User login

Correlating hospitalist work schedules with patient outcomes

Background: Studies show better outcomes, decreased length of stay, increased patient satisfaction, improved quality, and decreased readmission rates when hospitalist services are used. This study looks at how hospitalist schedules affect these outcomes.

Study design: Retrospective cohort study.

Setting: 229 hospitals in Texas.

Synopsis: This cohort study used 3 years of Medicare data from 229 hospitals in Texas. It included 114,777 medical admissions of patients with a 3- to 6-day length of stay. The study used the percentage of hospitalist working days that were blocks of 7 days or longer. ICU stays and patients requiring two or more E&M codes were excluded since they are associated with greater illness severity.

The primary outcome was mortality within 30 days of discharge and secondary outcomes were 30-day readmission rates, discharge destination, and 30-day postdischarge costs.

Patients receiving care from hospitalists working several days in a row had better outcomes. It is postulated that continuity of care by one hospitalist is important for several reasons. Most importantly, the development of rapport with patient and family is key to deciding the plan of care and destination post discharge as it is quite challenging to effectively transfer all important information during verbal or written handoffs.

Bottom line: Care provided by hospitalists working more days in a row improved patient outcomes. A variety of hospitalist schedules are being practiced currently; however, these findings must be taken into account as schedules are designed.

Citation: Goodwin JS et al. Association of the work schedules of hospitalists with patient outcomes of hospitalization. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180(2):215-22. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.5193.

Dr. Ahmed is assistant professor in the division of hospital medicine, Loyola University Medical Center, Maywood, Ill.

Background: Studies show better outcomes, decreased length of stay, increased patient satisfaction, improved quality, and decreased readmission rates when hospitalist services are used. This study looks at how hospitalist schedules affect these outcomes.

Study design: Retrospective cohort study.

Setting: 229 hospitals in Texas.

Synopsis: This cohort study used 3 years of Medicare data from 229 hospitals in Texas. It included 114,777 medical admissions of patients with a 3- to 6-day length of stay. The study used the percentage of hospitalist working days that were blocks of 7 days or longer. ICU stays and patients requiring two or more E&M codes were excluded since they are associated with greater illness severity.

The primary outcome was mortality within 30 days of discharge and secondary outcomes were 30-day readmission rates, discharge destination, and 30-day postdischarge costs.

Patients receiving care from hospitalists working several days in a row had better outcomes. It is postulated that continuity of care by one hospitalist is important for several reasons. Most importantly, the development of rapport with patient and family is key to deciding the plan of care and destination post discharge as it is quite challenging to effectively transfer all important information during verbal or written handoffs.

Bottom line: Care provided by hospitalists working more days in a row improved patient outcomes. A variety of hospitalist schedules are being practiced currently; however, these findings must be taken into account as schedules are designed.

Citation: Goodwin JS et al. Association of the work schedules of hospitalists with patient outcomes of hospitalization. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180(2):215-22. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.5193.

Dr. Ahmed is assistant professor in the division of hospital medicine, Loyola University Medical Center, Maywood, Ill.

Background: Studies show better outcomes, decreased length of stay, increased patient satisfaction, improved quality, and decreased readmission rates when hospitalist services are used. This study looks at how hospitalist schedules affect these outcomes.

Study design: Retrospective cohort study.

Setting: 229 hospitals in Texas.

Synopsis: This cohort study used 3 years of Medicare data from 229 hospitals in Texas. It included 114,777 medical admissions of patients with a 3- to 6-day length of stay. The study used the percentage of hospitalist working days that were blocks of 7 days or longer. ICU stays and patients requiring two or more E&M codes were excluded since they are associated with greater illness severity.

The primary outcome was mortality within 30 days of discharge and secondary outcomes were 30-day readmission rates, discharge destination, and 30-day postdischarge costs.

Patients receiving care from hospitalists working several days in a row had better outcomes. It is postulated that continuity of care by one hospitalist is important for several reasons. Most importantly, the development of rapport with patient and family is key to deciding the plan of care and destination post discharge as it is quite challenging to effectively transfer all important information during verbal or written handoffs.

Bottom line: Care provided by hospitalists working more days in a row improved patient outcomes. A variety of hospitalist schedules are being practiced currently; however, these findings must be taken into account as schedules are designed.

Citation: Goodwin JS et al. Association of the work schedules of hospitalists with patient outcomes of hospitalization. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180(2):215-22. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.5193.

Dr. Ahmed is assistant professor in the division of hospital medicine, Loyola University Medical Center, Maywood, Ill.

How often should we check EKGs in patients starting antipsychotic medications?

Determining relative risk with available data

Case

An 88-year-old woman with history of osteoporosis, hyperlipidemia, and a remote myocardial infarction presents to the ED with altered mental status and agitation. The patient is admitted to the medicine service for further management. Her current medications include a thiazide and a statin. Psychiatry is consulted and recommends administering intravenous haloperidol. A baseline EKG shows a corrected QT interval (QTc) of 486 milliseconds (ms). How often should subsequent EKGs be ordered?

Overview of issue

A prolonged QT interval can predispose a patient to dangerous arrhythmias such as Torsades de pointes (TdP), which results in sudden cardiac death in about 10% of cases.1,2 A prolonged QTc interval can be caused by cardiac, renal, or hepatic dysfunction; congenital Long QT Syndrome (LQTS)2; electrolyte abnormalities; or as a result of many drugs, including most antipsychotic medications such as quetiapine, olanzapine, risperidone and haloperidol.

To diminish risk of TdP while taking these medications, it is necessary to monitor the QTc interval. Before commencing a QT-prolonging medication, it is recommended to get a baseline EKG, then perform EKG monitoring after administering the medication.

According to American Heart Association guidelines, a prolonged QT interval is considered more than 460 ms in women or above 450 ms in men.3 If an abnormal rhythm and/or prolonged QTc is detected via EKG monitoring, then the drug dosage can be changed or an alternative therapy selected.4 However, there are no current guidelines recommending how often EKG monitoring should be performed after a QT-prolonging antipsychotic medication is administered on an inpatient medicine unit. Without guidelines, there is potential for health care providers to under- or over-order EKG monitoring, possibly putting patients at risk of TdP or wasting hospital resources, respectively.

Overview of the data

There are currently no universally accepted guidelines regarding inpatient EKG monitoring for patients started on QTc prolonging antipsychotic medications. A 2018 review of the literature surrounding assessment and management of patients on QTc prolonging medications was performed to analyze the available data and make recommendations; notably the evidence was limited as none of the studies were randomized controlled trials.

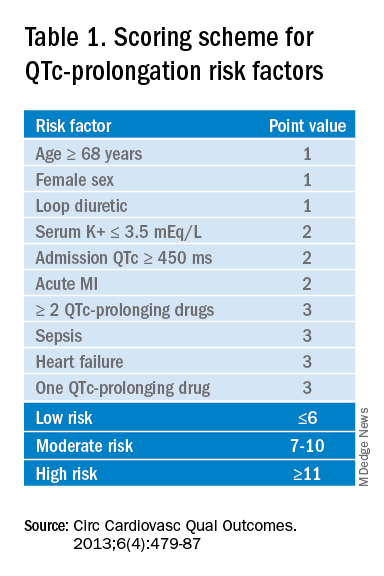

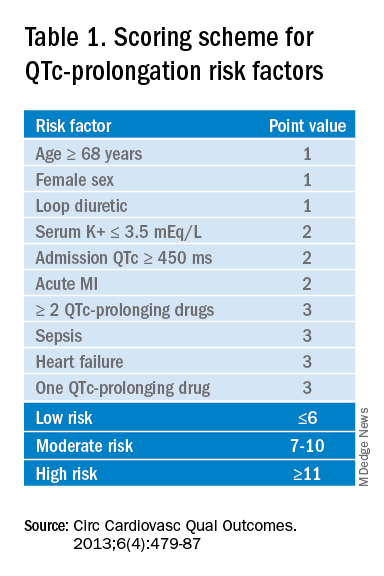

The authors recommend assessing the drug for QTc prolonging potential, and if possible, choosing alternative treatment in patients with baseline prolonged QTc. If the QT prolonging medication is the best or only option, then the next step is assessing the patient’s risk for QTc prolongation based on that person’s current condition and medical history.5 They recommend using the QTc prolonging risk point system developed by Tisdale and colleagues, which identified patient risk factors for elevated QTc intervals based on EKG findings in cardiac care units at a large tertiary hospital center.6

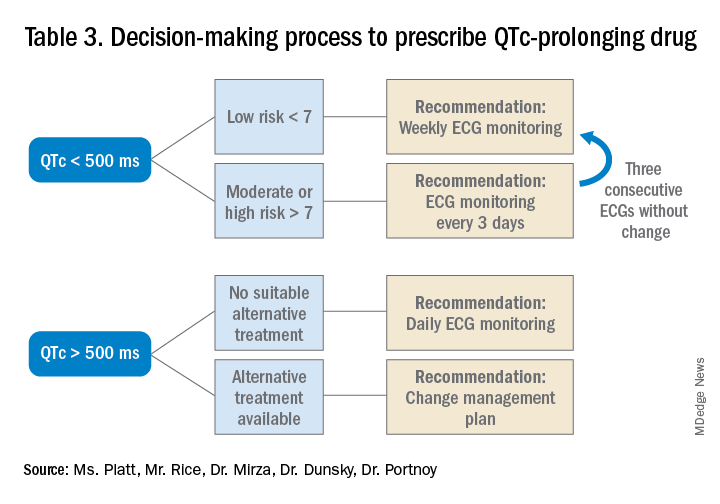

Based on the patient’s demographics, current condition, and medication list, the score can be used to stratify patients into low-, medium-, and high-risk categories (see Table 1).

