User login

Woman dies following cervical cone biopsy: $4.25M award

Woman dies following cervical cone biopsy: $4.25M award

A 46-year-old woman underwent a cervical cone biopsy at a Veterans Administration (VA) hospital on July 18. Following the test, significant bleeding occurred. The gynecologic surgeon attempted to control the hemorrhage by injecting fe

ESTATE'S CLAIM:

The surgeon’s actions were negligent. She removed too much tissue during the biopsy, injured the vaginal and uterine walls, and failed to timely diagnose and appropriately treat the injuries. The ferric subsulfate solution entered the abdominal cavity via the perforation, causing peritonitis and bowel injuries. A pathology report from the bowel resection surgery informed the surgeon that the bowel was not properly reconnected after the damaged portion was removed, but this condition was neither detected intraoperatively nor treated postoperatively.

DEFENDANTS' DEFENSE:

The surgeon moved for summary judgment, countering that, as a federal employee, she was exempt from personal liability for the services performed as an employee of the VA. That motion was denied. She then argued that injury to the vaginal/uterine wall is a known complication of the biopsy procedure.

VERDICT:

A $4.25 million Illinois verdict was returned in federal court.

Related article:

Reducing maternal mortality in the United States—Let’s get organized!

Needle stick not reported to patient

A woman delivered a baby assisted by an on-call ObGyn. When the baby developed fetal tachycardia, the ObGyn recommended expediting delivery and discussed various options and the risks of each option. The mother chose a vaginal forceps delivery. During the procedure, the mother experienced a 3rd-degree perineal laceration and a few minor lacerations, which were repaired. The mother was in pain, so the ObGyn performed a revision repair. During the procedure, the ObGyn accidentally stuck himself with a clean needle. He replaced the needle and changed his glove. The mother reported instant pain relief following revision and was discharged. After the needle incident, the ObGyn’s thumb became red and swollen, so he took antibiotics.

Two days after discharge, the patient reported to the ObGyn’s office with fever, pain, and a foul odor emanating from the surgery site. She was given the diagnosis of pelvic incisional cellulitis and was taken to the operating room for exploration and debridement. The patient developed septic shock and necrotizing fasciitis. She was placed on a ventilator and underwent 13 surgeries.

PATIENTS' CLAIM:

The ObGyn was negligent. The patient claimed breach of duty: the ObGyn did not disclose that his thumb was swollen and that he took antibiotics.

PHYSICIANS' DEFENSE:

There was no breach of duty. He did not feel the need to concern the patient about an injury to himself that did not affect her.

VERDICT:

A Kansas defense verdict was returned.

Related article:

2017 Update on infectious disease

Catheter removal, air embolism: $3.5M settlement

A 44-year-old woman underwent gynecologic surgery on April 22. She developed a rectovaginal fistula and other complications. Intravenous antibiotics were required and parenteral nutrition was delivered through a central venous catheter. On May 22, after a hospital nurse removed the catheter, an air embolism developed, causing a brain injury. The patient has a mental disability and residual leg tremors.

PATIENTS' CLAIM:

Because of the surgeon’s negligence during surgery, a fistula developed. The nurse negligently removed the catheter, causing the embolism.

DEFENDANTS' DEFENSE:

The case settled during the trial.

VERDICT:

A $3.5 million Illinois settlement was reached, including payments of $1 million from the surgeon and $2.5 million from the hospital.

These cases were selected by the editors of OBG Management from Medical Malpractice Verdicts, Settlements & Experts, with permission of the editor, Lewis Laska (www.verdictslaska.com). The information available to the editors about the cases presented here is sometimes incomplete. Moreover, the cases may or may not have merit. Nevertheless, these cases represent the types of clinical situations that typically result in litigation and are meant to illustrate nationwide variation in jury verdicts and awards.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Woman dies following cervical cone biopsy: $4.25M award

A 46-year-old woman underwent a cervical cone biopsy at a Veterans Administration (VA) hospital on July 18. Following the test, significant bleeding occurred. The gynecologic surgeon attempted to control the hemorrhage by injecting fe

ESTATE'S CLAIM:

The surgeon’s actions were negligent. She removed too much tissue during the biopsy, injured the vaginal and uterine walls, and failed to timely diagnose and appropriately treat the injuries. The ferric subsulfate solution entered the abdominal cavity via the perforation, causing peritonitis and bowel injuries. A pathology report from the bowel resection surgery informed the surgeon that the bowel was not properly reconnected after the damaged portion was removed, but this condition was neither detected intraoperatively nor treated postoperatively.

DEFENDANTS' DEFENSE:

The surgeon moved for summary judgment, countering that, as a federal employee, she was exempt from personal liability for the services performed as an employee of the VA. That motion was denied. She then argued that injury to the vaginal/uterine wall is a known complication of the biopsy procedure.

VERDICT:

A $4.25 million Illinois verdict was returned in federal court.

Related article:

Reducing maternal mortality in the United States—Let’s get organized!

Needle stick not reported to patient

A woman delivered a baby assisted by an on-call ObGyn. When the baby developed fetal tachycardia, the ObGyn recommended expediting delivery and discussed various options and the risks of each option. The mother chose a vaginal forceps delivery. During the procedure, the mother experienced a 3rd-degree perineal laceration and a few minor lacerations, which were repaired. The mother was in pain, so the ObGyn performed a revision repair. During the procedure, the ObGyn accidentally stuck himself with a clean needle. He replaced the needle and changed his glove. The mother reported instant pain relief following revision and was discharged. After the needle incident, the ObGyn’s thumb became red and swollen, so he took antibiotics.

Two days after discharge, the patient reported to the ObGyn’s office with fever, pain, and a foul odor emanating from the surgery site. She was given the diagnosis of pelvic incisional cellulitis and was taken to the operating room for exploration and debridement. The patient developed septic shock and necrotizing fasciitis. She was placed on a ventilator and underwent 13 surgeries.

PATIENTS' CLAIM:

The ObGyn was negligent. The patient claimed breach of duty: the ObGyn did not disclose that his thumb was swollen and that he took antibiotics.

PHYSICIANS' DEFENSE:

There was no breach of duty. He did not feel the need to concern the patient about an injury to himself that did not affect her.

VERDICT:

A Kansas defense verdict was returned.

Related article:

2017 Update on infectious disease

Catheter removal, air embolism: $3.5M settlement

A 44-year-old woman underwent gynecologic surgery on April 22. She developed a rectovaginal fistula and other complications. Intravenous antibiotics were required and parenteral nutrition was delivered through a central venous catheter. On May 22, after a hospital nurse removed the catheter, an air embolism developed, causing a brain injury. The patient has a mental disability and residual leg tremors.

PATIENTS' CLAIM:

Because of the surgeon’s negligence during surgery, a fistula developed. The nurse negligently removed the catheter, causing the embolism.

DEFENDANTS' DEFENSE:

The case settled during the trial.

VERDICT:

A $3.5 million Illinois settlement was reached, including payments of $1 million from the surgeon and $2.5 million from the hospital.

These cases were selected by the editors of OBG Management from Medical Malpractice Verdicts, Settlements & Experts, with permission of the editor, Lewis Laska (www.verdictslaska.com). The information available to the editors about the cases presented here is sometimes incomplete. Moreover, the cases may or may not have merit. Nevertheless, these cases represent the types of clinical situations that typically result in litigation and are meant to illustrate nationwide variation in jury verdicts and awards.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Woman dies following cervical cone biopsy: $4.25M award

A 46-year-old woman underwent a cervical cone biopsy at a Veterans Administration (VA) hospital on July 18. Following the test, significant bleeding occurred. The gynecologic surgeon attempted to control the hemorrhage by injecting fe

ESTATE'S CLAIM:

The surgeon’s actions were negligent. She removed too much tissue during the biopsy, injured the vaginal and uterine walls, and failed to timely diagnose and appropriately treat the injuries. The ferric subsulfate solution entered the abdominal cavity via the perforation, causing peritonitis and bowel injuries. A pathology report from the bowel resection surgery informed the surgeon that the bowel was not properly reconnected after the damaged portion was removed, but this condition was neither detected intraoperatively nor treated postoperatively.

DEFENDANTS' DEFENSE:

The surgeon moved for summary judgment, countering that, as a federal employee, she was exempt from personal liability for the services performed as an employee of the VA. That motion was denied. She then argued that injury to the vaginal/uterine wall is a known complication of the biopsy procedure.

