User login

CPT and relative value changes that may affect reimbursement to your ObGyn practice

Another year brings changes to Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes (which are developed and copyrighted by the American Medical Association) in the form of additions and revisions, and payments related to resource-based relative value scale (RBRVS) revisions for selected services. As of January 1, 2018, 2 new Category I codes pertain to laparoscopic treatments for gynecologic cancer, and the 4 existing codes for colporrhaphy have been revised to include cystourethroscopy. New Category III codes include 4 for fetal magnetocardiography and 1 for transvaginal tactile imaging. Medicare also has reevaluated certain relative value units (RVUs) in outpatient and facility settings.

New and revised Category I codes

Laparoscopic treatments for gynecologic cancer. Technologic advances in performing laparoscopic procedures have allowed for more extensive laparoscopic surgery for various gynecologic cancers and, to this end, 2 new codes have been added.

First, a new code was added to capture comprehensive laparoscopic surgical staging for gynecologic cancer. This new code, 38573, Laparoscopy, surgical; with bilateral total pelvic lymphadenectomy and peri-aortic lymph node sampling, peritoneal washings, peritoneal biopsy(ies), omentectomy, and diaphragmatic washings, including diaphragmatic and other serosal biopsy(ies), when performed, may not be reported with any other code that includes lymphadenectomy, omentectomy, or hysterectomy. It is intended primarily for a stand-alone staging procedure after an initial biopsy shows a gynecologic malignancy such as ovarian cancer. This new code has been valued at 33.59 RVUs.

Second, a new code was added to capture laparoscopic debulking in conjunction with hysterectomy. The new code, 58575, Laparoscopy, surgical, total hysterectomy for resection of malignancy (tumor debulking), with omentectomy including salpingo-oophorectomy, unilateral or bilateral, when performed, has been valued at 53.62 RVUs. The open equivalent to this new code is 58953, Bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy with omentectomy, total abdominal hysterectomy and radical dissection for debulking.

Cystourethroscopy. The revisions involve no longer permitting separate reporting of 52000, Cystourethroscopy (separate procedure), with the colporrhaphy codes 57240−57265. The rationale behind this change was that surgeons were routinely performing cystoscopy at the time of these procedures and therefore it should become part of the surgical procedure. Currently the Medicare National Correct Coding Initiative (NCCI) bundles 52000 with these 4 codes, but only code 57250 allows for the use of a modifier -59 to bypass the edit if the purpose of the cystoscopy was evaluation of a distinct complaint or problem (such as evaluating patient-expressed urinary symptoms prior to the surgery that were investigated at the time of the prolapse surgery). When codes 57240, 57260, or 57265 are billed along with 52000, the cystoscopy will be denied and a modifier -59 cannot be reported to bypass this edit.

New Category III codes

The new Category III codes represent emerging technology, and it is important to report them, rather than an unlisted code, if the procedures described are performed so that data can be collected for later consideration to make these Category I CPT codes. Since these codes are not assigned relative values, the provider will need to let the payer know which existing CPT Category I code most closely represents the work involved.

Fetal magnetocardiography. The new Category III codes for fetal magnetocardiography describe essentially a fetal electrocardiogram (ECG) that would be performed to assess fetal arrhythmias by placing up to 3 leads on the mother’s abdomen. Possible comparison codes for physician work might include 59050, fetal monitoring by consultant during labor; 93000−93010, 12-lead ECG, or 93040−93042, rhythm strip up to 3 leads. However, because the equipment is very expensive, these codes would not capture practice expense and the physician would have to negotiate a reasonable reimbursement level with the payer, if the magnetocardiography was a covered service. The new codes are as follows:

- 0475T, Recording of fetal magnetic cardiac signal using at least 3 channels; patient recording and storage, data scanning with signal extraction, technical analysis and result, as well as supervision, review, and interpretation of report by a physician or other qualified health care professional

- 0476T, Recording of fetal magnetic cardiac signal using at least 3 channels; patient recording, data scanning, with raw electronic signal transfer of data and storage

- 0477T, Recording of fetal magnetic cardiac signal using at least 3 channels; signal extraction, technical analysis, and result.

Transvaginal tactile imaging. The new Category III code, 0487T, Biomechanical mapping, transvaginal, with report, describes the use of a pressure sensor probe inserted into the vaginal canal to measure and collect data on pelvic muscle strength, elasticity, tissue integrity, and tone. These data produce images in real time that are mapped to produce a report for physician review, interpretation, and report. The data allow quantification of pelvic floor dysfunction and may be useful in determining the most appropriate treatment (whether surgical or medical) for this gynecologic condition. The procedure uses a transvaginal probe like an ultrasound, so using 76830, transvaginal ultrasound, would not be unreasonable as a comparison code as a start.

Medicare relative value changes

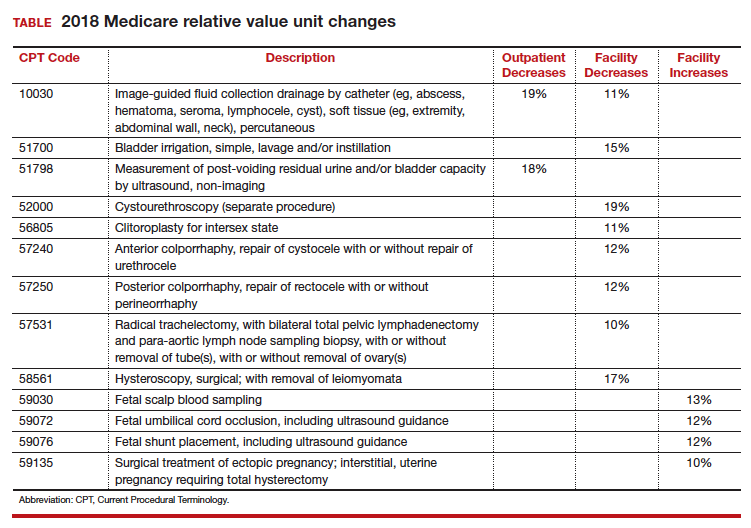

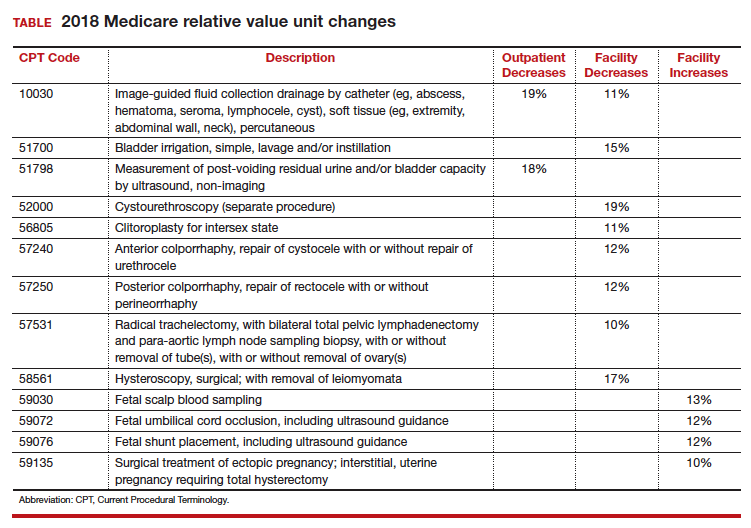

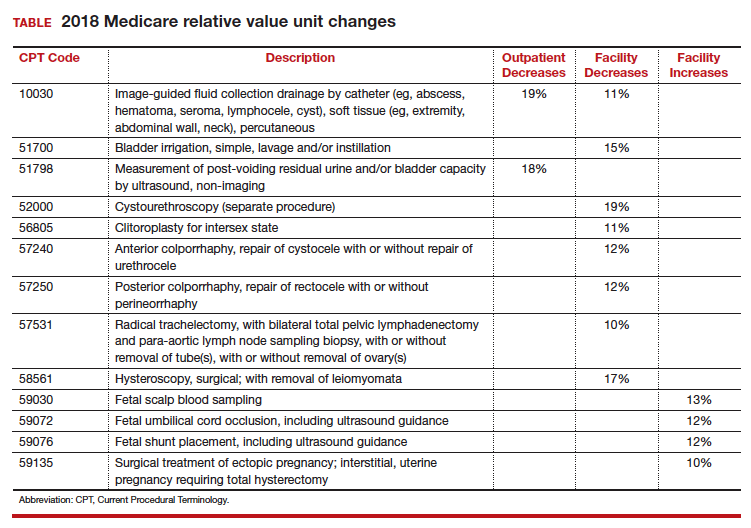

Every year, Medicare reevaluates potentially misvalued CPT codes and this year was no exception. The TABLE represents the winners and losers for codes in the outpatient and facility settings that have increased or decreased RVUs by more than 10%.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Another year brings changes to Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes (which are developed and copyrighted by the American Medical Association) in the form of additions and revisions, and payments related to resource-based relative value scale (RBRVS) revisions for selected services. As of January 1, 2018, 2 new Category I codes pertain to laparoscopic treatments for gynecologic cancer, and the 4 existing codes for colporrhaphy have been revised to include cystourethroscopy. New Category III codes include 4 for fetal magnetocardiography and 1 for transvaginal tactile imaging. Medicare also has reevaluated certain relative value units (RVUs) in outpatient and facility settings.

New and revised Category I codes

Laparoscopic treatments for gynecologic cancer. Technologic advances in performing laparoscopic procedures have allowed for more extensive laparoscopic surgery for various gynecologic cancers and, to this end, 2 new codes have been added.

First, a new code was added to capture comprehensive laparoscopic surgical staging for gynecologic cancer. This new code, 38573, Laparoscopy, surgical; with bilateral total pelvic lymphadenectomy and peri-aortic lymph node sampling, peritoneal washings, peritoneal biopsy(ies), omentectomy, and diaphragmatic washings, including diaphragmatic and other serosal biopsy(ies), when performed, may not be reported with any other code that includes lymphadenectomy, omentectomy, or hysterectomy. It is intended primarily for a stand-alone staging procedure after an initial biopsy shows a gynecologic malignancy such as ovarian cancer. This new code has been valued at 33.59 RVUs.

Second, a new code was added to capture laparoscopic debulking in conjunction with hysterectomy. The new code, 58575, Laparoscopy, surgical, total hysterectomy for resection of malignancy (tumor debulking), with omentectomy including salpingo-oophorectomy, unilateral or bilateral, when performed, has been valued at 53.62 RVUs. The open equivalent to this new code is 58953, Bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy with omentectomy, total abdominal hysterectomy and radical dissection for debulking.

