User login

Granular Cell Tumor

Granular cell tumors (GCTs) tend to present as solitary nodules, not uncommonly affecting the dorsum of the tongue but also involving the skin, breasts, and internal organs.1 Cutaneous GCTs typically present as 0.5- to 3-cm firm nodules with a verrucous or eroded surface.2 They most commonly present in dark-skinned, middle-aged women but have been reported in all age groups and in both sexes.3 Multiple GCTs are reported in up to 25% of cases, rarely in association with LEOPARD syndrome (consisting of lentigines, electrocardiographic abnormalities, ocular hypertelorism, pulmonary stenosis, abnormalities of genitalia, retardation of growth, and deafness).4 Granular cell tumors generally are benign with a metastatic rate of approximately 3%.2

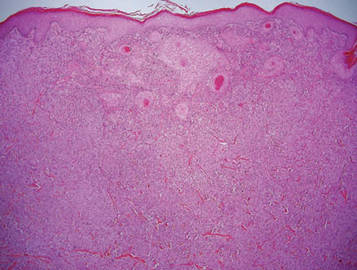

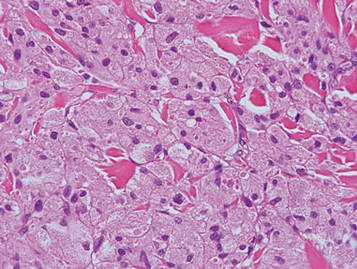

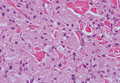

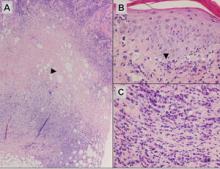

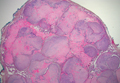

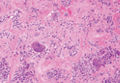

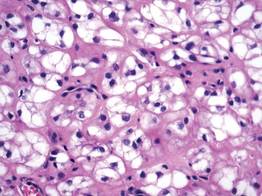

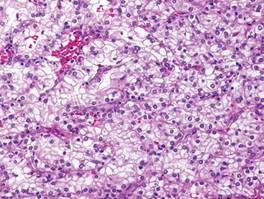

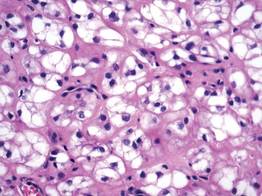

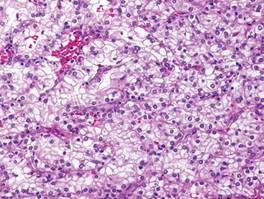

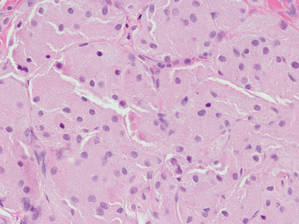

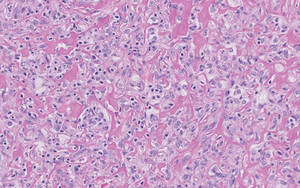

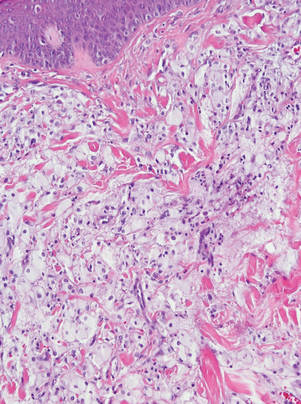

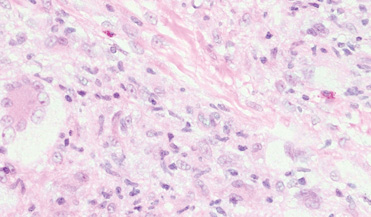

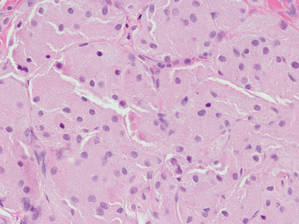

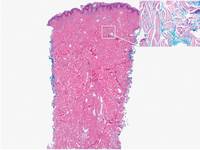

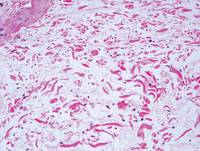

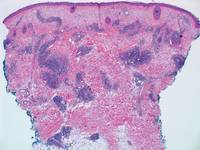

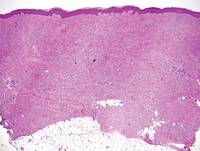

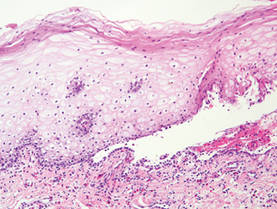

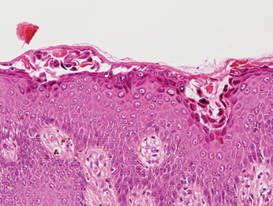

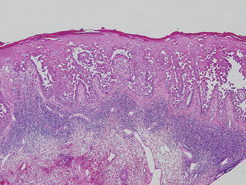

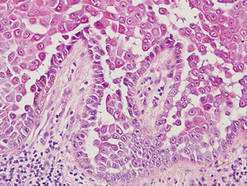

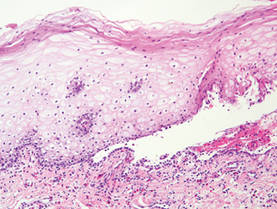

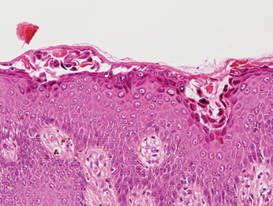

Granular cell tumors are histopathologically characterized by sheets of large polygonal cells with small, round, central nuclei; cytoplasm that is eosinophilic, coarse, and granular, as well as periodic acid–Schiff positive and diastase resistant; and distinct cytoplasmic membranes (Figure 1). Pustulo-ovoid bodies of Milian often generally appear as larger eosinophilic granules surrounded by a clear halo (Figure 2).5 Increased mitotic activity, a high nuclear-cytoplasmic ratio, pleomorphism, and necrosis suggest malignancy.6

|

|

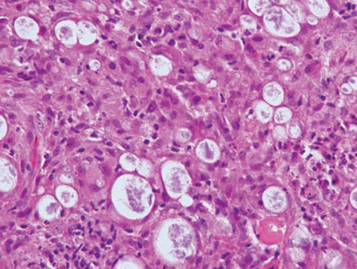

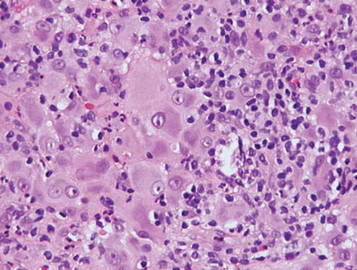

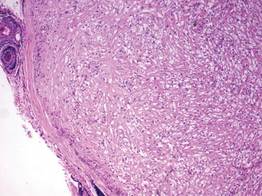

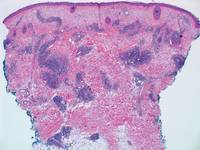

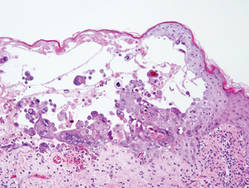

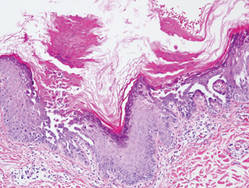

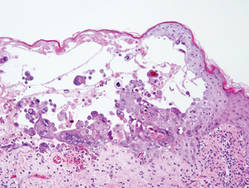

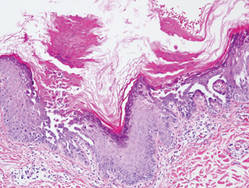

Lepromatous leprosy is characterized by sheets of histiocytes with vacuolated cytoplasm, some with clumped amphophilic bacilli known as globi (Figure 3). Mastocytoma can be distinguished from GCTs by the “fried egg” appearance of the mast cells (Figure 4). Although mast cells have a pale granular cytoplasm, they are smaller and lack pustulo-ovoid bodies and the polygonal shape of GCT cells. Reticulohistiocytoma, on the other hand, has two-toned dusty rose ground glass histiocytes (Figure 5), and xanthelasma can be distinguished histologically from GCT by the presence of a foamy rather than granular cytoplasm (Figure 6).

|

|

|

|

1. Elston DM, Ko C, Ferringer TC, et al, eds. Dermatopathology: Requisites in Dermatology. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders Elsevier; 2009.

2. Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV. Dermatology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2012.

3. van de Loo S, Thunnissen E, Postmus P, et al. Granular cell tumor of the oral cavity; a case series including a case of metachronous occurrence in the tongue and the lung [published online ahead of print June 1, 2014]. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. doi:10.4317/medoral.19867.

4. Schrader KA, Nelson TN, De Luca A, et al. Multiple granular cell tumors are an associated feature of LEOPARD syndrome caused by mutation in PTPN11. Clin Genet. 2009;75:185-189.

5. Epstein DS, Pashaei S, Hunt E Jr, et al. Pustulo-ovoid bodies of Milian in granular cell tumors. J Cutan Pathol. 2007;34:405-409.

6. Fanburg-Smith JC, Meis-Kindblom JM, Fante R, et al. Malignant granular cell tumor of soft tissue: diagnostic criteria and clinicopathologic correlation. Am J Surg Pathol. 1998;22:779-794.

Granular cell tumors (GCTs) tend to present as solitary nodules, not uncommonly affecting the dorsum of the tongue but also involving the skin, breasts, and internal organs.1 Cutaneous GCTs typically present as 0.5- to 3-cm firm nodules with a verrucous or eroded surface.2 They most commonly present in dark-skinned, middle-aged women but have been reported in all age groups and in both sexes.3 Multiple GCTs are reported in up to 25% of cases, rarely in association with LEOPARD syndrome (consisting of lentigines, electrocardiographic abnormalities, ocular hypertelorism, pulmonary stenosis, abnormalities of genitalia, retardation of growth, and deafness).4 Granular cell tumors generally are benign with a metastatic rate of approximately 3%.2

Granular cell tumors are histopathologically characterized by sheets of large polygonal cells with small, round, central nuclei; cytoplasm that is eosinophilic, coarse, and granular, as well as periodic acid–Schiff positive and diastase resistant; and distinct cytoplasmic membranes (Figure 1). Pustulo-ovoid bodies of Milian often generally appear as larger eosinophilic granules surrounded by a clear halo (Figure 2).5 Increased mitotic activity, a high nuclear-cytoplasmic ratio, pleomorphism, and necrosis suggest malignancy.6

|

|

Lepromatous leprosy is characterized by sheets of histiocytes with vacuolated cytoplasm, some with clumped amphophilic bacilli known as globi (Figure 3). Mastocytoma can be distinguished from GCTs by the “fried egg” appearance of the mast cells (Figure 4). Although mast cells have a pale granular cytoplasm, they are smaller and lack pustulo-ovoid bodies and the polygonal shape of GCT cells. Reticulohistiocytoma, on the other hand, has two-toned dusty rose ground glass histiocytes (Figure 5), and xanthelasma can be distinguished histologically from GCT by the presence of a foamy rather than granular cytoplasm (Figure 6).

|

|

|

|

Granular cell tumors (GCTs) tend to present as solitary nodules, not uncommonly affecting the dorsum of the tongue but also involving the skin, breasts, and internal organs.1 Cutaneous GCTs typically present as 0.5- to 3-cm firm nodules with a verrucous or eroded surface.2 They most commonly present in dark-skinned, middle-aged women but have been reported in all age groups and in both sexes.3 Multiple GCTs are reported in up to 25% of cases, rarely in association with LEOPARD syndrome (consisting of lentigines, electrocardiographic abnormalities, ocular hypertelorism, pulmonary stenosis, abnormalities of genitalia, retardation of growth, and deafness).4 Granular cell tumors generally are benign with a metastatic rate of approximately 3%.2

Granular cell tumors are histopathologically characterized by sheets of large polygonal cells with small, round, central nuclei; cytoplasm that is eosinophilic, coarse, and granular, as well as periodic acid–Schiff positive and diastase resistant; and distinct cytoplasmic membranes (Figure 1). Pustulo-ovoid bodies of Milian often generally appear as larger eosinophilic granules surrounded by a clear halo (Figure 2).5 Increased mitotic activity, a high nuclear-cytoplasmic ratio, pleomorphism, and necrosis suggest malignancy.6

|

|

Lepromatous leprosy is characterized by sheets of histiocytes with vacuolated cytoplasm, some with clumped amphophilic bacilli known as globi (Figure 3). Mastocytoma can be distinguished from GCTs by the “fried egg” appearance of the mast cells (Figure 4). Although mast cells have a pale granular cytoplasm, they are smaller and lack pustulo-ovoid bodies and the polygonal shape of GCT cells. Reticulohistiocytoma, on the other hand, has two-toned dusty rose ground glass histiocytes (Figure 5), and xanthelasma can be distinguished histologically from GCT by the presence of a foamy rather than granular cytoplasm (Figure 6).

|

|

|

|

1. Elston DM, Ko C, Ferringer TC, et al, eds. Dermatopathology: Requisites in Dermatology. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders Elsevier; 2009.

2. Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV. Dermatology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2012.

3. van de Loo S, Thunnissen E, Postmus P, et al. Granular cell tumor of the oral cavity; a case series including a case of metachronous occurrence in the tongue and the lung [published online ahead of print June 1, 2014]. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. doi:10.4317/medoral.19867.

4. Schrader KA, Nelson TN, De Luca A, et al. Multiple granular cell tumors are an associated feature of LEOPARD syndrome caused by mutation in PTPN11. Clin Genet. 2009;75:185-189.

5. Epstein DS, Pashaei S, Hunt E Jr, et al. Pustulo-ovoid bodies of Milian in granular cell tumors. J Cutan Pathol. 2007;34:405-409.

6. Fanburg-Smith JC, Meis-Kindblom JM, Fante R, et al. Malignant granular cell tumor of soft tissue: diagnostic criteria and clinicopathologic correlation. Am J Surg Pathol. 1998;22:779-794.

1. Elston DM, Ko C, Ferringer TC, et al, eds. Dermatopathology: Requisites in Dermatology. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders Elsevier; 2009.

2. Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV. Dermatology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2012.

3. van de Loo S, Thunnissen E, Postmus P, et al. Granular cell tumor of the oral cavity; a case series including a case of metachronous occurrence in the tongue and the lung [published online ahead of print June 1, 2014]. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. doi:10.4317/medoral.19867.

4. Schrader KA, Nelson TN, De Luca A, et al. Multiple granular cell tumors are an associated feature of LEOPARD syndrome caused by mutation in PTPN11. Clin Genet. 2009;75:185-189.

5. Epstein DS, Pashaei S, Hunt E Jr, et al. Pustulo-ovoid bodies of Milian in granular cell tumors. J Cutan Pathol. 2007;34:405-409.

6. Fanburg-Smith JC, Meis-Kindblom JM, Fante R, et al. Malignant granular cell tumor of soft tissue: diagnostic criteria and clinicopathologic correlation. Am J Surg Pathol. 1998;22:779-794.

Clear Cell Fibrous Papule

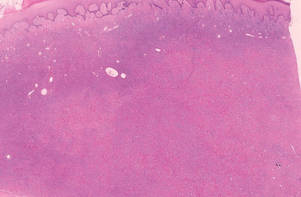

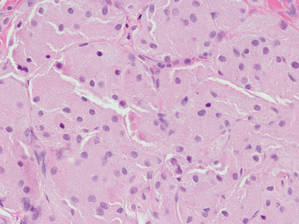

A fibrous papule is a common benign lesion that usually presents in adults on the face, especially on the lower portion of the nose. It typically presents as a small (2–5 mm), asymptomatic, flesh-colored, dome-shaped lesion that is firm and nontender. Several histopathologic variants of fibrous papules have been described, including clear cell, granular, epithelioid, hypercellular, pleomorphic, pigmented, and inflammatory.1 Clear cell fibrous papules are exceedingly rare. On microscopic examination the epidermis may be normal or show some degree of hyperkeratosis and parakeratosis, erosion, ulceration, or crust. The basal layer may show an increase of melanin. The dermis is expanded by a proliferation of clear cells arranged in sheets, clusters, or as single cells (Figure 1). The clear cells show variation in size and shape. The nuclei are small and round without pleomorphism, hyperchromasia, or mitoses. The nuclei may be centrally located or eccentrically displaced by a large intracytoplasmic vacuole (Figure 2). Some clear cells may exhibit finely vacuolated cytoplasm with nuclear scalloping. The surrounding stroma usually consists of sclerotic collagen and dilated blood vessels (Figure 3). Extravasated red blood cells may be present focally. Patchy lymphocytic infiltrates may be found in the stroma at the periphery of the lesion. Periodic acid–Schiff and mucicarmine staining of the clear cells is negative. On immunohistochemistry, the clear cells are diffusely positive for vimentin and negative for cytokeratin AE1/AE3, epithelial membrane antigen, carcinoembryonic antigen, and HMB-45 (human melanoma black 45).2,3 The clear cells often are positive for CD68, factor XIIIa, and NKI/C3 (anti-CD63) but also may be negative. The S-100 protein often is negative but may be focally positive.

The differential diagnosis for clear cell fibrous papules is broad but reasonably includes balloon cell nevus, clear cell hidradenoma, and cutaneous metastasis of clear cell (conventional) renal cell carcinoma (ccRCC). Balloon cell malignant melanoma is not considered strongly in the differential diagnosis because it usually exhibits invasive growth, cytologic atypia, and mitoses, all of which are not characteristic morphologic features of clear cell fibrous papules.

A balloon cell nevus may be difficult to distinguish from a clear cell fibrous papule on routine hematoxylin and eosin staining (Figure 4); however, the nuclei of a balloon cell nevus tend to be more rounded and centrally located. Any junctional nesting or nests of conventional nevus cells in the dermis also help differentiate a balloon cell nevus from a clear cell fibrous papule. Diffusely positive immunostaining for S-100 protein also is indicative of a balloon cell nevus.

Clear cell hidradenoma consists predominantly of cells with clear cytoplasm and small dark nuclei that may closely mimic a clear cell fibrous papule (Figure 5) but often shows a second population of cells with more vesicular nuclei and dark eosinophilic cytoplasm. Cystic spaces containing hyaline material and foci of squamoid change are common, along with occasional tubular lumina that may be prominent or inconspicuous. Further, the tumor cells of clear cell hidradenoma show positive immunostaining for epithelial markers (eg, cytokeratin AE1/AE3, CAM5.2).

Cutaneous metastasis of ccRCC is rare and usually presents clinically as a larger lesion than a clear cell fibrous papule. The cells of ccRCC have moderate to abundant clear cytoplasm and nuclei with varying degrees of pleomorphism (Figure 6). Periodic acid–Schiff staining demonstrates intracytoplasmic glycogen. The stroma is abundantly vascular and extravasated blood cells are frequently observed. On immunohistochemistry, the tumor cells of ccRCC stain positively for cytokeratin AE1/AE3, CAM5.2, epithelial membrane antigen, CD10, and vimentin.

- Bansal C, Stewart D, Li A, et al. Histologic variants of fibrous papule. J Cutan Pathol. 2005;32:424-428.

- Chiang YY, Tsai HH, Lee WR, et al. Clear cell fibrous papule: report of a case mimicking a balloon cell nevus. J Cutan Pathol. 2009;36:381-384.

- Lee AN, Stein SL, Cohen LM. Clear cell fibrous papule with NKI/C3 expression: clinical and histologic features in six cases. Am J Dermatopathol. 2005;27:296-300.

A fibrous papule is a common benign lesion that usually presents in adults on the face, especially on the lower portion of the nose. It typically presents as a small (2–5 mm), asymptomatic, flesh-colored, dome-shaped lesion that is firm and nontender. Several histopathologic variants of fibrous papules have been described, including clear cell, granular, epithelioid, hypercellular, pleomorphic, pigmented, and inflammatory.1 Clear cell fibrous papules are exceedingly rare. On microscopic examination the epidermis may be normal or show some degree of hyperkeratosis and parakeratosis, erosion, ulceration, or crust. The basal layer may show an increase of melanin. The dermis is expanded by a proliferation of clear cells arranged in sheets, clusters, or as single cells (Figure 1). The clear cells show variation in size and shape. The nuclei are small and round without pleomorphism, hyperchromasia, or mitoses. The nuclei may be centrally located or eccentrically displaced by a large intracytoplasmic vacuole (Figure 2). Some clear cells may exhibit finely vacuolated cytoplasm with nuclear scalloping. The surrounding stroma usually consists of sclerotic collagen and dilated blood vessels (Figure 3). Extravasated red blood cells may be present focally. Patchy lymphocytic infiltrates may be found in the stroma at the periphery of the lesion. Periodic acid–Schiff and mucicarmine staining of the clear cells is negative. On immunohistochemistry, the clear cells are diffusely positive for vimentin and negative for cytokeratin AE1/AE3, epithelial membrane antigen, carcinoembryonic antigen, and HMB-45 (human melanoma black 45).2,3 The clear cells often are positive for CD68, factor XIIIa, and NKI/C3 (anti-CD63) but also may be negative. The S-100 protein often is negative but may be focally positive.

The differential diagnosis for clear cell fibrous papules is broad but reasonably includes balloon cell nevus, clear cell hidradenoma, and cutaneous metastasis of clear cell (conventional) renal cell carcinoma (ccRCC). Balloon cell malignant melanoma is not considered strongly in the differential diagnosis because it usually exhibits invasive growth, cytologic atypia, and mitoses, all of which are not characteristic morphologic features of clear cell fibrous papules.

A balloon cell nevus may be difficult to distinguish from a clear cell fibrous papule on routine hematoxylin and eosin staining (Figure 4); however, the nuclei of a balloon cell nevus tend to be more rounded and centrally located. Any junctional nesting or nests of conventional nevus cells in the dermis also help differentiate a balloon cell nevus from a clear cell fibrous papule. Diffusely positive immunostaining for S-100 protein also is indicative of a balloon cell nevus.

Clear cell hidradenoma consists predominantly of cells with clear cytoplasm and small dark nuclei that may closely mimic a clear cell fibrous papule (Figure 5) but often shows a second population of cells with more vesicular nuclei and dark eosinophilic cytoplasm. Cystic spaces containing hyaline material and foci of squamoid change are common, along with occasional tubular lumina that may be prominent or inconspicuous. Further, the tumor cells of clear cell hidradenoma show positive immunostaining for epithelial markers (eg, cytokeratin AE1/AE3, CAM5.2).

Cutaneous metastasis of ccRCC is rare and usually presents clinically as a larger lesion than a clear cell fibrous papule. The cells of ccRCC have moderate to abundant clear cytoplasm and nuclei with varying degrees of pleomorphism (Figure 6). Periodic acid–Schiff staining demonstrates intracytoplasmic glycogen. The stroma is abundantly vascular and extravasated blood cells are frequently observed. On immunohistochemistry, the tumor cells of ccRCC stain positively for cytokeratin AE1/AE3, CAM5.2, epithelial membrane antigen, CD10, and vimentin.

