User login

RSS feeds are a versatile online tool

Recently I mentioned RSS news feeds as a useful, versatile online tool, but because it has been a while since I’ve discussed RSS feeds, an update is certainly in order.

The sheer volume of information on the web makes quick and efficient searching an indispensable skill, but once you have become quick and efficient at finding the information you need, a new problem arises: The information changes! All the good medical, news, and other information-based websites change and update their content on a regular, but unpredictable basis. And checking each one for new information can be very tedious, if you can remember to do it at all.

Many sites offer an e-mail service to notify you of new content, but multiple e-mail subscriptions clutter your inbox and often can’t select out the information you’re really interested in. RSS (which stands for “Rich Site Summary” or “Really Simple Syndication,” depending on whom you ask) is a file format, and websites use that format (or a similar one called Atom) to produce a summary file, or “feed,” of new content, along with links to full versions of that content. When you subscribe to a given website’s feed, you’ll receive a summary of new content each time the website is updated.

Thousands of websites now offer RSS feeds, including most of the large medical information services, all the major news organizations, and many web logs.

Many readers are free, but those with the most advanced features usually charge a fee of some sort. (As always, I have no financial interest in any enterprise discussed in this column.) A comprehensive and more or less up-to-date list of available readers can be found in the Wikipedia article “Comparison of feed aggregators.”

It’s not always easy to find out whether a particular website offers a feed, because there is no universally recognized method of indicating its existence. Look for a link to “RSS” or “Syndicate This,” or an orange rectangle with the letters “RSS,” or “XML” (don’t ask). These links are not always on the home page. You may need to consult the site map to find a link to a page explaining available feeds, and how to find them.

Some of the major sites have multiple feeds to choose from. For example, you can generate a feed of current stories related to the page that you are following on Google News by clicking the RSS link on any Google News page.

In addition to notifying you of important news headlines, changes to your favorite websites, and new developments in any medical (or other) field of interest to you, RSS feeds have many other uses. Some will notify you of new products in a store or catalog, new newsletter issues (including e-mail newsletters), weather and other changing-condition alerts, and the addition of new items to a database – or new members to a group.

It can work the other way as well: If you want readers of your website, blog, or podcast to receive the latest news about your practice, such as new treatments and procedures you’re offering – or if you want to know immediately anytime your name pops up in news or gossip sites – you can create your own RSS feed. Next month, I’ll explain exactly how to do that.

Dr. Eastern practices dermatology and dermatologic surgery in Belleville, N.J. He is the author of numerous articles and textbook chapters, and is a longtime monthly columnist for Dermatology News. Write to him at [email protected]

Recently I mentioned RSS news feeds as a useful, versatile online tool, but because it has been a while since I’ve discussed RSS feeds, an update is certainly in order.

The sheer volume of information on the web makes quick and efficient searching an indispensable skill, but once you have become quick and efficient at finding the information you need, a new problem arises: The information changes! All the good medical, news, and other information-based websites change and update their content on a regular, but unpredictable basis. And checking each one for new information can be very tedious, if you can remember to do it at all.

Many sites offer an e-mail service to notify you of new content, but multiple e-mail subscriptions clutter your inbox and often can’t select out the information you’re really interested in. RSS (which stands for “Rich Site Summary” or “Really Simple Syndication,” depending on whom you ask) is a file format, and websites use that format (or a similar one called Atom) to produce a summary file, or “feed,” of new content, along with links to full versions of that content. When you subscribe to a given website’s feed, you’ll receive a summary of new content each time the website is updated.

Thousands of websites now offer RSS feeds, including most of the large medical information services, all the major news organizations, and many web logs.

Many readers are free, but those with the most advanced features usually charge a fee of some sort. (As always, I have no financial interest in any enterprise discussed in this column.) A comprehensive and more or less up-to-date list of available readers can be found in the Wikipedia article “Comparison of feed aggregators.”

It’s not always easy to find out whether a particular website offers a feed, because there is no universally recognized method of indicating its existence. Look for a link to “RSS” or “Syndicate This,” or an orange rectangle with the letters “RSS,” or “XML” (don’t ask). These links are not always on the home page. You may need to consult the site map to find a link to a page explaining available feeds, and how to find them.

Some of the major sites have multiple feeds to choose from. For example, you can generate a feed of current stories related to the page that you are following on Google News by clicking the RSS link on any Google News page.

In addition to notifying you of important news headlines, changes to your favorite websites, and new developments in any medical (or other) field of interest to you, RSS feeds have many other uses. Some will notify you of new products in a store or catalog, new newsletter issues (including e-mail newsletters), weather and other changing-condition alerts, and the addition of new items to a database – or new members to a group.

It can work the other way as well: If you want readers of your website, blog, or podcast to receive the latest news about your practice, such as new treatments and procedures you’re offering – or if you want to know immediately anytime your name pops up in news or gossip sites – you can create your own RSS feed. Next month, I’ll explain exactly how to do that.

Dr. Eastern practices dermatology and dermatologic surgery in Belleville, N.J. He is the author of numerous articles and textbook chapters, and is a longtime monthly columnist for Dermatology News. Write to him at [email protected]

Recently I mentioned RSS news feeds as a useful, versatile online tool, but because it has been a while since I’ve discussed RSS feeds, an update is certainly in order.

The sheer volume of information on the web makes quick and efficient searching an indispensable skill, but once you have become quick and efficient at finding the information you need, a new problem arises: The information changes! All the good medical, news, and other information-based websites change and update their content on a regular, but unpredictable basis. And checking each one for new information can be very tedious, if you can remember to do it at all.

Many sites offer an e-mail service to notify you of new content, but multiple e-mail subscriptions clutter your inbox and often can’t select out the information you’re really interested in. RSS (which stands for “Rich Site Summary” or “Really Simple Syndication,” depending on whom you ask) is a file format, and websites use that format (or a similar one called Atom) to produce a summary file, or “feed,” of new content, along with links to full versions of that content. When you subscribe to a given website’s feed, you’ll receive a summary of new content each time the website is updated.

Thousands of websites now offer RSS feeds, including most of the large medical information services, all the major news organizations, and many web logs.

Many readers are free, but those with the most advanced features usually charge a fee of some sort. (As always, I have no financial interest in any enterprise discussed in this column.) A comprehensive and more or less up-to-date list of available readers can be found in the Wikipedia article “Comparison of feed aggregators.”

It’s not always easy to find out whether a particular website offers a feed, because there is no universally recognized method of indicating its existence. Look for a link to “RSS” or “Syndicate This,” or an orange rectangle with the letters “RSS,” or “XML” (don’t ask). These links are not always on the home page. You may need to consult the site map to find a link to a page explaining available feeds, and how to find them.

Some of the major sites have multiple feeds to choose from. For example, you can generate a feed of current stories related to the page that you are following on Google News by clicking the RSS link on any Google News page.

In addition to notifying you of important news headlines, changes to your favorite websites, and new developments in any medical (or other) field of interest to you, RSS feeds have many other uses. Some will notify you of new products in a store or catalog, new newsletter issues (including e-mail newsletters), weather and other changing-condition alerts, and the addition of new items to a database – or new members to a group.

It can work the other way as well: If you want readers of your website, blog, or podcast to receive the latest news about your practice, such as new treatments and procedures you’re offering – or if you want to know immediately anytime your name pops up in news or gossip sites – you can create your own RSS feed. Next month, I’ll explain exactly how to do that.

Dr. Eastern practices dermatology and dermatologic surgery in Belleville, N.J. He is the author of numerous articles and textbook chapters, and is a longtime monthly columnist for Dermatology News. Write to him at [email protected]

Accounting 101: Basics you need to know

Physicians practice medicine and communicate within the world of medical language, yet there is a lack of awareness and understanding by many health care professionals of the universal language of business, which is accounting. Just as Latin provides the basic framework for medically related terminology, accounting is the standard language used to convey financial information to both internal and external stakeholders.

