User login

Daily calorie intake requirements during pregnancy: Does one size fit all?

Most J, St Amant M, Hsia DS, et al. Evidence-based recommendations for energy intake in pregnant women with obesity. J Clin Invest. 2019;129:4682-4690.

EXPERT COMMENTARY

In 2009, the Institute of Medicine, now known as the National Academy of Medicine, updated its gestational weight gain guideline. This guideline’s major difference, compared with the 1990 guideline, is a specific weight gain range for women with obesity: 5 to 9 kg, or 11 to 20 lb.1 This weight gain range was chosen in part because it allows for a minimum weight gain that supports the growth and development of tissues (fetus, placenta, breast, uterus) and fluids (blood volume, intracellular and extracellular fluid), also known as the “fat-free” mass.

Many studies have since shown not only associations between lower-than-guideline-recommended weight gain and improved pregnancy outcomes (for example, reductions in preeclampsia and cesarean deliveries), but also increases in low birth weight for infants of women with obesity.2,3 Although the weight gain guideline differs based on a woman’s prepregnancy body mass index, the energy requirements, or how many additional calories a woman should consume daily, are the same for all, regardless of weight prior to pregnancy: an increase by 340 to 452 kcal/day in the second and third trimesters.1

Recently, Most and colleagues challenged this recommendation for energy requirements with results from their prospective observational study of 54 women with obesity during pregnancy.4 They aimed to evaluate energy intake with the energy intake-balance method (doubly labeled water and whole-room indirect calorimetry and body composition) according to tests done at 13 to 16 weeks’ gestation and 35 to 37 weeks’ gestation and according to the current National Academy of Medicine gestational weight gain guideline (inadequate, recommended, or excessive weight gain groups).4

Details of the study

Women who participated in this study were recruited from the Pennington Biomedical Research Center in Louisiana and were mostly multiparas (57%); about half had a college degree or higher (52%) and 41% were African American. The investigators found that gestational weight gain in their participants was similar to that found in other large epidemiologic studies in that 67% of women had excessive gestational weight gain.5

Findings. For women who gained the recommended amount of weight (n = 8), mean (SD) daily energy intake was 2,698 (99) kcal/day and energy expenditure was 2,824 (105) kcal/day. Therefore, to meet the recommended amount of weight gain, these women had a negative energy balance (-125 [52] kcal/day). Women with inadequate weight gain

(n = 10) also had a negative energy balance (-262 [32] kcal/day), but the difference was not significantly different compared with that in the recommended gestational weight gain group (P = .08). By contrast, women with excessive gestational weight gain (n = 36) had a mean (SD) positive energy balance of 186 (29) kcal/day.

Fat-free mass and fat mass weight gains. The body weight gains of the fat-free and fat mass compartments also were compared with linear mixed effect models among the 3 weight gain groups. There were no differences in the amount of fat-free mass gained among the 3 weight gain groups (P>.05), but women with excessive gestational weight gain had significantly higher increases in fat mass compared with the other 2 weight gain groups (P<.001).

Pregnancy outcomes. Although there were no differences in cesarean deliveries or birth weight among the 3 weight gain groups, the study was not powered to detect these differences.

Continue to: Study strengths and limitations...

Study strengths and limitations

It is important to note that this study by Most and colleagues was not a health behavior intervention for gestational weight gain. Women who participated in the study did not receive specific directions or advice on diet or physical activity. Furthermore, the study used the current gestational weight gain guideline as a reference to determine energy intake. As such, findings from this study alone cannot be used to adapt the current gestational weight gain guideline for women with obesity.

The study methods were rigorous in terms of the energy intake measurements, but a larger and more diverse sample size is needed to confirm the study findings.

Most and colleagues’ data suggest that maintaining energy balance can support obligatory growth and development of women and their fetuses during pregnancy (fat-free mass). In doing so, women with obesity meet the current gestational weight gain guideline. It is hoped that this important research will be used in future studies, with larger sample sizes, to evaluate energy requirements during pregnancy, especially in women with different classes of obesity. Ultimately, these new recommendations for energy requirements should be combined with studies of health behavior interventions for gestational weight gain.

The study by Most and colleagues supports the concept that energy requirements need to be individualized for women to meet the recommended amount of gestational weight gain. If women meet their gestational weight gain goals, they have the potential to improve their health and the health of their offspring.

MICHELLE A. KOMINIAREK, MD, MS

- Institute of Medicine and National Research Council Committee to Reexamine IOM Pregnacy Weight Guidelines. Rasmussen KM, Yaktine AL, eds. Weight Gain During Pregnancy: Reexamining the Guidelines. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2009.

- Kapadia MZ, Park CK, Beyene J, et al. Weight loss instead of weight gain within the guidelines in obese women during pregnancy: a systematic review and metaanalyses of maternal and infant outcomes. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0132650.

- Kapadia MZ, Park CK, Beyene J, et al. Can we safely recommend gestational weight gain below the 2009 guidelines in obese women? A systematic review and metaanalysis. Obes Rev. 2015;16:189-206.

- Most J, St Amant M, Hsia DS, et al. Evidence-based recommendations for energy intake in pregnant women with obesity. J Clin Invest. 2019;129:4682-4690.

- Deputy NP, Sharma AJ, Kim SY, et al. Prevalence and characteristics associated with gestational weight gain adequacy. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125:773-781.

Most J, St Amant M, Hsia DS, et al. Evidence-based recommendations for energy intake in pregnant women with obesity. J Clin Invest. 2019;129:4682-4690.

EXPERT COMMENTARY

In 2009, the Institute of Medicine, now known as the National Academy of Medicine, updated its gestational weight gain guideline. This guideline’s major difference, compared with the 1990 guideline, is a specific weight gain range for women with obesity: 5 to 9 kg, or 11 to 20 lb.1 This weight gain range was chosen in part because it allows for a minimum weight gain that supports the growth and development of tissues (fetus, placenta, breast, uterus) and fluids (blood volume, intracellular and extracellular fluid), also known as the “fat-free” mass.

Many studies have since shown not only associations between lower-than-guideline-recommended weight gain and improved pregnancy outcomes (for example, reductions in preeclampsia and cesarean deliveries), but also increases in low birth weight for infants of women with obesity.2,3 Although the weight gain guideline differs based on a woman’s prepregnancy body mass index, the energy requirements, or how many additional calories a woman should consume daily, are the same for all, regardless of weight prior to pregnancy: an increase by 340 to 452 kcal/day in the second and third trimesters.1

Recently, Most and colleagues challenged this recommendation for energy requirements with results from their prospective observational study of 54 women with obesity during pregnancy.4 They aimed to evaluate energy intake with the energy intake-balance method (doubly labeled water and whole-room indirect calorimetry and body composition) according to tests done at 13 to 16 weeks’ gestation and 35 to 37 weeks’ gestation and according to the current National Academy of Medicine gestational weight gain guideline (inadequate, recommended, or excessive weight gain groups).4

Details of the study

Women who participated in this study were recruited from the Pennington Biomedical Research Center in Louisiana and were mostly multiparas (57%); about half had a college degree or higher (52%) and 41% were African American. The investigators found that gestational weight gain in their participants was similar to that found in other large epidemiologic studies in that 67% of women had excessive gestational weight gain.5

Findings. For women who gained the recommended amount of weight (n = 8), mean (SD) daily energy intake was 2,698 (99) kcal/day and energy expenditure was 2,824 (105) kcal/day. Therefore, to meet the recommended amount of weight gain, these women had a negative energy balance (-125 [52] kcal/day). Women with inadequate weight gain

(n = 10) also had a negative energy balance (-262 [32] kcal/day), but the difference was not significantly different compared with that in the recommended gestational weight gain group (P = .08). By contrast, women with excessive gestational weight gain (n = 36) had a mean (SD) positive energy balance of 186 (29) kcal/day.

Fat-free mass and fat mass weight gains. The body weight gains of the fat-free and fat mass compartments also were compared with linear mixed effect models among the 3 weight gain groups. There were no differences in the amount of fat-free mass gained among the 3 weight gain groups (P>.05), but women with excessive gestational weight gain had significantly higher increases in fat mass compared with the other 2 weight gain groups (P<.001).

Pregnancy outcomes. Although there were no differences in cesarean deliveries or birth weight among the 3 weight gain groups, the study was not powered to detect these differences.

Continue to: Study strengths and limitations...

