User login

Surgical management of early pregnancy loss

CASE Concern for surgical management after repeat miscarriage

A 34-year-old woman (G3P0030) with a history of recurrent pregnancy loss was recently diagnosed with a 7-week missed abortion. After her second miscarriage, she had an evaluation for recurrent pregnancy loss which was unremarkable. Both prior miscarriages were managed with dilation & curettage (D&C), but cytogenetic testing of the tissue did not yield a result in either case. The karyotype from the first pregnancy resulted as 46, XX but was confirmed to be due to maternal cell contamination, and the karyotype from the second pregnancy resulted in cell culture failure. The patient is interested in surgical management for her current missed abortion to help with tissue collection for cytogenetic testing, she but is concerned about her risk of intrauterine adhesions with repeated uterine instrumentation given 2 prior D&Cs, one of which was complicated by retained products of conception.

How do you approach the surgical management of this patient with recurrent pregnancy loss?

Approximately 1 in every 8 recognized pregnancies results in miscarriage. The risk of loss is lowest in women with no history of miscarriage (11%), and increases by about 10% for each additional miscarriage, reaching 42% in women with 3 or more previous losses. The population prevalence of women who have had 1 miscarriage is 11%, 2 miscarriages is 2%, and 3 or more is <1%.1 While 90% of miscarriages occur in the first trimester, their etiology can be quite varied.2 A woman’s age is the most strongly associated risk factor, with both very young (<20 years) and older age (>35 years) groups at highest risk. This association is largely attributed to an age-related increase in embryonic chromosomal aneuploidies, of which trisomies, particularly trisomy 16, are the most common.3 Maternal anatomic anomalies such as leiomyomas, intrauterine adhesions, Müllerian anomalies, and adenomyosis have been linked to an increased risk of miscarriage in addition to several lifestyle and environmental factor exposures.1

Regardless of the etiology, women with recurrent miscarriage are exposed to the potential for iatrogenic harm from the management of their pregnancy loss, including intrauterine adhesions and retained products, which may negatively impact future reproductive attempts. The management of patients with recurrent miscarriages demands special attention to reduce the risk of iatrogenic harm, maximize diagnostic evaluation of the products of conception, and improve future reproductive outcomes.

Management strategies

First trimester pregnancy loss may be managed expectantly, medically, or surgically. Approximately 76% of women who opt for expectant management will successfully pass pregnancy tissue, but for 1 out of every 6 women it may take longer than 14 days.4 For patients who prefer to expedite this process, medication abortion is a highly effective and safe option. According to Schreiber and colleagues, a combination of mifepristone and misoprostol together resulted in expulsion in approximately 91% of 148 patients, although 9% still required surgical intervention for incomplete passage of tissue.5 Both expectant management and medical management strategies are associated with the potential for retained products of conception requiring subsequent instrumentation as well as tissue that is often unsuitable or contaminated for cytogenetic analysis.

The most definitive treatment option is surgical management via manual or electric vacuum aspiration or curettage, with efficacy approaching 99.6% in some series.6 While highly effective, even ultrasound-guided evacuation carries with it procedure-related risks that are of particular consequence for patients of reproductive age, including adhesion formation and retained products of conception.

In 1997, Goldenberg and colleagues reported on the use of hysteroscopy for the management of retained products of conception as a strategy to minimize trauma to the uterus and maximize excision of retained tissue, both of which reduce potential for adhesion formation.7 Based on these data, several groups have extended the use of hysteroscopic resection for retained tissue to upfront evacuation following pregnancy loss, in lieu of D&C.8,9 This approach allows for the direct visualization of the focal removal of the implanted pregnancy tissue, which can:

- decrease the risk of intrauterine adhesion formation

- decrease the risk of retained products of conception

- allow for directed tissue sampling to improve the accuracy of cytogenetic testing

- allow for detection of embryo anatomic anomalies that often go undetected on traditional cytogenetic analysis.

For the remainder of this article, we will discuss the advantages of hysteroscopic management of a missed abortion in greater detail.

Continue to: Hysteroscopic management...

Hysteroscopic management

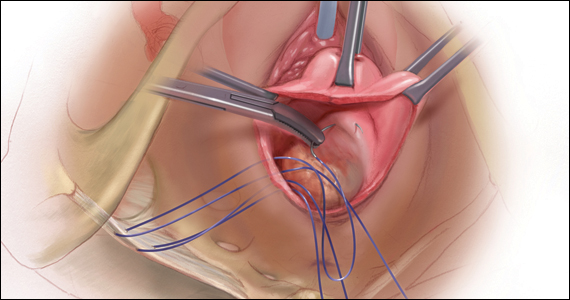

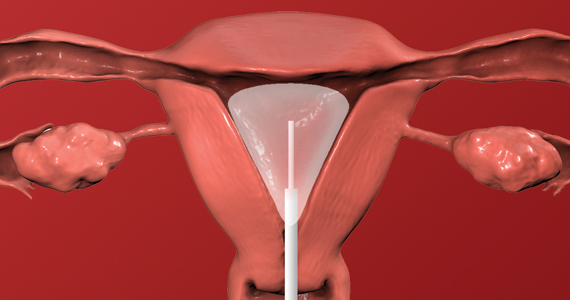

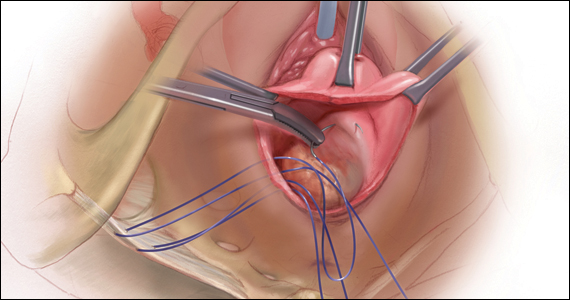

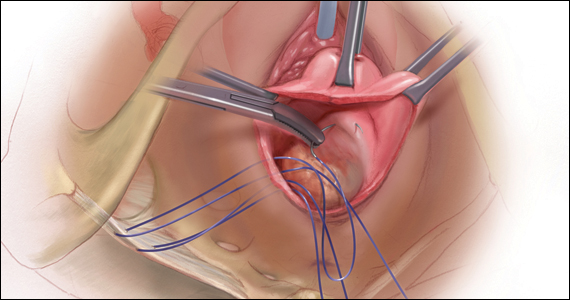

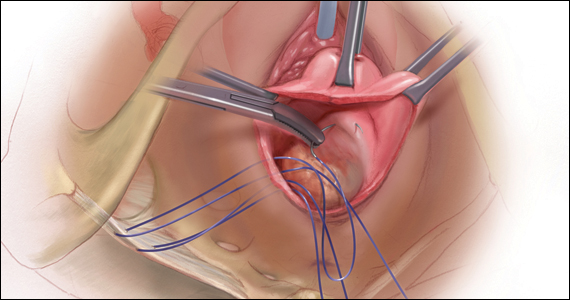

Like aspiration or curettage, hysteroscopic management may be offered once the diagnosis of fetal demise is confirmed on ultrasonography. The procedure may be accomplished in the office setting or in the operative room with either morcellation or resectoscopic instruments. Morcellation allows for improved visibility during the procedure given the ability of continuous suction to manage tissue fragments in the surgical field, while resectoscopic instruments offer the added benefit of electrosurgery should bleeding that is unresponsive to increased distention pressure be encountered. Use of the cold loop of the resectoscope to accomplish evacuation is advocated to avoid the thermal damage to the endometrium with electrosurgery. Regardless of the chosen instrument, there are several potential benefits for a hysteroscopic approach over the traditional ultrasound-guided or blind D&C.

