User login

Sprout Pregnancy Essentials

An app to help your patient with chronic pelvic pain (February 2013)

An app to help your patient remember to take her OC (July 2012)

An app to help your patient lose weight (May 2012)

This handy toolkit helps mothers-to-be record important details like weight gain, kicks, and contraction times, with personalized timelines, checklists, comprehensive information about fetal development, and a journaling option.

In this series, I review what I call prescription apps—apps that you might consider recommending to your patient to enhance her medical care. Many patients are already looking at medical apps and want to hear your opinion. Often the free apps I recommend to patients are downloaded before they leave my office. When recommending apps, their cost (not necessarily a measure of quality or utility) and platform (device that the app has been designed for) should be taken into account. It is important to know whether the app you are recommending is supported by your patient’s smartphone.

For moms-to-be: quality information and a tracking tool

When I practiced obstetrics, my group provided patients with a pocket-sized, trifold pregnancy tracker at their first prenatal visit for them to bring to each subsequent appointment. In addition to data such as Rh status and estimated due date, blood pressure, weight, and fundal height were also recorded. The pregnancy tracker served two purposes: 1) a backup mini medical record in case their chart didn’t make it from the medical records department to the clinic on a particular day and 2) a keepsake.

Pregnancy apps take the concept of that little piece of cardboard to a whole new level. One highly rated pregnancy app is Sprout™ Pregnancy Essentials (recommended by Consumer Reports2 and named one of the 50 Best iPhone Apps in 2012 by Time magazine3) from Med ART Studios.4

With Sprout, the user enters her due date and the app automatically tracks the pregnancy week by week. Each time the app is accessed, the screen shows a realistic image of a developing fetus at the appropriate gestational age along with a pregnancy timeline. Tools allow the user to track her weight at each Ob visit. There is also a kick counter as well as a contraction timer for when the time comes.

Each week of the pregnancy is linked to medical information appropriate for the gestational age, such as second trimester screening at week 15 and group B streptococcus testing at week 35. The information is brief, but high-quality, and covers everything from prenatal testing and screening for gestational diabetes to stretch marks and carpal tunnel syndrome. From each topic, the user seamlessly can add preloaded questions to an “M.D. visit planner” or pregnancy-related tasks (such as making an appointment for a glucose challenge test) to a “to do” list.

A free version called Sprout Lite comes in English and Japanese. The premium version for $3.99 is available in English, Spanish, Chinese, German, Italian, Japanese, and Portuguese. The premium version is free of ads; has more advanced images of a developing fetus, with striking graphics; allows the user to share information via Facebook and e-mail; and has a timeline that adjusts to the baby’s gestational age. Both Sprout apps are currently only available for the iPhone and iPad.

Pros. Sprout is easy to use, has beautiful graphics, and the medical information is accurate and accessible. Sprout Lite contains the same high-quality information.

Cons. There is no way to track other medical data in addition to weight, such as fundal height, Rh status, or vaccinations. There is also a price tag to have the app be free of advertisements, get the best graphics, and have a more interactive user experience.

Verdict. It is always nice to be able to recommend a product with high-quality medical information. Sprout Lite always can be road tested first, but for those who live on Facebook, enjoy a more interactive product, hate advertisements, or love impressive graphics, the $3.99 may very well be worth it.

Keep a journal and create a book

While leaving the app with its data on the iPhone or iPad may be enough of a keepsake for some women, those who want to create a pregnancy book can obtain a separate Sprout Pregnancy Journal app-to-book™.5

This app allows the user to write journal entries, upload photos, and then, if desired, download a PDF of the journal or incorporate the beautiful images from the Sprout app to create a bound pregnancy journal (softcover: $19.95 for the first 40 pages; hardcover: $34.95 for the first 40 pages; additional charge for added pages).

The journal app is free to download for a 2-week trial. At the end of 2 weeks there is a choice:

- $4.99 to continue to use the app; includes cloud backup of data

- $7.99 to get cloud backup plus the PDF download (includes a discount for prepaying for the PDF plus $7.99 discount for a print book)

- If the $7.99 prepaid option isn’t chosen at the end of the 2-week trial, the PDF is $9.95.

The Sprout Pregnancy Journal app is available for iPhone, iPad Touch, and iPad.

We want to hear from you! Tell us what you think.

Why (and how) you should encourage your patients’ search for health information on the Web

(December 2011)

To blog or not to blog? What’s the answer for you and your practice?

(August 2011)

For better or, maybe worse, patients are judging your care online

(March 2011)

Twitter 101 for ObGyns: Pearls, pitfalls, and potential

(September 2010)

1. Smith A. Nearly half of American adults are Smartphone owners. Pew Internet & American Life Project. http://pewinternet.org/Reports/2012/Smartphone-Update-2012/Findings.aspx. Published March 1, 2012. Accessed August 14, 2012.

2. Morris N. App review: Sprout for iPad and iPhone. Consumer Reports Web site. http://news.consumerreports.org/baby/2011/10/app-review-sprout-for-ipad-and-iphone.html. Published October 10, 2011. Accessed August 13, 2012.

3. Peckham M. 50 best iPhone apps 2012: Pregnancy (Sprout). http://techland.time.com/2012/02/15/50-best-iphone-apps-2012/?iid=tl-article-mostpop1#all. Published February 15, 2012. Accessed August 13, 2012.

4. Sprout Pregnancy Essentials. Med ART Studios Web site. http://medart-studios.com/sprout-pregnancy-iphone-app/. Accessed August 13, 2012.

5. Sprout Pregnancy Journal. Med ART Studios Web site. http://medart-studios.com/sprout-pregnancy-journal-iphone-app/. Accessed August 13, 2012.

An app to help your patient with chronic pelvic pain (February 2013)

An app to help your patient remember to take her OC (July 2012)

An app to help your patient lose weight (May 2012)

This handy toolkit helps mothers-to-be record important details like weight gain, kicks, and contraction times, with personalized timelines, checklists, comprehensive information about fetal development, and a journaling option.

In this series, I review what I call prescription apps—apps that you might consider recommending to your patient to enhance her medical care. Many patients are already looking at medical apps and want to hear your opinion. Often the free apps I recommend to patients are downloaded before they leave my office. When recommending apps, their cost (not necessarily a measure of quality or utility) and platform (device that the app has been designed for) should be taken into account. It is important to know whether the app you are recommending is supported by your patient’s smartphone.

For moms-to-be: quality information and a tracking tool

When I practiced obstetrics, my group provided patients with a pocket-sized, trifold pregnancy tracker at their first prenatal visit for them to bring to each subsequent appointment. In addition to data such as Rh status and estimated due date, blood pressure, weight, and fundal height were also recorded. The pregnancy tracker served two purposes: 1) a backup mini medical record in case their chart didn’t make it from the medical records department to the clinic on a particular day and 2) a keepsake.

Pregnancy apps take the concept of that little piece of cardboard to a whole new level. One highly rated pregnancy app is Sprout™ Pregnancy Essentials (recommended by Consumer Reports2 and named one of the 50 Best iPhone Apps in 2012 by Time magazine3) from Med ART Studios.4

With Sprout, the user enters her due date and the app automatically tracks the pregnancy week by week. Each time the app is accessed, the screen shows a realistic image of a developing fetus at the appropriate gestational age along with a pregnancy timeline. Tools allow the user to track her weight at each Ob visit. There is also a kick counter as well as a contraction timer for when the time comes.

Each week of the pregnancy is linked to medical information appropriate for the gestational age, such as second trimester screening at week 15 and group B streptococcus testing at week 35. The information is brief, but high-quality, and covers everything from prenatal testing and screening for gestational diabetes to stretch marks and carpal tunnel syndrome. From each topic, the user seamlessly can add preloaded questions to an “M.D. visit planner” or pregnancy-related tasks (such as making an appointment for a glucose challenge test) to a “to do” list.

A free version called Sprout Lite comes in English and Japanese. The premium version for $3.99 is available in English, Spanish, Chinese, German, Italian, Japanese, and Portuguese. The premium version is free of ads; has more advanced images of a developing fetus, with striking graphics; allows the user to share information via Facebook and e-mail; and has a timeline that adjusts to the baby’s gestational age. Both Sprout apps are currently only available for the iPhone and iPad.

