User login

Gynecologic Cancer

This Update reviews recent findings of importance to obstetricians and gynecologists. Late detection of ovarian cancer is still the main reason for the high mortality rate of the most deadly of the gynecologic cancers. Approximately 22,200 women will be newly diagnosed in the United States this year, and there will be 16,210 deaths. Since ovarian cancer is still initially detected in its advanced stages in more than 70% of cases, when cure rates are low, early detection and prevention remain our greatest challenge. The gynecologic oncologist’s opportunity to successfully treat malignancy depends on early detection, and therefore physicians providing primary care for women are our firstline guardians.

“Silent killer” may not be so stealthy

Women ultimately diagnosed with malignant masses had a triad of symptoms, as well as more recent onset and greater severity of symptoms than women with benign masses or no masses. A diagnostic workup employing transvaginal ultrasound and CA-125 should be considered when a woman says she has these symptoms.

Ovarian cancer is not a silent disease. It was believed to be a “silent killer” because it was thought to be asymptomatic until a woman had very advanced disease. However, Goff and colleagues, in a previous study, found that 95% of women with ovarian cancer had had symptoms prior to diagnosis—and that the type of symptoms was not significantly different, whether disease was early stage or late stage.

This new study aimed to identify the frequency, severity, and duration of symptoms typically associated with ovarian cancer, by comparing symptoms reported by different groups of women. Symptoms reported by women presenting to primary care clinics were compared with symptoms reported by a group of 128 women with ovarian masses. Importantly, women were surveyed about their symptoms before undergoing surgery, and before they had a diagnosis of cancer or benign disease.

Main findings:

- A triad of symptoms—abdominal bloating, an increase in abdominal girth, and urinary symptoms—occurred in 43% of women found to have ovarian cancer, but in only 8% of women who presented to a primary care clinic.

- The frequency and duration of symptoms in women with ovarian masses were more severe in the women with malignant masses, but were of a similar type regardless of whether the mass was benign or ovarian cancer.

- Onset of symptoms was more recent in women with ovarian cancer than in the control group.

Listening carefully and evaluating the severity, frequency, and duration of symptoms, especially abdominal bloating, an increase in abdominal girth, urinary symptoms, and abdominal pain, is all-important.

Ovarian cancer should be included in the differential diagnosis when a woman says she has these symptoms.

I found it interesting that symptoms with a more recent onset may be more consistent with ovarian cancer.

In an ideal world, a simple blood test with an absolute cutoff, with perfect sensitivity and specificity, would identify ovarian cancer at its earliest stages. However, until such a test exists, primary care physicians and ObGyns should continue to put weight on the symptoms the patient communicates.

Transvaginal ultrasound and CA-125

Consider performing a diagnostic workup employing transvaginal ultrasound and CA-125 measurement in women presenting with these complaints.

RELATED REFERENCES

- Goff BA, Mandell L, Muntz HG, Melancon CH. Ovarian cancer diagnosis: results of a national ovarian cancer survey. Cancer. 2000;89:2068–2075.

Whatever happened to the ovarian cancer blood test?

Ransohoff DF. Lessons from controversy: ovarian cancer screening and serum proteomics. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005;97:315–319.

Science is still seeking the Holy Grail—a blood test for early detection of ovarian cancer.

When Petricoin et al reported in 2002 that a serum proteomic profiling test had nearly 100% sensitivity and specificity, the media trumpeted the phenomenal news. The public’s hopes soared when news articles reported that a company would soon begin offering the test. Patients brought in these reports to their ObGyns and asked for the test.

Plans to introduce a commercial screening test by early 2004 were delayed, however, due to FDA concerns about its reliability. The reasons for claims, plans, and delays were reported in both professional journals and the lay press, but details on the “question about whether the approach of discovery-based serum proteomics can accurately and reliably diagnose ovarian cancer—or any cancer—have not been resolved,” Dr. Ransohoff explains in this thoughtful 2005 essay.

He describes in a simple and straightforward way the requirements of reproducibility, and what these new technologies must demonstrate. He concludes that serum proteomic profiling for the early detection of ovarian cancer has not demonstrated the reproducibility required of a clinical test.

“Chance and bias may cause erroneous results and inflated expectations in the kind of observational research being conducted in several ‘–omics’ fields to assess molecular markers for diagnosis and prognosis of cancer. To realize the potential of new –omics technology will require appropriate rules of evidence in the design, conduct, and interpretation of the clinical research,” writes Dr. Ransohoff.

While proteomic profiling clearly has promise, clinicians should insist that initial studies be validated

What to tell patients. I explain that the test appeared promising, and therefore was of great interest, but the FDA did not allow it to be put on the market because of insufficient evidence that the test consistently defines whether cancer is or is not present. Since either a negative or positive test would have profound effects, accuracy is an absolute requirement.

RELATED REFERENCES

- Baggerly KA, Morris JS, Edmonson SR, Coombes KR. Signal in noise: evaluating reported reproducibility of serum proteomic tests for ovarian cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005;97:307–309.

- Liotta LA, Lowenthal M, Mehta A, et al. Importance of communication between producers and consumers of publicly available experimental data. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005;97:310–314.

- Petricoin EF, Ardekani AM, Hitt BA, et al. Use of proteomic patterns in serum to identify ovarian cancer. Lancet. 2002;359:572–577.

Don’t hold back from counseling risk-reducing BSO when indicated

Metcalfe KA, Lynch HT, Ghadirian P, et al. The risk of ovarian cancer after breast cancer in BRCA1 and BRCA2 carriers. Gynecol Oncol. 2005;96:222–226.

Counsel women with breast cancer who are BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation carriers to consider prophylactic salpingo-oophorectomy after childbearing is complete. Tamoxifen and chemotherapy do not lower risk.

ObGyns should encourage young women with breast cancer or women with a strong family history of breast and/or ovarian cancer to undergo genetic testing.

Women with breast cancer who are found to be BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation carriers should be counseled by their gynecologists to consider prophylactic BSO after childbearing is complete. Even though these women’s greatest concern may be breast cancer recurrence, gynecologists should advise these women that they are also at risk for ovarian cancer, and that they can substantially decrease their risk by undergoing risk-reduction surgery. BRCA1 mutation carriers have up to an 80% lifetime risk of breast cancer and up to a 50% lifetime risk for ovarian cancer.

Recent data support intervention to decrease risk: BSO decreases risk of ovarian cancer by more than 90%, and decreases risk of breast cancer by 50% in BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation carriers. Metcalfe et al examined women with a BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation and a history of stage I or II breast cancer, and found that 10% developed an ovarian cancer, a fallopian tube cancer, or a peritoneal cancer. The median time was 8.1 years from the development of breast cancer to the development of ovarian cancer. The cumulative risk of developing ovarian cancer after breast cancer was 12.7% for BRCA1 mutation carriers and 6.8% for BRCA2 mutation carriers.

Tamoxifen or chemotherapy did not change this risk. The authors concluded that BSO could have prevented at least 43 to 46 ovarian cancers.

RELATED REFERENCES

- Rebbeck TR, Lynch HT, Neuhausen SL, et al. Prophylactic oophorectomy in carriers of BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:1616–1622.

- Kauff ND, Satagopan JM, Robson ME, et al. Risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy in women with a BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation. N Engl J Med. 2002; 346:1609–1615.

Serial histologic sectioning is vital for detecting occult malignancy

Powell CB, Kenley E, Chen LM, et al. Risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy in BRCA mutation carriers: role of serial sectioning in the detection of occult malignancy. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:127–132.

A specific 4-step protocol for salpingo-oophorectomy and pathologic examination increased the number of occult malignancies identified.

Is a risk-reducing BSO any different from a BSO for benign reasons? The evidence is a resounding YES. Given the strong data supporting prophylactic BSO in women with BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations, ObGyns are increasingly called upon to perform this procedure. Current recommendations are to offer surgery to mutation carriers after childbearing or in their mid- to late 30s and early 40s. A number of studies have discovered that carriers who undergo risk-reducing BSO are at increased risk for occult malignancies already existing in the ovaries and fallopian tubes.

These studies recommend use of a specific surgical approach and pathologic examination of specimens.

Powell et al found an increased number occult malignancies with this strategy:

- Complete removal of ovaries and fallopian tubes

- Serial histologic sectioning of both ovaries and fallopian tubes

- Peritoneal and omental biopsies

- Peritoneal washings for cytology

Of 67 procedures, 7 (10.4%) occult malignancies were discovered: 4 in the fallopian tubes and 3 in the ovaries. Six of the occult malignancies were microscopic.