A fibrous papule is a common benign lesion that usually presents in adults on the face, especially on the lower portion of the nose. It typically presents as a small (2–5 mm), asymptomatic, flesh-colored, dome-shaped lesion that is firm and nontender. Several histopathologic variants of fibrous papules have been described, including clear cell, granular, epithelioid, hypercellular, pleomorphic, pigmented, and inflammatory.1 Clear cell fibrous papules are exceedingly rare. On microscopic examination the epidermis may be normal or show some degree of hyperkeratosis and parakeratosis, erosion, ulceration, or crust. The basal layer may show an increase of melanin. The dermis is expanded by a proliferation of clear cells arranged in sheets, clusters, or as single cells (Figure 1). The clear cells show variation in size and shape. The nuclei are small and round without pleomorphism, hyperchromasia, or mitoses. The nuclei may be centrally located or eccentrically displaced by a large intracytoplasmic vacuole (Figure 2). Some clear cells may exhibit finely vacuolated cytoplasm with nuclear scalloping. The surrounding stroma usually consists of sclerotic collagen and dilated blood vessels (Figure 3). Extravasated red blood cells may be present focally. Patchy lymphocytic infiltrates may be found in the stroma at the periphery of the lesion. Periodic acid–Schiff and mucicarmine staining of the clear cells is negative. On immunohistochemistry, the clear cells are diffusely positive for vimentin and negative for cytokeratin AE1/AE3, epithelial membrane antigen, carcinoembryonic antigen, and HMB-45 (human melanoma black 45).2,3 The clear cells often are positive for CD68, factor XIIIa, and NKI/C3 (anti-CD63) but also may be negative. The S-100 protein often is negative but may be focally positive.

The differential diagnosis for clear cell fibrous papules is broad but reasonably includes balloon cell nevus, clear cell hidradenoma, and cutaneous metastasis of clear cell (conventional) renal cell carcinoma (ccRCC). Balloon cell malignant melanoma is not considered strongly in the differential diagnosis because it usually exhibits invasive growth, cytologic atypia, and mitoses, all of which are not characteristic morphologic features of clear cell fibrous papules.

A balloon cell nevus may be difficult to distinguish from a clear cell fibrous papule on routine hematoxylin and eosin staining (Figure 4); however, the nuclei of a balloon cell nevus tend to be more rounded and centrally located. Any junctional nesting or nests of conventional nevus cells in the dermis also help differentiate a balloon cell nevus from a clear cell fibrous papule. Diffusely positive immunostaining for S-100 protein also is indicative of a balloon cell nevus.

Clear cell hidradenoma consists predominantly of cells with clear cytoplasm and small dark nuclei that may closely mimic a clear cell fibrous papule (Figure 5) but often shows a second population of cells with more vesicular nuclei and dark eosinophilic cytoplasm. Cystic spaces containing hyaline material and foci of squamoid change are common, along with occasional tubular lumina that may be prominent or inconspicuous. Further, the tumor cells of clear cell hidradenoma show positive immunostaining for epithelial markers (eg, cytokeratin AE1/AE3, CAM5.2).

Cutaneous metastasis of ccRCC is rare and usually presents clinically as a larger lesion than a clear cell fibrous papule. The cells of ccRCC have moderate to abundant clear cytoplasm and nuclei with varying degrees of pleomorphism (Figure 6). Periodic acid–Schiff staining demonstrates intracytoplasmic glycogen. The stroma is abundantly vascular and extravasated blood cells are frequently observed. On immunohistochemistry, the tumor cells of ccRCC stain positively for cytokeratin AE1/AE3, CAM5.2, epithelial membrane antigen, CD10, and vimentin.

- Bansal C, Stewart D, Li A, et al. Histologic variants of fibrous papule. J Cutan Pathol. 2005;32:424-428.

- Chiang YY, Tsai HH, Lee WR, et al. Clear cell fibrous papule: report of a case mimicking a balloon cell nevus. J Cutan Pathol. 2009;36:381-384.

- Lee AN, Stein SL, Cohen LM. Clear cell fibrous papule with NKI/C3 expression: clinical and histologic features in six cases. Am J Dermatopathol. 2005;27:296-300.

- Bansal C, Stewart D, Li A, et al. Histologic variants of fibrous papule. J Cutan Pathol. 2005;32:424-428.

- Chiang YY, Tsai HH, Lee WR, et al. Clear cell fibrous papule: report of a case mimicking a balloon cell nevus. J Cutan Pathol. 2009;36:381-384.

- Lee AN, Stein SL, Cohen LM. Clear cell fibrous papule with NKI/C3 expression: clinical and histologic features in six cases. Am J Dermatopathol. 2005;27:296-300.

Lipidized Dermatofibroma

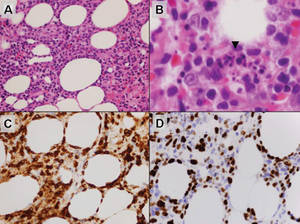

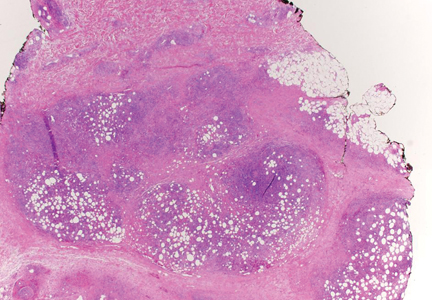

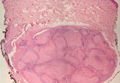

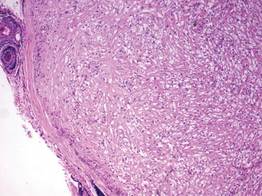

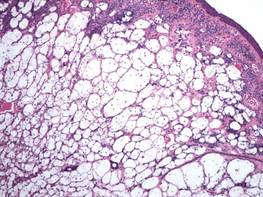

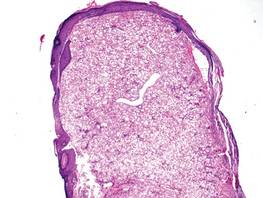

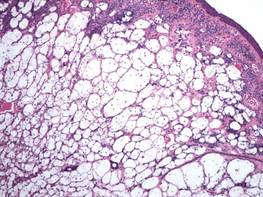

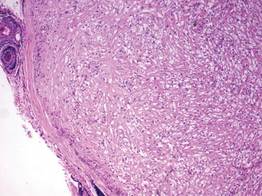

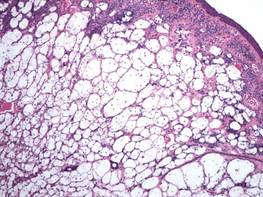

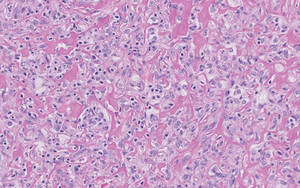

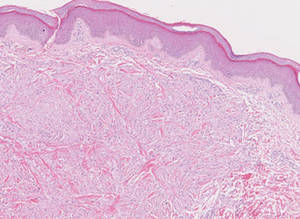

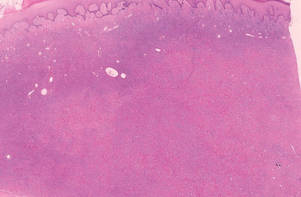

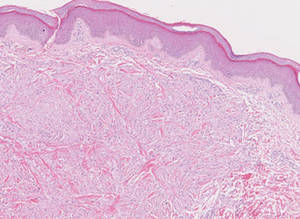

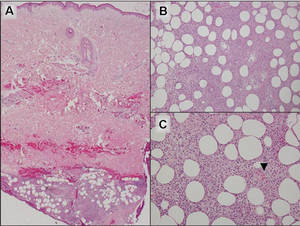

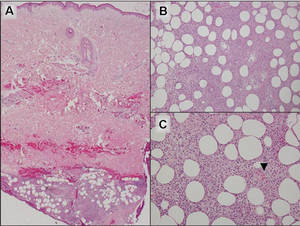

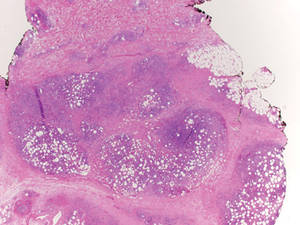

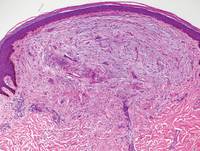

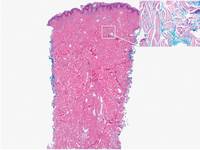

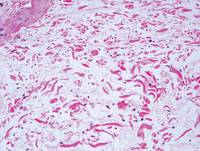

Lipidized dermatofibromas most commonly are found on the ankles, which has led some authors to refer to these lesions as ankle-type fibrous histiocytomas.1 Compared to ordinary dermatofibromas, patients with lipidized dermatofibromas tend to be older, most commonly presenting in the fifth or sixth decades of life, and are predominantly male. Lipidized dermatofibromas typically present as well-circumscribed solitary nodules in the dermis. Characteristic features include numerous xanthomatous cells dissected by distinctive hyalinized wiry collagen fibers (Figures 1 and 2).1 Xanthomatous cells can be round, polygonal, or stellate in shape. These characteristic features in combination with others of dermatofibromas (eg, epidermal acanthosis [Figure 1]) fulfill the criteria for diagnosis of a lipidized dermatofibroma. Additionally, lipidized dermatofibromas tend to be larger than ordinary dermatofibromas, which typically are less than 2 cm in diameter.1

|

Figure 1. Lipidized dermatofibromas are characterized by classic epidermal features of dermatofibromas, such as acanthosis, along with numerous foam cells and extensive stromal hyalinization (H&E, original magnification ×1.5). |

|

Figure 2. Higher-power view of a lipidized dermatofibroma shows the characteristic irregular dissection of hyalinized wiry collagen fibers between the xanthomatous cells (H&E, original magnification ×20). |

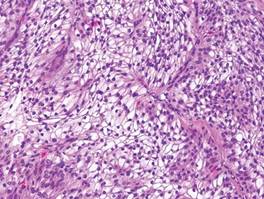

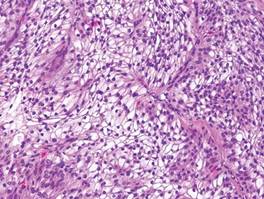

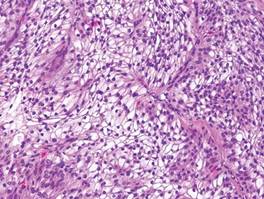

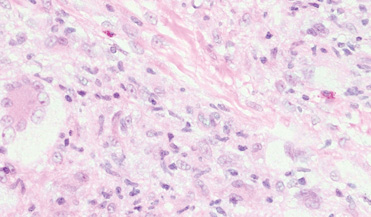

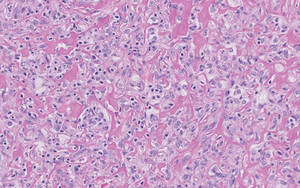

Eruptive xanthomas are characterized by a lacelike infiltrate of extravascular lipid deposits between collagen bundles (Figure 3).2 Granular cell tumors are composed of sheets and/or nests of large cells with abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm and may be confused with lipidized dermatofibromas, as they also may induce overlying pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia3; however, on closer examination of the cells, the cytoplasm is found to be granular (Figure 4), which contrasts the finely vacuolated cytoplasm of xanthomatous cells found in lipidized dermatofibromas. Giant lysosomal granules (eg, pustulo-ovoid bodies of Milian) are present in some cases.2 Of note, an unusual variant of dermatofibroma exists that features prominent granular cells.4

|

Figure 3. Lacelike deposition of extravascular lipid deposits is seen infiltrating between collagen bundles in an eruptive xanthoma (H&E, original magnification ×20). |

|

Figure 4. An abundant eosinophilic, finely granular cytoplasm is characteristic of granular cell tumor (H&E, original magnification ×40). |

Tuberous xanthomas most commonly occur around the pressure areas, such as the knees, elbows, and buttocks. Foam cells are a main feature of tuberous xanthomas and are arranged in large aggregates throughout the dermis.2 Tuberous xanthomas lack Touton giant cells or inflammatory cells. Older lesions tend to develop substantial fibrosis (Figure 5). Although foam cells can be present in older lesions, they are never as conspicuous as those found in other xanthomas.

