User login

Innovation requires experimentation

A call for more health care trials

Successful innovation requires experimentation, according to a recent editorial in BMJ Quality & Safety – that’s why health systems should engage in more experimenting, more systematically, to improve health care.

“Most health systems implement interventions without testing them against other designs,” said co-author Mitesh S. Patel, MD, MBA, MS, of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia. “This means that good ideas are often not spread (because we don’t know how impactful they are) and bad ones persist (because we don’t realize they don’t work).”

Dr. Patel, who is director of the Penn Medicine Nudge Unit at the Perelman Center for Advanced Medicine, encourages health systems and clinicians to implement new interventions in testable ways such as through a randomized trial, so that we can learn what works and why. A more systematic approach could help to expand programs that work and improve workflow and patient care.

“First, we must embed research teams within health systems in order to create the capacity for this kind of work. Expertise is required to identify a promising intervention, design the conceptual approach, conduct the technical implementation and rigorously evaluate the trial. These teams are also able to design interventions within the context of existing workflows in order to ensure that successful projects can be quickly scaled and that ineffective initiatives can be seamlessly terminated.” the authors wrote.

“Second, we must take advantage of existing data systems. The field of health care is ripe with detailed and reliable administrative data and electronic medical record data. These data offer the potential to do high-quality, low-cost, rapid trials. Third, we must measure a wide range of meaningful outcomes. We should examine the effect of interventions on health care costs, health care utilization and health outcomes.”

Next steps could be focused on thinking about the key priority areas and how can experiments be used to generate new knowledge on what works and what does not. “Luckily, the complex world of health care provides endless opportunities for rapid-cycle, randomized trials that target health care costs and outcomes,” Dr. Patel said.

Reference

1. Oakes AH, Patel MS. A nudge towards increased experimentation to more rapidly improve healthcare. BMJ Qual Saf. 2020;29:179-181. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2019-009948. Accessed Dec 3, 2019.

A call for more health care trials

A call for more health care trials

Successful innovation requires experimentation, according to a recent editorial in BMJ Quality & Safety – that’s why health systems should engage in more experimenting, more systematically, to improve health care.

“Most health systems implement interventions without testing them against other designs,” said co-author Mitesh S. Patel, MD, MBA, MS, of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia. “This means that good ideas are often not spread (because we don’t know how impactful they are) and bad ones persist (because we don’t realize they don’t work).”

Dr. Patel, who is director of the Penn Medicine Nudge Unit at the Perelman Center for Advanced Medicine, encourages health systems and clinicians to implement new interventions in testable ways such as through a randomized trial, so that we can learn what works and why. A more systematic approach could help to expand programs that work and improve workflow and patient care.

“First, we must embed research teams within health systems in order to create the capacity for this kind of work. Expertise is required to identify a promising intervention, design the conceptual approach, conduct the technical implementation and rigorously evaluate the trial. These teams are also able to design interventions within the context of existing workflows in order to ensure that successful projects can be quickly scaled and that ineffective initiatives can be seamlessly terminated.” the authors wrote.

“Second, we must take advantage of existing data systems. The field of health care is ripe with detailed and reliable administrative data and electronic medical record data. These data offer the potential to do high-quality, low-cost, rapid trials. Third, we must measure a wide range of meaningful outcomes. We should examine the effect of interventions on health care costs, health care utilization and health outcomes.”

Next steps could be focused on thinking about the key priority areas and how can experiments be used to generate new knowledge on what works and what does not. “Luckily, the complex world of health care provides endless opportunities for rapid-cycle, randomized trials that target health care costs and outcomes,” Dr. Patel said.

Reference

1. Oakes AH, Patel MS. A nudge towards increased experimentation to more rapidly improve healthcare. BMJ Qual Saf. 2020;29:179-181. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2019-009948. Accessed Dec 3, 2019.

Successful innovation requires experimentation, according to a recent editorial in BMJ Quality & Safety – that’s why health systems should engage in more experimenting, more systematically, to improve health care.

“Most health systems implement interventions without testing them against other designs,” said co-author Mitesh S. Patel, MD, MBA, MS, of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia. “This means that good ideas are often not spread (because we don’t know how impactful they are) and bad ones persist (because we don’t realize they don’t work).”

Dr. Patel, who is director of the Penn Medicine Nudge Unit at the Perelman Center for Advanced Medicine, encourages health systems and clinicians to implement new interventions in testable ways such as through a randomized trial, so that we can learn what works and why. A more systematic approach could help to expand programs that work and improve workflow and patient care.

“First, we must embed research teams within health systems in order to create the capacity for this kind of work. Expertise is required to identify a promising intervention, design the conceptual approach, conduct the technical implementation and rigorously evaluate the trial. These teams are also able to design interventions within the context of existing workflows in order to ensure that successful projects can be quickly scaled and that ineffective initiatives can be seamlessly terminated.” the authors wrote.

“Second, we must take advantage of existing data systems. The field of health care is ripe with detailed and reliable administrative data and electronic medical record data. These data offer the potential to do high-quality, low-cost, rapid trials. Third, we must measure a wide range of meaningful outcomes. We should examine the effect of interventions on health care costs, health care utilization and health outcomes.”

Next steps could be focused on thinking about the key priority areas and how can experiments be used to generate new knowledge on what works and what does not. “Luckily, the complex world of health care provides endless opportunities for rapid-cycle, randomized trials that target health care costs and outcomes,” Dr. Patel said.

Reference

1. Oakes AH, Patel MS. A nudge towards increased experimentation to more rapidly improve healthcare. BMJ Qual Saf. 2020;29:179-181. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2019-009948. Accessed Dec 3, 2019.

SHM Converge: New format, fresh content

While we all long for a traditional in-person meeting “like the good old days”, there are some significant advantages to a virtual meeting like Converge.

The most significant advantage is the ability to review more content than ever before, as we offer a combination of live and recorded “on-demand” sessions. This allows for incredible flexibility in garnering “top-shelf” content from hospital medicine experts around the country, without having to choose from competing sessions. We are especially looking forward to new sessions this year focused on COVID-19; diversity, equity, and inclusion; and resilience.

The Converge conference will still be offering networking sessions throughout – even in the virtual conference environment. We consider networking a vital and endearing part of the value equation for SHM members. For example, we now can participate in several Special Interest Forums, since many of us have several niche interests and want to take advantage of more than one of these networking opportunities. We also carefully preserved the signature “Update in Hospital Medicine” session, as well as the scientific abstract poster reception and the Best of Research and Innovation sessions. These are long-term favorites at the annual conference and lend themselves well to virtual transformation. Some of the workshops and special sessions have exclusive audience engagement and are not offered on demand, so signing up early for these sessions is highly recommended.

SHM remains the professional home for hospitalists, and we rely on the annual conference to keep us all informed on current and forward-thinking clinical practice, practice management, leadership, academics, research, and other topics. This is one of many examples of how SHM has been able to pivot to meet the needs of hospitalists throughout the pandemic. Not only have we successfully converted “traditional” meetings into virtual meetings, but we have been able to curate and deliver content faster and more seamlessly than ever before.

Whether via The Hospitalist, the Journal of Hospital Medicine, the SHM website, or our other educational platforms, SHM has remained committed to being the single “source of truth” for all things hospital medicine. Within the tumultuous political landscape of the past year, the SHM advocacy team has been more active and engaged than ever, in advocating for a myriad of hospitalist-related legislative changes. These are just a few of the ways SHM continues to add value to hospitalist members every day.

Although we will certainly miss seeing each other in person, we are confident that the SHM team will meet and exceed expectations on content delivery and will take advantage of the virtual format to improve content access. We look forward to “seeing” you at SHM Converge this year and hope you take advantage of the enhanced delivery and access to an array of amazing content!

Dr. Scheurer is president of the Society of Hospital Medicine. She is a hospitalist and chief quality officer, MUSC Health System, Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston.

While we all long for a traditional in-person meeting “like the good old days”, there are some significant advantages to a virtual meeting like Converge.

The most significant advantage is the ability to review more content than ever before, as we offer a combination of live and recorded “on-demand” sessions. This allows for incredible flexibility in garnering “top-shelf” content from hospital medicine experts around the country, without having to choose from competing sessions. We are especially looking forward to new sessions this year focused on COVID-19; diversity, equity, and inclusion; and resilience.