VERDICT:

A $4.25 million Illinois verdict was returned in federal court.

Related article:

Reducing maternal mortality in the United States—Let’s get organized!

Needle stick not reported to patient

A woman delivered a baby assisted by an on-call ObGyn. When the baby developed fetal tachycardia, the ObGyn recommended expediting delivery and discussed various options and the risks of each option. The mother chose a vaginal forceps delivery. During the procedure, the mother experienced a 3rd-degree perineal laceration and a few minor lacerations, which were repaired. The mother was in pain, so the ObGyn performed a revision repair. During the procedure, the ObGyn accidentally stuck himself with a clean needle. He replaced the needle and changed his glove. The mother reported instant pain relief following revision and was discharged. After the needle incident, the ObGyn’s thumb became red and swollen, so he took antibiotics.

Two days after discharge, the patient reported to the ObGyn’s office with fever, pain, and a foul odor emanating from the surgery site. She was given the diagnosis of pelvic incisional cellulitis and was taken to the operating room for exploration and debridement. The patient developed septic shock and necrotizing fasciitis. She was placed on a ventilator and underwent 13 surgeries.

PATIENTS' CLAIM:

The ObGyn was negligent. The patient claimed breach of duty: the ObGyn did not disclose that his thumb was swollen and that he took antibiotics.

PHYSICIANS' DEFENSE:

There was no breach of duty. He did not feel the need to concern the patient about an injury to himself that did not affect her.

VERDICT:

A Kansas defense verdict was returned.

Related article:

2017 Update on infectious disease

Catheter removal, air embolism: $3.5M settlement

A 44-year-old woman underwent gynecologic surgery on April 22. She developed a rectovaginal fistula and other complications. Intravenous antibiotics were required and parenteral nutrition was delivered through a central venous catheter. On May 22, after a hospital nurse removed the catheter, an air embolism developed, causing a brain injury. The patient has a mental disability and residual leg tremors.

PATIENTS' CLAIM:

Because of the surgeon’s negligence during surgery, a fistula developed. The nurse negligently removed the catheter, causing the embolism.

DEFENDANTS' DEFENSE:

The case settled during the trial.

VERDICT:

A $3.5 million Illinois settlement was reached, including payments of $1 million from the surgeon and $2.5 million from the hospital.

These cases were selected by the editors of OBG Management from Medical Malpractice Verdicts, Settlements & Experts, with permission of the editor, Lewis Laska (www.verdictslaska.com). The information available to the editors about the cases presented here is sometimes incomplete. Moreover, the cases may or may not have merit. Nevertheless, these cases represent the types of clinical situations that typically result in litigation and are meant to illustrate nationwide variation in jury verdicts and awards.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Considering work as an expert witness? Look before you leap!

Dear Dr. Mossman,

I am retired, but an attorney friend of mine has asked me to help out by performing forensic evaluations. I’m tempted to try it because the work sounds meaningful and interesting. I won’t have a doctor–patient relationship with the attorney’s clients, and I expect the work will take <10 hours a week. Do I need malpractice coverage? Should I consider any other medicolegal issues before I start?

Submitted by “Dr. B”

One of the great things about being a psychiatrist is the variety of available practice options. Like Dr. B, many psychiatrists contemplate using their clinical know-how to perform forensic evaluations. For some psychiatrists, part-time work as an expert witness may provide an appealing change of pace from their other clinical duties1 and a way to supplement their income.2

But as would be true for other kinds of medical practice, Dr. B is wise to consider the possible risks before jumping into forensic work. To help Dr. B decide about getting insurance coverage, we will:

- explain briefly the subspecialty of forensic psychiatry

- review the theory of malpractice and negligence torts

- discuss whether forensic evaluations can create doctor–patient relationships

- explore the availability and limitations of immunity for forensic work

- describe other types of liability with forensic work

- summarize steps to avoid liability.

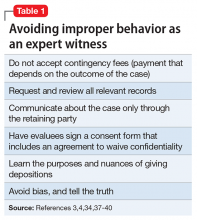

Introduction to forensic psychiatry

Some psychiatrists—and many people who are not psychiatrists—have a vague or incorrect understanding of forensic psychiatry. Put succinctly, “Forensic Psychiatry is a subspecialty of psychiatry in which scientific and clinical expertise is applied in legal contexts….”3 To practice forensic psychiatry well, a psychiatrist must have some understanding of the law and how to apply and translate clinical concepts to fit legal criteria.4 Psychiatrists who offer to serve as expert witnesses should be familiar with how the courtroom functions, the nuances of how expert testimony is used, and possible sources of bias.4,5

Forensic work can create role conflicts. For most types of forensic assessments, psychiatrists should not provide forensic opinions or testimony about their own patients.3 Even psychiatrists who only work as expert witnesses must balance duties of assisting the trier of fact, fulfilling the consultation role to the retaining party, upholding the standards and ethics of the profession, and striving to provide truthful, objective testimony.2

Special training usually is required

The most important qualification for being a good psychiatric expert witness is being a good psychiatrist, and courts do not require psychiatrists to have specialty training in forensic psychiatry to perform forensic psychiatric evaluations. Yet, the field of forensic psychiatry has developed over the past 50 years to the point that psychiatrists need special training to properly perform many, if not most, types of forensic evaluations.6 Much of forensic psychiatry involves writing specialized reports for lawyers and the court,7 and experts are supposed to meet professional standards, regardless of their training.8-10 Psychiatrists who perform forensic work are obligated to claim expertise only in areas where their knowledge, skills, training, and experience justify such claims. These considerations explain why, since 1999, the American Board of Psychiatry and Neurology has limited eligibility for board certification in forensic psychiatry to psychiatrists who have completed accredited forensic fellowships.11

Malpractice: A short review

To address Dr. B’s question about malpractice coverage, we first review what malpractice is.

“Tort” is a legal term for injury, and tort claims arise when one party harms another and the harmed party seeks money as compensation.9 In a tort claim alleging negligence, the plaintiff (ie, the person bringing the suit) asserts that the defendant had a legally recognized duty, that the defendant breached that duty, and that breach of duty harmed the plaintiff.8

Physicians have a legal duty to “possess the requisite knowledge and skill such as is possessed by the average member of the medical profession; … exercise ordinary and reasonable care in the application of such knowledge and skill; and … use best judgment in such application.”10 A medical malpractice lawsuit asserts that a doctor breached this duty and caused injury in the course of the medical practice.

Malpractice in forensic cases

Practicing medicine typically occurs within the context of treatment relationships. One might think, as Dr. B did, that because forensic evaluations do not involve treating patients, they do not create the kind of doctor–patient relationship that could lead to malpractice liability. This is incorrect, however, for several reasons.

Certain well-intended actions during a forensic evaluation, such as explaining the implications of a diagnosis, giving specific advice about a medication, or making a recommendation about where or how to obtain treatment, may create a doctor–patient relationship.12,13 Many states’ laws on what constitutes the practice of medicine include performing examinations, diagnosing, or referring to oneself as “Dr.” or as a medical practitioner.14-17 State courts have interpreted these laws to further define what constitutes medical practice and the creation of a doctor–patient relationship during a forensic examination.18,19 Some legal scholars20 and the American Medical Association (AMA)9 regard provision of expert testimony as practicing medicine because such testimony requires the application of medical science and rendering of diagnoses.

