User login

Are robotic surgery complications underreported?

Although US hospitals have been quick to embrace surgical robot technology over the past decade, a “slapdash” system of reporting complications paints an unclear picture of its safety, according to Johns Hopkins researchers.

The Johns Hopkins team, led by Martin A. Makary, MD, MPH, found that, among the 1 million or so robotic surgeries performed since 2000, only 245 complications—including 71 deaths—were reported to the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA).1 When an adverse event or device malfunction occurs, hospitals are required to report these incidents to the manufacturer, which in turn is required to report them to the FDA—but this reporting doesn’t always happen.

“The number reported is very low for any complex technology used over a million times,” says Dr. Makary, associate professor of surgery at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine. “Doctors and patients can’t properly evaluate safety when we have a haphazard system of collecting data that is not independent and not transparent. There may be some complications specific to the use of this device, but we can only learn about them if we accurately track outcomes.”

The use of the robot in surgery has skyrocketed. Between 2007 and 2011, for example, the number of procedures involving the robot increased by more than 400% in the United States and more than 300% internationally. At the end of 2011, there were 1,400 surgical robots installed in US hospitals, up from 800 just 4 years earlier.

Some incidents went unreported until the news media highlighted them

Dr. Makary and colleagues found several incidents reported in the national news media that were not reported to the FDA until after the stories appeared in the press, even though the incidents took place long before the media exposure. Dr. Makary says it’s likely that many other incidents go unreported, never to be captured by research like his or by the FDA.

“We need innovation in medicine and, in this country, we are tremendously good at introducing new technologies,” he says. “But we have to evaluate new technology properly so we don’t over-adopt—or under-adopt—important advances that could benefit patients.”

How the study was conducted

Makary and colleagues reviewed the FDA adverse events database from January 1, 2000, to August 1, 2012. They also searched legal judgments and adverse events using LexisNexis to scan news media, and PACER to scan court records. The cases then were cross-referenced to see if they matched. The investigators found that eight cases were not appropriately reported to the FDA, five of which were never reported and two of which were reported only after a story about them appeared in the press.

Complication rate was highest for hysterectomy

When investigators reviewed complications that were reported, the procedures most commonly associated with death were:

- gynecologic (22 of the 71 deaths)

- urologic (15 deaths)

- cardiothoracic (12 deaths).

The cause of death was most often excessive bleeding. In cases where patients survived, hysterectomy by far had the most complications (43% of injuries).

A call for standardized reporting

Dr. Makary contends that standardized reporting is needed for all adverse events related to robotic devices. One rare complication that occurs, he says, is that a surgeon can accidentally cut the aorta because the surgeon cannot feel its firmness. For reporting purposes, however, it’s unclear whether such an event is surgeon error or device-related error. The FDA currently collects only device-related errors.

Dr. Makary argues that errors such as inadvertent cutting of the aorta, although preventable with proper technique, should be tracked as device-related errors because they are more common with robotic surgery than with conventional surgery. Without better reporting standards, he says, these complications are less likely to be reported to the FDA at all. And if they go unreported, they cannot contribute to the understanding or identification of safety problems.

He suggests one solution: use of a database like the one maintained by the American College of Surgeons, in which independent nurses identify and track adverse events and complications of traditional operations.

Good information on robotic surgery is needed not only for research, but also to ensure that patients are fully informed about potential risks. Right now, Dr. Makary says, it’s too easy for a surgeon to claim that there are no additional risks related to robotic surgery because the evidence is nowhere to be found.

“Decisions should not be made based on the information in the FDA database,” he says. “We need to be able to give patients answers to their questions about safety and how much risk is associated with the robot. We have all suspected the answer has not been zero. We still don’t really know what the true answer is.”

We want to hear from you! Tell us what you think.

Although US hospitals have been quick to embrace surgical robot technology over the past decade, a “slapdash” system of reporting complications paints an unclear picture of its safety, according to Johns Hopkins researchers.

The Johns Hopkins team, led by Martin A. Makary, MD, MPH, found that, among the 1 million or so robotic surgeries performed since 2000, only 245 complications—including 71 deaths—were reported to the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA).1 When an adverse event or device malfunction occurs, hospitals are required to report these incidents to the manufacturer, which in turn is required to report them to the FDA—but this reporting doesn’t always happen.

“The number reported is very low for any complex technology used over a million times,” says Dr. Makary, associate professor of surgery at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine. “Doctors and patients can’t properly evaluate safety when we have a haphazard system of collecting data that is not independent and not transparent. There may be some complications specific to the use of this device, but we can only learn about them if we accurately track outcomes.”

The use of the robot in surgery has skyrocketed. Between 2007 and 2011, for example, the number of procedures involving the robot increased by more than 400% in the United States and more than 300% internationally. At the end of 2011, there were 1,400 surgical robots installed in US hospitals, up from 800 just 4 years earlier.

Some incidents went unreported until the news media highlighted them

Dr. Makary and colleagues found several incidents reported in the national news media that were not reported to the FDA until after the stories appeared in the press, even though the incidents took place long before the media exposure. Dr. Makary says it’s likely that many other incidents go unreported, never to be captured by research like his or by the FDA.

“We need innovation in medicine and, in this country, we are tremendously good at introducing new technologies,” he says. “But we have to evaluate new technology properly so we don’t over-adopt—or under-adopt—important advances that could benefit patients.”

How the study was conducted

Makary and colleagues reviewed the FDA adverse events database from January 1, 2000, to August 1, 2012. They also searched legal judgments and adverse events using LexisNexis to scan news media, and PACER to scan court records. The cases then were cross-referenced to see if they matched. The investigators found that eight cases were not appropriately reported to the FDA, five of which were never reported and two of which were reported only after a story about them appeared in the press.

Complication rate was highest for hysterectomy

When investigators reviewed complications that were reported, the procedures most commonly associated with death were:

- gynecologic (22 of the 71 deaths)

- urologic (15 deaths)

- cardiothoracic (12 deaths).

The cause of death was most often excessive bleeding. In cases where patients survived, hysterectomy by far had the most complications (43% of injuries).

A call for standardized reporting

Dr. Makary contends that standardized reporting is needed for all adverse events related to robotic devices. One rare complication that occurs, he says, is that a surgeon can accidentally cut the aorta because the surgeon cannot feel its firmness. For reporting purposes, however, it’s unclear whether such an event is surgeon error or device-related error. The FDA currently collects only device-related errors.

Dr. Makary argues that errors such as inadvertent cutting of the aorta, although preventable with proper technique, should be tracked as device-related errors because they are more common with robotic surgery than with conventional surgery. Without better reporting standards, he says, these complications are less likely to be reported to the FDA at all. And if they go unreported, they cannot contribute to the understanding or identification of safety problems.

He suggests one solution: use of a database like the one maintained by the American College of Surgeons, in which independent nurses identify and track adverse events and complications of traditional operations.

Good information on robotic surgery is needed not only for research, but also to ensure that patients are fully informed about potential risks. Right now, Dr. Makary says, it’s too easy for a surgeon to claim that there are no additional risks related to robotic surgery because the evidence is nowhere to be found.

“Decisions should not be made based on the information in the FDA database,” he says. “We need to be able to give patients answers to their questions about safety and how much risk is associated with the robot. We have all suspected the answer has not been zero. We still don’t really know what the true answer is.”

We want to hear from you! Tell us what you think.

Although US hospitals have been quick to embrace surgical robot technology over the past decade, a “slapdash” system of reporting complications paints an unclear picture of its safety, according to Johns Hopkins researchers.

The Johns Hopkins team, led by Martin A. Makary, MD, MPH, found that, among the 1 million or so robotic surgeries performed since 2000, only 245 complications—including 71 deaths—were reported to the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA).1 When an adverse event or device malfunction occurs, hospitals are required to report these incidents to the manufacturer, which in turn is required to report them to the FDA—but this reporting doesn’t always happen.

