User login

In reply: Menopause, vitamin D, and oral health

In Reply: Dr. Mascitelli and colleagues bring up an excellent point regarding the role of vitamin D. Vitamin D deficiency (and insufficiency) is such a widespead problem that it deserves attention in both dental and medical circles, and to be fair, it deserves an article of its own. Low vitamin D has been associated with bone loss and an increased risk for certain cancers and other chronic diseases.1 The literature also suggests that low levels of vitamin D are associated with periodontal disease,2 and that supplementation with vitamin D (and calcium) leads to better periodontal health.3,4 However, since vitamin D supplementation is not a recognized way to treat periodontitis, mentioning it with therapies adjudicated as treatment modalities (such as removal of biofilm, which we stressed in our paper) risks misinterpretation by clinicians less versed in periodontal and dental conditions in general.

Nevertheless, the comment brings to light that medical, dental, and nutritional colleagues are very interested in learning more about the pathophysiologic commonalities in the diseases we treat and in a common postmenopausal patient cohort. Our paper focused more closely on what periodontitis is, and on the more primary etiologic pathophysiology—what common resorptive pathways it shares with osteoporosis in the postmenopausal cohort, and biofilm, the primary etiology of periodontitis. But there is need for more discussion and research into bone development (during childhood and adolescence as well) and the role of nutrition during all stages of life.

- Holick M. Vitamin D deficiency. N Eng J Med 2007; 357:266–281.

- Dietrich T, Joshipura KJ, Dawson-Hughes B, Bischoff-Ferrari HA. Association between serum concentrations of 25-hydroxyvitamin D3 and periodontal disease in the US population. Am J Clin Nutr 2004; 80:108–113.

- Miley DD, Garcia MN, Hildebolt CF, et al. Cross-sectional study of vitamin d and calcium supplementation effects on chronic periodontitis. J Periodontol 2009; 80:1433–1439.

- Amano Y, Komiyama K, Makishima M. Vitamin D and periodontal disease. J Oral Sci 2009; 51:11–20.

In Reply: Dr. Mascitelli and colleagues bring up an excellent point regarding the role of vitamin D. Vitamin D deficiency (and insufficiency) is such a widespead problem that it deserves attention in both dental and medical circles, and to be fair, it deserves an article of its own. Low vitamin D has been associated with bone loss and an increased risk for certain cancers and other chronic diseases.1 The literature also suggests that low levels of vitamin D are associated with periodontal disease,2 and that supplementation with vitamin D (and calcium) leads to better periodontal health.3,4 However, since vitamin D supplementation is not a recognized way to treat periodontitis, mentioning it with therapies adjudicated as treatment modalities (such as removal of biofilm, which we stressed in our paper) risks misinterpretation by clinicians less versed in periodontal and dental conditions in general.

Nevertheless, the comment brings to light that medical, dental, and nutritional colleagues are very interested in learning more about the pathophysiologic commonalities in the diseases we treat and in a common postmenopausal patient cohort. Our paper focused more closely on what periodontitis is, and on the more primary etiologic pathophysiology—what common resorptive pathways it shares with osteoporosis in the postmenopausal cohort, and biofilm, the primary etiology of periodontitis. But there is need for more discussion and research into bone development (during childhood and adolescence as well) and the role of nutrition during all stages of life.

In Reply: Dr. Mascitelli and colleagues bring up an excellent point regarding the role of vitamin D. Vitamin D deficiency (and insufficiency) is such a widespead problem that it deserves attention in both dental and medical circles, and to be fair, it deserves an article of its own. Low vitamin D has been associated with bone loss and an increased risk for certain cancers and other chronic diseases.1 The literature also suggests that low levels of vitamin D are associated with periodontal disease,2 and that supplementation with vitamin D (and calcium) leads to better periodontal health.3,4 However, since vitamin D supplementation is not a recognized way to treat periodontitis, mentioning it with therapies adjudicated as treatment modalities (such as removal of biofilm, which we stressed in our paper) risks misinterpretation by clinicians less versed in periodontal and dental conditions in general.

Nevertheless, the comment brings to light that medical, dental, and nutritional colleagues are very interested in learning more about the pathophysiologic commonalities in the diseases we treat and in a common postmenopausal patient cohort. Our paper focused more closely on what periodontitis is, and on the more primary etiologic pathophysiology—what common resorptive pathways it shares with osteoporosis in the postmenopausal cohort, and biofilm, the primary etiology of periodontitis. But there is need for more discussion and research into bone development (during childhood and adolescence as well) and the role of nutrition during all stages of life.

- Holick M. Vitamin D deficiency. N Eng J Med 2007; 357:266–281.

- Dietrich T, Joshipura KJ, Dawson-Hughes B, Bischoff-Ferrari HA. Association between serum concentrations of 25-hydroxyvitamin D3 and periodontal disease in the US population. Am J Clin Nutr 2004; 80:108–113.

- Miley DD, Garcia MN, Hildebolt CF, et al. Cross-sectional study of vitamin d and calcium supplementation effects on chronic periodontitis. J Periodontol 2009; 80:1433–1439.

- Amano Y, Komiyama K, Makishima M. Vitamin D and periodontal disease. J Oral Sci 2009; 51:11–20.

- Holick M. Vitamin D deficiency. N Eng J Med 2007; 357:266–281.

- Dietrich T, Joshipura KJ, Dawson-Hughes B, Bischoff-Ferrari HA. Association between serum concentrations of 25-hydroxyvitamin D3 and periodontal disease in the US population. Am J Clin Nutr 2004; 80:108–113.

- Miley DD, Garcia MN, Hildebolt CF, et al. Cross-sectional study of vitamin d and calcium supplementation effects on chronic periodontitis. J Periodontol 2009; 80:1433–1439.

- Amano Y, Komiyama K, Makishima M. Vitamin D and periodontal disease. J Oral Sci 2009; 51:11–20.

Prostate cancer prevention

To the Editor: Thank you for the excellent review on prostate cancer screening and prevention by Eric A. Klein, MD, in your August 2009 issue.

Dr. Klein concludes that the results of the Prostate Cancer Prevention Trial (PCPT) and the Reduction by Dutasteride of Prostate Events (REDUCE) trial were “congruent” with respect to the magnitude of prostate cancer risk prevention, beneficial effects on benign prostatic hypertrophy, and toxicity. In other words, finasteride and dutasteride produced equivalent clinical results with respect to prostate health despite the fact that dutasteride inhibits 5-alpha-reductase types 1 and 2, while finasteride inhibits only type 2.

Over the years, many patients have been prescribed dutasteride rather than finasteride because of hopes that the former might be more effective for maintaining prostate health. In August 2009, the retail price on Drugstore.com of a 90-day supply of generic finasteride is $190, vs $321 for dutasteride (which is available only as branded Avodart). In my experience as a practicing primary care physician, most patients would prefer to save money by switching to the less expensive generic drug if it provides equivalent prostate health outcomes compared with the more expensive branded drug.

I would like to ask Dr. Klein’s opinion on allowing patients to switch from Avodart to generic finasteride in order to save money, and on the general issue of which agent to use first-line for prostate health concerns.

To the Editor: Thank you for the excellent review on prostate cancer screening and prevention by Eric A. Klein, MD, in your August 2009 issue.

Dr. Klein concludes that the results of the Prostate Cancer Prevention Trial (PCPT) and the Reduction by Dutasteride of Prostate Events (REDUCE) trial were “congruent” with respect to the magnitude of prostate cancer risk prevention, beneficial effects on benign prostatic hypertrophy, and toxicity. In other words, finasteride and dutasteride produced equivalent clinical results with respect to prostate health despite the fact that dutasteride inhibits 5-alpha-reductase types 1 and 2, while finasteride inhibits only type 2.

Over the years, many patients have been prescribed dutasteride rather than finasteride because of hopes that the former might be more effective for maintaining prostate health. In August 2009, the retail price on Drugstore.com of a 90-day supply of generic finasteride is $190, vs $321 for dutasteride (which is available only as branded Avodart). In my experience as a practicing primary care physician, most patients would prefer to save money by switching to the less expensive generic drug if it provides equivalent prostate health outcomes compared with the more expensive branded drug.

I would like to ask Dr. Klein’s opinion on allowing patients to switch from Avodart to generic finasteride in order to save money, and on the general issue of which agent to use first-line for prostate health concerns.

To the Editor: Thank you for the excellent review on prostate cancer screening and prevention by Eric A. Klein, MD, in your August 2009 issue.

Dr. Klein concludes that the results of the Prostate Cancer Prevention Trial (PCPT) and the Reduction by Dutasteride of Prostate Events (REDUCE) trial were “congruent” with respect to the magnitude of prostate cancer risk prevention, beneficial effects on benign prostatic hypertrophy, and toxicity. In other words, finasteride and dutasteride produced equivalent clinical results with respect to prostate health despite the fact that dutasteride inhibits 5-alpha-reductase types 1 and 2, while finasteride inhibits only type 2.