The Converge conference will still be offering networking sessions throughout – even in the virtual conference environment. We consider networking a vital and endearing part of the value equation for SHM members. For example, we now can participate in several Special Interest Forums, since many of us have several niche interests and want to take advantage of more than one of these networking opportunities. We also carefully preserved the signature “Update in Hospital Medicine” session, as well as the scientific abstract poster reception and the Best of Research and Innovation sessions. These are long-term favorites at the annual conference and lend themselves well to virtual transformation. Some of the workshops and special sessions have exclusive audience engagement and are not offered on demand, so signing up early for these sessions is highly recommended.

SHM remains the professional home for hospitalists, and we rely on the annual conference to keep us all informed on current and forward-thinking clinical practice, practice management, leadership, academics, research, and other topics. This is one of many examples of how SHM has been able to pivot to meet the needs of hospitalists throughout the pandemic. Not only have we successfully converted “traditional” meetings into virtual meetings, but we have been able to curate and deliver content faster and more seamlessly than ever before.

Whether via The Hospitalist, the Journal of Hospital Medicine, the SHM website, or our other educational platforms, SHM has remained committed to being the single “source of truth” for all things hospital medicine. Within the tumultuous political landscape of the past year, the SHM advocacy team has been more active and engaged than ever, in advocating for a myriad of hospitalist-related legislative changes. These are just a few of the ways SHM continues to add value to hospitalist members every day.

Although we will certainly miss seeing each other in person, we are confident that the SHM team will meet and exceed expectations on content delivery and will take advantage of the virtual format to improve content access. We look forward to “seeing” you at SHM Converge this year and hope you take advantage of the enhanced delivery and access to an array of amazing content!

Dr. Scheurer is president of the Society of Hospital Medicine. She is a hospitalist and chief quality officer, MUSC Health System, Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston.

While we all long for a traditional in-person meeting “like the good old days”, there are some significant advantages to a virtual meeting like Converge.

The most significant advantage is the ability to review more content than ever before, as we offer a combination of live and recorded “on-demand” sessions. This allows for incredible flexibility in garnering “top-shelf” content from hospital medicine experts around the country, without having to choose from competing sessions. We are especially looking forward to new sessions this year focused on COVID-19; diversity, equity, and inclusion; and resilience.

The Converge conference will still be offering networking sessions throughout – even in the virtual conference environment. We consider networking a vital and endearing part of the value equation for SHM members. For example, we now can participate in several Special Interest Forums, since many of us have several niche interests and want to take advantage of more than one of these networking opportunities. We also carefully preserved the signature “Update in Hospital Medicine” session, as well as the scientific abstract poster reception and the Best of Research and Innovation sessions. These are long-term favorites at the annual conference and lend themselves well to virtual transformation. Some of the workshops and special sessions have exclusive audience engagement and are not offered on demand, so signing up early for these sessions is highly recommended.

SHM remains the professional home for hospitalists, and we rely on the annual conference to keep us all informed on current and forward-thinking clinical practice, practice management, leadership, academics, research, and other topics. This is one of many examples of how SHM has been able to pivot to meet the needs of hospitalists throughout the pandemic. Not only have we successfully converted “traditional” meetings into virtual meetings, but we have been able to curate and deliver content faster and more seamlessly than ever before.

Whether via The Hospitalist, the Journal of Hospital Medicine, the SHM website, or our other educational platforms, SHM has remained committed to being the single “source of truth” for all things hospital medicine. Within the tumultuous political landscape of the past year, the SHM advocacy team has been more active and engaged than ever, in advocating for a myriad of hospitalist-related legislative changes. These are just a few of the ways SHM continues to add value to hospitalist members every day.

Although we will certainly miss seeing each other in person, we are confident that the SHM team will meet and exceed expectations on content delivery and will take advantage of the virtual format to improve content access. We look forward to “seeing” you at SHM Converge this year and hope you take advantage of the enhanced delivery and access to an array of amazing content!

Dr. Scheurer is president of the Society of Hospital Medicine. She is a hospitalist and chief quality officer, MUSC Health System, Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston.

Accessing data during EHR downtime

Reducing loss of efficiency

Electronic health record (EHR) implementations involve long downtimes, which are an under-recognized patient safety risk, as clinicians are forced to switch to completely manual, paper-based, and important unfamiliar workflows to care for their acutely ill patients, said Subha Airan-Javia, MD, FAMIA, a hospitalist at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

“In this setting, we discovered an unanticipated benefit of our tool [Carelign, initially built to digitize the handoff process] as a clinical resource during EHR downtime, giving clinicians access to critical data as well as an electronic platform to collaborate as a team around the care of their patients,” she said.

There are two important takeaways from their study on this issue. “The first is that Carelign was able to give clinicians access to clinical data that would otherwise have been unavailable, including vitals, labs, medications, care plans and care team assignments,” Dr. Airan-Javia said. “This undoubtedly mitigated patient safety risks during the EHR downtime.”

The second: “As many clinicians know, any change in workflow, even for a few hours, can make providing a high level of patient care very difficult,” she added. “During a downtime without a tool like Carelign, clinicians have to rely on paper and bedside charts, writing notes on paper and then re-typing them into the EHR when it is back up. This adds to the already excessive amount of administrative work that is burning clinicians out.” Using a tool like Carelign means no such loss in efficiency.

“A tool like Carelign, particularly because it is something that can be used without having to integrate it with the EHR, can put some control back into a hospitalist’s hands, to have a say in their workflow,” Dr. Airan-Javia said. “In a world where EHRs are designed to optimize billing, it can be game-changer to have a tool like Carelign that was created by a practicing clinician, for clinicians. Anyone interested in this area is welcome to reach out to me at [email protected] for collaboration or more information.”

Reference

1. Airan-Javia SL, et al. Mind the gap: Revolutionizing the EHR downtime experience with an interoperable workflow tool. Abstract published at Hospital Medicine 2019, March 24-27, National Harbor, Md. Abstract 380. https://www.shmabstracts.com/abstract/mind-the-gap-revolutionizing-the-ehr-downtime-experience-with-an-interoperable-workflow-tool/. Accessed Dec 11, 2019.

Reducing loss of efficiency

Reducing loss of efficiency

Electronic health record (EHR) implementations involve long downtimes, which are an under-recognized patient safety risk, as clinicians are forced to switch to completely manual, paper-based, and important unfamiliar workflows to care for their acutely ill patients, said Subha Airan-Javia, MD, FAMIA, a hospitalist at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

“In this setting, we discovered an unanticipated benefit of our tool [Carelign, initially built to digitize the handoff process] as a clinical resource during EHR downtime, giving clinicians access to critical data as well as an electronic platform to collaborate as a team around the care of their patients,” she said.

There are two important takeaways from their study on this issue. “The first is that Carelign was able to give clinicians access to clinical data that would otherwise have been unavailable, including vitals, labs, medications, care plans and care team assignments,” Dr. Airan-Javia said. “This undoubtedly mitigated patient safety risks during the EHR downtime.”

The second: “As many clinicians know, any change in workflow, even for a few hours, can make providing a high level of patient care very difficult,” she added. “During a downtime without a tool like Carelign, clinicians have to rely on paper and bedside charts, writing notes on paper and then re-typing them into the EHR when it is back up. This adds to the already excessive amount of administrative work that is burning clinicians out.” Using a tool like Carelign means no such loss in efficiency.

“A tool like Carelign, particularly because it is something that can be used without having to integrate it with the EHR, can put some control back into a hospitalist’s hands, to have a say in their workflow,” Dr. Airan-Javia said. “In a world where EHRs are designed to optimize billing, it can be game-changer to have a tool like Carelign that was created by a practicing clinician, for clinicians. Anyone interested in this area is welcome to reach out to me at [email protected] for collaboration or more information.”

Reference

1. Airan-Javia SL, et al. Mind the gap: Revolutionizing the EHR downtime experience with an interoperable workflow tool. Abstract published at Hospital Medicine 2019, March 24-27, National Harbor, Md. Abstract 380. https://www.shmabstracts.com/abstract/mind-the-gap-revolutionizing-the-ehr-downtime-experience-with-an-interoperable-workflow-tool/. Accessed Dec 11, 2019.

