User login

Chromoblastomycosis

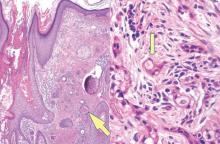

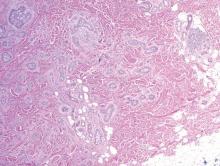

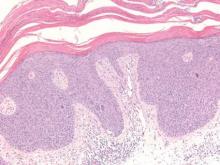

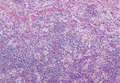

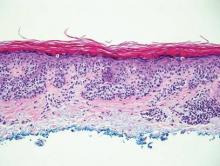

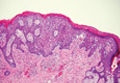

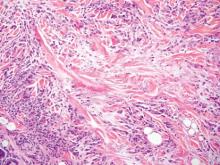

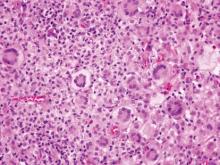

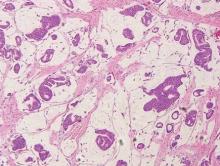

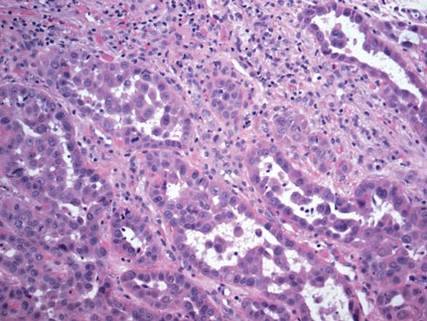

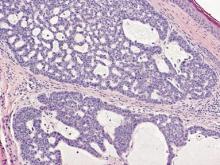

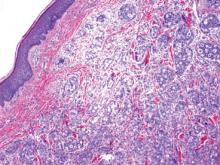

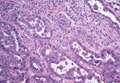

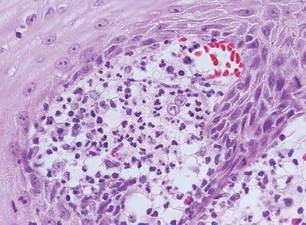

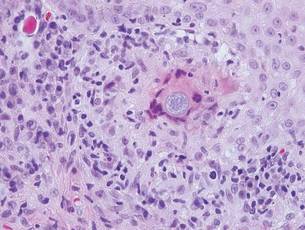

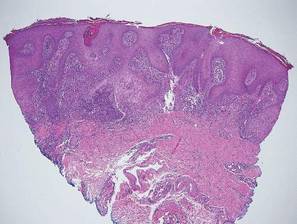

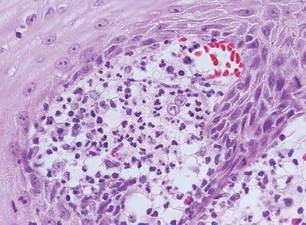

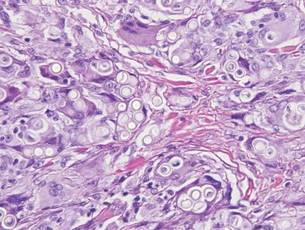

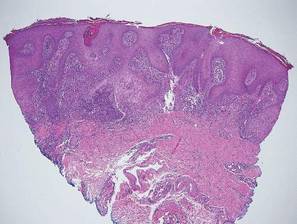

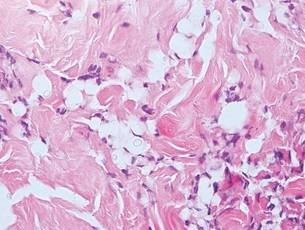

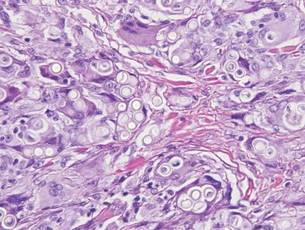

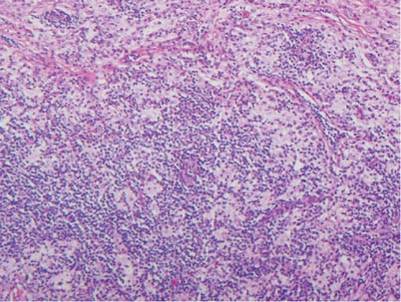

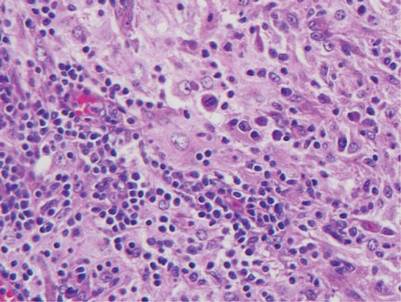

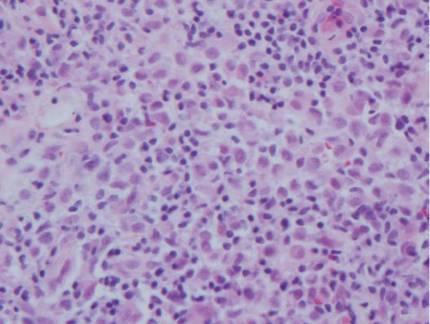

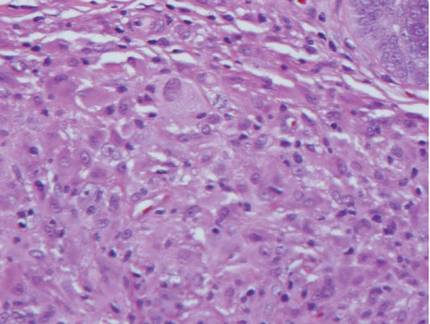

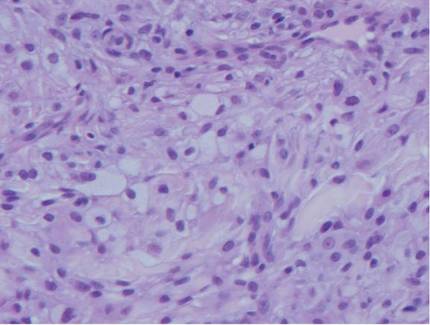

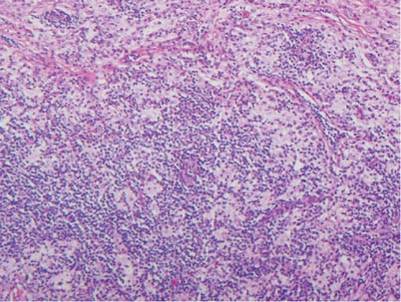

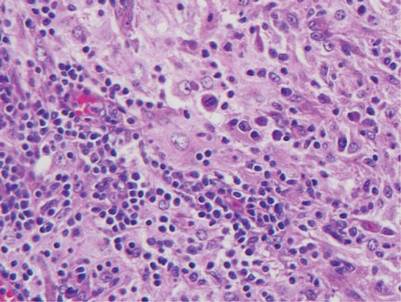

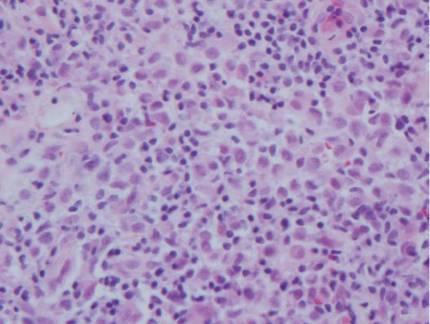

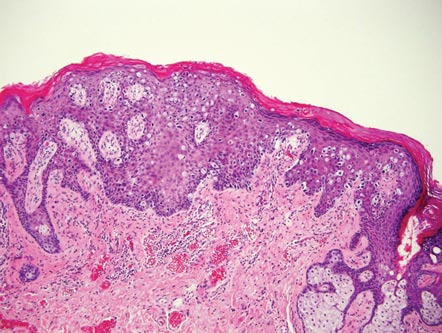

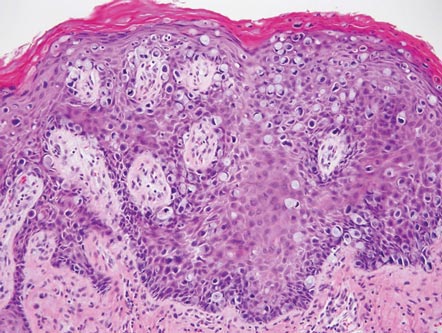

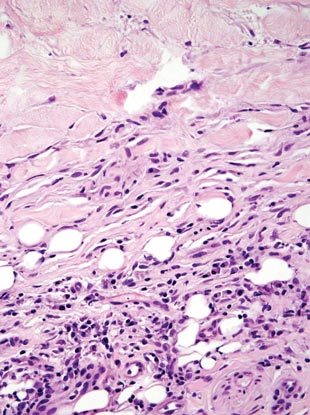

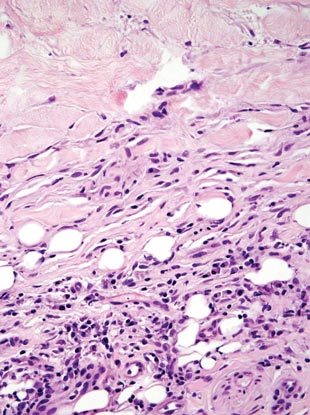

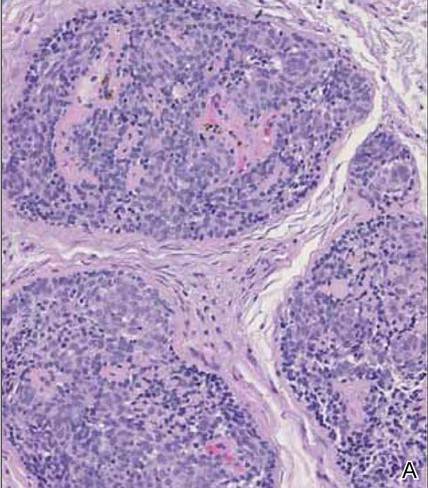

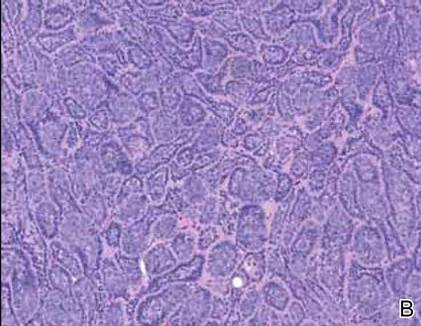

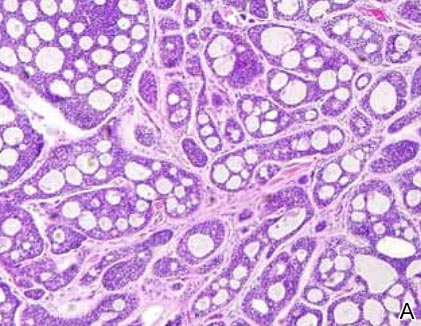

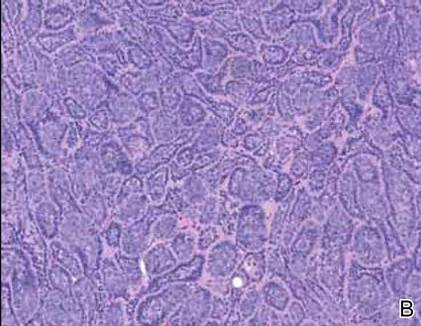

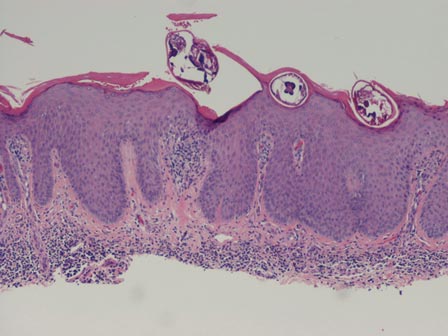

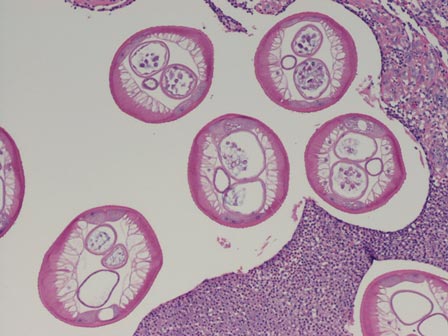

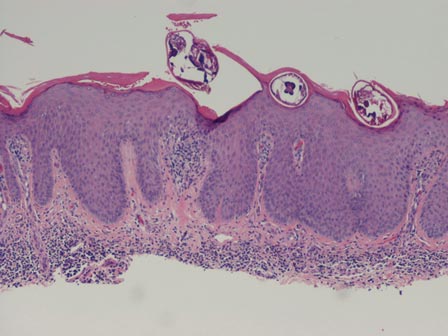

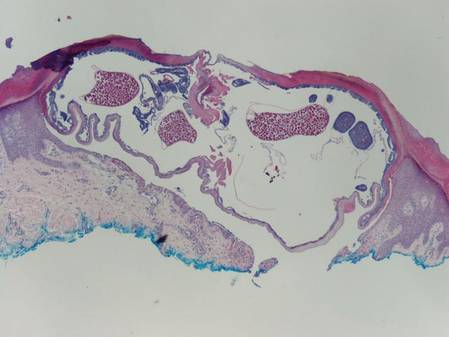

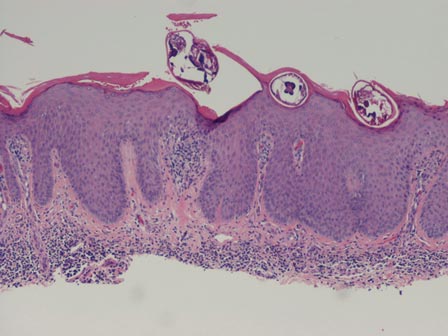

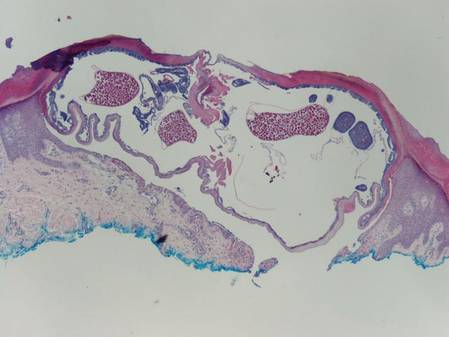

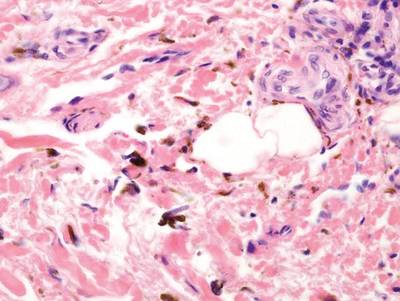

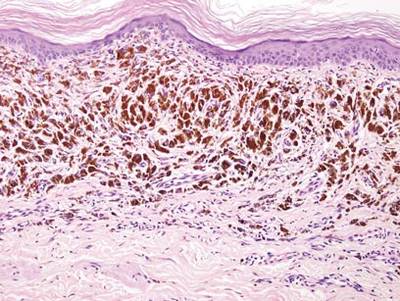

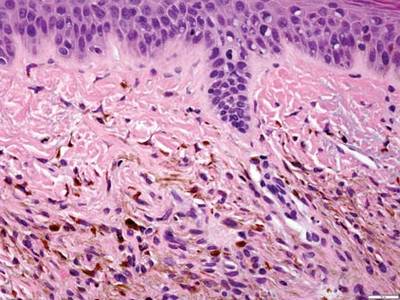

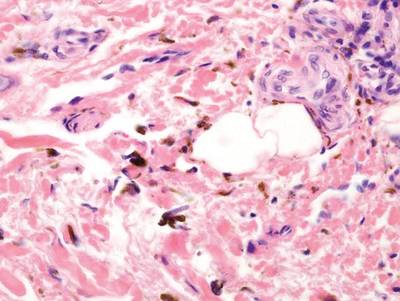

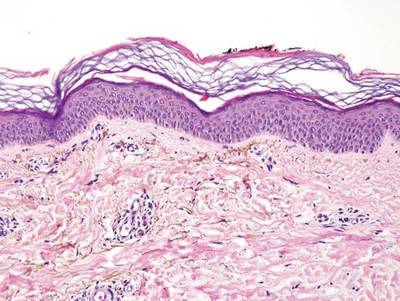

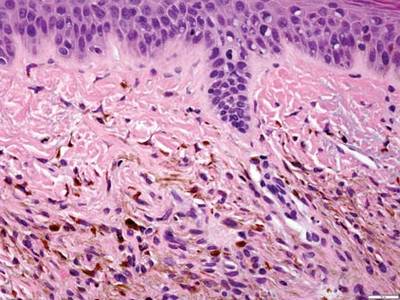

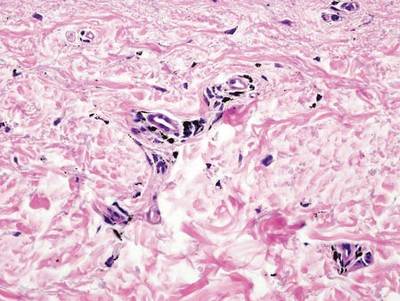

Chromoblastomycosis is a chronic fungal infection of the skin and subcutaneous tissues that demonstrates characteristic Medlar or sclerotic bodies that resemble copper pennies on histopathology.1 Cutaneous infection often results from direct inoculation, such as from a wood splinter. Clinically, the lesion typically is a pink papule that progresses to a verrucous plaque on the legs of farmers or rural workers in the tropics or subtropics. There usually are no associated constitutional symptoms. Several dematiaceous (darkly pigmented) fungi cause chromoblastomycosis, including Fonsecaea compacta, Cladophialophora carrionii, Rhinocladiella aquaspersa, Phialophora verrucosa, and Fonsecaea pedrosoi. Cellular division occurs by internal septation rather than budding. Skin biopsy can confirm the diagnosis.1 Chromoblastomycosis is histopathologically characterized by pseudoepitheli- omatous hyperplasia (Figure 1) with histiocytes and