User login

Ulcerated Nodule on the Scalp

The Diagnosis: Proliferating Pilar Tumor

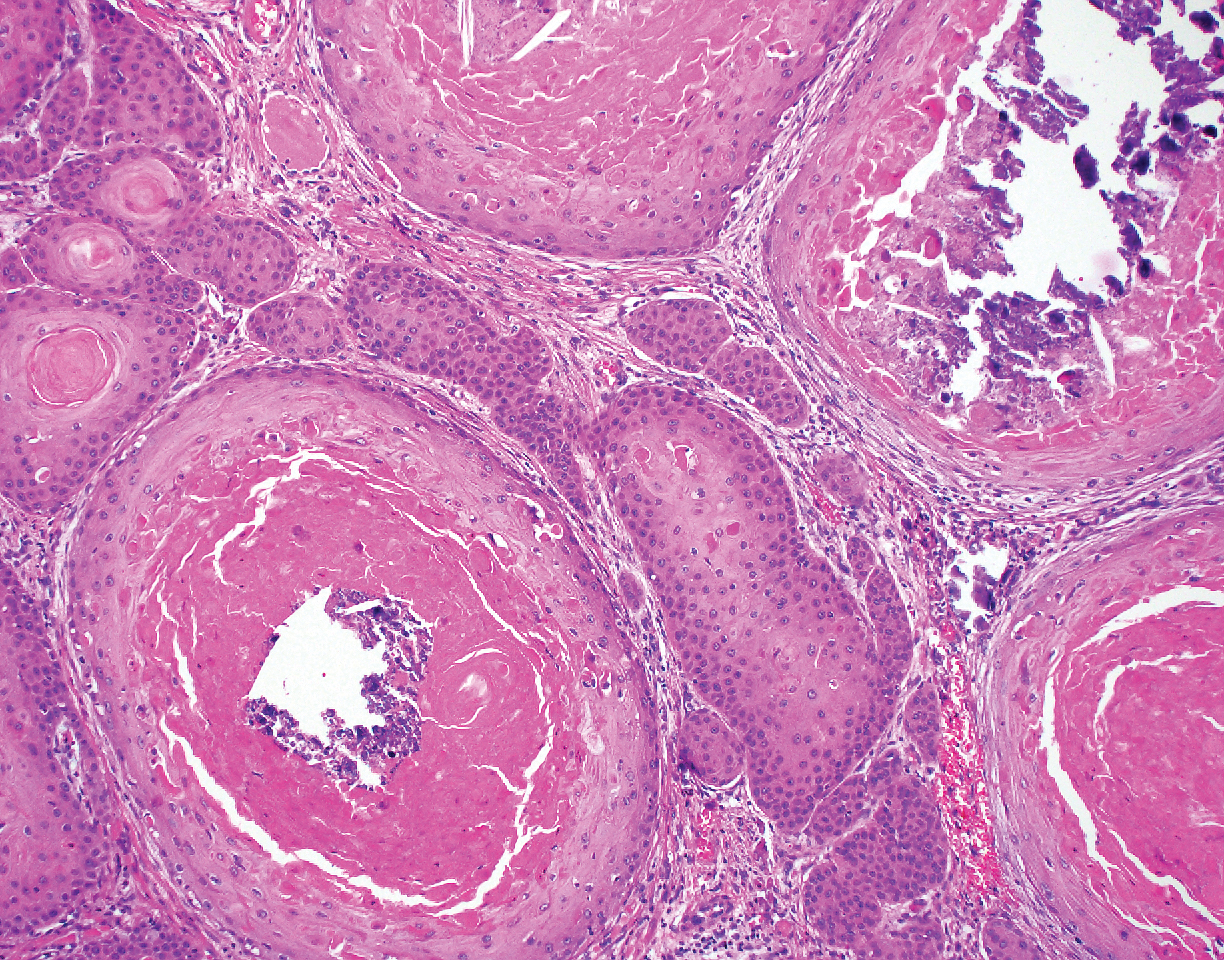

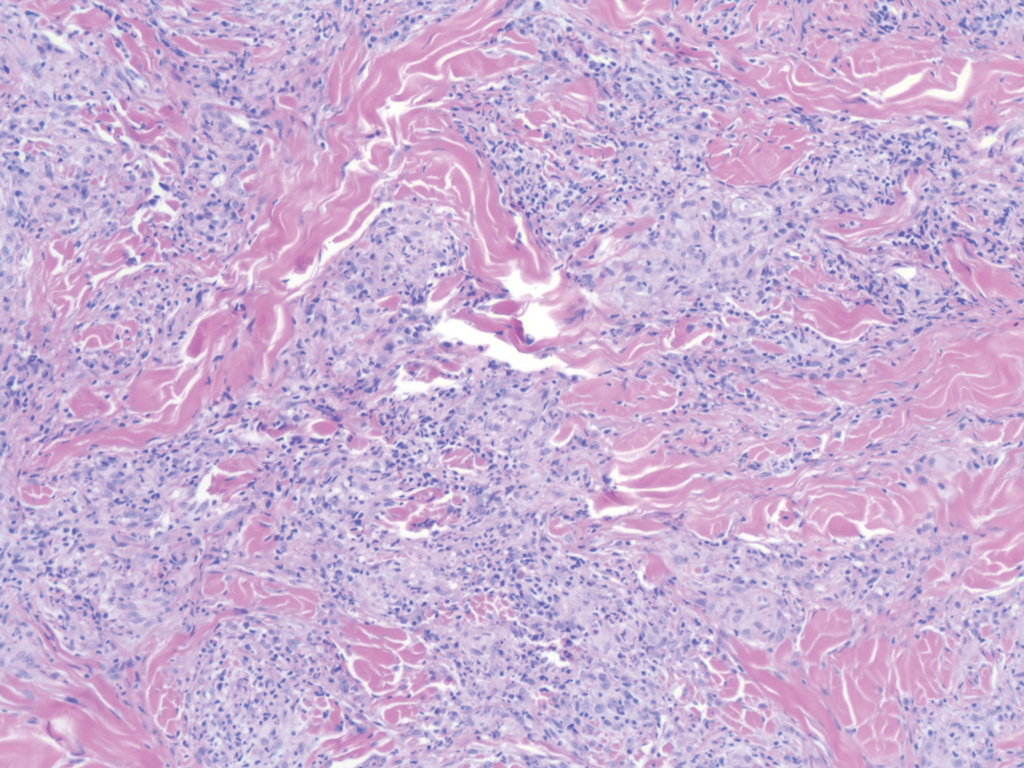

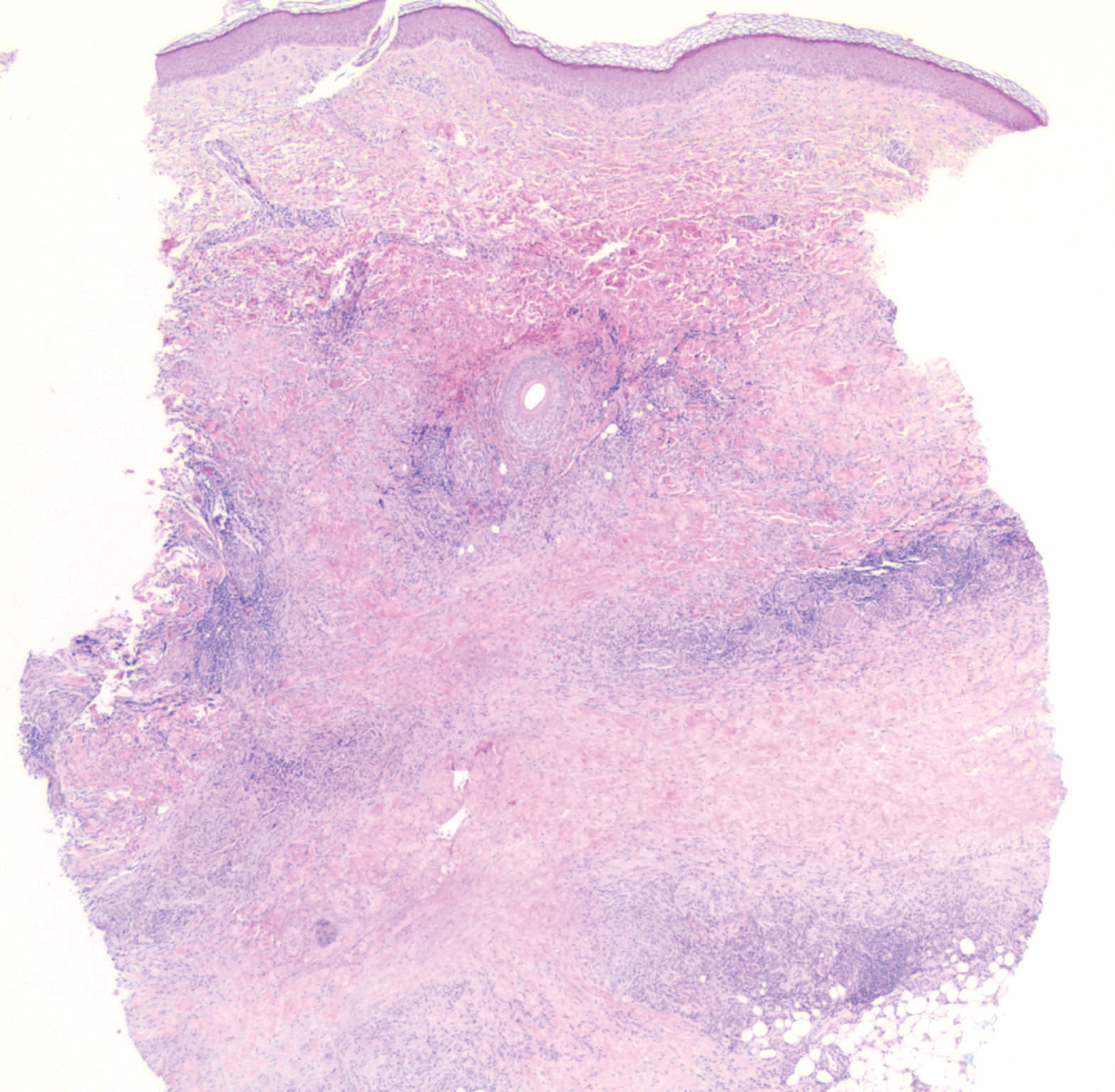

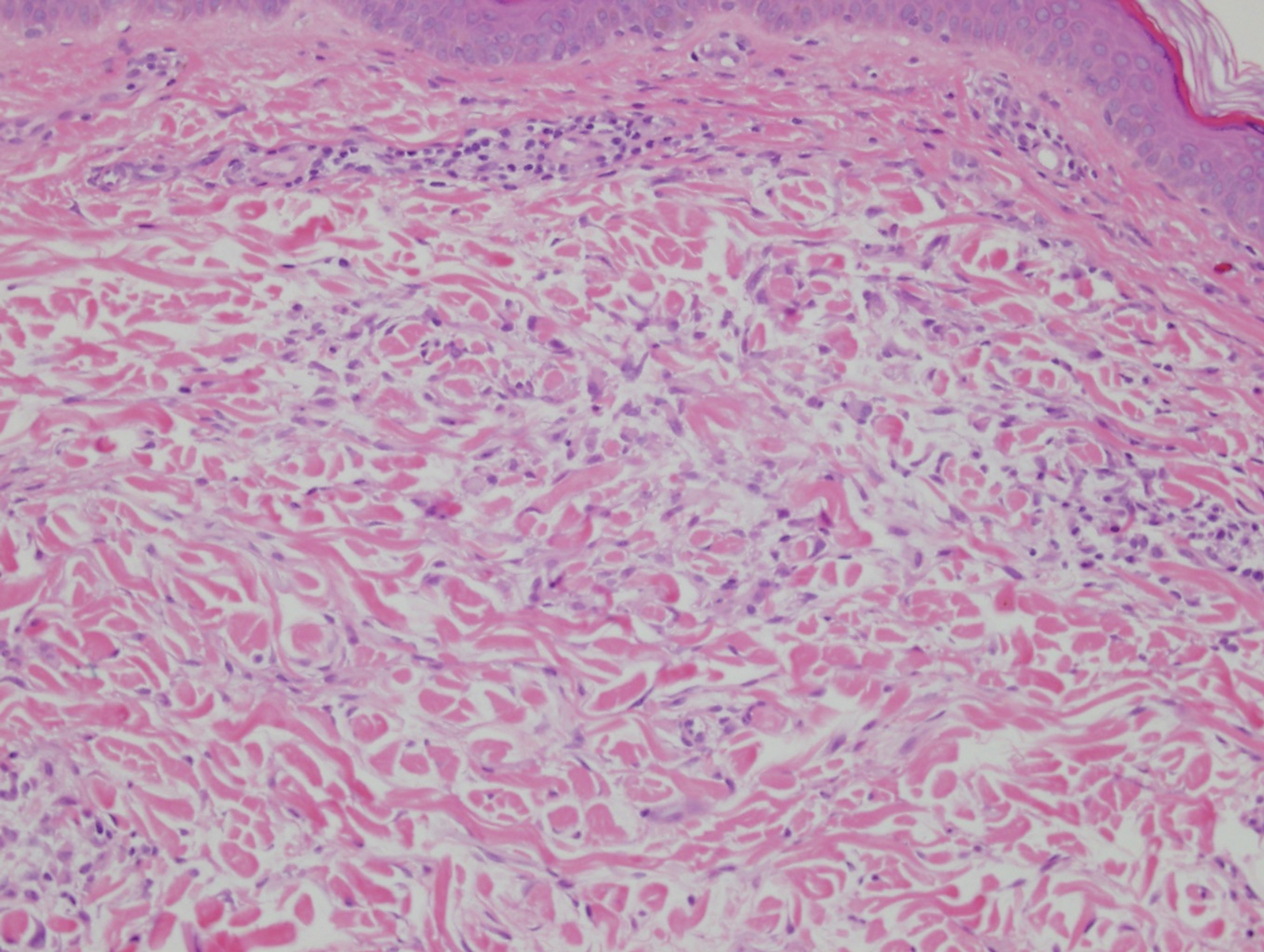

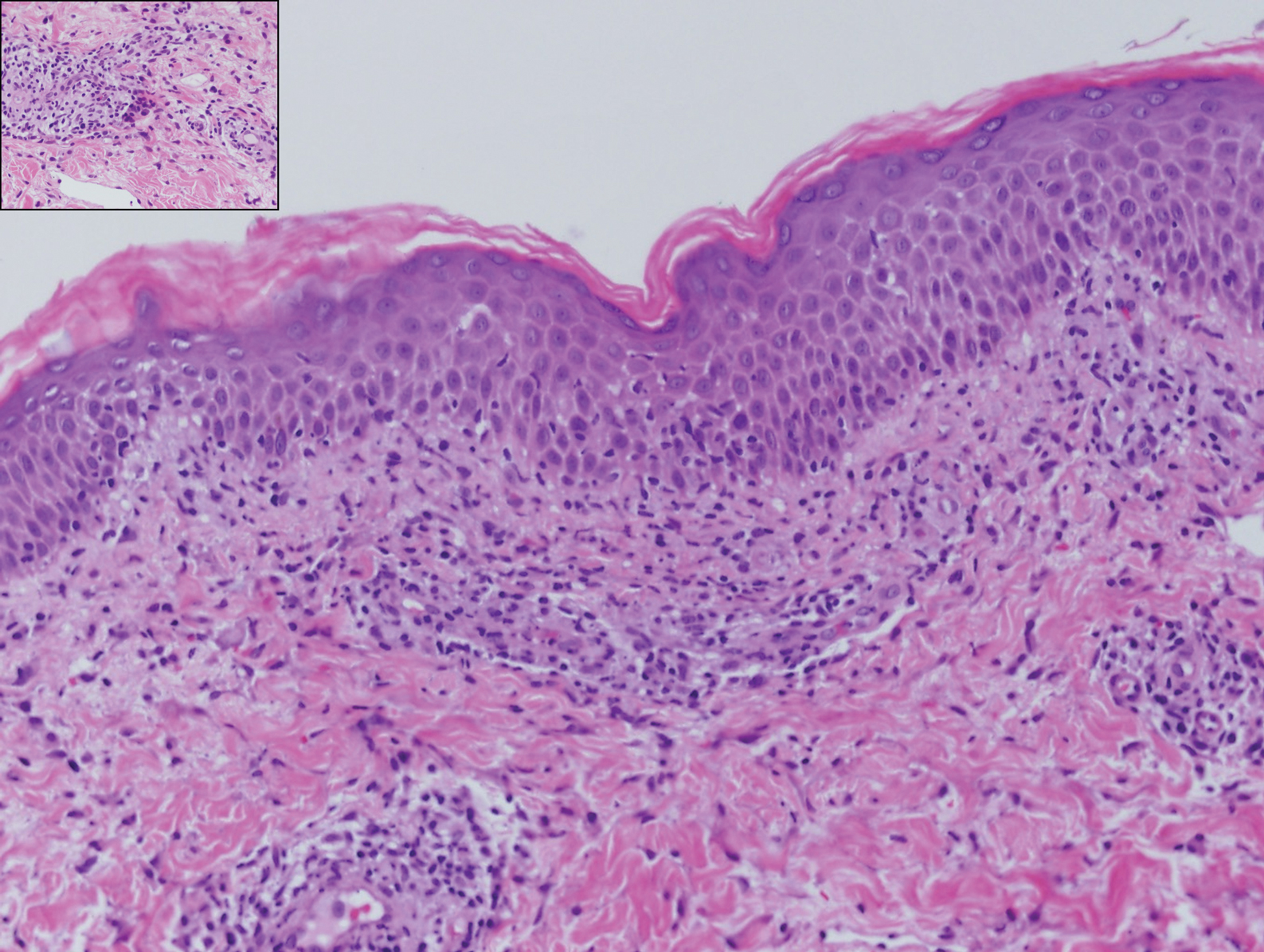

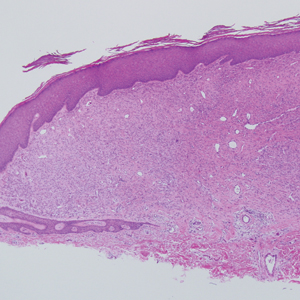

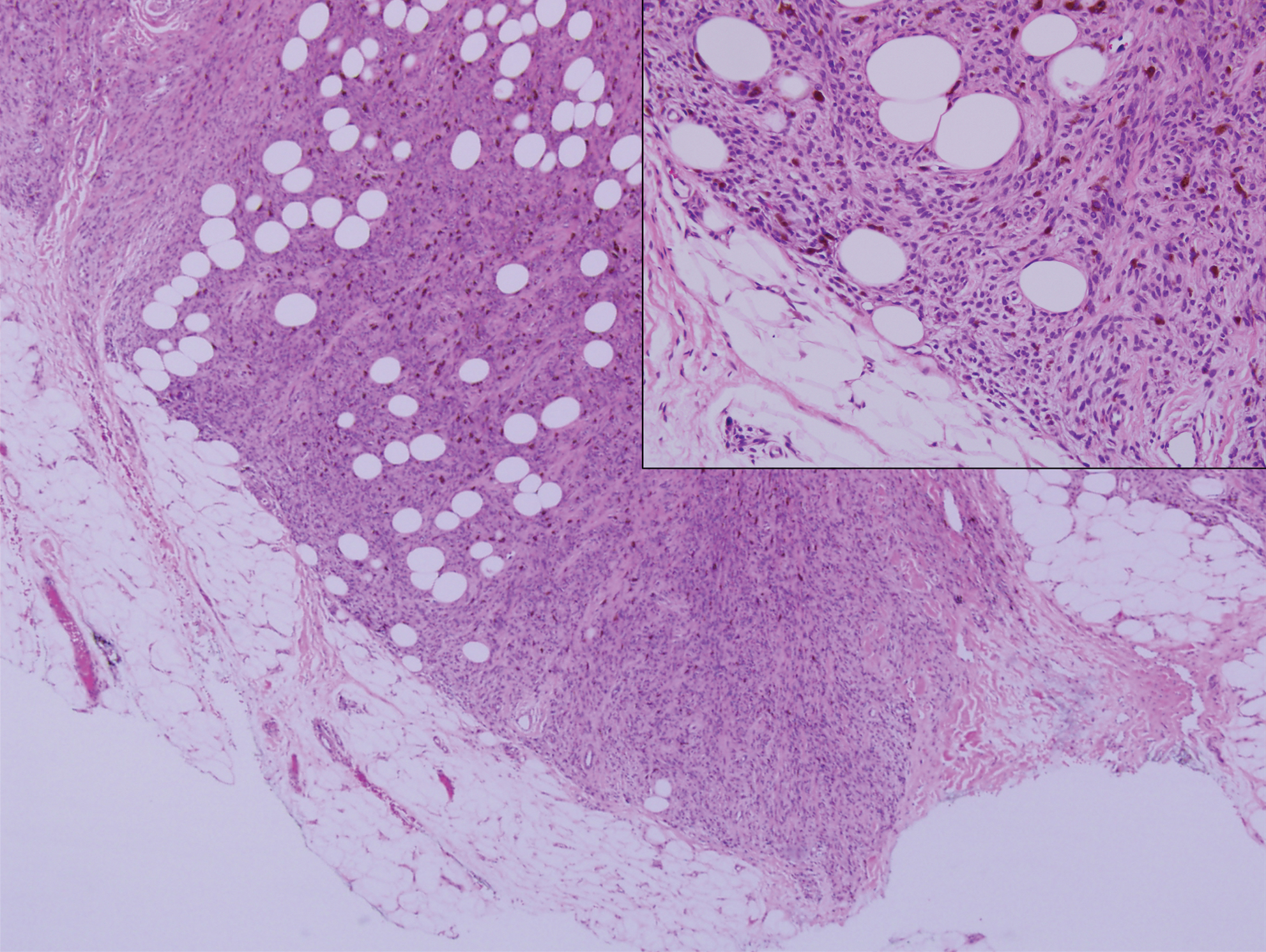

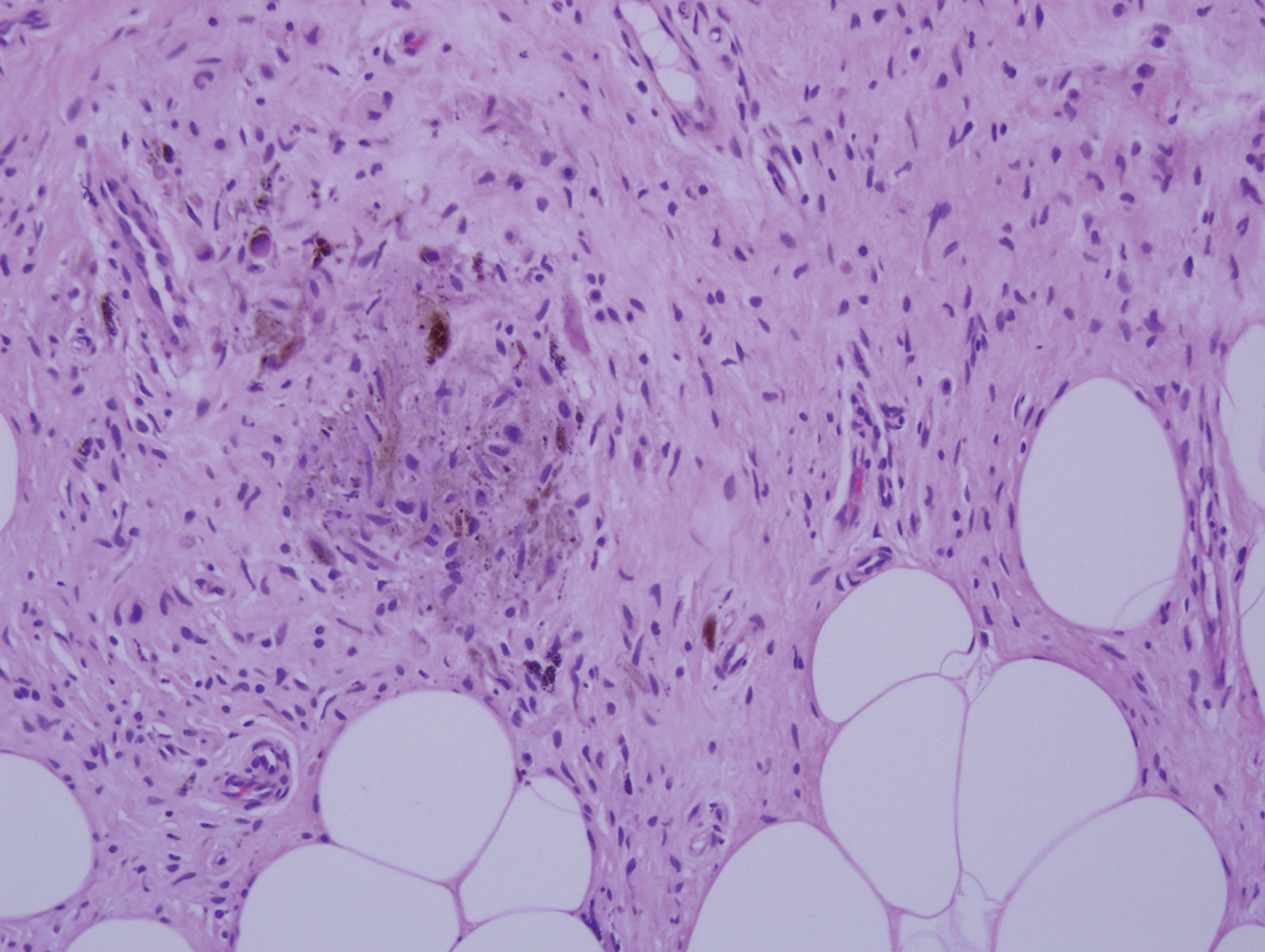

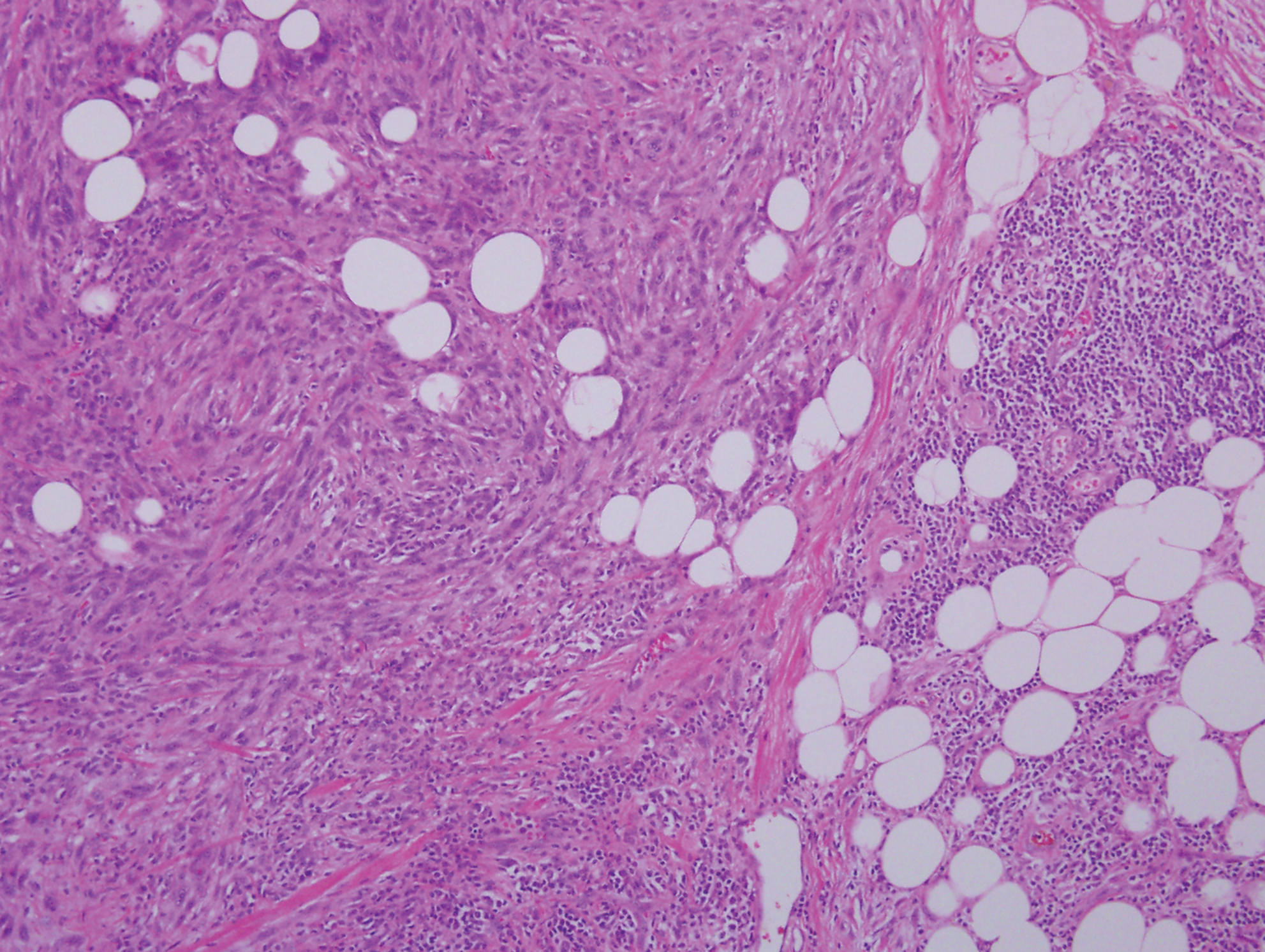

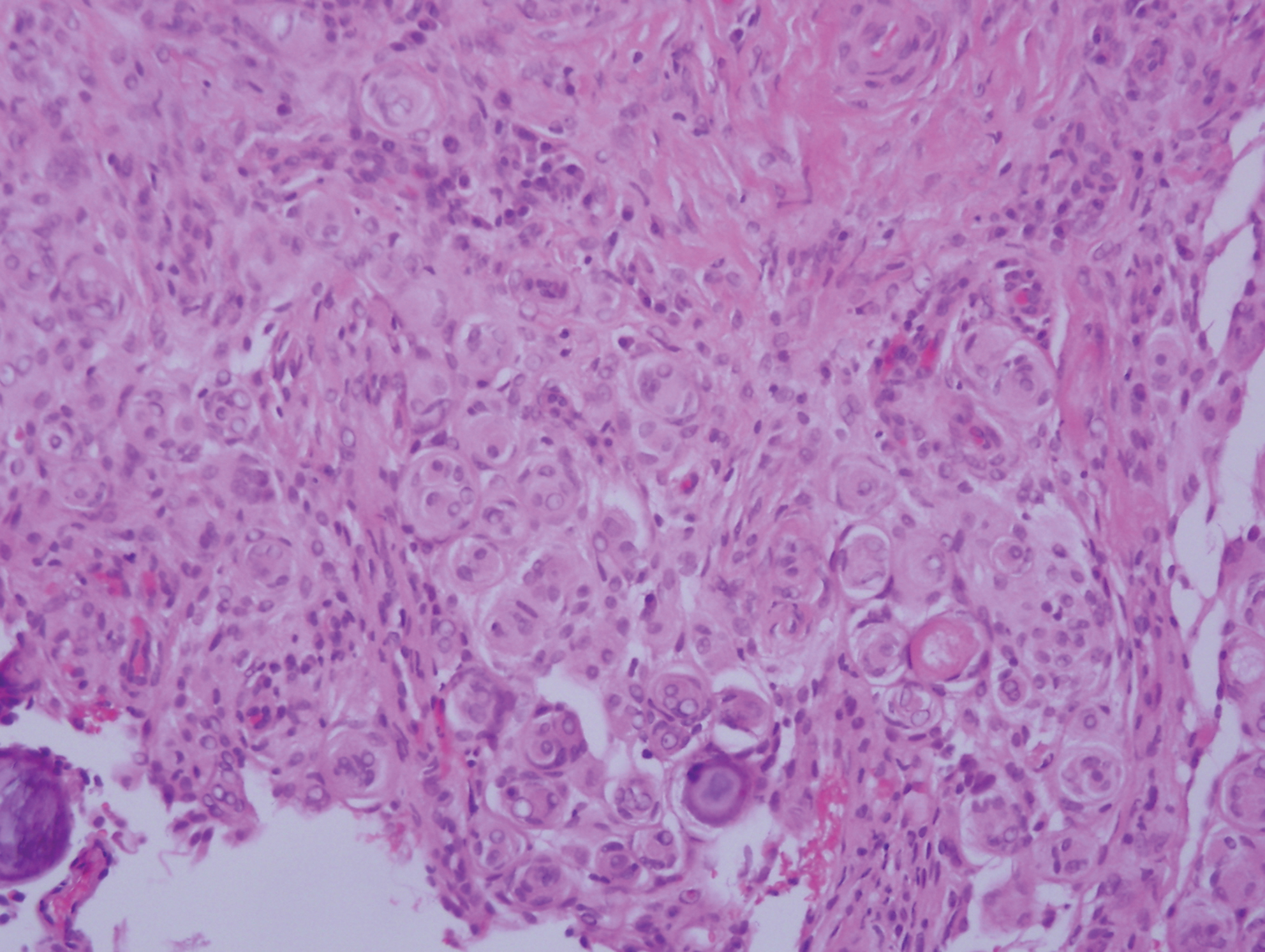

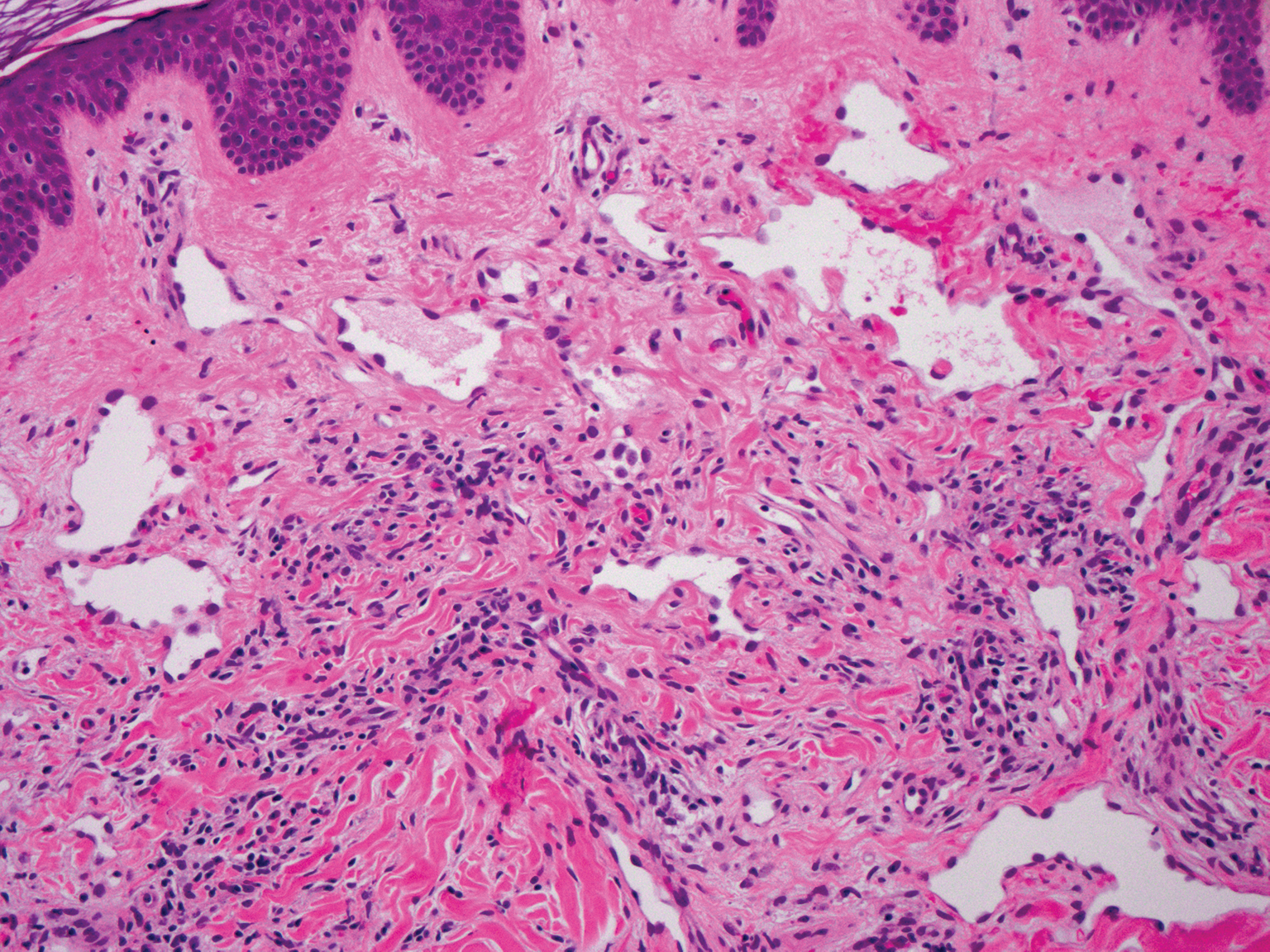

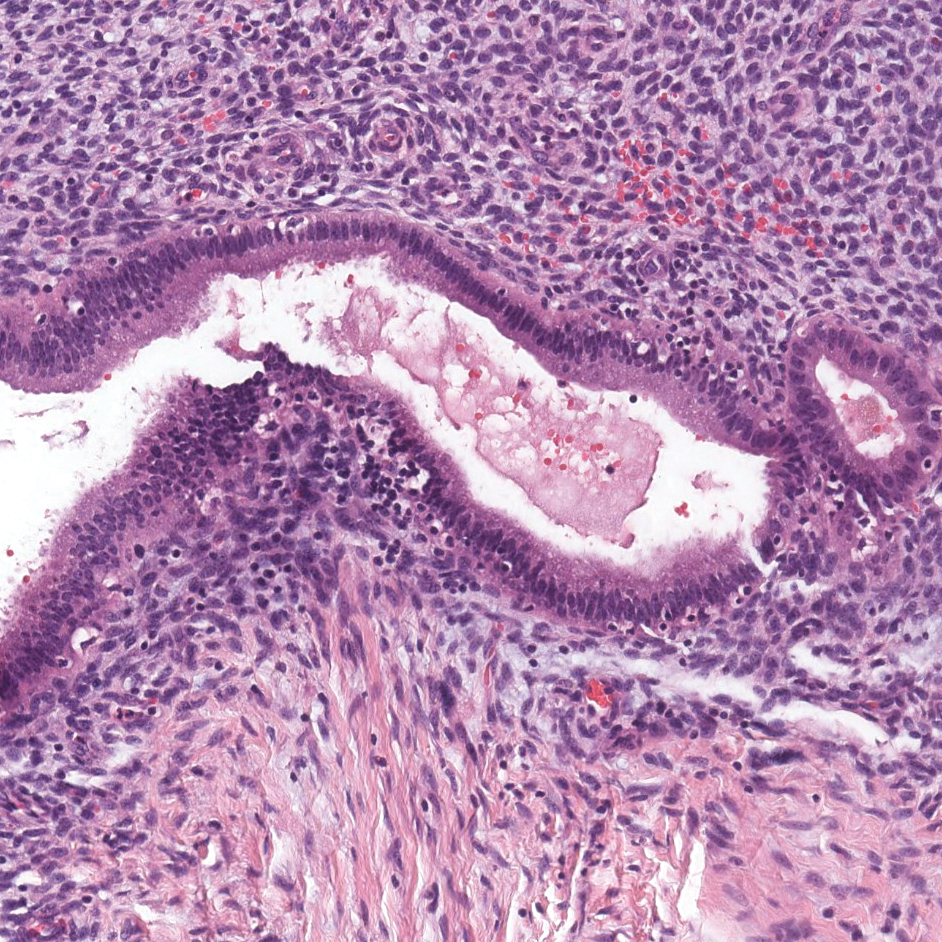

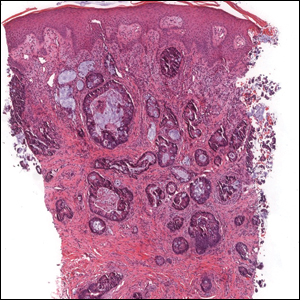

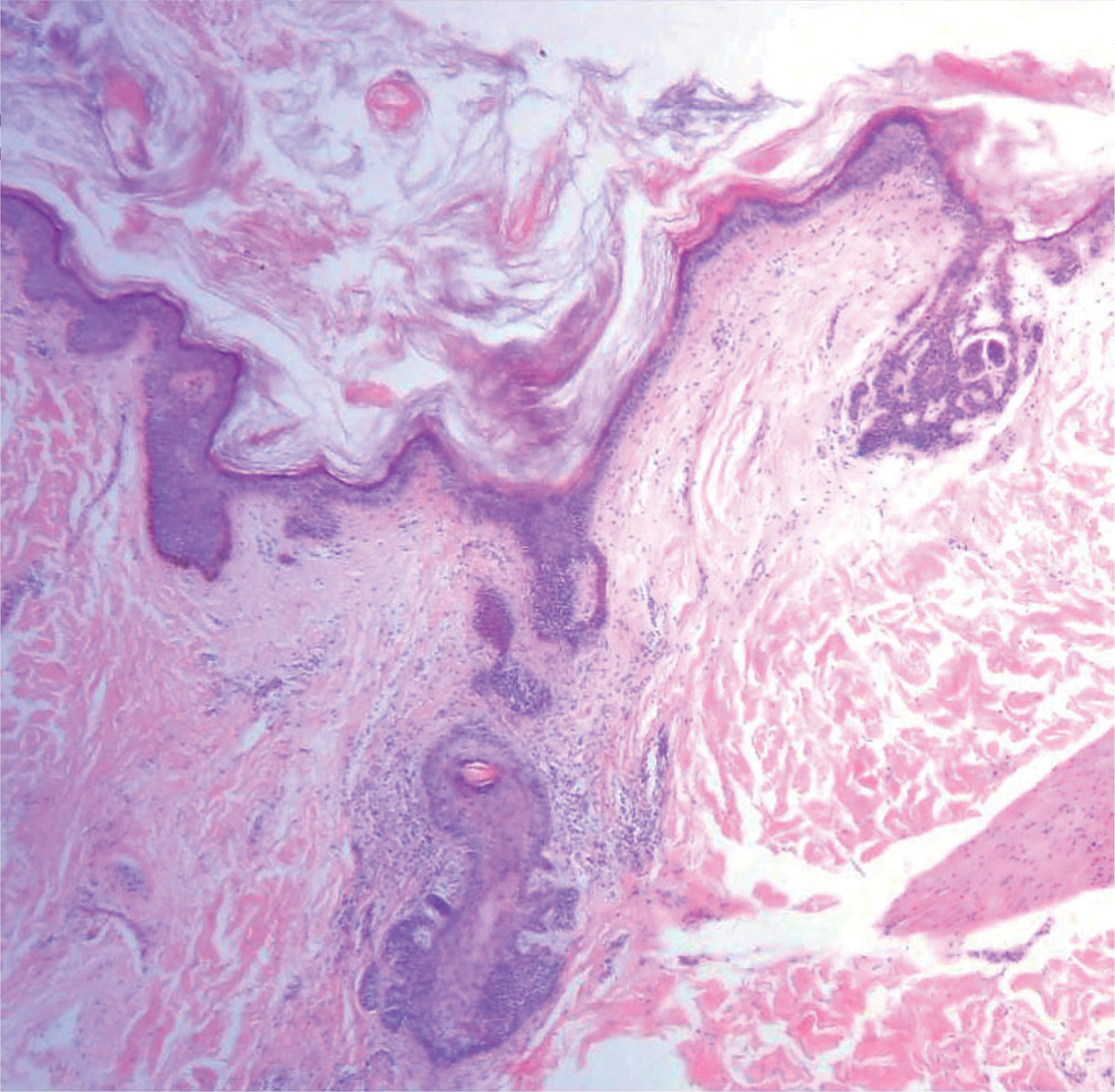

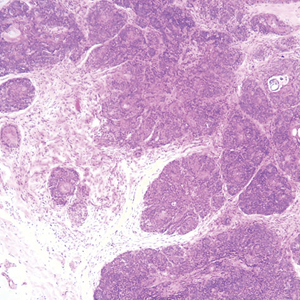

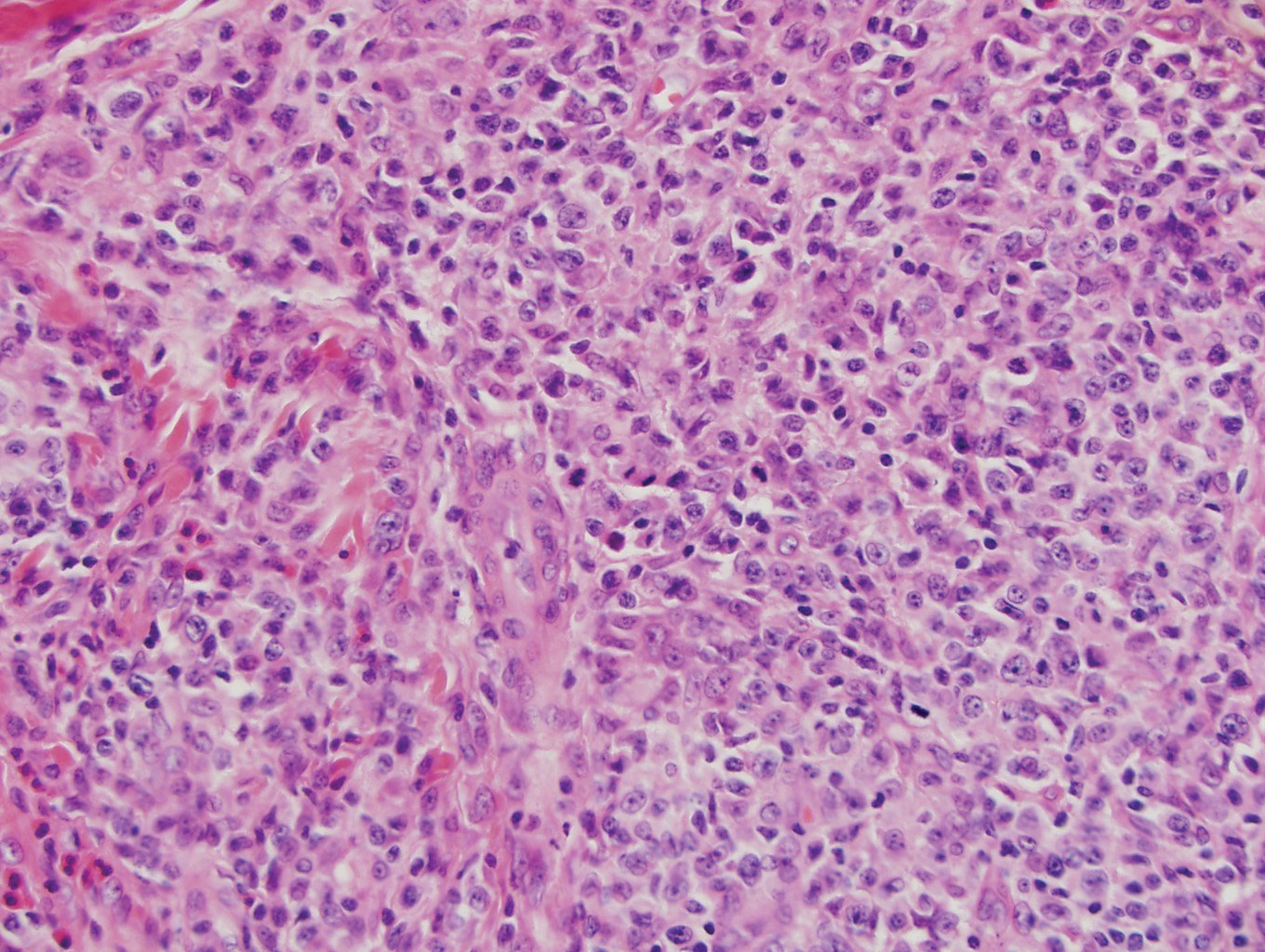

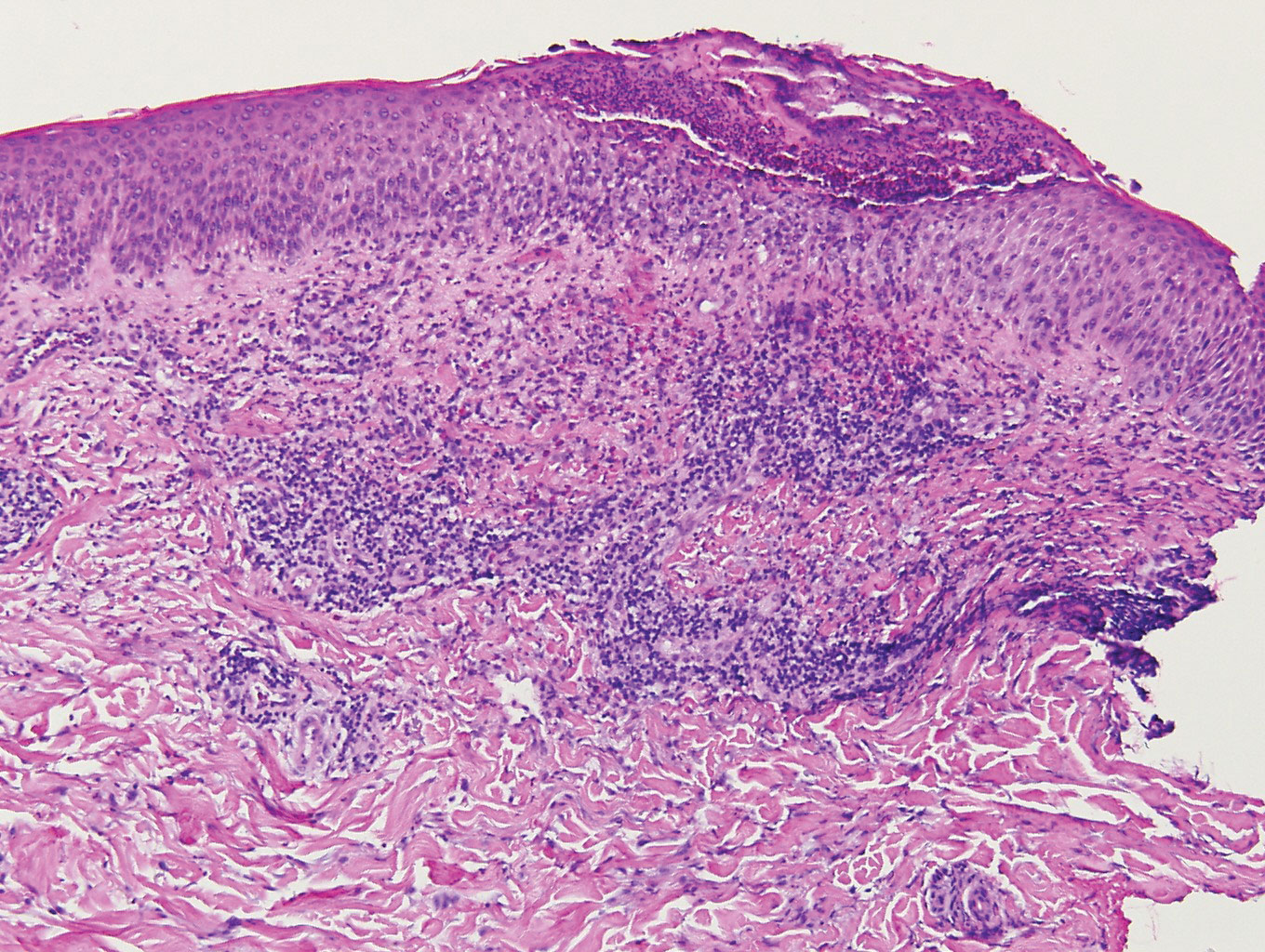

Proliferating pilar tumor (PPT), or cyst, is a neoplasm of trichilemmal keratinization first described by Wilson-Jones1 in 1966. Proliferating pilar tumors lie on a spectrum with malignant PPT, which is a rare adnexal neoplasm first described by Saida et al2 in 1983. The incidence of PPT is unknown given the paucity of cases and the possible misdiagnosis as squamous cell carcinoma (SCC). Proliferating pilar tumors tend to present on the head and neck of older females as a multilobular and sometimes ulcerating nodule.3 Although PPT can occur de novo, the majority of cases are thought to develop progressively from a benign pilar cyst. Histopathologically, PPT is characterized by cords and nests of squamous cells that display trichilemmal keratinization (quiz images).