Over the years, many patients have been prescribed dutasteride rather than finasteride because of hopes that the former might be more effective for maintaining prostate health. In August 2009, the retail price on Drugstore.com of a 90-day supply of generic finasteride is $190, vs $321 for dutasteride (which is available only as branded Avodart). In my experience as a practicing primary care physician, most patients would prefer to save money by switching to the less expensive generic drug if it provides equivalent prostate health outcomes compared with the more expensive branded drug.

I would like to ask Dr. Klein’s opinion on allowing patients to switch from Avodart to generic finasteride in order to save money, and on the general issue of which agent to use first-line for prostate health concerns.

In reply: Prostate cancer prevention

In Reply: Although the two drugs were not compared head to head, the data from randomized trials suggest that they have similar effects on the amelioration of lower urinary tract symptoms due to benign prostatic hypertrophy. The full results of the REDUCE trial are not yet available and until they are published it is not possible to comment any further on whether one or the other is the better choice for prevention of prostate cancer.

In Reply: Although the two drugs were not compared head to head, the data from randomized trials suggest that they have similar effects on the amelioration of lower urinary tract symptoms due to benign prostatic hypertrophy. The full results of the REDUCE trial are not yet available and until they are published it is not possible to comment any further on whether one or the other is the better choice for prevention of prostate cancer.

In Reply: Although the two drugs were not compared head to head, the data from randomized trials suggest that they have similar effects on the amelioration of lower urinary tract symptoms due to benign prostatic hypertrophy. The full results of the REDUCE trial are not yet available and until they are published it is not possible to comment any further on whether one or the other is the better choice for prevention of prostate cancer.

Letters to the Editor

Insulin is designated a high‐alert medication because of its potential to result in harm if it is used incorrectly.1 Despite this, changes in insulin regimens made in the inpatient setting are often poorly communicated to either the patient or his primary care physician at the time of discharge.2 Poor communication of medication instructions at the time of hospital discharge has been linked to medication errors and adverse drug events.3

We conducted a quality improvement project to improve and standardize the communication of insulin instructions to patients (and/or their caregivers) at hospital discharge. Specifically, we developed and implemented a standardized discharge instructions for insulin (DIFI) form and compared the comprehensiveness of insulin instructions and diabetes‐related readmissions before and after the introduction of the form.

