User login

2023 Update on bone health

I recently heard a lecture where the speaker quoted this statistic: “A 50-year-old woman who does not currently have heart disease or cancer has a life expectancy of 91.” Hopefully, anyone reading this article already is aware of the fact that as our patients age, hip fracture results in greater morbidity and mortality than early breast cancer. It should be well known to clinicians (and, ultimately, to our patients) that localized breast cancer has a survival rate of 99%,1 whereas hip fracture carries a 21% mortality in the first year after the event.2 In addition, approximately one-third of women who fracture their hip do not have osteoporosis.3 Furthermore, the role of muscle mass, strength, and performance in bone health has become well established.4

With this in mind, a recent encounter with a patient in my clinical practice illustrates what I believe is an increasing problem today. The patient had been on long-term prednisone systemically for polymyalgia rheumatica. Her dual energy x-ray absorptiometry (DXA) bone mass measurements were among the worst osteoporotic numbers I have witnessed. She related to me the “argument” that occurred between her rheumatologist and endocrinologist. One wanted her to use injectable parathyroid hormone analog daily, while the other advised yearly infusion of zoledronic acid. She chose the yearly infusion. I inquired if either physician had mentioned anything to her about using nonskid rugs in the bathroom, grab bars, being careful of black ice, a calcium-rich diet, vitamin D supplementation, good eyesight, illumination so she does not miss a step, mindful walking, and maintaining optimal balance, muscle mass, strength, and performance-enhancing exercise? She replied, “No, just which drug I should take.”

Realize that the goal for our patients should be to avoid the morbidity and mortality associated especially with hip fracture. The goal is not to have a better bone mass measurement on your DXA scan as you age. This is exactly why the name of this column, years ago, was changed from “Update on osteoporosis” to “Update on bone health.” Similarly, in 2021, the NOF (National Osteoporosis Foundation) became the BHOF (Bone Health and Osteoporosis Foundation). Thus, our understanding and interest in bone health should and must go beyond simply bone mass measurement with DXA technology. The articles highlighted in this year’s Update reflect the importance of this concept.

Know SERMs’ effects on bone health for appropriate prescribing

Goldstein SR. Selective estrogen receptor modulators and bone health. Climacteric. 2022;25:56-59.

Selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERMs) are synthetic molecules that bind to the estrogen receptor and can have agonistic activity in some tissues and antagonistic activity in others. In a recent article, I reviewed the known data regarding the effects of various SERMs on bone health.5

A rundown on 4 SERMs and their effects on bone

Tamoxifen is approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the prevention and treatment of breast cancer in women with estrogen receptor–positive tumors. The only prospective study of tamoxifen versus placebo in which fracture risk was studied in women at risk for but not diagnosed with breast cancer was the National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project (NSABP) P-1 trial. In this study, more than 13,000 women were randomly assigned to treatment with tamoxifen or placebo, with a primary objective of studying the incidence of invasive breast cancer in these high-risk women. With 7 years of follow-up, women receiving tamoxifen had significantly fewer fractures of the hip, radius, and spine (80 vs 116 in the placebo group), resulting in a combined relative risk (RR) of 0.68 (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.51–0.92).6

Raloxifene, another SERM, was extensively studied in the MORE (Multiple Outcomes of Raloxifene Evaluation) trial.7 This study involved more than 7,700 postmenopausal women with osteoporosis, average age 67. The incidence of first vertebral fracture was decreased from 4.3% with placebo to 1.9% with raloxifene (RR, 0.55; 95% CI, 0.29–0.71), and subsequent vertebral fractures were decreased from 20.2% with placebo to 14.1% with raloxifene (RR, 0.70; 95% CI, 0.60–0.90). In 2007, the FDA approved raloxifene for “reduction in risk of invasive breast cancer in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis” as well as for “postmenopausal women at high risk for invasive breast cancer” based on the Study of Tamoxifen and Raloxifene (STAR) trial that involved almost 20,000 postmenopausal women deemed at high risk for breast cancer.8

The concept of combining an estrogen with a SERM, known as a TSEC (tissue selective estrogen complex) was studied and brought to market as conjugated equine estrogen (CEE) 0.45 mg and bazedoxifene (BZA) 20 mg. CEE and BZA individually have been shown to prevent vertebral fracture.9,10 The combination of BZA and CEE has been shown to improve bone density compared with placebo.11 There are, however, no fracture prevention data for this combination therapy. This was the basis on which the combination agent received regulatory approval for prevention of osteoporosis in postmenopausal women. This combination drug is also FDA approved for treating moderate to severe vasomotor symptoms of menopause.

Ospemifene is yet another SERM that is clinically available, at an oral dose of 60 mg, and is indicated for the treatment of moderate to severe dyspareunia secondary to vulvovaginal atrophy, or genitourinary syndrome of menopause (GSM). Ospemifene effectively reduced bone loss in ovariectomized rats, with activity comparable to estradiol and raloxifene.12 Clinical data from three phase 1 or phase 2 clinical trials revealed that ospemifene 60 mg/day had a positive effect on biochemical markers for bone turnover in healthy postmenopausal women, with significant improvements relative to placebo and effects comparable to those of raloxifene.13 While actual fracture or bone mineral density (BMD) data in postmenopausal women are lacking, there is a good correlation between biochemical markers for bone turnover and occurrence of fracture.14 Women who need treatment for osteoporosis should not be treated with ospemifene, but women who use ospemifene for dyspareunia can expect positive activity on bone metabolism.

SERMs, unlike estrogen, have no class labeling. In fact, in the endometrium and vagina, they have variable effects. To date, however, in postmenopausal women, all SERMs have shown estrogenic activity in bone as well as being antiestrogenic in breast. Tamoxifen, well known for its use in estrogen receptor–positive breast cancer patients, demonstrates positive effects on bone and fracture reduction compared with placebo. Raloxifene is approved for prevention and treatment of osteoporosis and for breast cancer chemoprevention in high-risk patients. The TSEC combination of CEE and the SERM bazedoxifene is approved for treatment of moderate to severe vasomotor symptoms and prevention of osteoporosis. Finally, the SERM ospemifene, approved for treating moderate to severe dyspareunia or dryness due to vulvovaginal atrophy, or GSM, has demonstrated evidence of a positive effect on bone turnover and metabolism. Clinicians need to be aware of these effects when choosing medications for their patients.

Continue to: Gut microbiome constituents may influence the development of osteoporosis: A potential treatment target?...

Gut microbiome constituents may influence the development of osteoporosis: A potential treatment target?

Cronin O, Lanham-New SA, Corfe BM, et al. Role of the microbiome in regulating bone metabolism and susceptibility to osteoporosis. Calcif Tissue Int. 2022;110:273-284.

Yang X, Chang T, Yuan Q, et al. Changes in the composition of gut and vaginal microbiota in patients with postmenopausal osteoporosis. Front Immunol. 2022;13:930244.

The role of the microbiome in many arenas is rapidly emerging. Apparently, its relationship in bone metabolism is still in its infancy. A review of PubMed articles showed that 1 paper was published in 2012, none until 2 more in 2015, with a total of 221 published through November 1, 2022. A recent review by Cronin and colleagues on the microbiome’s role in regulating bone metabolism came out of a workshop held by the Osteoporosis and Bone Research Academy of the Royal Osteoporosis Society in the United Kingdom.15

The gut microbiome’s relationship with bone health

The authors noted that the human microbiota functions at the interface between diet, medication use, lifestyle, host immune development, and health. Hence, it is closely aligned with many of the recognized modifiable factors that influence bone mass accrual in the young and bone maintenance and skeletal decline in older populations. Microbiome research and discovery supports a role of the human gut microbiome in the regulation of bone metabolism and the pathogenesis of osteoporosis as well as its prevention and treatment.

Numerous factors which influence the gut microbiome and the development of osteoporosis overlap. These include body mass index (BMI), vitamin D, alcohol intake, diet, corticosteroid use, physical activity, sex hormone deficiency, genetic variability, and chronic inflammatory disorders.

Cronin and colleagues reviewed a number of clinical studies and concluded that “the available evidence suggests that probiotic supplements can attenuate bone loss in postmenopausal women, although the studies investigating this have been short term and individually have had small sample sizes. Moving forward, it will be important to conduct larger scale studies to evaluate if the skeletal response differs with different types of probiotic and also to determine if the effects are sustained in the longer term.”15

Composition of the microbiota

A recent study by Yang and colleagues focused on changes in gut and vaginal microbiota composition in patients with postmenopausal osteoporosis. They analyzed data from 132 postmenopausal women with osteoporosis (n = 34), osteopenia (n = 47), and controls (n = 51) based on their T-scores.16

Significant differences were observed in the microbial compositions of fecal samples between groups (P<.05), with some species enhanced in the control group whereas other species were higher in the osteoporosis group. Similar but less pronounced differences were seen in the vaginal microbiome but of different species.

The authors concluded that “The results show that changes in BMD in postmenopausal women are associated with the changes in gut microbiome and vaginal microbiome; however, changes in gut microbiome are more closely correlated with postmenopausal osteoporosis than vaginal microbiome.”16

While we are not yet ready to try to clinically alter the gut microbiome with various interventions, realizing that there is crosstalk between the gut microbiome and bone health is another factor to consider, and it begins with an appreciation of the various factors where the 2 overlap—BMI, vitamin D, alcohol intake, diet, corticosteroid use, physical activity, sex hormone deficiency, genetic variability, and chronic inflammatory disorders.

Continue to: Sarcopenia, osteoporosis, and frailty: A fracture risk triple play...

Sarcopenia, osteoporosis, and frailty: A fracture risk triple play

Laskou F, Fuggle NR, Patel HP, et al. Associations of osteoporosis and sarcopenia with frailty and multimorbidity among participants of the Hertfordshire Cohort Study. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 2022;13:220-229.