Classification of PPT as benign or malignant is challenging, though criteria have been proposed.3-7 Lesions with minimal infiltration into the surrounding dermis and scant mitosis typically behave in a benign manner, while lesions showing nuclear atypia, atypical mitosis, and irregular infiltration into the surrounding dermis can have up to a 50% locoregional recurrence rate.3 In addition, distinguishing a PPT from an SCC or trichilemmal carcinoma also can be difficult; however, SCC is favored when there is a lack of trichilemmal keratinization or when squamous atypia is present in the adjacent epidermis.8 Trichilemmal carcinoma is a rare tumor that has been questioned as a distinct entity.9-12

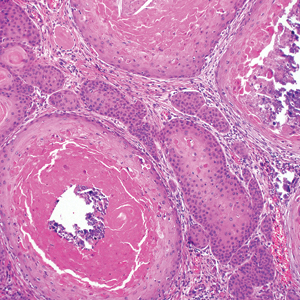

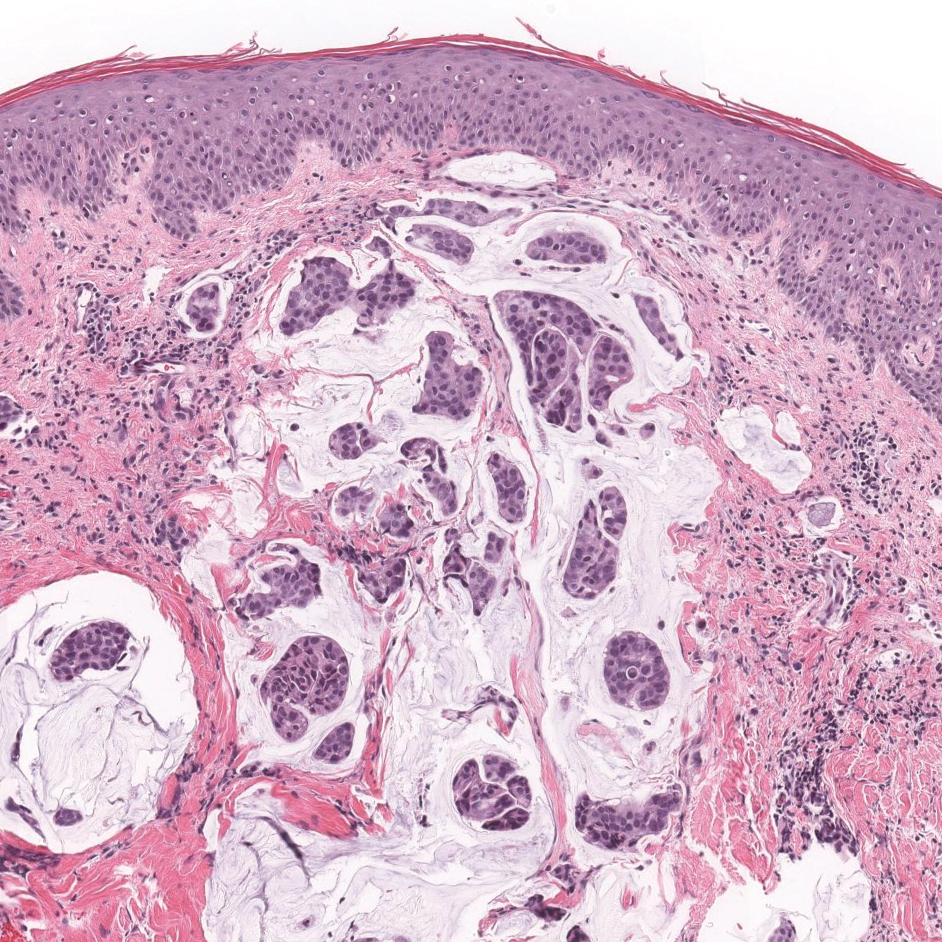

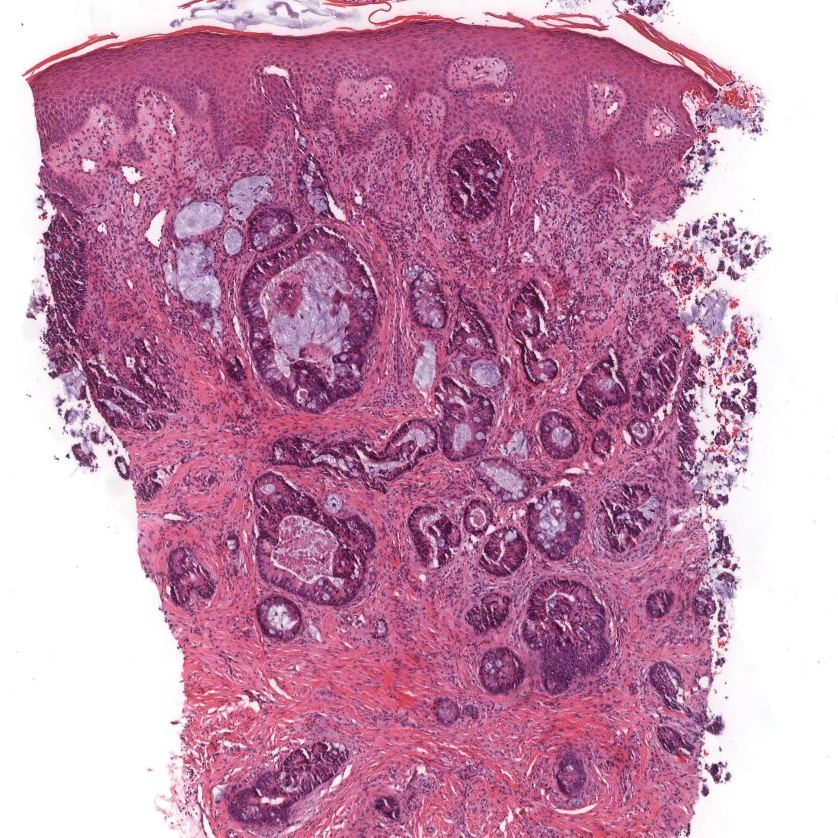

Pilomatricoma, also known as calcifying epithelioma of Malherbe, is a benign pilar tumor that presents as a slowly growing nodule on the head or neck area or arms.13,14 Most pilomatricomas develop by the second decade of life. Multiple lesions may be present in association with myotonic dystrophy or Gardner syndrome among other syndromes.15-17 Similar to PPT, pilomatricomas present as large dermal nodules; however, they tend to be circumscribed and have a trabecular network that consists of basophilic cells and eosinophilic keratinized shadow cells (Figure 1).18 Calcification may be seen and bone formation subsequently may occur.19

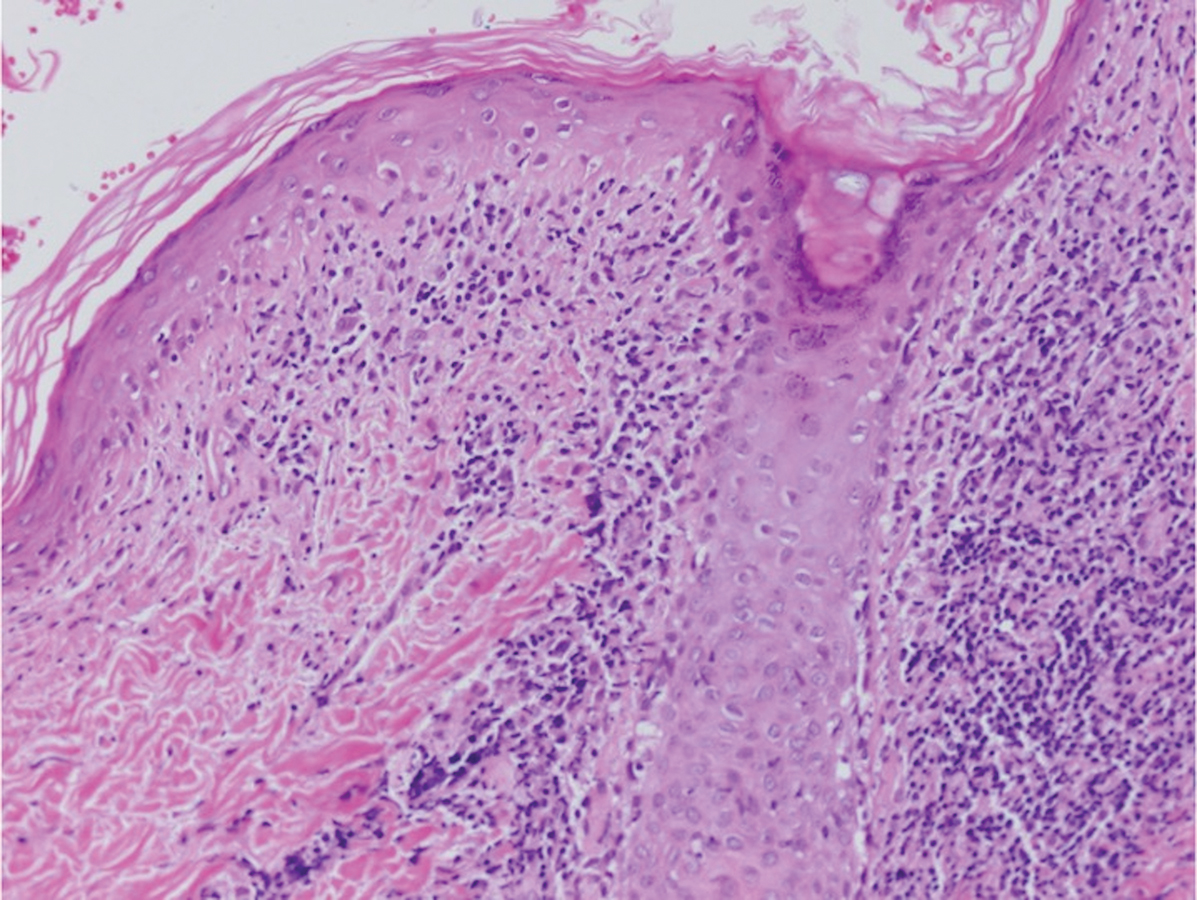

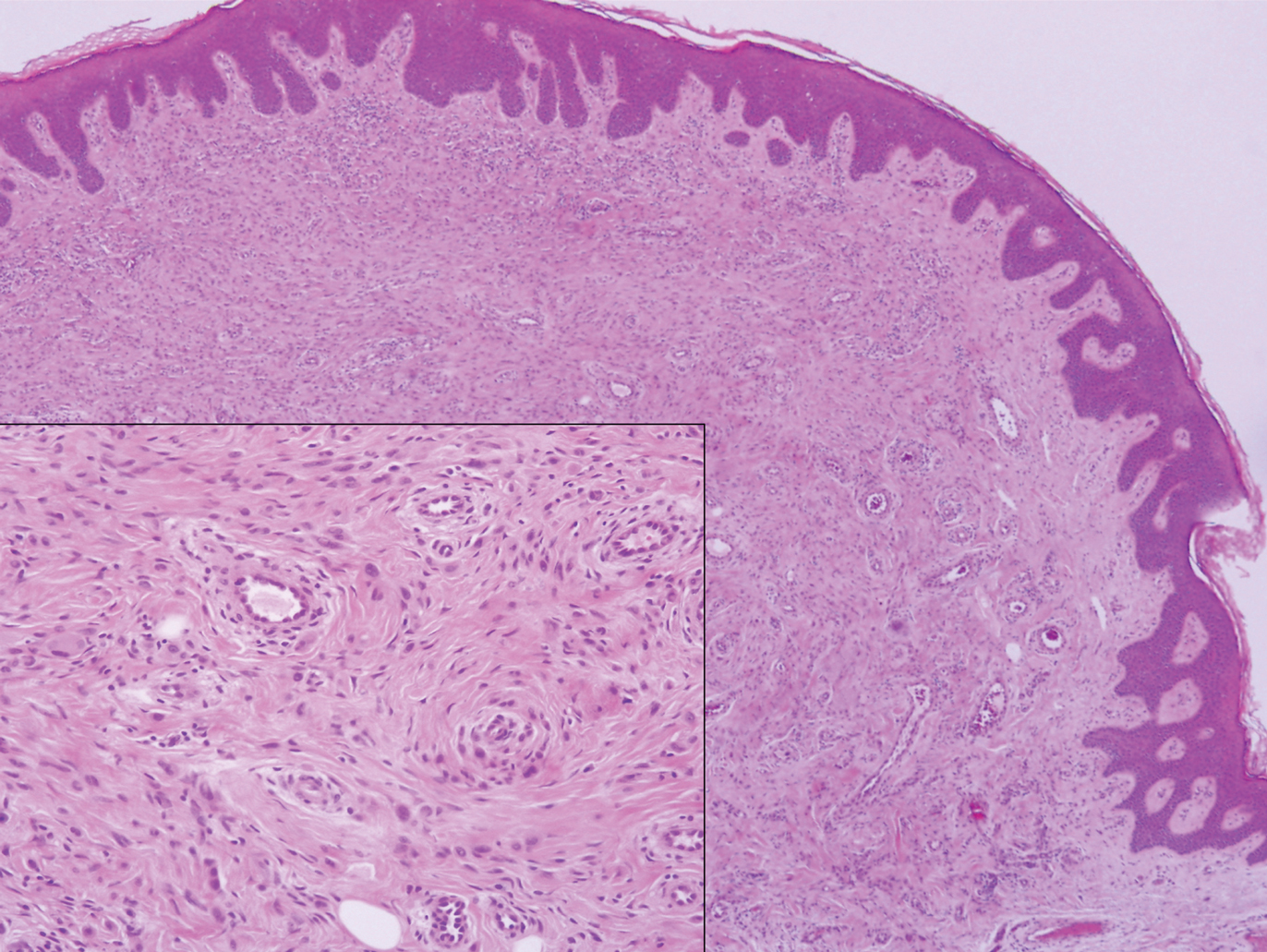

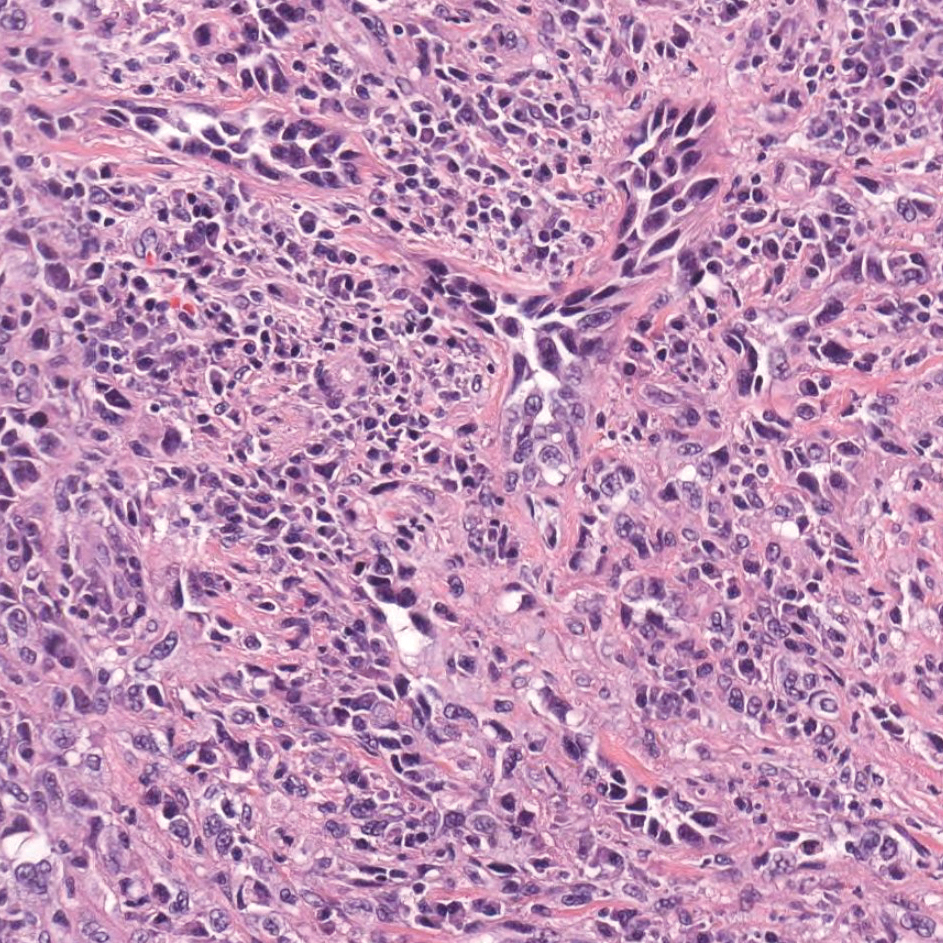

Most sources now consider keratoacanthoma (KA) as a well-differentiated SCC.20 The typical presentation consists of a rapidly growing erythematous to flesh-colored nodule with a central keratinous plug that develops over a period of weeks. If untreated, KAs may resolve over a period of months and leave a depressed scar. Local destruction can result from KAs, and they have the potential to transform into a more aggressive SCC. Accordingly, most clinicians use tissue destructive methods, excision, or Mohs micrographic surgery for treatment based on location. Histologically, a well-circumscribed proliferation of glassy cytoplasm is noted. A depressed keratin-filled center is surrounded by a lip of epithelium extending over the lesion (Figure 2).20,21 Pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia accompanied by hypergranulosis is seen in the center of KAs rather than at the periphery, which is typical of non-KA SCCs. Typical KAs lack acantholysis, a feature suggesting a non-KA type of SCC. Neutrophilic microabscesses and eosinophils commonly are seen in KAs.20,21

