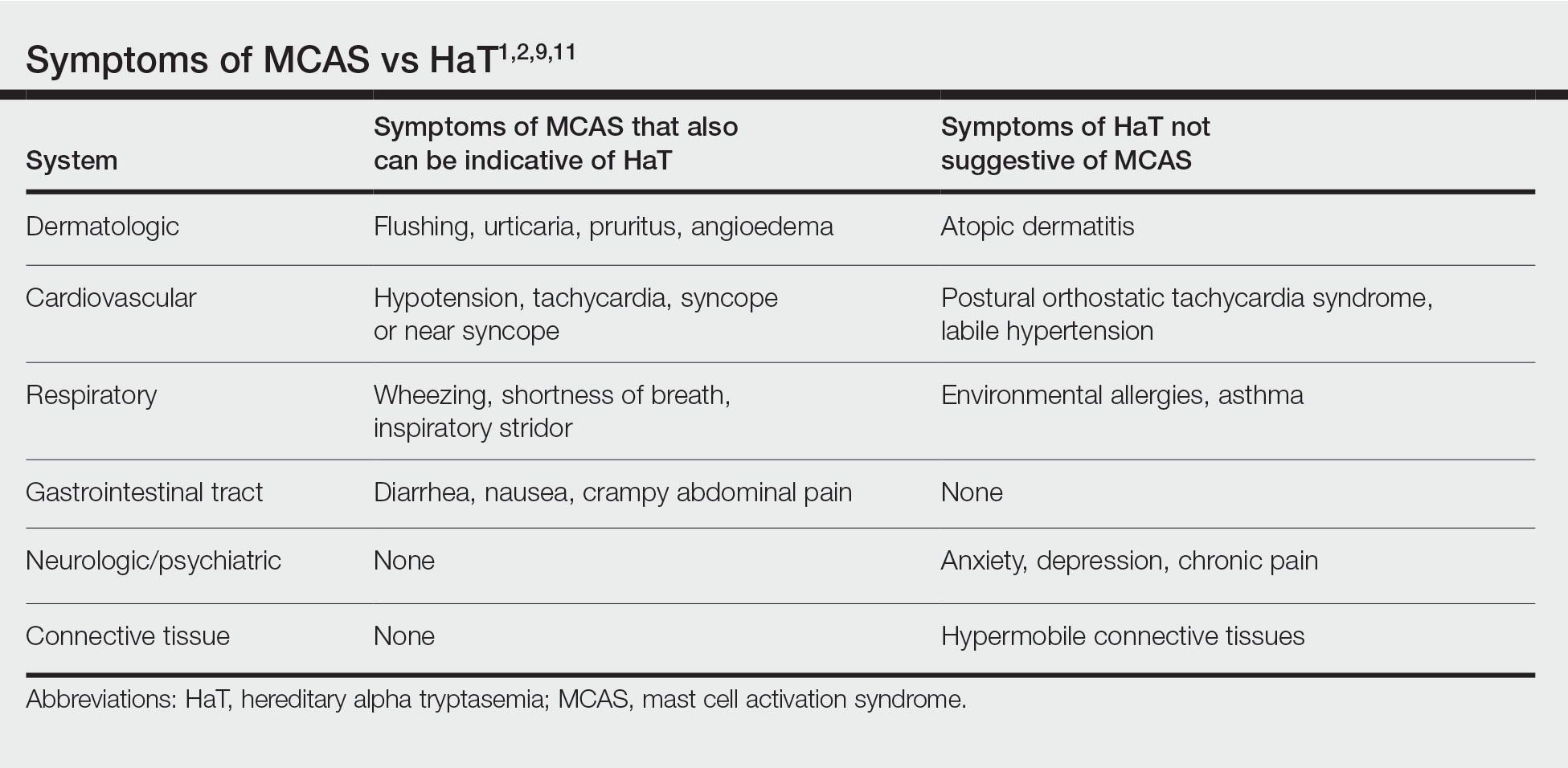

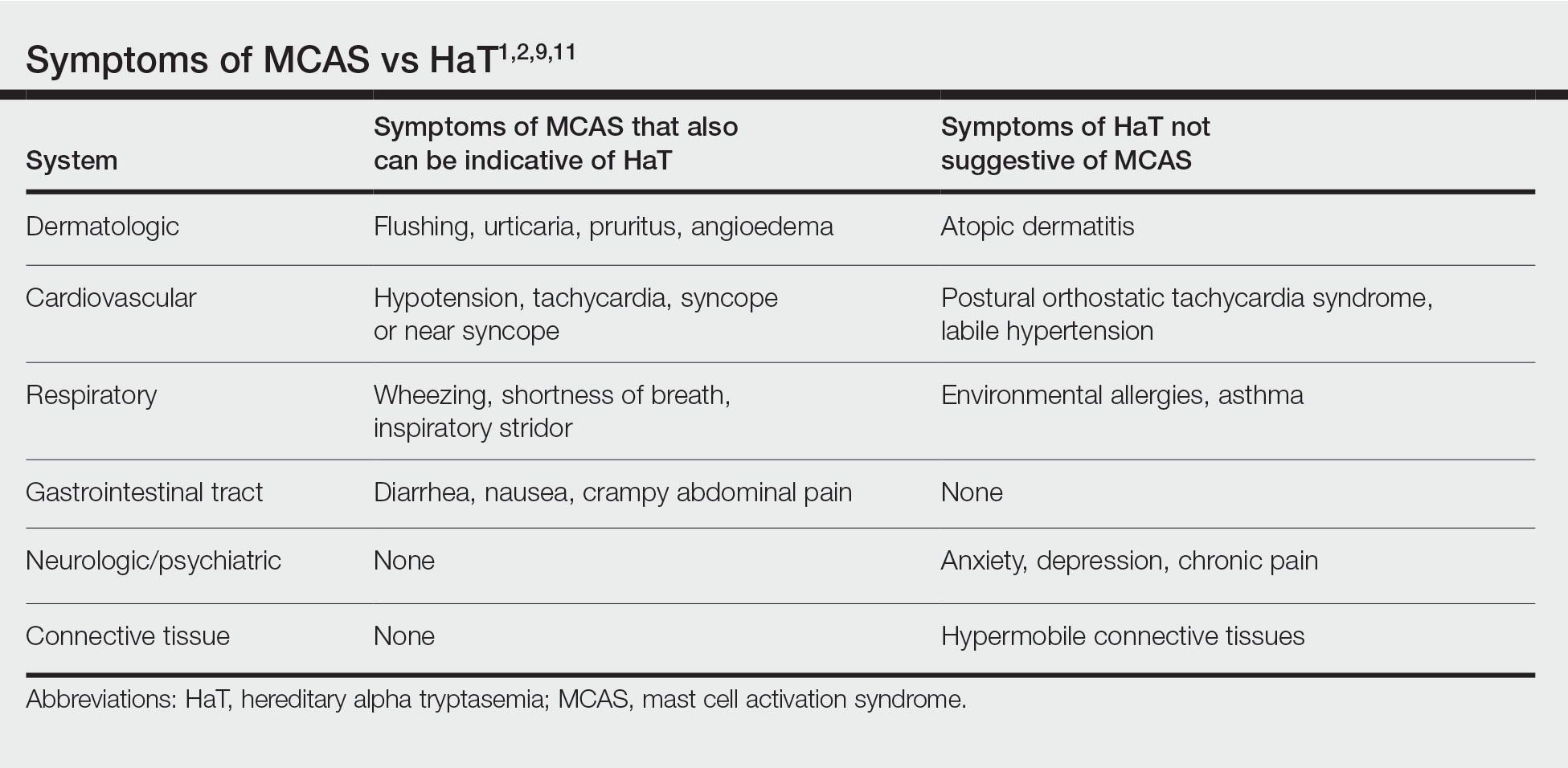

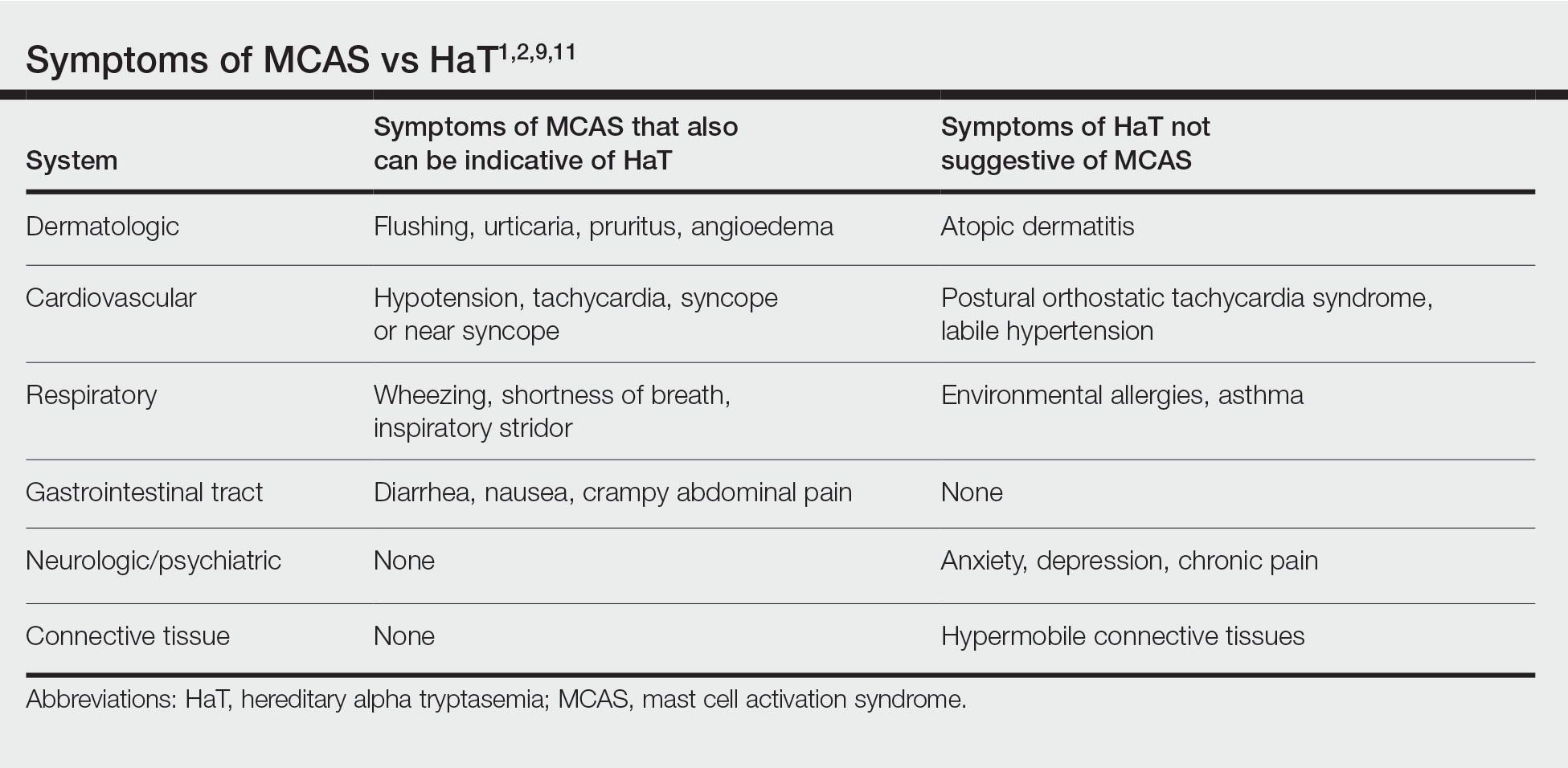

HaT and Mast Cell Activation Syndrome—In 2019, a Mast Cell Disorders Committee Work Group Report outlined recommendations for diagnosing and treating primary mast cell activation syndrome (MCAS), a disorder in which mast cells seem to be more easily activated. Mast cell activation syndrome is defined as a primary clinical condition in which there are episodic signs and symptoms of systemic anaphylaxis (Table) concurrently affecting at least 2 organ systems, resulting from secreted mast cell mediators.9,11 The 2019 report also touched on clinical criteria that lack precision for diagnosing MCAS yet are in use, including dermographism and several types of rashes.9 Episode triggers frequent in MCAS include hot water, alcohol, stress, exercise, infection, hormonal changes, and physical stimuli.

Hereditary alpha tryptasemia has been suggested to be a risk factor for MCAS, which also can be associated with SM and clonal MCAS.9 Patients with MCAS should be tested for increased α-tryptase gene copy number given the overlap in symptoms, the likely predisposition of those with HaT to develop MCAS, and the fact that these patients could be at an increased risk for anaphylaxis.4,7,9,11 However, the clinical phenotype for HaT includes allergic disorders affecting the skin as well as neuropsychiatric and connective tissue abnormalities that are distinctive from MCAS. Although HaT may be considered a heritable risk factor for MCAS, MCAS is only 1 potential phenotype associated with HaT.9

Implications of HaT