Electronic health record (EHR) implementations involve long downtimes, which are an under-recognized patient safety risk, as clinicians are forced to switch to completely manual, paper-based, and important unfamiliar workflows to care for their acutely ill patients, said Subha Airan-Javia, MD, FAMIA, a hospitalist at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

“In this setting, we discovered an unanticipated benefit of our tool [Carelign, initially built to digitize the handoff process] as a clinical resource during EHR downtime, giving clinicians access to critical data as well as an electronic platform to collaborate as a team around the care of their patients,” she said.

There are two important takeaways from their study on this issue. “The first is that Carelign was able to give clinicians access to clinical data that would otherwise have been unavailable, including vitals, labs, medications, care plans and care team assignments,” Dr. Airan-Javia said. “This undoubtedly mitigated patient safety risks during the EHR downtime.”

The second: “As many clinicians know, any change in workflow, even for a few hours, can make providing a high level of patient care very difficult,” she added. “During a downtime without a tool like Carelign, clinicians have to rely on paper and bedside charts, writing notes on paper and then re-typing them into the EHR when it is back up. This adds to the already excessive amount of administrative work that is burning clinicians out.” Using a tool like Carelign means no such loss in efficiency.

“A tool like Carelign, particularly because it is something that can be used without having to integrate it with the EHR, can put some control back into a hospitalist’s hands, to have a say in their workflow,” Dr. Airan-Javia said. “In a world where EHRs are designed to optimize billing, it can be game-changer to have a tool like Carelign that was created by a practicing clinician, for clinicians. Anyone interested in this area is welcome to reach out to me at [email protected] for collaboration or more information.”

Reference

1. Airan-Javia SL, et al. Mind the gap: Revolutionizing the EHR downtime experience with an interoperable workflow tool. Abstract published at Hospital Medicine 2019, March 24-27, National Harbor, Md. Abstract 380. https://www.shmabstracts.com/abstract/mind-the-gap-revolutionizing-the-ehr-downtime-experience-with-an-interoperable-workflow-tool/. Accessed Dec 11, 2019.

Akathisia: “Ants in the Pants”

Potentially poor outcome if untreated

Case

The patient is a 65-year-old female with increasing anxiety and agitation. She completed cycle 2 of chemotherapy for breast cancer several hours ago. Her premedication was Reglan (metoclopramide); her only other medication is tamoxifen. Other than breast cancer, she suffers only from osteoarthritis.

She is found pacing about the ward – almost uncontrollably. She feels she must move, only to have to stop and, shortly afterwards, feels the urge to move again. This has never happened to her before. She must move despite being fatigued. She also complains of an odd overall feeling; something akin to “ant in the pants.” She is nervous and exhausted. What is her diagnosis and what clues to it are in her presentation?

Background

The word “akathisia” is derived from the Greek language and means “unable to sit.” It is thought to occur as a consequence of dopaminergic blockade in the midbrain region. The decrease in dopaminergic activity leads to a subsequent decrease in inhibitory motor control which, in turn, manifests as involuntary movements.

In this malady, the patient is seen as perpetually in motion. The patient feels the need to move until they must stop. But once static, they have the urge to move again. They pace, they rock and they ‘fidget’ – they just cannot sit still. This feeling has been likened to having “ants in the pants.” Patients become anxious, agitated, and suffer from insomnia. They cannot rest.

If left unresolved akathisia can torment patients to sheer exhaustion. For some it serves as a harbinger of suicide. This toxicity is more commonly seen in the psychiatric pharmacy with the most common offender being haloperidol. The causative agents of the least notoriety are the non-antipsychotics.

Diagnosis and treatment

Akathisia is an extrapyramidal symptom found largely but NOT exclusively with psychiatric medications. There are drugs in the non-psychiatric field that can also cause it, including antiemetics (e.g., metoclopramide), antihypertensives (e.g., diltiazem), and narcotics (e.g., cocaine). Metoclopramide is given under circumstances ranging from diabetic gastroparesis to premedicating chemotherapy. It is a peripheral and centrally acting dopamine antagonist. There are no lab tests or radiographic workups to diagnose akathisia. Its manifestations are erratic and disturbing, and the prognosis is doleful if unresolved.

The primary intervention for the treatment of akathisia is its recognition and the discontinuation of the offending drug. Beyond this, for symptomatic care, there is a compendium of case reports and small studies supporting many drugs, but only a few have received consistent recommendation. Beta-adrenergic antagonists, such as propranolol, are considered the gold standard, the first choice for the treatment of akathisia. Their toxicities include orthostatic hypotension and bradycardia. Additionally, they are contraindicated in the setting of asthma.

Anticholinergics, such as benztropine (cogentin) and trihexylphenidyl (artane) are considered in the literature as 2nd line treatments, behind beta-blockers. However, the data advocating their use is limited. They have multiple side-effects including sedation, memory impairment, visual impairment, and urinary retention. They are also contraindicated in patients with closed-angle glaucoma.

An equivalent alternative to beta-blockers could also be the 5HT2a receptor antagonists such as mirtazapine (remeron) and cyproheptadine (periactin). This class of medications is thought to act by an inhibitory control of dopaminergic neurons. Sedation and weight gain are the primary toxicities, and they are contraindicated in patients who are breastfeeding.

Benzodiazepines, such as clonazepam (klonopin), have shown some efficacy in improving symptoms but the data is very limited. The risk of tolerance and dependence, coupled with the problems of sedation impacting the elderly, prompts their placement in reserve. Vitamin B6 (pyridoxine), when given in a high dose format, causes significant improvement in akathisia. However, it can cause headache and nausea. Chronic administration of high doses has also been found to cause a severe and irreversible sensory neuropathy as well as lead to seizures. Many other agents have been studied, but the data are too small to warrant recommendation.

Conclusion

Akathisia remains an extreme reaction to drugs not always in the psychotropic class. The hospitalist will likely deal with the acute onset, a dramatic form, and a potentially poor outcome if untreated. The patient’s only true defense is the physician’s clinical acumen and their ability to recognize it.

Dr. Killeen is a physician in Tampa, Fla. He practices internal medicine, hematology, and oncology, and has worked in hospice and hospital medicine.

Recommended reading

Van Gool AR, Doorduijn JK, Sevnaeve C. Severe akathisia as a side effect of metoclopramide. Pharm World Sci. 2010; 32(6):704-706.

Loonen AJM, Stahl SM. The mechanism of drug-induced akathisia. CNS Spectr. 2010;15(11):491-494.

Forcen FE, Matsoukas K, Alici Y. Antipsychotic-induced akathisia in delirium: A systemic review. Palliat Support Care. 2016;14(1):77-84.

Sethuram K, Gedzior J. Akathisia: Case presentation and review of newer treatment agents. Psychiatric Annals. 2014;44(8):391-396.

Pringsheim T, et al. The assessment and treatment of antipsychotic-induced akathisia. Can J Psychiatry. 2018;63(11): 719-729.

Tachere RO, Mandana M. Beyond anxiety and agitation: A clinical approach to akathisia. Royal Australian Coll Gen Practitioners. 2017;46(5): 296-298.

Key points

- Although associated more with psychiatric medications, akathisia can occur with non-psychotropics as well.

- To recognize the illness, the clinician must notice the repetitive involuntary movements and pacing as well as the “ants in the pants” fidgeting involved.

- Primary treatment consists of medication discontinuation with pharmaceutical intervention as a backup.

- Recognition is the key to successful treatment.

Classic signs of akathisia

- Fidgeting – “ants in the pants”

- Swinging the legs while seated

- Rocking from foot to foot

- Walking while in a static position

- Inability to sit or stand still – pacing

- Onset appears with the initiation or dose adjustment of an offending drug

Quiz

1. Which of the following findings occur in Akathisia?

A. Fidgeting

B. Pacing

C. Swinging the legs while seated

D. All the above

Answer: D

Akathisia is manifest as involuntary hyperactivity of the extremities, particularly the lower extremities. People feel the urge to move, to continue endlessly in motion, stopping only when fatigue sets in. The fidgeting has been described by patients as feeling like “ants in the pants.”

2. Which of the following interventions are used to treat akathisia?

A. Drug discontinuation

B. Propranolol

C. Mirtazapine

D. All the above

Answer: D

All the interventions mentioned are used to treat akathisia. The foremost is to stop the offending drug. Failing this, propranolol is the “gold standard” while 5HT2a antagonists, such as mirtazapine, are favored when beta-blockers either fail or are contraindicated.