Immunity and shifts away from it

For many years, courts granted civil immunity to expert witnesses for several policy reasons.8,9,13,20-22 Courts recognized that losing parties might want to blame whomever they could, and immunity could provide legal protection for expert witnesses. Without such protection, witnesses might feel more pressured to give testimony favorable to their side at the loss of objectivity,23,24 or experts might be discouraged from testifying at all. This would be true especially for academic psychiatrists who testify infrequently or for retired doctors, such as Dr. B, who might not want to carry insurance for just one case.21 According to this argument, rather than using the threat of litigation to keep out improper testimony, courts should rely on both admissibility standards25,26 and the adversarial nature of proceedings.21

Those who oppose granting immunity to experts argue that admissibility rules and cross-examination do too little to prevent bad testimony; the threat of liability, however, motivates experts to be more cautious and scientifically rigorous in their approach.21 Opponents also have argued that the threat of liability might reduce improper testimony, which they believe was partly responsible for rising malpractice premiums.20

Courts vary in how they consider granting immunity and to what extent. For example:

- Some courts will not grant immunity to so-called “friendly experts,” while others have limited immunity for adversarial experts.20-22

- Some courts have applied immunity to general fact witnesses but not to professional experts.21,24,27

- When immunity is considered, it is usually regarding actual testimony. Yet, some courts have included pretrial services.21,28-30

- Some courts have considered the testimonial issue at hand when deciding whether to extend immunity. For example, immunity may not apply if the issue is loss of profits21,31 or if an experiment is conducted to demonstrate the extent of a physical injury.21,32

If you plan to serve as an expert witness, find out what, if any, immunity is available in the jurisdiction where you expect to testify. If you do not have immunity, you may be subject to various malpractice claims, including alleged physical or emotional harm resulting from the evaluation1 (perhaps caused by misuse of empathic statements33), an accusation of negligent misdiagnosis of an evaluee,8 or failing to act upon a duty to warn or protect that arises during an assessment.34

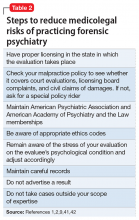

Other liability

Dr. B also asked about medicolegal issues other than malpractice. Although negligence is the claim that forensic psychiatrists most commonly encounter,10 other types of claims arise in practice-related legal actions. Potential causes of action include failure to obtain or attempt to obtain informed consent, breach of confidentiality, or not responding to a psychiatric emergency during evaluation. The plaintiff usually must show that the expert’s conduct was the cause-in-fact of injury.8

Besides civil lawsuits, forensic work may generate complaints to state medical boards.10 Occasionally, state medical boards have revoked psychiatrists’ licenses for improper testimony.20 Aggrieved parties may allege violations of the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996, such as mishandling protected health information. Psychiatrists also may face sanction by professional societies—for example, censure by the American Psychiatric Association9,10 or the AMA13 for ethics violations—if their improper testimony is considered unprofessional conduct. The theory behind this is that judges and jurors cannot be technical experts in every field, so the field must have a mechanism to police itself.20,35,36 Finally, forensic experts can face criminal charges for perjury if they lie under oath.8

How to protect yourself

Even when legal claims against psychiatrists turn out to be baseless, legal costs of defending oneself can mount quickly. Knowing this, Dr. B may conclude that obtaining malpractice insurance would be wise. But a malpractice policy alone may not meet all Dr. B’s needs, because some policies do not cover ordinary negligence or other potential causes of legal action against a psychiatrist.13 Some companies offer these extra types of coverage for work as an expert witness at no additional cost, and some offer access to risk management services with specialized knowledge about forensic psychiatric practice.

1. Appelbaum PS. Law and psychiatry: liability for forensic evaluations: a word of caution. Psychiatr Serv. 2001;52(7):885-886.

2. Shuman DW, Greenberg SA. The expert witness, the adversary system, and the voice of reason: reconciling impartiality and advocacy. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice. 2003;34(3):219-224.

3. American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law. Ethics guidelines for the practice of forensic psychiatry. http://www.aapl.org/ethics.htm. Published May 2005. Accessed July 11, 2017.

4. Gutheil TG. Forensic psychiatry as a specialty. Psychiatric Times. http://www.psychiatrictimes.com/articles/forensic-psychiatry-sp

5. Knoll J, Gerbasi J. Psychiatric malpractice case analysis: striving for objectivity. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2006;34(2):215-223.

6. Sadoff RL. The practice of forensic psychiatry: perils, problems, and pitfalls. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 1998;26(2):305-314.

7. Simon RI. Authorship in forensic psychiatry: a perspective. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2007;35(1):18-26.

8. Masterson LR. Witness immunity or malpractice liability for professionals hired as experts? Rev Litig. 1998;17(2):393-418.

9. Binder RL. Liability for the psychiatrist expert witness. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159(11):1819-1825.

10. Gold LH, Davidson JE. Do you understand your risk? Liability and third-party evaluations in civil litigation. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2007;35(2):200-210.

11. American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law. ABPN certification in the subspecialty of forensic psychiatry. http://www.aapl.org/abpn-certification. Accessed July 9, 2017.

12. Marett CP, Mossman D. What are your responsibilities after a screening call? Current Psychiatry. 2014;13(9):54-57.

13. Weinstock R, Garrick T. Is liability possible for forensic psychiatrists? Bull Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 1995;23(2):183-193.

14. Ohio Revised Code §4731.34.

15. Kentucky Revised Statutes §311.550(10) (2017).

16. California Business & Professions Code §2052.5 (through 2012 Leg Sess).

17. Oregon Revised Statutes §677.085 (2013).

18. Blake V. When is a patient-physician relationship established? Virtual Mentor. 2012;14(5):403-406.

19. Zettler PJ. Toward coherent federal oversight of medicine. San Diego Law Review. 2015;52:427-500.

20. Turner JA. Going after the ‘hired guns’: is improper expert witness testimony unprofessional conduct or the negligent practice of medicine? Spec Law Dig Health Care Law. 2006;328:9-43.

21. Weiss LS, Orrick H. Expert witness malpractice actions: emerging trend or aberration? Practical Litigator. 2004;15(2):27-38.

22. McAbee GN. Improper expert medical testimony. Existing and proposed mechanisms of oversight. J Leg Med. 1998;19(2):257-272.

23. Panitz v Behrend, 632 A 2d 562 (Pa Super Ct 1993).

24. Murphy v A.A. Mathews, 841 S.W. 2d 671 (Mo 1992).

25. Daubert v Merrell Dow Pharmaceuticals, 509 U.S. 579 (1993).

26. Rule 702. Testimony by expert witnesses. In: Michigan Legal Publishing Ltd. Federal Rules of evidence. Grand Rapids, MI: Michigan Legal Publishing Ltd; 2017:21.

27. Committee on Medical Liability and Risk Management. Policy statement—expert witness participation in civil and criminal proceedings. Pediatrics. 2009;124(1):428-438.

28. Mattco Forge, Inc., v Arthur Young & Co., 6 Cal Rptr 2d 781 (Cal Ct App 1992).

29. Marrogi v Howard, 248 F 3d 382 (5th Cir 2001).

30. Boyes-Bogie v Horvitz, 2001 WL 1771989 (Mass Super 2001).

31. LLMD of Michigan, Inc., v Jackson-Cross Co., 740 A. 2d 186 (Pa 1999).

32. Pollock v Panjabi, 781 A 2d 518 (Conn Super Ct 2000).

33. Brodsky SL, Wilson JK. Empathy in forensic evaluations: a systematic reconsideration. Behav Sci Law. 2013;31(2):192-202.

34. Heilbrun K, DeMatteo D, Marczyk G, et al. Standards of practice and care in forensic mental health assessment: legal, professional, and principles-based consideration. Psych Pub Pol L. 2008;14(1):1-26.

35. Appelbaum PS. Law & psychiatry: policing expert testimony: the role of professional organizations. Psychiatr Serv. 2002;53(4):389-390,399.

36. Austin v American Association of Neurological Surgeons, 253 F 3d 967 (7th Cir 2001).

37. Gutheil TG, Simon RI. Attorneys’ pressures on the expert witness: early warning signs of endangered honesty, objectivity, and fair compensation. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 1999;27(4):546-553; discussion 554-562.

38. Gold LH, Anfang SA, Drukteinis AM, et al. AAPL practice guideline for the forensic evaluation of psychiatric disability. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2008;36(suppl 4):S3-S50.

39. Knoll JL IV, Resnick PJ. Deposition dos and don’ts: how to answer 8 tricky questions. Current Psychiatry. 2008;7(3):25-28,36,39-40.

40. Hoge MA, Tebes JK, Davidson L, et al. The roles of behavioral health professionals in class action litigation. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2002;30(1):49-58; discussion 59-64.

41. Simon RI, Shuman DW. Conducting forensic examinations on the road: are you practicing your profession without a license? Licensure requirements for out-of-state forensic examinations. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2001;29(1):75-82.

42. Reid WH. Licensure requirements for out-of-state forensic examinations. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2000;28(4):433-437.

43. Collins B, ed. When in doubt, tell the truth: and other quotations from Mark Twain. New York, NY: Columbia University Press; 1997.

Dear Dr. Mossman,

I am retired, but an attorney friend of mine has asked me to help out by performing forensic evaluations. I’m tempted to try it because the work sounds meaningful and interesting. I won’t have a doctor–patient relationship with the attorney’s clients, and I expect the work will take <10 hours a week. Do I need malpractice coverage? Should I consider any other medicolegal issues before I start?