Xanthogranulomas commonly occur on the head and neck. Findings noted on low magnification include a well-circumscribed exophytic nodule and an epidermal collarette, which help to easily distinguish xanthogranulomas from lipidized dermatofibromas. Additionally, the presence of a more prominent inflammatory infiltrate, which often includes eosinophils, as well as multinucleated Touton giant cells (Figure 6) and histiocytes with more eosinophilic and less xanthomatous cytoplasm can help distinguish between the lesions.1,5 Notably, Touton giant cells also can be seen in lipidized dermatofibromas,1 but the presence of unique features such as distinctive stromal hyalinization are clues to the correct diagnosis of a lipidized dermatofibroma.

- Iwata J, Fletcher CD. Lipidized fibrous histiocytoma: clinicopathologic analysis of 22 cases. Am J Dermatopathol. 2000;22:126-134.

- Weedon D. Weedon’s Skin Pathology. 3rd ed. Edinburgh, Scotland: Elsevier Health Sciences; 2009.

- Elston DM, Ferringer T. Dermatopathology. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders Elsevier; 2009.

- Yogesh TL, Sowmya SV. Granules in granular cell lesions of the head and neck: a review. ISRN Pathol. 2011;2011:10.

- Fujita Y, Tsunemi Y, Kadono T, et al. Lipidized fibrous histiocytoma on the left condyle of the tibia. Int J Dermatol. 2011;50:634-636.

Lipidized dermatofibromas most commonly are found on the ankles, which has led some authors to refer to these lesions as ankle-type fibrous histiocytomas.1 Compared to ordinary dermatofibromas, patients with lipidized dermatofibromas tend to be older, most commonly presenting in the fifth or sixth decades of life, and are predominantly male. Lipidized dermatofibromas typically present as well-circumscribed solitary nodules in the dermis. Characteristic features include numerous xanthomatous cells dissected by distinctive hyalinized wiry collagen fibers (Figures 1 and 2).1 Xanthomatous cells can be round, polygonal, or stellate in shape. These characteristic features in combination with others of dermatofibromas (eg, epidermal acanthosis [Figure 1]) fulfill the criteria for diagnosis of a lipidized dermatofibroma. Additionally, lipidized dermatofibromas tend to be larger than ordinary dermatofibromas, which typically are less than 2 cm in diameter.1

|

Figure 1. Lipidized dermatofibromas are characterized by classic epidermal features of dermatofibromas, such as acanthosis, along with numerous foam cells and extensive stromal hyalinization (H&E, original magnification ×1.5). |

|

Figure 2. Higher-power view of a lipidized dermatofibroma shows the characteristic irregular dissection of hyalinized wiry collagen fibers between the xanthomatous cells (H&E, original magnification ×20). |

Eruptive xanthomas are characterized by a lacelike infiltrate of extravascular lipid deposits between collagen bundles (Figure 3).2 Granular cell tumors are composed of sheets and/or nests of large cells with abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm and may be confused with lipidized dermatofibromas, as they also may induce overlying pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia3; however, on closer examination of the cells, the cytoplasm is found to be granular (Figure 4), which contrasts the finely vacuolated cytoplasm of xanthomatous cells found in lipidized dermatofibromas. Giant lysosomal granules (eg, pustulo-ovoid bodies of Milian) are present in some cases.2 Of note, an unusual variant of dermatofibroma exists that features prominent granular cells.4

|

Figure 3. Lacelike deposition of extravascular lipid deposits is seen infiltrating between collagen bundles in an eruptive xanthoma (H&E, original magnification ×20). |

|

Figure 4. An abundant eosinophilic, finely granular cytoplasm is characteristic of granular cell tumor (H&E, original magnification ×40). |

Tuberous xanthomas most commonly occur around the pressure areas, such as the knees, elbows, and buttocks. Foam cells are a main feature of tuberous xanthomas and are arranged in large aggregates throughout the dermis.2 Tuberous xanthomas lack Touton giant cells or inflammatory cells. Older lesions tend to develop substantial fibrosis (Figure 5). Although foam cells can be present in older lesions, they are never as conspicuous as those found in other xanthomas.

Xanthogranulomas commonly occur on the head and neck. Findings noted on low magnification include a well-circumscribed exophytic nodule and an epidermal collarette, which help to easily distinguish xanthogranulomas from lipidized dermatofibromas. Additionally, the presence of a more prominent inflammatory infiltrate, which often includes eosinophils, as well as multinucleated Touton giant cells (Figure 6) and histiocytes with more eosinophilic and less xanthomatous cytoplasm can help distinguish between the lesions.1,5 Notably, Touton giant cells also can be seen in lipidized dermatofibromas,1 but the presence of unique features such as distinctive stromal hyalinization are clues to the correct diagnosis of a lipidized dermatofibroma.

Lipidized dermatofibromas most commonly are found on the ankles, which has led some authors to refer to these lesions as ankle-type fibrous histiocytomas.1 Compared to ordinary dermatofibromas, patients with lipidized dermatofibromas tend to be older, most commonly presenting in the fifth or sixth decades of life, and are predominantly male. Lipidized dermatofibromas typically present as well-circumscribed solitary nodules in the dermis. Characteristic features include numerous xanthomatous cells dissected by distinctive hyalinized wiry collagen fibers (Figures 1 and 2).1 Xanthomatous cells can be round, polygonal, or stellate in shape. These characteristic features in combination with others of dermatofibromas (eg, epidermal acanthosis [Figure 1]) fulfill the criteria for diagnosis of a lipidized dermatofibroma. Additionally, lipidized dermatofibromas tend to be larger than ordinary dermatofibromas, which typically are less than 2 cm in diameter.1

|

Figure 1. Lipidized dermatofibromas are characterized by classic epidermal features of dermatofibromas, such as acanthosis, along with numerous foam cells and extensive stromal hyalinization (H&E, original magnification ×1.5). |

|

Figure 2. Higher-power view of a lipidized dermatofibroma shows the characteristic irregular dissection of hyalinized wiry collagen fibers between the xanthomatous cells (H&E, original magnification ×20). |

Eruptive xanthomas are characterized by a lacelike infiltrate of extravascular lipid deposits between collagen bundles (Figure 3).2 Granular cell tumors are composed of sheets and/or nests of large cells with abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm and may be confused with lipidized dermatofibromas, as they also may induce overlying pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia3; however, on closer examination of the cells, the cytoplasm is found to be granular (Figure 4), which contrasts the finely vacuolated cytoplasm of xanthomatous cells found in lipidized dermatofibromas. Giant lysosomal granules (eg, pustulo-ovoid bodies of Milian) are present in some cases.2 Of note, an unusual variant of dermatofibroma exists that features prominent granular cells.4

|

Figure 3. Lacelike deposition of extravascular lipid deposits is seen infiltrating between collagen bundles in an eruptive xanthoma (H&E, original magnification ×20). |

|

Figure 4. An abundant eosinophilic, finely granular cytoplasm is characteristic of granular cell tumor (H&E, original magnification ×40). |

Tuberous xanthomas most commonly occur around the pressure areas, such as the knees, elbows, and buttocks. Foam cells are a main feature of tuberous xanthomas and are arranged in large aggregates throughout the dermis.2 Tuberous xanthomas lack Touton giant cells or inflammatory cells. Older lesions tend to develop substantial fibrosis (Figure 5). Although foam cells can be present in older lesions, they are never as conspicuous as those found in other xanthomas.

Xanthogranulomas commonly occur on the head and neck. Findings noted on low magnification include a well-circumscribed exophytic nodule and an epidermal collarette, which help to easily distinguish xanthogranulomas from lipidized dermatofibromas. Additionally, the presence of a more prominent inflammatory infiltrate, which often includes eosinophils, as well as multinucleated Touton giant cells (Figure 6) and histiocytes with more eosinophilic and less xanthomatous cytoplasm can help distinguish between the lesions.1,5 Notably, Touton giant cells also can be seen in lipidized dermatofibromas,1 but the presence of unique features such as distinctive stromal hyalinization are clues to the correct diagnosis of a lipidized dermatofibroma.

- Iwata J, Fletcher CD. Lipidized fibrous histiocytoma: clinicopathologic analysis of 22 cases. Am J Dermatopathol. 2000;22:126-134.

- Weedon D. Weedon’s Skin Pathology. 3rd ed. Edinburgh, Scotland: Elsevier Health Sciences; 2009.

- Elston DM, Ferringer T. Dermatopathology. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders Elsevier; 2009.

- Yogesh TL, Sowmya SV. Granules in granular cell lesions of the head and neck: a review. ISRN Pathol. 2011;2011:10.

- Fujita Y, Tsunemi Y, Kadono T, et al. Lipidized fibrous histiocytoma on the left condyle of the tibia. Int J Dermatol. 2011;50:634-636.

- Iwata J, Fletcher CD. Lipidized fibrous histiocytoma: clinicopathologic analysis of 22 cases. Am J Dermatopathol. 2000;22:126-134.

- Weedon D. Weedon’s Skin Pathology. 3rd ed. Edinburgh, Scotland: Elsevier Health Sciences; 2009.

- Elston DM, Ferringer T. Dermatopathology. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders Elsevier; 2009.

- Yogesh TL, Sowmya SV. Granules in granular cell lesions of the head and neck: a review. ISRN Pathol. 2011;2011:10.

- Fujita Y, Tsunemi Y, Kadono T, et al. Lipidized fibrous histiocytoma on the left condyle of the tibia. Int J Dermatol. 2011;50:634-636.

Subcutaneous Panniculitislike T-Cell Lymphoma

Subcutaneous panniculitislike T-cell lymphoma (SPTL) is a cutaneous lymphoma of α and β phenotype cytotoxic T cells in which the neoplastic cells are found almost exclusively in the subcutaneous layer and resemble a panniculitis.1 It affects males and females with equal incidence and is seen in both adults and children. Clinically, this disease presents as a nonspecific panniculitis with indurated but typically nonulcerated erythematous plaques and nodules most commonly located on the extremities. Plaques and nodules may appear on other body sites and may be generalized.1 In some cases, patients present with associated systemic symptoms including fever, malaise, weight loss, and fatigue.2

