User login

Coding considerations in investigating chronic pelvic pain

Nonsurgical interventions for chronic pelvic pain may include evaluation and management visits for managing medications, trigger point injections, or pelvic floor physical therapy. However, while these management options can be coded, some of them may have limitations imposed by payers on the frequency of care and by whom the care may be rendered.

For encounters that involve the management of pain medications, it is important that documentation for each of these visits clearly spells out the progress the patient is making in setting goals for pain management. Frequent office visits may send a flag to the payer for overutilization; complete documentation will go a long way to support the medical necessity of each visit at the level billed.

Who renders treatment?

Sometimes, chronic pelvic pain management involves pelvic floor physical therapy, such as teaching pelvic floor exercises or using biofeedback to control certain aspects of the pain. The majority of payers have strict guidelines dictating who can render these services by way of licensure and training if performed by someone other than the physician, and at what frequency. Typically, the person performing the therapy must be, at minimum, a licensed physical therapist.

Frequency

Frequency is often limited to 1 to 2 times a week in increments of 4 weeks before additional authorization is granted. Again, careful and detailed documentation of the patient’s progress will be crucial to continued therapy.

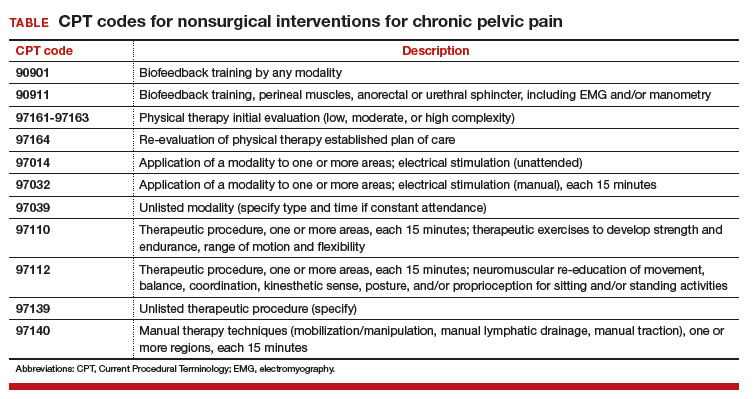

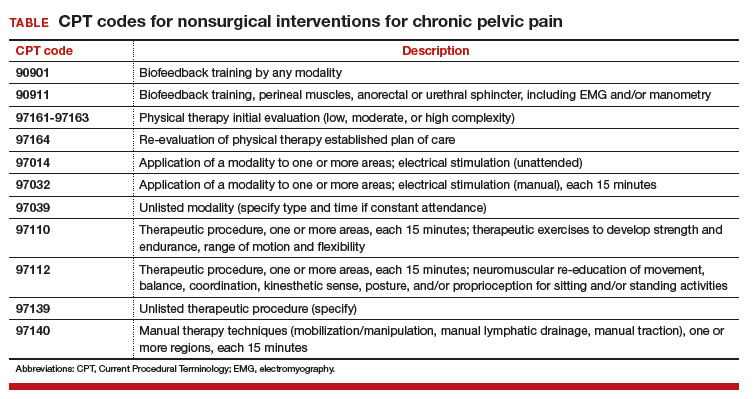

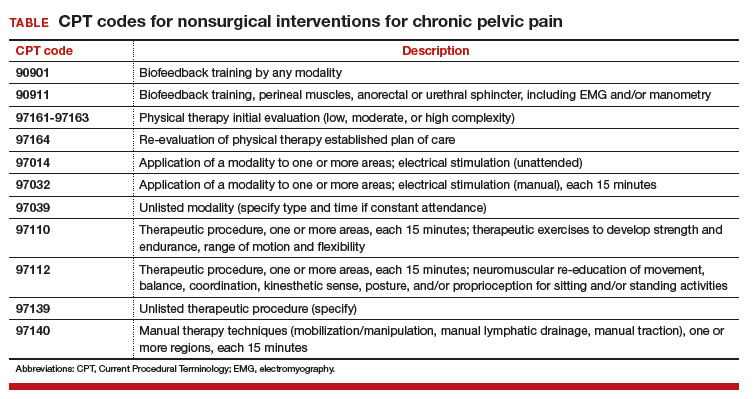

The TABLE shows typical Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes that might be authorized by the payer for this type of management.

Timed codes

Keep in mind that the “timed” codes listed above are based on the provider’s time spent one-on-one in direct contact with the patient. The time must have been used to provide skilled services and includes pre-, intra-, and posttreatment. CPT also has clarified that if “less than 15 minutes of service is provided, then the reduced services modifier -52 should be appended to the code to identify the reduction of service.” It will therefore be important that the provider accurately document the time involved in the therapy session for these codes.

Trigger point injections

Another treatment option is the use of trigger point injections to control pelvic pain. CPT provides 2 codes to report these:

- 20552, Injection(s); single or multiple trigger point(s), 1 or 2 muscle(s)

- 20553, Injection(s); single or multiple trigger point(s), 3 or more muscles.

Notice that the choice of code depends on the number of muscles the anesthetic is injected into, not the number of injections given at that muscle site.

The relative values units assigned to these codes are based on the injection procedure alone. Normally, the anesthetic used (lidocaine or bupivacaine) can be billed in addition; however, there are no specific Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System (HCPCS) “J” codes for either. Code J2001, Injection, lidocaine HCl, can only be reported for an intravenous infusion, not intramuscular, and the only current code for bupivacaine is an “S” code that is only recognized by some Blue Cross/Blue Shield payers (S0020, Injection, bupivacaine HCl, 30 ml).

Some physicians also inject sodium bicarbonate, but this, too, has no specific “J” code. Because of this, the only correct J code to report these drugs will be J3490, Unclassified drugs. Be sure to include the National Drug Code (NDC) number (usually found on the package insert) for each drug, and an invoice showing your cost with the claim.

ICD-10-CM codes needed for support

Billing for services will not be complete without a supporting diagnostic code. For pelvic pain in particular, 1 or more of the following ICD-10-CM codes may provide the medical justification for the provided nonsurgical services so long as there are no identified psychological factors:

- G89.0, Central pain syndrome

- G89.29, Other chronic pain

- N94.10, Unspecified dyspareunia

- N94.11, Superficial (introital) dyspareunia

- N94.12, Deep dyspareunia

- N94.19, Other specified dyspareunia

- N94.2, Vaginismus

- N94.4, Primary dysmenorrhea

- N94.5, Secondary dysmenorrhea

- N94.6, Dysmenorrhea, unspecified

- N94.810, Vulvar vestibulitis

- N94.818, Other vulvodynia

- N94.819, Vulvodynia, unspecified

- R10.2, Pelvic and perineal pain.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Nonsurgical interventions for chronic pelvic pain may include evaluation and management visits for managing medications, trigger point injections, or pelvic floor physical therapy. However, while these management options can be coded, some of them may have limitations imposed by payers on the frequency of care and by whom the care may be rendered.

For encounters that involve the management of pain medications, it is important that documentation for each of these visits clearly spells out the progress the patient is making in setting goals for pain management. Frequent office visits may send a flag to the payer for overutilization; complete documentation will go a long way to support the medical necessity of each visit at the level billed.

Who renders treatment?

Sometimes, chronic pelvic pain management involves pelvic floor physical therapy, such as teaching pelvic floor exercises or using biofeedback to control certain aspects of the pain. The majority of payers have strict guidelines dictating who can render these services by way of licensure and training if performed by someone other than the physician, and at what frequency. Typically, the person performing the therapy must be, at minimum, a licensed physical therapist.

Frequency

Frequency is often limited to 1 to 2 times a week in increments of 4 weeks before additional authorization is granted. Again, careful and detailed documentation of the patient’s progress will be crucial to continued therapy.

The TABLE shows typical Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes that might be authorized by the payer for this type of management.

Timed codes

Keep in mind that the “timed” codes listed above are based on the provider’s time spent one-on-one in direct contact with the patient. The time must have been used to provide skilled services and includes pre-, intra-, and posttreatment. CPT also has clarified that if “less than 15 minutes of service is provided, then the reduced services modifier -52 should be appended to the code to identify the reduction of service.” It will therefore be important that the provider accurately document the time involved in the therapy session for these codes.

Trigger point injections

Another treatment option is the use of trigger point injections to control pelvic pain. CPT provides 2 codes to report these:

- 20552, Injection(s); single or multiple trigger point(s), 1 or 2 muscle(s)

- 20553, Injection(s); single or multiple trigger point(s), 3 or more muscles.

Notice that the choice of code depends on the number of muscles the anesthetic is injected into, not the number of injections given at that muscle site.

The relative values units assigned to these codes are based on the injection procedure alone. Normally, the anesthetic used (lidocaine or bupivacaine) can be billed in addition; however, there are no specific Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System (HCPCS) “J” codes for either. Code J2001, Injection, lidocaine HCl, can only be reported for an intravenous infusion, not intramuscular, and the only current code for bupivacaine is an “S” code that is only recognized by some Blue Cross/Blue Shield payers (S0020, Injection, bupivacaine HCl, 30 ml).

Some physicians also inject sodium bicarbonate, but this, too, has no specific “J” code. Because of this, the only correct J code to report these drugs will be J3490, Unclassified drugs. Be sure to include the National Drug Code (NDC) number (usually found on the package insert) for each drug, and an invoice showing your cost with the claim.

ICD-10-CM codes needed for support

Billing for services will not be complete without a supporting diagnostic code. For pelvic pain in particular, 1 or more of the following ICD-10-CM codes may provide the medical justification for the provided nonsurgical services so long as there are no identified psychological factors:

- G89.0, Central pain syndrome

- G89.29, Other chronic pain

- N94.10, Unspecified dyspareunia

- N94.11, Superficial (introital) dyspareunia

- N94.12, Deep dyspareunia

- N94.19, Other specified dyspareunia

- N94.2, Vaginismus

- N94.4, Primary dysmenorrhea

- N94.5, Secondary dysmenorrhea

- N94.6, Dysmenorrhea, unspecified

- N94.810, Vulvar vestibulitis

- N94.818, Other vulvodynia

- N94.819, Vulvodynia, unspecified

- R10.2, Pelvic and perineal pain.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Nonsurgical interventions for chronic pelvic pain may include evaluation and management visits for managing medications, trigger point injections, or pelvic floor physical therapy. However, while these management options can be coded, some of them may have limitations imposed by payers on the frequency of care and by whom the care may be rendered.

For encounters that involve the management of pain medications, it is important that documentation for each of these visits clearly spells out the progress the patient is making in setting goals for pain management. Frequent office visits may send a flag to the payer for overutilization; complete documentation will go a long way to support the medical necessity of each visit at the level billed.

Who renders treatment?