Surgically, the entire ovary and fallopian tube should be removed. I perform washings and carefully look at the pelvis and paracolic gutters for small-volume disease.

Most importantly, ObGyns need to speak with the pathologist. For most benign cases in which the ovaries and fallopian tubes look grossly normal, pathologists take a single representative section of each ovary and fallopian tube for histologic diagnosis. However, in these high-risk cases, complete serial sectioning of ovaries and fallopian tubes is absolutely necessary to rule out microscopic cancer. Removal of the uterus should be based on other indications.

The author reports no financial relationships relevant to this article.

RELATED REFERENCES

- Lu KH, Garber JE, Cramer DW, et al. Occult ovarian tumors in women with BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations undergoing prophylactic oophorectomy. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18:2728–2732.

- Colgan TJ, Murphy J, Cole DE, Narod S, Rosen B. Occult carcinoma in prophylactic oophorectomy specimens: prevalence and association with BRCA germline mutation status. Am J Surg Pathol. 2001;25:1283–1289.

This Update reviews recent findings of importance to obstetricians and gynecologists. Late detection of ovarian cancer is still the main reason for the high mortality rate of the most deadly of the gynecologic cancers. Approximately 22,200 women will be newly diagnosed in the United States this year, and there will be 16,210 deaths. Since ovarian cancer is still initially detected in its advanced stages in more than 70% of cases, when cure rates are low, early detection and prevention remain our greatest challenge. The gynecologic oncologist’s opportunity to successfully treat malignancy depends on early detection, and therefore physicians providing primary care for women are our firstline guardians.

“Silent killer” may not be so stealthy

Women ultimately diagnosed with malignant masses had a triad of symptoms, as well as more recent onset and greater severity of symptoms than women with benign masses or no masses. A diagnostic workup employing transvaginal ultrasound and CA-125 should be considered when a woman says she has these symptoms.

Ovarian cancer is not a silent disease. It was believed to be a “silent killer” because it was thought to be asymptomatic until a woman had very advanced disease. However, Goff and colleagues, in a previous study, found that 95% of women with ovarian cancer had had symptoms prior to diagnosis—and that the type of symptoms was not significantly different, whether disease was early stage or late stage.

This new study aimed to identify the frequency, severity, and duration of symptoms typically associated with ovarian cancer, by comparing symptoms reported by different groups of women. Symptoms reported by women presenting to primary care clinics were compared with symptoms reported by a group of 128 women with ovarian masses. Importantly, women were surveyed about their symptoms before undergoing surgery, and before they had a diagnosis of cancer or benign disease.

Main findings:

- A triad of symptoms—abdominal bloating, an increase in abdominal girth, and urinary symptoms—occurred in 43% of women found to have ovarian cancer, but in only 8% of women who presented to a primary care clinic.

- The frequency and duration of symptoms in women with ovarian masses were more severe in the women with malignant masses, but were of a similar type regardless of whether the mass was benign or ovarian cancer.

- Onset of symptoms was more recent in women with ovarian cancer than in the control group.

Listening carefully and evaluating the severity, frequency, and duration of symptoms, especially abdominal bloating, an increase in abdominal girth, urinary symptoms, and abdominal pain, is all-important.

Ovarian cancer should be included in the differential diagnosis when a woman says she has these symptoms.

I found it interesting that symptoms with a more recent onset may be more consistent with ovarian cancer.

In an ideal world, a simple blood test with an absolute cutoff, with perfect sensitivity and specificity, would identify ovarian cancer at its earliest stages. However, until such a test exists, primary care physicians and ObGyns should continue to put weight on the symptoms the patient communicates.

Transvaginal ultrasound and CA-125

Consider performing a diagnostic workup employing transvaginal ultrasound and CA-125 measurement in women presenting with these complaints.

RELATED REFERENCES

- Goff BA, Mandell L, Muntz HG, Melancon CH. Ovarian cancer diagnosis: results of a national ovarian cancer survey. Cancer. 2000;89:2068–2075.

Whatever happened to the ovarian cancer blood test?

Ransohoff DF. Lessons from controversy: ovarian cancer screening and serum proteomics. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005;97:315–319.

Science is still seeking the Holy Grail—a blood test for early detection of ovarian cancer.

When Petricoin et al reported in 2002 that a serum proteomic profiling test had nearly 100% sensitivity and specificity, the media trumpeted the phenomenal news. The public’s hopes soared when news articles reported that a company would soon begin offering the test. Patients brought in these reports to their ObGyns and asked for the test.

Plans to introduce a commercial screening test by early 2004 were delayed, however, due to FDA concerns about its reliability. The reasons for claims, plans, and delays were reported in both professional journals and the lay press, but details on the “question about whether the approach of discovery-based serum proteomics can accurately and reliably diagnose ovarian cancer—or any cancer—have not been resolved,” Dr. Ransohoff explains in this thoughtful 2005 essay.

He describes in a simple and straightforward way the requirements of reproducibility, and what these new technologies must demonstrate. He concludes that serum proteomic profiling for the early detection of ovarian cancer has not demonstrated the reproducibility required of a clinical test.

“Chance and bias may cause erroneous results and inflated expectations in the kind of observational research being conducted in several ‘–omics’ fields to assess molecular markers for diagnosis and prognosis of cancer. To realize the potential of new –omics technology will require appropriate rules of evidence in the design, conduct, and interpretation of the clinical research,” writes Dr. Ransohoff.

While proteomic profiling clearly has promise, clinicians should insist that initial studies be validated

What to tell patients. I explain that the test appeared promising, and therefore was of great interest, but the FDA did not allow it to be put on the market because of insufficient evidence that the test consistently defines whether cancer is or is not present. Since either a negative or positive test would have profound effects, accuracy is an absolute requirement.

RELATED REFERENCES

- Baggerly KA, Morris JS, Edmonson SR, Coombes KR. Signal in noise: evaluating reported reproducibility of serum proteomic tests for ovarian cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005;97:307–309.

- Liotta LA, Lowenthal M, Mehta A, et al. Importance of communication between producers and consumers of publicly available experimental data. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005;97:310–314.

- Petricoin EF, Ardekani AM, Hitt BA, et al. Use of proteomic patterns in serum to identify ovarian cancer. Lancet. 2002;359:572–577.

Don’t hold back from counseling risk-reducing BSO when indicated

Metcalfe KA, Lynch HT, Ghadirian P, et al. The risk of ovarian cancer after breast cancer in BRCA1 and BRCA2 carriers. Gynecol Oncol. 2005;96:222–226.

Counsel women with breast cancer who are BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation carriers to consider prophylactic salpingo-oophorectomy after childbearing is complete. Tamoxifen and chemotherapy do not lower risk.

ObGyns should encourage young women with breast cancer or women with a strong family history of breast and/or ovarian cancer to undergo genetic testing.

Women with breast cancer who are found to be BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation carriers should be counseled by their gynecologists to consider prophylactic BSO after childbearing is complete. Even though these women’s greatest concern may be breast cancer recurrence, gynecologists should advise these women that they are also at risk for ovarian cancer, and that they can substantially decrease their risk by undergoing risk-reduction surgery. BRCA1 mutation carriers have up to an 80% lifetime risk of breast cancer and up to a 50% lifetime risk for ovarian cancer.

Recent data support intervention to decrease risk: BSO decreases risk of ovarian cancer by more than 90%, and decreases risk of breast cancer by 50% in BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation carriers. Metcalfe et al examined women with a BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation and a history of stage I or II breast cancer, and found that 10% developed an ovarian cancer, a fallopian tube cancer, or a peritoneal cancer. The median time was 8.1 years from the development of breast cancer to the development of ovarian cancer. The cumulative risk of developing ovarian cancer after breast cancer was 12.7% for BRCA1 mutation carriers and 6.8% for BRCA2 mutation carriers.

Tamoxifen or chemotherapy did not change this risk. The authors concluded that BSO could have prevented at least 43 to 46 ovarian cancers.

RELATED REFERENCES

- Rebbeck TR, Lynch HT, Neuhausen SL, et al. Prophylactic oophorectomy in carriers of BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:1616–1622.

- Kauff ND, Satagopan JM, Robson ME, et al. Risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy in women with a BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation. N Engl J Med. 2002; 346:1609–1615.