Laskou and colleagues aimed to explore the relationship between sarcopenia, osteoporosis, and frailty in community-dwelling adults participating in a cohort study in the United Kingdom and to determine if the coexistence of osteoporosis and sarcopenia is associated with a significantly heavier health burden.17

Study details

The authors examined data from 206 women with an average age of 75.5 years. Sarcopenia was defined using the European Working Group on Sarcopenia in Older People (EWGSOP) criteria, which includes low grip strength or slow chair rise and low muscle quantity. Osteoporosis was defined by standard measurements as a T-score of less than or equal to -2.5 standard deviations at the femoral neck or use of any osteoporosis medications. Frailty was defined using the Fried definition, which includes having 3 or more of the following 5 domains: weakness, slowness, exhaustion, low physical activity, and unintentional weight loss. Having 1 or 2 domains is “prefrailty” and no domains signifies nonfrail.

Frailty confers additional risk

The study results showed that among the 206 women, the prevalence of frailty and prefrailty was 9.2% and 60.7%, respectively. Of the 5 Fried frailty components, low walking speed and low physical activity followed by self-reported exhaustion were the most prevalent (96.6%, 87.5%, and 75.8%, respectively) among frail participants. Having sarcopenia only was strongly associated with frailty (odds ratio [OR], 8.28; 95% CI, 1.27–54.03; P=.027]). The likelihood of being frail was substantially higher with the presence of coexisting sarcopenia and osteoporosis (OR, 26.15; 95% CI, 3.31–218.76; P=.003).

Thus, both these conditions confer a high health burden for the individual as well as for health care systems. Osteosarcopenia is the term given when low bone mass and sarcopenia occur in consort. Previous data have shown that when osteoporosis or even osteopenia is combined with sarcopenia, it can result in a 3-fold increase in the risk of falls and a 4-fold increase in the risk of fracture compared with women who have osteopenia or osteoporosis alone.18

Sarcopenia, osteoporosis, and frailty are highly prevalent in older adults but are frequently underrecognized. Sarcopenia is characterized by progressive and generalized decline in muscle strength, function, and muscle mass with increasing age. Sarcopenia increases the likelihood of falls and adversely impacts functional independence and quality of life. Osteoporosis predisposes to low energy, fragility fractures, and is associated with chronic pain, impaired physical function, loss of independence, and higher risk of institutionalization. Clinicians need to be aware that when sarcopenia coexists with any degree of low bone mass, it will significantly increase the risk of falls and fracture compared with having osteopenia or osteoporosis alone.

Continue to: Denosumab effective in reducing falls, strengthening muscle...

Denosumab effective in reducing falls, strengthening muscle

Rupp T, von Vopelius E, Strahl A, et al. Beneficial effects of denosumab on muscle performance in patients with low BMD: a retrospective, propensity score-matched study. Osteoporos Int. 2022;33:2177-2184.

Results of a previous study showed that denosumab treatment significantly decreased falls and resulted in significant improvement in all sarcopenic measures.19 Furthermore, 1 year after denosumab was discontinued, a significant worsening occurred in both falls and sarcopenic measures. In that study, the control group, treated with alendronate or zoledronate, also showed improvement on some tests of muscle performance but no improvement in the risk of falls.

Those results agreed with the outcomes of the FREEDOM (Fracture Reduction Evaluation of Denosumab in Osteoporosis) trial.20 This study revealed that denosumab treatment not only reduced the risk of vertebral, nonvertebral, and hip fracture over 36 months but also that the denosumab-treated group had fewer falls compared with the placebo-treated group (4.5% vs 5.7%; P = .02).

Denosumab found to increase muscle strength

More recently, Rupp and colleagues conducted a retrospective cohort study that included women with osteoporosis or osteopenia who received vitamin D only (n = 52), alendronate 70 mg/week (n = 26), or denosumab (n = 52).21

After a mean follow-up period of 17.6 (SD, 9.0) months, the authors observed a significantly higher increase in grip force in both the denosumab (P<.001) and bisphosphonate groups (P = .001) compared with the vitamin D group. In addition, the denosumab group showed a significantly higher increase in chair rising test performance compared with the bisphosphonate group (denosumab vs bisphosphonate, P = 0.03). They concluded that denosumab resulted in increased muscle strength in the upper and lower limbs, indicating systemic rather than site-specific effects as compared with the bisphosphonate.

The authors concluded that based on these findings, denosumab might be favored over other osteoporosis treatments in patients with low BMD coexisting with poor muscle strength. ●

Osteoporosis and sarcopenia may share similar underlying risk factors. Muscle-bone interactions are important to minimize the risk of falls, fractures, and hospitalizations. In previous studies, denosumab as well as various bisphosphonates improved measures of sarcopenia, although only denosumab was associated with a reduction in the risk of falls. The study by Rupp and colleagues suggests that denosumab treatment may result in increased muscle strength in upper and lower limbs, indicating some systemic effect and not simply site-specific activity. Thus, in choosing a bone-specific agent for patients with abnormal muscle strength, mass, or performance, clinicians may want to consider denosumab as a choice for these reasons.

- American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts & Figures 2020. Atlanta, Georgia: American Cancer Society; 2020. Accessed November 7, 2022. https://www.cancer.org/content /dam/cancer-org/research/cancer-facts-and-statistics /annual-cancer-facts-and-figures/2020/cancer-facts-and -figures-2020.pdf

- Downey C, Kelly M, Quinlan JF. Changing trends in the mortality rate at 1-year post hip fracture—a systematic review. World J Orthop. 2019;10:166-175.

- Schuit SC, van der Klift M, Weel AE, et al. Fracture incidence and association with bone mineral density in elderly men and women: the Rotterdam study. Bone. 2004;34:195-202.

- de Villiers TJ, Goldstein SR. Update on bone health: the International Menopause Society White Paper 2021. Climacteric. 2021;24:498-504.

- Goldstein SR. Selective estrogen receptor modulators and bone health. Climacteric. 2022;25:56-59.

- Fisher B, Costantino JP, Wickerham DL, et al. Tamoxifen for the prevention of breast cancer: current status of the National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project P-1 study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005;97:1652-1662.

- Ettinger B, Black DM, Mitlak BH, et al; for the Multiple Outcomes of Raloxifene Evaluation (MORE) Investigators. Reduction of vertebral fracture risk in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis treated with raloxifene: results from a 3-year randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 1999;282:637645.

- Vogel VG, Costantino JP, Wickerham DL, et al; National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project (NSABP). Effects of tamoxifen vs raloxifene on the risk of developing invasive breast cancer and other disease outcomes: the NSABP Study of Tamoxifen and Raloxifene (STAR) P-2 trial. JAMA. 2006;295:2727-2741.

- Silverman SL, Christiansen C, Genant HK, et al. Efficacy of bazedoxifene in reducing new vertebral fracture risk in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis: results from a 3-year, randomized, placebo-, and active-controlled clinical trial. J Bone Miner Res. 2008;23:1923-1934.

- Anderson GL, Limacher M, Assaf AR, et al; Women’s Health Initiative Steering Committee. Effects of conjugated equine estrogen in postmenopausal women with hysterectomy: the Women’s Health Initiative randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2004:291:1701-1712.

- Lindsay R, Gallagher JC, Kagan R, et al. Efficacy of tissue-selective estrogen complex of bazedoxifene/conjugated estrogens for osteoporosis prevention in at-risk postmenopausal women. Fertil Steril. 2009;92:1045-1052.

- Kangas L, Härkönen P, Väänänen K, et al. Effects of the selective estrogen receptor modulator ospemifene on bone in rats. Horm Metab Res. 2014;46:27-35.

- Constantine GD, Kagan R, Miller PD. Effects of ospemifene on bone parameters including clinical biomarkers in postmenopausal women. Menopause. 2016;23:638-644.

- Gerdhem P, Ivaska KK, Alatalo SL, et al. Biochemical markers of bone metabolism and prediction of fracture in elderly women. J Bone Miner Res. 2004;19:386-393.

- Cronin O, Lanham-New SA, Corfe BM, et al. Role of the microbiome in regulating bone metabolism and susceptibility to osteoporosis. Calcif Tissue Int. 2022;110:273-284.

- Yang X, Chang T, Yuan Q, et al. Changes in the composition of gut and vaginal microbiota in patients with postmenopausal osteoporosis. Front Immunol. 2022;13:930244.

- Laskou F, Fuggle NR, Patel HP, et al. Associations of osteoporosis and sarcopenia with frailty and multimorbidity among participants of the Hertfordshire Cohort Study. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 2022;13:220-229.

- Hida T, Shimokata H, Sakai Y, et al. Sarcopenia and sarcopenic leg as potential risk factors for acute osteoporotic vertebral fracture among older women. Eur Spine J. 2016;25:3424-3431.

- El Miedany Y, El Gaafary M, Toth M, et al; Egyptian Academy of Bone Health, Metabolic Bone Diseases. Is there a potential dual effect of denosumab for treatment of osteoporosis and sarcopenia? Clin Rheumatol. 2021;40:4225-4232.

- Cummings SR, Martin JS, McClung MR, et al; FREEDOM trial. Denosumab for prevention of fractures in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:756-765.

- Rupp T, von Vopelius E, Strahl A, et al. Beneficial effects of denosumab on muscle performance in patients with low BMD: a retrospective, propensity score-matched study. Osteoporos Int. 2022;33:2177-2184.

I recently heard a lecture where the speaker quoted this statistic: “A 50-year-old woman who does not currently have heart disease or cancer has a life expectancy of 91.” Hopefully, anyone reading this article already is aware of the fact that as our patients age, hip fracture results in greater morbidity and mortality than early breast cancer. It should be well known to clinicians (and, ultimately, to our patients) that localized breast cancer has a survival rate of 99%,1 whereas hip fracture carries a 21% mortality in the first year after the event.2 In addition, approximately one-third of women who fracture their hip do not have osteoporosis.3 Furthermore, the role of muscle mass, strength, and performance in bone health has become well established.4

With this in mind, a recent encounter with a patient in my clinical practice illustrates what I believe is an increasing problem today. The patient had been on long-term prednisone systemically for polymyalgia rheumatica. Her dual energy x-ray absorptiometry (DXA) bone mass measurements were among the worst osteoporotic numbers I have witnessed. She related to me the “argument” that occurred between her rheumatologist and endocrinologist. One wanted her to use injectable parathyroid hormone analog daily, while the other advised yearly infusion of zoledronic acid. She chose the yearly infusion. I inquired if either physician had mentioned anything to her about using nonskid rugs in the bathroom, grab bars, being careful of black ice, a calcium-rich diet, vitamin D supplementation, good eyesight, illumination so she does not miss a step, mindful walking, and maintaining optimal balance, muscle mass, strength, and performance-enhancing exercise? She replied, “No, just which drug I should take.”