Reducing risk of iatrogenic harm

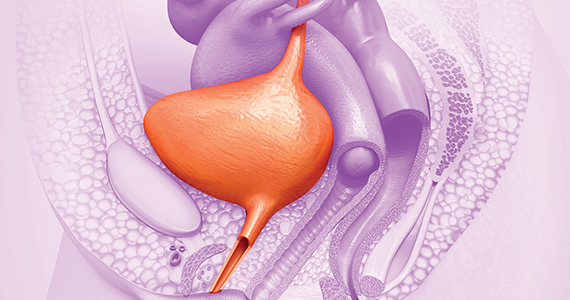

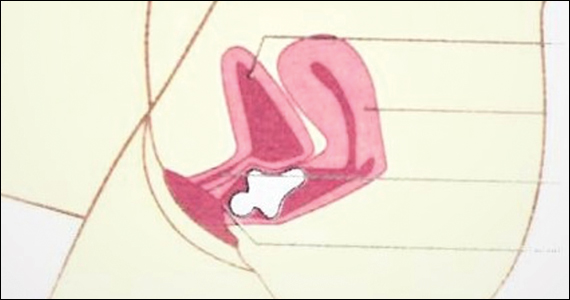

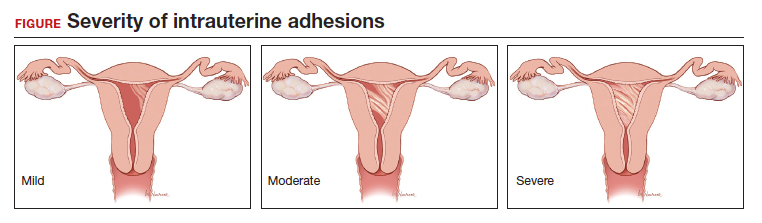

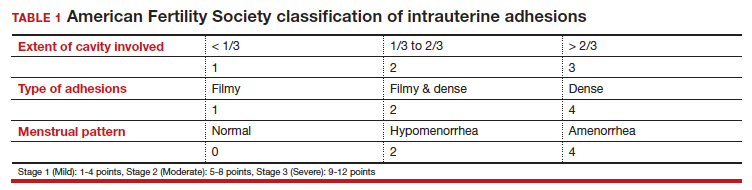

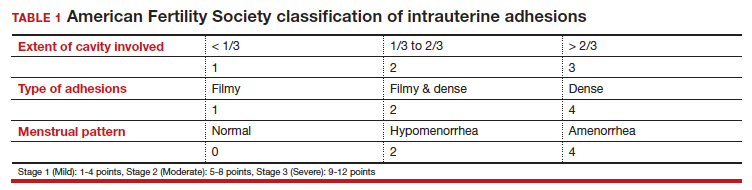

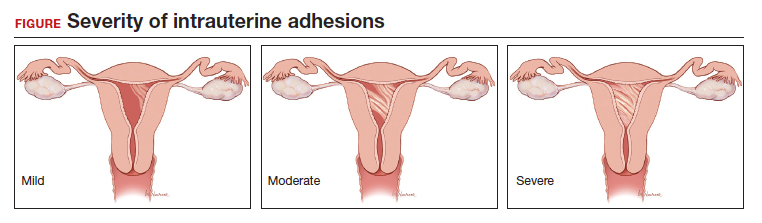

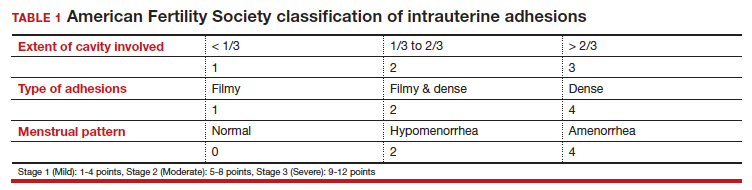

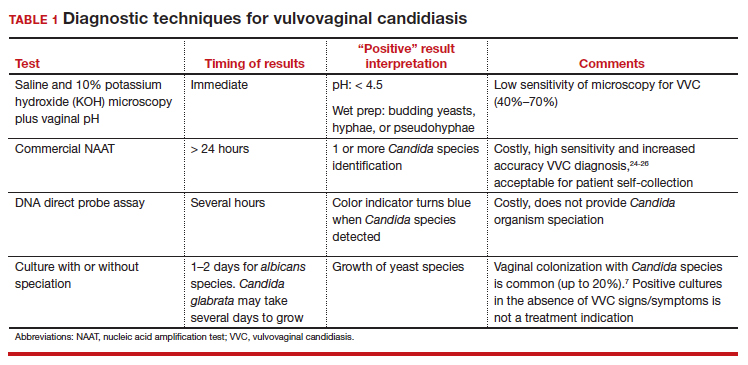

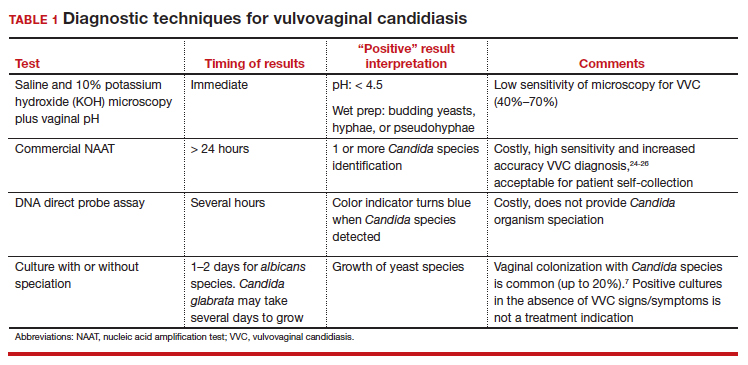

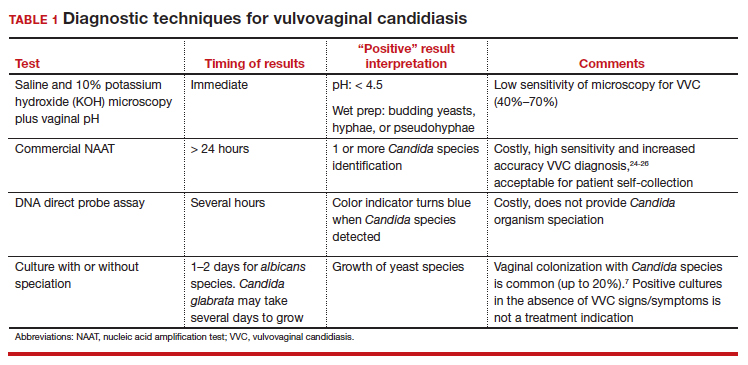

Intrauterine adhesions form secondary to trauma to the endometrial basalis layer, where a population of adult progenitor stem cells continuously work to regenerate the overlying functionalis layer. Once damaged, adhesions may form and range from thin, filmy adhesions to dense, cavity obliterating bands of scar tissue (FIGURE). The degree of severity and location of the adhesions account for the variable presentation that range from menstrual abnormalities to infertility and recurrent pregnancy loss. While several classification systems exist for scoring severity of adhesions, the American Fertility Society (now American Society for Reproductive Medicine) Classification system from 1988 is still commonly utilized (TABLE 1).

Intrauterine adhesions from D&C after pregnancy loss are not uncommon. A 2014 meta-analysis of 10 prospective studies including 912 women reported a pooled prevalence for intrauterine adhesions of 19.1% (95% confidence interval [CI], 12.8–27.5) on hysteroscopic evaluation within 12 months following curettage.10 Once formed, these adhesions are associated with long-term impairment in reproductive outcomes, regardless of if they were treated or not. In a long-term follow-up study of women with and without adhesions after recurrent D&C for miscarriage, women with treated adhesions reported lower live birth rates, longer time to pregnancy, higher rates of preterm birth and higher rates of peripartum complications compared with those without adhesions.11

Compared with curettage, hysteroscopy affords the surgeon complete visualization of the uterine cavity and tissue to be resected. This, in turn, minimizes trauma to the surrounding uterine cavity, minimizes the potential for post-procedural adhesion formation and their associated sequelae, and maximizes complete resection of tissue. Those treated with D&C appear to be significantly more likely to have adhesions than those treated via a hysteroscopic approach (30% vs 13%).12

Retained products of conception. Classically, a “gritty” sensation of the endometrium following evacuation of the uterus with a sharp curette has been used to indicate complete removal of tissue. The evolution from a nonvisualized procedure to ultrasound-guided vacuum aspiration of 1st trimester pregnancy tissue has been associated with a decreased risk of procedural complications and retained products of conception.13 However, even with intraoperative imaging, the risk of retained products of conception remains because it can be difficult to distinguish a small blood clot from retained pregnancy tissue on ultrasonography.

Retained pregnancy tissue can result in abnormal or heavy bleeding, require additional medical or surgical intervention, and is associated with endometrial inflammation and infection. Approximately 1 in every 4 women undergoing hysteroscopic resection of retained products are found to have evidence of endometritis in the resected tissue.14 This number is even higher in women with a diagnosis of recurrent pregnancy loss (62%).15

These complications from retained products of conception can be avoided with the hysteroscopic approach due to the direct visualization of the tissue removal. This benefit may be particularly beneficial in patients with known abnormal uterine cavities, such as those with Müllerian anomalies, uterine leiomyomas, preexisting adhesions, and history of placenta accreta spectrum disorder.

Continue to: Maximizing diagnostic yield...

Maximizing diagnostic yield

Many patients prefer surgical management of a missed abortion not for the procedural advantages, but to assist with tissue collection for cytogenetic testing of the pregnancy tissue. Given that embryonic chromosomal aneuploidy is implicated in 70% of miscarriages prior to 20 weeks’ gestation, genetic evaluation of the products of conception is commonly performed to identify a potential cause for the miscarriage.16 G-band karyotype is the most commonly performed genetic evaluation. Karyotype requires culturing of pregnancy tissue for 7-14 days to produce metaphase cells that are then chemically treated to arrest them at their maximally contracted stage. Cytogenetic evaluation is often curtailed when nonviable cells from products of conception fail to culture due to either time elapsed from diagnosis to demise or damage from tissue handling. Careful, directly observed tissue handling via a hysteroscopic approach may alleviate culture failure secondary to tissue damage.

Another concern with cultures of products of conception is the potential for maternal cell contamination. Early studies from the 1970s noted a significant skew toward 46, XX karyotype results in miscarried tissue as compared with 46, XY results. It was not until microsatellite analysis technology was available that it was determined that the result was due to analysis of maternal cells instead of products of conception.17 A 2014 study by Levy and colleagues and another by Lathi and colleagues that utilized single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) microarray found that maternal cell contamination affected 22% of all miscarriage samples analyzed and over half of karyotypes with a 46, XX result.18,19

Traditional “blind” suction and curettage may inadvertently collect maternal endometrial tissue and contaminate the culture of fetal cells, limiting the validity of karyotype for products of conception.20 The hysteroscopic approach may provide a higher diagnostic yield for karyotype analysis of fetal tissue by the nature of targeted tissue sampling under direct visualization, minimizing maternal cell contamination. One retrospective study by Cholkeri-Singh and colleagues evaluated rates of fetal chromosome detection without maternal contamination in a total of 264 patients undergoing either suction curettage or hysteroscopic resection. They found that fetal chromosomal detection without contamination was significantly higher in the hysteroscopy group compared with the suction curettage group (88.5 vs 64.8%, P< .001).21 Additionally, biopsies of tissue under direct visualization may enable the diagnosis of a true placental mosaicism and the study of the individual karyotype of each embryo in dizygotic twin missed abortions.