Submitted by “Dr. B”

One of the great things about being a psychiatrist is the variety of available practice options. Like Dr. B, many psychiatrists contemplate using their clinical know-how to perform forensic evaluations. For some psychiatrists, part-time work as an expert witness may provide an appealing change of pace from their other clinical duties1 and a way to supplement their income.2

But as would be true for other kinds of medical practice, Dr. B is wise to consider the possible risks before jumping into forensic work. To help Dr. B decide about getting insurance coverage, we will:

- explain briefly the subspecialty of forensic psychiatry

- review the theory of malpractice and negligence torts

- discuss whether forensic evaluations can create doctor–patient relationships

- explore the availability and limitations of immunity for forensic work

- describe other types of liability with forensic work

- summarize steps to avoid liability.

Introduction to forensic psychiatry

Some psychiatrists—and many people who are not psychiatrists—have a vague or incorrect understanding of forensic psychiatry. Put succinctly, “Forensic Psychiatry is a subspecialty of psychiatry in which scientific and clinical expertise is applied in legal contexts….”3 To practice forensic psychiatry well, a psychiatrist must have some understanding of the law and how to apply and translate clinical concepts to fit legal criteria.4 Psychiatrists who offer to serve as expert witnesses should be familiar with how the courtroom functions, the nuances of how expert testimony is used, and possible sources of bias.4,5

Forensic work can create role conflicts. For most types of forensic assessments, psychiatrists should not provide forensic opinions or testimony about their own patients.3 Even psychiatrists who only work as expert witnesses must balance duties of assisting the trier of fact, fulfilling the consultation role to the retaining party, upholding the standards and ethics of the profession, and striving to provide truthful, objective testimony.2

Special training usually is required

The most important qualification for being a good psychiatric expert witness is being a good psychiatrist, and courts do not require psychiatrists to have specialty training in forensic psychiatry to perform forensic psychiatric evaluations. Yet, the field of forensic psychiatry has developed over the past 50 years to the point that psychiatrists need special training to properly perform many, if not most, types of forensic evaluations.6 Much of forensic psychiatry involves writing specialized reports for lawyers and the court,7 and experts are supposed to meet professional standards, regardless of their training.8-10 Psychiatrists who perform forensic work are obligated to claim expertise only in areas where their knowledge, skills, training, and experience justify such claims. These considerations explain why, since 1999, the American Board of Psychiatry and Neurology has limited eligibility for board certification in forensic psychiatry to psychiatrists who have completed accredited forensic fellowships.11

Malpractice: A short review

To address Dr. B’s question about malpractice coverage, we first review what malpractice is.

“Tort” is a legal term for injury, and tort claims arise when one party harms another and the harmed party seeks money as compensation.9 In a tort claim alleging negligence, the plaintiff (ie, the person bringing the suit) asserts that the defendant had a legally recognized duty, that the defendant breached that duty, and that breach of duty harmed the plaintiff.8

Physicians have a legal duty to “possess the requisite knowledge and skill such as is possessed by the average member of the medical profession; … exercise ordinary and reasonable care in the application of such knowledge and skill; and … use best judgment in such application.”10 A medical malpractice lawsuit asserts that a doctor breached this duty and caused injury in the course of the medical practice.

Malpractice in forensic cases

Practicing medicine typically occurs within the context of treatment relationships. One might think, as Dr. B did, that because forensic evaluations do not involve treating patients, they do not create the kind of doctor–patient relationship that could lead to malpractice liability. This is incorrect, however, for several reasons.

Certain well-intended actions during a forensic evaluation, such as explaining the implications of a diagnosis, giving specific advice about a medication, or making a recommendation about where or how to obtain treatment, may create a doctor–patient relationship.12,13 Many states’ laws on what constitutes the practice of medicine include performing examinations, diagnosing, or referring to oneself as “Dr.” or as a medical practitioner.14-17 State courts have interpreted these laws to further define what constitutes medical practice and the creation of a doctor–patient relationship during a forensic examination.18,19 Some legal scholars20 and the American Medical Association (AMA)9 regard provision of expert testimony as practicing medicine because such testimony requires the application of medical science and rendering of diagnoses.

Immunity and shifts away from it

For many years, courts granted civil immunity to expert witnesses for several policy reasons.8,9,13,20-22 Courts recognized that losing parties might want to blame whomever they could, and immunity could provide legal protection for expert witnesses. Without such protection, witnesses might feel more pressured to give testimony favorable to their side at the loss of objectivity,23,24 or experts might be discouraged from testifying at all. This would be true especially for academic psychiatrists who testify infrequently or for retired doctors, such as Dr. B, who might not want to carry insurance for just one case.21 According to this argument, rather than using the threat of litigation to keep out improper testimony, courts should rely on both admissibility standards25,26 and the adversarial nature of proceedings.21

Those who oppose granting immunity to experts argue that admissibility rules and cross-examination do too little to prevent bad testimony; the threat of liability, however, motivates experts to be more cautious and scientifically rigorous in their approach.21 Opponents also have argued that the threat of liability might reduce improper testimony, which they believe was partly responsible for rising malpractice premiums.20

Courts vary in how they consider granting immunity and to what extent. For example:

- Some courts will not grant immunity to so-called “friendly experts,” while others have limited immunity for adversarial experts.20-22

- Some courts have applied immunity to general fact witnesses but not to professional experts.21,24,27

- When immunity is considered, it is usually regarding actual testimony. Yet, some courts have included pretrial services.21,28-30

- Some courts have considered the testimonial issue at hand when deciding whether to extend immunity. For example, immunity may not apply if the issue is loss of profits21,31 or if an experiment is conducted to demonstrate the extent of a physical injury.21,32

If you plan to serve as an expert witness, find out what, if any, immunity is available in the jurisdiction where you expect to testify. If you do not have immunity, you may be subject to various malpractice claims, including alleged physical or emotional harm resulting from the evaluation1 (perhaps caused by misuse of empathic statements33), an accusation of negligent misdiagnosis of an evaluee,8 or failing to act upon a duty to warn or protect that arises during an assessment.34

Other liability

Dr. B also asked about medicolegal issues other than malpractice. Although negligence is the claim that forensic psychiatrists most commonly encounter,10 other types of claims arise in practice-related legal actions. Potential causes of action include failure to obtain or attempt to obtain informed consent, breach of confidentiality, or not responding to a psychiatric emergency during evaluation. The plaintiff usually must show that the expert’s conduct was the cause-in-fact of injury.8

Besides civil lawsuits, forensic work may generate complaints to state medical boards.10 Occasionally, state medical boards have revoked psychiatrists’ licenses for improper testimony.20 Aggrieved parties may allege violations of the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996, such as mishandling protected health information. Psychiatrists also may face sanction by professional societies—for example, censure by the American Psychiatric Association9,10 or the AMA13 for ethics violations—if their improper testimony is considered unprofessional conduct. The theory behind this is that judges and jurors cannot be technical experts in every field, so the field must have a mechanism to police itself.20,35,36 Finally, forensic experts can face criminal charges for perjury if they lie under oath.8

How to protect yourself

Even when legal claims against psychiatrists turn out to be baseless, legal costs of defending oneself can mount quickly. Knowing this, Dr. B may conclude that obtaining malpractice insurance would be wise. But a malpractice policy alone may not meet all Dr. B’s needs, because some policies do not cover ordinary negligence or other potential causes of legal action against a psychiatrist.13 Some companies offer these extra types of coverage for work as an expert witness at no additional cost, and some offer access to risk management services with specialized knowledge about forensic psychiatric practice.

Dear Dr. Mossman,

I am retired, but an attorney friend of mine has asked me to help out by performing forensic evaluations. I’m tempted to try it because the work sounds meaningful and interesting. I won’t have a doctor–patient relationship with the attorney’s clients, and I expect the work will take <10 hours a week. Do I need malpractice coverage? Should I consider any other medicolegal issues before I start?

Submitted by “Dr. B”

One of the great things about being a psychiatrist is the variety of available practice options. Like Dr. B, many psychiatrists contemplate using their clinical know-how to perform forensic evaluations. For some psychiatrists, part-time work as an expert witness may provide an appealing change of pace from their other clinical duties1 and a way to supplement their income.2

But as would be true for other kinds of medical practice, Dr. B is wise to consider the possible risks before jumping into forensic work. To help Dr. B decide about getting insurance coverage, we will:

- explain briefly the subspecialty of forensic psychiatry

- review the theory of malpractice and negligence torts

- discuss whether forensic evaluations can create doctor–patient relationships

- explore the availability and limitations of immunity for forensic work

- describe other types of liability with forensic work

- summarize steps to avoid liability.