3. The use of pyridoxine (Vitamin B6) in the treatment of akathisia is associated with what toxicities?

A. Headache

B. Nausea

C. Seizures

D. All the above

Answer: D

The use of Vitamin B6 in the treatment of akathisia has several drawbacks. Its administration is associated with headache and nausea, and high dose usage increases the risk of seizure.

4. If unresolved, akathisia can lead to which of the following?

A. Insomnia

B. Suicide

C. Physical exhaustion

D. All the above

Answer: D

Akathisia, left unrecognized and untreated, can eventually lead to physical exhaustion, and is compounded by difficulties in trying to rest, hence insomnia. The physical and mental torment of this malady can lead to suicide.

Potentially poor outcome if untreated

Potentially poor outcome if untreated

Case

The patient is a 65-year-old female with increasing anxiety and agitation. She completed cycle 2 of chemotherapy for breast cancer several hours ago. Her premedication was Reglan (metoclopramide); her only other medication is tamoxifen. Other than breast cancer, she suffers only from osteoarthritis.

She is found pacing about the ward – almost uncontrollably. She feels she must move, only to have to stop and, shortly afterwards, feels the urge to move again. This has never happened to her before. She must move despite being fatigued. She also complains of an odd overall feeling; something akin to “ant in the pants.” She is nervous and exhausted. What is her diagnosis and what clues to it are in her presentation?

Background

The word “akathisia” is derived from the Greek language and means “unable to sit.” It is thought to occur as a consequence of dopaminergic blockade in the midbrain region. The decrease in dopaminergic activity leads to a subsequent decrease in inhibitory motor control which, in turn, manifests as involuntary movements.

In this malady, the patient is seen as perpetually in motion. The patient feels the need to move until they must stop. But once static, they have the urge to move again. They pace, they rock and they ‘fidget’ – they just cannot sit still. This feeling has been likened to having “ants in the pants.” Patients become anxious, agitated, and suffer from insomnia. They cannot rest.

If left unresolved akathisia can torment patients to sheer exhaustion. For some it serves as a harbinger of suicide. This toxicity is more commonly seen in the psychiatric pharmacy with the most common offender being haloperidol. The causative agents of the least notoriety are the non-antipsychotics.

Diagnosis and treatment

Akathisia is an extrapyramidal symptom found largely but NOT exclusively with psychiatric medications. There are drugs in the non-psychiatric field that can also cause it, including antiemetics (e.g., metoclopramide), antihypertensives (e.g., diltiazem), and narcotics (e.g., cocaine). Metoclopramide is given under circumstances ranging from diabetic gastroparesis to premedicating chemotherapy. It is a peripheral and centrally acting dopamine antagonist. There are no lab tests or radiographic workups to diagnose akathisia. Its manifestations are erratic and disturbing, and the prognosis is doleful if unresolved.

The primary intervention for the treatment of akathisia is its recognition and the discontinuation of the offending drug. Beyond this, for symptomatic care, there is a compendium of case reports and small studies supporting many drugs, but only a few have received consistent recommendation. Beta-adrenergic antagonists, such as propranolol, are considered the gold standard, the first choice for the treatment of akathisia. Their toxicities include orthostatic hypotension and bradycardia. Additionally, they are contraindicated in the setting of asthma.

Anticholinergics, such as benztropine (cogentin) and trihexylphenidyl (artane) are considered in the literature as 2nd line treatments, behind beta-blockers. However, the data advocating their use is limited. They have multiple side-effects including sedation, memory impairment, visual impairment, and urinary retention. They are also contraindicated in patients with closed-angle glaucoma.

An equivalent alternative to beta-blockers could also be the 5HT2a receptor antagonists such as mirtazapine (remeron) and cyproheptadine (periactin). This class of medications is thought to act by an inhibitory control of dopaminergic neurons. Sedation and weight gain are the primary toxicities, and they are contraindicated in patients who are breastfeeding.

Benzodiazepines, such as clonazepam (klonopin), have shown some efficacy in improving symptoms but the data is very limited. The risk of tolerance and dependence, coupled with the problems of sedation impacting the elderly, prompts their placement in reserve. Vitamin B6 (pyridoxine), when given in a high dose format, causes significant improvement in akathisia. However, it can cause headache and nausea. Chronic administration of high doses has also been found to cause a severe and irreversible sensory neuropathy as well as lead to seizures. Many other agents have been studied, but the data are too small to warrant recommendation.

Conclusion

Akathisia remains an extreme reaction to drugs not always in the psychotropic class. The hospitalist will likely deal with the acute onset, a dramatic form, and a potentially poor outcome if untreated. The patient’s only true defense is the physician’s clinical acumen and their ability to recognize it.

Dr. Killeen is a physician in Tampa, Fla. He practices internal medicine, hematology, and oncology, and has worked in hospice and hospital medicine.

Recommended reading

Van Gool AR, Doorduijn JK, Sevnaeve C. Severe akathisia as a side effect of metoclopramide. Pharm World Sci. 2010; 32(6):704-706.

Loonen AJM, Stahl SM. The mechanism of drug-induced akathisia. CNS Spectr. 2010;15(11):491-494.

Forcen FE, Matsoukas K, Alici Y. Antipsychotic-induced akathisia in delirium: A systemic review. Palliat Support Care. 2016;14(1):77-84.

Sethuram K, Gedzior J. Akathisia: Case presentation and review of newer treatment agents. Psychiatric Annals. 2014;44(8):391-396.

Pringsheim T, et al. The assessment and treatment of antipsychotic-induced akathisia. Can J Psychiatry. 2018;63(11): 719-729.

Tachere RO, Mandana M. Beyond anxiety and agitation: A clinical approach to akathisia. Royal Australian Coll Gen Practitioners. 2017;46(5): 296-298.

Key points

- Although associated more with psychiatric medications, akathisia can occur with non-psychotropics as well.

- To recognize the illness, the clinician must notice the repetitive involuntary movements and pacing as well as the “ants in the pants” fidgeting involved.

- Primary treatment consists of medication discontinuation with pharmaceutical intervention as a backup.

- Recognition is the key to successful treatment.

Classic signs of akathisia

- Fidgeting – “ants in the pants”

- Swinging the legs while seated

- Rocking from foot to foot

- Walking while in a static position

- Inability to sit or stand still – pacing

- Onset appears with the initiation or dose adjustment of an offending drug

Quiz

1. Which of the following findings occur in Akathisia?

A. Fidgeting

B. Pacing

C. Swinging the legs while seated

D. All the above

Answer: D

Akathisia is manifest as involuntary hyperactivity of the extremities, particularly the lower extremities. People feel the urge to move, to continue endlessly in motion, stopping only when fatigue sets in. The fidgeting has been described by patients as feeling like “ants in the pants.”

2. Which of the following interventions are used to treat akathisia?

A. Drug discontinuation

B. Propranolol

C. Mirtazapine

D. All the above

Answer: D

All the interventions mentioned are used to treat akathisia. The foremost is to stop the offending drug. Failing this, propranolol is the “gold standard” while 5HT2a antagonists, such as mirtazapine, are favored when beta-blockers either fail or are contraindicated.

3. The use of pyridoxine (Vitamin B6) in the treatment of akathisia is associated with what toxicities?

A. Headache

B. Nausea

C. Seizures

D. All the above

Answer: D

The use of Vitamin B6 in the treatment of akathisia has several drawbacks. Its administration is associated with headache and nausea, and high dose usage increases the risk of seizure.

4. If unresolved, akathisia can lead to which of the following?

A. Insomnia

B. Suicide

C. Physical exhaustion

D. All the above

Answer: D

Akathisia, left unrecognized and untreated, can eventually lead to physical exhaustion, and is compounded by difficulties in trying to rest, hence insomnia. The physical and mental torment of this malady can lead to suicide.

Case

The patient is a 65-year-old female with increasing anxiety and agitation. She completed cycle 2 of chemotherapy for breast cancer several hours ago. Her premedication was Reglan (metoclopramide); her only other medication is tamoxifen. Other than breast cancer, she suffers only from osteoarthritis.

She is found pacing about the ward – almost uncontrollably. She feels she must move, only to have to stop and, shortly afterwards, feels the urge to move again. This has never happened to her before. She must move despite being fatigued. She also complains of an odd overall feeling; something akin to “ant in the pants.” She is nervous and exhausted. What is her diagnosis and what clues to it are in her presentation?