“The number reported is very low for any complex technology used over a million times,” says Dr. Makary, associate professor of surgery at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine. “Doctors and patients can’t properly evaluate safety when we have a haphazard system of collecting data that is not independent and not transparent. There may be some complications specific to the use of this device, but we can only learn about them if we accurately track outcomes.”

The use of the robot in surgery has skyrocketed. Between 2007 and 2011, for example, the number of procedures involving the robot increased by more than 400% in the United States and more than 300% internationally. At the end of 2011, there were 1,400 surgical robots installed in US hospitals, up from 800 just 4 years earlier.

Some incidents went unreported until the news media highlighted them

Dr. Makary and colleagues found several incidents reported in the national news media that were not reported to the FDA until after the stories appeared in the press, even though the incidents took place long before the media exposure. Dr. Makary says it’s likely that many other incidents go unreported, never to be captured by research like his or by the FDA.

“We need innovation in medicine and, in this country, we are tremendously good at introducing new technologies,” he says. “But we have to evaluate new technology properly so we don’t over-adopt—or under-adopt—important advances that could benefit patients.”

How the study was conducted

Makary and colleagues reviewed the FDA adverse events database from January 1, 2000, to August 1, 2012. They also searched legal judgments and adverse events using LexisNexis to scan news media, and PACER to scan court records. The cases then were cross-referenced to see if they matched. The investigators found that eight cases were not appropriately reported to the FDA, five of which were never reported and two of which were reported only after a story about them appeared in the press.

Complication rate was highest for hysterectomy

When investigators reviewed complications that were reported, the procedures most commonly associated with death were:

- gynecologic (22 of the 71 deaths)

- urologic (15 deaths)

- cardiothoracic (12 deaths).

The cause of death was most often excessive bleeding. In cases where patients survived, hysterectomy by far had the most complications (43% of injuries).

A call for standardized reporting

Dr. Makary contends that standardized reporting is needed for all adverse events related to robotic devices. One rare complication that occurs, he says, is that a surgeon can accidentally cut the aorta because the surgeon cannot feel its firmness. For reporting purposes, however, it’s unclear whether such an event is surgeon error or device-related error. The FDA currently collects only device-related errors.

Dr. Makary argues that errors such as inadvertent cutting of the aorta, although preventable with proper technique, should be tracked as device-related errors because they are more common with robotic surgery than with conventional surgery. Without better reporting standards, he says, these complications are less likely to be reported to the FDA at all. And if they go unreported, they cannot contribute to the understanding or identification of safety problems.

He suggests one solution: use of a database like the one maintained by the American College of Surgeons, in which independent nurses identify and track adverse events and complications of traditional operations.

Good information on robotic surgery is needed not only for research, but also to ensure that patients are fully informed about potential risks. Right now, Dr. Makary says, it’s too easy for a surgeon to claim that there are no additional risks related to robotic surgery because the evidence is nowhere to be found.

“Decisions should not be made based on the information in the FDA database,” he says. “We need to be able to give patients answers to their questions about safety and how much risk is associated with the robot. We have all suspected the answer has not been zero. We still don’t really know what the true answer is.”

We want to hear from you! Tell us what you think.

An app to help your patient lose weight

HAVE YOU SEEN THESE OTHER APP REVIEWS BY DR. GUNTER?

An app to help your patient with chronic pelvic pain (February 2013)

Sprout Pregnancy Essentials: An app to help your patient track her pregnancy (September 2012)

An app to help your patient remember to take her OC (July 2012)

The increasing use of smartphones among women presents an opportunity to address health issues, such as obesity.

Forty-four percent of US women own a smartphone, according to the latest data.1 Ownership is highest among younger women, with more than 60% of women between the ages of 18 and 34 owning one of these devices.1

One of the features that makes a smartphone, well, smart is the ability to run apps (short for software “applications”). Apps started out as ways to enhance access to email or calendars, but the market has ex-ploded—both demand and supply—so that there are now apps for essentially anything you might ever need. Apple’s app store, the largest, boasts more than 500,000 apps, and more than 25 billion apps had been downloaded by March 2012.2 Medical app developers are keen to capitalize on our ever-increasing “app”-etite.

Medical apps can be divided into two categories: those that can help the patient and those that can help the provider. This series will review what I call prescription apps—in other words, apps that you might consider recommending to your patient to enhance her medical care.

Apps are not new to your patients

Many of your patients are already looking at medical apps and want to hear your opinion. I know that my smartphone users are uniformly interested in hearing my recommendations, and it is not uncommon that the free apps I recommend are downloaded before my patient leaves the office.

If you are not an app user yourself, there are two basic things that you should know. First, some apps are free and others are not, although that is not necessarily a measure of quality or utility. Second, apps must be written for the particular device, so it is important to know whether the app you are recommending is supported by your patient’s smartphone. As of February 2012, the most common devices are the Android (20% of cell phone users), iPhone (19%), and Blackberry (6%).1 Some apps can also be used on tablets (e.g., iPad, Galaxy) and e-book readers (e.g., Nook, Kindle). Use of these devices is also increasing; currently, 29% of Americans own either a tablet or an e-book reader.3

When the clinical need is weight loss

Lose It! is a weight-management app that tracks calories, exercise, and weight. Considering that more than 30% of US women are obese, working toward a healthy weight is a common office discussion and any additional tool is wel-come.4 Journaling, or recording every single thing that is eaten, is a key component of successful dieting. Smartphone users tend to have their phones with them wherever they are, so an app is an ideal tool for the journaling commitment needed for weight loss.

Lose It! is free and works on the following platforms:

- Android

- iPhone

- iPad

- Nook Color

- Nook Tablet.

Advantages include ease of use

The patient need only enter her current weight and height (measure your patient during the visit to ensure that she gets started with accurate numbers), the weight she hopes to attain (you can discuss this as well), and how many pounds she hopes to lose each week, and the app calculates the recommended calorie intake to achieve this goal. The app comes preloaded with thousands of foods, and it enables barcode scanning to upload the food and nutritional content with just a click of the phone’s camera.

The database can be expanded by adding unlisted foods and even recipes. Synchronizing the phone with Loseit.com allows for emailed summaries and reminders when the patient forgets to log a meal. There is also a wide repository of exercises to choose from when logging an activity.

A couple of cons

There is no Lose It! app for the Blackberry—and no plans to write one.

Another disadvantage is the extremely basic exercise journaling (no weekly or review function), and exercise calories are automatically added into the user’s daily allotment—not every dieter wants their calories set up this way.

This is the app I used to journal my 50-lb weight loss (and 6 months of maintenance). I think that testimonial speaks for itself.

In the next installment: an app that reminds your patient to take her birth control pills.

- Why (and how) you should encourage your patients' search for health information on the Web (December 2011)

- Does the risk of unplanned pregnancy outweight the risk of VTE from hormonal contraception? (Guest Editorial, October 2012)

- To blog or not to blog? What's the answer for you and your practice? (August 2011)

- For better or, maybe worse, patients are judging your care online (March 2011)

- Twitter 101 for ObGyns: Pearls, pitfalls, and potential (September 2010)

We want to hear from you! Tell us what you think.

1. Pew Internet & American Life Project. Nearly half of American adults are Smartphone owners. http://pewinternet.org/Reports/2012/Smartphone-Update-2012/Findings.aspx. Accessed April 9, 2012.

2. Apple app store downloads top 25 billion [press release]. http://www.apple.com/pr/library/2012/03/05Apples-App-Store-Downloads-Top-25-Billion.html. Accessed April 9, 2012 .

3. Pew Internet & American Life Project. Tablet and e-book reader ownership nearly doubled over the holiday gift-giving period. http://libraries.pewinternet.org/2012/01/23/tablet-and-e-book-reader-ownership-nearly-double-over-the-holiday-gift-giving-period/. Accessed April 9, 2012.