Study strengths and limitations

It is important to note that this study by Most and colleagues was not a health behavior intervention for gestational weight gain. Women who participated in the study did not receive specific directions or advice on diet or physical activity. Furthermore, the study used the current gestational weight gain guideline as a reference to determine energy intake. As such, findings from this study alone cannot be used to adapt the current gestational weight gain guideline for women with obesity.

The study methods were rigorous in terms of the energy intake measurements, but a larger and more diverse sample size is needed to confirm the study findings.

Most and colleagues’ data suggest that maintaining energy balance can support obligatory growth and development of women and their fetuses during pregnancy (fat-free mass). In doing so, women with obesity meet the current gestational weight gain guideline. It is hoped that this important research will be used in future studies, with larger sample sizes, to evaluate energy requirements during pregnancy, especially in women with different classes of obesity. Ultimately, these new recommendations for energy requirements should be combined with studies of health behavior interventions for gestational weight gain.

The study by Most and colleagues supports the concept that energy requirements need to be individualized for women to meet the recommended amount of gestational weight gain. If women meet their gestational weight gain goals, they have the potential to improve their health and the health of their offspring.

MICHELLE A. KOMINIAREK, MD, MS

Most J, St Amant M, Hsia DS, et al. Evidence-based recommendations for energy intake in pregnant women with obesity. J Clin Invest. 2019;129:4682-4690.

EXPERT COMMENTARY

In 2009, the Institute of Medicine, now known as the National Academy of Medicine, updated its gestational weight gain guideline. This guideline’s major difference, compared with the 1990 guideline, is a specific weight gain range for women with obesity: 5 to 9 kg, or 11 to 20 lb.1 This weight gain range was chosen in part because it allows for a minimum weight gain that supports the growth and development of tissues (fetus, placenta, breast, uterus) and fluids (blood volume, intracellular and extracellular fluid), also known as the “fat-free” mass.

Many studies have since shown not only associations between lower-than-guideline-recommended weight gain and improved pregnancy outcomes (for example, reductions in preeclampsia and cesarean deliveries), but also increases in low birth weight for infants of women with obesity.2,3 Although the weight gain guideline differs based on a woman’s prepregnancy body mass index, the energy requirements, or how many additional calories a woman should consume daily, are the same for all, regardless of weight prior to pregnancy: an increase by 340 to 452 kcal/day in the second and third trimesters.1

Recently, Most and colleagues challenged this recommendation for energy requirements with results from their prospective observational study of 54 women with obesity during pregnancy.4 They aimed to evaluate energy intake with the energy intake-balance method (doubly labeled water and whole-room indirect calorimetry and body composition) according to tests done at 13 to 16 weeks’ gestation and 35 to 37 weeks’ gestation and according to the current National Academy of Medicine gestational weight gain guideline (inadequate, recommended, or excessive weight gain groups).4

Details of the study

Women who participated in this study were recruited from the Pennington Biomedical Research Center in Louisiana and were mostly multiparas (57%); about half had a college degree or higher (52%) and 41% were African American. The investigators found that gestational weight gain in their participants was similar to that found in other large epidemiologic studies in that 67% of women had excessive gestational weight gain.5

Findings. For women who gained the recommended amount of weight (n = 8), mean (SD) daily energy intake was 2,698 (99) kcal/day and energy expenditure was 2,824 (105) kcal/day. Therefore, to meet the recommended amount of weight gain, these women had a negative energy balance (-125 [52] kcal/day). Women with inadequate weight gain

(n = 10) also had a negative energy balance (-262 [32] kcal/day), but the difference was not significantly different compared with that in the recommended gestational weight gain group (P = .08). By contrast, women with excessive gestational weight gain (n = 36) had a mean (SD) positive energy balance of 186 (29) kcal/day.

Fat-free mass and fat mass weight gains. The body weight gains of the fat-free and fat mass compartments also were compared with linear mixed effect models among the 3 weight gain groups. There were no differences in the amount of fat-free mass gained among the 3 weight gain groups (P>.05), but women with excessive gestational weight gain had significantly higher increases in fat mass compared with the other 2 weight gain groups (P<.001).

Pregnancy outcomes. Although there were no differences in cesarean deliveries or birth weight among the 3 weight gain groups, the study was not powered to detect these differences.

Continue to: Study strengths and limitations...

Study strengths and limitations

It is important to note that this study by Most and colleagues was not a health behavior intervention for gestational weight gain. Women who participated in the study did not receive specific directions or advice on diet or physical activity. Furthermore, the study used the current gestational weight gain guideline as a reference to determine energy intake. As such, findings from this study alone cannot be used to adapt the current gestational weight gain guideline for women with obesity.

The study methods were rigorous in terms of the energy intake measurements, but a larger and more diverse sample size is needed to confirm the study findings.

Most and colleagues’ data suggest that maintaining energy balance can support obligatory growth and development of women and their fetuses during pregnancy (fat-free mass). In doing so, women with obesity meet the current gestational weight gain guideline. It is hoped that this important research will be used in future studies, with larger sample sizes, to evaluate energy requirements during pregnancy, especially in women with different classes of obesity. Ultimately, these new recommendations for energy requirements should be combined with studies of health behavior interventions for gestational weight gain.

The study by Most and colleagues supports the concept that energy requirements need to be individualized for women to meet the recommended amount of gestational weight gain. If women meet their gestational weight gain goals, they have the potential to improve their health and the health of their offspring.

MICHELLE A. KOMINIAREK, MD, MS

- Institute of Medicine and National Research Council Committee to Reexamine IOM Pregnacy Weight Guidelines. Rasmussen KM, Yaktine AL, eds. Weight Gain During Pregnancy: Reexamining the Guidelines. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2009.

- Kapadia MZ, Park CK, Beyene J, et al. Weight loss instead of weight gain within the guidelines in obese women during pregnancy: a systematic review and metaanalyses of maternal and infant outcomes. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0132650.

- Kapadia MZ, Park CK, Beyene J, et al. Can we safely recommend gestational weight gain below the 2009 guidelines in obese women? A systematic review and metaanalysis. Obes Rev. 2015;16:189-206.

- Most J, St Amant M, Hsia DS, et al. Evidence-based recommendations for energy intake in pregnant women with obesity. J Clin Invest. 2019;129:4682-4690.

- Deputy NP, Sharma AJ, Kim SY, et al. Prevalence and characteristics associated with gestational weight gain adequacy. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125:773-781.

- Institute of Medicine and National Research Council Committee to Reexamine IOM Pregnacy Weight Guidelines. Rasmussen KM, Yaktine AL, eds. Weight Gain During Pregnancy: Reexamining the Guidelines. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2009.

- Kapadia MZ, Park CK, Beyene J, et al. Weight loss instead of weight gain within the guidelines in obese women during pregnancy: a systematic review and metaanalyses of maternal and infant outcomes. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0132650.

- Kapadia MZ, Park CK, Beyene J, et al. Can we safely recommend gestational weight gain below the 2009 guidelines in obese women? A systematic review and metaanalysis. Obes Rev. 2015;16:189-206.

- Most J, St Amant M, Hsia DS, et al. Evidence-based recommendations for energy intake in pregnant women with obesity. J Clin Invest. 2019;129:4682-4690.

- Deputy NP, Sharma AJ, Kim SY, et al. Prevalence and characteristics associated with gestational weight gain adequacy. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125:773-781.

The IUD string check: Benefit or burden?

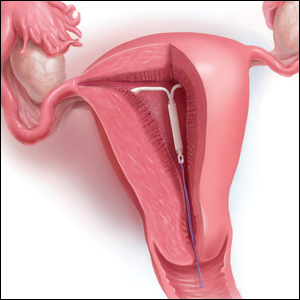

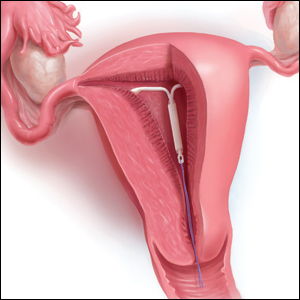

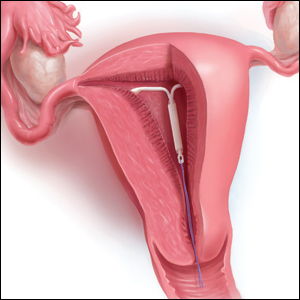

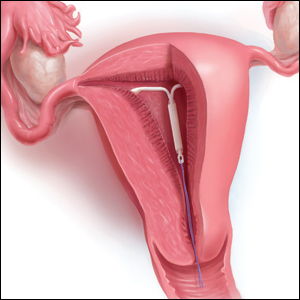

CASE A patient experiences unnessary inconvenience, distress, and cost following IUD placement

Ms. J had a levonorgestrel intrauterine device (IUD) placed at her postpartum visit. Her physician asked her to return for a string check in 4 to 6 weeks. She was dismayed at the prospect of re-presenting for care, as she is losing the Medicaid coverage that paid for her pregnancy care. One month later, she arranged for a babysitter so she could obtain the recommended string check. The physician told her the strings seemed longer than expected and ordered ultrasonography. Ms. J is distressed because of the mounting cost of care but is anxious to ensure that the IUD will prevent future pregnancy.