Risk factors include age over 68 years, female sex, prior MI, concurrent use of other QTc prolonging medications, and sepsis, all of which have differing ability to cause QTc prolongation and thus are weighted differentially. This scoring system is helpful in identifying high risk patients; however, the review does not include recommendations for management of these patients beyond removing the offending drug or monitoring EKGs more aggressively in higher risk patients once identified.6

Low-risk patients can be managed expectantly. If the baseline QTc is < 500 ms, then the provider may administer the medication, but should obtain follow-up EKG monitoring to ensure the QTc does not rise above 500 ms; if it does, a management change is necessitated. For moderate- to high-risk patients with a baseline QTc > 500 ms, they recommend not administering the medication and consulting a cardiologist. The review does not provide a recommendation on how often EKG monitoring should be performed after prescribing an antipsychotic medication in an inpatient setting.5

A 2018 review article explored patient risk factors for a prolonged QTc in the setting of prescribing potentially QTc prolonging antipsychotics.7 The authors reiterate that QTc prolonging risk factors are important considerations when prescribing antipsychotics that can lead to adverse events, though they note that much of the literature associating antipsychotics with negative outcomes consists of case reports in which patients had independent risk factors for development of TdP, such as preexisting ventricular arrhythmias.

In addition, the data regarding the risk of each individual antipsychotic agent are not comprehensive. Some medications that have been deemed “QTc prolonging” were identified as such in only a handful of cases where patients had confounding comorbid risk factors. This raises concern that some medications are being unduly stigmatized in situations where there is little chance of TdP. If there is no equivalent or alternate treatment available, this may lead to an antipsychotic medication being held unnecessarily, which may exacerbate the psychiatric illness.

The authors note that the trend toward ordering baseline EKGs in the inpatient setting following administration of a new antipsychotic may be partly attributed to the ready availability of EKG testing in hospitals. They recommend a baseline EKG to assess the patient’s risk. For most agents, they recommend no further EKG monitoring unless there is a change in patient risk factors. Follow-up EKGs should be done in patients with multiple or significant risk factors to assess their QTc stability. In patients with a QTc > 500 ms on a follow-up EKG, daily monitoring is encouraged alongside reassessment of the current treatment regimen.7

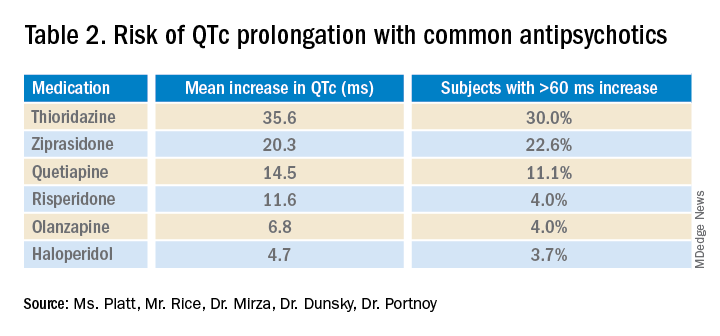

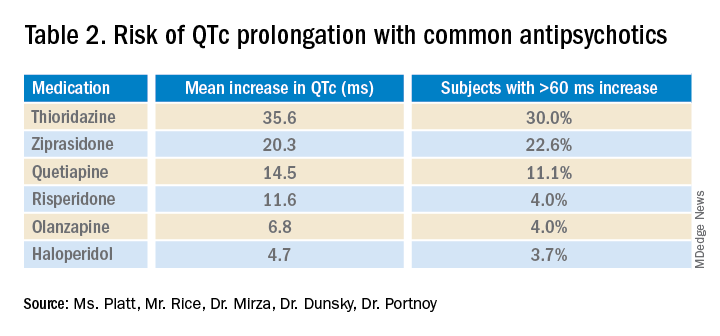

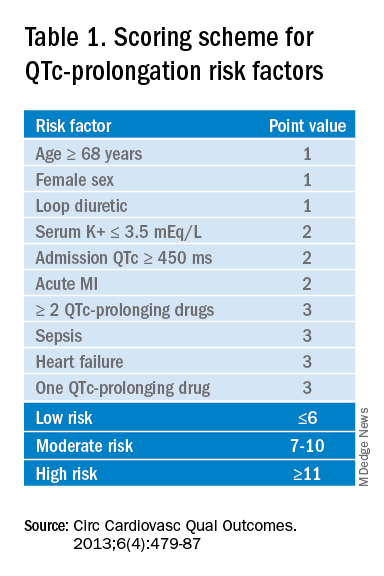

Overall, the current literature suggests that providers should know which antipsychotics carry a risk for QTc prolongation and what other treatment options are available. The risk of QTc prolongation for common antipsychotic agents is provided in Table 2.

Providers should assess their patients’ risk factors for QTc prolongation and order a baseline EKG to help quantify the cardiac risk associated with prescribing the drug. In patients with many risk factors or complicated medication regimens, a follow-up EKG should be performed to assess the new QTc baseline. If the subsequent QTc is > 500 ms, then an alternative medication should be strongly considered. The majority of patients, however, will not have a clinically significant increase in their QTc, in which case there is no need for a change in medication and monitoring frequency can be deescalated.

Application of data to the case

Our 88-year-old patient has multiple risk factors for a prolonged QTc, and according to the Tisdale scoring system is at moderate risk (7-10 points). Her risk of developing TdP increases with the addition of IV haloperidol to her regimen.

Because of her increased risk, it is reasonable to consider alternative management. If she can cooperate with PO medications, then olanzapine could be given, which has a lesser effect on the QTc interval. If unable to take oral medications, she could be given haloperidol intramuscularly, which causes less QTc prolongation than the IV formulation. If an antipsychotic is administered, she should receive EKG monitoring.