Finally, a hysteroscopic approach may afford the opportunity to also perform morphologic evaluation of the intact early fetus furthering the diagnostic utility of the procedure. With hysteroscopy, the gestational sac is identified and carefully entered, allowing for complete visualization of the early fetus and assessment of anatomic malformations that may provide insight into the pregnancy loss (ie, embryoscopy). In one series of 272 patients with missed abortions, while nearly 75% of conceptuses had abnormal karyotypes, 18% were found to have gross morphologic defects with a normal karyotype.22

Bottom line

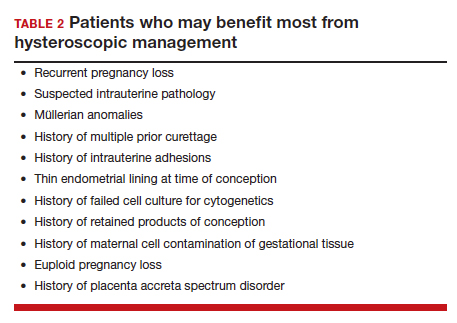

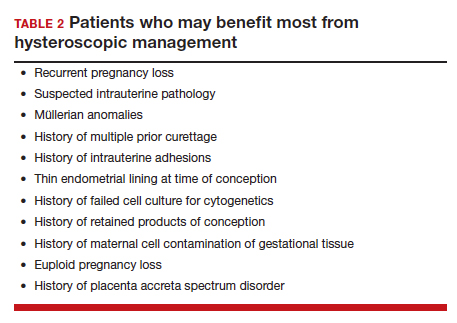

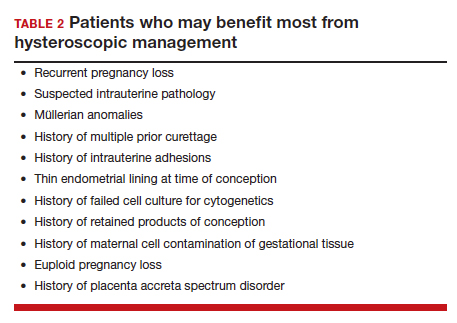

When faced with a patient with an early pregnancy loss, physicians should consider the decreased iatrogenic risks and improved diagnostic yield when deciding between D&C versus hysteroscopy for surgical management. There are certain patients with pre-existing risk factors that may stand to benefit the most (TABLE 2). Much like the opening case, those at risk for intrauterine adhesions, retained products of conception, or in whom a successful and accurate cytogenetic analysis is essential are the most likely to benefit from a hysteroscopic approach. The hysteroscopic approach also affords concurrent diagnosis and treatment of intrauterine pathology, such as leiomyomas and uterine septum, which are encountered approximately 12.5% of the time after one miscarriage and 29.4% of the time in patients with a history of more than one miscarriage.10 In the appropriately counseled patient and clinical setting, clinicians could also perform definitive surgical management during the same hysteroscopy. Finally, evaluation of the morphology of the demised fetus may provide additional information for patient counseling in those with euploid pregnancy losses.

CASE Resolved

Ultimately, our patient underwent complete hysteroscopic resection of the pregnancy tissue, which confirmed both a morphologically abnormal fetus and a 45, X karyotype of the products of conception. ●

- Quenby S, Gallos ID, Dhillon-Smith RK, et al. Miscarriage matters: the epidemiological, physical, psychological, and economic costs of early pregnancy loss. Lancet. 2021;397:1658-1667.

- Kolte AM, Westergaard D, Lidegaard Ø, et al. Chance of live birth: a nationwide, registry-based cohort study. Hum Reprod Oxf Engl. 2021;36:1065-1073.

- Magnus MC, Wilcox AJ, Morken N-H, et al. Role of maternal age and pregnancy history in risk of miscarriage: prospective register-based study. BMJ. 2019;364:869.

- Luise C, Jermy K, May C, et al. Outcome of expectant management of spontaneous first trimester miscarriage: observational study. BMJ. 2002;324:873-875.

- Schreiber CA, Creinin MD, Atrio J, et al. Mifepristone pretreatment for the medical management of early pregnancy loss. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:2161-2170.

- Ireland LD, Gatter M, Chen AY. Medical compared with surgical abortion for effective pregnancy termination in the first trimester. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;126:22-28.

- Goldenberg M, Schiff E, Achiron R, et al. Managing residual trophoblastic tissue. Hysteroscopy for directing curettage. J Reprod Med. 1997;42:26-28.

- Weinberg S, Pansky M, Burshtein I, et al. A pilot study of guided conservative hysteroscopic evacuation of early miscarriage. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2021;28:1860-1867.

- Young S, Miller CE. Hysteroscopic resection for management of early pregnancy loss: a case report and literature review. FS Rep. 2022;3:163-167.

- Hooker AB, Lemmers M, Thurkow AL, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of intrauterine adhesions after miscarriage: prevalence, risk factors and long-term reproductive outcome. Hum Reprod Update. 2014;20:262-278.

- Hooker AB, de Leeuw RA, Twisk JWR, et al. Reproductive performance of women with and without intrauterine adhesions following recurrent dilatation and curettage for miscarriage: long-term follow-up of a randomized controlled trial. Hum Reprod. 2021;36:70-81.

- Hooker AB, Aydin H, Brölmann HAM, et al. Longterm complications and reproductive outcome after the management of retained products of conception: a systematic review. Fertil Steril. 2016;105:156-164.e1-e2.

- Debby A, Malinger G, Harow E, et al. Transvaginal ultrasound after first-trimester uterine evacuation reduces the incidence of retained products of conception. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2006;27:61-64.

- Elder S, Bortoletto P, Romanski PA, et al. Chronic endometritis in women with suspected retained products of conception and their reproductive outcomes. Am J Reprod Immunol N Y N 1989. 2021;86:e13410.

- McQueen DB, Maniar KP, Hutchinson A, et al. Retained pregnancy tissue after miscarriage is associated with high rate of chronic endometritis. J Obstet Gynaecol J Inst Obstet Gynaecol. 2022;1-5.

- Soler A, Morales C, Mademont-Soler I, et al. Overview of chromosome abnormalities in first trimester miscarriages: a series of 1,011 consecutive chorionic villi sample karyotypes. Cytogenet Genome Res. 2017;152:81-89.

- Jarrett KL, Michaelis RC, Phelan MC, et al. Microsatellite analysis reveals a high incidence of maternal cell contamination in 46, XX products of conception consisting of villi or a combination of villi and membranous material. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2001;185:198-203.

- Levy B, Sigurjonsson S, Pettersen B, et al. Genomic imbalance in products of conception: single-nucleotide polymorphism chromosomal microarray analysis. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;124:202-209.

- Lathi RB, Gustin SLF, Keller J, et al. Reliability of 46, XX results on miscarriage specimens: a review of 1,222 first-trimester miscarriage specimens. Fertil Steril. 2014;101:178-182.

- Chung JPW, Li Y, Law TSM, et al. Ultrasound-guided manual vacuum aspiration is an optimal method for obtaining products of conception from early pregnancy loss for cytogenetic testing. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2022;147:106226.

- Cholkeri-Singh A, Zamfirova I, Miller CE. Increased fetal chromosome detection with the use of operative hysteroscopy during evacuation of products of conception for diagnosed miscarriage. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2020;27:160-165.

- Philipp T, Philipp K, Reiner A, et al. Embryoscopic and cytogenetic analysis of 233 missed abortions: factors involved in the pathogenesis of developmental defects of early failed pregnancies. Hum Reprod. 2003;18:1724-1732.

CASE Concern for surgical management after repeat miscarriage

A 34-year-old woman (G3P0030) with a history of recurrent pregnancy loss was recently diagnosed with a 7-week missed abortion. After her second miscarriage, she had an evaluation for recurrent pregnancy loss which was unremarkable. Both prior miscarriages were managed with dilation & curettage (D&C), but cytogenetic testing of the tissue did not yield a result in either case. The karyotype from the first pregnancy resulted as 46, XX but was confirmed to be due to maternal cell contamination, and the karyotype from the second pregnancy resulted in cell culture failure. The patient is interested in surgical management for her current missed abortion to help with tissue collection for cytogenetic testing, she but is concerned about her risk of intrauterine adhesions with repeated uterine instrumentation given 2 prior D&Cs, one of which was complicated by retained products of conception.

How do you approach the surgical management of this patient with recurrent pregnancy loss?

Approximately 1 in every 8 recognized pregnancies results in miscarriage. The risk of loss is lowest in women with no history of miscarriage (11%), and increases by about 10% for each additional miscarriage, reaching 42% in women with 3 or more previous losses. The population prevalence of women who have had 1 miscarriage is 11%, 2 miscarriages is 2%, and 3 or more is <1%.1 While 90% of miscarriages occur in the first trimester, their etiology can be quite varied.2 A woman’s age is the most strongly associated risk factor, with both very young (<20 years) and older age (>35 years) groups at highest risk. This association is largely attributed to an age-related increase in embryonic chromosomal aneuploidies, of which trisomies, particularly trisomy 16, are the most common.3 Maternal anatomic anomalies such as leiomyomas, intrauterine adhesions, Müllerian anomalies, and adenomyosis have been linked to an increased risk of miscarriage in addition to several lifestyle and environmental factor exposures.1

Regardless of the etiology, women with recurrent miscarriage are exposed to the potential for iatrogenic harm from the management of their pregnancy loss, including intrauterine adhesions and retained products, which may negatively impact future reproductive attempts. The management of patients with recurrent miscarriages demands special attention to reduce the risk of iatrogenic harm, maximize diagnostic evaluation of the products of conception, and improve future reproductive outcomes.

Management strategies

First trimester pregnancy loss may be managed expectantly, medically, or surgically. Approximately 76% of women who opt for expectant management will successfully pass pregnancy tissue, but for 1 out of every 6 women it may take longer than 14 days.4 For patients who prefer to expedite this process, medication abortion is a highly effective and safe option. According to Schreiber and colleagues, a combination of mifepristone and misoprostol together resulted in expulsion in approximately 91% of 148 patients, although 9% still required surgical intervention for incomplete passage of tissue.5 Both expectant management and medical management strategies are associated with the potential for retained products of conception requiring subsequent instrumentation as well as tissue that is often unsuitable or contaminated for cytogenetic analysis.