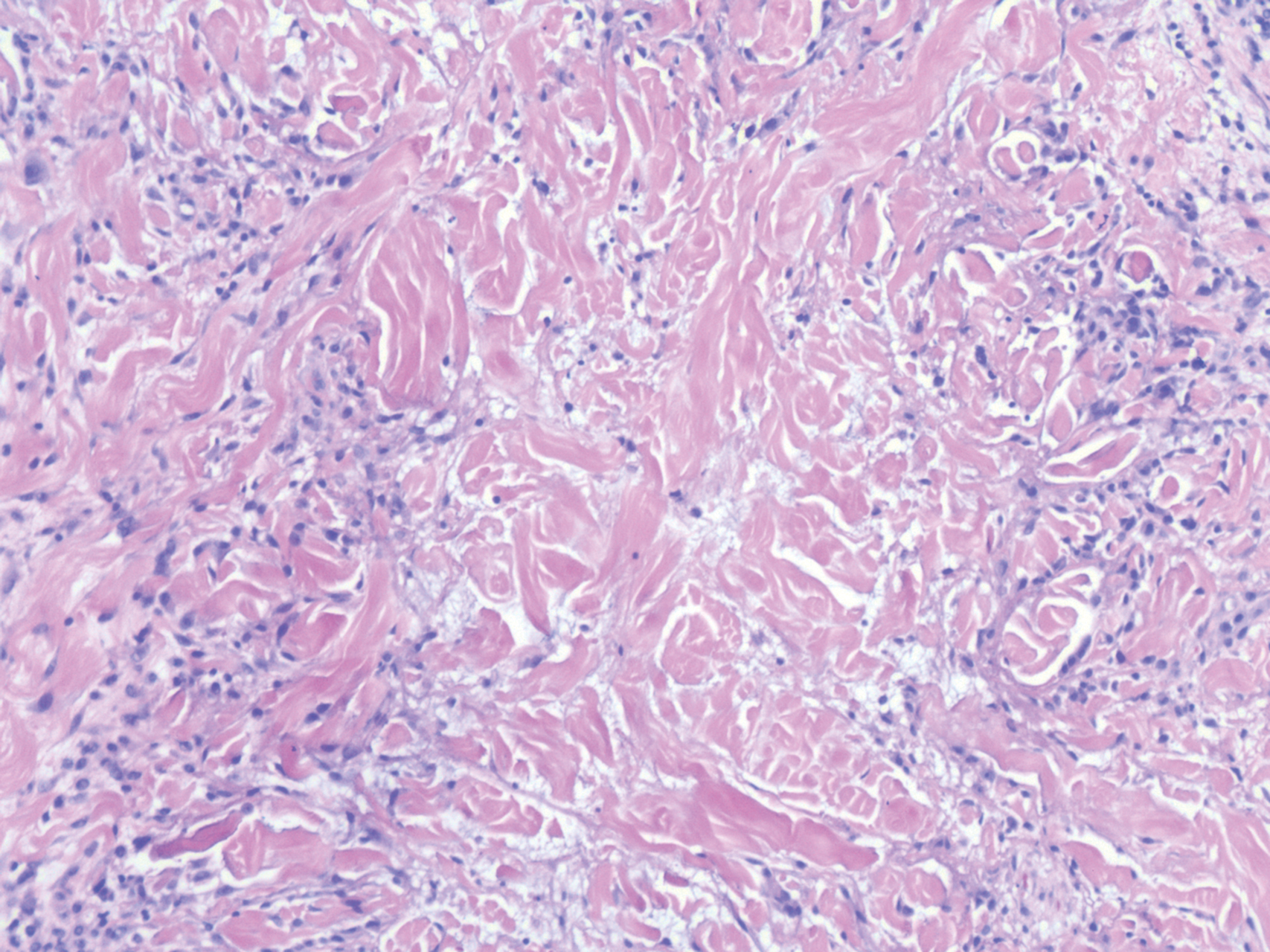

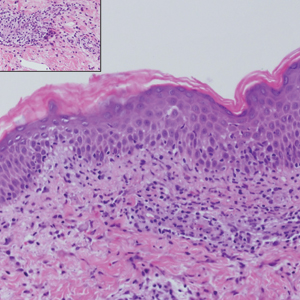

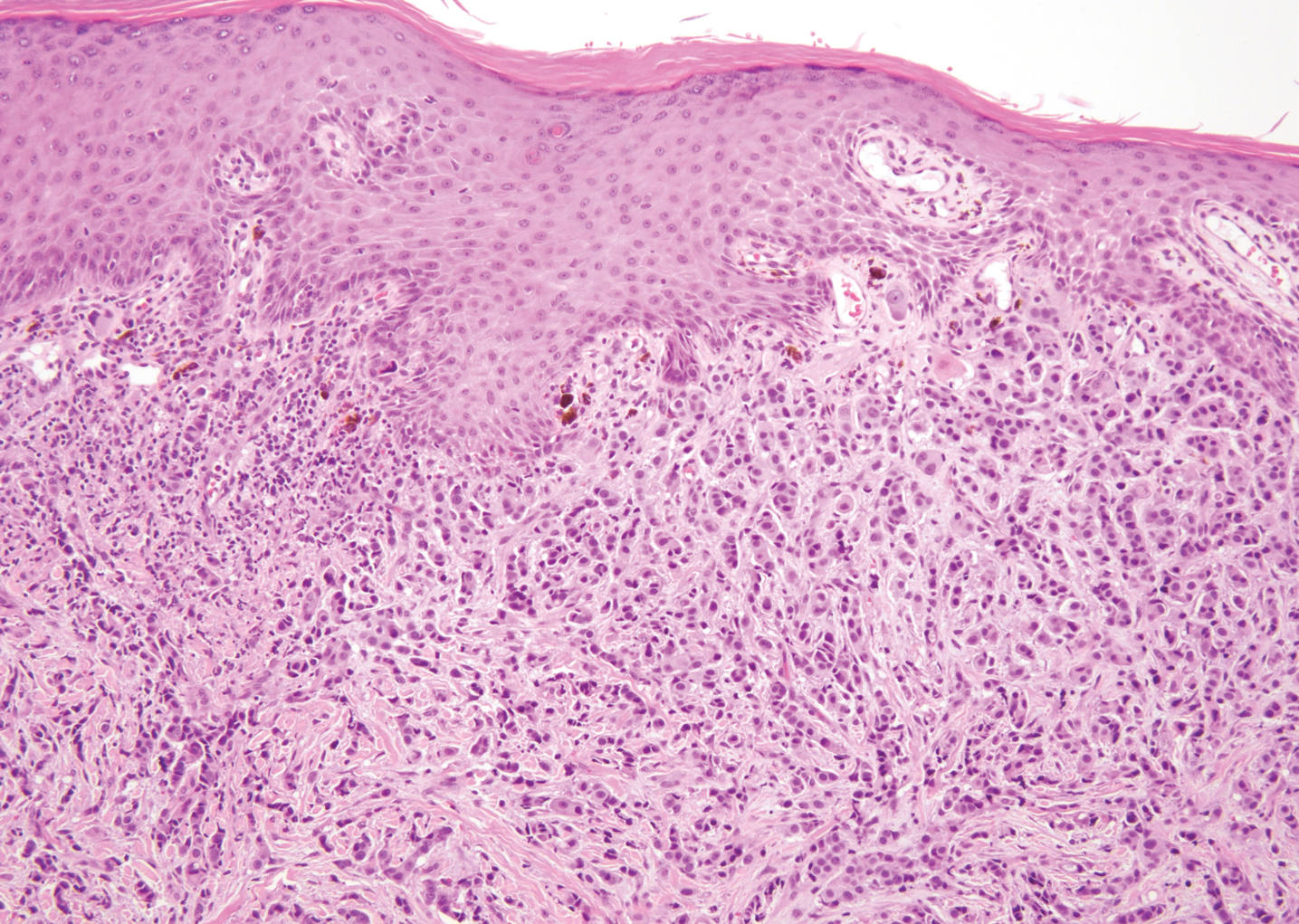

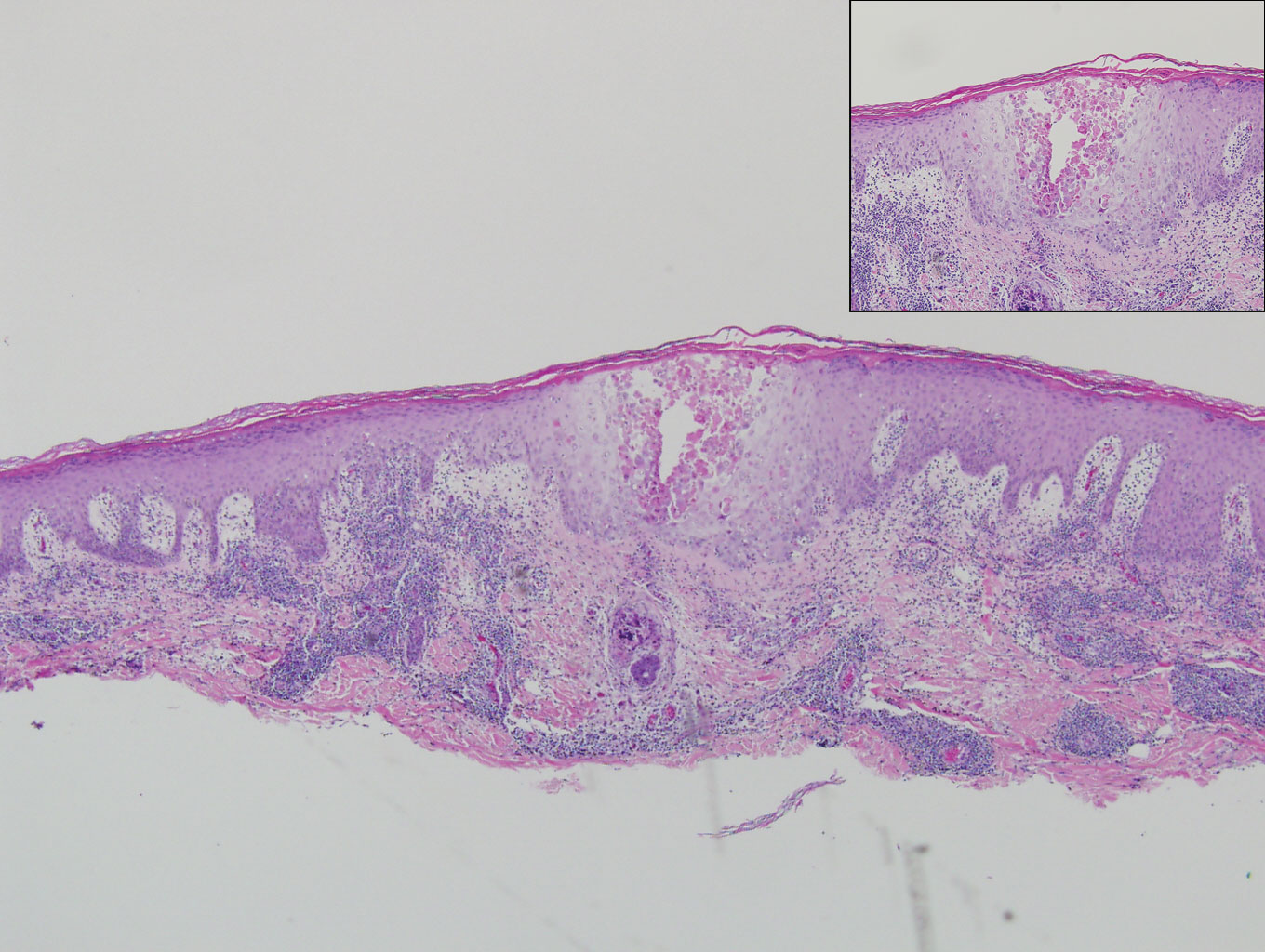

Inverted follicular keratosis is a benign tumor that gained traction as its own entity in the 1960s.22 These lesions typically develop from the follicular infundibulum, but some consider them a version of a wart or seborrheic keratosis.23 They generally are flesh-colored nodules on the upper cutaneous lip or face. Treatment usually consists of complete excision. There are many different growth patterns described, but they typically are endophytic tumors with eosinophilic squamous cells in the center and more basophilic cells at the periphery (Figure 3).24 Characteristically, there are squamous eddies throughout the tumor (Figure 3 [inset]). There also may be a scant lymphohistiocytic infiltrate within the dermis surrounding the lesion.

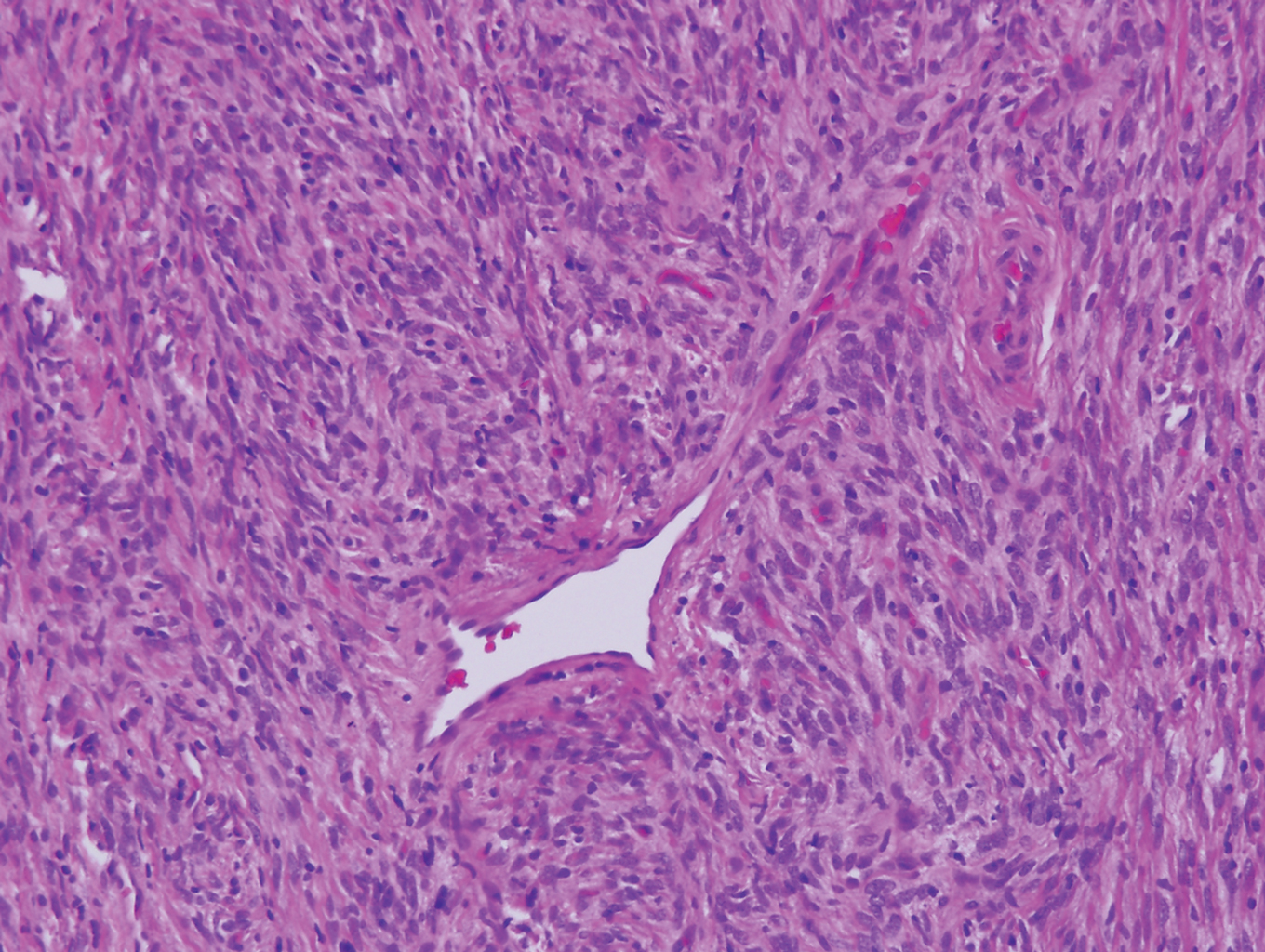

Trichilemmomas are flesh-colored adnexal neoplasms that may present as a solitary lesion or in clusters on the face. They have been reported to occur on all nonglabrous skin sites.25 Multiple lesions may occur in association with Cowden syndrome or with nevus sebaceous.26 A desmoplastic variant of trichilemmomas has been reported.27 Desmoplastic trichilemmomas appear as well-circumscribed tumors of outer root sheath differentiation with lobules extending down into the dermis.28 Vacuolated glycogen-filled keratinocytes are scattered throughout the lesion but are most prominent at the base. At the periphery of the lobules, peripheral palisading of basaloid cells is accompanied by a thickened eosinophilic basement membrane that is periodic acid-Schiff positive. Typical trichilemmomas also can display these features; however, the main differentiating feature of a desmoplastic trichilemmoma is the pink hyalinized stroma separating small islets of basophilic cells (Figure 4). Differentiation from an invasive malignant carcinoma sometimes can be challenging without a focus of typical trichilemmoma or if the biopsy specimen is too superficial.29

Pilar cysts are common tumors that typically arise on the scalp and sometimes are proliferating. Proliferating pilar tumor should be kept on the differential when secondary changes such as ulceration occur in the primary lesion of the scalp. Microscopically, and sometimes clinically, PPT can be difficult to differentiate from other mimickers.

- Wilson-Jones E. Proliferating epidermoid cysts. Arch Dermatol. 1966;94:11-19.

- Saida T, Oohara K, Hori Y, et al. Development of a malignant proliferating trichilemmal cyst in a patient with multiple trichilemmal cysts. Dermatologica. 1983;166:203-208.

- Ye J, Nappi O, Swanson PE, et al. Proliferating pilar tumours: a clinicopathological study of 76 cases with a proposal for definition of benign and malignant variants. Am J Clin Pathol. 2004;122:566-574.

- Garg PK, Dangi A, Khurana N, et al. Malignant proliferating trichilemmal cyst: a case report with review of literature. Malaysian J Pathol. 2009;31:71-76.

- Herrero J, Monteagudo C, Ruiz A, et al. Malignant proliferating trichilemmal tumors: a histopathological and immunohistochemical study of three cases with DNA ploidy and morphometric evaluation. Histopathology. 1998;33:542-546.

- Haas N, Audring H, Sterry W. Carcinoma arising in a proliferating trichilemmal cyst expresses fetal and trichilemmal hair phenotype. Am J Dermatopathol. 2002;24:340-344.

- Rutty GN, Richman PI, Laing JH. Malignant change in trichilemmal cysts: a study of cell proliferation and DNA content. Histopathology. 1992;21:465-468.

- Brownstein MH, Arluk DJ. Proliferating trichilemmal cyst: a simulant of squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer. 1981;48:1207-1214.

- Misago N, Ackerman AB. Tricholemmal carcinoma? Dermatopathol Pract Concept. 1999;5:205-206.

- Misago N, Narisawa Y. Tricholemmal carcinoma in continuity with trichoblastoma within nevus sebaceous. Am J Dermatopathol. 2002;24:149-155.

- Liang H, Wu H, Giorgadze TA, et al. Podoplanin is a highly sensitive and specific marker to distinguish primary skin adnexal carcinomas from adenocarcinomas metastatic to skin. Am J Surg Pathol. 2007;31:304-310.

- Swanson PE, Marrogi AJ, Williams DJ, et al. Trichilemmal carcinoma: clinicopathologic study of 10 cases. J Cutan Pathol. 1992;19:100-109.

- Mehregan AH. Hair follicle tumors of the skin. J Cutan Pathol. 1985;12:189-195.

- Julian CG, Bowers PW. A clinical review of 209 pilomatricomas. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;39:191-195.

- Marrogi AJ, Wick MR, Dehner LP. Pilomatrical neoplasms in children and young adults. Am J Dermatopathol. 1992;14:87-94.

- Berberian BJ, Colonna TM, Battaglia M, et al. Multiple pilomatricomas in association with myotonic dystrophy and a family history of melanoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;37:268-269.

- Cooper PH, Fechner RE. Pilomatricoma-like changes in the epidermal cysts of Gardner's syndrome. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1983;8:639-644.

- Kaddu S, Soyer HP, Cerroni L, et al. Clinical and histopathologic spectrum of pilomatricomas in adults. Int J Dermatol. 1994;33:705-708.

- Sano Y, Mihara M, Miyamoto T, et al. Simultaneous occurrence of calcification and amyloid deposit in pilomatricoma. Acta Derm Venereol. 1990;70:256-259.

- Schwartz RA. Keratoacanthoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;30:1-19.

- Kwiek B, Schwartz RA. Keratoacanthoma (KA): an update and review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:1220-1233.

- Mehregan AH. Inverted follicular keratosis. Arch Dermatol. 1964;89:117-123.

- Spielvogel RL, Austin C, Ackerman AB. Inverted follicular keratosis is not a specific keratosis but a verruca vulgaris (or seborrheic keratosis) with squamous eddies. Am J Dermatopathol. 1983;5:427-445.

- Mehregan AH. Inverted follicular keratosis is a distinct follicular tumor. Am J Dermatopathol. 1983;5:467-470.

- Brownstein MH. Trichilemmoma. benign follicular tumor or viral wart? Am J Dermatopathol. 1980;2:229-231.

- Brownstein MH. Multiple trichilemmomas in Cowden's syndrome. Arch Dermatol. 1979;115:111.

- Roson E, Gomez Centeno P, Sanchez Aguilar D, et al. Desmoplastic trichilemmoma arising within a nevus sebaceous. Am J Dermatopathol. 1998;20:495-497.

- Tellechea O, Reis JP, Baptista AP. Desmoplastic trichilemmoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 1992;14:107-114.

- Sharma R, Sirohi D, Sengupta P, et al. Desmoplastic trichilemmoma of the facial region mimicking invasive carcinoma. J Maxillofac Oral Surg. 2010;10:71-73.

The Diagnosis: Proliferating Pilar Tumor

Proliferating pilar tumor (PPT), or cyst, is a neoplasm of trichilemmal keratinization first described by Wilson-Jones1 in 1966. Proliferating pilar tumors lie on a spectrum with malignant PPT, which is a rare adnexal neoplasm first described by Saida et al2 in 1983. The incidence of PPT is unknown given the paucity of cases and the possible misdiagnosis as squamous cell carcinoma (SCC). Proliferating pilar tumors tend to present on the head and neck of older females as a multilobular and sometimes ulcerating nodule.3 Although PPT can occur de novo, the majority of cases are thought to develop progressively from a benign pilar cyst. Histopathologically, PPT is characterized by cords and nests of squamous cells that display trichilemmal keratinization (quiz images).

Classification of PPT as benign or malignant is challenging, though criteria have been proposed.3-7 Lesions with minimal infiltration into the surrounding dermis and scant mitosis typically behave in a benign manner, while lesions showing nuclear atypia, atypical mitosis, and irregular infiltration into the surrounding dermis can have up to a 50% locoregional recurrence rate.3 In addition, distinguishing a PPT from an SCC or trichilemmal carcinoma also can be difficult; however, SCC is favored when there is a lack of trichilemmal keratinization or when squamous atypia is present in the adjacent epidermis.8 Trichilemmal carcinoma is a rare tumor that has been questioned as a distinct entity.9-12

Pilomatricoma, also known as calcifying epithelioma of Malherbe, is a benign pilar tumor that presents as a slowly growing nodule on the head or neck area or arms.13,14 Most pilomatricomas develop by the second decade of life. Multiple lesions may be present in association with myotonic dystrophy or Gardner syndrome among other syndromes.15-17 Similar to PPT, pilomatricomas present as large dermal nodules; however, they tend to be circumscribed and have a trabecular network that consists of basophilic cells and eosinophilic keratinized shadow cells (Figure 1).18 Calcification may be seen and bone formation subsequently may occur.19

Most sources now consider keratoacanthoma (KA) as a well-differentiated SCC.20 The typical presentation consists of a rapidly growing erythematous to flesh-colored nodule with a central keratinous plug that develops over a period of weeks. If untreated, KAs may resolve over a period of months and leave a depressed scar. Local destruction can result from KAs, and they have the potential to transform into a more aggressive SCC. Accordingly, most clinicians use tissue destructive methods, excision, or Mohs micrographic surgery for treatment based on location. Histologically, a well-circumscribed proliferation of glassy cytoplasm is noted. A depressed keratin-filled center is surrounded by a lip of epithelium extending over the lesion (Figure 2).20,21 Pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia accompanied by hypergranulosis is seen in the center of KAs rather than at the periphery, which is typical of non-KA SCCs. Typical KAs lack acantholysis, a feature suggesting a non-KA type of SCC. Neutrophilic microabscesses and eosinophils commonly are seen in KAs.20,21

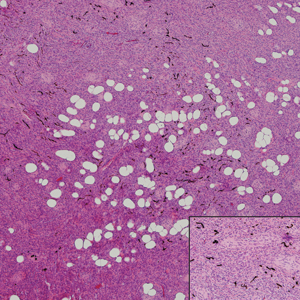

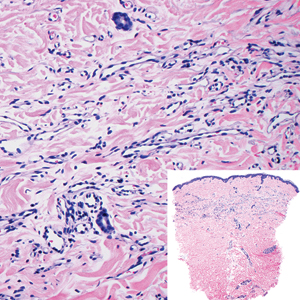

Inverted follicular keratosis is a benign tumor that gained traction as its own entity in the 1960s.22 These lesions typically develop from the follicular infundibulum, but some consider them a version of a wart or seborrheic keratosis.23 They generally are flesh-colored nodules on the upper cutaneous lip or face. Treatment usually consists of complete excision. There are many different growth patterns described, but they typically are endophytic tumors with eosinophilic squamous cells in the center and more basophilic cells at the periphery (Figure 3).24 Characteristically, there are squamous eddies throughout the tumor (Figure 3 [inset]). There also may be a scant lymphohistiocytic infiltrate within the dermis surrounding the lesion.

Trichilemmomas are flesh-colored adnexal neoplasms that may present as a solitary lesion or in clusters on the face. They have been reported to occur on all nonglabrous skin sites.25 Multiple lesions may occur in association with Cowden syndrome or with nevus sebaceous.26 A desmoplastic variant of trichilemmomas has been reported.27 Desmoplastic trichilemmomas appear as well-circumscribed tumors of outer root sheath differentiation with lobules extending down into the dermis.28 Vacuolated glycogen-filled keratinocytes are scattered throughout the lesion but are most prominent at the base. At the periphery of the lobules, peripheral palisading of basaloid cells is accompanied by a thickened eosinophilic basement membrane that is periodic acid-Schiff positive. Typical trichilemmomas also can display these features; however, the main differentiating feature of a desmoplastic trichilemmoma is the pink hyalinized stroma separating small islets of basophilic cells (Figure 4). Differentiation from an invasive malignant carcinoma sometimes can be challenging without a focus of typical trichilemmoma or if the biopsy specimen is too superficial.29

Pilar cysts are common tumors that typically arise on the scalp and sometimes are proliferating. Proliferating pilar tumor should be kept on the differential when secondary changes such as ulceration occur in the primary lesion of the scalp. Microscopically, and sometimes clinically, PPT can be difficult to differentiate from other mimickers.

The Diagnosis: Proliferating Pilar Tumor

Proliferating pilar tumor (PPT), or cyst, is a neoplasm of trichilemmal keratinization first described by Wilson-Jones1 in 1966. Proliferating pilar tumors lie on a spectrum with malignant PPT, which is a rare adnexal neoplasm first described by Saida et al2 in 1983. The incidence of PPT is unknown given the paucity of cases and the possible misdiagnosis as squamous cell carcinoma (SCC). Proliferating pilar tumors tend to present on the head and neck of older females as a multilobular and sometimes ulcerating nodule.3 Although PPT can occur de novo, the majority of cases are thought to develop progressively from a benign pilar cyst. Histopathologically, PPT is characterized by cords and nests of squamous cells that display trichilemmal keratinization (quiz images).

Classification of PPT as benign or malignant is challenging, though criteria have been proposed.3-7 Lesions with minimal infiltration into the surrounding dermis and scant mitosis typically behave in a benign manner, while lesions showing nuclear atypia, atypical mitosis, and irregular infiltration into the surrounding dermis can have up to a 50% locoregional recurrence rate.3 In addition, distinguishing a PPT from an SCC or trichilemmal carcinoma also can be difficult; however, SCC is favored when there is a lack of trichilemmal keratinization or when squamous atypia is present in the adjacent epidermis.8 Trichilemmal carcinoma is a rare tumor that has been questioned as a distinct entity.9-12

Pilomatricoma, also known as calcifying epithelioma of Malherbe, is a benign pilar tumor that presents as a slowly growing nodule on the head or neck area or arms.13,14 Most pilomatricomas develop by the second decade of life. Multiple lesions may be present in association with myotonic dystrophy or Gardner syndrome among other syndromes.15-17 Similar to PPT, pilomatricomas present as large dermal nodules; however, they tend to be circumscribed and have a trabecular network that consists of basophilic cells and eosinophilic keratinized shadow cells (Figure 1).18 Calcification may be seen and bone formation subsequently may occur.19

Most sources now consider keratoacanthoma (KA) as a well-differentiated SCC.20 The typical presentation consists of a rapidly growing erythematous to flesh-colored nodule with a central keratinous plug that develops over a period of weeks. If untreated, KAs may resolve over a period of months and leave a depressed scar. Local destruction can result from KAs, and they have the potential to transform into a more aggressive SCC. Accordingly, most clinicians use tissue destructive methods, excision, or Mohs micrographic surgery for treatment based on location. Histologically, a well-circumscribed proliferation of glassy cytoplasm is noted. A depressed keratin-filled center is surrounded by a lip of epithelium extending over the lesion (Figure 2).20,21 Pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia accompanied by hypergranulosis is seen in the center of KAs rather than at the periphery, which is typical of non-KA SCCs. Typical KAs lack acantholysis, a feature suggesting a non-KA type of SCC. Neutrophilic microabscesses and eosinophils commonly are seen in KAs.20,21

Inverted follicular keratosis is a benign tumor that gained traction as its own entity in the 1960s.22 These lesions typically develop from the follicular infundibulum, but some consider them a version of a wart or seborrheic keratosis.23 They generally are flesh-colored nodules on the upper cutaneous lip or face. Treatment usually consists of complete excision. There are many different growth patterns described, but they typically are endophytic tumors with eosinophilic squamous cells in the center and more basophilic cells at the periphery (Figure 3).24 Characteristically, there are squamous eddies throughout the tumor (Figure 3 [inset]). There also may be a scant lymphohistiocytic infiltrate within the dermis surrounding the lesion.