Methods

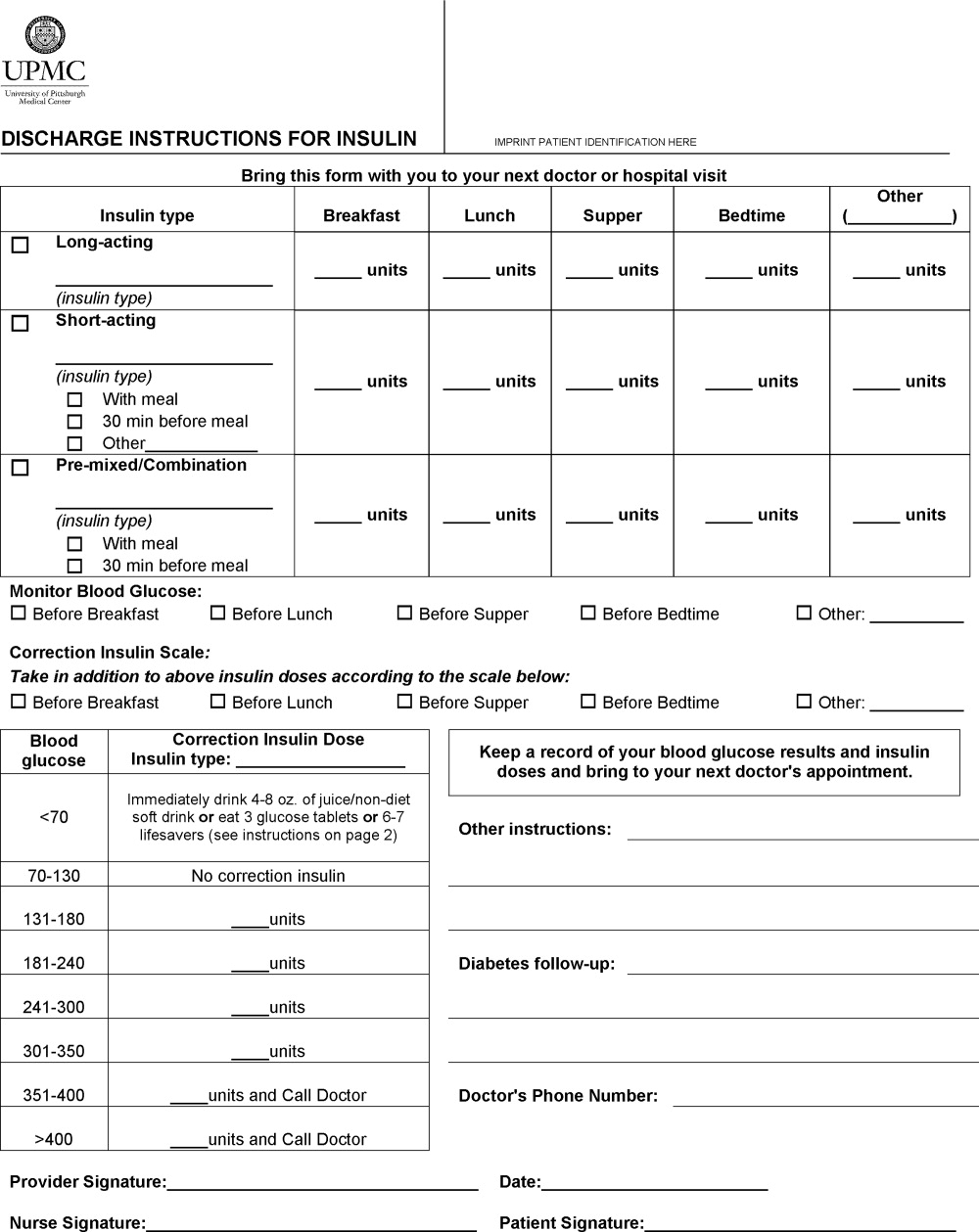

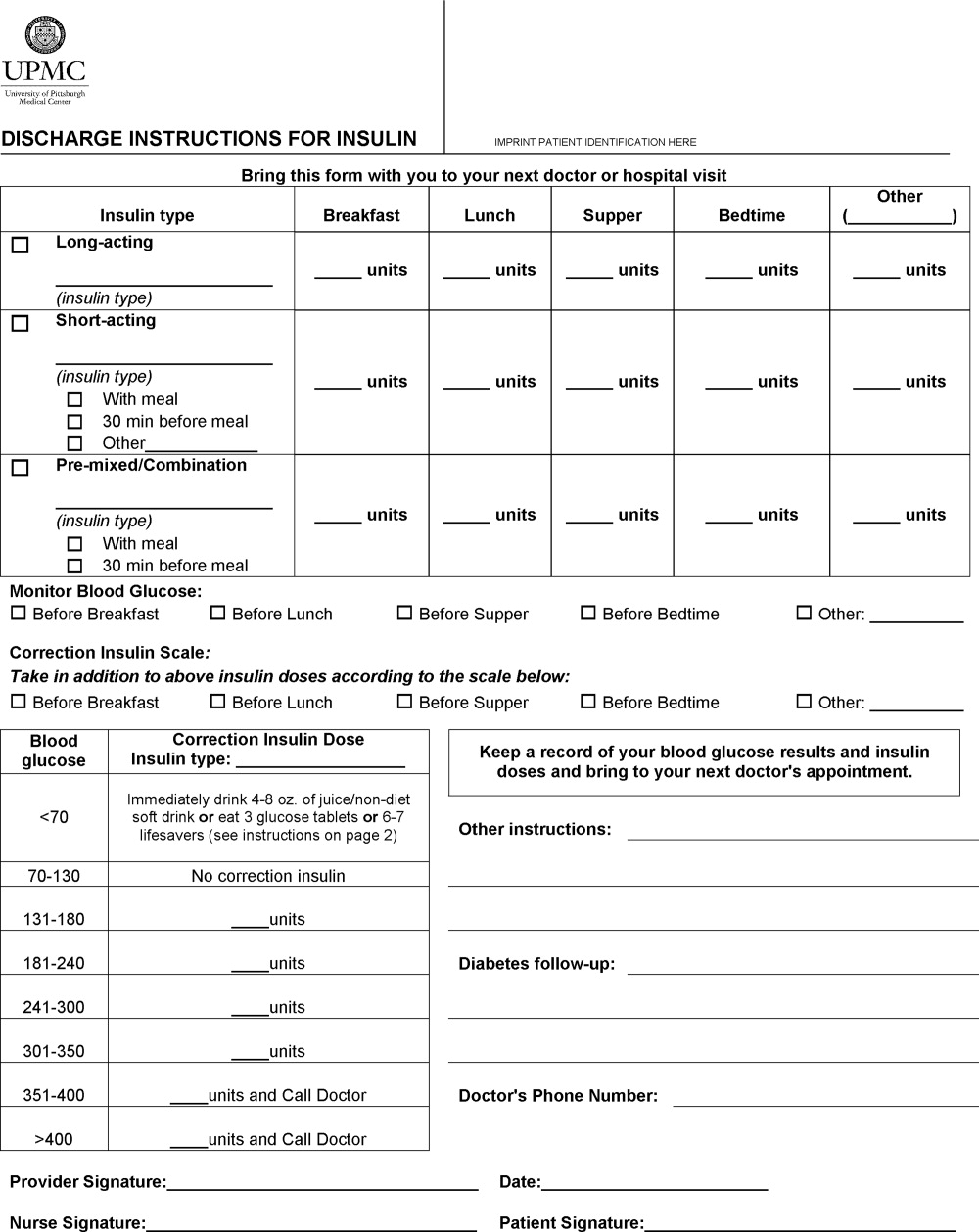

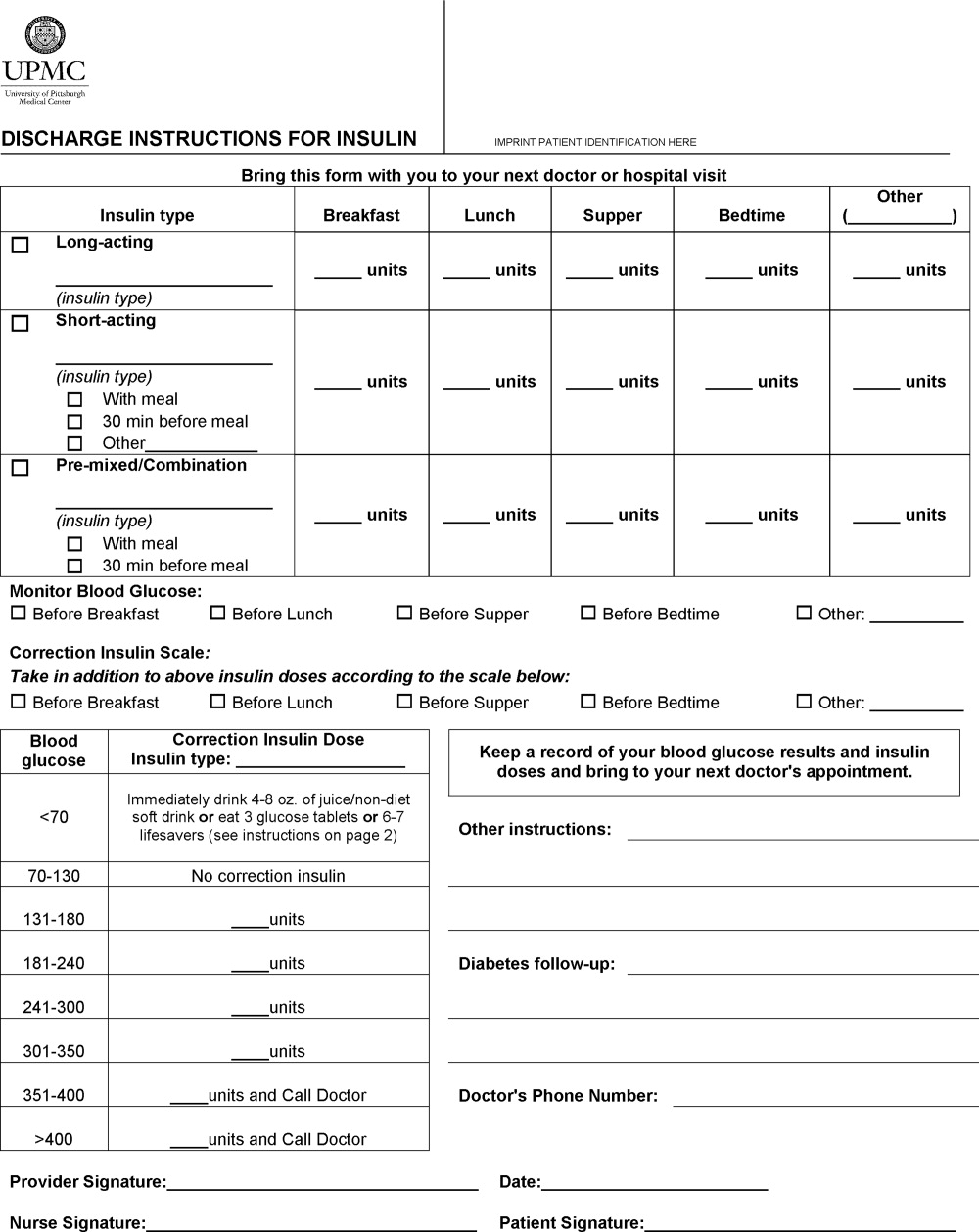

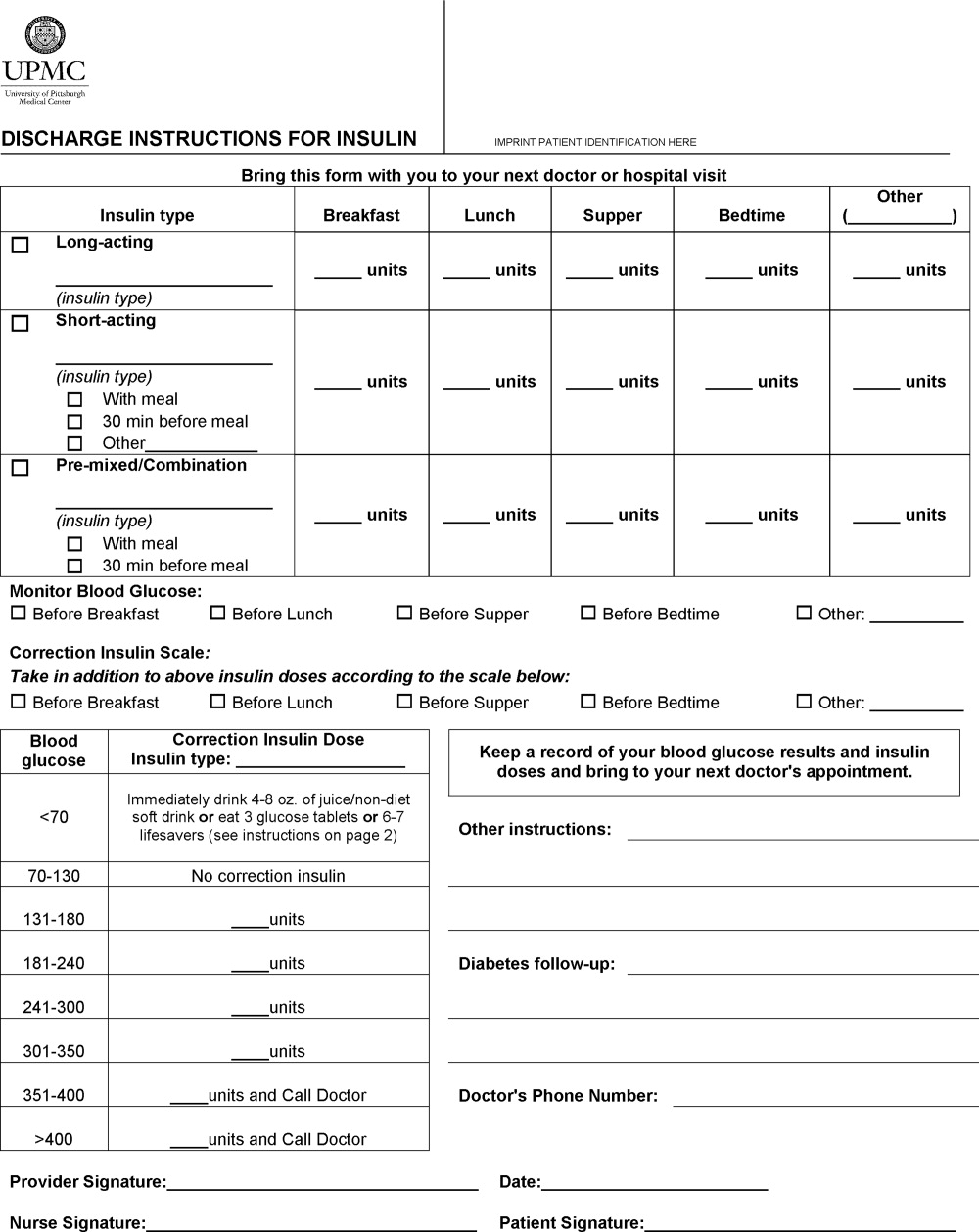

A multidisciplinary team4 created the DIFI form. Page 1 (Figure 1) includes sections for entering all insulin types and doses and the frequency of glucose monitoring and a space for specific diabetes instructions. Page 2 provides general information on symptom recognition and management of hyperglycemia and hypoglycemia. Page 3 is a blank glucose log.