Serial histologic sectioning is vital for detecting occult malignancy

Powell CB, Kenley E, Chen LM, et al. Risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy in BRCA mutation carriers: role of serial sectioning in the detection of occult malignancy. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:127–132.

A specific 4-step protocol for salpingo-oophorectomy and pathologic examination increased the number of occult malignancies identified.

Is a risk-reducing BSO any different from a BSO for benign reasons? The evidence is a resounding YES. Given the strong data supporting prophylactic BSO in women with BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations, ObGyns are increasingly called upon to perform this procedure. Current recommendations are to offer surgery to mutation carriers after childbearing or in their mid- to late 30s and early 40s. A number of studies have discovered that carriers who undergo risk-reducing BSO are at increased risk for occult malignancies already existing in the ovaries and fallopian tubes.

These studies recommend use of a specific surgical approach and pathologic examination of specimens.

Powell et al found an increased number occult malignancies with this strategy:

- Complete removal of ovaries and fallopian tubes

- Serial histologic sectioning of both ovaries and fallopian tubes

- Peritoneal and omental biopsies

- Peritoneal washings for cytology

Of 67 procedures, 7 (10.4%) occult malignancies were discovered: 4 in the fallopian tubes and 3 in the ovaries. Six of the occult malignancies were microscopic.

Surgically, the entire ovary and fallopian tube should be removed. I perform washings and carefully look at the pelvis and paracolic gutters for small-volume disease.

Most importantly, ObGyns need to speak with the pathologist. For most benign cases in which the ovaries and fallopian tubes look grossly normal, pathologists take a single representative section of each ovary and fallopian tube for histologic diagnosis. However, in these high-risk cases, complete serial sectioning of ovaries and fallopian tubes is absolutely necessary to rule out microscopic cancer. Removal of the uterus should be based on other indications.

The author reports no financial relationships relevant to this article.

RELATED REFERENCES

- Lu KH, Garber JE, Cramer DW, et al. Occult ovarian tumors in women with BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations undergoing prophylactic oophorectomy. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18:2728–2732.

- Colgan TJ, Murphy J, Cole DE, Narod S, Rosen B. Occult carcinoma in prophylactic oophorectomy specimens: prevalence and association with BRCA germline mutation status. Am J Surg Pathol. 2001;25:1283–1289.

This Update reviews recent findings of importance to obstetricians and gynecologists. Late detection of ovarian cancer is still the main reason for the high mortality rate of the most deadly of the gynecologic cancers. Approximately 22,200 women will be newly diagnosed in the United States this year, and there will be 16,210 deaths. Since ovarian cancer is still initially detected in its advanced stages in more than 70% of cases, when cure rates are low, early detection and prevention remain our greatest challenge. The gynecologic oncologist’s opportunity to successfully treat malignancy depends on early detection, and therefore physicians providing primary care for women are our firstline guardians.

“Silent killer” may not be so stealthy

Women ultimately diagnosed with malignant masses had a triad of symptoms, as well as more recent onset and greater severity of symptoms than women with benign masses or no masses. A diagnostic workup employing transvaginal ultrasound and CA-125 should be considered when a woman says she has these symptoms.

Ovarian cancer is not a silent disease. It was believed to be a “silent killer” because it was thought to be asymptomatic until a woman had very advanced disease. However, Goff and colleagues, in a previous study, found that 95% of women with ovarian cancer had had symptoms prior to diagnosis—and that the type of symptoms was not significantly different, whether disease was early stage or late stage.

This new study aimed to identify the frequency, severity, and duration of symptoms typically associated with ovarian cancer, by comparing symptoms reported by different groups of women. Symptoms reported by women presenting to primary care clinics were compared with symptoms reported by a group of 128 women with ovarian masses. Importantly, women were surveyed about their symptoms before undergoing surgery, and before they had a diagnosis of cancer or benign disease.

Main findings:

- A triad of symptoms—abdominal bloating, an increase in abdominal girth, and urinary symptoms—occurred in 43% of women found to have ovarian cancer, but in only 8% of women who presented to a primary care clinic.

- The frequency and duration of symptoms in women with ovarian masses were more severe in the women with malignant masses, but were of a similar type regardless of whether the mass was benign or ovarian cancer.

- Onset of symptoms was more recent in women with ovarian cancer than in the control group.

Listening carefully and evaluating the severity, frequency, and duration of symptoms, especially abdominal bloating, an increase in abdominal girth, urinary symptoms, and abdominal pain, is all-important.

Ovarian cancer should be included in the differential diagnosis when a woman says she has these symptoms.

I found it interesting that symptoms with a more recent onset may be more consistent with ovarian cancer.

In an ideal world, a simple blood test with an absolute cutoff, with perfect sensitivity and specificity, would identify ovarian cancer at its earliest stages. However, until such a test exists, primary care physicians and ObGyns should continue to put weight on the symptoms the patient communicates.

Transvaginal ultrasound and CA-125

Consider performing a diagnostic workup employing transvaginal ultrasound and CA-125 measurement in women presenting with these complaints.

RELATED REFERENCES

- Goff BA, Mandell L, Muntz HG, Melancon CH. Ovarian cancer diagnosis: results of a national ovarian cancer survey. Cancer. 2000;89:2068–2075.

Whatever happened to the ovarian cancer blood test?

Ransohoff DF. Lessons from controversy: ovarian cancer screening and serum proteomics. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005;97:315–319.

Science is still seeking the Holy Grail—a blood test for early detection of ovarian cancer.

When Petricoin et al reported in 2002 that a serum proteomic profiling test had nearly 100% sensitivity and specificity, the media trumpeted the phenomenal news. The public’s hopes soared when news articles reported that a company would soon begin offering the test. Patients brought in these reports to their ObGyns and asked for the test.

Plans to introduce a commercial screening test by early 2004 were delayed, however, due to FDA concerns about its reliability. The reasons for claims, plans, and delays were reported in both professional journals and the lay press, but details on the “question about whether the approach of discovery-based serum proteomics can accurately and reliably diagnose ovarian cancer—or any cancer—have not been resolved,” Dr. Ransohoff explains in this thoughtful 2005 essay.

He describes in a simple and straightforward way the requirements of reproducibility, and what these new technologies must demonstrate. He concludes that serum proteomic profiling for the early detection of ovarian cancer has not demonstrated the reproducibility required of a clinical test.

“Chance and bias may cause erroneous results and inflated expectations in the kind of observational research being conducted in several ‘–omics’ fields to assess molecular markers for diagnosis and prognosis of cancer. To realize the potential of new –omics technology will require appropriate rules of evidence in the design, conduct, and interpretation of the clinical research,” writes Dr. Ransohoff.

While proteomic profiling clearly has promise, clinicians should insist that initial studies be validated

What to tell patients. I explain that the test appeared promising, and therefore was of great interest, but the FDA did not allow it to be put on the market because of insufficient evidence that the test consistently defines whether cancer is or is not present. Since either a negative or positive test would have profound effects, accuracy is an absolute requirement.

RELATED REFERENCES

- Baggerly KA, Morris JS, Edmonson SR, Coombes KR. Signal in noise: evaluating reported reproducibility of serum proteomic tests for ovarian cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005;97:307–309.

- Liotta LA, Lowenthal M, Mehta A, et al. Importance of communication between producers and consumers of publicly available experimental data. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005;97:310–314.

- Petricoin EF, Ardekani AM, Hitt BA, et al. Use of proteomic patterns in serum to identify ovarian cancer. Lancet. 2002;359:572–577.

Don’t hold back from counseling risk-reducing BSO when indicated

Metcalfe KA, Lynch HT, Ghadirian P, et al. The risk of ovarian cancer after breast cancer in BRCA1 and BRCA2 carriers. Gynecol Oncol. 2005;96:222–226.

Counsel women with breast cancer who are BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation carriers to consider prophylactic salpingo-oophorectomy after childbearing is complete. Tamoxifen and chemotherapy do not lower risk.

ObGyns should encourage young women with breast cancer or women with a strong family history of breast and/or ovarian cancer to undergo genetic testing.

Women with breast cancer who are found to be BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation carriers should be counseled by their gynecologists to consider prophylactic BSO after childbearing is complete. Even though these women’s greatest concern may be breast cancer recurrence, gynecologists should advise these women that they are also at risk for ovarian cancer, and that they can substantially decrease their risk by undergoing risk-reduction surgery. BRCA1 mutation carriers have up to an 80% lifetime risk of breast cancer and up to a 50% lifetime risk for ovarian cancer.