Trichilemmomas are flesh-colored adnexal neoplasms that may present as a solitary lesion or in clusters on the face. They have been reported to occur on all nonglabrous skin sites.25 Multiple lesions may occur in association with Cowden syndrome or with nevus sebaceous.26 A desmoplastic variant of trichilemmomas has been reported.27 Desmoplastic trichilemmomas appear as well-circumscribed tumors of outer root sheath differentiation with lobules extending down into the dermis.28 Vacuolated glycogen-filled keratinocytes are scattered throughout the lesion but are most prominent at the base. At the periphery of the lobules, peripheral palisading of basaloid cells is accompanied by a thickened eosinophilic basement membrane that is periodic acid-Schiff positive. Typical trichilemmomas also can display these features; however, the main differentiating feature of a desmoplastic trichilemmoma is the pink hyalinized stroma separating small islets of basophilic cells (Figure 4). Differentiation from an invasive malignant carcinoma sometimes can be challenging without a focus of typical trichilemmoma or if the biopsy specimen is too superficial.29

Pilar cysts are common tumors that typically arise on the scalp and sometimes are proliferating. Proliferating pilar tumor should be kept on the differential when secondary changes such as ulceration occur in the primary lesion of the scalp. Microscopically, and sometimes clinically, PPT can be difficult to differentiate from other mimickers.

- Wilson-Jones E. Proliferating epidermoid cysts. Arch Dermatol. 1966;94:11-19.

- Saida T, Oohara K, Hori Y, et al. Development of a malignant proliferating trichilemmal cyst in a patient with multiple trichilemmal cysts. Dermatologica. 1983;166:203-208.

- Ye J, Nappi O, Swanson PE, et al. Proliferating pilar tumours: a clinicopathological study of 76 cases with a proposal for definition of benign and malignant variants. Am J Clin Pathol. 2004;122:566-574.

- Garg PK, Dangi A, Khurana N, et al. Malignant proliferating trichilemmal cyst: a case report with review of literature. Malaysian J Pathol. 2009;31:71-76.

- Herrero J, Monteagudo C, Ruiz A, et al. Malignant proliferating trichilemmal tumors: a histopathological and immunohistochemical study of three cases with DNA ploidy and morphometric evaluation. Histopathology. 1998;33:542-546.

- Haas N, Audring H, Sterry W. Carcinoma arising in a proliferating trichilemmal cyst expresses fetal and trichilemmal hair phenotype. Am J Dermatopathol. 2002;24:340-344.

- Rutty GN, Richman PI, Laing JH. Malignant change in trichilemmal cysts: a study of cell proliferation and DNA content. Histopathology. 1992;21:465-468.

- Brownstein MH, Arluk DJ. Proliferating trichilemmal cyst: a simulant of squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer. 1981;48:1207-1214.

- Misago N, Ackerman AB. Tricholemmal carcinoma? Dermatopathol Pract Concept. 1999;5:205-206.

- Misago N, Narisawa Y. Tricholemmal carcinoma in continuity with trichoblastoma within nevus sebaceous. Am J Dermatopathol. 2002;24:149-155.

- Liang H, Wu H, Giorgadze TA, et al. Podoplanin is a highly sensitive and specific marker to distinguish primary skin adnexal carcinomas from adenocarcinomas metastatic to skin. Am J Surg Pathol. 2007;31:304-310.

- Swanson PE, Marrogi AJ, Williams DJ, et al. Trichilemmal carcinoma: clinicopathologic study of 10 cases. J Cutan Pathol. 1992;19:100-109.

- Mehregan AH. Hair follicle tumors of the skin. J Cutan Pathol. 1985;12:189-195.

- Julian CG, Bowers PW. A clinical review of 209 pilomatricomas. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;39:191-195.

- Marrogi AJ, Wick MR, Dehner LP. Pilomatrical neoplasms in children and young adults. Am J Dermatopathol. 1992;14:87-94.

- Berberian BJ, Colonna TM, Battaglia M, et al. Multiple pilomatricomas in association with myotonic dystrophy and a family history of melanoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;37:268-269.

- Cooper PH, Fechner RE. Pilomatricoma-like changes in the epidermal cysts of Gardner's syndrome. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1983;8:639-644.

- Kaddu S, Soyer HP, Cerroni L, et al. Clinical and histopathologic spectrum of pilomatricomas in adults. Int J Dermatol. 1994;33:705-708.

- Sano Y, Mihara M, Miyamoto T, et al. Simultaneous occurrence of calcification and amyloid deposit in pilomatricoma. Acta Derm Venereol. 1990;70:256-259.

- Schwartz RA. Keratoacanthoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;30:1-19.

- Kwiek B, Schwartz RA. Keratoacanthoma (KA): an update and review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:1220-1233.

- Mehregan AH. Inverted follicular keratosis. Arch Dermatol. 1964;89:117-123.

- Spielvogel RL, Austin C, Ackerman AB. Inverted follicular keratosis is not a specific keratosis but a verruca vulgaris (or seborrheic keratosis) with squamous eddies. Am J Dermatopathol. 1983;5:427-445.

- Mehregan AH. Inverted follicular keratosis is a distinct follicular tumor. Am J Dermatopathol. 1983;5:467-470.

- Brownstein MH. Trichilemmoma. benign follicular tumor or viral wart? Am J Dermatopathol. 1980;2:229-231.

- Brownstein MH. Multiple trichilemmomas in Cowden's syndrome. Arch Dermatol. 1979;115:111.

- Roson E, Gomez Centeno P, Sanchez Aguilar D, et al. Desmoplastic trichilemmoma arising within a nevus sebaceous. Am J Dermatopathol. 1998;20:495-497.

- Tellechea O, Reis JP, Baptista AP. Desmoplastic trichilemmoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 1992;14:107-114.

- Sharma R, Sirohi D, Sengupta P, et al. Desmoplastic trichilemmoma of the facial region mimicking invasive carcinoma. J Maxillofac Oral Surg. 2010;10:71-73.

- Wilson-Jones E. Proliferating epidermoid cysts. Arch Dermatol. 1966;94:11-19.

- Saida T, Oohara K, Hori Y, et al. Development of a malignant proliferating trichilemmal cyst in a patient with multiple trichilemmal cysts. Dermatologica. 1983;166:203-208.

- Ye J, Nappi O, Swanson PE, et al. Proliferating pilar tumours: a clinicopathological study of 76 cases with a proposal for definition of benign and malignant variants. Am J Clin Pathol. 2004;122:566-574.

- Garg PK, Dangi A, Khurana N, et al. Malignant proliferating trichilemmal cyst: a case report with review of literature. Malaysian J Pathol. 2009;31:71-76.

- Herrero J, Monteagudo C, Ruiz A, et al. Malignant proliferating trichilemmal tumors: a histopathological and immunohistochemical study of three cases with DNA ploidy and morphometric evaluation. Histopathology. 1998;33:542-546.

- Haas N, Audring H, Sterry W. Carcinoma arising in a proliferating trichilemmal cyst expresses fetal and trichilemmal hair phenotype. Am J Dermatopathol. 2002;24:340-344.

- Rutty GN, Richman PI, Laing JH. Malignant change in trichilemmal cysts: a study of cell proliferation and DNA content. Histopathology. 1992;21:465-468.

- Brownstein MH, Arluk DJ. Proliferating trichilemmal cyst: a simulant of squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer. 1981;48:1207-1214.

- Misago N, Ackerman AB. Tricholemmal carcinoma? Dermatopathol Pract Concept. 1999;5:205-206.

- Misago N, Narisawa Y. Tricholemmal carcinoma in continuity with trichoblastoma within nevus sebaceous. Am J Dermatopathol. 2002;24:149-155.

- Liang H, Wu H, Giorgadze TA, et al. Podoplanin is a highly sensitive and specific marker to distinguish primary skin adnexal carcinomas from adenocarcinomas metastatic to skin. Am J Surg Pathol. 2007;31:304-310.

- Swanson PE, Marrogi AJ, Williams DJ, et al. Trichilemmal carcinoma: clinicopathologic study of 10 cases. J Cutan Pathol. 1992;19:100-109.

- Mehregan AH. Hair follicle tumors of the skin. J Cutan Pathol. 1985;12:189-195.

- Julian CG, Bowers PW. A clinical review of 209 pilomatricomas. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;39:191-195.

- Marrogi AJ, Wick MR, Dehner LP. Pilomatrical neoplasms in children and young adults. Am J Dermatopathol. 1992;14:87-94.

- Berberian BJ, Colonna TM, Battaglia M, et al. Multiple pilomatricomas in association with myotonic dystrophy and a family history of melanoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;37:268-269.

- Cooper PH, Fechner RE. Pilomatricoma-like changes in the epidermal cysts of Gardner's syndrome. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1983;8:639-644.

- Kaddu S, Soyer HP, Cerroni L, et al. Clinical and histopathologic spectrum of pilomatricomas in adults. Int J Dermatol. 1994;33:705-708.

- Sano Y, Mihara M, Miyamoto T, et al. Simultaneous occurrence of calcification and amyloid deposit in pilomatricoma. Acta Derm Venereol. 1990;70:256-259.

- Schwartz RA. Keratoacanthoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;30:1-19.

- Kwiek B, Schwartz RA. Keratoacanthoma (KA): an update and review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:1220-1233.

- Mehregan AH. Inverted follicular keratosis. Arch Dermatol. 1964;89:117-123.

- Spielvogel RL, Austin C, Ackerman AB. Inverted follicular keratosis is not a specific keratosis but a verruca vulgaris (or seborrheic keratosis) with squamous eddies. Am J Dermatopathol. 1983;5:427-445.

- Mehregan AH. Inverted follicular keratosis is a distinct follicular tumor. Am J Dermatopathol. 1983;5:467-470.

- Brownstein MH. Trichilemmoma. benign follicular tumor or viral wart? Am J Dermatopathol. 1980;2:229-231.

- Brownstein MH. Multiple trichilemmomas in Cowden's syndrome. Arch Dermatol. 1979;115:111.

- Roson E, Gomez Centeno P, Sanchez Aguilar D, et al. Desmoplastic trichilemmoma arising within a nevus sebaceous. Am J Dermatopathol. 1998;20:495-497.

- Tellechea O, Reis JP, Baptista AP. Desmoplastic trichilemmoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 1992;14:107-114.

- Sharma R, Sirohi D, Sengupta P, et al. Desmoplastic trichilemmoma of the facial region mimicking invasive carcinoma. J Maxillofac Oral Surg. 2010;10:71-73.

A 66-year-old woman presented to the dermatology clinic with a rapidly enlarging, draining lesion on the scalp. The lesion seemed to enlarge over the last 3 months from a lesion that had been there for years. Physical examination revealed a 2.2-cm ulcerated nodule on the right parietal scalp. A shave biopsy was obtained.

Tender Papules on the Bilateral Dorsal Hands

The Diagnosis: Interstitial Granulomatous Dermatitis

Interstitial granulomatous dermatitis (IGD) is rare, and the exact incidence is unknown, with only a few cases reported in the literature annually.1 Although IGD may arise in both children and adults, it occurs more commonly in adults, with an age of onset of 52 to 58.5 years. Interstitial granulomatous dermatitis also shows a female predominance.1

Interstitial granulomatous dermatitis may present as annular flesh-colored or erythematous to violaceous papules and plaques, or less commonly erythematous linear cordlike subcutaneous nodules (called the rope sign).1 Lesions often are asymptomatic but may be pruritic or tender. Interstitial granulomatous dermatitis has been associated with autoimmune conditions such as rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, and primary biliary cholangitis, and rarely malignancy.2 Interstitial granulomatous drug reactions can occur months to years after initiation of therapy with offending agents, and common causes include calcium channel blockers, statins, and tumor necrosis factor α inhibitors.3

Interstitial granulomatous dermatitis and palisaded neutrophilic and granulomatous dermatitis (PNGD) demonstrate overlapping clinical features and are thought to be part of the same spectrum of granulomatous dermatitis.4 Both IGD and PNGD may present with symmetric flesh-colored to erythematous papules or erythematous annular or linear plaques.5 Interstitial granulomatous dermatitis and PNGD may be differentiated through histopathologic examination.