We retrospectively reviewed the records of patients discharged to home on insulin from a general medicine unit during the 3‐month period before availability of the DIFI form and during the 3‐month period afterward. Approval for this project was obtained from the hospital's quality improvement review committee. The percentages of orders with specific instructions for the timing and dosing of basal, prandial, and correction insulin and home glucose monitoring were calculated. The number of patients readmitted within 2 weeks of discharge for a diabetes‐related problem was also determined. Fisher's exact tests were used to compare demographics and indicators in the preimplementation and postimplementation groups.

Results

Chart review was performed for 67 patients with insulin orders at discharge prior to the DIFI form and for 27 patients after implementation. There were no group differences in gender (female gender: 63% pre‐DIFI vs. 63% post‐DIFI, P = 0.49), previous history of diabetes (98.5% vs. 92.6%, P = 0.20), diabetes‐related admitting diagnosis (20.1% vs. 37%, P = 0.12), or insulin use prior to admission (95.5% vs. 85.2%, P = 0.10).

More orders written with the DIFI form contained specific instructions for timing and dosing of basal (67% vs. 100%, P = 0.0003), prandial (51% vs. 100%, P = 0.0008), and correction insulin (14% vs. 95%, P 0.0001) and for glucose monitoring (17.9% vs. 88.9%, P 0.0001). There were 4 diabetes‐related readmissions in the preimplementation group and none in the postimplementation group (P = not significant).

Discussion

It is important that patients receive clear directions at the time of hospital discharge to ensure a safe transition of care from the inpatient setting to the outpatient setting. This is particularly true for insulin regimens, which frequently consist of at least 2 different types of insulin and often include instructions for modifying doses on the basis of home glucose readings. The day of hospital discharge is not conducive to recall of verbal communication concerning complicated medication regimens.5 Additionally, our hospital's standard discharge form was not a satisfactory tool for providing detailed directions. We found that the DIFI form prompted a more consistent provision of specific instructions for insulin therapy and glucose monitoring in comparison with previous practice.

- Institute for Safe Medication Practices. ISMP's list of high‐alert medications. Available at: http://www.ismp.org/tools/highalertmedications.pdf. Accessed December 2008.

- , , , .Promoting effective transitions of care at hospital discharge: a review of key issues for hospitalists.J Hosp Med.2007;2:314–323.

- , , , , .The incidence and severity of adverse events affecting patients after discharge from the hospital.Ann Intern Med.2003;138:161–167.

- , , , , .Evolution of a diabetes inpatient safety committee.Endocr Pract.2006;12(suppl 3):91–99.

- , , , , .Scheduling of pharmacist‐provided medication education for hospitalized patients.Hosp Pharm.2008;43:121–126.

Insulin is designated a high‐alert medication because of its potential to result in harm if it is used incorrectly.1 Despite this, changes in insulin regimens made in the inpatient setting are often poorly communicated to either the patient or his primary care physician at the time of discharge.2 Poor communication of medication instructions at the time of hospital discharge has been linked to medication errors and adverse drug events.3

We conducted a quality improvement project to improve and standardize the communication of insulin instructions to patients (and/or their caregivers) at hospital discharge. Specifically, we developed and implemented a standardized discharge instructions for insulin (DIFI) form and compared the comprehensiveness of insulin instructions and diabetes‐related readmissions before and after the introduction of the form.

Methods

A multidisciplinary team4 created the DIFI form. Page 1 (Figure 1) includes sections for entering all insulin types and doses and the frequency of glucose monitoring and a space for specific diabetes instructions. Page 2 provides general information on symptom recognition and management of hyperglycemia and hypoglycemia. Page 3 is a blank glucose log.

We retrospectively reviewed the records of patients discharged to home on insulin from a general medicine unit during the 3‐month period before availability of the DIFI form and during the 3‐month period afterward. Approval for this project was obtained from the hospital's quality improvement review committee. The percentages of orders with specific instructions for the timing and dosing of basal, prandial, and correction insulin and home glucose monitoring were calculated. The number of patients readmitted within 2 weeks of discharge for a diabetes‐related problem was also determined. Fisher's exact tests were used to compare demographics and indicators in the preimplementation and postimplementation groups.

Results

Chart review was performed for 67 patients with insulin orders at discharge prior to the DIFI form and for 27 patients after implementation. There were no group differences in gender (female gender: 63% pre‐DIFI vs. 63% post‐DIFI, P = 0.49), previous history of diabetes (98.5% vs. 92.6%, P = 0.20), diabetes‐related admitting diagnosis (20.1% vs. 37%, P = 0.12), or insulin use prior to admission (95.5% vs. 85.2%, P = 0.10).

More orders written with the DIFI form contained specific instructions for timing and dosing of basal (67% vs. 100%, P = 0.0003), prandial (51% vs. 100%, P = 0.0008), and correction insulin (14% vs. 95%, P 0.0001) and for glucose monitoring (17.9% vs. 88.9%, P 0.0001). There were 4 diabetes‐related readmissions in the preimplementation group and none in the postimplementation group (P = not significant).

Discussion

It is important that patients receive clear directions at the time of hospital discharge to ensure a safe transition of care from the inpatient setting to the outpatient setting. This is particularly true for insulin regimens, which frequently consist of at least 2 different types of insulin and often include instructions for modifying doses on the basis of home glucose readings. The day of hospital discharge is not conducive to recall of verbal communication concerning complicated medication regimens.5 Additionally, our hospital's standard discharge form was not a satisfactory tool for providing detailed directions. We found that the DIFI form prompted a more consistent provision of specific instructions for insulin therapy and glucose monitoring in comparison with previous practice.

Insulin is designated a high‐alert medication because of its potential to result in harm if it is used incorrectly.1 Despite this, changes in insulin regimens made in the inpatient setting are often poorly communicated to either the patient or his primary care physician at the time of discharge.2 Poor communication of medication instructions at the time of hospital discharge has been linked to medication errors and adverse drug events.3

We conducted a quality improvement project to improve and standardize the communication of insulin instructions to patients (and/or their caregivers) at hospital discharge. Specifically, we developed and implemented a standardized discharge instructions for insulin (DIFI) form and compared the comprehensiveness of insulin instructions and diabetes‐related readmissions before and after the introduction of the form.

Methods

A multidisciplinary team4 created the DIFI form. Page 1 (Figure 1) includes sections for entering all insulin types and doses and the frequency of glucose monitoring and a space for specific diabetes instructions. Page 2 provides general information on symptom recognition and management of hyperglycemia and hypoglycemia. Page 3 is a blank glucose log.

We retrospectively reviewed the records of patients discharged to home on insulin from a general medicine unit during the 3‐month period before availability of the DIFI form and during the 3‐month period afterward. Approval for this project was obtained from the hospital's quality improvement review committee. The percentages of orders with specific instructions for the timing and dosing of basal, prandial, and correction insulin and home glucose monitoring were calculated. The number of patients readmitted within 2 weeks of discharge for a diabetes‐related problem was also determined. Fisher's exact tests were used to compare demographics and indicators in the preimplementation and postimplementation groups.

Results

Chart review was performed for 67 patients with insulin orders at discharge prior to the DIFI form and for 27 patients after implementation. There were no group differences in gender (female gender: 63% pre‐DIFI vs. 63% post‐DIFI, P = 0.49), previous history of diabetes (98.5% vs. 92.6%, P = 0.20), diabetes‐related admitting diagnosis (20.1% vs. 37%, P = 0.12), or insulin use prior to admission (95.5% vs. 85.2%, P = 0.10).

More orders written with the DIFI form contained specific instructions for timing and dosing of basal (67% vs. 100%, P = 0.0003), prandial (51% vs. 100%, P = 0.0008), and correction insulin (14% vs. 95%, P 0.0001) and for glucose monitoring (17.9% vs. 88.9%, P 0.0001). There were 4 diabetes‐related readmissions in the preimplementation group and none in the postimplementation group (P = not significant).

Discussion

It is important that patients receive clear directions at the time of hospital discharge to ensure a safe transition of care from the inpatient setting to the outpatient setting. This is particularly true for insulin regimens, which frequently consist of at least 2 different types of insulin and often include instructions for modifying doses on the basis of home glucose readings. The day of hospital discharge is not conducive to recall of verbal communication concerning complicated medication regimens.5 Additionally, our hospital's standard discharge form was not a satisfactory tool for providing detailed directions. We found that the DIFI form prompted a more consistent provision of specific instructions for insulin therapy and glucose monitoring in comparison with previous practice.

