User login

Malpractice Counsel: Don’t Miss Popeye

A 42-year-old man presented to the ED with left arm pain secondary to an injury he sustained at work. The patient stated that he had been helping to lift a heavy steel beam at a construction site when he experienced abrupt onset of pain in his left arm. He further noted that his left arm felt slightly weaker than normal after the injury.

The patient was left-hand dominant, denied any other injury, was otherwise in good health, and on no medications. With the exception of an appendectomy at age 12 years, his medical history was unremarkable. Regarding his social history, he admitted to smoking one pack of cigarettes per day, and to occasional alcohol consumption. He had no known drug allergies.

On physical examination, the patient’s vital signs were: blood pressure, 125/76 mm Hg; heart rate, 78 beats/min; respiratory rate, 16 breaths/min; and temperature, 98.6°F. Oxygen saturation was 99% on room air.

Examination of the patient’s left shoulder revealed no swelling or tenderness; he was able to fully internally/externally rotate the left shoulder, and lift his left hand above his head. The patient did have tenderness along the biceps area of the left arm, but no tenderness in the triceps area. The left elbow was tender in the antecubital fossa, but without swelling. He had full range of motion of the left elbow but with some pain. He likewise had full range of motion in his left wrist, but no tenderness or swelling. The left radial pulse was 2+. The patient had 5/5 grip strength with the left hand and good capillary refill.

The physician assistant (PA) evaluating the patient diagnosed an arm strain. At discharge, he referred the patient to an occupational health physician (OHP) for follow-up. He also instructed the patient to take ibuprofen 400 mg every 6 to 8 hours, and to limit use of his left arm for 3 days.

The patient followed up with the OHP approximately 3 weeks after discharge from the ED. The OHP was concerned the patient had experienced a distal biceps tendon rupture and referred the patient emergently to an orthopedic surgeon. The orthopedic surgeon saw the patient the next day, agreed with the diagnosis of a distal biceps tendon rupture, and attempted surgical repair the following day. The orthopedic surgeon informed the patient prior to the surgery that the delay in the referral and surgery could result in a poor functional outcome. The patient did have a difficult recovery period, and a second surgery was required, which did not result in any significant functional improvement.

The plaintiff sued the treating PA and supervising emergency physician (EP) for failure to properly diagnose the biceps tendon rupture, failure to appreciate the existence of a 3-week window of opportunity to repair the distal biceps tendon rupture, and failure to obtain an urgent orthopedic referral. The experts for the defense argued that the poor outcome was not a consequence of any delay in diagnosis or surgical repair. In addition, the defense disputed the existence of a 3-week window of opportunity for successful repair of a distal biceps tendon rupture. The jury returned a defense verdict.

Discussion

Proximal and Distal Biceps Tendon Ruptures

While both proximal and distal biceps tendon ruptures involve the biceps brachii, they are managed differently and have the potential for very different outcomes.1 At its proximal attachment, the biceps has two distinct tendinous insertions—the long head and the short head. For the distal attachment, the two muscle bellies unite at the midshaft of the humerus and attach as a single tendon on the radial tuberosity. In general, 96% of biceps tendon ruptures involve the long head, 1% involve the short head, and only 3% involve the distal tendon.1 Biceps tendon ruptures occur more commonly in men, patients who use anabolic steroids, cigarette smokers, patient history of tendinopathy, or patients who have a rotator cuff tear.1 Biceps tendon ruptures have not been found to be associated with statin use.2 The mechanism of injury includes heavy-lifting activities, such as weight lifting and rock climbing. However, when associated with a tendinopathy, minimal force may be involved.1

Signs and Symptoms

For proximal biceps tendon rupture, patients usually present with an acute or gradual onset of pain, swelling, and bruising of the upper arm and shoulder. Occasionally, if there is an inciting event, the patient may describe hearing or feeling a “popping” or “snapping” sound. On physical examination, the patient may exhibit a “Popeye” sign—a bulge in the distal biceps area due to the retracted biceps muscle belly. There is also tenderness along the biceps.

On testing, it has been estimated that patients can experience strength loss of approximately 30% with elbow flexion.1 In contrast, patients with distal biceps tendon ruptures usually complain of pain, swelling, and possibly bruising in the antecubital fossa, as was the case with this patient. Similar to proximal ruptures, the patient may admit to hearing or feeling a “popping” sound if there is an inciting event. The patient may exhibit a “reverse Popeye” deformity, with a bulge in the proximal arm secondary to retraction of the biceps muscle belly proximally.1

Diagnosis

There are two tests that can be performed to assist in making the diagnosis—the biceps squeeze test and the hook test.

Biceps Squeeze Test. The first test to assess for distal biceps tendon rupture is the biceps squeeze test, in which the clinician forcefully squeezes the patient’s biceps muscle to observe for forearm flexion/supination. This test is similar in principle to the Thompson test for Achilles tendon rupture. If there is no forearm movement, the injury is suspicious for a complete distal biceps tendon rupture. In one observational study of this test, 21 of 22 patients with a positive biceps squeeze test were found to have a complete distal biceps tendon tear at surgery.3

Hook Test. The second test is the hook test. While the patient actively supinates with the elbow flexed at 900, an intact hook test permits the examiner to “hook” his or her index finger under the intact biceps tendon from the lateral side. The absence of a “hook” means that there is no cord-like structure under which the examiner can hook a finger, indicating distal avulsion.4 In one study comparing the hook test to magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) in 33 patients with this suspected injury, the hook test had 100% sensitivity and specificity, while MRI only demonstrated a 92% sensitivity and 85% specificity.4

Imaging Techniques

The need for diagnostic imaging is based somewhat on the location of the rupture—proximal or distal. Ultrasound has been shown to have a high sensitivity and specificity for identifying normal tendons and complete tears of the long head biceps tendon (ie, proximal). It is not sensitive at identifying proximal partial tears, however. For distal ruptures, ultrasound imaging of the distal biceps tendon is technically difficult and not reliable. For patients with suspected distal biceps tendon ruptures, the EP should consult with orthopedic services prior to ordering an MRI. While MRI is considered the gold standard imaging test, it is neither 100% sensitive nor specific. The bottom line is that the absence of pathologic findings on MRI is not sufficient enough to exclude biceps tendon pathology.5

Treatment and Management

Regarding management, the majority of patients with proximal biceps tendon ruptures tend to do well with conservative management. The exception is for younger, active patients who are less willing to accept the cosmetic deformity, or patients whose occupation makes them unable to tolerate minimal weakness or fatigue cramping (eg, carpenters), in which case referral for a surgical repair (tenodesis) may be appropriate.1 However, multiple systematic reviews examining tenotomy vs tenodesis have not shown any functional improvement, only cosmetic.1,6,7

Distal biceps tendon ruptures are usually treated surgically, since conservative management results in a decrease of 30% to 50% supination strength and 20% flexion strength.1,8 This surgery, however, is not without complications. Approximately 20% of the patients will have a minor complication and 5% will have major complications following surgery on the distal biceps tendon.9 It is preferable to operate on distal ruptures less than 4 weeks from the initial injury; otherwise, these injuries may be more difficult to fix, require a graft, and have less predictable outcomes.1 Nonoperative management should be reserved for the elderly or less active patients with multiple comorbidities, especially if the nondominant arm is involved.10

Summary

The PA clearly missed the correct diagnosis on this patient. A more thorough history and focused physical examination would have led to the correct diagnosis sooner, along with earlier surgical repair. It is impossible, however, to know if the outcome would have been any different in this uncommon injury.

1. Smith D. Proximal versus distal biceps tendon ruptures: when to refer. BCMJ. 2017;59(2):85.

2. Spoendlin J, Layton JB, Mundkur M, Meier C, Jick SS, Meier CR. The risk of achilles or biceps tendon rupture in new statin users: a propensity score-matched sequential cohort study. Drug Safety. 2016;39(12):1229-1237. doi:10.1007/s40264-016-0462-5.

3. Ruland RT, Dunbar RP, Bowen JD. The biceps squeeze test for diagnosis of distal biceps tendon ruptures. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2005;437:128-131.

4. O’Driscoll SW, Goncalves LBJ, Dietz P. The hook test for distal biceps tendon avulsion. Am J Sports Med. 2007;35(11):1865-1969. doi:10.1177/0363546507305016.

5. Malavolta EA, Assunção JH, Guglielmetti CL, de Souza FF, Gracitelli ME, Ferreira Neto AA. Accuracy of preoperative MRI in the diagnosis of disorders of the long head of the biceps tendon. Eur J Radiol. 2015;84(11):2250-2254. doi:10.1016/j.ejrad.2015.07.031.

6. Tangari M, Carbone S, Gallo M, Campi A. Long head of the biceps tendon rupture in professional wrestlers: treatment with a mini-open tenodesis. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2011;20(3):409-413. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2010.08.008.

7. Eakin JL, Bailey JR, Dewing CB, Provencher MT. Subpectoral biceps tenodesis. Oper Tech Sports Med. 2012;20(3):244-252.

8. Thomas JR, Lawton JN. Biceps and triceps ruptures in athletes. Hand Clin. 2017;33(1):35-46. doi:10.1016/j.hcl.2016.08.019.

9. Beks RB, Claessen FM, Oh LS, Ring D, Chen NC. Factors associated with adverse events after distal biceps tendon repair or reconstruction. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2016;25(8):1229-1234. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2016.02.032.

10. Savin DD, Watson J, Youderian AR, et al. Surgical management of acute distal biceps tendon ruptures. J Bone Joint Surg. 2017;3(9):785-796. doi:0.2106/JBJS.17.00080.

A 42-year-old man presented to the ED with left arm pain secondary to an injury he sustained at work. The patient stated that he had been helping to lift a heavy steel beam at a construction site when he experienced abrupt onset of pain in his left arm. He further noted that his left arm felt slightly weaker than normal after the injury.