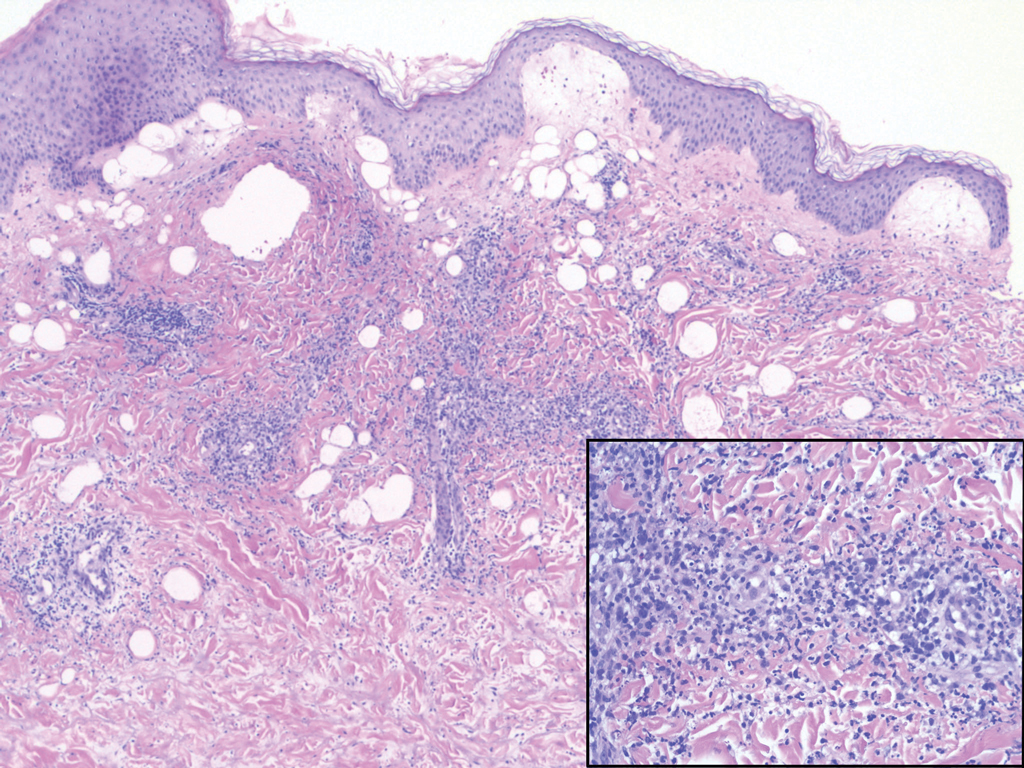

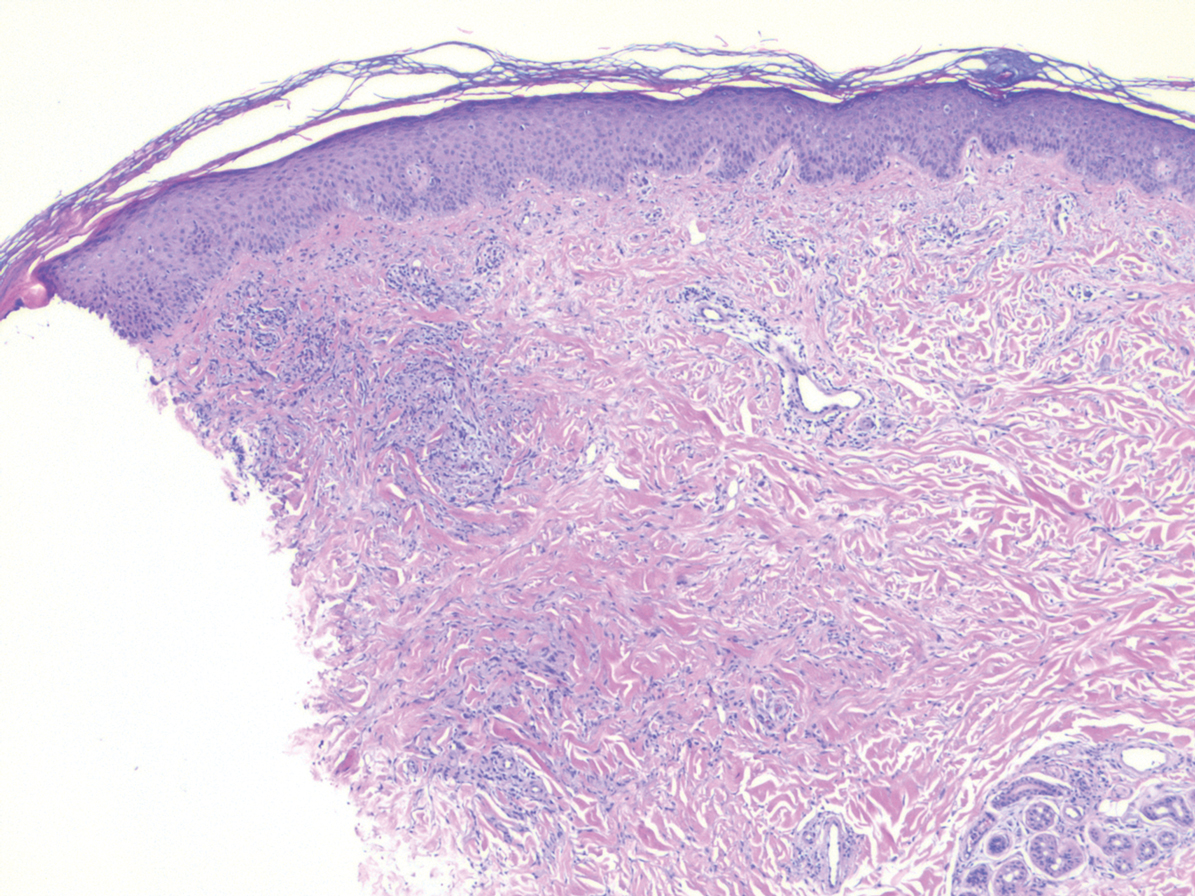

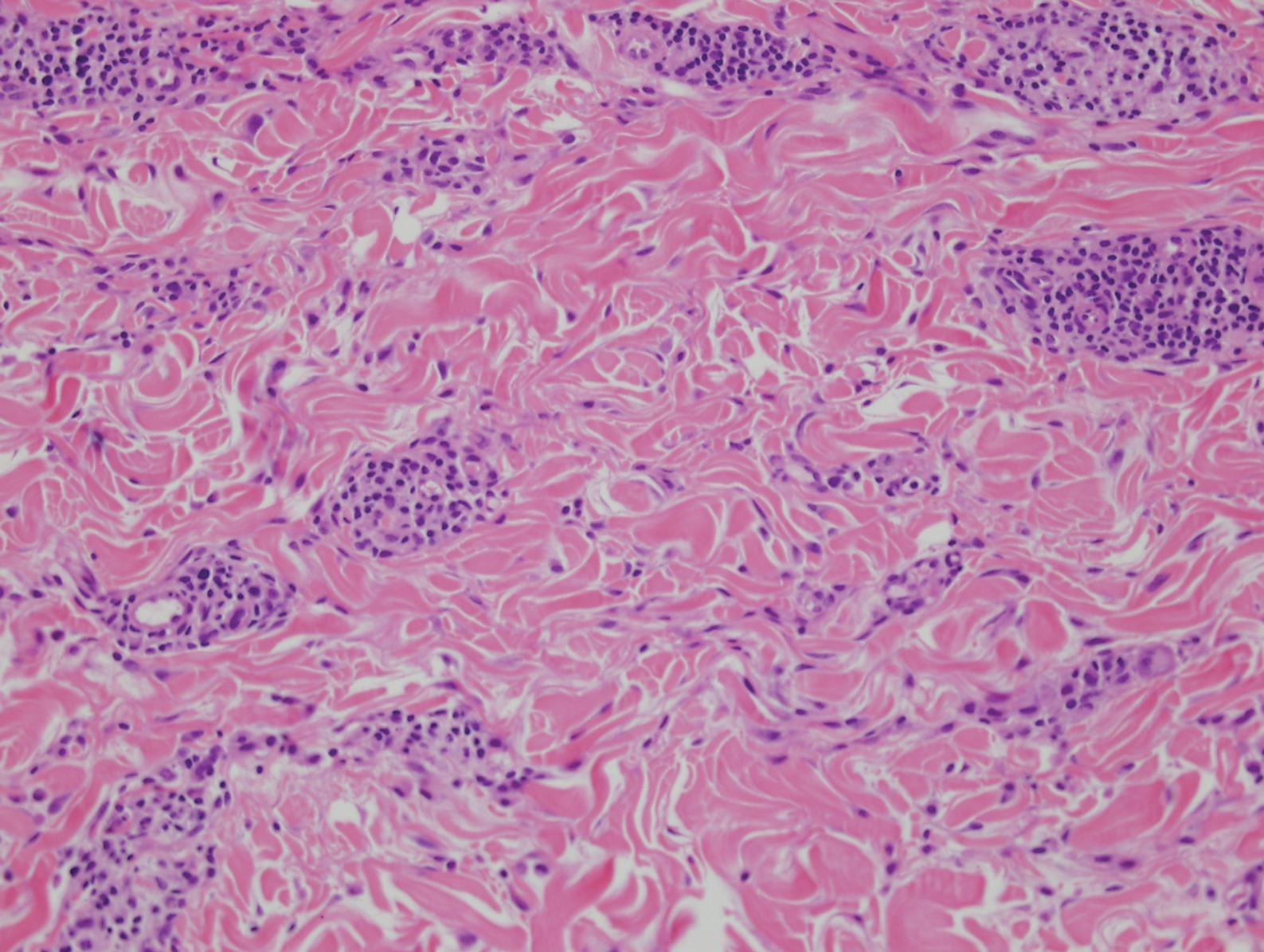

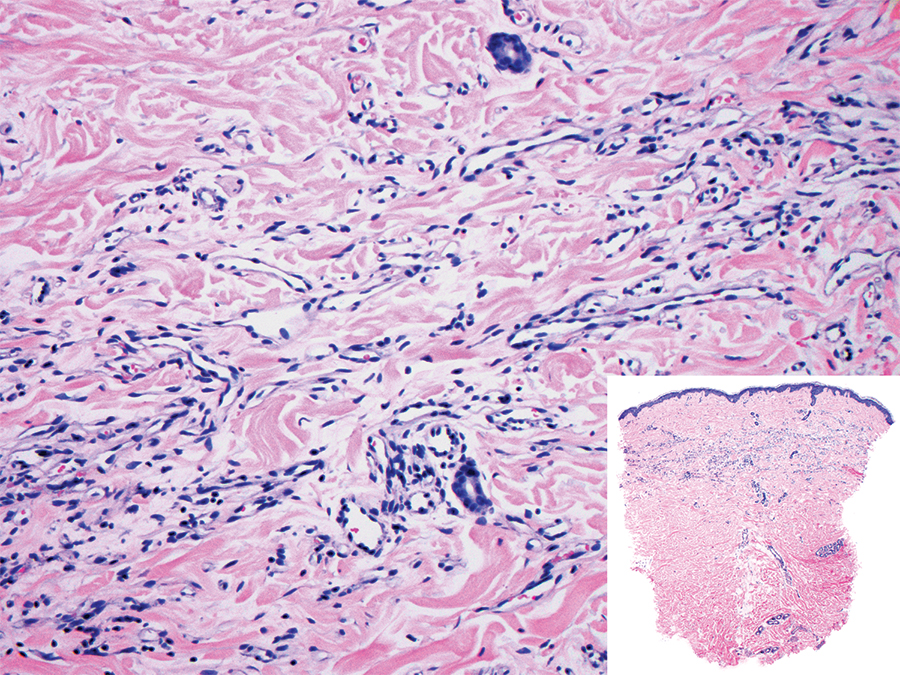

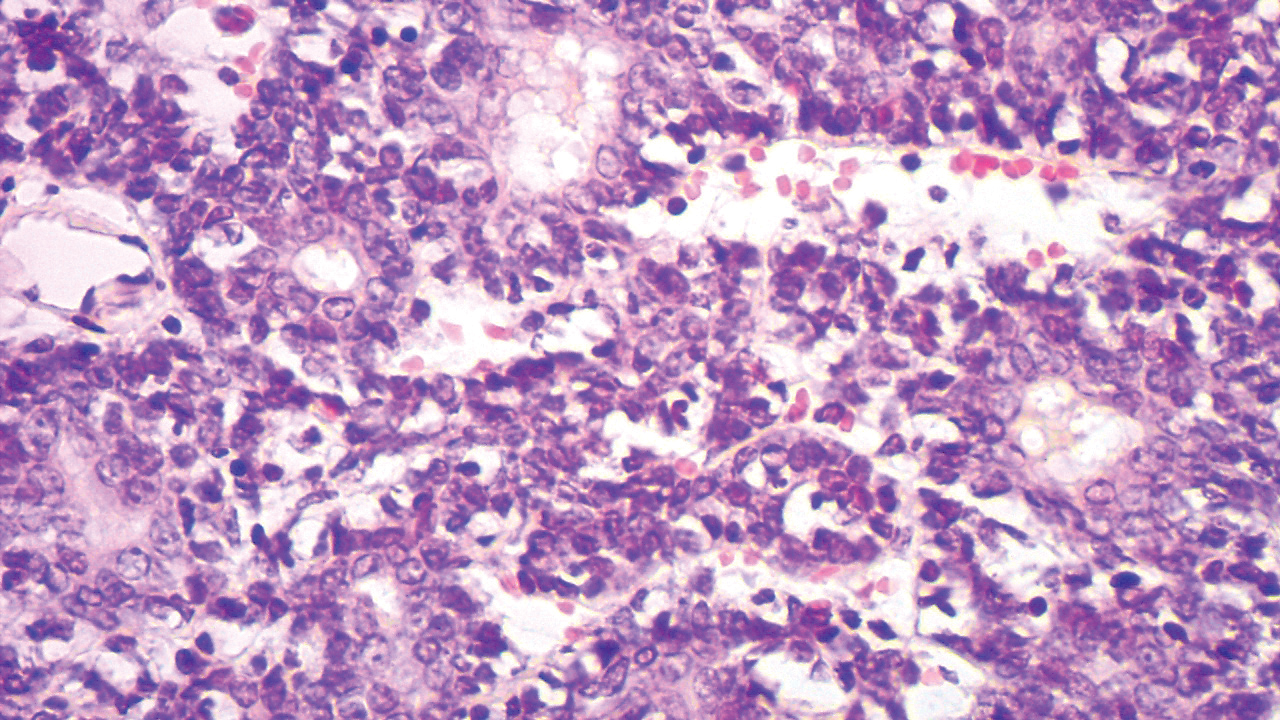

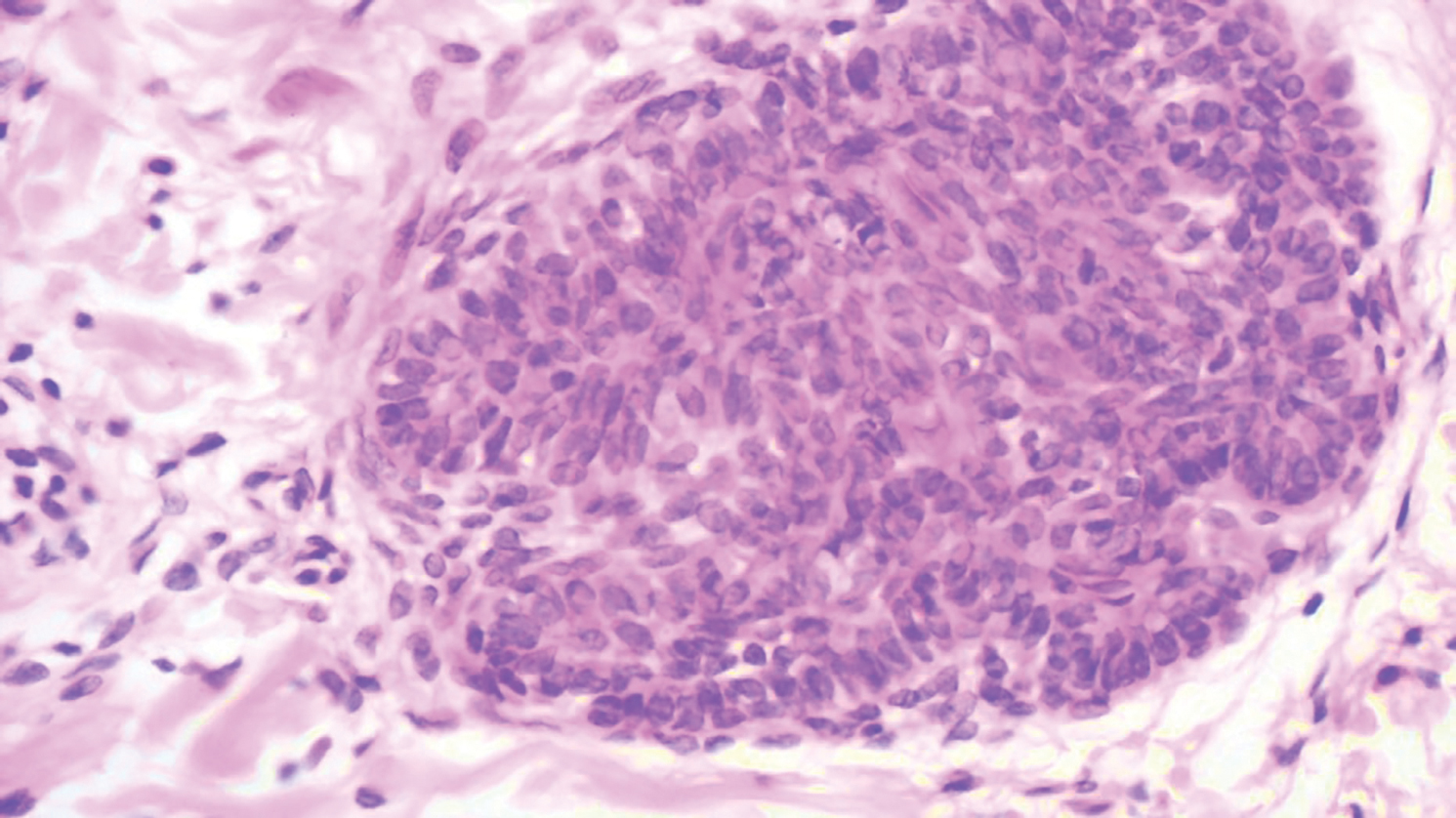

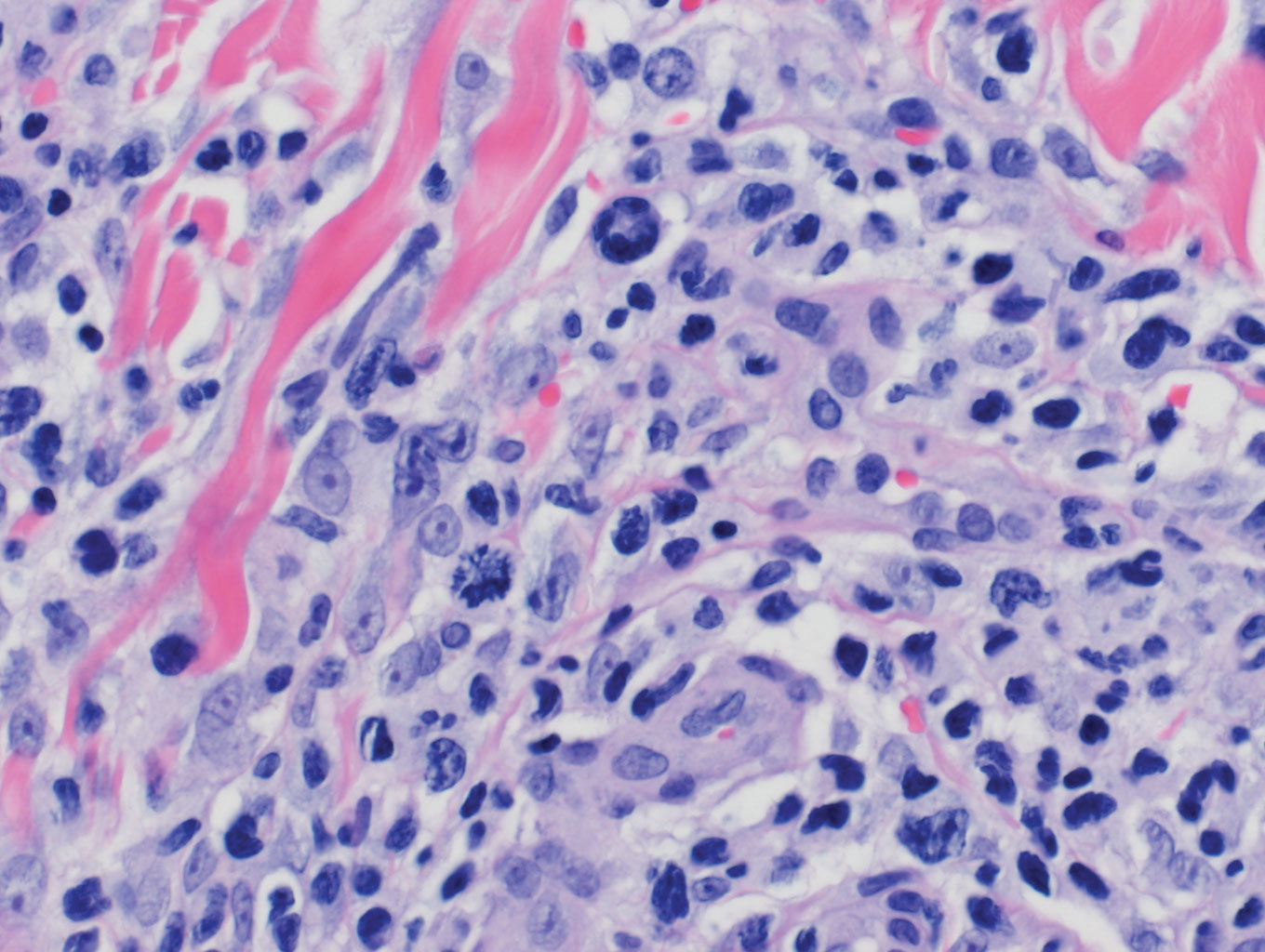

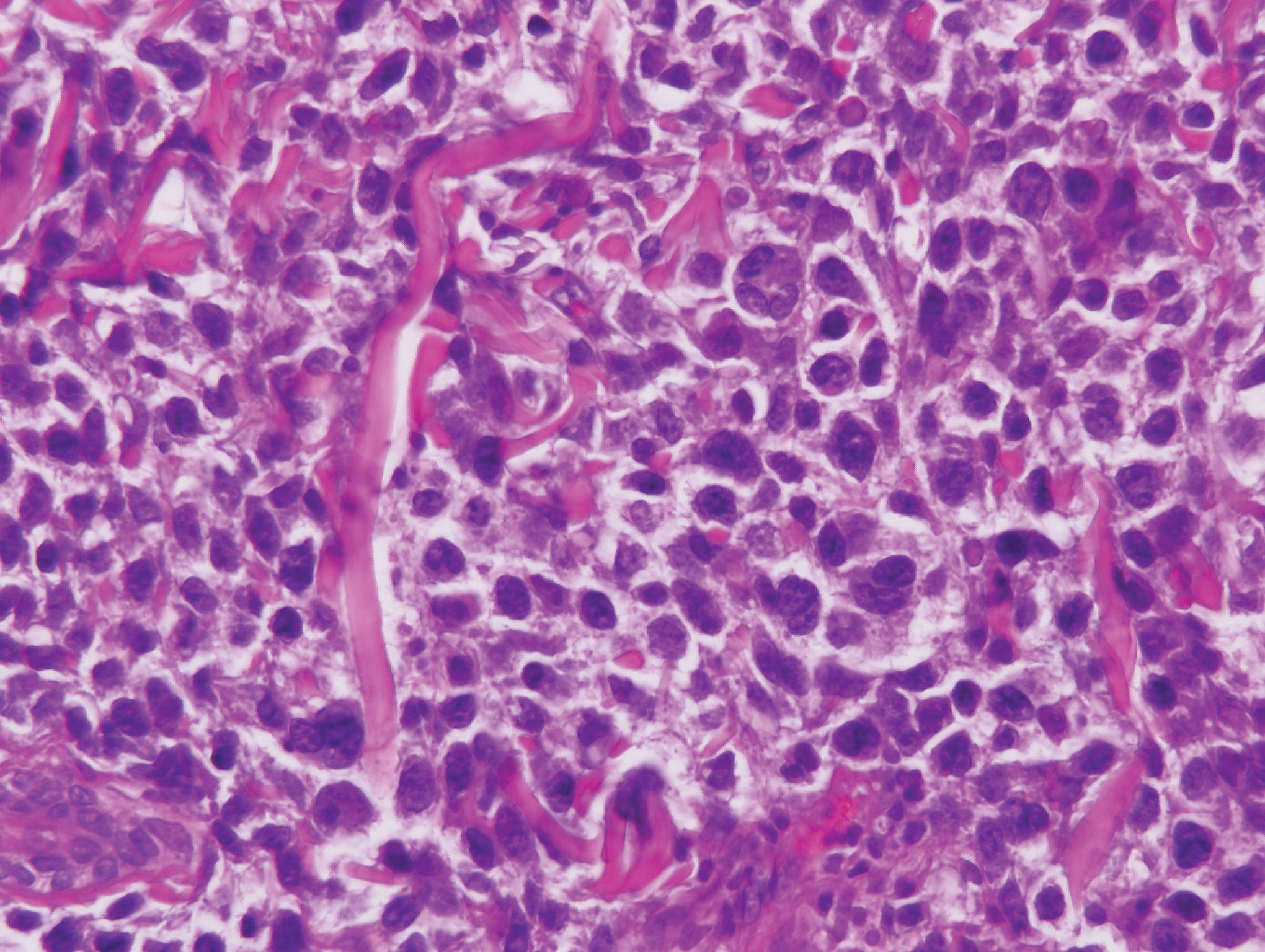

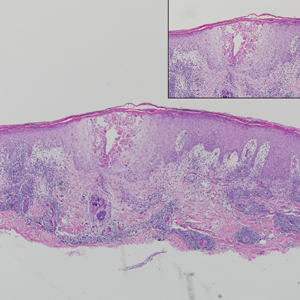

Histopathology of IGD shows an interstitial infiltrate of epithelioid histiocytes in the dermis, often surrounding foci of degenerated collagen resembling palisading granulomas (quiz images).1 Perivascular and interstitial lymphocytic infiltrates also are present in most cases. Epidermal changes are minimal in IGD but can be associated with interstitial granulomatous drug reactions.1 There usually is no vasculitis, and mucin typically is absent, unlike granuloma annulare (GA).3,6 In comparison, histopathologic examination of PNGD shows basophilic degenerated collagen surrounded by palisades of histiocytes, neutrophils, and nuclear debris with focal areas of leukocytoclastic vasculitis and rare mucin.5

No specific treatment is recommended, and lesions may resolve without any therapy. Reported treatments include topical, intralesional, or systemic steroids; nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; methotrexate; hydroxychloroquine; and cyclosporine.6 Due to the strong association with systemic diseases, it is important to evaluate patients with IGD for autoimmune diseases and conduct age-appropriate cancer screening. Furthermore, a review of medications is warranted to assess the possibility of interstitial granulomatous drug reactions.6 In our patient, rheumatologic workup and age-appropriate cancer screenings were negative, and the rash spontaneously resolved without treatment.

Granuloma annulare presents with asymptomatic flesh-colored to erythematous papules and plaques in an annular configuration. In the localized variant of GA, plaques frequently localize to the distal extremities, especially the dorsal hands, as in our patient. Other variants include generalized GA, subcutaneous GA, and perforating GA. Mucin and a palisading or interstitial pattern of granulomatous inflammation are key features on histopathology in all subtypes of GA (Figure 1).7 Patch GA is a rare variant that presents with asymptomatic erythematous to brown patches, is associated with interstitial-type inflammation on histopathology, and can be difficult to distinguish from IGD.8 Granuloma annulare with interstitial inflammation on histology can be differentiated from IGD by the comparative lack of mucin in IGD.7

Sweet syndrome (SS) is characterized by sudden-onset, painful, erythematous plaques and/or nodules, commonly associated with fever and leukocytosis. Clinical variants of SS include pustular and bullous SS; giant cellulitis-like SS; necrotizing SS; and neutrophilic dermatosis of the dorsal hands presenting with hemorrhagic bullae, plaques, and pustules.7-9 Histopathologic examination shows dense nodular or perivascular neutrophilic infiltrate in the dermis without evidence of vasculitis (Figure 2).10 Histopathologic variants include histiocytoid, lymphocytic, subcutaneous, and cryptococcoid.9 The classic variant of SS has a bandlike, predominantly neutrophilic infiltrate with marked leukocytoclasia, which can be differentiated from the histiocytoid infiltrate of IGD.11 It has been shown that the infiltrate of the histiocytoid variant of SS is composed of myeloperoxidase-positive, immature myeloid cells rather than true histiocytes, and therefore can be differentiated from IGD.12 Lastly, all variants of SS have dermal edema, which typically is absent in IGD, and SS has no evidence of necrobiosis.

Erythema elevatum diutinum (EED) is a rare disease that presents with bilateral violaceous or erythematous to brown papules, plaques, or nodules. Lesions frequently localize to extensor surfaces, including the hands and fingers, and may be asymptomatic or associated with pruritus, burning, or tingling.13 Early EED lesions are characterized by leukocytoclastic vasculitis of the papillary and mid-dermal vessels with a perivascular neutrophilic infiltrate and perivascular fibrinoid necrosis. With older EED lesions, dermal and perivascular onion skin-like fibrosis become more prominent (Figure 3).14 The neutrophilic infiltrate, dermal fibrosis, and chronic vasculitic changes distinguish EED from IGD.

Necrobiosis lipoidica (NL) is a rare disease that presents with well-demarcated, yellow to red-brown papules and nodules most commonly localized to the bilateral lower extremities on the pretibial area. Papules and nodules evolve into plaques over time, and ulceration is common.15 On histopathology, NL primarily exhibits granulomatous inflammation with parallel palisading (Figure 4). The hallmark feature is necrobiosis--or degeneration--of collagen; the alternation of necrobiotic collagen and inflammatory infiltrate creates a layered cake-like appearance on low power.16 The clinical presentation as well as the dermal necrobiotic granuloma consisting of a large confluent area of necrobiosis centered in the superficial dermis and subcutaneous tissue of NL distinguishes it from the histiocytic infiltrate of IGD.

- Peroni A, Colato C, Schena D, et al. Interstitial granulomatous dermatitis: a distinct entity with characteristic histological and clinical pattern. Br J Dermatol. 2012;166:775-783.

- Terziroli Beretta-Piccoli B, Mainetti C, Peeters MA, et al. Cutaneous granulomatosis: a comprehensive review. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2018;54:131-146.

- Rosenbach MA, Wanat KA, Reisenauer A, et al. Non-infectious granulomas. In: Bolognia J, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2018:1644-1663.

- Chu P, Connolly MK, LeBoit PE. The histopathologic spectrum of palisaded neutrophilic and granulomatous dermatitis in patients with collagen vascular disease. Arch Dermatol. 1994;130:1278-1283.

- Huizenga T, Kado JA, Pellicane B, et al. Interstitial granulomatous dermatitis and palisaded neutrophilic granulomatous dermatitis. Cutis. 2018;101:E19-E21.

- Rosenbach M, English JC 3rd. Reactive granulomatous dermatitis: a review of palisaded neutrophilic and granulomatous dermatitis, interstitial granulomatous dermatitis, interstitial granulomatous drug reaction, and a proposed reclassification. Dermatol Clin. 2015;33:373-387.

- Piette EW, Rosenbach M. Granuloma annulare: clinical and histologic variants, epidemiology, and genetics. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:457-465.

- Mutasim DF, Bridges AG. Patch granuloma annulare: clinicopathologic study of 6 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;42:417-421.

- Nelson CA, Stephen S, Ashchyan HJ, et al. Neutrophilic dermatoses: pathogenesis, Sweet syndrome, neutrophilic eccrine hidradenitis, and Behçet disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79:987-1006.

- Dabade TS, Davis MD. Diagnosis and treatment of the neutrophilic dermatoses (pyoderma gangrenosum, Sweet's syndrome). Dermatol Ther. 2011;24:273-284.

- Davis M, Moschella L. Neutrophilic dermatoses. In: Bolognia J, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2018:2102-2112.

- Requena L, Kutzner H, Palmedo G, et al. Histiocytoid Sweet syndrome: a dermal infiltration of immature neutrophilic granulocytes. Arch Dermatol. 2005;141:834-842.

- Gibson LE, el-Azhary RA. Erythema elevatum diutinum. Clin Dermatol. 2000;18:295-299.

- Sardiña LA, Jour G, Piliang MP, et al. Erythema elevatum diutinum a rare and poorly understood cutaneous vasculitis: a single institution experience. J Cutan Pathol. 2019;46:97-101.

- Reid SD, Ladizinski B, Lee K, et al. Update on necrobiosis lipoidica: a review of etiology, diagnosis, and treatment options. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:783-791.

- Sibbald C, Reid S, Alavi A. Necrobiosis lipoidica. Dermatol Clin. 2015;33:343-360.

The Diagnosis: Interstitial Granulomatous Dermatitis

Interstitial granulomatous dermatitis (IGD) is rare, and the exact incidence is unknown, with only a few cases reported in the literature annually.1 Although IGD may arise in both children and adults, it occurs more commonly in adults, with an age of onset of 52 to 58.5 years. Interstitial granulomatous dermatitis also shows a female predominance.1

Interstitial granulomatous dermatitis may present as annular flesh-colored or erythematous to violaceous papules and plaques, or less commonly erythematous linear cordlike subcutaneous nodules (called the rope sign).1 Lesions often are asymptomatic but may be pruritic or tender. Interstitial granulomatous dermatitis has been associated with autoimmune conditions such as rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, and primary biliary cholangitis, and rarely malignancy.2 Interstitial granulomatous drug reactions can occur months to years after initiation of therapy with offending agents, and common causes include calcium channel blockers, statins, and tumor necrosis factor α inhibitors.3

Interstitial granulomatous dermatitis and palisaded neutrophilic and granulomatous dermatitis (PNGD) demonstrate overlapping clinical features and are thought to be part of the same spectrum of granulomatous dermatitis.4 Both IGD and PNGD may present with symmetric flesh-colored to erythematous papules or erythematous annular or linear plaques.5 Interstitial granulomatous dermatitis and PNGD may be differentiated through histopathologic examination.

Histopathology of IGD shows an interstitial infiltrate of epithelioid histiocytes in the dermis, often surrounding foci of degenerated collagen resembling palisading granulomas (quiz images).1 Perivascular and interstitial lymphocytic infiltrates also are present in most cases. Epidermal changes are minimal in IGD but can be associated with interstitial granulomatous drug reactions.1 There usually is no vasculitis, and mucin typically is absent, unlike granuloma annulare (GA).3,6 In comparison, histopathologic examination of PNGD shows basophilic degenerated collagen surrounded by palisades of histiocytes, neutrophils, and nuclear debris with focal areas of leukocytoclastic vasculitis and rare mucin.5

No specific treatment is recommended, and lesions may resolve without any therapy. Reported treatments include topical, intralesional, or systemic steroids; nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; methotrexate; hydroxychloroquine; and cyclosporine.6 Due to the strong association with systemic diseases, it is important to evaluate patients with IGD for autoimmune diseases and conduct age-appropriate cancer screening. Furthermore, a review of medications is warranted to assess the possibility of interstitial granulomatous drug reactions.6 In our patient, rheumatologic workup and age-appropriate cancer screenings were negative, and the rash spontaneously resolved without treatment.

Granuloma annulare presents with asymptomatic flesh-colored to erythematous papules and plaques in an annular configuration. In the localized variant of GA, plaques frequently localize to the distal extremities, especially the dorsal hands, as in our patient. Other variants include generalized GA, subcutaneous GA, and perforating GA. Mucin and a palisading or interstitial pattern of granulomatous inflammation are key features on histopathology in all subtypes of GA (Figure 1).7 Patch GA is a rare variant that presents with asymptomatic erythematous to brown patches, is associated with interstitial-type inflammation on histopathology, and can be difficult to distinguish from IGD.8 Granuloma annulare with interstitial inflammation on histology can be differentiated from IGD by the comparative lack of mucin in IGD.7

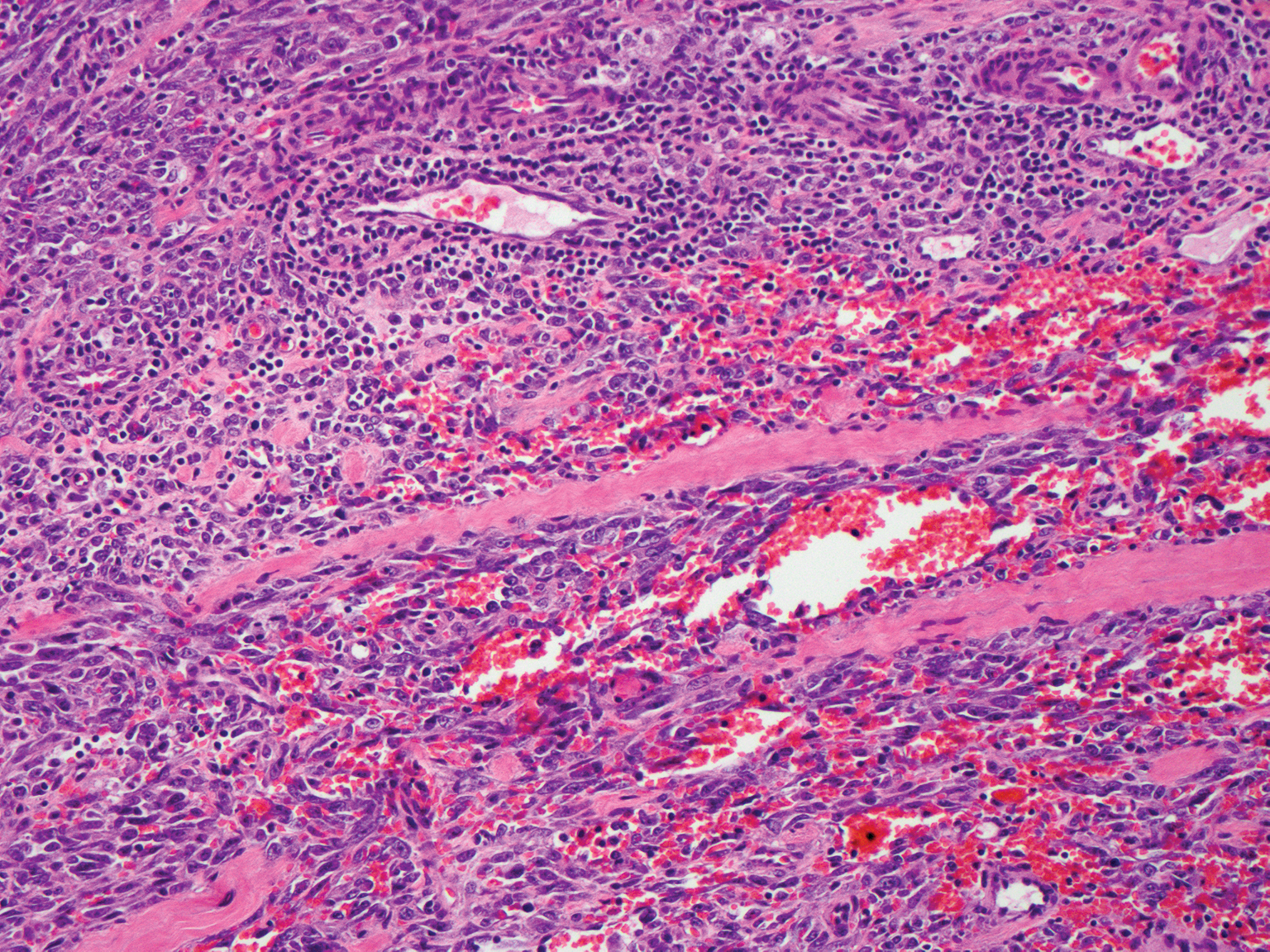

Sweet syndrome (SS) is characterized by sudden-onset, painful, erythematous plaques and/or nodules, commonly associated with fever and leukocytosis. Clinical variants of SS include pustular and bullous SS; giant cellulitis-like SS; necrotizing SS; and neutrophilic dermatosis of the dorsal hands presenting with hemorrhagic bullae, plaques, and pustules.7-9 Histopathologic examination shows dense nodular or perivascular neutrophilic infiltrate in the dermis without evidence of vasculitis (Figure 2).10 Histopathologic variants include histiocytoid, lymphocytic, subcutaneous, and cryptococcoid.9 The classic variant of SS has a bandlike, predominantly neutrophilic infiltrate with marked leukocytoclasia, which can be differentiated from the histiocytoid infiltrate of IGD.11 It has been shown that the infiltrate of the histiocytoid variant of SS is composed of myeloperoxidase-positive, immature myeloid cells rather than true histiocytes, and therefore can be differentiated from IGD.12 Lastly, all variants of SS have dermal edema, which typically is absent in IGD, and SS has no evidence of necrobiosis.

