User login

Hints of altered microRNA expression in women exposed to EDCs

Endocrine-disrupting chemicals (EDCs) are structurally similar to endogenous hormones and are therefore capable of mimicking these natural hormones, interfering with their biosynthesis, transport, binding action, and/or elimination. In animal studies and human clinical observational and epidemiologic studies of various EDCs, these chemicals have consistently been associated with diabetes mellitus, obesity, hormone-sensitive cancers, neurodevelopmental disorders in children exposed prenatally, and reproductive health.

In 2009, the Endocrine Society published a scientific statement in which it called EDCs a significant concern to human health (Endocr Rev. 2009;30[4]:293-342). Several years later, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the American Society for Reproductive Medicine issued a Committee Opinion on Exposure to Toxic Environmental Agents, warning that patient exposure to EDCs and other toxic environmental agents can have a “profound and lasting effect” on reproductive health outcomes across the life course and calling the reduction of exposure a “critical area of intervention” for ob.gyns. and other reproductive health care professionals (Obstet Gynecol. 2013;122[4]:931-5).

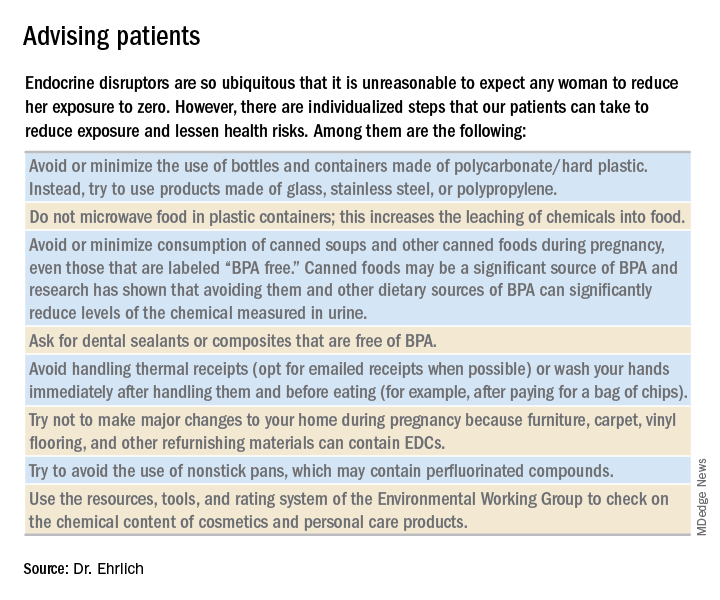

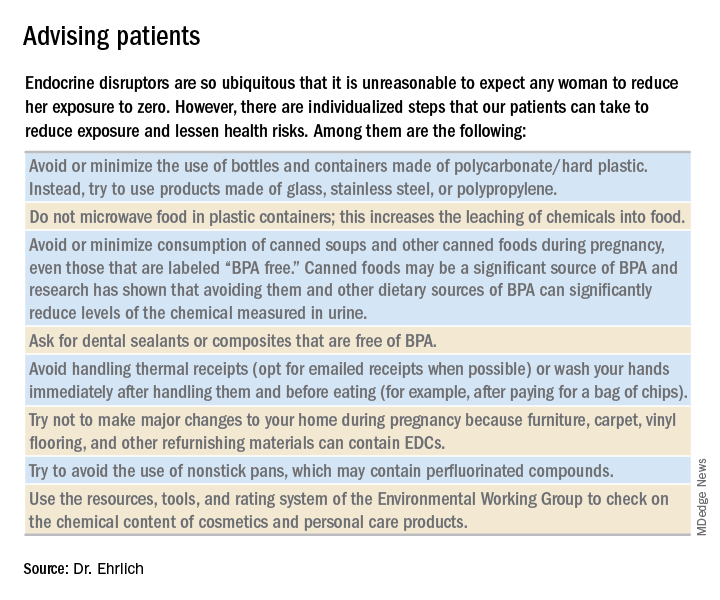

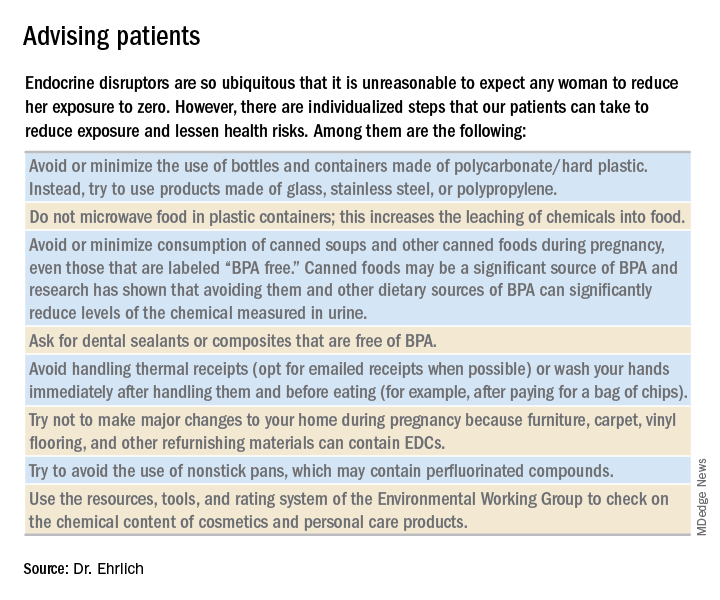

Despite strong calls by each of these organizations to not overlook EDCs in the clinical arena, as well as emerging evidence that EDCs may be a risk factor for gestational diabetes (GDM), EDC exposure may not be on the practicing ob.gyn.’s radar. Clinicians should know what these chemicals are and how to talk about them in preconception and prenatal visits. We should carefully consider their known – and potential – risks, and encourage our patients to identify and reduce exposure without being alarmist.

Low-dose effects

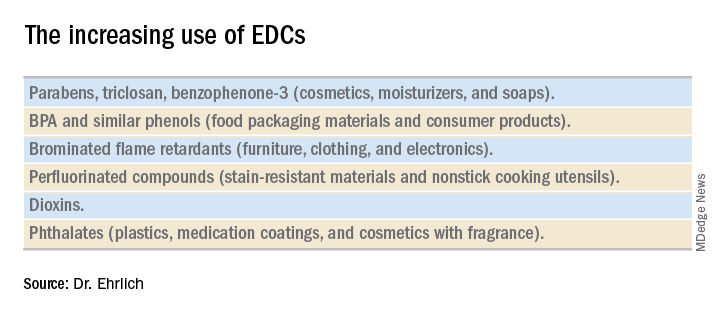

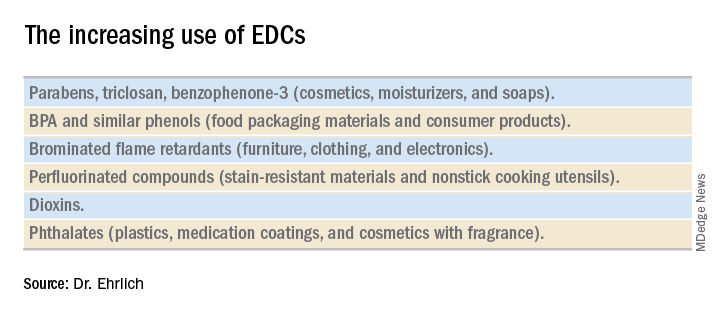

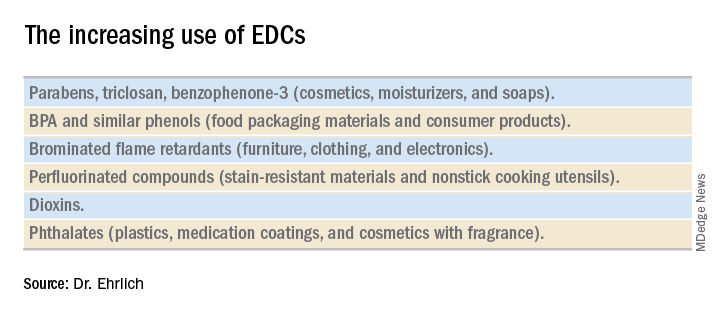

EDCs are used in the manufacture of pesticides, industrial chemicals, plastics and plasticizers, hand sanitizers, medical equipment, dental sealants, a variety of personal care products, cosmetics, and other common consumer and household products. They’re found, for example, in sunscreens, canned foods and beverages, food-packaging materials, baby bottles, flame-retardant furniture, stain-resistant carpet, and shoes. We are all ingesting and breathing them in to some degree.

Bisphenol A (BPA), one of the most extensively studied EDCs, is found in the thermal receipt paper routinely used by gas stations, supermarkets, and other stores. In a small study we conducted at Harvard, we found that urinary BPA concentrations increased after continual handling of receipts for 2 hours without gloves but did not increase significantly when gloves were used (JAMA. 2014 Feb 26;311[8]:859-60).