Accounting principles are important to physicians at any level. Whether you are starting out in private practice, running a clinical department, or working as an executive in a health care system, most decisions are based on the interpretation of financial data using accounting principles. Accounting standards in the United States are developed by the Financial Accounting Standard Board (FASB) and established as a set of principles and guidelines called Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP).1–3

Accrual- vs cash-based accounting

There are 2 approaches to recording financial transactions: accrual- and cash-based accounting methods. The main difference between them is in the timing of the recorded financial transactions (when revenue and expenses are recognized on the accounting books). Under GAAP, the matching principle, which is one of the most basic and utilized guidelines of accounting, specifies that accrual accounting be used. In the United States, most businesses (publically traded companies and moderate- to large-sized companies) use accrual accounting, while some individual and smaller businesses, including health care services such as physician practices, use the cash method.1–4

Accrual-based accounting

Accrual-based accounting specifies that revenues are recorded when they are earned, and expenses are recorded when they occur. A health care business may earn revenue for services on one day, but the cash may not be received or recorded on the accounting books for several weeks or months and at an amount less than billed.

Accrual-based accounting provides a more accurate representation of a business’ financial performance, since it uses the principle in which expenses are matched to revenues in the same time period. This enables a more precise representation of true financial performance during a given time frame.1–4

Cash-based accounting

Cash-based accounting is the easiest method to understand and implement because financial transactions are recorded in the accounting books when money is received or spent without the need for complex accounting techniques or integration of accounts receivable or payable.

Despite the ease of use and simplicity in tracking cash flow, this method can be deceiving because revenue may be received or expenses may need to be paid at times that are not consistent with when the revenue has been earned or expenses incurred. This can result in misleading information on the business’ health and the accuracy of tracking financial performance over time, since revenue and expenses for a particular transaction may occur at different times.1–4

Which accounting process to choose?

Even though accrual-based accounting may provide a more accurate financial representation of a business’ performance, many smaller businesses, including physician practices, prefer to use cash-based accounting. In addition, many health care businesses are eligible to use cash-based accounting per Internal Revenue Service (IRS) rules by qualifying for the Gross Receipts Test and being a qualified Personal Service Corporation (PSC):

- The Gross Receipts Test states that if the average annual gross receipts of the business are less than $5 million, the business can use the cash-based accounting method.

- If at least 95% of a business activity involves performing health care services, and at least 95% of the business is owned by employees performing health care services, then the business qualifies as a PSC that may use the cash-based accounting method.

Many physician practices qualify to use cash-based accounting, which reduces the complexity of following accrual-based accounting rules and simplifies overall cash-flow management.5

Read about insurance, capital equipment depreciation, more

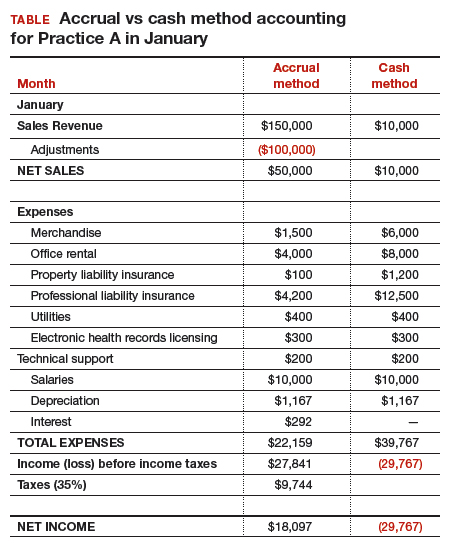

CASE New practice opens

Practice A opens its practice on January 1. The practice borrows $20,000 from the bank to purchase hysteroscopic equipment for office-based tubal sterilizations and an additional $50,000 for an ultrasound machine. Both loans have a 5% annual interest rate amortized over 5 years. The practice leases office space and pays rent 2 months in advance at $8,000 ($4,000 per month). On January 1, the practice pays a $1,200 premium for annual property and liability insurance and $12,500 for the first quarter payment for professional liability insurance ($50,000 annually, paid quarterly). Other costs the practice pays in January include: utilities, $400; EHR licensing, $300; technical support, $200; and salaries, $10,000.

The practice purchases 4 sets of sterilization spring devices at $1,500 each ($6,000) to have in stock. One hysteroscopic sterilization procedure is performed on a patient in January using 1 device. The practice is reimbursed $2,500 for the procedure.

In January, the practice bills $150,000 in charges, but after insurance contractual adjustments, January’s revenue is $50,000. Actual cash payments from billings received are $10,000 in January, $30,000 in February, and $10,000 in March.

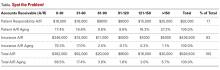

At first glance, there is a noticeable difference on the sales or recognition of revenues based on the type of accounting (TABLE). With the accrual method, because the billing charges are submitted in January when the services were provided (minus the insurance contractual adjustments), the $50,000 revenue is immediately counted and recognized, even though the practice only received $10,000 cash for those billings during January. While the benefit to accrual accounting is the timely recognition of the revenue when the service was provided, the downside is that much of those billings might actually be paid over 90 days, and some of those billings may go unpaid by the insurance company or the patients, which would require adjustments in later months.

The cash-based method is simpler to understand because the cash received for the month is recognized as the revenue, regardless of the amount charged that month.

Merchandise. In the accrual method, the cost of merchandise sold (the hysteroscopic sterilization implants) is recognized as an expense when the revenue is generated from its sale. In this case, the date that the patient has the hysteroscopic in-office sterilization procedure is when the revenue and the expense of the implant are recognized.

In a cash-based accounting method, the $6,000 cost of the implants is recognized at the time of purchase in January.

Lease. In this scenario, even though 2 months of lease for the office were paid, the accrual method only recognizes the January payment; the second payment is recognized in February. In the cash method, because both months were paid in January, the total expense of $8,000 is recognized in January.

Property liability insurance. The property liability insurance payment is required at the start of the year. In accrual accounting, this expense is divided over 12 months, while in the cash method, the expense is counted at the time the payment is made.

Professional liability insurance. The professional liability insurance expense of $50,000 per year is made in quarterly payments, so for the accrual method, the annual amount would be distributed over 12 months at $4,200 per month. With the cash method, it would be paid—and recognized as an expense—quarterly at $12,500, starting in January.

Capital equipment depreciation. Capital medical equipment (hysteroscopy and ultrasound) can be depreciated using a straight-line 5-year depreciation. A total $70,000 worth of equipment divided by 5 years is $14,000 per year, depreciated over 5 years. One-twelfth of $14,000 equals $1,167, which is recorded as a January depreciation expense. Because the Internal Revenue Code requires capital assets to be depreciated, even for cash-basis taxpayers, the common practice is to record depreciation expense for both cash- and accrual-basis income accounting.6

Interest on loans. A loan’s principal payment will not be included on the income statement. The principal payment, a reduction of a liability (loans payable), is reported on the balance sheet. Only the interest portion of a loan payment is reported on the income statement (interest expense). In accrual accounting, the accrued interest on the loan payment for the year is $3,500 ($292 for January). For the cash-basis method, because the interest is paid annually at year-end, interest will not be expensed until December.

Taxes. The IRS states that, “Individuals, including sole proprietors, partners, and S corporation shareholders, generally have to make estimated tax payments if they expect to owe tax of $1,000 or more when their return is filed. Corporations generally have to make estimated tax payments if they expect to owe tax of $500 or more when their return is filed.”7

Assuming 35% tax liability, the accrual method would create a tax liability of $9,744 on a profit of $27,841. With the cash method, there would be no tax liability because there was no net profit.

Other expenses. The utilities, EHR licensing, tech support, and salaries are expensed the same way for both methods.

Net income. The resulting final net income is vastly different for the month of January depending on the accounting method utilized. The accrual method results in a net income of $18,097, while the cash-basis method results in a net loss of $29,767. Over the course of the year, these imbalances are likely to even out.

Related article:

Business law critical to your practice

Choosing an accounting method

Depending on the accounting method, a practice’s performance and profit will seem very different. The type of accounting method chosen will depend on what goals the owners want to achieve.

The accrual method provides a more accurate picture of business flow and performance and will be less subject to monthly variations due to large purchases or variations in expenses. If the practice chooses this method using an income statement, it should also employ a cash-flow statement.

The cash method of accounting will give a convenient and practical summary of the practice’s cash flow.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- About the FASB. Financial Accounting Standards Board website. http://www.fasb.org/jsp/FASB/PageSectionPage&cid=1176154526495. Accessed November 7, 2017.

- What is the difference between accrual accounting and cash accounting? Investopedia. https://www.investopedia.com/ask/answers/121514/what-difference-between-accrual-accounting-and-cash-accounting.asp. Accessed November 7, 2017.