The patient was left-hand dominant, denied any other injury, was otherwise in good health, and on no medications. With the exception of an appendectomy at age 12 years, his medical history was unremarkable. Regarding his social history, he admitted to smoking one pack of cigarettes per day, and to occasional alcohol consumption. He had no known drug allergies.

On physical examination, the patient’s vital signs were: blood pressure, 125/76 mm Hg; heart rate, 78 beats/min; respiratory rate, 16 breaths/min; and temperature, 98.6°F. Oxygen saturation was 99% on room air.

Examination of the patient’s left shoulder revealed no swelling or tenderness; he was able to fully internally/externally rotate the left shoulder, and lift his left hand above his head. The patient did have tenderness along the biceps area of the left arm, but no tenderness in the triceps area. The left elbow was tender in the antecubital fossa, but without swelling. He had full range of motion of the left elbow but with some pain. He likewise had full range of motion in his left wrist, but no tenderness or swelling. The left radial pulse was 2+. The patient had 5/5 grip strength with the left hand and good capillary refill.

The physician assistant (PA) evaluating the patient diagnosed an arm strain. At discharge, he referred the patient to an occupational health physician (OHP) for follow-up. He also instructed the patient to take ibuprofen 400 mg every 6 to 8 hours, and to limit use of his left arm for 3 days.

The patient followed up with the OHP approximately 3 weeks after discharge from the ED. The OHP was concerned the patient had experienced a distal biceps tendon rupture and referred the patient emergently to an orthopedic surgeon. The orthopedic surgeon saw the patient the next day, agreed with the diagnosis of a distal biceps tendon rupture, and attempted surgical repair the following day. The orthopedic surgeon informed the patient prior to the surgery that the delay in the referral and surgery could result in a poor functional outcome. The patient did have a difficult recovery period, and a second surgery was required, which did not result in any significant functional improvement.

The plaintiff sued the treating PA and supervising emergency physician (EP) for failure to properly diagnose the biceps tendon rupture, failure to appreciate the existence of a 3-week window of opportunity to repair the distal biceps tendon rupture, and failure to obtain an urgent orthopedic referral. The experts for the defense argued that the poor outcome was not a consequence of any delay in diagnosis or surgical repair. In addition, the defense disputed the existence of a 3-week window of opportunity for successful repair of a distal biceps tendon rupture. The jury returned a defense verdict.

Discussion

Proximal and Distal Biceps Tendon Ruptures

While both proximal and distal biceps tendon ruptures involve the biceps brachii, they are managed differently and have the potential for very different outcomes.1 At its proximal attachment, the biceps has two distinct tendinous insertions—the long head and the short head. For the distal attachment, the two muscle bellies unite at the midshaft of the humerus and attach as a single tendon on the radial tuberosity. In general, 96% of biceps tendon ruptures involve the long head, 1% involve the short head, and only 3% involve the distal tendon.1 Biceps tendon ruptures occur more commonly in men, patients who use anabolic steroids, cigarette smokers, patient history of tendinopathy, or patients who have a rotator cuff tear.1 Biceps tendon ruptures have not been found to be associated with statin use.2 The mechanism of injury includes heavy-lifting activities, such as weight lifting and rock climbing. However, when associated with a tendinopathy, minimal force may be involved.1

Signs and Symptoms

For proximal biceps tendon rupture, patients usually present with an acute or gradual onset of pain, swelling, and bruising of the upper arm and shoulder. Occasionally, if there is an inciting event, the patient may describe hearing or feeling a “popping” or “snapping” sound. On physical examination, the patient may exhibit a “Popeye” sign—a bulge in the distal biceps area due to the retracted biceps muscle belly. There is also tenderness along the biceps.

On testing, it has been estimated that patients can experience strength loss of approximately 30% with elbow flexion.1 In contrast, patients with distal biceps tendon ruptures usually complain of pain, swelling, and possibly bruising in the antecubital fossa, as was the case with this patient. Similar to proximal ruptures, the patient may admit to hearing or feeling a “popping” sound if there is an inciting event. The patient may exhibit a “reverse Popeye” deformity, with a bulge in the proximal arm secondary to retraction of the biceps muscle belly proximally.1

Diagnosis

There are two tests that can be performed to assist in making the diagnosis—the biceps squeeze test and the hook test.

Biceps Squeeze Test. The first test to assess for distal biceps tendon rupture is the biceps squeeze test, in which the clinician forcefully squeezes the patient’s biceps muscle to observe for forearm flexion/supination. This test is similar in principle to the Thompson test for Achilles tendon rupture. If there is no forearm movement, the injury is suspicious for a complete distal biceps tendon rupture. In one observational study of this test, 21 of 22 patients with a positive biceps squeeze test were found to have a complete distal biceps tendon tear at surgery.3

Hook Test. The second test is the hook test. While the patient actively supinates with the elbow flexed at 900, an intact hook test permits the examiner to “hook” his or her index finger under the intact biceps tendon from the lateral side. The absence of a “hook” means that there is no cord-like structure under which the examiner can hook a finger, indicating distal avulsion.4 In one study comparing the hook test to magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) in 33 patients with this suspected injury, the hook test had 100% sensitivity and specificity, while MRI only demonstrated a 92% sensitivity and 85% specificity.4

Imaging Techniques

The need for diagnostic imaging is based somewhat on the location of the rupture—proximal or distal. Ultrasound has been shown to have a high sensitivity and specificity for identifying normal tendons and complete tears of the long head biceps tendon (ie, proximal). It is not sensitive at identifying proximal partial tears, however. For distal ruptures, ultrasound imaging of the distal biceps tendon is technically difficult and not reliable. For patients with suspected distal biceps tendon ruptures, the EP should consult with orthopedic services prior to ordering an MRI. While MRI is considered the gold standard imaging test, it is neither 100% sensitive nor specific. The bottom line is that the absence of pathologic findings on MRI is not sufficient enough to exclude biceps tendon pathology.5

Treatment and Management

Regarding management, the majority of patients with proximal biceps tendon ruptures tend to do well with conservative management. The exception is for younger, active patients who are less willing to accept the cosmetic deformity, or patients whose occupation makes them unable to tolerate minimal weakness or fatigue cramping (eg, carpenters), in which case referral for a surgical repair (tenodesis) may be appropriate.1 However, multiple systematic reviews examining tenotomy vs tenodesis have not shown any functional improvement, only cosmetic.1,6,7

Distal biceps tendon ruptures are usually treated surgically, since conservative management results in a decrease of 30% to 50% supination strength and 20% flexion strength.1,8 This surgery, however, is not without complications. Approximately 20% of the patients will have a minor complication and 5% will have major complications following surgery on the distal biceps tendon.9 It is preferable to operate on distal ruptures less than 4 weeks from the initial injury; otherwise, these injuries may be more difficult to fix, require a graft, and have less predictable outcomes.1 Nonoperative management should be reserved for the elderly or less active patients with multiple comorbidities, especially if the nondominant arm is involved.10

Summary

The PA clearly missed the correct diagnosis on this patient. A more thorough history and focused physical examination would have led to the correct diagnosis sooner, along with earlier surgical repair. It is impossible, however, to know if the outcome would have been any different in this uncommon injury.

A 42-year-old man presented to the ED with left arm pain secondary to an injury he sustained at work. The patient stated that he had been helping to lift a heavy steel beam at a construction site when he experienced abrupt onset of pain in his left arm. He further noted that his left arm felt slightly weaker than normal after the injury.

The patient was left-hand dominant, denied any other injury, was otherwise in good health, and on no medications. With the exception of an appendectomy at age 12 years, his medical history was unremarkable. Regarding his social history, he admitted to smoking one pack of cigarettes per day, and to occasional alcohol consumption. He had no known drug allergies.

On physical examination, the patient’s vital signs were: blood pressure, 125/76 mm Hg; heart rate, 78 beats/min; respiratory rate, 16 breaths/min; and temperature, 98.6°F. Oxygen saturation was 99% on room air.

Examination of the patient’s left shoulder revealed no swelling or tenderness; he was able to fully internally/externally rotate the left shoulder, and lift his left hand above his head. The patient did have tenderness along the biceps area of the left arm, but no tenderness in the triceps area. The left elbow was tender in the antecubital fossa, but without swelling. He had full range of motion of the left elbow but with some pain. He likewise had full range of motion in his left wrist, but no tenderness or swelling. The left radial pulse was 2+. The patient had 5/5 grip strength with the left hand and good capillary refill.

The physician assistant (PA) evaluating the patient diagnosed an arm strain. At discharge, he referred the patient to an occupational health physician (OHP) for follow-up. He also instructed the patient to take ibuprofen 400 mg every 6 to 8 hours, and to limit use of his left arm for 3 days.

The patient followed up with the OHP approximately 3 weeks after discharge from the ED. The OHP was concerned the patient had experienced a distal biceps tendon rupture and referred the patient emergently to an orthopedic surgeon. The orthopedic surgeon saw the patient the next day, agreed with the diagnosis of a distal biceps tendon rupture, and attempted surgical repair the following day. The orthopedic surgeon informed the patient prior to the surgery that the delay in the referral and surgery could result in a poor functional outcome. The patient did have a difficult recovery period, and a second surgery was required, which did not result in any significant functional improvement.

The plaintiff sued the treating PA and supervising emergency physician (EP) for failure to properly diagnose the biceps tendon rupture, failure to appreciate the existence of a 3-week window of opportunity to repair the distal biceps tendon rupture, and failure to obtain an urgent orthopedic referral. The experts for the defense argued that the poor outcome was not a consequence of any delay in diagnosis or surgical repair. In addition, the defense disputed the existence of a 3-week window of opportunity for successful repair of a distal biceps tendon rupture. The jury returned a defense verdict.