Recent data support intervention to decrease risk: BSO decreases risk of ovarian cancer by more than 90%, and decreases risk of breast cancer by 50% in BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation carriers. Metcalfe et al examined women with a BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation and a history of stage I or II breast cancer, and found that 10% developed an ovarian cancer, a fallopian tube cancer, or a peritoneal cancer. The median time was 8.1 years from the development of breast cancer to the development of ovarian cancer. The cumulative risk of developing ovarian cancer after breast cancer was 12.7% for BRCA1 mutation carriers and 6.8% for BRCA2 mutation carriers.

Tamoxifen or chemotherapy did not change this risk. The authors concluded that BSO could have prevented at least 43 to 46 ovarian cancers.

RELATED REFERENCES

- Rebbeck TR, Lynch HT, Neuhausen SL, et al. Prophylactic oophorectomy in carriers of BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:1616–1622.

- Kauff ND, Satagopan JM, Robson ME, et al. Risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy in women with a BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation. N Engl J Med. 2002; 346:1609–1615.

Serial histologic sectioning is vital for detecting occult malignancy

Powell CB, Kenley E, Chen LM, et al. Risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy in BRCA mutation carriers: role of serial sectioning in the detection of occult malignancy. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:127–132.

A specific 4-step protocol for salpingo-oophorectomy and pathologic examination increased the number of occult malignancies identified.

Is a risk-reducing BSO any different from a BSO for benign reasons? The evidence is a resounding YES. Given the strong data supporting prophylactic BSO in women with BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations, ObGyns are increasingly called upon to perform this procedure. Current recommendations are to offer surgery to mutation carriers after childbearing or in their mid- to late 30s and early 40s. A number of studies have discovered that carriers who undergo risk-reducing BSO are at increased risk for occult malignancies already existing in the ovaries and fallopian tubes.

These studies recommend use of a specific surgical approach and pathologic examination of specimens.

Powell et al found an increased number occult malignancies with this strategy:

- Complete removal of ovaries and fallopian tubes

- Serial histologic sectioning of both ovaries and fallopian tubes

- Peritoneal and omental biopsies

- Peritoneal washings for cytology

Of 67 procedures, 7 (10.4%) occult malignancies were discovered: 4 in the fallopian tubes and 3 in the ovaries. Six of the occult malignancies were microscopic.

Surgically, the entire ovary and fallopian tube should be removed. I perform washings and carefully look at the pelvis and paracolic gutters for small-volume disease.

Most importantly, ObGyns need to speak with the pathologist. For most benign cases in which the ovaries and fallopian tubes look grossly normal, pathologists take a single representative section of each ovary and fallopian tube for histologic diagnosis. However, in these high-risk cases, complete serial sectioning of ovaries and fallopian tubes is absolutely necessary to rule out microscopic cancer. Removal of the uterus should be based on other indications.

The author reports no financial relationships relevant to this article.

RELATED REFERENCES

- Lu KH, Garber JE, Cramer DW, et al. Occult ovarian tumors in women with BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations undergoing prophylactic oophorectomy. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18:2728–2732.

- Colgan TJ, Murphy J, Cole DE, Narod S, Rosen B. Occult carcinoma in prophylactic oophorectomy specimens: prevalence and association with BRCA germline mutation status. Am J Surg Pathol. 2001;25:1283–1289.

Management of obstetric hypertensive emergencies

Life-threatening obstetric hypertensive emergencies cannot be entirely prevented, but the risk of serious complications can be minimized.

The spectrum of hypertensive disease that can complicate pregnancy is broad—ranging from so-called “white coat” hypertension to gestational hypertension, chronic hypertension, chronic hypertension with superimposed preeclampsia, to preeclampsia.

Particularly challenging, however, is hypertension in pregnancy that becomes severe enough to qualify as a hypertensive crisis, bringing on immediate risk to both fetus and mother.

Risk may evolve over days—or hours—and may present as worsening blood pressure culminating in hypertensive crisis. Fetal morbidity and mortality, including placental abruption and acute fetal distress, are often directly linked to the maternal risks of hypertensive encephalopathy and cerebrovascular accident.

Placental abruption and fetal distress are common with severe hypertension even without encephalopathy and cerebrovascular accident. Abruption is unpredictable and potentially catastrophic, even with intense monitoring.

Aggressive BP control, while fundamental, needs to be balanced against the risks to both mother and fetus of overcorrection and undercorrection.

Defining a crisis

What truly defines hypertensive obstetric emergency is a matter of some debate.

Persistent blood pressures above 200 mm Hg systolic and/or 115 mm Hg diastolic qualify, but some have advocated 160/110 mm Hg as the threshold for emergent treatment of blood pressure. Others suggest that the rate of change in blood pressure is what precipitates the crisis, as opposed to the absolute blood pressure readings.

Why BP control is critical

The true pathophysiology of hypertensive crisis in pregnancy is obscure, but undoubtedly shares characteristics seen in the nonpregnant adult. Diagnosing a hypertensive emergency in the nonpregnant adult, in contrast to diagnosis of an obstetric hypertensive emergency, relies more on clinical manifestations of hypertension than on absolute blood pressure level.1

Pathophysiology

In the nonpregnant adult, 2 independent processes are thought to be necessary for the full-blown encephalopathic picture: dilation of the cerebral vasculature and fibrinoid necrosis. In the initial phases of severe hypertension, the cerebral vessels constrict to maintain cerebral perfusion pressure in the face of increased systemic arterial pressure. Once the limits of autoregulation are exceeded, reflex cerebral dilatation and resultant overperfusion lead to microvascular damage, exudation, microthrombus formation, and increased intracranial pressure, which in turn result in the encephalopathic picture.

In pregnancy, a prominent feature seems to be loss of cerebrovascular autoregulation, resulting in hypertensive encephalopathy once the upper limits of cerebral perfusion pressures are exceeded.2 Rapid control of blood pressure is needed even more because of the risks of placental abruption and stroke (See). Stroke is of special concern in the setting of thrombocytopenia or HELLP (hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, and low platelet count) syndrome. Cerebral edema may be more closely associated with endothelial cell injury than with blood pressure,3 although control of blood pressure may help minimize the endothelial cell injury.

Minimizing organ damage

First, restore normal BP

The most important clinical objective for treatment of acute hypertensive crisis in the nonpregnant adult is to minimize end organ damage, especially to the brain4; in obstetric cases, the major morbidity and mortality result from cardiac and renal, as well as cerebrovascular damage. Fetal morbidity and mortality, although not inconsequential, is often directly linked to the maternal condition, and therefore management is based on the triad of diagnosis, stabilization, and delivery.

The physiological dysfunctions described above are best tended to by aggressively controlling blood pressure. With restoration of acceptable blood pressures, generally in the range of 140 to 150 mm Hg systolic and 90 to 100 mm Hg diastolic, cardiac dysfunction begins to reverse, renal function tends to improve, and the restoration of cerebral autoregulatory capability lessens (but does not eliminate) the likelihood of stroke.

Rule out other causes

The foremost goal of therapy for malignant hypertension is to restore normal blood pressure, which depends on correct diagnosis so that appropriate pharmacotherapy may be initiated. For example, clinical situations that could cause malignant hypertension include such disparate entities as acute aortic dissection, acute left ventricular failure, pheochromocytoma, monoamine oxidase inhibitor–food (tyramine) interactions, eclampsia, and acute cocaine intoxication, to name but a few.

Frequently, chronic hypertension or severe preeclampsia defines the underlying “cause” of the severe hypertension, but consideration of other diagnoses, such as uncontrolled hyperthyroidism or pheochromocytoma, should not be overlooked. For example, in pheochromocytoma blood pressures tend to be paroxysmal with wide fluctuations. In hyperthyroidism, clinical signs or symptoms would be expected to accompany the clinical picture, such as the presence of proptosis, exophthalmos, lid lag, tremor, elevated temperature, and a wide pulse pressure, to name but a few.

Regimens to lower BP safely

It is imperative that blood pressure be lowered in a measured and safe manner, not to exceed a drop of 25% to 30% in the first 60 minutes, and not to drop below 150/95.4 Medications available for blood pressure reduction are listed in the Clip-and-save chart above.5

Every effort must be made to not overcorrect the hypertension. Too swift or too dramatic a reduction in blood pressure can have untoward consequences for both mother and fetus, including but not limited to acute fetal distress secondary to uteroplacental underperfusion, and the possibility of maternal myocardial or cerebral infarction. For these reasons, short-acting intravenous agents are recommended to treat hypertensive emergencies, and oral or sublingual compounds are to be avoided because they are more likely to cause precipitous and erratic drops in blood pressure.6

Pulmonary edema is not uncommon, due to capillary leakage and myocardial dysfunction. Aggressive use of furosemide along with a rapidly acting antihypertensive drug will best allow for improvement of the clinical picture in a timely manner.