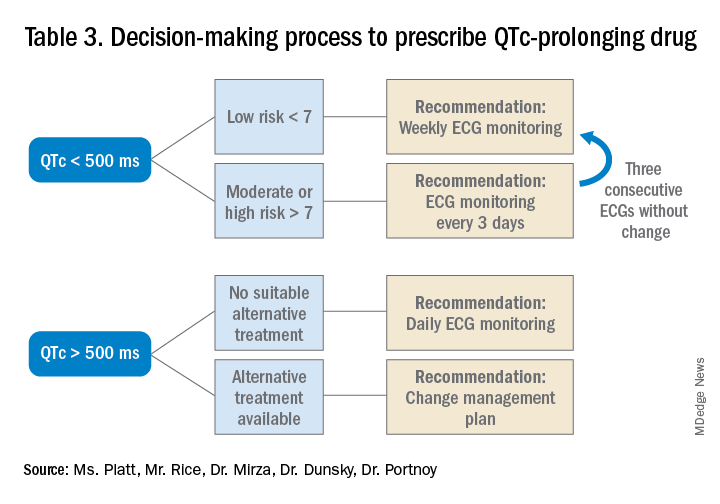

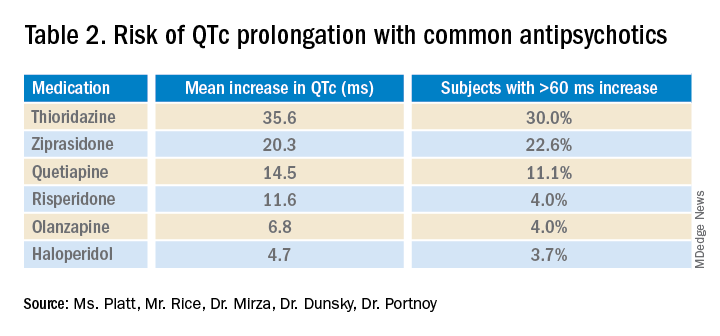

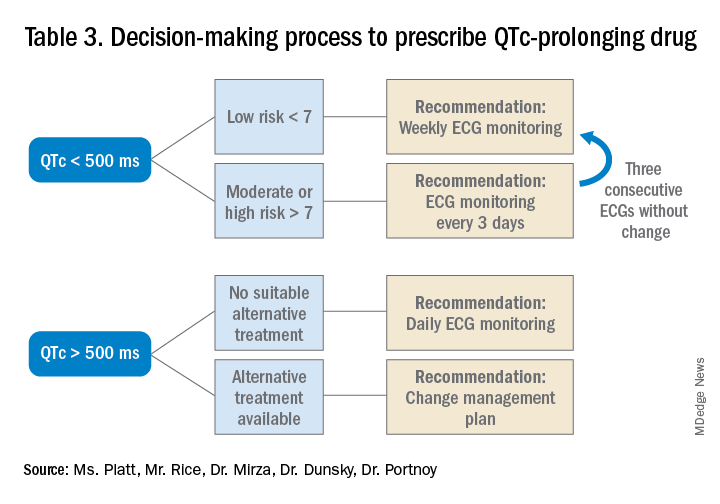

Given the lack of evidence on the optimal monitoring strategy, a protocol should be utilized that balances the ability to capture a clinically meaningful increase in the QTc with appropriate stewardship of resources. Our practice is to initially monitor the EKG every 3 days in moderate- to high-risk patients with baseline QTc < 500 ms. If the QTc remains below 500 ms over three EKGs, then treatment may continue with EKG monitoring weekly while the patient is hospitalized. If the QTc rises above 500 ms, then a management change would be indicated (either dose reduction or a change of agents). If antipsychotic medications are continued, we check the EKG daily while the QTc is >500 ms until there are three unchanged EKGS, and then consider deescalating monitoring to every 3 days.

Bottom line

Prior to prescribing, perform a baseline EKG and assess the patient’s risk of QTc prolongation. If the patient is at increased risk, avoid prescribing QTc prolonging medications where alternatives exist. If a QTc prolonging medication is used in a patient with a moderate- to high-risk score, check an EKG every 3 days or daily if the QTc increases to > 500 ms.

Ms. Platt is a medical student at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York. Mr. Rice is a medical student at the Icahn School of Medicine. Dr. Mirza is assistant clinical professor of psychiatry at the Icahn School of Medicine. Dr. Dunsky is a cardiologist and assistant professor at the Icahn School of Medicine. Dr. Portnoy is a hospitalist and assistant professor at the Icahn School of Medicine.

References

1. Darpö B. Spectrum of drugs prolonging QT interval and the incidence of torsades de pointes. Eur Heart J Supplements. 2001;3(suppl_K):K70-K80. doi: 10.1016/S1520-765X(01)90009-4.

2. Schwartz PJ, Woosley RL. Predicting the unpredictable: Drug-induced QT prolongation and torsades de pointes. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;67(13):1639-50. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2015.12.063.

3. Rautaharju PM et al. AHA/ACCF/HRS recommendations for the standardization and interpretation of the electrocardiogram. Part IV: The ST Segment, T and U Waves, and the QT Interval A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association Electrocardiography and Arrhythmias Committee, Council on Clinical Cardiology; the American College of Cardiology Foundation; and the Heart Rhythm Society Endorsed by the International Society for Computerized Electrocardiology. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009 Mar 17;53(11):982-91. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.12.014.

4. Drew BJ et al. Prevention of torsades de pointes in hospital settings: A scientific statement from the American Heart Association and the American College of Cardiology Foundation. Circulation. 2010;121(8):1047-60. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.192704.

5. Zolezzi M, Cheung L. A literature-based algorithm for the assessment, management, and monitoring of drug-induced QTc prolongation in the psychiatric population. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2019;15:105-14. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S186474.

6. Tisdale JE et al. Development and validation of a risk score to predict QT interval prolongation in hospitalized patients. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2013;6(4):479-87. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.113.000152.

7. Beach SR et al. QT prolongation, torsades de pointes, and psychotropic medications: A 5-year update. Psychosomatics. 2018;59(2):105-22. doi: 10.1016/j.psym.2017.10.009.

Key points

- An increased QTc interval can lead to TdP, ventricular fibrillation and cardiac death.

- The relative risk of each antipsychotic medication should be determined based on available data and the Tisdale scoring system can provide a system to assess a patient’s risk of QTc prolongation.

- Low-risk patients with a baseline QTc <500 ms should receive a baseline EKG and inpatient EKG monitoring weekly while moderate- to high-risk patients should receive EKG monitoring every 3 days.

- A QTc > 500 ms suggests the need for a management change (drug discontinuation, dose reduction, or a switch to another agent). If the antipsychotic is absolutely necessary, perform daily EKG monitoring until there are three unchanged EKGs, and then consider deescalating monitoring to every 3 days.

Additional reading

Beach SR et al. QT Prolongation, torsades de pointes, and psychotropic medications: A 5-year update. Psychosomatics. 2018;59(2):105-22. doi: 10.1016/j.psym.2017.10.009.

Drew BJ et al. Prevention of torsades de pointes in hospital settings: A scientific statement from the American Heart Association and the American College of Cardiology Foundation. Circulation. 2010;121(8):1047-60. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.192704.

Zolezzi M, Cheung L. A literature-based algorithm for the assessment, management, and monitoring of drug-induced QTc prolongation in the psychiatric population. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2019;15:105-14. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S186474.

Quiz

A 70-year-old male inpatient on furosemide with last known potassium level of 3.3 is going to be started on olanzapine. His baseline EKG has a QTc of 470 ms.

How often should he receive EKG monitoring?

A. Daily

B. Every 3 days

C. Weekly

D. Monthly

Answer (C): He is a low risk patient (6 points: over 70 yrs, loop diuretic, K+< 3.5, QTc > 450 ms), so he should receive weekly EKG monitoring.

Determining relative risk with available data

Determining relative risk with available data

Case

An 88-year-old woman with history of osteoporosis, hyperlipidemia, and a remote myocardial infarction presents to the ED with altered mental status and agitation. The patient is admitted to the medicine service for further management. Her current medications include a thiazide and a statin. Psychiatry is consulted and recommends administering intravenous haloperidol. A baseline EKG shows a corrected QT interval (QTc) of 486 milliseconds (ms). How often should subsequent EKGs be ordered?

Overview of issue

A prolonged QT interval can predispose a patient to dangerous arrhythmias such as Torsades de pointes (TdP), which results in sudden cardiac death in about 10% of cases.1,2 A prolonged QTc interval can be caused by cardiac, renal, or hepatic dysfunction; congenital Long QT Syndrome (LQTS)2; electrolyte abnormalities; or as a result of many drugs, including most antipsychotic medications such as quetiapine, olanzapine, risperidone and haloperidol.

To diminish risk of TdP while taking these medications, it is necessary to monitor the QTc interval. Before commencing a QT-prolonging medication, it is recommended to get a baseline EKG, then perform EKG monitoring after administering the medication.

According to American Heart Association guidelines, a prolonged QT interval is considered more than 460 ms in women or above 450 ms in men.3 If an abnormal rhythm and/or prolonged QTc is detected via EKG monitoring, then the drug dosage can be changed or an alternative therapy selected.4 However, there are no current guidelines recommending how often EKG monitoring should be performed after a QT-prolonging antipsychotic medication is administered on an inpatient medicine unit. Without guidelines, there is potential for health care providers to under- or over-order EKG monitoring, possibly putting patients at risk of TdP or wasting hospital resources, respectively.

Overview of the data

There are currently no universally accepted guidelines regarding inpatient EKG monitoring for patients started on QTc prolonging antipsychotic medications. A 2018 review of the literature surrounding assessment and management of patients on QTc prolonging medications was performed to analyze the available data and make recommendations; notably the evidence was limited as none of the studies were randomized controlled trials.

The authors recommend assessing the drug for QTc prolonging potential, and if possible, choosing alternative treatment in patients with baseline prolonged QTc. If the QT prolonging medication is the best or only option, then the next step is assessing the patient’s risk for QTc prolongation based on that person’s current condition and medical history.5 They recommend using the QTc prolonging risk point system developed by Tisdale and colleagues, which identified patient risk factors for elevated QTc intervals based on EKG findings in cardiac care units at a large tertiary hospital center.6

Based on the patient’s demographics, current condition, and medication list, the score can be used to stratify patients into low-, medium-, and high-risk categories (see Table 1).