Cystourethroscopy. The revisions involve no longer permitting separate reporting of 52000, Cystourethroscopy (separate procedure), with the colporrhaphy codes 57240−57265. The rationale behind this change was that surgeons were routinely performing cystoscopy at the time of these procedures and therefore it should become part of the surgical procedure. Currently the Medicare National Correct Coding Initiative (NCCI) bundles 52000 with these 4 codes, but only code 57250 allows for the use of a modifier -59 to bypass the edit if the purpose of the cystoscopy was evaluation of a distinct complaint or problem (such as evaluating patient-expressed urinary symptoms prior to the surgery that were investigated at the time of the prolapse surgery). When codes 57240, 57260, or 57265 are billed along with 52000, the cystoscopy will be denied and a modifier -59 cannot be reported to bypass this edit.

New Category III codes

The new Category III codes represent emerging technology, and it is important to report them, rather than an unlisted code, if the procedures described are performed so that data can be collected for later consideration to make these Category I CPT codes. Since these codes are not assigned relative values, the provider will need to let the payer know which existing CPT Category I code most closely represents the work involved.

Fetal magnetocardiography. The new Category III codes for fetal magnetocardiography describe essentially a fetal electrocardiogram (ECG) that would be performed to assess fetal arrhythmias by placing up to 3 leads on the mother’s abdomen. Possible comparison codes for physician work might include 59050, fetal monitoring by consultant during labor; 93000−93010, 12-lead ECG, or 93040−93042, rhythm strip up to 3 leads. However, because the equipment is very expensive, these codes would not capture practice expense and the physician would have to negotiate a reasonable reimbursement level with the payer, if the magnetocardiography was a covered service. The new codes are as follows:

- 0475T, Recording of fetal magnetic cardiac signal using at least 3 channels; patient recording and storage, data scanning with signal extraction, technical analysis and result, as well as supervision, review, and interpretation of report by a physician or other qualified health care professional

- 0476T, Recording of fetal magnetic cardiac signal using at least 3 channels; patient recording, data scanning, with raw electronic signal transfer of data and storage

- 0477T, Recording of fetal magnetic cardiac signal using at least 3 channels; signal extraction, technical analysis, and result.

Transvaginal tactile imaging. The new Category III code, 0487T, Biomechanical mapping, transvaginal, with report, describes the use of a pressure sensor probe inserted into the vaginal canal to measure and collect data on pelvic muscle strength, elasticity, tissue integrity, and tone. These data produce images in real time that are mapped to produce a report for physician review, interpretation, and report. The data allow quantification of pelvic floor dysfunction and may be useful in determining the most appropriate treatment (whether surgical or medical) for this gynecologic condition. The procedure uses a transvaginal probe like an ultrasound, so using 76830, transvaginal ultrasound, would not be unreasonable as a comparison code as a start.

Medicare relative value changes

Every year, Medicare reevaluates potentially misvalued CPT codes and this year was no exception. The TABLE represents the winners and losers for codes in the outpatient and facility settings that have increased or decreased RVUs by more than 10%.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Another year brings changes to Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes (which are developed and copyrighted by the American Medical Association) in the form of additions and revisions, and payments related to resource-based relative value scale (RBRVS) revisions for selected services. As of January 1, 2018, 2 new Category I codes pertain to laparoscopic treatments for gynecologic cancer, and the 4 existing codes for colporrhaphy have been revised to include cystourethroscopy. New Category III codes include 4 for fetal magnetocardiography and 1 for transvaginal tactile imaging. Medicare also has reevaluated certain relative value units (RVUs) in outpatient and facility settings.

New and revised Category I codes

Laparoscopic treatments for gynecologic cancer. Technologic advances in performing laparoscopic procedures have allowed for more extensive laparoscopic surgery for various gynecologic cancers and, to this end, 2 new codes have been added.

First, a new code was added to capture comprehensive laparoscopic surgical staging for gynecologic cancer. This new code, 38573, Laparoscopy, surgical; with bilateral total pelvic lymphadenectomy and peri-aortic lymph node sampling, peritoneal washings, peritoneal biopsy(ies), omentectomy, and diaphragmatic washings, including diaphragmatic and other serosal biopsy(ies), when performed, may not be reported with any other code that includes lymphadenectomy, omentectomy, or hysterectomy. It is intended primarily for a stand-alone staging procedure after an initial biopsy shows a gynecologic malignancy such as ovarian cancer. This new code has been valued at 33.59 RVUs.

Second, a new code was added to capture laparoscopic debulking in conjunction with hysterectomy. The new code, 58575, Laparoscopy, surgical, total hysterectomy for resection of malignancy (tumor debulking), with omentectomy including salpingo-oophorectomy, unilateral or bilateral, when performed, has been valued at 53.62 RVUs. The open equivalent to this new code is 58953, Bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy with omentectomy, total abdominal hysterectomy and radical dissection for debulking.

Cystourethroscopy. The revisions involve no longer permitting separate reporting of 52000, Cystourethroscopy (separate procedure), with the colporrhaphy codes 57240−57265. The rationale behind this change was that surgeons were routinely performing cystoscopy at the time of these procedures and therefore it should become part of the surgical procedure. Currently the Medicare National Correct Coding Initiative (NCCI) bundles 52000 with these 4 codes, but only code 57250 allows for the use of a modifier -59 to bypass the edit if the purpose of the cystoscopy was evaluation of a distinct complaint or problem (such as evaluating patient-expressed urinary symptoms prior to the surgery that were investigated at the time of the prolapse surgery). When codes 57240, 57260, or 57265 are billed along with 52000, the cystoscopy will be denied and a modifier -59 cannot be reported to bypass this edit.

New Category III codes

The new Category III codes represent emerging technology, and it is important to report them, rather than an unlisted code, if the procedures described are performed so that data can be collected for later consideration to make these Category I CPT codes. Since these codes are not assigned relative values, the provider will need to let the payer know which existing CPT Category I code most closely represents the work involved.

Fetal magnetocardiography. The new Category III codes for fetal magnetocardiography describe essentially a fetal electrocardiogram (ECG) that would be performed to assess fetal arrhythmias by placing up to 3 leads on the mother’s abdomen. Possible comparison codes for physician work might include 59050, fetal monitoring by consultant during labor; 93000−93010, 12-lead ECG, or 93040−93042, rhythm strip up to 3 leads. However, because the equipment is very expensive, these codes would not capture practice expense and the physician would have to negotiate a reasonable reimbursement level with the payer, if the magnetocardiography was a covered service. The new codes are as follows:

- 0475T, Recording of fetal magnetic cardiac signal using at least 3 channels; patient recording and storage, data scanning with signal extraction, technical analysis and result, as well as supervision, review, and interpretation of report by a physician or other qualified health care professional

- 0476T, Recording of fetal magnetic cardiac signal using at least 3 channels; patient recording, data scanning, with raw electronic signal transfer of data and storage

- 0477T, Recording of fetal magnetic cardiac signal using at least 3 channels; signal extraction, technical analysis, and result.

Transvaginal tactile imaging. The new Category III code, 0487T, Biomechanical mapping, transvaginal, with report, describes the use of a pressure sensor probe inserted into the vaginal canal to measure and collect data on pelvic muscle strength, elasticity, tissue integrity, and tone. These data produce images in real time that are mapped to produce a report for physician review, interpretation, and report. The data allow quantification of pelvic floor dysfunction and may be useful in determining the most appropriate treatment (whether surgical or medical) for this gynecologic condition. The procedure uses a transvaginal probe like an ultrasound, so using 76830, transvaginal ultrasound, would not be unreasonable as a comparison code as a start.

Medicare relative value changes

Every year, Medicare reevaluates potentially misvalued CPT codes and this year was no exception. The TABLE represents the winners and losers for codes in the outpatient and facility settings that have increased or decreased RVUs by more than 10%.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Beware the con

As I stepped from an exam room one recent busy morning, my office manager pulled me aside. “Someone from the county courthouse is on the phone and needs to talk to you,” she whispered.

“You know better than that,” I said. “While I’m seeing patients, I don’t take calls from anyone except colleagues and immediate family.”

I took the call.

“You failed to appear for jury duty,” the official-sounding voice said. “That’s a violation of state law, as you were warned when you received your summons. You’ll have to come down here and surrender yourself immediately, or else we’ll have to send deputies to your office. I don’t think you’ll want to be led through your waiting room in handcuffs.”

“Wait a minute,” I replied nervously. “I haven’t received a jury summons for 2 years, at least. There must be some mistake.”

“Perhaps we’ve confused you with a citizen with the same or a similar name,” he said. “Let me have your Social Security number and birth date.”

Alarm bells! “You should have that information already,” I replied. “Why don’t you read me what you have?”

A short silence, and then … click.

I immediately called the courthouse. “Citizens who fail to appear receive a warning letter and a new questionnaire, not a phone call,” said the jury manager. “And we use driver license numbers to keep track of jurors.”

The phone company traced the call, which dead-ended at a VoIP circuit, to no one’s surprise. The downside of VoIP (Voice over Internet Protocol) and similar technologies is that unscrupulous individuals can use them to appear to be calling you from a legitimate business when they are not.

Those of us of a certain age remember phony office calls offering great deals on supplies or waiting room magazine subscriptions. Those capers eventually disappeared; but scam artists are endlessly creative. This is especially true since the Internet took over, well, everything. There’s a real dark side to the information age.

The jury duty scheme, I learned, is an increasingly popular one. Others involve calls or e-mails from the “fraud department” of your bank, claiming to be investigating a breach of your account, or one of your credit or debit cards. Another purports to be a “Customs official” informing you that you owe a big duty payment on an overseas shipment. Victims of power outages due to natural disasters are hearing from crooks claiming to be from the local power company; the power won’t be restored, they say, without an advance payment.

In most cases, the common denominator – and the biggest red flag – is a request for a social security number, a birth date, a credit card number, or other private information that could be used to steal your identity or empty your accounts.

Here’s a summary of what my recent experience taught (or reminded) me:

- Never give out a bank account, social security, or credit card number online or over the telephone if you didn’t initiate the contact, no matter how legitimate the caller sounds. This is true of anyone claiming to be from a bank, a service company, or a government office, as well as anyone trying to sell you anything.

- No federal or state court will call to say you’ve missed jury duty – or that they are assembling jury pools and need to “prescreen” those who might be selected to serve on them. The jury manager I spoke with said she knew of no reason why anyone in my state would ever be called about jury service before mailing back a completed questionnaire, and even then, such a call would be extraordinary.