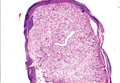

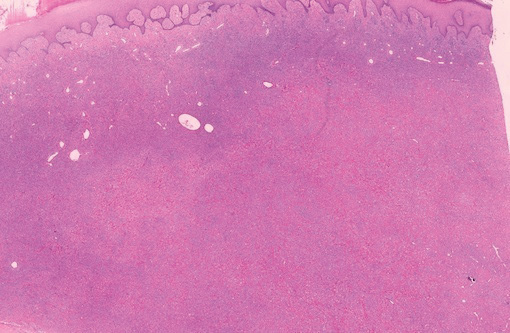

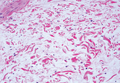

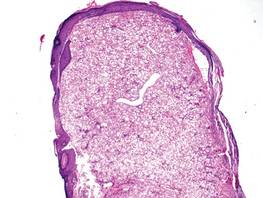

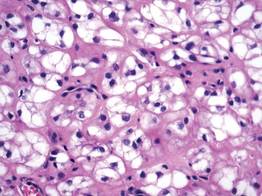

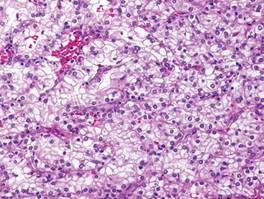

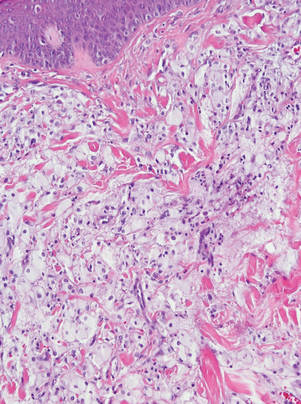

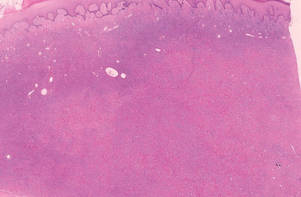

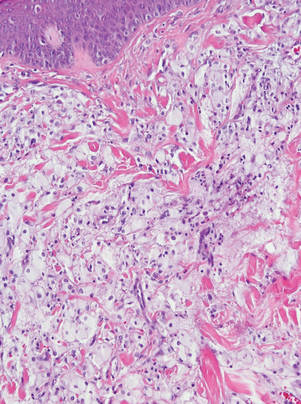

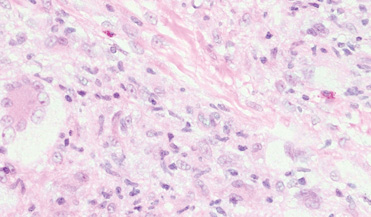

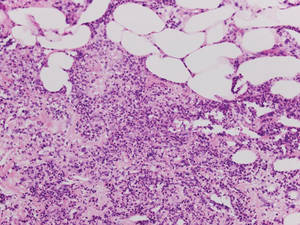

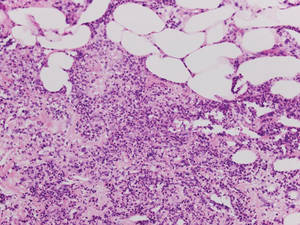

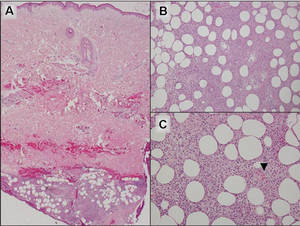

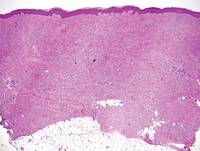

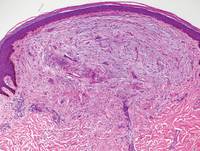

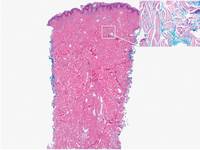

Histologically, SPTL presents as a predominantly lobular panniculitis (Figure 1) with rimming of adipocytes by neoplastic cells that appear as small and medium-sized atypical lymphocytes with hyperchromatic nuclei (Figure 2A). A less dominant septal component may be present, and neoplastic cells may encroach into the lower reticular dermis, rarely involving the papillary dermis or epidermis.2 Although rimming of adipocytes is classic, it is not specific to this entity, as rimming also can be found in other lymphomas and infectious panniculitis. Reactive lymphocytes and macrophages with ingested lipid material also are seen intermixed with neoplastic cells.2 Necrosis is a common finding, including destructive fragmentation of the nucleus, known as karyorrhexis. If necrosis is extensive, appreciation of other histologic features may be hindered.3 Histiocytes engulfing the nuclear debris known as beanbag cells also can be seen (Figure 2B). The diagnosis can be made on immunohistologic analysis demonstrating neoplastic cells with a cytotoxic α and β T-suppressor phenotype centered around and rimming the adipocytes in the subcutaneous fat.3 Immunohistochemistry reveals positive CD3, CD8 (Figure 2C), and βF1 markers, as well as T-cell intracellular antigen 1 (TIA-1), granzyme B, and perforin.1,2 The neoplastic cells often have a high proliferation index as evidenced by MIB-1 (Ki-67) labeling (Figure 2D). The neoplastic cells are negative for CD4, CD56, and CD30.1,2 Subcutaneous panniculitislike T-cell lymphoma cells are negative for Epstein-Barr virus by in situ hybridization.2

|

| Figure 1. Subcutaneous panniculitislike T-cell lymphoma showing a predominantly lobular panniculitis (H&E, original magnification ×20). |

|

| Figure 2. Rimming of adipocytes by hyperchromatic lymphocytes (A)(H&E, original magnification ×400). Arrowhead indicates a histiocyte (ie, beanbag cell) that has undergone cytophagocytosis of nuclear debris (B)(H&E, original magnification ×600). Immunohistochemistry with CD8 highlights the cells rimming the adipocytes (C)(original magnification ×600). Immunohistochemistry with MIB-1 shows an increased proliferative rate in the lymphocytes rimming the adipocytes (D)(original magnification ×600). |

Subcutaneous panniculitislike T-cell lymphoma must be distinguished from lupus erythematosus panniculitis (LEP) and other cutaneous lymphomas. Importantly, LEP and SPTL clinically may appear similar and are not mutually exclusive diagnoses.2 On histology, they may look similar, showing T cell aggregates and necrosis; however, thickening of the basement membrane, vacuolar change at the dermoepidermal junction, plasma cells, hyaline sclerosis, mucin deposition, a lymphocytic perivascular infiltrate, and nodular aggregates of B cells are more common in LEP (Figure 3).2,4 Additionally, in LEP the T cell aggregates typically will not have a high proliferative rate as evidenced by MIB-1.3

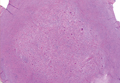

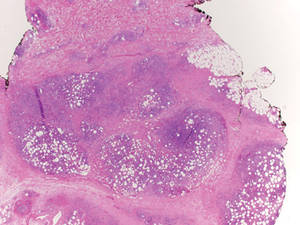

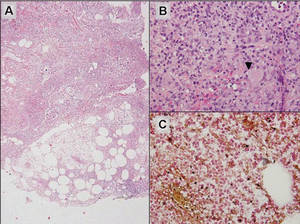

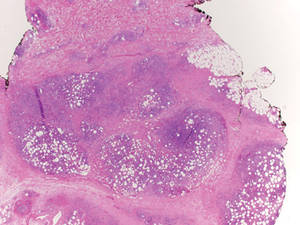

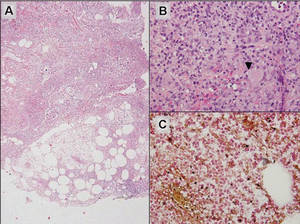

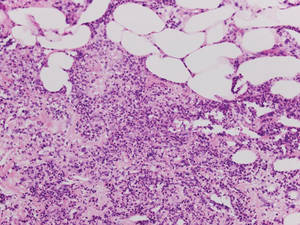

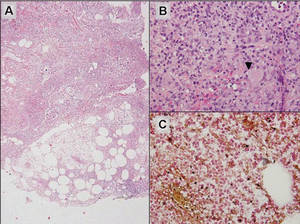

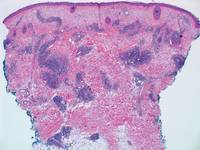

Additionally, other lobular panniculitides can be considered in the differential diagnosis, including erythema induratum (EI), α1-antitrypsin deficiency panniculitis (A1ATDP), and infectious panniculitis. Histologically, EI (Figure 4), also known as nodular vasculitis when not associated with Mycobacterium tuberculosis, has a lobular pattern of inflammation. Early in the disease process there are discrete collections of neutrophils; later, granulomas with histiocytes, giant cells, and foamy macrophages are seen.4 The reactive infiltrate of EI is more mixed than in SPTL, with small lymphocytes, plasma cells, and eosinophils. Leukocytoclastic vasculitis and extravascular caseous or fibrinoid necrosis also may be present.4,5 Substantial caseous necrosis may extend to the dermis and epidermis with EI. Importantly, EI lacks true tuberculoid granulomas and stains negative for acid-fast bacilli, as it is a reactive rather than a local infectious process, but a history of M tuberculosis exposure is common.4 α1-Antitrypsin deficiency panniculitis results from a deficiency of proteinase activity and can be distinguished from SPTL by a neutrophil-rich panniculitis (Figure 5) as well as the classic appearance of splaying of neutrophils between collagen bundles in the deep reticular dermis. Additionally, the panniculitis is characterized by focal areas of necrotic lobules and septa with an infiltrate of neutrophils and macrophages that abut areas of normal-appearing subcutaneous fat without infiltrate.6 Clinically, the A1ATDP lesions may have ulceration and express an oily substance from fat necrosis. Panniculitis with A1ATDP may precede liver and lung disease.4 Panniculitis from bacterial or fungal infection is more common in immunocompromised patients but should be considered when subcutaneous inflammation and/or necrosis is present. Depending on the responsible organism and the status of a patient’s immune system, infectious panniculitis can have variable presentations, including suppurative granulomas with mycobacterial organisms, a dermal focus of infection if the primary source is cutaneous, or a deeper reticular and subcuticular focus in the subcutaneous fat if the infectious panniculitis occurs from hematogenous spread.4 An example of an infectious panniculitis having more of a granulomatous pattern secondary to Cryptococcus can be seen in Figure 6. Ultimately, special stains to identify infectious organisms (eg, Gram, periodic acid–Schiff, Ziehl-Neelsen) can be ordered to aid in the diagnosis if a responsible organism is not visible on hematoxylin and eosin staining.

|

Figure 4. Erythema induratum is characterized by a lobular panniculitis (A and B)(both H&E, original magnifications ×40 and ×200). Vascular changes (arrowhead) are present in a majority of cases with endothelial swelling and extravasation of erythrocytes (C)(H&E, original magnification ×400). |

|

| Figure 5. Neutrophilic panniculitis that can be seen in α1-antitrypsin deficiency panniculitis (H&E, original magnification ×400). |

|

Figure 6. Infectious panniculitis secondary to Cryptococcus showing a granulomatous reaction in the subcutis (A)(H&E, original magnification ×40). Closer inspection shows a dense infiltrate of chronic inflammatory cells including numerous histiocytes and multinucleated giant cells. Some of the giant cells contain refractile organisms (arrowhead)(B)(H&E, original magnification ×400). Mucicarmine histochemical stain highlights the capsule of the organism (C)(original magnification ×400). |

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to thank Drake Poeschl, MD, St. Louis, Missouri, for proofreading the manuscript.

1. Willemze R, Jaffe ES, Burg G, et al. WHO-EORTC classification for cutaneous lymphomas. Blood. 2005;105:3765-3785.

2. Willemze R, Jansen PM, Cerroni L, et al. Subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma: definition, classification, and prognostic factors: an EORTC Cutaneous Lymphoma Group study of 83 cases. Blood. 2008;111:838-845.

3. Cerroni L, Gatter K, Kerl H. Subcutaneous “panniculitis-like” T-cell lymphoma. In: Cerroni L, Gatter K, Kerl H. Skin Lymphoma: The Illustrated Guide. 3rd ed. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell Publishing; 2011:87-96.

4. Requena L, Sánchez Yus E. Panniculitis. part II. mostly lobular panniculitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;45:325-361.

5. Sharon V, Goodarzi H, Chambers CJ, et al. Erythema induratum of Bazin. Dermatol Online J. 2010;16:1.

6. Rajagopal R, Malik AK, Murthy PS, et al. Alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency panniculitis. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2002;68:362-364.