Risk factors include age over 68 years, female sex, prior MI, concurrent use of other QTc prolonging medications, and sepsis, all of which have differing ability to cause QTc prolongation and thus are weighted differentially. This scoring system is helpful in identifying high risk patients; however, the review does not include recommendations for management of these patients beyond removing the offending drug or monitoring EKGs more aggressively in higher risk patients once identified.6

Low-risk patients can be managed expectantly. If the baseline QTc is < 500 ms, then the provider may administer the medication, but should obtain follow-up EKG monitoring to ensure the QTc does not rise above 500 ms; if it does, a management change is necessitated. For moderate- to high-risk patients with a baseline QTc > 500 ms, they recommend not administering the medication and consulting a cardiologist. The review does not provide a recommendation on how often EKG monitoring should be performed after prescribing an antipsychotic medication in an inpatient setting.5

A 2018 review article explored patient risk factors for a prolonged QTc in the setting of prescribing potentially QTc prolonging antipsychotics.7 The authors reiterate that QTc prolonging risk factors are important considerations when prescribing antipsychotics that can lead to adverse events, though they note that much of the literature associating antipsychotics with negative outcomes consists of case reports in which patients had independent risk factors for development of TdP, such as preexisting ventricular arrhythmias.

In addition, the data regarding the risk of each individual antipsychotic agent are not comprehensive. Some medications that have been deemed “QTc prolonging” were identified as such in only a handful of cases where patients had confounding comorbid risk factors. This raises concern that some medications are being unduly stigmatized in situations where there is little chance of TdP. If there is no equivalent or alternate treatment available, this may lead to an antipsychotic medication being held unnecessarily, which may exacerbate the psychiatric illness.

The authors note that the trend toward ordering baseline EKGs in the inpatient setting following administration of a new antipsychotic may be partly attributed to the ready availability of EKG testing in hospitals. They recommend a baseline EKG to assess the patient’s risk. For most agents, they recommend no further EKG monitoring unless there is a change in patient risk factors. Follow-up EKGs should be done in patients with multiple or significant risk factors to assess their QTc stability. In patients with a QTc > 500 ms on a follow-up EKG, daily monitoring is encouraged alongside reassessment of the current treatment regimen.7

Overall, the current literature suggests that providers should know which antipsychotics carry a risk for QTc prolongation and what other treatment options are available. The risk of QTc prolongation for common antipsychotic agents is provided in Table 2.

Providers should assess their patients’ risk factors for QTc prolongation and order a baseline EKG to help quantify the cardiac risk associated with prescribing the drug. In patients with many risk factors or complicated medication regimens, a follow-up EKG should be performed to assess the new QTc baseline. If the subsequent QTc is > 500 ms, then an alternative medication should be strongly considered. The majority of patients, however, will not have a clinically significant increase in their QTc, in which case there is no need for a change in medication and monitoring frequency can be deescalated.

Application of data to the case

Our 88-year-old patient has multiple risk factors for a prolonged QTc, and according to the Tisdale scoring system is at moderate risk (7-10 points). Her risk of developing TdP increases with the addition of IV haloperidol to her regimen.

Because of her increased risk, it is reasonable to consider alternative management. If she can cooperate with PO medications, then olanzapine could be given, which has a lesser effect on the QTc interval. If unable to take oral medications, she could be given haloperidol intramuscularly, which causes less QTc prolongation than the IV formulation. If an antipsychotic is administered, she should receive EKG monitoring.

Given the lack of evidence on the optimal monitoring strategy, a protocol should be utilized that balances the ability to capture a clinically meaningful increase in the QTc with appropriate stewardship of resources. Our practice is to initially monitor the EKG every 3 days in moderate- to high-risk patients with baseline QTc < 500 ms. If the QTc remains below 500 ms over three EKGs, then treatment may continue with EKG monitoring weekly while the patient is hospitalized. If the QTc rises above 500 ms, then a management change would be indicated (either dose reduction or a change of agents). If antipsychotic medications are continued, we check the EKG daily while the QTc is >500 ms until there are three unchanged EKGS, and then consider deescalating monitoring to every 3 days.

Bottom line

Prior to prescribing, perform a baseline EKG and assess the patient’s risk of QTc prolongation. If the patient is at increased risk, avoid prescribing QTc prolonging medications where alternatives exist. If a QTc prolonging medication is used in a patient with a moderate- to high-risk score, check an EKG every 3 days or daily if the QTc increases to > 500 ms.

Ms. Platt is a medical student at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York. Mr. Rice is a medical student at the Icahn School of Medicine. Dr. Mirza is assistant clinical professor of psychiatry at the Icahn School of Medicine. Dr. Dunsky is a cardiologist and assistant professor at the Icahn School of Medicine. Dr. Portnoy is a hospitalist and assistant professor at the Icahn School of Medicine.

References

1. Darpö B. Spectrum of drugs prolonging QT interval and the incidence of torsades de pointes. Eur Heart J Supplements. 2001;3(suppl_K):K70-K80. doi: 10.1016/S1520-765X(01)90009-4.

2. Schwartz PJ, Woosley RL. Predicting the unpredictable: Drug-induced QT prolongation and torsades de pointes. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;67(13):1639-50. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2015.12.063.

3. Rautaharju PM et al. AHA/ACCF/HRS recommendations for the standardization and interpretation of the electrocardiogram. Part IV: The ST Segment, T and U Waves, and the QT Interval A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association Electrocardiography and Arrhythmias Committee, Council on Clinical Cardiology; the American College of Cardiology Foundation; and the Heart Rhythm Society Endorsed by the International Society for Computerized Electrocardiology. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009 Mar 17;53(11):982-91. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.12.014.

4. Drew BJ et al. Prevention of torsades de pointes in hospital settings: A scientific statement from the American Heart Association and the American College of Cardiology Foundation. Circulation. 2010;121(8):1047-60. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.192704.

5. Zolezzi M, Cheung L. A literature-based algorithm for the assessment, management, and monitoring of drug-induced QTc prolongation in the psychiatric population. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2019;15:105-14. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S186474.

6. Tisdale JE et al. Development and validation of a risk score to predict QT interval prolongation in hospitalized patients. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2013;6(4):479-87. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.113.000152.

7. Beach SR et al. QT prolongation, torsades de pointes, and psychotropic medications: A 5-year update. Psychosomatics. 2018;59(2):105-22. doi: 10.1016/j.psym.2017.10.009.

Key points

- An increased QTc interval can lead to TdP, ventricular fibrillation and cardiac death.

- The relative risk of each antipsychotic medication should be determined based on available data and the Tisdale scoring system can provide a system to assess a patient’s risk of QTc prolongation.

- Low-risk patients with a baseline QTc <500 ms should receive a baseline EKG and inpatient EKG monitoring weekly while moderate- to high-risk patients should receive EKG monitoring every 3 days.

- A QTc > 500 ms suggests the need for a management change (drug discontinuation, dose reduction, or a switch to another agent). If the antipsychotic is absolutely necessary, perform daily EKG monitoring until there are three unchanged EKGs, and then consider deescalating monitoring to every 3 days.

Additional reading

Beach SR et al. QT Prolongation, torsades de pointes, and psychotropic medications: A 5-year update. Psychosomatics. 2018;59(2):105-22. doi: 10.1016/j.psym.2017.10.009.

Drew BJ et al. Prevention of torsades de pointes in hospital settings: A scientific statement from the American Heart Association and the American College of Cardiology Foundation. Circulation. 2010;121(8):1047-60. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.192704.

Zolezzi M, Cheung L. A literature-based algorithm for the assessment, management, and monitoring of drug-induced QTc prolongation in the psychiatric population. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2019;15:105-14. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S186474.

Quiz

A 70-year-old male inpatient on furosemide with last known potassium level of 3.3 is going to be started on olanzapine. His baseline EKG has a QTc of 470 ms.

How often should he receive EKG monitoring?

A. Daily

B. Every 3 days

C. Weekly

D. Monthly

Answer (C): He is a low risk patient (6 points: over 70 yrs, loop diuretic, K+< 3.5, QTc > 450 ms), so he should receive weekly EKG monitoring.

Case

An 88-year-old woman with history of osteoporosis, hyperlipidemia, and a remote myocardial infarction presents to the ED with altered mental status and agitation. The patient is admitted to the medicine service for further management. Her current medications include a thiazide and a statin. Psychiatry is consulted and recommends administering intravenous haloperidol. A baseline EKG shows a corrected QT interval (QTc) of 486 milliseconds (ms). How often should subsequent EKGs be ordered?

Overview of issue

A prolonged QT interval can predispose a patient to dangerous arrhythmias such as Torsades de pointes (TdP), which results in sudden cardiac death in about 10% of cases.1,2 A prolonged QTc interval can be caused by cardiac, renal, or hepatic dysfunction; congenital Long QT Syndrome (LQTS)2; electrolyte abnormalities; or as a result of many drugs, including most antipsychotic medications such as quetiapine, olanzapine, risperidone and haloperidol.

To diminish risk of TdP while taking these medications, it is necessary to monitor the QTc interval. Before commencing a QT-prolonging medication, it is recommended to get a baseline EKG, then perform EKG monitoring after administering the medication.