- Never send anyone a “commission” or “finder’s fee” as a condition of receiving funds. In legitimate transactions, such fees are merely deducted from the money being paid out.

- Examine your credit card and bank account statements each month. Immediately challenge any charges you don’t recognize.

Dr. Eastern practices dermatology and dermatologic surgery in Belleville, N.J. He is the author of numerous articles and textbook chapters and is a longtime monthly columnist for Dermatology News. Write to him at [email protected].

As I stepped from an exam room one recent busy morning, my office manager pulled me aside. “Someone from the county courthouse is on the phone and needs to talk to you,” she whispered.

“You know better than that,” I said. “While I’m seeing patients, I don’t take calls from anyone except colleagues and immediate family.”

I took the call.

“You failed to appear for jury duty,” the official-sounding voice said. “That’s a violation of state law, as you were warned when you received your summons. You’ll have to come down here and surrender yourself immediately, or else we’ll have to send deputies to your office. I don’t think you’ll want to be led through your waiting room in handcuffs.”

“Wait a minute,” I replied nervously. “I haven’t received a jury summons for 2 years, at least. There must be some mistake.”

“Perhaps we’ve confused you with a citizen with the same or a similar name,” he said. “Let me have your Social Security number and birth date.”

Alarm bells! “You should have that information already,” I replied. “Why don’t you read me what you have?”

A short silence, and then … click.

I immediately called the courthouse. “Citizens who fail to appear receive a warning letter and a new questionnaire, not a phone call,” said the jury manager. “And we use driver license numbers to keep track of jurors.”

The phone company traced the call, which dead-ended at a VoIP circuit, to no one’s surprise. The downside of VoIP (Voice over Internet Protocol) and similar technologies is that unscrupulous individuals can use them to appear to be calling you from a legitimate business when they are not.

Those of us of a certain age remember phony office calls offering great deals on supplies or waiting room magazine subscriptions. Those capers eventually disappeared; but scam artists are endlessly creative. This is especially true since the Internet took over, well, everything. There’s a real dark side to the information age.

The jury duty scheme, I learned, is an increasingly popular one. Others involve calls or e-mails from the “fraud department” of your bank, claiming to be investigating a breach of your account, or one of your credit or debit cards. Another purports to be a “Customs official” informing you that you owe a big duty payment on an overseas shipment. Victims of power outages due to natural disasters are hearing from crooks claiming to be from the local power company; the power won’t be restored, they say, without an advance payment.

In most cases, the common denominator – and the biggest red flag – is a request for a social security number, a birth date, a credit card number, or other private information that could be used to steal your identity or empty your accounts.

Here’s a summary of what my recent experience taught (or reminded) me:

- Never give out a bank account, social security, or credit card number online or over the telephone if you didn’t initiate the contact, no matter how legitimate the caller sounds. This is true of anyone claiming to be from a bank, a service company, or a government office, as well as anyone trying to sell you anything.

- No federal or state court will call to say you’ve missed jury duty – or that they are assembling jury pools and need to “prescreen” those who might be selected to serve on them. The jury manager I spoke with said she knew of no reason why anyone in my state would ever be called about jury service before mailing back a completed questionnaire, and even then, such a call would be extraordinary.

- Never send anyone a “commission” or “finder’s fee” as a condition of receiving funds. In legitimate transactions, such fees are merely deducted from the money being paid out.

- Examine your credit card and bank account statements each month. Immediately challenge any charges you don’t recognize.

Dr. Eastern practices dermatology and dermatologic surgery in Belleville, N.J. He is the author of numerous articles and textbook chapters and is a longtime monthly columnist for Dermatology News. Write to him at [email protected].

As I stepped from an exam room one recent busy morning, my office manager pulled me aside. “Someone from the county courthouse is on the phone and needs to talk to you,” she whispered.

“You know better than that,” I said. “While I’m seeing patients, I don’t take calls from anyone except colleagues and immediate family.”

I took the call.

“You failed to appear for jury duty,” the official-sounding voice said. “That’s a violation of state law, as you were warned when you received your summons. You’ll have to come down here and surrender yourself immediately, or else we’ll have to send deputies to your office. I don’t think you’ll want to be led through your waiting room in handcuffs.”

“Wait a minute,” I replied nervously. “I haven’t received a jury summons for 2 years, at least. There must be some mistake.”

“Perhaps we’ve confused you with a citizen with the same or a similar name,” he said. “Let me have your Social Security number and birth date.”

Alarm bells! “You should have that information already,” I replied. “Why don’t you read me what you have?”

A short silence, and then … click.

I immediately called the courthouse. “Citizens who fail to appear receive a warning letter and a new questionnaire, not a phone call,” said the jury manager. “And we use driver license numbers to keep track of jurors.”

The phone company traced the call, which dead-ended at a VoIP circuit, to no one’s surprise. The downside of VoIP (Voice over Internet Protocol) and similar technologies is that unscrupulous individuals can use them to appear to be calling you from a legitimate business when they are not.

Those of us of a certain age remember phony office calls offering great deals on supplies or waiting room magazine subscriptions. Those capers eventually disappeared; but scam artists are endlessly creative. This is especially true since the Internet took over, well, everything. There’s a real dark side to the information age.

The jury duty scheme, I learned, is an increasingly popular one. Others involve calls or e-mails from the “fraud department” of your bank, claiming to be investigating a breach of your account, or one of your credit or debit cards. Another purports to be a “Customs official” informing you that you owe a big duty payment on an overseas shipment. Victims of power outages due to natural disasters are hearing from crooks claiming to be from the local power company; the power won’t be restored, they say, without an advance payment.

In most cases, the common denominator – and the biggest red flag – is a request for a social security number, a birth date, a credit card number, or other private information that could be used to steal your identity or empty your accounts.

Here’s a summary of what my recent experience taught (or reminded) me:

- Never give out a bank account, social security, or credit card number online or over the telephone if you didn’t initiate the contact, no matter how legitimate the caller sounds. This is true of anyone claiming to be from a bank, a service company, or a government office, as well as anyone trying to sell you anything.

- No federal or state court will call to say you’ve missed jury duty – or that they are assembling jury pools and need to “prescreen” those who might be selected to serve on them. The jury manager I spoke with said she knew of no reason why anyone in my state would ever be called about jury service before mailing back a completed questionnaire, and even then, such a call would be extraordinary.

- Never send anyone a “commission” or “finder’s fee” as a condition of receiving funds. In legitimate transactions, such fees are merely deducted from the money being paid out.

- Examine your credit card and bank account statements each month. Immediately challenge any charges you don’t recognize.

Dr. Eastern practices dermatology and dermatologic surgery in Belleville, N.J. He is the author of numerous articles and textbook chapters and is a longtime monthly columnist for Dermatology News. Write to him at [email protected].

Factors critical to reducing US maternal mortality and morbidity

More women die from pregnancy complications in the United States than in any other developed country. The United States is the only industrialized nation with a rising maternal mortality rate.

Those 2 sentences should stop us all in our tracks.

In fact, the United States ranks 47th globally with the worst maternal mortality rate. More than half these deaths are likely preventable, with suicide and drug overdose the leading causes of maternal death in many states. All this occurs despite our advanced medical system, premier medical colleges and universities, embrace of high-tech medical advances, and high percentage of gross domestic product spent on health care.

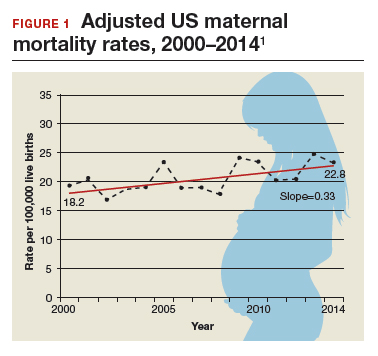

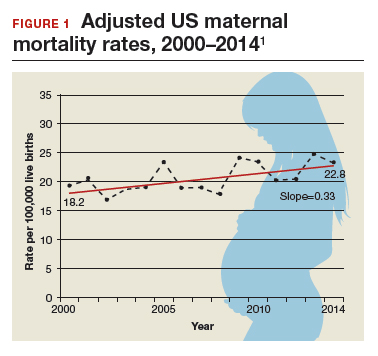

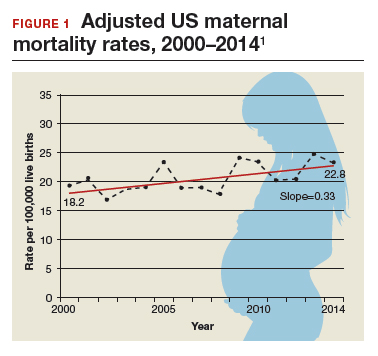

Need more numbers? According to a 2016 report in Obstetrics and Gynecology, the United States saw a 26% increase in the maternalmortality rate (unadjusted) in only 15 years: from 18.8 deaths per 100,000 live births in 2000 to 23.8 in 2014 (FIGURE 1).1

This problem received federal attention when, in 2000, the US Department of Health and Human Services launched Healthy People 2010. That health promotion and disease prevention agenda set a goal of reducing maternal mortality to 3.3 deaths per 100,000 live births by 2010, a goal clearly not met.

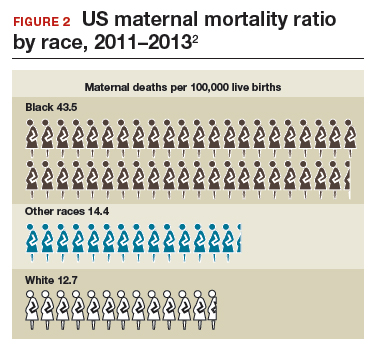

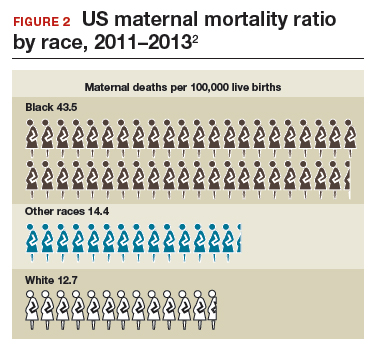

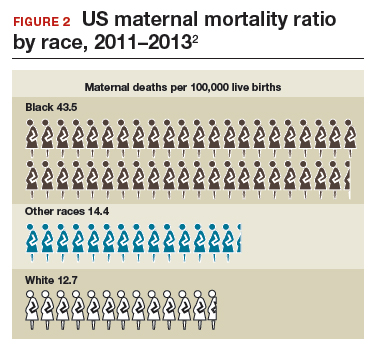

Considerable variations by race and by state

The racial disparities in maternal mortality are staggering and have not improved in more than 20 years: African American women are 3.4 times more likely to die than non-Hispanic white women of pregnancy-related complications. In 2011–2013, the maternal mortality ratio for non-Hispanic white women was 12.7 deaths per 100,000 live births compared with 43.5 deaths for non-Hispanic black women (FIGURE 2).2 American Indian or Alaska Native women, Asian women, and some Latina women also experience higher rates than non-Hispanic white women. The rate for American Indian or Alaska Native women is 16.9 deaths per 100,000 live births.3

Some states are doing better than others, showing that there is nothing inevitable about the maternal mortality crisis. Texas, for example, has seen the highest rate of maternal mortality increase. Its rate doubled from 2010 to 2012, while California reduced its maternal death rate by 30%, from 21.5 to 15.1, during roughly the same period.1

This is a challenge of epic proportions, and one that the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG), under the leadership of President Haywood Brown, MD, and Incoming President Lisa Hollier, MD, is determined to meet, ensuring that a high maternal death rate does not become our nation’s new normal.