Background

The word “akathisia” is derived from the Greek language and means “unable to sit.” It is thought to occur as a consequence of dopaminergic blockade in the midbrain region. The decrease in dopaminergic activity leads to a subsequent decrease in inhibitory motor control which, in turn, manifests as involuntary movements.

In this malady, the patient is seen as perpetually in motion. The patient feels the need to move until they must stop. But once static, they have the urge to move again. They pace, they rock and they ‘fidget’ – they just cannot sit still. This feeling has been likened to having “ants in the pants.” Patients become anxious, agitated, and suffer from insomnia. They cannot rest.

If left unresolved akathisia can torment patients to sheer exhaustion. For some it serves as a harbinger of suicide. This toxicity is more commonly seen in the psychiatric pharmacy with the most common offender being haloperidol. The causative agents of the least notoriety are the non-antipsychotics.

Diagnosis and treatment

Akathisia is an extrapyramidal symptom found largely but NOT exclusively with psychiatric medications. There are drugs in the non-psychiatric field that can also cause it, including antiemetics (e.g., metoclopramide), antihypertensives (e.g., diltiazem), and narcotics (e.g., cocaine). Metoclopramide is given under circumstances ranging from diabetic gastroparesis to premedicating chemotherapy. It is a peripheral and centrally acting dopamine antagonist. There are no lab tests or radiographic workups to diagnose akathisia. Its manifestations are erratic and disturbing, and the prognosis is doleful if unresolved.

The primary intervention for the treatment of akathisia is its recognition and the discontinuation of the offending drug. Beyond this, for symptomatic care, there is a compendium of case reports and small studies supporting many drugs, but only a few have received consistent recommendation. Beta-adrenergic antagonists, such as propranolol, are considered the gold standard, the first choice for the treatment of akathisia. Their toxicities include orthostatic hypotension and bradycardia. Additionally, they are contraindicated in the setting of asthma.

Anticholinergics, such as benztropine (cogentin) and trihexylphenidyl (artane) are considered in the literature as 2nd line treatments, behind beta-blockers. However, the data advocating their use is limited. They have multiple side-effects including sedation, memory impairment, visual impairment, and urinary retention. They are also contraindicated in patients with closed-angle glaucoma.

An equivalent alternative to beta-blockers could also be the 5HT2a receptor antagonists such as mirtazapine (remeron) and cyproheptadine (periactin). This class of medications is thought to act by an inhibitory control of dopaminergic neurons. Sedation and weight gain are the primary toxicities, and they are contraindicated in patients who are breastfeeding.

Benzodiazepines, such as clonazepam (klonopin), have shown some efficacy in improving symptoms but the data is very limited. The risk of tolerance and dependence, coupled with the problems of sedation impacting the elderly, prompts their placement in reserve. Vitamin B6 (pyridoxine), when given in a high dose format, causes significant improvement in akathisia. However, it can cause headache and nausea. Chronic administration of high doses has also been found to cause a severe and irreversible sensory neuropathy as well as lead to seizures. Many other agents have been studied, but the data are too small to warrant recommendation.

Conclusion

Akathisia remains an extreme reaction to drugs not always in the psychotropic class. The hospitalist will likely deal with the acute onset, a dramatic form, and a potentially poor outcome if untreated. The patient’s only true defense is the physician’s clinical acumen and their ability to recognize it.

Dr. Killeen is a physician in Tampa, Fla. He practices internal medicine, hematology, and oncology, and has worked in hospice and hospital medicine.

Recommended reading

Van Gool AR, Doorduijn JK, Sevnaeve C. Severe akathisia as a side effect of metoclopramide. Pharm World Sci. 2010; 32(6):704-706.

Loonen AJM, Stahl SM. The mechanism of drug-induced akathisia. CNS Spectr. 2010;15(11):491-494.

Forcen FE, Matsoukas K, Alici Y. Antipsychotic-induced akathisia in delirium: A systemic review. Palliat Support Care. 2016;14(1):77-84.

Sethuram K, Gedzior J. Akathisia: Case presentation and review of newer treatment agents. Psychiatric Annals. 2014;44(8):391-396.

Pringsheim T, et al. The assessment and treatment of antipsychotic-induced akathisia. Can J Psychiatry. 2018;63(11): 719-729.

Tachere RO, Mandana M. Beyond anxiety and agitation: A clinical approach to akathisia. Royal Australian Coll Gen Practitioners. 2017;46(5): 296-298.

Key points

- Although associated more with psychiatric medications, akathisia can occur with non-psychotropics as well.

- To recognize the illness, the clinician must notice the repetitive involuntary movements and pacing as well as the “ants in the pants” fidgeting involved.

- Primary treatment consists of medication discontinuation with pharmaceutical intervention as a backup.

- Recognition is the key to successful treatment.

Classic signs of akathisia

- Fidgeting – “ants in the pants”

- Swinging the legs while seated

- Rocking from foot to foot

- Walking while in a static position

- Inability to sit or stand still – pacing

- Onset appears with the initiation or dose adjustment of an offending drug

Quiz

1. Which of the following findings occur in Akathisia?

A. Fidgeting

B. Pacing

C. Swinging the legs while seated

D. All the above

Answer: D

Akathisia is manifest as involuntary hyperactivity of the extremities, particularly the lower extremities. People feel the urge to move, to continue endlessly in motion, stopping only when fatigue sets in. The fidgeting has been described by patients as feeling like “ants in the pants.”

2. Which of the following interventions are used to treat akathisia?

A. Drug discontinuation

B. Propranolol

C. Mirtazapine

D. All the above

Answer: D

All the interventions mentioned are used to treat akathisia. The foremost is to stop the offending drug. Failing this, propranolol is the “gold standard” while 5HT2a antagonists, such as mirtazapine, are favored when beta-blockers either fail or are contraindicated.

3. The use of pyridoxine (Vitamin B6) in the treatment of akathisia is associated with what toxicities?

A. Headache

B. Nausea

C. Seizures

D. All the above

Answer: D

The use of Vitamin B6 in the treatment of akathisia has several drawbacks. Its administration is associated with headache and nausea, and high dose usage increases the risk of seizure.

4. If unresolved, akathisia can lead to which of the following?

A. Insomnia

B. Suicide

C. Physical exhaustion

D. All the above

Answer: D

Akathisia, left unrecognized and untreated, can eventually lead to physical exhaustion, and is compounded by difficulties in trying to rest, hence insomnia. The physical and mental torment of this malady can lead to suicide.

Quick byte: Curing diabetes

Harvard biologist Doug Melton, PhD, is exploring the use of stem cells to create replacement beta cells that produce insulin, according to Time magazine.

In 2014, he co-founded Semma Therapeutics to develop the technology, which was acquired by Vertex Pharmaceuticals.

“The company has created a small, implantable device that holds millions of replacement beta cells, letting glucose and insulin through but keeping immune cells out. ‘If it works in people as well as it does in animals, it’s possible that people will not be diabetic,’ said Dr. Melton, co-director of the Harvard Stem Cell Institute and an investigator of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute. ‘They will eat and drink and play like those of us who are not.’”

Reference

Steinberg D. 12 innovations that will change health care and medicine in the 2020s. Time. 2019 Oct 25. https://time.com/5710295/top-health-innovations/ Accessed Dec 5, 2019.

Harvard biologist Doug Melton, PhD, is exploring the use of stem cells to create replacement beta cells that produce insulin, according to Time magazine.

In 2014, he co-founded Semma Therapeutics to develop the technology, which was acquired by Vertex Pharmaceuticals.

“The company has created a small, implantable device that holds millions of replacement beta cells, letting glucose and insulin through but keeping immune cells out. ‘If it works in people as well as it does in animals, it’s possible that people will not be diabetic,’ said Dr. Melton, co-director of the Harvard Stem Cell Institute and an investigator of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute. ‘They will eat and drink and play like those of us who are not.’”

Reference

Steinberg D. 12 innovations that will change health care and medicine in the 2020s. Time. 2019 Oct 25. https://time.com/5710295/top-health-innovations/ Accessed Dec 5, 2019.

Harvard biologist Doug Melton, PhD, is exploring the use of stem cells to create replacement beta cells that produce insulin, according to Time magazine.

In 2014, he co-founded Semma Therapeutics to develop the technology, which was acquired by Vertex Pharmaceuticals.