Acute management steps

Critical care facilities required. During the acute management phase, patients should be cared for in an intensive care unit (or a labor and delivery unit with critical care capabilities) under the direction of physicians skilled in managing critically ill patients. In most institutions, such management will include participation of anesthesiologists, maternalfetal medicine specialists, and nurses with critical care expertise.

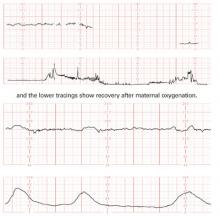

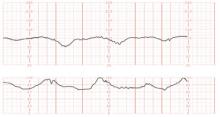

Delivery considerations. During initial management, the patient should have continuous fetal heart rate monitoring. Under such extreme circumstances, it is often not possible to prolong a pregnancy that is remote from term. Delivery decisions will need to balance prematurity risks against maternal risks of continuing the pregnancy.

Hypertension is not a contraindication to glucocorticoids for accelerating lung maturation in the fetus and minimizing neonatal risk of intracranial hemorrhage and necrotizing enterocolitis.7 Adjusting for gestational age, neonates of preeclamptic mothers are afforded no additional maturity compared with neonates born prematurely for other reasons. Delay of delivery for 48 to 72 hours may not be possible in many cases, however. Once the patient is stabilized, delivery must be considered.

Start magnesium sulfate, continue antihypertensives

At this point, it is prudent to start magnesium sulfate to prevent eclampsia. In most cases, however, excluding a diagnosis of preeclampsia in a timely manner is nearly impossible. Under these circumstances, magnesium sulfate is recommended, in addition to continued antihypertensive medications, to maintain BP control.

Magnesium sulfate is best administered intravenously, preferably through an infusion pump apparatus. A loading dose of 4 to 6 g (I prefer 6 g) is given as a 20% solution over 15 to 20 minutes, and then a continuous infusion may be initiated at a rate that depends on the patient’s renal function. In a patient with normal renal function, a rate of 2 g per hour is appropriate, but may need to be reduced if acute renal failure ensues.

In a report of 3 recent cases, investigators found magnesium sulfate was beneficial for controlling the clinical symptoms of pheochromocytoma when conventional therapy was unsuccessful. The presenting symptoms of these nonpregnant patients included hypertensive encephalopathy (2 patients) and catecholamine-induced cardiomyopathy (1 patient).6

In general, however, the role of magnesium sulfate should be for preventing progression to eclampsia, and not for acute blood pressure control.

Delivery decisions

Vaginal delivery is often less hemodynamically stressful for the mother, but not always practical. Many cases are remote from term with the fetus in a nonvertex presentation, or the uterine cervix is unfavorable for induction, or a protracted attempt at labor induction may not be prudent.

Under such circumstances, cesarean delivery must be considered and may be preferable. The reasons relate to the underlying maternal condition that often includes some degree of uteroplacental insufficiency. Altered placental function, combined with extreme prematurity, often results in the fetus being unable to tolerate labor for very long, necessitating emergent cesarean under potentially less controlled circumstances. The anesthesiologist and others on the critical care team must review the optimal anesthesia technique.

In most circumstances, and in the absence of coagulopathy, regional anesthesia affords the best results. When regional anesthesia is not an option, balanced general endotracheal anesthesia with antihypertensive premedication using a short-acting agent may be the safest alternative.

Maintain postpartum vigil

With delivery of the fetus, there may be a temptation to be less rigorous in maintaining blood pressure control during the post-partum period. In patients with chronic hypertension without superimposed preeclampsia, this may be acceptable, as these patients better tolerate higher blood pressures and still maintain appropriate cerebral vascular autoregulation.

For women who were previously normotensive, or who had superimposed preeclampsia, more rigorous control of blood pressure is recommended, especially if they show any degree of thrombocytopenia or pulmonary edema. (See Clip & save: Stepwise drug therapy for obstetric hypertensive crisis) The rationale relates to cerebral perfusion pressures and risk of stroke in these susceptible women, if thresholds are exceeded, and to the risk of worsening pulmonary edema in the setting of increased capillary hydrostatic pressure and reduced colloid osmotic pressure.

Additionally, continuation of magnesium sulfate is recommended for patients with superimposed preeclampsia until obvious signs of disease resolution, and for a minimum of 24 hours.

The author reports no financial relationships relevant to this article.

1. Tuncel M, Ram V. Hypertensive emergencies: etiology and management. Am J Cardiovasc Drugs. 2003;3:21-31.

2. Sibai BM. Hypertension. In: Gabbe SG, Niebyl JR, Simpson JL, eds. Obstetrics: Normal and Problem Pregnancies. 4th ed. New York, NY: Churchill Livingstone; 2002;945-1004.

3. Schwartz RB, Feske SK, Polak JF, et al. Preeclampsia-eclampsia: clinical and neuroradiographic correlates and insights into the pathogenesis of hypertensive encephalopathy. Radiology. 2000;2:371-376.

4. Williams O, Brust JC. Hypertensive encephalopathy. Curr Treat Cardiovasc Med. 2004;6:209-216.

5. Norwitz ER, Hsu CD, Repke JT. Acute complications of preeclampsia. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2002;45:308-329.

6. James MF, Cronje L. Pheochromocytoma crisis: the use of magnesium sulfate. Anesth Analg. 2004;99:680-686.

7. Hiett AK, Brown HL, Britton KA. Outcome of infants delivered at 24 to 28 weeks’ gestation in women with severe preeclampsia. J Maternal-Fetal Med. 2001;10:301-304.

Life-threatening obstetric hypertensive emergencies cannot be entirely prevented, but the risk of serious complications can be minimized.

The spectrum of hypertensive disease that can complicate pregnancy is broad—ranging from so-called “white coat” hypertension to gestational hypertension, chronic hypertension, chronic hypertension with superimposed preeclampsia, to preeclampsia.

Particularly challenging, however, is hypertension in pregnancy that becomes severe enough to qualify as a hypertensive crisis, bringing on immediate risk to both fetus and mother.

Risk may evolve over days—or hours—and may present as worsening blood pressure culminating in hypertensive crisis. Fetal morbidity and mortality, including placental abruption and acute fetal distress, are often directly linked to the maternal risks of hypertensive encephalopathy and cerebrovascular accident.

Placental abruption and fetal distress are common with severe hypertension even without encephalopathy and cerebrovascular accident. Abruption is unpredictable and potentially catastrophic, even with intense monitoring.

Aggressive BP control, while fundamental, needs to be balanced against the risks to both mother and fetus of overcorrection and undercorrection.

Defining a crisis

What truly defines hypertensive obstetric emergency is a matter of some debate.

Persistent blood pressures above 200 mm Hg systolic and/or 115 mm Hg diastolic qualify, but some have advocated 160/110 mm Hg as the threshold for emergent treatment of blood pressure. Others suggest that the rate of change in blood pressure is what precipitates the crisis, as opposed to the absolute blood pressure readings.

Why BP control is critical

The true pathophysiology of hypertensive crisis in pregnancy is obscure, but undoubtedly shares characteristics seen in the nonpregnant adult. Diagnosing a hypertensive emergency in the nonpregnant adult, in contrast to diagnosis of an obstetric hypertensive emergency, relies more on clinical manifestations of hypertension than on absolute blood pressure level.1

Pathophysiology

In the nonpregnant adult, 2 independent processes are thought to be necessary for the full-blown encephalopathic picture: dilation of the cerebral vasculature and fibrinoid necrosis. In the initial phases of severe hypertension, the cerebral vessels constrict to maintain cerebral perfusion pressure in the face of increased systemic arterial pressure. Once the limits of autoregulation are exceeded, reflex cerebral dilatation and resultant overperfusion lead to microvascular damage, exudation, microthrombus formation, and increased intracranial pressure, which in turn result in the encephalopathic picture.

In pregnancy, a prominent feature seems to be loss of cerebrovascular autoregulation, resulting in hypertensive encephalopathy once the upper limits of cerebral perfusion pressures are exceeded.2 Rapid control of blood pressure is needed even more because of the risks of placental abruption and stroke (See). Stroke is of special concern in the setting of thrombocytopenia or HELLP (hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, and low platelet count) syndrome. Cerebral edema may be more closely associated with endothelial cell injury than with blood pressure,3 although control of blood pressure may help minimize the endothelial cell injury.