The most definitive treatment option is surgical management via manual or electric vacuum aspiration or curettage, with efficacy approaching 99.6% in some series.6 While highly effective, even ultrasound-guided evacuation carries with it procedure-related risks that are of particular consequence for patients of reproductive age, including adhesion formation and retained products of conception.

In 1997, Goldenberg and colleagues reported on the use of hysteroscopy for the management of retained products of conception as a strategy to minimize trauma to the uterus and maximize excision of retained tissue, both of which reduce potential for adhesion formation.7 Based on these data, several groups have extended the use of hysteroscopic resection for retained tissue to upfront evacuation following pregnancy loss, in lieu of D&C.8,9 This approach allows for the direct visualization of the focal removal of the implanted pregnancy tissue, which can:

- decrease the risk of intrauterine adhesion formation

- decrease the risk of retained products of conception

- allow for directed tissue sampling to improve the accuracy of cytogenetic testing

- allow for detection of embryo anatomic anomalies that often go undetected on traditional cytogenetic analysis.

For the remainder of this article, we will discuss the advantages of hysteroscopic management of a missed abortion in greater detail.

Continue to: Hysteroscopic management...

Hysteroscopic management

Like aspiration or curettage, hysteroscopic management may be offered once the diagnosis of fetal demise is confirmed on ultrasonography. The procedure may be accomplished in the office setting or in the operative room with either morcellation or resectoscopic instruments. Morcellation allows for improved visibility during the procedure given the ability of continuous suction to manage tissue fragments in the surgical field, while resectoscopic instruments offer the added benefit of electrosurgery should bleeding that is unresponsive to increased distention pressure be encountered. Use of the cold loop of the resectoscope to accomplish evacuation is advocated to avoid the thermal damage to the endometrium with electrosurgery. Regardless of the chosen instrument, there are several potential benefits for a hysteroscopic approach over the traditional ultrasound-guided or blind D&C.

Reducing risk of iatrogenic harm

Intrauterine adhesions form secondary to trauma to the endometrial basalis layer, where a population of adult progenitor stem cells continuously work to regenerate the overlying functionalis layer. Once damaged, adhesions may form and range from thin, filmy adhesions to dense, cavity obliterating bands of scar tissue (FIGURE). The degree of severity and location of the adhesions account for the variable presentation that range from menstrual abnormalities to infertility and recurrent pregnancy loss. While several classification systems exist for scoring severity of adhesions, the American Fertility Society (now American Society for Reproductive Medicine) Classification system from 1988 is still commonly utilized (TABLE 1).

Intrauterine adhesions from D&C after pregnancy loss are not uncommon. A 2014 meta-analysis of 10 prospective studies including 912 women reported a pooled prevalence for intrauterine adhesions of 19.1% (95% confidence interval [CI], 12.8–27.5) on hysteroscopic evaluation within 12 months following curettage.10 Once formed, these adhesions are associated with long-term impairment in reproductive outcomes, regardless of if they were treated or not. In a long-term follow-up study of women with and without adhesions after recurrent D&C for miscarriage, women with treated adhesions reported lower live birth rates, longer time to pregnancy, higher rates of preterm birth and higher rates of peripartum complications compared with those without adhesions.11

Compared with curettage, hysteroscopy affords the surgeon complete visualization of the uterine cavity and tissue to be resected. This, in turn, minimizes trauma to the surrounding uterine cavity, minimizes the potential for post-procedural adhesion formation and their associated sequelae, and maximizes complete resection of tissue. Those treated with D&C appear to be significantly more likely to have adhesions than those treated via a hysteroscopic approach (30% vs 13%).12

Retained products of conception. Classically, a “gritty” sensation of the endometrium following evacuation of the uterus with a sharp curette has been used to indicate complete removal of tissue. The evolution from a nonvisualized procedure to ultrasound-guided vacuum aspiration of 1st trimester pregnancy tissue has been associated with a decreased risk of procedural complications and retained products of conception.13 However, even with intraoperative imaging, the risk of retained products of conception remains because it can be difficult to distinguish a small blood clot from retained pregnancy tissue on ultrasonography.

Retained pregnancy tissue can result in abnormal or heavy bleeding, require additional medical or surgical intervention, and is associated with endometrial inflammation and infection. Approximately 1 in every 4 women undergoing hysteroscopic resection of retained products are found to have evidence of endometritis in the resected tissue.14 This number is even higher in women with a diagnosis of recurrent pregnancy loss (62%).15

These complications from retained products of conception can be avoided with the hysteroscopic approach due to the direct visualization of the tissue removal. This benefit may be particularly beneficial in patients with known abnormal uterine cavities, such as those with Müllerian anomalies, uterine leiomyomas, preexisting adhesions, and history of placenta accreta spectrum disorder.

Continue to: Maximizing diagnostic yield...

Maximizing diagnostic yield

Many patients prefer surgical management of a missed abortion not for the procedural advantages, but to assist with tissue collection for cytogenetic testing of the pregnancy tissue. Given that embryonic chromosomal aneuploidy is implicated in 70% of miscarriages prior to 20 weeks’ gestation, genetic evaluation of the products of conception is commonly performed to identify a potential cause for the miscarriage.16 G-band karyotype is the most commonly performed genetic evaluation. Karyotype requires culturing of pregnancy tissue for 7-14 days to produce metaphase cells that are then chemically treated to arrest them at their maximally contracted stage. Cytogenetic evaluation is often curtailed when nonviable cells from products of conception fail to culture due to either time elapsed from diagnosis to demise or damage from tissue handling. Careful, directly observed tissue handling via a hysteroscopic approach may alleviate culture failure secondary to tissue damage.

Another concern with cultures of products of conception is the potential for maternal cell contamination. Early studies from the 1970s noted a significant skew toward 46, XX karyotype results in miscarried tissue as compared with 46, XY results. It was not until microsatellite analysis technology was available that it was determined that the result was due to analysis of maternal cells instead of products of conception.17 A 2014 study by Levy and colleagues and another by Lathi and colleagues that utilized single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) microarray found that maternal cell contamination affected 22% of all miscarriage samples analyzed and over half of karyotypes with a 46, XX result.18,19

Traditional “blind” suction and curettage may inadvertently collect maternal endometrial tissue and contaminate the culture of fetal cells, limiting the validity of karyotype for products of conception.20 The hysteroscopic approach may provide a higher diagnostic yield for karyotype analysis of fetal tissue by the nature of targeted tissue sampling under direct visualization, minimizing maternal cell contamination. One retrospective study by Cholkeri-Singh and colleagues evaluated rates of fetal chromosome detection without maternal contamination in a total of 264 patients undergoing either suction curettage or hysteroscopic resection. They found that fetal chromosomal detection without contamination was significantly higher in the hysteroscopy group compared with the suction curettage group (88.5 vs 64.8%, P< .001).21 Additionally, biopsies of tissue under direct visualization may enable the diagnosis of a true placental mosaicism and the study of the individual karyotype of each embryo in dizygotic twin missed abortions.

Finally, a hysteroscopic approach may afford the opportunity to also perform morphologic evaluation of the intact early fetus furthering the diagnostic utility of the procedure. With hysteroscopy, the gestational sac is identified and carefully entered, allowing for complete visualization of the early fetus and assessment of anatomic malformations that may provide insight into the pregnancy loss (ie, embryoscopy). In one series of 272 patients with missed abortions, while nearly 75% of conceptuses had abnormal karyotypes, 18% were found to have gross morphologic defects with a normal karyotype.22

Bottom line

When faced with a patient with an early pregnancy loss, physicians should consider the decreased iatrogenic risks and improved diagnostic yield when deciding between D&C versus hysteroscopy for surgical management. There are certain patients with pre-existing risk factors that may stand to benefit the most (TABLE 2). Much like the opening case, those at risk for intrauterine adhesions, retained products of conception, or in whom a successful and accurate cytogenetic analysis is essential are the most likely to benefit from a hysteroscopic approach. The hysteroscopic approach also affords concurrent diagnosis and treatment of intrauterine pathology, such as leiomyomas and uterine septum, which are encountered approximately 12.5% of the time after one miscarriage and 29.4% of the time in patients with a history of more than one miscarriage.10 In the appropriately counseled patient and clinical setting, clinicians could also perform definitive surgical management during the same hysteroscopy. Finally, evaluation of the morphology of the demised fetus may provide additional information for patient counseling in those with euploid pregnancy losses.

CASE Resolved

Ultimately, our patient underwent complete hysteroscopic resection of the pregnancy tissue, which confirmed both a morphologically abnormal fetus and a 45, X karyotype of the products of conception. ●

CASE Concern for surgical management after repeat miscarriage

A 34-year-old woman (G3P0030) with a history of recurrent pregnancy loss was recently diagnosed with a 7-week missed abortion. After her second miscarriage, she had an evaluation for recurrent pregnancy loss which was unremarkable. Both prior miscarriages were managed with dilation & curettage (D&C), but cytogenetic testing of the tissue did not yield a result in either case. The karyotype from the first pregnancy resulted as 46, XX but was confirmed to be due to maternal cell contamination, and the karyotype from the second pregnancy resulted in cell culture failure. The patient is interested in surgical management for her current missed abortion to help with tissue collection for cytogenetic testing, she but is concerned about her risk of intrauterine adhesions with repeated uterine instrumentation given 2 prior D&Cs, one of which was complicated by retained products of conception.

How do you approach the surgical management of this patient with recurrent pregnancy loss?