Informed consumers can then affect the market through their purchasing choices, but the removal of concerning chemicals from products takes a long time, and it’s not always immediately clear that replacement chemicals are safer. For instance, the BPA in “BPA-free” water bottles and canned foods has been replaced by bisphenol S (BPS), which has a very similar molecular structure to BPA. The potential adverse health effects of these replacement chemicals are now being examined in experimental and epidemiologic studies.

Through its National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has reported detection rates of between 75% and 99% for different EDCs in urine samples collected from a representative sample of the U.S. population. In other human research, several EDCs have been shown to cross the placenta and have been measured in maternal blood and urine and in cord blood and amniotic fluid, as well as in placental tissue at birth.

It is interesting to note that BPA’s structure is similar to that of diethylstilbestrol (DES). BPA was first shown to have estrogenic activity in 1936 and was originally considered for use in pharmaceuticals to prevent miscarriages, spontaneous abortions, and premature labor but was put aside in favor of DES. (DES was eventually found to be carcinogenic and was taken off the market.) In the 1950s, the use of BPA was resuscitated though not in pharmaceuticals.

A better understanding about the mechanisms of action and dose-response patterns of EDCs has indicated that EDCs can act at low doses, and in many cases a nonmonotonic dose-response association has been demonstrated. This is a paradigm shift for traditional toxicology in which it is “the dose that makes the poison,” and some toxicologists have been critical of the claims of low-dose potency for EDCs.

A team of epidemiologists, toxicologists, and other scientists, including myself, critically analyzed in vitro, animal, and epidemiologic studies as part of a National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences working group on BPA to determine the strength of the evidence for low-dose effects (doses lower than those tested in traditional toxicology assessments) of BPA. We found that consistent, reproducible, and often adverse low-dose effects have been demonstrated for BPA in cell lines, primary cells and tissues, laboratory animals, and human populations. We also concluded that EDCs can pose the greatest threats when exposure occurs during early development, organogenesis, and during critical postnatal periods when tissues are differentiating (Endocr Disruptors [Austin, Tex.]. 2013 Sep;1:e25078-1-13).

A potential risk factor for GDM

Quite a lot of research has been done on EDCs and the risk of type 2 diabetes. A recent meta-analysis that included 41 cross-sectional and 8 prospective studies found that serum concentrations of dioxins, polychlorinated biphenyls, and chlorinated pesticides – and urine concentrations of BPA and phthalates – were significantly associated with type 2 diabetes risk. Comparing the highest and lowest concentration categories, the pooled relative risk was 1.45 for BPA and phthalates. EDC concentrations also were associated with indicators of impaired fasting glucose and insulin resistance (J Diabetes. 2016 Jul;8[4]:516-32).

Despite the mounting evidence for an association between BPA and type 2 diabetes, and despite the fact that the increased incidence of GDM in the past 20 years has mirrored the increasing use of EDCs, there has been a dearth of research examining the possible relationship between EDCs and GDM. The effects of BPA on GDM were identified as a knowledge gap by the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences after a review of the literature from 2007 to 2013 (Environ Health Perspect. 2014 Aug:122[8]:775-86).

To understand the association between EDCs and GDM and the underlying mechanistic pathway of EDCs, we are conducting research that uses a growing body of evidence that suggests that environmental toxins are involved in the control of microRNA (miRNA) expression in trophoblast cells.

MiRNA, a single-stranded, short, noncoding RNA that is involved in posttranslational gene expression, can be packaged along with other signaling molecules inside extracellular vesicles in the placenta called exosomes. These exosomes appear to be shed from the placenta into the maternal circulation as early as 6-7 weeks into pregnancy. Once released into the maternal circulation, research has shown that the exosomes can target and reprogram other cells via the transfer of noncoding miRNAs, thereby changing the gene expression in these cells.

Such an exosome-mediated signaling pathway provides us with the opportunity to isolate exosomes, sequence the miRNAs, and look at whether women who are exposed to higher levels of EDCs (as indicated in urine concentration) have a particular miRNA signature that correlates with GDM. In other words, we’re working to determine whether particular EDCs and exposure levels affect the miRNA placental profiles, and if these profiles are predictive of GDM.

Thus far, in a pilot prospective cohort study of pregnant women, we are seeing hints of altered miRNA expression in relation to GDM. We have selected study participants who are at high risk of developing GDM (for example, prepregnancy body mass index greater than 30, past pregnancy with GDM, or macrosomia) because we suspect that, in many women, EDCs are a tipping point for the development of GDM rather than a sole causative factor. In addition to understanding the impact of EDCs on GDM, it is our hope that miRNAs in maternal circulation will serve as a noninvasive biomarker for early detection of GDM development or susceptibility.

Dr. Ehrlich is an assistant professor of pediatrics and environmental health at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center.

Endocrine-disrupting chemicals (EDCs) are structurally similar to endogenous hormones and are therefore capable of mimicking these natural hormones, interfering with their biosynthesis, transport, binding action, and/or elimination. In animal studies and human clinical observational and epidemiologic studies of various EDCs, these chemicals have consistently been associated with diabetes mellitus, obesity, hormone-sensitive cancers, neurodevelopmental disorders in children exposed prenatally, and reproductive health.

In 2009, the Endocrine Society published a scientific statement in which it called EDCs a significant concern to human health (Endocr Rev. 2009;30[4]:293-342). Several years later, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the American Society for Reproductive Medicine issued a Committee Opinion on Exposure to Toxic Environmental Agents, warning that patient exposure to EDCs and other toxic environmental agents can have a “profound and lasting effect” on reproductive health outcomes across the life course and calling the reduction of exposure a “critical area of intervention” for ob.gyns. and other reproductive health care professionals (Obstet Gynecol. 2013;122[4]:931-5).

Despite strong calls by each of these organizations to not overlook EDCs in the clinical arena, as well as emerging evidence that EDCs may be a risk factor for gestational diabetes (GDM), EDC exposure may not be on the practicing ob.gyn.’s radar. Clinicians should know what these chemicals are and how to talk about them in preconception and prenatal visits. We should carefully consider their known – and potential – risks, and encourage our patients to identify and reduce exposure without being alarmist.

Low-dose effects

EDCs are used in the manufacture of pesticides, industrial chemicals, plastics and plasticizers, hand sanitizers, medical equipment, dental sealants, a variety of personal care products, cosmetics, and other common consumer and household products. They’re found, for example, in sunscreens, canned foods and beverages, food-packaging materials, baby bottles, flame-retardant furniture, stain-resistant carpet, and shoes. We are all ingesting and breathing them in to some degree.

Bisphenol A (BPA), one of the most extensively studied EDCs, is found in the thermal receipt paper routinely used by gas stations, supermarkets, and other stores. In a small study we conducted at Harvard, we found that urinary BPA concentrations increased after continual handling of receipts for 2 hours without gloves but did not increase significantly when gloves were used (JAMA. 2014 Feb 26;311[8]:859-60).

Informed consumers can then affect the market through their purchasing choices, but the removal of concerning chemicals from products takes a long time, and it’s not always immediately clear that replacement chemicals are safer. For instance, the BPA in “BPA-free” water bottles and canned foods has been replaced by bisphenol S (BPS), which has a very similar molecular structure to BPA. The potential adverse health effects of these replacement chemicals are now being examined in experimental and epidemiologic studies.

Through its National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has reported detection rates of between 75% and 99% for different EDCs in urine samples collected from a representative sample of the U.S. population. In other human research, several EDCs have been shown to cross the placenta and have been measured in maternal blood and urine and in cord blood and amniotic fluid, as well as in placental tissue at birth.

It is interesting to note that BPA’s structure is similar to that of diethylstilbestrol (DES). BPA was first shown to have estrogenic activity in 1936 and was originally considered for use in pharmaceuticals to prevent miscarriages, spontaneous abortions, and premature labor but was put aside in favor of DES. (DES was eventually found to be carcinogenic and was taken off the market.) In the 1950s, the use of BPA was resuscitated though not in pharmaceuticals.

A better understanding about the mechanisms of action and dose-response patterns of EDCs has indicated that EDCs can act at low doses, and in many cases a nonmonotonic dose-response association has been demonstrated. This is a paradigm shift for traditional toxicology in which it is “the dose that makes the poison,” and some toxicologists have been critical of the claims of low-dose potency for EDCs.

A team of epidemiologists, toxicologists, and other scientists, including myself, critically analyzed in vitro, animal, and epidemiologic studies as part of a National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences working group on BPA to determine the strength of the evidence for low-dose effects (doses lower than those tested in traditional toxicology assessments) of BPA. We found that consistent, reproducible, and often adverse low-dose effects have been demonstrated for BPA in cell lines, primary cells and tissues, laboratory animals, and human populations. We also concluded that EDCs can pose the greatest threats when exposure occurs during early development, organogenesis, and during critical postnatal periods when tissues are differentiating (Endocr Disruptors [Austin, Tex.]. 2013 Sep;1:e25078-1-13).