Realize that the goal for our patients should be to avoid the morbidity and mortality associated especially with hip fracture. The goal is not to have a better bone mass measurement on your DXA scan as you age. This is exactly why the name of this column, years ago, was changed from “Update on osteoporosis” to “Update on bone health.” Similarly, in 2021, the NOF (National Osteoporosis Foundation) became the BHOF (Bone Health and Osteoporosis Foundation). Thus, our understanding and interest in bone health should and must go beyond simply bone mass measurement with DXA technology. The articles highlighted in this year’s Update reflect the importance of this concept.

Know SERMs’ effects on bone health for appropriate prescribing

Goldstein SR. Selective estrogen receptor modulators and bone health. Climacteric. 2022;25:56-59.

Selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERMs) are synthetic molecules that bind to the estrogen receptor and can have agonistic activity in some tissues and antagonistic activity in others. In a recent article, I reviewed the known data regarding the effects of various SERMs on bone health.5

A rundown on 4 SERMs and their effects on bone

Tamoxifen is approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the prevention and treatment of breast cancer in women with estrogen receptor–positive tumors. The only prospective study of tamoxifen versus placebo in which fracture risk was studied in women at risk for but not diagnosed with breast cancer was the National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project (NSABP) P-1 trial. In this study, more than 13,000 women were randomly assigned to treatment with tamoxifen or placebo, with a primary objective of studying the incidence of invasive breast cancer in these high-risk women. With 7 years of follow-up, women receiving tamoxifen had significantly fewer fractures of the hip, radius, and spine (80 vs 116 in the placebo group), resulting in a combined relative risk (RR) of 0.68 (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.51–0.92).6

Raloxifene, another SERM, was extensively studied in the MORE (Multiple Outcomes of Raloxifene Evaluation) trial.7 This study involved more than 7,700 postmenopausal women with osteoporosis, average age 67. The incidence of first vertebral fracture was decreased from 4.3% with placebo to 1.9% with raloxifene (RR, 0.55; 95% CI, 0.29–0.71), and subsequent vertebral fractures were decreased from 20.2% with placebo to 14.1% with raloxifene (RR, 0.70; 95% CI, 0.60–0.90). In 2007, the FDA approved raloxifene for “reduction in risk of invasive breast cancer in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis” as well as for “postmenopausal women at high risk for invasive breast cancer” based on the Study of Tamoxifen and Raloxifene (STAR) trial that involved almost 20,000 postmenopausal women deemed at high risk for breast cancer.8

The concept of combining an estrogen with a SERM, known as a TSEC (tissue selective estrogen complex) was studied and brought to market as conjugated equine estrogen (CEE) 0.45 mg and bazedoxifene (BZA) 20 mg. CEE and BZA individually have been shown to prevent vertebral fracture.9,10 The combination of BZA and CEE has been shown to improve bone density compared with placebo.11 There are, however, no fracture prevention data for this combination therapy. This was the basis on which the combination agent received regulatory approval for prevention of osteoporosis in postmenopausal women. This combination drug is also FDA approved for treating moderate to severe vasomotor symptoms of menopause.

Ospemifene is yet another SERM that is clinically available, at an oral dose of 60 mg, and is indicated for the treatment of moderate to severe dyspareunia secondary to vulvovaginal atrophy, or genitourinary syndrome of menopause (GSM). Ospemifene effectively reduced bone loss in ovariectomized rats, with activity comparable to estradiol and raloxifene.12 Clinical data from three phase 1 or phase 2 clinical trials revealed that ospemifene 60 mg/day had a positive effect on biochemical markers for bone turnover in healthy postmenopausal women, with significant improvements relative to placebo and effects comparable to those of raloxifene.13 While actual fracture or bone mineral density (BMD) data in postmenopausal women are lacking, there is a good correlation between biochemical markers for bone turnover and occurrence of fracture.14 Women who need treatment for osteoporosis should not be treated with ospemifene, but women who use ospemifene for dyspareunia can expect positive activity on bone metabolism.

SERMs, unlike estrogen, have no class labeling. In fact, in the endometrium and vagina, they have variable effects. To date, however, in postmenopausal women, all SERMs have shown estrogenic activity in bone as well as being antiestrogenic in breast. Tamoxifen, well known for its use in estrogen receptor–positive breast cancer patients, demonstrates positive effects on bone and fracture reduction compared with placebo. Raloxifene is approved for prevention and treatment of osteoporosis and for breast cancer chemoprevention in high-risk patients. The TSEC combination of CEE and the SERM bazedoxifene is approved for treatment of moderate to severe vasomotor symptoms and prevention of osteoporosis. Finally, the SERM ospemifene, approved for treating moderate to severe dyspareunia or dryness due to vulvovaginal atrophy, or GSM, has demonstrated evidence of a positive effect on bone turnover and metabolism. Clinicians need to be aware of these effects when choosing medications for their patients.

Continue to: Gut microbiome constituents may influence the development of osteoporosis: A potential treatment target?...

Gut microbiome constituents may influence the development of osteoporosis: A potential treatment target?

Cronin O, Lanham-New SA, Corfe BM, et al. Role of the microbiome in regulating bone metabolism and susceptibility to osteoporosis. Calcif Tissue Int. 2022;110:273-284.

Yang X, Chang T, Yuan Q, et al. Changes in the composition of gut and vaginal microbiota in patients with postmenopausal osteoporosis. Front Immunol. 2022;13:930244.

The role of the microbiome in many arenas is rapidly emerging. Apparently, its relationship in bone metabolism is still in its infancy. A review of PubMed articles showed that 1 paper was published in 2012, none until 2 more in 2015, with a total of 221 published through November 1, 2022. A recent review by Cronin and colleagues on the microbiome’s role in regulating bone metabolism came out of a workshop held by the Osteoporosis and Bone Research Academy of the Royal Osteoporosis Society in the United Kingdom.15

The gut microbiome’s relationship with bone health

The authors noted that the human microbiota functions at the interface between diet, medication use, lifestyle, host immune development, and health. Hence, it is closely aligned with many of the recognized modifiable factors that influence bone mass accrual in the young and bone maintenance and skeletal decline in older populations. Microbiome research and discovery supports a role of the human gut microbiome in the regulation of bone metabolism and the pathogenesis of osteoporosis as well as its prevention and treatment.

Numerous factors which influence the gut microbiome and the development of osteoporosis overlap. These include body mass index (BMI), vitamin D, alcohol intake, diet, corticosteroid use, physical activity, sex hormone deficiency, genetic variability, and chronic inflammatory disorders.

Cronin and colleagues reviewed a number of clinical studies and concluded that “the available evidence suggests that probiotic supplements can attenuate bone loss in postmenopausal women, although the studies investigating this have been short term and individually have had small sample sizes. Moving forward, it will be important to conduct larger scale studies to evaluate if the skeletal response differs with different types of probiotic and also to determine if the effects are sustained in the longer term.”15

Composition of the microbiota

A recent study by Yang and colleagues focused on changes in gut and vaginal microbiota composition in patients with postmenopausal osteoporosis. They analyzed data from 132 postmenopausal women with osteoporosis (n = 34), osteopenia (n = 47), and controls (n = 51) based on their T-scores.16

Significant differences were observed in the microbial compositions of fecal samples between groups (P<.05), with some species enhanced in the control group whereas other species were higher in the osteoporosis group. Similar but less pronounced differences were seen in the vaginal microbiome but of different species.

The authors concluded that “The results show that changes in BMD in postmenopausal women are associated with the changes in gut microbiome and vaginal microbiome; however, changes in gut microbiome are more closely correlated with postmenopausal osteoporosis than vaginal microbiome.”16

While we are not yet ready to try to clinically alter the gut microbiome with various interventions, realizing that there is crosstalk between the gut microbiome and bone health is another factor to consider, and it begins with an appreciation of the various factors where the 2 overlap—BMI, vitamin D, alcohol intake, diet, corticosteroid use, physical activity, sex hormone deficiency, genetic variability, and chronic inflammatory disorders.

Continue to: Sarcopenia, osteoporosis, and frailty: A fracture risk triple play...

Sarcopenia, osteoporosis, and frailty: A fracture risk triple play

Laskou F, Fuggle NR, Patel HP, et al. Associations of osteoporosis and sarcopenia with frailty and multimorbidity among participants of the Hertfordshire Cohort Study. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 2022;13:220-229.

Laskou and colleagues aimed to explore the relationship between sarcopenia, osteoporosis, and frailty in community-dwelling adults participating in a cohort study in the United Kingdom and to determine if the coexistence of osteoporosis and sarcopenia is associated with a significantly heavier health burden.17

Study details

The authors examined data from 206 women with an average age of 75.5 years. Sarcopenia was defined using the European Working Group on Sarcopenia in Older People (EWGSOP) criteria, which includes low grip strength or slow chair rise and low muscle quantity. Osteoporosis was defined by standard measurements as a T-score of less than or equal to -2.5 standard deviations at the femoral neck or use of any osteoporosis medications. Frailty was defined using the Fried definition, which includes having 3 or more of the following 5 domains: weakness, slowness, exhaustion, low physical activity, and unintentional weight loss. Having 1 or 2 domains is “prefrailty” and no domains signifies nonfrail.

Frailty confers additional risk

The study results showed that among the 206 women, the prevalence of frailty and prefrailty was 9.2% and 60.7%, respectively. Of the 5 Fried frailty components, low walking speed and low physical activity followed by self-reported exhaustion were the most prevalent (96.6%, 87.5%, and 75.8%, respectively) among frail participants. Having sarcopenia only was strongly associated with frailty (odds ratio [OR], 8.28; 95% CI, 1.27–54.03; P=.027]). The likelihood of being frail was substantially higher with the presence of coexisting sarcopenia and osteoporosis (OR, 26.15; 95% CI, 3.31–218.76; P=.003).