Sometimes, chronic pelvic pain management involves pelvic floor physical therapy, such as teaching pelvic floor exercises or using biofeedback to control certain aspects of the pain. The majority of payers have strict guidelines dictating who can render these services by way of licensure and training if performed by someone other than the physician, and at what frequency. Typically, the person performing the therapy must be, at minimum, a licensed physical therapist.

Frequency

Frequency is often limited to 1 to 2 times a week in increments of 4 weeks before additional authorization is granted. Again, careful and detailed documentation of the patient’s progress will be crucial to continued therapy.

The TABLE shows typical Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes that might be authorized by the payer for this type of management.

Timed codes

Keep in mind that the “timed” codes listed above are based on the provider’s time spent one-on-one in direct contact with the patient. The time must have been used to provide skilled services and includes pre-, intra-, and posttreatment. CPT also has clarified that if “less than 15 minutes of service is provided, then the reduced services modifier -52 should be appended to the code to identify the reduction of service.” It will therefore be important that the provider accurately document the time involved in the therapy session for these codes.

Trigger point injections

Another treatment option is the use of trigger point injections to control pelvic pain. CPT provides 2 codes to report these:

- 20552, Injection(s); single or multiple trigger point(s), 1 or 2 muscle(s)

- 20553, Injection(s); single or multiple trigger point(s), 3 or more muscles.

Notice that the choice of code depends on the number of muscles the anesthetic is injected into, not the number of injections given at that muscle site.

The relative values units assigned to these codes are based on the injection procedure alone. Normally, the anesthetic used (lidocaine or bupivacaine) can be billed in addition; however, there are no specific Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System (HCPCS) “J” codes for either. Code J2001, Injection, lidocaine HCl, can only be reported for an intravenous infusion, not intramuscular, and the only current code for bupivacaine is an “S” code that is only recognized by some Blue Cross/Blue Shield payers (S0020, Injection, bupivacaine HCl, 30 ml).

Some physicians also inject sodium bicarbonate, but this, too, has no specific “J” code. Because of this, the only correct J code to report these drugs will be J3490, Unclassified drugs. Be sure to include the National Drug Code (NDC) number (usually found on the package insert) for each drug, and an invoice showing your cost with the claim.

ICD-10-CM codes needed for support

Billing for services will not be complete without a supporting diagnostic code. For pelvic pain in particular, 1 or more of the following ICD-10-CM codes may provide the medical justification for the provided nonsurgical services so long as there are no identified psychological factors:

- G89.0, Central pain syndrome

- G89.29, Other chronic pain

- N94.10, Unspecified dyspareunia

- N94.11, Superficial (introital) dyspareunia

- N94.12, Deep dyspareunia

- N94.19, Other specified dyspareunia

- N94.2, Vaginismus

- N94.4, Primary dysmenorrhea

- N94.5, Secondary dysmenorrhea

- N94.6, Dysmenorrhea, unspecified

- N94.810, Vulvar vestibulitis

- N94.818, Other vulvodynia

- N94.819, Vulvodynia, unspecified

- R10.2, Pelvic and perineal pain.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

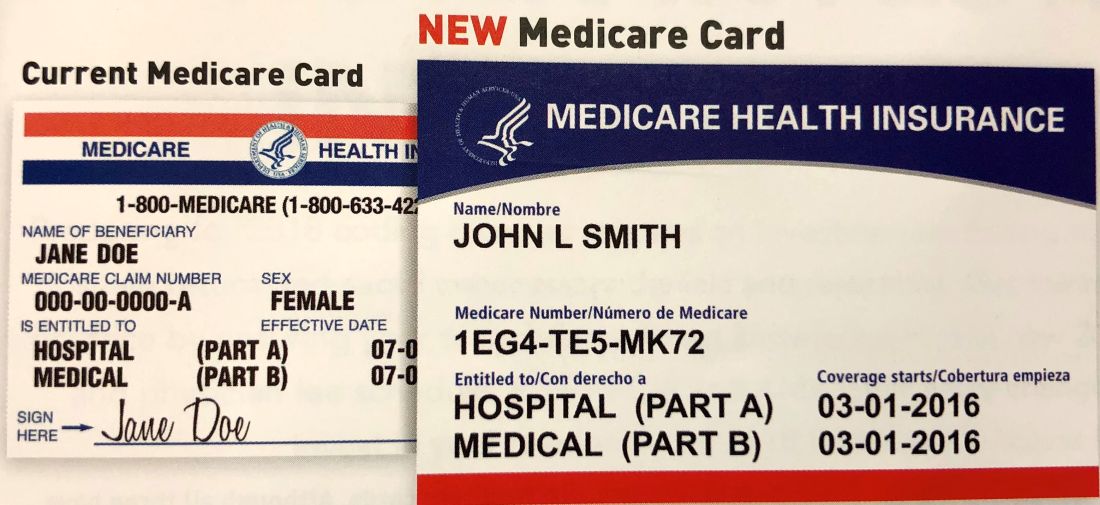

New Medicare cards

By now, you are probably aware that . The new, completely random number-letter combinations – dubbed Medicare Beneficiary Identifiers (MBI) – replace the old Social Security number–based Health Insurance Claim Numbers (HICN). The idea is to make citizens’ private information less vulnerable to identity thieves and other nefarious parties.

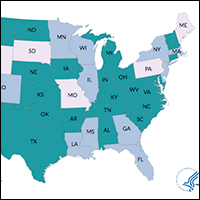

The switch began on April 1, and is expected to take about a year as the CMS processes about half a dozen states at a time. As I write this (at the beginning of May), the CMS is mailing out the first group of new cards to patients in Pennsylvania, Virginia, West Virginia, Maryland, Delaware, and the District of Columbia. But regardless of where you practice, you can expect to start seeing MBIs in your office soon – if you haven’t already – because people enrolling in Medicare for the first time are also receiving the new cards, no matter where they live.

Unlike the abrupt switch in 2015 from ICD-9 coding to ICD-10, this changeover has a transition period: Both HICNs and MBIs can be used on all billing and Medicare transactions from now until the end of 2019; after that, only claims with MBIs will be accepted. The last day of 2019 may sound like a long way off, but the time to get up to speed on everything MBI is now. That way, you can begin processing MBIs as soon as you start receiving them, and you will have time to solve any processing glitches well before the deadline.

First, you’ll need to make sure that your electronic health records and claims processing software will accept the new format, and that your electronic clearinghouse, if you use one, is geared up to accept and transmit the data on the new cards. Not all of them are. Some have been seduced by the year-and-a-half buffer – during which time HICNs can still be used – into dragging their feet on the MBI issue. Now is the time to find out if a vendor’s software is hard-wired to accept a maximum of 10 digits (MBIs have 11), not when your claims start bouncing.

Second, you will need to educate your front desk staff, so they will be able to recognize the new cards at a glance. Unfortunately, it looks a lot like the current card, though it is slightly smaller. It has the traditional red and blue colors with black printing, but there is no birthday or gender designation – again, in the interest of protecting patients’ identities. Knowing the difference will become particularly important after your state has been processed, when all of your Medicare patients should have the new card. Those who don’t will need to be identified and urged to get one before the December 2019 deadline.

Finally, once your staff and vendors are up to speed, you can begin educating your patients. Inevitably, some will not receive a new card, especially if they have moved and have not notified the CMS of the change; and some who are not expecting a new card will believe it is a duplicate, and throw it away. The CMS will be airing public service announcements and mailing education pieces to Medicare recipients, but a substantial portion of the education burden will fall on doctors and hospitals.

Have your front office staff remind patients to be sure their addresses are updated online with Medicare (www.Medicare.gov) or the Social Security Administration (www.ssa.gov). Encourage them to take advantage of the free resources available at www.cms.gov. These include both downloadable options and printed materials that illustrate what the new card will look like, explain how to update a mailing address with the Social Security Administration, and remind seniors to keep an eye out for their cards in the mail.

For the many Medicare-age patients who are not particularly computer savvy, the CMS has free resources for physicians as well. You will need to open an account at the agency’s Product Ordering website (productordering.cms.hhs.gov), which in turn needs to be approved by an administrator. The posters and other free literature can be displayed in your waiting room, exam rooms, and other “patient flow” areas. There is also a 1-minute video, downloadable from YouTube (https://youtu.be/DusRmgzQnLY), which can be looped in your waiting area.

Dr. Eastern practices dermatology and dermatologic surgery in Belleville, N.J. He is the author of numerous articles and textbook chapters, and is a longtime monthly columnist for Dermatology News. Write to him at [email protected].

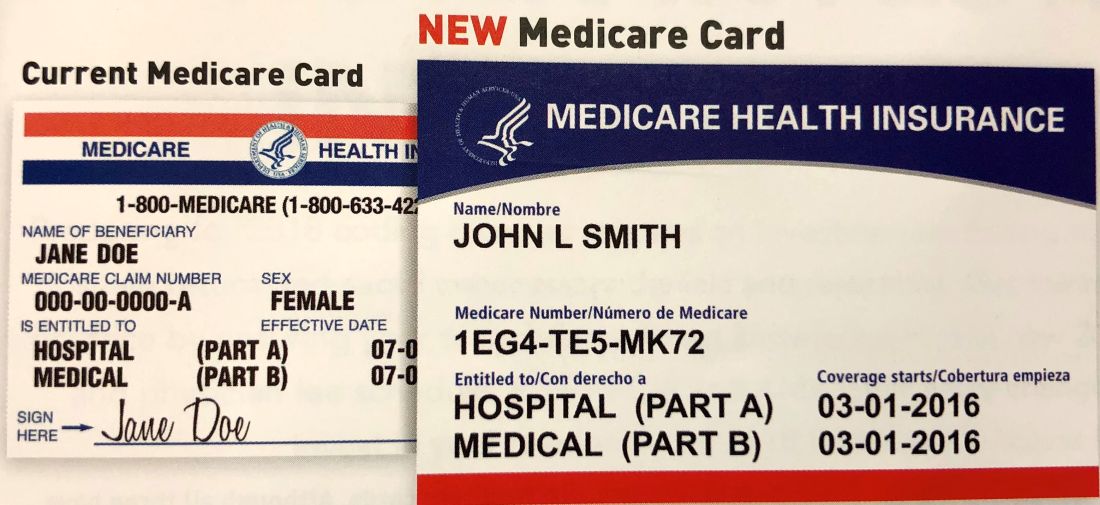

By now, you are probably aware that . The new, completely random number-letter combinations – dubbed Medicare Beneficiary Identifiers (MBI) – replace the old Social Security number–based Health Insurance Claim Numbers (HICN). The idea is to make citizens’ private information less vulnerable to identity thieves and other nefarious parties.

The switch began on April 1, and is expected to take about a year as the CMS processes about half a dozen states at a time. As I write this (at the beginning of May), the CMS is mailing out the first group of new cards to patients in Pennsylvania, Virginia, West Virginia, Maryland, Delaware, and the District of Columbia. But regardless of where you practice, you can expect to start seeing MBIs in your office soon – if you haven’t already – because people enrolling in Medicare for the first time are also receiving the new cards, no matter where they live.