A potential risk factor for GDM

Quite a lot of research has been done on EDCs and the risk of type 2 diabetes. A recent meta-analysis that included 41 cross-sectional and 8 prospective studies found that serum concentrations of dioxins, polychlorinated biphenyls, and chlorinated pesticides – and urine concentrations of BPA and phthalates – were significantly associated with type 2 diabetes risk. Comparing the highest and lowest concentration categories, the pooled relative risk was 1.45 for BPA and phthalates. EDC concentrations also were associated with indicators of impaired fasting glucose and insulin resistance (J Diabetes. 2016 Jul;8[4]:516-32).

Despite the mounting evidence for an association between BPA and type 2 diabetes, and despite the fact that the increased incidence of GDM in the past 20 years has mirrored the increasing use of EDCs, there has been a dearth of research examining the possible relationship between EDCs and GDM. The effects of BPA on GDM were identified as a knowledge gap by the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences after a review of the literature from 2007 to 2013 (Environ Health Perspect. 2014 Aug:122[8]:775-86).

To understand the association between EDCs and GDM and the underlying mechanistic pathway of EDCs, we are conducting research that uses a growing body of evidence that suggests that environmental toxins are involved in the control of microRNA (miRNA) expression in trophoblast cells.

MiRNA, a single-stranded, short, noncoding RNA that is involved in posttranslational gene expression, can be packaged along with other signaling molecules inside extracellular vesicles in the placenta called exosomes. These exosomes appear to be shed from the placenta into the maternal circulation as early as 6-7 weeks into pregnancy. Once released into the maternal circulation, research has shown that the exosomes can target and reprogram other cells via the transfer of noncoding miRNAs, thereby changing the gene expression in these cells.

Such an exosome-mediated signaling pathway provides us with the opportunity to isolate exosomes, sequence the miRNAs, and look at whether women who are exposed to higher levels of EDCs (as indicated in urine concentration) have a particular miRNA signature that correlates with GDM. In other words, we’re working to determine whether particular EDCs and exposure levels affect the miRNA placental profiles, and if these profiles are predictive of GDM.

Thus far, in a pilot prospective cohort study of pregnant women, we are seeing hints of altered miRNA expression in relation to GDM. We have selected study participants who are at high risk of developing GDM (for example, prepregnancy body mass index greater than 30, past pregnancy with GDM, or macrosomia) because we suspect that, in many women, EDCs are a tipping point for the development of GDM rather than a sole causative factor. In addition to understanding the impact of EDCs on GDM, it is our hope that miRNAs in maternal circulation will serve as a noninvasive biomarker for early detection of GDM development or susceptibility.

Dr. Ehrlich is an assistant professor of pediatrics and environmental health at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center.

Endocrine-disrupting chemicals (EDCs) are structurally similar to endogenous hormones and are therefore capable of mimicking these natural hormones, interfering with their biosynthesis, transport, binding action, and/or elimination. In animal studies and human clinical observational and epidemiologic studies of various EDCs, these chemicals have consistently been associated with diabetes mellitus, obesity, hormone-sensitive cancers, neurodevelopmental disorders in children exposed prenatally, and reproductive health.

In 2009, the Endocrine Society published a scientific statement in which it called EDCs a significant concern to human health (Endocr Rev. 2009;30[4]:293-342). Several years later, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the American Society for Reproductive Medicine issued a Committee Opinion on Exposure to Toxic Environmental Agents, warning that patient exposure to EDCs and other toxic environmental agents can have a “profound and lasting effect” on reproductive health outcomes across the life course and calling the reduction of exposure a “critical area of intervention” for ob.gyns. and other reproductive health care professionals (Obstet Gynecol. 2013;122[4]:931-5).

Despite strong calls by each of these organizations to not overlook EDCs in the clinical arena, as well as emerging evidence that EDCs may be a risk factor for gestational diabetes (GDM), EDC exposure may not be on the practicing ob.gyn.’s radar. Clinicians should know what these chemicals are and how to talk about them in preconception and prenatal visits. We should carefully consider their known – and potential – risks, and encourage our patients to identify and reduce exposure without being alarmist.

Low-dose effects

EDCs are used in the manufacture of pesticides, industrial chemicals, plastics and plasticizers, hand sanitizers, medical equipment, dental sealants, a variety of personal care products, cosmetics, and other common consumer and household products. They’re found, for example, in sunscreens, canned foods and beverages, food-packaging materials, baby bottles, flame-retardant furniture, stain-resistant carpet, and shoes. We are all ingesting and breathing them in to some degree.

Bisphenol A (BPA), one of the most extensively studied EDCs, is found in the thermal receipt paper routinely used by gas stations, supermarkets, and other stores. In a small study we conducted at Harvard, we found that urinary BPA concentrations increased after continual handling of receipts for 2 hours without gloves but did not increase significantly when gloves were used (JAMA. 2014 Feb 26;311[8]:859-60).

Informed consumers can then affect the market through their purchasing choices, but the removal of concerning chemicals from products takes a long time, and it’s not always immediately clear that replacement chemicals are safer. For instance, the BPA in “BPA-free” water bottles and canned foods has been replaced by bisphenol S (BPS), which has a very similar molecular structure to BPA. The potential adverse health effects of these replacement chemicals are now being examined in experimental and epidemiologic studies.

Through its National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has reported detection rates of between 75% and 99% for different EDCs in urine samples collected from a representative sample of the U.S. population. In other human research, several EDCs have been shown to cross the placenta and have been measured in maternal blood and urine and in cord blood and amniotic fluid, as well as in placental tissue at birth.

It is interesting to note that BPA’s structure is similar to that of diethylstilbestrol (DES). BPA was first shown to have estrogenic activity in 1936 and was originally considered for use in pharmaceuticals to prevent miscarriages, spontaneous abortions, and premature labor but was put aside in favor of DES. (DES was eventually found to be carcinogenic and was taken off the market.) In the 1950s, the use of BPA was resuscitated though not in pharmaceuticals.

A better understanding about the mechanisms of action and dose-response patterns of EDCs has indicated that EDCs can act at low doses, and in many cases a nonmonotonic dose-response association has been demonstrated. This is a paradigm shift for traditional toxicology in which it is “the dose that makes the poison,” and some toxicologists have been critical of the claims of low-dose potency for EDCs.

A team of epidemiologists, toxicologists, and other scientists, including myself, critically analyzed in vitro, animal, and epidemiologic studies as part of a National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences working group on BPA to determine the strength of the evidence for low-dose effects (doses lower than those tested in traditional toxicology assessments) of BPA. We found that consistent, reproducible, and often adverse low-dose effects have been demonstrated for BPA in cell lines, primary cells and tissues, laboratory animals, and human populations. We also concluded that EDCs can pose the greatest threats when exposure occurs during early development, organogenesis, and during critical postnatal periods when tissues are differentiating (Endocr Disruptors [Austin, Tex.]. 2013 Sep;1:e25078-1-13).

A potential risk factor for GDM

Quite a lot of research has been done on EDCs and the risk of type 2 diabetes. A recent meta-analysis that included 41 cross-sectional and 8 prospective studies found that serum concentrations of dioxins, polychlorinated biphenyls, and chlorinated pesticides – and urine concentrations of BPA and phthalates – were significantly associated with type 2 diabetes risk. Comparing the highest and lowest concentration categories, the pooled relative risk was 1.45 for BPA and phthalates. EDC concentrations also were associated with indicators of impaired fasting glucose and insulin resistance (J Diabetes. 2016 Jul;8[4]:516-32).

Despite the mounting evidence for an association between BPA and type 2 diabetes, and despite the fact that the increased incidence of GDM in the past 20 years has mirrored the increasing use of EDCs, there has been a dearth of research examining the possible relationship between EDCs and GDM. The effects of BPA on GDM were identified as a knowledge gap by the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences after a review of the literature from 2007 to 2013 (Environ Health Perspect. 2014 Aug:122[8]:775-86).

To understand the association between EDCs and GDM and the underlying mechanistic pathway of EDCs, we are conducting research that uses a growing body of evidence that suggests that environmental toxins are involved in the control of microRNA (miRNA) expression in trophoblast cells.

MiRNA, a single-stranded, short, noncoding RNA that is involved in posttranslational gene expression, can be packaged along with other signaling molecules inside extracellular vesicles in the placenta called exosomes. These exosomes appear to be shed from the placenta into the maternal circulation as early as 6-7 weeks into pregnancy. Once released into the maternal circulation, research has shown that the exosomes can target and reprogram other cells via the transfer of noncoding miRNAs, thereby changing the gene expression in these cells.

Such an exosome-mediated signaling pathway provides us with the opportunity to isolate exosomes, sequence the miRNAs, and look at whether women who are exposed to higher levels of EDCs (as indicated in urine concentration) have a particular miRNA signature that correlates with GDM. In other words, we’re working to determine whether particular EDCs and exposure levels affect the miRNA placental profiles, and if these profiles are predictive of GDM.