“The company has created a small, implantable device that holds millions of replacement beta cells, letting glucose and insulin through but keeping immune cells out. ‘If it works in people as well as it does in animals, it’s possible that people will not be diabetic,’ said Dr. Melton, co-director of the Harvard Stem Cell Institute and an investigator of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute. ‘They will eat and drink and play like those of us who are not.’”

Reference

Steinberg D. 12 innovations that will change health care and medicine in the 2020s. Time. 2019 Oct 25. https://time.com/5710295/top-health-innovations/ Accessed Dec 5, 2019.

Victorious endurance: To pass the breaking point and not break

I’ve been thinking a lot about endurance recently.

COVID-19 is surging in the United States. Health care workers exhausted from the first and second waves are quickly reaching the verge of collapse. I’m seeing more and more heartbreaking articles about the bone-deep fatigue, fear, and frustration health care workers are facing, and I weep. As horrible as it is to be fighting this terrifying, little-understood, invisible virus, health care workers are also fighting an equally distressing war against misinformation, recklessness, apathy, and outright denial.

As if that wasn’t enough, we are also dealing with racial and social unrest not seen in decades. The most significant cultural divisions and political animosity perhaps since the Civil War. A contested election. The fraying of our democratic institutions and our standing in the global community. The weakest economy since the Great Depression. Record unemployment. Many individuals and families facing or already experiencing eviction and food insecurity. Record-setting fires, hurricanes, and other natural disasters that are only projected to intensify due to climate change.

That’s a lot to endure. And we don’t have much choice other than to live through it. Some of us will break under the strain; others will disengage by giving up clinical work or even leaving health care altogether. Some of us will pack it in and retire, walk away from relationships with family members or longtime friends, or even emigrate to another country (New Zealand, anyone?). Some of us will passively hunker down, letting the challenges of this time overwhelm us and just hoping we can hang on long enough to emerge, albeit beaten and scarred, on the other side.

But some of us will experience victorious endurance – the kind that doesn’t just accept suffering but finds a way to triumph over it. I came across the concept of victorious endurance in the Bible, but its origin is earlier, from classical Greece. It comes from the ancient Greek word hupomone, which literally means “abiding under” – as in disciplining oneself to bear up under a trial when one would more naturally rebel, or just give up. The ancient Greeks were big on virtues like self-control, long-suffering, and perseverance in the face of seemingly insurmountable difficulties; Odysseus was a poster child for hupomone. I believe the concept of victorious endurance can be applicable for people across many belief systems, philosophies, and ways of life.

The late William Barclay, former professor of divinity and biblical criticism at the University of Glasgow, Scotland, said of hupomone:

It is untranslatable. It does not describe the frame of mind which can sit down with folded hands and bowed head and let a torrent of troubles sweep over it in passive resignation. It describes the ability to bear things in such a triumphant way that it transfigures them. Chrysostom has a great panegyric on this hupomone. He calls it “the root of all goods, the mother of piety, the fruit that never withers, a fortress that is never taken, a harbour that knows no storms” and “the queen of virtues, the foundation of right actions, peace in war, calm in tempest, security in plots.” It is the courageous and triumphant ability to pass the breaking-point and not to break and always to greet the unseen with a cheer. It is the alchemy which transmutes tribulation into strength and glory.

Barclay further noted that “Cicero defines patientia, its Latin equivalent, as: ‘The voluntary and daily suffering of hard and difficult things, for the sake of honour and usefulness.”

In the midst of the most challenging public health emergency of our lifetimes, I am seeing hospitalists – and nurses, respiratory therapists, and countless other health care workers – doing exactly this, every day. I’m so incredibly proud of you all, and thankful beyond words.

I doubt that victorious endurance comes naturally to any of us; it’s something we work at, pursue and nurture. What’s the secret to cultivating victorious endurance in the midst of unimaginable stress? I’m pretty sure there’s no specific formula. I don’t mean to sound like a Pollyanna or to make light of the tumult and turmoil of these times, but here are a few things that, based on my own experiences, may help cultivate this valuable virtue.

Be part of a support network. In the midst of great stress, and especially during this time of social distancing, it’s especially tempting to just hunker down, close in on ourselves, and shut others out – sometimes even our closest friends and loved ones. Maintaining relationships is just too exhausting. But you need people who can come alongside you and offer words of encouragement when you are at your lowest. And there’s nothing that will bring out the best in you like being there to encourage and support someone else. We all need to both receive and to give emotional support at a time like this.

Take the long view. When we’re in the middle of a serious crisis, it seems like the problems we’re facing will last forever. There’s no light at the end of the tunnel, no port in the storm. But even this pandemic won’t last forever. If we can keep in mind the fact that things will eventually get better and that the current situation isn’t permanent, it can help us maintain our perspective and have more patience with the current dysfunction.

Focus on who you want to be in this moment. This is the hardest time most of us have ever lived through, both professionally and personally. But let me throw you a challenge. When you look back on this time from the perspective of five years from now, or maybe ten, how will you want to remember yourself? Who will you want to have been during this time? Looking back, what will make you proud of how you handled this challenge? Be that person.

Look for things to be thankful for. In the midst of the chaos that is our lives and our work right now, I believe we can still occasionally see moments of grace if we keep our eyes open for them. If we aren’t looking for them, we may miss them entirely. And those small moments of love, touches of compassion, displays of selflessness, and even flashes of victorious endurance in yourself or others are gifts to be treasured and held on to – to give thanks for.

Embrace a cause greater than yourself. May I suggest that one thing that might help our efforts to cultivate the virtue of victorious endurance during difficult times might be to embrace a cause that is bigger than yourself; that is, one that lures you to focus beyond your immediate circumstances? What are you passionate about, outside of your life’s normal routine?

If you don’t have a passion, consider what you might become passionate about, with a little effort. For some of us, like me, this will be our faith in God. For others it may be advocating for an end to racism or for broader social justice issues. Maybe it’s working to overcome our cultural and political divisions or to strengthen the institutions of our democracy. Perhaps it’s getting involved with efforts to mitigate climate change. Maybe it’s reaching out to the homeless or hungry in your own community or mentoring a child who is being left behind by the demands of remote learning.

Or perhaps what you embrace is even closer to home: maybe it’s working to eliminate health disparities in your institution or health system, or figuring out how to use technology and resources differently to improve how care is being delivered during or after this pandemic. Maybe it’s as simple as re-committing yourself to personally care for every patient you see today with the very best you have to offer, and with patience, compassion, and grace.

Find something that sets your heart on fire. Something that makes you want to take this difficult time and “transmute tribulation into strength and glory.” Something that, when you look back on these days, will make you thankful that you didn’t just hunker down and subsist through them. Instead, you accomplished great things; you learned; you contributed; and you grew stronger and better.

That’s victorious endurance.

Ms. Flores is a partner at Nelson Flores Hospital Medicine Consultants in La Quinta, Calif. She serves on SHM’s Practice Analysis and Annual Conference Committees and helps to coordinate SHM’s biannual State of Hospital Medicine survey. This essay was published initially on The Hospital Leader, the official blog of SHM.

I’ve been thinking a lot about endurance recently.

COVID-19 is surging in the United States. Health care workers exhausted from the first and second waves are quickly reaching the verge of collapse. I’m seeing more and more heartbreaking articles about the bone-deep fatigue, fear, and frustration health care workers are facing, and I weep. As horrible as it is to be fighting this terrifying, little-understood, invisible virus, health care workers are also fighting an equally distressing war against misinformation, recklessness, apathy, and outright denial.

As if that wasn’t enough, we are also dealing with racial and social unrest not seen in decades. The most significant cultural divisions and political animosity perhaps since the Civil War. A contested election. The fraying of our democratic institutions and our standing in the global community. The weakest economy since the Great Depression. Record unemployment. Many individuals and families facing or already experiencing eviction and food insecurity. Record-setting fires, hurricanes, and other natural disasters that are only projected to intensify due to climate change.

That’s a lot to endure. And we don’t have much choice other than to live through it. Some of us will break under the strain; others will disengage by giving up clinical work or even leaving health care altogether. Some of us will pack it in and retire, walk away from relationships with family members or longtime friends, or even emigrate to another country (New Zealand, anyone?). Some of us will passively hunker down, letting the challenges of this time overwhelm us and just hoping we can hang on long enough to emerge, albeit beaten and scarred, on the other side.