neutrophils surrounding distinct copper-colored Medlar bodies (6–12 μm)(Figure 2), which are fungal spores.1-3 Several conditions demonstrate pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia with intraepidermal pustules and can be remembered by the mnemonic “here come big green leafy vegetables”: halogenoderma, chromoblastomycosis, blastomycosis, granuloma inguinale, leishmaniasis, and pemphigus vegetans.2 Treatment of chromoblastomycosis can be challenging, as no standard treatment has been established and therapy can be complicated by low cure rates and high relapse rates, especially in chronic and extensive disease. Treatment can include cryotherapy or surgical excision for small lesions in combination with systemic antifungals.4 Itraconazole (200–400 mg daily) for at least 6 months has been reported to have up to a 90% cure rate with mild to moderate disease and 44% with severe disease.5 Combination oral antifungal treatment with itraconazole and terbinafine has been recommended.6 There are reports of progression of chromoblastomycosis to squamous cell carcinoma, which is rare and occurred after long-standing, inadequately treated lesions.7

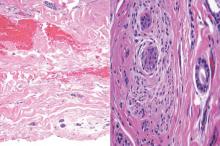

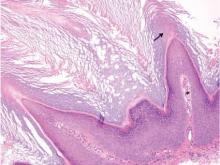

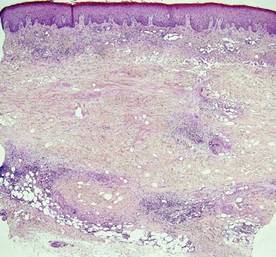

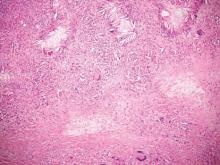

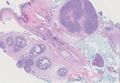

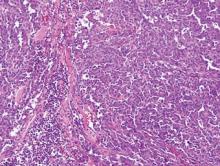

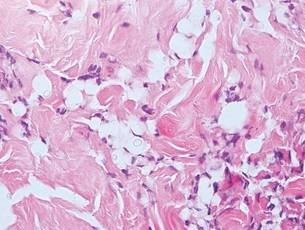

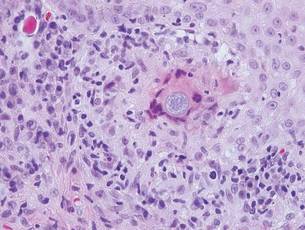

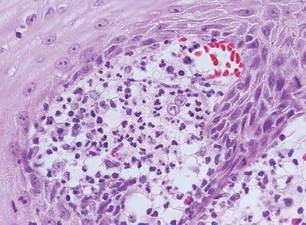

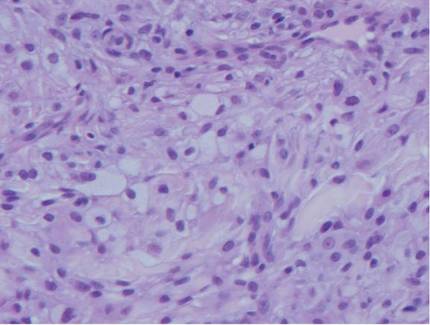

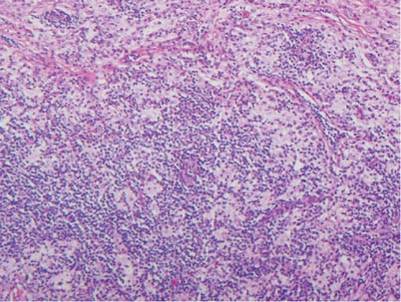

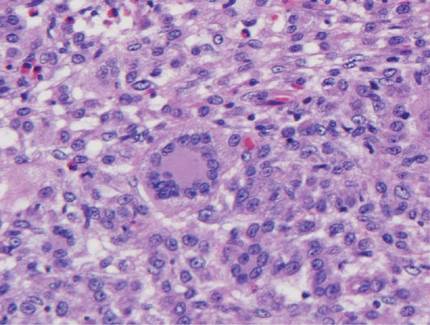

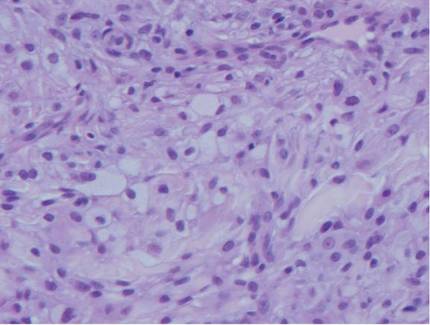

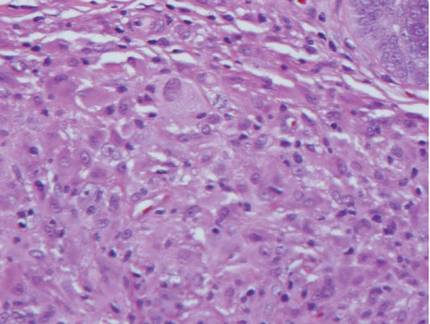

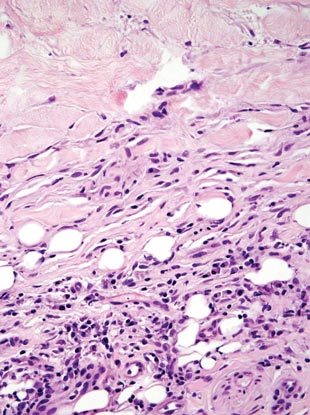

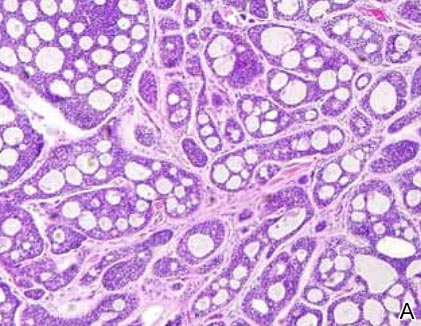

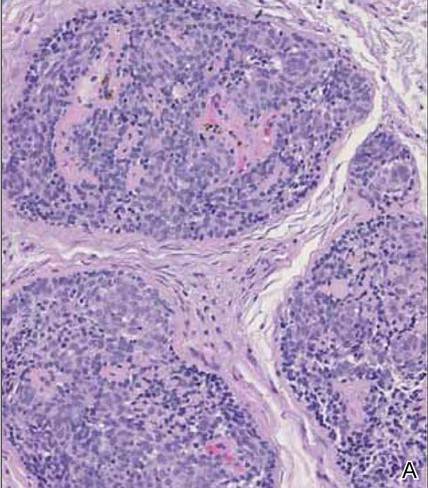

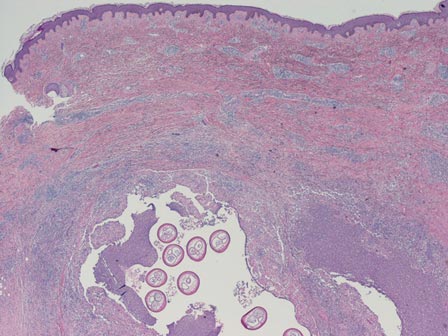

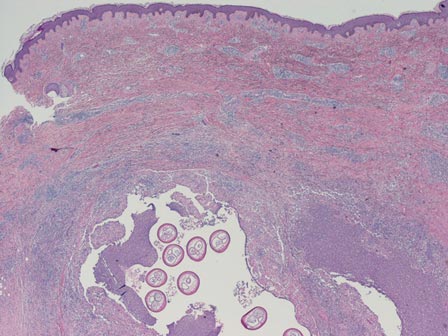

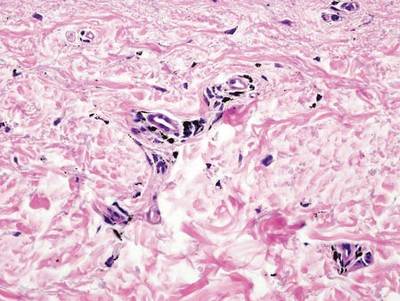

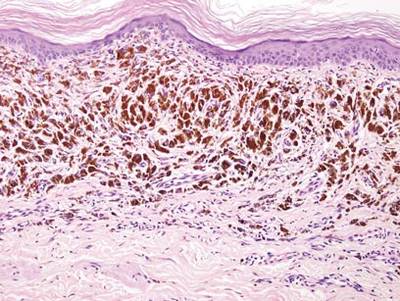

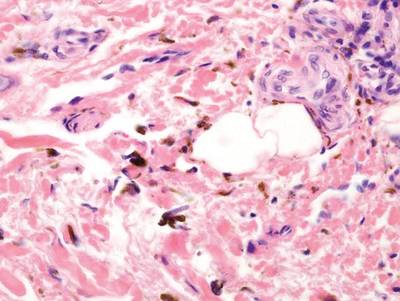

Blastomycosis also presents with pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia, as seen in chromoblastomycosis, but organisms typically are few in number and demonstrate a thick, asymmetrical, refractile wall and a dark nucleus. Although chromoblastomycosis and blastomycosis are similar in size (8–15 μm), the broad-based budding of blastomycosis (Figure 3) is a key feature and the yeast are not pigmented.1-3 Blastomycosis is caused by Blastomyces dermatitidis and is endemic to the Mississippi and Ohio River valleys, Great Lakes region, and Southeastern United States. Cutaneous infection typically occurs from inhalation of the dimorphic fungi into the lungs and occasional dissemination involving the skin, causing papulopustules and thick, crusted, warty plaques with central ulceration. Rarely, primary cutaneous blastomycosis can occur from direct inoculation, typically in a laboratory. Treatment of disseminated blastomycosis includes systemic antifungals.1