Introduction to forensic psychiatry

Some psychiatrists—and many people who are not psychiatrists—have a vague or incorrect understanding of forensic psychiatry. Put succinctly, “Forensic Psychiatry is a subspecialty of psychiatry in which scientific and clinical expertise is applied in legal contexts….”3 To practice forensic psychiatry well, a psychiatrist must have some understanding of the law and how to apply and translate clinical concepts to fit legal criteria.4 Psychiatrists who offer to serve as expert witnesses should be familiar with how the courtroom functions, the nuances of how expert testimony is used, and possible sources of bias.4,5

Forensic work can create role conflicts. For most types of forensic assessments, psychiatrists should not provide forensic opinions or testimony about their own patients.3 Even psychiatrists who only work as expert witnesses must balance duties of assisting the trier of fact, fulfilling the consultation role to the retaining party, upholding the standards and ethics of the profession, and striving to provide truthful, objective testimony.2

Special training usually is required

The most important qualification for being a good psychiatric expert witness is being a good psychiatrist, and courts do not require psychiatrists to have specialty training in forensic psychiatry to perform forensic psychiatric evaluations. Yet, the field of forensic psychiatry has developed over the past 50 years to the point that psychiatrists need special training to properly perform many, if not most, types of forensic evaluations.6 Much of forensic psychiatry involves writing specialized reports for lawyers and the court,7 and experts are supposed to meet professional standards, regardless of their training.8-10 Psychiatrists who perform forensic work are obligated to claim expertise only in areas where their knowledge, skills, training, and experience justify such claims. These considerations explain why, since 1999, the American Board of Psychiatry and Neurology has limited eligibility for board certification in forensic psychiatry to psychiatrists who have completed accredited forensic fellowships.11

Malpractice: A short review

To address Dr. B’s question about malpractice coverage, we first review what malpractice is.

“Tort” is a legal term for injury, and tort claims arise when one party harms another and the harmed party seeks money as compensation.9 In a tort claim alleging negligence, the plaintiff (ie, the person bringing the suit) asserts that the defendant had a legally recognized duty, that the defendant breached that duty, and that breach of duty harmed the plaintiff.8

Physicians have a legal duty to “possess the requisite knowledge and skill such as is possessed by the average member of the medical profession; … exercise ordinary and reasonable care in the application of such knowledge and skill; and … use best judgment in such application.”10 A medical malpractice lawsuit asserts that a doctor breached this duty and caused injury in the course of the medical practice.

Malpractice in forensic cases

Practicing medicine typically occurs within the context of treatment relationships. One might think, as Dr. B did, that because forensic evaluations do not involve treating patients, they do not create the kind of doctor–patient relationship that could lead to malpractice liability. This is incorrect, however, for several reasons.

Certain well-intended actions during a forensic evaluation, such as explaining the implications of a diagnosis, giving specific advice about a medication, or making a recommendation about where or how to obtain treatment, may create a doctor–patient relationship.12,13 Many states’ laws on what constitutes the practice of medicine include performing examinations, diagnosing, or referring to oneself as “Dr.” or as a medical practitioner.14-17 State courts have interpreted these laws to further define what constitutes medical practice and the creation of a doctor–patient relationship during a forensic examination.18,19 Some legal scholars20 and the American Medical Association (AMA)9 regard provision of expert testimony as practicing medicine because such testimony requires the application of medical science and rendering of diagnoses.

Immunity and shifts away from it

For many years, courts granted civil immunity to expert witnesses for several policy reasons.8,9,13,20-22 Courts recognized that losing parties might want to blame whomever they could, and immunity could provide legal protection for expert witnesses. Without such protection, witnesses might feel more pressured to give testimony favorable to their side at the loss of objectivity,23,24 or experts might be discouraged from testifying at all. This would be true especially for academic psychiatrists who testify infrequently or for retired doctors, such as Dr. B, who might not want to carry insurance for just one case.21 According to this argument, rather than using the threat of litigation to keep out improper testimony, courts should rely on both admissibility standards25,26 and the adversarial nature of proceedings.21

Those who oppose granting immunity to experts argue that admissibility rules and cross-examination do too little to prevent bad testimony; the threat of liability, however, motivates experts to be more cautious and scientifically rigorous in their approach.21 Opponents also have argued that the threat of liability might reduce improper testimony, which they believe was partly responsible for rising malpractice premiums.20

Courts vary in how they consider granting immunity and to what extent. For example:

- Some courts will not grant immunity to so-called “friendly experts,” while others have limited immunity for adversarial experts.20-22

- Some courts have applied immunity to general fact witnesses but not to professional experts.21,24,27

- When immunity is considered, it is usually regarding actual testimony. Yet, some courts have included pretrial services.21,28-30

- Some courts have considered the testimonial issue at hand when deciding whether to extend immunity. For example, immunity may not apply if the issue is loss of profits21,31 or if an experiment is conducted to demonstrate the extent of a physical injury.21,32

If you plan to serve as an expert witness, find out what, if any, immunity is available in the jurisdiction where you expect to testify. If you do not have immunity, you may be subject to various malpractice claims, including alleged physical or emotional harm resulting from the evaluation1 (perhaps caused by misuse of empathic statements33), an accusation of negligent misdiagnosis of an evaluee,8 or failing to act upon a duty to warn or protect that arises during an assessment.34

Other liability

Dr. B also asked about medicolegal issues other than malpractice. Although negligence is the claim that forensic psychiatrists most commonly encounter,10 other types of claims arise in practice-related legal actions. Potential causes of action include failure to obtain or attempt to obtain informed consent, breach of confidentiality, or not responding to a psychiatric emergency during evaluation. The plaintiff usually must show that the expert’s conduct was the cause-in-fact of injury.8

Besides civil lawsuits, forensic work may generate complaints to state medical boards.10 Occasionally, state medical boards have revoked psychiatrists’ licenses for improper testimony.20 Aggrieved parties may allege violations of the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996, such as mishandling protected health information. Psychiatrists also may face sanction by professional societies—for example, censure by the American Psychiatric Association9,10 or the AMA13 for ethics violations—if their improper testimony is considered unprofessional conduct. The theory behind this is that judges and jurors cannot be technical experts in every field, so the field must have a mechanism to police itself.20,35,36 Finally, forensic experts can face criminal charges for perjury if they lie under oath.8

How to protect yourself

Even when legal claims against psychiatrists turn out to be baseless, legal costs of defending oneself can mount quickly. Knowing this, Dr. B may conclude that obtaining malpractice insurance would be wise. But a malpractice policy alone may not meet all Dr. B’s needs, because some policies do not cover ordinary negligence or other potential causes of legal action against a psychiatrist.13 Some companies offer these extra types of coverage for work as an expert witness at no additional cost, and some offer access to risk management services with specialized knowledge about forensic psychiatric practice.

1. Appelbaum PS. Law and psychiatry: liability for forensic evaluations: a word of caution. Psychiatr Serv. 2001;52(7):885-886.

2. Shuman DW, Greenberg SA. The expert witness, the adversary system, and the voice of reason: reconciling impartiality and advocacy. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice. 2003;34(3):219-224.

3. American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law. Ethics guidelines for the practice of forensic psychiatry. http://www.aapl.org/ethics.htm. Published May 2005. Accessed July 11, 2017.

4. Gutheil TG. Forensic psychiatry as a specialty. Psychiatric Times. http://www.psychiatrictimes.com/articles/forensic-psychiatry-sp

5. Knoll J, Gerbasi J. Psychiatric malpractice case analysis: striving for objectivity. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2006;34(2):215-223.

6. Sadoff RL. The practice of forensic psychiatry: perils, problems, and pitfalls. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 1998;26(2):305-314.

7. Simon RI. Authorship in forensic psychiatry: a perspective. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2007;35(1):18-26.

8. Masterson LR. Witness immunity or malpractice liability for professionals hired as experts? Rev Litig. 1998;17(2):393-418.

9. Binder RL. Liability for the psychiatrist expert witness. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159(11):1819-1825.