Discussion

Proximal and Distal Biceps Tendon Ruptures

While both proximal and distal biceps tendon ruptures involve the biceps brachii, they are managed differently and have the potential for very different outcomes.1 At its proximal attachment, the biceps has two distinct tendinous insertions—the long head and the short head. For the distal attachment, the two muscle bellies unite at the midshaft of the humerus and attach as a single tendon on the radial tuberosity. In general, 96% of biceps tendon ruptures involve the long head, 1% involve the short head, and only 3% involve the distal tendon.1 Biceps tendon ruptures occur more commonly in men, patients who use anabolic steroids, cigarette smokers, patient history of tendinopathy, or patients who have a rotator cuff tear.1 Biceps tendon ruptures have not been found to be associated with statin use.2 The mechanism of injury includes heavy-lifting activities, such as weight lifting and rock climbing. However, when associated with a tendinopathy, minimal force may be involved.1

Signs and Symptoms

For proximal biceps tendon rupture, patients usually present with an acute or gradual onset of pain, swelling, and bruising of the upper arm and shoulder. Occasionally, if there is an inciting event, the patient may describe hearing or feeling a “popping” or “snapping” sound. On physical examination, the patient may exhibit a “Popeye” sign—a bulge in the distal biceps area due to the retracted biceps muscle belly. There is also tenderness along the biceps.

On testing, it has been estimated that patients can experience strength loss of approximately 30% with elbow flexion.1 In contrast, patients with distal biceps tendon ruptures usually complain of pain, swelling, and possibly bruising in the antecubital fossa, as was the case with this patient. Similar to proximal ruptures, the patient may admit to hearing or feeling a “popping” sound if there is an inciting event. The patient may exhibit a “reverse Popeye” deformity, with a bulge in the proximal arm secondary to retraction of the biceps muscle belly proximally.1

Diagnosis

There are two tests that can be performed to assist in making the diagnosis—the biceps squeeze test and the hook test.

Biceps Squeeze Test. The first test to assess for distal biceps tendon rupture is the biceps squeeze test, in which the clinician forcefully squeezes the patient’s biceps muscle to observe for forearm flexion/supination. This test is similar in principle to the Thompson test for Achilles tendon rupture. If there is no forearm movement, the injury is suspicious for a complete distal biceps tendon rupture. In one observational study of this test, 21 of 22 patients with a positive biceps squeeze test were found to have a complete distal biceps tendon tear at surgery.3

Hook Test. The second test is the hook test. While the patient actively supinates with the elbow flexed at 900, an intact hook test permits the examiner to “hook” his or her index finger under the intact biceps tendon from the lateral side. The absence of a “hook” means that there is no cord-like structure under which the examiner can hook a finger, indicating distal avulsion.4 In one study comparing the hook test to magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) in 33 patients with this suspected injury, the hook test had 100% sensitivity and specificity, while MRI only demonstrated a 92% sensitivity and 85% specificity.4

Imaging Techniques

The need for diagnostic imaging is based somewhat on the location of the rupture—proximal or distal. Ultrasound has been shown to have a high sensitivity and specificity for identifying normal tendons and complete tears of the long head biceps tendon (ie, proximal). It is not sensitive at identifying proximal partial tears, however. For distal ruptures, ultrasound imaging of the distal biceps tendon is technically difficult and not reliable. For patients with suspected distal biceps tendon ruptures, the EP should consult with orthopedic services prior to ordering an MRI. While MRI is considered the gold standard imaging test, it is neither 100% sensitive nor specific. The bottom line is that the absence of pathologic findings on MRI is not sufficient enough to exclude biceps tendon pathology.5

Treatment and Management

Regarding management, the majority of patients with proximal biceps tendon ruptures tend to do well with conservative management. The exception is for younger, active patients who are less willing to accept the cosmetic deformity, or patients whose occupation makes them unable to tolerate minimal weakness or fatigue cramping (eg, carpenters), in which case referral for a surgical repair (tenodesis) may be appropriate.1 However, multiple systematic reviews examining tenotomy vs tenodesis have not shown any functional improvement, only cosmetic.1,6,7

Distal biceps tendon ruptures are usually treated surgically, since conservative management results in a decrease of 30% to 50% supination strength and 20% flexion strength.1,8 This surgery, however, is not without complications. Approximately 20% of the patients will have a minor complication and 5% will have major complications following surgery on the distal biceps tendon.9 It is preferable to operate on distal ruptures less than 4 weeks from the initial injury; otherwise, these injuries may be more difficult to fix, require a graft, and have less predictable outcomes.1 Nonoperative management should be reserved for the elderly or less active patients with multiple comorbidities, especially if the nondominant arm is involved.10

Summary

The PA clearly missed the correct diagnosis on this patient. A more thorough history and focused physical examination would have led to the correct diagnosis sooner, along with earlier surgical repair. It is impossible, however, to know if the outcome would have been any different in this uncommon injury.

1. Smith D. Proximal versus distal biceps tendon ruptures: when to refer. BCMJ. 2017;59(2):85.

2. Spoendlin J, Layton JB, Mundkur M, Meier C, Jick SS, Meier CR. The risk of achilles or biceps tendon rupture in new statin users: a propensity score-matched sequential cohort study. Drug Safety. 2016;39(12):1229-1237. doi:10.1007/s40264-016-0462-5.

3. Ruland RT, Dunbar RP, Bowen JD. The biceps squeeze test for diagnosis of distal biceps tendon ruptures. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2005;437:128-131.

4. O’Driscoll SW, Goncalves LBJ, Dietz P. The hook test for distal biceps tendon avulsion. Am J Sports Med. 2007;35(11):1865-1969. doi:10.1177/0363546507305016.

5. Malavolta EA, Assunção JH, Guglielmetti CL, de Souza FF, Gracitelli ME, Ferreira Neto AA. Accuracy of preoperative MRI in the diagnosis of disorders of the long head of the biceps tendon. Eur J Radiol. 2015;84(11):2250-2254. doi:10.1016/j.ejrad.2015.07.031.

6. Tangari M, Carbone S, Gallo M, Campi A. Long head of the biceps tendon rupture in professional wrestlers: treatment with a mini-open tenodesis. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2011;20(3):409-413. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2010.08.008.

7. Eakin JL, Bailey JR, Dewing CB, Provencher MT. Subpectoral biceps tenodesis. Oper Tech Sports Med. 2012;20(3):244-252.

8. Thomas JR, Lawton JN. Biceps and triceps ruptures in athletes. Hand Clin. 2017;33(1):35-46. doi:10.1016/j.hcl.2016.08.019.

9. Beks RB, Claessen FM, Oh LS, Ring D, Chen NC. Factors associated with adverse events after distal biceps tendon repair or reconstruction. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2016;25(8):1229-1234. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2016.02.032.

10. Savin DD, Watson J, Youderian AR, et al. Surgical management of acute distal biceps tendon ruptures. J Bone Joint Surg. 2017;3(9):785-796. doi:0.2106/JBJS.17.00080.

1. Smith D. Proximal versus distal biceps tendon ruptures: when to refer. BCMJ. 2017;59(2):85.

2. Spoendlin J, Layton JB, Mundkur M, Meier C, Jick SS, Meier CR. The risk of achilles or biceps tendon rupture in new statin users: a propensity score-matched sequential cohort study. Drug Safety. 2016;39(12):1229-1237. doi:10.1007/s40264-016-0462-5.

3. Ruland RT, Dunbar RP, Bowen JD. The biceps squeeze test for diagnosis of distal biceps tendon ruptures. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2005;437:128-131.

4. O’Driscoll SW, Goncalves LBJ, Dietz P. The hook test for distal biceps tendon avulsion. Am J Sports Med. 2007;35(11):1865-1969. doi:10.1177/0363546507305016.

5. Malavolta EA, Assunção JH, Guglielmetti CL, de Souza FF, Gracitelli ME, Ferreira Neto AA. Accuracy of preoperative MRI in the diagnosis of disorders of the long head of the biceps tendon. Eur J Radiol. 2015;84(11):2250-2254. doi:10.1016/j.ejrad.2015.07.031.

6. Tangari M, Carbone S, Gallo M, Campi A. Long head of the biceps tendon rupture in professional wrestlers: treatment with a mini-open tenodesis. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2011;20(3):409-413. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2010.08.008.

7. Eakin JL, Bailey JR, Dewing CB, Provencher MT. Subpectoral biceps tenodesis. Oper Tech Sports Med. 2012;20(3):244-252.

8. Thomas JR, Lawton JN. Biceps and triceps ruptures in athletes. Hand Clin. 2017;33(1):35-46. doi:10.1016/j.hcl.2016.08.019.

9. Beks RB, Claessen FM, Oh LS, Ring D, Chen NC. Factors associated with adverse events after distal biceps tendon repair or reconstruction. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2016;25(8):1229-1234. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2016.02.032.

10. Savin DD, Watson J, Youderian AR, et al. Surgical management of acute distal biceps tendon ruptures. J Bone Joint Surg. 2017;3(9):785-796. doi:0.2106/JBJS.17.00080.

What Are You Worth? The Basics of Business in Health Care

Dana, an adult nurse practitioner, has been working for two years at a large, suburban primary care practice owned by the regional hospital system. She sees too many patients per day, never has enough time to chart properly, and is concerned by the expanding role of the medical assistants. She sees salary postings on social media and feels she is underpaid. She fantasizes about owning her own practice but would settle for making more money. She’s heard that some NPs have profit-sharing, but she’s not exactly sure what that means.

Kelsey, a PA, is looking for his first job out of school. He’s been offered a full-time, salaried position with benefits at an urgent care center, but he doesn’t know if this is a good deal for him or not. The family physicians there make $85,000 more per year than the PAs, although the roles are quite similar.

DOWN TO BUSINESS

The US health care crisis is, fundamentally, a financial crisis; our system is comprised of both for-profit and not-for-profit (NFP) businesses. Every day, NPs and PAs are making decisions that affect their job satisfaction, performance, and retention. Many lack confidence in their ability to make good decisions about their salaries, because they don’t understand the business of health care.1 To survive and thrive, NPs and PAs must understand the basics of the business end.2

So, what qualifies as a business? Any commercial, retail, or professional entity that earns and spends money. It doesn’t matter if it is a for-profit or NFP organization; it can’t survive unless it makes more money than it spends. How that money is earned varies, from selling services and/or goods to receiving grants, income from interest or rentals, or government subsidies.