Pros. Sprout is easy to use, has beautiful graphics, and the medical information is accurate and accessible. Sprout Lite contains the same high-quality information.

Cons. There is no way to track other medical data in addition to weight, such as fundal height, Rh status, or vaccinations. There is also a price tag to have the app be free of advertisements, get the best graphics, and have a more interactive user experience.

Verdict. It is always nice to be able to recommend a product with high-quality medical information. Sprout Lite always can be road tested first, but for those who live on Facebook, enjoy a more interactive product, hate advertisements, or love impressive graphics, the $3.99 may very well be worth it.

Keep a journal and create a book

While leaving the app with its data on the iPhone or iPad may be enough of a keepsake for some women, those who want to create a pregnancy book can obtain a separate Sprout Pregnancy Journal app-to-book™.5

This app allows the user to write journal entries, upload photos, and then, if desired, download a PDF of the journal or incorporate the beautiful images from the Sprout app to create a bound pregnancy journal (softcover: $19.95 for the first 40 pages; hardcover: $34.95 for the first 40 pages; additional charge for added pages).

The journal app is free to download for a 2-week trial. At the end of 2 weeks there is a choice:

- $4.99 to continue to use the app; includes cloud backup of data

- $7.99 to get cloud backup plus the PDF download (includes a discount for prepaying for the PDF plus $7.99 discount for a print book)

- If the $7.99 prepaid option isn’t chosen at the end of the 2-week trial, the PDF is $9.95.

The Sprout Pregnancy Journal app is available for iPhone, iPad Touch, and iPad.

We want to hear from you! Tell us what you think.

Why (and how) you should encourage your patients’ search for health information on the Web

(December 2011)

To blog or not to blog? What’s the answer for you and your practice?

(August 2011)

For better or, maybe worse, patients are judging your care online

(March 2011)

Twitter 101 for ObGyns: Pearls, pitfalls, and potential

(September 2010)

An app to help your patient with chronic pelvic pain (February 2013)

An app to help your patient remember to take her OC (July 2012)

An app to help your patient lose weight (May 2012)

This handy toolkit helps mothers-to-be record important details like weight gain, kicks, and contraction times, with personalized timelines, checklists, comprehensive information about fetal development, and a journaling option.

In this series, I review what I call prescription apps—apps that you might consider recommending to your patient to enhance her medical care. Many patients are already looking at medical apps and want to hear your opinion. Often the free apps I recommend to patients are downloaded before they leave my office. When recommending apps, their cost (not necessarily a measure of quality or utility) and platform (device that the app has been designed for) should be taken into account. It is important to know whether the app you are recommending is supported by your patient’s smartphone.

For moms-to-be: quality information and a tracking tool

When I practiced obstetrics, my group provided patients with a pocket-sized, trifold pregnancy tracker at their first prenatal visit for them to bring to each subsequent appointment. In addition to data such as Rh status and estimated due date, blood pressure, weight, and fundal height were also recorded. The pregnancy tracker served two purposes: 1) a backup mini medical record in case their chart didn’t make it from the medical records department to the clinic on a particular day and 2) a keepsake.

Pregnancy apps take the concept of that little piece of cardboard to a whole new level. One highly rated pregnancy app is Sprout™ Pregnancy Essentials (recommended by Consumer Reports2 and named one of the 50 Best iPhone Apps in 2012 by Time magazine3) from Med ART Studios.4

With Sprout, the user enters her due date and the app automatically tracks the pregnancy week by week. Each time the app is accessed, the screen shows a realistic image of a developing fetus at the appropriate gestational age along with a pregnancy timeline. Tools allow the user to track her weight at each Ob visit. There is also a kick counter as well as a contraction timer for when the time comes.

Each week of the pregnancy is linked to medical information appropriate for the gestational age, such as second trimester screening at week 15 and group B streptococcus testing at week 35. The information is brief, but high-quality, and covers everything from prenatal testing and screening for gestational diabetes to stretch marks and carpal tunnel syndrome. From each topic, the user seamlessly can add preloaded questions to an “M.D. visit planner” or pregnancy-related tasks (such as making an appointment for a glucose challenge test) to a “to do” list.

A free version called Sprout Lite comes in English and Japanese. The premium version for $3.99 is available in English, Spanish, Chinese, German, Italian, Japanese, and Portuguese. The premium version is free of ads; has more advanced images of a developing fetus, with striking graphics; allows the user to share information via Facebook and e-mail; and has a timeline that adjusts to the baby’s gestational age. Both Sprout apps are currently only available for the iPhone and iPad.

Pros. Sprout is easy to use, has beautiful graphics, and the medical information is accurate and accessible. Sprout Lite contains the same high-quality information.

Cons. There is no way to track other medical data in addition to weight, such as fundal height, Rh status, or vaccinations. There is also a price tag to have the app be free of advertisements, get the best graphics, and have a more interactive user experience.

Verdict. It is always nice to be able to recommend a product with high-quality medical information. Sprout Lite always can be road tested first, but for those who live on Facebook, enjoy a more interactive product, hate advertisements, or love impressive graphics, the $3.99 may very well be worth it.

Keep a journal and create a book

While leaving the app with its data on the iPhone or iPad may be enough of a keepsake for some women, those who want to create a pregnancy book can obtain a separate Sprout Pregnancy Journal app-to-book™.5

This app allows the user to write journal entries, upload photos, and then, if desired, download a PDF of the journal or incorporate the beautiful images from the Sprout app to create a bound pregnancy journal (softcover: $19.95 for the first 40 pages; hardcover: $34.95 for the first 40 pages; additional charge for added pages).

The journal app is free to download for a 2-week trial. At the end of 2 weeks there is a choice:

- $4.99 to continue to use the app; includes cloud backup of data

- $7.99 to get cloud backup plus the PDF download (includes a discount for prepaying for the PDF plus $7.99 discount for a print book)

- If the $7.99 prepaid option isn’t chosen at the end of the 2-week trial, the PDF is $9.95.

The Sprout Pregnancy Journal app is available for iPhone, iPad Touch, and iPad.

We want to hear from you! Tell us what you think.

Why (and how) you should encourage your patients’ search for health information on the Web

(December 2011)

To blog or not to blog? What’s the answer for you and your practice?

(August 2011)

For better or, maybe worse, patients are judging your care online

(March 2011)

Twitter 101 for ObGyns: Pearls, pitfalls, and potential

(September 2010)

1. Smith A. Nearly half of American adults are Smartphone owners. Pew Internet & American Life Project. http://pewinternet.org/Reports/2012/Smartphone-Update-2012/Findings.aspx. Published March 1, 2012. Accessed August 14, 2012.

2. Morris N. App review: Sprout for iPad and iPhone. Consumer Reports Web site. http://news.consumerreports.org/baby/2011/10/app-review-sprout-for-ipad-and-iphone.html. Published October 10, 2011. Accessed August 13, 2012.

3. Peckham M. 50 best iPhone apps 2012: Pregnancy (Sprout). http://techland.time.com/2012/02/15/50-best-iphone-apps-2012/?iid=tl-article-mostpop1#all. Published February 15, 2012. Accessed August 13, 2012.

4. Sprout Pregnancy Essentials. Med ART Studios Web site. http://medart-studios.com/sprout-pregnancy-iphone-app/. Accessed August 13, 2012.

5. Sprout Pregnancy Journal. Med ART Studios Web site. http://medart-studios.com/sprout-pregnancy-journal-iphone-app/. Accessed August 13, 2012.

1. Smith A. Nearly half of American adults are Smartphone owners. Pew Internet & American Life Project. http://pewinternet.org/Reports/2012/Smartphone-Update-2012/Findings.aspx. Published March 1, 2012. Accessed August 14, 2012.

2. Morris N. App review: Sprout for iPad and iPhone. Consumer Reports Web site. http://news.consumerreports.org/baby/2011/10/app-review-sprout-for-ipad-and-iphone.html. Published October 10, 2011. Accessed August 13, 2012.