Approximately 1 in every 8 recognized pregnancies results in miscarriage. The risk of loss is lowest in women with no history of miscarriage (11%), and increases by about 10% for each additional miscarriage, reaching 42% in women with 3 or more previous losses. The population prevalence of women who have had 1 miscarriage is 11%, 2 miscarriages is 2%, and 3 or more is <1%.1 While 90% of miscarriages occur in the first trimester, their etiology can be quite varied.2 A woman’s age is the most strongly associated risk factor, with both very young (<20 years) and older age (>35 years) groups at highest risk. This association is largely attributed to an age-related increase in embryonic chromosomal aneuploidies, of which trisomies, particularly trisomy 16, are the most common.3 Maternal anatomic anomalies such as leiomyomas, intrauterine adhesions, Müllerian anomalies, and adenomyosis have been linked to an increased risk of miscarriage in addition to several lifestyle and environmental factor exposures.1

Regardless of the etiology, women with recurrent miscarriage are exposed to the potential for iatrogenic harm from the management of their pregnancy loss, including intrauterine adhesions and retained products, which may negatively impact future reproductive attempts. The management of patients with recurrent miscarriages demands special attention to reduce the risk of iatrogenic harm, maximize diagnostic evaluation of the products of conception, and improve future reproductive outcomes.

Management strategies

First trimester pregnancy loss may be managed expectantly, medically, or surgically. Approximately 76% of women who opt for expectant management will successfully pass pregnancy tissue, but for 1 out of every 6 women it may take longer than 14 days.4 For patients who prefer to expedite this process, medication abortion is a highly effective and safe option. According to Schreiber and colleagues, a combination of mifepristone and misoprostol together resulted in expulsion in approximately 91% of 148 patients, although 9% still required surgical intervention for incomplete passage of tissue.5 Both expectant management and medical management strategies are associated with the potential for retained products of conception requiring subsequent instrumentation as well as tissue that is often unsuitable or contaminated for cytogenetic analysis.

The most definitive treatment option is surgical management via manual or electric vacuum aspiration or curettage, with efficacy approaching 99.6% in some series.6 While highly effective, even ultrasound-guided evacuation carries with it procedure-related risks that are of particular consequence for patients of reproductive age, including adhesion formation and retained products of conception.

In 1997, Goldenberg and colleagues reported on the use of hysteroscopy for the management of retained products of conception as a strategy to minimize trauma to the uterus and maximize excision of retained tissue, both of which reduce potential for adhesion formation.7 Based on these data, several groups have extended the use of hysteroscopic resection for retained tissue to upfront evacuation following pregnancy loss, in lieu of D&C.8,9 This approach allows for the direct visualization of the focal removal of the implanted pregnancy tissue, which can:

- decrease the risk of intrauterine adhesion formation

- decrease the risk of retained products of conception

- allow for directed tissue sampling to improve the accuracy of cytogenetic testing

- allow for detection of embryo anatomic anomalies that often go undetected on traditional cytogenetic analysis.

For the remainder of this article, we will discuss the advantages of hysteroscopic management of a missed abortion in greater detail.

Continue to: Hysteroscopic management...

Hysteroscopic management

Like aspiration or curettage, hysteroscopic management may be offered once the diagnosis of fetal demise is confirmed on ultrasonography. The procedure may be accomplished in the office setting or in the operative room with either morcellation or resectoscopic instruments. Morcellation allows for improved visibility during the procedure given the ability of continuous suction to manage tissue fragments in the surgical field, while resectoscopic instruments offer the added benefit of electrosurgery should bleeding that is unresponsive to increased distention pressure be encountered. Use of the cold loop of the resectoscope to accomplish evacuation is advocated to avoid the thermal damage to the endometrium with electrosurgery. Regardless of the chosen instrument, there are several potential benefits for a hysteroscopic approach over the traditional ultrasound-guided or blind D&C.

Reducing risk of iatrogenic harm

Intrauterine adhesions form secondary to trauma to the endometrial basalis layer, where a population of adult progenitor stem cells continuously work to regenerate the overlying functionalis layer. Once damaged, adhesions may form and range from thin, filmy adhesions to dense, cavity obliterating bands of scar tissue (FIGURE). The degree of severity and location of the adhesions account for the variable presentation that range from menstrual abnormalities to infertility and recurrent pregnancy loss. While several classification systems exist for scoring severity of adhesions, the American Fertility Society (now American Society for Reproductive Medicine) Classification system from 1988 is still commonly utilized (TABLE 1).

Intrauterine adhesions from D&C after pregnancy loss are not uncommon. A 2014 meta-analysis of 10 prospective studies including 912 women reported a pooled prevalence for intrauterine adhesions of 19.1% (95% confidence interval [CI], 12.8–27.5) on hysteroscopic evaluation within 12 months following curettage.10 Once formed, these adhesions are associated with long-term impairment in reproductive outcomes, regardless of if they were treated or not. In a long-term follow-up study of women with and without adhesions after recurrent D&C for miscarriage, women with treated adhesions reported lower live birth rates, longer time to pregnancy, higher rates of preterm birth and higher rates of peripartum complications compared with those without adhesions.11

Compared with curettage, hysteroscopy affords the surgeon complete visualization of the uterine cavity and tissue to be resected. This, in turn, minimizes trauma to the surrounding uterine cavity, minimizes the potential for post-procedural adhesion formation and their associated sequelae, and maximizes complete resection of tissue. Those treated with D&C appear to be significantly more likely to have adhesions than those treated via a hysteroscopic approach (30% vs 13%).12

Retained products of conception. Classically, a “gritty” sensation of the endometrium following evacuation of the uterus with a sharp curette has been used to indicate complete removal of tissue. The evolution from a nonvisualized procedure to ultrasound-guided vacuum aspiration of 1st trimester pregnancy tissue has been associated with a decreased risk of procedural complications and retained products of conception.13 However, even with intraoperative imaging, the risk of retained products of conception remains because it can be difficult to distinguish a small blood clot from retained pregnancy tissue on ultrasonography.

Retained pregnancy tissue can result in abnormal or heavy bleeding, require additional medical or surgical intervention, and is associated with endometrial inflammation and infection. Approximately 1 in every 4 women undergoing hysteroscopic resection of retained products are found to have evidence of endometritis in the resected tissue.14 This number is even higher in women with a diagnosis of recurrent pregnancy loss (62%).15

These complications from retained products of conception can be avoided with the hysteroscopic approach due to the direct visualization of the tissue removal. This benefit may be particularly beneficial in patients with known abnormal uterine cavities, such as those with Müllerian anomalies, uterine leiomyomas, preexisting adhesions, and history of placenta accreta spectrum disorder.

Continue to: Maximizing diagnostic yield...

Maximizing diagnostic yield

Many patients prefer surgical management of a missed abortion not for the procedural advantages, but to assist with tissue collection for cytogenetic testing of the pregnancy tissue. Given that embryonic chromosomal aneuploidy is implicated in 70% of miscarriages prior to 20 weeks’ gestation, genetic evaluation of the products of conception is commonly performed to identify a potential cause for the miscarriage.16 G-band karyotype is the most commonly performed genetic evaluation. Karyotype requires culturing of pregnancy tissue for 7-14 days to produce metaphase cells that are then chemically treated to arrest them at their maximally contracted stage. Cytogenetic evaluation is often curtailed when nonviable cells from products of conception fail to culture due to either time elapsed from diagnosis to demise or damage from tissue handling. Careful, directly observed tissue handling via a hysteroscopic approach may alleviate culture failure secondary to tissue damage.

Another concern with cultures of products of conception is the potential for maternal cell contamination. Early studies from the 1970s noted a significant skew toward 46, XX karyotype results in miscarried tissue as compared with 46, XY results. It was not until microsatellite analysis technology was available that it was determined that the result was due to analysis of maternal cells instead of products of conception.17 A 2014 study by Levy and colleagues and another by Lathi and colleagues that utilized single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) microarray found that maternal cell contamination affected 22% of all miscarriage samples analyzed and over half of karyotypes with a 46, XX result.18,19

Traditional “blind” suction and curettage may inadvertently collect maternal endometrial tissue and contaminate the culture of fetal cells, limiting the validity of karyotype for products of conception.20 The hysteroscopic approach may provide a higher diagnostic yield for karyotype analysis of fetal tissue by the nature of targeted tissue sampling under direct visualization, minimizing maternal cell contamination. One retrospective study by Cholkeri-Singh and colleagues evaluated rates of fetal chromosome detection without maternal contamination in a total of 264 patients undergoing either suction curettage or hysteroscopic resection. They found that fetal chromosomal detection without contamination was significantly higher in the hysteroscopy group compared with the suction curettage group (88.5 vs 64.8%, P< .001).21 Additionally, biopsies of tissue under direct visualization may enable the diagnosis of a true placental mosaicism and the study of the individual karyotype of each embryo in dizygotic twin missed abortions.

Finally, a hysteroscopic approach may afford the opportunity to also perform morphologic evaluation of the intact early fetus furthering the diagnostic utility of the procedure. With hysteroscopy, the gestational sac is identified and carefully entered, allowing for complete visualization of the early fetus and assessment of anatomic malformations that may provide insight into the pregnancy loss (ie, embryoscopy). In one series of 272 patients with missed abortions, while nearly 75% of conceptuses had abnormal karyotypes, 18% were found to have gross morphologic defects with a normal karyotype.22

Bottom line

When faced with a patient with an early pregnancy loss, physicians should consider the decreased iatrogenic risks and improved diagnostic yield when deciding between D&C versus hysteroscopy for surgical management. There are certain patients with pre-existing risk factors that may stand to benefit the most (TABLE 2). Much like the opening case, those at risk for intrauterine adhesions, retained products of conception, or in whom a successful and accurate cytogenetic analysis is essential are the most likely to benefit from a hysteroscopic approach. The hysteroscopic approach also affords concurrent diagnosis and treatment of intrauterine pathology, such as leiomyomas and uterine septum, which are encountered approximately 12.5% of the time after one miscarriage and 29.4% of the time in patients with a history of more than one miscarriage.10 In the appropriately counseled patient and clinical setting, clinicians could also perform definitive surgical management during the same hysteroscopy. Finally, evaluation of the morphology of the demised fetus may provide additional information for patient counseling in those with euploid pregnancy losses.