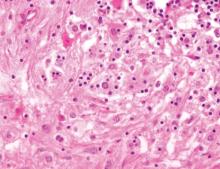

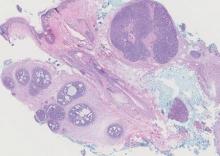

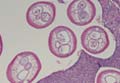

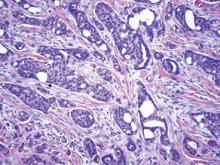

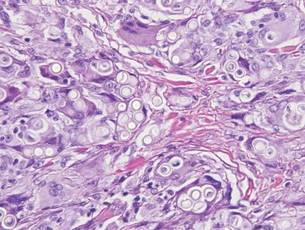

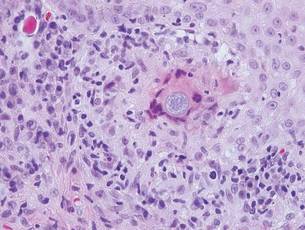

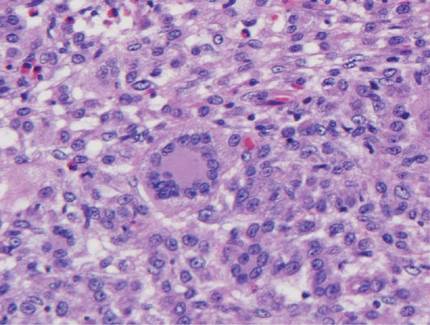

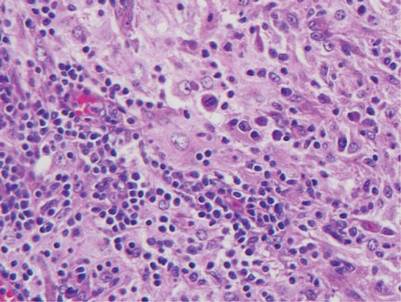

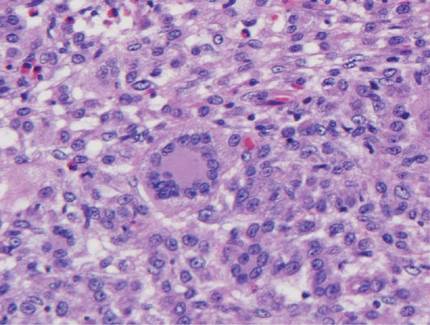

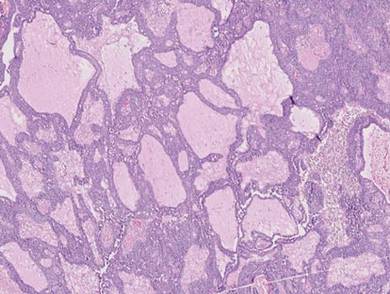

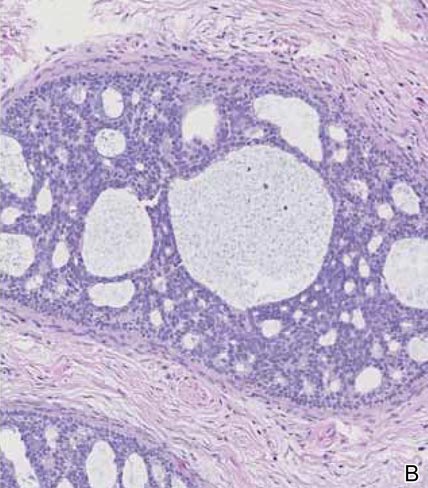

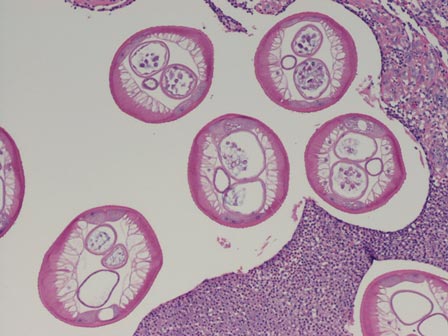

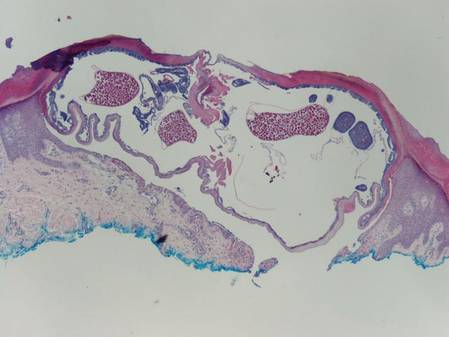

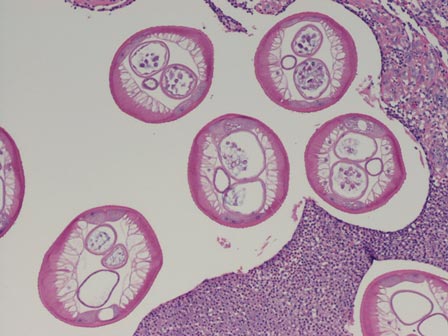

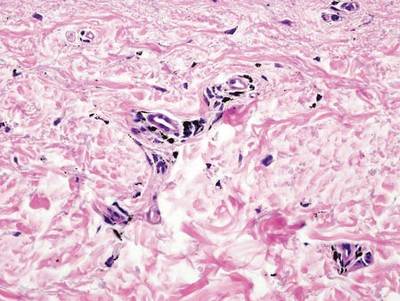

Coccidioidomycosis is characterized by large spherules (10–80 μm) with refractile walls and granular gray cytoplasm.2,3 Coccidioidomycosis spherules occasionally contain endospores2 and often are noticeably larger than surrounding histiocyte nuclei (Figure 4), whereas chromoblastomycosis, blastomycosis, cryptococcosis, and lobomycosis are more similar in size to histiocyte nuclei. Coccidioidomycosis is caused by Coccidioides immitis, a highly virulent dimorphic fungus found in the Southwestern United States, northern Mexico, and Central and South America. Pulmonary infection occurs by inhalation of arthroconidia, often from soil, and is asymptomatic in most patients; however, immunocompromised patients are predisposed to disseminated cutaneous infection. Facial lesions are most common and can present as papules, pustules, plaques, abscesses, sinus tracts, and/or ulcerations. Treatment of disseminated infection requires systemic antifungals; amphotericin B has proven most effective.1

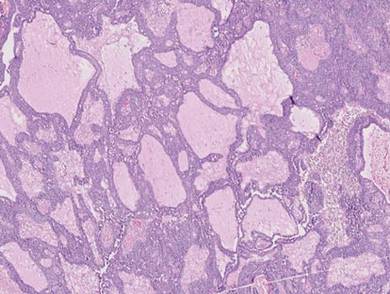

Cryptococcosis is characterized by vacuoles with small (2–20 μm), central, pleomorphic yeast (Figure 5). The vacuole is due to a gelati- nous capsule that stains red with mucicarmine and blue with Alcian blue.2,3 Cryptococcosis is caused by Cryptococcus neoformans and is associated with pigeon droppings. Disseminated infection in patients with human immunodefi- ciency virus often presents as umbilicated molluscumlike lesions and portends a poor prognosis with a mortality rate of up to 80%.8 Disseminated infection necessitates aggressive treatment with systemic antifungals.1

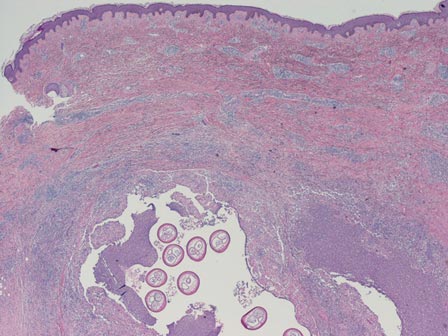

Lobomycosis demonstrates thick-walled, refractile spherules with surrounding histiocytes and multinucleated giant cells. The yeast of lobomycosis (6–12 μm) is of similar size to chromoblastomycosis and blastomycosis, but linear chains resembling a child’s pop beads are characteristic of this condition (Figure 6).2,3 Lobomycosis is caused by Lacazia loboi and is acquired most frequently through contact with dolphins in Central and South America. Clinically, lesions present as slow-growing, keloidlike nodules, often on the face, ears, and distal extremities. Surgical treatment may be required given that oral antifungals typically are ineffective.1

- Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Shaffer JV. Dermatology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2012.

- Elston DM, Ferringer TC, Ko C, et al. Dermatopathology: Requisites in Dermatology. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders Elsevier; 2014.

- Fernandez-Flores A, Saeb-Lima M, Arenas-Guzman R. Morphological findings of deep cutaneous fungal infections. Am J Dermatopathol. 2014;36:531-556.

- Ameen M. Chromoblastomycosis: clinical presentation and management. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34:849-854.

- Queiroz-Telles F, McGinnis MR, Salkin I, et al. Subcutaneous mycoses. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2003;17:59-85.

- Bonifaz A, Paredes-Solís, Saúl A. Treating chromoblastomycosis with systemic antifungals. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2004;5:247-254.

- Rojas OC, González GM, Moreno-Treviño M, et al. Chromoblastomycosis by Cladophialophora carrionii associated with squamous cell carcinoma and review of published reports. Mycopathologia. 2015;179:153-157.

- Durden FM, Elewski B. Cutaneous involvement with Cryptococcus neoformans in AIDS. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;30:844-848.

Chromoblastomycosis is a chronic fungal infection of the skin and subcutaneous tissues that demonstrates characteristic Medlar or sclerotic bodies that resemble copper pennies on histopathology.1 Cutaneous infection often results from direct inoculation, such as from a wood splinter. Clinically, the lesion typically is a pink papule that progresses to a verrucous plaque on the legs of farmers or rural workers in the tropics or subtropics. There usually are no associated constitutional symptoms. Several dematiaceous (darkly pigmented) fungi cause chromoblastomycosis, including Fonsecaea compacta, Cladophialophora carrionii, Rhinocladiella aquaspersa, Phialophora verrucosa, and Fonsecaea pedrosoi. Cellular division occurs by internal septation rather than budding. Skin biopsy can confirm the diagnosis.1 Chromoblastomycosis is histopathologically characterized by pseudoepitheli- omatous hyperplasia (Figure 1) with histiocytes and neutrophils surrounding distinct copper-colored Medlar bodies (6–12 μm)(Figure 2), which are fungal spores.1-3 Several conditions demonstrate pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia with intraepidermal pustules and can be remembered by the mnemonic “here come big green leafy vegetables”: halogenoderma, chromoblastomycosis, blastomycosis, granuloma inguinale, leishmaniasis, and pemphigus vegetans.2 Treatment of chromoblastomycosis can be challenging, as no standard treatment has been established and therapy can be complicated by low cure rates and high relapse rates, especially in chronic and extensive disease. Treatment can include cryotherapy or surgical excision for small lesions in combination with systemic antifungals.4 Itraconazole (200–400 mg daily) for at least 6 months has been reported to have up to a 90% cure rate with mild to moderate disease and 44% with severe disease.5 Combination oral antifungal treatment with itraconazole and terbinafine has been recommended.6 There are reports of progression of chromoblastomycosis to squamous cell carcinoma, which is rare and occurred after long-standing, inadequately treated lesions.7

Blastomycosis also presents with pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia, as seen in chromoblastomycosis, but organisms typically are few in number and demonstrate a thick, asymmetrical, refractile wall and a dark nucleus. Although chromoblastomycosis and blastomycosis are similar in size (8–15 μm), the broad-based budding of blastomycosis (Figure 3) is a key feature and the yeast are not pigmented.1-3 Blastomycosis is caused by Blastomyces dermatitidis and is endemic to the Mississippi and Ohio River valleys, Great Lakes region, and Southeastern United States. Cutaneous infection typically occurs from inhalation of the dimorphic fungi into the lungs and occasional dissemination involving the skin, causing papulopustules and thick, crusted, warty plaques with central ulceration. Rarely, primary cutaneous blastomycosis can occur from direct inoculation, typically in a laboratory. Treatment of disseminated blastomycosis includes systemic antifungals.1

Coccidioidomycosis is characterized by large spherules (10–80 μm) with refractile walls and granular gray cytoplasm.2,3 Coccidioidomycosis spherules occasionally contain endospores2 and often are noticeably larger than surrounding histiocyte nuclei (Figure 4), whereas chromoblastomycosis, blastomycosis, cryptococcosis, and lobomycosis are more similar in size to histiocyte nuclei. Coccidioidomycosis is caused by Coccidioides immitis, a highly virulent dimorphic fungus found in the Southwestern United States, northern Mexico, and Central and South America. Pulmonary infection occurs by inhalation of arthroconidia, often from soil, and is asymptomatic in most patients; however, immunocompromised patients are predisposed to disseminated cutaneous infection. Facial lesions are most common and can present as papules, pustules, plaques, abscesses, sinus tracts, and/or ulcerations. Treatment of disseminated infection requires systemic antifungals; amphotericin B has proven most effective.1

Cryptococcosis is characterized by vacuoles with small (2–20 μm), central, pleomorphic yeast (Figure 5). The vacuole is due to a gelati- nous capsule that stains red with mucicarmine and blue with Alcian blue.2,3 Cryptococcosis is caused by Cryptococcus neoformans and is associated with pigeon droppings. Disseminated infection in patients with human immunodefi- ciency virus often presents as umbilicated molluscumlike lesions and portends a poor prognosis with a mortality rate of up to 80%.8 Disseminated infection necessitates aggressive treatment with systemic antifungals.1

Lobomycosis demonstrates thick-walled, refractile spherules with surrounding histiocytes and multinucleated giant cells. The yeast of lobomycosis (6–12 μm) is of similar size to chromoblastomycosis and blastomycosis, but linear chains resembling a child’s pop beads are characteristic of this condition (Figure 6).2,3 Lobomycosis is caused by Lacazia loboi and is acquired most frequently through contact with dolphins in Central and South America. Clinically, lesions present as slow-growing, keloidlike nodules, often on the face, ears, and distal extremities. Surgical treatment may be required given that oral antifungals typically are ineffective.1

Chromoblastomycosis is a chronic fungal infection of the skin and subcutaneous tissues that demonstrates characteristic Medlar or sclerotic bodies that resemble copper pennies on histopathology.1 Cutaneous infection often results from direct inoculation, such as from a wood splinter. Clinically, the lesion typically is a pink papule that progresses to a verrucous plaque on the legs of farmers or rural workers in the tropics or subtropics. There usually are no associated constitutional symptoms. Several dematiaceous (darkly pigmented) fungi cause chromoblastomycosis, including Fonsecaea compacta, Cladophialophora carrionii, Rhinocladiella aquaspersa, Phialophora verrucosa, and Fonsecaea pedrosoi. Cellular division occurs by internal septation rather than budding. Skin biopsy can confirm the diagnosis.1 Chromoblastomycosis is histopathologically characterized by pseudoepitheli- omatous hyperplasia (Figure 1) with histiocytes and neutrophils surrounding distinct copper-colored Medlar bodies (6–12 μm)(Figure 2), which are fungal spores.1-3 Several conditions demonstrate pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia with intraepidermal pustules and can be remembered by the mnemonic “here come big green leafy vegetables”: halogenoderma, chromoblastomycosis, blastomycosis, granuloma inguinale, leishmaniasis, and pemphigus vegetans.2 Treatment of chromoblastomycosis can be challenging, as no standard treatment has been established and therapy can be complicated by low cure rates and high relapse rates, especially in chronic and extensive disease. Treatment can include cryotherapy or surgical excision for small lesions in combination with systemic antifungals.4 Itraconazole (200–400 mg daily) for at least 6 months has been reported to have up to a 90% cure rate with mild to moderate disease and 44% with severe disease.5 Combination oral antifungal treatment with itraconazole and terbinafine has been recommended.6 There are reports of progression of chromoblastomycosis to squamous cell carcinoma, which is rare and occurred after long-standing, inadequately treated lesions.7

Blastomycosis also presents with pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia, as seen in chromoblastomycosis, but organisms typically are few in number and demonstrate a thick, asymmetrical, refractile wall and a dark nucleus. Although chromoblastomycosis and blastomycosis are similar in size (8–15 μm), the broad-based budding of blastomycosis (Figure 3) is a key feature and the yeast are not pigmented.1-3 Blastomycosis is caused by Blastomyces dermatitidis and is endemic to the Mississippi and Ohio River valleys, Great Lakes region, and Southeastern United States. Cutaneous infection typically occurs from inhalation of the dimorphic fungi into the lungs and occasional dissemination involving the skin, causing papulopustules and thick, crusted, warty plaques with central ulceration. Rarely, primary cutaneous blastomycosis can occur from direct inoculation, typically in a laboratory. Treatment of disseminated blastomycosis includes systemic antifungals.1

Coccidioidomycosis is characterized by large spherules (10–80 μm) with refractile walls and granular gray cytoplasm.2,3 Coccidioidomycosis spherules occasionally contain endospores2 and often are noticeably larger than surrounding histiocyte nuclei (Figure 4), whereas chromoblastomycosis, blastomycosis, cryptococcosis, and lobomycosis are more similar in size to histiocyte nuclei. Coccidioidomycosis is caused by Coccidioides immitis, a highly virulent dimorphic fungus found in the Southwestern United States, northern Mexico, and Central and South America. Pulmonary infection occurs by inhalation of arthroconidia, often from soil, and is asymptomatic in most patients; however, immunocompromised patients are predisposed to disseminated cutaneous infection. Facial lesions are most common and can present as papules, pustules, plaques, abscesses, sinus tracts, and/or ulcerations. Treatment of disseminated infection requires systemic antifungals; amphotericin B has proven most effective.1

Cryptococcosis is characterized by vacuoles with small (2–20 μm), central, pleomorphic yeast (Figure 5). The vacuole is due to a gelati- nous capsule that stains red with mucicarmine and blue with Alcian blue.2,3 Cryptococcosis is caused by Cryptococcus neoformans and is associated with pigeon droppings. Disseminated infection in patients with human immunodefi- ciency virus often presents as umbilicated molluscumlike lesions and portends a poor prognosis with a mortality rate of up to 80%.8 Disseminated infection necessitates aggressive treatment with systemic antifungals.1

Lobomycosis demonstrates thick-walled, refractile spherules with surrounding histiocytes and multinucleated giant cells. The yeast of lobomycosis (6–12 μm) is of similar size to chromoblastomycosis and blastomycosis, but linear chains resembling a child’s pop beads are characteristic of this condition (Figure 6).2,3 Lobomycosis is caused by Lacazia loboi and is acquired most frequently through contact with dolphins in Central and South America. Clinically, lesions present as slow-growing, keloidlike nodules, often on the face, ears, and distal extremities. Surgical treatment may be required given that oral antifungals typically are ineffective.1

- Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Shaffer JV. Dermatology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2012.