According to American Heart Association guidelines, a prolonged QT interval is considered more than 460 ms in women or above 450 ms in men.3 If an abnormal rhythm and/or prolonged QTc is detected via EKG monitoring, then the drug dosage can be changed or an alternative therapy selected.4 However, there are no current guidelines recommending how often EKG monitoring should be performed after a QT-prolonging antipsychotic medication is administered on an inpatient medicine unit. Without guidelines, there is potential for health care providers to under- or over-order EKG monitoring, possibly putting patients at risk of TdP or wasting hospital resources, respectively.

Overview of the data

There are currently no universally accepted guidelines regarding inpatient EKG monitoring for patients started on QTc prolonging antipsychotic medications. A 2018 review of the literature surrounding assessment and management of patients on QTc prolonging medications was performed to analyze the available data and make recommendations; notably the evidence was limited as none of the studies were randomized controlled trials.

The authors recommend assessing the drug for QTc prolonging potential, and if possible, choosing alternative treatment in patients with baseline prolonged QTc. If the QT prolonging medication is the best or only option, then the next step is assessing the patient’s risk for QTc prolongation based on that person’s current condition and medical history.5 They recommend using the QTc prolonging risk point system developed by Tisdale and colleagues, which identified patient risk factors for elevated QTc intervals based on EKG findings in cardiac care units at a large tertiary hospital center.6

Based on the patient’s demographics, current condition, and medication list, the score can be used to stratify patients into low-, medium-, and high-risk categories (see Table 1).

Risk factors include age over 68 years, female sex, prior MI, concurrent use of other QTc prolonging medications, and sepsis, all of which have differing ability to cause QTc prolongation and thus are weighted differentially. This scoring system is helpful in identifying high risk patients; however, the review does not include recommendations for management of these patients beyond removing the offending drug or monitoring EKGs more aggressively in higher risk patients once identified.6

Low-risk patients can be managed expectantly. If the baseline QTc is < 500 ms, then the provider may administer the medication, but should obtain follow-up EKG monitoring to ensure the QTc does not rise above 500 ms; if it does, a management change is necessitated. For moderate- to high-risk patients with a baseline QTc > 500 ms, they recommend not administering the medication and consulting a cardiologist. The review does not provide a recommendation on how often EKG monitoring should be performed after prescribing an antipsychotic medication in an inpatient setting.5

A 2018 review article explored patient risk factors for a prolonged QTc in the setting of prescribing potentially QTc prolonging antipsychotics.7 The authors reiterate that QTc prolonging risk factors are important considerations when prescribing antipsychotics that can lead to adverse events, though they note that much of the literature associating antipsychotics with negative outcomes consists of case reports in which patients had independent risk factors for development of TdP, such as preexisting ventricular arrhythmias.

In addition, the data regarding the risk of each individual antipsychotic agent are not comprehensive. Some medications that have been deemed “QTc prolonging” were identified as such in only a handful of cases where patients had confounding comorbid risk factors. This raises concern that some medications are being unduly stigmatized in situations where there is little chance of TdP. If there is no equivalent or alternate treatment available, this may lead to an antipsychotic medication being held unnecessarily, which may exacerbate the psychiatric illness.

The authors note that the trend toward ordering baseline EKGs in the inpatient setting following administration of a new antipsychotic may be partly attributed to the ready availability of EKG testing in hospitals. They recommend a baseline EKG to assess the patient’s risk. For most agents, they recommend no further EKG monitoring unless there is a change in patient risk factors. Follow-up EKGs should be done in patients with multiple or significant risk factors to assess their QTc stability. In patients with a QTc > 500 ms on a follow-up EKG, daily monitoring is encouraged alongside reassessment of the current treatment regimen.7

Overall, the current literature suggests that providers should know which antipsychotics carry a risk for QTc prolongation and what other treatment options are available. The risk of QTc prolongation for common antipsychotic agents is provided in Table 2.

Providers should assess their patients’ risk factors for QTc prolongation and order a baseline EKG to help quantify the cardiac risk associated with prescribing the drug. In patients with many risk factors or complicated medication regimens, a follow-up EKG should be performed to assess the new QTc baseline. If the subsequent QTc is > 500 ms, then an alternative medication should be strongly considered. The majority of patients, however, will not have a clinically significant increase in their QTc, in which case there is no need for a change in medication and monitoring frequency can be deescalated.

Application of data to the case

Our 88-year-old patient has multiple risk factors for a prolonged QTc, and according to the Tisdale scoring system is at moderate risk (7-10 points). Her risk of developing TdP increases with the addition of IV haloperidol to her regimen.

Because of her increased risk, it is reasonable to consider alternative management. If she can cooperate with PO medications, then olanzapine could be given, which has a lesser effect on the QTc interval. If unable to take oral medications, she could be given haloperidol intramuscularly, which causes less QTc prolongation than the IV formulation. If an antipsychotic is administered, she should receive EKG monitoring.

Given the lack of evidence on the optimal monitoring strategy, a protocol should be utilized that balances the ability to capture a clinically meaningful increase in the QTc with appropriate stewardship of resources. Our practice is to initially monitor the EKG every 3 days in moderate- to high-risk patients with baseline QTc < 500 ms. If the QTc remains below 500 ms over three EKGs, then treatment may continue with EKG monitoring weekly while the patient is hospitalized. If the QTc rises above 500 ms, then a management change would be indicated (either dose reduction or a change of agents). If antipsychotic medications are continued, we check the EKG daily while the QTc is >500 ms until there are three unchanged EKGS, and then consider deescalating monitoring to every 3 days.

Bottom line

Prior to prescribing, perform a baseline EKG and assess the patient’s risk of QTc prolongation. If the patient is at increased risk, avoid prescribing QTc prolonging medications where alternatives exist. If a QTc prolonging medication is used in a patient with a moderate- to high-risk score, check an EKG every 3 days or daily if the QTc increases to > 500 ms.

Ms. Platt is a medical student at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York. Mr. Rice is a medical student at the Icahn School of Medicine. Dr. Mirza is assistant clinical professor of psychiatry at the Icahn School of Medicine. Dr. Dunsky is a cardiologist and assistant professor at the Icahn School of Medicine. Dr. Portnoy is a hospitalist and assistant professor at the Icahn School of Medicine.

References

1. Darpö B. Spectrum of drugs prolonging QT interval and the incidence of torsades de pointes. Eur Heart J Supplements. 2001;3(suppl_K):K70-K80. doi: 10.1016/S1520-765X(01)90009-4.

2. Schwartz PJ, Woosley RL. Predicting the unpredictable: Drug-induced QT prolongation and torsades de pointes. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;67(13):1639-50. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2015.12.063.

3. Rautaharju PM et al. AHA/ACCF/HRS recommendations for the standardization and interpretation of the electrocardiogram. Part IV: The ST Segment, T and U Waves, and the QT Interval A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association Electrocardiography and Arrhythmias Committee, Council on Clinical Cardiology; the American College of Cardiology Foundation; and the Heart Rhythm Society Endorsed by the International Society for Computerized Electrocardiology. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009 Mar 17;53(11):982-91. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.12.014.

4. Drew BJ et al. Prevention of torsades de pointes in hospital settings: A scientific statement from the American Heart Association and the American College of Cardiology Foundation. Circulation. 2010;121(8):1047-60. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.192704.

5. Zolezzi M, Cheung L. A literature-based algorithm for the assessment, management, and monitoring of drug-induced QTc prolongation in the psychiatric population. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2019;15:105-14. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S186474.

6. Tisdale JE et al. Development and validation of a risk score to predict QT interval prolongation in hospitalized patients. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2013;6(4):479-87. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.113.000152.

7. Beach SR et al. QT prolongation, torsades de pointes, and psychotropic medications: A 5-year update. Psychosomatics. 2018;59(2):105-22. doi: 10.1016/j.psym.2017.10.009.

Key points

- An increased QTc interval can lead to TdP, ventricular fibrillation and cardiac death.

- The relative risk of each antipsychotic medication should be determined based on available data and the Tisdale scoring system can provide a system to assess a patient’s risk of QTc prolongation.

- Low-risk patients with a baseline QTc <500 ms should receive a baseline EKG and inpatient EKG monitoring weekly while moderate- to high-risk patients should receive EKG monitoring every 3 days.

- A QTc > 500 ms suggests the need for a management change (drug discontinuation, dose reduction, or a switch to another agent). If the antipsychotic is absolutely necessary, perform daily EKG monitoring until there are three unchanged EKGs, and then consider deescalating monitoring to every 3 days.

Additional reading

Beach SR et al. QT Prolongation, torsades de pointes, and psychotropic medications: A 5-year update. Psychosomatics. 2018;59(2):105-22. doi: 10.1016/j.psym.2017.10.009.

Drew BJ et al. Prevention of torsades de pointes in hospital settings: A scientific statement from the American Heart Association and the American College of Cardiology Foundation. Circulation. 2010;121(8):1047-60. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.192704.

Zolezzi M, Cheung L. A literature-based algorithm for the assessment, management, and monitoring of drug-induced QTc prolongation in the psychiatric population. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2019;15:105-14. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S186474.