Unlike the abrupt switch in 2015 from ICD-9 coding to ICD-10, this changeover has a transition period: Both HICNs and MBIs can be used on all billing and Medicare transactions from now until the end of 2019; after that, only claims with MBIs will be accepted. The last day of 2019 may sound like a long way off, but the time to get up to speed on everything MBI is now. That way, you can begin processing MBIs as soon as you start receiving them, and you will have time to solve any processing glitches well before the deadline.

First, you’ll need to make sure that your electronic health records and claims processing software will accept the new format, and that your electronic clearinghouse, if you use one, is geared up to accept and transmit the data on the new cards. Not all of them are. Some have been seduced by the year-and-a-half buffer – during which time HICNs can still be used – into dragging their feet on the MBI issue. Now is the time to find out if a vendor’s software is hard-wired to accept a maximum of 10 digits (MBIs have 11), not when your claims start bouncing.

Second, you will need to educate your front desk staff, so they will be able to recognize the new cards at a glance. Unfortunately, it looks a lot like the current card, though it is slightly smaller. It has the traditional red and blue colors with black printing, but there is no birthday or gender designation – again, in the interest of protecting patients’ identities. Knowing the difference will become particularly important after your state has been processed, when all of your Medicare patients should have the new card. Those who don’t will need to be identified and urged to get one before the December 2019 deadline.

Finally, once your staff and vendors are up to speed, you can begin educating your patients. Inevitably, some will not receive a new card, especially if they have moved and have not notified the CMS of the change; and some who are not expecting a new card will believe it is a duplicate, and throw it away. The CMS will be airing public service announcements and mailing education pieces to Medicare recipients, but a substantial portion of the education burden will fall on doctors and hospitals.

Have your front office staff remind patients to be sure their addresses are updated online with Medicare (www.Medicare.gov) or the Social Security Administration (www.ssa.gov). Encourage them to take advantage of the free resources available at www.cms.gov. These include both downloadable options and printed materials that illustrate what the new card will look like, explain how to update a mailing address with the Social Security Administration, and remind seniors to keep an eye out for their cards in the mail.

For the many Medicare-age patients who are not particularly computer savvy, the CMS has free resources for physicians as well. You will need to open an account at the agency’s Product Ordering website (productordering.cms.hhs.gov), which in turn needs to be approved by an administrator. The posters and other free literature can be displayed in your waiting room, exam rooms, and other “patient flow” areas. There is also a 1-minute video, downloadable from YouTube (https://youtu.be/DusRmgzQnLY), which can be looped in your waiting area.

Dr. Eastern practices dermatology and dermatologic surgery in Belleville, N.J. He is the author of numerous articles and textbook chapters, and is a longtime monthly columnist for Dermatology News. Write to him at [email protected].

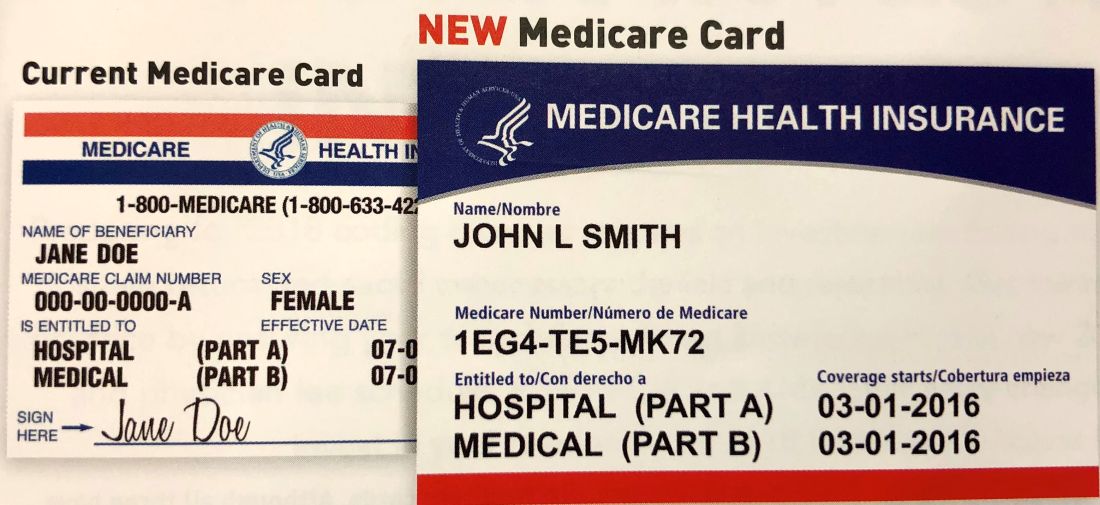

By now, you are probably aware that . The new, completely random number-letter combinations – dubbed Medicare Beneficiary Identifiers (MBI) – replace the old Social Security number–based Health Insurance Claim Numbers (HICN). The idea is to make citizens’ private information less vulnerable to identity thieves and other nefarious parties.

The switch began on April 1, and is expected to take about a year as the CMS processes about half a dozen states at a time. As I write this (at the beginning of May), the CMS is mailing out the first group of new cards to patients in Pennsylvania, Virginia, West Virginia, Maryland, Delaware, and the District of Columbia. But regardless of where you practice, you can expect to start seeing MBIs in your office soon – if you haven’t already – because people enrolling in Medicare for the first time are also receiving the new cards, no matter where they live.

Unlike the abrupt switch in 2015 from ICD-9 coding to ICD-10, this changeover has a transition period: Both HICNs and MBIs can be used on all billing and Medicare transactions from now until the end of 2019; after that, only claims with MBIs will be accepted. The last day of 2019 may sound like a long way off, but the time to get up to speed on everything MBI is now. That way, you can begin processing MBIs as soon as you start receiving them, and you will have time to solve any processing glitches well before the deadline.

First, you’ll need to make sure that your electronic health records and claims processing software will accept the new format, and that your electronic clearinghouse, if you use one, is geared up to accept and transmit the data on the new cards. Not all of them are. Some have been seduced by the year-and-a-half buffer – during which time HICNs can still be used – into dragging their feet on the MBI issue. Now is the time to find out if a vendor’s software is hard-wired to accept a maximum of 10 digits (MBIs have 11), not when your claims start bouncing.

Second, you will need to educate your front desk staff, so they will be able to recognize the new cards at a glance. Unfortunately, it looks a lot like the current card, though it is slightly smaller. It has the traditional red and blue colors with black printing, but there is no birthday or gender designation – again, in the interest of protecting patients’ identities. Knowing the difference will become particularly important after your state has been processed, when all of your Medicare patients should have the new card. Those who don’t will need to be identified and urged to get one before the December 2019 deadline.

Finally, once your staff and vendors are up to speed, you can begin educating your patients. Inevitably, some will not receive a new card, especially if they have moved and have not notified the CMS of the change; and some who are not expecting a new card will believe it is a duplicate, and throw it away. The CMS will be airing public service announcements and mailing education pieces to Medicare recipients, but a substantial portion of the education burden will fall on doctors and hospitals.

Have your front office staff remind patients to be sure their addresses are updated online with Medicare (www.Medicare.gov) or the Social Security Administration (www.ssa.gov). Encourage them to take advantage of the free resources available at www.cms.gov. These include both downloadable options and printed materials that illustrate what the new card will look like, explain how to update a mailing address with the Social Security Administration, and remind seniors to keep an eye out for their cards in the mail.

For the many Medicare-age patients who are not particularly computer savvy, the CMS has free resources for physicians as well. You will need to open an account at the agency’s Product Ordering website (productordering.cms.hhs.gov), which in turn needs to be approved by an administrator. The posters and other free literature can be displayed in your waiting room, exam rooms, and other “patient flow” areas. There is also a 1-minute video, downloadable from YouTube (https://youtu.be/DusRmgzQnLY), which can be looped in your waiting area.

Dr. Eastern practices dermatology and dermatologic surgery in Belleville, N.J. He is the author of numerous articles and textbook chapters, and is a longtime monthly columnist for Dermatology News. Write to him at [email protected].

How to decide on purchasing new medical equipment

Providing state-of-the-art health care for women often requires the use of various types of medical equipment, and decisions regarding their purchase can be complicated. With rising costs and reduced reimbursements, capital expenditures must be made with great care. Some equipment may not generate revenue but is required at a basic care-giving level: examination tables, procedure instruments, autoclaves, etc. Conversely, other equipment may not be necessary but strongly desired to offer a full complement of care. Unfortunately, sometimes a decision to buy expensive equipment is based more on a sales representative's ability to rationalize the purchase as a sound investment than on its necessity or practicality. This article focuses on tools to help you make a decision to obtain revenue-generating medical equipment.

First consideration: Nonfinancial evaluation

Nonfinancial criteria should be your first concern. They may have a greater impact on your practice than any financial consideration.

Does this investment align with your overall goals?

If your focus is to provide the best and most efficient obstetric care in the community, it may not make sense to purchase urodynamic equipment, even if using the equipment could be profitable.1 If the equipment begins to distract the practice from its strategic focus, then complications from managing this new equipment might be more harmful than helpful.

What are the pros and cons of the investment?

Concern that the equipment may not be effective or may become obsolete in a few years would preclude having to consider the financial purchase in the first place.1

Consider a PESTLE analysis

Before starting a new project, use a PESTLE analysis to assess external factors that are political, economic, social, technological, legal, and environmental. Its purpose is to identify issues that are beyond the control of the organization and have some level of impact on the organization.2,3

If you are considering the purchase of a laser hair removal machine, what could be the political considerations, such as your reputation among peers or other physicians who refer patients to your practice? What are the economic (financial) considerations? How would the social (or marketing) message be communicated, and do you have the organizational skills to implement a marketing strategy? What are the technical challenges required for maintaining this machine, and how much skill and training would be required to safely use it? What are the legal ramifications for implementing this service? Does your malpractice insurance cover it? And finally, what kind of environment (physical space) would be required?

What alternative investment opportunities might compete?

When considering a significant investment, other opportunities may no longer be feasible. Think about other ways your practice could use the money and which investment prospects would be the best fit.1 For instance, purchasing equipment that is very time intensive may not necessarily be the most profitable decision, especially if it takes the provider away from other services with higher margins. Could investing in expensive equipment delay bringing in another provider who might have a higher financial impact?

Next stage: Financial evaluation

To begin a basic cash flow analysis of the new investment, gather your practice's financial data. Estimate the cash flow resulting from the equipment investment, including any additional expenses and revenues. Here are some steps:

- Identify the revenue generated by each use of the equipment.

- Estimate the variable costs (costs that increase with each incremental unit of activity). Variable costs include expenses associated with each use, such as disposable accessories. For a hysteroscope, the variable cost may be the tubing and fluid used. Some procedures, such as office hysteroscopic sterilization, require the purchase of intratubal occlusion devices.