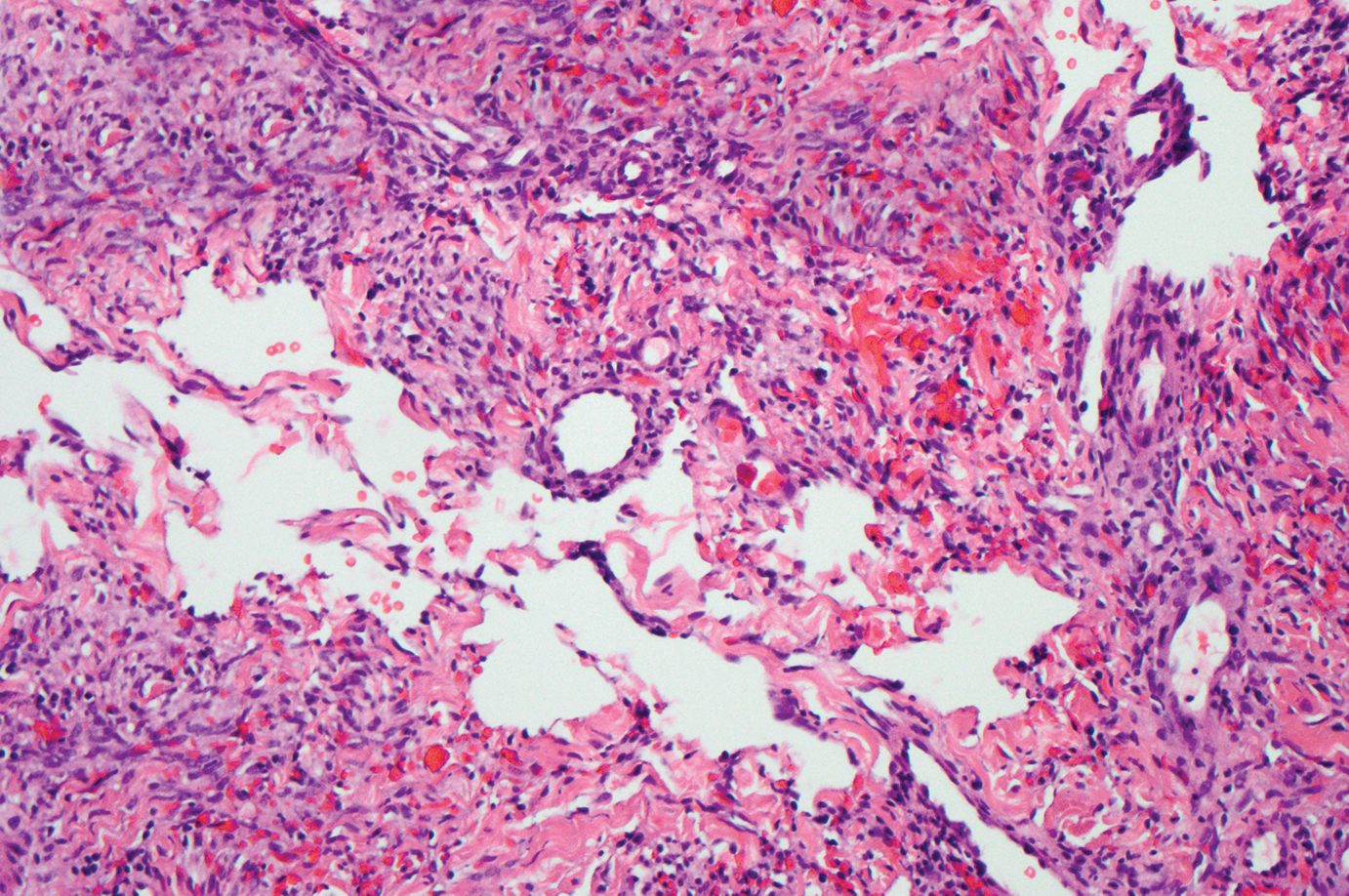

Erythema elevatum diutinum (EED) is a rare disease that presents with bilateral violaceous or erythematous to brown papules, plaques, or nodules. Lesions frequently localize to extensor surfaces, including the hands and fingers, and may be asymptomatic or associated with pruritus, burning, or tingling.13 Early EED lesions are characterized by leukocytoclastic vasculitis of the papillary and mid-dermal vessels with a perivascular neutrophilic infiltrate and perivascular fibrinoid necrosis. With older EED lesions, dermal and perivascular onion skin-like fibrosis become more prominent (Figure 3).14 The neutrophilic infiltrate, dermal fibrosis, and chronic vasculitic changes distinguish EED from IGD.

Necrobiosis lipoidica (NL) is a rare disease that presents with well-demarcated, yellow to red-brown papules and nodules most commonly localized to the bilateral lower extremities on the pretibial area. Papules and nodules evolve into plaques over time, and ulceration is common.15 On histopathology, NL primarily exhibits granulomatous inflammation with parallel palisading (Figure 4). The hallmark feature is necrobiosis--or degeneration--of collagen; the alternation of necrobiotic collagen and inflammatory infiltrate creates a layered cake-like appearance on low power.16 The clinical presentation as well as the dermal necrobiotic granuloma consisting of a large confluent area of necrobiosis centered in the superficial dermis and subcutaneous tissue of NL distinguishes it from the histiocytic infiltrate of IGD.

The Diagnosis: Interstitial Granulomatous Dermatitis

Interstitial granulomatous dermatitis (IGD) is rare, and the exact incidence is unknown, with only a few cases reported in the literature annually.1 Although IGD may arise in both children and adults, it occurs more commonly in adults, with an age of onset of 52 to 58.5 years. Interstitial granulomatous dermatitis also shows a female predominance.1

Interstitial granulomatous dermatitis may present as annular flesh-colored or erythematous to violaceous papules and plaques, or less commonly erythematous linear cordlike subcutaneous nodules (called the rope sign).1 Lesions often are asymptomatic but may be pruritic or tender. Interstitial granulomatous dermatitis has been associated with autoimmune conditions such as rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, and primary biliary cholangitis, and rarely malignancy.2 Interstitial granulomatous drug reactions can occur months to years after initiation of therapy with offending agents, and common causes include calcium channel blockers, statins, and tumor necrosis factor α inhibitors.3

Interstitial granulomatous dermatitis and palisaded neutrophilic and granulomatous dermatitis (PNGD) demonstrate overlapping clinical features and are thought to be part of the same spectrum of granulomatous dermatitis.4 Both IGD and PNGD may present with symmetric flesh-colored to erythematous papules or erythematous annular or linear plaques.5 Interstitial granulomatous dermatitis and PNGD may be differentiated through histopathologic examination.

Histopathology of IGD shows an interstitial infiltrate of epithelioid histiocytes in the dermis, often surrounding foci of degenerated collagen resembling palisading granulomas (quiz images).1 Perivascular and interstitial lymphocytic infiltrates also are present in most cases. Epidermal changes are minimal in IGD but can be associated with interstitial granulomatous drug reactions.1 There usually is no vasculitis, and mucin typically is absent, unlike granuloma annulare (GA).3,6 In comparison, histopathologic examination of PNGD shows basophilic degenerated collagen surrounded by palisades of histiocytes, neutrophils, and nuclear debris with focal areas of leukocytoclastic vasculitis and rare mucin.5

No specific treatment is recommended, and lesions may resolve without any therapy. Reported treatments include topical, intralesional, or systemic steroids; nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; methotrexate; hydroxychloroquine; and cyclosporine.6 Due to the strong association with systemic diseases, it is important to evaluate patients with IGD for autoimmune diseases and conduct age-appropriate cancer screening. Furthermore, a review of medications is warranted to assess the possibility of interstitial granulomatous drug reactions.6 In our patient, rheumatologic workup and age-appropriate cancer screenings were negative, and the rash spontaneously resolved without treatment.

Granuloma annulare presents with asymptomatic flesh-colored to erythematous papules and plaques in an annular configuration. In the localized variant of GA, plaques frequently localize to the distal extremities, especially the dorsal hands, as in our patient. Other variants include generalized GA, subcutaneous GA, and perforating GA. Mucin and a palisading or interstitial pattern of granulomatous inflammation are key features on histopathology in all subtypes of GA (Figure 1).7 Patch GA is a rare variant that presents with asymptomatic erythematous to brown patches, is associated with interstitial-type inflammation on histopathology, and can be difficult to distinguish from IGD.8 Granuloma annulare with interstitial inflammation on histology can be differentiated from IGD by the comparative lack of mucin in IGD.7

Sweet syndrome (SS) is characterized by sudden-onset, painful, erythematous plaques and/or nodules, commonly associated with fever and leukocytosis. Clinical variants of SS include pustular and bullous SS; giant cellulitis-like SS; necrotizing SS; and neutrophilic dermatosis of the dorsal hands presenting with hemorrhagic bullae, plaques, and pustules.7-9 Histopathologic examination shows dense nodular or perivascular neutrophilic infiltrate in the dermis without evidence of vasculitis (Figure 2).10 Histopathologic variants include histiocytoid, lymphocytic, subcutaneous, and cryptococcoid.9 The classic variant of SS has a bandlike, predominantly neutrophilic infiltrate with marked leukocytoclasia, which can be differentiated from the histiocytoid infiltrate of IGD.11 It has been shown that the infiltrate of the histiocytoid variant of SS is composed of myeloperoxidase-positive, immature myeloid cells rather than true histiocytes, and therefore can be differentiated from IGD.12 Lastly, all variants of SS have dermal edema, which typically is absent in IGD, and SS has no evidence of necrobiosis.

Erythema elevatum diutinum (EED) is a rare disease that presents with bilateral violaceous or erythematous to brown papules, plaques, or nodules. Lesions frequently localize to extensor surfaces, including the hands and fingers, and may be asymptomatic or associated with pruritus, burning, or tingling.13 Early EED lesions are characterized by leukocytoclastic vasculitis of the papillary and mid-dermal vessels with a perivascular neutrophilic infiltrate and perivascular fibrinoid necrosis. With older EED lesions, dermal and perivascular onion skin-like fibrosis become more prominent (Figure 3).14 The neutrophilic infiltrate, dermal fibrosis, and chronic vasculitic changes distinguish EED from IGD.

Necrobiosis lipoidica (NL) is a rare disease that presents with well-demarcated, yellow to red-brown papules and nodules most commonly localized to the bilateral lower extremities on the pretibial area. Papules and nodules evolve into plaques over time, and ulceration is common.15 On histopathology, NL primarily exhibits granulomatous inflammation with parallel palisading (Figure 4). The hallmark feature is necrobiosis--or degeneration--of collagen; the alternation of necrobiotic collagen and inflammatory infiltrate creates a layered cake-like appearance on low power.16 The clinical presentation as well as the dermal necrobiotic granuloma consisting of a large confluent area of necrobiosis centered in the superficial dermis and subcutaneous tissue of NL distinguishes it from the histiocytic infiltrate of IGD.

- Peroni A, Colato C, Schena D, et al. Interstitial granulomatous dermatitis: a distinct entity with characteristic histological and clinical pattern. Br J Dermatol. 2012;166:775-783.

- Terziroli Beretta-Piccoli B, Mainetti C, Peeters MA, et al. Cutaneous granulomatosis: a comprehensive review. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2018;54:131-146.

- Rosenbach MA, Wanat KA, Reisenauer A, et al. Non-infectious granulomas. In: Bolognia J, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2018:1644-1663.

- Chu P, Connolly MK, LeBoit PE. The histopathologic spectrum of palisaded neutrophilic and granulomatous dermatitis in patients with collagen vascular disease. Arch Dermatol. 1994;130:1278-1283.

- Huizenga T, Kado JA, Pellicane B, et al. Interstitial granulomatous dermatitis and palisaded neutrophilic granulomatous dermatitis. Cutis. 2018;101:E19-E21.

- Rosenbach M, English JC 3rd. Reactive granulomatous dermatitis: a review of palisaded neutrophilic and granulomatous dermatitis, interstitial granulomatous dermatitis, interstitial granulomatous drug reaction, and a proposed reclassification. Dermatol Clin. 2015;33:373-387.

- Piette EW, Rosenbach M. Granuloma annulare: clinical and histologic variants, epidemiology, and genetics. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:457-465.

- Mutasim DF, Bridges AG. Patch granuloma annulare: clinicopathologic study of 6 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;42:417-421.

- Nelson CA, Stephen S, Ashchyan HJ, et al. Neutrophilic dermatoses: pathogenesis, Sweet syndrome, neutrophilic eccrine hidradenitis, and Behçet disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79:987-1006.

- Dabade TS, Davis MD. Diagnosis and treatment of the neutrophilic dermatoses (pyoderma gangrenosum, Sweet's syndrome). Dermatol Ther. 2011;24:273-284.

- Davis M, Moschella L. Neutrophilic dermatoses. In: Bolognia J, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2018:2102-2112.

- Requena L, Kutzner H, Palmedo G, et al. Histiocytoid Sweet syndrome: a dermal infiltration of immature neutrophilic granulocytes. Arch Dermatol. 2005;141:834-842.

- Gibson LE, el-Azhary RA. Erythema elevatum diutinum. Clin Dermatol. 2000;18:295-299.

- Sardiña LA, Jour G, Piliang MP, et al. Erythema elevatum diutinum a rare and poorly understood cutaneous vasculitis: a single institution experience. J Cutan Pathol. 2019;46:97-101.

- Reid SD, Ladizinski B, Lee K, et al. Update on necrobiosis lipoidica: a review of etiology, diagnosis, and treatment options. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:783-791.

- Sibbald C, Reid S, Alavi A. Necrobiosis lipoidica. Dermatol Clin. 2015;33:343-360.

- Peroni A, Colato C, Schena D, et al. Interstitial granulomatous dermatitis: a distinct entity with characteristic histological and clinical pattern. Br J Dermatol. 2012;166:775-783.

- Terziroli Beretta-Piccoli B, Mainetti C, Peeters MA, et al. Cutaneous granulomatosis: a comprehensive review. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2018;54:131-146.

- Rosenbach MA, Wanat KA, Reisenauer A, et al. Non-infectious granulomas. In: Bolognia J, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2018:1644-1663.

- Chu P, Connolly MK, LeBoit PE. The histopathologic spectrum of palisaded neutrophilic and granulomatous dermatitis in patients with collagen vascular disease. Arch Dermatol. 1994;130:1278-1283.

- Huizenga T, Kado JA, Pellicane B, et al. Interstitial granulomatous dermatitis and palisaded neutrophilic granulomatous dermatitis. Cutis. 2018;101:E19-E21.

- Rosenbach M, English JC 3rd. Reactive granulomatous dermatitis: a review of palisaded neutrophilic and granulomatous dermatitis, interstitial granulomatous dermatitis, interstitial granulomatous drug reaction, and a proposed reclassification. Dermatol Clin. 2015;33:373-387.

- Piette EW, Rosenbach M. Granuloma annulare: clinical and histologic variants, epidemiology, and genetics. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:457-465.

- Mutasim DF, Bridges AG. Patch granuloma annulare: clinicopathologic study of 6 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;42:417-421.

- Nelson CA, Stephen S, Ashchyan HJ, et al. Neutrophilic dermatoses: pathogenesis, Sweet syndrome, neutrophilic eccrine hidradenitis, and Behçet disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79:987-1006.

- Dabade TS, Davis MD. Diagnosis and treatment of the neutrophilic dermatoses (pyoderma gangrenosum, Sweet's syndrome). Dermatol Ther. 2011;24:273-284.

- Davis M, Moschella L. Neutrophilic dermatoses. In: Bolognia J, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2018:2102-2112.

- Requena L, Kutzner H, Palmedo G, et al. Histiocytoid Sweet syndrome: a dermal infiltration of immature neutrophilic granulocytes. Arch Dermatol. 2005;141:834-842.

- Gibson LE, el-Azhary RA. Erythema elevatum diutinum. Clin Dermatol. 2000;18:295-299.

- Sardiña LA, Jour G, Piliang MP, et al. Erythema elevatum diutinum a rare and poorly understood cutaneous vasculitis: a single institution experience. J Cutan Pathol. 2019;46:97-101.

- Reid SD, Ladizinski B, Lee K, et al. Update on necrobiosis lipoidica: a review of etiology, diagnosis, and treatment options. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:783-791.

- Sibbald C, Reid S, Alavi A. Necrobiosis lipoidica. Dermatol Clin. 2015;33:343-360.

A 58-year-old woman with a medical history of asthma, hypertension, hypothyroidism, and hyperlipidemia presented with a painful rash of 10 days' duration. The rash was associated with fever at home (temperature, 38.5.2 °C), and a review of systems was positive for joint pain. Physical examination revealed numerous 8- to 10-mm, erythematous, discus-shaped papules on the bilateral dorsal hands, bilateral palms, right knee, and right dorsal foot with slight tenderness to palpation. A papule on the right dorsal hand was biopsied.

Solitary Papule on the Nose

The Diagnosis: Sclerosing Perineurioma

Sclerosing perineurioma, first described in 1997 by Fetsch and Miettinen,1 is a subtype of perineurioma with a strong predilection for the fingers and palms of young adults. Rare cases involving extra-acral sites including the forearm, elbow, axilla, back, neck, lower leg, thigh, knee, lips, nose, and mouth have been reported.2-4 Perineurioma is a relatively uncommon and benign peripheral nerve sheath tumor with exclusive perineurial differentiation.5 Perineurioma is divided into intraneural and extraneural types; the latter are further subclassified into soft tissue, sclerosing, reticular, and plexiform types. Other rare forms include the sclerosing, Pacinian corpuscle-like perineurioma, lipomatous perineurioma, perineurioma with xanthomatous areas, and perineurioma with granular cells.6,7