Should the routine IUD string check be reconsidered?

The string check dissension

Intrauterine devices offer reliable contraception with a high rate of satisfaction and a remarkably low rate of complications.1-3 With the increased uptake of IUDs, the value of “string checks” is being debated, with myriad responses from professional groups, manufacturers, and individual clinicians. For many practicing ObGyns, the question remains: Should patients be counseled about presenting for or doing their own IUD string checks?

Indeed, all IUD manufacturers recommend monthly self-examination to evaluate string presence.4-8 Manufacturers’ websites prominently display this information in material directed toward current or potential users, so many patients may be familiar already with this recommendation before their clinician visit. Yet, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention state that no routine follow-up or monitoring is needed.9

In our case scenario, follow-up is clearly burdensome and ultimately costly. Instead, clinicians can advise patients to return with rare but important to recognize complications (such as perforation, expulsion, infection), adverse effects, or desire for change. While no data are available to support in-office or at-home string checks, data do show that women reliably present when intervention is needed.

Here, we explore 5 questions relevant to IUD string checks and discuss why it is time to rethink this practice habit.

What is the purpose of a string check?

String checks serve as a surrogate for assessing an IUD’s position and function. A string check can be performed by a clinician, who observes the IUD strings on speculum exam or palpates the strings on bimanual exam, or by the patient doing a self-exam. A positive string check purportedly assures both the IUD user and the health care provider that an IUD remains in a fundal, intrauterine position, thus providing an ongoing reliable contraceptive effect.

However, string check reliability in detecting contraceptive effectiveness is uncertain. Strings that subjectively feel or appear longer than anticipated can lead to unnecessary additional evaluation and emotional distress: These are harms. By contrast, when an expulsion occurs, it often is a partial expulsion or displacement, with unclear effect on patient or physician perception of the strings on examination. One retrospective review identified women with a history of IUD placement and a positive pregnancy test; those with an intrauterine pregnancy (74%) frequently also had a malpositioned IUD (55%) and rarely identifiable string issues (16%).10 Before asking patients and clinicians to use resources for performing string evaluations, the association between this action and outcomes of interest must be elucidated.

If not for assessing risk of expulsion, IUD follow-up allows the clinician to evaluate for other complications or adverse effects and to address patient concerns. This practice often is performed when the patient is starting a new medication or medical intervention. However, a systematic review involving 4 studies of IUD follow-up visits or phone calls after contraceptive initiation generated limited data, with no notable impact on contraceptive continuation or indicated use.11

Most important, data show that patients present to their clinician when issues arise with IUD use. One prospective study of 280 women compared multiple follow-up visits with a single 6-week follow-up visit after IUD placement; 10 expulsions were identified, and 8 of these were noted at unscheduled visits when patients presented with symptoms.12 This study suggests that there is little benefit in scheduled follow-up or set self-checks.

Furthermore, in a study in Finland of more than 17,000 IUD users, the rare participants who became pregnant during IUD use promptly presented for care because of a change in menses, pain, or symptoms of pregnancy.13 While IUDs are touted as user independent, this overlooks the reality: Data show that device failure, although rare, is rapidly and appropriately addressed by the user.

Continue to: Does the risk of IUD expulsion warrant string checks?...

Does the risk of IUD expulsion warrant string checks?

The risk of IUD expulsion is estimated to be 1% at 1 month and 4% at 1 year, with a contraceptive failure rate of 0.4% at 1 year. The risk of expulsion does not differ by age group, including adolescents, or parity, but it is higher with use of the copper IUD (2% at 1 month, 6% at 1 year) and with prior expulsion (14%, limited by small numbers).1 Furthermore, risk of expulsion is higher with postplacental placement and second trimester abortion.14,15 Despite this risk, the contraceptive failure rate of all types of IUDs remains consistently lower than all other reversible methods besides the contraceptive implant.16

Furthermore, while IUD expulsion is rare, unnoticed expulsion is even more rare. In one study with more than 58,000 person-years of use, 132 pregnancies were noted, and 7 of these occurred in the setting of an unnoticed expulsion.13 Notably, a higher risk threshold is held for other medications. For example, statins are associated with a 3% risk of irreversible hepatic injury, yet serial liver function tests are not performed in patients without baseline liver dysfunction.17 A less than 0.1% risk of a non–life-threatening complication—unnoticed expulsion—does not warrant routine follow-up. Instead, the patient gauges the tolerability of that risk in making a follow-up plan, particularly given the varied individual preferences in patients’ management of the associated outcome of unintended pregnancy.

Are women interested in and able to perform their own string checks?

Recommendations to perform IUD string self-checks should consider whether women are willing and able to do so. In a study of 126 IUD users, 59% of women had attempted to check their IUD strings at home, and one-third were unable to do so successfully; all participants had visible strings on subsequent speculum exam.18 The women also were given the opportunity to perform a string self-check at the study visit. Overall, only 46% of participants found the exercise acceptable and were able to palpate the IUD strings.18 The authors aptly stated, “A universal recommendation for practice that is meant to identify a rare complication has no clinical utility if at least half of the women are unable to follow it.”

In which scenarios might a string check have clear utility?

The most important reason for follow-up after IUD placement or for patients to perform string self-checks is patient preference. At least anecdotally, some patients take comfort, particularly in the absence of menses, in palpating IUD strings regularly; these individuals should know that there is no necessity for but also no harm in this practice. In addition, patients may desire a string check or follow-up visit to discuss their new contraceptive’s goodness-of-fit.

While limited data show that routinely scheduling such visits does not improve contraceptive continuation, it is difficult to extrapolate these data to the select individuals who independently desire follow-up. (In addition, contraceptive continuance is hardly a metric of success, as clinicians and patients can agree that discontinuation in the setting of patient dissatisfaction is always appropriate.)

Clinicians should share with patients differing risks of IUD expulsion, and this may prompt more nuanced decisions about string checks and/or follow-up. Patients with postplacental or postabortion (second trimester) IUD placement or placement following prior expulsion may opt to perform string checks given the relatively higher risk of expulsion despite the maintained, absolutely low risk that such an event is unnoticed.

If a patient does present for a string check and strings are not visualized on exam, reasonable attempts should be made to identify the strings at that time. A cytobrush can be used to liberate and identify strings within the cervical canal. If the clinician cannot identify the strings or the patient is unable to tolerate such attempts, ultrasonography should be performed to localize the IUD. The ultrasound scan can be done in the office, if available, which is more cost-effective for women than a referral to radiology. If ultrasonography does not identify an intrauterine IUD, an x-ray is the next step to determine if the IUD has expulsed or perforated.

Continue to: Is a string check worth the cost?...

Is a string check worth the cost?

Health care providers may not be aware of the cost of care from the patient perspective. While the Affordable Care Act of 2010 mandates contraceptive coverage for women with insurance, a string check often is coded as a problem-based visit and thus may require a significant copay or out-of-pocket cost for high-deductible plans—without a proven benefit.19 Women who lack insurance coverage may forgo even necessary care due to the cost.20

The bottom line

The medical community and ObGyns specifically are familiar with a practice of patient self-examination falling by the wayside, as has been the case with breast self-examination.21 While counseling on string checks can complement conversations about risks and patients’ personal preferences regarding follow-up, no data support routine string checks in the clinic or at home. One of the great benefits of IUD use is its lack of barriers and resources for ongoing use. Physicians need not reintroduce burdens without benefits to those who desire this contraceptive method.

- Aoun J, Dines VA, Stovall DW, et al. Effects of age, parity, and device type on complications and discontinuation of intrauterine devices. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123:585-592.

- Peipert JF, Zhao Q, Allsworth JE, et al. Continuation and satisfaction of reversible contraception. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;117:1105-1113.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Gynecology Practice. Committee opinion No. 672. Clinical challenges of long-acting reversible contraceptive methods. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;128:e69-e77.

- Mirena website. Placement of Mirena. 2019. https://www.mirena-us.com/placement-of-mirena/. Accessed December 7, 2019.