Thus, both these conditions confer a high health burden for the individual as well as for health care systems. Osteosarcopenia is the term given when low bone mass and sarcopenia occur in consort. Previous data have shown that when osteoporosis or even osteopenia is combined with sarcopenia, it can result in a 3-fold increase in the risk of falls and a 4-fold increase in the risk of fracture compared with women who have osteopenia or osteoporosis alone.18

Sarcopenia, osteoporosis, and frailty are highly prevalent in older adults but are frequently underrecognized. Sarcopenia is characterized by progressive and generalized decline in muscle strength, function, and muscle mass with increasing age. Sarcopenia increases the likelihood of falls and adversely impacts functional independence and quality of life. Osteoporosis predisposes to low energy, fragility fractures, and is associated with chronic pain, impaired physical function, loss of independence, and higher risk of institutionalization. Clinicians need to be aware that when sarcopenia coexists with any degree of low bone mass, it will significantly increase the risk of falls and fracture compared with having osteopenia or osteoporosis alone.

Continue to: Denosumab effective in reducing falls, strengthening muscle...

Denosumab effective in reducing falls, strengthening muscle

Rupp T, von Vopelius E, Strahl A, et al. Beneficial effects of denosumab on muscle performance in patients with low BMD: a retrospective, propensity score-matched study. Osteoporos Int. 2022;33:2177-2184.

Results of a previous study showed that denosumab treatment significantly decreased falls and resulted in significant improvement in all sarcopenic measures.19 Furthermore, 1 year after denosumab was discontinued, a significant worsening occurred in both falls and sarcopenic measures. In that study, the control group, treated with alendronate or zoledronate, also showed improvement on some tests of muscle performance but no improvement in the risk of falls.

Those results agreed with the outcomes of the FREEDOM (Fracture Reduction Evaluation of Denosumab in Osteoporosis) trial.20 This study revealed that denosumab treatment not only reduced the risk of vertebral, nonvertebral, and hip fracture over 36 months but also that the denosumab-treated group had fewer falls compared with the placebo-treated group (4.5% vs 5.7%; P = .02).

Denosumab found to increase muscle strength

More recently, Rupp and colleagues conducted a retrospective cohort study that included women with osteoporosis or osteopenia who received vitamin D only (n = 52), alendronate 70 mg/week (n = 26), or denosumab (n = 52).21

After a mean follow-up period of 17.6 (SD, 9.0) months, the authors observed a significantly higher increase in grip force in both the denosumab (P<.001) and bisphosphonate groups (P = .001) compared with the vitamin D group. In addition, the denosumab group showed a significantly higher increase in chair rising test performance compared with the bisphosphonate group (denosumab vs bisphosphonate, P = 0.03). They concluded that denosumab resulted in increased muscle strength in the upper and lower limbs, indicating systemic rather than site-specific effects as compared with the bisphosphonate.

The authors concluded that based on these findings, denosumab might be favored over other osteoporosis treatments in patients with low BMD coexisting with poor muscle strength. ●

Osteoporosis and sarcopenia may share similar underlying risk factors. Muscle-bone interactions are important to minimize the risk of falls, fractures, and hospitalizations. In previous studies, denosumab as well as various bisphosphonates improved measures of sarcopenia, although only denosumab was associated with a reduction in the risk of falls. The study by Rupp and colleagues suggests that denosumab treatment may result in increased muscle strength in upper and lower limbs, indicating some systemic effect and not simply site-specific activity. Thus, in choosing a bone-specific agent for patients with abnormal muscle strength, mass, or performance, clinicians may want to consider denosumab as a choice for these reasons.

I recently heard a lecture where the speaker quoted this statistic: “A 50-year-old woman who does not currently have heart disease or cancer has a life expectancy of 91.” Hopefully, anyone reading this article already is aware of the fact that as our patients age, hip fracture results in greater morbidity and mortality than early breast cancer. It should be well known to clinicians (and, ultimately, to our patients) that localized breast cancer has a survival rate of 99%,1 whereas hip fracture carries a 21% mortality in the first year after the event.2 In addition, approximately one-third of women who fracture their hip do not have osteoporosis.3 Furthermore, the role of muscle mass, strength, and performance in bone health has become well established.4

With this in mind, a recent encounter with a patient in my clinical practice illustrates what I believe is an increasing problem today. The patient had been on long-term prednisone systemically for polymyalgia rheumatica. Her dual energy x-ray absorptiometry (DXA) bone mass measurements were among the worst osteoporotic numbers I have witnessed. She related to me the “argument” that occurred between her rheumatologist and endocrinologist. One wanted her to use injectable parathyroid hormone analog daily, while the other advised yearly infusion of zoledronic acid. She chose the yearly infusion. I inquired if either physician had mentioned anything to her about using nonskid rugs in the bathroom, grab bars, being careful of black ice, a calcium-rich diet, vitamin D supplementation, good eyesight, illumination so she does not miss a step, mindful walking, and maintaining optimal balance, muscle mass, strength, and performance-enhancing exercise? She replied, “No, just which drug I should take.”

Realize that the goal for our patients should be to avoid the morbidity and mortality associated especially with hip fracture. The goal is not to have a better bone mass measurement on your DXA scan as you age. This is exactly why the name of this column, years ago, was changed from “Update on osteoporosis” to “Update on bone health.” Similarly, in 2021, the NOF (National Osteoporosis Foundation) became the BHOF (Bone Health and Osteoporosis Foundation). Thus, our understanding and interest in bone health should and must go beyond simply bone mass measurement with DXA technology. The articles highlighted in this year’s Update reflect the importance of this concept.

Know SERMs’ effects on bone health for appropriate prescribing

Goldstein SR. Selective estrogen receptor modulators and bone health. Climacteric. 2022;25:56-59.

Selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERMs) are synthetic molecules that bind to the estrogen receptor and can have agonistic activity in some tissues and antagonistic activity in others. In a recent article, I reviewed the known data regarding the effects of various SERMs on bone health.5

A rundown on 4 SERMs and their effects on bone

Tamoxifen is approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the prevention and treatment of breast cancer in women with estrogen receptor–positive tumors. The only prospective study of tamoxifen versus placebo in which fracture risk was studied in women at risk for but not diagnosed with breast cancer was the National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project (NSABP) P-1 trial. In this study, more than 13,000 women were randomly assigned to treatment with tamoxifen or placebo, with a primary objective of studying the incidence of invasive breast cancer in these high-risk women. With 7 years of follow-up, women receiving tamoxifen had significantly fewer fractures of the hip, radius, and spine (80 vs 116 in the placebo group), resulting in a combined relative risk (RR) of 0.68 (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.51–0.92).6

Raloxifene, another SERM, was extensively studied in the MORE (Multiple Outcomes of Raloxifene Evaluation) trial.7 This study involved more than 7,700 postmenopausal women with osteoporosis, average age 67. The incidence of first vertebral fracture was decreased from 4.3% with placebo to 1.9% with raloxifene (RR, 0.55; 95% CI, 0.29–0.71), and subsequent vertebral fractures were decreased from 20.2% with placebo to 14.1% with raloxifene (RR, 0.70; 95% CI, 0.60–0.90). In 2007, the FDA approved raloxifene for “reduction in risk of invasive breast cancer in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis” as well as for “postmenopausal women at high risk for invasive breast cancer” based on the Study of Tamoxifen and Raloxifene (STAR) trial that involved almost 20,000 postmenopausal women deemed at high risk for breast cancer.8

The concept of combining an estrogen with a SERM, known as a TSEC (tissue selective estrogen complex) was studied and brought to market as conjugated equine estrogen (CEE) 0.45 mg and bazedoxifene (BZA) 20 mg. CEE and BZA individually have been shown to prevent vertebral fracture.9,10 The combination of BZA and CEE has been shown to improve bone density compared with placebo.11 There are, however, no fracture prevention data for this combination therapy. This was the basis on which the combination agent received regulatory approval for prevention of osteoporosis in postmenopausal women. This combination drug is also FDA approved for treating moderate to severe vasomotor symptoms of menopause.

Ospemifene is yet another SERM that is clinically available, at an oral dose of 60 mg, and is indicated for the treatment of moderate to severe dyspareunia secondary to vulvovaginal atrophy, or genitourinary syndrome of menopause (GSM). Ospemifene effectively reduced bone loss in ovariectomized rats, with activity comparable to estradiol and raloxifene.12 Clinical data from three phase 1 or phase 2 clinical trials revealed that ospemifene 60 mg/day had a positive effect on biochemical markers for bone turnover in healthy postmenopausal women, with significant improvements relative to placebo and effects comparable to those of raloxifene.13 While actual fracture or bone mineral density (BMD) data in postmenopausal women are lacking, there is a good correlation between biochemical markers for bone turnover and occurrence of fracture.14 Women who need treatment for osteoporosis should not be treated with ospemifene, but women who use ospemifene for dyspareunia can expect positive activity on bone metabolism.

SERMs, unlike estrogen, have no class labeling. In fact, in the endometrium and vagina, they have variable effects. To date, however, in postmenopausal women, all SERMs have shown estrogenic activity in bone as well as being antiestrogenic in breast. Tamoxifen, well known for its use in estrogen receptor–positive breast cancer patients, demonstrates positive effects on bone and fracture reduction compared with placebo. Raloxifene is approved for prevention and treatment of osteoporosis and for breast cancer chemoprevention in high-risk patients. The TSEC combination of CEE and the SERM bazedoxifene is approved for treatment of moderate to severe vasomotor symptoms and prevention of osteoporosis. Finally, the SERM ospemifene, approved for treating moderate to severe dyspareunia or dryness due to vulvovaginal atrophy, or GSM, has demonstrated evidence of a positive effect on bone turnover and metabolism. Clinicians need to be aware of these effects when choosing medications for their patients.

Continue to: Gut microbiome constituents may influence the development of osteoporosis: A potential treatment target?...

Gut microbiome constituents may influence the development of osteoporosis: A potential treatment target?