4. National Center for Health Statistics. Obesity in the United States, 2009–2010. NCHS Data Brief No. 82; January 2012.

HAVE YOU SEEN THESE OTHER APP REVIEWS BY DR. GUNTER?

An app to help your patient with chronic pelvic pain (February 2013)

Sprout Pregnancy Essentials: An app to help your patient track her pregnancy (September 2012)

An app to help your patient remember to take her OC (July 2012)

The increasing use of smartphones among women presents an opportunity to address health issues, such as obesity.

Forty-four percent of US women own a smartphone, according to the latest data.1 Ownership is highest among younger women, with more than 60% of women between the ages of 18 and 34 owning one of these devices.1

One of the features that makes a smartphone, well, smart is the ability to run apps (short for software “applications”). Apps started out as ways to enhance access to email or calendars, but the market has ex-ploded—both demand and supply—so that there are now apps for essentially anything you might ever need. Apple’s app store, the largest, boasts more than 500,000 apps, and more than 25 billion apps had been downloaded by March 2012.2 Medical app developers are keen to capitalize on our ever-increasing “app”-etite.

Medical apps can be divided into two categories: those that can help the patient and those that can help the provider. This series will review what I call prescription apps—in other words, apps that you might consider recommending to your patient to enhance her medical care.

Apps are not new to your patients

Many of your patients are already looking at medical apps and want to hear your opinion. I know that my smartphone users are uniformly interested in hearing my recommendations, and it is not uncommon that the free apps I recommend are downloaded before my patient leaves the office.

If you are not an app user yourself, there are two basic things that you should know. First, some apps are free and others are not, although that is not necessarily a measure of quality or utility. Second, apps must be written for the particular device, so it is important to know whether the app you are recommending is supported by your patient’s smartphone. As of February 2012, the most common devices are the Android (20% of cell phone users), iPhone (19%), and Blackberry (6%).1 Some apps can also be used on tablets (e.g., iPad, Galaxy) and e-book readers (e.g., Nook, Kindle). Use of these devices is also increasing; currently, 29% of Americans own either a tablet or an e-book reader.3

When the clinical need is weight loss

Lose It! is a weight-management app that tracks calories, exercise, and weight. Considering that more than 30% of US women are obese, working toward a healthy weight is a common office discussion and any additional tool is wel-come.4 Journaling, or recording every single thing that is eaten, is a key component of successful dieting. Smartphone users tend to have their phones with them wherever they are, so an app is an ideal tool for the journaling commitment needed for weight loss.

Lose It! is free and works on the following platforms:

- Android

- iPhone

- iPad

- Nook Color

- Nook Tablet.

Advantages include ease of use

The patient need only enter her current weight and height (measure your patient during the visit to ensure that she gets started with accurate numbers), the weight she hopes to attain (you can discuss this as well), and how many pounds she hopes to lose each week, and the app calculates the recommended calorie intake to achieve this goal. The app comes preloaded with thousands of foods, and it enables barcode scanning to upload the food and nutritional content with just a click of the phone’s camera.

The database can be expanded by adding unlisted foods and even recipes. Synchronizing the phone with Loseit.com allows for emailed summaries and reminders when the patient forgets to log a meal. There is also a wide repository of exercises to choose from when logging an activity.

A couple of cons

There is no Lose It! app for the Blackberry—and no plans to write one.

Another disadvantage is the extremely basic exercise journaling (no weekly or review function), and exercise calories are automatically added into the user’s daily allotment—not every dieter wants their calories set up this way.

This is the app I used to journal my 50-lb weight loss (and 6 months of maintenance). I think that testimonial speaks for itself.

In the next installment: an app that reminds your patient to take her birth control pills.

- Why (and how) you should encourage your patients' search for health information on the Web (December 2011)

- Does the risk of unplanned pregnancy outweight the risk of VTE from hormonal contraception? (Guest Editorial, October 2012)

- To blog or not to blog? What's the answer for you and your practice? (August 2011)

- For better or, maybe worse, patients are judging your care online (March 2011)

- Twitter 101 for ObGyns: Pearls, pitfalls, and potential (September 2010)

We want to hear from you! Tell us what you think.

HAVE YOU SEEN THESE OTHER APP REVIEWS BY DR. GUNTER?

An app to help your patient with chronic pelvic pain (February 2013)

Sprout Pregnancy Essentials: An app to help your patient track her pregnancy (September 2012)

An app to help your patient remember to take her OC (July 2012)

The increasing use of smartphones among women presents an opportunity to address health issues, such as obesity.

Forty-four percent of US women own a smartphone, according to the latest data.1 Ownership is highest among younger women, with more than 60% of women between the ages of 18 and 34 owning one of these devices.1

One of the features that makes a smartphone, well, smart is the ability to run apps (short for software “applications”). Apps started out as ways to enhance access to email or calendars, but the market has ex-ploded—both demand and supply—so that there are now apps for essentially anything you might ever need. Apple’s app store, the largest, boasts more than 500,000 apps, and more than 25 billion apps had been downloaded by March 2012.2 Medical app developers are keen to capitalize on our ever-increasing “app”-etite.

Medical apps can be divided into two categories: those that can help the patient and those that can help the provider. This series will review what I call prescription apps—in other words, apps that you might consider recommending to your patient to enhance her medical care.

Apps are not new to your patients

Many of your patients are already looking at medical apps and want to hear your opinion. I know that my smartphone users are uniformly interested in hearing my recommendations, and it is not uncommon that the free apps I recommend are downloaded before my patient leaves the office.

If you are not an app user yourself, there are two basic things that you should know. First, some apps are free and others are not, although that is not necessarily a measure of quality or utility. Second, apps must be written for the particular device, so it is important to know whether the app you are recommending is supported by your patient’s smartphone. As of February 2012, the most common devices are the Android (20% of cell phone users), iPhone (19%), and Blackberry (6%).1 Some apps can also be used on tablets (e.g., iPad, Galaxy) and e-book readers (e.g., Nook, Kindle). Use of these devices is also increasing; currently, 29% of Americans own either a tablet or an e-book reader.3

When the clinical need is weight loss

Lose It! is a weight-management app that tracks calories, exercise, and weight. Considering that more than 30% of US women are obese, working toward a healthy weight is a common office discussion and any additional tool is wel-come.4 Journaling, or recording every single thing that is eaten, is a key component of successful dieting. Smartphone users tend to have their phones with them wherever they are, so an app is an ideal tool for the journaling commitment needed for weight loss.

Lose It! is free and works on the following platforms:

- Android

- iPhone

- iPad

- Nook Color

- Nook Tablet.

Advantages include ease of use

The patient need only enter her current weight and height (measure your patient during the visit to ensure that she gets started with accurate numbers), the weight she hopes to attain (you can discuss this as well), and how many pounds she hopes to lose each week, and the app calculates the recommended calorie intake to achieve this goal. The app comes preloaded with thousands of foods, and it enables barcode scanning to upload the food and nutritional content with just a click of the phone’s camera.

The database can be expanded by adding unlisted foods and even recipes. Synchronizing the phone with Loseit.com allows for emailed summaries and reminders when the patient forgets to log a meal. There is also a wide repository of exercises to choose from when logging an activity.

A couple of cons

There is no Lose It! app for the Blackberry—and no plans to write one.

Another disadvantage is the extremely basic exercise journaling (no weekly or review function), and exercise calories are automatically added into the user’s daily allotment—not every dieter wants their calories set up this way.

This is the app I used to journal my 50-lb weight loss (and 6 months of maintenance). I think that testimonial speaks for itself.

In the next installment: an app that reminds your patient to take her birth control pills.