- Accounting Basics (Explanation). Part 2: Income Statement. Accounting Coach. https://www.accountingcoach.com/accounting-basics/explanation/2. Accessed November 7, 2017.

- Stickney C, Weil R. Financial Accounting: An Introduction to Concepts, Methods, and Uses. 11th ed. Nashville, TN: Southwestern College Publishing Group; 2006:97-110.

- Internal Revenue Service. Publication 538 (12/2016), Accounting Periods and Methods. https://www.irs.gov/publications/p538#en_US_201612_publink1000270634. Revised December 2016. Accessed November 7, 2017.

- Klinefelter D, McCorkle D, Klose S. Financial Management: Cash vs. Accrual Accounting. Risk Management. AgriLife Extension. Texas A&M System. http://agrilife.org/agecoext/files/2013/10/rm5-16.pdf. Published 2013. Accessed November 7, 2017.

- Internal Revenue Service. Small Business and Self-Employed Tax Center: Estimated Taxes. https://www.irs.gov/businesses/small-businesses-self-employed/estimated-taxes. Updated November 2, 2017. Accessed November 7, 2017.

Physicians practice medicine and communicate within the world of medical language, yet there is a lack of awareness and understanding by many health care professionals of the universal language of business, which is accounting. Just as Latin provides the basic framework for medically related terminology, accounting is the standard language used to convey financial information to both internal and external stakeholders.

Accounting principles are important to physicians at any level. Whether you are starting out in private practice, running a clinical department, or working as an executive in a health care system, most decisions are based on the interpretation of financial data using accounting principles. Accounting standards in the United States are developed by the Financial Accounting Standard Board (FASB) and established as a set of principles and guidelines called Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP).1–3

Accrual- vs cash-based accounting

There are 2 approaches to recording financial transactions: accrual- and cash-based accounting methods. The main difference between them is in the timing of the recorded financial transactions (when revenue and expenses are recognized on the accounting books). Under GAAP, the matching principle, which is one of the most basic and utilized guidelines of accounting, specifies that accrual accounting be used. In the United States, most businesses (publically traded companies and moderate- to large-sized companies) use accrual accounting, while some individual and smaller businesses, including health care services such as physician practices, use the cash method.1–4

Accrual-based accounting

Accrual-based accounting specifies that revenues are recorded when they are earned, and expenses are recorded when they occur. A health care business may earn revenue for services on one day, but the cash may not be received or recorded on the accounting books for several weeks or months and at an amount less than billed.

Accrual-based accounting provides a more accurate representation of a business’ financial performance, since it uses the principle in which expenses are matched to revenues in the same time period. This enables a more precise representation of true financial performance during a given time frame.1–4

Cash-based accounting

Cash-based accounting is the easiest method to understand and implement because financial transactions are recorded in the accounting books when money is received or spent without the need for complex accounting techniques or integration of accounts receivable or payable.

Despite the ease of use and simplicity in tracking cash flow, this method can be deceiving because revenue may be received or expenses may need to be paid at times that are not consistent with when the revenue has been earned or expenses incurred. This can result in misleading information on the business’ health and the accuracy of tracking financial performance over time, since revenue and expenses for a particular transaction may occur at different times.1–4

Which accounting process to choose?

Even though accrual-based accounting may provide a more accurate financial representation of a business’ performance, many smaller businesses, including physician practices, prefer to use cash-based accounting. In addition, many health care businesses are eligible to use cash-based accounting per Internal Revenue Service (IRS) rules by qualifying for the Gross Receipts Test and being a qualified Personal Service Corporation (PSC):

- The Gross Receipts Test states that if the average annual gross receipts of the business are less than $5 million, the business can use the cash-based accounting method.

- If at least 95% of a business activity involves performing health care services, and at least 95% of the business is owned by employees performing health care services, then the business qualifies as a PSC that may use the cash-based accounting method.

Many physician practices qualify to use cash-based accounting, which reduces the complexity of following accrual-based accounting rules and simplifies overall cash-flow management.5

Read about insurance, capital equipment depreciation, more

CASE New practice opens

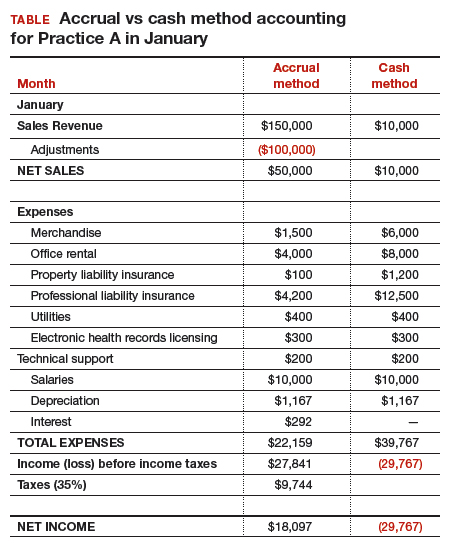

Practice A opens its practice on January 1. The practice borrows $20,000 from the bank to purchase hysteroscopic equipment for office-based tubal sterilizations and an additional $50,000 for an ultrasound machine. Both loans have a 5% annual interest rate amortized over 5 years. The practice leases office space and pays rent 2 months in advance at $8,000 ($4,000 per month). On January 1, the practice pays a $1,200 premium for annual property and liability insurance and $12,500 for the first quarter payment for professional liability insurance ($50,000 annually, paid quarterly). Other costs the practice pays in January include: utilities, $400; EHR licensing, $300; technical support, $200; and salaries, $10,000.

The practice purchases 4 sets of sterilization spring devices at $1,500 each ($6,000) to have in stock. One hysteroscopic sterilization procedure is performed on a patient in January using 1 device. The practice is reimbursed $2,500 for the procedure.

In January, the practice bills $150,000 in charges, but after insurance contractual adjustments, January’s revenue is $50,000. Actual cash payments from billings received are $10,000 in January, $30,000 in February, and $10,000 in March.

At first glance, there is a noticeable difference on the sales or recognition of revenues based on the type of accounting (TABLE). With the accrual method, because the billing charges are submitted in January when the services were provided (minus the insurance contractual adjustments), the $50,000 revenue is immediately counted and recognized, even though the practice only received $10,000 cash for those billings during January. While the benefit to accrual accounting is the timely recognition of the revenue when the service was provided, the downside is that much of those billings might actually be paid over 90 days, and some of those billings may go unpaid by the insurance company or the patients, which would require adjustments in later months.

The cash-based method is simpler to understand because the cash received for the month is recognized as the revenue, regardless of the amount charged that month.

Merchandise. In the accrual method, the cost of merchandise sold (the hysteroscopic sterilization implants) is recognized as an expense when the revenue is generated from its sale. In this case, the date that the patient has the hysteroscopic in-office sterilization procedure is when the revenue and the expense of the implant are recognized.

In a cash-based accounting method, the $6,000 cost of the implants is recognized at the time of purchase in January.

Lease. In this scenario, even though 2 months of lease for the office were paid, the accrual method only recognizes the January payment; the second payment is recognized in February. In the cash method, because both months were paid in January, the total expense of $8,000 is recognized in January.

Property liability insurance. The property liability insurance payment is required at the start of the year. In accrual accounting, this expense is divided over 12 months, while in the cash method, the expense is counted at the time the payment is made.

Professional liability insurance. The professional liability insurance expense of $50,000 per year is made in quarterly payments, so for the accrual method, the annual amount would be distributed over 12 months at $4,200 per month. With the cash method, it would be paid—and recognized as an expense—quarterly at $12,500, starting in January.

Capital equipment depreciation. Capital medical equipment (hysteroscopy and ultrasound) can be depreciated using a straight-line 5-year depreciation. A total $70,000 worth of equipment divided by 5 years is $14,000 per year, depreciated over 5 years. One-twelfth of $14,000 equals $1,167, which is recorded as a January depreciation expense. Because the Internal Revenue Code requires capital assets to be depreciated, even for cash-basis taxpayers, the common practice is to record depreciation expense for both cash- and accrual-basis income accounting.6

Interest on loans. A loan’s principal payment will not be included on the income statement. The principal payment, a reduction of a liability (loans payable), is reported on the balance sheet. Only the interest portion of a loan payment is reported on the income statement (interest expense). In accrual accounting, the accrued interest on the loan payment for the year is $3,500 ($292 for January). For the cash-basis method, because the interest is paid annually at year-end, interest will not be expensed until December.