Dr. Brown put it this way, “ACOG collaborative initiatives such as Levels of Maternal Care (LOMC) and implementation of OB safety bundles for hemorrhage, hypertension, and thromboembolism through the AIM [Alliance for Innovation on Maternal Health] Program target maternal morbidity and mortality at the community level. Bundles have also been developed to address the disparity in maternal mortality and for the opiate crisis.”

ACOG is making strides in putting in place nationwide meaningful, evidence-driven systems and care approaches that are proven to reduce maternal mortality and morbidity, saving mothers’ lives and keeping families whole.

Read about the AIM Program’s initiatives

ACOG’s AIM Program established to make an impact

The AIM Program (www.safehealthcare foreverywoman.org) is bringing together clinicians, public health officials, hospital administrators, patient safety organizations, and advocates to eliminate preventable maternal mortality throughout the United States. With funding and support from the US Health Resources and Services Administration, AIM is striving to:

- reduce maternal mortality by 1,000 deaths by 2018

- reduce severe maternal morbidity

- assist states and hospitals to improve outcomes

- create and encourage use of maternal safety bundles (evidence-based tool kits to guide the best care).

AIM offers participating physicians and hospitals online learning modules, checklists, work plans, and links to tool kits and published resources. Implementation data is shared with hospitals and states to further improve care. Physicians participating in AIM can receive Part IV maintenance of certification; continuing education units will soon be offered for nurses. In the future, AIM-participating hospitals may be able to receive reduced liability protection costs, too.

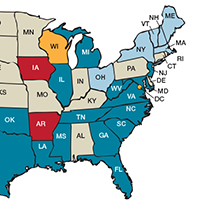

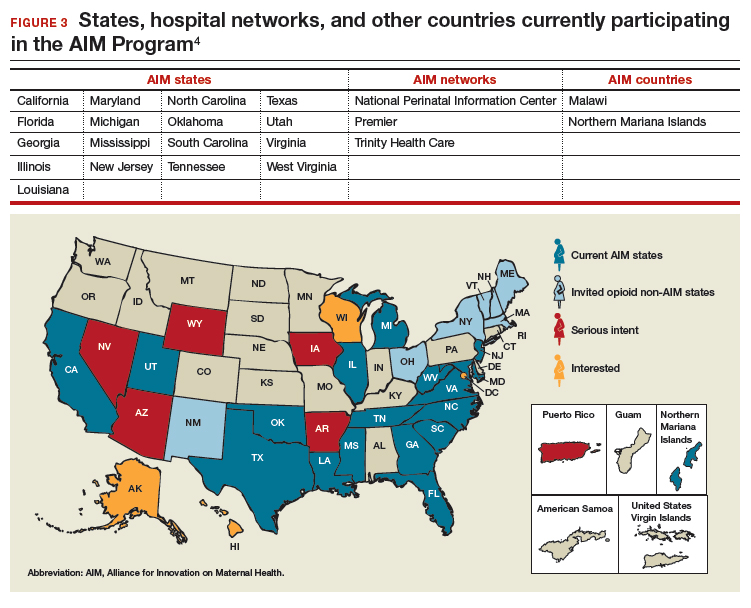

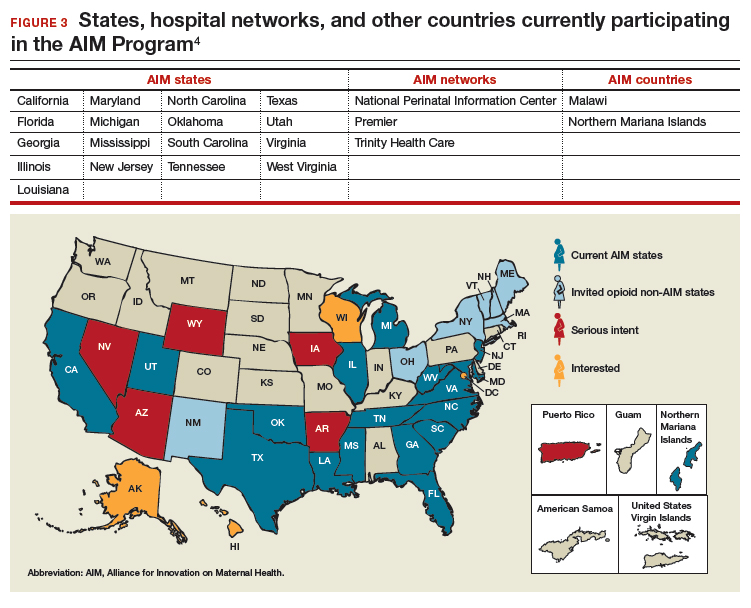

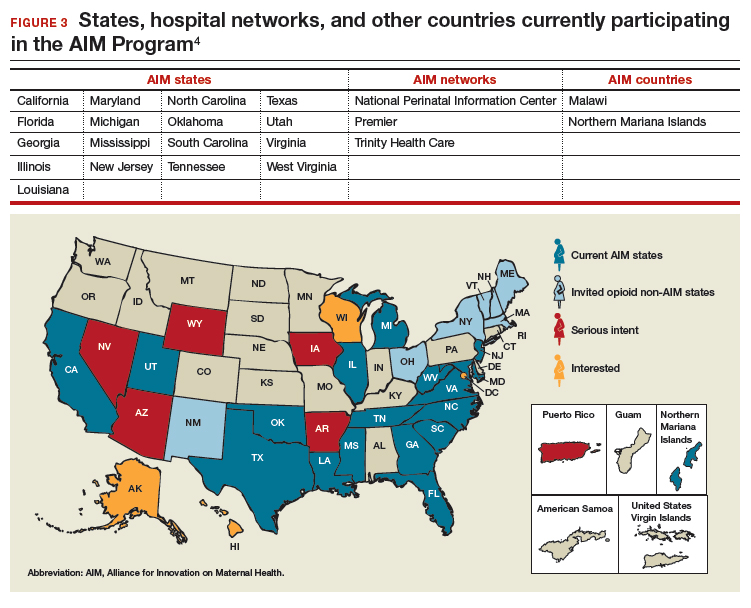

To date, 17 states are participating in the AIM initiative (FIGURE 3), with more states ready to enroll.4 States must demonstrate a commitment to lasting change to participate. Each AIM state must have an active maternal mortality review committee (MMRC); committed leadership from public health, hospital associations, and provider associations; and a commitment to report AIM data.

AIM thus far has released 9 obstetric patient safety bundles, including:

- reducing disparities in maternity care

- severe hypertension in pregnancy

- safe reduction of primary cesarean birth

- prevention of venous thromboembolism

- obstetric hemorrhage

- maternal mental health

- patient, family, and staff support following a severe maternal event

- postpartum care basics

- obstetric care of women with opioid use disorder (in use by Illinois, Massachusetts, Maryland, New Jersey, Maine, New Hampshire, Vermont, New York, Ohio, Oklahoma, Tennessee, Texas, and Virginia).

Read about how active MMRCS are critical to success

Review committees are critical to success

In use in many states, MMRCs are groups of local ObGyns, nurses, social workers, and other health care professionals who review specific cases of maternal deaths from their local area and recommend local solutions to prevent future deaths. MMRCs can be a critically important source of data to help us understand the underlying causes of maternal mortality.

Remember California’s success in reducing its maternal mortality rate, previously mentioned? That state was an early adopter of an active MMRC and has worked to bring best practices to maternity care throughout the state.

While every state should have an active MMRC, not every state does. ACOG is working with states, local leaders, and state and federal legislatures to help develop MMRCs in every state.

Dr. Brown pointed out that, “For several decades, Indiana had a legislatively authorized multidisciplinary maternal mortality review committee that I actively participated in and led in the late 1990s. The authorization for the program lapsed in the early 2000s, and the Indiana MMRC had to shut down. Bolstering the federal government’s capacity to help states like Indiana rebuild MMRCs, or start them from scratch, will help state public health officials, hospitals, and physicians take better care of moms and babies.”

Dr. Hollier explained, “In Texas, I chair our Maternal Mortality and Morbidity Task Force, which was legislatively authorized in 2013 in response to the rising rate of maternal death. The detailed state-based maternal mortality reviews provide critical information: verification of vital statistics data, assessment of the causes and contributing factors, and determination of pregnancy relatedness. These reviews identify opportunities for prevention and implementation of the most appropriate interventions to reduce maternal mortality on a local level. Support of essential review functions at the federal level would also enable data to be combined across jurisdictions for national learning that was previously not possible.”

Pending legislation will strengthen efforts

ACOG is working to enact into law the Preventing Maternal Deaths Act, HR 1318 and S1112. This is bipartisan legislation under which the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention would help states create or expand MMRCs and will require the Department of Health and Human Services to research ways to reduce disparities in maternal health outcomes.

Acknowledgement

The author thanks Jean Mahoney, ACOG’s Senior Director, AIM, for her generous assistance.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- MacDorman MF, Declerq E, Cabral H, Morton C. Recent increases in the US maternal mortality rate: disentangling trends from measurement issues. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;128(3):447–455.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Pregnancy mortality surveillance system. www.cdc.gov/reproductivehealth/maternalinfanthealth/pmss.html. Updated November 9, 2017. Accessed February 16, 2018.