3. Peckham M. 50 best iPhone apps 2012: Pregnancy (Sprout). http://techland.time.com/2012/02/15/50-best-iphone-apps-2012/?iid=tl-article-mostpop1#all. Published February 15, 2012. Accessed August 13, 2012.

4. Sprout Pregnancy Essentials. Med ART Studios Web site. http://medart-studios.com/sprout-pregnancy-iphone-app/. Accessed August 13, 2012.

5. Sprout Pregnancy Journal. Med ART Studios Web site. http://medart-studios.com/sprout-pregnancy-journal-iphone-app/. Accessed August 13, 2012.

Review your insurance

Insurance – so goes the hoary cliché – is the one product you buy hoping never to use. While no one enjoys foreseeing unforeseeable calamities, regular meetings with your insurance broker are important. Overinsuring is a waste of money, but underinsuring can prove even more costly, should the unforeseeable happen.

Malpractice premiums continue to rise. If yours are getting out of hand, ask your broker about alternatives.

"Occurrence" policies remain the coverage of choice where they are available and affordable, but they are becoming an endangered species as fewer insurers are willing to write them. "Claims-made" policies are usually cheaper, and provide the same coverage as long as you remain in practice. You will need "tail" coverage against belated claims after you retire, but many companies provide free tail coverage after you’ve been insured for a minimum period (usually 5 years).

Other alternatives are gaining popularity as the demand for more reasonably priced insurance increases. The most common, known as reciprocal exchanges, are very similar to traditional insurers, but differ in certain aspects of funding and operations. For example, most exchanges require policyholders to make capital contributions in addition to payment of premiums, at least in their early stages. You get your investment back, with interest, when (if) the exchange becomes solvent.

Another option, called a captive, is an insurance company formed by several noninsurance entities (such as medical practices) to write their own insurance policies. All participants are shareholders, and all premiums (less administrative expenses) go toward building the security of the captive. Most captives purchase reinsurance to protect against catastrophic losses. If all goes well, individual owners sell their shares at retirement for a nice profit, which has grown tax free in the interim.

Risk Retention Groups (RRGs) are a combination of exchanges and captives, in that capital investments are usually required, and the owners are the insureds themselves; but all responsibility for management and adequate funding falls on the insureds’ shoulders, and reinsurance is rarely an option. Most medical malpractice RRGs are licensed in Vermont or South Carolina, because of favorable laws in those states, but they can be based in any state that allows them.

Exchanges, captives, and RRGs all carry risk: A few large claims can eat up all the profits, and may even put you in a financial hole. But of course, traditional malpractice policies offer zero profit opportunity.

If your financial situation has changed since your last insurance review, your life insurance needs have probably changed, too. As your retirement savings accumulate, less insurance is necessary. And if you own any expensive whole life policies, you can probably convert them to much cheaper term insurance.

Disability insurance is not something to skimp on, but if you are approaching retirement age, you may be able to decrease your coverage, or even eliminate it entirely, if your retirement plan is far enough along.

Liability insurance is likewise no place to pinch pennies, but you might be able to add an umbrella policy providing comprehensive catastrophic coverage, which may allow you to decrease your regular coverage, or raise your deductible limits.

One additional policy to consider is Employment Practices Liability Insurance, which protects you from lawsuits brought by militant or disgruntled employees. More on that next month.

Health insurance premiums continue to soar; Obamacare might offer a favorable alternative for your office policy. Open enrollment began Oct. 1, with coverage scheduled to begin Jan. 1, 2014. If you are considering such an option, go to the Center for Consumer Information and Insurance Oversight and pick a plan for your employees to enroll in.

Workers’ compensation insurance is mandatory in most states, and heavily regulated, so there is little room for cutting expenses. However, some states do not require you, as the employer, to cover yourself, and eliminating that coverage could save you a substantial amount. This is only worth considering, of course, if you have adequate health and disability policies in place.

If you’re over 50 years old, look into long-term care insurance as well. It’s relatively inexpensive if you buy it while you’re still healthy, and it could save you and your heirs a load of money on the other end. If you have shouldered the expense of a chronically ill parent or grandparent, you know what I’m talking about.

Dr. Eastern practices dermatology and dermatologic surgery in Belleville, N.J., and has been a long-time monthly columnist for Dermatology News.

Insurance – so goes the hoary cliché – is the one product you buy hoping never to use. While no one enjoys foreseeing unforeseeable calamities, regular meetings with your insurance broker are important. Overinsuring is a waste of money, but underinsuring can prove even more costly, should the unforeseeable happen.

Malpractice premiums continue to rise. If yours are getting out of hand, ask your broker about alternatives.

"Occurrence" policies remain the coverage of choice where they are available and affordable, but they are becoming an endangered species as fewer insurers are willing to write them. "Claims-made" policies are usually cheaper, and provide the same coverage as long as you remain in practice. You will need "tail" coverage against belated claims after you retire, but many companies provide free tail coverage after you’ve been insured for a minimum period (usually 5 years).

Other alternatives are gaining popularity as the demand for more reasonably priced insurance increases. The most common, known as reciprocal exchanges, are very similar to traditional insurers, but differ in certain aspects of funding and operations. For example, most exchanges require policyholders to make capital contributions in addition to payment of premiums, at least in their early stages. You get your investment back, with interest, when (if) the exchange becomes solvent.

Another option, called a captive, is an insurance company formed by several noninsurance entities (such as medical practices) to write their own insurance policies. All participants are shareholders, and all premiums (less administrative expenses) go toward building the security of the captive. Most captives purchase reinsurance to protect against catastrophic losses. If all goes well, individual owners sell their shares at retirement for a nice profit, which has grown tax free in the interim.

Risk Retention Groups (RRGs) are a combination of exchanges and captives, in that capital investments are usually required, and the owners are the insureds themselves; but all responsibility for management and adequate funding falls on the insureds’ shoulders, and reinsurance is rarely an option. Most medical malpractice RRGs are licensed in Vermont or South Carolina, because of favorable laws in those states, but they can be based in any state that allows them.

Exchanges, captives, and RRGs all carry risk: A few large claims can eat up all the profits, and may even put you in a financial hole. But of course, traditional malpractice policies offer zero profit opportunity.

If your financial situation has changed since your last insurance review, your life insurance needs have probably changed, too. As your retirement savings accumulate, less insurance is necessary. And if you own any expensive whole life policies, you can probably convert them to much cheaper term insurance.

Disability insurance is not something to skimp on, but if you are approaching retirement age, you may be able to decrease your coverage, or even eliminate it entirely, if your retirement plan is far enough along.

Liability insurance is likewise no place to pinch pennies, but you might be able to add an umbrella policy providing comprehensive catastrophic coverage, which may allow you to decrease your regular coverage, or raise your deductible limits.

One additional policy to consider is Employment Practices Liability Insurance, which protects you from lawsuits brought by militant or disgruntled employees. More on that next month.

Health insurance premiums continue to soar; Obamacare might offer a favorable alternative for your office policy. Open enrollment began Oct. 1, with coverage scheduled to begin Jan. 1, 2014. If you are considering such an option, go to the Center for Consumer Information and Insurance Oversight and pick a plan for your employees to enroll in.

Workers’ compensation insurance is mandatory in most states, and heavily regulated, so there is little room for cutting expenses. However, some states do not require you, as the employer, to cover yourself, and eliminating that coverage could save you a substantial amount. This is only worth considering, of course, if you have adequate health and disability policies in place.

If you’re over 50 years old, look into long-term care insurance as well. It’s relatively inexpensive if you buy it while you’re still healthy, and it could save you and your heirs a load of money on the other end. If you have shouldered the expense of a chronically ill parent or grandparent, you know what I’m talking about.

Dr. Eastern practices dermatology and dermatologic surgery in Belleville, N.J., and has been a long-time monthly columnist for Dermatology News.

Insurance – so goes the hoary cliché – is the one product you buy hoping never to use. While no one enjoys foreseeing unforeseeable calamities, regular meetings with your insurance broker are important. Overinsuring is a waste of money, but underinsuring can prove even more costly, should the unforeseeable happen.