Also consider the cost of your time. One way to determine this is to investigate the hourly rate you would be paid if you were hypothetically hired by a third party to perform the procedure.

- Estimate the step costs. Step costs are constant over a narrow range of activity but shift to a higher level with increased activity. One example is staffing costs. If the number of these procedures significantly increases, additional staffing will be required. Include the hourly pay for your medical assistants in the analysis.

- Determine the contribution margin. Subtract the revenue from the sum of the variable and step costs to find the contribution margin (dollar contribution per unit) to your practice.4,5

- Estimate the approximate volume of procedures. It is hard to predict future demand, but a good rule of thumb is to estimate the best, expected, and pessimistic volumes. Then average the 3 scenarios and use that figure as the anticipated volume. Multiply the volume by the contribution margin to calculate profit.

Additional financial tools

Once the basic cash flow analysis of the new investment is undertaken, add these methods to your analysis:

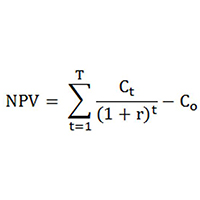

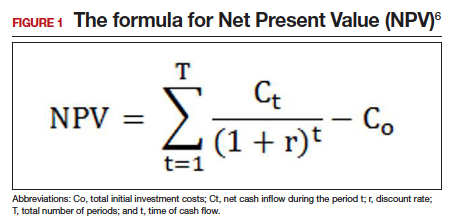

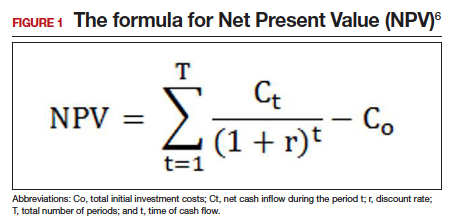

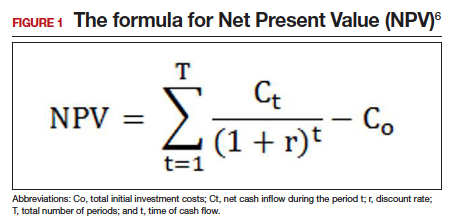

Net Present Value (NPV) is the difference between the present value of cash inflows and the present value of cash outflows (FIGURE 1).6 NPV takes into consideration the time value of money, where money in the present is worth more than the same value sometime in the future due to inflation and earning capacity. NPV is used in capital budgeting to analyze the profitability of a projected investment or project.1,4,5

Consider the discount rate as the expected rate of return or cost of capital. By discounting the future cash flow each year by the discount rate, you can get the present value of cash flow. Subtract the present value of cash flow from the original investment to get the NPV for the equipment's investment. A positive value is a favorable analysis to purchase the equipment; a negative value may suggest that the equipment may be a poor investment.

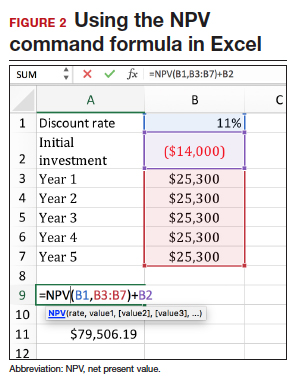

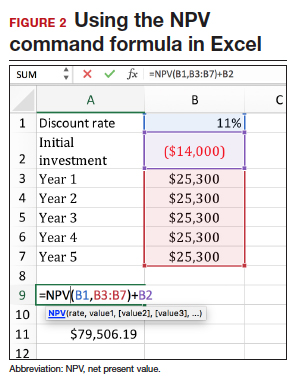

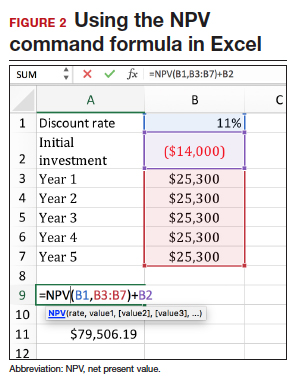

The NPV can be calculated in a spreadsheet using the following NPV command formula: NPV(rate,value1,[value2],...). This formula gives you the present value of cash inflows. The rate is the discount rate and the values are the series of cash flows occurring over a period of time. The NPV command formula in Excel, despite its misleading name, only gives the present value of cash flows.7 Therefore, it is important that the present value of cash inflows is subtracted from the initial capital investment to get the NPV.

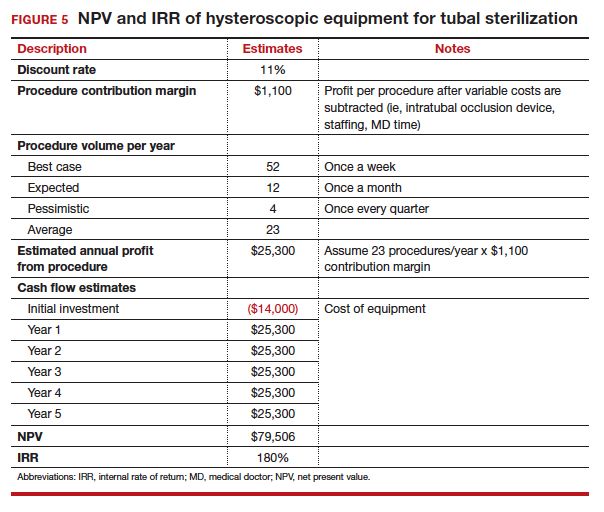

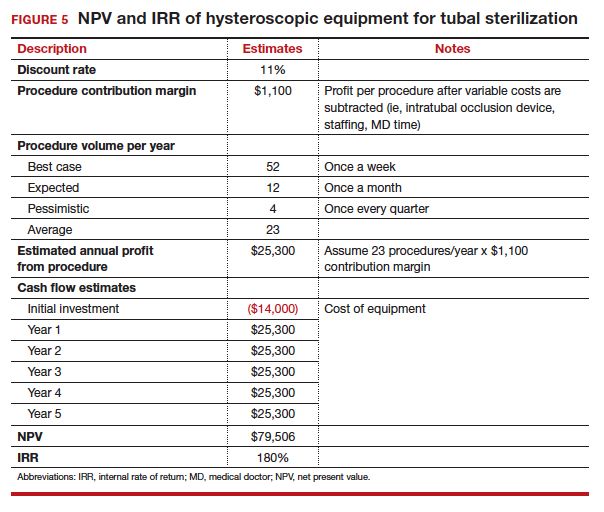

FIGURE 2 shows analysis of a piece of equipment that requires a $14,000 initial investment in Year 0. Each year the use of the equipment generates $25,300 per year through year 5. Assign a discount rate of 11%, about what you would expect for a stock market investment.

Consider other investment opportunities. The historical rate of return for a stock index fund is 11.5%.8 Using this discount rate, you can compare whether the money would be better invested in the medical equipment or stock.

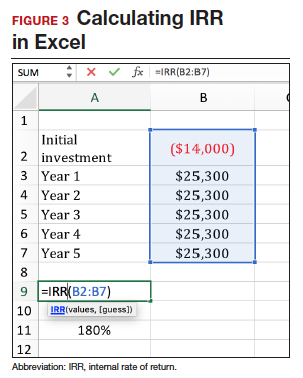

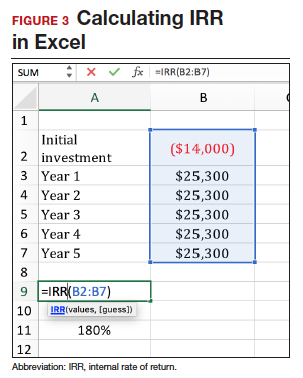

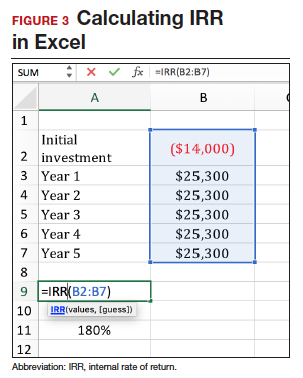

Internal rate of return (IRR) is a metric used in capital budgeting to measure the profitability of potential investments. The IRR determines if the discount rate at which the present value of expected net cash inflow is equal to the cash outlay. In other words, the IRR is the discount rate that makes the net present cash flows from a project equal zero. The decision rule related to the IRR criterion is to accept a project in which the IRR is greater than the required rate of return (cutoff rate). The formula for the IRR is the same as the NPV formula, except that the NPV is set at zero and the discount rate is calculated through iterative calculation. The IRR can be calculated in a spreadsheet using the following command formula: IRR(values, [guess]).1,5,9 In FIGURE 3, the IRR is 180%, far superior than the return you would find in other investments such as the stock market.

The IRR is somewhat different from return on investment (ROI). ROI is the percent of return on the initial investment over a period of time. Each piece of equipment has a different ROI over a different time period. ROI does not take into account the time value of money (TVM). Incorporating the IRR (or the TVM) allows for equal comparison between 2 pieces of equipment in the analysis.10

If you are not comparing 2 different types of equipment for purchase, then using the cutoff of 11.5% may be helpful (the historical average stock market return). If the IRR is less than 11.5%, then in theory, it would be better to put your money in the stock market than in new equipment.7

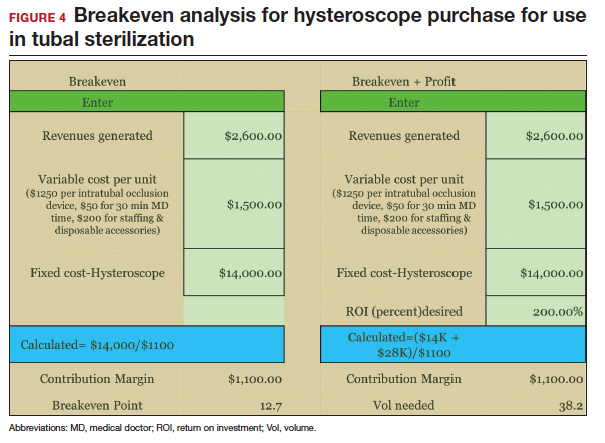

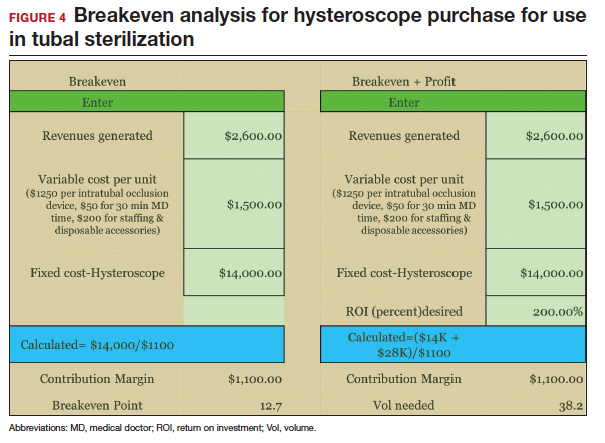

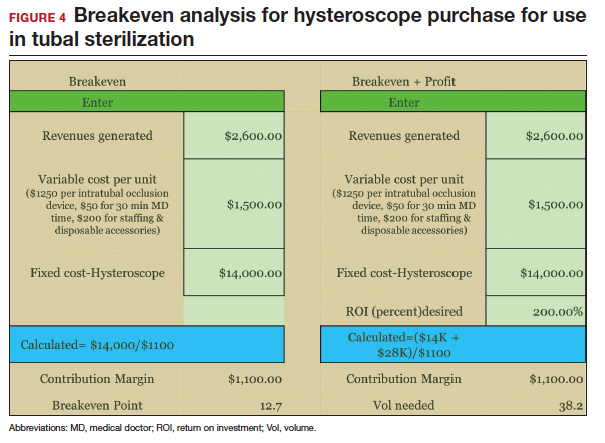

Breakeven analysis calculates the volume of procedures that would be needed to break even or make a profit. It can also determine if there is enough demand to meet the volume required to break even or profit. Unlike the first 2 methods, where you have to guess at future volume, this method calculates the volume required to break even, but does not specify a time period. Your practice would have to use subjective experience to determine how long it would take to reach that volume, given your patient population and the ability to reach the targeted market segment.