Minimizing organ damage

First, restore normal BP

The most important clinical objective for treatment of acute hypertensive crisis in the nonpregnant adult is to minimize end organ damage, especially to the brain4; in obstetric cases, the major morbidity and mortality result from cardiac and renal, as well as cerebrovascular damage. Fetal morbidity and mortality, although not inconsequential, is often directly linked to the maternal condition, and therefore management is based on the triad of diagnosis, stabilization, and delivery.

The physiological dysfunctions described above are best tended to by aggressively controlling blood pressure. With restoration of acceptable blood pressures, generally in the range of 140 to 150 mm Hg systolic and 90 to 100 mm Hg diastolic, cardiac dysfunction begins to reverse, renal function tends to improve, and the restoration of cerebral autoregulatory capability lessens (but does not eliminate) the likelihood of stroke.

Rule out other causes

The foremost goal of therapy for malignant hypertension is to restore normal blood pressure, which depends on correct diagnosis so that appropriate pharmacotherapy may be initiated. For example, clinical situations that could cause malignant hypertension include such disparate entities as acute aortic dissection, acute left ventricular failure, pheochromocytoma, monoamine oxidase inhibitor–food (tyramine) interactions, eclampsia, and acute cocaine intoxication, to name but a few.

Frequently, chronic hypertension or severe preeclampsia defines the underlying “cause” of the severe hypertension, but consideration of other diagnoses, such as uncontrolled hyperthyroidism or pheochromocytoma, should not be overlooked. For example, in pheochromocytoma blood pressures tend to be paroxysmal with wide fluctuations. In hyperthyroidism, clinical signs or symptoms would be expected to accompany the clinical picture, such as the presence of proptosis, exophthalmos, lid lag, tremor, elevated temperature, and a wide pulse pressure, to name but a few.

Regimens to lower BP safely

It is imperative that blood pressure be lowered in a measured and safe manner, not to exceed a drop of 25% to 30% in the first 60 minutes, and not to drop below 150/95.4 Medications available for blood pressure reduction are listed in the Clip-and-save chart above.5

Every effort must be made to not overcorrect the hypertension. Too swift or too dramatic a reduction in blood pressure can have untoward consequences for both mother and fetus, including but not limited to acute fetal distress secondary to uteroplacental underperfusion, and the possibility of maternal myocardial or cerebral infarction. For these reasons, short-acting intravenous agents are recommended to treat hypertensive emergencies, and oral or sublingual compounds are to be avoided because they are more likely to cause precipitous and erratic drops in blood pressure.6

Pulmonary edema is not uncommon, due to capillary leakage and myocardial dysfunction. Aggressive use of furosemide along with a rapidly acting antihypertensive drug will best allow for improvement of the clinical picture in a timely manner.

Acute management steps

Critical care facilities required. During the acute management phase, patients should be cared for in an intensive care unit (or a labor and delivery unit with critical care capabilities) under the direction of physicians skilled in managing critically ill patients. In most institutions, such management will include participation of anesthesiologists, maternalfetal medicine specialists, and nurses with critical care expertise.

Delivery considerations. During initial management, the patient should have continuous fetal heart rate monitoring. Under such extreme circumstances, it is often not possible to prolong a pregnancy that is remote from term. Delivery decisions will need to balance prematurity risks against maternal risks of continuing the pregnancy.

Hypertension is not a contraindication to glucocorticoids for accelerating lung maturation in the fetus and minimizing neonatal risk of intracranial hemorrhage and necrotizing enterocolitis.7 Adjusting for gestational age, neonates of preeclamptic mothers are afforded no additional maturity compared with neonates born prematurely for other reasons. Delay of delivery for 48 to 72 hours may not be possible in many cases, however. Once the patient is stabilized, delivery must be considered.

Start magnesium sulfate, continue antihypertensives

At this point, it is prudent to start magnesium sulfate to prevent eclampsia. In most cases, however, excluding a diagnosis of preeclampsia in a timely manner is nearly impossible. Under these circumstances, magnesium sulfate is recommended, in addition to continued antihypertensive medications, to maintain BP control.

Magnesium sulfate is best administered intravenously, preferably through an infusion pump apparatus. A loading dose of 4 to 6 g (I prefer 6 g) is given as a 20% solution over 15 to 20 minutes, and then a continuous infusion may be initiated at a rate that depends on the patient’s renal function. In a patient with normal renal function, a rate of 2 g per hour is appropriate, but may need to be reduced if acute renal failure ensues.

In a report of 3 recent cases, investigators found magnesium sulfate was beneficial for controlling the clinical symptoms of pheochromocytoma when conventional therapy was unsuccessful. The presenting symptoms of these nonpregnant patients included hypertensive encephalopathy (2 patients) and catecholamine-induced cardiomyopathy (1 patient).6

In general, however, the role of magnesium sulfate should be for preventing progression to eclampsia, and not for acute blood pressure control.

Delivery decisions

Vaginal delivery is often less hemodynamically stressful for the mother, but not always practical. Many cases are remote from term with the fetus in a nonvertex presentation, or the uterine cervix is unfavorable for induction, or a protracted attempt at labor induction may not be prudent.

Under such circumstances, cesarean delivery must be considered and may be preferable. The reasons relate to the underlying maternal condition that often includes some degree of uteroplacental insufficiency. Altered placental function, combined with extreme prematurity, often results in the fetus being unable to tolerate labor for very long, necessitating emergent cesarean under potentially less controlled circumstances. The anesthesiologist and others on the critical care team must review the optimal anesthesia technique.

In most circumstances, and in the absence of coagulopathy, regional anesthesia affords the best results. When regional anesthesia is not an option, balanced general endotracheal anesthesia with antihypertensive premedication using a short-acting agent may be the safest alternative.

Maintain postpartum vigil

With delivery of the fetus, there may be a temptation to be less rigorous in maintaining blood pressure control during the post-partum period. In patients with chronic hypertension without superimposed preeclampsia, this may be acceptable, as these patients better tolerate higher blood pressures and still maintain appropriate cerebral vascular autoregulation.

For women who were previously normotensive, or who had superimposed preeclampsia, more rigorous control of blood pressure is recommended, especially if they show any degree of thrombocytopenia or pulmonary edema. (See Clip & save: Stepwise drug therapy for obstetric hypertensive crisis) The rationale relates to cerebral perfusion pressures and risk of stroke in these susceptible women, if thresholds are exceeded, and to the risk of worsening pulmonary edema in the setting of increased capillary hydrostatic pressure and reduced colloid osmotic pressure.

Additionally, continuation of magnesium sulfate is recommended for patients with superimposed preeclampsia until obvious signs of disease resolution, and for a minimum of 24 hours.

The author reports no financial relationships relevant to this article.

Life-threatening obstetric hypertensive emergencies cannot be entirely prevented, but the risk of serious complications can be minimized.

The spectrum of hypertensive disease that can complicate pregnancy is broad—ranging from so-called “white coat” hypertension to gestational hypertension, chronic hypertension, chronic hypertension with superimposed preeclampsia, to preeclampsia.

Particularly challenging, however, is hypertension in pregnancy that becomes severe enough to qualify as a hypertensive crisis, bringing on immediate risk to both fetus and mother.

Risk may evolve over days—or hours—and may present as worsening blood pressure culminating in hypertensive crisis. Fetal morbidity and mortality, including placental abruption and acute fetal distress, are often directly linked to the maternal risks of hypertensive encephalopathy and cerebrovascular accident.

Placental abruption and fetal distress are common with severe hypertension even without encephalopathy and cerebrovascular accident. Abruption is unpredictable and potentially catastrophic, even with intense monitoring.

Aggressive BP control, while fundamental, needs to be balanced against the risks to both mother and fetus of overcorrection and undercorrection.

Defining a crisis

What truly defines hypertensive obstetric emergency is a matter of some debate.

Persistent blood pressures above 200 mm Hg systolic and/or 115 mm Hg diastolic qualify, but some have advocated 160/110 mm Hg as the threshold for emergent treatment of blood pressure. Others suggest that the rate of change in blood pressure is what precipitates the crisis, as opposed to the absolute blood pressure readings.