The major difference between a for-profit and a NFP organization is who controls the money.3 The owners of a for-profit company control the profits, which may be split among the owners or reinvested in the company. A NFP business may use its profits to provide charity care, offset losses of other programs, or invest in capital improvements (eg, new building, equipment). How the profits are to be used is outlined in the business goals or the mission statement of the entity. There are also federal and state regulations for both types of businesses; visit the Internal Revenue Service website for details (www.irs.gov/charities-non-profits; www.irs.gov/businesses/small-businesses-self-employed).

HOW YOU GET PAID FOR SERVICES

As a PA or NP, you generate income for your employer regardless of whether you work for a for-profit or NFP business. Your patients are billed for services rendered.

If you work for a fee-for-service or NFP practice with insurance contracts, the bill gets coded and electronically submitted for payment. Each insurer, whether private or government (ie, Medicare or Medicaid), has established what they will reimburse you for that service. The reimbursement rate is part of your contract with that insurer. Rates are determined based on your profession, licensure, geographic locale, type of facility, and the market rate. An insurance representative would be able to tell you your reimbursement rate for the most common procedure codes you use. (Your employer has this information but may or may not share it with you.) Medicare rates can be found online at www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/PhysicianFeeSched/.

If you work for a direct-pay practice, you collect what you bill directly from the patient, often at the time of the visit. A direct-pay practice does not have insurance contracts and does not bill insurers for patients who have insurance; rather, they provide a billing statement with procedure and diagnostic codes and NPI numbers to the patient, who can submit it directly to their insurer. If the insurer accepts out-of-network providers (those with whom they have no contract), they will reimburse the patient directly.

If you work in a fee-for-service or NFP practice, you may see patients who do not have insurance or who have very high deductibles and pay cash for their services. This does not make it a direct-pay practice. Also, by law, fee-for-service and NFP practices can only have one fee schedule for the entire practice. So, you can’t charge one patient $55 for a flu shot and another patient $25. These practices can offer discounts for cash payments at the time of service, to help reduce the set fees, if they choose.

TALKIN’ ’BOUT YOUR (REVENUE) GENERATION

To know how much you can negotiate for your salary and benefits—your total compensation package (of which benefits is often about 30%)—it is critical to know how much revenue you can generate for your employer.4 How can you figure this out?

If you are already working, you can ask your practice manager for some data. In some practices, this information is readily shared, perhaps as a means to boost productivity and even allow comparison between employees. If your practice manager is not forthcoming, you can collect the relevant information yourself. It may be challenging, but it is vital information to have. You need to know how many patients you see per day (keep a log for a month), what their payment source is (specific insurer or self-pay), and what the reimbursement rates are. Although reimbursement rates are deemed confidential per your insurance contract and therefore can’t be shared, you can find Medicare and Medicaid rates online. You can also call the provider representative from each insurer and ask for your reimbursement rates for your five or so most commonly used codes.

Another consideration is payment received (ie, not just what you charge). Do all patients pay everything they owe? Not always. Understand the difference between what you bill, what is allowed, and what you collect. The percentage of what is not collected is called the uncollectable rate. Factor that in.

Furthermore, how much do you contribute to the organization by testing? Dana works for a primary care clinic within a hospital system. Let’s assume her practice doesn’t offer colonoscopies or mammograms; how many referrals does she make to the hospital system for these tests? While she may not know the hospital’s profit margin on them, she can figure out how many she orders in a year. And what about the PA who works for a surgeon? Does he or she do the post-surgical checks? How much time does that save the surgeon, who can be providing higher revenue–producing services with the time saved? That contributes to the income of the practice, too! These are points you can make to justify your salary.