- Kyleena website. Let’s get started. 2019. https://www.kyleena-us.com/lets-get-started/what-to-expect/. Accessed December 7, 2019.

- Skyla website. What to expect. 2019. https://www.skyla-us.com/getting-skyla/index.php. Accessed December 7, 2019.

- Liletta website. What should I expect after Liletta insertion? 2020. https://www.liletta.com/about/what-to-expect-afterinsertion. Accessed December 7, 2019.

- Paragard website. What to expect with Paragard. 2019. https://www.paragard.com/what-can-i-expect-with-paragard/. Accessed December 7, 2019.

- Curtis KM, Jatlaoui TC, Tepper NK, et al. US selected practice recommendations for contraceptive use, 2016. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2016;65(4):1-66. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/ volumes/65/rr/pdfs/rr6504.pdf. Accessed February 19, 2020.

- Moschos E, Twickler DM. Intrauterine devices in early pregnancy: findings on ultrasound and clinical outcomes. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;204:427.e1-6.

- Steenland MW, Zapata LB, Brahmi D, et al. Appropriate follow up to detect potential adverse events after initiation of select contraceptive methods: a systematic review. Contraception 2013;87:611-624.

- Neuteboom K, de Kroon CD, Dersjant-Roorda M, et al. Follow-up visits after IUD-insertion: sense or nonsense? Contraception. 2003;68:101-104.

- Backman T, Rauramo I, Huhtala S, et al. Pregnancy during the use of levonorgestrel intrauterine system. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;190:50-54.

- Whitaker AK, Chen BA. Society of Family Planning guidelines: postplacental insertion of intrauterine devices. Contraception. 2018;97:2-13.

- Roe AH, Bartz D. Society of Family Planning clinical recommendations: contraception after surgical abortion. Contraception. 2019;99:2-9.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Practice Bulletins–Gynecology. Practice bulletin No. 186. Long-acting reversible contraception: implants and intrauterine devices. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130:e251-e269.

- US Food and Drug Administration. FDA drug safety communication: important safety label changes to cholesterol-lowering statin drugs. 2016. https://www .fda.gov/drugs/drug-safety-and-availability/fda-drugsafety-communication-important-safety-label-changescholesterol-lowering-statin-drugs. Accessed January 9, 2020.

- Melo J, Tschann M, Soon R, et al. Women’s willingness and ability to feel the strings of their intrauterine device. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2017;137:309-313.

- Healthcare.gov website. Health benefits & coverage: birth control benefits. 2020. https://www.healthcare.gov/ coverage/birth-control-benefits/. Accessed January 6, 2020.

- NORC at the University of Chicago. Americans’ views of healthcare costs, coverage, and policy. 2018;1-15. https:// www.norc.org/PDFs/WHI%20Healthcare%20Costs%20 Coverage%20and%20Policy/WHI%20Healthcare%20 Costs%20Coverage%20and%20Policy%20Issue%20Brief.pdf. Accessed February 19, 2020.

- Kosters JP, Gotzsche PC. Regular self-examination or clinical examination for early detection of breast cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003. CD003373.

CASE A patient experiences unnessary inconvenience, distress, and cost following IUD placement

Ms. J had a levonorgestrel intrauterine device (IUD) placed at her postpartum visit. Her physician asked her to return for a string check in 4 to 6 weeks. She was dismayed at the prospect of re-presenting for care, as she is losing the Medicaid coverage that paid for her pregnancy care. One month later, she arranged for a babysitter so she could obtain the recommended string check. The physician told her the strings seemed longer than expected and ordered ultrasonography. Ms. J is distressed because of the mounting cost of care but is anxious to ensure that the IUD will prevent future pregnancy.

Should the routine IUD string check be reconsidered?

The string check dissension

Intrauterine devices offer reliable contraception with a high rate of satisfaction and a remarkably low rate of complications.1-3 With the increased uptake of IUDs, the value of “string checks” is being debated, with myriad responses from professional groups, manufacturers, and individual clinicians. For many practicing ObGyns, the question remains: Should patients be counseled about presenting for or doing their own IUD string checks?

Indeed, all IUD manufacturers recommend monthly self-examination to evaluate string presence.4-8 Manufacturers’ websites prominently display this information in material directed toward current or potential users, so many patients may be familiar already with this recommendation before their clinician visit. Yet, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention state that no routine follow-up or monitoring is needed.9

In our case scenario, follow-up is clearly burdensome and ultimately costly. Instead, clinicians can advise patients to return with rare but important to recognize complications (such as perforation, expulsion, infection), adverse effects, or desire for change. While no data are available to support in-office or at-home string checks, data do show that women reliably present when intervention is needed.

Here, we explore 5 questions relevant to IUD string checks and discuss why it is time to rethink this practice habit.

What is the purpose of a string check?

String checks serve as a surrogate for assessing an IUD’s position and function. A string check can be performed by a clinician, who observes the IUD strings on speculum exam or palpates the strings on bimanual exam, or by the patient doing a self-exam. A positive string check purportedly assures both the IUD user and the health care provider that an IUD remains in a fundal, intrauterine position, thus providing an ongoing reliable contraceptive effect.

However, string check reliability in detecting contraceptive effectiveness is uncertain. Strings that subjectively feel or appear longer than anticipated can lead to unnecessary additional evaluation and emotional distress: These are harms. By contrast, when an expulsion occurs, it often is a partial expulsion or displacement, with unclear effect on patient or physician perception of the strings on examination. One retrospective review identified women with a history of IUD placement and a positive pregnancy test; those with an intrauterine pregnancy (74%) frequently also had a malpositioned IUD (55%) and rarely identifiable string issues (16%).10 Before asking patients and clinicians to use resources for performing string evaluations, the association between this action and outcomes of interest must be elucidated.

If not for assessing risk of expulsion, IUD follow-up allows the clinician to evaluate for other complications or adverse effects and to address patient concerns. This practice often is performed when the patient is starting a new medication or medical intervention. However, a systematic review involving 4 studies of IUD follow-up visits or phone calls after contraceptive initiation generated limited data, with no notable impact on contraceptive continuation or indicated use.11

Most important, data show that patients present to their clinician when issues arise with IUD use. One prospective study of 280 women compared multiple follow-up visits with a single 6-week follow-up visit after IUD placement; 10 expulsions were identified, and 8 of these were noted at unscheduled visits when patients presented with symptoms.12 This study suggests that there is little benefit in scheduled follow-up or set self-checks.

Furthermore, in a study in Finland of more than 17,000 IUD users, the rare participants who became pregnant during IUD use promptly presented for care because of a change in menses, pain, or symptoms of pregnancy.13 While IUDs are touted as user independent, this overlooks the reality: Data show that device failure, although rare, is rapidly and appropriately addressed by the user.

Continue to: Does the risk of IUD expulsion warrant string checks?...

Does the risk of IUD expulsion warrant string checks?

The risk of IUD expulsion is estimated to be 1% at 1 month and 4% at 1 year, with a contraceptive failure rate of 0.4% at 1 year. The risk of expulsion does not differ by age group, including adolescents, or parity, but it is higher with use of the copper IUD (2% at 1 month, 6% at 1 year) and with prior expulsion (14%, limited by small numbers).1 Furthermore, risk of expulsion is higher with postplacental placement and second trimester abortion.14,15 Despite this risk, the contraceptive failure rate of all types of IUDs remains consistently lower than all other reversible methods besides the contraceptive implant.16

Furthermore, while IUD expulsion is rare, unnoticed expulsion is even more rare. In one study with more than 58,000 person-years of use, 132 pregnancies were noted, and 7 of these occurred in the setting of an unnoticed expulsion.13 Notably, a higher risk threshold is held for other medications. For example, statins are associated with a 3% risk of irreversible hepatic injury, yet serial liver function tests are not performed in patients without baseline liver dysfunction.17 A less than 0.1% risk of a non–life-threatening complication—unnoticed expulsion—does not warrant routine follow-up. Instead, the patient gauges the tolerability of that risk in making a follow-up plan, particularly given the varied individual preferences in patients’ management of the associated outcome of unintended pregnancy.

Are women interested in and able to perform their own string checks?

Recommendations to perform IUD string self-checks should consider whether women are willing and able to do so. In a study of 126 IUD users, 59% of women had attempted to check their IUD strings at home, and one-third were unable to do so successfully; all participants had visible strings on subsequent speculum exam.18 The women also were given the opportunity to perform a string self-check at the study visit. Overall, only 46% of participants found the exercise acceptable and were able to palpate the IUD strings.18 The authors aptly stated, “A universal recommendation for practice that is meant to identify a rare complication has no clinical utility if at least half of the women are unable to follow it.”