- Singh GK. Maternal mortality in the United States, 1935−2007: Substantial racial/ethnic, socioeconomic, and geographic disparities persist. A 75th Anniversary Publication. Health Resources and Services Administration, Maternal and Child Health Bureau. Rockville, Maryland: US Department of Health and Human Services; 2010. https://www.hrsa.gov/sites/default/files/ourstories/mchb75th/mchb75maternalmortality.pdf. Accessed February 16, 2018.

- Council on Patient Safety in Women’s Health Care. Alliance for Innovation on Maternal Health Program: AIM states and systems. http://safehealthcareforeverywoman.org/aim-states-systems-2/#link_tab-1513011413196-9. Accessed February 20, 2018.

More women die from pregnancy complications in the United States than in any other developed country. The United States is the only industrialized nation with a rising maternal mortality rate.

Those 2 sentences should stop us all in our tracks.

In fact, the United States ranks 47th globally with the worst maternal mortality rate. More than half these deaths are likely preventable, with suicide and drug overdose the leading causes of maternal death in many states. All this occurs despite our advanced medical system, premier medical colleges and universities, embrace of high-tech medical advances, and high percentage of gross domestic product spent on health care.

Need more numbers? According to a 2016 report in Obstetrics and Gynecology, the United States saw a 26% increase in the maternalmortality rate (unadjusted) in only 15 years: from 18.8 deaths per 100,000 live births in 2000 to 23.8 in 2014 (FIGURE 1).1

This problem received federal attention when, in 2000, the US Department of Health and Human Services launched Healthy People 2010. That health promotion and disease prevention agenda set a goal of reducing maternal mortality to 3.3 deaths per 100,000 live births by 2010, a goal clearly not met.

Considerable variations by race and by state

The racial disparities in maternal mortality are staggering and have not improved in more than 20 years: African American women are 3.4 times more likely to die than non-Hispanic white women of pregnancy-related complications. In 2011–2013, the maternal mortality ratio for non-Hispanic white women was 12.7 deaths per 100,000 live births compared with 43.5 deaths for non-Hispanic black women (FIGURE 2).2 American Indian or Alaska Native women, Asian women, and some Latina women also experience higher rates than non-Hispanic white women. The rate for American Indian or Alaska Native women is 16.9 deaths per 100,000 live births.3

Some states are doing better than others, showing that there is nothing inevitable about the maternal mortality crisis. Texas, for example, has seen the highest rate of maternal mortality increase. Its rate doubled from 2010 to 2012, while California reduced its maternal death rate by 30%, from 21.5 to 15.1, during roughly the same period.1

This is a challenge of epic proportions, and one that the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG), under the leadership of President Haywood Brown, MD, and Incoming President Lisa Hollier, MD, is determined to meet, ensuring that a high maternal death rate does not become our nation’s new normal.

Dr. Brown put it this way, “ACOG collaborative initiatives such as Levels of Maternal Care (LOMC) and implementation of OB safety bundles for hemorrhage, hypertension, and thromboembolism through the AIM [Alliance for Innovation on Maternal Health] Program target maternal morbidity and mortality at the community level. Bundles have also been developed to address the disparity in maternal mortality and for the opiate crisis.”

ACOG is making strides in putting in place nationwide meaningful, evidence-driven systems and care approaches that are proven to reduce maternal mortality and morbidity, saving mothers’ lives and keeping families whole.

Read about the AIM Program’s initiatives

ACOG’s AIM Program established to make an impact

The AIM Program (www.safehealthcare foreverywoman.org) is bringing together clinicians, public health officials, hospital administrators, patient safety organizations, and advocates to eliminate preventable maternal mortality throughout the United States. With funding and support from the US Health Resources and Services Administration, AIM is striving to:

- reduce maternal mortality by 1,000 deaths by 2018

- reduce severe maternal morbidity

- assist states and hospitals to improve outcomes

- create and encourage use of maternal safety bundles (evidence-based tool kits to guide the best care).

AIM offers participating physicians and hospitals online learning modules, checklists, work plans, and links to tool kits and published resources. Implementation data is shared with hospitals and states to further improve care. Physicians participating in AIM can receive Part IV maintenance of certification; continuing education units will soon be offered for nurses. In the future, AIM-participating hospitals may be able to receive reduced liability protection costs, too.

To date, 17 states are participating in the AIM initiative (FIGURE 3), with more states ready to enroll.4 States must demonstrate a commitment to lasting change to participate. Each AIM state must have an active maternal mortality review committee (MMRC); committed leadership from public health, hospital associations, and provider associations; and a commitment to report AIM data.

AIM thus far has released 9 obstetric patient safety bundles, including:

- reducing disparities in maternity care

- severe hypertension in pregnancy

- safe reduction of primary cesarean birth

- prevention of venous thromboembolism

- obstetric hemorrhage

- maternal mental health

- patient, family, and staff support following a severe maternal event

- postpartum care basics

- obstetric care of women with opioid use disorder (in use by Illinois, Massachusetts, Maryland, New Jersey, Maine, New Hampshire, Vermont, New York, Ohio, Oklahoma, Tennessee, Texas, and Virginia).

Read about how active MMRCS are critical to success

Review committees are critical to success

In use in many states, MMRCs are groups of local ObGyns, nurses, social workers, and other health care professionals who review specific cases of maternal deaths from their local area and recommend local solutions to prevent future deaths. MMRCs can be a critically important source of data to help us understand the underlying causes of maternal mortality.

Remember California’s success in reducing its maternal mortality rate, previously mentioned? That state was an early adopter of an active MMRC and has worked to bring best practices to maternity care throughout the state.

While every state should have an active MMRC, not every state does. ACOG is working with states, local leaders, and state and federal legislatures to help develop MMRCs in every state.

Dr. Brown pointed out that, “For several decades, Indiana had a legislatively authorized multidisciplinary maternal mortality review committee that I actively participated in and led in the late 1990s. The authorization for the program lapsed in the early 2000s, and the Indiana MMRC had to shut down. Bolstering the federal government’s capacity to help states like Indiana rebuild MMRCs, or start them from scratch, will help state public health officials, hospitals, and physicians take better care of moms and babies.”

Dr. Hollier explained, “In Texas, I chair our Maternal Mortality and Morbidity Task Force, which was legislatively authorized in 2013 in response to the rising rate of maternal death. The detailed state-based maternal mortality reviews provide critical information: verification of vital statistics data, assessment of the causes and contributing factors, and determination of pregnancy relatedness. These reviews identify opportunities for prevention and implementation of the most appropriate interventions to reduce maternal mortality on a local level. Support of essential review functions at the federal level would also enable data to be combined across jurisdictions for national learning that was previously not possible.”

Pending legislation will strengthen efforts

ACOG is working to enact into law the Preventing Maternal Deaths Act, HR 1318 and S1112. This is bipartisan legislation under which the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention would help states create or expand MMRCs and will require the Department of Health and Human Services to research ways to reduce disparities in maternal health outcomes.

Acknowledgement

The author thanks Jean Mahoney, ACOG’s Senior Director, AIM, for her generous assistance.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

More women die from pregnancy complications in the United States than in any other developed country. The United States is the only industrialized nation with a rising maternal mortality rate.

Those 2 sentences should stop us all in our tracks.

In fact, the United States ranks 47th globally with the worst maternal mortality rate. More than half these deaths are likely preventable, with suicide and drug overdose the leading causes of maternal death in many states. All this occurs despite our advanced medical system, premier medical colleges and universities, embrace of high-tech medical advances, and high percentage of gross domestic product spent on health care.

Need more numbers? According to a 2016 report in Obstetrics and Gynecology, the United States saw a 26% increase in the maternalmortality rate (unadjusted) in only 15 years: from 18.8 deaths per 100,000 live births in 2000 to 23.8 in 2014 (FIGURE 1).1

This problem received federal attention when, in 2000, the US Department of Health and Human Services launched Healthy People 2010. That health promotion and disease prevention agenda set a goal of reducing maternal mortality to 3.3 deaths per 100,000 live births by 2010, a goal clearly not met.

Considerable variations by race and by state

The racial disparities in maternal mortality are staggering and have not improved in more than 20 years: African American women are 3.4 times more likely to die than non-Hispanic white women of pregnancy-related complications. In 2011–2013, the maternal mortality ratio for non-Hispanic white women was 12.7 deaths per 100,000 live births compared with 43.5 deaths for non-Hispanic black women (FIGURE 2).2 American Indian or Alaska Native women, Asian women, and some Latina women also experience higher rates than non-Hispanic white women. The rate for American Indian or Alaska Native women is 16.9 deaths per 100,000 live births.3

Some states are doing better than others, showing that there is nothing inevitable about the maternal mortality crisis. Texas, for example, has seen the highest rate of maternal mortality increase. Its rate doubled from 2010 to 2012, while California reduced its maternal death rate by 30%, from 21.5 to 15.1, during roughly the same period.1

This is a challenge of epic proportions, and one that the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG), under the leadership of President Haywood Brown, MD, and Incoming President Lisa Hollier, MD, is determined to meet, ensuring that a high maternal death rate does not become our nation’s new normal.

Dr. Brown put it this way, “ACOG collaborative initiatives such as Levels of Maternal Care (LOMC) and implementation of OB safety bundles for hemorrhage, hypertension, and thromboembolism through the AIM [Alliance for Innovation on Maternal Health] Program target maternal morbidity and mortality at the community level. Bundles have also been developed to address the disparity in maternal mortality and for the opiate crisis.”

ACOG is making strides in putting in place nationwide meaningful, evidence-driven systems and care approaches that are proven to reduce maternal mortality and morbidity, saving mothers’ lives and keeping families whole.

Read about the AIM Program’s initiatives

ACOG’s AIM Program established to make an impact

The AIM Program (www.safehealthcare foreverywoman.org) is bringing together clinicians, public health officials, hospital administrators, patient safety organizations, and advocates to eliminate preventable maternal mortality throughout the United States. With funding and support from the US Health Resources and Services Administration, AIM is striving to:

- reduce maternal mortality by 1,000 deaths by 2018

- reduce severe maternal morbidity

- assist states and hospitals to improve outcomes

- create and encourage use of maternal safety bundles (evidence-based tool kits to guide the best care).

AIM offers participating physicians and hospitals online learning modules, checklists, work plans, and links to tool kits and published resources. Implementation data is shared with hospitals and states to further improve care. Physicians participating in AIM can receive Part IV maintenance of certification; continuing education units will soon be offered for nurses. In the future, AIM-participating hospitals may be able to receive reduced liability protection costs, too.