- Institute for Safe Medication Practices. ISMP's list of high‐alert medications. Available at: http://www.ismp.org/tools/highalertmedications.pdf. Accessed December 2008.

- , , , .Promoting effective transitions of care at hospital discharge: a review of key issues for hospitalists.J Hosp Med.2007;2:314–323.

- , , , , .The incidence and severity of adverse events affecting patients after discharge from the hospital.Ann Intern Med.2003;138:161–167.

- , , , , .Evolution of a diabetes inpatient safety committee.Endocr Pract.2006;12(suppl 3):91–99.

- , , , , .Scheduling of pharmacist‐provided medication education for hospitalized patients.Hosp Pharm.2008;43:121–126.

- Institute for Safe Medication Practices. ISMP's list of high‐alert medications. Available at: http://www.ismp.org/tools/highalertmedications.pdf. Accessed December 2008.

- , , , .Promoting effective transitions of care at hospital discharge: a review of key issues for hospitalists.J Hosp Med.2007;2:314–323.

- , , , , .The incidence and severity of adverse events affecting patients after discharge from the hospital.Ann Intern Med.2003;138:161–167.

- , , , , .Evolution of a diabetes inpatient safety committee.Endocr Pract.2006;12(suppl 3):91–99.

- , , , , .Scheduling of pharmacist‐provided medication education for hospitalized patients.Hosp Pharm.2008;43:121–126.

Diabetic ketoacidosis

To the Editor: I read with interest the article by Hu and Isaacson1 on methods to distinguish type 1 from type 2 diabetes.

While a laboratory workup may be helpful in some hyperglycemic patients, I am unsure what value C-peptide testing (it costs approximately $40 at ARUP Laboratories, Salt Lake City, UT) would offer to the patient in question. Even without considering his age (48), two diabetic parents, and weight of 278 lb, the fact that he had controlled his diabetes for 6 years with diet and metformin makes a history of type 1 diabetes impossible. Could he have new-onset autoimmune diabetes complicating type 2 diabetes? His age makes this highly unlikely, and as the authors note, this is the phase of type 1 diabetes when a C-peptide level may still be normal. My guess is that the level was actually sent just “to see,” or as a rough measure of whether his pancreatitis had so impaired his insulin secretion that he would have an insulin-deficiency diabetes in addition to his type 2 diabetes. One hopes, however, that the severity of pancreatitis would be the primary clue to this possibility.

One test won’t break the camel’s back, but I write to promote the “booger rule” coined by a former mentor: ordering a test is like picking your nose—you have to know what you’re going to do with the result before you go digging. This advice encourages clinical problem-solving and reduces phlebotomy-induced anemia, venous access issues, and costs. (In my academic hospitalist practice, I can frequently cancel hundreds of dollars of “morning labs” on a nightly basis.) In some cases it may be crucial: as resident, I was unable to stop a cardiac catheterization we knew could not influence care, and biopsy of a brain mass in an elderly patient (too ill for any cancer care) that caused a lethal hemorrhage. As an attending, I have prevented a diagnostic colonoscopy on a patient with less than a week to live.

- Hu M, Isaacson JH. A 48-year-old man with uncontrolled diabetes. Cleve Clin J Med 2009; 76:413–416.

To the Editor: I read with interest the article by Hu and Isaacson1 on methods to distinguish type 1 from type 2 diabetes.

While a laboratory workup may be helpful in some hyperglycemic patients, I am unsure what value C-peptide testing (it costs approximately $40 at ARUP Laboratories, Salt Lake City, UT) would offer to the patient in question. Even without considering his age (48), two diabetic parents, and weight of 278 lb, the fact that he had controlled his diabetes for 6 years with diet and metformin makes a history of type 1 diabetes impossible. Could he have new-onset autoimmune diabetes complicating type 2 diabetes? His age makes this highly unlikely, and as the authors note, this is the phase of type 1 diabetes when a C-peptide level may still be normal. My guess is that the level was actually sent just “to see,” or as a rough measure of whether his pancreatitis had so impaired his insulin secretion that he would have an insulin-deficiency diabetes in addition to his type 2 diabetes. One hopes, however, that the severity of pancreatitis would be the primary clue to this possibility.

One test won’t break the camel’s back, but I write to promote the “booger rule” coined by a former mentor: ordering a test is like picking your nose—you have to know what you’re going to do with the result before you go digging. This advice encourages clinical problem-solving and reduces phlebotomy-induced anemia, venous access issues, and costs. (In my academic hospitalist practice, I can frequently cancel hundreds of dollars of “morning labs” on a nightly basis.) In some cases it may be crucial: as resident, I was unable to stop a cardiac catheterization we knew could not influence care, and biopsy of a brain mass in an elderly patient (too ill for any cancer care) that caused a lethal hemorrhage. As an attending, I have prevented a diagnostic colonoscopy on a patient with less than a week to live.

To the Editor: I read with interest the article by Hu and Isaacson1 on methods to distinguish type 1 from type 2 diabetes.

While a laboratory workup may be helpful in some hyperglycemic patients, I am unsure what value C-peptide testing (it costs approximately $40 at ARUP Laboratories, Salt Lake City, UT) would offer to the patient in question. Even without considering his age (48), two diabetic parents, and weight of 278 lb, the fact that he had controlled his diabetes for 6 years with diet and metformin makes a history of type 1 diabetes impossible. Could he have new-onset autoimmune diabetes complicating type 2 diabetes? His age makes this highly unlikely, and as the authors note, this is the phase of type 1 diabetes when a C-peptide level may still be normal. My guess is that the level was actually sent just “to see,” or as a rough measure of whether his pancreatitis had so impaired his insulin secretion that he would have an insulin-deficiency diabetes in addition to his type 2 diabetes. One hopes, however, that the severity of pancreatitis would be the primary clue to this possibility.

One test won’t break the camel’s back, but I write to promote the “booger rule” coined by a former mentor: ordering a test is like picking your nose—you have to know what you’re going to do with the result before you go digging. This advice encourages clinical problem-solving and reduces phlebotomy-induced anemia, venous access issues, and costs. (In my academic hospitalist practice, I can frequently cancel hundreds of dollars of “morning labs” on a nightly basis.) In some cases it may be crucial: as resident, I was unable to stop a cardiac catheterization we knew could not influence care, and biopsy of a brain mass in an elderly patient (too ill for any cancer care) that caused a lethal hemorrhage. As an attending, I have prevented a diagnostic colonoscopy on a patient with less than a week to live.

- Hu M, Isaacson JH. A 48-year-old man with uncontrolled diabetes. Cleve Clin J Med 2009; 76:413–416.

- Hu M, Isaacson JH. A 48-year-old man with uncontrolled diabetes. Cleve Clin J Med 2009; 76:413–416.

In reply: Diabetic ketoacidosis

In Reply: Dr. Jenkins brings up an important issue in his letter, and in fact we endorse his approach of ordering tests only if they will lead to a change in management. As we outlined in our case, clinical information alone strongly supported the diagnosis of type 2 diabetes mellitus.

In Reply: Dr. Jenkins brings up an important issue in his letter, and in fact we endorse his approach of ordering tests only if they will lead to a change in management. As we outlined in our case, clinical information alone strongly supported the diagnosis of type 2 diabetes mellitus.

In Reply: Dr. Jenkins brings up an important issue in his letter, and in fact we endorse his approach of ordering tests only if they will lead to a change in management. As we outlined in our case, clinical information alone strongly supported the diagnosis of type 2 diabetes mellitus.

Pregabalin for fibromyalgia

To the Editor: The article by Kim et al regarding the use of pregabalin (Lyrica) in fibromyalgia is interesting and timely.1 We would like make some additional comments.

They claim that “many hail pregabalin as an important advance in our understanding of the pathogenesis of fibromyalgia and how to treat it,” but they fail to cite who those “many” are. We contend that aside from the pharmaceutical company’s representatives, physicians on its speaker’s bureau, and those participating in paid drug studies, it would be difficult to substantiate this statement.

The authors’ historical overview discusses Gowers’ description of fibrositis but misinterprets his discussion. Gowers did not believe that “inflammation of muscles” was a problem, but that fibrous tissue itself was inflamed (thus the term “fibrositis,” not “myositis”) and could thus produce pain such as pharyngitis and sciatica, as well as “muscular rheumatism.”2

The authors review functional abnormalities in central nervous system processing as an etiology of pain. Russell et al are cited as elucidating the role of substance P in the process.3 Although they showed that substance P was three times higher in the cerebrospinal fluid of fibromyalgia patients compared with normal controls, the cited paper also notes that there was an inverse relationship between substance P levels and tenderness. Substance P also did not correlate with the Visual Analogue Scale self-assessment of pain severity or “with any other clinical variable.”3

A question of whether appropriate controls were chosen for the study has to be raised as well, since 25 of 32 fibromyalgia patients and only 3 of 30 controls had “possible depression.”3 The discussion of other therapies has limitations. The authors rely on two meta-analyses and a review to suggest that the efficacy of tricyclics is supported by a variety of studies. We don’t disagree, but as we previously noted, long-term studies don’t support prolonged efficacy of these drugs, which raises questions of treatment of a chronic illness.4 Duloxetine (Cymbalta) and milnacipran (Savella) are briefly mentioned. The authors should have used at least a sentence for each drug to indicate that the drugs have their own substantial shortcomings.