Taxes. The IRS states that, “Individuals, including sole proprietors, partners, and S corporation shareholders, generally have to make estimated tax payments if they expect to owe tax of $1,000 or more when their return is filed. Corporations generally have to make estimated tax payments if they expect to owe tax of $500 or more when their return is filed.”7

Assuming 35% tax liability, the accrual method would create a tax liability of $9,744 on a profit of $27,841. With the cash method, there would be no tax liability because there was no net profit.

Other expenses. The utilities, EHR licensing, tech support, and salaries are expensed the same way for both methods.

Net income. The resulting final net income is vastly different for the month of January depending on the accounting method utilized. The accrual method results in a net income of $18,097, while the cash-basis method results in a net loss of $29,767. Over the course of the year, these imbalances are likely to even out.

Related article:

Business law critical to your practice

Choosing an accounting method

Depending on the accounting method, a practice’s performance and profit will seem very different. The type of accounting method chosen will depend on what goals the owners want to achieve.

The accrual method provides a more accurate picture of business flow and performance and will be less subject to monthly variations due to large purchases or variations in expenses. If the practice chooses this method using an income statement, it should also employ a cash-flow statement.

The cash method of accounting will give a convenient and practical summary of the practice’s cash flow.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Physicians practice medicine and communicate within the world of medical language, yet there is a lack of awareness and understanding by many health care professionals of the universal language of business, which is accounting. Just as Latin provides the basic framework for medically related terminology, accounting is the standard language used to convey financial information to both internal and external stakeholders.

Accounting principles are important to physicians at any level. Whether you are starting out in private practice, running a clinical department, or working as an executive in a health care system, most decisions are based on the interpretation of financial data using accounting principles. Accounting standards in the United States are developed by the Financial Accounting Standard Board (FASB) and established as a set of principles and guidelines called Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP).1–3

Accrual- vs cash-based accounting

There are 2 approaches to recording financial transactions: accrual- and cash-based accounting methods. The main difference between them is in the timing of the recorded financial transactions (when revenue and expenses are recognized on the accounting books). Under GAAP, the matching principle, which is one of the most basic and utilized guidelines of accounting, specifies that accrual accounting be used. In the United States, most businesses (publically traded companies and moderate- to large-sized companies) use accrual accounting, while some individual and smaller businesses, including health care services such as physician practices, use the cash method.1–4

Accrual-based accounting

Accrual-based accounting specifies that revenues are recorded when they are earned, and expenses are recorded when they occur. A health care business may earn revenue for services on one day, but the cash may not be received or recorded on the accounting books for several weeks or months and at an amount less than billed.

Accrual-based accounting provides a more accurate representation of a business’ financial performance, since it uses the principle in which expenses are matched to revenues in the same time period. This enables a more precise representation of true financial performance during a given time frame.1–4

Cash-based accounting

Cash-based accounting is the easiest method to understand and implement because financial transactions are recorded in the accounting books when money is received or spent without the need for complex accounting techniques or integration of accounts receivable or payable.

Despite the ease of use and simplicity in tracking cash flow, this method can be deceiving because revenue may be received or expenses may need to be paid at times that are not consistent with when the revenue has been earned or expenses incurred. This can result in misleading information on the business’ health and the accuracy of tracking financial performance over time, since revenue and expenses for a particular transaction may occur at different times.1–4

Which accounting process to choose?

Even though accrual-based accounting may provide a more accurate financial representation of a business’ performance, many smaller businesses, including physician practices, prefer to use cash-based accounting. In addition, many health care businesses are eligible to use cash-based accounting per Internal Revenue Service (IRS) rules by qualifying for the Gross Receipts Test and being a qualified Personal Service Corporation (PSC):

- The Gross Receipts Test states that if the average annual gross receipts of the business are less than $5 million, the business can use the cash-based accounting method.

- If at least 95% of a business activity involves performing health care services, and at least 95% of the business is owned by employees performing health care services, then the business qualifies as a PSC that may use the cash-based accounting method.

Many physician practices qualify to use cash-based accounting, which reduces the complexity of following accrual-based accounting rules and simplifies overall cash-flow management.5

Read about insurance, capital equipment depreciation, more

CASE New practice opens

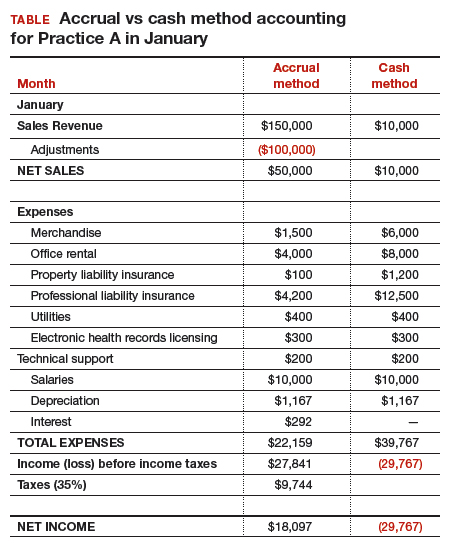

Practice A opens its practice on January 1. The practice borrows $20,000 from the bank to purchase hysteroscopic equipment for office-based tubal sterilizations and an additional $50,000 for an ultrasound machine. Both loans have a 5% annual interest rate amortized over 5 years. The practice leases office space and pays rent 2 months in advance at $8,000 ($4,000 per month). On January 1, the practice pays a $1,200 premium for annual property and liability insurance and $12,500 for the first quarter payment for professional liability insurance ($50,000 annually, paid quarterly). Other costs the practice pays in January include: utilities, $400; EHR licensing, $300; technical support, $200; and salaries, $10,000.

The practice purchases 4 sets of sterilization spring devices at $1,500 each ($6,000) to have in stock. One hysteroscopic sterilization procedure is performed on a patient in January using 1 device. The practice is reimbursed $2,500 for the procedure.

In January, the practice bills $150,000 in charges, but after insurance contractual adjustments, January’s revenue is $50,000. Actual cash payments from billings received are $10,000 in January, $30,000 in February, and $10,000 in March.

At first glance, there is a noticeable difference on the sales or recognition of revenues based on the type of accounting (TABLE). With the accrual method, because the billing charges are submitted in January when the services were provided (minus the insurance contractual adjustments), the $50,000 revenue is immediately counted and recognized, even though the practice only received $10,000 cash for those billings during January. While the benefit to accrual accounting is the timely recognition of the revenue when the service was provided, the downside is that much of those billings might actually be paid over 90 days, and some of those billings may go unpaid by the insurance company or the patients, which would require adjustments in later months.

The cash-based method is simpler to understand because the cash received for the month is recognized as the revenue, regardless of the amount charged that month.

Merchandise. In the accrual method, the cost of merchandise sold (the hysteroscopic sterilization implants) is recognized as an expense when the revenue is generated from its sale. In this case, the date that the patient has the hysteroscopic in-office sterilization procedure is when the revenue and the expense of the implant are recognized.

In a cash-based accounting method, the $6,000 cost of the implants is recognized at the time of purchase in January.

Lease. In this scenario, even though 2 months of lease for the office were paid, the accrual method only recognizes the January payment; the second payment is recognized in February. In the cash method, because both months were paid in January, the total expense of $8,000 is recognized in January.

Property liability insurance. The property liability insurance payment is required at the start of the year. In accrual accounting, this expense is divided over 12 months, while in the cash method, the expense is counted at the time the payment is made.

Professional liability insurance. The professional liability insurance expense of $50,000 per year is made in quarterly payments, so for the accrual method, the annual amount would be distributed over 12 months at $4,200 per month. With the cash method, it would be paid—and recognized as an expense—quarterly at $12,500, starting in January.