10. Gold LH, Davidson JE. Do you understand your risk? Liability and third-party evaluations in civil litigation. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2007;35(2):200-210.

11. American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law. ABPN certification in the subspecialty of forensic psychiatry. http://www.aapl.org/abpn-certification. Accessed July 9, 2017.

12. Marett CP, Mossman D. What are your responsibilities after a screening call? Current Psychiatry. 2014;13(9):54-57.

13. Weinstock R, Garrick T. Is liability possible for forensic psychiatrists? Bull Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 1995;23(2):183-193.

14. Ohio Revised Code §4731.34.

15. Kentucky Revised Statutes §311.550(10) (2017).

16. California Business & Professions Code §2052.5 (through 2012 Leg Sess).

17. Oregon Revised Statutes §677.085 (2013).

18. Blake V. When is a patient-physician relationship established? Virtual Mentor. 2012;14(5):403-406.

19. Zettler PJ. Toward coherent federal oversight of medicine. San Diego Law Review. 2015;52:427-500.

20. Turner JA. Going after the ‘hired guns’: is improper expert witness testimony unprofessional conduct or the negligent practice of medicine? Spec Law Dig Health Care Law. 2006;328:9-43.

21. Weiss LS, Orrick H. Expert witness malpractice actions: emerging trend or aberration? Practical Litigator. 2004;15(2):27-38.

22. McAbee GN. Improper expert medical testimony. Existing and proposed mechanisms of oversight. J Leg Med. 1998;19(2):257-272.

23. Panitz v Behrend, 632 A 2d 562 (Pa Super Ct 1993).

24. Murphy v A.A. Mathews, 841 S.W. 2d 671 (Mo 1992).

25. Daubert v Merrell Dow Pharmaceuticals, 509 U.S. 579 (1993).

26. Rule 702. Testimony by expert witnesses. In: Michigan Legal Publishing Ltd. Federal Rules of evidence. Grand Rapids, MI: Michigan Legal Publishing Ltd; 2017:21.

27. Committee on Medical Liability and Risk Management. Policy statement—expert witness participation in civil and criminal proceedings. Pediatrics. 2009;124(1):428-438.

28. Mattco Forge, Inc., v Arthur Young & Co., 6 Cal Rptr 2d 781 (Cal Ct App 1992).

29. Marrogi v Howard, 248 F 3d 382 (5th Cir 2001).

30. Boyes-Bogie v Horvitz, 2001 WL 1771989 (Mass Super 2001).

31. LLMD of Michigan, Inc., v Jackson-Cross Co., 740 A. 2d 186 (Pa 1999).

32. Pollock v Panjabi, 781 A 2d 518 (Conn Super Ct 2000).

33. Brodsky SL, Wilson JK. Empathy in forensic evaluations: a systematic reconsideration. Behav Sci Law. 2013;31(2):192-202.

34. Heilbrun K, DeMatteo D, Marczyk G, et al. Standards of practice and care in forensic mental health assessment: legal, professional, and principles-based consideration. Psych Pub Pol L. 2008;14(1):1-26.

35. Appelbaum PS. Law & psychiatry: policing expert testimony: the role of professional organizations. Psychiatr Serv. 2002;53(4):389-390,399.

36. Austin v American Association of Neurological Surgeons, 253 F 3d 967 (7th Cir 2001).

37. Gutheil TG, Simon RI. Attorneys’ pressures on the expert witness: early warning signs of endangered honesty, objectivity, and fair compensation. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 1999;27(4):546-553; discussion 554-562.

38. Gold LH, Anfang SA, Drukteinis AM, et al. AAPL practice guideline for the forensic evaluation of psychiatric disability. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2008;36(suppl 4):S3-S50.

39. Knoll JL IV, Resnick PJ. Deposition dos and don’ts: how to answer 8 tricky questions. Current Psychiatry. 2008;7(3):25-28,36,39-40.

40. Hoge MA, Tebes JK, Davidson L, et al. The roles of behavioral health professionals in class action litigation. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2002;30(1):49-58; discussion 59-64.

41. Simon RI, Shuman DW. Conducting forensic examinations on the road: are you practicing your profession without a license? Licensure requirements for out-of-state forensic examinations. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2001;29(1):75-82.

42. Reid WH. Licensure requirements for out-of-state forensic examinations. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2000;28(4):433-437.

43. Collins B, ed. When in doubt, tell the truth: and other quotations from Mark Twain. New York, NY: Columbia University Press; 1997.

1. Appelbaum PS. Law and psychiatry: liability for forensic evaluations: a word of caution. Psychiatr Serv. 2001;52(7):885-886.

2. Shuman DW, Greenberg SA. The expert witness, the adversary system, and the voice of reason: reconciling impartiality and advocacy. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice. 2003;34(3):219-224.

3. American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law. Ethics guidelines for the practice of forensic psychiatry. http://www.aapl.org/ethics.htm. Published May 2005. Accessed July 11, 2017.

4. Gutheil TG. Forensic psychiatry as a specialty. Psychiatric Times. http://www.psychiatrictimes.com/articles/forensic-psychiatry-sp

5. Knoll J, Gerbasi J. Psychiatric malpractice case analysis: striving for objectivity. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2006;34(2):215-223.

6. Sadoff RL. The practice of forensic psychiatry: perils, problems, and pitfalls. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 1998;26(2):305-314.

7. Simon RI. Authorship in forensic psychiatry: a perspective. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2007;35(1):18-26.

8. Masterson LR. Witness immunity or malpractice liability for professionals hired as experts? Rev Litig. 1998;17(2):393-418.

9. Binder RL. Liability for the psychiatrist expert witness. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159(11):1819-1825.

10. Gold LH, Davidson JE. Do you understand your risk? Liability and third-party evaluations in civil litigation. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2007;35(2):200-210.

11. American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law. ABPN certification in the subspecialty of forensic psychiatry. http://www.aapl.org/abpn-certification. Accessed July 9, 2017.

12. Marett CP, Mossman D. What are your responsibilities after a screening call? Current Psychiatry. 2014;13(9):54-57.

13. Weinstock R, Garrick T. Is liability possible for forensic psychiatrists? Bull Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 1995;23(2):183-193.

14. Ohio Revised Code §4731.34.

15. Kentucky Revised Statutes §311.550(10) (2017).

16. California Business & Professions Code §2052.5 (through 2012 Leg Sess).

17. Oregon Revised Statutes §677.085 (2013).

18. Blake V. When is a patient-physician relationship established? Virtual Mentor. 2012;14(5):403-406.

19. Zettler PJ. Toward coherent federal oversight of medicine. San Diego Law Review. 2015;52:427-500.

20. Turner JA. Going after the ‘hired guns’: is improper expert witness testimony unprofessional conduct or the negligent practice of medicine? Spec Law Dig Health Care Law. 2006;328:9-43.

21. Weiss LS, Orrick H. Expert witness malpractice actions: emerging trend or aberration? Practical Litigator. 2004;15(2):27-38.

22. McAbee GN. Improper expert medical testimony. Existing and proposed mechanisms of oversight. J Leg Med. 1998;19(2):257-272.

23. Panitz v Behrend, 632 A 2d 562 (Pa Super Ct 1993).

24. Murphy v A.A. Mathews, 841 S.W. 2d 671 (Mo 1992).

25. Daubert v Merrell Dow Pharmaceuticals, 509 U.S. 579 (1993).

26. Rule 702. Testimony by expert witnesses. In: Michigan Legal Publishing Ltd. Federal Rules of evidence. Grand Rapids, MI: Michigan Legal Publishing Ltd; 2017:21.

27. Committee on Medical Liability and Risk Management. Policy statement—expert witness participation in civil and criminal proceedings. Pediatrics. 2009;124(1):428-438.

28. Mattco Forge, Inc., v Arthur Young & Co., 6 Cal Rptr 2d 781 (Cal Ct App 1992).

29. Marrogi v Howard, 248 F 3d 382 (5th Cir 2001).

30. Boyes-Bogie v Horvitz, 2001 WL 1771989 (Mass Super 2001).

31. LLMD of Michigan, Inc., v Jackson-Cross Co., 740 A. 2d 186 (Pa 1999).

32. Pollock v Panjabi, 781 A 2d 518 (Conn Super Ct 2000).

33. Brodsky SL, Wilson JK. Empathy in forensic evaluations: a systematic reconsideration. Behav Sci Law. 2013;31(2):192-202.