Cronin O, Lanham-New SA, Corfe BM, et al. Role of the microbiome in regulating bone metabolism and susceptibility to osteoporosis. Calcif Tissue Int. 2022;110:273-284.

Yang X, Chang T, Yuan Q, et al. Changes in the composition of gut and vaginal microbiota in patients with postmenopausal osteoporosis. Front Immunol. 2022;13:930244.

The role of the microbiome in many arenas is rapidly emerging. Apparently, its relationship in bone metabolism is still in its infancy. A review of PubMed articles showed that 1 paper was published in 2012, none until 2 more in 2015, with a total of 221 published through November 1, 2022. A recent review by Cronin and colleagues on the microbiome’s role in regulating bone metabolism came out of a workshop held by the Osteoporosis and Bone Research Academy of the Royal Osteoporosis Society in the United Kingdom.15

The gut microbiome’s relationship with bone health

The authors noted that the human microbiota functions at the interface between diet, medication use, lifestyle, host immune development, and health. Hence, it is closely aligned with many of the recognized modifiable factors that influence bone mass accrual in the young and bone maintenance and skeletal decline in older populations. Microbiome research and discovery supports a role of the human gut microbiome in the regulation of bone metabolism and the pathogenesis of osteoporosis as well as its prevention and treatment.

Numerous factors which influence the gut microbiome and the development of osteoporosis overlap. These include body mass index (BMI), vitamin D, alcohol intake, diet, corticosteroid use, physical activity, sex hormone deficiency, genetic variability, and chronic inflammatory disorders.

Cronin and colleagues reviewed a number of clinical studies and concluded that “the available evidence suggests that probiotic supplements can attenuate bone loss in postmenopausal women, although the studies investigating this have been short term and individually have had small sample sizes. Moving forward, it will be important to conduct larger scale studies to evaluate if the skeletal response differs with different types of probiotic and also to determine if the effects are sustained in the longer term.”15

Composition of the microbiota

A recent study by Yang and colleagues focused on changes in gut and vaginal microbiota composition in patients with postmenopausal osteoporosis. They analyzed data from 132 postmenopausal women with osteoporosis (n = 34), osteopenia (n = 47), and controls (n = 51) based on their T-scores.16

Significant differences were observed in the microbial compositions of fecal samples between groups (P<.05), with some species enhanced in the control group whereas other species were higher in the osteoporosis group. Similar but less pronounced differences were seen in the vaginal microbiome but of different species.

The authors concluded that “The results show that changes in BMD in postmenopausal women are associated with the changes in gut microbiome and vaginal microbiome; however, changes in gut microbiome are more closely correlated with postmenopausal osteoporosis than vaginal microbiome.”16

While we are not yet ready to try to clinically alter the gut microbiome with various interventions, realizing that there is crosstalk between the gut microbiome and bone health is another factor to consider, and it begins with an appreciation of the various factors where the 2 overlap—BMI, vitamin D, alcohol intake, diet, corticosteroid use, physical activity, sex hormone deficiency, genetic variability, and chronic inflammatory disorders.

Continue to: Sarcopenia, osteoporosis, and frailty: A fracture risk triple play...

Sarcopenia, osteoporosis, and frailty: A fracture risk triple play

Laskou F, Fuggle NR, Patel HP, et al. Associations of osteoporosis and sarcopenia with frailty and multimorbidity among participants of the Hertfordshire Cohort Study. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 2022;13:220-229.

Laskou and colleagues aimed to explore the relationship between sarcopenia, osteoporosis, and frailty in community-dwelling adults participating in a cohort study in the United Kingdom and to determine if the coexistence of osteoporosis and sarcopenia is associated with a significantly heavier health burden.17

Study details

The authors examined data from 206 women with an average age of 75.5 years. Sarcopenia was defined using the European Working Group on Sarcopenia in Older People (EWGSOP) criteria, which includes low grip strength or slow chair rise and low muscle quantity. Osteoporosis was defined by standard measurements as a T-score of less than or equal to -2.5 standard deviations at the femoral neck or use of any osteoporosis medications. Frailty was defined using the Fried definition, which includes having 3 or more of the following 5 domains: weakness, slowness, exhaustion, low physical activity, and unintentional weight loss. Having 1 or 2 domains is “prefrailty” and no domains signifies nonfrail.

Frailty confers additional risk

The study results showed that among the 206 women, the prevalence of frailty and prefrailty was 9.2% and 60.7%, respectively. Of the 5 Fried frailty components, low walking speed and low physical activity followed by self-reported exhaustion were the most prevalent (96.6%, 87.5%, and 75.8%, respectively) among frail participants. Having sarcopenia only was strongly associated with frailty (odds ratio [OR], 8.28; 95% CI, 1.27–54.03; P=.027]). The likelihood of being frail was substantially higher with the presence of coexisting sarcopenia and osteoporosis (OR, 26.15; 95% CI, 3.31–218.76; P=.003).

Thus, both these conditions confer a high health burden for the individual as well as for health care systems. Osteosarcopenia is the term given when low bone mass and sarcopenia occur in consort. Previous data have shown that when osteoporosis or even osteopenia is combined with sarcopenia, it can result in a 3-fold increase in the risk of falls and a 4-fold increase in the risk of fracture compared with women who have osteopenia or osteoporosis alone.18

Sarcopenia, osteoporosis, and frailty are highly prevalent in older adults but are frequently underrecognized. Sarcopenia is characterized by progressive and generalized decline in muscle strength, function, and muscle mass with increasing age. Sarcopenia increases the likelihood of falls and adversely impacts functional independence and quality of life. Osteoporosis predisposes to low energy, fragility fractures, and is associated with chronic pain, impaired physical function, loss of independence, and higher risk of institutionalization. Clinicians need to be aware that when sarcopenia coexists with any degree of low bone mass, it will significantly increase the risk of falls and fracture compared with having osteopenia or osteoporosis alone.

Continue to: Denosumab effective in reducing falls, strengthening muscle...

Denosumab effective in reducing falls, strengthening muscle

Rupp T, von Vopelius E, Strahl A, et al. Beneficial effects of denosumab on muscle performance in patients with low BMD: a retrospective, propensity score-matched study. Osteoporos Int. 2022;33:2177-2184.

Results of a previous study showed that denosumab treatment significantly decreased falls and resulted in significant improvement in all sarcopenic measures.19 Furthermore, 1 year after denosumab was discontinued, a significant worsening occurred in both falls and sarcopenic measures. In that study, the control group, treated with alendronate or zoledronate, also showed improvement on some tests of muscle performance but no improvement in the risk of falls.

Those results agreed with the outcomes of the FREEDOM (Fracture Reduction Evaluation of Denosumab in Osteoporosis) trial.20 This study revealed that denosumab treatment not only reduced the risk of vertebral, nonvertebral, and hip fracture over 36 months but also that the denosumab-treated group had fewer falls compared with the placebo-treated group (4.5% vs 5.7%; P = .02).

Denosumab found to increase muscle strength

More recently, Rupp and colleagues conducted a retrospective cohort study that included women with osteoporosis or osteopenia who received vitamin D only (n = 52), alendronate 70 mg/week (n = 26), or denosumab (n = 52).21

After a mean follow-up period of 17.6 (SD, 9.0) months, the authors observed a significantly higher increase in grip force in both the denosumab (P<.001) and bisphosphonate groups (P = .001) compared with the vitamin D group. In addition, the denosumab group showed a significantly higher increase in chair rising test performance compared with the bisphosphonate group (denosumab vs bisphosphonate, P = 0.03). They concluded that denosumab resulted in increased muscle strength in the upper and lower limbs, indicating systemic rather than site-specific effects as compared with the bisphosphonate.

The authors concluded that based on these findings, denosumab might be favored over other osteoporosis treatments in patients with low BMD coexisting with poor muscle strength. ●

Osteoporosis and sarcopenia may share similar underlying risk factors. Muscle-bone interactions are important to minimize the risk of falls, fractures, and hospitalizations. In previous studies, denosumab as well as various bisphosphonates improved measures of sarcopenia, although only denosumab was associated with a reduction in the risk of falls. The study by Rupp and colleagues suggests that denosumab treatment may result in increased muscle strength in upper and lower limbs, indicating some systemic effect and not simply site-specific activity. Thus, in choosing a bone-specific agent for patients with abnormal muscle strength, mass, or performance, clinicians may want to consider denosumab as a choice for these reasons.

- American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts & Figures 2020. Atlanta, Georgia: American Cancer Society; 2020. Accessed November 7, 2022. https://www.cancer.org/content /dam/cancer-org/research/cancer-facts-and-statistics /annual-cancer-facts-and-figures/2020/cancer-facts-and -figures-2020.pdf

- Downey C, Kelly M, Quinlan JF. Changing trends in the mortality rate at 1-year post hip fracture—a systematic review. World J Orthop. 2019;10:166-175.

- Schuit SC, van der Klift M, Weel AE, et al. Fracture incidence and association with bone mineral density in elderly men and women: the Rotterdam study. Bone. 2004;34:195-202.

- de Villiers TJ, Goldstein SR. Update on bone health: the International Menopause Society White Paper 2021. Climacteric. 2021;24:498-504.

- Goldstein SR. Selective estrogen receptor modulators and bone health. Climacteric. 2022;25:56-59.

- Fisher B, Costantino JP, Wickerham DL, et al. Tamoxifen for the prevention of breast cancer: current status of the National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project P-1 study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005;97:1652-1662.

- Ettinger B, Black DM, Mitlak BH, et al; for the Multiple Outcomes of Raloxifene Evaluation (MORE) Investigators. Reduction of vertebral fracture risk in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis treated with raloxifene: results from a 3-year randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 1999;282:637645.

- Vogel VG, Costantino JP, Wickerham DL, et al; National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project (NSABP). Effects of tamoxifen vs raloxifene on the risk of developing invasive breast cancer and other disease outcomes: the NSABP Study of Tamoxifen and Raloxifene (STAR) P-2 trial. JAMA. 2006;295:2727-2741.

- Silverman SL, Christiansen C, Genant HK, et al. Efficacy of bazedoxifene in reducing new vertebral fracture risk in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis: results from a 3-year, randomized, placebo-, and active-controlled clinical trial. J Bone Miner Res. 2008;23:1923-1934.