Fixed costs are costs that do not change with the varying volume of units of service or products sold. After calculating the contribution margin, divide the fixed costs of the equipment by the contribution margin. Then you will have the volume required to break even (FIGURE 4). Add the dollar amount of profit you would like to attain to the fixed costs, then divide that total by the contribution margin, and you'll have the volume required to meet those specifications.1,4,5

Even though the calculations described above relate to medical equipment, you can use this same method to analyze the cost of adding new providers or any other business development project to determine the required volume to break even on the capital outlay.

CASE New equipment requests

A new ObGyn in your practice requests that you purchase a hysteroscope so that she can start performing office-based hysteroscopic sterilization. Another partner would like to acquire urodynamic equipment instead of referring urinary incontinent patients to a urogynecologist. How do you decide what to purchase?

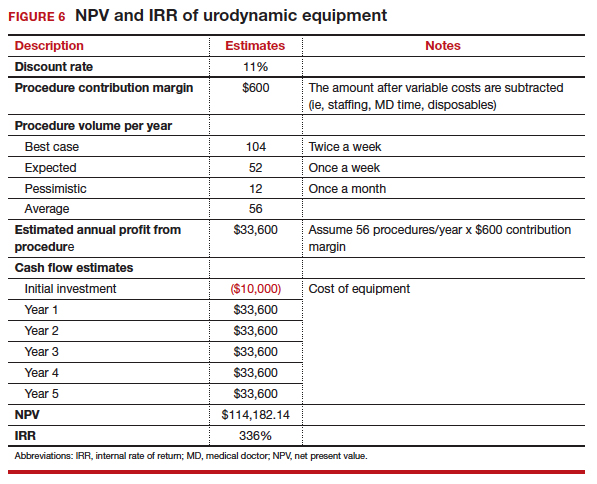

First calculate the contribution margins for each product. Next, since you do not know for certain the volume you might achieve for each procedure, create 3 scenarios for the best, expected, and pessimistic situations. Assume equal probability for each of these categories and average the volumes of the estimates. Even though you may keep the equipment longer, estimate the financial analysis over 5 years. In this example, we assume a discount rate of 11% for the NPV calculation for both pieces of equipment.

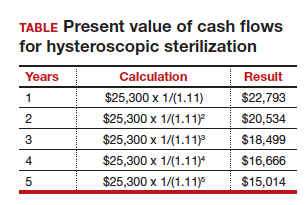

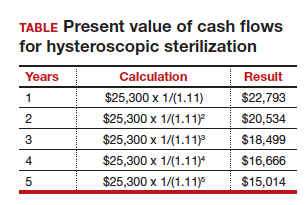

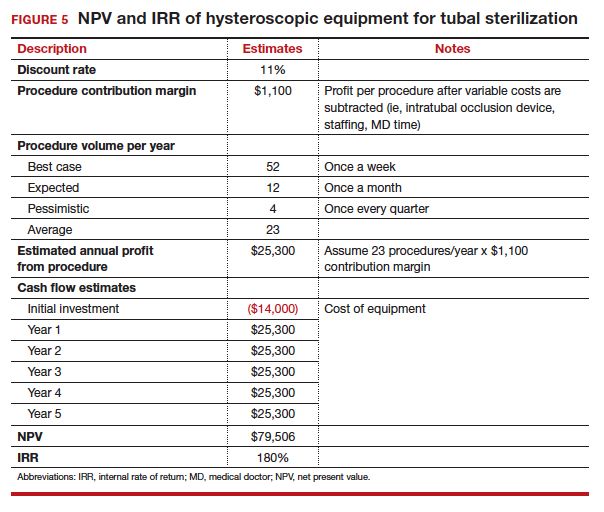

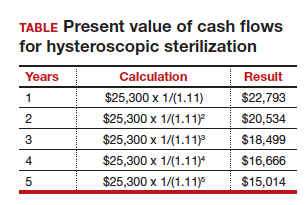

Calculate the IRR using a spreadsheet based on the cash flow for each piece of equipment. Say that the practice anticipates doing 23 hysteroscopic sterilizations per year. If the reimbursement is $2,600 per procedure, and the variable costs are $1,500, the contribution margin is $1,100. So 23 procedures multiplied by $1,100 equals an annual profit of $25,300. Then discount the $25,300 for each year. In this example, we use a discount rate of 11%. The TABLE shows the amount discounted each year.

The sum of the discounted cash flows is $93,506. However, we have to subtract the initial investment of $14,000, so the final NPV equals $79,506 (FIGURE 5).

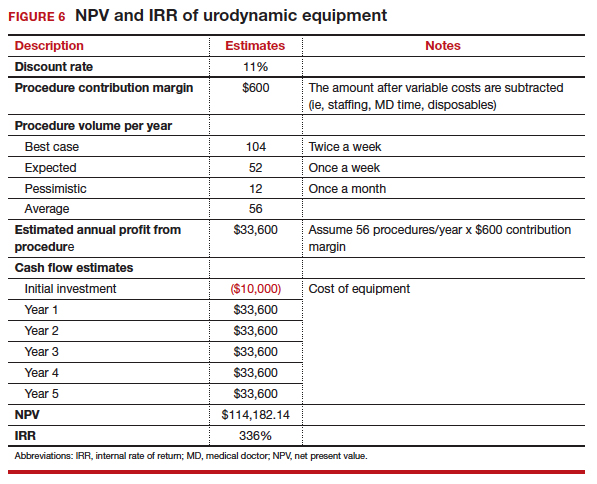

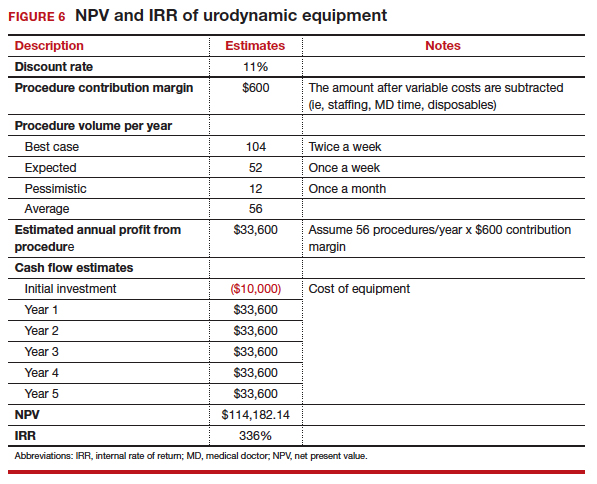

Apply the same financial NPV and IRR calculations used to assess the hysteroscope to the urodynamic equipment. From the analysis (FIGUREs 5 and 6), both purchases would be financially successful. However, it appears that the urodynamic equipment is a superior investment over the hysteroscope, with a higher NPV ($115,877 vs $81,880, respectively) and IRR (336% vs 180%, respectively). This is likely due to the higher anticipated volume of use with the urodynamic equipment and lower cost of initial investment, despite having a lower contribution margin than the hysteroscope.

Caveats

For simplicity, this analysis does not account for the fact that the hysteroscope could be used for other revenue-generating procedures such as diagnostic hysteroscopy. Factoring in these potential additional services using the same hysteroscope might change the decision analysis in favor of the hysteroscope.

Remember that, although the financial analysis is very helpful in decision making, nonfinancial evaluations should also influence your choice. In this example, while there may be a financial advantage to purchasing the urodynamic equipment over the hysteroscopic equipment, nonfinancial considerations can help you decide which purchase would be a better aligned with the goals and strategies of your practice.

These tools for nonfinancial and financial analysis can be used for any investment in your practice, whether it is in medical equipment, personnel, or development of other profit centers.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Willis DR. How to decide whether to buy new medical equipment. Fam Pract Manag. 2004;11(3):53−58.

- PESTLE Analysis Strategy Skills. http://www.free-management-ebooks.com/dldebk-pdf/fme-pestle-analysis.pdf. Published 2013. Accessed March 2, 2018.

- What is PESTLE analysis? A tool for business analysis. http://pestleanalysis.com/what-is-pestle-analysis/. Published 2018. Accessed March 2, 2018.

- Nowicki M, ed. Introduction to the Financial Management of Healthcare Organizations. 6th ed. Chicago, Illinois: Health Administration Press; 2014:150−151, 299−316.

- Ross SA, Westerfield RW, Jaffe J. Corporate Finance. 8th ed. New York, New York: McGraw Hill; 2008:271−288.

- Net Present Value - NPV. Investopia. https://www.investopedia.com/terms/n/npv.asp. Accessed April 10, 2018.

- NPV function. Microsoft Office Support. https://support.office.com/en-us/article/npv-function-8672cb67-2576-4d07-b67b-ac28acf2a568. Accessed April 10, 2018.

- Damodaran A. Annual Returns on Stock, T.Bonds and T.Bills: 1928 - Current. http://pages.stern.nyu.edu/~adamodar/New_Home_Page/datafile/histretSP.html. Updated January 5, 2018. Accessed March 2, 2018.

- IRR function. Microsoft Office Support. https://support.office.com/en-us/article/irr-function-64925eaa-9988-495b-b290-3ad0c163c1bc. Accessed April 10, 2018.

- Time Value of Money (TVM). Investopedia. https://www.investopedia.com/terms/t/timevalueofmoney.asp. Published 2018. Accessed March 2, 2018.