Why BP control is critical

The true pathophysiology of hypertensive crisis in pregnancy is obscure, but undoubtedly shares characteristics seen in the nonpregnant adult. Diagnosing a hypertensive emergency in the nonpregnant adult, in contrast to diagnosis of an obstetric hypertensive emergency, relies more on clinical manifestations of hypertension than on absolute blood pressure level.1

Pathophysiology

In the nonpregnant adult, 2 independent processes are thought to be necessary for the full-blown encephalopathic picture: dilation of the cerebral vasculature and fibrinoid necrosis. In the initial phases of severe hypertension, the cerebral vessels constrict to maintain cerebral perfusion pressure in the face of increased systemic arterial pressure. Once the limits of autoregulation are exceeded, reflex cerebral dilatation and resultant overperfusion lead to microvascular damage, exudation, microthrombus formation, and increased intracranial pressure, which in turn result in the encephalopathic picture.

In pregnancy, a prominent feature seems to be loss of cerebrovascular autoregulation, resulting in hypertensive encephalopathy once the upper limits of cerebral perfusion pressures are exceeded.2 Rapid control of blood pressure is needed even more because of the risks of placental abruption and stroke (See). Stroke is of special concern in the setting of thrombocytopenia or HELLP (hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, and low platelet count) syndrome. Cerebral edema may be more closely associated with endothelial cell injury than with blood pressure,3 although control of blood pressure may help minimize the endothelial cell injury.

Minimizing organ damage

First, restore normal BP

The most important clinical objective for treatment of acute hypertensive crisis in the nonpregnant adult is to minimize end organ damage, especially to the brain4; in obstetric cases, the major morbidity and mortality result from cardiac and renal, as well as cerebrovascular damage. Fetal morbidity and mortality, although not inconsequential, is often directly linked to the maternal condition, and therefore management is based on the triad of diagnosis, stabilization, and delivery.

The physiological dysfunctions described above are best tended to by aggressively controlling blood pressure. With restoration of acceptable blood pressures, generally in the range of 140 to 150 mm Hg systolic and 90 to 100 mm Hg diastolic, cardiac dysfunction begins to reverse, renal function tends to improve, and the restoration of cerebral autoregulatory capability lessens (but does not eliminate) the likelihood of stroke.

Rule out other causes

The foremost goal of therapy for malignant hypertension is to restore normal blood pressure, which depends on correct diagnosis so that appropriate pharmacotherapy may be initiated. For example, clinical situations that could cause malignant hypertension include such disparate entities as acute aortic dissection, acute left ventricular failure, pheochromocytoma, monoamine oxidase inhibitor–food (tyramine) interactions, eclampsia, and acute cocaine intoxication, to name but a few.

Frequently, chronic hypertension or severe preeclampsia defines the underlying “cause” of the severe hypertension, but consideration of other diagnoses, such as uncontrolled hyperthyroidism or pheochromocytoma, should not be overlooked. For example, in pheochromocytoma blood pressures tend to be paroxysmal with wide fluctuations. In hyperthyroidism, clinical signs or symptoms would be expected to accompany the clinical picture, such as the presence of proptosis, exophthalmos, lid lag, tremor, elevated temperature, and a wide pulse pressure, to name but a few.

Regimens to lower BP safely

It is imperative that blood pressure be lowered in a measured and safe manner, not to exceed a drop of 25% to 30% in the first 60 minutes, and not to drop below 150/95.4 Medications available for blood pressure reduction are listed in the Clip-and-save chart above.5

Every effort must be made to not overcorrect the hypertension. Too swift or too dramatic a reduction in blood pressure can have untoward consequences for both mother and fetus, including but not limited to acute fetal distress secondary to uteroplacental underperfusion, and the possibility of maternal myocardial or cerebral infarction. For these reasons, short-acting intravenous agents are recommended to treat hypertensive emergencies, and oral or sublingual compounds are to be avoided because they are more likely to cause precipitous and erratic drops in blood pressure.6

Pulmonary edema is not uncommon, due to capillary leakage and myocardial dysfunction. Aggressive use of furosemide along with a rapidly acting antihypertensive drug will best allow for improvement of the clinical picture in a timely manner.

Acute management steps

Critical care facilities required. During the acute management phase, patients should be cared for in an intensive care unit (or a labor and delivery unit with critical care capabilities) under the direction of physicians skilled in managing critically ill patients. In most institutions, such management will include participation of anesthesiologists, maternalfetal medicine specialists, and nurses with critical care expertise.

Delivery considerations. During initial management, the patient should have continuous fetal heart rate monitoring. Under such extreme circumstances, it is often not possible to prolong a pregnancy that is remote from term. Delivery decisions will need to balance prematurity risks against maternal risks of continuing the pregnancy.

Hypertension is not a contraindication to glucocorticoids for accelerating lung maturation in the fetus and minimizing neonatal risk of intracranial hemorrhage and necrotizing enterocolitis.7 Adjusting for gestational age, neonates of preeclamptic mothers are afforded no additional maturity compared with neonates born prematurely for other reasons. Delay of delivery for 48 to 72 hours may not be possible in many cases, however. Once the patient is stabilized, delivery must be considered.

Start magnesium sulfate, continue antihypertensives

At this point, it is prudent to start magnesium sulfate to prevent eclampsia. In most cases, however, excluding a diagnosis of preeclampsia in a timely manner is nearly impossible. Under these circumstances, magnesium sulfate is recommended, in addition to continued antihypertensive medications, to maintain BP control.

Magnesium sulfate is best administered intravenously, preferably through an infusion pump apparatus. A loading dose of 4 to 6 g (I prefer 6 g) is given as a 20% solution over 15 to 20 minutes, and then a continuous infusion may be initiated at a rate that depends on the patient’s renal function. In a patient with normal renal function, a rate of 2 g per hour is appropriate, but may need to be reduced if acute renal failure ensues.

In a report of 3 recent cases, investigators found magnesium sulfate was beneficial for controlling the clinical symptoms of pheochromocytoma when conventional therapy was unsuccessful. The presenting symptoms of these nonpregnant patients included hypertensive encephalopathy (2 patients) and catecholamine-induced cardiomyopathy (1 patient).6

In general, however, the role of magnesium sulfate should be for preventing progression to eclampsia, and not for acute blood pressure control.

Delivery decisions

Vaginal delivery is often less hemodynamically stressful for the mother, but not always practical. Many cases are remote from term with the fetus in a nonvertex presentation, or the uterine cervix is unfavorable for induction, or a protracted attempt at labor induction may not be prudent.

Under such circumstances, cesarean delivery must be considered and may be preferable. The reasons relate to the underlying maternal condition that often includes some degree of uteroplacental insufficiency. Altered placental function, combined with extreme prematurity, often results in the fetus being unable to tolerate labor for very long, necessitating emergent cesarean under potentially less controlled circumstances. The anesthesiologist and others on the critical care team must review the optimal anesthesia technique.

In most circumstances, and in the absence of coagulopathy, regional anesthesia affords the best results. When regional anesthesia is not an option, balanced general endotracheal anesthesia with antihypertensive premedication using a short-acting agent may be the safest alternative.

Maintain postpartum vigil

With delivery of the fetus, there may be a temptation to be less rigorous in maintaining blood pressure control during the post-partum period. In patients with chronic hypertension without superimposed preeclampsia, this may be acceptable, as these patients better tolerate higher blood pressures and still maintain appropriate cerebral vascular autoregulation.

For women who were previously normotensive, or who had superimposed preeclampsia, more rigorous control of blood pressure is recommended, especially if they show any degree of thrombocytopenia or pulmonary edema. (See Clip & save: Stepwise drug therapy for obstetric hypertensive crisis) The rationale relates to cerebral perfusion pressures and risk of stroke in these susceptible women, if thresholds are exceeded, and to the risk of worsening pulmonary edema in the setting of increased capillary hydrostatic pressure and reduced colloid osmotic pressure.

Additionally, continuation of magnesium sulfate is recommended for patients with superimposed preeclampsia until obvious signs of disease resolution, and for a minimum of 24 hours.

The author reports no financial relationships relevant to this article.

1. Tuncel M, Ram V. Hypertensive emergencies: etiology and management. Am J Cardiovasc Drugs. 2003;3:21-31.

2. Sibai BM. Hypertension. In: Gabbe SG, Niebyl JR, Simpson JL, eds. Obstetrics: Normal and Problem Pregnancies. 4th ed. New York, NY: Churchill Livingstone; 2002;945-1004.