Quiz

A 70-year-old male inpatient on furosemide with last known potassium level of 3.3 is going to be started on olanzapine. His baseline EKG has a QTc of 470 ms.

How often should he receive EKG monitoring?

A. Daily

B. Every 3 days

C. Weekly

D. Monthly

Answer (C): He is a low risk patient (6 points: over 70 yrs, loop diuretic, K+< 3.5, QTc > 450 ms), so he should receive weekly EKG monitoring.

Navigating challenges in COVID-19 care

Early strategies for adapting to a moving target

During the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic, hospital groups and systems scrambled to create protocols and models to respond to the novel coronavirus. In the pre-pandemic world, hospital groups have traditionally focused on standardizing clinical protocols and care models that rely on evidence-based medical practices or extended experience.

During COVID-19, however, our team at Dell Medical School needed to rapidly and iteratively standardize care based on evolving science, effectively communicate that approach across rotating hospital medicine physicians and residents, and update care models, workflows, and technology every few days. In this article, we review our initial experiences, describe the strategies we employed to respond to these challenges, and reflect on the lessons learned and our proposed strategy moving forward.

Early pandemic challenges

Our initial inpatient strategies focused on containment, infection prevention, and bracing ourselves rather than creating a COVID Center of Excellence (COE). In fact, our hospital network’s initial strategy was to have COVID-19 patients transferred to a different hospital within our network. However, as March progressed, we became the designated COVID-19 hospital in our area’s network because of the increasing volume of patients we saw.

Patients from the surrounding regional hospitals were transferring their COVID-19 patients to us and we quickly saw the wide spectrum of illness, ranging from mild pneumonia to severe disease requiring mechanical ventilation upon admission. All frontline providers felt the stress of needing to find treatment options quickly for our sickest patients. We realized that to provide safe, effective, and high-quality care to COVID-19 patients, we needed to create a sustainable and standardized interdisciplinary approach.

COVID-19 testing was a major challenge when the pandemic hit as testing kits and personal protective equipment were in limited supply. How would we choose who to test or empirically place in COVID-19 isolation? In addition, we faced questions surrounding safe discharge practices, especially for patients who could not self-isolate in their home (if they even had one).

In March, emergency use authorization (EUA) for hydroxychloroquine was granted by the U.S. FDA despite limited data. This resulted in pressure from the public to use this drug in our patients. At the same time, we saw that some patients quickly got better on their own with supportive care. As clinicians striving to practice evidence-based medicine, we certainly did not want to give patients an unproven therapy that could do more harm than good. We also felt the need to respond with statements about what we could do that worked – rather than negotiate about withholding certain treatments featured in the news. Clearly, a “one-size-fits-all” approach to therapeutics was not going to work in treating patients with COVID-19.

We realized we were going to have to learn and adapt together – quickly. It became apparent that we needed to create structures to rapidly adjudicate and integrate emerging science into standardized clinical care delivery.

Solutions in the form of better structures

In response to these challenges, we created early morning meetings or “huddles” among COVID-19 care teams and hospital administration. A designated “COVID ID” physician from Infectious Diseases would meet with hospitalist and critical care teams each morning in our daily huddles to review all newly admitted patients, current hospitalized patients, and patients with pending COVID-19 tests or suspected initial false-negative tests.

Together, and via the newly developed Therapeutics and Informatics Committee, we created early treatment recommendations based upon available evidence, treatment availability, and the patient’s severity of illness. Within the first ten days of admitting our first patient, it had become standard practice to review eligible patients soon after admission for therapies such as convalescent plasma, and, later, remdesivir and steroids.

We codified these consensus recommendations and processes in our Dell Med COVID Manual, a living document that was frequently updated and disseminated to our group. It created a single ‘true north’ of standardized workflows for triage, diagnosis, management, discharge coordination, and end-of-life care. The document allowed for continuous and asynchronous multi-person collaboration and extremely rapid cycles of improvement. Between March and December 2020, this 100-page handbook went through more than 130 iterations.

Strategy for the future

This approach – communicating frequently, adapting on a daily to weekly basis, and continuously scanning the science for opportunities to improve our care delivery – became the foundation of our approach and the Therapeutics and Informatics Committee. Just as importantly, this created a culture of engagement, collaboration, and shared problem-solving that helped us stay organized, keep up to date with the latest science, and innovate rather than panic when faced with ongoing unpredictability and chaos in the early days of the pandemic.

As the pandemic enters into its 13th month, we carry this foundation and our strategies forward. The infrastructure and systems of communication that we have set in place will allow us to be nimble in our response as COVID-19 numbers surge in our region.

Dr. Gandhi is an assistant professor in the department of internal medicine at Dell Medical School, University of Texas, Austin. Dr. Mondy is chief of the division of infectious disease and associate professor in the department of internal medicine at Dell Medical School. Dr. Busch and Dr. Brode are assistant professors in the department of internal medicine at Dell Medical School. This article is part of a series originally published in The Hospital Leader, the official blog of SHM.

Early strategies for adapting to a moving target

Early strategies for adapting to a moving target

During the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic, hospital groups and systems scrambled to create protocols and models to respond to the novel coronavirus. In the pre-pandemic world, hospital groups have traditionally focused on standardizing clinical protocols and care models that rely on evidence-based medical practices or extended experience.

During COVID-19, however, our team at Dell Medical School needed to rapidly and iteratively standardize care based on evolving science, effectively communicate that approach across rotating hospital medicine physicians and residents, and update care models, workflows, and technology every few days. In this article, we review our initial experiences, describe the strategies we employed to respond to these challenges, and reflect on the lessons learned and our proposed strategy moving forward.

Early pandemic challenges

Our initial inpatient strategies focused on containment, infection prevention, and bracing ourselves rather than creating a COVID Center of Excellence (COE). In fact, our hospital network’s initial strategy was to have COVID-19 patients transferred to a different hospital within our network. However, as March progressed, we became the designated COVID-19 hospital in our area’s network because of the increasing volume of patients we saw.

Patients from the surrounding regional hospitals were transferring their COVID-19 patients to us and we quickly saw the wide spectrum of illness, ranging from mild pneumonia to severe disease requiring mechanical ventilation upon admission. All frontline providers felt the stress of needing to find treatment options quickly for our sickest patients. We realized that to provide safe, effective, and high-quality care to COVID-19 patients, we needed to create a sustainable and standardized interdisciplinary approach.

COVID-19 testing was a major challenge when the pandemic hit as testing kits and personal protective equipment were in limited supply. How would we choose who to test or empirically place in COVID-19 isolation? In addition, we faced questions surrounding safe discharge practices, especially for patients who could not self-isolate in their home (if they even had one).

In March, emergency use authorization (EUA) for hydroxychloroquine was granted by the U.S. FDA despite limited data. This resulted in pressure from the public to use this drug in our patients. At the same time, we saw that some patients quickly got better on their own with supportive care. As clinicians striving to practice evidence-based medicine, we certainly did not want to give patients an unproven therapy that could do more harm than good. We also felt the need to respond with statements about what we could do that worked – rather than negotiate about withholding certain treatments featured in the news. Clearly, a “one-size-fits-all” approach to therapeutics was not going to work in treating patients with COVID-19.

We realized we were going to have to learn and adapt together – quickly. It became apparent that we needed to create structures to rapidly adjudicate and integrate emerging science into standardized clinical care delivery.

Solutions in the form of better structures

In response to these challenges, we created early morning meetings or “huddles” among COVID-19 care teams and hospital administration. A designated “COVID ID” physician from Infectious Diseases would meet with hospitalist and critical care teams each morning in our daily huddles to review all newly admitted patients, current hospitalized patients, and patients with pending COVID-19 tests or suspected initial false-negative tests.

Together, and via the newly developed Therapeutics and Informatics Committee, we created early treatment recommendations based upon available evidence, treatment availability, and the patient’s severity of illness. Within the first ten days of admitting our first patient, it had become standard practice to review eligible patients soon after admission for therapies such as convalescent plasma, and, later, remdesivir and steroids.

We codified these consensus recommendations and processes in our Dell Med COVID Manual, a living document that was frequently updated and disseminated to our group. It created a single ‘true north’ of standardized workflows for triage, diagnosis, management, discharge coordination, and end-of-life care. The document allowed for continuous and asynchronous multi-person collaboration and extremely rapid cycles of improvement. Between March and December 2020, this 100-page handbook went through more than 130 iterations.

Strategy for the future

This approach – communicating frequently, adapting on a daily to weekly basis, and continuously scanning the science for opportunities to improve our care delivery – became the foundation of our approach and the Therapeutics and Informatics Committee. Just as importantly, this created a culture of engagement, collaboration, and shared problem-solving that helped us stay organized, keep up to date with the latest science, and innovate rather than panic when faced with ongoing unpredictability and chaos in the early days of the pandemic.