To date, 17 states are participating in the AIM initiative (FIGURE 3), with more states ready to enroll.4 States must demonstrate a commitment to lasting change to participate. Each AIM state must have an active maternal mortality review committee (MMRC); committed leadership from public health, hospital associations, and provider associations; and a commitment to report AIM data.

AIM thus far has released 9 obstetric patient safety bundles, including:

- reducing disparities in maternity care

- severe hypertension in pregnancy

- safe reduction of primary cesarean birth

- prevention of venous thromboembolism

- obstetric hemorrhage

- maternal mental health

- patient, family, and staff support following a severe maternal event

- postpartum care basics

- obstetric care of women with opioid use disorder (in use by Illinois, Massachusetts, Maryland, New Jersey, Maine, New Hampshire, Vermont, New York, Ohio, Oklahoma, Tennessee, Texas, and Virginia).

Read about how active MMRCS are critical to success

Review committees are critical to success

In use in many states, MMRCs are groups of local ObGyns, nurses, social workers, and other health care professionals who review specific cases of maternal deaths from their local area and recommend local solutions to prevent future deaths. MMRCs can be a critically important source of data to help us understand the underlying causes of maternal mortality.

Remember California’s success in reducing its maternal mortality rate, previously mentioned? That state was an early adopter of an active MMRC and has worked to bring best practices to maternity care throughout the state.

While every state should have an active MMRC, not every state does. ACOG is working with states, local leaders, and state and federal legislatures to help develop MMRCs in every state.

Dr. Brown pointed out that, “For several decades, Indiana had a legislatively authorized multidisciplinary maternal mortality review committee that I actively participated in and led in the late 1990s. The authorization for the program lapsed in the early 2000s, and the Indiana MMRC had to shut down. Bolstering the federal government’s capacity to help states like Indiana rebuild MMRCs, or start them from scratch, will help state public health officials, hospitals, and physicians take better care of moms and babies.”

Dr. Hollier explained, “In Texas, I chair our Maternal Mortality and Morbidity Task Force, which was legislatively authorized in 2013 in response to the rising rate of maternal death. The detailed state-based maternal mortality reviews provide critical information: verification of vital statistics data, assessment of the causes and contributing factors, and determination of pregnancy relatedness. These reviews identify opportunities for prevention and implementation of the most appropriate interventions to reduce maternal mortality on a local level. Support of essential review functions at the federal level would also enable data to be combined across jurisdictions for national learning that was previously not possible.”

Pending legislation will strengthen efforts

ACOG is working to enact into law the Preventing Maternal Deaths Act, HR 1318 and S1112. This is bipartisan legislation under which the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention would help states create or expand MMRCs and will require the Department of Health and Human Services to research ways to reduce disparities in maternal health outcomes.

Acknowledgement

The author thanks Jean Mahoney, ACOG’s Senior Director, AIM, for her generous assistance.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- MacDorman MF, Declerq E, Cabral H, Morton C. Recent increases in the US maternal mortality rate: disentangling trends from measurement issues. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;128(3):447–455.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Pregnancy mortality surveillance system. www.cdc.gov/reproductivehealth/maternalinfanthealth/pmss.html. Updated November 9, 2017. Accessed February 16, 2018.

- Singh GK. Maternal mortality in the United States, 1935−2007: Substantial racial/ethnic, socioeconomic, and geographic disparities persist. A 75th Anniversary Publication. Health Resources and Services Administration, Maternal and Child Health Bureau. Rockville, Maryland: US Department of Health and Human Services; 2010. https://www.hrsa.gov/sites/default/files/ourstories/mchb75th/mchb75maternalmortality.pdf. Accessed February 16, 2018.

- Council on Patient Safety in Women’s Health Care. Alliance for Innovation on Maternal Health Program: AIM states and systems. http://safehealthcareforeverywoman.org/aim-states-systems-2/#link_tab-1513011413196-9. Accessed February 20, 2018.

- MacDorman MF, Declerq E, Cabral H, Morton C. Recent increases in the US maternal mortality rate: disentangling trends from measurement issues. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;128(3):447–455.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Pregnancy mortality surveillance system. www.cdc.gov/reproductivehealth/maternalinfanthealth/pmss.html. Updated November 9, 2017. Accessed February 16, 2018.

- Singh GK. Maternal mortality in the United States, 1935−2007: Substantial racial/ethnic, socioeconomic, and geographic disparities persist. A 75th Anniversary Publication. Health Resources and Services Administration, Maternal and Child Health Bureau. Rockville, Maryland: US Department of Health and Human Services; 2010. https://www.hrsa.gov/sites/default/files/ourstories/mchb75th/mchb75maternalmortality.pdf. Accessed February 16, 2018.

- Council on Patient Safety in Women’s Health Care. Alliance for Innovation on Maternal Health Program: AIM states and systems. http://safehealthcareforeverywoman.org/aim-states-systems-2/#link_tab-1513011413196-9. Accessed February 20, 2018.

The role of patient-reported outcomes in women’s health

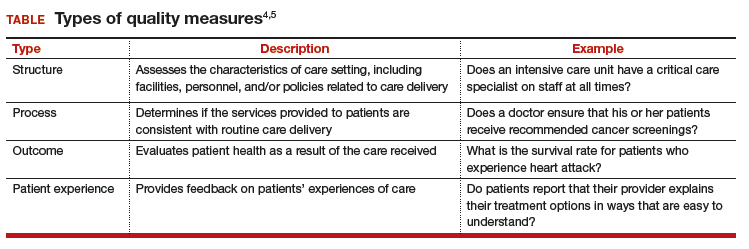

In its landmark publication, “Crossing the quality chasm: A new health system for the 21st century,” the Institute of Medicine (now the National Academy of Medicine) called for an emphasis on patient-centered care that it defined as “Providing care that is respectful of and responsive to individual patient preferences, needs, and values and ensuring that patient values guide all clinical decisions.”1 Studies suggest that the patient’s view of health care delivery determines outcome and satisfaction.2 Therefore, we need to expend more effort to understand what patients need or want from their treatment or interaction with the health care system.

Measuring patient-reported outcomes (PROs) is an attempt to recognize and address patient concerns. Although currently PROs are focused primarily in the arena of clinical research, their use has the potential to transform daily clinical patient encounters and improve the cost and quality of health care.3

In this article, we provide a brief overview of PROs and describe how they can be used to improve individual patient care, clinical research, and health care quality. We also offer examples of how PROs can be used in specific women’s health conditions.

What exactly are PROs?

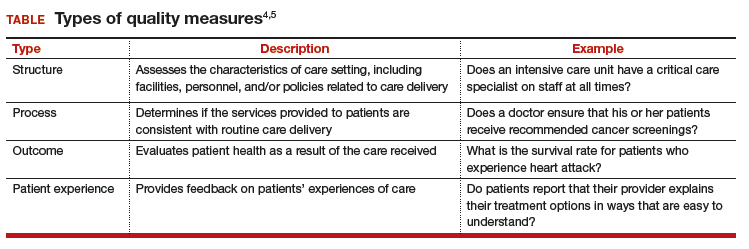

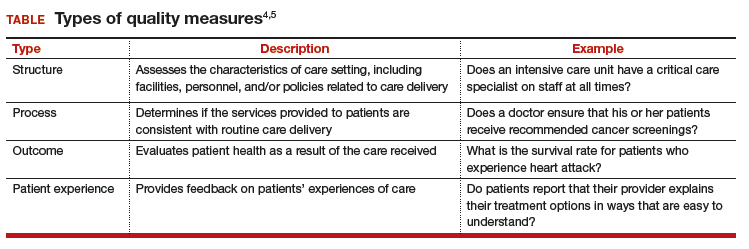

PROs are reports of the status of a patient’s health condition, health behavior, or experience with health care; they come directly from the patient, without anyone else (such as a clinician or caregiver) interpreting the patient’s response.4 PROs usually pertain to general health, quality of life, functional status, or preferences associated with health care or treatment.5 Usually PROs are elicited via a self-administered survey and provide the patient’s perspective on treatment benefits, side effects, change in symptoms, general perceptions of feelings or well-being, or satisfaction with care. Often they represent the outcomes that are most important to patients.6 The survey usually consists of several questions or items. It can be general or condition specific, and it may represent one or more health care dimensions.

The term patient-reported outcome measure (PROM) refers to the survey instrument used to collect PROs. Patient-reported experience measures (PREMs), such as satisfaction surveys, are considered a subset of PROMs.7

Standardized PROs developed out of clinical trials

The use of PROs evolved from clinical trials. The proliferation of PROs resulted in an inability to compare outcomes across trials or different conditions. This led to a need to standardize and possibly harmonize measures and to reach consensus about properties required for a “good” measure and requirements needed for “adequate” reporting. Many investigators and several national and international organizations have provided iterative guidance, including the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), European Medicines Agency, National Institutes of Health (NIH) Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS), International Consortium for Health Outcomes Measurement (ICHOM), University of Oxford Patient Reported Outcomes Measurement Group, Cochrane Systematic Reviews, Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials–Patient Reported Outcomes (CONSORT-PRO) extension (how to report PROs with the CONSORT checklist), and the International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research (ISPOR).4,5,8–18

In the United States, the RAND Medical Outcomes Study led to the development of the 12- and 36-item short form surveys, which are widely recognized and commonly used PROMs for health-related quality of life.19 The study generated multiple additional survey instruments that evaluate other domains and dimensions of health. These surveys have been translated into numerous languages, and the RAND website lists over 100 publications.19

In 2002, the NIH sponsored PROMIS, a cooperative program designed to develop, validate, and standardize item banks to measure PROs that were relevant across multiple, common medical conditions. Based on literature review, feedback from both healthy and sick patients, and clinical expert opinion, the PROMIS investigators developed a consensus-based framework for self-reported health that included the following domains: pain, fatigue, emotional distress, physical functioning, and social role participation; these domains were evaluated on paper or with computer-assisted technology.11–14 PROMIS is now a web-based resource with approximately 70 domains pertinent to children and adults in the general population and in those with chronic disease. Measures have been translated into more than 40 languages, and PROMIS-related work has resulted in more than 400 publications.14