- Elston DM, Ferringer TC, Ko C, et al. Dermatopathology: Requisites in Dermatology. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders Elsevier; 2014.

- Fernandez-Flores A, Saeb-Lima M, Arenas-Guzman R. Morphological findings of deep cutaneous fungal infections. Am J Dermatopathol. 2014;36:531-556.

- Ameen M. Chromoblastomycosis: clinical presentation and management. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34:849-854.

- Queiroz-Telles F, McGinnis MR, Salkin I, et al. Subcutaneous mycoses. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2003;17:59-85.

- Bonifaz A, Paredes-Solís, Saúl A. Treating chromoblastomycosis with systemic antifungals. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2004;5:247-254.

- Rojas OC, González GM, Moreno-Treviño M, et al. Chromoblastomycosis by Cladophialophora carrionii associated with squamous cell carcinoma and review of published reports. Mycopathologia. 2015;179:153-157.

- Durden FM, Elewski B. Cutaneous involvement with Cryptococcus neoformans in AIDS. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;30:844-848.

- Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Shaffer JV. Dermatology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2012.

- Elston DM, Ferringer TC, Ko C, et al. Dermatopathology: Requisites in Dermatology. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders Elsevier; 2014.

- Fernandez-Flores A, Saeb-Lima M, Arenas-Guzman R. Morphological findings of deep cutaneous fungal infections. Am J Dermatopathol. 2014;36:531-556.

- Ameen M. Chromoblastomycosis: clinical presentation and management. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34:849-854.

- Queiroz-Telles F, McGinnis MR, Salkin I, et al. Subcutaneous mycoses. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2003;17:59-85.

- Bonifaz A, Paredes-Solís, Saúl A. Treating chromoblastomycosis with systemic antifungals. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2004;5:247-254.

- Rojas OC, González GM, Moreno-Treviño M, et al. Chromoblastomycosis by Cladophialophora carrionii associated with squamous cell carcinoma and review of published reports. Mycopathologia. 2015;179:153-157.

- Durden FM, Elewski B. Cutaneous involvement with Cryptococcus neoformans in AIDS. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;30:844-848.

Syringoid Eccrine Carcinoma

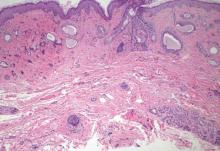

Syringoid eccrine carcinoma is a rare malignant adnexal tumor with eccrine differentiation that histologically resembles a syringoma.1 Originally described as eccrine epithelioma by Freeman and Winklemann2 in 1969, syringoid eccrine carcinoma has been reported in the literature as eccrine carcinoma, eccrine syringomatous carcinoma, and sclerosing sweat duct carcinoma.3 Clinically, syringoid eccrine carcinoma most commonly presents as a tender plaque or nodule on the scalp, and histologic examination generally reveals a dermal-based lesion that rarely shows epidermal connection. It demonstrates syringomalike tadpole morphology (epithelial strands with lumen formation) composed of basaloid epithelium with uniform hyperchromatic nuclei (Figure 1). There usually is an infiltrative growth pattern to the subcutis (Figure 2 [left]) or skeletal muscle as well as remarkable perineural invasion (Figure 2 [right]). Mitotic activity is minimal to absent. The tumor cells of syringoid eccrine carcinoma typically show positive immuno-staining for high- and low-molecular-weight cytokeratin, while the lumina are highlighted by epithelial membrane antigen and carcinoembryonic antigen.4 However, immunohistochemistry often is not contributory in diagnosing primary eccrine carcinomas.

The differential diagnosis of syringoid eccrine carcinoma includes cutaneous adenoid cystic carcinoma, metastatic adenocarcinoma, sclerosing basal cell carcinoma, and syringoma. Cutaneous adenoid cystic carcinoma is a rare, slow-growing, flesh-colored tumor that consists of lobules, islands, and cords of basaloid cells with prominent cystic cribriforming (Figure 3). The tumor cells typically are small, cuboidal, and monomorphic. Metastatic adenoid cystic carcinoma, such as from a primary tumor of the salivary glands or breasts, must be excluded before rendering a diagnosis of primary cutaneous disease.

Metastatic adenocarcinoma of the skin usually presents in patients with a clinical history of preexisting disease. The breasts, colon, stomach, and ovaries are common origins of metastases. The histopathologic and immunohistochemical findings depend on the particular site of origin of the metastasis. Compared with primary eccrine carcinomas, metastatic adenocarcinomas of the skin generally are high-grade lesions with prominent atypia, mitosis, and necrosis (Figure 4).

Sclerosing basal cell carcinoma shows basaloid tumor cells with deep infiltration. Unlike syringoid eccrine carcinoma, basal cell carcinoma is an epidermal tumor that does not have true lumen formation. Furthermore, other variants of basal cell carcinoma, including nodular, micronodular, or superficial multicentric tumors, often coexist with the sclerosing variant in the same lesion and constitute a useful diagnostic clue (Figure 5). Staining for epithelial membrane antigen may be useful in identifying the absence of lumen formation, and Ber-EP4 highlights the epidermal origin of the lesion.5

Syringomas most commonly present as multiple small flesh-colored papules on the eyelids. On histology, syringomas present as small superficial dermal lesions composed of small ducts that may form tadpolelike structures in a fibrotic stroma (Figure 6). The ducts are lined by benign cuboidal cells. In contrast to syringoid eccrine carcinomas, syringomas usually present as multiple lesions that are microscopically superficial without perineural involvement.

1. Sidiropoulos M, Sade S, Al-Habeeb A, et al. Syringoid eccrine carcinoma: a clinicopathological and immunohistochemical study of four cases. J Clin Pathol. 2011;64:788-792.

2. Freeman RG, Winklemann RK. Basal cell tumor with eccrine differentiations (eccrine epithelioma). Arch Dermatol. 1969;100:234-242.

3. Nishizawa A, Nakanishi Y, Sasajima Y, et al. Syringoid carcinoma with apparently aggressive transformation: case report and review of the literature. Int J Dermatol. 2006;45:1218-1221.

4. Urso C, Bondi R, Paglierani M, et al. Carcinomas of sweat glands: report of 60 cases. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2001;125:498-505.

5. Cassarino D. Diagnostic Pathology: Neoplastic Dermatopathology. Salt Lake City, UT: Amirsys Publishing Inc; 2012.

Syringoid eccrine carcinoma is a rare malignant adnexal tumor with eccrine differentiation that histologically resembles a syringoma.1 Originally described as eccrine epithelioma by Freeman and Winklemann2 in 1969, syringoid eccrine carcinoma has been reported in the literature as eccrine carcinoma, eccrine syringomatous carcinoma, and sclerosing sweat duct carcinoma.3 Clinically, syringoid eccrine carcinoma most commonly presents as a tender plaque or nodule on the scalp, and histologic examination generally reveals a dermal-based lesion that rarely shows epidermal connection. It demonstrates syringomalike tadpole morphology (epithelial strands with lumen formation) composed of basaloid epithelium with uniform hyperchromatic nuclei (Figure 1). There usually is an infiltrative growth pattern to the subcutis (Figure 2 [left]) or skeletal muscle as well as remarkable perineural invasion (Figure 2 [right]). Mitotic activity is minimal to absent. The tumor cells of syringoid eccrine carcinoma typically show positive immuno-staining for high- and low-molecular-weight cytokeratin, while the lumina are highlighted by epithelial membrane antigen and carcinoembryonic antigen.4 However, immunohistochemistry often is not contributory in diagnosing primary eccrine carcinomas.

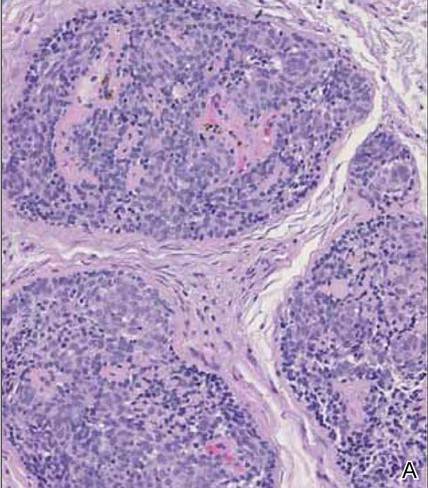

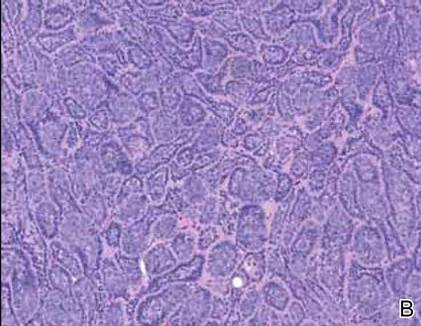

The differential diagnosis of syringoid eccrine carcinoma includes cutaneous adenoid cystic carcinoma, metastatic adenocarcinoma, sclerosing basal cell carcinoma, and syringoma. Cutaneous adenoid cystic carcinoma is a rare, slow-growing, flesh-colored tumor that consists of lobules, islands, and cords of basaloid cells with prominent cystic cribriforming (Figure 3). The tumor cells typically are small, cuboidal, and monomorphic. Metastatic adenoid cystic carcinoma, such as from a primary tumor of the salivary glands or breasts, must be excluded before rendering a diagnosis of primary cutaneous disease.

Metastatic adenocarcinoma of the skin usually presents in patients with a clinical history of preexisting disease. The breasts, colon, stomach, and ovaries are common origins of metastases. The histopathologic and immunohistochemical findings depend on the particular site of origin of the metastasis. Compared with primary eccrine carcinomas, metastatic adenocarcinomas of the skin generally are high-grade lesions with prominent atypia, mitosis, and necrosis (Figure 4).

Sclerosing basal cell carcinoma shows basaloid tumor cells with deep infiltration. Unlike syringoid eccrine carcinoma, basal cell carcinoma is an epidermal tumor that does not have true lumen formation. Furthermore, other variants of basal cell carcinoma, including nodular, micronodular, or superficial multicentric tumors, often coexist with the sclerosing variant in the same lesion and constitute a useful diagnostic clue (Figure 5). Staining for epithelial membrane antigen may be useful in identifying the absence of lumen formation, and Ber-EP4 highlights the epidermal origin of the lesion.5

Syringomas most commonly present as multiple small flesh-colored papules on the eyelids. On histology, syringomas present as small superficial dermal lesions composed of small ducts that may form tadpolelike structures in a fibrotic stroma (Figure 6). The ducts are lined by benign cuboidal cells. In contrast to syringoid eccrine carcinomas, syringomas usually present as multiple lesions that are microscopically superficial without perineural involvement.

Syringoid eccrine carcinoma is a rare malignant adnexal tumor with eccrine differentiation that histologically resembles a syringoma.1 Originally described as eccrine epithelioma by Freeman and Winklemann2 in 1969, syringoid eccrine carcinoma has been reported in the literature as eccrine carcinoma, eccrine syringomatous carcinoma, and sclerosing sweat duct carcinoma.3 Clinically, syringoid eccrine carcinoma most commonly presents as a tender plaque or nodule on the scalp, and histologic examination generally reveals a dermal-based lesion that rarely shows epidermal connection. It demonstrates syringomalike tadpole morphology (epithelial strands with lumen formation) composed of basaloid epithelium with uniform hyperchromatic nuclei (Figure 1). There usually is an infiltrative growth pattern to the subcutis (Figure 2 [left]) or skeletal muscle as well as remarkable perineural invasion (Figure 2 [right]). Mitotic activity is minimal to absent. The tumor cells of syringoid eccrine carcinoma typically show positive immuno-staining for high- and low-molecular-weight cytokeratin, while the lumina are highlighted by epithelial membrane antigen and carcinoembryonic antigen.4 However, immunohistochemistry often is not contributory in diagnosing primary eccrine carcinomas.

The differential diagnosis of syringoid eccrine carcinoma includes cutaneous adenoid cystic carcinoma, metastatic adenocarcinoma, sclerosing basal cell carcinoma, and syringoma. Cutaneous adenoid cystic carcinoma is a rare, slow-growing, flesh-colored tumor that consists of lobules, islands, and cords of basaloid cells with prominent cystic cribriforming (Figure 3). The tumor cells typically are small, cuboidal, and monomorphic. Metastatic adenoid cystic carcinoma, such as from a primary tumor of the salivary glands or breasts, must be excluded before rendering a diagnosis of primary cutaneous disease.

Metastatic adenocarcinoma of the skin usually presents in patients with a clinical history of preexisting disease. The breasts, colon, stomach, and ovaries are common origins of metastases. The histopathologic and immunohistochemical findings depend on the particular site of origin of the metastasis. Compared with primary eccrine carcinomas, metastatic adenocarcinomas of the skin generally are high-grade lesions with prominent atypia, mitosis, and necrosis (Figure 4).