- Why (and how) you should encourage your patients' search for health information on the Web (December 2011)

- Does the risk of unplanned pregnancy outweight the risk of VTE from hormonal contraception? (Guest Editorial, October 2012)

- To blog or not to blog? What's the answer for you and your practice? (August 2011)

- For better or, maybe worse, patients are judging your care online (March 2011)

- Twitter 101 for ObGyns: Pearls, pitfalls, and potential (September 2010)

We want to hear from you! Tell us what you think.

1. Pew Internet & American Life Project. Nearly half of American adults are Smartphone owners. http://pewinternet.org/Reports/2012/Smartphone-Update-2012/Findings.aspx. Accessed April 9, 2012.

2. Apple app store downloads top 25 billion [press release]. http://www.apple.com/pr/library/2012/03/05Apples-App-Store-Downloads-Top-25-Billion.html. Accessed April 9, 2012 .

3. Pew Internet & American Life Project. Tablet and e-book reader ownership nearly doubled over the holiday gift-giving period. http://libraries.pewinternet.org/2012/01/23/tablet-and-e-book-reader-ownership-nearly-double-over-the-holiday-gift-giving-period/. Accessed April 9, 2012.

4. National Center for Health Statistics. Obesity in the United States, 2009–2010. NCHS Data Brief No. 82; January 2012.

1. Pew Internet & American Life Project. Nearly half of American adults are Smartphone owners. http://pewinternet.org/Reports/2012/Smartphone-Update-2012/Findings.aspx. Accessed April 9, 2012.

2. Apple app store downloads top 25 billion [press release]. http://www.apple.com/pr/library/2012/03/05Apples-App-Store-Downloads-Top-25-Billion.html. Accessed April 9, 2012 .

3. Pew Internet & American Life Project. Tablet and e-book reader ownership nearly doubled over the holiday gift-giving period. http://libraries.pewinternet.org/2012/01/23/tablet-and-e-book-reader-ownership-nearly-double-over-the-holiday-gift-giving-period/. Accessed April 9, 2012.

4. National Center for Health Statistics. Obesity in the United States, 2009–2010. NCHS Data Brief No. 82; January 2012.

Inside Hospitalists' Evolving Scope of Practice

In the October 2012 issue of The Hospitalist, the “Survey Insights” article discussed hospitalists’ evolving scope of practice based on information published in the 2012 State of Hospital Medicine report. The report remains the most authoritative, comprehensive source of information about our rapidly developing specialty, and this important topic is worthy of continued attention.

As I begin to orient a new class of hospitalists in my own HM group (HMG), I emphasize the five S’s of HMGs: scope, salary, schedule, structure, and society. HMGs define who they are largely by these constructs. As a specialty, we will define who we are by how we develop these constructs as a community. And it may indeed be the scope that most confirms our identity.

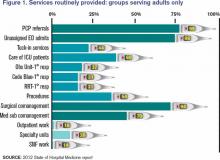

The survey (www.hospitalmedicine.org/survey) paints a self-portrait: What do we see when we look at that image? Figure 1 (below) lists information about services routinely provided by hospitalists, and one could divide the findings into three general categories.

First and foremost, there is the core work. It is clear that virtually all HMGs attended to primary-care-physician referrals and unassigned ED hospitalizations, and they also served as at least consultants for surgical comanagement. Most HMGs are now doing medical subspecialty comanagement, and the data would indicate that we are admitting and attending many of these patients. This raises the question about whether our identity will morph to that of the “universal admitter.” Many contend that health-care change forces will continue to pressure in this direction unless, and until, medical subspecialties develop their own dedicated hospitalists. Many hospitals may not be able to resource this; hence, there will likely be persistent pressure for the HMGs to provide this scope of care.

Perhaps half of HMGs provide the second group of services, which includes primary clinical care for rapid-response teams, code blue teams, and observation units. Forty-four percent of adult hospitalist programs provide a “tuck-in” service (nighttime coverage for other providers), and about 50% of HMGs reported performing procedures. Although this graph might suggest a decline in the proportion of groups caring for ICU patients compared with the 78% that was reported in 2011, this data set includes academic practices (the 2011 data didn’t). For nonacademic adult medicine practices, the proportion doing ICU work actually rose to 83.5% in 2012 from 78% in 2011. Larger hospitals and university settings are increasingly employing intensivists for ICU coverage, but the national deficit of intensivists will likely continue the external pressure for hospitalists to provide ICU care in many settings.

The final group of services represents the “road less traveled”—work in outpatient settings in such specialty units as long-term acute care, psychiatric wings, and skilled nursing facilities. These might prove to be niche opportunities or possible distractions.

There remains, however, the core work that identifies our specialty. We all do it, people depend on us to have it done, and it largely defines who we are as individuals, as HMGs, and as the fastest-growing specialty in American medical history.

Dr. Landis is medical director of Wellspan Hospitalists in York, Pa., and a member of SHM’s Practice Analysis Committee.

In the October 2012 issue of The Hospitalist, the “Survey Insights” article discussed hospitalists’ evolving scope of practice based on information published in the 2012 State of Hospital Medicine report. The report remains the most authoritative, comprehensive source of information about our rapidly developing specialty, and this important topic is worthy of continued attention.

As I begin to orient a new class of hospitalists in my own HM group (HMG), I emphasize the five S’s of HMGs: scope, salary, schedule, structure, and society. HMGs define who they are largely by these constructs. As a specialty, we will define who we are by how we develop these constructs as a community. And it may indeed be the scope that most confirms our identity.

The survey (www.hospitalmedicine.org/survey) paints a self-portrait: What do we see when we look at that image? Figure 1 (below) lists information about services routinely provided by hospitalists, and one could divide the findings into three general categories.

First and foremost, there is the core work. It is clear that virtually all HMGs attended to primary-care-physician referrals and unassigned ED hospitalizations, and they also served as at least consultants for surgical comanagement. Most HMGs are now doing medical subspecialty comanagement, and the data would indicate that we are admitting and attending many of these patients. This raises the question about whether our identity will morph to that of the “universal admitter.” Many contend that health-care change forces will continue to pressure in this direction unless, and until, medical subspecialties develop their own dedicated hospitalists. Many hospitals may not be able to resource this; hence, there will likely be persistent pressure for the HMGs to provide this scope of care.

Perhaps half of HMGs provide the second group of services, which includes primary clinical care for rapid-response teams, code blue teams, and observation units. Forty-four percent of adult hospitalist programs provide a “tuck-in” service (nighttime coverage for other providers), and about 50% of HMGs reported performing procedures. Although this graph might suggest a decline in the proportion of groups caring for ICU patients compared with the 78% that was reported in 2011, this data set includes academic practices (the 2011 data didn’t). For nonacademic adult medicine practices, the proportion doing ICU work actually rose to 83.5% in 2012 from 78% in 2011. Larger hospitals and university settings are increasingly employing intensivists for ICU coverage, but the national deficit of intensivists will likely continue the external pressure for hospitalists to provide ICU care in many settings.

The final group of services represents the “road less traveled”—work in outpatient settings in such specialty units as long-term acute care, psychiatric wings, and skilled nursing facilities. These might prove to be niche opportunities or possible distractions.

There remains, however, the core work that identifies our specialty. We all do it, people depend on us to have it done, and it largely defines who we are as individuals, as HMGs, and as the fastest-growing specialty in American medical history.

Dr. Landis is medical director of Wellspan Hospitalists in York, Pa., and a member of SHM’s Practice Analysis Committee.

In the October 2012 issue of The Hospitalist, the “Survey Insights” article discussed hospitalists’ evolving scope of practice based on information published in the 2012 State of Hospital Medicine report. The report remains the most authoritative, comprehensive source of information about our rapidly developing specialty, and this important topic is worthy of continued attention.

As I begin to orient a new class of hospitalists in my own HM group (HMG), I emphasize the five S’s of HMGs: scope, salary, schedule, structure, and society. HMGs define who they are largely by these constructs. As a specialty, we will define who we are by how we develop these constructs as a community. And it may indeed be the scope that most confirms our identity.