In which scenarios might a string check have clear utility?

The most important reason for follow-up after IUD placement or for patients to perform string self-checks is patient preference. At least anecdotally, some patients take comfort, particularly in the absence of menses, in palpating IUD strings regularly; these individuals should know that there is no necessity for but also no harm in this practice. In addition, patients may desire a string check or follow-up visit to discuss their new contraceptive’s goodness-of-fit.

While limited data show that routinely scheduling such visits does not improve contraceptive continuation, it is difficult to extrapolate these data to the select individuals who independently desire follow-up. (In addition, contraceptive continuance is hardly a metric of success, as clinicians and patients can agree that discontinuation in the setting of patient dissatisfaction is always appropriate.)

Clinicians should share with patients differing risks of IUD expulsion, and this may prompt more nuanced decisions about string checks and/or follow-up. Patients with postplacental or postabortion (second trimester) IUD placement or placement following prior expulsion may opt to perform string checks given the relatively higher risk of expulsion despite the maintained, absolutely low risk that such an event is unnoticed.

If a patient does present for a string check and strings are not visualized on exam, reasonable attempts should be made to identify the strings at that time. A cytobrush can be used to liberate and identify strings within the cervical canal. If the clinician cannot identify the strings or the patient is unable to tolerate such attempts, ultrasonography should be performed to localize the IUD. The ultrasound scan can be done in the office, if available, which is more cost-effective for women than a referral to radiology. If ultrasonography does not identify an intrauterine IUD, an x-ray is the next step to determine if the IUD has expulsed or perforated.

Continue to: Is a string check worth the cost?...

Is a string check worth the cost?

Health care providers may not be aware of the cost of care from the patient perspective. While the Affordable Care Act of 2010 mandates contraceptive coverage for women with insurance, a string check often is coded as a problem-based visit and thus may require a significant copay or out-of-pocket cost for high-deductible plans—without a proven benefit.19 Women who lack insurance coverage may forgo even necessary care due to the cost.20

The bottom line

The medical community and ObGyns specifically are familiar with a practice of patient self-examination falling by the wayside, as has been the case with breast self-examination.21 While counseling on string checks can complement conversations about risks and patients’ personal preferences regarding follow-up, no data support routine string checks in the clinic or at home. One of the great benefits of IUD use is its lack of barriers and resources for ongoing use. Physicians need not reintroduce burdens without benefits to those who desire this contraceptive method.

CASE A patient experiences unnessary inconvenience, distress, and cost following IUD placement

Ms. J had a levonorgestrel intrauterine device (IUD) placed at her postpartum visit. Her physician asked her to return for a string check in 4 to 6 weeks. She was dismayed at the prospect of re-presenting for care, as she is losing the Medicaid coverage that paid for her pregnancy care. One month later, she arranged for a babysitter so she could obtain the recommended string check. The physician told her the strings seemed longer than expected and ordered ultrasonography. Ms. J is distressed because of the mounting cost of care but is anxious to ensure that the IUD will prevent future pregnancy.

Should the routine IUD string check be reconsidered?

The string check dissension

Intrauterine devices offer reliable contraception with a high rate of satisfaction and a remarkably low rate of complications.1-3 With the increased uptake of IUDs, the value of “string checks” is being debated, with myriad responses from professional groups, manufacturers, and individual clinicians. For many practicing ObGyns, the question remains: Should patients be counseled about presenting for or doing their own IUD string checks?

Indeed, all IUD manufacturers recommend monthly self-examination to evaluate string presence.4-8 Manufacturers’ websites prominently display this information in material directed toward current or potential users, so many patients may be familiar already with this recommendation before their clinician visit. Yet, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention state that no routine follow-up or monitoring is needed.9

In our case scenario, follow-up is clearly burdensome and ultimately costly. Instead, clinicians can advise patients to return with rare but important to recognize complications (such as perforation, expulsion, infection), adverse effects, or desire for change. While no data are available to support in-office or at-home string checks, data do show that women reliably present when intervention is needed.

Here, we explore 5 questions relevant to IUD string checks and discuss why it is time to rethink this practice habit.

What is the purpose of a string check?

String checks serve as a surrogate for assessing an IUD’s position and function. A string check can be performed by a clinician, who observes the IUD strings on speculum exam or palpates the strings on bimanual exam, or by the patient doing a self-exam. A positive string check purportedly assures both the IUD user and the health care provider that an IUD remains in a fundal, intrauterine position, thus providing an ongoing reliable contraceptive effect.

However, string check reliability in detecting contraceptive effectiveness is uncertain. Strings that subjectively feel or appear longer than anticipated can lead to unnecessary additional evaluation and emotional distress: These are harms. By contrast, when an expulsion occurs, it often is a partial expulsion or displacement, with unclear effect on patient or physician perception of the strings on examination. One retrospective review identified women with a history of IUD placement and a positive pregnancy test; those with an intrauterine pregnancy (74%) frequently also had a malpositioned IUD (55%) and rarely identifiable string issues (16%).10 Before asking patients and clinicians to use resources for performing string evaluations, the association between this action and outcomes of interest must be elucidated.

If not for assessing risk of expulsion, IUD follow-up allows the clinician to evaluate for other complications or adverse effects and to address patient concerns. This practice often is performed when the patient is starting a new medication or medical intervention. However, a systematic review involving 4 studies of IUD follow-up visits or phone calls after contraceptive initiation generated limited data, with no notable impact on contraceptive continuation or indicated use.11

Most important, data show that patients present to their clinician when issues arise with IUD use. One prospective study of 280 women compared multiple follow-up visits with a single 6-week follow-up visit after IUD placement; 10 expulsions were identified, and 8 of these were noted at unscheduled visits when patients presented with symptoms.12 This study suggests that there is little benefit in scheduled follow-up or set self-checks.

Furthermore, in a study in Finland of more than 17,000 IUD users, the rare participants who became pregnant during IUD use promptly presented for care because of a change in menses, pain, or symptoms of pregnancy.13 While IUDs are touted as user independent, this overlooks the reality: Data show that device failure, although rare, is rapidly and appropriately addressed by the user.

Continue to: Does the risk of IUD expulsion warrant string checks?...

Does the risk of IUD expulsion warrant string checks?

The risk of IUD expulsion is estimated to be 1% at 1 month and 4% at 1 year, with a contraceptive failure rate of 0.4% at 1 year. The risk of expulsion does not differ by age group, including adolescents, or parity, but it is higher with use of the copper IUD (2% at 1 month, 6% at 1 year) and with prior expulsion (14%, limited by small numbers).1 Furthermore, risk of expulsion is higher with postplacental placement and second trimester abortion.14,15 Despite this risk, the contraceptive failure rate of all types of IUDs remains consistently lower than all other reversible methods besides the contraceptive implant.16

Furthermore, while IUD expulsion is rare, unnoticed expulsion is even more rare. In one study with more than 58,000 person-years of use, 132 pregnancies were noted, and 7 of these occurred in the setting of an unnoticed expulsion.13 Notably, a higher risk threshold is held for other medications. For example, statins are associated with a 3% risk of irreversible hepatic injury, yet serial liver function tests are not performed in patients without baseline liver dysfunction.17 A less than 0.1% risk of a non–life-threatening complication—unnoticed expulsion—does not warrant routine follow-up. Instead, the patient gauges the tolerability of that risk in making a follow-up plan, particularly given the varied individual preferences in patients’ management of the associated outcome of unintended pregnancy.

Are women interested in and able to perform their own string checks?

Recommendations to perform IUD string self-checks should consider whether women are willing and able to do so. In a study of 126 IUD users, 59% of women had attempted to check their IUD strings at home, and one-third were unable to do so successfully; all participants had visible strings on subsequent speculum exam.18 The women also were given the opportunity to perform a string self-check at the study visit. Overall, only 46% of participants found the exercise acceptable and were able to palpate the IUD strings.18 The authors aptly stated, “A universal recommendation for practice that is meant to identify a rare complication has no clinical utility if at least half of the women are unable to follow it.”

In which scenarios might a string check have clear utility?

The most important reason for follow-up after IUD placement or for patients to perform string self-checks is patient preference. At least anecdotally, some patients take comfort, particularly in the absence of menses, in palpating IUD strings regularly; these individuals should know that there is no necessity for but also no harm in this practice. In addition, patients may desire a string check or follow-up visit to discuss their new contraceptive’s goodness-of-fit.