MIX IT UP

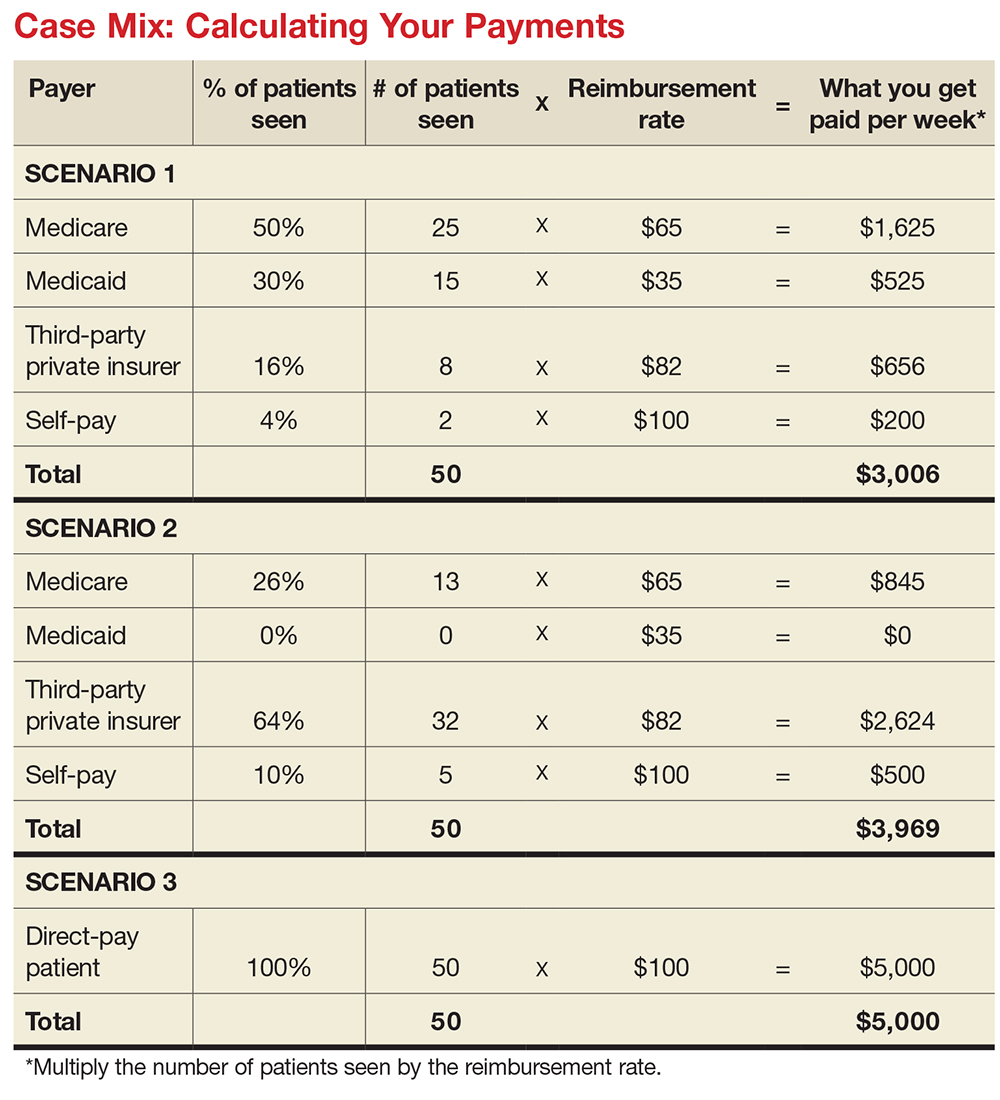

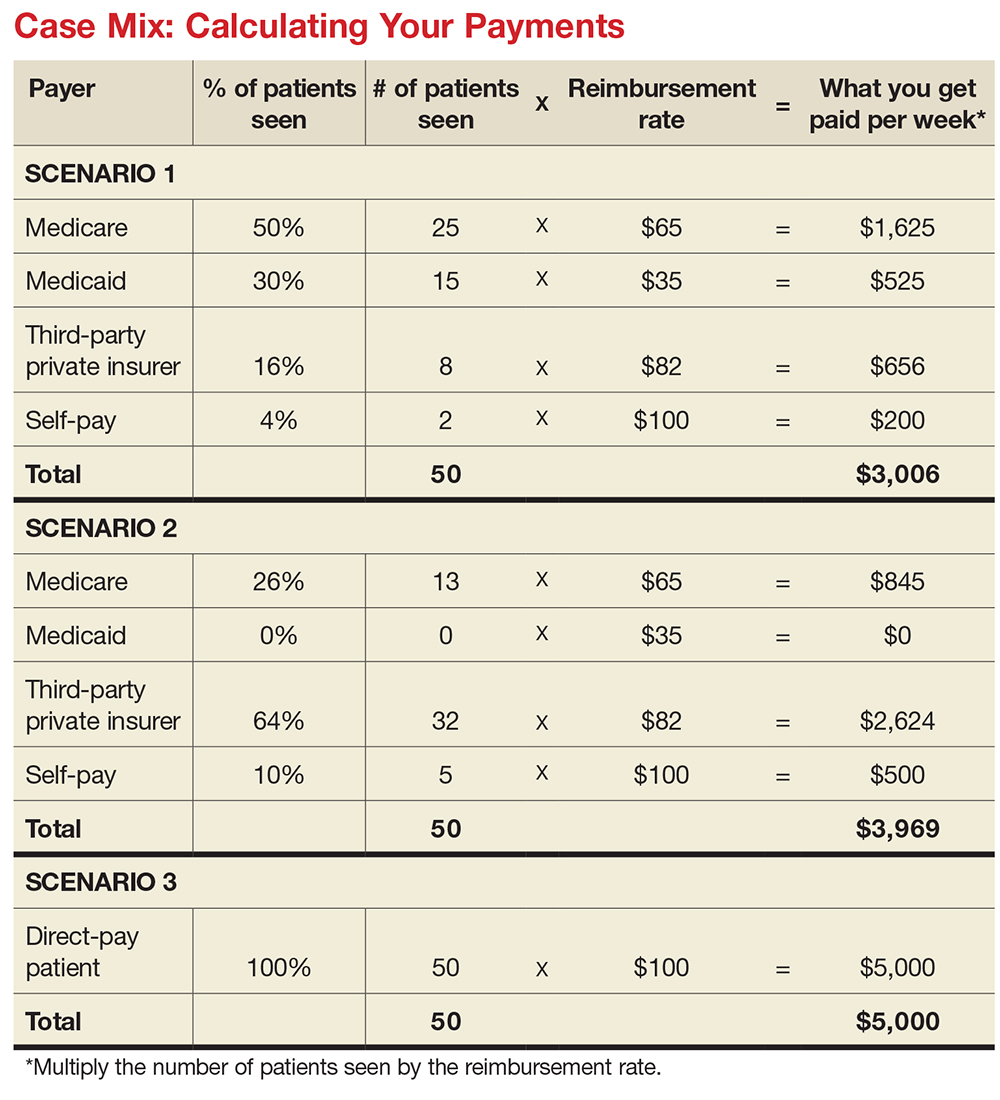

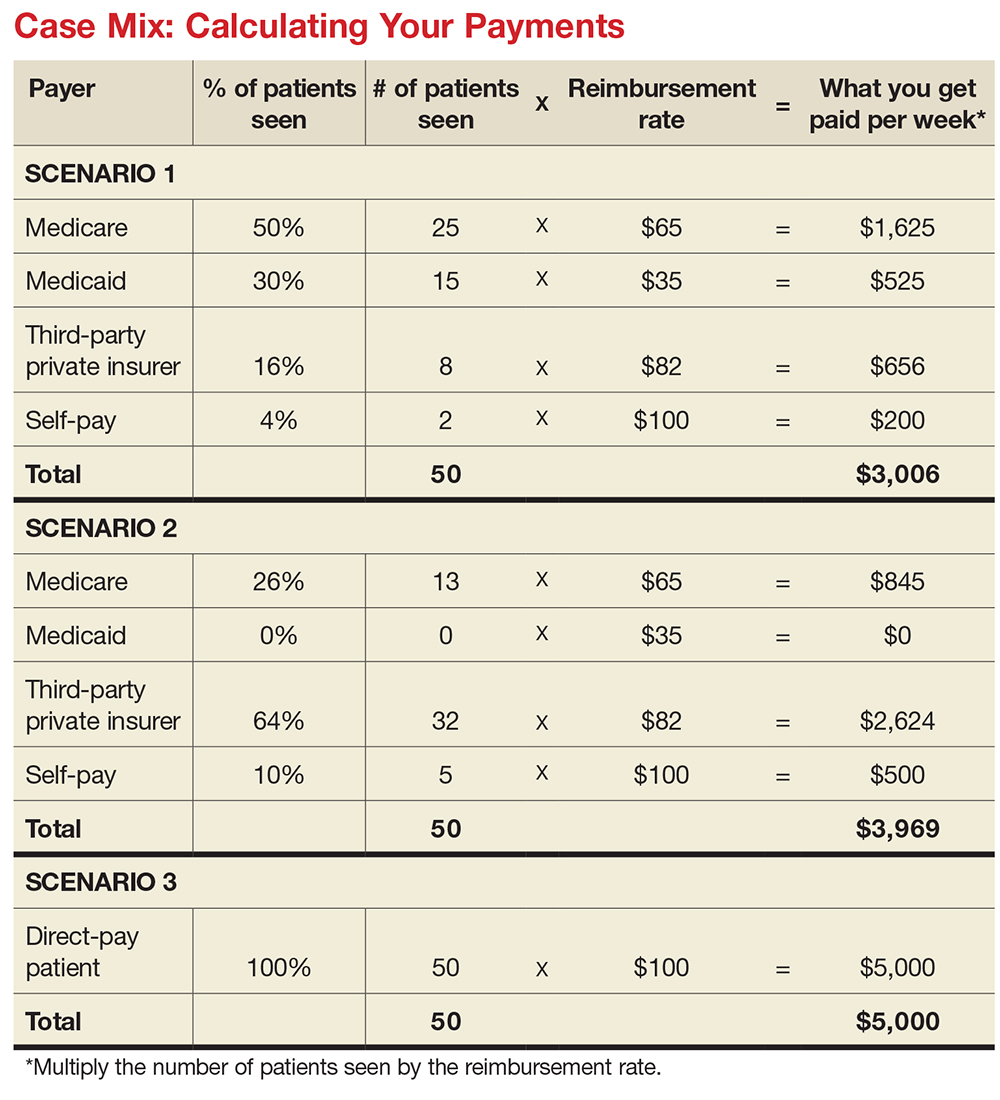

There is another major consideration for computing your financial contribution to the practice: understanding case mix. Let’s say your most common visit is billed as a 99213 and you charge $100 for this visit. You use this code 50 times in a week. Do you collect $100 x 50 or $5,000 per week? If you have a direct-pay practice and you collect all of it, yes, you will. If your practice accepts insurance, the number of patients you see with different insurers is called your case mix.

Let’s look at the impact of case mix on what you generate. Remember, it will take you about the same amount of time and effort to see these patients regardless of their insurer. Ask your practice manager what your case mix is. If he/she is not willing to share this information, you can get an estimate by looking at the demographics of your patient community. How many are older than 65? How many are on public assistance? Community needs assessments will provide you with this data; you can also check the patient’s chart or ask what insurance they have and add this to your log.

How much will you generate by seeing 50 patients in a week for a 99213 for which you charge $100? Let’s start with sample (not actual) base rates to illustrate the concept: $65 for Medicare, $35 for Medicaid, $82 for third-party private insurance, and $100 for self-pay.

Now let’s explore how case mix impacts revenue, with three different scenarios (see charts). In Scenario 1, 50% of your patients have Medicare, 30% have Medicaid, 16% have third-party private insurance, and 4% pay cash (self-pay). In Scenario 2, 26% have Medicare, 0% have Medicaid, 64% have private insurance, and 10% self-pay. In Scenario 3, your practice is a direct-pay practice with 100% self-payers and a 0% uncollectable rate.

In Scenario 1, with a case mix of 80% of your patient payments from Medicare or Medicaid, you generate $3,006 per week. If you see patients 48 weeks per year, you generate $144,288. In Scenario 2, with a case mix of 74% of your patient payments from private insurance, you generate $3,969 per week. In a year, you generate $190,512. And in Scenario 3, with 100% direct-pay patients, you generate $5,000 per week or $240,000 per year.

This example illustrates how case mix influences health care business, based on the current US reimbursement system. If you work for a practice that serves mostly Medicare and Medicaid patients, you do not command the same salary as an NP or PA who works for a direct-pay practice or one with a majority of privately insured patients.

OVERHEAD, OR IN OVER YOUR HEAD?

Now you have a better understanding of what your worth is to a practice. But what does it cost a practice to employ you? What’s your practice’s overhead?

Overhead includes the cost of processing claims; salaries and benefits; physician collaboration, if needed; rent, utilities, insurance, and depreciation. Overhead rates can range from 20% to 50%—meaning, if you generate $225,000 in revenue, it costs $45,000 to $112,500 to employ you. That leaves $112,500 (with higher overhead) to $180,000 (with lower overhead) for your salary. This revenue generation is an average: Many clinicians generate more than $225,000, while new graduates often generate less.

But in addition to generating more revenue, it can be beneficial to examine what you can do to help decrease the practice overhead. Because the bulk of overhead costs is salary, consider how many full-time-equivalent employees are needed to support you. Some NPs and PAs work with a full-time medical assistant or nurse, while others function very efficiently without one.

While providers like Dana and Kelsey can’t control what their practices pay for rent, utilities, or staffing, they can suggest improvements. Suggestions about scheduling, decreasing no-show rates, and improving recalls, immunization rates, and follow-up visits can all help increase revenue by decreasing day-to-day operating costs.

CONCLUSION

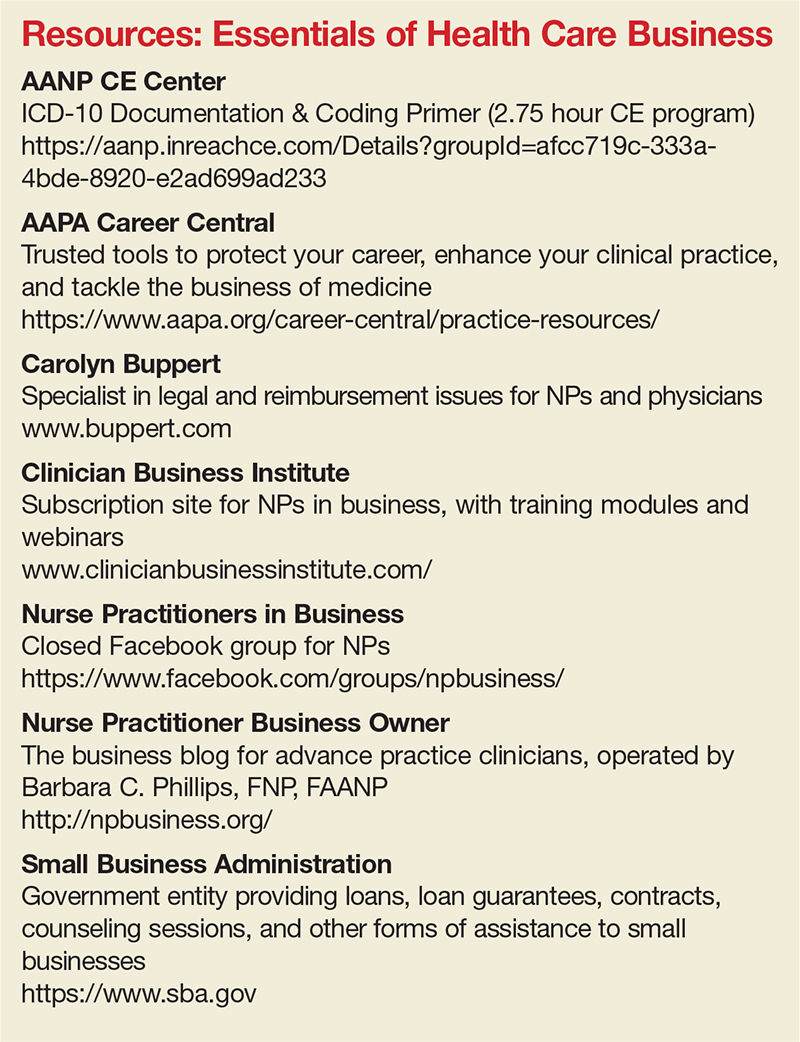

Most NPs and PAs went into their profession to help people—but that altruistic goal doesn’t mean you have to undervalue your own worth. Understanding the basic business of health care can help you negotiate your salary, maximize your income, and create new revenue models for patient care. While this may seem daunting to anyone who went to nursing or medical school, there are great resources to help you educate yourself on the essentials of health care business (see box).