Providing state-of-the-art health care for women often requires the use of various types of medical equipment, and decisions regarding their purchase can be complicated. With rising costs and reduced reimbursements, capital expenditures must be made with great care. Some equipment may not generate revenue but is required at a basic care-giving level: examination tables, procedure instruments, autoclaves, etc. Conversely, other equipment may not be necessary but strongly desired to offer a full complement of care. Unfortunately, sometimes a decision to buy expensive equipment is based more on a sales representative's ability to rationalize the purchase as a sound investment than on its necessity or practicality. This article focuses on tools to help you make a decision to obtain revenue-generating medical equipment.

First consideration: Nonfinancial evaluation

Nonfinancial criteria should be your first concern. They may have a greater impact on your practice than any financial consideration.

Does this investment align with your overall goals?

If your focus is to provide the best and most efficient obstetric care in the community, it may not make sense to purchase urodynamic equipment, even if using the equipment could be profitable.1 If the equipment begins to distract the practice from its strategic focus, then complications from managing this new equipment might be more harmful than helpful.

What are the pros and cons of the investment?

Concern that the equipment may not be effective or may become obsolete in a few years would preclude having to consider the financial purchase in the first place.1

Consider a PESTLE analysis

Before starting a new project, use a PESTLE analysis to assess external factors that are political, economic, social, technological, legal, and environmental. Its purpose is to identify issues that are beyond the control of the organization and have some level of impact on the organization.2,3

If you are considering the purchase of a laser hair removal machine, what could be the political considerations, such as your reputation among peers or other physicians who refer patients to your practice? What are the economic (financial) considerations? How would the social (or marketing) message be communicated, and do you have the organizational skills to implement a marketing strategy? What are the technical challenges required for maintaining this machine, and how much skill and training would be required to safely use it? What are the legal ramifications for implementing this service? Does your malpractice insurance cover it? And finally, what kind of environment (physical space) would be required?

What alternative investment opportunities might compete?

When considering a significant investment, other opportunities may no longer be feasible. Think about other ways your practice could use the money and which investment prospects would be the best fit.1 For instance, purchasing equipment that is very time intensive may not necessarily be the most profitable decision, especially if it takes the provider away from other services with higher margins. Could investing in expensive equipment delay bringing in another provider who might have a higher financial impact?

Next stage: Financial evaluation

To begin a basic cash flow analysis of the new investment, gather your practice's financial data. Estimate the cash flow resulting from the equipment investment, including any additional expenses and revenues. Here are some steps:

- Identify the revenue generated by each use of the equipment.

- Estimate the variable costs (costs that increase with each incremental unit of activity). Variable costs include expenses associated with each use, such as disposable accessories. For a hysteroscope, the variable cost may be the tubing and fluid used. Some procedures, such as office hysteroscopic sterilization, require the purchase of intratubal occlusion devices.

Also consider the cost of your time. One way to determine this is to investigate the hourly rate you would be paid if you were hypothetically hired by a third party to perform the procedure.

- Estimate the step costs. Step costs are constant over a narrow range of activity but shift to a higher level with increased activity. One example is staffing costs. If the number of these procedures significantly increases, additional staffing will be required. Include the hourly pay for your medical assistants in the analysis.

- Determine the contribution margin. Subtract the revenue from the sum of the variable and step costs to find the contribution margin (dollar contribution per unit) to your practice.4,5

- Estimate the approximate volume of procedures. It is hard to predict future demand, but a good rule of thumb is to estimate the best, expected, and pessimistic volumes. Then average the 3 scenarios and use that figure as the anticipated volume. Multiply the volume by the contribution margin to calculate profit.

Additional financial tools

Once the basic cash flow analysis of the new investment is undertaken, add these methods to your analysis:

Net Present Value (NPV) is the difference between the present value of cash inflows and the present value of cash outflows (FIGURE 1).6 NPV takes into consideration the time value of money, where money in the present is worth more than the same value sometime in the future due to inflation and earning capacity. NPV is used in capital budgeting to analyze the profitability of a projected investment or project.1,4,5

Consider the discount rate as the expected rate of return or cost of capital. By discounting the future cash flow each year by the discount rate, you can get the present value of cash flow. Subtract the present value of cash flow from the original investment to get the NPV for the equipment's investment. A positive value is a favorable analysis to purchase the equipment; a negative value may suggest that the equipment may be a poor investment.

The NPV can be calculated in a spreadsheet using the following NPV command formula: NPV(rate,value1,[value2],...). This formula gives you the present value of cash inflows. The rate is the discount rate and the values are the series of cash flows occurring over a period of time. The NPV command formula in Excel, despite its misleading name, only gives the present value of cash flows.7 Therefore, it is important that the present value of cash inflows is subtracted from the initial capital investment to get the NPV.

FIGURE 2 shows analysis of a piece of equipment that requires a $14,000 initial investment in Year 0. Each year the use of the equipment generates $25,300 per year through year 5. Assign a discount rate of 11%, about what you would expect for a stock market investment.

Consider other investment opportunities. The historical rate of return for a stock index fund is 11.5%.8 Using this discount rate, you can compare whether the money would be better invested in the medical equipment or stock.

Internal rate of return (IRR) is a metric used in capital budgeting to measure the profitability of potential investments. The IRR determines if the discount rate at which the present value of expected net cash inflow is equal to the cash outlay. In other words, the IRR is the discount rate that makes the net present cash flows from a project equal zero. The decision rule related to the IRR criterion is to accept a project in which the IRR is greater than the required rate of return (cutoff rate). The formula for the IRR is the same as the NPV formula, except that the NPV is set at zero and the discount rate is calculated through iterative calculation. The IRR can be calculated in a spreadsheet using the following command formula: IRR(values, [guess]).1,5,9 In FIGURE 3, the IRR is 180%, far superior than the return you would find in other investments such as the stock market.

The IRR is somewhat different from return on investment (ROI). ROI is the percent of return on the initial investment over a period of time. Each piece of equipment has a different ROI over a different time period. ROI does not take into account the time value of money (TVM). Incorporating the IRR (or the TVM) allows for equal comparison between 2 pieces of equipment in the analysis.10

If you are not comparing 2 different types of equipment for purchase, then using the cutoff of 11.5% may be helpful (the historical average stock market return). If the IRR is less than 11.5%, then in theory, it would be better to put your money in the stock market than in new equipment.7

Breakeven analysis calculates the volume of procedures that would be needed to break even or make a profit. It can also determine if there is enough demand to meet the volume required to break even or profit. Unlike the first 2 methods, where you have to guess at future volume, this method calculates the volume required to break even, but does not specify a time period. Your practice would have to use subjective experience to determine how long it would take to reach that volume, given your patient population and the ability to reach the targeted market segment.

Fixed costs are costs that do not change with the varying volume of units of service or products sold. After calculating the contribution margin, divide the fixed costs of the equipment by the contribution margin. Then you will have the volume required to break even (FIGURE 4). Add the dollar amount of profit you would like to attain to the fixed costs, then divide that total by the contribution margin, and you'll have the volume required to meet those specifications.1,4,5

Even though the calculations described above relate to medical equipment, you can use this same method to analyze the cost of adding new providers or any other business development project to determine the required volume to break even on the capital outlay.

CASE New equipment requests

A new ObGyn in your practice requests that you purchase a hysteroscope so that she can start performing office-based hysteroscopic sterilization. Another partner would like to acquire urodynamic equipment instead of referring urinary incontinent patients to a urogynecologist. How do you decide what to purchase?

First calculate the contribution margins for each product. Next, since you do not know for certain the volume you might achieve for each procedure, create 3 scenarios for the best, expected, and pessimistic situations. Assume equal probability for each of these categories and average the volumes of the estimates. Even though you may keep the equipment longer, estimate the financial analysis over 5 years. In this example, we assume a discount rate of 11% for the NPV calculation for both pieces of equipment.

Calculate the IRR using a spreadsheet based on the cash flow for each piece of equipment. Say that the practice anticipates doing 23 hysteroscopic sterilizations per year. If the reimbursement is $2,600 per procedure, and the variable costs are $1,500, the contribution margin is $1,100. So 23 procedures multiplied by $1,100 equals an annual profit of $25,300. Then discount the $25,300 for each year. In this example, we use a discount rate of 11%. The TABLE shows the amount discounted each year.

The sum of the discounted cash flows is $93,506. However, we have to subtract the initial investment of $14,000, so the final NPV equals $79,506 (FIGURE 5).

Apply the same financial NPV and IRR calculations used to assess the hysteroscope to the urodynamic equipment. From the analysis (FIGUREs 5 and 6), both purchases would be financially successful. However, it appears that the urodynamic equipment is a superior investment over the hysteroscope, with a higher NPV ($115,877 vs $81,880, respectively) and IRR (336% vs 180%, respectively). This is likely due to the higher anticipated volume of use with the urodynamic equipment and lower cost of initial investment, despite having a lower contribution margin than the hysteroscope.

Caveats

For simplicity, this analysis does not account for the fact that the hysteroscope could be used for other revenue-generating procedures such as diagnostic hysteroscopy. Factoring in these potential additional services using the same hysteroscope might change the decision analysis in favor of the hysteroscope.

Remember that, although the financial analysis is very helpful in decision making, nonfinancial evaluations should also influence your choice. In this example, while there may be a financial advantage to purchasing the urodynamic equipment over the hysteroscopic equipment, nonfinancial considerations can help you decide which purchase would be a better aligned with the goals and strategies of your practice.

These tools for nonfinancial and financial analysis can be used for any investment in your practice, whether it is in medical equipment, personnel, or development of other profit centers.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Providing state-of-the-art health care for women often requires the use of various types of medical equipment, and decisions regarding their purchase can be complicated. With rising costs and reduced reimbursements, capital expenditures must be made with great care. Some equipment may not generate revenue but is required at a basic care-giving level: examination tables, procedure instruments, autoclaves, etc. Conversely, other equipment may not be necessary but strongly desired to offer a full complement of care. Unfortunately, sometimes a decision to buy expensive equipment is based more on a sales representative's ability to rationalize the purchase as a sound investment than on its necessity or practicality. This article focuses on tools to help you make a decision to obtain revenue-generating medical equipment.

First consideration: Nonfinancial evaluation

Nonfinancial criteria should be your first concern. They may have a greater impact on your practice than any financial consideration.

Does this investment align with your overall goals?

If your focus is to provide the best and most efficient obstetric care in the community, it may not make sense to purchase urodynamic equipment, even if using the equipment could be profitable.1 If the equipment begins to distract the practice from its strategic focus, then complications from managing this new equipment might be more harmful than helpful.

What are the pros and cons of the investment?

Concern that the equipment may not be effective or may become obsolete in a few years would preclude having to consider the financial purchase in the first place.1

Consider a PESTLE analysis

Before starting a new project, use a PESTLE analysis to assess external factors that are political, economic, social, technological, legal, and environmental. Its purpose is to identify issues that are beyond the control of the organization and have some level of impact on the organization.2,3

If you are considering the purchase of a laser hair removal machine, what could be the political considerations, such as your reputation among peers or other physicians who refer patients to your practice? What are the economic (financial) considerations? How would the social (or marketing) message be communicated, and do you have the organizational skills to implement a marketing strategy? What are the technical challenges required for maintaining this machine, and how much skill and training would be required to safely use it? What are the legal ramifications for implementing this service? Does your malpractice insurance cover it? And finally, what kind of environment (physical space) would be required?