Finally, the authors conclude their article by asking, “What role for pregabalin?” A careful reading of that section does not appear to provide an answer. We recently presented a study suggesting that pregabalin and standard therapy were equally effective (or equally not effective), suggesting that pregabalin neither represents a major pharmaceutical advance in therapy nor is likely to “advance our understanding of the pathogenesis of fibromyalgia.”5 We do agree with the authors that medications are only part of a comprehensive program of therapy, and further point out that fibromyalgia undoubtedly represents the end point of a variety of etiologic insults and is unlikely to be one specific syndrome.

- Kim L, Lipton S, Deodhar A. Pregabalin for fibromyalgia: some relief but no cure. Cleve Clin J Med 2009; 76:255–261.

- Abeles M. Fibromyalgia syndrome. In:Manu P, Editor: Functional Somatic Syndromes. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1998:32–57.

- Russell IJ, Orr MD, Littman B, et al. Elevated cerebrospinal fluid levels of substance P in patients with fibromyalgia syndrome. Arthritis Rheum 1994; 37:1593–1601.

- Abeles M, Abeles SR, Abeles AM. Fibromyalgia remains a controversial medical enigma [letter]. Am Fam Physician 2008; 77:1220.

- Abeles M, Abeles AM. Is pregabalin better than conventional therapy in fibromyalgia? [abstract] Arthritis Rheum 2008; 58( suppl):S396.

To the Editor: The article by Kim et al regarding the use of pregabalin (Lyrica) in fibromyalgia is interesting and timely.1 We would like make some additional comments.

They claim that “many hail pregabalin as an important advance in our understanding of the pathogenesis of fibromyalgia and how to treat it,” but they fail to cite who those “many” are. We contend that aside from the pharmaceutical company’s representatives, physicians on its speaker’s bureau, and those participating in paid drug studies, it would be difficult to substantiate this statement.

The authors’ historical overview discusses Gowers’ description of fibrositis but misinterprets his discussion. Gowers did not believe that “inflammation of muscles” was a problem, but that fibrous tissue itself was inflamed (thus the term “fibrositis,” not “myositis”) and could thus produce pain such as pharyngitis and sciatica, as well as “muscular rheumatism.”2

The authors review functional abnormalities in central nervous system processing as an etiology of pain. Russell et al are cited as elucidating the role of substance P in the process.3 Although they showed that substance P was three times higher in the cerebrospinal fluid of fibromyalgia patients compared with normal controls, the cited paper also notes that there was an inverse relationship between substance P levels and tenderness. Substance P also did not correlate with the Visual Analogue Scale self-assessment of pain severity or “with any other clinical variable.”3

A question of whether appropriate controls were chosen for the study has to be raised as well, since 25 of 32 fibromyalgia patients and only 3 of 30 controls had “possible depression.”3 The discussion of other therapies has limitations. The authors rely on two meta-analyses and a review to suggest that the efficacy of tricyclics is supported by a variety of studies. We don’t disagree, but as we previously noted, long-term studies don’t support prolonged efficacy of these drugs, which raises questions of treatment of a chronic illness.4 Duloxetine (Cymbalta) and milnacipran (Savella) are briefly mentioned. The authors should have used at least a sentence for each drug to indicate that the drugs have their own substantial shortcomings.

Finally, the authors conclude their article by asking, “What role for pregabalin?” A careful reading of that section does not appear to provide an answer. We recently presented a study suggesting that pregabalin and standard therapy were equally effective (or equally not effective), suggesting that pregabalin neither represents a major pharmaceutical advance in therapy nor is likely to “advance our understanding of the pathogenesis of fibromyalgia.”5 We do agree with the authors that medications are only part of a comprehensive program of therapy, and further point out that fibromyalgia undoubtedly represents the end point of a variety of etiologic insults and is unlikely to be one specific syndrome.

To the Editor: The article by Kim et al regarding the use of pregabalin (Lyrica) in fibromyalgia is interesting and timely.1 We would like make some additional comments.

They claim that “many hail pregabalin as an important advance in our understanding of the pathogenesis of fibromyalgia and how to treat it,” but they fail to cite who those “many” are. We contend that aside from the pharmaceutical company’s representatives, physicians on its speaker’s bureau, and those participating in paid drug studies, it would be difficult to substantiate this statement.

The authors’ historical overview discusses Gowers’ description of fibrositis but misinterprets his discussion. Gowers did not believe that “inflammation of muscles” was a problem, but that fibrous tissue itself was inflamed (thus the term “fibrositis,” not “myositis”) and could thus produce pain such as pharyngitis and sciatica, as well as “muscular rheumatism.”2

The authors review functional abnormalities in central nervous system processing as an etiology of pain. Russell et al are cited as elucidating the role of substance P in the process.3 Although they showed that substance P was three times higher in the cerebrospinal fluid of fibromyalgia patients compared with normal controls, the cited paper also notes that there was an inverse relationship between substance P levels and tenderness. Substance P also did not correlate with the Visual Analogue Scale self-assessment of pain severity or “with any other clinical variable.”3

A question of whether appropriate controls were chosen for the study has to be raised as well, since 25 of 32 fibromyalgia patients and only 3 of 30 controls had “possible depression.”3 The discussion of other therapies has limitations. The authors rely on two meta-analyses and a review to suggest that the efficacy of tricyclics is supported by a variety of studies. We don’t disagree, but as we previously noted, long-term studies don’t support prolonged efficacy of these drugs, which raises questions of treatment of a chronic illness.4 Duloxetine (Cymbalta) and milnacipran (Savella) are briefly mentioned. The authors should have used at least a sentence for each drug to indicate that the drugs have their own substantial shortcomings.

Finally, the authors conclude their article by asking, “What role for pregabalin?” A careful reading of that section does not appear to provide an answer. We recently presented a study suggesting that pregabalin and standard therapy were equally effective (or equally not effective), suggesting that pregabalin neither represents a major pharmaceutical advance in therapy nor is likely to “advance our understanding of the pathogenesis of fibromyalgia.”5 We do agree with the authors that medications are only part of a comprehensive program of therapy, and further point out that fibromyalgia undoubtedly represents the end point of a variety of etiologic insults and is unlikely to be one specific syndrome.

- Kim L, Lipton S, Deodhar A. Pregabalin for fibromyalgia: some relief but no cure. Cleve Clin J Med 2009; 76:255–261.

- Abeles M. Fibromyalgia syndrome. In:Manu P, Editor: Functional Somatic Syndromes. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1998:32–57.

- Russell IJ, Orr MD, Littman B, et al. Elevated cerebrospinal fluid levels of substance P in patients with fibromyalgia syndrome. Arthritis Rheum 1994; 37:1593–1601.

- Abeles M, Abeles SR, Abeles AM. Fibromyalgia remains a controversial medical enigma [letter]. Am Fam Physician 2008; 77:1220.

- Abeles M, Abeles AM. Is pregabalin better than conventional therapy in fibromyalgia? [abstract] Arthritis Rheum 2008; 58( suppl):S396.

- Kim L, Lipton S, Deodhar A. Pregabalin for fibromyalgia: some relief but no cure. Cleve Clin J Med 2009; 76:255–261.

- Abeles M. Fibromyalgia syndrome. In:Manu P, Editor: Functional Somatic Syndromes. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1998:32–57.

- Russell IJ, Orr MD, Littman B, et al. Elevated cerebrospinal fluid levels of substance P in patients with fibromyalgia syndrome. Arthritis Rheum 1994; 37:1593–1601.

- Abeles M, Abeles SR, Abeles AM. Fibromyalgia remains a controversial medical enigma [letter]. Am Fam Physician 2008; 77:1220.

- Abeles M, Abeles AM. Is pregabalin better than conventional therapy in fibromyalgia? [abstract] Arthritis Rheum 2008; 58( suppl):S396.

In reply: Pregabalin for fibromyalgia

In Reply: We would like to thank the Drs. Abeles for reading our paper1 and providing valuable input. We are, however, surprised by their question as to who the “many” people are who believe that pregabalin is an important advance in the treatment of fibromyalgia. Anyone who is involved in taking care of fibromyalgia patients would know that several patients regularly report being helped by this medication to a varying degree. These patients rightly believe that this drug—the first drug approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for their oft-misunderstood condition—has started a much-needed dialogue in the medical community, and that in itself is a major advance.

We accept that Gowers, in his original paper on “fibrositis,” believed that fibrous tissue and not muscle was the source of inflammation in this condition.