- Anderson GL, Limacher M, Assaf AR, et al; Women’s Health Initiative Steering Committee. Effects of conjugated equine estrogen in postmenopausal women with hysterectomy: the Women’s Health Initiative randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2004:291:1701-1712.

- Lindsay R, Gallagher JC, Kagan R, et al. Efficacy of tissue-selective estrogen complex of bazedoxifene/conjugated estrogens for osteoporosis prevention in at-risk postmenopausal women. Fertil Steril. 2009;92:1045-1052.

- Kangas L, Härkönen P, Väänänen K, et al. Effects of the selective estrogen receptor modulator ospemifene on bone in rats. Horm Metab Res. 2014;46:27-35.

- Constantine GD, Kagan R, Miller PD. Effects of ospemifene on bone parameters including clinical biomarkers in postmenopausal women. Menopause. 2016;23:638-644.

- Gerdhem P, Ivaska KK, Alatalo SL, et al. Biochemical markers of bone metabolism and prediction of fracture in elderly women. J Bone Miner Res. 2004;19:386-393.

- Cronin O, Lanham-New SA, Corfe BM, et al. Role of the microbiome in regulating bone metabolism and susceptibility to osteoporosis. Calcif Tissue Int. 2022;110:273-284.

- Yang X, Chang T, Yuan Q, et al. Changes in the composition of gut and vaginal microbiota in patients with postmenopausal osteoporosis. Front Immunol. 2022;13:930244.

- Laskou F, Fuggle NR, Patel HP, et al. Associations of osteoporosis and sarcopenia with frailty and multimorbidity among participants of the Hertfordshire Cohort Study. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 2022;13:220-229.

- Hida T, Shimokata H, Sakai Y, et al. Sarcopenia and sarcopenic leg as potential risk factors for acute osteoporotic vertebral fracture among older women. Eur Spine J. 2016;25:3424-3431.

- El Miedany Y, El Gaafary M, Toth M, et al; Egyptian Academy of Bone Health, Metabolic Bone Diseases. Is there a potential dual effect of denosumab for treatment of osteoporosis and sarcopenia? Clin Rheumatol. 2021;40:4225-4232.

- Cummings SR, Martin JS, McClung MR, et al; FREEDOM trial. Denosumab for prevention of fractures in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:756-765.

- Rupp T, von Vopelius E, Strahl A, et al. Beneficial effects of denosumab on muscle performance in patients with low BMD: a retrospective, propensity score-matched study. Osteoporos Int. 2022;33:2177-2184.

- American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts & Figures 2020. Atlanta, Georgia: American Cancer Society; 2020. Accessed November 7, 2022. https://www.cancer.org/content /dam/cancer-org/research/cancer-facts-and-statistics /annual-cancer-facts-and-figures/2020/cancer-facts-and -figures-2020.pdf

- Downey C, Kelly M, Quinlan JF. Changing trends in the mortality rate at 1-year post hip fracture—a systematic review. World J Orthop. 2019;10:166-175.

- Schuit SC, van der Klift M, Weel AE, et al. Fracture incidence and association with bone mineral density in elderly men and women: the Rotterdam study. Bone. 2004;34:195-202.

- de Villiers TJ, Goldstein SR. Update on bone health: the International Menopause Society White Paper 2021. Climacteric. 2021;24:498-504.

- Goldstein SR. Selective estrogen receptor modulators and bone health. Climacteric. 2022;25:56-59.

- Fisher B, Costantino JP, Wickerham DL, et al. Tamoxifen for the prevention of breast cancer: current status of the National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project P-1 study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005;97:1652-1662.

- Ettinger B, Black DM, Mitlak BH, et al; for the Multiple Outcomes of Raloxifene Evaluation (MORE) Investigators. Reduction of vertebral fracture risk in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis treated with raloxifene: results from a 3-year randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 1999;282:637645.

- Vogel VG, Costantino JP, Wickerham DL, et al; National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project (NSABP). Effects of tamoxifen vs raloxifene on the risk of developing invasive breast cancer and other disease outcomes: the NSABP Study of Tamoxifen and Raloxifene (STAR) P-2 trial. JAMA. 2006;295:2727-2741.

- Silverman SL, Christiansen C, Genant HK, et al. Efficacy of bazedoxifene in reducing new vertebral fracture risk in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis: results from a 3-year, randomized, placebo-, and active-controlled clinical trial. J Bone Miner Res. 2008;23:1923-1934.

- Anderson GL, Limacher M, Assaf AR, et al; Women’s Health Initiative Steering Committee. Effects of conjugated equine estrogen in postmenopausal women with hysterectomy: the Women’s Health Initiative randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2004:291:1701-1712.

- Lindsay R, Gallagher JC, Kagan R, et al. Efficacy of tissue-selective estrogen complex of bazedoxifene/conjugated estrogens for osteoporosis prevention in at-risk postmenopausal women. Fertil Steril. 2009;92:1045-1052.

- Kangas L, Härkönen P, Väänänen K, et al. Effects of the selective estrogen receptor modulator ospemifene on bone in rats. Horm Metab Res. 2014;46:27-35.

- Constantine GD, Kagan R, Miller PD. Effects of ospemifene on bone parameters including clinical biomarkers in postmenopausal women. Menopause. 2016;23:638-644.

- Gerdhem P, Ivaska KK, Alatalo SL, et al. Biochemical markers of bone metabolism and prediction of fracture in elderly women. J Bone Miner Res. 2004;19:386-393.

- Cronin O, Lanham-New SA, Corfe BM, et al. Role of the microbiome in regulating bone metabolism and susceptibility to osteoporosis. Calcif Tissue Int. 2022;110:273-284.

- Yang X, Chang T, Yuan Q, et al. Changes in the composition of gut and vaginal microbiota in patients with postmenopausal osteoporosis. Front Immunol. 2022;13:930244.

- Laskou F, Fuggle NR, Patel HP, et al. Associations of osteoporosis and sarcopenia with frailty and multimorbidity among participants of the Hertfordshire Cohort Study. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 2022;13:220-229.

- Hida T, Shimokata H, Sakai Y, et al. Sarcopenia and sarcopenic leg as potential risk factors for acute osteoporotic vertebral fracture among older women. Eur Spine J. 2016;25:3424-3431.

- El Miedany Y, El Gaafary M, Toth M, et al; Egyptian Academy of Bone Health, Metabolic Bone Diseases. Is there a potential dual effect of denosumab for treatment of osteoporosis and sarcopenia? Clin Rheumatol. 2021;40:4225-4232.

- Cummings SR, Martin JS, McClung MR, et al; FREEDOM trial. Denosumab for prevention of fractures in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:756-765.

- Rupp T, von Vopelius E, Strahl A, et al. Beneficial effects of denosumab on muscle performance in patients with low BMD: a retrospective, propensity score-matched study. Osteoporos Int. 2022;33:2177-2184.

Janus Kinase Inhibitors: A Promising Therapeutic Option for Allergic Contact Dermatitis

Allergic contact dermatitis (ACD) is a delayed type IV hypersensitivity reaction that usually manifests with eczematous lesions within hours to days after exposure to a contact allergen. The primary treatment of ACD consists of allergen avoidance, but medications also may be necessary to manage symptoms, particularly in cases where avoidance alone does not lead to resolution of dermatitis. At present, no medical therapies are explicitly approved for use in the management of ACD. Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors are a class of small molecule inhibitors that are used for the treatment of a range of inflammatory diseases, such as rheumatoid arthritis and psoriatic arthritis. Several oral and topical JAK inhibitors also have recently been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for atopic dermatitis (AD). In this article, we discuss this important class of medications and the role that they may play in the off-label management of refractory ACD.

JAK/STAT Signaling Pathway

The JAK/signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT) pathway plays a crucial role in many biologic processes. Notably, JAK/STAT signaling is involved in the development and regulation of the immune system.1 The cascade begins when a particular transmembrane receptor binds a ligand, such as an interferon or interleukin.2 Upon ligand binding, the receptor dimerizes or oligomerizes, bringing the relevant JAK proteins into close approximation to each other.3 This allows the JAK proteins to autophosphorylate or transphosphorylate.2-4 Phosphorylation activates the JAK proteins and increases their kinase activity.3 In humans, there are 4 JAK proteins: JAK1, JAK2, JAK3, and tyrosine kinase 2.4 When activated, the JAK proteins phosphorylate specific tyrosine residues on the receptor, which creates a docking site for STAT proteins. After binding, the STAT proteins then are phosphorylated, leading to their dimerization and translocation to the nucleus.2,3 Once in the nucleus, the STAT proteins act as transcription factors for target genes.3