Sclerosing basal cell carcinoma shows basaloid tumor cells with deep infiltration. Unlike syringoid eccrine carcinoma, basal cell carcinoma is an epidermal tumor that does not have true lumen formation. Furthermore, other variants of basal cell carcinoma, including nodular, micronodular, or superficial multicentric tumors, often coexist with the sclerosing variant in the same lesion and constitute a useful diagnostic clue (Figure 5). Staining for epithelial membrane antigen may be useful in identifying the absence of lumen formation, and Ber-EP4 highlights the epidermal origin of the lesion.5

Syringomas most commonly present as multiple small flesh-colored papules on the eyelids. On histology, syringomas present as small superficial dermal lesions composed of small ducts that may form tadpolelike structures in a fibrotic stroma (Figure 6). The ducts are lined by benign cuboidal cells. In contrast to syringoid eccrine carcinomas, syringomas usually present as multiple lesions that are microscopically superficial without perineural involvement.

1. Sidiropoulos M, Sade S, Al-Habeeb A, et al. Syringoid eccrine carcinoma: a clinicopathological and immunohistochemical study of four cases. J Clin Pathol. 2011;64:788-792.

2. Freeman RG, Winklemann RK. Basal cell tumor with eccrine differentiations (eccrine epithelioma). Arch Dermatol. 1969;100:234-242.

3. Nishizawa A, Nakanishi Y, Sasajima Y, et al. Syringoid carcinoma with apparently aggressive transformation: case report and review of the literature. Int J Dermatol. 2006;45:1218-1221.

4. Urso C, Bondi R, Paglierani M, et al. Carcinomas of sweat glands: report of 60 cases. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2001;125:498-505.

5. Cassarino D. Diagnostic Pathology: Neoplastic Dermatopathology. Salt Lake City, UT: Amirsys Publishing Inc; 2012.

1. Sidiropoulos M, Sade S, Al-Habeeb A, et al. Syringoid eccrine carcinoma: a clinicopathological and immunohistochemical study of four cases. J Clin Pathol. 2011;64:788-792.

2. Freeman RG, Winklemann RK. Basal cell tumor with eccrine differentiations (eccrine epithelioma). Arch Dermatol. 1969;100:234-242.

3. Nishizawa A, Nakanishi Y, Sasajima Y, et al. Syringoid carcinoma with apparently aggressive transformation: case report and review of the literature. Int J Dermatol. 2006;45:1218-1221.

4. Urso C, Bondi R, Paglierani M, et al. Carcinomas of sweat glands: report of 60 cases. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2001;125:498-505.

5. Cassarino D. Diagnostic Pathology: Neoplastic Dermatopathology. Salt Lake City, UT: Amirsys Publishing Inc; 2012.

Trichilemmoma

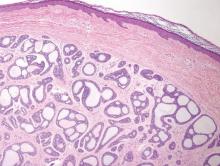

Trichilemmomas are benign follicular neoplasms that exhibit differentiation toward the outer root sheath of the pilosebaceous follicular epithelium.1 Trichilemmomas clinically present as individual or multiple, slowly growing, verrucous papules appearing most commonly on the face or neck. The lesions may coalesce to form small plaques. Although trichilemmomas typically are isolated, patients with multiple trichilemmomas require a cancer screening workup due to their association with Cowden disease, which results from a mutation in the phosphatase and tensin homolog tumor suppressor gene, PTEN.2 An easy way to remember the association between trichilemmomas and Cowden disease is to alter the spelling to “trichile-moo-moo,” using the “moo moo” sound of an animal cow as a clue linking the tumor to Cowden disease.

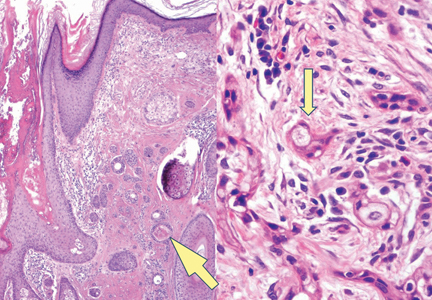

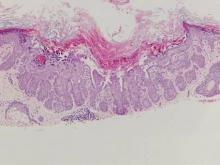

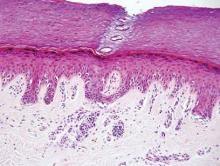

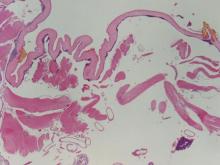

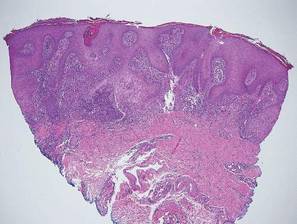

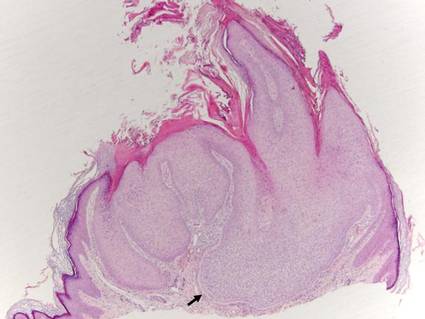

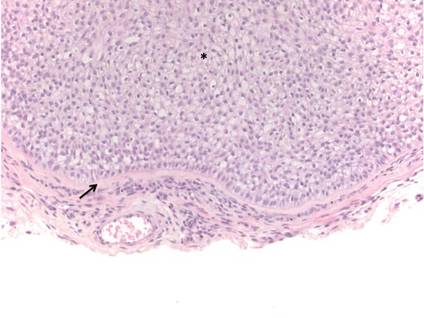

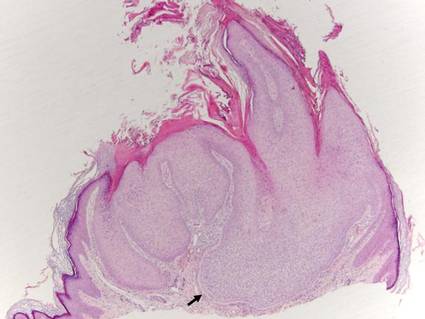

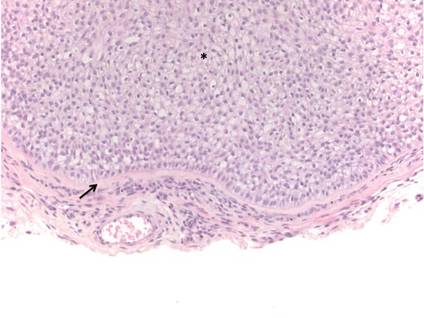

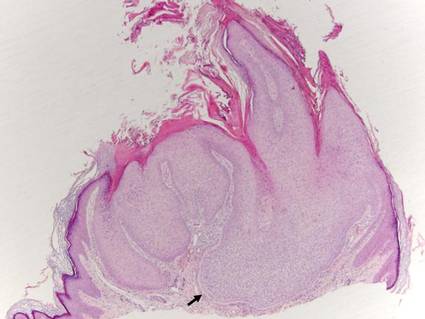

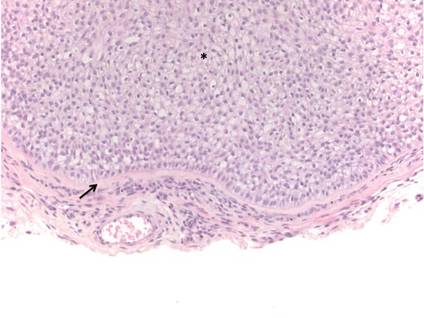

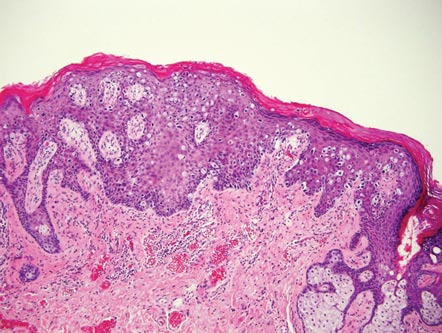

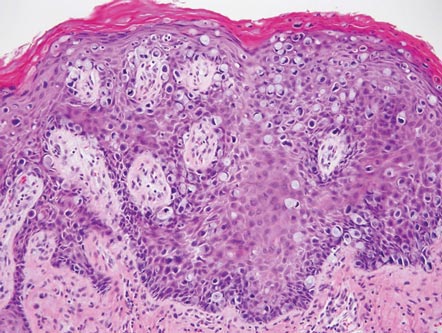

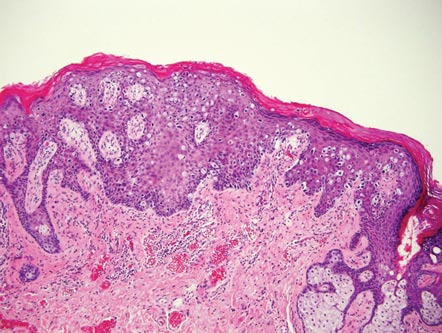

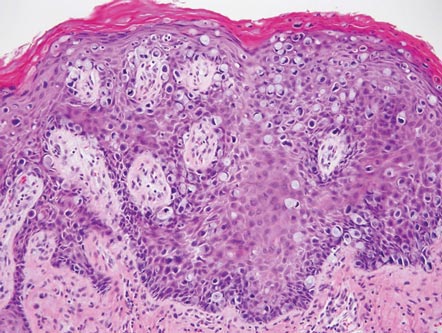

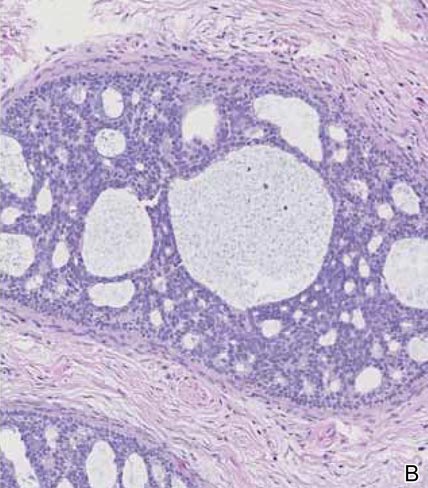

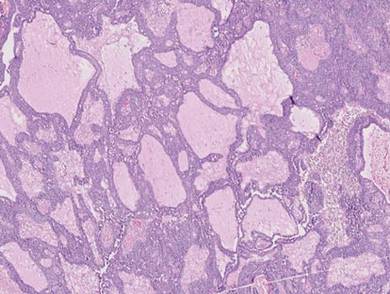

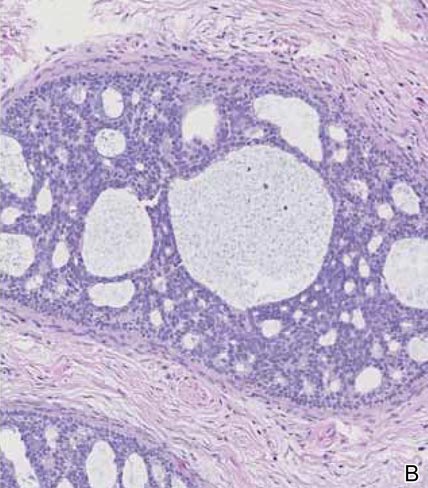

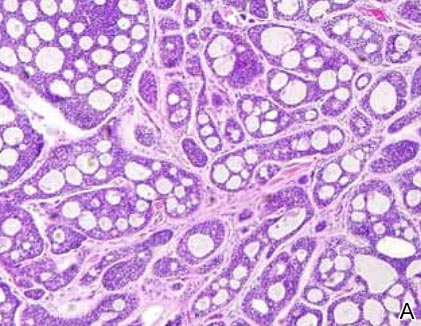

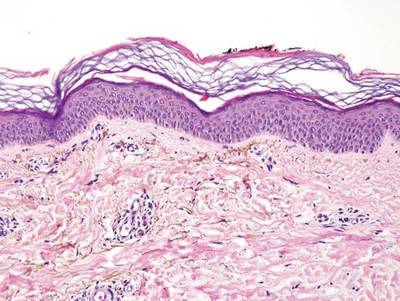

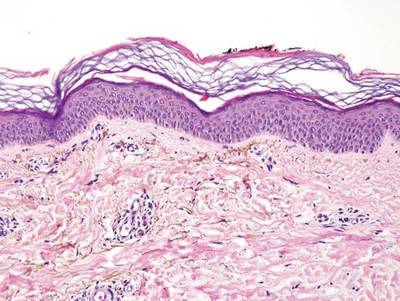

Histologically, trichilemmomas exhibit a lobular epidermal downgrowth into the dermis (Figure 1). The surface of the lesion may be hyperkeratotic and somewhat papillomatous. Cells toward the center of the lobule are pale staining, periodic acid–Schiff positive, and diastase labile due to high levels of intracellular glycogen (Figure 2). Cells toward the periphery of the lobule usually appear basophilic with a palisading arrangement of the peripheral cells. The entire lobule is enclosed within an eosinophilic basement membrane that stains positively with periodic acid–Schiff (Figure 2).1 Consistent with the tumor’s differentiation toward the outer root sheath of the hair follicle, trichilemmomas have been reported to express CD34 focally or diffusely.3

|

|

Similar to trichilemmoma, inverted follicular keratosis (IFK) commonly presents as a solitary asymptomatic papule on the face. Inverted follicular keratosis is a somewhat controversial entity, with some authorities arguing IFK is a variant of verruca vulgaris or seborrheic keratosis. Histologically, IFKs can be differentiated by the presence of squamous eddies (concentric layers of squamous cells in a whorled pattern), which are diagnostic, and central longitudinal crypts that contain keratin and are lined by squamous epithelium.4 Basaloid cells can be seen at the periphery of the tumors; however, IFKs lack an eosinophilic basement membrane surrounding the tumor (Figure 3).

Squamous cell carcinoma in situ classically appears as an erythematous hyperkeratotic papule or plaque on sun-exposed sites that can become crusted or ulcerated. Microscopically, squamous cell carcinoma in situ displays full-thickness disorderly maturation of keratinocytes. The keratinocytes exhibit nuclear pleomorphism. Atypical mitotic figures and dyskeratotic keratinocytes also can be seen throughout the full thickness of the epidermis (Figure 4).5

Verruca vulgaris (Figure 5) histologically demonstrates hyperkeratosis with tiers of parakeratosis, digitated epidermal hyperplasia, and dilated tortuous capillaries within the dermal papillae. At the edges of the lesion there often is inward turning of elongated rete ridges,6,7 which can be thought of as the rete reaching out for a hug of sorts to spread the human papillomavirus infection. Although the surface of a trichilemmoma can bear resemblance to a verruca vulgaris, the remainder of the histologic features can be used to help differentiate these tumors. Additionally, there has been no evidence suggestive of a viral etiology for trichilemmomas.8

Warty dyskeratoma features an umbilicated papule, usually on the face, head, or neck, that is associated with a follicular unit. The papule shows a cup-shaped, keratin-filled invagination; suprabasilar clefting; and acantholytic dyskeratotic cells, which are features that are not seen in trichilemmomas (Figure 6).9

Acknowledgment—The authors would like to thank Brandon Litzner, MD, St Louis, Missouri, for proofreading the manuscript.