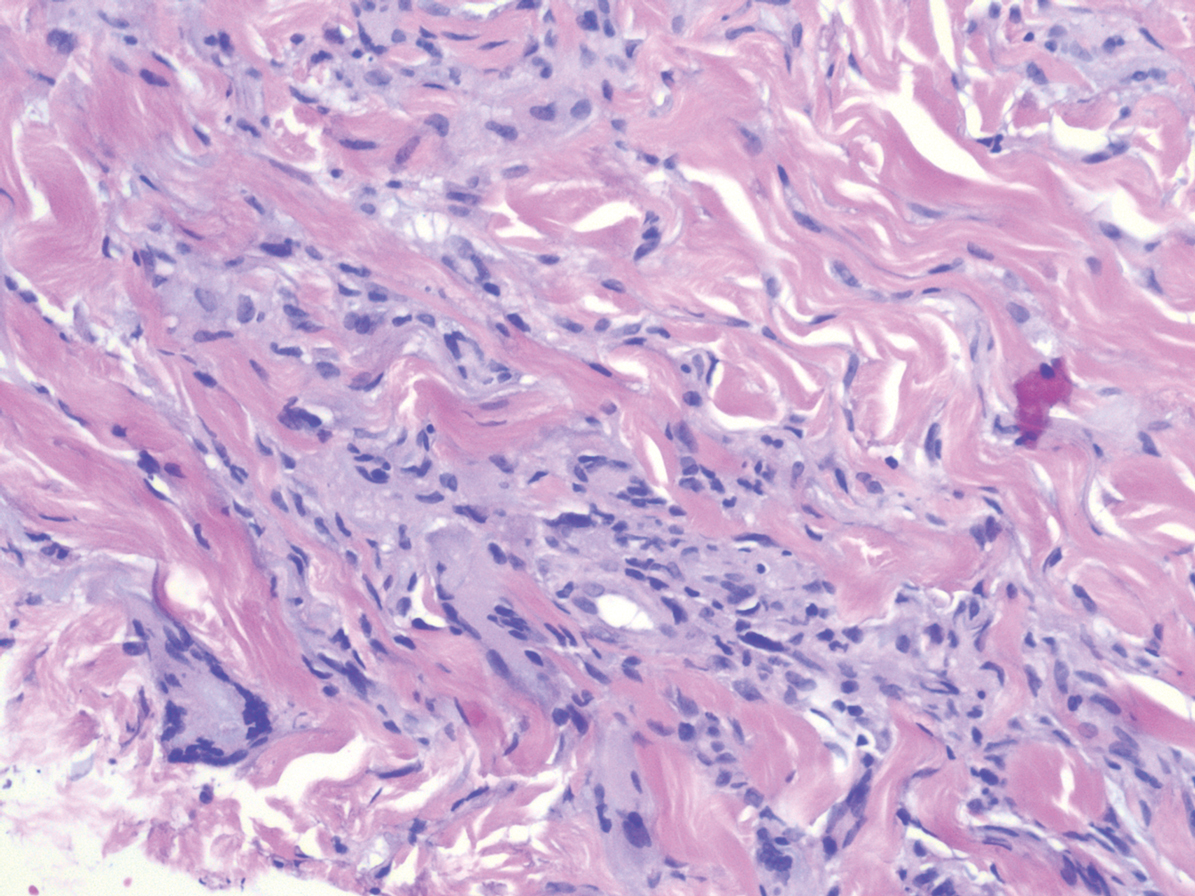

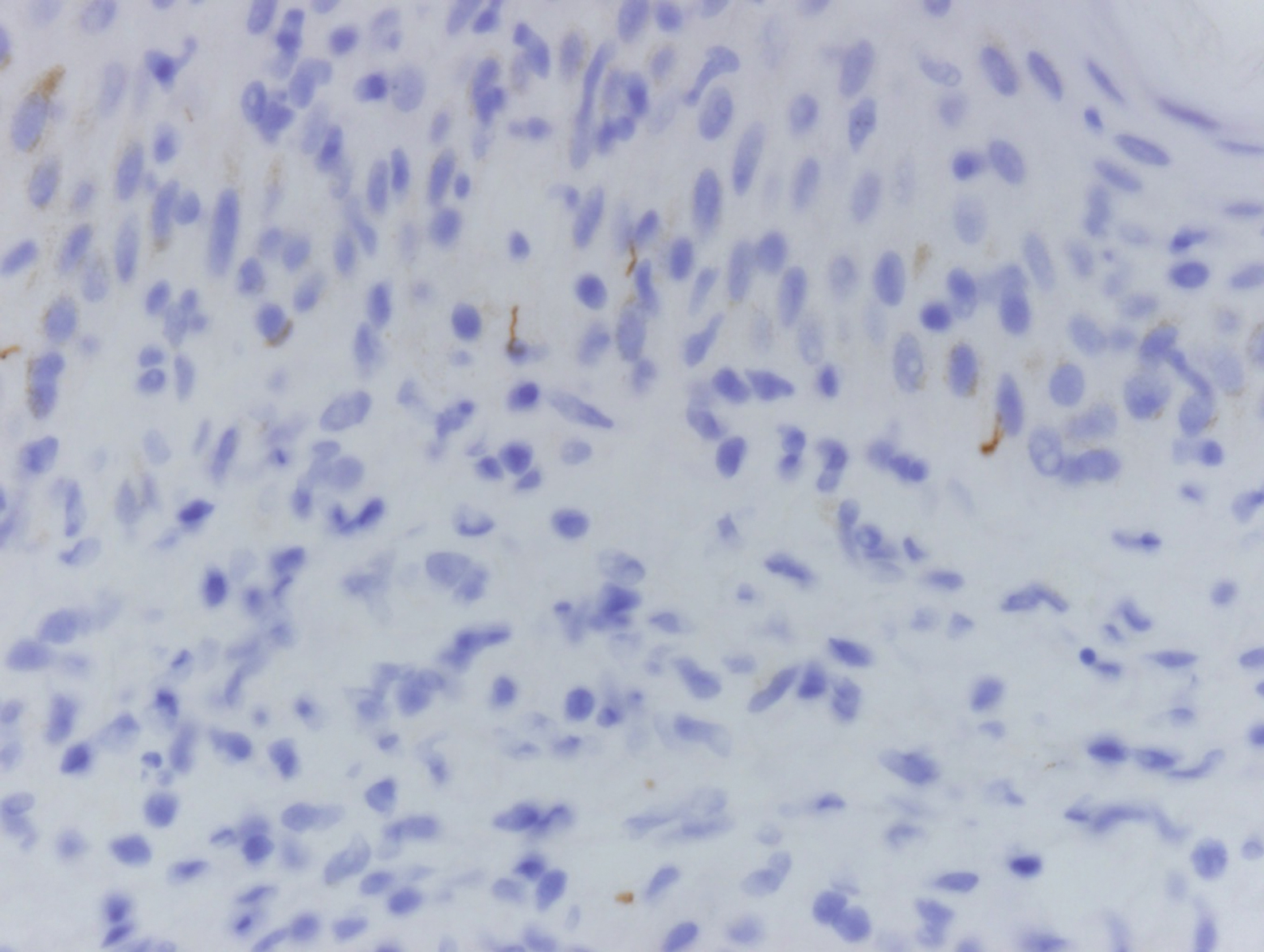

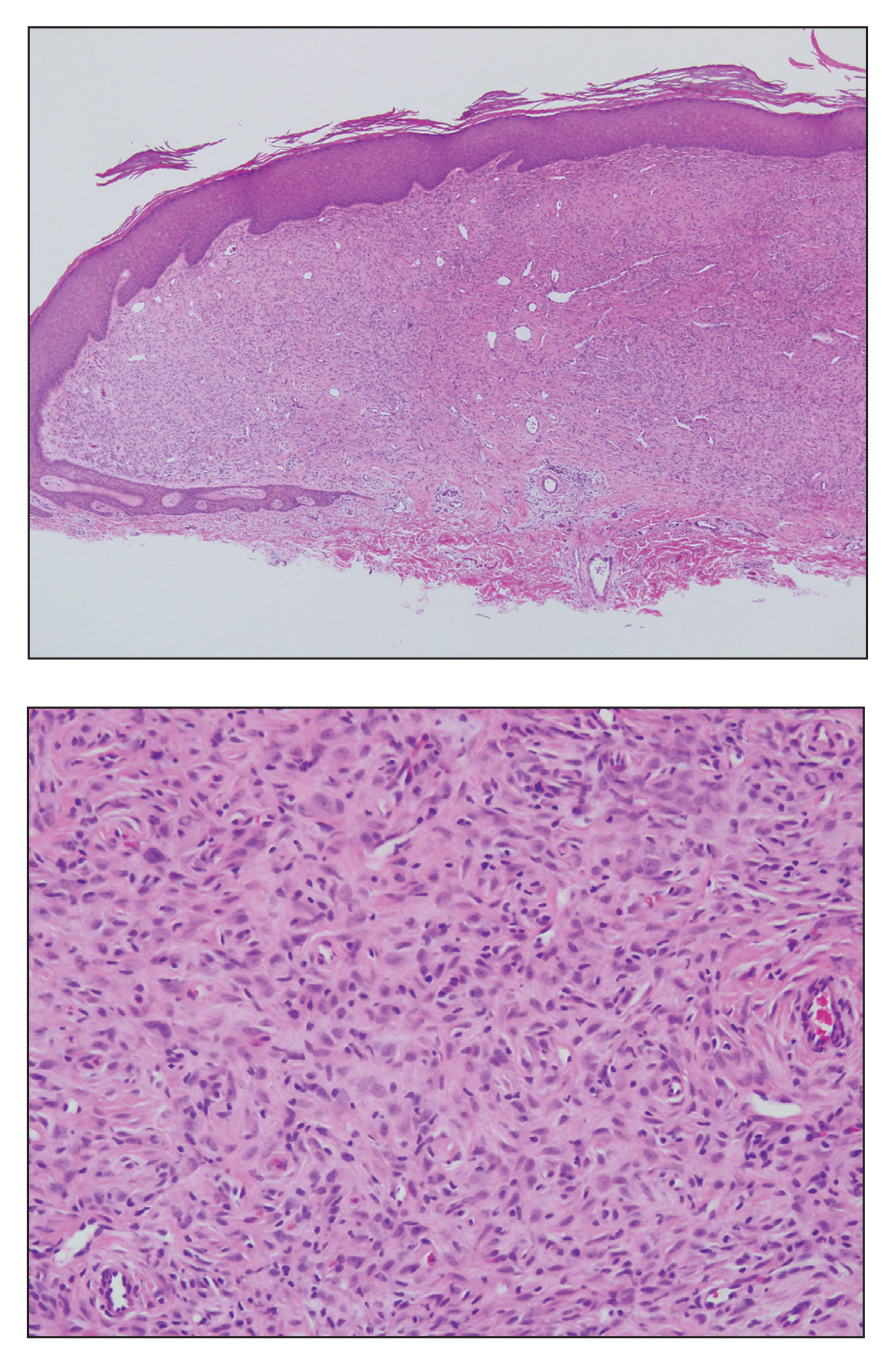

Clinically, sclerosing perineurioma usually presents as a solitary lesion; however, rare cases of multiple lesions have been reported.8 Our patient presented with a solitary papule on the nose. Histopathologically, sclerosing perineurioma demonstrates slender spindle cells in a whorled growth pattern (onion skin) embedded in a hyalinized, lamellar, and dense collagenous stroma with intervening cleftlike spaces. Immunohistochemically, the spindle cells of our case stained positive for epithelial membrane antigen (quiz images). Other positive immunostains for perineurioma include claudin-1 and glucose transporter 1 (GLUT1). Perineurioma lacks expression of S-100 but can express CD34.2 As a benign tumor, the prognosis of sclerosing perineurioma is excellent. Complete local excision is considered curative.1

Angiofibroma, also known as fibrous papule, is a common and benign lesion located primarily on or in close proximity to the nose.9 Angiofibromas can be associated with genodermatoses such as tuberous sclerosis, multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1, or Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome. When angiofibromas involve the penis, they are called pearly penile papules. Ungual angiofibroma, also known as Koenen tumor, occurs underneath the nail.10-12 Both facial angiofibromas (>3) and ungual angiofibromas (>2) are independent major criteria for tuberous sclerosis.13 Clinically, angiofibroma presents as a small, dome-shaped, pink papule arising on the lower portion of the nose or nearby area of the central face. Histopathologically, angiofibromas classically demonstrate increased dilated vessels and fibrosis in the dermis. Stellate, plump, spindle-shaped, and multinucleated cells can be seen in the collagenous stroma. The collagen fibers around hair follicles are arranged concentrically, resulting in an onion skin-like appearance. The epidermal rete ridges can be effaced (Figure 1). Increased numbers of single-unit melanocytes along the dermoepidermal junction can be seen in some cases. Immunohistochemically, a variable number of spindled and multinucleated cells in the dermis stain with factor XIIIa. There are at least 7 histologic variants of angiofibroma including hypercellular, pigmented, inflammatory, pleomorphic, clear cell, granular cell, and epithelioid.9,14

Desmoplastic nevus (DN) is a benign melanocytic neoplasm characterized by predominantly spindle-shaped nevus cells embedded within a fibrotic stroma. Although it can resemble a Spitz nevus, it is recognized as a distinct entity.15-17 Clinically, DN presents as a small and flesh-colored, erythematous or slightly pigmented papule or nodule that usually occurs on the arms and legs of young adults. Histopathologically, DN demonstrates a dermal-based proliferation of spindled melanocytes embedded in a dense collagenous stroma with sparse or absent melanin deposition. The collagen bundles often show artifactual clefts and onion skin-like accentuation around vessels. Melanocytes may be epithelioid (Figure 2).16 Immunohistochemically, DN expresses melanocytic markers such as S-100, Melan-A, and human melanoma black 45, but epithelial membrane antigen is negative. Human melanoma black 45 demonstrates maturation with stronger staining in superficial portions of the lesion and diminution of staining with increasing dermal depth.18 Many other melanocytic tumors share histologic similarities to DN including blue nevus and desmoplastic melanoma.17,19,20

Palisaded encapsulated neuroma, also referred to as solitary circumscribed neuroma, was first described by Reed et al21 in 1972. It is a benign and solitary, firm, dome-shaped, flesh-colored papule that occurs in middle-aged adults, predominately near mucocutaneous junctions of the face. Other locations include the oral mucosa, eyelid, nasal fossa, shoulder, arm, hand, foot, and glans penis.22,23 Histopathologically, palisaded encapsulated neuroma demonstrates a solitary, well-circumscribed, partially encapsulated, intradermal nodule composed of interweaving fascicles of spindle cells with prominent clefts (Figure 3). Rarely, palisaded encapsulated neuroma may have a plexiform or multinodular architecture.24 Immunohistochemically, tumor cells stain positively for S-100 protein, type IV collagen, and vimentin. The capsule, composed of perineural cells, stains positive for epithelial membrane antigen. A neurofilament stain will highlight axons within the tumor.24,25 Currently, palisaded encapsulated neuroma does not have a well-established link to known neurocutaneous or inherited syndromes. Excision is curative with a low risk of recurrence.26

Sclerotic fibromas (SFs) were first reported by Weary et al27 as multiple tumors involving the tongues of patients with Cowden syndrome. Sporadic or solitary SFs of the skin in patients without Cowden syndrome have been reported, and both multiple and solitary SFs present with similar pathologic changes.28-30 Clinically, the solitary variant manifests as a well-demarcated, flesh-colored to erythematous, waxy papule or nodule with no site or sex predilection.30,31 Histologically, SF demonstrates a well-demarcated, nonencapsulated dermal nodule composed of hypocellular and sclerotic collagen bundles with scattered spindled cells and prominent clefts resembling Vincent van Gogh's Starry Night or plywood (Figure 4). Immunohistochemically, the spindled cells strongly express CD34. Factor XIIIa and markers of melanocytic, neural, and muscular differentiation are negative. When rendering a diagnosis in a patient with multiple SFs, a comment regarding the possibility of Cowden syndrome should be mentioned.32

- Fetsch JF, Miettinen M. Sclerosing perineurioma: a clinicopathologic study of 19 cases of a distinctive soft tissue lesion with a predilection for the fingers and palms of young adults. Am J Surg Pathol. 1997;21:1433-1442.

- Fox MD, Gleason BC, Thomas AB, et al. Extra-acral cutaneous/soft tissue sclerosing perineurioma: an under-recognized entity in the differential of CD34-positive cutaneous neoplasms. J Cutan Pathol. 2010;37:1053-1056.

- Erstine EM, Ko JS, Rubin BP, et al. Broadening the anatomic landscape of sclerosing perineurioma: a series of 5 cases in nonacral sites. Am J Dermatopathol. 2017;39:679-681.

- Senghore N, Cunliffe D, Watt-Smith S, et al. Extraneural perineurioma of the face: an unusual cutaneous presentation of an uncommon tumour. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2001;39:315-319.

- Lazarus SS, Trombetta LD. Ultrastructural identification of a benign perineurial cell tumor. Cancer. 1978;41:1823-1829.

- Macarenco RS, Cury-Martins J. Extra-acral cutaneous sclerosing perineurioma with CD34 fingerprint pattern. J Cutan Pathol. 2017;44:388-392.

- Santos-Briz A, Godoy E, Canueto J, et al. Cutaneous intraneural perineurioma: a case report. Am J Dermatopathol. 2013;35:E45-E48.

- Rubin AI, Yassaee M, Johnson W, et al. Multiple cutaneous sclerosing perineuriomas: an extensive presentation with involvement of the bilateral upper extremities. J Cutan Pathol. 2009;36(suppl 1):60-65.

- Damman J, Biswas A. Fibrous papule: a histopathologic review. Am J Dermatopathol. 2018;40:551-560.

- Macri A, Tanner LS. Cutaneous angiofibroma. StatPearls. https://www.statpearls.com/kb/viewarticle/17566/. Updated January 24, 2019. Accessed October 21, 2019.

- Darling TN, Skarulis MC, Steinberg SM, et al. Multiple facial angiofibromas and collagenomas in patients with multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1. Arch Dermatol. 1997;133:853-857.

- Schaffer JV, Gohara MA, McNiff JM, et al. Multiple facial angiofibromas: a cutaneous manifestation of Birt-Hogg-Dube syndrome. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53:S108-S111.

- Northrup H, Krueger DA; International Tuberous Sclerosis Complex Consensus Group. Tuberous sclerosis complex diagnostic criteria update: recommendations of the 2012 International Tuberous Sclerosis Complex Consensus Conference. Pediatr Neurol. 2013;49:243-254.

- Bansal C, Stewart D, Li A, et al. Histologic variants of fibrous papule. J Cutan Pathol. 2005;32:424-428.

- Harris GR, Shea CR, Horenstein MG, et al. Desmoplastic (sclerotic) nevus: an underrecognized entity that resembles dermatofibroma and desmoplastic melanoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 1999;23:786-794.

- Ferrara G, Brasiello M, Annese P, et al. Desmoplastic nevus: clinicopathologic keynotes. Am J Dermatopathol. 2009;31:718-722.

- Sherrill AM, Crespo G, Prakash AV, et al. Desmoplastic nevus: an entity distinct from Spitz nevus and blue nevus. Am J Dermatopathol. 2011;33:35-39.

- Kucher C, Zhang PJ, Pasha T, et al. Expression of Melan-A and Ki-67 in desmoplastic melanoma and desmoplastic nevi. Am J Dermatopathol. 2004;26:452-457.

- Sidiropoulos M, Sholl LM, Obregon R, et al. Desmoplastic nevus of chronically sun-damaged skin: an entity to be distinguished from desmoplastic melanoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2014;36:629-634.

- Kiuru M, Patel RM, Busam KJ. Desmoplastic melanocytic nevi with lymphocytic aggregates. J Cutan Pathol. 2012;39:940-944.

- Reed RJ, Fine RM, Meltzer HD. Palisaded, encapsulated neuromas of the skin. Arch Dermatol. 1972;106:865-870.

- Newman MD, Milgraum S. Palisaded encapsulated neuroma (PEN): an often misdiagnosed neural tumor. Dermatol Online J. 2008;14:12.

- Beutler B, Cohen PR. Palisaded encapsulated neuroma of the trunk: a case report and review of palisaded encapsulated neuroma. Cureus. 2016;8:E726.

- Jokinen CH, Ragsdale BD, Argenyi ZB. Expanding the clinicopathologic spectrum of palisaded encapsulated neuroma. J Cutan Pathol. 2010;37:43-48.

- Argenyi ZB. Immunohistochemical characterization of palisaded, encapsulated neuroma. J Cutan Pathol. 1990;17:329-335.

- Batra J, Ramesh V, Molpariya A, et al. Palisaded encapsulated neuroma: an unusual presentation. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2018;9:262-264.

- Weary PE, Gorlin RJ, Gentry WC Jr, et al. Multiple hamartoma syndrome (Cowden's disease). Arch Dermatol. 1972;106:682-690.

- Mahmood MN, Salama ME, Chaffins M, et al. Solitary sclerotic fibroma of skin: a possible link with pleomorphic fibroma with immunophenotypic expression for O13 (CD99) and CD34. J Cutan Pathol. 2003;30:631-636.

- Nakashima K, Yamada N, Adachi K, et al. Solitary sclerotic fibroma of the skin: morphological characterization of the 'plywood-like pattern'. J Cutan Pathol. 2008;35(suppl 1):74-79.

- Rapini RP, Golitz LE. Sclerotic fibromas of the skin. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1989;20:266-271.

- Abbas O, Ghosn S, Bahhady R, et al. Solitary sclerotic fibroma on the scalp of a young girl: reactive sclerosis pattern? J Dermatol. 2010;37:575-577.

- Hanft VN, Shea CR, McNutt NS, et al. Expression of CD34 in sclerotic ("plywood") fibromas. Am J Dermatopathol. 2000;22:17-21.

The Diagnosis: Sclerosing Perineurioma

Sclerosing perineurioma, first described in 1997 by Fetsch and Miettinen,1 is a subtype of perineurioma with a strong predilection for the fingers and palms of young adults. Rare cases involving extra-acral sites including the forearm, elbow, axilla, back, neck, lower leg, thigh, knee, lips, nose, and mouth have been reported.2-4 Perineurioma is a relatively uncommon and benign peripheral nerve sheath tumor with exclusive perineurial differentiation.5 Perineurioma is divided into intraneural and extraneural types; the latter are further subclassified into soft tissue, sclerosing, reticular, and plexiform types. Other rare forms include the sclerosing, Pacinian corpuscle-like perineurioma, lipomatous perineurioma, perineurioma with xanthomatous areas, and perineurioma with granular cells.6,7

Clinically, sclerosing perineurioma usually presents as a solitary lesion; however, rare cases of multiple lesions have been reported.8 Our patient presented with a solitary papule on the nose. Histopathologically, sclerosing perineurioma demonstrates slender spindle cells in a whorled growth pattern (onion skin) embedded in a hyalinized, lamellar, and dense collagenous stroma with intervening cleftlike spaces. Immunohistochemically, the spindle cells of our case stained positive for epithelial membrane antigen (quiz images). Other positive immunostains for perineurioma include claudin-1 and glucose transporter 1 (GLUT1). Perineurioma lacks expression of S-100 but can express CD34.2 As a benign tumor, the prognosis of sclerosing perineurioma is excellent. Complete local excision is considered curative.1

Angiofibroma, also known as fibrous papule, is a common and benign lesion located primarily on or in close proximity to the nose.9 Angiofibromas can be associated with genodermatoses such as tuberous sclerosis, multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1, or Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome. When angiofibromas involve the penis, they are called pearly penile papules. Ungual angiofibroma, also known as Koenen tumor, occurs underneath the nail.10-12 Both facial angiofibromas (>3) and ungual angiofibromas (>2) are independent major criteria for tuberous sclerosis.13 Clinically, angiofibroma presents as a small, dome-shaped, pink papule arising on the lower portion of the nose or nearby area of the central face. Histopathologically, angiofibromas classically demonstrate increased dilated vessels and fibrosis in the dermis. Stellate, plump, spindle-shaped, and multinucleated cells can be seen in the collagenous stroma. The collagen fibers around hair follicles are arranged concentrically, resulting in an onion skin-like appearance. The epidermal rete ridges can be effaced (Figure 1). Increased numbers of single-unit melanocytes along the dermoepidermal junction can be seen in some cases. Immunohistochemically, a variable number of spindled and multinucleated cells in the dermis stain with factor XIIIa. There are at least 7 histologic variants of angiofibroma including hypercellular, pigmented, inflammatory, pleomorphic, clear cell, granular cell, and epithelioid.9,14

Desmoplastic nevus (DN) is a benign melanocytic neoplasm characterized by predominantly spindle-shaped nevus cells embedded within a fibrotic stroma. Although it can resemble a Spitz nevus, it is recognized as a distinct entity.15-17 Clinically, DN presents as a small and flesh-colored, erythematous or slightly pigmented papule or nodule that usually occurs on the arms and legs of young adults. Histopathologically, DN demonstrates a dermal-based proliferation of spindled melanocytes embedded in a dense collagenous stroma with sparse or absent melanin deposition. The collagen bundles often show artifactual clefts and onion skin-like accentuation around vessels. Melanocytes may be epithelioid (Figure 2).16 Immunohistochemically, DN expresses melanocytic markers such as S-100, Melan-A, and human melanoma black 45, but epithelial membrane antigen is negative. Human melanoma black 45 demonstrates maturation with stronger staining in superficial portions of the lesion and diminution of staining with increasing dermal depth.18 Many other melanocytic tumors share histologic similarities to DN including blue nevus and desmoplastic melanoma.17,19,20

Palisaded encapsulated neuroma, also referred to as solitary circumscribed neuroma, was first described by Reed et al21 in 1972. It is a benign and solitary, firm, dome-shaped, flesh-colored papule that occurs in middle-aged adults, predominately near mucocutaneous junctions of the face. Other locations include the oral mucosa, eyelid, nasal fossa, shoulder, arm, hand, foot, and glans penis.22,23 Histopathologically, palisaded encapsulated neuroma demonstrates a solitary, well-circumscribed, partially encapsulated, intradermal nodule composed of interweaving fascicles of spindle cells with prominent clefts (Figure 3). Rarely, palisaded encapsulated neuroma may have a plexiform or multinodular architecture.24 Immunohistochemically, tumor cells stain positively for S-100 protein, type IV collagen, and vimentin. The capsule, composed of perineural cells, stains positive for epithelial membrane antigen. A neurofilament stain will highlight axons within the tumor.24,25 Currently, palisaded encapsulated neuroma does not have a well-established link to known neurocutaneous or inherited syndromes. Excision is curative with a low risk of recurrence.26

Sclerotic fibromas (SFs) were first reported by Weary et al27 as multiple tumors involving the tongues of patients with Cowden syndrome. Sporadic or solitary SFs of the skin in patients without Cowden syndrome have been reported, and both multiple and solitary SFs present with similar pathologic changes.28-30 Clinically, the solitary variant manifests as a well-demarcated, flesh-colored to erythematous, waxy papule or nodule with no site or sex predilection.30,31 Histologically, SF demonstrates a well-demarcated, nonencapsulated dermal nodule composed of hypocellular and sclerotic collagen bundles with scattered spindled cells and prominent clefts resembling Vincent van Gogh's Starry Night or plywood (Figure 4). Immunohistochemically, the spindled cells strongly express CD34. Factor XIIIa and markers of melanocytic, neural, and muscular differentiation are negative. When rendering a diagnosis in a patient with multiple SFs, a comment regarding the possibility of Cowden syndrome should be mentioned.32

The Diagnosis: Sclerosing Perineurioma

Sclerosing perineurioma, first described in 1997 by Fetsch and Miettinen,1 is a subtype of perineurioma with a strong predilection for the fingers and palms of young adults. Rare cases involving extra-acral sites including the forearm, elbow, axilla, back, neck, lower leg, thigh, knee, lips, nose, and mouth have been reported.2-4 Perineurioma is a relatively uncommon and benign peripheral nerve sheath tumor with exclusive perineurial differentiation.5 Perineurioma is divided into intraneural and extraneural types; the latter are further subclassified into soft tissue, sclerosing, reticular, and plexiform types. Other rare forms include the sclerosing, Pacinian corpuscle-like perineurioma, lipomatous perineurioma, perineurioma with xanthomatous areas, and perineurioma with granular cells.6,7

Clinically, sclerosing perineurioma usually presents as a solitary lesion; however, rare cases of multiple lesions have been reported.8 Our patient presented with a solitary papule on the nose. Histopathologically, sclerosing perineurioma demonstrates slender spindle cells in a whorled growth pattern (onion skin) embedded in a hyalinized, lamellar, and dense collagenous stroma with intervening cleftlike spaces. Immunohistochemically, the spindle cells of our case stained positive for epithelial membrane antigen (quiz images). Other positive immunostains for perineurioma include claudin-1 and glucose transporter 1 (GLUT1). Perineurioma lacks expression of S-100 but can express CD34.2 As a benign tumor, the prognosis of sclerosing perineurioma is excellent. Complete local excision is considered curative.1

Angiofibroma, also known as fibrous papule, is a common and benign lesion located primarily on or in close proximity to the nose.9 Angiofibromas can be associated with genodermatoses such as tuberous sclerosis, multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1, or Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome. When angiofibromas involve the penis, they are called pearly penile papules. Ungual angiofibroma, also known as Koenen tumor, occurs underneath the nail.10-12 Both facial angiofibromas (>3) and ungual angiofibromas (>2) are independent major criteria for tuberous sclerosis.13 Clinically, angiofibroma presents as a small, dome-shaped, pink papule arising on the lower portion of the nose or nearby area of the central face. Histopathologically, angiofibromas classically demonstrate increased dilated vessels and fibrosis in the dermis. Stellate, plump, spindle-shaped, and multinucleated cells can be seen in the collagenous stroma. The collagen fibers around hair follicles are arranged concentrically, resulting in an onion skin-like appearance. The epidermal rete ridges can be effaced (Figure 1). Increased numbers of single-unit melanocytes along the dermoepidermal junction can be seen in some cases. Immunohistochemically, a variable number of spindled and multinucleated cells in the dermis stain with factor XIIIa. There are at least 7 histologic variants of angiofibroma including hypercellular, pigmented, inflammatory, pleomorphic, clear cell, granular cell, and epithelioid.9,14