3. Schwartz RB, Feske SK, Polak JF, et al. Preeclampsia-eclampsia: clinical and neuroradiographic correlates and insights into the pathogenesis of hypertensive encephalopathy. Radiology. 2000;2:371-376.

4. Williams O, Brust JC. Hypertensive encephalopathy. Curr Treat Cardiovasc Med. 2004;6:209-216.

5. Norwitz ER, Hsu CD, Repke JT. Acute complications of preeclampsia. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2002;45:308-329.

6. James MF, Cronje L. Pheochromocytoma crisis: the use of magnesium sulfate. Anesth Analg. 2004;99:680-686.

7. Hiett AK, Brown HL, Britton KA. Outcome of infants delivered at 24 to 28 weeks’ gestation in women with severe preeclampsia. J Maternal-Fetal Med. 2001;10:301-304.

1. Tuncel M, Ram V. Hypertensive emergencies: etiology and management. Am J Cardiovasc Drugs. 2003;3:21-31.

2. Sibai BM. Hypertension. In: Gabbe SG, Niebyl JR, Simpson JL, eds. Obstetrics: Normal and Problem Pregnancies. 4th ed. New York, NY: Churchill Livingstone; 2002;945-1004.

3. Schwartz RB, Feske SK, Polak JF, et al. Preeclampsia-eclampsia: clinical and neuroradiographic correlates and insights into the pathogenesis of hypertensive encephalopathy. Radiology. 2000;2:371-376.

4. Williams O, Brust JC. Hypertensive encephalopathy. Curr Treat Cardiovasc Med. 2004;6:209-216.

5. Norwitz ER, Hsu CD, Repke JT. Acute complications of preeclampsia. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2002;45:308-329.

6. James MF, Cronje L. Pheochromocytoma crisis: the use of magnesium sulfate. Anesth Analg. 2004;99:680-686.

7. Hiett AK, Brown HL, Britton KA. Outcome of infants delivered at 24 to 28 weeks’ gestation in women with severe preeclampsia. J Maternal-Fetal Med. 2001;10:301-304.

Impact of Mental Health Disorders

INFECTIOUS DISEASE

New findings I selected for this Update affect the management of 4 common and potentially serious clinical problems: acute cystitis, gonorrhea and chlamydia infection, chorioamnionitis, and varicella.

- A comparison of amoxicillin-clavulanic acid vs ciprofloxacin for uncomplicated lower urinary tract infections yielded surprising results, and more evidence on E coli’s resistance to antibiotics.

- Sexual partners of women with gonorrhea or chlamydia are more likely to receive appropriate treatment if it is offered by the women themselves or by the women’s caregivers.

- Short-course therapy for chorioamnionitis had a very high cure rate, equal to the traditional course, and furthers the possibility of shorter hospitalizations and cost savings without compromising outcomes.

- The CDC’s 1995 call for universal childhood vaccination for varicella has already sharply reduced varicella-related mortality in adults; still, we must determine immunity in our reproductive-age patients.

Acute cystitis: Ciprofloxacin prevails in E coli skirmish

Hooton TM, Scholes D, Gupta K, Stapleton AE, Roberts PL, Stamm WE. Amoxicillin-clavulanate vs ciprofloxacin for the treatment of uncomplicated cystitis in women: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2005;293:949–955.

Amoxicillin-clavulanate was not as effective as ciprofloxacin even in women who were infected with bacteria sensitive to amoxicillin-clavulanate.

A total of 320 nonpregnant women, aged 18 to 45 years, with uncomplicated acute cystitis were treated for 3 days with either oral amoxicillin-clavulanate (500 mg/125 mg twice daily) or oral ciprofloxacin (250 mg twice daily). Two weeks after treatment, 95% of women treated with ciprofloxacin were clinically cured, compared with only 76% of women treated with amoxicillin-clavulanate (P<.001).

Start with ciprofloxacin

The difference in outcome was attributed to a marked difference in vaginal colonization with the single most common pathogen in acute cystitis—Escherichia coli—at the 2-week follow-up (45% in the amoxicillinclavulanate group vs 10% in the ciprofloxacin group, P<.001).

Even though successful treatment of cystitis usually is possible with short courses (3–7 days) of oral antibiotics, persistent and recurrent infections may occur and usually are related to persistent vaginal colonization with E coli.

Treatment may require an extended course of oral antibiotics.

Initial selection of an antibiotic for acute cystitis is empiric and should be based on probable susceptibility of the dominant uropathogens. For many years, the typical initial antibiotic has been ampicillin.

E coli resistance. Now, however, more than a third of E coli strains, as well as most strains of K pneumoniae, are resistant to ampicillin. Therefore, ampicillin no longer should be used for the empiric treatment of cystitis.1

Surprising results

In theory, amoxicillin-clavulanate should have enhanced activity against E coli and other enteric organisms.

Therefore, these findings are surprising. The outcome with amoxicillin-clavulanate was inferior to that of ciprofloxacin, even in women who seemingly had susceptible uropathogens.

Based on this study, ciprofloxacin clearly is a more effective (and less expensive) empiric treatment in nonpregnant women.

In gravidas, start with nitrofurantoin

Ciprofloxacin is not appropriate for treatment of cystitis or asymptomatic bacteriuria in pregnant women. The quinolone antibiotics may cause injury to the developing cartilage of the fetus and are contraindicated in pregnant and lactating women, and in children younger than 17 years.1

What, then, is the most appropriate choice for treatment of uncomplicated cystitis during pregnancy?

One reasonable selection is oral trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, double-strength, twice daily. However, increasing resistance of E coli to this antibiotic has been documented recently.2,3

Therefore, a better choice is nitrofurantoin monohydrate macrocrystals, 100 mg twice daily.4 One organism that is not susceptible to nitrofurantoin is Proteus. When this organism is suspected, use trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole.

Follow-up is a must

Because persistent and recurrent infections are common, patients should be followed with urine dipstick assessment or urine culture to be certain that the infection is resolved.

Follow-up is particularly important when infected women are pregnant, because of the risk of ascending infection leading to preterm labor, sepsis, or acute respiratory disease syndrome.

Treat sex partners, sight-unseen?

Golden MR, Whittington WL, Handsfield HH, et al. Effect of expedited treatment of sex partners on recurrent or persistent gonorrhea or chlamydial infection. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:676–685.

Providing a separate prescription for the partner(s) resulted in a 24% decrease in the frequency of persistent or recurrent infection.

Almost 2,000 men and women with uncomplicated gonorrhea or chlamydia infection were included in this study of expedited treatment compared with standard referral. In the standard referral group, investigators treated 931 patients and referred their sex partners to other physicians or facilities for evaluation and treatment. In the expedited treatment group, 929 patients were treated and also were provided with antibiotics to give to their partners. The partners of patients who were unwilling to do so were contacted and treated by the investigators.

At follow-up 21 to 126 days after treatment), persistent or recurrent infection was found in 13% of standard referral patients and 10% of expedited treatment patients (relative risk, 0.76; 95% confidence interval, 0.59–0.98).

Expedited treatment decreased the rate of persistent or recurrent gonorrhea more than that of persistent or recurrent chlamydia.

Patients in the expedited group were more likely to report that all of their partners were treated, and less likely to report having had sex with an untreated partner.

Advantages of the direct approach

The challenge for the ObGyn is how to arrange treatment for the female patient’s sex partner(s). This study indicates that a proactive approach is likely to be more effective than simply asking the patient to encourage her partner to seek medical attention. Direct provision of a separate prescription for the partner(s) resulted in a 24% decrease in the frequency of persistent or recurrent infection.

Failure to treat the patient’s sex partner is the principal cause of persistent or recurrent infection, which may lead to pelvic inflammatory disease, Fitz-Hugh-Curtis syndrome, and infertility. Gonorrhea may disseminate and manifest primarily by arthritis and dermatitis. If a pregnant woman is colonized with gonorrhea or chlamydia at the time of delivery, her infant may acquire gonococcal or chlamydial conjunctivitis or chlamydial pneumonia.

6 caveats

Although the results of this investigation are impressive and of great practical importance, these caveats should be noted.

- The oral drug used to treat gonorrhea in this study, cefixime (400 mg), is not presently available, and although another oral drug such as ciprofloxacin (500 mg) would be highly effective, it should not be used in pregnant or lactating women, or women younger than 17 years.1

- Although ceftriaxone, 125 mg intramuscularly, also is a superb drug for treatment of uncomplicated gonorrhea, the logistical problems of arranging for the partner to receive an intramuscular injection are daunting.