JAK Inhibitors

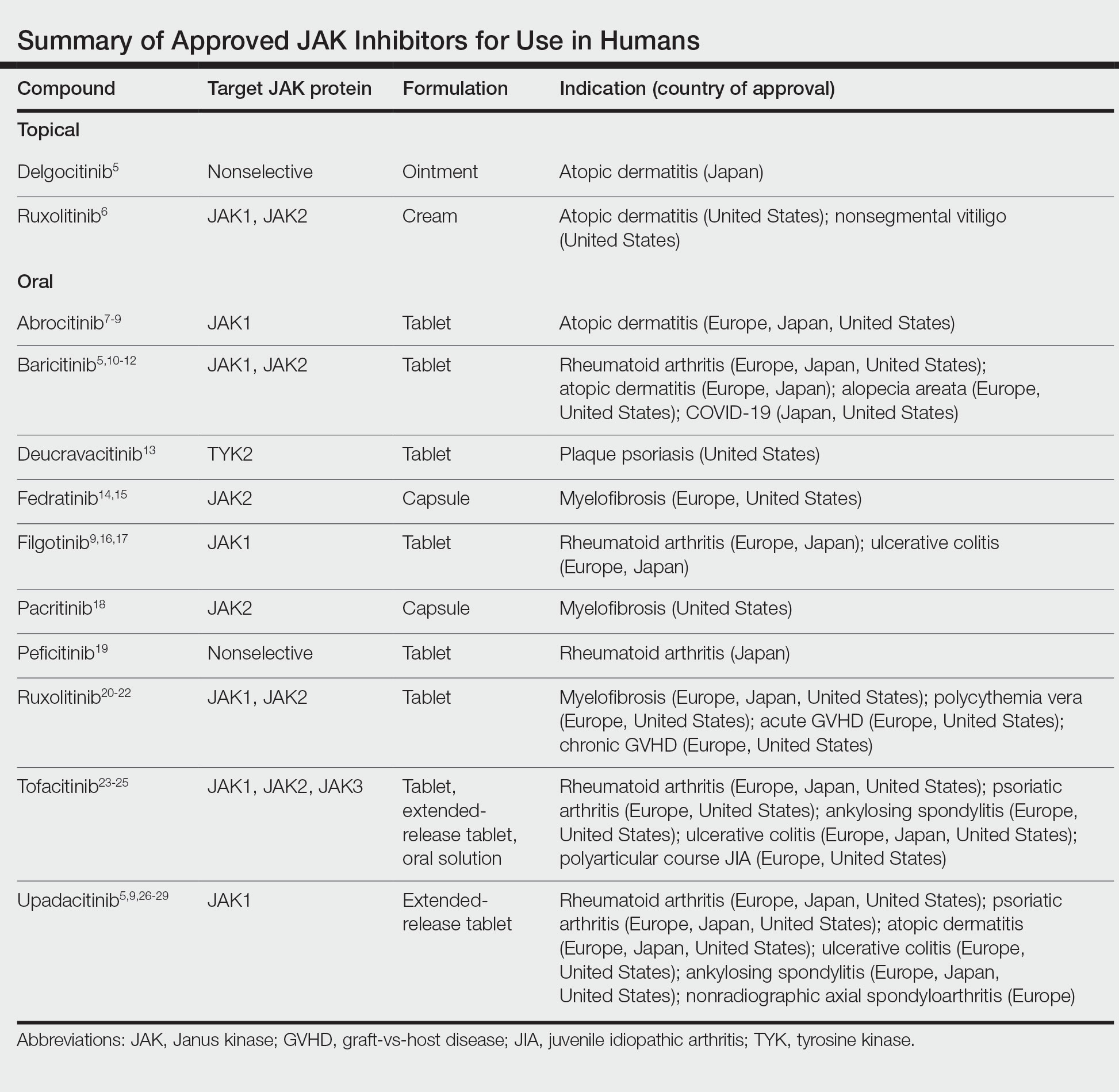

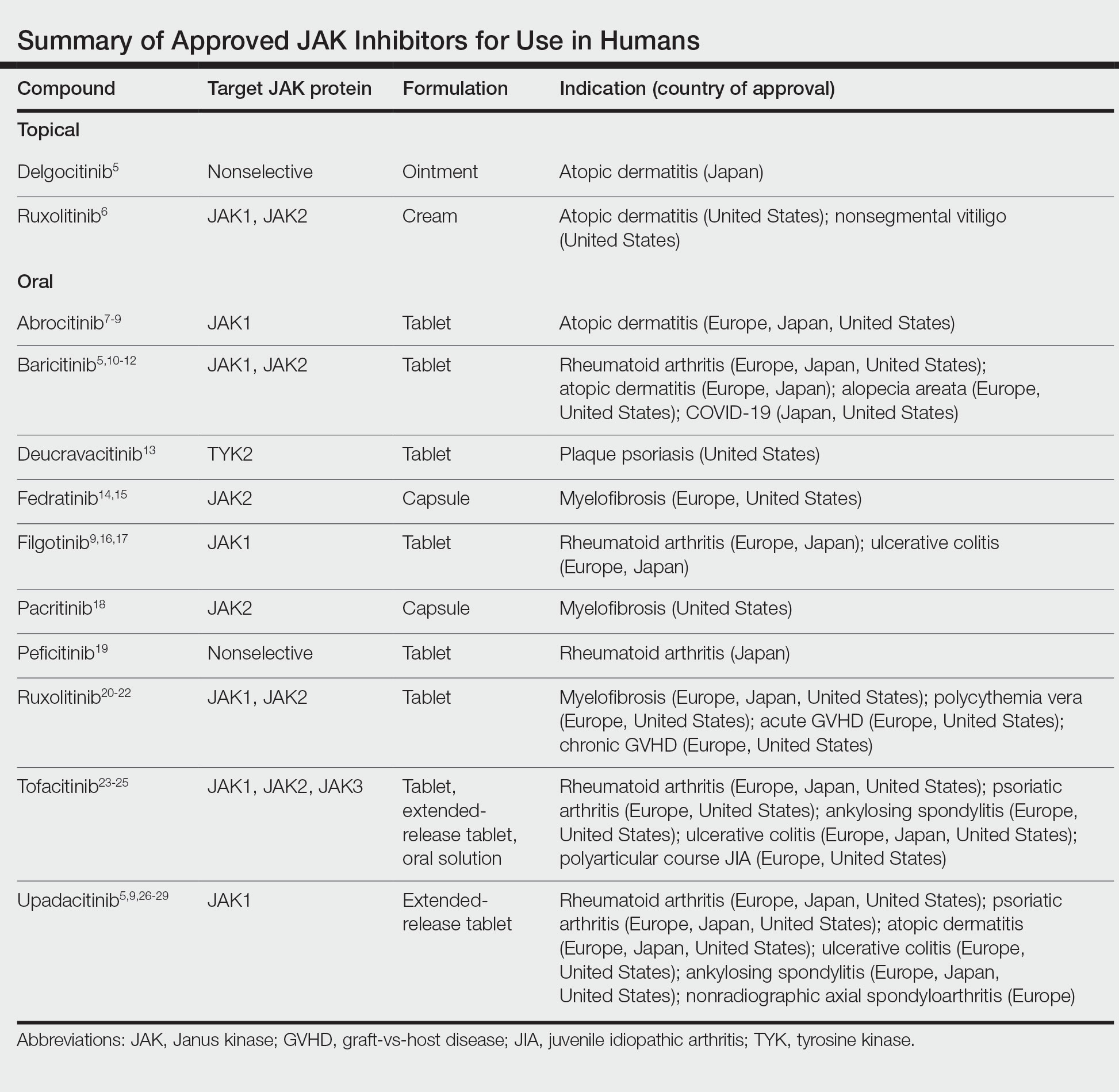

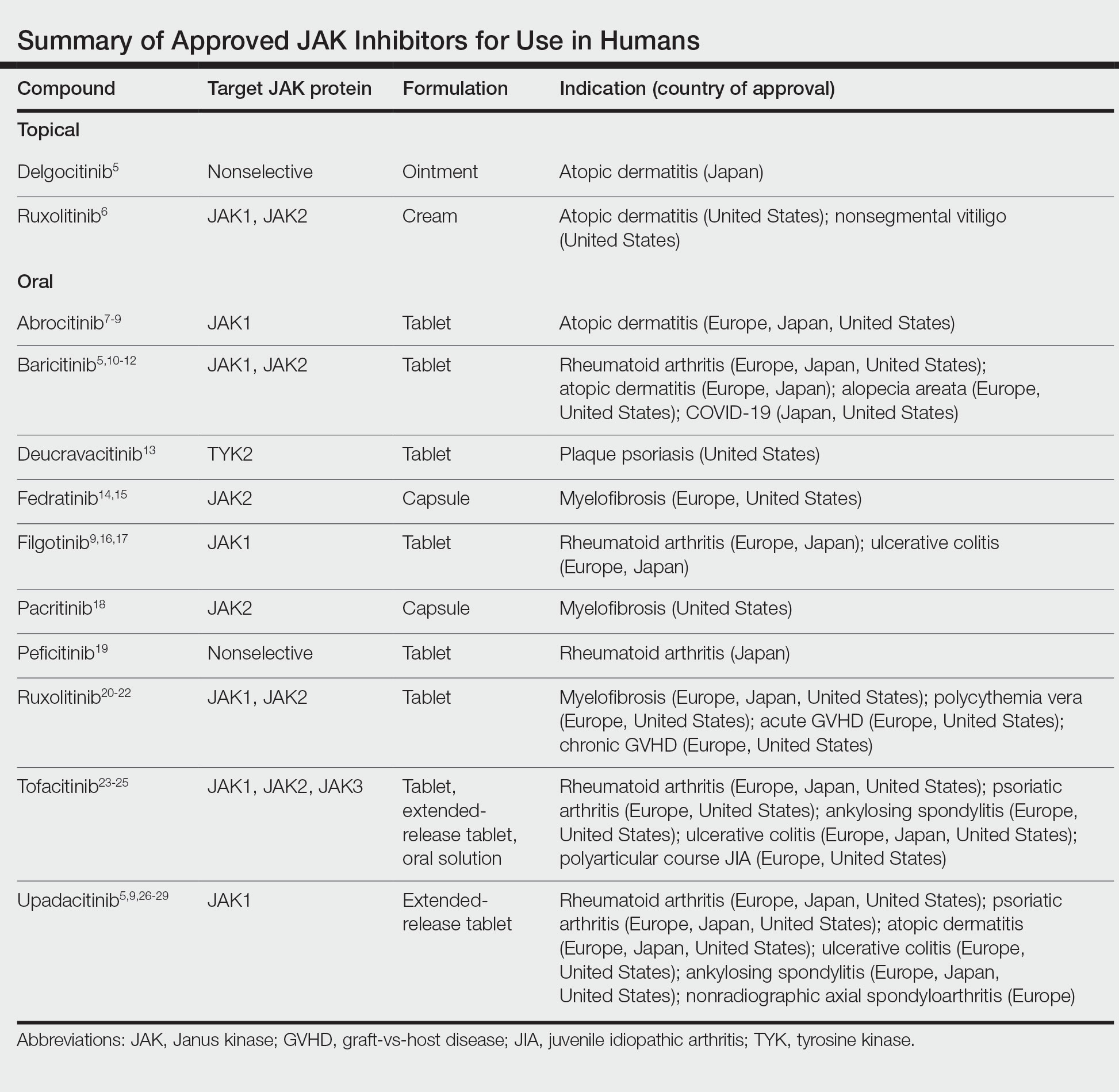

Janus kinase inhibitors are immunomodulatory medications that work through inhibition of 1 or more of the JAK proteins in the JAK/STAT pathway. Through this mechanism, JAK inhibitors can impede the activity of proinflammatory cytokines and T cells.4 A brief overview of the commercially available JAK inhibitors in Europe, Japan, and the United States is provided in the Table.5-29