34. Heilbrun K, DeMatteo D, Marczyk G, et al. Standards of practice and care in forensic mental health assessment: legal, professional, and principles-based consideration. Psych Pub Pol L. 2008;14(1):1-26.

35. Appelbaum PS. Law & psychiatry: policing expert testimony: the role of professional organizations. Psychiatr Serv. 2002;53(4):389-390,399.

36. Austin v American Association of Neurological Surgeons, 253 F 3d 967 (7th Cir 2001).

37. Gutheil TG, Simon RI. Attorneys’ pressures on the expert witness: early warning signs of endangered honesty, objectivity, and fair compensation. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 1999;27(4):546-553; discussion 554-562.

38. Gold LH, Anfang SA, Drukteinis AM, et al. AAPL practice guideline for the forensic evaluation of psychiatric disability. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2008;36(suppl 4):S3-S50.

39. Knoll JL IV, Resnick PJ. Deposition dos and don’ts: how to answer 8 tricky questions. Current Psychiatry. 2008;7(3):25-28,36,39-40.

40. Hoge MA, Tebes JK, Davidson L, et al. The roles of behavioral health professionals in class action litigation. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2002;30(1):49-58; discussion 59-64.

41. Simon RI, Shuman DW. Conducting forensic examinations on the road: are you practicing your profession without a license? Licensure requirements for out-of-state forensic examinations. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2001;29(1):75-82.

42. Reid WH. Licensure requirements for out-of-state forensic examinations. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2000;28(4):433-437.

43. Collins B, ed. When in doubt, tell the truth: and other quotations from Mark Twain. New York, NY: Columbia University Press; 1997.

Suture found in bladder after hysterectomy

Suture found in bladder after hysterectomy

A 40-year-old woman underwent a hysterectomy due to dysmenorrhea. Despite the presence of blood in the catheter bag after the procedure, the surgeon did not consult a urologist or perform a cystoscopy. Later, when the patient reported urinary retention, urinary leakage, and dyspareunia, a urologist performed a cystoscopy and discovered a suture in the bladder wall and a vesicovaginal fistula.

PATIENTS' CLAIM:

During the procedure, the gynecologic surgeon inadvertently placed a suture in the bladder wall. The presence of blood in the Foley catheter required an immediate urology consult and cystoscopy, during which the presence of the errant suture would have been discovered. Repair surgery then would have prevented subsequent injuries.

PHYSICIANS' DEFENSE:

The surgeon used reasonable judgment, as there were explanations for the blood in the catheter due to a difficult catheter placement and lysis of bladder adhesions.

VERDICT:

A Michigan defense verdict was returned.

Related article:

How to avoid intestinal and urinary tract injuries during gynecologic laparoscopy

Bowel injury during tubal ligation

A 40-year-old woman underwent laparoscopic tubal ligation using cauterization at an outpatient surgery center. Two hours after the procedure, her BP began to drop. She was promptly transferred to a hospital and underwent emergency surgery that revealed a bowel injury. Part of the patient’s small intestine was resected.

PATIENTS' CLAIM:

The gynecologic surgeon committed a medical error when she injured the bowel during trocar insertion.

DEFENDANTS' DEFENSE:

The bowel injury was a known complication of the surgery.

VERDICT:

A Louisiana defense verdict was returned.

Related article:

How to avoid major vessel injury during gynecologic laparoscopy

Colon injured twice: $1M settlement

A 59-year-old woman underwent laparoscopic total hysterectomy and salpingectomy. Her history included an umbilical hernia repair.

Two days after surgery, the patient experienced abdominal pain, chills, abdominal distention, and a foul-smelling discharge from her umbilical suture site. She went to the emergency department where a computed tomography scan revealed 2 injuries in the bowel. Emergency laparotomy included transverse colon resection and right colon colostomy with Hartmann’s pouch. She wore an ostomy bag for 8 months. She developed an infection because of the colostomy and also required operations to resolve a bowel obstruction and repair incisional hernias.

PATIENTS' CLAIM:

The gynecologic surgeon was negligent when performing the surgery. When he inserted the Veress needle and trocar through the patient’s umbilicus, the transverse colon was injured twice with a 3-cm anterior tear and a 1-cm posterior laceration. The injuries were not discovered during the procedure. He should have been more careful knowing that she had undergone prior umbilical hernia surgery.

PHYSICIANS' DEFENSE:

The case was settled before the trial began.

VERDICT:

A $1 million Virginia settlement was reached.

Chronic pain after sling procedure: $2M verdict

A 63-year-old woman reported urinary incontinence to her gynecologist, who performed a transobturator midurethral sling procedure. After surgery, the patient experienced pelvic pain, urinary urgency, intermittent incontinence, and dyspareunia. She returned to the gynecologist twice. He performed a cystoscopy after the second visit but found nothing wrong.

The patient sought a second opinion. A gynecologic surgeon found a large mass in the patient’s bladder consisting of a crystallized piece of tape that had been used to secure the sling supporting the bladder. The mass was removed and the patient reported that, although surgery alleviated many symptoms, she was not pain-free.

PATIENTS' CLAIM:

The gynecologist negligently inserted the end of the sling through one wall of her bladder and failed to detect the malpositioning during surgery or later. He failed to diagnose and treat bladder stones that resulted from the sling’s malpositioning. He failed to perform a cystoscopy when she first reported symptoms and improperly performed cystoscopy at the second visit.

DEFENDANTS' DEFENSE:

There was no negligence on the part of the gynecologist. The patient did not report ongoing symptoms until 1 year after sling insertion.

VERDICT:

A $2 million Pennsylvania verdict was returned.

These cases were selected by the editors of OBG Management from Medical Malpractice Verdicts, Settlements & Experts, with permission of the editor, Lewis Laska (www.verdictslaska.com). The information available to the editors about the cases presented here is sometimes incomplete. Moreover, the cases may or may not have merit. Nevertheless, these cases represent the types of clinical situations that typically result in litigation and are meant to illustrate nationwide variation in jury verdicts and awards.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Suture found in bladder after hysterectomy

A 40-year-old woman underwent a hysterectomy due to dysmenorrhea. Despite the presence of blood in the catheter bag after the procedure, the surgeon did not consult a urologist or perform a cystoscopy. Later, when the patient reported urinary retention, urinary leakage, and dyspareunia, a urologist performed a cystoscopy and discovered a suture in the bladder wall and a vesicovaginal fistula.

PATIENTS' CLAIM:

During the procedure, the gynecologic surgeon inadvertently placed a suture in the bladder wall. The presence of blood in the Foley catheter required an immediate urology consult and cystoscopy, during which the presence of the errant suture would have been discovered. Repair surgery then would have prevented subsequent injuries.

PHYSICIANS' DEFENSE:

The surgeon used reasonable judgment, as there were explanations for the blood in the catheter due to a difficult catheter placement and lysis of bladder adhesions.

VERDICT:

A Michigan defense verdict was returned.

Related article:

How to avoid intestinal and urinary tract injuries during gynecologic laparoscopy

Bowel injury during tubal ligation

A 40-year-old woman underwent laparoscopic tubal ligation using cauterization at an outpatient surgery center. Two hours after the procedure, her BP began to drop. She was promptly transferred to a hospital and underwent emergency surgery that revealed a bowel injury. Part of the patient’s small intestine was resected.

PATIENTS' CLAIM:

The gynecologic surgeon committed a medical error when she injured the bowel during trocar insertion.

DEFENDANTS' DEFENSE:

The bowel injury was a known complication of the surgery.

VERDICT:

A Louisiana defense verdict was returned.

Related article:

How to avoid major vessel injury during gynecologic laparoscopy

Colon injured twice: $1M settlement

A 59-year-old woman underwent laparoscopic total hysterectomy and salpingectomy. Her history included an umbilical hernia repair.

Two days after surgery, the patient experienced abdominal pain, chills, abdominal distention, and a foul-smelling discharge from her umbilical suture site. She went to the emergency department where a computed tomography scan revealed 2 injuries in the bowel. Emergency laparotomy included transverse colon resection and right colon colostomy with Hartmann’s pouch. She wore an ostomy bag for 8 months. She developed an infection because of the colostomy and also required operations to resolve a bowel obstruction and repair incisional hernias.

PATIENTS' CLAIM:

The gynecologic surgeon was negligent when performing the surgery. When he inserted the Veress needle and trocar through the patient’s umbilicus, the transverse colon was injured twice with a 3-cm anterior tear and a 1-cm posterior laceration. The injuries were not discovered during the procedure. He should have been more careful knowing that she had undergone prior umbilical hernia surgery.