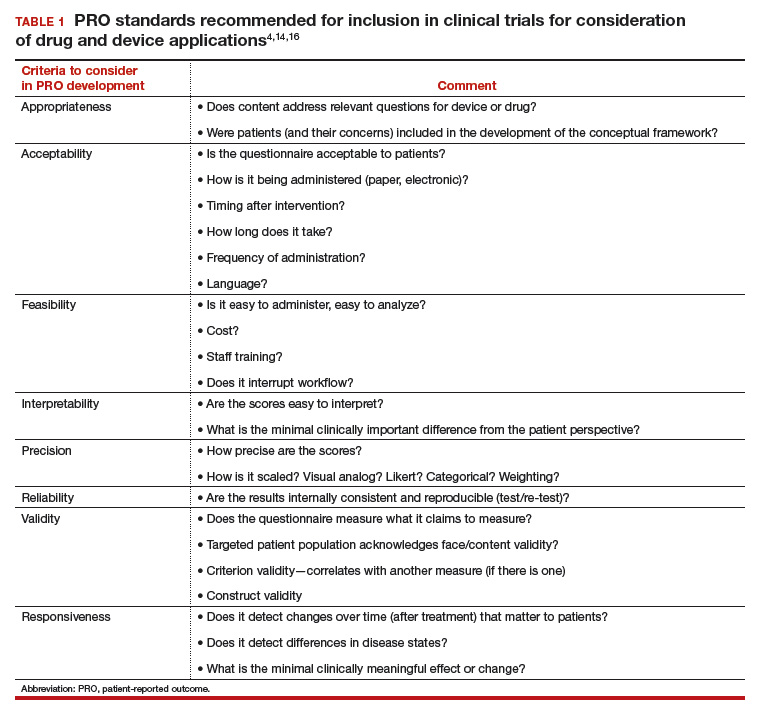

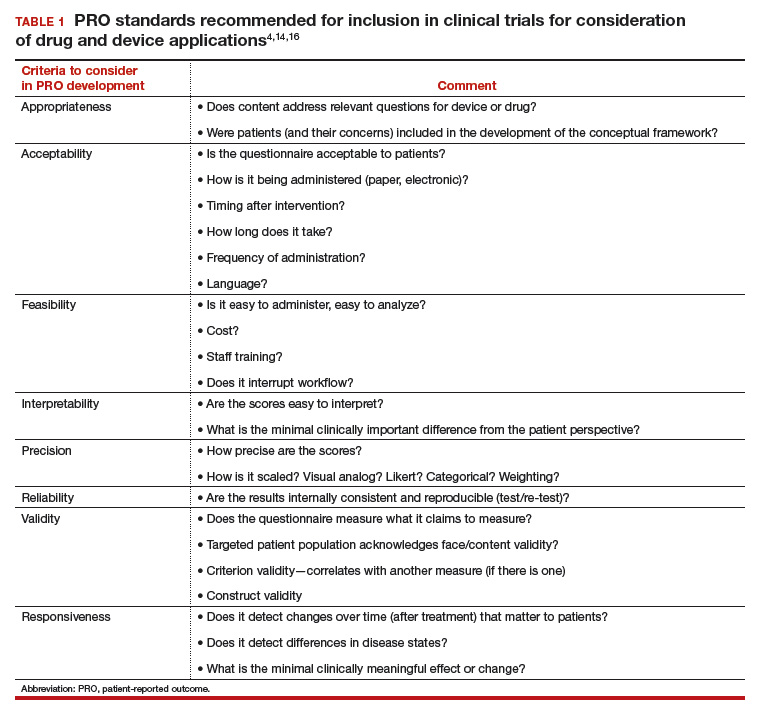

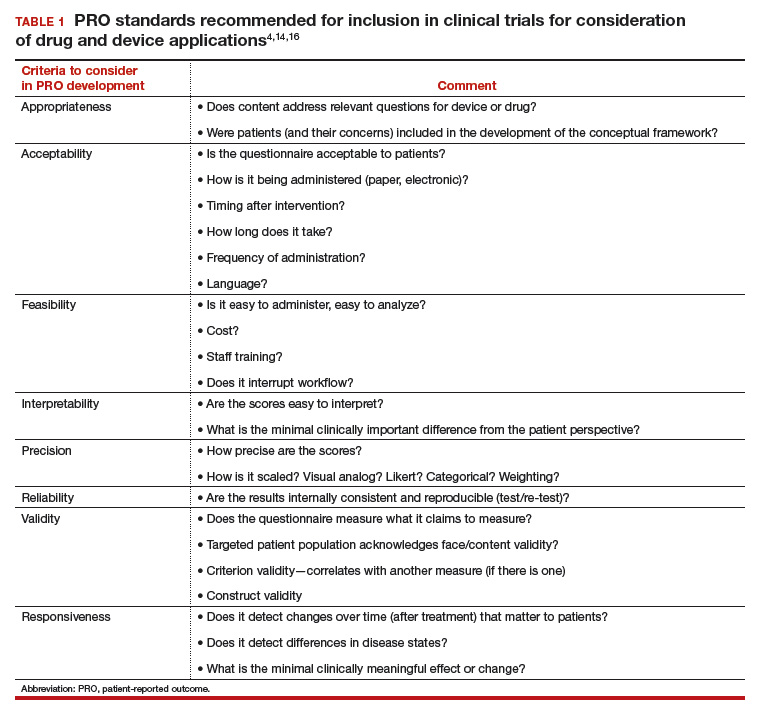

In 2006, the FDA issued a draft document regarding the PRO standards that should be included in clinical trials for consideration of drug and device applications (TABLE 1). These recommendations, updated in 2009, were largely drawn from work published by PROMIS and University of Oxford investigators.4,14,16

Because PROs are infrequently measured in routine clinical practice and PROMs that are used vary between countries, global comparison is difficult. Hence, ICHOM convened in 2012 to develop consensus-based, globally agreed on sets of outcomes that are intended to reflect what matters most to patients.

ICHOM specified 2 goals: 1) the core sets should be used in routine clinical practice, and 2) the core sets should be used as end points in clinical studies.15

As of May 2015, 12 standard sets of outcomes have been developed, representing 35% of the global burden of disease. ICHOM currently is creating networks of hospitals around the world to begin measuring, benchmarking, and performing outcome comparisons that can ultimately be used to inform global health system learning and clinical care improvement.15

Read about the evolving use of PROs

Use of PROs is evolving

Historically, PROMs have been used primarily in clinical trials to document the relative benefits of an intervention. With today’s focus on patient-centered care, however, there is a growing mandate to integrate PROMs into clinical care, quality improvement, and ultimately reimbursement. Recently, Basch and colleagues eloquently described the benefit of routine collection of PROs for cancer patients and the opportunity for improved care across the health system.20

PROs can be applied on various levels. For example, if a patient reports a symptom (X), or a change in symptom X, the following options are possible:

- Clinician level: Symptom management with altered dose or change in medication. This is associated with improved self-efficacy for the patient, a shift toward goal-oriented care, improved communication with the provider, and improved patient satisfaction.

- Researcher level: PROs should be used as a primary end point, in addition to traditional outcomes (mortality, survival, physiologic markers), to allow for comparative effectiveness studies or patient-centered outcomes research studies that evaluate what matters most to patients relative to the specific health condition, intervention, and symptom management.

- Health system level: Quality assurance, quality improvement activities. How effective is the health system in the management of symptom X? Are all clinicians using the same medication or the same dose? Is there a best practice for managing symptom X?

- Population level: Provides evidence for other clinicians and patients to make decisions about what to expect with treatment for symptom X.

From a reimbursement level, clinicians and providers are paid based on performance—the more satisfied patients are about X, the higher the reimbursement. This has been pertinent particularly in high-volume orthopedic conditions in which anatomic correction of hip or knee joints has not consistently demonstrated improvement in quality of life as measured by the following PROs: perception of pain, mobility, physical functioning, social functioning, and emotional distress. Because of concerns about high volume, high cost, and inconsistent outcomes, the US Department of Health and Human Services has specified that 50% of Medicare and 90% of Medicaid reimbursements will be based on outcomes or value-based purchasing options.21

Studies have shown that it is possible to collect PRO data for cancer patients—despite age or severity of illness—and integrate it into clinical care delivery. These data can provide useful, actionable information, resulting in decreased emergency department visits, longer toleration of chemotherapy, and improved survival.22 Similar results have been demonstrated in other medical conditions, although challenges exist when transitioning from research settings to routine care. Challenges include privacy concerns, patient recruitment and tracking, encouraging patients to complete the PRO surveys (nonresponse leads to biased data), real and perceived administrative burden to staff, obtaining clinician buy in, and costs related to surveys and data analysis.23

Read about the benefits of PROs to patients and clients

Using PROs in women’s health care: Benefits for patients and clinicians

According to a study by Frosch, patients want to know if a prescribed therapy actually improves outcomes, not whether it changes an isolated biomarker that does not translate into subjective improvement.24 They want to know if the trade-off (adverse effects or higher cost) associated with a new drug or therapy is worth the improved mobility or time spent pain free.

Intuitively, all clinicians have similar opportunities for discussions with regard to the risks, benefits, and alternatives of medical treatment, surgical treatment, or expectant management. We routinely document this discussion daily. However, in this era of patient-centered care, when a patient asks, “What should I do, doctor?” we no longer can respond with a default recommendation. We must engage the patient and ask, “What do you want to do? What is most important to you?”

ObGyns are well suited to benefit from standardized efforts to collect PROs, as we frequently discuss with our patients trade-offs regarding treatment risks and benefits and their personal values and preferences. Examples include contraception options, hormone treatment for menopause, medication use during pregnancy, decisions at the limits of viability, preterm delivery for severe preeclampsia, induction/augmentation versus spontaneous labor, epidural versus physiologic labor, repeat cesarean versus vaginal birth after cesarean, and even elective primary cesarean versus vaginal birth.