Capital equipment depreciation. Capital medical equipment (hysteroscopy and ultrasound) can be depreciated using a straight-line 5-year depreciation. A total $70,000 worth of equipment divided by 5 years is $14,000 per year, depreciated over 5 years. One-twelfth of $14,000 equals $1,167, which is recorded as a January depreciation expense. Because the Internal Revenue Code requires capital assets to be depreciated, even for cash-basis taxpayers, the common practice is to record depreciation expense for both cash- and accrual-basis income accounting.6

Interest on loans. A loan’s principal payment will not be included on the income statement. The principal payment, a reduction of a liability (loans payable), is reported on the balance sheet. Only the interest portion of a loan payment is reported on the income statement (interest expense). In accrual accounting, the accrued interest on the loan payment for the year is $3,500 ($292 for January). For the cash-basis method, because the interest is paid annually at year-end, interest will not be expensed until December.

Taxes. The IRS states that, “Individuals, including sole proprietors, partners, and S corporation shareholders, generally have to make estimated tax payments if they expect to owe tax of $1,000 or more when their return is filed. Corporations generally have to make estimated tax payments if they expect to owe tax of $500 or more when their return is filed.”7

Assuming 35% tax liability, the accrual method would create a tax liability of $9,744 on a profit of $27,841. With the cash method, there would be no tax liability because there was no net profit.

Other expenses. The utilities, EHR licensing, tech support, and salaries are expensed the same way for both methods.

Net income. The resulting final net income is vastly different for the month of January depending on the accounting method utilized. The accrual method results in a net income of $18,097, while the cash-basis method results in a net loss of $29,767. Over the course of the year, these imbalances are likely to even out.

Related article:

Business law critical to your practice

Choosing an accounting method

Depending on the accounting method, a practice’s performance and profit will seem very different. The type of accounting method chosen will depend on what goals the owners want to achieve.

The accrual method provides a more accurate picture of business flow and performance and will be less subject to monthly variations due to large purchases or variations in expenses. If the practice chooses this method using an income statement, it should also employ a cash-flow statement.

The cash method of accounting will give a convenient and practical summary of the practice’s cash flow.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- About the FASB. Financial Accounting Standards Board website. http://www.fasb.org/jsp/FASB/PageSectionPage&cid=1176154526495. Accessed November 7, 2017.

- What is the difference between accrual accounting and cash accounting? Investopedia. https://www.investopedia.com/ask/answers/121514/what-difference-between-accrual-accounting-and-cash-accounting.asp. Accessed November 7, 2017.

- Accounting Basics (Explanation). Part 2: Income Statement. Accounting Coach. https://www.accountingcoach.com/accounting-basics/explanation/2. Accessed November 7, 2017.

- Stickney C, Weil R. Financial Accounting: An Introduction to Concepts, Methods, and Uses. 11th ed. Nashville, TN: Southwestern College Publishing Group; 2006:97-110.

- Internal Revenue Service. Publication 538 (12/2016), Accounting Periods and Methods. https://www.irs.gov/publications/p538#en_US_201612_publink1000270634. Revised December 2016. Accessed November 7, 2017.

- Klinefelter D, McCorkle D, Klose S. Financial Management: Cash vs. Accrual Accounting. Risk Management. AgriLife Extension. Texas A&M System. http://agrilife.org/agecoext/files/2013/10/rm5-16.pdf. Published 2013. Accessed November 7, 2017.

- Internal Revenue Service. Small Business and Self-Employed Tax Center: Estimated Taxes. https://www.irs.gov/businesses/small-businesses-self-employed/estimated-taxes. Updated November 2, 2017. Accessed November 7, 2017.

- About the FASB. Financial Accounting Standards Board website. http://www.fasb.org/jsp/FASB/PageSectionPage&cid=1176154526495. Accessed November 7, 2017.

- What is the difference between accrual accounting and cash accounting? Investopedia. https://www.investopedia.com/ask/answers/121514/what-difference-between-accrual-accounting-and-cash-accounting.asp. Accessed November 7, 2017.

- Accounting Basics (Explanation). Part 2: Income Statement. Accounting Coach. https://www.accountingcoach.com/accounting-basics/explanation/2. Accessed November 7, 2017.

- Stickney C, Weil R. Financial Accounting: An Introduction to Concepts, Methods, and Uses. 11th ed. Nashville, TN: Southwestern College Publishing Group; 2006:97-110.

- Internal Revenue Service. Publication 538 (12/2016), Accounting Periods and Methods. https://www.irs.gov/publications/p538#en_US_201612_publink1000270634. Revised December 2016. Accessed November 7, 2017.

- Klinefelter D, McCorkle D, Klose S. Financial Management: Cash vs. Accrual Accounting. Risk Management. AgriLife Extension. Texas A&M System. http://agrilife.org/agecoext/files/2013/10/rm5-16.pdf. Published 2013. Accessed November 7, 2017.

- Internal Revenue Service. Small Business and Self-Employed Tax Center: Estimated Taxes. https://www.irs.gov/businesses/small-businesses-self-employed/estimated-taxes. Updated November 2, 2017. Accessed November 7, 2017.

The clear and present future: Telehealth and telemedicine in obstetrics and gynecology

I recently spoke with 2 outstanding leaders in our field, members of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) task force on telehealth and telemedicine, about the future of providing health care to women in remote locations.

Haywood Brown, MD, is President of ACOG for 2017–2018 and is F. Bayard Carter Professor of Obstetrics and Gynecology at Duke University Medical Center in Durham, North Carolina, and Peter Nielsen, MD, is Professor and Vice Chair of the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston, Texas, and Obstetrician-in-Chief at Children’s Hospital of San Antonio. Dr. Nielsen is a retired US Army colonel.

Why an ACOG telehealth task force?

Haywood Brown, MD: Our overall goals in telehealth and telemedicine are to coordinate and better facilitate the health care of women in remote locations and to improve maternal morbidity and mortality. Telehealth can be used on both an outpatient and an inpatient basis.

Outpatient telehealth is used for consultations. In maternal-fetal medicine, for instance, we use it for ultrasonography consultations. I also have used telehealth technology to “see” a pregnant patient with type 1diabetes. During our sessions, I managed her blood sugar levels and did all the other things I would have done if we had been together at my clinic. Without telehealth technology, however, this patient would have needed to drive 4 hours round-trip for each appointment.

Our colleagues in rural communities and at lower-level hospitals can use telehealth and telemedicine as aids in treating their high-risk patients, such as those with preeclampsia, prematurity risk, or other conditions. Physicians can consult with specialists through a face-to-face conversation that takes place through telecommunications. The result is that the quality of care for women in our communities is improved.

Genetic counseling, infertility consultation, and fetal anomaly management are some of the other applications. Our task force is discussing different ways to improve patient care and ways to collaborate with our colleagues around the country. Ultimately, we are developing best practices—a model for the best uses of technology to improve women’s health care in the United States.

Task force focus: Telehealth technology, billing, services

Dr. Brown: Our task force, a diverse group of members from all over the country, represents the spectrum of ObGyns. Although task force members have various levels of telehealth experience, all are very interested in these new channels of communication. The task force also includes billers, who understand billing ramifications, and payers, who know firsthand what will and will not be paid.

Technology and its availability is the most important topic for the task force. While some communities have Internet service, not all do. We need to determine which areas need service, how much it would cost, and who pays for it. Can a hospital afford it? A practice? Their partners? Identifying partners in tertiary care settings is a task force goal.

We are engaging a broad range of experts to study all the components and associated costs of technology, licensing, and cross-state credentialing. Gathering this information will help in developing a best practices model that general ObGyns can use.

Telehealth is redefining aspects of care: prenatal care (how many visits are required?), postpartum care, and other types of services that can be done remotely. Genetic counseling—who can provide it, what education is required—is another topic of discussion. Once we surmount the billing obstacles, we can do much with teleconferencing, such as provide genetic consultation with ObGyns in various settings.

The terms "telehealth" and "telemedicine" are often used interchangeably. Telemedicine is the older phrase, while telehealth entered the vernacular more recently and encompasses a broader definition.

The HealthIT.gov website explains the differences in terminology this way1:

- The Health Resources Services Administration defines telehealth as the use of electronic information and telecommunications technologies to support long-distance clinical health care, patient and professional health-related education, public health and health administration. Technologies include videoconferencing, the Internet, store-and-forward imaging, streaming media, and terrestrial and wireless communications.

- Telehealth is different from telemedicine because it refers to a broader scope of remote health care services than telemedicine. While telemedicine refers specifically to remote clinical services, telehealth can refer to remote nonclinical services, such as provider training, administrative meetings, and continuing medical education, in addition to clinical services.