While limited data show that routinely scheduling such visits does not improve contraceptive continuation, it is difficult to extrapolate these data to the select individuals who independently desire follow-up. (In addition, contraceptive continuance is hardly a metric of success, as clinicians and patients can agree that discontinuation in the setting of patient dissatisfaction is always appropriate.)

Clinicians should share with patients differing risks of IUD expulsion, and this may prompt more nuanced decisions about string checks and/or follow-up. Patients with postplacental or postabortion (second trimester) IUD placement or placement following prior expulsion may opt to perform string checks given the relatively higher risk of expulsion despite the maintained, absolutely low risk that such an event is unnoticed.

If a patient does present for a string check and strings are not visualized on exam, reasonable attempts should be made to identify the strings at that time. A cytobrush can be used to liberate and identify strings within the cervical canal. If the clinician cannot identify the strings or the patient is unable to tolerate such attempts, ultrasonography should be performed to localize the IUD. The ultrasound scan can be done in the office, if available, which is more cost-effective for women than a referral to radiology. If ultrasonography does not identify an intrauterine IUD, an x-ray is the next step to determine if the IUD has expulsed or perforated.

Continue to: Is a string check worth the cost?...

Is a string check worth the cost?

Health care providers may not be aware of the cost of care from the patient perspective. While the Affordable Care Act of 2010 mandates contraceptive coverage for women with insurance, a string check often is coded as a problem-based visit and thus may require a significant copay or out-of-pocket cost for high-deductible plans—without a proven benefit.19 Women who lack insurance coverage may forgo even necessary care due to the cost.20

The bottom line

The medical community and ObGyns specifically are familiar with a practice of patient self-examination falling by the wayside, as has been the case with breast self-examination.21 While counseling on string checks can complement conversations about risks and patients’ personal preferences regarding follow-up, no data support routine string checks in the clinic or at home. One of the great benefits of IUD use is its lack of barriers and resources for ongoing use. Physicians need not reintroduce burdens without benefits to those who desire this contraceptive method.

- Aoun J, Dines VA, Stovall DW, et al. Effects of age, parity, and device type on complications and discontinuation of intrauterine devices. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123:585-592.

- Peipert JF, Zhao Q, Allsworth JE, et al. Continuation and satisfaction of reversible contraception. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;117:1105-1113.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Gynecology Practice. Committee opinion No. 672. Clinical challenges of long-acting reversible contraceptive methods. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;128:e69-e77.

- Mirena website. Placement of Mirena. 2019. https://www.mirena-us.com/placement-of-mirena/. Accessed December 7, 2019.

- Kyleena website. Let’s get started. 2019. https://www.kyleena-us.com/lets-get-started/what-to-expect/. Accessed December 7, 2019.

- Skyla website. What to expect. 2019. https://www.skyla-us.com/getting-skyla/index.php. Accessed December 7, 2019.

- Liletta website. What should I expect after Liletta insertion? 2020. https://www.liletta.com/about/what-to-expect-afterinsertion. Accessed December 7, 2019.

- Paragard website. What to expect with Paragard. 2019. https://www.paragard.com/what-can-i-expect-with-paragard/. Accessed December 7, 2019.

- Curtis KM, Jatlaoui TC, Tepper NK, et al. US selected practice recommendations for contraceptive use, 2016. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2016;65(4):1-66. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/ volumes/65/rr/pdfs/rr6504.pdf. Accessed February 19, 2020.

- Moschos E, Twickler DM. Intrauterine devices in early pregnancy: findings on ultrasound and clinical outcomes. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;204:427.e1-6.

- Steenland MW, Zapata LB, Brahmi D, et al. Appropriate follow up to detect potential adverse events after initiation of select contraceptive methods: a systematic review. Contraception 2013;87:611-624.

- Neuteboom K, de Kroon CD, Dersjant-Roorda M, et al. Follow-up visits after IUD-insertion: sense or nonsense? Contraception. 2003;68:101-104.

- Backman T, Rauramo I, Huhtala S, et al. Pregnancy during the use of levonorgestrel intrauterine system. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;190:50-54.

- Whitaker AK, Chen BA. Society of Family Planning guidelines: postplacental insertion of intrauterine devices. Contraception. 2018;97:2-13.

- Roe AH, Bartz D. Society of Family Planning clinical recommendations: contraception after surgical abortion. Contraception. 2019;99:2-9.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Practice Bulletins–Gynecology. Practice bulletin No. 186. Long-acting reversible contraception: implants and intrauterine devices. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130:e251-e269.

- US Food and Drug Administration. FDA drug safety communication: important safety label changes to cholesterol-lowering statin drugs. 2016. https://www .fda.gov/drugs/drug-safety-and-availability/fda-drugsafety-communication-important-safety-label-changescholesterol-lowering-statin-drugs. Accessed January 9, 2020.

- Melo J, Tschann M, Soon R, et al. Women’s willingness and ability to feel the strings of their intrauterine device. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2017;137:309-313.

- Healthcare.gov website. Health benefits & coverage: birth control benefits. 2020. https://www.healthcare.gov/ coverage/birth-control-benefits/. Accessed January 6, 2020.

- NORC at the University of Chicago. Americans’ views of healthcare costs, coverage, and policy. 2018;1-15. https:// www.norc.org/PDFs/WHI%20Healthcare%20Costs%20 Coverage%20and%20Policy/WHI%20Healthcare%20 Costs%20Coverage%20and%20Policy%20Issue%20Brief.pdf. Accessed February 19, 2020.

- Kosters JP, Gotzsche PC. Regular self-examination or clinical examination for early detection of breast cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003. CD003373.

- Aoun J, Dines VA, Stovall DW, et al. Effects of age, parity, and device type on complications and discontinuation of intrauterine devices. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123:585-592.

- Peipert JF, Zhao Q, Allsworth JE, et al. Continuation and satisfaction of reversible contraception. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;117:1105-1113.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Gynecology Practice. Committee opinion No. 672. Clinical challenges of long-acting reversible contraceptive methods. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;128:e69-e77.

- Mirena website. Placement of Mirena. 2019. https://www.mirena-us.com/placement-of-mirena/. Accessed December 7, 2019.

- Kyleena website. Let’s get started. 2019. https://www.kyleena-us.com/lets-get-started/what-to-expect/. Accessed December 7, 2019.

- Skyla website. What to expect. 2019. https://www.skyla-us.com/getting-skyla/index.php. Accessed December 7, 2019.

- Liletta website. What should I expect after Liletta insertion? 2020. https://www.liletta.com/about/what-to-expect-afterinsertion. Accessed December 7, 2019.

- Paragard website. What to expect with Paragard. 2019. https://www.paragard.com/what-can-i-expect-with-paragard/. Accessed December 7, 2019.

- Curtis KM, Jatlaoui TC, Tepper NK, et al. US selected practice recommendations for contraceptive use, 2016. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2016;65(4):1-66. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/ volumes/65/rr/pdfs/rr6504.pdf. Accessed February 19, 2020.

- Moschos E, Twickler DM. Intrauterine devices in early pregnancy: findings on ultrasound and clinical outcomes. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;204:427.e1-6.

- Steenland MW, Zapata LB, Brahmi D, et al. Appropriate follow up to detect potential adverse events after initiation of select contraceptive methods: a systematic review. Contraception 2013;87:611-624.

- Neuteboom K, de Kroon CD, Dersjant-Roorda M, et al. Follow-up visits after IUD-insertion: sense or nonsense? Contraception. 2003;68:101-104.

- Backman T, Rauramo I, Huhtala S, et al. Pregnancy during the use of levonorgestrel intrauterine system. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;190:50-54.

- Whitaker AK, Chen BA. Society of Family Planning guidelines: postplacental insertion of intrauterine devices. Contraception. 2018;97:2-13.

- Roe AH, Bartz D. Society of Family Planning clinical recommendations: contraception after surgical abortion. Contraception. 2019;99:2-9.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Practice Bulletins–Gynecology. Practice bulletin No. 186. Long-acting reversible contraception: implants and intrauterine devices. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130:e251-e269.

- US Food and Drug Administration. FDA drug safety communication: important safety label changes to cholesterol-lowering statin drugs. 2016. https://www .fda.gov/drugs/drug-safety-and-availability/fda-drugsafety-communication-important-safety-label-changescholesterol-lowering-statin-drugs. Accessed January 9, 2020.