Validated PROMs exist for benign gynecology, such as abnormal uterine bleeding, fibroids, polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), infertility, pelvic organ prolapse and/or urinary incontinence, and surgery for benign gynecology symptoms, as well as for cancer (breast, ovarian, cervical).25–39

From the PCOS literature we can glean a poignant example of the importance of PROs. Martin and colleagues compared patient and clinician interviews regarding important PROs from the patient perspective.29 Patients identified pain, cramping, heavy bleeding, and bloating as important, whereas clinicians did not consider these symptoms important to patients with PCOS. Clinicians thought “issues with menstruation,” characterized as irregular or no periods, were important, whereas patients were more concerned with heavy bleeding or bleeding of long duration. The authors concluded that concepts frequently expressed by patients and considered important from their perspective did not register with clinicians as being relevant and are not captured on current PRO instruments, emphasizing our knowledge gap and the need to pay attention to what patients want.29

Surprisingly, although pregnancy and childbirth is the number one cause for hospital admissions, a highly preference-driven condition, and a leading cause of morbidity, mortality, and costs, there are few published PROs in the field. In a systematic review of more than 1,700 articles describing PROs published in English through 2014, Martin found that fewer than 1% included PROs specific to pregnancy and childbirth.40

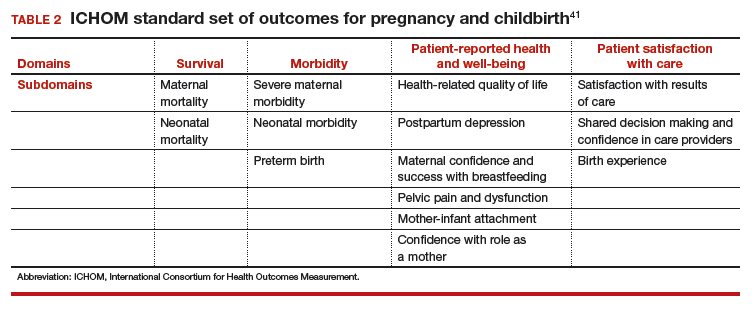

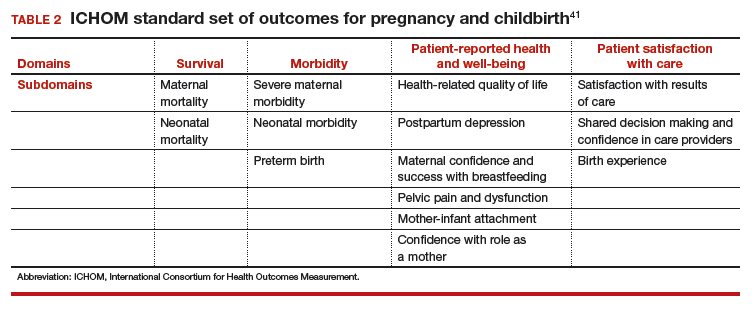

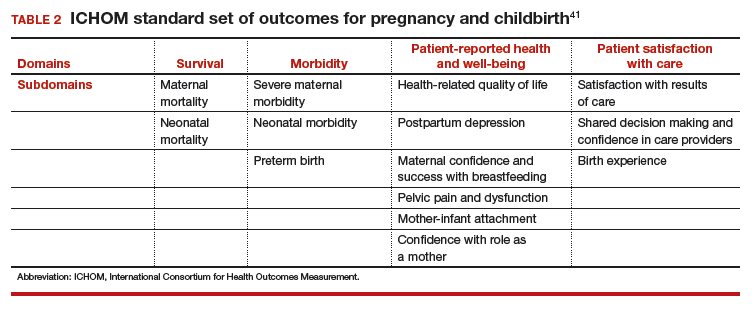

ICHOM has created a standard set of outcomes for pregnancy and childbirth based on consensus recommendations from physicians, measurement experts, and patients.41 The consortium describes 4 domains and 14 subdomains (TABLE 2) and provides suggestions for a validated PROM if known or where appropriate.

Similar domains and subdomains have been corroborated by our research team (the Maternal Quality Indicator [MQI] Work Group), the Childbirth Connection, and Gartner and colleagues.42–44 The MQI Work Group recently conducted a national survey of what women want and what they think is important for their childbirth experience. We identified 19 domains, consistent with those of other investigators.42 Gartner and colleagues advocate for a composite outcome measure that combines the core domains into one preference-based utility measure that is weighted.44 The rationale for this recommendation is that the levels of the domains might contribute differently to the overall birth experience. For example, communication might contribute more to an overall measure than pain management.44 The development of a childbirth-specific survey to evaluate patient-reported outcomes and patient-reported experiences with care is needed if we are to provide value-based care in this arena.45

Looking forward

PROs, PROMs, and PREMs are here to stay. They no longer are limited to clinical research, but increasingly will be incorporated into clinical care, providing us with opportunities to improve the quality of health care delivery, efficiency of patient/clinician interactions, and patients’ ratings of their health care experience.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Committee on Quality of Health Care in America, Institute of Medicine. Crossing the quality chasm: a new health system for the 21st century. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2001:6.

- Stewart M, Brown JB, Donner A, et al. The impact of patient-centered care on outcomes. J Fam Pract. 2000;49(9):796–804.

- Rickert J. Patient-centered care: what it means and how to get there. Health Affairs website. http://healthaffairs.org/blog/2012/01/24/patient-centered-care-what-it-means-and-how-to-get-there/. Published January 24, 2012. Accessed October 15, 2017.

- US Food and Drug Administration. Guidance for industry: Patient reported outcome measures: use in medical product development to support labeling claims. https://www.fda.gov/downloads/drugs/guidances/ucm193282.pdf. Published December 2009. Accessed February 6, 2018.

- Higgins JP, Green S, eds. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions, version 5.1.0 (updated March 2011). Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons; 2008. http://handbook.cochrane.org. Accessed October 15, 2017.

- Patrick DL, Guyatt PD, Acquadro C. Patient-reported outcomes. In: Higgins JP, Green S, eds. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions, version 5.1.0 (updated March 2011). Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons; 2008:chap 17. http://handbook-5-1.cochrane.org/. Accessed October 15, 2017.

- Weldring T, Smith SM. Patient-reported outcomes (PROs) and patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs). Health Serv Insights. 2013;6:61–68.

- McLeod LD, Coon CD, Martin SA, Fehnel SE, Hays RD. Interpreting patient-reported outcome results: US FDA guidance and emerging methods. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2011;11(2):163–169.

- European Medicines Agency, Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use. Reflection paper on the regulatory guidance for the use of health-related quality of life (HRQL) measures in the evaluation of medicinal products. https://www.ispor.org/workpaper/emea-hrql-guidance.pdf. Published July 27, 2005. Accessed February 7, 2018.

- Venkatesan P. New European guidance on patient-reported outcomes. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17(6):e226.

- Cella D, Yount S, Rothrock N, et al; PROMIS Cooperative Group. The Patient-Reported Outcomes Mesurement Information System (PROMIS): progress of an NIH Roadmap cooperative group during its first two years. Med Care. 2007;45(5 suppl 1):S3–S11.

- Cella D, Riley W, Stone A, et al; PROMIS Cooperative Group. The Patient-Reported Outcomes Mesurement Information System (PROMIS) developed and tested its first wave of adult self-reported health outcome item banks: 2005–2008. J Clin Epidemiol. 2010;63(11):1179–1194.

- Craig BM, Reeve BB, Brown PM, et al. US valuation of health outcomes measured using the PROMIS-29. Value Health. 2014;17(8):846–853.

- National Institutes of Health. Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS). https://commonfund.nih.gov/promis/index. Reviewed May 8, 2017. Accessed October 15, 2017.

- International Consortium for Health Outcomes Measurement (ICHOM). http://www.ichom.org/. Accessed October 15, 2017.

- University of Oxford, Patient Reported Outcomes Measurement Group http://phi.uhce.ox.ac.uk/. Accessed October 15, 2017.

- CONSORT. Patient-Reported Outcomes (CONSORT PRO). http://www.consort-statement.org/extensions/overview/consort-pro. Accessed October 15, 2017.

- International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research. https://www.ispor.org/. Accessed October 15, 2017.

- RAND Health. RAND medical outcomes study: measures of quality of life core survey from RAND Health. https://www.rand.org/health/surveys_tools/mos.html. Accessed October 15, 2017.

- Basch EM, Deal AM, Dueck A, et al. Overall survival results of a randomized trial assessing patient-reported outcomes for symptom monitoring during routine cancer treatment [abstract LBA2]. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(18)(suppl).

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Better care. Smarter spending. Healthier people: paying providers for value, not volume. https://www.cms.gov/Newsroom/MediaReleaseDatabase/Fact-sheets/2015-Fact-sheets-items/2015-01-26-3.html. Accessed October 15, 2017.

- Basch E, Deal AM, Kris MG, et al. Symptom monitoring with patient-reported outcomes during routine cancer treatment: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(6):557–565.

- Chenok K, Teleki S, SooHoo NF, Huddleston J, Bozic KJ. Collecting patient-reported outcomes: lessons from the California Joint Replacement Registry. EGEMS (Wash DC). 2015;3(1):1196.

- Frosch DL. Patient-reported outcomes as a measure of healthcare quality. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30(10):1383–1384.

- Gibbons E, Mackintosh A, Fitzpatrick R; Patient-Reported Outcome Measurement Group, Oxford. A structured review of patient-reported outcome measures for people undergoing elective procedures for benign gynaecological conditions of the uterus, 2010. http://phi.uhce.ox.ac.uk/pdf/ElectiveProcedures/PROMs_Oxford_Gynaecological%20procedures_012011.pdf. Accessed October 23, 2017.

- Matteson KA, Boardman LA, Munro MG, Clark MA. Abnormal uterine bleeding: a review of patient-based outcome measures. Fertil Steril. 2009;92(1):205–216.

- Matteson KA, Scott DM, Raker CA, Clark MA. The menstrual bleeding questionnaire: development and validation of a comprehensive patient-reported outcome instrument for heavy menstrual bleeding. BJOG. 2015;122(5):681–689.

- Coyne KS, Margolis MK, Bradley LD, Guido R, Maxwell GL, Spies JB. Further validation of the uterine fibroid symptom and quality-of-life questionnaire. Value Health. 2012;15(1):135–142.

- Martin ML, Halling K, Eek D, Krohe M, Paty J. Understanding polycystic ovary syndrome from the patient perspective: a concept elicitation patient interview study. Health Quality Life Outcomes. 2017;15(1):162.

- Malik-Aslam A, Reaney MD, Speight J. The suitability of polycystic ovary syndrome-specific questionnaires for measuring the impact of PCOS on quality of life in clinical trials. Value Health. 2010;13(4):440–446.

- Kitchen H, Aldhouse N, Trigg A, Palencia R, Mitchell S. A review of patient-reported outcome measures to assess female infertility-related quality of life. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2017;15(1):86.

- Sung VW, Joo K, Marques F, Myers DL. Patient-reported outcomes after combined surgery for pelvic floor disorders in older compared to younger women. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2009;201(5):534.e1–e5.

- Sung VW, Rogers RG, Barber MD, Clark MA. Conceptual framework for patient-important treatment outcomes for pelvic organ prolapse. Neurourol Urodynam. 2014;33(4):414–419.