As the pandemic enters into its 13th month, we carry this foundation and our strategies forward. The infrastructure and systems of communication that we have set in place will allow us to be nimble in our response as COVID-19 numbers surge in our region.

Dr. Gandhi is an assistant professor in the department of internal medicine at Dell Medical School, University of Texas, Austin. Dr. Mondy is chief of the division of infectious disease and associate professor in the department of internal medicine at Dell Medical School. Dr. Busch and Dr. Brode are assistant professors in the department of internal medicine at Dell Medical School. This article is part of a series originally published in The Hospital Leader, the official blog of SHM.

During the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic, hospital groups and systems scrambled to create protocols and models to respond to the novel coronavirus. In the pre-pandemic world, hospital groups have traditionally focused on standardizing clinical protocols and care models that rely on evidence-based medical practices or extended experience.

During COVID-19, however, our team at Dell Medical School needed to rapidly and iteratively standardize care based on evolving science, effectively communicate that approach across rotating hospital medicine physicians and residents, and update care models, workflows, and technology every few days. In this article, we review our initial experiences, describe the strategies we employed to respond to these challenges, and reflect on the lessons learned and our proposed strategy moving forward.

Early pandemic challenges

Our initial inpatient strategies focused on containment, infection prevention, and bracing ourselves rather than creating a COVID Center of Excellence (COE). In fact, our hospital network’s initial strategy was to have COVID-19 patients transferred to a different hospital within our network. However, as March progressed, we became the designated COVID-19 hospital in our area’s network because of the increasing volume of patients we saw.

Patients from the surrounding regional hospitals were transferring their COVID-19 patients to us and we quickly saw the wide spectrum of illness, ranging from mild pneumonia to severe disease requiring mechanical ventilation upon admission. All frontline providers felt the stress of needing to find treatment options quickly for our sickest patients. We realized that to provide safe, effective, and high-quality care to COVID-19 patients, we needed to create a sustainable and standardized interdisciplinary approach.

COVID-19 testing was a major challenge when the pandemic hit as testing kits and personal protective equipment were in limited supply. How would we choose who to test or empirically place in COVID-19 isolation? In addition, we faced questions surrounding safe discharge practices, especially for patients who could not self-isolate in their home (if they even had one).

In March, emergency use authorization (EUA) for hydroxychloroquine was granted by the U.S. FDA despite limited data. This resulted in pressure from the public to use this drug in our patients. At the same time, we saw that some patients quickly got better on their own with supportive care. As clinicians striving to practice evidence-based medicine, we certainly did not want to give patients an unproven therapy that could do more harm than good. We also felt the need to respond with statements about what we could do that worked – rather than negotiate about withholding certain treatments featured in the news. Clearly, a “one-size-fits-all” approach to therapeutics was not going to work in treating patients with COVID-19.

We realized we were going to have to learn and adapt together – quickly. It became apparent that we needed to create structures to rapidly adjudicate and integrate emerging science into standardized clinical care delivery.

Solutions in the form of better structures

In response to these challenges, we created early morning meetings or “huddles” among COVID-19 care teams and hospital administration. A designated “COVID ID” physician from Infectious Diseases would meet with hospitalist and critical care teams each morning in our daily huddles to review all newly admitted patients, current hospitalized patients, and patients with pending COVID-19 tests or suspected initial false-negative tests.

Together, and via the newly developed Therapeutics and Informatics Committee, we created early treatment recommendations based upon available evidence, treatment availability, and the patient’s severity of illness. Within the first ten days of admitting our first patient, it had become standard practice to review eligible patients soon after admission for therapies such as convalescent plasma, and, later, remdesivir and steroids.

We codified these consensus recommendations and processes in our Dell Med COVID Manual, a living document that was frequently updated and disseminated to our group. It created a single ‘true north’ of standardized workflows for triage, diagnosis, management, discharge coordination, and end-of-life care. The document allowed for continuous and asynchronous multi-person collaboration and extremely rapid cycles of improvement. Between March and December 2020, this 100-page handbook went through more than 130 iterations.

Strategy for the future

This approach – communicating frequently, adapting on a daily to weekly basis, and continuously scanning the science for opportunities to improve our care delivery – became the foundation of our approach and the Therapeutics and Informatics Committee. Just as importantly, this created a culture of engagement, collaboration, and shared problem-solving that helped us stay organized, keep up to date with the latest science, and innovate rather than panic when faced with ongoing unpredictability and chaos in the early days of the pandemic.

As the pandemic enters into its 13th month, we carry this foundation and our strategies forward. The infrastructure and systems of communication that we have set in place will allow us to be nimble in our response as COVID-19 numbers surge in our region.

Dr. Gandhi is an assistant professor in the department of internal medicine at Dell Medical School, University of Texas, Austin. Dr. Mondy is chief of the division of infectious disease and associate professor in the department of internal medicine at Dell Medical School. Dr. Busch and Dr. Brode are assistant professors in the department of internal medicine at Dell Medical School. This article is part of a series originally published in The Hospital Leader, the official blog of SHM.

Making a difference

Hospitalists engaging in advocacy efforts

Hospitalists around the country are devoting large portions of their spare time to a wide range of advocacy efforts. From health policy to caring for the unhoused population to diversity and equity to advocating for fellow hospitalists, these physicians are passionate about their causes and determined to make a difference.

Championing the unhoused

Sarah Stella, MD, FHM, a hospitalist at Denver Health, was initially drawn there because of the population the hospital serves, which includes a high concentration of people experiencing homelessness. As she cared for her patients, Dr. Stella, who is also associate professor of hospital medicine at the University of Colorado, increasingly felt the desire to help prevent the negative downstream outcomes the hospital sees.

To understand the experiences of the unhoused outside the hospital, Dr. Stella started talking to her patients and people in community-based organizations that serve this population. “I learned a ton,” she said. “Homelessness feels like such an intractable, hopeless thing, but the more I talked to people, the more opportunities I saw to work toward something better.”

This led to a pilot grant to work with the Colorado Coalition for the Homeless to set up a community advisory panel. “My goal was to better understand their experiences and to develop a shared vision for how we collectively can do better,” said Dr. Stella. Eventually, she also received a grant from the University of Colorado, and multiple opportunities have sprung up ever since.

For the past several years, Dr. Stella has worked with Denver Health leadership to improve care for the homeless. “Right now, I’m working with a community team on developing an idea to provide peer support from people with a shared lived experience for people who are experiencing homelessness when they’re hospitalized. That’s really where my passion has been in working on the partnership,” she said.

Her advocacy role has been beneficial in her work as a hospitalist, particularly when COVID began. Dr. Stella again partnered with the Colorado Coalition for the Homeless to start a joint task force. “Everyone on our task force is motivated by this powerful desire to improve the health and lives of this community and that’s one of the silver linings in this pandemic for me,” said Dr. Stella.

Advocacy work has also increased Dr. Stella’s knowledge of what community support options are available for the unhoused. This allows her to educate her patients about their options and how to access them.

While she has colleagues who are able to compartmentalize their work, “I absolutely could not be a hospitalist without being an advocate,” Dr. Stella said. “For me, it has been a protective strategy in terms of burnout because I have to feel like I’m working to advocate for better policies and more appropriate resources to address the gaps that I’m seeing.”

Dr. Stella believes that physicians have a special credibility to advocate, tell stories, and use data to back their stories up. “We have to realize that we have this power, and we have it so we can empower others,” she said. “The people I’ve seen in my community who are working so hard to help people who are experiencing homelessness are the heroes. Understanding that and giving power to those people through our voice and our well-respected place in society drives me.”

Strengthening diversity, equity, and inclusion

In September 2020, Michael Bryant, MD, became the inaugural vice chair of Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion for the department of pediatrics at Children’s Hospital Los Angeles, where he is also the division head of pediatric hospital medicine. “I was motivated to apply for this position because I wanted to be an agent for change to eliminate the institutional racism, social injustice, and marginalization that continues to threaten the lives and well-beings of so many Americans,” Dr. Bryant said.

Between the pandemic, the economic decline it has created, and the divisive political landscape, people of color have been especially affected. “These are poignant examples of the ever-widening divide and disenfranchisement many Americans feel,” said Dr. Bryant. “Gandhi said, ‘Be the change that you want to see,’ and that is what I want to model.”

At work, advocacy for diversity, equality, and inclusion is an innate part of everything he does. From the new physicians he recruits to the candidates he considers for leadership positions, Dr. Bryant strives “to have a workforce that mirrors the diversity of the patients we humbly care for and serve.”

Advocacy is intrinsic to Dr. Bryant’s worldview, in his quest to understand and accept each individual’s uniqueness, his desire “to embrace cultural humility,” his recognition that “our differences enhance us instead of diminishing us,” and his willingness to engage in difficult conversations.