Hereditary alpha tryptasemia should be considered in all patients with basal tryptase levels greater than 8 ng/mL. Cutaneous symptoms are among the most common presentations for individuals with HaT and can include AD, chronic or episodic urticaria, pruritus, flushing, and angioedema. However, HaT is unique because of the coupling of these common dermatologic findings with other abnormalities, including abdominal pain and diarrhea, hypermobile joints, and autonomic dysfunction. Patients with HaT also may manifest psychiatric concerns of anxiety, depression, and chronic pain, all of which have been linked to this disorder.

It is unclear in HaT if the presence of extra-allelic copies of tryptase in an individual is directly pathogenic. The effects of increased basal tryptase and α2β2 tetramers have been shown to likely be responsible for some of the clinical features in these individuals but also may magnify other individual underlying disease(s) or diathesis in which mast cells are naturally abundant.8 In the skin, this increased mast cell activation and subsequent histamine release frequently are visible as dermatographia and urticaria. However, mast cell numbers also are known to be increased in both psoriatic and AD skin lesions,12 thus severe presentation of these diseases in conjunction with the other symptoms associated with mast cell activation should prompt suspicion for HaT.

Effects of HaT on Other Cutaneous Disease—Given the increase of mast cells in AD skin lesions and fact that 94% of patients in the 2014 Lyons et al1 study cited a history of AD, HaT may be a risk factor in the development of AD. Interestingly, in addition to the increased mast cells in AD lesions, PAR2+ nerve fibers also are increased in AD lesions and have been implicated in the nonhistaminergic pruritus experienced by patients with AD.12 Thus, given the proposed propensity for α2β2 tetramers to activate PAR2, it is possible this mechanism may contribute to severe pruritus in individuals with AD