Of the approved JAK inhibitors, more than 40% are indicated for AD. The first JAK inhibitor to be approved in the topical form was delgocitinib in 2020 in Japan.5 In a phase 3 trial, delgocitinib demonstrated significant reductions in modified Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI) score (P<.001) as well as Peak Pruritus Numerical Rating Scale (P<.001) when compared with vehicle.30 Topical ruxolitinib soon followed when its approval for AD was announced by the FDA in 2021.31 Results from 2 phase 3 trials found that significantly more patients achieved investigator global assessment (IGA) treatment success (P<.0001) and a significant reduction in itch as measured by the Peak Pruritus Numerical Rating Scale (P<.001) with topical ruxolitinib vs vehicle.32

The first oral JAK inhibitor to attain approval for AD was baricitinib in Europe and Japan, but it is not currently approved for this indication in the United States by the FDA.11,12,33 Consistent findings across phase 3 trials revealed that baricitinib was more effective at achieving IGA treatment success and improved EASI scores compared with placebo.33

Upadacitinib, another oral JAK inhibitor, was subsequently approved for AD in Europe and Japan in 2021 and in the United States in early 2022.5,9,26,27 Two replicate phase 3 trials demonstrated significant improvement in EASI score, itch, and quality of life with upadacitinib compared with placebo (P<.0001).34 Abrocitinib was granted FDA approval for AD in the same time period, with phase 3 trials exhibiting greater responses in IGA and EASI scores vs placebo.35

Potential for Use in ACD

Given the successful use of JAK inhibitors in the management of AD, there is optimism that these medications also may have potential application in ACD. Recent literature suggests that the 2 conditions may be more closely related mechanistically than previously understood. As a result, AD and ACD often are managed with the same therapeutic agents.36

Although the exact etiology of ACD is still being elucidated, activation of T cells and cytokines plays an important role.37 Notably, more than 40 cytokines exert their effects through the JAK/STAT signaling pathway, including IL-2, IL-6, IL-17, IL-22, and IFN-γ.37,38 A study on nickel contact allergy revealed that JAK/STAT activation may regulate the balance between IL-12 and IL-23 and increase type 1 T-helper (TH1) polarization.39 Skin inflammation and chronic pruritus, which are major components of ACD, also are thought to be mediated in part by JAK signaling.34,40

Animal studies have suggested that JAK inhibitors may show benefit in the management of ACD. Rats with oxazolone-induced ACD were found to have less swelling and epidermal thickening in the area of induced dermatitis after treatment with oral tofacitinib, comparable to the effects of cyclosporine. Tofacitinib was presumed to exert its effects through cytokine suppression, particularly that of IFN-γ, IL-22, and tumor necrosis factor α.41 In a separate study on mice with toluene-2,4-diisocyanate–induced ACD, both tofacitinib and another JAK inhibitor, oclacitinib, demonstrated inhibition of cytokine production, migration, and maturation of bone marrow–derived dendritic cells. Both topical and oral formulations of these 2 JAK inhibitors also were found to decrease scratching behavior; only the topicals improved ear thickness (used as a marker of skin inflammation), suggesting potential benefits to local application.42 In a murine model, oral delgocitinib also attenuated contact hypersensitivity via inhibition of antigen-specific T-cell proliferation and cytokine production.37 Finally, in a randomized clinical trial conducted on dogs with allergic dermatitis (of which 10% were presumed to be from contact allergy), oral oclacitinib significantly reduced pruritus and clinical severity scores vs placebo (P<.0001).43

There also are early clinical studies and case reports highlighting the effective use of JAK inhibitors in the management of ACD in humans. A 37-year-old man with occupational airborne ACD to Compositae saw full clearance of his dermatitis with daily oral abrocitinib after topical corticosteroids and dupilumab failed.44 Another patient, a 57-year-old woman, had near-complete resolution of chronic Parthenium-induced airborne ACD after starting twice-daily oral tofacitinib. Allergen avoidance, as well as multiple medications, including topical and oral corticosteroids, topical calcineurin inhibitors, and azathioprine, previously failed in this patient.45 Finally, a phase 2 study on patients with irritant and nonirritant chronic hand eczema found that significantly more patients achieved treatment success (as measured by the physician global assessment) with topical delgocitinib vs vehicle (P=.009).46 Chronic hand eczema may be due to a variety of causes, including AD, irritant contact dermatitis, and ACD. Thus, these studies begin to highlight the potential role for JAK inhibitors in the management of refractory ACD.

Side Effects of JAK Inhibitors

The safety profile of JAK inhibitors must be taken into consideration. In general, topical JAK inhibitors are safe and well tolerated, with the majority of adverse events (AEs) seen in clinical trials considered mild or unrelated to the medication.30,32 Nasopharyngitis, local skin infection, and acne were reported; a systematic review found no increased risk of AEs with topical JAK inhibitors compared with placebo.30,32,47 Application-site reactions, a common concern among the existing topical calcineurin and phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitors, were rare (approximately 2% of patients).47 The most frequent AEs seen in clinical trials of oral JAK inhibitors included acne, nasopharyngitis/upper respiratory tract infections, nausea, and headache.33-35 Herpes simplex virus infection and worsening of AD also were seen. Although elevations in creatine phosphokinase levels were reported, patients often were asymptomatic and elevations were related to exercise or resolved without treatment interruption.33-35

As a class, JAK inhibitors carry a boxed warning for serious infections, malignancy, major adverse cardiovascular events, thrombosis, and mortality. The FDA placed this label on JAK inhibitors because of the results of a randomized controlled trial of oral tofacitinib vs tumor necrosis factor α inhibitors in RA.48,49 Notably, participants in the trial had to be 50 years or older and have at least 1 additional cardiovascular risk factor. Postmarket safety data are still being collected for patients with AD and other dermatologic conditions, but the findings of safety analyses have been reassuring to date.50,51 Regular follow-up and routine laboratory monitoring are recommended for any patient started on an oral JAK inhibitor, which often includes monitoring of the complete blood cell count, comprehensive metabolic panel, and lipids, as well as baseline screening for tuberculosis and hepatitis.52,53 For topical JAK inhibitors, no specific laboratory monitoring is recommended.

Finally, it must be considered that the challenges of off-label prescribing combined with high costs may limit access to JAK inhibitors for use in ACD.

Final Interpretation

Early investigations, including studies on animals and humans, suggest that JAK inhibitors are a promising option in the management of treatment-refractory ACD. Patients and providers should be aware of both the benefits and known side effects of JAK inhibitors prior to treatment initiation.

- Ghoreschi K, Laurence A, O’Shea JJ. Janus kinases in immune cell signaling. Immunol Rev. 2009;228:273-287.

- Bousoik E, Montazeri Aliabadi H. “Do we know Jack” about JAK? a closer look at JAK/STAT signaling pathway. Front Oncol. 2018;8:287.

- Jatiani SS, Baker SJ, Silverman LR, et al. Jak/STAT pathways in cytokine signaling and myeloproliferative disorders: approaches for targeted therapies. Genes Cancer. 2010;1:979-993.

- Seif F, Khoshmirsafa M, Aazami H, et al. The role of JAK-STAT signaling pathway and its regulators in the fate of T helper cells. Cell Commun Signal. 2017;15:23.

- Traidl S, Freimooser S, Werfel T. Janus kinase inhibitors for the therapy of atopic dermatitis. Allergol Select. 2021;5:293-304.

- Opzelura (ruxolitinib) cream. Prescribing information. Incyte Corporation; 2022. Accessed January 20, 2023. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2022/215309s001lbl.pdf

- Cibinqo (abrocitinib) tablets. Prescribing information. Pfizer Labs; 2022. Accessed January 20, 2023. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2022/213871s000lbl.pdf

- Cibinqo. Product information. European Medicines Agency. Published December 17, 2021. Updated November 10, 2022. Accessed January 20, 2023. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/EPAR/cibinqo

- New drugs approved in FY 2021. Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency. Accessed January 20, 2023. https://www.pmda.go.jp/files/000246734.pdf

- Olumiant (baricitinib) tablets. Prescribing information. Eli Lilly and Company; 2022. Accessed January 20, 2023. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2022/207924s007lbl.pdf

- Olumiant. Product information. European Medicines Agency. Published March 16, 2017. Updated June 29, 2022. Accessed January 20, 2023. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/EPAR/olumiant

- Review report: Olumiant. Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency. April 21, 2021. Accessed January 20, 2023. https://www.pmda.go.jp/files/000243207.pdf

- Sotyktu (deucravacitinib) tablets. Prescribing information. Bristol-Myers Squibb Company; 2022. Accessed January 20, 2023.https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2022/214958s000lbl.pdf

- Inrebic (fedratinib) capsules. Prescribing information. Celgene Corporation; 2019. Accessed January 20, 2023. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2019/212327s000lbl.pdf

- Inrebic. Product information. European Medicines Agency. Published March 3, 2021. Updated December 8, 2022. Accessed January 20, 2023. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/EPAR/inrebic

- Jyseleca. Product information. European Medicines Agency. Published September 28, 2020. Updated November 9, 2022. Accessed January 20, 2023. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/product-information/jyseleca-epar-product-information_en.pdf

- Review report: Jyseleca. Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency. September 8, 2020. Accessed January 20, 2023. https://www.pmda.go.jp/files/000247830.pdf

- Vonjo (pacritinib) capsules. Prescribing information. CTI BioPharma Corp; 2022. Accessed January 20, 2023. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2022/208712s000lbl.pdf

- Review report: Smyraf. Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency. February 28, 2019. Accessed January 20, 2023. https://www.pmda.go.jp/files/000233074.pdf

- Jakafi (ruxolitinib) tablets. Prescribing information. Incyte Corporation; 2021. Accessed January 20, 2023. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2021/202192s023lbl.pdf