“Advocacy means that I acknowledge that intent does not equal impact and that I must accept that what I do and what I say may have unintended consequences,” he said. “When that happens, I must resist becoming defensive and instead be willing to listen and learn.”

Dr. Bryant is proud of his accomplishments and enjoys his advocacy work. In his workplace, there are few African Americans in leadership roles. This means that he is in high demand when it comes to making sure there’s representation during various processes such as hiring and vetting, a disparity known as the “minority tax.”

“I am thankful for the opportunities, but it does take a toll at times,” Dr. Bryant said, which is yet another reason why he is a proponent of increasing diversity and inclusion. “This allows us to build the resource pool as these needs arise and minimizes the toll of the ‘minority tax’ on any single person or small group of individuals.”

This summer, physicians from Dr. Bryant’s hospital participated in the national “White Coats for Black Lives” effort. He found it to be “an incredibly moving event” that hundreds of his colleagues participated in.

Dr. Bryant’s advice for hospitalists who want to get involved in advocacy efforts is to check out the movie “John Lewis: Good Trouble.” “He was a champion of human rights and fought for these rights until his death,” Dr. Bryant said. “He is a true American hero and a wonderful example.”

Bolstering health care change

Since his residency, Joshua Lenchus, DO, FACP, SFHM, has developed an ever-increasing interest in legislative advocacy, particularly health policy. Getting involved in this arena requires an understanding of civics and government that goes beyond just the basics. “My desire to affect change in my own profession really served as the catalyst to get involved,” said Dr. Lenchus, the regional chief medical officer at Broward Health Medical Center in Fort Lauderdale, Fla. “What better way to do that than by combining what we do on a daily basis in the practice of medicine with this new understanding of how laws are passed and promulgated?”

Dr. Lenchus has been involved with both state and national medical organizations and has served on public policy committees as a member and as a chair. “The charge of these committees is to monitor and navigate position statements and policies that will drive the entire organization,” he said. This means becoming knowledgeable enough about a topic to be able to talk about it eloquently and adding supporting personal or professional illustrations that reinforce the position to lawmakers.

He finds his advocacy efforts “incredibly rewarding” because they contribute to his endeavors “to help my colleagues practice medicine in a safe, efficient, and productive manner.” For instance, some of the organizations Dr. Lenchus was involved with helped make changes to the Affordable Care Act that ended up in its final version, as well as changes after it passed. “There are tangible things that advocacy enables us to do in our daily practice,” he said.

When something his organizations have advocated for does not pass, they know they need to try a different outlet. “You can’t win every fight,” he said. “Every time you go and comment on an issue, you have to understand that you’re there to do your best, and to the extent that the people you’re talking to are willing to listen to what you have to say, that’s where I think you can make the most impact.” When changes he has helped fight for do pass, “it really is amazing that you can tell your colleagues about your role in achieving meaningful change in the profession.”

Dr. Lenchus acknowledges that advocacy “can be all-consuming at times. We have to understand our limits.” That said, he thinks not engaging in advocacy could increase stress and potential burnout. “I think being involved in advocacy efforts really helps people conduct meaningful work and educates them about what it means not just to them, but to the rest of the medical profession and the patients that we serve,” he said.

For hospitalists who are interested in health policy advocacy, there are many ways to get involved, Dr. Lenchus said. You could join an organization (many organized medical societies have public policy committees), participate in advocacy activities, work on a political campaign, or even run for office yourself. “Ultimately, education and some level of involvement really will make the difference in who navigates our future as hospitalists,” he said.

Questioning co-management practices

Though he says he’s in the minority, Hardik Vora, MD, SFHM, medical director for hospital medicine at Riverside Regional Medical Center in Newport News, Va., believes that co-management is going to “make or break hospital medicine. It’s going to have a huge impact on our specialty.”

In the roughly 25-year history of hospital medicine, it has evolved from admitting and caring for patients of primary care physicians to patients of specialists and, more recently, surgical patients. “Now there are (hospital medicine) programs across the country that are pretty much admitting everything,” said Dr. Vora.

As a recruiter for the Riverside Health System for the past eight years, “I have not met a single resident who is trained to do what we’re doing in hospital medicine, because you’re admitting surgical patients all the time and you have primary attending responsibility,” Dr. Vora said. “I see that as a cause of a significant amount of stress because now you’re responsible for something that you don’t have adequate training for.”

In the co-management discussion, Dr. Vora notes that people often bring up the research that shows that the practice has improved surgeon satisfaction. “What bothers me is that…you need to add one more question – how does it affect your hospitalists? And I bet the answer to that question is ‘it has a terrible effect.’”

The expectations surrounding hospitalists these days is a big concern in terms of burnout, Dr. Vora said. “We talk a lot about the drivers of burnout, whether it’s schedule or COVID,” he said. The biggest issue when it comes to burnout, as he sees it, is not COVID; it’s when hospitalists are performing tasks that make them feel they aren’t adding value. “I think that’s a huge topic in hospital medicine right now.”

Dr. Vora believes there should be more discussion and awareness of the potential pitfalls. “Hospitalists should get involved in co-management where they are adding value and certainly not take up the attending responsibility where they’re not adding value and it’s out of the scope of their training and expertise,” he said. “Preventing scope creep and burnout from co-management are some of the key issues I’m really passionate about.”

Dr. Vora said it is important to set realistic goals and remember that it takes time to make change when it comes to advocacy. “You still have to operate within whatever environment is given to you and then you can make change from within,” he said.

His enthusiasm for co-management awareness has led to creating a co-management forum through SHM in his local Hampton Roads chapter. He was also a panelist for an SHM webinar in February 2021 in which the panelists debated co-management.

“I think we really need to look at this as a specialty. Are we going in the right direction?” Dr. Vora asked. “We need to come together as a specialty and make a decision, which is going to be hard because there are competing financial interests and various practice models.”

Improving patient care

Working as a hospitalist at University Medical Center, a safety net hospital in New Orleans, Celeste Newby, MD, PhD, sees plenty of patients who are underinsured or not insured at all. “A lot of my interest in health policy stems from that,” she said.

During her residency, which she finished in 2015, Louisiana became a Medicaid expansion state. This impressed upon Dr. Newby how much Medicaid improved the lives of patients who had previously been uninsured. “We saw procedures getting done that had been put on hold because of financial concerns or medicines that were now affordable that weren’t before,” she said. “It really did make a difference.”

When repeated attempts to repeal the Affordable Care Act began, “it was a call to do health policy work for me personally that just hadn’t come up in the past,” said Dr. Newby, who is also assistant professor of medicine at Tulane University in New Orleans. “I personally found that the best way to do (advocacy work) was to go through medical societies because there is a much stronger voice when you have more people saying the same thing,” she said.

Dr. Newby sits on the Council of Legislation for the Louisiana State Medical Society and participates in the Leadership and Health Policy (LEAHP) Program through the Society of General Internal Medicine.

The LEAHP Program has been instrumental in expanding Dr. Newby’s knowledge of how health policy is made and the mechanisms behind it. It has also taught her “how we can either advise, guide, leverage, or advocate for things that we think would be important for change and moving the country in the right direction in terms of health care.”

Another reason involvement in medical societies is helpful is because, as a busy clinician, it is impossible to keep up with everything. “Working with medical societies, you have people who are more directly involved in the legislature and can give you quicker notice about things that are coming up that are going to be important to you or your co-workers or your patients,” Dr. Newby said.

Dr. Newby feels her advocacy work is an outlet for stress and “a way to work at more of a macro level on problems that I see with my individual patients. It’s a nice compliment.” At the hospital, she can only help one person at a time, but with her advocacy efforts, there’s potential to make changes for many.

“Advocacy now is such a large umbrella that encompasses so many different projects at all kinds of levels,” Dr. Newby said. She suggests looking around your community to see where the needs lie. If you’re passionate about a certain topic or population, see what you can do to help advocate for change there.

Hospitalists engaging in advocacy efforts

Hospitalists engaging in advocacy efforts

Hospitalists around the country are devoting large portions of their spare time to a wide range of advocacy efforts. From health policy to caring for the unhoused population to diversity and equity to advocating for fellow hospitalists, these physicians are passionate about their causes and determined to make a difference.

Championing the unhoused

Sarah Stella, MD, FHM, a hospitalist at Denver Health, was initially drawn there because of the population the hospital serves, which includes a high concentration of people experiencing homelessness. As she cared for her patients, Dr. Stella, who is also associate professor of hospital medicine at the University of Colorado, increasingly felt the desire to help prevent the negative downstream outcomes the hospital sees.

To understand the experiences of the unhoused outside the hospital, Dr. Stella started talking to her patients and people in community-based organizations that serve this population. “I learned a ton,” she said. “Homelessness feels like such an intractable, hopeless thing, but the more I talked to people, the more opportunities I saw to work toward something better.”