- Melo J, Tschann M, Soon R, et al. Women’s willingness and ability to feel the strings of their intrauterine device. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2017;137:309-313.

- Healthcare.gov website. Health benefits & coverage: birth control benefits. 2020. https://www.healthcare.gov/ coverage/birth-control-benefits/. Accessed January 6, 2020.

- NORC at the University of Chicago. Americans’ views of healthcare costs, coverage, and policy. 2018;1-15. https:// www.norc.org/PDFs/WHI%20Healthcare%20Costs%20 Coverage%20and%20Policy/WHI%20Healthcare%20 Costs%20Coverage%20and%20Policy%20Issue%20Brief.pdf. Accessed February 19, 2020.

- Kosters JP, Gotzsche PC. Regular self-examination or clinical examination for early detection of breast cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003. CD003373.

What is the role of the ObGyn in preventing and treating obesity?

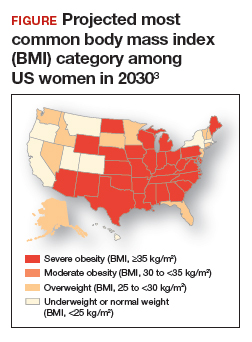

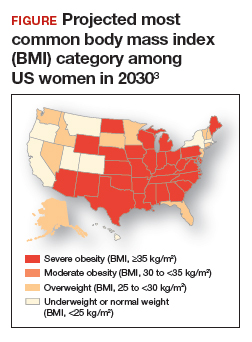

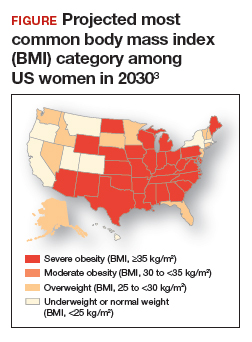

Obesity is a disease causing a public health crisis. In the United States, tobacco use and obesity are the two most important causes of preventable premature death. They result in an estimated 480,0001 and 300,0002 premature deaths per year, respectively. Obesity is a major contributor to diabetes mellitus, hypertension, dyslipidemia, and coronary heart disease. Obesity is also associated with increased rates of colon, breast, and endometrial cancer. Experts predict that in 2030, 50% of adults in the United States will have a body mass index (BMI) ≥ 30 kg/m2, and 25% will have a BMI ≥ 35 kg/m2.3 More women than men are predicted to be severely obese (FIGURE).3

As clinicians we need to increase our efforts to reduce the epidemic of obesity. ObGyns can play an important role in preventing and managing obesity, by recommending primary-care weight management practices, prescribing medications that influence central metabolism, and referring appropriate patients to bariatric surgery centers of excellence.

Primary-care weight management

Measuring BMI and recommending interventions to prevent and treat obesity are important components of a health maintenance encounter. For women who are overweight or obese, dietary changes and exercise are important recommendations. The American Heart Association recommends the following lifestyle interventions4:

- Eat a high-quality diet that includes vegetables, fruit, whole grains, beans, legumes, nuts, plant-based protein, lean animal protein, and fish.

- Limit intake of sugary drinks and foods, fatty or processed meats, full-fat dairy products, eggs, highly processed foods, and tropical oils.

- Exercise at least 150 minutes weekly at a moderate activity level, including muscle-strengthening activity.

- Reduce prolonged intervals of sitting.

- Consider using an activity tracker to monitor activity level.

Clinicians should consider referring overweight and obese patients to a nutritionist for a consultation to plan how to consume a high-quality, low-calorie diet. A nutritionist can spend time with patients explaining options for implementing a calorie-restricted diet. In addition, some health insurers will require patients to participate in a supervised calorie-restricted diet plan for at least 6 months before authorizing coverage of expensive weight loss medications or bariatric surgery. In addition to recommending diet and exercise, ObGyns may consider prescribing metformin for their obese patients.

Continue to: Metformin...

Metformin

Metformin is approved for the treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Unlike insulin therapy, which is associated with weight gain, metformin is associated with modest weight loss. The Diabetes Prevention Program (DPP) randomly assigned 3,234 nondiabetic participants with a fasting glucose level between 95 and 125 mg/dL and impaired glucose tolerance (140 to 199 mg/dL) after a 75-g oral glucose load to intensive lifestyle changes (calorie-restricted diet to achieve 7% weight loss plus 150 minutes of exercise weekly), metformin (850 mg twice daily), or placebo.5,6 The mean age of the participants was 51 years, with a mean BMI of 34 kg/m2. Most (68%) of the participants were women.

After 12 months of follow-up, mean weight loss in the intensive lifestyle change, metformin, and placebo groups was 6.5%, 2.7%, and 0.4%, respectively. After 2 years of treatment, weight loss among those who reliably took their metformin pills was approximately 4%, while participants in the placebo group had a 1% weight gain. Among those who continued to reliably take their metformin pills, the weight loss persisted through 9 years of follow up.

The mechanisms by which metformin causes weight loss are not clear. Metformin stimulates phosphorylation of adenosine monophosphate (AMP)-activated protein kinase, which regulates mitochondrial function, hepatic and muscle fatty acid oxidation, glucose transport, insulin secretion, and lipogenesis.7

Many ObGyns have experience in using metformin for the treatment of polycystic ovary syndrome or gestational diabetes. Hence, the dosing and adverse effects of metformin are familiar to many obstetricians-gynecologists. Metformin is contraindicated in individuals with creatinine clearance less than 30 mL/min. Rarely, metformin can cause lactic acidosis. According to Lexicomp,8 the most common adverse effects of metformin extended release (metformin ER) are diarrhea (17%), nausea and vomiting (7%), and decreased vitamin B12 concentration (7%) due to malabsorption in the terminal ileum. Of note, in the DPP study, hemoglobin concentration was slightly lower over time in the metformin compared with the placebo group (13.6 mg/dL vs 13.8 mg/dL, respectively; P<.001).6 Some experts recommend annual vitamin B12 measurement in individuals taking metformin.

In my practice, I only prescribe metformin ER. I usually start metformin treatment with one 750 mg ER tablet with dinner. If the patient tolerates that dose, I increase the dose to two 750 mg ER tablets with dinner. Metformin-induced adverse effects include diarrhea (17%) and nausea and vomiting (7%). Metformin ER is inexpensive. A one-month supply of metformin (sixty 750 mg tablets) costs between $4 and $21 at major pharmacies.9 Health insurance companies generally do not require preauthorization to cover metformin prescriptions.

Weight loss medications

US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved weight loss medications include: liraglutide (Victoza), orlistat (Xenical, Alli), combination phentermine-extended release topiramate (Qsymia), and combination extended release naltrexone-bupropion (Contrave). All FDA-approved weight loss medications result in mean weight loss in the range of 6% to 10%. Many of these medications are very expensive (more than $200 per month).10 Insurance preauthorization is commonly required for these medications. For ObGyns, it may be best to refer patients who would like to use a weight loss medication to a specialist or specialty center with expertise in using these medications.

Sustainable weight loss is very difficult to achieve through dieting alone. A multitude of dietary interventions have been presented as “revolutionary approaches” to the challenging problem of sustainable weight loss, including the Paleo diet, the Vegan diet, the low-carb diet, the Dukan diet, the ultra-lowfat diet, the Atkins diet, the HCG diet, the Zone diet, the South Beach diet, the plant-based diet, the Mediterranean diet, the Asian diet, and intermittent fasting. Recently, intermittent fasting has been presented as the latest and greatest approach to dieting, with the dual goals of achieving weight loss and improved health.1 In some animal models, intermittent dieting has been shown to increase life-span, a finding that has attracted great interest. A major goal of intermittent fasting is to promote “metabolic switching” with increased reliance on ketones to fuel cellular energy needs.

Two approaches to “prescribing” an intermittent fasting diet are to limit food intake to a period of 6 to 10 hours each day or to markedly reduce caloric intake one or two days per week, for example to 750 calories in a 24-hour period. There are no long-term studies of the health outcomes associated with intermittent fasting. In head-to-head clinical trials of intermittent fasting and daily calorie restriction (classic dieting), both diets result in similar weight loss. For example, in one clinical trial 100 obese participants, with a mean body mass index (BMI) of 34 kg/m2 , including 86 women, were randomly assigned to2:

1. intermittent fasting (25% of energy needs every other day)

2. daily calorie restriction (75% of energy needs every day), or

3. no intervention.

After 12 months of follow up, the participants in the no intervention group had gained 0.5% of their starting weight. The intermittent fasting and the daily calorie restriction groups had similar amounts of weight loss, approximately 5% of their starting weight. More individuals dropped out of the study from the intermittent fasting group than the daily calorie restriction group (38% vs 29%, respectively).