Subcutaneous panniculitislike T-cell lymphoma (SPTL) is a cutaneous lymphoma of α and β phenotype cytotoxic T cells in which the neoplastic cells are found almost exclusively in the subcutaneous layer and resemble a panniculitis.1 It affects males and females with equal incidence and is seen in both adults and children. Clinically, this disease presents as a nonspecific panniculitis with indurated but typically nonulcerated erythematous plaques and nodules most commonly located on the extremities. Plaques and nodules may appear on other body sites and may be generalized.1 In some cases, patients present with associated systemic symptoms including fever, malaise, weight loss, and fatigue.2

Histologically, SPTL presents as a predominantly lobular panniculitis (Figure 1) with rimming of adipocytes by neoplastic cells that appear as small and medium-sized atypical lymphocytes with hyperchromatic nuclei (Figure 2A). A less dominant septal component may be present, and neoplastic cells may encroach into the lower reticular dermis, rarely involving the papillary dermis or epidermis.2 Although rimming of adipocytes is classic, it is not specific to this entity, as rimming also can be found in other lymphomas and infectious panniculitis. Reactive lymphocytes and macrophages with ingested lipid material also are seen intermixed with neoplastic cells.2 Necrosis is a common finding, including destructive fragmentation of the nucleus, known as karyorrhexis. If necrosis is extensive, appreciation of other histologic features may be hindered.3 Histiocytes engulfing the nuclear debris known as beanbag cells also can be seen (Figure 2B). The diagnosis can be made on immunohistologic analysis demonstrating neoplastic cells with a cytotoxic α and β T-suppressor phenotype centered around and rimming the adipocytes in the subcutaneous fat.3 Immunohistochemistry reveals positive CD3, CD8 (Figure 2C), and βF1 markers, as well as T-cell intracellular antigen 1 (TIA-1), granzyme B, and perforin.1,2 The neoplastic cells often have a high proliferation index as evidenced by MIB-1 (Ki-67) labeling (Figure 2D). The neoplastic cells are negative for CD4, CD56, and CD30.1,2 Subcutaneous panniculitislike T-cell lymphoma cells are negative for Epstein-Barr virus by in situ hybridization.2

|

| Figure 1. Subcutaneous panniculitislike T-cell lymphoma showing a predominantly lobular panniculitis (H&E, original magnification ×20). |

|

| Figure 2. Rimming of adipocytes by hyperchromatic lymphocytes (A)(H&E, original magnification ×400). Arrowhead indicates a histiocyte (ie, beanbag cell) that has undergone cytophagocytosis of nuclear debris (B)(H&E, original magnification ×600). Immunohistochemistry with CD8 highlights the cells rimming the adipocytes (C)(original magnification ×600). Immunohistochemistry with MIB-1 shows an increased proliferative rate in the lymphocytes rimming the adipocytes (D)(original magnification ×600). |

Subcutaneous panniculitislike T-cell lymphoma must be distinguished from lupus erythematosus panniculitis (LEP) and other cutaneous lymphomas. Importantly, LEP and SPTL clinically may appear similar and are not mutually exclusive diagnoses.2 On histology, they may look similar, showing T cell aggregates and necrosis; however, thickening of the basement membrane, vacuolar change at the dermoepidermal junction, plasma cells, hyaline sclerosis, mucin deposition, a lymphocytic perivascular infiltrate, and nodular aggregates of B cells are more common in LEP (Figure 3).2,4 Additionally, in LEP the T cell aggregates typically will not have a high proliferative rate as evidenced by MIB-1.3

Additionally, other lobular panniculitides can be considered in the differential diagnosis, including erythema induratum (EI), α1-antitrypsin deficiency panniculitis (A1ATDP), and infectious panniculitis. Histologically, EI (Figure 4), also known as nodular vasculitis when not associated with Mycobacterium tuberculosis, has a lobular pattern of inflammation. Early in the disease process there are discrete collections of neutrophils; later, granulomas with histiocytes, giant cells, and foamy macrophages are seen.4 The reactive infiltrate of EI is more mixed than in SPTL, with small lymphocytes, plasma cells, and eosinophils. Leukocytoclastic vasculitis and extravascular caseous or fibrinoid necrosis also may be present.4,5 Substantial caseous necrosis may extend to the dermis and epidermis with EI. Importantly, EI lacks true tuberculoid granulomas and stains negative for acid-fast bacilli, as it is a reactive rather than a local infectious process, but a history of M tuberculosis exposure is common.4 α1-Antitrypsin deficiency panniculitis results from a deficiency of proteinase activity and can be distinguished from SPTL by a neutrophil-rich panniculitis (Figure 5) as well as the classic appearance of splaying of neutrophils between collagen bundles in the deep reticular dermis. Additionally, the panniculitis is characterized by focal areas of necrotic lobules and septa with an infiltrate of neutrophils and macrophages that abut areas of normal-appearing subcutaneous fat without infiltrate.6 Clinically, the A1ATDP lesions may have ulceration and express an oily substance from fat necrosis. Panniculitis with A1ATDP may precede liver and lung disease.4 Panniculitis from bacterial or fungal infection is more common in immunocompromised patients but should be considered when subcutaneous inflammation and/or necrosis is present. Depending on the responsible organism and the status of a patient’s immune system, infectious panniculitis can have variable presentations, including suppurative granulomas with mycobacterial organisms, a dermal focus of infection if the primary source is cutaneous, or a deeper reticular and subcuticular focus in the subcutaneous fat if the infectious panniculitis occurs from hematogenous spread.4 An example of an infectious panniculitis having more of a granulomatous pattern secondary to Cryptococcus can be seen in Figure 6. Ultimately, special stains to identify infectious organisms (eg, Gram, periodic acid–Schiff, Ziehl-Neelsen) can be ordered to aid in the diagnosis if a responsible organism is not visible on hematoxylin and eosin staining.

|

Figure 4. Erythema induratum is characterized by a lobular panniculitis (A and B)(both H&E, original magnifications ×40 and ×200). Vascular changes (arrowhead) are present in a majority of cases with endothelial swelling and extravasation of erythrocytes (C)(H&E, original magnification ×400). |

|

| Figure 5. Neutrophilic panniculitis that can be seen in α1-antitrypsin deficiency panniculitis (H&E, original magnification ×400). |

|

Figure 6. Infectious panniculitis secondary to Cryptococcus showing a granulomatous reaction in the subcutis (A)(H&E, original magnification ×40). Closer inspection shows a dense infiltrate of chronic inflammatory cells including numerous histiocytes and multinucleated giant cells. Some of the giant cells contain refractile organisms (arrowhead)(B)(H&E, original magnification ×400). Mucicarmine histochemical stain highlights the capsule of the organism (C)(original magnification ×400). |

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to thank Drake Poeschl, MD, St. Louis, Missouri, for proofreading the manuscript.

Subcutaneous panniculitislike T-cell lymphoma (SPTL) is a cutaneous lymphoma of α and β phenotype cytotoxic T cells in which the neoplastic cells are found almost exclusively in the subcutaneous layer and resemble a panniculitis.1 It affects males and females with equal incidence and is seen in both adults and children. Clinically, this disease presents as a nonspecific panniculitis with indurated but typically nonulcerated erythematous plaques and nodules most commonly located on the extremities. Plaques and nodules may appear on other body sites and may be generalized.1 In some cases, patients present with associated systemic symptoms including fever, malaise, weight loss, and fatigue.2

Histologically, SPTL presents as a predominantly lobular panniculitis (Figure 1) with rimming of adipocytes by neoplastic cells that appear as small and medium-sized atypical lymphocytes with hyperchromatic nuclei (Figure 2A). A less dominant septal component may be present, and neoplastic cells may encroach into the lower reticular dermis, rarely involving the papillary dermis or epidermis.2 Although rimming of adipocytes is classic, it is not specific to this entity, as rimming also can be found in other lymphomas and infectious panniculitis. Reactive lymphocytes and macrophages with ingested lipid material also are seen intermixed with neoplastic cells.2 Necrosis is a common finding, including destructive fragmentation of the nucleus, known as karyorrhexis. If necrosis is extensive, appreciation of other histologic features may be hindered.3 Histiocytes engulfing the nuclear debris known as beanbag cells also can be seen (Figure 2B). The diagnosis can be made on immunohistologic analysis demonstrating neoplastic cells with a cytotoxic α and β T-suppressor phenotype centered around and rimming the adipocytes in the subcutaneous fat.3 Immunohistochemistry reveals positive CD3, CD8 (Figure 2C), and βF1 markers, as well as T-cell intracellular antigen 1 (TIA-1), granzyme B, and perforin.1,2 The neoplastic cells often have a high proliferation index as evidenced by MIB-1 (Ki-67) labeling (Figure 2D). The neoplastic cells are negative for CD4, CD56, and CD30.1,2 Subcutaneous panniculitislike T-cell lymphoma cells are negative for Epstein-Barr virus by in situ hybridization.2

|

| Figure 1. Subcutaneous panniculitislike T-cell lymphoma showing a predominantly lobular panniculitis (H&E, original magnification ×20). |

|

| Figure 2. Rimming of adipocytes by hyperchromatic lymphocytes (A)(H&E, original magnification ×400). Arrowhead indicates a histiocyte (ie, beanbag cell) that has undergone cytophagocytosis of nuclear debris (B)(H&E, original magnification ×600). Immunohistochemistry with CD8 highlights the cells rimming the adipocytes (C)(original magnification ×600). Immunohistochemistry with MIB-1 shows an increased proliferative rate in the lymphocytes rimming the adipocytes (D)(original magnification ×600). |

Subcutaneous panniculitislike T-cell lymphoma must be distinguished from lupus erythematosus panniculitis (LEP) and other cutaneous lymphomas. Importantly, LEP and SPTL clinically may appear similar and are not mutually exclusive diagnoses.2 On histology, they may look similar, showing T cell aggregates and necrosis; however, thickening of the basement membrane, vacuolar change at the dermoepidermal junction, plasma cells, hyaline sclerosis, mucin deposition, a lymphocytic perivascular infiltrate, and nodular aggregates of B cells are more common in LEP (Figure 3).2,4 Additionally, in LEP the T cell aggregates typically will not have a high proliferative rate as evidenced by MIB-1.3

Additionally, other lobular panniculitides can be considered in the differential diagnosis, including erythema induratum (EI), α1-antitrypsin deficiency panniculitis (A1ATDP), and infectious panniculitis. Histologically, EI (Figure 4), also known as nodular vasculitis when not associated with Mycobacterium tuberculosis, has a lobular pattern of inflammation. Early in the disease process there are discrete collections of neutrophils; later, granulomas with histiocytes, giant cells, and foamy macrophages are seen.4 The reactive infiltrate of EI is more mixed than in SPTL, with small lymphocytes, plasma cells, and eosinophils. Leukocytoclastic vasculitis and extravascular caseous or fibrinoid necrosis also may be present.4,5 Substantial caseous necrosis may extend to the dermis and epidermis with EI. Importantly, EI lacks true tuberculoid granulomas and stains negative for acid-fast bacilli, as it is a reactive rather than a local infectious process, but a history of M tuberculosis exposure is common.4 α1-Antitrypsin deficiency panniculitis results from a deficiency of proteinase activity and can be distinguished from SPTL by a neutrophil-rich panniculitis (Figure 5) as well as the classic appearance of splaying of neutrophils between collagen bundles in the deep reticular dermis. Additionally, the panniculitis is characterized by focal areas of necrotic lobules and septa with an infiltrate of neutrophils and macrophages that abut areas of normal-appearing subcutaneous fat without infiltrate.6 Clinically, the A1ATDP lesions may have ulceration and express an oily substance from fat necrosis. Panniculitis with A1ATDP may precede liver and lung disease.4 Panniculitis from bacterial or fungal infection is more common in immunocompromised patients but should be considered when subcutaneous inflammation and/or necrosis is present. Depending on the responsible organism and the status of a patient’s immune system, infectious panniculitis can have variable presentations, including suppurative granulomas with mycobacterial organisms, a dermal focus of infection if the primary source is cutaneous, or a deeper reticular and subcuticular focus in the subcutaneous fat if the infectious panniculitis occurs from hematogenous spread.4 An example of an infectious panniculitis having more of a granulomatous pattern secondary to Cryptococcus can be seen in Figure 6. Ultimately, special stains to identify infectious organisms (eg, Gram, periodic acid–Schiff, Ziehl-Neelsen) can be ordered to aid in the diagnosis if a responsible organism is not visible on hematoxylin and eosin staining.

|

Figure 4. Erythema induratum is characterized by a lobular panniculitis (A and B)(both H&E, original magnifications ×40 and ×200). Vascular changes (arrowhead) are present in a majority of cases with endothelial swelling and extravasation of erythrocytes (C)(H&E, original magnification ×400). |

|

| Figure 5. Neutrophilic panniculitis that can be seen in α1-antitrypsin deficiency panniculitis (H&E, original magnification ×400). |

|

Figure 6. Infectious panniculitis secondary to Cryptococcus showing a granulomatous reaction in the subcutis (A)(H&E, original magnification ×40). Closer inspection shows a dense infiltrate of chronic inflammatory cells including numerous histiocytes and multinucleated giant cells. Some of the giant cells contain refractile organisms (arrowhead)(B)(H&E, original magnification ×400). Mucicarmine histochemical stain highlights the capsule of the organism (C)(original magnification ×400). |

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to thank Drake Poeschl, MD, St. Louis, Missouri, for proofreading the manuscript.