and concurrent HaT, as those with HaT express increased α2β2 tetramers. However, no study to date has directly compared AD symptoms in patients with concurrent HaT vs patients without it. Further research is needed on how HaT impacts other allergic and inflammatory skin diseases such as AD and psoriasis, but one may reasonably consider HaT when treating chronic inflammatory skin diseases refractory to typical interventions and/or severe presentations. Although HaT is an autosomal-dominant disorder, it is not detected by standard whole exome sequencing or microarrays. A commercial test is available, utilizing a buccal swab to test for TPSAB1 copy number.

HaT and Mast Cell Disorders—When evaluating someone with suspected HaT, it is important to screen for other symptoms of mast cell activation. For instance, in the GI tract increased mast cell activation results in activation of motor neurons and nociceptors and increases secretion and peristalsis with consequent bloating, abdominal pain, and diarrhea.10 Likewise, tryptase also has neuromodulatory effects that amplify the perception of pain and are likely responsible for the feelings of hyperalgesia reported in patients with HaT.13

There is substantial overlap in the clinical pictures of HaT and MCAS, and HaT is considered a heritable risk factor for MCAS. Consequently, any patient undergoing workup for MCAS also should be tested for HaT. Although HaT is associated with consistently elevated tryptase, MCAS is episodic in nature, and an increase in tryptase levels of at least 20% plus 2 ng/mL from baseline only in the presence of other symptoms reflective of mast cell activation (Table) is a prerequisite for diagnosis.9 Chronic signs and symptoms of atopy, chronic urticaria, and severe asthma are not indicative of MCAS but are frequently seen in HaT.