1. Brownstein MH, Shapiro L. Trichilemmoma: analysis of 40 new cases. Arch Dermatol. 1973;107:866-869.

2. Al-Zaid T, Ditelberg J, Prieto V, et al. Trichilemmomas show loss of PTEN in Cowden syndrome but only rarely in sporadic tumors. J Cutan Pathol. 2012;39:493-499.

3. Tardío JC. CD34-reactive tumors of the skin. an updated review of an ever-growing list of lesions. J Cutan Pathol. 2009;36:89-102.

4. Mehregan A. Inverted follicular keratosis is a distinct follicular tumor. Am J Dermatopathol. 1983;5:467-470.

5. Cockerell CJ. Histopathology of incipient intraepidermal squamous cell carcinoma (“actinic keratosis”). J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;42(1, pt 2):11-17.

6. Jabłonska S, Majewski S, Obalek S, et al. Cutaneous warts. Clin Dermatol. 1997;15:309-319.

7. Hardin J, Gardner J, Colome M, et al. Verrucous cyst with melanocytic and sebaceous differentiation. Arch Path Lab Med. 2013;137:576-579.

8. Johnson BL, Kramer EM, Lavker RM. The keratotic tumors of Cowden’s disease: an electron microscopy study. J Cutan Pathol. 1987;14:291-298.

9. Kaddu S, Dong H, Mayer G, et al. Warty dyskeratoma—“follicular dyskeratoma”: analysis of clinicopathologic features of a distinctive follicular adnexal neoplasm. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;47:423-428.

Trichilemmomas are benign follicular neoplasms that exhibit differentiation toward the outer root sheath of the pilosebaceous follicular epithelium.1 Trichilemmomas clinically present as individual or multiple, slowly growing, verrucous papules appearing most commonly on the face or neck. The lesions may coalesce to form small plaques. Although trichilemmomas typically are isolated, patients with multiple trichilemmomas require a cancer screening workup due to their association with Cowden disease, which results from a mutation in the phosphatase and tensin homolog tumor suppressor gene, PTEN.2 An easy way to remember the association between trichilemmomas and Cowden disease is to alter the spelling to “trichile-moo-moo,” using the “moo moo” sound of an animal cow as a clue linking the tumor to Cowden disease.

Histologically, trichilemmomas exhibit a lobular epidermal downgrowth into the dermis (Figure 1). The surface of the lesion may be hyperkeratotic and somewhat papillomatous. Cells toward the center of the lobule are pale staining, periodic acid–Schiff positive, and diastase labile due to high levels of intracellular glycogen (Figure 2). Cells toward the periphery of the lobule usually appear basophilic with a palisading arrangement of the peripheral cells. The entire lobule is enclosed within an eosinophilic basement membrane that stains positively with periodic acid–Schiff (Figure 2).1 Consistent with the tumor’s differentiation toward the outer root sheath of the hair follicle, trichilemmomas have been reported to express CD34 focally or diffusely.3

|

|

Similar to trichilemmoma, inverted follicular keratosis (IFK) commonly presents as a solitary asymptomatic papule on the face. Inverted follicular keratosis is a somewhat controversial entity, with some authorities arguing IFK is a variant of verruca vulgaris or seborrheic keratosis. Histologically, IFKs can be differentiated by the presence of squamous eddies (concentric layers of squamous cells in a whorled pattern), which are diagnostic, and central longitudinal crypts that contain keratin and are lined by squamous epithelium.4 Basaloid cells can be seen at the periphery of the tumors; however, IFKs lack an eosinophilic basement membrane surrounding the tumor (Figure 3).

Squamous cell carcinoma in situ classically appears as an erythematous hyperkeratotic papule or plaque on sun-exposed sites that can become crusted or ulcerated. Microscopically, squamous cell carcinoma in situ displays full-thickness disorderly maturation of keratinocytes. The keratinocytes exhibit nuclear pleomorphism. Atypical mitotic figures and dyskeratotic keratinocytes also can be seen throughout the full thickness of the epidermis (Figure 4).5

Verruca vulgaris (Figure 5) histologically demonstrates hyperkeratosis with tiers of parakeratosis, digitated epidermal hyperplasia, and dilated tortuous capillaries within the dermal papillae. At the edges of the lesion there often is inward turning of elongated rete ridges,6,7 which can be thought of as the rete reaching out for a hug of sorts to spread the human papillomavirus infection. Although the surface of a trichilemmoma can bear resemblance to a verruca vulgaris, the remainder of the histologic features can be used to help differentiate these tumors. Additionally, there has been no evidence suggestive of a viral etiology for trichilemmomas.8

Warty dyskeratoma features an umbilicated papule, usually on the face, head, or neck, that is associated with a follicular unit. The papule shows a cup-shaped, keratin-filled invagination; suprabasilar clefting; and acantholytic dyskeratotic cells, which are features that are not seen in trichilemmomas (Figure 6).9

Acknowledgment—The authors would like to thank Brandon Litzner, MD, St Louis, Missouri, for proofreading the manuscript.

Trichilemmomas are benign follicular neoplasms that exhibit differentiation toward the outer root sheath of the pilosebaceous follicular epithelium.1 Trichilemmomas clinically present as individual or multiple, slowly growing, verrucous papules appearing most commonly on the face or neck. The lesions may coalesce to form small plaques. Although trichilemmomas typically are isolated, patients with multiple trichilemmomas require a cancer screening workup due to their association with Cowden disease, which results from a mutation in the phosphatase and tensin homolog tumor suppressor gene, PTEN.2 An easy way to remember the association between trichilemmomas and Cowden disease is to alter the spelling to “trichile-moo-moo,” using the “moo moo” sound of an animal cow as a clue linking the tumor to Cowden disease.

Histologically, trichilemmomas exhibit a lobular epidermal downgrowth into the dermis (Figure 1). The surface of the lesion may be hyperkeratotic and somewhat papillomatous. Cells toward the center of the lobule are pale staining, periodic acid–Schiff positive, and diastase labile due to high levels of intracellular glycogen (Figure 2). Cells toward the periphery of the lobule usually appear basophilic with a palisading arrangement of the peripheral cells. The entire lobule is enclosed within an eosinophilic basement membrane that stains positively with periodic acid–Schiff (Figure 2).1 Consistent with the tumor’s differentiation toward the outer root sheath of the hair follicle, trichilemmomas have been reported to express CD34 focally or diffusely.3

|

|

Similar to trichilemmoma, inverted follicular keratosis (IFK) commonly presents as a solitary asymptomatic papule on the face. Inverted follicular keratosis is a somewhat controversial entity, with some authorities arguing IFK is a variant of verruca vulgaris or seborrheic keratosis. Histologically, IFKs can be differentiated by the presence of squamous eddies (concentric layers of squamous cells in a whorled pattern), which are diagnostic, and central longitudinal crypts that contain keratin and are lined by squamous epithelium.4 Basaloid cells can be seen at the periphery of the tumors; however, IFKs lack an eosinophilic basement membrane surrounding the tumor (Figure 3).

Squamous cell carcinoma in situ classically appears as an erythematous hyperkeratotic papule or plaque on sun-exposed sites that can become crusted or ulcerated. Microscopically, squamous cell carcinoma in situ displays full-thickness disorderly maturation of keratinocytes. The keratinocytes exhibit nuclear pleomorphism. Atypical mitotic figures and dyskeratotic keratinocytes also can be seen throughout the full thickness of the epidermis (Figure 4).5

Verruca vulgaris (Figure 5) histologically demonstrates hyperkeratosis with tiers of parakeratosis, digitated epidermal hyperplasia, and dilated tortuous capillaries within the dermal papillae. At the edges of the lesion there often is inward turning of elongated rete ridges,6,7 which can be thought of as the rete reaching out for a hug of sorts to spread the human papillomavirus infection. Although the surface of a trichilemmoma can bear resemblance to a verruca vulgaris, the remainder of the histologic features can be used to help differentiate these tumors. Additionally, there has been no evidence suggestive of a viral etiology for trichilemmomas.8

Warty dyskeratoma features an umbilicated papule, usually on the face, head, or neck, that is associated with a follicular unit. The papule shows a cup-shaped, keratin-filled invagination; suprabasilar clefting; and acantholytic dyskeratotic cells, which are features that are not seen in trichilemmomas (Figure 6).9

Acknowledgment—The authors would like to thank Brandon Litzner, MD, St Louis, Missouri, for proofreading the manuscript.

1. Brownstein MH, Shapiro L. Trichilemmoma: analysis of 40 new cases. Arch Dermatol. 1973;107:866-869.

2. Al-Zaid T, Ditelberg J, Prieto V, et al. Trichilemmomas show loss of PTEN in Cowden syndrome but only rarely in sporadic tumors. J Cutan Pathol. 2012;39:493-499.

3. Tardío JC. CD34-reactive tumors of the skin. an updated review of an ever-growing list of lesions. J Cutan Pathol. 2009;36:89-102.

4. Mehregan A. Inverted follicular keratosis is a distinct follicular tumor. Am J Dermatopathol. 1983;5:467-470.

5. Cockerell CJ. Histopathology of incipient intraepidermal squamous cell carcinoma (“actinic keratosis”). J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;42(1, pt 2):11-17.

6. Jabłonska S, Majewski S, Obalek S, et al. Cutaneous warts. Clin Dermatol. 1997;15:309-319.

7. Hardin J, Gardner J, Colome M, et al. Verrucous cyst with melanocytic and sebaceous differentiation. Arch Path Lab Med. 2013;137:576-579.

8. Johnson BL, Kramer EM, Lavker RM. The keratotic tumors of Cowden’s disease: an electron microscopy study. J Cutan Pathol. 1987;14:291-298.

9. Kaddu S, Dong H, Mayer G, et al. Warty dyskeratoma—“follicular dyskeratoma”: analysis of clinicopathologic features of a distinctive follicular adnexal neoplasm. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;47:423-428.

1. Brownstein MH, Shapiro L. Trichilemmoma: analysis of 40 new cases. Arch Dermatol. 1973;107:866-869.

2. Al-Zaid T, Ditelberg J, Prieto V, et al. Trichilemmomas show loss of PTEN in Cowden syndrome but only rarely in sporadic tumors. J Cutan Pathol. 2012;39:493-499.

3. Tardío JC. CD34-reactive tumors of the skin. an updated review of an ever-growing list of lesions. J Cutan Pathol. 2009;36:89-102.

4. Mehregan A. Inverted follicular keratosis is a distinct follicular tumor. Am J Dermatopathol. 1983;5:467-470.

5. Cockerell CJ. Histopathology of incipient intraepidermal squamous cell carcinoma (“actinic keratosis”). J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;42(1, pt 2):11-17.

6. Jabłonska S, Majewski S, Obalek S, et al. Cutaneous warts. Clin Dermatol. 1997;15:309-319.

7. Hardin J, Gardner J, Colome M, et al. Verrucous cyst with melanocytic and sebaceous differentiation. Arch Path Lab Med. 2013;137:576-579.

8. Johnson BL, Kramer EM, Lavker RM. The keratotic tumors of Cowden’s disease: an electron microscopy study. J Cutan Pathol. 1987;14:291-298.

9. Kaddu S, Dong H, Mayer G, et al. Warty dyskeratoma—“follicular dyskeratoma”: analysis of clinicopathologic features of a distinctive follicular adnexal neoplasm. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;47:423-428.

Rosai-Dorfman Disease

Rosai-Dorfman disease (RDD), also known as sinus histiocytosis with massive lymphadenopathy, is a rare benign histioproliferative disorder of unknown etiology.1 Clinically, it is most frequently characterized by massive painless cervical lymphadenopathy with other systemic manifestations, including fever, night sweats, and weight loss. Accompanying laboratory findings include leukocytosis with neutrophilia, elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and polyclonal hypergammaglobulinemia. Extranodal involvement has been noted in more than 40% of cases, and cutaneous lesions represent the most common form of extranodal disease.2 Cutaneous RDD is a distinct and rare entity limited to the skin without lymphadenopathy or other extracutaneous involvement.3 Patients with cutaneous RDD typically present with papules and plaques that can grow to form nodules with satellite lesions that resolve into fibrotic plaques before spontaneous regression.4

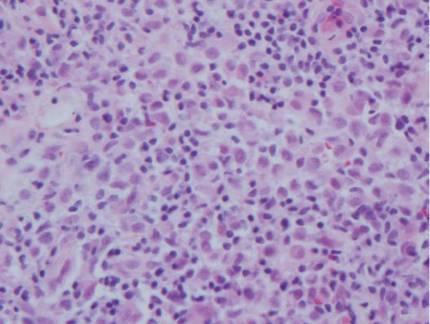

Histologic examination of cutaneous lesions of RDD reveals a dense nodular dermal and often subcutaneous infiltrate of characteristic large polygonal histiocytes termed Rosai-Dorfman cells, which feature abundant pale to eosinophilic cytoplasm, indistinct borders, and large vesicular nuclei with prominent nucleoli (Figure 1).4,5 Some multinucleate forms may be seen. These Rosai-Dorfman cells display positive staining for CD68 and S-100, and negative staining for CD1a on immunohistochemistry. Lymphocytes and plasma cells often are admixed with the Rosai-Dorfman cells, and neutrophils and eosinophils also may be present in the infiltrate.4 The histologic hallmark of RDD is emperipolesis, a phenomenon whereby inflammatory cells such as lymphocytes and plasma cells reside intact within the cytoplasm of histiocytes (Figure 2).5

|

|

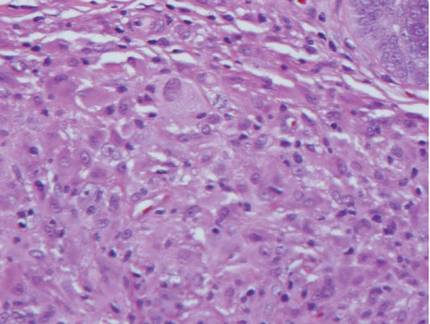

The histologic differential diagnosis of cutaneous lesions of RDD includes other histiocytic and xanthomatous diseases, including eruptive xanthoma, juvenile xanthogranuloma, Langerhans cell histiocytosis, and solitary reticulohistiocytoma, which should not display emperipolesis. Eruptive xanthomas display collections of foamy histiocytes in the dermis and typically contain extracellular lipid. They may contain infiltrates of lymphocytes (Figure 3). Juvenile xanthogranuloma also features a dense infiltrate of histiocytes in the papillary and reticular dermis but distinctly shows Touton giant cells and lipidization of histiocytes (Figure 4). Both eruptive xanthomas and juvenile xanthogranulomas typically stain negatively for S-100. Langerhans cell histiocytosis is histologically characterized by a dermal infiltrate of Langerhans cells that have their own distinctive morphologic features. They are uniformly ovoid with abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm. Their nuclei are smaller than those of Rosai-Dorfman cells and have a kidney bean shape with inconspicuous nucleoli (Figure 5). Epidermotropism of these cells can be observed. Immunohistochemically, Langerhans cell histiocytosis typically is S-100 positive, CD1a positive, and langerin positive. Reticulohistiocytoma features histiocytes that have a characteristic dusty rose or ground glass cytoplasm with two-toned darker and lighter areas (Figure 6). Reticulohistiocytoma cells stain positively for CD68 but typically stain negatively for both CD1a and S-100.

|

| ||

|

|

1. Rosai J, Dorfman RF. Sinus histiocytosis with massive lymphadenopathy. a newly recognized benign clinicopathological entity. Arch Pathol. 1969;87:63-70.