1. Willemze R, Jaffe ES, Burg G, et al. WHO-EORTC classification for cutaneous lymphomas. Blood. 2005;105:3765-3785.

2. Willemze R, Jansen PM, Cerroni L, et al. Subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma: definition, classification, and prognostic factors: an EORTC Cutaneous Lymphoma Group study of 83 cases. Blood. 2008;111:838-845.

3. Cerroni L, Gatter K, Kerl H. Subcutaneous “panniculitis-like” T-cell lymphoma. In: Cerroni L, Gatter K, Kerl H. Skin Lymphoma: The Illustrated Guide. 3rd ed. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell Publishing; 2011:87-96.

4. Requena L, Sánchez Yus E. Panniculitis. part II. mostly lobular panniculitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;45:325-361.

5. Sharon V, Goodarzi H, Chambers CJ, et al. Erythema induratum of Bazin. Dermatol Online J. 2010;16:1.

6. Rajagopal R, Malik AK, Murthy PS, et al. Alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency panniculitis. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2002;68:362-364.

1. Willemze R, Jaffe ES, Burg G, et al. WHO-EORTC classification for cutaneous lymphomas. Blood. 2005;105:3765-3785.

2. Willemze R, Jansen PM, Cerroni L, et al. Subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma: definition, classification, and prognostic factors: an EORTC Cutaneous Lymphoma Group study of 83 cases. Blood. 2008;111:838-845.

3. Cerroni L, Gatter K, Kerl H. Subcutaneous “panniculitis-like” T-cell lymphoma. In: Cerroni L, Gatter K, Kerl H. Skin Lymphoma: The Illustrated Guide. 3rd ed. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell Publishing; 2011:87-96.

4. Requena L, Sánchez Yus E. Panniculitis. part II. mostly lobular panniculitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;45:325-361.

5. Sharon V, Goodarzi H, Chambers CJ, et al. Erythema induratum of Bazin. Dermatol Online J. 2010;16:1.

6. Rajagopal R, Malik AK, Murthy PS, et al. Alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency panniculitis. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2002;68:362-364.

Pretibial Myxedema

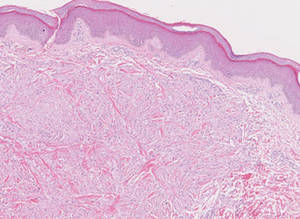

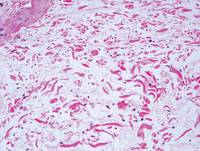

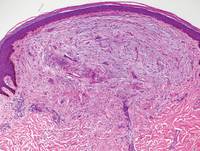

Pretibial myxedema (PM) is a cutaneous mucinosis associated with thyroid dysfunction. It most commonly presents in the setting of Graves disease and is seen less often in patients with hypothyroidism and euthyroidism.1 The anterior tibia is most frequently affected, but lesions also may present on the feet, thighs, and upper extremities. Physical examination generally demonstrates skin thickening, hyperkeratosis, hyperpigmentation, yellow-red discoloration, and hyperhidrosis. Classically, the term peau d’orange has been used to characterize these clinical features.1 Histologic examination of PM typically reveals marked deposition of mucin throughout the reticular dermis with sparing of the papillary dermis (Figure 1) and may be accompanied by overlying hyperkeratosis. Collagen fibers are splayed and appear decreased in density (Figure 2). Alcian blue, periodic acid–Schiff, colloidal iron, and toluidine blue staining can be used to highlight dermal mucin.

|

|

Figure 1. Prominent mucin deposition throughout the reticular dermis in pretibial myxedema (H&E, original magnification ×40). | Figure 2. Increased mucin deposition and collagen fiber splaying in pretibial myxedema (H&E, original magnification ×200). |

|

|

Figure 3. Scleredema with increased dermal thickness (H&E, original magnification ×20) and interstitial mucin on colloidal iron–stained sections (inset in upper right corner, original magnification ×400). | Figure 4. Scleromyxedema with mucin deposition primarily in the superficial dermis as well as increased cellularity and fibrosis (H&E, original magnification ×200). |

|

|

Figure 5. Nephrogenic systemic fibrosis with prominent mucinous fibrosis (H&E, original magnification ×40). | Figure 6. Tumid lupus erythematosus with a superficial and perivascular lymphoid infiltrate as well as increased dermal mucin (H&E, original magnification ×40). |

Similar to PM, histologic examination of scleredema and scleromyxedema usually demonstrate prominent mucin deposition. In scleredema, mucin primarily is visualized in the deep dermis between thick collagen bundles and typically is localized to the back (Figure 3). Scleromyxedema is distinguished by mucin deposition in the superficial dermis with associated fibroblast proliferation and fibrosis (Figure 4).

Nephrogenic systemic fibrosis is characterized by proliferation of CD34+ dermal spindle cells, fibroblasts, interstitial mucin, altered elastic fibers, and thickened collagen bundles that involve the dermis and subcutaneous septa (Figure 5).2 Tumid lupus erythematosus classically demonstrates perivascular and periadnexal superficial and deep lymphocytic inflammation (Figure 6). Similar to scleredema and PM, mucin deposition in tumid lupus erythematosus is interspersed between collagen bundles in the reticular dermis.3

1. Fatourechi V. Pretibial myxedema: pathophysiology and treatment options. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2005;6:295-309.

2. Cowper SE, Lyndon DS, Bhawan J, et al. Nephro-genic fibrosing dermopathy. Am J Dermatopathol.2001;23:383-393.

3. Kuhn A, Dagmar RH, Oslislo C, et al. Lupus erythematosus tumidus: a neglected subset of cutaneous lupus erythematosus: report of 40 cases. Arch Dermatol. 2000;136:1033-1041.

Pretibial myxedema (PM) is a cutaneous mucinosis associated with thyroid dysfunction. It most commonly presents in the setting of Graves disease and is seen less often in patients with hypothyroidism and euthyroidism.1 The anterior tibia is most frequently affected, but lesions also may present on the feet, thighs, and upper extremities. Physical examination generally demonstrates skin thickening, hyperkeratosis, hyperpigmentation, yellow-red discoloration, and hyperhidrosis. Classically, the term peau d’orange has been used to characterize these clinical features.1 Histologic examination of PM typically reveals marked deposition of mucin throughout the reticular dermis with sparing of the papillary dermis (Figure 1) and may be accompanied by overlying hyperkeratosis. Collagen fibers are splayed and appear decreased in density (Figure 2). Alcian blue, periodic acid–Schiff, colloidal iron, and toluidine blue staining can be used to highlight dermal mucin.

|

|

Figure 1. Prominent mucin deposition throughout the reticular dermis in pretibial myxedema (H&E, original magnification ×40). | Figure 2. Increased mucin deposition and collagen fiber splaying in pretibial myxedema (H&E, original magnification ×200). |

|

|

Figure 3. Scleredema with increased dermal thickness (H&E, original magnification ×20) and interstitial mucin on colloidal iron–stained sections (inset in upper right corner, original magnification ×400). | Figure 4. Scleromyxedema with mucin deposition primarily in the superficial dermis as well as increased cellularity and fibrosis (H&E, original magnification ×200). |

|

|

Figure 5. Nephrogenic systemic fibrosis with prominent mucinous fibrosis (H&E, original magnification ×40). | Figure 6. Tumid lupus erythematosus with a superficial and perivascular lymphoid infiltrate as well as increased dermal mucin (H&E, original magnification ×40). |

Similar to PM, histologic examination of scleredema and scleromyxedema usually demonstrate prominent mucin deposition. In scleredema, mucin primarily is visualized in the deep dermis between thick collagen bundles and typically is localized to the back (Figure 3). Scleromyxedema is distinguished by mucin deposition in the superficial dermis with associated fibroblast proliferation and fibrosis (Figure 4).

Nephrogenic systemic fibrosis is characterized by proliferation of CD34+ dermal spindle cells, fibroblasts, interstitial mucin, altered elastic fibers, and thickened collagen bundles that involve the dermis and subcutaneous septa (Figure 5).2 Tumid lupus erythematosus classically demonstrates perivascular and periadnexal superficial and deep lymphocytic inflammation (Figure 6). Similar to scleredema and PM, mucin deposition in tumid lupus erythematosus is interspersed between collagen bundles in the reticular dermis.3

Pretibial myxedema (PM) is a cutaneous mucinosis associated with thyroid dysfunction. It most commonly presents in the setting of Graves disease and is seen less often in patients with hypothyroidism and euthyroidism.1 The anterior tibia is most frequently affected, but lesions also may present on the feet, thighs, and upper extremities. Physical examination generally demonstrates skin thickening, hyperkeratosis, hyperpigmentation, yellow-red discoloration, and hyperhidrosis. Classically, the term peau d’orange has been used to characterize these clinical features.1 Histologic examination of PM typically reveals marked deposition of mucin throughout the reticular dermis with sparing of the papillary dermis (Figure 1) and may be accompanied by overlying hyperkeratosis. Collagen fibers are splayed and appear decreased in density (Figure 2). Alcian blue, periodic acid–Schiff, colloidal iron, and toluidine blue staining can be used to highlight dermal mucin.

|

|

Figure 1. Prominent mucin deposition throughout the reticular dermis in pretibial myxedema (H&E, original magnification ×40). | Figure 2. Increased mucin deposition and collagen fiber splaying in pretibial myxedema (H&E, original magnification ×200). |

|

|

Figure 3. Scleredema with increased dermal thickness (H&E, original magnification ×20) and interstitial mucin on colloidal iron–stained sections (inset in upper right corner, original magnification ×400). | Figure 4. Scleromyxedema with mucin deposition primarily in the superficial dermis as well as increased cellularity and fibrosis (H&E, original magnification ×200). |

|

|

Figure 5. Nephrogenic systemic fibrosis with prominent mucinous fibrosis (H&E, original magnification ×40). | Figure 6. Tumid lupus erythematosus with a superficial and perivascular lymphoid infiltrate as well as increased dermal mucin (H&E, original magnification ×40). |

Similar to PM, histologic examination of scleredema and scleromyxedema usually demonstrate prominent mucin deposition. In scleredema, mucin primarily is visualized in the deep dermis between thick collagen bundles and typically is localized to the back (Figure 3). Scleromyxedema is distinguished by mucin deposition in the superficial dermis with associated fibroblast proliferation and fibrosis (Figure 4).

Nephrogenic systemic fibrosis is characterized by proliferation of CD34+ dermal spindle cells, fibroblasts, interstitial mucin, altered elastic fibers, and thickened collagen bundles that involve the dermis and subcutaneous septa (Figure 5).2 Tumid lupus erythematosus classically demonstrates perivascular and periadnexal superficial and deep lymphocytic inflammation (Figure 6). Similar to scleredema and PM, mucin deposition in tumid lupus erythematosus is interspersed between collagen bundles in the reticular dermis.3

1. Fatourechi V. Pretibial myxedema: pathophysiology and treatment options. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2005;6:295-309.