CASE Resolved

Ultimately, our patient underwent complete hysteroscopic resection of the pregnancy tissue, which confirmed both a morphologically abnormal fetus and a 45, X karyotype of the products of conception. ●

- Quenby S, Gallos ID, Dhillon-Smith RK, et al. Miscarriage matters: the epidemiological, physical, psychological, and economic costs of early pregnancy loss. Lancet. 2021;397:1658-1667.

- Kolte AM, Westergaard D, Lidegaard Ø, et al. Chance of live birth: a nationwide, registry-based cohort study. Hum Reprod Oxf Engl. 2021;36:1065-1073.

- Magnus MC, Wilcox AJ, Morken N-H, et al. Role of maternal age and pregnancy history in risk of miscarriage: prospective register-based study. BMJ. 2019;364:869.

- Luise C, Jermy K, May C, et al. Outcome of expectant management of spontaneous first trimester miscarriage: observational study. BMJ. 2002;324:873-875.

- Schreiber CA, Creinin MD, Atrio J, et al. Mifepristone pretreatment for the medical management of early pregnancy loss. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:2161-2170.

- Ireland LD, Gatter M, Chen AY. Medical compared with surgical abortion for effective pregnancy termination in the first trimester. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;126:22-28.

- Goldenberg M, Schiff E, Achiron R, et al. Managing residual trophoblastic tissue. Hysteroscopy for directing curettage. J Reprod Med. 1997;42:26-28.

- Weinberg S, Pansky M, Burshtein I, et al. A pilot study of guided conservative hysteroscopic evacuation of early miscarriage. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2021;28:1860-1867.

- Young S, Miller CE. Hysteroscopic resection for management of early pregnancy loss: a case report and literature review. FS Rep. 2022;3:163-167.

- Hooker AB, Lemmers M, Thurkow AL, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of intrauterine adhesions after miscarriage: prevalence, risk factors and long-term reproductive outcome. Hum Reprod Update. 2014;20:262-278.

- Hooker AB, de Leeuw RA, Twisk JWR, et al. Reproductive performance of women with and without intrauterine adhesions following recurrent dilatation and curettage for miscarriage: long-term follow-up of a randomized controlled trial. Hum Reprod. 2021;36:70-81.

- Hooker AB, Aydin H, Brölmann HAM, et al. Longterm complications and reproductive outcome after the management of retained products of conception: a systematic review. Fertil Steril. 2016;105:156-164.e1-e2.

- Debby A, Malinger G, Harow E, et al. Transvaginal ultrasound after first-trimester uterine evacuation reduces the incidence of retained products of conception. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2006;27:61-64.

- Elder S, Bortoletto P, Romanski PA, et al. Chronic endometritis in women with suspected retained products of conception and their reproductive outcomes. Am J Reprod Immunol N Y N 1989. 2021;86:e13410.

- McQueen DB, Maniar KP, Hutchinson A, et al. Retained pregnancy tissue after miscarriage is associated with high rate of chronic endometritis. J Obstet Gynaecol J Inst Obstet Gynaecol. 2022;1-5.

- Soler A, Morales C, Mademont-Soler I, et al. Overview of chromosome abnormalities in first trimester miscarriages: a series of 1,011 consecutive chorionic villi sample karyotypes. Cytogenet Genome Res. 2017;152:81-89.

- Jarrett KL, Michaelis RC, Phelan MC, et al. Microsatellite analysis reveals a high incidence of maternal cell contamination in 46, XX products of conception consisting of villi or a combination of villi and membranous material. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2001;185:198-203.

- Levy B, Sigurjonsson S, Pettersen B, et al. Genomic imbalance in products of conception: single-nucleotide polymorphism chromosomal microarray analysis. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;124:202-209.

- Lathi RB, Gustin SLF, Keller J, et al. Reliability of 46, XX results on miscarriage specimens: a review of 1,222 first-trimester miscarriage specimens. Fertil Steril. 2014;101:178-182.

- Chung JPW, Li Y, Law TSM, et al. Ultrasound-guided manual vacuum aspiration is an optimal method for obtaining products of conception from early pregnancy loss for cytogenetic testing. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2022;147:106226.

- Cholkeri-Singh A, Zamfirova I, Miller CE. Increased fetal chromosome detection with the use of operative hysteroscopy during evacuation of products of conception for diagnosed miscarriage. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2020;27:160-165.

- Philipp T, Philipp K, Reiner A, et al. Embryoscopic and cytogenetic analysis of 233 missed abortions: factors involved in the pathogenesis of developmental defects of early failed pregnancies. Hum Reprod. 2003;18:1724-1732.

- Quenby S, Gallos ID, Dhillon-Smith RK, et al. Miscarriage matters: the epidemiological, physical, psychological, and economic costs of early pregnancy loss. Lancet. 2021;397:1658-1667.

- Kolte AM, Westergaard D, Lidegaard Ø, et al. Chance of live birth: a nationwide, registry-based cohort study. Hum Reprod Oxf Engl. 2021;36:1065-1073.

- Magnus MC, Wilcox AJ, Morken N-H, et al. Role of maternal age and pregnancy history in risk of miscarriage: prospective register-based study. BMJ. 2019;364:869.

- Luise C, Jermy K, May C, et al. Outcome of expectant management of spontaneous first trimester miscarriage: observational study. BMJ. 2002;324:873-875.

- Schreiber CA, Creinin MD, Atrio J, et al. Mifepristone pretreatment for the medical management of early pregnancy loss. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:2161-2170.

- Ireland LD, Gatter M, Chen AY. Medical compared with surgical abortion for effective pregnancy termination in the first trimester. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;126:22-28.

- Goldenberg M, Schiff E, Achiron R, et al. Managing residual trophoblastic tissue. Hysteroscopy for directing curettage. J Reprod Med. 1997;42:26-28.

- Weinberg S, Pansky M, Burshtein I, et al. A pilot study of guided conservative hysteroscopic evacuation of early miscarriage. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2021;28:1860-1867.

- Young S, Miller CE. Hysteroscopic resection for management of early pregnancy loss: a case report and literature review. FS Rep. 2022;3:163-167.

- Hooker AB, Lemmers M, Thurkow AL, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of intrauterine adhesions after miscarriage: prevalence, risk factors and long-term reproductive outcome. Hum Reprod Update. 2014;20:262-278.

- Hooker AB, de Leeuw RA, Twisk JWR, et al. Reproductive performance of women with and without intrauterine adhesions following recurrent dilatation and curettage for miscarriage: long-term follow-up of a randomized controlled trial. Hum Reprod. 2021;36:70-81.

- Hooker AB, Aydin H, Brölmann HAM, et al. Longterm complications and reproductive outcome after the management of retained products of conception: a systematic review. Fertil Steril. 2016;105:156-164.e1-e2.

- Debby A, Malinger G, Harow E, et al. Transvaginal ultrasound after first-trimester uterine evacuation reduces the incidence of retained products of conception. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2006;27:61-64.

- Elder S, Bortoletto P, Romanski PA, et al. Chronic endometritis in women with suspected retained products of conception and their reproductive outcomes. Am J Reprod Immunol N Y N 1989. 2021;86:e13410.

- McQueen DB, Maniar KP, Hutchinson A, et al. Retained pregnancy tissue after miscarriage is associated with high rate of chronic endometritis. J Obstet Gynaecol J Inst Obstet Gynaecol. 2022;1-5.

- Soler A, Morales C, Mademont-Soler I, et al. Overview of chromosome abnormalities in first trimester miscarriages: a series of 1,011 consecutive chorionic villi sample karyotypes. Cytogenet Genome Res. 2017;152:81-89.

- Jarrett KL, Michaelis RC, Phelan MC, et al. Microsatellite analysis reveals a high incidence of maternal cell contamination in 46, XX products of conception consisting of villi or a combination of villi and membranous material. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2001;185:198-203.

- Levy B, Sigurjonsson S, Pettersen B, et al. Genomic imbalance in products of conception: single-nucleotide polymorphism chromosomal microarray analysis. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;124:202-209.

- Lathi RB, Gustin SLF, Keller J, et al. Reliability of 46, XX results on miscarriage specimens: a review of 1,222 first-trimester miscarriage specimens. Fertil Steril. 2014;101:178-182.

- Chung JPW, Li Y, Law TSM, et al. Ultrasound-guided manual vacuum aspiration is an optimal method for obtaining products of conception from early pregnancy loss for cytogenetic testing. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2022;147:106226.

- Cholkeri-Singh A, Zamfirova I, Miller CE. Increased fetal chromosome detection with the use of operative hysteroscopy during evacuation of products of conception for diagnosed miscarriage. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2020;27:160-165.

- Philipp T, Philipp K, Reiner A, et al. Embryoscopic and cytogenetic analysis of 233 missed abortions: factors involved in the pathogenesis of developmental defects of early failed pregnancies. Hum Reprod. 2003;18:1724-1732.

2022 Update on pelvic floor dysfunction

Knowledge of the latest evidence on the management of pelvic floor disorders is essential for all practicing ObGyns. In this Update, we review long-term outcomes for a polyacrylamide hydrogel urethral bulking agent for the treatment of stress urinary incontinence (SUI) that presents a viable alternative to the gold standard, midurethral sling. We review the new recommendations from the American Urogynecologic Society (AUGS) regarding the administration of anticholinergics, highlighting a paradigm shift in the management of overactive bladder (OAB). In addition, we present data on a proposed threshold glycosylated hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) level for patients undergoing pelvic organ prolapse (POP) surgery that may help reduce the risk of perioperative complications. Finally, we consider new evidence on the long-term efficacy and safety of transvaginal mesh for repair of POP.