Another cause of persistently elevated tryptase levels is SM. Systemic mastocytosis is defined by aberrant clonal mast cell expansion and systemic involvement11 and can cause persistent symptoms, unlike MCAS alone. However, SM also can be associated with MCAS.9 Notably, a baseline serum tryptase level greater than 20 ng/mL—much higher than the threshold of greater than 8 ng/mL for suspicion of HaT—is seen in 75% of SM cases and is part of the minor diagnostic criteria for the disease.9,11 However, the 2016 study identifying increased TPSAB1 α-tryptase–encoding sequences as the causative entity for HaT by Lyons et al2 found the average (SD) basal serum tryptase level in individuals with α-tryptase–encoding sequence duplications to be 15 (5) ng/mL and 24 (6) ng/mL in those with triplications. Thus, there likely is no threshold for elevated baseline tryptase levels that would indicate SM over HaT as a more likely diagnosis. However, SM will present with new persistently elevated tryptase levels, whereas the elevation in HaT is believed to be lifelong.5 Also in contrast to HaT, SM can present with liver, spleen, and lymph node involvement; bone sclerosis; and cytopenia.11,14

Mastocytosis is much rarer than HaT, with an estimated prevalence of 9 cases per 100,000 individuals in the United States.11 Although HaT diagnostic testing is noninvasive, SM requires a bone marrow biopsy for definitive diagnosis. Given the likely much higher prevalence of HaT than SM and the patient burden of a bone marrow biopsy, HaT should be considered before proceeding with a bone marrow biopsy to evaluate for SM when a patient presents with persistent systemic symptoms of mast cell activation and elevated baseline tryptase levels. Furthermore, it also would be prudent to test for HaT in patients with known SM, as a cohort study by Lyons et al5 indicated that HaT is likely more common in those with SM (12.2% [10/82] of cohort with known SM vs 5.3% of 398 controls), and patients with concurrent SM and HaT were at a higher risk for severe anaphylaxis (RR=9.5; P=.007).

Studies thus far surrounding HaT have not evaluated timing of initial symptom onset or age of initial presentation for HaT. Furthermore, there is no guarantee that those with increased TPSAB1 copy number will be symptomatic, as there have been reports of asymptomatic individuals with HaT who had basal serum levels greater than 8 ng/mL.7 As research into HaT continues and larger cohorts are evaluated, questions surrounding timing of symptom onset and various factors that may make someone more likely to display a particular phenotype will be answered.

Treatment—Long-term prognosis for individuals with HaT is largely unknown. Unfortunately, there are limited data to support a single effective treatment strategy for managing HaT, and treatment has varied based on predominant symptoms. For cutaneous and GI tract symptoms, trials of maximal H1 and H2 antihistamines twice daily have been recommended.4 Omalizumab was reported to improve chronic urticaria in 3 of 3 patients, showing potential promise as a treatment.4 Mast cell stabilizers, such as oral cromolyn, have been used for severe GI symptoms, while some patients also have reported improvement with oral ketotifen.6 Other medications, such as tricyclic antidepressants, clemastine fumarate, and gabapentin, have been beneficial anecdotally.6 Given the lack of harmful effects seen in individuals who are α-tryptase deficient, α-tryptase inhibition is an intriguing target for future therapies.

Conclusion

Patients who present with a constellation of dermatologic, allergic, GI tract, neuropsychiatric, respiratory, autonomic, and connective tissue abnormalities consistent with HaT may receive a prompt diagnosis if the association is recognized. The full relationship between HaT and other chronic dermatologic disorders is still unknown. Ultimately, heightened interest and research into HaT will lead to more treatment options available for affected patients.

1. Lyons JJ, Sun G, Stone KD, et al. Mendelian inheritance of elevated serum tryptase associated with atopy and connective tissue abnormalities. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;133:1471-1474.

2. Lyons JJ, Yu X, Hughes JD, et al. Elevated basal serum tryptase identifies a multisystem disorder associated with increased TPSAB1 copy number. Nat Genet. 2016;48:1564-1569.

3. Schwartz L. Diagnostic value of tryptase in anaphylaxis and mastocytosis. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am. 2006;6:451-463.

4. Giannetti MP, Weller E, Bormans C, et al. Hereditary alpha-tryptasemia in 101 patients with mast cell activation–related symptomatology including anaphylaxis. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2021;126:655-660.

5. Lyons JJ, Chovanec J, O’Connell MP, et al. Heritable risk for severe anaphylaxis associated with increased α-tryptase–encoding germline copy number at TPSAB1. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2020;147:622-632.

6. Lyons JJ. Hereditary alpha tryptasemia: genotyping and associated clinical features. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am. 2018;38:483-495.

7. Robey RC, Wilcock A, Bonin H, et al. Hereditary alpha-tryptasemia: UK prevalence and variability in disease expression. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2020;8:3549-3556.

8. Le QT, Lyons JJ, Naranjo AN, et al. Impact of naturally forming human α/β-tryptase heterotetramers in the pathogenesis of hereditary α-tryptasemia. J Exp Med. 2019;216:2348-2361.

9. Weiler CR, Austen KF, Akin C, et al. AAAAI Mast Cell Disorders Committee Work Group Report: mast cell activation syndrome (MCAS) diagnosis and management. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2019;144:883-896.

10. Ramsay DB, Stephen S, Borum M, et al. Mast cells in gastrointestinal disease. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y). 2010;6:772-777.