The survey (www.hospitalmedicine.org/survey) paints a self-portrait: What do we see when we look at that image? Figure 1 (below) lists information about services routinely provided by hospitalists, and one could divide the findings into three general categories.

First and foremost, there is the core work. It is clear that virtually all HMGs attended to primary-care-physician referrals and unassigned ED hospitalizations, and they also served as at least consultants for surgical comanagement. Most HMGs are now doing medical subspecialty comanagement, and the data would indicate that we are admitting and attending many of these patients. This raises the question about whether our identity will morph to that of the “universal admitter.” Many contend that health-care change forces will continue to pressure in this direction unless, and until, medical subspecialties develop their own dedicated hospitalists. Many hospitals may not be able to resource this; hence, there will likely be persistent pressure for the HMGs to provide this scope of care.

Perhaps half of HMGs provide the second group of services, which includes primary clinical care for rapid-response teams, code blue teams, and observation units. Forty-four percent of adult hospitalist programs provide a “tuck-in” service (nighttime coverage for other providers), and about 50% of HMGs reported performing procedures. Although this graph might suggest a decline in the proportion of groups caring for ICU patients compared with the 78% that was reported in 2011, this data set includes academic practices (the 2011 data didn’t). For nonacademic adult medicine practices, the proportion doing ICU work actually rose to 83.5% in 2012 from 78% in 2011. Larger hospitals and university settings are increasingly employing intensivists for ICU coverage, but the national deficit of intensivists will likely continue the external pressure for hospitalists to provide ICU care in many settings.

The final group of services represents the “road less traveled”—work in outpatient settings in such specialty units as long-term acute care, psychiatric wings, and skilled nursing facilities. These might prove to be niche opportunities or possible distractions.

There remains, however, the core work that identifies our specialty. We all do it, people depend on us to have it done, and it largely defines who we are as individuals, as HMGs, and as the fastest-growing specialty in American medical history.

Dr. Landis is medical director of Wellspan Hospitalists in York, Pa., and a member of SHM’s Practice Analysis Committee.

Multiple Approaches to Combat High Hospital Patient Census

In this age of cost containment and fiscal frugality, how do you handle high-census periods without jeopardizing patient care?

–Michael P. Mason, Tulsa, Okla.

Dr. Hospitalist responds:

Your group must first define the term “high census,” because workload is based on many factors. Seeing 20 patients a day in a large inner-city hospital is much different from seeing 20 patients in a suburban hospital in an affluent part of town. Also, seeing 20 patients geographically located on the same floor is much easier than 20 patients spread all over the hospital. Mid-level or nurse case-management support also makes a difference.

Once defined, there are many different ways to handle the high census; each hospitalist group must decide what works for them.

Many groups rely on their compensation structure to entice their physicians to see higher numbers of patients. The pay structure may be production-based and entice many of the group members to see more patients. Typically, for the member that does not want to see the large volumes, there are usually colleagues who are more than happy to cover the excess patients.

Some groups employ a hybrid system, with their compensation based on production and salary. Generally, bonuses or incentives are applied after meeting a specific relative value unit (RVU) threshold. These thresholds vary and usually are raised periodically based on the percentage of staff able to collect. Again, some group members may volunteer to see the excess patients for higher compensation. It is up to the group to develop mechanisms to measure the quality of care of these high producers and monitor for burnout.

Then there are groups that have no volume incentives and everyone is paid a salary. Many groups that utilize any of these compensation models have group members “on call” to come in when needed and see the excess patients. Many pay the on-call person some nominal amount just for being on call, or a per-patient or hourly rate if they have to come in. Others make it a mandatory part of the schedule without any additional compensation.

Many groups have integrated advanced-practice providers (nurse practitioners and physician assistants) into their systems. They can help hospitalists improve efficiency by seeing patients that are less ill or awaiting placement, or by performing such labor-intensive tasks as admissions and discharges.

HM groups should collaborate with the hospital’s chief financial officer. Like clinicians, most administrators recognize it is very difficult to deliver high-quality and efficient care when the numbers get high. It is in their best interest to help devise strategies and models that deliver quality care and the metrics needed to sustain support.

HM has become such a large specialty that there is no-one-size-fits-all solution to high censuses. In the end, you have to be comfortable with the system created by your group, work to help improve it, or seek a better fit.

Do you have a problem or concern that you’d like Dr. Hospitalist to address? Email your questions to [email protected].

In this age of cost containment and fiscal frugality, how do you handle high-census periods without jeopardizing patient care?

–Michael P. Mason, Tulsa, Okla.

Dr. Hospitalist responds:

Your group must first define the term “high census,” because workload is based on many factors. Seeing 20 patients a day in a large inner-city hospital is much different from seeing 20 patients in a suburban hospital in an affluent part of town. Also, seeing 20 patients geographically located on the same floor is much easier than 20 patients spread all over the hospital. Mid-level or nurse case-management support also makes a difference.

Once defined, there are many different ways to handle the high census; each hospitalist group must decide what works for them.

Many groups rely on their compensation structure to entice their physicians to see higher numbers of patients. The pay structure may be production-based and entice many of the group members to see more patients. Typically, for the member that does not want to see the large volumes, there are usually colleagues who are more than happy to cover the excess patients.

Some groups employ a hybrid system, with their compensation based on production and salary. Generally, bonuses or incentives are applied after meeting a specific relative value unit (RVU) threshold. These thresholds vary and usually are raised periodically based on the percentage of staff able to collect. Again, some group members may volunteer to see the excess patients for higher compensation. It is up to the group to develop mechanisms to measure the quality of care of these high producers and monitor for burnout.

Then there are groups that have no volume incentives and everyone is paid a salary. Many groups that utilize any of these compensation models have group members “on call” to come in when needed and see the excess patients. Many pay the on-call person some nominal amount just for being on call, or a per-patient or hourly rate if they have to come in. Others make it a mandatory part of the schedule without any additional compensation.

Many groups have integrated advanced-practice providers (nurse practitioners and physician assistants) into their systems. They can help hospitalists improve efficiency by seeing patients that are less ill or awaiting placement, or by performing such labor-intensive tasks as admissions and discharges.

HM groups should collaborate with the hospital’s chief financial officer. Like clinicians, most administrators recognize it is very difficult to deliver high-quality and efficient care when the numbers get high. It is in their best interest to help devise strategies and models that deliver quality care and the metrics needed to sustain support.

HM has become such a large specialty that there is no-one-size-fits-all solution to high censuses. In the end, you have to be comfortable with the system created by your group, work to help improve it, or seek a better fit.

Do you have a problem or concern that you’d like Dr. Hospitalist to address? Email your questions to [email protected].

In this age of cost containment and fiscal frugality, how do you handle high-census periods without jeopardizing patient care?

–Michael P. Mason, Tulsa, Okla.

Dr. Hospitalist responds:

Your group must first define the term “high census,” because workload is based on many factors. Seeing 20 patients a day in a large inner-city hospital is much different from seeing 20 patients in a suburban hospital in an affluent part of town. Also, seeing 20 patients geographically located on the same floor is much easier than 20 patients spread all over the hospital. Mid-level or nurse case-management support also makes a difference.

Once defined, there are many different ways to handle the high census; each hospitalist group must decide what works for them.

Many groups rely on their compensation structure to entice their physicians to see higher numbers of patients. The pay structure may be production-based and entice many of the group members to see more patients. Typically, for the member that does not want to see the large volumes, there are usually colleagues who are more than happy to cover the excess patients.

Some groups employ a hybrid system, with their compensation based on production and salary. Generally, bonuses or incentives are applied after meeting a specific relative value unit (RVU) threshold. These thresholds vary and usually are raised periodically based on the percentage of staff able to collect. Again, some group members may volunteer to see the excess patients for higher compensation. It is up to the group to develop mechanisms to measure the quality of care of these high producers and monitor for burnout.