Malpractice premiums continue to rise. If yours are getting out of hand, ask your broker about alternatives.

"Occurrence" policies remain the coverage of choice where they are available and affordable, but they are becoming an endangered species as fewer insurers are willing to write them. "Claims-made" policies are usually cheaper, and provide the same coverage as long as you remain in practice. You will need "tail" coverage against belated claims after you retire, but many companies provide free tail coverage after you’ve been insured for a minimum period (usually 5 years).

Other alternatives are gaining popularity as the demand for more reasonably priced insurance increases. The most common, known as reciprocal exchanges, are very similar to traditional insurers, but differ in certain aspects of funding and operations. For example, most exchanges require policyholders to make capital contributions in addition to payment of premiums, at least in their early stages. You get your investment back, with interest, when (if) the exchange becomes solvent.

Another option, called a captive, is an insurance company formed by several noninsurance entities (such as medical practices) to write their own insurance policies. All participants are shareholders, and all premiums (less administrative expenses) go toward building the security of the captive. Most captives purchase reinsurance to protect against catastrophic losses. If all goes well, individual owners sell their shares at retirement for a nice profit, which has grown tax free in the interim.

Risk Retention Groups (RRGs) are a combination of exchanges and captives, in that capital investments are usually required, and the owners are the insureds themselves; but all responsibility for management and adequate funding falls on the insureds’ shoulders, and reinsurance is rarely an option. Most medical malpractice RRGs are licensed in Vermont or South Carolina, because of favorable laws in those states, but they can be based in any state that allows them.

Exchanges, captives, and RRGs all carry risk: A few large claims can eat up all the profits, and may even put you in a financial hole. But of course, traditional malpractice policies offer zero profit opportunity.

If your financial situation has changed since your last insurance review, your life insurance needs have probably changed, too. As your retirement savings accumulate, less insurance is necessary. And if you own any expensive whole life policies, you can probably convert them to much cheaper term insurance.

Disability insurance is not something to skimp on, but if you are approaching retirement age, you may be able to decrease your coverage, or even eliminate it entirely, if your retirement plan is far enough along.

Liability insurance is likewise no place to pinch pennies, but you might be able to add an umbrella policy providing comprehensive catastrophic coverage, which may allow you to decrease your regular coverage, or raise your deductible limits.

One additional policy to consider is Employment Practices Liability Insurance, which protects you from lawsuits brought by militant or disgruntled employees. More on that next month.

Health insurance premiums continue to soar; Obamacare might offer a favorable alternative for your office policy. Open enrollment began Oct. 1, with coverage scheduled to begin Jan. 1, 2014. If you are considering such an option, go to the Center for Consumer Information and Insurance Oversight and pick a plan for your employees to enroll in.

Workers’ compensation insurance is mandatory in most states, and heavily regulated, so there is little room for cutting expenses. However, some states do not require you, as the employer, to cover yourself, and eliminating that coverage could save you a substantial amount. This is only worth considering, of course, if you have adequate health and disability policies in place.

If you’re over 50 years old, look into long-term care insurance as well. It’s relatively inexpensive if you buy it while you’re still healthy, and it could save you and your heirs a load of money on the other end. If you have shouldered the expense of a chronically ill parent or grandparent, you know what I’m talking about.

Dr. Eastern practices dermatology and dermatologic surgery in Belleville, N.J., and has been a long-time monthly columnist for Dermatology News.

The Why and How Data Mining Is Applicable to Hospital Medicine

Click here to listen to excerpts of our interview with Dr. Deitelzweig, chair of SHM’s Practice Analysis Committee.

Click here to listen to excerpts of our interview with Dr. Deitelzweig, chair of SHM’s Practice Analysis Committee.

Click here to listen to excerpts of our interview with Dr. Deitelzweig, chair of SHM’s Practice Analysis Committee.

MGMA Surveys Make Hospitalists' Productivity Hard to Assess

The Medical Group Management Association (MGMA) surveys regard both a doctor who works the standard number of annual shifts their practice defines as full time, and a doctor who works many extra shifts, as one full-time equivalent (FTE). This can cause confusion when assessing productivity per FTE (see “SHM and MGMA Survey History,” right).

For example, consider a hospitalist who generated 4,000 wRVUs while working 182 shifts—the standard number of shifts to be full time in that doctor’s practice—during the survey year. In the same practice, another hospitalist worked 39 extra shifts over the same year for a total of 220 shifts, generating 4,860 wRVUs. If the survey contained only these two doctors, it would show them both as full time, with an average productivity per FTE of 4,430 wRVUs. But that would be misleading because 1.0 FTE worth of work as defined by their practice for both doctors would have come to 4,000 wRVUs generated while working 182 shifts.

In prior columns, I’ve highlighted some other numbers in hospitalist productivity and compensation surveys that can lead to confusion. But the MGMA survey methodology, which assigns a particular FTE to a single doctor, may be the most confusing issue, potentially leading to meaningful misunderstandings.

More Details on FTE Definition

MGMA has been conducting physician compensation and productivity surveys across essentially all medical specialties for decades. Competing organizations conduct similar surveys, but most regard the MGMA survey as the most relevant and valuable.

For a long time, MGMA has regarded as “full time” any doctor working 0.75 FTE or greater, using the respondent practice’s definition of an FTE. No single doctor can ever be counted as more than 1.0 FTE, regardless of how much extra the doctor may have worked. Any doctor working 0.35-0.75 FTE is regarded as part time, and those working less than 0.35 FTE are excluded from the survey report. The fact that each practice might have a different definition of what constitutes an FTE is addressed by having a large number of respondents in most medical specialties.

I’m uncertain how MGMA ended up not counting any single doctor as more than 1.0 FTE, even when they work a lot of extra shifts. But my guess is that for the first years, or even decades, that MGMA conducted its survey, few, if any, medical practices even had a strict definition of what constituted 1.0 FTE and simply didn’t keep track of which doctors worked extra shifts or days. So even if MGMA had wanted to know, for example, when a doctor worked extra shifts and should be counted as more than 1.0 FTE, few if any practices even thought about the precise number of shifts or days worked constituting full time versus what was an “extra” shift. So it probably made sense to simply have two categories: full time and part time.

As more practices began assigning FTE with greater precision, like nearly all hospitalist practices do, then using 0.75 FTE to separate full time and part time seemed practical, though imprecise. But keep in mind it also means that all of the doctors who work from 0.75 to 0.99 FTE (that is, something less than 1.0) offset, at least partially, those who work lots of extra shifts (i.e., above 1.0 FTE).

Data Application

My anecdotal experience is that a large portion of hospitalists, probably around half, work more shifts than what their practice regards as full time. I don’t know of any survey database that quantifies this, but my guess is that 25% to 35% of full-time hospitalists work extra shifts at their own practice, and maybe another 15% to 20% moonlight at a different practice. Let’s consider only those in the first category.

Chronic staffing shortages is one of the reasons hospitalists so commonly work extra shifts at their own practice. Extra shifts are sometimes even required by the practice to make up for open positions. And in some places, the hospitalists choose not to fill positions to preserve their ability to continue working more than the number of shifts required to be full time.

It would be great if we had a precise way to adjust the MGMA survey data for hospitalists who work above 1.0 FTE. For example, let’s make three assumptions so that we can then adjust the reported compensation and productivity data to remove the effect of the many doctors working extra shifts, thereby more clearly matching 1.0 FTE. These numbers are my guesses based on lots of anecdotal experience. But they are only guesses. Don’t make too much of them.

Assume 25% of hospitalists nationally work an average of 20% more than the full-time number of shifts for their practice. That is my best guess and intentionally leaves out those who moonlight for a practice other than their own.

Some portion of those working extra shifts (above 1.0 FTE) is offset by survey respondents working between 0.75 and 1.0 FTE, resulting in a wild guess of a net 20% of hospitalists working extra shifts.

Last, let’s assume that their productivity and compensation on extra shifts is identical to their “normal” shifts. This is not true for many practices, but when aggregating the data, it is probably reasonably close.