11. Giannetti A, Filice E, Caffarelli C, et al. Mast cell activation disorders. Medicina (Kaunas). 2021;57:124.

12. Siiskonen H, Harvima I. Mast cells and sensory nerves contribute to neurogenic inflammation and pruritus in chronic skin inflammation. Front Cell Neurosci. 2019;13:422.

13. Varrassi G, Fusco M, Skaper SD, et al. A pharmacological rationale to reduce the incidence of opioid induced tolerance and hyperalgesia: a review. Pain Ther. 2018;7:59-75.

14. Núñez E, Moreno-Borque R, García-Montero A, et al. Serum tryptase monitoring in indolent systemic mastocytosis: association with disease features and patient outcome. PLoS One. 2013;8:E76116.

Hereditary alpha tryptasemia (HaT), an autosomal-dominant disorder of tryptase overproduction, was first described in 2014 by Lyons et al.1 It has been associated with multiple dermatologic, allergic, gastrointestinal (GI) tract, neuropsychiatric, respiratory, autonomic, and connective tissue abnormalities. These multisystem concerns may include cutaneous flushing, chronic pruritus, urticaria, GI tract symptoms, arthralgia, and autonomic dysfunction.2 The diverse symptoms and the recent discovery of HaT make recognition of this disorder challenging. Currently, it also is believed that HaT is associated with an elevated risk for anaphylaxis and is a biomarker for severe symptoms in disorders with increased mast cell burden such as mastocytosis.3-5

Given the potential cutaneous manifestations and the fact that dermatologic symptoms may be the initial presentation of HaT, awareness and recognition of this condition by dermatologists are essential for diagnosis and treatment. This review summarizes the cutaneous presentations consistent with HaT and discusses various conditions that share overlapping dermatologic symptoms with HaT.

Background on HaT

Mast cells are known to secrete several vasoactive mediators including tryptase and histamine when activated by foreign substances, similar to IgE-mediated hypersensitivity reactions. In their baseline state, mast cells continuously secrete immature forms of tryptases called protryptases.6 These protryptases come in 2 forms: α and β. Although mature tryptase is acutely elevatedin anaphylaxis, persistently elevated total serum tryptase levels frequently are regarded as indicative of a systemic mast cell disorder such as systemic mastocytosis (SM).3 Despite the wide-ranging phenotype of HaT, all individuals with the disorder have an elevated basal serum tryptase level (>8 ng/mL). Hereditary alpha tryptasemia has been identified as another possible cause of persistently elevated levels.2,6

Genetics and Epidemiology of HaT—The humantryptase locus at chromosome 16p13.3 is composed of 4 paralog genes: TPSG1, TPSB2, TPSAB1, and TPSD1.4 Only TPSAB1 encodes for α-tryptase, while both TPSB2 and TPSAB1 encode for β-tryptase.4 Hereditary alpha tryptasemia is an autosomal-dominant disorder resulting from a copy number increase in the α-tryptase encoding sequence within the TPSAB1 gene. Despite the wide-ranging phenotype of HaT, all individuals identified with the disorder have a basal serum tryptase level greater than 8 ng/mL, with mean (SD) levels of 15 (5) ng/mL and 24 (6) ng/mL with gene duplication and triplication, respectively (reference range, 0–11.4 ng/mL).2,6 Hereditary alpha tryptasemia likely is common and largely undiagnosed, with a recently estimated prevalence of 5% in the United Kingdom7 and 5.6% in a cohort of 125 individuals from Italy, Slovenia, and the United States.5

Implications of Increased α-tryptase Levels—After an inciting stimulus, the active portions of α-protryptase and β-protryptase are secreted as tetramers by activated mast cells via degranulation. In vitro, β-tryptase homotetramers have been found to play a role in anaphylaxis, while α-homotetramers are nearly inactive.8,9 Recently, however, it has been discovered that α2β2 tetramers also can form and do so in a higher ratio in individuals with increased α-tryptase–encoding gene copies, such as those with HaT.8 These heterotetramers exhibit unique properties compared with the homotetramers and may stimulate epidermal growth factor–like module-containing mucinlike hormone receptor 2 and protease-activated receptor 2 (PAR2). Epidermal growth factor–like module-containing mucinlike hormone receptor 2 activation likely contributes to vibratory urticaria in patients, while activation of PAR2 may have a range of clinical effects, including worsening asthma, inflammatory bowel disease, pruritus, and the exacerbation of dermal inflammation and hyperalgesia.8,10 Thus, α- and β-tryptase tetramers can be considered mediators that may influence the severity of disorders in which mast cells are naturally prevalent and likely contribute to the phenotype of those with HaT.7 Furthermore, these characteristics have been shown to potentially increase in severity with increasing tryptase levels and with increased TPSAB1 duplications.1,2 In contrast, more than 25% of the population is deficient in α-tryptase without known deleterious effects.5

Cutaneous Manifestations of HaT

A case series reported by Lyons et al1 in 2014 detailed persistent elevated basal serum tryptase levels in 9 families with an autosomal-dominant pattern of inheritance. In this cohort, 31 of 33 (94%) affected individuals had a history of atopic dermatitis (AD), and 26 of 33 (79%) affected individuals reported symptoms consistent with mast cell degranulation, including urticaria; flushing; and/or crampy abdominal pain unprovoked or triggered by heat, exercise, vibration, stress, certain foods, or minor physical stimulation.1 A later report by Lyons et al2 in 2016 identified the TPSAB1 α-tryptase–encoding sequence copy number increase as the causative entity for HaT by examining a group of 96 patients from 35 families with frequent recurrent cutaneous flushing and pruritus, sometimes associated with urticaria and sleep disruption. Flushing and pruritus were found in 45% (33/73) of those with a TPSAB1 duplication and 80% (12/15) of those with a triplication (P=.022), suggesting a gene dose effect regarding α-tryptase encoding sequence copy number and these symptoms.2