A World Health Organization report, however, uses the 2 terms synonymously and interchangeably, defining telemedicine as2:

- The delivery of health care services, where distance is a critical factor, by all health care professionals using information and communication technologies for the exchange of valid information for diagnosis, treatment and prevention of disease and injuries, research and evaluation, and for the continuing education of health care providers, all in the interests of advancing the health of individuals and their communities.

The American Telemedicine Association (ATA) describes their use of the terms this way3:

- ATA largely views telemedicine and telehealth to be interchangeable terms, encompassing a wide definition of remote healthcare, although telehealth may not always involve clinical care.

References

- HealthIT.gov website. Frequently asked questions. https://www.healthit.gov/providers-professionals/frequently-asked-questions/485. Accessed November 15, 2017.

- World Health Organization. Telemedicine: opportunities and developments in member states. 2010. http://www.who.int/goe/publications/goe_telemedicine_2010.pdf. Accessed November 15, 2017.

- American Telemedicine Association. About telemedicine: the ultimate frontier for superior healthcare delivery. http://www.americantelemed.org/about/about-telemedicine. Accessed November 15, 2017.

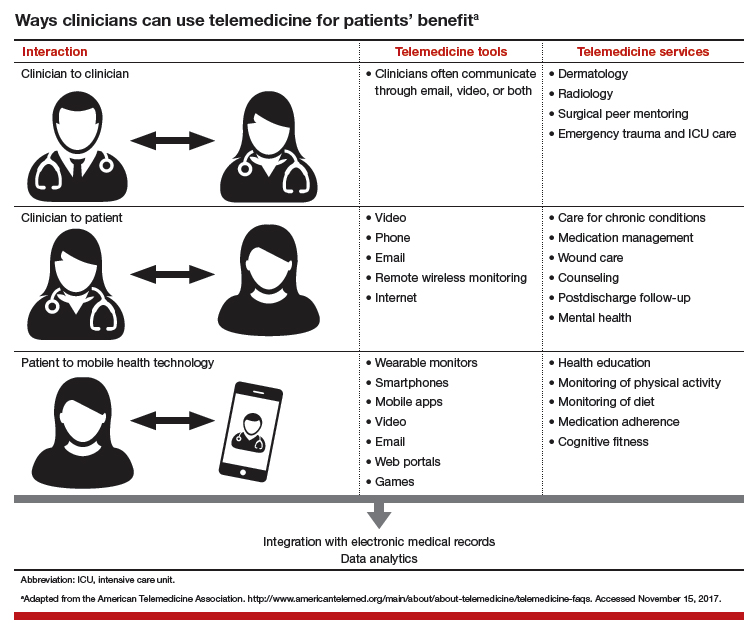

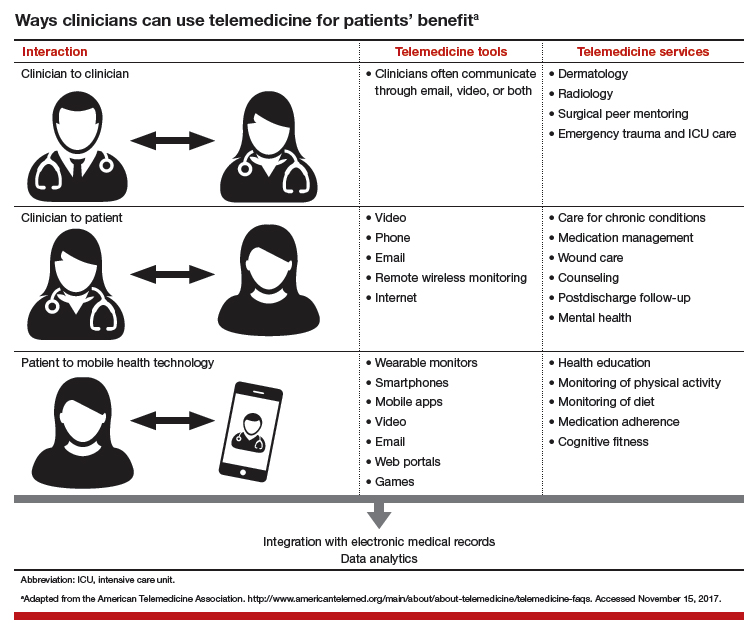

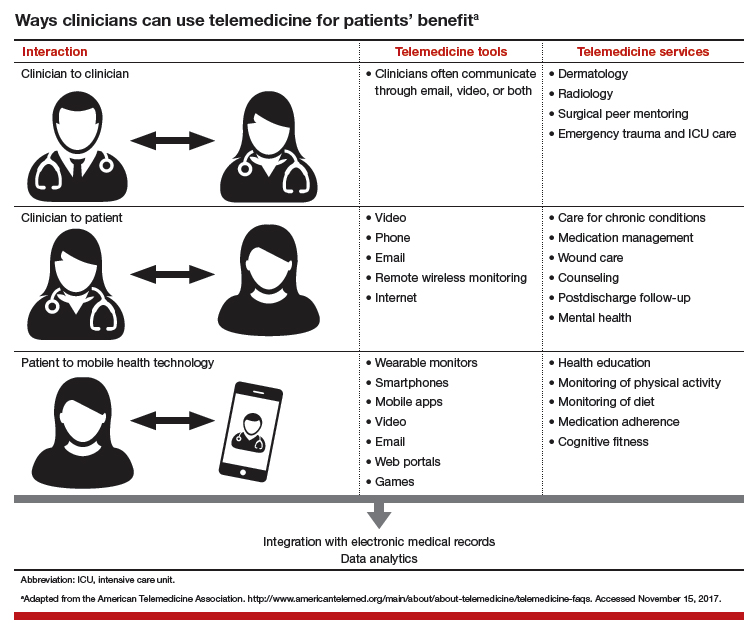

Learn about ways clinicians can use telemedicine.

Making progress in rural and underserved communities

Peter Nielsen, MD: When we saw that some high-risk obstetrics patients were having a difficult time getting to our downtown San Antonio office—the trip from surrounding communities was taking too long, or city driving and parking were stressful or too costly—we looked to improve access to care. Collaborating with a health care network that has a hospital in a town north of San Antonio, we set up a pilot program to provide telemedicine perinatal consultation services.

In this kind of service, which occurs entirely in real time, ultrasound images taken at the hospital are streamed by high-speed fiberoptic cable to our office, where a maternal-fetal medicine physician views them. If a repeat image or a different image is needed, the physician requests another scan. Linked to the physician and listening through an earpiece, the ultrasonographer performs the new scan with little delay and without disturbing the patient. The conversation between physician and ultrasonographer is private.

After ultrasound scanning is complete, the patient goes to a private room at the hospital for a video conference with our physician in San Antonio, who has reviewed the images in the PACS (picture archiving and communication system) or ultrasound recording system. They discuss the images, the findings, and the follow-up.

We tested the technology during a 6-month pilot program to make sure it worked at the highest quality and safety levels. Then the program went live and we started seeing patients remotely. Now we have a robust telemedicine training capability at that hospital outside San Antonio, and we are looking to expand to other south and west Texas areas, some even farther from our office.

I have done some of these remote consultations. In response to my informal queries about the experience, patients said that no one else was offering it, and they were participating for the first time. Naturally they had questions and concerns. Nevertheless, patients, family members, and the ultrasonographer and physicians in the communities seem to think this is a high-quality, safe program that makes it easier for patients to access health care.

Patients uniformly describe these consultations in positive terms. They do not have to drive far, into the city, and deal with traffic; parking is easy and free; and less travel means much less time off from work. Given these very practical advantages, patients are interested in having more appointments done remotely. In addition, they say the appointment itself is easy, being there is effortless, and they feel their physician is sitting in the same room. It is like video chatting with family members—they are comfortable with the technology.

Related article:

Landmark women’s health care remains law of the land

The patients’ perspective

Dr. Brown: Patient satisfaction is an important issue. In psychiatry, dermatology, and other disciplines, patients have indicated that they are very satisfied with telehealth sessions. Telehealth in obstetrics and gynecology, I think, will receive similar positive feedback.