What alternative investment opportunities might compete?

When considering a significant investment, other opportunities may no longer be feasible. Think about other ways your practice could use the money and which investment prospects would be the best fit.1 For instance, purchasing equipment that is very time intensive may not necessarily be the most profitable decision, especially if it takes the provider away from other services with higher margins. Could investing in expensive equipment delay bringing in another provider who might have a higher financial impact?

Next stage: Financial evaluation

To begin a basic cash flow analysis of the new investment, gather your practice's financial data. Estimate the cash flow resulting from the equipment investment, including any additional expenses and revenues. Here are some steps:

- Identify the revenue generated by each use of the equipment.

- Estimate the variable costs (costs that increase with each incremental unit of activity). Variable costs include expenses associated with each use, such as disposable accessories. For a hysteroscope, the variable cost may be the tubing and fluid used. Some procedures, such as office hysteroscopic sterilization, require the purchase of intratubal occlusion devices.

Also consider the cost of your time. One way to determine this is to investigate the hourly rate you would be paid if you were hypothetically hired by a third party to perform the procedure.

- Estimate the step costs. Step costs are constant over a narrow range of activity but shift to a higher level with increased activity. One example is staffing costs. If the number of these procedures significantly increases, additional staffing will be required. Include the hourly pay for your medical assistants in the analysis.

- Determine the contribution margin. Subtract the revenue from the sum of the variable and step costs to find the contribution margin (dollar contribution per unit) to your practice.4,5

- Estimate the approximate volume of procedures. It is hard to predict future demand, but a good rule of thumb is to estimate the best, expected, and pessimistic volumes. Then average the 3 scenarios and use that figure as the anticipated volume. Multiply the volume by the contribution margin to calculate profit.

Additional financial tools

Once the basic cash flow analysis of the new investment is undertaken, add these methods to your analysis:

Net Present Value (NPV) is the difference between the present value of cash inflows and the present value of cash outflows (FIGURE 1).6 NPV takes into consideration the time value of money, where money in the present is worth more than the same value sometime in the future due to inflation and earning capacity. NPV is used in capital budgeting to analyze the profitability of a projected investment or project.1,4,5

Consider the discount rate as the expected rate of return or cost of capital. By discounting the future cash flow each year by the discount rate, you can get the present value of cash flow. Subtract the present value of cash flow from the original investment to get the NPV for the equipment's investment. A positive value is a favorable analysis to purchase the equipment; a negative value may suggest that the equipment may be a poor investment.

The NPV can be calculated in a spreadsheet using the following NPV command formula: NPV(rate,value1,[value2],...). This formula gives you the present value of cash inflows. The rate is the discount rate and the values are the series of cash flows occurring over a period of time. The NPV command formula in Excel, despite its misleading name, only gives the present value of cash flows.7 Therefore, it is important that the present value of cash inflows is subtracted from the initial capital investment to get the NPV.

FIGURE 2 shows analysis of a piece of equipment that requires a $14,000 initial investment in Year 0. Each year the use of the equipment generates $25,300 per year through year 5. Assign a discount rate of 11%, about what you would expect for a stock market investment.

Consider other investment opportunities. The historical rate of return for a stock index fund is 11.5%.8 Using this discount rate, you can compare whether the money would be better invested in the medical equipment or stock.

Internal rate of return (IRR) is a metric used in capital budgeting to measure the profitability of potential investments. The IRR determines if the discount rate at which the present value of expected net cash inflow is equal to the cash outlay. In other words, the IRR is the discount rate that makes the net present cash flows from a project equal zero. The decision rule related to the IRR criterion is to accept a project in which the IRR is greater than the required rate of return (cutoff rate). The formula for the IRR is the same as the NPV formula, except that the NPV is set at zero and the discount rate is calculated through iterative calculation. The IRR can be calculated in a spreadsheet using the following command formula: IRR(values, [guess]).1,5,9 In FIGURE 3, the IRR is 180%, far superior than the return you would find in other investments such as the stock market.

The IRR is somewhat different from return on investment (ROI). ROI is the percent of return on the initial investment over a period of time. Each piece of equipment has a different ROI over a different time period. ROI does not take into account the time value of money (TVM). Incorporating the IRR (or the TVM) allows for equal comparison between 2 pieces of equipment in the analysis.10

If you are not comparing 2 different types of equipment for purchase, then using the cutoff of 11.5% may be helpful (the historical average stock market return). If the IRR is less than 11.5%, then in theory, it would be better to put your money in the stock market than in new equipment.7

Breakeven analysis calculates the volume of procedures that would be needed to break even or make a profit. It can also determine if there is enough demand to meet the volume required to break even or profit. Unlike the first 2 methods, where you have to guess at future volume, this method calculates the volume required to break even, but does not specify a time period. Your practice would have to use subjective experience to determine how long it would take to reach that volume, given your patient population and the ability to reach the targeted market segment.

Fixed costs are costs that do not change with the varying volume of units of service or products sold. After calculating the contribution margin, divide the fixed costs of the equipment by the contribution margin. Then you will have the volume required to break even (FIGURE 4). Add the dollar amount of profit you would like to attain to the fixed costs, then divide that total by the contribution margin, and you'll have the volume required to meet those specifications.1,4,5

Even though the calculations described above relate to medical equipment, you can use this same method to analyze the cost of adding new providers or any other business development project to determine the required volume to break even on the capital outlay.

CASE New equipment requests

A new ObGyn in your practice requests that you purchase a hysteroscope so that she can start performing office-based hysteroscopic sterilization. Another partner would like to acquire urodynamic equipment instead of referring urinary incontinent patients to a urogynecologist. How do you decide what to purchase?

First calculate the contribution margins for each product. Next, since you do not know for certain the volume you might achieve for each procedure, create 3 scenarios for the best, expected, and pessimistic situations. Assume equal probability for each of these categories and average the volumes of the estimates. Even though you may keep the equipment longer, estimate the financial analysis over 5 years. In this example, we assume a discount rate of 11% for the NPV calculation for both pieces of equipment.

Calculate the IRR using a spreadsheet based on the cash flow for each piece of equipment. Say that the practice anticipates doing 23 hysteroscopic sterilizations per year. If the reimbursement is $2,600 per procedure, and the variable costs are $1,500, the contribution margin is $1,100. So 23 procedures multiplied by $1,100 equals an annual profit of $25,300. Then discount the $25,300 for each year. In this example, we use a discount rate of 11%. The TABLE shows the amount discounted each year.

The sum of the discounted cash flows is $93,506. However, we have to subtract the initial investment of $14,000, so the final NPV equals $79,506 (FIGURE 5).

Apply the same financial NPV and IRR calculations used to assess the hysteroscope to the urodynamic equipment. From the analysis (FIGUREs 5 and 6), both purchases would be financially successful. However, it appears that the urodynamic equipment is a superior investment over the hysteroscope, with a higher NPV ($115,877 vs $81,880, respectively) and IRR (336% vs 180%, respectively). This is likely due to the higher anticipated volume of use with the urodynamic equipment and lower cost of initial investment, despite having a lower contribution margin than the hysteroscope.

Caveats

For simplicity, this analysis does not account for the fact that the hysteroscope could be used for other revenue-generating procedures such as diagnostic hysteroscopy. Factoring in these potential additional services using the same hysteroscope might change the decision analysis in favor of the hysteroscope.

Remember that, although the financial analysis is very helpful in decision making, nonfinancial evaluations should also influence your choice. In this example, while there may be a financial advantage to purchasing the urodynamic equipment over the hysteroscopic equipment, nonfinancial considerations can help you decide which purchase would be a better aligned with the goals and strategies of your practice.

These tools for nonfinancial and financial analysis can be used for any investment in your practice, whether it is in medical equipment, personnel, or development of other profit centers.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Willis DR. How to decide whether to buy new medical equipment. Fam Pract Manag. 2004;11(3):53−58.

- PESTLE Analysis Strategy Skills. http://www.free-management-ebooks.com/dldebk-pdf/fme-pestle-analysis.pdf. Published 2013. Accessed March 2, 2018.

- What is PESTLE analysis? A tool for business analysis. http://pestleanalysis.com/what-is-pestle-analysis/. Published 2018. Accessed March 2, 2018.

- Nowicki M, ed. Introduction to the Financial Management of Healthcare Organizations. 6th ed. Chicago, Illinois: Health Administration Press; 2014:150−151, 299−316.

- Ross SA, Westerfield RW, Jaffe J. Corporate Finance. 8th ed. New York, New York: McGraw Hill; 2008:271−288.

- Net Present Value - NPV. Investopia. https://www.investopedia.com/terms/n/npv.asp. Accessed April 10, 2018.

- NPV function. Microsoft Office Support. https://support.office.com/en-us/article/npv-function-8672cb67-2576-4d07-b67b-ac28acf2a568. Accessed April 10, 2018.

- Damodaran A. Annual Returns on Stock, T.Bonds and T.Bills: 1928 - Current. http://pages.stern.nyu.edu/~adamodar/New_Home_Page/datafile/histretSP.html. Updated January 5, 2018. Accessed March 2, 2018.

- IRR function. Microsoft Office Support. https://support.office.com/en-us/article/irr-function-64925eaa-9988-495b-b290-3ad0c163c1bc. Accessed April 10, 2018.

- Time Value of Money (TVM). Investopedia. https://www.investopedia.com/terms/t/timevalueofmoney.asp. Published 2018. Accessed March 2, 2018.

- Willis DR. How to decide whether to buy new medical equipment. Fam Pract Manag. 2004;11(3):53−58.

- PESTLE Analysis Strategy Skills. http://www.free-management-ebooks.com/dldebk-pdf/fme-pestle-analysis.pdf. Published 2013. Accessed March 2, 2018.

- What is PESTLE analysis? A tool for business analysis. http://pestleanalysis.com/what-is-pestle-analysis/. Published 2018. Accessed March 2, 2018.

- Nowicki M, ed. Introduction to the Financial Management of Healthcare Organizations. 6th ed. Chicago, Illinois: Health Administration Press; 2014:150−151, 299−316.

- Ross SA, Westerfield RW, Jaffe J. Corporate Finance. 8th ed. New York, New York: McGraw Hill; 2008:271−288.

- Net Present Value - NPV. Investopia. https://www.investopedia.com/terms/n/npv.asp. Accessed April 10, 2018.

- NPV function. Microsoft Office Support. https://support.office.com/en-us/article/npv-function-8672cb67-2576-4d07-b67b-ac28acf2a568. Accessed April 10, 2018.