Understanding the infrastructure of the health care system will help NPs and PAs become leaders who can impact health care change. These basic business skills are necessary to ensure fair and full compensation for the roles they play.

1. LaFevers D, Ward-Smith P, Wright W. Essential nurse practitioner business knowledge: an interprofessional perspective. J Am Assoc Nurse Pract. 2015;4:181-184.

2. Buppert C. Nurse Practitioner’s Business and Legal Guide. 6th ed. Burlington, MA: Jones and Bartlett Learning; 2018: 311-324.

3. Fritz J. How is a nonprofit different from a for-profit business? Getting beyond the myths. The Balance. April 3, 2017. www.thebalance.com/how-is-a-nonprofit-different-from-for-profit-business-2502472. Accessed November 20, 2017.

4. Dillon D, Hoyson P. Beginning employment: a guide for the new nurse practitioner. J Nurse Pract. 2014;1:55-59.

Dana, an adult nurse practitioner, has been working for two years at a large, suburban primary care practice owned by the regional hospital system. She sees too many patients per day, never has enough time to chart properly, and is concerned by the expanding role of the medical assistants. She sees salary postings on social media and feels she is underpaid. She fantasizes about owning her own practice but would settle for making more money. She’s heard that some NPs have profit-sharing, but she’s not exactly sure what that means.

Kelsey, a PA, is looking for his first job out of school. He’s been offered a full-time, salaried position with benefits at an urgent care center, but he doesn’t know if this is a good deal for him or not. The family physicians there make $85,000 more per year than the PAs, although the roles are quite similar.

DOWN TO BUSINESS

The US health care crisis is, fundamentally, a financial crisis; our system is comprised of both for-profit and not-for-profit (NFP) businesses. Every day, NPs and PAs are making decisions that affect their job satisfaction, performance, and retention. Many lack confidence in their ability to make good decisions about their salaries, because they don’t understand the business of health care.1 To survive and thrive, NPs and PAs must understand the basics of the business end.2

So, what qualifies as a business? Any commercial, retail, or professional entity that earns and spends money. It doesn’t matter if it is a for-profit or NFP organization; it can’t survive unless it makes more money than it spends. How that money is earned varies, from selling services and/or goods to receiving grants, income from interest or rentals, or government subsidies.

The major difference between a for-profit and a NFP organization is who controls the money.3 The owners of a for-profit company control the profits, which may be split among the owners or reinvested in the company. A NFP business may use its profits to provide charity care, offset losses of other programs, or invest in capital improvements (eg, new building, equipment). How the profits are to be used is outlined in the business goals or the mission statement of the entity. There are also federal and state regulations for both types of businesses; visit the Internal Revenue Service website for details (www.irs.gov/charities-non-profits; www.irs.gov/businesses/small-businesses-self-employed).

HOW YOU GET PAID FOR SERVICES

As a PA or NP, you generate income for your employer regardless of whether you work for a for-profit or NFP business. Your patients are billed for services rendered.

If you work for a fee-for-service or NFP practice with insurance contracts, the bill gets coded and electronically submitted for payment. Each insurer, whether private or government (ie, Medicare or Medicaid), has established what they will reimburse you for that service. The reimbursement rate is part of your contract with that insurer. Rates are determined based on your profession, licensure, geographic locale, type of facility, and the market rate. An insurance representative would be able to tell you your reimbursement rate for the most common procedure codes you use. (Your employer has this information but may or may not share it with you.) Medicare rates can be found online at www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/PhysicianFeeSched/.

If you work for a direct-pay practice, you collect what you bill directly from the patient, often at the time of the visit. A direct-pay practice does not have insurance contracts and does not bill insurers for patients who have insurance; rather, they provide a billing statement with procedure and diagnostic codes and NPI numbers to the patient, who can submit it directly to their insurer. If the insurer accepts out-of-network providers (those with whom they have no contract), they will reimburse the patient directly.

If you work in a fee-for-service or NFP practice, you may see patients who do not have insurance or who have very high deductibles and pay cash for their services. This does not make it a direct-pay practice. Also, by law, fee-for-service and NFP practices can only have one fee schedule for the entire practice. So, you can’t charge one patient $55 for a flu shot and another patient $25. These practices can offer discounts for cash payments at the time of service, to help reduce the set fees, if they choose.

TALKIN’ ’BOUT YOUR (REVENUE) GENERATION

To know how much you can negotiate for your salary and benefits—your total compensation package (of which benefits is often about 30%)—it is critical to know how much revenue you can generate for your employer.4 How can you figure this out?

If you are already working, you can ask your practice manager for some data. In some practices, this information is readily shared, perhaps as a means to boost productivity and even allow comparison between employees. If your practice manager is not forthcoming, you can collect the relevant information yourself. It may be challenging, but it is vital information to have. You need to know how many patients you see per day (keep a log for a month), what their payment source is (specific insurer or self-pay), and what the reimbursement rates are. Although reimbursement rates are deemed confidential per your insurance contract and therefore can’t be shared, you can find Medicare and Medicaid rates online. You can also call the provider representative from each insurer and ask for your reimbursement rates for your five or so most commonly used codes.

Another consideration is payment received (ie, not just what you charge). Do all patients pay everything they owe? Not always. Understand the difference between what you bill, what is allowed, and what you collect. The percentage of what is not collected is called the uncollectable rate. Factor that in.

Furthermore, how much do you contribute to the organization by testing? Dana works for a primary care clinic within a hospital system. Let’s assume her practice doesn’t offer colonoscopies or mammograms; how many referrals does she make to the hospital system for these tests? While she may not know the hospital’s profit margin on them, she can figure out how many she orders in a year. And what about the PA who works for a surgeon? Does he or she do the post-surgical checks? How much time does that save the surgeon, who can be providing higher revenue–producing services with the time saved? That contributes to the income of the practice, too! These are points you can make to justify your salary.

MIX IT UP

There is another major consideration for computing your financial contribution to the practice: understanding case mix. Let’s say your most common visit is billed as a 99213 and you charge $100 for this visit. You use this code 50 times in a week. Do you collect $100 x 50 or $5,000 per week? If you have a direct-pay practice and you collect all of it, yes, you will. If your practice accepts insurance, the number of patients you see with different insurers is called your case mix.

Let’s look at the impact of case mix on what you generate. Remember, it will take you about the same amount of time and effort to see these patients regardless of their insurer. Ask your practice manager what your case mix is. If he/she is not willing to share this information, you can get an estimate by looking at the demographics of your patient community. How many are older than 65? How many are on public assistance? Community needs assessments will provide you with this data; you can also check the patient’s chart or ask what insurance they have and add this to your log.

How much will you generate by seeing 50 patients in a week for a 99213 for which you charge $100? Let’s start with sample (not actual) base rates to illustrate the concept: $65 for Medicare, $35 for Medicaid, $82 for third-party private insurance, and $100 for self-pay.

Now let’s explore how case mix impacts revenue, with three different scenarios (see charts). In Scenario 1, 50% of your patients have Medicare, 30% have Medicaid, 16% have third-party private insurance, and 4% pay cash (self-pay). In Scenario 2, 26% have Medicare, 0% have Medicaid, 64% have private insurance, and 10% self-pay. In Scenario 3, your practice is a direct-pay practice with 100% self-payers and a 0% uncollectable rate.

In Scenario 1, with a case mix of 80% of your patient payments from Medicare or Medicaid, you generate $3,006 per week. If you see patients 48 weeks per year, you generate $144,288. In Scenario 2, with a case mix of 74% of your patient payments from private insurance, you generate $3,969 per week. In a year, you generate $190,512. And in Scenario 3, with 100% direct-pay patients, you generate $5,000 per week or $240,000 per year.

This example illustrates how case mix influences health care business, based on the current US reimbursement system. If you work for a practice that serves mostly Medicare and Medicaid patients, you do not command the same salary as an NP or PA who works for a direct-pay practice or one with a majority of privately insured patients.

OVERHEAD, OR IN OVER YOUR HEAD?

Now you have a better understanding of what your worth is to a practice. But what does it cost a practice to employ you? What’s your practice’s overhead?

Overhead includes the cost of processing claims; salaries and benefits; physician collaboration, if needed; rent, utilities, insurance, and depreciation. Overhead rates can range from 20% to 50%—meaning, if you generate $225,000 in revenue, it costs $45,000 to $112,500 to employ you. That leaves $112,500 (with higher overhead) to $180,000 (with lower overhead) for your salary. This revenue generation is an average: Many clinicians generate more than $225,000, while new graduates often generate less.

But in addition to generating more revenue, it can be beneficial to examine what you can do to help decrease the practice overhead. Because the bulk of overhead costs is salary, consider how many full-time-equivalent employees are needed to support you. Some NPs and PAs work with a full-time medical assistant or nurse, while others function very efficiently without one.

While providers like Dana and Kelsey can’t control what their practices pay for rent, utilities, or staffing, they can suggest improvements. Suggestions about scheduling, decreasing no-show rates, and improving recalls, immunization rates, and follow-up visits can all help increase revenue by decreasing day-to-day operating costs.