Thus far, in a pilot prospective cohort study of pregnant women, we are seeing hints of altered miRNA expression in relation to GDM. We have selected study participants who are at high risk of developing GDM (for example, prepregnancy body mass index greater than 30, past pregnancy with GDM, or macrosomia) because we suspect that, in many women, EDCs are a tipping point for the development of GDM rather than a sole causative factor. In addition to understanding the impact of EDCs on GDM, it is our hope that miRNAs in maternal circulation will serve as a noninvasive biomarker for early detection of GDM development or susceptibility.

Dr. Ehrlich is an assistant professor of pediatrics and environmental health at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center.

Studying the gestational diabetes risk associated with endocrine-disrupting chemicals

Pregnancy presents a unique opportunity for ob.gyns. to counsel their patients on the benefits of adopting healthy lifestyle habits. Women routinely seek care from a practitioner on a regular basis. Expectant mothers are highly motivated to take care of themselves for the sake of their developing babies. Patients can be much more receptive to recommendations from their health care teams during pregnancy than they might be outside of pregnancy. Frequent biometric analyses allow ob.gyns. to monitor patients’ progress and let them know, in a supportive manner, where they might be “falling short” of their health goals.

There are a number of chemicals with which we come in contact every day, sometimes multiple times in a day, which may deeply affect our health. This month’s Master Class highlights one such group of compounds, endocrine-disrupting chemicals, the most widely known of which is bisphenol A (BPA).

Several years ago, our guest author, Dr. Shelley Ehrlich of the University of Cincinnati, spoke at a diabetes in pregnancy meeting about her research on BPA and its potential association with the development of gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM). As a perinatologist who worked for many years with patients who had diabetes in pregnancy, I was particularly struck by her preliminary findings which indicated that BPA might be altering gene expression, thereby leading to pregnancy-related disorders. At the time, Dr. Ehrlich’s research was still in the very early stages. However, her results were a new way of answering the age-old question of why some women, including those without other overt risk factors, might develop GDM.

Therefore, I’m delighted that Dr. Ehrlich agreed to author this month’s class to provide an overview of where her last few years of research has taken her.

Dr. Reece, who specializes in maternal-fetal medicine, is vice president for medical affairs at the University of Maryland, Baltimore, as well as the John Z. and Akiko K. Bowers Distinguished Professor and dean of the school of medicine. Dr. Reece said he had no relevant financial disclosures. He is the medical editor of this column. Contact him at [email protected].

Pregnancy presents a unique opportunity for ob.gyns. to counsel their patients on the benefits of adopting healthy lifestyle habits. Women routinely seek care from a practitioner on a regular basis. Expectant mothers are highly motivated to take care of themselves for the sake of their developing babies. Patients can be much more receptive to recommendations from their health care teams during pregnancy than they might be outside of pregnancy. Frequent biometric analyses allow ob.gyns. to monitor patients’ progress and let them know, in a supportive manner, where they might be “falling short” of their health goals.

There are a number of chemicals with which we come in contact every day, sometimes multiple times in a day, which may deeply affect our health. This month’s Master Class highlights one such group of compounds, endocrine-disrupting chemicals, the most widely known of which is bisphenol A (BPA).

Several years ago, our guest author, Dr. Shelley Ehrlich of the University of Cincinnati, spoke at a diabetes in pregnancy meeting about her research on BPA and its potential association with the development of gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM). As a perinatologist who worked for many years with patients who had diabetes in pregnancy, I was particularly struck by her preliminary findings which indicated that BPA might be altering gene expression, thereby leading to pregnancy-related disorders. At the time, Dr. Ehrlich’s research was still in the very early stages. However, her results were a new way of answering the age-old question of why some women, including those without other overt risk factors, might develop GDM.

Therefore, I’m delighted that Dr. Ehrlich agreed to author this month’s class to provide an overview of where her last few years of research has taken her.

Dr. Reece, who specializes in maternal-fetal medicine, is vice president for medical affairs at the University of Maryland, Baltimore, as well as the John Z. and Akiko K. Bowers Distinguished Professor and dean of the school of medicine. Dr. Reece said he had no relevant financial disclosures. He is the medical editor of this column. Contact him at [email protected].

Pregnancy presents a unique opportunity for ob.gyns. to counsel their patients on the benefits of adopting healthy lifestyle habits. Women routinely seek care from a practitioner on a regular basis. Expectant mothers are highly motivated to take care of themselves for the sake of their developing babies. Patients can be much more receptive to recommendations from their health care teams during pregnancy than they might be outside of pregnancy. Frequent biometric analyses allow ob.gyns. to monitor patients’ progress and let them know, in a supportive manner, where they might be “falling short” of their health goals.

There are a number of chemicals with which we come in contact every day, sometimes multiple times in a day, which may deeply affect our health. This month’s Master Class highlights one such group of compounds, endocrine-disrupting chemicals, the most widely known of which is bisphenol A (BPA).

Several years ago, our guest author, Dr. Shelley Ehrlich of the University of Cincinnati, spoke at a diabetes in pregnancy meeting about her research on BPA and its potential association with the development of gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM). As a perinatologist who worked for many years with patients who had diabetes in pregnancy, I was particularly struck by her preliminary findings which indicated that BPA might be altering gene expression, thereby leading to pregnancy-related disorders. At the time, Dr. Ehrlich’s research was still in the very early stages. However, her results were a new way of answering the age-old question of why some women, including those without other overt risk factors, might develop GDM.

Therefore, I’m delighted that Dr. Ehrlich agreed to author this month’s class to provide an overview of where her last few years of research has taken her.

Dr. Reece, who specializes in maternal-fetal medicine, is vice president for medical affairs at the University of Maryland, Baltimore, as well as the John Z. and Akiko K. Bowers Distinguished Professor and dean of the school of medicine. Dr. Reece said he had no relevant financial disclosures. He is the medical editor of this column. Contact him at [email protected].

Anterior discoid resection using a ‘squeeze’ technique

Rectosigmoid endometriosis has been estimated to affect between 4% and 37% of patients with endometriosis and is one of the most advanced and complex forms of the disease. Bowel endometriosis can be asymptomatic but often involves severe dysmenorrhea, dyspareunia, and a spectrum of bowel symptoms such as dyschezia, diarrhea, constipation, bloating, and rectal bleeding. Deep infiltrating rectovaginal endometriosis causes persistent or recurrent pain and is best treated by surgical removal of nodular lesions.

I have found that laparoscopic full-thickness disc resection (anterior discoid resection) with primary two-layer closure is often feasible and avoids the need for a complete bowel reanastomosis. It may not be an option in cases of multifocal rectal involvement (which may affect between one-quarter and one-third of patients with bowel endometriosis) or in cases involving large rectal nodules or luminal stenosis secondary to advanced fibrosis. In these cases, segmental bowel resection (low anterior resection) is often necessary. When anterior discoid resection is feasible, however, patients face significantly less morbidity with comparable outcomes.

Less morbidity

Preoperative evaluation is far from straightforward, and practices vary. Transvaginal ultrasonography is used for diagnosing rectal endometriosis in select centers in certain regions of the world, but there are important limitations; not only is it highly operator dependent, but its limited range does not allow for the detection of endometriosis higher in the sigmoid colon. Endorectal ultrasonography can be an excellent tool for more fully evaluating rectal wall involvement, but it does not usually allow for the evaluation of disease elsewhere in the pelvis.

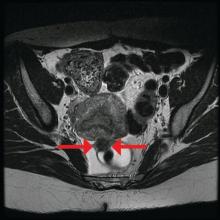

The preoperative tool we utilize most often along with clinical examination is MRI with vaginal and rectal contrast. MRI provides us with a superior anatomic perspective on the disease. Not only can we assess the depth of bowel wall infiltration and the distribution of the affected areas of the bowel, but we can see the bladder, the uterosacral ligaments, and how the uterus is situated relative to areas of disease. However, there are individualized limits to how high the contrast will travel, even with bowel preparation; disease that occurs significantly above the uterus often cannot be visualized as well as disease that occurs lower.

My general surgeon colleague and I have been working together for years, and we both are involved in counseling the patient suspected of having deep infiltrating disease. I typically talk with the patient about the probability of segmental resection based on my exam and preoperative MRI, and my colleague expands on this discussion with further explanation of the risks of bowel surgery.

Segmental resection has been associated with significant postoperative complications. In a single-center series of 436 laparoscopic colorectal resections for deep infiltrating endometriosis, rectovaginal and anastomotic fistula were among the most frequent postoperative complications (3.2% and 1.1%), along with transient urinary retention, which occurred in almost 20% (Surg Endosc. 2010 Jan;24:63-7).

Patients undergoing discoid resection for deep infiltrating endometriosis also had a significantly lower rate of temporary ileostomy (2.1% vs. 9.1%), a reduced rate of postoperative fever, and a reduced rate of gastrointestinal complications, mainly anastomotic leak or rectovaginal fistula (2.1% vs. 5.6%). There were no significant differences in the recurrence rate (13.8% vs. 11.5%).