We do believe that the paper by Russell et al2 was one of the many investigations that helped establish the role of central sensitization or abnormalities in pain processing in the central nervous system as the root cause of fibromyalgia pain. However, we do not believe our paper on pregabalin was the right place to discuss the merits or shortcomings of that paper in any more detail.

As we mentioned in our paper, therapies for fibromyalgia have limitations, and duloxetine and milnacipran are no exceptions. However, both these drugs were approved after our review was completed. We believe that the role of pregabalin in the treatment of fibromyalgia is going to be limited simply because medications overall form a small part of the comprehensive program of therapy for this condition.

- Kim L, Lipton S, Deodhar A. Pregabalin for fibromyalgia: some relief but no cure. Cleve Clin J Med 2009; 76:255–261.

- Russell IJ, Orr MD, Littman B, et al. Elevated cerebrospinal fluid levels of substance P in patients with fibromyalgia syndrome. Arthritis Rheum 1994; 37:1593–1601.

In Reply: We would like to thank the Drs. Abeles for reading our paper1 and providing valuable input. We are, however, surprised by their question as to who the “many” people are who believe that pregabalin is an important advance in the treatment of fibromyalgia. Anyone who is involved in taking care of fibromyalgia patients would know that several patients regularly report being helped by this medication to a varying degree. These patients rightly believe that this drug—the first drug approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for their oft-misunderstood condition—has started a much-needed dialogue in the medical community, and that in itself is a major advance.

We accept that Gowers, in his original paper on “fibrositis,” believed that fibrous tissue and not muscle was the source of inflammation in this condition.

We do believe that the paper by Russell et al2 was one of the many investigations that helped establish the role of central sensitization or abnormalities in pain processing in the central nervous system as the root cause of fibromyalgia pain. However, we do not believe our paper on pregabalin was the right place to discuss the merits or shortcomings of that paper in any more detail.

As we mentioned in our paper, therapies for fibromyalgia have limitations, and duloxetine and milnacipran are no exceptions. However, both these drugs were approved after our review was completed. We believe that the role of pregabalin in the treatment of fibromyalgia is going to be limited simply because medications overall form a small part of the comprehensive program of therapy for this condition.

In Reply: We would like to thank the Drs. Abeles for reading our paper1 and providing valuable input. We are, however, surprised by their question as to who the “many” people are who believe that pregabalin is an important advance in the treatment of fibromyalgia. Anyone who is involved in taking care of fibromyalgia patients would know that several patients regularly report being helped by this medication to a varying degree. These patients rightly believe that this drug—the first drug approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for their oft-misunderstood condition—has started a much-needed dialogue in the medical community, and that in itself is a major advance.

We accept that Gowers, in his original paper on “fibrositis,” believed that fibrous tissue and not muscle was the source of inflammation in this condition.

We do believe that the paper by Russell et al2 was one of the many investigations that helped establish the role of central sensitization or abnormalities in pain processing in the central nervous system as the root cause of fibromyalgia pain. However, we do not believe our paper on pregabalin was the right place to discuss the merits or shortcomings of that paper in any more detail.

As we mentioned in our paper, therapies for fibromyalgia have limitations, and duloxetine and milnacipran are no exceptions. However, both these drugs were approved after our review was completed. We believe that the role of pregabalin in the treatment of fibromyalgia is going to be limited simply because medications overall form a small part of the comprehensive program of therapy for this condition.

- Kim L, Lipton S, Deodhar A. Pregabalin for fibromyalgia: some relief but no cure. Cleve Clin J Med 2009; 76:255–261.

- Russell IJ, Orr MD, Littman B, et al. Elevated cerebrospinal fluid levels of substance P in patients with fibromyalgia syndrome. Arthritis Rheum 1994; 37:1593–1601.

- Kim L, Lipton S, Deodhar A. Pregabalin for fibromyalgia: some relief but no cure. Cleve Clin J Med 2009; 76:255–261.

- Russell IJ, Orr MD, Littman B, et al. Elevated cerebrospinal fluid levels of substance P in patients with fibromyalgia syndrome. Arthritis Rheum 1994; 37:1593–1601.

In reply: Radiologic workup of a palpable breast mass

The authors thank Dr. Keller for his readership. (On a personal note, Dr. Chellman-Jeffers spent her childhood in the Los Angeles area near his practice.) Dr. Keller brings up several interesting points regarding breast MRI, a subject that fills entire subspecialty textbooks.

On the subject of a palpable abnormality, a breast MRI’s field of view encompasses the entire breast, and although breast MRI is quite sensitive, it is known to have a lower specificity than other modalities.1 This means that more findings—which may or may not be related to the actual palpable abnormality—will lead to more studies and more biopsies, with proportionately fewer cancers found.

As for regions of tissue coverage with mammography, the axillary tail is actually more consistently imaged with mammography and ultrasonography than with MRI because of the cardiac pulsation artifact in the plane of the heart, as well as the breastcoil image centering on the breast. MRI-guided biopsy in the axilla is also generally not possible. These limitations are typical for breast MRI equipment. The expense of breast MRI is indeed considerable, but cost is not the main reason for the preference of other modalities.

In contrast, targeted ultrasonography is exquisitely suited to specifically image a palpable abnormality. With its small field of view (4 cm and smaller), a very high percentage of palpable masses can be seen. It is also more personal and comfortable and can be patient-directed. You can ask the patient to physically show you what is being felt and then scan it in real time. Needle biopsy can then be performed, often during the same visit (at many facilities), using ultrasonography as a real-time guidance tool in any location within the breast, including the axilla.

In the algorithm implied by your question, the patient feels a lump and has a negative diagnostic mammogram (including specific, problem-directed views) and targeted ultrasonography, which, again, is more focused than MRI and more capable of imaging the axilla or areas out of the breast coil for this purpose. Then, based on clinical suspicion or patient anxiety, these two very good tests are disregarded or not believed. At this point, the patient should be seen by a specialist, usually a surgeon, for evaluation for palpation-guided biopsy. It is true that some palpable masses are not identified by mammography and ultrasonography. But it is also true that MRI does not find every cancer, and it can find many more lesions that are not cancerous and that have a dubious relation to the original area of concern. This can easily turn into the proverbial wild-goose chase. No matter the outcome of the MRI, the patient still needs to be seen by a surgeon.

Our two major indications for breast MRI are currently in the preoperative extent-of-disease workup for known breast cancer and as an additional screening examination for high-risk patients (lifetime risk greater than 20%–25% by BRCAPRO, Gail, or other model method per the 2007 American Cancer Society guidelines2). We always require a comparative review of mammography in the completed interpretation of breast MRI and, as such, do not consider MRI a viable (or statistically proven) substitute for screening mammography for patients with sensitive breasts. Breast MRI is in fact more physically challenging for most patients than mammography, because the patient needs to remain motionless in a prone position in an enclosed space for an extended period of time (our protocol is 17 minutes). Gadolinium contrast must also be given, which requires renal function laboratory tests and intravenous access. The study must also be scheduled in all premenopausal patients in the postmenstrual phase of her cycle (around days 7–14) to avoid diffuse hormonally related enhancement and to minimize false-positive results.

- Orel S. Who should have breast magnetic resonance imaging evaluation? J Clin Oncol 2008; 26:703–711.

- Saslow D, Boetes C, Burke W, et al; American Cancer Society Breast Cancer Advisory Group. American Cancer Society guidelines for breast cancer screening with MRI as an adjunct to mammography, CA Cancer J Clin 2007; 57:75–89. Erratum in: CA Cancer J Clin 2007; 57:185.

The authors thank Dr. Keller for his readership. (On a personal note, Dr. Chellman-Jeffers spent her childhood in the Los Angeles area near his practice.) Dr. Keller brings up several interesting points regarding breast MRI, a subject that fills entire subspecialty textbooks.

On the subject of a palpable abnormality, a breast MRI’s field of view encompasses the entire breast, and although breast MRI is quite sensitive, it is known to have a lower specificity than other modalities.1 This means that more findings—which may or may not be related to the actual palpable abnormality—will lead to more studies and more biopsies, with proportionately fewer cancers found.

As for regions of tissue coverage with mammography, the axillary tail is actually more consistently imaged with mammography and ultrasonography than with MRI because of the cardiac pulsation artifact in the plane of the heart, as well as the breastcoil image centering on the breast. MRI-guided biopsy in the axilla is also generally not possible. These limitations are typical for breast MRI equipment. The expense of breast MRI is indeed considerable, but cost is not the main reason for the preference of other modalities.

In contrast, targeted ultrasonography is exquisitely suited to specifically image a palpable abnormality. With its small field of view (4 cm and smaller), a very high percentage of palpable masses can be seen. It is also more personal and comfortable and can be patient-directed. You can ask the patient to physically show you what is being felt and then scan it in real time. Needle biopsy can then be performed, often during the same visit (at many facilities), using ultrasonography as a real-time guidance tool in any location within the breast, including the axilla.