- Damodaran A. Annual Returns on Stock, T.Bonds and T.Bills: 1928 - Current. http://pages.stern.nyu.edu/~adamodar/New_Home_Page/datafile/histretSP.html. Updated January 5, 2018. Accessed March 2, 2018.

- IRR function. Microsoft Office Support. https://support.office.com/en-us/article/irr-function-64925eaa-9988-495b-b290-3ad0c163c1bc. Accessed April 10, 2018.

- Time Value of Money (TVM). Investopedia. https://www.investopedia.com/terms/t/timevalueofmoney.asp. Published 2018. Accessed March 2, 2018.

IN THIS ARTICLE

- Financial evaluation steps

- Breakeven analysis

- Compare 2 investment opportunities

Take action to prevent maternal mortality

The facts

While other industrialized nations are seeing a decrease in their maternal mortality rates, the United States has noted a 26% increase over a 15-year period. This is especially true for women of color: black women are nearly 4 times as likely to die from pregnancy related causes as compared to non-Hispanic white women. Postpartum hemorrhage and preeclampsia are often the leading causes of maternal death; however, suicide and overdoses are becoming increasingly more common. This information is highlighted in the March 2018 OBG Management article “Factors critical to reducing US maternal mortality and morbidity,” by Lucia DiVenere, MA, Government and Political Affairs, at the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG).1

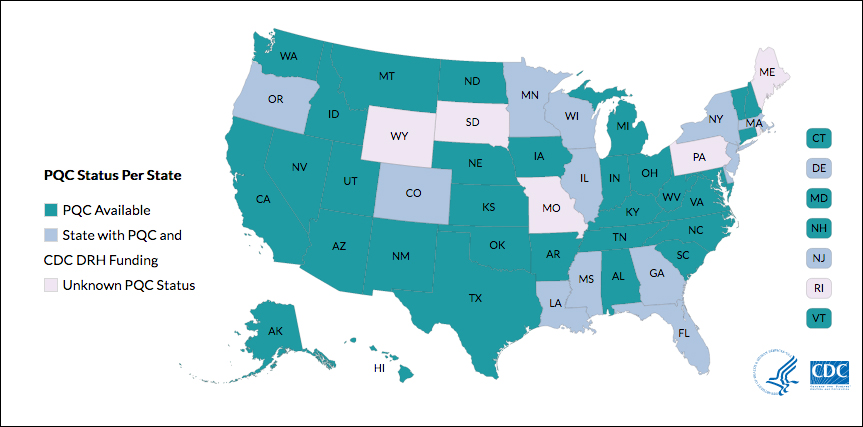

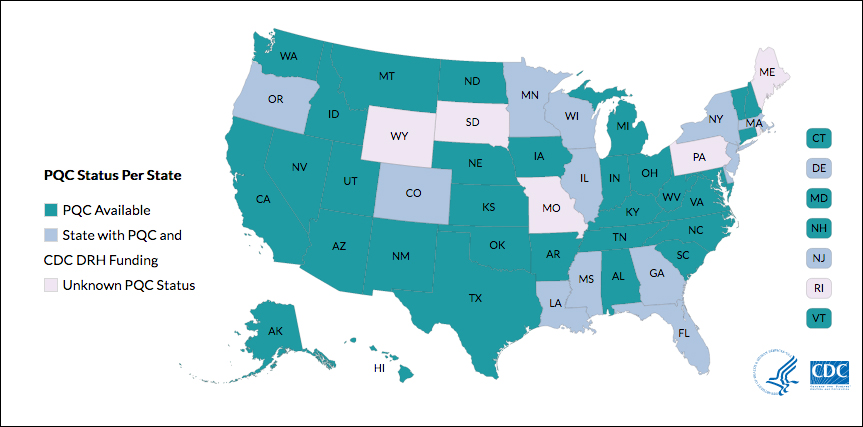

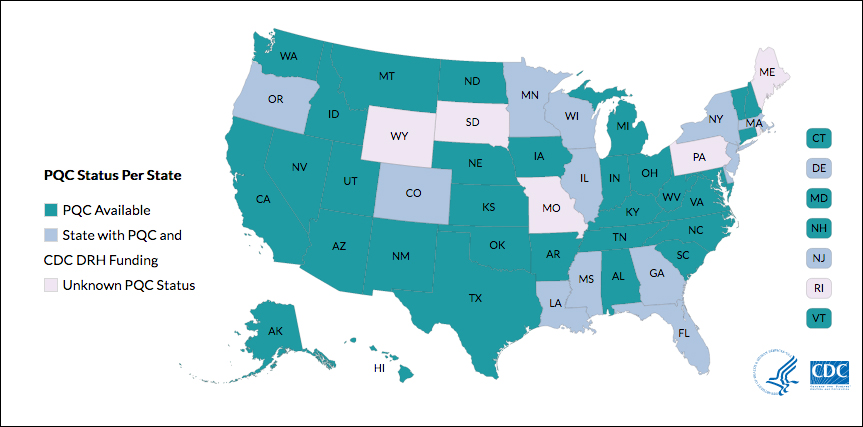

Although there are efforts to improve these outcomes, programs vary by state. One initiative is the perinatal quality collaboratives (PQCs), state or multistate networks of teams working to improve the quality of care for mothers and babies (see “Has your state established a perinatal quality collaborative?”).

Currently, only 33 states have a maternal mortality review committee (MMRC) comprised of an interdisciplinary team of ObGyns, nurses, and other stakeholders. The MMRC reviews each maternal death in their state and provides recommendations and policy changes to help prevent further loss of life.

Many states currently have active collaboratives, and others are in development. The CDC’s Division of Reproductive Health (DRH) currently provides support for state-based PQCs in Colorado, Delaware, Florida, Georgia, Illinois, Louisiana, Massachusetts, Minnesota, Mississippi, New Jersey, New York, Oregon, and Wisconsin. The status of PQCs in Maine, Rhode Island, Pennsylvania, Missouri, South Dakota, and Wyoming is unknown.1

The CDC can help people establish a collaborative. Visit: https://www.cdc.gov/reproductivehealth/maternalinfanthealth/pqc-states.html.

Reference

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Reproductive health: State Perinatal Quality Collaboratives. CDC website. https://www.cdc.gov/reproductivehealth/maternalinfanthealth/pqc-states.html Updated October 17, 2017. Accessed April 4, 2018.

The bill

Preventing Maternal Deaths Act/Maternal Health Accountability Act (H.R. 1318/S. 1112) is a bipartisan, bicameral effort to reduce maternal mortality and reduce health care disparities.

The bills authorize the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) to help states create or expand state MMRCs through annual grant funding of $7 million through fiscal year 2022. Through the MMRCs, the CDC would have the ability to gather data on maternal mortality and health care disparities, allowing the agency to better understand leading causes of maternal death as well as a state’s successes and pitfalls in interventions.

Currently the House bill (H.R. 1318) has 102 cosponsors (https://cqrcengage.com/acog/app/bill/903056?0) and the Senate bill (S. 1112) has 17 cosponsors (https://cqrcengage.com/acog/app/bill/943204?1). Click these links to see if your representative is a cosponsor.

Not sure who your representative is? Click here to find out: http://cqrcengage.com/acog/app/lookup?1&m=29525.

Take action

Both the Senate and House bills have been referred to health committees. However, no advances have been made since March 2017. In order for the bills to move forward, your representatives need to hear from you.

If your representative is a cosponsor of the bill, thank them for their support, but also ask what we can do to ensure this bill becomes law.

If your representative is not a cosponsor, follow this link to email your representative: http://cqrcengage.com/acog/app/onestep-write-a-letter?0&engagementId=306574. You also can call your representative’s office and speak directly to a staff member.

When calling or emailing, highlight the following:

- I am an ObGyn and I am asking [your Representative/Senator] to support H.R. 1318 or S. 1112.

- While maternal mortality rates are decreasing in other parts of the world, they are increasing in the United States. We have the highest maternal mortality rate in the developing world.

- This bill gives all states the opportunity to have a maternal mortality review committee, allowing health care leaders to review each maternal death and analyze how further deaths can be prevented.

- Congress has invested in programs addressing infant mortality, birth defects, and preterm birth. It is time we put the same investment into saving our nation’s mothers.

- As an ObGyn, I urge you to support this bill.

More from ACOG

Want to know what other advocacy opportunities are available? Check out ACOG action at http://cqrcengage.com/acog/home?3.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- DiVenere L. Factors critical to reducing US maternal mortality and morbidity. OBG Manag. 2018;30(3):30−33.

The facts

While other industrialized nations are seeing a decrease in their maternal mortality rates, the United States has noted a 26% increase over a 15-year period. This is especially true for women of color: black women are nearly 4 times as likely to die from pregnancy related causes as compared to non-Hispanic white women. Postpartum hemorrhage and preeclampsia are often the leading causes of maternal death; however, suicide and overdoses are becoming increasingly more common. This information is highlighted in the March 2018 OBG Management article “Factors critical to reducing US maternal mortality and morbidity,” by Lucia DiVenere, MA, Government and Political Affairs, at the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG).1

Although there are efforts to improve these outcomes, programs vary by state. One initiative is the perinatal quality collaboratives (PQCs), state or multistate networks of teams working to improve the quality of care for mothers and babies (see “Has your state established a perinatal quality collaborative?”).

Currently, only 33 states have a maternal mortality review committee (MMRC) comprised of an interdisciplinary team of ObGyns, nurses, and other stakeholders. The MMRC reviews each maternal death in their state and provides recommendations and policy changes to help prevent further loss of life.

Many states currently have active collaboratives, and others are in development. The CDC’s Division of Reproductive Health (DRH) currently provides support for state-based PQCs in Colorado, Delaware, Florida, Georgia, Illinois, Louisiana, Massachusetts, Minnesota, Mississippi, New Jersey, New York, Oregon, and Wisconsin. The status of PQCs in Maine, Rhode Island, Pennsylvania, Missouri, South Dakota, and Wyoming is unknown.1

The CDC can help people establish a collaborative. Visit: https://www.cdc.gov/reproductivehealth/maternalinfanthealth/pqc-states.html.

Reference

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Reproductive health: State Perinatal Quality Collaboratives. CDC website. https://www.cdc.gov/reproductivehealth/maternalinfanthealth/pqc-states.html Updated October 17, 2017. Accessed April 4, 2018.

The bill

Preventing Maternal Deaths Act/Maternal Health Accountability Act (H.R. 1318/S. 1112) is a bipartisan, bicameral effort to reduce maternal mortality and reduce health care disparities.

The bills authorize the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) to help states create or expand state MMRCs through annual grant funding of $7 million through fiscal year 2022. Through the MMRCs, the CDC would have the ability to gather data on maternal mortality and health care disparities, allowing the agency to better understand leading causes of maternal death as well as a state’s successes and pitfalls in interventions.