But some of us will experience victorious endurance – the kind that doesn’t just accept suffering but finds a way to triumph over it. I came across the concept of victorious endurance in the Bible, but its origin is earlier, from classical Greece. It comes from the ancient Greek word hupomone, which literally means “abiding under” – as in disciplining oneself to bear up under a trial when one would more naturally rebel, or just give up. The ancient Greeks were big on virtues like self-control, long-suffering, and perseverance in the face of seemingly insurmountable difficulties; Odysseus was a poster child for hupomone. I believe the concept of victorious endurance can be applicable for people across many belief systems, philosophies, and ways of life.

The late William Barclay, former professor of divinity and biblical criticism at the University of Glasgow, Scotland, said of hupomone:

It is untranslatable. It does not describe the frame of mind which can sit down with folded hands and bowed head and let a torrent of troubles sweep over it in passive resignation. It describes the ability to bear things in such a triumphant way that it transfigures them. Chrysostom has a great panegyric on this hupomone. He calls it “the root of all goods, the mother of piety, the fruit that never withers, a fortress that is never taken, a harbour that knows no storms” and “the queen of virtues, the foundation of right actions, peace in war, calm in tempest, security in plots.” It is the courageous and triumphant ability to pass the breaking-point and not to break and always to greet the unseen with a cheer. It is the alchemy which transmutes tribulation into strength and glory.

Barclay further noted that “Cicero defines patientia, its Latin equivalent, as: ‘The voluntary and daily suffering of hard and difficult things, for the sake of honour and usefulness.”

In the midst of the most challenging public health emergency of our lifetimes, I am seeing hospitalists – and nurses, respiratory therapists, and countless other health care workers – doing exactly this, every day. I’m so incredibly proud of you all, and thankful beyond words.

I doubt that victorious endurance comes naturally to any of us; it’s something we work at, pursue and nurture. What’s the secret to cultivating victorious endurance in the midst of unimaginable stress? I’m pretty sure there’s no specific formula. I don’t mean to sound like a Pollyanna or to make light of the tumult and turmoil of these times, but here are a few things that, based on my own experiences, may help cultivate this valuable virtue.

Be part of a support network. In the midst of great stress, and especially during this time of social distancing, it’s especially tempting to just hunker down, close in on ourselves, and shut others out – sometimes even our closest friends and loved ones. Maintaining relationships is just too exhausting. But you need people who can come alongside you and offer words of encouragement when you are at your lowest. And there’s nothing that will bring out the best in you like being there to encourage and support someone else. We all need to both receive and to give emotional support at a time like this.

Take the long view. When we’re in the middle of a serious crisis, it seems like the problems we’re facing will last forever. There’s no light at the end of the tunnel, no port in the storm. But even this pandemic won’t last forever. If we can keep in mind the fact that things will eventually get better and that the current situation isn’t permanent, it can help us maintain our perspective and have more patience with the current dysfunction.

Focus on who you want to be in this moment. This is the hardest time most of us have ever lived through, both professionally and personally. But let me throw you a challenge. When you look back on this time from the perspective of five years from now, or maybe ten, how will you want to remember yourself? Who will you want to have been during this time? Looking back, what will make you proud of how you handled this challenge? Be that person.

Look for things to be thankful for. In the midst of the chaos that is our lives and our work right now, I believe we can still occasionally see moments of grace if we keep our eyes open for them. If we aren’t looking for them, we may miss them entirely. And those small moments of love, touches of compassion, displays of selflessness, and even flashes of victorious endurance in yourself or others are gifts to be treasured and held on to – to give thanks for.

Embrace a cause greater than yourself. May I suggest that one thing that might help our efforts to cultivate the virtue of victorious endurance during difficult times might be to embrace a cause that is bigger than yourself; that is, one that lures you to focus beyond your immediate circumstances? What are you passionate about, outside of your life’s normal routine?

If you don’t have a passion, consider what you might become passionate about, with a little effort. For some of us, like me, this will be our faith in God. For others it may be advocating for an end to racism or for broader social justice issues. Maybe it’s working to overcome our cultural and political divisions or to strengthen the institutions of our democracy. Perhaps it’s getting involved with efforts to mitigate climate change. Maybe it’s reaching out to the homeless or hungry in your own community or mentoring a child who is being left behind by the demands of remote learning.

Or perhaps what you embrace is even closer to home: maybe it’s working to eliminate health disparities in your institution or health system, or figuring out how to use technology and resources differently to improve how care is being delivered during or after this pandemic. Maybe it’s as simple as re-committing yourself to personally care for every patient you see today with the very best you have to offer, and with patience, compassion, and grace.

Find something that sets your heart on fire. Something that makes you want to take this difficult time and “transmute tribulation into strength and glory.” Something that, when you look back on these days, will make you thankful that you didn’t just hunker down and subsist through them. Instead, you accomplished great things; you learned; you contributed; and you grew stronger and better.

That’s victorious endurance.

Ms. Flores is a partner at Nelson Flores Hospital Medicine Consultants in La Quinta, Calif. She serves on SHM’s Practice Analysis and Annual Conference Committees and helps to coordinate SHM’s biannual State of Hospital Medicine survey. This essay was published initially on The Hospital Leader, the official blog of SHM.

I’ve been thinking a lot about endurance recently.

COVID-19 is surging in the United States. Health care workers exhausted from the first and second waves are quickly reaching the verge of collapse. I’m seeing more and more heartbreaking articles about the bone-deep fatigue, fear, and frustration health care workers are facing, and I weep. As horrible as it is to be fighting this terrifying, little-understood, invisible virus, health care workers are also fighting an equally distressing war against misinformation, recklessness, apathy, and outright denial.

As if that wasn’t enough, we are also dealing with racial and social unrest not seen in decades. The most significant cultural divisions and political animosity perhaps since the Civil War. A contested election. The fraying of our democratic institutions and our standing in the global community. The weakest economy since the Great Depression. Record unemployment. Many individuals and families facing or already experiencing eviction and food insecurity. Record-setting fires, hurricanes, and other natural disasters that are only projected to intensify due to climate change.

That’s a lot to endure. And we don’t have much choice other than to live through it. Some of us will break under the strain; others will disengage by giving up clinical work or even leaving health care altogether. Some of us will pack it in and retire, walk away from relationships with family members or longtime friends, or even emigrate to another country (New Zealand, anyone?). Some of us will passively hunker down, letting the challenges of this time overwhelm us and just hoping we can hang on long enough to emerge, albeit beaten and scarred, on the other side.

But some of us will experience victorious endurance – the kind that doesn’t just accept suffering but finds a way to triumph over it. I came across the concept of victorious endurance in the Bible, but its origin is earlier, from classical Greece. It comes from the ancient Greek word hupomone, which literally means “abiding under” – as in disciplining oneself to bear up under a trial when one would more naturally rebel, or just give up. The ancient Greeks were big on virtues like self-control, long-suffering, and perseverance in the face of seemingly insurmountable difficulties; Odysseus was a poster child for hupomone. I believe the concept of victorious endurance can be applicable for people across many belief systems, philosophies, and ways of life.

The late William Barclay, former professor of divinity and biblical criticism at the University of Glasgow, Scotland, said of hupomone:

It is untranslatable. It does not describe the frame of mind which can sit down with folded hands and bowed head and let a torrent of troubles sweep over it in passive resignation. It describes the ability to bear things in such a triumphant way that it transfigures them. Chrysostom has a great panegyric on this hupomone. He calls it “the root of all goods, the mother of piety, the fruit that never withers, a fortress that is never taken, a harbour that knows no storms” and “the queen of virtues, the foundation of right actions, peace in war, calm in tempest, security in plots.” It is the courageous and triumphant ability to pass the breaking-point and not to break and always to greet the unseen with a cheer. It is the alchemy which transmutes tribulation into strength and glory.

Barclay further noted that “Cicero defines patientia, its Latin equivalent, as: ‘The voluntary and daily suffering of hard and difficult things, for the sake of honour and usefulness.”

In the midst of the most challenging public health emergency of our lifetimes, I am seeing hospitalists – and nurses, respiratory therapists, and countless other health care workers – doing exactly this, every day. I’m so incredibly proud of you all, and thankful beyond words.