2. Foucar E, Rosai J, Dorfman RF. Sinus histiocytosis with massive lymphadenopathy (Rosai-Dorfman disease): a review of the entity. Semin Diagn Pathol. 1990;7:19-73.

3. Brenn T, Calonje E, Granter SR, et al. Cutaneous Rosai-Dorfman disease is a distinct clinical entity. Am J Dermatopathol. 2002;24:385-391.

4. Wang KH, Chen WY, Lie HN, et al. Cutaneous Rosai-Dorfman disease: clinicopathological profiles, spectrum and evolution of 21 lesions in six patients. Br J Dermatol. 2006;154:277-286.

5. Chu P, LeBoit PE. Histologic features of cutaneous sinus histiocytosis (Rosai-Dorfman disease): study of cases both with and without systemic involvement. J Cutan Pathol. 1992;19:201-206.

Rosai-Dorfman disease (RDD), also known as sinus histiocytosis with massive lymphadenopathy, is a rare benign histioproliferative disorder of unknown etiology.1 Clinically, it is most frequently characterized by massive painless cervical lymphadenopathy with other systemic manifestations, including fever, night sweats, and weight loss. Accompanying laboratory findings include leukocytosis with neutrophilia, elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and polyclonal hypergammaglobulinemia. Extranodal involvement has been noted in more than 40% of cases, and cutaneous lesions represent the most common form of extranodal disease.2 Cutaneous RDD is a distinct and rare entity limited to the skin without lymphadenopathy or other extracutaneous involvement.3 Patients with cutaneous RDD typically present with papules and plaques that can grow to form nodules with satellite lesions that resolve into fibrotic plaques before spontaneous regression.4

Histologic examination of cutaneous lesions of RDD reveals a dense nodular dermal and often subcutaneous infiltrate of characteristic large polygonal histiocytes termed Rosai-Dorfman cells, which feature abundant pale to eosinophilic cytoplasm, indistinct borders, and large vesicular nuclei with prominent nucleoli (Figure 1).4,5 Some multinucleate forms may be seen. These Rosai-Dorfman cells display positive staining for CD68 and S-100, and negative staining for CD1a on immunohistochemistry. Lymphocytes and plasma cells often are admixed with the Rosai-Dorfman cells, and neutrophils and eosinophils also may be present in the infiltrate.4 The histologic hallmark of RDD is emperipolesis, a phenomenon whereby inflammatory cells such as lymphocytes and plasma cells reside intact within the cytoplasm of histiocytes (Figure 2).5

|

|

The histologic differential diagnosis of cutaneous lesions of RDD includes other histiocytic and xanthomatous diseases, including eruptive xanthoma, juvenile xanthogranuloma, Langerhans cell histiocytosis, and solitary reticulohistiocytoma, which should not display emperipolesis. Eruptive xanthomas display collections of foamy histiocytes in the dermis and typically contain extracellular lipid. They may contain infiltrates of lymphocytes (Figure 3). Juvenile xanthogranuloma also features a dense infiltrate of histiocytes in the papillary and reticular dermis but distinctly shows Touton giant cells and lipidization of histiocytes (Figure 4). Both eruptive xanthomas and juvenile xanthogranulomas typically stain negatively for S-100. Langerhans cell histiocytosis is histologically characterized by a dermal infiltrate of Langerhans cells that have their own distinctive morphologic features. They are uniformly ovoid with abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm. Their nuclei are smaller than those of Rosai-Dorfman cells and have a kidney bean shape with inconspicuous nucleoli (Figure 5). Epidermotropism of these cells can be observed. Immunohistochemically, Langerhans cell histiocytosis typically is S-100 positive, CD1a positive, and langerin positive. Reticulohistiocytoma features histiocytes that have a characteristic dusty rose or ground glass cytoplasm with two-toned darker and lighter areas (Figure 6). Reticulohistiocytoma cells stain positively for CD68 but typically stain negatively for both CD1a and S-100.

|

| ||

|

|

Rosai-Dorfman disease (RDD), also known as sinus histiocytosis with massive lymphadenopathy, is a rare benign histioproliferative disorder of unknown etiology.1 Clinically, it is most frequently characterized by massive painless cervical lymphadenopathy with other systemic manifestations, including fever, night sweats, and weight loss. Accompanying laboratory findings include leukocytosis with neutrophilia, elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and polyclonal hypergammaglobulinemia. Extranodal involvement has been noted in more than 40% of cases, and cutaneous lesions represent the most common form of extranodal disease.2 Cutaneous RDD is a distinct and rare entity limited to the skin without lymphadenopathy or other extracutaneous involvement.3 Patients with cutaneous RDD typically present with papules and plaques that can grow to form nodules with satellite lesions that resolve into fibrotic plaques before spontaneous regression.4

Histologic examination of cutaneous lesions of RDD reveals a dense nodular dermal and often subcutaneous infiltrate of characteristic large polygonal histiocytes termed Rosai-Dorfman cells, which feature abundant pale to eosinophilic cytoplasm, indistinct borders, and large vesicular nuclei with prominent nucleoli (Figure 1).4,5 Some multinucleate forms may be seen. These Rosai-Dorfman cells display positive staining for CD68 and S-100, and negative staining for CD1a on immunohistochemistry. Lymphocytes and plasma cells often are admixed with the Rosai-Dorfman cells, and neutrophils and eosinophils also may be present in the infiltrate.4 The histologic hallmark of RDD is emperipolesis, a phenomenon whereby inflammatory cells such as lymphocytes and plasma cells reside intact within the cytoplasm of histiocytes (Figure 2).5

|

|

The histologic differential diagnosis of cutaneous lesions of RDD includes other histiocytic and xanthomatous diseases, including eruptive xanthoma, juvenile xanthogranuloma, Langerhans cell histiocytosis, and solitary reticulohistiocytoma, which should not display emperipolesis. Eruptive xanthomas display collections of foamy histiocytes in the dermis and typically contain extracellular lipid. They may contain infiltrates of lymphocytes (Figure 3). Juvenile xanthogranuloma also features a dense infiltrate of histiocytes in the papillary and reticular dermis but distinctly shows Touton giant cells and lipidization of histiocytes (Figure 4). Both eruptive xanthomas and juvenile xanthogranulomas typically stain negatively for S-100. Langerhans cell histiocytosis is histologically characterized by a dermal infiltrate of Langerhans cells that have their own distinctive morphologic features. They are uniformly ovoid with abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm. Their nuclei are smaller than those of Rosai-Dorfman cells and have a kidney bean shape with inconspicuous nucleoli (Figure 5). Epidermotropism of these cells can be observed. Immunohistochemically, Langerhans cell histiocytosis typically is S-100 positive, CD1a positive, and langerin positive. Reticulohistiocytoma features histiocytes that have a characteristic dusty rose or ground glass cytoplasm with two-toned darker and lighter areas (Figure 6). Reticulohistiocytoma cells stain positively for CD68 but typically stain negatively for both CD1a and S-100.

|

| ||

|

|

1. Rosai J, Dorfman RF. Sinus histiocytosis with massive lymphadenopathy. a newly recognized benign clinicopathological entity. Arch Pathol. 1969;87:63-70.

2. Foucar E, Rosai J, Dorfman RF. Sinus histiocytosis with massive lymphadenopathy (Rosai-Dorfman disease): a review of the entity. Semin Diagn Pathol. 1990;7:19-73.

3. Brenn T, Calonje E, Granter SR, et al. Cutaneous Rosai-Dorfman disease is a distinct clinical entity. Am J Dermatopathol. 2002;24:385-391.

4. Wang KH, Chen WY, Lie HN, et al. Cutaneous Rosai-Dorfman disease: clinicopathological profiles, spectrum and evolution of 21 lesions in six patients. Br J Dermatol. 2006;154:277-286.

5. Chu P, LeBoit PE. Histologic features of cutaneous sinus histiocytosis (Rosai-Dorfman disease): study of cases both with and without systemic involvement. J Cutan Pathol. 1992;19:201-206.

1. Rosai J, Dorfman RF. Sinus histiocytosis with massive lymphadenopathy. a newly recognized benign clinicopathological entity. Arch Pathol. 1969;87:63-70.

2. Foucar E, Rosai J, Dorfman RF. Sinus histiocytosis with massive lymphadenopathy (Rosai-Dorfman disease): a review of the entity. Semin Diagn Pathol. 1990;7:19-73.

3. Brenn T, Calonje E, Granter SR, et al. Cutaneous Rosai-Dorfman disease is a distinct clinical entity. Am J Dermatopathol. 2002;24:385-391.

4. Wang KH, Chen WY, Lie HN, et al. Cutaneous Rosai-Dorfman disease: clinicopathological profiles, spectrum and evolution of 21 lesions in six patients. Br J Dermatol. 2006;154:277-286.

5. Chu P, LeBoit PE. Histologic features of cutaneous sinus histiocytosis (Rosai-Dorfman disease): study of cases both with and without systemic involvement. J Cutan Pathol. 1992;19:201-206.

Extramammary Paget Disease

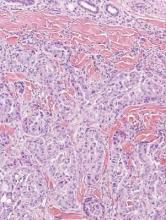

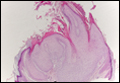

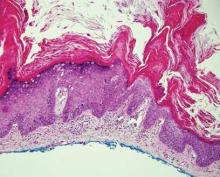

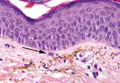

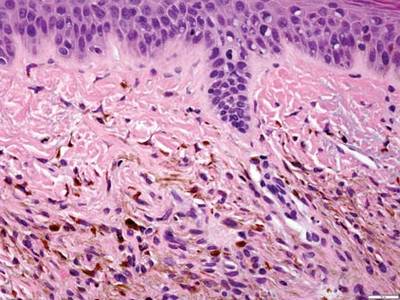

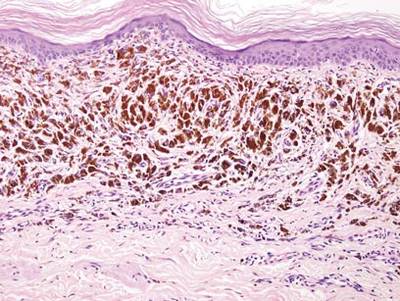

Extramammary Paget disease (EMPD) is an uncommon condition that usually presents in apocrine sweat gland–rich areas, most commonly the vulva followed by the perianal region. Lesions clinically present as erythematous, well-demarcated plaques that may become ulcerated, erosive, scaly, or eczematous. Extramammary Paget disease has a female predominance and usually occurs in the sixth to eighth decades of life.1 Histologically, EMPD displays intraepidermal spread of large cells with plentiful amphophilic cytoplasm and large nuclei (Figure 1). These atypical cells may be seen “spit out” whole into the stratum corneum rather than keratinizing into parakeratotic cells (Figure 2). Frequently, the cytoplasm of these tumor cells is positive on mucicarmine staining, which indicates the presence of mucin, giving the cytoplasm a bluish gray color on hematoxylin and eosin–stained sections. Typically, EMPD cells can be found alone or in nests throughout the epithelium. The basal layer of the epithelium will appear crushed but not infiltrated by these atypical cells in some areas.2 Extramammary Paget disease is epithelial membrane antigen and cytokeratin 7 positive, unlike other conditions in the differential diagnosis such as benign acral nevus, Bowen disease, mycosis fungoides, and superficial spreading melanoma in situ, with the rare exception of cytokeratin 7 positivity in Bowen disease.3

|

|

Benign acral nevi, similar to melanoma in situ, can have melanocytes scattered above the basal layer, but they usually appear in the lower half of the epidermis without cytologic atypia.4 When present, these pagetoid cells are most often limited to the center of a well-delineated lesion. The compact thick stratum corneum characteristic of acral skin also is helpful in distinguishing a benign acral nevus from EMPD, which does not involve acral sites (Figure 3).2

Bowen disease (squamous cell carcinoma in situ) may have pagetoid spread (or buckshot scatter) through the epidermis similar to EMPD and melanoma in situ. However, in Bowen disease the malignant cells are keratinocytes that keratinize and become incorporated into the stratum corneum as parakeratotic nuclei rather than intact “spit out” cells, as seen in melanoma in situ and EMPD. Usually the pagetoid spread is only focal in Bowen disease with other areas of more characteristic full-thickness keratinocyte atypia (Figure 4).2

Mycosis fungoides displays atypical lymphocytes with large dark nuclei and minimal to no cytoplasm scattered throughout the epidermis. The atypical cells have irregular nuclear contours and often a clear perinuclear space (Figure 5). These cells tend to line up along the dermoepidermal junction and form intraepidermal clusters known as Pautrier microabscesses. Papillary dermal fibroplasia also is usually present in mycosis fungoides.2

Similar to EMPD, superficial spreading melanoma in situ shows single or nested atypical cells scattered throughout all levels of the epithelium and may be “spit out” whole into the stratum corneum rather than keratinizing into parakeratotic cells. However, in melanoma, nests of atypical melanocytes predominate and involve the basal layer (Figure 6), whereas clusters of cells in EMPD typically are located superficial to the basal layer. The cells of melanoma also lack the amphophilic mucinous cytoplasm of EMPD.1

1. Calonje E, Brenn T, Lazar A, et al. McKee’s Pathology of the Skin. 4th ed. London, England: Elsevier Saunders; 2011.

2. Ferringer T, Elston D, eds. Dermatopathology. 2nd ed. London, England: Elsevier; 2014.

3. Sah SP, Kelly PJ, McManus DT, et al. Diffuse CK7, CAM5.2 and BerEP4 positivity in pagetoid squamous cell carcinoma in situ (pagetoid Bowen’s disease) of the perianal region: a mimic of extramammary Paget’s disease. Histopathology. 2013;62:511-514.