Using these assumptions (guesses, really), we can decrease both the reported survey mean and median productivity and compensation by about 5% to more accurately reflect results for hospitalists doing only the number of shifts required by the practice to be full time—no extra shifts. I’ll spare you the simple math showing how I arrived at the approximately 5%, but basically it is removing the 20% additional compensation and productivity generated by the net 20% of hospitalists who work extra shifts above 1.0 FTE.

Does It Really Matter?

The whole issue of hospitalists working many extra shifts yet only counting as 1.0 FTE in the MGMA survey might matter a lot for some, and others might see it as useless hand-wringing. As long as a meaningful number of hospitalists work extra shifts, then survey values for productivity and compensation will always be a little higher than the “average” 1.0 FTE hospitalists working no extra shifts. But it may still be well within the range of error of the survey anyway. And the compensation per unit of work (wRVUs or encounters) probably isn’t much affected by this FTE issue.

Dr. Nelson has been a practicing hospitalist since 1988. He is co-founder and past president of SHM, and principal in Nelson Flores Hospital Medicine Consultants. He is co-director for SHM’s “Best Practices in Managing a Hospital Medicine Program” course. Write to him at [email protected].

The Medical Group Management Association (MGMA) surveys regard both a doctor who works the standard number of annual shifts their practice defines as full time, and a doctor who works many extra shifts, as one full-time equivalent (FTE). This can cause confusion when assessing productivity per FTE (see “SHM and MGMA Survey History,” right).

For example, consider a hospitalist who generated 4,000 wRVUs while working 182 shifts—the standard number of shifts to be full time in that doctor’s practice—during the survey year. In the same practice, another hospitalist worked 39 extra shifts over the same year for a total of 220 shifts, generating 4,860 wRVUs. If the survey contained only these two doctors, it would show them both as full time, with an average productivity per FTE of 4,430 wRVUs. But that would be misleading because 1.0 FTE worth of work as defined by their practice for both doctors would have come to 4,000 wRVUs generated while working 182 shifts.

In prior columns, I’ve highlighted some other numbers in hospitalist productivity and compensation surveys that can lead to confusion. But the MGMA survey methodology, which assigns a particular FTE to a single doctor, may be the most confusing issue, potentially leading to meaningful misunderstandings.

More Details on FTE Definition

MGMA has been conducting physician compensation and productivity surveys across essentially all medical specialties for decades. Competing organizations conduct similar surveys, but most regard the MGMA survey as the most relevant and valuable.

For a long time, MGMA has regarded as “full time” any doctor working 0.75 FTE or greater, using the respondent practice’s definition of an FTE. No single doctor can ever be counted as more than 1.0 FTE, regardless of how much extra the doctor may have worked. Any doctor working 0.35-0.75 FTE is regarded as part time, and those working less than 0.35 FTE are excluded from the survey report. The fact that each practice might have a different definition of what constitutes an FTE is addressed by having a large number of respondents in most medical specialties.

I’m uncertain how MGMA ended up not counting any single doctor as more than 1.0 FTE, even when they work a lot of extra shifts. But my guess is that for the first years, or even decades, that MGMA conducted its survey, few, if any, medical practices even had a strict definition of what constituted 1.0 FTE and simply didn’t keep track of which doctors worked extra shifts or days. So even if MGMA had wanted to know, for example, when a doctor worked extra shifts and should be counted as more than 1.0 FTE, few if any practices even thought about the precise number of shifts or days worked constituting full time versus what was an “extra” shift. So it probably made sense to simply have two categories: full time and part time.

As more practices began assigning FTE with greater precision, like nearly all hospitalist practices do, then using 0.75 FTE to separate full time and part time seemed practical, though imprecise. But keep in mind it also means that all of the doctors who work from 0.75 to 0.99 FTE (that is, something less than 1.0) offset, at least partially, those who work lots of extra shifts (i.e., above 1.0 FTE).

Data Application

My anecdotal experience is that a large portion of hospitalists, probably around half, work more shifts than what their practice regards as full time. I don’t know of any survey database that quantifies this, but my guess is that 25% to 35% of full-time hospitalists work extra shifts at their own practice, and maybe another 15% to 20% moonlight at a different practice. Let’s consider only those in the first category.

Chronic staffing shortages is one of the reasons hospitalists so commonly work extra shifts at their own practice. Extra shifts are sometimes even required by the practice to make up for open positions. And in some places, the hospitalists choose not to fill positions to preserve their ability to continue working more than the number of shifts required to be full time.

It would be great if we had a precise way to adjust the MGMA survey data for hospitalists who work above 1.0 FTE. For example, let’s make three assumptions so that we can then adjust the reported compensation and productivity data to remove the effect of the many doctors working extra shifts, thereby more clearly matching 1.0 FTE. These numbers are my guesses based on lots of anecdotal experience. But they are only guesses. Don’t make too much of them.

Assume 25% of hospitalists nationally work an average of 20% more than the full-time number of shifts for their practice. That is my best guess and intentionally leaves out those who moonlight for a practice other than their own.

Some portion of those working extra shifts (above 1.0 FTE) is offset by survey respondents working between 0.75 and 1.0 FTE, resulting in a wild guess of a net 20% of hospitalists working extra shifts.

Last, let’s assume that their productivity and compensation on extra shifts is identical to their “normal” shifts. This is not true for many practices, but when aggregating the data, it is probably reasonably close.

Using these assumptions (guesses, really), we can decrease both the reported survey mean and median productivity and compensation by about 5% to more accurately reflect results for hospitalists doing only the number of shifts required by the practice to be full time—no extra shifts. I’ll spare you the simple math showing how I arrived at the approximately 5%, but basically it is removing the 20% additional compensation and productivity generated by the net 20% of hospitalists who work extra shifts above 1.0 FTE.

Does It Really Matter?

The whole issue of hospitalists working many extra shifts yet only counting as 1.0 FTE in the MGMA survey might matter a lot for some, and others might see it as useless hand-wringing. As long as a meaningful number of hospitalists work extra shifts, then survey values for productivity and compensation will always be a little higher than the “average” 1.0 FTE hospitalists working no extra shifts. But it may still be well within the range of error of the survey anyway. And the compensation per unit of work (wRVUs or encounters) probably isn’t much affected by this FTE issue.

Dr. Nelson has been a practicing hospitalist since 1988. He is co-founder and past president of SHM, and principal in Nelson Flores Hospital Medicine Consultants. He is co-director for SHM’s “Best Practices in Managing a Hospital Medicine Program” course. Write to him at [email protected].

The Medical Group Management Association (MGMA) surveys regard both a doctor who works the standard number of annual shifts their practice defines as full time, and a doctor who works many extra shifts, as one full-time equivalent (FTE). This can cause confusion when assessing productivity per FTE (see “SHM and MGMA Survey History,” right).

For example, consider a hospitalist who generated 4,000 wRVUs while working 182 shifts—the standard number of shifts to be full time in that doctor’s practice—during the survey year. In the same practice, another hospitalist worked 39 extra shifts over the same year for a total of 220 shifts, generating 4,860 wRVUs. If the survey contained only these two doctors, it would show them both as full time, with an average productivity per FTE of 4,430 wRVUs. But that would be misleading because 1.0 FTE worth of work as defined by their practice for both doctors would have come to 4,000 wRVUs generated while working 182 shifts.

In prior columns, I’ve highlighted some other numbers in hospitalist productivity and compensation surveys that can lead to confusion. But the MGMA survey methodology, which assigns a particular FTE to a single doctor, may be the most confusing issue, potentially leading to meaningful misunderstandings.

More Details on FTE Definition

MGMA has been conducting physician compensation and productivity surveys across essentially all medical specialties for decades. Competing organizations conduct similar surveys, but most regard the MGMA survey as the most relevant and valuable.

For a long time, MGMA has regarded as “full time” any doctor working 0.75 FTE or greater, using the respondent practice’s definition of an FTE. No single doctor can ever be counted as more than 1.0 FTE, regardless of how much extra the doctor may have worked. Any doctor working 0.35-0.75 FTE is regarded as part time, and those working less than 0.35 FTE are excluded from the survey report. The fact that each practice might have a different definition of what constitutes an FTE is addressed by having a large number of respondents in most medical specialties.