2. Cowper SE, Lyndon DS, Bhawan J, et al. Nephro-genic fibrosing dermopathy. Am J Dermatopathol.2001;23:383-393.

3. Kuhn A, Dagmar RH, Oslislo C, et al. Lupus erythematosus tumidus: a neglected subset of cutaneous lupus erythematosus: report of 40 cases. Arch Dermatol. 2000;136:1033-1041.

1. Fatourechi V. Pretibial myxedema: pathophysiology and treatment options. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2005;6:295-309.

2. Cowper SE, Lyndon DS, Bhawan J, et al. Nephro-genic fibrosing dermopathy. Am J Dermatopathol.2001;23:383-393.

3. Kuhn A, Dagmar RH, Oslislo C, et al. Lupus erythematosus tumidus: a neglected subset of cutaneous lupus erythematosus: report of 40 cases. Arch Dermatol. 2000;136:1033-1041.

Hailey-Hailey Disease

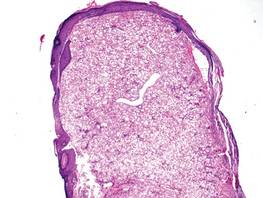

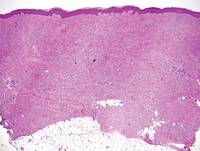

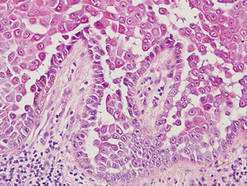

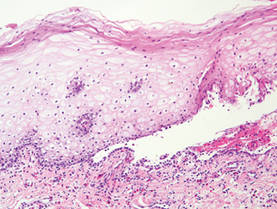

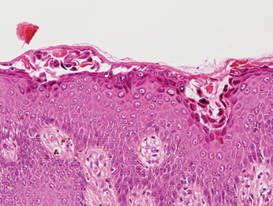

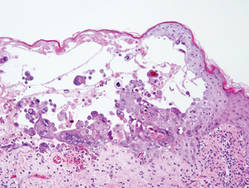

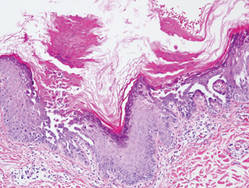

Hailey-Hailey disease (HHD), or benign familial chronic pemphigus, typically presents as suprabasal blisters with a perivascular and interstitial lymphocytic infiltrate (Figure 1).1 Villi, or elongated dermal papillae lined with a single layer of basal cells, protrude into the bullae (Figure 2). In HHD lesions, the epidermis is thickened with scale-crust, and at least the lower half of the epidermis shows acantholysis. Despite the acantholytic changes, a few intact intercellular bridges remain, giving the appearance of a dilapidated brick wall (Figure 2). There may be dyskeratotic cells among the acantholytic cells, though they are scant in many cases. These acantholytic dyskeratotic cells have eosinophilic polygonal-shaped cytoplasm. Hailey-Hailey disease typically does not show adnexal extension of the acantholysis. Direct immunofluorescence is negative in HHD.

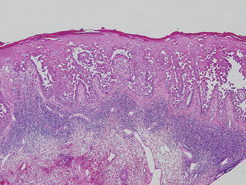

Pemphigus vulgaris is an autoimmune intraepidermal bullous disease that presents with suprabasal acantholysis (Figure 3).2 The epidermis is not thickened and acantholysis is limited to the suprabasal layer. Acantholytic cells with eosinophils and/or neutrophils are found within the bullae. Perivascular and interstitial infiltrates of lymphocytes, eosinophils, and occasionally neutrophils are seen; however, the inflammatory cell infiltrate can vary from extensive to scant. Direct immunofluorescence usually reveals IgG and/or C3 deposition on the surface of the keratinocytes throughout the epidermis.

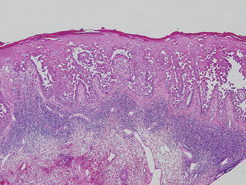

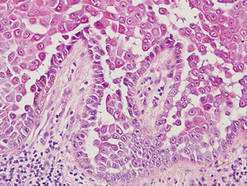

Pemphigus foliaceus is another autoimmune intraepidermal bullous disease that is characterized by acantholysis in the granular or upper spinous layers (Figure 4).3 The epidermis is not thickened. Sometimes acantholytic cells show dyskeratotic change (Figure 4). Some biopsy specimens do not contain the roof of the bullae; therefore, only erosion is seen and the diagnosis may be missed. Moreover, when only the adnexal epithelium shows acantholysis without epidermal involvement, diagnosis can be difficult.4 Acantholysis is accompanied with a superficial perivascular and interstitial inflammatory cell infiltrate consisting of lymphocytes, eosinophils, and occasionally neutrophils. The amount of inflammatory cell infiltrate may vary. Bullous impetigo and staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome reveal a similar histopathologic pattern. Direct immunofluorescence usually discloses IgG and/or C3 deposition on cell surfaces of keratinocytes in the entire or upper epidermis.

Herpesvirus infection shows ballooning (intracellular edema) of keratinocytes. Eventually acantholysis occurs and intraepidermal bullae are formed. In the bullae, virus-associated acantholytic keratinocytes, some that are multinucleated, can be easily found (Figure 5).5 These cells are larger than normal keratinocytes and have steel gray nuclei with peripheral accentuation. Some of these cells are necrotic, and the remains of necrotic multinucleated acantholytic cells are easily recognized. Adnexal epithelial cells occasionally are affected by herpesvirus infection; nuclear change is similar to the epidermis. A perivascular and interstitial infiltrate of lymphocytes and neutrophils is seen. Neutrophils accumulate within the old bullae, clinically manifesting as a pustule.

Darier disease is characterized by suprabasal clefts and acantholysis above the basal layer (Figure 6).6 Similar to HHD, villi protrude within the clefts (Figure 6). Conspicuous columns of parakeratosis above the acantholytic epidermis often are observed. Dyskeratotic cells exist among acantholytic ke-ratinocytes in the granular layer and parakeratotic column, which are known as corps ronds and crops grains, respectively. A scant to moderate lymphocytic infiltrate is found in the upper dermis.

- Hernandez-Perez E. Familial benign chronic pemphigus. Cutis. 1987;39:75-77.

- Venugopal SS, Murrell DF. Diagnosis and clinical features of pemphigus vulgaris. Dermatol Clin. 2011;29:373-380, vii.

- Dasher D, Rubenstein D, Diaz LA. Pemphigus foliaceus. Curr Dir Autoimmun. 2008;10:182-194.

- Ohata C, Akamatsu K, Imai N, et al. Localized pemphigus foliaceus exclusively involving the follicular infundibulum: a novel peau d’orange appearance. Eur J Dermatol. 2011;21:392-395.

- King DF, King LA. Giant cells in lesions of varicella and herpes zoster. Am J Dermatopathol. 1986;8:456-458.

- Burge S. Management of Darier’s disease. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1999;24:53-56.

Hailey-Hailey disease (HHD), or benign familial chronic pemphigus, typically presents as suprabasal blisters with a perivascular and interstitial lymphocytic infiltrate (Figure 1).1 Villi, or elongated dermal papillae lined with a single layer of basal cells, protrude into the bullae (Figure 2). In HHD lesions, the epidermis is thickened with scale-crust, and at least the lower half of the epidermis shows acantholysis. Despite the acantholytic changes, a few intact intercellular bridges remain, giving the appearance of a dilapidated brick wall (Figure 2). There may be dyskeratotic cells among the acantholytic cells, though they are scant in many cases. These acantholytic dyskeratotic cells have eosinophilic polygonal-shaped cytoplasm. Hailey-Hailey disease typically does not show adnexal extension of the acantholysis. Direct immunofluorescence is negative in HHD.

Pemphigus vulgaris is an autoimmune intraepidermal bullous disease that presents with suprabasal acantholysis (Figure 3).2 The epidermis is not thickened and acantholysis is limited to the suprabasal layer. Acantholytic cells with eosinophils and/or neutrophils are found within the bullae. Perivascular and interstitial infiltrates of lymphocytes, eosinophils, and occasionally neutrophils are seen; however, the inflammatory cell infiltrate can vary from extensive to scant. Direct immunofluorescence usually reveals IgG and/or C3 deposition on the surface of the keratinocytes throughout the epidermis.

Pemphigus foliaceus is another autoimmune intraepidermal bullous disease that is characterized by acantholysis in the granular or upper spinous layers (Figure 4).3 The epidermis is not thickened. Sometimes acantholytic cells show dyskeratotic change (Figure 4). Some biopsy specimens do not contain the roof of the bullae; therefore, only erosion is seen and the diagnosis may be missed. Moreover, when only the adnexal epithelium shows acantholysis without epidermal involvement, diagnosis can be difficult.4 Acantholysis is accompanied with a superficial perivascular and interstitial inflammatory cell infiltrate consisting of lymphocytes, eosinophils, and occasionally neutrophils. The amount of inflammatory cell infiltrate may vary. Bullous impetigo and staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome reveal a similar histopathologic pattern. Direct immunofluorescence usually discloses IgG and/or C3 deposition on cell surfaces of keratinocytes in the entire or upper epidermis.

Herpesvirus infection shows ballooning (intracellular edema) of keratinocytes. Eventually acantholysis occurs and intraepidermal bullae are formed. In the bullae, virus-associated acantholytic keratinocytes, some that are multinucleated, can be easily found (Figure 5).5 These cells are larger than normal keratinocytes and have steel gray nuclei with peripheral accentuation. Some of these cells are necrotic, and the remains of necrotic multinucleated acantholytic cells are easily recognized. Adnexal epithelial cells occasionally are affected by herpesvirus infection; nuclear change is similar to the epidermis. A perivascular and interstitial infiltrate of lymphocytes and neutrophils is seen. Neutrophils accumulate within the old bullae, clinically manifesting as a pustule.

Darier disease is characterized by suprabasal clefts and acantholysis above the basal layer (Figure 6).6 Similar to HHD, villi protrude within the clefts (Figure 6). Conspicuous columns of parakeratosis above the acantholytic epidermis often are observed. Dyskeratotic cells exist among acantholytic ke-ratinocytes in the granular layer and parakeratotic column, which are known as corps ronds and crops grains, respectively. A scant to moderate lymphocytic infiltrate is found in the upper dermis.

Hailey-Hailey disease (HHD), or benign familial chronic pemphigus, typically presents as suprabasal blisters with a perivascular and interstitial lymphocytic infiltrate (Figure 1).1 Villi, or elongated dermal papillae lined with a single layer of basal cells, protrude into the bullae (Figure 2). In HHD lesions, the epidermis is thickened with scale-crust, and at least the lower half of the epidermis shows acantholysis. Despite the acantholytic changes, a few intact intercellular bridges remain, giving the appearance of a dilapidated brick wall (Figure 2). There may be dyskeratotic cells among the acantholytic cells, though they are scant in many cases. These acantholytic dyskeratotic cells have eosinophilic polygonal-shaped cytoplasm. Hailey-Hailey disease typically does not show adnexal extension of the acantholysis. Direct immunofluorescence is negative in HHD.

Pemphigus vulgaris is an autoimmune intraepidermal bullous disease that presents with suprabasal acantholysis (Figure 3).2 The epidermis is not thickened and acantholysis is limited to the suprabasal layer. Acantholytic cells with eosinophils and/or neutrophils are found within the bullae. Perivascular and interstitial infiltrates of lymphocytes, eosinophils, and occasionally neutrophils are seen; however, the inflammatory cell infiltrate can vary from extensive to scant. Direct immunofluorescence usually reveals IgG and/or C3 deposition on the surface of the keratinocytes throughout the epidermis.