A retrospective cohort study from our institution similarly showed decreased operative time, blood loss, hospital stay, and a lower rate of anastomotic strictures in patients who underwent laparoscopic anterior discoid resection between 2001 and 2009. The ADR group consistently had higher increments of improvement in bowel symptoms and dyspareunia, compared with patients who were selected to have segmental resection. Patients were followed for a mean of 41 months (JSLS. 2011;15[3]:331-8).

In general, there is agreement among surgeons that for consideration of discoid resection, nodule diameter should not exceed 3 cm, with a maximum of half of the bowel circumference and a maximum of 60% stenosis. I view these numbers as guiding principles, however, and not firm rules. Surgical decisions should be personalized based on the patient, the surgeon’s impression of the extent of the disease, and the ability to perform anterior discoid resection without compromising the rectal lumen with primary closure of the defect.

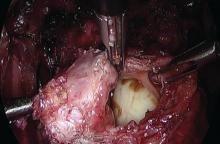

The technique

Rectosigmoid endometriotic nodules may present within the context of an obliterated posterior cul-de-sac, but the avascular pararectal space can be used to approach the nodules. Detailed knowledge of the avascular planes of this space, as well as the rectovaginal space, is crucial. Development of the rectovaginal space frees the bowel from its attachments to the posterior uterus and vagina. Judicious use of energized instruments in sharp dissection, and frequently sharp cold cutting, should be used near the bowel serosa to prevent thermal injury.

Presurgical imaging usually offers a good assessment of a nodule’s size and location, but intraoperatively, I typically use an atraumatic grasper to further assess size and contour and to determine if the nodule is suitable for discoid resection. If so, a suture is placed through the nodule to improve manipulation, and enucleation of the nodule itself is achieved through a “squeeze” technique in which an advanced bipolar device is used to circumscribe the lesion, dissecting the nodule as the device bounces off the thick endometriotic tissue.

The ENSEAL bipolar device (Ethicon, Somerville, N.J.) was designed as a vessel sealer, but because it will not cut through hard tissue as will other laparoscopic cutting devices, it serves as a useful tool for resecting endometriotic nodules while minimizing the removal of healthy rectal tissue. The device bounces off the nodule because it will avoid cutting through the thick tissue; in the process, it facilitates a fairly complete enucleation of the endometriotic nodule, starting with dissection until an intentional colotomy/enterotomy is made and followed by circumscription of the lesion once the rectum is entered.

Gentle traction and counter-traction increase the efficiency of dissection and minimize the amount of normal rectal tissue removed. Quick cutting with short bursts of energy allows for good hemostasis and minimizes thermal spread, which will maximize tissue healing from subsequent repair.

I then use a rectal probe as a template for repair. The probe is advanced underneath the defect between the distal and proximal portions, and the tissue is moved over the probe to ensure that the repair will be tension free. An ability to reapproximate the defect while keeping the probe in place indicates that the defect can be safely closed. (For a video presentation of the surgery, see www.surgeryu.com/leeobgyn.) If suturing is not feasible, the general surgeon is called to perform segmental resection.

The integrity of the repair is then thoroughly assessed with an air leak test. A bowel clamp is placed across the rectum and the pelvis is filled with sterile saline. Air is placed into the rectum with a rigid proctoscope while the operative field is inspected for evidence of an air leak.

Discoid resection may also be performed with a circular stapler. While this technique is faster than suturing, its use is limited by nodule size and has the potential to compromise complete excision of the nodule.

Dr. Lee is director of minimally invasive gynecologic surgery, Magee-Women’s Hospital of the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center.

Rectosigmoid endometriosis has been estimated to affect between 4% and 37% of patients with endometriosis and is one of the most advanced and complex forms of the disease. Bowel endometriosis can be asymptomatic but often involves severe dysmenorrhea, dyspareunia, and a spectrum of bowel symptoms such as dyschezia, diarrhea, constipation, bloating, and rectal bleeding. Deep infiltrating rectovaginal endometriosis causes persistent or recurrent pain and is best treated by surgical removal of nodular lesions.

I have found that laparoscopic full-thickness disc resection (anterior discoid resection) with primary two-layer closure is often feasible and avoids the need for a complete bowel reanastomosis. It may not be an option in cases of multifocal rectal involvement (which may affect between one-quarter and one-third of patients with bowel endometriosis) or in cases involving large rectal nodules or luminal stenosis secondary to advanced fibrosis. In these cases, segmental bowel resection (low anterior resection) is often necessary. When anterior discoid resection is feasible, however, patients face significantly less morbidity with comparable outcomes.

Less morbidity

Preoperative evaluation is far from straightforward, and practices vary. Transvaginal ultrasonography is used for diagnosing rectal endometriosis in select centers in certain regions of the world, but there are important limitations; not only is it highly operator dependent, but its limited range does not allow for the detection of endometriosis higher in the sigmoid colon. Endorectal ultrasonography can be an excellent tool for more fully evaluating rectal wall involvement, but it does not usually allow for the evaluation of disease elsewhere in the pelvis.

The preoperative tool we utilize most often along with clinical examination is MRI with vaginal and rectal contrast. MRI provides us with a superior anatomic perspective on the disease. Not only can we assess the depth of bowel wall infiltration and the distribution of the affected areas of the bowel, but we can see the bladder, the uterosacral ligaments, and how the uterus is situated relative to areas of disease. However, there are individualized limits to how high the contrast will travel, even with bowel preparation; disease that occurs significantly above the uterus often cannot be visualized as well as disease that occurs lower.

My general surgeon colleague and I have been working together for years, and we both are involved in counseling the patient suspected of having deep infiltrating disease. I typically talk with the patient about the probability of segmental resection based on my exam and preoperative MRI, and my colleague expands on this discussion with further explanation of the risks of bowel surgery.

Segmental resection has been associated with significant postoperative complications. In a single-center series of 436 laparoscopic colorectal resections for deep infiltrating endometriosis, rectovaginal and anastomotic fistula were among the most frequent postoperative complications (3.2% and 1.1%), along with transient urinary retention, which occurred in almost 20% (Surg Endosc. 2010 Jan;24:63-7).

Patients undergoing discoid resection for deep infiltrating endometriosis also had a significantly lower rate of temporary ileostomy (2.1% vs. 9.1%), a reduced rate of postoperative fever, and a reduced rate of gastrointestinal complications, mainly anastomotic leak or rectovaginal fistula (2.1% vs. 5.6%). There were no significant differences in the recurrence rate (13.8% vs. 11.5%).

A retrospective cohort study from our institution similarly showed decreased operative time, blood loss, hospital stay, and a lower rate of anastomotic strictures in patients who underwent laparoscopic anterior discoid resection between 2001 and 2009. The ADR group consistently had higher increments of improvement in bowel symptoms and dyspareunia, compared with patients who were selected to have segmental resection. Patients were followed for a mean of 41 months (JSLS. 2011;15[3]:331-8).

In general, there is agreement among surgeons that for consideration of discoid resection, nodule diameter should not exceed 3 cm, with a maximum of half of the bowel circumference and a maximum of 60% stenosis. I view these numbers as guiding principles, however, and not firm rules. Surgical decisions should be personalized based on the patient, the surgeon’s impression of the extent of the disease, and the ability to perform anterior discoid resection without compromising the rectal lumen with primary closure of the defect.

The technique

Rectosigmoid endometriotic nodules may present within the context of an obliterated posterior cul-de-sac, but the avascular pararectal space can be used to approach the nodules. Detailed knowledge of the avascular planes of this space, as well as the rectovaginal space, is crucial. Development of the rectovaginal space frees the bowel from its attachments to the posterior uterus and vagina. Judicious use of energized instruments in sharp dissection, and frequently sharp cold cutting, should be used near the bowel serosa to prevent thermal injury.

Presurgical imaging usually offers a good assessment of a nodule’s size and location, but intraoperatively, I typically use an atraumatic grasper to further assess size and contour and to determine if the nodule is suitable for discoid resection. If so, a suture is placed through the nodule to improve manipulation, and enucleation of the nodule itself is achieved through a “squeeze” technique in which an advanced bipolar device is used to circumscribe the lesion, dissecting the nodule as the device bounces off the thick endometriotic tissue.

The ENSEAL bipolar device (Ethicon, Somerville, N.J.) was designed as a vessel sealer, but because it will not cut through hard tissue as will other laparoscopic cutting devices, it serves as a useful tool for resecting endometriotic nodules while minimizing the removal of healthy rectal tissue. The device bounces off the nodule because it will avoid cutting through the thick tissue; in the process, it facilitates a fairly complete enucleation of the endometriotic nodule, starting with dissection until an intentional colotomy/enterotomy is made and followed by circumscription of the lesion once the rectum is entered.