I’m uncertain how MGMA ended up not counting any single doctor as more than 1.0 FTE, even when they work a lot of extra shifts. But my guess is that for the first years, or even decades, that MGMA conducted its survey, few, if any, medical practices even had a strict definition of what constituted 1.0 FTE and simply didn’t keep track of which doctors worked extra shifts or days. So even if MGMA had wanted to know, for example, when a doctor worked extra shifts and should be counted as more than 1.0 FTE, few if any practices even thought about the precise number of shifts or days worked constituting full time versus what was an “extra” shift. So it probably made sense to simply have two categories: full time and part time.

As more practices began assigning FTE with greater precision, like nearly all hospitalist practices do, then using 0.75 FTE to separate full time and part time seemed practical, though imprecise. But keep in mind it also means that all of the doctors who work from 0.75 to 0.99 FTE (that is, something less than 1.0) offset, at least partially, those who work lots of extra shifts (i.e., above 1.0 FTE).

Data Application

My anecdotal experience is that a large portion of hospitalists, probably around half, work more shifts than what their practice regards as full time. I don’t know of any survey database that quantifies this, but my guess is that 25% to 35% of full-time hospitalists work extra shifts at their own practice, and maybe another 15% to 20% moonlight at a different practice. Let’s consider only those in the first category.

Chronic staffing shortages is one of the reasons hospitalists so commonly work extra shifts at their own practice. Extra shifts are sometimes even required by the practice to make up for open positions. And in some places, the hospitalists choose not to fill positions to preserve their ability to continue working more than the number of shifts required to be full time.

It would be great if we had a precise way to adjust the MGMA survey data for hospitalists who work above 1.0 FTE. For example, let’s make three assumptions so that we can then adjust the reported compensation and productivity data to remove the effect of the many doctors working extra shifts, thereby more clearly matching 1.0 FTE. These numbers are my guesses based on lots of anecdotal experience. But they are only guesses. Don’t make too much of them.

Assume 25% of hospitalists nationally work an average of 20% more than the full-time number of shifts for their practice. That is my best guess and intentionally leaves out those who moonlight for a practice other than their own.

Some portion of those working extra shifts (above 1.0 FTE) is offset by survey respondents working between 0.75 and 1.0 FTE, resulting in a wild guess of a net 20% of hospitalists working extra shifts.

Last, let’s assume that their productivity and compensation on extra shifts is identical to their “normal” shifts. This is not true for many practices, but when aggregating the data, it is probably reasonably close.

Using these assumptions (guesses, really), we can decrease both the reported survey mean and median productivity and compensation by about 5% to more accurately reflect results for hospitalists doing only the number of shifts required by the practice to be full time—no extra shifts. I’ll spare you the simple math showing how I arrived at the approximately 5%, but basically it is removing the 20% additional compensation and productivity generated by the net 20% of hospitalists who work extra shifts above 1.0 FTE.

Does It Really Matter?

The whole issue of hospitalists working many extra shifts yet only counting as 1.0 FTE in the MGMA survey might matter a lot for some, and others might see it as useless hand-wringing. As long as a meaningful number of hospitalists work extra shifts, then survey values for productivity and compensation will always be a little higher than the “average” 1.0 FTE hospitalists working no extra shifts. But it may still be well within the range of error of the survey anyway. And the compensation per unit of work (wRVUs or encounters) probably isn’t much affected by this FTE issue.

Dr. Nelson has been a practicing hospitalist since 1988. He is co-founder and past president of SHM, and principal in Nelson Flores Hospital Medicine Consultants. He is co-director for SHM’s “Best Practices in Managing a Hospital Medicine Program” course. Write to him at [email protected].

New Rules for Value-Based Purchasing, Readmission Penalties, Admissions

October is the beginning of a new year—in this case, fiscal-year 2014 for the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS). It’s a time when the new rules kick in. This month, we’ll look at some highlights, focusing on the new developments affecting your practice. Because you are held accountable for hospital-side performance on programs such as hospital value-based purchasing (HVBP) and the Readmissions Reduction Program, a working knowledge of the 2014 edition of the programs is crucial.

Close the Loop on HVBP

How will your hospital get paid under the 2014 version of HVBP? This past July, your hospital received a report outlining how its Medicare payments will be affected based on your hospital’s performance on process of care (heart failure, pneumonia, myocardial infarction, and surgery), patient experience (HCAHPS), and outcomes (30-day mortality for heart failure, pneumonia, and myocardial infarction).

Here are two hypothetical hospitals and how their performance in the program affects their 2014 payment. As background, in 2014, all hospitals have their base diagnosis related group (DRG) payments reduced by 1.25% for HVBP. They can earn back some, all, or an amount in excess of the 1.25% based on their performance. Payment is based on performance during the April 1 to Dec. 31, 2012, period. Under HVBP, CMS incentive payments occur at the level of individual patients, each of which is assigned a DRG.

Let’s look at two examples:

Hospital 1

- Base DRG payment reduction: 1.25% (all hospitals).

- Portion of base DRG earned back based on performance (process/patient experience/outcome metrics): 1.48%.

- Net change in base DRG payment: +0.23%.

Hospital 2

- Base DRG payment reduction: 1.25% (all hospitals).

- Portion of base DRG earned back based on performance (process/patient experience/outcome metrics): 1.08%.

- Net change in base DRG payment: -0.17%.

Hospital 1 performed relatively well, getting a bump of 0.23% in its base DRG rate. Hospital 2 did not perform so well, so it took a 0.17% hit on its base DRG rate.

In order to determine total dollars made or lost for your hospital, one multiplies the total number of eligible Medicare inpatients for 2014 times the base DRG payment times the percent change in base DRG payment. If Hospital 1 has 10,000 eligible patients in 2014 and a base DRG payment of $5,000, the value is 10,000 x $5,000 x 0.0023 (0.23%) = $115,000 gained. Hospital 2, with the same number of patients and base DRG payment, loses (10,000 x $5,000 x 0.0017 = $85,000).

Readmissions and Penalties

For 2014, CMS is adding 30-day readmissions for COPD to readmissions for heart failure, pneumonia, and myocardial infarction for its penalty program. CMS added COPD because it is the fourth-leading cause of readmissions, according to a recent Medicare Payment Advisory Commission report, and because there is wide variation in the rates (from 18% to 25%) of COPD hospital readmissions.

For 2014, CMS raises the ceiling on readmission penalties to a maximum of 2% of reimbursement for all of a hospital’s Medicare inpatients. (The maximum hit during the first round of readmission penalties, which began in October 2012, was 1%.) More than 2,200 U.S. hospitals will face some financial penalty for excess 30-day readmissions.

Disappointingly, CMS did not add a risk adjustment for socioeconomic status despite being under pressure to do so. There is growing evidence that these factors have a major impact on readmission rates.1,2

New Definition of an Admission

Amidst confusion from many and major blowback from beneficiaries saddled with large out-of-pocket expenses for observation stays and subsequent skilled-nursing-facility stays, CMS is clarifying the definition of an inpatient admission. The agency will define an admission as a hospital stay that spans at least two midnights. If a patient is in the hospital for a shorter period of time, CMS will deem the patient to be on observation status, unless medical record documentation supports a physician’s expectation “that the beneficiary would need care spanning at least two midnights” but unanticipated events led to a shorter stay.

Plan of Attack

For HVBP, make contact with your director of quality to understand your hospital’s performance and payment for 2014. If you have incentive compensation riding on HVBP, make sure you understand how your employer or contracted hospital is calculating the payout (because, for example, the performance period was in 2012!) and that your hospitalist group understands the payout calculation.

For COPD readmissions prevention, ensure patients have a home management plan; appropriate specialist follow-up and that they understand medication use, including inhalers and supplemental oxygen; and that you consider early referral for pulmonary rehabilitation for eligible patients.