Then there are groups that have no volume incentives and everyone is paid a salary. Many groups that utilize any of these compensation models have group members “on call” to come in when needed and see the excess patients. Many pay the on-call person some nominal amount just for being on call, or a per-patient or hourly rate if they have to come in. Others make it a mandatory part of the schedule without any additional compensation.

Many groups have integrated advanced-practice providers (nurse practitioners and physician assistants) into their systems. They can help hospitalists improve efficiency by seeing patients that are less ill or awaiting placement, or by performing such labor-intensive tasks as admissions and discharges.

HM groups should collaborate with the hospital’s chief financial officer. Like clinicians, most administrators recognize it is very difficult to deliver high-quality and efficient care when the numbers get high. It is in their best interest to help devise strategies and models that deliver quality care and the metrics needed to sustain support.

HM has become such a large specialty that there is no-one-size-fits-all solution to high censuses. In the end, you have to be comfortable with the system created by your group, work to help improve it, or seek a better fit.

Do you have a problem or concern that you’d like Dr. Hospitalist to address? Email your questions to [email protected].

Among Physicians, 59% Would Not Recommend a Medical Career

Percentage of practicing physicians who would not recommend a medical career to a young person, according to Filling The Void: 2013 Physician Outlook Practice Trends, a national physician practice survey conducted by health-care staffing firm Jackson Healthcare.6 “Physician discontent appears to be creating a void in the health-care field,” with dissatisfaction and burnout leading to early retirement, the report stated. Discontent is driven by decreased autonomy, decreased reimbursement, administrative and regulatory distractions, corporatization of medicine, and fear of litigation, according to the report. Thirty-six percent of the respondents reported a generally negative outlook about their career, compared with only 16% who had a generally favorable outlook.

Larry Beresford is a freelance writer in San Francisco.

References

- Hartocollis A. With money at risk, hospitals push staff to wash hands. The New York Times website. Available at: http://www.nytimes.com/2013/05/29/nyregion/hospitals-struggle-to-get-workers-to-wash-their-hands.html?pagewanted=all&_r=0. Accessed May 28, 2013.

- Cumbler E, Castillo L, Satorie L, et al. Culture change in infection control: applying psychological principles to improve hand hygiene. J Nurs Care Qual. 2013 May 10 [Epub ahead of print].

- Bernhard B. High tech hand washing comes to St. Louis hospital. St. Louis Post-Dispatch website. Available at: http://www.stltoday.com/lifestyles/health-med-fit/health/high-tech-hand-washing-comes-to-st-louis-hospital/article_9379065d-85ff-5643-bae2-899254cb22fa.html. Accessed June 27, 2013.

- Lowe TJ, Partovian C, Kroch E, Martin J, Bankowitz R. Measuring cardiac waste: the Premier cardiac waste measures. Am J Med Qual. 2013 May 29 [Epub ahead of print].

- Elixhauser A, Steiner C. Readmissions to U.S. hospitals by diagnosis, 2010. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project website. Available at: http://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/statbriefs/sb153.pdf. Accessed July 15, 2013.

- Jackson Healthcare. Filling the void: 2013 physician outlook & practice trends. Jackson Healthcare website. Available at: http://www.jacksonhealthcare.com/media/193525/jc-2013physiciantrends-void_ebk0513.pdf. Accessed July 15, 2013.

Percentage of practicing physicians who would not recommend a medical career to a young person, according to Filling The Void: 2013 Physician Outlook Practice Trends, a national physician practice survey conducted by health-care staffing firm Jackson Healthcare.6 “Physician discontent appears to be creating a void in the health-care field,” with dissatisfaction and burnout leading to early retirement, the report stated. Discontent is driven by decreased autonomy, decreased reimbursement, administrative and regulatory distractions, corporatization of medicine, and fear of litigation, according to the report. Thirty-six percent of the respondents reported a generally negative outlook about their career, compared with only 16% who had a generally favorable outlook.

Larry Beresford is a freelance writer in San Francisco.

References

- Hartocollis A. With money at risk, hospitals push staff to wash hands. The New York Times website. Available at: http://www.nytimes.com/2013/05/29/nyregion/hospitals-struggle-to-get-workers-to-wash-their-hands.html?pagewanted=all&_r=0. Accessed May 28, 2013.

- Cumbler E, Castillo L, Satorie L, et al. Culture change in infection control: applying psychological principles to improve hand hygiene. J Nurs Care Qual. 2013 May 10 [Epub ahead of print].

- Bernhard B. High tech hand washing comes to St. Louis hospital. St. Louis Post-Dispatch website. Available at: http://www.stltoday.com/lifestyles/health-med-fit/health/high-tech-hand-washing-comes-to-st-louis-hospital/article_9379065d-85ff-5643-bae2-899254cb22fa.html. Accessed June 27, 2013.

- Lowe TJ, Partovian C, Kroch E, Martin J, Bankowitz R. Measuring cardiac waste: the Premier cardiac waste measures. Am J Med Qual. 2013 May 29 [Epub ahead of print].

- Elixhauser A, Steiner C. Readmissions to U.S. hospitals by diagnosis, 2010. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project website. Available at: http://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/statbriefs/sb153.pdf. Accessed July 15, 2013.

- Jackson Healthcare. Filling the void: 2013 physician outlook & practice trends. Jackson Healthcare website. Available at: http://www.jacksonhealthcare.com/media/193525/jc-2013physiciantrends-void_ebk0513.pdf. Accessed July 15, 2013.

Percentage of practicing physicians who would not recommend a medical career to a young person, according to Filling The Void: 2013 Physician Outlook Practice Trends, a national physician practice survey conducted by health-care staffing firm Jackson Healthcare.6 “Physician discontent appears to be creating a void in the health-care field,” with dissatisfaction and burnout leading to early retirement, the report stated. Discontent is driven by decreased autonomy, decreased reimbursement, administrative and regulatory distractions, corporatization of medicine, and fear of litigation, according to the report. Thirty-six percent of the respondents reported a generally negative outlook about their career, compared with only 16% who had a generally favorable outlook.

Larry Beresford is a freelance writer in San Francisco.

References

- Hartocollis A. With money at risk, hospitals push staff to wash hands. The New York Times website. Available at: http://www.nytimes.com/2013/05/29/nyregion/hospitals-struggle-to-get-workers-to-wash-their-hands.html?pagewanted=all&_r=0. Accessed May 28, 2013.

- Cumbler E, Castillo L, Satorie L, et al. Culture change in infection control: applying psychological principles to improve hand hygiene. J Nurs Care Qual. 2013 May 10 [Epub ahead of print].

- Bernhard B. High tech hand washing comes to St. Louis hospital. St. Louis Post-Dispatch website. Available at: http://www.stltoday.com/lifestyles/health-med-fit/health/high-tech-hand-washing-comes-to-st-louis-hospital/article_9379065d-85ff-5643-bae2-899254cb22fa.html. Accessed June 27, 2013.

- Lowe TJ, Partovian C, Kroch E, Martin J, Bankowitz R. Measuring cardiac waste: the Premier cardiac waste measures. Am J Med Qual. 2013 May 29 [Epub ahead of print].

- Elixhauser A, Steiner C. Readmissions to U.S. hospitals by diagnosis, 2010. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project website. Available at: http://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/statbriefs/sb153.pdf. Accessed July 15, 2013.

- Jackson Healthcare. Filling the void: 2013 physician outlook & practice trends. Jackson Healthcare website. Available at: http://www.jacksonhealthcare.com/media/193525/jc-2013physiciantrends-void_ebk0513.pdf. Accessed July 15, 2013.