In another clinical trial, 107 overweight or obese premenopausal women, average age 40 years and mean BMI 31 kg/m2 , were randomly assigned to intermittent fasting (25% of energy needs 2 days per week) or daily calorie restriction (75% of energy needs daily) for 6 months. The mean weight of the participants at baseline was 83 kg. Weight loss was similar in the intermittent fasting and daily calorie restriction groups, 6.4 kg (-7.7%) and 5.6 kg (-6.7%), respectively (P=.4).3

The investigators concluded that intermittent fasting and daily calorie restriction could both be offered as effective approaches to weight loss. My conclusion is that intermittent fasting is not a miracle dietary intervention, but it is another important option in the armamentarium of weight loss interventions.

References

1. de Cabo R, Mattson MP. Effects of intermittent fasting on health, aging and disease. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:2541-2551.

2. Trepanowski JF, Kroeger CM, Barnosky A, et al. Effect of alternate-day fasting on weight loss, weight maintenance, and cardioprotection among metabolically healthy obese adults: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177:930-938.

3. Harvie MN, Pegington M, Mattson MP, et al. The effects of intermittent or continuous energy restriction on weight loss and metabolic disc disease risk markers: a randomized trial in young overweight women. Int J Obes (Lond). 2011;35:714-727.

Sleeve gastrectomy

Two children are playing in a school yard. One child proudly states, “My mother is an endocrinologist. She treats diabetes.” Not to be outdone, the other child replies, “My mother is a bariatric surgeon. She cures diabetes.”

The dialogue reflects the reality that bariatric surgery results in more reliable and significant weight loss than diet, exercise, or weight loss medications. Diet, exercise, and weight loss medications often result in a 5% to 10% decrease in weight, but bariatric surgery typically results in a 25% decrease in weight. Until recently, 3 bariatric surgical procedures were commonly performed: Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB), sleeve gastrectomy (SG), and adjustable gastric banding (AGB). AGB is now seldom performed because it is less effective than RYGB and SG. Two recently published randomized trials compared the long-term outcomes associated with RYGB and SG. The studies found that SG and RYGB result in a similar degree of weight loss. RYGB resulted in slightly more weight loss than SG, but SG was associated with a lower rate of major complications, such as internal hernias. SG takes much less time to perform than RYGB. SG has become the most commonly performed bariatric surgery in premenopausal women considering pregnancy because of the low risk of internal hernias.

In the Swiss Multicenter Bypass or Sleeve Study (SM-BOSS), 217 participants with a mean BMI of 44 kg/m2 and mean age of 45.5 years were randomly assigned to RYGB or SG and followed for 5 years.11 The majority (72%) of the participants were women. At 5 years of follow-up, in the RYGB and SG groups, mean weight loss was 37 kg and 33 kg, respectively (P=.19). In both groups, weight loss nadir was reached 12 to 24 months after surgery. Expressed as a percentage of original weight, weight loss in the RYGB and SG groups was -29% and -25%, respectively (P=.02). Gastric reflux worsened in both the RYGB and SG groups (6% vs 32%, respectively). The number of reoperations in the RYGB and SG groups was 22% and 16%. Of note, among individuals with prevalent diabetes, RYGB and SG resulted in remission of the diabetes in 68% and 62% of participants, respectively.

In the Sleeve vs Bypass study (SLEEVEPASS), 240 participants, with mean BMI of 46 kg/m2 and mean age of 48 years, were randomly assigned to RYGB or SG and followed for 5 years.12 Most (70%) of the participants were women. Following bariatric surgery, BMI decreased significantly in both groups. In the RYGB group, BMI decreased from 48 kg/m2 preoperatively to 35.4 kg/m2 at 5 years of follow up. In the SG group, BMI decreased from 47 kg/m2 preoperatively to 36.5 kg/m2 at 5 years of follow up. Late major complications (defined as complications occurring from 30 days to 5 years postoperatively) occurred more frequently in the RYGB group (15%) versus the SG group (8%). All the late major complications required reoperation. In the SG group, 7 of 10 reoperations were for severe gastric reflux disease. In the RYGB group 17 of 18 reoperations were for suspected internal hernia, requiring closure of a mesenteric defect at reoperation. There was no treatment-related mortality during the 5-year follow up.

Guidelines for bariatric surgery are BMI ≥ 40 kg/m2 without a comorbid illness or BMI ≥ 35 kg/m2 with at least one serious comorbid disease, such as diabetes.13 ObGyns can build a synergistic relationship with bariatric surgeons by referring eligible patients for surgical consultation and, in return, accepting referrals. A paradox and challenge is that many health insurers require patients to complete a supervised medical weight loss management program prior to being approved for bariatric surgery. However, the medical weight loss program might result in the patient no longer being eligible for insurance coverage of their surgery. For example, a patient who had a BMI of 42 kg/m2 prior to a medical weight loss management program who then lost enough weight to achieve a BMI of 38 kg/m2 might no longer be eligible for insurance coverage of a bariatric operation.14

Continue to: ObGyns need to prioritize treatment for obesity...

ObGyns need to prioritize treatment for obesity

Between 1959 and 2014, US life expectancy increased from 69.9 years to 79.1 years. However, in 2015 and 2016 life expectancy in the United States decreased slightly to 78.9 years, while continuing to improve in other countries.15 What could cause such an unexpected trend? Some experts believe that excess overweight and obesity in the US population, resulting in increased rates of diabetes, hypertension, and heart disease, accounts for a significant proportion of the life expectancy gap between US citizens and those who reside in Australia, Finland, Japan, and Sweden.16,17 All frontline clinicians play an important role in reversing the decades-long trend of increasing rates of overweight and obesity. Interventions that ObGyns could prioritize in their practices for treating overweight and obese patients include: a calorie-restricted diet, exercise, metformin, and SG.

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The Health Consequences of Smoking—50 Years of Progress. A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health; 2014.

- Allison DB, Fontaine KR, Manson JE, et al. Annual deaths attributable to obesity in the United States. JAMA. 1999;282:1530-1538.

- Ward ZJ, Bleich SN, Cradock AL, et al. Projected U.S. state-level prevalence of adult obesity and severe obesity. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:2440-2450.

- American Heart Association. My life check | Life’s simple 7. https://www.heart.org/en/healthyliving/healthy-lifestyle/my-life-check--lifessimple-7. Reviewed May 2, 2018. Accessed February 10, 2020.

- Knowler WC, Barrett-Connor E, Fowler SE, et al; Diabetes Prevention Program Research Group. Reduction in the incidence of type 2 diabetes with lifestyle intervention or metformin. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:393-403.

- Diabetes Prevention Program Research Group. Long-term safety, tolerability and weight loss associated with metformin in the Diabetes Prevention Program Outcomes Study. Diabetes Care. 2012;35:731-737.

- Winder WW, Hardie DG. Inactivation of acetylCoA carboxylase and activation of AMP-activated protein kinase in muscle during exercise. Am J Physiol. 1996;270(2 pt 1):E299-E304.

- Lexicomp. https://online.lexi.com/lco/action/ home. Accessed February 13, 2020.

- Metformin ER (Glucophage XR). GoodRX website. https://www.goodrx.com/metformin-erglucophage-xr?dosage=750mg&form=tablet&la bel_override=metformin+ER+%28Glucophage+X R%29&quantity=60. Accessed February 13, 2020.

- GoodRX website. www.goodrx.com. Accessed February 10, 2020.

- Peterli R, Wolnerhanssen BK, Peters T, et al. Effect of laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy vs laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass on weight loss in patients with morbid obesity: the SM-BOSS randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2018;319:255-265.

- Salminen P, Helmiö M, Ovaska J, et al. Effect of laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy versus laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass on weight loss at 5 years among patients with morbid obesity: The SLEEVEPASS randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2018;319:241-254.

- Rubino F, Nathan DM, Eckel RH, et al; Delegates of the 2nd Diabetes Surgery Summit. Metabolic surgery in the treatment algorithm for type 2 diabetes: a joint statement by international diabetes organizations. Obes Surg. 2017;27:2-21.

- Gebran SG, Knighton B, Ngaage LM, et al. Insurance coverage criteria for bariatric surgery: a survey of policies. Obes Surg. 2020;30:707-713.

- Woolf SH, Schoomaker H. Life expectancy and mortality rates in the United States, 1959-2017. JAMA. 2019;322:1996-2016.