For the new definition of inpatient admission, work with your hospital’s physician advisor and case management to ensure your group is getting appropriate guidance on documentation requirements. You are probably being held accountable for your hospital’s total number of observation hours, so remember to track these metrics following implementation of the new rule, as they (hopefully) should decrease. If they do, take some of the credit!

References

- Joynt KE, Orav EJ, Jha AK. Thirty-day readmission rates for Medicare beneficiaries by race and site of care. JAMA. 2011;305(7):675-681.

- Lindenauer PK, Lagu T, Rothberg MB, et al. Income inequality and 30 day outcomes after acute myocardial infarction, heart failure, and pneumonia: retrospective cohort study. BMJ. 2013;346:f521.

Dr. Whitcomb is medical director of healthcare quality at Baystate Medical Center in Springfield, Mass. He is co-founder and past president of SHM. Email him at [email protected].

October is the beginning of a new year—in this case, fiscal-year 2014 for the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS). It’s a time when the new rules kick in. This month, we’ll look at some highlights, focusing on the new developments affecting your practice. Because you are held accountable for hospital-side performance on programs such as hospital value-based purchasing (HVBP) and the Readmissions Reduction Program, a working knowledge of the 2014 edition of the programs is crucial.

Close the Loop on HVBP

How will your hospital get paid under the 2014 version of HVBP? This past July, your hospital received a report outlining how its Medicare payments will be affected based on your hospital’s performance on process of care (heart failure, pneumonia, myocardial infarction, and surgery), patient experience (HCAHPS), and outcomes (30-day mortality for heart failure, pneumonia, and myocardial infarction).

Here are two hypothetical hospitals and how their performance in the program affects their 2014 payment. As background, in 2014, all hospitals have their base diagnosis related group (DRG) payments reduced by 1.25% for HVBP. They can earn back some, all, or an amount in excess of the 1.25% based on their performance. Payment is based on performance during the April 1 to Dec. 31, 2012, period. Under HVBP, CMS incentive payments occur at the level of individual patients, each of which is assigned a DRG.

Let’s look at two examples:

Hospital 1

- Base DRG payment reduction: 1.25% (all hospitals).

- Portion of base DRG earned back based on performance (process/patient experience/outcome metrics): 1.48%.

- Net change in base DRG payment: +0.23%.

Hospital 2

- Base DRG payment reduction: 1.25% (all hospitals).

- Portion of base DRG earned back based on performance (process/patient experience/outcome metrics): 1.08%.

- Net change in base DRG payment: -0.17%.

Hospital 1 performed relatively well, getting a bump of 0.23% in its base DRG rate. Hospital 2 did not perform so well, so it took a 0.17% hit on its base DRG rate.

In order to determine total dollars made or lost for your hospital, one multiplies the total number of eligible Medicare inpatients for 2014 times the base DRG payment times the percent change in base DRG payment. If Hospital 1 has 10,000 eligible patients in 2014 and a base DRG payment of $5,000, the value is 10,000 x $5,000 x 0.0023 (0.23%) = $115,000 gained. Hospital 2, with the same number of patients and base DRG payment, loses (10,000 x $5,000 x 0.0017 = $85,000).

Readmissions and Penalties

For 2014, CMS is adding 30-day readmissions for COPD to readmissions for heart failure, pneumonia, and myocardial infarction for its penalty program. CMS added COPD because it is the fourth-leading cause of readmissions, according to a recent Medicare Payment Advisory Commission report, and because there is wide variation in the rates (from 18% to 25%) of COPD hospital readmissions.

For 2014, CMS raises the ceiling on readmission penalties to a maximum of 2% of reimbursement for all of a hospital’s Medicare inpatients. (The maximum hit during the first round of readmission penalties, which began in October 2012, was 1%.) More than 2,200 U.S. hospitals will face some financial penalty for excess 30-day readmissions.

Disappointingly, CMS did not add a risk adjustment for socioeconomic status despite being under pressure to do so. There is growing evidence that these factors have a major impact on readmission rates.1,2

New Definition of an Admission

Amidst confusion from many and major blowback from beneficiaries saddled with large out-of-pocket expenses for observation stays and subsequent skilled-nursing-facility stays, CMS is clarifying the definition of an inpatient admission. The agency will define an admission as a hospital stay that spans at least two midnights. If a patient is in the hospital for a shorter period of time, CMS will deem the patient to be on observation status, unless medical record documentation supports a physician’s expectation “that the beneficiary would need care spanning at least two midnights” but unanticipated events led to a shorter stay.

Plan of Attack

For HVBP, make contact with your director of quality to understand your hospital’s performance and payment for 2014. If you have incentive compensation riding on HVBP, make sure you understand how your employer or contracted hospital is calculating the payout (because, for example, the performance period was in 2012!) and that your hospitalist group understands the payout calculation.

For COPD readmissions prevention, ensure patients have a home management plan; appropriate specialist follow-up and that they understand medication use, including inhalers and supplemental oxygen; and that you consider early referral for pulmonary rehabilitation for eligible patients.

For the new definition of inpatient admission, work with your hospital’s physician advisor and case management to ensure your group is getting appropriate guidance on documentation requirements. You are probably being held accountable for your hospital’s total number of observation hours, so remember to track these metrics following implementation of the new rule, as they (hopefully) should decrease. If they do, take some of the credit!

References

- Joynt KE, Orav EJ, Jha AK. Thirty-day readmission rates for Medicare beneficiaries by race and site of care. JAMA. 2011;305(7):675-681.

- Lindenauer PK, Lagu T, Rothberg MB, et al. Income inequality and 30 day outcomes after acute myocardial infarction, heart failure, and pneumonia: retrospective cohort study. BMJ. 2013;346:f521.

Dr. Whitcomb is medical director of healthcare quality at Baystate Medical Center in Springfield, Mass. He is co-founder and past president of SHM. Email him at [email protected].

October is the beginning of a new year—in this case, fiscal-year 2014 for the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS). It’s a time when the new rules kick in. This month, we’ll look at some highlights, focusing on the new developments affecting your practice. Because you are held accountable for hospital-side performance on programs such as hospital value-based purchasing (HVBP) and the Readmissions Reduction Program, a working knowledge of the 2014 edition of the programs is crucial.

Close the Loop on HVBP

How will your hospital get paid under the 2014 version of HVBP? This past July, your hospital received a report outlining how its Medicare payments will be affected based on your hospital’s performance on process of care (heart failure, pneumonia, myocardial infarction, and surgery), patient experience (HCAHPS), and outcomes (30-day mortality for heart failure, pneumonia, and myocardial infarction).

Here are two hypothetical hospitals and how their performance in the program affects their 2014 payment. As background, in 2014, all hospitals have their base diagnosis related group (DRG) payments reduced by 1.25% for HVBP. They can earn back some, all, or an amount in excess of the 1.25% based on their performance. Payment is based on performance during the April 1 to Dec. 31, 2012, period. Under HVBP, CMS incentive payments occur at the level of individual patients, each of which is assigned a DRG.

Let’s look at two examples:

Hospital 1

- Base DRG payment reduction: 1.25% (all hospitals).

- Portion of base DRG earned back based on performance (process/patient experience/outcome metrics): 1.48%.

- Net change in base DRG payment: +0.23%.

Hospital 2

- Base DRG payment reduction: 1.25% (all hospitals).

- Portion of base DRG earned back based on performance (process/patient experience/outcome metrics): 1.08%.

- Net change in base DRG payment: -0.17%.

Hospital 1 performed relatively well, getting a bump of 0.23% in its base DRG rate. Hospital 2 did not perform so well, so it took a 0.17% hit on its base DRG rate.

In order to determine total dollars made or lost for your hospital, one multiplies the total number of eligible Medicare inpatients for 2014 times the base DRG payment times the percent change in base DRG payment. If Hospital 1 has 10,000 eligible patients in 2014 and a base DRG payment of $5,000, the value is 10,000 x $5,000 x 0.0023 (0.23%) = $115,000 gained. Hospital 2, with the same number of patients and base DRG payment, loses (10,000 x $5,000 x 0.0017 = $85,000).