In the algorithm implied by your question, the patient feels a lump and has a negative diagnostic mammogram (including specific, problem-directed views) and targeted ultrasonography, which, again, is more focused than MRI and more capable of imaging the axilla or areas out of the breast coil for this purpose. Then, based on clinical suspicion or patient anxiety, these two very good tests are disregarded or not believed. At this point, the patient should be seen by a specialist, usually a surgeon, for evaluation for palpation-guided biopsy. It is true that some palpable masses are not identified by mammography and ultrasonography. But it is also true that MRI does not find every cancer, and it can find many more lesions that are not cancerous and that have a dubious relation to the original area of concern. This can easily turn into the proverbial wild-goose chase. No matter the outcome of the MRI, the patient still needs to be seen by a surgeon.

Our two major indications for breast MRI are currently in the preoperative extent-of-disease workup for known breast cancer and as an additional screening examination for high-risk patients (lifetime risk greater than 20%–25% by BRCAPRO, Gail, or other model method per the 2007 American Cancer Society guidelines2). We always require a comparative review of mammography in the completed interpretation of breast MRI and, as such, do not consider MRI a viable (or statistically proven) substitute for screening mammography for patients with sensitive breasts. Breast MRI is in fact more physically challenging for most patients than mammography, because the patient needs to remain motionless in a prone position in an enclosed space for an extended period of time (our protocol is 17 minutes). Gadolinium contrast must also be given, which requires renal function laboratory tests and intravenous access. The study must also be scheduled in all premenopausal patients in the postmenstrual phase of her cycle (around days 7–14) to avoid diffuse hormonally related enhancement and to minimize false-positive results.

The authors thank Dr. Keller for his readership. (On a personal note, Dr. Chellman-Jeffers spent her childhood in the Los Angeles area near his practice.) Dr. Keller brings up several interesting points regarding breast MRI, a subject that fills entire subspecialty textbooks.

On the subject of a palpable abnormality, a breast MRI’s field of view encompasses the entire breast, and although breast MRI is quite sensitive, it is known to have a lower specificity than other modalities.1 This means that more findings—which may or may not be related to the actual palpable abnormality—will lead to more studies and more biopsies, with proportionately fewer cancers found.

As for regions of tissue coverage with mammography, the axillary tail is actually more consistently imaged with mammography and ultrasonography than with MRI because of the cardiac pulsation artifact in the plane of the heart, as well as the breastcoil image centering on the breast. MRI-guided biopsy in the axilla is also generally not possible. These limitations are typical for breast MRI equipment. The expense of breast MRI is indeed considerable, but cost is not the main reason for the preference of other modalities.

In contrast, targeted ultrasonography is exquisitely suited to specifically image a palpable abnormality. With its small field of view (4 cm and smaller), a very high percentage of palpable masses can be seen. It is also more personal and comfortable and can be patient-directed. You can ask the patient to physically show you what is being felt and then scan it in real time. Needle biopsy can then be performed, often during the same visit (at many facilities), using ultrasonography as a real-time guidance tool in any location within the breast, including the axilla.

In the algorithm implied by your question, the patient feels a lump and has a negative diagnostic mammogram (including specific, problem-directed views) and targeted ultrasonography, which, again, is more focused than MRI and more capable of imaging the axilla or areas out of the breast coil for this purpose. Then, based on clinical suspicion or patient anxiety, these two very good tests are disregarded or not believed. At this point, the patient should be seen by a specialist, usually a surgeon, for evaluation for palpation-guided biopsy. It is true that some palpable masses are not identified by mammography and ultrasonography. But it is also true that MRI does not find every cancer, and it can find many more lesions that are not cancerous and that have a dubious relation to the original area of concern. This can easily turn into the proverbial wild-goose chase. No matter the outcome of the MRI, the patient still needs to be seen by a surgeon.

Our two major indications for breast MRI are currently in the preoperative extent-of-disease workup for known breast cancer and as an additional screening examination for high-risk patients (lifetime risk greater than 20%–25% by BRCAPRO, Gail, or other model method per the 2007 American Cancer Society guidelines2). We always require a comparative review of mammography in the completed interpretation of breast MRI and, as such, do not consider MRI a viable (or statistically proven) substitute for screening mammography for patients with sensitive breasts. Breast MRI is in fact more physically challenging for most patients than mammography, because the patient needs to remain motionless in a prone position in an enclosed space for an extended period of time (our protocol is 17 minutes). Gadolinium contrast must also be given, which requires renal function laboratory tests and intravenous access. The study must also be scheduled in all premenopausal patients in the postmenstrual phase of her cycle (around days 7–14) to avoid diffuse hormonally related enhancement and to minimize false-positive results.

- Orel S. Who should have breast magnetic resonance imaging evaluation? J Clin Oncol 2008; 26:703–711.

- Saslow D, Boetes C, Burke W, et al; American Cancer Society Breast Cancer Advisory Group. American Cancer Society guidelines for breast cancer screening with MRI as an adjunct to mammography, CA Cancer J Clin 2007; 57:75–89. Erratum in: CA Cancer J Clin 2007; 57:185.

- Orel S. Who should have breast magnetic resonance imaging evaluation? J Clin Oncol 2008; 26:703–711.

- Saslow D, Boetes C, Burke W, et al; American Cancer Society Breast Cancer Advisory Group. American Cancer Society guidelines for breast cancer screening with MRI as an adjunct to mammography, CA Cancer J Clin 2007; 57:75–89. Erratum in: CA Cancer J Clin 2007; 57:185.

Radiologic workup of a palpable breast mass

To the Editor: Thank you for the excellent review, “The radiologic workup of a palpable breast mass” in your March 2009 issue.1

The authors stated that magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the breast “does not currently have a role in the workup of a palpable abnormality.” This may be true in general, because breast MRI is more expensive than mammography plus or minus ultrasonography. However, breast surgeons are currently ordering preoperative MRI to evaluate biopsy-proven breast cancer to help them plan the surgery. This is because MRI provides superior three-dimensional spatial resolution and image quality as compared with ultrasonography or mammography.

My question is whether breast MRI might be useful in the prebiopsy diagnostic workup of breast masses in special cases. For example, some women have very sensitive breasts and refuse to undergo mammography, which requires compression of the breast. Another special case is when the palpable mass is located in a portion of the breast which is not amenable to mammography, such as in the axillary tail of the breast. In these cases, MRI might be helpful if the palpable mass is not definitively imaged with ultrasonography. Would the authors care to comment?

- Stein L, Chellman-Jeffers M. Radiologic workup of a palpable breast mass. Cleve Clin J Med 2009; 76:175–180.

To the Editor: Thank you for the excellent review, “The radiologic workup of a palpable breast mass” in your March 2009 issue.1

The authors stated that magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the breast “does not currently have a role in the workup of a palpable abnormality.” This may be true in general, because breast MRI is more expensive than mammography plus or minus ultrasonography. However, breast surgeons are currently ordering preoperative MRI to evaluate biopsy-proven breast cancer to help them plan the surgery. This is because MRI provides superior three-dimensional spatial resolution and image quality as compared with ultrasonography or mammography.

My question is whether breast MRI might be useful in the prebiopsy diagnostic workup of breast masses in special cases. For example, some women have very sensitive breasts and refuse to undergo mammography, which requires compression of the breast. Another special case is when the palpable mass is located in a portion of the breast which is not amenable to mammography, such as in the axillary tail of the breast. In these cases, MRI might be helpful if the palpable mass is not definitively imaged with ultrasonography. Would the authors care to comment?

To the Editor: Thank you for the excellent review, “The radiologic workup of a palpable breast mass” in your March 2009 issue.1

The authors stated that magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the breast “does not currently have a role in the workup of a palpable abnormality.” This may be true in general, because breast MRI is more expensive than mammography plus or minus ultrasonography. However, breast surgeons are currently ordering preoperative MRI to evaluate biopsy-proven breast cancer to help them plan the surgery. This is because MRI provides superior three-dimensional spatial resolution and image quality as compared with ultrasonography or mammography.

My question is whether breast MRI might be useful in the prebiopsy diagnostic workup of breast masses in special cases. For example, some women have very sensitive breasts and refuse to undergo mammography, which requires compression of the breast. Another special case is when the palpable mass is located in a portion of the breast which is not amenable to mammography, such as in the axillary tail of the breast. In these cases, MRI might be helpful if the palpable mass is not definitively imaged with ultrasonography. Would the authors care to comment?

- Stein L, Chellman-Jeffers M. Radiologic workup of a palpable breast mass. Cleve Clin J Med 2009; 76:175–180.

- Stein L, Chellman-Jeffers M. Radiologic workup of a palpable breast mass. Cleve Clin J Med 2009; 76:175–180.