A 2019 study further explored the clinical finding of urticaria in patients with HaT by specifically examining if vibration-induced urticaria was affected by TPSAB1 gene dosage.8 A cohort of 56 volunteers—35 healthy and 21 with HaT—underwent tryptase genotyping and cutaneous vibratory challenge. The presence of TPSAB1 was significantly correlated with induction of vibration-induced urticaria (P<.01), as the severity and prevalence of the urticarial response increased along with α- and β-tryptase gene ratios.8

Urticaria and angioedema also were seen in 51% (36/70) of patients in a cohort of HaT patients in the United Kingdom, in which 41% (29/70) also had skin flushing. In contrast to prior studies, these manifestations were not more common in patients with gene triplications or quintuplications than those with duplications.7 In another recent retrospective evaluation conducted at Brigham and Women’s Hospital (Boston, Massachusetts)(N=101), 80% of patients aged 4 to 85 years with confirmed diagnoses of HaT had skin manifestations such as urticaria, flushing, and pruritus.4

HaT and Mast Cell Activation Syndrome—In 2019, a Mast Cell Disorders Committee Work Group Report outlined recommendations for diagnosing and treating primary mast cell activation syndrome (MCAS), a disorder in which mast cells seem to be more easily activated. Mast cell activation syndrome is defined as a primary clinical condition in which there are episodic signs and symptoms of systemic anaphylaxis (Table) concurrently affecting at least 2 organ systems, resulting from secreted mast cell mediators.9,11 The 2019 report also touched on clinical criteria that lack precision for diagnosing MCAS yet are in use, including dermographism and several types of rashes.9 Episode triggers frequent in MCAS include hot water, alcohol, stress, exercise, infection, hormonal changes, and physical stimuli.

Hereditary alpha tryptasemia has been suggested to be a risk factor for MCAS, which also can be associated with SM and clonal MCAS.9 Patients with MCAS should be tested for increased α-tryptase gene copy number given the overlap in symptoms, the likely predisposition of those with HaT to develop MCAS, and the fact that these patients could be at an increased risk for anaphylaxis.4,7,9,11 However, the clinical phenotype for HaT includes allergic disorders affecting the skin as well as neuropsychiatric and connective tissue abnormalities that are distinctive from MCAS. Although HaT may be considered a heritable risk factor for MCAS, MCAS is only 1 potential phenotype associated with HaT.9

Implications of HaT

Hereditary alpha tryptasemia should be considered in all patients with basal tryptase levels greater than 8 ng/mL. Cutaneous symptoms are among the most common presentations for individuals with HaT and can include AD, chronic or episodic urticaria, pruritus, flushing, and angioedema. However, HaT is unique because of the coupling of these common dermatologic findings with other abnormalities, including abdominal pain and diarrhea, hypermobile joints, and autonomic dysfunction. Patients with HaT also may manifest psychiatric concerns of anxiety, depression, and chronic pain, all of which have been linked to this disorder.

It is unclear in HaT if the presence of extra-allelic copies of tryptase in an individual is directly pathogenic. The effects of increased basal tryptase and α2β2 tetramers have been shown to likely be responsible for some of the clinical features in these individuals but also may magnify other individual underlying disease(s) or diathesis in which mast cells are naturally abundant.8 In the skin, this increased mast cell activation and subsequent histamine release frequently are visible as dermatographia and urticaria. However, mast cell numbers also are known to be increased in both psoriatic and AD skin lesions,12 thus severe presentation of these diseases in conjunction with the other symptoms associated with mast cell activation should prompt suspicion for HaT.

Effects of HaT on Other Cutaneous Disease—Given the increase of mast cells in AD skin lesions and fact that 94% of patients in the 2014 Lyons et al1 study cited a history of AD, HaT may be a risk factor in the development of AD. Interestingly, in addition to the increased mast cells in AD lesions, PAR2+ nerve fibers also are increased in AD lesions and have been implicated in the nonhistaminergic pruritus experienced by patients with AD.12 Thus, given the proposed propensity for α2β2 tetramers to activate PAR2, it is possible this mechanism may contribute to severe pruritus in individuals with AD and concurrent HaT, as those with HaT express increased α2β2 tetramers. However, no study to date has directly compared AD symptoms in patients with concurrent HaT vs patients without it. Further research is needed on how HaT impacts other allergic and inflammatory skin diseases such as AD and psoriasis, but one may reasonably consider HaT when treating chronic inflammatory skin diseases refractory to typical interventions and/or severe presentations. Although HaT is an autosomal-dominant disorder, it is not detected by standard whole exome sequencing or microarrays. A commercial test is available, utilizing a buccal swab to test for TPSAB1 copy number.

HaT and Mast Cell Disorders—When evaluating someone with suspected HaT, it is important to screen for other symptoms of mast cell activation. For instance, in the GI tract increased mast cell activation results in activation of motor neurons and nociceptors and increases secretion and peristalsis with consequent bloating, abdominal pain, and diarrhea.10 Likewise, tryptase also has neuromodulatory effects that amplify the perception of pain and are likely responsible for the feelings of hyperalgesia reported in patients with HaT.13

There is substantial overlap in the clinical pictures of HaT and MCAS, and HaT is considered a heritable risk factor for MCAS. Consequently, any patient undergoing workup for MCAS also should be tested for HaT. Although HaT is associated with consistently elevated tryptase, MCAS is episodic in nature, and an increase in tryptase levels of at least 20% plus 2 ng/mL from baseline only in the presence of other symptoms reflective of mast cell activation (Table) is a prerequisite for diagnosis.9 Chronic signs and symptoms of atopy, chronic urticaria, and severe asthma are not indicative of MCAS but are frequently seen in HaT.