Readmissions and Penalties

For 2014, CMS is adding 30-day readmissions for COPD to readmissions for heart failure, pneumonia, and myocardial infarction for its penalty program. CMS added COPD because it is the fourth-leading cause of readmissions, according to a recent Medicare Payment Advisory Commission report, and because there is wide variation in the rates (from 18% to 25%) of COPD hospital readmissions.

For 2014, CMS raises the ceiling on readmission penalties to a maximum of 2% of reimbursement for all of a hospital’s Medicare inpatients. (The maximum hit during the first round of readmission penalties, which began in October 2012, was 1%.) More than 2,200 U.S. hospitals will face some financial penalty for excess 30-day readmissions.

Disappointingly, CMS did not add a risk adjustment for socioeconomic status despite being under pressure to do so. There is growing evidence that these factors have a major impact on readmission rates.1,2

New Definition of an Admission

Amidst confusion from many and major blowback from beneficiaries saddled with large out-of-pocket expenses for observation stays and subsequent skilled-nursing-facility stays, CMS is clarifying the definition of an inpatient admission. The agency will define an admission as a hospital stay that spans at least two midnights. If a patient is in the hospital for a shorter period of time, CMS will deem the patient to be on observation status, unless medical record documentation supports a physician’s expectation “that the beneficiary would need care spanning at least two midnights” but unanticipated events led to a shorter stay.

Plan of Attack

For HVBP, make contact with your director of quality to understand your hospital’s performance and payment for 2014. If you have incentive compensation riding on HVBP, make sure you understand how your employer or contracted hospital is calculating the payout (because, for example, the performance period was in 2012!) and that your hospitalist group understands the payout calculation.

For COPD readmissions prevention, ensure patients have a home management plan; appropriate specialist follow-up and that they understand medication use, including inhalers and supplemental oxygen; and that you consider early referral for pulmonary rehabilitation for eligible patients.

For the new definition of inpatient admission, work with your hospital’s physician advisor and case management to ensure your group is getting appropriate guidance on documentation requirements. You are probably being held accountable for your hospital’s total number of observation hours, so remember to track these metrics following implementation of the new rule, as they (hopefully) should decrease. If they do, take some of the credit!

References

- Joynt KE, Orav EJ, Jha AK. Thirty-day readmission rates for Medicare beneficiaries by race and site of care. JAMA. 2011;305(7):675-681.

- Lindenauer PK, Lagu T, Rothberg MB, et al. Income inequality and 30 day outcomes after acute myocardial infarction, heart failure, and pneumonia: retrospective cohort study. BMJ. 2013;346:f521.

Dr. Whitcomb is medical director of healthcare quality at Baystate Medical Center in Springfield, Mass. He is co-founder and past president of SHM. Email him at [email protected].

How To Avoid Medicare Denials for Critical-Care Billing

Are your critical-care claims at risk for denial or repayment upon review? Several payors have identified increased potential for critical-care reporting discrepancies, which has resulted in targeted prepayment reviews of this code.1 Some payors have implemented 100% review when critical care is reported in settings other than inpatient hospitals, outpatient hospitals, or emergency departments.2 To ensure a successful outcome, make sure the documentation meets the basic principles of the critical-care guidelines.

Defining Critical Illness/Injury

CPT and the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) define “critical illness or injury” as a condition that acutely impairs one or more vital organ systems such that there is a high probability of imminent or life-threatening deterioration in the patient’s condition (e.g. central-nervous-system failure; circulatory failure; shock; renal, hepatic, metabolic, and/or respiratory failure).3 The provider’s time must be solely directed toward the critically ill patient. Highly complex decision-making and interventions of high intensity are required to prevent the patient’s inevitable decline if left untreated. Payment may be made for critical-care services provided in any reasonable location, as long as the care provided meets the definition of critical care. Critical-care services cannot be reported for a patient who is not critically ill but happens to be in a critical-care unit, or when a particular physician is only treating one of the patient’s conditions that is not considered the critical illness.4

Examples of patients who may not satisfy Medicare medical-necessity criteria, do not meet critical-care criteria, or who do not have a critical-care illness or injury and therefore are not eligible for critical-care payment:

- Patients admitted to a critical-care unit because no other hospital beds were available;

- Patients admitted to a critical-care unit for close nursing observation and/or frequent monitoring of vital signs (e.g. drug toxicity or overdose);

- Patients admitted to a critical-care unit because hospital rules require certain treatments (e.g. insulin infusions) to be administered in the critical-care unit; and

- Care of only a chronic illness in the absence of caring for a critical illness (e.g. daily management of a chronic ventilator patient; management of or care related to dialysis for an ESRD).

These circumstances would require using subsequent hospital care codes (99231-99233), initial hospital care codes (99221-99223), or hospital consultation codes (99251-99255) when applicable.3,5

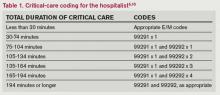

Because critical-care time is a cumulative service, providers keep track of their total time throughout a single calendar day. For each date and encounter entry, the physician’s progress notes shall document the total time that critical-care services were provided (e.g. 45 minutes).4 Some payors impose the notation of “start-and-stop time” per encounter (e.g. 10 to 10:45 a.m.).

Code This Case

Consider the following scenario: A hospitalist admits a 75-year-old patient to the ICU with acute respiratory failure. He spends 45 minutes in critical-care time. The patient’s family arrives soon thereafter to discuss the patient’s condition with a second hospitalist. The discussion lasts an additional 20 minutes, and the decision regarding the patient’s DNR status is made.

Family meetings must take place at the bedside or on the patient’s unit/floor. The patient must participate, unless they are medically unable or clinically incompetent to participate. A notation in the chart should indicate the patient’s inability to participate and the reason. Meeting time can only involve obtaining a medical history and/or discussing treatment options or the limitations of treatment. The conversation must bear directly on patient management.5,6 Meetings that take place for family grief counseling (90846, 90847, 90849) are not included in critical-care time and cannot be billed separately.

Do not count time associated with periodic condition updates to the family or answering questions about the patient’s condition that are unrelated to decision-making.

Family discussions can take place via phone as long as the physician is calling from the patient’s unit/floor and the conversation involves the same criterion identified for face-to-face family meetings.6

Critically ill patients often require the care of multiple providers.3 Payors implement code logic in their systems that allow reimbursement for 99291 once per day when reported by physicians of the same group and specialty.8 Physicians of different specialties can separately report critical-care hours. Documentation must demonstrate that care is not duplicative of other specialists and does not overlap the same time period of any other physician reporting critical-care services.

Same-specialty physicians (two hospitalists from the same group practice) bill and are paid as one physician. The initial critical-care hour (99291) must be met by a single physician. Medically necessary critical-care time beyond the first hour (99292) may be met individually by the same physician or collectively with another physician from the same group. Cumulative physician time should be reported under one provider number on a single invoice in order to prevent denials from billing 99292 independently (see “Critical-Care Services: Time Reminders,”).

When a physician and a nurse practitioner (NP) see a patient on the same calendar day, critical-care reporting is handled differently. A single unit of critical-care time cannot be split or shared between a physician and a qualified NP. One individual must meet the entire time requirement of the reported service code.

More specifically, the hospitalist must individually meet the criteria for the first critical-care hour before reporting 99291, and the NP must individually meet the criteria for an additional 30 minutes of critical care before reporting 99292. The same is true if the NP provided the initial hour while the hospitalist provided the additional critical-care time.

Payors who recognize NPs as independent billing providers (e.g. Medicare and Aetna) require a “split” invoice: an invoice for 99291 with the hospitalist NPI and an invoice for 99292 with the NP’s NPI.9 This ensures reimbursement-rate accuracy, as the physician receives 100% of the allowable rate while the NP receives 85%. If the 99292 invoice is denied due to the payor’s system edits disallowing separate invoicing of add-on codes, appeal with documentation by both the hospitalist and NP to identify the circumstances and reclaim payment.

References

- Cahaba Government Benefit Administrators LLC. Widespread prepayment targeted review notification—CPT 99291. Cahaba Government Benefit Administrators LLC website. Available at: http://www.cahabagba.com/news/widespread-prepayment-targeted-review-notification-part-b/. Accessed May 4, 2013.