CONCLUSION

Most NPs and PAs went into their profession to help people—but that altruistic goal doesn’t mean you have to undervalue your own worth. Understanding the basic business of health care can help you negotiate your salary, maximize your income, and create new revenue models for patient care. While this may seem daunting to anyone who went to nursing or medical school, there are great resources to help you educate yourself on the essentials of health care business (see box).

Understanding the infrastructure of the health care system will help NPs and PAs become leaders who can impact health care change. These basic business skills are necessary to ensure fair and full compensation for the roles they play.

Dana, an adult nurse practitioner, has been working for two years at a large, suburban primary care practice owned by the regional hospital system. She sees too many patients per day, never has enough time to chart properly, and is concerned by the expanding role of the medical assistants. She sees salary postings on social media and feels she is underpaid. She fantasizes about owning her own practice but would settle for making more money. She’s heard that some NPs have profit-sharing, but she’s not exactly sure what that means.

Kelsey, a PA, is looking for his first job out of school. He’s been offered a full-time, salaried position with benefits at an urgent care center, but he doesn’t know if this is a good deal for him or not. The family physicians there make $85,000 more per year than the PAs, although the roles are quite similar.

DOWN TO BUSINESS

The US health care crisis is, fundamentally, a financial crisis; our system is comprised of both for-profit and not-for-profit (NFP) businesses. Every day, NPs and PAs are making decisions that affect their job satisfaction, performance, and retention. Many lack confidence in their ability to make good decisions about their salaries, because they don’t understand the business of health care.1 To survive and thrive, NPs and PAs must understand the basics of the business end.2

So, what qualifies as a business? Any commercial, retail, or professional entity that earns and spends money. It doesn’t matter if it is a for-profit or NFP organization; it can’t survive unless it makes more money than it spends. How that money is earned varies, from selling services and/or goods to receiving grants, income from interest or rentals, or government subsidies.

The major difference between a for-profit and a NFP organization is who controls the money.3 The owners of a for-profit company control the profits, which may be split among the owners or reinvested in the company. A NFP business may use its profits to provide charity care, offset losses of other programs, or invest in capital improvements (eg, new building, equipment). How the profits are to be used is outlined in the business goals or the mission statement of the entity. There are also federal and state regulations for both types of businesses; visit the Internal Revenue Service website for details (www.irs.gov/charities-non-profits; www.irs.gov/businesses/small-businesses-self-employed).

HOW YOU GET PAID FOR SERVICES

As a PA or NP, you generate income for your employer regardless of whether you work for a for-profit or NFP business. Your patients are billed for services rendered.

If you work for a fee-for-service or NFP practice with insurance contracts, the bill gets coded and electronically submitted for payment. Each insurer, whether private or government (ie, Medicare or Medicaid), has established what they will reimburse you for that service. The reimbursement rate is part of your contract with that insurer. Rates are determined based on your profession, licensure, geographic locale, type of facility, and the market rate. An insurance representative would be able to tell you your reimbursement rate for the most common procedure codes you use. (Your employer has this information but may or may not share it with you.) Medicare rates can be found online at www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/PhysicianFeeSched/.

If you work for a direct-pay practice, you collect what you bill directly from the patient, often at the time of the visit. A direct-pay practice does not have insurance contracts and does not bill insurers for patients who have insurance; rather, they provide a billing statement with procedure and diagnostic codes and NPI numbers to the patient, who can submit it directly to their insurer. If the insurer accepts out-of-network providers (those with whom they have no contract), they will reimburse the patient directly.

If you work in a fee-for-service or NFP practice, you may see patients who do not have insurance or who have very high deductibles and pay cash for their services. This does not make it a direct-pay practice. Also, by law, fee-for-service and NFP practices can only have one fee schedule for the entire practice. So, you can’t charge one patient $55 for a flu shot and another patient $25. These practices can offer discounts for cash payments at the time of service, to help reduce the set fees, if they choose.

TALKIN’ ’BOUT YOUR (REVENUE) GENERATION

To know how much you can negotiate for your salary and benefits—your total compensation package (of which benefits is often about 30%)—it is critical to know how much revenue you can generate for your employer.4 How can you figure this out?

If you are already working, you can ask your practice manager for some data. In some practices, this information is readily shared, perhaps as a means to boost productivity and even allow comparison between employees. If your practice manager is not forthcoming, you can collect the relevant information yourself. It may be challenging, but it is vital information to have. You need to know how many patients you see per day (keep a log for a month), what their payment source is (specific insurer or self-pay), and what the reimbursement rates are. Although reimbursement rates are deemed confidential per your insurance contract and therefore can’t be shared, you can find Medicare and Medicaid rates online. You can also call the provider representative from each insurer and ask for your reimbursement rates for your five or so most commonly used codes.

Another consideration is payment received (ie, not just what you charge). Do all patients pay everything they owe? Not always. Understand the difference between what you bill, what is allowed, and what you collect. The percentage of what is not collected is called the uncollectable rate. Factor that in.

Furthermore, how much do you contribute to the organization by testing? Dana works for a primary care clinic within a hospital system. Let’s assume her practice doesn’t offer colonoscopies or mammograms; how many referrals does she make to the hospital system for these tests? While she may not know the hospital’s profit margin on them, she can figure out how many she orders in a year. And what about the PA who works for a surgeon? Does he or she do the post-surgical checks? How much time does that save the surgeon, who can be providing higher revenue–producing services with the time saved? That contributes to the income of the practice, too! These are points you can make to justify your salary.

MIX IT UP

There is another major consideration for computing your financial contribution to the practice: understanding case mix. Let’s say your most common visit is billed as a 99213 and you charge $100 for this visit. You use this code 50 times in a week. Do you collect $100 x 50 or $5,000 per week? If you have a direct-pay practice and you collect all of it, yes, you will. If your practice accepts insurance, the number of patients you see with different insurers is called your case mix.

Let’s look at the impact of case mix on what you generate. Remember, it will take you about the same amount of time and effort to see these patients regardless of their insurer. Ask your practice manager what your case mix is. If he/she is not willing to share this information, you can get an estimate by looking at the demographics of your patient community. How many are older than 65? How many are on public assistance? Community needs assessments will provide you with this data; you can also check the patient’s chart or ask what insurance they have and add this to your log.

How much will you generate by seeing 50 patients in a week for a 99213 for which you charge $100? Let’s start with sample (not actual) base rates to illustrate the concept: $65 for Medicare, $35 for Medicaid, $82 for third-party private insurance, and $100 for self-pay.

Now let’s explore how case mix impacts revenue, with three different scenarios (see charts). In Scenario 1, 50% of your patients have Medicare, 30% have Medicaid, 16% have third-party private insurance, and 4% pay cash (self-pay). In Scenario 2, 26% have Medicare, 0% have Medicaid, 64% have private insurance, and 10% self-pay. In Scenario 3, your practice is a direct-pay practice with 100% self-payers and a 0% uncollectable rate.

In Scenario 1, with a case mix of 80% of your patient payments from Medicare or Medicaid, you generate $3,006 per week. If you see patients 48 weeks per year, you generate $144,288. In Scenario 2, with a case mix of 74% of your patient payments from private insurance, you generate $3,969 per week. In a year, you generate $190,512. And in Scenario 3, with 100% direct-pay patients, you generate $5,000 per week or $240,000 per year.

This example illustrates how case mix influences health care business, based on the current US reimbursement system. If you work for a practice that serves mostly Medicare and Medicaid patients, you do not command the same salary as an NP or PA who works for a direct-pay practice or one with a majority of privately insured patients.

OVERHEAD, OR IN OVER YOUR HEAD?

Now you have a better understanding of what your worth is to a practice. But what does it cost a practice to employ you? What’s your practice’s overhead?

Overhead includes the cost of processing claims; salaries and benefits; physician collaboration, if needed; rent, utilities, insurance, and depreciation. Overhead rates can range from 20% to 50%—meaning, if you generate $225,000 in revenue, it costs $45,000 to $112,500 to employ you. That leaves $112,500 (with higher overhead) to $180,000 (with lower overhead) for your salary. This revenue generation is an average: Many clinicians generate more than $225,000, while new graduates often generate less.

But in addition to generating more revenue, it can be beneficial to examine what you can do to help decrease the practice overhead. Because the bulk of overhead costs is salary, consider how many full-time-equivalent employees are needed to support you. Some NPs and PAs work with a full-time medical assistant or nurse, while others function very efficiently without one.

While providers like Dana and Kelsey can’t control what their practices pay for rent, utilities, or staffing, they can suggest improvements. Suggestions about scheduling, decreasing no-show rates, and improving recalls, immunization rates, and follow-up visits can all help increase revenue by decreasing day-to-day operating costs.

CONCLUSION

Most NPs and PAs went into their profession to help people—but that altruistic goal doesn’t mean you have to undervalue your own worth. Understanding the basic business of health care can help you negotiate your salary, maximize your income, and create new revenue models for patient care. While this may seem daunting to anyone who went to nursing or medical school, there are great resources to help you educate yourself on the essentials of health care business (see box).

Understanding the infrastructure of the health care system will help NPs and PAs become leaders who can impact health care change. These basic business skills are necessary to ensure fair and full compensation for the roles they play.

1. LaFevers D, Ward-Smith P, Wright W. Essential nurse practitioner business knowledge: an interprofessional perspective. J Am Assoc Nurse Pract. 2015;4:181-184.

2. Buppert C. Nurse Practitioner’s Business and Legal Guide. 6th ed. Burlington, MA: Jones and Bartlett Learning; 2018: 311-324.

3. Fritz J. How is a nonprofit different from a for-profit business? Getting beyond the myths. The Balance. April 3, 2017. www.thebalance.com/how-is-a-nonprofit-different-from-for-profit-business-2502472. Accessed November 20, 2017.

4. Dillon D, Hoyson P. Beginning employment: a guide for the new nurse practitioner. J Nurse Pract. 2014;1:55-59.

1. LaFevers D, Ward-Smith P, Wright W. Essential nurse practitioner business knowledge: an interprofessional perspective. J Am Assoc Nurse Pract. 2015;4:181-184.