Another cause of persistently elevated tryptase levels is SM. Systemic mastocytosis is defined by aberrant clonal mast cell expansion and systemic involvement11 and can cause persistent symptoms, unlike MCAS alone. However, SM also can be associated with MCAS.9 Notably, a baseline serum tryptase level greater than 20 ng/mL—much higher than the threshold of greater than 8 ng/mL for suspicion of HaT—is seen in 75% of SM cases and is part of the minor diagnostic criteria for the disease.9,11 However, the 2016 study identifying increased TPSAB1 α-tryptase–encoding sequences as the causative entity for HaT by Lyons et al2 found the average (SD) basal serum tryptase level in individuals with α-tryptase–encoding sequence duplications to be 15 (5) ng/mL and 24 (6) ng/mL in those with triplications. Thus, there likely is no threshold for elevated baseline tryptase levels that would indicate SM over HaT as a more likely diagnosis. However, SM will present with new persistently elevated tryptase levels, whereas the elevation in HaT is believed to be lifelong.5 Also in contrast to HaT, SM can present with liver, spleen, and lymph node involvement; bone sclerosis; and cytopenia.11,14

Mastocytosis is much rarer than HaT, with an estimated prevalence of 9 cases per 100,000 individuals in the United States.11 Although HaT diagnostic testing is noninvasive, SM requires a bone marrow biopsy for definitive diagnosis. Given the likely much higher prevalence of HaT than SM and the patient burden of a bone marrow biopsy, HaT should be considered before proceeding with a bone marrow biopsy to evaluate for SM when a patient presents with persistent systemic symptoms of mast cell activation and elevated baseline tryptase levels. Furthermore, it also would be prudent to test for HaT in patients with known SM, as a cohort study by Lyons et al5 indicated that HaT is likely more common in those with SM (12.2% [10/82] of cohort with known SM vs 5.3% of 398 controls), and patients with concurrent SM and HaT were at a higher risk for severe anaphylaxis (RR=9.5; P=.007).

Studies thus far surrounding HaT have not evaluated timing of initial symptom onset or age of initial presentation for HaT. Furthermore, there is no guarantee that those with increased TPSAB1 copy number will be symptomatic, as there have been reports of asymptomatic individuals with HaT who had basal serum levels greater than 8 ng/mL.7 As research into HaT continues and larger cohorts are evaluated, questions surrounding timing of symptom onset and various factors that may make someone more likely to display a particular phenotype will be answered.

Treatment—Long-term prognosis for individuals with HaT is largely unknown. Unfortunately, there are limited data to support a single effective treatment strategy for managing HaT, and treatment has varied based on predominant symptoms. For cutaneous and GI tract symptoms, trials of maximal H1 and H2 antihistamines twice daily have been recommended.4 Omalizumab was reported to improve chronic urticaria in 3 of 3 patients, showing potential promise as a treatment.4 Mast cell stabilizers, such as oral cromolyn, have been used for severe GI symptoms, while some patients also have reported improvement with oral ketotifen.6 Other medications, such as tricyclic antidepressants, clemastine fumarate, and gabapentin, have been beneficial anecdotally.6 Given the lack of harmful effects seen in individuals who are α-tryptase deficient, α-tryptase inhibition is an intriguing target for future therapies.

Conclusion

Patients who present with a constellation of dermatologic, allergic, GI tract, neuropsychiatric, respiratory, autonomic, and connective tissue abnormalities consistent with HaT may receive a prompt diagnosis if the association is recognized. The full relationship between HaT and other chronic dermatologic disorders is still unknown. Ultimately, heightened interest and research into HaT will lead to more treatment options available for affected patients.

Hereditary alpha tryptasemia (HaT), an autosomal-dominant disorder of tryptase overproduction, was first described in 2014 by Lyons et al.1 It has been associated with multiple dermatologic, allergic, gastrointestinal (GI) tract, neuropsychiatric, respiratory, autonomic, and connective tissue abnormalities. These multisystem concerns may include cutaneous flushing, chronic pruritus, urticaria, GI tract symptoms, arthralgia, and autonomic dysfunction.2 The diverse symptoms and the recent discovery of HaT make recognition of this disorder challenging. Currently, it also is believed that HaT is associated with an elevated risk for anaphylaxis and is a biomarker for severe symptoms in disorders with increased mast cell burden such as mastocytosis.3-5

Given the potential cutaneous manifestations and the fact that dermatologic symptoms may be the initial presentation of HaT, awareness and recognition of this condition by dermatologists are essential for diagnosis and treatment. This review summarizes the cutaneous presentations consistent with HaT and discusses various conditions that share overlapping dermatologic symptoms with HaT.