MGMA Physician Compensation Survey Raises Questions About Performance Pay

Sorting out whether a hospitalist’s bonus and other compensation elements are in line with survey data often leads to confusion. The 2013 MGMA Physician Compensation and Production Survey report, based on 2012 data, shows median compensation of $240,352 for internal-medicine hospitalists (I’ll round it to $240,000 for the rest of this piece). So is your compensation in line with survey medians if your base pay is $230,000 and you have a performance bonus of up to $20,000?

The problem is that you can’t know in advance how much of the $20,000 performance bonus you will earn. And isn’t a bonus supposed to be on top of typical compensation? To be in line with the survey, shouldn’t your base pay equal the $240,000 median, with any available bonus dollars on top of that? (Base pay means all forms of compensation other than a performance bonus; it could be productivity-based compensation, pay connected to numbers of shifts or hours worked, or a fixed annual salary, etc.)

The short answer is no, and to demonstrate why, I’ll first review some facts about the survey itself, then apply that knowledge to the hospitalist marketplace.

I want to emphasize that in this article, I’m not taking a position on the right amount of workload, compensation, or bonus for any hospitalist practice. And I’m using survey medians just to simplify the discussion, not because they’re optimal for any particular practice.

Survey Data

The most important thing to know about the survey data is that the $240,000 figure takes into account all forms of pay, including extra shift pay and any bonuses that might have been paid to each provider in the data set. Such benefits as health insurance and retirement-plan contribution are not included in this figure.

There are several ways a hospitalist might have earned compensation that matches the survey median. He or she might have a fixed annual salary equal to the median with no bonus available or had a meaningful bonus (e.g. $10,000 to $20,000) available and failed to earn any of it. Or the base might have come to $230,000, and he or she earned half of the available $20,000 performance bonus. Many other permutations of bonus and other salary elements could occur to arrive at the same $240,000 figure.

The important thing to remember is that whatever bonus dollars were paid, they are included in the salary figure from the survey—not added on top of that figure. So if all bonus dollars earned were subtracted from the survey, the total “nonbonus” compensation would be lower than $240,000.

How much lower?

Typical Hospitalist Bonus Amounts

The MGMA survey doesn’t report the portion of compensation tied to a bonus, but SHM’s does. SHM’s 2012 State of Hospital Medicine Report, based on 2011 data (www.hospitalmedicine.org/survey), is based on the most recent data available, and it showed (on page 60) that an average of 7% of pay was tied to performance for nonacademic hospitalist groups serving adults only. This included any payments for good individual or group performance on quality, efficiency, service, satisfaction, and/or other nonproduction measures. In conversation, this often is referred to as a “bonus” rather than “performance compensation.”

One way to estimate the nonbonus compensation would be to reduce the total pay by 7%, which comes to $223,200. Keep in mind that there are all kinds of mathematical and methodological problems in manipulating the reported survey numbers from two separate surveys to derive additional benchmarks. But this seems like a reasonable guess.

An increasing portion of hospitalist groups have some pay tied to performance, and the portion of total pay tied to performance seems to be going up at least a little. It was 5% of pay in 2010 and 4% in 2011, compared with 7% in the 2012 survey.

Keep in mind two things. First, this 7% reflects the performance or bonus dollars actually paid out, not the total amount available. In other words, even if the median total bonus dollars available were 20% of compensation, hospitalists earned less than that. Some hospitalists earned all dollars available, and some earned only a portion of what was available. And second, some hospitalists fail to earn any bonus or don’t have one available at all. So the survey would show for them zero compensation tied to bonus.

Making Sense of the Numbers

If you follow the reasoning above, then you probably agree that if your goal is to match mean compensation from the MGMA survey (I’m not suggesting that is the best goal, merely using it for simplicity), then you would set nonbonus compensation 7% below median—as long as you’re likely to get the same portion of a bonus as the median practice.

In some practices, performance thresholds are set at a level that is very easy to achieve, meaning the hospitalists are almost guaranteed to get all of the bonus compensation available. To be consistent with survey medians, it would be appropriate for them to set nonbonus compensation by subtracting all bonus dollars from the survey median. For example, if a $20,000 bonus is available and all of it is likely to be earned by the hospitalists, then total nonbonus compensation would be $220,000.

However, what if the bonus requires significant improvements in performance by the doctors (which seems most appropriate to me; why have a bonus otherwise?) and it is likely they will earn only 25% of all bonus dollars available? If the total available bonus is $20,000, then something like 25%, or $5,000, should be subtracted from the median to yield a total nonbonus compensation of $235,000.

Simple Thinking

I think it makes most sense to set total nonbonus compensation below the targeted total compensation. Failure to achieve any performance thresholds means no bonus and compensation will be below target that year. Meeting some thresholds (some improvement in performance) should result in matching the target compensation, and truly terrific performance that meets or exceeds all thresholds should result in the doctor being paid above the target.

Dr. Nelson has been a practicing hospitalist since 1988. He is co-founder and past president of SHM, and principal in Nelson Flores Hospital Medicine Consultants. He is co-director for SHM’s “Best Practices in Managing a Hospital Medicine Program” course. Write to him at [email protected].

Sorting out whether a hospitalist’s bonus and other compensation elements are in line with survey data often leads to confusion. The 2013 MGMA Physician Compensation and Production Survey report, based on 2012 data, shows median compensation of $240,352 for internal-medicine hospitalists (I’ll round it to $240,000 for the rest of this piece). So is your compensation in line with survey medians if your base pay is $230,000 and you have a performance bonus of up to $20,000?

The problem is that you can’t know in advance how much of the $20,000 performance bonus you will earn. And isn’t a bonus supposed to be on top of typical compensation? To be in line with the survey, shouldn’t your base pay equal the $240,000 median, with any available bonus dollars on top of that? (Base pay means all forms of compensation other than a performance bonus; it could be productivity-based compensation, pay connected to numbers of shifts or hours worked, or a fixed annual salary, etc.)

The short answer is no, and to demonstrate why, I’ll first review some facts about the survey itself, then apply that knowledge to the hospitalist marketplace.

I want to emphasize that in this article, I’m not taking a position on the right amount of workload, compensation, or bonus for any hospitalist practice. And I’m using survey medians just to simplify the discussion, not because they’re optimal for any particular practice.

Survey Data

The most important thing to know about the survey data is that the $240,000 figure takes into account all forms of pay, including extra shift pay and any bonuses that might have been paid to each provider in the data set. Such benefits as health insurance and retirement-plan contribution are not included in this figure.

There are several ways a hospitalist might have earned compensation that matches the survey median. He or she might have a fixed annual salary equal to the median with no bonus available or had a meaningful bonus (e.g. $10,000 to $20,000) available and failed to earn any of it. Or the base might have come to $230,000, and he or she earned half of the available $20,000 performance bonus. Many other permutations of bonus and other salary elements could occur to arrive at the same $240,000 figure.

The important thing to remember is that whatever bonus dollars were paid, they are included in the salary figure from the survey—not added on top of that figure. So if all bonus dollars earned were subtracted from the survey, the total “nonbonus” compensation would be lower than $240,000.

How much lower?

Typical Hospitalist Bonus Amounts

The MGMA survey doesn’t report the portion of compensation tied to a bonus, but SHM’s does. SHM’s 2012 State of Hospital Medicine Report, based on 2011 data (www.hospitalmedicine.org/survey), is based on the most recent data available, and it showed (on page 60) that an average of 7% of pay was tied to performance for nonacademic hospitalist groups serving adults only. This included any payments for good individual or group performance on quality, efficiency, service, satisfaction, and/or other nonproduction measures. In conversation, this often is referred to as a “bonus” rather than “performance compensation.”

One way to estimate the nonbonus compensation would be to reduce the total pay by 7%, which comes to $223,200. Keep in mind that there are all kinds of mathematical and methodological problems in manipulating the reported survey numbers from two separate surveys to derive additional benchmarks. But this seems like a reasonable guess.