The issue of driving distance led us to reconsider the number of face-to-face prenatal visits a normal, healthy patient needs. These days, a patient can use a prenatal care app to track her weight and blood pressure and send the data to her physician. Besides being convenient, these monitoring apps can give a patient an important sense of control. Our pilot programs found that a patient who self-monitors understands her weight gain better and is more in tune with it. Apps and other technologies can thus improve quality of care and, in reducing the number of trips to an office, increase patient satisfaction.

Many people use or are familiar with the programs Skype and FaceTime (audiovideo chat software), and I envision that our postpartum task force will recommend using such programs for follow-up appointments. For each visit, the question to ask is whether the patient really needs to meet with her physician in person, or can she stay with her new baby and receive postpartum counseling at home. I am excited about the potential of telehealth in obstetrics and gynecology. Our task force is exploring that potential.

Telehealth for both routine and specialized care

Dr. Brown: Specialized care applications are here. In a pilot program in Wisconsin, a colleague has been providing remote psychiatric care. Perhaps such a program can be used to follow up on patients with postpartum depression. In addition, other psychiatry colleagues have long been using telehealth for adolescent behavior follow-ups, and we can do this too.

Another colleague has been performing remote perinatal follow-up for children with congenital anomalies. The physician interacts with the parent or parents as well as the patient. This seems to represent only the tip of the iceberg of what can be done in terms of follow-up.

We can also use telehealth in infertility settings. High-risk patients can benefit, too. Our guidelines say patients with preeclampsia should be seen within 3 days to 1 week. Many are transferred from low-access hospitals to our office. This follow-up, however, also can be done remotely, with patients at health department clinics or even at home. Reporting blood pressure readings and health-related feelings to a physician during a teleconsultation removes driving as a potential inconvenience or obstacle.

Telemedicine can be advantageous in gynecology. Physicians are doing important work with telecolposcopy as a follow-up to abnormal Pap test findings in patients in sub-Saharan Africa.

Routine wound care, which is commonly needed, can be performed in the home by a home health nurse telecommunicating with a physician. I can see broad telehealth use, and indeed our dermatology colleagues have been practicing telemedicine for quite some time.

Read about solving financial barriers and physician shortages.

An affordable solution to financial barriers and physician shortages

Dr. Nielsen: Telehealth can reduce barriers to care. For example, knowing that our teleconsultation services are covered by insurance, referring physicians and patients are more likely to try them and continue to use them. Payers are on board as well. Other barriers can be harder to overcome, particularly for patients at risk for complex diagnoses and medical decisions. Our pilot program, however, has demonstrated success in this area. It has provided safe, high-quality imaging, accurate diagnoses, productive discussions, and helpful management recommendations.

Telehealth also helps address relative and absolute physician shortages. In some areas, a relative shortage may indicate misdistribution. In other areas, specialists simply are too few in number. This absolute shortage of specialists likely will increase, as many communities are too small to sustain and support having them in person.

Outpatients can obtain care 5 days a week with telemedicine, as opposed to only 1 to 3 times a month in person. Physicians travel to remote clinics that are staffed only 1 or 2 days a month. Where the window for care is so small, patients and physicians are likely to turn to telemedicine. In addition, that utility results in better use of resources. For example, studies that were performed earlier would not need to be repeated, since you could access centrally located archives.

Related article:

ICD-10-CM code changes: What's new for 2018

Dr. Brown: For teleconsultations and televisits, all that payers need do is modify the billing codes they use for our usual services. Once that is done, payers can develop a payment model that works for both themselves and the teleconsultants.

The US health care system is fragmented. Health care is provided in various facilities, including federally qualified health centers and health department clinics. As Dr. Nielsen said, physicians travel to remote facilities once or twice a week or even a month, whereas telehealth can be offered 5 days a week. Many residents go to remote clinics, where an attending physician is required. Instead of an attending driving there, he or she could be teleconsulting—interacting with residents and patients from afar. So, telehealth is a win-win situation. It increases access to physicians and facilitates appropriate interactions with them, wherever they are. Telehealth can be an important contribution to developing a more effective health care delivery system than the fragmented one we have now.

Effective health care delivery is so important for obstetrics and gynecology, and the reported workforce challenges are real. A maternal-fetal medicine physician is unlikely to travel to remote communities once a week or even every 2 weeks, but that same physician can teleconsult multiple days each week.

How telehealth can close service gaps

Dr. Brown: Having established relationships with physicians in other clinics and communities paves the way for teleconsultation and remote supervision. Technology can help Planned Parenthood and other clinics continue to provide contraceptive counseling and other health care services. Even medical abortions can be supervised through teleconsultation.

With funds to Medicaid being cut, with the potential for Planned Parenthood to be defunded, physicians must think of ways they can continue to provide care to all patients and communities. By addressing these issues now, we will be ready to take charge of patient care, wherever it is needed.

But, we need partners, no question. We need hospital partners in all communities, and especially in rural communities. Rural hospitals and maternity care are at risk. Health care in rural communities faces many challenges. Telehealth, teleconferencing, and teleconsultation not only can improve access to services, but also can curb travel costs as well as costs to the communities and hospitals.

Who pays the operating costs, and who benefits

Dr. Brown: Payers are already discovering that teleconsultations are as billable as in-person visits. In addition, physicians are realizing that remote consultation can work as well as in-person consultation, with its own merits and advantages. Education is key—education about billing and about what is doable in telehealth. We can learn from colleagues in other specialties.

Dr. Nielsen: Several entities and groups must start covering the technology costs. Federal and state entities need to determine how the country’s information infrastructure can be improved to give rural areas access to high-quality, high-speed, wide-bandwidth communications, which will help expand telehealth and increase other industries’ opportunities to grow and sustain these communities. Improving the infrastructure also can help keep rural areas sustainable.

Health care systems themselves can join federal, state, and local governments in building this infrastructure. They can also start identifying opportunities to support and sustain physicians and hospitals in smaller towns and start combating the perception that the infrastructure is being developed only to migrate patients over to accessing their care through telehealth provided by physicians in the larger cities.

Many payers see telehealth as improving access and outcomes and already support it, but more payers need to become involved. All need to understand how routine and complex consultations, even inpatient consultations, can be performed remotely and can be properly reimbursed, and incentivized with payments for improved outcomes and value.

As barriers fall and telehealth improves, acceptance by patients and physicians will increase. In addition, telehealth will enter medical education in a significant way. The instruction that students, residents, and Fellows receive will be enhanced by new telehealth approaches in various specialties, and residents will come out of these programs with telehealth experience and a sense of both financial benefits and payment structures. This early exposure will pique their interest in using telehealth and advocating its use where it may never before have been considered, owing to real and perceived barriers.

Read about telehealth solutions for ObGyns.

Learning from other specialties and agencies

Dr. Brown: The physician shortage negatively affects access to health care in rural areas. Many city and suburban physicians, including ObGyns, want to stay where they are. Education is needed to show them that a rural practice can be successful. They would have a good patient base and be able to use telehealth to improve care and maintain contact with tertiary care centers.

Several task force members have described their experience within their health systems, and we hope to borrow from that. A health system in South Dakota received a Health Resources and Services Administration grant to use telehealth and teleconsultation in the Indian Health Service (IHS). To women who access their health care through the IHS, being able to remain in the community is culturally important. Telehealth and teleconsultation bring care to these women where they live.

To develop the best telehealth and teleconsultation model, we are borrowing from these health systems and from the experience of our colleagues in dermatology, behavioral health, psychiatry, and other disciplines. These physicians already have overcome many hurdles and discovered the importance of patient satisfaction in providing remote health care.

Patients will benefit in various ways, and here is another example: A clinic refers a patient to an ObGyn to discuss whether it is possible to have a vaginal birth after a cesarean delivery. The drive to the ObGyn’s office takes an hour, but the patient just as easily could have had all her questions answered during a teleconsultation.

Related articles:

Telehealth and you (4-part audiocast)

Telehealth recommendations for ObGyns

Dr. Brown: Our task force will develop recommended best practices for telehealth. We will outline how a practice can engage with telehealth and will address licensing requirements, as a practice must be licensed in each state where it uses telehealth. Our goal is to help our specialty get started in telehealth and telemedicine.

In practices with telehealth, it will be incumbent on ObGyns to identify any barriers to care. For example, we are concerned about early discontinuation of breastfeeding, particularly among African American communities. Fortunately, we have learned that video chat follow-ups can help improve breastfeeding continuation rates.