Background on HaT

Mast cells are known to secrete several vasoactive mediators including tryptase and histamine when activated by foreign substances, similar to IgE-mediated hypersensitivity reactions. In their baseline state, mast cells continuously secrete immature forms of tryptases called protryptases.6 These protryptases come in 2 forms: α and β. Although mature tryptase is acutely elevatedin anaphylaxis, persistently elevated total serum tryptase levels frequently are regarded as indicative of a systemic mast cell disorder such as systemic mastocytosis (SM).3 Despite the wide-ranging phenotype of HaT, all individuals with the disorder have an elevated basal serum tryptase level (>8 ng/mL). Hereditary alpha tryptasemia has been identified as another possible cause of persistently elevated levels.2,6

Genetics and Epidemiology of HaT—The humantryptase locus at chromosome 16p13.3 is composed of 4 paralog genes: TPSG1, TPSB2, TPSAB1, and TPSD1.4 Only TPSAB1 encodes for α-tryptase, while both TPSB2 and TPSAB1 encode for β-tryptase.4 Hereditary alpha tryptasemia is an autosomal-dominant disorder resulting from a copy number increase in the α-tryptase encoding sequence within the TPSAB1 gene. Despite the wide-ranging phenotype of HaT, all individuals identified with the disorder have a basal serum tryptase level greater than 8 ng/mL, with mean (SD) levels of 15 (5) ng/mL and 24 (6) ng/mL with gene duplication and triplication, respectively (reference range, 0–11.4 ng/mL).2,6 Hereditary alpha tryptasemia likely is common and largely undiagnosed, with a recently estimated prevalence of 5% in the United Kingdom7 and 5.6% in a cohort of 125 individuals from Italy, Slovenia, and the United States.5

Implications of Increased α-tryptase Levels—After an inciting stimulus, the active portions of α-protryptase and β-protryptase are secreted as tetramers by activated mast cells via degranulation. In vitro, β-tryptase homotetramers have been found to play a role in anaphylaxis, while α-homotetramers are nearly inactive.8,9 Recently, however, it has been discovered that α2β2 tetramers also can form and do so in a higher ratio in individuals with increased α-tryptase–encoding gene copies, such as those with HaT.8 These heterotetramers exhibit unique properties compared with the homotetramers and may stimulate epidermal growth factor–like module-containing mucinlike hormone receptor 2 and protease-activated receptor 2 (PAR2). Epidermal growth factor–like module-containing mucinlike hormone receptor 2 activation likely contributes to vibratory urticaria in patients, while activation of PAR2 may have a range of clinical effects, including worsening asthma, inflammatory bowel disease, pruritus, and the exacerbation of dermal inflammation and hyperalgesia.8,10 Thus, α- and β-tryptase tetramers can be considered mediators that may influence the severity of disorders in which mast cells are naturally prevalent and likely contribute to the phenotype of those with HaT.7 Furthermore, these characteristics have been shown to potentially increase in severity with increasing tryptase levels and with increased TPSAB1 duplications.1,2 In contrast, more than 25% of the population is deficient in α-tryptase without known deleterious effects.5

Cutaneous Manifestations of HaT

A case series reported by Lyons et al1 in 2014 detailed persistent elevated basal serum tryptase levels in 9 families with an autosomal-dominant pattern of inheritance. In this cohort, 31 of 33 (94%) affected individuals had a history of atopic dermatitis (AD), and 26 of 33 (79%) affected individuals reported symptoms consistent with mast cell degranulation, including urticaria; flushing; and/or crampy abdominal pain unprovoked or triggered by heat, exercise, vibration, stress, certain foods, or minor physical stimulation.1 A later report by Lyons et al2 in 2016 identified the TPSAB1 α-tryptase–encoding sequence copy number increase as the causative entity for HaT by examining a group of 96 patients from 35 families with frequent recurrent cutaneous flushing and pruritus, sometimes associated with urticaria and sleep disruption. Flushing and pruritus were found in 45% (33/73) of those with a TPSAB1 duplication and 80% (12/15) of those with a triplication (P=.022), suggesting a gene dose effect regarding α-tryptase encoding sequence copy number and these symptoms.2

A 2019 study further explored the clinical finding of urticaria in patients with HaT by specifically examining if vibration-induced urticaria was affected by TPSAB1 gene dosage.8 A cohort of 56 volunteers—35 healthy and 21 with HaT—underwent tryptase genotyping and cutaneous vibratory challenge. The presence of TPSAB1 was significantly correlated with induction of vibration-induced urticaria (P<.01), as the severity and prevalence of the urticarial response increased along with α- and β-tryptase gene ratios.8

Urticaria and angioedema also were seen in 51% (36/70) of patients in a cohort of HaT patients in the United Kingdom, in which 41% (29/70) also had skin flushing. In contrast to prior studies, these manifestations were not more common in patients with gene triplications or quintuplications than those with duplications.7 In another recent retrospective evaluation conducted at Brigham and Women’s Hospital (Boston, Massachusetts)(N=101), 80% of patients aged 4 to 85 years with confirmed diagnoses of HaT had skin manifestations such as urticaria, flushing, and pruritus.4

HaT and Mast Cell Activation Syndrome—In 2019, a Mast Cell Disorders Committee Work Group Report outlined recommendations for diagnosing and treating primary mast cell activation syndrome (MCAS), a disorder in which mast cells seem to be more easily activated. Mast cell activation syndrome is defined as a primary clinical condition in which there are episodic signs and symptoms of systemic anaphylaxis (Table) concurrently affecting at least 2 organ systems, resulting from secreted mast cell mediators.9,11 The 2019 report also touched on clinical criteria that lack precision for diagnosing MCAS yet are in use, including dermographism and several types of rashes.9 Episode triggers frequent in MCAS include hot water, alcohol, stress, exercise, infection, hormonal changes, and physical stimuli.