4. LeBoit PE. A diagnosis for maniacs. Am J Dermatopathol. 2000;22:556-558.

Extramammary Paget disease (EMPD) is an uncommon condition that usually presents in apocrine sweat gland–rich areas, most commonly the vulva followed by the perianal region. Lesions clinically present as erythematous, well-demarcated plaques that may become ulcerated, erosive, scaly, or eczematous. Extramammary Paget disease has a female predominance and usually occurs in the sixth to eighth decades of life.1 Histologically, EMPD displays intraepidermal spread of large cells with plentiful amphophilic cytoplasm and large nuclei (Figure 1). These atypical cells may be seen “spit out” whole into the stratum corneum rather than keratinizing into parakeratotic cells (Figure 2). Frequently, the cytoplasm of these tumor cells is positive on mucicarmine staining, which indicates the presence of mucin, giving the cytoplasm a bluish gray color on hematoxylin and eosin–stained sections. Typically, EMPD cells can be found alone or in nests throughout the epithelium. The basal layer of the epithelium will appear crushed but not infiltrated by these atypical cells in some areas.2 Extramammary Paget disease is epithelial membrane antigen and cytokeratin 7 positive, unlike other conditions in the differential diagnosis such as benign acral nevus, Bowen disease, mycosis fungoides, and superficial spreading melanoma in situ, with the rare exception of cytokeratin 7 positivity in Bowen disease.3

|

|

Benign acral nevi, similar to melanoma in situ, can have melanocytes scattered above the basal layer, but they usually appear in the lower half of the epidermis without cytologic atypia.4 When present, these pagetoid cells are most often limited to the center of a well-delineated lesion. The compact thick stratum corneum characteristic of acral skin also is helpful in distinguishing a benign acral nevus from EMPD, which does not involve acral sites (Figure 3).2

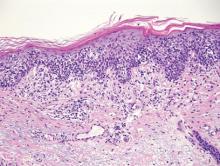

Bowen disease (squamous cell carcinoma in situ) may have pagetoid spread (or buckshot scatter) through the epidermis similar to EMPD and melanoma in situ. However, in Bowen disease the malignant cells are keratinocytes that keratinize and become incorporated into the stratum corneum as parakeratotic nuclei rather than intact “spit out” cells, as seen in melanoma in situ and EMPD. Usually the pagetoid spread is only focal in Bowen disease with other areas of more characteristic full-thickness keratinocyte atypia (Figure 4).2

Mycosis fungoides displays atypical lymphocytes with large dark nuclei and minimal to no cytoplasm scattered throughout the epidermis. The atypical cells have irregular nuclear contours and often a clear perinuclear space (Figure 5). These cells tend to line up along the dermoepidermal junction and form intraepidermal clusters known as Pautrier microabscesses. Papillary dermal fibroplasia also is usually present in mycosis fungoides.2

Similar to EMPD, superficial spreading melanoma in situ shows single or nested atypical cells scattered throughout all levels of the epithelium and may be “spit out” whole into the stratum corneum rather than keratinizing into parakeratotic cells. However, in melanoma, nests of atypical melanocytes predominate and involve the basal layer (Figure 6), whereas clusters of cells in EMPD typically are located superficial to the basal layer. The cells of melanoma also lack the amphophilic mucinous cytoplasm of EMPD.1

Extramammary Paget disease (EMPD) is an uncommon condition that usually presents in apocrine sweat gland–rich areas, most commonly the vulva followed by the perianal region. Lesions clinically present as erythematous, well-demarcated plaques that may become ulcerated, erosive, scaly, or eczematous. Extramammary Paget disease has a female predominance and usually occurs in the sixth to eighth decades of life.1 Histologically, EMPD displays intraepidermal spread of large cells with plentiful amphophilic cytoplasm and large nuclei (Figure 1). These atypical cells may be seen “spit out” whole into the stratum corneum rather than keratinizing into parakeratotic cells (Figure 2). Frequently, the cytoplasm of these tumor cells is positive on mucicarmine staining, which indicates the presence of mucin, giving the cytoplasm a bluish gray color on hematoxylin and eosin–stained sections. Typically, EMPD cells can be found alone or in nests throughout the epithelium. The basal layer of the epithelium will appear crushed but not infiltrated by these atypical cells in some areas.2 Extramammary Paget disease is epithelial membrane antigen and cytokeratin 7 positive, unlike other conditions in the differential diagnosis such as benign acral nevus, Bowen disease, mycosis fungoides, and superficial spreading melanoma in situ, with the rare exception of cytokeratin 7 positivity in Bowen disease.3

|

|

Benign acral nevi, similar to melanoma in situ, can have melanocytes scattered above the basal layer, but they usually appear in the lower half of the epidermis without cytologic atypia.4 When present, these pagetoid cells are most often limited to the center of a well-delineated lesion. The compact thick stratum corneum characteristic of acral skin also is helpful in distinguishing a benign acral nevus from EMPD, which does not involve acral sites (Figure 3).2

Bowen disease (squamous cell carcinoma in situ) may have pagetoid spread (or buckshot scatter) through the epidermis similar to EMPD and melanoma in situ. However, in Bowen disease the malignant cells are keratinocytes that keratinize and become incorporated into the stratum corneum as parakeratotic nuclei rather than intact “spit out” cells, as seen in melanoma in situ and EMPD. Usually the pagetoid spread is only focal in Bowen disease with other areas of more characteristic full-thickness keratinocyte atypia (Figure 4).2

Mycosis fungoides displays atypical lymphocytes with large dark nuclei and minimal to no cytoplasm scattered throughout the epidermis. The atypical cells have irregular nuclear contours and often a clear perinuclear space (Figure 5). These cells tend to line up along the dermoepidermal junction and form intraepidermal clusters known as Pautrier microabscesses. Papillary dermal fibroplasia also is usually present in mycosis fungoides.2

Similar to EMPD, superficial spreading melanoma in situ shows single or nested atypical cells scattered throughout all levels of the epithelium and may be “spit out” whole into the stratum corneum rather than keratinizing into parakeratotic cells. However, in melanoma, nests of atypical melanocytes predominate and involve the basal layer (Figure 6), whereas clusters of cells in EMPD typically are located superficial to the basal layer. The cells of melanoma also lack the amphophilic mucinous cytoplasm of EMPD.1

1. Calonje E, Brenn T, Lazar A, et al. McKee’s Pathology of the Skin. 4th ed. London, England: Elsevier Saunders; 2011.

2. Ferringer T, Elston D, eds. Dermatopathology. 2nd ed. London, England: Elsevier; 2014.

3. Sah SP, Kelly PJ, McManus DT, et al. Diffuse CK7, CAM5.2 and BerEP4 positivity in pagetoid squamous cell carcinoma in situ (pagetoid Bowen’s disease) of the perianal region: a mimic of extramammary Paget’s disease. Histopathology. 2013;62:511-514.

4. LeBoit PE. A diagnosis for maniacs. Am J Dermatopathol. 2000;22:556-558.

1. Calonje E, Brenn T, Lazar A, et al. McKee’s Pathology of the Skin. 4th ed. London, England: Elsevier Saunders; 2011.

2. Ferringer T, Elston D, eds. Dermatopathology. 2nd ed. London, England: Elsevier; 2014.

3. Sah SP, Kelly PJ, McManus DT, et al. Diffuse CK7, CAM5.2 and BerEP4 positivity in pagetoid squamous cell carcinoma in situ (pagetoid Bowen’s disease) of the perianal region: a mimic of extramammary Paget’s disease. Histopathology. 2013;62:511-514.

4. LeBoit PE. A diagnosis for maniacs. Am J Dermatopathol. 2000;22:556-558.

Necrobiosis Lipoidica Diabeticorum

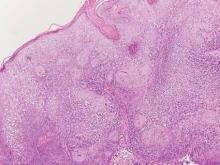

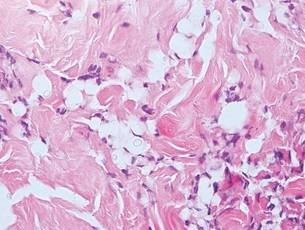

Necrobiosis lipoidica diabeticorum (NLD) is a rare granulomatous skin manifestation that is strongly associated with diabetes mellitus. Necrobiosis lipoidica diabeticorum is more common among females and occurs primarily in the pretibial area.1 Necrobiosis lipoidica diabeticorum may clinically manifest as single or multiple lesions that begin as small red papules and progress into patches or plaques. Lesions ultimately develop into areas of yellowish brown atrophic tissue with central depression and telangiectasia. The etiology of NLD is not completely understood, but it is thought to be a presentation of diabetic microangiopathy.1 Histologically, NLD demonstrates broad horizontal zones of necrobiosis with a surrounding inflammatory infiltrate that is principally composed of histiocytes but also may contain multinucleated giant cells, lymphocytes, and plasma cells (Figures 1 and 2). Occasionally, sarcoidal granulomas are seen in NLD. There also may be thickening of vessel walls and edema of the endothelial cells.1

|

|

Cutaneous Rosai-Dorfman disease (RDD) is characterized by the presence of diffuse, large, pale histiocytes (commonly known as Rosai-Dorfman cells) with an admixed infiltrate of lymphocytes and plasma cells (Figure 3).2 Additionally, Rosai-Dorfman cells display emperipolesis. They stain positively for S-100 protein and CD68 and negatively for CD1a.2 Clinically, cutaneous RDD has a myriad of manifestations but most commonly presents as cutaneous nodules that can be tender or pruritic. It also may be associated with systemic symptoms. Patients with cutaneous RDD often have an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate and concomitant anemia.2

Granuloma annulare demonstrates necrobiosis and palisaded granulomatous dermatitis similar to NLD; however, the necrobiotic foci in granuloma annulare usually are more focal than in NLD and typically are surrounded by well-formed palisaded granulomas. There also is an increase in dermal mucin (Figure 4), which can be highlighted on colloidal iron or Alcian blue staining.1 Granuloma annulare also typically has scattered eosinophils rather than plasma cells as seen in NLD. Granuloma annulare also may present in an interstitial pattern, with scattered histiocytes, mucin, and eosinophils between collagen bundles. Granuloma annulare clinically presents as variably colored papules arranged in an annular pattern on the distal extremities but also can present as widespread papules or plaques.

Juvenile xanthogranuloma (JXG) is a benign condition typically seen in children that is characterized by the presence of 1 or more pink or yellow nodules, most commonly presenting on the head and neck. Histologically, JXG demonstrates a dermal collection of histiocytes, lymphocytes, eosinophils, and characteristic Touton giant cells, which contain nuclei that are arranged in a wreathlike pattern and exhibit peripheral xanthomatization (Figure 5).3 The histiocytes in JXG typically stain positive for CD68 and negative for S-100 protein, though occasional S-100–positive cases are reported.3

Necrobiotic xanthogranuloma presents as yellowish to brown plaques and nodules most commonly in the periorbital area. Necrobiotic xanthogranuloma is strongly associated with monoclonal gammopathy, typically IgGk monoclonal gammopathy. Necrobiotic xanthogranuloma is histologically similar to NLD but is distinguished by a nodular pattern of inflammation and the frequent presence of cholesterol clefts (Figure 6).4

Figure 6. Necrobiotic xanthogranuloma is distinguished by the nodularity

of the infiltrate, with necrobiotic collagen, palisaded histiocytes and giant

cells, and the presence of cholesterol clefts (H&E, original

magnification ×40).

1. Kota SK, Jammula S, Kota SK, et al. Necrobiosis lipoidica diabeticorum: a case-based review of literature. Indian J Endocrinol Metab. 2012;16:614-620.

2. Khoo JJ, Rahmat BO. Cutaneous Rosai-Dorfman disease. Malays J Pathol. 2007;29:49-52.

3. Cypel TK, Zuker RM. Juvenile xanthogranuloma: case report and review of the literature. Can J Plast Surg. 2008;16:175-177.

4. Inthasotti S, Wanitphakdeedecha R, Manonukul J. A 7-year history of necrobiotic xanthogranuloma following asymptomatic multiple myeloma: a case report. Dermatol Res Pract. 2011;2011:927852.

Necrobiosis lipoidica diabeticorum (NLD) is a rare granulomatous skin manifestation that is strongly associated with diabetes mellitus. Necrobiosis lipoidica diabeticorum is more common among females and occurs primarily in the pretibial area.1 Necrobiosis lipoidica diabeticorum may clinically manifest as single or multiple lesions that begin as small red papules and progress into patches or plaques. Lesions ultimately develop into areas of yellowish brown atrophic tissue with central depression and telangiectasia. The etiology of NLD is not completely understood, but it is thought to be a presentation of diabetic microangiopathy.1 Histologically, NLD demonstrates broad horizontal zones of necrobiosis with a surrounding inflammatory infiltrate that is principally composed of histiocytes but also may contain multinucleated giant cells, lymphocytes, and plasma cells (Figures 1 and 2). Occasionally, sarcoidal granulomas are seen in NLD. There also may be thickening of vessel walls and edema of the endothelial cells.1

|

|

Cutaneous Rosai-Dorfman disease (RDD) is characterized by the presence of diffuse, large, pale histiocytes (commonly known as Rosai-Dorfman cells) with an admixed infiltrate of lymphocytes and plasma cells (Figure 3).2 Additionally, Rosai-Dorfman cells display emperipolesis. They stain positively for S-100 protein and CD68 and negatively for CD1a.2 Clinically, cutaneous RDD has a myriad of manifestations but most commonly presents as cutaneous nodules that can be tender or pruritic. It also may be associated with systemic symptoms. Patients with cutaneous RDD often have an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate and concomitant anemia.2

Granuloma annulare demonstrates necrobiosis and palisaded granulomatous dermatitis similar to NLD; however, the necrobiotic foci in granuloma annulare usually are more focal than in NLD and typically are surrounded by well-formed palisaded granulomas. There also is an increase in dermal mucin (Figure 4), which can be highlighted on colloidal iron or Alcian blue staining.1 Granuloma annulare also typically has scattered eosinophils rather than plasma cells as seen in NLD. Granuloma annulare also may present in an interstitial pattern, with scattered histiocytes, mucin, and eosinophils between collagen bundles. Granuloma annulare clinically presents as variably colored papules arranged in an annular pattern on the distal extremities but also can present as widespread papules or plaques.

Juvenile xanthogranuloma (JXG) is a benign condition typically seen in children that is characterized by the presence of 1 or more pink or yellow nodules, most commonly presenting on the head and neck. Histologically, JXG demonstrates a dermal collection of histiocytes, lymphocytes, eosinophils, and characteristic Touton giant cells, which contain nuclei that are arranged in a wreathlike pattern and exhibit peripheral xanthomatization (Figure 5).3 The histiocytes in JXG typically stain positive for CD68 and negative for S-100 protein, though occasional S-100–positive cases are reported.3