2. Buppert C. Nurse Practitioner’s Business and Legal Guide. 6th ed. Burlington, MA: Jones and Bartlett Learning; 2018: 311-324.

3. Fritz J. How is a nonprofit different from a for-profit business? Getting beyond the myths. The Balance. April 3, 2017. www.thebalance.com/how-is-a-nonprofit-different-from-for-profit-business-2502472. Accessed November 20, 2017.

4. Dillon D, Hoyson P. Beginning employment: a guide for the new nurse practitioner. J Nurse Pract. 2014;1:55-59.

The end of the line: Concluding your practice when facing serious illness

Dear Dr. Mossman,

I have a possibly fatal disease. So far, my symptoms and treatment haven’t kept me from my usual activities. But if my illness worsens, I’ll have to quit practicing psychiatry. What should I be doing now to make sure I fulfill my ethical and legal obligations to my patients?

Submitted by “Dr. F”

“Remember, with great power comes great responsibility.”

- Peter Parker, Spider-Man (2002)

Peter Parker’s movie-ending statement applies to doctors as well as Spider-Man. Although we don’t swing from building to building to save cities from heinous villains, practicing medicine is a privilege that society bestows only upon physicians who retain the knowledge, skills, and ability to treat patients competently.

Doctors retire from practice for many reasons, including when deteriorating physical health or cognitive capacity prevents them from performing clinical duties properly. Dr. F’s situation is not rare. As the physician population ages,1,2 a growing number of his colleagues will face similar circumstances,3,4 and with them, the responsibility and emotional turmoil of arranging to end their medical practices.

In many ways, concluding a psychiatric practice is similar to retiring from practice in other specialties. But because we care for patients’ minds as well as their bodies, retirement affects psychiatrists in distinctive ways that reflect our patients’ feelings toward us and our feelings toward them. To answer Dr. F’s question, this article considers having to stop practicing from 3 vantage points:

- the emotional impact on patients

- the emotional impact on the psychiatrist

- fulfilling one’s legal obligations while attending to the emotions of patients as well as oneself.

Emotional impact on patients

A content analysis study suggests that the traits patients appreciate in family physicians include the availability to listen, caring and compassion, trusted medical judgment, conveying the patient’s importance during encounters, feelings of connectedness, knowledge and understanding of the patient’s family, and relationship longevity.5 The same factors likely apply to relationships between psychiatrists and their patients, particularly if treatment encounters have extended over years and have involved conversations beyond those needed merely to write prescriptions.

Psychoanalytic publications offer many descriptions of patients’ reactions to the illness or death of their mental health professional. A 1978 study of 27 analysands whose physicians died during ongoing therapy reported reactions that ranged from a minimal impact to protracted mourning accompanied by helplessness, intense crying, and recurrent dreams about the analyst.6 Although a few patients were relieved that death had ended a difficult treatment, many were angry at their doctor for not attending to self-care and for breaking their treatment agreement, or because they had missed out on hoped-for benefits.

A 2010 study described the pain and distress that patients may experience following the death of their analyst or psychotherapist. These accounts emphasized the emotional isolation of grieving patients, who do not have the social support that bereaved persons receive after losing a loved one.7 Successful psychotherapy provides a special relationship characterized by trust, intimacy, and safety. But if the therapist suddenly dies, this relationship “is transformed into a solitude like no other.”8

Because the sudden “rupture of an analytic process is bound to be traumatic and may cause iatrogenic injury to the patient,” Traesdal9 advocates that therapists in situations similar to Dr. F’s discuss their possible death “on the reality level at least once during any analysis or psychotherapy.… It is extremely helpful to a patient to have discussed … how to handle the situation” if the therapist dies. This discussion also offers the patient an opportunity to confront a cultural taboo around death and to increase capacity to tolerate pain, illness, and aging.10,11

Most psychiatric care today is not psychoanalysis; psychiatrists provide other forms of care that create less intense doctor–patient relationships. Yet knowledge of these kinds of reactions may help Dr. F stay attuned to his patients’ concerns and to contemplate what they may experience, to greater or lesser degrees, if his health declines.

Retirement’s emotional impact on the psychiatrist

Published guidance on concluding a psychiatric practice is sparse, considering that all psychiatrists are mortal and stop practicing at some point.12Not thinking about or planning for retirement is a psychiatric tradition that started with Freud. He saw patients until shortly before his death and did not seem to have planned for ending his practice, despite suffering with jaw cancer for 16 years.13

Practicing medicine often is more than just a career; it is a core aspect of many physicians’ identity.14 Most of us spend a large fraction of our waking hours caring for patients and meeting other job requirements (eg, teaching, maintaining knowledge and skills), and many of us have scant time to pursue nonmedical interests. An intense prioritization of one’s “medical identity” makes retirement a blow to a doctor’s self-worth and sense of meaning in life.15,16

Because their work is not physically demanding, most psychiatrists continue to practice beyond the age of 65 years.12,17 More important, perhaps, is that being a psychiatrist is uniquely rewarding. As Benjamin Rush observed in an 1810 letter to Pennsylvania Hospital, successfully treating any medical disease is gratifying, but “what is this pleasure compared with that of restoring a fellow creature from the anguish and folly of madness and of reviving in him the knowledge of himself, his family, his friends, and his God!”18

Physicians in any specialty that involves repeated contact with the same patients form emotional bonds with their patients that retirement breaks.14 Psychiatrists’ interest in how patients think, feel, and cope with problems creates special attachments17 that can make some terminations “emotionally excruciating.”12

Psychiatrists with serious illness

What guidance might Dr. F find regarding whether to broach the subject of his illness with patients, and if so, how? No one has conducted controlled trials to answer these questions. Rather, published discussion of psychiatrists’ serious illness is found mainly in the psychotherapy literature. What’s available consists of individual accounts and case series that lack scientific rigor and offer little clarity about what the therapist should say, when to say it, and how to initiate the discussion.19,20 Yet Dr. F may find some of these authors’ ideas and suggestions helpful, particularly if his psychiatric practice includes providing psychotherapy.

As a rule, psychiatrists avoid talking about themselves, but having a serious illness that could affect treatment often justifies deviating from this practice. Although Dr. F (like many psychiatrists) may be concerned that discussing his health will make patients anxious or “contaminate” what they are able or willing to say,21 not providing information or avoiding discussion (especially if a patient asks about your health) may quickly undermine a patient’s trust.21,22 Even in psychoanalytic treatment, it makes little sense to encourage patients “to speak freely on the pretense that all is well, despite obvious evidence to the contrary.”19

Physicians often deny—or at least avoid thinking about—their own mortality.23 But avoiding talking about something so important (and often so obvious) as one’s illness may risk supporting patients’ denial of crucial matters in their own lives.19,21 Moreover, Dr. F’s inadvertent self-disclosure (eg, by displaying obvious signs of illness) may do more harm to therapy than a planned statement in which Dr. F has prepared what he’ll say to answer his patients’ questions.20

That Dr. F has continued working while suffering from a potentially fatal illness seems noble. Yet by doing so, he accepts not only the burdens of his illness but also the obligation to continue to serve his patients competently. This requires maintaining emotional steadiness and not using patients for emotional support, but instead obtaining and using the support of his friends, colleagues, family, consultants, and caregivers.20

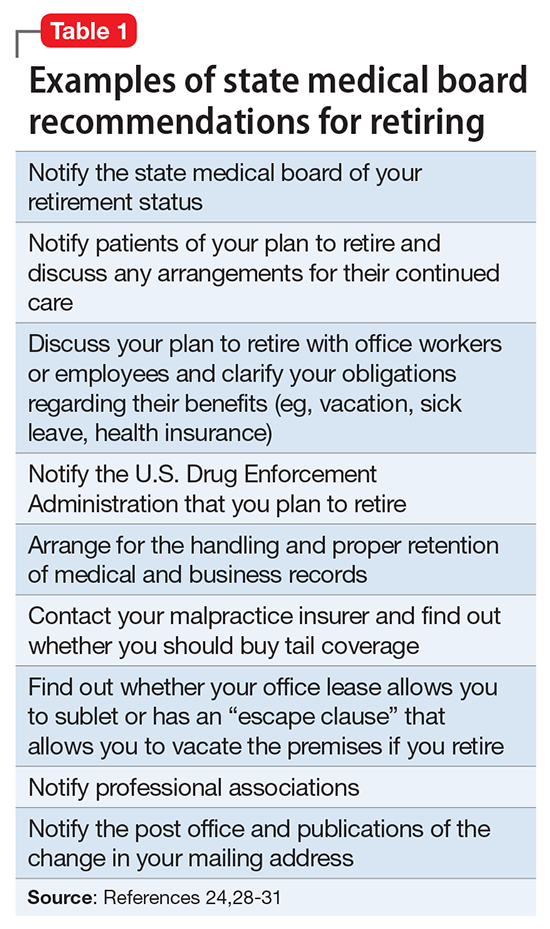

Legal obligations

Retirement does not end a physician’s professional legal obligations.24 The legal rules and duties for psychiatrists who leave their practices are similar to those that apply to other physicians. Mishandling these aspects of retirement can result in various legal, licensure-related, or economic consequences, depending on your circumstances and employment arrangements.

Employment contracts in hospital or group practices often require notice of impending departures. If applicable to Dr. F’s situation, failure to comply with such conditions may lead to forfeiture of buyout payments, paying for malpractice tail coverage, or lawsuits claiming violation of contractual agreements.25

Retirement also creates practical and legal responsibilities to patients that are separate from the interpersonal and emotional issues previously discussed. How will those who need ongoing care and coverage be cared for? When withdrawing from a patient’s care (because of retirement or other reasons), a physician should give the patient enough advance notice to set up satisfactory treatment arrangements elsewhere and should facilitate transfer of the patient’s care, if appropriate.26 Failure to meet this ethical obligation may lead to a malpractice action alleging abandonment, which is defined as “the unilateral severance of the professional relationship … without reasonable notice at a time when there is still the necessity of continuing medical attention.”27