Periurethral injection with polyacrylamide hydrogel is a long-term durable and safe option for women with SUI

Brosche T, Kuhn A, Lobodasch K, et al. Seven-year efficacy and safety outcomes of Bulkamid for the treatment of stress urinary incontinence. Neurourol Urodyn. 2021;40:502-508. doi:10.1002/nau.24589.

Urethral bulking agents are a less invasive management option for women with SUI compared with the gold standard, midurethral sling. Treatment with a polyacrylamide hydrogel (PAHG; Bulkamid)—a nonparticulate hydrogel bulking agent—showed long-term efficacy and a favorable safety profile at 7 years’ follow-up.

Study details

Brosche and colleagues conducted a retrospective cohort study that included women with SUI or stress-predominant mixed urinary incontinence (MUI) who underwent transurethral PAHG injections for primary treatment of their incontinence symptoms. The study objective was to evaluate the long-term efficacy of PAHG based on patient satisfaction. Treatment safety was a secondary outcome.

Pad counts and validated questionnaires were used to determine treatment effectiveness. Additional data on reinjection rates, perioperative complications, and postoperative complications also were collected.

Long-term outcomes favorable

During the study time period, 1,200 patients were treated with PAHG, and 7-year data were available for 553 women. Of the 553 patients, 67% reported improvement or cure of their SUI symptoms when PAHG was performed as a primary procedure, consistent with previously published 12-month data. There were no perioperative complications. Postoperative complications were transient. Short-term subjective prolonged bladder emptying was the most common complication and occurred in 15% of patients.

PAHG injection is a durable and safe alternative for the treatment of stress urinary incontinence in women who are not candidates for or who decline treatment with alternative methods, such as a midurethral sling.

Continue to: New society guidance...

New society guidance on the use of anticholinergic medications for the treatment of OAB

AUGS Clinical Consensus Statement: Association of anticholinergic medication use and cognition in women with overactive bladder. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2021;27:69-71. doi:10.1097/ SPV.0000000000001008.

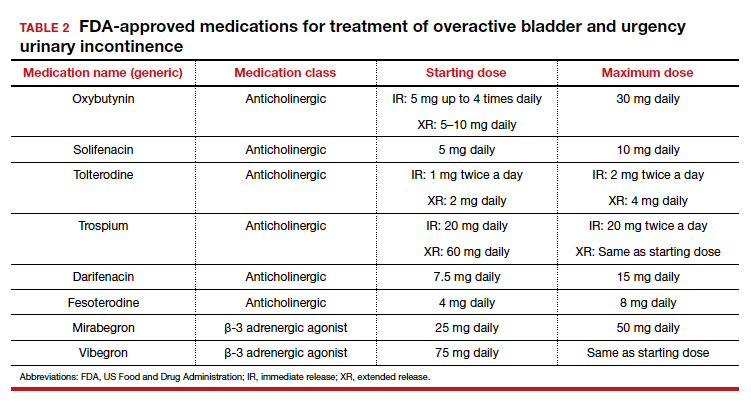

In 2021, AUGS updated its consensus statement on the use of anticholinergic medications for the treatment of OAB. This action was in response to growing evidence that supports the association of anticholinergic medications with long-term cognitive adverse effects, including cognitive impairment, dementia, and Alzheimer disease.

Here, we summarize the most recent modifications, which differentiate the updated statement from the preceding consensus document published in 2017.

Updated AUGS recommendations

- If considering anticholinergic medications, counsel patients about the risk of cognitive adverse effects and weigh these risks against the potential benefits to their quality of life and overall health.

- Use the lowest possible dose when prescribing anticholinergics and consider alternatives such as β3 agonists (for example, mirabegron or vibegron).

- Avoid using anticholinergic medications in women older than age 70. However, if an anticholinergic must be used, consider a medication that has low potential to cross the blood-brain barrier (for example, trospium).

For patients who are unresponsive to behavioral therapies for OAB, medical management may be considered. However, the risks of anticholinergic medications may outweigh the benefits—especially for older women—and these medications should be prescribed with caution after discussing the potential cognitive adverse effects with patients. β3 agonists should be preferentially prescribed when appropriate. Consider referral to a urogynecologist for discussion of third-line therapies in patients who prefer to forego or may not be candidates for medical management of their OAB symptoms.

HbA1c levels > 8% may increase complications risk in urogyn surgery

Ringel NE, de Winter KL, Siddique M, et al. Surgical outcomes in urogynecology—assessment of perioperative and postoperative complications relative to preoperative hemoglobin A1c—a Fellows Pelvic Research Network study. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2022;28:7-13. doi:10.1097/ SPV.0000000000001057.

Diabetes mellitus is a known risk factor for complications following surgery. Adoption of an HbA1c level threshold for risk stratification before urogynecologic surgery may help improve patient outcomes.

Study details

Ringel and colleagues conducted a multicenter retrospective cohort study that included women with diabetes mellitus who underwent prolapse and/or SUI surgery between 2013 and 2018. The aim of the study was to identify a hemoglobin A1C threshold that would help predict increased risk for perioperative complications in women undergoing pelvic reconstructive surgery. Demographics, preoperative HbA1c levels, and surgical data were collected.

Complication risks correlated with higher HbA1c threshold

The study included 807 women with HbA1c values that ranged from 5% to 12%. The overall complication rate was 44%. Sensitivity analysis was performed to compare complication rates between patients with varying HbA1c levels and determine a threshold HbA1c value with the greatest difference in complication rates.

The authors concluded that women with an HbA1c level ≥ 8% showed the greatest increase of perioperative complications. Patients with an HbA1c ≥ 8%, compared with those who had an HbA1c < 8%, had a statistically significantly increased rate of overall (58% vs 42%, P = .002) and severe (27% vs 13%, P< .001) perioperative complications.

After multivariate logistic regression, the risk of overall complications remained elevated, with a 1.9-times higher risk of perioperative complications for women with an HbA1c ≥ 8%.

Women should be medically optimized before undergoing surgery and, while this study was restricted to urogynecologic surgery patients, it seems reasonable to assume that a similar HbA1c threshold would be beneficial for women undergoing other gynecologic procedures. Appropriately screening patients and referring them for early intervention with their primary care clinician or endocrinologist may improve surgical outcomes, especially in women with an HbA1c level > 8%.

Continue to: Success is similar for TV mesh and native tissue repair...

Success is similar for TV mesh and native tissue repair

Kahn B, Varner RE, Murphy M, et al. Transvaginal mesh compared with native tissue repair for pelvic organ prolapse. Obstet Gynecol. 2022;139:975-985. doi:10.1097/AOG.0000000000004794.

The distribution of vaginal mesh kits for the repair of POP was halted by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2019. However, concerns have been raised about the measures used by the FDA to justify pulling these devices from the market. A cohort study compared 36-month outcomes between women who underwent prolapse repair with newer generation transvaginal mesh versus native tissue repair.

Study details

In a nonrandomized prospective multicenter cohort study, Kahn and colleagues compared outcomes in women with POP who underwent native tissue repair or transvaginal mesh repair with the Uphold LITE vaginal support system. The study’s objective was to compare the safety and efficacy of native tissue and transvaginal mesh prolapse repairs at 36 months postoperatively.

Treatment success was measured based on composite and individual measures of anatomic and subjective success, need for retreatment, and the occurrence of adverse events. Quality of life (QoL) measures also were obtained using validated questionnaires. Intention-to-treat and per-protocol analyses were performed.

Composite success rate was higher for mesh repair

A total of 710 patients were screened for eligibility (225 received transvaginal mesh and 485 received native tissue repair). Transvaginal mesh placement was found to be significantly superior to native tissue repair for composite success (84% vs 73%, P = .009) when prolapse within the hymen (that is, Ba and/or C < 0 on the Pelvic Organ Prolapse Quantification System) was used to define anatomic success.

Adverse events were similar between transvaginal mesh and native tissue repair groups, with most adverse events occurring within the first 6 months. The mesh exposure rate was 4.9%. Of the 13 incidents of mesh exposure, 4 patients required surgical intervention and 1 incident was considered a serious adverse event. QoL measures demonstrated improvement without any statistically significant differences between the treatment cohorts. ●

This study established the superiority and safety of newer generation transvaginal mesh used for the treatment of pelvic organ prolapse. Women who received newer generation transvaginal mesh can be reassured that the prolapse recurrence rates are low and that adverse events related to their mesh are rare—even when compared with those of native tissue repair. Patients also may be reassured that most adverse events would have occurred within 6 months of the initial prolapse repair surgery

Knowledge of the latest evidence on the management of pelvic floor disorders is essential for all practicing ObGyns. In this Update, we review long-term outcomes for a polyacrylamide hydrogel urethral bulking agent for the treatment of stress urinary incontinence (SUI) that presents a viable alternative to the gold standard, midurethral sling. We review the new recommendations from the American Urogynecologic Society (AUGS) regarding the administration of anticholinergics, highlighting a paradigm shift in the management of overactive bladder (OAB). In addition, we present data on a proposed threshold glycosylated hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) level for patients undergoing pelvic organ prolapse (POP) surgery that may help reduce the risk of perioperative complications. Finally, we consider new evidence on the long-term efficacy and safety of transvaginal mesh for repair of POP.

Periurethral injection with polyacrylamide hydrogel is a long-term durable and safe option for women with SUI

Brosche T, Kuhn A, Lobodasch K, et al. Seven-year efficacy and safety outcomes of Bulkamid for the treatment of stress urinary incontinence. Neurourol Urodyn. 2021;40:502-508. doi:10.1002/nau.24589.