Gentle traction and counter-traction increase the efficiency of dissection and minimize the amount of normal rectal tissue removed. Quick cutting with short bursts of energy allows for good hemostasis and minimizes thermal spread, which will maximize tissue healing from subsequent repair.

I then use a rectal probe as a template for repair. The probe is advanced underneath the defect between the distal and proximal portions, and the tissue is moved over the probe to ensure that the repair will be tension free. An ability to reapproximate the defect while keeping the probe in place indicates that the defect can be safely closed. (For a video presentation of the surgery, see www.surgeryu.com/leeobgyn.) If suturing is not feasible, the general surgeon is called to perform segmental resection.

The integrity of the repair is then thoroughly assessed with an air leak test. A bowel clamp is placed across the rectum and the pelvis is filled with sterile saline. Air is placed into the rectum with a rigid proctoscope while the operative field is inspected for evidence of an air leak.

Discoid resection may also be performed with a circular stapler. While this technique is faster than suturing, its use is limited by nodule size and has the potential to compromise complete excision of the nodule.

Dr. Lee is director of minimally invasive gynecologic surgery, Magee-Women’s Hospital of the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center.

Rectosigmoid endometriosis has been estimated to affect between 4% and 37% of patients with endometriosis and is one of the most advanced and complex forms of the disease. Bowel endometriosis can be asymptomatic but often involves severe dysmenorrhea, dyspareunia, and a spectrum of bowel symptoms such as dyschezia, diarrhea, constipation, bloating, and rectal bleeding. Deep infiltrating rectovaginal endometriosis causes persistent or recurrent pain and is best treated by surgical removal of nodular lesions.

I have found that laparoscopic full-thickness disc resection (anterior discoid resection) with primary two-layer closure is often feasible and avoids the need for a complete bowel reanastomosis. It may not be an option in cases of multifocal rectal involvement (which may affect between one-quarter and one-third of patients with bowel endometriosis) or in cases involving large rectal nodules or luminal stenosis secondary to advanced fibrosis. In these cases, segmental bowel resection (low anterior resection) is often necessary. When anterior discoid resection is feasible, however, patients face significantly less morbidity with comparable outcomes.

Less morbidity

Preoperative evaluation is far from straightforward, and practices vary. Transvaginal ultrasonography is used for diagnosing rectal endometriosis in select centers in certain regions of the world, but there are important limitations; not only is it highly operator dependent, but its limited range does not allow for the detection of endometriosis higher in the sigmoid colon. Endorectal ultrasonography can be an excellent tool for more fully evaluating rectal wall involvement, but it does not usually allow for the evaluation of disease elsewhere in the pelvis.

The preoperative tool we utilize most often along with clinical examination is MRI with vaginal and rectal contrast. MRI provides us with a superior anatomic perspective on the disease. Not only can we assess the depth of bowel wall infiltration and the distribution of the affected areas of the bowel, but we can see the bladder, the uterosacral ligaments, and how the uterus is situated relative to areas of disease. However, there are individualized limits to how high the contrast will travel, even with bowel preparation; disease that occurs significantly above the uterus often cannot be visualized as well as disease that occurs lower.

My general surgeon colleague and I have been working together for years, and we both are involved in counseling the patient suspected of having deep infiltrating disease. I typically talk with the patient about the probability of segmental resection based on my exam and preoperative MRI, and my colleague expands on this discussion with further explanation of the risks of bowel surgery.

Segmental resection has been associated with significant postoperative complications. In a single-center series of 436 laparoscopic colorectal resections for deep infiltrating endometriosis, rectovaginal and anastomotic fistula were among the most frequent postoperative complications (3.2% and 1.1%), along with transient urinary retention, which occurred in almost 20% (Surg Endosc. 2010 Jan;24:63-7).

Patients undergoing discoid resection for deep infiltrating endometriosis also had a significantly lower rate of temporary ileostomy (2.1% vs. 9.1%), a reduced rate of postoperative fever, and a reduced rate of gastrointestinal complications, mainly anastomotic leak or rectovaginal fistula (2.1% vs. 5.6%). There were no significant differences in the recurrence rate (13.8% vs. 11.5%).

A retrospective cohort study from our institution similarly showed decreased operative time, blood loss, hospital stay, and a lower rate of anastomotic strictures in patients who underwent laparoscopic anterior discoid resection between 2001 and 2009. The ADR group consistently had higher increments of improvement in bowel symptoms and dyspareunia, compared with patients who were selected to have segmental resection. Patients were followed for a mean of 41 months (JSLS. 2011;15[3]:331-8).

In general, there is agreement among surgeons that for consideration of discoid resection, nodule diameter should not exceed 3 cm, with a maximum of half of the bowel circumference and a maximum of 60% stenosis. I view these numbers as guiding principles, however, and not firm rules. Surgical decisions should be personalized based on the patient, the surgeon’s impression of the extent of the disease, and the ability to perform anterior discoid resection without compromising the rectal lumen with primary closure of the defect.

The technique

Rectosigmoid endometriotic nodules may present within the context of an obliterated posterior cul-de-sac, but the avascular pararectal space can be used to approach the nodules. Detailed knowledge of the avascular planes of this space, as well as the rectovaginal space, is crucial. Development of the rectovaginal space frees the bowel from its attachments to the posterior uterus and vagina. Judicious use of energized instruments in sharp dissection, and frequently sharp cold cutting, should be used near the bowel serosa to prevent thermal injury.

Presurgical imaging usually offers a good assessment of a nodule’s size and location, but intraoperatively, I typically use an atraumatic grasper to further assess size and contour and to determine if the nodule is suitable for discoid resection. If so, a suture is placed through the nodule to improve manipulation, and enucleation of the nodule itself is achieved through a “squeeze” technique in which an advanced bipolar device is used to circumscribe the lesion, dissecting the nodule as the device bounces off the thick endometriotic tissue.

The ENSEAL bipolar device (Ethicon, Somerville, N.J.) was designed as a vessel sealer, but because it will not cut through hard tissue as will other laparoscopic cutting devices, it serves as a useful tool for resecting endometriotic nodules while minimizing the removal of healthy rectal tissue. The device bounces off the nodule because it will avoid cutting through the thick tissue; in the process, it facilitates a fairly complete enucleation of the endometriotic nodule, starting with dissection until an intentional colotomy/enterotomy is made and followed by circumscription of the lesion once the rectum is entered.

Gentle traction and counter-traction increase the efficiency of dissection and minimize the amount of normal rectal tissue removed. Quick cutting with short bursts of energy allows for good hemostasis and minimizes thermal spread, which will maximize tissue healing from subsequent repair.

I then use a rectal probe as a template for repair. The probe is advanced underneath the defect between the distal and proximal portions, and the tissue is moved over the probe to ensure that the repair will be tension free. An ability to reapproximate the defect while keeping the probe in place indicates that the defect can be safely closed. (For a video presentation of the surgery, see www.surgeryu.com/leeobgyn.) If suturing is not feasible, the general surgeon is called to perform segmental resection.

The integrity of the repair is then thoroughly assessed with an air leak test. A bowel clamp is placed across the rectum and the pelvis is filled with sterile saline. Air is placed into the rectum with a rigid proctoscope while the operative field is inspected for evidence of an air leak.

Discoid resection may also be performed with a circular stapler. While this technique is faster than suturing, its use is limited by nodule size and has the potential to compromise complete excision of the nodule.

Dr. Lee is director of minimally invasive gynecologic surgery, Magee-Women’s Hospital of the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center.

Discoid resection of rectal endometriotic nodules

The treatment of the rectovaginal endometriotic nodule continues to be controversial. While proponents of “shaving” the nodule are quick to point out that compared with segmental bowel resection, pelvic pain, dyspareunia, dysmenorrhea, and postoperative pregnancy rates are similarly reduced, most comparative studies are retrospective and are not randomized. That is, patients with larger nodules or multifocal disease with deep infiltration into the muscularis layer of the bowel, or involving more than half of the bowel wall circumference, with surrounding severe fibrosis, invariably are more likely to undergo segmental bowel resection. Even with performance of segmental bowel resection to treat more extensive disease, there is a trend toward greater improvement of pain-related symptoms when compared with the “shaving” technique. Furthermore, the risk of rectal recurrence is acknowledged to be greater in patients undergoing endometriotic rectal nodule shaving.

Concern must be raised with segmental bowel resection. Not only is the risk of temporary ileostomy increased, but subsequent anastomotic leakage and rectovaginal fistula is noted in up to 10% of women. Although reduced with nerve sparing techniques, bladder denervation secondary to damage of the parasympathetic plexus causes urinary retention. In a study of 436 cases of laparoscopic colorectal resection, 9.5% presented after 30 days with persistent urinary retention and 4.2% with constipation (Surg Endosc. 2010 Jan;24:63-7).