An increasing portion of hospitalist groups have some pay tied to performance, and the portion of total pay tied to performance seems to be going up at least a little. It was 5% of pay in 2010 and 4% in 2011, compared with 7% in the 2012 survey.

Keep in mind two things. First, this 7% reflects the performance or bonus dollars actually paid out, not the total amount available. In other words, even if the median total bonus dollars available were 20% of compensation, hospitalists earned less than that. Some hospitalists earned all dollars available, and some earned only a portion of what was available. And second, some hospitalists fail to earn any bonus or don’t have one available at all. So the survey would show for them zero compensation tied to bonus.

Making Sense of the Numbers

If you follow the reasoning above, then you probably agree that if your goal is to match mean compensation from the MGMA survey (I’m not suggesting that is the best goal, merely using it for simplicity), then you would set nonbonus compensation 7% below median—as long as you’re likely to get the same portion of a bonus as the median practice.

In some practices, performance thresholds are set at a level that is very easy to achieve, meaning the hospitalists are almost guaranteed to get all of the bonus compensation available. To be consistent with survey medians, it would be appropriate for them to set nonbonus compensation by subtracting all bonus dollars from the survey median. For example, if a $20,000 bonus is available and all of it is likely to be earned by the hospitalists, then total nonbonus compensation would be $220,000.

However, what if the bonus requires significant improvements in performance by the doctors (which seems most appropriate to me; why have a bonus otherwise?) and it is likely they will earn only 25% of all bonus dollars available? If the total available bonus is $20,000, then something like 25%, or $5,000, should be subtracted from the median to yield a total nonbonus compensation of $235,000.

Simple Thinking

I think it makes most sense to set total nonbonus compensation below the targeted total compensation. Failure to achieve any performance thresholds means no bonus and compensation will be below target that year. Meeting some thresholds (some improvement in performance) should result in matching the target compensation, and truly terrific performance that meets or exceeds all thresholds should result in the doctor being paid above the target.

Dr. Nelson has been a practicing hospitalist since 1988. He is co-founder and past president of SHM, and principal in Nelson Flores Hospital Medicine Consultants. He is co-director for SHM’s “Best Practices in Managing a Hospital Medicine Program” course. Write to him at [email protected].

Sorting out whether a hospitalist’s bonus and other compensation elements are in line with survey data often leads to confusion. The 2013 MGMA Physician Compensation and Production Survey report, based on 2012 data, shows median compensation of $240,352 for internal-medicine hospitalists (I’ll round it to $240,000 for the rest of this piece). So is your compensation in line with survey medians if your base pay is $230,000 and you have a performance bonus of up to $20,000?

The problem is that you can’t know in advance how much of the $20,000 performance bonus you will earn. And isn’t a bonus supposed to be on top of typical compensation? To be in line with the survey, shouldn’t your base pay equal the $240,000 median, with any available bonus dollars on top of that? (Base pay means all forms of compensation other than a performance bonus; it could be productivity-based compensation, pay connected to numbers of shifts or hours worked, or a fixed annual salary, etc.)

The short answer is no, and to demonstrate why, I’ll first review some facts about the survey itself, then apply that knowledge to the hospitalist marketplace.

I want to emphasize that in this article, I’m not taking a position on the right amount of workload, compensation, or bonus for any hospitalist practice. And I’m using survey medians just to simplify the discussion, not because they’re optimal for any particular practice.

Survey Data

The most important thing to know about the survey data is that the $240,000 figure takes into account all forms of pay, including extra shift pay and any bonuses that might have been paid to each provider in the data set. Such benefits as health insurance and retirement-plan contribution are not included in this figure.

There are several ways a hospitalist might have earned compensation that matches the survey median. He or she might have a fixed annual salary equal to the median with no bonus available or had a meaningful bonus (e.g. $10,000 to $20,000) available and failed to earn any of it. Or the base might have come to $230,000, and he or she earned half of the available $20,000 performance bonus. Many other permutations of bonus and other salary elements could occur to arrive at the same $240,000 figure.

The important thing to remember is that whatever bonus dollars were paid, they are included in the salary figure from the survey—not added on top of that figure. So if all bonus dollars earned were subtracted from the survey, the total “nonbonus” compensation would be lower than $240,000.

How much lower?

Typical Hospitalist Bonus Amounts

The MGMA survey doesn’t report the portion of compensation tied to a bonus, but SHM’s does. SHM’s 2012 State of Hospital Medicine Report, based on 2011 data (www.hospitalmedicine.org/survey), is based on the most recent data available, and it showed (on page 60) that an average of 7% of pay was tied to performance for nonacademic hospitalist groups serving adults only. This included any payments for good individual or group performance on quality, efficiency, service, satisfaction, and/or other nonproduction measures. In conversation, this often is referred to as a “bonus” rather than “performance compensation.”

One way to estimate the nonbonus compensation would be to reduce the total pay by 7%, which comes to $223,200. Keep in mind that there are all kinds of mathematical and methodological problems in manipulating the reported survey numbers from two separate surveys to derive additional benchmarks. But this seems like a reasonable guess.

An increasing portion of hospitalist groups have some pay tied to performance, and the portion of total pay tied to performance seems to be going up at least a little. It was 5% of pay in 2010 and 4% in 2011, compared with 7% in the 2012 survey.

Keep in mind two things. First, this 7% reflects the performance or bonus dollars actually paid out, not the total amount available. In other words, even if the median total bonus dollars available were 20% of compensation, hospitalists earned less than that. Some hospitalists earned all dollars available, and some earned only a portion of what was available. And second, some hospitalists fail to earn any bonus or don’t have one available at all. So the survey would show for them zero compensation tied to bonus.

Making Sense of the Numbers

If you follow the reasoning above, then you probably agree that if your goal is to match mean compensation from the MGMA survey (I’m not suggesting that is the best goal, merely using it for simplicity), then you would set nonbonus compensation 7% below median—as long as you’re likely to get the same portion of a bonus as the median practice.

In some practices, performance thresholds are set at a level that is very easy to achieve, meaning the hospitalists are almost guaranteed to get all of the bonus compensation available. To be consistent with survey medians, it would be appropriate for them to set nonbonus compensation by subtracting all bonus dollars from the survey median. For example, if a $20,000 bonus is available and all of it is likely to be earned by the hospitalists, then total nonbonus compensation would be $220,000.

However, what if the bonus requires significant improvements in performance by the doctors (which seems most appropriate to me; why have a bonus otherwise?) and it is likely they will earn only 25% of all bonus dollars available? If the total available bonus is $20,000, then something like 25%, or $5,000, should be subtracted from the median to yield a total nonbonus compensation of $235,000.

Simple Thinking

I think it makes most sense to set total nonbonus compensation below the targeted total compensation. Failure to achieve any performance thresholds means no bonus and compensation will be below target that year. Meeting some thresholds (some improvement in performance) should result in matching the target compensation, and truly terrific performance that meets or exceeds all thresholds should result in the doctor being paid above the target.

Dr. Nelson has been a practicing hospitalist since 1988. He is co-founder and past president of SHM, and principal in Nelson Flores Hospital Medicine Consultants. He is co-director for SHM’s “Best Practices in Managing a Hospital Medicine Program” course. Write to him at [email protected].

Patient Satisfaction Surveys Not Accurate Measure of Hospitalists’ Performance

Feeling frustrated with your group’s patient-satisfaction performance? Wondering why your chief (fill in the blank) officer glazes over when you try to explain why your hospitalist group’s Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and System (HCAHPS) scores for doctor communication are in a percentile rivaling the numeric age of your children?

It is likely that the C-suite administrator overseeing your hospitalist group has a portion of their pay based on HCAHPS or other patient-satisfaction (also called patient experience) scores. And for good reason: The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) Hospital Value-Based Purchasing (HVBP) program that started Oct. 1, 2012, has placed your hospital’s Medicare reimbursement at risk based on its HCAHPS scores.

HVBP and Patient Satisfaction