PHYSICIANS' DEFENSE:

The case was settled before the trial began.

VERDICT:

A $1 million Virginia settlement was reached.

Chronic pain after sling procedure: $2M verdict

A 63-year-old woman reported urinary incontinence to her gynecologist, who performed a transobturator midurethral sling procedure. After surgery, the patient experienced pelvic pain, urinary urgency, intermittent incontinence, and dyspareunia. She returned to the gynecologist twice. He performed a cystoscopy after the second visit but found nothing wrong.

The patient sought a second opinion. A gynecologic surgeon found a large mass in the patient’s bladder consisting of a crystallized piece of tape that had been used to secure the sling supporting the bladder. The mass was removed and the patient reported that, although surgery alleviated many symptoms, she was not pain-free.

PATIENTS' CLAIM:

The gynecologist negligently inserted the end of the sling through one wall of her bladder and failed to detect the malpositioning during surgery or later. He failed to diagnose and treat bladder stones that resulted from the sling’s malpositioning. He failed to perform a cystoscopy when she first reported symptoms and improperly performed cystoscopy at the second visit.

DEFENDANTS' DEFENSE:

There was no negligence on the part of the gynecologist. The patient did not report ongoing symptoms until 1 year after sling insertion.

VERDICT:

A $2 million Pennsylvania verdict was returned.

These cases were selected by the editors of OBG Management from Medical Malpractice Verdicts, Settlements & Experts, with permission of the editor, Lewis Laska (www.verdictslaska.com). The information available to the editors about the cases presented here is sometimes incomplete. Moreover, the cases may or may not have merit. Nevertheless, these cases represent the types of clinical situations that typically result in litigation and are meant to illustrate nationwide variation in jury verdicts and awards.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Suture found in bladder after hysterectomy

A 40-year-old woman underwent a hysterectomy due to dysmenorrhea. Despite the presence of blood in the catheter bag after the procedure, the surgeon did not consult a urologist or perform a cystoscopy. Later, when the patient reported urinary retention, urinary leakage, and dyspareunia, a urologist performed a cystoscopy and discovered a suture in the bladder wall and a vesicovaginal fistula.

PATIENTS' CLAIM:

During the procedure, the gynecologic surgeon inadvertently placed a suture in the bladder wall. The presence of blood in the Foley catheter required an immediate urology consult and cystoscopy, during which the presence of the errant suture would have been discovered. Repair surgery then would have prevented subsequent injuries.

PHYSICIANS' DEFENSE:

The surgeon used reasonable judgment, as there were explanations for the blood in the catheter due to a difficult catheter placement and lysis of bladder adhesions.

VERDICT:

A Michigan defense verdict was returned.

Related article:

How to avoid intestinal and urinary tract injuries during gynecologic laparoscopy

Bowel injury during tubal ligation

A 40-year-old woman underwent laparoscopic tubal ligation using cauterization at an outpatient surgery center. Two hours after the procedure, her BP began to drop. She was promptly transferred to a hospital and underwent emergency surgery that revealed a bowel injury. Part of the patient’s small intestine was resected.

PATIENTS' CLAIM:

The gynecologic surgeon committed a medical error when she injured the bowel during trocar insertion.

DEFENDANTS' DEFENSE:

The bowel injury was a known complication of the surgery.

VERDICT:

A Louisiana defense verdict was returned.

Related article:

How to avoid major vessel injury during gynecologic laparoscopy

Colon injured twice: $1M settlement

A 59-year-old woman underwent laparoscopic total hysterectomy and salpingectomy. Her history included an umbilical hernia repair.

Two days after surgery, the patient experienced abdominal pain, chills, abdominal distention, and a foul-smelling discharge from her umbilical suture site. She went to the emergency department where a computed tomography scan revealed 2 injuries in the bowel. Emergency laparotomy included transverse colon resection and right colon colostomy with Hartmann’s pouch. She wore an ostomy bag for 8 months. She developed an infection because of the colostomy and also required operations to resolve a bowel obstruction and repair incisional hernias.

PATIENTS' CLAIM:

The gynecologic surgeon was negligent when performing the surgery. When he inserted the Veress needle and trocar through the patient’s umbilicus, the transverse colon was injured twice with a 3-cm anterior tear and a 1-cm posterior laceration. The injuries were not discovered during the procedure. He should have been more careful knowing that she had undergone prior umbilical hernia surgery.

PHYSICIANS' DEFENSE:

The case was settled before the trial began.

VERDICT:

A $1 million Virginia settlement was reached.

Chronic pain after sling procedure: $2M verdict

A 63-year-old woman reported urinary incontinence to her gynecologist, who performed a transobturator midurethral sling procedure. After surgery, the patient experienced pelvic pain, urinary urgency, intermittent incontinence, and dyspareunia. She returned to the gynecologist twice. He performed a cystoscopy after the second visit but found nothing wrong.

The patient sought a second opinion. A gynecologic surgeon found a large mass in the patient’s bladder consisting of a crystallized piece of tape that had been used to secure the sling supporting the bladder. The mass was removed and the patient reported that, although surgery alleviated many symptoms, she was not pain-free.

PATIENTS' CLAIM:

The gynecologist negligently inserted the end of the sling through one wall of her bladder and failed to detect the malpositioning during surgery or later. He failed to diagnose and treat bladder stones that resulted from the sling’s malpositioning. He failed to perform a cystoscopy when she first reported symptoms and improperly performed cystoscopy at the second visit.

DEFENDANTS' DEFENSE:

There was no negligence on the part of the gynecologist. The patient did not report ongoing symptoms until 1 year after sling insertion.

VERDICT:

A $2 million Pennsylvania verdict was returned.

These cases were selected by the editors of OBG Management from Medical Malpractice Verdicts, Settlements & Experts, with permission of the editor, Lewis Laska (www.verdictslaska.com). The information available to the editors about the cases presented here is sometimes incomplete. Moreover, the cases may or may not have merit. Nevertheless, these cases represent the types of clinical situations that typically result in litigation and are meant to illustrate nationwide variation in jury verdicts and awards.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Premature birth after preeclampsia: $23.1M verdict

Premature birth after preeclampsia: $23.1M verdict

When a woman saw her ObGyn on August 16 at 24 weeks’ gestation, test results showed proteinuria and high blood pressure (BP). The following day, she was hospitalized for a 24-hour urine test and BP evaluation supervised by an on-call ObGyn and her ObGyn. Test results confirmed preeclampsia. She was released from the hospital. A few days later, she was found to have continued high BP and increased proteinuria, and restricted fetal growth was detected. On August 29 at 26 weeks’ gestation, the baby girl was born with severe cystic periventricular leukomalacia by emergency cesarean delivery. She cannot perform basic tasks and will need 24-hour care for the rest of her life.

PARENTS' CLAIM:

The hospital staff and 2 ObGyns failed to timely diagnose and treat preeclampsia. The treating ObGyn neither prescribed medication to treat preeclampsia nor administered antenatal corticosteroids to enhance fetal lung and brain development, both of which should have been started on August 17. Hospital health care providers failed to transfer her to a Level III facility equipped to handle a premature birth of less than 33 weeks’ gestation.

DEFENDANTS' DEFENSE:

The hospital and ObGyn denied negligence.

VERDICT:

Prior to trial, the mother settled with the on-call ObGyn for an undisclosed amount. A $23.15 million Florida verdict was returned, apportioning 70% liability to the treating ObGyn and 30% to the hospital.

Related article:

For the management of labor, patience is a virtue

Shoulder dystocia, paralysis: $950,000 settlement

During delivery, shoulder dystocia was encountered. The ObGyn used maneuvers to release the shoulder and completed the delivery. The child has a brachial plexus injury. Despite nerve graft surgery, her right arm, shoulder, and hand are paralyzed.

PARENTS' CLAIM:

The ObGyn failed to properly manage the delivery. Shoulder dystocia had been encountered during the delivery of a sibling, but the ObGyn failed to communicate the need for cesarean delivery in future pregnancies.

DEFENDANTS' DEFENSE:

There was no negligence. The case settled during trial.

VERDICT:

A $950,000 California settlement was reached with the hospital and ObGyn.

Related article:

Shoulder dystocia: Taking the fear out of management

Child has brachial plexus injury