For this edition of the Master Class in Gynecologic Surgery, I have invited Ted Lee, MD, director of minimally invasive gynecologic surgery, Magee-Womens Hospital of the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, to discuss laparoscopic rectosigmoid resection for a deep endometriotic nodule. While many surgeons utilize a single-use curved circular stapler, I appreciate Dr. Lee’s innovative technique, for both its ease of use and its safety.

Dr. Lee has received multiple awards for his efforts, including best surgical video presentation by the AAGL. He is also the only five-time winner of the prestigious Golden Laparoscope Award for best surgical video from the AAGL.

A highly-regarded lecturer and surgeon, Dr. Lee has taught and performed live surgeries around the world.

Dr. Lee’s practice is entirely dedicated to minimally invasive surgical options for women. He is a firm believer that virtually all benign gynecologic surgical conditions should be treated using a minimally invasive approach. Dr. Lee’s clinical expertise includes minimally invasive surgery for treatments of endometriosis (including severe endometriosis involving bowel, bladder, and ureter); fibroids; abnormal uterine bleeding; urinary incontinence; and pelvic organ prolapse.

It is a great honor for the Master Class in Gynecologic Surgery to have Dr. Lee as guest author for this important area of our surgical arena.

Dr. Miller is a minimally invasive gynecologic surgeon in Naperville, Ill., and a past president of the AAGL.

The treatment of the rectovaginal endometriotic nodule continues to be controversial. While proponents of “shaving” the nodule are quick to point out that compared with segmental bowel resection, pelvic pain, dyspareunia, dysmenorrhea, and postoperative pregnancy rates are similarly reduced, most comparative studies are retrospective and are not randomized. That is, patients with larger nodules or multifocal disease with deep infiltration into the muscularis layer of the bowel, or involving more than half of the bowel wall circumference, with surrounding severe fibrosis, invariably are more likely to undergo segmental bowel resection. Even with performance of segmental bowel resection to treat more extensive disease, there is a trend toward greater improvement of pain-related symptoms when compared with the “shaving” technique. Furthermore, the risk of rectal recurrence is acknowledged to be greater in patients undergoing endometriotic rectal nodule shaving.

Concern must be raised with segmental bowel resection. Not only is the risk of temporary ileostomy increased, but subsequent anastomotic leakage and rectovaginal fistula is noted in up to 10% of women. Although reduced with nerve sparing techniques, bladder denervation secondary to damage of the parasympathetic plexus causes urinary retention. In a study of 436 cases of laparoscopic colorectal resection, 9.5% presented after 30 days with persistent urinary retention and 4.2% with constipation (Surg Endosc. 2010 Jan;24:63-7).

For this edition of the Master Class in Gynecologic Surgery, I have invited Ted Lee, MD, director of minimally invasive gynecologic surgery, Magee-Womens Hospital of the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, to discuss laparoscopic rectosigmoid resection for a deep endometriotic nodule. While many surgeons utilize a single-use curved circular stapler, I appreciate Dr. Lee’s innovative technique, for both its ease of use and its safety.

Dr. Lee has received multiple awards for his efforts, including best surgical video presentation by the AAGL. He is also the only five-time winner of the prestigious Golden Laparoscope Award for best surgical video from the AAGL.

A highly-regarded lecturer and surgeon, Dr. Lee has taught and performed live surgeries around the world.

Dr. Lee’s practice is entirely dedicated to minimally invasive surgical options for women. He is a firm believer that virtually all benign gynecologic surgical conditions should be treated using a minimally invasive approach. Dr. Lee’s clinical expertise includes minimally invasive surgery for treatments of endometriosis (including severe endometriosis involving bowel, bladder, and ureter); fibroids; abnormal uterine bleeding; urinary incontinence; and pelvic organ prolapse.

It is a great honor for the Master Class in Gynecologic Surgery to have Dr. Lee as guest author for this important area of our surgical arena.

Dr. Miller is a minimally invasive gynecologic surgeon in Naperville, Ill., and a past president of the AAGL.

The treatment of the rectovaginal endometriotic nodule continues to be controversial. While proponents of “shaving” the nodule are quick to point out that compared with segmental bowel resection, pelvic pain, dyspareunia, dysmenorrhea, and postoperative pregnancy rates are similarly reduced, most comparative studies are retrospective and are not randomized. That is, patients with larger nodules or multifocal disease with deep infiltration into the muscularis layer of the bowel, or involving more than half of the bowel wall circumference, with surrounding severe fibrosis, invariably are more likely to undergo segmental bowel resection. Even with performance of segmental bowel resection to treat more extensive disease, there is a trend toward greater improvement of pain-related symptoms when compared with the “shaving” technique. Furthermore, the risk of rectal recurrence is acknowledged to be greater in patients undergoing endometriotic rectal nodule shaving.

Concern must be raised with segmental bowel resection. Not only is the risk of temporary ileostomy increased, but subsequent anastomotic leakage and rectovaginal fistula is noted in up to 10% of women. Although reduced with nerve sparing techniques, bladder denervation secondary to damage of the parasympathetic plexus causes urinary retention. In a study of 436 cases of laparoscopic colorectal resection, 9.5% presented after 30 days with persistent urinary retention and 4.2% with constipation (Surg Endosc. 2010 Jan;24:63-7).

For this edition of the Master Class in Gynecologic Surgery, I have invited Ted Lee, MD, director of minimally invasive gynecologic surgery, Magee-Womens Hospital of the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, to discuss laparoscopic rectosigmoid resection for a deep endometriotic nodule. While many surgeons utilize a single-use curved circular stapler, I appreciate Dr. Lee’s innovative technique, for both its ease of use and its safety.

Dr. Lee has received multiple awards for his efforts, including best surgical video presentation by the AAGL. He is also the only five-time winner of the prestigious Golden Laparoscope Award for best surgical video from the AAGL.

A highly-regarded lecturer and surgeon, Dr. Lee has taught and performed live surgeries around the world.

Dr. Lee’s practice is entirely dedicated to minimally invasive surgical options for women. He is a firm believer that virtually all benign gynecologic surgical conditions should be treated using a minimally invasive approach. Dr. Lee’s clinical expertise includes minimally invasive surgery for treatments of endometriosis (including severe endometriosis involving bowel, bladder, and ureter); fibroids; abnormal uterine bleeding; urinary incontinence; and pelvic organ prolapse.

It is a great honor for the Master Class in Gynecologic Surgery to have Dr. Lee as guest author for this important area of our surgical arena.

Dr. Miller is a minimally invasive gynecologic surgeon in Naperville, Ill., and a past president of the AAGL.

Is 17-OHPC effective for reducing risk of preterm birth?

In 2003, the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development’s Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units (MFMU) Network reported on a placebo-controlled randomized study of 17–alpha hydroxyprogesterone caproate (17-OHPC) in women with a history of spontaneous preterm delivery. The study demonstrated a 33% reduction in recurrent preterm birth after weekly treatment with 17-OHPC, which was initiated at 16-20 weeks of gestation.

This landmark study, led by Paul Meis, MD, validated what had been suggested in an earlier meta-analysis (1990) by Mark Keirse, MD – and it quickly altered clinical practice. It set into motion a string of studies on the use of 17-OHPC and other progestational compounds in women with a variety of conditions associated with an increased risk for preterm birth.

It is not surprising, then, that the literature has become muddied and full of contradictory findings since publication of the Meis study and the initial studies on vaginal progesterone in women with a midtrimester short cervix. Further confounding our ability to judge a treatment’s effectiveness is the fact that spontaneous preterm birth is increasingly understood to be a multifactorial, highly heterogeneous condition. We cannot, with a broad stroke, say that all women with a prior preterm birth, for instance, will respond to progestogens in a similar manner or are at the same level of risk of recurrent spontaneous preterm birth (sPTB).

The number of large, randomized clinical trials evaluating progestins is actually quite small but opinions abound about the data from these studies. Below, I have categorized these treatments according to my view at this time of the currently available data.

Consensus

One area in which there is agreement concerns the use of 17-OHPC intramuscular injections in multifetal gestations. Two randomized clinical trials undertaken by the MFMU Network – one in twins and one in triplets – concluded that 17-OHPC is ineffective in reducing the rate of preterm birth. Moreover, in another, more recent MFMU Network study, there was a negative linear relationship between concentrations of 17-OHPC and gestational age at delivery. Women with twin gestations who had higher concentrations of 17-OHPC delivered at earlier gestational ages than women with lower concentrations (Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012;207[5]:396.e1-8).

Other investigators have similarly shown in clinical trials that the preterm birth rate actually seems to be worsened in multifetal gestations when 17-OHPC is used. There is now widespread agreement that the compound should not be used in these patients.

In addition, an MFMU Network study led by William A. Grobman, MD, demonstrated that 17-OHPC (250-mg injections) does not provide any benefit to nulliparous women with a sonographic cervical length less than 30 mm (Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012;207[5]:390.e1-8). Other studies utilizing higher doses of 17-OHPC similarly found no benefit. There is also agreement that 17-OHPC has no benefit in treating women with preterm premature rupture of the membranes, preterm labor, or as a maintenance treatment after an episode of preterm labor.