Urethral bulking agents are a less invasive management option for women with SUI compared with the gold standard, midurethral sling. Treatment with a polyacrylamide hydrogel (PAHG; Bulkamid)—a nonparticulate hydrogel bulking agent—showed long-term efficacy and a favorable safety profile at 7 years’ follow-up.

Study details

Brosche and colleagues conducted a retrospective cohort study that included women with SUI or stress-predominant mixed urinary incontinence (MUI) who underwent transurethral PAHG injections for primary treatment of their incontinence symptoms. The study objective was to evaluate the long-term efficacy of PAHG based on patient satisfaction. Treatment safety was a secondary outcome.

Pad counts and validated questionnaires were used to determine treatment effectiveness. Additional data on reinjection rates, perioperative complications, and postoperative complications also were collected.

Long-term outcomes favorable

During the study time period, 1,200 patients were treated with PAHG, and 7-year data were available for 553 women. Of the 553 patients, 67% reported improvement or cure of their SUI symptoms when PAHG was performed as a primary procedure, consistent with previously published 12-month data. There were no perioperative complications. Postoperative complications were transient. Short-term subjective prolonged bladder emptying was the most common complication and occurred in 15% of patients.

PAHG injection is a durable and safe alternative for the treatment of stress urinary incontinence in women who are not candidates for or who decline treatment with alternative methods, such as a midurethral sling.

Continue to: New society guidance...

New society guidance on the use of anticholinergic medications for the treatment of OAB

AUGS Clinical Consensus Statement: Association of anticholinergic medication use and cognition in women with overactive bladder. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2021;27:69-71. doi:10.1097/ SPV.0000000000001008.

In 2021, AUGS updated its consensus statement on the use of anticholinergic medications for the treatment of OAB. This action was in response to growing evidence that supports the association of anticholinergic medications with long-term cognitive adverse effects, including cognitive impairment, dementia, and Alzheimer disease.

Here, we summarize the most recent modifications, which differentiate the updated statement from the preceding consensus document published in 2017.

Updated AUGS recommendations

- If considering anticholinergic medications, counsel patients about the risk of cognitive adverse effects and weigh these risks against the potential benefits to their quality of life and overall health.

- Use the lowest possible dose when prescribing anticholinergics and consider alternatives such as β3 agonists (for example, mirabegron or vibegron).

- Avoid using anticholinergic medications in women older than age 70. However, if an anticholinergic must be used, consider a medication that has low potential to cross the blood-brain barrier (for example, trospium).

For patients who are unresponsive to behavioral therapies for OAB, medical management may be considered. However, the risks of anticholinergic medications may outweigh the benefits—especially for older women—and these medications should be prescribed with caution after discussing the potential cognitive adverse effects with patients. β3 agonists should be preferentially prescribed when appropriate. Consider referral to a urogynecologist for discussion of third-line therapies in patients who prefer to forego or may not be candidates for medical management of their OAB symptoms.

HbA1c levels > 8% may increase complications risk in urogyn surgery

Ringel NE, de Winter KL, Siddique M, et al. Surgical outcomes in urogynecology—assessment of perioperative and postoperative complications relative to preoperative hemoglobin A1c—a Fellows Pelvic Research Network study. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2022;28:7-13. doi:10.1097/ SPV.0000000000001057.

Diabetes mellitus is a known risk factor for complications following surgery. Adoption of an HbA1c level threshold for risk stratification before urogynecologic surgery may help improve patient outcomes.

Study details

Ringel and colleagues conducted a multicenter retrospective cohort study that included women with diabetes mellitus who underwent prolapse and/or SUI surgery between 2013 and 2018. The aim of the study was to identify a hemoglobin A1C threshold that would help predict increased risk for perioperative complications in women undergoing pelvic reconstructive surgery. Demographics, preoperative HbA1c levels, and surgical data were collected.

Complication risks correlated with higher HbA1c threshold

The study included 807 women with HbA1c values that ranged from 5% to 12%. The overall complication rate was 44%. Sensitivity analysis was performed to compare complication rates between patients with varying HbA1c levels and determine a threshold HbA1c value with the greatest difference in complication rates.

The authors concluded that women with an HbA1c level ≥ 8% showed the greatest increase of perioperative complications. Patients with an HbA1c ≥ 8%, compared with those who had an HbA1c < 8%, had a statistically significantly increased rate of overall (58% vs 42%, P = .002) and severe (27% vs 13%, P< .001) perioperative complications.

After multivariate logistic regression, the risk of overall complications remained elevated, with a 1.9-times higher risk of perioperative complications for women with an HbA1c ≥ 8%.

Women should be medically optimized before undergoing surgery and, while this study was restricted to urogynecologic surgery patients, it seems reasonable to assume that a similar HbA1c threshold would be beneficial for women undergoing other gynecologic procedures. Appropriately screening patients and referring them for early intervention with their primary care clinician or endocrinologist may improve surgical outcomes, especially in women with an HbA1c level > 8%.

Continue to: Success is similar for TV mesh and native tissue repair...

Success is similar for TV mesh and native tissue repair

Kahn B, Varner RE, Murphy M, et al. Transvaginal mesh compared with native tissue repair for pelvic organ prolapse. Obstet Gynecol. 2022;139:975-985. doi:10.1097/AOG.0000000000004794.

The distribution of vaginal mesh kits for the repair of POP was halted by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2019. However, concerns have been raised about the measures used by the FDA to justify pulling these devices from the market. A cohort study compared 36-month outcomes between women who underwent prolapse repair with newer generation transvaginal mesh versus native tissue repair.

Study details

In a nonrandomized prospective multicenter cohort study, Kahn and colleagues compared outcomes in women with POP who underwent native tissue repair or transvaginal mesh repair with the Uphold LITE vaginal support system. The study’s objective was to compare the safety and efficacy of native tissue and transvaginal mesh prolapse repairs at 36 months postoperatively.

Treatment success was measured based on composite and individual measures of anatomic and subjective success, need for retreatment, and the occurrence of adverse events. Quality of life (QoL) measures also were obtained using validated questionnaires. Intention-to-treat and per-protocol analyses were performed.

Composite success rate was higher for mesh repair

A total of 710 patients were screened for eligibility (225 received transvaginal mesh and 485 received native tissue repair). Transvaginal mesh placement was found to be significantly superior to native tissue repair for composite success (84% vs 73%, P = .009) when prolapse within the hymen (that is, Ba and/or C < 0 on the Pelvic Organ Prolapse Quantification System) was used to define anatomic success.

Adverse events were similar between transvaginal mesh and native tissue repair groups, with most adverse events occurring within the first 6 months. The mesh exposure rate was 4.9%. Of the 13 incidents of mesh exposure, 4 patients required surgical intervention and 1 incident was considered a serious adverse event. QoL measures demonstrated improvement without any statistically significant differences between the treatment cohorts. ●

This study established the superiority and safety of newer generation transvaginal mesh used for the treatment of pelvic organ prolapse. Women who received newer generation transvaginal mesh can be reassured that the prolapse recurrence rates are low and that adverse events related to their mesh are rare—even when compared with those of native tissue repair. Patients also may be reassured that most adverse events would have occurred within 6 months of the initial prolapse repair surgery

Knowledge of the latest evidence on the management of pelvic floor disorders is essential for all practicing ObGyns. In this Update, we review long-term outcomes for a polyacrylamide hydrogel urethral bulking agent for the treatment of stress urinary incontinence (SUI) that presents a viable alternative to the gold standard, midurethral sling. We review the new recommendations from the American Urogynecologic Society (AUGS) regarding the administration of anticholinergics, highlighting a paradigm shift in the management of overactive bladder (OAB). In addition, we present data on a proposed threshold glycosylated hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) level for patients undergoing pelvic organ prolapse (POP) surgery that may help reduce the risk of perioperative complications. Finally, we consider new evidence on the long-term efficacy and safety of transvaginal mesh for repair of POP.

Periurethral injection with polyacrylamide hydrogel is a long-term durable and safe option for women with SUI

Brosche T, Kuhn A, Lobodasch K, et al. Seven-year efficacy and safety outcomes of Bulkamid for the treatment of stress urinary incontinence. Neurourol Urodyn. 2021;40:502-508. doi:10.1002/nau.24589.

Urethral bulking agents are a less invasive management option for women with SUI compared with the gold standard, midurethral sling. Treatment with a polyacrylamide hydrogel (PAHG; Bulkamid)—a nonparticulate hydrogel bulking agent—showed long-term efficacy and a favorable safety profile at 7 years’ follow-up.

Study details

Brosche and colleagues conducted a retrospective cohort study that included women with SUI or stress-predominant mixed urinary incontinence (MUI) who underwent transurethral PAHG injections for primary treatment of their incontinence symptoms. The study objective was to evaluate the long-term efficacy of PAHG based on patient satisfaction. Treatment safety was a secondary outcome.

Pad counts and validated questionnaires were used to determine treatment effectiveness. Additional data on reinjection rates, perioperative complications, and postoperative complications also were collected.

Long-term outcomes favorable

During the study time period, 1,200 patients were treated with PAHG, and 7-year data were available for 553 women. Of the 553 patients, 67% reported improvement or cure of their SUI symptoms when PAHG was performed as a primary procedure, consistent with previously published 12-month data. There were no perioperative complications. Postoperative complications were transient. Short-term subjective prolonged bladder emptying was the most common complication and occurred in 15% of patients.

PAHG injection is a durable and safe alternative for the treatment of stress urinary incontinence in women who are not candidates for or who decline treatment with alternative methods, such as a midurethral sling.

Continue to: New society guidance...

New society guidance on the use of anticholinergic medications for the treatment of OAB

AUGS Clinical Consensus Statement: Association of anticholinergic medication use and cognition in women with overactive bladder. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2021;27:69-71. doi:10.1097/ SPV.0000000000001008.