I doubt that victorious endurance comes naturally to any of us; it’s something we work at, pursue and nurture. What’s the secret to cultivating victorious endurance in the midst of unimaginable stress? I’m pretty sure there’s no specific formula. I don’t mean to sound like a Pollyanna or to make light of the tumult and turmoil of these times, but here are a few things that, based on my own experiences, may help cultivate this valuable virtue.

Be part of a support network. In the midst of great stress, and especially during this time of social distancing, it’s especially tempting to just hunker down, close in on ourselves, and shut others out – sometimes even our closest friends and loved ones. Maintaining relationships is just too exhausting. But you need people who can come alongside you and offer words of encouragement when you are at your lowest. And there’s nothing that will bring out the best in you like being there to encourage and support someone else. We all need to both receive and to give emotional support at a time like this.

Take the long view. When we’re in the middle of a serious crisis, it seems like the problems we’re facing will last forever. There’s no light at the end of the tunnel, no port in the storm. But even this pandemic won’t last forever. If we can keep in mind the fact that things will eventually get better and that the current situation isn’t permanent, it can help us maintain our perspective and have more patience with the current dysfunction.

Focus on who you want to be in this moment. This is the hardest time most of us have ever lived through, both professionally and personally. But let me throw you a challenge. When you look back on this time from the perspective of five years from now, or maybe ten, how will you want to remember yourself? Who will you want to have been during this time? Looking back, what will make you proud of how you handled this challenge? Be that person.

Look for things to be thankful for. In the midst of the chaos that is our lives and our work right now, I believe we can still occasionally see moments of grace if we keep our eyes open for them. If we aren’t looking for them, we may miss them entirely. And those small moments of love, touches of compassion, displays of selflessness, and even flashes of victorious endurance in yourself or others are gifts to be treasured and held on to – to give thanks for.

Embrace a cause greater than yourself. May I suggest that one thing that might help our efforts to cultivate the virtue of victorious endurance during difficult times might be to embrace a cause that is bigger than yourself; that is, one that lures you to focus beyond your immediate circumstances? What are you passionate about, outside of your life’s normal routine?

If you don’t have a passion, consider what you might become passionate about, with a little effort. For some of us, like me, this will be our faith in God. For others it may be advocating for an end to racism or for broader social justice issues. Maybe it’s working to overcome our cultural and political divisions or to strengthen the institutions of our democracy. Perhaps it’s getting involved with efforts to mitigate climate change. Maybe it’s reaching out to the homeless or hungry in your own community or mentoring a child who is being left behind by the demands of remote learning.

Or perhaps what you embrace is even closer to home: maybe it’s working to eliminate health disparities in your institution or health system, or figuring out how to use technology and resources differently to improve how care is being delivered during or after this pandemic. Maybe it’s as simple as re-committing yourself to personally care for every patient you see today with the very best you have to offer, and with patience, compassion, and grace.

Find something that sets your heart on fire. Something that makes you want to take this difficult time and “transmute tribulation into strength and glory.” Something that, when you look back on these days, will make you thankful that you didn’t just hunker down and subsist through them. Instead, you accomplished great things; you learned; you contributed; and you grew stronger and better.

That’s victorious endurance.

Ms. Flores is a partner at Nelson Flores Hospital Medicine Consultants in La Quinta, Calif. She serves on SHM’s Practice Analysis and Annual Conference Committees and helps to coordinate SHM’s biannual State of Hospital Medicine survey. This essay was published initially on The Hospital Leader, the official blog of SHM.

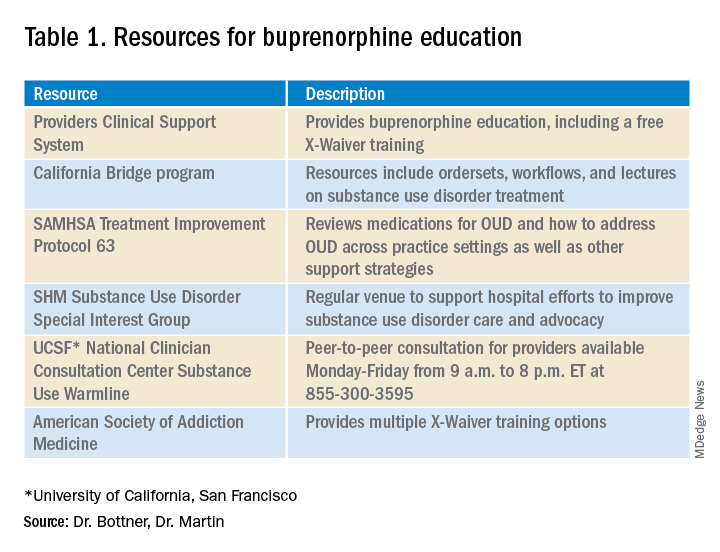

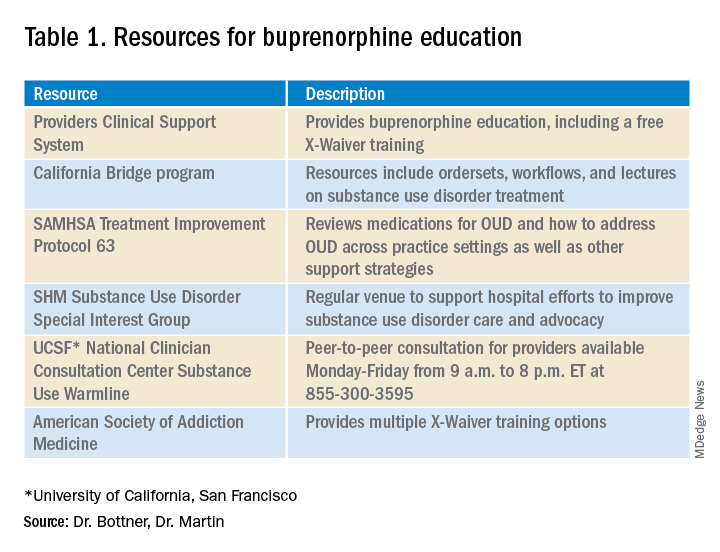

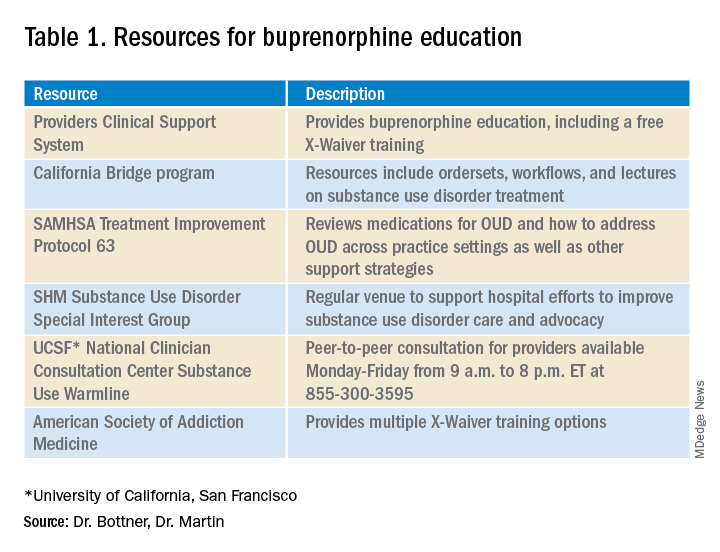

When the X-Waiver gets X’ed: Implications for hospitalists

There are two pandemics permeating the United States: COVID-19 and addiction. To date, more than 468,000 people have died from COVID-19 in the U.S. In the 12-month period ending in May 2020, over 80,000 died from a drug related cause – the highest number ever recorded in a year. Many of these deaths involved opioids.

COVID-19 has worsened outcomes for people with addiction. There is less access to treatment, increased isolation, and worsening psychosocial and economic stressors. These factors may drive new, increased, or more risky substance use and return to use for people in recovery. As hospitalists, we have been responders in both COVID-19 and our country’s worsening overdose and addiction crisis.

In December 2020’s Journal of Hospital Medicine article “Converging Crises: Caring for hospitalized adults with substance use disorder in the time of COVID-19”, Dr. Honora Englander and her coauthors called on hospitalists to actively engage patients with substance use disorders during hospitalization. The article highlights the colliding crises of addiction and COVID-19 and provides eight practical approaches for hospitalists to address substance use disorders during the pandemic, including initiating buprenorphine for opioid withdrawal and prescribing it for opioid use disorder (OUD) treatment.