General agreement without consensus

There is general agreement that women with a singleton gestation and a prior spontaneous preterm birth should be offered 17-OHPC, and that women with a singleton gestation and a midtrimester shortened cervical length should be offered vaginal progesterone and not 17-OHPC. However, even in these populations, there are questions about efficacy, dosing, and other issues.

In the Meis study (N Engl J Med. 2003;348:2379-85), treatment with 17-OHPC in women with a singleton gestation and a prior preterm delivery significantly reduced the risk of another preterm birth at less than 37 weeks’ gestation (36.3% in the progesterone group vs. 54.9% in the placebo group; relative risk, 0.66), at less than 35 weeks’ gestation (RR, 0.67), and at less than 32 weeks’ gestation (RR, 0.58). The exceptionally high rate of preterm delivery in the placebo group, however, prompted other investigators to express concern in published correspondence that the study was potentially flawed.

We reported an inverse relationship between 17-OHPC concentration and spontaneous preterm birth as part of a study conducted with the MFMU Network and the Obstetrical-Fetal Pharmacology Research Units Network. All women in the study had singleton gestations and received 250 mg weekly 17-OHPC (the broader study was designed to evaluate the benefit of omega-3 supplementation). We measured plasma concentrations of 17-OHPC and found that women with concentrations in the lowest quartile had a significantly higher risk of preterm birth and delivered at significantly earlier gestational ages than did women in the second through fourth quartiles (Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2014;210[2]:128.e1-6).

Other studies/abstracts similarly evaluating the relationship between 17-OHPC concentrations and preterm birth have reported mixed results, with both validation and refutation of our findings.

Research underway may help settle the controversy. In an ongoing, open-label pharmacology study being conducted by the Obstetrical-Fetal Pharmacology Research Units Network, women with singleton pregnancies and a history of prior preterm birth are being randomly assigned to receive either 250 mg (the empirically chosen, currently recommended dose) or 500 mg 17-OHPC. A relationship between the plasma concentration of 17-OHPC at 26-30 weeks’ gestation and the incidence of preterm birth would offer proof of efficacy and could help elucidate the therapeutic dosing; if there is no relationship, we revert to the question of whether the agent really works. Based on current evidence, both the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine (SMFM) and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) support the use of 17-OHPC for prevention of sPTB in women with a prior sPTB.

Questions about vaginal progesterone have also been somewhat unsettled. Eduardo B. Fonseca, MD, reported in 2007 that asymptomatic women with a short cervix (defined as 15 mm or less) who were randomized to receive vaginal progesterone at a median of 22 weeks’ gestation had a significantly lower rate of preterm birth before 34 weeks’ gestation than those who received placebo (RR, 0.56; N Engl J Med. 2007;357[5]:462-9). Research that followed offered mixed conclusions, with a study by Sonia S. Hassan, MD, showing benefit and a study by Jane E. Norman, MD, showing no benefit. Notably, in 2012, the Food and Drug Administration voted against approval of a sustained-release progesterone vaginal gel, citing research results that were not sufficiently compelling.

Still, vaginal progesterone has been endorsed by both ACOG and by the SMFM for women with a short cervical length in the midtrimester. This is supported by a new review and meta-analysis of individual patient data by Roberto Romero, MD, in which vaginal progesterone was found to significantly decrease the risk of preterm birth in singleton gestations with a midtrimester cervical length of 25 mm or less. The reduction occurred over a wide range of gestational ages, including at less than 33 weeks of gestation (RR, 0.62; Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018 Feb;218[2]:161-80).

Disagreement

Some have argued that vaginal progesterone should be offered to women with a history of prior spontaneous preterm birth, but the largest study to look at this application – a randomized multinational trial reported by John M. O’Brien, MD, and his colleagues in 2007 – found that use of the compound did not reduce the frequency of recurrent preterm birth at or before 32 weeks. Others have argued that vaginal progesterone is of benefit in this group of women based on a combination of multiple subgroup analyses. There is disagreement between ACOG and SMFM on this issue. ACOG supports the use of vaginal progesterone for women with a prior preterm birth but the SMFM strongly rejects this treatment and only endorses 17-OHPC for this indication.

Unresolved

The value of vaginal progesterone supplementation in reducing preterm births in women with twin gestations is under continuing investigation, including a study of women with twin gestation and a short cervix. This MFMU Network randomized trial, now underway, is evaluating the effectiveness of vaginal progesterone or pessary, compared with placebo, in preventing early preterm birth in women carrying twins who have a cervical length less than 30 mm.

Another question about the use of progesterone concerns the woman who delivered preterm during a twin gestation and is now pregnant with a singleton gestation. Should anything be offered to her? This is a question that has not yet been addressed in the literature.

What does seem clear is that spontaneous preterm birth is a multifactorial condition with numerous causes, and quite possibly an interaction between genetics, maternal characteristics, and the environment surrounding each pregnancy (Semin Perinatol. 2016;40[5]:273-80). Certainly, there are different pathways and mechanisms at play in patients who deliver at 35-36 weeks, for instance, compared with those who deliver at 25-26 weeks.

We recently obtained cervical fluid from pregnant women with prior preterm births and analyzed the samples for concentrations of cytokines and matrix metalloproteinases. Women with a prior early preterm delivery at less than 26 weeks had elevations in five cervical cytokines – an inflammatory signature, in essence – while those whose prior preterm birth occurred at a later gestational age had no elevations of these cytokines (Am J Perinatol. 2017 Nov 15. doi: 10.1055/s-0037-1608631).

Hopefully, we soon will be able to identify subpopulations of pregnant women who will benefit more from progesterone supplementation. More research needs to be done at a granular level, with more narrowly defined populations – and with consideration of various pharmacologic, genetic and environmental factors – in order to develop a more specific treatment approach. In the meantime, it is important to appreciate the unknowns that underlie the highly variable clinical responses and outcomes seen in our clinical trials.

Dr. Caritis is professor of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive sciences at Magee-Womens Hospital, University of Pittsburgh. He has no disclosures relevant to this Master Class.

In 2003, the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development’s Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units (MFMU) Network reported on a placebo-controlled randomized study of 17–alpha hydroxyprogesterone caproate (17-OHPC) in women with a history of spontaneous preterm delivery. The study demonstrated a 33% reduction in recurrent preterm birth after weekly treatment with 17-OHPC, which was initiated at 16-20 weeks of gestation.

This landmark study, led by Paul Meis, MD, validated what had been suggested in an earlier meta-analysis (1990) by Mark Keirse, MD – and it quickly altered clinical practice. It set into motion a string of studies on the use of 17-OHPC and other progestational compounds in women with a variety of conditions associated with an increased risk for preterm birth.

It is not surprising, then, that the literature has become muddied and full of contradictory findings since publication of the Meis study and the initial studies on vaginal progesterone in women with a midtrimester short cervix. Further confounding our ability to judge a treatment’s effectiveness is the fact that spontaneous preterm birth is increasingly understood to be a multifactorial, highly heterogeneous condition. We cannot, with a broad stroke, say that all women with a prior preterm birth, for instance, will respond to progestogens in a similar manner or are at the same level of risk of recurrent spontaneous preterm birth (sPTB).

The number of large, randomized clinical trials evaluating progestins is actually quite small but opinions abound about the data from these studies. Below, I have categorized these treatments according to my view at this time of the currently available data.

Consensus

One area in which there is agreement concerns the use of 17-OHPC intramuscular injections in multifetal gestations. Two randomized clinical trials undertaken by the MFMU Network – one in twins and one in triplets – concluded that 17-OHPC is ineffective in reducing the rate of preterm birth. Moreover, in another, more recent MFMU Network study, there was a negative linear relationship between concentrations of 17-OHPC and gestational age at delivery. Women with twin gestations who had higher concentrations of 17-OHPC delivered at earlier gestational ages than women with lower concentrations (Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012;207[5]:396.e1-8).

Other investigators have similarly shown in clinical trials that the preterm birth rate actually seems to be worsened in multifetal gestations when 17-OHPC is used. There is now widespread agreement that the compound should not be used in these patients.

In addition, an MFMU Network study led by William A. Grobman, MD, demonstrated that 17-OHPC (250-mg injections) does not provide any benefit to nulliparous women with a sonographic cervical length less than 30 mm (Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012;207[5]:390.e1-8). Other studies utilizing higher doses of 17-OHPC similarly found no benefit. There is also agreement that 17-OHPC has no benefit in treating women with preterm premature rupture of the membranes, preterm labor, or as a maintenance treatment after an episode of preterm labor.

General agreement without consensus

There is general agreement that women with a singleton gestation and a prior spontaneous preterm birth should be offered 17-OHPC, and that women with a singleton gestation and a midtrimester shortened cervical length should be offered vaginal progesterone and not 17-OHPC. However, even in these populations, there are questions about efficacy, dosing, and other issues.