It also will be incumbent on ObGyns to think differently about how best to follow up. For a patient who calls to say she thinks she has mastitis, much of the consultation can be handled by telephone or video conference with the physician and a nurse practi‑tioner, and then medication can be prescribed without the need for in-person follow-up. We must then determine how to ensure these follow-up methods are compensated.

Direct-to-patient virtual visits

- Virtual home visits

- Low-risk pregnancy

- Postpartum visits

- Lactation support

- Routine gynecologic care

- Postoperative follow-up

Remote patient monitoring

- Chronic disease management

- Antenatal testing

- Fetal heart rate monitoring

- Transfer of care

Final thoughts

Dr. Nielsen: It is time for all US health care players to more seriously and aggressively consider how telehealth can improve health care access, quality, and safety. Even more important, patients and physicians in small communities need to feel that they can access specialists and care that is as good as those available in larger communities without having to pull up stakes and move.

Telehealth can help small communities become sustainable over the long term. As the majority of the people in this country are born in and receive health care in community hospitals, not large tertiary care centers, the state of US health care should be measured by the ability to provide as much care as is technically possible in the small communities where patients live and work and raise their kids.

Dr. Brown: More than 50% of all babies are born in hospitals where fewer than 1,000 deliveries are performed, and almost 40% are born in hospitals where fewer than 500 are performed. To provide high-level care and have patients feel comfortable, to improve morbidity and mortality, we need telehealth and telemedicine.

If I can help a physician in East Africa place a Bakri balloon for postpartum hemorrhaging, surely I can help a physician in rural areas of Wyoming, South Dakota, or North Carolina deal with this obstetric emergency. In obstetrics and gynecology, telehealth and telemedicine have great potential in terms of morbidity and mortality, but we are also doing genetic counseling and a great deal of patient follow-up, and so much more can be done.

That is the key, and the reason for the training, the task force, the deliberations, and the best practices model that we will be sharing with our colleagues.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

I recently spoke with 2 outstanding leaders in our field, members of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) task force on telehealth and telemedicine, about the future of providing health care to women in remote locations.

Haywood Brown, MD, is President of ACOG for 2017–2018 and is F. Bayard Carter Professor of Obstetrics and Gynecology at Duke University Medical Center in Durham, North Carolina, and Peter Nielsen, MD, is Professor and Vice Chair of the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston, Texas, and Obstetrician-in-Chief at Children’s Hospital of San Antonio. Dr. Nielsen is a retired US Army colonel.

Why an ACOG telehealth task force?

Haywood Brown, MD: Our overall goals in telehealth and telemedicine are to coordinate and better facilitate the health care of women in remote locations and to improve maternal morbidity and mortality. Telehealth can be used on both an outpatient and an inpatient basis.

Outpatient telehealth is used for consultations. In maternal-fetal medicine, for instance, we use it for ultrasonography consultations. I also have used telehealth technology to “see” a pregnant patient with type 1diabetes. During our sessions, I managed her blood sugar levels and did all the other things I would have done if we had been together at my clinic. Without telehealth technology, however, this patient would have needed to drive 4 hours round-trip for each appointment.

Our colleagues in rural communities and at lower-level hospitals can use telehealth and telemedicine as aids in treating their high-risk patients, such as those with preeclampsia, prematurity risk, or other conditions. Physicians can consult with specialists through a face-to-face conversation that takes place through telecommunications. The result is that the quality of care for women in our communities is improved.

Genetic counseling, infertility consultation, and fetal anomaly management are some of the other applications. Our task force is discussing different ways to improve patient care and ways to collaborate with our colleagues around the country. Ultimately, we are developing best practices—a model for the best uses of technology to improve women’s health care in the United States.

Task force focus: Telehealth technology, billing, services

Dr. Brown: Our task force, a diverse group of members from all over the country, represents the spectrum of ObGyns. Although task force members have various levels of telehealth experience, all are very interested in these new channels of communication. The task force also includes billers, who understand billing ramifications, and payers, who know firsthand what will and will not be paid.

Technology and its availability is the most important topic for the task force. While some communities have Internet service, not all do. We need to determine which areas need service, how much it would cost, and who pays for it. Can a hospital afford it? A practice? Their partners? Identifying partners in tertiary care settings is a task force goal.

We are engaging a broad range of experts to study all the components and associated costs of technology, licensing, and cross-state credentialing. Gathering this information will help in developing a best practices model that general ObGyns can use.

Telehealth is redefining aspects of care: prenatal care (how many visits are required?), postpartum care, and other types of services that can be done remotely. Genetic counseling—who can provide it, what education is required—is another topic of discussion. Once we surmount the billing obstacles, we can do much with teleconferencing, such as provide genetic consultation with ObGyns in various settings.

The terms "telehealth" and "telemedicine" are often used interchangeably. Telemedicine is the older phrase, while telehealth entered the vernacular more recently and encompasses a broader definition.

The HealthIT.gov website explains the differences in terminology this way1:

- The Health Resources Services Administration defines telehealth as the use of electronic information and telecommunications technologies to support long-distance clinical health care, patient and professional health-related education, public health and health administration. Technologies include videoconferencing, the Internet, store-and-forward imaging, streaming media, and terrestrial and wireless communications.

- Telehealth is different from telemedicine because it refers to a broader scope of remote health care services than telemedicine. While telemedicine refers specifically to remote clinical services, telehealth can refer to remote nonclinical services, such as provider training, administrative meetings, and continuing medical education, in addition to clinical services.

A World Health Organization report, however, uses the 2 terms synonymously and interchangeably, defining telemedicine as2:

- The delivery of health care services, where distance is a critical factor, by all health care professionals using information and communication technologies for the exchange of valid information for diagnosis, treatment and prevention of disease and injuries, research and evaluation, and for the continuing education of health care providers, all in the interests of advancing the health of individuals and their communities.

The American Telemedicine Association (ATA) describes their use of the terms this way3:

- ATA largely views telemedicine and telehealth to be interchangeable terms, encompassing a wide definition of remote healthcare, although telehealth may not always involve clinical care.

References

- HealthIT.gov website. Frequently asked questions. https://www.healthit.gov/providers-professionals/frequently-asked-questions/485. Accessed November 15, 2017.

- World Health Organization. Telemedicine: opportunities and developments in member states. 2010. http://www.who.int/goe/publications/goe_telemedicine_2010.pdf. Accessed November 15, 2017.

- American Telemedicine Association. About telemedicine: the ultimate frontier for superior healthcare delivery. http://www.americantelemed.org/about/about-telemedicine. Accessed November 15, 2017.

Learn about ways clinicians can use telemedicine.

Making progress in rural and underserved communities

Peter Nielsen, MD: When we saw that some high-risk obstetrics patients were having a difficult time getting to our downtown San Antonio office—the trip from surrounding communities was taking too long, or city driving and parking were stressful or too costly—we looked to improve access to care. Collaborating with a health care network that has a hospital in a town north of San Antonio, we set up a pilot program to provide telemedicine perinatal consultation services.

In this kind of service, which occurs entirely in real time, ultrasound images taken at the hospital are streamed by high-speed fiberoptic cable to our office, where a maternal-fetal medicine physician views them. If a repeat image or a different image is needed, the physician requests another scan. Linked to the physician and listening through an earpiece, the ultrasonographer performs the new scan with little delay and without disturbing the patient. The conversation between physician and ultrasonographer is private.

After ultrasound scanning is complete, the patient goes to a private room at the hospital for a video conference with our physician in San Antonio, who has reviewed the images in the PACS (picture archiving and communication system) or ultrasound recording system. They discuss the images, the findings, and the follow-up.

We tested the technology during a 6-month pilot program to make sure it worked at the highest quality and safety levels. Then the program went live and we started seeing patients remotely. Now we have a robust telemedicine training capability at that hospital outside San Antonio, and we are looking to expand to other south and west Texas areas, some even farther from our office.

I have done some of these remote consultations. In response to my informal queries about the experience, patients said that no one else was offering it, and they were participating for the first time. Naturally they had questions and concerns. Nevertheless, patients, family members, and the ultrasonographer and physicians in the communities seem to think this is a high-quality, safe program that makes it easier for patients to access health care.